The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rats in the Belfry, by John York Cabot This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Rats in the Belfry Author: John York Cabot Release Date: June 19, 2010 [EBook #32900] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RATS IN THE BELFRY *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Amazing Stories January 1943. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

This little guy Stoddard was one of the toughest customers I'd ever done business with. To look at him you'd think he was typical of the mild pleasant little sort of suburban home owner who caught the eight-oh-two six days a week and watered the lawn on the seventh. Physically, his appearance was completely that of the inconspicuous average citizen. Baldish, fortiesh, bespectacled, with the usual behind-the-desk bay window that most office workers get at his age, he looked like nothing more than the amiable citizen you see in comic cartoons on suburban life.

Yet, what I'm getting at is that this Stoddard's appearance was distinctly deceptive. He was the sort of customer that we in the contracting business would label as a combination grouser and eccentric.

When he and his wife came to me with plans for the home they wanted built in Mayfair's second subdivision, they were already full of ideas on exactly what they wanted.

This Stoddard—his name was George B. Stoddard in full—had painstakingly outlined about two dozen sheets of drafting paper with some of the craziest ideas you have ever seen.

"These specifications aren't quite down to the exact inchage, Mr. Kermit," Stoddard had admitted, "for I don't pretend to be a first class architectural draftsman. But my wife and I have had ideas on what sort of a house we want for years, and these plans are the result of our years of decision."

I'd looked at the "plans" a little sickly. The house they'd decided on was a combination of every architectural nightmare known to man. It was the sort of thing a respectable contractor would envision if he ever happened to be dying of malaria fever.

I could feel them watching me as I went over their dream charts. Watching me for the first faint sign of disapproval or amusement or disgust on my face. Watching to snatch the "plans" away from me and walk out of my office if I showed any of those symptoms.

"Ummmhumm," I muttered noncommittally.

"What do you think of them, Kermit?" Stoddard demanded.

I had a hunch that they'd been to contractors other than me. Contractors who'd been tactless enough to offend them into taking their business elsewhere.

"You have something distinctly different in mind here, Mr. Stoddard," I answered evasively.

George B. Stoddard beamed at his wife, then back to me.

"Exactly, sir," he said. "It is our dream castle."

I shuddered at the expression. If you'd mix ice cream with pickles and beer and herring and lie down for a nap, it might result in a dream castle.

"It will be a difficult job, Mr. Stoddard," I said. "This is no ordinary job you've outlined here."

"I know that," said Stoddard proudly. "And I am prepared to pay for the extra special work it will probably require."

That was different. I perked up a little.

"I'll have to turn over these plans to my own draftsman," I told him, "before I can give you an estimate on the construction."

George B. Stoddard turned to his wife.

"I told you, Laura," he said, "that sooner or later we'd find a contractor with brains and imagination."

It took fully two months haggling over the plans with Stoddard and my own draftsmen before we were able to start work on the nightmare my clients called their dream castle. Two months haggling in an effort to make Stoddard relinquish some of his more outlandish ideas on his proposed dwelling. But he didn't budge an inch, and by the time we'd laid the foundation for the dream shack, every last building quirk he'd had originally on those "plans" still held.

I took a lot of ribbing from contractors in that vicinity once the word got round that I was building Stoddard's house for him. It seems that he'd been to them all before he got around to me.

But I didn't mind the ribbing much at first. Even though Stoddard was a barrel full of trouble hanging around the building lot with an eagle eye to see that nothing was omitted, I had already cashed his first few payment checks on the construction.

He'd meant what he said about his willingness to pay more for the extra trouble entailed in the mad construction pattern we had to follow, and I couldn't call him stingy with his extra compensation by a long shot.

Financially, I was doing nicely, thank you. Mentally, I was having the devil's own time with Stoddard.

He didn't know a damned thing about architecture or construction, of course. But he did know what he wanted. Good Lord, how he knew what he wanted!

"The basement boiler layout isn't what I had on my plans!" he'd call me up to squawk indignantly.

"But it isn't greatly different the way we have it," I'd plead. "Besides, it's far safer than what you originally planned."

"Is it humanly possible to put it where I planned it?" my troublesome client would demand.

"Yes," I'd admit. "But saf—"

"Then put it where I planned it!" he would snap, hanging up. And, of course, I'd have to put it where he'd planned it.

The workmen on the job also presented a problem. They were getting fed up with Stoddard's snooping, and going crazy laying out patterns which were in absolute contradiction to sanity and good taste.

But in spite of all this, the monstrosity progressed.

If you can picture a gigantic igloo fronted by southern mansion pillars and dotted with eighteenth century gables, and having each wing done in a combination early Mexican and eastern Mosque style, you'll have just the roughest idea of what it was beginning to look like. For miles around, people were driving out to see that house in the evenings after construction men had left.

But the Stoddards were pleased. They were as happy about the whole mess as a pair of kids erecting a Tarzan dwelling in a tree. And the extra compensations I was getting for the additional trouble wasn't hurting me any.

I'll never forget the day when we completed the tiny belfry which topped off the monstrosity. Yes, a belfry. Just the kind you still see on little country churches and schoolhouses, only, of course a trifle different.

The Stoddards had come out to the lot to witness this momentous event; the completion, practically, of their dream child.

I was almost as happy as they were, for it stood as the symbol of the ending of almost all the grief for me.

My foreman came over to where I was standing with the Stoddards.

"You gonna put a bell in that belfry?" he asked.

George Stoddard looked at him as if he'd gone mad.

"What for?" he demanded.

"So you can use the belfry," the foreman said.

"Don't be so ridiculous, my good man," Stoddard snorted. "It will be of pleasurable use enough to us, just looking at it."

When the foreman had marched off, scratching his head, I turned to the Stoddards.

"Well, it's almost done," I said. "Pleased with it?"

Stoddard beamed. "You have no idea, Mr. Kermit," he said solemnly, "what a tremendous moment this is for my wife and me."

I looked at the plain, drab, smiling Laura Stoddard. From the shine in her eyes, I guess Stoddard meant what he said. Then I looked up at the belfry, and shuddered.

As I remarked before, even the belfry wasn't quite like any belfry human eyes had ever seen before. It angled in all the way around in as confusing a maze of geometrical madness you have ever seen. It was a patterned craziness, of course, having some rhyme to it, but no reason.

Looking at it, serenely topping that crazy-quilt house, I had the impression of its being an outrageously squashed cherry topping, the whipped cream of as madly a concocted sundae that a soda jerk ever made. A pleasant impression.

Stoddard's voice broke in on my somewhat sickish contemplation.

"When will we be able to start moving in?" he asked eagerly.

"The latter part of next week," I told him. "We should have it set by then."

"Good," said Stoddard. "Splendid." He put his arm around his wife, and the two of them stared starry eyed at their home. It made a lump come to your throat, seeing the bliss in their eyes as they stood there together. It made a lump come into your throat, until you realized what they were staring at.

"Incidentally," I said casually, figuring now was as good a time as any to get them used to the idea. "The startlingly different construction pattern you've had us follow will result in, ah, minor repairs in the house being necessary from time to time. Remember my telling you that at the start?"

Stoddard nodded, brushing the information away casually.

"Yes, certainly I remember your saying something about that. But don't worry. I won't hold you responsible for any minor repairs which the unique construction causes."

"Thanks," I told him dryly. "I just wanted to make certain we had that point clear."

The Stoddards moved in just as soon as the last inch of work on their dream monster was finished. I paid off my men, banked a nice profit on the job, and went back to building actual houses again. I thought my troubles with the Stoddards at an end.

But of course I was wrong.

It was fully a month after the Stoddards had been in their madhouse that I got my first indignant telephone call from George B. Stoddard himself.

"Mr. Kermit," said the angry voice on the phone, "this is George B. Stoddard."

I winced at the name and the all too familiar voice, but managed to sound cheerfully friendly.

"Yes, indeed, Mr. Stoddard," I oozed. "How are you and the Missus getting along in your dream castle?"

"That," said George B. Stoddard, "is what I called about. We have been having considerable difficulty for which I consider your construction men to be responsible."

"Now just a minute," I began. "I thought we agreed—"

"We agreed that I was to expect certain occasional minor repairs to be necessary due to the construction of the house," Stoddard broke in. "I know that."

"Then what's the trouble?" I demanded.

"This house is plagued with rats," said Stoddard angrily.

"Rats?" I echoed.

"Exactly!" my client snapped.

"But how could that be possible?" I demanded. "It's a brand new house, and rats don't—"

Stoddard broke in again. "The devil they don't. We have them, and it can't be due to any fault but those construction men of yours."

"How could it be their fault?" I was getting a little sore.

"Because it isn't my fault, nor my wife's. And the building, as you observed a minute ago, is practically new."

"Now listen," I began.

"I wish you'd come out here and see for yourself," Stoddard demanded.

"Have you caught any?"

"No," he answered.

"Have you seen any?" I demanded.

"No," Stoddard admitted, "but—"

This time I did the cutting in.

"Then how do you know you have rats?" I demanded triumphantly.

"Because," Stoddard almost shouted, "as I was going to tell you, I can hear them, and my wife can hear them."

I hadn't thought of that. "Oh," I said. Then: "Are you sure?"

"Yes, I am very sure. Now, will you please come out here and see what this is all about?" he demanded.

"Okay," I said. "Okay." And then I hung up and looked around for my hat. My visit wasn't going to be any fun, I knew. But what the hell. I had to admit that if Stoddard and his wife were hearing noises that sounded like rats, they had a legitimate squawk. For I built the house, and no amount of crazy ideas in its design by Stoddard could explain the presence of vermin.

Both the Stoddards met me at the door when I arrived out in the Mayfair subdivision where I'd built their monstrosity. As they led me into the living room, I caught a pretty good idea of their new home furnishings. They hadn't changed ideas, even to the mixing of a wild mess of various nations and periods in the junk they'd placed all around the house.

They led me past an early American library table to a deep Moroccan style couch, and both pulled up chairs of French and Dutch design before me.

Feeling thus surrounded by a small little circle of indignation, I began turning my hat around in my hands, staring uncomfortably at my surroundings.

"Nice place you've got here," I said.

"We know that," Stoddard declared, dismissing banalities. "But we'd best get immediately to the point."

"About the rats?" I asked.

"About the rats," said Stoddard. His wife nodded emphatically.

There was a silence. Maybe a minute passed. I cleared my throat.

"I thought you—" I began.

"Shhhh!" Stoddard hissed. "I want you to sit here and hear the noises, just as we have. Then you can draw your own conclusions. Silence, please."

So I didn't say a word, and neither did mine hosts. We sat there like delegates to a convention of mutes who were too tired to use their hands. This time the silence seemed even more ominous.

Several minutes must have passed before I began to hear the sounds. That was because I'd been listening for rat scrapings, and not prepared for the noises I actually began to hear.

Mr. and Mrs. Stoddard had their heads cocked to one side, and were staring hard at me, waiting for a sign that I was catching the sounds.

At first the noises seemed faint, blurred perhaps, like an almost inaudible spattering of radio static. Then, as I adjusted my ear to them, I began to get faint squeaks, and small, sharp noises that were like far distant poppings of small firecrackers.

I looked up at the Stoddards.

"Okay," I admitted. "I hear the noises. They seem to be coming from behind the walls, if anywhere."

Stoddard looked smugly triumphant.

"I told you so," he smirked.

"But they aren't rat scrapings," I said. "I know the sounds rats make, and those aren't rat sounds."

Stoddard sat bolt upright. "What?" he demanded indignantly. "Do you mean to sit there and tell me—"

"I do," I cut in. "Ever heard rat noises?"

Stoddard looked at his wife. Both of them frowned. He looked back at me.

"No-o," he admitted slowly. "That is, not until we got these rats. Never had rats before."

"So you jumped to conclusions and thought they were rat noises," I said, "even though you wouldn't recognize a rat noise if you heard one."

Stoddard suddenly stood up. "But dagnabit, man!" he exploded. "If those aren't rat noises, what are they?"

I shrugged. "I don't know," I admitted. "They sound as if they might be coming through the pipes. Perhaps we ought to take a look around the house, beginning with the basement, eh?"

Stoddard considered this a minute. Then he nodded.

"That seems reasonable enough," he admitted.

I followed the amateur designer-owner of this madhouse down into the basement. There we began our prowl for the source of the noise. He snapped on the light switch, and I had a look around. The boiler and everything else in the basement was exactly as I remembered it—in the wrong place.

There was an array of sealed tin cans, each holding about five gallons, banked around the boiler. I tapped on the sides of these and asked Stoddard what they were.

"Naphtha," he explained, "for my wife's cleaning."

"Hell of a place to put them," I commented.

A familiar light came into Stoddard's stubborn eyes.

"That's where I want to put them," he said.

I shrugged. "Okay," I told him. "But don't let the insurance people find out about it."

We poked around the basement some more, and finally, on finding nothing that seemed to indicate a source of the sound, we went back up to the first floor.

Our investigation of pipes and other possible sound carriers on the first floor was also fruitless, although the sounds grew slightly stronger than they'd been in the basement.

I looked at Stoddard, shrugging. "We'd better try the second floor," I said.

I followed him upstairs to the second floor. Aside from the crazy belfry just above the attic, it was the top floor of the wildly constructed domicile.

The sounds were distinctly more audible up there, especially in the center bedroom. We covered the second floor twice and ended back up in that center bedroom again before I realized that we were directly beneath the attic.

I mentioned this to Stoddard.

"We might as well look through the attic, then," Stoddard said.

I led the way this time as we clambered up into the attic.

"Ever looked for your so-called rats up here?" I called over my shoulder.

Stoddard joined me, snapping on a flashlight, spraying the beam around the attic rafters. "No," he said. "Of course not."

I was opening my mouth to answer, when I suddenly became aware that the noises were now definitely louder. Noises faint, but not blurred any longer. Noises which weren't really noises, but were actually voices!

I grabbed Stoddard by the arm.

"Listen!" I ordered.

We stood there silently for perhaps half a minute. Yes, there wasn't any question about it now. I knew that the faint sounds were those of human voices.

"Good heavens!" Stoddard exclaimed.

"Rats, eh?" I said sarcastically.

"But, but—" Stoddard began. He was obviously bewildered.

"There's a sort of central pipe and wiring maze up here," I told him, "due to the plans we were forced to follow in building this house of yours. Those faint voices are carried through the pipes and wires for some reason of sound vibration, and hurled up here. Just tell me where you keep your radio, and we'll solve your problem."

Stoddard looked at me a minute.

"But we don't own a radio," he said quietly.

I was suddenly very much deflated.

"Are you sure?" I demanded.

"Don't be silly," Stoddard told me.

I stood there scratching my head and feeling foolish. Then I got another idea.

"Have you been up in that, ah, ornamental belfry since you moved in?" I asked.

"Of course not," Stoddard said. "It's to look at. Not to peek out of."

"I have a hunch the sounds might be even more audible up there," I said.

"Why?"

I scratched my head. "Just a hunch."

"Well it's a dammed fool one," Stoddard said. He turned around and started out of the attic. I followed behind him.

"You have to admit you haven't rats," I said.

Stoddard muttered something I couldn't catch. When we got down to the first floor again, Mrs. Stoddard was waiting expectantly for our arrival.

"Did you discover where the rats are?" she demanded.

Stoddard shot me a glance. "They aren't rats," he said with some reluctance. "The noises, we'd swear, are faint voices and sounds of human beings moving around. Were you talking to yourself while we were upstairs, Laura?"

Mrs. Stoddard gave her husband a surprised look. "Who was there to talk with, George?" she asked.

I had had about enough of this. I was damned tired of trotting around the weirdly laid out floors of the Stoddard home trying to track down rats which weren't rats but voices.

"If there are inexplicable echoes in this building," I said, "it is due to the construction. And don't forget, you wanted it this way. Now that I have proved to your satisfaction that you don't have rats, I might as well go. Good day."

I got my hat, and neither Stoddard nor his wife had much to say as they saw me to the door. Their accusing attitudes had vanished, however, and they both seemed even a trifle sheepish.

It was two o'clock when I left them. I'd killed better than an hour and a half prowling around the place, and another half hour driving out. I was damned disgusted by the time I got back to my office.

You can imagine my state of mind, consequently, some twenty-five minutes after I'd been back in my office, when I answered the telephone to hear Stoddard's voice coming over it.

"Mr. Kermit," he babbled excitedly, "this is George B. Stoddard again, Mr. Kermit!"

"What've you got now?" I demanded. "And don't tell me termites!"

"Mr. Kermit," Stoddard gasped, "you have to come back right away, Mr. Kermit!"

"I will like hell," I told him flatly, hanging up.

The telephone rang again in another half minute. It was Stoddard again.

"Mr. Kermit, pleeeease listen to me! I beg of you, come out here at once. It's terribly important!"

I didn't say a word this time. I just hung right up.

In another half minute the telephone was jangling again. I was purple when I picked it up this time.

"Listen," I bellowed. "I don't care what noises you're hearing now—"

Stoddard cut in desperately, shouting at the top of his lungs to do so.

"I'm not only hearing the noises, Kermit," he yelled, "I'm seeing the people who cause them!"

This caught me off balance.

"Huh?" I gulped.

"The belfry," he yelled, "I went up in the belfry, and you can see the people who's voices we heard!" There was a pause, while he found breath, then he shouted, "You have to come over. You're the only one I can think of to show this to!"

Stoddard was an eccentric, but only so far as his tastes in architecture were concerned. I realized this, as I sat there gaping foolishly at the still vibrating telephone in my hand.

"Okay," I said, for no earthly reason that I could think of, "okay, hang on. I'll be there in twenty minutes."

Mrs. Stoddard met me at the door this time. She was worried, almost frightened, and very bewildered.

"George is upstairs, Mr. Kermit. He won't let me come up there. He told me to send you up the minute you arrived. He's up in the attic."

"What on earth," I began.

"I don't know," his wife said. "I was down in the basement drying some clothes, when I heard this terrible yelling from George. Then he was calling you on the telephone. I don't know what it's all about."

I raced up to the attic in nothing flat, almost knocking my teeth out on the bottom step of the attic stairs.

Then I stumbled into the darkness of the attic, and saw Stoddard's flashlight bobbing around in a corner.

"Kermit?"

It was Stoddard's voice.

"Yes," I answered. "What in the hell is up? It had better be goo—."

"Hurry," Stoddard said. "Over here, quickly!"

I stumbled across the board spacings until I was standing beside Stoddard and peering up at what the beam of his flashlight revealed on the ceiling—a ragged, open hole, which he'd made by tearing several coatings of insulation from the spot.

For a minute, I couldn't make out anything in that flash beam glare. Stoddard had hold of my arm, and was saying one word over and over, urgently.

"Look. Look. Look!"

Then my eyes got adjusted to the light change, and I was aware that I was gazing up into the interior of the crazy belfry atop the monstrous house. Gazing up into the interior, while voices, quite loud and clearly distinguishable, were talking in a language which I didn't recognize immediately. As far as my vision was concerned, I might as well have been looking at a sort of grayish vaporish screen of some sort, that was all I saw.

"Shhhh!" Stoddard hissed now. "Don't say a word. Just listen to them!"

I held my breath, although it wasn't necessary. As I said, the voices coming down from that belfry were audible enough to have been a scant ten or twelve feet away. But I held my breath anyway, meanwhile straining my eyes to pierce that gray screen of vapor on which the light was focused.

And then I got it. The voices were talking in German, two of them, both harsh, masculine.

"What in the hell," I began. "Is there a short wave set up there or—"

Stoddard cut me off. "Can't you see it yet?" he hissed.

The voices went on talking, while I strained my eyes even more in an effort to pierce that gray fog covering the rent in the ceiling. And then I saw. Saw at first, as if through a thin gray screen of gauze.

I was looking up into a room of some sort. A big room. An incredibly big room. A room so big that two dozen belfry rooms would have fit into it!

And then it got even clearer. There was a desk at the end of the room. A tremendously ornate desk. A desk behind which was sitting a small, gray uniformed, moustached man.

There was another uniformed person of porcine girth standing beside that desk and pointing to a map on the wall in front of him. He was jabbering excitedly to the little man at the desk, and he wore a uniform that was so plushily gaudy it was almost ridiculous.

The two kept chattering back and forth to each other in German, obviously talking about the map at which the fat, plush-clad one was pointing.

I turned incredulously to Stoddard.

"Wh-wh-what in the hell goes?" I demanded.

Stoddard seemed suddenly vastly relieved. "So you see it and hear it, too!" he exclaimed. "Thank God for that! I thought I'd lost my mind!"

I grabbed hard on his arm. "But listen," I began.

"Listen, nothing," he hissed. "We both can't be crazy. Those are the voices we kept hearing before. And those two people are the talkers. Those two German (five words censored) louses. Hitler and Goering!"

There, he'd said it. I hadn't dared to. It sounded too mad, too wildly, babblingly insane to utter. But now I looked back through that thin gray cheesecloth of fog, back into the room.

The two occupants couldn't be anyone other than Hitler and Goering. And I was suddenly aware that the map Goering pointed to so frequently was a map of Austria.

"But what," I started again.

Stoddard looked me in the eye. "I can understand a little German," he said. "They're talking about an invasion of Austria, and if you will look hard at the corner of that map, you'll see a date marked—1938!"

I did look hard, and of course I saw that date. I turned back to Stoddard.

"We're both crazy," I said a little wildly, "we're both stark, raving nuts. Let's get out of here."

"We are looking back almost five years into the past," Stoddard hissed. "We are looking back five years into Germany, into a room in which Hitler and Goering are talking over an approaching invasion of a country called Austria. I might have believed I was crazy when I first found this alone, but not now!"

Maybe we were both crazy. Maybe he was wrong. But then and there I believed him, and I knew that somehow, in some wild, impossible fashion, that belfry on Stoddard's asinine house had become a door leading through space and time, back five years into Germany, into the same room where Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering planned the conquest of Austria!

Stoddard was taking something out of his pocket.

"Now that you're here I can try it," he said. "I didn't dare do so before, since I felt I couldn't trust my own mind alone in the thing."

I looked at what he held in his hands. A stone, tied to a long piece of string.

"What's that for?" I demanded.

"I want to see if that veil, that gray fog door, can be penetrated," he hissed.

Stoddard was swinging the stone on a string in a sharp arc now. And suddenly he released it, sending it sailing through the grayish aperture in the ceiling, straight into the belfry, or rather, the big room.

I saw and heard the stone on the string hit the marble floor of that room. Then, just as sharply, Stoddard jerked it back, yanking it into the attic again.

The result in the room beyond the fog sheet was instantaneous. Goering wheeled from the map on the wall, glaring wildly around the room. A pistol was in his hand.

Hitler had half risen behind that ornate desk, and was searching the vast, otherwise unoccupied room wildly with his eyes.

Of course neither saw anything. Stoddard, breathing excitedly at my side, had pulled the stone back into our section of time and space. But his eyes were gleaming.

"It can be done," he whispered fiercely. "It can be crossed!"

"But what on—" I started. He cut me off with a wave of his hand, pointing back to the gray screen covering the hole in the ceiling.

Goering had put the pistol back in the holster at his side, and was grinning sheepishly at der Fuehrer, who was resuming his seat behind the desk in confused and angry embarrassment.

The voices picked up again.

"They're saying how silly, to be startled by a sound," Stoddard hissed in my ear.

Then he grabbed my arm. "But come, we can't wait any longer. Something has to be done immediately."

He was pulling me away from the rent in the ceiling, away from the door that had joined our time and space to the time and space of a world and scene five years ago.

As we emerged from the attic and started blinkingly down the steps, Stoddard almost ran ahead of me.

"We must hurry," he said again and again.

"To where?" I demanded bewilderedly. "Hadn't we better do something about th—"

"Exactly," Stoddard panted. "We're really going to do something about that phenomenon in the belfry. We're going to the first place in two where we can buy two rifles, quick!"

"Rifles?" I gasped, still not getting it.

"For that little moustached swine up there," Stoddard said, pointing toward the attic. "If a stone can cross that gray barrier, so can bullets. We are both going to draw bead on Adolf Hitler in the year of 1938, and thus avert this hell he's spread since then. With two of us firing, we can't miss."

And then, of course, I got it. It was incredible, impossible. But that gray screen covering the rent in the attic ceiling upstairs wasn't impossible. I'd seen it. Neither was the room behind it, the room where the belfry was supposed to be, but where Adolf Hitler's inner sanctum was instead. I'd seen that, too. So was it impossible that we'd be able to eliminate the chief cause of the world's trouble by shooting accurately back across time and space?

At that moment I didn't think so!

Our mad clattering dash down the attic steps, and then down to the first floor brought Mrs. Stoddard up from the basement. She looked frightenedly from her husband to me, then back to him again.

"What's wrong?" she quavered.

"Nothing," Stoddard said, pushing her gently but quickly aside as we dashed for the door.

"But, George!" Mrs. Stoddard shrilled behind us. We heard her footsteps hurrying toward the door, even as we were out of it.

"My car," I yelled. "It's right in front. I know the closest place where we can get the guns!"

Stoddard and I piled into the car like a pair of high school kids when the last bell rings. Then I was gunning the motor, while out of the corner of my eye I could see Stoddard's wife running down the front steps shouting shrilly after us.

We jumped from the curb like a plane from a catapult, doing fifty by my quick shift to second gear. Then we were tearing the quiet streets of Mayfair's second subdivision apart with the noise of a blasting horn and a snarling motor.

It was ten minutes later when I screeched to a stop in front of the sports and gun store I'd remembered existed in Mayfair's first subdivision. The clerk was amazed at the wild speed with which we raced in, grabbed the guns, threw the money on the counter, and dashed out.

We must have looked like something out of a gangster movie as we raced back to Stoddard's place.

I was doing the driving, and Stoddard had clambered in beside me, both rifles, and several cartridge packages in his hands. He was rocking back and forth in mad impatience, as if by rocking he could increase our speed. The expression on his face was positively bloodthirsty.

And then we heard the sirens behind us. Shrill, coming up like comet wails in spite of our own speed.

"Oh, God!" Stoddard groaned. "Police!"

I squinted up into my rear vision mirror. We were less than two blocks from the Stoddard house, now, and the thought of being overhauled by police at the juncture was sickening, unbearable even to contemplate.

And then I saw the reason for the sirens. Saw them in the rear vision mirror. Two fire engines, one a hook and ladder outfit, the other a hose truck!

"It's all right," I yelped. "It's only two fire trucks!"

"Thank God!" Stoddard gasped.

We were a block from his place now, with only one corner left to turn before we'd see the mad architectural monstrosity he called him home; before we'd see the crazy belfry which held the salvation of the world in its screwballish, queer-angled lines.

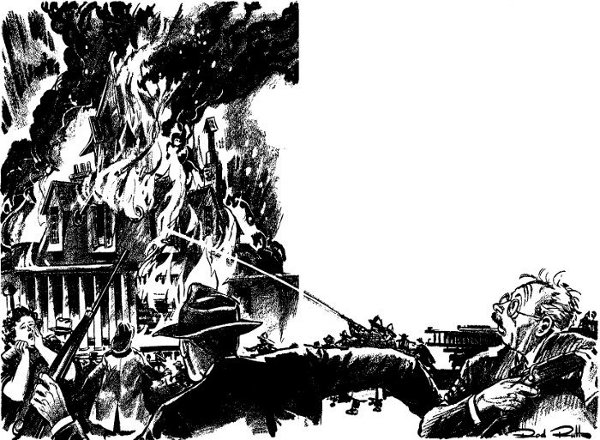

And then the fire trucks and the sirens were nearer and louder, less than a block behind us. At that instant we turned the corner and came into full view of the Stoddard place.

It was a mass of flames, utterly, roaringly ablaze!

I almost drove us off the street and into a tree. And by the time I'd gotten a grip on myself, we were just a few houses away from the blazing inferno of Stoddard's crazy quilt dwelling.

I stopped by the curb, and clambered out of the car onto knees which would scarcely support me. My stomach was turning over and over in an apparently endless series of nauseating somersaults.

Stoddard, white-faced, frozen, stood there beside me, clutching the guns and the cartridge boxes foolishly in his hands.

Then someone was running up to us. Running and crying sobbingly, breathlessly. It was Stoddard's wife.

The fire trucks screeched to a stop before the blazing building at that instant, and her first words were drowned in the noise they made.

"... just drying out some clothes, George," she sobbed. "Just drying them out and turned on the furnace to help dry them. You left like that, and I got frightened. I ran to a neighbor's. The explosion and fire started not five minutes later."

Sickly, I thought of the naphtha Stoddard had piled near his boiler. I didn't say anything, though, for I knew he was thinking of it also.

He dropped the guns and cartridge boxes, and in a tight, strained voice, while putting his arms comfortingly around his wife, said: "That's all right, Laura. It wasn't your fault. We'll have another house like this. So help me God, just like this!"

It has been six months now since Stoddard's architectural eyesight burned to the ground. He started rebuilding immediately after that. I turned over all the drafts my company made from his first crude "plans," and he handed them to the supervisor of the construction company he bought out. You see, he took every dime he owned, sold out his insurance business, and has gone into the building game in dead earnest.

He explained it to me this way.

"I couldn't go on having house after house built and torn down on the same spot, Kermit. It would break me in no time. This way, with my own company to construct the house every time, I'll save about half each time."

"Then you're going to build precisely the same house?" I demanded.

His jaw went hard, and he peered from behind his spectacles with the intense glare of a fanatic. For once he didn't look like Mr. Suburbanite.

"You know damned well I am," he said. "And until it is precisely the same as the first, I'll keep tearing 'em down and putting 'em up again. I don't care if I have to build a thousand to do it, right on this spot!"

Of course I knew what he meant by precisely the same. And I wondered what on earth the odds were he was bucking. Through chance and a mad combination of angles, that time and space door had appeared the first time. But it might have been hanging on the tiniest atom of a fractional difference.

Stoddard has already finished his second house, and although it looks exactly like the monstrosity I first built for him, it can't be precisely like it. For he didn't get the gray shrouded door when he poked a hole in the attic ceiling and looked up into the second crazy belfry. All he saw was the belfry.

Tomorrow he starts tearing down to build another, and pretty soon people are going to be certain he's crazy.

As a matter of fact, they'll soon be pretty sure I'm loony also. For of course I can't help going over there now and then to sort of lend a hand....

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Rats in the Belfry, by John York Cabot

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RATS IN THE BELFRY ***

***** This file should be named 32900-h.htm or 32900-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/3/2/9/0/32900/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

[email protected]. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.