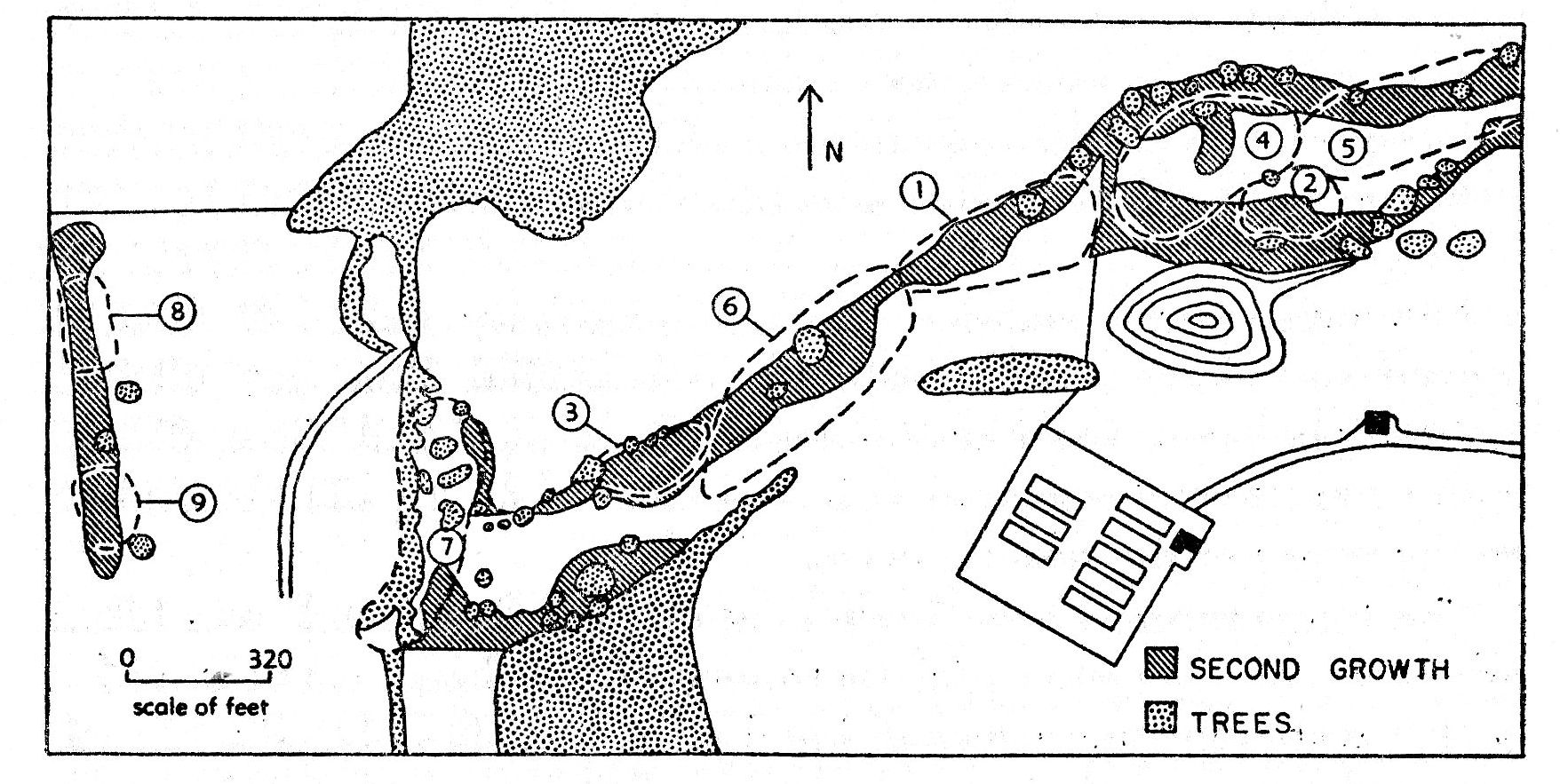

Fig. 1. Map of the study

area near the University of Kansas Laboratory of Aquatic Biology. The

dashed lines mark the approximate territorial boundaries of the original

nine pairs of Bell Vireos from May 1960 to early June 1960.

Fig. 1. Map of the study

area near the University of Kansas Laboratory of Aquatic Biology. The

dashed lines mark the approximate territorial boundaries of the original

nine pairs of Bell Vireos from May 1960 to early June 1960.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Natural History of the Bell Vireo, Vireo bellii Audubon, by Jon C. Barlow This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Natural History of the Bell Vireo, Vireo bellii Audubon Author: Jon C. Barlow Release Date: June 17, 2010 [EBook #32855] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BELL VIREO *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| PAGE | |

| Contents | 243 |

| Introduction | 245 |

| Acknowledgments | 245 |

| Methods of Study | 246 |

| Study Area | 247 |

| Considerations of Habitat | 248 |

| Seasonal Movement | 250 |

| Arrival in Spring | 250 |

| Fall Departure | 251 |

| General Behavior | 252 |

| Flight | 252 |

| Foraging and Food Habits | 252 |

| Bathing | 253 |

| Vocalizations | 254 |

| Singing Postures | 255 |

| Flight Song | 255 |

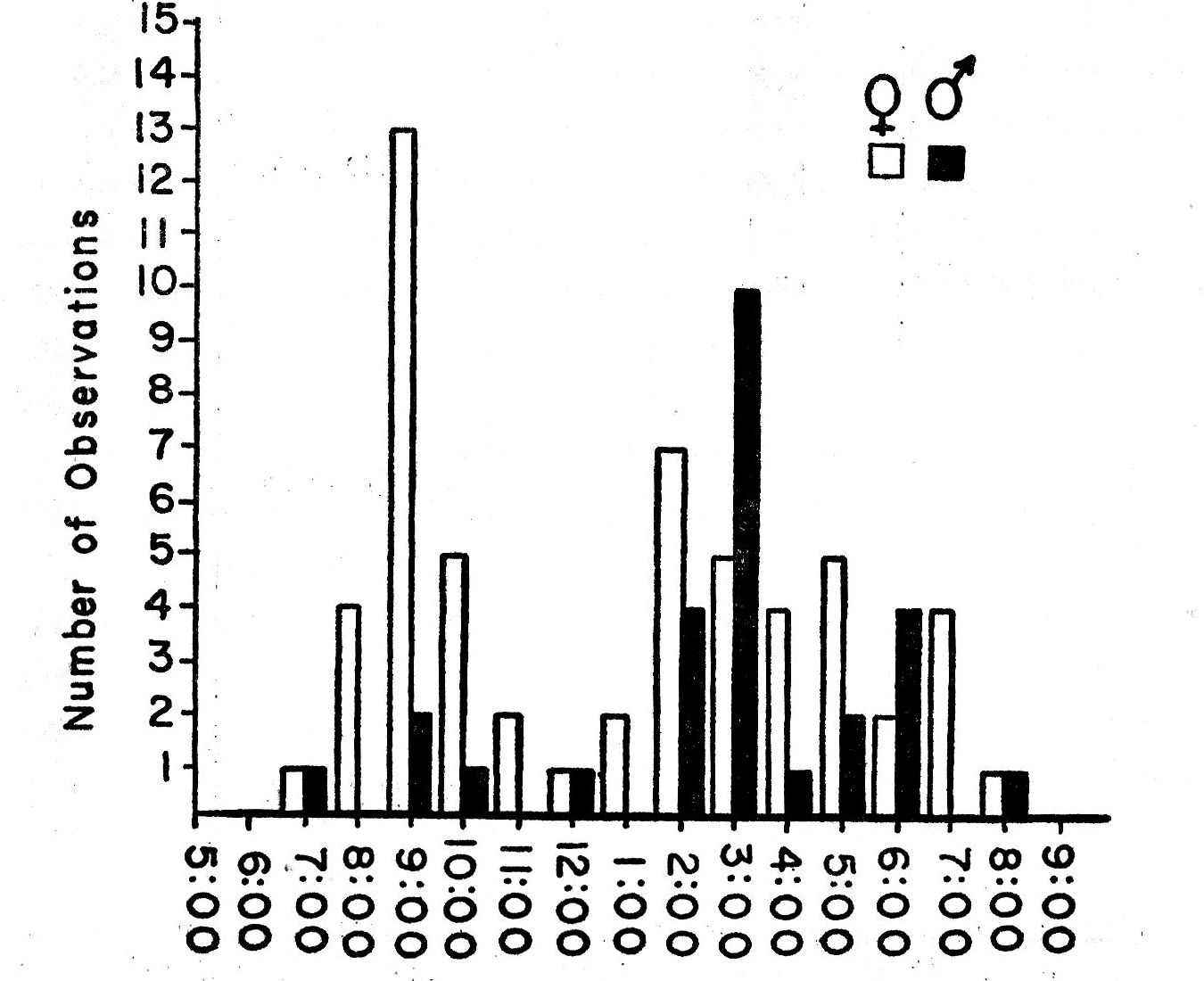

| Daily Frequency of Song | 255 |

| Types of Vocalizations | 255 |

| Territoriality | 258 |

| Establishment of Territory | 259 |

| Size of Territories | 259 |

| Permanence of Territories | 260 |

| Maintenance of Territory | 260 |

| Aggressive Behavior of the Female | 264 |

| Interspecific Relationships | 264 |

| Discussion | 265 |

| Courtship Behavior | 267 |

| Displays and Postures | 268 |

| Discussion[Pg 244] | 270 |

| Selection of Nest-site and Nestbuilding | 272 |

| Building | 274 |

| Gathering of Nesting Materials | 276 |

| Length and Hours of Nestbuilding | 277 |

| Abortive Nestbuilding Efforts | 277 |

| Renesting | 277 |

| The Nest | 277 |

| Egglaying and Incubation | 278 |

| Egglaying | 278 |

| Clutch-size | 279 |

| Incubation | 280 |

| The Roles of the Sexes in Incubation | 280 |

| Relief of Partners in Incubation | 283 |

| Nestling Period | 283 |

| Hatching Sequence | 283 |

| Development of the Nestlings | 284 |

| Parental Behavior | 285 |

| Feeding of the Nestlings | 286 |

| Nest Sanitation | 287 |

| Fledging | 287 |

| Nest Parasites | 287 |

| Fledgling Life | 288 |

| Second Broods | 288 |

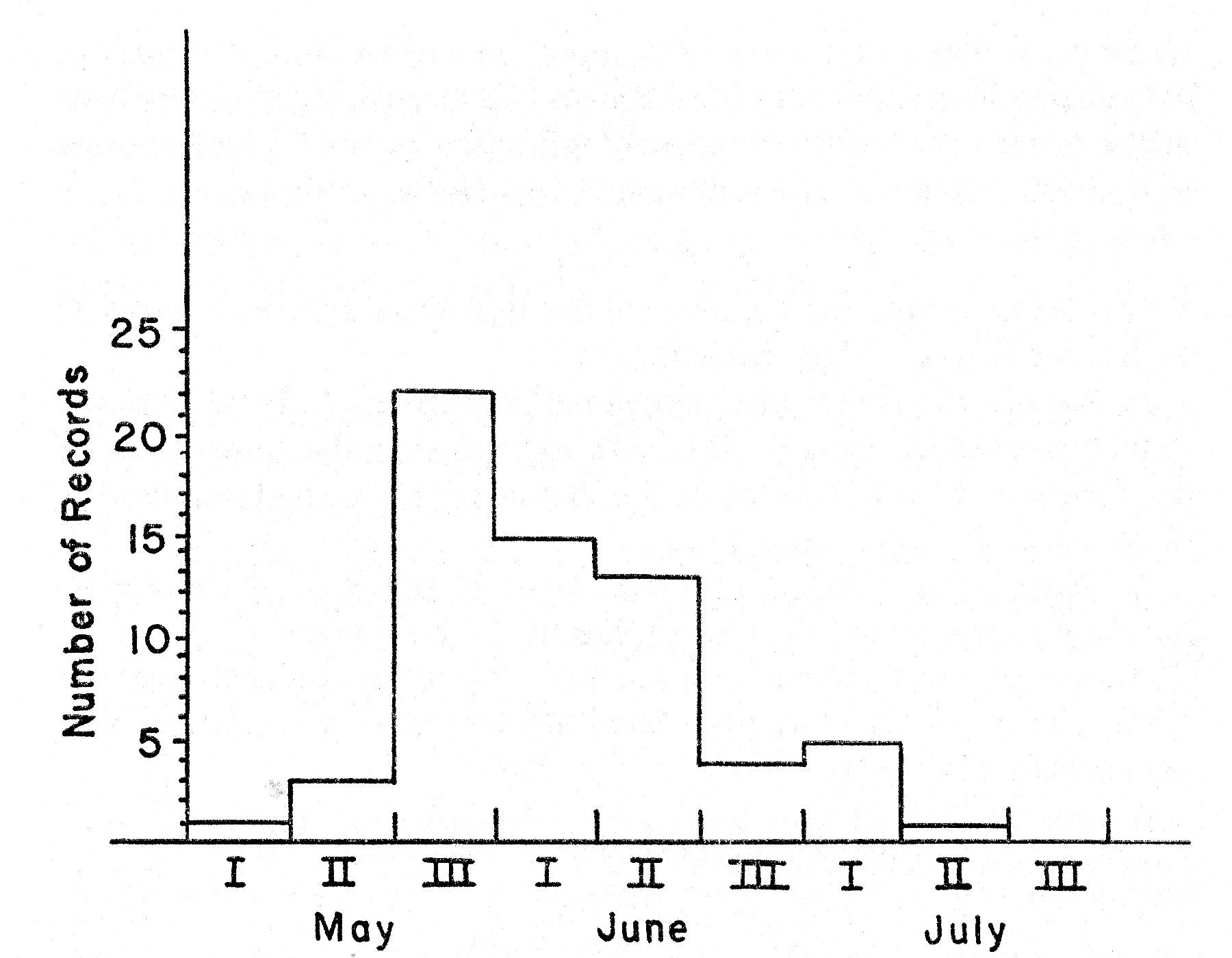

| Reproductive Success | 289 |

| Behavior | 290 |

| Predation | 291 |

| Cowbird Parasitism | 291 |

| Summary | 292 |

| Literature Cited | 294 |

The Bell Vireo (Vireo bellii Aud.) is a summer resident in riparian and second growth situations in the central United States south of North Dakota. In the last two decades this bird has become fairly common in western, and to a lesser extent in central, Indiana and is apparently shifting its breeding range eastward in that state (Mumford, 1952; Nolan, 1960). In northeastern Kansas the species breeds commonly and occurs in most tracts of suitable habitat.

The literature contains several reports dealing exclusively with the Bell Vireo, notably those of Bennett (1917), Nice (1929), Du Bois (1940), Pitelka and Koestner (1942), Hensley (1950) and Mumford (1952). Bent (1950) has summarized the information available on the species through 1943. Nolan (1960) recently completed an extensive report based on a small, banded population at Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana. He validated for this species many points of natural history previously based on estimates and approximations, especially concerning the post-fledging life of the young and the movement of the adults from one "home range" to another in the course of a single season.

None of these reports, however, has emphasized the ritualized behavioral patterns associated with the maintenance of territory and with courtship. Among the North American Vireonidae, the behavior of the Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) is best documented (Sutton, 1949; Lawrence, 1953; Southern, 1958). With this species authors have concentrated on the mechanics of the breeding season and their reports contain little discussion of the aggressive and epigamic behavior of the bird.

The amount of information on the ritualized behavior of the Bell Vireo and related species heretofore has been meager. I observed breeding behavior from its inception in early May through the summer of 1960. It is hoped the resulting information will serve as a basis of comparison in future studies of behavior of vireos; such ethological data are becoming increasingly important, especially as an aid in systematics.

To professors Frank B. Cross, Henry S. Fitch, and Richard F. Johnston of the Department of Zoology of the University of Kansas I am grateful for comments and suggestions in various phases of the study and the preparation of the manuscript. Professor Johnston [Pg 246] also made available data on the breeding of the Bell Vireo from the files of the Kansas Ornithological Society. I am indebted to my wife, Judith Barlow, for many hours of typing and copy reading. Mrs. Lorna Cordonnier prepared the map, Thomas H. Swearingen drew the histograms, and Professor A. B. Leonard photographed and developed the histograms. Dr. Robert M. Mengel contributed the sketch of the Bell Vireo and George P. Young prepared the dummy Bell Vireo used in the field work. Thomas R. Barlow, Donald A. Distler, Abbot S. Gaunt, John L. Lenz, Gary L. Packard, A. Wayne Wiens, and John Wellman assisted in various phases of the field work.

Daily observations were made from May 11 to June 26 in 1959 and from April 15 through July 15 in 1960. Six additional visits were made to the study area in September of 1959, and ten others in July and August, 1960. Periods of from one hour to eleven hours were spent in the field each day, and a total of about five hundred hours were logged in the field.

Each territory was visited for at least five minutes each day but more often for twenty minutes. The breeding activities of the pairs were rarely synchronous. Consequently several stages in the cycle of building were simultaneously available for study.

Nine young and one adult were banded in 1959. No Bell Vireos were banded in 1960. Individual pairs could be recognized because of their exclusive use of certain segments of the study area and by the individual variation in the song of the males. Sexes were distinguishable on the basis of differences in vocalizations and plumages.

Most nests were located by the observer searching, watching a pair engaged in building, or following a singing male until the increased tempo of his song indicated proximity to a nest. As the season progressed and the foliage grew more dense, it became increasingly difficult to locate completed nests. Blinds were unnecessary because of the density of vegetation. Observations were facilitated by a 7 × 50 binocular. Data were recorded on the spot in a field notebook. Eggs were numbered by means of Higgins Engrossing ink as they were laid.

Individual trees in which males sang most were marked over a three-week period. Then the distances between the most remote perches were paced. These distances aided in determining the [Pg 247] size of the territories. The general configuration of the vegetation within each territory determined the location of one or more boundaries of the territory. Each territory was given a number, 1, 2, 3, etc., as it was discovered; consequently there is no numerical relationship between the designations of the territories established in 1959 and 1960. Nests within a territory were designated as 1-a, 1-b, 1-c, etc.

Although experimentation was not a primary source of data, it proved useful in certain instances. A stuffed Blue Jay elicited mobbing behavior from nesting pairs. A dummy Bell Vireo elicited both agonistic and epigamic behavior from nesting pairs, depending on the phase of the nesting cycle.

The temperature at the beginning of each day's work was taken by means of a Weston dial thermometer. A hand counter and a pocket watch having a second hand were used in determining such data as frequency of song and periods of attentiveness by the sexes. Histological cross-sections, prepared by A. Wayne Wiens, of the ventral epidermis of both sexes were used to study brood patches.

The intensive field work was on a 39-acre tract (fig. 1) extending approximately 7/10 of a mile west from U. S. highway 59, which in 1959-1960 constituted the western city limit of Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas. The eastern boundary of the study area is approximately 1-1/2 miles southwest of the County Courthouse in Lawrence. The eastern ten acres is associated with the Laboratory of Aquatic Biology of the University of Kansas. The 15 acres adjacent to this on the southwest is owned by the University of Kansas Endowment Association, but is used by Mr. E. H. Chamney for the grazing of cattle. This portion is bounded on the west by a stone fence, beyond which lies a 14-acre field of natural prairie owned by Dr. C. D. Clark that is bordered on the extreme west by a narrow thicket of elm saplings.

The principal topographic feature of the area is an arm of Mount Oread, that rises some 80 feet above the surrounding countryside. About 200 feet from the crest of the southwestern slope of the hill a 40-foot-wide diversion terrace directs run-off toward the two-acre reservoir that is the source of water for eight experimental fish ponds of the laboratory.

The predominant shrub-vegetation consists of Osage orange (Maclura pomifera), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), and [Pg 248] American elm (Ulmus americana). These saplings, ranging in height from 3 to 25 feet, grow in dense thickets as well as singly and in clumps of twos and threes. Larger trees of these same species grow along the crest of the hill, along the eastern and southeastern boundaries of the area, and along the stone fence separating University land from that owned by Dr. Clark. A dense growth of coralberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus) forms the understory just below the crest of the hill. Isolated clumps of dogwood (Cornus drummondi) and hawthorn (Crataegus mollis) are scattered throughout the area. These species of shrubs grow densely along the stone fence. The isolated thicket on the Clark land is composed primarily of elm and boxelder (Acer negundo), but includes scattered clumps of dogwood, Osage orange, and honey locust. Poplars (Populus deltoides) are the only large trees in this area.

Fig. 1. Map of the study

area near the University of Kansas Laboratory of Aquatic Biology. The

dashed lines mark the approximate territorial boundaries of the original

nine pairs of Bell Vireos from May 1960 to early June 1960.

Fig. 1. Map of the study

area near the University of Kansas Laboratory of Aquatic Biology. The

dashed lines mark the approximate territorial boundaries of the original

nine pairs of Bell Vireos from May 1960 to early June 1960.

The open areas between the thickets are grown up in red top (Triodia flava), bluestem (Andropogon scoparius), Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), bush clover (Lespedeza capitata) and mullen (Verbascum thapsus). Shrubby vegetation occupies about 65 per cent of the total area, but in the Clark portion constitutes only about 35 per cent of the ground cover.

Nolan (1960:226), summarizing the available information on habitat preferences of the Bell Vireo, indicates that this species tolerates "a rather wide range of differences in cover." He pointed [Pg 249] out that a significant factor in habitat selection by this species may be avoidance of the White-eyed Vireo (V. griseus) where the two species are sympatric.

In Douglas County where the Bell Vireo is the common species, the White-eyed Vireo reaches the western extent of its known breeding range in Kansas. At the Natural History Reservation of the University of Kansas, where both species breed, the Bell Vireo occurs in "brush thickets in open places" (Fitch, 1958:270) and the White-eyed Vireo occupies "brush thickets, scrubby woodland and woodland edge" (Fitch, op. cit., 268). Along the Missouri River in extreme northeastern Kansas, Linsdale (1928:588-589) found the White-eyed Vireo "at the edge of the timber on the bluff, and in small clearings in the timber," while "the Bell Vireo was characteristic of the growths of willow thickets on newly formed sand bars." Elsewhere in northeastern Kansas I have found the Bell Vireo in shrubbery of varying density and often in habitat indistinguishable from that occupied by White-eyed Vireos at the Natural History Reservation. In the periphery of the region of sympatry the rarer species is confronted with a much higher population density of the common species and consequently might well be limited primarily to habitat less suitable for the common species. This would seem to be the case in eastern Kansas, presuming that interspecific competition exists.

The Bell Vireo has followed the prairie peninsula into Indiana, aided by the development of land for agriculture. In nearby Kentucky where thousands of miles of forest edge are found, and where little brushy habitat of the type preferred by the Bell Vireo occurs, the White-eyed Vireo is abundant whereas the Bell Vireo is unknown as a breeding bird (R. M. Mengel, personal communication).

In more central portions of the area of sympatry, nevertheless, the two species do occur within the same habitat (Ridgway, 1889:191; Bent, 1950:254) and occasionally within the same thicket (Ridgway, in Pitelka and Koestner, 1942:105); their morphological and behavioral differences, although slight, probably minimize interspecific conflict. The Bell Vireo and the Black-capped Vireo (V. atricapillus) have been found nesting in the same tree in Oklahoma by Bunker (1910:72); the nest of the black-cap was situated centrally and that of the Bell Vireo peripherally in the tree. Bell Vireos invariably place their nests in the outer portions of trees and peripherally in thickets. This placement would further obviate interspecific conflict with the white-eye since its nests are placed centrally in the denser portions of a thicket.

[Pg 250] A critical feature of the habitat preferred by the Bell Vireo is the presence of water. In far western Kansas this species is restricted to riparian growth along the more permanent waterways. This in itself is not adequate proof of the significance of water supply because thicket growth in that part of the state is found only along waterways. The 20 areas over the state that I have visited where Bell Vireos were present were closely associated with at least a semi-permanent source of water. Fifteen other areas indistinguishable from the 20 just mentioned, but lacking a permanent supply of water, also lacked Bell Vireos. Nevertheless areas in which Bell Vireos typically nest are decidedly less mesic than those frequented by White-eyed Vireos.

Once the Bell Vireo was probably more local in its distribution being restricted to thickets associated with permanent water. Clearing of woodland for agricultural and other use, and subsequent encroachment of second growth concomitant with the creation of man-made lakes and ponds, has greatly increased the available habitat for this bird. The preferred species of shrubs for nesting are reported (Bent, 1950:254) to be various wild plums (Prunus sp.). The widespread distribution and abundance of the exotic Osage orange has greatly augmented the supply of trees suitable for nesting.

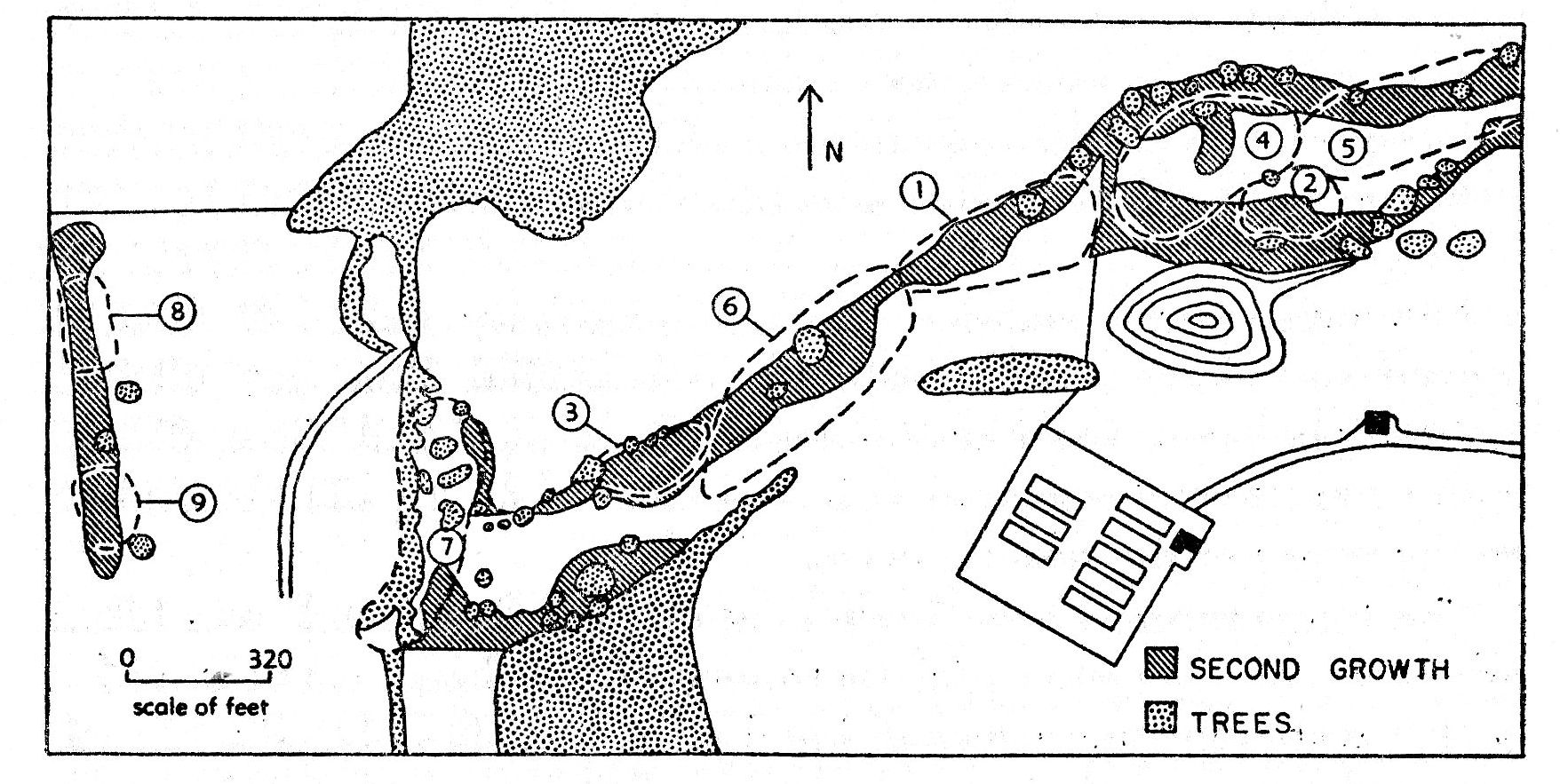

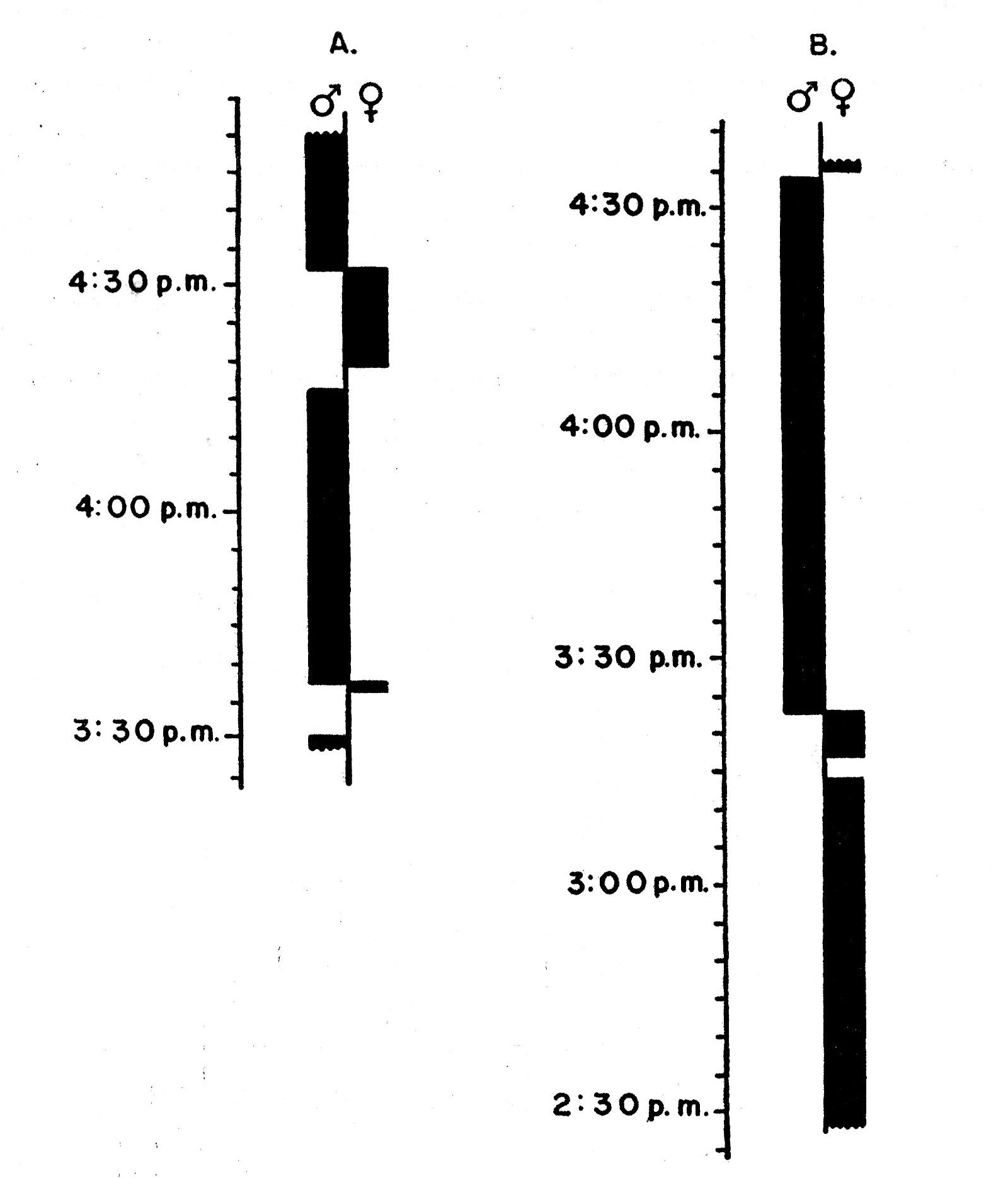

The subspecies of the Bell Vireo breeding in Kansas, V. b. bellii, winters regularly from Guerrero and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec south to Guatemala, El Salvador, and northern Nicaragua (A. O. U. Check-list, Fifth Edition, 1957:469-470). In the United States migrating birds are first recorded in early March (Cooke, 1909:119). The Bell Vireo is a relatively slow migrator, moving primarily at night and covering little more than 20 miles at a time (Cooke, op. cit. 119). The average date of arrival, based on 27 records, for northeastern Kansas is May 8; the earliest record is April 22, 1925, from Manhattan, Riley County, Kansas (fig. 2-A).

In 1959 the first bird arrived at the study tract about May 5. No additional birds were heard singing until the third week of the month, in which eight new males were noted. As mentioned, in 1960 field work was begun in mid-April and the study area was traversed daily. No birds were detected until late afternoon of May 3, when one, presumably a male, was seen foraging.

[Pg 251] Lawrence (1953:50) has reported that males of the Red-eyed Vireo precede females in the breeding area by as much as two weeks; the male Red-eyed Vireo forages but sings little in the pre-nesting period. The male Bell Vireo arrives first at the breeding area but precedes the female by only a few days. On the morning of May 4 the first male was singing from a number of perches while ranging over an area of seven acres. This area encompassed territories later occupied by three pairs, 2 (1960), 4 (1960), and 5 (1960). Late on the afternoon of May 4 the first courtship songs were heard and the first male was seen with a mate at 6:20 p.m. Eight additional males arrived from May 6 through May 18. A tenth male was discovered in the vicinity of territory 9 (1960) on June 18, 1960.

Fig. 2. Seasonal movement as

indicated by the curve for spring arrival (A), based on the earliest dates for

27 years, and the curve for autumn departure (B), based on the latest dates for

21 years in northeastern Kansas.

Fig. 2. Seasonal movement as

indicated by the curve for spring arrival (A), based on the earliest dates for

27 years, and the curve for autumn departure (B), based on the latest dates for

21 years in northeastern Kansas.

The average date of departure for 21 years in northeastern Kansas is September 3 (fig. 2-B). The earliest date is August 14 from Concordia, Cloud County, Kansas (Porter, unpublished field notes). The latest date is September 27 (Bent, 1950:262) from Onaga, Pottawatomie County, Kansas. In 1959 the last vireo was seen at the study tract on September 14. The birds do not all depart at the [Pg 252] same time. On September 1 there were still five singing males in the study area; by September 10 there were three and on September 13, only one.

In "straight-away" flight the Bell Vireo undulates slightly. In a typical flight several rapid, but shallow, wing beats precede a fixed-wing glide of from 1 to 15 feet in length. Because the wings are extended horizontally during the glide, the bird does not move distinctly above or below the plane of flight. The White-eyed Vireo generally appears to be slower and more lethargic in flight than the Bell Vireo. In the breeding season most flights of the Bell Vireo are no longer than a few feet between adjacent shrubs and trees, but occasional sustained flights are as long as 300 feet. The birds fly as low as 2 feet above ground, but have often been observed as high as 70 feet above the ground.

In courtship and protracted territorial disputes, where chase between sexual partners or a pair of antagonists occurs, looping flights are observed. The wings are beaten as the birds climb and many aerial maneuvers are performed in the course of the glide.

The Bell Vireo has been characterized as a thicket forager (Hamilton, 1958:311; Pitelka and Koestner, 1942:104), but in my experience it is not restricted to low level strata; birds forage from ground level upward, both in thickets and isolated trees ranging in height from 3 feet to 65 feet. The tendency to forage at higher levels is in part dictated by the presence of tall trees within the various territories.

Territories 1 through 7 (1960) contained from three to ten trees surpassing 40 feet in height. They grew singly or in small groves. The Bell Vireos foraged fully 20 per cent of the time in these trees. Food was sought throughout the leaf canopy.

Behavior in foraging in larger trees followed a routine pattern. Typically a pair alighted in a tree at a height of 15 feet. Then the female hopped to a perch a foot above the one upon which she landed. The male succeeded her to the perch she had previously occupied. The pair in effect spiraled around some large, essentially upright, branch, in foraging. The birds usually reached higher [Pg 253] perches in this manner rather than by flying upward 10 to 15 feet to them. This manner of progression within a tree is reminiscent of a similar habit of the Cyanocitta jays. Presumably, the habit of the Bell Vireo of foraging in higher strata is facilitated by the absence of other species of arboreal foraging vireos.

Chapin (1925:25) found the Bell Vireo to be more insectivorous in its food habits than any other North American vireo. He found 99.3 per cent of all food contained in 52 stomachs to be of animal origin. Only three times have I seen a Bell Vireo take food of vegetable origin. On September 9, 10, and 14, 1959, I noted a male eating wild cherries over a period of 65 minutes of observation. Chapin (1925:27) noted that beginning in July vegetable matter represented 1.57 per cent of the bird's subsistence, and thereafter slightly more until fall migration.

Animal food, consisting primarily of insects and spiders, is actively sought along branches and under leaves. Often a foraging bird will leap to the underside of a branch and hover, mothlike, beneath a cluster of leaves while extracting some insect. Some individuals hung upside down on small branches, paridlike, while foraging. Lawrence (1953:710), and Southern (1958:201) have recorded similar behavior of the Red-eyed Vireo. Occasionally, I have seen a Bell Vireo fly from a perch and capture an insect in the manner of a flycatcher. The birds do not appear to be adept at this type of food-getting. Nolan (1960:242) mentions Bell Vireos holding hard-bodied insects by means of their feet while breaking the exoskeleton with the beak to obtain the soft parts. Southern (1958:201) recorded a female Red-eyed Vireo foraging on the ground; I have seen a Bell Vireo on the ground but once, and it was gathering nesting material.

On May 14, 1960, in a rill that empties into the northeastern edge of the reservoir a female flew down from a perch six inches above the surface, barely dipped into the water, flew to a perch 12 inches above the water, violently shook her ruffled body feathers, quivered her wings, and rapidly flicked her fanned tail. The entire procedure was repeated three times in five minutes. She was accompanied by a singing male that did not bathe.

Nolan (1960:241) reports a male Bell Vireo bathing by rubbing against leaves wet with dew; he notes that the White-eyed Vireo bathes in a similar manner. Southern (1958:201) twice observed [Pg 254] Red-eyed Vireos bathing in water that dropped from wet leaves. In my study area in 1960, only territories 7, 8, 9, and 10 were not immediately adjacent to permanent water. The pairs of Bell Vireos in those territories presumably had to reply on wet vegetation for bathing.

The male Bell Vireo begins to sing regularly soon after its arrival in spring. Some daily singing continues following the cessation of breeding activities until departure of the species in late summer or early fall. The highest sustained rate of song occurs on the first and second days of nest building. Because careful records of meteorological data were not kept, I cannot significantly correlate rates of song and specific temperatures and other weather conditions. Frequency of song was reduced when the temperature rose above 90° F., as it did on many days in June, 1960. Nice (1929:17) mentions a similar decrease in singing when the temperature exceeded 85° F.

Passerine birds typically sing at a high rate throughout courtship and nestbuilding, but at a markedly lower rate thereafter. Most vireos are atypical in this respect. In the study area in 1960 Bell Vireos sang more often than Robins, Mockingbirds, Field Sparrows, Brown Thrashers, Catbirds, and Doves breeding in the same habitat, about as often as the Meadow Larks in the adjacent fields, and less often than Painted Buntings.

The Bell Vireo seems to sing less often in the undisturbed state than when aware of the presence of an observer. Observations from my car, at a site approximately equidistant from territories 1 (1960), 2 (1960), 4 (1960), and 6 (1960) indicate that the rate of song during incubation is decidedly less when no disturbing influence is present. Normally, in this period, song aids in maintaining contact between the members of a pair, serving to locate the male as he forages. Mumford (1952:230) noted that the males often came out to meet him as he entered their territories, singing as they approached. The male typically continues to sing for some time after the intruder has departed. Here the song acquires the additional functions of alerting the female to danger and threatening the trespasser. Even after allowance is made for this reaction to disturbance, Bell Vireos sing more often than most of their nesting associates, and, on a seasonal basis, they are vocal for a much longer time.

In the normal singing posture the body of the Bell Vireo is maintained at an angle of 35° to the horizontal. Occasionally, during nest building, I have observed the body held at angles as severe as 80° from the horizontal.

The head of the White-eyed Vireo is distinctly bobbed up and down, two or three times, during the utterance of a song phrase. A bob involves a deliberate withdrawal of the head towards the body and subsequent sharp, almost vertical, extension of the neck. The head of the Bell Vireo does not bob, although it vibrates as the song is delivered.

The Bell Vireo does not have a distinctive flight song; in fact, it rarely sings or calls while in flight. Nolan (1960:240) has recorded a male singing the normal song while in flight. Sharp scold-notes are uttered in mid-air when a bird is agitated or actually attacking an enemy. These notes and songs recorded by Nolan hardly qualify as flight song, for this term implies use of a distinctive vocalization not uttered in other circumstances.

In the morning, Bell Vireos usually began singing a few minutes before sunrise. Their songs were invariably preceded in the study area by those of Western Kingbirds, Robins, Mourning Doves, Mockingbirds, Cardinals and Meadow Larks. Bell Vireos sang relatively little after 6:30 p.m., even on the longest days of the year. The latest daytime singing that was recorded was seven songs at 7:18 p.m. on June 20, 1960. A Cardinal in the vicinity sang for a full hour after this.

Six vocalizations were readily distinguishable in the field. These are divisible into songs and call notes.

1. Primary song. It has been described by Pitelka and Koestner (1942:103) as an "irregular series of harsh and sharp, but slurred notes preceded by a few distinct notes of the same quality and ending with a decided ascending or descending note of similar harshness." The terminal note may also be somewhat abbreviated and intermediate between an ascending or descending note. The song is sometimes delivered as a couplet that consists of a phrase ending on a descending note. This delivery is typical of incubation and later renesting. During early season activities, the bird utters [Pg 256] a phrase ending on the descending note as many as 15 times before a phrase ending on an ascending note is heard.

A sonagram of a single phrase, one of several recorded on May 9, 1960 (the third day of building of nest 1-b 1960), consists of 10 notes, the first of which is distinct. The remaining notes are slurred. This phrase is 1.4 seconds in length.

Songs are delivered most rapidly in the course of territorial disputes and defense. The song is loudest in times of nestbuilding and periods of aggressive behavior. At these times, on clear, calm days, the songs are audible 100 yards away. Singing in the nestling period and post-breeding season is audible at distances of no more than 50 feet; such notes have been termed "whisper songs." Table 1 summarizes singing rates at different periods of the nesting cycle in several situations and under various weather conditions.

Songs are of equal frequency in the immediate vicinity of the nest and elsewhere in the territory. Nice (1929:17) also found this to be true. Perches can be almost at ground level or as high as 60 feet. Forty per cent of my data on song concern singing at heights of more than 20 feet. As indicated in foraging, the lack of competition from aboreal species of vireos presumably contributes to the use of higher perches by Bell Vireos.

No female song was recorded in 1959, but on May 26, 1960, a female was heard to sing once. She appeared at nest 1-f (1960) shortly after the male arrived. Unlike him, she did not participate in building, but seemed to be inspecting the nest. After 30 seconds she sang once—a low garbled phrase—and also scolded once. After this she left. In the meantime the continuously singing male moved two feet away from the nest, then back to it and resumed construction.

The song of the female signaled to the male her departure. Pitelka and Koestner (1942:103) heard a female sing twice after she replaced the male on the nest. Females of three other species of vireos, the Black-capped Vireo, V. atricapillus (Lloyd, 1887:295), the Philadelphia Vireo, V. philadelphicus (Lewis, 1921:33), and the Latimer Vireo, V. latimeri (Spaulding in Pitelka and Koestner, 1942:103) have been heard singing. Lewis and Spaulding also suggest that the song of the female functions as a signal prior to exchange at the nest.

The primary song identifies the singer as a male Bell Vireo. It aids in securing a mate and in warning potential adversaries; also, the song is a signal in certain situations and serves to locate the male.[Pg 257]

| Circumstance | Instances | Average rate per minute |

|---|---|---|

| Attraction of mate | 2 | 6.3 |

| Territorial dispute | 5 | 12.8 |

| Nestbuilding | 6 | 7.0 |

| Egglaying | 1 | 3.0 |

| Incubation | 6 | 3.9 |

| Exchange of partners in the incubation period | 1 | 4.0[A] |

| Foraging | 2 | 2.2 |

| "Morning" song | 1 | 28.6[A] |

| "Evening" song | 1 | 1.9[A] |

| Overall average rate per minute 6.3 | ||

2. Courtship song. It is here termed the "congested" song and is comparable to the adult "run-on" song mentioned by Nolan (1960:240). The congested song is a squeaky version of the primary song and is given when birds are engaged in pair-formation, nestbuilding, and egglaying. The delivery is rapid and the sound can be likened to that made by rapidly scraping a bow across a taut violin string. Nolan (in Mumford, 1952:230) is probably speaking of this song when he describes a "tuneless" song that "had a jerky, sputtering quality that characterizes part of the song of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula)." More recently (1960:240) he applies the adjectives "twanging," "Bobolink-like," "bubbling," "jerky," and "squeaky." This song is often blended with the primary song and is audible for 75 feet.

A specialized version of the congested song is associated with pre- and post-copulatory display but differs from the typical squeaky performance in terminating in two ascending notes reminiscent of the ascending phrase of the primary song.

3. Distress call. It was heard only once, when a captured bird was being freed from a net. When the bird was almost disentangled it uttered 10 high-pitched, plaintive notes. The quality of the notes suggested a relationship to the song phrase rather than to other types of vocalization. A nesting pair of Bell Vireos, 10 feet away, became extremely excited when they heard the distress notes. They "scolded" vigorously and flew around my head at a distance of six feet.[Pg 258]

4. Alarm note. This is a specialized, three-note call of the male and was heard only from the onset of pair-formation through early nestbuilding. This whinnying, flickerlike call, phonetically eh-eH-EH, each succeeding note of which is louder than the one before, is given whenever the male is disturbed by an unfamiliar object. This call is generally succeeded by the chee, but occasionally blends into an extended "whinny," and is typically given from some perch affording an unobstructed view of the offending object. The male stretches his neck and cocks his head, the wings and tail are not flicked or fanned, and no feather tracts are erected. The bird, nevertheless, flits nervously from perch to perch when uttering the call.

5. The zip. The male has a special "scold" note of his own that is heard when an intruder first approaches the nest. Phonetically it is zip-zip-zip. It is not so loud as the chee, and the delivery is more deliberate than that note. If the intruder remains near the nest, the zip is usually replaced by the chee.

6. The generalized call note or chee. The call notes associated with several situations are combined under this subheading since all can be rendered in English by the same phonetic equivalent—chee. The chee associated with nestbuilding is of moderate pitch and delivered deliberately at a rate of about 40 per minute. The feeding call of the adults is a soft slurred chee, while that of the nestlings has a mewing quality. In general, the chee utilized in signal situations consists of a few repetitions of the basic note emitted at a moderate pitch. The chee associated with hostile and courtship behavior is higher pitched and the delivery is much more rapid, approximately 200 per minute. Nolan (1960:240) reports a continuous rate of 25 per five seconds when an adult Bell Vireo is alarmed. The chee of extreme anxiety is a loud emphatic buzz, phonetically ZZ-ZZ-ZZ-ZZ.

The Bell Vireo exhibits "classic" passerine territoriality. Within a specific area, a pair of this species carries out pair-formation, courtship activities, copulation, nesting, rearing the young, and foraging. With the cessation of reproductive activities, a pair continues to restrict its other daily activities to the same general area.

In early May the segment of the total suitable habitat within which a Bell Vireo restricts its activities is not rigidly defined and the first male of the season ranges over an area too large to be maintained permanently—one that seems greatly to exceed the needs of breeding. Male 1 (1960), for instance, was first seen foraging over an area of approximately seven acres. With the influx of other males, portions of this large tract were usurped and the territory of the original male was gradually reduced to an area of little more than an acre.

In this initial period, a male becomes identified with a large area but is restricted to an area of nearly typical size by the encroachment of other males. Territorial disputes in this period often involve physical contact, as well as protracted sessions of high-intensity singing at rates exceeding three hundred song-phrases per hour.

Eventually the carrying capacity of the habitat is reached and no further partitioning occurs. The beginning of nestbuilding coincides with this relative stabilization of the territorial boundaries. Through the remainder of the cycle of behavior associated with any one nest, all activity is that of the occupant pair within its territory.

The nine original territories established in 1960 varied in size from 0.26 acre to 3.1 acres (Table 2). Fitch (1958:270) found the territories of several pairs of Bell Vireos at the University of Kansas Natural History Reservation to vary from 0.4 to 1 acre. Hensley (1950:243) estimated the size of the territory of a pair of Bell Vireos observed in Piatt County, Illinois, at 3.1 acres. Nolan (1960:227) records home ranges of 2 to 3 acres. The pairs that he studied were sole occupants of fields several acres larger than the portions actually utilized. His description of the vegetation indicates that most of the second growth was not much taller than 7 feet. As indicated elsewhere, the second-growth in my tract averaged 15 feet tall. The smaller average size of territory (1.25 acres) that I found is probably a function both of this greater vertical range of available foraging area and the much higher gross density of birds (40 pairs per 100 acres).

Most pairs remain in their original territories throughout the summer, although some shift certain territorial boundaries. In 1960 pairs 2 and 6, in the course of selecting a site for a replacement nest, annexed adjacent areas previously occupied by other pairs. Pair 2 relocated in a space that originally included territories 1 and 4, and pair 6 built a nest in an area formerly occupied by pair 7. Males 1 and 4 were sacrificed for specimens and pair 7 probably was destroyed by a predator. Owing to the presence of a nest, the annexed area becomes the focal point of the activities of a pair, but the original area is regularly visited and may be returned to in a later renesting.

| Territory | Date first occupied | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | May 3, 1960 | 1.6 acres |

| 2. | May 5, 1960 | 0.6 acre |

| 3. | May 7, 1960 | 0.26 acre |

| 4. | May 11, 1960 | 1.03 acres |

| 5. | May 12, 1960 | 2.07 acres |

| 6. | May 14, 1960 | 3.1 acres |

| 7. | May 13, 1960 | 1.7 acres |

| 8. | May 14, 1960 | 0.46 acre |

| 9. | May 14, 1960 | 0.4 acre |

| Average 1.25 acres | ||

Except in the early stages of nesting, territory is maintained primarily by song. In the period of incubation a male regularly patrols his territory between sessions of sitting on the eggs. He sings several songs from each of several perches. A male follows a predictable path, rarely traveling more than 150 feet from the nest. Incipient patrolling is seen early in the breeding season when territorial boundaries are in a state of flux.

The male White-eyed Vireo travels a semi-predictable route, as does the Solitary Vireo (R. F. Johnston, MS). According to Lawrence (1953:50), the male Red-eyed Vireo has a distinct singing area completely divorced from the nest area dominated by the female. Southern (1958:109), working with this same species in Michigan, did not recognize separate areas, but found that the male wandered randomly over the territory.

[Pg 261] In a species so highly active as the Bell Vireo, the degrees of hostile action associated with an encounter overlap in such a fashion that no clearcut distinction can be drawn among the various displays. Nevertheless, certain generalized patterns are characteristic of all situations in which members of this species are in a state of anxiety. The threat displays described in the succeeding paragraphs may all be utilized within as little as two minutes; mutual agonism may be terminated at any stage by concerted attack of the dominant bird.

1. Vocal threat. When an intruder is discovered the resident male markedly increases his rate of singing. The alarm note, eh-eH-EH, is the first call uttered during the nestbuilding and egglaying periods.

2. Head-forward threat. If the intruder does not flee, the resident male adopts a specific threat posture. The head and neck are extended. The feathers of the crown are erected, but those of the body are sleeked. The bird crouches slightly and the tail is flicked laterally, but not fanned. The intensity of the singing increases and is supplemented by scolding, also delivered at a rapid rate. The intruder normally retreats at this juncture.

3. Wing-flicking and submaximal tail-fanning. If the interloper remains, the anxiety of the resident male increases. He slightly depresses the tail and, at the same time, rapidly fans and closes it. The tail is only partially fanned. The wings are held slightly away from the body and rapidly flicked above the back. This flicking should not be confused with quivering of the wings associated with begging and other solicitory postures. Song is now almost completely replaced by high-intensity scolding. Associated with this high degree of anxiety are displacement behaviorisms, including bill-wiping, reversal of direction on a single perch, and a nervous hopping from one perch to another.

4. Ruffling and maximum tail-fanning. This display is most often seen in conjunction with the harassment of predators, but occasionally it is observed in territorial disputes occurring at the boundary of adjacent territories where neither male is strictly dominant and in which there is much vacillation prior to attack. The feathers of the abdomen are ruffled. The term "ruffled" pertains to a full erection of the feathers, giving a ragged appearance to the body outline (Morris, 1956:80). Ruffling of the abdominal feathers emphasizes their yellow color and seemingly heightens the intimidatory effect. The tail is fully fanned, and so maintained, [Pg 262] for a few seconds at a time; it is held at a 45° angle to the body. The scold becomes an extremely intense, stacatto buzz, ZZ-ZZ-ZZ-ZZ.

5. Supplanting attack. The attack directed against a trespassing male is initiated as a lunge that results in a collision with the opponent in mid-air or on his perch. The bird attacked is struck by his adversary's open beak or body.

Hinde (1952:71-72) indicates four courses of action followed by a Great Tit (Parus major) when attacked under similar circumstances. "(a) It flies away: The attacker usually flies after it and a chase ensues. (b) It shifts its perch a few inches: the attacker lands in its place, and both usually show head-up postures. (c) It remains where it is, but adopts a head-up posture: the attacker usually then shows upright flight. (d) It may fly up and meet the attacker in mid-air: in that case an actual combat may result, or both combatants may show upright flight."

Head-up posturing and upright flight are not presently recognized components of the behavior of the Bell Vireo. The behavior of the attacked Bell Vireo is similar to that described in (a), (b), and (d) above, and is clearly dictated by the proximity of his own "home base."

Eleven disputes among occupants of adjacent territories were witnessed between May 6 and June 3, 1960, in which some or all of the described threat displays were manifest (Table 3). In each instance, patrolling males were gradually attracted to each other. As they approached, their rates of song increased from an average of six repetitions per minute to 15 per minute. Eight of the disputes involved physical combat.

On May 6, 1960, when male 2 (1960) was in the process of usurping an eastern segment of the original territory of male 1 (1960), a violent, protracted dispute was observed. By this date male 1 (1960) had obtained a mate and had begun construction of nest 1-a (1960); male 2 (1960) had not yet acquired a mate. At first the two males were singing vigorously, from one to 10 feet apart. Female 1 (1960) followed her mate closely and scolded, at the same time partially fanning her tail. In the course of vocal dueling the males had traveled to within 50 feet of nest 1-a (1960), when male 1 (1960) suddenly lunged at 2 (1960). The males plunged to the ground, locking bills and clutching at each other with their feet as they fell. As soon as they touched the ground they separated. [Pg 263] Male 2 flew east with male 1 in pursuit. This conflict lasted three minutes.

Additional physical combat was witnessed several minutes later. This again involved striking with the bill, wings and feet. A high pitched squeaky chee was uttered by both combatants. The female scolded from a nearby perch. Upon separating, the males engaged in a wild, looping flight. At about 350 feet from nest 1-a (1960), the chase abruptly ended. For ten minutes thereafter, both males sang at a high rate from perches about 10 feet apart. This terminated the physical combat, but three additional protracted, vocal duels occurred in the remainder of the morning.

| Number of conflicts | Vocal dueling | Combat | Average length of disputes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenesting | 3 | 3 | 2 | 6 min. 40 sec. |

| Building | 8 | 8 | 6 | 3 min. 8 sec. |

| Incubation | 1[B] | 1 | ... | 20 min. |

| Totals | 12 | 12 | 8 | 5 min. 30 sec. |

[B] Directed against a stuffed Bell Vireo.

Probably as a direct result of these conflicts, a neutral zone approximately 300 feet wide developed between the two territories. By May 14 this intervening area was occupied by male 4 (1960). By this date both 1 (1960) and 2 (1960) were involved in nestbuilding and 4 (1960) was not challenged for several days.

Maximum tail-fanning prior to attack also appears as an element of aggressive behavior in White-eyed Vireos. A brief skirmish between a male of this species and a small, greenish passerine was observed at the Natural History Reservation on May 25, 1960. The White-eyed Vireo was singing from a perch 30 feet high in a dead elm, when the unidentified passerine landed 10 feet distant. The white-eye ceased regular song and uttered several catbirdlike calls, and at the same time slightly depressed and fully fanned the tail. After 10 seconds, the white-eye lunged at the intruder, striking it in mid-air. A brief looping flight ensued through the branches of the elm before the intruder was able effectively to retreat.

The female Bell Vireo is concerned primarily with the defense of the nest and the young and she rarely assists the male in defense of distant parts of the territory. She employs the same threat displays as the male.

A number of meetings between Bell Vireos and other species were observed in the course of the study (Table 4). Resident pairs of this species exhibited different degrees of tolerance toward other species. Many birds, including Cardinals, Field Sparrows, Painted Buntings and Mourning Doves were ignored completely. Chickadees evoked responses characterized by slight increase in song and some anxiety; this was perhaps owing to similarity in size, motion and call notes. Warblers, when met with, were invariably chased. They may be momentarily mistaken for rival vireos.

| Species | Number of conflicts | Phase of breeding cycle | Behavior of Bell Vireos | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFT[C] | S | TF | A | |||

| Coccyzus americanus | 1 | Nestling period | x | |||

| Cyanocitta cristata | 3[D] | Nestling and incubation period | x | x | x | x |

| Parus atricapillus | 1 | Prenesting | x | |||

| Molothrus ater | 1 | Nestling period | x | x | ||

| Dendroica petechia | 1 | Prenesting | x | x | ||

| Geothlypis trichas | 1 | Nestbuilding | x | x | ||

| Pituophis catenifer[E] | 1 | Post-fledging | x | x | ||

[C] HFT = head-forward threat; S = scolding; TF = tail-fanning; A = attack.

[D] Includes attack against a dummy Blue Jay.

[E] The Bull Snake is here included because the vireos directed typical aggressive displays towards it.

Blue Jays were vigorously attacked, especially late in incubation and throughout the nestling period of the Bell Vireo. I did not see a jay struck, but a vireo would circle one closely as it perched and pursue it when it flew, following as far as 100 yards beyond territorial bounds. The buzz, ZZ-ZZ-ZZ-ZZ, was uttered in conjunction with this harassment.

A stuffed jay placed eight feet from a nest elicited threat display and displacement behavior from the owners of the nest, but no [Pg 265] attack. Incubation had just begun at this nest. A dummy Bell Vireo placed close to another nest only momentarily disturbed the male, and the female completely ignored it. Incubation had also recently begun at this nest. At this same general stage, moreover, nesting pairs showed little inclination to harass me.

Hinde (1956:341-342) indicates that territory has been defined in a number of ways by many workers. All of the definitions involve modification of Howard's classic "defended area." Pitelka (1959:253) has reacted against this behaviorally-oriented concept. He thinks that the concept of territory should be based on exclusive use of an area by its occupants, and not so much the defense by which they maintain it.

Methods of treating territoriality in the Bell Vireo seemingly incorporate features of both schools of thought. The area used exclusively for all biological needs by a single pair of Bell Vireos is vigorously defended both physically and vocally early in the breeding season and vocally as the season progresses.

In the period of territorial establishment a relatively large area is actively defended. The building of a nest establishes a focal point of activity in a somewhat more restricted area than that originally occupied. After the success or failure of a nest, a new site is selected to which the focal point of activity is shifted. If suitable habitat adjacent to the extant territory is unoccupied by other Bell Vireos the unoccupied area may be annexed in the course of searching for a new site. Such annexation occurs only when pairs formerly occupying adjacent suitable habitat disappear from this territory; possibly the size of the territory of any one pair is dictated by the density of population of the species as well as by the presence of suitable habitat. This may not always be true as indicated by Kliujver (1951:40), who in studying the Great Tit, found no appreciable difference in the size of territory in two different habitats even though there was a marked difference in population density of the birds.

Fluctuation of territorial boundaries is not uncommon in passerines, especially when no rivals exist to contest movement. Hinde (1956:351) indicates that fluctuations in size of territory are to be expected although the territories of different species of birds have different mean sizes.

Once nesting activities commence there is a marked reduction in [Pg 266] the amount of territory utilized and a distinct decrease in the aggressive tendencies of the male; it would seem that energy previously utilized in regular fighting is rechanneled for nestbuilding, incubation and care of the young. Further, contraction of the area of activity obviates high-intensity territorial defense, as adjacent males, even in regions of high population density, are isolated from one another by an area no longer regularly traversed.

With cessation of breeding activities physiological mechanisms governing maintenance of territory seemingly are no longer active and yet the pairs of Bell Vireos remain within a restricted area which they alone use. Earlier definitions of territory as a "defended area" do not adequately cover such situations and yet from the standpoint of Pitelka the area still retains the characteristics of true territory. In fact, territory as defined by Pitelka is clearly manifest at this time. Whether the birds remain in an area through "force of habit" is of little consequence.

I have retained the term "territory" in preference to the term "home range" used by Nolan (1960:227). His failure to observe territorial defense is responsible for his terminology, although it is readily understandable that such defense would be lacking in a population of relatively low density in which pairs were isolated from one another by areas of unfavorable habitat. This isolation in itself would tend to preclude territorial conflict but territories were, in fact, maintained.

The marked similarity in the essential features of aggressive behavior in North American vireos attests to their close relationship. Flicking and fanning of the tail are distinct components of the hostile behavior of the Bell Vireo, White-eyed Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo (Lawrence, 1953:69), and the Black-whiskered Vireo (Vireo altiloquus; Bent, 1950:319), and, presumably, of the remaining species of the genus. The occurrence of these same displays as intrinsic behavioral elements of interspecific hostility suggests a common derivation. Moynihan (1955:256) indicates that all intraspecific hostile displays, and probably most interspecific hostile displays, evolved originally as social signals having the same general function. Further, Hinde (1956:344) points out that there is a fundamental similarity in the motor patterns used in fighting in different contexts, including both interspecific and intraspecific fighting.

The precise mechanism of pair-formation in the Bell Vireo is not known. My experience has been to find a male one day and then one or two days later to discover that it has a mate. Lawrence (1953:53), tells of a male Red-eyed Vireo singling out a female from a flock of migrants passing through his territory and violently driving her to the ground. Shortly after this attack the pair was seen searching for a nest site. But such an incident has not been reported for other vireos, nor have I witnessed such behavior myself.

Early courtship activities of the Bell Vireo are characteristically violent affairs, with the male directing strong aggressive attacks toward the female. Rapid, looping flights through the thickets occur, the female leading the male. Occasionally he deliberately collides with her in mid-air, but the pair quickly separate. This violent sexual chasing is manifest prior to the inception of nestbuilding. With commencement of this activity, sexual chases through the territory subside.

Absence of sexual dimorphism in the Bell Vireo obviously suggests that behavioral criteria are used by the birds in sex-recognition. The lack of aggression by the female upon initial aggression by the male is an essential component of recognition of sex; she is clearly subordinate. Such subordination is also the significant feature of continued sex-recognition. Courtship display by a resident male, directed toward a stuffed male and a wounded male which sat motionless, supports the contention that a subordinate or submissive attitude of the female is a key factor in sex-determination.

Nestbuilding and courtship are intimately associated in this species. The male constructs the suspension apparatus of the nest, the completion of which coincides with the assumption of nestbuilding activity by the female. Roles of the sexes in nestbuilding are described in the section on nestbuilding. The male frequently interrupts construction to court the female. This, in combination with perpetual song as he works, serves to strengthen the pair-bond and stimulate nestbuilding tendencies of the female.

It is doubtful that any attempts at copulation are successful up to this time. The female is singularly unresponsive to the advances of the male; a female retreats before most violent attacks and is seemingly oblivious to less vigorous behavior. After the female [Pg 268] assumes the responsibility of building, the tempo of courtship activities increases.

The female becomes increasingly more receptive and her work is often interrupted by advances of the male. Copulation occurs frequently from about the third day of nestbuilding through the first day of egglaying, a period of four to six days. Male displays and vocalizations associated with courtship continue through the fourth or fifth day of incubation.

The principal courtship displays and postures that were seen throughout the nestbuilding phase are as follows:

1. Greeting ceremonies. Both birds are crouched from one to five inches apart. The feathers on one (the male?) are sleeked, and on the other are fluffed. Fluffing (Morris, 1956:80) denotes partial erection of the body feathers producing a rounded, unbroken body line and is not to be confused with ruffling, mentioned in the sections pertaining to territoriality and pre- and post-copulatory display. Fluffing is generally considered to be an appeasement display and it is seen in a variety of situations involving a dominant-subordinate relationship. Both birds flick wings and tails rapidly and reverse directions on their perches frequently. A low, rapid chee is uttered during this performance. This ceremony is repeated often in the first three days of nestbuilding, but less frequently thereafter. It usually occurs after building by one or both partners and prior to another trip in search of nesting material. It lasts from 10 to 50 seconds and is not immediately followed by any additional courtship activities. Nolan (1960:228-229) observed mutual displays between periods of violent sexual chase that suggest that the greeting ceremonies that I have described are an integral part of pair-formation as well as a component of continued maintenance of the bond.

2. "Pouncing." The female rapidly quarter-fans and partially depresses her tail. She utters a high pitched scold (chee). The male, from a perch within two feet of the female, fans the tail fully and depresses it vertically, and, with mouth open, lunges at the female; or, with similar tail mannerisms, the abdominal feathers ruffled, the wings held horizontally, and the primaries spread, he sways from side to side from four to six times, and then lunges at the female. The male is silent when he pounces; the chee or the courtship song is emitted when swaying precedes pouncing. The male strikes the female with his breast or with his open beak. The female rarely flees although she is usually displaced several inches [Pg 269] along the branch upon which she is sitting. However, the female may fly several inches to a new perch. The failure of the female to adopt a solicitation posture presumably indicates sexual unreadiness. Instances of the male deliberately colliding with the female as she flies in the course of gathering nesting material are probably analogous to pouncing. In none of the above situations are females observed to fight back in any way. Nice (1943:174) believed pouncing to be analogous to sexual chasing found in such species as the Red-winged Blackbird. In the Song Sparrow, pouncing is observed most often in the first and second days of nestbuilding.

3. "Leap-flutter." The male, in the course of displaying with the tail fanned before the female, suddenly leaps eight inches to ten inches vertically and flutters in mid-air several seconds, before dropping to the original perch. This display occurs in full view of the female. It is often associated with pouncing and is also seen prior to copulation. In the latter instance it is probably pragmatically functional, for it permits the male to orient above the female before dropping to her back to copulate. No vocalization is uttered during the leap-flutter.

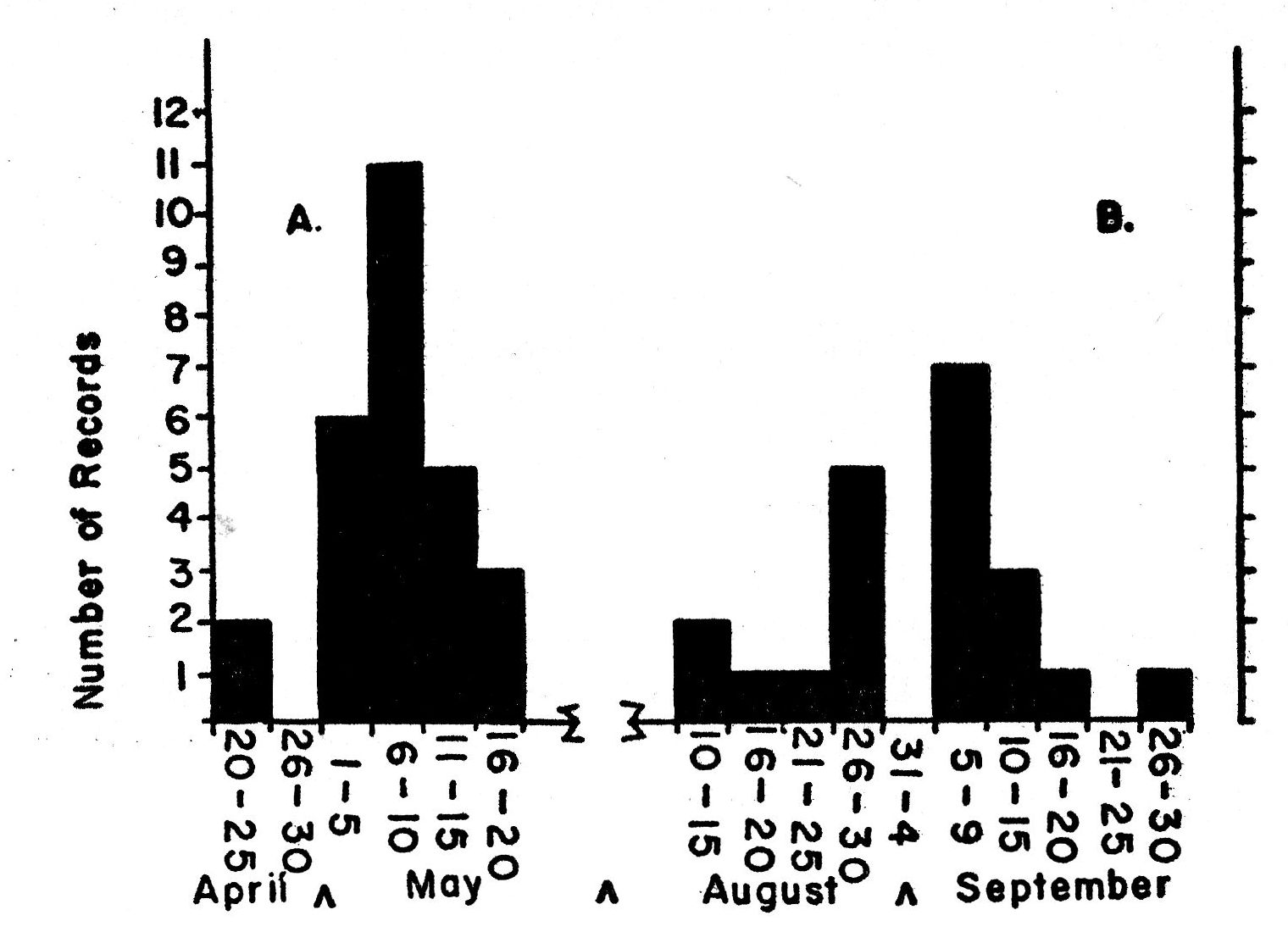

Fig. 3. A single male Bell Vireo

in the pre-copulatory display. Note the ruffled dorsal and ventral body feathers.

The male on the left has reached the zenith of a single swing. The male on the

right has nearly reached the low point of a swing.

Fig. 3. A single male Bell Vireo

in the pre-copulatory display. Note the ruffled dorsal and ventral body feathers.

The male on the left has reached the zenith of a single swing. The male on the

right has nearly reached the low point of a swing.

4. Pre-copulatory display (Fig. 3). The male faces the female. The tail is fanned fully and depressed at a sharp vertical angle to the body. Body feathers, both dorsal and ventral, are ruffled, almost tripling the apparent volume of the thorax. The head is withdrawn and slightly thrown back. Feathers of the head are not erected. [Pg 270] The mouth is opened wide. The legs are slightly flexed and the body is swayed laterally. Horizontally, the head and body traverse an arc of about 100°; vertically, they traverse an arc slightly less than 180°. At the low point of any one swing, the delivery of the courtship song begins. At the termination of the swing the two normal, ascending notes are emitted. This performance may last as long as three minutes.

The pre-copulatory display of the male elicits receptive behavior in the female. She crouches in a solicitous manner, with the body feathers fluffed and the tail raised slightly, and utters a muted chee.

5. Copulation. The male abruptly terminates his swaying display with a leap-flutter that positions him above the female's back. He then descends and copulation occurs. The male continues to flutter his wings to maintain balance throughout the two seconds of cloacal contact. Following an unsuccessful copulation on June 23, 1960, displacement preening and bill wiping were performed by both sexes.

6. Post-copulatory display. On June 25, 1960, after a second attempt at copulation with a stuffed bird in which semen was actually deposited on the dummy's back, male 10 (1960) performed a swaying display. In this instance, however, instead of addressing the dummy from the front, the male alighted one inch to the right of the stuffed bird. When swaying to the left (toward the dummy) the head of the displaying male actually passed above the neck of the stuffed bird. This ritualized behavior could conceivably be derived from hetero-preening.

Within the scope of my research it was difficult to detect the over-all sequence of epigamic displays that result in synchronization of the physiological states of the sexes throughout the period of courtship. Possibly all displays, except the post-copulatory one, occur in no particular order in the courtship period. However, each ritualized display seemingly strengthens the pair-bond.

Swaying has been recorded in a variety of situations of a sexual and semi-sexual nature for the Solitary Vireo (V. solitarius; Townsend, 1920:158) and the Red-eyed Vireo (Tyler, 1912:230; Bent, 1950:342). In every instance the body feathers of the swaying birds were sleeked. Courtship behavior in any species of North American vireo seems closely to resemble that of any other; pairing [Pg 271] and nestbuilding of a female V. solitarius and a male V. flavifrons as reported by Hauser (1959:383) support the idea of close resemblance.

A marked similarity will be detected between certain basic elements of aggressive and epigamic displays. These basic elements are wing- and tail-flicking, tail-fanning, and high-intensity delivery of the chee. Pouncing and supplanting attacks are essentially similar. Such similarities suggest either a common origin for certain aggressive and epigamic displays or the derivation of one from the other.

High-intensity cheeing is obviously a function of excitement, whether in conjunction with hostility or sexual behavior. According to Andrew (1956:179), flicking of wing and tail in passerines are intention movements of flight. These actions have been emancipated from incomplete take-offs and incorporated in ritualized courtship and agonistic behavior. In incipient courtship behavior the male is governed by three conflicting tendencies; to flee, to attack, or to behave sexually before his mate (Tinbergen and Hinde, 1958:256). When pairing, Bell Vireos interrupt sexual chase with "greeting ceremonies," the male's tendency to attack and the female's tendency to flee are momentarily reduced, and the forming bond is strengthened. Thus, the intention movements become an integral part of courtship.

In situations where attacking and fleeing are the two conflicting tendencies, wing-flicking and tail-flicking are incorporated into threat display, but do not lose all of their original function, for they facilitate attack. Tail-fanning, as a display element, increases the awesome aspect of the threatening bird and in courtship presumably makes the sexes more attractive to one another.

Courtship feeding has not been recorded for the Bell Vireo. In general, it is unknown in North American vireos, with the exception of the red-eye (Lawrence, 1953:53). It would serve no "practical" purpose in the Bell Vireo since the male regularly relieves the female during incubation, thus allowing her ample opportunity to forage. In the Red-eyed Vireo, only the female regularly incubates, and courtship feeding is definitely functional. Nolan (1960:228) described a brief pecking or pulling with their bills between pairing birds. This may be incipient "symbolic" courtship feeding, or perhaps mutual preening.

As far as can be determined, the nest-site is selected by the female. Typically, the pair makes short, low-level flights from tree to tree with the female invariably in the lead. The birds usually forage within each tree; the female interrupts this activity to inspect small forks of low, pendant branches and the male occasionally pauses to sing. The singing is loud but not particularly regular, as it is later when the male accompanies the female during actual nestbuilding. Method of selection of site resembles that described by Lawrence (1953:53) for the Red-eyed Vireo.

Nests are suspended from lateral or terminal forks about 27 inches high in bushes and small trees that, in the study area, averaged 11 feet, four inches in height (Table 5). The height above ground of the nests does not vary appreciably as the season progresses as is the case with nests of Red-eyed Vireos, for which Lawrence (1953:54) noted that late nests were placed higher than those built earlier in the season.

Most nests are so situated that they are protected and concealed by the dense foliage of trees. Where nests are placed in low bushes, as coralberry or dogwood, the bush is invariably overhung by the foliage of a much taller shrub or tree.

The nest tree or shrub was in every instance situated at the edge of a thicket or isolated from adjacent trees by several feet. Preference for open situations is characteristic of the species. In contrast, the nest of the White-eyed Vireo (Bent, 1950:229) is placed toward the center of thickets.

In the choice of sites in the study area, the Bell Vireos were almost unopposed by other avian species, owing to the size of the [Pg 273] fork utilized and the fact that the nests are located peripherally, rather than centrally, in the bush or tree. This lack of competition for a nest-site provides a Bell Vireo with an ample supply of nest-sites within any one territory.

| Plant | Number of nests | Average height of plant | Average height of nest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulmus americana | 4 | 7 ft. 6 in. | 2 ft. 3 in. |

| Maclura pomifera | 20 | 13 ft. 11 in. | 1 ft. 11 in. |

| Crataegus mollis | 1 | 11 ft. | 3 ft. 1 in. |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | 2 | 15 ft. 6 in. | 1 ft. 9 in. |

| Acer negundo | 4 | 8 ft. 9 in. | 2 ft. 5 in. |

| Cornus drummondi | 2 | 8 ft. | 2 ft. 8 in. |

| Symphoricarpos orbiculatus | 3 | 3 ft. | 1 ft. 10 in. |

| 7 | 36 | 11 ft. 4 in. | 2 ft. 3 in. |

Selection of the first nest-site may take as long as two days, possibly owing to incomplete development of the nesting tendency, but more likely to a general lack of familiarity with the territory. Red-eyed Vireos require five to six days to choose the first nest-site (Lawrence, 1953:54). Later sites of the Bell Vireo are chosen in as little as three hours. Nest 1-c (1960) was abandoned at about 11:00 a.m. on May 14, 1960, when part of the thicket on the edge of which this nest was located was removed by brush-cutters clearing a power line right-of-way. By 2:00 p.m. this pair had begun construction of 1-d (1960) in an Osage orange 110 feet southwest of 1-c (1960).

This particular site is of further interest because it is the same one utilized for nest 1-a (1960). In all, four instances of utilization of a nest-site a second time were recorded. Two-a (1960) and 2-d (1960) were built in the same fork; 1-c (1960) and 1-h (1960) were in the same tree, but not the same fork. It should be mentioned that 1-a (1960) and 2-a (1960) were abortive attempts that did not progress beyond the suspension apparatus. Nice (1929:16) recorded a similar instance of the re-use of a nest tree, but different forks were used.

Re-use of an exact nest-site would ordinarily be impossible if the initial attempt were not abortive, because the presence of a completed nest would pose problems in construction with which the birds would probably be unable to cope. (A report by Morse in Bent, 1950:256 of a double nest indicates that this may not always be true. At the time of discovery one nest contained two eggs and the other nest contained young.) Since nests are used only once there would be no tendency to adopt the old nest. However, abortive nests, usually little more than a few strands of nesting material secured to the fork, might stimulate the birds to continue building. Re-use of a single nest-site in 15.8 per cent of 38 nests built in 1960 seems to be more than fortuitous circumstance. This re-use may have physiological benefits in conjunction with apportionment of energy for other nesting activities, because rapid location of a nest-site would mean that energy normally expended in searching and selecting could be rechanneled for actual construction. In each of the instances of rebuilding, the new nest was [Pg 274] begun on the same day that the previous nest was abandoned.

The re-nesting of pair 9 (1960) is worthy of note. These birds were established in the elm thicket on Clark land. Elm was by far the most abundant tree, with dogwood, Osage orange and honey locust also relatively common. There were only six boxelders in the territory and yet the four nests built by this pair were placed in them. This is the only instance of seeming preference.

Nestbuilding by Bell Vireos can be best discussed in terms of the phases of construction described for the Red-eyed Vireo, Lawrence (1953:57), which are: (1) construction of the suspension apparatus, (2) construction of the bag, (3) lining of the bag and smoothing and polishing of the exterior, and (4) adornment of the exterior. Red-eyes (Lawrence, 1953:59) may continue adornment far into the period of incubation. Both the male and female Bell Vireo have been observed to add spider egg sacs and other silk to the exterior of the nest as late as the sixth day of incubation.

Nice (1929:16) recorded only the female Bell Vireo building, but she did recall, from previous studies, having seen males aiding somewhat. Pitelka and Koestner (1942:102) wrongly concluded that the female Bell Vireo builds unaided, but Hensley (1950:243) observed that both sexes participated in nestbuilding, and Mumford (1952:229) reported two instances of building by both adults. His description of the activities viewed in mid-May suggest that they were of the transitional period between the first and second phases. On the second occasion he recorded both adults building during the second phase. Since no details accompany this second observation I assume that it pertained to activity not necessarily typical of this phase of construction. Whereas both sexes of the Bell Vireo cooperate in building the nest, only the female Red-eyed Vireo builds according to Lawrence (1953:56). But Common (1934:242) saw both Red-eyed Vireos building a nest.

The suspension apparatus is constructed by only the male on the first day. He punctuates each trip to the nest with song. The single song phrase is given from three to eight times when the male, carrying nesting material in his bill, arrives in the tree. Typically, he alights on several perches within the nest tree before flying to the nest. He often interrupts his work with several songs; when he has finished adding a load of material he sings from several perches [Pg 275] within the nest tree before departing. The male periodically stops building to court the female.

In eight hours (494 minutes) of observing the first phase of construction at five different nests, I saw the female come to the nest 28 times; the male made 95 trips. The female came alone only once, and brought nesting material ten times, but did not build; on the other 18 occasions her visits were brief and she usually confined her activities to an inspection of the nest. Twenty of the visits by the female were made late in the first phase, marking a gradual transition to her assumption of building responsibility. (The delay by the female in beginning to build is puzzling; because all evidence indicates that she helps select the nest-site, I would expect her to help with the initial building. There seems to be no clear advantage in her delay in beginning to build.) The courtship and building activities of the male plus the presence of a partly completed nest seem to stimulate the female to commence building. Her visits become more frequent as construction of the suspension apparatus nears completion. At a time early in the second day the transition has taken place, and the female becomes the sole worker.

On May 7, 1960, male 2 (1960), at the time unmated, was observed as he came upon a nest of the previous year. The nest, after a year's weathering, suggested in appearance perhaps an early second-day nest. The bird flew to the nest and tugged and wove loose strands of grass for three minutes. Before leaving the site, the bird sang twice from different perches. This observation suggests that a partly constructed nest can elicit nestbuilding behavior, even in an unmated male.

The techniques of building by the male consist primarily of laying pieces of grass or bark across the fork, or along one of its branches, and then fastening them in place with pieces of animal silk. Once a "racket" has been formed, spider egg cases and plant down are emplaced among the fibers. The male employs weaving, twisting, and pecking motions of the head to emplace material.

As previously indicated, the female is the principal worker in the second and third phases of construction. The male infrequently visits the nest, but regularly visits the nest tree. The molding of the bag is accomplished by piling leaves, grasses and plant down onto the suspension apparatus. This material is also bound in with animal silk. As the amount of material accumulates, the female begins to trample it and gradually the bag takes shape. When trampling is [Pg 276] first attempted, the nest often fails to support the female and she falls through the bottom of the nest. Such an occurrence was observed on May 23, 1960, on three consecutive trips by female 1 (1960), in constructing nest 1-e (1960). As the bag deepens, additional strands of grass are added to the wall and woven into place.

The male is extremely attentive during this and the following phase. He follows the female as she gathers nest-material accompanying both this activity and her building with rapid song; he may give an average of seven song phrases per minute. The male brings to the nest a strand of grass, or some other material, about every twentieth trip. He frequently inspects the nest and the activities of the female from perches near the nest. Construction of the bag is ordinarily completed in the third day.

The third phase, the lining of the interior and the smoothing of the exterior, involves an additional one and one-half to two days. Smoothing of the exterior refers to tightening of the grasses woven into the bag and addition of more animal silk. In lining the nest, the female stands on one of the branches of the fork and emplaces one end of a long, thin strand of some relatively stiff piece of grass or strip of bark. She then jumps into the bag and, while slowly turning around, pecks it into place, thus coiling the strand neatly around the interior of the bag.

As previously mentioned, the fourth phase overlaps the periods of lining, smoothing, egglaying, and incubation. The principal activity is the addition of white spider egg sacs to the exterior. The trips are infrequent; but, occasionally, birds will interrupt an hour of incubation with three or four minutes of active adornment, during which several trips may be made. Both sexes participate in this phase.

Nesting materials were gathered anywhere within the territory. Occasionally materials were collected from within the nest tree, but usually they were obtained 20 to 200 feet from the nest-site. On several occasions I observed birds inspecting stems or branches where bark was frayed. Loose ends are grasped in the beak and torn free with an upward jerk of the head. Possibly the notch near the distal end of the upper mandible aids in grasping these strands. Plant down is first extracted and then rolled into a ball by means of the beak while held with the feet before being transported to the nest.

As indicated by Nolan (1960:230), accurate determination of the length of nestbuilding is difficult because of continued adornment and polishing after the nest is functionally complete. Most of the early nests for which I have records took from four and one-half to five days to construct. A four-to five-day period of building is reported by other observers (Nice, 1929:16; Pitelka and Koestner, 1942:99; Hensley, 1950:242; Nolan, 1960:230).

One instance of protracted building was recorded. Nest 6-d (1960) was begun on May 29, 1960, and not completed until nine days later on June 6, 1960. In contrast nest 1-g (1960) begun on May 31, 1960, was finished three days later on June 2, 1960. Nestbuilding occurs between the hours of 6:00 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. Heavy rain in the early morning may delay building.

Eight of 38 nests started in 1960 were never completed (Table 6). Six of these abortive attempts were abandoned during, or shortly after, the completion of the suspension apparatus. Five of these nests were abandoned because the female did not begin building following the end of work by the male. The early abandonment of the other three nests 1-a (1960), 2-c (1960) and 6-e (1960) was attributable to the interruption of building by the male because of heavy rain and protracted territorial conflicts. The occurrence of these abortive nests at any time within the nesting efforts of a single pair indicates that such attempts are not examples of "false nestbuilding."

Renesting after desertion or successful fledging occurs within two to thirty-six hours. Young were fledged from 1-a (1959) on June 19, 1959, and nest 1-b (1959) was discovered when late in the second phase of construction on June 22. If the nest was started on June 20, then renesting took place within 15 hours after fledging.

Several authors have described various aspects of the nest of the Bell Vireo, notably Goss (1891:535); Simmons (in Bent, 1950:256), Nice (1929:13) and Nolan (1960:230-231). I can add but little to these descriptions.