Project Gutenberg's The Story of Chautauqua, by Jesse Lyman Hurlbut This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Story of Chautauqua Author: Jesse Lyman Hurlbut Release Date: June 10, 2010 [EBook #32768] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF CHAUTAUQUA *** Produced by Emmy, Tor Martin Kristiansen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

An ancient writer—I forget his name—declared that in one of the city-states of Greece there was the rule that when any citizen proposed a new law or the repeal of an old one, he should come to the popular assembly with a rope around his neck, and if his proposition failed of adoption, he was to be immediately hanged. It is said that amendments to the constitution of that state were rarely presented, and the people managed to live under a few time-honored laws. It is possible that some such drastic treatment may yet be meted out to authors—and perhaps to publishers—as a last resort to check the flood of useless literature. To anticipate this impending constitutional amendment, it is incumbent upon every writer of a book to show that his work is needed by the world, and this I propose to do in these prefatory pages.

Is Chautauqua great enough, original enough, sufficiently beneficial to the world to have its history written? We will not accept the votes of the[viii] thousands who beside the lake, in the Hall of Philosophy, or under the roof of the amphitheater, have been inoculated with the Chautauqua spirit. We will seek for the testimony of sane, intelligent, and thoughtful people, and we will be guided in our conclusions by their opinions. Let us listen to the words of the wise and then determine whether a book about Chautauqua should be published. We have the utterances by word of mouth and the written statements of public men, governors, senators, presidents; of educators, professors, and college presidents; of preachers and ecclesiastics in many churches; of speakers upon many platforms; of authors whose works are read everywhere; and we present their testimonials as a sufficient warrant for the preparation and publication of The Story of Chautauqua.

The Hon. George W. Atkinson, Governor of West Virginia, visited Chautauqua in 1899, and in his Recognition Day address on "Modern Educational Requirements" spoke as follows:

It (Chautauqua) is the common people's College, and its courses of instruction are so admirably arranged that it somehow induces the toiling millions to voluntarily grapple with all subjects and with all knowledge.

My Chautauqua courses have taught me that what we need most is only so much knowledge as we can[ix] assimilate and organize into a basis for action; for if more be given it may become injurious.

Chautauqua is doing more to nourish the intellects of the masses than any other system of education extant; except the public schools of the common country.

Here is the testimony of ex-Governor Adolph O. Eberhardt of Minnesota:

If I had the choice of being the founder of any great movement the world has ever known, I would choose the Chautauqua movement.

The Hon. William Jennings Bryan, from the point of view of a speaker upon many Chautauqua platforms, wrote:

The privilege and opportunity of addressing from one to seven or eight thousand of his fellow Americans in the Chautauqua frame of mind, in the mood which almost as clearly asserts itself under the tent or amphitheater as does reverence under the "dim, religious light"—this privilege and this opportunity is one of the greatest that any patriotic American could ask. It makes of him, if he knows it and can rise to its requirements, a potent human factor in molding the mind of the nation.

Viscount James Bryce, Ambassador of Great Britain to the United States, and author of The American Commonwealth, the most illuminating[x] work ever written on the American system of government, said, while visiting Chautauqua:

I do not think any country in the world but America could produce such gatherings as Chautauqua's.

Six presidents of the United States have thought it worth while to visit Chautauqua, either before, or during, or after their term of office. These were Grant, Hayes, Garfield, McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft. Theodore Roosevelt was at Chautauqua four times. He said on his last visit, in 1905, "Chautauqua is the most American thing in America"; and also:

This Chautauqua has made the name Chautauqua a name of a multitude of gatherings all over the Union, and there is probably no other educational influence in the country quite so fraught with hope for the future of the nation as this and the movement of which it is the archtype.

Let us see what some journalists and writers have said about Chautauqua. Here is the opinion of Dr. Lyman Abbott, editor of The Outlook, and a leader of thought in our time:

Chautauqua has inspired the habit of reading with a purpose. It is really not much use to read, except as an occasional recreation, unless the reading inspires one to think his own thoughts, or at least make the writer's thoughts his own. Reading without reflection,[xi] like eating without digestion, produces dyspepsia. The influence and guidance of Chautauqua will long be needed in America.

The religious influence of Chautauqua has been not less valuable. Chautauqua has met the restless questioning of the age in the only way in which it can be successfully met, by converting it into a serious seeking for rest in truth.

Dr. Edwin E. Slosson, formerly professor in Columbia University, now literary editor of the Independent, wrote in that paper:

If I were a cartoonist, I should symbolize Chautauqua by a tall Greek goddess, a sylvan goddess with leaves in her hair—not vine leaves, but oak, and tearing open the bars of a cage wherein had been confined a bird, say an owl, labeled "Learning." For that is what Chautauqua has done for the world—it has let learning loose.

From the American Review of Reviews, July, 1914:

The president of a large technical school is quoted as having said that ten per cent. of the students in the institution over which he presides owe their presence to Chautauqua influence. A talk on civic beauty or sanitation by an expert from the Chautauqua platform often results in bringing these matters to local attention for the first time.

Here is an extract from The World To-day[xii]:

Old-time politics is dead in the States of the Middle West. The torchlight parade, the gasoline lamps, and the street orator draw but little attention. The "Republican Rally" in the court-house and the "Democratic Barbecue" in the grove have lost their potency. People turn to the Chautauquas to be taught politics along with domestic science, hygiene, and child-welfare.

Mr. John Graham Brooks, lecturer on historical, political, and social subjects, author of works widely circulated and highly esteemed, has given courses of lectures at Chautauqua, and has expressed his estimate in these words:

After close observation of the work at Chautauqua, and at other points in the country where its affiliated work goes on, I can say with confidence that it is among the most enlightening of our educational agencies in the United States.

Dr. A. V. V. Raymond, while President of Union College in New York State, gave this testimony:

Chautauqua has its own place in the educational world, a place as honorable as it is distinctive; and those of us who are laboring in other fields, by other methods, have only admiration and praise for the great work which has made Chautauqua in the best sense a household word throughout the land.

Mr. Edward Howard Griggs, who is in greater demand than almost any other lecturer on literary[xiii] and historical themes, in his Recognition Day address, in 1904, on "Culture Through Vocation," said as follows:

The Chautauqua movement as conceived by its leaders is a great movement for cultivating an avocation apart from the main business of life, not only giving larger vision, better intellectual training, but giving more earnest desire and greater ability to serve and grow through the vocation.

This from Dr. William T. Harris, United States Commissioner of Education:

Think of one hundred thousand persons of mature age following up a well-selected course of reading for four years in science and literature, kindling their torches at a central flame! Think of the millions of friends and neighbors of this hundred thousand made to hear of the new ideas and of the inspirations that result to the workers!

It is a part of the great missionary movement that began with Christianity and moves onward with Christian civilization.

I congratulate all members of Chautauqua Reading Circles on their connection with this great movement which has begun under such favorable auspices and has spread so widely, is already world-historical, and is destined to unfold so many new phases.

Prof. Albert S. Cook, of Yale University, wrote in The Forum[xiv]:

As nearly as I can formulate it, the Chautauqua Idea is something like this: A fraternal, enthusiastic, methodical, and sustained attempt to elevate, enrich, and inspire the individual life in its entirety, by an appeal to the curiosity, hopefulness, and ambition of those who would otherwise be debarred from the greatest opportunities of culture and spiritual advancement. To this end, all uplifting and stimulating forces, whether secular or religious, are made to conspire in their impact upon the person whose weal is sought. . . . Can we wonder that Chautauqua is a sacred and blessed name to multitudes of Americans?

The late Principal A. M. Fairbairn, of Mansfield College, Oxford, foremost among the thinkers of the last generation, gave many lectures at Chautauqua, and expressed himself thus:

The C. L. S. C. movement seems to me the most admirable and efficient organization for the direction of reading, and in the best sense for popular instruction. To direct the reading for a period of years for so many thousands is to affect not only their present culture, but to increase their intellectual activity for the period of their natural lives, and thus, among other things, greatly to add to the range of their enjoyment. It appears to me that a system which can create such excellent results merits the most cordial praise from all lovers of men.

Colonel Francis W. Parker, Superintendent of Schools, first at Quincy, Mass., and later at[xv] Chicago, one of the leading educators of the land, gave this testimony, after his visit to Chautauqua:

The New York Chautauqua—father and mother of all the other Chautauquas in the country—is one of the great institutions founded in the nineteenth century. It is essentially a school for the people.

Prof. Hjalmar H. Boyesen, of Columbia University, wrote:

Nowhere else have I had such a vivid sense of contact with what is really and truly American. The national physiognomy was defined to me as never before; and I saw that it was not only instinct with intelligence, earnestness, and indefatigable aspiration, but that it revealed a strong affinity for all that makes for righteousness and the elevation of the race. The confident optimism regarding the future which this discovery fostered was not the least boon I carried away with me from Chautauqua.

Mrs. Alice Freeman Palmer, President of Wellesley College, expressed this opinion in a lecture at Chautauqua:

I could say nothing better than to say over and over again the great truths Chautauqua has taught to everyone, that if you have a rounded, completed education you have put yourselves in relation with all the past, with all the great life of the present; you have reached on to the infinite hope of the future.

I venture to say there is no man or woman educating[xvi] himself or herself through Chautauqua who will not feel more and more the opportunity of the present moment in a present world.

The character of Chautauqua's training has been that she has made us wiser than we were about things that last.

Rev. Charles M. Sheldon, author of In His Steps, a story of which three million copies were sold, said:

During the past two years I have met nearly a million people from the platform, and no audiences have impressed me as have the Chautauqua people for earnestness, deep purpose, and an honest desire to face and work out the great issues of American life.

This is from the Rev. Robert Stuart MacArthur, the eminent Baptist preacher:

I regard the Chautauqua Idea as one of the most important ideas of the hour. This idea, when properly utilized, gives us a "college at home." It is a genuine inspiration toward culture, patriotism, and religion. The general adoption of this course for a generation would give us a new America in all that is noblest in culture and character.

Dr. Edward Everett Hale, of Boston, Chaplain of the United States Senate, in his Tarry At Home Travels, wrote:

If you have not spent a week at Chautauqua, you do not know your own country. There, and in no[xvii] other place known to me, do you meet Baddeck and Newfoundland and Florida and Tiajuara at the same table; and there you are of one heart and one soul with the forty thousand people who will drift in and out—people all of them who believe in God and their country.

More than a generation ago, the name of Joseph Cook was known throughout the continent as a thinker, a writer, and a lecturer. This is what he wrote of Chautauqua:

I keep Chautauqua in a fireside nook of my inmost affections and prayers. God bless the Literary and Scientific Circle, which is so marvelously successful already in spreading itself as a young vine over the trellis-work of many lands! What rich clusters may ultimately hang on its cosmopolitan branches! It is the glory of America that it believes that all that anybody knows everybody should know.

Phillips Brooks, perhaps the greatest of American preachers, spoke as follows in a lecture on "Literature and Life":

May we not believe—if the students of Chautauqua be indeed what we have every right to expect that they will be, men and women thoroughly and healthily alive through their perpetual contact with the facts of life—that when they take the books which have the knowledge in them, like pure water in silver urns, though they will not drink as deeply, they will drink more healthily than many of those who in the deader and[xviii] more artificial life of college halls bring no such eager vitality to give value to their draught? If I understand Chautauqua, this is what it means: It finds its value in the vitality of its students. . . . It summons those who are alive with true human hunger to come and learn of that great world of knowledge of which he who knows the most knows such a very little, and feels more and more, with every increase of his knowledge, how very little it is that he knows.

Julia Ward Howe, author of the song beginning "Mine eyes have seen the glory," and honored throughout the land as one of the greatest among the women of America, wrote as follows:

I am obliged for your kind invitation to be present at the celebration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of Chautauqua Assembly. As I cannot well allow myself this pleasure, I send you my hearty congratulations in view of the honorable record of your association. May its good work long continue, even until its leaven shall leaven the whole body of our society.

The following letter was received by Dr. Vincent from one of the most distinguished of the older poets:

Dear Friend: I have been watching the progress of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle inaugurated by thyself, and take some blame to myself for not sooner expressing my satisfaction in regard to[xix] its objects and working thus far. I wish it abundant success, and that its circles, like those from the agitated center of the Lake, may widen out, until our entire country shall feel their beneficent influences. I am very truly thy friend,

After these endorsements, we may confidently affirm that a book on Chautauqua, its story, its principles, and its influence in the world, is warranted.

And now, a few words of explanation as to this particular book. The tendency in preparing such a work is to make it documentary, the recital of programs, speakers, and subjects. In order to lighten up the pages, I have sought to tell the story of small things as well as great, the witty as well as the wise words spoken, the record of by-play and repartee upon the platform, in those days when Chautauqua speakers were a fraternity. In fact, the title by which the body of workers was known among its members was "the Gang." Some of these stories are worth preserving, and I have tried to recall and retain them in these pages.

Feb. 1, 1921.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | vii | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | —The Place | 3 |

| II. | —The Founders | 11 |

| III. | —Some Primal Principles | 27 |

| IV. | —The Beginnings | 38 |

| V. | —The Early Development | 63 |

| VI. | —The National Centennial Year | 72 |

| VII. | —A New Name and New Faces | 93 |

| VIII. | —The Chautauqua Reading Circle | 116 |

| IX. | —Chautauqua All the Year | 141 |

| X. | —The School of Languages | 160 |

| XI. | —Hotels, Headquarters, and Handshaking (1880) | 172 |

| XII. | —Democracy and Aristocracy at Chautauqua (1881) | 187 |

| XIII. | —The First Recognition Day (1882) | 196 |

| XIV. | —Some Stories of the C. L. S. C. (1883, 1884) | 209[xxii] |

| XV. | —The Chaplain's Leg and Other True Tales (1885-1888) | 224 |

| XVI. | —A New Leaf in Luke's Gospel (1889-1892) | 239 |

| XVII. | —Club Life at Chautauqua (1893-1896) | 253 |

| XVIII. | —Rounding out the Old Century (1897-1900) | 271 |

| XIX. | —Opening the New Century (1901-1904) | 283 |

| XX. | —President Roosevelt at Chautauqua (1905-1908) | 295 |

| XXI. | —The Pageant of the Past (1909-1912) | 308 |

| XXII. | —War Clouds and War Drums (1913-1916) | 321 |

| XXIII. | —War and Its Aftermath (1917-1920) | 338 |

| XXIV. | —Chautauqua's Elder Daughters | 361 |

| XXV. | —Younger Daughters of Chautauqua | 385 |

| Appendix | 395 | |

| Index | 421 | |

| PAGE | |

| Lewis Miller | Facing title-page |

| John H. Vincent | 4 |

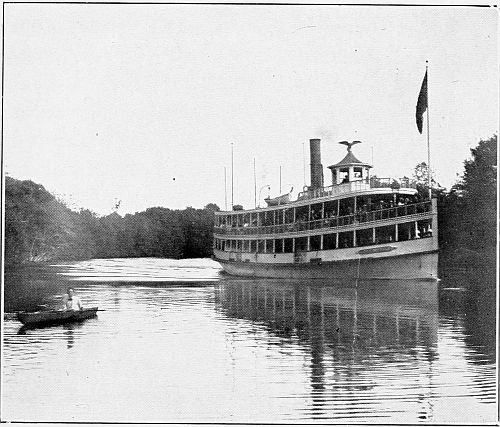

| Steamer in the Outlet | 8 |

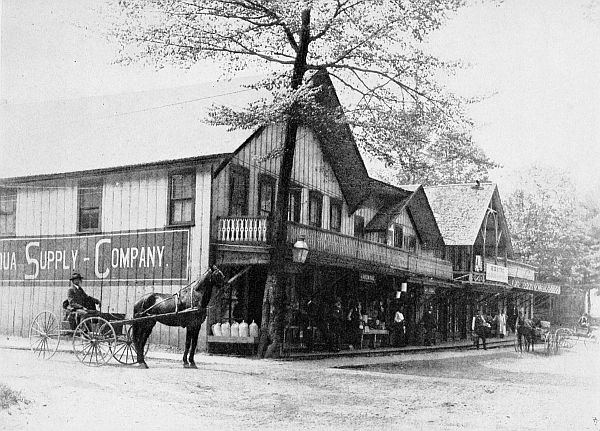

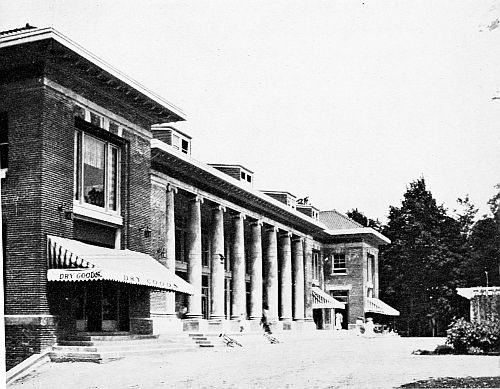

| Old Business Block | 16 |

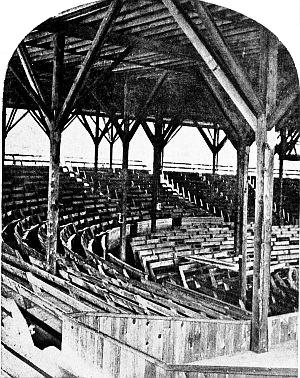

| Old Amphitheater | 24 |

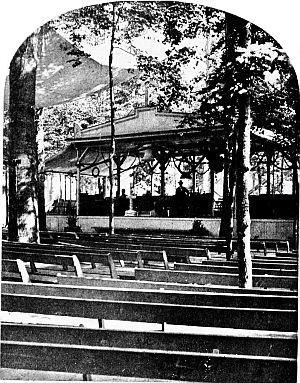

| Old Auditorium | 24 |

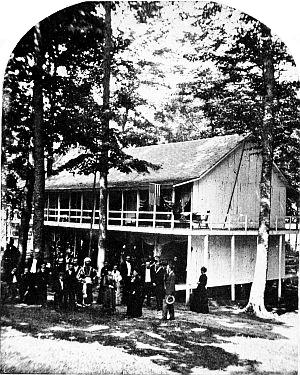

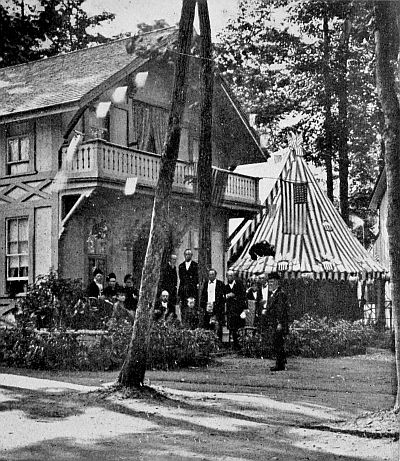

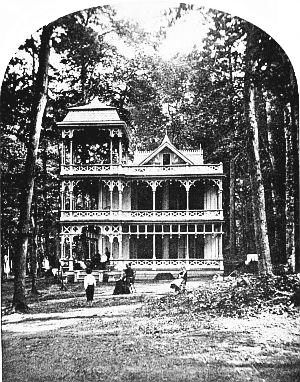

| Old Guest House "The Ark" | 32 |

| Old Children's Temple | 32 |

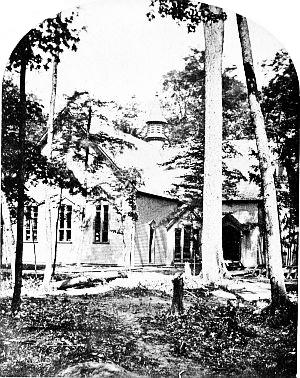

| Lewis Miller Cottage | 40 |

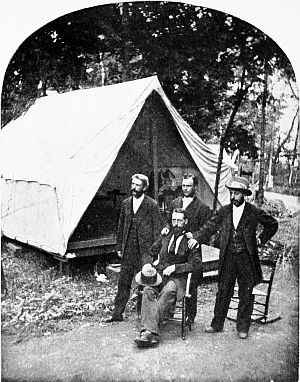

| Bishop Vincent's Tent | 40 |

| Old Steamer "Jamestown" | 50 |

| Oriental House | 50 |

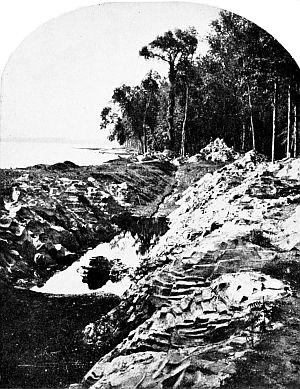

| Palestine Park | 60 |

| Tent Life | 60 |

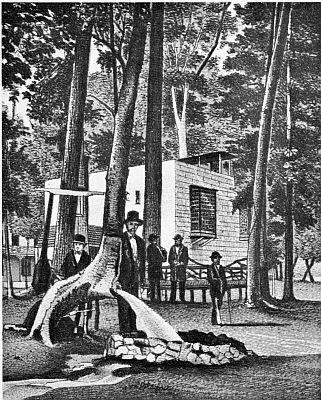

| Spouting Tree | 70 |

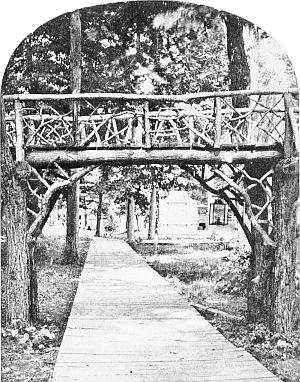

| Rustic Bridge | 76 |

| Amphitheater Audience | 84 |

| Old Palace Hotel, etc. | 92 |

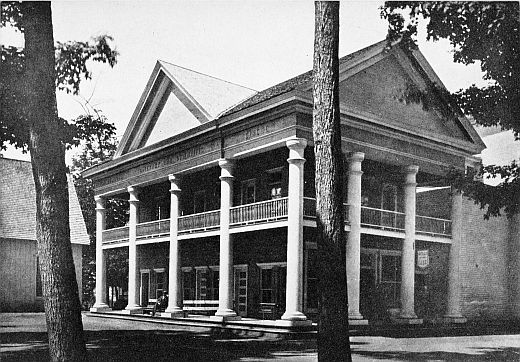

| Old Hall of Philosophy | 100 |

| [xxiv]The Golden Gate | 100 |

| Flower Girls (2 pictures) | 116 |

| Pioneer Hall | 122 |

| Old College Building | 122 |

| C.L.S.C. Alumni Hall | 130 |

| Chautauqua Book Store | 140 |

| Hall of the Christ | 150 |

| Hall of Philosophy, Entrance | 150 |

| Congregational House | 160 |

| Fenton Memorial | 160 |

| Baptist Headquarters and Mission House | 170 |

| Presbyterian Headquarters and Mission House | 170 |

| Methodist Headquarters | 180 |

| Disciples Headquarters | 180 |

| Unitarian Headquarters | 190 |

| Episcopal Chapel | 190 |

| Lutheran Headquarters | 200 |

| United Presbyterian Chapel | 200 |

| South Ravine | 220 |

| Muscallonge | 220 |

| Jacob Bolin Gymnasium | 220 |

| Athletic Club | 230 |

| Boys' Club Headed for Camp | 230 |

| Woman's Club House | 240 |

| [xxv]Rustic Bridge | 240 |

| Post Office Building | 250 |

| Business and Administration | 250 |

| Golf Course | 260 |

| Sherwood Memorial | 260 |

| Traction Station | 260 |

| Arts and Crafts Building | 270 |

| Miller Bell Tower | 270 |

| South Gymnasium | 280 |

| A Corner of the Playground | 290 |

John Heyl Vincent—a name that spells Chautauqua to millions—said: "Chautauqua is a place, an idea, and a force." Let us first of all look at the place, from which an idea went forth with a living force into the world.

John H. Vincent (1876)

John H. Vincent (1876)

The State of New York, exclusive of Long Island, is shaped somewhat like a gigantic foot, the heel being at Manhattan Island, the crown at the St. Lawrence River, and the toe at the point where Pennsylvania touches upon Lake Erie. Near this toe of New York lies Lake Chautauqua. It is eighteen miles long besides the romantic outlet of three miles, winding its way through forest primeval, and flowing into a shallow stream, the Chadakoin River, thence in succession into the Allegheny, the Ohio, the Mississippi, and finally resting in the bosom of the Gulf of Mexico. As we look at it upon the map, or sail upon it in the steamer, we[4] perceive that it is about three miles across at its widest points, and moreover that it is in reality two lakes connected by a narrower channel, almost separated by two or three peninsulas. The earliest extant map of the lake, made by the way for General Washington soon after the Revolution (now in the Congressional Library at Washington), represents two separate lakes with a narrow stream between them. The lake receives no rivers or large streams. It is fed by springs beneath, and by a few brooks flowing into it. Consequently its water is remarkably pure, since none of the surrounding settlements are permitted to send their sewage into it.

The surface of Lake Chautauqua is 1350 feet above the level of the ocean; said to be the highest navigable water in the United States. This is not strictly correct, for Lake Tahoe on the boundary between Nevada and California is more than 6000 feet above sea-level. But Tahoe is navigated only by motor-boats and small steamers; while Lake Chautauqua, having a considerable town, Mayville, at its northern end, Jamestown, a flourishing city at its outlet, and its shores fringed with villages, bears upon its bosom many sizable steam-vessels.

It is remarkable that while Lake Erie falls into the St. Lawrence and empties into the Atlantic at[5] iceberg-mantled Labrador and Newfoundland, Lake Chautauqua only seven miles distant, and of more than seven hundred feet higher altitude, finds its resting place in the warm Gulf of Mexico. Between these two lakes is the watershed for this part of the continent. An old barn is pointed out, five miles from Lake Chautauqua, whereof it is said that the rain falling on one side of its roof runs into Lake Erie and the St. Lawrence, while the drops on the other side through a pebbly brook find their way by Lake Chautauqua into the Mississippi.

Nobody knows, or will ever know, how this lake got its smooth-sounding Indian name. Some tell us that the word means "the place of mists"; others, "the place high up"; still others that its form, two lakes with a passage between, gave it the name, "a bag tied in the middle," or "two moccasins tied together." Mr. Obed Edson of Chautauqua County, who made a thorough search among old records and traditions, which he embodied in a series of articles in The Chautauquan in 1911-12, gives the following as a possible origin. A party of Seneca Indians were fishing in the lake and caught a large muskallonge. They laid it in their canoe, and going ashore carried the canoe over the well-known portage to Lake Erie. To their surprise,[6] they found the big fish still alive, for it leaped from the boat into the water, and escaped. Up to that time, it is said, no muskallonge had ever been caught in that lake; but the eggs in that fish propagated their kind, until it became abundant. In the Seneca language, ga-jah means fish; and ga-da-quah is "taken out" or as some say, "leaped out." Thus Chautauqua means "where the fish was taken out," or "the place of the leaping fish." The name was smoothed out by the French explorers, who were the earliest white men in this region, to "Tchadakoin," still perpetuated in the stream, Chadakoin, connecting the lake with the Allegheny River. In an extant letter of George Washington, dated 1788, the lake is called, "Jadaqua."

From the shore of Lake Erie, where Barcelona now stands, to the site of Mayville at the head of Lake Chautauqua ran a well-marked and often-followed Indian trail, over which canoes and furs were carried, connecting the Great Lakes with the river-system of the mid-continent. If among the red-faced warriors of those unknown ages there had arisen a Homer to sing the story of his race, a rival to the Iliad and the Nibelungen might have made these forests famous, for here was the borderland between that remarkable Indian confederacy of central New York, the Iroquois or Five Nations,—after[7] the addition of the Tuscaroras, the Six Nations—those fierce Assyrians of the Western Continent who barely failed in founding an empire, and their antagonists the Hurons around Lake Erie. The two tribes confronting each other were the Eries of the Huron family and the Senecas of the Iroquois; and theirs was a life and death struggle. Victory was with the Senecas, and tradition tells that the shores of Chautauqua Lake were illuminated by the burning alive of a thousand Erie prisoners.

It is said that the first white man to launch his canoe on Lake Chautauqua was Étienne Brule, a French voyageur. Five years before the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, with a band of friendly Hurons he came over the portage from Lake Erie, and sailed down from Mayville to Jamestown, thence through the Chadakoin to the Allegheny and the Ohio, showing to the French rulers in Canada that by this route lay the path to empire over the continent.

Fifteen years later, in 1630, La Salle, the indomitable explorer and warrior, passed over the portage and down the lake to the river below. Fugitives from the French settlements in Nova Scotia, the Acadia of Longfellow's Evangeline, also passed over the same trail and watercourses in their search for[8] a southern home under the French flag. In 1749, Captain Bienville de Celoron led another company of pioneers, soldiers, sailors, Indians, and a Jesuit priest over the same route, bearing with him inscribed leaden plates to be buried in prominent places, as tokens of French sovereignty over these forests and these waters. Being a Frenchman, and therefore perhaps inclined to gayety, he might have been happy if he could have foreseen that in a coming age, the most elaborate amusement park on the border of Tchadakoin (as he spelled it on his leaden plates) would hand down the name of Celoron to generations then unborn!

Steamer in the Outlet

Steamer in the Outlet

In order to make the French domination of this important waterway sure, Governor Duquesne of Canada sent across Lake Erie an expedition, landing at Barcelona, to build a rough wagon-road over the portage to Lake Chautauqua. Traces of this "old French road" may still be seen. Those French surveyors and toilers little dreamed that in seven years their work would become an English thoroughfare, and their empire in the new world would be exploited by the descendants of the Puritan and Huguenot!

During the American Revolution, the Seneca tribe of Indians, who had espoused the British side, established villages at Bemus and Griffiths points[9] on Lake Chautauqua; and a famous British regiment, "The King's Eighth," still on the rolls of the British army, passed down the lake, and encamped for a time beside the Outlet within the present limits of Jamestown. Thus the redskin, the voyageur, and the redcoat in turn dipped their paddles into the placid waters of Lake Chautauqua. They all passed away, and the American frontiersman took their place; he too was followed by the farmer and the vinedresser. In the last half of the nineteenth century a thriving town, Mayville, was growing at the northern end of the lake; the city of Jamestown was rising at the end of the Outlet; while here and there along the shores were villages and hamlets; roads, such as they were before the automobile compelled their improvement, threaded the forests and fields. A region situated on the direct line of travel between the east and the west, and also having Buffalo on the north and Pittsburgh on the south, could not long remain secluded. Soon the whistle of the locomotive began to wake the echoes of the surrounding hills.

In its general direction the lake lies southeast and northwest, and its widest part is about three miles south of Mayville. Here on its northwestern shore a wide peninsula reaches forth into the water. At the point it is a level plain, covered with stately[10] trees; on the land side it rises in a series of natural terraces marking the altitude and extent of the lake in prehistoric ages; for the present Chautauqua Lake is only the shrunken hollow of a vaster body in the geologic periods. In the early 'seventies of the last century this peninsula was known as Fair Point; but in a few years, baptized with a new name Chautauqua, it was destined to make the little lake famous throughout the world and to entitle an important chapter in the history of education.

Every idea which becomes a force in the world has its primal origin in a living man or woman. It drops as a seed into one mind, grows up to fruitage, and from one man is disseminated to a multitude. The Chautauqua Idea became incarnate in two men, John Heyl Vincent and Lewis Miller, and by their coördinated plans and labors made itself a mighty power. Let us look at the lives of these two men, whose names are ever one in the minds of intelligent Chautauquans.

John Heyl Vincent was of Huguenot ancestry. The family came from the canton of Rochelle, a city which was the Protestant capital of France in the period of the Reformation. From this vicinity Levi Vincent (born 1676), a staunch Protestant, emigrated to America in the persecuting days of Louis XIV., and settled first at New Rochelle, N. Y., later removed to New Jersey, and died there in 1736. For several generations the family lived in New Jersey; but at the time of John Heyl Vincent's[12] birth on February 23, 1832, his father, John Himrod Vincent, the great-great-grandson of the Huguenot refugee, was dwelling at Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Dr. Vincent used to say that he began his ministry before he was six years old, preaching to the little negroes around his home. The family moved during his early childhood to a farm near Lewisburg, Pa., on Chillisquasque Creek, where at the age of fifteen he taught in the public school.

When not much above sixteen he was licensed as a local preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church. He soon became a junior preacher on a four weeks' circuit along the Lehigh River, which at that time seems to have been in the bounds of the old Baltimore Conference. He rode his circuit on horseback, with a pair of saddlebags behind him, and boarded 'round among his parishioners. His saintly mother, of whose character and influence he always spoke in the highest reverence, died at this time, and soon after he went to visit relatives in Newark, N. J. There he served as an assistant in the city mission, and at the same time studied in the Wesleyan Academy on High Street. A fellow student, who became and continued through a long life one of his most intimate friends, the Rev. George H. Whitney, said that young Vincent differed from most of his classmates in his eager[13] desire for education, his appetite for book-knowledge leading him to read almost every volume that came his way, and his visions, then supposed to be mere dreams, of plans for the intellectual uplift of humanity. It was his keenest sorrow that he could not realize his intense yearning for a course in college; but perhaps his loss in youth became a nation's gain in his maturer years.

In 1853 he was received formally as a member "on trial" in the New Jersey Conference, at that time embracing the entire State. His first charge as pastor was at North Belleville, later known as Franklin, now Nutley, where a handsome new church bears his name and commemorates his early ministry. His second charge was at a small suburb of Newark, then called Camptown, now the thriving borough of Irvington. His ministry from the beginning had been marked by an interest in childhood and youth, and a strong effort to strengthen the work of the Sunday School. At Camptown he established a definite course of Bible teaching for teachers and young people. Near the church he staked out a map of Palestine, marked its mountains and streams, its localities and battlefields, and led his teachers and older scholars on pilgrimages from Dan to Beersheba, pausing at each of the sacred places while a member of the class told its[14] story. The lessons of that Palestine Class, taught on the peripatetic plan in the fifties, are still in print, showing the requirements for each successive grade of Pilgrim, Resident in Palestine, Dweller in Jerusalem, Explorer of other Bible Lands, and after a final and searching examination, Templar, wearing a gold medal. At each of his pastoral charges after this, he conducted his Palestine Class and constructed his outdoor map of the Holy Land. May we not find here the germ destined to grow into the Palestine Park of the Chautauqua Assembly?

After four years in New Jersey young Vincent was transferred in 1857 to Illinois, where in succession he had charge of four churches, beginning with Joliet, where he met a young lady teacher, Miss Elizabeth Dusenbury, of Portville, N. Y., who became his wife, and in the after years by her warm heart, clear head, and wise judgment greatly contributed to her husband's success. He was a year at Mount Morris, the seat of the Rock River Conference Seminary, at which he studied while pastor in the community. For two years, 1860 and '61, he was at Galena, and found in his congregation a quiet ex-army officer, named Ulysses S. Grant, who afterward said when introducing him to President Lincoln, "Dr. Vincent was my pastor at Galena,[15] Ill., and I do not think that I missed one of his sermons while I lived there." Long after the Civil War days Bishop Vincent expressed in some autobiographical notes his estimate of General Grant. He wrote: "General Grant was one of the loveliest and most reverent of men. He had a strong will under that army overcoat of his, but he was the soul of honor and as reverent as he was brave." After two years at Rockford—two years having been until 1864 the limit for a pastorate in American Methodism—in 1865 he was appointed to Trinity Church, Chicago, then the most important church of his denomination in that city.

Chicago opened the door of opportunity to a wider field. The pastor of Trinity found in that city a group of young men, enthusiasts in the Sunday School, and progressive in their aims. Dr. Vincent at once became a leader among them and by their aid was able to introduce a Uniform Lesson in the schools of the city. He established in 1865 a Sunday School Quarterly, which in the following years became the Sunday School Teacher, in its editorials and its lesson material setting a new standard for Sunday School instruction. His abilities were soon recognized by the authorities in his church, and he was called to New York to become first General Agent of the Sunday School[16] Union, the organization directing Methodist Episcopal Sunday Schools throughout the world, and in 1868, secretary and editor. He organized and set in circulation the Berean Uniform Lessons for his denomination, an important link in the chain of events which in 1873 made the Sunday School lessons uniform throughout America and the world. It is the fashion now to depreciate the Uniform Lesson Plan as unpedagogic and unpsychologic; but its inauguration was the greatest forward step ever taken in the evolution of the Sunday School; for it instituted systematic study of the Bible, and especially of the Old Testament; it brought to the service of the teacher the ablest Bible scholars on both sides of the Atlantic; it enabled the teachers of a school, a town, or a city to unite in the preparation of their lessons. Chicago, New York, Brooklyn, Boston, and many other places soon held study-classes of Sunday School teachers, of all grades, of a thousand or more gathered on a week-day to listen to the lectures of great instructors. The Plainfield (N. J.) Railroad Class was not the only group of Sunday School workers who spent their hour on the train passing to and from business in studying together their Sunday School lesson.

Old Business Block and Post-Office

Old Business Block and Post-Office

Soon after Dr. Vincent assumed the charge of general Sunday School work, having his office in[17] New York, he took up his residence in Plainfield, N. J., a suburban city which felt his influence and responded to it for twenty years. Having led the way to one summit in his ideals, he saw other mountain-heights beyond, and continually pointed his followers upward. When he succeeded to the editorship of the Sunday School Journal, the teachers' magazine of his church, he found a circulation of about five thousand. With the Uniform Lesson, and his inspiring editorials, it speedily rose to a hundred thousand, and a few years later to two hundred thousand subscribers, while his lesson leaves and quarterlies went into the millions. With voice—that wonderful, awakening, thrilling voice—and with a pen on fire, he appealed everywhere for a training that should fit Sunday School teachers for their great work. He established in many places the Normal Class, and marked out a course of instruction for its students. This was the step which led directly to the Chautauqua Assembly, which indeed made some such institution a necessity.

The Normal Class proposed a weekly meeting of Sunday School teachers or of young people seeking preparation for teaching, a definite course of study, examinations at regular stages, and a diploma to those who met its standards. Dr. Vincent conceived[18] the plan of bringing together a large body of teacher-students, who should spend at least a fortnight in daily study, morning and afternoon, and thus accomplish more work than in six months of weekly meetings. He aimed also to have lectures on inspiring themes, with a spice of entertainment to impart variety. While this ideal was rising before him and shaping in his mind, he found a kindred spirit, a genius in invention, and a practical, wise business man whose name was destined to stand beside his own in equal honor wherever and whenever Chautauqua is named—Lewis Miller of Akron, Ohio, the first and until his death in 1899 the only president of Chautauqua.

Lewis Miller was born on July 24, 1829, at Greentown, Ohio. He received in his childhood the limited education in "the three R's—reading, 'riting and 'rithmetic," usual in the country school; and at the age of sixteen was himself a school teacher. In 1849, twenty years old, he began work at the plastering trade, but at the same time was attending school. He became a partner in the manufacturing firm of Aultman, Ball and Co., which soon became Aultman, Miller and Co., and was removed from Greentown to Canton, Ohio. Here, about 1857, Mr. Miller invented and put into successful operation the Buckeye Mower and[19] Reaper, which made him famous, and with other inventions brought to him a fortune. His home was for many years, and until his death, at Akron. From his earliest years he was interested in education, and especially in education through the Sunday School. He became Sunday School Superintendent of the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Akron, and made it more than most of the Sunday Schools in that generation a school, and not merely a meeting for children. He organized a graded system and required his pupils to pass from grade to grade through the door of an examination in Bible knowledge. He was one of the earliest Sunday School superintendents to organize a Normal Class for the equipment and training of young people for teaching in his school. At a certain stage in the promotions every young man and young woman passed one year or two years in the Normal Grade; for which he arranged the course until one was provided by Dr. Vincent after he became Secretary of Sunday School work for the denomination in 1868; and in the planning of that early normal course, Mr. Miller took an active part, for he met in John H. Vincent one who, like himself, held inspiring ideals for the Sunday School, and the two leaders were often in consultation. It was an epoch in the history of the American[20] Sunday School when Mr. Miller built the first Sunday School hall in the land according to a plan originated by himself; its architectural features being wrought out under his direction by his fellow-townsman and friend, Mr. Jacob Snyder, an architect of distinction. In this building, then unique but now followed by thousands of churches, there was a domed central assembly hall, with rooms radiating from it in two stories, capable of being open during the general exercises, but closed in the lesson period so that each class could be alone with its teacher while studying.

Mr. Miller was also interested in secular education, was for years president of the Board of Education in Akron, always aiming for higher standards in teaching. He was also a trustee of Mount Union College in his own State. Two men such as Vincent and Miller, both men of vision, both leaders in education through the Sunday School, both aiming to make that institution more efficient, would inevitably come together; and it was fortunate that they were able to work hand in hand, each helping the other.

These two men had thoughts of gatherings of Sunday School workers, not in conventions, to hear reports and listen to speeches, not to go for one-day or two- or three-day institutes, but to[21] spend weeks together in studying the Bible and methods of Sunday School work. They talked over their plans, and they found that while they had much in common in their conception each one could supplement the other in some of the details. It had been Dr. Vincent's purpose to hold his gathering of Sunday School workers and Bible students within the walls of a large church, in some city centrally located and easily reached by railroad. He suggested to Mr. Miller that his new Sunday School building, with its many classrooms opening into one large assembly hall, would be a suitable place for launching the new enterprise.

One cannot help asking the question—what would have been the result if Dr. Vincent's proposal had been accepted, and the first Sunday School Assembly had been held in a city and a church? Surely the word "Chautauqua" would never have appeared as the name of a new and mighty movement in education. Moreover, it is almost certain that the movement itself would never have arisen to prominence and to power. It is a noteworthy fact that no Chautauqua Assembly has ever succeeded, though often attempted, in or near a large city. One of the most striking and drawing features of the Chautauqua movement has been its out-of-doors and in-the-woods[22] habitat. The two founders did not dream in those days of decision that the fate of a great educational system was hanging in the balance.

An inspiration came to Lewis Miller to hold the projected series of meetings in a forest, and under the tents of a camp meeting. Camp meetings had been held in the United States since 1799, when the first gathering of this name took place in a grove on the banks of the Red River in Kentucky led by two brothers McGee, one a Presbyterian, the other a Methodist. In those years churches were few and far apart through the hamlets and villages of the west and south. The camp meeting brought together great gatherings of people who for a week or more listened to sermons, held almost continuous prayer meetings, and called sinners to repentance. The interest died down somewhat in the middle of the nineteenth century, but following the Civil War, a wave of enthusiasm for camp meetings swept over the land. In hundreds of groves, east and west, land was purchased or leased, lots were sold, tents were pitched, and people by the thousand gathered for soul-stirring services. In one of the oldest and most successful of these camp meetings, that on Martha's Vineyard, tents had largely given place to houses, and a city had arisen in the forest. This example had been followed,[23] and on many camp-meeting grounds houses of a primitive sort straggled around the open circle where the preaching services were held. Most of these buildings were mere sheds, destitute of architectural beauty, and innocent even of paint on their walls of rough boards. Many of these antique structures may still be seen at Chautauqua, survivals of the camp-meeting period, in glaring contrast with the more modern summer homes beside them.

At first Dr. Vincent did not take kindly to the thought of holding his training classes and their accompaniments in any relationship to a camp meeting or even upon a camp ground. He was not in sympathy with the type of religious life manifested and promoted at these gatherings. The fact that they dwelt too deeply in the realm of emotion and excitement, that they stirred the feelings to the neglect of the reasoning and thinking faculties, that the crowd called together on a camp-meeting ground would not represent the sober, sane, thoughtful element of church life—all these repelled Dr. Vincent from the camp meeting.

Mr. Miller had recently become one of the trustees of a camp meeting held at Fair Point on Lake Chautauqua, and proposed that Dr. Vincent should visit the place with him. Somewhat unwillingly,[24] yet with an open mind, Vincent rode with Miller by train to Lakewood near the foot of the lake, and then in a small steamer sailed to Fair Point. A small boy was with them, sitting in the prow of the boat, and as it touched the wharf he was the first of its passengers to leap on the land—and in after years, George Edgar Vincent, LL.D., was wont to claim that he, at the mature age of nine years, was the original discoverer of Chautauqua!

Old Amphitheater

Old Amphitheater

|  Old Auditorium in Miller Park

Old Auditorium in Miller Park

|

It was in the summer of 1873, soon after the fourth session of the Erie Conference Camp Meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church, that Dr. Vincent came, saw, and was conquered. His normal class and its subsidiary lectures and entertainments should be held under the beeches, oaks, and maples shading the terraced slopes rising up from Lake Chautauqua.

A lady who had attended the camp meeting in 1871, its second session upon the grounds at Fair Point, afterward wrote her first impressions of the place. She said that the superintendent of the grounds, Mr. Pratt (from whom an avenue at Chautauqua received its name some years afterward), told her that until May, 1870, "the sound of an axe had not been heard in those woods." This lady (Mrs. Kate P. Bruch) wrote:[25]

Many of the trees were immense in size, and in all directions, from the small space occupied by those who were tenting there, we could walk through seas of nodding ferns; while everywhere through the forest was a profusion of wild flowers, creeping vines, murmuring pine, beautiful mosses and lichens. The lake itself delighted us with its lovely shores; where either highly cultivated lands dotted with farmhouses, or stretches of pine forest, met on all sides the cool, clear water that sparkled or danced in the sunlight, or gave subdued but beautiful reflection of the moonlight. We were especially charmed with the narrow, tortuous outlet of the lake—then so closely resembling the streams of tropical climes. With the trees pressing closely to the water's edge, covered with rich foliage, tangled vines clinging and swaying from their branches; and luxuriant undergrowth, through which the bright cardinal flowers were shining, it was not difficult to fancy one's self far from our northern clime, sailing over water that never felt the cold clasp of frost and snow.

The steamers winding their way through the romantic outlet were soon to be laden with new throngs looking for the first time upon forest, farms, and lake. Those ivy-covered and moss-grown terraces of Fair Point were soon to be trodden by the feet of multitudes; and that camp-meeting stand from which fervent appeals to repentance had sounded forth, to meet responses of raptured shouts from saints, and cries for mercy[26] from seekers, was soon to become the arena for religious thought and aspiration of types contrasted with those of the camp meeting of former years.

We have looked at the spot chosen for this new movement, and we have become somewhat acquainted with its two leaders. Let us now look at its foundations, and note the principles upon which it was based. We shall at once perceive that the original plans of the Fair Point Assembly were very narrow in comparison with those of Chautauqua to-day. Yet those aims were of such a nature, like a Gothic Church, as would readily lend themselves to enlargement on many sides, and only add to the unique beauty of the structure.

In this chapter we are not undertaking to set forth the Chautauqua Idea, as it is now realized—for everybody, everywhere, and in every department of knowledge, inspired by a Christian faith. Whatever may have been in the mind of either founder, this wide-reaching aim was not in those early days made known. Both Miller and Vincent were interested in education, and each of them felt his own lack of college training, but[28] during the first three or four years of Chautauqua's history all its aims were in the line of religious education through the Sunday School. We are not to look for the traits of its later development, in those primal days. Ours is the story of an evolution, and not a philosophical treatise.

The first assembly on Chautauqua Lake was held under the sanction and direction of the governing Sunday School Board of the Methodist Episcopal Church, by resolution of the Board in New York at its meeting in October, 1873, in response to a request from the executive committee of the Chautauqua Lake Camp Ground Association, and upon the recommendation of Dr. Vincent, whose official title was Corresponding Secretary of the Sunday School Union of the Methodist Episcopal Church. The Normal Committee of the Union was charged with the oversight of the projected meetings; Lewis Miller was appointed President, and John H. Vincent, Superintendent of Instruction.

Although held upon a camp ground and inheriting some of the camp-meeting opportunities, the gathering was planned to be unlike a camp meeting in its essential features, and to reach a constituency outside that of the camp ground. Its name was a new one, "The Assembly," and its[29] sphere was announced to be that of the Sunday School. There was to be a definite and carefully prepared program of a distinctly educational cast, with no opening for spontaneous, go-as-you-please meetings to be started at any moment. This was arranged to keep a quietus on both the religious enthusiast and the wandering Sunday School orator who expected to make a speech on every occasion. On my first visit to Fair Point—which was not in '74 but in '75—I found a prominent Sunday School talker from my own State, grip-sack in hand, leaving the ground. He explained, "This is no place for me. They have a cut-and-dried program, and a fellow can't get a word in anywhere. I'm going home. Give me the convention where a man can speak if he wants to."

In most of the camp meetings, but not in all, Sunday was the great day, a picnic on a vast scale, bringing hundreds of stages, carryalls, and wagons from all quarters, special excursion trains loaded with visitors, fleets of boats on the lake or river, if the ground could be reached by water route. No doubt some good was wrought. Under the spell of a stirring preacher some were turned from sin to righteousness. But much harm was also done, in the emptying of churches for miles around, the bringing together of a horde of people intent on[30] pleasure, and utter confusion taking the place of a sabbath-quiet which should reign on a ground consecrated to worship. Against this desecration of the holy day, Miller and Vincent set themselves firmly. As a condition of accepting the invitation of the Camp Meeting Association to hold the proposed Assembly at Fair Point, the gates were to be absolutely closed against all visitors on Sunday; and notice was posted that no boats would be allowed to land on that day at the Fair Point pier. In those early days everybody came to Fair Point by boat. There was indeed a back-door entrance on land for teams and foot passengers; but few entered through it. In these modern days of electricity, now that the lake is girdled with trolley lines, and a hundred automobiles stand parked outside the gates, the back door has become the front door, and the steamboats are comparatively forsaken.

In addition to the name Assembly, the exact order of exercises, and the closed ground on Sunday, there was another startling departure from camp-meeting usages—a gate fee. The overhead expenses of a camp meeting were comparatively light. Those were not the days when famous evangelists like Sam Jones and popular preachers such as DeWitt Talmage received two hundred[31] dollars for a Sunday sermon. Board and keep were the rewards of the ministers, and the "keep" was a bunk in the preachers' tent. The needed funds were raised by collections, which though nominally "voluntary" were often obtained under high-pressure methods. But the Assembly, with well-known lecturers, teachers of recognized ability, and the necessary nation-wide advertising to awaken interest in a new movement would of necessity be expensive. How should the requisite dollars by the thousand be raised? The two heads of the Assembly resolved to dispense with the collections, and have a gate fee for all comers. Fortunately the Fair Point grounds readily lent themselves to this plan, for they were already surrounded on three sides by a high picket-fence, and only the small boys knew where the pickets were loose, and they didn't tell.

The Sunday closing and the entrance charge raised a storm of indignation all around the lake. The steamboat owners—in those days there were no steamer corporations; each boat big or little, was owned by its captain—the steamboat owners saw plainly that Sunday would be a "lost day" to them if the gates were closed; and the thousands of visitors to the camp meeting who had squeezed out a dime, or even a penny, when the basket went[32] around, bitterly complained outside the gates at a quarter for daily admission, half of what they had cheerfully handed over when the annual circus came to town. During the first Assembly in 1874, the gatekeepers needed all their patience and politeness to restrain some irate visitors from coming to blows over the infringement of their right to free entrance upon the Fair Point Camp Ground. There were holders of leases upon lots who expected free entrance for themselves and their families—and "family" was stretched to include visitors. Then there were the preachers who could not comprehend why they should buy a ticket for entrance to the holy ground! The financial and restrictive regulations were left largely to Lewis Miller, who possessed the suaviter in modo so graciously that many failed to realize underneath it the fortiter in re. Behind that smiling countenance of the President of Chautauqua was an uncommonly stiff backbone. Rules once fixed were kept in the teeth of opposition from both sinners and saints.

The Old Guest House. "The Ark"

The Old Guest House. "The Ark"

|  Old Children's Temple

Old Children's Temple

|

Let me anticipate some part of our story by saying that at the present time there are from six to eight hundred all-the-year residents upon Chautauqua grounds. Before the Assembly opens on July 1st, every family must obtain season[33] tickets to the public exercises for all except the very youngest members and bedridden invalids. A lease upon Chautauqua property does not entitle the holder to admission to the grounds. If he owns an automobile, it must be parked outside, and cannot be brought through the gates without the payment of an entrance fee, and an officer riding beside the chauffeur to see that in Chautauqua's narrow streets and thronged walks all care is taken against accident. The only exception to this rule is in favor of physicians who are visiting patients within the enclosure.

The catholicity of the plans for the first Assembly must not be forgotten. Both its founders were members of the Methodist Episcopal Church and loyal to its institutions. But they were also believers in and members of the Holy Catholic Church, the true church of Christ on earth, wherein every Christian body has a part. They had no thought to ignore the various denominations, but aimed to make every follower of Christ at home. Upon the program appeared the names of men eminent in all the churches; and it was a felicitous thought to hold each week on one evening the prayer meetings of the several churches, each by itself, also to plan on one afternoon in different places on the ground, for denominational conferences[34] where the members of each church could freely discuss their own problems and provide for their own interests. This custom established at the first assembly has become one of the traditions of Chautauqua. Every Wednesday evening, from seven to eight, is assigned for denominational prayer meetings, and on the second Wednesday afternoon in August, two hours are set apart for the Denominational Conferences. The author of this volume knows something about one of those meetings; for year after year it has brought him to his wit's end, to provide a program that will not be a replica of the last one, and then sometimes, to persuade the conferences to confer. But if a list were made of the noble names that have taken part in these gatherings, it would show that the interdenominational plan of the founders has been justified by the results. It is a great fact that for nearly fifty years the loyal members of almost every church in the land have come together at Chautauqua, all in absolute freedom to speak their minds, yet with never the least friction or controversy. And this relation was not one of an armed neutrality between bodies in danger of breaking out into open war. It did not prevent a good-natured raillery on the Chautauqua platform between speakers of different denominations.[35] If anyone had a joke at the expense of the Baptists or the Methodists or the Presbyterians, he never hesitated to tell it before five thousand people, even with the immediate prospect of being demolished by a retort from the other side.

A conversation that occurred at least ten years after the session of '74 belongs here logically, if not chronologically. A tall, long-coated minister whose accent showed his nativity in the southern mountain-region said to me, "I wish to inquire, sir, what is the doctrinal platform of this assembly." "There is none, so far as I know," I answered. "You certainly do not mean, sir," he responded, "that there is not an understanding as to the doctrines allowed to be taught on this platform. Is there no statement in print of the views that must or must not be expressed by the different speakers?" "I never heard of any," I said, "and if there was such a statement I think that I should know about it." "What, sir, is there to prevent any speaker from attacking the doctrines of some other church, or even from speaking against the fundamental doctrines of Christianity?" "Nothing in the world," I said, "except that nobody at Chautauqua ever wishes to attack any other Christian body. If anyone did such a thing, I don't believe that it would be[36] thought necessary to disown or even to answer him. But I am quite certain that it would be his last appearance on the Chautauqua platform."

In this chapter I have sought to point out the foundation stones of Chautauqua, as they were laid nearly half a century ago. Others were placed later in the successive years; but these were the original principles, and these have been maintained for more than a generation. Let us fix them in memory by a restatement and an enumeration. First, Chautauqua, now an institution for general and popular education, began in the department of religion as taught in the Sunday School. Second, it was an out-of-doors school, held in the forest, blazing the way and setting the pace of summer schools in the open air throughout the nation and the world. Third, although held upon a camp-meeting ground it was widely different in aim and method, spirit and clientele from the old-fashioned camp meeting. Fourth, it maintained the sanctity of the Sabbath, closed its gates, and frowned upon every attempt to secularize or commercialize the holy day, or to make it a day of pleasure. Fifth, the enterprise was supported, not by collections at its services, or by contributions from patrons, but by a fee upon entrance from every comer. Sixth, it was to represent not one branch of the[37] church, but to bring together all the churches in acquaintance and friendship, to promote, not church union, but church unity. And seventh, let it be added that it was to be in no sense a money-making institution. There were trustees but no stockholders, and no dividends. If any funds remained after paying the necessary expenses, they were to be used for improvement of the grounds or the enlargement of the program. Upon these foundations Chautauqua has stood and has grown to greatness.

But let us come to the opening session of the Assembly, destined to greater fortune and fame than even its founders at that time dreamed. It was named "The Sunday School Teachers' Assembly," for the wider field of general education then lay only in the depths of one founder's mind. For the sake of history, let us name the officers of this first Assembly. They were as follows:

| Chairman—Lewis Miller, Esq., of Akron, Ohio. |

| Department of Instruction—Rev. John H. Vincent, D.D., of New York. |

| Department of Entertainment—Rev. R. W. Scott, Mayville, N. Y. |

| Department of Supplies—J. E. Wesener, Esq., Akron, Ohio. |

| Department of Order—Rev. R. M. Warren, Fredonia, N. Y. |

| Department of Recreation—Rev. W. W. Wythe, M.D., Meadville, Pa. |

| Sanitary Department—J. C. Stubbs, M.D., Corry, Pa. |

The property of the Camp Meeting Association, leased for the season to the Assembly, embraced less than one fourth of the present dimensions of Chautauqua, even without the golf course and other property outside the gates. East and west it extended as it does now from the Point and the Pier to the public highway. But on the north where Kellogg Memorial Hall now stands was the boundary indicated by the present Scott Avenue, though at that time unmarked. The site of Normal Hall and all north of it were outside the fence. And on the south its boundary was the winding way of Palestine Avenue. The ravine now covered by the Amphitheater was within the bounds, but the site of the Hotel Athenæum was without the limit.

Lewis Miller, Cottage and Tent

Lewis Miller, Cottage and Tent

He who rambles around Chautauqua in our day sees a number of large, well-kept hotels, and many inns and "cottages" inviting the visitor to comfortable rooms and bountiful tables. But in those early days there was not one hotel or boarding-house at Fair Point. Tents could be rented, and a cottager might open a room for a guest, but it was forbidden to supply table board for pay. Everybody, except such as did their own cooking, ate their meals at the dining-hall, which was a long tabernacle of rough unpainted boards, with a[40] leaky roof, and backless benches where the feeders sat around tables covered with oilcloth. And as for the meals—well, if there was high thinking at Chautauqua there was certainly plain living. Sometimes it rained, and D.D.'s, LL.D.'s, professors, and plain people held up umbrellas with one hand and tried to cut tough steaks with the other. But nobody complained at the fare, for the feast of reason and flow of soul made everybody forget burnt potatoes and hard bread.

Bishop Vincent's Tent-Cottage

Bishop Vincent's Tent-Cottage

What is now Miller Park, the level ground and lovely grove at the foot of the hill, was then the Auditorium, where stood a platform and desk sheltered from sun on some days and rain on others. Before it was an array of seats, lacking backs, instead of which the audience used their own backbones. Perhaps two thousand people could find sitting-room under the open sky, shaded by the noble trees. A sudden shower would shoot up a thousand umbrellas. One speaker said that happening to look up from his manuscript he perceived that an acre of toadstools had sprouted in a minute. At the lower end of this park stood the tent wherein Dr. Vincent dwelt during many seasons; at the upper end was the new cottage of the Miller family with a tent frame beside it for guests. At this Auditorium all the great lectures were given for the[41] first four years of Chautauqua history, except when continued rain forbade. Then an adjournment, sometimes hasty, was made to a large tent up the hill, known as the Tabernacle.

One day, during the second season of the Assembly in 1875, Professor William F. Sherwin, singer, chorus leader, Bible teacher, and wit of the first water, was conducting a meeting in the Auditorium. The weather had been uncertain, an "open and shut day," and people hardly knew whether to meet for Sherwin's service in the grove or in the tent on the hill. Suddenly a tall form, well known at Chautauqua, came tearing down the hill and up the steps of the platform, breathless, wild-eyed, with mop of hair flying loose, bursting into the professor's address with the words, "Professor Sherwin, I come as a committee of fifty to invite you to bring your meeting up to the Tabernacle, safe from the weather, where a large crowd is gathered!" "Well," responded Sherwin, "you may be a committee of fifty, but you look like sixty!" And from that day ever after at Chautauqua a highly respected gentleman from Washington, D.C., was universally known as "the man who looks like sixty."

When we speak of Sherwin, inevitably we think of Frank Beard, the cartoonist, whose jokes were[42] as original as his pictures. He would draw in presence of the audience a striking picture, seemingly serious, and then in a few quick strokes transform it into something absurdly funny. For instance, his "Moses in the Bulrushes" was a beautiful baby surrounded by waving reeds. A sudden twist of the crayon, and lo, a wild bull was charging at the basket and its baby. This was "The Bull Rushes." Beard was as gifted with tongue as with pen, and in the comradeship of the Chautauqua platform he and Sherwin were continually hurling jokes at each other. Oftentimes the retort was so pat that one couldn't help an inward question whether the two jesters had not arranged it in advance.

Frank Beard used to hold a question drawer occasionally. There was a show of collecting questions from the audience, but those to be answered had been prepared by Mr. Beard and his equally witty wife, and written on paper easily recognized. One by one, these were taken out, read with great dignity, and answered in a manner that kept the crowd in a roar. On one occasion Professor Sherwin was presiding at Mr. Beard's question drawer—for it was the rule that at every meeting there must be a chairman as well as the speaker. The question was drawn out, "Will Mr.[43] Beard please explain the difference between a natural consequence and a miracle?" Mr. Beard did explain thus: "This difficult question can be answered by a very simple illustration. There is Professor Sherwin. If Professor Sherwin says to me, 'Mr. Beard, lend me five dollars,' and I should let him have it, that would be a natural consequence. If Professor Sherwin should ever pay it back, that would be a miracle!" It is needless to say that the opportunity soon arrived for Mr. Sherwin to repay Mr. Beard for full value of debt with abundant interest.

Mention has been made that at each address or public platform meeting a chairman must be in charge. In the old camp-meeting days all the ministers had been wont to sit on the platform behind the preacher; and some of them could not reconcile themselves to Dr. Vincent's rule that only the chairman and the speaker of the hour should occupy "the preachers' stand." Notwithstanding repeated announcements, some clergymen continued to invade the platform. The head of the Department of Order once pointed to a well-known minister and said to the writer, "Four times I have told that man—and a good man he is—that he must not take a seat on the platform." Whoever casts his eyes on the platform of the Amphitheater[44] may notice that before every public service, the janitor places just the number of chairs needed, and no more. This is one of the Chautauqua traditions, begun under the Vincent régime.

Before we come to the more serious side of our story let us notice another instance of the contrast between the camp meeting and Chautauqua. A widely known Methodist came, bringing with him a box of revival song-books, compiled by himself. He was a leader of a "praying band," and accustomed to hold meetings where the enthusiasm was pumped up to a high pitch. One Sunday at a certain hour he noticed that the Auditorium in the grove was unoccupied; and gathering a group of friends with warm hearts and strong voices, he mounted the platform and in stentorian tones began a song from his own book. The sound brought people from all the tents and cottages around, and soon his meeting was in full blast, with increasing numbers responding to his ardent appeals. Word came to Dr. Vincent who speedily marched into the arena. He walked upon the platform, held up his hand in a gesture compelling silence, and calling upon the self-appointed leader by name, said:

"This meeting is not on the program, nor appointed by the authorities, and it cannot be held."[45]

"What?" spoke up the praying-band commander. "Do you mean to say that we can't have a service of song and prayer on these grounds?"

"Yes," replied Dr. Vincent, "I do mean it. No meeting of any kind can be held without the order of the authorities. You should have come to me for permission to hold this service."

The man was highly offended, gathered up his books, and left the grounds on the next day. He would have departed at once, but it was Sunday, and the gates were closed. Let it be said, however, that six months later, when he had thought it over, he wrote to Dr. Vincent an ample apology for his conduct and said that he had not realized the difference between a camp meeting and a Sunday School Assembly. He ended by an urgent request that Dr. Vincent should come to the camp ground at Round Lake, of which he was president, should organize and conduct an assembly to be an exact copy of Chautauqua in its program and speakers, with all the resources of Round Lake at his command. His invitation was accepted. In due time, with this man's loyal support, Dr. Vincent organized and set in motion the Round Lake Assembly, upon the Chautauqua pattern, which continues to this day, true to the ideals of the founder.[46]

One unique institution on the Fair Point of those early days must not be omitted—the Park of Palestine. Following the suggestion of Dr. Vincent's church lawn model of the Holy Land, Dr. Wythe of Meadville, an adept in other trades than physic and preaching, constructed just above the pier on the lake shore a park one hundred and twenty feet long, and seventy-five feet wide, shaped to represent in a general way the contour of the Holy Land. It was necessary to make the elevations six times greater than longitudinal measurements; and if one mountain is made six times as large as it should be, some other hills less prominent in the landscape or less important in the record must be omitted. The lake was taken to represent the Mediterranean Sea, and on the Sea-Coast Plain were located the cities of the Philistines, north of them Joppa and Cæsarea, and far beyond them on the shore, Tyre and Sidon. The Mountain Region showed the famous places of Israelite history from Beersheba to Dan, with the sacred mountains Olivet and Zion, Ebal and Gerizim having Jacob's Well beside them, Gilboa with its memories of Gideon's victory and King Saul's defeat, the mountain on whose crown our Lord preached his sermon, and overtopping all, Hermon, where he was transfigured. From two[47] springs flowed little rills to represent the sources of the River Jordan which wound its way down the valley, through the two lakes, Merom and the Sea of Galilee, ending its course in the Dead Sea. There were Jericho and the Brook Jabbok, the clustered towns around the Galilean Sea, and at the foot of Mount Hermon, Cæsarea-Philippi. Across the Jordan rose the Eastern Tableland, with its mountains and valleys and brooks and cities even as far as Damascus.

As the Assembly was an experiment, and might be transferred later to other parts of the country, the materials for this Palestine Park were somewhat temporary. The mountains were made of stumps, fragments of timber, filled in with sawdust from a Mayville mill, and covered with grassy sods. But the park constructed from makeshift materials proved one of the most attractive features of the encampment. Groups of Bible students might be seen walking over it, notebooks in their hands, studying the sacred places. A few would even pluck and preserve a spear of grass, carefully enshrining it in an envelope duly marked. A report went abroad, indeed, that soil from the Holy Land itself had been spread upon the park, constituting it a sort of Campo Santo, but this claim was never endorsed by either its architect or its originator.[48] The park of Palestine still stands, having been rebuilt several times, enlarged to a length of 350 feet, and now, as I write, with another restoration promised.

One fact in this sacred geography must needs be stated, in the interests of exact truth. In order to make use of the lake shore, north had to be in the south, and east in the west. Chautauqua has always been under a despotic though paternal government, and its visitors easily accommodate themselves to its decrees. But the sun persists in its independence, rises over Chautauqua's Mediterranean Sea where it should set, and continues its sunset over the mountains of Gilead, where it should rise. Dr. Vincent and Lewis Miller could bring to pass some remarkable, even seemingly impossible, achievements, but they were not able to outdo Joshua, and not only make the sun stand still, but set it moving in a direction opposite to its natural course.

In one of his inimitable speeches, Frank Beard said that Palestine Park had been made the model for all the beds on Fair Point. He slept, as he asserted, on Palestine, with his head on Mount Hermon, his body sometimes in the Jordan valley, at other times on the mountains of Ephraim; and one night when it rained, he found his feet in the Dead Sea.[49]

In the early days of Chautauqua a tree was standing near Palestine Park, which invited the attention of every child, and many grown folks. It was called "the spouting tree." Dr. Wythe found a tree with one branch bent over near the ground and hollow. He placed a water-pipe in the branch and sent a current of fresh water through it, so that the tree seemed to be pouring forth water. At all times a troop of children might be seen around it. At least one little girl made her father walk down every day to the wonder, to the neglect of other walks on the Assembly ground. Afterward at home from an extended tour, they asked her what was the most wonderful thing that she had seen in her journey. They expected her to say, "Niagara Falls," but without hesitation she answered, "The tree that spouted water at Chautauqua." The standards of greatness in the eyes of childhood differ from those of the grown-up folks.

The true Chautauqua, aided as it was by the features of mirth and entertainment and repartee, was in the daily program followed diligently by the assembled thousands. Here is in part the schedule, taken from the printed report. It was opened on Tuesday evening, August 4, 1874, in the out-of-doors auditorium, now Miller Park, beginning with a brief responsive service of Scripture and song,[50] prepared by Dr. Vincent. Chautauqua clings to ancient customs; and that same service, word for word, has been rendered every year on the first Tuesday evening in August, at what is known as "Old First Night."

Old Steamer "Jamestown"

Old Steamer "Jamestown"

|  Oriental House; Museum

Oriental House; Museum

|

Bishop Vincent afterward wrote of that memorable first meeting:

The stars were out, and looked down through trembling leaves upon a goodly well-wrapped company, who sat in the grove, filled with wonder and hope. No electric light brought platform and people face to face that night. The old-fashioned pine fires on rude four-legged stands covered with earth, burned with unsteady, flickering flame, now and then breaking into brilliancy by the contact of a resinous stick of the rustic fireman, who knew how to snuff candles and how to turn light on the crowd of campers-out. The white tents around the enclosure were very beautiful in that evening light.

At this formal opening on August 4, 1874, brief addresses were given by Dr. Vincent and by a Baptist, a Presbyterian, a Methodist, and a Congregational pastor. This opening showed the broad brotherhood which was to mark the history of Chautauqua.