The Project Gutenberg eBook, Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China, by

Evariste Regis Huc, Translated by W. Hazlitt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China

During the years 1844-5-6. Volume 1 [of 2]

Author: Evariste Regis Huc

Release Date: June 8, 2010 [eBook #32747]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII)

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAVELS IN TARTARY, THIBET, AND

CHINA***

This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler.

BY M. HUC.

translated from the french by w. hazlitt.

VOL. I.

illustrated with fifty engravings on wood.

london:

office of the national illustrated

library,

227 strand.

london:

vizetelly and company, printers and engravers,

peterborough court, fleet street.

The Pope having, about the year 1844, been pleased to establish an Apostolic Vicariat of Mongolia, it was considered expedient, with a view to further operations, to ascertain the nature and extent of the diocese thus created, and MM. Gabet and Huc, two Lazarists attached to the petty mission of Si-Wang, were accordingly deputed to collect the necessary information. They made their way through difficulties which nothing but religious enthusiasm in combination with French elasticity could have overcome, to Lha-Ssa, the capital of Thibet, and in this seat of Lamanism were becoming comfortably settled, with lively hopes and expectations of converting the Talé-Lama into a branch-Pope, when the Chinese Minister, the noted Ke-Shen, interposed on political grounds, and had them deported to China. M. Gabet was directed by his superiors to proceed to France, and lay a complaint before his Government, of the arbitrary treatment which he and his fellow Missionary had experienced. In the steamer which conveyed him from Hong Kong to Ceylon, he found Mr. Alexander Johnstone, secretary to Her Majesty’s p. iiPlenipotentiary in China; and this gentleman perceived so much, not merely of entertainment, but of important information in the conversations he had with M. Gabet, that he committed to paper the leading features of the Reverend Missionary’s statements, and on his return to his official post, gave his manuscripts to Sir John Davis, who, in his turn, considered their contents so interesting, that he embodied a copy of them in a dispatch to Lord Palmerston. Subsequently the two volumes, here translated, were prepared by M. Huc, and published in Paris. Thus it is, that to Papal aggression in the East, the Western World is indebted for a work exhibiting, for the first time, a complete representation of countries previously almost unknown to Europeans, and indeed considered practically inaccessible; and of a religion which, followed by no fewer than 170,000,000 persons, presents the most singular analogies in its leading features with the Catholicism of Rome.

|

Page |

Preface |

|

Contents |

|

List of Illustrations |

|

CHAPTER I. |

|

French Mission of Peking—Glance at the Kingdom of Ouniot—Preparations for Departure—Tartar-Chinese Inn—Change of Costume—Portrait and Character of Samdadchiemba—Sain-Oula (the Good Mountain)—The Frosts on Sain-Oula, and its Robbers—First Encampment in the Desert—Great Imperial Forest—Buddhist Monuments on the summit of the Mountains—Topography of the Kingdom of Gechekten—Character of its Inhabitants—Tragical working of a Mine—Two Mongols desire to have their horoscope taken—Adventure of Samdadchiemba—Environs of the town of Tolon-Noor |

|

CHAPTER II. |

|

Inn at Tolon-Noor—Aspect of the City—Great Foundries of Bells and Idols—Conversation with the Lamas of Tolon-Noor—Encampment—Tea Bricks—Meeting with Queen Mourguevan—Taste of the Mongols for Pilgrimages—Violent Storm—Account from a Mongol Chief of the War of the English against China—Topography of the Eight Banners of the Tchakar—The Imperial Herds—Form and Interior of the Tents—Tartar Manners and Customs—Encampment at the Three Lakes—Nocturnal Apparitions—Samdadchiemba relates the Adventures of his Youth—Grey Squirrels of Tartary—Arrival at Chaborté |

|

Festival of the Loaves of the Moon—Entertainment in a Mongol Tent—Toolholos, or Rhapsodists of Tartary—Invocation to Timour—Tartar Education—Industry of the Women—Mongols in quest of missing Animals—Remains of an abandoned City—Road from Peking to Kiaktha—Commerce between China and Russia—Russian Convent at Peking—A Tartar solicits us to cure his Mother from a dangerous Illness—Tartar Physicians—The Intermittent Fever Devil—Various forms of Sepulture in use among the Mongols—Lamasery of the Five Towers—Obsequies of the Tartar Kings—Origin of the kingdom of Efe—Gymnastic Exercises of the Tartars—Encounter with three Wolves—Mongol Carts |

|

CHAPTER IV. |

|

Young Lama converted to Christianity—Lamasery of Tchortchi—Alms for the Construction of Religious Houses—Aspect of the Buddhist Temples—Recitation of Lama Prayers—Decorations, Paintings, and Sculptures of the Buddhist Temples—Topography of the Great Kouren in the country of the Khalkhas—Journey of the Guison-Tamba to Peking—The Kouren of the Thousand Lamas—Suit between the Lama-King and his Ministers—Purchase of a Kid—Eagles of Tartary—Western Toumet—Agricultural Tartars—Arrival at the Blue Town—Glance at the Mantchou Nation—Mantchou Literature—State of Christianity in Mantchouria—Topography and productions of Eastern Tartary—Skill of the Mantchous with the Bow |

|

CHAPTER V. |

|

The Old Blue Town—Quarter of the Tanners—Knavery of the Chinese Traders—Hotel of the Three Perfections—Spoliation of the Tartars by the Chinese—Money Changer’s Office—Tartar Coiner—Purchase of two Sheep-skin Robes—Camel Market—Customs of the Cameleers—Assassination of a Grand Lama of the Blue Town—Insurrection of the Lamaseries—Negociation between the Court of Peking and that of Lha-Ssa—Domestic Lamas—Wandering Lamas—Lamas in Community—Policy of the Mantchou Dynasty with reference to the Lamaseries—Interview with a Thibetian Lama—Departure from the Blue Town |

|

A Tartar-eater—Loss of Arsalan—Great Caravan of Camels—Night Arrival at Tchagan-Kouren—We are refused Admission into the Inns—We take up our abode with a Shepherd—Overflow of the Yellow River-Aspect of Tchagan-Kouren—Departure across the Marshes—Hiring a Bark—Arrival on the Banks of the Yellow River—Encampment under the Portico of a Pagoda—Embarkation of the Camels—Passage of the Yellow River—Laborious Journey across the Inundated Country—Encampment on the Banks of the River |

|

CHAPTER VII. |

|

Mercurial Preparation for the Destruction of Lice—Dirtiness of the Mongols—Lama Notions about the Metempsychosis—Washing—Regulations of Nomadic Life—Aquatic and Passage Birds—The Yuen-Yang—The Dragon’s Foot—Fishermen of the Paga-Gol—Fishing Party—Fisherman Bit by a Dog—Kou-Kouo, or St. Ignatius’s Bean—Preparations for Departure—Passage of the Paga-Gol—Dangers of the Voyage—Devotion of Samdadchiemba—The Prime Minister of the King of the Ortous—Encampment |

|

CHAPTER VIII. |

|

Glance at the Country of the Ortous—Cultivated Lands—Sterile, sandy steppes of the Ortous—Form of the Tartar-Mongol Government—Nobility—Slavery—A small Lamasery—Election and Enthronization of a Living Buddha—Discipline of the Lamaseries—Lama Studies—Violent Storm—Shelter in some Artificial Grottoes—Tartar concealed in a Cavern—Tartaro-Chinese Anecdote—Ceremonies of Tartar Marriages—Polygamy—Divorce—Character and Costume of the Mongol Women |

|

CHAPTER IX. |

|

Departure of the Caravan—Encampment in a fertile Valley—Intensity of the Cold—Meeting with numerous Pilgrims—Barbarous and Diabolical Ceremonies of Lamanism—Project for the Lamasery of Rache-Tchurin—Dispersion and rallying of the little Caravan—Anger of Samdadchiemba—Aspect of the Lamasery of Rache-Tchurin—Different Kinds of Pilgrimages around the Lamaseries—Turning Prayers—Quarrel between two Lamas—Similarity of the Soil—Description of the Tabsoun-Noor or Salt Sea—Remarks on the Camels of Tartary |

|

Purchase of a Sheep—A Mongol Butcher—Great Feast à la Tartare—Tartar Veterinary Surgeons—Strange Cure of a Cow—Depth of the Wells of the Ortous—Manner of Watering the Animals—Encampment at the Hundred Wells—Meeting with the King of the Alechan—Annual Embassies of the Tartar Sovereigns to Peking—Grand Ceremony in the Temple of the Ancestors—The Emperor gives Counterfeit Money to the Mongol Kings—Inspection of our Geographical Map—The Devils Cistern—Purification of the Water—A Lame Dog—Curious Aspect of the Mountains—Passage of the Yellow River |

|

CHAPTER XI. |

|

Sketch of the Tartar Nations |

|

CHAPTER XII. |

|

Hotel of Justice and Mercy—Province of Kan-Sou—Agriculture—Great Works for the Irrigation of the Fields—Manner of Living in Inns—Great Confusion in a Town caused by our Camels—Chinese Lifeguard—Mandarin Inspector of the Public Works—Ning-Hia—Historical and Topographical Details—Inn of the Five Felicities—Contest with a Mandarin, Tchong-Wei—Immense Mountains of Sand—Road to Ili—Unfavourable aspect of Kao-Tan-Dze—Glance at the Great Wall—Inquiry after the Passports—Tartars travelling in China—Dreadful Hurricane—Origin and Manners of the Inhabitants of Kan-Sou—The Dchiahours—Interview with a Living Buddha—Hotel of the Temperate Climates—Family of Samdadchiemba—Mountain of Ping-Keou—Fight between an Innkeeper and his Wife—Water-mills—Knitting—Sí-Ning-Fou—House of Rest—Arrival at Tang-Keou-Eul |

|

|

page |

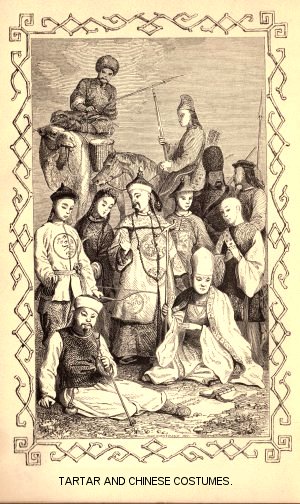

Frontispiece, Chinese and Tartar Costumes |

|

Title-page, Portraits of MM. Gabet and Huc |

|

View of the City of Peking |

|

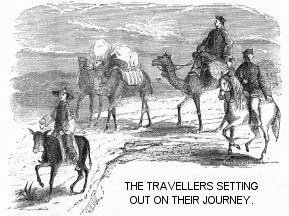

The Travellers setting out on their Journey |

|

Kang of a Tartar-Chinese Inn |

|

The Missionaries in their Lamanesque Costumes |

|

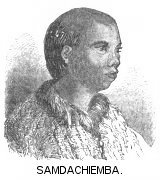

Portrait of Samdadchiemba |

|

Mountain of Sain-Oula |

|

First Encampment |

|

Buddhist Monuments |

|

Military Mandarin |

|

Chinese Idol |

|

View of the City of Tolon-Noor |

|

Bell and Idol Foundry |

|

The Queen of Mourguevan |

|

The Emperor Tao-Kouang |

|

Tartar Encampment |

|

Interior of a Tartar Tent |

|

Russian Convent at Peking |

|

Lamasery of the Five Towers |

|

Lamasery of Tchortchi |

|

Buddhist Temple |

|

Interior of Buddhist Temple |

|

Tartar Agriculturist |

|

Chinese Soldier |

|

Chinese Money-changers |

|

The Camel Market |

|

View of Tchagan-Kouren |

|

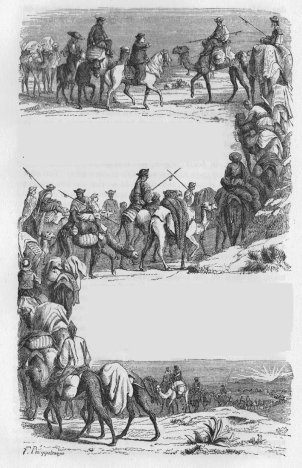

Caravan crossing the Desert |

|

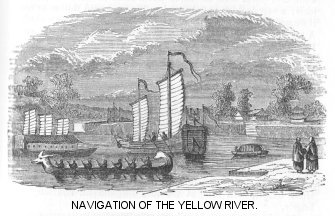

Navigation of the Yellow River |

|

Camel of Tartary |

|

Water-fowl and Birds of Passage |

|

A Fishing Party |

|

Election of a Living Buddha |

|

The Steppes of Ortous |

|

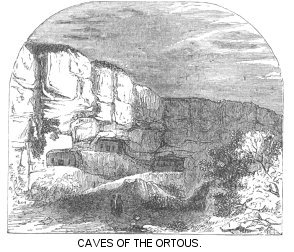

Caves of the Ortous |

|

Barbarous Lamanesque Ceremony |

|

Lamasery of Rache-Tchurin |

|

Turning Prayers |

|

Mongol Butcher |

|

Encampment at the Hundred Wells |

|

Grand Ceremony at the Ancestral Temple |

|

Chinese Idol |

|

Chinese and Tartar Arms |

|

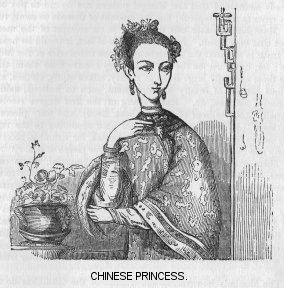

Chinese Princess |

|

Chinese Caricature |

|

Irrigation of the Fields |

|

Root of the Jin-Seng |

French Mission of Peking—Glance at the Kingdom of Ouniot—Preparations for Departure—Tartar-Chinese Inn—Change of Costume—Portrait and Character of Samdadchiemba—Sain-Oula (the Good Mountain)—The Frosts on Sain-Oula, and its Robbers—First Encampment in the Desert—Great Imperial Forest—Buddhist monuments on the summit of the mountains—Topography of the Kingdom of Gechekten—Character of its Inhabitants—Tragical working of a Mine—Two Mongols desire to have their horoscope taken—Adventure of Samdadchiemba—Environs of the town of Tolon-Noor.

The French mission of Peking, once so flourishing under the

early emperors of the Tartar-Mantchou dynasty, was almost

extirpated by the constant persecutions of Kia-King, the fifth

monarch of that dynasty, who ascended the throne in 1799.

The missionaries were dispersed or put to death, and at that time

Europe was herself too deeply agitated to enable her to send

succour to this distant Christendom, which remained for a time

abandoned. Accordingly, when the French Lazarists

re-appeared at Peking, they found there scarce a vestige of the

true faith. A great number of Christians, to avoid p.

10the persecutions of the Chinese authorities, had passed

the Great Wall, and sought peace and liberty in the deserts of

Tartary, where they lived dispersed upon small patches of land

which the Mongols permitted them to cultivate. By dint of

perseverance the missionaries collected together these dispersed

Christians, placed themselves at their head, and hence

superintended the mission of Peking, the immediate administration

of which was in the hands of a few Chinese Lazarists. The

French missionaries could not, with any prudence, have resumed

their former position in the capital of the empire. Their

presence would have compromised the prospects of the scarcely

reviving mission.

The French mission of Peking, once so flourishing under the

early emperors of the Tartar-Mantchou dynasty, was almost

extirpated by the constant persecutions of Kia-King, the fifth

monarch of that dynasty, who ascended the throne in 1799.

The missionaries were dispersed or put to death, and at that time

Europe was herself too deeply agitated to enable her to send

succour to this distant Christendom, which remained for a time

abandoned. Accordingly, when the French Lazarists

re-appeared at Peking, they found there scarce a vestige of the

true faith. A great number of Christians, to avoid p.

10the persecutions of the Chinese authorities, had passed

the Great Wall, and sought peace and liberty in the deserts of

Tartary, where they lived dispersed upon small patches of land

which the Mongols permitted them to cultivate. By dint of

perseverance the missionaries collected together these dispersed

Christians, placed themselves at their head, and hence

superintended the mission of Peking, the immediate administration

of which was in the hands of a few Chinese Lazarists. The

French missionaries could not, with any prudence, have resumed

their former position in the capital of the empire. Their

presence would have compromised the prospects of the scarcely

reviving mission.

In visiting the Chinese Christians of Mongolia, we more than once had occasion to make excursions into the Land of Grass, (Isao-Ti), as the uncultivated portions of Tartary are designated, and to take up our temporary abode beneath the tents of the Mongols. We were no sooner acquainted with this nomadic people, than we loved them, and our hearts were filled with a passionate desire to announce the gospel to them. Our whole leisure was therefore devoted to acquiring the Tartar dialects, and in 1842, the Holy See at length fulfilled our desires, by erecting Mongolia into an Apostolical Vicariat.

Towards the commencement of the year 1844, couriers arrived at Si-wang, a small Christian community, where the vicar apostolic of Mongolia had fixed his episcopal residence. Si-wang itself is a village, north of the Great Wall, one day’s journey from Suen-hoa-Fou. The prelate sent us instructions for an extended voyage we were to undertake for the purpose of studying the character and manners of the Tartars, and of ascertaining as nearly as possible the extent and limits of the Vicariat. This journey, then, which we had so long meditated, was now determined upon; and we sent a young Lama convert in search of some camels which we had put to pasture in the kingdom of Naiman. Pending his absence, we hastened the completion of several Mongol works, the translation of which had occupied us for a considerable time. Our little books of prayer and doctrine were ready, still our young Lama had not returned; but thinking he could not delay much longer, we quitted the valley of Black Waters (Hé-Chuy), and proceeded on to await his arrival at the Contiguous Defiles (Pié-lié-Keou) which seemed more favourable for the completion of our preparations. The days passed away in futile expectation; the coolness of the autumn was becoming somewhat biting, and we feared that we should have to begin our journey across the deserts of Tartary during the frosts of winter. We determined, therefore, to dispatch some one in quest of our camels and our Lama. A friendly p. 11catechist, a good walker and a man of expedition, proceeded on this mission. On the day fixed for that purpose he returned; his researches had been wholly without result. All he had ascertained at the place which he had visited was, that our Lama had started several days before with our camels. The surprise of our courier was extreme when he found that the Lama had not reached us before himself. “What!” exclaimed he, “are my legs quicker than a camel’s! They left Naiman before me, and here I am arrived before them! My spiritual fathers, have patience for another day. I’ll answer that both Lama and camels will be here in that time.” Several days, however, passed away, and we were still in the same position. We once more dispatched the courier in search of the Lama, enjoining him to proceed to the very place where the camels had been put to pasture, to examine things with his own eyes, and not to trust to any statement that other people might make.

During this interval of painful suspense, we continued to inhabit the Contiguous Defiles, a Tartar district dependent on the kingdom of Ouniot. [11] These regions appear to have been affected by great revolutions. The present inhabitants state that, in the olden time, the country was occupied by Corean tribes, who, expelled thence in the course of various wars, took refuge in the peninsula which they still possess, between the Yellow Sea and the sea of Japan. You often, in these parts of Tartary, meet with the remains of great towns, and the ruins of fortresses, very nearly resembling those of the middle ages in Europe, and, upon turning up the soil in these places, it is not unusual to find lances, arrows, portions of farming implements, and urns filled with Corean money.

Towards the middle of the 17th century, the Chinese began to penetrate into this district. At that period, the whole landscape was still one of rude grandeur; the mountains were covered with fine forests, and the Mongol tents whitened the valleys, amid rich pasturages. For a very moderate sum the Chinese obtained permission to cultivate the desert, and as cultivation advanced, the Mongols were obliged to retreat, conducting their flocks and herds elsewhere.

From that time forth, the aspect of the country became entirely changed. All the trees were grubbed up, the forests disappeared from the hills, the prairies were cleared by means of fire, and the new cultivators set busily to work in exhausting the fecundity of the soil. Almost the entire region is now in the hands of the Chinese, and it is probably to their system of devastation that we must p. 12attribute the extreme irregularity of the seasons which now desolate this unhappy land. Droughts are of almost annual occurrence; the spring winds setting in, dry up the soil; the heavens assume a sinister aspect, and the unfortunate population await, in utter terror, the manifestation of some terrible calamity; the winds by degrees redouble their violence, and sometimes continue to blow far into the summer months. Then the dust rises in clouds, the atmosphere becomes thick and dark; and often, at mid-day, you are environed with the terrors of night, or rather, with an intense and almost palpable blackness, a thousand times more fearful than the most sombre night. Next after these hurricanes comes the rain: but so comes, that instead of being an object of desire, it is an object of dread, for it pours down in furious raging torrents. Sometimes the heavens suddenly opening, pour forth in, as it were, an immense cascade, all the water with which they are charged in that quarter; and immediately the fields and their crops disappear under a sea of mud, whose enormous waves follow the course of the valleys, and carry everything before them. The torrent rushes on, and in a few hours the earth reappears; but the crops are gone, and worse even than that, the arable soil also has gone with them. Nothing remains but a ramification of deep ruts, filled with gravel, and thenceforth incapable of being ploughed.

Hail is of frequent occurrence in these unhappy districts, and the dimensions of the hailstones are generally enormous. We have ourselves seen some that weighed twelve pounds. One moment sometimes suffices to exterminate whole flocks. In 1843, during one of these storms, there was heard in the air a sound as of a rushing wind, and therewith fell, in a field near a house, a mass of ice larger than an ordinary millstone. It was broken to pieces with hatchets, yet, though the sun burned fiercely, three days elapsed before these pieces entirely melted.

The droughts and the inundations together, sometimes occasion famines which well nigh exterminate the inhabitants. That of 1832, in the twelfth year of the reign of Tao-Kouang, [12] is the most terrible of these on record. The Chinese report that it was everywhere announced by a general presentiment, the exact nature of which no one could explain or comprehend. During the winter of 1831, a dark rumour grew into circulation. Next year, it was said, there will be neither rich nor poor; blood will cover the mountains; bones will fill the valleys (Ou fou, ou kioung; hue man chan, kou man tchouan.) These words were in every one’s mouth; the children repeated them in their sports; all were under the p. 13domination of these sinister apprehensions when the year 1832 commenced. Spring and summer passed away without rain, and the frosts of autumn set in while the crops were yet green; these crops of course perished, and there was absolutely no harvest. The population was soon reduced to the most entire destitution. Houses, fields, cattle, everything was exchanged for grain, the price of which attained its weight in gold. When the grass on the mountain sides was devoured by the starving creatures, the depths of the earth were dug into for roots. The fearful prognostic, that had been so often repeated, became accomplished. Thousands died upon the hills, whither they had crawled in search of grass; dead bodies filled the roads and houses; whole villages were depopulated to the last man. There was, indeed, neither rich nor poor; pitiless famine had levelled all alike.

It was in this dismal region that we awaited with impatience the courier, whom, for a second time, we had dispatched into the kingdom of Naiman. The day fixed for his return came and passed, and several others followed, but brought no camels, nor Lama, nor courier, which seemed to us most astonishing of all. We became desperate; we could not longer endure this painful and futile suspense. We devised other means of proceeding, since those we had arranged appeared to be frustrated. The day of our departure was fixed; it was settled, further, that one of our Christians should convey us in his car to Tolon-Noor, distant from the Contiguous Defiles about fifty leagues. At Tolon-Noor we were to dismiss our temporary conveyance, proceed alone into the desert, and thus start on our pilgrimage as well as we could. This project absolutely stupified our Christian friends; they could not comprehend how two Europeans should undertake by themselves a long journey through an unknown and inimical country: but we had reasons for abiding by our resolution. We did not desire that any Chinese should accompany us. It appeared to us absolutely necessary to throw aside the fetters with which the authorities had hitherto contrived to shackle missionaries in China. The excessive caution, or rather the imbecile pusillanimity of a Chinese catechist, was calculated rather to impede than to facilitate our progress in Tartary.

On the Sunday, the day preceding our arranged departure, every thing was ready; our small trunks were packed and padlocked, and the Christians had assembled to bid us adieu. On this very evening, to the infinite surprise of all of us, our courier arrived. As he advanced his mournful countenance told us before he spoke, that his intelligence was unfavourable. “My spiritual fathers,” said he, “all is lost; you have nothing to hope; in the kingdom of Naiman there no longer exists any camels of the Holy Church. The Lama p. 14doubtless has been killed; and I have no doubt the devil has had a direct hand in the matter.”

Doubts and fears are often harder to bear than the certainty of evil. The intelligence thus received, though lamentable in itself, relieved us from our perplexity as to the past, without in any way altering our plan for the future. After having received the condolences of our Christians, we retired to rest, convinced that this night would certainly be that preceding our nomadic life.

The night was far advanced, when suddenly numerous voices were heard outside our abode, and the door was shaken with loud and repeated knocks. We rose at once; the Lama, the camels, all had arrived; there was quite a little revolution. The order of the day was instantly changed. We resolved to depart, not on the Monday, but on the Tuesday; not in a car, but on camels, in true Tartar fashion. We returned to our beds perfectly delighted; but we could not sleep, each of us occupying the remainder of the night with plans for effecting the equipment of the caravan in the most expeditious manner possible.

Next day, while we were making our preparations for departure, our Lama explained his extraordinary delay. First, he had undergone a long illness; then he had been occupied a considerable time in pursuing a camel which had escaped into the desert; and finally, he had to go before some tribunal, in order to procure the restitution of a mule which had been stolen from him. A law-suit, an illness, and a camel hunt were amply sufficient reasons for excusing the delay which had occurred. Our courier was the only person who did not participate in the general joy; he saw it must be evident to every one that he had not fulfilled his mission with any sort of skill.

All Monday was occupied in the equipment of our caravan. Every person gave his assistance to this object. Some repaired our travelling-house, that is to say, mended or patched a great blue linen tent; others cut for us a supply of wooden tent pins; others mended the holes in our copper kettle, and renovated the broken leg of a joint stool; others prepared cords, and put together the thousand and one pieces of a camel’s pack. Tailors, carpenters, braziers, rope-makers, saddle-makers, people of all trades assembled in active co-operation in the court-yard of our humble abode. For all, great and small, among our Christians, were resolved that their spiritual fathers should proceed on their journey as comfortably as possible.

On Tuesday morning, there remained nothing to be done but to perforate the nostrils of the camels, and to insert in the aperture a wooden peg, to use as a sort of bit. The arrangement of this was p. 15left to our Lama. The wild piercing cries of the poor animals pending the painful operation, soon collected together all the Christians of the village. At this moment, our Lama became exclusively the hero of the expedition. The crowd ranged themselves in a circle around him; every one was curious to see how, by gently pulling the cord attached to the peg in its nose, our Lama could make the animal obey him, and kneel at his pleasure. Then, again, it was an interesting thing for the Chinese to watch our Lama packing on the camels’ backs the baggage of the two missionary travellers. When the arrangements were completed, we drank a cup of tea, and proceeded to the chapel; the Christians recited prayers for our safe journey; we received their farewell, interrupted with tears, and proceeded on our way. Samdadchiemba, our Lama cameleer, gravely mounted on a black, stunted, meagre mule, opened the march, leading two camels laden with our baggage; then came the two missionaries, MM. Gabet and Huc, the former mounted on a tall camel, the latter on a white horse.

Upon our departure we were resolved to lay aside our

accustomed usages, and to become regular Tartars. Yet we

did not at the outset, and all at once, become exempt from the

Chinese system. Besides that, for the first mile or two of

our journey, we were escorted by our Chinese Christians, some on

foot, and some on horseback; our first stage was to be an inn

kept by the Grand Catechist of the Contiguous Defiles.

Upon our departure we were resolved to lay aside our

accustomed usages, and to become regular Tartars. Yet we

did not at the outset, and all at once, become exempt from the

Chinese system. Besides that, for the first mile or two of

our journey, we were escorted by our Chinese Christians, some on

foot, and some on horseback; our first stage was to be an inn

kept by the Grand Catechist of the Contiguous Defiles.

p. 16The progress of our little caravan was not at first wholly successful. We were quite novices in the art of saddling and girdling camels, so that every five minutes we had to halt, either to rearrange some cord or piece of wood that hurt and irritated the camels, or to consolidate upon their backs, as well as we could, the ill-packed baggage that threatened, ever and anon, to fall to the ground. We advanced, indeed, despite all these delays, but still very slowly. After journeying about thirty-five lis, [16] we quitted the cultivated district and entered upon the Land of Grass. There we got on much better; the camels were more at their ease in the desert, and their pace became more rapid.

We ascended a high mountain, where the camels evinced a decided tendency to compensate themselves for their trouble, by browzing, on either side, upon the tender stems of the elder tree or the green leaves of the wild rose. The shouts we were obliged to keep up, in order to urge forward the indolent beasts, alarmed infinite foxes, who issued from their holes and rushed off in all directions. On attaining the summit of the rugged hill we saw in the hollow beneath the Christian inn of Yan-Pa-Eul. We proceeded towards it, our road constantly crossed by fresh and limpid streams, which, issuing from the sides of the mountain, reunite at its foot and form a rivulet which encircles the inn. We were received by the landlord, or, as the Chinese call him, the Comptroller of the Chest.

Inns of this description occur at intervals in the deserts of Tartary, along the confines of China. They consist almost universally of a large square enclosure, formed by high poles interlaced with brushwood. In the centre of this enclosure is a mud house, never more than ten feet high. With the exception of a few wretched rooms at each extremity, the entire structure consists of one large apartment, serving at once for cooking, eating, and sleeping; thoroughly dirty, and full of smoke and intolerable stench. Into this pleasant place all travellers, without distinction, are ushered, the portion of space applied to their accommodation being a long, wide Kang, as it is called, a sort of furnace, occupying more than three-fourths of the apartment, about four feet high, and the flat, smooth surface of which is covered with a reed mat, which the richer guests cover again with a travelling carpet of felt, or with furs. In front of it, three immense coppers, set in glazed earth, serve for the preparation of the traveller’s milk-broth. The apertures by which these monster boilers are heated communicate with the interior of the Kang, so that its temperature is constantly maintained at a high elevation, even in the terrible cold of winter.

Upon the arrival of guests, the Comptroller of the Chest invites them to ascend the Kang, where they seat themselves, their legs crossed tailor-fashion, round a large table, not more than six inches high. The lower part of the room is reserved for the people of the inn, who there busy themselves in keeping up the fire under the cauldrons, boiling tea, and pounding oats and buckwheat into flour for the repast of the travellers. The Kang of these Tartar-Chinese inns is, till evening, a stage full of animation, where the guests eat, drink, smoke, gamble, dispute, and fight: with night-fall, the refectory, tavern, and gambling-house of the day is suddenly converted into a dormitory. The travellers who have any bed-clothes unroll and arrange them; those who have none, settle themselves as best they may in their personal attire, and lie down, side by side, round the table. When the guests are very numerous they arrange themselves in two circles, feet to feet. Thus reclined, those so disposed, sleep; others, awaiting sleep, smoke, drink tea, and gossip. The effect of the scene, dimly exhibited by an imperfect wick floating amid thick, dirty, stinking oil, whose receptacle is ordinarily a broken tea-cup, is fantastic, and to the stranger, fearful.

p. 18The Comptroller of the Chest had prepared his own room for our accommodation. We washed, but would not sleep there; being now Tartar travellers, and in possession of a good tent, we determined to try our apprentice hand at setting it up. This resolution offended no one, it was quite understood we adopted this course, not out of contempt towards the inn, but out of love for a patriarchal life. When we had set up our tent, and unrolled on the ground our goat-skin beds, we lighted a pile of brushwood, for the nights were already growing cold. Just as we were closing our eyes, the Inspector of Darkness startled us with beating the official night alarum, upon his brazen tam-tam, the sonorous sound of which, reverberating through the adjacent valleys struck with terror the tigers and wolves frequenting them, and drove them off.

We were on foot before daylight. Previous to our departure we had to perform an operation of considerable importance—no other than an entire change of costume, a complete metamorphosis. The missionaries who reside in China, all, without exception, wear the secular dress of the people, and are in no way distinguishable from them; they bear no outward sign of their religious character. It is a great pity that they should be thus obliged to wear the secular costume, for it is an obstacle in the way of their preaching the gospel. Among the Tartars, a black man—so they discriminate the laity, as wearing their hair, from the clergy, who have their heads close shaved—who should talk about religion would be laughed at, as impertinently meddling with things, the special province of the Lamas, and in no way concerning him. The reasons which appear to have introduced and maintained the custom of wearing the secular habit on the part of the missionaries in China, no longer applying to us, we resolved at length to appear in an ecclesiastical exterior becoming our sacred mission. The views of our vicar apostolic on the subject, as explained in his written instructions, being conformable with our wish, we did not hesitate. We resolved to adopt the secular dress of the Thibetian Lamas; that is to say, the dress which they wear when not actually performing their idolatrous ministry in the Pagodas. The costume of the Thibetian Lamas suggested itself to our preference as being in unison with that worn by our young neophyte, Samdadchiemba.

We announced to the Christians of the inn that we were resolved no longer to look like Chinese merchants; that we were about to cut off our long tails, and to shave our heads. This intimation created great agitation: some of our disciples even wept; all sought by their eloquence to divert us from a resolution which seemed to them fraught with danger; but their pathetic remonstrances were of no avail; one touch of a razor, in the hands of Samdadchiemba p. 19sufficed to sever the long tail of hair, which, to accommodate Chinese fashions, we had so carefully cultivated ever since our departure from France. We put on a long yellow robe, fastened at the right side with five gilt buttons, and round the waist by a long red sash; over this was a red jacket, with a collar of purple velvet; a yellow cap, surmounted by a red tuft, completed our new costume. Breakfast followed this decisive operation, but it was silent and sad. When the Comptroller of the Chest brought in some glasses and an urn, wherein smoked the hot wine drunk by the Chinese, we told him that having changed our habit of dress, we should change also our habit of living. “Take away,” said we, “that wine and that chafing dish; henceforth we renounce drinking and smoking. You know,” added we, laughing, “that good Lamas abstain from wine and tobacco.” The Chinese Christians who surrounded us did not join in the laugh; they looked at us without speaking and with deep commiseration, fully persuaded that we should inevitably perish of privation and misery in the deserts of Tartary. Breakfast finished, while the people of the inn were packing up our tent, saddling the camels, and preparing for our departure, we took a couple of rolls, baked in the steam of the furnace, and walked out to complete our meal with some wild currants growing on the bank of the adjacent rivulet. It was soon announced to us that everything was ready—so, mounting our respective animals, we proceeded on the road to Tolon-Noor, accompanied by Samdadchiemba.

We were now launched, alone and without a guide, amid a new

world. We had no longer before us paths traced out by the

old p.

20missionaries, for we were in a country where none before

us had preached Gospel truth. We should no longer have by

our side those earnest Christian converts, so zealous to serve

us; so anxious, by their friendly care, to create around us as it

were an atmosphere of home. We were abandoned to ourselves,

in a hostile land, without a friend to advise or to aid us, save

Him by whose strength we were supported, and whose name we were

seeking to make known to all the nations of the earth.

We were now launched, alone and without a guide, amid a new

world. We had no longer before us paths traced out by the

old p.

20missionaries, for we were in a country where none before

us had preached Gospel truth. We should no longer have by

our side those earnest Christian converts, so zealous to serve

us; so anxious, by their friendly care, to create around us as it

were an atmosphere of home. We were abandoned to ourselves,

in a hostile land, without a friend to advise or to aid us, save

Him by whose strength we were supported, and whose name we were

seeking to make known to all the nations of the earth.

As we have just observed, Samdadchiemba was our only

travelling companion. This young man was neither Chinese,

nor Tartar, nor Thibetian. Yet, at the first glance, it was

easy to recognise in him the features characterizing that which

naturalists call the Mongol race. A great flat nose,

insolently turned up; a large mouth, slit in a perfectly straight

line, thick, projecting lips, a deep bronze complexion, every

feature contributed to give to his physiognomy a wild and

scornful aspect. When his little eyes seemed starting out

of his head from under their lids, wholly destitute of eyelash,

and he looked at you wrinkling his brow, he inspired you at once

with feelings of dread and yet of confidence. The face was

without any decisive character: it exhibited neither the

mischievous knavery of the Chinese, nor the frank good-nature of

the Tartar, nor the courageous energy of the Thibetian; but was

made up of a mixture of all three. Samdadchiemba was a

Dchiahour. We shall hereafter have occasion to speak

more in detail of the native country of our young cameleer.

As we have just observed, Samdadchiemba was our only

travelling companion. This young man was neither Chinese,

nor Tartar, nor Thibetian. Yet, at the first glance, it was

easy to recognise in him the features characterizing that which

naturalists call the Mongol race. A great flat nose,

insolently turned up; a large mouth, slit in a perfectly straight

line, thick, projecting lips, a deep bronze complexion, every

feature contributed to give to his physiognomy a wild and

scornful aspect. When his little eyes seemed starting out

of his head from under their lids, wholly destitute of eyelash,

and he looked at you wrinkling his brow, he inspired you at once

with feelings of dread and yet of confidence. The face was

without any decisive character: it exhibited neither the

mischievous knavery of the Chinese, nor the frank good-nature of

the Tartar, nor the courageous energy of the Thibetian; but was

made up of a mixture of all three. Samdadchiemba was a

Dchiahour. We shall hereafter have occasion to speak

more in detail of the native country of our young cameleer.

At the age of eleven, Samdadchiemba had escaped from his Lamasery, in order to avoid the too frequent and too severe corrections of the master under whom he was more immediately placed. He afterwards passed the greater portion of his vagabond youth, sometimes in the Chinese towns, sometimes in the deserts of Tartary. It is easy to comprehend that this independent course of life had not tended to modify the natural asperity of his character; his intellect was entirely uncultivated; but, on the other hand, his muscular power was enormous, and he was not a little vain of this quality, which he took great pleasure in parading. After having p. 21been instructed and baptized by M. Gabet, he had attached himself to the service of the missionaries. The journey we were now undertaking was perfectly in harmony with his erratic and adventurous taste. He was, however, of no mortal service to us as a guide across the deserts of Tartary, for he knew no more of the country than we knew ourselves. Our only informants were a compass, and the excellent map of the Chinese empire by Andriveau-Goujon.

The first portion of our journey, after leaving Yan-Pa-Eul, was accomplished without interruption, sundry anathemas excepted, which were hurled against us as we ascended a mountain, by a party of Chinese merchants, whose mules, upon sight of our camels and our own yellow attire, became frightened, and took to their heels at full speed, dragging after them, and in one or two instances, overturning the waggons to which they were harnessed.

The mountain in question is called Sain-Oula (Good Mountain), doubtless ut lucus a non lucendo, since it is notorious for the dismal accidents and tragical adventures of which it is the theatre. The ascent is by a rough, steep path, half-choked up with fallen rocks. p. 22Mid-way up is a small temple, dedicated to the divinity of the mountain, Sain-Nai, (the good old Woman;) the occupant is a priest, whose business it is, from time to time, to fill up the cavities in the road, occasioned by the previous rains, in consideration of which service he receives from each passenger a small gratuity, constituting his revenue. After a toilsome journey of nearly three hours we found ourselves at the summit of the mountain, upon an immense plateau, extending from east to west a long day’s journey, and from north to south still more widely. From this summit you discern, afar off in the plains of Tartary, the tents of the Mongols, ranged semi-circularly on the slopes of the hills, and looking in the distance like so many bee-hives. Several rivers derive their source from the sides of this mountain. Chief among these is the Chara-Mouren (Yellow River—distinct, of course, from the great Yellow River of China, the Hoang-Ho)—the capricious, course of which the eye can follow on through the kingdom of Gechekten, after traversing which, and then the district of Naiman, it passes the stake-boundary into Mantchouria, and flowing from north to south, falls into the sea, approaching which it assumes the name Léao-Ho.

The Good Mountain is noted for its intense frosts. There is not a winter passes in which the cold there does not kill many travellers. Frequently whole caravans, not arriving at their destination on the other side of the mountain, are sought and found on its bleak road, man and beast frozen to death. Nor is the danger less from the robbers and the wild beasts with whom the mountain is a favourite haunt, or rather a permanent station. Assailed by the brigands, the unlucky traveller is stripped, not merely of horse and money, and baggage, but absolutely of the clothes he wears, and then left to perish from cold and hunger.

Not but that the brigands of these parts are extremely polite all the while; they do not rudely clap a pistol to your ear, and bawl at you: “Your money or your life!” No; they mildly advance with a courteous salutation: “Venerable elder brother, I am on foot; pray lend me your horse—I’ve got no money, be good enough to lend me your purse—It’s quite cold to-day, oblige me with the loan of your coat.” If the venerable elder brother charitably complies, the matter ends with, “Thanks, brother;” but otherwise, the request is forthwith emphasized with the arguments of a cudgel; and if these do not convince, recourse is had to the sabre.

The sun declining ere we had traversed this platform, we resolved to encamp for the night. Our first business was to seek a position combining the three essentials of fuel, water, and pasturage; and, having due regard to the ill reputation of the Good Mountain, privacy from observation as complete as could be effected. Being novices in travelling, the idea of robbers haunted us incessantly, and we took everybody we saw to be a suspicious character, against whom we must be on our guard. A grassy nook, surrounded by tall trees, appertaining to the Imperial Forest, fulfilled our requisites. Unlading our dromedaries, we raised, with no slight labour, our tent beneath the foliage, and at its entrance installed our faithful porter, Arsalan, a dog whose size, strength, and courage well entitled him to his appellation, which, in the Tartar-Mongol dialect, means “Lion.” Collecting some argols [23] and dry branches of trees, our kettle was soon in agitation, and we threw into the boiling water some Kouamien, prepared paste, something like Vermicelli, which, seasoned with some parings of bacon, given us by our friends at Yan-Pa-Eul, we hoped would furnish satisfaction for the hunger that began to gnaw us. No sooner was the repast ready, than each of us, drawing forth from his girdle his wooden cup, filled it with Kouamien, and raised it to his lips. The preparation was detestable—uneatable. The manufacturers of Kouamien always salt it for its longer preservation; but this paste of ours had been salted beyond all endurance. Even Arsalan would not eat the composition. Soaking it p. 24for a while in cold water, we once more boiled it up, but in vain; the dish remained nearly as salt as ever: so, abandoning it to Arsalan and to Samdadchiemba, whose stomach by long use was capable of anything, we were fain to content ourselves with the dry-cold, as the Chinese say; and, taking with us a couple of small loaves, walked into the Imperial Forest, in order at least to season our repast with an agreeable walk. Our first nomade supper, however, turned out better than we had expected, Providence placing in our path numerous Ngao-la-Eul and Chan-ly-Houng trees, the former, a shrub about five inches high, which bears a pleasant wild cherry; the other, also a low but very bushy shrub, producing a small scarlet apple, of a sharp agreeable flavour, of which a very succulent jelly is made.

The Imperial Forest extends more than a hundred leagues from north to south, and nearly eighty from east to west. The Emperor Khang-Hi, in one of his expeditions into Mongolia, adopted it as a hunting ground. He repaired thither every year, and his successors regularly followed his example, down to Kia-King, who, upon a hunting excursion, was killed by lightning at Ge-ho-Eul. There has been no imperial hunting there since that time—now twenty-seven years ago. Tao-Kouang, son and successor of Kia-King, being persuaded that a fatality impends over the exercise of the chase, since his accession to the throne has never set foot in Ge-ho-Eul, which may be regarded as the Versailles of the Chinese potentates. The forest, however, and the animals which inhabit it, have been no gainers by the circumstance. Despite the penalty of perpetual exile decreed against all who shall be found, with arms in their hands, in the forest, it is always half full of poachers and woodcutters. Gamekeepers, indeed, are stationed at intervals throughout the forest; but they seem there merely for the purpose of enjoying a monopoly of the sale of game and wood. They let any one steal either, provided they themselves get the larger share of the booty. The poachers are in especial force from the fourth to the seventh moon. At this period, the antlers of the stags send forth new shoots, which contain a sort of half-coagulated blood, called Lou-joung, which plays a distinguished part in the Chinese Materia Medica, for its supposed chemical qualities, and fetches accordingly an exorbitant price. A Lou-joung sometimes sells for as much as a hundred and fifty ounces of silver.

Deer of all kinds abound in the forest; and tigers, bears, wild boars, panthers, and wolves are scarcely less numerous. Woe to the hunters and wood-cutters who venture otherwise than in large parties into the recesses of the forest; they disappear, leaving no vestige behind.

p. 25The fear of encountering one of these wild beasts kept us from prolonging our walk. Besides, night was setting in, and we hastened back to our tent. Our first slumber in the desert was peaceful, and next morning early, after a breakfast of oatmeal steeped in tea, we resumed our march along the great Plateau. We soon reached the great Obo, whither the Tartars resort to worship the Spirit of the Mountain. The monument is simply an enormous pile of stones, heaped up without any order, and surmounted with dried branches of trees, from which hang bones and strips of cloth, on which are inscribed verses in the Thibet and Mongol languages.

At its base is a large granite urn in which the devotees burn incense. They offer, besides, pieces of money, which the next Chinese passenger, after sundry ceremonious genuflexions before the Obo, carefully collects and pockets for his own particular benefit.

These Obos, which occur so frequently throughout Tartary, and which are the objects of constant pilgrimages on the part of the Mongols, remind one of the loca excelsa denounced by the Jewish prophets.

It was near noon before the ground, beginning to slope, intimated that we approached the termination of the plateau. We then descended rapidly into a deep valley, where we found a small Mongolian encampment, which we passed without pausing, and set up our tent for the night on the margin of a pool further on. We p. 26were now in the kingdom of Gechekten, an undulating country, well watered, with abundance of fuel and pasturage, but desolated by bands of robbers. The Chinese, who have long since taken possession of it, have rendered it a sort of general refuge for malefactors; so that “man of Gechekten” has become a synonyme for a person without fear of God or man, who will commit any murder, and shrink from no crime. It would seem as though, in this country, nature resented the encroachments of man upon her rights. Wherever the plough has passed, the soil has become poor, arid, and sandy, producing nothing but oats, which constitute the food of the people. In the whole district there is but one trading town, which the Mongols call Altan-Somé, (Temple of Gold). This was at first a great Lamasery, containing nearly 2000 Lamas. By degrees Chinese have settled there, in order to traffic with the Tartars. In 1843, when we had occasion to visit this place, it had already acquired the importance of a town. A highway, commencing at Altan-Somé, proceeds towards the north, and after traversing the country of the Khalkhas, the river Keroulan, and the Khinggan mountains, reaches Nertechink, a town of Siberia.

The sun had just set, and we were occupied inside the tent boiling our tea, when Arsalan warned us, by his barking, of the approach of some stranger. We soon heard the trot of a horse, and presently a mounted Tartar appeared at the door. “Mendou,” he exclaimed, by way of respectful salutation to the supposed Lamas, raising his joined hands at the same time to his forehead. When we invited him to drink a cup of tea with us, he fastened his horse to one of the tent-pegs, and seated himself by the hearth. “Sirs Lamas,” said he, “under what quarter of the heavens were you born?” “We are from the western heaven; and you, whence come you?” “My poor abode is towards the north, at the end of the valley you see there on our right.” “Your country is a fine country.” The Mongol shook his head sadly, and made no reply. “Brother,” we proceeded, after a moment’s silence, “the Land of Grass is still very extensive in the kingdom of Gechekten. Would it not be better to cultivate your plains? What good are these bare lands to you? Would not fine crops of corn be preferable to mere grass?” He replied, with a tone of deep and settled conviction, “We Mongols are formed for living in tents, and pasturing cattle. So long as we kept to that in the kingdom of Gechekten, we were rich and happy. Now, ever since the Mongols have set themselves to cultivating the land, and building houses, they have become poor. The Kitats (Chinese) have taken possession of the country; flocks, herds, lands, houses, all have passed into their hands. There remain to us only a few prairies, on which still live, under their tents, such of the p. 27Mongols as have not been forced by utter destitution to emigrate to other lands.” “But if the Chinese are so baneful to you, why did you let them penetrate into your country?” “Your words are the words of truth, Sirs Lamas; but you are aware that the Mongols are men of simple hearts. We took pity on these wicked Kitats, who came to us weeping, to solicit our charity. We allowed them, through pure compassion, to cultivate a few patches of land. The Mongols insensibly followed their example, and abandoned the nomadic life. They drank the wine of the Kitats, and smoked their tobacco, on credit; they bought their manufactures on credit at double the real value. When the day of payment came there was no money ready, and the Mongols had to yield, to the violence of their creditors, houses, lands, flocks, everything.” “But could you not seek justice from the tribunals?” “Justice from the tribunals! Oh, that is out of the question. The Kitats are skilful to talk and to lie. It is impossible for a Mongol to gain a suit against a Kitat. Sirs Lamas, the kingdom of Gechekten is undone!” So saying, the poor Mongol rose, bowed, mounted his horse, and rapidly disappeared in the desert.

We travelled two more days through this kingdom, and everywhere witnessed the poverty and wretchedness of its scattered inhabitants. Yet the country is naturally endowed with astonishing wealth, especially in gold and silver mines, which of themselves have occasioned many of its worst calamities. Notwithstanding the rigorous prohibition to work these mines, it sometimes happens that large bands of Chinese outlaws assemble together, and march, sword in hand, to dig into them. These are men professing to be endowed with a peculiar capacity for discovering the precious metals, guided, according to their own account, by the conformation of mountains, and the sorts of plants they produce. One single man, possessed of this fatal gift, will suffice to spread desolation over a whole district. He speedily finds himself at the head of thousands and thousands of outcasts, who overspread the country, and render it the theatre of every crime. While some are occupied in working the mines others pillage the surrounding districts, sparing neither persons nor property, and committing excesses which the imagination could not conceive, and which continue until some mandarin, powerful and courageous enough to suppress them, is brought within their operation, and takes measures against them accordingly.

Calamities of this nature have frequently desolated the kingdom of Gechekten; but none of them are comparable with what happened in the kingdom of Ouniot, in 1841. A Chinese mine discoverer, having ascertained the presence of gold in a particular mountain, announced the discovery, and robbers and vagabonds p. 28at once congregated around him, from far and near, to the number of 12,000. This hideous mob put the whole country under subjection, and exercised for two years its fearful sway. Almost the entire mountain passed through the crucible, and such enormous quantities of metal were produced, that the price of gold fell in China fifty per cent. The inhabitants complained incessantly to the Chinese mandarins, but in vain; for these worthies only interfere where they can do so with some benefit to themselves. The King of Ouniot himself feared to measure his strength with such an army of desperadoes.

One day, however, the Queen of Ouniot, repairing on a pilgrimage to the tomb of her ancestors, had to pass the valley in which the army of miners was assembled. Her car was surrounded; she was rudely compelled to alight, and it was only upon the sacrifice p. 29of her jewels that she was permitted to proceed. Upon her return home, she reproached the King bitterly for his cowardice. At length, stung by her words, he assembled the troops of his two banners, and marched against the miners. The engagement which ensued was for a while doubtful; but at length the miners were driven in by the Tartar cavalry, who massacred them without mercy. The bulk of the survivors took refuge in the mine. The Mongols blocked up the apertures with huge stones. The cries of the despairing wretches within were heard for a few days, and then ceased for ever. Those of the miners who were taken alive had their eyes put out, and were then dismissed.

We had just quitted the kingdom of Gechekten, and entered that of Thakar, when we came to a military encampment, where were stationed a party of Chinese soldiers charged with the preservation of the public safety. The hour of repose had arrived; but these soldiers, instead of giving us confidence by their presence, increased, on the contrary, our fears; for we knew that they were themselves the most daring robbers in the whole district. We turned aside, therefore, and ensconced ourselves between two rocks, where we found just space enough for our tent. We had scarcely set up our temporary abode, when we observed, in the distance, on the slope of the mountains, a numerous body of horsemen at full gallop. Their rapid but irregular evolutions seemed to indicate that they were pursuing something which constantly evaded them. By-and-by, two of the horsemen, perceiving us, dashed up to our tent, dismounted, and threw themselves on the ground at the door. They were Tartar-Mongols. “Men of prayer,” said they, with voices full of emotion, “we come to ask you to draw our horoscope. We have this day had two horses stolen from us. We have fruitlessly sought traces of the robbers, and we therefore come to you, men whose power and learning is beyond all limit, to tell us where we shall find our property.” “Brothers,” said we, “we are not Lamas of Buddha; we do not believe in horoscopes. For a man to say that he can, by any such means, discover that which is stolen, is for them to put forth the words of falsehood and deception.” The poor Tartars redoubled their solicitations; but when they found that we were inflexible in our resolution, they remounted their horses, in order to return to the mountains.

Samdadchiemba, meanwhile, had been silent, apparently paying no attention to the incident, but fixed at the fire-place, with his bowl of tea to his lips. All of a sudden he knitted his brows, rose, and came to the door. The horsemen were at some distance; but the Dchiahour, by an exertion of his strong lungs, induced them to turn round in their saddles. He motioned to them, and they, supposing p. 30we had relented, and were willing to draw the desired horoscope, galloped once more towards us. When they had come within speaking distance:—“My Mongol brothers,” cried Samdadchiemba, “in future be more careful; watch your herds well, and you won’t be robbed. Retain these words of mine on your memory: they are worth all the horoscopes in the world.” After this friendly address, he gravely re-entered the tent, and seating himself at the hearth, resumed his tea.

We were at first somewhat disconcerted by this singular proceeding; but as the horsemen themselves did not take the matter in ill part, but quietly rode off, we burst into a laugh. “Stupid Mongols!” grumbled Samdadchiemba; “they don’t give themselves the trouble to watch their animals, and then, when they are stolen from them, they run about wanting people to draw horoscopes for them. After all, perhaps, it’s no wonder, for nobody but ourselves tells them the truth. The Lamas encourage them in their credulity; for they turn it into a source of income. It is difficult to deal with such people. If you tell them you can’t draw a horoscope, they don’t believe you, and merely suppose you don’t choose to oblige them. To get rid of them, the best way is to give them an answer haphazard.” And here Samdadchiemba laughed with such expansion, that his little eyes were completely buried. “Did you ever draw a horoscope?” asked we. “Yes,” replied he still laughing. “I was very young at the time, not more than fifteen. I was travelling through the Red Banner of Thakar, when I was addressed by some Mongols who led me into their tent. There they entreated me to tell them, by means of divination, where a bull had strayed, which had been missing three days. It was to no purpose that I protested to them I could not perform divination, that I could not even read. ‘You deceive us,’ said they; ‘you are a Dchiahour, and we know that the Western Lamas can all divine more or less.’ As the only way of extricating myself from the dilemma, I resolved to imitate what I had seen the Lamas do in their divinations. I directed one person to collect eleven sheep’s droppings, the dryest he could find. They were immediately brought. I then seated myself very gravely; I counted the droppings over and over; I arranged them in rows, and then counted them again; I rolled them up and down in threes; and then appeared to meditate. At last I said to the Mongols, who were impatiently awaiting the result of the horoscope: ‘If you would find your bull, go seek him towards the north.’ Before the words were well out of my mouth, four men were on horseback, galloping off towards the north. By the most curious chance in the world, they had not proceeded far, before the missing animal made its appearance, quietly browzing. I at once got the character p. 31of a diviner of the first class, was entertained in the most liberal manner for a week, and when I departed had a stock of butter and tea given me enough for another week. Now that I belong to Holy Church, I know that these things are wicked and prohibited; otherwise I would have given these horsemen a word or two of horoscope, which perhaps would have procured for us, in return, a good cup of tea with butter.”

The stolen horses confirmed in our minds the ill reputation of the country in which we were now encamped; and we felt ourselves necessitated to take additional precaution. Before night-fall we brought in the horse and the mule, and fastened them by cords to pins at the door of our tent, and made the camels kneel by their side, so as to close up the entrance. By this arrangement no one could get near us without our having full warning given us by the camels, which, at the least noise, always make an outcry loud enough to awaken the deepest sleeper. Finally, having suspended from one of the tent-poles our travelling lantern, which we kept burning all the night, we endeavoured to obtain a little repose, but in vain; the night passed away, without our getting a wink of sleep. As to the Dchiahour, whom nothing ever troubled, we heard him snoring with all the might of his lungs until daybreak.

We made our preparations for departure very early, for we were eager to quit this ill-famed place, and to reach Tolon-Noor, which was now distant only a few leagues.

On our way thither, a horseman stopped his galloping steed, and, after looking at us for a moment, addressed us: “You are the chiefs of the Christians of the Contiguous Defiles?” Upon our replying in the affirmative, he dashed off again; but turned his head once or twice, to have another look at us. He was a Mongol, who had charge of some herds at the Contiguous Defiles. He had often seen us there; but the novelty of our present costume at first prevented his recognising us. We met also the Tartars who, the day before, had asked us to draw a horoscope for them. They had repaired by daybreak, to the horse-fair at Tolon-Noor, in the hope of finding their stolen animals; but their search had been unsuccessful.

The increasing number of travellers, Tartars and Chinese, whom we now met, indicated the approach to the great town of Tolon-Noor. We already saw in the distance, glittering under the sun’s rays, the gilt roofs of two magnificent Lamaseries that stand in the northern suburbs of the town. We journeyed for some time through a succession of cemeteries; for here, as elsewhere, the present generation is surrounded by the ornamental sepulchres of past generations. As we observed the numerous population of that large town, environed as it were by a vast circle of bones and monumental stones, p. 32it seemed as though death was continuously engaged in the blockade of life. Here and there, in the vast cemetery which completely encircles the city, we remarked little gardens, where, by dint of extreme labour, a few miserable vegetables were extracted from the earth: leeks, spinach, hard bitter lettuces, and cabbages, which, introduced some years since from Russia, have adapted themselves exceedingly well to the climate of Northern China.

With the exception of these few esculents, the environs of Tolon-Noor produce absolutely nothing whatever. The soil is dry and sandy, and water terribly scarce. It is only here and there that a few limited springs are found, and these are dried up in the hot season.

Inn at Tolon-Noor—Aspect of the City—Great Foundries of Bells and Idols—Conversation with the Lamas of Tolon-Noor—Encampment—Tea Bricks—Meeting with Queen Mourguevan—Taste of the Mongols for Pilgrimages—Violent Storm—Account from a Mongol Chief of the War of the English against China—Topography of the Eight Banners of the Tchakar—The Imperial herds—Form and Interior of the Tents—Tartar Manners and Customs—Encampment at the Three Lakes—Nocturnal Apparitions—Samdadchiemba relates the Adventures of his Youth—Grey Squirrels of Tartary—Arrival at Chaborté.

Our entrance into the city of Tolon-Noor was fatiguing and full of perplexity; for we knew not where to take up our abode. We wandered about for a long time in a labyrinth of narrow, tortuous streets, encumbered with men and animals and goods. At last we found an inn. We unloaded our dromedaries, deposited the baggage in small room, foddered the animals, and then, having affixed to the door of our room the padlock which, as is the custom, our landlord gave us for that purpose, we sallied forth in quest of dinner. A triangular flag floating before a house in the next p. 34street, indicated to our joyful hearts an eating-house. A long passage led us into a spacious apartment, in which were symmetrically set forth a number of little tables. Seating ourselves at one of these, a tea-pot, the inevitable prelude in these countries to every meal, was set before each of us. You must swallow infinite tea, and that boiling hot, before they will consent to bring you anything else. At last, when they see you thus occupied, the Comptroller of the Table pays you his official visit, a personage of immensely elegant manners, and ceaseless volubility of tongue, who, after entertaining you with his views upon the affairs of the world in general, and each country in particular, concludes by announcing what there is to eat, and requesting your judgment thereupon. As you mention the dishes you desire, he repeats their names in a measured chant, for the information of the Governor of the Pot. Your dinner is served up with admirable promptitude; but before you commence the meal, etiquette requires that you rise from your seat, and invite all the other company present to partake. “Come,” you say, with an engaging gesture, “come my friends, come and drink a glass of wine with me; come and eat a plate of rice;” and so on. “No, thank you,” replies every body; “do you rather come and seat yourself at my table. It is I who invite you;” and so the matter ends. By this ceremony you have “manifested your honour,” as the phrase runs, and you may now sit down and eat it in comfort, your character as a gentleman perfectly established.

When you rise to depart, the Comptroller of the Table again appears. As you cross the apartment with him, he chants over again the names of the dishes you have had, this time appending the prices, and terminating with the sum total, announced with especial emphasis, which, proceeding to the counter, you then deposit in the money-box. In general, the Chinese restaurateurs are quite as skilful as those of France in exciting the vanity of the guests, and promoting the consumption of their commodities.

Two motives had induced us to direct our steps, in the first instance, to Tolon-Noor: we desired to make more purchases there to complete our travelling equipment, and, secondly, it appeared to us necessary to place ourselves in communication with the Lamas of the country, in order to obtain information from them as to the more important localities of Tartary. The purchases we needed to make gave us occasion to visit the different quarters of the town. Tolon-Noor (Seven Lakes) is called by the Chinese Lama-Miao (Convent of Lamas). The Mantchous designate it Nadan-Omo, and the Thibetians, Tsot-Dun, both translations of Tolon-Noor, and, equally with it, meaning “Seven Lakes.” p. 35On the map published by M. Andriveau-Goujon, [35] this town is called Djo-Naiman-Soumé, which in Mongol means, “The Hundred and Eight Convents.” This name is perfectly unknown in the country itself.

Tolon-Noor is not a walled city, but a vast agglomeration of hideous houses, which seem to have been thrown together with a pitchfork. The carriage portion of the streets is a marsh of mud and putrid filth, deep enough to stifle and bury the smaller beasts of burden that not unfrequently fall within it, and whose carcases remain to aggravate the general stench; while their loads become the prey of the innumerable thieves who are ever on the alert. The foot-path is a narrow, rugged, slippery line on either side, just wide enough to admit the passage of one person.

Yet, despite the nastiness of the town itself, the sterility of the environs, the excessive cold of its winter, and the intolerable heat of its summer, its population is immense, and its commerce enormous. Russian merchandise is brought hither in large quantities by the way of Kiakta. The Tartars bring incessant herds of camels, oxen, and horses, and carry back in exchange tobacco, linen, and tea. This constant arrival and departure of strangers communicates to the city an animated and varied aspect. All sorts of hawkers are at every corner offering their petty wares; the regular traders, from behind their counters, invite, with honeyed words and tempting offers, the passers-by to come in and buy. The Lamas, in their red and yellow robes, gallop up and down, seeking admiration for their equestrianism, and the skilful management of their fiery steeds.

The trade of Tolon-Noor is mostly in the hands of men from the province of Chan-Si, who seldom establish themselves permanently in the town; but after a few years, when their money-chest is filled, return to their own country. In this vast emporium, the Chinese invariably make fortunes, and the Tartars invariably are ruined. Tolon-Noor, in fact, is a sort of great pneumatic pump, constantly at work in emptying the pockets of the unlucky Mongols.

The magnificent statues, in bronze and brass, which issue from the great foundries of Tolon-Noor, are celebrated not only throughout Tartary, but in the remotest districts of Thibet. Its immense workshops supply all the countries subject to the worship of Buddha with idols, bells, and vases employed in that idolatry. While we were in the town, a monster statue of Buddha, a present p. 36from a friend of Oudchou-Mourdchin to the Talè-Lama, was packed for Thibet, on the backs of six camels. The larger statues are cast in detail, the component parts being afterwards soldered together.

We availed ourselves of our stay at Tolon-Noor to have a figure of Christ constructed on the model of a bronze original which we had brought with us from France. The workmen so marvellously excelled, that it was difficult to distinguish the copy from the original. The Chinese work more rapidly and cheaply, and their complaisance contrasts most favourably with the tenacious self-opinion of their brethren in Europe.

During our stay at Tolon-Noor, we had frequent occasion to visit the Lamaseries, or Lama monasteries, and to converse with the idolatrous priests of Buddhism. The Lamas appeared to us persons of very limited information; and as to their symbolism, in general, it is little more refined or purer than the creed of the vulgar. Their doctrine is still undecided, fluctuating amidst a vast fanaticism of which they can give no intelligible account. When we asked them for some distinct, clear, positive idea what they meant, they were always thrown into utter embarrassment, and p. 37stared at one another. The disciples told us that their masters knew all about it; the masters referred us to the omniscience of the Grand Lamas; the Grand Lamas confessed themselves ignorant, but talked of some wonderful saint, in some Lamasery at the other end of the country: he could explain the whole affair. However, all of them, disciples and masters, great Lamas and small, agreed in this, that their doctrine came from the West. “The nearer you approach the West,” said they unanimously, “the purer and more luminous will the doctrine manifest itself.” When we expounded to them the truths of Christianity, they never discussed the matter; they contented themselves with calmly saying, “Well, we don’t suppose that our prayers are the only prayers in the world. The Lamas of the West will explain everything to you. We believe in the traditions that have come from the West.”

In point of fact there is no Lamasery of any importance in Tartary, the Grand Lama or superior of which is not a man from Thibet. Any Tartar Lama who has visited Lha-Ssa [Land of Spirits], or Monhe-Dhot [Eternal Sanctuary], as it is called in the Mongol dialect, is received, on his return, as a man to whom the mysteries of the past and of the future have been unveiled.

After maturely weighing the information we had obtained from the Lamas, it was decided that we should direct our steps towards the West. On October 1st we quitted Tolon-Noor; and it was not without infinite trouble that we managed to traverse the filthy town with our camels. The poor animals could only get through the quagmire streets by fits and starts; it was first a stumble, then a convulsive jump, then another stumble and another jump, and so on. Their loads shook on their backs, and at every step we expected to see the camel and camel-load prostrate in the mud. We considered ourselves lucky when, at distant intervals, we came to a comparatively dry spot, where the camels could travel, and we were thus enabled to re-adjust and tighten the baggage. Samdadchiemba got into a desperate ill temper; he went on, and slipped, and went on again, without uttering a single word, restricting the visible manifestation of his wrath to a continuous biting of the lips.

Upon attaining at length the western extremity of the town, we got clear of the filth indeed, but found ourselves involved in another evil. Before us there was no road marked out, not the slightest trace of even a path. There was nothing but an apparently interminable chain of small hills, composed of fine, moving sand, over which it was impossible to advance at more than a snail’s pace, and this only with extreme labour. Among these sand-hills, moreover, we were oppressed with an absolutely stifling heat. Our p. 38animals were covered with perspiration, ourselves devoured with a burning thirst; but it was in vain that we looked round in all directions, as we proceeded, for water; not a spring, not a pool, not a drop presented itself.

It was already late, and we began to fear we should find no spot favourable for the erection of our tent. The ground, however, grew by degrees firmer, and we at last discerned some signs of vegetation. By-and-by, the sand almost disappeared, and our eyes were rejoiced with the sight of continuous verdure. On our left, at no great distance, we saw the opening of a defile. M. Gabet urged on his camel, and went to examine the spot. He soon made his appearance at the summit of a hill, and with voice and hand directed us to follow him. We hastened on, and found that Providence had led us to a favourable position. A small pool, the waters of which were half concealed by thick reeds and other marshy vegetation, some brushwood, a plot of grass: what could we under the circumstances desire more? Hungry, thirsty, weary as we were, the place seemed a perfect Eden.