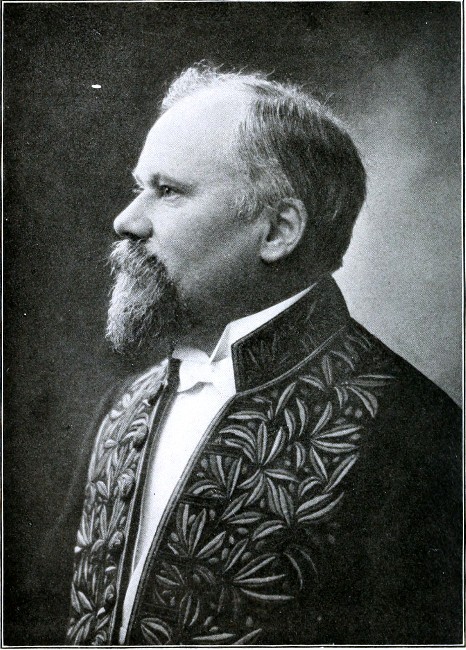

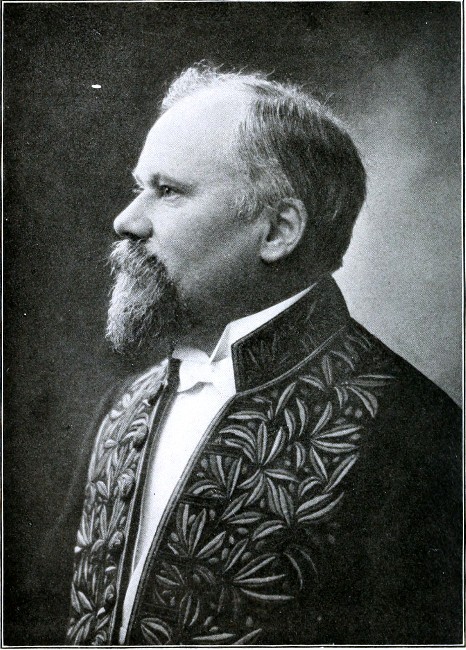

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the Third French Republic, by C. H. C. Wright This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A History of the Third French Republic Author: C. H. C. Wright Release Date: June 6, 2010 [EBook #32715] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY--THIRD FRENCH REPUBLIC *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY CHARLES H. C. WRIGHT

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published May 1916

I. The Antecedents of the Franco-Prussian War. 1

II. The Franco-Prussian War—The Government Of

National Defence (September, 1870, to February,

1871). 11

III. The Administration of Adolphe Thiers (February,

1871, to May, 1873). 31

IV. The Administration of the Maréchal de Mac-Mahon

(May, 1873, To January, 1879). 50

V. The Administration of Jules Grévy (January,

1879, to December, 1887). 75

VI. The Administration of Sadi Carnot (December,

1887, To June, 1894). 96

VII. The Administrations of Jean Casimir-Perier (June,

1894, To January, 1895) and of Félix Faure

(January, 1895, to February, 1899). 115

VIII. The Administration of Emile Loubet (February,

1899, to February, 1906). 134

IX. The Administration of Armand Fallières (February,

1906, to February, 1913). 159

X. The Administration of Raymond Poincaré (February,

1913-). 176

Appendix: Presiding Officers of French Cabinets. 187

Bibliography. 193

Index. 199

Raymond Poincaré Frontispiece

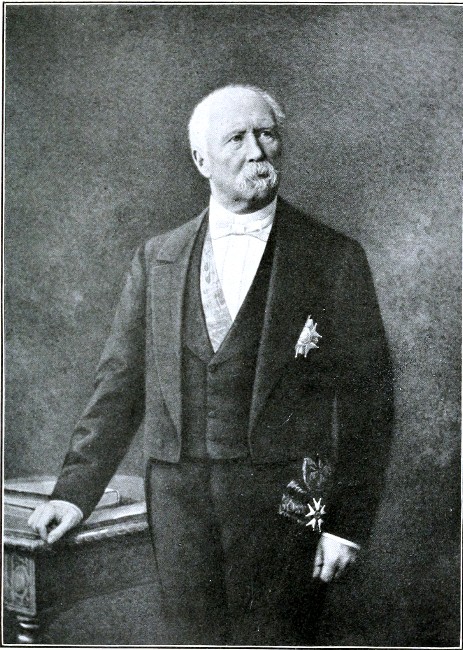

Adolphe Thiers 32

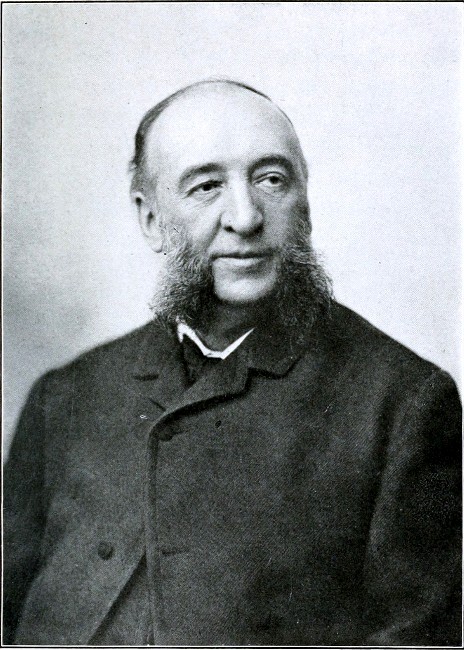

Edme-Patrice-Maurice de Mac-Mahon 50

Léon Gambetta 70

Jules Ferry 78

Sadi Carnot 96

Marie-Georges Picquart 124

René Waldeck-Rousseau 136

Two men were largely responsible, each in his own way, for the third French Republic, Napoleon III and Bismarck. The one, endeavoring partly at his wife's instigation to renew the prestige of a weakening Empire, and the other, furthering the ambitions of the Prussian Kingdom, set in motion the forces which culminated in the Fourth of September.

The causes of the downfall of the Empire can be traced back several years. Napoleon III was, at heart, a man of peace and had, in all sincerity, soon after his accession, uttered the famous saying: "L'empire, c'est la paix." But the military glamour of the Napoleonic name led the nephew, like the uncle, into repeated wars. These had, in most cases, been successful, exceptions, such as the unfortunate Mexican expedition, seeming negligible. They had[Pg 2] sometimes even resulted in territorial aggrandizement. Napoleon III was, therefore, desirous of establishing once for all the so-called "natural" frontiers of France along the Rhine by the annexation of those Rhenish provinces which, during the First Empire and before, had for a score of years been part of the French nation.

On the other hand, though France was still considered the leading continental power, and though its military superiority seemed unassailable, the imperial régime was unquestionably growing "stale." The Emperor himself, always a mystical fatalist rather than the hewer of his own fortune, felt the growing inertia of his final malady. A lavishly luxurious court had been imitated by a pleasure-loving capital. This had brought in its train relaxed standards of governmental morals and had seriously weakened the fibre of many military commanders. Outwardly the Empire seemed as glorious as ever, and in 1867 France invited the world to a gorgeous exposition in the "Ville-lumière." But Paris was more emotional year by year, and the Tuileries and Saint-Cloud were dominated by a narrow-minded[Pg 3] and spoiled Empress. Court intrigues were rife and drawing-room generals were to be found in real life, as well as in Offenbach's "Grande Duchesse." But nobody, except perhaps Napoleon himself, realized how the Empire had declined. The Empress merely felt that it was time to do something stirring, and, without necessarily waging war, to assert again the pre-eminence in Europe of France, weakened in 1866 by the unexpected outcome of the rivalry between Austria and Prussia for preponderance among the German States.

Beyond the eastern frontier of France a nation was growing in ambition and power. Prussia still remembered the warlike achievements of Frederick the Great, although since those days its military efficiency had at times undergone a decline. But now, under the reign of King William, guided by a vigorous minister, Bismarck, an example, whatever his admirers may say, of the brutal and unscrupulous Junker, the Prussian Government had for some time tried to impose its leadership on the other German States. Some of these were far from anxious to accept it. In the furtherance of Prussian schemes, Bismarck had been able to[Pg 4] inflict a diplomatic rebuff on Napoleon, as well as a severe military defeat on Austria.

In 1866, Prussia won from Austria the important victory of Königgrätz or Sadowa, and thereby asserted its leadership. The outcome was a check to Napoleon, who had expected a different result. Moreover, by it Bismarck was encouraged to pursue his plans for the consolidation of Germany under a still more openly acknowledged Prussian supremacy. A crafty and utterly unscrupulous diplomat, he was able to mislead Napoleon and his unskilful ministers.

Soon after Sadowa the Emperor tried to obtain territorial compensation from Prussia. He wished, in return for recognition of Prussia's new position and of the projected union of North and South Germany minus Austria, to obtain the cession of territories on the left bank of the Rhine, or an alliance for the conquest and annexation of Belgium to France. Such schemes having failed, Napoleon tried next to satisfy French jingoism by the acquisition of the Duchy of Luxembourg. This move resulted only in securing the evacuation by its Prussian garrison of the Luxembourg fortress[Pg 5] and the neutralization of the duchy. From that time on, tension increased between France and Prussia. Bismarck was, indeed, more anxious for war than Napoleon. He suspected the weakness of the French Empire, he despised its leaders, he realized the advance in military efficiency of his own country, and his aim was unswerving to establish a Prussianized German Empire at the cost, if possible, of the downfall of France. As a matter of fact, France, as now, was far from being permeated with militarism and, a few months before the war in 1870, the military budget was actually reduced.

The occasion for a dispute arrived with the suggested candidacy of Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a German prince related to the King of Prussia, to the crown of Spain. As early as 1868, intrigues had begun to put a Prussian on the Spanish throne, but Napoleon had not as yet been disturbed. It was not until 1870 that he took the matter seriously. In July, Prince Leopold accepted the crown, egged on by Bismarck, and with the fiction of the approval of King William as head of the Hohenzollerns, as distinguished from his position as King of Prussia.[Pg 6]

At that time the French Emperor was in precarious health and scarcely in full control of his powers. The French people at large were pacifically inclined and would have asked for nothing better than to remain at home instead of fighting about a foreigner's candidacy to an alien throne. But, unfortunately, the Empress Eugénie was for war. The Government, too, was in the hands of second-rate and hesitating diplomats. Emile Ollivier, the chief of the Cabinet, was an orator more than a statesman, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the duc de Gramont, was a conceited mediocrity more and more involved in his own mistakes. In consequence, the attitude of the Government was not so much deliberate desire for war as provocative bluster, of which Bismarck was quick to take advantage. The Cabinet was egged on by Eugénie's adherents, the militants, who had been looking for an insult since Sadowa, and by obstreperous journalists and noisy boulevard mobs, whose manifestations were unfortunately taken, even by the Corps législatif, for the voice of France.

In consequence, blunder after blunder was made. The ministers worked at cross-purposes,[Pg 7] without due consultation and without consideration of the effect of their actions on an inflamed public opinion or on prospective European alliances. Stated in terms of diplomatic procedure, the aim of the French Cabinet was to humiliate Prussia by forcing its Government to acknowledge a retreat. King William was not seeking war and was probably willing to make honorable concessions. Bismarck, on the contrary, desired war, if it could be under favorable diplomatic auspices, and the Hohenzollern candidacy was a direct provocation. He wanted France to seem the aggressor, in view of the effect both on neutral Europe, and particularly on the South German States, which he wished to draw into alliance under the menace of French attack.

The French Ambassador to the King of Prussia, Benedetti, was instructed to demand the withdrawal of Prince Leopold's candidacy. This demand followed a very arrogant statement to the Corps législatif, on July 6, by the duc de Gramont. The assumption was that Prince Leopold's presence on the Spanish throne would be dangerous to the honor and interests of France, by exposing the country[Pg 8] on two sides to Prussian influence. King William was, on the whole, willing to make a concession to avoid international complications, but he obviously wished not to appear to act under pressure. M. Benedetti went to Ems and, on July 9, he laid the French demands before the King. After long-drawn-out discussion the French Government asked for a categorical reply by July 12. On that day the father of Prince Leopold, Prince Antony of Hohenzollern, in a telegram to Spain, formally withdrew his son's name. The King had planned to give his consent to this apparently spontaneous action on the part of the candidate's family, when officially informed. Thus France would obtain its ends and the King himself would not be involved.

Unfortunately the thoughtlessness of the head of the French Ministry spoiled everything. Instead of waiting a day for the King's ratification, Emile Ollivier, desirous also of peace, hastened to make public the telegram from the Prince of Hohenzollern. Thereupon the leaders of the war party in the Corps législatif at once pointed out that the telegram was not accompanied by the signature of the Prussian[Pg 9] monarch, declared that the Cabinet had been outwitted, and clamored for definite guarantees. Stung by the charge of inefficiency, the would-be statesman Gramont immediately accentuated his stipulations and demanded that the King of Prussia guarantee not to support in future the candidacy of a Hohenzollern to the Spanish throne.

Matters were rapidly reaching an impasse, and Bismarck was correspondingly elated, because France was appearing to Europe a trouble-maker. The duc de Gramont and Emile Ollivier committed the error of dictating a letter to the Prussian Ambassador for him to transmit to the King, to be in turn sent back as his reply. King William was offended by this high-handed procedure. He had already told comte Benedetti at Ems that a satisfactory letter was on its way from Prince Antony and had promised him another interview upon its arrival. After receiving the dispatch from his ambassador at Paris communicating Gramont's formulas, he sent word to Benedetti that Prince Leopold was no longer a candidate and that the incident was closed. Nor was the King willing to grant[Pg 10] Benedetti's urgent requests for an interview (July 13).

The King and the French Ambassador had remained perfectly courteous, and the next day, at the railway station, they took leave of each other with marks of respect. Things were not yet hopeless, until Bismarck, by a trick of which he afterwards bragged, caused a dispatch to be published implying that Benedetti had been so persistent in pushing his demands that King William had been obliged to snub him. The French were led to believe that their representative had been insulted, and neutrals sided with Prussia as the aggrieved party. After deliberation the French Ministry decided on war and the decision was blindly ratified by the Corps législatif on July 15. At this meeting Emile Ollivier made his famous remark that the Ministry accepted responsibility for the war with a "clear conscience." His actual words, "le cœur léger," seemed, however, to imply "with a light heart", and thereafter weighed heavily against him in the minds of Frenchmen.

On July 19 the French Embassy at Berlin declared a state of war. Paris was wild with enthusiasm and eager for an advance on Berlin. The provinces were for the most part cool, but accepted the war calmly because they were assured of an easy victory. The leaders of the two nations had for each other equal contempt. "Ce n'est pas un homme sérieux," Napoleon had once said of Bismarck, and Bismarck thought Napoleon "stupid and sentimental." Meanwhile each nation had eyes on the territory of the other: France was ready to claim the Rhine frontier; Prussia wanted all it could get, and certainly Alsace and Lorraine. The idea, so often repeated by the Germans since the war, that these provinces were annexed because they had once been German, was not in Bismarck's mind,—"that is a Professor's reason," he said.[1] He wanted Strassburg because[Pg 12] its commanding position and the wedge of Wissembourg could cut off northern from southern Germany. The frontier of the Vosges was as desirable to the Germans as the Rhine to the French.

From the beginning all went wrong in France. The Government found itself left in the lurch by the European states whose alliance it had expected. Moreover, mobilization proceeded slowly and in utter confusion. In spite of Marshal Le Bœuf's famous exclamation ("Il ne manquera pas un bouton de guêtre"), never did a nation enter on a war less prepared than the French. On the other hand, all Germany, well trained and ready, sprang to the side of Prussia. The whole military force was grouped in three armies—under Steinmetz, Prince Frederick Charles, and the Crown Prince. But, meanwhile, it seemed necessary to the French to give a semblance of military achievement. The Emperor had started from Paris on July 28 leaving the Empress as regent. On August 2, a vain military display with largely superior forces was made across the frontier at Saarbrücken, a practically unprotected place was taken, and the Emperor was[Pg 13] able to send home word that the Prince Imperial had received his "baptism of fire" and that the soldiers wept at seeing him calmly pick up a bullet. The same day King William took command of the German forces at Mainz, and on August 4 the army of the Crown Prince entered Alsace and defeated at Wissembourg the division of about twelve thousand men of General Abel Douay, who was killed. On the 6th Mac-Mahon, with a larger force, met the still more numerous Germans somewhat farther back at Wörth, Fröschwiller, and Reichsoffen, and was utterly routed with a loss of over ten thousand in killed, wounded, and taken. Alsace was thus completely exposed to the enemy, and the road was open to Lunéville and Nancy. On the same day, German armies under Steinmetz and Prince Frederick Charles crossed into Lorraine at Saarbrücken and engaged the troops of the French general Frossard at Forbach and Spicheren, inflicting on them a severe repulse. Meanwhile Frossard's superior, Bazaine, though not far away, did not move a finger to help him. "If Frossard wanted the baton of marshal of France he could win it alone."[Pg 14]

The news of these disasters was a terrible shock to Paris. The "liberal" Ollivier Cabinet was overthrown and replaced by a reactionary one led by General Cousin-Montauban, comte de Palikao. The Emperor withdrew from military leadership and Marshal Bazaine received supreme command. Bazaine was a brave soldier, but a poor general-in-chief, and withal a self-seeking man, incompetent to deal with the difficulties in which France found itself. He was perhaps not a conscious traitor in the great disaster which soon came to pass, but he thought more of himself than of his country. At the time we are concerned with he was considered the coming man. Meanwhile Mac-Mahon, cut off from Bazaine's main army, fell back, between August 6 and August 17, to Châlons. Bazaine was apparently without intelligent strategic plans. He professed to be desirous of concentrating at Verdun, but was afraid to get out of reach of Metz. He won first an indecisive battle at Borny (August 14), which was unproductive of any concrete advantage. On August 16, he let himself be turned back, by an enemy only half as numerous, at Rezonville (Vionville, Mars-la-Tour).[Pg 15] On the 18th, he encountered, on the contrary, a much larger force at Saint-Privat (Gravelotte) and let himself be cooped up in Metz. Critics of Bazaine say that he could have turned both Rezonville and Gravelotte to the advantage of the French.

The familiar military uncertainties now began to show themselves in the movements of Mac-Mahon and his troops. The armies of Steinmetz and of Frederick Charles were united under command of the latter to beleaguer Metz, and a smaller force under Prince Albert of Saxony was thrown off to coöperate with the army of the Crown Prince in its advance on Paris. Mac-Mahon had collected about one hundred and twenty thousand men, and Napoleon, without real authority except as a meddler, was with him. The plan was originally to fall back for the protection of Paris, but the Empress-Regent was afraid to have a defeated Emperor return to the capital lest revolution ensue, and Palikao urged a swift advance to rescue Metz, crushing Prince Albert of Saxony on the way, taking Frederick Charles between the two fires of rescuers and besieged, with the Crown Prince still too[Pg 16] far away to be dangerous. Meanwhile Mac-Mahon moved to Reims, which was neither on the direct road to Paris nor to Metz, and at last started to the rescue of Bazaine by the roundabout route of Montmédy, continually hesitating and retracing his steps. On receiving news of his progress, the armies of the Crown Prince and of Prince Albert converged northward. Mac-Mahon's right wing, under General de Failly, was surprised at Beaumont, and finally the French army in disorder drew up in most unfavorable positions between the Meuse and the Belgian frontier, to face a foe twice as numerous and already nearly completely surrounding it. The battle of Sedan broke out on September 1. Mac-Mahon was wounded early in the fight and gave over the command to Ducrot, in turn superseded by Wimpffen, already designated by the Ministry to replace Mac-Mahon in case of accident. After a fierce battle it fell to General de Wimpffen to capitulate on September 2. By the disaster of Sedan the Germans captured the Emperor, a marshal of France, and the whole of one of its two armies.

The news of the overwhelming defeat of[Pg 17] Sedan struck Paris like a thunderbolt. Jules Favre proposed to the Corps législatif the overthrow of Napoleon and of his dynasty; Thiers, who favored the restoration of the Orléans family, wished the convocation of a Constituent Assembly; the comte de Palikao asked for a provisional governing commission of which he should be the lieutenant-general. But, before anything was done, the Paris mob invaded the legislative chamber. Gambetta, with the majority of the Paris Deputies, went to the Hôtel de Ville, and to prevent a more radical set from seizing the Government, proclaimed the Republic (September 4). A Government of National Defence was constituted of which General Trochu became President, Jules Favre Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Gambetta Minister of the Interior. Thiers was not a member, but gave his support. Eugénie escaped from the Tuileries to the home of her American dentist, Dr. Evans, and then fled to England.

Jules Favre was innocent enough to think that the Germans would be satisfied with the overthrow of Napoleon, and he was rash enough to declare that France would not yield[Pg 18] "an inch of its territory or a stone of its fortresses." But, in an interview with Bismarck at Ferrières, on September 19, he realized the oppressiveness of the German demands. The rhetorical and emotional, even tearful, Jules Favre was faced by a harsh and unrelenting conqueror, and the meeting ended without an agreement. Meanwhile Paris was invested by the German forces of the Crown Prince and the Prince of Saxony after a defeat of some French troops at Châtillon. William, Bismarck, and Moltke took up their station at Versailles. Europe, made suspicious by the numerous changes of government in France in the nineteenth century, and moved also by selfish reasons, refused its aid and looked on with indifference. Thiers made a fruitless quest through Europe for practical aid, bringing home only meaningless expressions of sympathy.

Unfortunately even a number of people in the provinces, relaxed by the factitious prosperity of the imperial régime, were too willing to yield to the invaders. Where resistance was brave it appeared fruitless: Strassburg capitulated on September 28, after the Germans[Pg 19] had burned its library and bombarded the cathedral. A scratch army on the Loire, under La Motterouge, was beaten at Artenay (October 10) and had to evacuate Orléans. On October 18, the Germans captured Châteaudun after heroic resistance by National Guards and sharpshooters.

Though one of the two great French armies was in captivity and the other besieged in Metz, the idea of submission never for a moment entered Gambetta's head. Paris was under the command of Trochu, patriotic and brave, but military critic rather than leader, discouraged from the beginning, and unable to take advantage of opportunities. A delegation of the Government of National Defence had established itself at Tours to avoid the German besiegers, but two of its members, Crémieux and Glais-Bizoin, were elderly and weak. Admiral Fourichon was the most competent. Gambetta escaped from Paris by balloon on October 7, and, reaching Tours in safety, made himself by his energy and patriotic inspiration, practically dictator and organizer of resistance to the invaders.

Léon Gambetta, a young lawyer politician[Pg 20] of thirty-two, of inexhaustible energy and impassioned eloquence, was the son of an Italian grocer settled at Cahors. With the help of his assistant Charles de Freycinet, he levied and armed in four months six hundred thousand men, an average of five thousand a day. Everything was done in haste and unsatisfactorily,—the army of General Chanzy was equipped with guns of fifteen different patterns. But Gambetta did the task of a giant, in spite of another crushing blow to France, the surrender of Metz.

Bazaine had let himself be cooped up in Metz. Instead of being moved by patriotism, he thought only of his own interests and ambitions. In the midst of the cataclysm which had fallen on France he aspired to hold the position of power. The Emperor gone and the Republic destined, Bazaine thought, to fall, he would be left at the head of the only army. His would be the task of treating for peace with Germany, and then he would perhaps become in France regent instead of the Empress, or Marshal-Lieutenant of the Empire, like the Spanish marshals. So he neglected favorable military opportunities, and dallied over[Pg 21] plans of peace, while Bismarck misled him with fruitless propositions or false emissaries like the adventurer Regnier. Finally, on October 27, Bazaine had to surrender Metz, with three marshals (himself, Canrobert, and Le Bœuf), sixty generals, six thousand officers, and one hundred and seventy-three thousand men. France was deprived of her last trained forces, and the besieging army of Frederick Charles was set free to help in the conquest of France. After the war Bazaine was condemned to death, by court-martial, for treason. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but he afterwards escaped from the fortress in which he was confined and died in obscurity and disgrace at Madrid.

No sooner did the news of the capitulation of Metz reach Paris than a regrettable affair took place. There was much dissatisfaction with the indecision of the Provisional Government, and, on October 31, a mob invaded the Hôtel de Ville and arrested the chief members of the commission. Fortunately they were released later the same day and a plebiscite of November 3 confirmed the powers of the Government of National Defence. Fortunately,[Pg 22] too, within a few days came news of the first real success of the French during the war, the battle of Coulmiers (November 9).

Gambetta had succeeded during October in organizing the Army of the Loire which, under General d'Aurelle de Paladines, defeated the Bavarian forces of von der Thann at Coulmiers and recaptured Orléans. The plan was to push on to Paris and the objections of d'Aurelle were overcome by Gambetta. But the fall of Metz had released German reinforcements. After an unsuccessful contest by the right wing at Beaune-la-Rolande (November 28), and a partial victory at Villepion, the French were defeated in turn on December 2 at Loigny or Patay (left wing), on December 3 at Artenay. The Germans reoccupied Orléans and the first Army of the Loire was dispersed. The Government moved from Tours to Bordeaux.

After Coulmiers General Trochu had planned a sortie from Paris to meet the Army of the Loire. This advance was under command of General Ducrot, but was delayed by trouble with pontoon bridges. The various battles of the Marne (November 30-December 2)[Pg 23] culminated in the terrible fight and repulse of Villiers and Champigny. In the north, a small army hastily brought together under temporary command of General Favre was defeated at Villers-Bretonneux and Amiens (November 27).

The last phase of the Franco-Prussian War begins with the crushing of the Army of the Loire and the check of the advance to Champigny. With unwearied tenacity Gambetta tried to reorganize the Army of the Loire. A portion became the second Army of the Loire or of the West, under Chanzy. The rest, under Bourbaki, became the Army of the East. Faidherbe tried to revive the Army of the North.

To Chanzy, on the whole the most capable French general of the war, was assigned the task of trying, with a smaller force, what d'Aurelle had already failed in accomplishing, a drive on Paris. In this task Bourbaki and Faidherbe were expected by Gambetta to coöperate. Instead of succeeding, Chanzy, bravely fighting, was driven back, first down the Loire, in the long-contested battle of Josnes (Villorceau or Beaugency) (December 7-10),[Pg 24] then up the valley of the tributary Loir to Vendôme and Le Mans. There the army, reduced almost to a mob, made a new stand. In a battle between January 10 and 12, this army was again routed and what was left thrown back to Laval.

Faidherbe, taking the offensive in the north, fought an indecisive contest at Pont-Noyelles (December 23) and took Bapaume (January 3). But his endeavor to proceed to the assistance of Paris was frustrated, he was unable to relieve Péronne, which fell on January 9, and was defeated at Saint-Quentin on January 19.

Bourbaki, in spite of his reputation, showed himself inferior to Chanzy and Faidherbe. He let his army lose morale by his hesitation, and then accepted with satisfaction Freycinet's plan to move east upon Germany instead of to the rescue of Paris. On the eastern frontier Colonel Denfert-Rochereau was tenaciously holding Belfort, which was never captured by the Germans during the whole war.[2] Bourbaki's dishearteningly slow progress received no effective assistance from Garibaldi. This[Pg 25] Italian soldier of fortune, now somewhat in his decline, had offered his services to France and was in command of a small body of guerillas and sharpshooters, the Army of the Vosges. With alternate periods of inactivity, failure, and success, Garibaldi perhaps did more harm than good to France. He monopolized the services of several thousand men, and yet, through his prestige as a distinguished foreign volunteer, he could not be brought under control. Bourbaki won the battle of Villersexel on January 9. Pushing on to Belfort he was defeated only a few miles from the town in the battle of Héricourt, or Montbéliard, along the river Lisaine. The army, now transformed into panic-stricken fugitives, made its way painfully through bitter cold and snow, and Bourbaki tried to commit suicide. He was succeeded by General Clinchant. When Paris capitulated, on January 28, and an armistice was signed, this Army of the East was omitted. Jules Favre at Paris failed to notify Gambetta in the provinces of this exception, and the army, hearing of the armistice, ceased its flight, only to be relentlessly followed by the Germans. Finally, on February 1, the remnants[Pg 26] of the army fled across the Swiss frontier and found safety on neutral soil.

Meanwhile, in Paris the tightening of the Prussian lines had made the food problem more and more difficult, and the population were reduced to small rations and unpalatable diet. After Champigny the German general von Moltke communicated with the besieged, informing them of the defeat of Orléans, and the means seemed opened for negotiations. But the opportunity was rejected, and the Government even refused to be represented at an international conference, then opening in London, because of its unwillingness to apply to Bismarck for a safe-conduct for its representative. A chance to bring the condition of France before the Powers was neglected. Between December 21 and 26, a sally to Le Bourget was driven back, and, on the next day, the bombardment of the forts began. On January 5, the Prussian batteries opened fire on the city itself. On January 18, the Germans took a spectacular revenge for the conquests of Louis XIV by the coronation of King William of Prussia as Emperor of the united German people. The ceremony took place in[Pg 27] the great Galerie des Glaces of Louis's magnificent palace of Versailles. The very next day the triumph of the Germans received its consecration, not only by the battle of Saint-Quentin (already mentioned), but by the repulse of the last offensive movement from Paris. To placate the Paris population an advance was made on Versailles with battalions largely composed of National Guards. At Montretout and Buzenval they were routed and driven back in a panic to Paris. General Trochu was forced to resign the military governorship of Paris, though by a strange contradiction he kept the presidency of the Government of National Defence, and was replaced by General Vinoy. On January 22, a riot broke out in the capital in which blood was shed in civil strife. Finally, on January 28, Jules Favre had to submit to the conqueror's terms. Paris capitulated and the garrison was disarmed, with the exception of a few thousand regulars to preserve order, and the National Guard; a war tribute was imposed on the city and an armistice of twenty-one days was signed to permit the election and gathering of a National Assembly to pass on terms[Pg 28] of peace. With inexcusable carelessness Jules Favre neglected to warn Gambetta in the provinces that this armistice began for the rest of France only on the thirty-first and that, as already stated, the Army of the East was excepted from its provisions.

Gambetta was furious at the surrender and at the presumption of Paris to decide for the provinces. He preached a continuation of the war, and the intervention of Bismarck was necessary to prevent him from excluding from the National Assembly all who had had any connection with the imperial régime. Jules Simon was sent from Paris to counteract Gambetta's efforts. The latter yielded before the prospect of civil war, withdrew from power, and, on February 8, elections were held for the National Assembly.

The downfall of what had been considered the chief military nation of Europe was due to many involved causes. The Empire was responsible for the débâcle and the Government of National Defence was unable to create everything out of nothing. Many people were ready to be discouraged after a first defeat, and few realized what Germany's demands[Pg 29] were going to be. The imperial army was insufficiently equipped and the majority of its generals were inefficient and lacking in initiative: there was no preparation, no system, little discipline.

During the period of National Defence the members of the Government themselves were usually wanting in experience and in diplomacy, and the badly trained armies made up of raw recruits were liable to panics or unable to follow up an advantage. There was jealousy, mistrust, and frequent unwillingness to subordinate politics to patriotism, or, at any rate, to make allowances for other forms of patriotism than one's own. Gambetta and Jules Favre were primarily orators and tribunes and indulged in too many wordy proclamations, in which habit they were followed by General Trochu. The patriotism and enthusiasm of Gambetta were undeniable, but he was imbued with the principles and memories of the French Revolution, including the efficacy of national volunteers, the ability of France to resist all Europe, and the subordination of military to civil authority. Consequently, in a time of stress he nagged the generals[Pg 30] and interfered, and gave free rein to Freycinet to do the same. They upset plans made by experienced generals, and sent civilians to spy over them, with power to retire them from command. They were, moreover, trying to thrust a republic down the throats of a hostile majority of the population, for a large proportion of those not Bonapartists were in favor of a monarchy. The wonder is, therefore, that France was able to do so much. M. de Freycinet was not boasting when he wrote later, "Alone, without allies, without leaders, without an army, deprived for the first time of communication with its capital, it resisted for five months, with improvised resources, a formidable enemy that the regular armies of the Empire, though made up of heroic soldiers, had not been able to hold back five weeks."[3]

[1] Moritz Busch, Bismarck, vol. 1, chap. 1.

[2] He surrendered by order of the Government. The isolated incident of the resistance of the town of Bitche through all the war is no less noteworthy.

[3] La guerre en province, quoted by Welschinger, La guerre de 1870, vol. II, p. 295.

The elections were held in hot haste. The short time allowed before the convening of the Assembly made the usual campaign impossible. It met at Bordeaux on February 13, 1871. The peace party was in very considerable majority, and though Gambetta received the distinction of a multiple election in nine separate districts, Thiers was chosen in twenty-six. The radicals and advocates of guerilla warfare and of a "guerre à outrance" found themselves few in numbers. Many of the representatives had only local or rural reputation. They were new to parliamentary life, and in the majority of cases were averse to a permanent republican form of government. They would have preferred a monarchy, but they were ready to accept a provisional republic which would incur the task of settling the war with Germany and bear the onus of defeat. They were especially suspicious of[Pg 32] Paris, and hostile to it as the home of fickleness, of irresponsibility, and of mob rule. They were largely provincial lawyers and rural landed gentry, conservative and clerical, who felt that too much importance had been usurped by the Parisian Government of National Defence.

ADOLPHE THIERS

ADOLPHE THIERS

The new Assembly, therefore, gradually fell into several groups. On the conservative side came the Extreme Right, made up of out-and-out Legitimists, believing in absolutism and the divine right of kings; the Right, composed of monarchists desirous of conciliating the old régime with the demands of modern times and of making it a practical form of government; the Right Centre, consisting of constitutional monarchists and followers of the Orléans branch of the house of Bourbon. Among the anti-republicans the Bonapartists were almost negligible. Next came the Left Centre of conservative Republicans, the republican Left, and the radical Union républicaine, partisans of Gambetta and advanced "reformers."

At the first public session of the Assembly Jules Grévy was chosen presiding officer. A[Pg 33] former leader of the opposition to the Empire, he had not participated in affairs since the Fourth of September, and, therefore, had not yet identified himself with any set. Among the Republicans he was averse to Gambetta and remained so even when the latter became moderate. On February 17, Adolphe Thiers, the "peace-maker," was by an almost unanimous vote elected "Chief of the Executive Power of the French Republic." It was he who, thirty years before, had fortified Paris that had now fallen only by famine, who had opposed the war when it might yet have been averted, who had travelled over Europe to defend the interests of France, who had been elected representative by the choice of twenty-six departments.

M. Thiers formed a coalition cabinet representing different shades of political feeling, and in one of his early speeches, on March 10, he formulated a plan of party truce for the purpose of national reorganization. This plan was acquiesced in by the Assembly and bears in history the name of the Compact of Bordeaux (pacte de Bordeaux). France was to continue under a republican government, without[Pg 34] injury to the later claims of any party. Thiers, himself, as a former Orléanist, advocated, at least in his relations with the monarchists, a Restoration, with the sine qua non that an attempt should be made at a fusion of the Legitimists and the Orléanists. Meanwhile he was the chief executive official of a republic.

But, even before the formulation of the truce of parties, Thiers was in eager haste to settle the terms of peace with Germany before the expiration of the armistice. The preliminaries were discussed between Thiers and Bismarck at Versailles. The Germans were almost as anxious as the French to see the end of the war, and the objections and delays of Bismarck were partly tactical. Brief successive prolongations of the armistice were obtained, and finally the preliminaries were signed on February 26. Thiers made herculean efforts to keep for France Belfort, which Bismark claimed, and finally succeeded on condition that the German army should occupy Paris from March 1 to the ratification of the preliminaries by the Assembly. France was to give up Alsace and a part of Lorraine, including Metz, and pay an indemnity of five[Pg 35] billion francs. German troops were to occupy the conquered districts and evacuate them progressively as the indemnity was paid. The peace discussions afterwards continued at Brussels, and the final treaty was signed at Frankfort on May 10, 1871.

No sooner were the preliminaries signed than Thiers returned post-haste to Bordeaux, and obtained an almost immediate assent (March 1), so that the Germans were obliged to forego a large part of their plans for a triumphal entry into Paris and a review by the Emperor. Only one body of thirty thousand men marched in through one section and, two days later, evacuated the city.

The same meeting which ratified the preliminaries of peace officially proclaimed the expulsion of the imperial dynasty and declared Napoleon III responsible for the invasion, the ruin and dismemberment of France. The same day also beheld the pathetic withdrawal of the representatives of Alsace and of Lorraine, turned over to the conqueror.

The misfortunes of France were far from ended. Paris was soon to break out into rebellion under the eyes of the Germans still in[Pg 36] possession of many of the suburbs. The enemy looked on and saw Frenchman killing Frenchman in civil war.

It had become obvious that the division of administration between Bordeaux and Paris was making government difficult. The Assembly, still suspicious of Paris, decided to transfer its place of meeting to Versailles. But Paris itself was in a state of nervous hysteria as a result of the long and exhausting siege (fièvre obsidionale). The Paris proletariat were as jealous and suspicious of the Assembly as the Assembly of them. The suggestion of a transfer to Versailles instead of to Paris seemed a direct challenge. Versailles recalled too easily Louis XIV and the Bourbons. The monarchical sympathies of the Assembly were, moreover, well known, and the Parisians dreaded the restoration of royalty. The people were hungry and penniless, and industry and commerce had almost completely ceased. The city was full, besides, of soldiers disarmed through the armistice and ready for riot. On the other hand, the National Guards, a large body of semi-disciplined militia made up, at least in part, of the dregs of the populace, had[Pg 37] been allowed to retain their weapons, and many of them gave their time to drunkenness, loafing, and listening to agitators. Some rather injudicious condemnations of leaders in the October riots merely aggravated the dissatisfaction. All this led to the Commune.

The leaders of the Commune were, some of them, sincere though visionary reformers, whose hearts rankled at the sufferings of the poor and the inequalities of wealth and privilege. The majority were mischief-makers and café orators, loquacious but incompetent or inexperienced, without definite plans and unfit to be leaders, some vicious and some dishonest. The rank and file soon became a lawless mob, ready to burn and murder, imitating, in their ignorant cult of "liberty," the worst phases of the French Revolution and its Reign of Terror. Still, the Communards have their admirers to-day, and, as the world advances in radicalism, it is not unlikely that the Jacobin Charles Delescluze, the bloodthirsty Raoul Rigault, and the brilliant and scholarly Gustave Flourens will be considered heroic precursors.

The idea of the Commune was decentralization.[Pg 38] It was an experiment aiming at a free and autonomous Paris serving as model for the other self-governing communes of France, united merely for their common needs. It amounted almost to the quasi-independence of each separate town. But mixed up with the theorists of the Commune were countless anarchist revolutionaries, followers of the teachings of Blanqui, as well as admirers of the great Revolution which overthrew the old régime, and socialists of various types.

The germs of the movement which was to culminate in the Commune were visible at an early hour. The dissatisfaction of the Radicals with the moderation of the Government of National Defence, the riots of October 31 and January 22 were all symptoms of the discontent of the proletariat. Indeed, the proclamation of the Republic, on September 4, was itself an object lesson in illegality to the malcontents. Organized dissatisfaction began to centre about the obstreperous and disorderly, but armed and now "federated" National Guards. Manifestoes signed by self-appointed committees of plebeian patriots appeared on the walls of Paris. These committees[Pg 39] finally merged into the "Comité central," or were replaced by it. This committee advocated the trial and imprisonment of the members of the Government of National Defence, and protested against the disarmament of the National Guards and the entrance of the Germans into Paris.

The Government was almost helpless. The few regulars left under arms in Paris were of doubtful reliance, and General d'Aurelle de Paladines, now in command of the National Guards, was not obeyed. A certain number of artillery guns in Paris had been paid for by popular subscription, and the rumor spread at one time that these were to be turned over to the Germans. The populace seized them and dragged them to different parts of the city.

The Government decided at last to act boldly and, on March 18, dispatched General Lecomte with some troops to seize the guns at Montmartre. But the mob surrounded the soldiers, and these mutinied and refused to obey orders to fire, and arrested their own commander. Later in the day General Lecomte was shot with General Clément Thomas, a former commander of the National Guard,[Pg 40] who rather thoughtlessly and out of curiosity had mingled with the crowd and was recognized.

Thus armed forces in Paris were in direct rebellion. Other outlying quarters had also sprung into insurrection. M. Thiers, who had recently arrived from Bordeaux, and the chief government officials quartered in Paris, withdrew to Versailles. Paris had to be besieged again and conquered by force of arms.

In Paris the first elections of the Commune were held on March 26. On April 3 an armed sally of the Communards towards Versailles was repulsed with the loss of some of their chief leaders, including Flourens. Meanwhile, the Army of Versailles had been organized and put under the command of Mac-Mahon. Discipline was restored and the advance on Paris began.

As time passed in the besieged city the saner men were swept into the background and reckless counsels prevailed. Some of the military leaders were competent men, such as Cluseret, who had been a general in the American army during the Civil War, or Rossel, a trained officer of engineers. But many were[Pg 41] foreign adventurers and soldiers of fortune: Dombrowski, Wrobleski, La Cecilia. The civil administration grew into a reproduction of the worst phases of the Reign of Terror. Frenzied women egged on destruction and slaughter, and when at last the national troops fought their way into the conquered city, it was amid the flaming ruins of many of its proudest buildings and monuments.

The siege lasted two months. On May 21, the Army of Versailles crossed the fortifications and there followed the "Seven Days' Battle," a street-by-street advance marked by desperate resistance by the Communards and bloodthirsty reprisals by the Versaillais. Civil war is often the most cruel and the Versailles troops, made up in large part of men recently defeated by the Germans, were glad to conquer somebody. Over seventeen thousand were shot down by the victors in this last week. The French to-day are horrified and ashamed at the cruel massacres of both sides and try to forget the Commune. Suffice it here to say that the last serious resistance was made in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise, where those fédérés taken arms in hand were lined up[Pg 42] against a wall and shot. Countless others, men, women, and children, herded together in bands, were tried summarily and either executed, imprisoned, or deported thousands of miles away to New Caledonia, until, years after, in 1879 and 1880, the pacification of resentments brought amnesty to the survivors.[4]

Fortunately, M. Thiers had more inspiring tasks to deal with than the repression of the Commune. One was the liberation of French soil from German occupation, another the reorganization of the army. With wonderful speed and energy the enormous indemnity was raised and progressively paid, the Germans simultaneously evacuating sections of French territory. By March, 1873, France was in a position to agree to pay the last portion of the war tribute the following September (after the fall of Thiers, as it proved), thus[Pg 43] ridding its soil of the last German many months earlier than had been provided for by the Treaty of Frankfort. The recovery of France aroused the admiration of the civilized world, and the anger of Bismarck, sorry not to have bled the country more. He viewed also with suspicion the organization of the army and the law of July, 1872, establishing practically universal military service. He affected to see in it France's desire for early revenge for the loss of Alsace and Lorraine.

M. Thiers, the great leader, did not find his rule uncontested. Brought into power as the indispensable man to guide the nation out of war, his conceit was somewhat tickled and he wanted to remain necessary. Though over seventy he had shown the energy and endurance of a man in his prime joined to the wisdom and experience of a life spent in public service and the study of history. Elected by an anti-Republican Assembly and himself originally a Royalist, the formulator also of the Bordeaux Compact, he began to feel, nevertheless, in all sincerity that a conservative republic would be the best government, and his vanity made him think himself its best[Pg 44] leader. This conviction was intensified for a while by his successful tactics in threatening to resign, when thwarted, and thus bringing the Assembly to terms. But he tried the scheme once too often.

The majority in the Assembly was not, in fact, anxious to give free rein to Thiers, and it had wanted to avoid committing itself definitely to a republic. It wanted also to insure its own continuation as long as possible, contrary to the wishes of advanced Republicans like Gambetta, who declared that the National Assembly no longer stood for the expression of the popular will and should give way to a real constituent assembly to organize a permanent republic.

The first endeavor of the Royalists was to bring about a restoration of the monarchy. The princes of the Orléanist branch were readmitted to France and restored to their privileges. A fusion between the two branches of the house of Bourbon was absolutely necessary to accomplish anything. The members of the younger or constitutionalist Orléans line, and notably its leader, the comte de Paris, were disposed to yield to the representative[Pg 45] of the legitimist branch, the comte de Chambord. He was an honorable and upright man, yet one who in statesmanship and religion was unable to understand anything since the Revolution. He had not been in France for over forty years, he was permeated with a religious mystical belief not only in the divinity of royalty, but in his own position as God-given (Dieudonné was one of his names) and the only saviour of France. Moreover, he could not forgive his cousins the fact that their great-grandfather had voted for the execution of Louis XVI. So he treated their advances haughtily, declined to receive the comte de Paris, and issued a manifesto to the country proclaiming his unwillingness to give up the white flag for the tricolor. Henry V could not let anybody tear from his hand the white standard of Henry IV, of Francis I, and of Jeanne d'Arc.

Such mediævalism dealt the monarchical cause a crushing blow. The Royalists had already begun to look askance at M. Thiers and hinted that his readiness to go on with the Republic was a tacit violation of the Bordeaux Compact. Under the circumstances, however,[Pg 46] his sincerity need not be doubted in believing a republic the only outcome, and his ambition or vanity may be excused for wishing to continue its leader. By the Rivet-Vitet measure of August 31, 1871, M. Thiers, hitherto "chief of executive power," was called "President of the French Republic." He was to exercise his functions so long as the Assembly had not completed its work and was to be responsible to the Assembly. Thus the legislative body elected for an emergency was taking upon itself constituent authority and was tending to perpetuate the Republic which the majority disliked.

From this time the tension grew greater between Thiers and the Assembly, which begrudged him the credit for the negotiations still proceeding, and already mentioned above, for the evacuation of France by the Germans. It thwarted the wish of the Republicans to transfer the seat of the executive and legislature to Paris. Thiers was, indeed, working away from the Bordeaux Compact and was advocating a republic, though a conservative one. This "treachery" the monarchists could not forgive, though bye-elections were[Pg 47] constantly increasing the Republican membership. Thiers did not, on the other hand, welcome the advanced republicanism of Gambetta declaring war on clericalism, and proclaiming the advent of a new "social stratum" (une couche sociale nouvelle) for the government of the nation.

By the middle of 1872, Thiers was the open advocate of "la République conservatrice," and this gradual transformation of a transitional republic into a permanent one was what the monarchists could not accept. So they declared open war on M. Thiers. On November 29, 1872, a committee of thirty was appointed at Thiers's instigation to regulate the functions of public authority and the conditions of ministerial responsibility. This was inevitably another step toward the affirmation of a permanent republic by the clearer specification of governmental attributes. The majority of the committee were hostile to M. Thiers and were determined to overthrow him. The Left was also growing dissatisfied with his opposition to a dissolution. He found it increasingly difficult to ride two horses. The committee of thirty wished to prevent Thiers[Pg 48] from exercising pressure on the Assembly by intervention in debates and threats to resign. In February and March, 1873, it proposed that the President should notify the Assembly by message of his intention to speak, and the ensuing discussion was not to take place in his presence. M. Thiers protested in vain against this red tape (chinoiseries). The effect was to drive him more and more from the Assembly, where his personal influence might be felt.

The crisis became acute when Jules Grévy, President of the Assembly, a partisan of Thiers, resigned his office after a disagreement on a parliamentary matter. His successor, M. Buffet, at once rigorously supported the hostile Right. In April an election in Paris brought into opposition Charles de Rémusat, Minister of Foreign Affairs and personal friend of Thiers, and Barodet, candidate of the advanced and disaffected Republicans. The governmental candidate was defeated. Encouraged by this the duc de Broglie, leader of the Right, followed up the attack, declaring the Government unable to withstand radicalism. In May he made an interpellation on[Pg 49] the governmental policy. Thiers invoked his right of reply and, on May 24, gave a brilliant defence of his past actions, formulating his plans for the future organization of the Republic. A resolution was introduced by M. Ernoul, censuring the Government and calling for a rigidly conservative policy. The government was put in the minority by a close vote and M. Thiers forthwith resigned. The victors at once chose as his successor the candidate of the Rights, the maréchal de Mac-Mahon, duc de Magenta, the defeated general of Sedan, a brave and upright man, but a novice in politics and statecraft. He declared his intention of pursuing a conservative policy and of re-establishing and maintaining "l'ordre moral."

[4] The fierceness of hatreds engendered by the Commune may be illustrated by the following untranslatable comment by Alexandre Dumas fils on Gustave Courbet, a famous writer and a famous painter: "De quel accouplement fabuleux d'une limace et d'un paon, de quelles antithèses génésiaques, de quel suintement sébacé peut avoir été générée cette chose qu'on appelle M. Gustave Courbet? Sous quelle cloche, à l'aide de quel fumier, par suite de quelle mixture de vin, de bière, de mucus corrosif et d'œdème flatulent a pu pousser cette courge sonore et poilue, ce ventre esthétique, incarnation du moi imbécile et impuissant?" (Quoted in Fiaux's history of the Commune, pp. 582-83.)

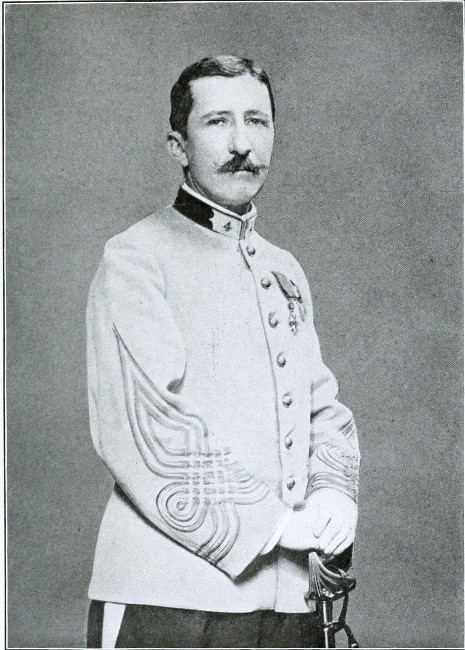

EDME-PATRICE-MAURICE DE MAC-MAHON

EDME-PATRICE-MAURICE DE MAC-MAHON

"L'ordre moral," such was the political catchword of the new administration. Just what it meant was not very clear. In general, however, it was obviously intended to imply resistance to radicalism (republicanism) and the maintenance of a strictly conservative policy, strongly tinged with clericalism.[5] The victors over M. Thiers had revived their desire of a monarchical restoration and many of them hoped that the maréchal de Mac-Mahon would shortly make way for the comte de Chambord. But though an anti-republican he was never willing to lend himself to any really illegal or dishonest manœuvres, and his sense of honor was of great help to him in his want of political competence. So he did not prove the pliant tool of his creators, and his term[Pg 51] of office saw the definite establishment of the Republic.

The first Cabinet was led by the duc de Broglie who took the portfolio of Foreign Affairs. The new Government was viewed askance by the conquerors at Berlin, who disliked such an orderly transmission of powers as an indication of national recovery and stability. Bismarck even exacted new credentials from the French Ambassador. Meanwhile, the Minister of the Interior, Beulé, proceeded to consolidate the authority of the new Cabinet by numerous changes in the prefects of the departments, turning out the "rascals" of Thiers's administration to make room for appointees more amenable to new orders.

The time now seemed ripe for another effort to establish the monarchy under the comte de Chambord. It culminated in the "monarchical campaign" of October, 1873. The monarchical sympathizers were hand-in-glove with the Clericals and for the most part coincided with them. The Royalists were inevitably clerical if for no other reason than that monarchy and religion both seemed to involve continuity, and the legitimacy of the monarchy[Pg 52] had always been blessed by the Church. The revolutionary Rights of Man were held to be inconsistent with the traditional Rights of God and the monarchy. Moreover, the founders of the third republic had, with noteworthy exceptions like the devout Trochu, been mildly anti-clerical. They were for the most part religious liberals and deists, rarely atheists, but that was enough to array the bishops, like monseigneur Pie of Poitiers, against them. Indeed, a quick religious revival swept over the land, as was shown by numerous pilgrimages, including one to Paray-le-Monial, home of the cult of the Sacred Heart. France herself should be consecrated to the Sacred Heart, and the idea was evolved, afterwards carried out, of the erection of the great votive basilica of the Sacré Cœur on the heights of Montmartre.

The first step toward the restoration of "Henry V" was to persuade the comte de Paris to make new efforts for a fusion of the two branches. Swallowing his pride, the comte de Paris generously went to the home of the comte de Chambord at Frohsdorf, in Austria, in August, and paid his respects to[Pg 53] him as head of the family. As the comte de Chambord had no children, it was expected that the comte de Paris would be his successor. But the old difficulty about the white flag cropped up, and the comte de Chambord stubbornly refused to rule over a country above which waved the revolutionary tricolor.

Matters dragged on through the summer, during the parliamentary recess, and the conservative leaders were outspoken as to their plans to overthrow the Republic. It was hoped that some compromise might be reached by which could be reconciled, as to the flag, the desires of the Assembly which was expected to recall the pretender and those of the comte de Chambord who considered his divinely inspired will superior to that of the representatives of the people. It was suggested that the question of the flag might be settled after his accession to the throne. The embassy to Salzburg, in October, of M. Chesnelong, an emissary of a committee of nine of the Royalist leaders, achieved only a half-success, but left matters sufficiently indeterminate to encourage them in continuing their plans. Matters seemed progressing swimmingly when,[Pg 54] on October 27, an unexpected letter from the pretender to M. Chesnelong categorically declared that nothing would induce him to sacrifice the white banner.

The effect of this letter was to make all hopes of a restoration impossible. Everybody knew that the majority of Frenchmen would never give up their flag for the white one, whether this were dignified by the name of "standard of Arques and Ivry," or whether one called it irreverently a "towel," as did Pope Pius IX, impatient at the obstinacy of the comte de Chambord. In the midst of the general confusion only one thing seemed feasible if governmental anarchy were to be avoided, namely, the prorogation of Mac-Mahon's authority, as a rampart against rising democracy and a permanent republic. This condition the Orléanist Right Centre turned to their advantage. By a vote of November 20, the executive power was conferred for a definite period of seven years on the maréchal de Mac-Mahon. Thus a head of the nation was provided who might perhaps outlast the Assembly. The vote might be interpreted either as the beginning of a permanent[Pg 55] republican régime, as it proved to be, or as the establishment of a definite interlude in anticipation of a new attempt to set up a monarchy, this time to the advantage of the younger branch. Many hoped that the comte de Chambord would soon be dead, his white flag forgotten, and the way open to the comte de Paris. The Orléanists were pleased by this latter idea, the Republicans were glad to have the republican régime recognized for, at any rate, seven years to come, accompanied by the promise of a constitutional commission of thirty members. The Legitimists alone were disappointed, and, oblivious of the fact that the comte de Chambord had lost through his folly, they were before long ready to vent their wrath on Mac-Mahon and his adviser, the duc de Broglie, who was responsible for the presidential prorogation.

The pretender had been completely taken aback at the impression produced by his letter. Convinced of his divinely inspired omniscience, and certain that he was the foreordained ruler of France, he had thought that the Assembly would give way on the question of the flag, or that the army would follow him,[Pg 56] or that Mac-Mahon would yield. His state coach had been made ready and a military uniform awaited him at a tailor's. He hastened in secret to Versailles, where he remained for a while in retirement to watch events, and where Mac-Mahon refused to see him. Then, after the vote on the presidency, he sadly returned into exile forever.

Never was a greater service done to France than when the comte de Chambord refused to give up his flag. Completely out of touch with the country through a life spent in exile, inspired with the feeling of his divine rights and their superiority to the will of democracy, he would scarcely have ascended the throne before some conflict would have broken out and the history of France would have registered one revolution more.

The duc de Broglie had considered it good form to resign after the vote of November 20, but Mac-Mahon immediately entrusted to him the selection of a second Cabinet. In this Cabinet the portfolio of Foreign Affairs was given to the duc Decazes, a skilled diplomat, but the Legitimists were offended by some of the cabinet changes and their dislike of the[Pg 57] duc de Broglie gradually became more acute. Finally, after several months of parliamentary skirmishing the second Broglie Cabinet fell before a coalition vote of Republicans and extreme Royalists with a few Bonapartists, on May 16, 1874. The Right Centre and Left Centre had unsuccessfully joined in support of the Cabinet. The nation was taking another step toward republican control and the overthrow of the conservatives.

From now on, Mac-Mahon's task became increasingly difficult. After the split in the conservative majority it was necessary to rely on combination ministries, representing different sets and harder to reconcile or to propitiate. The result of Mac-Mahon's first efforts was a Cabinet led by a soldier, General de Cissey, and having no pronounced political tendencies.

Party differences were becoming accentuated. The downfall of the Broglie Cabinet had been largely due to the extreme Royalists and the Orléanists could not forgive them. The situation was made worse by differences in interpretation of the law of November 20, establishing the "septennat" of the maréchal de Mac-Mahon. Some of the Monarchists[Pg 58] maintained the "septennat personnel," namely, the election of one specific person to hold office for seven years, with the idea that he could withdraw at any time in favor of a king. Others interpreted the law as establishing a "septennat impersonnel," a definite truce of seven years, which should still hold even if Mac-Mahon had to be replaced before the expiration of the time by another President. Then, they hoped, their enemy Thiers would be dead. The Republicans were, of course, desirous of making the impersonal "septennat" lead to a permanent republic, and declared that Mac-Mahon was not the President of a seven years' republic, but President, for seven years, of the Republic.

In this state of affairs the Bonapartists now became somewhat active again. Strangely enough, the disasters of 1870 were already growing sufficiently remote for some of the anti-Republicans to turn again to the prospect of empire. This menace frightened the moderate Royalists into what they had kept hesitating to do; that is to say, into spurring to activity the purposely inactive and dilatory constitutional commission.[Pg 59]

The stumbling-block was the recognition of the Republic itself and the admission that the form of government existing in France was to be permanent. There was much parliamentary skirmishing over various plans, rejected one after the other, inclining in turn toward the Republic and a monarchy. Finally, some of the Monarchists, discouraged by the rising tide of "radicalism," and frightened lest unwillingness to accept a conservative republic now might result still worse for them in the future, rallied in support of the motion of M. Wallon, known as the "amendement Wallon," which was adopted by a vote of 353 to 352 (January, 1875): "The President of the Republic is elected by absolute majority of votes by the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies united as a National Assembly. He is chosen for seven years and is re-eligible."

In this vote the fateful statement was made concerning the election of a President other than Mac-Mahon and the transmission of power in a republic. The third Republic received its definite consecration by a majority of one vote.

The vote on the Wallon amendment dealt[Pg 60] with only one article of a project not yet voted as a whole, but it was the crossing of the Rubicon. The other articles were adopted by increased majorities.

The Ministry of General de Cissey had already resigned upon a minor question, but had held over at the President's request. Mac-Mahon now asked the Monarchist M. Buffet to form a conservative conciliation Cabinet, which was made up almost entirely from the Right Centre (Orléanists) and the Left Centre (moderate Republicans) and accepted at first by the Republican Left. By this Cabinet still one more step was taken toward Republican preponderance.

During the Buffet Ministry three important matters occupied public attention. One was the completion of the new constitution. A second was the creation of "free" universities, not under control of the State. This step was advocated in the name of intellectual freedom, but the whole scheme was backed by the Catholics and merely resulted in the creation of Catholic faculties in several great cities. A third matter was the intense anxiety over the prospect of a rupture with Germany.[Pg 61] Bismarck was renewing his policy of pin-pricks. The French army had been strengthened by a battalion to every regiment, and so Bismarck complained of the strictures of French and Belgian bishops on his anti-papal policy. Whether he only meant to humiliate France still more, or whether he actually desired a new rupture so as to crush the country finally, is not clear. At any rate, with the aid of England and especially of Russia, France showed that she was not helpless, and Bismarck protested that he was absolutely friendly.

By the close of 1875, the measures constituting the new Government had been voted and, on December 31, the Assembly, which had governed France since the Franco-Prussian War, was dissolved to make way for the new legislature. During the succeeding elections M. Buffet's Cabinet, antagonized by the Republicans and rent by internal dissensions, went to pieces, M. Buffet personally suffered disastrously at the polls. The slate was clear for a totally new organization. The Assembly had done many a good service, but its dilatoriness in establishing a permanent government, its ingratitude to M. Thiers, its clericalism,[Pg 62] and its stubbornness in trying to foist a king on the people made it pass away unregretted by a country which had far outstripped it in republicanism.

The "Constitution of 1875," under which, with some modifications, France is still governed, is not a single document constructed a priori, like the Constitution of the United States. It was partly the result of the evolution of the National Assembly itself, partly the result of compromises and dickerings between hostile groups. Particularly, it expressed the jealousy of a monarchical assembly for a President of a republic, and the desire, therefore, to keep power in the hands of its own legislative successor. The Assembly took it for granted that the Chamber of Deputies would have the same opinions as itself. As a matter of fact, the political complexion of the legislature has been consistently toward radicalism, and the result has hindered a strong executive and promoted legislative demagogy.

The Constitution of 1875 may be considered as consisting of the Constitutional Law of February 25, relating to the organization of the public powers (President, Senate, Chamber[Pg 63] of Deputies, Ministers, etc.); the Constitutional Law of the previous day, February 24, relating to the organization of the Senate; the Constitutional Law of July 16, on the relations of the public powers. Subsidiary "organic laws" voted later determined the procedure for the election of Senators and Deputies. The vote of February 25 was the crucial one in the definite establishment of the Republican régime. The Constitution has undergone certain slight modifications since its adoption.

By the Constitution of 1875 the government of the French Republic was vested in a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. The Senate consisted of 300 members, of whom 75 were chosen for life by the expiring Assembly, their successors to be elected by co-optation in the Senate itself. The other 225, chosen for nine years and renewable by thirds, were to be elected by a method of indirect selection. In 1884, the choice of life Senators ceased and the seats, as they fell vacant, have been distributed among the Departments of the country. The Deputies were elected by universal suffrage for a period of four years. Unless a[Pg 64] candidate obtained an absolute majority of the votes cast, the election was void, and a new one was necessary. Except during the period from 1885 to 1889, the Deputies have represented districts determined, unless for densely populated ones, by the administrative arrondissements. From 1885 to 1889, the scrutin de liste was in operation: the whole Department voted on a ticket containing as many names as there were arrondissements. The prerogatives of the two houses were identical except that financial measures were to originate in the Chamber of Deputies. As a matter of fact, the Senate has fallen into the background, and the habit of considering the vote of the Chamber rather than that of the Senate as important in a change of Ministry has made it the true source of government in France. The two houses met at Versailles until 1879; since then Paris has been the capital, except for the election of a President. After separate decision by each house to do so, or the request of the President, they could meet in joint assembly as a Constitutional Convention to revise the constitution.

The Senate and Chamber, united in joint[Pg 65] session as a National Assembly, were to choose a President for a definite term of seven years, not to fill out an incomplete term vacated by another President. The President could be re-elected. With the consent of the Senate he could dissolve the Chamber, but this restriction made the privilege almost inoperative in practice. He was irresponsible, the nominal executive and figurehead of the State, but all his acts had to be countersigned by a responsible Minister, by which his initiative was greatly reduced. In fact the President had really less power than a constitutional king.

The real executive authority was in the hands of the Cabinet, headed by a Premier or Président du conseil.[6] The Ministry was responsible to the Senate and Chamber (in practice, as we have seen, to the Chamber), and was expected to resign as a whole if put by a vote in the minority. By custom the President selects the Premier from the majority and the latter selects his colleagues in the Cabinet, trying to make them representatives[Pg 66] of the wishes of the Parliament. The French Republic is therefore managed by a parliamentary government.

The first elections under the new constitution resulted very much as might be expected: the Senate became in personnel the true successor of the Assembly, the Chamber of Deputies contained most of the new men. The Senate was conservative and monarchical, the Chamber was republican. Therefore, the President of the Republic entrusted the formation of a Ministry to M. Jules Dufaure, of the Left Centre, the views of which group differed hardly at all from those of the Right Centre, except in a full acceptance of the new conditions. Unfortunately, M. Dufaure found it impossible to ride two horses at once and to satisfy both the conservative Senate and the majority in the Chamber of more advanced Republicans than himself. He mistrusted the Republican leader Gambetta, though the latter was now far more moderate, and he sympathized too much with the Clericals to suit the new order of things. So his Cabinet resigned (December 2, 1876), less than nine months after its appointment, and the maréchal[Pg 67] de Mac-Mahon felt it necessary, very much against his will, to call to power Jules Simon. He had previously tried unsuccessfully to form a Cabinet from the Right Centre under the duc de Broglie.

The duc de Broglie remained, however, the power behind the throne. The President was under the political advice of the conservative set, whose firm conviction he shared, that the new Republic was advancing headlong into irreligion. The course of political events now took on a strong religious flavor. Jules Simon was a liberal, which was considered a misfortune, though he announced himself now as "deeply republican and deeply conservative." But people knew his unfriendly relations with Gambetta, which dated from 1871, when he checkmated the dictator at Bordeaux. It was hoped that open dissension might break out in the Republican party which would justify measures tending to a conservative reaction, and help tide over the time until 1880. Then the constitution might be revised at the expiration of Mac-Mahon's term and the monarchy perhaps restored.

Gambetta was, however, now a very different[Pg 68] man. Discarding his former unbending radicalism, he was now the advocate of the "political policy of results," or opportunism, a method of conciliation, of compromise, and of waiting for the favorable opportunity. This was to be, henceforth, the policy closely connected with his name and fame. So Jules Simon soon was sacrificed.

The efforts of the Clerical party bore chiefly in two directions: control of education and advocacy of increased papal authority, particularly of the temporal power of the Pope, dispossessed of his states a few years before by the Government of Victor Emmanuel. This latter course could only tend to embroil France with Italy. So convinced was Gambetta of the unwise and disloyal activities of the Ultramontanes that on May 4, in a speech to the Chamber, he uttered his famous cry: "Le cléricalisme, voilà l'ennemi!"

Jules Simon found himself in a very difficult position. Desirous of conciliating Mac-Mahon and his clique, he adopted a policy somewhat at variance with his former liberal religious views. On the other hand, he could not satisfy the President, who had always disliked him,[Pg 69] or those who had determined upon his overthrow. The crisis came on May 16, 1877, when Mac-Mahon, taking advantage of some very minor measures, wrote a haughty and indignant letter to Jules Simon, to say that the Minister no longer had his confidence. Jules Simon, backed up by a majority in the Chamber, could very well have engaged in a constitutional struggle with Mac-Mahon, but he rather weakly resigned the next day.[7] Thus was opened the famous conflict known in French history, from its date, as the "Seize-Mai."

No sooner was Jules Simon out of the way than Mac-Mahon appointed a reactionary coalition Ministry of Orléanists and Imperialists headed by the duc de Broglie, and held apparently ready in waiting. The Ministers were at variance on many political questions, but united as to clericalism. The plan was to dissolve the Republican Chamber with the co-operation of the anti-Republican Senate, in the hope that a new election, under official[Pg 70] pressure, would result in a monarchical lower house also. The Chamber of Deputies was therefore prorogued until June 16 and then dissolved. At the meeting of May 18, the Republicans presented a solid front of 363 in their protest against the high-handed action of the maréchal de Mac-Mahon.

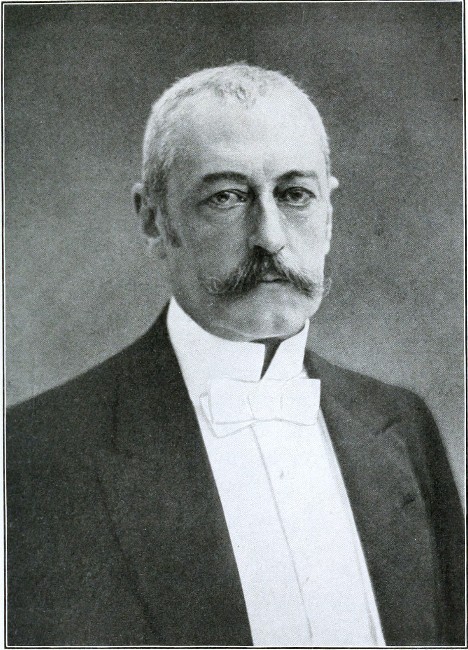

LÉON GAMBETTA

LÉON GAMBETTA