The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Hell Ship, by Raymond Alfred Palmer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Hell Ship Author: Raymond Alfred Palmer Release Date: May 31, 2010 [EBook #32615] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HELL SHIP *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

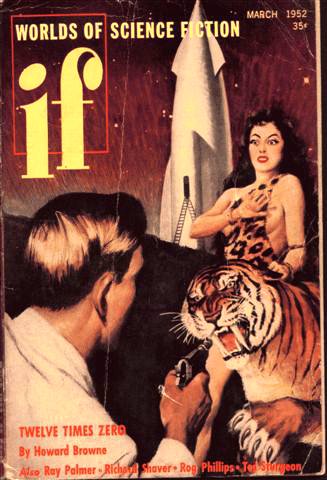

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from If Worlds of Science Fiction March 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

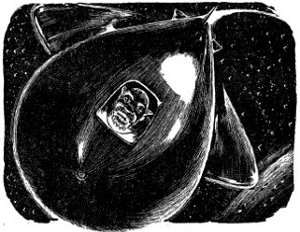

The giant space liner swung down in a long arc, hung for an instant on columns of flame, then settled slowly into the blast-pit. But no hatch opened; no air lock swung out; no person left the ship. It lay there, its voyage over, waiting.

The thing at the controls had great corded man-like arms. Its skin was black with stiff fur. It had fingers ending in heavy talons and eyes bulging from the base of a massive skull. Its body was ponderous, heavy, inhuman.

After twenty minutes, a single air lock swung clear and a dozen armed men in Company uniforms went aboard. Still later, a truck lumbered up, the cargo hatch creaked aside, and a crane reached its long neck in for the cargo.

Still no creature from the ship was seen to emerge. The truck driver, idly smoking near the hull, knew this was the Prescott, in from the Jupiter run—that this was the White Sands Space Port. But he didn't know what was inside the Prescott and he'd been told it wasn't healthy to ask.

Gene O'Neil stood outside the electrified wire that surrounded the White Sands port and thought of many things. He thought of the eternal secrecy surrounding space travel; of the reinforced hush-hush enshrouding Company ships. No one ever visited the engine rooms. No one in all the nation had ever talked with a spaceman. Gene thought of the glimpse he'd gotten of the thing in the pilot's window. Then his thoughts drifted back to the newsrooms of Galactic Press Service; to Carter in his plush office.

"Want to be a hero, son?"

"Who, me? Not today. Maybe tomorrow. Maybe the next day."

"Don't be cute. It's an assignment. Get into White Sands."

"Who tried last?"

"Jim Whiting."

"Where is Whiting now?"

"Frankly we don't know. But—"

"And the four guys who tried before Whiting?"

"We don't know. But we'd like to find out."

"Try real hard. Maybe you will."

"Cut it out. You're a newspaperman aren't you?"

"God help me, yes. But there's no way."

"There's a way. There's always a way. Like Whiting and the others. Your pals."

Back at the port looking through the hot wire. Sure there was a way. Ask questions out loud. Then sit back and let them throw a noose around you. And there was a place where you could do the sitting in complete comfort. Where Whiting had done it—but only to vanish off the face of the earth. Damn Carter to all hell!

Gene turned and walked up the sandy road toward the place where the gaudy neons of the Blue Moon told hard working men where they could spend their money. The Blue Moon. It was quite a place.

Outside, beneath the big crescent sign, Gene stopped to watch the crowds eddying in and out. Then he went in, to watch them cluster around the slot machines and bend in eager rows over the view slots of the peep shows.

He moved into the bar, dropped on one of the low stools. He ordered a beer and let his eyes drift around.

A man sat down beside him. He was husky, tough looking. "Ain't you the guy who's been asking questions about the crews down at the Port?"

Gene felt it coming. He looked the man over. His heavy face was flushed with good living, eyes peculiarly direct of stare as if he was trying to keep them from roving suspiciously by force of will. He was well dressed, and his heavy hands twinkled with several rather large diamonds. The man went on: "I can give you the information you want—for a price, of course." He nodded toward an exit. "Too public in here, though."

Gene grinned without mirth as he thought, move over Whiting—here I come, and followed the man toward the door.

Outside the man waited, and Gene moved up close.

"You see, it's this way...."

Something exploded against Gene's skull. Even as fiery darkness closed down he knew he'd found the way. But only a stupid newspaperman would take it. Damn Carter!

Gene went out.

He seemed to be dreaming. Over him bent a repulsive, man-like face. But the man had fingernails growing on his chin where his whiskers should have been. And his eyes were funny—walled, as though he bordered on idiocy. In the dream, Gene felt himself strapped into a hammock. Then something pulled at him and made a terrible racket for a long time. Then it got very quiet except for a throbbing in his head. He went back to sleep.

She had on a starched white outfit, but it wasn't a nurse's uniform. There wasn't much skirt, and what there was of it was only the back part. The neckline plunged to the waist and stopped there. It was a peculiar outfit for a nurse to be wearing. But it looked familiar.

Her soft hands fixed something over his eyes, something cold and wet. He felt grateful, but kept on trying to remember. Ah, he had it; the girls wore that kind of outfit in the Blue Moon in one of the skits they did, burlesquing a hospital. He took off the wet cloth and looked again.

She was a dream. Even with her lips rouge-scarlet, her cheeks pink with makeup, her eyes heavy with artifice.

"What gives, beautiful?" He was surprised at the weakness of his voice.

Her voice was hard, but nice, and it was bitter, as though she wanted hard people to know she knew the score, could be just a little harder. "You're a spaceman now! Didn't you know?"

Gene grinned weakly. "I don't know a star from a street light. Nobody gets on the space crews these days—it's a closed union."

Her laugh was full of a knowledge denied him. "That's what I used to think!"

She began to unstrap him from the hammock. Then she pushed back his hair, prodded at the purple knob on his head with careful fingertips.

"How come you're on this ship?" asked Gene, wincing but letting her fingers explore.

"Shanghaied, same as you. I'm from the Blue Moon. I stepped out between acts for a breath of fresh air, and wham, a sack over the head and here I am. They thought you might have a cracked skull. One of the monsters told me to check you. No doctor on the ship."

Gene groaned. "Then I didn't dream it—there is a guy on this ship with fingernails instead of a beard on his chin!"

She nodded. "You haven't seen anything yet!"

"Why are we here?"

"You've been shanghaied to work the ship, I'm here for a different purpose—these men can't get off the ship and they've got to be kept contented. We've got ourselves pleasant jobs, with monsters for playmates, and we can't get fired. It'll be the rottenest time of our lives, and the rest of our lives, as far as I can see."

Gene sank down, put the compress back on his bump. "I don't get it."

"You will. I'm not absolutely sure I'm right, but I know a little more about it than you."

"What's your name?"

"They call me Queenie Brant. A name that fits this business. My real name is Ann O'Donnell."

"Queenie's a horse's name—I'll call you Ann. Me, I'm Gene O'Neil."

"That makes us both Irish," she said. He lifted the compress and saw the first really natural smile on her face. It was a sweet smile, introspective, dewy, young.

"You were only a dancer." He said it flatly.

For a long instant she looked at him, "Thanks. You got inside the gate on that one."

"It's in your eyes. I'm glad to know you, Ann. And I'd like to know you better."

"You will. There'll be plenty of time; we're bound for Io."

"Where's Io?"

"One of Jupiter's moons, you Irish ignoramus. It has quite a colony around the mines. Also it has a strange race of people. But Ann O'Donnell is going to live there if she can get off this ship. I don't want fingernails growing on my chin."

O'Neil sat up. "I get it now! It's something about the atomic drive that changes the crew!"

"What else?"

Gene looked at Ann, let his eyes rove over her figure.

"Take a good look," she said bitterly. "Maybe it won't stay like this very long!"

"We've got to get off this ship!" said Gene hoarsely.

The door of the stateroom opened. A sharp-nosed face peered in, followed by a misshapen body of a man in a dirty blue uniform. Hair grew thick all around his neck and clear up to his ears. It also covered the skin from chin to shirt opening. The hair bristled, coarse as an animal's. His voice was thick, his words hissing as though his tongue was too heavy to move properly.

"Captain wants you, O'Neil."

Gene got up, took a step. He went clear across the room, banged against the wall. The little man laughed.

"We're in space," Ann said. "We have a simulated gravity about a quarter normal. Here, let me put on your metal-soled slippers. They're magnetized to hold you to the floor." She bent and slipped the things on his feet, while Gene held his throbbing head.

The little man opened the door and went out. Gene followed, his feet slipping along awkwardly. After a minute his nausea lessened. At the end of the long steel corridor the little man knocked, then opened the door to a low rumble of command. He didn't enter, just stood aside for Gene. Gene walked in, stood staring.

The eyes in the face he saw were black pools of nothingness, without emotion, yet behind them an active mind was apparent. Gene realized this hairy thing was the Captain—even though he didn't even wear a shirt!

"You've shanghaied me," said Gene. "I don't like it."

The voice was huge and cold, like wind from an ice field. "None of us like it, chum. But the ships have got to sail. You're one of us now, because we're on our way and by the time you get there, there'll be no place left for you to work, unless it's in a circus as a freak."

"I didn't ask for it," said Gene.

"You did. You wanted to know too much about the crew—and if you found out, you'd spread it. You see, the drives are not what they were cooked up to be—the atomics leak, and it wasn't found out until too late. After they learned, they hid the truth, because the cargo we bring is worth millions. All the shielding they've used so far only seems to make it worse. But that won't stop the ships—they'll get crews the way they got you, and nosey people will find out more than they bargain for."

"I won't take it sitting down!" said Gene angrily.

The Captain ignored him. "Start saying sir. It's etiquette aboard ship to say sir to the Captain."

"I'll never say sir to anyone who got me into this...."

The Captain knocked him down.

Gene had plenty of time to block the blow. He had put up his arms, but the big fist went right through and crashed against his chin. Gene sat down hard, staring up at the hairy thing that had once been a man. He suddenly realized the Captain was standing there waiting for an excuse to kill him.

Through split and bleeding lips, while his stomach turned over and his head seemed on the point of bursting, Gene said: "Yes, sir!"

The Captain turned his back, sat down again. He shoved aside a mass of worn charts, battered instruments, cigar butts, ashtrays with statuettes of naked girls in a half-dozen startling poses, comic books, illustrated magazines with sexy pictures, and made a space on the top. He thrust forward a sheet of paper. He picked up a fountain pen, flirted it so that ink spattered the tangle of junk on his desk, then handed it to Gene. "Sign on the dotted line."

Gene picked up the document. It was an ordinary kind of form, an application for employment as a spacehand, third class. The ship was not named, but merely called a cargo boat. This was the paper the Company needed to keep the investigators satisfied that no one was forced to work on the ships against their will. Anger blinded him. He didn't take the pen. He just stood looking at the Captain and wondering how to keep himself from being beaten to death.

After a long moment of silence the Captain laid the pen down, grinned horribly. He gave a snort. "It's just a formality. I'm supposed to turn these things over to the authorities, but they never bother us anymore. Sign it later, after you've learned. You'll be glad to sign, then."

"What's my job, Captain?"

"Captain Jorgens, and don't forget the sir!"

"Captain Jorgens, sir."

"I'll put you with the Chief Engineer. He'll find work for you down in the pile room."

The Captain laughed a nasty laugh, repeating the last phrase with relish. "The pile room! There's a place for you, Mr. O'Neil. When you decide to sign your papers, we'll get you a job in some other part of this can!"

Gene found his way back to the cabin he had just left. The little guy with the hairy neck was there, leering at the girl.

"Put you in the pile gang didn't he?"

Gene nodded, sat down wearily. "I want to sleep," he said.

"Nuts," said the little man. "I'm here to take you to the Chief Engineer. You go on duty in half an hour. Come on!"

Gene got up. He was too sick to argue. Ann looked at him sympathetically, noting his split lips. He managed a grin at her, "If I never see you again, Ann, it's been nice knowing you, very nice."

"I'll see you, Gene. They'll find us tougher than they bargained for."

The engine room looked like some of the atomic power stations he'd seen. Only smaller. There was no heavy concrete shielding, no lead walls. There was shielding around the central pile, and Gene knew that inside it was the hell of atomic chain reaction under the control of the big levers that moved the cadmium bars. There was a steam turbine at one end, and a huge boiler at the other. Gene didn't even try to guess how the pile activated the jets that drove the space ship. Somehow it "burned" the water.

This pile had been illegal from the first. Obviously some official had been bribed to permit the first use of it on a spaceship. Certainly no one who knew anything about the subject would have allowed human beings to work around a thing like this.

Gene's skin crawled and prickled with the energies that saturated the room. Little sparks leaped here and there, off his fingertips, off his nose.

The Chief Engineer was on a metal platform above the machinery level. The face had hair all over it, even on the eyelids. The eyes, popping weirdly, were double. They looked as if second eyes had started growing inside the original ones. They weren't reasonable; they weren't even sane. The look of them made Gene sick.

The Engineer shook his head back and forth to focus the awful, mutilated eyes. His voice was infinitely weary, strangely muffled. "Another sacrifice to Moloch, an's the pity! So they put you down here, as if there was anything to be done? Well, it'll be nice to work with someone who still has his buttons—as long as they last. Sit down."

Gene sat down and the metal chair gave him a shock that made him jump. "I don't know anything about this kind of work."

The man shrugged, "Who does? The pile runs itself. Ain't enough of it moves to need much greasing. You ought to be able to find the grease cups—they're painted red. Fill them, wipe off the dust, and wait. Then do it over again."

"What's the score on this bucket?"

"We're all signed on with a billy to the knob. And kept aboard by a guard system that's pretty near perfect. After awhile the emanations get to our brains and we don't care anymore. Then we're trusted employees. Only reason I don't blow her loose, it wouldn't do any good."

He got up, a fragile old body clad in dirty overalls. He beckoned Gene to follow him. He led the way to a periscope arrangement over the shielded pile. Gene peered in. It was like a look into boiling Hell. As Gene stared, the old man talked in his ear.

"Supposed to be perfectly shielded, and maybe they are. But something gets out. I think it happens in the jet assembly. A tiny trickle of high pressure steam crosses the atomic beam just above a pinhole that leads into the jet tube. It's exploded by the beam, exploded into God knows what, and the result is your jet. It's a wonderful drive, with plenty of power for the purpose. But I think it forms a strong field of static over the whole shell of the ship, a kind of sphere of reflection that throws the emanations back into the ship from every point. Just my theory, but it explains why you get these physical changes, because that process of reflection gives a different ray than was observed in the ordinary shielded jet."

Gene nodded, asked: "Can I look at the jet assembly?"

"Ain't no way to look at it! It's sealed up to hold in the expanding gases from that exploded steam. Looking in this periscope is what changed my eyes. Only other place the unshielded emanations could escape is from the jet chamber. Only way they can get back into the ship is by reflection from some ionized layer around the ship. If I could talk to some of those big-brained birds that developed this drive, I'd sure have things to say."

Gene was convinced the old man knew what he was talking about. "Why don't you try to put your information where it'll do some good? How about the Captain?"

"He's coocoo." The old man slapped the cover back on the periscope, tottered back to his perch on the platform. "He sure has changed the last two years. Won't listen to reason."

Gene squatted on the steps, just beneath the old engineer's chair. The old man seemed glad to have someone to talk to.

"It's got us trapped. And it's so well covered up from the people. Old spacers are changed physically, changed mentally. They know they can't go back to normal life, because it's gone too far. They'd be freaks. No woman would want a monstrosity around. Besides, it don't stop, even after you leave the ships. God knows what we'll look like in the end."

Gene shivered. "But you're all grown men! A fight with no chance of winning is better than this! Why do you take it?"

"Because the mind changes along with the body. It goes dead in some ways, gets more active in others. The personality shifts inside, until you're not sure of yourself, and can't make decisions any more. That's why nobody does anything. Something about those rays destroys the will. Nobody leaves the ships."

"I will!" Gene said confidently. "When the time comes, I'll go. All Hell can't stop me."

The old man yawned. "Hope you do, son. Hope you do. I'm going to take me a nap." He propped his feet up on the platform rail and in seconds was snoring.

Gene clenched his fists, growing despair in his thoughts.

"Tain't no worse than dying in a war," muttered the old man in his sleep.

The days went by and Gene learned. He understood why these men didn't actively resent the deal they were getting. No wonder the secrecy was so effective! The radiations deadened the mind, gave one the feeling of numbness, so that nothing mattered but the next meal, the next movie in the recreation lounge, the next drink of water. Values changed and shifted, and none of them seemed important.

The chains that began to bind him were far stronger than steel. The chains were mental deterioration, degeneration, mutation within the very cells of the mind. He knew that now he must tend this monster forever, grease and wipe the ugly metal of it, and sit and talk idly to MacNamara, its keeper. He realized it, and didn't know how to care!

The anger and hate came later. The real, abiding anger, and the living hate. At first the numbness, the sudden incomprehensible enormity of what had happened to him, then the anger. Hate churned and ground away inside him, getting stronger by the hour. It all revolved around the Captain who tramped eternally around the corridors bellowing orders, punching with his huge fists. He knew there was more to it; the lying owners of the Company, the bribe-taking officials, the health officers who failed to examine the ships and the men and the ships' papers. But somehow it all boiled down to the Captain.

Sometimes he was sure he must be crazy already. Sometimes he would wake up screaming from a nightmare only to find reality more horrible.

Then he would go to Ann.

Ann was not the only woman aboard ship. There were three others, and to the crew of twenty imprisoned, enslaved men they represented all beauty, all womanhood. They lived with the men—as the men—and nobody cared. Here, so close to the raging elementals of the pile, life itself was elemental.

As one of them expressed it to Gene: "Why worry? We're all sterile from the radioactivity anyway. Or didn't you know?" She had been on the ship for years, and was covered with a fine fur, like a cat's. Her eyes were wide, placid, empty; an animal's unthinking eyes. Gene prayed Ann would never turn monster before his eyes; hoped desperately they could get away in time.

"We've got to fight, Ann," he said to her one day. "We must find a way to get off at the end of the trip, or it will be too late for us to live normal lives. It's then or never. Besides that, we've got to warn people of what's going on. They think space travel is safe. In time this could effect the whole race. The world must be told, so something can be done."

Ann's young face showed signs of the strain. The fear of turning into some hideous thing was preying on her mind. She spoke rapidly, her voice breaking a little. "I've been talking to several of the crew, the old-timers, trying to get an understanding of why nothing is done. It's this way: when the ships land, guards come aboard. They're posted at the cargo locks and the passenger entrances. The only door aboard the ship that leads to the passenger compartment is in the Captain's cabin, and it's locked from both sides. Even our Captain never meets the passengers. There's only one chance, a mutiny. Then we could open the door, show the passengers."

"It wouldn't do any good. When we landed, they'd find a way to shut us all up before we got to anybody. They've had a lot of practice keeping this quiet. They know the answers."

She stamped a foot angrily. "It was you who said we had to fight! Now you say it's hopeless!"

Gene leaned against the wall and passed a hand across his eyes. He looked at Ann's flushed beauty and managed a grin. "Guess I'm getting as bad as the rest of them, baby. We'll fight. Sure we'll fight."

It started with Schwenky. Schwenky was a gigantic Swede. He was the boss freight handler. It was his job to sort the cargo for the next port of call. He would get it into the cargo lock, then seal the doors so nobody would try to smuggle themselves out with the freight. Schwenky was intensely loyal and stupid enough not to understand the real reason behind their imprisonment—which was why he held his job. No one got by Schwenky.

But this time, in Marsport, something was missing. They'd driven the trucks up to the cargo port, unloaded everything, and then compared invoices with the material. They swore some claimed machinery parts were due them. Schwenky swore he'd placed them in the cargo lock, and that the truckers were trying to hold up the Company.

The Captain allowed the truckers claim and after the ship had blasted off into space, called Schwenky in to bawl him out. They must have gotten really steamed up, because Gene and Frank Maher heard the racket clear down on the next deck where they were cleaning freight out of a sealed compartment for the next stop.

Gene and Frank raced up the ladders to the top deck, and Gene found the break he had prayed for. Schwenky holding the Captain against the wall; beating the monstrosity that had once been a man with terrible fists. Gene felt a sudden thrill. In a situation like this you used any weapon you could find. Schwenky was a deadly weapon.

Gene laid a hand on Schwenky's massive shoulder. "Hold it man! You'll kill him!"

Schwenky turned a face, red and popeyed, to Gene. "The Captain make a mistake. He try to knock Schwenky down. No man do that to Schwenky."

"When he comes to, he'll lock you in the brig, put you on bread and water...."

Suddenly Schwenky realized the enormity of his offense. It was obvious from his face that he considered himself already dead. "Nah, my friend Gene! Now they kill Schwenky. Bad! But what I do?"

Gene eyed him carefully. "Put the Captain in the brig, of course. What else? Then he can't kill you."

"Lock him up, eh? Good idea! Then we think, you and I, what we do next. Maybe something come to us, eh?"

Gene bent over the Captain's body, found the pistol in his hip pocket, put it in his own. He took the ring of keys from the belt.

"Bring him along, Schwenky. If we meet anyone, I'll use this." Gene patted the gun. "I won't let them hurt my friend, Schwenky."

"Damn! let them come! I fix them! Don't have to shoot them. I got fists!"

"I'd rather be shot, myself," said Gene, watching the ease with which the giant freight handler lifted the huge body of the Captain, tossing it over his shoulder like a sack of straw.

"I'll go ahead," said Frank Maher. "If I run into Perkins, the First, I'll whistle once. If I run into Symonds, the Second, I'll whistle twice. I don't think there's another soul aboard we need worry about. All we got to do is slap the Cap in the brig, round up Perkins and Symonds, and the ship is ours. What worries me, Gene, then what do we do?"

"It's Schwenky's mutiny," grinned Gene. "Ask him."

"Nah!" said Schwenky hastily. "I don' know. Maybe we just sail on till we find good place, leave ship, go look for job."

Maher said, "Me with my lumpy face? And the Chief with hair on his cheekbones and double eyeballs? And Heinie with fingernails growing where his collar button should be? I wonder what we can do, if we get free?"

They got down the first stairwell, but passing along the rather lengthy companionway to the next stairhead, they heard Maher whistle twice. Schwenky put the Captain down, conked him with one massive fist to make sure he stayed out, then stood there, waiting. The Second came up out of the stairwell, turned and started toward them. Gene put his hand on the gun butt, waiting until he had to pull it. Schwenky said: "Come here, Mr. Perkins, sir. Look see what has happened!"

The Englishman peered at the shapeless, hairy mass of the unconscious Captain. His face went white. Gene knew he was wondering if he could keep the crew from mutiny without the Captain present to cow them. Perkins straightened, his face a pallid mask in the dimness. "What happened, Schwenky?"

"This, Mr. Perkins, sir—" said Schwenky. He slapped an open palm against the side of Perkins' head. Perkins sprawled full length on the steel deck, but he wasn't out, which surprised Gene. He lay there, staring up at the gigantic Swede, his face half red from the terrible blow, the other half white with the fear in him. His hand was tugging at his side and Gene realized he was after his gun. Gene pulled out his own weapon even as he leaped upon the slim body of the man on the floor. His feet missed the moving arm, the hand came out with a snub-nosed automatic in it. Gene grabbed it, bore down. But the gun went off, the bullet ricocheting off the wall-plates with a scream. Gene slugged the man across the head with the barrel of the Captain's gun. Perkins went limp. Maher came up now and grabbed Perkins' gun.

"Lead on," said Gene. He picked Perkins up and put him over his shoulder. Schwenky retrieved the slumbering Captain and they proceeded on their way to the cell on the bottom deck.

But the shot had been heard, and from above came the sound of running feet. Gene began to trot, almost fell down the last flight of stairs, went along the companionway at a run. At the cell door he dropped Perkins, tried four or five keys frantically. One fit. He pulled open the door and Schwenky drove in, kicking the body of Perkins over the sill. The Captain dropped heavily to the deck and Schwenky was out again. Gene was locking the door when he heard the shout from Symonds, running toward them.

"What's going on there, men?"

Schwenky started to amble toward the dark, wiry Second, his big face smiling like that of a simpleton. "We haf little trouble, Mr. Symonds, sir. Maybe we should call you, but we did not haf time. Everything is all right now. You come see, we explain everything...."

He made a grab for the little Second Mate's neck with one big paw. But the Second was wary, ducked quickly, was off. Gene and Maher sprang after him. Gene shouted: "Stop or I'll fire, Symonds! You're all alone now!"

Gene let one shot angle off the wall, close beside the fleeing form, but the man didn't stop. Instead he headed for the bridge. Gene realized he could lock himself in, keep them from the ship controls. He could hold out there the rest of the voyage.

"We've got to stop him!"

Maher close behind, they ran up the stairs on the Second's heels. Up the companionway they pounded, the Second increasing his lead. A door opened ahead of him and Ann O'Donnell appeared.

Symonds cursed and tried to pass her. Ann deftly slid out one pretty leg and the officer turned a somersault, and brought up against the wall at the foot of the stairs to the upper deck and the bridge.

But the Second was too frightened to let a little thing like a fall stop him. He went scrambling up the stairs on all fours. Gene was still too far away, and Ann moved like a streak of light. She sailed through the air in a long dancer's leap and with two bounds was up the stair, ahead of the scrambling, fear-stricken officer.

"Out of my way, bitch," and Symonds hurled himself toward Ann.

Gene leaped forward, but he needn't have bothered. Ann lifted one of her educated feet, caught the Second under the chin and he came down the stair like a sack of meal. Gene caught his full weight.

The two men fell in a scramble of flailing arms and legs, knocking the props out from under Maher, who had started out after them. Just how the mixup might have turned out they were not to know, for just then the vast weight of Schwenky descended upon the three and Maher let out a scream of anguish. But Gene and Symonds were on the bottom, too crushed by this tactic to make a sound.

It was minutes later when Gene came back to consciousness, finding his head resting in Ann O'Donnell's lap while her swift hands prodded him here and there, looking for broken bones.

"I'm dead for sure," groaned Gene.

"You've just had the wind knocked out of you. You'll be all right," and Ann let his head fall from her grasp with a thump. She stood up, a little abashed at the going over she'd been giving him.

"Where're my mutineers?" Gene asked.

"Went to lock Symonds with the others. What is going to happen now? I'm not sure I like this development, now it's happened."

"You should have thought of that before you tripped Symonds," said Gene. "But I'll admit there are problems. For instance, with all the officers in the brig, how can we be sure we can keep this atomic junk heap headed in the right direction?"

"What is the correct direction?" asked Ann, squatting down beside him.

"I don't know. We'll have to figure it out, then see if we can point her that way."

"Let's get up to the bridge," she said.

Schwenky and Maher found them brooding over the series of levers and buttons which comprised the control board. Schwenky noted their baffled frowns. His big face took on a worried look. "You fix!" he said. "You good fellow, Gene. We run ship, let officers go to hell. Yah!"

Maher scratched one patch of greying hair over his left eye. The rest of his skull was covered with brown bumps like fungus growths. "It's just possible we'll wreck the ship, let the air out of her or something, if we experiment," he warned.

"Go get MacNamara," said Gene. "He's been on the ship longer than any of us. Maybe he'll know."

He didn't. "All I know is grease cups," he reminded Gene.

Hours later eighteen men and four women gathered together in the recreation room to discuss a plan of action. Everyone had his or her ideas, but after an hour of wrangling, they got nowhere. Finally Gene held up a hand and shouted for silence.

"Let's decide who's boss, then follow orders," he said. "If I may be so bold, how about me?"

"Yah!" said Schwenky. "I do what you say. I like you!"

Old MacNamara grumbled to himself. "Do nothing, I say. We ought to stick to our duty, and save the lives of those who would have to take our places...." The unguarded pile had given MacNamara a martyr complex.

Maher looked over at him. "Your idea of sacrifice is all very fine, MacNamara. But we're not all anxious to die. You know what would happen now if we gave up!"

Gene spoke up again. "Let me summarize the position we're in—maybe then we can make a better decision."

"Go ahead," said Ann. The others nodded and fell silent, waiting.

Gene cleared his throat. "The way it looks to me, we've had a lucky accident in getting control of the ship. So far, we've not contacted the passengers. They know nothing of the change that's taken place. As it is, I see no point in contacting them. It might force us to face another mutiny, that of the passengers, who would regard us as what we are, mutineers, and when they found we weren't going to our destination, they'd certainly not all take it lying down. Point number one, then, is to ignore the passengers, keep the knowledge of a mutiny from them.

"Now, our real purpose in this mutiny is to expose this whole vicious secret slavery, tell Earth of the danger of the unshielded piles in space ships, destroy the Company's monopoly, and bring about new research which I'm sure would eventually overcome the difficulty. Just how are we going to do that? The answer is simple—we must get back to Earth, and we must get back in a way the Company will not be able to intercept us. As I understand it, this won't be easy. The Company is in complete control of space travel, and they have the ships to knock us out of space before we can get near Earth. Somehow we've got to win through. Can we do it by a direct return to Earth? I doubt it. However, say we do it. Then where do we go? The government might look upon us as mutineers and thus give the Company a chance to quash the whole affair.

"So we've got to go directly to the people, who, once they see us, and realize what space travel with these piles means, will demand an explanation with such public feeling even the government can't avoid a showdown. It's the secrecy we must break. Thus, we must land on Earth with the biggest possible splurge of publicity. We've got to do it so no Company ship can prevent it.

"Then there's this to consider. Most of you would find it a difficult thing to take up a life on Earth. I know that many of you want to take off for some remote world, and try to live out your lives by yourselves. I say that would be a cowardly thing to do. So, before we decide anything else, I say let's decide here and now that the only thing we will do is go back to Earth."

One of the most grotesquely deformed of the crew spoke up. "No woman would ever look at me," he said defiantly. "Children would stare at me and scream in terror. I've suffered enough. Why should I suffer more?"

The woman in the fine fur got to her feet and walked over to him. She sat down beside him and took his hand in hers. "I will look at you," she said. "When we get back to Earth, I will marry you and live with you—if you are brave enough to take me there."

For an instant the crewman stared at her out of his horribly bulging popeyes, then he swallowed hard and clutched her hand fiercely.

"The Devil himself will not keep me from it!" he said hoarsely.

Gene, staring at the man, felt a warm hand slip into his, and he turned to find Ann.

"I think that answers for all of us," she said.

The room rang with the shouts of approval.

Once more Gene began talking. "All right, then, I've a plan. First, we'll try to find out how to maneuver this craft. I believe we can persuade one of the Mates to show us the controls without much trouble."

"Yah!" interrupted Schwenky. "They show!"

"We'll set a course for Earth by the sun. We'll come in with the sun at our back, which means we'll have to make a wide circle off the traveled spacelanes, through unknown space, and come in from the direction of the inner planets, which are uninhabited and unvisited. Also, with the sun behind us, we won't be observed from Earth. Then, with all our speed, we'll come in, land at high noon in Chicago, right in front of the offices of the Sentinel, the newspaper for which I work."

There was a chorus of exclamations. Ann looked at him in amazement. "You, a newspaperman!" she gasped.

"Yes. I was sent out by my boss to find out what was behind the secrecy of the space ships. I got shanghaied as a crew member. Now, with your help, maybe I can complete my assignment. Once we get to my boss, the show will be over. He'll blast the story wide open."

"Wonderful!" shouted Maher. "Come, Schwenky! We will get Perkins and make him show us how to run the ship!"

Schwenky chortled in glee. "Yah! We get. By golly, I know that Gene O'Neill is good man! Maybe I get my picture in newspaper?"

Maher stared at him. "God forbid!" he said. "Unless it's in the comic section!"

"Yah!" agreed Schwenky. "In comic section!"

Two weeks later, as the ship crossed Earth's orbit and headed in behind the planet in the plane of the sun, the meteorite hit. It tore a great hole in the passenger side of the ship, and knocked out the port jets.

The ship veered crazily under the influence of its lopsided blast, and the crew was hurled against the wall and pinned there as the continuing involuntary maneuver built up acceleration.

Gene, who had been in his bunk, was pressed against the wall by a giant hand. Savagely he fought to adjust himself into a more bearable position, then tried to figure out what had happened. Obviously the ship was veering about, out of control.

"Meteorite!" he gasped. "We've been hit."

He pulled himself from the bunk, slid along the wall to the door. It was all he could do to open it, but once in the companionway outside, he found that he could crawl along one wall, off the floor, in an inching progress. He made it finally to the control room, and forced his body around the door jamb and inside. Against the far wall Maher was plastered, dazed, but conscious. At his feet lay Heinie, his head crushed, obviously dead.

"Cut off the rest of the jets!" gasped Maher. "I can't make it!"

Gene crawled slowly around the room, following the wall, until he could reach the controls, then he pulled the lever that controlled the jet blast. The ship's unnatural veering stopped instantly and both Maher and Gene dropped heavily to the floor.

Gene was up first and helped Maher to his feet. Together they turned to the indicators.

"Passenger deck's out!" said Maher. "Except for a few compartments. The automatic seals have operated. But there must be somebody left alive in them."

"We've got to get them," said Gene. "But first, we've got to check up on what damage has been done here, and how many casualties we have."

"Heinie's dead," said Maher. "He hit the wall with his head."

Gene shuddered, and deep in his stomach nausea churned. He thought of Ann and his blood froze in his veins. "You take below decks, I'll go up," he said. Ann's cabin was on the deck above.

Maher nodded and staggered away. Gene scrambled up the stairwell as fast as he could, and ran down the corridor. At Ann's door he stopped, turned the knob. The door opened. The room was empty.

Suddenly he heard running footsteps, and Ann threw herself into his arms, sobbing.

"Where were you?" he asked, almost savagely.

"I went to your cabin, to see if you were hurt. What happened to the ship?"

"Meteorite hit us. Knocked out the passenger deck. Most of the passengers will be dead, but we've got to go in and rescue the survivors."

Doors were opening here and there and the crew members able to make it were congregating around them. They went to the recreation room. There Gene counted noses. Five crewmen were missing. Of those present, six men were injured, and one woman exhibited a black eye, accentuating her other abnormalities. The three prisoners were reported unharmed.

"What about the missing men?" Gene asked.

"Three dead," Maher replied, "two badly hurt. We'll need somebody to look after them."

"I'll go," volunteered Ann. The woman in fur stepped forward also, and they left the room behind Maher and Schwenky.

Gene faced the rest. "We've got a real problem now. With a reduced crew, we'll have to finish a trip that would have been tough with an uninjured ship. But first, we've got to search the passenger deck and remove the survivors. All of you who are able, put on pressure suits and come with me."

He led the way to the locker containing the pressure suits. Seven men, those who were not too deformed to don the suits, made up the party. Gene led the way to the Captain's stateroom, ordered the door sealed behind them, then opened the only door to the damaged deck. The air rushed out as the door swung open, and suddenly complete silence descended upon them. There would be no more communication between them except for signs.

In an hour they had determined the truth. All passengers but one, a woman, had been killed instantly. The woman was unconscious, but suffering only from bruises. It had been necessary, after discovering her unpierced cabin, to return to the deck above and cut through with a torch.

When she regained consciousness and saw her rescuers, she screamed.

"That'll give us some idea of how the people back on Earth will receive us," said Gene. "If we get there, that is."

Later, in the control room, Maher and MacNamara gave their report.

"We can make it," said MacNamara, "but we'll come in limping like a wounded moose. If any of the Company ships sight us, we'll be a sitting duck. But maybe it will be better that way. This is like war, and some of us must die...." His voice trailed off in a mumble.

"Some of us are dying," said Maher. "But he's right, Gene; we can make it, with luck. We'll not be able to come in fast, nor land in the city, but we'll make it to Earth."

"That's enough," decided Gene. "If we can land near Chicago, I think I can manage the rest."

They turned to the controls, and MacNamara went back to his pile room. Once more the ship limped on, this time directly toward the ball of Earth, looming a scant twenty million miles away.

It took eight days to come within a million miles of their goal. Then tragedy struck again. The cabin on the passenger deck from which they had removed the sole survivor blew its door, and the air on the deck above rushed out through the hole they had burned into the cabin. It had been forgotten, and it meant the lives of three more crew members.

Then, as they prepared to bring the ship into the atmosphere, Maher, peering through the telescope, let out a shout. "Company ship, coming up fast! They're after us!"

Gene leaped to the telescope and peered through. Far to the left, a glowing silver streak in the sky, was the familiar shape of a space ship, growing larger by the minute. Studying it, Gene saw that it was an armed cruiser.

"They've got wise," said Maher. "I thought they would, when we didn't check in at Io. Probably radioed back to be on the lookout for us."

"Call MacNamara," said Gene. "We've got to see if he can set us down faster. Maybe there's some way to step up that pile."

Maher rushed off, and Ann came in. "What's up?" she asked.

"Cruiser after us," said Gene, his face grim. "Looks like we won't get to Chicago unless MacNamara has something up that old sleeve of his."

Ann went white, and together they waited for the old Engineer.

When he came in, Gene gestured to the telescope. "Take a look."

MacNamara squinted through the eyepiece with his double popeyes. "Don't see a thing," he grumbled.

"Well, it's a Company Cruiser, gunned to the limit. She's going to be near enough to shoot us down in about three hours."

"Three hours, you say?" MacNamara scratched his head. "How near we to Earth?"

"Half a million miles."

"You could make it in the lifeboat."

Gene snorted. "That Cruiser'd shoot down the lifeboat as easy as it will the ship—a lot easier."

"If they can catch you," said MacNamara. "Some of us must die, that the rest may live."

"Don't start that again, Mac," said Maher impatiently. "What we want to know is whether you can soup up that pile so we can beat that Cruiser down to Earth?"

"Not a thing I can do," said the Chief Engineer. "We've only one set of tubes. Full power would shoot us all over the sky. But I can do something as good."

"What?"

The old Engineer considered them through his double eyes. "The rest of you'll take the lifeboat and make for Earth. I'll remain here on the ship and shield your flight. I'm sure I can hide the little boat for awhile, and then, even with one jet, I think I can delay the cruiser until you get away. Someone's got to make a sacrifice. I'm old, and I didn't want any of this to begin with."

Maher gasped. "Mac, you old fool. D'ya mind if I apologize for what I just said? But you're right, that's a possible answer. Only I'll be the one to stay."

"Do you know how to adjust the pile and the jets to make a weapon out of them?" asked MacNamara.

"No ..." began Maher.

MacNamara grinned, "Nor am I going to tell you! So, you see, you can't be the one to stay."

Maher gripped the old man's hand and pumped it. "You win," he said. "You old ... crackpot!" There was real affection in his voice.

"Then be off with you," said the Chief Engineer. "You've not a minute to lose. Every man jack of you into the boat, including the Captain and the Mates. I'll not have my ship cluttered up with extra hands that might cramp my style...." And turning, the old man made his way back to the pile room, mumbling to himself.

Eyes wet, Gene gave the orders to abandon ship, and within thirty minutes every living soul was aboard the lifeboat.

MacNamara had finished his work with the pile and was back in the control room, waiting for the lifeboat to cast off. As it did so, he waved, then turned to the controls.

As the lifeboat darted away on its chemical jet engines, they could see the old man maneuvering the big ship so as to keep it ever between them and the Cruiser. An hour later when they were within a hundred thousand miles of Earth, MacNamara sent up a flare denoting surrender.

Tensely they watched the distant speck of light that was the ship with MacNamara on it. Then, around its side came the Company Cruiser, steering in toward it to make the capture. It was scarcely a thousand miles from the disabled ship. Gradually it drew closer, then edged in. Now it was only a few miles away, and at this distance, both specks seemed to merge.

"They got him!" Maher said.

"Yah!" Schwenky boomed, disappointment in his voice. "Me, I should have been the one to stay. I would slap them."

Suddenly, out in space, a bright flower grew. A flower of incandescent light that blossomed with terrifying rapidity, until it seemed to engulf all space in the area of the two ships. The familiar sphere of brilliance that marked an exploding atom bomb hung there in the heavens an instant, then it was gone. In its place was only a vast cloud of smoke, the dust and scattered atoms that were all that remained of two gigantic space ships.

"He detonated the pile!" said Gene, "He turned himself into an atom bomb!"

"Yah!" said Schwenky, his voice strangely muted. "Yah!" Awkwardly he turned and patted Ann's head as she began to sob.

"Is it not handsome?" asked Schwenky proudly, holding the front page of the newspaper up for all to see. "I have my picture in the paper! Is it not nice?"

Laughing, Ann kissed the big Swede right on the lips, and hugged him, paper and all. "It's beautiful, you big lug!" she said. "The handsomest picture I've ever seen in any paper."

"Nah!" denied Schwenky. "It is not the handsomest. All of us have our pictures in the paper. We are all very good looking! Not only Schwenky. Is it not so, Gene, my friend?"

Gene grinned at him, and at the others. Maher pounded him on the back, and over the uproar came the voice of the editor of the Sentinel. "Telephone for Mr. Schwenky!"

Schwenky looked dazed, cocked his big ears at the editor. "For Schwenky?" he asked stupidly. "Telephone? Who would call Schwenky on the telephone?"

"How do I know?" said the editor. "It's some lady...." He thrust the phone into the big Swede's hand.

"Lady?" said Schwenky wonderingly. "Hello ... lady ..." he spoke into the receiver, his booming voice making it rattle.

"The other ..." began Gene, then desisted. "Never mind, she'll hear you...."

"What? You want to marry me? Lady...." Schwenky's eyes bulged even more, and he roared into the transmitter. "Lady! You wait! I come!" He thrust the phone into the editor's hands and made for the door like a lumbering bull.

"Where you going?" yelled Gene.

Schwenky halted, turned with a big grin, "I go to marry lady. She asked me to become my wife!"

"Where is she?" asked Gene. "Where are you going to meet her?"

Schwenky looked stupidly at the now silent phone. "By golly! I forget to ask her!" There was tragedy in his voice. "Now I never find her!"

The editor laughed. "Never mind—you'll get a hundred more proposals before the day's over. You can take your pick!"

Schwenky's eyes opened wide. Then he grinned again. "Yah!" he roared. "I take my pick! She will be so beautiful! Yah!"

The chatter of the teletype interrupted him, and the editor turned to watch the tape as it came from the machine. Then he began to read:

"Washington. April 23. President Walworth has grounded all spaceships and ordered all those enroute to proceed to the nearest port. A Congressional committee has been picked, including top members of the cabinet, to investigate the ships, the atomic drives, and the system of secret slavery among crews. In a statement to the Press, President Walworth said that space travel will not be resumed until proper shields are developed. But he added that he had been informed by leading physicists that the problem can be solved within a year if sufficient funds were available. Said the President: 'I will see that the funds are made available!'"

The editor dropped the tape and turned to Gene. "I have one more bit of information, this one direct from the President by phone. He has asked me to inform you that he has appointed you new head of FAST."

"FAST?" asked Gene. "What's that?"

"Federal Agency for Space Travel," grinned the editor. "And congratulations. I hate to lose a good reporter, but maybe you'll be back after you finish in Washington—at a substantial increase in salary."

Gene grinned back. "Maybe I will," he said. "And I'll need the money." He put an arm around Ann and drew her to him. "Two can't live as cheap as one, you know."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Hell Ship, by Raymond Alfred Palmer

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HELL SHIP ***

***** This file should be named 32615-h.htm or 32615-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/2/6/1/32615/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

[email protected]. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.