The Project Gutenberg EBook of Reminiscences, 1819-1899, by Julia Ward Howe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Reminiscences, 1819-1899 Author: Julia Ward Howe Release Date: May 30, 2010 [EBook #32603] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMINISCENCES, 1819-1899 *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Julia Ward Howe.

FROM SUNSET RIDGE: Poems Old and New. 12mo, $1.50.

REMINISCENCES. With many Portraits and other Illustrations. Crown 8vo, $2.50.

IS POLITE SOCIETY POLITE? and other Essays. With a Portrait of Mrs. Howe. Square 8vo, $1.50.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

Boston and New York.

BY

JULIA WARD HOWE

WITH PORTRAITS AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1899

COPYRIGHT, 1899, BY JULIA WARD HOWE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| I. Birth, Parentage, Childhood | 1 |

| II. Literary New York | 21 |

| III. New York Society | 29 |

| IV. Home Life: My Father | 43 |

| V. My Studies | 56 |

| VI. Samuel Ward and the Astors | 64 |

| VII. Marriage: Tour in Europe | 81 |

| VIII. First Years in Boston | 144 |

| IX. Second Visit to Europe | 188 |

| X. A Chapter about Myself | 205 |

| XI. Anti-Slavery Attitude: Literary Work: Trip to Cuba | 218 |

| XII. The Church of the Disciples: in War Time | 244 |

| XIII. The Boston Radical Club: Dr. F. H. Hedge | 281 |

| XIV. Men and Movements in the Sixties | 304 |

| XV. A Woman's Peace Crusade | 327 |

| XVI. Visits to Santo Domingo | 345 |

| XVII. The Woman Suffrage Movement | 372 |

| XVIII. Certain Clubs | 400 |

| XIX. Another European Trip | 410 |

| XX. Friends and Worthies: Social Successes | 428 |

| PAGE | |

| Julia Ward Howe From a photograph by Hardy, 1897. | Frontispiece |

| Sarah Mitchell, Niece of General Francis Marion and Grandmother of Mrs. Howe From a painting by Waldo and Jewett. | 4 |

| Julia Ward and her Brothers, Samuel and Henry From a miniature by Anne Hall. | 8 |

| Julia Cutler Ward, Mother of Mrs. Howe From a miniature by Anne Hall. | 12 |

| Samuel Ward, Father of Mrs. Howe From a miniature by Anne Hall. | 46 |

| Samuel Ward, Jr From a painting by Baron Vogel. | 68 |

| Florence Nightingale From a photograph. | 138 |

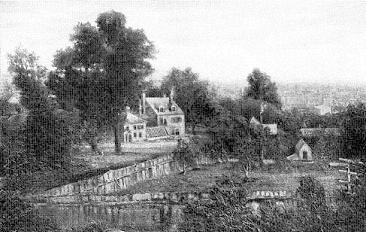

| The South Boston Home of Mr. and Mrs. Howe From a painting in the possession of M. Anagnos. | 152 |

| Wendell Phillips, at the Age of 48 From a photograph lent by Francis J. Garrison, Boston. | 158 |

| Theodore Parker From a photograph by J. J. Hawes. | 166 |

| Julia Ward Howe From a painting (1847) by Joseph Ames. | 176 |

| Samuel Gridley Howe, M. D. From a photograph by Black, about 1859. | 230 |

| James Freeman Clarke From a photograph by the Notman Photographic Company. | 246 |

| John Brown From a photograph (about 1857) lent by Francis J. Garrison, Boston. | 254 |

| John A. Andrew From a photograph by Black. | 262 |

| Julia Ward Howe From a photograph by J. J. Hawes, about 1861. | 270 |

| Facsimile of the First Draft of the Battle Hymn of the Republic From the original MS. in the possession of Mrs. E. P. Whipple, Boston. | 276 |

| Ralph Waldo Emerson From a photograph by Black. | 292 |

| Frederic Henry Hedge, D. D. From a photograph lent by his daughter, Charlotte A. Hedge. | 302 |

| Samuel Gridley Howe, M. D. From a photograph by A. Marshall (1870), in the possession of the Massachusetts Club. | 328 |

| Lucy Stone From a photograph by the Notman Photographic Company. | 376 |

| Maria Mitchell From a photograph. | 386 |

| The Newport Home of Mr. and Mrs. Howe From a photograph by Briskham and Davidson. | 406 |

| Thomas Gold Appleton From a photograph lent by Mrs. John Murray Forbes. | 432 |

| Julia Romana Anagnos From a photograph. | 440 |

I have been urgently asked to put together my reminiscences. I could wish that I had begun to do so at an earlier period of my life, because at this time of writing the lines of the past are somewhat confused in my memory. Yet, with God's help, I shall endeavor to do justice to the individuals whom I have known, and to the events of which I have had some personal knowledge.

Let me say at the very beginning that I esteem this century, now near its close, to have eminently deserved a record among those which have been great landmarks in human history. It has seen the culmination of prophecies, the birth of new hopes, and a marvelous multiplication both of the ideas which promote human happiness and of the resources which enable man to make himself master of the world. Napoleon is said to have forbidden his subordinates to tell him that any order of his was impossible of fulfillment. One might [p. 2]think that the genius of this age must have uttered a like injunction. To attain instantaneous communication with our friends across oceans and through every continent; to command locomotion whose swiftness changes the relations of space and time; to steal from Nature her deepest secrets, and to make disease itself the minister of cure; to compel the sun to keep for us the record of scenes and faces, of the great shows and pageants of time, of the perishable forms whose charm and beauty deserve to remain in the world's possession,—these are some of the achievements of our nineteenth century. Even more wonderful than these may we esteem the moral progress of the race; the decline of political and religious enmities, the growth of good-will and mutual understanding between nations, the waning of popular superstition, the spread of civic ideas, the recognition of the mutual obligations of classes, the advancement of woman to dignity in the household and efficiency in the state. All this our century has seen and approved. To the ages following it will hand on an inestimable legacy, an imperishable record.

While my heart exults at these grandeurs of which I have seen and known something, my contribution to their history can be but of fragmentary and fitful interest. On the world's great scene, each of us can only play his little part, often [p. 3]with poor comprehension of the mighty drama which is going on around him. If any one of us undertakes to set this down, he should do it with the utmost truth and simplicity; not as if Seneca or Tacitus or St. Paul were speaking, but as he himself, plain Hodge or Dominie or Mrs. Grundy, is moved to speak. He should not borrow from others the sentiments which he ought to have entertained, but relate truthfully how matters appeared to him, as they and he went on. Thus much I can promise to do in these pages, and no more.

I was born on May 27, 1819, in the city of New York, in Marketfield Street, near the Battery. My father was of Rhode Island birth and descent. One of his grandmothers was the beautiful Catharine Ray to whom are addressed some of Benjamin Franklin's published letters. His father attained the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the war of the Revolution, being himself the son of Governor Samuel Ward, of Rhode Island,[1] married [p. 4]to a daughter of Governor Greene, of the same state. My mother was grandniece to General Francis Marion, of Huguenot descent, known in the Revolution as the Swamp-fox of southern campaigns. Her father was Benjamin Clarke Cutler, whose first ancestor in this country was John De Mesmekir, of Holland.

Let me here remark that an expert in chiromancy, after making a recent examination of my hand, exclaimed, "You inherit military blood; your hand shows it."

My own earliest recollections are of a fine house on the Bowling Green, a region of high fashion in those days. In the summer mornings my nurse sometimes walked abroad with me, and showed me the young girls of our neighborhood, engaged with their skipping ropes. Our favorite resort was the Battery, where the flagstaff used in the Revolution was still to be seen. The fort at Castle Garden had already been converted into a pleasure resort, where fireworks and ices might be enjoyed.

We were six children in all, yet Wordsworth's little maid would have reckoned us as seven, as a sister of four years had died shortly before my birth, leaving me her name and the dignity of eldest daughter. She was always mentioned in the family as the first little Julia.

[p. 5] My two eldest brothers, Samuel and Henry Ward, were pupils at Round Hill School. The third, Francis Marion, named for the General, was my junior by fifteen months, and continued to be my constant playmate until, at the proper age, he joined the others at Round Hill School.

A few words regarding my mother may not here be out of place. Married at sixteen, she died at the age of twenty-seven, so beloved and mourned by all who knew her that my early years were full of the testimony borne by surviving friends to the beauty and charm of her character. She had been a pupil at the school of Mrs. Elizabeth Graham, of saintly memory, and had inherited from her own mother a taste for intellectual pursuits. She was especially fond of poetry and a few lovely poems of hers remain to show that she was no stranger to its sacred domain. One of these was printed in a periodical of her own time, and is preserved in Griswold's "Female Poets of America." Another set of verses is addressed to me in the days of my babyhood. All of these bear the imprint of her deeply religious character.

Mrs. Margaret Armstrong Astor, of whom more will be said in these annals, remembered my mother as prominent in the society of her youth, and spoke of her as beautiful in countenance. An old lady, resident in Bordentown, N. J., where Joseph, ex-king of Spain, made his home for many years, had seen my mother arrayed for a dinner at this [p. 6] royal residence, in a white dress, probably of embroidered cambric, and a lilac turban. Her early death was a lifelong misfortune to her children, who, although tenderly bred and carefully watched, have been forced to pass their days without the dear refuge of a mother's heart, the wise guidance of a mother's inspiration.

A dear old cousin of my father's, who lived to the age of one hundred and two years, loved to talk of a visit which she had made in her youth to my grandfather Ward, then resident in New York. She had not quite forgiven him for not allowing her to attend an assembly on which, being only sixteen years of age, she had set her heart. Years after this time, when such vanities had quite gone out of her mind, she again visited relatives in the city, and came to spend the day with my mother. Of this occasion she said to me: "Julia, your mother's tact was remarkable, and she showed it on that day, for, knowing me to be a young woman of serious character, she presented me on my arrival with a plain linen collar which she had made for me. On a table beside her lay Law's 'Serious Call to the Unconverted.' Don't you see how well she had suited matters to my taste?"

This aged relative used to boast that she had never read a novel. She desired to make one exception in favor of the story of the Schönberg-Cotta [p. 7]family, but, hearing that it was a work of fiction, esteemed it safest to adhere to the rule which she had observed for so many years.

Her son, lately deceased, once told me that when she felt called upon to chastise him for some childish offense, she would pray over him so long that he would cry out: "Mother, it's time to begin whipping."

Her husband was a son of General Nathanael Greene, of Revolutionary fame.

The attention bestowed upon impressions of childhood to-day will, I hope, justify me in recording some of the earliest points in consciousness which I still recall. I remember when a thimble was first given to me, some simple bit of work being at the same time placed in my hand. Some one said, "Take the needle in this hand." I did so, and, placing the thimble on a finger of the other hand, I began to sew without its aid, to the amusement of my teacher. This trifle appears to me an early indication of a want of perception as to the use of tools which has accompanied me through life. I remember also that, being told that I must ask pardon for some childish fault, I said to my mother, with perfect contentment, "Oh yes, I pardon you," and was surprised to hear that in this way I had not made the amende honorable.

I encountered great difficulty in acquiring the [p. 8]th sound, when my mother tried to teach me to call her by that name. "Muzzer, muzzer," was all that I could manage to say. But the dear parent presently said, "If you cannot do better than that, you will have to go back and call me mamma." The shame of going back moved me to one last effort, and, summoning my utmost strength of tongue, I succeeded in saying "mother," an achievement from which I was never obliged to recede.

A journey up the Hudson River was undertaken, when I was very young, for the bettering of my mother's health. An older sister of hers went with us, as well as a favorite waiting-woman, and a young physician whose care had saved my father's life a year or more before my own birth. After reaching Albany, we traveled in my father's carriage; the grown persons occupying the seats, and I sitting in my little chair at their feet. A book of short tales and poems was often resorted to for my amusement, and I still remember how the young doctor read to me, "Pity the sorrows of a poor old man," and how my tears came, and could not be hidden.

The sight of Niagara caused me much surprise. Playing on the piazza of the hotel, one day, with only the doctor for my companion, I ventured to ask him, "Who made that great hole where the water comes down?" He replied, "The great [p. 9]Maker of all." "Who is that?" I innocently inquired; and he said, "Do you not know? Our Father who art in heaven." I felt that I ought to have known, and went away somewhat abashed.

Another day my mother told me that we were going to visit Red Jacket, a great Indian chief, and that I must be very polite to him. She gave me a twist of tobacco tied with a blue ribbon, which I was to present to him, and bade me observe the silver medal which I should see hung on his neck, and which, she said, had been given to him by General Washington. We drove to the Indian encampment, of which I dimly remember the extent and the wigwams. A tall figure advanced to the carriage. As its door was opened, I sprang forward, clasped my arms around the neck of the noble savage, and was astonished at his cool reception of such a greeting. I was surprised and grieved afterwards to learn that I had not done exactly the right thing. The Indians, in those days and long after, occupied numerous settlements in the western part of the State of New York, where one often saw the boys with their bows and arrows, and the squaws carrying their papooses on their backs.

The journey here mentioned must have taken place when I was little more than four years old. Another year and a half brought me the burden of a great sorrow. I recall months of sweet companionship [p. 10]with the first and dearest of friends, my mother. The last summer of her life was passed at a fine country-seat in Bloomingdale, which was then a picturesque country place, about six miles from New York, but is now incorporated in the city.

My father was fond of fine horses, and the pets of the stable played no unimportant part in our childish affection. The family coach was an early institution with us, and in the days of which I now speak, its exterior was of a delicate yellow, known as straw-color, while the lining and cushions were of bright blue cloth. This combination of color was effected to please my dear mother, who was accounted in her time a woman of excellent taste.

I remember this summer as a particularly happy period. My younger brother and I had our lessons in a lovely green bower. Our French teacher came out at intervals in the Bloomingdale stage. My mother often took me with her for a walk in the beautiful garden, from which she plucked flowers that she arranged with great taste. There was much mysterious embroidering of small caps and gowns, the purpose of which I little guessed. The autumn came, and with it our return to town. And then, one bitter morning, I awoke to hear the words, "Julia, your mother is dead." Before this my father had announced to us that a [p. 11] little sister had arrived. "And she can open and shut her eyes," he said, smiling.

His grief at the loss of my mother was so intense as to lay him prostrate with illness. He told me, years after this time, that he had welcomed the physical agony which perforce diverted his thoughts from the cause of his mental suffering. The little sister of whose coming he had told us so joyfully was for a long time kept from his sight. The rest of us were gathered around him, but this feeble little creature was not asked for. At last my dear old grandfather came to visit us, and learned the state of my father's feelings. The old gentleman went into the nursery, took the tiny infant from its nurse, and laid it in my father's arms. The little one thenceforth became the object of his most tender affection.

He regarded all his children with great solicitude, feeling, as he afterward said to one of us, that he must now be mother as well as father. My mother's last request had been that her unmarried sister, the same one who had accompanied us on the journey to Niagara, should be sent for to have charge of us, and this arrangement was speedily effected.

This aunt of ours had long been a care-taker in her mother's household, where she had had much to do with bringing up her younger sisters and brothers. My mother had been accustomed to [p. 12] borrow her from time to time, and my aunt had threatened to hang out a sign over the door with the inscription, "Cheering done here by the job, by E. Cutler." She was a person of rare honesty, entirely conscientious in character, possessed of few accomplishments, but endowed with the keenest sense of humor. She watched over our early years with incessant care. We little ones were kept much in our warm nursery. We were taken out for a drive in fine weather, but rarely went out on foot. As a consequence of this overcherishing, we were constantly liable to suffer from colds and sore throats. The young physician of whom I have already spoken became an inmate of our house soon after my mother's death. He was afterward well known in New York society as an excellent practitioner, and as a man of a certain genius. Those were the days of mighty doses, and the slightest indisposition was sure to call down upon us the administration of the drugs then in favor with the faculty, but now rarely used.

[p. 13] My father's affliction was such that a change of scene became necessary for him. The beautiful house at the Bowling Green was sold, with the new furniture which had been ordered expressly for my mother's pleasure, and which we never saw uncovered. We removed to Bond Street, which was then at the upper extremity of New York city. My father's friends said to him, "Mr. Ward, you are going out of town." And so indeed it seemed at that time. We occupied one of three white freestone houses, and saw from our windows the gradual building up of the street, which is now in the central part of New York. My father had purchased a large lot of land at the corner of our street and Broadway. On a part of this he subsequently erected a house which was considered one of the finest in the city.

My father was disposed to be extremely careful in the choice of our associates, and intended, no doubt, that we should receive our education at home. At a later day his plans were changed somewhat, and after some experience of governesses and masters I was at last sent to a school in the near neighborhood of our house. I was nine years old at this time, somewhat precocious for my age, and endowed with a good memory. This fact may have led to my being at once placed in a class of girls much older than myself, especially occupied with the study of Paley's "Moral Philosophy." I managed to commit many pages of this book to memory, in a rather listless and perfunctory manner. I was much more interested in the study of chemistry, although it was not illustrated by any experiments. The system of education followed at that time consisted largely in memorizing from the text-books then in use. Removing to another school, I had excellent instruction in [p. 14]penmanship, and enjoyed a course of lectures on history, aided by the best set of charts that I have ever seen, the work of Professor Bostwick. In geometry I made quite a brilliant beginning, but soon fell off from my first efforts. The study of languages was very congenial to me; I had been accustomed to speak French from my earliest years. To this I was enabled to add some knowledge of Latin, and afterward of Italian and German.

The routine of my school life was varied now and then by a concert and by Handel's oratorios, which were given at long intervals by an association whose title I cannot now recall. I eagerly anticipated, and yet dreaded, these occasions, for my enjoyment of them was succeeded by a reaction of intense melancholy.

The musical "stars" of those days are probably quite out of memory in these later times, but I remember some of them with pleasure. It is worth noticing that, while the earliest efforts in music in Boston produced the Handel and Haydn Society, and led to the occasional performance of a symphony of Beethoven or of Mozart, the taste of New York inclined more to operatic music. The brief visit of Garcia and his troupe had brought the best works of Rossini before the public. These performances were followed, at long intervals, by seasons of English opera, in which Mrs. [p. 15]Austin was the favorite prima donna. This lady sang also in oratorio, and I recall her rendering of the soprano solos in Handel's "Messiah" as somewhat mannered, but on the whole quite impressive.

A higher grade of talent came to us in the person of Mrs. Wood, famous before her marriage as Miss Paton. I heard great things of her performance in "La Sonnambula," which I was not allowed to see. I did hear her, however, at concerts and in oratorios, and I particularly remember her rendering of the famous soprano song, "To mighty kings he gave his acts." Her voice was beautiful in quality and of considerable extent. It possessed a liquid and fluent flexibility, quite unlike the curious staccato and tremolo effects so much in favor to-day.

My father's views of religious duty became much more stringent after my mother's death. I had been twice taken to the opera during the Garcia performances, when I was scarcely more than seven years of age, and had seen and heard the Diva Malibran, then known as Signorina Garcia, in the rôles of Cenerentola (Cinderella) and Rosina in the "Barbiere di Seviglia." Soon after this time the doors were shut, and I knew of theatrical matters only by hearsay. The religious people of that period had set their faces against the drama in every form. I remember the destruction by [p. 16]fire of the first Bowery Theatre, and how this was spoken of as a "judgment" upon the wickedness of the stage and of its patrons. A well-known theatre in Richmond, Va., took fire while a performance was going on, and the result was a deplorable loss of life. The pulpits of the time "improved" this event by sermons which reflected severely upon the frequenters of such places of amusement, and the "judgment" was long spoken of with holy horror.

My musical education, in spite of the limitations of opportunity just mentioned, was the best that the time could afford. I had my first lessons from a very irritable French artist, of whom I stood in such fear that I could remember nothing that he taught me. A second teacher, Mr. Boocock, had more patience, and soon brought me forward in my studies. He had been a pupil of Cramer, and his taste had been formed by hearing the best music in London, which then, as now, commanded all the great musical talent of Europe. He gave me lessons for many years, and I learned from him to appreciate the works of the great composers, Beethoven, Handel, and Mozart. When I grew old enough for the training of my voice, Mr. Boocock recommended to my father Signor Cardini, an aged Italian, who had been an intimate of the Garcia family, and was well acquainted with Garcia's admirable method. Under his care my [p. 17] voice improved in character and in compass, and the daily exercises in holding long notes gave strength to my lungs. I think that I have felt all my life through the benefit of those early lessons. Signor Cardini remembered Italy before the invasion of Napoleon I., and sometimes entertained me with stories of the escapades of his student life. He had resided long in London, and had known the Duke of Wellington. He related to me that once, when he was visiting the great soldier at his country-seat near the sea, the duke invited him to look through his telescope, saying, "Signor Cardini, venez voir comme on travaille les Français." This must have had reference to some manœuvre of the English fleet, I suppose. Mr. Boocock thought that it would be desirable for me to take part in concerted pieces, with other instruments. This exercise brought me great delight in the performance of certain trios and quartettes. The reaction from this pleasure, however, was very painful, and induced at times a visitation of morbid melancholy which threatened to affect my health.

While I greatly disapprove of the scope and suggestions presented by Count Tolstoï in his "Kreutzer Sonata," I yet think that, in the training of young persons, some regard should be had to the sensitiveness of youthful nerves, and to the overpowering response which they often make to [p. 18] the appeals of music. The dry practice of a single instrument and the simple drill of choral exercises will not be apt to overstimulate the currents of nerve force. On the other hand, the power and sweep of great orchestral performances, or even the suggestive charm of some beautiful voice, will sometimes so disturb the mental equilibrium of the hearer as to induce in him a listless melancholy, or, worse still, an unreasoning and unreasonable discontent.

The early years of my youth were passed in the seclusion not only of home life, but of a home most carefully and jealously guarded from all that might be represented in the orthodox trinity of evil, the world, the flesh, and the devil. My father had become deeply imbued with the religious ideas of the time. He dreaded for his children the dissipations of fashionable society, and even the risks of general intercourse with the unsanctified many. He early embraced the cause of temperance, and became president of the first temperance society formed in this country. As a result, wine was excluded from his table. This privation gave me no trouble, but my brothers felt it, especially the eldest, who had passed some years in Europe, where the use of wine was, as it still is, universal. I was walking with my father one evening when we met my two younger brothers, each with a cigar in his mouth. My father was [p. 19] much troubled, and said, "Boys, you must give this up, and I will give it up, too. From this time I forbid you to smoke, and I will join you in relinquishing the habit." I am afraid that this sacrifice on my father's part did not have the desired effect, but am quite certain that he never witnessed the infringement of his command.

At the time of which I speak, my father's family all lived in our immediate neighborhood. He had considerably distanced his brothers in fortune, and had built for himself the beautiful house of which I have already spoken. In the same street with us lived my music-loving uncle, Henry, somewhat given to good cheer, and of a genial disposition. In a house nearer to us resided my grandfather, Samuel Ward, with an unmarried daughter and three bachelor sons, John, Richard, and William. The outings of my young girlhood were confined to this family circle. I went to school, indeed, but never to dancing-school, a sober little dancing-master giving us lessons at home. I used to hear, with some envy, of Monsieur Charnaud's classes and of his "publics," where my schoolfellows disported themselves in their best clothes. My grandfather was a stately old gentleman, a good deal more than six feet in height, very mild in manner, and fond of a game of whist. With us children he used to play a very simple game called "Tom, come tickle me." [p. 20] Cards were not allowed in my father's house, and my brothers used to resort to the grand-paternal mansion when they desired this diversion.

The eldest of my father's unmarried brothers was my uncle John, a man more tolerant than my father, and full of kindly forethought for his nieces and nephews. In his youth he had sustained an injury which deprived him of speech for more than a year. His friends feared that he would never speak again, but his mother, trying one day to render him some small assistance, did not succeed to her mind, and said, "I am a poor, awkward old woman." "No, you are not!" he exclaimed, and at once recovered his power of speech. He was anxious that his nieces should be well instructed in practical matters, and perhaps he grudged a little the extra time which we were accustomed to devote to books and music. He was fond of sending materials for dresses to me and my sisters, but insisted that we should make them up for ourselves. This we managed to do, with a good deal of help from the family seamstress. When I had published my first literary venture, uncle John showed me in a newspaper a favorable notice of my work, saying, "This is my little girl who knows about books, and writes an article and has it printed, but I wish that she knew more about housekeeping,"—a sentiment which in after years I had occasion to echo with fervor. [p. 21]

Although the New York of my youth had little claim to be recognized as a literary centre, it yet was a city whose tastes and manners were much influenced by people of culture. One of these, Robert Sands, was the author of a poem entitled "Yamoyden," its theme being an Indian story or legend. His family dated back to the Sands who once owned a considerable part of Block Island, and from whom Sands Point takes its name. If I do not mistake, these Sands were connected by marriage with one of my ancestors, who were also settlers in Block Island. I remember having seen the poet Sands in my childhood, a rather awkward, near-sighted man. His life was not a long one. A sister of his, Julia Sands, wrote a biographical sketch of her brother, and was spoken of as a literary woman.

William Cullen Bryant resided in New York many years. He took a prominent part in politics, but mingled little in general society, being much absorbed in his duties as editor of the "Evening Post," of which he was also the founder. [p. 22]

I first heard of Fitz-Greene Halleck as the author of various satirical pieces of verse relating to personages and events of nearly eighty years ago. He is now best remembered by his "Marco Bozzaris," a noble lyric which we have heard quoted in view of recent lamentable encounters between Greek and Barbarian.

Among the lecturers who visited New York, I remember Professor Silliman of Yale College, Dr. Follen, who spoke of German literature, George Combe, and Mr. Charles Lyell.

Charles King, for many years editor of a daily paper entitled "The New York American," was a man of much literary taste. He had been a pupil at Harrow when Byron was there. He was an appreciative friend of my father, although as convivial in his tastes as my father was the reverse. I remember that once, when a temperance meeting was going on in one of our large parlors, Mr. King called and, finding my father thus engaged, began to frolic with us young people. He even dared to say: "How I should like to open those folding doors just wide enough to fire off a bottle of champagne at those temperance folks!"

He was the patron of my early literary ventures, and kindly allowed my fugitive pieces to appear in his paper. He always advocated the abolition of slavery, and could never forgive Henry Clay his part in effecting the Missouri Compromise. [p. 23] He and his brother James, my father's junior partner, were sons of Rufus King, a man eminent in public life. I was a child of perhaps eight years when I heard my elders say with regret that "old Mr. King was dying."

Quite late in his life, Mr. Charles King became President of Columbia College. This institution, with the houses of its officers, occupied the greater part of Park Place. Its professors were well known in society. The college was very conservative in its management. The professor of mathematics was asked one day by one of his class whether the sun did not really stand still in answer to the prayer of Joshua. He laughed at the question, and was in consequence reprimanded by the faculty.

Professor Anthon, of the college, became known through his school and college editions of many Latin classics. Professor Moore, in the department of Hellenics, was popular among the undergraduates, partly, it was said, on account of his very indulgent method of conducting examinations. Professor McVickar, in the chair of Philosophy, was one of the early admirers of Ruskin. The families of these gentlemen mingled a good deal in the society of the time, and contributed no doubt to impart to it a tone of polite culture. I should say that before the forties the sons of the best families of New York city were usually sent to [p. 24] Columbia College. My own brothers, three in number, were among its graduates. New York parents in those days looked upon Harvard as a Unitarian institution, and shunned its influence for their sons.

The venerable Lorenzo Da Ponte was for many years a resident of New York, and a teacher of the Italian language and literature. When Dominick Lynch introduced the first opera troupe to the New York public, sometime in the twenties, the audience must surely have comprised some of the old man's pupils, well versed in the language of the librettos. In earlier life, he had furnished the text of several of Mozart's operas, among them "Don Giovanni" and "Le Nozze di Figaro."

Dominick Lynch, whom I have just mentioned, was an enthusiastic lover of music. His visits to my father's house were occasions of delight to me. He was without a rival as an interpreter of ballads, and especially of the songs of Thomas Moore. His voice, though not powerful, was clear and musical, and his touch on the pianoforte was perfect. I remember creeping under the instrument to hide my tears when I heard him sing the ballad of "Lord Ullin's Daughter."

Charles Augustus Davis, the author of the "Letters of J. Downing, Major, Downingville Militia, Second Brigade, to his old Friend Mr. Dwight, of the New York Daily Advertiser," was [p. 25] a gentleman well known in the New York society of my youth. The letters in question contained imaginary reports of a tour which the writer professed to have made with General Jackson, when the latter was a candidate for reëlection to the Presidency. They were very popular at the time, but have long passed into oblivion. I remember that in one of them, Major Downing describes an occasion on which it was important that the general should interlard his address with a few Latin quotations. Not possessing any learning of that kind, he concluded his speech with: "E pluribus unum, gentlemen, sine qua non."

The great literary boast of the city at the time of which I speak was undoubtedly Washington Irving. I was still a child in the nursery when I heard of his return to America, after a residence of some years in Spain. A public dinner was given in honor of this event. One who had been present at it told of Mr. Irving's embarrassment when he was called upon for a speech. He rose, waved his hand in the air, and could only utter a few sentences, which were heard with difficulty.

Many years after this time I was present, with other ladies, at a public dinner given in honor of Charles Dickens by prominent citizens of New York. We ladies were not bidden to the feast, but were allowed to occupy a small anteroom whose open door commanded a view of the tables. [p. 26] When the speaking was about to begin, a message came, suggesting that we should take possession of some vacant seats at the great table. This we were glad to do. Washington Irving was president of the evening, and upon him devolved the duty of inaugurating proceedings by an address of welcome to the distinguished guest. People who sat near me whispered, "He'll break down—he always does." Mr. Irving rose, and uttered a sentence or two. His friends interrupted him by applause which was intended to encourage him, but which entirely overthrew his self-possession. He hesitated, stammered, and sat down, saying, "I cannot go on." It was an embarrassing and painful moment, but Mr. John Duer, an eminent lawyer, came to his friend's assistance, and with suitable remarks proposed the health of Charles Dickens, to which Mr. Dickens promptly responded. This he did in his happiest manner, covering Mr. Irving's defeat by a glowing eulogy of his literary merits.

"Whose books do I take to bed with me, night after night? Washington Irving's! as one who is present can testify." This one was evidently Mrs. Dickens, who was seated beside me. Mr. Dickens proceeded to speak of international copyright, saying that the prime object of his visit to America was the promotion of this important measure. I met Washington Irving several times at the [p. 27] house of John Jacob Astor. He was silent in general company, and usually fell asleep at the dinner-table. This occurrence was indeed so common with him that the guests present only noticed it with a smile. After a nap of some ten minutes he would open his eyes and take part in the conversation, apparently unconscious of having been asleep.

In his youth, Mr. Irving had traveled quite extensively in Europe. While in Rome, he had received marked attention from the banker Torlonia, who repeatedly invited him to dinner parties, the opera, and so on. He was at a loss to account for this until his last visit to the banker, when Torlonia, taking him aside, said, "Pray tell me, is it not true that you are a grandson of the great Washington?"

Mr. Irving had in early life given offense to the descendants of old Dutch families in New York by the publication of "Knickerbocker's History of New York," in which he had presented some of their forbears in a humorous light. The solid fame which he acquired in later days effaced the remembrance of this old-time grievance, and in the days in which I had the pleasure of his acquaintance, he held an enviable position in the esteem and affection of the community.

He always remained a bachelor, owing, it was said, to an attachment, the object of which had [p. 28] been removed by death. I have even heard that the lady in question was a beautiful Jewess, the same one whom Walter Scott has depicted in his well-known Rebecca. This legend of the beautiful Jewess was current in my youth. A later authority informs us that Mr. Irving was really engaged to Matilda, daughter of Josiah Ogden Hoffman, a noted lawyer of New York, and that the death of the lady prevented the intended marriage from taking place. "He could never, to his dying day, endure to hear her name mentioned," it is said, "and, nearly thirty years after her death, the accidental discovery of a piece of her embroidery saddened him so that he could not speak." [p. 29]

It has been explained that the continued prosperity of France under very varying forms of government is due to the fact that the municipal administration of the country is not affected by these changes, but continues much the same under king, emperor, and republican president.

I find something analogous to this in the perseverance of certain underlying tendencies in society despite the continual variations which diversify the surface of the domain of Fashion.

The earliest social function which I remember is a ball given by my father and mother when I must have been about four years of age. Quite late in the evening, I was taken out of bed and arrayed in an embroidered cambric slip. Some one tried to fasten a pink rosebud on the waist of my dress, but did not succeed to her mind. I was brought into our drawing-rooms, which had undergone a surprising transformation. The floors were bare, and from the ceiling of either room was suspended a circle of wax lights and artificial flowers. The orchestra included a double bass. [p. 30] I surveyed the company of the dancers, but soon curled myself up on a sofa, where one of the dowagers fed me with ice-cream. This entertainment took place at our house on Bowling Green, a neighborhood which has long been given up to business.

As a child, I remember silver forks as in use at my father's dinner parties. On ordinary occasions, we used the three-pronged steel fork which is now rarely seen. My father sometimes admonished my maternal grandmother not to put her knife into her mouth. In her youth every one used the knife in this way.

Meats were carefully roasted in what was called a tin kitchen, before an open fire. Desserts on state occasions consisted of pastry, wine jelly, blanc-mange, with pyramids of ice-cream. This last was always supplied by a French resident, Jean Contoit by name, whose very modest garden long continued to be the principal place from which such a dainty could be obtained. It may have been M. Contoit who, speaking to a compatriot of his first days in America, said, "Imagine! when I first came to this country, people cooked vegetables with water only, and the calf's head was thrown away!"

Of the dress of that period I remember that ladies wore white cambric gowns, finely embroidered, in winter as well as in summer, and walked [p. 31] abroad in thin morocco slippers. Pelisses were worn in cold weather, often of some bright color, rose pink or blue. I have found in a family letter of that time the following description of a bride's toilet: "Miss E. was married in a frock of white merino, with a full suit of steel: comb, earrings, and so on." I once heard Mrs. William Astor, née Armstrong, tell of a pair of brides, twin sisters, who appeared at church dressed in pelisses of white merino, trimmed with chinchilla, with caps of the same fur. They were much admired at the time.

Among the festivities of old New York, the observance of New Year's Day held an important place. In every house of any pretension, the ladies of the family sat in their drawing-rooms, arrayed in their best dresses, and the gentlemen of their acquaintance made short visits, during which wine and rich cakes were offered them. It was allowable to call as early as ten o'clock in the morning. The visitor sometimes did little more than appear and disappear, hastily muttering something about "the compliments of the season." The gentlemen prided themselves upon the number of visits paid, the ladies upon the number received. Girls at school vexed each other with emulative boasting: "We had fifty calls on New Year's Day." "Oh! but we had sixty-five." This perfunctory performance grew very tedious [p. 32] by the time the calling hours were ended, but apart from this, the day was one on which families were greeted by distant relatives rarely seen, while old friends met and revived their pleasant memories.

In our house, the rooms were all thrown open. Bright fires burned in the grates. My father, after his adoption of temperance principles, forbade the offering of wine to visitors, and ordered it to be replaced by hot coffee. We were rather chagrined at this prohibition, but his will was law.

I recall a New Year's Day early in the thirties, on which a yellow chariot stopped before our door. A stout, elderly gentleman descended from it, and came in to pay his compliments to my father. This gentleman was John Jacob Astor, who was already known to be possessed of great wealth.

The pleasant custom just described was said to have originated with the Dutch settlers of the olden time. As the city grew in size, it became difficult and well-nigh impossible for gentlemen to make the necessary number of visits. Finally, a number of young men of the city took it upon themselves to call in squads at houses which they had no right to molest, consuming the refreshments provided for other guests, and making themselves disagreeable in various ways. This offense against good manners led to the discontinuance, [p. 33] by common consent, of the New Year's receptions.

A younger sister of my mother, named Louisa Cordé Cutler, was one of the historic beauties of her time. She was a frequent and beloved guest at my father's house, but her marriage took place at my grandmother's residence in Jamaica Plain. The bridegroom was the only son of Judge McAllister, of Savannah, Georgia. One of my aunt's bridesmaids, Miss Elizabeth Danforth, a lady much esteemed in the older Boston, once gave me the following account of the marriage:—

"Yes, this is my beautiful bride. [My aunt was now about sixty years old.] Well do I recall the evening of her marriage. I was to be her bridesmaid, you know, and when the time came, I was all dressed and ready. But the Dorchester coach was wanted for old Madam Blake's funeral, and as there was no other conveyance to be had, I was obliged to wait for it. The time seemed endless while I was walking up and down the hall in my bridesmaid's dress, my mother from time to time exhorting me to have patience, without much effect.

"At last the coach came, and in it I was driven to your grandmother's house in Jamaica Plain. As I entered the door I met the bridal party coming downstairs. Your mother said to me, 'Oh! Elizabeth, we thought you were not coming.' [p. 34] After this all passed off pleasantly. Your grandmother was dressed in a lilac silk gown of rather antiquated fashion, adorned with frills and furbelows which had passed out of date. Your mother, who had come on from New York for the ceremony, said to her later in the evening, 'Dear mamma, you must make a present of that gown to some theatrical friend. It is only fit for the boards.'"

The officiating clergyman of the occasion was the Reverend Benjamin Clarke Cutler, brother of the bride. It was his first service of the kind, and the company were somewhat amused when, in absence or confusion of mind, he pronounced the nuptial blessing upon M and N, the letters which stand in the church ritual for the names of the parties contracting. Accordingly, at the wedding supper, the first toast was drunk "to the health and happiness of M and N," and responded to with much merriment.

I have further been told that the bride's elder sister, afterwards known as Mrs. Francis, danced "in stocking-feet" with my father's elder brother, this having been the ancient rule when the younger children were married before the older ones.

In spite of the costume which met with her daughter's disapproval, my maternal grandmother was not indifferent to dress. She used to lament [p. 35] the ugliness of modern fashions, and to extol those of her youth, in which she was one of the élégantes of Southern society. She remembered with pleasure that General Washington once crossed a ball-room to speak with her. This was probably when she was the wife or widow of Colonel Herne, to whom she was married at the age of fourteen (when her dolls, she told me, were taken away from her), and whose death occurred before she had attained legal majority. She had received a good musical education for those times, and Colonel Perkins of Boston once told me that he remembered her as a fascinating young widow with a lovely voice. It must have been during her visit to Boston that she met my grandfather Cutler, who straightway fell in love with and married her. When past her sixtieth year she would sometimes sing an old-time duet with my father. She had a great love of good literature. Here is what she told me about the fashions of her youth:

"We wore our hair short, and créped all over in short curls, which were kept in place by a spangled ribbon, bound around the head. Powder was universally worn. The Maréchale powder was most becoming to the complexion, having a slight yellowish tinge. We wore trains, but had a set of cords by which we pulled them up in festoons, when we went to dance. Brocades were much worn. I wanted one, but could not find one at [p. 36] the time, so I embroidered a pretty yellow silk dress of mine, and made a brocade of it."

She once mentioned having known, in days long distant, of a company of ladies who had banded themselves together for some new departure of a patriotic intent, and who had waited upon General Washington in a body. I have since ascertained that they called themselves "Daughters of Liberty." A kindred association had been formed of "Sons of Liberty." Perhaps these ladies were of the mind of Mrs. John Adams, who, when congratulating her husband upon the liberties assured to American men by the then new Constitution of the United States, thought it "a pity that the legislators had not also done something for the ladies."

Among the familiar figures of my early life is that of Dr. John Wakefield Francis. I wish it were in my power to give any adequate description of this remarkable man, who was certainly one of the worthies of his time. As already said, he was my uncle by marriage, and for many years a resident in my father's house. He was of German origin, florid in complexion and mercurial in temperament. His fine head was crowned with an abundance of silken curly hair. He always wore gold-bowed glasses, being very near-sighted, was a born humorist, and delighted in jest and hyperbole. He was an omnivorous reader, and [p. 37] was so constituted that four hours of sleep nightly sufficed to keep him in health. This was fortunate for him, as he had an extensive practice, and was liable to be called out at all hours of the night. A candle always stood on a table beside his pillow, and with it a pile of books and papers, which he habitually perused long before the coming of daylight. It so happened, however, that he waked one morning at about four of the clock, and saw his wife, wrapped in shawls, sitting near the fire, reading something by candlelight. The following conversation ensued:—

"Eliza, what book is that you are reading?"

"'Uncle Tom's Cabin,' dear."

"Is it? I don't need to know anything more about it—it must be the greatest book of the age."

His humor was extravagant. I once heard him exclaim, "How brilliant is the light which streams through the fissure of a cracked brain!" Again he spoke of "a fellow who couldn't go straight in a ropewalk." His anecdotes of things encountered in the exercise of his profession were most amusing.

He found us seated in the drawing-room, one evening, to receive a visit from a very shy professor of Brown University. The doctor, surveying the group, seized this poor man, lifted him from the floor, and carried him round the circle, to [p. 38] express his pleasure at seeing an old friend. The countenance of the guest meanwhile showed an agony of embarrassment and terror.

The doctor was very temperate in everything except tea, which he drank in the green variety, in strong and copious libations. Indeed, he had no need of wine or other alcoholic stimulants, his temperament being almost incandescent. Overflowing as he was with geniality, he yet accommodated himself easily to the requirements of a sick room, and showed himself tender, vigilant, and most sympathetic. He attended many people who could not, and some who would not, pay for his visits. One of these last, having been brought by him through an attack of cholera, was so much impressed with the kindness and skill of the doctor that he at once and for the first time sent him a check in recognition of services that money could not repay.

After many years of residence with us, my uncle and aunt Francis removed, first to lodgings, and later to a house of their own. Here my aunt busied herself much with the needs of rich and poor. Ladies often came to her seeking good servants, her recommendation being considered an all-sufficient security. Women out of place came to her seeking employment, which she often found for them. These acts of kindness, often involving a considerable expenditure of time and [p. 39] trouble, the dear lady performed with no thought of recompense other than the assurance that she had been helpful to those who needed her assistance in manifold ways. In her new abode Auntie lived with careful economy, dispensing her simple hospitality with a generous hand. She was famous among her friends for delicious coffee and for excellent tea, which she always made herself, on the table.

She sometimes invited friends for an evening party, but made it a point to invite those who were not her favorites for a separate occasion, not wishing to dilute her enjoyment of the chosen few, and, on the other hand, desiring not to hurt the feelings of any of her acquaintance by wholly leaving them out. When Edgar Allan Poe first became known in New York, Dr. Francis invited him to the house. It was on one of Auntie's good evenings, and her room was filled with company. The poet arrived just at a moment when the doctor was obliged to answer the call of a patient. He accordingly opened the parlor door, and pushed Mr. Poe into the room, saying, "Eliza, my dear, the Raven!" after which he immediately withdrew. Auntie had not heard of the poem, and was entirely at a loss to understand this introduction of the new-comer.

It was always a pleasure to welcome distinguished strangers to New York. Mrs. Jameson's [p. 40] visit to the United States, in the year 1835, gave me the opportunity of making acquaintance with that very accomplished lady and author. I was then a girl of sixteen summers, but I had read the "Diary of an Ennuyée," which first brought Mrs. Jameson into literary prominence. I read afterwards with avidity the two later volumes in which she gives so good an account of modern art work in Europe. In these she speaks with enthusiasm of certain frescoes in Munich which I was sorry, many years later, to be obliged to consider less beautiful than her description of them would have warranted one in believing. When I perused these works, having myself no practical knowledge of art, their graphic style seemed to give me clear vision of the things described. The beautiful Pinakothek and Glyptothek of Munich became to me as if I actually saw them, and when it was my good fortune to visit them I seemed, especially in the case of the marbles, to meet with old friends. Mrs. Jameson's connoisseurship was not limited to pictorial and sculptural art. Of music also she was passionately fond. In the book just spoken of she describes an evening passed with the composer Wieck in his German home. In this she speaks of his daughter Clara, and of her lover, young Schumann. Clara Wieck, afterwards Madame Schumann, became well known in Europe as a pianist of eminence, and of Schumann [p. 41] as a composer it needs not now to speak. There were various legends regarding Mrs. Jameson's private history. It was said that her husband, marrying her against his will, parted from her at the church door, and thereafter left England for Canada, where he was residing at the time of her visit. I first met her at an evening party at the house of a friend. I was invited to make some music, and sang, among other things, a brilliant bravura air from "Semiramide." When I would have left the piano, Mrs. Jameson came to me and said, "Altra cosa, my dear." My voice had been cultivated with care, and though not of great power was considered pleasing in quality, and was certainly very flexible. I met Mrs. Jameson at several other entertainments devised in her honor. She was of middle height, her hair red blond in color. Her face was not handsome, but sensitive and sympathetic in expression. The elegant dames of New York were somewhat scandalized at her want of taste in dress. I actually heard one of them say, "How like the devil she does look!"

After a winter passed in Canada, Mrs. Jameson again visited New York, on her way to England. She called upon me one day with a friend, and asked to see my father's pictures. Two of these, portraits of Charles First and his queen, were supposed to be by Vandyke. Mrs. Jameson [p. 42] doubted this. She spoke of her intimacy with the celebrated Mrs. Somerville, and said, "I think of her as a dear little woman who is very fond of drawing." When I went to return her visit, I found her engaged in earnest conversation with a son of Sir James Mackintosh. When he had taken leave, she said to me, "Mr. Mackintosh and I were almost at daggers drawing." So far as I could learn, their dispute related to democratic forms of government, and the society therefrom resulting, which he viewed with favor and she with bitter dislike. I inquired about her winter in Canada. She replied, "As the Irishman said, I had everything that a pig could want." A volume from her hand appeared soon after this time, entitled "Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada." Her work on "Sacred and Legendary Art" and her "Legends of the Madonna" were published some years later. [p. 43]

I left school at the age of sixteen, and began thereafter to study in good earnest. Until that time a certain over-romantic and imaginative turn of mind had interfered much with the progress of my studies. I indulged in day-dreams which appeared to me far higher in tone than the humdrum of my school recitations. When these were at an end, I began to feel the necessity of more strenuous application, and at once arranged for myself hours of study, relieved by the practice of vocal and instrumental music.

At this juncture, a much esteemed friend of my father came to pass some months with us. This was Joseph Green Cogswell, founder and principal of Round Hill School, at which my three brothers had been among his pupils. The school, a famous one in its day, was now finally closed. Our new guest was an accomplished linguist, and possessed an admirable power of imparting knowledge. With his aid, I resumed the German studies which I had already begun, but in which I had made but little progress. Under [p. 44] his tuition, I soon found myself able to read with ease the masterpieces of Goethe and Schiller.

Rev. Leonard Woods, son of a well-known pastor of that name, was a familiar guest at my father's house. He took some interest in my studies, and at length proposed that I should become a contributor to the "Theological Review," of which he was editor at that time. I undertook to furnish a review of Lamartine's "Jocelyn," which had recently appeared. When I had done my best with this, Dr. Cogswell went over the pages with me very carefully, pointing out defects of style and arrangement. The paper attracted a good deal of attention, and some comments on it gave occasion to the admonition which my dear uncle thought fit to administer to me, as already mentioned.

The house of my young ladyhood (I use this term, as it was the one in use at the time of which I write) was situated at the corner of Bond Street and Broadway. When my father built it, the fashion of the city had not proceeded so far up town. The model of the house was a noble one. Three spacious rooms and a small study occupied the first floor. These were furnished with curtains of blue, yellow, and red silk. The red room was that in which we took our meals. The blue room was the one in which we received visits, and passed the evenings. The [p. 45] yellow room was thrown open only on high occasions, but my desk and grand piano were placed in it, and I was allowed to occupy it at will. This and the blue room were adorned by beautiful sculptured mantelpieces, the work of Thomas Crawford, afterwards known as a sculptor of great merit. Many years after this time he became the husband of the sister next me in age, and the father of F. Marion Crawford, the now celebrated novelist.

Our family was patriarchal in its dimensions, including my aunt and uncle Francis, whose children were all born in my father's house, and were very dear to him. My maternal grandmother also passed much time with us. My two younger brothers, Henry and Marion, were at home with us after a term of years at Round Hill School. My eldest brother, Samuel (afterwards the Sam. Ward of the Lobby), a most accomplished and agreeable young man, had recently returned from Europe, bringing with him a fine library. My father, having already added to his large house a spacious art gallery, now built a study, whose walls were entirely occupied by my brother's books. I had free access to these, and did not neglect to profit by it.

From what I have just said, it may rightly be inferred that my father was a man of fine tastes, inclined to generous and even lavish expenditure. [p. 46] He desired to give us the best educational opportunities, the best and most expensive masters. He filled his art gallery with the finest pictures that money could command in the New York of that day. He gave largely to public undertakings, was one of the founders of the New York University, and was one of the foremost promoters of church building in the then distant West. He demurred only at expenses connected with dress and fashionable entertainment, for he always disliked and distrusted the great world. My dear eldest brother held many arguments with him on this theme. He saw, as we did, that our father was disposed to ignore the value of ordinary social intercourse. On one occasion the dispute between them became quite animated.

"Sir," said my brother, "you do not keep in view the importance of the social tie."

"The social what?" asked my father.

"The social tie, sir."

"I make small account of that," said the elder gentleman.

"I will die in defense of it!" impetuously rejoined the younger. My father was so much amused at this sally that he spoke of it to an intimate friend: "He will die in defense of the social tie, indeed!"

Our way of living was simple. The table was abundant, but not with the richest food. For [p. 47]many years, as I have said, no alcoholic stimulant appeared on it. My father gave away by dozens the bottles of costly wine stored in his cellar, but neither tasted their contents nor allowed us to do so. He was for a great part of his life a martyr to rheumatic gout, and a witty friend of his once said: "Ward, it must be the poor man's gout that you have, as you drink only water."

We breakfasted at eight in winter, at half past seven in summer. My father read prayers before breakfast and before bedtime. If my brothers lingered over the morning meal, he would come in, hatted and booted for the day, and would say: "Young gentlemen, I am glad that you can afford to take life so easily. I am old and must work for my living," a speech which usually broke up our morning coterie. Dinner was served at four o'clock, a light lunch abbreviating the fast for those at home. At half past seven we sat down to tea, a meal of which toast, preserves, and cake formed the staple. In the evening we usually sat together with books and needlework, often with an interlude of music. An occasional lecture, concert, or evening party varied this routine. My brothers went much into fashionable society, but my own participation in its doings came only after my father's death, and after the two years' mourning which, according to the usage of those days, followed it. [p. 48]

My father retained the Puritan feeling with regard to Saturday evening. He would remark that it was not a proper evening for company, regarding it as a time of preparation for the exercises of the day following, the order of which was very strict. We were indeed indulged on Sunday morning with coffee and muffins at breakfast, but, besides the morning and afternoon services at church, we young folks were expected to attend the two meetings of the Sunday-school. We were supposed to read only Sunday books, and I must here acknowledge my indebtedness to Mrs. Sherwood, an English writer now almost forgotten, whose religious stories and romances were supposed to come under this head. In the evening, we sang hymns, and sometimes received a quiet visitor.

My readers, if I have any, may ask whether this restricted routine satisfied my mind, and whether I was at all sensible of the privileges which I really enjoyed, or ought to have enjoyed. I must answer that, after my school-days, I greatly coveted an enlargement of intercourse with the world. I did not desire to be counted among "fashionables," but I did aspire to much greater freedom of association than was allowed me. I lived, indeed, much in my books, and my sphere of thought was a good deal enlarged by the foreign literatures, German, French, and Italian, [p. 49] with which I became familiar. Yet I seemed to myself like a young damsel of olden time, shut up within an enchanted castle. And I must say that my dear father, with all his noble generosity and overweening affection, sometimes appeared to me as my jailer.

My brother's return from Europe and subsequent marriage opened the door a little for me. It was through his intervention that Mr. Longfellow first visited us, to become a valued and lasting friend. Through him in turn we became acquainted with Professor Felton, Charles Sumner, and Dr. Howe. My brother was very fond of music, of which he had heard the best in Paris and in Germany. He often arranged musical parties at our house, at which trios of Beethoven, Mozart, and Schubert were given. His wit, social talent, and literary taste opened a new world to me, and enabled me to share some of the best results of his long residence in Europe.

My father's jealous care of us was by no means the result of a disposition tending to social exclusiveness. It proceeded, on the contrary, from an over-anxiety as to the moral and religious influences to which his children might become subjected. His ideas of propriety were very strict. He was, moreover, not only a strenuous Protestant, but also an ardent "Evangelical," or Low Churchman, holding the Calvinistic views [p. 50] which then characterized that portion of the American Episcopal church. I remember that he once spoke to me of the anguish he had felt at the death of his own father, of the orthodoxy of whose religious opinions he had had no sufficient assurance. My grandfather, indeed, was supposed, in the family, to be of a rather skeptical and philosophizing turn of mind. He fell a victim to the first visitation of the cholera in 1832.

Despite a certain austerity of character, my father was much beloved and honored in the business world. He did much to give to the firm of Prime, Ward and King the high position which it attained and retained during his lifetime. He told me once that when he first entered the office, he found it, like many others, a place where gossip circulated freely. He determined to put an end to this, and did so. Among the foreign correspondents of his firm were the Barings of London, and Hottinguer et Cie. of Paris.

In the great financial troubles which followed Andrew Jackson's refusal to renew the charter of the Bank of the United States, several States became bankrupt, and repudiated the obligations incurred by their bonds, to the great indignation of business people in both hemispheres. The State of New York was at one time on the verge of pursuing this course, which my father strenuously opposed. He called meeting after meeting, [p. 51] and was unwearied in his efforts to induce the financiers of the State to hold out. When this appeared well-nigh impossible, he undertook that his firm should negotiate with English correspondents a loan to carry the State over the period of doubt and difficulty. This he was able to effect. My eldest brother came home one day and said to me:—

"As I walked up from Wall Street to-day, I saw a dray loaded with kegs on which were inscribed the letters, 'P. W. & K.' Those kegs contained the gold just sent to the firm from England to help our State through this crisis."

My father once gave me some account of his early experiences in Wall Street. He had been sent, almost a boy, to New York, to try his fortune. His connection with Block Island families through his grandmother, Catharine Ray Greene, had probably aided in securing for him a clerk's place in the banking house of Prime and Sands, afterwards Prime, Ward and King. He soon ascertained that the Spanish dollars brought to the port by foreign trading vessels could be sold in Wall Street at a profit. He accordingly employed his leisure hours in the purchase of these coins, which he carried to Wall Street and there sold. This was the beginning of his fortune.

A work published a score or more of years since, entitled "The Merchant Princes of Wall [p. 52] Street," concluded some account of my father by the statement that he died without fortune. This was far from true. His death came indeed at a very critical moment, when, having made extensive investments in real estate, his skill was requisite to carry this extremely valuable property over a time of great financial disturbance. His brother, our uncle, who became the guardian of our interests, was familiar with the stock market, but little versed in real estate transactions. By untimely sales, much of my father's valuable estate was scattered; yet it gave to each of his six children a fair inheritance for that time; for the millionaire fever did not break out until long afterwards.

The death of this dear and noble parent took place when I was a little more than twenty years of age. Six months later I attained the period of legal responsibility, but before this a new sense of the import of life had begun to alter the current of my thoughts. With my father's death came to me a sense of my want of appreciation of his great kindness, and of my ingratitude for the many comforts and advantages which his affection had secured to me. He had given me the most delightful home, the most careful training, the best masters and books. He had even, as I have said, built a picture gallery for my especial instruction and enjoyment. All this I had taken, as a matter [p. 53] of course, and as my natural right. He had done his best to keep me out of frivolous society, and had been extremely strict about the visits of young men to the house. Once, when I expostulated with him upon these points, he told me that he had early recognized in me a temperament and imagination over-sensitive to impressions from without, and that his wish had been to guard me from exciting influences until I should appear to him fully able to guard and guide myself. It was hardly to be expected that a girl in her teens, or just out of them, should acquiesce in this restrictive guardianship, tender and benevolent as was its intention. My little acts of rebellion were met with some severity, but I now recall my father's admonitions as

"Soft rebukes with blessings ended."

I cannot, even now, bear to dwell upon the desolate hush which fell upon our house when its stately head lay, silent and cold, in the midst of weeping friends and children. Six of us were made orphans, three sons and three daughters. We had had our little disagreements and dissensions, but the blow which now fell upon us drew us together with the bond of a common sorrow. My eldest brother had recently gone to reside in a house of his own. The second one, Henry by name, became at this time my great intimate. He was a high-strung youth, very chivalrous in [p. 54] disposition, full of fun and humor, but with a deep vein of thought. He was already betrothed to one whom I held dear, and I looked forward to many years brightened by his happiness, but alas! an attack of typhoid fever took him from us in the bloom of his youth. I was with him day and night during his illness, and when he closed his eyes, I would gladly, oh, so gladly, have died with him! The great anguish of this loss told heavily upon me, and I remember the time as one without light or comfort. I sought these indeed. A great religious revival was going on in New York, and a zealous young friend persuaded me to attend some of the meetings held in a neighboring church. I had never taken very seriously the doctrines of the religious body in which I had been reared. They now came home to me with terrible force, and a season of depression and melancholy followed, during which I remained in a measure cut off from the wholesome influences which reconcile us to life, even when it must be embittered by a sense of irreparable loss.

At the time of my father's death, my dear bachelor uncle John, already mentioned, left his own house and came to live with us. When our paternal mansion was sold, some years later, he removed with us to the house of my eldest brother, who was already a widower. After my marriage my uncle again occupied a house of his own, in [p. 55] which for many years he made us all at home, even with our later incumbrances of children and nurses. He was, in short, the best and kindest of uncles. In business he was more adventurous than his rather deliberate manner would have led one to suppose. It was said that, in the course of his life, he had made and lost several fortunes. In the end he left a very fair estate, which was divided among the several sets of his nieces and nephews.

Long before this he had become one of the worthies of Wall Street, and was universally spoken of as "Uncle John." Shortly after his retirement from active business, the Board of Brokers of New York requested him to sit to A. H. Wenzler for a portrait, to be hung in their place of meeting. The portrait was executed with entire success. I ought to mention in this connection that the directors of the New York Bank of Commerce, of which my father was the founder and first president, ordered a portrait of him from the well-known artist, Huntington. [p. 56]

As a love of study has been a leading influence in my life, I will here employ a little time, at the risk of some repetition, in tracing the way in which my thoughts had mostly tended up to the period when, after two years of deep depression, I suddenly turned to practical life with an eager desire to profit by its opportunities.

From early days my dear mother noticed in me an introspective tendency, which led her to complain that when I went with her to friends' houses I appeared dreamy and little concerned with what was going on around me. My early education, received at home, interested me more than most of my school work. While one person devoted time and attention to me, I repaid the effort to my best ability. In the classes of my school-days, the contact between teacher and pupil was less immediate. I shall always remember with pleasure Mrs. B.'s "Conversations" on Chemistry, which I studied with great pleasure, albeit that I never saw one of the experiments therein described. I remember that Paley's "Evidences [p. 57] of Christianity" interested me more than his "Philosophy," and that Blair's "Rhetoric," with its many quotations from the poets, was a delight to me. As I have before said, I was not inapt at algebra and geometry, but was too indolent to acquire any mastery in mathematics. The French language was somehow burnt into my mind by a cruel French teacher, who made my lessons as unpleasant as possible. My fear of him was so great that I really exerted myself seriously to meet his requirements. I have profited in later life by his severity, having been able not only to speak French fluently but also to write it with ease.

I was fourteen years of age when I besought my father to allow me to have some lessons in Italian. These were given me by Professor Lorenzo Da Ponte, son of the veteran of whom I have already spoken. With him I read the dramas of Metastasio and of Alfieri.

Through all these years there went with me the vision of some great work or works which I myself should give to the world. I should write the novel or play of the age. This, I need not say, I never did. I made indeed some progress in a drama founded upon Scott's novel of "Kenilworth," but presently relinquished this to begin a play suggested by Gibbon's account of the fall of Constantinople. Such successes as I did manage to achieve were in quite a different line, that of [p. 58] lyric poetry. A beloved music-master, Daniel Schlesinger, falling ill and dying, I attended his funeral and wrote some stanzas descriptive of the scene, which were printed in various papers, attracting some notice. I set them to music of my own, and sang them often, to the accompaniment of a guitar.

Although the reading of Byron was sparingly conceded to us, and that of Shelley forbidden, the morbid discontent which characterized these poets made itself felt in our community as well as in England. Here, as elsewhere, it brought into fashion a certain romantic melancholy. It is true that at school we read Cowper's "Task," and did our parsing on Milton's "Paradise Lost," but what were these in comparison with:—

"The cold in clime are cold in blood,"

or:—

"I loved her, Father, nay, adored."

After my brother's return from Europe, I read such works of George Sand and Balzac as he would allow me to choose from his library. Of the two writers, George Sand appeared to me by far the superior, though I then knew of her works only "Les Sept Cordes de la Lyre," "Spiridion," "Jacques," and "André." It was at least ten years after this time that "Consuelo" revealed to the world the real George Sand, and [p. 59] thereby made her peace with the society which she had defied and scandalized. Of my German studies I have already made mention. I began them with a class of ladies under the tuition of Dr. Nordheimer. But it was with the later aid of Dr. Cogswell that I really mastered the difficulties of the language. It was while I was thus engaged that my eldest brother returned from Germany. In conversing with him, I acquired the use of colloquial German. Having, as I have said, the command of his fine library, I was soon deep in Goethe's "Faust" and "Wilhelm Meister," reading also the works of Jean Paul, Matthias Claudius, and Herder.

Thus was a new influence introduced into the life of one who had been brought up after the strictest rule of New England Puritanism. I derived from these studies a sense of intellectual freedom so new to me that it was half delightful, half alarming. My father undertook one day to read an English translation of "Faust." He presently came to me and said,—

"My daughter, I hope that you have not read this wicked book!"