Project Gutenberg's The Blind Lion of the Congo, by Elliott Whitney This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Blind Lion of the Congo Author: Elliott Whitney Illustrator: Dan Sayre Groesbeck Release Date: May 24, 2010 [EBook #32508] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BLIND LION OF THE CONGO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, David K. Park, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

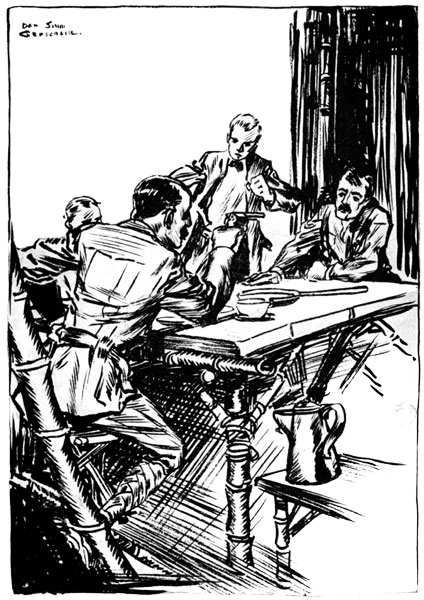

Without the least trace of excitement in his voice Mr.

Wallace had whipped out his revolver and covered the other. "Keep your hands on the table, Montenay!"

Without the least trace of excitement in his voice Mr.

Wallace had whipped out his revolver and covered the other. "Keep your hands on the table, Montenay!"

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | An Amazing Proposal | 9 |

| II | Critchfield is Interviewed | 21 |

| III | The Decision | 34 |

| IV | Outfitting | 46 |

| V | The Congo | 58 |

| VI | The Mark | 71 |

| VII | Critch's Rhino | 84 |

| VIII | Captain Mac Suspected | 97 |

| IX | The White Pigmies | 110 |

| X | The Sacred Ankh | 125 |

| XI | Mvita Saves Burt's Life | 137 |

| XII | Montenay Returns | 150 |

| XIII | In The Pigmy Village | 163 |

| XIV | The Sacred Lion | 176 |

| XV | The Ivory Zareba | 189 |

| XVI | Burt Left Alone | 202 |

| XVII | The Diary | 214 |

| XVIII | Burt Comes to Life | 228 |

| XIX | The Raft | 241 |

| XX | Down the Makua | 255 |

"What's on for to-night, Burt?"

Mr. St. John, a large automobile manufacturer of New Britain, Connecticut, looked across the dinner table at his son Burton. The latter was a boy of seventeen. Although he was sturdy for his age, his features were pale and denoted hard study. As his father and mother watched him there was just a hint of anxiety in their faces.

"Lots," replied the boy. "Got a frat meeting on at seven. Then I've got to finish my last paper for the history prof."

"Can't you let the paper go?" asked his mother. "You've been working pretty hard, Burt!"

"Yes," added Mr. St. John heartily. "Forget the work, son. You've done enough papers lately for a dozen boys."

"Not much!" answered Burt earnestly. "I'm goin' to grab that Yale[Pg 10] scholarship. There's only a week till school's out now."

At that moment a maid appeared at the dining room door.

"Mr. St. John, there's a man called, sir. He didn't give me any name and—"

She was interrupted by a tall, fur-overcoated form that brushed her aside. The visitor's hawk-like face broke instantly into an eager smile.

"Hello, good people!" cried the man, as Mr. St. John sprang to his feet. "Forgotten me, Tom?"

"George!"

"Wallace!"

"Uncle George!"

The three members of the family broke into three simultaneous cries of surprise. The next instant Mrs. St. John was in the arms of the tall man, who supported her with one hand and with the other greeted her.

"Hello, Burt! How's your grip?" he cried as he released the couple and seized the hand of their son.

"Ouch!" yelled the boy, his grin changing to expression of pain. "I[Pg 11] ain't no wooden man!"

"Where on earth did you come from?" exclaimed Mr. St. John, taking his brother-in-law's big coat and handing it to the astonished maid. "We haven't heard from you for a year!"

"Give me something to eat, Tom, and I'll talk later." As the hawk-faced man sat down, Burt gazed at him admiringly. George William Wallace, his uncle, was the boy's greatest hero. Famous under the name of "George William" for his books on little-traveled countries, he was known widely at every end of the world. He had crossed the Turkestan deserts, helped to survey the Cape to Cairo railway, led armies in China and South America, and explored the recesses of the Sahara. In his brief intervals of relaxation he lived with the St. Johns, having no home of his own.

As he gazed, Burt half wished that his own face was not so square and angular and more like that of his uncle. Mr. Wallace was thin but of very large frame. His close-cropped hair revealed a high forehead, beneath which two intensely black eyes. A long, curving nose gave his face itshawk-like effect, and thin lips and strong chin completed the[Pg 12] likeness to some great bird of prey.

"What are you doing with that fur overcoat in June, George?" asked Mrs. St. John with smile.

"Keeping warm!" shot back the explorer as he pushed away his plate. "This beastly rain goes to the bone, Etta. I landed only yesterday and got the first train up here after leaving my cases at the Explorers' Club."

"Come on with the yarn, uncle!" exclaimed Burt eagerly. "Where've you been this time?"

Mr. Wallace lit one of his brother-in-law's cigars with huge enjoyment and led the way to the library without answering. When all four were comfortably ensconced about the big table he started in.

"Let's see. I wrote you from Naples last time, wasn't it?" The others nodded. "That was just before the war. I got a chance to go to the front as special correspondent, and snapped it up. I hung around for a while at Tripoli, then took a trip to the Turkish camp. There I got into a scrap with a Turk officer and had to run for it. There was no place to run except into the desert, so it took me quite a while to make civilization again.

"Good Heavens!" exclaimed Burt's father. "I suppose you circled around and made Algiers?"

"Tried to, but a bunch of Gharian slave dealers pulled me into the mountains. I spent two months in the chain gang; then they sold me south. There was no help for it. Instead of escaping to French territory I sneaked off with a racing camel and ended up at the Gold Coast two months ago."

"What!" Mr. St. John leaped up in amazement. "Do you mean to say you crossed the whole Sahara a second time, from north to south?"

"That's what," declared Mr. Wallace. Burt stared at him wide-eyed. "Found some of my old friends and they helped me along. How are you fixed, Tom? Can you put me up all right, Etta?"

"Your old room hasn't been touched," smiled Mrs. St. John as she glanced at her husband. The latter nodded.

"All fine and dandy, old man. Oh, I'm getting along pretty well. We've got some new buildings over at the works. Turning out some great little old cars too. Say, how long are you going to stay?"

"That depends." Mr. Wallace smiled whimsically. "I have a book that I[Pg 14] want to finish this time. But I also have a notion that I want to do some ivory hunting in the Congo. If the pull doesn't get too strong I may stay a month or two."

"Hurray!" chipped in Burt, enthusiastically. "Come along to the frat meeting and tell us about the war last year! We got a 'nitiation on an' you can boss it!"

"No thanks!" laughed his uncle heartily. "When I want to do any lecturing I'll let you know, Burt. By gracious, Tom, the boy looks like a ghost! Been sick?"

"No," replied Mr. St. John gravely. "I'm afraid he's overworked. He's been trying for a scholarship at Yale that the high school offers, and the strain has been a little too much."

"Hm! Won't do, Burt," declared Mr. Wallace. "Books are all right but no use running 'em into the ground. Play baseball?"

"Sure!" replied Burt. "Not this spring though. Been too busy. Besides, I've been helpin' Critch with some stuff."

"Critch?" repeated his uncle, puzzled. "Who's Critch?"

"Howard Critchfield," replied Mr. St. John. "His father is my head[Pg 15] draftsman and Burt and Howard are great chums. Howar d has a room down at the shops where he works afternoons and putters around at taxidermy."

Burt glanced at his watch and rose hastily. It was past seven and he had forgotten the time.

"See you later, uncle!" he said as he went to the door. What a tale he would have for the other boys! Despite his uncle's refusal to come with him Burt knew that once he got "the crowd" up to the house Mr. Wallace would provide a most delightful evening.

The next day the explorer's trunks arrived and he got settled in his old quarters. These were filled with hunting trophies, guns and foreign costumes from every quarter of the world. For two days Burt did not see his uncle except at meals, but on Friday evening Mr. Wallace announced that he would like to take a look at the works the next day. Burt promptly volunteered his services, which were accepted.

"You don't look right to me, Burt!" stated Mr. Wallace as they walked down the street after breakfast. "If we were down on the West Coast now[Pg 16] I would say you were in for a good dose of fever."

"Did you ever have it?" asked Burt. He did not relish such close interest in his health, which seemed good enough to him. He also had vivid memories of a vile-tasting remedy which his uncle had proposed for a cold, years before.

"A dozen times," came the reply. "A chap gets it in high and low countries alike in Africa. So you've been helping young Critchfield, eh?"

"A little, sir. We haven't much chance of course but we've got some birds and rabbits and an old weasel we shot. It's heaps of fun."

"Hm!" Mr. Wallace cast a sharp glance at Burt but the boy did not observe it. They were nearing the factories now and presently Burt turned into a large fence-enclosed ground where the works stood.

They did not visit the old shops, which Mr. Wallace had seen before but went through the new assembling rooms and display building. The explorer was much interested in all that he saw and proved to have no slight knowledge of mechanics himself. Mr. St. John saw them from his private office and came out. By his orders they were treated to the unusual[Pg 17] sight of a complete machine lying on the floor in pieces and inside of five minutes ready to run.

"Say!" cried the explorer in admiration. "Civilization certainly can produce wonders, Tom! I suppose that some day there'll be a shop like this in the heart of Africa! But let's have a squint at this chum of yours, Burt. I'd like to size him up a bit."

They left the new buildings and went to one of the older ones where Howard had been given a small room. Without stopping to knock, Burt threw open the door and ushered in his uncle proudly.

As he did so his look of confident pride vanished. Before him stood Critch, his freckled face streaked with dust and blood, his long apron spotted and stained and on the table before him two rabbits half-skinned.

"Gosh! You look like a murderer!" exclaimed Burt in dismay. "Uncle George, this is Critch. He ain't always in this shape though."

"Sorry I can't shake hands, Mr. Wallace!" said the red-haired boy. To his surprise the explorer laughed and stuck out his hand.[Pg 18]

"Nonsense, lad! Shake!"

Critch dropped his knife, wiped his hand hastily on his apron and gripped that of the explorer heartily. "Frank Gates brought in those tame rabbits of his that died," he explained. "I told him it wasn't worth while stuffing them this weather, but he had the coin to pay for 'em and pretty near got sore about it, so I took on the job. I'm awful glad to meet you, sir! I've heard a heap about you, and Burt's lent me all your books."

"Go right ahead," insisted Mr. Wallace. "I'd like to see how you do it. Many's the skin I've had to put up in a hurry if I wanted it, but I'd sooner tramp a hundred miles than handle the beastly things!"

Critch picked up his knife and Mr. Wallace glanced around the little room. On the walls stood shelves of books and stuffed birds and animals. Bottles of liquids stood in the corners, and over the door was a stuffed horned owl mounted on a tree branch.

"That looks good!" commented the explorer approvingly. "That owl's a mighty good piece of work, boys!" He turned to Howard. "There you have[Pg 19] him—nice and clean! You know how to handle a knife, I see. Ever hear how we tackle the big skins?"

"No," replied Critch with interest. "Tell us about it, Mr. Wallace, if you don't mind! I've read a little, but nothing definite."

"With soft-skinned animals like deer we usually do just what you're doing with those rabbits—simply make incisions, slit 'em from neck to tail and peel off the skins. By the way, what do you use for preservative?"

"Get it ready-mixed," replied Critch and pointed to the bottles. "It's odorless, takes the grease out o' the skin, and don't cost much. Guess I'll use arsenic on these, though. They need something pretty strong."

"I see," went on Mr. Wallace. "Well, with thick skins like elephant or rhino, it's a different matter. I never fixed an elephant skin myself but I've seen other fellows do it. They take it off in sections, rub it well with salt and let it dry after the fat's gone. Then a dozen blacks get around each section with their paring knives and get busy."

"Paring knives!" cried Burt. "What for?"

Pare down the skin," smiled Mr. Wallace.[Pg 20] "Thick skins are too heavy to carry and too thick to be pliable, so the skinners often spend a week paring down a skin till it's portable. Then it's rubbed with salt again or else packed in brine and shipped down to the coast or back wherever your agents are, who get it preserved right for you."

They talked for half an hour while the rabbits were being finished. Then Burt and his uncle left the building, and finding that Mr. St. John had already gone to lunch, started home themselves.

"Say, Burt," said Mr. Wallace as they walked down the street, "how'd you like to come to Africa with me next month?"

"What! Me?" Burt stopped short and stared at his uncle. Mr. Wallace chuckled and lifted one eyebrow.

"Of course, if you don't want to go—" he began.

"Want to!" shouted Burt, careless of the passers-by who were looking at them curiously. "You can bet your life I want to! I'd give a million dollars to go with you!" His face dropped suddenly. "What's the use, Uncle George? You know's well as I do, the folks ain't going to stand for anything like that. Why, dad'd have a fit if he thought I was in Africa. What's the use of dreaming?"

"Here—trot along!" His uncle seized his arm and drew him on toward home. "I guess you're right about that, Burt. Anyhow, you keep mum and let me do the talking. Mind, now, don't you butt in anywhere along the line. I'm dead in earnest, young man. Maybe we'll be able to do[Pg 22] something if you lie low and let me handle it. Understand?"

"I understand," replied Burt a trifle more hopefully. "Gee! If I could only go! Could I shoot real lions and elephants, uncle?"

"Dozens of 'em!" laughed Mr. Wallace cheerfully. "Where I want to go there are no game laws to hinder. You'd have a tough time for a while, though. It's not like a camping trip up the Maine coast."

"Oh, shucks!" replied the boy eagerly. "Why, there ain't a boy in the world that wouldn't be crazy to hike with you. They've got to let me go!"

Although nearly bursting with his secret Burt said nothing of it until he returned to the shops that afternoon and joined Critch. Then he was unable to hold in and he poured out the story to his chum. Critch listened in incredulous amazement, which changed to cheerful envy when he found Burt was not joking.

"Why, you dog-goned old bookworm!" he exclaimed when Burt finished. The red-headed boy was genuinely delighted over his chum's good luck. "Think of you out there shootin' your head off, while I'm plugging away here at[Pg 23] home! Think your folks'll kick?"

"Of course they will," groaned Burt gloomily. "Ever know a feller to want any fun, without his folks kicking like sin? They like Uncle George a heap, but when it comes to takin' the darlin' boy where he can have a reg'lar circus, it's no go. Darn it, I wish I was grown-up and didn't have any boss!"

"It'll be a blamed shame if they don't let you go, old sport!" agreed Critch with a smile. "But you haven't asked 'em yet. Mebbe they'll come around all right."

"Huh!" grunted Burt sarcastically. "Mebbe I'll find a million dollars in my clothes to-morrow morning! Say—"

"Well? Spit her out!" laughed Critch as Burt paused suddenly.

"S'pose I could work you in on the game!" cried Burt enthusiastically. "That'd help a lot if the folks knew you were going, too, and if your dad would fall for it we might take you as some kind of assistant! I tell you—I'll take you as my personal servant, my valet! How'd that strike you, just for a bluff?"

"Strike me fine," responded Critch vigorously. "I'd be willin' to work my way—"

"Oh, shucks! I didn't mean that. I mean to get your expenses paid that way, see? After we got going—"

"Come out of it!" interrupted Critch. "You talk as if you was really going. Where do you reckon my dad comes in? S'pose he'll stand for any game like that? Not on your life! Dad's figgering on pulling me into the office when school's out."

Burt left for home greatly sobered by the practical common sense of his chum. He was quickly enthusiastic over any project and was apt to be carried away by it, while Critch was just the opposite. None the less, Burt was determined that if it was possible for him to go, his chum should go too.

After dinner that evening while the family was sitting in the library, Mr. Wallace cautiously introduced the subject to Burt's parents. Burt was upstairs in his own room.

"Etta, isn't that boy of yours getting mighty peaked?"

"I'm afraid so," sighed Mrs. St. John anxiously. "But we can't make him[Pg 25] give up that scholarship. I'll be glad when school is over next week."

"I guess we'll pack him off with Howard," put in Mr. St. John. "I'll send 'em up the Kennebec on a canoe trip."

"Nonsense!" snorted the explorer. "What the boy needs is something different. Complete change—ocean air—make him forget all about his books for six months!"

"There's a good deal in that, Tom," agreed his sister thoughtfully. "Perhaps if I took him abroad for a month or two—"

"Stop right there!" interrupted the explorer. "Take him abroad, indeed! Tie him to your apron strings and lead him to bang-up hotels? Dress him up every day, stuff him on high-class grub? Nonsense! If you want him to go abroad, for goodness sake give him a flannel shirt and a letter of credit, and let him go. Don't baby him! Give him a chance to develop his own resources. Guess you didn't have any indulgent papa, Tom! All the boy wants is a chance. Why won't you let him have it?"

"Don't be a fool, George!" cautioned his sister, smiling at the outburst. "You know perfectly well that I don't want my boy running[Pg 26] wild. He's all we have, and we intend to take care of him. And I warn you right here not to put any of your notions into his head. It's bad enough to have one famous man in the family!"

The explorer laughed and winked at Mr. St. John, who was enjoying the discussion from the shelter of his cigar smoke. At this, however, he came to the aid of his brother-in-law.

"Yes, George is perfectly right, Etta. Burt needs to shift for himself a bit, and I think the Kennebec trip will be just the thing for him if we give him a free hand and let him suit himself. I don't want to send him off to foreign countries all alone."

"Look here, Tom." Mr. Wallace leaned forward and spoke very earnestly. "That kind of a vacation isn't worth much to a good, healthy boy. He wants something he has earned, not something that's shoved at him. Make Burt earn some money while he's having a good time. He'll enjoy it twice as much. Make him pay his own expenses somewhere; do something that will repay him, or get busy on some outdoor stunt that will give him[Pg 27] something new and interesting to absorb him. Think it over!"

The conversation ended there for the night. Mr. Wallace was satisfied that he had sown good seed, however, and went up to Burt's room with a smile.

"Hello, uncle!" cried the boy, giving up his chair and flinging himself down on the bed. "Say anything to the folks yet?"

"A little. We'll have to go slow, remember! Now just what do you know about putting up skins and taking them from their rightful owners?"

"Me? Not a whole lot. Let's see. I helped Critch skin an' mount Chuck Evan's bulldog, some birds, a weasel—"

"Hold on!" laughed Mr. Wallace. "That's not what I mean. Know anything about horned animals?"

"No," admitted Burt. "I've read up 'bout 'em though. So's Critch."

"Suppose you had a deer's horns to take off. How'd you do it?"

"Take his skin off by cuttin' straight down the breast to the tail," replied Burt promptly.[Pg 28]

"Make cross-cuts down the inside o' each leg an' turn him inside out. For the horns you make a cut between 'em, then back down the neck a little."

"Wouldn't you take his skull?" questioned Mr. Wallace.

"Sure! I forgot that. You'd have to cut between the lids and eye-sockets down to the lips an' cut these from the bone. For the skull, cut her off and boil her."

"Pretty good!" commented his uncle. "I guess you've got the knowledge all right. How'd you do in Africa about the skin?"

"Nothing," grinned Burt. "'Cording to your books you just salt 'em well and ship 'em to the coast."

"All right!" laughed his uncle. "Get those rabbits done up?"

"You bet!" Burt made a wry face. "We rubbed them with arsenic. That's about the only stuff that'll hold them in this weather. We make money though—or Critch does. We've done lots of birds for a dollar each, and we got five for Chuck's bulldog."

"I wish you'd take me over to your friend's home to-morrow night if[Pg 29] you've nothing special on," replied Mr. Wallace. "I'd like to have a little chat with him. Are his parents living?"

"His father is, but not his mother. They only live about three blocks down the line. We'll go over after supper."

"Well, I'll go back and write another chapter before going to bed." Mr. Wallace rose and departed. He left Burt wondering. Why did his uncle want to see Critch?

He wondered more than ever the next evening. When they arrived at the small frame house in which Howard and his father lived, Mr. Wallace chatted with the boys for a little and then turned to Mr. Critchfield, a kindly, shrewd-eyed man of forty-five.

"Mr. Critchfield, suppose we send the boys off for a while? I'd like to have a little talk with you if you don't mind."

"All right, uncle," laughed Burt. "We'll skin out. Come on up to the house, Critch."

When they got outside, the red-haired boy's curiosity got the better of him and he asked Burt what his uncle wanted with his father.

"Search me," answered Burt thoughtfully."

"He put me through the third degree yesterday about skinning deer. Next time he gives me a chance I'll ask him about taking you along."

"What!" exclaimed Howard. "Have your folks come around?"

"I don't know. I'm leaving it all to Uncle George. Believe me, they've got to come around or I'll—I'll run away!"

"Yes, I've got a picture o' you running away!" grinned Critch. "Mebbe dad'll tell me what's up when I get home."

But Critch was not enlightened that night nor for many nights thereafter. This was the last week of school and Burt was too busy with his examinations to waste much time speculating on the African trip. Howard was also pretty well occupied, although not trying for any scholarship, and for the rest of the week both boys gave all their attention to school. On Friday evening Burt arrived home jubilantly.

"Done!" he shouted, bursting in on his mother and uncle. "Got it!"

"What, the scholarship? How do you know?" asked his mother in surprise.

"Prof. Garwood tipped me off. Won't get the reg'lar announcement till[Pg 31] commencement exercises next week but he says I needn't worry! Hurray! One more year and then Yale for mine!"

"Good boy!" cried Mr. Wallace. "Guess you've plugged for it though. Burt, I'll have that book finished next week. If she goes through all right I'll be off by the end of the month for Africa." He winked meaningly. "Guess I'll take you along."

"What!" exclaimed Mrs. St. John in amazement. "Take him along? Why, George William Wallace, what do you mean?"

"What on earth d'you suppose I mean?" chuckled her brother. "Why shouldn't Burt take his vacation with me if he wants to? Don't you think I am competent to take care of him?"

Burt was quivering with eagerness and his mother hesitated as she caught the anxious light in his eyes. He stood waiting in silence, however.

"George," replied his mother at last, "are you serious about this? Do you really mean—"

"Of course I do!" laughed the explorer confidently. "If I know anything about it, Burt'd come back twice as much a man as he is now. Besides[Pg 32] we ought to pull out ahead of the game, because I'm going after ivory."

"Wait till Tom comes home," declared Burt's mother with decision. "We'll talk it over at dinner. You'll have a hard task to convince me that there's any sense in such a scheme, George!"

As her brother was quite aware of that fact he forbore to press the subject just then. A little later Mr. St. John came home from the works and at the dinner table his wife brought up the subject herself.

"Tom, this foolish brother of mine wants to take Burton away to Africa with him next month! Did you ever hear of anything so silly?"

"Don't know about that," replied Mr. St. John, to his son's intense surprise. "It depends on what part of Africa, Etta. You must remember that the world's not so small as it used to be. You can jump on a boat in New York and go to Africa or China or Russia and never have to bother your head about a thing. What's the proposition, George?"

"I've been thinking that it would do Burt a lot of good to go with me to the Congo," answered the explorer. "The sea voyage would set him up in fine shape, and we would keep out of the low lands, you know."

"The Congo!" cried his sister in dismay. "Why, that's where they torture people! Do you—"

"Nonsense!" interrupted Mr. Wallace impatiently. "The Congo is just as civilized as parts of our own country. We can take a steamer at the mouth and travel for thousands of miles by it. I have one recruit from New Britain already, and I'd like to have Burt if you'll spare him."

"Why, who's going from here?" asked Mr. St. John in surprise.

"Young Critchfield," came the reply.

"Critch!" shouted Burt, unable to restrain his amazement. His parents looked equally incredulous and Mr. Wallace explained with a smile.

"Yes, Howard Critchfield. You see, I'd like to bring back some skins and things but I detest the beastly work of getting them off and putting them in shape. So when I found that Critch was no slouch at taxidermy and only needed the chance, it occurred to me to take him along. I saw his father about it and proposed to pay all his expenses and a small salary. Mr. Critchfield came around after a little. He saw that it would be a splendid education for the boy—would give him a knowledge of the world and would develop him amazingly."

"Why didn't Critch tell me about it?" cried Burt indignantly.

"He didn't know!" laughed his uncle. "His father and I agreed that we'd let him get safely through school without having other things to[Pg 35] think of. Now look at the thing sensibly, you folks. We wouldn't be away longer than six months at most. Burt would be in far more danger in his canoe on the Kennebec than in a big steamer on the Congo."

"But after you leave the steamer? You can't shoot ivory from the boat, I presume," protested Mr. St. John.

"And what about snakes and savage tribes?" put in his wife.

"My dear Etta," replied the explorer patiently, "we will be near few savage tribes. I might almost say that there are none. As for snakes, I've seen only three deadly ones in all the years I've spent in Africa. After we leave the steamer, Tom, we'll get out of the jungles into the highlands. Burt stands just as much chance of getting killed here as there. An auto might run over him any day, a mad dog might bite him or a chimney might fall on him!"

For all his anxiety Burt joined heartily in the laugh that went up at his uncle's concluding words. The laughter cleared the somewhat tense situation, and the discussion was carried into the library. Burt saw, much to his relief, that his father was not absolutely opposed to the[Pg 36] trip, although his mother seemed anxious enough.

"Now give us your proposition, George," said his father as they settled down around the table. "What's your definite idea about it?"

"Good! Now we're getting down to cases!" cried the explorer with a smile at his sister. "Burt, get us that large atlas over there." Burt had the atlas on the table in an instant. "Let's see—Africa—here we are. Get around here, folks!" As he spoke Mr. Wallace pulled out a pencil and pointed to the mouth of the Congo River.

"Here's the mouth of the Congo, you see. Here we step aboard one of the State steamers. These are about like the steamers plying between New York and Boston. Following the Congo up and around for twelve hundred miles, roughly speaking, we come to the Aruwimi river. Up this—and here we are at Yambuya, the head of navigation on the Aruwimi. From here we'll go on up by boat or launch for three or four hundred miles farther, then strike off after elephants."

"But how do you get down there in the first place?" asked Mr. St. John, who seemed keenly interested.

"Any way you want to!" returned the explorer. "There are lines running to Banana Point or Boma, the capital, from Antwerp, Lisbon, Bordeaux, Hamburg, or from England. We'll probably go from England though."

"My gracious!" said Burt's mother. "I had no idea that the Congo was so near civilization as all that! Are there real launches away up there in the heart of Africa?"

"Launches? Automobiles, probably!" laughed her husband.

"Of course," agreed Mr. Wallace. "There are motor trucks in service at several points. We could even take the trip by railroad if we wished, and we'll telegraph you direct when we reach there!"

"Well that's news to me!" declared Mr. St. John. "I thought that Central Africa was a blank wilderness filled with gorillas and savages. Seems to me I remember something about game laws in Roosevelt's book. How about that?"

"There are stringent laws in Uganda and British East Africa," replied Mr. Wallace. "But I intend to depend on trade more than on shooting for[Pg 38] my ivory. Now look at this Makua river that runs west, up north of the Aruwimi. I'm not going to take any chances on being held up at Boma after getting out. There are several trading companies who'd be tickled to death to let me bring out a bunch of ivory and then rob me of it at the last minute. So we're going right up to the Makua and down that river to the French Congo. I've got a mighty strong pull with the French people ever since they made me a Commander of the Legion of Honor for my Sahara explorations."

"I see." Burt's father gazed at the map reflectively then looked up with a sudden smile. "You say 'we' as if it was all settled, George!"

"Oh, I was talking about young Critchfield and myself," laughed the explorer. "Come now, Etta, doesn't it sound a whole lot more reasonable than it did at first?"

"Yes," admitted his sister. "I must say it does. Especially if it is all so civilized as you say."

"Now look here." Mr. Wallace bent over the map again and traced down the Congo to Stanley Falls. "A railroad runs from here over to the Great[Pg 39] Lakes, at Mahagi on the Albert Nyanza. The Great Lakes are all connected and have steamer lines on them, so that you can get on a train or boat at the west coast and travel right through to the east coast just like going from New York to Duluth. Get me?"

"Why," exclaimed Burt, "I thought you had to have porters and all that? Can you just hop on a train and shoot?"

"Not exactly," laughed his uncle. "When we leave the Aruwimi we'll probably take a hundred bearers with us."

"Well, it's not a question that we can decide on the spur of the moment," annournced Mrs. St. John. "We'll talk it over, George. If conditions are as you say, perhaps—"

"Hurray!" burst out her son excitedly. "You've got to give in, dad! Mother's on our side!" And Burt darted off to find his chum.

"The fact that you've won over Mr. Critchfield counts a good deal," smiled Mr. St. John as the door slammed. "He's a solid, level-headed chap and, besides, I really think it might do Burt good."

Burt found his chum in a state of high excitement. Critch's father had just told him about Mr. Wallace's proposal and his own qualified[Pg 40] consent.

"I'll have to think it over some more," he had said. "It's too big to rush into blindly. As it stands, however, I see no reason why you shouldn't go and make a little money, besides getting the trip."

Burt and Critch got an atlas and went over the route that Mr. Wallace had traced. When Burt reported all that his uncle had said about civilization in the Congo, Critch heaved a deep sigh.

"Seems 'most too good to be true," he said. "To think of us away over there! I don't see where your uncle's going to clear up much coin, though. It must cost like smoke."

"So does ivory," grinned Burt. He was in high spirits now that there actually seemed to be some hope of his taking the trip. "He ain't worried about the money. Say, I'm mighty glad I've been learning French! It'll come in handy down there."

"You won't have any pleasure tour," put in Mr. Critchfield quietly. "Mr. Wallace means business. He told me he meant to leave the whole[Pg 41] matter of skins and heads to you two chaps."

"Wonder what he wants them for?" speculated Burt. "Mebbe he's going to start a museum."

"Hardly," laughed Mr. Critchfield. "He said he wanted to give them to some Explorers' Club in New York. That means they'll have to be well done, Howard. I want you to be a credit to him if he takes you on this trip."

"I will." Howard nodded with confident air. "Just let me get a chance! How's the scholarship? Hear anything yet?"

"Got her cinched," replied Burt happily. "Well, guess I'll get back. See you to-morrow!"

For the next week the question of the African trip was left undecided. When Burt had received his definite announcement of the scholarship, dependent on his next year's work, Mr. Wallace urged that the matter be brought to a decision one way or the other. On the following Saturday evening Mr. Critchfield and Howard arrived at the St. John residence and the "Board of Directors went into executive session," as the explorer laughingly said.

"There's one thing to be considered," announced Mr. Critchfield. "That's[Pg 42] the length of your absence. Next year is Howard's last year in high school and I wouldn't like his course to be smashed up." Mr. St. John nodded approval and all looked at Mr. Wallace expectantly.

"I anticipated that," he replied quietly. "I saw Mr. Garwood, the superintendent of schools, yesterday. I told him just what we wanted to do and asked him about Burt's scholarship. School will not begin till the twentieth of September. He said if you boys were back by November and could make up a reasonable amount of work he'd make an exception in your cases owing to your good records. I'm fairly confident that we'll be back by November."

"I don't see how," interposed Mr. St. John. "I've been reading up on Stanley's journeys in that country and—"

"Hold on!" laughed Mr. Wallace. "Please remember, Tom, that Stanley made his trips in the eighties—nearly thirty-five years ago. Where it took him months to penetrate we can go in hours and days. This is the end of June. By the first of August we'll be steaming up the Congo. I don't think it'll take us two months to cross from the Aruwimi to the Makua and reach French territories. In any case, I intend to return direct[Pg 43] from Loango, a port in the French Congo. We'll come down the river under the French flag in a French steamer, turn the corner to Loango and there'll be a steamer there waiting to bring us and our stuff direct to New York. I'm almost sure we'll be back by November."

"Even if we aren't," put in Howard, "it'll only throw us out half a semester."

"Supposing they do miss connections, Critchfield," said Mr. St. John, "I wouldn't worry. It is a great thing for the boys and perhaps an extra six months in school won't do any harm. However, figure on getting back."

"I guess it's up to you, Etta!" laughed Mr. Wallace. "What do you say? Yes or no?"

As Burt said afterward, "I came so near havin' heart failure for a minute that I could see the funeral procession." Mrs. St. John hesitated, her head on her hand. Then looking up, her eye met Burt's and she smiled.

"Yes—"

"Hurray!" Critch joined Burt in a shout of delight, while the latter[Pg 44] gave his mother a stout hug of gratitude.

"I don't know what we'll do here without you," she continued when freed. "When will you start, George?"

"Since we have to be back by November," replied the explorer, "we'll leave here Monday morning and catch the Carmania from New York Tuesday. I'll wire to-night for accommodations."

"Monday!" cried Mr. St. John in amazement. "Why, there'll be no time to get the boys outfits or pack their trunks, or—"

"We don't want outfits or trunks, eh, Burt?" smiled Mr. Wallace. "The comfort of traveling, Tom, is to be able to take a suit case and light out for anywhere on earth in an hour. That's what we'll do. Wear a decent suit of clothes, boys, and take a few changes of linen. We'll reach Liverpool Friday night and London on Saturday. We'll get the outfits there, and if we hustle we can pick up one of the African Steamship Company's steamers Tuesday or Wednesday."

"But your book?" asked Mrs. St. John. "Is that finished?"

"Bother the book!" ejaculated her brother impatiently. "I'll write the last chapter to-night and if the publishers don't like it they can[Pg 45] change it around to suit themselves. I'm going to Africa and I'm going to leave New York Tuesday morning rain or shine!"

"That's the way to talk!" shouted Burt, wildly excited. "Good for you, mother! I'll bring you back a lion skin for your den, dad!"

Had Burt been able to foresee just what lion skin he would bring back and what he would pass through before he got it he might not have been so enthusiastic over the prospect of his African trip.

The trip was begun very much as Mr. Wallace had outlined. The news spread rapidly that Burt and Howard were going to Africa, and when the two boys arrived at the station early Monday morning a good-sized crowd of friends was present to see them off.

"Take good care of yourself," cautioned Mrs. St. John as she kissed her son good-bye. "Don't be afraid to telegraph us!"

The train pulled out with a last cheer from the frat fellows, and Burt and Howard realized that they were actually off. They arrived in New York at noon and Mr. Wallace took them direct to the Explorers' Club for luncheon.

Here they first began to feel in touch with the outside world. The club was an institution composed of explorers, hunters and wanderers in foreign lands. Its walls were decorated with game heads, arms and armor of many savage tribes, while in glass cases were hung odd costumes and[Pg 47] headgear and unique relics and curios. At the dining-room tables the boys saw bronzed and bearded men who nodded to Mr. Wallace like old friends or spoke to him in strange tongues.

"You fellows wait for me in the library," said the explorer as they finished luncheon. "I guess you'll find plenty to amuse you there. We'll stop here for to-night. I'm going down to send off some cables now and get part of our outfit ordered ahead. When I come back we'll go out and see the town a little."

"Did you get rooms on the steamer?" asked Critch.

"Wired last night. The answer will be down here at the office but there's not much doubt about getting them. See you in the library."

The boys made themselves at home in the library and in half an hour Mr. Wallace returned with the stateroom slips. Then they took a taxi and made a few purchases for the voyage. As there was nothing to be obtained except some clean linen and a steamer rug each, they spent most of the afternoon "seeing" New York City.

The evening spent at the club was a wonderful one to the boys. On talking it over later they found that they had only a confused memory[Pg 48] of meeting several famous men and of hearing some surprising stories.

"Critch!" whispered Burt as they lay in bed. "'Member that thin fellow with the scar on his chin? S'pose his yarn was true!"

"What? About being tortured by New Guinea cannibals?" returned his chum. "Prob'ly. That sure was a whopper though that the man with the black beard told! The one that'd been in China, I mean."

"Said he had photos of the Forbidden City, didn't he?" asked Burt. "Gee! That story of his about the joss with the emerald eyes and the ropes of pearls—"

So it went until long past midnight when the boys finally fell asleep. They were up early and after breakfast took a taxi again and went on board the Carmania, which was to sail at ten.

The voyage was uneventful to Mr. Wallace but proved of tremendous novelty to the boys. By the time they reached Liverpool Burt felt like new. His color was returning fast and the sea air had filled out his lungs once more and put him into prime condition. The question of their outfit was what puzzled the boys most until they put it up to Mr.[Pg 49] Wallace.

"Oh, we'll get all that in London," he explained. "I cabled ahead so that most of it will be ready. You see, boys, these outfitters put up boxes of food in regular amounts for each day. All I have to do is to tell 'em how long we'll be gone and how many of us there are. They pack a box—chop-boxes, they're called—holding enough for so many days. According to custom the blacks only expect to carry sixty pounds, so these boxes are made up at that weight. All are of tin, hermetically sealed. Some firms use colored bands to distinguish the boxes but ours numbers each box and furnishes us with lists of what they contain."

"Some system, isn't it!" exclaimed Critch admiringly. "Do we have to carry everything with us? Must be an awful freight bill!"

"Can't go to Africa for nothing," laughed Mr. Wallace. "Yes, we'll get most of that stuff here. We could get it at Boma but I'd sooner depend on the English firm."

"Wish we could stay longer in London," sighed Burt. "I hate to rush off[Pg 50] without seeing anything of the city."

"Well, our boat leaves Tuesday afternoon and this is Friday," replied his uncle. "Our chop-boxes are already on board, I suppose. Our trunks—tin-lined by the way—will probably go down Monday night if we get our stuff Saturday. I'd like to spend a week in London myself but if we're to be back home by November we haven't much time to waste."

The Liverpool customs did not delay them long as they had only a suit case each, and they took the night express for London. The boys were much surprised and not a little dismayed when they entered the English compartment cars, so different from the coaches they were used to. They soon found that it was much nicer to travel by themselves, however, as Mr. Wallace interviewed the guard and provided against intrusion. In the morning they awoke to find themselves in London.

Mr. Wallace took them to the famous Carleton House for breakfast, now entirely rebuilt after its fire of the year before. When they had finished, all three went to the writing room.[Pg 51]

"Take out your pencils now," said the explorer, "and get busy. I know just about what I want to take and a list ready-made will save a lot of time in the shops. Ready?"

The two boys were not only ready but anxious. The lists that they wrote out were identical. Here is that of their personal effects and clothes as Burt made it out.

Four suits underwear, Indian gauze.

Two ditto, woolen.

Two heavy gabardine shooting suits.

Two flannel shirts, khaki cartridge pockets.

Two pair high boots. One pair of soft leather.

Extra thick leggings, two pairs.

Camelshair poncho blanket, convertible.

Kid-lined gloves, two pairs.

Sleeping bag, waterproof.

Wool socks and pajamas.

Two khaki helmets.

Mosquito net for head and body.

Cholera belt, flannel.

Zeiss field glasses.

Large colored silk handkerchiefs, six.

Compass. Toilet articles.

"There," exclaimed Mr. Wallace as he ran over Burt's list, "that looks pretty good to me. You won't need the wool underwear unless you get[Pg 52] prickly heat. The leggings are the most important. If you get scratched up by spear-grass and thorns and then step into some swamp-pool it's all off. You'd get craw-craw sure."

"What's that?" asked Critch. "Sounds like crow!"

"It's a skin disease," replied Mr. Wallace. "Something frightful, too. The poncho will serve for blanket and raincoat, but this is the dry season. Must have the mosquito net, though. When we get up the Aruwimi we'll find little bees about as big as gnats but a whole lot worse, and it'll need thick nets to keep 'em out. New for the armament."

Burt's "armory" consisted of the following weapons:

Double-barreled Holland .450 cordite rifle, for close quarters.

Winchester .405 rifle for general use.

Twenty-gauge Parker shotgun.

Eight-inch skinning knife.

"Ain't we going to take revolvers?" asked Burt disappointedly as his uncle finished.[Pg 53]

"No," replied the latter. "They're of no use whatever. I'll take mine from force of habit but you chaps will never need one. Oh, the ammunition! Put down a hundred solid and a hundred soft-nosed cartridges for the Hollands; for the Winchesters two hundred of each, and six boxes of shells. That'll be enough to last us double the time."

"How 'bout a camera?" asked Critch anxiously. "Will we be able to tote one along?"

"Surest thing you know!" replied Mr. Wallace. "We'll take one of those new moving-picture machines. They're no larger than a camera and you can take motion pictures or straight shots on the reel."

"Gee! That'll be great!" cried Burt delightedly. "But won't the heat spoil the reels? An' don't they cost like fury?"

"The reels will be hermetically sealed before and after using," explained his uncle. "Needn't worry 'bout them. The whole outfit only costs twelve or thirteen pounds—say sixty dollars. It's well worth it, too. Now for the tents. We're going to travel light as possible, so put down two double-roofed ridge tents twelve by ten, with[Pg 54] ground-sheets. Three cots without mattresses. You'll have to do without them or pillows—they're a beastly nuisance to pack along. Canvas bath each and condensing outfit to supply fresh water."

"Why's that, uncle?" asked Burt in surprise. "Lots of fresh water, ain't there?"

"Lots," smiled his uncle, "and lots o' guinea worms, fever germs, poisons and other things in it. Better add a four-quart canteen, glass stoppers, to your personal list. Can't take any cork or the roaches'll eat it. Two blankets for each person, and six towels. I guess that's all we need put down now, boys."

"Hold on there!" cried practical Critch abruptly. "How 'bout eatin' utensils and fryin' pans, medicine, can openers and all them things?"

"All arranged for," laughed Mr. Wallace. "The cooking part of it will be up to John Quincy Adams Washington."

"John—who?" stammered Burt. "Say it again, please!"

For answer Mr. Wallace pressed a button and a footman appeared.

"Send the manager here at once, please." The man bowed and withdrew and while the boys were still staring at the explorer in wonder a dapper[Pg 55] little man appeared bowing.

"Mr. Wallace? Glad to see you looking so well, sir! What can I do for you?"

"I want that fellow Washington," smiled the explorer. "Can you let me have him for say three months? I'm going down to Africa and he'll have to go along."

"Certainly! I'll send him right up, sir." The manager vanished with another bow and Mr. Wallace turned to the boys.

"Washington—or John rather—is a Liberia boy I picked up five years ago. He's the best cook on earth! He's been in China and South America with me and whenever I don't need him he has a steady jo as fifth chef here. Ah, here he is!"

An immense black man appeared, wearing a grin that almost hid his face, as Burt expressed it. He stepped up and caught the explorer's hand, not shaking it but pressing it to his forehead as he spoke.

"Glad to see you, sar! What for you want John now?"

"Africa, John. This is my nephew, Mr. St. John, and my friend, Mr.[Pg 56] Critchfield, who will go along. We leave for the Congo Tuesday."

"Pleased to meet you, sar!" The grinning black pressed the hands of Burt and Howard to his forehead in turn. "What boat we leave, sar?"

"The Benguela. African Steamship Company docks."

"Hit's Liverpool boat, sar! What time hit leave London docks?"

"Three o'clock, John. Here's a hundred pounds." Mr. Wallace peeled off five twenty-pound bank notes and handed them to the negro; "that ought to buy your outfit, eh?"

"By hall means, sar! Thank you. Hi'll 'ave most helegant brass pots, sar!"

"Good gracious!" exclaimed Burt as the cook withdrew. "You hand out bank notes as if you're made o' money! S'pose the coon'll ever show up with all that wad on him?"

"Show up?" repeated Mr. Wallace. "Why, I'd turn over my bill book to him and never count it when he gave it back! He's a blamed sight more honest than most white men you'll meet down there. And nerve! He carried me five miles on his back once, in northern China, stopping occasionally[Pg 57] to fight off a bunch of bandits. That's the kind of man John is."

"Funny accent he's got," said Critch. "I thought all coons talked like they do down south."

"You'll get over that pretty quick!" laughed the explorer heartily. "John can use West Coast, cockney, Spanish and half a dozen other accents accordin' to whom he's been mixing up with latest. When we strike the Congo he'll probably fall into French. Well, let's trot along to Piccadilly and get measured. It's gettin' on toward noon."[Pg 58]

The boys were now due to receive another surprise. When their taxi drew up they jumped out, fully expecting to see a wonderful store like those of New York. Instead they found themselves before a dingy little shop whose aspect gave them distinct disappointment.

"No," laughed Mr. Wallace as he dismissed the taxi, "it's all right! Doesn't look up to much but it sends out good stuff."

This was the gunshop and they found it very different inside. Mr. Wallace had no time to waste in having special guns made, so the clerks measured the boys' shoulders and arms and that was all there was to it, for the guns would be slightly altered and sent on board.

Now the party went to the Boma Trading Company's store. Here they found that the chop-boxes had all gone on board their ship. Mr. Wallace ordered three Borroughs and Wellcome medicine cases, specially made up for the West Coast. He also procured two hypodermic syringes and a[Pg 59] small quantity of Pasteur serums.

"We'll probably never need them," he explained, as they left the store, "but in case our men strike a snake a quick hypodermic is the only thing to save them. Then we have poisoned arrows to consider also. If we happened to get into the pigmy country—which I hope we won't—it'll take a powerful anti-tetanic serum to kill their poisons."

After a lunch they returned to the Boma Company. The lists which Mr. Wallace had given the clerks had been filled and now each of them was measured for the clothes and personal equipment. This consumed an hour, after which they took another taxi and went to a camera supply house.

The boys went into extravagant delight over the small and compact moving-picture outfit. Burt promptly took charge of this, or rather promised to take charge, for when the whole outfit had been sealed up it would be sent down to the steamer like the other supplies.

"Tell you what," he cried, "we'll get some great little old pictures! You let an elephant chase you, Uncle George, while I get a good view and[Pg 60] Critch shoots him!"

"Don't want much, do you?" laughed his uncle. "Nothing like that for mine. I'd sooner have an elephant after me, at that, than a big buffalo. That's the most dangerous animal we'll find in Africa."

"How 'bout rhinoceros?" challenged Critch.

"All poppycock," snorted the explorer. "A rhino can't see ten feet away. He goes by smell. He'll usually run away unless he's wounded. But a buffalo doesn't wait to be wounded. You rouse him up out of a comfortable feeding place and he'll go for you. Takes more than one bullet to kill him unless you're lucky."

The boys now stocked up with fresh linen for the voyage while Mr. Wallace looked up his own guns, which he usually stored in London. They stopped at the Carleton over Sunday and Monday. As Burt's father had[Pg 61] sales offices in London they secured a large touring car without cost and spent the two days riding about the historic city. There were various minor details of their outfits to be attended to on Monday and on Tuesday noon they went aboard the Benguela, when she arrived from Liverpool.

She proved to be a large cargo and passenger boat and was very comfortably fitted up. They had seen nothing of John Quincy Adams Washington but Mr. Wallace smilingly assured them that he would show up in time. Sure enough, when they went up the gangplank the big negro was waiting with his all-embracing grin.

"Good mornin', sar, good mornin'!" he cried, taking charge of their hand baggage and assuming a lordly attitude over the stewards. "Very hauspicious day, sar! John t'ink we 'ave very fine trip, sar!"

And a fine trip they had. There were a dozen other passengers on board. Most of these were clerks or traders going out to positions at Sierra Leone or the Gold Coast, with one or two Frenchmen and officials of the Congo State. When they crossed the Equator there were the usual ceremonies and horseplay among the sailors, and the boys thoroughly enjoyed themselves. By the time they left the Gold Coast behind and headed for Banana Point Burt felt better than he had ever been in his[Pg 62] life and his uncle assured him that he need not worry about the fever.

Finally the long reddish cliffs and grassy up-lands of the Congo coast drew into sight late on the fifteenth afternoon. The Benguela took a black pilot aboard and proceeded straight up to the port of Banana. Mr. Wallace and the boys at once disembarked and interviewed the customs officials and took a launch up to the capital, Boma. The steamer would follow them after discharging some cargo.

The next morning Mr. Wallace put on his ribbon of Commander of the Legion of Honor. The boys were amazed at the respect which this gained for all of them when they sought an audience with the governor general. After explaining to him the object of their trip and the length of time they would be gone, Mr. Wallace arranged to have all the necessary papers made out and to charter one of the State steamers to take their outfit up the river.

"I can give you only a small one," said the governor general. "Unfortunately, there are few at my disposal just now. Stay! You might[Pg 63] arrange with Captain Montenay. He chartered La Belgique two days since for a similar trip, but surely he'll have plenty of room to spare."

"Montenay?" repeated Mr. Wallace. "Isn't he the Scotch explorer?"

"Yes!" smiled the governor. "Come to think of it I believe he is at the palace now." Clapping his hands, he dispatched a gendarme. "If you can arrange matters with him I will see that your baggage is passed directly to La Belgique through the customs. You have no liquor, I presume?"

"Half a dozen pint flasks of brandy," replied the explorer and the governor nodded. It is one of the strictest laws of the Congo that no liquors shall be brought into the country, save in small personal amounts. A moment later the gendarme returned with a small, khaki-clad man. He was very sallow of complexion, had dark hair and eyes, and carried his left arm awkwardly. When the governor introduced him to the three Americans his thin face lit up with a quick smile and he gripped Mr. Wallace's hand impulsively.

"So you're Wallace!" he cried, looking deep into the other's eyes. "Man, I've been wantin' to meet ye for ten years! I ran across your trail in[Pg 64] China and got within fifty miles o' ye when the Cape to Cairo was surveyin'. Man, I'm pleased to meet ye!"

"I'm mighty glad to meet you, too," smiled Mr. Wallace. "I've heard a lot about you, Montenay!"

Mr. Wallace then introduced the boys and suggested that they have a talk in another room of the palace. Thanking the governor for his assistance and kindness they followed the gendarme to another room.

"Now, Captain," said Mr. Wallace, "we're going up the Aruwimi after ivory. We can't get a large boat here and the Governor suggested that you could take us up on the Belgique."

"O' course I can!" exclaimed the small but famous Scotchman. "An' that's precisely where I'm bound for too. How'd ye guess it?"

"Good!" cried Mr. Wallace. "When do you start up?"

"I was meanin' to go in the mornin'," answered the other, rubbing his stubbly chin reflectively. "We'll get your stuff out o' the Benguela to-morrow or ma name ain't McAllister Montenay!"

"We'll split expenses on the Belgique, of course," declared the[Pg 65] American. "It's mighty good of—"

"None o' that now, none o' that," interrupted Captain Montenay hastily. "Why, man, I'd give a hundred pound for the benefeet o' your company up the stream! Ivory, you say?"

"Partly." Mr. Wallace answered the keen questioning look with a nod. "I'm going up past the Avatiko country to the Makua and down the river under the French flag. I've chartered a tramp to be waiting at Loanga by November. Get the idea?"

"Aye!" Montenay threw back his head in a noiseless laugh. "Man, ye're no fool! I brought down ten tusks two year gone. When I got down to Stanley Pool the Afrique Concessions jumped me an' laid claim to the lot. The rank thieves! They had witnesses to swear that I got the ivory in their land an' before I knew where I was they fined me twenty pound—an' the ivory! By cripes, they won't monkey twice with McAllister Montenay though! Well, let's be movin'. It'll be vera tiresome gettin' these blacks to work."

As they passed a water cooler on their way out the captain paused. The boys saw him take a bottle from his pocket and pour out a palmful of[Pg 66] white powder into a cigarette paper. This he rolled up and threw into his mouth, tossing a glass of water after it.

"Quinine," he explained, although he called it "queeneen."

"Pretty big dose, wasn't it?" asked Mr. Wallace.

"'Bout fifty grain," replied the other calmly, to the intense astonishment of the boys. "Fever gets me bad down here on the coast. By cripes, ye're a lucky beggar!" he continued as they came in sight of John standing guard over their valises. "That's your man Washington? I've heard o' him. They say he's a magneeficent cook."

"Better than that," laughed Mr. Wallace. "He'll take charge of your blacks and get real work out of 'em. Do you mean what you said about going up the Aruwimi?"

"Aye." Montenay nodded. "We'll talk that over later. Ye'll be wantin' yer mosquito nets, so better bring the stuff down to the Belgique. We'll sleep on board her to-night."

As they had stayed at the hotel the night before, the boys had not been troubled much by the insects. They were much more worried by the[Pg 67] quantities of quinine that Mr. Wallace insisted on their taking. When Burt had protested at taking ten grains all at once his uncle had laughed.

"Nonsense! I'm running this trip! Why, it's nothing unusual for men to take seventy and eighty grains out here. So put it down and shut up or I'll send you back home!"

They found the Belgique to be a small but comfortable little steamer manned by a crew of a dozen blacks and a Swiss pilot. The Benguela came up the river that afternoon and the smaller steamer was placed alongside her. By special arrangement with the customs people the boxes belonging to Mr. Wallace were slung right out to the deck of La Belgique. Here John was in charge of the blacks and under his heavy-handed rule the cases were rapidly stowed away.

Mr. Wallace and the boys got out all their personal equipment at once. The heat was intense and the boys naturally suffered from it greatly at first, although the two older men did not seem to mind it in the least.[Pg 68] By the next afternoon their loading was completed and the Belgique headed upstream without further delay.

Their five days' trip got the boys inured to the heat somewhat. They never tired of watching the tropical forest on either bank of the river and the strange craft that plied around them. Although there were many other steamers and State launches as well as trading companies' boats, there was no lack of dugouts and big thirty-foot canoes laden with merchandise from the trading posts. The two explorers lay back in their canvas chairs and recounted their experiences in strange lands, while the boys listened eagerly as they watched their new surroundings.

The water-maker, as John called it, was installed the first day out. The boys found their cook to be all that Mr. Wallace had stated and more, while Captain Montenay was so delighted that he laughingly offered John exorbitant wages to desert the American, but in vain. The Belgique made stops for wood only and after four days they arrived at the mile-wide mouth of the Aruwimi River.

On the fifth day they arrived at Yambuya, just below the great cataracts which stopped further navigation. Here the two experienced explorers[Pg 69] unloaded the chop-boxes, tents and other supplies and proceeded to make arrangements for hiring bearers. This was accomplished through the local chief with the aid of the government representative, who was an Italian. Indeed, the boys found that not only were Belgians and French employed all through the country, but men of every nationality, from "remittance men" of England to Swiss and Cubans.

After a two days' delay at Yambuya the caravan was formed. It consisted of one hundred Bantu porters under the directions of a head-chief who spoke French fairly well, as do many of the natives. Besides the porters there were tent boys, skinners, gun-bearers and cooks to the number of thirty. Captain Montenay spoke Bantu to some extent and all the orders were given by him direct while the river trip was continued.

The expedition started from the other side of the cataracts in five immense dugout canoes paddled by the porters. For the white men had been provided a small antiquated launch with which the canoes were easily able to keep up.

"Well," said Mr. Wallace as they puffed away from the shore, "the real[Pg 70] trip's begun, boys! We'll arrive at Makupa to-morrow and then up to the Makua!"

"Makupa?" exclaimed Captain Montenay. "Why, that's only a hundred and fifty miles up! Well, we can talk it over later. John, fill a canvas tub. I feel the need o' havin' a bath."

And Captain McAllister Montenay's bath was the first indication that the boys received of the Blind Lion.[Pg 71]

The folding tubs they all used were more like little canvas rooms, open at the top. The crew of their launch consisted of two Bantus. One of these helped John fill the tub by the simple method of standing on a chair and pouring water on the head of the occupant of the tiny chamber after his clothes had been thrown out.

The boys were watching the proceedings and intended to follow the captain's example. As he finished he told the Bantu boy to hand him his clothes and stretched out an arm through the slit in the canvas walls. As it happened, this opening faced the boys.

The Bantu held up the bundle of clothes. As Captain Montenay took them the boys saw the black recoil suddenly and sink to his knees with a low groan, his face gray. Burt immediately leaped to his feet and caught the Bantu but the latter thrust him away and staggered back to the[Pg 72] engine. Here he sank on a locker and buried his face in his knees.

"Well I'll be jiggered!" exclaimed Burt half angrily. "What's the matter with him?" He was about to call his uncle who was up under the forward awning when Critch caught his arm.

"Shut up!" the red-haired boy whispered excitedly. "Come over here." When they reached the rail he turned on Burt. "Didn't you see it, you chump? What's the matter with you, anyway?"

"Me?" gasped Burt, bewildered by this sudden attack. "Say—"

"Thought you saw it sure," interrupted his chum hurriedly. "Didn't you see Cap'n Mac's arm?"

"No," returned Burt shortly. "Like any other arm, ain't it? I was lookin' at the sick nigger."

"Sick nothin'," retorted Critch. "Cap'n Mac's got a shoulder on him enough to scare a cat! When he shoved the canvas back I could see it all twisted up an' dead white, with a big red scar on the corner o' the shoulder. That nigger wasn't sick—he was scared!"[Pg 73]

"Scared!" Burt stared at Critch and then turned to look at the Bantu boy crouched on the locker. "Golly! Mebbe he is! Say, what was the scar like?"

"Looked to me like a cross but I didn't see it well. Come on, we'll ask the coon. He talks French some."

They stopped beside the Bantu. The second black was sitting in the bow at the wheel and had noticed nothing. Critch took the black by the shoulder and gave him a shake, while Burt addressed him in French.

"Wake up, boy! What scared you?"

The Bantu gave one terrified shudder and his eyes were rolling wildly as his head came up "Pongo! L'emblème de Pon—" he began with a frightened gasp and then stopped. His face resumed its normally blank expression and he glanced around quickly.

"What's Pongo?" questioned Burt. "What do you mean by the sign of Pongo?"

"No savvy, m'sieu, no savvy." The Bantu shook his head and absolutely refused to say another word in spite of threats and commands.

"Come on," said Critch disgustedly. "He's wise to something but he won't[Pg 74] let on. There's Cap'n Mac. Shut up."

They rejoined the captain and Mr. Wallace in the bow. Evidently the Scotchman had neither seen nor heard anything unusual, for he at once plunged into discussing plans with Mr. Wallace.

"Look here," he said finally. "I can't give up that cook o' yours, Wallace! Ye've got a good Scots name too. S'pose we make one party?"

"One party!" exclaimed Mr. Wallace. "I thought you were going more to the east?"

"Aye, but I ain't over parteec'lar. Mind, I'm no sayin' I'll go clear to the Makua wi' ye, but I may."

"Here's John with the dinner," said Mr. Wallace. "We'll talk it over while we eat. Looks mighty good to me, Montenay! I'd like you to go with us if you will."

"Hello, what's this stuff?" cried Burt as he leaned over his bowl and sniffed suspiciously. John stood by with a triumphant grin.

"Smells good," commented Critch. Captain Mac, as they had come to call him, winked at Mr. Wallace.

"It's vera good for fever," he said solemnly. "They make it out o' chopped[Pg 75] snakes an' nigger bones."

The boys looked up in dismay but were reassured by Mr. Wallace's smile and John's ever present grin. Burt put the question to the latter.

"Palm-oil chop, sar! Chicken chop-chop, palm-oil, peppers, hother t'ings halso, sar. Hit be good."

The boys cautiously sampled the concoction and found it to be new but not unpleasant. Before they had been in the country another week they were vociferously demanding palm-oil chop from John every day. The launch tied up at a plantation dock for the night and at daylight proceeded on her way.

"Hello!" exclaimed Critch as he emerged from the tiny cabin for breakfast. "That's funny! Thought it was in my outside pocket."

"What's bitin' you?" asked Burt with a rather sickly smile. He also was fishing in his pockets.

"My compass—it's gone!"

"Same here," confessed Burt after a moment. "I'll be jiggered! My coin's all right!"

"What's the matter?" inquired Mr. Wallace. He was just coming out and behind him was Captain Mac. The boys explained their strange loss and[Pg 76] Montenay frowned.

"That's queer," he said thoughtfully. "Mine's safe. How's yours, Wallace?"

"Here." Mr. Wallace produced his own silver-set compass from an inner pocket. "You've probably dropped 'em around the cabin, boys."

The two turned and vanished hastily but reappeared shaking their heads. The missing instruments were not to be found on board, although a thorough search was made of the launch and men.

"Na doot they were stolen," said Captain Mac as they sat at breakfast. "These blacks will steal anythin' that ain't nailed down, an' they were prowlin' all about last night. Well, we'll get new ones at Makupa from the trader when we get there to-night."

"It's decidedly queer, Montenay!" Mr. Wallace looked out over the river with a perplexed frown. "Why should these two compasses vanish, when nothing else in the cabin was touched? I don't like it."

"Ye know what ju-ju is, o' course?" Captain Mac leaned back easily in his chair as the American explorer nodded. "The Bantus think compasses[Pg 77] are ju-ju."

"What's that?" asked Critch.

"Anything they don't understand and that savors of witchcraft or mystery is ju-ju," explained Mr. Wallace. "In that case, Montenay, our compasses will be looked upon as the gods of a Bantu village, eh?"

"Aye. Let's get our business done with, Wallace." Montenay deftly rolled himself a quinine capsule and swallowed it. "What d'ye say? Shall we combine or no?"

"I don't see why we shouldn't," returned Mr. Wallace thoughtfully. "We're both after ivory. One caravan will cut down expenses for each of us. You're not sure about making the Makua with us?"

"Well," replied the other slowly with a sharp glance at Mr. Wallace, "I'm no sure yet. There's some mighty queer country north o' here that I'd like to have a look at. Mind, I'm no promisin' anythin' whatever. I'll be free to come an' go."

"Of course," answered Mr. Wallace. "Then it's agreed, Captain! We'll leave Makupa together in the morning."[Pg 78]

"Vera good. Now I'll be lookin' after a letter or so under the awnin' aft where the shakin' ain't so strong." Montenay rose and strolled aft and was immediately absorbed in his traveling writing-case. Mr. Wallace gazed after him reflectively.

"There's a curious man, boys! We're in luck to have him along. There probably aren't a dozen men in Africa who haven't heard of him and there probably aren't a dozen who know him outside of officials. He always travels alone. If he strikes in at Zanzibar or Nairobi he's likely to come out at Cairo or the Cape."

"Strikes me as a good sport," agreed Burt heartily. "He don't say much but I'd hate to monkey with him when he gets mad. Say! Ever hear o' Pongo, Uncle George?"

"Pongo?" repeated the explorer as he stared hard at Burt. "Pongo? No, don't think I have. What is it?"

The boys explained what had taken place the previous afternoon but to their surprise Mr. Wallace frowned disapproval. "Whatever it is, boys, it's his business. If you'll look at his arm you'll see a dozen scars. I have a few myself. That's where a native chief cuts a gash in his arm[Pg 79] and ours, the cuts are rubbed together and we are then termed 'blood-brothers.' It may have been some such mark that scared the black boy."

"No it wasn't," asserted Critch positively. "It looked like a cross. Wasn't cut either. Looked like a burn more than anything else."

"Then forget it," commanded Mr. Wallace decisively. "It's none of our business. I must say that Montenay's mighty indefinite though. He says he's after ivory and wants to have a look at the country. But if I know anything he's not worrying about ivory this trip."

"Why not?" asked Burt. "D'you mean he's lying?"

"Lying is a strong term, Burt!" smiled his uncle. "It's not a nice word to use either. No, I think he's keeping us in the dark about his own projects. Probably he has some new animal or some new tribe he wants to be sure of getting all the credit for discovering. Naturally he wouldn't want to run any risk of our cutting in on him."

Just then the subject of their discussion rejoined them and the topic was changed. On up the river they went all that day while the big[Pg 80] canoes followed closely with the paddling-chants of the men rising from time to time. The breeze created by their motion relieved them of the clouds of mosquitoes and other insects but the heat was so great that it even affected John to some extent.

Just before sunset they reached the Makupa station. This consisted of a large native village dominated by the State trading post, a corrugated iron building whose whitewashed walls contrasted strongly with the palm thatched huts of the blacks all around. The trader met them at the landing and proved to be a Belgian, pleasant and courteous in every way.

They spent the night here. In the morning they were up before daybreak and Mr. Wallace mentioned the compasses as they were dressing. At that moment Burt was speaking to Captain Montenay, and he saw a peculiar light flash into the little explorer's face when his uncle spoke. That look puzzled Burt somewhat. He was still more puzzled when Montenay rushed through his dressing and hurried from the room. The sudden change in the man had evidently been caused by his uncle's words, but Burt[Pg 81] could not see any connection whatever.

When they entered the lamp-lit dining room for breakfast they found the agent and Captain Mac together. The former sprang up and greeted them effusively, hastily stuffing something into his pocket that looked to Burt like banknotes. Still, the boy remembered his uncle's words of the day before and made up his mind not to bother about other people's affairs.

"Oh, the compasses!" ejaculated Mr. Wallace as the black boys brought in fruit and coffee. "Lieutenant, we lost two compasses coming up the river. It would be a great assistance if you would sell us a couple from your stores."

"Alas!" An expression of dismay rose to the Belgian's face and he spread out his hands helplessly. "My friend, I am grieved deeply to have to inform you that we have none! A trading party came down the river last week and completely cleaned me out, even to my own instrument. I am desolated, my heart is torn, but it is impossible!"

A sudden suspicion flashed across Burt's mind but as he glanced sharply at Captain Mac he dismissed it. Montenay was the picture of dismay, but[Pg 82] to all their suggestions and queries the Belgian only returned a "desolated" shrug.

"Well, never mind." Mr. Wallace smiled at Montenay in resignation. "We still have ours. Two should be enough. Now make a good breakfast, boys! We eat from chop-boxes after this."

With sunrise the caravan started north from the station. The river bottom was low but Captain Mac asserted that after a day's journey they would find themselves on the higher plains, and this proved quite true. On the second day they entered the great forests and left behind the half-civilized tribes. As they drew up to the top of a hill-crest that rose among the trees Critch caught Burt's arm and pointed ahead to where the jungle thinned out.

"There we are, ol' sport! Look at 'em, just look at 'em!"

And Burt saw through his glasses a number of black groups of animals, grazing and moving slowly about.

"What are they, Uncle George?" he cried in high excitement to Mr. Wallace who was also looking through his glasses.[Pg 83]

"Hartebeest, bushbuck and antelope," replied the explorer calmly. "If I'm not mistaken there's a rhino in that patch of bush about two miles to the right—see it? John, O John! Get those gun-boys on deck, will you?"[Pg 84]

"Are we going to have a hunt?" asked Burt as they left the hill and plunged forward into the jungle again at the head of the caravan.

"Not to-day," laughed Mr. Wallace. "We won't get out of this till night, will we?"

"Hardly," replied Montenay. "Once we get out o' this thick jungle and up to those plains we'll have clear sailin'. I'm no meanin' that we'll find no jungle there, mind, for we will. But by night we'll be in more decent veldt-country I'm thinkin'."

They camped at sunset in a grassy space clear of trees. As Captain Mac had predicted, the low and malarial jungle was left behind them and they were now getting into the higher lands. These were scattered with patches of dense forest and jungle, but there were also great plains or veldts covered with game and animal life.

"Now we'll make those gun-boys earn their pay," said Mr. Wallace the next morning.[Pg 85]

"We'll shoot half a dozen antelope every day to give the bearers meat."

"We'll be shootin' more than that," grimly added Captain Mac as he held up his hand for silence. "Hear that?"

All listened. It seemed to Burt and Critch that in the distance sounded a faint mutter of far-away thunder, and they looked at the older men expectantly.

"Lion," laughed Mr. Wallace shortly. "If we only had ponies we'd land him to-day!"

The advisability of taking horses along had been discussed but the explorer had vetoed it finally. "It would only be an experiment," he had declared. "In other parts of the country it might work but not in the Congo. We have too many jungles to wade through and a horse would be stung to death in a day or two."

Three or four of the Bantu hunters were sent ahead, and toward noon, as they approached a little rise, one of these came running back. He said something to Captain Mac, who translated.

"Get your guns! They've located a herd of wildebeest an' hartebeest just ahead."

The boys excitedly took their second-weight guns from the bearers. The heavy guns were not needed for the antelope. They all moved forward,[Pg 86] while the porters halted in charge of John, and after a half hour reached the crest of the rise, wading through the deep grass and bush. Here the Bantus made a gesture of caution and carefully parted the grass ahead of them.