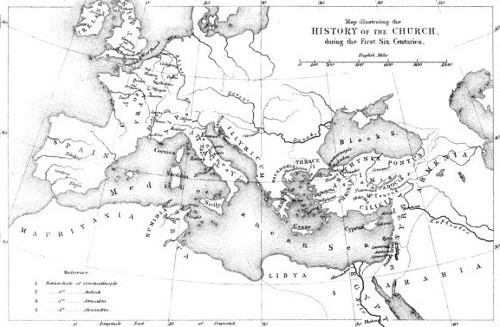

Map illustrating the HISTORY OF THE CHURCH, during the

First Six Centuries.

Map illustrating the HISTORY OF THE CHURCH, during the

First Six Centuries.

Project Gutenberg's Sketches of Church History, by James Craigie Robertson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Sketches of Church History

From A.D. 33 to the Reformation

Author: James Craigie Robertson

Release Date: May 22, 2010 [EBook #32483]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SKETCHES OF CHURCH HISTORY ***

Produced by Paul Dring, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

OF

From A.D. 33 to the Reformation.

BY THE LATE

Rev. J. C. ROBERTSON, M.A.

CANON OF CANTERBURY.

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE TRACT COMMITTEE.

LONDON:

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE,

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, CHARING CROSS, W.C.

43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C.

26, ST. GEORGE'S PLACE, HYDE PARK CORNER, S.W.

BRIGHTON: 135, NORTH STREET.

New York: E. & J. B. YOUNG & CO.

1887.

(To be read after Chapter XXII.)

[Pg xi] The Map is meant to give the names of such places only as are mentioned in the History.

The bounds of the patriarchates of Constantinople, Antioch, and Jerusalem are marked as they were settled at the Council of Chalcedon, in the year 451.

Only the northern part of the Alexandrian patriarchate is seen, as the Map does not reach far enough to take in Abyssinia, which belonged to it.

At the time of the Council of Nicæa (A.D. 325) the bishop of Rome's patriarchate was confined to the middle and the south of Italy, with the Islands of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. It afterwards grew by degrees, until at length it took in all the countries of the west, although it had lost Illyricum, which was once a part of it. But this was not until long after the time to which our little book relates, and in the meanwhile its extent varied very much. The reason why its bounds, at the time of the Council of Chalcedon, or in the days of Gregory the Great, cannot well be marked in a map is, that in some countries the bishops of Rome had much influence, but had not power. They gave advice to the bishops of Gaul (or France), Spain, and Africa, and sometimes ventured to give them directions. But they could not make the bishops of those countries obey their directions, and had not authority over them in the same way as the patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, or Jerusalem had over the bishops within their patriarchates. To mark such countries as belonging to the Roman patriarchate would be too much; to mark them as if they had no connexion with it would be too little.

SKETCHES

OF

CHURCH HISTORY.

THE AGE OF THE APOSTLES.

FROM A.D. 33 TO A.D. 100.

[Pg 1] The beginning of the Christian Church is reckoned from the great day on which the Holy Ghost came down, according as our Lord had promised to His Apostles. At that time, "Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven," were gathered together at Jerusalem, to keep the Feast of Pentecost (or Feast of Weeks), which was one of the three holy seasons at which God required His people to appear before Him in the place which He had chosen (Deuteronomy xvi. 16). Many of these devout men were converted, by what they then saw and heard, to believe the Gospel; and, when they returned to their own countries, they carried back with them the news of the wonderful things which had taken place at Jerusalem. After this, the Apostles went forth "into all the world," as their Master had ordered them, to "preach the Gospel to every creature" (St. Mark xvi. 15). The Book of Acts tells us something of what they did, and we may learn something more about it from the Epistles. And, although this be but a small part of the whole, it will give us a notion of the rest, if we consider that, while St. Paul was preaching in Asia Minor,[Pg 2] in Greece, and at Rome, the other Apostles were busily doing the same work in other countries.

We must remember, too, the constant coming and going which in those days took place throughout the world; how Jews from all quarters went up to keep the passover and other feasts at Jerusalem; how the great Roman empire stretched from our own island of Britain as far as Persia and Ethiopia, and people from all parts of it were continually going to Rome and returning. We must consider how merchants travelled from country to country on account of their trade; how soldiers were sent into all quarters of the empire, and were moved about from one country to another. And from these things we may get some understanding of the way in which the knowledge of the Gospel would be spread, when once it had taken root in the great cities of Jerusalem and Rome. Thus it came to pass, that, by the end of the first hundred years after our Saviour's birth, something was known of the Christian faith throughout all the Roman empire, and even in countries beyond it; and if in many cases, only a very little was known, still even that was a gain, and served as a preparation for more.

The last chapter of the Acts leaves St. Paul at Rome, waiting for his trial on account of the things which the Jews had laid to his charge. We find from the Epistles that he afterwards got his liberty, and returned into the East. There is reason to suppose that he also visited Spain, as he had spoken of doing in his Epistle to the Romans (ch. xv. 28); and it has been thought by some that he even preached in Britain; but this does not seem likely. He was at last imprisoned again at Rome, where the wicked Emperor Nero persecuted the Christians very cruelly; and it is believed that both St. Peter and St. Paul were put to death there in the year of our Lord 68. The bishops of Rome afterwards set up claims to great power and honour, because they said that St. Peter was the first bishop of their church, and that they were his successors. But although we may reasonably believe that the Apostle was martyred at Rome, there does not appear to be any [Pg 3] good ground for thinking that he had been settled there as bishop of the city.

All the Apostles, except St. John, are supposed to have been martyred (or put to death for the sake of the Gospel). St. James the Less, who was bishop of Jerusalem, was killed by the Jews in an uproar, about the year 62. Soon after this, the Romans sent their armies into Judea, and, after a bloody war, they took the city of Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple, and scattered the Jews all over the earth. Thus the Jews were punished, as our Lord had foretold, for the great sin of which they had been guilty in refusing to believe in Him, and in putting Him to death.

Thirty years after Nero's time another cruel emperor, Domitian, raised a fresh persecution against the Christians (A.D. 95). Among those who suffered were some of his own near relations; for the Gospel had now made its way among the great people of the earth, as well as among the poor, who were the first to listen to it. There is a story that the emperor was told that some persons of the family of David were living in the Holy Land, and that he sent for them, because he was afraid lest the Jews should set them up as princes, and should rebel against his government. They were two grandchildren of St. Jude, who was one of our Lord's kinsmen after the flesh, and therefore belonged to the house of David and the old kings of Judah. But these two were plain countrymen, who lived quietly and contentedly on their little farm, and were not likely to lead a rebellion, or to claim earthly kingdoms. And when they were carried before the emperor, they showed him their hands, which were rough and horny from working in the fields; and in answer to his questions about the kingdom of Christ, they said that it was not of this world, but spiritual and heavenly, and that it would appear at the end of the world, when the Saviour would come again to judge both the quick and the dead. So the emperor saw that there was nothing to fear from them, and he let them go.

It was during Domitian's persecution that St. John was banished to the island of Patmos, where he saw the visions [Pg 4] which are described in his "Revelation." All the other Apostles had been long dead, and St. John had lived many years at Ephesus, where he governed the churches of the country around. After his return from Patmos he went about to all these churches, that he might repair the hurt which they had suffered in the persecution. In one of the towns which he visited, he noticed a young man of very pleasing looks, and called him forward, and desired the bishop of the place to take care of him. The bishop did so, and, after having properly trained the youth, he baptised and confirmed him. But when this had been done, the bishop thought that he need not watch over him so carefully as before; and the young man fell into vicious company, and went on from bad to worse, until at length he became the head of a band of robbers, who kept the whole country in terror. When the Apostle next visited the town, he asked after the charge which he had put into the bishop's hands. The bishop, with shame and grief, answered that the young man was dead, and, on being further questioned, he explained that he meant dead in sins, and told all the story. St. John, after having blamed him because he had not taken more care, asked where the robbers were to be found, and set off on horseback for their haunt, where he was seized by some of the band, and was carried before the captain. The young man, on seeing him, knew him at once, and could not bear his look, but ran away to hide himself. But the Apostle called him back, told him that there was yet hope for him through Christ, and spoke in such a moving way that the robber agreed to return to the town. There he was once more received into the Church as a penitent; and he spent the rest of his days in repentance for his sins, and in thankfulness for the mercy which had been shown to him.

St. John, in his old age, was much troubled by false teachers, who had begun to corrupt the Gospel. These persons are called heretics, and their doctrines are called heresy, from a Greek word which means to choose, because they chose to follow their own fancies, instead of receiving[Pg 5] the Gospel as the Apostles and the Church taught it. Simon the sorcerer, who is mentioned in the eighth chapter of the Acts, is counted as the first heretic, and even in the time of the Apostles a number of others arose, such as Hymenæus, Philetus, and Alexander, who are mentioned by St. Paul (1 Tim. i. 19, 20; 2 Tim. ii. 17, 18). These earliest heretics were mostly of the kind called Gnostics,—a word which means that they pretended to be more knowing than ordinary Christians; and perhaps St. Paul may have meant them especially when he warned Timothy against "science" (or knowledge) "falsely so called" (1 Tim. vi. 20). Their doctrines were a strange mixture of Jewish and heathen notions with Christianity; and it is curious that some of the very strangest of their opinions have been brought up again from time to time by people who fancied that they had found out something new, while they had only fallen into old errors, which had been condemned by the Church hundreds of years before.

St. John lived to about the age of a hundred. He was at last so weak that he could not walk into the church; so he was carried in, and used to say continually to his people, "Little children, love one another." Some of them, after a time, began to be tired of hearing this, and asked him why he repeated the words so often, and said nothing else to them. The Apostle answered, "Because it is the Lord's commandment, and if this be done it is enough."

ST. IGNATIUS.

A.D. 116.

When our Lord ascended into Heaven, He left the government of His Church to the Apostles. We are told that during the forty days between His rising from the grave and His ascension, He gave commandments unto the [Pg 6] Apostles, and spoke of the things pertaining (or belonging) to the kingdom of God (Acts i. 2, 3). Thus they knew what they were to do when their Master should be no longer with them; and one of the first things which they did, even without waiting until His promise of sending the Holy Ghost should be fulfilled, was to choose St. Matthias into the place which had been left empty by the fall of the traitor Judas (Acts i. 15-26).

After this we find that they appointed other persons to help them in their work. First, they appointed the deacons, to take care of the poor and to assist in other services. Then they appointed presbyters (or elders), to undertake the charge of congregations. Afterwards, we find St. Paul sending Timothy to Ephesus, and Titus into the island of Crete (now called Candia), with power to "ordain elders in every city" (Tit. i. 5), and to govern all the churches within a large country. Thus, then, three kinds (or orders) of ministers of the Church are mentioned in the Acts and Epistles. The deacons are lowest; the presbyters, or elders, are next; and, above these, there is a higher order, made up of the Apostles themselves, with such persons as Timothy and Titus, who had to look after a great number of presbyters and deacons, and were also the chief spiritual pastors (or shepherds) of the people who were under the care of these presbyters and deacons. In the New Testament, the name of bishops (which means overseers) is sometimes given to the Apostles and other clergy of the highest order, and sometimes to the presbyters; but after a time it was given only to the highest order, and when the Apostles were dead, the bishops had the chief government of the Church. It has since been found convenient that some bishops should be placed above others, and should be called by higher titles, such as archbishops and patriarchs; but these all belong to the same order of bishops; just as in a parish, although the rector and the curate have different titles, and one of them is above the other, they are both most commonly presbyters (or, as we now say, priests), and so they both belong to the same order in the ministry.

[Pg 7] One of the most famous among the early bishops was St. Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, the place where the disciples were first called Christians (Acts xi. 26). Antioch was the chief city of Syria, and was so large that it had more than two hundred thousand inhabitants. St. Peter himself is said to have been its bishop for some years; and, although this is perhaps a mistake, it is worth remembering, because we shall find by-and-by that much was said about the bishops of Antioch being St. Peter's successors, as well as the bishops of Rome.

Ignatius had known St. John, and was made bishop of Antioch about thirty years before the Apostle's death. He had governed his church for forty years or more, when the Emperor Trajan came to Antioch. In the Roman history, Trajan is described as one of the best among the emperors; but he did not treat the Christians well. He seems never to have thought that the Gospel could possibly be true, and thus he did not take the trouble to inquire what the Christians really believed or did. They were obliged in those days to hold their worship in secret, and mostly by night, or very early in the morning, because it would not have been safe to meet openly; and hence, the heathens, who did not know what was done at their meetings, were tempted to fancy all manner of shocking things, such as that the Christians practised magic; that they worshipped the head of an ass; that they offered children in sacrifice; and that they ate human flesh! It is not likely that the Emperor Trajan believed such foolish tales as these; and, when he did make some inquiry about the ways of the Christians, he heard nothing but what was good of them. But still he might think that there was some mischief behind; and he might fear lest the secret meetings of the Christians should have something to do with plots against his government; and so, as I have said, he was no friend to them.

When Trajan came to Antioch, St. Ignatius was carried before him. The emperor asked what evil spirit possessed him, so that he not only broke the laws by refusing to serve [Pg 8] the gods of Rome, but persuaded others to do the same. Ignatius answered, that he was not possessed by any evil spirit; that he was a servant of Christ; that by His help he defeated the malice of evil spirits; and that he bore his God and Saviour within his heart. After some more questions and answers, the emperor ordered that he should be carried in chains to Rome, and there should be devoured by wild beasts. When Ignatius heard this terrible sentence, he was so far from being frightened, that he burst forth into thankfulness and rejoicing, because he was allowed to suffer for his Saviour, and for the deliverance of his people.

It was a long and toilsome journey, over land and sea, from Antioch to Rome; and an old man, such as Ignatius, was ill able to bear it, especially as winter was coming on. He was to be chained, too, and the soldiers who had the charge of him behaved very rudely and cruelly to him. And no doubt the emperor thought that, by sending so venerable a bishop in this way to suffer so fearful and so disgraceful a death (to which only the very lowest wretches were usually sentenced), he should terrify other Christians into forsaking their faith. But instead of this, the courage, and the patience with which St. Ignatius bore his sufferings gave the Christians fresh spirit to endure whatever might come on them.

The news that the holy bishop of Antioch was to be carried to Rome soon spread, and at many places on the way the bishops, clergy, and people flocked together, that they might see him, and pray and talk with him, and receive his blessing. And when he could find time, he wrote letters to various churches, exhorting them to stand fast in the faith, to be at peace among themselves, to obey the bishops who were set over them, and to advance in all holy living. One of the letters was written to the Church at Rome, and was sent on by some persons who were travelling by a shorter way. St. Ignatius begs, in this letter, that the Romans will not try to save him from death. "I am the wheat of God," he says, "let me be ground by the teeth of beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ.[Pg 9] Rather do ye encourage the beasts, that they may become my tomb, and may leave nothing of my body, so that, when dead, I may not be troublesome to any one." He even says that, if the lions should hang back, he will himself provoke them to attack him. It would not be right for ordinary people to speak in this way, and the Church has always disapproved of those who threw themselves in the way of persecution. But a holy man who had served God for so many years as Ignatius, might well speak in a way which would not become ordinary Christians. When he was called to die for his people and for the truth of Christ, he might even take it as a token of God's favour, and might long for his deliverance from the troubles and the trials of this world, as St. Paul said of himself, that he "had a desire to depart, and to be with Christ" (Phil. i. 23).

He reached Rome just in time for some games which were to take place a little before Christmas; for the Romans were cruel enough to amuse themselves with setting wild beasts to tear and devour men, in vast places called amphitheatres, at their public games. When the Christians of Rome heard that Ignatius was near the city, great numbers of them went out to meet him, and they said that they would try to persuade the people in the amphitheatre to beg that he might not be put to death. But he entreated, as he had before done in his letter, that they would do nothing to hinder him from glorifying God by his death; and he knelt down with them, and prayed that they might continue in faith and love, and that the persecution might soon come to an end. As it was the last day of the games, and they were nearly over, he was then hurried into the amphitheatre (called the Coliseum), which was so large that tens of thousands of people might look on. And in this place (of which the ruins are still to be seen), St. Ignatius was torn to death by wild beasts, so that only a few of his larger bones were left, which the Christians took up and conveyed to his own city of Antioch.

ST. JUSTIN, MARTYR.

A.D. 166.

[Pg 10] Although Trajan was no friend to the Gospel, and put St. Ignatius to death, he made a law which must have been a great relief to the Christians. Until then, they were liable to be sought out, and any one might inform against them; but Trajan ordered that they should not be sought out, although, if they were discovered, and refused to give up their faith, they were to be punished. The next emperor, too, whose name was Hadrian (A.D. 117 to 138), did something to make their condition better; but it was still one of great hardship and danger. Notwithstanding the new laws, any governor of a country, who disliked the Christians, had the power to persecute and vex them cruelly. And the common people among the heathens still believed the horrid stories of their killing children and eating human flesh. If there was a famine or a plague,—if the river Tiber, which runs through Rome, rose above its usual height and did mischief to the neighbouring buildings,—or if the emperor's armies were defeated in war, the blame of all was laid on the Christians. It was said that all these things were judgments from the gods, who were angry because the Christians were allowed to live. And then at the public games, such as those at which St. Ignatius was put to death, the people used to cry out, "Throw the Christians to the lions! away with the godless wretches!" For, as the Christians were obliged to hold their worship secretly, and had no images like those of the heathen gods, and did not offer any sacrifices of beasts, as the heathens did, it was thought that they had no God at all; since the heathens could not raise their minds to the thought of that God who is a spirit, and who is not to be worshipped under any bodily shape. It was, therefore, a great relief[Pg 11] when the Emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138 to 161), who was a mild and gentle old man, ordered that governors and magistrates should not give way to such outcries, and that the Christians should no longer be punished for their religion only, unless they were found to have done wrong in some other way.

There were now many learned men in the Church, and some of these began to write books in defence of their faith. One of them, Athenagoras, had undertaken, while he was a heathen, to show that the Gospel was all a deceit; but when he looked further into the matter, he found that it was very different from what he had fancied; and then he was converted, and, instead of writing against the Gospel, he wrote in favour of it.

Another of these learned men was Justin, who was born at Samaria, and was trained in all the wisdom of the Greeks. For the Greeks, as they were left without such light as God had given to the Jews, set themselves to seek out wisdom in all sorts of ways. And, as they had no certain truth from heaven to guide them, they were divided into a number of different parties, such as the Epicureans, and the Stoics, who disputed with St. Paul at Athens (Acts xvii. 18). These all called themselves philosophers (which means, lovers of wisdom); and each kind of them thought to be wiser than all the rest. Justin, then, having a strong desire to know the truth, tried one kind of philosophy after another, but could not find rest for his spirit in any of them.

One day, as he was walking thoughtfully on the sea-shore, he observed an old man of grave and mild appearance, who was following him closely, and at length entered into talk with him. The old man told Justin that it was of no use to search after wisdom in the books of the philosophers; and went on to speak of God the maker of all things, of the prophecies which He had given to men in the time of the Old Testament, and how they had been fulfilled in the life and death of the blessed Jesus. Thus Justin was brought to the knowledge of the Gospel; and the more he [Pg 12] learnt of it, the more was he convinced of its truth, as he came to know how pure and holy its doctrines and its rules were, and as he saw the love which Christians bore towards each other, and the patience and firmness with which they endured sufferings and death for their Master's sake. And now, although he still called himself a philosopher, and wore the long cloak which was the common dress of philosophers, the wisdom which he taught was not heathen but Christian wisdom. He lived mostly at Rome, where scholars flocked to him in great numbers. And he wrote books in defence of the Gospel against heathens, Jews, and heretics, or false Christians.

The old Emperor Antoninus Pius, under whom the Christians had been allowed to live in peace and safety, died in the year 161, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, whom he had adopted as his son. Marcus Aurelius was not only one of the best emperors, but in many ways was one of the best of all the heathens. He had a great character for gentleness, kindness, and justice, and he was fond of books, and liked to have philosophers and learned men about him. But, unhappily, these people gave him a very bad notion of Christianity; and, as he knew no more of it than what they told him, he took a strong dislike to it. And thus, although he was just and kind to his other subjects, the Christians suffered more under his reign than they had ever done before. All the misfortunes that took place, such as rebellions, defeats in war, plague, and scarcity, were laid to the blame of the Christians; and the emperor himself seems to have thought that they were in fault, as he made some new laws against them.

Now the success which Justin had as a teacher at Rome had long raised the envy and malice of the heathen philosophers; and, when these new laws against the Christians came out, one Crescens, a philosopher of the kind called Cynics, or doggish (on account of their snarling, currish ways), contrived that Justin should be carried before a judge, on the charge of being a Christian. The judge [Pg 13] questioned him as to his belief, and as to the meetings of the Christians; to which Justin answered that he believed in one God, and in the Saviour Christ, the Son of God, but he refused to say anything which could betray his brethren to the persecutors. The judge then threatened him with scourging and death: but Justin replied that the sufferings of this world were nothing to the glory which Christ had promised to His people in the world to come. Then he and the others who had been brought up for trial with him were asked whether they would offer sacrifice to the gods of the heathen, and as they refused to do this, and to forsake their faith, they were all beheaded (A.D. 166). And on account of the death which he thus suffered for the Gospel, Justin has ever since been especially styled "The Martyr."

ST. POLYCARP.

A.D. 166.

About the same time with Justin the Martyr, St. Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, was put to death. He was a very old man; for it was almost ninety years since he had been converted from heathenism. He had known St. John, and is supposed to have been made bishop of Smyrna by that Apostle himself; and he had been a friend of St. Ignatius, who, as we have seen, suffered martyrdom fifty years before. From all these things, and from his wise and holy character, he was looked up to as a father by all the Churches, and his mild advice had sometimes put an end to differences of opinion which but for him might have turned into lasting quarrels.

When the persecution reached Smyrna, in the reign of Marcus Aurelius, a number of Christians suffered with great constancy, and the heathen multitude, being provoked [Pg 14] at their refusal to give up their faith, cried out for the death of Polycarp. The aged bishop, although he was ready to die for his Saviour, remembered that it was not right to throw himself in the way of danger; so he left the city, and went first to one village in the neighbourhood, and then to another. But he was discovered in his hiding-place, and when he saw the soldiers who were come to seize him, he calmly said, "God's will be done!" He desired that some food should be given to them, and, while they were eating, he spent the time in prayer. He was then set on an ass, and led towards Smyrna; and, when he was near the town, one of the heathen magistrates came by in his chariot, and took him up into it. The magistrate tried to persuade Polycarp to sacrifice to the gods; but finding that he could make nothing of him, he pushed him out of the chariot so roughly that the old man fell and broke his leg. But Polycarp bore the pain without showing how much he was hurt, and the soldiers led him into the amphitheatre, where great numbers of people were gathered together. When all these saw him, they set up loud cries of rage and savage delight; but Polycarp thought, as he entered the place, that he heard a voice saying to him, "Be strong and play the man!" and he did not heed all the shouting of the crowd. The governor desired him to deny Christ, and said that, if he would, his life should be spared. But the faithful bishop answered, "Fourscore and six years have I served Christ, and He hath never done me wrong; how then can I now blaspheme my King and Saviour?" The governor again and again urged him, as if in a friendly way, to sacrifice; but Polycarp stedfastly refused. He next threatened to let wild beasts loose on him; and as Polycarp still showed no fear, he said that he would burn him alive. "You threaten me," said the bishop, "with a fire which lasts but a short time; but you know not of that eternal fire which is prepared for the wicked." A stake was then set up, and a pile of wood was collected around it. Polycarp walked to the place with a calm and cheerful look, and, as the executioners were [Pg 15] going to fasten him to the stake with iron cramps, he begged them to spare themselves the trouble: "He who gives me the strength to bear the flames," he said, "will enable me to remain steady." He was therefore only tied to the stake with cords, and as he stood thus bound, he uttered a thanksgiving for being allowed to suffer after the pattern of his Lord and Saviour. When his prayer was ended, the wood was set on fire, but we are told that the flames swept round him, looking like the sail of a ship swollen by the wind, while he remained unhurt in the midst of them. One of the executioners, seeing this, plunged a sword into the martyr's breast, and the blood rushed forth in such a stream that it put out the fire. But the persecutors, who were resolved that the Christians should not have their bishop's body, lighted the wood again, and burnt the corpse, so that only a few of the bones remained; and these the Christians gathered out, and gave them an honourable burial. It was on Easter eve that St. Polycarp suffered, in the year of our Lord 166.

THE MARTYRS OF LYONS AND VIENNE.

A.D. 177.

Many other martyrs suffered in various parts of the empire under the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Among the most famous of these are the martyrs of Lyons and Vienne, in the south of France (or Gaul, as it was then called), where a company of missionaries from Asia Minor had settled with a bishop named Pothinus at their head. The persecution at Lyons and Vienne was begun by the mob of those towns, who insulted the Christians in the streets, broke into their houses, and committed other such outrages against them. Then a great number of Christians were [Pg 16] seized, and imprisoned in horrid dungeons, where many died from want of food, or from the bad and unwholesome air. The bishop, Pothinus, who was ninety years of age, and had long been very ill, was carried before the governor, and was asked, "Who is the God of Christians?" Pothinus saw that the governor did not put this question from any good feeling; so he answered, "If thou be worthy, thou shalt know." The bishop, old and feeble as he was, was then dragged about by soldiers, and such of the mob as could reach him gave him blows and kicks, while others, who were further off, threw anything which came to hand at him; and, after this cruel usage, he was put into prison, where he died within two days.

The other prisoners were tortured for six days together in a variety of horrible ways. Their limbs were stretched on the rack; they were cruelly scourged; some had hot plates of iron applied to them, and some were made to sit in a red-hot iron chair. The firmness with which they bore these dreadful trials gave courage to some of their brethren, who at first had agreed to sacrifice, so that these now again declared themselves Christians, and joined the others in suffering. As all the tortures were of no effect, the prisoners were at length put to death. Some were thrown to wild beasts; but those who were citizens of Rome were beheaded; for it was not lawful to give a Roman citizen up to wild beasts, just as we know from St. Paul's case at Philippi that it was not lawful to scourge a citizen (Acts xvi. 37).

Among the martyrs was a boy from Asia, only fifteen years old, who was taken every day to see the tortures of the rest, in the hope that he might be frightened into denying his Saviour; but he was not shaken by the terrible sights, and for his constancy he was cruelly put to death on the last day. The greatest cruelties of all, however, were borne by a young woman named Blandina. She was slave to a Christian lady; and, although the Christians regarded their slaves with a kindness very unlike the usual feeling of heathen masters towards them, this lady seems[Pg 17] yet to have thought that a slave was not likely to endure tortures so courageously as a free person; and she was the more afraid because Blandina was not strong in body. But the poor slave's faith was not to be overcome. Day after day she bravely bore every cruelty that the persecutors could think of; and all that they could wring out from her was, "I am a Christian, and nothing wrong is done among us!"

The heathen were not content with putting the martyrs to death with tortures, or allowing them to die in prison. They cast their dead bodies to the dogs, and caused them to be watched day and night, lest the other Christians should give them burial; and after this, they burnt the bones, and threw the ashes of them into the river Rhone, by way of mocking at the notion of a resurrection. For, as St. Paul had found at Athens (Acts xvii. 32), and elsewhere, there was no part of the Gospel which the heathen in general thought so hard to believe as the doctrine that that which is "sown in corruption" shall hereafter be "raised in incorruption;" that that which "is sown a natural body" will one day be "raised a spiritual body" (1 Cor. xv. 42-44).

TERTULLIAN—PERPETUA AND HER COMPANIONS.

A.D. 181-206.

The Emperor Marcus Aurelius died in 181, and the Church was little troubled by persecution for the following twenty years.

About this time a false teacher named Montanus made much noise in the world. He was born in Phrygia, and seems to have been crazed in his mind. He used to fall into fits, and while in them, he uttered ravings which were taken for prophecies, or messages from heaven: and some [Pg 18] women who followed him also pretended to be prophetesses. These people taught a very strict way of living, and thus many persons who wished to lead holy lives were deceived into running after them. One of these was Tertullian, of Carthage, in Africa, a very clever and learned man, who had been converted from heathenism, and had written some books in defence of the Gospel. But he was of a proud and impatient temper, and did not rightly consider how our Lord Himself had said that there would always be a mixture of evil with the good in His Church on earth (St. Matt. xiii. 38, 48). And hence, when Montanus pretended to set up a new church, in which there should be none but good and holy people, Tertullian fell into the snare, and left the true Church to join the Montanists (as the followers of Montanus were called). From that time he wrote very bitterly against the Church; but he still continued to defend the Gospel in his books against Jews and heathens, and all kinds of false teachers, except Montanus. And when he was dead, his good deeds were remembered more than his fall, so that, with all his faults, his name has always been held in respect.

After more than twenty years of peace, there were cruel persecutions in some places, under the reign of Severus. The most famous of the martyrs who then suffered were Perpetua and her companions, who belonged to the same country with Tertullian, and perhaps to his own city, Carthage. Perpetua was a young married lady, and had a little baby only a few weeks old. Her father was a heathen, but she herself had been converted, and was a catechumen—which was the name given to converts who had not yet been baptized, but where in a course of catechising, or training for baptism. When Perpetua had been put into prison, her father went to see her, in the hope that he might persuade her to give up her faith. "Father," she said, "you see this vessel standing here; can you call it by any other than its right name?" He answered, "No." "Neither," said Perpetua, "can I call myself anything else than what I am—a Christian." On hearing this, her father [Pg 19] flew at her in such anger that it seemed as if he would tear out her eyes; but she stood so quietly that he could not bring himself to hurt her; and he went away and did not come again for some time.

In the meanwhile Perpetua and some of her companions were baptized; and at her baptism she prayed for grace to bear whatever sufferings might be in store for her. The prison in which she and the others were shut up was a horrible dungeon, where Perpetua suffered much from the darkness, the crowded state of the place, the heat and closeness of the air, and the rude behaviour of the guards. But most of all she was distressed about her poor little child, who was separated from her, and was pining away. Some kind Christians, however, gave money to the keepers of the prison, and got leave for Perpetua and her friends to spend some hours of the day in a lighter part of the building, where her child was brought to see her. And after a while she took him to be always with her, and then she felt as cheerful as if she had been in a palace.

The martyrs were comforted by dreams, which served to give them courage and strength to bear their sufferings, by showing them visions of blessedness which was to follow. When the day was fixed for their trial, Perpetua's father went again to see her. He begged her to take pity on his old age, to remember all his kindness to her, and how he had loved her best of all his children. He implored her to think of her mother and her brothers, and of the disgrace which would fall on all the family if she were to be put to death as an evil-doer. The poor old man shed a flood of tears; he humbled himself before her, kissing her hands, throwing himself at her feet, and calling her Lady instead of Daughter. But, although Perpetua was grieved to the heart, she could only say, "God's pleasure will be done on us. We are not in our own power, but in His!"

One day, as the prisoners were at dinner, they were suddenly hurried off to their trial. The market-place, where the judge was sitting, was crowded with people, and when Perpetua was brought forward, her father crept as close to [Pg 20] her as he could, holding out her child, and said, "Take pity on your infant." The judge himself entreated her to pity the little one and the old man, and to sacrifice; but, painful as the trial was, she steadily declared that she was a Christian, and that she could not worship false gods. At these words, her father burst out into such loud cries that the judge ordered him to be put down from the place where he was standing, and to be beaten with rods. Perhaps the judge did not mean so much to punish the old man for being noisy as to try whether the sight of his suffering might not move his daughter; but, although Perpetua felt every blow as if it had been laid upon herself, she knew that she must not give way. She was condemned, with her companions, to be exposed to wild beasts; and, after she had been taken back to prison, her father visited her once more. He seemed as if beside himself with grief; he tore his white beard, he cursed his old age, and spoke in a way that might have moved a heart of stone. But still Perpetua could only be sorry for him; she could not give up her Saviour.

The prisoners were kept for some time after their condemnation, that they might be put to death at some great games which were to be held on the birthday of one of the emperor's sons; and during this confinement their behaviour had a great effect on many who saw it. The gaoler himself was converted by it, and so were others who had gone to gaze at them. At length the appointed day came, and the martyrs were led into the amphitheatre. The men were torn by leopards and bears; Perpetua and a young woman named Felicitas, who had been a slave, were put into nets and thrown before a furious cow, who tossed them and gored them cruelly: and when this was over, Perpetua seemed as if she had not felt it, but were awaking from a trance, and she asked when the cow was to come. She then helped Felicitas to rise from the ground, and spoke words of comfort and encouragement to others. When the people in the amphitheatre had seen as much as they wished of the wild beasts, they called out [Pg 21] that the prisoners should be killed. Perpetua and the rest then took leave of each other, and walked with cheerful looks and firm steps into the middle of the amphitheatre, where men with swords fell on them and dispatched them. The executioner who was to kill Perpetua was a youth, and was so nervous that he stabbed her in a place where the hurt was not deadly; but she herself took hold of his sword, and showed him where to give her the death-wound.

ORIGEN.

A.D. 185-254.

The same persecution in which Perpetua and her companions suffered at Carthage raged also at Alexandria in Egypt, where a learned man named Leonides was one of the martyrs (A.D. 202). Leonides had a son named Origen, whom he had brought up very carefully, and had taught to get some part of the Bible by heart every day. And Origen was very eager to learn, and was so good and so clever that his father was afraid to show how fond and how proud he was of him, lest the boy should become forward and conceited. So when Origen asked questions of a kind which few boys would have thought of asking, his father used to check him; but when he was asleep Leonides would steal to his bedside and kiss him, thanking God for having given him such a child, and praying that Origen might always be kept in the right way.

When the persecution began, Origen, who was then about seventeen years old, wished that he might be allowed to die for his faith; but his mother hid his clothes, and so obliged him to stay at home; and all that he could do was to write to his father in prison, and to beg that he would not fear lest the widow and orphans should be left destitute, but [Pg 22] would be steadfast in his faith, and would trust in God to provide for their relief.

The persecutors were not content with killing Leonides, but seized on all his property, so that the widow was left in great distress, with seven children, of whom Origen was the eldest. A Christian lady kindly took Origen into her house; and after a time, young as he was, he was made master of the Catechetical School, a sort of college, where the young Christians of Alexandria were instructed in religion and learning. The persecution had slackened for a while, but it began again, and some of Origen's pupils were martyred. He went with them to their trial, and stood by them in their sufferings; but although he was ill-used by the mob of Alexandria, he was himself allowed to go free.

Origen had read in the Gospel, "Freely ye have received, freely give" (St. Matt. x. 8), and he thought that therefore he ought to teach for nothing. In order, therefore, that he might be able to do this, he sold a quantity of books which he had written out, and lived for a long time on the price of them, allowing himself only about fivepence a day. His food was of the poorest kind; he had but one coat, through which he felt the cold of winter severely; he sat up the greater part of the night, and then lay down on the bare floor. When he grew older, he came to understand that he had been mistaken in some of his notions as to these things, and to regret that, by treating himself so hardly, he had hurt his health beyond repair. But still, mistaken as he was, we must honour him for going through so bravely with what he took to be his duty.

He soon grew so famous as a teacher, that even Jews, heathens, and heretics went to hear him; and many of them were so led on by him that they were converted to the Gospel. He travelled a great deal: some of his journeys were taken because he had been invited into foreign countries that he might teach the Gospel to people who were desirous of instruction in it, or that he might settle disputes about religion. And he was invited to go on a visit to the mother of the Emperor Alexander Severus, who was himself [Pg 23] friendly to Christianity, although not a Christian. Origen, too, wrote a great number of books in explanation of the Bible, and on other religious subjects; and he worked for no less than eight-and-twenty years at a great book, called the Hexapla, which was meant to show how the Old Testament ought to be read in Hebrew and in Greek.

But, although he was a very good, as well as a very learned man, Origen fell into some strange opinions, from wishing to clear away some of those difficulties which, as St. Paul says, made the Gospel seem "foolishness" to the heathen philosophers (1 Cor. i. 23). Besides this, Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria, although he had been his friend, had some reasons for not wishing to ordain him to be one of the clergy; and when Origen had been ordained a presbyter (or priest) in the Holy Land, where he was on a visit, Demetrius was very angry. He said that no man ought to be ordained in any church but that of his own home; and he brought up stories about some rash things which Origen had done in his youth, and questions about the strange doctrines which he held. Origen, finding that he could not hope for peace at Alexandria, went back to his friend the bishop of Cæsarea, by whom he had been ordained, and he spent many years at Cæsarea, where he was more sought after as a teacher than ever. At one time he was driven into Cappadocia, by the persecution of a savage emperor named Maximin, who had murdered the gentle Alexander Severus; but he returned to Cæsarea, and lived there until another persecution began under the Emperor Decius.

This was by far the worst persecution that had yet been known. It was the first which was carried on throughout the whole empire, and no regard was now paid to the old laws which Trajan and other emperors had made for the protection of the Christians. They were sought out, and were made to appear in the market-place of every town, where they were required by the magistrates to sacrifice, and, if they refused, were sentenced to severe punishment. The emperor wished most to get at the bishops and clergy; for [Pg 24] he thought that, if the teachers were put out of the way, the people would soon give up the Gospel. Although many martyrs were put to death at this time, the persecutors did not so much wish to kill the Christians, as to make them disown their religion; and, in the hope of this, many of them were starved, and tortured, and sent into banishment in strange countries, among wild people who had never before heard of Christ. But here the emperor's plans were notably disappointed; for the banished bishops and clergy had thus an opportunity of making the Gospel known to those poor wild tribes, whom it might not have reached for a long time if the Church had been left in quiet.

We shall hear more about the persecution in the next chapter. Here I shall only say that Origen was imprisoned and cruelly tortured. He was by this time nearly seventy years old, and was weak in body from the labours which he had gone through in study, and from having hurt his health by hard and scanty living in his youth; so that he was ill able to bear the pains of the torture, and, although he did not die under it, he died of its effects soon after (A.D. 254).

Decius himself was killed in battle (A.D. 251), and his persecution came to an end. And when it was over, the faithful understood that it had been of great use, not only by helping to spread the Gospel, in the way which has been mentioned, but in purifying the Church, and in rousing Christians from the carelessness into which too many of them had fallen during the long time of ease and quiet which they had before enjoyed. For the trials which God sends on His people in this world are like the chastisements of a loving Father; and, if we accept them rightly, they will all be found to turn out to our good.

ST. CYPRIAN.

PART I. A.D. 200-253.

[Pg 25] About the same time with Origen lived St Cyprian, bishop of Carthage. He was born about the year 200, and had been long famous as a professor of heathen learning, when he was converted at the age of forty-five. He then gave up his calling as a teacher, and, like the first Christians at Jerusalem (Acts iv. 34-5), he sold a fine house and gardens, which he had near the town, and gave the price, with a large part of his other money, to the poor. He became one of the clergy of Carthage, and when the bishop died, about three years after, Cyprian was so much loved and respected that he was chosen in his place (A.D. 248).

Cyprian tried with all his power to do the duties of a good bishop, and to get rid of many wrong things which had grown upon his Church during the long peace which it had enjoyed. But about two years after he was made bishop, the persecution under Decius broke out, when, as was said in the last chapter, the persecutors tried especially to strike at the bishops and clergy, and to force them to deny their faith. Now Cyprian would have been ready and glad to die, if it would have served the good of his people; but he remembered how our Lord had said, "When they persecute you in this city, flee ye into another" (St. Matt. x. 23), and how He Himself withdrew from the rage of His enemies, because His "hour was not yet come" (St. John viii. 20, 59; xi. 54). And it seemed to the good bishop, that for the present it would be best to go out of the way of his persecutors. But he kept a constant watch over all that was done in his church, and he often wrote to his clergy and people from the place where he was hidden.

But in the meanwhile, things went on badly at Carthage. [Pg 26] Many had called themselves Christians in the late quiet times who would not have done so if there had been any danger about it. And now, when the danger came, numbers of them ran into the market-place at Carthage, and seemed quite eager to offer sacrifice to the gods of the heathen. Others, who did not sacrifice, bribed some officers of the Government to give them tickets, certifying that they had sacrificed; and yet they contrived to persuade themselves that they had done nothing wrong by their cowardice and deceit! There were, too, some mischievous men among the clergy, who had not wished Cyprian to be bishop, and had borne him a grudge ever since he was chosen. And now these clergymen set on the people who had lapsed (or fallen) in the persecution, to demand that they should be taken back into the Church, and to say that some martyrs had given them letters which entitled them to be admitted at once.

In those days it was usual, when any Christian was known to have been guilty of a heavy sin, that (as is said in our Commination service), he should be "put to open penance" by the Church; that is, that he should be required to show his repentance publicly. Persons who were in this state were not allowed to receive the holy sacrament of the Lord's Supper, as all other Christians then did very often. The worst sinners were obliged to stand outside the church-door, where they begged those who were going in to pray that their sins might be forgiven; and those of the penitents who were let into the church had places in it separate from other Christians. Sometimes penance lasted for years; and always until the penitents had done enough to prove that they were truly grieved for their sins, so that the clergy might hope that they were received to God's mercy for their Redeemer's sake. But as it was counted a great and glorious thing to die for the truth of Christ, and martyrs were highly honoured in the Church, penitents had been in the habit of going to them while they were in prison awaiting death, and of entreating the martyrs to plead with the Church for the shortening of the appointed penance. And [Pg 27] it had been usual, out of regard for the holy martyrs, to forgive those to whom they had given letters desiring that the penitents might be gently treated. But now these people at Carthage, instead of showing themselves humble, as true penitents would have been, came forward in an insolent manner, as if they had a right to claim that they might be restored to the Church; and the martyrs' letters (or rather what they called martyrs' letters) were used in a way very different from anything that had ever been allowed. Cyprian had a great deal of trouble with them; but he dealt wisely in the matter, and at length had the comfort of settling it. But, as people are always ready to find fault in one way or another, some blamed him for being too strict with the lapsed, and others for being too easy; and each of these parties went so far as to set up a bishop of its own against him. After a time, however, he got the better of these enemies, although the straiter sect (who were called Novatianists, after Novatian, a presbyter of Rome) lasted for three hundred years or more.

Shortly after the end of the persecution, a terrible plague passed through the empire, and carried off vast numbers of people. Many of the heathen thought that the plague was sent by their gods to punish them for allowing the Christians to live; and the mobs of towns broke out against the Christians, killing some of them, and hurting them in other ways.

But instead of returning evil for evil, the Christians showed what a spirit of love they had learnt from their Lord and Master; and there was no place where this was more remarkably shown than at Carthage. The heathen there were so terrified by the plague that they seemed to have lost all natural feeling, and almost to be out of their senses. When their friends fell sick, they left them to die without any care; when they were dead, they cast out their bodies into the street; and the corpses which lay about unburied [Pg 28] were not only shocking to look at, but made the air unwholesome, so that there was much more danger of the plague than before. But while the heathen were behaving in this way, and each of them thought only of himself, Cyprian called the Christians of Carthage together, and told them that they were bound to do very differently. "It would be no wonder," he said, "if we were to attend to our own friends; but Christ our Lord charges us to do good to heathens and publicans also, and to love our enemies. HE prayed for them that persecuted Him, and if we are His disciples, we ought to do so too." And then the good bishop went on to tell his people what part each of them should take in the charitable work. Those who had money were to give it, and were to do such acts of kindness as they could besides. The poor, who had no silver or gold to spare, were to give their labour in a spirit of love. So all classes set to their tasks gladly, and they nursed the sick and buried the dead, without asking whether they were Christian or heathens.

When the heathens saw these acts of love, many of them were brought to wonder what it could be that made the Christians do them; and how they came to be so kind to poor and old people, to widows, and orphans, and slaves; and how it was that they were always ready to raise money for buying the freedom of captives, or for helping their brethren who were in any kind of trouble. And from wondering and asking what it was that led Christians to do such things, which they themselves would never have thought of doing, many of the heathen were brought to see that the Gospel was the true religion, and they forsook their idols to follow Christ.

After this, Cyprian had a disagreement with Stephen, bishop of Rome. Rome was the greatest city in the whole world, and the capital of the empire. There were many Christians there even in the time of the Apostles, and, as years went on, the church of Rome grew more and more, so that it was the greatest, and richest, and most important church of all. Now the bishops who were at the head of [Pg 29] this great church were naturally reckoned the foremost of all bishops, and had more power than any other; so that if a proud man got the bishopric of Rome, it was too likely that he might try to set himself up above his brethren, and to lay down the law to them. Stephen was, unhappily, a man of this kind, and he gave way to the temptation, and tried to lord it over other bishops and their churches. But Cyprian held out against him, and made him understand that the bishop of Rome had no right to give laws to other bishops, or to meddle with the churches of other countries. He showed that, although St. Peter (from whom Stephen pretended that the bishops of Rome had received power over others) was the first of the Apostles, he was not of a higher class or order than the rest; and, therefore, that, although the Roman bishops stood first, the other bishops were their equals, and had received an equal share in the Christian ministry. So Stephen was not able to get the power which he wished for over other churches, and, after his death, Carthage and Rome were at peace again.

About six years after the death of the Emperor Decius, a fresh persecution arose under another emperor, named Valerian (A.D. 257). He began by ordering that the Christians should not be allowed to meet for worship, and that the bishops and clergy should be separated from their flocks. Cyprian was carried before the governor of Africa; and, on being questioned by him, he said, "I am a Christian and a bishop. I know no other gods but the one true God, who made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them. It is this God that we Christians serve; to Him we pray day and night, for ourselves and all mankind, and for the welfare of the emperors themselves." The governor asked him about his clergy. "Our laws," said Cyprian, "forbid them to throw themselves in your way, and I may not inform against them; but if they be sought after, they will be found, each at his post." The governor said that [Pg 30] no Christians must meet for worship, under pain of death; and he sentenced Cyprian to be banished to a place called Curubis, about forty miles from Carthage. It was a pleasant abode, and Cyprian lived there a year, during which time he was often visited by his friends, and wrote many letters of advice and comfort to his brethren. And, as many of these were worse treated than himself, by being carried off into savage places, or set to work underground in mines, he did all that he could to relieve their distress, by sending them money and other presents.

At the end of the year, the bishop was carried back to Carthage, where a new governor had just arrived. The emperor had found that his first law against the Christians was of little use; so he now made a second law, which was much more severe. It ordered that bishops and clergy should be put to death; that such Christians as were persons of worldly rank should lose all that they had, and be banished or killed; but it said nothing about the poorer Christians who do not seem to have been in any danger. Cyprian thought that his time was now come; and when his friends entreated him to save himself by flight, he refused. He was carried off to the governor's country house, about six miles from Carthage, where he was treated with much respect, and was allowed to have some friends with him at supper. Great numbers of his people, on hearing that he was seized, went from Carthage to the place where he was, and watched all night outside the house in fear lest their bishop should be put to death, or carried off into banishment without their knowledge. Next morning Cyprian was led to the place of judgment, which was a little way from the governor's palace. He was heated with the walk, under a burning sun; and, as he was waiting for the governor's arrival, a soldier of the guard, who had once been a Christian, kindly offered him some change of clothes. "Why," said the bishop, "should we trouble ourselves to remedy evils which will probably come to an end to-day?"

The governor took his seat, and required Cyprian to [Pg 31] sacrifice to the gods. He refused; and the governor then desired him to consider his safety. "In so righteous a cause," answered the bishop, "there is no need of consideration;" and, on hearing the sentence, which condemned him to be beheaded, he exclaimed, "Praise be to God!" A cry arose from the Christians, "Let us go and be beheaded with him!" He was then led by soldiers to the place of execution. Many of his people climbed up into the trees which surrounded it, that they might see the last of their good bishop. After having prayed, he took off his upper clothing; he gave some money to the executioner, and as it was necessary that he should be blindfolded before suffering, he tied the bandage over his own eyes. Two of his friends then bound his hands, and the Christians placed cloths and handkerchiefs around him, that they might catch some of his blood. And thus St. Cyprian was martyred, in the year 258.

Valerian's attempts against the Gospel were all in vain. The Church had been purified and strengthened by the persecution under Decius, so that there were now very few who fell away for fear of death. The faith was spread by the banished bishops, in the same way as it had been in the last persecution[1]; and, as has ever been found, "the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the Church."

NOTES

FROM GALLIENUS TO THE END OF THE LAST PERSECUTION.

A.D. 261-313.

Valerian, who had treated the Christians so cruelly, came to a miserable end. He led his army into Persia, where he was defeated and taken prisoner. He was kept for some time in captivity; and we are told that he used to be led forth, [Pg 32] loaded with chains, but with the purple robes of an emperor thrown over him, that the Persians might mock at his misfortunes. And when he had died from the effects of shame and grief, it is said that his skin was stuffed with straw, and was kept in a temple, as a remembrance of the triumph which the Persians had gained over the Romans, whose pride had never been so humbled before.

When Valerian was taken prisoner, his son Gallienus became emperor (A.D. 261). Gallienus sent forth a law by which the Christians, for the first time, got the liberty of serving God without the risk of being persecuted. We might think him a good emperor for making such a law; but he really does not deserve much credit for it, since he seems to have made it merely because he did not care much either for his own religion, or for any other.

And now there is hardly anything to be said of the next forty years, except that the Christians enjoyed peace and prosperity. Instead of being obliged to hold their services in the upper rooms of houses, or in burial-places under ground, and in the dead of night, they built splendid churches, which they furnished with gold and silver plate, and with other costly ornaments. Christians were appointed to high offices, such as the government of countries; and many of them held places in the emperor's palace. And, now that there was no danger or loss to be risked by being Christians, multitudes of people joined the Church who would have kept at a distance from it if there had been anything to fear. But, unhappily, the Christians did not make a good use of all their prosperity. Many of them grew worldly and careless, and had little of the Christian about them except the name; and they quarrelled and disputed among themselves, as if they were no better than mere heathens. But it pleased God to punish them severely for their faults; for at length there came such a persecution as had never before been known.

At this time there were no fewer than four emperors at once; for Diocletian, who became emperor in the year 284, afterwards took in Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius, [Pg 33] to share his power, and to help him in the labour of government. Galerius and Constantius, however, were not quite so high, and had not such full authority, as the other two. Galerius married Diocletian's daughter, and it was supposed that both this lady and the empress, her mother, were Christians. The priests and others, whose interest it was to keep up the old heathenism, began to be afraid lest the empresses should make Christians of their husbands; and they sought how this might be prevented.

Now the heathens had some ways by which they used to try to find out the will of their gods. Sometimes they offered sacrifices of beasts, and, when the beasts were killed, they cut them open, and judged from the appearance of the inside, whether the gods were well pleased or angry. And at certain places there were what they called oracles, where people who wished to know the will of the gods went through some ceremonies, and expected a voice to come from this or that god in answer to them. Sure enough, the voice very often did come, although it was not really from any god, but was managed by the juggling of the priests. And the answers which these voices gave were often contrived very cunningly, that they might have more than one meaning, so that, however things might turn out, the oracle was sure to come true. And now the priests set to frighten Diocletian with tricks of this kinds. When he sacrificed, the insides of the victims (as the beasts offered in sacrifice were called) were said to look in such a way as to show that the gods were angry. When he consulted the oracles, answers were given declaring that, so long as Christians were allowed to live on the earth, the gods would be displeased. And thus Diocletian, although at first he had been inclined to let them alone, became terrified, and was ready to persecute.

The first order against the Christians was a proclamation requiring that all soldiers, and all persons who held any office under the emperor, should sacrifice to the heathen gods (A.D. 298). And five years after this, Galerius, who was a cruel man, and very bitter against the Christians [Pg 34] (although his wife was supposed to be one), persuaded Diocletian to begin a persecution in earnest.

Diocletian did not usually live at Rome, like the earlier emperors, but at Nicomedia, a town in Asia Minor, on the shore of the Propontis (now called the Sea of Marmora). And there the persecution began, by his sending forth an order that all who would not serve the gods of Rome should lose their offices; that their property should be seized, and, if they were persons of rank, they should lose their rank. Christians were no longer allowed to meet for worship; their churches were to be destroyed, and their holy books were to be sought out and burnt (Feb. 24, 303). As soon as this proclamation was set forth, a Christian tore it down, and broke into loud reproaches against the emperors. Such violent acts and words were not becoming in a follower of Him, "who, when he was reviled, reviled not again, and when he suffered, threatened not" (1 Peter ii. 23). But the man who had forgotten himself so far, showed the strength of his principles in the patience with which he bore the punishment of what he had done, for he was roasted alive at a slow fire, and did not even utter a groan.

This was in February, 303; and before the end of that year, Diocletian put forth three more proclamations against the Christians. One of them ordered that the Christian teachers should be imprisoned; and very soon the prisons were filled with bishops and clergy, while the evil-doers who were usually confined in them were turned loose. The next proclamation ordered that the prisoners should either sacrifice or be tortured; and the fourth directed that not only the bishops and clergy, but all Christians, should be required to sacrifice, on pain of torture.

These cruel laws were put in execution. Churches were pulled down, beginning with the great church of Nicomedia, which was built on a height, and overlooked the emperor's palace. All the Bibles and service-books that could be found, and a great number of other Christian writings, were thrown into the flames; and many Christians, who refused to give up their holy books, were put to death. The plate [Pg 35] of churches was carried off, and was turned to profane uses, as the vessels of the Jewish temple had formerly been by Belshazzar.

The sufferings of the Christians were frightful, but after what has been already said of such things, I shall not shock you by telling you much about them here. Some were thrown to wild beasts; some were burnt alive, or roasted on gridirons; some had their skins pulled off, or their flesh scraped from their bones; some were crucified; some were tied to branches of trees, which had been bent so as to meet, and then they were torn to pieces by the starting asunder of the branches. Thousands of them perished by one horrible death or other, so that the heathens themselves grew tired and disgusted with inflicting or seeing their sufferings; and at length, instead of putting them to death, they sent them to work in mines, or plucked out one of their eyes, or lamed one of their hands or feet, or set bishops to look after horses or camels, or to do other work unfit for persons of their venerable character. And it is impossible to think what miseries even those who escaped must have undergone; for the persecution lasted ten years, and they had not only to witness the sufferings of their own dear relations, or friends, or teachers, but knew that the like might, at any hour, come on themselves.

It was in the East that the persecution was hottest and lasted longest; for in Europe it was not much felt after the first two years. The Emperor Constantius, who ruled over Gaul (now called France), Spain and Britain, was kind to the Christians; and after his death, his son Constantine was still more favourable to them. There were several changes among the other emperors, and the Christians felt them for better or for worse, according to the character of each emperor; but it is needless to speak much of them in a little book like this. Galerius went on in his cruelty until, at the end of eight years, he found that it had been of no use towards putting down the Gospel, and that he was sinking under a fearful disease, something like that of [Pg 36] which Herod, who had killed St. James, died (Acts xii. 23). He then thought with grief and horror of what he had done, and (perhaps in the hope of getting some relief from the God of Christians) he sent forth a proclamation allowing them to rebuild their churches, and to hold their worship, and begging them to remember him in their prayers. Soon after this he died (A.D. 311).

The cruellest of all the persecutors was Maximin, who, from the year 305, had possession of Asia Minor, Syria, the Holy Land, and Egypt. When Galerius made his law in favour of the Christians, Maximin for a while pretended to give them the same kind of liberty in his dominions. But he soon changed again, and required that all his subjects should sacrifice—even that little babies should take some grains of incense into their hands, and should burn it in honour of the heathen gods; and when a season of great plenty followed after this, Maximin boasted that it was a sign of the favour with which the gods received his law. But it very soon appeared how false his boast was, for famine and plague began to rage throughout his dominions. The Christians, of course, had their share in the distress; but instead of triumphing over their persecutors, they showed the true spirit of the Gospel by treating them with kindness, by relieving the poor, by tending the sick, and by burying the dead, who had been abandoned by their own nearest relations.

Although there is no room to give any particular account of the martyrs here, there is one of them who especially deserves to be remembered, because he was the first who suffered in our own island. This good man, Alban, while he was yet a heathen, fell in with a poor Christian priest, who was trying to hide himself from the persecutors. Alban took him into his own house, and sheltered him there; and he was so much struck with observing how the priest prayed to God, and spent long hours of the night in religious exercises, that he soon became a believer in Christ. But the priest was hotly searched for, and information was given that he was hidden in Alban's house. And when the [Pg 37] soldiers came to look for him there, Alban knew their errand, and put on the priest's dress, so that the soldiers seized him and carried him before the judge. The judge found that they had brought the wrong man, and, in his rage at the disappointment, he told Alban that he must himself endure the punishment which had been meant for the other. Alban heard this without any fear, and on being questioned, he declared that he was a Christian, a worshipper of the one true God, and that he would not sacrifice to idols which could do no good. He was put to the torture, but bore it gladly for his Saviour's sake, and then, as he was still firm in professing his faith, the judge gave orders that he should be beheaded. And when he had been led out to the place of execution, which was a little grassy knoll that rose gently on one side of the town, the soldier, who was to have put him to death, was so moved by the sight of Alban's behaviour, that he threw away his sword, and desired to be put to death with him. They were both beheaded, and the town of Verulam, where they suffered, has since been called St. Alban's, from the name of the first British martyr.

This martyrdom took place early in the persecution; but, (as we have seen,) Constantius afterwards protected the British Christians, and his son Constantine, who succeeded to his share in the empire, treated them with yet greater favour. In the year 312, Constantine marched against Maxentius, who had usurped the government of Italy and Africa. Constantine seems to have been brought up by his father to believe in one God, although he did not at all know who this God was, nor how He had revealed Himself in Holy Scripture. But as he was on his way to fight Maxentius, he saw in the sky a wonderful appearance, which seemed like the figure of a cross, with words around it—"By this conquer." He then caused the cross to be put on the standards (or colours) of his army; and when he had defeated Maxentius, he set up at Rome a statue of himself, with a cross in its right hand, and with an inscription which declared that he owed his victory to that saving [Pg 38] sign. About the same time that Constantine overcame Maxentius, Licinius put down Maximin in the East. The two conquerors now had possession of the whole empire; and they joined in publishing laws by which Christians were allowed to worship God freely according to their conscience (A.D. 313).

CONSTANTINE THE GREAT.

A.D. 313-337.

It was a great thing for the Church that the emperor of Rome should give it liberty; and Constantine, after sending forth the laws which put an end to the persecution, went on to make other laws in favour of the Christians. But he did not himself become a Christian all at once, although he built many churches, and gave rich presents to others, and although he was fond of keeping company with bishops, and of conversing with them about religion. Licinius, the emperor of the East, who had joined with Constantine in his first laws, afterwards quarrelled with him, and persecuted the eastern Christians cruelly. But Constantine defeated him in battle (A.D. 324), and the whole empire was once more united under one head.

After his victory over Licinius, Constantine declared himself a Christian, which he had not done before; and he used to attend the services of the Church very regularly, and to stand all the time that the bishops were preaching, however long their sermons might be. He used even himself to write a kind of discourses something like sermons, and to read them aloud in the palace to all his court; but he really knew very little of Christian doctrine, although he was very fond of taking part in disputes about it. And, although he professed to be a Christian, he had not yet been made a member of Christ by baptism; for, in [Pg 39] those days, people had so high a notion of the grace of baptism, that many of them put off their baptism until they supposed that they were on their death-bed, for fear lest they should sin after being baptized, and so should lose the benefit of the sacrament. This was of course wrong; for it was a sad mistake to think that they might go on in sin so long as they were not baptized. God, we know, might have cut them off at any moment in the midst of all their sins; and even if they were spared, there was a great danger that, when they came to beg for baptism at last, they might not have that true spirit of repentance and faith without which they could not be fit to receive the grace of the sacrament. And therefore the teachers of the Church used to warn people against putting off their baptism out of a love for sin; and when any one had received clinical baptism, as it was called (that is to say, baptism on a sick-bed), if he afterwards got well again, he was thought but little of in the Church.

But to come back to Constantine. He had many other faults besides his unwillingness to take on himself the duties of a baptized Christian; and, although we are bound to thank God for having turned his heart to favour the Church, we must not be blind to the emperor's faults. Yet, with all these faults, he really believed the Gospel, and meant to do what he could for the truth.