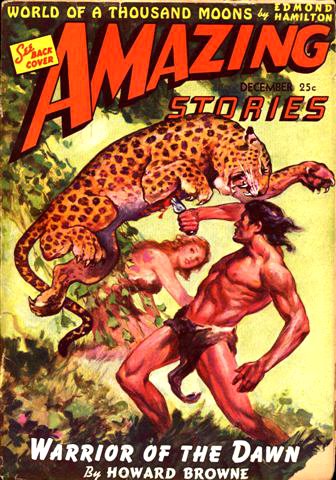

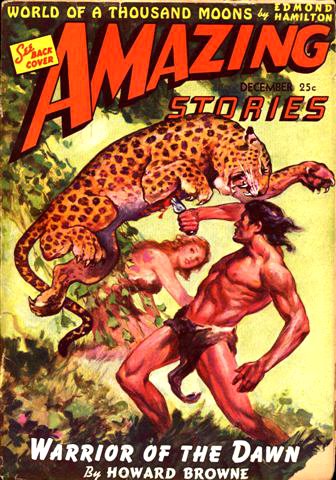

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Warrior of the Dawn, by Howard Carleton Browne This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Warrior of the Dawn Author: Howard Carleton Browne Release Date: May 20, 2010 [EBook #32462] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WARRIOR OF THE DAWN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Roger L. Holda, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Amazing Stories December 1942 and January 1943. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I. In Quest of Vengeance

CHAPTER II. Dylara

CHAPTER III. The Strange City

CHAPTER IV. Came Tharn

CHAPTER V. Pursuit

CHAPTER VI. Katon

CHAPTER VII. Woman Against Woman

CHAPTER VIII. Abduction

CHAPTER IX. Torture

CHAPTER X. The Hairy Men

CHAPTER XI. From Jungle Depths

CHAPTER XII. Enter--Pryak

CHAPTER XIII. Death Stalks the Princess

CHAPTER XIV. Forest Trails

CHAPTER XV. Treachery

CHAPTER XVI. Return to Sephar

CHAPTER XVII .Reunion

CHAPTER XVIII. Death in a Bowl

CHAPTER XIX. A Lesson in Archery

CHAPTER XX. Revolt!

CHAPTER XXI. Conclusion

Tharn stared in amazement at the city that lay before him

Tharn swung the nearest warrior bodily into the air

Mog snatched Alurna into his arms and made off through the forest

A rope hissed through the air and Tarlok reared high

It was late afternoon. Neela, the zebra, and his family of fifteen grazed quietly near the center of a level stretch of grassland. In the distance, and encircling the expanse of prairie, stood a solid wall of forest and close-knit jungle.

For the past two hours of this long hot afternoon Neela had shown signs of increasing nervousness. Feeding a short distance from the balance of his charges, he lifted his head from time to time to stare intently across the wind-stirred grasses to the east. Twice he had started slowly in that direction, only to stop short, stamp and snort uneasily, then wheel about and retrace his steps.

The remainder of the herd cropped calmly at the long grasses, apparently heedless of their leader's unrest, tails slapping flanks clear of biting flies.

Meanwhile, some two hundred yards to the eastward, three half-naked white hunters, belly-flat in the concealing growth, continued their cautious advance.

Wise in the ways of wary grass-eaters were these three members of a Cro-Magnard tribe, living in a day some twenty thousand years before the founding of Rome.[A] With the wind against their faces, with their passage as soundless as only veteran hunters may make it, they knew the zebra had no cause for alarm beyond a vague suspicion born of instinct alone.

And so the three men slipped forward, a long spear trailing in each right hand, their only guide the keen ears this primitive life had developed.

One of the three, a stocky man with a square, strong face and heavily muscled body, deep-tanned, paused to adjust his grasp on the stone-tipped spear he carried. As he did so there was a quick stir in the tangled grasses near his hand and Sleeza, the snake, struck savagely at his fingers.

With a startled, involuntary shout, the man jerked away, barely avoiding the deadly fangs. And then he snatched the flint knife from his loin-cloth and plunged it fiercely again and again into Sleeza's threshing body.

When finally he stopped, the mottled coils were limp in death. He saw then that his companions were standing erect, staring to the west.

From his sitting position he looked up at the others.

"Neela—?" he began.

"—has fled," finished one of the hunters. "He heard you quarreling with Sleeza. We cannot catch him, now."

The third man grinned. "Next time, Barkoo, let Sleeza bite you. While you may die, at least our food will not run away!"

Ignoring the grim attempt at humor, Barkoo scrambled to his feet and watched, in helpless rage, the bobbing heads and flying legs of Neela and his flock, now far away.

Barkoo swore mightily. "And it's too late to hunt further," he growled. "As it is, darkness will come before we reach the caves of Tharn. To return empty-handed besides—" One of his companions suddenly caught Barkoo by the arm. "Look!" he cried, pointing toward the west.

A young man, clad only in an animal skin about his middle, had leaped from a clump of grasses less than twenty yards from the fleeing herd. In one hand was a long war-spear held aloft as he swooped toward them.

Instantly the herd turned aside and with a fresh burst of speed sought to out-run this new danger.

"Look at him run!" Barkoo shouted.

With the speed of a charging lion the youth was covering the ground in mighty bounds, slanting rapidly up to the racing animals. A moment later and he had drawn abreast of a sleek young mare, her slim ears backlaid in terror.

Still running at full speed, the young man drew back his arm and sent his spear flashing across the gap between him and the mare, catching her full in the exposed side.

As though her legs had been jerked from under her, the creature turned a complete circle in mid-air before crashing to the ground, her scream of agony coming clearly to the three watching hunters.

Barkoo, when the young man knelt beside the kill, shook his head in tight-lipped tribute.

"I might have known he would do something like this," he said, exasperated. "When I asked him to come with us he refused; the sun was too hot. Now he will laugh at us—taunt us as bad hunters."

"Some day he will not come back from the hunt," predicted one of the men. "He takes too many chances. He goes out alone after Jalok, the panther, and Tarlok, the leopard, with only a knife and a rope. Why, just a sun ago, I heard him say Sadu, the lion, was to be next. Smart hunters leave Sadu alone!"

Tharn, the son of Tharn, watched the three come slowly toward him. His unbelievably sharp eyes of gray caught Barkoo's attempt at an unimpressed expression, and his own lean handsome face broke in a wide smile, the small even white teeth contrasting vividly with his sun-baked skin.

He wondered what had caused the zebra herd to bolt before the hunters could attempt their kill. He had caught sight of them an hour before from the high-flung branches of a tree, and had hidden in the grass near the probable route of the animals once Barkoo and his men had charged them.

Barkoo, seeming to ignore the son of his chief, came up to the dead zebra and nudged it with an appraising toe.

"Not much meat here," he said to Korgul. "A wise hunter would have picked a fatter one."

Tharn's lips twitched with amusement. He knew Barkoo—knew he found fault only to hide an extravagant satisfaction that the chief's son had succeeded where older heads had failed; for Barkoo had schooled him in forest lore almost from the day Tharn had first walked.

That had been a little more than twenty summers ago; today Tharn was more at home in the jungles and on the plains than any other member of his tribe. His confidence had grown with his knowledge until he knew nothing of fear and little of caution. He took impossible chances for the pure love of danger, flaunting his carelessness in the face of his former teacher, jeering at the other's gloomy prophecies of disaster.

Tharn pursed his lips solemnly. "It is true," he admitted soberly, "that a wiser hunter would have made a better choice. That is, if he were not so clumsy that the meat would run away first. Then the wise hunter would not be able to kill even a little Neela. Wise old men cannot run fast."

Barkoo glared at him. "It was Sleeza," he snapped, then reddened at being trapped into a defense. He wheeled on the grinning Korgul. "Get a strong branch," he said sharply....

With the dead weight of the kill swinging from the branch between Korgul and Torbat, the four Cro-Magnon hunters set out for the distant caves of their tribe.

Soon they entered the mouth of a beaten elephant path leading into the depths of dense jungle to the west. It was nearly dark here beneath the over-spreading forest giants, the huge moss-covered boughs festooned with loops and whorls of heavy vines. The air was overladen with the heavy smell of rotting vegetation; the sounds of innumerable small life were constantly in the hunters' ears. Here in the humid jungle, the bodies of the men glistened with perspiration.

By the time they had crossed the belt of woods to come into the open at the beginning of another prairie, Dyta, the sun, was close to the western horizon. Hazy in the far distance were three low hills, their common base buried among a sizable clump of trees. In those hills were the caves of the tribe, and at sight of them the four men quickened their steps.

They were perhaps a third of the way across the open ground, when Tharn, in the lead, halted abruptly, his eyes on a section of the grasses some hundred yards ahead.

Barkoo came up beside him. "What is it?" he asked tensely.

Tharn shrugged. "I don't know—yet. The wind is wrong. But something is crawling toward us very slowly and with many pauses."

Barkoo grunted. Tharn's uncanny instinct in locating and identifying unseen creatures annoyed him. It smacked too strongly of kinship with the wild beasts; it was not natural for a human to possess that sort of ability.

"Come," said Tharn. With head erect, the long spear trailing in his right hand, he set out at a brisk pace, his companions close on his heels.

They had gone half the way when a low moan came to the sharp ears of the younger man. In it was a note of human suffering and physical agony so pitiful that Tharn abandoned all caution and plunged forward.

And then he was parting the rank grasses from above the motionless body of a boy, lying there face down. From a purple-edged hole in his right side blood dripped in great red blobs to form a widening pool beneath him.

Tenderly Tharn slipped an arm beneath the shoulders of the youngster and carefully turned him to his back. Even as he recognized the familiar features, pale beneath a coat of bronze, he was aware of Barkoo behind him. Before he could turn, a strong hand thrust him roughly to one side and the older man was kneeling beside the wounded boy.

"Dartoog!" he cried, his tone a blending of fear and horror and monstrous rage. "Dartoog, my son! What has happened? Who has done this to you?"

Weakly the boy's eyes opened. In the brown depths at first were only weariness and pain. Then they focused on the face of the man and lighted up wonderfully, while a faint smile struggled for a place on the graying lips.

"Father!" he gasped.

"Who did this?" demanded Barkoo for the second time.

The eyes closed. Haltingly at first, then more smoothly as though finding strength in reliving the story, Dartoog spoke:

"It happened only a little while ago. I was near the foot of one of the hills, making a spear. A few warriors and women were near me; the rest of our people were in the caves.

"Then, suddenly, many strange fighting-men sprang out from behind trees at the edge of the clearing. They were as many as leaves on a big tree. With loud war-cries they ran at us; and before we could get away they had thrown their spears. I tried to run; but a big warrior caught me and struck me with his knife."

The son of Barkoo fell silent. Tharn, a flaming rage growing within him, bent nearer. Behind him were Korgul and Torbat, both very still, their faces strained.

"Then," the boy continued, "came Tharn, the chief, with our fighting-men. They came running from the caves and threw themselves upon the strangers.

"It was a great fight! Many times did the strange warriors try to beat back our men, and as many times did they fail. Tharn, our chief, was the reason. So many men that I could not count them, died beneath his knife and spear. But at last he, too, fell with a spear in his back.

"While they were fighting I crawled to the trees. Then I got to my feet and ran this way as far as I could. I wanted to find you, father, that you might go and kill them all."

Dartoog's voice, growing weaker, now ceased altogether. Twice he opened his lips to speak but no words came. Then, his throat swelling with a supreme effort, he cried out: "Go, father! Go, before they—" His voice broke, his body stiffened, then relaxed and he fell back, sighing.

Gently the father cradled his son's head in the circle of his arms. Once more the clear brown eyes opened. The man bent an ear to the lips framing further words.

"It—is—so—dark," came the barely audible whisper. As the boy finished speaking, his body slumped, his head dropped back and life left him.

Barkoo sat as graven in stone, head bowed above the dead body of his only son. There was no sound but that of the rustling grasses stirring lazily in the early evening breeze from the east.

Young Tharn was the first to move. Shaking his head like a hurt lion, he leaped to his feet, caught up his spear and set out at a run toward the distant caves.

By the time he had passed through the trees bounding the clearing before the hills, darkness was very near.

He came into the center of utter confusion. Everywhere about the wide clearing were bodies—some dead, others desperately wounded. Instantly Tharn set about organizing the dazed survivors; and it was only after the injured had been cared for and the dead placed in long rows in two of the recesses, that he found sufficient courage to ask about his father.

"We took a spear from his back and carried him to his own cave," was the answer. "I do not know if he still lives; he was not dead when we took him there."

Tharn, closer to knowing fear than he could ever remember, raced upward along the narrow ledges before the cave mouths. Near the crest he passed through the wide entrance of a large natural cavern, its interior lighted by means of dishes of animal fat in which were burning wicks of twisted grasses.

A group of warriors and women at the rear of the cave, drew aside as Tharn approached, revealing the magnificent figure of their leader lying upon a great pile of furry pelts. Although the eyes were closed and the strong regular features bore evidence of suffering, Tharn's heart lost its burden when he saw the broad chest rising and falling evenly.

Seated on a small flat-topped boulder beside the bed was Old Myrdon, pressing juices from herbs in a stone bowl. Old Myrdon had brought back to health more wounded fighting men than he could remember; and his long familiarity with death and suffering had completely soured his naturally acid disposition.

The young man placed a hand on the forehead of the sleeping chief, gratified to find the skin cool and moist. He noticed the compress of herbs bound in place high up on his father's back, and knew, then, the spear had not touched a vital spot, that with proper care rapid recovery would follow.

He moved to Myrdon's side. "Take good care of him, Old One," he said quietly.

The healer jerked his shoulder from under Tharn's hand. "I do not need advice from you," he growled, his wrinkled fingers grinding the rock pestle savagely against the bowl's contents. "If he lives it will be because I want him to live."

Tharn's grim expression did not change. "Take good care of him," he repeated evenly. "If he dies—you die!"

Startled, Myrdon raised his head. But Tharn had turned away and was striding toward the exit.

At the foot of the cliff he found Barkoo and Korgul and Torbat talking with a group of warriors. The son of the chief shouldered his way to the center. Darkness had come while he had been aloft and the only light came from two resinous flares.

In silence they looked at Tharn's set face. He was aware that they were regarding him strangely—almost expectantly. They seemed to sense that the carefree boy they had known was gone—replaced by a young warrior.

"Which way," demanded Tharn, "did they go?"

A tall, thin warrior with a bloody scratch across his forehead replied: "When they saw they could not gain the caves, they fell back. After they had disappeared among the trees, I followed for a time. Their path led into the south along the trail where we slew Pandor, the elephant, two suns ago."

Barkoo rubbed a hand thoughtfully across his smooth-scraped chin. "When Dyta comes again," he said, "we will start after them."

Tharn's mouth hardened. "You can wait for Dyta if you wish," he said slowly. "I am going after them now. They had no quarrel with us, but many of my friends—and yours—are dead. They killed Dartoog. They tried to kill my father. I am not going to wait."

"What can you hope to do alone, against many?" Barkoo asked in matter-of-fact tones. "Wait; go with us when it is light. There will be fighting enough for you then."

Without replying, Tharn stooped and caught up a flint-tipped war-spear. Then he re-coiled the folds of his grass rope about his shoulders and made sure the stone knife was secure in the folds of his loin-cloth.

He turned to the watching men. "I am going now," he said quietly. An instant later the black void of jungle had swallowed him up.

Uda, the moon, had not yet risen above the trees when the Cro-Magnon youth plunged into the wilderness of growing things. As a result he found his way purely by his familiarity with the territory and a store of jungle lore not surpassed by the beasts themselves. Because of the dense darkness, he was guided by three senses alone: smell, hearing and touch; but these were ample when backed by the keen mind and superhuman strength bequeathed by heritage and environment.

The narrow game trail underfoot swerved abruptly to the west and rose rapidly. For several hundred feet the way was steep, became level for a short distance, then fell away in a long gentle slope to flatness once more.

All this was familiar ground to Tharn. The ridge containing the homes of his people was behind him now; from here on for a day's march was nothing but level country.

Now came Uda, her shining half-disc swinging low above the towering reaches of the trees, her white rays seeking to pierce the matted growth below. What little light came through was enough for Tharn's eyes to regain some degree of usefulness.

He was moving ahead at a slow trot, an hour afterward, when the shrill scream of a leopard broke suddenly from the trail ahead. Another time, and Tharn might have gone on—too proud to change his course in the face of possible peril. But tonight he had more urgent business than a brawl with Tarlok.

Turning at right angles into the wall of undergrowth lining the path, he vaulted into the lower branches of a sturdy tree. With the graceful agility of little Nobar, the monkey, he swung swiftly westward again, threading his way with deceptive ease along the network of swaying boughs, now and then swinging perilously across a wide span from one tree to the next.

Directly below was the beaten path; and now he caught sight of the animal whose scream he had heard. Tarlok was pacing leisurely in the same direction as that of the man overhead, pausing occasionally to give voice to his hunting squall, his spotted form barely visible among the shadows. Tharn passed silently above him, the leopard unaware of his nearness.

Onward raced the Cro-Magnard, his thoughts filled with the quest he had undertaken alone. His savage, untamed mind had dwelt so steadily upon the outrageous attack, that it finally brought an emotion so powerful as to be almost tangible: Hate, and for a companion, Revenge.

Never would he rest until this unknown tribe had felt the weight of his own personal wrath. For what they had done they must pay a thousandfold in lives and misery.

Without warning, the forest ended; and the cave lord dropped to the ground at the edge of a great plain, its bounds hidden in the ghostly moonlight.

A line of broken grasses began where the game path ended. So fresh was the trail, now, that Tharn knew he had best wait for sunrise before continuing the chase. He had no wish to dash headlong among the ranks of the very enemy he pursued.

A few moments later Tharn was sleeping soundly in a crotch of a high tree, his slumber undisturbed by the long familiar noises of a jungle night.

The sun was an hour high when he awakened. His first act was to climb to the highest pinnacle of the tree, and from that point attempt to pick out, if possible, the goal of those he sought.

He was immediately successful. Due west, far in the distance, he saw hills rising steeply amidst another forest. His sharp eyes followed a wide line of broken grasses, noting that it pointed unerringly toward those same heights.

Tharn smiled grimly to himself. Soon the first member of that war-party would make the initial payment on the blood-debt. Making certain his weapons were in place, the broad-shouldered young man slid to the ground and took up a circuitous route, avoiding the open plain, which brought him finally to the forest's edge at a considerable distance away from the others' point of entry at the far side of the plain. If he had crossed the plain, sharp eyes might have noted his pursuit from just within the forest edge.

Once the trail was picked up again, he took to the comparative safety of the middle terraces. Soon he was moving in absolute silence above a narrow pathway winding into the gloomy interior, the imprints of many naked feet clear in the thick dust. But he no longer needed such evidence; the humid breeze was bringing the assorted smells of a Cro-Magnon settlement close ahead.

So close were the hills by this time that he was momentarily expecting the trees to thin out, when he caught the sound of a faint movement from below. Warily he slipped downward until, parting the foliage with a stealthy hand, he made out the figure of a tall muscular warrior standing in the trail, his attitude that of a sentry.

Tharn felt his pulses quicken as a new emotion came to him. In all his twenty-two years he had never been called upon to take a human life, and he found the prospect somewhat disquieting. Yet it was just such a purpose that he had in mind and there was no point in wasting time with self-analysis.

Noiselessly he slid to the ground and stepped onto the trail a few paces behind the stranger. With infinite stealth he lessened the space between the unsuspecting warrior and his own half crouched figure. Forgotten was the knife at his belt; his purpose was to close fingers about the other's throat.

Now, he was sufficiently near. The muscles of his legs tensed for the spring—and the enemy whirled to face him!

When the guard saw the young giant's nearness and threatening position, his eyes flew wide in surprise and fear. His jaw dropped, but no sound came; his arms seemed frozen to his sides.

Before he could recover, Tharn was upon him. As the young cave-man's fingers clamped on the stranger's throat, a knee came up with savage force into Tharn's stomach, almost tearing loose his hold. But the maneuver cost the man his balance, and he fell backward with Tharn's weight across his chest.

Frantically the warrior fought to loosen the terrible grip cutting off his breath. He clawed wildly at the iron fingers, struck heavy blows at his attacker's face and body. But Tharn only tightened his hold, waiting grimly as the efforts to dislodge him became increasingly weaker. Then a convulsive shudder passed through the body, followed by complete limpness. The man was dead.

Tharn got to his feet. For a long moment he stood there, staring in wonder at the dead, distorted face. His thoughts were a jumble of conflicting emotions: pride at vanquishing a grown man by bare hands alone; strong satisfaction in an enemy's death; and a feeling of guilt at taking a human life. What was it that Barkoo had told him, long ago?

"Death cannot be understood, completely, by one who has never killed. A true warrior takes no life without knowing regret. Slay only when your life is in danger, or when someone has wronged you. Those who kill for the love of killing are beneath the beasts; for beasts kill only for cause."

Tharn stooped, swung the corpse across his shoulder and entered the jungle. There he concealed the body and once more took to the trees.

The forest ended suddenly, some fifty yards from the base of an immense overhanging cliff. A single glance told Tharn that he had reached the trail's end, and he leaped lightly into the branches of a tree at the lip of the clearing. Swiftly he swarmed upward until a broad bough was reached that pointed outward toward the hillside.

Below and before him went on the everyday life of a Cro-Magnon village. Four women carved steaks from the freshly killed body of a deer; naked children climbed in and out of the caves and ran about the open ground; two girls, several seasons short of woman-hood, scraped hair, by means of flint tools, from a deerskin staked flat to the ground.

There was but one thing lacking in this peaceful, commonplace picture, and Tharn noted its absence at once. There was not a single grown male in sight! Did this mean a trap had been laid for the pursuit which the warriors of this tribe had every reason to expect? Were they, then, lying in wait for Barkoo and his men at the outer rim of the forest?

Tharn was about to start back toward the prairie, when he suddenly stiffened to attention. A woman—a girl, rather; she could not have been more than eighteen—had slid to the ground from one of the caves. The man in the trees half rose to watch her.

She was a bit above average in height, slim, yet perfectly formed. That part of her body not covered by the soft folds of panther skin was evenly tanned but not darkly so. Soft, lustrous brown hair fell to her bare shoulders in lovely half-curls that gave off reddish glints when touched by the sun's direct rays.

This breath-taking young person was coming straight toward the very tree that sheltered him. As she drew nearer, he could make out her features more clearly, and he saw that the wide eyes were also brown, flecked with tiny bits of Dyta, the sun (or so he thought); her cheeks were high but not too prominent, her nose rather small but beautifully shaped. She walked gracefully, shoulders back, her head lifted proudly, an almost saucy tilt to her chin.

She passed beneath him and went on into the forest. Tharn came down quickly and set out to follow. Why he did so was not considered; some strange force drew him on. Less than twenty feet separated them, now; but so guarded were his movements that the girl was not aware of being trailed.

And now a small treeless glade stopped the stalker. Not daring to follow further, he watched her take an empty gourd from its hiding place in a clump of grasses and set about filling it with rich, red fruit from a cluster of low bushes.

Tharn watched her intently from behind the bole of a mighty tree. His eyes feasted on the matchless beauty of her face and form. Forgotten completely was the driving motive that had brought him this far from home. The flaming thirst for revenge was dead, quenched entirely by a flooding emotion, new to him but old as life itself.

A little later he saw that the girl's search for berries was bringing her close to a tree some fifty feet to his left. Swinging easily into the foliage overhead, he moved silently along the boughs until the strange princess was directly below.

And as he drew to a pause, Tarlok, the leopard, rose from the screen of leaves just beneath him and, crouching briefly, sprang without warning at the golden form fifteen feet below.

That second of hesitation on the part of the cat, saved the girl's life. Tharn, trained to think and to act in the same instant, was in mid-air as Tarlok's claws left the bark. And so, inches from that softly curved back, the beast was swept aside by the impact of a hundred and seventy pounds of muscular manhood.

Snarling its rage, the cat wheeled as it struck the earth, then pounced, almost in the same motion, at Tharn's half-kneeling figure. But, swift as was the movement, the man was quicker. Crouching under the arc of the hurtling body, the Cro-Magnard drove his long knife to the hilt in the white-furred belly. The force of the leap, plus the power behind that strong right arm, tore a long, deep gash, and the animal fell, screaming with pain and hate. Quickly he regained his feet and again threw himself at the two-legged creature in his path. But Tharn easily avoided the charge and vaulted into a nearby tree.

Blood streamed from the fatally wounded leopard as it turned to the man's leafy haven and attempted to scramble into the lower branches. The effort cost Tarlok his remaining strength, however, and he toppled heavily to earth. Once more he sought to regain his feet, only to collapse and move no more.

As Tharn came down to the floor of the glade, he wondered why the scream of the giant cat had not brought enemy warriors running to the scene. That none had appeared made certain his belief that they were elsewhere in the neighborhood, and he breathed easier.

As soon as Tharn reappeared, the girl whose life he had saved rose from a clump of bushes a few feet away. And thus they stood there, each eyeing the other with frank interest.

Tharn's brain was awhirl. So much that was new and exciting had crowded into it within the last few hours that he was incapable of rational thinking. But this he knew: something had been born within him that had not been there an hour ago.

He spoke first. "I am Tharn," he said.

The girl did not at once respond to his implied question. She seemed hesitant, uncertain as to the wisdom of remaining there.

"I am Dylara," she said at last, her voice low and soft, yet wonderfully clear. "My father is chief of the tribe that bears his name. The caves of Majok are there," and she pointed toward the cliff, hidden from them by intervening trees.

Under the impetus of crystallizing realization, Tharn said what he had wanted to say from the first. "I kept Tarlok from getting you," he reminded her. "Now you belong to me!"

The brown-haired girl flushed with mingled astonishment and anger.

"You are a fool!" she retorted. "I belong to no one. Because you saved me from Tarlok, I will not call my people if you go away at once."

She turned and would have left him had not Tharn reached out and caught her by the arm.

Instantly she wheeled and struck him savagely across the mouth with her free hand, struggling to break his hold as she did so.

Then Tharn, his face smarting, hesitated no longer. With an effortless motion he drew her into the circle of his arms, tossed her lightly across one broad shoulder and broke into a run, heading back in the direction of home. His prisoner let out a single cry for help; then a calloused palm covered her lips.

And hardly had the echoes of that shout faded than six brawny fighting-men rose from the edge of the jungle, directly in Tharn's path!

At sight of the newcomers, Tharn whirled to his left, and raced away with enormous bounding strides despite the handicap of his burden. With loud yells and frightful threats beating against his ears, the cave man vanished into the tangled maze beyond the clearing.

Pursuit was immediate. For several hundred yards the chase continued at break-neck speed. Compared to those behind him, Tharn's passage was almost silent, his lithe figure slipping smoothly among the tree trunks. And then into view came the shallow, swift-flowing stream which he had scented while still in the clearing. Dashing into the water he splashed rapidly up-stream for a hundred yards, a sharp bend hiding him from the point at which he had entered.

Now he saw ahead of him that which he had hoped to find—the immense branch of a jungle giant, hanging low above the water's shimmering surface. Upon reaching the limb he drew himself and his captive into the leaves; then, stepping lightly from bough to bough, his balance controlled by a single hand, he moved rapidly inland, passing easily from tree to tree. Now and then he paused to listen for some indication of pursuit, but nothing reached those keen ears except the familiar sounds of a semi-tropical forest.

Tharn was beginning to wonder what far-reaching effects this half-mad abduction would have on his future life. He tried to picture his father's face when he saw his son returning with a strange mate, and the image was not an altogether pleasant one. Taking a mate by force was not entirely uncommon among Cro-Magnon people, although he had heard the elder Tharn declare that no true man would do so. The Hairy Ones took their women in that fashion; but then they were hardly more than the beasts.

And Barkoo! Tharn shuddered at the thought of his teacher's reaction. He would say much—remarks that would sear the hide of Pandor, the elephant!

He shrugged mentally. Let them, then! Many would envy him his prize; for certainly none among the women of the tribe was half so fair. He hoped that between now and the time Dylara and he arrived home, she would prove more tractable. Were she to repulse him in front of the others.... He dropped the thought as though it were white-hot.

An hour later he descended at the edge of a small natural clearing. A spring bubbled in one corner, and beside it the girl was lowered to her feet. The man and the girl knelt to drink, then sat up.

Tharn glanced at her, and grinned when she promptly turned her back. She was angrily rubbing her wrists to restore the circulation his strong grasp had partially cut off.

"Where are you taking me?" she demanded, her head still turned away.

"To my caves and my tribe," Tharn replied. "You shall be my mate. Someday I shall be chief."

The quiet words brought the beautiful head quickly around, and the girl glared at him hotly.

"I would sooner mate with Gubo, the hyena!" she snapped.

Tharn's grin required effort. "I think not," he said calmly. "I will be good to you. You shall have the finest skins to warm you, the best food to eat. Your cave will be large and light, and no one will tell you what to do. Except me, of course," he added slyly.

She searched wildly for a telling retort. "I—I hate you!"

Tharn met the angry eyes with a serenity he secretly was far from feeling.

"You will love me. I will make you love me," he assured her.

By this time Dylara was so exasperated that she had almost forgotten her fright. What good did it do to argue with this headstrong youth? He turned back every command, every retort, with an unruffled aplomb that filled her with helpless fury. It was, she thought, like beating bare fists against a boulder. Angry tears welled up in her eyes, and she turned away, ashamed to show the extent of her agitation. Her father, she knew, would have warriors scouring the countryside in search of her. But how could they hope to follow a trail that led through the forest top? In all her life she had never heard of a man who used the pathway ordinarily reserved for little Nobar, the monkey. True, many of the tribesmen were accomplished tree-climbers, often ambushing game from their branches. But such climbing faded to nothingness when compared with this amazing man's superhuman agility and strength.

She stole a glance at his face. The broad, high forehead, the bronzed clean-scraped cheeks, the strong jaw and mobile, sensitive lips stirred something deep within her. She caught herself wishing she had met him under more favorable conditions. But, by taking her forcibly, he had turned her forever against him; she hated him with all the intensity of which she was capable.

And then, woman-like, her next words had nothing to do with her thoughts. "I am hungry," she said abruptly.

Tharn blinked at the abrupt change in the course of their conversation, but obediently he stood up.

"Then we shall eat," he assured her. "And it will be meat, too; I will show you that I am a great hunter."

It was a boast meant to impress. Dylara's lips twitched with amusement, but she said nothing.

Tharn raised his head, sniffed at the pungent jungle air, then set out through the trees, Dylara at his heels. Moving toward the east they came, a half hour later, to the banks of a narrow river. This they followed downstream until a game trail was reached.

Motioning for the girl to seek the concealing foliage of a tree, Tharn slipped behind the bole of another bordering the pathway. Drawing his knife, he froze into complete immobility.

Ten minutes, twenty—a half an hour dragged by. From her elevated position Dylara watched the young man, marveling at the indomitable patience that could keep him motionless, waiting. The strong lines of his body appealed vividly to her, although she was quick to insist it was entirely impersonal; she would have been as responsive, she told herself, had it been the figure of Sadu, the lion, crouching there.

Then—although she had heard nothing—she saw Tharn stiffen expectantly. Two full minutes passed. And then, stepping daintily, every sense alert for hidden danger, came sleek Bana—the deer.

Here was food fit for the mate of a chief! The man of the caves tightened his strong fingers about the knife hilt.

On came Bana. Tharn drew his legs beneath him like a great cat.

And then events followed one another in rapid sequence. As the unsuspecting animal drew abreast of him, Tharn, with a long, lithe bound, sprang full on its back, at the same instant driving the stone blade behind Bana's left foreleg and into the heart. The deer stumbled and fell. Dylara dropped from the tree, reaching Tharn's side as he rose from the body of the kill.

As he stood erect, still clutching the reddened blade, an arrow sped through the sunlight and raked a deep groove along his naked side.

At the shock of pain which followed, Tharn whirled about in a movement so rapid that his body seemed to blur. Before he could do more, however, a heavy wooden club flashed from a clump of undergrowth at his back, striking him a terrible blow aside the head. A searing white light seemed to explode before him; then blackness came and he knew no more.

Dylara was first aware of a dull pain centering at the juncture of cheek and jaw. Half conscious, she put her fingers to the aching spot—and opened her eyes.

"How do you feel?" asked a man's deep voice.

Dylara, blinking in the strong sunlight, sat up. In front of her, squatted on his haunches before a small grass-fed fire, was a slender, wirily built man of uncertain age, his narrow hawk-like face creased in a thin-lipped smile as he squinted at her.

"I don't.... What—" Dylara began in a dazed voice.

The man fished a bit of scorched meat from the flames and bit off a mouthful. "The next time," he said thickly, "be careful whose face you scratch. Trokar doesn't make a habit of hitting girls, but you turned on him like a panther when he tried to keep you from running away. He'll carry the marks for a while!"

Memories flooded in on her. She saw the sun-dappled trail; saw Tharn rise from the body of Bana, only to go down under the cruel impact of a heavy club; saw the horde of oddly dressed men spring from concealment and rush toward her. She had turned to run, but a grinning warrior had intercepted her. And when she had raked her nails across his cheek, his good-humored expression had darkened—she remembered no more.

"But—but Tharn?" she cried. "Where is he? Did you—Is he—"

The man shrugged. "If you mean the man who was with you ... well, we intended only to stun him. There is need in Sephar for strong slaves. But the club that brought him down was thrown too hard."

"Then he is—dead?"

The hawk-faced one nodded.

Dylara was too shocked to attempt analysis of her feelings. She knew only that an unbearable weight had come into her heart; beyond that her thoughts refused to go. Sudden tears stung her eyes.

The man rose and set about stamping out the fire. Watching him, the girl began to note how greatly this man differed from one of her own tribe. To begin with, he was smaller, both in build and in stature. His skin, under its heavy tan, was somewhat darker; his hair very black. He wore a tunic of some coarsely woven grayish white material; rude sandals of deerskin covered his feet. A quiver of arrows and a bow—both completely unfamiliar objects to the girl—swung from his shoulders, and a long thin knife of flint was thrust under a belt of skin at his waist.

His speech, too, had shown he was of another race. While it had been intelligible, his enunciation was puzzling at times; occasionally hardly understandable. The similarity to the Cro-Magnon tongue was far stronger than basic; still, there was considerable difference in subtle shadings of pronunciation and sentence structure.

He turned to her, finally. "Are you hungry?"

"No," she said dully.

"Good. We have delayed too long, as it is. Sephar is more than two suns away, and we are anxious to return."

He raised his voice in a half-shouted, "Ho!" In response a half-score of men rose from the tall grasses nearby.

"Trokar," called the hawk-faced one.

"Yes, Vulcar." A slender young man came forward.

"Here is the girl who improved your looks! It will be your duty to look after her on the way back to Sephar."

Trokar fingered three angry red welts along one cheek, and grinned without speaking.

In single file they set out toward the south. For several hours they pushed steadily ahead across gently rolling prairie land. The girl's spirits sagged lower and lower as she trudged on, going she knew not where. She thought of her father and the grief he must be suffering; of her friends and her people. She thought of Tharn once or twice; if he were alive, these men would not hold her for long. But he was dead, and the realization brought so strong a pang that she forced her thoughts away from him.

They camped that night at the edge of a great forest. All during the dark hours a heavy fire was kept going, while the men alternated, in pairs, at sentry duty. Several times during the night Dylara was awakened by hunting cries of roving meat-eaters but apparently none came near the camp.

All the following day the party of twelve skirted the edge of the forest, moving always due south. By evening the ground underfoot had become much more uneven, and hills began to appear frequently. The nearby jungle was thinning out, as well, and the air was noticeably cooler. Just at sunset they finished scaling a particularly steep incline and paused at the crest to camp for the night.

Not far to the south, Dylara saw a low range of mountains extending to the horizons. Narrow valleys cut between the peaks, none of the latter high enough to be snow-capped. Through one ravine tumbled the waters of a mountain stream. The fading sunlight, reflected from water and glistening rocks, gave the scene an aura of majestic magnificence, bringing an involuntary murmur of delight to the lips of the girl.

"Beyond those heights lies Sephar." It was Vulcar, he of the hawk face, who spoke from beside her.

Dylara glanced at him, seeing the great pride in his expression.

"Sephar?" she echoed questioningly.

"Home!" he said. "It is like nothing you have ever seen. We do not live in caves; we are beyond that. It is from tribes such as yours that we take our slaves. Long ago the people of Sephar and Ammad were such as you. But because they were greater and wiser, and learned many things which you of the caves do not know, we have come to think of your kind as little more than animals."

Early the following morning they were underway once more. Shortly before noon they scaled the last few yards to a great tableland among the peaks. And it was then that Dylara got her first glimpse of Sephar.

A little below where she stood was a wide, shallow valley, most of it filled with heavy forest and jungle. Directly in the center of this valley, a jewel in a setting of green, lay a city. A city of stone buildings, gray and box-like, erected in the most simple of architectural design. With a few exceptions, all buildings were of one story; none more than two. Broad, clean streets were much in evidence, the principal ones running spokewise to converge at the exact center of the wheel-like pattern. Encircling all this was a great wall of dull gray stone.

But the most arresting feature of the entire city was situated at the hub of it all. Here, rising four full stories above the carefully tended plot of ground surrounding it, stood a tremendous structure of pure white stone, its shining walls adding materially to the dazzling effect given the awe-struck Dylara.

A hand touched her shoulder. Vulcar was smiling at her expression. "That," he said proudly, "is Sephar."

The girl could find no words to answer him. Here was something that all the tales repeated around a hundred cave-fires, during the rainy seasons, had never approached. Here might dwell the gods; those who sent the rain and the flaming bolts from the skies....

"Come," Vulcar said at last, and the little party started down the grass-covered incline toward the valley floor—and Sephar.

The princess Alurna was angry. A few moments ago she had driven her slave woman from the room, hastening the girl's departure with a thrown vase. Raging, the princess paced the chamber's length, kicking the soft fur rugs from her path. Bed coverings were scattered about the floor, flung there during this—her latest—tantrum.

It is doubtful whether Alurna, herself, knew what brought on these savage fits of temper. Actually, it was boredom; life to the girl—still in her early twenties—went on in Sephar in the same uneventful fashion as it had since her great-great grandfather had led a host across the tremendous valley between the present site of Sephar and the northern slopes of Ammad.

Finally the princess threw herself face down on the disordered bed and burst into hysterical weeping. She had about cried herself out, when a hand touched her arm.

"Go away, Anela!" she snapped, without looking up. "I told you to stay out until I sent for you."

"It is I," said a deep voice, "Urim, your father."

The girl scrambled hastily from the bed, at the same time wiping away the traces of tears.

"I'm sorry, father. I thought it was Anela, come back to look after me."

The man chuckled. "If I know anything, she won't be back until you fetch her. She is huddled in one corner of the hall outside, shaking as though Sadu had chased her!"

Despite his fifty years, Urim, ruler of Sephar, was still an imposing figure. Larger than the average Sepharian, he had retained much of the splendid physique an active life had given him. Of late years, however, he had been content to lead a more sedentary life; this, and a growing fondness for foods and wine, had added inches to his middle and fullness to his face, while mellowing still further a kindly disposition.

Alurna sat down on the edge of her bed and sought to tidy the cloud of loosely bound dark curls framing her lovely head. She was taller, by an inch or two, than the average Sepharian girl, with a lithe, softly rounded figure, small firm breasts, rather delicate features and a clear olive skin. She was wearing a sleeveless tunic which fell from neck to knees, caught at the waist by a wide belt of the same material. Her shapely legs were bare, the feet encased in heelless sandals of leather.

Urim drew up a chair and sat down. He watched Alurna as she freshened her appearance, his face reflecting a father's pride.

"Come, child," he said at last. "It is time for the mid-day meal. And that brings out what I came to tell you."

Alurna glanced at him with quick interest. "I thought so! I can always tell when you've got some surprise for me. What is it this time?"

"Visitors," Urim replied. "Three noble-born young men have traveled from Ammad to pay their respects. They have brought gifts from your uncle—many of them for you!"

Visitors from the mother country were rare, since few elected to attempt the perilous journey to Sephar. Alurna's uncle was king in Ammad, and the two brothers were warm friends. Urim, himself, had been born in Ammad, having come to Sephar as ruler when the former king, old Pyron, had died childless. Alurna had never seen the city of her father's birth, having been born in Sephar.

When Alurna had completed her toilet, she joined her father, and together they descended the broad central staircase of the palace to the lower hall. After passing through several well-furnished rooms, they entered a crowded dining hall and took seats at the head of a long table. The other diners had risen at their entry; they remained standing until Urim motioned for them to sit again.

Another group entered the hall, now, and all, save Urim and his daughter, rose to greet them. These newcomers were the visitors from Ammad, and as they approached vacant benches near the table's head, Urim stood to welcome them, his arms folded to signify friendship, a broad smile on his lips.

He turned to Alurna. "My daughter, welcome the friends of my brother. This is Tamar; this, Javan; and Jotan—my daughter, Alurna."

The girl smiled dutifully to the three. Two were of the usual type about her—slight, small-boned, graceful men with little to distinguish them.

But the other—Jotan—caught her attention from the first. He was truly big—standing a full six feet, with heavy broad shoulders and muscular arms and legs. His eyes were a cold flinty blue, deep-set in a strong masculine face. His jaw was square and firm, the recently scraped skin ruddy and clear. He carried himself with no hint of self-consciousness at being in the presence of royalty; his bearing as regal as that of Urim, himself.

One after the other the three visitors touched the princess' hand. Jotan, the last, held her fingers a trifle longer than was necessary, while his eyes flashed a look of admiration that turned red the girl's cheeks. She withdrew her hand abruptly, hiding her confusion by hurried speech.

"My father and I are happy that you have come to Sephar," she said. "Food shall be brought to refresh you after so long and tiring a journey."

At a sign from Urim, slaves began to fetch in steaming platters, placing them at frequent intervals along the board. Baked-clay cups were put at the right hand of each diner and filled with the wine-like beverage common to Sephar and Ammad; an alcoholic drink fermented from a species of wild grape. Of utensils there was none, the hands serving to convey food to the mouth.

After spilling a few drops of wine to the floor as a tribute to the God-Whose-Name-May-Not-Be-Spoken-Aloud, each diner set about the business of eating.

At last the mounds of viands had disappeared; the cups, drained and refilled many times during the course of the feast, were replenished again, and the Sepharians settled back to talk.

"Scarcely five marches from here, we were beset by a great band of cave-dwellers." Javan was speaking. "We beat them back easily enough; our bows and arrows evidently were unknown to them and sent scores to their deaths.

"But I tell you it was exciting for a time! They were huge brutes and unbelievably strong. Their spears—crude, barbaric things—were thrown with such force that twice I saw them go entirely through two of our men.

"But, as I say, we repulsed them, losing only four of our party, while over forty of the cave people died. We were not able to take prisoners; they fought too stubbornly to be subdued alive."

Alurna leaned forward eagerly.

"We have many slaves who once were such as you have described," she broke in. "But they do not take kindly to slavery. They often are morose and hate us, and need beatings to be kept in place. Yet their men are strong and fearless—and usually quite handsome."

From his place at the table, Jotan watched the face of the princess as she spoke. She seemed vivid and forceful—much more so that any other woman he had ever met; and her beauty of face and figure was breath-taking. He resolved to become better acquainted with her.

The manner in which Tamar straightened at her last words, showed they had stung him—just why, was not altogether clear to Alurna.

"They are only brutes—animals!" he said heatedly. "They know nothing of such splendor—" he waved an arm to include the room's rich furnishings "—no tables or chairs, no soft covers on their cave floors. There are no walls to protect them from raids by their enemies; no ability in warfare beyond blind courage. They are half-naked savages—nothing more!"

A sudden commotion at the doorway caused the conversation to end here. A short, alert man with a hawk-like face and a distinct military bearing, strode into the room and bowed before Urim.

"Well, Vulcar," greeted the king, without rising, "what are you doing here?"

"I come," replied the warrior, "to report the capture of a young cave-woman. A hunting party slew her mate and captured her a few marches from Sephar."

"Bring her in to us," Urim commanded. "I should like our visitors to see for themselves what cave people are like."

Vulcar bowed again, then returned to the doorway and beckoned to someone outside.

Two Sepharian warriors entered, Dylara between them. She was disheveled and rumpled, the protecting skin of Jalok, the panther, was awry; but her head was unbowed, her shoulders erect, and her glance as haughty as that of the princess, Alurna, herself.

No one said anything for a long moment. The sheer beauty of the girl captive seemingly had struck them dumb.

Jotan broke the silence. "By the God!" he gasped. "Are you jesting? This is no half-wild savage!"

Alurna, her eyes flashing dangerously, turned toward the speaker. The first man ever to attract her, and already raving over some unwashed barbarian who soon was to be a common slave!

"Perhaps you would like to have her as your mate," she said sweetly, but with an ominous note in her tone.

Urim shot a startled glance at his daughter. He had heard that edge to her voice before this, and usually it meant trouble for someone.

Jotan kept his eyes on the prisoner. "She would grace the life of any man," he declared with enthusiasm, totally unaware of Alurna's mounting jealousy.

Tamar, seated next to Jotan, forced a loud laugh. "My friend loves to jest," he announced in a palpable attempt to break the sudden tension. "Pay no attention to him."

Although Dylara understood most of what was being said, she was too upset to follow the conversation itself. She was awed and a little frightened by the undreamed-of magnificence about her. As much as she had hated Tharn, being with him was far better than belonging to those who had her now. But Tharn was dead, stricken down by a slender stick and heavy club.

"Take her to the slave quarters," instructed Urim finally. "Later, I shall decide what is to be done with her."

Dylara was led up two broad flights of stairs and deep within the left wing of the palace, her escort halting at last before massive twin doors. Here, two armed guards raised a heavy timber from its sockets, the doors swung wide, and she was led down a long hall past several small doors on either side of the corridor.

The men stopped before one of these doors, unbarred it, and thrust Dylara into the room beyond. Then the door closed and she heard the bar drop into place.

At first, her eyes were hard put to distinguish objects in the faint light entering through a long narrow, stone-barred opening set high up close to the ceiling. Soon, however, she was able to make out the simple furnishings: a low bed, formed by hairy pelts on a wooden framework; a low bench; a stand, upon which were a large clay bowl and a length of clean, rough cloth; and, on the floor, a soft rug of some woven material unfamiliar to the cave-girl.

Utterly weary, the girl threw herself on the bed. Thoughts of Tharn came unbidden to her mind. How she longed for his confidence-instilling presence! Not that she cared for him in any way; of that she was very certain. It was only that he was one of her own kind; he spoke as she did, clothed himself as she was accustomed to seeing men clothed.

It was unthinkable that he was dead; impossible to believe that that mighty heart had ceased to beat! Yet she had heard the dull impact of wood against bone as the club had felled him, and he had not stirred when the strange men broke from the bushes to seize her.

Yes, he was dead; and Dylara's eyes suddenly brimmed with burning tears. She told herself that her sorrow was not so much from his death as the fact that, without him alive, she could never hope to leave this place.

The show of bravado, maintained before her captors, began to slip away. She was so lonely and afraid here in this grimly beautiful city. What would become of her? And that proud, lovely girl at the table with all those people—why had she looked at Dylara with such frank hatred?

She cried a little, there in the dim light, and still sobbing, fell asleep.

Sadu, the lion, rounding a bend in the trail, came to an abrupt halt as his eyes fell on the carcass of Bana lying across the path a few yards ahead.

An idle breeze ruffled his heavy mane as he stood there, one great paw half-lifted as though caught in mid-stride. Then, very slowly, impelled solely by curiosity, he moved toward the dead animal.

Suddenly something stirred beyond the bulk of the deer. Sadu froze to immobility again as the dusty blood-stained figure of a half-naked man got to an upright position and faced him.

For a full minute the man and the lion stared woodenly into each other's eyes, across a space of hardly more than a dozen paces.

Sadu's principal emotion was puzzled uncertainty. There was nothing of menace in the attitude of this two-legged creature; neither did it show any indication of being alarmed. Experience had taught the lion to expect one or the other of those reactions upon such meetings as this, and the absence of either was responsible for his own indecision.

As for Tharn, he was experiencing difficulty in seeing clearly. The figure of the giant cat seemed to shimmer in the sunlight; to expand awesomely, then contract almost to nothing. A whirlpool of roaring pain sucked at his mind, drawing the strength from every muscle of his body.

Tharn realized the moment was fast approaching when either he or Sadu must make some move. If the lion's decision was to attack, the empty-handed cave-man would prove easy prey.

Almost at Tharn's feet lay his heavy war-spear. To stoop to retrieve it might precipitate an immediate charge. But that might come anyway, he reasoned, catching him without means of defence.

What followed required only seconds. Tharn crouched, caught up the flint-tipped weapon, and straightened—all in one supple motion. Sadu slid back on his haunches, reared up with fore-legs extended, gave one mighty roar—then turned and in wild flight vanished into the jungle!

It required the better part of an hour for the cave lord to hack a supply of meat from Bana's flank and cache it in a high fork of the nearest tree. The blow from a Sepharian war-club had resulted in a nasty concussion and the constant waves of dizziness and nausea made his movements slow and uncertain.

For two full days he lay on a rude platform of branches in that tree, most of the time in semi-stupor. Twice in that time he risked descent for water from the nearby river.

It was not until morning of the third day that he awoke comparatively clear-headed. For a little while he raced through the branches of neighboring trees, testing the extent of his recovery. And when he discovered that, beyond a dull ache in one side of his head, he was himself once more, he ate the remainder of his stock of deer meat and came down to the trail to pick up the two-day-spoor of Dylara's captors.

That those who had struck him down had also taken his intended mate, Tharn never doubted. She—and he!—had been too well ambushed for escape. What her fate would be after capture depended upon the identity of her abductors.

But when Tharn had picked up those traces not obliterated by the movements of jungle denizens during the two days, he was as much in the dark as before. Never in his own considerable experience had he come upon the prints of sandals before this; nor had he known of a tribe who wore coverings on their feet.

He shrugged. After all, who had taken Dylara was beside the point. She had been taken; and he must follow, to rescue her if she were still alive—for vengeance if they had slain her.

By noon of the next day Tharn was drawing himself up to the edge of the tableland at almost the same spot from whence Dylara had her first glimpse of Sephar. And when he rose to his feet and saw the city of stone and its great circular wall, he was no less electrified than the girl had been. He, however, felt no dread at the prospect of entering; indeed, his adventurous blood urged him to waste no time in doing so.

As he raced through the trees toward Sephar, his thoughts were of Dylara. Reason insisted that she still lived—a captive behind that grim stone wall. He knew, now, that his love for her was no temporary madness, but an emotion that would rule his life until death claimed him. Her proud, slender figure with its scanty covering of panther skin rose unbidden before him, and he felt a sudden uncomfortable tightness where ribs and belly met. Love was teaching Tharn of other aches than physical bruises....

It was mid-afternoon when he reached the forest's edge nearest to Sephar. Several hundred yards of level open ground lay between the trees and the mighty wall, which evidently encircled the entire city.

From where he crouched on a strong branch high above the ground, he saw two wide gateways not more than fifty yards apart, both of them guarded by parties of armed men. His keen eyes picked out details of their figures and clothing, both of which excited his keenest interest. With its entrances so closely guarded it would be folly to approach closer during the day. While impatient to reach Dylara's side, he was quite aware that any attempt at rescue now would doubtless cost him his own freedom, if not his life, thereby taking from the girl her only hope of escape. He must wait for night to come, hoping the guards would then be withdrawn.

Reminded that he had not eaten since early morning, Tharn swung back through the trees in search of meat. The plains of this valley appeared to abound with grass-eaters; and not long after, a wild horse fell before his careful stalking. Squatting on the body of his kill, he gorged himself on raw flesh, unwilling to chance some unfriendly eye noticing smoke from a fire.

His appetite cared for, the cave-man bathed in the waters of a small stream. He then knelt on the bank, and using the water as a mirror, cut the sprouting beard from his face by means of a small, very sharp bit of flint taken from a pouch of his loin-cloth. Comfort, rather than vanity, was responsible; a bearded face increased the discomfort of a tropical day.

The sun was low in the west by the time he had returned to his former vantage point, and shortly afterward the heavy wooden gates were pulled shut by their guards, who then withdrew into the city.

Now, the grounds about Sephar were deserted, and soon the sun slipped behind the far horizon. Swiftly twilight gave way to darkness, and stars began to glow softly against the bosom of a clear semi-tropical night.

Two hours—three—went by and still Tharn did not leave his station. Somewhere below him an unidentified animal crashed noisily through the thick undergrowth and moved deeper into the black shadows. Far back in the forest a panther screamed shrilly once and was still; to be answered promptly by the thunderous challenge of Sadu, the lion.

Finally the giant white man rose to his feet on the swaying branch and leisurely stretched. Silently and swiftly he slipped to the ground. He paused there for a moment, ears and nose alert for an indication of danger, then set out across the level field toward the towering wall of Sephar—enigmatic city of mystery and peril.

After Vulcar had led the captive cave-girl from the dining room, a general discussion sprang up. Any reference to the cave people, however, was carefully avoided; the subject, for some reason that nobody quite understood, seemed suddenly taboo.

While the others were rapidly drinking themselves into a drunken stupor, Jotan sat as one apart, head bowed in thought. He found it impossible to dismiss the impression given him by the half-naked girl of the caves. She was so different from the usual girl with whom he came in contact—more vital, more alive. There was nothing fragile or clinging about her. He could not help but compare that fine, healthy, well-rounded figure with the pallid, artificial women of his acquaintance. Her clean sparkling eyes, clear tanned skin and graceful posture made those others seem dull and uninviting.

"Jotan!"

The visitor came back to his surroundings with a start.

Urim, his round face flushed from much wine, had called his name.

"Come, man," he laughed, "of what do you dream? A girl in far-off Ammad, perhaps?"

Jotan reddened, but replied calmly enough, "No, my king; no flower of Ammad holds my heart."

The faint stress he placed on the name of his own country passed unnoticed by all except Alurna.

"'Of Ammad,' you say, Jotan," she cut in. "Perhaps so soon you have found love here in Sephar."

The remark struck too close to home for the man's comfort.

"You read strange meanings in my words, my princess," he said evasively; then suddenly he thrust back his bench and arose.

"O Urim," he said, "my friends and I would like to look about Sephar. Also, if you will have someone show us the quarters we are to use during our visit...."

"Of course," Urim agreed heartily. "The captain of my own guards shall act as your guide."

Vulcar was sent for. When he arrived, Urim bade him heed every wish the three guests might express.

As they passed from the palace into the street beyond, Tamar said softly:

"Whatever possessed you, Jotan, to say such things where others could hear you? A noble of Ammad, raving about some half-clad barbarian girl! What must they think of you!"

Jotan was mid-way between laughter and anger. Tamar's reaction had been so typical, however, that he checked an angry retort. Tamar was so completely the snob, so entirely conscious of class distinction, that his present attitude was not surprising.

"It might be interesting," he admitted.

Tamar was puzzled. "What might?"

"To know what they think."

Tamar sniffed audibly, and moved away to join Javan.

They spent the balance of the afternoon walking about Sephar's streets, viewing the sights. Shortly before dusk Vulcar led them to their quarters in a large building near the juncture of two streets—a building with square windows barred by slender columns of stone. Slaves brought food; and after the three men had eaten, the room was cleared that they might sleep.

Jotan yawned. "Even my bones are weary," he said. "I'm going to bed."

Tamar stood up abruptly. He had been silently rehearsing a certain speech all afternoon, and he was determined to have his say.

"Wait, Jotan," he said. "I'd like to talk to you, first."

Jotan looked at his friend with mock surprise. He knew perfectly well what was coming, and he rather welcomed this opportunity to declare himself and, later, to enlist the aid of his friends.

Javan was regarding them with mild amazement on his good-natured, rather stupid face. He was the least aggressive of the three, usually content to follow the lead of the others.

"All right," Jotan said. "I'm listening."

"I suppose the whole thing doesn't really amount to much." Tamar forced a laugh. "But I think it was wrong for you to carry on the way you did over that cave-girl today. Only the God knows what the nobles of Sephar, and Urim and his daughter, thought of your remarks. Why, anyone would have thought you had fallen in love with the girl!"

Jotan smiled—a slow, easy smile. "I have!" he said.

Tamar stiffened as though he had been struck. His face darkened. "No! Jotan, do you know what you're saying? A naked wild creature in an animal skin! You talk like a fool!

"Javan!" He whirled on the silent one. "Javan, are you going to sit there and let this happen? Help me reason with this madman."

Javan sat with mouth agape. "But I—why—what—"

Jotan leaned back and sighed. "Listen, Tamar," he said placatingly. "We have been friends too long to quarrel over my taste in choosing a mate. Tomorrow I shall ask Urim for the girl."

"Your mate? I might have known it." In his agitation Tamar began to pace the floor. "We should have stayed in Ammad. I have a good mind to go to Urim and plead with him not to give her to you."

"You shall do nothing of the kind, Tamar," Jotan said quietly. He was no longer smiling. "I will not permit you to interfere in this. This girl is to be my mate. You, as my friend, will help me."

Tamar snorted. "When our friends see her, see her as the mate of noble Jotan, you will wish that I had interfered. A dirty half-wild savage! You will be laughed at, my friend, and the ridicule will soon end your infatuation."

Jotan looked at him with level eyes. "You've said enough, Tamar. Understand this: Tomorrow I shall ask Urim for the cave girl. Now I am going to sleep."

Tamar shrugged and silently turned away. Amidst a deep silence the three men spread their sleeping-furs, extinguished the candles and turned in.

As Tharn neared Sephar's outer wall, Uda, the moon, pushed her shining edge above the trees, causing the Cro-Magnon to increase his pace lest he be seen by some observer from within the city.

He reached the dense shadows of the wall directly in front of one mighty gateway, its barrier of heavy planks seemingly as solid as the stone wall on either side.

Tharn pressed an ear to a crack of the wood. He could hear nothing from beyond. Bending slightly forward, he dug his bare feet into the ground, placed one broad shoulder against the rough surface, and pushed. At first the pressure was gentle; but when the gate did not give, he gradually increased the force until all his superhuman strength strove to loosen the barrier.

But the stubborn wood refused to give way, and Tharn realized he must find another means of entry.

A single glance was enough to convince him that the rim of the wall was beyond leaping distance. It was beginning to dawn on the cave-man that getting into this strange lair was not to be so easy as he had at first expected.

He concluded finally that there was nothing left to do but circle the entire wall in hopes that some way to enter would show itself. Perhaps one of the several gates would have been left carelessly ajar, although he was not trusting enough to have much faith in that possibility.

After covering possibly half a mile, and testing two other gateways without success, his sharp gray eyes spied a broken timber near the top of the wall directly above one of the gates. An end of the plank protruded a foot beyond the sheer surface of rock.

Tharn grinned. Those within might as well have left the gate itself open. Drawing the grass rope from his shoulders, he formed a slip knot at one end, and with his first effort managed to cast the loop about the jagged bit of wood. This done, it was a simple matter to draw himself up to the timber. There he paused to restore the rope about his shoulders, then he cautiously poked his head over the wall and peered into the strange world below.

There was no one in sight. Still smiling confidently, keenly aware that he might never leave this place alive, he lowered himself over the edge, swung momentarily by his hands, then dropped soundlessly to the street below. The first obstacle in the search for Dylara had been overcome.

Slowly and without sound the massive door to Dylara's room swung open, permitting a heavily-laden figure to enter. Placing its burden on the table, the figure closed the door, crossed to the side of the sleeping girl and bent above her, listening to the slow even breathing. Satisfied, the visitor stepped back to the table and, with a coal from an earthen container, ignited the wicks of dishes of animal fat. The soft light revealed the newcomer as a woman.

Quietly she arranged the dishes she had brought, using the low stand as a table. That done, she came to Dylara's side and shook her gently by a shoulder.

The daughter of Majok awakened with a start, blinking the sleep from her eyes. At sight of the other, she sat up in quick alarm.

The woman smiled reassuringly. "You must not be afraid," she said softly. "I am your friend. They sent me here with food for you. See?" She pointed to the dishes.

The words brought a measure of comfort to Dylara's troubled mind. She noticed this woman's speech had in it nothing of the strange accent peculiar to Sephar's inhabitants.

"Who are you?" Dylara asked.

"I am Nada—a slave."

The girl nodded. Who was it this woman reminded her of? "I am Dylara, Nada. Tell me, why is it you speak as do the cave people?"

"I am of the cave people," replied the woman. "There are many of us here. The mountains about Sephar contain the caves of many tribes. Often Sephar's warriors make war on our people and carry many away to become slaves."

Dylara watched her as she spoke. Despite a youthful appearance, she must have been twice the cave-girl's age; about the same height but more fully developed. Her figure, under the simple tunic, was beautifully proportioned; her face the loveliest Dylara had ever seen. There was an indefinable air of breeding and poise in her manner, softened by warm brown eyes and an expression of sympathetic understanding.

Nada endured the close appraisal without self-consciousness. Finally she said: "You must be hungry. Come; sit here and eat."

Dylara obeyed without further urging. Nada watched her in silence until the girl's appetite had been dulled, then said: "How did they happen to get you?"

Dylara told her, briefly. For some obscure reason she could not bring herself to mention Tharn by name. Just the thought of him, falling beneath a Sepharian club, brought a sharp ache to her throat.

There was a far-away expression in Nada's eyes as Dylara finished her story. "I knew a warrior once—one very much like the young man who took you from your father's caves. He was a mighty chief—and my mate. Many summers ago I was captured near our caves as I walked at the jungle's edge. A war party from a strange tribe had crept close to our caves during the night, planning to raid us at dawn. They seized me; but my cries aroused my people, and the war party fled, taking me with them. They lost their way in the darkness, and after many weary marches stumbled across a hunting party from Sephar. In the fight that followed they killed almost all of us, sparing only three—and me. I have been here ever since."

Dylara caught the undercurrent of utter hopelessness in the woman's words, and she felt a sudden rush of sympathy well up within her.

"Tharn was a chief's son," she said. "Had he lived, I am sure he—" She stopped there, stricken into silence by the horror on Nada's face.

The slave woman rose unsteadily from the bed and seized Dylara's hands.

"Tharn—did you say Tharn?"

The girl, shocked by the pain and grief in the face of the woman, could only nod.

"He—is—dead?"

Again Dylara nodded.

Nada swayed and would have fallen had not Dylara held tightly to her wrists. Tears began to squeeze from her closed eyes, to trickle down the drawn white cheeks.

And then Dylara found her voice. "What is it, Nada? What is wrong?"

The woman swallowed with an effort, fighting for control. "I," she whispered, "am Tharn's mate!"

At first, Dylara thought she meant he whom the Sepharians had slain. And then the truth came to her.

The Tharn she had known was Nada's son!

Impulsively she drew the woman down beside her, holding her tightly until the tearing sobs subsided. For a little while there was silence within the room.

Without changing her position, Nada began to speak. "It was my son who was with you. Twelve summers before my capture I bore him; his father gave him his own name. And now he is dead. He is dead."

A draft of air from the window above caused the candle flame to waver, setting the shadows dancing.

Nada sat up and dried her eyes. "I will not cry any more," she said quietly. "Let us talk of other things."

Dylara pressed her hand in quick understanding. "Of course. Tell me, Nada, what will happen to me in Sephar?"

"You are a slave," Nada replied, "and belong to Urim, whose own warriors captured you. Perhaps you will be given certain duties in the palace, or the mate or daughter of some noble may ask for you as a hand-maiden. As a rule they treat us kindly; but if we are troublesome they whip us, or sometimes give us to the priests. That is the worst of all."

"They have gods, then?" Dylara asked.

"Only one, who is both good and evil. If they fall in battle, He has caused it; if they come through untouched, He has helped them."

The Cro-Magnon girl could not grasp this strange contradiction, for she knew certain gods sought to destroy man, while other gods tried to protect him....

"Then I must spend the rest of my life as a slave?" she asked.

"Yes—unless some free man asks for you as a mate. And that may happen because you are very beautiful."

The girl shook her head. "I do not want that," she declared. "I want only to return to my father and people."

"It will be best," Nada said, "to give up that foolish dream. Sometimes cave-men escape from Sephar; the women, never."

She rose, saying: "I must leave you now. The guards will be wondering what has kept me. Tomorrow I will come again."

The two embraced. "Farewell, Nada," whispered the girl. "I shall try to sleep again. Being here does not seem so bad, now that I know you."