|

|

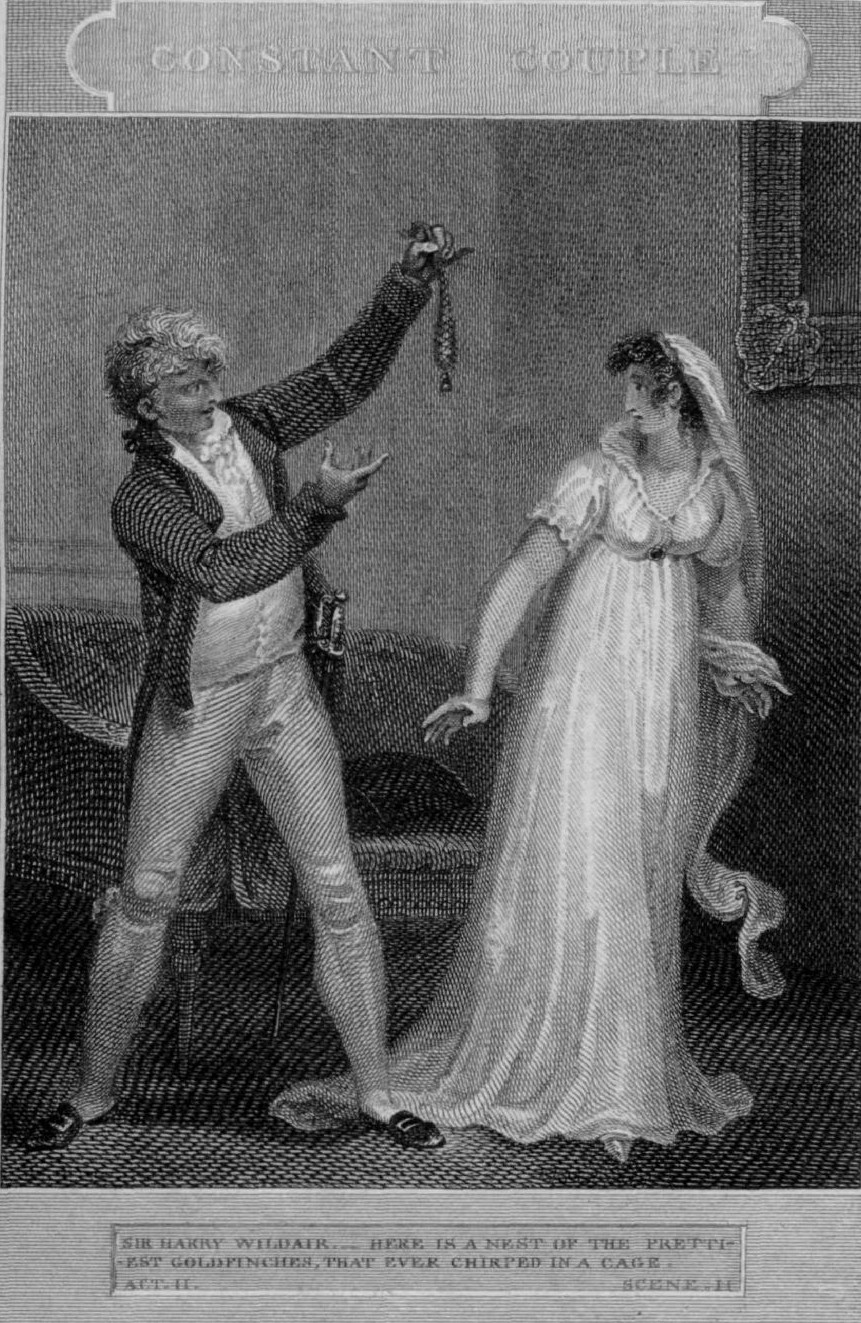

SIR HARRY WILDAIR.— HERE IS A NEST OF THE PRETTIEST GOLDFINCHES, THAT EVER CHIRPED IN A CAGE ACT. II. SCENE. II. Click to ENLARGE |

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Constant Couple

or, A Trip to the Jubilee

Author: George Farquhar

Release Date: May 18, 2010 [eBook #32419]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CONSTANT COUPLE***

George Farquhar, the author of this comedy, was the son of a clergyman in the north of Ireland. He was born in the year 1678, discovered an early taste for literature, and wrote poetic stanzas at ten years of age.

In 1694 he was sent to Trinity College, Dublin, and there made such progress in his studies as to acquire considerable reputation. But he was volatile and poor—the first misfortune led him to expense; the second, to devise means how to support his extravagance.

The theatre has peculiar charms for men of letters. Whether as a subject of admiration or animadversion, it is still a source of high amusement; and here Farquhar fixed his choice of a profession, in the united expectations of pleasure and of profit—he appeared on the stage as an actor, and was disappointed of both.

The author of this licentious comedy is said to have possessed the advantages of person, manners, and elocution, to qualify him for an actor; but that he could never overcome his natural timidity. Courage is a whimsical virtue. It acts upon one man so as to make him expose his whole body to danger, whilst he dares not venture into the slightest peril one sentiment of his mind. Such is often the soldier's valour.—Another trembles to expose his person either to a wound or to the eye of criticism, and yet will dare to publish every thought that ever found entrance into his imagination. Such is often the valour of a poet.

Farquhar, abashed on exhibiting his person upon the stage, sent boldly thither his most indecorous thoughts, and was rewarded for his audacity.

In the year 1700 he brought out this comedy of "The Constant Couple; or, A Trip to the Jubilee." It was then the Jubilee year at Rome, and the author took advantage of that occurrence to render the title of his drama popular; for which cause alone it must be supposed he made any thing in his play refer to that festival, as no one material point is in any shape connected with it.

At the time Farquhar was a performer, a sincere friendship was formed between him and Wilks, the celebrated fine gentleman of the stage—for him, Farquhar wrote the character of Sir Harry Wildair; and Wilks, by the very admirable manner in which he supported the part, divided with the author those honours which the first appearance of the work obtained him.

As a proof that this famed actor's abilities, in the representation of the fine gentlemen of his day, were not over-rated, no actor, since he quitted the stage, has been wholly successful in the performance of this character; and, from Wilks down to the present time, the part has only been supported, with celebrity, by women.

The noted Mrs. Woffington was highly extolled in Sir Harry; and Mrs. Jordan has been no less admired and attractive.

But it must be considered as a disgrace to the memory of the men of fashion, of the period in which Wildair was brought on the stage, that he has ever since been justly personated, by no other than the female sex. In this particular, at least, the present race of fashionable beaux cannot be said to have degenerated; for, happily, they can be represented by men.

The love story of Standard and Lurewell, in this play, is interesting to the reader, though, in action, an audience scarcely think of either of them; or of any one in the drama, with whom the hero is not positively concerned. Yet these two lovers, it would seem, love with all the usual ardour and constancy of gallants and mistresses in plays and novels—unfortunately, with the same short memories too! Authors, and some who do not generally deal in wonders, often make persons, the most tenderly attached to each other, so easily forget the shape, the air, the every feature of the dear beloved, as to pass, after a few years separation, whole days together, without the least conjecture that each is the very object of the other's search! Whilst all this surprising forgetfulness possesses them, as to the figure, face, and mind of him or her whom they still adore, show either of them but a ring, a bracelet, a mole, a scar, and here remembrance instantly occupies its place, and both are immediately inspired with every sensation which first testified their mutual passion. Still the sober critic must arraign the strength of this love with the shortness of its recollection; and charge the renewal of affection for objects that no longer appear the same, to fickleness rather than to constancy.

The biographers of Farquhar, who differ in some articles concerning him, all agree that he was married, in the year 1704, to a lady, who was so violently in love with him, that, despairing to win him by her own attractions, she contrived a vast scheme of imposition, by which she allured him into wedlock, with the full conviction that he had married a woman of immense fortune.

The same biographers all bestow the highest praise upon poor Farquhar for having treated this wife with kindness; humanely forgiving the fault which had deprived him of that liberty he was known peculiarly to prize, and reduced him to the utmost poverty, in order to support her and her children.

This woman, whose pretended love was of such fatal import to its object, not long enjoyed her selfish happiness—her husband's health gradually declined, and he died four years after his marriage. It is related that he met death with fortitude and cheerfulness. He could scarcely do otherwise, when life had become a burden to him. He had, however, some objects of affection to leave behind, as appears by the following letter, which he wrote a few days before his decease, and directed to his friend Wilks:—

"Dear Bob,

"I have not any thing to leave you to perpetuate my memory, except two helpless girls; look upon them sometimes, and think of him that was, to the last moment of his life, thine,

"George Farquhar."

Wilks protected the children—their mother died in extreme indigence.

| DRURY LANE. | COVENT GARDEN. | |

| Sir Harry Wildair | Mr. Elliston. | Mr. Lewis. |

| Alderm. Smuggler | Mr. Dowton. | Mr. Quick. |

| Colonel Standard | Mr. Barrymore. | Mr. Farren. |

| Clincher, Jun. | Mr. Collins. | Mr. Blanchard. |

| Beau Clincher | Mr. Bannister. | Mr. Cubitt. |

| Vizard | Mr. Holland. | Mr. Macready. |

| Tom Errand | Mr. Wewitzer. | Mr. Powell. |

| Dicky | Mr. Purser. | Mr. Simmons. |

| Constable | Mr. Maddocks. | Mr. Thompson. |

| Servants | Mr. Fisher, &c. | |

| Lady Lurewell | Mrs. Powell. | Miss Chapman. |

| Lady Darling | Miss Tidswell. | Miss Platt. |

| Angelica | Miss Mellon. | Mrs. Mountain. |

| Parly | Mrs. Scott. | Miss Stuart. |

| Tom Errand's Wife | Mrs. Maddocks. | |

| SCENE—London. | ||

The Park

Enter Vizard with a Letter, his Servant following.

Vizard. Angelica send it back unopened! say you?

Serv. As you see, sir?

Vizard. The pride of these virtuous women is more insufferable than the immodesty of prostitutes—After all my encouragement, to slight me thus!

Serv. She said, sir, that imagining your morals sincere, she gave you access to her conversation; but that your late behaviour in her company has convinced her that your love and religion are both hypocrisy, and that she believes your letter, like yourself, fair on the outside, and foul within; so sent it back unopened.

Vizard. May obstinacy guard her beauty till wrinkles bury it.—I'll be revenged the very first opportunity.——Saw you the old Lady Darling, her mother?

Serv. Yes, sir, and she was pleased to say much in your commendation.

Vizard. That's my cue——An esteem grafted in old age is hardly rooted out; years stiffen their opinions with their bodies, and old zeal is only to be cozened by young hypocrisy. [Aside.] Run to the Lady Lurewell's, and know of her maid whether her ladyship will be at home this evening. Her beauty is sufficient cure for Angelica's scorn.

[Exit Servant. Vizard pulls out a Book, reads,

and walks about.

Enter Smuggler.

Smug. Ay, there's a pattern for the young men o' th' times; at his meditation so early; some book of pious ejaculations, I'm sure.

Vizard. This Hobbes is an excellent fellow! [Aside.] Oh, uncle Smuggler! To find you at this end o' th' town is a miracle.

Smug. I have seen a miracle this morning indeed, cousin Vizard.

Vizard. What is it, pray, sir?

Smug. A man at his devotion so near the court—I'm very glad, boy, that you keep your sanctity untainted in this infectious place; the very air of this park is heathenish, and every man's breath I meet scents of atheism.

Vizard. Surely, sir, some great concern must bring you to this unsanctified end of the town.

Smug. A very unsanctified concern, truly, cousin.

Vizard. What is it?

Smug. A lawsuit, boy—Shall I tell you?—My ship, the Swan, is newly arrived from St. Sebastian, laden with Portugal wines: now the impudent rogue of a tide-waiter has the face to affirm it is French wines in Spanish casks, and has indicted me upon the statute——Oh, conscience! conscience! these tide-waiters and surveyors plague us more than the war—Ay, there's another plague of the nation—

Enter Colonel Standard.

A red coat and cockade.

Vizard. Colonel Standard, I'm your humble servant.

Colonel S. May be not, sir.

Vizard. Why so?

Colonel S. Because——I'm disbanded.

Vizard. How! Broke?

Colonel S. This very morning, in Hyde-Park, my brave regiment, a thousand men, that looked like lions yesterday, were scattered, and looked as poor and simple as the herd of deer that grazed beside them.

Smug. Tal, al deral. [Singing.] I'll have a bonfire this night as high as the monument.

Colonel S. A bonfire! Thou dry, withered, ill-nature; had not those brave fellows' swords defended you, your house had been a bonfire ere this, about your ears.——Did we not venture our lives, sir?

Smug. And did we not pay for your lives, sir?—Venture your lives! I'm sure we ventured our money, and that's life and soul to me.——Sir, we'll maintain you no longer.

Colonel S. Then your wives shall, old Actæon. There are five and thirty strapping officers gone this morning to live upon free quarter in the city.

Smug. Oh, lord! oh, lord! I shall have a son within these nine months, born with a leading staff in his hand.——Sir, you are——

Colonel S. What, sir?

Smug. Sir, I say that you are——

Colonel S. What, sir?

Smug. Disbanded, sir, that's all——I see my lawyer yonder. [Exit.

Vizard. Sir, I'm very sorry for your misfortune.

Colonel S. Why so? I don't come to borrow money of you; if you're my friend, meet me this evening at the Rummer; I'll pay my foy, drink a health to my king, prosperity to my country, and away for Hungary to-morrow morning.

Vizard. What! you won't leave us?

Colonel S. What! a soldier stay here, to look like an old pair of colours in Westminster Hall, ragged and rusty! No, no——I met yesterday a broken lieutenant, he was ashamed to own that he wanted a dinner, but wanted to borrow eighteen pence of me to buy a new scabbard for his sword.

Vizard. Oh, but you have good friends, colonel!

Colonel S. Oh, very good friends! My father's a lord, and my elder brother, a beau; mighty good indeed!

Vizard. But your country may, perhaps, want your sword again.

Colonel S. Nay, for that matter, let but a single drum beat up for volunteers between Ludgate and Charing Cross, and I shall undoubtedly hear it at the walls of Buda.

Vizard. Come, come, colonel, there are ways of making your fortune at home—Make your addresses to the fair; you're a man of honour and courage.

Colonel S. Ay, my courage is like to do me wondrous service with the fair. This pretty cross cut over my eye will attract a duchess—I warrant 'twill be a mighty grace to my ogling—Had I used the stratagem of a certain brother colonel of mine, I might succeed.

Vizard. What was it, pray?

Colonel S. Why, to save his pretty face for the women, he always turned his back upon the enemy.—He was a man of honour for the ladies.

Vizard. Come, come, the loves of Mars and Venus will never fail; you must get a mistress.

Colonel S. Pr'ythee, no more on't—You have awakened a thought, from which, and the kingdom, I would have stolen away at once.——To be plain, I have a mistress.

Vizard. And she's cruel?

Colonel S. No.

Vizard. Her parents prevent your happiness?

Colonel S. Not that.

Vizard. Then she has no fortune?

Colonel S. A large one. Beauty to tempt all mankind, and virtue to beat off their assaults. Oh, Vizard! such a creature!

Enter Sir Harry Wildair, crosses the Stage singing, with Footmen after him.

Heyday! who the devil have we here?

Vizard. The joy of the playhouse, and life of the park; Sir Harry Wildair, newly come from Paris.

Colonel S. Sir Harry Wildair! Did not he go a volunteer some three or four years ago?

Vizard. The same.

Colonel S. Why, he behaved himself very bravely.

Vizard. Why not? Dost think bravery and gaiety are inconsistent? He's a gentleman of most happy circumstances, born to a plentiful estate; has had a genteel and easy education, free from the rigidness of teachers, and pedantry of schools. His florid constitution being never ruffled by misfortune, nor stinted in its pleasures, has rendered him entertaining to others, and easy to himself. Turning all passion into gaiety of humour, by which he chuses rather to rejoice with his friends, than be hated by any; as you shall see.

Enter Sir Harry Wildair.

Sir H. Ha, Vizard!

Vizard. Sir Harry!

Sir H. Who thought to find you out of the Rubric so long? I thought thy hypocrisy had been wedded to a pulpit-cushion long ago.—Sir, if I mistake not your face, your name is Standard?

Colonel S. Sir Harry, I'm your humble servant.

Sir H. Come, gentlemen, the news, the news o' th' town, for I'm just arrived.

Vizard. Why, in the city end o' th' town we're playing the knave, to get estates.

Colonel S. And in the court end playing the fool, in spending them.

Sir H. Just so in Paris. I'm glad we're grown so modish.

Vizard. We are so reformed, that gallantry is taken for vice.

Colonel S. And hypocrisy for religion.

Sir H. A-la-mode de Paris again.

Vizard. Nothing like an oath in the city.

Colonel S. That's a mistake; for my major swore a hundred and fifty last night to a merchant's wife in her bed-chamber.

Sir H. Pshaw! this is trifling; tell me news, gentlemen. What lord has lately broke his fortune at the clubs, or his heart at Newmarket, for the loss of a race? What wife has been lately suing in Doctor's-Commons for alimony: or what daughter run away with her father's valet? What beau gave the noblest ball at Bath, or had the gayest equipage in town? I want news, gentlemen.

Colonel S. 'Faith, sir, these are no news at all.

Vizard. But, pray, Sir Harry, tell us some news of your travels.

Sir H. With all my heart.—You must know, then, I went over to Amsterdam in a Dutch ship. I went from thence to Landen, where I was heartily drubbed in battle, with the butt end of a Swiss musket. I thence went to Paris, where I had half a dozen intrigues, bought half a dozen new suits, fought a couple of duels, and here I am again in statu quo.

Vizard. But we heard that you designed to make the tour of Italy: what brought you back so soon?

Sir H. That which brought you into the world, and may perhaps carry you out of it;—a woman.

Colonel S. What! quit the pleasures of travel for a woman?

Sir H. Ay, colonel, for such a woman! I had rather see her ruelle than the palace of Louis le Grand. There's more glory in her smile, than in the jubilee at Rome! and I would rather kiss her hand than the Pope's toe.

Vizard. You, colonel, have been very lavish in the beauty and virtue of your mistress; and Sir Harry here has been no less eloquent in the praise of his. Now will I lay you both ten guineas a-piece, that neither of them is so pretty, so witty, or so virtuous, as mine.

Colonel S. 'Tis done.

Sir H. I'll double the stakes—But, gentlemen, now I think on't, how shall we be resolved? For I know not where my mistress may be found; she left Paris about a month before me, and I had an account——

Colonel S. How, sir! left Paris about a month before you?

Sir H. Yes, sir, and I had an account that she lodged somewhere in St. James's.

Vizard. How! somewhere in St. James's say you?

Sir H. Ay, sir, but I know not where, and perhaps may'nt find her this fortnight.

Colonel S. Her name, pray, Sir Harry?

Vizard. Ay, ay, her name; perhaps we know her.

Sir H. Her name! Ay, she has the softest, whitest hand that ever was made of flesh and blood; her lips so balmy sweet——

Colonel S. But her name, sir?

Sir H. Then her neck and——

Vizard. But her name, sir? her quality?

Sir H. Then her shape, colonel?

Colonel S. But her name I want, sir.

Sir H. Then her eyes, Vizard!

Colonel S. Pshaw, Sir Harry! her name, or nothing!

Sir H. Then if you must have it, she's called the Lady——But then her foot, gentlemen! she dances to a miracle. Vizard, you have certainly lost your wager.

Vizard. Why, you have certainly lost your senses; we shall never discover the picture, unless you subscribe the name.

Sir H. Then her name is Lurewell.

Colonel S. 'Sdeath! my mistress! [Aside.

Vizard. My mistress, by Jupiter! [Aside.

Sir H. Do you know her, gentlemen?

Colonel S. I have seen her, sir.

Sir H. Canst tell where she lodges? Tell me, dear colonel.

Colonel S. Your humble servant, sir. [Exit.

Sir H. Nay, hold, colonel; I'll follow you, and will know. [Runs out.

Vizard. The Lady Lurewell his mistress! He loves her: but she loves me.——But he's a baronet, and I plain Vizard; he has a coach, and I walk on foot; I was bred in London, and he in Paris.——That very circumstance has murdered me——Then some stratagem must be laid to divert his pretensions.

Enter Wildair.

Sir H. Pr'ythee, Dick, what makes the colonel so out of humour?

Vizard. Because he's out of pay, I suppose.

Sir H. 'Slife, that's true! I was beginning to mistrust some rivalship in the case.

Vizard. And suppose there were, you know the colonel can fight, Sir Harry.

Sir H. Fight! Pshaw—but he cannot dance, ha!—We contend for a woman, Vizard. 'Slife, man, if ladies were to be gained by sword and pistol only, what the devil should all we beaux do?

Vizard. I'll try him farther. [Aside.] But would not you, Sir Harry, fight for this woman you so much admire?

Sir H. Fight! Let me consider. I love her——that's true;——but then I love honest Sir Harry Wildair better. The Lady Lurewell is divinely charming——right——but then a thrust i' the guts, or a Middlesex jury, is as ugly as the devil.

Vizard. Ay, Sir Harry, 'twere a dangerous cast for a beau baronet to be tried by a parcel of greasy, grumbling, bartering boobies, who would hang you, purely because you're a gentleman.

Sir H. Ay, but on t'other hand, I have money enough to bribe the rogues with: so, upon mature deliberation, I would fight for her. But no more of her. Pr'ythee, Vizard, cannot you recommend a friend to a pretty mistress by the bye, till I can find my own? You have store, I'm sure; you cunning poaching dogs make surer game, than we that hunt open and fair. Pr'ythee now, good Vizard.

Vizard. Let me consider a little.—Now love and revenge inspire my politics! [Aside.

[Pauses whilst Sir Harry walks, singing.

Sir H. Pshaw! thou'rt longer studying for a new mistress, than a waiter would be in drawing fifty corks.

Vizard. I design you good wine; you'll therefore bear a little expectation.

Sir H. Ha! say'st thou, dear Vizard?

Vizard. A girl of nineteen, Sir Harry.

Sir H. Now nineteen thousand blessings light on thee.

Vizard. Pretty and witty.

Sir H. Ay, ay, but her name, Vizard!

Vizard. Her name! yes—she has the softest, whitest hand that e'er was made of flesh and blood; her lips so balmy sweet——

Sir H. Well, well, but where shall I find her, man?

Vizard. Find her!—but then her foot, Sir Harry! she dances to a miracle.

Sir H. Pr'ythee, don't distract me.

Vizard. Well then, you must know, that this lady is the greatest beauty in town; her name's Angelica: she that passes for her mother is a private bawd, and called the Lady Darling: she goes for a baronet's lady, (no disparagement to your honour, Sir Harry) I assure you.

Sir H. Pshaw, hang my honour! but what street, what house?

Vizard. Not so fast, Sir Harry; you must have my passport for your admittance, and you'll find my recommendation in a line or two will procure you very civil entertainment; I suppose twenty or thirty pieces handsomely placed, will gain the point.

Sir H. Thou dearest friend to a man in necessity! Here, sirrah, order my carriage about to St. James's; I'll walk across the park. [To his Servant.

Enter Clincher Senior.

Clinch. Here, sirrah, order my coach about to St. James's, I'll walk across the park too—Mr. Vizard, your most devoted—Sir, [To Wildair.] I admire the mode of your shoulder-knot; methinks it hangs very emphatically, and carries an air of travel in it: your sword-knot too is most ornamentally modish, and bears a foreign mien. Gentlemen, my brother is just arrived in town; so that, being upon the wing to kiss his hands, I hope you'll pardon this abrupt departure of, gentlemen, your most devoted, and most faithful humble servant. [Exit.

Sir H. Pr'ythee, dost know him?

Vizard. Know him! why, it is Clincher, who was apprentice to my uncle Smuggler, the merchant in the city.

Sir H. What makes him so gay?

Vizard. Why, he's in mourning.

Sir H. In mourning?

Vizard. Yes, for his father. The kind old man in Hertfordshire t'other day broke his neck a fox-hunting; the son, upon the news, has broke his indentures; whipped from behind the counter into the side-box. He keeps his coach and liveries, brace of geldings, leash of mistresses, talks of nothing but wines, intrigues, plays, fashions, and going to the jubilee.

Sir H. Ha! ha! ha! how many pounds of pulvil must the fellow use in sweetening himself from the smell of hops and tobacco? Faugh!—I' my conscience methought, like Olivia's lover, he stunk of Thames-Street. But now for Angelica, that's her name: we'll to the prince's chocolate-house, where you shall write my passport. Allons. [Exeunt.

Lady Lurewell's Lodgings.

Enter Lady Lurewell, and her Maid Parly.

Lady L. Parly, my pocket-book—let me see—Madrid, Paris, Venice, London!—Ay, London! They may talk what they will of the hot countries, but I find love most fruitful under this climate——In a month's space have I gained—let me see, imprimis, Colonel Standard.

Parly. And how will your ladyship manage him?

Lady L. As all soldiers should be managed; he shall serve me till I gain my ends, then I'll disband him.

Parly. But he loves you, madam.

Lady L. Therefore I scorn him;

I hate all that don't love me, and slight all that do;

'Would his whole deluding sex admir'd me,

Thus would I slight them all.

My virgin and unwary innocence

Was wrong'd by faithless man;

But now, glance eyes, plot brain, dissemble face,

Lie tongue, and

Plague the treacherous kind.——

Let me survey my captives.——

The colonel leads the van; next, Mr. Vizard,

He courts me out of the "Practice of Piety,"

Therefore is a hypocrite;

Then Clincher, he adores me with orangerie,

And is consequently a fool;

Then my old merchant, Alderman Smuggler,

He's a compound of both;—out of which medley of

lovers, if I don't make good diversion——What d'ye

think, Parly?

Parly. I think, madam, I'm like to be very virtuous in your service, if you teach me all those tricks that you use to your lovers.

Lady L. You're a fool, child; observe this, that though a woman swear, forswear, lie, dissemble, backbite, be proud, vain, malicious, any thing, if she secures the main chance, she's still virtuous; that's a maxim.

Parly. I can't be persuaded, though, madam, but that you really loved Sir Harry Wildair in Paris.

Lady L. Of all the lovers I ever had, he was my greatest plague, for I could never make him uneasy: I left him involved in a duel upon my account: I long to know whether the fop be killed or not.

Enter Colonel Standard.

Oh lord! no sooner talk of killing, but the soldier is conjured up. You're upon hard duty, colonel, to serve your king, your country, and a mistress too.

Colonel S. The latter, I must confess, is the hardest; for in war, madam, we can be relieved in our duty; but in love, he, who would take our post, is our enemy; emulation in glory is transporting, but rivals here intolerable.

Lady L. Those that bear away the prize in arms, should boast the same success in love; and, I think, considering the weakness of our sex, we should make those our companions who can be our champions.

Colonel S. I once, madam, hoped the honour of defending you from all injuries, through a title to your lovely person; but now my love must attend my fortune. My commission, madam, was my passport to the fair; adding a nobleness to my passion, it stamped a value on my love; 'twas once the life of honour, but now its winding sheet; and with it must my love be buried.

Parly. What? disbanded, Colonel?

Colonel S. Yes, Mrs. Parly.

Parly. Faugh, the nauseous fellow! he stinks of poverty already. [Aside.

Lady L. His misfortune troubles me, because it may prevent my designs. [Aside.

Colonel S. I'll chuse, madam, rather to destroy my passion by absence abroad, than have it starved at home.

Lady L. I'm sorry, sir, you have so mean an opinion of my affection, as to imagine it founded upon your fortune. And, to convince you of your mistake, here I vow, by all that's sacred, I own the same affection now as before. Let it suffice, my fortune is considerable.

Colonel S. No, madam, no; I'll never be a charge to her I love! The man, that sells himself for gold, is the worst of prostitutes.

Lady L. Now, were he any other creature but a man, I could love him. [Aside.

Colonel S. This only last request I make, that no title recommend a fool, no office introduce a knave, nor red coat a coward, to my place in your affections; so farewell my country, and adieu my love. [Exit.

Lady L. Now the devil take thee for being so honourable: here, Parly, call him back, I shall lose half my diversion else. Now for a trial of skill.

Enter Colonel Standard.

Sir, I hope you'll pardon my curiosity. When do you take your journey?

Colonel S. To-morrow morning, early, madam.

Lady L. So suddenly! which way are you designed to travel?

Colonel S. That I can't yet resolve on.

Lady L. Pray, sir, tell me; pray, sir; I entreat you; why are you so obstinate?

Colonel S. Why are you so curious, madam?

Lady L. Because——

Colonel S. What?

Lady L. Because, I, I——

Colonel S. Because, what, madam?—Pray tell me.

Lady L. Because I design to follow you. [Crying.

Colonel S. Follow me! By all that's great, I ne'er was proud before. Follow me! By Heavens thou shalt not. What! expose thee to the hazards of a camp!—Rather I'll stay, and here bear the contempt of fools, and worst of fortune.

Lady L. You need not, shall not; my estate for both is sufficient.

Colonel S. Thy estate! No, I'll turn a knave, and purchase one myself; I'll cringe to the proud man I undermine; I'll tip my tongue with flattery, and smooth my face with smiles; I'll turn informer, office-broker, nay, coward, to be great; and sacrifice it all to thee, my generous fair.

Lady L. And I'll dissemble, lie, swear, jilt, any thing, but I'll reward thy love, and recompense thy noble passion.

Colonel S. Sir Harry, ha! ha! ha! poor Sir Harry, ha! ha! ha! Rather kiss her hand than the Pope's toe; ha! ha! ha!

Lady L. What Sir Harry, Colonel? What Sir Harry?

Colonel S. Sir Harry Wildair, madam.

Lady L. What! is he come over?

Colonel S. Ay, and he told me—but I don't believe a syllable on't——

Lady L. What did he tell you?

Colonel S. Only called you his mistress; and pretending to be extravagant in your commendation, would vainly insinuate the praise of his own judgment and good fortune in a choice.

Lady L. How easily is the vanity of fops tickled by our sex!

Colonel S. Why, your sex is the vanity of fops.

Lady L. On my conscience, I believe so. This gentleman, because he danced well, I pitched on for a partner at a ball in Paris, and ever since he has so persecuted me with letters, songs, dances, serenading, flattery, foppery, and noise, that I was forced to fly the kingdom.——And I warrant you he made you jealous?

Colonel S. 'Faith, madam, I was a little uneasy.

Lady L. You shall have a plentiful revenge; I'll send him back all his foolish letters, songs, and verses, and you yourself shall carry them: 'twill afford you opportunity of triumphing, and free me from his further impertinence; for of all men he's my aversion. I'll run and fetch them instantly. [Exit.

Colonel S. Dear madam, a rare project! Now shall I bait him, like Actæon, with his own dogs.——Well, Mrs. Parly, it is ordered by act of parliament, that you receive no more pieces, Mrs. Parly.

Parly. 'Tis provided by the same act, that you send no more messages by me, good Colonel; you must not presume to send any more letters, unless you can pay the postage.

Colonel S. Come, come, don't be mercenary; take example by your lady, be honourable.

Parly. A-lack-a-day, sir, it shows as ridiculous and haughty for us to imitate our betters in their honour, as in their finery; leave honour to nobility that can support it: we poor folks, Colonel, have no pretence to't; and truly, I think, sir, that your honour should be cashiered with your leading-staff.

Colonel S. 'Tis one of the greatest curses of poverty to be the jest of chambermaids!

Enter Lurewell.

Lady L. Here's the packet, Colonel; the whole magazine of love's artillery.

[Gives him the Packet.

Colonel S. Which, since I have gained, I will turn upon the enemy. Madam, I'll bring you the news of my victory this evening. Poor Sir Harry, ha! ha! ha! [Exit.

Lady L. To the right about as you were; march, Colonel. Ha! ha! ha!

| Vain man, who boasts of studied parts and wiles! |

| Nature in us, your deepest art beguiles, |

| Stamping deep cunning in our frowns and smiles. |

| You toil for art, your intellects you trace; |

| Woman, without a thought, bears policy in her face. |

| [Exeunt. |

Clincher Junior's Lodgings.

Enter Clincher Junior, opening a Letter; Servant

following.

Clinch. jun. [Reads.] Dear Brother—I will see you

presently: I have sent this lad to wait on you; he can

instruct you in the fashions of the town. I am your

affectionate brother, Clincher.

Very well; and what's your name, sir?

Dicky. My name is Dicky, sir.

Clinch. jun. Dicky!

Dicky. Ay, Dicky, sir.

Clinch. jun. Very well; a pretty name! And what can you do, Mr. Dicky?

Dicky. Why, sir, I can powder a wig, and pick up a whore.

Clinch. jun. Oh, lord! Oh, lord! a whore! Why, are there many in this town?

Dicky. Ha! ha! ha! many! there's a question, indeed!——Harkye, sir; do you see that woman there, in the pink cloak and white feathers.

Clinch. jun. Ay, sir! what then?

Dicky. Why, she shall be at your service in three minutes, as I'm a pimp.

Clinch. jun. Oh, Jupiter Ammon! Why, she's a gentlewoman.

Dicky. A gentlewoman! Why so they are all in town, sir.

Enter Clincher senior.

Clinch. sen. Brother, you're welcome to London.

Clinch. jun. I thought, brother, you owed so much to the memory of my father, as to wear mourning for his death.

Clinch. sen. Why, so I do, fool; I wear this, because I have the estate; and you wear that, because you have not the estate. You have cause to mourn, indeed, brother. Well, brother, I'm glad to see you; fare you well. [Going.

Clinch. jun. Stay, stay, brother.——Where are you going?

Clinch. sen. How natural 'tis for a country booby to ask impertinent questions!—Harkye, sir; is not my father dead?

Clinch. jun. Ay, ay, to my sorrow.

Clinch. sen. No matter for that, he's dead; and am not I a young, powdered, extravagant English heir?

Clinch. jun. Very right, sir.

Clinch. sen. Why then, sir, you may be sure that I am going to the Jubilee, sir.

Clinch. jun. Jubilee! What's that?

Clinch. sen. Jubilee! Why, the Jubilee is——'Faith I don't know what it is.

Dicky. Why, the Jubilee is the same thing as our Lord Mayor's day in the city; there will be pageants, and squibs, and raree-shows, and all that, sir.

Clinch. jun. And must you go so soon, brother?

Clinch. sen. Yes, sir; for I must stay a month at Amsterdam, to study poetry.

Clinch. jun. Then I suppose, brother, you travel through Muscovy, to learn fashions; don't you, brother?

Clinch. sen. Brother! Pr'ythee, Robin, don't call me brother; sir will do every jot as well.

Clinch. jun. Oh, Jupiter Ammon! why so?

Clinch. sen. Because people will imagine you have a spite at me.—But have you seen your cousin Angelica yet, and her mother, the Lady Darling?

Clinch. jun. No; my dancing-master has not been with me yet. How shall I salute them, brother?

Clinch. sen. Pshaw! that's easy; 'tis only two scrapes, a kiss, and your humble servant. I'll tell you more when I come from the Jubilee. Come along. [Exeunt.

|

|

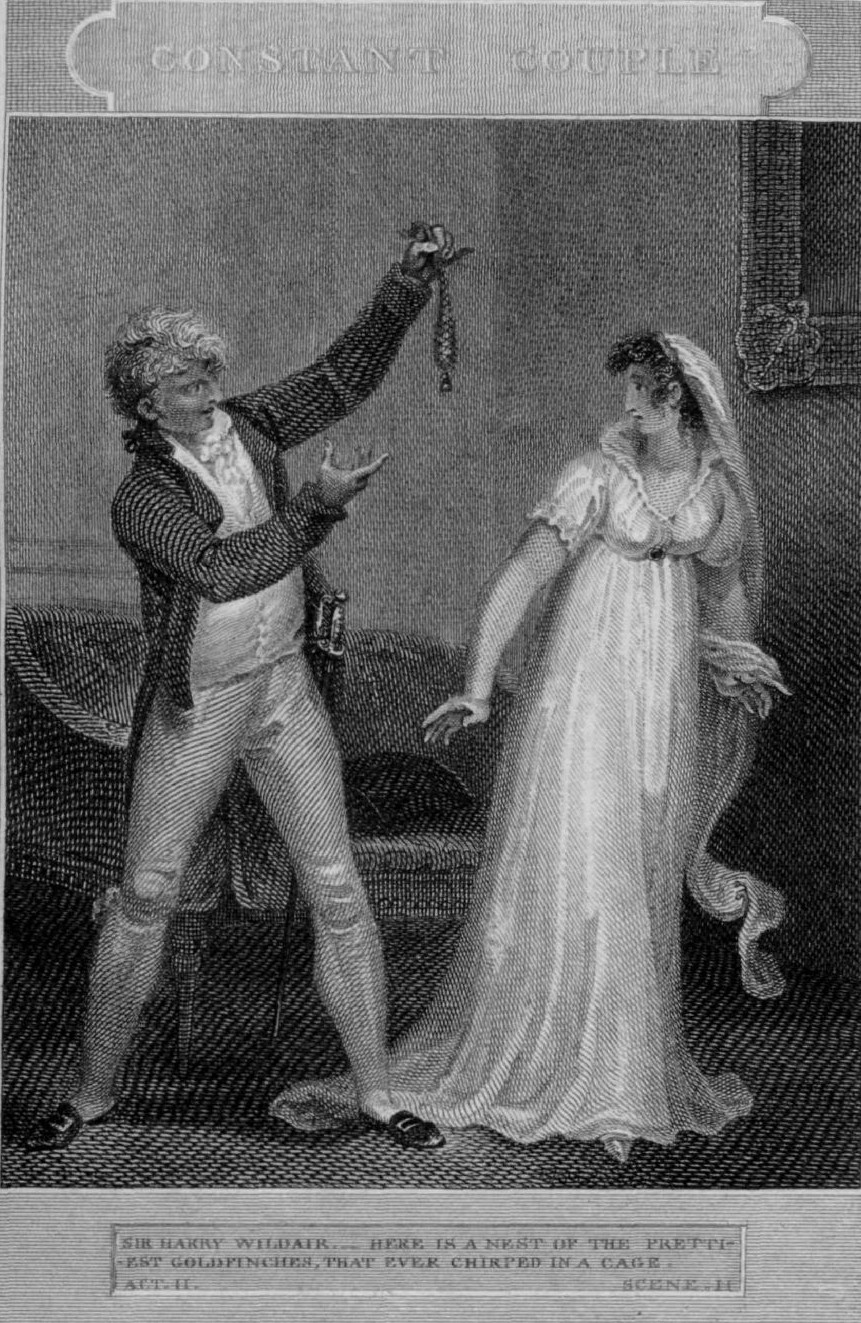

SIR HARRY WILDAIR.— HERE IS A NEST OF THE PRETTIEST GOLDFINCHES, THAT EVER CHIRPED IN A CAGE ACT. II. SCENE. II. Click to ENLARGE |

Lady Darling's House.

Enter Sir H. Wildair with a Letter.

Sir H. Like light and heat, incorporate we lay;

We bless'd the night, and curs'd the coming day.

Well, if this paper kite flies sure, I'm secure of my

game——Humph!—the prettiest bourdel I have seen;

a very stately genteel one——

Footmen cross the Stage.

Heyday! equipage too!——'Sdeath, I'm afraid I've mistaken the house!

Enter Lady Darling.

No, this must be the bawd, by her dignity.

Lady D. Your business, pray, sir?

Sir H. Pleasure, madam.

Lady D. Then, sir, you have no business here.

Sir H. This letter, madam, will inform you farther. Mr. Vizard sent it, with his humble service to your ladyship.

Lady D. How does my cousin, sir?

Sir H. Ay, her cousin, too! that's right procuress again. [Aside.

Lady D. [Reads.] Madam——Earnest inclination to serve——Sir Harry——Madam——court my cousin——Gentleman——fortune——

Your ladyships most humble servant, Vizard.

Sir, your fortune and quality are sufficient to recommend you any where; but what goes farther with me is the recommendation of so sober and pious a young gentleman as my cousin Vizard.

Sir H. A right sanctified bawd o' my word! [Aside.

Lady D. Sir Harry, your conversation with Mr. Vizard argues you a gentleman, free from the loose and vicious carriage of the town. I shall therefore call my daughter. [Exit.

Sir H. Now go thy way for an illustrious bawd of Babylon:—she dresses up a sin so religiously, that the devil would hardly know it of his making.

Enter Lady Darling with Angelica.

Lady D. Pray, daughter, use him civilly; such matches don't offer every day. [Exit Lady Darl.

Sir H. Oh, all ye powers of love! an angel!—'Sdeath, what money have I got in my pocket? I can't offer her less than twenty guineas——and, by Jupiter, she's worth a hundred.

Ang. 'Tis he! the very same! and his person as agreeable as his character of good humour.——Pray Heaven his silence proceed from respect!

Sir H. How innocent she looks! How would that modesty adorn virtue, when it makes even vice look so charming!——By Heaven, there's such a commanding innocence in her looks, that I dare not ask the question!

Ang. Now, all the charms of real love and feigned indifference assist me to engage his heart; for mine is lost already.

Sir H. Madam—I—I——Zouns, I cannot speak to her!—Oh, hypocrisy! hypocrisy! what a charming sin art thou!

Ang. He is caught; now to secure my conquest—I thought, sir, you had business to communicate.

Sir H. Business to communicate! How nicely she words it!——Yes, madam, I have a little business to communicate. Don't you love singing-birds, madam?

Ang. That's an odd question for a lover—Yes, sir.

Sir H. Why, then, madam, here's a nest of the prettiest goldfinches that ever chirp'd in a cage; twenty young ones, I assure you, madam.

Ang. Twenty young ones! What then, sir?

Sir H. Why then, madam, there are——twenty young ones——'Slife, I think twenty is pretty fair.

Ang. He's mad, sure!——Sir Harry, when you have learned more wit and manners, you shall be welcome here again. [Exit.

Sir H. Wit and manners! 'Egad, now, I conceive there is a great deal of wit and manners in twenty guineas—I'm sure 'tis all the wit and manners I have about me at present. What shall I do?

Enter Clincher Junior and Dicky.

What the devil's here? Another cousin, I warrant ye!—Harkye, sir, can you lend me ten or a dozen guineas instantly? I'll pay you fifteen for them in three hours, upon my honour.

Clinch. jun. These London sparks are plaguy impudent! This fellow, by his assurance, can be no less than a courtier.

Dicky. He's rather a courtier by his borrowing.

Clinch. jun. 'Faith, sir, I han't above five guineas about me.

Sir H. What business have you here then, sir?—For, to my knowledge, twenty won't be sufficient.

Clinch. jun. Sufficient! for what, sir?

Sir H. What, sir! Why, for that, sir; what the devil should it be, sir? I know your business, notwithstanding all your gravity, sir.

Clinch. jun. My business! Why, my cousin lives here.

Sir H. I know your cousin does live here, and Vizard's cousin, and every body's cousin——Harkye, sir, I shall return immediately; and if you offer to touch her till I come back, I shall cut your throat, rascal. [Exit.

Clinch. jun. Why, the man's mad, sure!

Dicky. Mad, sir! Ay——Why, he's a beau.

Clinch. jun. A beau! What's that? Are all madmen beaux?

Dicky. No, sir; but most beaux are madmen.—But now for your cousin. Remember your three scrapes, a kiss, and your humble servant. [Exeunt.

A Street.

Enter Sir Harry Wildair, Colonel Standard

following.

Colonel S. Sir Harry! Sir Harry!

Sir H. I am in haste, Colonel; besides, if you're in no better humour than when I parted with you in the park this morning, your company won't be very agreeable.

Colonel S. You're a happy man, Sir Harry, who are never out of humour. Can nothing move your gall, Sir Harry?

Sir H. Nothing but impossibilities, which are the same as nothing.

Colonel S. What impossibilities?

Sir H. The resurrection of my father to disinherit me, or an act of parliament against wenching. A man of eight thousand pounds per annum to be vexed! No, no; anger and spleen are companions for younger brothers.

Colonel S. Suppose one called you a son of a whore behind your back.

Sir H. Why, then would I call him rascal behind his back; so we're even.

Colonel S. But suppose you had lost a mistress.

Sir H. Why, then I would get another.

Colonel S. But suppose you were discarded by the woman you love; that would surely trouble you.

Sir H. You're mistaken, Colonel; my love is neither romantically honourable, nor meanly mercenary; 'tis only a pitch of gratitude: while she loves me, I love her; when she desists, the obligation's void.

Colonel S. But to be mistaken in your opinion, sir; if the Lady Lurewell (only suppose it) had discarded you—I say, only suppose it——and had sent your discharge by me.

Sir H. Pshaw! that's another impossibility.

Colonel S. Are you sure of that?

Sir H. Why, 'twere a solecism in nature. Why, we are finger and glove, sir. She dances with me, sings with me, plays with me, swears with me, lies with me.

Colonel S. How, sir?

Sir H. I mean in an honourable way; that is, she lies for me. In short, we are as like one another as a couple of guineas.

Colonel S. Now that I have raised you to the highest pinnacle of vanity, will I give you so mortifying a fall, as shall dash your hopes to pieces.—I pray your honour to peruse these papers.

[Gives him the Packet.

Sir H. What is't, the muster-roll of your regiment, colonel?

Colonel S. No, no, 'tis a list of your forces in your last love campaign; and, for your comfort, all disbanded.

Sir H. Pr'ythee, good metaphorical colonel, what d'ye mean?

Colonel S. Read, sir, read; these are the Sibyl's leaves, that will unfold your destiny.

Sir H. So it be not a false deed to cheat me of my estate, what care I—[Opening the Packet.] Humph! my hand!—To the Lady Lurewell—To the Lady Lurewell—To the Lady Lurewell—What the devil hast thou been tampering with, to conjure up these spirits?

Colonel S. A certain familiar of your acquaintance, sir. Read, read.

Sir H. [Reading.] Madam, my passion——so natural——your beauty contending——force of charms——mankind——eternal admirer, Wildair.—I ne'er was ashamed of my name before.

Colonel S. What, Sir Harry Wildair out of humour! ha! ha! ha! Poor Sir Harry! More glory in her smile than in the Jubilee at Rome; ha! ha! ha! But then her foot, Sir Harry; she dances to a miracle! ha! ha! ha! Fie, Sir Harry; a man of your parts write letters not worth keeping!

Sir H. Now, why should I be angry that a woman

is a woman? Since inconstancy and falsehood are

grounded in their natures, how can they help it?—Here's

a copy of verses too: I must turn poet, in the

devil's name—Stay—'Sdeath, what's here?—This is

her hand——Oh, the charming characters!—[Reading.]—My

dear Wildair,—That's I, 'egad!—This

huff-bluff Colonel—that's he—is the rarest fool in nature—the

devil he is!—and as such have I used him.—With

all my heart, 'faith!—I had no better way of letting

you know that I lodge in Pall Mall—Lurewell.

——Colonel,

I am your most humble servant.

Colonel S. Hold, sir, you shan't go yet; I ha'n't delivered half my message.

Sir H. Upon my faith, but you have, colonel.

Colonel S. Well, well, own your spleen; out with it; I know you're like to burst.

Sir H. I am so, 'egad; ha! ha! ha!

[Laugh and point at one another.

Colonel S. Ay, with all my heart; ha! ha! Well, well, that's forced, Sir Harry.

Sir H. I was never better pleased in all my life, by Jupiter.

Colonel S. Well, Sir Harry, 'tis prudence to hide your concern, when there's no help for it. But, to be serious, now; the lady has sent you back all your papers there——I was so just as not to look upon them.

Sir H. I'm glad on't, sir; for there were some things that I would not have you see.

Colonel S. All this she has done for my sake; and I desire you would decline any further pretensions for your own sake. So, honest, goodnatured Sir Harry, I'm your humble servant. [Exit.

Sir H. Ha! ha! ha! poor colonel! Oh, the delight of an ingenious mistress! what a life and briskness it adds to an amour.—A legerdemain mistress, who, presto! pass! and she's vanished; then hey! in an instant in your arms again. [Going.

Enter Vizard.

Vizard. Well met, Sir Harry—what news from the island of love?

Sir H. 'Faith, we made but a broken voyage by your chart; but now I am bound for another port: I told you the colonel was my rival.

Vizard. The colonel—curs'd misfortune! another. [Aside.

Sir H. But the civilest in the world; he brought me word where my mistress lodges. The story's too long to tell you now, for I must fly.

Vizard. What, have you given over all thoughts of Angelica?

Sir H. No, no; I'll think of her some other time. But now for the Lady Lurewell. Wit and beauty calls.

| That mistress ne'er can pall her lover's joys, |

| Whose wit can whet, whene'er her beauty cloys. |

| Her little amorous frauds all truths excel, |

| And make us happy, being deceived so well. |

| [Exit. |

Vizard. The colonel my rival too!——How shall I manage? There is but one way——him and the knight will I set a tilting, where one cuts t'other's throat, and the survivor's hanged: so there will be two rivals pretty decently disposed of. [Exit.

Lady Lurewell's Lodgings.

Enter Lady Lurewell and Parly.

Lady L. Has my servant brought me the money from my merchant?

Parly. No, madam: he met Alderman Smuggler at Charing-Cross, who has promised to wait on you himself immediately.

Lady L. 'Tis odd that this old rogue should pretend to love me, and at the same time cheat me of my money.

Parly. 'Tis well, madam, if he don't cheat you of your estate; for you say the writings are in his hands.

Lady L. But what satisfaction can I get of him?——Oh! here he comes!

Enter Smuggler.

Mr. Alderman, your servant; have you brought me any money, sir?

Smug. 'Faith, madam, trading is very dead; what with paying the taxes, losses at sea abroad, and maintaining our wives at home, the bank is reduced very low; money is very scarce.

Lady L. Come, come, sir; these evasions won't serve your turn: I must have money, sir—I hope you don't design to cheat me?

Smug. Cheat you, madam! have a care what you say: I'm an alderman, madam——Cheat you, madam! I have been an honest citizen these five-and-thirty years.

Lady L. An honest citizen! Bear witness, Parly—I shall trap him in more lies presently. Come, sir, though I am a woman, I can take a remedy.

Smug. What remedy, madam? You'll go to law, will ye? I can maintain a suit of law, be it right or wrong, these forty years—thanks to the honest practice of the courts.

Lady L. Sir, I'll blast your reputation, and so ruin your credit.

Smug. Blast my reputation! he! he! he! Why, I'm a religious man, madam; I have been very instrumental in the reformation of manners. Ruin my credit! Ah, poor woman! There is but one way, madam——you have a sweet leering eye.

Lady L. You instrumental in the reformation?—How?

Smug. I whipp'd all the pau-pau women out of the parish—Ah, that leering eye! Ah, that lip! that lip!

Lady L. Here's a religious rogue for you, now!—As I hope to be saved, I have a good mind to beat the old monster.

Smug. Madam, I have brought you about two hundred and fifty guineas (a great deal of money, as times go) and——

Lady L. Come, give 'em me.

Smug. Ah, that hand, that hand! that pretty, soft, white——I have brought it; but the condition of the obligation is such, that whereas that leering eye, that pouting lip, that pretty soft hand, that—you understand me; you understand; I'm sure you do, you little rogue——

Lady L. Here's a villain, now, so covetous, that he would bribe me with my own money. I'll be revenged. [Aside.]—Upon my word, Mr. Alderman, you make me blush,—what d'ye mean, pray?

Smug. See here, madam. [Pulls his Purse out.]—Buss and guinea! buss and guinea! buss and guinea!

Lady L. Well, Mr. Alderman, you have such pretty winning ways, that I will—ha! ha! ha!

Smug. Will you, indeed, he! he! he! my little cocket? And when, and where, and how?

Lady L. 'Twill be a difficult point, sir, to secure both our honours: you must therefore be disguised, Mr. Alderman.

Smug. Pshaw! no matter; I am an old fornicator; I'm not half so religious as I seem to be. You little rogue, why I'm disguised as I am; our sanctity is all outside, all hypocrisy.

Lady L. No man is seen to come into this house after dark; you must therefore sneak in, when 'tis dark, in woman's clothes.

Smug. With all my heart——I have a suit on purpose, my little cocket; I love to be disguised; 'ecod, I make a very handsome woman, 'ecod, I do.

Enter Servant, who whispers Lady Lurewell.

Lady L. Oh, Mr. Alderman, shall I beg you to walk into the next room? Here are some strangers coming up.

Smug. Buss and guinea first—Ah, my little cocket! [Exit.

Enter Sir H. Wildair.

Sir H. My life, my soul, my all that Heaven can give!——

Lady L. Death's life with thee, without thee death to live. Welcome, my dear Sir Harry——I see you got my directions.

Sir H. Directions! in the most charming manner, thou dear Machiavel of intrigue.

Lady L. Still brisk and airy, I find, Sir Harry.

Sir H. The sight of you, madam, exalts my air, and makes joy lighten in my face.

Lady L. I have a thousand questions to ask you, Sir Harry. Why did you leave France so soon?

Sir H. Because, madam, there is no existing where you are not.

Lady L. Oh, monsieur, je vous suis fort obligée——But, where's the court now?

Sir H. At Marli, madam.

Lady L. And where my Count La Valier?

Sir H. His body's in the church of Nôtre Dame; I don't know where his soul is.

Lady L. What disease did he die of?

Sir H. A duel, madam; I was his doctor.

Lady L. How d'ye mean?

Sir H. As most doctors do; I kill'd him.

Lady L. En cavalier, my dear knight-errant—Well, and how, and how: what intrigues, what gallantries are carrying on in the beau monde?

Sir H. I should ask you that question, madam, since your ladyship makes the beau-monde wherever you come.

Lady L. Ah, Sir Harry, I've been almost ruined, pestered to death here, by the incessant attacks of a mighty colonel; he has besieged me.

Sir H. I hope your ladyship did not surrender, though.

Lady L. No, no; but was forced to capitulate. But since you are come to raise the siege, we'll dance, and sing, and laugh——

Sir H. And love, and kiss——Montrez moi votre chambre?

Lady L. Attends, attends, un peu——I remember, Sir Harry, you promised me, in Paris, never to ask that impertinent question again.

Sir H. Pshaw, madam! that was above two months ago: besides, madam, treaties made in France are never kept.

Lady L. Would you marry me, Sir Harry?

Sir H. Oh! I do detest marriage.—But I will marry you.

Lady L. Your word, sir, is not to be relied on: if a gentleman will forfeit his honour in dealings of business, we may reasonably suspect his fidelity in an amour.

Sir H. My honour in dealings of business! Why, madam, I never had any business in all my life.

Lady L. Yes, Sir Harry, I have heard a very odd story, and am sorry that a gentleman of your figure should undergo the scandal.

Sir H. Out with it, madam.

Lady L. Why, the merchant, sir, that transmitted your bills of exchange to you in France, complains of some indirect and dishonourable dealings.

Sir H. Who, old Smuggler?

Lady L. Ay, ay, you know him, I find.

Sir H. I have some reason, I think; why, the rogue has cheated me of above five hundred pounds within these three years.

Lady L. 'Tis your business then to acquit yourself publicly; for he spreads the scandal every where.

Sir H. Acquit myself publicly! I'll drive instantly into the city, and cane the old villain: he shall run the gauntlet round the Royal Exchange.

Lady L. Why, he is in the house now, sir.

Sir H. What, in this house?

Lady L. Ay, in the next room.

Sir H. Then, sirrah, lend me your cudgel.

Lady L. Sir Harry, you won't raise a disturbance in my house?

Sir H. Disturbance, madam! no, no, I'll beat him with the temper of a philosopher. Here, Mrs. Parly, show me the gentleman.

[Exit with Parly.

Lady L. Now shall I get the old monster well beaten, and Sir Harry pestered next term with bloodsheds, batteries, costs, and damages, solicitors and attorneys; and if they don't tease him out of his good humour, I'll never plot again. [Exit.

Another Room in the same House.

Enter Smuggler.

Smug. Oh, this damned tide-waiter! A ship and cargo worth five thousand pounds! Why, 'tis richly worth five hundred perjuries.

Enter Sir H. Wildair.

Sir H. Dear Mr. Alderman, I'm your most devoted and humble servant.

Smug. My best friend, Sir Harry, you're welcome to England.

Sir H. I'll assure you, sir, there's not a man in the king's dominions I am gladder to meet, dear, dear Mr. Alderman.

[Bowing very low.

Smug. Oh, lord, sir, you travellers have the most obliging ways with you!

Sir H. There is a business, Mr. Alderman, fallen out, which you may oblige me infinitely by——I am very sorry that I am forced to be troublesome; but necessity, Mr. Alderman——

Smug. Ay, sir, as you say, necessity——But, upon my word, sir, I am very short of money at present; but——

Sir H. That's not the matter, sir; I'm above an obligation that way: but the business is, I'm reduced to an indispensable necessity of being obliged to you for a beating——Here, take this cudgel.

Smug. A beating, Sir Harry! ha! ha! ha! I beat a knight baronet! an alderman turn cudgel-player! Ha! ha! ha!

Sir H. Upon my word, sir, you must beat me, or I cudgel you; take your choice.

Smug. Pshaw! pshaw! you jest.

Sir H. Nay, 'tis sure as fate——So, Alderman, I hope you'll pardon my curiosity.

[Strikes him.

Smug. Curiosity! Deuce take your curiosity, sir!—What d'ye mean?

Sir H. Nothing at all; I'm but in jest, sir.

Smug. Oh, I can take any thing in jest! but a man might imagine, by the smartness of the stroke, that you were in downright earnest.

Sir H. Not in the least, sir; [Strikes him.] not in the least, indeed, sir.

Smug. Pray, good sir, no more of your jests; for they are the bluntest jests that ever I knew.

Sir H. [Strikes.] I heartily beg your pardon, with all my heart, sir.

Smug. Pardon, sir! Well, sir, that is satisfaction enough from a gentleman. But, seriously, now, if you pass any more of your jests upon me, I shall grow angry.

Sir H. I humbly beg your permission to break one or two more. [Strikes him.

Smug. Oh, lord, sir, you'll break my bones! Are you mad, sir? Murder, felony, manslaughter!

[Sir Harry knocks him down.

Sir H. Sir, I beg you ten thousand pardons; but I am absolutely compelled to it, upon my honour, sir: nothing can be more averse to my inclinations, than to jest with my honest, dear, loving, obliging friend, the Alderman.

[Striking him all this while: Smuggler tumbles over and over.

Enter Lady Lurewell.

Lady L. Oh, lord! Sir Harry's murdering the poor old man.

Smug. Oh, dear madam, I was beaten in jest, till I am murdered in good earnest.

Lady L. Oh! you barbarous man!—Now the devil take you, Sir Harry, for not beating him harder—Well, my dear, you shall come at night, and I'll make you amends.

[Here Sir Harry takes Snuff.

Smug. Madam, I will have amends before I leave the place——Sir, how durst you use me thus!

Sir H. Sir?

Smug. Sir, I say that I will have satisfaction.

Sir H. With all my heart.

[Throws Snuff into his Eyes.

Smug. Oh, murder! blindness! fire! Oh, madam, madam, get me some water. Water! fire! fire! water!

[Exit with Lady Lurewell.

Sir H. How pleasant is resenting an injury without passion! 'Tis the beauty of revenge.

| No spleen, no trouble, shall my time destroy: |

| Life's but a span, I'll ev'ry inch enjoy. |

| [Exit. |

The Street.

Enter Colonel Standard and Vizard.

Colonel S. I bring him word where she lodged? I the civilest rival in the world? 'Tis impossible.

Vizard. I shall urge it no farther, sir. I only thought, sir, that my character in the world might add authority to my words, without so many repetitions.

Colonel S. Pardon me, dear Vizard. Our belief struggles hard, before it can be brought to yield to the disadvantage of what we love. But what said Sir Harry?

Vizard. He pitied the poor credulous colonel, laughed heartily, flew away with all the raptures of a bridegroom, repeating these lines:

| A mistress ne'er can pall her lover's joys, |

| Whose wit can whet, whene'er her beauty cloys. |

Colonel S. A mistress ne'er can pall! By all my wrongs he whores her, and I am made their property.——Vengeance——Vizard, you must carry a note for me to Sir Harry.

Vizard. What, a challenge? I hope you don't design to fight?

Colonel S. What, wear the livery of my king, and pocket an affront? 'Twere an abuse to his sacred Majesty: a soldier's sword, Vizard, should start of itself, to redress its master's wrong.

Vizard. However, sir, I think it not proper for me to carry any such message between friends.

Colonel S. I have ne'er a servant here; what shall I do?

Vizard. There's Tom Errand, the porter, that plies at the Blue Posts, one who knows Sir Harry and his haunts very well; you may send a note by him.

Colonel S. Here, you, friend.

Vizard. I have now some business, and must take my leave; I would advise you, nevertheless, against this affair.

Colonel S. No whispering now, nor telling of friends, to prevent us. He, that disappoints a man of an honourable revenge, may love him foolishly like a wife, but never value him as a friend.

Vizard. Nay, the devil take him, that parts you, say I. [Exit.

Enter Tom Errand.

Tom. Did your honour call porter?

Colonel S. Is your name Tom Errand?

Tom. People call me so, an't like your worship.

Colonel S. D'ye know Sir Harry Wildair?

Tom. Ay, very well, sir; he's one of my best masters; many a round half crown have I had of his worship; he's newly come home from France, sir.

Colonel S. Go to the next coffee-house, and wait for me.——Oh, woman, woman, how blessed is man, when favoured by your smiles, and how accursed when all those smiles are found but wanton baits to sooth us to destruction. [Exeunt.

Enter Sir H. Wildair, and Clincher Senior, following.

Clinch. sen. Sir, sir, sir, having some business of importance to communicate to you, I would beg your attention to a trifling affair, that I would impart to your understanding.

Sir H. What is your trifling business of importance, pray, sweet sir?

Clinch. sen. Pray, sir, are the roads deep between this and Paris?

Sir H. Why that question, sir?

Clinch. sen. Because I design to go to the jubilee, sir. I understand that you are a traveller, sir; there is an air of travel in the tie of your cravat, sir: there is indeed, sir——I suppose, sir, you bought this lace in Flanders.

Sir H. No, sir, this lace was made in Norway.

Clinch. sen. Norway, sir?

Sir H. Yes, sir, of the shavings of deal boards.

Clinch. sen. That's very strange now, 'faith—Lace made of the shavings of deal boards! 'Egad, sir, you travellers see very strange things abroad, very incredible things abroad, indeed. Well, I'll have a cravat of the very same lace before I come home.

Sir H. But, sir, what preparations have you made for your journey?

Clinch. sen. A case of pocket-pistols for the bravos, and a swimming-girdle.

Sir H. Why these, sir?

Clinch. sen. Oh, lord, sir, I'll tell you——Suppose us in Rome now; away goes I to some ball—for I'll be a mighty beau. Then, as I said, I go to some ball, or some bear-baiting—'tis all one, you know—then comes a fine Italian bona roba, and plucks me by the sleeve: Signior Angle, Signior Angle—She's a very fine lady, observe that—Signior Angle, says she—Signiora, says I, and trips after her to the corner of a street, suppose it Russel Street, here, or any other street: then, you know, I must invite her to the tavern; I can do no less——There up comes her bravo; the Italian grows saucy, and I give him an English dowse on the face: I can box, sir, box tightly; I was a 'prentice, sir——But then, sir, he whips out his stiletto, and I whips out my bull-dog—slaps him through, trips down stairs, turns the corner of Russel Street again, and whips me into the ambassador's train, and there I'm safe as a beau behind the scenes.

Sir H. Is your pistol charged, sir?

Clinch. sen. Only a brace of bullets, that's all, sir.

Sir H. 'Tis a very fine pistol, truly; pray let me see it.

Clinch. sen. With all my heart, sir.

Sir H. Harkye, Mr. Jubilee, can you digest a brace of bullets?

Clinch. sen. Oh, by no means in the world, sir.

Sir H. I'll try the strength of your stomach, however. Sir, you're a dead man.

[Presenting the Pistol to his Breast.

Clinch. sen. Consider, dear sir, I am going to the Jubilee: when I come home again, I am a dead man at your service.

Sir H. Oh, very well, sir; but take heed you are not so choleric for the future.

Clinch. sen. Choleric, sir! Oons, I design to shoot seven Italians in a week, sir.

Sir H. Sir, you won't have provocation.

Clinch. sen. Provocation, sir! Zouns, sir, I'll kill any man for treading upon my corns: and there will be a devilish throng of people there: they say that all the princes of Italy will be there.

Sir H. And all the fops and fiddlers in Europe——But the use of your swimming girdle, pray sir?

Clinch. sen. Oh lord, sir, that's easy. Suppose the ship cast away; now, whilst, other foolish people are busy at their prayers, I whip on my swimming girdle, clap a month's provision in my pocket, and sails me away, like an egg in a duck's belly. Well, sir, you must pardon me now, I'm going to see my mistress. [Exit.

Sir H. This fellow's an accomplished ass before he goes abroad. Well, this Angelica has got into my heart, and I cannot get her out of my head. I must pay her t'other visit. [Exit.

Lady Darling's House.

Enter Angelica, Lady Darling, Clincher Junior,

and Dicky.

Lady D. This is my daughter, cousin.

Dicky. Now sir, remember your three scrapes.

Clinch. jun. [Saluting Angelica.] One, two, three, your humble servant. Was not that right, Dicky?

Dicky. Ay, 'faith, sir; but why don't you speak to her?

Clinch. jun. I beg your pardon, Dicky; I know my distance. Would you have me to speak to a lady at the first sight?

Dicky. Ay sir, by all means; the first aim is the surest.

Clinch. jun. Now for a good jest, to make her laugh heartily——By Jupiter Ammon, I'll give her a kiss.

[Goes towards her.

Enter Wildair, interposing.

Sir H. 'Tis all to no purpose; I told you so before; your pitiful five guineas will never do. You may go; I'll outbid you.

Clinch. jun. What the devil! the madman's here again.

Lady D. Bless me, cousin, what d'ye mean? Affront a gentleman of his quality in my house?

Clinch. jun. Quality!—Why, madam, I don't know what you mean by your madmen, and your beaux, and your quality——they're all alike, I believe.

Lady D. Pray, sir, walk with me into the next room.

[Exit Lady Darling, leading Clincher, Dicky following.

Ang. Sir, if your conversation be no more agreeable than 'twas the last time, I would advise you to make your visit as short as you can.

Sir H. The offences of my last visit, madam, bore their punishment in the commission; and have made me as uneasy till I receive pardon, as your ladyship can be till I sue for it.

Ang. Sir Harry, I did not well understand the offence, and must therefore proportion it to the greatness of your apology; if you would, therefore, have me think it light, take no great pains in an excuse.

Sir H. How sweet must the lips be that guard that tongue! Then, madam, no more of past offences; let us prepare for joys to come. Let this seal my pardon.

[Kisses her Hand.

Ang. Hold, sir: one question, Sir Harry, and pray answer plainly—D'ye love me?

Sir H. Love you! Does fire ascend? Do hypocrites dissemble? Usurers love gold, or great men flattery? Doubt these, then question that I love.

Ang. This shows your gallantry, sir, but not your love.

Sir H. View your own charms, madam, then judge my passion.

Ang. If your words be real, 'tis in your power to raise an equal flame in me.

Sir H. Nay, then, I seize——

Ang. Hold, sir; 'tis also possible to make me detest and scorn you worse than the most profligate of your deceiving sex.

Sir H. Ha! a very odd turn this. I hope, madam, you only affect anger, because you know your frowns are becoming.

Ang. Sir Harry, you being the best judge of your own designs, can best understand whether my anger should be real or dissembled; think what strict modesty should bear, then judge of my resentment.

Sir H. Strict modesty should bear! Why, 'faith, madam, I believe, the strictest modesty may bear fifty guineas, and I don't believe 'twill bear one farthing more.

Ang. What d'ye mean, sir?

Sir H. Nay, madam, what do you mean? If you go to that. I think now, fifty guineas is a fine offer for your strict modesty, as you call it.

Ang. I'm afraid you're mad, sir.

Sir H. Why, madam, you're enough to make any man mad. 'Sdeath, are you not a——

Ang. What, sir?

Sir H. Why, a lady of—strict modesty, if you will have it so.

Ang. I shall never hereafter trust common report, which represented you, sir, a man of honour, wit, and breeding; for I find you very deficient in them all three. [Exit.

Sir H. Now I find, that the strict pretences, which the ladies of pleasure make to strict modesty, is the reason why those of quality are ashamed to wear it.

Enter Vizard.

Vizard. Ah! Sir Harry, have I caught you? Well, and what success?

Sir H. Success! 'Tis a shame for you young fellows in town here, to let the wenches grow so saucy. I offered her fifty guineas, and she was in her airs presently, and flew away in a huff. I could have had a brace of countesses in Paris for half the money, and je vous remercie into the bargain.

Vizard. Gone in her airs, say you! and did not you follow her?

Sir H. Whither should I follow her?

Vizard. Into her bedchamber, man; she went on purpose. You a man of gallantry, and not understand that a lady's best pleased when she puts on her airs, as you call it!

Sir H. She talked to me of strict modesty, and stuff.

Vizard. Certainly. Most women magnify their modesty, for the same reason that cowards boast their courage—because they have least on't. Come, come, Sir Harry, when you make your next assault, encourage your spirits with brisk Burgundy: if you succeed, 'tis well; if not, you have a fair excuse for your rudeness. I'll go in, and make your peace for what's past. Oh, I had almost forgot——Colonel Standard wants to speak with you about some business.

Sir H. I'll wait upon him presently; d'ye know where he may be found?

Vizard. In the piazza of Covent Garden, about an hour hence, I promised to see him: and there you may meet him—to have your throat cut. [Aside.] I'll go in and intercede for you.

Sir H. But no foul play with the lady, Vizard. [Exit.

Vizard. No fair play, I can assure you. [Exit.

The Street before Lady Lurewell's Lodgings.

Clincher Senior, and Lurewell, coquetting in

the Balcony.—Enter Standard.

Colonel S. How weak is reason in disputes of love! I've heard her falsehood with such pressing proofs, that I no longer should distrust it. Yet still my love would baffle demonstration, and make impossibilities seem probable. [Looks up.] Ha! That fool too! What, stoop so low as that animal?—'Tis true, women once fallen, like cowards in despair, will stick at nothing; there's no medium in their actions. They must be bright as angels, or black as fiends. But now for my revenge; I'll kick her cully before her face, call her whore, curse the whole sex, and leave her. [Goes in.

A Dining Room.

Enter Lady Lurewell and Clincher Senior.

Lady L. Oh lord, sir, it is my husband! What will become of you?

Clinch. sen. Ah, your husband! Oh, I shall be murdered! What shall I do? Where shall I run? I'll creep into an oven—I'll climb up the chimney—I'll fly—I'll swim;——I wish to the lord I were at the Jubilee now.

Lady L. Can't you think of any thing, sir?

Clinch. sen. Think! not I; I never could think to any purpose in my life.

Lady L. What do you want, sir?

Enter Tom Errand.

Tom. Madam, I am looking for Sir Harry Wildair; I saw him come in here this morning; and did imagine he might be here still, if he is not gone.

Lady L. A lucky hit! Here, friend, change clothes with this gentleman, quickly, strip.

Clinch. sen. Ay, ay, quickly strip; I'll give you half a crown to boot. Come here; so.

[They change Clothes.

Lady L. Now slip you [To Clinch Senior.] down stairs, and wait at the door till my husband be gone; and get you in there [To Tom Errand.] till I call you.

[Puts Errand in the next Room.

Enter Colonel Standard.

Oh, sir, are you come? I wonder, sir, how you have the confidence to approach me, after so base a trick.

Colonel S. Oh, madam, all your artifices won't avail.

Lady L. Nay, sir, your artifices won't avail. I thought, sir, that I gave you caution enough against troubling me with Sir Harry Wildair's company, when I sent his letters back by you; yet you, forsooth, must tell him where I lodged, and expose me again to his impertinent courtship!

Colonel S. I expose you to his courtship!

Lady L. I'll lay my life you'll deny it now. Come, come, sir: a pitiful lie is as scandalous to a red coat, as an oath to a black.

Colonel S. You're all lies; first, your heart is false; your eyes are double; one look belies another; and then your tongue does contradict them all—Madam, I see a little devil just now hammering out a lie in your pericranium.

Lady L. As I hope for mercy, he's in the right on't. [Aside.

Colonel. S. Yes, yes, madam, I exposed you to the courtship of your fool Clincher, too; I hope your female wiles will impose that upon me——also——

Lady L. Clincher! Nay, now you're stark mad. I know no such person.

Colonel S. Oh, woman in perfection! not know him! 'Slife, madam, can my eyes, my piercing jealous eyes, be so deluded? Nay, madam, my nose could not mistake him; for I smelt the fop by his pulvilio, from the balcony down to the street.

Lady L. The balcony! ha! ha! ha! the balcony! I'll be hanged but he has mistaken Sir Harry Wildair's footman, with a new French livery, for a beau.

Colonel S. 'Sdeath, madam! what is there in me that looks like a cully? Did I not see him?

Lady L. No, no, you could not see him; you're dreaming, colonel. Will you believe your eyes, now that I have rubbed them open?—Here, you friend.

Enter Tom Errand, in Clincher Senior's Clothes.

Colonel S. This is illusion all; my eyes conspire against themselves. Tis legerdemain.

Lady L. Legerdemain! Is that all your acknowledgment for your rude behaviour?—Oh, what a curse is it to love as I do!—Begone sir, [To Tom Errand.] to your impertinent master, and tell him I shall never be at leisure to receive any of his troublesome visits.—Send to me to know when I should be at home!—Begone, sir. [Exit Tom Errand.] I am sure he has made me an unfortunate woman. [Weeps.

Colonel S. Nay, then there is no certainty in nature; and truth is only falsehood well disguised.

Lady L. Sir, had not I owned my fond, foolish passion, I should not have been subject to such unjust suspicions: but it is an ungrateful return. [Weeping.

Colonel S. Now, where are all my firm resolves? I hope, madam, you'll pardon me, since jealousy, that magnified my suspicion, is as much the effect of love, as my easiness in being satisfied.

Lady L. Easiness in being satisfied! No, no, sir; cherish your suspicions, and feed upon your jealousy: 'tis fit meat for your squeamish stomach.

| With me all women should this rule pursue: |

| Who think us false, should never find us true. |

| [Exit in a Rage. |

Enter Clincher Senior in Tom Errand's Clothes.

Clinch. sen. Well, intriguing is the prettiest, pleasantest thing for a man of my parts.—How shall we laugh at the husband, when he is gone?—How sillily he looks! He's in labour of horns already.—To make a colonel a cuckold! 'Twill be rare news for the alderman.

Colonel S. All this Sir Harry has occasioned; but he's brave, and will afford me a just revenge.—Oh, this is the porter I sent the challenge by——Well sir, have you found him?

Clinch. sen. What the devil does he mean now?

Colonel S. Have you given Sir Harry the note, fellow?

Clinch. sen. The note! what note?

Colonel S. The letter, blockhead, which I sent by you to Sir Harry Wildair; have you seen him?

Clinch. sen. Oh, lord, what shall I say now? Seen him? Yes, sir—no, sir.—I have, sir—I have not, sir.

Colonel S. The fellow's mad. Answer me directly, sirrah, or I'll break your head.

Clinch. sen. I know Sir Harry very well, sir; but as to the note, sir, I can't remember a word on't: truth is, I have a very bad memory.

Colonel S. Oh, sir, I'll quicken your memory. [Strikes him.

Clinch. sen. Zouns, sir, hold!—I did give him the note.

Colonel S. And what answer?

Clinch. sen. I mean, I did not give him the note.

Colonel S. What, d'ye banter, rascal? [Strikes him again.

Clinch. sen. Hold, sir, hold! He did send an answer.

Colonel S. What was't, villain?

Clinch. sen. Why, truly sir, I have forgot it: I told you that I had a very treacherous memory.

Colonel S. I'll engage you shall remember me this month, rascal.

[Beats him, and exit.

Enter Lurewell and Parly.

Lady L. Oh, my poor gentleman! and was it beaten?

Clinch. sen. Yes, I have been beaten. But where's my clothes? my clothes?

Lady L. What, you won't leave me so soon, my dear, will ye?

Clinch. sen. Will ye!—If ever I peep into the colonel's tent again, may I be forced to run the gauntlet. But my clothes, madam.

Lady L. I sent the porter down stairs with them: did not you meet him?

Clinch. sen. Meet him? No, not I.

Parly. No! He went out at the back door, and is run clear away, I'm afraid.

Clinch. sen. Gone, say you, and with my clothes, my fine Jubilee clothes?—Oh, the rogue, the thief!—I'll have him hang'd for murder—But how shall I get home in this pickle?

Parly. I'm afraid, sir, the colonel will be back presently, for he dines at home.

Clinch. sen. Oh, then I must sneak off. Was ever such an unfortunate beau, To have his coat well thrash'd, and lose his coat also! [Exit.

Parly. Methinks, madam, the injuries you have suffered by men must be very great, to raise such heavy resentments against the whole sex;—and, I think, madam, your anger should be only confined to the author of your wrongs.

Lady L. The author! alas, I know him not.

Parly. Not know him? Tis odd, madam, that a man should rob you of that same jewel, and you not know him.

Lady L. Leave trifling: 'tis a subject that always sours my temper: but since, by thy faithful service, I have some reason to confide in your secresy, hear the strange relation.—Some twelve years ago, I lived at my father's house in Oxfordshire, blest with innocence, the ornamental, but weak guard of blooming beauty. Then it happened that three young gentlemen from the university coming into the country, and being benighted, and strangers, called at my father's: he was very glad of their company, and offered them the entertainment of his house.

Parly. Which they accepted, no doubt. Oh, these strolling collegians are never abroad, but upon some mischief.

Lady L. Two of them had a heavy, pedantic air: but the third——

Parly. Ah, the third, madam—the third of all things, they say, is very critical.

Lady L. He was—but in short, nature formed him for my undoing. His very looks were witty, and his expressive eyes spoke softer, prettier things, than words could frame.

Parly. There will be mischief by and by; I never heard a woman talk so much of eyes, but there were tears presently after.

Lady L. My father was so well pleased with his conversation, that he begged their company next day; they consented, and next night, Parly——

Parly. Ah, next night, madam——next night (I'm afraid) was a night indeed.

Lady L. He bribed my maid, with his gold, out of her modesty; and me, with his rhetoric, out of my honour. [Weeps.] He swore that he would come down from Oxford in a fortnight, and marry me.

Parly. The old bait, the old bait—I was cheated just so myself. [Aside.] But had not you the wit to know his name all this while?

Lady L. He told me that he was under an obligation to his companions, of concealing himself then, but, that he would write to me in two days, and let me know his name and quality. After all the binding oaths of constancy, I gave him a ring with this motto—"Love and Honour"—then we parted, and I never saw the dear deceiver more.

Parly. No, nor never will, I warrant you.

Lady L. I need not tell my griefs, which my father's death made a fair pretence for; he left me sole heiress and executrix to three thousand pounds a year: at last, my love for this single dissembler turned to a hatred of the whole sex; and, resolving to divert my melancholy, I went to travel. Here I will play my last scene; then retire to my country-house, and live solitary. We shall have that old impotent lecher, Smuggler, here to-night; I have a plot to swinge him, and his precise nephew, Vizard.

Parly. I think, madam, you manage every body that comes in your way.

Lady L. No, Parly; those men, whose pretensions I found just and honourable, I fairly dismissed, by letting them know my firm resolutions never to marry, But those villains, that would attempt my honour, I've seldom failed to manage.

Parly. What d'ye think of the colonel, madam? I suppose his designs are honourable.