The Project Gutenberg EBook of Home Pork Making, by A. W. Fulton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Home Pork Making

Author: A. W. Fulton

Release Date: May 18, 2010 [EBook #32414]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOME PORK MAKING ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

|

| Home Pork Making |

A complete guide for the farmer,

the country butcher and the suburban

dweller,

in all that pertains to hog slaughtering,

curing, preserving and

storing pork product—

from scalding vat to kitchen table and dining room. |

| By A. W. FULTON |

Commercial editor American Agriculturist

and Orange Judd Farmer, assisted

by Pork

Specialists in the United States and England. |

New York and Chicago

Orange Judd Company

1900 |

Of all the delicacies in the whole mundus edibiles, I will maintain

roast pig to be the most delicate. There is no flavor comparable, I will

contend, to that of the crisp, tawny, well-watched, not over-roasted

crackling, as it is well called—the very teeth are invited to their share

of the pleasure at this banquet in overcoming the coy, brittle

resistance—with the adhesive oleaginous—oh, call it not fat! but an

indefinable sweetness growing up to it—the tender blossoming of fat—fat

cropped in the bud—taken in the shoot—in the first innocence—the cream

and quintessence of the child-pig’s yet pure food—the lean, no lean, but

a kind of animal manna—or rather fat and lean (if it must be so) so

blended and running into each other that both together make but one

ambrosian result or common substance.—[Charles Lamb.

Copyright 1900

BY

ORANGE JUDD COMPANY

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Introduction. |

| Pork making on the farm nearly a lost art—General merit of homemade

pork—Acknowledgments. |

| Chapter I.—Pork Making on the Farm. |

| Best time for killing—A home market for farm pork—Opportunities for

profit—Farm census of live stock for a series of years. |

| Chapter II.—Finishing Off Hogs for Bacon. |

| Flesh forming rations—Corn as a fat producer—Just the quality of bacon

wanted—Normandy Hogs. |

| Chapter III.—Slaughtering. |

| Methods employed—Necessary apparatus—Heating water for scalding. |

| Chapter IV.—Scalding and Scraping. |

| Saving the bristles—Scalding tubs and vats—Temperature for

scalding—“Singeing pigs”—Methods of Singeing. |

| Chapter V.—Dressing and Cutting. |

| Best time for dressing—Opening the carcass—Various useful

appliances—Hints on dressing—How to cut up a hog. |

| Chapter VI.—What to do With the Offal. |

| Portions classed as offal—Recipes and complete directions for utilizing

the wholesome parts, aside from the principal pieces—Sausage, scrapple, jowls and head, brawn, head-cheese. |

| Chapter VII.—The Fine Points in Making Lard. |

| Kettle and steam rendered—Time required in making—Storing. |

| Chapter VIII.—Pickling and Barreling. |

| A clean barrel one of the first considerations—The use of salt on pork

strips—Pickling by covering with brine—Renewing pork brine. |

| Chapter IX.—Care of Hams and Shoulders. |

| A first-class ham—A general cure for ham and shoulders—Pickling

preparatory to smoking—Westphalian hams. |

| Chapter X.—Dry Salting Bacon and Sides. |

| Proper proportion of salt to meat—Other preservatives—Applying the

salt—Best distribution of the salt—Time required in curing—Pork for the south. |

| Chapter XI.—Smoking and Smokehouses. |

| Treatment previous to smoking—Simple but effective

smokehouses—Controlling the fire in smoke formation—Materials to produce

best flavor—The choice of weather—Variety in smokehouses. |

| Chapter XII.—Keeping Hams and Bacon. |

| The ideal meat house—Best temperature and surroundings—Precautions

against skippers—To exclude the bugs entirely. |

| Chapter XIII.—Side Lights on Pork Making. |

| Growth of the big packing houses—Average weight of live hogs—“Net to

gross”—Relative weights of various portions of the carcass. |

| Chapter XIV.—Packing House Cuts of Pork. |

| Descriptions of the leading cuts of meat known as the speculative

commodities in the pork product—Mess pork, short ribs, shoulders and hams, English bacon, varieties of lard. |

| Chapter XV.—Magnitude of the Swine Industry. |

| Importance of the foreign demand—Statistics of the trade—Receipts at

leading points—Prices for a series of years—Co-operative curing houses in Denmark. |

| Chapter XVI.—Discovering the Merits of Roast Pig. |

| The immortal Charles Lamb on the art of roasting—An oriental luxury of luxuries. |

| Chapter XVII.—Recipes for Cooking and Serving Pork. |

| Success in the kitchen—Prize methods of best cooks—Unapproachable list

of especially prepared recipes—Roasts, pork pie, cooking bacon, pork and

beans, serving chops and cutlets, use of spare ribs, the New England boiled dinner, ham and sausage, etc. |

[Pg v]

INTRODUCTION.

Hog killing and pork making on the farm have become almost lost arts in

these days of mammoth packing establishments which handle such enormous

numbers of swine at all seasons of the year. Yet the progressive farmer of

to-day should not only provide his own fresh and cured pork for family

use, but also should be able to supply at remunerative prices such persons

in his neighborhood as appreciate the excellence and general merit of

country or “homemade” pork product. This is true, also, though naturally

in a less degree, of the townsman who fattens one or two pigs on the

family kitchen slops, adding sufficient grain ration to finish off the

pork for autumn slaughter.

The only popular book of the kind ever published, “Home Pork Making”

furnishes in a plain manner just such detailed information as is needed to

enable the farmer, feeder, or country butcher to successfully and

economically slaughter his own hogs and cure his own pork. All stages of

the work are fully presented, so that even without experience or special

equipment any intelligent person can readily follow the instructions.

Hints are given about finishing off hogs for bacon, hams, etc. Then,

beginning with proper methods of slaughtering, the various processes are

clearly presented, including every needful detail from the scalding vat to

the kitchen baking dish and dining-room table.

The various chapters treat successively of the following, among other

branches of the art of pork[Pg vi] making: Possibilities of profit in home

curing and marketing pork; finishing off hogs for bacon; class of rations

best adapted, flesh and fat forming foods; best methods of slaughtering

hogs, with necessary adjuncts for this preliminary work; scalding and

scraping; the construction of vats; dressing the carcass; cooling and

cutting up the meat; best disposition of the offal; the making of sausage

and scrapple; success in producing a fine quality of lard and the proper

care of it.

Several chapters are devoted to putting down and curing the different cuts

of meat in a variety of ways for many purposes. Here will be found the

prized recipes and secret processes employed in making the popular pork

specialties for which England, Virginia, Kentucky, New England and other

sections are noted. Many of these points involve the old and well-guarded

methods upon which more than one fortune has been made, as well as the

newest and latest ideas for curing pork and utilizing its products. Among

these the subject of pickling and barreling is thoroughly treated,

renewing pork brine; care of barrels, etc. The proper curing of hams and

shoulders receives minute attention, and so with the work of dry salting

bacon and sides. A chapter devoted to smoking and smokehouses affords all

necessary light on this important subject, including a number of helpful

illustrations; success in keeping bacon and hams is fully described,

together with many other features of the work of home curing. The

concluding portion of the book affords many interesting details relating

to the various cuts of meat in the big packing houses, magnitude of the

swine industry and figures covering the importance of our home and foreign

trade in pork and pork product.

In completing this preface, descriptive of the various features of the

book, the editor wishes to give credit to our friends who have added to

its value[Pg vii] through various contributions and courtesies. A considerable

part of the chapters giving practical directions for cutting and curing

pork are the results of the actual experience of B. W. Jones of Virginia;

we desire also to give due credit to contributions by P. H. Hartwell,

Rufus B. Martin, Henry Stewart and many other practical farmers; to Hately

Brothers, leading packers at Chicago; North Packing and Provision Co. of

Boston, and to a host of intelligent women on American farms, who, through

their practical experience in the art of cooking, have furnished us with

many admirable recipes for preparing and serving pork.

[Pg 1]

CHAPTER I.

PORK MAKING ON THE FARM.

During the marvelous growth of the packing industry the past generation,

methods of slaughtering and handling pork have undergone an entire

revolution. In the days of our fathers, annual hog-killing time was as

much an event in the family as the harvesting of grain. With the coming of

good vigorous frosts and cold weather, reached in the Northern states

usually in November, every farmer would kill one, two or more hogs for

home consumption, and frequently a considerable number for distribution

through regular market channels. Nowadays, however, the big pork packing

establishments have brought things down to such a fine point, utilizing

every part of the animal (or, as has been said, “working up everything but

the pig’s squeal”), that comparatively few hogs out of all the great

number fattened are slaughtered and cut up on the farm.

Unquestionably there is room for considerable business of this character,

and if properly conducted, with a thorough understanding, farmers can

profitably convert some of their hogs into cured meats, lard, hams, bacon,

sausage, etc., finding a good market at home and in villages and towns.

Methods now in use are not greatly different from those followed years

ago, although of course improvement is the order of the day, and some

important changes have taken place, as will be seen in a study of our

pages. A few fixtures and implements are necessary to properly cure and

pack[Pg 2] pork, but these may be simple, inexpensive and at the same time

efficient. Such important portions of the work as the proper cutting of

the throat, scalding, scraping, opening and cleaning the hog should be

undertaken by someone not altogether a novice. And there is no reason why

every farmer should not advantageously slaughter one or more hogs each

year, supplying the family with the winter’s requirements and have

something left over to sell.

THE POSSIBILITIES OF PROFIT

in the intelligent curing and selling of homemade pork are suggested by

the far too general custom of farmers buying their pork supplies at the

stores. This custom is increasing, to say nothing of the very large number

of townspeople who would be willing to buy home cured pork were it

properly offered them. Probably it is not practicable that every farmer

should butcher his own swine, but in nearly every neighborhood one or two

farmers could do this and make good profits. The first to do so, the first

to be known as having home cured pork to sell, and the first to make a

reputation on it, will be the one to secure the most profit.

In the farm census of live stock, hogs are given a very important place.

According to the United States census of 1890 there were on farms in this

country 57,409,583 hogs. Returns covering later years place the farm

census of hogs, according to compilations of American Agriculturist and

Orange Judd Farmer, recognized authorities, at 47,061,000 in 1895,

46,302,000 in 1896, and 48,934,000 in 1899. According to these authorities

the average farm value of all hogs in 1899 was $4.19 per head. The

government report placed the average farm price in 1894 at $5.98, in ’93,

$6.41, and in 1892, $4.60.

[Pg 3]

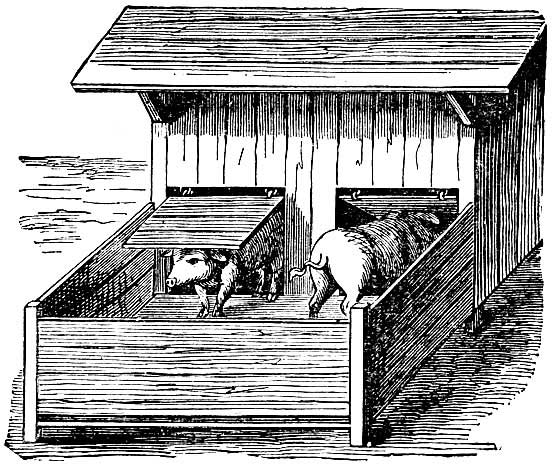

A TRAVELING PIGPEN.

It is often desirable to change the location of a pigpen, especially where

a single pig is kept. It may be placed in the garden at the time when

there are waste vegetables to be disposed of, or it may be penned in a

grass lot. A portable pen, with an open yard attached, is seen in the

accompanying illustrations. Figure 1 presents the pen, the engraving

showing it so clearly that no description is needed. The yard, seen in

Fig. 2, is placed with the open space next to the door of the pen, so that

the pig can go in and out freely. The yard is attached to the pen by hooks

and staples, and both of them are provided with handles, by which they can

be[Pg 4] lifted and carried from place to place. Both the yard and pen should

be floored, to prevent the pig from tearing up the ground. The floors

should be raised a few inches from the ground, that they may be kept dry

and made durable.

FIG. 1. PORTABLE PEN.

FIG. 2. YARD ATTACHMENT.

[Pg 5]

CHAPTER II.

FINISHING OFF HOGS FOR BACON.

The general subject of feeding and fattening hogs it is not necessary here

to discuss. It will suffice to point out the advisability of using such

rations as will finish off the swine in a manner best fitted to produce a

good bacon hog. An important point is to feed a proper proportion of

flesh-forming ration rather than one which will serve to develop fat at

the expense of lean. The proper proportion of these will best subserve the

interest of the farmer, whether he is finishing off swine for family use

or for supplying the market with home cured bacon. A diet composed largely

of protein (albuminoids) results in an increased proportion of lean meat

in the carcass. On the other hand, a ration made up chiefly of feeds which

are high in starchy elements, known as carbohydrates, yields very largely

in fat (lard). A most comprehensive chart showing the relative values of

various fodders and feeding stuffs has been prepared by Herbert Myrick,

editor of American Agriculturist, and will afford a good many valuable

hints to the farmer who wishes to feed his swine intelligently. This

points out the fact that such feeds as oats, barley, cowpea hay, shorts,

red clover hay and whole cottonseed are especially rich in flesh-forming

properties.

Corn, which is rich in starch, is a great fat producer and should not be

fed too freely in finishing off hogs for the best class of bacon. In

addition to the important[Pg 6] muscle-producing feeds noted above, there are

others rich in protein, such as bran, skim milk, buttermilk, etc. While

corn is naturally the standby of all swine growers, the rations for bacon

purposes should include these muscle-producing feeds in order to bring the

best results. If lean, juicy meat is desired, these muscle forming foods

should be continued to the close. In order to get

JUST THE QUALITY OF BACON THAT IS WANTED,

feeders must so arrange the ration that it will contain a maximum of

muscle and a minimum of fat. This gives the sweet flavor and streaked meat

which is the secret of the popularity of the Irish and Danish bacon. Our

American meats are as a rule heavy, rich in fat and in marked contrast

with the light, mild, sweet flavored pork well streaked with lean, found

so generally in the English market and cured primarily in Ireland and

Denmark. What is wanted is a long, lean, smooth, bacon hog something after

the Irish hog. Here is a hint for our American farmers.

England can justly boast of her hams and bacon, but for sweet, tender,

lean pork the Normandy hogs probably have no superior in the world. They

are fed largely on meat-producing food, as milk, peas, barley, rye and

wheat bran. They are not fed on corn meal alone. They are slaughtered at

about six months. The bristles are burned off by laying the carcass on

straw and setting it on fire. Though the carcasses come out black, they

are scraped white and clean, and dressed perfectly while warm. It is

believed that hogs thus dressed keep better and that the meat is sweeter.

SELF-CLOSING DOOR FOR PIGPEN.

Neither winter snows nor the spring and summer rains should be allowed to

beat into a pigpen. But the[Pg 7] difficulty is to have a door that will shut

itself and can be opened by the animals whenever they desire. The

engraving, Fig. 3, shows a door of this kind that can be applied to any

pen, at least any to which a door can be affixed at all. It is hung on

hooks and staples to the lintel of the doorway, and swinging either way

allows the inmates of the pen to go out or in, as they please,—closing

automatically. If the door is intended to fit closely, leather strips two

inches wide should be nailed around the frame of the doorway, then as the

door closes it presses tightly against these strips.

FIG. 3. AUTOMATIC DOOR.

A HOG-FEEDING CONVENIENCE.

The usual hog’s trough and the usual method of getting food into it are

conducive to a perturbed state of mind on the part of the feeder, because

the hog is accustomed to get bodily into the trough, where he is likely to

receive a goodly portion of his breakfast or dinner upon the top of his

head. The ordinary trough too, is difficult to clean out for a similar

reason—the[Pg 8] pig usually standing in it. The diagram shown herewith, Fig.

4 gives a suggestion for a trough that overcomes some of the difficulties

mentioned, as it is easily accessible from the outside, both for pouring

in food and for removing any dirt or litter that may be in it. The

accompanying sketch so plainly shows the construction that detailed

description does not appear to be necessary.

FIG. 4. PROTECTED TROUGH.

[Pg 9]

CHAPTER III.

SLAUGHTERING.

Whatever may be said as to the most humane modes of putting to death

domestic animals intended for food, butchering with the knife, all things

considered, is the best method to pursue with the hog. The hog should be

bled thoroughly when it is killed. Butchering by which the heart is

pierced or the main artery leading from it severed, does this in the most

effectual way, ridding the matter of the largest percentage of blood, and

leaving it in the best condition for curing and keeping well. The very

best bacon cannot be made of meat that has not been thoroughly freed from

blood, and this is a fact that should be well remembered. Expert butchers,

who know how to seize and hold the hog and insert the knife at the proper

place, are quickly through with the job, and often before the knife can be

withdrawn from the incision, the blood will spurt out in a stream and

insensibility and death will speedily ensue. It is easy, however, for a

novice to make a botch of it; hence the importance that none but an expert

be given a knife for this delicate operation.

There are some readily made devices by which one man at killing time may

do as much as three or four, and with one helper a dozen hogs may be made

into finished pork between breakfast and dinner, and without any

excitement or worry or hard work. It is supposed that the hogs are in a

pen or pens, where they may be easily roped by a noose around one hind

leg. This being done, the animal is led to the door and[Pg 10] guided into a

box, having a slide door to shut it in. The bottom of the box is a hinged

lid. As soon as the hog is safely in the box and shut in by sliding down

the back door, and fastening it by a hook, the box is turned over,

bringing the hog on his back. The bottom of the box is opened immediately

and one man seizes a hind foot, to hold the animal, while the other sticks

the hog in the usual manner. The box is turned and lifted from the hog,

which, still held by the rope is moved to the dressing bench. All this may

be done while the previous hog is being scalded and dressed, or the work

may be so managed that as soon as one hog is hung and cleaned the next one

is ready for the scalding.

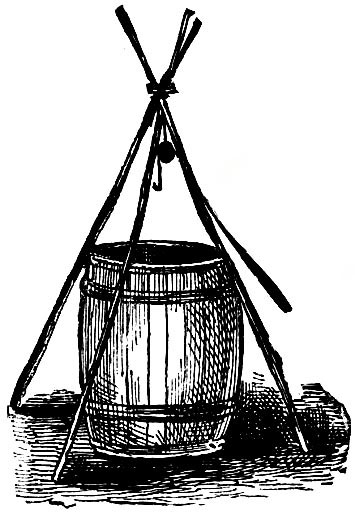

FIG. 5. HEATING WATER IN KETTLES.

NECESSARY AIDS.

Before the day for slaughter arrives, have everything ready for performing

the work in the best manner. There may be a large boiler for scalding set

in masonry with a fireplace underneath and a flue to carry off the smoke.

If this is not available, a large hogshead may be utilized at the proper

time. A long table, strong and immovable, should be fixed close to the

boiler, on which the hogs are to be drawn after having been scalded, for

scraping. On each side of this table scantlings should be laid in the form

of an open flooring,[Pg 11] and upon this the farmer and helpers may stand while

at work, thus keeping their feet off the ground, out of the water and mud

that would otherwise be disagreeable. An appreciated addition on a rainy

day would be a substantial roof over this boiler and bench. This should be

strong and large enough so that the hog after it is cleaned may be

properly hung up. Hooks and gambrels are provided, knives are sharpened, a

pile of dry wood is placed there, and everything that will be needed on

the day of butchering is at hand.

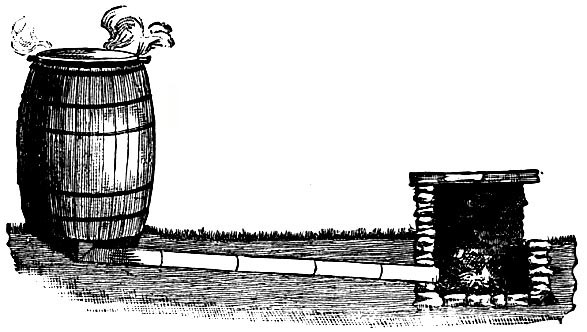

HEATING WATER FOR SCALDING.

For heating scalding water and rendering lard, when one has no kettles or

cauldrons ready to set in brick or stone, a simple method is to put down

two forked stakes firmly, as shown in Fig. 5, lay in them a pole to

support the kettles, and build a wood fire around them on the ground. A

more elaborate arrangement is shown in Fig. 6, which serves not only to

heat the water, but as a scalding tub as well. It is made of two-inch pine

boards, six feet long and two feet wide, rounded at the ends. A heavy

plate of sheet iron is nailed with wrought nails on the bottom and ends[Pg 12]

Let the iron project fully one inch on each side. The ends, being rounded,

will prevent the fire from burning the woodwork. They also make it handier

for dipping sheep, scalding hogs, or for taking out the boiled food. The

box is set on two walls 18 inches high, and the rear end of the brickwork

is built into a short chimney, affording ample draft.

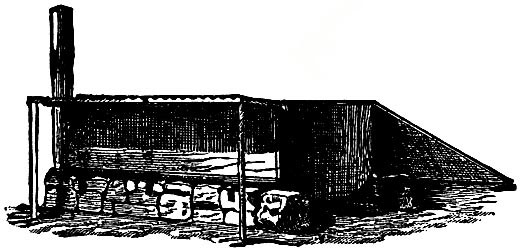

FIG. 6. PRACTICAL HEATING AND SCALDING VAT.

[Pg 13]

CHAPTER IV.

SCALDING AND SCRAPING.

Next comes the scalding and dressing of the carcass. Lay the hog upon the

table near the boiler and let the scalders who stand ready to handle it

place it in the water heated nearly to a boiling point. The scalders keep

the hog in motion by turning it about in the water, and occasionally they

try the bristles to see if they will come away readily. As soon as

satisfied on this point, the carcass is drawn from the boiler and placed

upon the bench, where it is rapidly and[Pg 14] thoroughly scraped. The bristles

or hair that grow along the back of the animal are sometimes sold to brush

makers, the remainder of the hair falling beside the table and gathered up

for the manure heap. The carcass must not remain too long in the hot

water, as this will set the hair. In this case it will not part from the

skin, and must be scraped off with sharp knives. For this reason an

experienced hand should attend to the scalding. The hair all off, the

carcass is hung upon the hooks, head down, nicely scraped and washed with

clean water preparatory to disemboweling.

FIG. 7. TACKLE FOR HEAVY HOGS.

SCALDING TUBS AND VATS.

Various devices are employed for scalding hogs, without lifting them by

main force. For heavy hogs, one may use three strong poles, fastened at

the top with a log chain, which supports a simple tackle, Fig. 7. A very

good arrangement is shown in Fig. 8. A sled is made firm with driven

stakes and covered with planks or boards. At the rear end the scalding

cask is set in the ground, its upper edge on a level with the platform and

inclined as much as it can be and hold sufficient water. A large, long hog

is scalded one end at a time. The more the cask is inclined, the easier

will be the lifting.

FIG. 8. SCALDING CASK ON SLED.

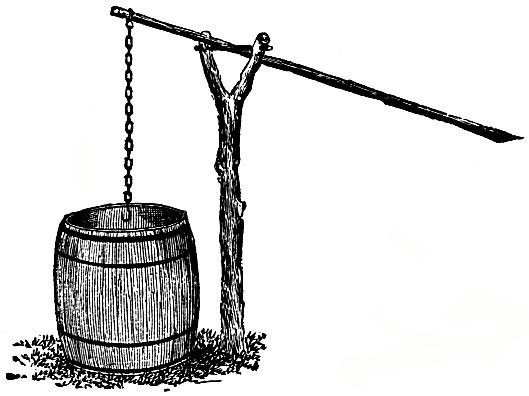

A modification of the above device is shown in Fig. 9. A lever is rigged

like a well sweep, using a[Pg 15] crotched stick for the post, and a strong pole

for the sweep. The iron rod on which the sweep moves must be strong and

stiff. A trace chain is attached to the upper end, and if the end of the

chain has a ring instead of a hook, it will be quite convenient. In use, a

table is improvised, unless a strong one for the purpose is at hand, and

this is set near the barrel. A noose is made with the chain about the leg

of the hog, and he is soused in, going entirely under water, lifted out

when the bristles start easily, and laid upon the table, while another is

made ready.

FIG. 9. SCALDING IN A HOGSHEAD.

Figure 10 shows a more permanent arrangement. It is a trough of plank with

a sheet iron bottom, which can be set over a temporary fireplace made in

the ground. The vat may be six feet long, three feet wide and two and

one-half feet deep, so as to be large enough for a good-sized hog. Three

ropes are fastened on one side, for the purpose of rolling the hog over

into the vat and rolling it out on the other side when it is scalded. A

number of slanting crosspieces are fitted in, crossing each other, so as

to form a hollow bed in which the carcass lies, with the ropes under it,

by which it can be moved and drawn out. These[Pg 16] crosspieces protect the

sheet iron bottom and keep the carcass from resting upon it. A large,

narrow fireplace is built up in the ground, with stoned sides, and the

trough is set over it. A stovepipe is fitted at one end, and room is made

at the front by which wood may be supplied to the fire to heat the water.

A sloping table is fitted at one side for the purpose of rolling up the

carcass, when too large to handle otherwise, by means of the rope

previously mentioned. On the other side is a frame made of hollowed boards

set on edge, upon which the hog is scraped and cleaned. The right

temperature for scalding a hog is 180 degrees, and with a thermometer

there need be no fear of overscalding or a failure from the lack of

sufficient heat, while the water can be kept at the right temperature by

regulating the fuel under the vat. If a spot of hair is obstinate, cover

it with some of the removed hair and dip on hot water. Always pull out

hair and bristles; shaving any off leaves unpleasant stubs in the skin.

SINGEING PIGS.

A few years ago, “singers” were general favorites with a certain class of

trade wanting a light bacon pig, weighing about 170 lbs., the product

being exported to England for bacon purposes. Packers frequently paid a

small premium for light hogs suitable for this end, but more recently the

demand is in other directions. The meat of singed hogs is considered by

some to possess finer flavor than that of animals the hair of which has

been removed by the ordinary process. Instead of being scalded and scraped

in the ordinary manner, the singeing process consists in lowering the

carcass into an iron or steel box by means of a heavy chain, the

receptacle having been previously heated to an exceedingly high

temperature. After remaining[Pg 17] there a very few seconds the hog is removed

and upon being placed in hot water the hair comes off instantly.

An old encyclopedia, published thirty years ago, in advocating the

singeing process, has this to say: “The hog should be swealed (singed),

and not scalded, as this method leaves the flesh firm and more solid. This

is done by covering the hog lightly with straw, then set fire to it,

renewing the fuel as it is burned away, taking care not to burn the skin.

After sufficient singeing, the skin is scraped, but not washed. After

cutting up, the flesh side of the cuts is rubbed with salt, which should

be changed every four or five days. The flitches should also be

transposed, the bottom ones at the top and the top ones at the bottom.

Some use four ounces saltpetre and one pound coarse sugar or molasses for

each hog. Six weeks is allowed for thus curing a hog weighing 240 lbs. The

flitches before smoking are rubbed with bran or very fine sawdust and

after smoking are often kept in clear, dry wood ashes or very dry sand.”

FIG. 10. PERMANENT VAT FOR SCALDING.

[Pg 18]

CHAPTER V.

DRESSING AND CUTTING.

When the carcasses have lost the animal heat they are put away till the

morrow, by which time, if the weather is fairly cold, the meat is stiff

and firm and in a condition to cut out better than it does when taken in

its soft and pliant state. If the weather is very cold, however, and there

is danger that the meat will freeze hard before morning, haste is made to

cut it up the same day, or else it is put into a basement or other warm

room, or a large fire made near it to prevent it from freezing. Meat that

is frozen will not take salt, or keep from spoiling if salted. Salting is

one of the most important of the several processes in the art of curing

good bacon, and the pork should be in just the right condition for taking

or absorbing the salt. Moderately cold and damp weather is the best for

this.

AS THE CARCASS IS DRESSED

it is lifted by a hook at the end of a swivel lever mounted on a post and

swung around to a hanging bar, placed conveniently. This bar has sliding

hooks made to receive the gambrel sticks, which have a hook permanently

attached to each so that the carcass is quickly removed from the swivel

lever to the slide hook on the bar. The upper edge of the bar is rounded

and smoothed and greased to help the hooks to slide on it. This serves to

hang all the hogs on the bar until they are cooled. If four persons are

employed this work may be done very quickly, as they may divide[Pg 19] the work

between them; one hog is being scalded and cleaned while another is being

dressed.

FIG. 11. EASY METHOD OF HANGING A CARCASS.

Divested of its coat, the carcass is washed off nicely with clean water

before being disemboweled. For opening the hog, the operator needs a sharp

butcher’s knife, and should know how to use it with dexterity, so as not

to cut the entrails. The entrails and paunch, or stomach, are first

removed, care being taken not to cut any; then the liver, the “dead ears”

removed from the heart, and the heart cut open to remove any clots of

blood that it may contain. The windpipe is then slit open, and the whole

together is hung upon the gambrel beside the hog or placed temporarily

into a tub of water. The “stretcher,” a small stick some sixteen inches

long, is then placed across the bowels to hold the sides well open and

admit the air to cool the carcass, and a chip or other small object is

placed in the mouth to hold it open, and the interior parts of the hog

about the shoulders and gullet are nicely washed to free them from stains

of blood. The[Pg 20] carcass is then left to hang upon the gallows in order to

cool thoroughly before it is cut into pieces or put away for the night.

Where ten or twelve hogs are dressed every year, it will pay to have a

suitable building arranged for the work. An excellent place may be made in

the driveway between a double corncrib, or in a wagon shed or an annex to

the barn where the feeding pen is placed. The building should have a

stationary boiler in it, and such apparatus as has been suggested, and a

windlass used to do the lifting.

HOG KILLING MADE EASY.

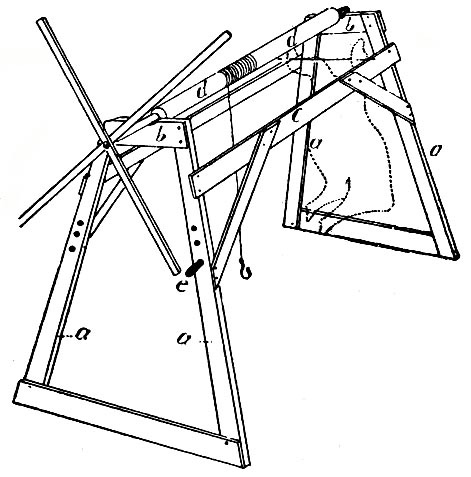

In the accompanying cut, Fig. 11, the hoister represents a homemade

apparatus that has been in use many years and it has been a grand success.

The frames, a, a, a, a, are of 2x4 inch scantling, 8 ft. in

length; b, b, are 2x6 inch and 2 ft. long with a round notch in the

center of the upper surface for a windlass, d, to turn in; c, c are

2x4 and 8 ft. long, or as long as desired, and are bolted to a, a. Ten

inches beyond the windlass, d, is a 4x4 inch piece with arms bolted on

the end to turn the windlass and draw up the carcass, which should be

turned lengthwise of the hoister until it passes between c, c. The

gambrel should be long enough to catch on each side when turned crosswise,

thus relieving the windlass so that a second carcass may be hoisted. The

peg, e, is to place in a hole of upright, a, to hold the windlass.

Brace the frame in proportion to the load that is to be placed upon it.

The longer it is made, the more hogs can be hung at the same time.

THE SAWBUCK SCAFFOLD.

Figure 12 shows a very cheap and convenient device for hanging either hogs

or beeves. The device is in[Pg 21] shape much like an old-fashioned “sawbuck,”

with the lower rounds between the legs omitted. The legs, of which there

are two pairs, should be about ten feet long and set bracing, in the

manner shown in the engraving. The two pairs of legs are held together by

an inch iron rod, five or six feet in length, provided with threads at

both ends. The whole is made secure by means of two pairs of nuts, which

fasten the legs to the connecting iron rod. A straight and smooth wooden

roller rests in the forks made by the crossing of the legs, and one end

projects about sixteen inches. In this two augur holes are bored, in which

levers may be inserted for turning the roller. The rope, by means of which

the carcass is raised, passes over the rollers in such a way that in

turning, by means of the levers, the animal is raised from the ground.

When sufficiently elevated, the roller is fastened by one of the levers to

the nearest leg.

FIG. 12. RAISING A CARCASS.

[Pg 22]

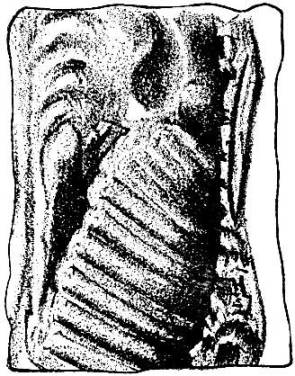

PROPER SHAPE OF GAMBRELS.

Gambrels should be provided of different lengths, if the hogs vary much in

size. That shown in Fig. 13 is a convenient shape. These should be of

hickory or other tough wood for safety, and be so small as to require

little gashing of the legs to receive them.

FIG. 13. A CONVENIENT GAMBREL.

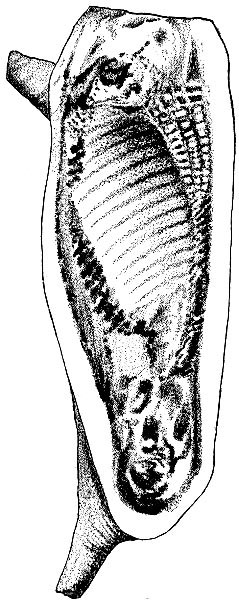

GALLOWS FOR DRESSED HOGS.

The accompanying device, Fig. 14, for hanging dressed hogs, consists of a

stout, upright post, six or eight inches square and ten feet long, the

lower three feet being set into the ground. Near the upper end are two

mortises, each 2x4 inches, quite through the post, one above the other, as

shown in the engraving, for the reception of the horizontal arms. The

latter are six feet long and just large enough to fit closely into the

mortises. They should be of white oak or hickory. At butchering time the

dead hogs are hung on the scaffold by slipping the gambrels upon the

horizontal crosspieces.

ADDITIONAL HINTS ON DRESSING.

Little use of the knife is required to loosen the entrails. The fingers,

rightly used, will do most of the severing. Small, strong strings, cut in

proper lengths, should be always at hand to quickly tie the severed ends

of any small intestines cut or broken by chance. An expert will catch the

entire offal in a large tin pan or wooden vessel, which is held between

himself and[Pg 23] the hog. Unskilled operators, and those opening very large

hogs, need an assistant to hold this. The entrails and then the liver,

heart, etc., being all removed, thoroughly rinse out any blood or filth

that may have escaped inside. Removing the lard from the long intestines

requires expertness that can be learned only by practice. The fingers do

most of this cleaner, safer and better than a knife. A light feed the

night before killing leaves the intestines less distended and less likely

to be broken.

FIG. 14. SIMPLE SUPPORT FOR DRESSED HOG.

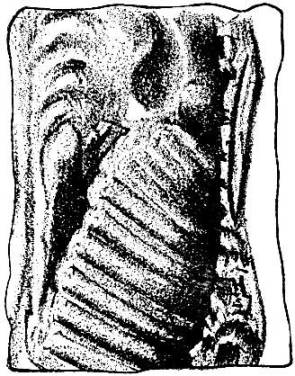

HOW TO CUT UP A HOG.

With a sharp ax and a sharp butcher’s knife at hand, lay the hog on the

chopping bench, side down. With the knife make a cut near the ear clear

across the neck and down to the bone. With a dextrous stroke of the ax

sever the head from the body. Lay the carcass on the back, a boy holding

it upright and keeping the forelegs well apart. With the ax proceed to

take out the chine or backbone. If it is desired to put as much of the hog

into neat meat as possible, trim to the chine very close, taking out none

of the skin or outside fat with it. Otherwise, the cutter need not be

particular how much meat comes away with the bone. What does not go with

the neat meat will be in the offal or sausage, and nothing will be lost.

Lay the[Pg 24] chine aside and with the knife finish separating the two

divisions of the hog. Next, strip off with the hands the leaves or flakes

of fat from the middle to the hams. Seize the hock of the ham with the

left hand and with the knife in the other, proceed to round out the ham,

giving it a neat, oval shape. Be very particular in shaping the ham. If it

is spoiled in the first cutting, no subsequent trimming will put it into a

form to exactly suit the fastidious public eye. Trim off the surplus lean

and fat and projecting pieces of bone. Cut off the foot just above the

hock joint. The piece when finished should have nearly the form of a

regular oval, with its projecting handle or hock.

With the ax cut the shoulder from the middling, making the cut straight

across near the elbow joint. Take off the end ribs or “spare bone” from

the shoulder, trim the piece and cut off the foot. For home use, trim the

shoulder, as well as the other pieces, very closely, taking off all of

both lean and fat that can be spared. If care is taken to cut away the

head near the ear, the shoulder will be at first about as wide as long,

having a good deal of the neck attached. If the meat is intended for sale

and the largest quantity of bacon is the primary object, let the piece

remain so. But if it is preferred to have plenty of lard and sausage, cut

a smart strip from off the neck side of the shoulder and make the piece

assume the form of a parallelogram, with the hock attached to one end.

Trim a slice of fat from the back for lard, take off the “short ribs,”

and, if preferred, remove the long ribs from the whole piece. The latter,

however, is not often done by the farmers. Put the middling in nice shape

by trimming it wherever needed, which, when finished, will be very much

like a square in form, perhaps a little longer than broad, with a small

circular piece cut out from the end next the ham.

[Pg 25]The six pieces of neat meat are now ready for the salter. The head is next

cut open longitudinally from side to side, separating the jowl from the

top or “head,” so-called. The jawbone of the jowl is cut at the angle or

tip and the “swallow,” which is the larynx or upper part of the windpipe,

is taken out. The headpiece is next cut open vertically and the lobe of

the brain is taken out, and the ears and nose are removed.

The bone of the chine is cut at several places for the convenience of the

cook, and the task of the cutter is finished. Besides the six pieces of

neat meat, there are the chine, souse, jowl, head, fat, sausage, two spare

and two short ribs and various other small bits derived from each hog. A

good cutter, with an assistant to carry away the pieces and help

otherwise, can cut out from 50 to 60 hogs in a day.

[Pg 26]

CHAPTER VI.

WHAT TO DO WITH THE OFFAL.

Aside from the pieces of meat into which a hog is usually cut, there will

be left as offal the chine or backbone, the jowl, the souse, the liver and

lungs, pig’s feet, two spareribs and two short ribs or griskins. Nearly

every housekeeper knows what disposition to make of all this, yet too

often these wholesome portions of the hog are not utilized to best

advantage.

PORK SAUSAGE.

Sausage has formed a highly prized article of food for a good many hundred

years. Formed primarily as now, by chopping the raw meat very fine, and

adding salt and other flavoring materials, and often meal or bread crumbs,

the favorite varieties of to-day might not be considered any improvement

over the recipes of the ancient Romans were they to pass judgment on the

same. History tells us that these early Italian sausages were made of

fresh pork and bacon, chopped fine, with the addition of nuts, and

flavored with cumin seed, pepper, bay leaves and various pot herbs. Italy

and Germany are still celebrated for their bologna sausages and with many

people these smoked varieties are highly prized.

Like pure lard, sausage is too often a scarce article in the market. Most

city butchers mix a good deal of beef with the pork, before it is ground,

and so have a sausage composed of two sorts of meat, which does not

possess that agreeable, sweet, savory taste peculiar[Pg 27] to nice fresh pork.

The bits of lean, cut off when trimming the pieces of neat meat, the

tenderloins, and slices of lean from the shoulders and hams, together with

some fat, are first washed nicely, cleared of bone and scraps of skin,

then put into the chopper, and ground fine. If a great deal of sausage is

wanted, the neat meat is trimmed very close, so as to take all the lean

that can be spared from the pieces. Sometimes whole shoulders are cut up

and ground. The heads, too, or the fleshy part, make good sausage. Some

housekeepers have the livers and “lights,” or lungs, ground up and

prepared for sausage, and they make a tolerable substitute. This

preparation should be kept separate from the other, however, and be eaten

while cold weather lasts, as it will not keep as long as the other kind.

After sausage is properly ground, add salt, sage, rosemary, and red or

black pepper to suit the taste. The rosemary may be omitted, but sage is

essential. All these articles should be made fine before mixing them with

the meat. In order to determine accurately whether the sausage contains

enough of these ingredients, cook a little and taste it.

If sausage is to be kept in jars, pack it away closely in them, as soon as

it is ground and seasoned, and set the jars, securely closed, in a cool

room. But it is much better to provide for smoking some of it, to keep

through the spring and early summer. When the entrails are ready, stuff

them full with the meat, after which the ends are tied and drawn together,

and the sausage hung up in the smokehouse for smoking. This finishes the

process of making pork sausage. Put up in this way, it deserves the name

of sausage and it makes a dish good enough for any one. It is one of the

luxuries of life which may be manufactured at home.

[Pg 28]

BOLOGNA SAUSAGE.

The popular theory is that these familiar sausages originated in the

Italian city of that name, where the American visitor always stops for a

bit of “the original.” Many formulas are used in the preparation of

bologna sausages, or rather many modifications of a general formula. Lean,

fresh meat trimmings are employed and some add a small proportion of

heart, all chopped very fine. While being chopped, spices and seasoning

are added, with a sufficient quantity of salt. The meat employed is for

the most part beef, to which is added some fresh or salted pork. When

almost completed, add gradually a small quantity of potato flour and a

little water. The mixture being of the proper consistency, stuff in beef

casings, tie the ends together into rings of fair length and smoke

thoroughly. This accomplished, boil until the sausages rise to the top,

when they are ready for use. Some recipes provide for two parts of beef

and one part of fat pork and the addition of a little ground coriander

seed to the seasoning.

WESTPHALIAN SAUSAGES

are made in much the same manner as frankforts, chopped not quite so fine,

and, after being cased, are smoked about a week.

FRANKFORT SAUSAGES.

Clean bits of pork, both fat and lean, are chopped fine and well moistened

with cold water. These may be placed in either sheep or hog casings

through the use of the homemade filler shown on another page.

SUABIAN SAUSAGES.

Chop very finely fat and lean meat until the mass becomes nearly a paste,

applying a sprinkling of cold[Pg 29] water during the operation. Suabian

sausages are prepared by either smoking or boiling, and in the latter case

may be considered sufficiently cooked when they rise to the surface of the

water in which they are boiled.

ITALIAN PORK SAUSAGES.

The preparation of these requires considerable care, but the product is

highly prized by many. For every nine pounds of raw pork add an equal

amount of boiled salt pork and an equal amount of raw veal. Then add two

pounds selected sardines with all bones previously removed. Chop together

to a fine mass and then add five pounds raw fat pork previously cut into

small cubes. For the seasoning take six ounces salt, four ounces ground

pepper, eight ounces capers, eight ounces pistachio nuts peeled and boiled

in wine. All of these ingredients being thoroughly mixed, add about one

dozen pickled and boiled tongues cut into narrow strips. Place the sausage

in beef casings of good size. In boiling, the sausages should be wrapped

in a cloth with liberal windings of stout twine and allowed to cook about

an hour. Then remove to a cool place about 24 hours.

TONGUE SAUSAGE.

To every pound of meat used add two pounds of tongues, which have

previously been cut into small pieces, mixing thoroughly. These are to be

placed in large casings and boiled for about an hour. The flavor of the

product may be improved if the tongues are previously placed for a day in

spiced brine. Pickled tongues are sometimes used, steeped first in cold

water for several hours.

BLACK FOREST SAUSAGES.

This is an old formula followed extensively in years gone by in Germany.

Very lean pork is chopped[Pg 30] into a fine mass and for every ten pounds,

three pounds of fat bacon are added, previously cut comparatively fine.

This is properly salted and spiced and sometimes a sprinkling of blood is

added to improve the color. Fill into large casings, place over the fire

in a kettle of cold water and simmer without boiling for nearly an hour.

LIVER SAUSAGE.

The Germans prepare this by adding to every five pounds of fat and lean

pork an equal quantity of ground rind and two and one-half pounds liver.

Previously partly cook the rind and pork and chop fine, then add the raw

liver well chopped and press through a coarse sieve. Mix all thoroughly

with sufficient seasoning. As the raw liver will swell when placed in

boiling water, these sausages should be filled into large skins, leaving

say a quarter of the space for expansion. Boil nearly one hour, dry, then

smoke four or five days.

ROYAL CAMBRIDGE SAUSAGES

are made by adding rice in the proportion of five pounds to every ten

pounds of lean meat and six pounds of fat. Previously boil the rice about

ten minutes, then add gradually to the meat while being chopped fine, not

forgetting the seasoning. The rice may thus be used instead of bread, and

it is claimed to aid in keeping the sausages fresh and sweet.

BRAIN SAUSAGES.

Free from all skin and wash thoroughly the brain of two calves. Add one

pound of lean and one pound of fat pork previously chopped fine. Use as

seasoning four or five raw grated onions, one ounce salt, one-half ounce

ground pepper. Mix thoroughly, place in beef[Pg 31] casings and boil about five

minutes. Afterward hang in a cool place until ready for use.

TOMATO SAUSAGES.

Add one and one-half pounds pulp of choice ripe tomatoes to every seven

pounds of sausage meat, using an addition of one pound of finely crushed

crackers, the last named previously mixed with a quart of water and

allowed to stand for some time before using. Add the mixture of tomato and

cracker powder gradually to the meat while the latter is being chopped.

Season well and cook thoroughly.

SPANISH SAUSAGE

is made by using one-third each leaf lard, lean and fat pork, first

thoroughly boiling and chopping fine the meat. Add to this the leaf lard

previously chopped moderately fine, mix well and add a little blood to

improve the color and moisten the whole. This sausage is to be placed in

large casings and tied in links eight to twelve inches long. In an old

recipe for Spanish sausage seasoning it is made of seven pounds ground

white pepper, six ounces ground nutmeg, eight ounces ground pimento or

allspice and a sprinkling of bruised garlic.

ANOTHER SAUSAGE SEASONING.

To five pounds salt add two pounds best ground white pepper, three ounces

ground mace, or an equal quantity of nutmeg, four ounces ground coriander

seed, two ounces powdered cayenne pepper and mix thoroughly.

ADMIXTURE OF BREAD.

Very often concerns which manufacture sausage on a large scale add

considerable quantities of bread.[Pg 32] This increases the weight at low cost,

thus cheapening the finished product, and is also said to aid in keeping

qualities. While this is no doubt thoroughly wholesome, it is not in vogue

by our most successful farmers who have long made a business of preparing

home-cured sausage. Bread used for sausages should have the crust removed,

should be well soaked in cold water for some time before required, then

pressed to remove the surplus moisture, and added gradually to the pork

while being chopped. Some sausage manufacturers add 10 to 15 per cent in

weight of crushed crackers instead of bread to sausage made during hot

weather. This is to render the product firm and incidentally to increase

the weight through thoroughly mixing the cracker crumbs or powder with an

equal weight or more of water before adding to the meat.

SAUSAGE IN CASES.

Many prefer to pack in sausage casings, either home prepared or purchased

of a dealer in packers’ supplies. Latest improved machines for rapidly

filling the cases are admirably adapted to the work, and this can also be

accomplished by a homemade device. Figure 15 shows a simple bench and

lever arrangement to be used with the common sausage filler, which

lightens the work so much that even a small boy can use it with ease, and

any person can get up the whole apparatus at home with little or no

expense. An inch thick pine board one foot wide and four and one-fourth

feet long is fitted with four legs, two and one-half feet long, notched

into its edges, with the feet spread outward to give firmness. Two oak

standards eighteen inches high are set thirty-four inches apart, with a

slot down the middle of each, for the admission of an oak lever eight feet

long. The left upright has three or four holes, one above another, for the

lever pin, as shown in the[Pg 33] engraving. The tin filler is set into the

bench nearer the left upright and projects below for receiving the skins.

Above the filler is a follower fitting closely into it, and its top

working very loosely in the lever to allow full play as it moves up and

down. The engraving shows the parts and mode of working.

FIG. 15. HOMEMADE SAUSAGE FILLER.

PHILADELPHIA SCRAPPLE.

This is highly prized in some parts of the country, affording a breakfast

dish of great relish. A leading Philadelphia manufacturer has furnished us

with the following recipe: To make 200 lbs. of scrapple, take about 80

lbs. of good clean pork heads, remove the eyes, brains, snout, etc. Put in

about 20 gals. of water and cook until it is thoroughly done. Then take

out, separate the bones and chop the meat fine. Take about 15 gals, of the

liquor left after boiling the heads, and if the water has boiled down to a

quantity less than 15 gals., make up its bulk with hot water; if more than

15 gals. remain, take some of the water out, but be sure to keep some of

the good fat liquor. Put this quantity of the liquor into a kettle, add

the chopped meat, together with 10 oz. pure white pepper, 8 oz. sweet

marjoram, 2 lbs. fine salt. Stir well until the[Pg 34] liquor comes to a good

boil. Have ready for use at this time 25 lbs. good Indian meal and 7 lbs.

buckwheat flour. As soon as the liquor begins to boil add the meal and

flour, the two being previously mixed dry. Be careful to put the meal in a

little at a time, scattering it well and stirring briskly, that it may not

burn to the kettle. Cook until well done, then place in pans to cool. The

pans should be well greased, also the dipper used, to prevent the scrapple

sticking to the utensils. When cold, the scrapple is cut into slices and

fried in the ordinary manner as sausage. Serve hot.

SOUSE.

After being carefully cleaned and soaked in cold water, the feet, ears,

nose and sometimes portions of the head may be boiled, thoroughly boned,

and pressed into bowls or other vessels for cake souse. But frequently

these pieces, instead of being boned, are placed whole in a vessel and

covered with a vinegar, and afterwards taken a little at a time, as

wanted, and fried.

JOWLS AND HEAD.

If not made into souse or sausage, these may be boiled unsmoked, with

turnips, peas or beans; or smoked and cooked with cabbage or salad. The

liver and accompanying parts, if not converted into sausage, may be

otherwise utilized.

THE SPARERIBS AND SHORT BONES

may be cooked in meat pies with a crust, the same as chicken, or they may

be fried or boiled. The large end of the chine makes a good piece for

baking. The whole chine may be smoked and will keep a long time.

CRACKNELS.

This is the portion of the fat meat which is left after the lard is

cooked, and is used by many as an[Pg 35] appetizing food. The cracknels may be

pressed and thus much more lard secured. This latter, however, should be

used before the best lard put away in tubs. After being pressed the

cracknels are worked into a dough with corn meal and together made into

cracknel bread.

BRAWN

is comparatively little used in this country, though formerly a highly

relished dish in Europe, where it was often prepared from the flesh of the

wild boar. An ancient recipe is as follows: “The bones being taken out of

the flitches (sides) or other parts, the flesh is sprinkled with salt and

laid on a tray, that the blood may drain off, after which it is salted a

little and rolled up as hard as possible. The length of the collar of

brawn should be as much as one side of the boar will permit; so that when

rolled up the piece may be nine or ten inches in diameter. After being

thus rolled up, it is boiled in a copper or large kettle, till it is so

tender that you may run a stiff straw through it. Then it is set aside

till it is thoroughly cold, put into a pickle composed of water, salt, and

wheat-bran, in the proportion of two handfuls of each of the latter to

every gallon of water, which, after being well boiled together, is

strained off as clear as possible from the bran, and, when quite cold, the

brawn is put into it.”

HEAD CHEESE.

This article is made usually of pork, or rather from the meat off the

pig’s head, skins, and coarse trimmings. After having been well boiled,

the meat is cut into pieces, seasoned well with sage, salt, and pepper,

and pressed a little, so as to drive out the extra fat and water. Some add

the meat from a beef head to make[Pg 36] it lean. Others add portions of heart

and liver, heating all in a big pan or other vessel, and then running

through a sausage mill while hot.

BLOOD PUDDINGS

are usually made from the hog’s blood with chopped pork, and seasoned,

then put in casings and cooked. Some make them of beef’s blood, adding a

little milk; but the former is the better, as it is thought to be the

richer.

SPICED PUDDINGS.

These are made somewhat like head-cheese, and often prepared by the German

dealers, some of whom make large quantities. They are also made of the

meat from the pig’s chops or cheeks, etc., well spiced and boiled. Some

smoke them.

[Pg 37]

CHAPTER VII.

THE FINE POINTS IN MAKING LARD.

Pure lard should contain less than one per cent of water and foreign

matter. It is the fat of swine, separated from the animal tissue by the

process of rendering. The choicest lard is made from the whole “leaf.”

Lard is also made by the big packers from the residue after rendering the

leaf and expressing a “neutral” lard, which is used in the manufacture of

oleomargarine. A good quality of lard is made from back-fat and leaf

rendered together. Fat from the head and intestines goes to make the

cheaper grades. Lard may be either “kettle” or “steam rendered,” the

kettle process being usually employed for the choicer fat parts of the

animal, while head and intestinal fat furnish the so-called “steam lard.”

Steam lard, however, is sometimes made from the leaf. On the other hand,

other parts than the leaf are often kettle rendered. Kettle rendered lard

usually has a fragrant cooked odor and a slight color, while steam lard

often has a strong animal odor.

TO REFINE LARD,

a large iron pot is set over a slow fire of coals, a small quantity of

water is put into the bottom of the pot, and this is then filled to the

brim with the fat, after it has first been cut into small pieces and

nicely washed, to free it from blood and other impurities. If necessary to

keep out soot, ashes, etc., loose covers or lids are placed over the

vessels, and the contents are made to simmer slowly for several hours.

This work requires a careful and experienced[Pg 38] hand to superintend it.

Everything should be thoroughly clean, and the attendant must possess

patience and a practical knowledge of the work. It will not do to hurry

the cooking. A slow boil or simmer is the proper way. The contents are

occasionally stirred as the cooking proceeds, to prevent burning. The

cooking is continued until the liquid ceases to bubble and becomes clear.

So long as there is any milky or cloudy appearance about the fat, it

contains water, and in this condition will not keep well in summer—a

matter of importance to the country housekeeper.

It requires six to eight hours constant cooking to properly refine a

kettle or pot of fat. The time will depend, of course, somewhat upon the

size of the vessel containing it and the thickness of the fat, and also

upon the attention bestowed upon it by the cook. By close watching, so as

to keep the fire just right all the time, it will cook in a shorter

period, and vice versa. When the liquid appears clear the pots are set

aside for the lard to cool a little before putting it into the vessels in

which it is to be kept. The cracknels are first dipped from the pots and

put into colanders, to allow the lard to drip from them. Some press the

cracknels, and thus get a good deal more lard. As the liquid fat is dipped

from the pots it is carefully strained through fine colanders or wire

sieves. This is done to rid it of any bits of cracknel, etc., that may

remain in the lard. Some country people when cooking lard add a few sprigs

of rosemary or thyme, to impart a pleasant flavor to it. A slight taste of

these herbs is not objectionable. Nothing else whatever is put into the

lard as it is cooked, and if thoroughly done, nothing else is needed. A

little salt is sometimes added, to make it firmer and keep it better in

summer, but the benefit, if any, is slight, and too much salt is

objectionable.

[Pg 39]

LEAF LARD.

In making lard, all the leaf or flake fat, the two leaves of almost solid

fat that grow just above the hams on either side about the kidneys, and

the choice pieces of fat meat cut off in trimming the pork should be tried

or rendered first and separate from the remainder. This fat is the best

and makes what is called the leaf lard. It may be put in the bottom of the

cans, for use in summer, or else into separate jars or cans, and set away

in a cool place. The entrail fat and bits of fat meat are cooked last and

put on top of the other, or into separate vessels, to be used during cool

weather. This lard is never as good as the other, and will not keep sweet

as long; hence the pains taken by careful housewives to keep the two sorts

apart. It must be admitted, however, that many persons, when refining lard

for market, do not make any distinction, but lump all together, both in

cooking and afterward. But for pure, honest “leaf” lard not a bit of

entrail fat should be mixed with the flakes.

A PARTICULARLY IMPORTANT POINT

in making lard is to take plenty of time. The cooking must not be hurried

in the least. It requires time to thoroughly dry out all the water, and

the keeping quality of the lard depends largely upon this. A slow fire of

coals only should be placed under the kettle, and great care exercised

that no spark snaps into it, to set fire to the hot oil. It is well to

have at hand some close-fitting covers, to be put immediately over the

kettle, closing it tightly in case the oil should take fire. The mere

exclusion of air will put out the fire at once. Cook slowly in order not

to burn any of the fat in the least, as that will impart a very[Pg 40]

unpleasant flavor to the lard. The attendants should stir well with a long

ladle or wooden stick during the whole time of cooking. It requires

several hours to thoroughly cook a vessel of lard, when the cracknels will

eventually rise to the top.

A cool, dry room, such as a basement, is the best place for keeping lard.

Large stone jars are perhaps the best vessels to keep it in, but tins are

cheaper, and wooden casks, made of oak, are very good. Any pine wood,

cedar or cypress will impart a taste of the wood. The vessels must be kept

closed, to exclude litter, and care should be observed to prevent ants,

mice, etc., from getting to the lard. A secret in keeping lard firm and

good in hot weather is first to cook it well, and then set it in a cool,

dry cellar, where the temperature remains fairly uniform throughout the

year. Cover the vessels after they are set away in the cellar with closely

fitting tops over a layer of oiled paper.

[Pg 41]

CHAPTER VIII.

PICKLING AND BARRELING.

For salt pork, one of the first considerations is a clean barrel, which

can be used over and over again after yearly renovation. A good way to

clean the barrel is to place about ten gallons of water and a peck of

clean wood ashes in the barrel, then throw in well-heated irons, enough to

boil the water, cover closely, and by adding a hot iron occasionally, keep

the mixture boiling a couple of hours. Pour out, wash thoroughly with

fresh water, and it will be as sweet as a new barrel. Next cover the

bottom of the barrel with coarse salt, cut the pork into strips about six

inches wide, stand edgewise in the barrel, with the skin next the outside,

until the bottom is covered. Cover with a thick coat of salt, so as to

hide the pork entirely. Repeat in the same manner until the barrel is

full, or the pork all in, covering the top thickly with another layer of

salt. Let stand three or four days, then put on a heavy flat stone and

sufficient cold water to cover the pork. After the water is on, sprinkle

one pound best black pepper over all. An inch of salt in the bottom and

between each layer and an inch and a half on top will be sufficient to

keep the pork without making brine.

When it is desired to pickle pork by pouring brine over the filled barrel,

the following method is a favorite: Pack closely in the barrel, first

rubbing the salt well into the exposed ends of bones, and sprinkle well

between each layer, using no brine until forty-eight[Pg 42] hours after, and

then let the brine be strong enough to bear an egg. After six weeks take

out the hams and bacon and hang in the smokehouse. When warm weather

brings danger of flies, smoke a week with hickory chips; avoid heating the

air much. If one has a dark, close smokehouse, the meat can hang in it all

summer; otherwise pack in boxes, putting layers of sweet, dry hay between.

This method of packing is preferred by some to packing in dry salt or

ashes.

FIG. 16. BOX FOR SALTING MEATS.

RENEWING PORK BRINE.

Not infrequently from insufficient salting and unclean barrels, or other

cause, pork placed in brine begins to spoil, the brine smells bad, and the

contents, if not soon given proper attention, will be unfit for food. As

soon as this trouble is discovered, lose no time in removing the contents

from the barrel, washing each piece of meat separately in clean water.

Boil the brine for half an hour, frequently removing the scum and

impurities that will rise to the surface. Cleanse the barrel thoroughly by

washing with hot water and hard wood ashes. Replace the meat after

sprinkling it with a little fresh salt, putting the purified[Pg 43] brine back

when cool, and no further trouble will be experienced, and if the work be

well done, the meat will be sweet and firm. Those who pack meat for home

use do not always remove the blood with salt. After meat is cut up it is

better to lie in salt for a day and drain before being placed in the brine

barrel.

A HANDY SALTING BOX.

A trough made as shown at Fig. 16 is very handy for salting meats, such as

hams, bacon and beef, for drying. It is made of any wood which will not

flavor the meat; ash, spruce or hemlock plank, one and a half inches

thick, being better than any others. A good size is four feet long by two

and one-half wide and one and one-half deep. The joints should be made

tight with white lead spread upon strips of cloth, and screws are vastly

better than nails to hold the trough together.

[Pg 44]

CHAPTER IX.

CARE OF HAMS AND SHOULDERS.

In too many instances farmers do not have the proper facilities for curing

hams, and do not see to it that such are at hand, an important point in

success in this direction. A general cure which would make a good ham

under proper conditions would include as follows: To each 100 lbs. of ham

use seven and a half pounds Liverpool fine salt, one and one-half pounds

granulated sugar and four ounces saltpeter. Weigh the meat and the

ingredients in the above proportions, rub the meat thoroughly with this

mixture and pack closely in a tierce. Fill the tierce with water and roll

every seven days until cured, which in a temperature of 40 to 50 degrees

would require about fifty days for a medium ham. Large hams take about ten

days more for curing. When wanted for smoking, wash the hams in water or

soak for twelve hours. Hang in the smokehouse and smoke slowly forty-eight

hours and you will have a very good ham. While this is not the exact

formula followed in big packing houses, any more than are other special

recipes given here, it is a general ham cure that will make a first-class

ham in every respect if proper attention is given it.

Another method of pickling hams and shoulders, preparatory to smoking,

includes the use of molasses. Though somewhat different from the above

formula, the careful following of directions cannot fail to succeed

admirably. To four quarts of fine salt and two ounces of pulverized

saltpeter, add sufficient[Pg 45] molasses to make a pasty mixture. The hams

having hung in a dry, cool place for three or four days after cutting up,

are to be covered all over with the mixture, more thickly on the flesh

side, and laid skin side down for three or four days. In the meantime,

make a pickle of the following proportions, the quantities here named

being for 100 lbs. of hams. Coarse salt, seven pounds; brown sugar, five

pounds; saltpeter, two ounces; pearlash or potash, one-half ounce; soft

water, four gallons. Heat gradually and as the skim rises remove it.

Continue to do this as long as any skim rises, and when it ceases, allow

the pickle to cool. When the hams have remained the proper time immersed

in this mixture, cover the bottom of a clean, sweet barrel with salt about

half an inch deep. Pack in the hams as closely as possible, cover them

with the pickle, and place over them a follower with weights to keep them

down. Small hams of fifteen pounds and less, also shoulders, should remain

in the pickle for five weeks; larger ones will require six to eight weeks,

according to size. Let them dry well before smoking.

WESTPHALIAN HAMS.

This particular style has long been a prime favorite in certain markets of

Europe, and to a small extent in this country also. Westphalia is a

province of Germany in which there is a large industry in breeding swine

for the express purpose of making the most tender meat with the least

proportion of fat. Another reason for the peculiar and excellent qualities

which have made Westphalian hams so famous, is the manner of feeding and

growing for the hams, and finally the preserving, curing, and last of all,

smoking the hams. The Ravensberg cross breed of swine is a favorite for

this purpose. They are rather large animals, having[Pg 46] slender bodies, flat

groins, straight snouts and large heads, with big, overhanging ears. The

skin is white, with straight little bristles.

A principal part of the swine food in Westphalia is potatoes; these are

cooked and then mashed in the potato water. The pulp thus obtained is

thoroughly mixed with wheat bran in a dry, raw state; little corn is used.

In order to avoid overproduction of fat and at the same time further the

growth of flesh of young pigs, some raw cut green feed, such as cabbage,

is used; young pigs are also fed sour milk freely. In pickling the hams

they are first vigorously rubbed with saltpeter and then with salt. The

hams are pressed in the pickling vat and entirely covered with cold brine,

remaining in salt three to five weeks. After this they are taken out of

the pickle and hung in a shady but dry and airy place to “air-dry.” Before

the pickled hams can be put in smoke they are exposed for several weeks to

this drying in the open air. As long as the outside of the ham is not

absolutely dry, appearing moist or sticky, it is kept away from smoke.

Smoking is done in special large chambers, the hams being hung from the

ceiling. In addition to the use of sawdust and wood shavings in making

smoke, branches of juniper are often used, and occasionally beech and

alder woods; oak and resinous woods are positively avoided. The smoking is

carried on slowly. It is recommended to smoke for a few days cautiously,

that is, to have the smoke not too strong. Then expose the hams for a few

days in the fresh air, repeating in this way until they are brown enough.

The hams are actually in smoke two or three weeks, thus the whole process

of smoking requires about six weeks. Hams are preserved after their

smoking in a room which is shady, not accessible to the light, but at the

same time dry, cool and airy.

[Pg 47]

THE PIG AND THE ORCHARD.

The two go together well. The pig stirs up the soil about the trees,

letting in the sunshine and moisture to the roots and fertilizing them,

while devouring many grubs that would otherwise prey upon the fruit. But

many orchards cannot be fenced and many owners of fenced orchards, even,

would like to have the pig confine his efforts around the trunk of each

tree. To secure this have four fence panels made and yard the pig for a

short time in succession about each tree, as suggested in the diagram,

Fig. 17.

FIG. 17. FENCE FOR ORCHARD TREE.

[Pg 48]

CHAPTER X.

DRY SALTING BACON AND SIDES.

For hogs weighing not over 125 or 130 lbs. each, intended for dry curing,

one bushel fine salt, two pounds brown sugar and one pound saltpeter will

suffice for each 800 lbs. pork before the meat is cut out; but if the meat

is large and thick, or weighs from 150 to 200 lbs. per carcass, from a

gallon to a peck more of salt and a little more of both the other articles

should be taken. Neither the sugar nor the saltpeter is absolutely

necessary for the preservation of the meat, and they are often omitted.

But both are preservatives; the sugar improves the flavor of the bacon,

and the saltpeter gives it greater firmness and a finer color, if used

sparingly. Bacon should not be so sweet as to suggest the “sugar-cure;”

and saltpeter, used too freely, hardens the tissues of the meat, and

renders it less palatable. The quantity of salt mentioned is enough for

the first salting. A little more

NEW SALT IS ADDED AT THE SECOND SALTING

and used together with the old salt that has not been absorbed. If sugar

and saltpeter are used, first apply about a teaspoonful of pulverized

saltpeter on the flesh side of the hams and shoulders, and then taking a

little sugar in the hand, apply it lightly to the flesh surface of all the

pieces. A tablespoonful is enough for any one piece.

If the meat at the time of salting is moist and yielding to the touch,

rubbing the skin side with the[Pg 49] gloved hand, or the “sow’s ear,” as is

sometimes insisted on, is unnecessary; the meat will take salt readily

enough without this extra labor. But if the meat is rigid, and the weather

very cold, or if the pieces are large and thick, rubbing the skin side to

make it yielding and moist causes the salt to penetrate to the center of

the meat and bone. On the flesh side it is only necessary to sprinkle the

salt over all the surface. Care must be taken to get some salt into every

depression and into the hock end of all joints. An experienced meat salter

goes over the pieces with great expedition. Taking a handful of the salt,

he applies it dextrously by a gliding motion of the hand to all the

surface, and does not forget the hock end of the bones where the feet have

been cut off. Only dry salt is used in this method of curing. The meat is

never put into brine or “pickle,” nor is any water added to the salt to

render it more moist.

BEST DISTRIBUTION OF THE SALT.

A rude platform or bench of planks is laid down, on which the meat is

packed as it is salted. A boy hands the pieces to the packer, who lays

down first a course of middlings and then sprinkles a little more salt on

all the places that do not appear to have quite enough. Next comes a layer

of shoulders and then another layer of middlings, until all these pieces