Larger Image

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Battle of Blenheim, by Hilaire Belloc This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Battle of Blenheim Author: Hilaire Belloc Release Date: May 1, 2010 [EBook #32195] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BATTLE OF BLENHEIM *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

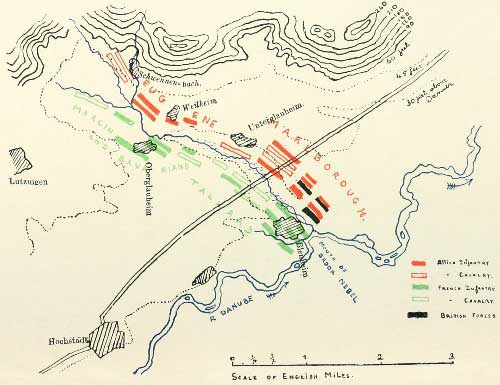

Plate I. The Battle of Blenheim.

Frontispiece.

| PAGE | ||||

| PART | I. | THE POLITICAL OBJECTIVE | 9 | |

| " | II. | THE EARLY WAR | 17 | |

| " | III. | THE MARCH TO THE DANUBE | 32 | |

| " | IV. | THE SEVEN WEEKS—THE THREE PHASES | 68 | |

| " | V. | THE ACTION | 109 | |

| PAGE | ||

| The General Situation in 1703 | 27 | |

| Map showing the peril of Marlborough’s March to the Danube beyond the Hills which separate the Rhine from the Danube | 45 | |

| Map illustrating Marlborough’s March to the Danube | 59 | |

| Map illustrating the March of Marlborough and Baden across Marcin’s front, from the neighbourhood of Ulm to Donauwörth | 71 | |

| Map showing how Donauwörth is the key of Bavaria from the North-West | 76 | |

| Map showing Eugene’s March on the Danube from the Black Forest | 92 | |

| Map showing the Situation when Eugene suddenly appeared at Hochstadt, August 5-7, 1704 | 95 | |

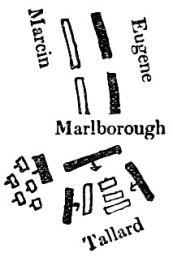

| The Elements of the Action of Blenheim | 118 |

The proper understanding of a battle and of its historical significance is only possible in connection with the campaign of which it forms a part; and the campaign can only be understood when we know the political object which it was designed to serve.

A battle is no more than an incident in a campaign. However decisive in its immediate result upon the field, its value to the general conducting it depends on its effect upon the whole of his operations, that is, upon the campaign in which he is engaged.

A campaign, again, is but the armed effort of one society to impose its will in some[Pg 10] particular upon another society. Every such effort must have a definite political object. If this object is served the campaign is successful. If it is not served the campaign is a failure. Many a campaign which began or even concluded with a decisive action in favour of one of the two belligerents has failed because, in the result, the political object which the victory was attempting was not reached. Conversely, many a campaign, the individual actions of which were tactical defeats, terminated in favour of the defeated party, upon whom the armed effort was not sufficient to impose the will of his adversary, or to compel him to that political object which the adversary was seeking. In other words, military success can be measured only in terms of civil policy.

It is therefore essential, before approaching the study of any action, even of one so decisive and momentous as the Battle of Blenheim, to start with a general view of the political situation which brought about hostilities, and of the political object of those hostilities; only then, after grasping the measure in which the decisive action in question affected the whole campaign, can we judge how the campaign, in its turn, compassed the political end for which it was designed.

[Pg 11]The war whose general name is that of the Spanish Succession was undertaken by certain combined powers against Louis XIV. of France (and such allies as that monarch could secure upon his side) in order to prevent the succession of his grandson to the crown of Spain.

With the various national objects which Holland, England, the Empire and certain of the German princes, as also Savoy and Portugal, may have had in view when they joined issue with the French monarch, military history is not concerned. It is enough to know that their objects, though combining them against a common foe, were not identical, and the degrees of interest with which they regarded the compulsion of Louis XIV. to forego the placing of his grandson upon the Spanish throne were very different. It is this which will largely explain the various conduct of the allies during the progress of the struggle; but all together sought the humiliation of Louis, and joined on the common ground of the Spanish Succession.

The particular object, then, of the campaign of Blenheim (and of those campaigns which immediately preceded and succeeded it) was the prevention of the unison of the crowns of France and Spain[Pg 12] in the hands of two branches of the same family. Tested by this particular issue alone, the campaign of Blenheim, and the whole series of campaigns to which it belongs, failed. Louis XIV. maintained his grandson upon the throne of Spain; and the issue of the long war could not impose upon him the immediate political object of the allies.

But there was a much larger and more general object engaged, which was no less than the defence of Austria—more properly the Empire—and of certain minor States, against what had grown to be the overwhelming power of the French monarchy.

From this standpoint the whole period of Louis XIV.’s reign—all the last generation of the seventeenth century and the first decade and more of the eighteenth—may be regarded as a struggle between the soldiers of Louis XIV. (and their allies) upon the one hand, and Austria, with certain minor powers concerned in the defence of their independence or integrity, upon the other.

In this struggle Great Britain was neutral or benevolent in its sympathies in so far as those sympathies were Stuart; but all that part of English public life called Whig, all the group of English aristocrats who desired[Pg 13] the abasement of the Crown, perhaps the mass of the nation also, was opposed, both in its interests and in its opinions, to the supremacy of Louis XIV. upon the Continent.

William of Orange, who had been called to the English throne by the Revolution of 1688, was the most determined opponent Louis had in Europe. Apart from him, the general interests of the London merchants, and the commercial interests of the nation as a whole, were in antagonism to the claims of the Bourbon monarchy. We therefore find the forces of Great Britain, in men, ships, guns, and money, arrayed against Louis throughout the end of his reign, and especially during this last great war.

Now, from this general standpoint—by far the most important—the war of the Spanish Succession is but part of the general struggle against Louis XIV.; and in that general struggle the campaign of 1704, and the battle of Blenheim which was its climax, are at once of the highest historical importance, and a singular example of military success.

For if the general political object be considered, which was the stemming of the French tide of victory and the checking of the Bourbon power, rather than the particular matter of the succession of the[Pg 14] Spanish throne, then it was undoubtedly the campaign of 1704 which turned the tide; and Blenheim must always be remembered in history as the great defeat from which dates the retreat of the military power of the French in that epoch, and the gradual beating back of Louis XIV.’s forces to those frontiers which may be regarded as the natural boundaries of France.

Not all the French conquests were lost, nor by any means was the whole great effort of the reign destroyed. But the peril which the military aptitude of the French under so great a man as Louis XIV. presented to the minor States of Europe and to the Austrian empire was definitely checked when the campaign of Blenheim was brought to its successful conclusion. That battle was the first of the great defeats which exhausted the resources of Louis, put him, for the first time in his long reign, upon a close defensive, and restored the European balance which his years of unquestioned international power had disturbed.

Blenheim, then, may justly rank among the decisive actions of European history.

In connection with the campaign of which it formed a part, it gave to that campaign all its meaning and all its complete success.

[Pg 15]In connection with the general struggle against Louis, that campaign formed the turning point between the flow and the ebb in the stream of military power which Louis XIV. commanded and had set in motion.

From the day of Blenheim, August 13th, 1704, onwards, the whole French effort was for seven years a desperate losing game, which, if its end was saved from disaster by the high statesmanship of the king and the devotion of his people, was none the less the ruin of that ambitious policy which had coincided with the great days of Versailles.

The war was conducted, as I have said, by various allies. Its success depended, therefore, upon various commanders regarded as coequal, acting as colleagues rather than as principals and subordinates. But the story of the great march to the Danube and its harvest at Blenheim, which we are about to review, sufficiently proves that the deciding genius in the whole affair was that of John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough. The plan was indeed Eugene’s; and in the battle itself he shared the glory with his English friend and colleague.[Pg 16] Again, the British troops present were few indeed compared with the total of the allied forces. At Blenheim, in particular, they amounted to less than a third of the numbers present. The excellence of their material, however, their magnificent work at the Schellenberg and on Blenheim field itself, coupled with the fact that the general to whom the final success is chiefly due was the great military genius of this country, warrants the historian in classing this battle among British actions, and in treating its story as a national affair.

I will approach the story of the campaign and of the battle by a conspectus of the field of war in which Marlborough was so unexpectedly to show the military genius which remains his single title to respect and his chief claim to renown.

In order to grasp the strategic problem presented to Marlborough and the allies in the spring of 1704, it is first necessary to understand the diplomatic position at the outbreak of the war, and the military disposition of the two years 1702 and 1703, and thus the general position of the armies which preceded Marlborough’s march to the Danube.

Louis XIV. recognised his grandson as king of Spain late in 1700. The coalition immediately formed against him was at first imperfect. Savoy, with its command of the passes over the Alps into Austrian territory, was in Louis’ favour. England, whose support of his enemies was (for reasons to be described) a capital factor in the issue, had not yet joined those enemies. But, from several causes, among the chief of which was Louis’ recognition of the Pretender as king of England after James[Pg 18] the II.’s death, the opinion of the English aristocracy, and perhaps of the English people, was fixed, and in the last months of 1701 the weight of England was thrown into the balance against France.

Why have I called this—the decision of the English Parliament—a capital factor in the issue of the war?

Excepting for a moment the military genius of Marlborough—whose great capacity had not yet been tested in so large a field—two prime characters gave to Great Britain a deciding voice in what was to follow. The first of these was her wealth, the second that aristocratic constitution of her polity which was now definitely established, and which, for nearly a century and a half, was to make her strength unique in its quality among all the elements of European competition.

As to the first of these—the Wealth of England—it is a matter of such importance to the comprehension of all the eighteenth century and most of the nineteenth that it should merit a far longer analysis and affirmation than can be devoted to it in these few lines. It must be enough for our purpose to say that Great Britain, from about 1680 onwards, was not only wealthier (in proportion to her population) than the[Pg 19] powers with whom she had to deal as enemies or allies, but was also proceeding to increase that wealth at a rate far exceeding that of her rivals. Again, what was perhaps, for the purposes of war, the chief point of all, England held that wealth in a mobile, fluid form, which could at once be translated into munitions, the wages of mercenaries, or the hire of transports, within the shortest time, and at almost any point in Western and Northern Europe.

Essentially commercial, already possessed of a solid line of enterprises beyond the seas, having defeated and passed the Dutch in the race for mercantile supremacy, England could afford or withhold at her choice the most valuable and rapid form of support—money.

How true this was, even those in Europe who had not appreciated the changed conditions of Great Britain immediately perceived when the determination of Parliament, at the end of 1701, to support the alliance against Louis XIV., took the form of voting 40,000 men, all of whom would be immediately supplied and paid with English money.

True, of the 40,000 not half were British; but (save for the excellent quality of the[Pg 20] British troops), the point was more or less indifferent. The important thing was that England was able to provide and to maintain this immense accretion to the coalition against France, and to use it where she would. We shall see later how this power turned the fate of the war.

If I have insisted so strongly upon the financial factor, it is both because that factor is misappreciated in most purely military histories, and also because, in the changed circumstances of our own time, it is not easy for the reader to take for granted, as did his ancestors, the overwhelming superiority which England once enjoyed in mobilised wealth, usable after this kind. It can best be compared to the similar superiority enjoyed in the Middle Ages by the Republic of Venice, to whose fortunes, both good and ill, the story of modern England affords so strange a parallel.

The second factor I have mentioned—the aristocratic constitution of the country—though almost equally important, is somewhat more elusive, and might be more properly challenged by a critic.

England had not, in the first years of the eighteenth century, reached that calm and undisturbed solidity which is the mark of an aristocratic State at its zenith.[Pg 21] Faction was bitter, the opposition between the old loyalty to the Crown and the new national régime was so determined as to make civil war possible at any moment. This condition of affairs was to last for a generation, and it was not until the middle of the eighteenth century was passed that it disappeared.

Nevertheless, compared with the Continental States, Great Britain already presented by 1701 that elasticity in substance and tenacity in policy which accompany aristocratic institutions. Corruption might be rife, but it was already growing difficult to purchase the services of a member of the governing class against the national interests. That knowledge of public affairs, diffused throughout a small and closely combined social class, which is the mark of an aristocracy, was already apparent. The power of choosing, from a narrow and well-known field, the best talents for any particular office (which is another mark of aristocracy), was already a power apparent in the government of this country. The solidarity which, in the face of a common enemy, an aristocracy always displays, the long-livedness, as of a corporate body, which an aristocracy enjoys, and which permits it to follow with[Pg 22] such strict continuity whatever line of foreign policy it has undertaken, was clearly defining itself at the moment of which I write.

In a word, the new settlement of English life upon the basis of class government, the exclusion of the mass of the people from public affairs, the decay (if you will) of a lively public opinion, the presence of that hopeless disinherited class which now forms the majority of our industrial population; the organisation of the universities, of justice, of the legislature, of the executive, as parts of one social class; the close grasp which that class now had upon the land and capital of the whole country, which it could utilise immediately for interior development or for a war—all this marked the youth and vigour of an oligarchic England, which was for so long to be at once invulnerable and impregnable.

At what expense in morals, and therefore in ultimate strength and happiness, such experiments are played, is no matter for discussion in a military history. We must be content to remark what vigour her new constitution gave to the efforts of England in the field, while yet that constitution was young.

England, then, having thrown this great[Pg 23] weight into the scale of the Empire, and against France, the campaign of 1702 was entered upon with the chances in favour of the former, and with the latter in an anxiety very different from the pride which Louis XIV. had taken for granted in the early part of his reign.

If the reader will consider the map of Western Europe, the effect of England’s joining the allies will be apparent.

The frontier between the Spanish Netherlands and Holland—that is, between modern Belgium and Holland—was the frontier between the forces of Louis XIV. and those of opponents upon the north. Thus Antwerp and Ostend were in the hands of the Bourbon, for the Spanish Netherlands had passed into the hands of the French king’s grandson, and the French and Spanish forces were combined. Further east, towards the Upper Rhine, a French force lay in the district of Cleves, and all the fortresses on the Meuse, running in a line south of that post, with the exception of Maestricht, were in French hands.

French armies held or threatened the Middle Rhine. Upon the Upper Rhine and upon the Danube an element of the highest[Pg 24] moment in favour of France had appeared when the Elector of Bavaria had declared for Louis XIV., and against Austria.

Had not England intervened with the great weight of gold and that considerable contingent of men (in all, eighteen of the new forty thousand), France would have easily held her northern position upon the frontier of Holland and the Lower Rhine, while the Elector of Bavaria, joining forces with the French army upon the Upper Rhine, would have marched upon Vienna.

The Emperor was harried by the rising of the Hungarians behind him; and as the principal forces of the French king would not have been detained in the north, the whole weight of France, combined with her new ally the Elector of Bavaria, would have been thrown upon the Upper Danube.

As it was, this plan was, in its inception at least, partially successful, but only in its inception, and only partially.

For, with the summer of 1702, Marlborough, though hampered by the fears of the Dutch with whom he had to act in concert, cleared the French out of Cleves, caused them to retire southward in the face of the great accession of strength which he brought with the new troops in English pay and the English contingents. Following the[Pg 25] French retirement, he swept the whole valley of the Meuse,[1] and took its fastnesses from Liége downwards, all along the course of the stream.

By the end of the year this northern front of the French armies was imperilled, and Marlborough and his allies in that part hoped to undertake with the next season the reduction of the Spanish Netherlands.

It must be remembered, in connection with this plan, that France has always been nervous with regard to her north-eastern frontier; that the loss of this frontier leaves a way open to Paris: an advance from Belgium was to the French monarchy what an advance along the Danube was to Austria—the prime peril of all. As yet, France was nowhere near grave peril in this quarter, but pressure there marred her general plans upon the Danube.

Nevertheless, the march upon Vienna by the Upper Danube had been prepared with some success. While part of the northern frontier was thus being pressed and part menaced, while the Meuse was being cleared of French garrisons, and the French fortresses on it taken by Marlborough and his[Pg 26] allies, the Elector of Bavaria had seized Ulm. The French upon the Upper Rhine, under Villars, defeated the Prince of Baden at Friedlingen, and established a road through the New Forest by which Louis XIV.’s forces, combined with those of the Elector of Bavaria, could advance eastward upon the Emperor’s capital. It was designed that in the next year, 1703, the troops of Savoy, in alliance with those of France, should march from North Italy through the passes of the Alps and the Tyrol upon Vienna, while at the same time the Franco-Bavarian forces should march down the Danube towards the same objective.

When the campaign of 1703 opened, however, two unexpected events determined what was to follow.

The first was the failure of Marlborough in the north to take Antwerp, and in general his inability to press France further at that point; the second, the defection of Savoy from the French alliance.

As to the first—Marlborough’s failure against Antwerp. The Spanish Netherlands were now solidly held; the forces of the allies were indeed increasing perpetually in this neighbourhood, but it appeared as though the attempt to reduce Brabant, Hainault, and Flanders, which are here the bulwark of France, would be tedious, and perhaps barren. A sort of “consolation” advance was indeed made upon the Rhine, and Bonn was captured; but no more was done in this quarter.

The General Situation in 1703.

[Pg 28]As to the second point, the solid occupation of the Upper Danube by the Franco-Bavarians was indeed fully accomplished. The imperial forces were defeated upon the bank of that river at Hochstadt, but the advance upon Vienna failed, for the second half of the plan, the march from Northern Italy upon Austria, through the Tyrol, had come to nothing, through the defection of Savoy. The turning of the scale against Louis by the action of England was beginning to have its effect; Portugal had already joined the coalition, and now Savoy had refused to continue her help of the Bourbons.

The year 1704 opened, therefore, with this double situation: to the south Austria had been saved for the moment, but was open to immediate attack in the campaign to come; meanwhile, the French had proved so solidly seated in the Spanish Netherlands (or Belgium) that repeated attacks on them in this quarter would in all probability prove barren.

It was under these circumstances that[Pg 29] Eugene of Savoy came to the great decision which marked the year of Blenheim. He determined that it was best—if he could persuade his colleagues—to carry the war into that territory which was particularly menaced. He conceived the plan of marching a great force from the Netherlands right down to the field of the Upper Danube. There could be checked the proposed march upon the heart of the coalition, which was Vienna. There, if fortune served the allies, they would by victory make all further chance of marching a Franco-Bavarian force down the Danube impossible; meanwhile, and at any rate, the new step would alarm all French effort towards the Upper Rhine, weaken the French organisation upon its northern frontier, and so permit of a return of the allies to an attack there at a later time.

Eugene of Savoy was a member of the cadet branch of that royal house. His grandfather, the younger son of Charles Emmanuel, had founded the family called Savoy Carignan. His father had been married to one of Mazarin’s nieces. Eugene was her fifth son, and at this moment not quite forty years of age.

His character, motives, and genius must be clearly seized if we are to appreciate the campaign and the battle of Blenheim.

[Pg 30]It was the Italian blood which formed that character most, but he was thoroughly French by birth and training. Born in Paris, and desiring a career in the French army, it was a slight offered to his mother by the French king that gave his whole life a personal hatred of Louis XIV. for its motive. From boyhood till his death, between sixty and seventy, this great captain directed his energies uniquely against the fortunes of the French king. When, later in life, there was an attempt to acquire his talents for the French service, he replied that he hoped to re-enter France, but only as an invader. It has been complained that he lacked precision in detail, and that as an organiser he was somewhat at fault; but he had no equal for rapidity of vision, and for seizing the essential point in a strategic problem. From that day in his twentieth year when he had assisted at Sobiesky’s destruction of the Turks before Vienna, through his own great victory which crushed that same enemy somewhat later at Zenta, in all his career this quality of immediate perception had been supremely apparent.

He was at this moment—the end of the campaign of 1703—the head of the imperial council of war; and he it was who first[Pg 31] grasped the strategic necessity which 1703 had created. The determination to carry the defence of the empire into the valley of the Upper Danube was wholly his own. He wrote to Marlborough suggesting a withdrawal of forces as considerable as possible from the northern field to the southern.

By a happy accident, the judgment of the Englishman exactly coincided with his own, and indeed there was so precise a sympathy between these two very different men that when they met in the course of the ensuing campaign there sprang up between them not only a lasting friendship, but a mutual comprehension which made the combination of their talents invincible during those half dozen years of the war which all but destroyed the French power.

Such was the origin of Marlborough’s advance southward from the Netherlands in the early summer of 1704, an advance famous in history under the title of “the march to the Danube.”

The position of the enemy at the moment when Marlborough’s march to the Danube from the Netherlands was conceived may be observed in the sketch map on page 59.

Under Villeroy, who must be regarded as the chief of the French commanders of the moment, lay the principal army of Louis XIV., with the duty of defending the northern front and of watching the Lower Rhine.

It was this main force which was expected to have to meet the attack of Marlborough and the Dutch in the same field of operations as had seen the troops in English pay at work during the two preceding years. But Villeroy was, of course, free to detach troops southwards somewhat towards the Middle Rhine, or the valley of the Moselle, if, as later seemed[Pg 33] likely, an attack should be made in that direction.

On the Upper Rhine, and in Alsace generally, lay Tallard with his corps. This marshal had captured certain crossing-places over the Rhine, but had all his munitions and the mass of his strength permanently on the left bank.

Finally, Marcin, with his French contingent, and Max-Emanuel, the Elector of Bavaria, with the Bavarian army, held the whole of the Upper Danube, from Ulm right down to and past the Austrian frontier.

Over against these forces of the French and their Bavarian allies we must set, first, the Dutch forces in the north, including the garrisons of the towns on the Meuse which Marlborough had conquered and occupied; and, in the same field, the forces in the pay of England (including the English contingents). These amounted in early 1704 to 50,000 men, which Marlborough was to command.

Next, upon the Middle Rhine, and watching Tallard in Alsace, was Prince Eugene, who had been summoned from Hungary by the Imperial government to defend this bulwark of Germany, but his army was small compared to the forces in the north.

[Pg 34]Finally, the Margrave of Baden, Louis, with another separate army, was free to act at will in Upper Germany, to occupy posts in the Black Forest, or to retire eastward into the heart of Germany or towards the Danube as circumstances might dictate. This force was also small. It was supplemented by local militia raised to defend particular passes in the Black Forest, and these, again, were supported by the armed peasantry.

It is essential to a comprehension of the whole scheme to understand that before the march to the Danube the whole weight of the alliance against the French lay in the north, upon the frontier of Holland, the valley of the Meuse, and the Lower Rhine. The successes of Bavaria in the previous year had given the Bavarian army, with its French contingent, a firm grip upon the Upper Danube, and the possibility of marching upon Vienna itself when the campaign of 1704 should open.

The great march upon the Danube which Eugene had conceived, and which Marlborough was to execute so triumphantly, was a plan to withdraw the weight of the allied forces suddenly from the north to the south; to transfer the main weapon acting against France from the Netherlands[Pg 35] to Bavaria itself; to do this so rapidly and with so little leakage of information to the enemy as would prevent his heading off the advance by a parallel and faster movement upon his part, or his strengthening his forces upon the Danube before Marlborough’s should reach that river.

Such was the scheme of the march to the Danube which we are now about to follow; but before undertaking a description of the great and successful enterprise, the reader must permit me a word of distinction between a strategic move and that tactical accident which we call a battle. In the absence of such a distinction, the campaign of Blenheim and the battle which gives it its name would be wholly misread.

A great battle, especially if it be of a decisive character, not only changes history, but has a dramatic quality about it which fixes the attention of mankind.

The general reader, therefore, tends to regard the general movements of a campaign as mere preliminaries to, or explanations of, the decisive action which may conclude it.

This is particularly the case with the readers attached to the victorious side.[Pg 36] The French layman, in the days before universal service in France, wrote and read his history of 1805 as though the march of the Grand Army were deliberately intended to conclude with Austerlitz. The English reader and writer still tends to read and write of Marlborough’s march to the Danube as though it were aimed at the field of Blenheim.

This error or illusion is part of that general deception so common to historical study which has been well called “reading history backwards.” We know the event; to the actors in it the future was veiled. Our knowledge of what is to come colours and distorts our judgment of the motive and design of a general.

The march to the Danube was, like all strategic movements, a general plan animated by a general objective. It was not a particular thrust at a particular point, destined to achieve a highly particular result at that point.

Armies are moved with the object of imposing political changes upon an opponent. If that opponent accepts these changes, not necessarily after a pitched battle, but in any other fashion, the strategical object of the march is achieved.

Though the march conclude in a defeat,[Pg 37] it may be strategically sound; though it conclude in a victory, it may be strategically unsound. Napoleon’s march into Russia in 1812 was strategically sound. Had Russia risked a great battle and lost it, the historical illusion of which I speak would treat the campaign as a designed preface to the battle. Had Russia risked such a battle and been successful, the historical illusion of which I speak would call the strategy of the advance faulty.

As we know, the advance failed partly through the weather, partly through the spirit of the Russian people, not through a general action. But in conception and in execution the strategy of Napoleon in that disastrous year was just as excellent as though the great march had terminated not in disaster but in success.

Similarly, the reputation justly earned by Marlborough when he brought his troops from the Rhine to the Danube must be kept distinct from his tactical successes in the field at the conclusion of the effort. He was to run a grave risk at Donauwörth, he was to blunder badly in attacking the village of Blenheim, he was to be in grave peril even in the last phase of the battle, when Eugene just saved the centre with his cavalry.

[Pg 38]Had chance, which is the major element in equal combats, foiled him at Donauwörth or broken his attempt at Blenheim, the march to the Danube would still remain a great thing in history. Had Tallard refused battle on that day, as he certainly should have done, the march to the Danube would still deserve its great place in the military records of Europe.

When we have seized the fact that Marlborough’s great march was but a general strategic movement of which the action at Blenheim was the happy but accidental close, we must next remark that the advance to the Danube was the more meritorious, and gives the higher lustre to Marlborough’s fame as a general, from the fact that it was an attempt involving a great military hazard, and that yet that attempt had to be made in the face of political difficulties of peculiar severity.

In other words, Marlborough was handicapped in a fashion which lends his success a character peculiar to itself, and worthy of an especial place in history.

This handicap may be stated by a consideration of three points which cover its whole character.

[Pg 39]The first of these points concerns the physical conditions of the move; the other two are peculiar to the political differences of the allies.

It was in the nature of the move that a high hazard was involved in it. The general had calculated, as a general always must, the psychology of his opponent. If he were wrong in his calculation, the advance on the Danube could but lead to disaster. It was for him to judge whether the French were so nervous about the centre of their position upon the Rhine as to make them cling to it to the last moment, and tend to believe that it was either along the Moselle or (when he had left that behind) in Alsace that he intended to attack. In other words, it was for him to make the French a little too late in changing their dispositions, a little too late in discovering what his real plan was, and therefore a little too late in massing larger reinforcements upon the Upper Danube, where he designed to be before them.

Marlborough guessed his opponent’s psychology rightly; the French marshals hesitated just too long, their necessity of communicating with Louis at Versailles further delayed them, and the great hazard which he risked was therefore risked with[Pg 40] judgment. But a hazard it remained until almost the last days of its fruition. The march must be rapid; it involved a thousand details, each requiring his supervision and his exact calculation, his knowledge of what could be expected of his troops, and his survey of daily supply.

There was another element of hazard.

Arrived at his destination upon the plains of the Danube, Marlborough would be very far from any good base of supply.

The country lying in the triangle between the Upper Danube and the Middle Rhine, especially that part of it which is within striking distance of the Danube, is mountainous and ill provided with those large towns, that mobilisable wealth, and those stores of vehicles, munitions, food, and remounts which are the indispensable sustenance of an army.

The industry of modern Germany has largely transformed this area, but even to-day it is one in which good depots would be rare to find. Two hundred years ago, the tangle of hills was far more deserted and far worse provided.

By the time Marlborough should have effected his junction with his ally in the upper valley of the Danube only two bases of supply would be within any useful distance[Pg 41] of the new and distant place to which he was transferring his great force.

The most important of these, his chief base, and his only principal store of munitions and every other requisite, was Nuremberg; and that town was a good week from the plains upon the bank of the Danube where he proposed to act. As an advanced base nearer to the river, he could only count upon the lesser town of Nordlingen.

Therefore, even if he should successfully reach the field of action which he proposed, cross the hills between the two river basins without loss or delay, and be ready to act as he hoped upon the banks of the Danube before the end of June, his stay could not be indefinitely prolonged there, and his every movement would be undertaken under the anxiety which must ever haunt a commander dependent on an insufficient or too distant base of supply. This anxiety, be it noted, would rapidly increase with every march he might have to take southward of the Danube, and with every day’s advance into Bavaria itself, if, as he hoped, the possibility of such an advance should crown his efforts.

We have seen that the great hazard which Marlborough risked made it necessary, as he advanced southward up the Rhine during[Pg 42] the first half of his march, to keep Villeroy and Tallard doubtful as to whether his objective was the Moselle or, later, Alsace; and while they were still in suspense, abruptly to leave the valley of the Rhine and make for the crossing of the hills towards the Danube. So long as the French marshals remained uncertain of his intentions, they would not dare to detach any very large body of troops from the Rhine valley to the Elector’s aid: under the conditions of the time, the clever handling of movement and information might create a gap of a week at least between his first divergence from the Rhine and his enemy’s full appreciation that he was heading for the south-east.

He so concealed his information and so ordered his baffling movements as to achieve that end.

So much for the general hazard which would have applied to any commander undertaking such an advance.

But, as I have said, there were two other points peculiar to Marlborough’s political position.

The first was, that he was not wholly free to act, as, for instance, Cæsar in Gaul was free, or Napoleon after 1799. He must perpetually arrange matters, in the first stages with the Dutch commissioner, later with the[Pg 43] imperial general, Prince Louis of Baden, who was his equal in command. He must persuade and even trick certain of his allies in all the first steps of the great business; he must accommodate himself to others throughout the whole of it.

Secondly, the direction in which he took himself separated him from the possibility of rapidly communicating his designs, his necessities, his chances, or his perils to what may be called his moral base. This moral base, the seat both of his own Government and of the Dutch (his principal concern), lay, of course, near the North Sea, and under the immediate supervision of England and the Hague. This is a point which the modern reader may be inclined to ridicule until he remembers under what conditions the shortest message, let alone detailed plans and the execution of considerable orders, could alone be performed two hundred years ago. By a few bad roads, across a veritable dissected map of little independent or quasi-independent polities, each with its own frontier and prejudices and independent government, the messenger (often a single messenger) must pass through a space of time equivalent to the passage of a continent to-day, and through risks and difficulties such as would to-day be wholly eliminated[Pg 44] by the telegraph. The messenger was further encumbered by every sort of change from town to town, in local opinion, and the opportunities for aid.

More than this, in marching to the Danube, Marlborough was putting between himself and that upon which he morally, and most of all upon which he physically, relied, a barrier of difficult mountain land.

Having mentioned this barrier, it is the place for me to describe the physical conditions of that piece of strategy, and I will beg the reader to pay particular attention to the accompanying map, and to read what follows closely in connection with it.

In all war, strategy considers routes, and routes are determined by obstacles.

Had the world one flat and uniform surface, the main problems of strategy would not exist.

The surface of the world is diversified by certain features—rivers, chains of hills, deserts, marshes, seas, etc.—the passage across which presents difficulties peculiar to an army, and it is essential to the reading of military history to appreciate these difficulties; for the degrees of impediment which natural features present to thousands upon the march are utterly different from those which they present to individuals or to civilian parties in time of peace. Since it is to difficulties of this latter sort that we are most accustomed by our experience, the student of a campaign will often ask himself (if he is new to his subject) why such and such an apparently insignificant stream or narrow river, such and such a range of hills over which he has walked on some holiday without the least embarrassment, have been treated by the great captains as obstacles of the first moment.

Map showing the peril of Marlborough’s march to the Danube,

beyond the hills which separate the Rhine from the Danube.

[Pg 46]The reason that obstacles of any sort present the difficulty they do to an army, and present it in the high degree which military history discovers, is twofold.

First, an army consists in a great body of human beings, artificially gathered together under conditions which do not permit of men supplying their own wants by agriculture or other forms of labour. They are gathered together for the principal purpose of fighting. They must be fed; they must be provided with ammunition, usually with shelter and with firing, and if possible with remounts for their cavalry; reinforcements for every branch of their service must be able to reach them along known and friendly (or well-defended) roads, called their lines of communication. These must proceed from some base, that is from some secure[Pg 47] place in which stores of men and material can be accumulated.

Next, it is important to notice that variations in speed between two opposed forces will nearly always put the slow at a disadvantage in the face of the more prompt. For just as in boxing the quicker man can stop one blow and get another in where the slower man would fail, or just as in football the faster runner can head off the man with the ball, so in war superior mobility is a fixed factor of advantage—but a factor far more serious than it is in any game. The force which moves most quickly can “walk round” its opponent, can choose its field for action, can strike in flank, can escape, can effect a junction where the slower force would fail.

It is these two causes, then—the artificial character of an army, with its vast numbers collected in one place and dependent for existence upon the labour of others and the supreme importance of rapidity—which between them render obstacles that seem indifferent to a civilian in time of peace so formidable to a General upon the march.

The heavy train, the artillery, the provisioning of the force, can in general only proceed upon good ways or by navigable rivers. At any rate, if the army departs[Pg 48] from these, a rival army in possession of such means of progress will have the supreme advantage of mobility.

Again, upon the flat an army may proceed by many parallel roads, and thus in a number of comparatively short columns, marching upon one front towards a common rendezvous. But in hilly country it will be confined to certain defiles, sometimes very few, often reduced to one practicable pass. There is no possibility of an advance by many routes in short columns, each in touch with its neighbours; the whole advance resolves itself into one interminable file.

Now, in proportion to the length of a column, the units of which must each march one directly behind the other, do the mechanical difficulties of conducting such a column increase. Every accident or shock in the long line is aggravated in proportion to the length of the line. Finally, a force thus drawn out on the march in one exiguous and lengthy trail is in the worst possible disposition for meeting an attack delivered upon it from either side.

All this, which is true of the actual march of the army, is equally true of its power to maintain its supply over a line of hills (to take that example of an obstacle); and therefore a line of hills, especially if these[Pg 49] hills be confused and steep, and especially if they be provided with but bad roads across them, will dangerously isolate an army whose general base lies upon the further side of them.

What the reader has just read explains the peculiar character which the valley of the Upper Danube has always had in the history of Western European war.

The Rhine and its tributaries form one great system of communications, diversified, indeed, by many local accidents of hill and marsh and forest, with which, for the purposes of this study, we need not concern ourselves.

In a lesser degree, the upper valley of the Danube and its tributaries, though these are largely in the nature of mountain torrents, forms another system of communications, nourishing considerable towns, drawing upon which communications, and relying upon which towns as centres of supply, an army may manœuvre.

But between the system of the Rhine and that of the Danube there runs a long sweep of very broken country, the Black Forest merging into the Swabian Jura, which in a military sense cuts off the one basin from the other.

At the opening of the eighteenth century,[Pg 50] when that great stretch of hills had but a score of roads, none of them well kept up, when no town of any importance could be found in their valleys, and when no communication, even of a verbal message, could proceed faster than a mounted man, this sweep of hills was a very formidable obstacle indeed.

It was these hills, when Marlborough determined to strike across them, and to engage himself in the valley of the Upper Danube, which formed the chief physical factor of his hazard; for, once engaged in them, still more when he had crossed them, his appeals for aid, his reception of advice, perhaps eventually a reinforcement of men or supplies, must depend upon the Rhine valley.

True he had, the one within a week of the Danube, the other within two days of it, the couple of depots mentioned above, the principal one at Nuremberg, the advanced one at Nordlingen. Nevertheless, so long as he was upon the further or eastern side of the hills, his position would remain one of great risk, unless, indeed, or until, he had had the good fortune to destroy the forces of the enemy.

All this being before the reader, the progress of the great march may now be briefly described.

[Pg 51]In the winter between 1703 and 1704 domestic irritation and home intrigues, with which we are not here concerned, almost persuaded Marlborough to give up his great rôle upon the Continent of Europe.

Luckily for the alliance against Louis and for the history of British arms, he returned upon this determination or phantasy, and with the very beginning of the year began his plans for the coming campaign.

He crossed first to Holland in the middle of January 1704, persuaded the Dutch Government to grant a subsidy to the German troops in the South, pretended (since he knew how nervous the Dutch would be if they heard of the plan for withdrawing a great army from their frontiers to the Danube) that he intended operating upon the Moselle, returned to England, saw with the utmost activity to the raising of recruits and to the domestic organisation of the expedition, and reached Holland again to undertake the most famous action of his life in the latter part of April.

It was upon the 5th of May that he left the Hague. He was at Maestricht till the 14th, superintending every detail and ordering the construction of bridges over the Meuse by which the advance was to begin. Upon the 16th he left by the southward road for[Pg 52] Bedburg, and immediately his army broke winter quarters for the great march.

It was upon the 18th of May that the British regiments marched out of Ruremonde by the bridges constructed over the Meuse, aiming for the rendezvous at Bedburg.

The very beginning of the march was disturbed by the fears of the Dutch and of others, though Marlborough had carefully kept secret the design of marching to the Danube, and though all imagined that the valley of the Moselle was his objective.

Marlborough quieted these fears, and was in a better position to insist from the fact that he claimed control over the very large force which was directly in the pay of England.

He struck for the Rhine, up the valley of which he would receive further contingents, supplied by the minor members of the Grand Alliance, as he marched.

By the 23rd he was at Bonn with the cavalry, his brother Churchill following with the infantry. Thence the heavy baggage and the artillery proceeded by water up the river to Coblentz, and when Coblentz was reached (upon the 25th of May) it was apparent that the Moselle at least was not his objective, for on the next day, the 26th,[Pg 53] he crossed both that river and the Rhine with his army, and continued his march up the right bank of the Rhine.

But this did not mean that he might not still intend to carry the war into Alsace. He was at Cassel, opposite Mayence, three days after leaving Coblentz; four days later the head of the column had reached the Neckar at Ladenberg, where bridges had already been built by Marlborough’s orders, and upon the 3rd of June the troops crossed over to the further bank.

Here was the decisive junction where Marlborough must show his hand: the first few miles of his progress south-eastward across the bend of the Neckar would make it clear that his object was not Alsace, but the Danube.

He had announced to the Dutch and all Europe an attack upon the valley of the Moselle; that this was a ruse all could see when he passed Coblentz without turning up the valley of that river. The whole week following, and until he reached the Neckar, it might still be imagined that he meditated an attack upon Alsace, for he was still following the course of the Rhine. Once he diverged from the valley of this river and struck across the bend of the Neckar to the south and east, the alternative[Pg 54] he had chosen of making the Upper Danube the seat of war was apparent.

It is therefore at this point in his advance that we must consider the art by which he had put the enemy in suspense, and confused their judgment of his design.

The first point in the problem for a modern reader to appreciate is the average rate at which news would travel at that time and in that place. A very important dispatch could cover a hundred miles and more in the day with special organisation for its delivery, and with the certitude that it had gone from one particular place to another particular place. But general daily information as to the movements of a moving enemy could not be so organised.

We must take it that the French commanders upon the left bank of the Rhine at Landau, or upon the Meuse (where Villeroy was when Marlborough began his march), would require full forty-eight hours to be informed of the objective of each new move.

For instance, on the 25th of May Marlborough’s forces were approaching Coblentz. To find out what they were going to do next, the French would have to know whether they were beginning to turn up the valley of the Moselle, which begins at[Pg 55] Coblentz, or to cross that river and be going on further south. A messenger might have been certain that the latter was their intention by midday of the 26th, but Tallard, right away on the Upper Rhine, would hardly have known this before the morning of the 29th, and by the morning of the 29th Marlborough was already opposite Mayence.

It is this gap of from one to three days in the passage of information which is so difficult for a modern man to seize, and which yet made possible all Marlborough’s manœuvres to confuse the French.

Villeroy was bound to watch until, at least, the 29th of May for the chance of a campaign upon the Moselle.

Meanwhile, Tallard was not only far off in the valley of the Upper Rhine, but occupied in a remarkable operation which, had he not subsequently suffered defeat at Blenheim, would have left him a high reputation as a general.

This operation was the reinforcement of the army under the Elector of Bavaria and Marcin by a dash right through the enemy’s country in the Black Forest.

Early in May the Elector of Bavaria had urgently demanded reinforcements of the French king.

[Pg 56]The mountains between the Bavarian army and the French were held by the enemy, but the Elector hurried westward along the Danube, while Tallard, with exact synchrony and despatch, hurried eastward; each held out a hand to the other, as it were, for a rapid touch; the business of Tallard was to hand over the new troops and provisions at one exact moment, the business of the Elector was to catch the junction exactly. If it succeeded it was to be followed by a sharp retreat of either party, the one back upon the Danube eastward for his life, the other back westward upon the Rhine.

Tallard had crossed the Rhine on the 13th of May with a huge convoy of provisionment and over 7000 newly recruited troops. Within a week the thing was done. He had handed over in the nick of time the whole mass of men and things to the Elector.[2] He had done this in the midst of the Black Forest and in the heart of the enemy’s country, and he immediately began his retirement upon the Rhine. Tallard was thus particularly delayed in receiving daily information of Marlborough’s march.

[Pg 57]Let us take a typical date.

On the 29th of May Tallard, retiring from the dash to help Bavaria, was still at Altenheim, on the German bank of the Rhine. It was only on that day that he learnt from Villeroy that Marlborough had no idea of marching up the Moselle, but had gone on up the Rhine towards Mayence. Marlborough had crossed the Moselle and the Rhine on the 26th, but it took Tallard three days to know it. Tallard, knowing this, would not know whether Marlborough might not still be thinking of attacking Alsace: to make that alternative loom large in the mind of the French commanders, Marlborough had had bridges prepared in front of his advance at Philipsburg—though he had, of course, no intention at all of going as far up as Philipsburg.

It was on June 3rd, as we have seen, that the foremost of Marlborough’s forces were nearing the banks of the Neckar, and upon the 4th that anyone observing his troops would have clearly seen for the first time that they were striking for the Danube. But it was twenty-four hours before Tallard, who had by this time come down the Rhine as far as Lauterberg to defend a possible attack upon Alsace, knew certainly[Pg 58] that the Danube, and not the Rhine, would be the field of war.

All this time it was guessed at Versailles, and thought possible by the French generals at the front, that the Danube was Marlborough’s aim. But a guess was not good enough to risk Alsace upon.

By the time it was certain Marlborough was marching for the Danube—June 4th and 5th—Tallard’s force was much further from the Elector of Bavaria than was Marlborough’s, as a glance at the map will show. There was no chance then for heading Marlborough off, and the chief object of the English commander’s strategy was accomplished. He had kept the enemy in doubt[3] as to his intentions up to the moment when his forces were safe from interference, and he could strike for the Danube quite unmolested.

Map illustrating Marlborough’s march to the Danube.

[Pg 60]Villeroy at once came south in person, and joined Tallard at Oberweidenthal. The two commanders met upon the 7th of June to confer upon the next move, but at this point appeared that capital element of delay which hampered the French forces throughout the campaign, namely, the necessity of consulting with the King at Versailles. The next day, the 8th, Tallard and Villeroy, who had gone back to their respective commands after their conference, sent separate reports to Versailles. It was not until the 12th that Louis answered, leaving the initiative with his generals at the front, but advising a strong offensive upon the Rhine in order to immobilise there a great portion of the enemy’s forces.

The advice was not unwise. It did, as a fact, immobilise Eugene for the moment, and kept him upon the Rhine for some weeks, but, as we shall see later, that General was able to escape when the worst pressure was put upon him, to cross the Black Forest with excellent secrecy and speed, and to effect his junction with Marlborough in time for the battle of Blenheim.

But, meanwhile, Baden had chased the Elector of Bavaria out of the Black Forest and down on to the Upper Danube. Marlborough might, at any moment, join hands[Pg 61] with Baden. The Elector sent urgent requests for yet more reinforcements from the French, and Tallard, in a letter to Versailles of the 16th of June, advised the capture and possession of such points in the Black Forest as would give him free access across the mountains, the proper provisioning of his line of supply when he should cross them, and the accomplishment of full preparations for joining the Elector of Bavaria in a campaign upon the Upper Danube.

Let the day when the French court received this letter be noted, for the coincidence is curious. At the very moment when Tallard’s letter reached Versailles, the 22nd of June, Marlborough was effecting his junction with Baden outside the gates of Ulm at Ursprung. The decision of Louis XIV., that Tallard should advance beyond the hills in force to the aid of the Elector, exactly coincides with the appearance of the English General upon the Danube, and it was on the 23rd of June, the morrow, that the King wrote to Villeroy the decisive letter recommending Tallard to cross over from Alsace towards Bavaria with forty battalions and fifty squadrons, say 25,000 men.

But this advance of Tallard’s across the Black Forest and his final junction with the[Pg 62] Elector and Marcin before the battle of Blenheim did not take place until after Marlborough had joined Baden and the march to the Danube was accomplished. It must therefore be dealt with in the next division, which is its proper place. For the moment we must return to Marlborough’s advance upon the Danube, which we left at the point where he crossed the Neckar upon the 3rd and 4th of June. He had, as we have just seen, and by methods which we have reviewed, completely succeeded in saving the rest of his advance from interference.

Safe from pursuit, and with no further need for concealing his plan, Marlborough lingered in the neighbourhood of the Neckar, partly to effect a full concentration of his forces, partly to rest his cavalry. It was a week before he found himself at Mundelsheim, between Heilbron and Stuttgart, and at the foot of the range which still divided him from the basin of the Danube. Here Eugene, the author of the whole business, met Marlborough; between them the two men drew up the plans which were to lead to so momentous a result, and knitted in that same interview a friendship based upon the mutual recognition of genius, which was to determine seven years of war.

[Pg 63]Upon the 13th of June these great captains met and conferred also with the Margrave, Louis of Baden, who commanded all the troops in the hills, and who was to be the third party to their plan. He was a man, cautious, but able, easily ruffled in his dignity, often foolishly jealous of another’s power. He insisted that Marlborough and he should take command upon alternate days—he would not serve as second—and in all that followed, the personal relations between himself and Marlborough grew less and less cordial up to the eve of the great battle. His prudence and arrangement, however, his exact synchrony of movement and good hold over his troops, made Marlborough’s decisions fruitful.

Upon the 14th of June the passage of Marlborough’s column over the hills between the Rhine and the Danube began. Baden went back to the command of his army, which already lay in the plain of the Upper Danube, and awaited the arrival of Marlborough’s command, and the junction of it with his own force before Ulm.

A heavy rain, drenched and bad roads, marked Marlborough’s crossing of the range. It was not until the 20th that the cavalry reached the foot of the final ascent, but in two days the whole body had passed over.[Pg 64] It was thus upon the 22nd of June that the junction between Marlborough and Baden was effected. From that day on their combined forces were prepared to operate as one army upon the plain of the Upper Danube. They stood joined at the gates of Ulm, and in their united force far superior to the Franco-Bavarians, who had but just escaped Baden’s army, and who lay in the neighbourhood watching this fatal junction of their rivals.

I say, “who had but just escaped Baden’s army,” for it was part of the general plan (and a part most ably executed) that not only should the seat of war be brought into the valley of the Upper Danube by Marlborough’s march to join Baden, but, as a preparation for this, that the army of the Elector, with his French allies under Marcin, should be driven eastward out of the mountains and cut off from the main French forces upon the Rhine.

This chasing of the Franco-Bavarians down on to the Danube and out of the Black Forest was begun just after the spirited piece of generalship by which Tallard had, as we have seen, reinforced the Elector of Bavaria in the middle of May. That rapid and brilliant piece of work had been effected only just in time. Hardly[Pg 65] was it accomplished when Baden’s force in the mountains marched, as part of Marlborough’s general plan, against the Elector, with the object of forcing him back into the Danube valley at full speed.

It was on the 18th of May that the British regiments were crossing the Meuse, and the advance upon the Danube had begun.

It was on the 18th of May that Louis of Baden appeared at the head of his army in the Black Forest and initiated that separation of the Bavarian forces from the French which was a necessary part of the general plan we have spoken of. It was but a few hours since Tallard had stretched out his hand and passed the recruits and the provisions over to the Franco-Bavarian forces.

The Elector of Bavaria had with him certain French regiments, and Marshal Marcin was under his commands, while Marlborough’s plan was still quite unknown. Therefore no large French force could apparently be spared from the valley of the Rhine to help the Elector in that of the Danube; the Duke of Baden could have things his own way against the lesser force opposed to him.

On the 19th he was advancing on Ober[Pg 66] and Neder Ersasch. The Duke of Bavaria had evacuated these villages upon the 20th, and on the same night the Duke of Baden reached Meidlingen. Pursuer and pursued were marching almost parallel, separated only by the little river of Villingen. Now and then they came so close that Baden’s artillery could drop a shot into the hurrying ranks of the Elector.

On the 21st Baden was at Geisingen, threatening Tuttlingen. On the 23rd he had reached Stockach, and was pressing so hard that his van had actually come in contact with the rear of the Bavarians, a situation reminiscent of the Esla Bridge in Moore’s retreat on Coruña.

The valley of the Danube opened out before the two opponents. The Elector found it possible to maintain his exhausted but rapid retreat, and, ten days later, he had escaped. For by the 3rd of June the Franco-Bavarian forces lay at Elchingen, the Duke of Baden was no nearer than Echingen, and the former was saved after a fortnight of very anxious going; but, though saved, they were now completely cut off for the moment from French reinforcement. Marlborough was approaching the hills; he would cross them in a few days. He would join Baden’s army; and[Pg 67] the moment Marlborough should have joined Baden, the Elector would be in peril of overwhelming adversaries.

We have seen how the plan matured. Three weeks after the Bavarian army’s escape from the Black Forest, upon the 22nd of June, Marlborough’s force had crossed the range and made one with Baden’s before Ulm.

From the day when the Duke had appeared upon the southern side of the mountains, and was debouching into the plains of the Danube, to the day when he broke the French line at Blenheim, is just over seven weeks; to be accurate, it is seven weeks and three days. It was on the last Sunday but one of the month of June that he passed the mountains; it was upon the second Wednesday of August that he won his great victory.

These seven weeks divide themselves into three clear phases.

The first is the march of Marlborough and Baden upon Donauwörth and the capture of that city, which was the gate of Bavaria.

The second is the consequent invasion and ravaging of Bavaria, the weakening of the Elector, and his proposal to capitulate;[Pg 69] the consequent precipitate advance of Tallard to the aid of the Elector, and the corresponding secret march of Eugene to help Marlborough.

The third occupies the last few days only: it is concerned with the manœuvres immediately preceding the battle, and especially with the junction of Marlborough and Eugene, which made the victory possible.

From the junction of Marlborough and Baden to the fall of Donauwörth

When the Duke of Marlborough had joined hands with the forces of Baden upon the 22nd of June 1704 his general plan was clear: the last of his infantry, under his brother Churchill, would at once effect their junction with the rest at Ursprung, and he and Baden had but to go forward.

His great march had been completely successful. He had eluded and confused his enemy. He was safe on the Danube watershed, and within a march of the river itself. The only enemies before him on this side of the hills were greatly inferior in number to his own and his ally’s. His determination to carry the war into Bavaria could at once be carried into effect.

[Pg 70]With this junction the first chapter in that large piece of strategy which may be called “the campaign of Blenheim” comes to an end.

Between the successful termination of his first effort, which was accomplished when he joined forces with Baden upon the Danube side of the watershed in the village of Ursprung, and the great battle by which Marlborough is chiefly remembered, there elapsed, I say, seven summer weeks. These seven weeks are divided into the three parts just distinguished.

In order to understand the strategy of each part of those seven weeks, we must first clearly grasp the field.

The accompanying map shows the elements of the situation.

East of the Black Forest lay open that upper valley of the Danube and its tributaries which was so difficult of access from the valley of the Rhine. In the hills to the north of the Danube, and one day’s march from the town of Ulm, were now concentrated the forces of Marlborough and the Duke of Baden. They were advancing, ninety-six battalions strong, with two hundred and two squadrons and forty-eight guns: in all, say, somewhat less than 70,000 men.

Map illustrating the march of Marlborough and Baden across

Marcin’s front from the neighbourhood of Ulm to Donauwörth.

[Pg 72]At Ulm lay Marcin, and in touch with him, forming part of the same army, the Elector of Bavaria was camped somewhat further down the river, near Lauingen.

The combined forces of Marcin and the Elector of Bavaria numbered, all told, some 45,000 men, and their inferiority to the hostile armies, which had just effected their junction north of Ulm at Ursprung, was the determining factor in what immediately followed.

Marcin crossed the Danube to avoid so formidable a menace, and took up his next station behind the river at Leipheim, watching to see what Marlborough and the Duke of Baden would do. The Elector of Bavaria, in command of the bridge at Lauingen, stood fast, ready to retire behind the stream. The necessity of such a retreat was spared him. The object of his enemies was soon apparent by the direction their advance assumed.

For the immediate object of Marlborough and Baden was not an attack upon the inferior forces of the Elector and Marcin, but, for reasons that will presently be seen, the capture of Donauwörth, and their direct march upon Donauwörth took them well north of the Danube. On the 26th, therefore, Marcin thought it prudent to recross[Pg 73] the Danube. He and the Elector joined forces on the north side of the Danube, and lay from Lauingen to Dillingen, commanding two bridges behind them for the crossing of the stream, and fairly entrenched upon their front. Meanwhile their enemies, the allies, passed north of them at Gingen. This situation endured for three days.[4]

When it was apparent that the allied forces of the English general and the Duke of Baden intended to make themselves masters of Donauwörth (and the Elector of Bavaria could have no doubt of their[Pg 74] intentions after the 29th of July, when their march eastward from Gingen was resumed), a Franco-Bavarian force was at once detached by him to defend that town, and it is necessary henceforward to understand why Donauwörth was of such importance to Marlborough’s plan.

It was his intention to enter Bavaria so as to put a pressure upon the Elector, whose immediate and personal interests were bound up with the villages and towns of his possessions. The Elector could not afford to neglect the misfortunes of its civilian inhabitants, even for the ends of his own general strategy; still less could he sacrifice those subjects of his for the strategic advantage of the King of France and his marshal.

This Marlborough knew. To enter Bavaria, to occupy its towns (only one of which, Ingolstadt, was tolerably fortified), and if possible to take its capital, Munich, had been from its inception the whole business and strategic motive of his march to the Danube.

But if Marlborough desired to enter Bavaria, Donauwörth was the key to Bavaria from the side upon which he was approaching.

This word “key” is so often used in military history, without any explanation of[Pg 75] it which may render it significant to the reader, that I will pause a moment to show why Donauwörth might properly be called in metaphor the “key” of Bavaria to one advancing from the north and west.

Bavaria could only be reached by a general coming as Marlborough came, on condition of his possessing and holding some crossing-place over the Danube, for Marlborough’s supplies lay north of that river (principally at Nördlingen), and the passing of the enormous supply of an army over one narrow point, such as is a bridge over such an obstacle as a broad river, demands full security.

It will further be seen from the map that yet another obstacle, defending Southern Bavaria and its capital towards the west, as the Danube does towards the north, is the river Lech; a passage over this was therefore also of high importance to the Duke of Marlborough and his allies. Now, a man holding Donauwörth can cross both rivers at the same time unmolested, for they meet in its neighbourhood.

Further, Donauwörth was a town amply provisioned, full of warehouse room, and in general affording a good advanced base of supply for any army marching across the Danube. It afforded an opportunity for concentration of supplies, it contained waggons and horses and food. Supplies, it must be remembered, were the great difficulty of each of the two opposed forces, in this moving of great numbers of men east of the Black Forest, in a comparatively poor country, largely heath and forest, and ill populated.

Map showing how Donauwörth is the key of Bavaria from the North-West.

[Pg 77]No serious permanent defences, such as could delay the capture of the town, surrounded Donauwörth; but up above it lies a hill, called from its shape “the Schellenberg” or “Bell Hill.” This hill is not isolated, but joins on the higher ground to its north by a sort of flat isthmus, which is level with the summit or nearly so.[5]

The force which, on perceiving the Duke of Marlborough’s intention of capturing Donauwörth, the Elector of Bavaria very rapidly detached to defend that town, was under the command of Count d’Arco; it consisted of two regiments of cavalry and about 10,000 infantry (of whom a quarter were French). D’Arco had orders to entrench the hill above the town as rapidly as might be and to defend it from attack; for whoever held the Schellenberg was[Pg 78] master of Donauwörth below. But the Elector could only spare eight guns for this purpose from his inferior forces.

Upon the 2nd of July, in the early morning, Marlborough, by one of those rapid movements which were a prime element in his continuous success, marched before dawn with something between seven and eight thousand infantry carefully chosen for the task and thirty-five squadrons of horse for the attack on the Schellenberg. It was Marlborough’s alternate day of command.

With all his despatch, he could not arrive on the height of the hill nor attack its imperfect but rapidly completing works until the late afternoon. It is characteristic of his generalship that he risked an assault with this advance body of his without waiting for the main part of the army under the Duke of Baden to come up. With sixteen battalions only, of whom a third were British, he attempted to carry works behind which a force equal to his own in strength was posted. The risk was high, for he could hardly hope to carry the works with such a force, and all depended upon the main body coming up in time. There was but an hour or two of daylight left.

The check which Marlborough necessarily[Pg 79] received in such an attempt incidentally gave proof of the excellent material of his troops. More than a third of these fell in the first furious and undecided hour. They failed to carry the works. They had already once begun to break and once again rallied, but had suffered no final dissolution under the ordeal—though it was both the first to which the men were subjected during this campaign, and probably also the most severe of any they were to endure.

Whether they, or indeed any other troops, could long have survived such conditions as an attempt to storm works against equal numbers is not open to proof; for, while the issue was still doubtful (but the advantage naturally with the force behind the trenches), the mass of the army under the Duke of Baden came up in good time upon the right (that is, from the side of the town), poured almost unopposed over the deserted earthworks of that side, and, five to one, overwhelmed the 12,000 Franco-Bavarians upon the hill.

After one of those short stubborn and futile attempts at resistance which such situations discover in all wars, the inevitable dissolution of d’Arco’s command came before the darkness. It was utterly routed; and[Pg 80] we may justly presume that not 4000—more probably but 3000—rejoined the army of Marcin and of the Elector of Bavaria.

The loss of the Schellenberg had cost Marlborough’s enemies, whose forces were already gravely inferior to his own, eight guns and close upon one-fifth of their effective numbers. The Franco-Bavarians hurried south to entrench themselves under Augsburg, while Donauwörth, and with it the passage of the two great rivers and the entry into Bavaria, lay in the possession of Marlborough and his ally.

The balance of military and historical opinion will decide that Marlborough played for too high stakes in beginning the assault so late in the evening and with so small a force. But he was playing for speed, and he won the hazard.

It was a further reward of his daring that he could point after this first engagement to the fine quality of his British contingent.[6]

It was upon the evening of July the 2nd, then, that this capital position was stormed. It was upon the 5th that Marcin and the Elector lay hopeless and immobile before Augsburg, while their enemies entered a now[Pg 81] defenceless Bavaria by its north-western gate. And this complete achievement of Marlborough’s plan was but the end of the first phase in the campaign upon the Danube.

Meanwhile, a large French reinforcement under Tallard was already far up on its way from the Rhine, across the Black Forest, to join Marcin and the Elector of Bavaria and set back the tide of war, and, when it should have effected its junction with those who awaited it at Augsburg, to oppose to Marlborough and the Duke of Baden a total force greater than their own.

The French marshal, Tallard, was in command of the army thus rapidly approaching in relief of the Franco-Bavarians. His arrival, if he came without loss, disease, or mishap, promised a complete superiority over the English and their allies, unless, indeed, by some accident or stroke of genius, reinforcement should reach them also before the day of the battle.

This reinforcement, in the event, Marlborough did receive. He owed it, as we shall see, to the high talents of Prince Eugene; and it is upon the successful march of this general, his junction with Marlborough, and the consequent success of Blenheim, that the rest of the campaign turns.

[Pg 82]We turn next, then, to follow the second phase of the seven weeks, which consists in Tallard’s advance to join the Elector, and in Eugene’s rapid parallel march, which brought him, just in time, to Marlborough’s aid.

The Advance of Tallard

To follow the second phase of the seven weeks, that is, the phase subsequent to the capture of the Schellenberg and the retirement of Marcin and the Elector of Bavaria on to Augsburg, it is necessary to hark back a little, and to trace from its origin that advance of Tallard’s reinforcements which was to find on the field of Blenheim so disastrous a termination.