The Project Gutenberg EBook of Astounding Stories, June, 1931, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Author: Various Release Date: April 5, 2010 [EBook #31893] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASTOUNDING STORIES, JUNE, 1931 *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN ADVENTURES AND WESTERN LOVE STORIES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

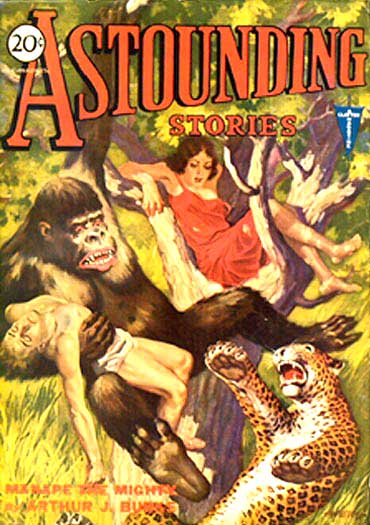

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSO | |

| Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in "Manape the Mighty." | ||

| THE MAN FROM 2071 | SEWELL PEASLEE WRIGHT | 295 |

| Out of the Flow of Time There Appears to Commander John Hanson a Man of Mystery from the Forgotten Past. | ||

| MANAPE THE MIGHTY. | ARTHUR J. BURKS | 308 |

| High in Jungle Treetops Swings Young Bentley—His Human Brain Imprisoned in a Mighty Ape. (A Complete Novelette.) | ||

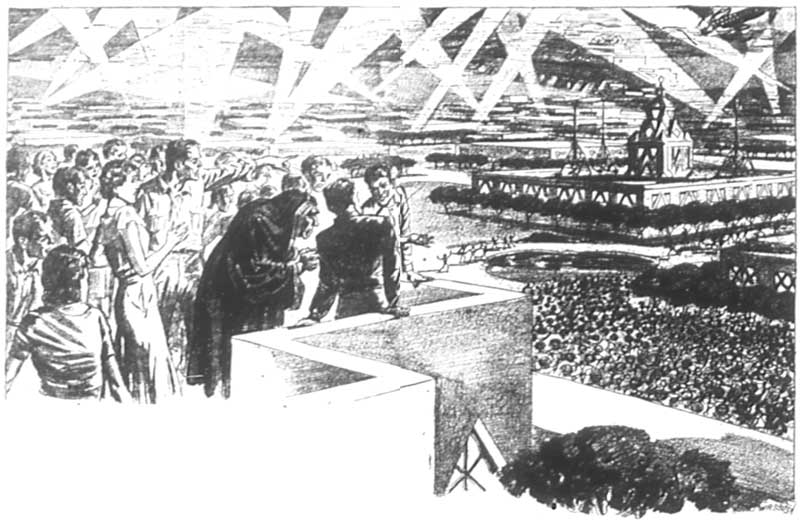

| HOLOCAUST | CHARLES WILLARD DIFFIN | 356 |

| The Extraordinary Story of "Paul," Who for Thirty Days Was Dictator of the World. | ||

| THE EARTHMAN'S BURDEN | R. F. STARZL | 375 |

| There is Foul Play on Mercury—until Danny Olear of the Interplanetary Flying Police Gets After His Man. | ||

| THE EXILE OF TIME | RAY CUMMINGS | 386 |

| Larry and George from 1935, Mary from 1777—All Are Caught up in the Treacherous Tugh's Revolt of the Robots in the Time World of 2930. (Part Three of a Four-Part Novel.) | ||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 416 |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | ||

Single Copies, 20 Cents In Canada, 25 Cents Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by The Clayton Magazines, Inc., 80 Lafayette St., New York. N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Francis P. Pace, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group. For advertising rates address The Newsstand Group, Inc., 80 Lafayette Street, New York; or The Wrigley Bldg., Chicago.

By Sewell Peaslee Wright

Perhaps this story does not belong with my other tales of the Special Patrol Service. And yet, there is, or should be, a report somewhere in the musty archives of the Service, covering the incident.

Not accurately, and not in detail. Among a great mass of old records which I was browsing through the other day, I happened across that report; it occupied exactly three lines in the log-book of the [296]Ertak:

"Just before departure, discovered stowaway, apparently demented, and ejected him."

For the hard-headed higher-ups of the Service, that was report enough. Had I given the facts, they would have called me to the Base for a long-winded investigation. It would have taken weeks and weeks, filled with fussy questioning. Dozens of stoop-shouldered laboratory men would have prodded and snooped and asked for long, written accounts. In those days, keeping the log-book was writing enough for me and being grounded at Base for weeks would have been punishment.

Nothing would have been gained by a detailed report. The Service needed action rather than reports, anyway. But now that I am an old man, on the retired list, I have time to write; and it will be a particular pleasure to write this account, for it will go to prove that these much-honored scientists of ours, with all their tremendous appropriations and long-winded discussions, are not nearly so wonderful as they think they are. They are, and always have been, too much interested in abstract formulas, and not enough in their practical application. I have never had a great deal of use for them.

had received orders to report to Earth, regarding a dull routine matter of reorganizing the emergency Base which had been established there. Earth, I might add, for the benefit of those of you who have forgotten your geography of the Universe, is not a large body, but its people furnish almost all of the officer personnel of the Special Patrol Service. Being a native of Earth, I received the assignment with considerable pleasure, despite its dry and uninteresting nature.

It was a good sight to see old Earth, bundled up in her cottony clouds, growing larger and larger in the television disc. No matter how much you wander around the Universe, no matter how small and insignificant the world of your birth, there is a tie that cannot be denied. I have set my ships down upon many a strange and unknown world, with danger and adventure awaiting me, but there is, for me, no thrill which quite duplicates that of viewing again that particular little ball of mud from whence I sprang. I've said that before; I shall probably say it again. I am proud to claim Earth as my birth-place, small and out-of-the way as she is.

Our Base on Earth was adjacent to the city of Greater Denver, on the Pacific Coast. I could not help wondering, as we settled swiftly over the city, whether our historians and geologists and other scientists were really right in saying that Denver had at one period been far from the Pacific. It seemed impossible, as I gazed down on that blue, tranquil sea, that it had engulfed, hundreds of years ago, such a vast portion of North America. But I suppose the men of science know.

need not go into the routine business that brought me to Earth. Suffice it to say that it was settled quickly, by the afternoon of the second day: I am referring, of course, to Earth days, which are slightly less than half the length of an enaren of Universe time.

A number of my friends had come to meet me, visit with me during my brief stay on Earth; and, having finished my business with such dispatch, I decided to spend that evening with them, and leave the following morning. It was very late when my friends departed, and I strolled out with them to their mono-car, returning the salute of the Ertak's lone sentry, who was pacing his post before the huge circular exit of the ship.

Bidding my friends farewell, I stood there for a moment under the[297] heavens, brilliant with blue, cold stars, and watched the car sweep swiftly and soundlessly away towards the towering mass of the city. Then, with a little sigh, I turned back to the ship.

The Ertak lay lightly upon the earth, her polished sides gleaming in the light of the crescent moon. In the side toward me, the circular entrance gaped like a sleepy mouth; the sentry, knowing the eyes of his commander were upon him, strode back and forth with brisk, military precision. Slowly, still thinking of my friends, I made my way toward the ship.

I had taken but a few steps when the sentry's challenge rang out sharply, "Halt! Who goes there?"

I glanced up in surprise. Shiro, the man on guard, had seen me leave, and he could have had no difficulty in recognizing me. But—the challenge had not been meant for me.

etween myself and the Ertak there stood a strange figure. An instant before, I would have sworn that there was no human in sight, save myself and the sentry; now this man stood not twenty feet away, swaying as though ill or terribly weary, barely able to lift his head and turn it toward the sentry.

"Friend," he gasped; "friend!" and I think he would have fallen to the ground if I had not clapped an arm around his shoulders and supported him.

"Just ... a moment," whispered the stranger. "I'm a bit faint.... I'll be all right...."

I stared down at the man, unable to reply. This was a nightmare; no less. I could feel the sentry staring, too.

The man was dressed in a style so ancient that I could not remember the period: Twenty-first Century, at least; perhaps earlier. And while he spoke English, which is a language of Earth, he spoke it with a harsh and unpleasant accent that made his words difficult, almost impossible, to understand. Their meaning did not fully sink in until an instant after he had finished speaking.

"Shiro!" I said sharply. "Help me take this man inside. He's ill."

"Yes, sir!" The guard leaped to obey the order, and together we led him into the Ertak, and to my own stateroom. There was some mystery here, and I was eager to get at the root of it. The man with the ancient costume and the strange accent had not come to the spot where we had seen him by any means with which I was familiar; he had materialized out of the thin air. There was no other way to account for his presence.

e propped the stranger in my most comfortable chair, and I turned to the sentry. He was staring at our weird visitor with wondering, fearful eyes, and when I spoke he started as though stung by an electric shock.

"Very well," I said briskly. "That will be all. Resume your post immediately. And—Shiro!"

"Yes, sir?"

"It will not be necessary for you to make a report of this incident. I will attend to that. Understand?"

"Yes, sir!" And I think it is to the man's everlasting credit, and to the credit of the Service which had trained him, that he executed a snappy salute, did an about-face, and left the room without another glance at the man slumped down in my big easy chair.

With a feeling of cold, nervous apprehension such as I have seldom experienced in a rather varied and active life, I turned then to my visitor.

He had not moved, save to lift his head. He was staring at me, his eyes fixed in his chalky white face. They were dark, long eyes—abnormally long—and they glittered with a strange, uncanny light.

"You are feeling better?" I asked.[298]

His thin, bloodless lips moved, but for a moment no sound came from them. He tried again.

"Water," he said.

I drew him a glass from the tank in the wall of my room. He downed it at a gulp, and passed the empty glass back to me.

"More," he whispered. He drank the second glass more slowly, his eyes darting swiftly, curiously, around the room. Then his brilliant, piercing glance fell upon my face.

"Tell me," he commanded sharply, "what year is this?"

stared at him. It occurred to me that my friends might have conceived and executed an elaborate hoax—and then I dismissed the idea, instantly. There were no scientists among them who could make a man materialize out of nothingness.

"Are you in your right mind?" I asked slowly. "Your question strikes me as damnably odd, sir."

The man laughed wildly, and slowly straightened up in the chair. His long, bony fingers clasped and unclasped slowly, as though feeling were just returning to them.

"Your question," he replied in his odd, unfamiliar accent, "is not unnatural, under the circumstances. I assure you that I am of sound mind; of very sound mind." He smiled, rather a ghastly smile, and made a vague, slight gesture with one hand. "Will you be good enough to answer my question? What year is this?"

"Earth year, you mean?"

He stared at me, his eyes flickering.

"Yes," he said. "Earth year. There are other ways of ... figuring time now?"

"Certainly. Each inhabited world has its own system. There is a master system for the Universe. Who are you, what are you, that you should ask me a question the smallest child should know?"

"First," he insisted, "tell me what year this is, Earth reckoning."

I told him, and the light flickered up in his eyes again—a cruel, triumphant light.

"Thank you," he nodded; and then, slowly and softly, as though he spoke to himself, he added, "Less than half a century off. Less than a half a century! And they laughed at me. How—how I shall laugh at them, presently!"

"You choose to be mysterious, sir?" I asked impatiently.

"No. Presently you shall understand, and then you will forgive me, I know. I have come through an experience such as no man has ever known before. If I am shaken, weak, surprising to you, it is because of that experience."

e paused for a moment, his long, powerful fingers gripping the arms of the chair.

"You see," he added, "I have come out of the past into the present. Or from the present into the future. It depends upon one's viewpoint. If I am distraught, then forgive me. A few minutes ago, I was Jacob Harbauer, in a little laboratory on the edge of a mountain park, near Denver; now I am a nameless being hurtled into the future, pausing here, many centuries from my own era. Do you wonder now that I am unnerved?"

"Do you mean," I said slowly, trying to understand what he had babbled forth, "that you have come out of the past? That you ... that you...." It was too monstrous to put into words.

"I mean," he replied, "that I was born in the year 2028. I am forty-three years old—or I was a few minutes ago. But,"—and his eyes flickered again with that strange, mad light—"I am a scientist! I have left my age behind me for a time; I have done what no other human being has ever done: I have gone centuries into the future!"

"I—I do not understand." Could[299] he, after all, be a madman? "How can a man leave his own age and travel ahead to another?"

"Even in this age of yours they have not discovered that secret?" Harbauer exulted. "You travel the Universe, I gather, and yet your scientists have not yet learned to move in time? Listen! Let me explain to you how simple the theory is.

take it you are an intelligent man; your uniform and its insignia would seem to indicate a degree of rank. Am I correct?"

"I am John Hanson, Commander of the Ertak, of the Special Patrol Service," I informed him.

"Then you will be capable of grasping, in part at least, what I have to tell you. It is really not so complex. Time is a river, flowing steadily, powerful, at a fixed rate of speed. It sweeps the whole Universe along on its bosom at that same speed. That is my conception of it; is it clear to you?"

"I should think," I replied, "that the Universe is more like a great rock in the middle of your stream of time, that stands motionless while the minutes, the hours, and the days roll by."

"No! The Universe travels on the breast of the current of time. It leaves yesterday behind, and sweeps on towards to-morrow. It has always been so until I challenged this so-called immutable law. I said to myself, why should a man be a helpless stick upon the stream of time? Why need he be borne on this slow current at the same speed? Why cannot he do as a man in a boat, paddle backwards or forwards; back to a point already passed; ahead, faster than the current, to a point that, drifting, he would not reach so soon? In other words, why can he not slip back through time to yesterday; or ahead to to-morrow? And if to to-morrow, why not to next year, next century?

hese are the questions I asked myself. Other men have asked themselves the same questions, I know; they were not new. But,"—Harbauer drew himself far forward in his chair, and leaned close to me, almost as though he prepared himself to spring—"no other man ever found the answer! That remained for me.

"I was not entirely correct, of course. I found that one could not go back in time. The current was against one. But to go ahead, with the current at one's back, was different. I spent six years on the problem, working day and night, handicapped by lack of funds, ridiculed by the press—Look!"

Harbauer reached inside his antiquated costume and drew forth a flat packet which he passed to me. I unfolded it curiously, my fingers clumsy with excitement.

I could hardly believe my eyes. The thing Harbauer had handed me was a folded fragment of newspaper, such as I had often seen in museums. I recognized the old-fashioned type, and the peculiar arrangement of the columns. But, instead of being yellow and brittle with age, and preserved in fragments behind sealed glass, this paper was fresh and white, and the ink was as black as the day it had been printed. What this man said, then, must be true! He must—

"I can understand your amazement," said Harbauer. "It had not occurred to me that a paper which, to me, was printed only yesterday, would seem so antique to you. But that must appear as remarkable to you as fresh papyrus, newly inscribed with the hieroglyphics of the ancient Egyptians, would seem to one of my own day and age. But read it; you will see how my world viewed my efforts!" There was a sharpness, a bitterness, in his voice that made me vaguely uneasy; even though he had solved the riddle of moving in time as men have always moved in[300] space, my first conjecture that I had a madman to deal with might not be so far from the truth. Ridicule and persecution have unseated the reason of all too many men.

The type was unfamiliar to me, and the spelling was archaic, but I managed to stumble through the article. It read, as nearly as I can recall it, like this:

Harbauer Says Time

Is Like Great River

Jacob Harbauer, local inventor, in an exclusive interview, propounds the theory that man can move about in time exactly as a boat moves about on the surface of a swift-flowing river, save that he cannot go back into time, on account of the opposition of the current.

That is very fortunate, this writer feels; it would be a terrible thing for example, if some good-looking scamp from our present Twenty-first Century were to dive into the past and steal Cleopatra from Antony, or start an affair with Josephine and send Napoleon scurrying back from the front and let the Napoleonic wars go to pot. We'd have to have all our histories rewritten!

Harbauer is well-known in Denver as the eccentric inventor who, for the last five or six years, has occupied a lonely shack in the mountains, guarded by a high fence of barbed wire. He claims that he has now perfected equipment which will enable him to project himself forward in time, and expects to make the experiment in the very near future.

This writer was permitted to view the equipment which Harbauer says will shoot him into the future. The apparatus is housed in a low, barn-like building in the rear of his shack.

Along one side of the room is a veritable bank of electrical apparatus with innumerable controls, many huge tubes of unfamiliar shape and appearance, a mighty generator of some kind and an intricate maze of gleaming copper bus-bar.

In the center of the room is a circle of metal, about a foot in thickness, insulated from the flooring by four truncated cones of fluted glass. This disc is composed of two unfamiliar metals, arranged in concentric circles.

Above this disc, at a height of about eight feet, is suspended a sort of grid, composed of extremely fine silvery wires, supported on a frame-work of black insulating material.

Asked for a demonstration of his apparatus, Harbauer finally consented to perform an experiment with a dog—a white, short-haired mongrel that, Harbauer informed us, he kept to warn him of approaching strangers.

He bound the dog's legs together securely, and placed the struggling animal in the center of the heavy metal disc. Then the inventor hurried to the central control panel and manipulated several switches, which caused a number of things to happen almost at once.

The big generator started with a growl, and settled immediately into a deep hum; a whole row of tubes glowed with a purplish brilliancy. There was a crackling sound in the air, and the grid above the disc seemed to become incandescent, although it gave forth no apparent heat. From the rim of the metal disc, thin blue streamers of electric flame shot up toward the grid, and the little white dog began to whine nervously.

"Now watch!" shouted Harbauer. He closed another switch,[301] and the space between the disc and the grid became a cylinder of livid light, for a period of perhaps two seconds. Then Harbauer pulled all the switches, and pointed triumphantly to the disc. It was empty.

We looked around the room for the dog, but he was not visible anywhere.

"I have sent him nearly a century into the future," said Harbauer. "We will let him stay there a moment, and then bring him back."

"You mean to say," we asked, "that the pup is now roaming around somewhere in the Twenty-second Century?" Harbauer said he meant just that, and added that he would now bring the dog back to the present time. The switches were closed again, but this time it was the metal plate that seemed incandescent, and the grid above that shot out the streaks of thin blue flame. As he closed the last switch, the cylinder of light appeared again, and when the switches were opened, there was the dog in the center of the disc, howling and struggling against his bonds.

"Look!" cried Harbauer. "He's been attacked by another dog, or some other animal, while in the future. See the blood on his shoulders?"

We ventured the humble opinion that the dog had scratched or bit himself in struggling to free himself from the cords with which Harbauer had bound him, and the inventor flew into a terrible rage, cursing and waving his arms as though demented. Feeling that discretion was the better part of valor, we beat a hasty retreat, pausing at the barbed-wire gate only long enough to ask Mr. Harbauer if he would be good enough, sometime when he had a few minutes of leisure, to dash into next week and bring back some stock market reports to aid us in our investment efforts.

Under the circumstances, we did not wait for a response, but we presume we are persona non grata at the Harbauer establishment from this time on.

All in all, we are not sorry.

I folded the paper and passed it back to him; some of the allusions I did not understand, but the general tone of the article was very clear indeed.

ou see?" said Harbauer, his voice grating with anger. "I tried to be courteous to that man; to give him a simple, convincing demonstration of the greatest scientific achievement in centuries. And the fool returned to write this: to hold me up to ridicule, to paint me as a crack-brained, wild-eyed fanatic."

"It's hard for the layman to conceive of a great scientific achievement," I said soothingly. "All great inventions and inventors have been laughed at by the populace at large."

"True. True." Harbauer nodded his head solemnly. "But just the same—" He broke off suddenly, and forced a smile. I found myself wishing that he had completed that broken sentence, however; I felt that he had almost revealed something that would have been most enlightening.

"But enough of that fool and his babblings," he continued. "I am here as living proof that my experiment is a success, and I have a tremendous curiosity about the world in which I find myself. This, I take it, is a ship for navigating space?"

"Right! The Ertak, of the Special Patrol Service. Would you care to look around a bit?"

"I would, indeed." There was a tremendous eagerness in the man's voice.[302]

"You're not too tired?"

"No; I am quite recovered from my experience." Harbauer leaped to his feet, those abnormally long, slitted eyes of his glowing. "I am a scientist, and I am most curious to see what my fellows have created since—since my own era."

I picked up my dressing gown and tossed it to him.

"Slip this on, then, to cover your clothing. You would be an object of too much curiosity to those men who are on duty," I suggested.

I was taller than he, and the garment came within a few inches of the floor. He knotted the cincture around his middle and thrust his hands into the pockets, turning to me for approval. I nodded, and motioned for him to precede me through the door.

s an officer of the Special Patrol Service, it has often been my duty to show parties and individuals through my ship. Most of these parties are composed of females, who have only exclamations to make instead of intelligent comment, and who possess an unbounded capacity for asking utterly asinine questions. It was, therefore, a real pleasure to show Harbauer through the ship.

He was a keen, eager listener. When he asked a question, and he asked many of them, he showed an amazing grasp of the principles involved. My knowledge of our equipment was, of course, only practical, save for the rudimentary theoretical knowledge that everyone has of present-day inventions and devices.

The ethon tubes which lighted the ship, interested him but little. The atomic generators, the gravity pads, their generators, and the disintegrator-ray, however, he delved into with that frenzied ardor of which only a scientist, I believe, is capable.

Questions poured out of him, and I answered them as best I could: sometimes completely, and satisfactorily, so that he nodded and said, "I see! I see!" and sometimes so poorly that he frowned, and cross-questioned me insistently until he obtained the desired information.

In the big, sound-proof navigating room, I explained the operation of the numerous instruments, including the two three-dimensional charts, actuated by super-radio reflexes, the television disc, the attraction meter, the surface-temperature gauge and the complex control system.

"Forward," I added, "is the operating room. You can see it through these glass partitions. The navigating officer in command relays his orders to men in the operating room, who attend to the actual execution of those orders."

"Just as a pilot, or the navigating officer of a ship of my day gives his orders to the quartermaster at the wheel," nodded Harbauer, and began firing questions at me again, going over the ground we had covered, to check up on his information. I was amazed at the uncanny accuracy with which he had grasped such a great mass of technical detail. It had taken me years of study to pick up what he had taken from me, and apparently retained intact, in something more than an hour, Earth time.

glanced at the Earth-time clock on the wall of the navigating room as he triumphantly finished his questioning. Less than an hour remained before the time set for our return trip.

"I'm sorry," I commented, "to be an ungracious host, but I am wondering what your plans may be? You see, we are due to start in less than an hour, and—"

"A passenger would be in your way?" Harbauer smiled as he uttered the words, but there was a gleam in his long eyes that rather startled me, and I wondered if I only imagined the steeliness of his voice. "Don't let that worry you, sir."[303]

"It's not worrying me," I replied, watching him closely. "I have enjoyed a very remarkable, a very pleasant experience. If you should care to remain aboard the Ertak, I should like exceedingly to have you accompany us to our Base, where I could place you in touch with other laboratory men, with whom you would have much in common."

Harbauer threw back his head and laughed—not pleasantly.

"Thanks!" he said. "But I have no time for that. They could give me no knowledge that I need, now; you have told me and showed me enough. I understand how you have released atomic energy; it is a matter so simple that a child should have guessed it, and man has wondered about it for centuries, knowing that the power was there, but lacking a key to unfetter it. And now I have that key!"

"True. But perhaps our scientists would like, in exchange, the secret of moving forward in time," I suggested, reasonably enough.

"What do I care about them?" snapped Harbauer. He loosened the cord of the robe with a quick, impatient gesture, as though it confined him too tightly, and threw the garment from him.

hen, suddenly, he took a quick stride toward me, and thrust out his ugly head.

"I know enough now to give me power over all my world," he cried. "Haven't you guessed the reason for my interest in your engines of destruction? I came down the centuries ahead of my generation so that I might come back with power in my hand; power to wipe out the fools who have made a mock of me. And I have that power—here!" He tapped his forehead dramatically with his left hand.

"I will bring a new regime to my era!" he continued, fairly shouting now. "I will be what many men have tried to be, and what no man has ever been—master of the world! Absolute, unquestioned, supreme master!" He paused, his eyes glaring into mine—and I knew from the light that shone behind those long, narrow slits, that I was dealing with a madman.

"True; you will," I said gently, moving carelessly toward the microphone. With that in my hand, a slight pressure on the General Attention signal, and I would have the whole crew of the Ertak here in a moment. But I had explained the workings of the navigating room's equipment only too well.

"Stop!" snarled Harbauer, and his right hand flashed up. "See this? Perhaps you don't know what it is; I'll tell you. It's an automatic pistol—not so efficient as your disintegrator-ray, but deadly enough. There is certain death for eight men in my hand. Understand?"

"Perfectly." What an utter fool I had been! I was not armed, and I knew that Harbauer spoke the truth. I had often seen weapons similar to the one he held in the military museums. They are still there, if you are curious—rusty and broken, but not unlike our present atomic pistols in general appearance. They propelled the bullet by the explosion of a sort of powder; inefficient, of course, but, as he had said, deadly enough for the purpose.

ood! You are a good sort Hanson, but don't take any chances. I'm not going to, I promise you. You see,"—and he laughed again, the light in his long eyes dancing with evil—"I'm not likely to be punished for a few killings committed centuries after I'm dead. I have never killed a man, but I won't hesitate to do so now, if one—or more—should get in my way."

"But why," I asked soothingly, "should you wish to kill anyone? You have what you came for, you say; why not depart in peace?"[304]

He smiled crookedly, and his eyes narrowed with cunning.

"You approve of my little plan to dominate the world?" he asked softly, his eyes searching my face.

"No," I said boldly, refusing to lie to him. "I do not, and you know it."

"Very true." He pulled out his watch with his left hand, and held it before his eyes so that he could observe the time without losing sight of me for even an instant. "I doubted that I could secure your willing cooperation; therefore, I am commanding it.

"You see, there are certain instruments and pieces of equipment that I should like to take back to my laboratory with me. Perhaps I would be able to reproduce them without models, but with the models my task will be much easier.

"The question remaining is a simple one: will you give the proper orders to have this equipment removed to the spot where you first saw me, or shall I be obliged to return to my own era without this equipment—leaving behind me a dead commander of the Special Patrol Service, and any other who may try to stop me?"

tried to keep cool under the lash of his mocking voice. I have never been adept at holding my temper when I should, but somehow I managed it this time. Frowning, I kept him waiting for a reply, utilizing the time to do what was perhaps the hardest, fastest thinking of my life.

There wasn't a particle of doubt in my mind regarding his ability to make good his threat, nor his readiness to do so. I caught the faint glimmering of an idea and fenced with it eagerly.

"How are you going to go back to your own period—your own era?" I asked him. "You told me, I believe, that it was impossible to move backward in time."

"That's not answering my question," he said, leering. "Don't think you're fooling me! But I'll tell you, just the same. I can go back to my own era: that is, back to my own actual existence. I shall return just two hours after I leave; I could not go back farther than that, and it's not necessary that I do so. I can go back only because I came from that present; I am not really of this future at all. I go back from whence I came."

"But," I objected, thinking of something I had read in the clipping he had showed me, "you're not going back to your own era. You cannot. If you returned, you would put your project into execution, and history does not record that activity." I saw from the sudden narrowing of his abnormally long eyes that I had caught his interest, and I pressed my advantage hastily. "Remember that all the history of your time is written, Harbauer. It is in the books of Earth's history, with which every child of this age, into which you have thrust yourself, is familiar. And those histories do not record the domination of the world by yourself. So—you are confronted by an impossibility!"

y reasoning, now, sounds specious, and yet it was a line of thought which could not be waved aside. I saw Harbauer's black brows knit together, and mounting anger darken his face. I do not know, but I believe I was never nearer death than I was at that instant.

"Fool!" he cried. "Idiot! Imbecile! Do you think you can confuse me, turn me from my purpose, with words? Do you? Do you believe me to be a child, or a weakling? I tell you, I have planned this thing to the last detail. If I had not found what I sought on this first trip, I would have taken another, a dozen, a score, until I found the information I sought. The last six years of my life[305] I have worked day and night to this end; your histories and your words—"

My plan had worked. The man was beside himself with insane anger. And in his rage he forgot, for an instant, that he was my captor.

Taking a desperate chance, I launched myself at his legs. His weapon roared over my head, just as I struck. I felt the hot gas from the thing beat against my neck; I caught the reeking scent of the smoke. Then we were both on the floor, and locked in a mad embrace.

Harbauer was a smaller man than myself, but he had the amazing strength of a Zenian. He fought viciously, using every ounce of his strength against me, striving to bring his weapon into use, hammering my head upon the floor, racking my body mercilessly, grunting, cursing, mumbling constantly as he did so.

But I was in better trim than Harbauer. I have never seen a laboratory man who could stand the strain of prolonged physical exertion. Bending over test-tubes and meters is no life for a man. At grips with him, I was in my own element, and he was out of his. I let him wear himself out, exerting myself as little as possible, confining my efforts to keeping his weapon where he could not use it.

I felt him weakening at last. His breath was coming in great sobs, and his long eyes started from their sockets with the strained effort he was putting forth. And then, with a single mighty effort, I knocked the pistol from his hand, so that it slid across the floor and brought up with a crash against a wall of the room.

"Now!" I said, and turned on him.

e knew, at that moment when I put forth my strength, that I had been playing with him. I read the shock of sudden fear in his eyes. My right arm went about him in a deadly hold; I had him in a grip that paralyzed him. Grimly, I jerked him to his feet, and he stood there trembling with weakness, his shoulders heaving as his breath came and went between his teeth.

"You realize, of course, that you're not going back?" I said quietly.

"Back?" Half dazed, he stared at me through the quivering lids of his peculiar eyes. "What do you mean?"

"I mean that you're not going back to your own era. You have come to us, uninvited, and—you're going to stay here."

"No!" he shouted, and struggled so desperately to free himself that I was hard put to it to hold him, without tightening my grip sufficiently to dislocate his shoulders. "You wouldn't do that! I must return; I must prove to them—"

"That's exactly what must not happen, and what shall not happen," I interrupted. "And what will not happen. You are in a strange predicament, Harbauer; it is already written that you do not return. Can't you see that, man? If it were to be that you left this age and returned to your own, you would make known your discovery. History would record it. And history does not record it. You are struggling, not against me, but against—against a fate that has been sealed all these centuries."

hen I had finished, he stared at me as though hypnotized, motionless and limp in my grasp. Then, suddenly, he began to shake and I saw such depths of terror and horror in his eyes as I hope never to see again.

Mechanically, he glanced down at his watch, lifting his wrist into his line of vision as slowly and ponderously as though it bore a great weight.

"Two ... two minutes," he whispered huskily. "Then the automatic[306] switch will close, back in my laboratory. If I am not standing where ... where you found me ... between the disc and the grid of my time machine, where the reversed energy can reach me, to ... to take me back ... God!"

He sagged in my arms and dropped to his knees, sobbing.

"And yet ... what you say is true. It is already written that I did not return." His sobs cut harshly through the silence of the room. Pitying his despair, I reached down to give him a sympathetic pat on the shoulder. It is a terrible thing to see a man break down as Harbauer had done.

As he felt my grip on him relax, he suddenly shot his fist into the pit of my stomach, and leaped to his feet. Groaning, I doubled up, weak and nerveless, for the instant, from the vicious, unexpected blow.

"Ah!" shrieked Harbauer. "You soft-hearted fool!" He struck me in the face, sending me crashing to the floor, and snatched up his pistol.

"I'm going, now," he shouted. "Going! What do I care for your records and your histories? They are not yet written; if they were I'd change them." He bent over me and snatched from my hand the ring of keys, one of which I had used to unlock the door of the navigating room. I tried to grip him around the legs, but he tore himself loose, laughing insanely in a high-pitched, cackling sound that seemed hardly human.

"Farewell!" he called mockingly from the doorway. Then the door slammed, and as I staggered to my feet, I heard the lock click.

must have acted then by instinct or inspiration. There was no time to think. It would take him not more than three or four seconds to make his way to the exit, stroll by the guard to the spot where we had found him, and—disappear. By the time I could arouse the crew, and have my orders executed, his time would be up, and—unless the whole affair were some terrible nightmare—he would go hurtling back through time to his own era, armed with a devastating knowledge.

There was only one possible means of preventing his escape in time. I ran across the room to the emergency operating controls, cut in the atomic generators with one hand and pulled the Vertical-Ascent lever to Full Power.

There was a sudden shriek of air, and my legs almost thrust themselves through my body. Quickly, I pushed the lever back until, with my eye on the altimeter, I held the Ertak at her attained height—something over a mile, as I recall it. Then I pressed the General Attention signal, and snatched up the microphone.

Less than a minute later Correy and Hendricks, fellow officers, were in the room and besieging me with solicitous questions.

t had been my idea, of course, to keep Harbauer from leaving the ship, but it was not so destined.

Shiro, the sentry on duty outside the Ertak, was the only witness to Harbauer's fate.

"I was walking my post, sir," he reported, "watching the sun come up, when suddenly I heard the sound of running feet inside the ship. I turned towards the entrance and drew my pistol, to be in readiness. I saw the stranger we had taken into the ship appear at the exit, which, as you know, was open.

"Just as I opened my mouth to command him to halt, the Ertak shot up from the ground at terrific speed. The stranger had been about to leap upon me; indeed, he had discharged some sort of weapon at me, for I heard a crash of sound, and a missile of some kind, as you know, passed through my left arm.[307]

"As the ship left the ground, he tried to draw back, but he was off balance, and the inertia of his body momentarily incapacitated him, I think. He slipped, clutched at the gangway across the threads which seal the exit, and then, at a height I estimate to be around five hundred feet, he fell. The Ertak shot on up until it was lost to sight, and the stranger crashed to the ground a few feet from where I was standing—on almost exactly the spot where we first saw him, sir.

nd now, sir, comes the part I guess you'll find hard to believe. When he struck the ground, he was smashed flat; he died instantly. I started to run toward him, and then—and then I stopped. My eyes had not left the spot for a moment, sir, but he—his body, that is—suddenly disappeared. That's the truth, sir, for I saw it with my own eyes. There wasn't a sign of him left."

"I see," I replied. I believe that I did. We had gone straight up, and his body, by no great coincidence, had fallen upon the spot close to the exit of the Ertak where we had first found him. And his machine, in operation, had brought him, or rather, his mangled body, back to his own age. "You have not mentioned this affair to anyone, Shiro?"

"No, sir. It wasn't anything you'd be likely to tell: nobody would believe you. I went at once to have my arm attended to, and then reported here according to orders."

"Very good, Shiro. Keep the entire affair to yourself. I will make all the necessary reports. That is an order—understand?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then that will be all. Take good care of your arm."

He saluted with his good hand and left me.

ater in the day I wrote in the log-book of the Ertak the report I mentioned at the beginning of this tale:

"Just before departure, discovered stowaway, apparently demented, and ejected him."

That was a perfectly truthful statement, and it served its purpose. I have given the whole story in detail just to prove what I have so often contended: that these owlish laboratory men whom this age reveres so much are not nearly so wise and omnipotent as they think they are.

I am quite sure that they would have discredited, or attempted to discredit, my story, had I told it at the time. They would have resented the idea that someone so much ahead of them had discovered a principle that still baffles this age of ours, and I would have had no evidence to present.

Perhaps even now the story will be discredited; if so, I do not care. I am much too old, and too near the portals of that impenetrable mystery, in the shadow of which I have stood so many times, to concern myself with what others may think or say.

I know that what I have related here is the truth, and in my mind I have a vivid and rather pitiful picture of a mangled body, bloody and alone, in the barn-like structure the ancient paper had described; a body, broken and motionless, lying athwart the striated metal disc, like a sacrificial victim—a victim and a sacrifice of science.

There have been many such.

There, the words were written.

There, the words were written.

ee Bentley never knew how many others, if any, lived on after the Bengal Queen struck the hidden reef and sank like a stone. He had only a hazy memory of the catastrophe, and recalled that when she had struck and the alarm had gone rocketing through the great passenger boat—though no alarm was really necessary because she went to pieces so fast—that he had leaped far over the rail and swam straight out, fast, in order to escape being dragged down by the suction of the sinking liner.

The screaming of frightened women and children would ring in his ears until the day the grave closed over him—screaming that was made all the more terrible by the crashing roar of the raging black seas which came out of the darkness to make the affair all the more hideous,[309] and to bear down beneath them into the sea the feeble struggling ones who had no chance for their lives. Lifeboats had been smashed in their davits.

Bentley swam straight away after he was satisfied at last that he could do nothing more. He had helped men and women reach bits of wreckage until he could scarcely any longer keep his wearied arms to the task of keeping his own head above water. He knew even as he helped the white-faced ones that few of them would ever live through it, but he was doing the best he knew—a man's job.

When absolutely sure that he could do nothing further, when he could no longer hear cries of distress, or discover struggling forms in the sea which he might aid, he[310] had turned his back on the graveyard of the Bengal Queen and had struck for shore. He remembered the direction, for before sunset that evening, in company with several ship's under officers, he had studied the navigation charts upon which each day's run of the Bengal Queen was shown. Ahead of him now was the coast of Africa, though what part of it he knew but in the haziest way. He might not guess within a hundred miles.

ne thing only he remembered exactly. The second officer had said, apropos of nothing in particular:

"This wouldn't be a happy place to be shipwrecked. This section of the coast is a regular hangout of the great anthropoid apes. You know, those babies that can pick a man apart as a man would pluck the legs off a fly."

Bentley had merely grinned. The second officer's remarks had sounded to him as though the fellow had been reading more than his fair share of lurid fiction of the South African jungles.

However, apes or no apes, the shore would look good to Lee Bentley now. And he fully intended making it. He knew he could swim for hours if it became necessary, and he refused to think of the possibility of sharks. If one got him, well, that was one of the chances one had to take when one was shipwrecked against one's will.

So he alternately swam toward where he expected to find land, and floated on his back to rest.

"A swell ending to a great life, if I don't make it," he told himself. "I wonder how the old man will take it when the world reads that the Bengal Queen went down with all on board? He'll be relieved, maybe, for he was about ready to wash his hands of me if I can read signs at all."

t might be said that Bentley was his own worst critic, for he really was not a bad sort of a fellow. He was a good American, over-educated perhaps, with a yen to delve into forbidden places usually avoided by his own kind, and of digging into books which were better left with the pages unturned. There were strange ruins in Africa, he knew. He had gathered a weird fund of information from such books as he could unearth relative to ancient ruins and vanished races, to the lurid accounts of strange deaths of the various scientists who had taken active part in the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamen.

There were queer things in the heart of darkest Africa, and such things intrigued him. He could take whatever chances with his life he saw fit, for his only relative was a father, and he had never attached himself to any woman nor permitted any woman to attach herself to him—because he could never be sure that her interest might not primarily be in his bank account.

"If, as, and when," he told himself as he rode the waves through the night, "I reach the coast I'll be tossed into black Africa in a way I was not expecting. Anyway, if I live through, I can at least go about my work without the governor interfering. I only hope it won't be hard on the old fellow. He isn't a bad egg at all, and I guess I have given him plenty to think about and worry over."

He turned on his stomach again and struck out. He had managed to rid himself of all of his clothing except his underwear. They had only weighed him down, and he recalled, with a wry grin, that Africa as a whole went in but little for the latest in men's sport wear.

t must have been a good hour since he had lost the Bengal Queen back there in the raging deep,[311] that he heard the faint call through the murk.

"Help, for God's sake!"

He listened for a repetition of the call, minded to believe that his ears had tricked him. He fancied it had been a woman's voice, but no woman could have lived so long in those raging seas, in which any moment Bentley himself expected to be overwhelmed. For himself he regarded death more or less philosophically, but a woman out there, crying for help, was a different matter entirely. It tore at his heartstrings, mostly because he realized his inability to be of material assistance.

He was sure that he had been mistaken about the cry, when it came again.

"For God's sake, help!"

It came from his left and this time it was unmistakable, piteous and unnerving. Lee Bentley had the horrible fear that he would never reach her in time to help—though what help he could give, when he could barely manage to keep himself afloat, he could not forsee.

He was swimming down the side of a monster wave. He could see something white in the trough, and he struggled manfully to make headway, while the angry waters tossed him about like a bit of cork and seemed bent on defeating his most furious efforts. He saw the bit of white ride high on the next wave, pass over it and vanish. He dived straight through the wave as it towered over him. He came up, gasping, his hands all but clutching at a pair of hands that reached out of the waters and grasped with a last desperate effort at the sky.

Ahead of the hands was a broken piece of oar. Those hands had just despairingly relinquished their grip on the one chance of safety, if any chance there could possibly be in that mad midnight waste.

He pulled on the wrists and a white face came to view. Wild, staring eyes looked into his. Black hair flowed back from a face whose lips were blue and thin.

"Take it easy," he counseled. "Turn on your back and rest while I see if I can get back your life-boat."

e captured the oar, and found it practically useless to sustain any appreciable weight, but he clung to it because it was at least better than nothing at all. It had held the girl afloat for over an hour and might be made to serve again somehow. With his left hand under the woman's head and his right grasping the oar he turned on his back to regain his breath. He was deep in the water because the woman was now almost on top of him; but her face was above water. He knew instinctively that she had fainted, and he was a little glad. If she were the usual hysterical woman her fighting would drown them both. As a dead weight she was easier to handle.

They drifted on, and hope began to mount high in the heart of Lee Bentley—the hope that they might yet reach land. When, hours later, he could hear the roaring of breakers he was sure of it—if the breakers could be passed in safety. After that their fate was in the lap of the gods.

The girl too must have heard, for she turned at last in Bentley's arms and began to swim for herself. She was a strong swimmer and the period during which she had been out of things had revived her amazingly. She even managed a smile as she swam beside Bentley into the creamy breakers behind which they could make out the blackness of shore.

They were so close together that at times their hands touched as they swam, and could make themselves heard by dint of shouting, though they both husbanded their strength and their breathing for swimming.

"I'm not dressed for company," he[312] told her. "I left my tuxedo aboard the Bengal Queen!"

It was then that her lips twisted into a smile.

"I wouldn't even allow my maid into my stateroom if I were dressed as I am at the moment," she answered strongly, "but we're both grown up I think, and there are times when conventions go by the board. We'll pretend it doesn't matter!"

Then mutually helping each other they fought through the breakers into the calmer water behind, and managed at last to stand in water hip deep, with the undertow dragging at their limbs. They looked at each other and clasped hands without a word. They strode to the sandy beach beyond which the jungle reached away to some invisible horizon, and continued on until they were at last beyond the reach of the waves.

hey did not look at each other again, though Bentley did notice that her garb was as scanty almost as his own, consisting mostly of a slip which the water had pasted fast against her flesh. Beyond noting that she seemed to be young, Bentley did not intrude. Nor did he think of the future. It was enough for the moment that they had escaped the might of angry Neptune, god of the seas.

They dropped to the sands side by side, and the sands were warm. That the jungle behind them might be alive with wild beasts they did not pause to consider. Bentley had gazed at the jungle a moment before dropping down.

He had noticed but one thing—a moving light somewhere among the tangled mass, a light as of a monster firefly erratically darting through the deeper gloom.

The girl—he had noted she was as much girl as woman—dropped to the sand and stretched herself out. Bentley looked about him for a moment, just now realizing what he had been through. Then he dropped down beside the girl, and put one arm over her protectively, an instinctive movement. The two were alone in an alien world, and even this slight contact gave Bentley a feeling of companionship he found at the time peculiarly appealing.

The girl was in a drugged sort of sleep, but she stirred at the touch of his arm, and her hand came up so that her fingertips touched his cheek.

He slept heavily, while outside on the raging deep the storm swept on along the coast, bearing with it the secret of the rest of those who only last night had looked forward to a pleasant voyage aboard the Bengal Queen.

The last thought in Bentley's mind was of that flickering light he had seen. It was not important, but memory of it clung, and followed him into his sleep with his dreams—in which he seemed to be following a darting, erratic light through a jungle without end.

He wakened with the sun burning his face and torso, and turned on his stomach with a groan. The heat ate into his back unbearably and he finally sat up, rubbed his eyes and stared out to sea. Then it all came back and he looked about him for the girl. She had disappeared.

He rose to his feet and shouted.

An answering cry came back to him, and after a moment the girl appeared around a bend in a shoreline where she had been masked by a wall of the jungle and came toward him. She was carrying something in her hands. When she stood at last before him he noted that she carried a bundle of cloth that was dripping wet.

"We need something to cover us," she said simply. "I was tempted[313] to garb myself, but I did not wish to seem like a simpering prudish female, which I'm not at all. So I brought my findings here so that we could get together and fix up something to protect us from the sun."

"You're a sensible woman," said Bentley. "I've never understood why people should be so sensitive about their bodies. Mine isn't bad and yours, if you'll pardon me, is superb. That's not a compliment, just a statement of fact—which will help us to understand each other better. I've a hunch we're going to be some time in each other's company and we may as well know things about each other. My name's Lee Bentley."

"Mine is Ellen Estabrook."

Solemnly they shook hands. And their hands clung convulsively, for as though their handshake had been a signal there came a strange sound from the jungle behind them.

A burst of laughter that was plainly human—and another sound which caused the short hair at the base of Bentley's skull to rise, shift oddly, and settle back again.

The sound was like the beating of a skin-tight drumhead by the fists of a jungle savage. But if such it was the drum was a mighty drum, and the savage was a giant, for the sound went rolling through the jungle like an invisible tidal wave of sound.

Both the laughter and the drumming ceased as suddenly as they had sounded.

The man and woman laughed jerkily, dropped to the sand side by side and considered the necessity of clothes.

hey had to smile together at the results achieved with the bedraggled bits of cloth. Bentley suspected that they had been taken from bodies washed ashore as gruesome reminders of the catastrophe which had befallen the Bengal Queen, and because he did suspect this he did not ask questions that might cause Ellen to remember any longer than was necessary. Not that he doubted her courage, for she had proved that sufficiently; and she had proved that she was sensible, with none of the notions of the proprieties which would have made any other girl of Bentley's acquaintance a nuisance.

Their next concern was food, which they must find in the jungle, or from other wreckage cast ashore from the Bengal Queen. Now, hand in hand—which seemed natural in the circumstances—they began to walk along the shore, heading into the north by mutual consent.

As they walked Bentley kept pondering on that strange laughter he had heard and on the sound of savage drumming. The laughter puzzled him. If there were anyone in the jungle back of them, why had he or they failed to challenge them?

As for the drumming sound—Bentley remembered what the second officer had said about this section of the coast. It was a bit of jungle inhabited by the great apes in large numbers. So, that drumming had been a challenge, the man-ape's manner of mocking an enemy by beating himself on his barrel chest with his huge fists. But that the ape had not been challenging Bentley and the girl Bentley felt quite sure, as the brute would certainly have shown himself in that case.

They trudged on through the sand, while the sun beat down unmercifully on their uncovered heads. Ellen Estabrook strode along at Bentley's side without complaint.

fter perhaps an hour of this unbearable effort, when both felt as though the sun had sucked[314] them dry of perspiration, they encountered a rough footpath leading into the jungle. The path suggested human habitation somewhere near. The inhabitants might be hostile natives, even cannibals perhaps, but in this unknown land they would have to take a chance on that.

With a sigh of relief, and refusing to look ahead too far, or try to guess what lay in wait for them in the black mystery of the jungle, they turned into the footpath. The jungle was fetid and sweaty, but even this was a relief from the intolerable sun which could not reach them here because the jungle had closed its leafy arms over the trail instantly. One could not tell from the path whether it had been made by natives or by whites, for it was packed hard. It led straight away from the shoreline.

"We'll have to keep a sharp lookout for possible poisoned spring darts, Ellen," said Bentley.

"I'm not afraid, Lee," she answered stoutly. "Fate wouldn't allow us to come through what we have only to end things with poisoned darts. It just couldn't happen that way!"

Thus simply they addressed each other. It seemed as though years had been squeezed into a matter of hours. They knew each other as well as they would, in other circumstances, have known each other after a year of constant association. Here barriers of conventions were razed as simply and naturally as among children.

hey had pressed well into the gloom of the jungle when the first sound came.

Not the laughter they had heard before, but the drumming. It was ahead and somewhat to the left, and as they stopped without speaking they could distinctly hear the threshing of a huge body through the underbrush. The sound seemed to be approaching and for a minute or so they listened. Then the sound was repeated off to the right, a trifle further away.

"Can you climb, Ellen?" asked Bentley simply. "This section is filled with anthropoid apes, according to the second officer of the Bengal Queen. We may have to take to the trees."

"I can climb," she said, "but from what I've studied of the habits of these brutes they do a great deal of bluffing before they actually charge, and may not molest us at all if we pay no attention."

Bentley felt almost nude because he had no weapons save his own fists. And he would not have admitted even to himself how deeply he was concerned over the girl. As far as he knew, this section might be entirely uninhabited. It might be given over entirely to the anthropoids. In this case he shuddered to think of what might happen to Ellen Estabrook if he were slain.

He quickened his pace until Ellen kept stride with him with difficulty. The object uppermost in Bentley's mind was to get as far away as possible from the ominous drumbeats.

They rounded a bend in the trail and stopped stock-still.

Within fifty yards of them, blocking the trail, was a brute whose great size sent a thrill of horror through Bentley. It towered to the height of a big man, and must have weighed in the neighborhood of four hundred pounds. It was larger by far than any bull ape Bentley had seen in captivity.

It had been waiting for them, silently, with almost human cunning; but now that it was discovered the shaggy creature rose to his hind legs and screamed a challenge, at the same time striking his chest with blows of his hairy fists which rolled in a dull booming of sound through the jungle. At the same time the creature moved forward.[315]

entley whirled to run, his hand clasping tighter the hand of Ellen Estabrook. But they had not retreated ten steps down the pathway when their way was blocked by another of the great shaggy brutes. And they could hear others on both sides.

Bentley's face was chalk-white as he turned to the girl. Her calm acceptance of their predicament, an attitude in which he could read no slightest vestige of fear, helped him to regain control of his own nerves, which had threatened to send him into a panic. She even smiled, and Lee felt a trifle ashamed of himself.

Now the crashing sounds were closing in. The two brutes before and behind on the trail were pressing in upon them. But no general headlong charge had yet begun. Bentley looked around him, seeking a tree with limbs low enough for them to reach and thus climb to safety.

"There's one!" cried Ellen. Tugging at his hand she began to run.

At the same moment the great apes bellowed and charged.

But the charge was never finished, for through the drumming of their mighty fists on mighty barrel-like chests, through the sound of their charge, through the crackling underbrush came again that sound of laughter. There was fierce joy in the laughter, and the laughter was followed by words of a strange gibberish which Bentley could not recall as being from any language he had ever heard.

The great apes paused. Out of the jungle to the right of the fugitives burst a white man. He was well past middle age, for his white hair hung almost to his shoulders, which were stooped with the weight of years. He was a wisp of a man whose smooth shaven face was apple-red. His eyes were black and expressionless as obsidian, and when Lee encountered the full gaze of them he was conscious of that feeling which he had experienced at various times in his life when he knew that some deadly reptile was close by.

"Stand still a moment!" cried the old man. His voice was strangely high-pitched and cracked.

rom his right hand a whip with a long lash uncurled like a snake.

This he swung back and hurled to the front, and the snap of it was like a pistol shot. The great ape on the path ahead cowered back, bearing his fangs, roaring in anger. But that he feared the whip of the old man was plain to be seen. The crashing sound in the jungle died away rapidly, immediately the first report of the whip lash sounded in the trail.

Fearlessly the little man dashed upon the first of the great brutes the castaways had seen. His lash curled about the great beast's body, and the animal bellowed with pain. It clawed at the lash, but was not fast enough to capture it. In the end the brute broke and fled.

The animal which had blocked their path in the rear had already disappeared.

Now the little man came back to face the fugitives, and his lips were parted in a cordial smile. He coiled his whip and tucked it under his arm. He was dressed in well worn corduroy with high boots that were rather the worse for wear. Bentley saw that his lips were too red—like blood—and somehow he disliked the man instantly.

"Welcome to Barterville," said the old man. "It has been years since I have seen any of my own kind. People avoid this section of the jungle."

"I don't wonder," said Bentley, sighing deeply with relief. "Those brutes would make anybody keep away from here, if they knew about them. I thought they had us for a few minutes. They planned an ambush[316] almost as well as human beings could have done it—but that's absurd of course, merely a coincidence."

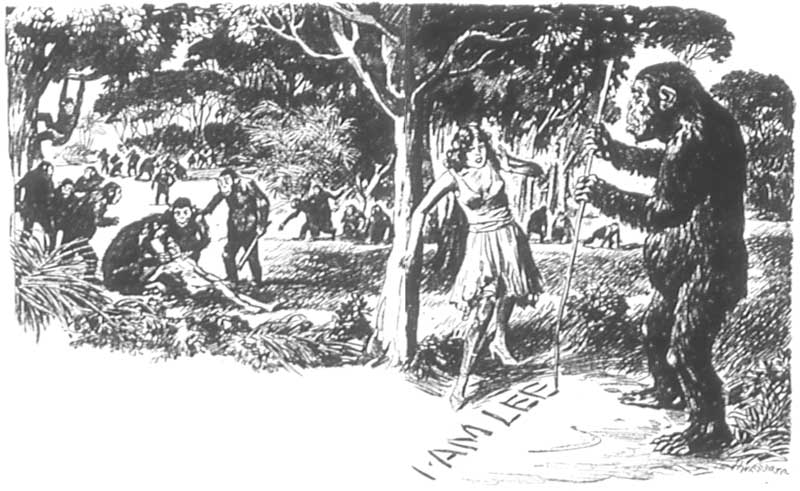

oincidence?" snapped the old man, a hint of asperity in his words. "Coincidence? I see you do not know the great apes, sir. I have always maintained that apes could be trained to do anything men can do. I have maintained that they have a language of their own, and even ways of communicating without words, a sort of jungle writing which men of course have never yet learned. I've devoted my life to learning the secrets of the great apes, their life histories, and so forth. I am Professor Caleb Barter!"

"Professor Caleb Barter!" ejaculated Ellen Estabrook. "Why I've heard of him! He went on an expedition among the great apes ten years ago and was never heard of again."

"I am Caleb Barter," said the old man. "I decided to disappear from the world I knew, to let other fool scientists think me dead in order that I might continue my investigations without molestation. And now I have almost reached the place where I can go back to civilization with information that will startle the world. There yet remains one experiment. Now I hope to make that experiment. No! No! Don't ask me what it is. It is my secret and nobody will ever wrest it from me."

Bentley studied the old man. He seemed slightly demented, Bentley thought, but that might be merely the mental evolution of a man who had made a hermit of himself for so many years—if this chap actually were Professor Barter.

"Professor Barter," went on Ellen, "was the scientific leader of his day. Others followed where he led. He made greater strides in surgery and medicine, and in unravelling the mysteries of evolution, than anyone else up to his time. Of course I believe you are Professor Barter. My name is Ellen Estabrook, and this gentleman is Lee Bentley. We believe ourselves to be the only survivors of the Bengal Queen. Perhaps you can lead us to food and water?"

"Yes, oh yes! Indeed. One forgets how to be hospitable, I fear. I am sorry to hear there was a wreck and that lives were lost—but it may mean a great gain to the world of science. I am happier to see you than you can possibly know!"

entley felt the cold chills racing along his spine as he listened to the old man's flow of words. He behaved well, but Bentley could feel in spite of that, that there was a hidden current of menace in the old man's behavior. He wished that Ellen would keep him talking, would somehow make sure of his identity. Perhaps the same thought was in her mind, for it had scarcely come to him when the girl spoke again.

"Before he disappeared Professor Barter wrote a learned treatise on—"

"I am Professor Barter, I tell you, young woman. But if you wish proof the title of the treatise was 'The Language of the Great Apes.'"

Ellen turned quickly to Bentley and nodded. She was satisfied that the man was the person he claimed to be. He didn't ask how Ellen happened to know about him, and Bentley himself considered the proof entirely lacking in conclusiveness. Anyone might know about the last treatise of Barter.

However, they could but await developments.

They followed Barter along the trail. Now and again apes challenged from the jungle, and Barter answered them with that strange laughter of his, or with a flow of gibberish that was like nothing human.[317]

Bentley shivered. Barter, by his laughter, was identifying himself to the great anthropoids. But with his gibberish was he actually conversing with them?

"This experiment of yours," said Bentley when the period of silence became unbearable, "—won't you tell us about it?"

The old man cackled.

"You'll know all about it—soon! You'll know everything, but the secret will still rest with Caleb Barter. Do not be too curious, my friends."

"We are anxious to reach civilization, Professor," said Bentley, deciding to be placative with the old man. "Perhaps you can arrange for guides for us?"

Barter laughed.

"I could not permit you to leave me for some time," he said. "I want you to witness my experiment. The world would never believe me without the evidence of reliable witnesses."

Barter laughed again.

hey entered a clean clearing which was a riot of flowers. At the further edge was a log cabin of huge proportions. The whole thing had a decidedly homely appearance, but it was a welcome sight to the castaways. There were cages in which strange birds chattered shrilly in their own language at sight of the three. A pair of tame monkeys chased each other on the roof of the house, whose corners were almost hidden by climbing vines whose growth one could almost see.

Barter led the way at a swift walk across the clearing and into the house.

Bentley gasped. Ellen Estabrook exclaimed with pleasure.

The reception room was as neat as though it received the hourly attentions of a fussy housewife. It was cozily furnished, yet it was evident that the furniture had been made on the spot of rough wood and skins of various animals. Deep skin rugs covered the floor and walls. There were three doors giving off of the reception room, all three of which were closed.

"You are not married?" he asked the two.

"No!" snapped Bentley.

"That center door leads to your room, Bentley. The one next to it is for the young lady. The other door? Ah, the other door my friends! That door you must never open. But to make sure that curiosity does not overcome caution, let me show you!"

hey followed him to the door. He swung it open.

Both visitors started back and a gasp of terror burst from the lips of Ellen Estabrook. Beads of perspiration burst forth on Bentley.

They saw a huge room. In one corner was a bed. The other held a great cage—and in the cage was an anthropoid ape larger even than the great brute they had met on the trail!

Barter laughed. He stepped into the room, uncoiled his whip and hurled the lash at the cage. A great bellowing roar fairly shook the house, while the brute tore at the bars which held him prisoner until the whole massive cage seemed to dance. Barter laughed and continued to goad him.

"Barter," yelled Bentley, "stop that! If that beast should ever happen accidentally to get free he'd tear you to pieces!"

"I know," said Barter grimly, "and that's part of the experiment! Now we shall eat, and you, young lady, shall tell me what other fool scientists had to say about me after I disappeared—to escape their parrot-like repeating of my discoveries!"

Bentley started to offer protest as Barter began preparation for the meal, which obviously was to be taken in the room which held the[318] cage of the giant anthropoid, but Ellen put her fingers to her lips and shook her head. Her eyes were dancing with excitement.

he meal consisted of various fruits, some meat which Bentley could not identify, and wild honey which was delicious. The bread tasted queer but was distinctly edible. The castaways ate ravenously, but even as he ate Bentley noticed that Ellen's face was chalky pale, and that in spite of a distinct effort of will she simply had to look at intervals toward the great beast in the cage.

Caleb Barter sat with his back to the animal. Bentley sat at the left of the old scientist, Ellen Estabrook at his right. The great beast was quiet now, but he squatted within his prison and his red-rimmed eyes swerved from one person to the other in the room with a peculiar intentness.

"I'd swear that beast can almost read our thoughts!" ejaculated Bentley at last, after he had somewhat sated his appetite.

Barter smiled with those too-red lips of his.

"He can—almost. You'd be surprised to know how nearly human the great apes are, and how nearly human this particular one is. Ah!"

"What do you mean, this particular one?" asked Bentley curiously. "He doesn't look any different to me from the others I've seen except that he is far and away the largest."

"I don't see why you should be so curious," said Barter testily. "It's none of your business you know—yet."

"What do you mean?" demanded Bentley, nettled by Barter's tone.

"Lee, hush," said Ellen. "Professor Barter is not on trial for any crime."

Bentley looked at her in hurt surprise, inclined to be angry with her for the tone she was taking, but he saw such a look of appeal in her eyes that he choked back the words that rushed to his lips for utterance. He was decidedly on edge, more, he felt, than he should have been despite what they had gone through. When their eyes met he saw her glance quickly toward the ape, and noted a frown of worry between her brows.

entley glanced at the ape. The brute now was staring at the girl in a way that made Bentley's flesh crawl. It was preposterous of course, but he had the feeling, something which seemed to flow out of that mighty cage like some evil emanation from a dank tarn, that the ape knew the girl's sex—and that he desired her! It was horrible in the extreme to contemplate, yet Bentley knew when he glanced swiftly at the girl that she had sensed the same thing and was fighting to keep the natural horror she felt at such a ghastly thought from being noticeable. It was absurd. The ape was a prisoner. But....

"Professor Barter," said Bentley, "you're accustomed to being with this brute, but it isn't so nice for us, especially for Miss Estabrook."

Barter now frowned angrily.

"My dear Bentley," he said with that odd testiness which he had assumed toward Bentley before, "I refuse to have any interference with my experiment. This is part of it."

"You mean—" began Bentley.

"I mean that I'm training that ape—I call him Manape—to behave like human beings. How better can he learn than by watching our behavior?"

"Just the same," said Bentley, "I don't like it."

"It's all right, Lee," said Ellen quickly. "I don't mind."

But Bentley knew that it wasn't all right, and that she did mind, terribly.[319]

arter finished eating. Bentley had noticed that despite the long years he had been a virtual hermit, Barter ate as fastidiously as he probably had done when he had lived among his own kind. He pushed back his chair with a swift movement.

Instantly the roaring of Manape rang through the room. The great brute rose to his full height and grasped the bars of his cage, shaking them with savage fury. He glared at his master and bestial rage glittered from his red-rimmed eyes. He was a horrible sight. Ellen Estabrook, with no apology, stepped around the table and crouched wide-eyed in the arm of Lee Bentley.

"Lee," she said, "I'm terribly afraid. I almost wish we had trusted ourselves in the jungle."

"I'll look out for you," he whispered, as Barter turned his attention to the great ape.

But Bentley was watching the animal. So was Barter. The eyes of the scientist were shining like coals of fire. For the moment he appeared to have forgotten his guests.

"It is a success!" he cried. "As far as it goes, I mean!"

What did Barter mean? Seeking some answer to the enigma, Bentley studied the ape anew. Now he was positive of another thing: Manape was scarcely concerned with Barter, whom he appeared to hate with an utterly satanic hatred. His beady eyes were staring at Bentley instead!

"The brute is jealous of me!" thought Bentley. "Good God, what does it mean, anyway?"

Barter turned back to them and all at once became the genial host.

"Shall we return to the other room?" he asked politely.

t was a relief to the castaways to put that awful room behind them. Barter closed and barred the door with deliberate slowness.

Why had this old man shut himself away from civilization like this? How long had he held this great ape in captivity? What was the purpose of it? What experiment was he performing? What part of it had the castaways been witnessing that they had not recognized? Bentley, recalling the distinct impression that the ape had stared at Ellen almost with the eyes of a lustful man, and had even appeared to be jealous of him because the girl had gone into his arms—Bentley felt a shiver of revulsion course through him as it struck him now how human the regard and the jealousy of the creature had been!

He felt like clutching at the girl and racing with her into the hazards of the jungle. But he remembered the anthropoids out there, and Barter's peculiar domination of the brutes.

Barter was now watching the two with interest, studying them in turn speculatively, unmindful of the impertinence of his studious regard and silence.

"I have it!" he said. "Will you two be good enough to excuse me? You will need rest, I am sure. I am going away for a little time, but I shall return shortly after dark. Make yourselves at home. But remember—don't enter that room!"

"You need not worry," said Bentley grimly. "I sincerely hope we take our next meal in some other room."

Barter laughed and passed out of the door without a backward glance.

From the jungle immediately afterward came the drumming of the great apes, and now and again the laughter of Barter—high-pitched at first, but dying away as Barter apparently moved off into the jungle.