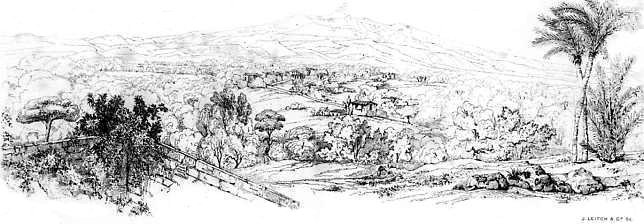

View of Etna from Catania

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Etna, by G. F. Rodwell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Etna

A History of the Mountain and of its Eruptions

Author: G. F. Rodwell

Release Date: March 30, 2010 [EBook #31827]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ETNA ***

Produced by Steven Gibbs, Adam Styles and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved.]

While preparing an account of Mount Etna for the Encyclopædia Britannica, I was surprised to find that there exists no single work in the English language devoted to the history of the most famous volcano in the world. I was consequently induced to considerably enlarge the Encyclopædia article, and the following pages are the result. The facts recorded have been collected from various sources—German, French, Italian, and English, and from my own observations made during the summer of 1877. I desire to express my indebtedness to Mr. Frank Rutley, of H.M. Geological Survey, for his careful examination of the lavas which were collected during my ascent of the mountain, and for the account which he has written of them; also to[Pg viii] Mr. John Murray for permission to copy figures from Lyell's "Principles of Geology." My thanks are also due to Mr. George Dennis, H.M. Consul-General in Sicily; Mr. Robert O. Franck, Vice-Consul in Catania; and to Prof. Orazio Silvestri, for information with which they have severally supplied me.

G. F. RODWELL.

Marlborough,

September 6th, 1878.

Position.—Name.—Mention of Etna by early writers.— Pindar.—Æschylus.—Thucydides.—Virgil.—Strabo.— Lucretius.—Lucilius Junior.—Etna the home of early myths.—Cardinal Bembo.—Fazzello.—Filoteo.—Early Maps of the Mountain.—Hamilton.—Houel.—Brydone. —Ferrara.—Recupero.—Captain Smyth.—Gemellaro; his Map of Etna.—Elie de Beaumont.—Abich.— Hoffmann.—Von Waltershausen's Atlas des Aetna.— Lyell.—Map of the Italian Stato Maggiore.—Carlo Gemellaro.—Orazio Silvestri.

Height.—Radius of Vision from the summit.—Boundaries. —Area.—Population.—General aspect of Etna.—The Val del Bove.—Minor Cones.—Caverns.—Position and extent of the three Regions.—Regione Coltivata.— Regione Selvosa.—Regione Deserta.—Botanical Regions.—Divisions of Rafinesque-Schmaltz, and of Presl.—Animal life in the upper Regions.

The most suitable time for ascending Etna.—The Ascent commenced.—Nicolosi.—Etna mules.—Night journey through the upper Regions of the mountain.—Brilliancy of the Stars.—Proposed Observatory on Etna.—The Casa Inglesi.—Summit of the Great Crater.—Sunrise from the summit.—The Crater.—Descent from the Mountain.—Effects of Refraction.—Fatigue of the Ascent.

Paterno.—Ste. Maria di Licodia.—The site of the ancient town of Aetna.—Biancavilla.—Aderno.—Sicilian Inns. —Adranum.—Bronte.—Randazzo.—Mascali.—Giarre. —Aci Reale.—Its position.—The Scogli de' Ciclopi.— Catania, its early history, and present condition.

Their frequency within the historical period.—525 b.c.—477 b.c.—426 b.c.—396 b.c.—140 b.c.—134 b.c.—126 b.c. —122 b.c.—49 b.c.—43 b.c.—38 b.c.—32 b.c.—40 a.d.— 72.—253.—420.—812.—1169.—1181.—1285.—1329.— 1333.—1371.—1408.—1444.—1446.—1447.—Close of the Fifteenth Century.—1536.—1537.—1566.—1579.—1603. —1607.—1610.—1614.—1619.—1633.—1646.—1651.— 1669.—1682.—1688.—1689.—1693.—1694.—1702.— 1723.—1732.—1735.—1744.—1747.—1755.—Flood of 1755.—1759.—1763.—1766.—1780.—1781.—1787.— 1792.—1797.—1798.—1799.—1800.—1802.—1805.— 1808.—1809.—1811.—1819.—1831.—1832.—1838.— 1842.—1843.—1852.—1865.—1874.—General character of the Eruptions.

Elie de Beaumont's classification of the rocks of Etna.—Hoffman's geological map.—Lyell's researches.—The period of earliest eruption.—The Val del Bove.—Two craters of eruption.—Antiquity of Etna.—The lavas of Etna.— Labradorite.—Augite.—Olivine.—Analcime.—Titaniferous iron.—Mr. Rutley's examination of Etna lavas under the microscope.

|

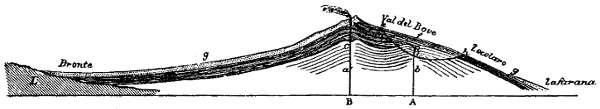

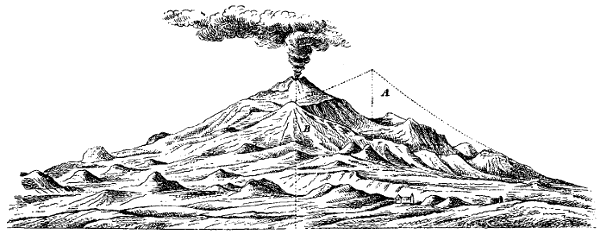

View of Etna from Catania Topographical Map of Etna Sections of Etna Grotto delle Palombe The Casa Inglesi and Cone of Etna View of the Val de Bove View of Etna from Bronte Island of Columnar Basalt off Trezza Geological Map of Etna Map of the Val del Bove (woodcut) Ideal Section of Mount Etna Profile of Etna Sections of Etna Lavas seen under the Microscope, |

To face Title. To face page " " " " " " " to face p. |

1 30 36 52 58 66 74 114 117 119 121 138 |

Position.—Name.—Mention of Etna by early writers.—Pindar.—Æschylus.—Thucydides.—Virgil.—Strabo.—-Lucretius.—Lucilius Junior.—Etna the home of early myths.—Cardinal Bembo.—Fazzello.—Filoteo.—Early Maps of the Mountain.—Hamilton.—Houel.—Brydone.—Ferrara.—Recupero.—Captain Smyth.—Gemellaro; his Map of Etna.—Elie de Beaumont.—Abich.—Hoffmann.—Von Waltershausen's Atlas des Aetna.—Lyell.—Map of the Italian Stato Maggiore.—Carlo Gemellaro.—Orazio Silvestri.

The principal mountain chain of Sicily skirts the

North and a portion of the North-eastern coast, and

would appear to be a prolongation of the Apennines.

An inferior group passes through the centre of the

island, diverging towards the South, as it approaches

the East coast. Between the two ranges, and completely

[Pg 2]separated from them by the valleys of the Alcantara

and the Simeto, stands the mighty mass of Mount Etna,

which rises in solitary grandeur from the eastern sea-board

of the island. Volcanoes, by the very mode of

their formation, are frequently completely isolated; and,

if they are of any magnitude, they thus acquire an

imposing contour and a majesty, which larger mountains,

forming parts of a chain, do not possess. This specially

applies to Etna. "Cœlebs degit," says Cardinal Bembo,

"et nullius montis dignata conjugium, caste intra suos

terminos continetur." It is not alone the conspicuous

appearance of the mountain which has made it the

most famous volcano either of ancient or modern times:—the

number and violence of its eruptions, the extent

of its lava streams, its association with antiquity, and

its history prolonged over more than 2400 years, have

all tended to make it celebrated.

The geographical position of Etna was first accurately determined by Captain Smyth in 1814. He estimated the latitude of the highest point of the bifid peak of the great crater at 37° 43' 31" N.; and the longitude at 15° East of Greenwich. Elie de Beaumont repeated the observations in 1834 with nearly the same result; and these determinations have been very generally adopted. In the new Italian map recently constructed by the Stato Maggiore, the latitude of the centre of the crater is stated to be 37° 44' 55" N., and the longitude [Pg 3]44' 55" E. of the meridian of Naples, which passes through the Observatory of Capo di Monte.

According to Bochart the name of Etna is derived from the Phœnician athana—a furnace; others derive it from αι′θω—to burn. Professor Benfey of Gottingen, a great authority on the subject, considers that the word was created by one of the early Indo-Germanic races. He identifies the root ait with the Greek αι′θ and the Latin aed—to burn, as in aes-tu. The Greek name Αιτνα was known to Hesiod. The more modern name, Mongibello, by which the mountain is still commonly known to the Sicilians, is a combination of the Arabic Gibel, and the Italian Monte. During the Saracenic occupation of Sicily, Etna was called Gibel Uttamat—the mountain of fire; and the last syllables of Mongibello are a relic of the Saracenic name. A mountain near Palermo is still called Gibel Rosso—the red mountain; and names may not unfrequently be found in the immediate neighbourhood of Etna which are partly, or sometimes even entirely, composed of Arabic words; such, for example, as Alcantara—the river of the bridge. Etna is also often spoken of distinctively as Il Monte—the mountain par excellence; a name which, in its capacity of the largest mountain in the kingdom of Italy, and the loftiest volcano in Europe, it fully justifies.

Etna is frequently alluded to by classical writers. By the poets it was sometimes feigned to be the prison of [Pg 4]the giant Enceladus or Typhon, sometimes the forge of Hephaistos, and the abode of the Cyclops.

It is strange that Homer, who has so minutely described certain portions of the contiguous Sicilian coast, does not allude to Etna. This has been thought by some to be a proof that the mountain was in a quiescent state during the period which preceded and coincided with the time of Homer.

Pindar (b.c. 522-442) is the first writer of antiquity who has described Etna. In the first of the Pythian Odes for Hieron, of the town of Aitna, winner in the chariot race in b.c. 474, he exclaims:

. . . "He (Typhon) is fast bound by a pillar of the sky, even by snowy Etna, nursing the whole year's length her dazzling snow. Whereout pure springs of unapproachable fire are vomited from the inmost depths: in the daytime the lava-streams pour forth a lurid rush of smoke; but in the darkness a red rolling flame sweepeth rocks with uproar to the wide deep sea . . . That dragon-thing (Typhon) it is that maketh issue from beneath the terrible fiery flood."[1]

Æschylus (b.c. 525-456) speaks also of the "mighty Typhon," (Prometheus V.):

. . . . . "He lies

A helpless, powerless carcase, near the strait

Of the great sea, fast pressed beneath the roots

[Pg 5]

Of ancient Etna, where on highest peak

Hephæstos sits and smites his iron red hot,

From whence hereafter streams of fire shall burst,

Devouring with fierce jaws the golden plains

Of fruitful, fair Sikelia."[2]

Herein he probably refers to the eruption which had occurred a few years previously (b.c. 476).

Thucydides (b.c. 471-402) alludes in the last lines of the Third Book to several early eruptions of the mountain in the following terms: "In the first days of this spring, the stream of fire issued from Etna, as on former occasions, and destroyed some land of the Catanians, who live upon Mount Etna, which is the largest mountain in Sicily. Fifty years, it is said, had elapsed since the last eruption, there having been three in all since the Hellenes have inhabited Sicily."[3]

Virgil's oft-quoted description of the mountain (Eneid, Bk. 3) we give in the spirited translation of Conington:

Many other early writers speak of the mountain, among them Theokritos, Aristotle, Ovid, Livy, Seneca, Lucretius, Pliny, Lucan, Petronius, Cornelius Severus, Dion Cassius, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Lucilius Junior. Seneca makes various allusions to Etna, and mentions the fact that lightning sometimes proceeded from its smoke.

Strabo has given a very fair description of the mountain. He asserts that in his time the upper part of it was bare, and covered with ashes, and in winter with snow, while the lower slopes were clothed with forests. The summit was a plain about twenty stadia in circumference, surrounded by a ridge, within which there was a small hillock, the smoke from which ascended to a considerable height. He further mentions a second crater. Etna was commonly ascended in Strabo's time from the south-west.

While the poets on the one hand had invested the mountain with various supernatural attributes, and had made it the prison-house of a chained giant, and the workshop of a swart god, Lucretius endeavoured to show that the eruptions and other phenomena could be easily explained by the ordinary operations of nature. "And now at last," he writes, "I will explain in what ways yon flame, roused to fury in a moment, blazes forth from the huge furnaces of Aetna. And, first, the nature of the whole mountain is hollow underneath,[Pg 7] underpropped throughout with caverns of basalt rocks. Furthermore, in all caves are wind and air, for wind is produced when the air has been stirred and put in motion. When this air has been thoroughly heated, and, raging about, has imparted its heat to all the rocks around, wherever it comes in contact with them, and to the earth, and has struck out from them fire burning with swift flames, it rises up and then forces itself out on high, straight through the gorges; and so carries its heat far, and scatters far its ashes, and rolls on smoke of a thick pitchy blackness, and flings out at the same time stones of prodigious weight—leaving no doubt that this is the stormy force of air. Again, the sea, to a great extent, breaks its waves and sucks back its surf at the roots of that mountain. Caverns reach from this sea as far as the deep gorges of the mountain below. Through these you must admit [that air mixed up with water passes; and] the nature of the case compels [this air to enter in from that] open sea, and pass right within, and then go out in blasts, and so lift up flame, and throw out stones, and raise clouds of sand; for on the summit are craters, as they name them in their own language, what we call gorges and mouths."[4]

These ideas were developed by Lucilius Junior in a poem consisting of 644 hexameters entitled Aetna. The [Pg 8]authorship of this poem has long been a disputed point; it has been attributed to Virgil, Claudian, Quintilius Varus, Manilius, and, by Joseph Scaliger[5] and others, to Cornelius Severus. Wensdorff was the first to adduce reasons for attributing the poem to Lucilius Junior, and his views are generally adopted. Lucilius Junior was Procurator of Sicily under Nero, and, while resident in the Island, he ascended Etna; and it is said that he proposed writing a detailed history of the mountain. He adopted the scientific opinions of Epicurus, as established in Rome by Lucretius, and was more immediately a disciple of Seneca. The latter dedicated to him his Quæstiones Naturales, in which he alludes more than once to Etna. M. Chenu speaks of the poem of Lucilius Junior as "sans doute très-póetique, mais assez souvent dur, heurté, concis, et parcela même, d'une obscurité parfois désespérante."[6] At the commencement of the poem, Lucilius ridicules the ideas of the poets as regards the connection of Etna with Vulcan and the Cyclops. He has no belief in the practice, which apparently prevailed in his time, of ascending to the edge of the crater and there offering incense to the [Pg 9]tutelary gods of the mountain. He adopts to a great extent the tone and style of Lucretius, in his explanation of the phenomena of the mountain. Water filters through the crevices and cracks in the rocks, until it comes into contact with the internal fires, when it is converted into vapour and expelled with violence. The internal fires are nourished by the winds which penetrate into the mountain. He traces some curious connection between the plants which grow upon the mountain, and the supply of sulphur and bitumen to the interior, which is, at best, but partly intelligible.

Many of the myths developed by the earlier poets had their home in the immediate neighbourhood, sometimes upon the very sides, of Etna—Demeter seeking Persephone; Acis and Galatea; Polyphemus and the Cyclops. Mr. Symonds tells us that the one-eyed giant Polyphemus was Etna itself, with its one great crater, while the Cyclops were the many minor cones. "Persephone[Pg 10] was the patroness of Sicily, because amid the billowy corn-fields of her mother Demeter, and the meadow-flowers she loved in girlhood, are ever found sulphurous ravines, and chasms breathing vapour from the pit of Hades."[7]

It is said that both Plato and the Emperor Hadrian ascended Etna in order to witness the sunrise from its summit. The story of

is too trite to need repetition. A ruined tower near the head of the Val del Bove, 9,570 feet above the sea, has from time immemorial been called the Torre del Filosofo, and is asserted to have been the observatory of Empedokles. Others regard it as the remains of a Roman tower, which was possibly erected on the occasion of Hadrian's ascent of the mountain.

During the Middle Ages Etna is frequently alluded to, among others by Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and Cardinal Bembo. The latter gives a description of the mountain in the form of a dialogue, which Ferrara characterises as "erudito, e grecizzante, ma sensa nervi." He describes its general appearance, its well-wooded sides, and sterile summit. When he visited the mountain it had two craters about a stone's throw [Pg 11]apart; the larger of the two was said to be about three miles in circumference, and it stood somewhat above the other.[8]

In 1541 Fazzello made an ascent of the mountain, which he briefly describes in the fourth chapter of his bulky volume De Rebus Siculis.[9] This chapter is entitled "De Aetna monte et ejus ignibus;" it contains a short history of the mountain, and some mention of the principal towns which he enumerates in the following order: Catana, Tauromenium, Caltabianco, Linguagrossa, Castroleone, Francavilla, Rocella, Randatio (Randazzo), Bronte, Adrano, Paterno, and Motta. Fazzello speaks of only one crater.

In 1591 Antonio Filoteo, who was born on Etna, published a work in Venice in which he describes the general features of the mountain, and gives a special account of an eruption which he witnessed in 1536.[10] The mountain was then, as now, divided into three Regions. The first and uppermost of these, he asserts, is very arid, rugged, and uneven, and full of broken [Pg 12]rocks; the second is covered with forests; and the third is cultivated in the ordinary manner. Of the height he remarks, "Ascensum triginta circiter millia passuum ad plus habet." In regard to the name, Mongibello, he makes a curious error, deriving it from Mulciber, one of the names of Vulcan, who, as we have seen, was feigned by the earlier poets to have had his forge within the mountain.

In 1636 Carrera gave an account of Etna, followed by that of the Jesuit Kircher, in 1638. The great eruption of 1669 was described at length by various eye-witnesses, and furnished the subject of the first detailed description of the eruptive phenomena of the mountain. Public attention was now very generally drawn to the subject in all civilised countries. It was described by the naturalist, Borelli, and in our own Philosophical Transactions. Lord Winchelsea, our ambassador at Constantinople, was returning to England by way of the Straits of Messina at the time of the eruption, and he forwarded to Charles II "A true and exact relation of the late prodigious earthquake and eruption of Mount Ætna, or Monte Gibello."

The first map of the mountain which we have been able to meet with, was published in reference to the eruption of 1669; it is entitled, "Plan du Mont Etna communenent dit Mount Gibel en l'Isle de Scicille et de t'incedie arrive par un treblement de terre le 8me [Pg 13]Mars dernier 1669." This plan is in the Bibliothèque Nationale, in Paris; it was probably drawn from a simple description, or perhaps altogether from the imagination, as it is utterly unlike the mountain, the sides of which possess an impossible steepness. Another very inaccurate map was published in Nuremberg about 1680, annexed to a map of Sicily, which is entitled, "Regnorum Siciliæ et Sardiniæ, Nova Tabula." Again, in 1714 H. Moll, "geographer in Devereux Street, Strand," published a new map of Italy, in which there is a representation of Etna during the eruption of 1669. This also was probably drawn from the imagination; no one who has ever seen the mountain would recognise it, for it has a small base, and sides which rival the Matterhorn in abruptness. Over against the coast of Sicily, and near the mountain, is written:—"Mount Etna, or Mount Gibello. This mountain sometimes issues out pure flame, and at other times a thick smoak with ashes; streams of fire run down with great quantities of burning stones, and has made many eruptions."

During the eighteenth century Etna was frequently ascended, and as frequently described. We have the accounts of Massa (1703), Count D'Orville (1727), Riedesel (1767), Sir William Hamilton (1769), Brydone (1776), Houel (1786), Dolomieu (1788), Spallanzani (1790), and many minor writers, such as Borch, Brocchi, [Pg 14]Swinburne, Denon, and Faujas de Saint Fond. There is great sameness in all of these narratives, and much repetition of the same facts; some of them, however, merit a passing notice.

Sir William Hamilton's Campi Phlegræi relates mainly to Vesuvius and the surrounding neighbourhood; but one of the letters "addressed to the Secretary of the Royal Society on October 17th, 1769," describes an ascent of Etna. Hamilton ascended on June 24th with the Canon Recupero and other companions; the few observations of any value which he made have been alluded to elsewhere under the head of the special subjects to which they refer. The illustrations of the Campi Phlegræi, specially the original water-colours which are contained in one of the British Museum copies, are magnificent, and convey a better idea of volcanic phenomena than any amount of simple reading. From them we can well realise the opening of a long rift extending down the sides of a mountain during its eruption, and the formation of subsidiary craters along the line of fire thus opened. Various volcanic products are also admirably painted. In the picture of Etna, however, which was drawn by Antonio Fabris, the artist has scarcely been more successful than his predecessors, and the slope of the sides of the mountain has been greatly exaggerated.

M. Houel, in his Voyage pittoresque dans les Deux [Pg 15]Siciles, 1781-1786, has given a fairly good account of Etna, accompanied by some really excellent engravings.

In 1776 Patrick Brydone, a clever Irishman with a good deal of native shrewdness and humour, published two volumes of a Tour in Sicily and Malta, in which he devoted several chapters to Mount Etna. He made the ascent of the mountain, and collected from the Canon Recupero, and from others, many facts concerning its then present, and its past history. He also made observations as to the height, temperature of the air at various elevations, brightness of the stars, and so on. Sir William Hamilton calls Brydone "a very ingenious and accurate observer," and adds that he was well acquainted with Alpine measurements. M. Elie de Beaumont, writing in 1836, speaks of him as le celebre Brydone; while, on the other hand, the Abbé Spallanzani, displeased at certain remarks which he made concerning Roman Catholicism in Sicily, never fails to deprecate his work, and deplores "his trivial and insipid pleasantries." Albeit Brydone's chapters on Etna furnished a more complete account of the volcano than any which had appeared in English up to that time; his remarks are frequently very sound and just, and we shall have occasion more than once to quote him.

It was reserved, however, for the Abate Francesco Ferrara, Professor of Physical Science in the University [Pg 16]of Catania, to furnish the first history of Etna and of its eruptions, which had any just claim to completeness. It is entitled, Descrizione dell' Etna, con la Storia delle Eruzioni e il Catalogo del prodotti. The first edition appeared in 1793, and a second was printed in Palermo in 1818. The author had an enthusiastic love for his subject:—"Nato sopra l'Etna," he writes, "che io conobbi ben presto palmo a palmo la mia passione per lo studio fissò la mia attenzione sul bello, e terribile fenomeno che avea avanti agli occhi." The work commences with a general description of the mountain—its height, the temperature of the different regions, the view from the summit, the mass, the water-springs, the vegetable and animal life, and the internal fires. This extends over sixty-nine octavo pages. The second part of the book—eighty pages—gives a history of the eruptions from the earliest times to the year 1811; the third part—sixty-seven pages—treats of the nature of the volcanic products; and the fourth part—thirty-four pages—discusses certain geological and physical considerations concerning the mountain. At the end there are a few badly drawn and engraved woodcuts, and a map which, although the trend of the coast-line is quite wrong, is otherwise fairly good. The engravings represent the mountain as seen from Catania; the Isole dei Ciclopi, and the neighbouring coast; the Montagna della Motta; and a view from Catania of the eruption of 1787. This [Pg 17]work has evidently to a great extent been a labour of love; it is full of personal observations, and also embodies the results of many other observers. It has furnished the foundation of much that has since been written concerning Etna.

The Canon Recupero has been alluded to above; he accompanied Hamilton, Brydone, and others to the summit of the mountain, and he was employed by the Government to report on the flood which, in 1755, descended with extraordinary violence through the Val del Bove. Beyond this, Recupero does not appear to have published anything concerning Etna, although it was well known that he had plenty of materials. He died in 1778, and it was not till the year 1815 that his results were published under the title of Storia Naturale et Generale dell' Etna, del Canonico Giuseppe Recupero.—Opera Postuma. This work consists of two bulky quarto volumes, the first of which is devoted to a general description of the mountain, the second to a history of the eruptions, and an account of the products of eruptions. Some idea may be formed of the extreme prolixity of the author if we mention that two chapters, together containing twelve quarto pages, are devoted to the discussion of the height of Etna, while the first volume is terminated by sixty-three closely printed pages of annotations. A few rough woodcuts accompany the volumes; a view of the mountain which, as usual, is [Pg 18]out of all reason as regards abruptness of ascent, and a carta oryctographia di Mongibello in which the trend of the coast-line between Catania and Taormina is altogether inexact, complete the illustrations of this most detailed of histories.

During the years 1814-1816 Captain Smyth, acting under orders from the Admiralty, made a survey of the coast of Sicily, and of the adjacent islands. At this time the Mediterranean charts were very defective; some places on the coast of Sicily were mapped as much as twenty miles out of their true position, and even the exact positions of the observatories at Naples, Palermo, and Malta were not known. Among other results, Smyth carefully determined the latitude and longitude of Etna, accurately measured its height, and examined the surroundings of the mountain. His results were published in 1824, and are often regarded as the most accurate that we possess.

In 1824 Dr. Joseph Gemellaro, who lived all his life on the mountain, and made it his constant study, published an "Historical and Topographical Map of the Eruptions of Etna from the era of the Sicani to the year 1824." In it he delineates the extent of the three Regions, Coltivata, Selvosa, and Deserta; he places the minor cones, to the number of seventy-four, in their proper places, and he traces the course of the various lava-streams which have flowed from them and from the [Pg 19]great crater. This map is the result of much patient labour and study, and it is a great improvement upon those of Ferrara and Recupero, but of course it is impossible for one man to survey with much accuracy an area of nearly 500 square miles, and to trace the tortuous course of a large number of lava-streams. Hence we must be prepared for inaccuracies, and they are not uncommon—the coast line is altogether wrong as to its bearings, some of the small towns on the sides of the mountain are misplaced, and but little attention has been paid to scale. Still the map is very useful, as it is the only one which shows the course of the lava-streams.

Mario Gemellaro, brother of the preceding, made almost daily observations of the condition of Etna, between the years 1803 and 1832. These results were tabulated, and they are given in the Vulcanologia dell' Etna of his brother, Professor Carlo Gemellaro, under the title of Registro di Osservazioni del Sigr. Mario Gemellaro.

Carlo Gemellaro contributed many memoirs on subjects connected with the mountain. They are chiefly to be found in the Atti dell' Accademia Gioenia of Catania, and they extend over a number of years. Perhaps the most important is the treatise entitled "La Vulcanologia dell' Etna che comprende la Topographia, la Geologia, la Storia, delle sue Eruzioni." It was published in Catania [Pg 20]in 1858, and is dedicated to Sir Charles Lyell, who ascended the mountain under the guidance of the author. The latter also published a Breve Raggualio della Eruzione dell' Etna, del 21 Agosto 1852, which contains the most authentic account of this important eruption, accompanied by some graphic sketches made on the spot. The last contribution of Carlo Gemellaro to the history of Etna, is fitly entitled Un Addio al Maggior Vulcano di Europa. It was published in 1866, and with pardonable vanity the author reviews his work in connection with the mountain, extending over a period of more than forty years. He commences his somewhat florid farewell with the following apostrophe:—"O Etna! splendida e perenne manifestazione della esistenza dei Fuochi sotteranei massimo fra quanti altri monti, dalle coste meridionali di Europa, dalle orientali dell' Asia e delle settentrionali dell' Africa si specchiano nel Mediterraneo: tremendo pei tuoi incendii: benigno per la fertilità del vulcanico tuo terreno ridotto a prospera coltivazione . . . io, nato appiè del vasto tuo cono, in quella Città che hai minacciato più d'una volta di sepellire sotto le tue infocate correnti: allogato, nella mia prima età, in una stanza della casa paterna, che signoreggiava in allora più basse abizioni vicine, ed intiera godeva la veduta della estesa parte meridionalè della tua mole, io non potera non averti di continuo sotto gli occhi, e non essere spettatore dei tuoi visibili fenomeni!"

[Pg 21]In 1834, M. Elie de Beaumont commenced a minute geological examination of the mountain. His results were published in 1838, under the title of Recherches sur la structure et sur l'origine du Mont Etna, and they extend over 225 pages.[11] He re-determined the latitude and longitude of the mountain, measured the slope of the cone, and the diameter of the great crater, and minutely examined the structure of the rocks at the base of the mountain. He also gives a good sectional view, elevations taken from each quarter of the compass, and a geological map, which although accurate in its general details, can scarcely be considered very satisfactory. A relief map of Etna, a copy of which is in the Royal School of Mines, was afterwards constructed from the flat map, and this was, we believe, at the same time, the first geological map, and the first map in relief, which had been made of the mountain. Elie de Beaumont considers granite as the basis of the mountain, because it is sometimes ejected from the crater; old basaltic rocks appear in the Isole dei Ciclopi, and near Paterno, Licodia, and Aderno; cailloux roulés near Motta; ancient lavas on each side of the Val del Bove; modern lavas in every part of the mountain, and calcareous and arenaceous rocks in the surrounding mountains.

[Pg 22]In 1836, Abich published some excellent sections of Etna, and an accurate view of the interior of the crater, in a work entitled Vues illustratives de quelques Phénomènes Géologiques prises sur le Vésuve et l'Etna pendant les années 1833 and 1834.

The whole of the thirteenth volume (1839) of the Berlin Archiv für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Berghau und Hüttenkunde, is occupied by an elaborate memoir on the geology of Sicily[12] by Friedrich Hoffmann, accompanied by an excellent geological map. A long account of the geology of Etna is given, and an enlarged map of the mountain was afterwards constructed and published in the Vulkanen Atlas of Dr. Leonhard in 1850.[13]

In 1836 Baron Sartorius Von Waltershausen commenced a minute survey of Etna, preparatory to a complete description of the mountain, both geological and otherwise. He was assisted by Professor Cavallari of Palermo, Professor Peters of Hensbourg, and Professor Roos of Mayence. The survey occupied six years, (1836-1842), and the results of direct observation in the form of maps and drawings, occupied a hundred sheets 160 millimetres (6¼ inches) long, by 133 m.m. [Pg 23](5¼ inches) broad. Twenty-nine separate points were made use of in the triangulation; and the scale chosen was 1 in 50,000. The results were published in a large folio atlas, which appeared in eight parts; the first in 1845 and the last in 1861, when the death of Von Waltershausen put an end to the further publication. There are 26 fine coloured maps, and 31 engravings. The cost of the atlas is £12. The maps are both geological and topographical, and they are accompanied by outline engravings of various details of special interest. The Atlas des Aetna furnishes the most exhaustive history of any one mountain on the face of the earth, and Sartorius Von Waltershausen will always be the principal authority on the subject of Etna.

Sir Charles Lyell visited Etna in 1824, 1857, and again in 1858. He embodied his researches in a paper presented to the Royal Society in 1859, and in a lengthy chapter in the Principles of Geology. His investigations have added much to our knowledge of the formation and geological characteristics of the mountain, especially of that part of it called the Val del Bove.

Later writers usually quote Von Waltershausen and Lyell, and do not add much original matter. The facts of all subsequent writers are taken more or less directly from these authors. The latest addition to the literature of the mountain, is the Wanderungen am Aetna of [Pg 24]Dr. Baltzer, in the journal of the Swiss Alpine Club for 1874.[14]

A fine map of Sicily, on the unusually large scale of 1 in 50,000, or 1·266 inch to a mile, was constructed by the Stato Maggiore of the Italian government, between 1864 and 1868. The portion relating to Etna, and its immediate surroundings occupies four sheets. All the small roads and rivulets are introduced; the minor cones and monticules are placed in their proper positions, and the elevation of the ground is given at short intervals of space over the entire map. An examination of this map shows us that distances, areas, and heights, have been repeatedly misstated, the minor cones misplaced, and the trend of the coast line misrepresented. For example, if we draw a line due north and south through Catania, and a second line from the Capo di Taormina, (the north-eastern limit of the base of Etna), until it meets the first line at Catania, the lines, will be found to enclose an angle of 26°. If we adopt the same plan with Gemellaro's map, the included angle is found to be 53°, and in the case of the maps of Ferrara and Recupero more than 60°. Again, it has been stated on good authority, that the lava of 396 b.c. which enters the sea at Capo di Schiso flowed for a distance of nearly 30 miles; the map shows us that its true course was less than 16 miles. [Pg 25]Lyell in 1858 gives a section of the mountain from West 20° N., to East 20° S., but a comparison with the new map proves that the section is really taken from West 35° N. to East 35° S., an error which at a radius of ten miles from the crater would amount to a difference of nearly three miles.

The mantle of Carlo Gemellaro appears to have fallen upon Cav. Orazio Silvestri, Professor of Chemistry in the University of Catania. He has devoted himself with unwearying vigour to the study of the mountain, and his memoirs have done much to elucidate its past and present history. His most recent work of importance on the subject is entitled I Fenomeni Vulcanici presentati dall' Etna nel 1863-64-65-66. It was published in Catania in 1867, and contains an account of some very elaborate chemico-geological researches.

[1] Translated by Ernest Myers, m.a., 1874.

[2] Translated by E. Myers.

[3] Translated by E. Crawley.

[4] De Naturâ Rerum, Book 6, p. 580. Translated by E. Munro 1864.

[5] See Lucilius Junioris Aetna. Recensuit notasque Jos. Scaligeri, Frid. Lindenbruchii et suas addidit Fridericus Jacob. Lipsiæ, 1826.

[6] L'Etna de Lucilius Junior. Traduction nouvelle par Jules Chenu. Paris, 1843.

[7] Sketches in Italy and Greece, p. 201.

[8] Petri Bembi De Aetna. Ad Angelum Chabrielem Liber Impressum Venetiis Aedibus Aldi Romani. Mense Februario anno M.V.D. (1495).

[9] Fazzellus T. De Rebus Siculis. Panormi, 1558; folio.

[10] Antonii Philothei de Homodeis Siculi, Aetnæ Topographia, incendiorum Aetnæorum Historia. Venetiis. 1591. Preface dated September, 1590.

[11] Printed in vol. IV. of Mémoires pour servir a une description Geologique de la France. Par M.M. Dufrénoy et Elie de Beaumont.

[12] Entitled Geognostiche Beobachtungen Gesammelt auf einer Reise durch Italian und Sicilien, in den jahren 1830 bis 1832, von Friedrich Hoffmann.

[13] Vulkanen Atlas zur naturgeschichte der Erde von K. G. Von Leonhard. Stuttgardt. 1850.

[14] Jahrbuch des Schweizer Alpen Club. Neunter Jahrgang, 1873-1874. Bern 1874.

Height.—Radius of Vision from the summit.—Boundaries.—Area.—Population.—General aspect of Etna.—The Val del Bove.—Minor Cones.—Caverns.—Position and extent of the three Regions.—Regione Coltivata.—Regione Selvosa.—Regione Deserta.—Botanical Regions.—Divisions of Rafinesque-Schmaltz, and of Presl.—Animal life in the upper Regions.

In the preceding chapter we have discussed the

history of Mount Etna; the references to its phenomena

afforded by writers of various periods; and the present

state of the literature of the subject. We have now to

consider the general aspect and physical features of the

mountain, together with the divisions of its surface into

distinct regions.

The height of Etna has been often determined. The earlier writers had very extravagant notions on the subject, and three miles has sometimes been assigned to it. Brydone, Saussure, Shuckburgh, Irvine, and others, obtained approximations to the real height; it must be borne in mind, however, that the cone of a volcano is liable to variations in height at different [Pg 27]periods, and a diminution of as much as 300 feet occurred during one of the eruptions of Etna, owing to the falling in of the upper portion of the crater. During the last sixty years, however, the height of the mountain has been practically constant. In 1815 Captain Smyth determined it to be 10,874 feet. In 1824 Sir John Herschel, who was unacquainted with Smyth's results, estimated it at 10,872½ feet. The new map of the Stato Maggiore gives 3312·61 metres = 10867·94 feet.

When the Canon Recupero devoted two chapters of his quarto volume to a discussion of the height of Etna, no such exact observations had been made, consequently he compared, and critically examined, the various determinations which then existed. The almost perfect concordance of the results given by Smyth, Herschel, and the Stato Maggiore, render it unnecessary for us to further discuss a subject about which there can now be no difference of opinion.

Professor Jukes says, "If we were to put Snowdon, the highest mountain in Wales, on the top of Ben Nevis, the highest in Scotland, and Carrantuohill, the highest in Ireland, on the summit of both, we should make a mountain but a very little higher than Etna, and we should require to heap up a great number of other mountains round the flanks of our new one in order to build a gentle sloping pile which should equal Etna in bulk."

[Pg 28]The extent of radius of vision from the summit of Etna is very variously stated. The exaggerated notions of the earlier writers, that the coast of Africa and of Greece are sometimes visible, may be at once set aside. Lord Ormonde's statement that he saw the Gulf of Taranta, and the mountains of Terra di Lecce beyond it—a distance of 245 miles—must be received with caution. It is, however, a fact that Malta, 130 miles distant, is often visible; and Captain Smyth asserts that a considerable portion of the upper part of the mountain may sometimes be seen, and that he once saw more than half of it, from Malta, although that island is usually surrounded by a sea-horizon. It is stated on good authority that Monte S. Giuliano above Trapani, and the Œgadean Isles, 160 miles distant, are sometimes seen. Other writers give 128 miles as the limit. The fact is, that atmospheric refraction varies so much with different conditions of the atmosphere that it is almost impossible to give any exact statement. The more so when we remember that there may be many layers of atmosphere of different density between the observer and the horizon. Distant objects seem to be just under one's feet when seen from the summit of the mountain. Smyth gives the radius of vision as 150·7 miles: and this we are inclined to adopt as the nearest approach to the truth, because Smyth was an accurate observer, and he made careful corrections both for error of instruments and for refraction. This radius [Pg 29]gives an horizon of 946·4 miles of circumference, and an included area of 39,900 square miles—larger than the area of Ireland. If a circle be traced with the crater of Etna as a centre, and a radius of 150·7 miles, it will be found to take in the whole of Sicily and Malta, to cut the western coast of Italy at Scalca in Calabria, leaving the south-east coast near Cape Rizzuto. Such a circle will include the whole of Ireland, or if we take Derby as the centre, its circumference will touch the sea beyond Yarmouth on the East, the Isle of Wight on the South, the Irish Channel on the West, and it will pass beyond Carlisle and Newcastle-on-Tyne on the North.

The road which surrounds the mountain is carried along its lower slopes, and is 87 miles in length. It passes through the towns of Paterno, Aderno, Bronte, Randazzo, Linguaglossa, Giarre, and Aci Reale. It is considered by some writers to define the base of the mountain, which is hence most erroneously said to have a circumference of 87 miles; but the road frequently passes over high beds of lava, and winds considerably. It is about 10 miles from the crater on the North, East, and West sides, increasing to 15½ miles at Paterno, (S.W.). The elevation on the North and West flanks of the mountain is nearly 2,500 feet, while on the South it falls to 1,500 feet, and on the East to within 50 feet of the level of the sea. It is quite clear that it cannot [Pg 30]be asserted with any degree of accuracy to define the base of the mountain.

The "natural boundaries" of Etna are the rivers Alcantara and Simeto on the North, West, and South, and the sea on the East to the extent of 23 miles of coast, along which lava streams have been traced, sometimes forming headlands several hundred feet in height. The base of the mountain, as defined by these natural boundaries, is said to have a circumference of "at least 120 miles," an examination of the new map, however, proves that this is over-estimated.

If we take the sea as the eastern boundary, the river Alcantara, (immediately beyond which Monte di Mojo, the most northerly minor cone of Etna is situated), as the northern boundary, and the river Simeto as the boundary on the west and south, we obtain a circumference of 91 miles for the base of Etna. In this estimate the small sinuosities of the river have been neglected, and the southern circuit has been completed by drawing a line from near Paterno to Catania, because the Simeto runs for the last few miles of its course through the plain of Catania, quite beyond the most southerly stream of lava. The Simeto (anciently Simæthus) is called the Giaretta along the last three miles of its course, after its junction with the Gurna Longa.

The area of the region enclosed by these boundaries is approximately 480 square miles. Reclus gives the area [Pg 31]of the mountain as 1,200 square kilometres—461 square miles. (Nouvelle Geographie Universelle, 1875.) The last edition of a standard Gazetteer states it as "849 square miles;" but this estimate is altogether absurd. This would require a circle having a radius of between sixteen and seventeen miles. If a circle be drawn with a radius of sixteen miles from the crater, it will pass out to sea to a distance of 4½ miles on the East, while on the West and North it will pass through limestone and sandstone formations far beyond the Alcantara and the Simeto, and beyond the limit of the lava streams.

There are two cities, Catania and Aci Reale, and sixty-two towns or villages on Mount Etna. It is far more thickly populated than any other part of Sicily or Italy, for while the population of the former is 228 per square mile, and of the latter 233, the population of the habitable zone of Etna amounts to 1,424 per square mile. More than 300,000 persons live on the slopes of the mountain. Thus with an area rather larger than that of Bedfordshire (462 square miles) the mountain has more than double the population; and with an area equal to about one-third that of Wiltshire, the population of the mountain is greater by nearly 50,000 inhabitants. We have stated above that the area of Etna is 480 square miles, but it must be borne in mind that the habitable zone only commences at a distance of about 9¼ miles from the [Pg 32]crater. A circle, having a radius of 9¼ miles, encloses an area of 269 square miles; and 480 minus 269 leaves 211 square miles as the approximate area of the habitable zone. Only a few insignificant villages on the East side are nearer to the crater than 9¼ miles. Taking the inhabitants as 300,000, we find, by dividing this number by 211, (the area of the habitable zone), that the population amounts to 1,424 per square mile. Even Lancashire, the most populous county in Great Britain, (of course excepting Middlesex), and the possessor of two cities, which alone furnish more than a million inhabitants, has a population of only 1,479 to the square mile.

Some idea of the closeness of the towns and villages may be found by examining the south-east corner of the map. If we draw a line from Aci Reale to Nicolosi, and from Nicolosi to Catania, we enclose a nearly equilateral triangle, having the coast line between Aci Reale and Catania as its third side.

Starting from Aci Reale with 24,151 inhabitants, and moving westwards to Nicolosi, we come in succession to Aci S. Lucia, Aci Catena, Aci S. Antonio, Via Grande, Tre Castagni, Pedara, Nicolosi, completing the first side of the triangle; then turning to the south-east and following the Catania road, we pass Torre di Grifo, Mascalucia, Gravina, and reach Catania with 85,055 inhabitants; while on the line of coast between Catania [Pg 33]and Aci Reale we have Ognina, Aci Castello, and Trezza. Within the triangle we find Aci Patane, Aci S. Filippo, Valverde, Bonacorsi, S. Gregorio, Tremestieri, Piano, S. Agata, Trappeto, and S. Giovanni la Punta: in all twenty-five, two of which are cities, several of the others towns of about 3,000 inhabitants, and the rest villages. These are all included within an area of less than thirty square miles, which constitutes the most populous portion of the habitable zone of Etna.

That the population is rapidly increasing is well shown by a comparison of the number of inhabitants of some of the more important towns in 1824 and in 1876.[15]

Catania Aci Reale Giarre Paternò Aderno Bronte Biancavilla Linguaglossa Randazzo Piedimonte Etnea Zaffarana Etnea Pedara Trecastagni |

1824 45,081 14,094 13,705 9,808 6,623 9,153 5,870 2,415 4,700 1,404 700 2,068 2,406 |

1876 85,055 24,151 17,965 16,512 15,657 15,081 13,261 9,120 8,378 4,924 3,884 3,181 3,061 |

[Pg 34]The general aspect of Etna is that of a pretty regular cone, covered with vegetation, except near the summit. The regularity is broken on the East side by a slightly oval valley, four or five miles in diameter, called the Val del Bove, or in the language of the district Val del Bue. This commences about two miles from the summit, and is bounded on three sides by nearly vertical precipices from 3,000 to 4,000 feet in height. The bottom of the valley is covered with lavas of various date, and several minor craters have from time to time been upraised from it. Many eruptions have commenced in the immediate neighbourhood of the Val del Bove, and Lyell believes that there formerly existed a centre of permanent eruption in the valley. The Val del Bove is altogether sterile; but the mountain at the same level is, on other sides, clothed with trees. The vast mass of the mountain is realised by the fact that, after twelve miles of the ascent from Catania, the summit looks as far off as it did at starting. Moreover, Mount Vesuvius might be almost hidden away in the Val del Bove.

A remarkable feature of Etna is the large number of minor craters which are scattered over its sides. They look small in comparison with the great mass of the mountain, but in reality some of them are of large dimensions. Monte Minardo, near Bronte, the largest of these minor cones, is still 750 feet high, although [Pg 35]its base has been raised by modern lava-streams which have flowed around it. There are 80 of the more conspicuous of these minor cones, but Von Waltershausen has mapped no less than 200 within a ten mile radius from the great crater, while neglecting many monticules of ashes. As to the statement made by Reclus to the effect that there are 700 minor cones, and by Jukes, that the number is 600, it is to be supposed that they include not only the most insignificant monticules and heaps of cinders, but also the bocche and boccarelle from which at any time lava or fire has issued. If these be included, no doubt these numbers are not exaggerations.

The only important minor cone which has been produced during the historical period, is the double mountain known as Monti Rossi, from the red colour of the cinders which compose it. This was raised from the plain of Nicolosi during the eruption of 1669; it is 450 feet in height, and two miles in circumference at the base. In a line between the Monti Rossi and the great crater, thirty-three minor cones may be counted. Hamilton counted forty-four, looking down from the summit towards Catania, and Captain Smyth was able to discern fifty at once from an elevated position on the mountain. Many of these parasitic cones are covered with vegetation, as the names Monte Faggi, Monte Ilice, Monte Zappini, indicate. The names have not been happily chosen; thus there are [Pg 36]several cones in different parts of the mountain called by the same name—Monte Arso, Monte Nero, Monte Rosso, Monte Frumento, are the most common of the duplicates. Moreover, the names have from time to time been altered, and it thus sometimes becomes difficult to trace a cone which has been alluded to under a former name, or by an author who wrote before the name was changed. In addition to the minor cones from which lava once proceeded, there are numerous smaller vents for the subterranean fires called Bocche, or if very small, Boccarelle, del Fuoco. In the eruption of 1669, thirteen mouths opened in the course of a few days; and in the eruption of 1809, twenty new mouths opened one after the other in a line about six miles long. Two new craters were formed in the Val del Bove in 1852, and seven craters in 1865. The outbursts of lava from lateral cones are no doubt due to the fact that the pressure of lava in the great crater, which is nearly 1000 feet in depth, becomes so great that the lava is forced out at some lower point of less resistance. The most northerly of the minor cones is Monte di Mojo, from whence issued the lava of 396 b.c., it is 11½ miles from the crater; the most southerly cone is Monte Ste Sofia, 16 miles from the crater. Nearly all the minor cones are within 10 miles of the crater, and the majority are collected between south-east, and west, that is, in an angular space of 135°, starting [Pg 37]midway between east and south, (45° south of due east) to due west, (90° west of due south). Lyell speaks of the minor cones "as the most grand and original feature in the physiognomy of Etna."

A number of caverns are met with in various parts of Etna; Boccacio speaks of the Cavern of Thalia, and several early writers allude to the Grotto delle Palombe near Nicolosi. The latter is situated in front of Monte Fusara, and the entrance to it is evidently the crater of an extinct monticule. It descends for 78 feet, and at the bottom a cavern is entered by a long shaft; this leads to a second cavern, which abruptly descends, and appears to be continued into the heart of the neighbouring Monti Rossi. Brydone says that people have lost their senses in these caverns, "imagining that they saw devils, and the spirits of the damned; for it is still very generally believed that Etna is the mouth of Hell." Many of the caverns near the upper part of the mountain are used for storing snow, and sometimes as places of shelter for shepherds. We have already seen to what extent Lucretius attributed the eruptions to air pent up within the interior caverns of the mountains.

The surface of the mountain has been divided into three zones or regions—the Piedimontana or Coltivata; the Selvosa or Nemorosa; and the Deserta or Discoperta. Sometimes the name of Regione del Fuoco is given to [Pg 38]the central cone and crater. As regards temperature, the zones correspond more or less to the Torrid, Temperate, and Frigid. The lowest of these, the Cultivated Region, yields in abundance all the ordinary Sicilian products. The soil, which consists of decomposed lava, is extremely fertile, although of course large tracts of land are covered by recent lavas, or by those which decompose slowly. In this region the vine flourishes, and abundance of corn, olives, pistachio nuts, oranges, lemons, figs, and other fruit trees.

The breadth of this region varies; it terminates at an approximate height of 2000 feet. A circle drawn with a radius of 10 miles from the crater, roughly defines the limit. The elevation of this on the north is 2,310 feet near Randazzo; on the south, 2,145 feet near Nicolosi; on the east, 600 feet near Mascali; and on the west, 1,145 feet near Bronte. The breadth of this cultivated zone is about 2 miles on the north, east, and west, and 9 or 10 on the south, if we take for the base of the mountain the limits proposed above.

The Woody Region commences where the cultivated region ends, and extends as a belt of varying width to an approximate height of 6,300 feet. It is terminated above by a circle having a radius of nearly 1½ miles from the crater. There are fourteen separate forests in this region: some abounding with the oak, beech, [Pg 39]pine, and poplar, others with the chestnut, ilex, and cork tree.

The celebrated Castagno di Cento Cavalli, one of the largest and oldest trees in the world, is in the Forest of Carpinetto, on the East side of the mountain, five miles above Giarre. This tree has the appearance of five separate trunks united into one, but Ferrara declares that by digging a very short distance below the surface he found one single stem. The public road now passes through the much-decayed trunk. Captain Smyth measured the circumference a few feet from the ground, and found it to be 163 feet, which would give it a diameter of more than 50 feet. The tree derives its name from the story that one of the Queens of Arragon took shelter in its trunk with a suite of 100 horsemen. Near this patriarch are several large chestnuts, which, without a shadow of doubt, are single trees; one of these is 18 feet in diameter, and a second 15 feet, while the Castagno della Galea, higher up on the mountain, is 25 feet in diameter, and probably more than 1000 years old. The breadth of the Regione Selvosa varies considerably, as may be seen by reference to the accompanying map; in the direction of the Val del Bove it is very narrow, while elsewhere it frequently has a breadth of from 6 to 8 miles.

The Desert Region is embraced between the limit of 6,300 feet and the summit. It occupies about 10 square miles, and consists of a dreary waste of black sand, [Pg 40]scoriæ, ashes, and masses of ejected lava. In winter it remains permanently covered with snow, and even in the height of summer snow may be found in certain rifts.

Botanists have divided the surface of Etna into seven regions. The first extends from the level of the sea to 100 feet above it, and in it flourishes the palm, banana, Indian fig or prickly pear, sugar-cane, mimosa, and acacia. It must be remembered, however, that it is only on the east side of the mountain that the level within the base sinks to 100 feet above the sea; and, moreover, that the palm, banana, and sugar-cane, are comparative rarities in this part of Sicily. Prickly pears and vines are the most abundant products of the lower slopes of the eastern side of Etna. The second, or hilly region, reaches from 100 to 2000 feet above the sea, and therefore constitutes, with the preceding, the Regione Coltivata of our former division. In it are found cotton, maize, orange, lemon, shaddock, and the ordinary Sicilian produce. The culture of the vine ceases near its upward limit. The third, or woody region, reaches from 2000 to 4000 feet, and the principal trees within it are the cork, oak, maple, and chestnut. The fourth region extends from 4000 to 6000 feet, and contains the beech, Scotch fir, birch, dock, plaintain, and sandworth. The fifth, or sub-Alpine region, extending from 6000 to 7000 feet, contains the barberry, soapwort, [Pg 41]toad-flax, and juniper. In the sixth region, 7,500 to 9000 feet, are found soapwort, sorrel, and groundsel; while the last narrow zone, 9000 to 9,200 feet, contains a few lichens, the commonest of which is the Stereocaulon Paschale. The flora of Etna comprises 477 species, only 40 of which are found between 7000 feet and the summit, while in the last 2000 feet only five phanerogamous species are found, viz., Anthemis Etnensis, Senecio Etnensis, Robertsia taraxacoides, (which are peculiar to Etna), Tanacetum vulgare, and Astragulus Siculus. Common ferns, such as the pteris aquilina, are found in abundance beneath the trees in the Regione Selvosa.

This division has been advocated by Presl in his Flora Sicula.[16] He names the different regions beginning from below: Regio Subtropica, Regio Collina, Regio Sylvatica inferior, Regio fagi Sylvestris. These four are common to all Sicily. The three remaining regions, Regio Subalpina, Regio Alpina, and Regio Lichenum, together extending from 6000 to 9,200 feet, belong to Etna alone.

At the conclusion of the first volume of Recupero's Storia Naturale et Generale dell' Etna we find a somewhat different botanical division proposed by Signor [Pg 42]Rafinesque-Schmaltz.[17] He makes his divisions in the following manner:—

In the latter region, (to which he assigns no limit as to height), he found Potentilla Argentea, Rumex Scutatus, Tanacetum Vulgare, Anthemis Montana, Jacobæa Chrysanthemifolia, Seriola Uniflora, and Phalaris Alpina.

As regards the animal life on Etna, of course it is the same as that of the eastern sea-board of Sicily, except in the higher regions, where it becomes more sparse. The only living creatures in the upper regions are ants, a little lower down Spallanzani found a few partridges, jays, thrushes, ravens, and kites.

Brydone says of the three regions: "Besides the corn, the wine, the oil, the silk, the spice, and delicious fruits of its lower region; the beautiful forests, the flocks, the game, the tar, the cork, the honey of its second; the snow and ice of its third; it affords from its caverns a variety of minerals and other productions—cinnabar, mercury, sulphur, alum, nitre, and vitriol; so that this wonderful mountain at the same time produces every necessary, and every luxury of life."

[15] I am indebted for these figures to Mr. George Dennis, H.M. Consul General for Sicily.

[16] "Flora sicula: exhibens Plantas vasculosas in Sicilia aut sponte crescentes aut frequentissime cultas, secundum systema naturale digestas." Auctore G. B. Presl. Pragæ, 1824.

[17] Chloris Aetnensis: o le quattro Florule dell' Etna, opusculo del Sig. C. S. Rafinesque-Schmaltz, Palermo. Dicembre, 1813.

The most suitable time for ascending Etna.—The ascent commenced.—Nicolosi.—Etna mules.—Night journey through the upper Regions of the mountain.—Brilliancy of the Stars.—Proposed Observatory on Etna.—The Casa Inglesi.—Summit of the Great Crater.—Sunrise from the summit.—The Crater.—Descent from the Mountain.—Effects of Refraction.—Fatigue of the Ascent.

The ascent of Mount Etna has been described many times

during the last eighteen centuries, from Strabo in the

second century to Dr. Baltzer in 1875. One of the most

interesting accounts is certainly that of Brydone, and in

this century perhaps that of Mr. Gladstone. Of course

the interest of the expedition is greatly increased if it can

be combined with that spice of danger which is afforded

by the fact of the mountain being in a state of eruption

at the time.

The best period for making the ascent is between May and September, after the melting of the winter snows, and before the autumnal rains. In winter snow frequently extends from the summit downwards for nine or [Pg 44]ten miles; the paths are obliterated, and the guides refuse to accompany travellers. Even so late in the spring as May 29th Brydone had to traverse seven miles of snow before reaching the summit. Moreover, violent storms often rage in the upper regions of the mountain, and the wind acquires a force which it is difficult to withstand, and is at the same time piercingly cold. Sir William Hamilton, in relating his ascent on the night of June 26th, 1769, remarks that, if they had not kindled a fire at the halting place, and put on much warm clothing, they would "surely have perished with the cold." At the same time the wind was so violent that they had several times to throw themselves on their faces to avoid being overthrown. Yet the guides said that the wind was not unusually violent. Some writers, well used to Alpine climbing, have asserted that the cold on Etna was more severe than anything they have ever experienced in the Alps.

The writer of this memoir made the ascent of the mountain in August 1877, accompanied by a courier and a guide. We took with us two mules; some thick rugs; provisions consisting of bread, meat, wine, coffee, and brandy; wooden staves for making the ascent of the cone; a geological hammer; a bag for specimens; and a few other requisites. It has to be remembered that absolutely nothing is to be met with at the Casa Inglesi, where the halt is made for the night; even firewood has [Pg 45]to be taken, a fire being most necessary in those elevated regions even during a midsummer's night. For some time previous to our ascent the weather had been uniformly bright and fine, and there had been no rain for more than three months. The mean temperature in the shade at Catania, and generally along the eastern sea-base of the mountain, was 82° F.

As we desired to see the sunrise from the summit of the mountain, we determined to ascend during the cool of the evening, resting for an hour or two before sunrise at the Casa Inglesi at the foot of the cone. Accordingly we left Catania soon after midday, and drove to Nicolosi, twelve miles distant, and 2,288 feet above the sea. The road for some distance passed through a very fertile district; on either side there were corn fields and vineyards, and gardens of orange and lemon trees, figs and almonds, growing luxuriantly in the decomposed lava. About half way between Catania and Nicolosi stands the village of Gravina, and a mile beyond it Mascalucia, a small town containing nearly 4000 inhabitants. Near this is the ruined church of St. Antonio, founded in 1300. Nine miles from Catania the village of Torre di Grifo is passed, and the road then enters a nearly barren district covered with the lava and scoriæ of 1527. The only prominent form of vegetation is a peculiar tall broom—Genista Etnensis—which here flourishes. We are now entering the region of minor cones; the vineclad [Pg 46]cone of Monpilieri is visible on the left, and just above it Monti Rossi, 3,110 feet above the sea; to the right of the latter we see Monte San Nicola, Serrapizzuta, and Monte Arso. We reach Nicolosi at half-past four; for although the distance is short, the road is very rugged and steep.

Nicolosi has a population of less than 3,000; it consists of a long street, bordered by one-storied cottages of lava. In the church the priests were preparing for a festa in honour of S. Anthony of Padua. They politely took us into the sacristy, and exhibited with much pride some graven images of rather coarse workmanship, which were covered with gilding and bright coloured paint. Near Nicolosi stands the convent of S. Nicola dell' Arena, once inhabited by Benedictine monks, who however were compelled to abandon it in consequence of the destruction produced by successive shocks of earthquake. Nicolosi itself has been more than once shaken to the ground. We dined pretty comfortably, thanks to the courier who acted as cook, in the one public room of the one primitive inn of the town; starting for the Casa Inglesi at 6 o'clock. The good people of the inn surrounded us at our departure and with much warmth wished us a safe and successful journey.

For a short distance above Nicolosi, stunted vines are seen growing in black cinders, but these soon give place to a large tract covered with lava and ashes, with here [Pg 47]and there patches of broom. There was no visible path, but the mules seemed to know the way perfectly, and they continued to ascend with the same easy even pace without any guidance, even after the sun had disappeared behind the western flank of the mountain. In fact, you trust yourself absolutely to your mule, which picks his way over the roughest ground, and rarely stumbles or changes his even step. I found it quite easy to write notes while ascending, and even to use a pocket spectroscope at the time of the setting sun. Subsequently we saw a man extended at full length, and fast asleep upon a mule, which was leisurely plodding along the highway. The same confidence must not however be extended to the donkeys of Etna, as I found to my cost a few days later at Taormina. Here the only animal to be procured to carry me down to the sea-shore, 800 feet below, was a donkey. It was during the hottest part of the day, and it was necessary to carry an umbrella in one hand, and comfortable to wear a kind of turban of many folds of thin muslin round one's cap. The donkey after carefully selecting the roughest and most precipitous part of the road, promptly fell down, leaving me extended at full length on the road, with the open umbrella a few yards off. At the same time the turban came unfolded, and stretched itself for many a foot upon the ground. Altogether it was a most comical sight, and it reminded me forcibly, and at the instant, of a picture which I once [Pg 48]saw over the altar of a church in Pisa, and which represented S. Thomas Aquinas discomfiting Plato, Aristotle, and Averröes. The latter was completely overthrown, and in the most literal sense, for he was grovelling in the dust at the feet of S. Thomas, while his disarranged turban had fallen from him.

The district of lava and ashes above Nicolosi is succeeded by forests of small trees, and we are now fairly within the Regione Selvosa. At half-past 8 o'clock the temperature was 66°, at Nicolosi at 4 o'clock it was 80°. About 9 o'clock we arrived at the Casa del Bosco, (4,216 feet), a small house in which several men in charge of the forest live. Here we rested till 10 o'clock, and then after I had put on a great-coat and a second waistcoat, we started for the higher regions. At this time the air was extraordinarily still, the flame of a candle placed near the open door of the house did not flicker. The ascent from this point carried us through forests of pollard oaks, in which it was quite impossible to see either a path or any obstacles which might lie in one's way. The guide carried a lantern, and the mules seemed well accustomed to the route. At about 6,300 feet we entered the Regione Deserta, a lifeless waste of black sand, ashes, and lava; the ascent became more steep, and the air was bitterly cold. There was no moon, but the stars shone with an extraordinary brilliancy, and sparkled like particles of white-hot steel. I had never before seen [Pg 49]the heavens studded with such myriads of stars. The milky-way shone like a path of fire, and meteors flashed across the sky in such numbers that I soon gave up any attempt to count them. The vault of heaven seemed to be much nearer than when seen from the earth, and more flat, as if only a short distance above our heads, and some of the brighter stars appeared to be hanging down from the sky. Brydone, in speaking of his impressions under similar circumstances says:

"The sky was clear, and the immense vault of heaven appeared in awful majesty and splendour. We found ourselves more struck with veneration than below, and at first were at a loss to know the cause, till we observed with astonishment that the number of the stars seemed to be infinitely increased, and the light of each of them appeared brighter than usual. The whiteness of the milky-way was like a pure flame that shot across the heavens, and with the naked eye we could observe clusters of stars that were invisible in the regions below. We did not at first attend to the cause, nor recollect that we had now passed through ten or twelve thousand feet of gross vapour, that blunts and confuses every ray before it reaches the surface of the earth. We were amazed at the distinctness of vision, and exclaimed together, 'What a glorious situation for an observatory! had Empedocles had the eyes of Galileo, what discoveries must he not [Pg 50]have made!' We regretted that Jupiter was not visible, as I am persuaded we might have discovered some of his satellites with the naked eye, or at least with a small glass which I had in my pocket."

Brydone wrote a hundred years ago, but his idea of erecting an observatory on Mount Etna was only revived last year, when Prof. Tacchini the Astronomer Royal at Palermo, communicated a paper to the Accademia Gioenia, entitled "Della Convenienza ed utilita di erigere sull' Etna una Stazione Astronomico-Meteorologico." Tacchini mentions the extraordinary blueness of the sky as seen from Etna, and the appearance of the sun, which is "whiter and more tranquil" than when seen from below. Moreover, the spectroscopic lines are defined with wonderful distinctness. In the evening at 10 o'clock, Sirius appeared to rival Venus, the peculiarities of the ring of Saturn were seen far better than at Palermo; and Venus emitted a light sufficiently powerful to cast shadows; it also scintillated. When the chromosphere of the sun was examined the next morning by the spectroscope, the inversion of the magnesium line, and of the line 1474 was immediately apparent, although it was impossible to obtain this effect at Palermo. Tacchini proposes that an observatory should be established at the Casa Inglesi, in connection with the University of Catania, and that it be provided with a good six-inch refracting telescope, and with [Pg 51]meteorological instruments. In this observatory, constant observations should be made from the beginning of June to the end of September, and the telescope should then be transported to Catania, where a duplicate mounting might be provided for it, and observations continued for the rest of the year. There seems to be every probability that this scheme will be carried out in the course of next year.

During this digression we have been toiling along the slopes of the Regione Deserta and looking at the sky; at length we reach the Piano del Lago or Plain of the Lake, so called because a lake produced by the melting of the snows existed here till 1607, when it was filled up by lava. The air is now excessively cold, and a sharp wind is blowing. Progress is very slow, the soil consists of loose ashes, and the mules frequently stop; the guide assures us that the Casa Inglesi is quite near, but the stoppages become so frequent that it seems a long way off; at length we dismount, and drag the mules after us, and after a toilsome walk the small lava-built house, called the Casa Inglesi, is reached (1.30 a.m., temperature 40° F.) It stands at a height of 9,652 feet above the sea, near the base of the cone of the great crater, and it takes its name from the fact that it was erected by the English officers stationed in Sicily in 1811. It has suffered severely from time to time from the pressure of snow and from earthquakes, but it was thoroughly [Pg 52]repaired in 1862, on the occasion of the visit of Prince Humbert, and is now in tolerable preservation. It consists of three rooms, containing a few deal chairs, a table, and several shelves like the berths of ships furnished with plain straw mattresses; there is also a rough fireplace. We had no sooner reached this house, very weary and so cold that we could scarcely move, than it was discovered that the courier had omitted to get the key from Nicolosi, and there seemed a prospect of spending the hours till dawn in the open air. Fortunately we had with us a chisel and a geological hammer, and by the aid of these we forced open the shutter serving as a window, and crept into the house; ten minutes later a large wood fire was blazing up the chimney, our eatables were unpacked, some hot coffee was made, and we were supremely comfortable.

At 3 a.m. we left the Casa Inglesi for the summit of the great crater, 1,200 feet above us, in order to be in time to witness the sunrise. Our road lay for a short distance over the upper portion of the Piano del Lago, and the walking was difficult. The brighter stars had disappeared, and it was much darker than it had been some hours before. The guide led the way with a lantern. The ascent of the cone was a very stiff piece of work; it consists of loose ashes and blocks of lava, and slopes at an angle of "45° or more" according [Pg 53]to one writer, and of 33° according to another; probably the slope varies on different sides of the cone: we do not think that the slope much exceeds 33° anywhere on the side of the cone which we ascended. Fortunately there was no strong wind, and we did not suffer from the sickness of which travellers constantly complain in the rarefied air of the summit. We reached the highest point at 4.30 a.m., and found a temperature of 47° F.

When Sir William Hamilton ascended towards the end of June the temperature at the base of the mountain was 84° F., and at the summit 56° F. When Brydone left Catania on May 26th, 1770, the temperature was 76° F., Bar. 29 in. 8½ lines; at Nicolosi at midday on the 27th it was 73° F., Bar. 27 in. 1½ lines; at the Spelonca del Capriole (6,200 feet), 61° F., Bar. 26 in. 5½ lines; at the foot of the crater, temp. 33° F., Bar. 20 in. 4½ lines, and at the summit of the crater just before sunrise, temp. 27° F., Bar. 19 in. 4 lines.

On reaching the summit we noticed that a quantity of steam and sulphurous acid gas issued from the ground under our feet, and in some places the cinders were so hot that it was necessary to choose a cool place to sit down upon. A thermometer inserted just beneath the soil from which steam issued registered 182° F. For a short time we anxiously awaited the rising of the sun. Nearly all the stars had faded away; the vault of heaven was a pale blue, becoming a darker and darker [Pg 54]grey towards the west, where it appeared to be nearly black. Just before sunrise the sky had the appearance of an enormous arched spectrum, extremely extended at the blue end. Above the place where the sun would presently appear there was a brilliant red, shading off in the direction of the zenith to orange and yellow; this was succeeded by pale green, then a long stretch of pale blue, darker blue, dark grey, ending opposite the rising sun with black. This effect was quite distinct, it lasted some minutes, and was very remarkable. This was succeeded by the usual rayed appearance of the rising sun, and at ten minutes to 5 o'clock the upper limb of the sun was seen above the mountains of Calabria. Examined by the spectroscope the Fraunhofer lines were extremely distinct, particularly two lines near the red end of the spectrum.

The top of the mountain was now illuminated, while all below was in comparative darkness, and a light mist floated over the lower regions. We were so fortunate as to witness a phenomenon which is not always visible, viz., the projection of the triangular shadow of the mountain across the island, a hundred miles away. The shadow appeared vertically suspended in space at or beyond Palermo, and resting on a slightly misty atmosphere; it gradually sank until it reached the surface of the island, and as the sun rose it approached nearer and nearer to the base of the mountain. In a short time [Pg 55]the flood of light destroyed the first effects of light and shadow. The mountains of Calabria and the west coast of Italy appeared very close, and Stromboli and the Lipari Islands almost under our feet; the east coast of Sicily could be traced until it ended at Cape Passaro and turned to the west, forming the southern boundary of the island, while to the west distant mountains appeared. No one would have the hardihood to attempt to describe the various impressions which rapidly float through the mind during the contemplation of sunrise from the summit of Etna. Brydone, who is by no means inclined to be rapturous or ecstatic in regard to the many wonderful sights he saw in the course of his tour, calls this "the most wonderful and most sublime sight in nature." "Here," he adds, "description must ever fall short, for no imagination has dared to form an idea of so glorious and so magnificent a scene. Neither is there on the surface of this globe any one point that unites so many awful and sublime objects. The immense elevation from the surface of the earth, drawn as it were to a single point, without any neighbouring mountains for the senses and imagination to rest upon, and recover from their astonishment in their way down to the world. This point or pinnacle, raised on the brink of a bottomless gulph, as old as the world, often discharging rivers of fire and throwing out burning rocks with a noise that shakes the whole island. [Pg 56]Add to this, the unbounded extent of the prospect, comprehending the greatest diversity and the most beautiful scenery in nature, with the rising sun advancing in the east to illuminate the scene."