The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson - Swanston Edition Vol. 24 (of 25), by Robert Louis Stevenson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson - Swanston Edition Vol. 24 (of 25) Author: Robert Louis Stevenson Other: Andrew Lang Release Date: March 28, 2010 [EBook #31809] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORKS OF STEVENSON *** Produced by Marius Masi, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Of this SWANSTON EDITION in Twenty-five

Volumes of the Works of ROBERT LOUIS

STEVENSON Two Thousand and Sixty Copies

have been printed, of which only Two Thousand

Copies are for sale.

This is No. ............

TEMBINOKA, KING OF APEMAMA, WITH THE HEIR-APPARENT

For permission to use the Letters in the

Swanston Edition of Stevenson’s Works

the Publishers are indebted to the kindness of

Messrs. Methuen & Co., Ltd.

VII. THE RIVIERA AGAIN—MARSEILLES AND HYÈRES | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory | 3 |

| Letters— | |

| To the Editor of the New York Tribune | 7 |

| To R. A. M. Stevenson | 8 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 9 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 9 |

| To Trevor Haddon | 10 |

| [Mrs. R. L. Stevenson to John Addington Symonds] | 11 |

| To Charles Baxter | 14 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 15 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 16 |

| To W. E. Henley | 17 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 21 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 22 |

| To W. E. Henley | 23 |

| To Mrs. Sitwell | 24 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 26 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 27 |

| To the Same | 28 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 29 |

| To the Same | 30 |

| To W. E. Henley | 31 |

| To the Same | 32 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 33 |

| To W. E. Henley | 34 |

| To the Same | 36 |

| To Jules Simoneau | 36 |

| To W. E. Henley | 37 |

| To Trevor Haddon | 39 |

| To Jules Simoneau | 41 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 44 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 45 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 46 |

| To W. E. Henley | 47 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 50 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 52 |

| To W. E. Henley | 54 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 55 |

| To W. E. Henley | 57 |

| To W. H. Low | 57 |

| To R. A. M. Stevenson | 59 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 62 |

| To W. H. Low | 63 |

| To W. E. Henley | 65 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 66 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 67 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 69 |

| To Mrs. Milne | 70 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 71 |

| To W. E. Henley | 72 |

| To W. H. Low | 73 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 74 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 75 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 76 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 78 |

| To W. E. Henley | 79 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 81 |

| To Mr. Dick | 83 |

| To Cosmo Monkhouse | 85 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 87 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 88 |

| To W. H. Low | 89 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 90 |

| To W. E. Henley | 91 |

| To Trevor Haddon | 93 |

| To Cosmo Monkhouse | 95 |

| To W. E. Henley | 96 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 97 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 98 |

| To the Same | 99 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 100 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 101 |

| To W. E. Henley | 102 |

VIII. LIFE AT BOURNEMOUTH | |

| Introductory | 104 |

| Letters— | |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 110 |

| To Andrew Chatto | 110 |

| To W. E. Henley | 111 |

| To the Rev. Professor Lewis Campbell | 113 |

| To W. E. Henley | 115 |

| To W. H. Low | 115 |

| To Sir Walter Simpson | 117 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 118 |

| To the Same | 119 |

| To W. E. Henley | 120 |

| To Charles Baxter | 121 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 121 |

| To Charles Baxter | 122 |

| To W. E. Henley | 123 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 125 |

| To Austin Dobson | 126 |

| To W. E. Henley | 127 |

| To Henry James | 127 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 130 |

| To W. E. Henley | 131 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 132 |

| To W. E. Henley | 133 |

| To H. A. Jones | 133 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 134 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 135 |

| To Sidney Golvin | 136 |

| To the Same | 137 |

| To J. A. Symonds | 138 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 140 |

| To W. H. Low | 142 |

| To P. G. Hamerton | 143 |

| To W. E. Henley | 146 |

| To the Same | 147 |

| To William Archer | 147 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Pennell | 149 |

| To Mrs. Fleeming Jenkin | 150 |

| To the Same | 151 |

| To C. Howard Carrington | 152 |

| To Katharine de Mattos | 152 |

| To W. H. Low | 153 |

| To W. E. Henley | 155 |

| To William Archer | 156 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 159 |

| To Henry James | 160 |

| To William Archer | 161 |

| To the Same | 163 |

| To W. H. Low | 166 |

| To Mrs. de Mattos | 167 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 167 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 168 |

| To W. H. Low | 169 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 173 |

| To James Payn | 176 |

| To W. H. Low | 177 |

| To Charles J. Guthrie | 178 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 179 |

| To C. W. Stoddard | 180 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 181 |

| To J. A. Symonds | 183 |

| To F. W. H. Myers | 184 |

| To W. H. Low | 185 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 186 |

| To Mrs. Fleeming Jenkin | 187 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 189 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 190 |

| To Miss Monroe | 191 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 192 |

| To Miss Monroe | 193 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 196 |

| To R. A. M. Stevenson | 196 |

| To the Same | 198 |

| To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 199 |

| To Charles Baxter | 200 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 200 |

| To Thomas Stevenson | 201 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 202 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 202 |

| To T. Watts-Dunton | 203 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 204 |

| To Frederick Locker-Lampson | 205 |

| To the Same | 206 |

| To the Same | 207 |

| To the Same | 208 |

| To Auguste Rodin | 209 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 210 |

| To Lady Taylor | 211 |

| To the Same | 213 |

| To Henry James | 214 |

| To Frederick Locker-Lampson | 215 |

| To Henry James | 215 |

| To Auguste Rodin | 216 |

| To W. H. Low | 217 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 219 |

| To Alison Cunningham | 220 |

| To Mrs. Fleeming Jenkin | 221 |

| To the Same | 225 |

| To Miss Rawlinson | 227 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 228 |

| To Sir Walter Simpson | 229 |

| To W. E. Henley | 229 |

| To W. H. Low | 230 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 231 |

| To Messrs. Chatto and Windus | 231 |

IX. THE UNITED STATES AGAINWINTER IN THE ADIRONDACKS | |

| Introductory | 233 |

| Letters— | |

| To Sidney Colvin | 235 |

| To the Same | 236 |

| To Henry James | 237 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 238 |

| To W. E. Henley | 239 |

| To R. A. M. Stevenson | 240 |

| To Sir Walter Simpson | 242 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 244 |

| To W. H. Low | 245 |

| To Charles Fairchild | 246 |

| To William Archer | 247 |

| To W. E. Henley | 248 |

| To Henry James | 249 |

| To Charles Baxter | 251 |

| To Charles Scribner | 252 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 253 |

| To the Same | 254 |

| To John Addington Symonds | 254 |

| To W. E. Henley | 257 |

| To Mrs. Fleeming Jenkin | 258 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 259 |

| To Charles Baxter | 260 |

| To Miss Munroe | 261 |

| To Henry James | 262 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 264 |

| To the Same | 265 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 267 |

| To Charles Baxter | 268 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 268 |

| To William Archer | 270 |

| To the Same | 272 |

| To the Same | 273 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 273 |

| To the Same | 274 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 275 |

| To the Rev. Dr. Charteris | 276 |

| To Edmund Gosse | 277 |

| To Henry James | 278 |

| To the Rev. Dr. Charteris | 279 |

| To S. R. Crockett | 280 |

| To Miss Ferrier | 282 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 283 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 284 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 285 |

| To Charles Baxter | 286 |

| To Lady Taylor | 286 |

| To Homer St. Gaudens | 287 |

| To Henry James | 288 |

X. PACIFIC VOYAGESYACHT CASCO—SCHOONER EQUATOR—S.S. JANET NICOLL | |

| Introductory | 290 |

| Letters— | |

| To Sidney Colvin | 293 |

| To Charles Baxter | 294 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 295 |

| To Charles Baxter | 296 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 297 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 298 |

| To William and Thomas Archer | 300 |

| To Charles Baxter | 301 |

| To the Same | 303 |

| To John Addington Symonds | 304 |

| To Thomas Archer | 305 |

| [Mrs. R. L. Stevenson to Sidney Colvin] | 308 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 316 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 319 |

| To Charles Baxter | 322 |

| To R. A. M. Stevenson | 323 |

| To Marcel Schwob | 327 |

| To Charles Baxter | 327 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 329 |

| [Mrs. R. L. Stevenson to Mrs. Sitwell] | 331 |

| To Henry James | 334 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 336 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 338 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 339 |

| To Charles Baxter | 343 |

| To the Same | 344 |

| To W. H. Low | 345 |

| [Mrs. R. L. Stevenson to Sidney Colvin] | 347 |

| To Mrs. R. L. Stevenson | 349 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 353 |

| To James Payn | 355 |

| To Lady Taylor | 357 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 357 |

| To the Same | 362 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 367 |

| To Charles Baxter | 369 |

| To Lady Taylor | 372 |

| To Dr. Scott | 374 |

| To Charles Baxter | 375 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 377 |

| To James Payn | 381 |

| To Henry James | 382 |

| To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson | 383 |

| To Charles Baxter | 384 |

| To Sidney Colvin | 385 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 387 |

| To Charles Baxter | 392 |

| To E. L. Burlingame | 394 |

| To Henry James | 396 |

| To Marcel Schwob | 397 |

| To Andrew Lang | 399 |

| To Miss Adelaide Boodle | 401 |

| To Mrs. Charles Fairchild | 403 |

In the two years and odd months since his return from California, Stevenson had made no solid gain of health. His winters, and especially his second winter, at Davos had seemed to do him much temporary good; but during the summers in Scotland he had lost as much as he had gained, or more. Loving the Mediterranean shores of France from of old, he now made up his mind to try them once again.

As the ways and restrictions of a settled invalid were repugnant to Stevenson’s character and instincts, so were the life and society of a regular invalid station depressing and uncongenial to him. He determined, accordingly, to avoid settling in one of these, and hoped to find a suitable climate and habitation that should be near, though not in, some centre of the active and ordinary life of man, with accessible markets, libraries, and other resources. In September 1882 he started with his cousin Mr. R. A. M. Stevenson in search of a new home, and 4 thought first of trying the Languedoc coast, a region new to him. At Montpellier, he was laid up again with a bad bout of his lung troubles; and, the doctor not recommending him to stay, returned to Marseilles. Here he was rejoined by his wife, and after a few days’ exploration in the neighbourhood they lighted on what seemed exactly the domicile they wanted. This was a roomy and attractive enough house and garden called the Campagne Defli, near the manufacturing suburb of St. Marcel, in a sheltered position in full view of the shapely coastward hills. By the third week in October they were installed, and in eager hopes of pleasant days to come and a return to working health. These hopes were not realised. Week after week went on, and the hemorrhages and fits of fever and exhaustion did not diminish. Work, except occasional verses, and a part of the story called The Treasure of Franchard, would not flow, and the time had to be whiled away with games of patience and other resources of the sick man. Nearly two months were thus passed; during the whole of one of them Stevenson had not been able to go beyond the garden; and by Christmas he had to face the fact that the air of the place was tainted. An epidemic of fever, due to some defect of drainage, broke out, and it became clear that this could be no home for Stevenson. Accordingly, at his wife’s instance, though having scarce the strength to travel, he left suddenly for Nice, she staying behind to pack their chattels and wind up their affairs and responsibilities as well as might be. Various misadventures, miscarriages of telegrams, journeys taken at cross purposes and the like, making existence uncomfortably dramatic at the moment, caused the couple to believe for a while that they had fairly lost each other. Mrs. Stevenson allows me to print a letter from herself 5 to Mr. J. A. Symonds vividly relating these predicaments (see p. 11 foll.). At last, in the course of January, they came safely together at Marseilles, and next made a few weeks’ stay at Nice, where Stevenson’s health quickly mended. Thence they returned as far as Hyères. Staying here through the greater part of February, at the Hôtel des Îles d’Or, and finding the place to their liking, they cast about once more for a resting-place, and were this time successful.

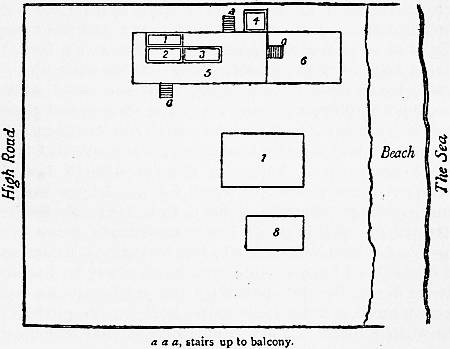

The house chosen by the Stevensons at Hyères was not near the sea, but inland, on the road above the old town and beneath the ruins of the castle. The Chalet La Solitude it was called; a cramped but habitable cottage built in the Swiss manner, with a pleasant strip of garden, and a view and situation hardly to be bettered. Here he and his family lived for the next sixteen months (March 1883 to July 1884). To the first part of this period he often afterwards referred as the happiest time of his life. His malady remained quiescent enough to afford, at least to his own buoyant spirit, a strong hope of ultimate recovery. He delighted in his surroundings, and realised for the first time the joys of a true home of his own. The last shadow of a cloud between himself and his parents had long passed away; and towards his father, now in declining health, and often suffering from moods of constitutional depression, the son begins on his part to assume, how touchingly and tenderly will be seen from the following letters, a quasi-paternal attitude of encouragement and monition. At the same time his work on the completion of the Silverado Squatters, on Prince Otto, the Child’s Garden of Verses (for which his own name was Penny Whistles), on the Black Arrow (designated hereinafter, on account of its Old English 6 dialect, as “tushery”), and other undertakings prospered well. In the autumn the publication of Treasure Island in book form brought with it the first breath of popular applause. The reader will see how modest a price Stevenson was content, nay, delighted, to receive for this classic. It was two or three years yet before he could earn enough to support himself and his family by literature: a thing he had always been earnestly bent on doing, regarding it as the only justification for his chosen way of life. In the meantime, it must be understood, whatever help he needed from his father was from the hour of his marriage always amply and ungrudgingly given.

In September of the same year, 1883, Stevenson had felt deeply the death of his old friend James Walter Ferrier (see the essay Old Mortality and the references in the following letters). But still his health held out fairly, until, in January 1884, on a visit to Nice, he was unexpectedly prostrated anew by an acute congestion of the internal organs, which for the time being brought him to death’s door. Returning to his home, his recovery had been only partial when, after four months (May 1884), a recurrence of violent hemorrhages from the lung once more prostrated him completely; soon after which he quitted Hyères, and the epidemic of cholera which broke out there the same summer prevented all thoughts of his return.

The Hyères time, both during the happy and hard-working months of March-December 1883, and the semi-convalescence of February-May 1884, was a prolific one in the way of correspondence; and there is perhaps no period of his life when his letters reflect so fully the variety of his moods and the eagerness of his occupations.

To the Editor of the New York Tribune

At Marseilles, while waiting to occupy the house which he had leased in the suburbs of that city, Stevenson learned that his old friend and kind adviser, Mr. James Payn, with whom he had been intimate as sub-editor of the Cornhill Magazine under Mr. Leslie Stephen in the ’70’s, had been inadvertently represented in the columns of the New York Tribune as a plagiarist of R. L. S. In order to put matters right, he at once sent the following letter both to the Tribune and to the London Athenæum:—

Terminus Hotel, Marseilles, October 16, 1882.

SIR,—It has come to my ears that you have lent the authority of your columns to an error.

More than half in pleasantry—and I now think the pleasantry ill-judged—I complained in a note to my New Arabian Nights that some one, who shall remain nameless for me, had borrowed the idea of a story from one of mine. As if I had not borrowed the ideas of the half of my own! As if any one who had written a story ill had a right to complain of any other who should have written it better! I am indeed thoroughly ashamed of the note, and of the principle which it implies.

But it is no mere abstract penitence which leads me to beg a corner of your paper—it is the desire to defend the honour of a man of letters equally known in America and England, of a man who could afford to lend to me and yet be none the poorer; and who, if he would so far condescend, has my free permission to borrow from me all that he can find worth borrowing.

Indeed, sir, I am doubly surprised at your correspondent’s error. That James Payn should have borrowed from me is already a strange conception. The author of Lost Sir Massingberd and By Proxy may be trusted to invent his own stories. The author of A Grape from a Thorn knows enough, in his own right, of the humorous and pathetic sides of human nature.

But what is far more monstrous—what argues total ignorance of the man in question—is the idea that James 8 Payn could ever have transgressed the limits of professional propriety. I may tell his thousands of readers on your side of the Atlantic that there breathes no man of letters more inspired by kindness and generosity to his brethren of the profession, and, to put an end to any possibility of error, I may be allowed to add that I often have recourse, and that I had recourse once more but a few weeks ago, to the valuable practical help which he makes it his pleasure to extend to younger men.

I send a duplicate of this letter to a London weekly; for the mistake, first set forth in your columns, has already reached England, and my wanderings have made me perhaps last of the persons interested to hear a word of it.—I am, etc.,

Robert Louis Stevenson.

To R. A. M. Stevenson

Terminus Hotel, Marseille, Saturday [October 1882].

MY DEAR BOB,—We have found a house!—at Saint Marcel, Banlieue de Marseille. In a lovely valley between hills part wooded, part white cliffs; a house of a dining-room, of a fine salon—one side lined with a long divan—three good bedrooms (two of them with dressing-rooms), three small rooms (chambers of bonne and sich), a large kitchen, a lumber room, many cupboards, a back court, a large olive yard, cultivated by a resident paysan, a well, a berceau, a good deal of rockery, a little pine shrubbery, a railway station in front, two lines of omnibus to Marseille.

£48 per annum.

It is called Campagne Defli! query Campagne Debug? The Campagne Demosquito goes on here nightly, and is very deadly. Ere we can get installed, we shall be beggared to the door, I see.

I vote for separations; F.’s arrival here, after our 9 separation, was better fun to me than being married was by far. A separation completed is a most valuable property; worth piles.—Ever your affectionate cousin,

R. L. S.

To Thomas Stevenson

Terminus Hotel, Marseille, le 17th October 1882.

MY DEAR FATHER,—We grow, every time we see it, more delighted with our house. It is five miles out of Marseilles, in a lovely spot, among lovely wooded and cliffy hills—most mountainous in line—far lovelier, to my eyes, than any Alps. To-day we have been out inventorying; and though a mistral blew, it was delightful in an open cab, and our house with the windows open was heavenly, soft, dry, sunny, southern. I fear there are fleas—it is called Campagne Defli—and I look forward to tons of insecticide being employed.

I have had to write a letter to the New York Tribune and the Athenæum. Payn was accused of stealing my stories! I think I have put things handsomely for him.

Just got a servant!!!—Ever affectionate son,

R. L. Stevenson.

Our servant is a Muckle Hash of a Weedy!

To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson

The next two months’ letters had perforce to consist of little save bulletins of back-going health, and consequent disappointment and incapacity for work.

Campagne Defli, St. Marcel, Banlieue de Marseille, November 13, 1882.

MY DEAR MOTHER,—Your delightful letters duly arrived this morning. They were the only good feature of the day, which was not a success. Fanny was in bed—she begged I would not split upon her, she felt so guilty; but as I believe she is better this evening, and has a good 10 chance to be right again in a day or two, I will disregard her orders. I do not go back, but do not go forward—or not much. It is, in one way, miserable—for I can do no work; a very little wood-cutting, the newspapers, and a note about every two days to write, completely exhausts my surplus energy; even Patience I have to cultivate with parsimony. I see, if I could only get to work, that we could live here with comfort, almost with luxury. Even as it is, we should be able to get through a considerable time of idleness. I like the place immensely, though I have seen so little of it—I have only been once outside the gate since I was here! It puts me in mind of a summer at Prestonpans and a sickly child you once told me of.

Thirty-two years now finished! My twenty-ninth was in San Francisco, I remember—rather a bleak birthday. The twenty-eighth was not much better; but the rest have been usually pleasant days in pleasant circumstances.

Love to you and to my father and to Cummy.

From me and Fanny and Wogg.

R. L. S.

To Trevor Haddon

Campagne Defli, St. Marcel, Dec. 29th, 1882.

DEAR SIR,—I am glad you sent me your note, I had indeed lost your address, and was half thinking to try the Ringstown one; but far from being busy, I have been steadily ill. I was but three or four days in London, waiting till one of my friends was able to accompany me, and had neither time nor health to see anybody but some publisher people. Since then I have been worse and better, better and worse, but never able to do any work and for a large part of the time forbidden to write and even to play Patience, that last of civilised amusements. In brief, I have been “the sheer hulk” to a degree almost outside of my experience, and I desire all my friends to 11 forgive me my sins of omission this while back. I only wish you were the only one to whom I owe a letter, or many letters.

But you see, at least, you had done nothing to offend me; and I dare say you will let me have a note from time to time, until we shall have another chance to meet.—Yours sincerely,

Robert Louis Stevenson.

An excellent new year to you, and many of them.

If you chance to see a paragraph in the papers describing my illness, and the “delicacies suitable to my invalid condition” cooked in copper, and the other ridiculous and revolting yarns, pray regard it as a spectral illusion, and pass by.

[Mrs. R. L. Stevenson

to John Addington Symonds

I intercalate here Mrs. Stevenson’s extremely vivid and characteristic account of the weird misadventures that befell the pair during their retreat from St. Marcel in search of a healthier home.

[Campagne Defli, St. Marcel, January 1883.]

MY DEAR MR. SYMONDS,—What must you think of us? I hardly dare write to you. What do you do when people to whom you have been the dearest of friends requite you by acting like fiends? I do hope you heap coals of fire on their heads in the good old Christian sense.

Louis has been very ill again. I hasten to say that he is now better. But I thought at one time he would never be better again. He had continual hemorrhages and became so weak that he was twice insensible in one day, and was for a long time like one dead. At the worst fever broke out in this village, typhus, I think, and all day the death-bells rang, and we could hear the chanting whilst the wretched villagers carried about their dead lying bare to the sun on their coffin-lids, so spreading the contagion through the streets. The evening of the day when Louis was so long insensible the weather changed, becoming very 12 clear and fine and greatly refreshing and reviving him. Then I said if it held good he should start in the morning for Nice and try what a change might do. Just at that time there was not money enough for the two of us, so he had to start alone, though I expected soon to be able to follow him. During the night a peasant-man died in a house in our garden, and in the morning the corpse, hideously swollen in the stomach, was lying on its coffin-lid at our gates. Fortunately it was taken away just before Louis went, and he didn’t see it nor hear anything about it until afterwards. I had been back and forth all the morning from the door to the gates, and from the gates to the door, in an agony lest Louis should have to pass it on his way out.

I was to have a despatch from Toulon where Louis was to pass the night, two hours from St. Marcel, and another from Nice, some few hours further, the next day. I waited one, two, three, four days, and no word came. Neither telegram nor letter. The evening of the fourth day I went to Marseilles and telegraphed to the Toulon and Nice stations and to the bureau of police. I had been pouring out letters to every place I could think of. The people at Marseilles were very kind and advised me to take no further steps to find my husband. He was certainly dead, they said. It was plain that he stopped at some little station on the road, speechless and dying, and it was now too late to do anything; I had much better return at once to my friends. “Eet ofen ’appens so,” said the Secretary, and “Oh yes, all right, very well,” added a Swiss in a sympathetic voice. I waited all night at Marseilles and got no answer, all the next day and got no answer; then I went back to St. Marcel and there was nothing there. At eight I started on the train with Lloyd who had come for his holidays, but it only took us to Toulon where again I telegraphed. At last I got an answer the next day at noon. I waited at Toulon for the train I had reason to believe Louis travelled by, 13 intending to stop at every station and inquire for him until I got to Nice. Imagine what those days were to me. I never received any of the letters Louis had written to me, and he was reading the first he had received from me when I knocked at his door. A week afterwards I had an answer from the police. Louis was much better: the change and the doctor, who seems very clever, have done wonderful things for him. It was during this first day of waiting that I received your letter. There was a vague comfort in it like a hand offered in the darkness, but I did not read it until long after.

We have had many other wild misadventures, Louis has twice (started) actually from Nice under a misapprehension. At this moment I believe him to be at Marseilles, stopping at the Hotel du Petit Louvre; I am supposed to be packing here at St. Marcel, afterwards we are to go somewhere, perhaps to the Lake of Geneva. My nerves were so shattered by the terrible suspense I endured that memorable week that I have not been fit to do much. When I was returning from Nice a dreadful old man with a fat wife and a weak granddaughter sat opposite me and plied me with the most extraordinary questions. He began by asking if Lloyd was any connection of mine, and ended I believe by asking my mother’s maiden name. Another of the questions he put to me was where Louis wished to be buried, and whether I could afford to have him embalmed when he died. When the train stopped the only other passenger, a quiet man in a corner who looked several times as if he wished to interfere and stop the old man but was too shy, came to me and said that he knew Sidney Colvin and he knew you, and that you were both friends of Louis; and that his name was Basil Hammond,1 and he wished to stay on a day in Marseilles and help me work off my affairs. I accepted his offer with heartfelt thanks. I was extremely ill next day, but we 14 two went about and arranged about giving up this house and what compensation, and did some things that I could not have managed alone. My French is useful only in domestic economy, and even that, I fear, is very curious and much of it patois. Wasn’t that a good fellow, and a kind fellow?—I cannot tell you how grateful I am, words are such feeble things—at least for that purpose. For anger, justifiable wrath, they are all too forcible. It was very bad of me not to write to you, we talked of you so often and thought of you so much, and I always said—“now I will write”—and then somehow I could not....

Fanny V. de G. Stevenson.]

To Charles Baxter

After his Christmas flight to Marseilles and thence to Nice, Stevenson began to mend quickly. In this letter to Mr. Baxter he acknowledges the receipt of a specimen proof, set up for their private amusement, of Brashiana, the series of burlesque sonnets he had written at Davos in memory of the Edinburgh publican already mentioned. It should be explained that in their correspondence Stevenson and Mr. Baxter were accustomed to keep up an old play of their student days by merging their identities in those of two fictitious personages, Thomson and Johnson, imaginary types of Edinburgh character, and ex-elders of the Scottish Kirk.

Grand Hotel, Nice, 12th January ’83.

DEAR CHARLES,—Thanks for your good letter. It is true, man, God’s trüth, what ye say about the body Stevison. The deil himsel, it’s my belief, couldnae get the soul harled oot o’ the creature’s wame, or he had seen the hinder end o’ they proofs. Ye crack o’ Mæcenas, he’s naebody by you! He gied the lad Horace a rax forrit by all accounts; but he never gied him proofs like yon. Horace may hae been a better hand at the clink than Stevison—mind, I’m no sayin’ ’t—but onyway he was never sae weel prentit. Damned, but it’s bonny! Hoo mony pages will there be, think ye? Stevison maun hae sent ye the feck o’ twenty sangs—fifteen I’se warrant. Weel, that’ll can make thretty pages, gin ye were to prent 15 on ae side only, whilk wad be perhaps what a man o’ your great idees would be ettlin’ at, man Johnson. Then there wad be the Pre-face, an’ prose ye ken prents oot langer than po’try at the hinder end, for ye hae to say things in’t. An’ then there’ll be a title-page and a dedication and an index wi’ the first lines like, and the deil an’ a’. Man, it’ll be grand. Nae copies to be given to the Liberys.

I am alane myself, in Nice, they ca’t, but damned, I think they micht as well ca’t Nesty. The Pile-on,2 ’s they ca’t, ’s aboot as big as the river Tay at Perth; and it’s rainin’ maist like Greenock. Dod, I’ve seen ’s had mair o’ what they ca’ the I-talian at Muttonhole. I-talian! I haenae seen the sun for eicht and forty hours. Thomson’s better, I believe. But the body’s fair attenyated. He’s doon to seeven stane eleeven, an’ he sooks awa’ at cod liver ile, till it’s a fair disgrace. Ye see he tak’s it on a drap brandy; and it’s my belief, it’s just an excuse for a dram. He an’ Stevison gang aboot their lane, maistly; they’re company to either, like, an’ whiles they’ll speak o’ Johnson. But he’s far awa’, losh me! Stevison’s last book ’s in a third edeetion; an’ it’s bein’ translated (like the psaulms of David, nae less) into French; and an eediot they ca’ Asher—a kind o’ rival of Tauchnitz—is bringin’ him oot in a paper book for the Frenchies and the German folk in twa volumes. Sae he’s in luck, ye see.—Yours,

Thomson.

To Sidney Colvin

Stevenson here narrates in his own fashion by what generalship he at last got rid of the Campagne Defli without having to pay compensation as his wife expected.

Hotel du Petit Louvre, Marseille, 15 Feb. 1883.

DEAR SIR,—This is to intimate to you that Mr. and Mrs. Robert Louis Stevenson were yesterday safely delivered

of a

Campagne.

The parents are both doing much better than could be expected; particularly the dear papa.

There, Colvin, I did it this time. Huge success. The propriétaires were scattered like chaff. If it had not been the agent, may Israel now say, if it had not been the agent who was on our side! But I made the agent march! I threatened law; I was Immense—what do I say?—Immeasurable. The agent, however, behaved well and is a fairly honest little one-eared, white-eyed tom-cat of an opera-going gold-hunter. The propriétaire non est inventa; we countermarched her, got in valuators; and in place of a hundred francs in her pocket, she got nothing, and I paid one silver biscuit! It might go further but I am convinced will not, and anyway, I fear not the consequences.

The weather is incredible; my heart sings; my health satisfies even my wife. I did jolly well right to come after all and she now admits it. For she broke down as I knew she would, and I from here, without passing a night at the Defli, though with a cruel effusion of coach-hires, took up the wondrous tale and steered the ship through. I now sit crowned with laurel and literally exulting in kudos. The affair has been better managed than our two last winterings,—I am yours,

Brabazon Drum.

To Alison Cunningham

The verses referred to in the following are those of the Child’s Garden.

[Nice, February 1883.]

MY DEAR CUMMY,—You must think, and quite justly, that I am one of the meanest rogues in creation. But though I do not write (which is a thing I hate), it by no means follows that people are out of my mind. It is natural that I should always think more or less about you, and still more natural that I should think of you when I went back to Nice. But the real reason why you 17 have been more in my mind than usual is because of some little verses that I have been writing, and that I mean to make a book of; and the real reason of this letter (although I ought to have written to you anyway) is that I have just seen that the book in question must be dedicated to

Alison Cunningham,

the only person who will really understand it, I don’t know when it may be ready, for it has to be illustrated, but I hope in the meantime you may like the idea of what is to be; and when the time comes, I shall try to make the dedication as pretty as I can make it. Of course, this is only a flourish, like taking off one’s hat; but still, a person who has taken the trouble to write things does not dedicate them to any one without meaning it; and you must just try to take this dedication in place of a great many things that I might have said, and that I ought to have done, to prove that I am not altogether unconscious of the great debt of gratitude I owe you. This little book, which is all about my childhood, should indeed go to no other person but you, who did so much to make that childhood happy.

Do you know, we came very near sending for you this winter. If we had not had news that you were ill too, I almost believe we should have done so, we were so much in trouble.

I am now very well; but my wife has had a very, very bad spell, through overwork and anxiety, when I was lost! I suppose you heard of that. She sends you her love, and hopes you will write to her, though she no more than I deserves it. She would add a word herself, but she is too played out.—I am, ever your old boy,

R. L. S.

To W. E. Henley

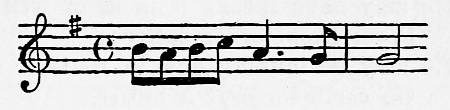

Stevenson was by this time beginning to send home some of the MS. of the Child’s Garden, the title of which had not yet been settled. 18 The pieces as first numbered are in a different order from that afterwards adopted, but the reader will easily identify the references.

[Nice, March 1883.]

MY DEAR LAD,—This is to announce to you the MS. of Nursery Verses, now numbering XLVIII. pieces or 599 verses, which, of course, one might augment ad infinitum.

But here is my notion to make all clear.

I do not want a big ugly quarto; my soul sickens at the look of a quarto. I want a refined octavo, not large—not larger than the Donkey book, at any price.

I think the full page might hold four verses of four lines, that is to say, counting their blanks at two, of twenty-two lines in height. The first page of each number would only hold two verses or ten lines, the title being low down. At this rate, we should have seventy-eight or eighty pages of letterpress.

The designs should not be in the text, but facing the poem; so that if the artist liked, he might give two pages of design to every poem that turned the leaf, i.e. longer than eight lines, i.e. to twenty-eight out of the forty-six. I should say he would not use this privilege (?) above five times, and some he might scorn to illustrate at all, so we may say fifty drawings. I shall come to the drawings next.

But now you see my book of the thickness, since the drawings count two pages, of 180 pages; and since the paper will perhaps be thicker, of near two hundred by bulk. It is bound in a quiet green with the words in thin gilt. Its shape is a slender, tall octavo. And it sells for the publisher’s fancy, and it will be a darling to look at; in short, it would be like one of the original Heine books in type and spacing.

Now for the pictures. I take another sheet and begin to jot notes for them when my imagination serves: I will run through the book, writing when I have an idea. There, I have jotted enough to give the artist a notion. Of course, I don’t do more than contribute ideas, but I will 19 be happy to help in any and every way. I may as well add another idea; when the artist finds nothing much to illustrate, a good drawing of any object mentioned in the text, were it only a loaf of bread or a candlestick, is a most delightful thing to a young child. I remember this keenly.

Of course, if the artist insists on a larger form, I must, I suppose, bow my head. But my idea I am convinced is the best, and would make the book truly, not fashionably pretty.

I forgot to mention that I shall have a dedication; I am going to dedicate ’em to Cummy; it will please her, and lighten a little my burthen of ingratitude. A low affair is the Muse business.

I will add no more to this lest you should want to communicate with the artist; try another sheet. I wonder how many I’ll keep wandering to.

O I forgot. As for the title, I think “Nursery Verses” the best. Poetry is not the strong point of the text, and I shrink from any title that might seem to claim that quality; otherwise we might have “Nursery Muses” or “New Songs of Innocence” (but that were a blasphemy), or “Rimes of Innocence”: the last not bad, or—an idea—“The Jews’ Harp,” or—now I have it—“The Penny Whistle.”

THE PENNY WHISTLE

NURSERY VERSES

BY

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

ILLUSTRATED BY —— —— ——

And here we have an excellent frontispiece, of a party playing on a P. W. to a little ring of dancing children.

THE PENNY WHISTLE

is the name for me.

Fool! this is all wrong, here is the true name:—

PENNY WHISTLES

FOR SMALL WHISTLERS.

The second title is queried, it is perhaps better, as simply PENNY WHISTLES.

|

Nor you, O Penny Whistler, grudge That I your instrument debase: By worse performers still we judge, And give that fife a second place! |

Crossed penny whistles on the cover, or else a sheaf of ’em.

SUGGESTIONS

IV. The procession—the child running behind it. The procession tailing off through the gates of a cloudy city.

IX. Foreign Lands.—This will, I think, want two plates—the child climbing, his first glimpse over the garden wall, with what he sees—the tree shooting higher and higher like the beanstalk, and the view widening. The river slipping in. The road arriving in Fairyland.

X. Windy Nights.—The child in bed listening—the horseman galloping.

XII. The child helplessly watching his ship—then he gets smaller, and the doll joyfully comes alive—the pair landing on the island—the ship’s deck with the doll steering and the child firing the penny cannon. Query two plates? The doll should never come properly alive.

XV. Building of the ship—storing her—Navigation—Tom’s accident, the other child paying no attention.

XXXI. The Wind.—I sent you my notion of already.

XXXVII. Foreign Children.—The foreign types dancing in a jing-a-ring, with the English child pushing in the middle. The foreign children looking at and showing each other marvels. The English child at the leeside of a roast of beef. The English child sitting thinking with his picture-books 21 all round him, and the jing-a-ring of the foreign children in miniature dancing over the picture-books.

XXXIX. Dear artist, can you do me that?

XLII. The child being started off—the bed sailing, curtains and all, upon the sea—the child waking and finding himself at home; the corner of toilette might be worked in to look like the pier.

XLVII. The lighted part of the room, to be carefully distinguished from my child’s dark hunting grounds. A shaded lamp.

R. L. S.

To Mrs. Thomas Stevenson

Hôtel des Îles d’Or, Hyères, Var, March 2 [1883].

MY DEAR MOTHER,—It must be at least a fortnight since we have had a scratch of a pen from you; and if it had not been for Cummy’s letter, I should have feared you were worse again: as it is, I hope we shall hear from you to-day or to-morrow at latest.

Health.—Our news is good: Fanny never got so bad as we feared, and we hope now that this attack may pass off in threatenings. I am greatly better, have gained flesh, strength, spirits; eat well, walk a good deal, and do some work without fatigue. I am off the sick list.

Lodging.—We have found a house up the hill, close to the town, an excellent place though very, very little. If I can get the landlord to agree to let us take it by the month just now, and let our month’s rent count for the year in case we take it on, you may expect to hear we are again installed, and to receive a letter dated thus:—

La Solitude,

Hyères-les-Palmiers,

Var.

If the man won’t agree to that, of course I must just give it up, as the house would be dear enough anyway at 22 2000 f. However, I hope we may get it, as it is healthy, cheerful, and close to shops, and society, and civilisation. The garden, which is above, is lovely, and will be cool in summer. There are two rooms below with a kitchen, and four rooms above, all told.—Ever your affectionate son,

R. L. Stevenson.

To Thomas Stevenson

“Cassandra” was a nickname of the elder Mr. Stevenson for his daughter-in-law. The scheme of a play to be founded on Great Expectations was one of a hundred formed in these days and afterwards given up.

Hôtel des Îles d’Or, but my address will be Chalet

la Solitude, Hyères-les-Palmiers, Var, France,

March 17, 1883.

Dear Sir,—Your undated favour from Eastbourne came to hand in course of post, and I now hasten to acknowledge its receipt. We must ask you in future, for the convenience of our business arrangements, to struggle with and tread below your feet this most unsatisfactory and uncommercial habit. Our Mr. Cassandra is better; our Mr. Wogg expresses himself dissatisfied with our new place of business; when left alone in the front shop, he bawled like a parrot; it is supposed the offices are haunted.

To turn to the matter of your letter, your remarks on Great Expectations are very good. We have both re-read it this winter, and I, in a manner, twice. The object being a play; the play, in its rough outline, I now see: and it is extraordinary how much of Dickens had to be discarded as unhuman, impossible, and ineffective: all that really remains is the loan of a file (but from a grown-up young man who knows what he was doing, and to a convict who, although he does not know it is his father—the father knows it is his son), and the fact of the convict-father’s return and disclosure of himself to the son whom he has made rich. Everything else has been thrown 23 aside; and the position has had to be explained by a prologue which is pretty strong. I have great hopes of this piece, which is very amiable and, in places, very strong indeed: but it was curious how Dickens had to be rolled away; he had made his story turn on such improbabilities, such fantastic trifles, not on a good human basis, such as I recognised. You are right about the casts, they were a capital idea; a good description of them at first, and then afterwards, say second, for the lawyer to have illustrated points out of the history of the originals, dusting the particular bust—that was all the development the thing would bear. Dickens killed them. The only really well executed scenes are the riverside ones; the escape in particular is excellent; and I may add, the capture of the two convicts at the beginning. Miss Havisham is, probably, the worst thing in human fiction. But Wemmick I like; and I like Trabb’s boy; and Mr. Wopsle as Hamlet is splendid.

The weather here is greatly improved, and I hope in three days to be in the chalet. That is, if I get some money to float me there.

I hope you are all right again, and will keep better. The month of March is past its mid career; it must soon begin to turn toward the lamb; here it has already begun to do so; and I hope milder weather will pick you up. Wogg has eaten a forpet of rice and milk, his beard is streaming, his eyes wild. I am besieged by demands of work from America.

The £50 has just arrived; many thanks; I am now at ease.—Ever your affectionate son, pro Cassandra, Wogg and Co.,

R. L. S.

To W. E. Henley

[Chalet la Solitude, Hyères, April 1883.]

My head is singing with Otto; for the first two weeks I wrote and revised and only finished IV chapters: last 24 week, I have just drafted straight ahead, and I have just finished Chapter XI. It will want a heap of oversight and much will not stand, but the pace is good; about 28 Cornhill pp. drafted in seven days, and almost all of it dialogue—indeed I may say all, for I have dismissed the rest very summarily in the draft: one can always tickle at that. At the same rate, the draft should be finished in ten days more; and then I shall have the pleasure of beginning again at the beginning. Ah damned job! I have no idea whether or not Otto will be good. It is all pitched pretty high and stilted; almost like the Arabs, at that; but of course there is love-making in Otto, and indeed a good deal of it. I sometimes feel very weary; but the thing travels—and I like it when I am at it.

Remember me kindly to all.—Your ex-contributor,

R. L. S.

To Mrs. Sitwell

His correspondent had at his request been writing and despatching to him fair copies of the various sets of verses for the Child’s Garden (as the collection was ultimately called), which he had been from time to time sending home.

Chalet la Solitude, Hyères [April 1883].

MY DEAR FRIEND,—I am one of the lowest of the—but that’s understood. I received the copy, excellently written, with I think only one slip from first to last. I have struck out two, and added five or six; so they now number forty-five; when they are fifty, they shall out on the world. I have not written a letter for a cruel time; I have been, and am, so busy, drafting a long story (for me, I mean), about a hundred Cornhill pages, or say about as long as the Donkey book: Prince Otto it is called, and is, at the present hour, a sore burthen but a hopeful. If I had him all drafted, I should whistle and sing. But no: then I’ll have to rewrite him; and then there will be the 25 publishers, alas! But some time or other, I shall whistle and sing, I make no doubt.

I am going to make a fortune, it has not yet begun, for I am not yet clear of debt; but as soon as I can, I begin upon the fortune. I shall begin it with a halfpenny, and it shall end with horses and yachts and all the fun of the fair. This is the first real grey hair in my character: rapacity has begun to show, the greed of the protuberant guttler. Well, doubtless, when the hour strikes, we must all guttle and protube. But it comes hard on one who was always so willow-slender and as careless as the daisies.

Truly I am in excellent spirits. I have crushed through a financial crisis; Fanny is much better; I am in excellent health, and work from four to five hours a day—from one to two above my average, that is; and we all dwell together and make fortunes in the loveliest house you ever saw, with a garden like a fairy story, and a view like a classical landscape.

Little? Well, it is not large. And when you come to see us, you will probably have to bed at the hotel, which is hard by. But it is Eden, madam, Eden and Beulah and the Delectable Mountains and Eldorado and the Hesperidean Isles and Bimini.3

We both look forward, my dear friend, with the greatest eagerness to have you here. It seems it is not to be this season: but I appoint you with an appointment for next season. You cannot see us else: remember that. Till my health has grown solid like an oak-tree, till my fortune begins really to spread its boughs like the same monarch of the woods (and the acorn, ay de mi! is not yet planted), I expect to be a prisoner among the palms.

Yes, it is like old times to be writing you from the Riviera, and after all that has come and gone, who can predict anything? How fortune tumbles men about! 26 Yet I have not found that they change their friends, thank God.

Both of our loves to your sister and yourself. As for me, if I am here and happy, I know to whom I owe it; I know who made my way for me in life, if that were all, and I remain, with love, your faithful friend,

Robert Louis Stevenson.

To Edmund Gosse

“Gilder” in the following is of course the late R. W. Gilder, for many years the admirable editor of the Century Magazine.

Chalet la Solitude, Hyères [April 1883].

MY DEAR GOSSE,—I am very guilty; I should have written to you long ago; and now, though it must be done, I am so stupid that I can only boldly recapitulate. A phrase of three members is the outside of my syntax.

First, I like the Rover better than any of your other verse. I believe you are right, and can make stories in verse. The last two stanzas and one or two in the beginning—but the two last above all—I thought excellent. I suggest a pursuit of the vein. If you want a good story to treat, get the Memoirs of the Chevalier Johnstone, and do his passage of the Tay; it would be excellent: the dinner in the field, the woman he has to follow, the dragoons, the timid boatmen, the brave lasses. It would go like a charm; look at it, and you will say you owe me one.

Second, Gilder asking me for fiction, I suddenly took a great resolve, and have packed off to him my new work, The Silverado Squatters. I do not for a moment suppose he will take it; but pray say all the good words you can for it. I should be awfully glad to get it taken. But if it does not mean dibbs at once, I shall be ruined for life. Pray write soon and beg Gilder your prettiest for a poor gentleman in pecuniary sloughs.

Fourth, next time I am supposed to be at death’s door 27 write to me like a Christian, and let not your correspondence attend on business.—Yours ever,

R. L. S.

P.S.—I see I have led you to conceive the Squatters are fiction. They are not, alas!

To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson

Chalet la Solitude, May 5 [1883].

MY DEAREST PEOPLE,—I have had a great piece of news. There has been offered for Treasure Island—how much do you suppose? I believe it would be an excellent jest to keep the answer till my next letter. For two cents I would do so. Shall I? Anyway, I’ll turn the page first. No—well—A hundred pounds, all alive, O! A hundred jingling, tingling, golden, minted quid. Is not this wonderful? Add that I have now finished, in draft, the fifteenth chapter of my novel, and have only five before me, and you will see what cause of gratitude I have.

The weather, to look at the per contra sheet, continues vomitable; and Fanny is quite out of sorts. But, really, with such cause of gladness, I have not the heart to be dispirited by anything. My child’s verse book is finished, dedication and all, and out of my hands—you may tell Cummy; Silverado is done, too, and cast upon the waters; and this novel so near completion, it does look as if I should support myself without trouble in the future. If I have only health, I can, I thank God. It is dreadful to be a great, big man, and not be able to buy bread.

O that this may last!

I have to-day paid my rent for the half year, till the middle of September, and got my lease: why they have been so long, I know not.

I wish you all sorts of good things.

When is our marriage day?—Your loving and ecstatic son,

Treesure Eilaan.

It has been for me a Treasure Island verily.

To Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Stevenson

La Solitude, Hyères, May 8, 1883.

MY DEAR PEOPLE,—I was disgusted to hear my father was not so well. I have a most troubled existence of work and business. But the work goes well, which is the great affair. I meant to have written a most delightful letter; too tired, however, and must stop. Perhaps I’ll find time to add to it ere post.

I have returned refreshed from eating, but have little time, as Lloyd will go soon with the letters on his way to his tutor, Louis Robert (!!!!), with whom he learns Latin in French, and French, I suppose, in Latin, which seems to me a capital education. He, Lloyd, is a great bicycler already, and has been long distances; he is most new-fangled over his instrument, and does not willingly converse on other subjects.

Our lovely garden is a prey to snails; I have gathered about a bushel, which, not having the heart to slay, I steal forth withal and deposit near my neighbour’s garden wall. As a case of casuistry, this presents many points of interest. I loathe the snails, but from loathing to actual butchery, trucidation of multitudes, there is still a step that I hesitate to take. What, then, to do with them? My neighbour’s vineyard, pardy! It is a rich, villa, pleasure-garden of course; if it were a peasant’s patch, the snails, I suppose, would have to perish.

The weather these last three days has been much better, though it is still windy and unkind. I keep splendidly well, and am cruelly busy, with mighty little time even for a walk. And to write at all, under such pressure, must be held to lean to virtue’s side.

My financial prospects are shining. O if the health will hold, I should easily support myself.—Your ever affectionate son,

R. L. S.

To Edmund Gosse

La Solitude, Hyères-les-Palmiers, Var [May 20, 1883].

MY DEAR GOSSE,—I enclose the receipt and the corrections. As for your letter and Gilder’s, I must take an hour or so to think; the matter much importing—to me. The £40 was a heavenly thing.

I send the MS. by Henley, because he acts for me in all matters, and had the thing, like all my other books, in his detention. He is my unpaid agent—an admirable arrangement for me, and one that has rather more than doubled my income on the spot.

If I have been long silent, think how long you were so and blush, sir, blush.

I was rendered unwell by the arrival of your cheque, and, like Pepys, “my hand still shakes to write of it.” To this grateful emotion, and not to D.T., please attribute the raggedness of my hand.

This year I should be able to live and keep my family on my own earnings, and that in spite of eight months and more of perfect idleness at the end of last and beginning of this. It is a sweet thought.

This spot, our garden and our view, are sub-celestial. I sing daily with my Bunyan, that great bard,

“I dwell already the next door to Heaven!”

If you could see my roses, and my aloes, and my fig-marigolds, and my olives, and my view over a plain, and my view of certain mountains as graceful as Apollo, as severe as Zeus, you would not think the phrase exaggerated.

It is blowing to-day a hot mistral, which is the devil or a near connection of his.

This to catch the post.—Yours affectionately,

R. L. Stevenson.

To Edmund Gosse

La Solitude, Hyères-les-Palmiers, Var, France, May 21, 1883.

MY DEAR GOSSE,—The night giveth advice, generally bad advice; but I have taken it. And I have written direct to Gilder to tell him to keep the book4 back and go on with it in November at his leisure. I do not know if this will come in time; if it doesn’t, of course things will go on in the way proposed. The £40, or, as I prefer to put it, the 1000 francs, has been such a piercing sun-ray as my whole grey life is gilt withal. On the back of it I can endure. If these good days of Longman and the Century only last, it will be a very green world, this that we dwell in and that philosophers miscall. I have no taste for that philosophy; give me large sums paid on the receipt of the MS. and copyright reserved, and what do I care about the non-bëent? Only I know it can’t last. The devil always has an imp or two in every house, and my imps are getting lively. The good lady, the dear, kind lady, the sweet, excellent lady, Nemesis, whom alone I adore, has fixed her wooden eye upon me. I fall prone; spare me, Mother Nemesis! But catch her!

I must now go to bed; for I have had a whoreson influenza cold, and have to lie down all day, and get up only to meals and the delights, June delights, of business correspondence.

You said nothing about my subject for a poem. Don’t you like it? My own fishy eye has been fixed on it for prose, but I believe it could be thrown out finely in verse, and hence I resign and pass the hand. Twig the compliment?—Yours affectionately,

R. L. S.

To W. E. Henley

“Tushery” had been a name in use between Stevenson and Mr. Henley for romances of the Ivanhoe type. He now applies it to his own tale of the Wars of the Roses, The Black Arrow, written for Mr. Henderson’s Young Folks, of which the office was in Red Lion Court.

[Hyères, May 1883.]

... The influenza has busted me a good deal; I have no spring, and am headachy. So, as my good Red Lion Courier begged me for another Butcher’s Boy—I turned me to—what thinkest ’ou?—to Tushery, by the mass! Ay, friend, a whole tale of tushery. And every tusher tushes me so free, that may I be tushed if the whole thing is worth a tush. The Black Arrow: A Tale of Tunstall Forest is his name: tush! a poor thing!

Will Treasure Island proofs be coming soon, think you?

I will now make a confession. It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot John Silver in Treasure Island. Of course, he is not in any other quality or feature the least like you; but the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you.

Otto is, as you say, not a thing to extend my public on. It is queer and a little, little bit free; and some of the parties are immoral; and the whole thing is not a romance, nor yet a comedy; nor yet a romantic comedy; but a kind of preparation of some of the elements of all three in a glass jar. I think it is not without merit, but I am not always on the level of my argument, and some parts are false, and much of the rest is thin; it is more a triumph for myself than anything else; for I see, beyond it, better stuff. I have nine chapters ready, or almost ready, for press. My feeling would be to get it placed anywhere for as much as could be got for it, and rather in the shadow, till one saw the look of it in print.—Ever yours,

Pretty Sick.

To W. E. Henley

La Solitude, Hyères-les-Palmiers, May 1883.

MY DEAR LAD,—The books came some time since, but I have not had the pluck to answer: a shower of small troubles having fallen in, or troubles that may be very large.

I have had to incur a huge vague debt for cleaning sewers; our house was (of course) riddled with hidden cesspools, but that was infallible. I have the fever, and feel the duty to work very heavy on me at times; yet go it must. I have had to leave Fontainebleau, when three hours would finish it, and go full-tilt at tushery for a while. But it will come soon.

I think I can give you a good article on Hokusai; but that is for afterwards; Fontainebleau is first in hand.

By the way, my view is to give the Penny Whistles to Crane or Greenaway. But Crane, I think, is likeliest; he is a fellow who, at least, always does his best.

Shall I ever have money enough to write a play?

O dire necessity!

A word in your ear: I don’t like trying to support myself. I hate the strain and the anxiety; and when unexpected expenses are foisted on me, I feel the world is playing with false dice.—Now I must Tush, adieu.

An Aching, Fevered, Penny-Journalist.

A lytle Jape of TUSHERIE.

By A. Tusher.

|

The pleasant river gushes Among the meadows green; At home the author tushes; For him it flows unseen. The Birds among the Bŭshes May wanton on the spray; But vain for him who tushes The brightness of the day! The frog among the rushes Sits singing in the blue. By’r la’kin! but these tushes Are wearisome to do! The task entirely crushes The spirit of the bard: God pity him who tushes— His task is very hard. The filthy gutter slushes, The clouds are full of rain, But doomed is he who tushes To tush and tush again. At morn with his hair-brushes, Still “tush” he says, and weeps; At night again he tushes, And tushes till he sleeps. And when at length he pŭshes Beyond the river dark— ’Las, to the man who tushes, “Tush,” shall be God’s remark! |

To Sidney Colvin

[Chalet la Solitude, Hyères, May 1883.]

COLVIN,—The attempt to correspond with you is vain. Well, well, then so be it. I will from time to time write you an insulting letter, brief but monstrous harsh. I regard you in the light of a genteel impostor. Your name figures in the papers but never to a piece of letter-paper: well, well.

News. I am well: Fanny been ill but better: Otto about three-quarters done; Silverado proofs a terrible job—it is a most unequal work—new wine in old bottles—large rats, small bottles:5 as usual, penniless—O but penniless: still, with four articles in hand (say £35) and the £100 for Silverado imminent, not hopeless.

Why am I so penniless, ever, ever penniless, ever, ever penny-penny-penniless and dry?

|

The birds upon the thorn, The poppies in the corn, |

They surely are more fortunate or prudenter than I!

In Arabia, everybody is called the Father of something or other for convenience or insult’s sake. Thus you are “the Father of Prints,” or of “Bummkopferies,” or “Father of Unanswered Correspondence.” They would instantly dub Henley “the Father of Wooden Legs”; me they would denominate the “Father of Bones,” and Matthew Arnold “the Father of Eyeglasses.”

I have accepted most of the excisions. Proposed titles:—

|

The Innocent Muse. A Child’s Garden of Rhymes. Songs of the Playroom. Nursery Songs. |

I like the first?

R. L. S.

To W. E. Henley

La Solitude, Hyères, May or June 1883.

DEAR LAD,—Snatches in return for yours; for this little once, I’m well to windward of you.

Seventeen chapters of Otto are now drafted, and finding I was working through my voice and getting screechy, I have turned back again to rewrite the earlier part. It has, I do believe, some merit: of what order, of course, I am the last to know; and, triumph of triumphs, my wife—my wife who hates and loathes and slates my women—admits a great part of my Countess to be on the spot.

Yes, I could borrow, but it is the joy of being before the public, for once. Really, £100 is a sight more than Treasure Island is worth.

The reason of my dèche? Well, if you begin one house, have to desert it, begin another, and are eight months without doing any work, you will be in a dèche too. I am not in a dèche, however; distingue—I would fain distinguish; I am rather a swell, but not solvent. At a touch the edifice, ædificium, might collapse. If my creditors began to babble around me, I would sink with a slow strain of music into the crimson west. The difficulty in my elegant villa is to find oil, oleum, for the dam axles. But I’ve paid my rent until September; and beyond the chemist, the grocer, the baker, the doctor, the gardener, Lloyd’s teacher, and the great chief creditor Death, I can snap my fingers at all men. Why will people spring bills on you? I try to make ’em charge me at the moment; they won’t, the money goes, the debt remains.—The Required Play is in the Merry Men.

Q. E. F.

I thus render honour to your flair; it came on me of a clap; I do not see it yet beyond a kind of sunset glory. But it’s there: passion, romance, the picturesque, involved: startling, simple, horrid: a sea-pink in sea-froth! S’agit de la désenterrer. “Help!” cries a buried masterpiece.

Once I see my way to the year’s end, clear, I turn to plays; till then I grind at letters; finish Otto; write, say, a couple of my Traveller’s Tales; and then, if all my ships come home, I will attack the drama in earnest. I 36 cannot mix the skeins. Thus, though I’m morally sure there is a play in Otto, I dare not look for it: I shoot straight at the story.

As a story, a comedy, I think Otto very well constructed; the echoes are very good, all the sentiments change round, and the points of view are continually, and, I think (if you please), happily contrasted. None of it is exactly funny, but some of it is smiling.

R. L. S.

To W. E. Henley

The verses alluded to are some of those afterwards collected in Underwoods.

[Chalet la Solitude, Hyères, May or June 1883.]

DEAR HENLEY,—You may be surprised to hear that I am now a great writer of verses; that is, however, so. I have the mania now like my betters, and faith, if I live till I am forty, I shall have a book of rhymes like Pollock, Gosse, or whom you please. Really, I have begun to learn some of the rudiments of that trade, and have written three or four pretty enough pieces of octosyllabic nonsense, semi-serious, semi-smiling. A kind of prose Herrick, divested of the gift of verse, and you behold the Bard. But I like it.

R. L. S.

To Jules Simoneau

This friend was the keeper of the inn and restaurant where Stevenson had boarded at Monterey in the autumn of 1879. In writing French, as will be seen, Stevenson had always more grip of idiom than of grammar.

[La Solitude, Hyères, May or June 1883.]

MON CHER ET BON SIMONEAU,—J’ai commencé plusieurs fois de vous écrire; et voilà-t-il pas qu’un empêchement quelconque est arrivé toujours. La lettre ne part pas; et je vous laisse toujours dans le droit de soupçonner mon 37 cœur. Mon bon ami, ne pensez pas que je vous ai oublié ou que je vous oublierai jamais. Il n’en est de rien. Votre bon souvenir me tient de bien près, et je le garderai jusqu’à la mort.

J’ai failli mourir de bien près; mais me voici bien rétabli, bien que toujours un peu chétif et malingre. J’habite, comme vous voyez, la France. Je travaille beaucoup, et je commence à ne pas être le dernier; déjà on me dispute ce que j’écris, et je n’ai pas à me plaindre de ce que l’on appelle les honoraires. Me voici alors très affairé, très heureux dans mon ménage, gâté par ma femme, habitant la plus petite maisonette dans le plus beau jardin du monde, et voyant de mes fen êtres la mer, les isles d’Hyères, et les belles collines, montagnes et forts de Toulon.

Et vous, mon très cher ami? Comment celà va-t-il? Comment vous portez-vous? Comment va le commerce? Comment aimez vous le pays? et l’enfant? et la femme? Et enfin toutes les questions possibles. Écrivez-moi donc bien vite, cher Simoneau. Et quant à moi, je vous promets que vous entendrez bien vîte parler de moi; je vous récrirai sous peu, et je vous enverrai un de mes livres. Ceci n’est qu’un serrement de main, from the bottom of my heart, dear and kind old man.—Your friend,

Robert Louis Stevenson.

To W. E. Henley

The “new dictionary” means, of course, the first instalments of the great Oxford Dictionary of the English Language, edited by Dr. J. A. H. Murray.

La Solitude, Hyères [June 1883].

DEAR LAD,—I was delighted to hear the good news about ——. Bravo, he goes uphill fast. Let him beware of vanity, and he will go higher; let him be still discontented, and let him (if it might be) see the merits and not the faults of his rivals, and he may swarm at last to 38 the top-gallant. There is no other way. Admiration is the only road to excellence; and the critical spirit kills, but envy and injustice are putrefaction on its feet.

Thus far the moralist. The eager author now begs to know whether you may have got the other Whistles, and whether a fresh proof is to be taken; also whether in that case the dedication should not be printed therewith; Bulk Delights Publishers (original aphorism; to be said sixteen times in succession as a test of sobriety).

Your wild and ravening commands were received; but cannot be obeyed. And anyway, I do assure you I am getting better every day; and if the weather would but turn, I should soon be observed to walk in hornpipes. Truly I am on the mend. I am still very careful. I have the new dictionary; a joy, a thing of beauty, and—bulk. I shall be raked i’ the mools before it’s finished; that is the only pity; but meanwhile I sing.

I beg to inform you that I, Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Brashiana and other works, am merely beginning to commence to prepare to make a first start at trying to understand my profession. O the height and depth of novelty and worth in any art! and O that I am privileged to swim and shoulder through such oceans! Could one get out of sight of land—all in the blue? Alas not, being anchored here in flesh, and the bonds of logic being still about us.

But what a great space and a great air there is in these small shallows where alone we venture! and how new each sight, squall, calm, or sunrise! An art is a fine fortune, a palace in a park, a band of music, health, and physical beauty; all but love—to any worthy practiser. I sleep upon my art for a pillow; I waken in my art; I am unready for death, because I hate to leave it. I love my wife, I do not know how much, nor can, nor shall, unless I lost her; but while I can conceive my being widowed, I refuse the offering of life without my art. I am not but in my art; it is me; I am the body of it merely.

And yet I produce nothing, am the author of Brashiana and other works: tiddy-iddity—as if the works one wrote were anything but ’prentice’s experiments. Dear reader, I deceive you with husks, the real works and all the pleasure are still mine and incommunicable. After this break in my work, beginning to return to it, as from light sleep, I wax exclamatory, as you see.

|

Sursum Corda: Heave ahead: Here’s luck. Art and Blue Heaven, April and God’s Larks. Green reeds and the sky-scattering river. A stately music. Enter God! |

R. L. S.

Ay, but you know, until a man can write that “Enter God,” he has made no art! None! Come, let us take counsel together and make some!

To Trevor Haddon

During the height of the Provençal summer, for July and part of August, Stevenson went with his wife to the Baths of Royat in Auvergne (travelling necessarily by way of Clermont-Ferrand). His parents joined them at Royat for part of their visit. This and possibly the next following letters were written during the trip. The news here referred to was that his correspondent had won a scholarship at the Slade School.

La Solitude, Hyères. But just now writing from

Clermont-Ferrand, July 5, 1883.

DEAR MR. HADDON,—Your note with its piece of excellent news duly reached me. I am delighted to hear of your success: selfishly so; for it is pleasant to see that one whom I suppose I may call an admirer is no fool. I wish you more and more prosperity, and to be devoted to your art. An art is the very gist of life; it grows with you; you will never weary of an art at which you 40 fervently and superstitiously labour. Superstitiously: I mean, think more of it than it deserves; be blind to its faults, as with a wife or father; forget the world in a technical trifle. The world is very serious; art is the cure of that, and must be taken very lightly; but to take art lightly, you must first be stupidly owlishly in earnest over it. When I made Casimir say “Tiens” at the end, I made a blunder. I thought it was what Casimir would have said and I put it down. As your question shows, it should have been left out. It was a “patch” of realism, and an anti-climax. Beware of realism; it is the devil; ’tis one of the means of art, and now they make it the end! And such is the farce of the age in which a man lives, that we all, even those of us who most detest it, sin by realism.

Notes for the student of any art.

1. Keep an intelligent eye upon all the others. It is only by doing so that you come to see what Art is: Art is the end common to them all, it is none of the points by which they differ.

2. In this age beware of realism.

3. In your own art, bow your head over technique. Think of technique when you rise and when you go to bed. Forget purposes in the meanwhile; get to love technical processes; to glory in technical successes; get to see the world entirely through technical spectacles, to see it entirely in terms of what you can do. Then when you have anything to say, the language will be apt and copious.

My health is better.

I have no photograph just now; but when I get one you shall have a copy. It will not be like me; sometimes I turn out a capital, fresh bank clerk; once I came out the image of Runjeet Singh; again the treacherous sun has fixed me in the character of a travelling evangelist. It’s quite a lottery; but whatever the next venture proves to be, soldier, sailor, tinker, tailor, you shall have a proof. Reciprocate. The truth is I have no appearance; a certain air of disreputability is the one 41 constant character that my face presents: the rest change like water. But still I am lean, and still disreputable.

Cling to your youth. It is an artistic stock in trade. Don’t give in that you are ageing, and you won’t age. I have exactly the same faults and qualities still; only a little duller, greedier and better tempered; a little less tolerant of pain and more tolerant of tedium. The last is a great thing for life but—query?—a bad endowment for art?

Another note for the art student.

4. See the good in other people’s work; it will never be yours. See the bad in your own, and don’t cry about it; it will be there always. Try to use your faults; at any rate use your knowledge of them, and don’t run your head against stone walls. Art is not like theology; nothing is forced. You have not to represent the world. You have to represent only what you can represent with pleasure and effect, and the only way to find out what that is is by technical exercise.—Yours sincerely,

Robert Louis Stevenson.

To Jules Simoneau

[Hyères or Royat, Summer 1883.]

MY DEAR FRIEND SIMONEAU,—It would be difficult to tell how glad I was to get your letter with your good news and kind remembrances, it did my heart good to the bottom. I shall never forget the good time we had together, the many long talks, the games of chess, the flute on an occasion, and the excellent food. Now I am in clover, only my health a mere ruined temple; the ivy grows along its shattered front, otherwise, I have no wish that is not fulfilled: a beautiful large garden, a fine view of plain, sea and mountain; a wife that suits me down to the ground, and a barrel of good Beaujolais. To this I must add that my books grow steadily more 42 popular, and if I could only avoid illness I should be well to do for money, as it is, I keep pretty near the wind. Have I other means? I doubt it. I saw François here; and it was in some respects sad to see him, pining in the ungenial life and not, I think, very well pleased with his relatives. The young men, it is true, adored him, but his niece tried to pump me about what money I had, with an effrontery I was glad to disappoint. How he spoke of you I need not tell you. He is your true friend, dear Simoneau, and your ears should have tingled when we met, for we talked of little but yourself.