The Project Gutenberg EBook of Training the Teacher, by

A. F. Schauffler and Antoinette Abernethy Lamoreaux and Martin G. Brumbaugh and Marion Lawrance

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Training the Teacher

Author: A. F. Schauffler

Antoinette Abernethy Lamoreaux

Martin G. Brumbaugh

Marion Lawrance

Release Date: March 26, 2010 [EBook #31791]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAINING THE TEACHER ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Organizing and Conducting a Teacher-Training Class | 5 | |

| Charles A. Oliver | ||

| 1. | The Book | 11 |

| A. F. Schauffler, D.D. | ||

| How the Bible Came to Us | 123 | |

| Ira Maurice Price, Ph.D. | ||

| The Gist of the Books | 129 | |

| Compiled | ||

| 2. | The Pupil | 139 |

| Antoinette Abernethy Lamoreaux | ||

| 3. | The Teacher | 181 |

| Martin G. Brumbaugh, Ph.D., LL.D. | ||

| 4. | The School | 219 |

| Marion Lawrance | ||

| Appendix | ||

| Teaching Hints | 259 | |

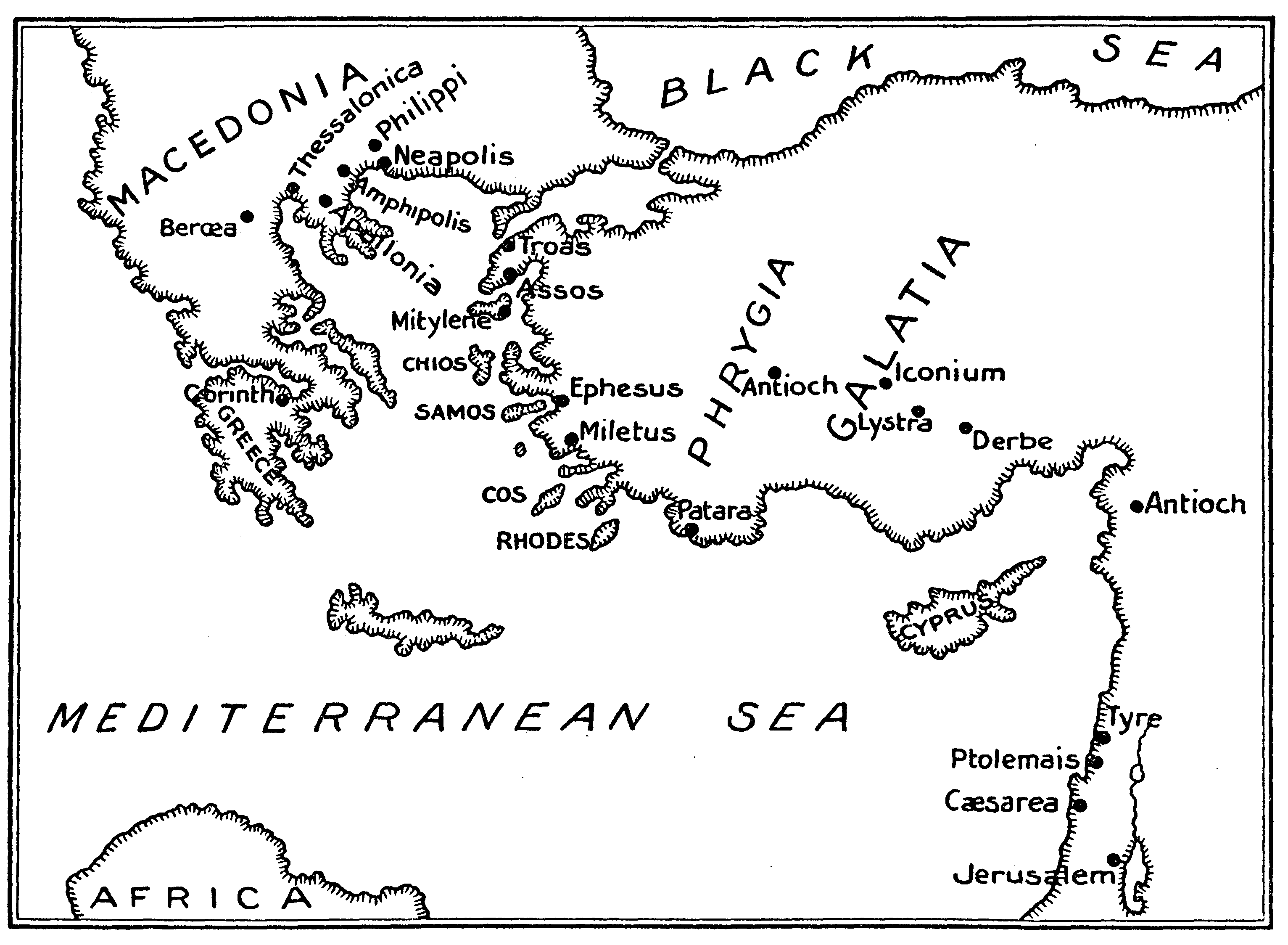

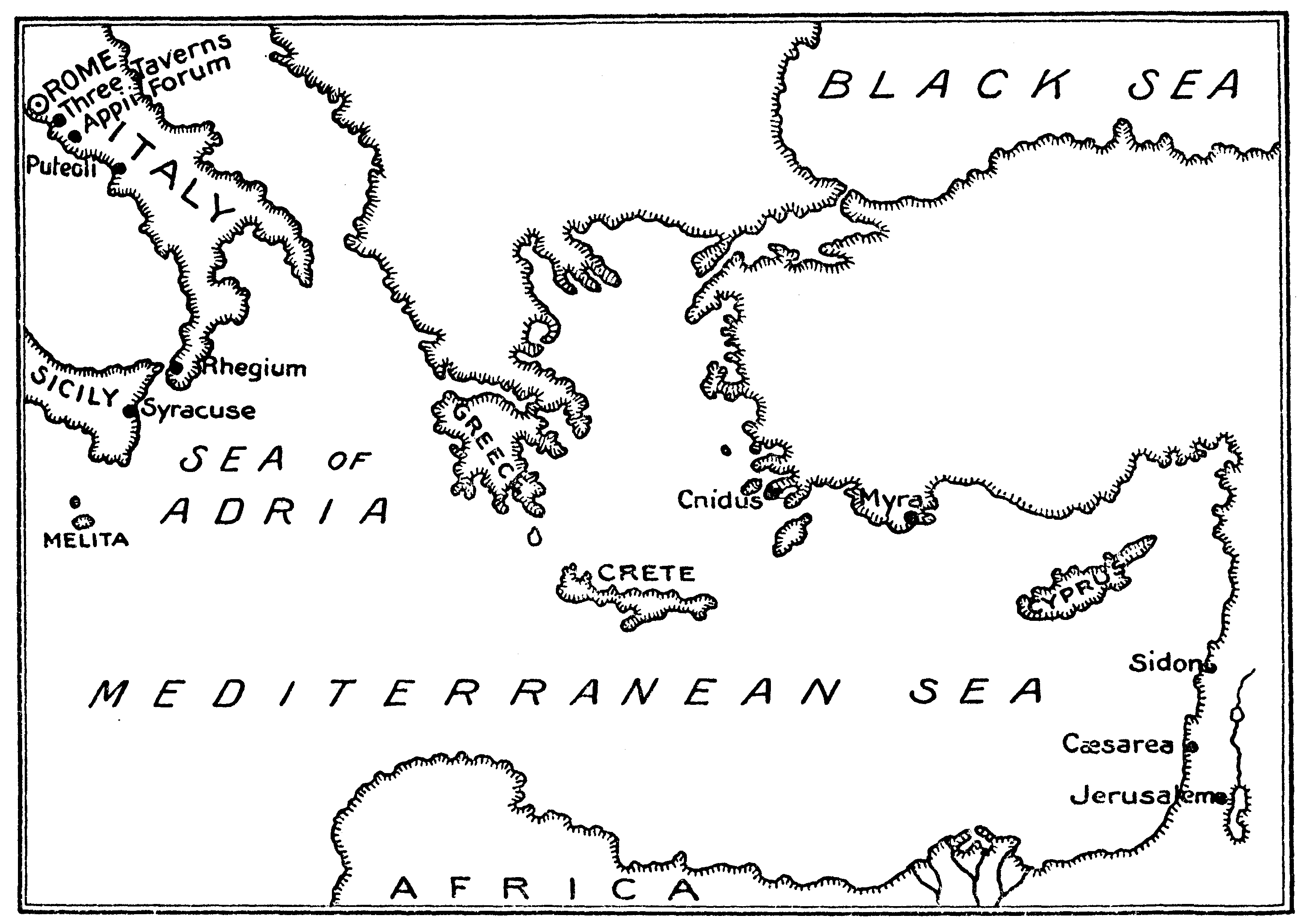

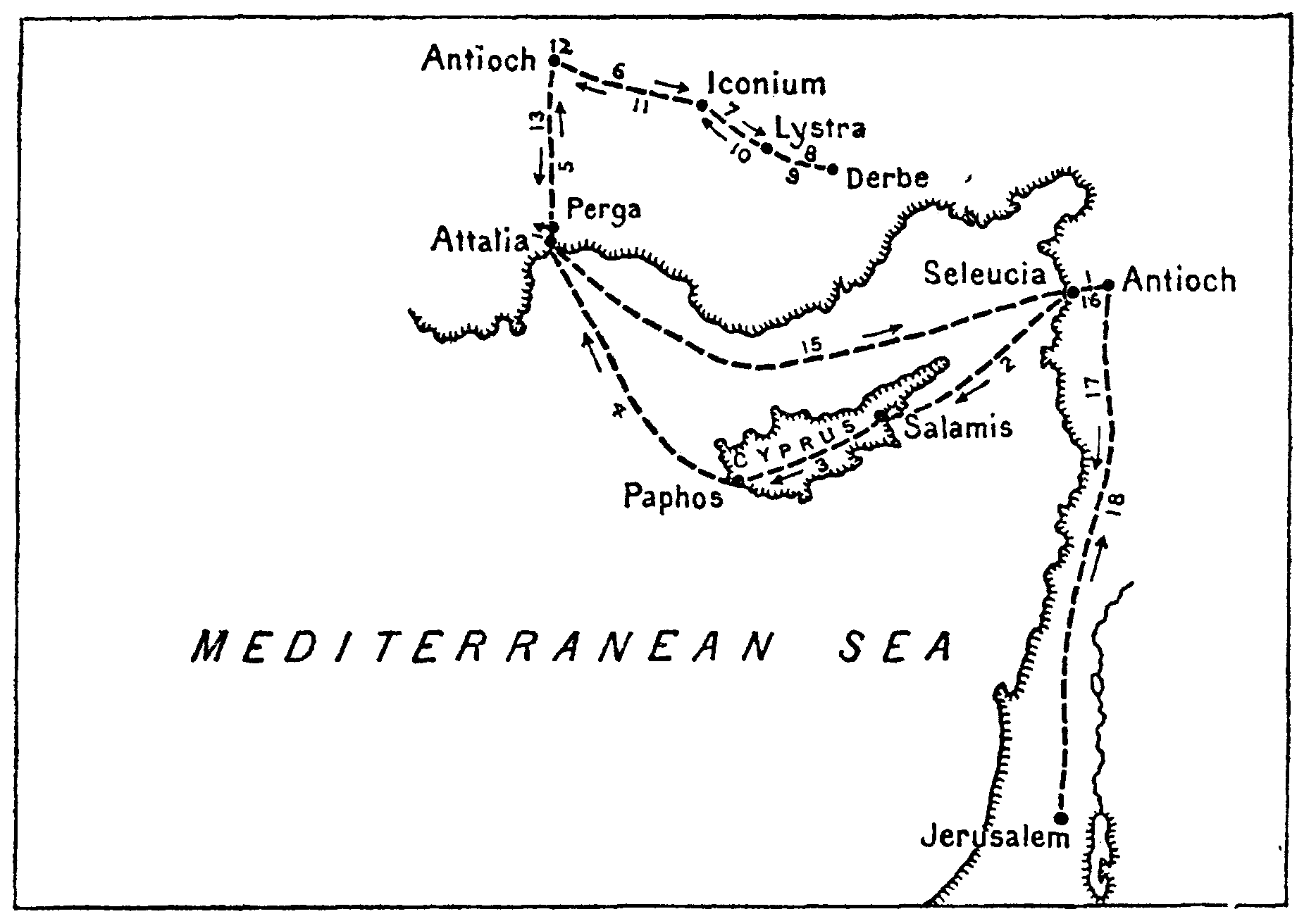

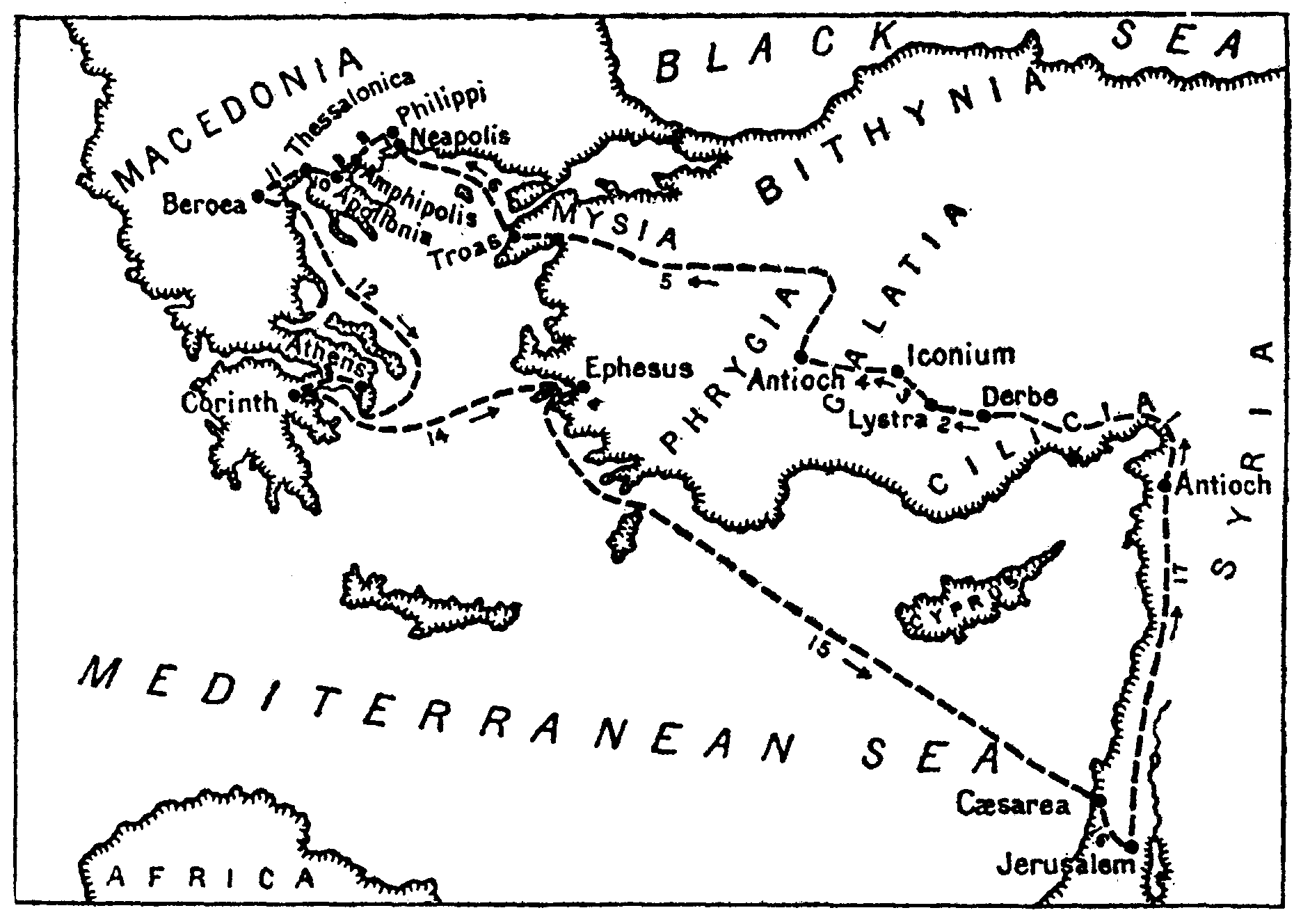

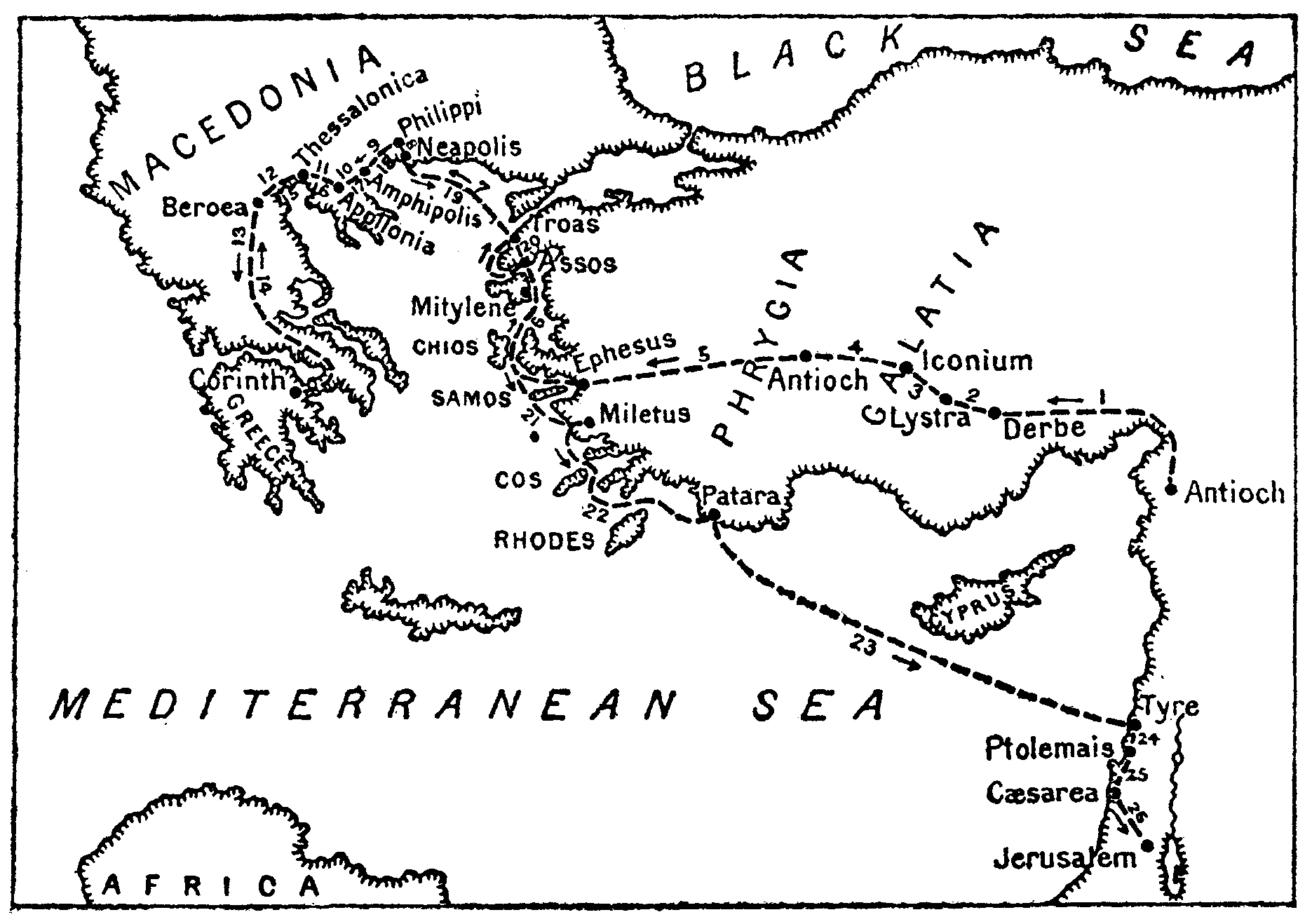

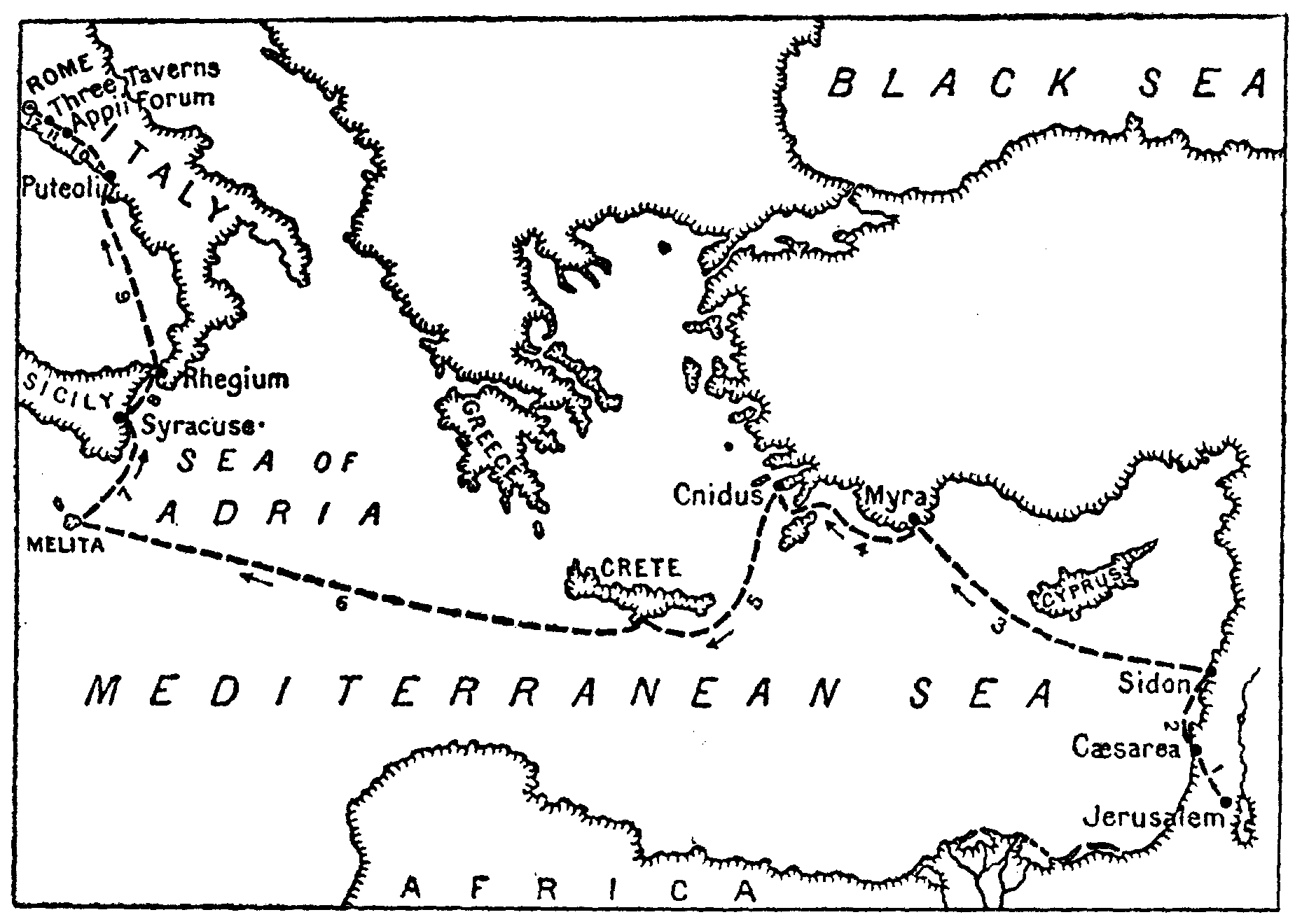

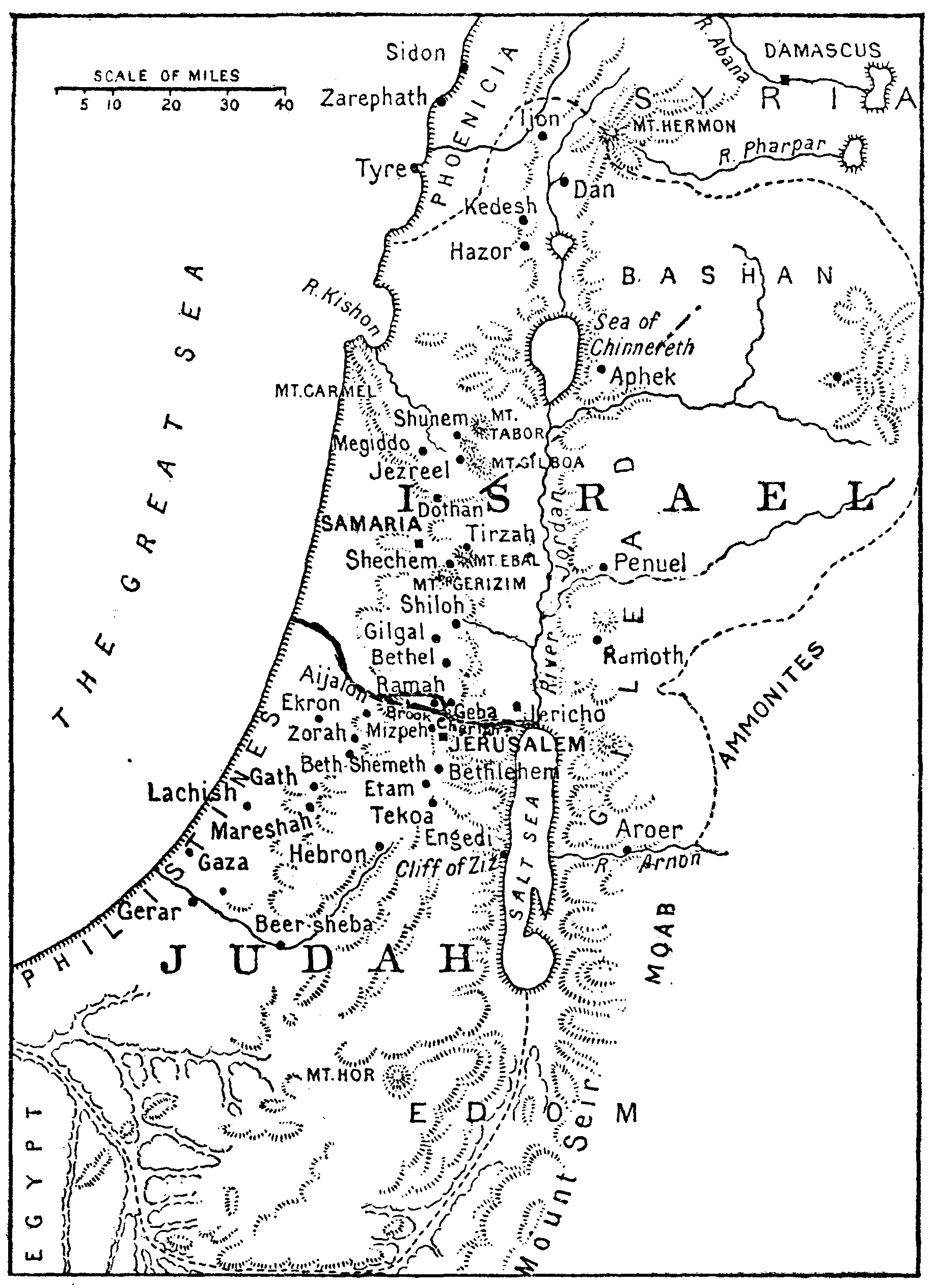

| Paul's Journeys | 266 | |

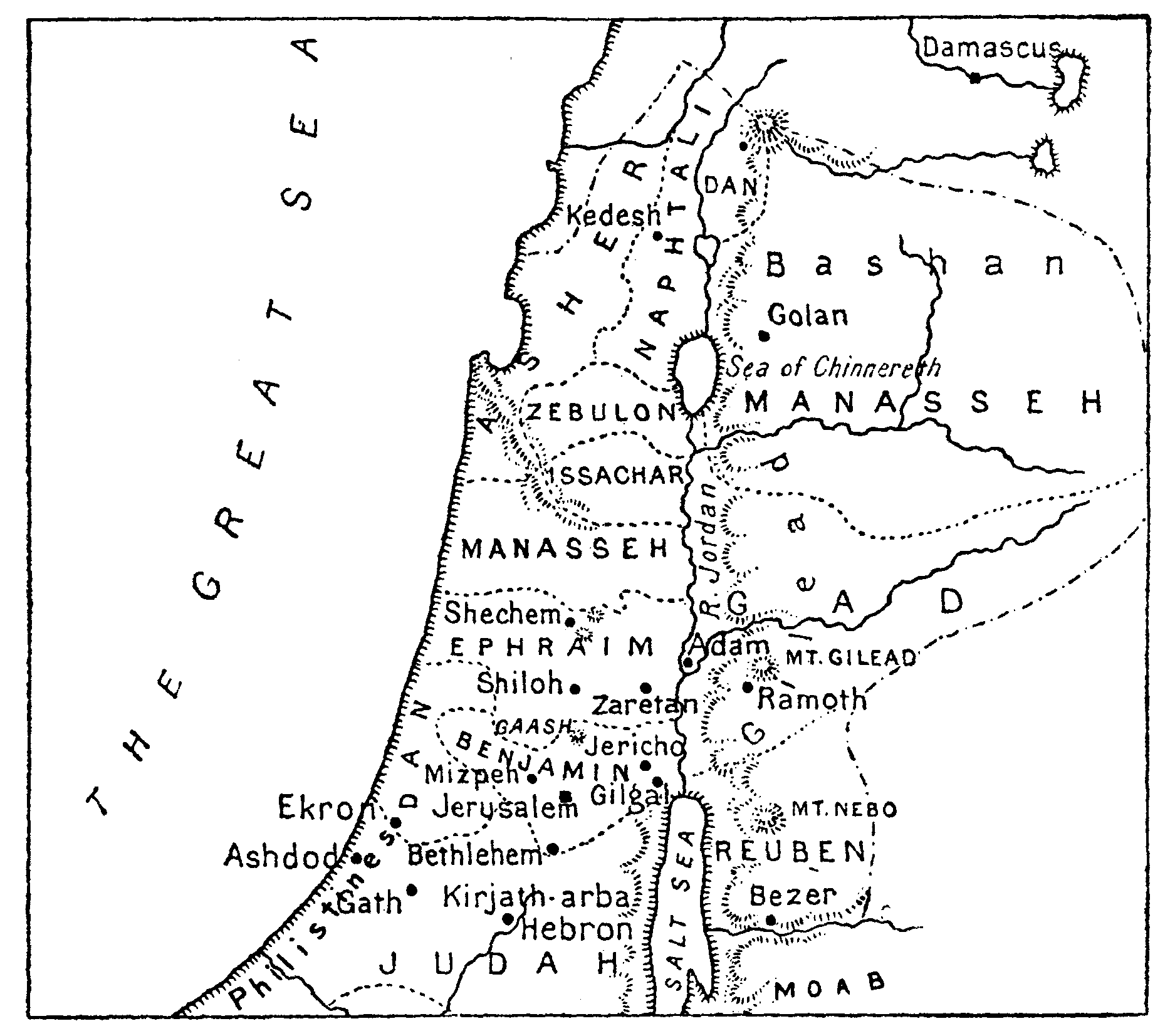

| The Twelve Tribes, Map | 270 | |

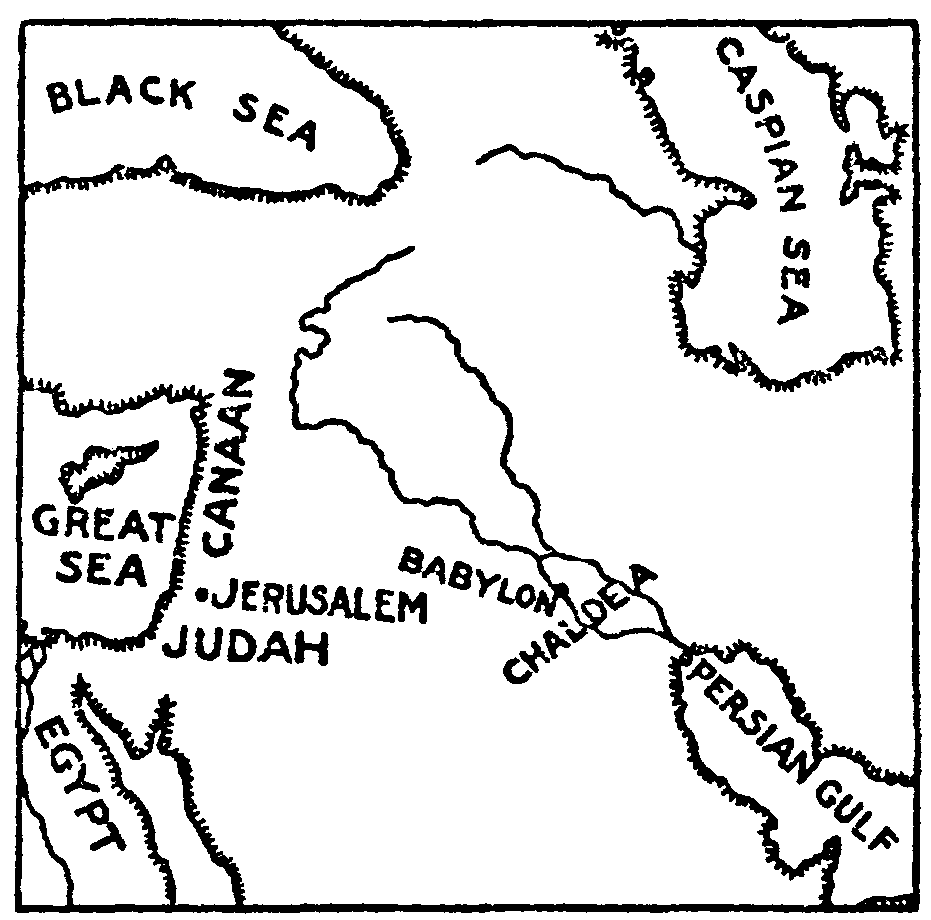

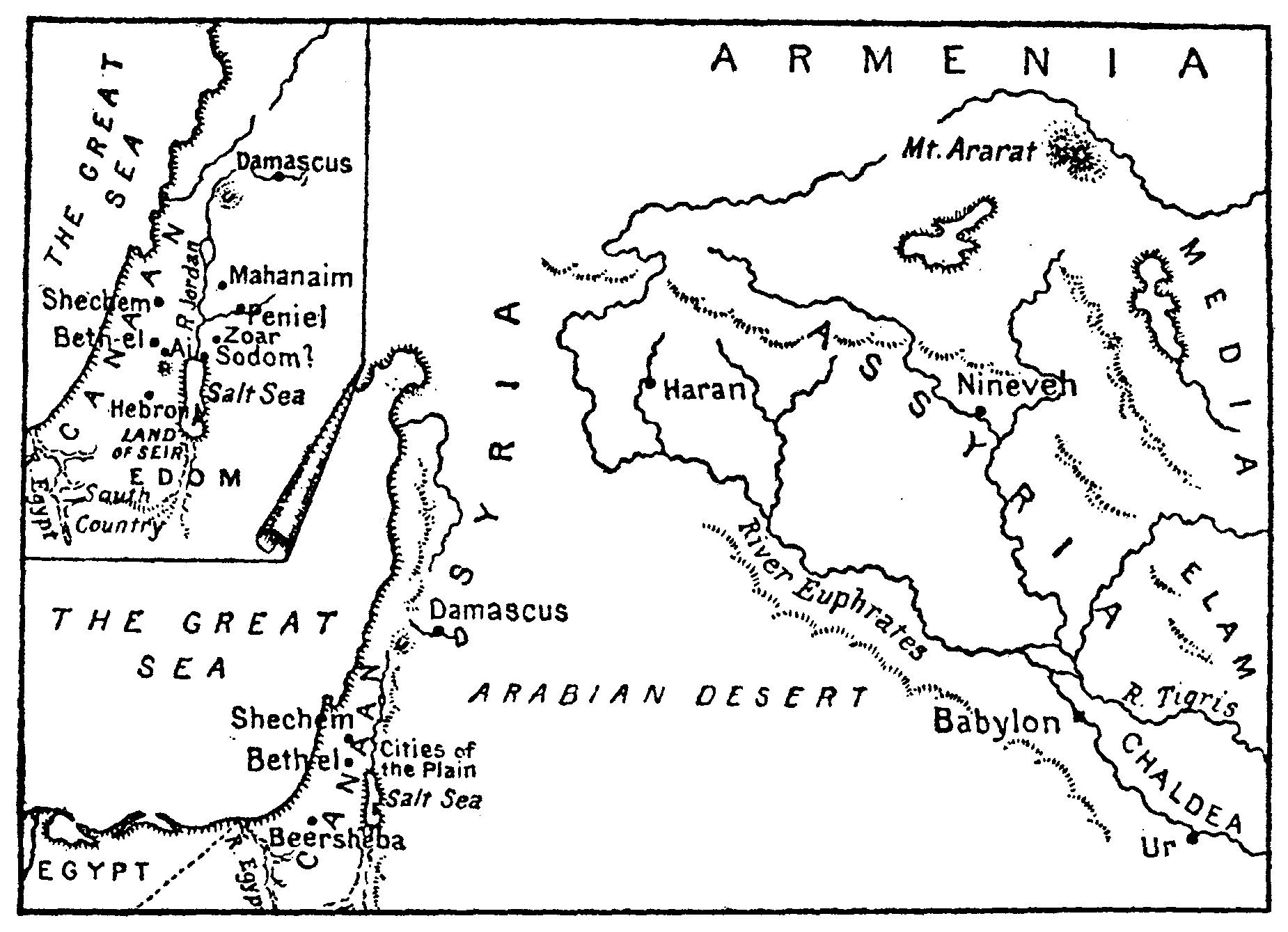

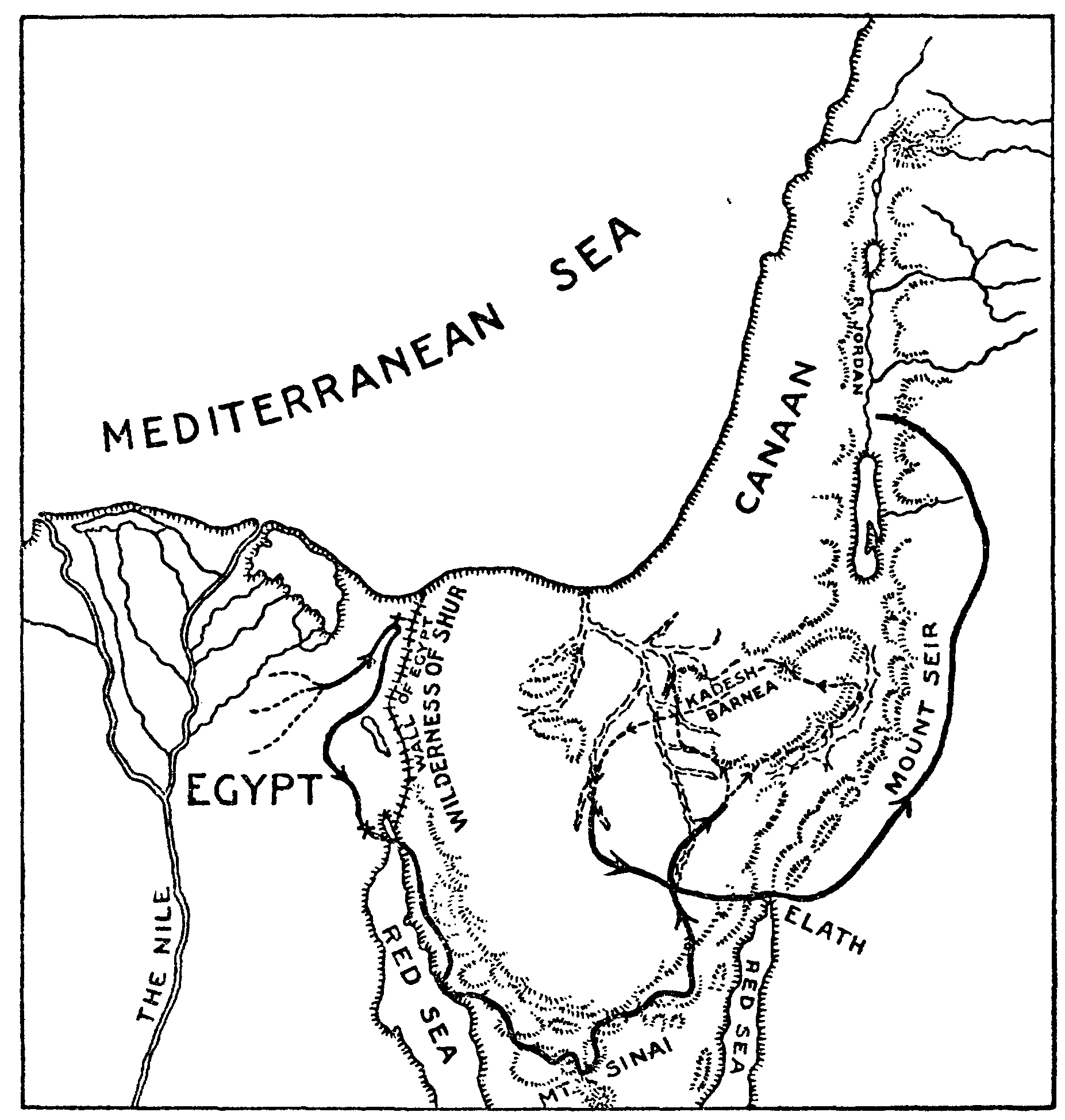

| Assyria and Canaan, Map | 270 | |

| Exodus and Wanderings, Map | 271 | |

Teacher-training Needed.—No more serious problem faces the Sunday-school to-day than the question of securing more teachers and better teaching. We owe it to those who are called to teach the Word to see that means of thorough preparation be brought within their reach. The best teachers will welcome a better training for Christ's service and many good people who have not found their place in the work of the church will gladly engage in Sunday-school teaching after they have been specially instructed in the Bible and in the principles of teaching.

This book provides the essential elements for the teacher-training course in four sections: (1) The Bible material which is the basis for all Sunday-school instruction, under the title of "The Book," by Dr. Schauffler. (2) A study of the working of the mind at various ages and under differing conditions (a brief study of psychology), under the title of "The Pupil," by Mrs. Lamoreaux. (3) A study of teaching principles and the application of these principles (a brief study of pedagogy), under the title of "The Teacher," by Dr. Brumbaugh. (4) A study of the place in which this instruction should be given, that is, "The School," by Mr. Lawrance. Additional material for instruction will be found in the chapter "How the Bible came to Us" by Professor Ira Maurice Price, and "The Gist of the Books."

Starting a Class.—(1) No better beginning can be made than a prayerful conference between the pastor and the Sunday-school superintendent to determine the need and possibilities of teacher-training within the local school. (2) The nearest representative of organized Sunday-school work in your county or State will gladly furnish you with printed matter pointing[Pg 6] out the teacher-training plans in successful use in your denomination. (3) Select your text-book and familiarize yourself with it. (4) Call the teachers and officers together. Have a half-hour social feature, to be followed with an earnest address on the need and the plan of teacher-training. Teach a sample lesson from the text-book. Endeavor in that meeting to secure at least a few persons who will agree to enter a class and will promise to do personal work to secure other members. But do not make the mistake of requiring a large class before beginning. A leader and two or more students will constitute a class.

Who Should Enter the Class?—Two general plans are now in operation. One provides for a training class for present teachers. This class should meet at a convenient time during the week to follow the course in a teacher-training text-book. A whole evening could profitably be given to class work. If this is not feasible the class may meet for study at the time of the weekly teachers'-meeting or before or after the mid-week prayer service.

A second plan provides for the training of prospective teachers, and this may be done in a class meeting at the time of the regular school session. These should be found in the senior and adult departments of the school and should be sixteen years of age or older. The most promising young people in the school should be sought for membership in this class. If possible, a separate room should be provided so that the time of the closing exercises of the school could be added to the lesson period of the class. This will enable the class to devote ten minutes to a brief study of the spiritual teachings of the general Bible lesson for the day and yet leave a half-hour or more for the training lesson.

It should not be overlooked that if a class for present teachers is established, the officers of the school will find the course invaluable and parents will secure very helpful instruction in the care and nurture of young children.

Making the Class a Success.—It is possible for one student to follow a teacher-training course alone, but it is very desirable for two or more to join and take the course in class. Several persons meeting for conference will bring better results than the same persons studying individually. The class should have a leader who is a sympathetic, patient, tactful Christian man or[Pg 7] woman, who will inspire the members to continue in their work, and who will see that every session of the class is a conference and not a lecture. Indifferent work should be discouraged. The members of the class are more likely to continue to the end of the course if they have the consciousness of mastering the work. The question and answer method should be emphasized, and the entire period of the class should be given at frequent intervals to reviews. Illuminating essays and talks may be brought into the class, but these should be brief, and should deal in a simple way with side-lights on the lesson assigned for that period.

It is very desirable that the class should be enrolled with the denominational teacher-training department and with the State Sunday School Association. This enrolment will furnish the officers of these organizations with information which will enable them to keep in touch with the class and to send from time to time helpful and inspirational suggestions. The enrolment of the class will also cause the members to feel the importance of the course and will strengthen the sense of obligation to do thorough work.

The official examinations are of the greatest importance, and should be taken by every member of the class. These examination tests intensify interest, and help to hold the class together until the end of the course.

Great encouragement will be given to the members of the class if public recognition is made of their work from time to time. Brief words spoken in public commending the work which is being done will often tide some faltering member over the crisis of hesitation. The denominational Sunday-school leaders and officers of organized Sunday-school work frequently may be called upon to lend encouragement by their helpful presence at some public function of the class.

The diploma issued by the denominations or by the International Sunday School Association is a fitting recognition of work done, and gives the student a place in the enlarging fellowship of trained teachers. Alumni Associations are being formed in the States with annual reunions. Graduating exercises should be provided, and these should be impressive and dignified services[Pg 8] that will show to the church and community the emphasis the Sunday-school is placing on high grade work.

The Sunday School Times Company does not offer any certificates or diplomas, nor does it conduct any teacher-training classes. All this is carried on by the denominations, or through the agency of the State Sunday School Associations.

| Page | ||

| The Bible | 11 | |

| Lesson | (Old Testament) | |

| 1. | The Old Testament Division | 14 |

| 2. | From Creation to Abraham | 19 |

| 3. | From Abraham to Jacob | 23 |

| 4. | Joseph | 28 |

| 5. | Moses | 33 |

| 6. | Joshua to Samson | 39 |

| 7. | Saul to Solomon | 44 |

| 8. | Rehoboam to Hoshea | 49 |

| 9. | Abijam to Zedekiah | 54 |

| 10. | Elijah | 59 |

| 11. | Return from Captivity | 64 |

| (New Testament) | ||

| 1. | New Testament Division | 71 |

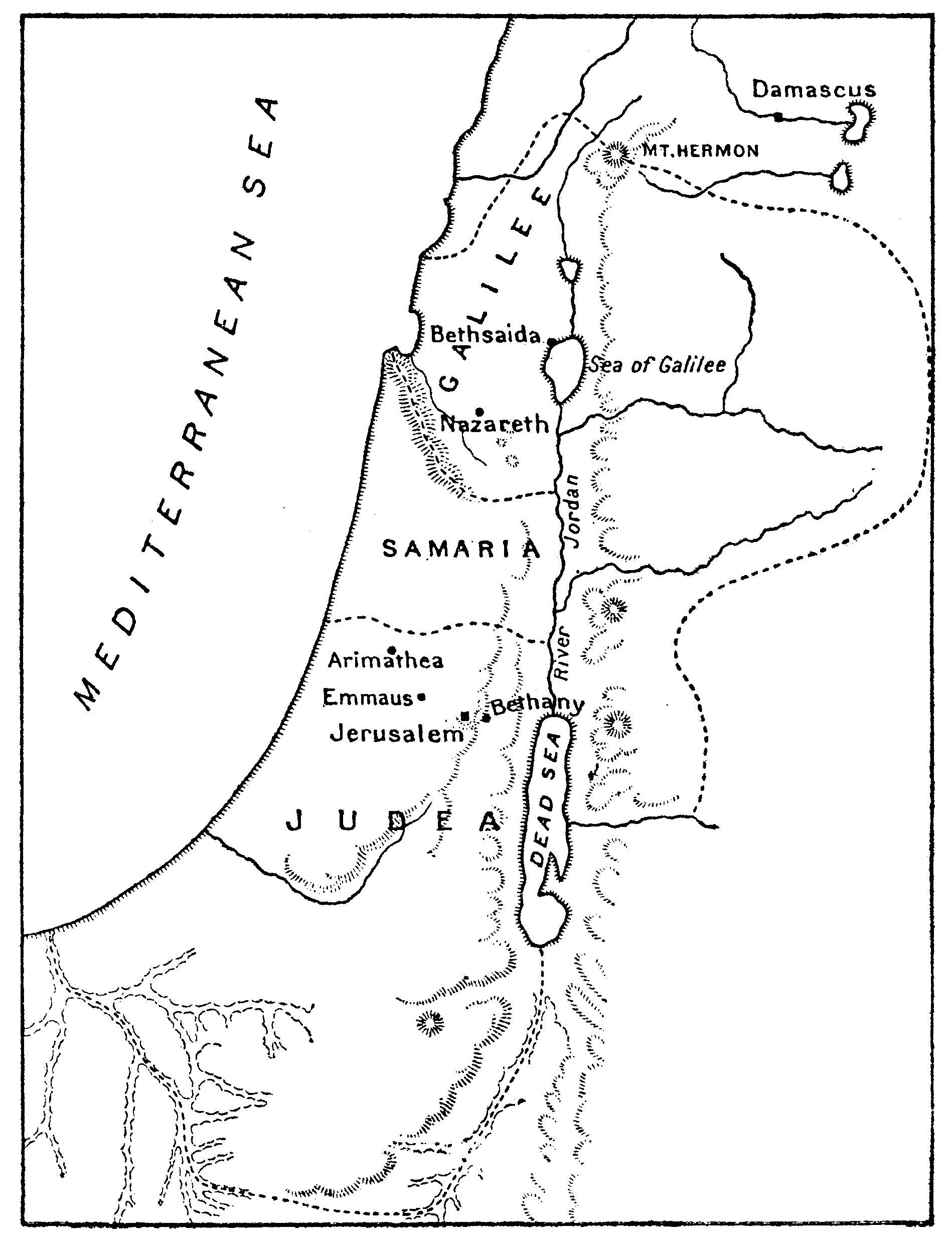

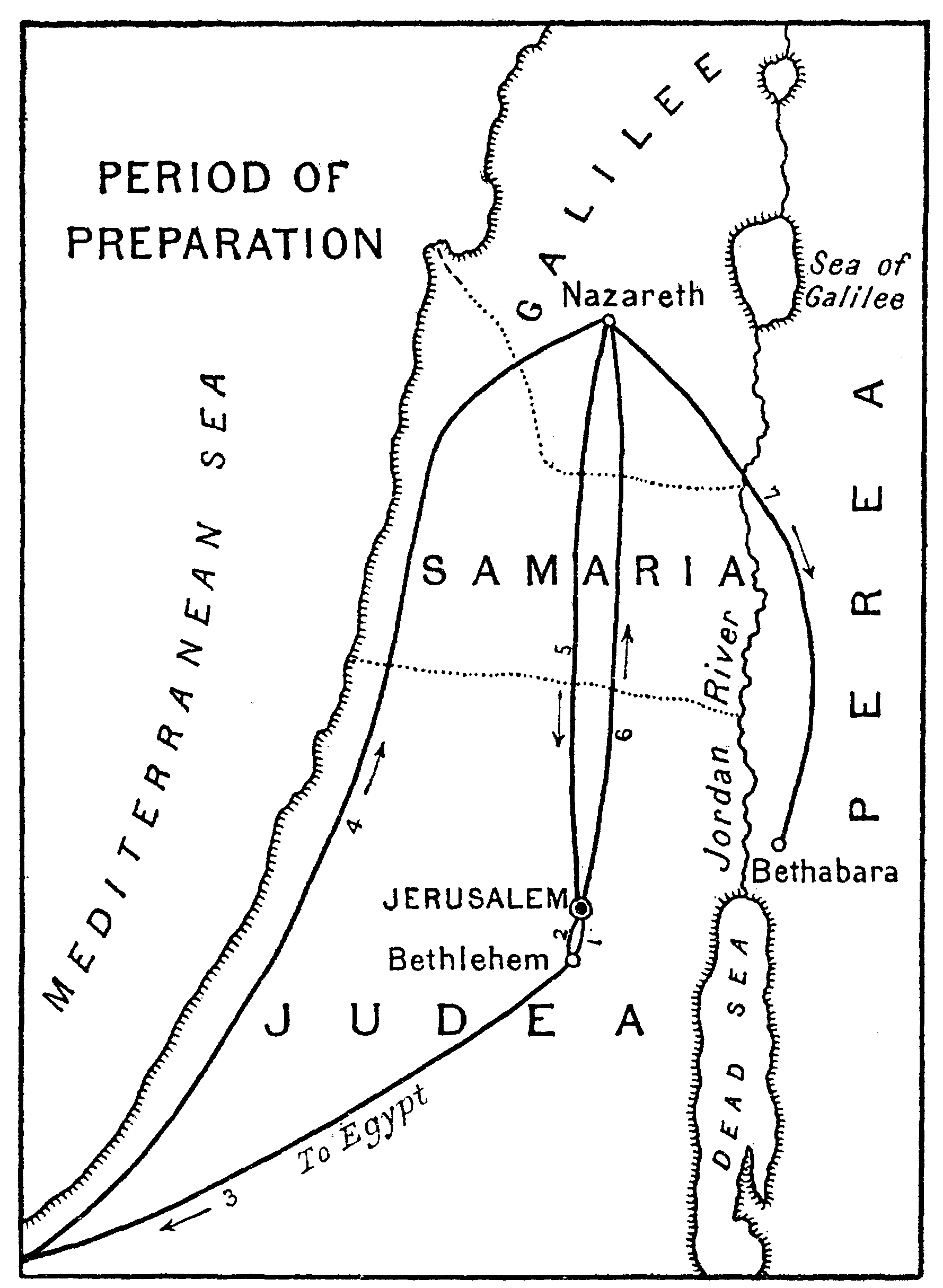

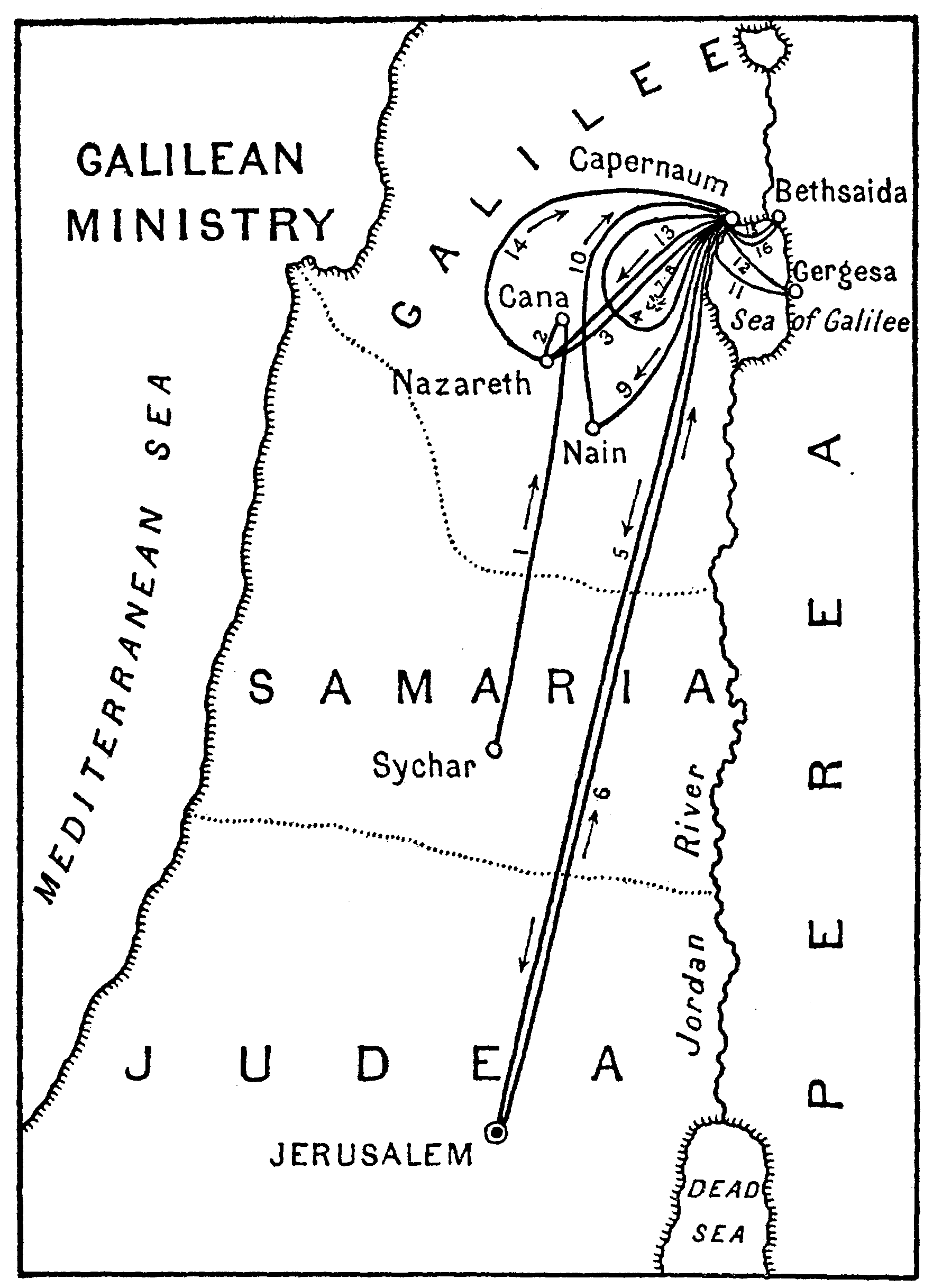

| 2. | The Life of Jesus—Thirty Years of Preparation | 76 |

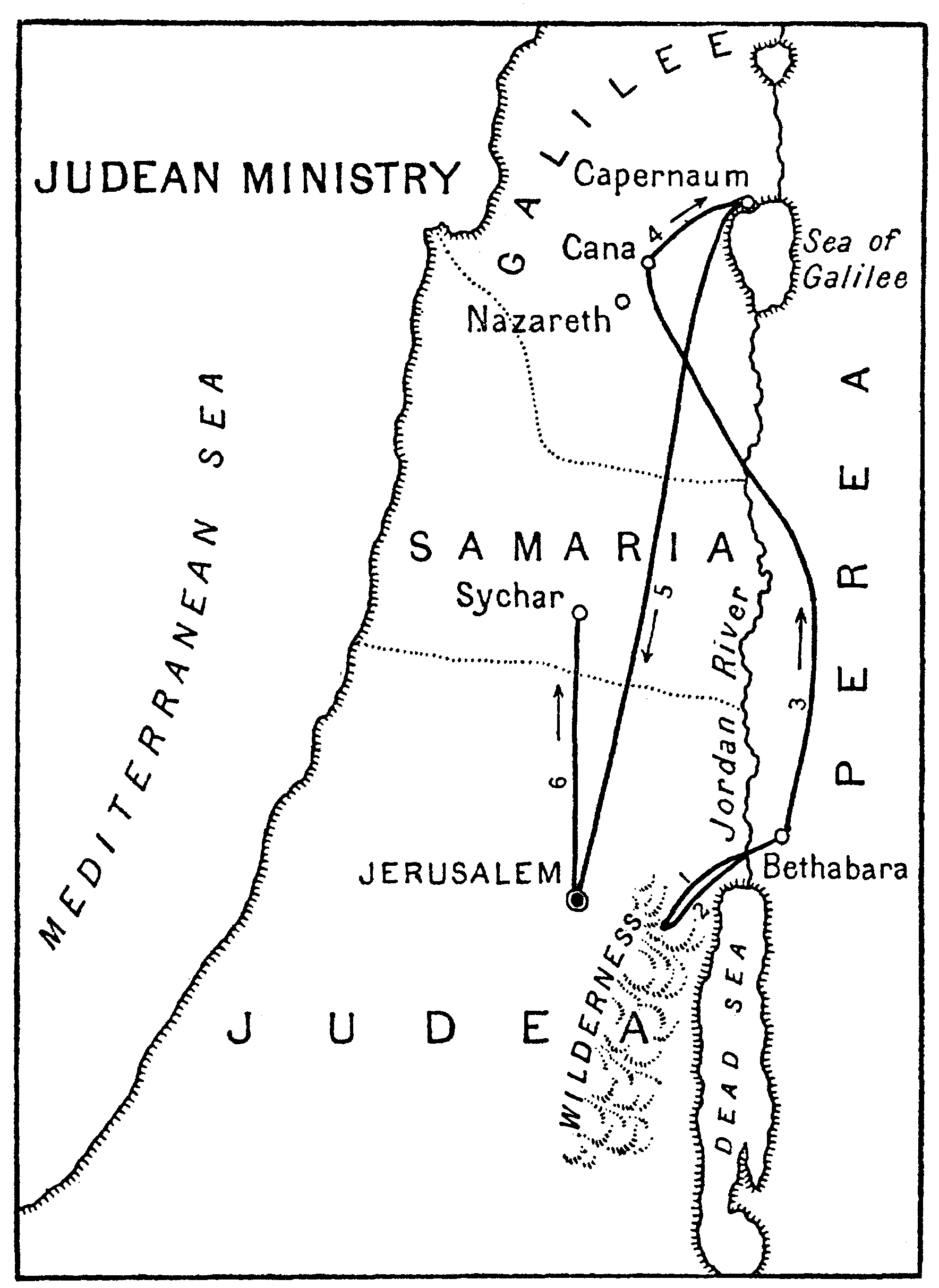

| 3. | The Year of Obscurity | 82 |

| 4. | The Year of Popularity | 88 |

| 5. | The Year of Opposition | 94 |

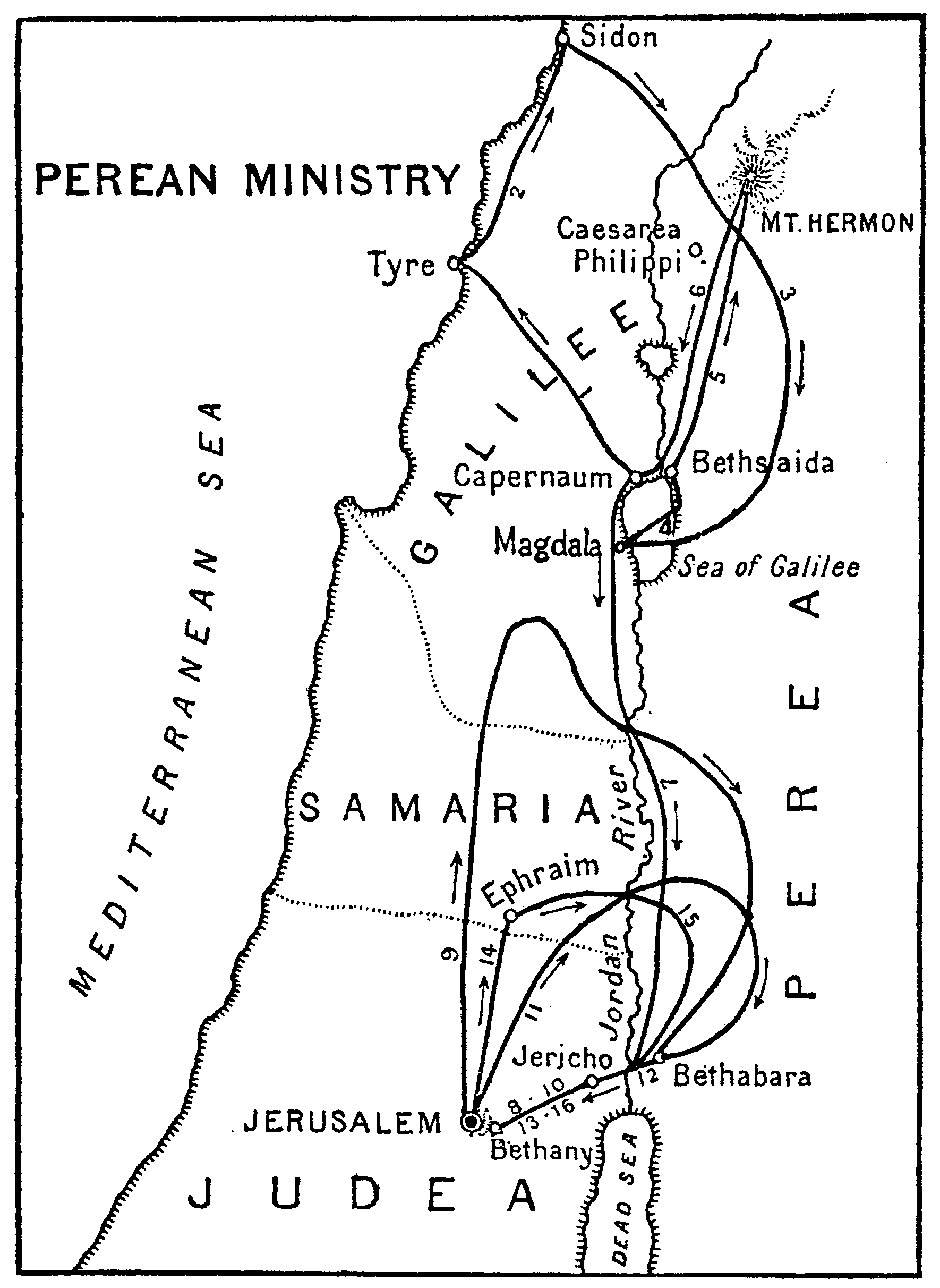

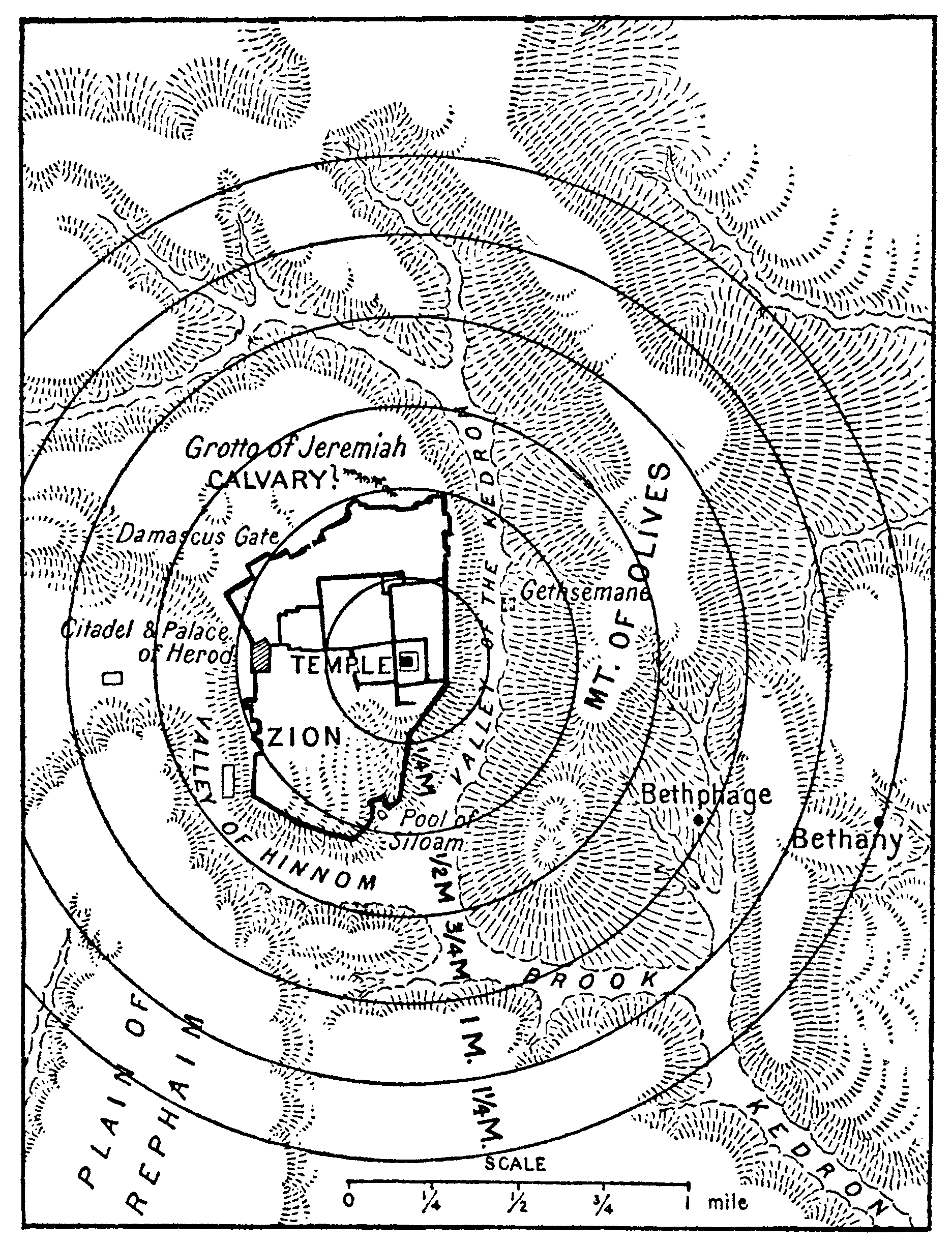

| 6. | The Closing Week | 100 |

| 7. | The Forty Days | 106 |

| 8. | The Early Church | 110 |

| 9. | The Life of Paul | 116 |

| How the Bible Came to Us | 123 | |

| Ira Maurice Price, Ph.D. | ||

| The Gist of the Books | 129 | |

| Compiled | ||

Leaders of classes, and individuals pursuing these studies apart from classes, are urged to read the chapter entitled "Teaching Hints," on page 259, before beginning this section

1. Methods of Bible Study.—Microscopic study of the Bible is the study of smaller portions, such as single verses, or parts of chapters. Many sermons adopt this method. It is good for many purposes. But it fails to give the larger views of Bible history that the teacher needs for effective work. The telescopic method takes in large sections of the Word, and considers them in their relation to the whole of revelation. This is the method that will be adopted in these studies.

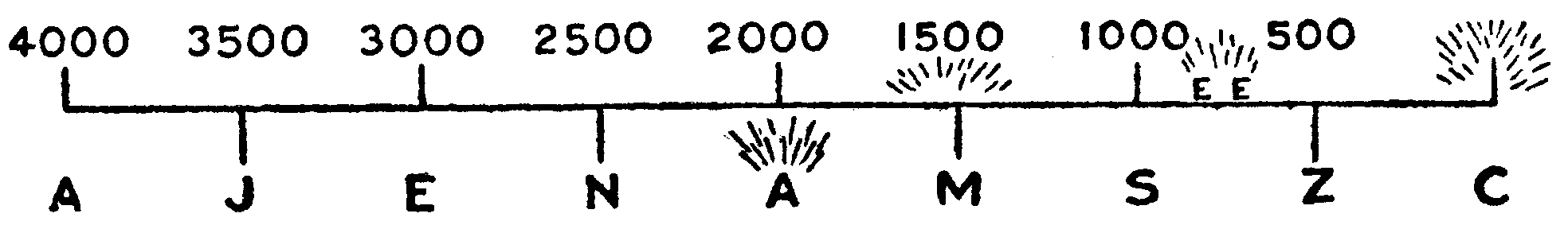

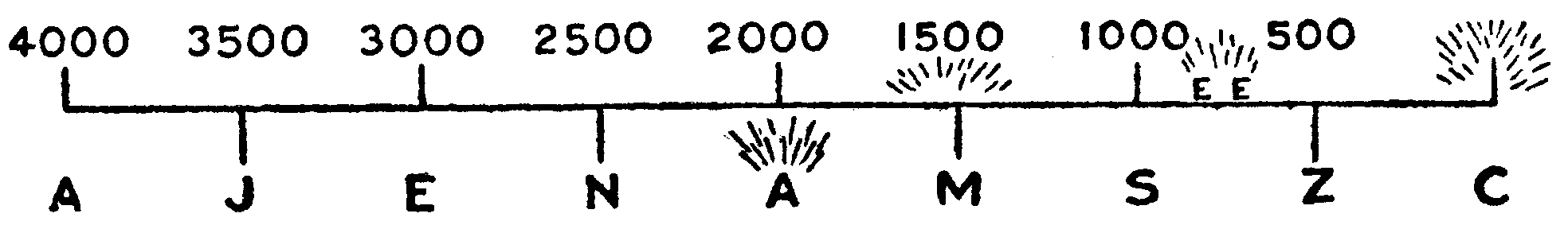

2. To assist in the study of a general survey of Bible history, we give as a memory outline above a chart of the centuries between Adam and Christ. We use in this the chronology in our Bibles, not because it is correct, but because scholars have not yet agreed on a better, especially for the ages before Abraham.

All the names are well-known but that of Jared, and his is put in merely to mark the close of the first half-millennium. Memorize these names so that you can reproduce the chart without looking at the book. This exercise of memory will enable you to locate the chief events of Bible history roughly in their appropriate chronological environment. Are you reading about any event in the wanderings of Israel? Of course you are between the letters M. and S. Is it a story of Elijah that you are studying? Then the event must lie between the letters S. and Z. Or is it the biography of Nehemiah that forms your lesson? Then it must lie to the right of the letter Z.

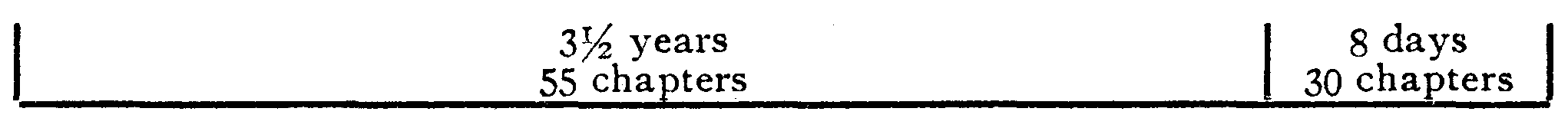

3. One peculiarity of the Bible narrative is that at times it is quite diffuse, and covers much space on the sacred page, while at other times it is most highly condensed. For example, the first twelve chapters of Genesis cover over 2000 years at the lowest computation. All the rest of Genesis (thirty-eight chapters) covers the lives of four men, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. The first chapter of Exodus covers centuries[Pg 12] while all the rest of Exodus, all of Leviticus, all of Numbers and all of Deuteronomy cover only forty years. Surely there must be some good reason for this. Again, two chapters in Matthew and two in Luke cover thirty years of our Lord's life, while all the rest of the four Gospels cover only three and a half years.

4. Another peculiarity of the Word is that the miraculous element is very unevenly distributed. At times miracles abound, and at other times they are but few in number. In the first eleven chapters of Genesis, covering more than 2000 years, there are few miracles, outside of those of the creation. But in the period after that, covered by the four great Patriarchs, we find more miracles than before.

During the Mosaic period, beginning with Exodus 2, we find that miracles begin to multiply as never before. For instance, God fed his people for forty years (except on the Sabbath) with manna. Again, in the times of Elijah and Elisha, the narrative amplifies, and the miracles multiply. And once more when we come to the Messianic period, as exemplified in the story of Christ, the narrative becomes fourfold, and the miracles multiply as never before. What is the reason for this amplification of narrative and simultaneous multiplication of the miraculous? It is because these periods were exceptionally significant. In them God was trying to teach men lessons of peculiar importance. So he led the writers to tell the story more in full, and he himself emphasized the teaching by his own Divine interposition.

5. In the Patriarchal period God was calling out him who was to be the founder of that people which was to preserve God's law through the ages, and from whom at last was to come Jesus, the Redeemer of the world. This was a most important period, and one with which we might well become acquainted.

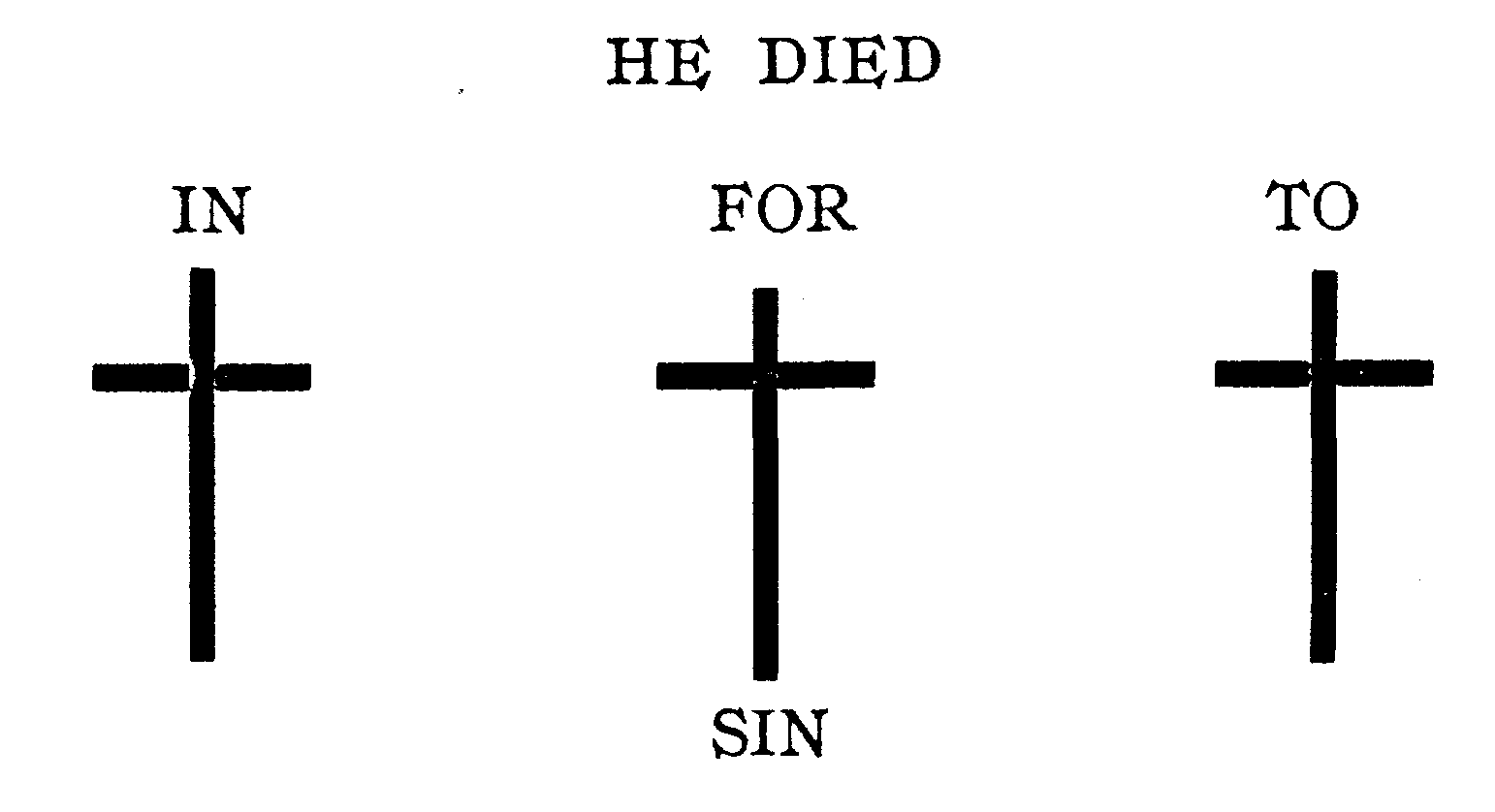

6. In the Mosaic period God was bringing out his people from bondage and was giving to them laws that were to shape their national life for all time. He was also giving to them a typology in high priest, tabernacle, and sacrifice that was to lead them in the way of truth until, in the fulness of the time, he was to come who was the fulfilment of both law and type, Jesus of Nazareth, the Lamb of God, and the Son of God.

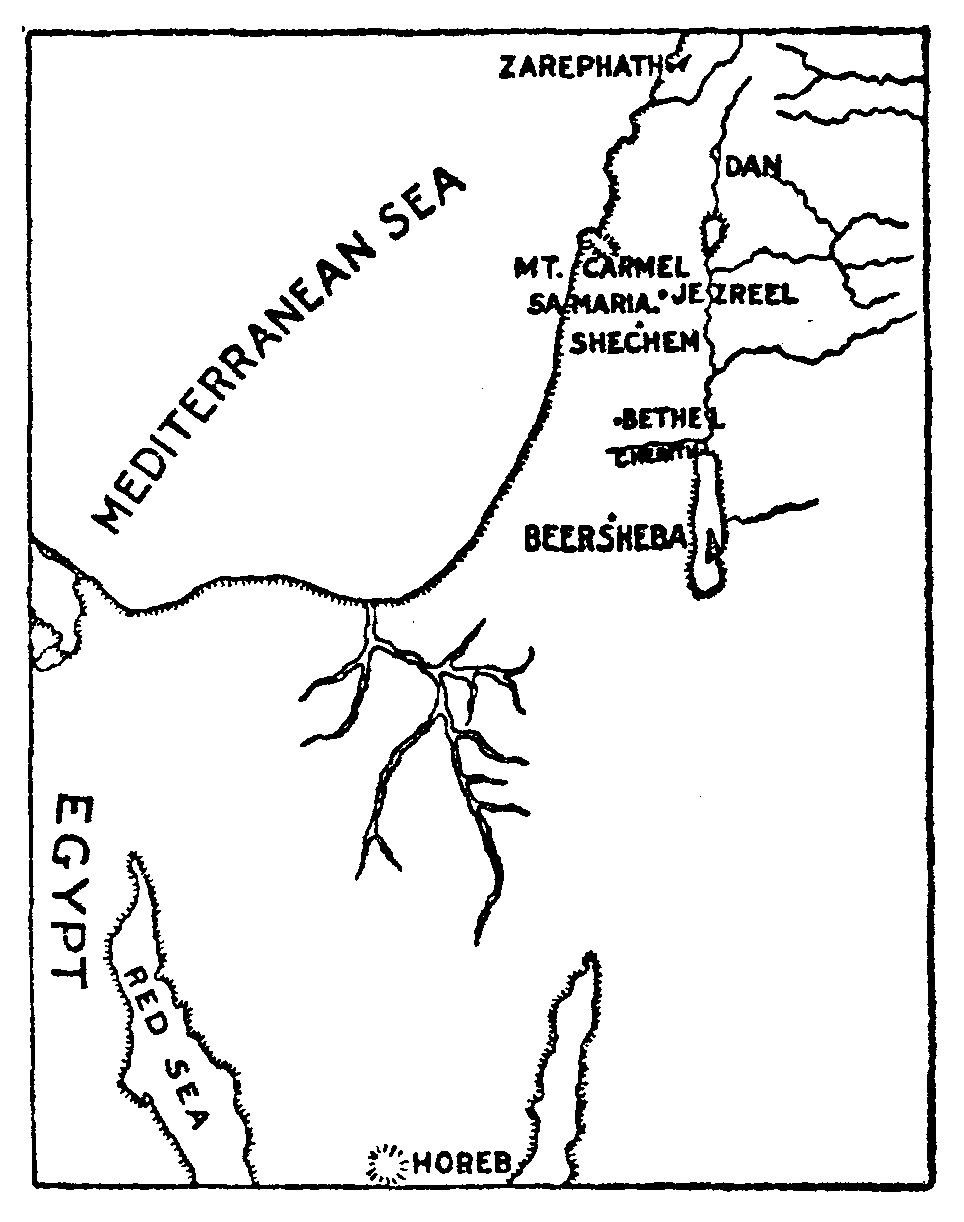

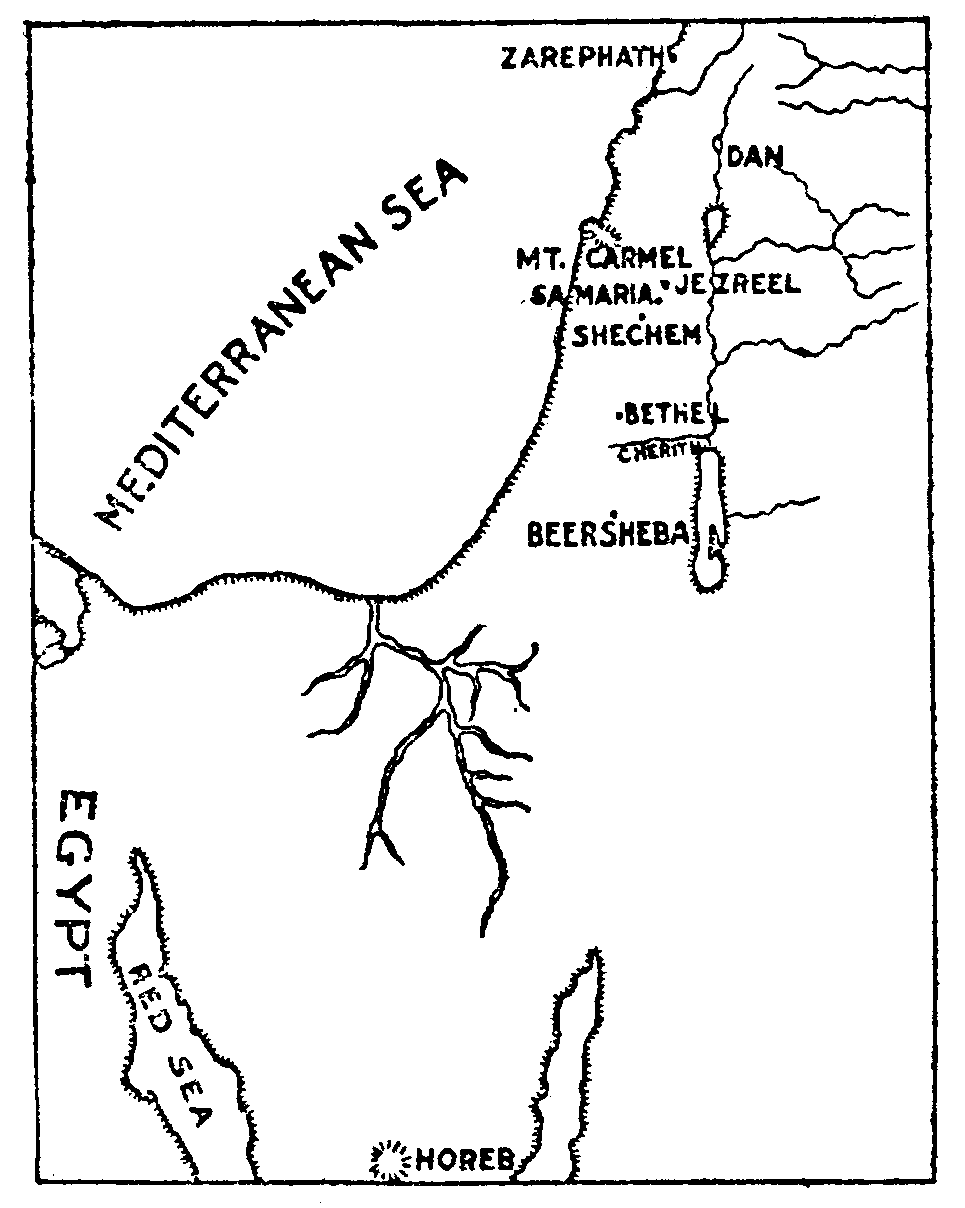

7. In the period of Elijah and his great pupil, Elisha,[Pg 13] God was making a great effort to call back to himself Israel, or the Northern Kingdom, which had been led into gross idolatry by Jeroboam, and later by Ahab.

8. In the Messianic period God was fulfilling all that he had promised from the beginning as to a Redeemer who was to come. He who had spoken to the fathers through the prophets, and the various types, was now to speak to men through the person of his Son. Good reason then why, at the four periods to which we have called attention, God should provide that the narrative should be more full than at other times, and that simultaneously there should be the marked intervention of the miraculous, to prove that God was truly speaking to men, and giving them divine directions as to how to act, and what to believe.

9. It follows, then, that there are four periods to which we should pay especial attention, as being of unusual importance, and these are the Patriarchal period, the Mosaic period, the period of Elijah and Elisha, and the period of the Messiah. If the student be well posted as to the occurrences during these periods, and their teaching, he will have at least a good working outline of the whole of the Bible history in its most important developments. To emphasize these periods we have added on the chart in the Memory Outline the dots that will be seen, multiplying them at each period somewhat in proportion to the multiplication of the miraculous element in the narrative.

What two ways are there of studying the Bible?

What advantage is there for our purposes in the second method?

Give the nine names that divide the Old Testament times into periods of five centuries each.

What chronological peculiarity do we find in the Bible narrative?

Give some examples of this. (Pick out other instances of this yourself.)

What peculiarity do we find in the distribution of the miracles?

Name the four periods in which the narrative amplifies and at the same time the miracles multiply.

PRINCIPAL EVENTS

Prelude.—The story of creation (Gen. 1, 2). God was the author of all and no idolatry was to be permitted.

First Period.—Adam, the first man; sinned and fell (Gen. 3).

Second Period.—Noah, the head of a family, saved in the ark from a devastating flood; a new beginning for the human race, followed by another failure (Gen. 6, 7, 8). The tower of Babel (Gen. 11:4). Confusion of tongues (Gen. 11:5-9).

Third Period.—The chosen family, under Abraham, broadens to tribal life. The descent to Egypt (Gen. 46). Prosperity (Gen. 47:11), followed by oppression (Exod. 1:8-22). Moses the deliverer (Exod. 3:1-11). The march out of Egypt (Exod. 12). Legislation at Mount Sinai (Exod. 20). Entry into Canaan (Josh. 1-4). Times of the Judges. (Judg. 1 to 21).

Fourth Period.—Three kings in all Israel—Saul, David, Solomon (1 Sam. 10 to 1 Kings 12). The divided kingdom.

Fifth Period.—The captivity (2 Kings 25). The return. Ezra and Nehemiah.

Leading Names.—First and Second periods—Adam, Noah; Third period—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Joshua, Samuel; Fourth period—Saul, David, Hezekiah, Josiah, Elijah, Elisha, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, Hosea; Fifth period—Zerubbabel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi.

TIME.—From an unknown time to about 400 B. C.

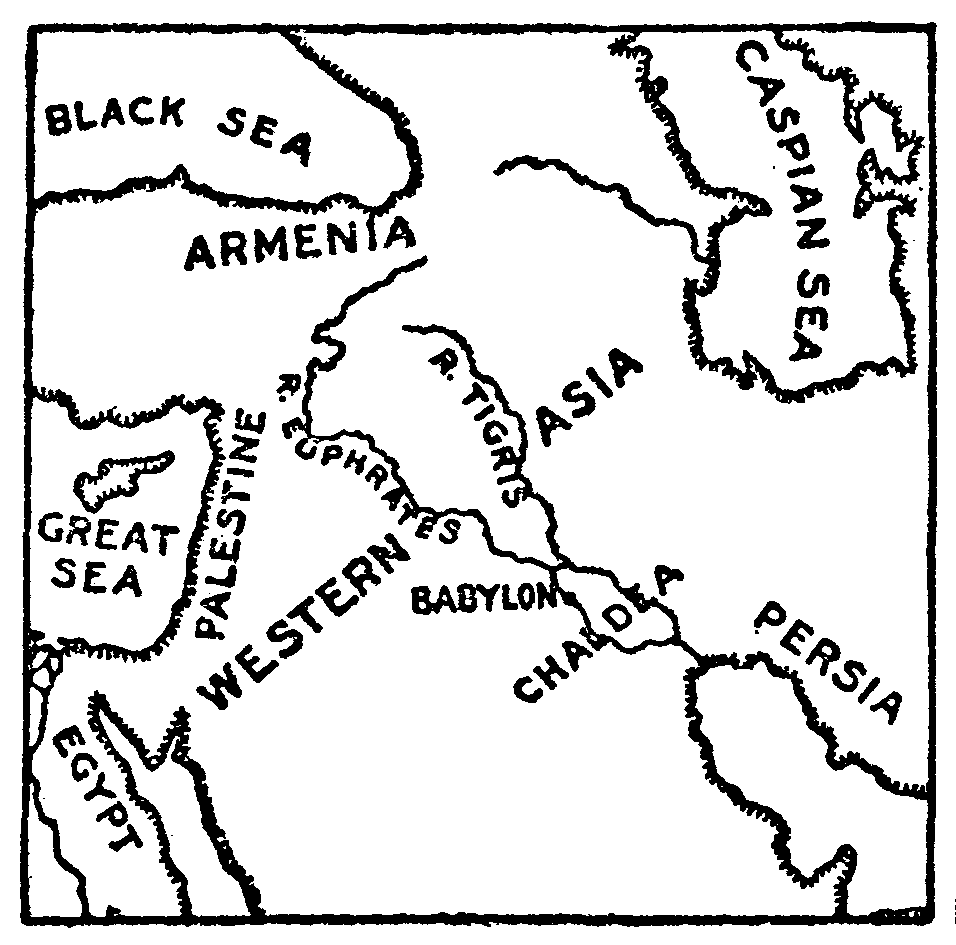

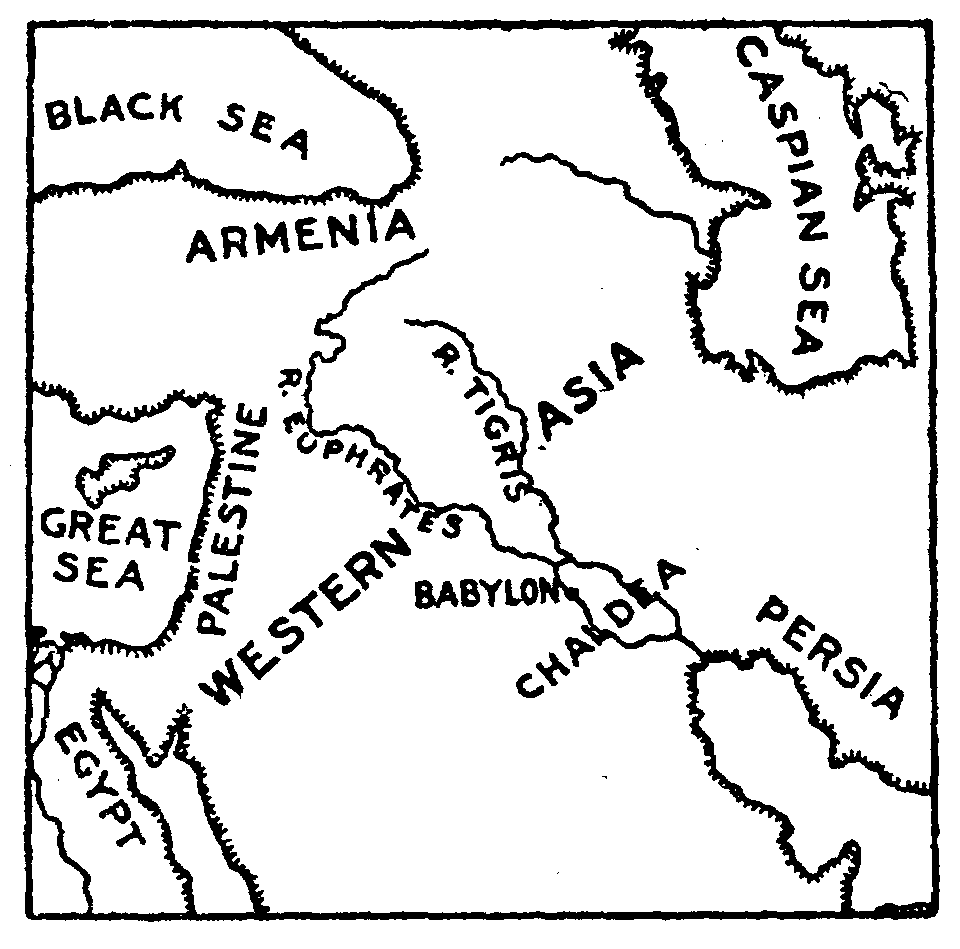

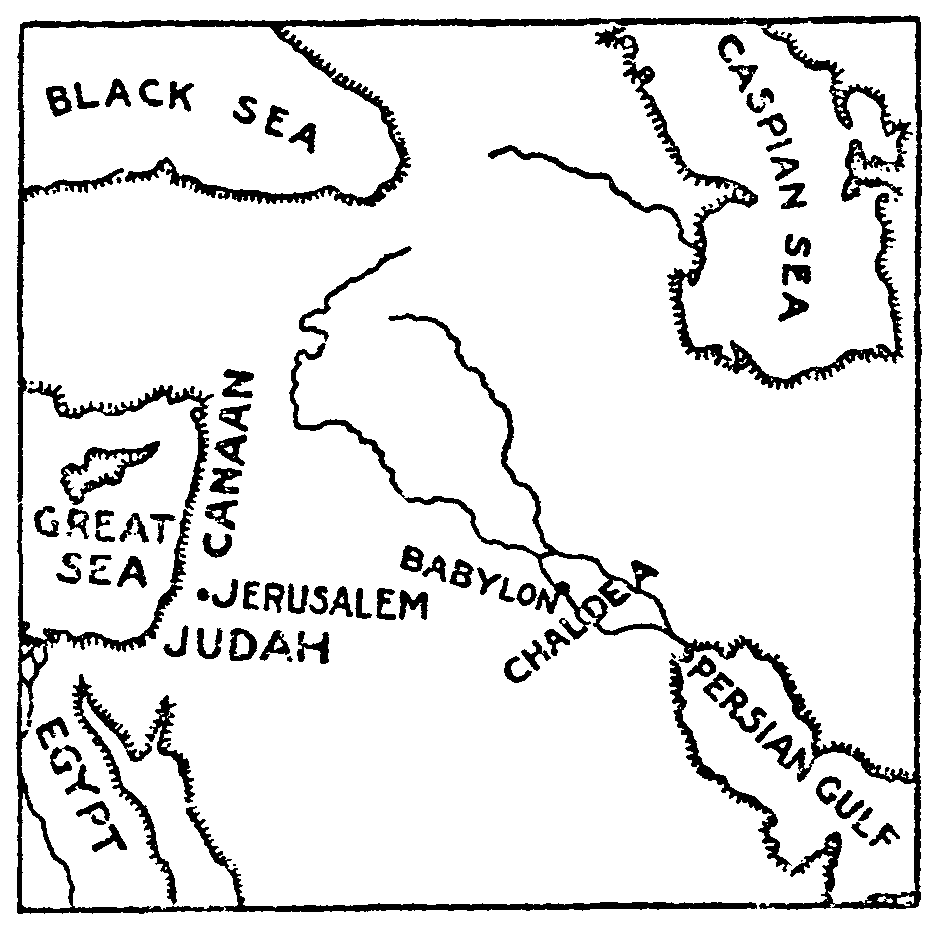

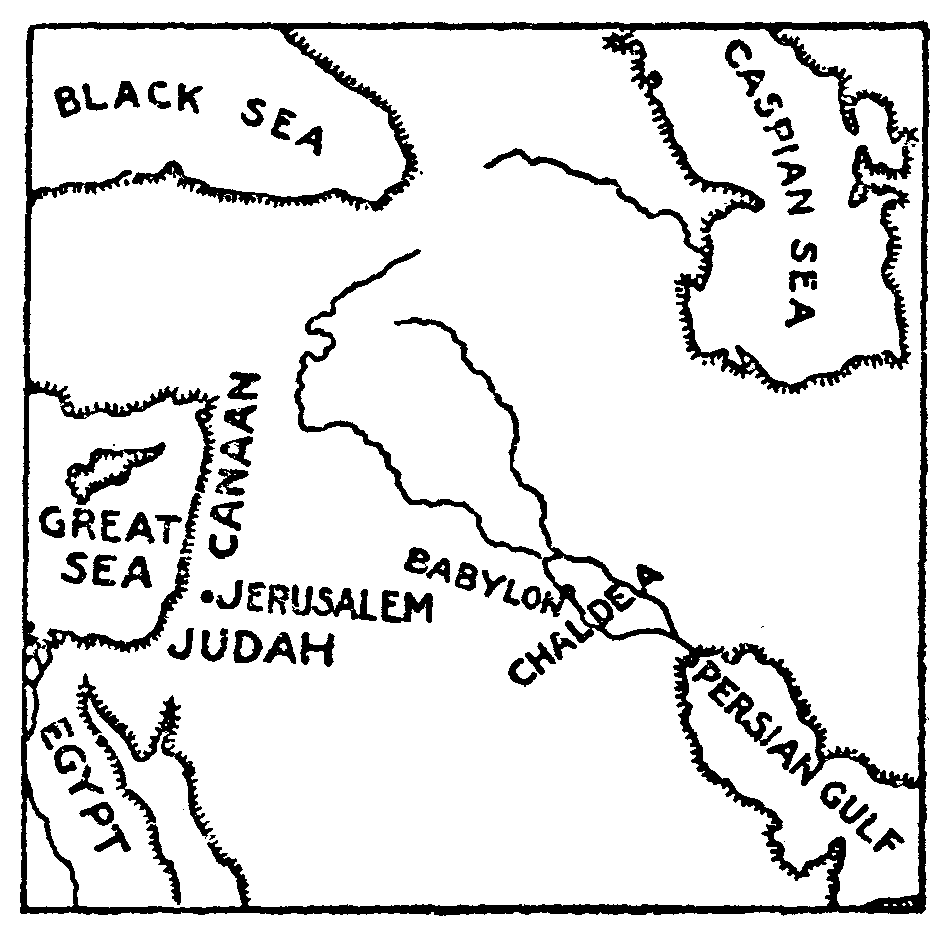

LANDS.—Armenia, Chaldea, Palestine, Egypt, Persia.

[Pg 15] SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—The Old Testament begins with a statement of the creation; tells of the introduction of man, "made in the image of God;" records the downfall of man and God's many efforts to redeem him; recites the incidents of God's dealings with chosen individuals, selected families and a particular nation; continues with this nation separated into two parts and held captive by a foreign power, and closes with the return of a part of Judah. With the entrance of sin came the promise of salvation through one who should come out of the chosen (Jewish) nation.

1. Two Great Divisions.—In biblical history here are two great divisions, that of the Old Testament and that of the New Testament. It is well to have clear outlines in our minds with regard to the great outstanding characteristics of these periods. In making these divisions into the periods that follow we have no "Thus saith the Lord" for our guidance, but use the best common sense that we have. Others might make a different division, but we give that below as at the least suggestive.

2. Prelude.—The great prelude of creation. Here we are told that all things find their origin in God. This teaching is in contradistinction to the claim that matter is eternal. It also denies the doctrine that the world was made by chance. It places the beginning of all things seen in the power of One who is from eternity to eternity. This satisfies the cravings of the human heart as no other teaching does.

3. First Period.—Adam to Noah. Here we have the first stage in the drama of human history. In it we find the beginnings of the human race, of sin, and of redemption. Three most important beginnings. It is covered by Genesis 2 to 5 inclusive. It is marked by total failure on the part of man. "Every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually" (Gen. 6:5). Man proved himself recreant to God's holy law.[Pg 16]

4. Second Period.—Noah to Abraham. Chapters 6 to 12. God makes a new beginning with the family of Noah. But, as before, man proves himself disobedient and faithless to his God. We find a great civilization, but little godliness. For the second time man proves a failure, so far as obedience to God's law is concerned. Man in his pride says, "Come, let us build," while God on his part says, "Come, let us confound" (Gen. 11:4 and 7).

But little space is given in the Bible to these two periods, for they are in reality preliminary to the third, which is of vastly more importance than the two put together.

5. Third Period.—Abraham to Kings. Genesis 12 through to 1 Samuel 9. This is a most important period. Here God changes his method of treating man. From henceforth he will chiefly communicate truth to mankind through a chosen family and nation. Not that no man outside of this circle can know God's will, but that especially through Abraham and his seed God chooses to make his will known, until, in the fulness of time, Jesus, the son of Abraham according to the flesh, shall come and reveal clearly God's love and redemption to men.

In this section we have the story of the patriarchal family, first coming out of Ur of the Chaldees, and living for a while in Canaan. Then they go down to Egypt, and at last are oppressed. After being welded together in the furnace of affliction they are brought out with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, and in the wilderness they receive the law of God through their great leader, Moses. Here too they learn the way of acceptable worship, and are prepared for entry into the Land of Promise. Then follows the conquest of the land under Moses' successor, Joshua. Now comes the period of the Judges, when God rules his people directly through these divinely called men. This is easily seen to be a most important period. All this time Israel only is monotheistic (believing in one God), but all the other nations of the earth are grossly idolatrous. During this period we see that so long as God's chosen people obey him they prosper, while as soon as they disobey disasters begin to multiply.

In this period, too, was given that legislation which has been[Pg 17] the foundation of all the legislation of civilized nations from that time to this. Here also we have the foundations of that system of types that culminated in Jesus, great David's greater Son. Sacrifice, high priest, tabernacle, here have their origin or their development. In all the history of the world up to that time there was no period so fraught with blessings for mankind as was this period.

6. Fourth Period.—Kings to captivity. 1 Samuel 9 to 2 Kings 25. This may be divided into two parts:

(1) The united monarchy. This lasted one hundred and twenty years, and had three kings, Saul, David, Solomon. Saul brought something of order out of national chaos. David carried this still farther and made Israel truly a great nation. Solomon, however, through too much luxury and many political alliances, sowed the seeds of national decay.

(2) Now comes the division of the monarchy, brought on by the folly of Rehoboam, Solomon's son. Because of his refusal to lighten the heavy taxes, ten tribes revolted and established a kingdom under Jeroboam. Ever after this they were known as Israel, also called by us the Northern Kingdom. The Kingdom of Judah is also known as the Southern Kingdom.

Israel, or the Northern Kingdom went from the worship of the golden calves to that of Baal, and continued on the downward course until they went into captivity. They had only one good king, named Jehu, and he was none too good.

Judah, or the Southern Kingdom fared somewhat better, though even here there was much idolatry. At last Judah too went into captivity, on account of its sin. It is most suggestive to compare the triumphant entry of Israel into the land, and its shameful exit in chains and tears. It was all brought about through abandoning the God of Abraham. There are some in modern days who claim that Israel had naturally a monotheistic tendency, and on that account slowly worked its way out of polytheism into monotheism. The writer does not so read the history, but finds that Israel had an inveterate tendency to polytheism, and that God only cured it of this sin through the sorrows of the captivity.

7. Fifth Period.—Captivity and return. Read Ezra and[Pg 18] Nehemiah. This is not a period of great glory, like that of Solomon's reign. But it is a period most remarkable on account of the fact that Judah was now strictly monotheistic, and from that day to this, over two thousand years, it has remained so. In the furnace fires of captivity God cured his people once and forever of their besetting sin, idolatry. This is a most remarkable fact, for the nations into which they went as captives were themselves totally idolatrous.

In this period comes the building of the second temple, the reform under Ezra, and the building of the walls of Jerusalem, under Nehemiah.

8. Now the story closes for four centuries and does not open until the New Testament times (with which we shall deal later on) begin.

Into what two great divisions is the Bible divided?

Give the theme of the Prelude to the Old Testament.

Give the extent of the first period.

What was its outcome?

Give the extent of the second period.

In what moral condition did its termination find mankind?

From whom to whom did the third period reach?

What change in God's method of revelation did the third period manifest?

With what family did God begin now to deal more specifically?

Where did family life merge into national life?

What two important phases of divine revelation did this period include?

Give the limits of the fourth period.

Give the two divisions of period four.

Give the cause of the division of the United Kingdom.

What was the course of history in the Northern Kingdom?

What course did history take in the Southern Kingdom?

Give the two prominent features of period five.

What marked change had come over Judah between the captivity and the return?

Give the great names that are prominent in the several periods into which we have divided the Old Testament times.

PRINCIPAL EVENTS

Prelude.

Account of the Creation.—The creation days: Light (Gen. 1:3-5); firmament (1:6-8); land and water separated, vegetation (1:9-13); heavenly bodies—sun, moon, stars (1:14-19); fish, birds and animals (1:19-25); man (1:26-31).

First Period.

Creation of Man.—Man made in God's image (Gen. 1:27); creation of Eve (Gen. 2:21, 22). Entrance of sin and the fall (3:1-6); Cain, son of Adam and Eve, killed his brother Abel (4:3-8).

Second Period.

The Flood.—The prevalence of wickedness (Gen. 6:5) caused God to destroy the population of the world by flood, with the exception of Noah, his family, and selected animals (Gen. 6-8). God made a covenant with Noah not to destroy the people again by flood (9:8-17)

The Tower of Babel.—The wickedness in the heart of men found expression in the building of the great tower of Babel, and the punishment therefor was the confusion of tongues (11:1-9).

TIME.—From an unknown time to 1928 B. C.

PLACES.—Garden of Eden, Western Asia, Babylon.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—The creative period marks God as the supreme author of the universe and of its inhabi[Pg 20]tants; sinless at first, man falls, and begins the battle with evil which shall cease only with the ultimate complete triumph of Christ, the Redeemer. The flood marks the first of a series of tremendous efforts to save the world from the thraldom of sin.

9. Prelude.—This is the beginning of all things, and well suits the cravings of the human mind. It says, "In the beginning God created." This beginning does not go as far back as that of John 1:1, for that antedates creation and points to a beginning before God created. That is, John sweeps back to that beginning when as yet there was none but God. If this statement of Genesis 1:1 is compared with creation myths as found among other nations, it will at once be seen to be far grander and more in accord with our best thoughts of the divine activity. Unbelief may say, "In the beginning matter," or "in the beginning force," but that does not satisfy the human heart as do the words of the sacred writer.

In this beginning we see the origin of all things. Genesis means "beginnings," and in this book we find the beginnings of matter, of vegetable life, of animal life, of man, of sin, of sacrifice, of material civilization, of the Covenant People, and of Redemption. Truly a wonderful book. Well has it been said that "Genesis enfolds all that the rest of the Bible unfolds." In this book we find the germ of all that is to follow. If we would know the inner significance of all that we find in Genesis we must look to Revelation.

10. Period One.—Adam to Noah. Here comes the story of the creation of man. Innocent he was at the first, but in the trial to which he is brought, man fails, and disobeys. As sinner, he now hides from the face of God, and has to be sought out by his heavenly Father. Sin created a barrier between God the Holy One and man the sinner. Then it is that God begins his work of redemption, and in Genesis 3:15 we see the first promise of that redemption that is to be fulfilled in Jesus in later days. In this period we see the first sacrifice, and in it, too, we come across the full fruitage of hatred, which culminated in[Pg 21] murder. Man proves to be a sad failure, and the record is that God looks down from heaven to see how man is acting. "And Jehovah saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually" (Gen. 6:5). From that day to this, man when left to himself reproduces this picture, as may be seen in those lands where there is no light of the gospel of the grace of God.

The chief characters of this period are Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Enoch, who "walked with God: and he was not; for God took him," Noah and his three sons—Shem, Ham, and Japheth.

11. Period Two.—This lasts from Noah to Abraham. God blots out the human race as it then existed and begins it anew. So far, all that we know of the human race lived in the Euphrates valley, and all modern research confirms the Bible statement with regard to this. It need not be maintained that the flood was universal, in the sense that it covered the whole world, as we now know it. All that is needful to believe is that the "known world" was subject to a devastating flood that caused the human race to perish, with the exception of Noah and his family. Warned by God Noah builds the ark, and embarks in it. The rains descend and the fountains of the great deep are broken up, and the land is submerged. In due time, the rains cease, and the floods dry up, and Noah sends out first a raven, which returns not. Then he sends out a dove, which comes back to the ark, not finding any resting-place. In seven days he sends out another dove, which returns bringing an olive-leaf in her mouth. The third time he sends forth a dove, which returns not. Then in due time Noah goes forth from the ark, which had rested on Mount Ararat in Armenia.

12. Now follows the beautiful story of the sacrifice that Noah offers, and the promise of God never again to send a deluge on the earth. This promise is confirmed by the symbol of the rainbow. Of course there had been rainbows before this, but this time God takes the rainbow and makes it a symbol of his mercy to sinful man.

13. The Tower of Babel.—In this period we there is a great[Pg 22] advance in civilization, as may be seen by a careful reading of Genesis 10:1-32. Cities are built and nations are founded by the descendants of the Patriarch Noah. But the evil tendency of the human heart again shows itself, and the pride of man's achievement fills the heart of the descendants of Noah. Then comes the story of the tower of Babel, and in this we read most significantly, "And they said, Come, let us build." To this God's reply is "Come, let us confound." Man's pride is to be abased, and put to confusion. So the human race is scattered abroad and its cherished plans are broken up. For the second time, man is seen to be a failure, and there is call for another way of dealing with the race if the truth is to be preserved. This third beginning is to be found in Period Three, with which our next lesson will deal.

State how the Gospel of John has a sweep farther back even than Genesis 1:1.

What beginnings may we find in the book of Genesis?

How does man act toward God, as soon as he transgresses his law?

Where do we find the beginning of the story of redemption?

Give the names of the chief actors in this first period of Bible history.

Give the divine estimate of the moral condition of man before the flood.

Where does the Bible place the story of the beginnings of the human race?

Give the story of the building of the ark and of the flood.

In the second period, what may we say of civilization? How did its magnitude show itself?

Give the record of the scattering of the human race.

Was the second trial of man any more successful than the first, regarded from the religious standpoint?

LEADING PERSONS

Abraham.—Lived in Ur of the Chaldees. Called by God to leave country and home and kindred to go to Canaan, the promised land (Gen. 12:1 to 25:11).

Isaac.—Son of Abraham (Gen. 21). Proposed as a sacrifice (Gen. 22:1-19). Married Rebekah (Gen. 24).

Esau.—Son of Isaac. Sold his birthright to his brother (Gen. 25:27-34).

Jacob.—Son of Isaac. By a trick secured his father's parting blessing, to which Esau was entitled (Gen. 27:1-45). Journeyed in search of a wife, and married (Gen. 28:10 to 31:16). Returned and was forgiven by Esau (Gen. 31:17 to 33:20). His name changed to Israel and he became the father of the Jewish nation (Gen. 35:9-15). Had twelve sons, who become the heads of the Twelve Tribes of Israel (Gen. 35:23-27).

TIME.—1928 B. C. to the birth of Joseph, 1752 B. C.

PLACES.—Ur of Chaldees, Canaan, Egypt.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—With Abraham God began a course of dealings with man which continued for about two thousand years. Setting apart Abraham with his family was really the beginning of the chosen nation, although the national life did not begin until after the escape from Egypt (see Lesson 5).

14. The Bible Deals Largely in Biographies.—If you know well the stories of the great Patriarchs, you know the best part of Genesis. Again, if you know the stories of Moses, Joshua, Gideon, Samuel, David, you will have mastered most of the history of Israel from Exodus through 2 Samuel. This is the reason why in these lessons we deal so largely with Bible biographies.

15. Abraham.—Abraham was one of the greatest men in all history. He was the founder of that people through whom we have received all of the Bible, excepting only what Luke, the beloved Physician, has given us. This of itself is no small distinction. But more. He is the great progenitor of him whom we know as the Messiah and the world's Redeemer.

16. Abraham and his Call.—The call came to him in his home in Ur of the Chaldees. Exactly in what way it came we are not told. It may have been an inward call, such as believers to this day have at times. Bear in mind that Abraham's ancestors were idolaters, and that the land in which he lived was totally idolatrous.

This call was twofold. It was a call "out of," and a call "in to." Out of home and family and religious antecedent. In to a new environment geographically, socially, religiously.

This call he obeyed at once, and forth he went, not knowing his ultimate destination. At Haran he paused until the death of his father. Then on he went. How he knew what direction to take we are not told. It may have been that he pushed forward as the migrating bird pushes ahead, driven by a kind of inward impulse, blindly but surely. This at least is my idea.

17. Abraham and the Land.—At last Abraham comes to Shechem, and there for the first time God tells him that this is the land of which he had spoken. There, for the first time in that land, an altar was raised to the true God. From that day to this, and to the end of time, that land and the Chosen People have been and will be identified.

18. Abraham and Egypt.—Driven by famine, the Patriarch goes down to Egypt. There is no record that he was divinely guided in this, and from the fact that there he gets into trouble,[Pg 25] and that God does not appear to him at all in Egypt, we may infer that this was not any part of the divine plan. God does not appear to his servant again until he returns to the Land, and builds his altar "where it was at the first" (Gen. 13:1-18).

19. Abraham and Lot.—Lot was Abraham's nephew. His character differs widely from that of his uncle. Mark, in his dealings with his greedy nephew, the grandeur of the Patriarch's character. As the land cannot "bear" the two sets of flocks, Abraham gives Lot the first choice of the land, and declares that he will take what Lot leaves. This is not after the manner of the "natural man." Decency would have led Lot to decline his uncle's generous offer. But Lot was not decent, and so seized all that he could. In the end this led to Lot's ruin. It is most suggestive to note the steps in Lot's career. First he pitched his tent "towards" Sodom. Then we find him "in" Sodom. Then he sits in "the gate" of Sodom—that is, he has become a prominent man in that accursed city. Soon we see him involved in the overthrow of Sodom by the four kings. Still he returns to that city, after his rescue by his uncle. And at last he has to escape from its final ruin, penniless. We read in 2 Peter 2:7 that Lot was vexed with the wicked life of the Sodomites. It has always seemed a pity that he was not sufficiently vexed to get out from the city, bag and baggage, long before he did.

Again look at Abraham when he had gained the victory over the kings as told in Genesis 14. How grandly he stands, refusing to touch what comes from Sodom from a thread to a shoe latchet. By the laws of war in that time all the "loot" was his. But he would not touch it. Bear in mind that this was 2000 years before the Golden Rule was given, yet here we have a man exemplifying it grandly. What a contrast between Abraham and some of the troops in modern sieges, where they have seized all that they could lay their hands on. This was nearly 2000 years after Jesus uttered the Golden Rule. Who was more truly Christ-like, Abraham 2000 years B. C. or we, 2000 years A. D.?

20. Abraham and Hagar.—The Patriarch was not a perfect man. He sinned in Egypt (Gen. 12:10-20), and again, as told in Genesis 20:1-16. Again, his faith in God's promise that he should[Pg 26] have a son seems to have grown dim. So he yields to Sarah's suggestion, and takes Hagar. (Gen. 16). In judging him for this, bear in mind that he had not the light that came in later days, through the further revelation of God's will. Then Ishmael was born. It is most suggestive that from Ishmael, who was not a "child of faith," sprang in later days Muhammad the great antagonist of Jesus Christ, who came from Abraham through Isaac, the "child of faith."

21. Abraham and Isaac.—To understand the command of God in relation to the sacrifice of Isaac, we must bear in mind the customs of those days in Canaan. As we now know, through excavations in that land, human sacrifices were common. Remembering this, my own impression is that God intended to teach his servant two things by this command. First, that all human sacrifices were abhorrent to God; and second, that his obedience must be unquestioning. God never intended that Isaac should be sacrificed. This is apparent from the whole narrative. His command was a "test" of the utter obedience of the Patriarch. This test Abraham met grandly. He was willing to trust God to the last, though he could not see the reason why. Then God showed him that his son was not to be sacrificed, and provided in Isaac's place a ram for an offering.

The story of procuring a wife for Isaac is truly oriental in its setting. But bear in mind, it was accompanied with prayer. Though it is not in accord with Western methods of courtship, it turned out quite as well as many modern marriages made after the custom of twentieth century "society."

22. Abraham and Sodom.—Here again we have this man in a grand light. He pleads for Sodom, and that, in spite of its utter worthlessness. But there are not in all of Sodom twenty righteous men to be found. Lot's family even, merely scoff at him, and refuse to believe his warning. It is most suggestive in this connection, that "God remembered Abraham, and sent Lot out of the midst of the overthrow." (Gen. 19:29.) Lot's best asset in his life was not his real estate in Sodom, but his godly uncle far from that wicked city. Just so the best asset that any modern city has, is not its stocks and bonds, or real estate, but the truly godly people who live in its midst.[Pg 27]

23. Abraham and Machpelah.—There are two places in Canaan most intimately associated with Abraham. These are Shechem, where he first learned that he was in "the Land" at last, and Machpelah, where he laid Sarah to rest and where he himself was buried. Here also were buried Isaac, Jacob, Rebekah, and Leah. (See Gen. 25:9, 49:30, and 50:13.) It would not be very surprising if some day we were to recover their bodies from that historic burying-place. Stranger things have happened.

In what does the Bible deal largely?

Give the names of the great characters of the Old Testament up to David.

In what two respects was Abraham one of the greatest men of history?

In what respect was the call of Abraham a twofold call?

What was the religious environment of the Patriarch in his home?

Where did Abraham first know that he was in "the Land"?

What did he there "raise" at once?

What makes us think that God did not direct Abraham to go to Egypt?

What characteristics did the Patriarch show in his relations with Lot?

How did Abraham's faith show somewhat of an eclipse in the matter of Hagar?

Who was one of Ishmael's descendants, and what does this suggest?

To whom did Lot owe his deliverance from Sodom at its overthrow?

Who were buried in the Cave of Machpelah?

LEADING PERSON

Joseph.—Son of Jacob. A favorite son (Gen. 37:3) and a dreamer (Gen. 37:5-11). Hated by his brothers and sold into Egypt (Gen. 37:12-28). A slave, but honored; then cast into prison (Gen. 39:1-20). By interpreting a dream of Pharaoh he was brought into high honor, and became Pharaoh's prime minister (Gen. 40:1 to 41:45). Stored up grain in Egypt to provide for a famine; relieved the needs of his brothers, who journeyed to Egypt in search of food; finally invited his father's family to live in Egypt (Gen. 42:1 to 47:12).

Other Persons.—Pharaoh, king of Egypt. Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, owner of Joseph the slave. The butler and the baker of Pharaoh, confined in prison while Joseph was there, and the indirect means of Joseph's exaltation. Jacob, Joseph's father; and Joseph's brothers who sold him into Egypt.

TIME.—1752 B. C. to 1643 B. C.

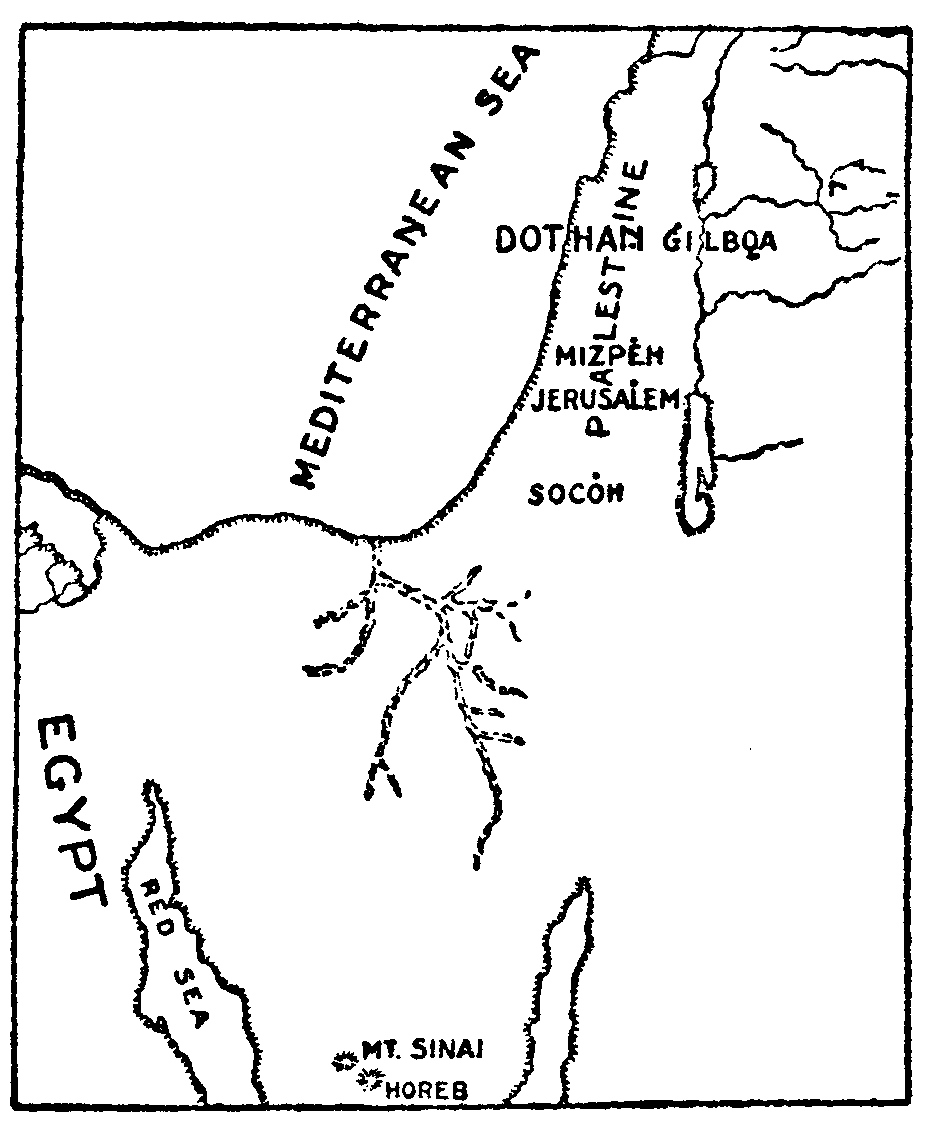

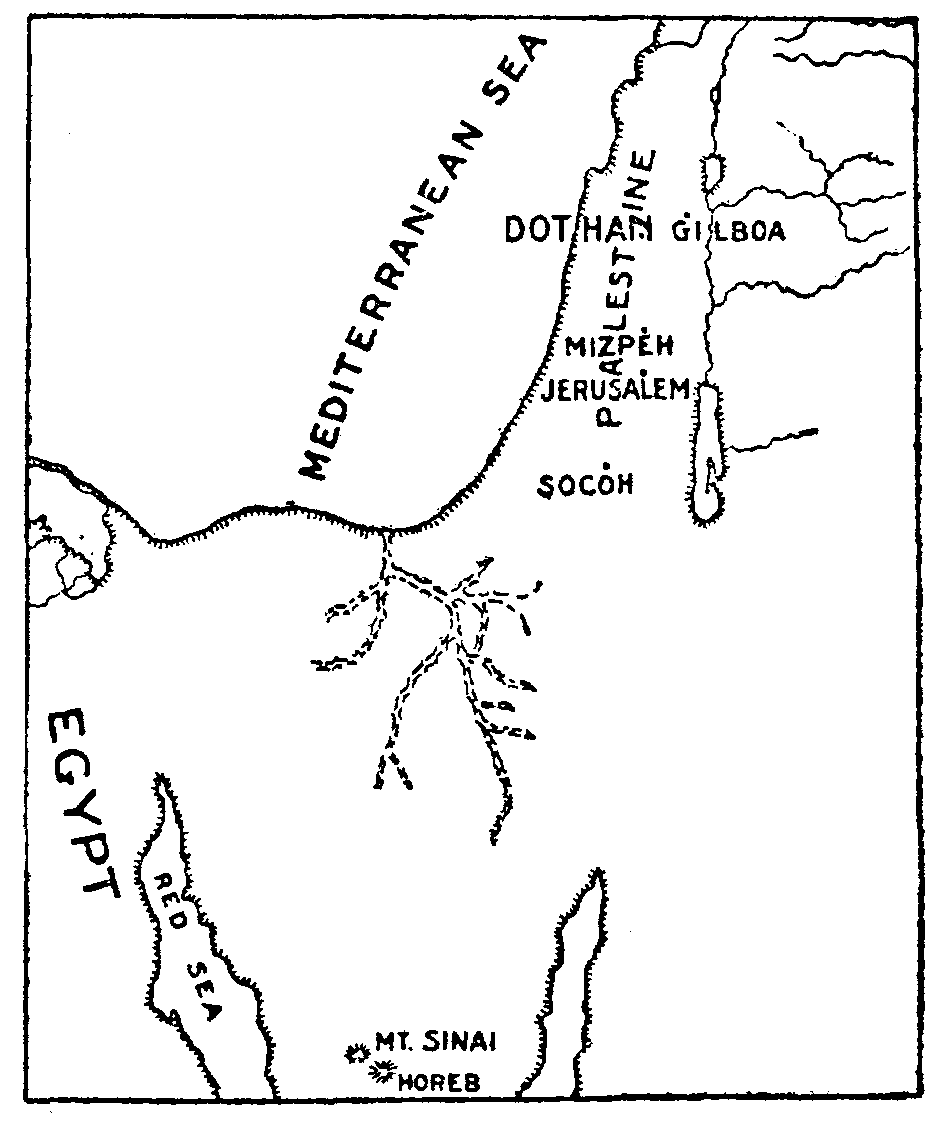

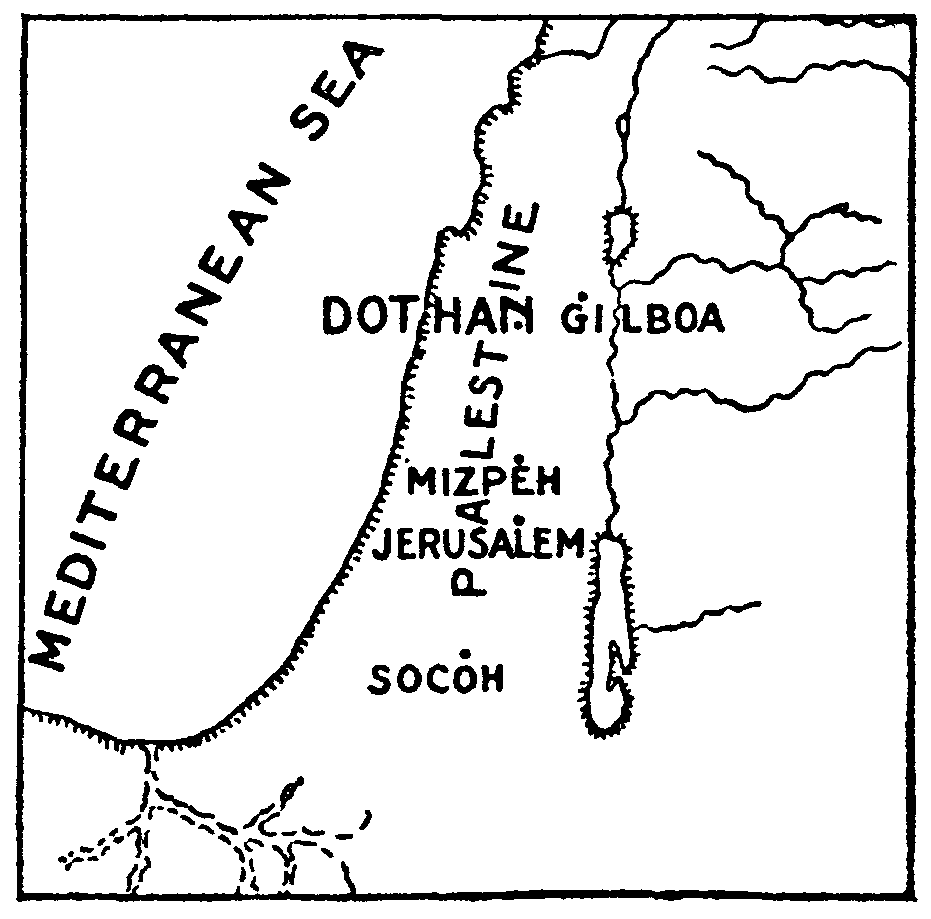

PLACES.—Dothan, in Palestine. Egypt.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—As a result of Joseph's invitation to his father and brothers, with their family, to come to Egypt and partake of his bounty, the Hebrew nation, through its leader, was transplanted to Egypt. Their sojourn as a people lasted many years; and brought them into subjection to the Egyptian monarch (Exod. 1:8-14).

Here we have a wonderful character. The life of Joseph may be divided into two parts. First, his humiliation. Second, his exaltation.

24. Joseph's Humiliation.—Genesis 37, 39, and 40. We see him first as his father's favorite, unwisely made conspicuous by the dress that his doting father gave him. This arouses his brothers' envy. This envy was further intensified when Joseph told them the dreams that he had, which plainly foretold his exaltation, but which made them angry. Even his father seems to have balked at the second dream (Gen. 37:10). Now comes the cruel plot of the heartless brothers, planned at Dothan, though, through the providence of God, not fully carried out. Their definite purpose is to put him out of the way, "and we shall see what will become of his dreams."

25. Here then we have a clear statement of God's plans and men's plans with regard to this seventeen-year-old lad. God proposes to make him mighty in deeds for the welfare of God's people. Men propose to put him to death. These two plans cannot both be carried into effect. Which is to prevail? The story is a fascinating unrolling of the divine plan and the complete thwarting of the human plan.

26. Joseph the Slave.—The brothers change their plan, and sell Joseph to traveling Midianites. These take him to Egypt, and sell him to Potiphar, an officer in Pharaoh's court. Note here his fidelity in all things, so that he becomes really the overseer in Potiphar's house (Gen. 39:6). Instead of resenting his purchase by Potiphar, he takes things most patiently, and does his duty bravely.

27. Joseph in Prison.—Once more, through no fault of his own, Joseph suffers further degradation. To prison he goes. We said "through no fault of his own." This is an understatement, for it was on account of his fidelity to his master that he was shamefully traduced, and so sent to jail. Yet even here his spirit of loyalty to duty did not desert him. Again we find him trusted and put in charge of all prison matters. (Gen. 39:22, 23.) But what has become all this time of God's plans for Joseph?[Pg 30] Are they to be thwarted? Nay, wait until the fulness of time, and then note how God's plans ripen, and are fully perfected. In the meantime note Joseph's wonderfully sweet spirit. See how he notices the sad countenances of butler and baker in prison. Note how he sympathizes with them, and tries to help them. Here again, as in the case of Abraham, we see the exemplification of the Golden Rule, long before it was uttered. Had Joseph been like some modern men, he would have taken vengeance on the butler and baker, they being Egyptians. He would have said, "These Egyptians have enslaved and imprisoned me for no fault of mine. Now is my chance, and I will pay them back." But no such bitter thoughts seem to have entered his pure mind. In the meantime note his steadfast faith in God and his persistent loyalty to duty, however hard that might be.

28. Joseph's Exaltation.—This came with a leap. The story is familiar. But in studying the lesson, let the student not fail to read it once more, most carefully. If it seem somewhat incredible that Pharaoh should make a prime minister out of a prisoner at one stroke, bear in mind that in the East they do not do things in Western fashion. Even to this day

"East is East, and West is West,

And never the two shall meet."

The writer during his boyhood knew of a case illustrating Eastern methods, which took place when he was living in his home in Constantinople. The Sultan had a dentist. One day while his dentist was off hunting, the Sultan got a toothache. He sent for his dentist, but could not get him. His courtiers then got hold of a poor dentist who could hardly make his living. He went to the palace and extracted the offending molar. At once the Sultan deposed his regular dentist, put this man in his place, created him a pasha, or peer of the realm, gave him a large stipend, and a palace in the city and another in the country. Thus at one stroke the man passed from obscurity to prominence, and from poverty to wealth. This is the manner of the East.

Now we begin to see God's plans working out manifestly. Yet all this time his brothers think that their plans have succeeded[Pg 31] and that the "dreamer's" career is ended. No, the "dreamer's" career has just begun.

29. The Seven Years of Plenty.—Now follow years of great activity, and of much honor for the former prisoner. Up and down the land he goes and gathers grain in untold quantities. As he goes they all cry, "Bow the knee," and prostrate themselves in the dust before him. At seventeen years of age he was sold by his brothers. For thirteen years he was slave, or prisoner. Now for seven years he is prime minister. Yet all the time Jacob thinks that his boy is dead. How little did the old Patriarch suspect that during all these weary years God was working out his blessed plans for his people.

30. The Seven Years of Famine.—Once more Joseph and his brothers stand face to face. The last they saw of him was when they heard his bitter cry, and turned a deaf ear to his entreaty. Twenty years have made a great change in him and they do not recognize him. His treatment of them may seem harsh, but he knew what kind of natures theirs were, and that to do them good he must first humiliate them. Out of kindness he was stern. To mend them and their ways he must first break them.

31. Israel in Egypt.—God had told Abraham that his seed must go down to Egypt, and now comes the fulfilment of that prophecy (Gen. 15:13-15). During the life of Joseph all went well with the sons of Jacob. They had the best of the land, and dwelt in peace. God's plans have been carried out to the minutest details, and the plans of evil-minded men have miscarried. God has caused even the wrath of man to praise him, and the remainder he has restrained. Joseph's brethren are content to bow before him, and even Jacob sees that his words of Genesis 37:10 were not wise. The wisdom of man is seen to be folly, and it has been proved that "the foolishness of God is wiser than men." (1 Cor. 1:25.)

32. Joseph's Faith.—On his death-bed Joseph takes an oath of his people saying that God will surely visit his people and bring them in due time to the land promised to Abraham. He charges them to remember his body when they march out, and take it with them, and lay it away in its final resting-place in the Land of Promise. Many years pass. Liberty is exchanged for oppression.[Pg 32] The bitter cry of the people rises to God. All this time the body of Joseph (doubtless embalmed) is not finally buried. His real funeral has not yet taken place. This is the longest delayed funeral on record. Then at last comes the Exodus, and lo, they remember that oath that Joseph took of them, years before, and out with them goes his body. For forty years they carry it with them, and only then they lay it away in the Land of Promise. (See Gen. 50:24-26. Exod. 13:19, and Josh. 24:32.)

Into what two sections may we divide Joseph's life?

Why were his brethren envious of him?

What further intensified their hatred?

Give the plan of God and the plans of men with regard to Joseph.

What action did Joseph's brethren finally take with regard to him?

Into whose household did the lad come in Egypt?

What signs have we that in all this Joseph did not lose his faith in God, or lose his convictions as to duty?

How did Joseph's exaltation come so suddenly?

Give an illustration of this from modern Eastern life.

How long was it between the sale of Joseph and the first appearance of his brethren to buy corn?

Why did Joseph treat his brothers as he did when they first came to him?

What remarkable proof have we of Joseph's steadfast faith in God's promise?

What two most peculiar facts may be noted with regard to Joseph's body?

LEADING PERSONS

Moses.—Son of Amram and Jochebed (Exod. 6:20). Adopted by Pharaoh's daughter (Exod. 2:1-10). Took the part of the oppressed and had to flee (Exod. 2:11-14). Shepherd for forty years and married (Exod. 2:21). Called to deliver his people, but was timid (Exod. 3:1-10). Had various contests with Pharaoh (Exod. 5 to 12). Led people out of Egypt triumphantly (Exod. 14). Received the Ten Commandments (Exod. 20). Built the Tabernacle (Exod. 25). Led the people to the borders of the Promised Land, but was turned back on account of their sins (Num. 13:1 to 14:34). Died on Mount Nebo (Deut. 34). Reappeared on Mount of Transfiguration (Matt. 17:3).

Aaron.—Brother of Moses. Made high priest (Exod. 28 and 29). Sinned in the matter of the golden calf (Exod. 32). Died on Mount Hor (Deut. 10:6).

TIME.—1578 B. C. to 1458 B. C.

PLACES.—Egypt and Sinaitic Peninsula, then east of the Jordan valley.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—The "going out" of the Hebrews from Egypt marked the beginning of their national life, and laws were given governing their relation to God and to each other. The breaking of God's laws cost the nation forty years of wilderness wandering before they entered their "promised land."

33. By far the greatest man in Old Testament history is Moses. In point of moral uplift, no man in all the world, until Christ, can be compared with him. His life divides itself into three equal sections—

(1) Life at Pharaoh's court.—Forty years.

(2) Life as shepherd in the desert.—Forty years.

(3) Life in the desert as leader of God's people.—Forty years.

34. Life at Pharaoh's court.—Moses was born at the time of Israel's greatest oppression, when, as a measure of self-defense, Pharaoh had ordered all Hebrew male children to be cast into the Nile. Hence the Hebrew proverb, "When the tale of bricks is doubled, then comes Moses." As in the case of Joseph, we see at once the collision between God's plan and that of earth's greatest monarch. God's plan was that Moses must live; Pharaoh's plan, that Moses must die. Again we see the successful issue of God's plan, and the overthrow of the human plan. In carrying out his plan, God makes use of a mother's wit, a sister's fidelity, a woman's curiosity, and a baby's tears. For all this read carefully Exodus 2:1-10. These are the minute links in the chain of God's providence which, welded together, restore that babe to his mother's arms in less than twenty-four hours, now with the shield of royalty protecting him. Had any one of these links broken, Moses' fate might have been sealed.

35. As illustrating these links, in a different sphere, read the following: Professor Darwin tells that he noticed that pansies would not grow wild near English villages, but would grow far away from them. Investigation revealed that in English villages dogs go at large. Where dogs go at large, cats must stay at home; where cats stay at home, field-mice abound; where field-mice abound, bumblebees' nests are destroyed; where bumblebees' nests are destroyed, there in no fertilization of pollen. Therefore, where there are dogs, there are no wild pansies. Apply this to the case in hand. No mother's wit, no ark of bulrushes; no ark no sister's watch-care, and no chance to arouse the curi[Pg 35]osity of the princess. Therefore, no discovery of the babe weeping. Consequently, no saving of the future deliverer of his people. Thus God worked through natural agencies to thwart the decree of Pharaoh. During these forty years Moses enjoyed all the educational advantages of the most civilized nation of that day. So he was prepared by the king himself to deliver the Hebrews from his control.

36. Life as Shepherd in the Desert.—Moses' life at court came to a sudden end, through his patriotic effort to deliver one of his race from the cruelty of an Egyptian. As a result he had to flee for his life, as even Pharaoh could not defend him for slaying one of the ruling race for cruelty to a mere slave. For forty years we find him on the Sinaitic peninsula, herding sheep. These must have been years of deep thought. Often he must have wondered why God had given him such deliverance, only to let him languish in the desert while at the same time his people, whom he might have helped, were ground down under the heel of the taskmaster. At the same time these years of solitude must have been rich in opportunity for meditation and communion upward. The city is not the best place for deep thought. Elijah was no city man, neither was John the Baptist. In solitude these men learned much that the city never could teach them.

37. Life as a Leader of God's People in the Desert.—His life of solitude came to a sudden close, when God called to him out of the midst of the burning bush, and bade him return to Egypt and deliver his people. At first Moses begged to be excused, for he doubtless well remembered that because of his effort to deliver one Hebrew, he had been an exile for forty years. How then could he succeed in delivering a nation? But on God's promise to be with him, he and his brother Aaron undertook the task.

38. Here we note the collision between God's plan and that of the king. God's plan is, Let my people go. Pharaoh's plan is, they shall stay right here. So the battle was joined. Note that Pharaoh, as a result of the consecutive plagues, relents and tries compromises. For these read carefully the story of the plagues, noting especially these passages: Exodus 8:8, 15, 25,[Pg 36] 32; Exodus 9:28, 35; Exodus 10:11, 20, 24, 28. And at last, when his pride is utterly broken, comes Exodus 12:31.

39. Then came that night, much to be observed, on which Israel marched out in triumph, while Egypt mourned, and Pharaoh repented ever resisting the divine command. To this day all Jews observe that great night, called the night of the Passover.

40. Under the crags of Mount Sinai, Moses spent one year with his people. That was a most significant year, as there he received the ten commandments, and the instructions as to the building of the Tabernacle and the Ark of the Covenant. There, too, he received directions as to the sacrifices that were to be typical of that great sacrifice on Mount Calvary, hundreds of years later. There, too, he had his bitter experience with his people in the matter of the worship of the golden calf; a presage of much that was to follow in the history of that wonderful but stiffnecked people as they continued their journeys through the wilderness.

41. Mark in the life of this wonderful man the incredible contrast between his highest and his lowest moods. In his agony over the idolatry of his people while he was on the Mount receiving the ten commandments, Moses pleads with God for them, and even goes so far as to beg that, if need be, his own name might be blotted out of God's book. If he or the people must perish, let it be he, and not the people. This is most noble, and reminds one of what Paul later on said, in the same strain (Rom. 9:1-3). Yet later on Moses yields to incomprehensible murmuring, when the people have again transgressed. "Moses was displeased. And Moses said unto Jehovah—Have I conceived all this people?... that thou shouldest say unto me, Carry them in thy bosom?... I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me. And if thou deal thus with me, kill me, I pray thee, out of hand" (Num. 11:10-15). Is this the same man who speaks in the matter of the golden calf, as we saw above? And in this extraordinary fall we learn a lesson of humility and self-distrust. "Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall."

42. At last, after forty years of wandering, Israel is on the borders of the Land of Promise, but on account of his unad[Pg 37]vised speech, Moses is not permitted to enter. On Mount Nebo he dies, alone, and there God lays his body away until the great resurrection day.

43. But again we see Moses. This time not outside of the Land of Promise, but in the midst of it. On the Mount of Transfiguration he appears, and this time with Israel's great prophet, Elijah, and with Israel's Messiah. There they talk of the death so soon to be accomplished in Jerusalem. Then he and the prophet return to the spirit world.

44. Yet once more Moses is brought to our attention. On the Isle of Patmos, John in vision sees and hears much of what goes on in the eternal world of bliss. And lo, he hears the ransomed sing the song of Moses and the Lamb (Rev. 15:3). To this man is given the privilege accorded to none other of the sons of men, to have his name coupled with that of the Son of God in the glad songs of heaven. Truly a privilege so exalted that we cannot possibly magnify it too much!

Into what three divisions does Moses' life fall?

State the plan of God and man in relation to this babe.

Give the links in the carrying out of God's plan, on the birth of the child.

What illustration is given to make these links more clear?

What event terminated Moses' life at court?

How long did his desert life as shepherd last?

What brought this period of his life to its close?

Give again the conflict between the plan of God and that of Pharaoh with regard to the people.

Give the various attempts at compromise on the part of Pharaoh.

Where did Israel spend the first year after the Exodus?

What two great revelations did Moses receive at Sinai?

Give the two instances of Moses' action that are apparently contradictory to each other.

Where did Moses die?[Pg 38]

Why could he not enter the Land of Promise?

Where do we next meet him?

Give the final mention of this man in the Word.

1. Give the reasons why the following periods are important. Patriarchal; Mosaic; of Elijah and Elisha; of the Messiah.

2. Name the four periods in which the narrative amplifies and miracles multiply.

3. Give the extent of the first, second, and third periods.

4. Give two divisions of period four.

5. What was the cause of the division of the United Kingdom?

6. Give the names of the chief actors in the first period of Bible history.

7. Name the great characters of the Old Testament up to David.

8. Who were buried in the Cave of Machpelah?

9. Into what two sections may we divide Joseph's life?

10. Into whose household did Joseph go in Egypt?

11. What two peculiar facts may be noted with regard to Joseph's body?

12. State the three divisions of Moses' life.

13. Where did Israel spend the first year after the Exodus?

14. What two great revelations did Moses receive at Sinai?

15. Where did Moses die?

Conquest of Canaan.—Joshua became leader (Josh. 1:2). Received command from God (Josh. 1:6-9). Victory at Jericho (Josh. 6), followed by defeat at Ai (Josh. 7). Central Palestine conquered, and a great assemblage held at Shechem (Josh. 8:30-35). Southern and northern Palestine partially conquered (Josh. 10:1 to 11). Joshua's farewell (Josh. 23 to 24:27) and death (Josh. 24:29-33).

Israel under Judges.—Othniel delivered the people from Mesopotamia (Judg. 3:5-11). Ehud delivered from Moab (Judg. 3:12-30). Deborah and Barak delivered from Canaanites (Judg. 4:1 to 5:31). Terrible oppression under the Midianites, delivery by Gideon (Judg. 6:1 to 7:25). Jephthah delivered from Philistines and Ammonites (Judg. 10:6 to 12:7). Samson delivered from Philistines (Judg. 13:1 to 16:31).

TIME.—1458 B. C. to Samuel, 1121 B. C.

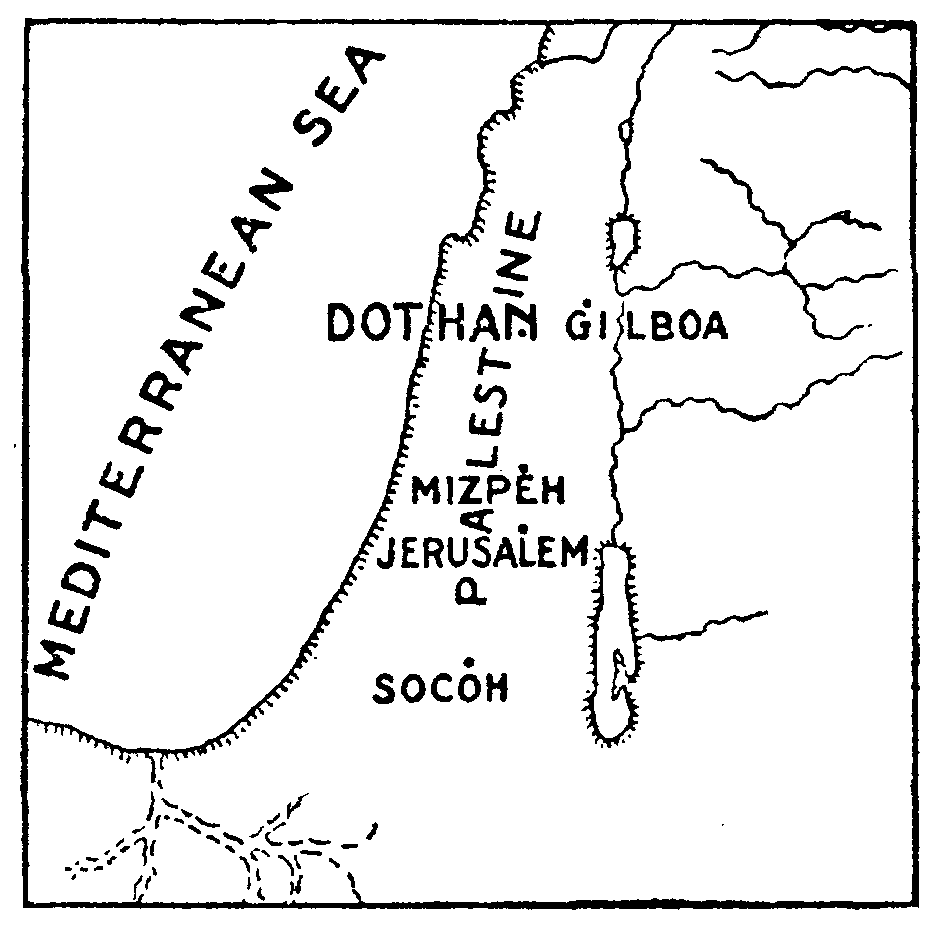

PLACES.—Palestine.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—The Jewish nation under Joshua achieved success just so long as they obeyed fully the commands of God. The Judges, as leaders, were direct representatives of God—who was the actual head of the nation—and so far as God's laws were strictly obeyed, the nation prospered.

45. Joshua Becomes Leader.—At the death of Moses we see Israel on the east side of the Jordan, opposite Jericho. Joshua[Pg 40] succeeds Moses as leader. To him comes God's command, "Moses, my servant, is dead; now therefore arise, go over this Jordan." (Josh. 1:2.) Note here no sign of discouragement. Moses may be dead, but God still lives, and will work through Joshua as well as through Moses. Notice in the orders given by God to Joshua that no mention at all is made of sword, spear, or bow, but only of obedience. This is emphasized again and again and rightly, for in obedience to God's law lay Israel's hope (read Josh. 1:6-9).

46. Now follows the contest for the possession of the land. Jericho is taken, but at Ai defeat is experienced, on account of disobedience. So Israel learns a costly but salutary lesson. Then follows the conquest of the central part of Palestine, ending at Shechem. Next in turn came southern Palestine, and then the northern part of the land (Josh. 10:1 to 11). Yet at the close of Joshua's life, not all of the land had been taken possession of. Still the heathen tribes held on in various places; and, indeed, they were not thoroughly subdued until the time of David.

47. Reading the Laws of Moses.—Worthy of note was the great assemblage at Shechem, between the mountains of Ebal and Gerizim, in the very center of the land, where the law of Moses was read, with its blessings and curses, to all the people (Josh. 8:30-35). Noteworthy also is the final address of the aged Joshua to his people, at Shechem, beseeching them to obey the law of Moses, recorded in chapter 24.

48. The Period of the Judges.—After the death of Joshua, the people seem to have become more or less disorganized. The tribes ruled themselves—at times well, and at times ill. During the times of the Judges the general trend of their history was as follows: Israel would fall into sin, and then as a punishment God allowed their foes whom they had spared to rule over them. Then in due time Israel would "lament after the Lord," that is, repent and call on the God of their fathers for deliverance. Then God would allow them respite, and by the hand of some one of the judges, whom he raised up, would give them deliverance (see Judg. 2:11-18). The chronology of the book of Judges is not very clear, and it is most probable that there were times[Pg 41] when the "oppression" was not felt over all the land, but was only sectional. Just the lines for a right chronology are uncertain.

49. Comparison of Periods of Oppression and Deliverance.—Now if we desire in a general way to judge as to the proportion of godliness as compared with idolatry, that prevailed in these times, we can do so by adding up the years of "oppression" and those of deliverance. This will afford us a rough criterion as to the way in which Israel obeyed and disobeyed their God. For remember that the "oppressions" were the result of disobedience, while the "deliverances" were the result of true repentance. Worked out in this way, we have the following statement, in which the name stands for the country to which the people were in temporary bondage:

Mesopotamia, bondage 8 years,—rest 32 years.

Moab, bondage 18 years,—rest 22 years.

Canaan, bondage 20 years,—rest 20 years.

Midian, bondage 7 years,—rest 32 years.

Philistia and Ammon, bondage 18 years,—rest 7, 10, and 8 years.

Philistia, bondage 40 years,—rest 20 years.

Adding all these up, we find that the people were in bondage in whole or in part for 111 years, while they had "rest" as the result of their repentance for 151 years. Without pressing this mathematical calculation too far, we must nevertheless conclude that for more than half the time the nation at large obeyed God fairly well.

50. Great Leaders among the Judges.—Deborah and Barak, who, by their combined forces drove out the oppressors of Canaan, under Jabin their king. This man had mightily oppressed the people, he having nine hundred chariots of iron, against which poor Israel could bring no corresponding force. Yet when the Lord's time came, he was able to overthrow the armies of Jabin, through the courage and combination of the two persons named. Then the land had rest for forty years. (For a wonderful setting of the song of triumph that Deborah and Barak sang, let the student turn to Professor Moulton's "Literary Study of the Bible," pp. 133-142.)

51. After this came the terrible oppression of the Midianites, who, with their camels, their flocks, and herds came on the land[Pg 42] like grasshoppers, and ate up everything. Fortunately this oppression lasted only for seven years, otherwise there would have been nothing left. The deliverance from the hosts of Midian came through Gideon, whose three hundred men with torches and trumpets wrought havoc among the Midianite army. What the three hundred at Thermopylæ were to Greece, that this three hundred were to the people of Israel.

52. Another terrible experience of Israel was that which came to them in connection with their oldtime foes, the Philistines and the Ammonites. Study the story as told in Judges 10:6-18, together with the narrative of their deliverance under Jephthah. Here the student will see clearly set forth the cause of the "oppression," verses 6-9, and the cause of the deliverance, verses 10-18. Jephthah was a rude man of his times, but then we must realize that rude times call for violent men.

53. The only other case to which attention is called here that of the longest of all the periods of oppression,—the second under the Philistines, which lasted forty years. Here it was Samson who was to deliver the people from the iron hand of the Philistines, and it took the iron hand of a Samson to do the work.

54. Not a Time of National Unity.—During all these many years, the government of the people was largely that of the tribal leaders. There was not the national unity that we saw in the days of their two great leaders, Moses and Joshua. Nor was there the same unity of action that came later on under the kings. But none the less, the great need of the people during these years was not so much political as religious. Had they only obeyed the commands of God as given to Moses, and as reiterated by the angel of the Lord to Joshua, God would not have permitted them to be ground under the heel of their oppressors as they were. We fail to read the story aright unless we seize the truth that righteousness exalts a people, while sin is a reproach to any nation. This truth has its modern as well as its ancient application.

Where was Israel at the time of the death of Moses?

Whom did God appoint to be Moses' successor?

What peculiarity was there in God's directions to Joshua?

In what order were the different parts of the land conquered?

Tell of the great assembly at Shechem.

What was the general trend of the history of Israel during the times of the Judges?

What was the cause of each period of "oppression"?

What was the cause of each "deliverance"?

Give the proportion of the years of "oppression" and those of "rest."

Give the first two leaders named as deliverers.

Who brought relief from the oppression of Midian?

Who delivered the people from the first Philistine bondage?

Who did the same thing in the case of the second Philistine bondage?

What was the condition of the people politically during the period of the rule of the Judges?

LEADING PERSONS

Samuel.—The connecting link between the times of the Judges and of the kings (1 Sam. 1-8).

Saul.—First king, who made a good beginning (1 Sam. 10:1-27). He united the people, breaking down factions. Spurned Samuel's advice (1 Sam. 15:1-35). He became jealous of David, and angered at his own son, Jonathan (1 Sam. 18:8 to 19:11). Rejected by God as king (1 Sam. 15). Killed in battle at Gilboa (1 Sam. 31:1-13).

David.—A shepherd boy, noted for bravery (1 Sam. 16-31). Chosen king and ruled over Judah seven years (2 Sam. 2). Then became king over all Israel, and greatly enlarged the nation's borders. Made Jerusalem the capital (2 Sam. 5:6-9). A great religious leader and composer of Psalms. Sinned against Uriah (2 Sam. 11:1 to 12:14). His son Absalom rebelled (2 Sam. 15 to 18).

Solomon.—Son of David. Began his reign with a wise choice (1 Kings 3). Built the Temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 5). Sinned in his marriages (1 Kings 11). He was noted for his great wisdom and riches. He lived in luxury, the people were heavily taxed, and the outward prosperity was accompanied by inward spiritual decay. See Samuel's warning in 1 Samuel 8:1-18.

Other Persons.—Goliath, the Philistine giant, whom David slew.—Jonathan, Saul's son, a great friend of David.

PLACES.—Mizpeh, Socoh, Gilboa, Jerusalem.

[Pg 45] TIME.—1121 B. C. to 983 B. C.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EVENTS.—David's reign as king brought the people to the place of their greatest national success, and David's reign and that of Solomon were politically the best in all Israel's history. David was signally honored in becoming an ancestor of Mary, the mother of Jesus.

55. Israel Asks for a King.—Ostensibly because Samuel's sons were worthless men, but also and largely because they wished to be "like the nations around them," Israel asked the prophet Samuel to appoint a king over them. This Samuel was reluctant to do. But commanded by God to acquiesce, he anointed Saul, the son of Kish, to be king over Israel. That God did not consider the change from government by judges to government by kings to be an improvement, is apparent from his saying, "they have rejected me, that I should not be king over them" (1 Sam. 8:7).

56. The First King, Saul.—Saul found the nation somewhat disorganized, and split into many factions. His task was to unite the people, so that they could show a bold and successful front against their foes. Prominent among these foes were the Philistines, who lived on the southwest of Israel, and who were a courageous and persistent folk. In all this work Saul was somewhat successful. He began well, but before very long, owing to self-will, he swerved aside from the advice of the aged Samuel. During his reign the great war with the Philistines took place in which Goliath and David figured so dramatically (1 Sam. 17).

57. Saul's evil disposition grew worse and worse, showing itself in his twice-repeated effort to kill David and his one effort to kill his own son Jonathan for his friendship for David (see 1 Sam. 18:10, 11; 19:10; 20:32, 33). On account of his distinct disobedience to God's command, and his hypocrisy, God rejected him from being king (1 Sam. 15). Still Saul continued to rule for some years. Then came the end when, in battle with his old foes, the Philistines, Saul and his sons fell, near Mount Gilboa[Pg 46] (1 Sam. 31). He ruled about forty years, and was a sad instance of a man who began well, who had a superb counselor in Samuel, but who, through self-will and disobedience, perished at last most miserably.

58. David Becomes King.—After the death of Saul, Judah turned to David as its rightful leader and king. He was therefore anointed at Hebron as king of Judah. Seven years later the remainder of the tribes came to him and asked him to rule over them. This he did, and in this way he was king over all Israel for thirty-three years. His remarkable character and executive ability soon showed itself. His reign was most successful, and he enlarged the bounds of the kingdom to their utmost extent. It extended from the Red Sea and Egypt to the Euphrates, as promised by God (Gen. 15:18 and Josh. 1:4). He captured Jerusalem and made it the political and the religious capital of the nation (2 Sam. 5:6-9). Thither he brought up the Ark of the Covenant, and here he established the worship of Jehovah. He organized the whole of the ritual of worship, and formed choirs of singers to make a glad noise unto the Lord. Everywhere he brought order out of chaos, and made the name of Israel one to be feared by the surrounding nations. Thus to the Israelite both of his day and of subsequent centuries he became their ideal king.

59. His later life was saddened by his own sin in the matter of Uriah and Bathsheba, where he erred most grievously. In recalling this sin, and in condemning the king for it, we must also bear in mind his true repentance, and also recognize that in his time there was no king who would have thought it worth while to give a second thought to the whole matter (see 2 Sam. 11:1-12:14).

60. The Rebellion of Absalom.—The end of David's life was further embittered by the rebellion of his favorite son, Absalom. This nearly brought David to a violent death. Only the indomitable spirit that the king possessed, together with the ability of his chief general Joab, saved the day (2 Sam. 15-18). David was Israel's sweet singer. He composed many Psalms, which have come down to us as specimens of his poetic ability. (The writer is, of course, aware that some modern critics[Pg 47] deny that any of the Psalms are by David, but he has never seen any conclusive proof of this.)

61. In general, until his later years, when too much prosperity had dulled his spiritual life, David's character was singularly pure and unselfish. His dealings with Saul while the latter was seeking his life show a most chivalrous spirit, in that twice he spared his enemy's life when he had him in his power (1 Sam. 24:1-22; 26:1-25). In his friendship for Jonathan he shows an affection which, reciprocated by Jonathan, constitutes one of the classic friendships of history. Taken all in all, and remembering the times in which he lived, David was perhaps the finest king that the world ever saw.

62. Solomon.—On David's death his son Solomon ascended the throne. Bathsheba was his mother. He began his reign well. When God gave him his choice between riches and wisdom, he chose the latter (1 Kings 3:5-15). He it was who carried out David's plan for a "magnifical" temple in Jerusalem, where he built the most splendid temple that the world had so far seen. His prayer at the dedication of the temple is a most remarkable one (1 Kings 8). His fame spread through the world, and on one occasion the Queen of Sheba, in Arabia, journeyed over one thousand miles to make him a visit. Her astonishment at what she saw and heard in Jerusalem is told in 1 Kings 10. In amazement she cries out, "Howbeit I believed not the words, until I came, and mine eyes had seen it: and, behold, the half was not told me; thy wisdom and prosperity exceed the fame which I heard."

63. But alas! Solomon did not continue as well as he began. To enhance his glory and extend his political power, he made alliances with idolatrous sovereigns. He married the daughter of Pharaoh, and besides this had multitudes of wives, who led his heart astray (1 Kings 11:1-8). God's warning, given in the same chapter, seems to have been disregarded.

64. Samuel's Warnings come True.—In Solomon all the warnings of Samuel as to what would come on the nation if they persisted in their choice of a king were fulfilled (1 Sam. 8:1-18). He also disregarded what God had said through the mouth of Moses, as recorded in Deuteronomy 17:14-20. He multiplied[Pg 48] taxes to such a degree that the people were not able to bear them. His court life was most luxurious and enervating, and the demands of his wives for all manner of indulgences were continuous. In this way, though there was much outward prosperity, the seeds of decay were sown with prodigal hands. Of course the end of such a policy could be only disaster, though the king in his mad search after power and luxury failed to see the approaching storm. However wise he may have been, as shown in his proverbs, he lacked that practical wisdom which begins in the fear of God. He went steadily down hill, and only his fame, and his reputation as being the son of David, saved him from overthrow. But immediately on his death the consequences of his misrule showed themselves in a most pronounced way, in the disruption of the kingdom. Like Saul and David, he also ruled over Israel for forty years.

What ostensible reason did the Israelites give for asking for a king?

What other and truer reason did they urge?

What had God to say about this request of the people?

What good did Saul accomplish?

Why was Saul rejected by God from being king?

How did Saul come to his end?

Over what tribe did David rule alone for seven years?

Give the boundaries of David's kingdom at its largest.

What did David do for the establishment of religion, and in what city?

Into what bitter sin did David fall?