The Project Gutenberg EBook of What Shall I Be?, by Rev. Francis Cassily

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: What Shall I Be?

A Chat With Young People

Author: Rev. Francis Cassily

Other: A. J. Burrows

Remegius Lafort

Cardinal John Murphy Farley

Release Date: March 18, 2010 [EBook #31688]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT SHALL I BE? ***

Produced by Michael Gray

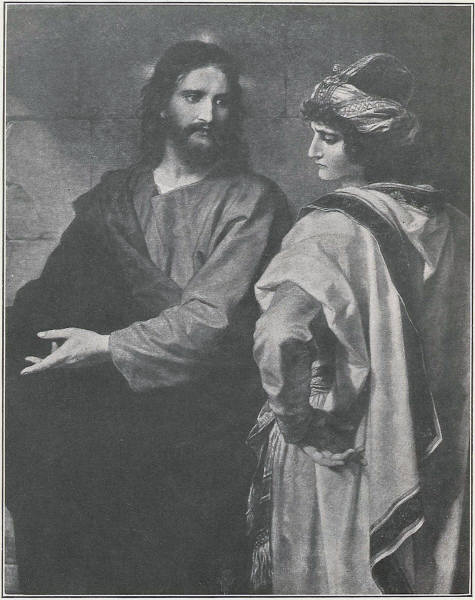

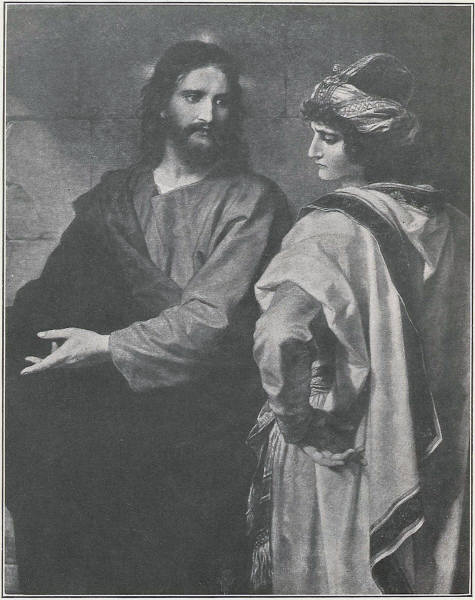

If thou wilt be perfect go sell what thou hast and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in Heaven and come follow Me.

—Matt. xix: 21.

BY THE

REVEREND FRANCIS CASSILLY, S.J.

"And every one that hath left house, or brothers, or sisters, or father, or mother, or wife, or children, or lands for My name, shall receive a hundredfold, and shall possess life everlasting." (Matt. xix: 29)

NEW YORK

THE AMERICA PRESS

1914

IMPRIMI POTEST

A. J. BURROWES, S.J.

Provincial Missouri Province

NIHIL OBSTAT

REMEGIUS LAFORT

Censor

IMPRIMATUR

JOHN CARDINAL

FARLEY

JOHN CARDINAL

FARLEY

Archbishop of New York

COPYRIGHT 1914

BY

THE AMERICA PRESS

LETTER TO THE AUTHOR

FROM REVEREND A. VERMEERSCH, S.J.

Louvain, le 23 février, 1914.

Mon Révérend Père: P. C.

Votre petit livre me plaît extrêmement. Il expose une doctrine très solide avec une merveilleuse clarté. D' une lecture agréable, il intéressera la jeunesse des écoles, et l'encouragera à faire un choix généreux d' état de vie. J' estime que, traduit en flamand et en français, il ferait également du bien à nos collegiens de Belgique.

Votre dévoué en N. S. et M. I.

A. Vermeersch.

TRANSLATION

My Reverend Father:

Your little book pleases me exceedingly. Its doctrine is very sound and set forth with wonderful clearness. It makes pleasant reading, and will interest the young of school age, and encourage them to make a generous choice of a state of life. In my opinion, a Flemish and French translation would also be profitable to our college students in Belgium.

Devotedly yours in Our Lord and Mary Immaculate,

A. Vermeersch.

TO THE THOUSANDS

OF TRUE-HEARTED BOYS AND GIRLS

HE HAS BEEN BLESSED TO KNOW

OF WHOM

SOME ARE GONE TO HEAVEN

AND MANY ARE BATTLING FOR THE RIGHT

IN THE SANCTUARY

THE CLOISTER OR THE WORLD

AND WITH ALL OF WHOM

HE HOPES ONE DAY TO BE REUNITED

FOREVERMORE

IN GOD'S OWN COURTS

THIS LITTLE BOOK

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

BY THE AUTHOR

PREFACE

In this little book the writer has aimed to present, in brief and simple form, sound principles which may assist the young in deciding their future course of life. The subject of vocation, as it is called, has suffered much, during the last two or three centuries, at the hands of rigorist authors, who so hedged the approach to religious life with difficulties and restrictions, as to frighten or repel many aspiring hearts from it.

Great stress was laid by these writers on the special interior attraction, by which God was supposed always to manifest His call, so that no one might legitimately enter the state of perfection, unless he felt this unmistakable impulse from within. And on the other hand, given this evidence of the Divine predilection, to disregard it was a sinful preferring of one's own will to God's, which, in all likelihood, would be attended with grave consequences for this world and the next.

Spiritual writers of the last decade have been rereading the Fathers and great Theologians upon this subject, and as a result the cobwebs of misconception are being swept away. The Reverend A. Vermeersch, S.J., of Louvain, deserves the gratitude of all for his lucid and convincing treatment of religious vocation, in his "De Religiosis Institutis et Personis" (Vol. II, Supplement III; also Vol. I, P. 4, C. I), where he clearly shows from Scripture, the writings of the Fathers and leading theologians, the true nature of the invitation to the evangelical life. The reader is also referred to the article on "Vocation," by the same author, in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Another document throwing light on the subject, is the Decree of July 15, 1912, framed by a special commission of Cardinals appointed to examine the work of Canon Joseph Lahitton on "La Vocation Sacerdotale." This Decree, approved by the Holy Father, contains the following passage: Vocation to the priesthood "by no means consists, at least necessarily and according to the ordinary law, in a certain interior inclination of the person, or promptings of the Holy Spirit, to enter the priesthood. But on the contrary, nothing more is required of the person to be ordained, in order that he may be called by the bishop, than that he have a right intention, and such fitness of nature and grace, as evidenced in integrity of life and sufficiency of learning, which will give a well-founded hope of his rightly discharging the office and obligations of the priesthood." This Decree does away, at once, with the special spiritual attraction, always and essentially required by so many for vocation to the priesthood.

It may not be rash to conclude, in a similar way, of a religious vocation "that nothing more is required of the person who is a candidate for religious life, in order that he may be admitted to the novitiate by the lawful superior of an order, than that he have a right intention, and such fitness of nature and grace required by the order, as will give a well-founded hope of his rightly discharging the obligations of the religious life in that order."

The present treatise aims at no more than putting in form suitable to the young the sound conclusions of such reliable authors as Father Vermeersch, Canon Lahitton and Rev. P. Bouvier, S.J.

As to the advisability of priests, parents and teachers fostering and developing in the young the desire of a religious life, the words of St. Thomas are positive: "They who induce others to enter religion, not only commit no sin, but even merit a great reward." (Summa, 2a, 2æ, Quæst. 189, art. 9.)

And the Third Council of Baltimore, urging priests to develop vocations to the priesthood, says: "We exhort in the Lord and earnestly entreat pastors and other priests diligently to search after and find out, among the boys committed to their care, those who seem suited and called to the clerical state. If they find any boys of good disposition, of pious inclination, of devout and generous minds, and able to learn; who give promise of persevering in the sacred ministry, let them nourish the zeal of such, and sedulously foster these precious germs of vocation." (Paragraph 136.)

Priests, teachers, confessors and others who have dealings with the young, will find it very practical to have at hand several copies of some reliable booklet on the priesthood and religious life, which they may give or lend, as occasion offers, to promising boys and girls. Such books will, at least, make their readers think, and God's grace frequently acts through the medium of the written or spoken word.

Creighton University, Omaha,

Easter Sunday, 1914.

|

CHAPTER |

|

|

I. |

|

|

II. |

|

|

III. |

|

|

IV. |

|

|

V. |

|

|

VI. |

|

|

VII. |

|

|

VIII. |

|

|

IX. |

|

|

X. |

|

|

XI. |

|

|

XII. |

|

|

XIII. |

|

|

XIV. |

|

|

XV. |

Youth is the dream time of life. It views the world through the prism of fancy, tinting all with rainbow colors. It lives in a creation of its own, where it rules with magic wand, conjuring into its realm the beautiful, the heroic and the magnificent, and banishing only the prosaic and commonplace. To the youthful dreamer, every ruler is all-powerful, every soldier brave, every fire-fighter a hero, and every editor a wizard, at whose nod the news of the world flies to the huge cylinder presses, and then flutters away in white-winged sheets through town and country.

But gradually, the stern realities of life forcing themselves on the maturing mind, it realizes that it must choose from the various activities that make up the sum of human existence. The thoughtful boy and girl then begin to ask the question, "What shall I be?" or "What shall I do?" The various walks of life spread out before them like a maze of tracks in a railway station, all leading away in dwindling perspective to the witching land of the unknown.

An ambitious boy views with delight the various professions, and pictures to himself in turn the great deeds and triumphs of the soldier, the statesman, the lawyer, the physician, the architect, and finally perhaps the electrician, who plays with the lightning and harnesses it to the ever-extending service of mankind. All these are votaries of noble avocations, and he who excels in any one of them is a hero, and a benefactor of his kind. Every occupation which is useful to the human race, which contributes to the sum of man's comfort and happiness, is laudable and worthy an intelligent being. St. Paul was a tent-maker by trade, and he gloried in the fact that, even during the days of his apostleship, he was not a burden to others, but supported himself by the labor of his hands.

Life pursuits rank in dignity and worth, according to the perfection or benefit they bestow upon the worker himself, and his fellow-man. Far above the artisan or husbandman, who occupies himself with the material needs of his neighbor, with providing him food, raiment and shelter, rise the teacher, writer and professional man, who minister to the needs of the mind. And highest, perhaps, of natural callings is the conduct of the government, which gives peace, order and happiness to entire nations.

But not every pursuit is suited to all dispositions, nor can any one hope to excel in all trades and professions. The strength of body and skill of hand required of a mechanic may be lacking to a professional man, and the long years of study and experience demanded of a physician are possible to but few. Nature destines some for a life of action and adventure, for the command of armies or the conquering of the wilderness; others it dowers with literary tastes, or the power to thrill an audience or guide a State.

No one is necessarily tied down to any special occupation of life. According to your disposition and character, your ability and inclination, education and training, you are free to select any sphere of action within your reach and opportunity. But this very freedom of choice sometimes leads to mistakes. One without the proper temperament or ability, lacking in patience and sympathy, and unable to make a diagnosis, aims to be a physician, and he becomes only a quack. Many a one, who aspires to direct the destinies of the State, achieves only the station of a political subordinate or spoilsman. And one whom nature destines for the free and independent life of a farmer, often sentences himself to life imprisonment behind the "cribbed and cabined" desk of a counting house.

Perhaps the most frequent mistake of young people is to tear themselves away from school, where they have the opportunity to prepare themselves for the higher positions of life, and by so doing deliberately limit themselves to a life of mediocrity. They have an ambition, but a false one. Eager to enter, though unprepared, the arena of life and accomplish great deeds, they lack the student's patience and industry, which would crown them in after years with the laurel of success.

Be ambitious then, my young friend, aim high in life; endeavor to achieve something great for yourself and for mankind. You will have only one life in this world, then make the most of it. Take advantage of your opportunities. Attend school as long as you can, because generally the greater your knowledge and learning, your training and preparation, the higher and wider the career that will open before you.

All legitimate pursuits of life have been illustrated and adorned by numberless Christian heroes and heroines, who served God, sanctified themselves, and brought glory to the Christian name by their fidelity to duty. Would you be a soldier? Could there be more glorious names than those of St. Sebastian and St. Martin; the Crusader, Godfrey de Bouillon, and the Grand Knight of Malta, de la Valette?

Do you long to ride the ocean waves, and brave the tempest? What more heroic predecessor would you have than the great "Admiral," the navigator and discoverer, Columbus? If your ambition be to sit in the councils of State, to steer your country safely through breakers and shoals, fix your gaze on Sir Thomas More, Daniel O'Connell, Windthorst or Garcia Moreno—Christian heroes all.

In a garden are flowers varying in hue and form and size. The roses blow red and white and pink, scenting the air with their myriad petals, the lilies lift up their delicate calyxes to the wandering bee, the perfumed violets hide their modest heads in beds of green, and the fuchsias sway from their stems in languid beauty. But varied as are the flowers in charm, each is perfect of its kind. No artist could improve their tints nor trace truer curves; no carver chisel more delicate or finished forms.

And God's Church is a spiritual garden, where bloom souls varying in every virtue, charm and grace, and all breathing forth the good odor of Christ. In it are school-boys, gentle maidens, devoted mothers and fathers of families, rich and poor of every nation and clime, of every station and calling. God made them all; He loves them all, and on each He has grafted the bud of faith, which will blossom forth into all supernatural virtues.

God also wishes each one in His garden to be perfect of his kind. Jesus, sitting on the Mount of the Beatitudes, and teaching the multitudes that were ranged on the grass about Him, bade them "be perfect as also your heavenly Father is perfect." (Matt. v: 48.) [1] This, then, is the perfection Christ expects us to aim at, the perfection of God Himself, in Whom there is nor spot nor wrinkle. He will not be satisfied with us, so long as low aims, imperfect motives, disfigure our souls and stain our conduct.

As St. Paul says in his letter to the Ephesians, God chose us before the foundation of the world to be "holy and unspotted in His sight." (Eph. i: 4.) In fact, St. Paul, whenever he addresses the Christians, calls them "saints" because every Christian man, woman and child, is expected to be holy, holy in the grace of God, in conduct, in thought and act, at every time and place. Every Christian must be sacred, a shrine wherein dwells the Divinity, and whose doors must be closed to everything profane. "Know you not, that your members are the temple of the Holy Ghost, who is in you, whom you have from God; and you are not your own?" (I Cor. vi: 19.) Your soul, then, my child, is holy, consecrate to God, and into it must enter nothing defiled, nothing savoring of the world, its maxims and principles. Keep your soul pure as the roseate dawn, clear as starlight and bright as the sun.

"Every one of you," said Christ Himself, "who doth not renounce all that he possesseth, cannot be my disciple." (Luke xiv: 33.) This seems a hard doctrine, for who would be able to give up all he has, parents, home and possessions? There are occasions when the love of God and the love of creatures come into conflict; and when this occurs the true disciple of Christ will not hesitate. He will fearlessly sacrifice everything, even life itself, rather than forsake his Creator. The martyrs did this. St. Agnes gave up suitor, home and wealth, and laid down her innocent young life, to become the spouse of Christ. The boy Pancratius faced the panther in the arena, and the yells of a bloodthirsty mob, rather than abjure his faith; and so won a martyr's crown.

Perfection then is our destiny. In heaven we shall attain to it, and in this life we should begin to practice it. If we would have God's love in its fulness, if we would always be worthy to nestle in His bosom, to feel the arms of His affection drawn close about us, we must never sully our conscience with the least taint of sin. For all the world we would not offend our parents, and God is to us in place of father and mother and all. He is the infinitely perfect; He is love and beauty and tenderness itself, and His absorbing desire is to reproduce similar qualities in us.

But how are we to be perfect? By always doing His holy Will, as we see it and know it, to the best of our ability. Christ issues the clarion call to all Christians, to take up their cross daily and follow Him. He who always does his best, and, obeying the dictates of conscience, walks by faith and charity in all his actions before God, and conducts himself in all circumstances of life according to the principles of faith and reason, is living up to the Divine call, and striving after perfection.

"But are there any such persons in the world?" some one may ask. "They say that there is nothing perfect under the sun, and this time-honored adage, no doubt, applies to persons as well as to things." It is true that very few are perfect in the sense that they sojourn in the world, unmoved, like the angels, by the least ruffling of passion. But there are many, very many, pure, holy souls, who aim constantly at perfection, and who attain to it substantially; for day by day, year in and year out, they keep themselves from the guilt of serious sin, and delighting to carry out God's will in all their actions, frequently draw nigh the Tabernacle to commune in heavenly raptures with their Love "behind the trellis."

Nor is the number of these elect souls limited to any one calling or profession, for they are found in the seclusion of home, in the crowded mart, in the stress of business and professional life. When the week-day Mass is over in the parish church, and the little band of devout worshippers descend from the church steps, would one not say that there is a look of heavenly peace upon their countenances, a peace that overflows to their features from the deep well-springs of charity within? No legitimate walk of life, then, is alien to perfection. All Christians are urged to it; and many attain to it. They use the things of this world "as though they used them not," their hearts are free from undue attachment to the possessions of earth, and they go through life as pilgrims to their final home; and should God be pleased to reward their constancy by sending them trials and sufferings, they will come forth from the ordeal like pure, refined gold.

[1] While this text refers primarily to the perfection of forgiving enemies, it is applied also by commentators to perfection in general, for the reason that it is closely connected with the preceding and following exhortation of Our Lord to many and various virtues. And even if the text were limited expressly to one virtue, the fact that God's children are urged to the perfection of this virtue because it is found perfectly in their Heavenly Father, would seem to imply that He, so far as imitable by creatures, is the measure and standard of their perfection, and hence, as He is the All-Perfect, that they too should strive to be perfect in all virtue.

Speaking one day to the multitude, Our Lord likened the Kingdom of Heaven "to a merchant seeking good pearls, who, finding one pearl of great price, went away and sold everything he had and bought it." (Matt. xiii: 45-46.) What is this precious pearl that so charmed the merchant as to make him sacrifice all he had to gain possession of it? It is doubtless the true Church, or faith in Christ, but theologians apply the parable also to the highest union with God by charity, or Christian perfection. Perfection, then, may be called this lustrous pearl, more precious and radiant than any which gleams in royal diadem. You may buy it, but the price is the same to all. You must offer in exchange all that you have, keeping nothing back. Are you willing to make the bargain?

There have been many Christians throughout the centuries who were enamored of this perfection. They sighed and longed for it, but, alas! the conditions in which they lived, the temptations that lay about them, the cares of raising a family and struggling for a livelihood, so engrossed their attention and seduced their affections, that they almost despaired of living entirely for God, and thus attaining perfection. A young man of high aspirations one day came to Jesus, and asked Him what he must do to gain eternal life. The Master replied, "Keep the commandments." But the young man was not satisfied with this; he wished to do something more for heaven, as we learn from his reply, "All these have I kept from my youth; what is still wanting to me?" Then Jesus spoke the memorable words that have echoed down the ages, "If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor . . . and come, follow me." (Matt. xix: 21.)

The questioner, so the Scripture records, went away sorrowful, for he had great wealth. He was willing, no doubt, to give alms and bountifully, but to sacrifice all his possessions and live in poverty—this was beyond his generosity. Christ's advice, however, has not fallen by the wayside. Theologians tell us that in His brief words Our Lord indicated the evangelical life, which He elsewhere explained more fully, bidding the youth become poor and then come and follow Him in perfect chastity and obedience (Suarez, "De Religione," lib. iii, c. 2).

The teaching thus presented by Christ has never been fruitless in the Church. Myriads of chosen souls, more magnanimous than the young man, have heeded the Saviour's admonition and hastened to sacrifice all for His sake. The nature of the evangelical life—so called because taught in the "Evangelium," the Latin word for Gospel—consists in the practice of the three counsels, voluntary poverty, perfect chastity and obedience. And why is the exercise of these three counsels so excellent? Because by them a Christian parts with everything that is most pleasing to mere nature. By poverty he renounces his possessions and the right of ownership; by perfect chastity, the pleasures of the body; and by obedience, his free will. Could one do more than to give up everything he owns, and then complete the renunciation by dedicating his body, aye, his very soul, to Christ? Nothing is left that he may call his own. He is a stranger in the world, without home, parents or family, money or earthly ties; he is all to God, and God is all to him.

While a person may be in the way of perfection, by observing the counsels privately, with or without a vow, if he takes perpetual vows in a religious order or congregation approved by the Church, he is in what is called "the state of perfection," or "the religious state." The vows give a final touch to the holocaust in either case, since by them he offers all he has and is and forever, so that it becomes unlawful for him to retract his offering. He who exemplifies all Christian virtues to a high degree of excellence, according to his condition of life, may be called perfect, and to this perfection all Christians are called. But, religious, that is, they who live in the religious state, bind themselves by profession to aim at living a perfect life. They have heeded Christ's invitation, "If thou wilt be perfect," and engaged themselves, under the sanction of the Church, to the obligation of striving for perfection.

No one could claim that all religious men and women are actually perfect; but they are in the state of perfection—that is, by virtue of their state and profession they are bound to the observance of their vows and rules, which observance, in the course of time, will be able to lead them to the attainment of such perfection as weak mortals, with God's grace, can hope to acquire in this life. In response to Christ's exhortations, we find throughout the world to-day a great army of religious men and women, white-robed Dominicans, brown-garbed Franciscans, followers of St. Benedict, St. Augustine, St. Alphonsus, St. Vincent de Paul, and St. De la Salle, the Blessed Madeleine Sophie Barat, Julie Billiart, Jean Eudes, and of numerous other saints, who, under the standards of their varied institutes, march steadily in the footprints of the lowly Nazarene, Who had not whereon to lay His head.

The ambitious Christian boy and girl, then, will aim at doing their best, and must, if they desire close companionship with Christ, strive after perfection, for such is the Master's desire. But should a youth have further ambitions, and say to himself, "I desire to distinguish myself in God's service, to lead for Him a life of action and achievement, wherein my exertions will bring amplest returns for eternity," will he refuse to consider the life of the counsels? Will he not rather ask himself whether this manner of life is practicable, and possibly even meant and intended for him? Choose then, my young friend, your sphere of life but deliberately and carefully, remembering that on your decision will largely depend your greater happiness in this world and the next.

The boy or girl who is deliberating on a future career will naturally ask, "Who are invited to the higher life? Is the invitation extended to all, or limited to the chosen few?"

Let us try to find out the answer to these questions. One day the disciples of Our Lord having asked Him (Matt. xix: 11-12) whether it were not better to abstain from marriage, He replied, "All men take not this word, but they to whom it is given. . . . He that can take it, let him take it." St. Paul also writes to the Corinthians (I Cor. vii: 7-8), "I wish you all to be as myself, . . . but I say to the unmarried . . . it is good for them, if they so continue, even as I."

Now, let us examine these passages, according to the interpretations of the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, so that there will be no danger of reading a wrong meaning into them. There is question in both texts of abstaining from marriage, of advising the unmarried not to marry, which, of course, is equivalent to advising them to practice perpetual chastity. St. Paul says clearly and forcibly that he would desire all to remain unmarried like himself. However, in the next verse he exempts from his advice those who do not control themselves. What does he mean by this? There are some who have strong passions, or who by self-indulgence have so strengthened their lower nature and weakened their will-power, that lifelong continence seems beyond them. Such persons, therefore, who know from experience that they will not overcome temptation and sin, or who find the struggle too hard to continue, he advises to marry.

We may now inquire whom Our Lord meant by those "to whom it is given." Does He mean that the power of practicing virginal chastity is given only to the selected few or to the many? St. Chrysostom, interpreting His words, says that this gift of chastity "is given to those who choose it of their own accord," adding that the "necessary help from on high is prepared for all who wish to be victors in the struggle with nature" (M. P. G., t. 58, c. 600). [1] St. Jerome tells us that this gift "is given to those who ask it, who wish it and labor to obtain it" (M. P. L., t. 26, c. 135). St. Basil explains that "to embrace the evangelical mode of life is the privilege of every one." (M. P. G., t. 32, c. 647.) To the sophistical objection that if all persons practiced virginity marriage would cease, and so the human race would perish, St. Thomas (Summa, 2a 2æ, Quæst. 189, art. 7) gives the reply of St. Jerome, "This virtue is uncommon and desired by comparatively few"; and then adds, "This fear is just as foolish as that of one who hesitates to take a drink of water, for fear of drying up the river."

Can it be said, then, that every boy and girl, with the exception noted by St. Paul, is advised and exhorted to preserve virginal chastity throughout life? To understand aright the answer to this question, we must remember that there are two general courses of life, the married and the unmarried, open to all; every person necessarily being found in the one or the other. And each individual of the race is privileged to make a free and voluntary choice of either condition; no one having the right to interfere with this personal liberty, by forbidding or prescribing wedlock to any properly qualified person.

Both these states have been created by God, and both are His gifts to man. The nuptial tie, elevated to the dignity of a sacrament, is likened by St. Paul to the union existing between Christ and the Church. "A prudent wife," says the Book of Proverbs (xix: 14), "is properly from the Lord." Whoever marries "in the Lord" performs a virtuous act, and the Church, to show her appreciation and approbation of it, invests the wedding contract with a rich and hallowed ceremonial. They, then, who wed do something pleasing to God; but they who, for virtue's sake, forego their natural right of marrying, make an offering still more grateful to Him.

This is the doctrine in the abstract. But in its application to individual cases we find some so situated, so hampered by their own temperament and disposition, or by actual conditions about them, that a life of perfect continence seems impracticable for them. One, for instance, who yearns for the safety and seclusion of the cloister, and yet sees its doors closed against him for some reason, feels himself constrained to take refuge from the storm and stress of the world in the sanctuary of marriage. On such persons the Creator does not impose a burden above their strength. Wishing us to be happy and content even in this life, as well as the next, He asks of us here only a "reasonable service."

Guided by these principles, the great majority of the faithful in all ages have deemed it prudent and expedient for them to marry. And the wisdom and prudence of their choice God approves and commends. For His Providence manifests itself to us in all the events and circumstances of life, dwelling alike in the fall of the leaf and the roll of the wave, and speaking to our hearts by the voice of all creatures. While, then, external or internal impediments may prevent some from hearkening to Christ's call, and their own will may deter others, His invitation of itself does not exclude any; it is general, ever waiting for those able and willing to accept it.

But does not a person have to feel a special call before binding himself to perpetual chastity? To answer this let us suppose that one is considering the advisability of daily attendance at Mass or of total abstinence from intoxicating liquor. In themselves these are good works and under proper advice a person might engage himself to their performance. Grace would be required for them, as for every other act of supernatural virtue, but no one would say that to assume such obligations a special call from heaven is prerequisite. Now, chastity is governed by the same laws as other virtues, by the same laws as mortification, alms-deeds and works of charity. Every virtuous act requires two things, the grace and the will to cooperate with the grace; and these two are also the only requisites for the exercise of continence; a special inspiration being no more necessary for it than for perpetual abstinence from meat or spirituous liquors.

Lifelong virginity is, of course, a higher, nobler and more far-reaching virtue than the others mentioned, but it involves no special personal call. If this were required, in addition to the general invitation of Scripture, the doctrine of the Fathers that all are invited could scarcely be true. If all are invited, then he who wishes must have the power to accept the invitation. If two calls are necessary, one general and the other particular, he who has only the first may be said to have only half an invitation, which seems very absurd, and certainly is contrary to the practically unanimous teaching of the Fathers.

St. Thomas tells us: "We should accept the words of Christ which are given in Scripture as if we heard them from the mouth of Christ. . . . The counsel (to perfection) is to be followed by each one not less than if it came from the Lord's mouth to each one personally. (Opusc. 17, c. 9.) And even granted that the devil urges one to enter religious life, it is a good work, and there is no danger in yielding to his impulse." (Opusc. 17, c. 10.)

Taking these words of the Angelic Doctor for our guidance, we realize that the invitation and exhortation of St. Paul is general, that it embraces all unmarried persons who feel the well-grounded hope within them that with God's grace they can live up to it.

We may go further and say that, as St. Paul was speaking not his own doctrine, but the doctrine of Christ, which is unchangeable, it applies equally to-day. So one who is convinced that no obstacle, except his own will, prevents his acceptance of the Apostle's advice, can readily imagine Christ standing before him and saying, "My child, you should be more pleasing to Me were you to remain unmarried for My sake." If Jesus Christ really stood before you, dear reader, and thus addressed you, what would be your reply? There can be no doubt that it would be prompt and in accordance with His wish. You would say, "If God so loves me as to make a suggestion to me, as to sue for my undivided heart, I shall be only too glad to give Him all I have, to make any sacrifice for His sake." But God does speak thus, through the mouth of the Apostle, to all who are "zealous for the better gifts."

Now, what says your heart? Will it reject the special love Christ offers? He says, "I give you the choice of two gifts, matrimony or virginity; virginity is by far the more precious—but take which you wish." Will you be so irresponsive as to reply, "Give me the lesser gift; Thy best treasures and best love bestow on my companions"?

Speak thus if you are so minded. God will love you still; but can you be surprised if He cherish other generous souls more? Take or reject virginity as you like. It is yours for the taking, but if you reject it do not say, "I have no call, no invitation to the higher life." You have the invitation now, in common with other Christians; and the great-souled ones are they who accept it, for "many are called, but few are chosen."

It may now be asked whether what has been said about the observance of chastity applies also to poverty and obedience. Spiritual writers tell us that the full and entire evangelical life includes all these three counsels, and that the principles on which one rests are common to all. Christ in His call invites those who are not hindered by insuperable obstacles, to follow Him in the practice of all the counsels, the reason for all being the same, namely, to sacrifice everything for His sake. It is evident, however, that there may be more hindrances to the observance of all three counsels than to the keeping of only one. Some religious orders, for example, on account of their special work, may demand from applicants health, or youth, or talent, or learning, or other qualifications, which every person does not possess. For community life, too, a peaceable temper and agreeable manners are usually necessary. Moreover, one may be so bound by obligations of justice and charity to his parents or others, that he cannot leave them. [2] The general principle, however, is fixed and sure, that the clarion call to the practice of the counsels is in itself general, and applicable to all who are not hindered by circumstances or impediments from accepting it. No further special invitation is necessary. You who are free have the invitation—take it if you wish.

[1] This and similar references are to the Migne edition of the Greek and Latin Fathers.

[2] It may still be possible, however, for a person who is prevented from entering community life, to practice the counsels while living in the world.

Said a boy one day, "How in the world does a person ever know he is to be a priest?" This little lad was a budding philosopher: he wanted to know the reason of things. But many an older person has been puzzled by the same question. Some boys and girls, having a distorted notion of the nature of a vocation, imagine that Almighty God picks out certain persons, without consulting them, and destines them for the priesthood or religious life, whereas all other persons he excludes from this privilege. In other words, they think God does it all.

Of course, we know there is an overruling Providence, Who watches over all His creatures, and particularly over His elect, distributing His graces and favors as He wills, and bringing all things to their appointed ends. If, for instance, a boy is blind, and for this reason no religious congregation will accept him, it is apparent that God does not design him for the religious life, though even for him the private practice of the counsels might still be open.

But we must not imagine that God settles everything in this world independently of our free will. He wishes us not to steal, but we may, if we choose, become thieves. Two boys of the same qualifications, let us say, have the general invitation of the Scripture to a life of perfection; they both have the same grace, which one accepts and the other rejects. What makes the vocation in the one case? The action of the boy himself in choosing to follow the invitation. And why has not the other boy a vocation? Because he declines to correspond with the grace. God does His part; He issues the call to all who are free from impediment and hindrance. Any one who wishes can accept the call and thus, in a sense, make his own vocation, for God's necessary help is ever ready to hand for those who will use it.

We may here remark that, while the practice of all virtue comes from man's free will, it also springs in a higher and greater degree from God, the author of grace. Without Him we can do nothing. "Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not received?" asks St. Paul (I Cor. iv: 7). God's grace must necessarily precede and accompany every supernatural action. In a very true sense, while a religious may say: "I am such voluntarily of my own free choice," he must also admit, "I am a religious by the grace of God, Who prepared me, aided me by external and internal helps, enlightened my mind and strengthened my will to embrace the life He designs for me."

In much the same way, a daily communicant may say: "It is of my own accord and wish that I receive daily, but it is God's predilection that has prompted me to this design, given me the opportunity and strength of purpose to carry it out, and keeps me faithful to it, so that it is by His grace and Providence that I am a daily communicant." Countless others could adopt the same practice, were they not too sluggish or indifferent to ask for or correspond with the grace of doing so.

Most ordinary vocations have several stages of development. Very many persons, with all the qualities required for the evangelical life, and unimpeded by any obstacle, begin to consider, under the influence of grace, the advisability of embracing that kind of life. This may be called the remote stage of a vocation. One who finds himself in this condition of mind, if he prays for light and guidance, is faithful to duty and generous in the service of God, may be enabled by a further enlightenment of grace to perceive that this life is best for him, and consequently that it will be more pleasing to God for him to adopt it, and finally he may decide to do so. Such a one has a proximate vocation, the only further step required being to carry out his purpose. This decision, be it observed, is the result of the action of his free will, aided by efficacious grace, which is a mark of God's special love.

A little illustration may assist us to get a clearer idea of the matter. Suppose Christ were to walk into your class-room, how would He act? Would He pick out four or five pupils and say, "I wish you to be religious, the others I do not want, and I forbid them such aspirations?" Do you think our loving, gentle Redeemer would speak in this harsh way? And yet some good, but ill-informed Christians think this a faithful representation of God's method of action in this important matter.

How, then, would Christ really address the class? He would say, "My dear children, I want as many of you as possible to follow closely in My footsteps, to become perfect. I should be glad to have all of you, who are not prevented by some insuperable obstacle, such as ill-health, lack of talent, home difficulties, or extreme giddiness of character. I hope to have a large number of volunteers." How many children in that class-room, do you think, would joyfully hold up their hands, and beg Him to take them?

Now, this is truly the way God acts with the individual soul. He comes to it perhaps not once only but repeatedly, and makes the general offer, using for this purpose the living voice of His minister, or the written page, or a prompting impulse from within. And when God's desire is so manifested, all that the soul needs is to cooperate with grace, if it will.

That this interpretation of the general call of Scripture to a higher life is in accord with sound doctrine, we can perceive from St. Thomas, who says that the resolution of entering the religious state, whether it comes from the general invitation of Scripture or an internal impulse, is to be approved. And in his "Catena Aurea," commenting on St. Matt. xix, he quotes St. Chrysostom, who holds that "the reason all do not take Christ's advice is because they do not wish to do so." The words "to whom it is given," according to this Greek father, show that "unless we received the help of grace, the exhortation would profit us nothing. But this help of grace is not denied to those who wish it."

This is also the teaching of St. Ignatius in his "Spiritual Exercises," where he designates three occasions in which to elect a state of life: the first, when God appeals to the soul in some extraordinary way; the second, when grace moves the heart by consolation and desolation, and the third, when the soul without any special motion of grace, "that is, when not agitated by diverse spirits, makes use of its natural powers" to elect the state of life which seems best suited to the praise of God and the salvation of one's soul. Evidently a vocation decided in the last-mentioned time, implies no special call beyond the general scriptural invitation and the determination to accept it.

Some one may ask how it is then that so many virtuous boys and girls, endowed with all needful qualifications, prompt and ready to respond to the suggestions of grace, yet have no efficacious desire of the higher life. It is not for us to search into the secrets of hearts, nor to penetrate into the mystery of grace and free-will. The Spirit breatheth where He wills, and God distributes to each man his own proper gift. But, at least, one thing seems certain, that many fail to recognize God's will, because they expect it to be manifested in some extraordinary or palpable manner. Perhaps, too, they have prepossessions against it, they have already marked out their own career, they never think about the counsels, or pray for guidance. If all our young people only realized that Christ's invitation is general and meant for them, provided no impediment exist, and they wish to embrace it; if at the same time they kept their hearts free from worldly amusements, and applied themselves to prayer and self-control, volunteers in greater number would rally to Christ's standard.

Some boys and girls, with hearts of gold, have often said: "I feel no attraction for the higher life. I appreciate it, admire it, and yet I fear it is not for me, as I have no inclination to it. If God wanted me, He would so perceptibly draw me to Him that there could be no mistaking His designs."

Almighty God is wonderful in His ways, and He "draws all things to Himself," but by methods varying as the temperaments and characteristics of the human soul. Sometimes He speaks to His chosen ones in thunder tones, as when He struck down St. Paul from his horse, on the road to Damascus, saying from heaven, "Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? . . . It is hard for thee to kick against the goad." (Acts ix: 4.) Again He speaks in gentle accents, as to St. Matthew, the publican, when he sat at his door taking customs, saying to him, "Follow me!" At other times He seems silent and indifferent, standing quietly by, letting reason and conscience argue within us, and point out our line of action.

There is what is called vocation by attraction, and also such a thing as vocation by conviction. Some of the great saints from earliest childhood felt a strong, irresistible charm in the higher life; they were drawn by the golden chain of love to the cloister. "I have never in my life," said a boy, "thought of being anything but a religious." Some young people have no difficulty in making up their minds to follow Christ, their whole bent of thought and character being for the nobler life. Like Stanislaus, they ever say, "I was born for higher things." It was such a precocious disposition of heart that led St. Teresa to foreshadow her saintly career when, as a little girl, she ran away from home to become a hermit.

But feeling is not always a trustworthy guide, either in temporal or spiritual matters; reason, slow but sure, is generally much safer. You feel the fascination of worldly things, of company and society, fine clothes, luxuries and comforts, the dazzling stage of life with its applause of men. Is that a sign God destines you for worldly vanities? Quite the contrary, for all Christians are warned against the seductions of the world and the flesh; and the life of the counsels is essentially a constant struggle with nature and its allurements. "The kingdom of heaven," we are told, "suffers violence, and the violent bear it away."

If the following of Christ were easy and agreeable to the senses, where would be the merit and reward of it? Just in proportion as it involves effort and the overcoming of natural repugnance, does it become high and sublime. "Do not think," says Our Lord (Matt. x: 34), "that I came to send peace upon earth: I came not to send peace, but the sword. For I came to set a man at variance with his father, and the daughter with her mother. . . . He that loveth father or mother more than me, is not worthy of me."

Natural antipathy then to the higher life, far from indicating that God does not want us, merely shows that the inferior powers of the soul are striving against the superior. In fact, when this aversion becomes pronounced, it is sometimes evidence of a keen strife going on within us between nature and grace, which could scarcely happen unless grace were endeavoring to gain the mastery by winning us to Christ.

"But," it may be objected, "if nature rebels, does not God always give a counter supernatural attraction to those whom He calls, so as to smooth the way before them?" Certainly God gives the necessary grace to perform good actions, but grace is not always accompanied by sensible consolation. Suppose a boy is chided by his parents for a fault and he is tempted to deny it; but overcoming the suggestion he admits his wrong-doing and expresses sorrow for it. In this he acts bravely and with no sense of accompanying satisfaction, since the pain of his parents' displeasure is so keen as to overcome for the moment any other feeling. His action is prompted simply by the conviction of duty.

Accordingly, if a young man knows and clearly sees that he has every qualification for the religious life, and has even been told so by a competent adviser; if he has sufficient talent and learning, a steady disposition and virtuous habits, and the persuasion that the duties of this state are not above his strength; in short, if he is convinced that there is no obstacle, save his own will, between him and the higher life, can he truly say, "I feel no inclination to such a career, and therefore, I have no vocation"? Such a person, of course, is free to say, "I will not enter religion," because there is no obligation incumbent upon him to this state, but he cannot justly say that God withholds from him the opportunity or invitation to do so. He has already what is called a remote vocation, as was explained in the fifth chapter, and what he needs is a clearer vision and alacrity of will, which he may have good hope of obtaining by earnest prayer and a generous and insistent offering of self to the disposal of the Divine good pleasure. For Our Lord Himself tells us: "All things whatsoever you ask when ye pray, believe that you shall receive, and they shall come unto you." (Mark xi: 24.)

Remove then, my dear young friend, from your mind that false and pernicious notion, which has been destructive of so many incipient vocations, that because you feel no supernatural inclination or sensible attraction, you are not called of God.

In general, it is sufficient that the aspirant to religious life be free from impediments, and be desirous of entering it. For eligibility to a particular religious congregation the applicant must be fit, that is, he must have the gifts or endowments of mind, heart and body which that institute demands; his desire to enter must be based on good and solid motives drawn from reason and faith, and he must have the firm resolve to persevere in the observance of the rule. When to this subjective capacity is added the acceptance of the candidate by a lawful superior, his vocation becomes complete.

The requisites, then, are three, two on the part of the applicant, namely, fitness and an upright intention, and one on the part of the superior, the acceptance or call. Nothing more, nothing less is required. If any one of these three essentials is wanting, there is no vocation to that particular institute.

It is worthy of observation, however, that these qualifications of the applicant need be fully evident only towards the end of the novitiate, when the time comes for taking the vows and assuming the obligations. To enter the noviceship, as a rule, much less is required, though even for this preparatory step a person must have the serious intention of trying the life and discovering whether it is suitable to him, and there should be a reasonable prospect of his developing the needful qualifications.

For spiritual directors, then, to regard a vocation as something exceeding rare and intricate, to subject the candidate and his conscience to searching and critical analysis, to harassing cross-examination and prolonged tests, as though he were a criminal entertaining a fell project, to endeavor to probe into the secret workings of grace within him, is only to cloud in fatal obscurity an otherwise very simple subject.

A high-souled youth or maiden may still be deterred by the thought, "I now see that I have all the necessary qualifications for the higher life, and hence may embrace it if I choose, but I fear it will be too difficult for me to carry the yoke without sensible devotion or consolation." In answer to this, we must remember that a hundredfold in this world and life everlasting in the next are promised to those who leave all to follow Christ. In this hundredfold are included many privileges and favors bestowed by God upon His chosen spouses. Make the effort, overcome nature, decide to embrace God's offer, and you will find yourself overwhelmed by a deluge of spiritual consolations, which God has been withholding from you to try your generosity and courage; you will experience the truth of Christ's words, "My yoke is sweet, and my burden light." Sensible consolations, in fact, nearly always follow the performance of a virtuous act, but seldom do they precede it. A hungry person, before sitting down to table, may feel cross and out of humor, but as soon as he begins to partake of the generous viands a feeling of genial content and satisfaction with all the world steals over him.

It would, of course, be an error for any one to think that of his own natural powers he could observe the counsels; since this, being a supernatural work, demands strength above nature. But he who feels helpless of himself, should place his entire trust and confidence in God's grace and assistance, saying, with the Apostle, "I can do all things in him who strengthened me" (Ph. iv: 13).

Come, then, to the banquet prepared for you by the great King. Regale yourself with the spiritual viands set before you, and not only will you be strengthened to do God's will, but transported beyond measure with spiritual delights.

A young man once exclaimed to a friend, "Suppose I make a mistake! I could not bear the disgrace of leaving a religious order after entering it." Having wrestled with this thought for some time, he finally determined to try the religious life, with the result that after taking the habit, he was too happy to dream of ever laying it aside.

However, it is not wrong, but highly prudent, for any one to consider whether he has the courage and constancy to persevere. Religious life is not a pathway of roses. It is meant only for true men and valiant women, not for soft, languid characters, nor for fickle minds, which change as a weather vane. Marriage also is a serious step, for it brings much "tribulation of the flesh," and so he who would enter on it must earnestly consider whether he can live up to the obligations it entails. But because marriage has many cares and responsibilities, is that a prohibitive reason against embracing it? A soldier's life, too, is hard, and a farmer's; in fact, all pursuits and vocations in this world have their sombre side. But he who would win success in any career must be ready "with a heart for any fate" to meet and overcome all the trials and hardships that await him.

On one occasion Our Lord made use of the following parable (Luke xiv: 28): "Which of you having a mind to build a tower, doth not first sit down and reckon the charges that are necessary, whether he have wherewithal to finish it: lest after he hath laid the foundation, and is not able to finish it, all that see it begin to mock him, saying, 'This man began to build and was not able to finish'?" This parable Our Lord seems to apply to those who have the call to the Faith, and He concludes with the words, "So likewise every one of you that doth not renounce all that he possesseth, cannot be my disciple."

But His advice is also applicable to one who contemplates a closer following of Christ by the pathway of the counsels. Certainly, by all means, deliberate before taking any step of importance in this world. Never act on inconsiderate impulse in any matter of moment, but weigh carefully the obligations you are to assume, and consider whether you have sufficient strength of character to persevere in any good work you are undertaking.

Still, when all is said and done, it remains true that timidity is not prudence, nor cowardice caution. Nothing great was ever accomplished in this world without courage. Prudence and caution may be overdone, and easily degenerate into sloth and inactivity. In a battle he who hesitates is lost, and life is the sharpest of conflicts. Had Columbus wavered, he would not have discovered America. Close followers of Christ must be brave and noble souls, willing to risk all, to sacrifice all in the service of their leader. If you are excessively timid and fearful of making a misstep in your every action, it is a fault of character, and unless you overcome it you will never do great things for yourself or others.

When reason and conscience point the way, plunge boldly forward, trusting to the Lord for all the necessary helps you may need to carry out your designs. He will never desert you when once you enlist under His flag. When it comes to "supposing," there is no end to the dreadful things that might happen, but never will. Little children have a game called "supposing," each one making his supposition in turn, but even they do not anticipate that their creations of fancy will ever prove true. A man once said: "I have lived forty years, and have had many troubles, but most of them never happened," meaning that he had often anticipated and dreaded evils which never came to pass.

Let us, however, grant that occasionally a novice leaves his order: is that such a disgrace? By no means; he, at least, deserves credit for attempting the higher life. He is far more courageous than many Christians who are too timorous even to try. After all, what is a novitiate for, if not to discover whether the candidate has the requisite qualities? And judicious superiors will be the first to advise a young man or woman to leave, if he or she has wandered into the wrong place.

There is, moreover, a danger on the opposite side that wavering souls often fail to take into account. What if they make a mistake by not entering religious life? Is it better to err on the side of generosity to God, or on the side of pusillanimity? If one make a mistake by entering religion he can easily retrace his steps before it is too late, but once he commits himself to worldly obligations, he can seldom break their fetters; and many a man, when overwhelmed with the cares and anxieties of life, has regretted, when all too late, that he had not hearkened to the voice of grace that invited him to the calm and peace of the cloister.

St. Ignatius thus forcibly expresses the same thought: "More certain signs are required to decide that God wills one to remain in the secular state, than that He wishes him to enter on the way of the counsels, for the Lord so openly urged the counsels, while He insisted on the great dangers of the other state." (Directory, c. 23.)

The devil, who employs every ruse to wreck a vocation, has one favorite stratagem, which unfortunately succeeds only too often. When he cannot induce a person to give up entirely the idea of following Christ closely, he frequently induces him, under a variety of pretexts, to postpone its execution. If he can get the person to wait, to delay, he feels he has scored a victory, for thus he will have ample opportunity to lure his victim to a love of the world, to present the vanities of life in such enticing colors, as finally to withdraw him altogether from his first purpose. This disaster, unfortunately, is only too common, and many a one finds out, to his cost, that unseasonable delay has destroyed in him the spiritual savor, and made shipwreck of his vocation.

If, then, you see clearly it is best for you to tread the pathway of the counsels, go boldly on without delay or hesitation, and if difficulties loom big before you, they will fade away at your approach, like the fog before the sun; or, if they remain, you will be surprised at the ease with which you will vanquish them, for when the Lord is with you, who will be against you? You will be guarded against possible rashness in choosing the higher life by consulting a prudent director or confessor, at least, so far as to get his approval of the step you propose to take. For the knowledge such a one has of the secrets of your conscience gives him a specially favorable opportunity to judge whether you have the virtue and determination of character to persevere in the pathway of the counsels.

Some young people endeavor to persuade themselves that as the world needs good men, they can better serve Church and State by remaining in the secular life. The world, of course, does need good men and women, and it has them, too; but even if there were a dearth of good Christian laymen, is that any reason for you to refuse God's invitation and sacrifice your own spiritual advancement and happiness in order to help others? Our first duty is to ourselves. Are we to be so enamored of benefiting others as to forego God's special love, and to rest satisfied with a lower place in heaven? God invites you to Him, and you turn away to devote yourselves to others, who perhaps care little for you, and will profit less by your example.

And, moreover, once absorbed in the business and cares of life, you may find yourself, like most others, so preoccupied in your own personal advancement, in providing for yourself and those dependent on you, that scarce a thought remains for the interests of your neighbor. And thus your initial high resolve may soon sink to the low level of beneficent effort you see in others. Selfishness, to a large extent, rules in the world, and how can you promise yourself that you will escape its grasp? He certainly is rash who thinks he can, single-handed, contend against the world and its spirit.

No doubt many men and women of the world are devout Christians, and in a thousand ways spread about them the good odor of Christ. Countless brave Christian soldiers, upright statesmen, kings and peasants, matrons and maids, are the pride of Christianity for what they have done and dared in behalf of their neighbor. All honor to the virtuous laity throughout the world to-day, who by their edifying lives, their sacrifices for the faith, their unwearying industry, and fidelity to Mother Church, are sanctifying their own souls, and assisting others by example, counsel and charitable deed.

But for every layman that has distinguished himself by heroic devotion to the welfare of his neighbor, many religious could be mentioned who have done the same. We have all heard of Father Damien, who banished himself to the isle of Molokai, where the outcast lepers of the Sandwich Islands had been herded to rot and die; and there taking up his abode, soon changed the lepers, who were living like wild beasts, without law or morality, into gentle and fervent Christians. Having no priest as a companion, he on one occasion rowed out to a passing steamer, which was not allowed to land, to make his confession to a bishop aboard. And while he sat in his row boat, because forbidden to climb into the vessel, and shouted his sins to the bishop on the deck above, the passengers looking curiously on, he certainly must have been a spectacle to men and angels. And his sacrifice became complete when he contracted the leprosy from his people, and thus gave up his life for his flock.

Nor is this a solitary instance of such magnanimity. A short time ago, when a Canadian bishop entered a convent and called for volunteers to start a leper hospital, every nun stood up to offer her services. You have heard of the great Apostle of the Indies, St. Francis Xavier, who is said to have baptized more than a million pagans. St. Teresa, the mystic, was not prevented by her cloister and her ecstacies from helping her neighbor, for she founded a large number of convents, both for men and women. Blessed Margaret Mary was only a simple nun in the Visitation Convent of Paray-le-Monial, yet God chose her to make known and spread the great devotion of the Sacred Heart, a devotion which has brought more comfort and consolation to sorrowing humanity than the combined philanthropic efforts of a century. God took a gay cavalier, whose only ambition was to wear foppish clothes and thrum a guitar, made him into a friar, and bade him found the great Franciscan Order, whose glorious works for mankind cannot be enumerated.

And if we ponder the nature of religious life, the marvels accomplished by simple religious cease to astonish us. One who devotes the major portion of his time and attention to a definite object will certainly attain great results. Now, most religious seek their own sanctification in concentrating their energies on the welfare of their neighbor, in ever studying, working, planning for his betterment. The love of God, as shown in charity to others, is the absorbing purpose of their life. On the other hand, the man of the world must generally care first and foremost for himself and family, and only the time he has left, incidentally as it were, can he bestow upon others.

This point is thus forcibly expressed by St. Paul (I Cor. vii: 32-34): "He who is unmarried is solicitous for the things of the Lord, how he may please God. But he who is married is solicitous for the things of the world, how he may please his wife; and he is divided. And the woman, unmarried and a virgin, thinketh on the things of the Lord, that she may be holy in body and soul. But she who is married, thinketh on the things of the world, how she may please her husband."

The works of the religious orders are varied and numerous. Some care for the outcasts of society, some for the sick or the old, the orphan and the homeless; others, leaving the comforts and conveniences of modern life, cheerfully face the danger and hardships of remotest lands to bring the light of the Gospel to pagan nations. More than a million Chinese to-day are fervent Christians, and to whom do they owe their faith under God? To religious missionaries. The Benedictines of old spent their lives in the pursuit of learning, and in teaching barbarous tribes the art of husbandry. The glorious Knights Templar were a militant order; and the members of the Order of the Blessed Trinity for the redemption of captives, the first to wear our national colors of freedom, the red, white and blue, sold themselves into slavery for the release of others. Scarcely a want or need of the human race has not been provided for by some religious body.

But probably the most common pursuit of religious bodies in our day is teaching. Hundreds of thousands of religious men and women, in all lands whence they are not banished, spend their lives in the class-room. And the reason for this preference is the extraordinary demand for schools in every direction. The young must be taught, and Holy Mother Church knows only too well that religious training must be woven into the fibre of secular learning if we would not have a conscienceless and irreligious generation. So she issues her stirring appeal for volunteer teachers, and a vast multitude of religious have responded in solid phalanx. Some one has said that if all the sisterhoods were taken out of our schools in the United States, we should soon have to close half our churches.

Religious, then, are carrying on vast and important works for the benefit of the Church and society. Many other services which they render might be mentioned, such as preaching and hearing confessions, the publication of books and periodicals, the cultivation of the arts, science, literature and theology. But enough has been said to show that they are leading a strenuous life, and that boy or maid, who is emulous of heart-stirring deeds, could scarcely find a more propitious field of action than in the religious state.

It is not the purpose of the writer to exaggerate, to frighten or coerce persons into religious life, by holding out threats of God's displeasure to those who refuse, or by citing examples of those whose careers were blighted through failure to heed the Divine call. It is His desire rather to imitate Christ's manner of action, portraying the beauty and excellence of virtue, and then leaving it to the promptings of aspiring hearts to follow the leadings of grace.

Christ, all mildness and meekness as He was, uttered terrible denunciations against sin and the false leaders of the people; but nowhere do we read that He denounced or threatened those who failed to accept His tender and loving call to the life of perfection. To draw men's hearts He used not compulsion, but the lure of kindness and affection.

Our Lord sometimes commanded and sometimes counselled and between these there is a difference. When a command is given by lawful superiors it must be obeyed, and that under penalty. God gave the commandments amidst thunder and lightning on Mount Sinai, and those commandments, as precepts of the natural law, or because corroborated in the New Testament, persist in the main to-day, and any one who violates them, refuses to keep them, is guilty of disobedience to God, commits a sin. But when Christ proclaimed the counsels, He was merely giving advice or exhortation, and hence no one was obliged to follow them under pain of His displeasure. Suppose a mother has two sons, who both obey exactly her every command, and one also takes her advice in a certain matter, while the other does not; she will love the second not less, but the first more. So of two boys, who are both favorites of God, if one accept and the other decline a proffered vocation, He will love the latter as before, but the former how much more tenderly!

Moreover, God loves the cheerful giver. By doing, out of an abundance of charity and fervor, what you are not obliged to do, you gain ampler merit for yourself, since you perform more than your duty, and at the same time you give greater glory to God, showing that He has willing children, who bound their service to Him by no bargaining considerations of weight and measure. But if, through fear of threat or punishment, you make an offering to God, your gift loses, to an extent, the worth and spontaneity of a heart-token.

Some think that not to accept the invitation to the counsels, is to show disregard and contempt for God's grace and favor, and hence sinful. But how does a young person act when he declines this proffered gift? He equivalently says, with tears in his eyes, "My Saviour, I appreciate deeply Thy invitation to the higher life; I envy my companions who are so courageous as to follow Thy counsel; but, please be not offended with me if I have not the courage to imitate their example. I beg Thee to let me serve Thee in some other way." Is there anything of contempt in such a reply? No more than if a child would tearfully pray its mother not to send it into a dark room to fetch something; and as such a mother, instead of insisting on her request, would only kiss away her child's tears, so will God treat one who weeps because he cannot muster courage to tread closely in His blood-stained footsteps.

The young have little relish for argumentative quotations and texts, but it may interest them to know that Saints Basil, Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianzen, Cyprian, Augustine and other Fathers all speak in a similar strain, holding that, as a vocation is a free gift or counsel, it may be declined without sin. [1] The great Theologians, St. Thomas, Suarez, Bellarmine and Cornelius a Lapide also agree on this point.

But putting aside the question of sin, we must admit that one who clearly realizes that the religious life is best for him and consequently more pleasing to God, would, by neglecting to avail himself of this grace, betray a certain ungenerosity of soul and a lack of appreciation of spiritual things, in depriving himself of a gift which would be the source of so many graces and spiritual advantages.

Do not, then, dear reader, embrace the higher life merely from motives of fear—which were unworthy an ingenuous child of God—but rather to please the Divine Majesty. You are dear to Him, dearer than the treasures of all the world. He loves you so much that He died for you, and now He asks you in return to nestle close to His heart, where He may ever enfold His arms about you, and lavish his blandishments upon your soul. Will you come to Him, your fresh young heart still sweet with the dew of innocence, and become His own forevermore? Will you say farewell to creatures, and rest upon that Bosom whose love and tenderness for you is high as the stars, wide as the universe, and deep as the sea? Come to the tender embraces of your heavenly spouse, and heaven will have begun for you on earth.

[1] The hypothetical case, sometimes mentioned by casuists, of one who is convinced that for him salvation outside of religion is impossible, can here safely be passed over as unpractical for young readers.

Many a young person, when confronted with the thought of his vocation, puts it out of mind, with the off-hand remark, "Oh, there is plenty of time to consider that; I am too young, and have had no experience of the world." This method of procedure is summary, if not judicious, and it meets with the favor of some parents, who fear, as they think, to lose their children. It was also evidently highly acceptable to Luther, who is quoted by Bellarmine as teaching that no one should enter religious life until he is seventy or eighty years of age.

In deciding a question of this nature, however, we should not allow our prepossessions to bias our judgment, nor take without allowance the opinion of those steeped in worldly wisdom, but lacking in spiritual insight. Father William Humphrey, S.J., in his edition of Suarez's "Religious Life" (page 49), says: "Looking merely to natural law, it is lawful at any age freely to offer oneself to the perpetual service of God. There is no natural principle by which should be fixed any certain age for such an act."

Christ did not prescribe any age for those who wished to enter His special service, and He rebuked the apostles for keeping children from Him, saying, "Let the little ones come unto Me." And St. Thomas (Summa, 2a 2æ, Quæst. 189, art. 5), quotes approvingly the comment of Origen on this text, viz.: "We should be careful lest in our superior wisdom we despise the little ones of the Church and prevent them from coming to Jesus." And speaking in the same article of St. Gregory's statement that the Roman nobility offered their sons to St. Benedict to be brought up in the service of God, the Angelic Doctor approves this practice on the principle that "it is good for a man to bear the yoke from his youth," and adds that it is in accord with the usual "custom of setting boys to the duties and occupations in which they are to spend their life."

The remark concerning St. Benedict recalls to mind the interesting fact that in olden times, not only boys of twelve and fourteen became little monks, but that children of three, four or five years of age were brought in their parents' arms and dedicated to the monasteries. According to the "Benedictine Centuries," "the reception of a child in those days was almost as solemn as a profession in our own. His parents carried him to the church. Whilst they wrapped his hand, which held the petition, in the sacred linen of the altar, they promised, in the presence of God and His saints, stability in his name." These children remained during infancy and childhood within the monastery enclosure, and on reaching the age of fourteen, they were given the choice of returning home, if they preferred, or of remaining for life. [1]

The discipline of the Church, which as a wise Mother, she modifies to suit the exigencies of time and place, is somewhat different in our day. The ordinary law now prohibits religious profession before the age of sixteen; and the earliest age at which subjects are commonly admitted is fifteen. Orders which accept younger candidates, in order to train and prepare them for reception, cannot, as a rule, clothe them with the habit. A very recent decree also requires clerical students to have completed four years' study of Latin before admission as novices into any order.

Persons who object to early entrance into religion seem to forget that the young have equal rights with their elders to personal sanctification, and to the use of the means afforded for this purpose by the Church. It is now passed into history, how some misguided individuals forbade frequent Communion to the faithful at large, and altogether excluded from the Holy Table children under twelve or fourteen, and this notwithstanding the plain teaching of the Council of Trent to the contrary. To correct the error, the Holy See was obliged to issue decrees on the subject, which may be styled the charter of Eucharistic freedom for all the faithful, and especially for children. As the Eucharist is not intended solely for the mature or aged, so neither is religious life meant only for the decrepit, or those who have squandered youth and innocence. Its portals are open to all the qualified, and particularly to the young, who wish to bring not a part of their life only, but the whole of it, along with youthful enthusiasm and generosity, to God's service.

How many young religious have attained heroic sanctity which would never have been theirs had religion been closed against them by an arbitrary or unreasonable age restriction! A too rigid attitude on this point would have barred those patrons of youth, Aloysius, Stanislaus Kostka and Berchmans, from religion and perhaps even from the honors of the altar. St. Thomas, the great theological luminary of the Church, was offered to the Benedictines when five years old, and he joined the Dominicans at fifteen or sixteen; and St. Rose of Lima made a vow of chastity at five. The Lily of Quito, Blessed Mary Ann, made the three vows of poverty, chastity and obedience before her tenth birthday, and the Little Flower was a Carmelite at fifteen. And uncounted others, who lived and died in the odor of sanctity, dedicated themselves by vow to the perpetual service of God, while still in the fragrance and bloom of childhood or youth.

"What a pity!" some exclaim, when a youth or maid enters religion. "How much better for young people to wait a few years and see something of the world, so they will know what they are giving up." This is ever the comment of the worldly spirit, which aims to crush out entirely spiritual aspirations, and failing in that, to delay their fulfilment indefinitely. And yet the wise do not reason similarly in other matters. One who proposes to cultivate a marked musical talent is never advised to try his hand first at carpentering or tailoring, that he may make an intelligent choice between them. Nor is a promising law student counselled to spend several years in the study of engineering and dentistry, to avoid making a possible mistake. Why then wish a youth, of evident religious inclination, to mingle in the frivolity and gayeties of the world, with the certain risk of imbibing its spirit and losing his spiritual relish? "He who loves the danger," says the Scripture, "will perish in it."