Montezuma's Castle, the ruined cliff dwelling on Beaver

Creek between the Coconino and Prescott National Forests, Arizona

Montezuma's Castle, the ruined cliff dwelling on Beaver

Creek between the Coconino and Prescott National Forests, Arizona

Project Gutenberg's Through Our Unknown Southwest, by Agnes C. Laut This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Through Our Unknown Southwest Author: Agnes C. Laut Release Date: March 15, 2010 [EBook #31646] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THROUGH OUR UNKNOWN SOUTHWEST *** Produced by Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

Montezuma's Castle, the ruined cliff dwelling on Beaver

Creek between the Coconino and Prescott National Forests, Arizona

Montezuma's Castle, the ruined cliff dwelling on Beaver

Creek between the Coconino and Prescott National Forests, Arizona

Author of The Conquest of the Great Northwest, Lords of the North

and Freebooters of the Wilderness

NEW YORK

McBRIDE, NAST & COMPANY

1913

Copyright, 1913, By

McBRIDE, NAST & CO.

Second Printing

October, 1913

Published May, 1913

PAGE

Introduction i

I The National Forests 1

II National Forests of the Southwest 22

III Through the Pecos Forests 44

IV The City of the Dead 60

V The Enchanted Mesa of Acoma 78

VI Across the Painted Desert 100

VII Across the Painted Desert (continued) 116

VIII Grand Cañon and the Petrified Forests 137

IX The Governor's Palace of Santa Fe 153

X The Governor's Palace (continued) 169

XI Taos, the Promised Land 183

XII Taos, the Most Ancient City in America 196

XIII San Antonio, the Cairo of America 214

XIV Casa Grande and the Gila 226

XV San Xavier Del Bac Mission 251

Cliff dwelling ruins, known as Montezuma Castle, Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

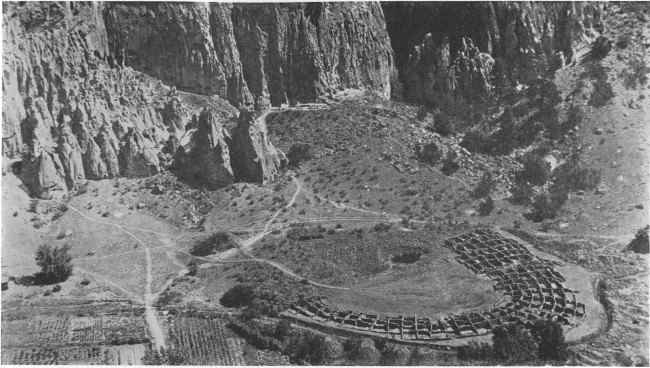

South House of Frijoles Cañon ii

Indian woman making pottery xii

Indian girl of Isleta, N. M. xx

One way of entering the desert 4

In the Coconino Forest of Arizona 14

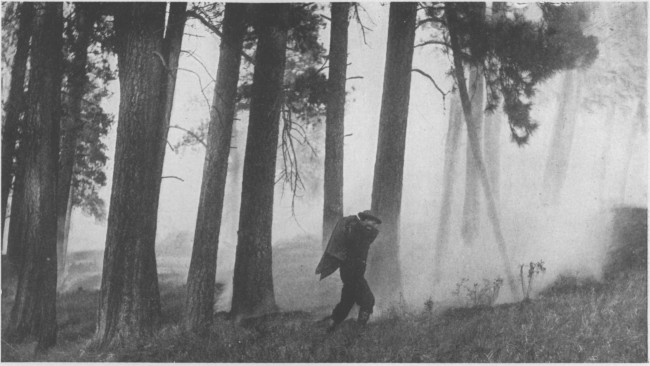

Forest ranger fighting a ground fire with his blanket 22

Pueblo boys at play 34

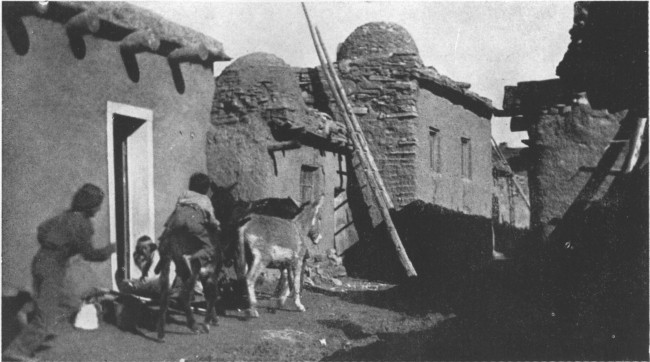

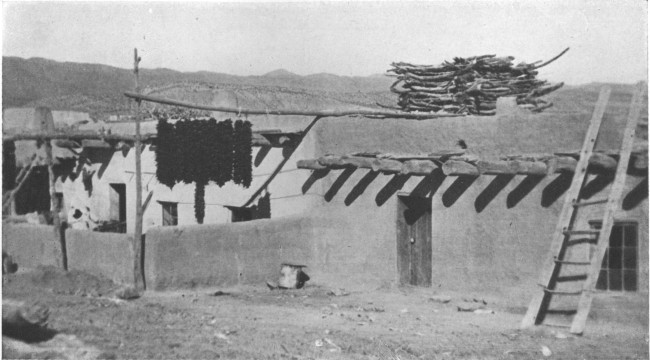

Chili peppers drying outside pueblo dwelling 46

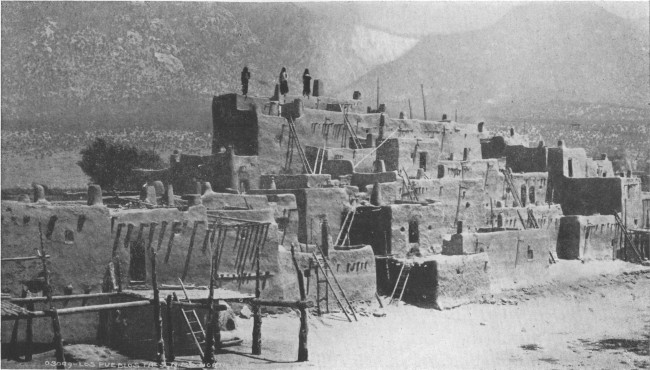

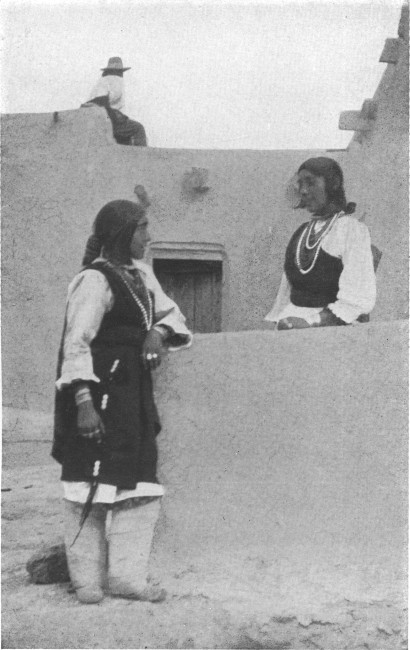

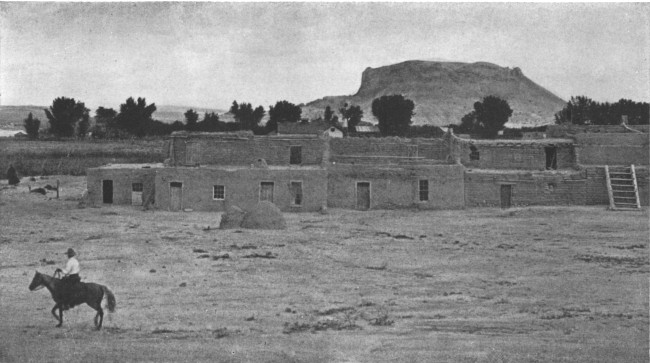

Los Pueblos, Taos, N. M. 56

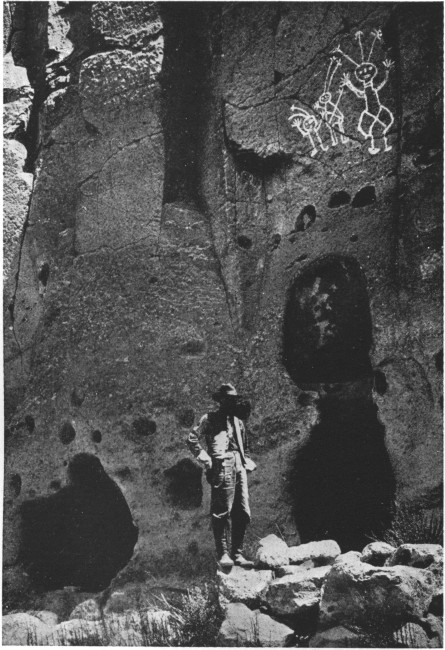

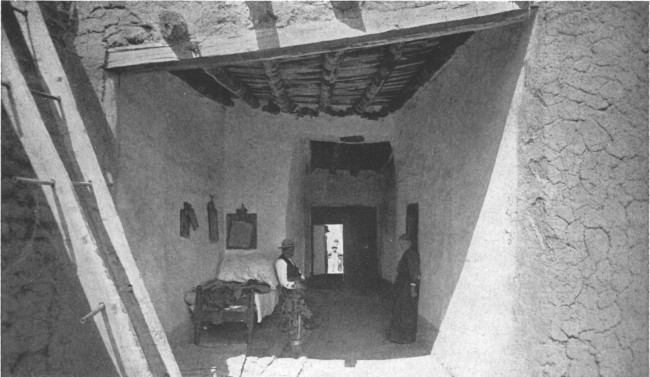

Entrance to a cliff dwelling 64

Ruins of Frijoles Cañon 74

A Hopi wooing 80

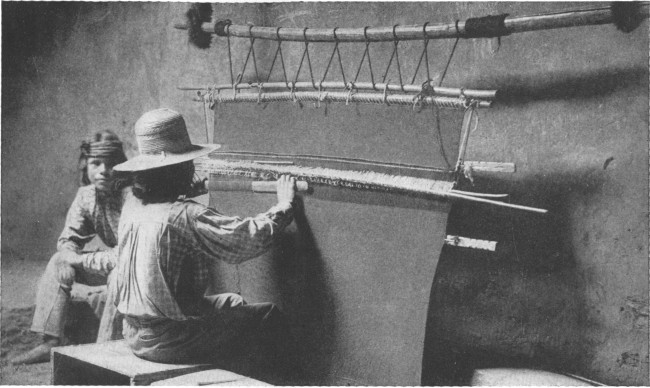

A Hopi weaver 86

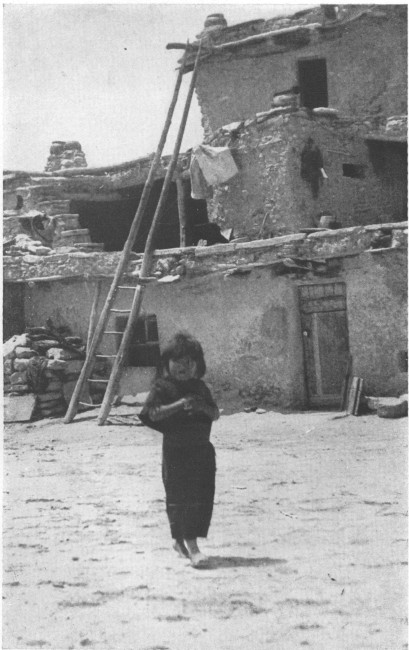

A shy little Hopi maid 92

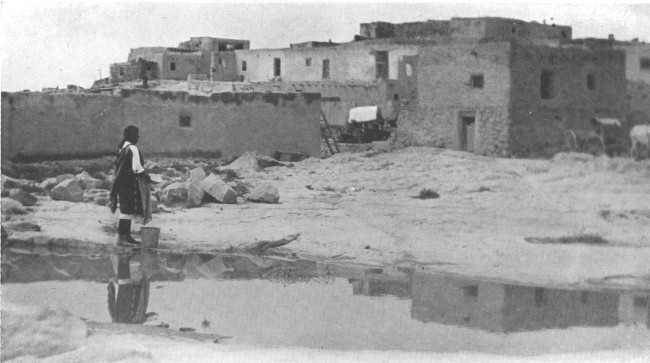

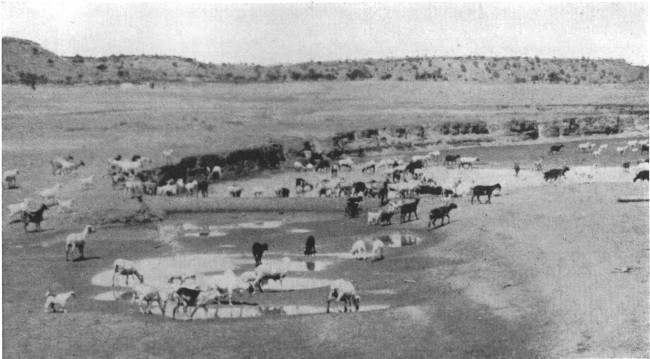

At the water hole on the outskirts of Laguna 96

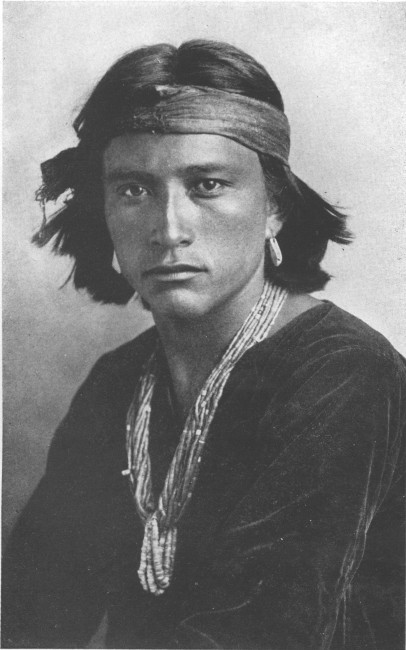

A handsome Navajo boy 106

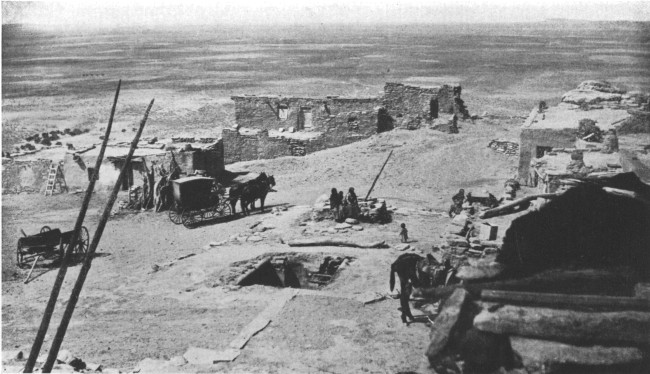

The Pueblo of Walpi 122

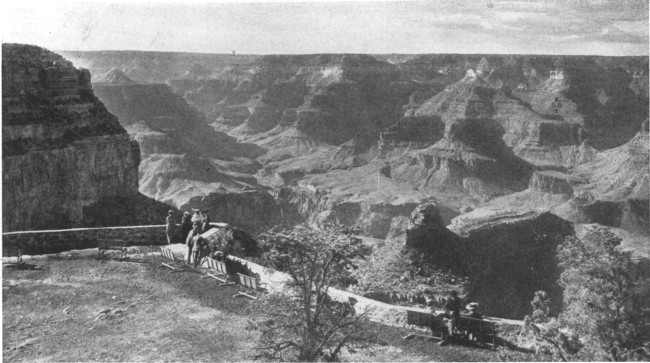

The Grand Cañon 140

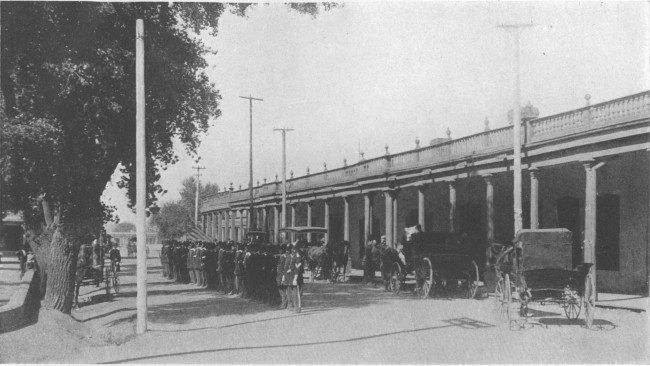

The Governor's Palace at Santa Fe 154

A pool in the Painted Desert 160

Street in Santa Fe 166

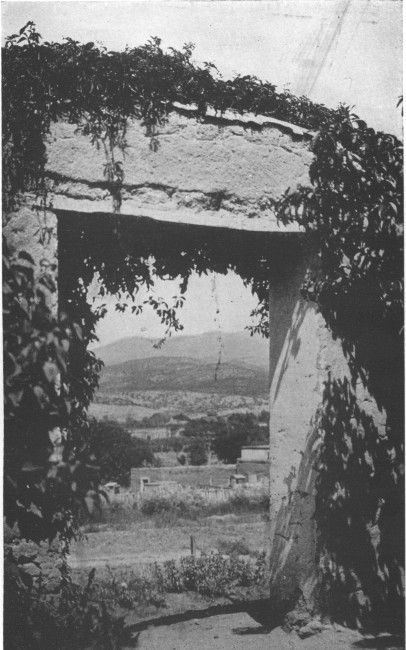

Ancient adobe gateway 172

San Ildefonso 180

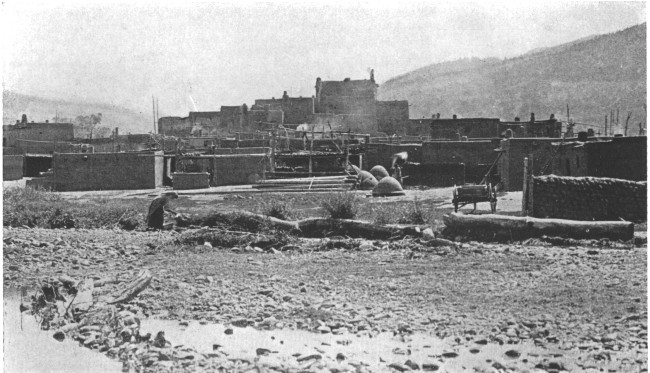

Taos 188

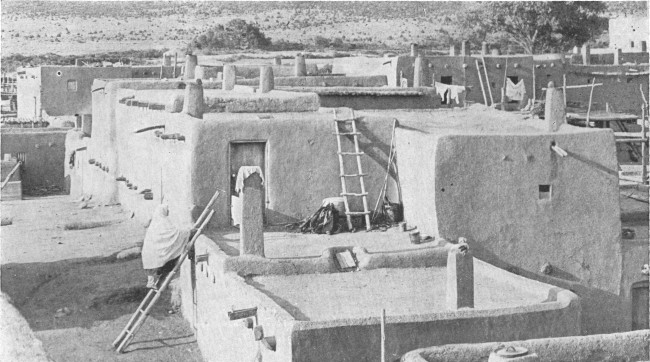

Over the roofs of Taos 198

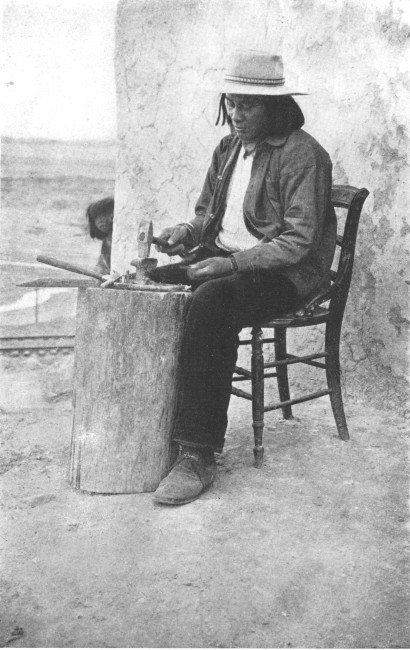

A metal worker of Taos 208

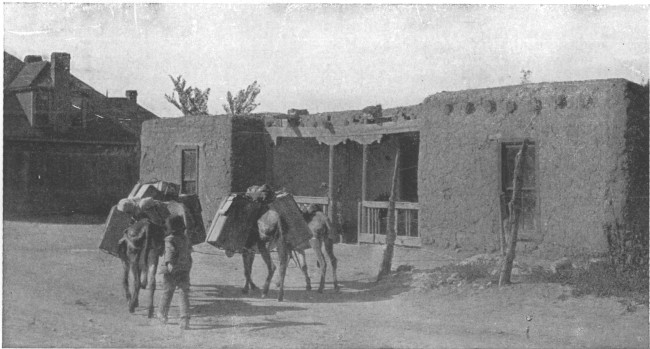

A mud house of the Southwest 220

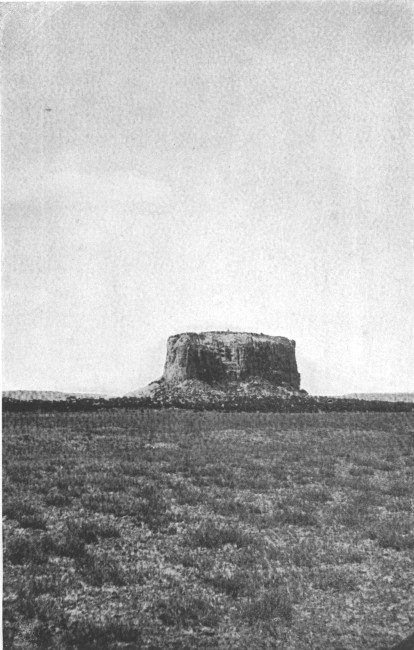

The enchanted Mesa of Acoma 230

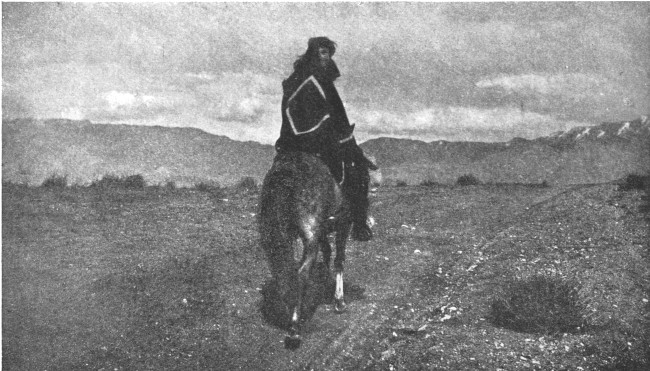

Navajo crossing mesa 246

At the Mission of San Xavier 254

A Moki City on a mesa 262

I am sitting in the doorway of a house of the Stone Age—neolithic, paleolithic, troglodytic man—with a roofless city of the dead lying in the valley below and the eagles circling with lonely cries along the yawning caverns of the cliff face above.

My feet rest on the topmost step of a stone stairway worn hip-deep in the rocks of eternity by the moccasined tread of foot-prints that run back, not to A. D. or B. C., but to those post-glacial æons when the advances and recessions of an ice invasion from the Poles left seas where now are deserts; when giant sequoia forests were swept under the sands by the flood waters, and the mammoth and the dinosaur and the brontosaur wallowed where now nestle farm hamlets.

Such a tiny doorway it is that Stone Man must have been obliged to welcome a friend by hauling him shoulders foremost through the entrance, or able to speed the parting foe down the steep stairway with a rock on his head. Inside, behind me, is a little dome-roofed room, with calcimined walls, and squared stone meal bins, and a little, high fireplace, and stone pillows, and a homemade flour mill in the form of a flat metate stone with a round grinding[Pg ii] stone on top. From the shape and from the remnants of pottery shards lying about, I suspect one of these hewn alcoves in the inner wall was the place for the family water jar.

On each side the room are tiny doorways leading by stone steps to apartments below and to rooms above; so that you may begin with a valley floor room which you enter by ladder and go halfway to the top of a 500-foot cliff by a series of interior ladders and stone stairs. Flush with the floor at the sides of these doors are the most curious little round "cat holes" through the walls—"cat holes" for a people who are not supposed to have had any cats; yet the little round holes run from room to room through all the walls.

On some of the house fronts are painted emblems of the sun. Inside, round the wall of the other houses, runs a drawing of the plumed serpent—"Awanya," guardian of the waters—whose presence always presaged good cheer of water in a desert land growing drier and drier as the Glacial Age receded, and whose serpent emblem in the sky you could see across the heavens of a starry night in the Milky Way. Lying about in other cave houses are stone "bells" to call to meals or prayers, and cobs of corn, and prayer plumes—owl or turkey feathers. Don't smile and be superior! It isn't a hundred years ago since the common Christian idea of angels was feathers and wings; and these Stone People lived—well, when did they live? Not later than 400 A. D., for that was when the period of desiccation, or drought from the recession of the glacial waters, began.

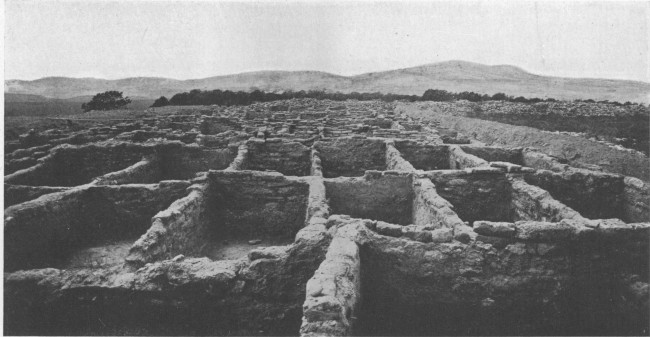

Ruins of South House, one of the great communal dwellings

of Frijoles Cañon, after excavation

Ruins of South House, one of the great communal dwellings

of Frijoles Cañon, after excavation

"The existence of man in the Glacial Period is established," says Winchell, the great western geologist, "that implies man during the period when flourished the large mammals now extinct. In short, there is as much evidence pointing to America as to Asia as the primal birthplace of man." Now the ice invasion began hundreds of thousands of years ago; and the last great recession is set at about 10,000 years; and the implements of Stone Age man are found contemporaneous with the glacial silt.

There is not another section in the whole world where you can wander for days amid the houses and dead cities of the Stone Age; where you can literally shake hands with the Stone Age.

Shake hands? Isn't that putting it a little strong? It doesn't sound like the dry-as-dust dead collections of museums. It may be putting it strong; but it is also meticulously and simply—true. A few doors away from the cave-house where I sit, lies a little body—no, not a mummy! We are not in Egypt. We are in America; but we often have to go to Egypt to find out the wonders of America. Lies a little body, that of a girl of about eighteen or twenty, swathed in otter and beaver skins with leg bindings of woven yucca fiber something like modern burlap. Woven cloth from 20,000 to 10,000 B. C.? Yes! That is pretty strong, isn't it? 'Tis when you come to consider it; our European ancestors at that date[Pg iv] were skipping through Hyrcanian Forests clothed mostly in the costume Nature gave them; Herbert Spencer would have you believe, skipping round with simian gibbering monkey jaws and claws, clothed mostly in apes' hair. Yet there lies the little lady in the cave to my left, the long black hair shiny and lustrous yet, the skin dry as parchment still holding the finger bones together, head and face that of a human, not an ape, all well preserved owing to the gypsum dust and the high, dry climate in which the corpse has lain.

In my collection, I have bits of cloth taken from a body which archæologists date not later than 400 A. D. nor earlier than 8,000 B. C., and bits of corn and pottery from water jars, placed with the dead to sustain them on the long journey to the Other World. For the last year, I have worn a pin of obsidian which you would swear was an Egyptian scarab if I had not myself obtained it from the ossuaries of the Cave Dwellers in the American Southwest.

Come out now to the cave door and look up and down the cañon again! To right and to left for a height of 500 feet the face of the yellow tufa precipice is literally pitted with the windows and doors of the Stone Age City. In the bottom of the valley is a roofless dwelling of hundreds of rooms—"the cormorant and the bittern possess it; the owl also and the raven dwell in it; stones of emptiness; thorns in the palaces; nettles and brambles in the fortresses; and the screech owl shall rest there."

Listen! You can almost hear it—the fulfillment[Pg v] of Isaiah's old prophecy—the lonely "hoo-hoo-hoo" of the turtle dove; and the lonelier cry of the eagle circling, circling round the empty doors of the upper cliffs! Then, the sharp, short bark-bark-bark of a fox off up the cañon in the yellow pine forests towards the white snows of the Jemez Mountains; and one night from my camp in this cañon, I heard the coyotes howling from the empty caves.

Below are the roofless cities of the dead Stone Age, and the dancing floors, and the irrigation canals used to this day, and the stream leaping down from the Jemez snows, which must once have been a rushing torrent where wallowed such monsters as are known to-day only in modern men's dreams.

Far off to the right, where the worshipers must always have been in sight of the snowy mountains and have risen to the rising of the desert sun over cliffs of ocher and sands of orange and a sky of turquoise blue, you can see the great Kiva or Ceremonial Temple of the Stone Age people who dwelt in this cañon. It is a great concave hollowed out of the white pumice rock almost at the cliff top above the tops of the highest yellow pines. A darksome, cavernous thing it looks from this distance, but a wonderful mid-air temple for worshipers when you climb the four or five hundred ladder steps that lead to it up the face of a white precipice sheer as a wall. What sights the priests must have witnessed! I can understand their worshiping the rising sun as the first rays came over the cañon walls in a shield of fire. Alcoves for meal, for incense, for water urns, mark[Pg vi] the inner walls of this chamber, too. Where the ladder projects up through the floor, you can descend to the hollowed underground chamber where the priests and the council met; a darksome, eerie place with sipapu—the holes in the floor—for the mystic Earth Spirit to come out for the guidance of his people. Don't smile at that idea of an Earth Spirit! What do we tell a man, who has driven his nerves too hard in town?—To go back to the Soil and let Dame Nature pour her invigorating energies into him! That's what the Earth Spirit, the Great Earth Magician, signified to these people.

Curious how geology and archæology agree on the rise and evanishment of these people. Geology says that as the ice invasion advanced, the northern races were forced south and south till the Stone Age folk living in the roofless City of the Dead on the floor of the valley were forced to take refuge from them in the caves hollowed out of the cliff. That was any time between 20,000 B.C. and 10,000 B.C. Archæology says as the Utes and the Navajo and the Apache—Asthapascan stock—came ramping from the North, the Stone Men were driven from the valleys to the inaccessible cliffs and mesa table lands. "It was not until the nomadic robbers forced the pueblos that the Southwestern people adopted the crowded form of existence," says Archæology. Sounds like an explanation of our modern skyscrapers and the real estate robbers of modern life, doesn't it?[Pg vii]

Then, as the Glacial Age had receded and drought began, the cave men were forced to come down from their cliff dwellings and to disperse. Here, too, is another story. There may have been a great cataclysm; for thousands of tons of rock have fallen from the face of the cañon, and the rooms remaining are plainly only back rooms. The Hopi and Moki and Zuñi have traditions of the "Heavens raining fire;" and good cobs of corn have been found embedded in what may be solid lava, or fused adobe. Pajarito Plateau, the Spanish called this region—"place of the bird people," who lived in the cliffs like swallows; but thousands of years before the Spanish came, the Stone Age had passed and the cliff people dispersed.

What in the world am I talking about, and where? That's the curious part of it. If it were in Egypt, or Petræ, or amid the sand-covered columns of Phrygia, every tourist company in the world would be arranging excursions to it; and there would be special chapters devoted to it in the supplementary readers of the schools; and you wouldn't be—well, just au fait, if you didn't know; but do you know this wonder-world is in America, your own land? It is less than forty miles from the regular line of continental travel; $6 a single rig out, $14 a double; $1 to $2 a day at the ranch house where you can board as you explore the amazing ancient civilization of our own American Southwest. This particular ruin is in the Frijoles Cañon; but there are hundreds,[Pg viii] thousands, of such ruins all through the Southwest in Colorado and Utah and Arizona and New Mexico. By joining the Archæological Society of Santa Fe, you can go out to these ruins even more inexpensively than I have indicated.

A general passenger agent for one of the largest transcontinental lines in the Northwest told me that for 1911, where 60,000 people bought round-trip tickets to our own West and back—pleasure, not business—over 120,000 people bought tickets for Europe and Egypt. I don't know whether his figures covered only the Northwest of which he was talking, or the whole continental traffic association; but the amazing fact to me was the proportion he gave—one to our own wonders, to two for abroad. I talked to another agent about the same thing. He thought that the average tourist who took a trip to our own Pacific Coast spent from $300 to $500, while the average tourist who went to Europe spent from $1,000 to $2,000. Many European tourists went at $500; but so many others spent from $3,000 to $5,000, that he thought the average spendings of the tourist to Europe should be put at $1,000 to $2,000. That puts your proportion at a still more disastrous discrepancy—thirty million dollars versus one hundred and twenty million. The Statist of London places the total spent by Americans in Europe at nearer three hundred million dollars than one hundred and twenty million.

Of the 3,700,000 people who went to the Seattle[Pg ix] Exposition, it is a pretty safe guess that not 100,000 Easterners out of the lot saw the real West. What did they see? They saw the Exposition, which was like any other exposition; and they saw Western cities, that are imitations of Eastern cities; and they patronized Western hotel rotundas and dining places, where you pay forty cents for Grand Junction and Hood River fruit, which you can buy in the East for twenty-five; and they rode in the rubberneck cars with the gramophone man who tells Western variations of the same old Eastern lies; and they came back thoroughly convinced that there was no more real West.

And so 120,000 Americans yearly go to Europe spending a good average of $1,000 apiece. We scour the Alps for peaks that everybody has climbed, though there are half a dozen Switzerlands from Glacier Park in the north to Cloudcroft, New Mexico, with hundreds of peaks which no one has climbed and which you can visit for not more than fifty dollars for a four weeks' holiday. We tramp through Spain for the picturesque, quite oblivious of the fact that the most picturesque bit of Spain, about 10,000 years older than Old Spain, is set right down in the heart of America with turquoise mines from which the finest jewel in King Alphonso's crown was taken. We rent a "shootin' box in Scotland" at a trifling cost of from $1,200 to $12,000 a season, because game is "so scarce out West, y' know." Yet I can direct you to game haunts out West where you can shoot a grizzly a week at no cost at all but your own[Pg x] courage; and bag a dozen wild turkeys before breakfast; and catch mountain trout faster than you can string them and pose for a photograph; and you won't need to lie about the ones that got away, nor boast of what it cost you; for you can do it at two dollars a day from start to finish. It would take you a good half-day to count up the number of tourist and steamboat agencies that organize sightseeing excursions to go and apostrophize the Sphinx, and bark your shins and swear and sweat on the Pyramids. Yet it would be a safe wager that outside official scientific circles, there is not a single organization in America that knows we have a Sphinx of our own in the West that antedates Egyptian archæology by 8,000 years, and stone lions older than the columns of Phrygia, and kings' palaces of 700 and 1,000 rooms. Am I yarning; or dreaming? Neither! Perfectly sober and sane and wide awake and just in from spending two summers in those same rooms and shaking hands with a corpse of the Stone Age.

A young Westerner, who had graduated from Harvard, set out on the around-the-world tour that was to give him that world-weary feeling that was to make him live happy ever afterwards. In Nagasaki, a little brown Jappy-chappie of great learning, who was a prince or something or other of that sort, which made it possible for Harvard to know him, asked in choppy English about "the gweat, the vely gweat anti-kwatties in y'or Souf Wes'." When young Harvard got it through his head that "anti-kwatties"[Pg xi] meant antiquities, he rolled a cigarette and went out for a smoke; but it came back at him again in Egypt. They were standing below the chin of an ancient lady commonly called the Sphinx, when an English traveler turned to young America. "I say," he said; "Yankeedom beats us all out on this old dame, doesn't it? You've a carved colossus in your own West a few trifling billion years older than this, haven't you?" Young America, with a weakness somewhere in his middle, "guessed they had." Then looking over the old jewels taken from the ruins of Pompeii, he was asked, "how America was progressing excavating her ruins;" and he heard for the first time in his life that the finest crown jewel in Europe came from a mine just across the line from his own home State. The experience gave him something to think about.

The incident is typical of many of the 120,000 people who yearly trek to Europe for holiday. We have to go abroad to learn how to come home. We go to Europe and find how little we have seen of America. It is when you are motoring in France that you first find out there is a great "Camino Real" almost 1,000 miles long, much of it above cloud line, from Wyoming to Texas. It's some European who has "a shootin' box" out in the Pecos, who tells you about it. Of course, if you like spending $12,000 a year for "a shootin' box" in Scotland, that is another matter. There are various ways of having a good time; but when I go fishing I like to catch trout and not be a sucker.[Pg xii]

Spite of the legend, "Why go to Europe? See America first," we keep on going to Europe to see America. Why? For a lot of reasons; and most of them lies.

Some fool once said, and we keep on repeating it—that it costs more to go West than it does to go to Europe. So it does, if "going West" means staying at hotels that are weak imitations of the Waldorf and the Plaza, where you never get a sniff of the real West, nor meet anyone but traveling Easterners like yourself; but if you strike away from the beaten trail, you can see the real West, and have your holiday, and go drunk on the picturesque, and break your neck mountain climbing, and catch more trout than you can lie about, and kill as much bear meat as you have courage, at less expense than it will cost you to stay at home. From Chicago to the backbone of the Rockies will cost you something over $33 or $50 one way. You can't go halfway across the Atlantic for that, unless you go steerage; and if you go West "colonist," you can go to the backbone of the Rockies for a good deal less than thirty dollars. Now comes the crucial point! If you land in a Western city and stay at a good hotel, expenses are going to out-sprint Europe; and you will not see any more of the West than if you had gone to Europe. Choose your holiday stamping ground, Sundance Cañon, South Dakota; or the New Glacier Park; or the Pecos, New Mexico; or the White Mountains, Arizona; or the Indian Pueblo towns of the Southwest; or the White Rock Cañon of the Rio Grande, where the most important of the wonderful prehistoric remains exist; and you can stay at a ranch house where food and cleanliness will be quite as good as at the Waldorf for from $1.50 to $2 a day.

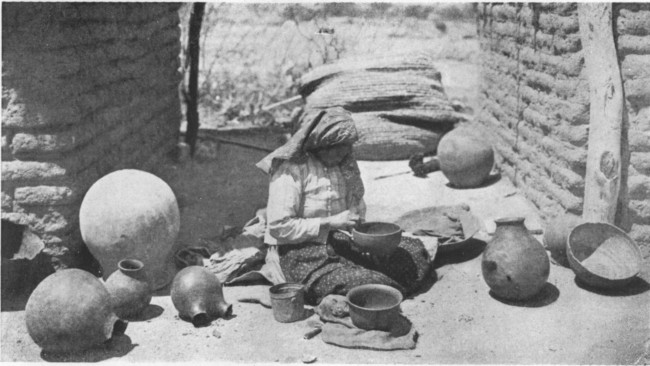

In the bright Arizona sunshine before their little square

adobe houses Indian women are fashioning pottery into curious shapes

In the bright Arizona sunshine before their little square

adobe houses Indian women are fashioning pottery into curious shapes

[Pg xiii] You can usually find the name of the ranch house by inquiries from the station agent where you get off. The ranch house may be of adobe and look squatty; but remember that adobe squattiness is the best protection against wind and heat; and inside, you will find hot and cold water, bathroom, and meals equal to the best hotels in Chicago and New York. In New York or Chicago, that amount would afford you mighty chancy fare and only a back hall room. I know of hundreds of such ranch houses all along the backbone of the Rockies.

Next comes the matter of horses and rigs. If you stay at one of the big hotels, you will pay from $5 to $10 a day for a rig, and $20 for a motor. Out at the ranch house, you can rent team, driver and double rig at $4; or a pony at $20 for a month, or buy a burro outright for from $5 to $10. Even if the burro takes a prize for ugliness, remember he also takes a prize for sure-footedness; and he doesn't take a prize for bucking, which the broncho often does. Figure up now the cost of a month's holiday; and I repeat—it will cost you less than staying at home. But if this total is still too high, there are ways of reducing the expense by half. Take your own tent; and $20 will not exceed "the grub box" contents for a month. Or all through the Rockies are deserted shacks, mining and lumber shanties,[Pg xiv] herders' cabins, horse camps. You can quarter yourself in one of these for nothing; and the sole expense will be "the grub box;" and my tin trunk for camp cooking has never cost me more than $50 a month for four people. Or best and most novel experience of all—along White Rock Cañon of the Rio Grande, in Mesa Verde Park, Colorado, are thousands of plastered caves, the homes of the cliff dwellers. You reach them by ladder. There is no danger of wolves, or damp. Camp in one of them for nothing wherever the water in the brook below happens to be good. Hundreds of archæologists, who come from Egypt, Greece, Italy, England, to visit these remains, spend their summer holiday this way. Why can't you? Or if you are not a good adventurer into the Unknown alone, then join the summer school that goes out to the caves from Santa Fe every summer.

Is it safe? That question to a Westerner is a joke. Safer, much safer, than in any Eastern city! I have slept in ranch cabins of the White Mountains, in caves of the cliff dwellers on the Rio Grande, in tents on the Saskatchewan; and I never locked a door, because there wasn't any lock; and I never attempted to bar the door, because there wasn't any need. Can you say as much of New York, or Chicago, or Washington? The question may be asked—Will this kind of a holiday not be hot in summer? You remember, perhaps, crossing the backbone of the Rockies some mid-summer, when nearly everything inside the pullman car melted into a jelly. Yes, it[Pg xv] will be hot if you follow the beaten trail; for a railroad naturally follows the lowest grade. But if you go back to the ranch houses of the Upper Mesas and of foothills and cañons, you will be from 7,000 to 10,000 feet above sea level, and will need winter wraps each night, and may have to break the ice for your washing water in the morning—I did.

Another reason why so many Americans do not see their own country is that while one species of fool has scared away holiday seekers by tales of extortionate cost, another sort of fool wisely promulgates the lie—a lie worn shiny from repetition—that "game is scarce in the West." "No more big game"—and your romancer leans back with wise-acre air to let that lie sink in, while he clears his throat to utter another—"trout streams all fished out." In the days when we had to swallow logic undigested in college, we had it impressed upon us that one single specific fact was sufficient to refute the broadest generality that was ever put in the form of a syllogism. Well, then,—for a few facts as to that "no-game" lie!

In one hour you can catch in the streams of the Pecos, or the Jemez, or the White Mountains, or the Upper Sierras of California, or the New Glacier Park of the North, more trout than you can put on a string. If you want confirmation of that fact, write to the Texas Club that has its hunting lodge opposite Grass Mountain, and they will send you the picture of one hour's trout catch. By measurement,[Pg xvi] the string is longer than the height of a water barrel; and these were fish that didn't get away.

Last year, twenty-six bear were shot in the Sangre de Christo Cañon in three months.

Two years ago, mountain lions became so thick in the Pecos that hunters were hired to hunt them for bounty; and the first thing that happened to one of the hunters, his horse was throttled and killed by a mountain lion, though his little spaniel got revenge by treeing four lions a few weeks later, and the hunter got three out of the four.

Near Glorieta, you can meet a rancher who last year earned $3,000 of hunting bounty scrip, if he could have got it cashed.

In the White Mountains last year, two of the largest bucks ever known in the Rockies were trailed by every hunter of note and trailed in vain. Later, one was shot out of season by stalking behind a burro; but the other still haunts the cañons defiant of repeater.

From the caves of the cliff-dwellers along the Rio Grande, you can nightly hear the coyote and the fox bark as they barked those dim stone ages when the people of these silent caves hunted here.

The week I reached Frijoles Cañon, a flock of wild turkeys strutted in front of Judge Abbott's Ranch House not a gun length from the front door.

The morning I was driving over the Pajarito Mesa home from the cliff caves, we disturbed a herd of deer.

Does all this sound as if game was depleted? It[Pg xvii] is if you follow the beaten trail, just as depleted as it would be if you tried to hunt wild turkey down Broadway, New York; but it isn't if you know where to look for it. Believe me—though it may sound a truism—you won't find big game in hotel rotundas or pullman cars.

Or, if your quest is not hunting but studying game, what better ground for observation than the Wichita in Oklahoma? Here a National Forest has been constituted a perpetual breeding ground for native American game. Over twenty buffalo taken from original stock in the New York Park are there—back on their native heath; and there are two or three very touching things about those old furry fellows taken back to their own haunts. In New York's parks, they were gradually degenerating—getting heavier, less active, ceasing to shed their fur annually. When they were set loose in the Wichita Game Resort, they looked up, sniffed the air from all four quarters, and rambled off to their ancestral pasture grounds perfectly at home. When the Comanches heard that the buffalo had come back to the Wichita, the whole tribe moved in a body and camped outside the fourteen-foot fence. There they stayed for the better part of a week, the buffalo and the Comanches, silently viewing each other. It would have been worth Mr. Nature Faker's while to have known their mutual thoughts.

There is another lie about not holidaying West, which is not only persistent but cruel. When the worker is a health as well as rest seeker, he is told[Pg xviii] that the West does not want him, especially if he is what is locally called "a lung-er;" and there is just enough truth in that lie to make it persistent. It is true the consumptive is not wanted on the beaten trail, in the big general hotel, in the train where other people want draughts of air, but he can't stand them. On the beaten trail, he is a danger both to himself and to others—especially if he hasn't money and may fall a burden on the community; but that is only a half truth which is usually a lie. Let the other half be known! All through the West along the backbone of the Rockies, from Montana to Texas, especially in New Mexico and Arizona, are the tent cities—communities of health seekers living in half-boarded tents, or mosquito-wired cabins that can be steam-heated at night. There are literally thousands of such tent dwellers all through the Rocky Mountain States; and the cost is as you make it. If you go to a sanitarium tent city, you will have to pay all the way from $15 to $25 a week for house, board, nurse, medicine and doctor's attendance; but if you buy your own portable house and do your own catering, the cost will be just what you make it. A house will cost $50 to $100; a tent, $10 to $20.

Still another baneful lie that keeps the American from seeing America first is that our New World West lacks "human interest;" lacks "the picturesqueness of the shepherds in Spain and Switzerland," for instance; lacks "the historic marvels" of church and monument and relic.[Pg xix]

If there be any degree in lies, this is the pastmaster of them all. Will you tell me why "the human interest" of a legend about Dick Turpin's head festering on Newgate, England, is any greater to Americans than the truth about Black Jack of Texas, whose head flew off into the crowd, when the support was removed from his feet and he was hanged down in New Mexico? Dick Turpin was a highwayman. Black Jack was a lone-hand train robber. Will you tell me why the outlaws of the borderland between England and Scotland are more interesting to Americans than the bands of outlaws who used to frequent Horse-Thief Cañon up the Pecos, or took possession of the cliff-dwellers' caves on the Rio Grande after the Civil War? Why are Copt shepherds in Egypt more picturesque than descendants of the Aztecs herding countless moving masses of sheep on our own sky-line, lilac-misty, Upper Mesas? What is the difference in quality value between a donkey in Spain trotting to market and a burro in New Mexico standing on the plaza before a palace where have ruled eighty different governors, three different nations? Why are skeletons and relics taken from Pompeii more interesting than the dust-crumbled bodies lying in the caves of our own cliffs wrapped in cloth woven long before Europe knew the art of weaving? Why is the Sphinx more wonderful to us than the Great Stone Face carved on the rock of a cliff near Cochiti, New Mexico, carved before the Pharaohs reigned; or the stone lions of an Assyrian ruin more marvelous than the[Pg xx] two great stone lions carved at Cochiti? When you find a church in England dating before William the Conqueror, you may smack your lips with the zest of the antiquarian; but you'll find in New Mexico not far from Santa Fe ruins of a church—at the Gates of the Waters, Guardian of the Waters—that was a pagan ruin a thousand years old when the Spaniards came to America.

You may hunt up plaster cast reproduction of reptilian monsters in the Kensington Museum, London; but you will find the real skeleton of the gentleman himself, with pictures of the three-toed horse on the rocks, and legends of a Plumed Serpent not unlike the wary fellow who interviewed Eve—all right here in your own American Southwest, with the difference in favor of the American legend; for the Satanic wriggler, who walked into the Garden on his tail, went to deceive; whereas the Plumed Serpent of New Mexican legend came to guard the pools and the springs.

To be sure, there are 400,000 miles of motor roads in Europe; but isn't it worth while to climb a few mountains in America by motor? That is what you can do following the "Camino Real" from Texas to Wyoming, or crossing the mountains of New Mexico by the great Scenic Highway built for motors to the very snow tops.

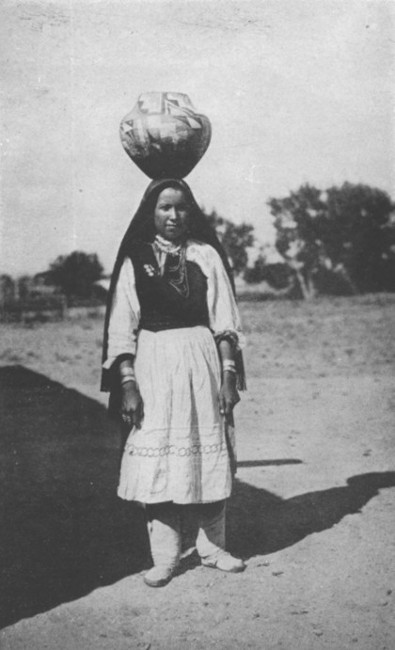

An Indian girl of Isleta, New Mexico, carrying a water

jar.

An Indian girl of Isleta, New Mexico, carrying a water

jar.

And if you take to studying native Indian life, at Laguna, at Acoma, at Taos, you will find yourself in such a maze of the picturesque and the legendary as you cannot find anywhere else in the wide world but America. This is a story by itself—a beautiful one, also in spots a funny one. For instance, one summer a woman of international fame from Oxford, England, took quarters in one of the pueblos at Santa Clara or thereabout to study Indian arts and crafts. One night in her adobe quarters, her orderly British soul was aroused by such a dire din of shouting, fighting, screams, as she thought could come only from some inferno of crime. She sprang out of bed and dashed across the placito in her nightdress to her guardian protector in the person of an old Indian. He ran through the dark to see what the matter was, while she stood in hiding of the wall shadows curdling in horror of "bluggy deeds."

"Pah," said the old fellow coming back, "dat not'ing! Young man, he git marry an' dey—how you call?—chiv-ar-ee-heem."

"Then, what are you laughing at?" demanded the irate British dame; for she could not help seeing that the old fellow was literally doubling in suffocated laughter. "How dare you laugh?"

"I laugh, Mees," he sputtered out, "'cos you scare me so bad when you call, I jomp in my coat mistake for my pants. Dat's all."

It would pay to cultivate a little home sentiment, wouldn't it? It would pay to let a little daylight in on the abysmal blank regarding the wonder-land of our own world—wouldn't it?

I don't know whether the affectation recognized as "the foreign pose" comes foremost or hindermost[Pg xxii] as a cause of this neglect of the wonders of our own land. When you go to our own Western Wonder Land, you can't say you have been abroad with a great long capital A; and it is wonderful what a paying thing that pose is in a harvest of "fooleries." There is a well-known case of an American author, who tried his hand on delineating American life and was severely let alone because he was too—not abroad, but broad. He dropped his own name, assumed the pose of a grand dame familiar with the inner penetralia and sacred secrets of the exclusive circle of the American Colony in Paris. His books have "gone off" like hot cross buns. Before, they were broad. Now they are abroad; and, like the tourist tickets, they are selling two to one.

The stock excuse among foreign poseurs for the two to one preference of Europe to America is that "America lacks the picturesque, the human, the historic." A straightforward falsehood you can always answer; but an implied falsehood masking behind knowledge, which is a vacuum, and superiority, which is pretense—is another matter. Let us take the dire and damning deficiencies of America!

"America lacks the picturesque." Did the ancient dwelling of the Stone Age sound to you as if it lacked the picturesque? I could direct you to fifty such picturesque spots in the Southwest alone.

There is the Enchanted Mesa, with its sister mesa of Acoma—islands of rock, sheer precipice of yellow tufa for hundreds of feet—amid the Desert sand, light shimmering like a stage curtain, herds exaggerated[Pg xxiii] in huge, grotesque mirage against the lavender light, and Indian riders, brightly clad and picturesque as Arabs, scouring across the plain; all this reachable two hours' drive from a main railroad. Or there are the three Mesas of the Painted Desert, cities on the flat mountain table lands, ancient as the Aztecs, overlooking such a roll of mountain and desert and forest as the Tempter could not show beneath the temple. Or, there is the White House, an ancient ruin of Cañon de Chelly (Shay) forty miles from Fort Defiance, where you could put a dozen White Houses of Washington.

"But," your European protagonist declares, "I don't mean the ancient and the primeval. I mean the modern peopled hamlet type." All right! What is the matter with Santa Fe? Draw a circle from New Orleans up through Santa Fe to Santa Barbara, California; and you'll find old missions galore, countless old towns of which Santa Fe, with its twin-towered Cathedral and old San Miguel Church, is a type. Santa Fe, itself, is a bit of old Spain set down in mosaic in hustling, bustling America. There is the Governor's Palace, where three different nations have held sway; and there is the Plaza, where the burros trot to market under loads of wood picturesque as any donkeys in Spain; and there is the old Exchange Hotel, the end of the Santa Fe Trail, where Stephen B. Elkins came in cowhide boots forty years ago to carve out a colossal fortune. At one end of a main thoroughfare, you can see the site of the old Spanish Gareta prison, in the walls of[Pg xxiv] which bullets were found embedded in human hair. And if you want a little Versailles of retreat away from the braying of the burros and of the humans, away from the dust of street and of small talk—then of a May day when the orchard is in bloom and the air alive with the song of the bees, go to the old French garden of the late Bishop Lamy! Through the cobwebby spring foliage shines the gleam of the snowy peaks; and the air is full of dreams precious as the apple bloom.

What was the other charge? Oh, yes—"lacks the human," whatever that means. Why are legends of border forays in Scotland more thrilling than true tales of robber dens in Horse-Thief Cañon and the cliff houses of Flagstaff and the Frijoles, where renegades of the Civil War used to hide? Why are the multi-colored peasant workers of Brittany or Belgium more interesting than the gayly dressed peons of New Mexico, or the Navajo boys scouring up and down the sandy arroyos? Why is the story of Jack Cade any more "human" than the tragedy of the three Vermont boys, Stott, Scott and Wilson, hanged in the Tonto Basin for horses they did not steal in order that their assassins might pocket $5,000 of money which the young fellows had brought out from the East with them? Why are not all these personages of good repute and ill repute as famous to American folklore hunters as Robin Hood or any other legendary heroes of the Old World?

Driven to the last redoubt, your protagonist for Europe against America usually assumes the air of[Pg xxv] superiority supposed to be the peculiar prerogative of the gods of Olympus, and declares: "Yes—but America lacks the history and the art of the old associations in Europe."

"Lacks history?" Go back fifty years in our own West to the transition period from fur trade to frontier, from Spanish don living in idle baronial splendor to smart Yankeedom invading the old exclusive domain in cowhide boots! Go back another fifty years! You are in the midst of American feudalism—fur lords of the wilderness ruling domains the area of a Europe, Spanish Conquistadores marching through the desert heat clad cap-à-pie in burnished mail; Governor Prince's collection at Santa Fe has one of those cuirasses dug up in New Mexico with the bullet hole through the metal right above the heart. Another fifty years back—and the century war for a continent with the Indians, the downing of the old civilization of America before a sort of Christian barbarism, the sword in one hand, the cross in the other, and behind the mounted troops the big iron chest for the gold—iron chests that you can see to this day among the Spanish families of the Southwest, rusted from burial in time of war, but strong yet as in the centuries when guarded by secret springs such iron treasure boxes hid all the gold and the silver of some noble family in New Spain. When you go back beyond the days of New Spain, you are amid a civilization as ancient as Egypt's—an era that can be compared only to the myth age of the Norse Gods, when Loki, Spirit of Evil, smiled[Pg xxvi] with contempt at man's poor efforts to invade the Realm of Death. It was the age when puny men of the Stone Era were alternately chasing south before the glacial drift and returning north as the waters receded, when huge leviathans wallowed amid sequoia groves; and if man had domesticated creatures, they were three-toed horses, and wolf dogs, and wild turkeys and quail. Curiously enough, remnants of some sort of domesticated creatures are found in the cave men's houses, centuries before the coming of horses and cattle and sheep with the Spanish. The trouble is, up to the present when men like Curtis and dear old Bandelier and Burbank, and the whole staff of the Smithsonian and the School of Santa Fe have gone to work, we have not taken the trouble in America to gather up the prehistoric legends and ferret out their race meaning. We have fallen too completely in the last century under the blight of evolution, which presupposes that these cave races were a sort of simian-jawed, long-clawed, gibbering apes spending half their time up trees throwing stones on the heads of the other apes below, and the other half of their time either licking their chops in gore or dragging wives back to caves by the hair of their heads. You remember Kipling's poem on the neolithic man, and Jack London's fiction. Now as a matter of fact—which is a bit disturbing to all these accretions of pseudo-science—the remains of these cave people don't show them to have been simian-jawed apes at all. They had woven clothing when our ancestors were a bit liable to Anthony[Pg xxvii] Comstock's activities as to clothes. They had decorated pottery ware of which we have lost the pigments, and a knowledge of irrigation which would be unique in apes, and a technique in basketry that I never knew a monkey to possess. Some day, when the evolutionary piffle has passed, we'll study out these prehistoric legends and their racial meaning.

As to the "lack of art," pray wake up! The late Edwin Abbey declared that the most hopeful school of art in America was the School of the Southwest. Look up Lotave's mural drawings at Santa Fe, or Lungrun's wonderful desert pictures, or Moran's or Gamble's, or Harmon's Spanish scenes—then talk about "lack of decadent art" if you will, but don't talk about "lack of art." Why, in the ranch house of Lorenzo Hubbell, the great Navajo trader, you'll find a $200,000 collection of purely Southwestern pictures.

How many of the two to one protagonists of Europe know, for instance, that scenic motor highways already run to the very edge of the grandest scenery in America? You can motor now from Texas to Wyoming, up above 10,000 feet much of it, above cloud line, above timber line, over the leagueless sage-bush plains, in and out of the great yellow pine forests, past Cloudcroft—the sky-top resort—up through the orchard lands of the Rio Grande, across the very backbone of the Rockies over the Santa Fe Ranges and on north up to the Garden of the Gods and all the wonders of Colorado's National Park.[Pg xxviii] With the exception of a very bad break in the White Mountains of Arizona, you can motor West past the southern edge of the Painted Desert, past Laguna and Acoma and the Enchanted Mesa, past the Petrified Forests, where a deluge of sand and flood has buried a sequoia forest and transmuted the beauty of the tree's life into the beauty of the jewel, into bars and beams and spars of agate and onyx the color of the rainbow. Then, before going on down to California, you can swerve into Grand Cañon, where the gods of fire and flood have jumbled and tumbled the peaks of Olympus dyed blood-red into a swimming cañon of lavender and primrose light deep as the highest peaks of the Rockies.

In California, you can either motor up along the coast past all the old Spanish Missions, or go in behind the first ridge of mountains and motor along the edge of the Big Trees and the Yosemite and Tahoe. You can't take your car into these Parks; first, because you are not allowed; second, because the risks of the road do not permit it even if you were allowed.

Is it safe? As I said before, that question is a joke. I can answer only from a life-time knowledge of pretty nearly all parts of the West—and that from a woman's point of view. Believe me the days of "shootin' irons" and "faintin' females" are forever past, except in the undergraduate's salad dreams. You are safer in the cave dwellings of the Stone Age, in the Pajarito Plateau of the cliff "bird people," in the Painted Desert, among the Indians of[Pg xxix] the Navajo Reserve than you are in Broadway, New York, or Piccadilly, London. I would trust a young friend of mine—boy or girl—quicker to the Western environment than the Eastern. You can get into mischief in the West if you hunt for it; but the mischief doesn't come out and hunt you. Also, danger spots are self-evident on precipices of the Western wilds. They aren't self-evident; danger spots are glazed and paved to the edges over which youth goes to smash in the East.

What about cost? Aye, there's the rub!

First, there's the steamboat ticket to Europe, about the same price as or more than the average round trip ticket to the Coast and back; but—please note, please note well—the agent who sells the steamboat ticket gets from forty to 100 per cent. bigger commission on it than the agent who sells the railroad tickets; so the man who is an agent for Europe can afford to advertise from forty to 100 per cent. more than the man who sells the purely American ticket.

Secondly, European hotel men are adepts at catering to the lure of the American sightseer. (Of course they are: it's worth one hundred to two hundred million dollars to them a year.) In the American West, everybody is busy. Except for the real estate man, they don't care one iota whether you come or stay.

Thirdly, when you go to Europe, a thousand hands are thrust out to point you the way to the interesting places. Incidentally, also, a thousand hands are[Pg xxx] thrust out to pick your pocket, or at least relieve it of any superfluous weight. In our West, who cares a particle what you do; or who will point you the way? The hotels are expensive and for the most part located in the most expensive zone—the commercial center. It is only when you get out of the expense zone away from commercial centers and railway, that you can live at $1 or $2 a day, or if you have your own tent at fifty cents a day; but it isn't to the real estate agent's interests to have you go away from the commercial center or expense zone. Who is there to tell you what or where to see off the line of heat and tips? Outside the National Park wardens and National Forest Rangers, there isn't anyone.

How, then, are you to manage? Frankly, I never knew of either monkeys or men accomplishing anything except in one way—just going out and doing it. Choose what you want to see; and go there! The local railroad agent, the local Forest Ranger, the local ranch house, will tell you the rest; and naturally, when you go into the wilderness, don't leave all your courtesy and circumspection and common-sense back in town. Equipped with those three, you can "See America First," and see it cheaply.

If a health resort and national playground were discovered guaranteed to kill care, to stab apathy into new life, to enlarge littleness and slay listlessness and set the human spirit free from the nagging worries and toil-wear that make you feel like a washed-out rag at the end of a humdrum year—imagine the stampede of the lame and the halt in body and spirit; the railroad excursions and reduced fares; the disputations of the physicians and the rage of the thought-ologists at present coining money rejuvenating neurotic humanity!

Yet such a national playground has been discovered; and it isn't in Europe, where statisticians compute that Americans yearly spend from a quarter to half a billion dollars; and it isn't the Coast-to-Coast trip which the president of a transcontinental told me at least a hundred thousand people a year traverse. A health resort guaranteed to banish care, to stab apathy, to enlarge littleness, to slay listlessness, would pretty nearly put the thought-ologists out of commission. Yet such a summer resort exists at the very doors of every American capable of scraping together a few hundred dollars—$200 at[Pg 2] the least, $400 at the most. It exists in that "twilight zone" of dispute and strong language and peanut politics known as the National Forests.

In America, we have foolishly come to regard National Forests as solely allied with conservation and politics. That is too narrow. National Forests stand for much more. They stand for a national playground and all that means for national health and sanity and joy in the exuberant life of the clean out-of-doors. In Germany, the forests are not only a source of great revenue in cash; they are a source of greater revenue in health. They are a holiday playground. In America, the playground exists, the most wonderful, the most beautiful playground in the whole world—and the most accessible; but we haven't yet discovered it.

Of the three or four million people who have attended the Pacific Coast Expositions of the past ten years, it is a safe wage that half went, not to see the Exposition (for people from a radius round Chicago and Jamestown and Buffalo had already seen a great Exposition) but they went to see the Exposition as an exponent of the Great West. How much of the Great West did they really see? They saw the Alaska Exhibit. Well—the Alaska Exhibit was afterwards shown in New York. They saw the special buildings assigned to the special Western States. Well—the special Western States had special buildings at the other expositions. What else[Pg 3] of the purely West they saw, I shall give in the words of three travelers:

"Been a great trip" (Two Chicagoans talking in duet). "We've seen everything and stopped off everywhere. We stopped at Denver and Salt Lake and Los Angeles and San Francisco and Portland and Seattle!"

"What did you do at these places?"

"Took a taxi and saw the sights, drove through the parks and so on. Saw all the residences and public buildings. Been a great trip. Tell you the West is going ahead."

"It has been a detestable trip" (A New Yorker relieving surcharged feelings). "It has been a skin game from start to finish, pullman, baggage, hotels, everything. And how much of the West have we really seen? Not a glimpse of it. We had all seen these Western cities before. They are not the West. They are bits of the East taken up and set down in the West. How is the Easterner to see the West? It isn't seeing it to go flying through these prairie stations. Settlement and real life and wild life are always back from the railroad. How are we to get out and see that unless we can pay ten dollars a day for guides? I don't call it seeing the mountains to ride on a train through the easiest passes and sleep through most of them. Tell us how we are to get out and see and experience the real thing?"

"H'm, talk about seeing the West" (This time from a Texas banker). "Only time we got away[Pg 4] from the excursion party was when a land boomster took us up the river to see an irrigation project. That wasn't seeing the West. That was a buy-and-sell proposition same as we have at home. What I want to know is how to get away from that. That boomster fellow was an Easterner, anyway."

Which of these three really found the playground each was seeking? Not the duet that went round the cities in a sightseeing car and judged the West from hotel rotundas. Not the New Yorker, who saw the prairie towns fly past the car windows. Not the Texans who were guided round a real estate project by an Eastern land boomster. And each wanted to find the real thing—had paid money to find a holiday playground, to forget care and stab apathy and enlarge life. And each complained of the extortionate charges on every side in the city life. And two out of three went back a little disappointed that they had not seen the fabled wonders of the West—the big trees, the peaks at close range, the famous cañons, the mountain lakes, the natural bridges. When I tried to explain to the New Yorker that at a cost of one-tenth what the big hotels charge, you could go straight into the heart of the mountain western wilds, whether you are a man, woman, child, or group of all three—could go straight out to the fabled wonders of big trees and mountain lakes and snowy peaks—I was greeted with that peculiarly New Yorky look suggestive of Ananias and De Rougement.

One way of entering the desert is with wagons and tents,

but unless it is the rainy season the tents are unnecessary

One way of entering the desert is with wagons and tents,

but unless it is the rainy season the tents are unnecessary

Sadder is the case of the invalid migrating West. He has come with high hopes looking for the national health resort. Does he find it? Not once in a thousand cases. If health seekers have money, they take a private house in the city, where the best of air is at its worst; but many invalids are scarce of money, and come seeking the health resort at great pecuniary sacrifice. Do they find it? Certainly not knocking from boarding house to boarding house and hotel to hotel, re-infecting themselves with their own germs till the very telephone booths have to be guarded. At one famous "lung" city where I stayed, I heard three invalids coughing life away along the corridor where my room happened to be. The charge for those stuffy rooms was $2 and $3 and $5 a day without meals. At a cost of $10 for train fare, I went out to one of the National Forests—the pass over the Divide 11,000 feet, the village center of the Forest 8,000 feet above sea level, the charge with meals at the hotel $10 a week. Better still, $10 for a roomy tent, $1.50 for a camp stove and as much or as little as you like for a fur rug, and the cost of meals would have been seventy-five cents a day at the hotel, seventy-five cents for life in air that was almost constant sunshine, air as pure and life-giving as the sun on Creation's first day. That altitude would probably not suit all invalids—that is for a doctor to say; but certainly, whether one is out for health or play, that regimen is cheaper and more life-giving than a stuffy hotel at $2, $3 and $5 a day for a room alone.[Pg 6]

It is incredible when you come to think of it. Here is a nation of ninety million people scouring the earth for a playground; and there is an undiscovered playground in its own back yard, the most wonderful playground of mountain and forest and lake in the whole world; a playground in actual area half the size of a Germany, or France, with wonders of cave and waterway and peak unknown to Germany or France. What are the railroads thinking about? If three million people visited an exposition to see the West, how many would yearly visit the National Forests if the railroads granted facilities, and the ninety million Americans knew how? It is absurd to regard the National Forests purely as timber; and timber for politics! They are a nation's playground and health resort; and one of these times will come a Peary or an Abruzzi discovering them. Then we'll give him a prize and begin going.

You will not find Newport; and you will not find Lenox; and you will not find Saratoga in the National Forests. Neither will you find a dress parade except the painter's brush with its vesture of flame in the upper alpine meadows. And you will not find gaping on-lookers to break down fences and report your doings, unless it be a Douglas squirrel swearing at you for coming too near his cache of pine cones at the foot of some giant conifer. There is small noise of things doing in the National Forests; but there is a great tinkling of waters; and there are many voices of rills with a roar of flood torrents at[Pg 7] rain time, or thunder of avalanche when the snows come over a far ridge in spray fine as a waterfall. In fair weather, you may spare yourself the trouble of a tent and camp under a stretch of sky hung with stars, resinous of balsams, spiced with the life of the cinnamon smells and the ozone tang. There will be lakes of light as well as lakes of water, and an all-day diet of condensed sunbeams every time you take a breath. Your bed will be hemlock boughs—be sure to lay the branch-end out and the soft end in or you'll dream of sleeping transfixed and bayoneted on a nine foot redwood stump. Sage brush smells and cedar odors, you will have without paying for a cedar chest. If you want softer bed and mixed perfumes, better stay in Newport.

The Forestry Department will not resent your coming. Their men will welcome you and help you to find camping ground.

Meanwhile, before the railroads have wakened up to the possibilities of the National Forests as a playground, how is the lone American man, woman, child, or group of all three, to find the way to the National Forests? What will the outfit cost; and how is the camper to get established?

Take a map of the Western States. Though there are bits of National Forests in Nebraska and Kansas and the Ozarks, for camping and playground purposes draw a line up parallel with the Rockies from New Mexico to Canada. Your playground is from that line westward. To me, there is a peculiar attraction[Pg 8] in the forests of Colorado. Nearly all are from 8,000 to 11,000 feet above sky-line—high, dry park-like forests of Engelmann spruce clear of brush almost as your parlor floor. You will have no difficulty in recognizing the Forests as the train goes panting up the divide. Windfall, timber slash, stumps half as high as a horse, brushwood, the bare poles and blackened logs of burnt areas lie on one side—Public Domain. Trees with two notches and a blaze mark the Forest bounds; trees with one notch and one blaze, the trail; and across that trail, you are out of the Public Domain in the National Forests. There is not the slightest chance of your not recognizing the National Forests. Windfall, there is almost none. It has been cleared out and sold. Of timber slash, there is not a stick. Wastage and brush have been carefully burned up during snowfall. Windfall, dead tops and ripe trees, all have been cut or stamped with the U. S. hatchet for logging off. These Colorado Forests are more like a beautiful park than wild land.

Come up to Utah; and you may vary your camping in the National Forests there, by trips to the wonderful cañons out from Ogden, or to the natural bridges in the South. In the National Forests of California, you have pretty nearly the best that America can offer you: views of the ocean in Santa Barbara and Monterey; cloudless skies everywhere; the big trees in the Sequoia Forest; the Yosemite in the Stanislaus; forests in the northern part of the State where you could dance on the stump of a redwood or build a cabin out of a single sapling; and everywhere in the[Pg 9] northern mountains, are the voices of the waters and the white, burnished, shining peaks. I met a woman who found her playground one summer by driving up in a tented wagon through the National Forests from Colorado to Montana. Camp stove and truck bed were in the democrat wagon. An outfitter supplied the horses for a rental which I have forgotten. The borders of most of the National Forests may be reached by wagon. The higher and more intimate trails may be essayed only on foot or on horseback.

How much will the trip cost? You must figure that out for yourself. There is, first of all, your railway fare from the point you leave. Then there is the fare out to the Forest—usually not $10. Go straight to the supervisor or forester of the district. He will recommend the best hotel of the little mountain village where the supervisor's office is usually located. At those hotels, you will board as a transient at $10 a week; as a permanent, for less. In many of the mountain hamlets are outfitters who will rent you a team of horses and tented wagon; and you can cater for yourself. In fact, as to clothing, and outfit, you can buy cheaper camp kit at these local stores than in your home town. Many Eastern things are not suitable for Western use. For instance, it is foolish to go into the thick, rough forests of heavy timber with an expensive eastern riding suit for man or woman. Better buy a $4 or $6 or $8 khaki suit that you can throw away when you have torn it to tatters. An Eastern waterproof coat will[Pg 10] cost you from $10 to $30. You can get a yellow cowboy slicker (I have two), which is much more serviceable for $2.50 or $3. As to boots, I prefer to get them East, as I like an elk-skin leather which never shrinks in the wet, with a good deal of cork in the sole to save jars, also a broad sole to save your foot in the stirrup; but avoid a conventional riding boot. Too hot and too stiff! I like an elk-skin that will let the water out fast as it comes in if you ever have to wade, and which will not shrink in the drying. If you forswear hotels and take to a sky tent, or canvas in misty weather, better carry eatables in what the guides call a tin "grub box," in other words a cheap $2 tin trunk. It keeps out ants and things; and you can lock it when you go away on long excursions. As to beds, each to his own taste! Some like the rolled rubber mattress. Too much trouble for me. Besides, I am never comfortable on it. If you camp near the snow peaks, a chill strikes up to the small of your back in the small of the morning. I don't care to feel like using a derrick every time I roll over. The most comfortable bed I know is a piece of twenty-five cent oilcloth laid over the slicker on hemlock boughs, fur rug over that, with suit case for pillow, and a plain gray blanket. The hardened mountaineer will laugh at the next recommendation; but the town man or woman going out for play or health is not hardened, and to attempt sudden hardening entails the endurance of a lot of aches that are apt to spoil the holiday. You may say you like the cold plunge in the icy water coming off a snowy mountain.[Pg 11] I confess I don't; and you'll acknowledge, even if you do like it, you are in such a hurry to come out of it that you don't linger to scrub. I like my hot scrub; and you can have that only by taking along (no, not a rubber bath) a $1.50 camp stove to heat the water in the tent while you are eating your supper out round the camp fire that burns with such a delicious, barky smell. Besides, late in the season, there will be rains and mist. Your camp stove will dry out the tent walls and keep your kit free of rain mold. Do you need a guide? That depends entirely on yourself. If you camp under direction and within range of the district forester, I do not think you do.

Whether you go out as a health seeker, or a pleasure seeker, $8 to $10 will buy you a miner's tent—a miner's, preferable to a tepee because the walls lift the canvas roof high enough not to bump your head; $2 will buy you a tin trunk or grub box; $1.50 will cover the price of oilcloth to spread over the boughs which you lay all over the floor to keep you above the earth damp; $2 will buy you a little tin camp stove to keep the inside of your tent warm and dry for the hot night bath; $10 will cover cost of pail and cooking utensils. That leaves of what would be your monthly expenses at even a moderate hotel, $125 for food—bacon, flour, fresh fruit; and your food should not exceed $10 each a month. If you are a good fisherman, you will add to the larder, by whipping the mountain streams for trout. If you need an attendant, that miner's tent is big enough for two. Or if you will stand $5 or $6 more expense,[Pg 12] buy a tepee tent for a bath and toilet room. There will be windy days in fall and spring when an extra tent with a camp stove in it will prove useful for the nightly hot bath.

What reward do you reap for all the bother? You are away from all dust irritating to weak lungs. You are away from all possibility of re-infecting yourself with your own disease. Except in late autumn and early spring, you are living under almost cloudless skies, in an atmosphere steeped in sunshine, spicy with the healing resin of the pines and hemlocks and spruce, that not only scent the air but literally permeate it with the essences of their own life. You are living far above the vapors of sea level, in a region luminous of light. Instead of the clang of street car bells and the jangle of nerves tangled from too many humans in town, you hear the flow and the sing and the laughter and the trebles of the glacial streams rejoicing in their race to the sea. You climb the rough hills; and your town lungs blow like a whale as you climb; and every beat pumps inertia out and the sun-healing air in. If an invalid, you had better take a doctor's advice as to how high you should camp and climb. In town, amid the draperies and the portières and the steam-heated rooms, an invalid is seeking health amid the habitat of mummies. In the Forests, whether you will or not, you live in sunshine that is the very elixir of life; and though the frost sting at night, it is the sting of pulsing, superabundant life, not the lethargy of a gradual decay.[Pg 13]

At the southern edge of the National Forests in the Southwest dwell the remnants of a race, can be seen the remnants of cities, stand houses near enough the train to be touched by your hand, that run back in unbroken historic continuity to dynasties preceding the Aztecs of Mexico or the Copts of Egypt. When the pyramids were young, long before the flood gates of the Ural Mountains had broken before the inundating Aryan hordes that overran the forests and mountains of Europe to the edge of the Netherland seas, this race which you can see to-day dwelling in New Mexico and Arizona were spinning their wool, working their silver mines, and on the approach of the enemy, withdrawing to those eagle nests on the mountain tops which you can see, where only a rope ladder led up to the city, or uncertain crumbling steps cut in the face of the sheer red sandstone.

And besides the prehistoric in the Forests—what will you find? The plains below you like a scroll, the receding cities, a patch of smoke. You had thought that sky above the plains a cloudless one, air that was pure, buoyant champagne without dregs. Now the plains are vanishing in a haze of dust, and you—you are up in that cloudless air, where the light hits the rocks in spangles of pure crystal, and the tang of the clearness of it pricks your sluggish blood to a new, buoyant, pulsing life. You feel as if somehow or other that existence back there in towns and under roofs had been a life with cobwebs on the brain and weights on the wings of the spirit. I wonder if it wasn't? I wonder if the[Pg 14] ancients, after all, didn't accord with science in ascribing to the sun, to the god of Light, the source of all our strength? Things are accomplished not in the thinking, but in the clearness of the thinking; and here is the realm of pure light.

Presently, the train carrying you up to the Forests of the Southwest gives a bump. You are in darkness—diving through some tunnel or other; and when you come out, you could drop a stone sheer down to the plains a couple of miles. That is not so far as up in South Dakota. In Sundance Cañon off the National Forests there, you can drop a pebble down seven miles. That's not as the crow flies. It is as the train climbs. But patience! The road into Sundance Cañon takes you to the top of the world, to be sure; but that is only 7,000 feet up; and this little Moffat Road in Colorado takes you above timber line, above cloud line, pretty nearly above growth line, 12,000 feet above the sea; at 11,600 you can take your lunch inside a snow shed on the Moffat Road.

Long ago, men proved their superiority to other men by butchering each other in hordes and droves and shambles; Alva must have had a good 100,000 corpses to his credit in the Netherlands. To-day, men make good by conquering the elements. For four hours, this little Colorado road has been cork-screwing up the face of a mountain pretty nearly sheer as a wall; and for every twist and turn and tunnel, some engineer fellow on the job has performed mathematical acrobatics; and some capitalist behind the engineer—the man behind the modern gun of conquest—has paid the cost. In this case, it was David Moffat paid for our dance in the clouds—a mining man, who poked his brave little road over the mountains across the desert towards the Pacific.

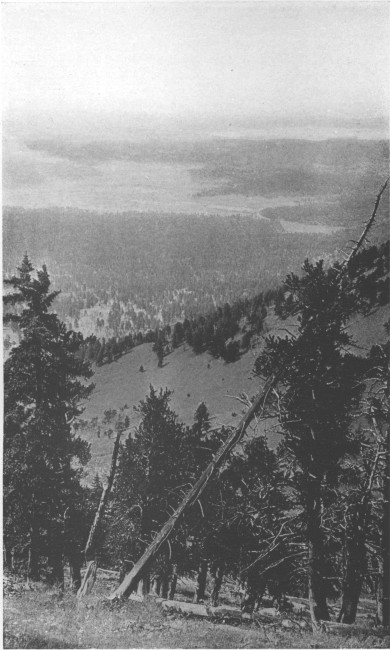

From a lookout point in the Coconino Forest of Arizona

From a lookout point in the Coconino Forest of Arizona

You come through those upper tunnels still higher. Below, no longer lie the plains, but seas of clouds; and it is to the everlasting credit of the sense and taste of Denver people, that they have dotted the outer margin of this rock wall with slab and log and shingle cottages, built literally on the very backbone of the continent overlooking such a stretch of cloud and mountain and plain as I do not know of elsewhere in the whole world. In Sundance Cañon, South Dakota, summer people have built in the bottom of the gorge. Here, they are dwellers in the sky. Rugged pines cling to the cliff edge blasted and bare and wind torn; but dauntlessly rooted in the everlasting rocks. Little mining hamlets composed of matchbox houses cling to the face of the precipice like cardboards stuck on a nail. Then, you have passed through the clouds, and are above timber line; and a lake lies below you like a pool of pure turquoise; and you twist round the flank of the great mountain, and there is a pair of green lakes below you—emerald jewels pendant from the neck of the old mountain god; and with a bump and a rattle of the wheels, clear over the top of the Continental Divide you go—believe me, a greater conquest than any Napoleon's march to Moscow, or Alva's shambles of headless victims in the Netherlands.

You take lunch in a snow shed on the very crest of[Pg 16] the Continental Divide. I wish you could taste the air. It isn't air. It's champagne. It isn't champagne, it's the very elixir of life. There can never be any shadows here; for there is nothing to cast the shadow. Nightfall must wrap the world here in a mantle of rest, in a vespers of worship and quiet, in a crystal of dying chrysoprase above the green enameled lake and the forests below, looking like moss, and the pearl clouds, a sea of fire in the sunset, and the plain—there are no more plains—this is the top of the world!

Yet it is not always a vesper quiet in the high places. When I came back this way a week later, such a blizzard was raging as I have never seen in Manitoba or Alberta. The high spear grass tossed before it like the waves of a sea; and the blasted pines on the cliffs below—you knew why their roots had taken such grip of the rocks like strong natures in disaster. The storm might break them. It could not bend them, nor wrench them from their roots. The telegraph wires, for reasons that need not be told are laid flat on the ground up here.

When you cross the Divide, you enter the National Forests. National Forests above tree line? To be sure! These deep, coarse upper grasses provide ideal pasturage for sheep from June to September; and the National Forests administer the grazing lands for the general use of all the public, instead of permitting them to be monopolized by the big rancher, who promptly drove the weaker man off by cutting the throats of intruding flocks and herds.[Pg 17]

Then, the train is literally racing down hill—with the trucks bumping heels like the wheels of a wagon on a sluggish team; and a new tang comes to the ozone—the tang of resin, of healing balsam, of cinnamon smells, of incense and frankincense and myrrh, of spiced sunbeams and imprisoned fragrance—the fragrance of thousands upon thousands of years of dew and light, of pollen dust and ripe fruit cones; the attar, not of Persian roses, but of the everlasting pines.

The train takes a swift swirl round an escarpment of the mountain; and you are in the Forests proper, serried rank upon rank of the blue spruce and the lodgepole pine. No longer spangles of light hitting back from the rocks in sparks of fire! The light here is sifted pollen dust—pollen dust, the primordial life principle of the tree—with the purple, cinnamon-scented cones hanging from the green arms of the conifers like the chevrons of an enranked army; and the cones tell you somewhat of the service as the chevrons do of the soldier man. Some conifers hold their cones for a year before they send the seed, whirling, swirling, broadside to the wind, aviating pixy parachutes, airy armaments for the conquest of arid hills to new forest growth, though the process may take the trifling æon of a thousand years or so. At one season, when you come to the Forests, the air is full of the yellow pollen of the conifers, gold dust whose alchemy, could we but know it, would unlock the secrets of life. At another season—the season when I happened to be in the Colorado Forests—the[Pg 18] very atmosphere is alive with these forest airships, conifer seeds sailing broadside to the wind. You know why they sail broadside, don't you? If they dropped plumb like a stone, the ground would be seeded below the heavily shaded branches inches deep in self-choking, sunless seeds; but when the broadside of the sail to the pixy's airship tacks to the veering wind, the seed is carried out and away and far beyond the area of the shaded branches; to be caught up by other counter currents of wind and hurled, perhaps, down the mountain side, destined to forest the naked side of a cliff a thousand years hence. It is a fact, too, worth remembering and crediting to the wiles and ways of Dame Nature that destruction by fire tends but to free these conifer seeds from the cones; so that they fall on the bare burn and grow slowly to maturity under the protecting nursery of the tremulous poplars and pulsing cottonwoods.

The train has not gone very far in the National Forests before you see the sleek little Douglas squirrel scurrying from branch to branch. From the tremor of his tiny body and the angry chitter of his parted teeth, you know he is swearing at you to the utmost limit of his squirrel (?) language; but that is not surprising. This little rodent of the evergreens is the connoisseur of all conifers. He, and he alone, knows the best cones for reproductive seed. No wonder he is so full of fire when you consider he diets on the fruit of a thousand years of sunlight and dew; so when the ranger seeks seed to reforest the[Pg 19] burned or scant slopes, he rifles the cache of this little furred forester, who suspects your noisy trainload of robbery—robbery—sc—scur—r—there!

Then, the train bumps and jars to a stop with a groaning of brakes on the steep down grade, for a drink at the red water tank; and you drop off the high car steps with a glance forward to see that the baggage man is dropping off your kit. The brakes reverse. With a scrunch, the train is off again, racing down hill, a blur of steamy vapor like a cloud against the lower hills. Before the rear car has disappeared round the curve, you have been accosted by a young man in Norfolk suit of sage green wearing a medal stamped with a pine tree—the ranger, absurdly young when you consider each ranger patrols and polices 100,000 acres compared to the 1,700 which French and German wardens patrol and daily deals with criminal problems ten times more difficult than those confronting the Northwest Mounted Police, without the military authority which backs that body of men.

You have mounted your pony—men and women alike ride astride in the Western States. It heads of its own accord up the bridle trail to the ranger's house, in this case 9,000 feet above sea level, 1,000 feet above ordinary cloud line. The hammer of a woodpecker, the scur of a rasping blue jay, the twitter of some red bills, the soft thug of the unshod broncho over the trail of forest mold, no other sound unless the soul of the sea from the wind harping in the trees. Better than the jangle of city cars in that[Pg 20] stuffy hotel room of the germ-infested town, isn't it?

If there is snow on the peaks above, you feel it in the cool sting of the air. You hear it in the trebling laughter, in the trills and rills of the brook babbling down, sound softened by the moss as all sounds are hushed and low keyed in this woodland world. And all the time, you have the most absurd sense of being set free from something. By-and-by when eye and ear are attuned, you will see the light reflected from the pine needles glistening like metal, and hear the click of the same needles like fairy castanets of joy. Meantime, take a long, deep, full breath of these condensed sunbeams spiced with the incense of the primeval woods; for you are entering a temple, the temple where our forefathers made offerings to the gods of old, the temple which our modern churches imitate in Gothic spire and arch and architrave and nave. Drink deep in open, full lungs; for you are drinking of an elixir of life which no apothecary can mix. Most of us are a bit ill mentally and physically from breathing the dusty street sweepings of filth and germs which permeate the hived towns. They will not stay with you here! Other dust is in this air, the gold dust of sunlight and resin and ozone. They will make you over, will these forest gods, if you will let them, if you will lave in their sunlight, and breathe their healing, and laugh with the chitter and laughter of the squirrels and streams.

And what if your spirit does not go out to meet the spirit of the woods halfway? Then, the woods will[Pg 21] close round you with a chill loneliness unutterable. You are an alien and an exile. They will have none of you and will reveal to you none of their joyous, dauntless life secrets.