HIS DIARIES LETTERS AND REPORTS

EDITED AND ARRANGED BY

AUTHOR OF 'NORWEGIAN PICTURES' ETC

WITH A PORTRAIT, TWO MAPS AND

FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

THIRD AND CHEAPER EDITION

56 Paternoster Row, 65 St Paul's Churchyard

1895

|

O Christ, in Thee my soul hath found, |

This book in its more expensive forms has been before the public for nearly two years. It has been very widely read, and it has received extraordinary attention from many sections of the press. The author has received from all parts of the world most striking testimonies as to the way in which this record of James Gilmour's heroic self-sacrifice for the Lord Jesus and on behalf of his beloved Mongols for the Master's sake has touched the hearts of Christian workers. It has deepened their faith, strengthened their zeal, nerved them for whole-hearted consecration to the same Master, and cheered many a solitary and lonely heart.

Many requests have been received for an edition at a price which will place the book within the reach of Sunday School teachers, of those Christian workers who have but little to spend upon books, and of the elder scholars in our schools. The Committee of the Religious Tract Society have gladly met this request at the earliest possible moment.

In this new form their hope and prayer is that James Gilmour, being dead, may yet speak to many hearts, arousing them to diligent, and faithful, and self-denying service for Jesus Christ.

The book, in this its newest form, is identical in all respects with the first and second editions, except that only one portrait is given and the appendices are left out.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Early Years and Education | 15 |

| II. | Beginning Work | 46 |

| III. | Mongolian Apprenticeship | 55 |

| IV. | The First Campaign in Mongolia | 88 |

| V. | Marriage | 98 |

| VI. | 'In Journeyings often, in Perils of Rivers' | 105 |

| VII. | The Visit to England in 1882 | 134 |

| VIII. | Sunshine and Shadow | 154 |

| IX. | A Change of Field | 176 |

| X. | Personal Characteristics as Illustrated by Letters to Relatives and Friends |

228 |

| XI. | Closing Labours | 256 |

| XII. | The Last Days | 298 |

| Portrait of James Gilmour from a Photograph taken at Tientsin on April 1891 | Frontispiece |

| A Mongol Encampment | 109 |

| A Mongol Camel Cart | 139 |

| A Chinese Mule Litter | 156 |

| James Gilmour Equipped for his Walking Expedition in Mongolia in February 1884 | 159 |

| James Gilmour's Tent | 245 |

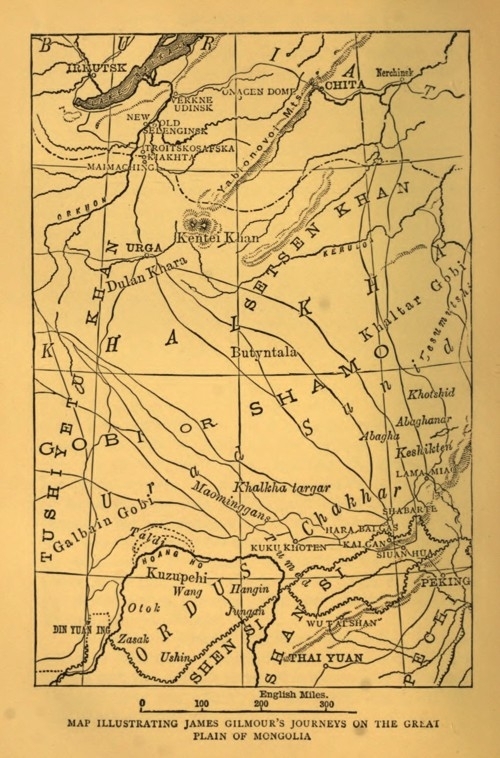

| 1. Map Illustrating James Gilmour's Journeys on the Great Plain of Mongolia | 54 |

| 2. Map Illustrating James Gilmour's Labours in Eastern Mongolia | 178 |

For readers of James Gilmour of Mongolia not familiar with Among the Mongols, a new Edition of that Work has been prepared and published, price Two Shillings and Sixpence.

James Gilmour, of Mongolia, the son of James Gilmour and Elizabeth Pettigrew his wife, was born at Cathkin on Monday, June 12, 1843. He was the third in a family of six sons, all but one of whom grew up to manhood. His father was in very comfortable circumstances, and consequently James Gilmour never had the struggle with poverty through which so many of his great countrymen have had to pass. Cathkin, an estate of half a dozen farms in the parish of Carmunnock, is only five miles from Glasgow, and was owned by Humphrey Ewing Maclae, a retired India merchant, who resided in the substantial mansion-house on the estate. There were also the houses of a few residents, and a smithy and wright's workshops, for the convenience of the surrounding district. James Gilmour's father was the occupant of the wright's shop, as his father had been before him.

His brother John, one of three who have survived him, has furnished the following interesting sketch of the family life in which James Gilmour was trained, and to which he[Pg 16] owed so much of the charm and power which he manifested in later years:—

'Our grandfather, Matthew Gilmour, combined the trades of mason and wright, working himself at both as occasion required; and our father, James Gilmour, continued the combination in his time in a modified degree, gradually discarding the mason trade and developing the wright's. Grandmother (father's mother) was a woman of authority, skill, and practical usefulness among the little community in which she resided. In cases requiring medical treatment, she was always in request; and in order to obtain the lymph pure for the vaccination of children she would take it herself direct from the cow. She was also a neat and skilful needlewoman.

'Matthew Gilmour and his wife were people of strict integrity and Christian living. They walked regularly every Sunday the five miles to the Congregational Church in Glasgow, though there were several places of worship within two miles of their residence. I have often heard the old residents of the steep and rough country road they used to take for a short cut when nearing home tell how impressed they have been by the sight of the worthy couple and their family wending their way along in the dark winter Sabbath evenings by the light of a hand-lantern. Our parents continued the connection with the same body of worshippers in Glasgow as long as they resided in Cathkin, being members of Dr. Ralph Wardlaw's church. It was under his earnest eloquence, and by his wise pastoral care, we were trained.

'The distance of our home from the place of worship did not admit of our attending as children any other than[Pg 17] the regular Sabbath services; but we were not neglected in this respect at home, so far as it lay in our parents' ability to help us. We regularly gathered around our mother's knee, reading the impressive little stories found in such illustrated booklets as the Teacher's Offering, the Child's Companion, the Children's Missionary Record (Church of Scotland), the Tract Magazine, and Watts' Divine Songs for Children. These readings were always accompanied with touching serious comments on them by mother, which tended very considerably to impress the lessons contained in them on our young hearts. I remember how she used to add: "Wouldn't it be fine if some of you, when you grow up, should be able to write such nice little stories as these for children, and do some good in the world in that way!" I have always had an idea that James' love of contributing short articles from China and Mongolia to the children's missionary magazines at home was due to these early impressions instilled into his mind by his mother. Father, too, on Sabbath evenings, generally placed the "big" Bible (Scott and Henry's) on the table, and read aloud the comments therein upon some portion of Scripture for our edification and entertainment. During the winter week-nights some part of the evening was often spent in reading aloud popular books then current, such as Uncle Tom's Cabin.

'Family worship, morning and evening, was also a most regular and sacred observance in our house, and consisted of first, asking a blessing; second, singing twelve lines of a psalm or paraphrase, or a hymn from Wardlaw's Hymn-book; third, reading a chapter from the Old Testament in the mornings, and from the New in the evenings;[Pg 18] and fourth, prayer. The chapters read were taken day by day in succession, and at the evening worship we read two verses each all round. This proved rather a trying ordeal for some of the apprentices, one or more of whom we usually had boarding with us, or to a new servant-girl, as their education in many cases had not been of too liberal a description. But they soon got more proficient, and if it led them to nothing higher, it was a good educational help. These devotional exercises were not common in the district in the mornings, and were apt to be broken in upon by callers at the wright's shop; but that was never entertained as an excuse for curtailing them. I suppose people in the district got to know of the custom, and avoided making their calls at a time when they would have to wait some little while for attention. Our parents, however, never allowed this practice or their religious inclinations to obtrude on their neighbours; all was done most unassumingly and humbly, as a matter of everyday course.

'Our maternal grandfather, John Pettigrew by name, was a farmer and meal-miller on the estate of Cathkin, and was considered a man of sterling worth and integrity. Having had occasion to send his minister, the parson of Carmunnock parish, some bags of oatmeal from his mill, the minister suspected from some cause or other that he had got short weight or measure. The worthy miller was rather nettled at being thus impeached by his spiritual overseer, and that same night proceeded to the manse with the necessary articles required for determining the accuracy of the minister's suspicions. When this was done, it was found there remained something to the good, instead of a deficiency; this the miller swung over his shoulder in a bag[Pg 19] and took back with him to the mill, as a lesson to the crestfallen divine to be more careful in future about challenging the integrity of his humble parishioner's transactions.

'While James was quite a child the family removed to Glasgow, where our father entered into partnership with his brother Alexander as timber merchants. During this stay in Glasgow mother's health proved very unsatisfactory, and latterly both she and father having been prostrated and brought to death's door by a malignant fever, it was decided to relinquish the partnership and return to their former place in the country. James was five years old at that time. When he was between seven and eight he was sent with his older brothers to the new Subscription School in Bushyhill, Cambuslang, a distance of two miles. Here he remained till he was about twelve, when he and I were sent to Gorbals Youths' School in Greenside Street, Glasgow. We had thus five miles to go morning and evening, but we had season-tickets for the railway part of the distance, viz. between Rutherglen and Glasgow. Thomas Neil was master of this school. We were in the private room, rather a privileged place, compared with the rest of the school, seeing we received the personal attentions of Mr. Neil, and were almost free from corporal punishment, which was not by any means the case in the public rooms of the school—Mr. Neil being, I was going to say, a terror to evildoers, but he was in fact a terror to all kinds of doers, from the excitability of his temper and general sternness.

'Here James usually kept the first or second place in the class, which was a large one; and if he happened to be turned to the bottom (an event which occurred pretty often[Pg 20] to all the members of the class with Mr. Neil), he would determinedly endeavour to stifle a tearful little "cry," thus demonstrating the state of his feelings at being so abased. But he never remained long at the bottom; like a cork sunk in water, he would rise at the first opportunity to his natural level at the top of the class. It was because of his diligence and success in his classes while at this school, I suppose, more than from any definite idea of what career he might follow in the future, that after leaving he was allowed to prosecute his studies at the Glasgow High School, where he gained many prizes, and fully justified his parents' decision of allowing him to go on with his studies instead of taking him away to a trade. At home he prosecuted his studies very untiringly both during session and vacation.

'After entering the classes of the Glasgow University he studied in an attic room, the window of which overlooked an extensive and beautiful stretch of the Vale of Clyde. I remember feeling compassion for him sometimes as he sat at this window, knowing what an act of self-denial it must have been to one so boisterous and full of fun as he was to see us, after our work was over of an evening, having a jolly game at rounders, or something of that sort, while he had to sit poring over his books.

'James was not a serious, melancholy student; he was indeed the very opposite of that when his little intervals of recreation occurred. During the day he would be out about the workshop and saw-mill, giving each in turn a poking and joking at times very tormenting to the recipients. If we had any little infirmity or weakness, he was sure to enlarge upon it and make us try to amend it, assuming[Pg 21] the rôle and aspect of a drill-sergeant for the time being. He used to have the mid-finger of the right hand extended in such a way that he could nip and slap you with it very painfully. He used this finger constantly to pound and drill his comrades, all being done of course in the height of glee, frolic, and good-humour. This finger, no doubt by the unlawful use to which he put it, at one time developed a painful tumour, to the delight of those who were in the habit of receiving punishment from it. James pulled a long face, and acknowledged that it was a punishment sent him for using the finger in so mischievous a manner.

'There was a pond or dam in connection with the sawmill. In this James was wont to practise the art of swimming. I remember he devised a plan of increasing his power of stroke in the water. He made four oval pieces of wood rather larger than his hands and feet, tacking straps on one side, so that his hands and feet would slip tightly into them. But my recollection is that they were soon discarded as an unsuitable addition to his natural resources. He was fond of hunting after geological specimens, getting the local blacksmith to make him a pocket hammer to take with him on his rambles for that purpose. He seldom cared for company in these wanderings among the mountains, glens, and woods of his native place and country. He would start early in the morning, and accomplish feats of walking and climbing during the course of a day. Indeed, none of his brothers ever thought of asking James to go with them in their little holiday trips, knowing that anything not the conception of his own fancy was but very rarely acceptable to him; and he was never one who would pander to your gratification merely to please you.[Pg 22]

'James was fond of boating. Once he hired a small skiff near the suspension-bridge at Glasgow Green, and proceeded with it up the river. Having gone a good way up, the idea appears to have taken him to endeavour to get the whole way to Hamilton, where, father having retired from business in 1866, our parents were now residing. This proved to be a very arduous task, as in a great many places on that part of the Clyde there is not depth of water to carry a boat. He managed, however, to accomplish the task by divesting himself of jacket, stockings, and shoes, and pulling the boat over all such shallow and rocky places (including the weir at Blantyre Mills, where the renowned African missionary and explorer, Dr. Livingstone, worked in his boyhood), until he reached the bridge on the river between Hamilton and Motherwell, a distance of eleven miles or more from Glasgow in a straight line, and much more following the numerous bends of the river. Here he made the boat secure and proceeded home, a distance of a mile, very tired and ravenously hungry. The great drawback to his satisfaction in this feat was his fear of the displeasure the boat-owner might feel at his not having returned the same night, and the rough usage to which he had subjected the boat in hauling it over the rocky places. He was much delighted, when he arrived with the boat down the river during the day, to find that the man was rather pleased than otherwise at his plucky exploit, telling him that he only remembered it being attempted once before.

'During part of the time James attended college at Glasgow University, the classes were at so early an hour that he could not take advantage of the railway, and so had[Pg 23] to walk in the whole way. This was an anxious time for his mother, who was ever most particular in seeing to the household duties herself, and always careful that her children should have a substantial breakfast when they went from home. I remember some of those winter mornings. Amidst the bustle of making and partaking of an early breakfast so as to be on the road in time, mother would press him to partake more liberally of something she had thoughtfully prepared for him; he would ejaculate: "Can't take it—no time!" and if she still insisted he would add in a solemn manner: "Mother, what if the door should be shut when I get there?" which, being understood by her as a scriptural quotation, was sufficient to quench her solicitations.

'To avoid the worry of getting up so early, it was decided after a time that he should take advantage of an unlet three or four apartment house in a tenement which belonged to father in Cumberland Street, Glasgow. So a couple of chairs, table, bed, and some cooking-utensils were got together, and James entered into possession, cooking his own breakfast, and getting his other meals there or outside as his fancy or inclination prompted. Here I think he enjoyed himself very much. He had plenty of quiet time for study, and he could roam about the city and suburbs for experience, recreation, and instruction, visiting mills and other large manufacturing industries as he was inclined.

'After our parents had removed to Hamilton, James took lodgings in George Street, a regular students' resort when the old college was in the High Street. It is now removed to the magnificent pile of buildings at Gilmorehill, in the western district of the city. The site of the old one in the High Street which James attended is now occupied by the[Pg 24] North British and Glasgow and South-Western Railway Companies.'

James Gilmour left England to begin his Mongolian life-work in February 1870, and then commenced keeping a diary, from which we shall often quote, and which he carefully continued amid, oftentimes, circumstances of the greatest difficulty until his death. He gives the following reasons for this practice at the time when he was living in a Mongol tent learning the language, hundreds of miles away from his nearest fellow-worker:—

'I think it a special duty to my friends, specially my mother, to keep this diary, and to be particular in adding my state of mind in addition to my mere outward circumstances. In my present isolated position, which may be more isolated soon, any accident might happen at any moment, after which I could not send home a letter, and I think that by keeping my diary punctually and fully my friends might have the melancholy satisfaction of following me to the grave, as it were, through my writing.'

In the record of his first outward voyage he included a sketch of his early life, which we briefly reproduce here, as the correlative and complement of the picture outlined by his brother:—

'The earliest that I can remember of my life is the portion that was spent in Glasgow, before I came with my parents out to the country. Of this time I have only a vague recollection. Then followed a number of years not very eventful beyond the general lot of the years of childhood. One circumstance of these years often comes up to my mind. One Sabbath all were at church except the servant, Aggie Leitch, and myself. She took down an old copy of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, with rude plates, and[Pg 25] by the help of the pictures was explaining the whole book to me. I had not heard any of it before, and was deeply interested. We had just got as far as the terrible doings of Giant Despair and the horrors of Doubting Castle, when all at once, without warning, there came a terrible knock at our front door. I really thought the giant was upon us. It was some wayfaring man asking the way or something, but the terror I felt has made an indelible impression on me.

'When of the approved age I went to school, wondering whether I should ever be able to learn and do as others did. I was very nervous and much afraid, and wrought so hard and was so ably superintended by my mother that I made rapid progress, and was put from one class to another with delightful rapidity. I was dreadfully jealous of any one who was a good scholar like myself, and to have any one above me in class annoyed me to such a degree that I could not play cheerfully with him.

'The date of my going to college was, I think, the November of the year 1862, so that my first session at Glasgow University was 1862-63. The classes I took were junior Latin and junior Greek. In Latin I got about the twelfth prize, and in Greek I think the third. The summer I spent partly in study, partly in helping my father in his trade of a wright and joiner.

'During 1863 and 1864 I lived in Glasgow, and worked very hard, taking the first prize in middle Greek and a prize in senior Latin, as well as a prize for private work in Greek, and another for the same kind of work in Latin. This last I was specially proud of, as in it I beat the two best fellows in the Latin class. Next session (1864-65) I took a prize in senior Greek. I got nothing in the logic, but in moral philosophy in 1865 I was one of those who took an active part in the rebellion against Dr. Fleming, who, though he was entitled to the full retiring pension,[Pg 26] preferred to remain on as professor, taking the fees and appointing a student to do the work. We made a stand against this, and were able to bring him out to his work; but it was too much for him, and he died in harness, as he had wished.

'In English literature I made no appearance in the pieces noted by the students, but came out second in the competitive examination, which of course astonished a good deal some of the noisy men who had answered so much in the class and yet knew so little. I was really proud of this prize, as I was sure it was honestly won, and as I also felt that from my position in class I failed to get credit for anything like what I knew. This session I went in for the classical and philosophy parts of the degree, and got them. I enjoyed a happy week after it was known that I had passed; and the next thing I had to look forward to was going to the Theological Hall of the Congregational Church of Scotland, which met in Edinburgh in the beginning of May. The session at Edinburgh I enjoyed very much. I had not too much work, and used at odd times to take long walks and go long excursions. I was often on the heights, and about Leith and Portobello.'

The Rev. John Paterson of Airdrie, N.B., Gilmour's most intimate college friend at Glasgow, thus records his recollections of what he was in those days:—

'I first made James Gilmour's acquaintance in the winter session of 1864-5 at Glasgow University. He came to college with the reputation of being a good linguist. This reputation was soon confirmed by distinction in his classes, especially in Latin and Greek. Though his advantages had been superior to most of us, and his mental calibre was of a high order, he was always humble, utterly[Pg 27] devoid of pride or vanity. No doubt he was firm as a rock on any question of conviction, but he was tender in the extreme, and full of sympathy with the struggling. He was such a strong man all round that he could afford to give every one justice, and such a gentleman that he could not but be considerate. One day a country student through sheer nervousness missed a class question in the Junior Humanity, though the answer was on his tongue: the answering of such a question would have brought any man to the front, and with a sad heart he told his experience to Gilmour, whose look of sympathy is remembered to this day. He always seemed anxious to be useful, and he succeeded. During our second session, a brother of mine married a cousin of his, and this union led to a closer intimacy between us, and in future sessions we lodged together.

'Throughout his college career Gilmour was a very hard-working student; his patience, perseverance, and powers of application were marvellous; and yet, as a rule, he was bright and cheerful, able in a twinkling to throw off the cares of work, and enter with zest into the topics of the day. He had a keen appreciation of the humorous side of things, and his merry laugh did one good. Altogether he was a delightful companion, and was held in universal esteem. One of Gilmour's leading thoughts was unquestionably the unspeakable value of time, and this intensified with years. There was not a shred of indolence in his nature; it may be truthfully said that he never wilfully lost an hour. Even when the college work was uncongenial, he never scamped it, but mastered the subject. He could not brook the idea of skimming a subject merely[Pg 28] to pass an examination, and there were few men of his time with such wide and accurate knowledge.

'Unlike many of his fellows, he did not relax his energies in summer. During the recess he might have been seen wending his way from the old home at Cathkin to the college library, and returning laden with books. His superior scholarship secured for him excellent certificates and many prizes, both for summer and winter work, and it was noticeable that he shone most in written examinations. On one occasion, in the Moral Philosophy class, which then suffered from the failing health of the professor, the teacher pro tem. appended, as a criticism of an essay of Gilmour's on Utilitarianism, the words, "Wants thoroughness." This was a problem to the diligent student, who tackled his critic at the end of the hour, and apparently had the best of the argument; for he told me afterwards that he had puzzled the judge to explain his own verdict. There was a strong vein of combativeness in him; he liked to try his strength, both mentally and physically, with others; and it was no child's play to wrestle with him in either sense, though he never harboured ill-feeling. He had the advantage of being in easy circumstances, but was severely economical, wasting nothing. He had quite a horror of intoxicating drinks. On one occasion, perhaps for reasons of hospitality, some beer had found its way into our room: he quietly lifted the window and poured the dangerous liquid on the street, saying, "Better on God's earth than in His image."

'As the close of his career in Glasgow drew near, some of us could see that all through he had been preparing for some great work on which the whole ambition of his life[Pg 29] was set. He always shrank from speaking about himself, and in those days was not in the habit of obtruding sacred things on his fellow-students. His views on personal dealing then were changing, and became very decided in after years. Earnest, honest, faithful to his convictions, as a student he endeavoured to influence others for good more by the silent eloquence of a holy life than by definite exhortations, and I feel sure his power over some of us was all the greater on that account. When it became known that Gilmour intended to be a foreign missionary, there was not a little surprise expressed, especially among rival fellow-students—men who had competed with him to their cost. The moral effect of such a distinguished scholar giving his life for Christ among the heathen was very great indeed. To me his resolve to go abroad, though it induced a painful separation, proved an unspeakable blessing. The reserve which had so long prevailed between us on sacred things began to give way, and much of our correspondence during his residence at Cheshunt College was of a religious turn, though still more theological than practical.

'The last evening we spent together before he left for China can never be forgotten. We parted on Bothwell Bridge. We had walked from the village without speaking a word, burdened with the sorrow of separation. As we shook hands, he said with intense earnestness, "Paterson, let us keep close to Christ." He knew Him and loved Him much better than I did then; but about nine years ago, after hearing good news from me, he wrote to say that for twelve years he had prayed for me every day, and now praised God for the answer.'

In the diary from which we have already quoted Gilmour thus concludes the sketch of his education:—

'Near the close of the session of 1867 I opened negotiations with the London Missionary Society, the consequence of which was that I was removed to Cheshunt College in September of that same year. Here (1867-1868) a new experience awaited me—resident college life. At Glasgow we dined out, presented ourselves at classes only, and did with ourselves whatever we liked in the interval. At Cheshunt it was different. All the students live in the buildings of the college, which can accommodate forty. Of course I felt a little strange at first, and even long after had serious doubts as to the settlement of the question, Which is better, life in or out of college? The lectures, as a rule, were all in the forenoon.

'The summer vacation I spent in studying for the Soper scholarship, value twenty pounds, which was to be bestowed after examination.

'I commenced the 1868 and 1869 session at Cheshunt, very busily, and in addition to the class work and the Soper work, read some books which gave almost a new turn to my mind and my ideas of pastoral or missionary life. These books were James's Earnest Ministry, Baxter's Reformed Pastor, and some of Bunyan's works, which, through God's blessing, affected me very much for good.

'The Soper examination should have come off before Christmas, but it did not, so that I remained over Christmas at Cheshunt, grinding away as hard as I could. I was longing eagerly for the time when the examination would be over, that I might the more earnestly devote myself to the work of preaching and evangelising. Well, the examination came and passed off satisfactorily, and I got the twenty pounds.

'Now was the decisive point. Now had I come to[Pg 31] another period, when there was an opportunity of going on a new tack; but I found myself tempted to seek after another honour, the first prize in Cheshunt College. In my first session I had got the second only, and now I had an opportunity of trying for the first. It was a temptation indeed, but God triumphed. I looked back on my life, and saw how often I had been tempted on from one thing to another, after I had resolved that I would leave my time more free and at my disposal for God, but always was I tempted on. So now I made a stand, threw ambition to the winds, and set to reading my Bible in good earnest. I made it my chief study during the last three months of my residence at Cheshunt, and I look back upon that period of my stay there as the most profitable I had.

'In September, 1869, I entered the missionary seminary at Highgate, and also studied Chinese in London with Professor Summers. I went home again at Christmas, and on returning to London learned that I could go to China as soon as I liked. I said I would go as soon as the necessary arrangements could be made, and February 22, 1870, was fixed upon as the date of my departure.'

In this brief and rapid manner James Gilmour sketched, with not a few most characteristic touches, the first twenty-six years of his life. He enables us to see the quick, merry, receptive lad, developing, after a brilliant collegiate course and a careful training in theology and in practical Christian life, into the strong, resolute missionary. No one who knew him during this time failed to perceive the force of his character and the charm of his personality. The writer first came under his influence during his second session at Cheshunt. He was then in the prime of his early manhood, in the full possession of physical and intellectual[Pg 32] vigour, and his soul was aflame with love to the Saviour and to the perishing heathen.

He retained, moreover, the love of fun, the high spirits, the keen enjoyment of a good joke, and the constant readiness for an argument upon any subject under the sun, which had endeared him to his comrades in Glasgow. Every Cheshunt man of that day readily recalls, and rejoices as he does so, the memory of his good-natured practical joking, of his racy and pointed speeches upon all momentous 'house questions,' of his power as a reciter, and of his glowing personal piety. To know him even slightly was to respect him; and to enter at all into sympathy with him was to love him as long as life lasted.

There are many reminiscences of those Cheshunt days, from which we can cull only a sufficient number to enable the reader to understand what manner of man he then was. These are drawn from the letters of his fellow-students, and from their recollections of his sayings and doings. 'How well,' writes one, 'I remember his coming to Cheshunt! I was acting-senior at the opening of that session, and, according to custom with the new men, went to his room to shake hands with him. He said, "Who are you?" I told him. "What do you want?" I told him I had come according to custom to welcome him, and held out my hand, whereupon he put his hands behind him and said, "Time eno' to shake hands when we've quarrelled. But where do you live?" "Immediately over your head." "Then look here," said he, "don't make a row;" and so we parted. Dear old fellow! his memory makes life richer.'

Another writes: 'He was a good elocutionist. He was also a keen debater, and so fond of argument that he would[Pg 33] not hesitate to take opposite ground to his own cherished convictions and beliefs, simply for the sake of provoking discussion. So earnestly and logically (for he was a good dialectician) would he carry on the discussion that it was difficult to believe that he did not really hold the opinions for which he so pertinaciously contended. Sometimes this habit of mind reacted very amusingly upon himself, as the following will show. The subject fixed one Friday evening for debate in the discussion class was, "Have animals souls?" Though fully accepting the common belief that they have not, Gilmour, purely for the sake of argument, took the affirmative, and with such enthusiasm pleaded his cause that he brought himself to believe, as he told me afterwards, that animals have souls.'

'At no time during his residence at Cheshunt could there have been any doubt as to Gilmour's piety or consecration to the great work of his future life; but during the second year it must have been manifest to all who knew him intimately that there was a deepening and broadening of his spiritual life. As I look back over the interval of years I can see that it was then he began to reach the high-water mark in Christian life and devotion which was so steadily maintained throughout his career in China and Mongolia. An apostolic passion for the salvation of his fellow-men took hold upon him. He would go out in the evening, mostly alone, and conduct short open-air services at Flamstead End, among the cottagers near Cheshunt railway station; seize opportunities of speaking to labourers working by the roadside or in the field through which he might be passing. He became very solicitous for the conversion of friends in Scotland, and would come to[Pg 34] my study and ask me to kneel and pray with him that God's grace might be manifested to them, and that His blessing might rest upon letters which he had written and was sending to them. The ordinary style of preaching towards which students usually aspire lost its attractions for him, and his sermons assumed more and more the character of earnest exhortations, and addresses to the unconverted. When he knew what was to be his field of labour after his college course was over, how solicitous he was to go out fully prepared and fitted in spiritual equipment! The needs of the perishing heathen were very real and weighed heavily upon his heart, and he was very anxious to win volunteers among his college friends for this all-important work. How he longed and prayed for China's perishing millions only his most intimate friends know.'

The Rev. H. R. Reynolds, D.D., for the past thirty years the honoured President of Cheshunt College, has recalled some of his early recollections of James Gilmour.

'Though brusque and outspoken in manner, he was in many respects reserved and shy, and very slow to show or accept confidence. We all felt, however, that underneath a canny demeanour there was burning a very intense enthusiasm, and that a character of marked features was already formed, and would only develop along certain lines, settled, but not as yet fully disclosed to others.

There was not a particle of make-believe in his composition. He shrank from praise, and was obviously anxious not to appear more reverential or wise or devoted than he knew himself to be. He even used, because it was natural to him, a rugged style of expression when speaking of things or persons or institutions which for the most part[Pg 35] uplift our diction and generally induce us to adorn or make careful selection of our vocabulary. He rapped out expressions which might have suggested carelessness or irreverence or suppressed doubt, but I soon found that there was an intense fire of evangelistic zeal and an almost stormy enthusiasm for the conversion of souls to Christ.

'Some special services were held at Cheshunt Street Chapel, in which Gilmour took part, and the part was at least as demonstrative, perhaps more so, except the music, as that of the modern Salvation Army ensign or commissioner. He started from the chapel entrance, on the Sunday evening, when considerable numbers were as usual parading the country street, and bare-headed approached every passer-by with some piquant, vigorous inquiry, or message or warning. In the main, his bold summons was, "Do you believe on the Lord Jesus Christ?" The entire population in the thoroughfare was stirred, and uncomplimentary jeers mingled with some awe-struck impressions that were then produced.

'During the year 1869 he had those interviews with the late Mrs. Swan, of Edinburgh, which led to his choice by the London Missionary Society, at her instance, to reopen the long-suspended mission in Mongolia. For a while he remained in Peking preparing himself by familiarity with the people, their ideas, their language, and religion, for those almost historic bursts into the great desert and across the caravan routes to the huge fairs, and the renowned temples, to the living lamas and famous shrines of the nomadic Mongols, incessantly acting the part of travelling Hakim, itinerant book vendor, and fiery preacher of the Gospel of Christ.'[Pg 36]

In the year 1869 the policy of the London Missionary Society in the education of its students was very different from that which now obtains. After a course at a theological college of two, three, or four years, according to the literary attainments of the man at the time of his acceptance by the Directors, he was sent to the institution at Highgate designed to give training suitable for the special requirements of the embryo missionaries. In theory this institution was admirable; in practice Gilmour and others, much as they esteemed the principal, the Rev. J. Wardlaw, found it—or thought they found it—very largely a waste of time. The year 1869 saw the beginning of an investigation which ended in closing the missionary college at Highgate, and in the steps that led to the enquiry Gilmour took a leading part. One of his contemporaries at Highgate has thus described his influence upon both his fellow-students and the institution to which they belonged.

'I first met Gilmour at Farquhar House, Highgate, the London Missionary Society's Institution, where in those days missionary students spent their last six months before going to the field. Some spent the time in studying the elements of the language of the land to which they were going; others attended University College Hospital, for the purpose of getting a little medical knowledge; while all tried to make themselves acquainted with the history of the people among whom they were to labour. Courses of special missionary lectures, which were highly valued by the men, were delivered by the Rev. J., afterwards Dr., Wardlaw.

'Some of us were at Highgate a day or two before Gilmour came up from Scotland; and as his fame, or rather reports about him, had reached us from Cheshunt[Pg 37] College, we were all very anxious to meet with him. When he did arrive we were, I think, all more or less disappointed, and yet I doubt if any of us could have told why, except that he was not the man we had pictured from the reports we had heard. When he walked quietly into the library I, for one, could hardly believe that the almost boyish-looking, open-faced, bright-eyed young man was really Gilmour. His dress made him appear even more youthful than he was, while there was an aspect of good humour about his face and a glance of his eye revealing any amount of fun and frolic. A great writer has said: "Nature has written a letter of credit on some men's faces, which is honoured almost wherever presented." James Gilmour's was a face on which Nature had written no ordinary letter of credit; for there was a sense in which one might very truly have said that his "face was his fortune." Honesty, good nature, and true manliness were so stamped upon every feature and line of it, that you had only to see him to feel that he was one of God's noblest works, and to be drawn to the man as by a magnetic influence.

'Gilmour was a puzzle to most of our fellow-students, and they could not quite make him out. By some he was: regarded as very eccentric, which is another way of saying that he preserved a very marked individuality, and always had the courage of his convictions. They did not seem to understand how so much playfulness and piety, fervour and frolicsomeness could dwell in the same person. Long before we parted, however, in January, 1870, I feel certain that all had come to have not only a profound respect, but also a real heart-love for "dear old Gillie"!

'The night before Gilmour left Highgate for the Christmas[Pg 38] vacation we were all in his study, when someone, remarking on the risk he was running in going home to Scotland by sea, instead of by train, said in a jocular way: "Suppose the steamer is wrecked and you get drowned, to whom do you leave your books, Gilmour?" "Yes," he said at once, "that is well thought of. Come along, you fellows, and pick out the books you would like to keep in memory of me, if I never return." Of course we only laughed and said it was all a joke; but he said, "It is no joke with me, I mean what I say;" and so he did. He was in dead earnest, and nothing would satisfy him but that each should pick out the book or books he would like to have if he never returned. He then turned to me and said: "Now, I leave the rest to your care, and if I never return I want all on this shelf sent to my father and mother, and you can do anything you like with the rest." Had anyone else acted in that way, we should have certainly suspected that he had gone "queer"; but it was Gilmour, and we all understood the straight, matter-of-fact way in which he went about everything he did.

'Through a misunderstanding, as we afterwards discovered, the students at Highgate came into collision with the Directors of the Society over the studies to be prosecuted. Additional classes were arranged, and these some of us declined to attend. This act of rebellion, as it was regarded at the Mission House, had to be put down with a firm hand, and a special meeting of the Board of Directors was called to deal with us.

'The night before we were to meet the Board we met in Gilmour's study, to settle what we were to say to the Directors when we met them. One only of our number,[Pg 39] when he saw that there was likely to be a rather serious interchange of ideas between us and the Directors, caved in completely, and would have nothing further to do with our resistance.

'When we met the Board Gilmour made his defence in his frank, straightforward way, and, I am afraid, upset some of the Directors very much by his plain speaking. They did not know the man, and regarded him as one of the ringleaders in rebellion, and, of course, were not in the humour to do him justice. But when we met the subcommittee appointed to deal with us the misunderstanding came to an end, and they admitted that we had been in the right in objecting to the extra classes thus imposed.'

During these last months in England James Gilmour paid much earnest heed to the culture of his soul. Just before he sailed for China, he set forth his inner experience and his keen sense of the difficulties of the course upon which he was embarking in the following letter to a Cheshunt friend:—

'Companions I can scarcely hope to meet, and the feeling of being alone comes over me till I think of Christ and His blessed promise, "Lo, I am with you alway, even to the end of the world." No one who does not go away, leaving all and going alone, can feel the force of this promise; and when I begin to feel my heart threatening to go down, I betake myself to this companionship, and, thank God, I have felt the blessedness of this promise rushing over me repeatedly when I knelt down and spoke to Jesus as a present companion, from whom I am sure to find sympathy. I have felt a tingle of delight thrilling over me as I felt His presence, and thought that wherever I may go He is still with me. I have once or twice lately felt a melting sweetness[Pg 40] in the name of Jesus as I spoke to Him and told Him my trouble. Yes, and the trouble went away, and I arose all right. Is it not blessed of Christ to care so much for us poor feeble men, so sinful and so careless about honouring Him? the moment we come to Him He is ready with His consolations for us!

'I have been thinking lately over some of the inducements we have to live for Christ, and to confess Him and preach Him before men, not conferring with flesh and blood. Why should we be trammelled by the opinions and customs of men? Why should we care what men say of us? Salvation and damnation are realities, Christ is a reality, Eternity is a reality, and we shall soon be there in reality, and time shall soon be finished; and from our stand in eternity we shall look back on what we did in time, and what shall we think of it? Shall we be able to understand why we were afraid to speak to this man or that woman about salvation? Shall we be able to understand how we were ashamed to do what we knew was a Christian duty before one whom we knew to be a mocker at religion? Our cowardice shall seem small to us then. Let us now measure our actions by the standard of that scene, let us now look upon the things of time in the light of eternity, and we shall see them better as they are, and live more as we shall wish then we had done. It is not too late. We can secure yet what remains of our life. The present still is ours. Let us use it. It may be that we can't be great, let us be good; if we can't shine as great lights, let us make our light shine as God has made it to shine. Let us live lives as in the presence of Christ, anxious for His approval, and glad to take the condemnation of the world, and of Christ's professed servants even, if we get the commendation of angels and our Master. The "well done!" is to the faithful servant—to the faithful, not the great. Let[Pg 41] us watch and pray that we may be faithful. It is a little hard to be this, and to care little for man.

'Yesterday afternoon I preached here at home, and took the most earnest sermon I had, "Behold, I stand at the door and knock." Well, in doing so, I thought I was acting quite independently of man; and even after I had preached it, thought I would not care for man. But one man praised it, and I felt pleased, and, as might then be expected, felt a little hurt when a friend called this morning and told me that what I gave them yesterday was no sermon at all. Now, if I had been regarding Christ alone, I would not have been moved by either the one or the other of these criticisms; and I wish that I could get above this sort of thing, and get beyond the attempt at pleasing men at all. Why should we confer with men?'

James Gilmour was ordained as a missionary to Mongolia in Augustine Chapel, Edinburgh, on February 10, 1870, and, in accordance with Nonconformist custom, he made a statement about the development of his religious life from which we take the following extract:—

'My conversion took place after I had begun to attend the Arts course in the University of Glasgow. I had gone to college with no definite aim as to preparing for a profession; an opportunity was offered me of attending classes, and I embraced it gladly, confident that whatever training or knowledge I might there acquire would prove serviceable to me afterwards in some way or other.

'After I became satisfied that I had found the "way of life," I decided to tell others of that way, and felt that I lay under responsibility to do what I could to extend Christ's kingdom. Among other plans of usefulness that suggested themselves to me was that of entering the ministry. But, in my opinion, there were two things that everyone who[Pg 42] sought the office of the ministry should have, viz., an experimental knowledge of the truth which it is the work of the minister to preach, and a good education to help him to do it; the former I believed I had, the latter I hoped to obtain. So I quietly pursued the college course till I entered on the last session, when, after prayerful consideration and mature deliberation, I thought it my duty to offer myself as a candidate for the ministry.

'Having decided as to the capacity in which I should labour in Christ's kingdom, the next thing which occupied my serious attention was the locality where I should labour. Occasionally before I had thought of the relative claims of the home and foreign fields, but during the summer, session in Edinburgh I thought the matter out, and decided for the mission field; even on the low ground of common sense I seemed to be called to be a missionary. Is the kingdom a harvest field? Then I thought it reasonable that I should seek to work where the work was most abundant and the workers fewest. Labourers say they are overtaxed at home; what then must be the case abroad, where there are wide stretching plains already white to harvest, with scarcely here and there a solitary reaper? To me the soul of an Indian seemed as precious as the soul of an Englishman, and the Gospel as much for the Chinese as for the European; and as the band of missionaries was few compared with the company of home ministers, it seemed to me clearly to be my duty to go abroad.

'But I go out as a missionary not that I may follow the dictates of common sense, but that I may obey that command of Christ, "Go into all the world and preach." He who said "preach," said also, "Go ye into and preach," and what Christ hath joined together let not man put asunder.

'This command seems to me to be strictly a missionary injunction, and, as far as I can see, those to whom it was first delivered regarded it in that light, so that, apart altogether[Pg 43] from choice and other lower reasons, my going forth is a matter of obedience to a plain command; and in place of seeking to assign a reason for going abroad, I would prefer to say that I have failed to discover any reason why I should stay at home.'

On February 22, 1870, James Gilmour embarked at Liverpool upon the steamship Diomed, and thus fairly started on the work of his life. Among his extant correspondence is a long letter which describes the voyage to China, and the way in which he utilised the opportunities it afforded for trying to do his Master's will.

'We sailed from Liverpool, and my father saw me off. The passengers were few—nine or ten. We had a cabin each. There was a Wesleyan medical missionary named Hardey going out to Hankow. We soon drew together. The doctor of the ship was a young fellow from Greenock, and had been at Glasgow College when I was there last. Among the 1,200 we had not stumbled upon each other. The married man was something or other in the Consular service. A young lady passenger was the daughter of a judge in China. A young man was going out to try his fortune in China: his qualifications were some knowledge of tea and a love of drink. Another decent young fellow was going out to China as a tea-taster. Another young fellow was going out to Australia viâ Singapore. Thus, you see, I was the only parson on board; and as the ship's company was High Church, and I a Dissenter, it may be seen that we did not fit each other exactly. Some of the passengers were so High Church that one of them told me he thought we Dissenters were sunk more deeply in error than the Papists.

'The captain was a sensible kind of rough seaman, and I at once volunteered my services as chaplain, and was[Pg 44] accepted, though with some caution. He evidently thought me too young to be trusted with a sermon; the Church of England prayers I might read, and he put into my hands a book with a sermon for any Sunday and holy-day in the year. I took the book and said I would look through it. The Bay of Biscay was calm when we crossed it, but on Sunday morning we were tumbling about off the Rock of Lisbon. As I could hardly keep my legs, I did not think we should have had service; but we crowded into the smoking-saloon (we were afraid to venture below, for sickness), and I read prayers. Next Sunday I read a sermon from the book. All the Sundays after that I gave them my own, and, as I was under the impression that they had not heard much plain preaching, did my best to let them hear the gospel pure and simple. I half suspected they did not quite like it. It was hinted to me that they complained of my preaching. The next Sunday came, and, under the impression it might be the last time I would have the opportunity, I made the most earnest and direct appeal to them I possibly could. I was not a little thankful and astonished when, soon after, in place of being asked to shut up, I was thanked for it, and assured it was the best I had given them, and told that it was a waste of, &c., &c., for me to go out as a missionary—I should have stopped at home. After that I had no trouble with the passengers, and we got on well together.

'As for the men, from captain to cabin-boy there were about sixty. Among these was one earnest Christian man, a German and a Baptist. He was a quarter-master. He was a little peculiar in appearance, and spoke English not quite smoothly. On one occasion, when some of the passengers were laughing at something he had done and said, the captain happened to pass, and, seeing what was up, remarked that the man was a first-rate fellow—he never caught him idle. If you except this man, the captain,[Pg 45] and the boy, the whole ship's company swore like troopers. So universal was the vice that the men, I almost think, were hardly aware that they did swear. I was puzzled. Sometimes when I went out in the morning I would hear a volley of oaths coming from the mouth of a man who had been talking quite seriously with me over-night.

Few of the men came to the service, and as they would not come to us we went to them. Hardey and I, usually in the evenings, conducted short little services in the forecastle as often as we thought desirable. We were always well received and listened to respectfully. I think I may say safely that all on board had repeated opportunities of hearing the gospel as plainly as I could put it, and a good many had something more than mere opportunities. After it was dark I used to go out and get the men one by one, as they sat in corners during their watch in the night. All they had to do was to be within call when wanted, and many a good long talk I have had with a good many of them. Of course, my object in accosting them was religious conversation, and this I usually succeeded in having; but on many occasions, that we might be quite on a footing of equality, I had in return to listen to their yarns. The man on the look-out was a frequent victim. I was always sure to find a man there, generally alone, and never asleep. The man, also, was changed at regular intervals, so that I knew exactly when I would find a fresh man. When I talked to the look-out man, I used to keep a sharp lookout myself, lest by distracting his attention I should get him into trouble. Many a good hour have I stood at the prow as we passed through the warm Indian Ocean, till my clothes were wet with the dew of night; and then I would find my way down to my cabin about midnight, with my head so full of the ghost-stories I had just heard that I was really afraid I might meet a real ghost coming out of my cabin.'

In 1817 two missionaries, the Rev. E. Stallybrass and the Rev. W. Swan, left England to begin Christian work among the Buriats, a Mongolian tribe living under Russian authority. At Selenginsk and at Onagen Dome they laboured for many years; but in 1841 the Russian Emperor ordered them to leave the country. From the command of the autocrat there was no appeal, and the mission came to an end. But in the good providence of God the two missionaries had translated the whole Bible into Buriat; the Old Testament being printed in Siberia in 1840, the New Testament in London in 1846. Notwithstanding the suppression of the mission, the Word of God in the Mongol tongue continued to circulate among the people.

It was to the reopening and development of this missionary work among the Mongol tribes that James Gilmour consecrated his life. He was appointed, in the first instance, to the London Mission at Peking, and that centre formed his first base of operations. He continued also a member of that mission until the close of his life. He reached the Chinese capital on May 18, 1870. At once he settled down to hard and continuous work at the Chinese language, endeavouring also from the first to discover the best means[Pg 47] of restarting the Mongol Mission. The very full diary which he kept lies before us as we write, and enables us to understand the varying progress and hindrance, encouragement and despondency of this time.

'June 11, 1870.—Mr. Gulick advises me to pay little attention to the Chinese and go in hot and strong for the Mongolian. I am not quite sure that he is not right, after all. However, I mean to stick into the Chinese yet for a time to come with my teacher and to mix among the people as much as I can. I went out to-night and with the gate-keeper and two of his companions had a lot of talk, in which I learned a good lot. I hope to benefit largely by this pleasant mode of study. Perhaps by this means I may be able to do them good. Lord grant it!'

'June 12, 1870.—I am to-day twenty-seven years of age, and what have I done? Let the time that is past suffice to have wrought the will of the flesh. The prospect I have before me now is the most inspiriting one any man can have. Health, strength, as much conscious ability as makes one hope to be able to get the language of the people to whom I am sent, a new field of work among men who are decidedly religious and simple-minded, left pretty much to my own ideas as to what is best to be done in the attempted evangelization of Mongolia, friends left in Britain behind me praying for me, comfort and peace here in the prosecution of my present studies, the idea that what I do is for eternity, and that this life is but the short prelude to an eternal state, the thought that after death there shall break on my view a thousand truths that now I long in vain to know—these thoughts and many others make my present life happy, and in a manner careless as to what should come. In time may I be able to do my part as I ought, and may God have great mercy upon me!'

On June 22, 1870, the news of the Tientsin massacre reached Peking. A Roman Catholic convent had been destroyed and thirteen French people killed. Very great uncertainty prevailed as to whether this indicated a further purpose of attacking all missions and all foreigners, and for a while things looked very dark. It was a time in which the nerve and courage and faith of men were severely tried, and splendidly did Gilmour endure the test. While unable to escape wholly from the fears common to all, his reply to the counsels of worldly prudence and selfish dread was advance in his work. When others were wondering whether they might not have to retreat, he, alone, in almost total ignorance of the language, entirely unfamiliar with the country, went up to the great Mongolian plain, and entered upon the service so close to his heart—personal intercourse with and effort for the Mongols.

How trying a season this was his diary reveals. Under date of June 23, 1870, the day after the first tidings of the outbreak had been received, he writes:—

'The Roman Catholic missionaries have suffered severely, and the Protestant missionaries are not in a very safe condition. We are living on the slope of a volcano that may put forth its slumbering rage at any moment. For example, people ask why there is no rain, and blame the foreigners for it; and should a famine ensue, we may fare hard for it. Now is the time for trying what stuff a man's religion is made of. We may be all dead men directly; are we afraid to die? Our death might further the cause of Christ more than our life could do. We must die some time or other; now that we have a near view of its possibility, how can we look forward to it? God! do Thou make my faith firm and bright, so that death may[Pg 49] seem small and not to be feared. Help me to trust Thee and Christ implicitly, so that with calm mind I may work while Thou dost let me live, and when Thou dost call me home, let me come gladly.'

The further entries in his Diary at this time depict his inner experience from day to day:—

'July 10.—Rose 6.20. Dull morning, rained a little. Felt uncomfortable at the idea of being killed; felt troubled at the idea of leaving Peking. How am I to pack and carry my goods? Felt troubled at remaining in the midst of a troubled city, with a government weak and stupid. How is my mission to get on beginning thus? O God, let me cast all my care upon Thee, and commit my soul also to Thy safe keeping. Keep me, O God, in perfect peace! Rain made a thin meeting this morning, but all was quiet. In afternoon went with Mr. Edkins to the west; things uncommonly quiet and peaceful.

'July 12.—While others are writing to papers and trying to stir up the feelings of the people, so that they may take action in the matter, perhaps I may be able to do some good moving Heaven. My creed leads me to think that prayer is efficacious, and surely a day's asking God to overrule all these events for good is not lost. Still, there is a great feeling that when a man is praying he is doing nothing, and this feeling, I am sure, makes us give undue importance to work, sometimes even to the hurrying over or even to the neglect of prayer.

'July 22.—A good deal troubled about the present state of matters. I don't exactly know how to estimate rumours and reports, and this may cause me more uneasiness than there is any need for. Still, I don't know. At times I feel a great revulsion from being killed, at other times I feel as if I could be killed quietly, and not dislike the thing much. Sometimes the tone of those about us is hopeful, and that[Pg 50] causes hope also. Sometimes the prospect of a speedy removal, a half flight, comes upon me with great force, and to see all its annoyance, not to speak of the danger, is not pleasant at all. Oh for the simple, childlike faith that can trust all things to God and leave all care upon Him! Ought we not to have it? Is God not the same God now that He was when He delivered His people from Egypt, and His saints from the hands of their enemies, from the mouth of the lions, and the fiery furnace? Cannot God keep us yet—will He not do it? But then comes the thought, perhaps God does not wish us to live, but to die. Often has He allowed His saints to be slain. What then? Well, as the men in the furnace said of God, "Will He care to defend us? if not, be it known unto you we will not yield." I might have died in childhood, in youth, before conversion, and if then, alas! alas! I can remember the time when the pains of hell got such a terrible hold upon me that I would have gladly changed places in the world with anyone who had the hope of salvation. Death, life, prospects, honour, shame, seemed nothing compared with this hope of salvation, which I was then without. "Could I ever be saved?" was the question; "would I ever have the hope that I knew others had?" Had I died in darkness—God be thanked, the light has shined forth, and I have the hope of eternal life. May God make me more Christlike, and give me stronger hope! Well, then, this hope I have; from this fearful pit I have been delivered; in the light I now walk. God I call my Father, Christ my Saviour, heaven my home, earth and the life here the entrance to real life. If there is anything in our faith or in our belief, then heaven is as much better than earth as it is higher than earth, and our souls life is insured from all harm. If a man is insured against all possible harm, why should he be afraid? Not one hair of our head shall perish! O Lord, help me to live this faith and to be in this frame of mind. In this city are[Pg 51] many foreigners, who came here to learn the language, &c., and many of them have no great hope of heaven. They seem calm enough, and are no doubt calm enough; shall the courage of the world, shall the courage of scepticism, shall the courage of carelessness be greater and produce better fruit than the courage of the Christian? O Lord, preserve me from the sin of dishonouring Thy name through fear and cowardice! Let us be bold in the Lord!'

By the end of July 1870, Gilmour had reached a fixed resolution to go to Mongolia as soon as the necessary arrangements could be made. A severe test had been applied to him, and the way in which he met it gives the key to the whole of his after life. He used the trial as a help onwards in the path of duty, and the chain of events which would have led many men to postpone indefinitely the beginning of a new and hard work only drove him the more eagerly into new fields. The reasons that influenced him are set forth in his official report written many months later.

'After the massacre at Tientsin, very grave fears prevailed at Peking; no one could tell how far the ramifications of the plot might extend, and it was impossible to sift the matter. The people openly talked of an extermination, and claimed to have the tacit favour of the Government in this; nay more, the Government itself issued ambiguous, if not insinuating, proclamations, which fomented the excitement of the populace to such an extent that the days were fixed for the "Clearing of Peking." The mob was thoroughly quieted on the first of the days fixed by a twenty hours' pour of tremendous rain, which converted Peking into a muddy, boatless Venice, and kept the people safely at home in their helpless felt shoes, as securely as if their feet had been put into the stocks. This was Friday.[Pg 52] Tuesday was the reserve day; Saturday and Sabbath one felt the tide of excitement rising, and on Monday morning the Peking Gazette came out with an Imperial edict that at once allayed the excitement, and assured us that there was no danger for the present.

'We had then to draw breath and look about us calmly, and the general conclusion that the "Old Pekingers" came to was that the French would be compelled to resort to force of arms to gain redress. The attitude of the Chinese people and Government made them think so, and so they determined to wait on quietly in Peking till things should get thick, and then it would be time to go south. I think I may safely say that everyone drew out an inventory of his things, and not a few had their most necessary things packed "on the sly," and were ready to start on short notice.

'Up to this point I stood quietly aside; but now was my time to reason, and on the data they supplied I reasoned thus: "If I go south, no Mongol can be prevailed on to go with me, and so I am shut out from my work, and that for an indefinite time. If I can get away north, then I can go on with the language, and perhaps come down after the smoke clears away, knowing Mongolian, and having lost no time." I felt a great aversion to travelling so far alone, and with such imperfect knowledge of the language, but as I thought it over from day to day I was more and more convinced that to run the risk of having to go south would be to prove unfaithful to duty, and so I conferred no longer with likings or dislikings, resolved to go should an opportunity offer, and in the meantime worked away at Chinese.

'By-and-by a Russian merchant turned up; he was going to Kiachta, so I started with him. I could not go sooner, as it was not safe to travel in the country before the Imperial edict was issued; to wait longer was to run the risk of not going at all.'

The name Mongolia denotes a vast and almost unknown territory situated between China Proper and Siberia, constituting the largest dependency of the Chinese Empire. It stretches from the Sea of Japan on the east to Turkestan on the west, a distance of nearly 3,000 miles; and from the southern boundary of Asiatic Russia to the Great Wall of China, a distance of about 900 miles. It consists of high tablelands, lifted up considerably above the level of Northern China, and is approached only through rugged mountain passes. The central portion of this enormous area is called the Desert of Gobi.

A kind of highway for the considerable commercial traffic between China and Russia runs through the eastern central part of Mongolia, leaving China at the frontier town of Kalgan, and touching Russia at the frontier town of Kiachta. Along this route during all but the winter months, caravans of camel-carts and ox-carts attended by companies of Mongols and Chinese are constantly passing. The staple export from China is tea; the chief imports are salt, soda, hides, and timber.

The west and the centre of Mongolia is occupied by nomad Mongols. They have clusters of huts and tents in[Pg 56] fixed locations which form their winter dwellings. But in summer they journey over the great plains in search of the best pasturage for their flocks and herds. They are consequently exceedingly difficult to reach by any other method than that of sharing their roving tent life. In the southeastern district of Mongolia there are large numbers of agricultural Mongols who speak both Chinese and Mongolian. The towns in this part are almost wholly inhabited by Chinese.

The winter in Mongolia is both long and severe; in the summer the heat is often very oppressive, and the great Plain is subject to severe storms of dust, rain and wind.

Buddhism is all-powerful, and the larger half of the male population are lamas or Buddhist priests. 'Meet a Mongol on the road, and the probability is that he is saying his prayers and counting his beads as he rides along. Ask him where he is going, and on what errand, as the custom is, and likely he will tell you he is going to some shrine to worship. Follow him to the temple, and there you will find him one of a company with dust-marked forehead, moving lips, and the never absent beads, going the rounds of the sacred place, prostrating himself at every shrine, bowing before every idol, and striking pious attitudes at every new object of reverence that meets his eye. Go to Mongolia itself, and probably one of the first great sights that meet your eye will be a temple of imposing grandeur, resplendent from afar in colours and gold.'

'The Mongol's religion marks out for him certain seemingly indifferent actions as good or bad, meritorious or sinful. There is scarcely one single step in life, however insignificant, which he can take without first consulting[Pg 57] his religion through his priest. Not only does his religion insist on moulding his soul, and colouring his whole spiritual existence, but it determines for him the colour and cut of his coat. It would be difficult to find another instance in which any religion has grasped a country so universally and completely as Buddhism has Mongolia.'[1]

[1] Among the Mongols, p. 211.

It was to the herculean task of attempting single-handed to evangelise a region and a people like this that James Gilmour addressed himself. His early journeys are fully set forth in Among the Mongols, and we do not propose to repeat them here. Our object rather is to depict, so far as possible, the inner life of James Gilmour, and the real nature of the work he accomplished. He left Peking on August 5, and reached Kalgan four days later. On August 27 he started for his first trip across the great plain of Mongolia to Kiachta. A Russian postmaster was to be his companion, but, to avoid travelling on Sunday, Gilmour started a day ahead, and then waited for the Russian to come up. Here is his first view of scenes he was so often in later life to visit.

'Sabbath, August 28.—Awoke about 5 A.M. just as it was drawing towards light, and saw that we were right out into the Plain.

'I am writing up my diary, with a lot of people looking into my cart. I have just given them a Mongol Catechism, and I hope it may do them good. God, do Thou bless it to them! Would I could speak to them, but I cannot. I am glad to be saved the trouble of travelling to-day. My mind feels at rest for the present. I am looking about me, and having my first look at the life I am likely to lead.[Pg 58] There are several more Mongol dwellings within sight, plenty of camels, horses, and oxen. The Mongols have a tent of their own, and the "commandant's" tent has also been put up. A Mongol has just come up and changed his dress, his cloak serving him as a tent meantime. I am hesitating whether to try to read in my cart or go off a little way with my plaid and umbrella.

'Had not a very intellectual or spiritual day after all. Went in the afternoon away to the east. Had a good view and a time of devotion at a cairn from which an eagle rose as I approached. Returned to the camp and bought milk and some cheese. Intended to make porridge, but the fire was not good on account of the blowing, so I drank off my milk, ate some bread, and went to sleep.'

The journey across the desert, including a visit to Urga, occupied a month. It was full of intense interest for the traveller, and many of the most abiding impressions of his life and work were then received. His diary reveals the deep yearnings of his heart for the salvation of the Mongols. Under the date September 11, 1870, he writes:—

'Astir by daybreak. Camels watering; made porridge and tea. This is the Lord's day; help me, O Lord, to be in the spirit, and to be glad and rejoice in the day which Thou hast made! Several huts in sight. When shall I be able to speak to the people? O Lord, suggest by the Spirit how I should come among them, and guide me in gaining the language, and in preparing myself to teach the life and love of Christ Jesus! Oh, let me live for Christ, and feel day by day the blessedness of a will given up to God, and the happiness of a life which has its every circumstance working for my good!'

His constant rule was to rest from all journeying, so far as possible, on the Sabbath. After another week's experience, on September 18 he thus records his impressions:—

'Encamped just over the plain we saw at sunset last night. We are some distance from the real exit, but not far. This is the Lord's day; God help me to be in the spirit notwithstanding all distractions. Oh that God would give me more of His Spirit, more of His felt Presence, more of the spirit and power of prayer, that I may bring down blessings on this poor people of Mongolia! As I look at them and their huts I ask again and again how am I to go among them; in comfort and in a waggon, with all my things about me; or in poverty, reducing myself to their level? If I go among them rich, they will be continually begging, and perhaps regard me more as a source of gifts than anything else. If I go with nothing but the Gospel, there will be nothing to distract their attention from the unspeakable gift.

'8.15 A.M.-3.15 P.M. Good long walk. Met camels and came upon a cart encampment, estimated at one hundred and seventy. Know where I am on the map. There is a camel encampment where we are. Two huts from which comes fuel. Read to-day in II Chronicles xvi. God never failed those who trusted in Him and appealed to Him. God was displeased with the King of Judah because, after the deliverance from the Lubims, Ethiopians, &c., he trusted to the arm of flesh to deliver him from the Syrians. Do we not in our day rest too much on the arm of flesh? Cannot the same wonders be done now as of old? Do not the eyes of the Lord run to and fro throughout the whole earth, still to show Himself strong on behalf of those who put their trust in Him? Oh that God would give me more practical faith in Him! Where is now the Lord God of Elijah? He is waiting for Elijah to call on Him. God[Pg 60] give me some of Elijah's spirit, and let my power be of God, and my hope from Him for the conversion of this people.

'It is nothing to the Lord to save by many or by them that have no power. Help me, O God, for I rest on Thee, and in Thy name I go against this multitude!'

Kiachta, on the southern frontier of Siberia, was reached September 28, 1870, and there Gilmour was at once plunged into a series of troubles. The Russian and Chinese authorities would not recognise his passport, and he had to wait months before another could be obtained from Peking. He found absolutely no sympathy in his work. He knew next to nothing of the Mongol language. Yet with robust faith, with whole-hearted courage, with a resolution that nothing could daunt, he set to work. A Scotch trader, named Grant, was kind to him, and found accommodation for him at his house. At first he tried the orthodox plan of getting a Mongol teacher to visit and instruct him. Before he secured one he used to visit such Mongols as he found in the neighbourhood, trying to acquire a vocabulary from them, asking the names of the articles they were using, their actions, and all such other matters as he could make them understand. But his loneliness, his ignorance of the language, the inaction to which he was condemned, partly by his difficulty in getting a suitable teacher, and partly by the uncertainty as to whether the authorities would allow him to remain, told upon his eager spirit as week after week passed by, and he became subject to fits of severe depression. Here is a picture of one of these early days. He had been trying to talk with a Buriat carpenter, in a place called Kudara, not far from Kiachta:[Pg 61]—