The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Wilderness Trail, by Frank Williams This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Wilderness Trail Author: Frank Williams Illustrator: Douglas Duer Release Date: January 11, 2010 [EBook #30925] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WILDERNESS TRAIL *** Produced by Gardner Buchanan

“And you accuse me of that?”

Donald McTavish glared down into the heavy, ugly face of his superior—a face that concealed behind its mask of dignity emotions as potent and lasting as the northland that bred them.

“I accuse you of nothing.” Fitzpatrick pawed his white beard. “I only know that a great quantity of valuable furs, trapped in your district, have not been turned in to me here at the factory. It is to explain this discrepancy that I have called you down by dogs in the dead of winter. Where are those furs?” He looked up out of the great chair in which he was sitting, and regarded his inferior with cold insolence. For half an hour now, the interview had been in progress, half an hour of shame and dismay for McTavish, and the same amount of satisfaction for the factor.

“I tell you I have no idea where they are,” returned the post captain. “So far as I know, the usual number of pelts have been traded for at the fort. If any have disappeared, it is a matter of the white trappers and the Indians, not my affair.”

“Yes,” agreed the other suavely; “but who is in charge of Fort Dickey?”

“I am.”

“Then, how can you say it is not your affair when the Company is losing twenty thousand pounds a year from your district?”

The young man ground his teeth helplessly, torn between the desire to throttle ugly old Fitzpatrick where he sat, or to turn on his heel, and walk out without another word. He did neither. Either would have been disastrous, as he well knew. He had not come up three years with the spring brigade from the Dickey and Lake Bolsover without knowing the autocratic, almost royal, rule of old Angus. Fitzpatrick, factor at Fort Severn for these two decades.

So, now, he choked back his wrath, and walked quietly up and down, pondering what to do. The room was square, low, and heavily raftered. Donald had to duck his head for one particular beam at each passage back and forth. Beneath his feet were great bearskins in profusion; a moose's head decorated one end of the place. The furniture was heavy and home-made.

At last, he turned upon the factor.

“Look here!” he said simply. “What have you got against me? You know as well as I do that there isn't another man in your whole district you would call in from a winter post to accuse in this way. What have I done? How have I failed in my duty? Have I taken advantage of my position as the chief commissioner's son?”

Fitzpatrick pawed his beard again, and shot a sharp, inquisitive glance at the young captain. That mention of his father's position was slightly untoward. In turn, he pondered a minute.

“Up to this time,” he said at last, “you have done your work well. You know the business pretty thoroughly, and your Indians seem to be contented. I have nothing against you—”

“No,” burst out McTavish, “you have nothing against me. That's just it. Virtues with you are always negative; never have I heard you grant a positive quality in all the time I have known you. And, to be frank, I think that you have something against me. But what it is I cannot find out.” He paused eloquently before the white-haired figure that seemed as immovable as a block of granite.

“This is hardly the time for personalities, McTavish,” said the other, harshly. “What I want to know is, what steps will you take to restore the furs that have disappeared from your district?”

“How do you know they have disappeared from my district?” Donald blazed forth.

“I know everything in this country,” replied Fitzpatrick, dryly.

“Then, am I under the surveillance of your spying Indians?”

“Enough!” roared the factor, at last roused from his calm. “I am not here to be questioned. Answer me! What are you going to do?”

McTavish dropped his clenched hands with a gesture of hopeless weariness.

“I'll swallow your insulting innuendoes, and try to dig up some evidence to support your accusation,” he said, quietly. “If I get track of any leakage, I'll do my best to stop it. If not, you shall learn as soon as possible.”

“The leakage exists,” rejoined the factor, doggedly. “Plug the hole, or—” He paused suggestively.

“Or what?” cried the younger man, whirling upon him furiously.

“Plug the hole—that's all.”

Shaking with the fury that possessed him, McTavish turned away from his chief, and walked to a window, lest he should lose all control of himself. But a thought came to him that restored the proud angle of his head, and crushed his anger into nothingness.

What McTavish yet had been the fool of a narrow-minded, disgruntled superior, and showed it by losing his temper? None. The name of McTavish rang down the hall of the Hudson Bay Company's history like a bugle. Three generations of them had served this fearful master—he was the third. His father, now chief commissioner, had served an apprenticeship of twenty years in the wilds, beginning as a mere lad. He himself, when barely fifteen, had felt the call in his blood, and gone out on the trail with Peter Rainy, a devoted Indian of his father's. Peter was still with him, but now as body-servant, and not as instructor in woodcraft.

Donald thought of these things as he looked out of the chunky, square window into the snow-muffled courtyard. So engrossed was he that he failed to hear the door of the room open, and the light footfalls of Tee-ka-mee, Fitzpatrick's bowman and body-servant. The Indian, sensing some unpleasantness in the air, went directly to the factor, and handed him a message, explaining that Pierre Cardepie, one of McTavish's companions at the Dickey River post, had sent it by Indian runner.

Through the window the post-captain saw opposite him a corner made by two walls meeting at right angles. Even in summer, they were stout, heavy walls; but, now, with twenty feet of snow muffling and locking them in an unshakable grip, they were monstrous. Above the walls, a bastion of squared logs, looped-holed for four- and six-pounders, rose. There was another one at the opposite corner of the square, and together they commanded all approaches.

Angus Fitzpatrick opened the message Tee-ka-mee handed to him, and read it. His only sign of emotion was the lifting of an eyebrow. Then, he waved the Indian out.

“McTavish!” he called sharply, and the younger man turned wearily from the window to face his superior.

“I suppose you know that half-breed, Charley Seguis, in your district? He comes up with the brigade every spring, I believe.”

“Yes, I know him. He is a skilful trapper and a half-breed of remarkable intelligence.”

“Huh! That's the trouble; he's got too much intelligence to make him safe as a half-breed. What do you know about him? Is he a bad one?”

“Quite the contrary, so far as I have observed.”

“Well, he's been bad this time. Read that.” Fitzpatrick handed Cardepie's scrawl to McTavish, and watched keenly as the latter read:

SIR:

Yesterday Charley Seguis murder Cree Johnny. No reason I can find. I send this by runner so Mr. McTavish get it before he starts back.

CARDEPIE.

“That's most remarkable, sir,” said Donald, genuinely puzzled. “I never would have suspected Charley of that. He has brains enough to know the consequences of murder. I can't understand it.”

“Neither can Cardepie, evidently. He says he knows no reason for the deed.” Fitzpatrick heaved himself up, and leaned forward interestedly. “You know,” he went on, “that this thing cannot go unpunished. Charley Seguis must be captured, and brought to the fort here.”

“Will the mounted police get here before—?” began McTavish.

“The mounted police be hanged! There are only seven hundred of them, and they have to cover a country as big as Siberia. You don't suppose I'm going to wait for them, do you? Nominally, they're the law here, but literally I and the men under me are. Retribution in this case must be swift and sure, as it always has been from Fort Severn.” Fitzpatrick paused to breathe.

“Then, you mean that I must go out and get him,” Donald interpreted, calmly.

“You spare me the trouble of saying it,” replied the other. “When can you start?”

“In three hours.”

Fitzpatrick glanced at the clock on the wall.

“Too late now,” he said. “Better wait until to-morrow. The feed and the night's rest will do you good. Whatever happens, you've got to be faster than that half-breed.” He paused a minute. “If you go at dawn, I probably won't see you again. In that case, let me remind you, McTavish, of the matter of which we were speaking before this murder came up. I—”

“You don't need to remind me. I remember it perfectly.” Donald moved toward the door.

Fitzpatrick leaned still farther forward in his great chair, his eyes glinting, his lips curved in a snarl.

“And don't forget,” he rasped at the other's back, “that I want that half-breed, dead or alive—and that he's a mighty fast man with a gun!”

The young man vouchsafed no reply, but passed out of the door that Tee-ka-mee opened from the other side. For fully a minute after the door had closed, Fitzpatrick continued to lean forward, the snarl on his lips, the evil light in his eyes. Then he fell back heavily, with a harsh, mirthless cackle.

“If he only knew—if he only knew!” he muttered to himself. “He must know soon, or there won't be half the pleasure in it for me.”

Then, thirst being upon him, he clanged the bell for Tee-ka-mee, and that faithful servitor, divining the order, brought the aged factor wherewithal to warm himself.

Donald found Peter Rainy gossiping with a couple of the Indian servants in the barracks, and informed his attendant of the intended departure next morning. Then, he returned to the factor's house, unexpected and unaccompanied, and was admitted silently by an Indian woman, into whose hand he slipped a tiny mirror by way of recompense.

“Will you tell Miss Jean that I'm here?” he said, in the soft native Ojibway of the woman.

She nodded assent, and disappeared, only the sharp creaking of the stairs under her tread betraying her movements. For some time, then, Donald sat alone in the low-ceiled parlor. At one end of the room a roaring fire burned in the rough stone fireplace; there were a couple of tables along either wall, with mid-Victorian novels scattered over them; Oriental rugs and great furs smothered the floor, and there was even a new mahogany davenport in one corner, which the yearly ship from England had brought the summer before. While the room of the other interview was palpably that of the factor, there was something about this one, a certain pervasive touch of femininity, that marked it as that of the daughters of the house.

After a few minutes, there sounded a second creaking of the stairs accompanied by a soft rustling that was not of Indian garments. Donald rose to his feet expectantly, his finely molded head inclined in an attitude of listening, and a flickering light in his dark-blue eyes. There was a moment's pause, and then a girl entered the narrow doorway.

She was tall, slender, and dressed in gray wool, warmed by touches of red velvet at waist and throat and cuffs. Her skin was clear and soft, toned to the rich hues of perfect health by the whipping winds of the North. Her eyes, too, were blue, but of a lighter color than were the man's, while her hair, against the firelight, was a flaming aureole of bronze.

Donald caught a quick breath of admiration, as he took the hand she held out to him. Each time, it came involuntarily—this breath of admiration. Last spring, when the brigade had come to the fort after the winter's trapping; last fall, when he had gone away from the fort, after a few weeks' hazardous attentions under the malicious eyes of old Fitzpatrick; and here, again, this winter... And, as he saw her now, after their long separation, there arose in him a need as imperative as hunger, and as fierce. Years in the solitudes had instilled into Donald something of the habits and instincts of the animals he trapped, and now, as he approached thirty, this longing that was of both soul and body, laid hold of him with an unreasoning, compelling grip which could not be ignored.

“They told me you were here,” said Jean Fitzpatrick, “and I think it nice of you to give one of your precious hours for a call on me.”

“You know I would give them all if I could,” returned McTavish, simply. “I would sledge the width of Keewatin for half a day with you.”

“Donald, you mustn't say those things; I don't understand them quite, and, besides, father made himself clear about your privileges last summer, didn't he?”

McTavish looked at the girl, and told himself that he must remember her limitations before he lost his patience. For he knew that, despite her pure Scotch descent, she had never been more than two days' journey from Fort Severn in all her life. The only men she had ever known were Indians, half-breeds, French-Canadians, and a few pure-white fort captains like himself. And of these last, perhaps three in all her experience had been worthy an hour's chat. And, as to these three, orders emanating from the secret councils in Winnipeg had moved them out of her sphere before she had more than merely met them.

Innocent, but not ignorant (for her eyes could see the life about her), she was the product of an unnatural environment, the foster-child of hardship, grim determination, and abrupt destiny. Donald remembered these things, as, with less patience, he recalled the fact that old Fitzpatrick was opposed to Jean's marrying until Laura, the elder sister, had been taken off his hands. This had been intimated from various sources during the turbulent weeks of the summer, and Jean was now referring to it again.

Had old Fitzpatrick possessed the eyes of Jean's few admirers, he would have laid the blame for his predicament on his angular first-born, where it belonged, and not on the perversity of young men in general.

“Look here, Jean,” said Donald, after grave consideration. “You are old enough to think for yourself—twenty-four, aren't you?” The girl nodded assent.

“Well, then,” he continued, “please don't remind me of what your father said last summer, if it is in opposition to our wishes and desires.”

“I wouldn't if it was in opposition to them,” she retorted, calmly. He looked at her with startled eyes, a sudden, breathless pain stabbing him.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“I mean, Donald,” she replied, looking at him squarely with her fearless, truthful eyes, “that last summer was a mistake, as far as I am concerned.”

“Jean!” McTavish rose to his feet unsteadily, his face white with pain. “Jean! What has happened? What have I done? What lies has anyone been telling you?” He spoke in a sharp voice; yet, even in the midst of his bewilderment, he could not but admire her straightforward cutting to the heart of the matter. There was no coquetry or false gentleness about her. That was the pattern of his own nature and he loved her the more for it.

She shrugged her shoulders in the way he adored, and smiled wanly.

“There's an Indian proverb that says, 'When the wind dies, there is no more music in the corn,'” she replied. “There is no more music in my heart, that is all.”

“What made it die?”

“I can't tell you.” bash: /p: No such file or directory “Evil reports about me?” he snarled suddenly, drawing down his dark brows, and fixing her with piercing eyes that had gone almost black.

“Not evil reports; merely half-baked rumors that, really, had very little to do with you, after all. Yet, they changed me.” She was still wholly frank.

“Who carried them to you?” he demanded tensely, the muscles of his firm jaws tightening as his teeth clenched. “Tell me who spread them, and I'll run him to earth, if he leads me through the heart of Labrador.”

“I don't know,” she returned earnestly, rising in her turn. “That's the trouble with rumors. They're like a summer wind; they go everywhere unseen, but everyone hears them, and none can say out of which direction they first came or when they will cease blowing. I don't know.”

Baffled, shocked, embittered, Donald turned passionately upon her.

“You don't know what was in my heart when I came here to-day,” he cried. “You don't know what has been in it ever since the fall when the brigade went south. I need you. I want you. This winter, everything has gone against me, but the thought of your sympathy and affection made those troubles easy to bear. I stand now under the shadow of such a despicable thievery as the lowest half-breed rarely commits. They say I cache and dispose of furs for my own profit—I, in whom honor and loyalty to the Company have been bred for a hundred years. Tomorrow I start out on the almost hopeless task of proving myself innocent. And not only that! A half-breed in my district, Charley Seguis, has murdered an Indian, and I, as captain of Fort Dickey, must run him to earth, and bring him back here, if I can get the drop on him first. If I can't—but never mind that part of it. My honor and even my life are at stake, but those are little things, if I know you love me. I wanted to go away to-morrow with the knowledge of your faith in me, and the promise that, when I came back, we might be married. Oh, Jean, I need you, I need you, and now—” He broke off abruptly.

The girl had paled beneath her tan. She stood looking at him, her hands gripped tightly together in front of her, her eyes wide with wonder and perplexity.

“I can't help it, Donald,” she said, in a low voice. “I'm sorry, truly I am sorry. I—I didn't know these things. And, perhaps, you'll be shot, you say? No, that must not be. You must come back, even if things aren't what they were.”

“You do care for me!” cried McTavish eagerly, Stepping toward her.

“Yes, yes, I do; but not the way you mean,” she stammered, a sudden instinctive fear of his masculine domination rising in her. “I can't marry you now, or when you come back, or—ever!”

The fire in the man's eyes died out; his frame relaxed hopelessly, and he fumbled for his fur cap.

“I'm sorry I spoke, Jean,” he said, stretching out his hand. “Good-by.”

Suddenly, the door leading into the rear room opened, and in the frame stood the heavy figure of Angus Fitzpatrick, his eyes glittering under the beetling white brows. For a silent moment, he took in the scene before him.

“Jean,” he said harshly, “what does this mean? You know my orders. Do you disobey me?” The girl flushed painfully.

“Mr. McTavish is going now, father,” she said, quietly. “I'm sending him away.”

“I'll look to that Indian woman,” muttered Fitzpatrick. “She had orders not to admit him.” Then, aloud:

“Mr. McTavish, in the future, kindly do not confuse your business at this factory with your personal desires. I do not wish it.”

“Very well,” replied the captain impersonally, without looking at the factor.

His eyes were fixed hungrily upon the face of the girl, searching for a sign of tender emotion. But there was none. Only confusion, fear, and surprise struggled for mastery there. Hopelessly, he bowed stiffly to her, and went out of the door.

Crossing the courtyard by a path that was a veritable canyon of snow, he gained his quarters in the barracks. There, he found Peter Rainy, gaunt and with a wrinkled, leathern face, starting to gather the packs for the early start next morning. Donald filled and lit his pipe solemnly, and then sat down to ponder.

Something intangible and ill-favored had been streaked across the clean page of his life. Angus Fitzpatrick's increasing malice toward him was not the sudden whim of an irascible old man. He knew that, all other things being equal, the factor was really just, in a rough and ungracious way. Any other man in the service would have hesitated long before accusing him, with his father's and grandfather's records, glorious as they were, and his own unimpeachable, as far as he knew. Some event or circumstances over which he had no control had raised itself, and defamed him to these persons who held his honor and his happiness in their hands. This much he sensed; else why had the factor taken such half-hidden, but malicious, joy in sending him forth on these two Herculean tasks; else, why had the rumor poisoned the mind of Jean against him, and held her aloof and unapproachable?

That Jean should not love him under the circumstances did not surprise him, but he groped in vain for an explanation of old Fitzpatrick's evident hatred. The old factor and the elder McTavish, now commissioner, had known each other for years, the latter's incumbency of the York factory having kept them in fairly close touch. This in itself, thought Donald, should be a matter in his favor, and not an obstacle, as it appeared to be. Pondering, searching, he racked his weary brain feverishly until Peter Rainy unobtrusively announced that dinner was ready. Then, occupied with other things, he put the matter from his mind.

The sluggish dawn had barely cast its first glow across the measureless snows when Rainy roused him from heavy sleep. After a breakfast of boiled fat, meat, tea and hard bread, they gathered the four dogs together, and with much difficulty got them into traces. Mistisi, the leader, a bad dog when not working, strained impatiently in the moose-hide harness. Donald, when the packs had been strapped securely on, gave a quick final inspection, and then a word that sent the train moving toward the gate in the wall.

But few men were about, and an indifferent wave of the hand from these sped the party on its way. Outside the gate, Peter Rainy took the lead, breaking a path for the dogs with his snowshoes, while McTavish walked beside the loaded sled. Their course ran westward up the frozen Dickey River, which now lay adamant beneath the iron cold and drifting snow. Forty miles they would follow it, to the fork that led on the north to Beaver Lake, and on the south to Bolsover. Taking the south branch, they would then struggle across the wind-swept body of water, and follow the river ten miles farther, to a headland upon which stood the snow-muffled block-house of Fort Dickey.

If you draw a straight line north from Ashland, Wisconsin, and follow it for six hundred and fifty miles, you will find yourself in the vicinity of Fort Dickey, in the midst of the most appalling wilderness on the face of the globe. In that journey, you will have crossed Lake Superior and the great tangle of spruce that extends for two hundred miles north of it. North of Lake St. Joseph, which is the head of the great Albany River, whence the waters drain to Hudson Bay, you will strike north across the Keewatin barrens: Bald, fruitless rocks, piled as by an indifferent hand; great stretches of almost impenetrable forest, ravines, lakes, rivers, and rapids; all these will hinder and baffle your progress. Add to such conditions snow, ice, and eighty degrees of frost, and you have the situation that Donald McTavish faced the day he left Fort Severn.

“What do you know about this murder?”

Donald sat at the dinner table in Fort Dickey with John Buller and Pierre Cardepie, his two assistants. A roaring log fire barely fought off the cold as they ate their caribou steak, beans, bread, and tea.

“Not much,” replied Buller. “The day after you left, one of the Indians tore in at midnight with the news. He said that he and his partner, the murdered man, had been met by Charley Seguis while running their trap-line, and that Charley had drawn the other aside in private conversation. Half an hour later, there had been sudden words, followed by blows, and, before Johnny could defend himself, Seguis had stabbed him. What they had been talking about the Indian didn't know, for Charley had hurried off immediately after the murder.”

“What direction did he take?” asked McTavish.

“The rumor declared that he went north, toward Beaver Lake.”

“Could he give any motive for the deed?”

“No. So far as he knew, Johnny had never seen Charley Seguis before.”

“Well, boys, I'm off in the morning after him. The factor is particularly keen for having him brought in right away. He also wants to know what I have done with all the furs that he claims have disappeared from this district during the last year.” Donald's tone was contemptuous.

“I didn't know any had disappeared,” said Buller, in amazement.

“Nor me! I tink dat Feetzpatreeck ees gone crazy in hees old age,” added Cardepie, with a snort.

“Well, whatever it is, he claims the Company has lost twenty thousand pounds, and that I'm to blame for it,” said Donald.

“There's something wrong here, Mac,” remarked Duller, decisively. “This isn't all accident, and, if you say so, I'll go with you to-morrow.”

“It's awfully good of you, John, but I think I'll tackle it alone.” And McTavish wearily rose from the table.

The next morning, he again took the trail, but this time alone. On his feet were the light moose-webbed snowshoes; from head to heel, he was clad in white caribou such as the Indian hunters affect, and on his capote he bore the branching antlers that were left there as a decoy for the wary animals. With a long whip in one hand and his rifle held easily in the other, he strode beside the straining dog-train. In the east, the frost-mist hung low like a fog. In the south, the sun, which barely showed itself above the horizon each day, was commencing to engrave faint tree shadows on the snow. The west was purplish gray, but the north was unrelenting iron. There was no beaten path to guide him now, and sometimes the trees were so closely set as barely to permit the passage of the sledge. On the new snow could be seen the dainty tracks of ermine, and beside them the cleanly indented marks of a fox. There were triplicate clusters of impressions, showing where the hare had passed, and occasionally the huge, splayed imprints of a caribou. But, though the life of the wild creatures was teeming at this season, there was no sound in all the leagues of forest, except the sharp crack of some freezing tree-trunk and the noise of Donald's own passage.

Late in the afternoon the traveler found the cabin of a white trapper for which he had started that morning.

“Can you tell me where Charley Seguis is?” he asked.

“Went north, toward Beaver Lake, three days ago,” replied the other, shortly. “He stopped here on his way up, and said he was looking for better grounds.”

“Going to set out a new line of traps then, was he?”

“Yes, Mr. McTavish,” assented the trapper.

“Thanks,” said McTavish, gathering up the whip. “I must be going.”

“What! Going to travel all night? Better stay and bunk with me.”

“Can't do it, friend.” And a few minutes later, the captain of Fort Dickey was on his way again.

He knew that Charley Seguis had three days' start of him. He knew also that Charley was an exceptionally intelligent half-breed, and would travel well out of the district before allowing himself breathing space. McTavish intended surprising him by the swiftness of pursuit. So, lighted on his way by the brilliant stars and the silent, flaunting banners of the northern lights, he plodded doggedly on until midnight. Then he built a fire, thawed fish for the dogs, and prepared food for himself, finally lying down on his bed of spruce boughs, his feet to the flames.

Two hours before dawn found him shivering with bitter cold, and heaping logs upon the fire for the morning tea; and, while the stars were fading, Mistisi, his leader, plunged into the traces for the long day's march. It was grilling work. The cold seemed something vital, sentient, alive, which opposed him with all its might. The wind and snow appeared cunning allies of the one great enemy; and, to make matters worse, the very underbrush and trees themselves apparently conspired against this one microscopic human who dared invade the regions of death.

But Donald McTavish was not thinking of these things as he toiled north. His mind was centered on Charley Seguis, the Indian, the man who must be conquered. There lay his duty; hazardous, fatal, perhaps; but still his duty. It was the first law of the company that justice should be infallible among its servants, and right triumphant.

Donald crossed the tracks of two hunters that morning, but saw no one. By this time, he was well into the Beaver Lake district. Seventy-five miles north were the low, desolate shores of Hudson Bay, and as many miles directly east lay Fort Severn. At the thought, a short spasm of pain clutched his heart, for he could not forget that the lonely post contained the world for him.

The splendors and luxuries of civilization in great cities were as nothing to him now. Only the vast wild, and this one wonderful creature of the wild, Jean Fitzpatrick, spoke to him in a language that he understood. He had vague recollections of operas and theaters and dances, and all the colorful life of Montreal and Winnipeg; but they only stirred within him a sense of imprisonment and unrest.

“Better to fight and die alone in the deep woods than to live all one's life as a jellyfish,” was the concise fashion in which he summed the matter up.

At two o'clock that afternoon McTavish consulted a map he had made of the district near Fort Dickey, and laid his course for the trapping shanty of an Indian called Whiskey Bill. It was on the bank of a little beaver stream that debouched into Beaver River. The stream was frozen to a thickness of three feet, and Donald drove his dog team smartly down the snow-covered ice, riding on the sledge for the first time in many hours. But he finally arrived at Whiskey Bill's shanty only to find the place deserted, and the little building slowly disintegrating under the investigations of animals.

“That's funny,” thought Donald uncertainly. “I can't understand it at all. He said he was coming in to his old shanty on this fork of the Beaver when the fall trapping began.”

He closely examined the rickety structure. It showed signs of having been inhabited up to a month previous. The woodsman shook his head in uncertain amazement, and again consulted his map. Ten miles father east, on the north shore of Beaver Lake, lived a Frenchman named Voudrin.

McTavish cracked his whip over the dogs' backs, and, leaping on the sledge as it passed, shot down the river to the big lake. But there, after a swift trip of an hour and a half, he found the same conditions. Voudrin's cabin, however, showed signs of more recent occupancy than had Whiskey Bill's. A pair of snowshoes bound high against the wall, an old pair of fur gloves, and a few pots and pans, indicated that the Frenchman would probably return. But, in the meantime, McTavish had these questions to answer: Where had the men gone? And why?

The swift darkness was coming on, and, in the absence of information regarding Seguis, Donald decided to spend the night in Voudrin's cabin, in the hope that the man might return by daylight. It was possible the Frenchman had a three-day line of traps, and was out making the rounds, camping in the forest trails, wherever darkness overtook him.

Though chafing at the delay and the tricks of circumstance, Donald knew that he could do no better than follow this plan, and so set about unpacking for the night and preparing food for both himself and his dogs. Soon there was a roaring fire in the stone fireplace at the end of the one-room shanty, and the odor of frying meat pervaded the atmosphere. Presently, he went outside to cut fresh spruce boughs for the rough bunk.

In the woods he heard a noise. He looked up and found himself face to face with two silent Indians, who stood looking at him gravely. Although he was not sure, he thought he recognized them as a couple of the early risers that had waved him good-by the day he started from Fort Severn. The impression was only a passing one, however.

“Well, what do you want?” demanded the Scotchman, crisply.

For reply, one of the men reached inside his hunting-coat, and fumbled a moment. Then he drew forth a scrap of very dirty, wrinkled paper, which he extended without a word.

Amazed, Donald took it and tried to read the hastily scribbled contents. The handwriting alone made his heart leap with surprise and hope. It must have been five minutes before he finished struggling in the dim light. Then, with his face puckered in a scowl of perplexity, he turned to address the bearers of the message.

They were gone. So intense had been his concentration that they had shuffled away in the darkness unnoticed.

Still scowling, Donald thrust the note into a pocket, gathered up a double armful of spruce boughs, and went inside the shanty. There, he sat down on an upturned box, and pulled forth the note again. He read:

If you wish to do the company a great service drop your pursuit of Charley Seguis and head for Sturgeon Lake. You will find there something of great importance, but what it is I have no idea, as my informants could not say. There is a gathering there, but I know nothing more than that. In sending this to you by bearers (they ought to reach Fort Dickey almost as you leave in search of Seguis), I am acting on my own responsibility. What you said the other day about my being old enough to think for myself has taken root, you see. If you profit by this suggestion I shall be happy.

Sincerely,

JEAN FITZPATRICK.

In a sort of stupefaction induced by many emotions clamoring for recognition at once, Donald sat staring at the fire while the meat burned black. In love though he was, first and foremost into his mind leaped consideration of the Company. He had been sent to hunt down a murderer. By the unwritten code, he must hang to the trail like a bulldog, even if the chase required six months and led him through the Selkirks to the Pacific. Charley Seguis must answer before a tribunal for his crime.

Now came this imperious call to drop the pursuit, and to take up something else, which was claimed to be of greater importance to the Company. That it was of great moment Donald was sure; else, Jean, a factor's daughter, would not have sent him the word. Since she sent it, why had it not been official from her father? Ah, yes; she had acted upon her own responsibility. Evidently, she had received word of this strange, new thing through the Indian woman who served her, and who hated her father. It was probably too indefinite to bring before the irascible old factor, and the girl had taken this method of protecting the Company, while at the same time giving him a chance for new laurels.

Knowing Jean's straightforward truthfulness, McTavish dared not disregard the message. He knew there was something in it, and something much more grave than either of them suspected, probably. But yet—to leave the trail of Charley Seguis! He shook his head distractedly, and came to his senses in time to rescue the pieces of caribou before they turned to cinders.

The fish for the dogs being softened to a certain pliancy, he fed the ravening animals, and then made a meal himself, sitting abstractedly on the up-ended box, his thawed bread in one hand and his chilling tea in the other. Meantime, he wrestled stubbornly with his problem. It was not until he had almost finished his first pipe that he came to a decision. Then, jumping up, he slapped his thigh, and cried aloud:

“By George! I'll do it. Charley Seguis can wait. I'll back Jean's common sense and intuition against the blue laws of the whole Hudson Bay Company.”

Presently, he began to dream over the last part of the almost impersonal letter, reading into it his own fond interpretations, and holding imaginary interviews with this girl, who looked like a saint in a stained-glass window, because of the glorious aureole of her red-bronze hair.

What a woman she was! What a woman! Innocent, clean-minded, vigorous, virile with that feminine aristocracy of perfect pureness! Ah, she was no wife for your dance-haunting young millionaire. The man who won her must fight for her, fight like a tiger for its young, fight even the girl herself, because in her unstirred nature was all the virginal resistance to surrender that belongs to a wild creature of the dim trails.

So, Donald dreamed on, while the traveling wolf-packs howled in the distance, the trees split with the report of ordnance, and the fire burned low.

From Voudrin's tumble-down shanty Sturgeon Lake was nearly a hundred miles southwest. Given rivers and lakes to traverse, McTavish could almost do the distance in a day, for Mistisi, his leader dog, was an animal of tremendous strength and remarkable intelligence. But in this wilderness of rock-strewn barrens and thick forest it would take at least two.

Leaving notice of his having occupied the cabin by marking a clean board with a charred ember, McTavish set forth again, and by the hardest kind of work covered fifty miles the first day. The second morning, finding caribou tracks, he delayed his departure until he had killed a fat cow, for his supplies were running low.

His way now led up one of the tiny tributaries of the Sachigo. At a point directly east of a little river that emptied into the southern end of Sturgeon Lake', he struck across country again until he reached this stream. From there his work was simpler, and the dogs, again on a river-bed, made fast time.

Having once determined to give up his chase of Charley Seguis temporarily, McTavish put the matter out of his mind, and bent all his energies to the work at hand. Late on the afternoon of the second day, he knew he was approaching the lake, and proceeded cautiously, hugging the banks with their dark background of forests. At length, the shore suddenly widened, and he looked across a vast expanse of glaring snow. Ten miles ahead, on the right shore of the lake, was a headland. Pointing this out to Mistisi, he set the dog's nose toward it, and climbed into the sledge. The lake seemed utterly deserted. No dark, moving figures betrayed the presence of men or dog-trains. Under cover of the growing darkness, he felt comparatively secure, and resolved to camp for the night under the lee of the headland.

And, now, a faint stirring of fear that Jean's message had been a false alarm took possession of him. If it were so, his pursuit of Charley Seguis was delayed just that much longer. No feeling of shame accompanied his thought. The certainty of ultimate success that has made the white man the inevitable ruler of wildernesses was strong in him. He merely did not like the prospect of the half-breed's additional start.

Reaching the headland, Donald halted the dogs, and disembarked. He had turned his back to unstrap the pack, when he heard a sound behind him.

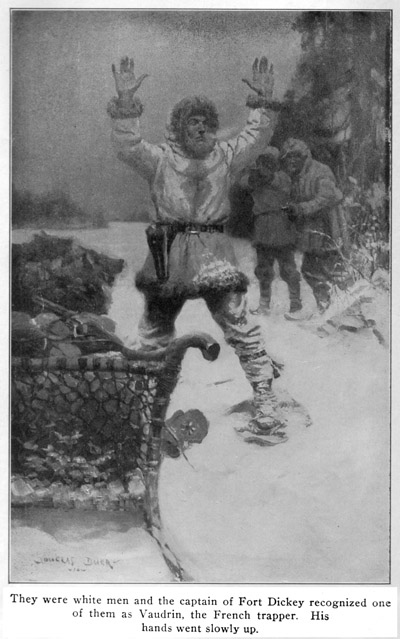

“Hands up!” said a stern voice, and, whirling, McTavish looked into the barrels of two leveled rifles in the steady hands of as many men.

They were white men, and the captain of Fort Dickey recognized one of them as Voudrin, the French trapper. His hands went slowly up.

Protected by the rifle of his companion, the other relieved Donald of the rifle, revolver, sheath-knife, and hooked-shaped hunter's knife. Then, they permitted him to lower his hands. Voudrin climbed into the sledge, and, shouting, “Marche donc, marche donc,” started the dogs around the headland. His companion followed on foot in company with the captive.

“What does this mean?” demanded McTavish savagely, his blue eyes dark with anger. “I am McTavish, of the Fort Dickey post, and, when the factor hears of this, it will go hard with you men. I am on official business, and I demand an explanation of such treatment.”

“You'll have it soon enough,” replied the other, unmoved. “You see, it isn't our idea that the factor hear of the occurrence.”

There was something cold and threatening in his tone that caused Donald to eye the fellow curiously.

“Just what do you mean by that, my friend?” he inquired.

“Don't ask so many questions,” replied the other curtly, and continued thereafter to maintain a stubborn silence.

On the far side of the headland they came upon very definite signs of civilization. Tucked into a little bay was a sort of settlement. A long, rough log house was the main building, and around it were grouped some score or more shanties such as that Voudrin had occupied on the Beaver River. On one side of the settlement, a high stockade of heavy timber was set. It appeared that it was at first intended to surround the entire group, but that the cold weather had put a stop to the work.

Voudrin, with the dog-train and sledge, was already ashore on the beach where a number of men had run down from the large main building. These now advanced over the frozen lake to greet the two on foot. McTavish looked them over with keen eyes, memorizing their faces for future use. It was not long before he located Whiskey Bill and a number of the other hunters and trappers that were frequent visitors to the Dickey River-post.

In almost total silence, the procession reached the beach, and wound up the slight declivity to the large house in the center of the settlement. Here McTavish was led inside, and discovered that the building was divided off into a number of small rooms. Into one of these he was pushed, and the heavy door swung after him. A little while later an Indian packer appeared with the traps that had been taken off his sledge, and dumped them into the room, telling him to make his own supper. Nothing was missing, even matches, and McTavish built a small chip fire such as he was accustomed to burn on the trail, taking the material from a pile of seasoned logs in one corner of the room. The floor was beaten earth as hard as a rock.

Perplexed and amazed at the mysterious goings-on about him, the Scotchman vainly sought to explain the presence of the men here, and his own extraordinary position. Not for ten years, except in the case of the pursued criminal turning at bay, had an officer in the Company been subjected to such insulting and disrespectful treatment. Here, discipline and propriety, the two cardinal virtues among the Company's servants, had been grossly violated, and by men who knew the consequences.

Discipline and propriety! On those great beams of organization had the mighty structure of the Hudson Bay Trading Company been built. It was reverence for them that caused a dozen men a thousand miles from the nearest settlement to sit down to dinner in order of precedence, and be served correctly in that order. It was reverence for them that caused traders to thrash insolent Indians two years after their insults had been spoken!

And these men had violated all the canons of this discipline, frankly and completely, knowing the penalty, but evidently utterly careless of it. McTavish could not but feel a certain admiration for their daring. To him, as to nearly all of its servants, the Company was a huge, unseen, intangible force; a stern monster that demanded of its subjects such loyalty and unfaltering obedience as patriots rarely give their country's cause. A stern, but kindly, master in good repute, and a grim, relentless avenger in ill.

When he had finished his meal, Donald McTavish filled his pipe, and lay along the ground on his couch made of robes, awaiting events.

Barely half an hour later, footsteps sounded outside the door, and a pounding upon it brought him to his feet. Presently the timbers swung back, and a man stood in the opening.

“Come with me,” the newcomer said, and McTavish preceded him down the narrow corridor that ran the length of the long building.

Two-thirds of the distance they had walked, when suddenly the walls fell away, and Donald found himself in a large, low room, bare-floored and cheerless, that occupied the other third. Smoky torches of wood standing out from crevices in the logs gave light, and around the wall he could see perhaps fifty men, standing or squatting. Directly before him at the opposite end was a sort of low platform, on which a huge stump served for a table, and another smaller one, behind it, for a chair. A lone man stood there, looking at him. Owing to the smoke and the dim light, McTavish could not at first make out his features. Then, with a start of amazement he recognized him. It was Charley Seguis.

How had he got here? What was he doing here, this intelligent half-breed? These and a hundred other questions flashed through the prisoner's mind.

Suddenly, Seguis began to speak. He was a tall, finely-formed man, with a clearness of cut to his features that betokened English parentage on the one side, and the blood of chiefs on the other.

“We are in council to-night to decide what to do with Captain McTavish,” he said slowly, using the excellent English at his command. “How he has come here, I do not know. Who told him of the Free-Traders' Brotherhood, I do not know. As one man against another, we have nothing against him. He was always good to us, and gave us large presents for our best skins. But he is one of the Hudson Bay men, and, therefore, something must be done. It must be done quickly. We are in council; each man shall have his say.”

Donald's eyes had become more and more accustomed to the dimness in the huge room. Now, looking about, he saw great bales of pelts piled indiscriminately, thousands and thousands of dollars' worth. So, these were free-traders! This was the magnet that had drawn the hardy trappers from their allegiance to the Hudson Bay! He shrugged his shoulders. Whatever happened to him, it was they who would suffer in the end, for this mighty, intangible thing, the Company, did not look kindly upon free-traders. Ever since 1859, when the monopoly legally expired, free-traders had been at war with the great concern, and in the Northwest had established a brisk and growing competition.

But here, in the vast district between Labrador and the west shore of the bay, their invasions had, without exception, met with failure. More than that, those brave men who had undertaken to beard this lion in his iron wilderness had very rarely returned to tell the tale of the bearding. Warned once or twice, the more timid retired, baffled and unsuccessful. Persistent, the trader fell a victim to gun “accidents,” canoe “upsets,” or even starvation carefully engineered by unseen, but competent, agents.

All these things were traditions of the Company, and McTavish had been brought up on them. He had never taken part in such doings, but he was certain in his own mind that they were not all fiction, for such fictions do not spring to life miraculously in regions where emotions are naked and primitive, and existence is pared down to the raw.

Here were men who had evidently banded themselves into a Free-Traders' Brotherhood. How many had enlisted in its ranks besides those in this room, he had no idea; perhaps there were hundreds. It had evidently been well organized, for it had taken shape with amazing swiftness and certainty.

Jean had been right. This was more important, vastly more important, than the pursuit of a renegade half-breed... But that half-breed was himself at the head of the organization.

“That's what half an intelligence will do for a man!” said McTavish to himself, with contempt. “This fellow is just bright enough to be better than his class. He therefore immediately sets himself up as a leader to buck the Company. God help him!”

But the captain's thoughts almost immediately turned to his own case. What was that old Indian saying? He listened.

“In the past history of the Company, when a rival appeared, there had been much killing. Murder, violence, Intrigue, conspiracy—all these have flourished when a rival took the field. We may look for them now, and he who strikes first forestalls the other. It is, of course, impossible for this Captain McTavish to reach Fort Dickey or Fort Severn again. Three sentences from him, and we are discovered, and the chase begun. We are not strong enough yet for open conflict. By spring, perhaps, but not now. McTavish must never tell. A strong arm, a well-directed blow—”

“But, my good brother, you do not counsel murder in cold blood?” asked Seguis, in a tone of horror. “To kill our old friend, Captain McTavish, because he has happened to come upon us here—oh, no, no, no! It is impossible. But, yet,” he added, “he must not tell what he has seen.”

He turned to McTavish.

“Will you give an oath never to reveal what you have seen and heard here?”

“No,” Donald said bluntly. “I won't.”

“By refusal, you sign your own death-warrant,” warned the half-breed, not unkindly. “For the sake of all of us, give this oath.”

“Seguis,” replied Donald, just as quietly, “you know you ask the impossible. Let's not waste any more time over it. Decide what you are going to do with me—and do it!”

“Why not keep him with us here a prisoner?” suggested an old buck; only to be cried down loudly as a doddering dotard, whose blood had turned to water.

“What?” one shouted, wrathfully. “Have another mouth to feed all winter, while the owner of it stays idle? Never! Anyone that eats with us must work.”

For a long minute, Seguis sat with his chin in his hand, meditating. Then, he ordered Donald's captors to take their prisoner back to the little room, saying:

“I have a plan in mind, which we must discuss—privately, out of the captain's hearing.” He turned to the Hudson Bay man, and spoke decisively: “You shall hear our decision to-night, sir, whatever it is.”

Without answer, Donald wheeled, and walked away in the company of his guards to the room that served as a cell, where again he was left in solitary confinement.

It was, perhaps, an hour later when Donald, just beginning to drowse before his little fire, heard someone approach and unlock his door, for the second time that night. In anticipation of any desperate emergency, the captive sprang to his feet, and retreated to a corner of the room farthest from the door, watching with wary eyes for his visitor's appearance.

“Who is it?” he demanded, as the door was flung open.

“It's me, Charley Seguis,” was the reply, in the voice of the half-breed. Even in this moment of stress, Donald noticed half-wonderingly the mellow cadences in the voice of this man of mixed blood. While speaking, Seguis had entered the room, and he now shut the door behind him. “I come friendly,” he continued, with a suggestion of softness in his tones, though there was no lack of firmness. “I wish to talk friendly for half an hour. Will you sit with me by the fire?”

“I don't trust you, Seguis,” retorted Donald, bluntly. “If you have been delegated by lot to kill me, do it at once. That would be the only possible kindliness from you to me. I can stand anything better than waiting... I am unarmed—as you know.”

The half-breed shook his head slowly, as though in mourning that his intentions should be thus questioned.

“I don't come to harm you,” he said at last, with a certain dignity. “I've given you my word that I come friendly. I am armed, but that is to prevent your attacking me.”

Donald uttered an ejaculation of impatience.

“Absurd!” he exclaimed. “Why should I attack you?” For the instant, in realization of his own plight, he had forgotten that the original purpose of his quest had been the capture of this man who was now become his captor... But the half-breed's words recalled the fact forcibly enough.

“Don't you suppose, captain, that I've known you were on my trail for days? I have the sense to know that. But what brought you veering off the trail to Sturgeon Lake is beyond me.”

Donald heaved a sigh of relief. At least, Jean's message was unknown to the leader of the free-traders, and there would be no risk of the girl's suffering in person for her loyal zeal. In this relief, his thoughts reverted curiously to the crime he had been sent to revenge.

“Did you kill Cree Johnny?” he demanded, abruptly.

The face of the half-breed remained immobile, inscrutable.

“I'll tell you nothing about that,” was the crisp reply. “Let's talk of what is more important now, and that is yourself—and what's to become of you.”

“As you will,” Donald agreed, grudgingly. It wounded his self-esteem that this man should be able thus to manage the interview at pleasure. Yet, even while his anger mounted high, the Scotchman felt himself compelled to an involuntary admiration for the authoritative composure in the manner of one who, by the accident of birth, was no better than a barbarian—was, indeed, something worse, since the crossing of the civilized blood with the savage is usually a disastrous thing. This was the Hudson Bay man's first experience of indignity visited on himself, and, for that reason, he felt a double humiliation over the seriousness of his situation. Exasperation grew in him over the fact that even now his many and varied emotions did not include in the least such repulsion as he had imagined a tête-à-tête with a murderer must produce. On the contrary, he was aware of an indefinable air of genuineness, of nobility even, about this Montagnais Englishman. It was incredible, surely—none the less, it was true. Donald's instinct set him to wondering involuntarily whether, after all, the man before him could really be guilty of the crime charged. His reason rallied to argument that this fellow was of a vicious strain, capable of any treachery, of any cowardly violence. In such as Seguis, the vices of two races blend, for vice knows little distinction of tribe or creed; the mingling of a dozen bloods will but serve to strengthen the violence in each. The virtues, on the contrary, are matters of geography, in great part—to each race its own. They are prone to vanishing in the mixed blood. Usually, too, the civilized white man who degrades himself to mate with a savage woman is himself a wastrel, essentially evil, likely to beget nothing good.

Such reasoning is sound enough, in the main, as Donald, despite his bewilderment, knew well. Nevertheless, in this instance the product of miscegenation seemed to offer in his own person a subtle contradiction. The man stood in a serenity that proclaimed an assured self-respect. The dark eyes above the high cheekbones were glowing clearly, as they stared in level interrogation on the prisoner. The features, coarse, yet of a pleasing harmoniousness, were set in lines of a strength that was at once calm and masterful. Whatever might be the blackness hidden in his heart, the half-breed's outer seeming was one to command respect... In quick appreciation of the truth, Donald was constrained to admit that his own conduct thus far had not been of a sort to match the courtesy of his jailer.

“What do you want to say to me about myself?” he questioned, finally; his voice came milder than hitherto.

Seguis answered immediately, with directness.

“After an hour in council, I come here, delegated by the brotherhood, to make you a proposition.” His gaze met that of his prisoner fairly, as he continued: “The Hudson Bay Company is a hard master, as you know very well. It expects more, and gives less, than any other organization in the world. If it's hard to us, then it's also hard to you. After your years with the Company, do you think you've achieved the position you deserve? Certainly not! We're all agreed on that.” The half-breed appeared to hesitate for a moment, then threw back his head proudly, in a gesture of resolve, and continued with a new emphasis in his words.

“Can't you see that your superior, the factor at Fort Severn, hates you bitterly? I, myself—I've seen things there. Last summer, I was at the fort, you remember. I was there all the time you were. I watched you—and Miss Jean—”

“Stop!” Donald interrupted, furiously... He fought back his rage as best he might, and went on less violently. “Now, no more of this beating about the bush. Just say what you have to say, and begone!”

Seguis remained wholly undisturbed by the outburst. At once, he went on speaking, imperturbably:

“I was about to state,” he said evenly, “that I have noticed the factor's expression behind your back, and I want to warn you against him. He's your superior, you know, Captain McTavish. Well, then, how can you expect to rise in the Company, when he's your enemy?” He paused, waiting for a reply.

Again, Donald experienced a sensation that was akin to dismay. He had not expected such perspicacity on the part of one whom he had contemptuously esteemed as merely a savage. Moreover, in addition to his indignant confusion over the introduction of Jean's name into the conversation, there was something vastly disturbing to him in realization of the fact that his own belief of hostility on the part of the factor was thus proven by the observation of the half-breed. To hide his disconcertment, the young man ignored the question of Seguis, and spoke sharply:

“Get to the point—if there is one!”

“The point's this,” came the instant reply, uttered with a slight show of asperity; “that we, the Brotherhood of Free-Traders, offer you a position with us—at our head, if you'll take it. In other words, I'll step down to second place—if you'll step up to first.”

Donald stared at the speaker in amazement that any one should dare in such fashion to suggest the possibility of his turning traitor. Seguis, however, endured his angry scrutiny without any lessening of the tranquillity that had characterized him throughout the interview. So, since silent rebuke failed completely, the Hudson Bay official was driven to verbal expression of his resentment.

“What cause have I ever given for you to believe that I was anything but loyal to the Company?” he demanded, harshly.

“None,” Seguis admitted.

“If I've given no cause for such an idea,” Donald went on, fiercely, “what reason have you to come here and insult me with such a proposition as you've just offered?”

In his shame over a proposal that in itself contained an accusation of disloyalty, the young man had thought only for himself. He gave no heed to the significance of the suggested plan in its bearing on the one who offered it. He failed altogether to appreciate the sacrifice that Charley Seguis stood ready to make. The half-breed was, in fact, as he had just declared, at the head of the organization that called itself the Brotherhood of Free-Traders. Now, from his own announcement, he was prepared to withdraw from the chief place, in order to make room for Captain McTavish. It might well be believed that the man had gratified his life's ambition in attaining such eminence among his fellow foes of the Company, yet he was willing to renounce his authority in favor of one whom he deemed worthy to supersede him. Here, surely, was a course of action that had no origin in selfishness, but sprang rather from some ideal of duty, rudely shaped, perhaps, but vital in its influence... Yet, to all this, Donald gave no concern just now, even though at his question Seguis shrank as if from a physical blow.

Then, the half-breed straightened to the full of his height, and spoke with coldness in which was a hint of scorn under unjust accusation.

“I come to you, a prisoner and a burden on us,” he said, bitterly. “I come with courteous words, and, in return, I get insults. In spite of your attitude, I'll give you another chance for your life... Will you come into the brotherhood as its leader?”

The threatening phrase in the other's words had caught and held Donald's attention with sinister intentness.

“What do you mean?” he demanded. “A chance for my life?”

The explanation was prompt, unequivocal.

“I mean that, if you don't accept this offer, your life isn't worth—that!” With the word, Seguis snapped under his heel a twig from the little fire. “Either you stay with us, and know everything—or you go from us, to die with the secret!” The voice was monotonous in its emotionless calm, but it was inexorable.

At the saying, a chill of fear fell on Donald, a fear formless at the first; then, swiftly, taking malignant, fatal shape. Out of memory leaped tales of terror, unbelieved, yet hideous. Now was born a new credulity, begotten of dread. His face whitened a little, and his eyes widened as he regarded the half-breed with growing alarm. His voice quavered, despite his will, when he put the question that was tormenting him:

“You don't mean that you'd send me on the—on the Death Trail?” he cried, aghast. The enormity of the peril swept over him in a flood, set him a-tremble. Though he questioned so wildly, he knew the truth, and the awfulness of it put his manhood in revolt, made him coward for the moment. The Death Trail! ... He had not been prepared for that. To back against the wall, and fight to the end like a trapped animal were one thing—a thing for which he had been prepared... But, the Death Trail—!

Suddenly, with the incongruity that is frequent in a highly wrought mind, his memory slipped back through the years to the time when first he heard of this half-mythical thing, which was called the Death Trail. He had run away from his nurse in Victoria Square, in Montreal, and, after his recapture, the girl had threatened him with the Death Trail as a punishment, should he ever repeat his offense. That night, he had questioned his father, the commissioner of the Company, as to this fearsome thing... And the commissioner had merely laughed, unconcernedly.

“Oh, that, my boy!” he had exclaimed. “Why, that's an exploded yarn. Some people say the Company sent free-traders to their deaths that way. But who knows? Who can tell? I can't.”

Then, the father had added some description as to the nature of this rumored Death Trail: how a man with a knife, but no gun; snowshoes, but no dogs; and not even a compass, was turned loose in the forest with a few days' food on his back, and told to save himself—how he wandered, starving and weakened day by day, until the terrible cold snuffed out his life, or he was pulled down by a roving wolf-pack.

And it was this fate that faced Donald now... The words of the half-breed in answer to his question confirmed the dread suspicion.

“So the council has decided,” came the quiet statement, in reply to the prisoner's startled question. “We can't kill you outright. To do that would be more than flesh and blood—even Indian flesh and blood—could stand in your case, Captain McTavish. You've been our friend for three years. You have never harmed us. We've traded with you peaceably. But we can't keep you, and we can't let you return with our secret. All that's left is the Death Trail. It's the only way out for us... It has been decided on.”

“No—oh, no!” Donald cried imploringly, suddenly impassioned by the stark horror of this thing that stared at him out of the darkness. “No, I beg of you. Anything but that! Tell off a squad; take me out, and shoot me... Or, better yet, let me fight for my life, somehow!”

Seguis shook his head in denial. There was commiseration in his steady glance, but there was no suggestion of yielding in his voice as he answered.

“For our own sakes, we can't,” he explained concisely. “Any of those things would bring us to the gallows, and we can't afford that.”

“Why should you care?” Donald retorted vindictively, with futile fierceness. “You're going to swing anyway, as soon as another man can get on your trail.” He spoke with all the viciousness he could contrive, hoping by insults to arouse the fury of the half-breed, and thus provoke the fight for he longed.

But the keen mind of Seguis detected instantly the ruse, and he merely smiled by way of answer, a smile that was half-pitiful, half-mocking.

“You might try suicide,” he suggested, with an intent of kindness. “That way would spare the feelings of us all.”

It was Donald's turn to shake his head in refusal now. As yet, such an action on his part appeared impossible to him. The love of life was too strong to permit the conceivability of such a choice. He was too much the fighter to confess defeat, and so lay down his life voluntarily. The McTavishes were not in the habit of giving up any struggle before it was fairly begun... But the antagonism aroused in him by the suggestion steadied his nerves, restored him to some measure at least of his usual self-control.

“When do I go?” he asked. Face to face with the inevitable, a desolate calm fell upon him.

“To-morrow morning,” Seguis replied, stolidly. Then, abruptly, the half-breed's manner softened, and he spoke in a different tone. “We're all disappointed, Captain McTavish, that you won't join us. We've been hoping for that—not for your death. And, perhaps, you don't quite understand, after all. We're starting this brotherhood honorably, with no malice toward any man. There's still hope for you, if you'll give your oath not to divulge what you've learned here, and not to follow me in this Cree Johnny affair. If you'll do that, we'll give you your belongings, and set you on your way, and—”

Donald held up his hand, with a gesture of finality.

“You know I can't do that,” he said, drearily. “Don't make it any harder for me. I understand your position now, in a way, and I suppose I'll have to take my medicine. But let me warn you.” His tones grew menacing. “If I get out of this alive, though the chance that I shall isn't one in a thousand, you will pay the penalty for your crime.”

The half-breed showed no trace of disturbance before the threat, but moved away toward the door.

“I'll take the risk of that,” he said quietly; and he went out of the room.

Left to himself, Donald fell a prey to melancholy brooding for a few brief moments, then resolutely cast the mood off his spirit. He was little given to morbid reflections. Men whose lives are daily liable to forfeit rarely are. It was characteristic of him that, in this supreme hour of peril, his chief distress was over the injury wrought on the Company he served, for which he was about to lay down his life. If only he might send warning! If only, even in his last minutes of life, he might meet a friendly trapper, tell the great news, and send a messenger speeding north to Fort Severn, or east to Fort Dickey! That much accomplished, he could resign himself to die. ... Such the loyalty and devotion that this grim, silent, far-reaching thing, the Company, breeds in its servants!

Of a sudden, another thought brought new bitterness to his soul, for, despite all the masterfulness of his loyalty to the Company, he was yet a man and a lover with a heart brimming over fondness for the one woman. Now, it came to him that, were he indeed to die somewhere out there in the wilderness, starved, frozen, alone, Jean would never know how his last act had been in the faithful following of her command. No, she could never know the truth concerning his fate. There was poignant torment in the thought. It might be months, years even, before his bleached, unrecognizable skeleton would be found somewhere in the remotest waste, with the bones of a wolf or two beside it, to indicate his desperate last stand.

With difficulty, McTavish shook off the evil thoughts that preyed upon him, and stretched his blankets and robes on the hard earth. Then, he cast more wood on his fire, and wrapped himself snugly, covering his head completely, Indian fashion, to prevent his face from freezing.

It was an hour before sleep came to him, and it seemed to him that he had scarcely dropped off when he felt himself shaken by the shoulder, and told to get up.

For a moment, Donald did not realize where he was, then the horrid truth rushed in upon him with sickening reality, and he sat up, blinking. His companion, he saw, was an Indian, who began to cook breakfast over the fire, upon which he had thrown more wood immediately after his entrance.

McTavish forced himself to eat heartily this last full meal he was, perhaps, ever to know. Then, obeying the guttural words of the Indian, he made his blankets into a pack, and unfalteringly followed outside.

There, the men were gathered around a dog-train, with two trappers, who, McTavish knew instinctively, were to be his companions for a distance into the wilderness. Throwing his blankets on the sledge, where he observed also a small pack of provisions, he climbed aboard.

Now, Charley Seguis appeared, and offered the Hudson Bay man a last chance. But Donald waved him aside, and requested that the start be made at once. Then, without a sound except the tinkling of the bells on the dogs' harness, the train got under way, and the last thing the Scotchman saw as he plunged into the woods was the silent group of men looking after him from in front of the big log house.

Straight north they took him, into the wildest country of all that desolation. Through forest aisles, beside great expanses of muskeg, over barren rock ridges, wound the unmarked trail. An army of caribou, drifting south in the distance, was all the life the doomed man saw in that long morning. Even the small live creatures seemed to have deserted this maddening region.

At noon, they camped for an hour, and then, with scarcely a word, took up the trail again. At last, when the darkness had begun to come, one of the Indians halted the dogs, and motioned McTavish off the sledge. While he was turning the dogs around, the other laid the victim's pack on the snow and presented two knives—the long, crooked hunter's knife, and the straight sheath-knife.

Then, with a grunt, they “mushed” the dogs on the back trail, and left the Hudson Bay man alone for his grapple with the wilderness.

For a time, he stood there dazed. Then, the realization of his doom rushed upon him, and, in mute desperation, he made a few swift steps after the departed sledge as though he would overtake it. But, in a moment, he recovered himself, and went back to where his pitiful belongings rested on the crusted snow. The stern resolve, the iron will that had made the McTavishes great, each in his generation, returned to him, and, without a word, he faced forward upon the Death Trail.

Morning found the world swathed in a great blanket of white. Snow that started as Donald made camp had fallen steadily through the dark hours, so that now rock and windfall and back trail were obliterated. Even the pines themselves were conical ghosts. As though he had been dropped from the skies, McTavish stood absolutely isolated in the trackless waste.

There was light upon the earth, but the leaden clouds diffused it evenly, so that he could not distinguish east from west, or south from north. If there had ever been a trail blazed here, the big snowflakes had long since hidden the notches in the bark.

Mechanically, the man reached into his pack for the compass he carried. A moment's search failed to reveal it, and he suddenly stood upright again, cut through with the knowledge that it had been taken from him.

How should he tell directions? How make progress except in fatal circles?

Looking up at the snowy pine-tops, he scrutinized them carefully. Their tips seemed to lean ever so slightly in one direction. Fearful lest his eyes had deceived him, he closed them for a few moments, and then looked again. The trees still leaned slightly to the right. He tried others, with the same result. Good! That was east! Ever in nature there is the unconscious longing for the life-giving sun, and it was in yearning toward its point of rising that the trees betrayed the secret. Here and there, tufts of shrub-growth pointed through the snow in one direction. That, he knew, should be south, and yet he must prove it. With his snowshoes, he dug busily at the base of a tree until he found the roots running into the iron ground. Circling the trunk, he at last found the growth of moss he was hunting. He compared it with the pointing tufts of shrub-growth, and found that his theory had been proven. For moss only grows on the shady side of trees, and in the far northland this is the north side, the sun rising almost directly in the south, except during the summer months.

With the north to the left, McTavish passed his pack-strap about his forehead, and started on the weary march. He knew that somewhere before him was Beaver Lake, and he remembered that there were two or three trappers along its shores. Just where they were, he could not specify, for his private map had been taken from him at the time his pack was made up. If they were loyal to the Company, he had a bare chance of reaching them; if, as he supposed, they belonged to the brotherhood—He did not finish out the thought. He was certain they were not loyal, else his exile would have been south instead of north.

As he toiled along, foxes whisked from his path, their splendid brushes held straight behind them; snow-bunting and chattering whiskey-jacks scattered at his approach. Clever rabbits, their long ears laid flat, a dull gleam in their half-opened eyes, impersonated snow-covered stumps under a thicket of bristling shrubs.

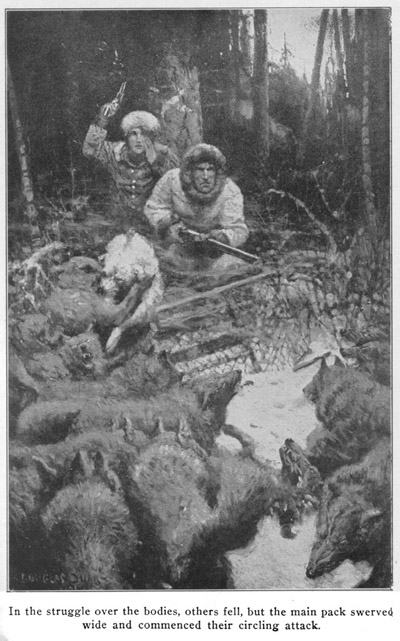

With every hour, Donald thanked Providence that he had not heard the howl of a traveling wolf-pack, for a man well armed is no match for these ham-stringing villains once they catch him away from his fire, and a man with only two knives has his choice of starvation in a tree, or quick death under the gleaming fangs.

A little after noon, the wanderer reached a ravine, and stopped to make tea in its shelter. Above him, and leaning out at a precarious angle, a pine-tree, heavily coated with snow, seemed about to plunge downward from the weight of its white burden. Taking care to avoid the space beneath it, the man built his little fire, and boiled snow-water. He ate nothing now, having reduced his food to a living ration morning and evening. Having drunk the steaming stuff, he was about to return the tin cup to the pack when a rustling, sliding sound aroused him. He turned in time to see a great mass of snow from a tree higher up fall full upon the overloaded head of the protruding pine. The latter quivered for a moment under the impact, and then, with a loud snapping of branches and muffled tearing of roots, fell crashing to the crusted snow beneath, leaving a gaping wound in the earth.

McTavish looked with interest. Then, his jaw dropped, and his eyes widened in terror, for, bursting out of the hole, frothing with rage, came a huge bear, whose long winter nap had been thus rudely disturbed.

For an instant, blinded by the glare of the gray day, the creature stopped, rising on its hind legs and snarling fearfully. Donald, petrified with surprise, stood as though rooted to the ground. A moment later, the bear saw the man, and, without pause, started for him.

From an infuriated bear, there is but one means of escape—speed. In a flash, McTavish knew that he could outstrip the clumsy animal, for the latter would constantly break through the thin crust of the snow. But, in the same flash, he realized what escape would mean. His pack lay open. The hungry animal would rifle it completely, gulp down the priceless fat meat, and strew the rest of the provisions about. Then, the bear would go back to bed; the man would starve, and freeze to death in two or three days.

No! Running was out of the question.

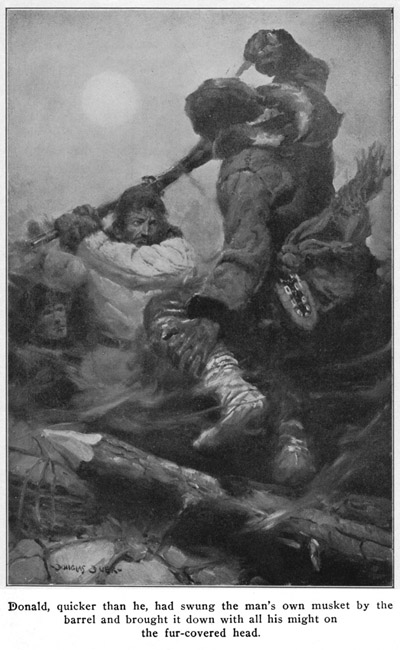

Donald's doom had suddenly crystallized into a matter of minutes. To think with him was to act. Instantly, he drew his two knives, the long, keen hunter's blade in his right hand, the other in his left.

And, now, the bear was but twenty feet away, and coming on all-fours, its eyes gleaming wickedly, its mouth slavering. At ten feet, it suddenly rose on its hind legs, and then McTavish acted. With two swift, sliding steps forward on his snowshoes, his face was buried in the coarse fur of the animal's chest before the creature had fathomed the movement.

Then, the knives played wickedly. The long one in the right hand shot to the hilt in the heart; the one in the left went deep into the throat, and McTavish slipped downward before the great clasp —which would have broken his back—could close upon him... Turning, he ran as he had never run before.

But there was little need. The bear, stricken in two vital spots, coughed hoarsely once or twice, spraying the clean snow scarlet, and dropped on all-fours. There, it swayed a moment, suddenly turned round and round swiftly, and fell motionless.

The victor approached cautiously. The animal was dead. The man withdrew his two knives, and, with all haste, skinned the animal in part, for now another danger presented itself. Although he had pushed starvation several days away, yet the smell of the kill would draw the wild folk, particularly the wolves. Quickly, he cut what he could safely carry of the choicest meat, and bestowed it in the pack, taking every precaution that no blood should drip along his trail. Then, he slipped the strap into place across his forehead, and sped eastward... And now, instead of the dread companions—fear and starvation—that had dogged his footsteps, he ran hand in hand with hope.

Morning brought him out of the forest to the open prairie, fortunately a fairly level tract of land. This meant fast going, and McTavish, stronger than he had been for many hours past, on account of a hearty meal of bear meat, swung off across the crust at a kind of loping run. He did not walk now, but went forward on long, sliding strokes that would have kept a dog at a fast trot. Far, far in the distance, he saw the friendly shelter of woods, and, with eyes on the hard snow-crust beneath him, laid a course thither. Here on the prairie, the crust was the result of the soft Chinook west winds that came across the ranges, and melted the snow swiftly—only to let it freeze again into a sheathing of armor-plate.