The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Boys of ’98 by James Otis

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Boys of ’98 Author: James Otis Release Date: December 15, 2009 [Ebook #30684] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOYS OF ’98***

THE BOYS OF ’98

STORIES of

AMERICAN HISTORY

By James Otis

| 1. | When We Destroyed the Gaspee |

|---|---|

| 2. | Boston Boys of 1775 |

| 3. | When Dewey Came to Manila |

| 4. | Off Santiago with Sampson |

| 5. | When Israel Putnam Served the King |

| 6. | The Signal Boys of ’75 (A Tale of the Siege of Boston) |

| 7. | Under the Liberty Tree (A Story of the Boston Massacre) |

| 8. | The Boys of 1745 (The Capture of Louisburg) |

| 9. | An Island Refuge (Casco Bay in 1676) |

| 10. | Neal the Miller (A Son of Liberty) |

| 11. | Ezra Jordan’s Escape (The Massacre at Fort Loyall) |

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

Publishers

Estes Press, Summer St., Boston

Illustrated by

J. STEEPLE DAVIS

FRANK T. MERRILL

And with Reproductions of Photographs

ELEVENTH THOUSAND

BOSTON

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Battle-ship Maine | 1 |

| II. | The Preliminaries | 19 |

| III. | A Declaration of War | 38 |

| IV. | The Battle of Manila Bay | 64 |

| V. | News of the Day | 92 |

| VI. | Cardenas and San Juan | 117 |

| VII. | From All Quarters | 130 |

| VIII. | Hobson and the Merrimac | 149 |

| IX. | By Wire | 171 |

| X. | Santiago de Cuba | 194 |

| XI. | El Caney and San Juan Heights | 224 |

| XII. | The Spanish Fleet | 254 |

| XIII. | The Surrender of Santiago | 290 |

| XIV. | Minor Events | 302 |

| XV. | The Porto Rican Campaign | 320 |

| XVI. | The Fall of Manila | 335 |

| XVII. | Peace | 345 |

| Appendix A—The Philippine Islands | 355 | |

| Appendix B—War-ships and Signals | 370 | |

| Appendix C—Santiago de Cuba | 379 | |

| Appendix D—Porto Rico | 383 | |

| Appendix E—The Bay of Guantanamo | 386 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | ||

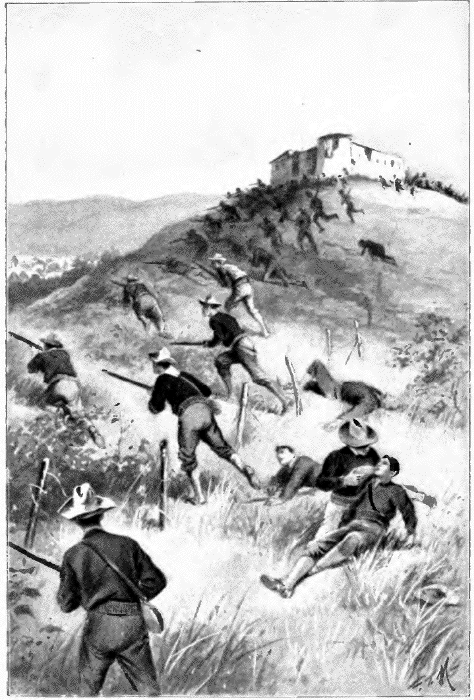

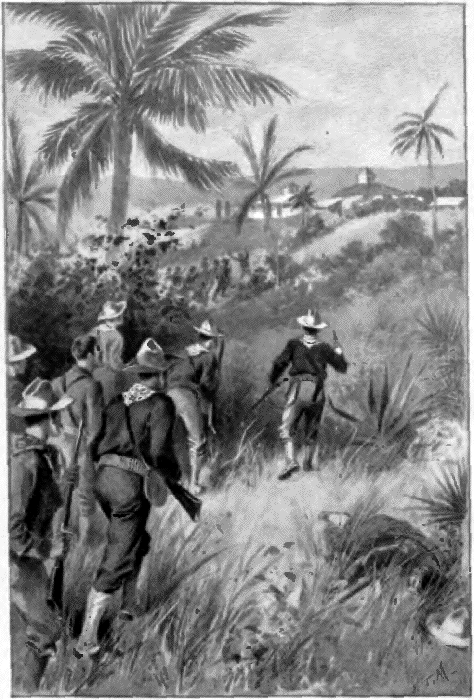

| The Charge at El Caney | Frontispiece | |

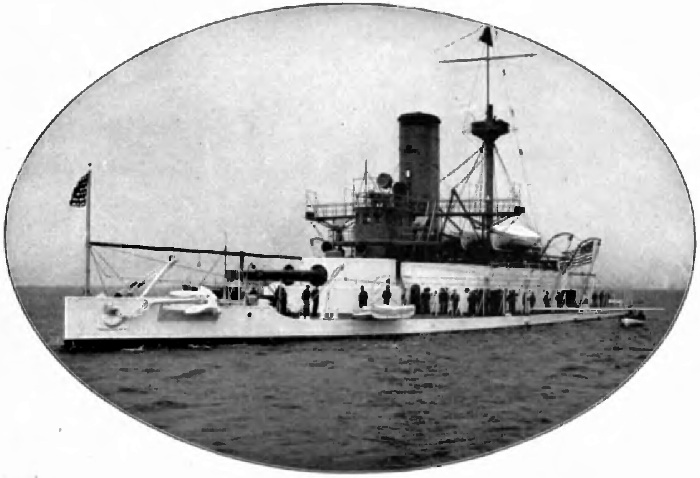

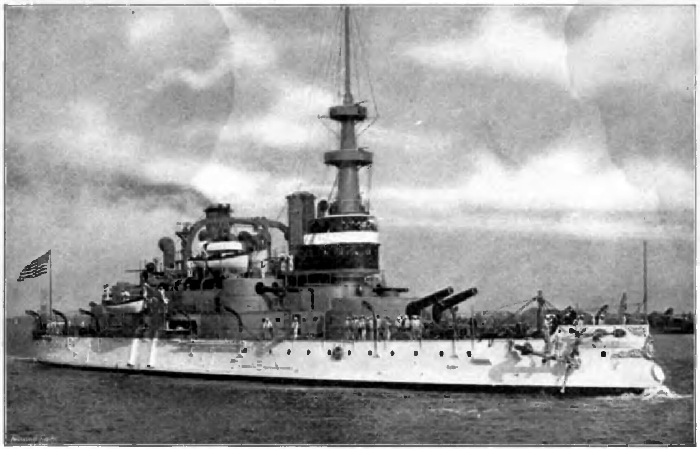

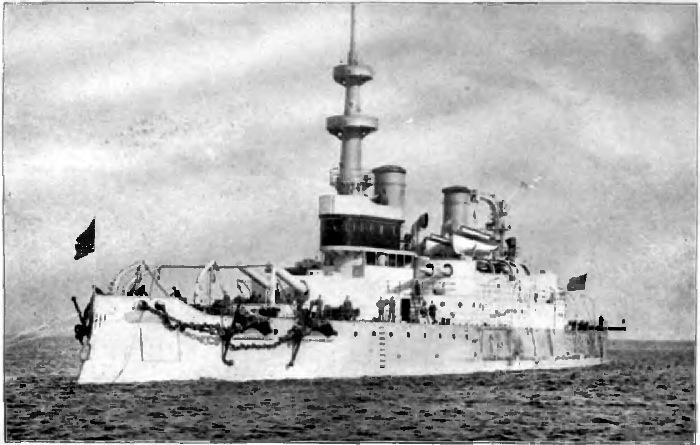

| U. S. S. Maine | 7 | |

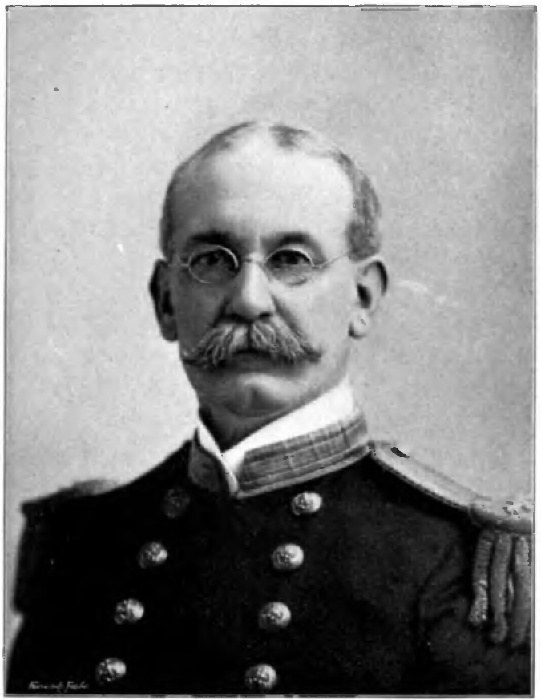

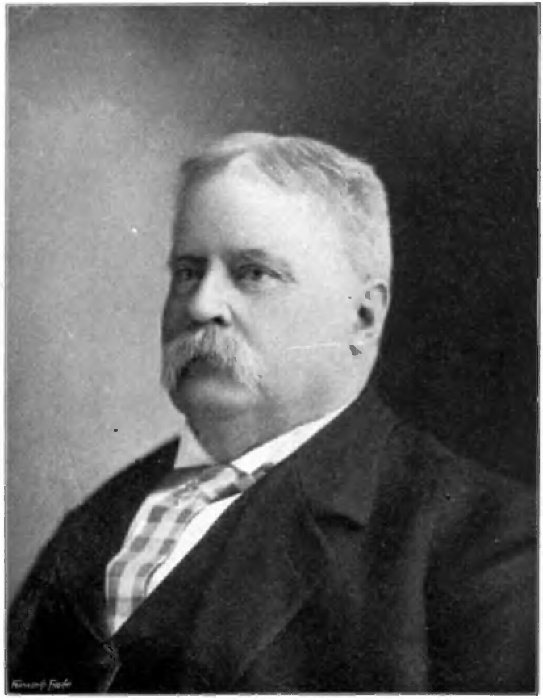

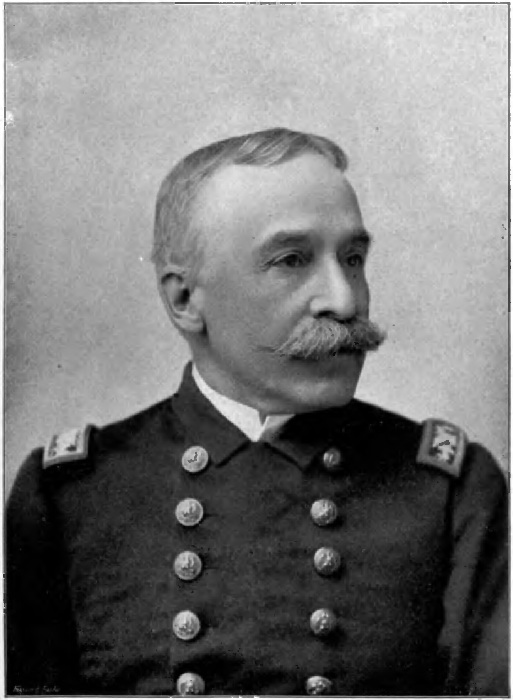

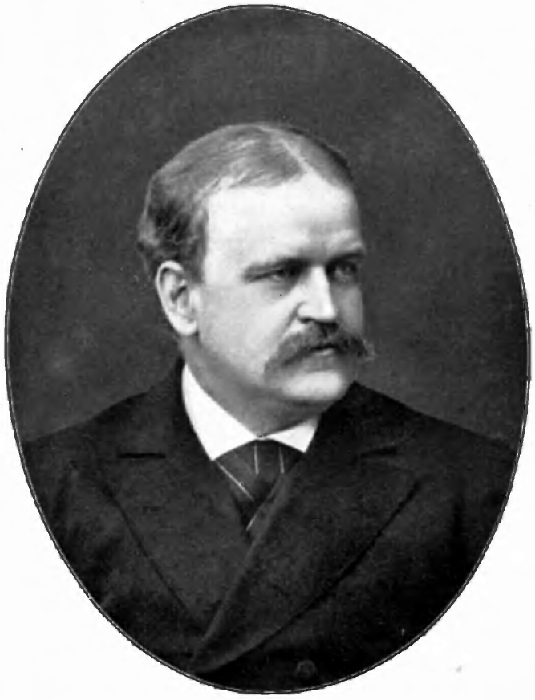

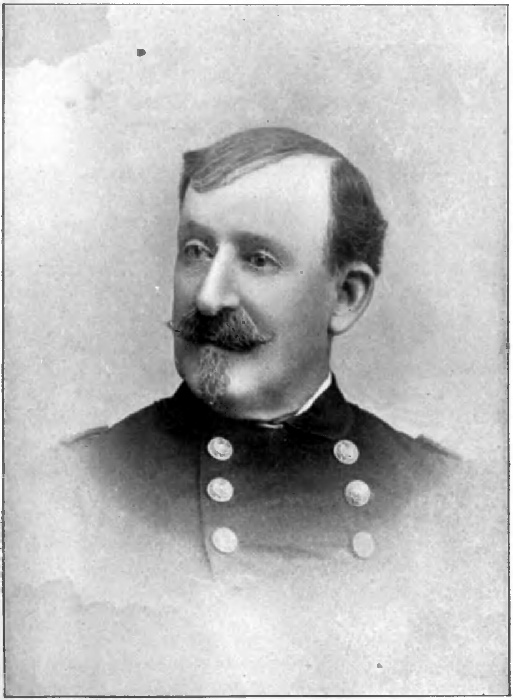

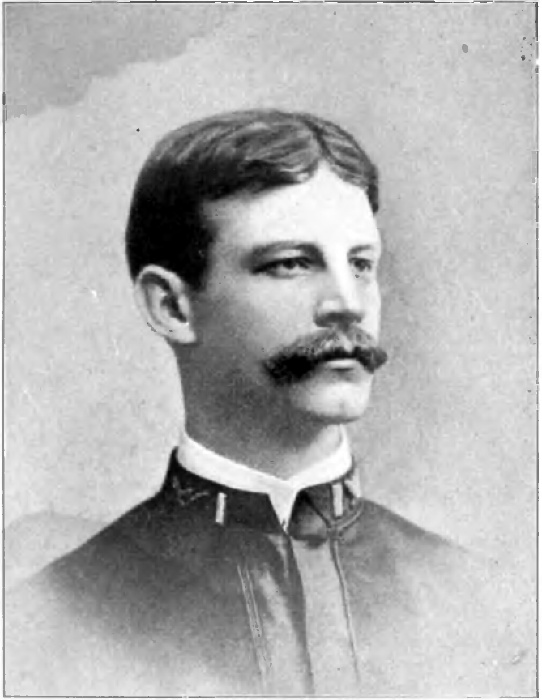

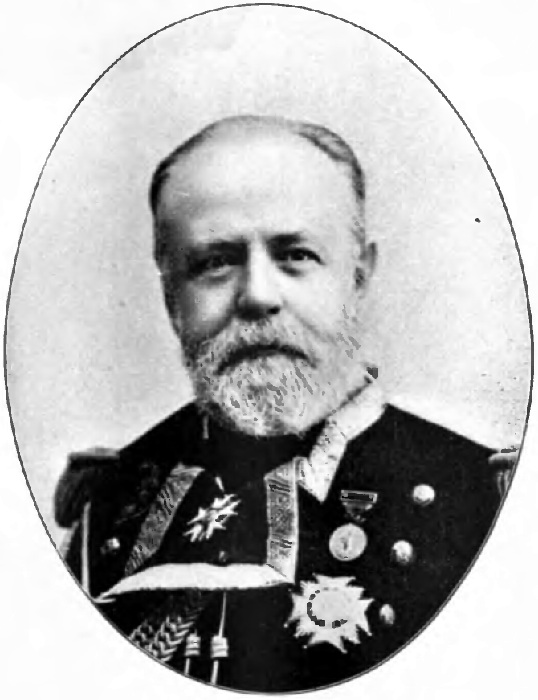

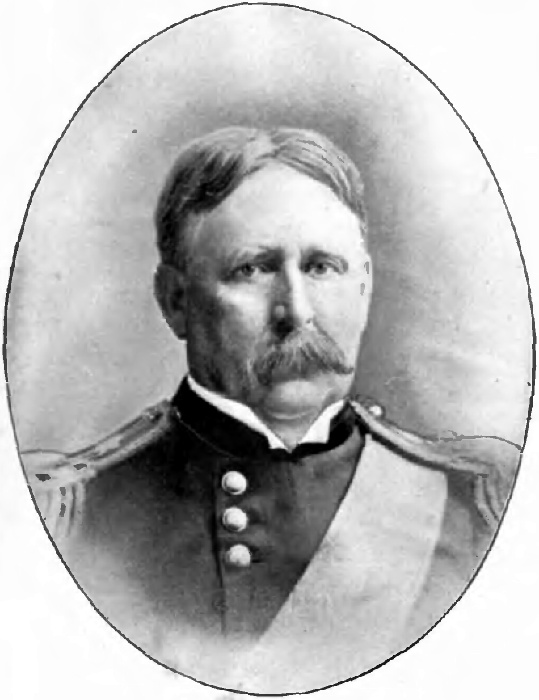

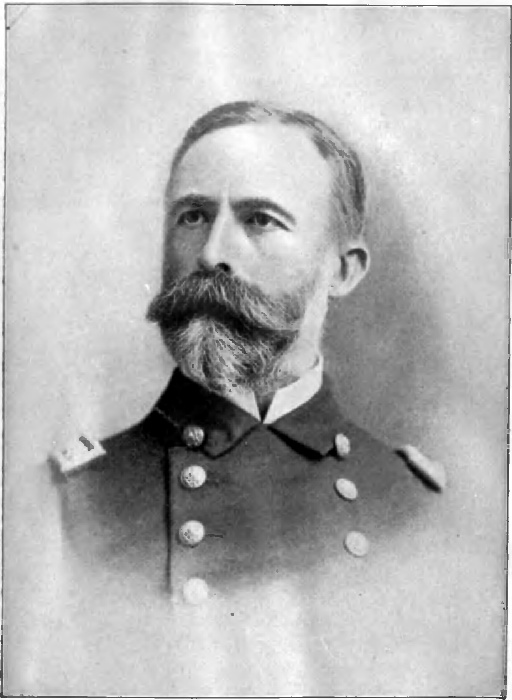

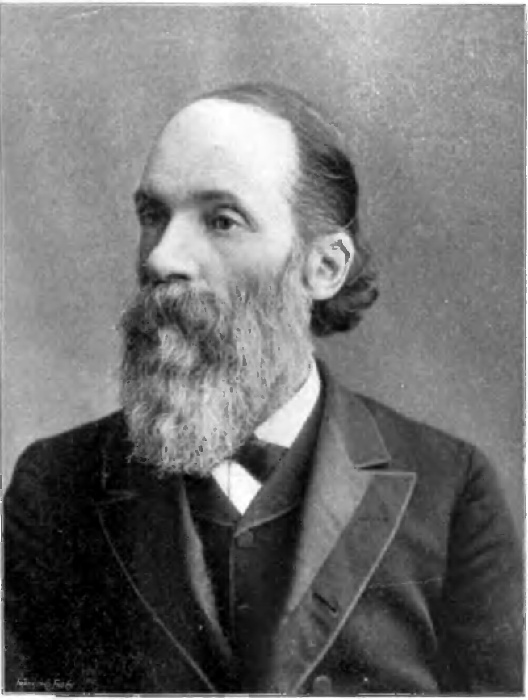

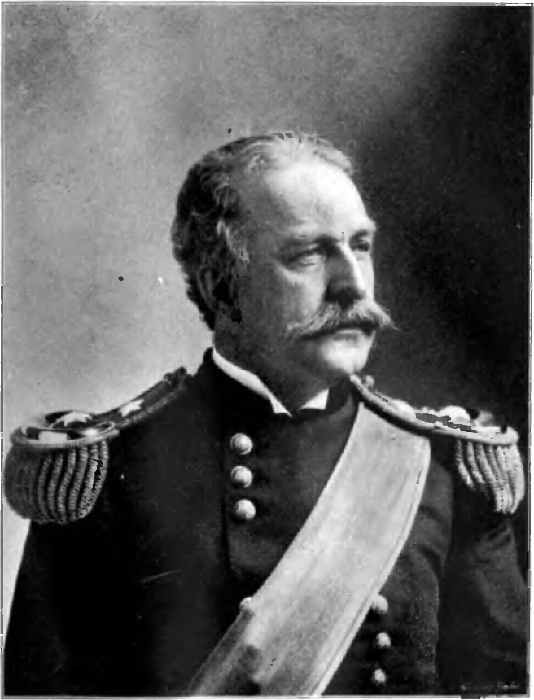

| Captain C. D. Sigsbee | 12 | |

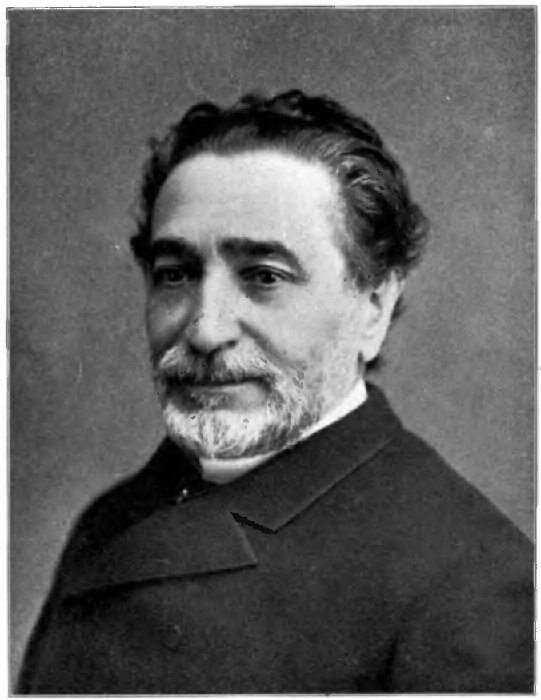

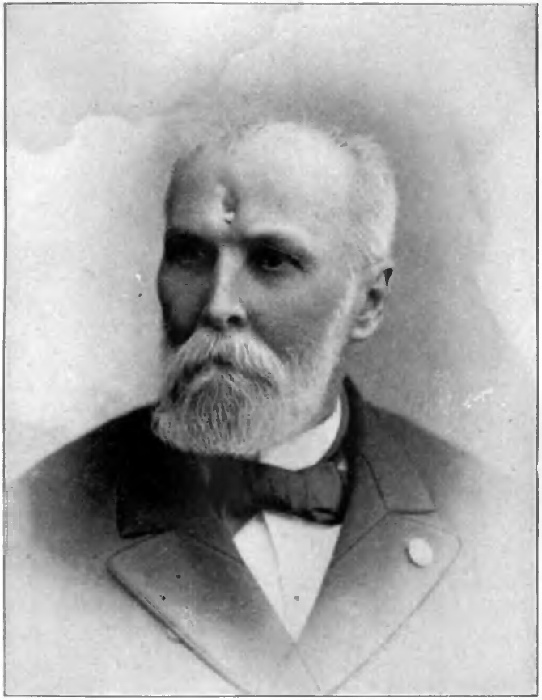

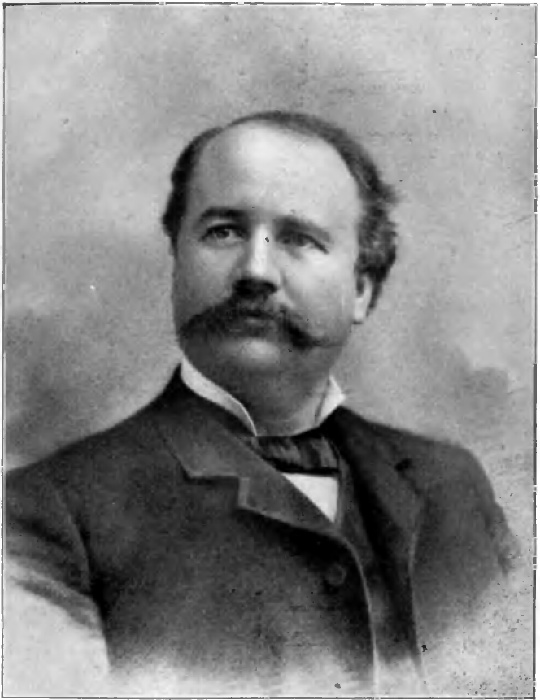

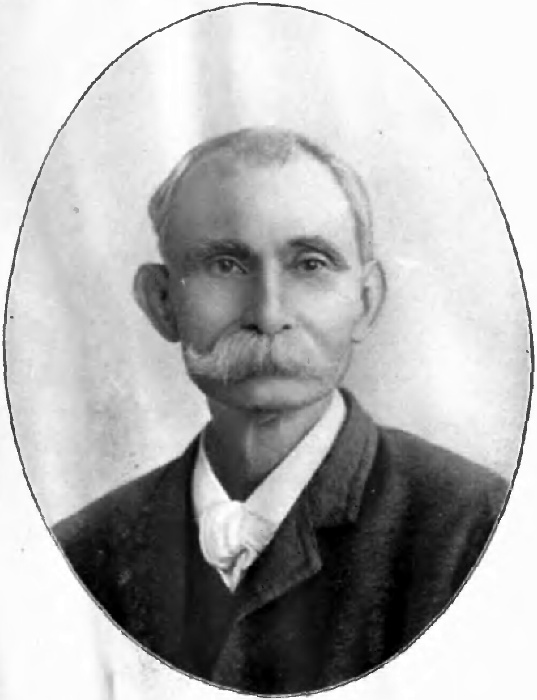

| Ex-Minister de Lome | 20 | |

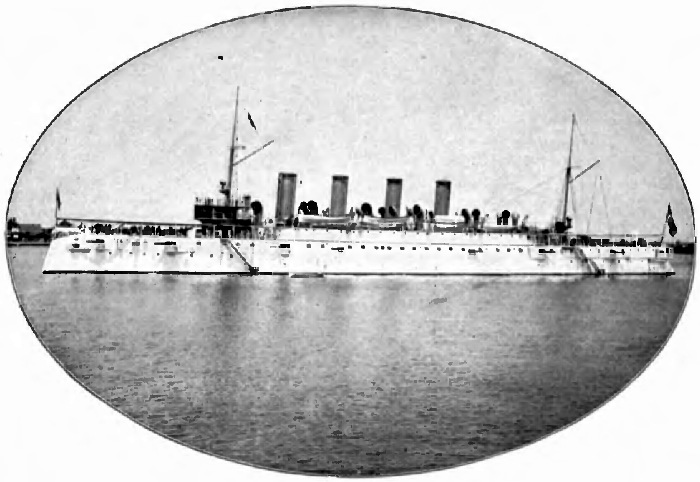

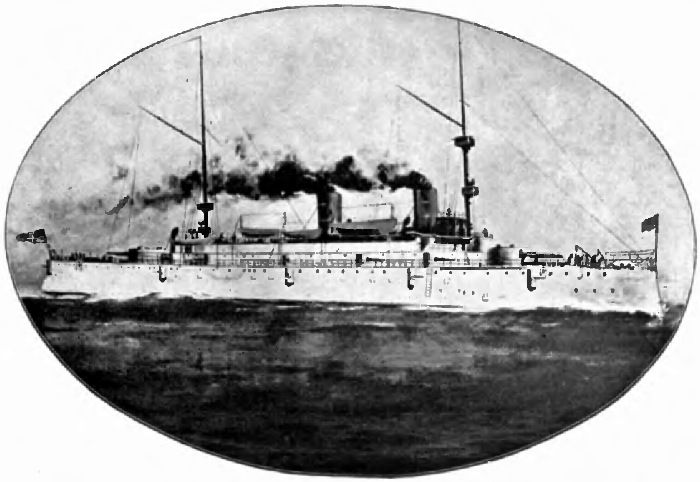

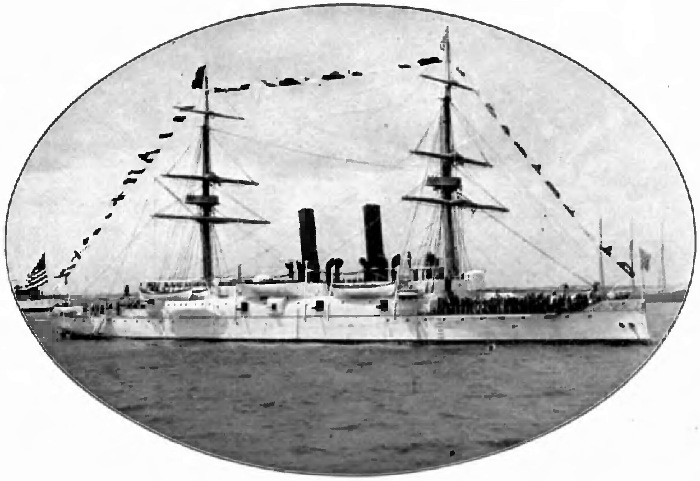

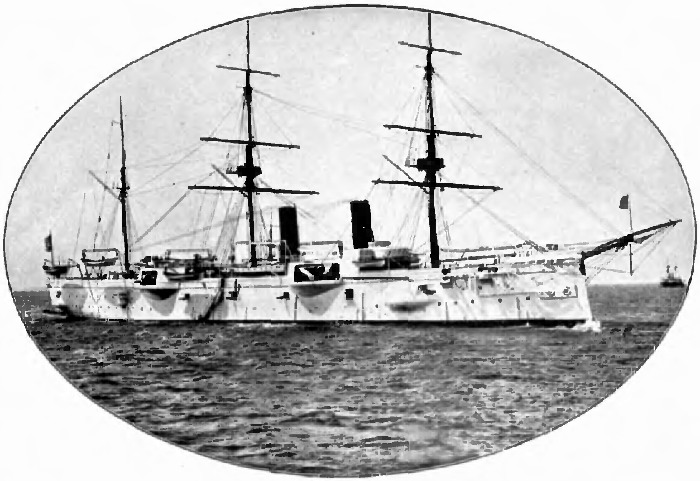

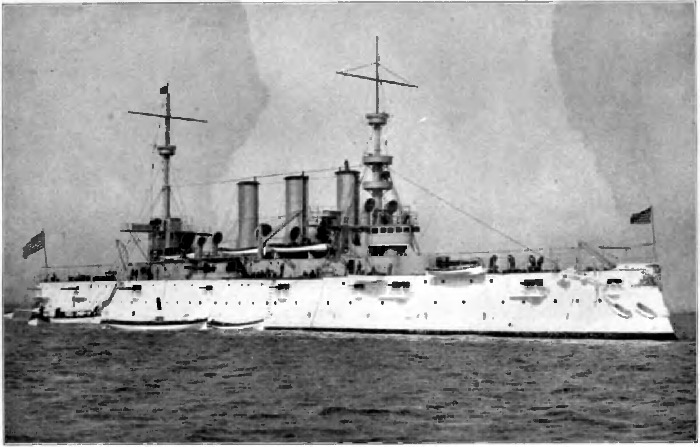

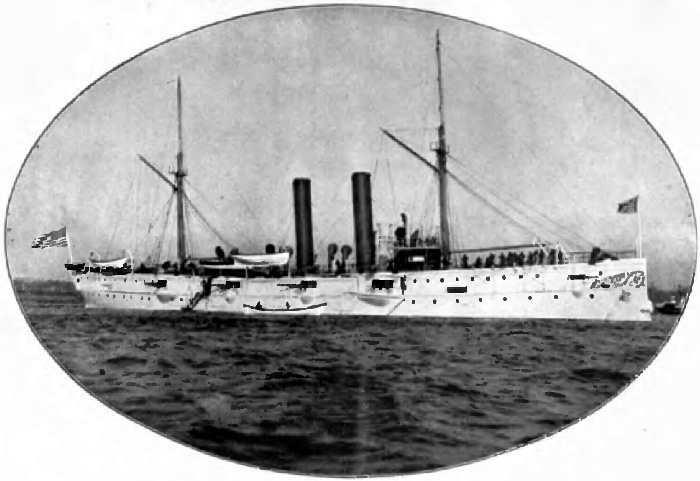

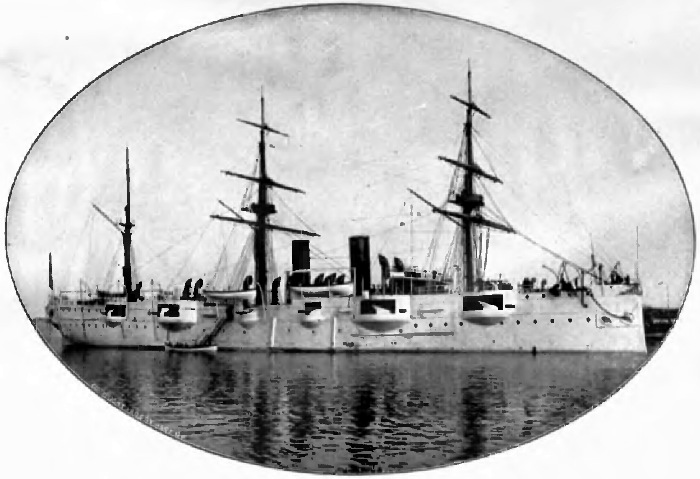

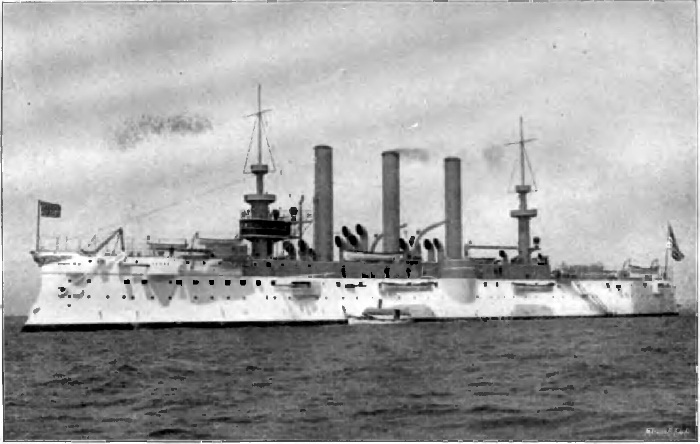

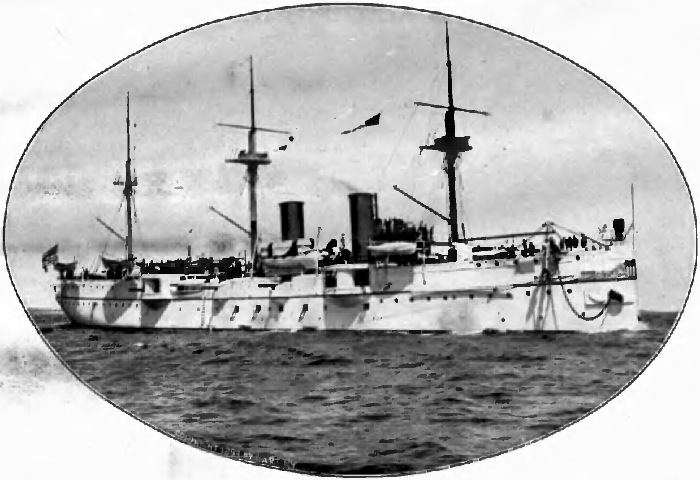

| U. S. S. Montgomery | 24 | |

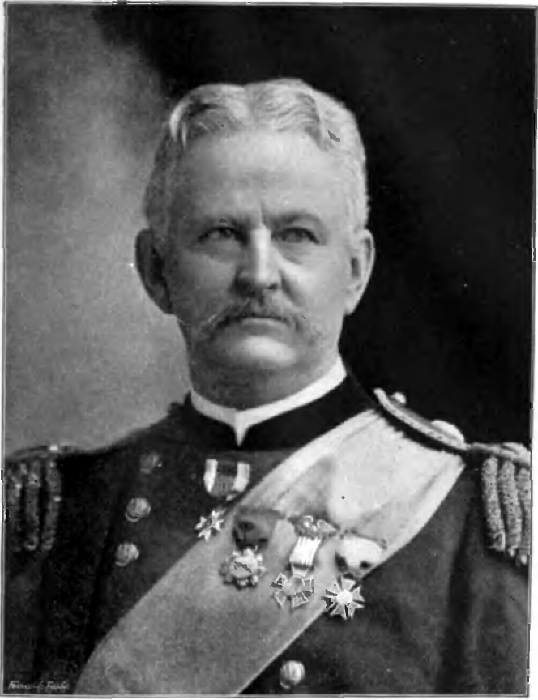

| Major-General Fitzhugh Lee | 30 | |

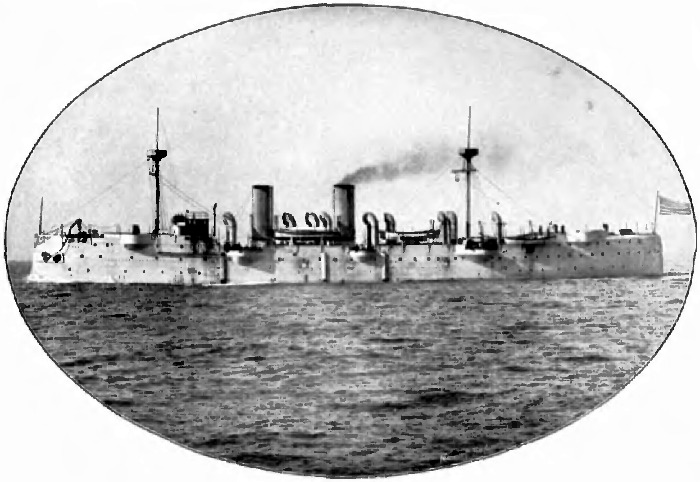

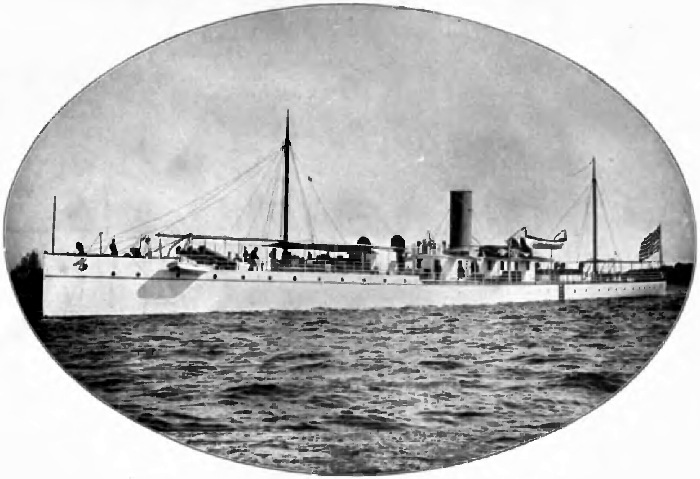

| U. S. S. Columbia | 38 | |

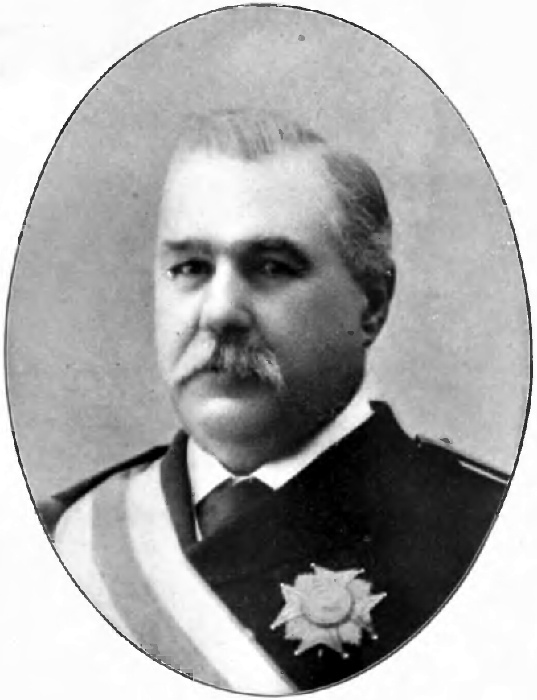

| Captain-General Blanco | 44 | |

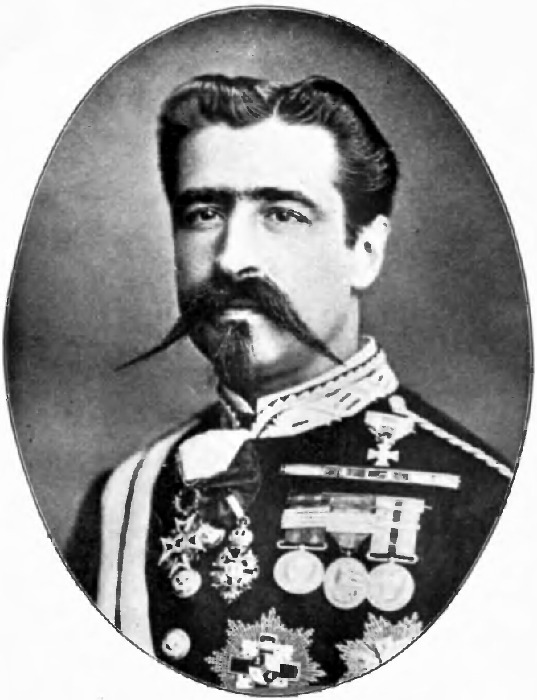

| Premier Sagasta | 49 | |

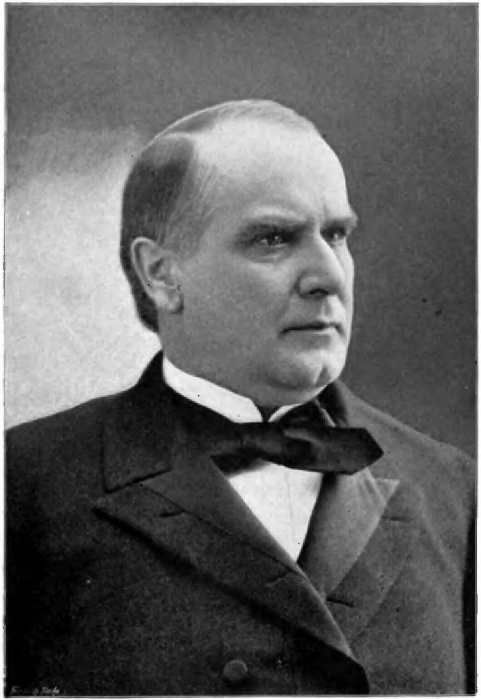

| President William Mckinley | 55 | |

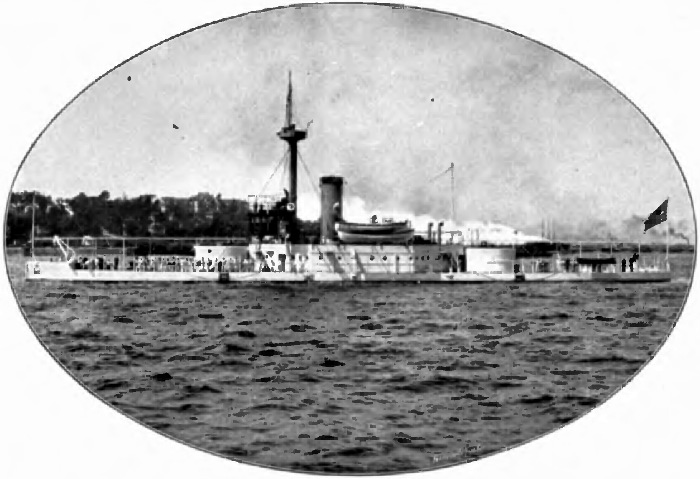

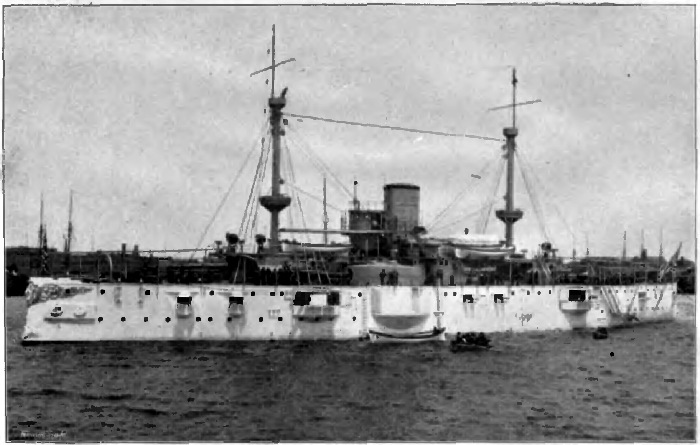

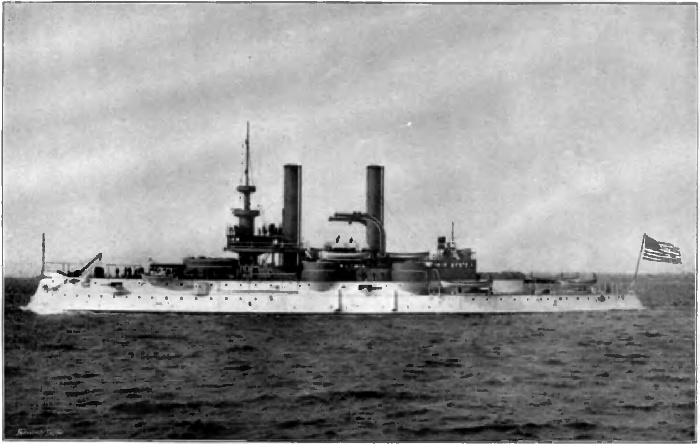

| U. S. S. Puritan | 58 | |

| Admiral George Dewey | 64 | |

| U. S. S. Olympia | 69 | |

| U. S. S. Baltimore | 72 | |

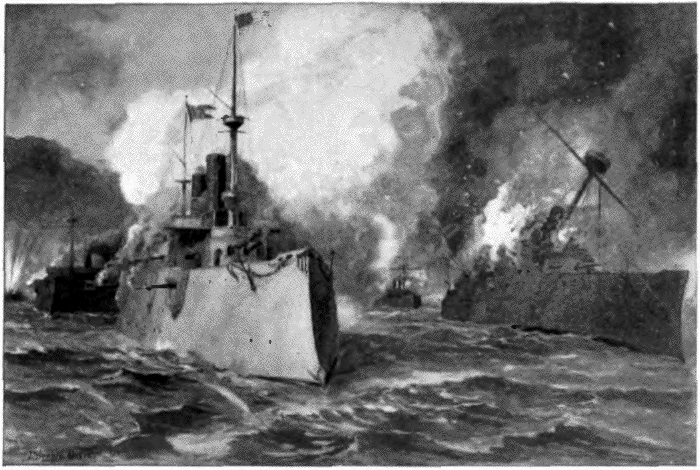

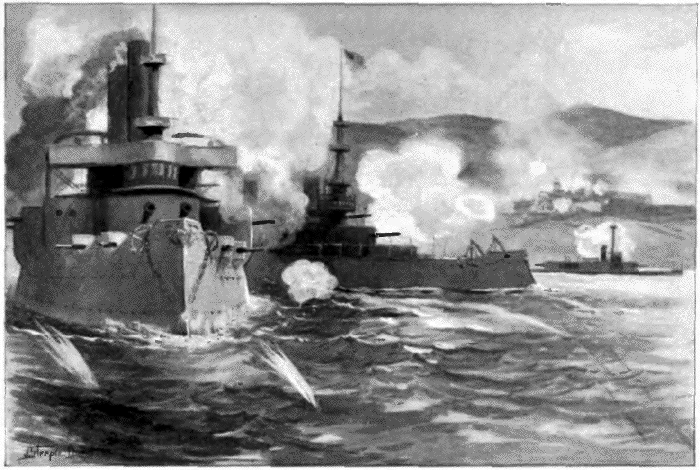

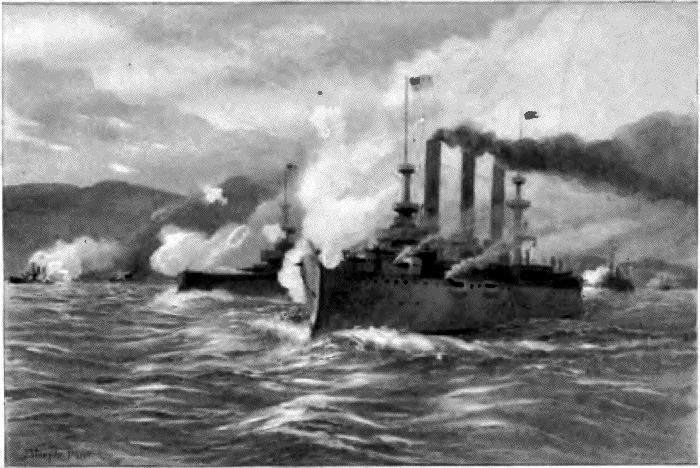

| Battle of Manila Bay | 75 | |

| U. S. S. Boston | 77 | |

| U. S. S. Concord | 82 | |

| U. S. S. Terror | 99 | |

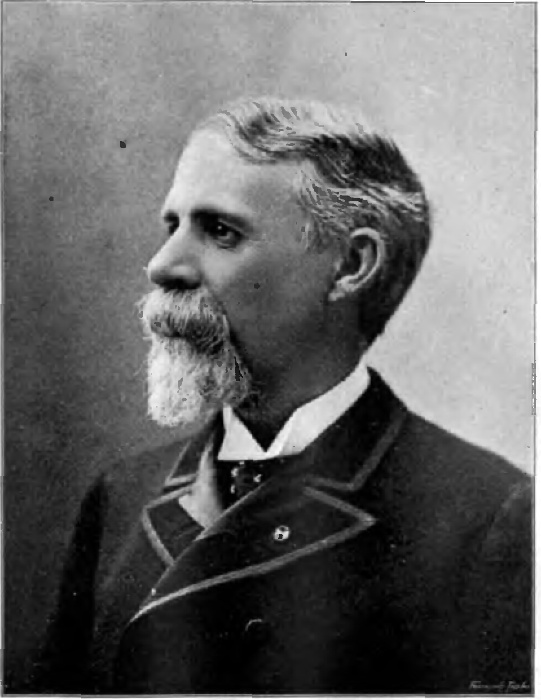

| John D. Long, Secretary of Navy | 107 | |

| U. S. S. Chicago | 117 | |

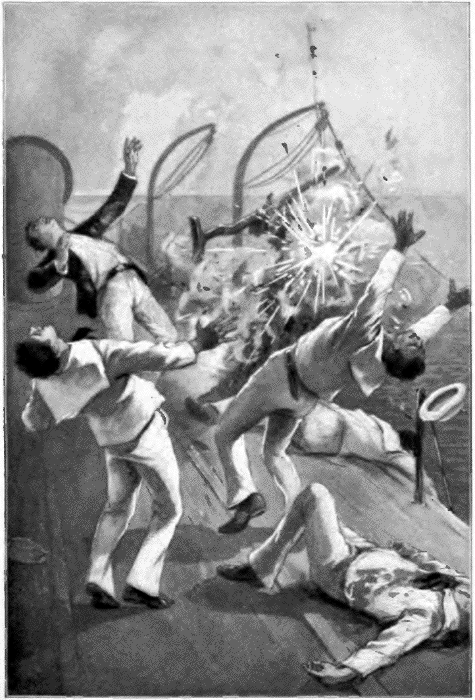

| The Tragedy of the Winslow | 119 | |

| U. S. S. Amphitrite | 123 | |

| The Bombardment of San Juan, Porto Rico | 127 | |

| U. S. S. Miantonomah | 130 | |

| Admiral Schley | 135 | |

| U. S. S. Monterey | 144 | |

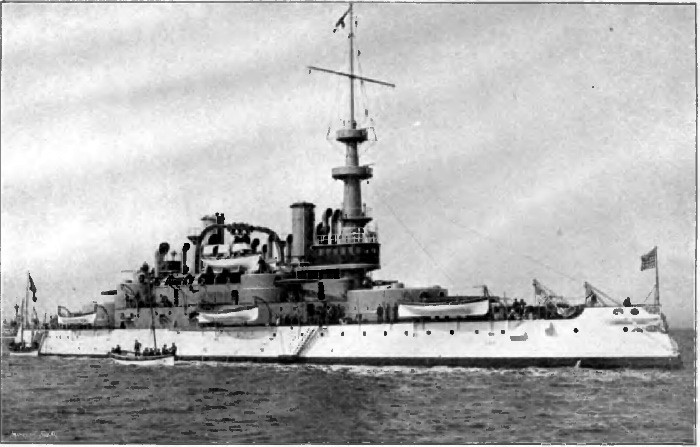

| U. S. S. Massachusetts | 151 | |

| Lieutenant Hobson | 156 | |

| U. S. S. New York | 161 | |

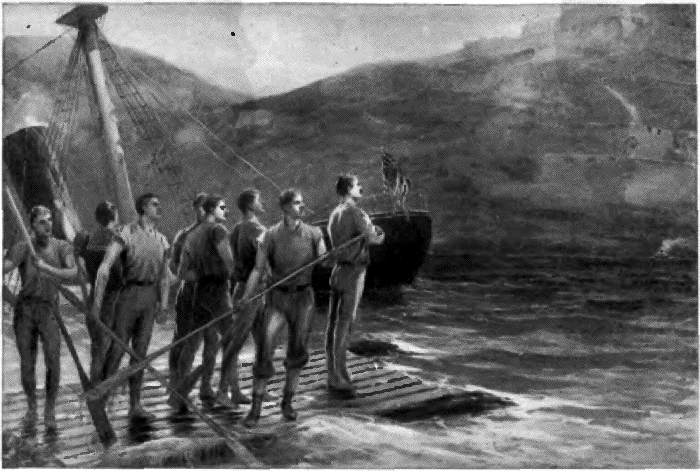

| Hobson and His Men on the Raft | 166 | |

| Admiral Cervera | 169 | |

| Queen Regent, Maria Christina of Spain | 171 | |

| General Garcia | 181 | |

| Admiral Camara | 186 | |

| General Augusti | 192 | |

| U. S. S. Marblehead | 201 | |

| U. S. S. Vesuvius | 207 | |

| U. S. S. Texas | 215 | |

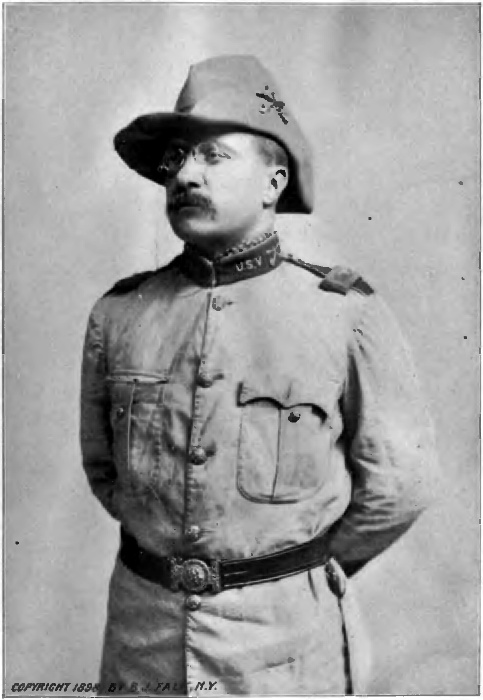

| Colonel Theodore Roosevelt | 218 | |

| Major-General Shafter | 224 | |

| The Attack on San Juan Hill | 229 | |

| Vice-President Hobart | 234 | |

| U. S. S. Newark | 239 | |

| Admiral W. T. Sampson | 243 | |

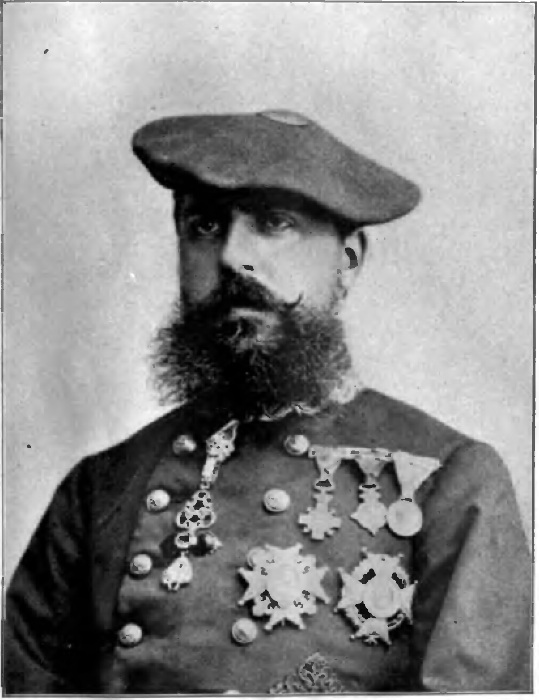

| General Weyler | 254 | |

| Captain R. D. Evans | 256 | |

| U. S. S. Iowa | 262 | |

| The Destruction of Cervera’s Fleet | 266 | |

| U. S. S. Indiana | 269 | |

| U. S. S. Oregon | 275 | |

| U. S. S. Brooklyn | 282 | |

| Major-General Joseph Wheeler | 292 | |

| King Alphonso XIII. of Spain | 300 | |

| General Gomez | 311 | |

| U. S. S. New Orleans | 314 | |

| U. S. S. San Francisco | 318 | |

| Major-General Miles | 320 | |

| Major-General Brooke | 327 | |

| General Brooke Receiving the News of the Protocol |

333 | |

| General Russell A. Alger, Secretary of War | 334 | |

| Major-General Wesley Merritt | 344 | |

| Don Carlos | 349 |

THE BOYS OF ’98.

CHAPTER I.

THE BATTLE-SHIP MAINE.

At or about eleven o’clock on the morning of January 25th the United States battle-ship Maine steamed through the narrow channel which gives entrance to the inner harbour of Havana, and came to anchor at Buoy No. 4, in obedience to orders from the captain of the port, in from five and one-half to six fathoms of water. She swung at her cables within five hundred yards of the arsenal, and about two hundred yards distant from the floating dock.

Very shortly afterward the rapid-firing guns on her bow roared out a salute as the Spanish colours were run up to the mizzenmast-head, and this thunderous announcement of friendliness was first answered by Morro Castle, followed a few moments later by the Spanish cruiser Alphonso XII. and a German school-ship.

The reverberations had hardly ceased before the [pg 2]captain of the port and an officer from the Spanish war-vessel, each in his gaily decked launch, came alongside the battle-ship in accordance with the rules of naval etiquette.

Lieut. John J. Blandin, officer of the deck, received the visitors at the head of the gangway and escorted them to the captain’s cabin. A few moments later came an officer from the German ship, and the courtesies of welcoming the Americans were at an end.

The Maine was an armoured, twin-screw battle-ship of the second class, 318 feet in length, 57 feet in breadth, with a draught of 21 feet, 6 inches; of 6,648 tons displacement, with engines of 9,293 indicated horse-power, giving her a speed of 17.75 knots. She was built in the Brooklyn navy yard, according to act of Congress, August 3, 1886. Work on her was commenced October 11, 1888; she was launched November 18, 1890, and put into commission September 17, 1895. She was built after the designs of chief constructor T. D. Wilson. The delay in going into commission is said to have been due to the difficulty in getting satisfactory armour. The side armour was twelve inches thick; the two steel barbettes were each of the same thickness, and the walls of the turrets were eight inches thick.

In her main battery were four 10-inch and six 6-inch breech-loading rifles; in the secondary battery seven 6-pounder and eight 1-pounder rapid-fire guns and four Gatlings. Her crew was made up of [pg 3]370 men, and the following officers: Capt. C. D. Sigsbee, Lieut.-Commander R. Wainwright, Lieut. G. F. W. Holman, Lieut. J. Hood, Lieut. C. W. Jungen, Lieut. G. P. Blow, Lieut. F. W. Jenkins, Lieut. J. J. Blandin, Surgeon S. G. Heneberger, Paymaster C. M. Ray, Chief Engineer C. P. Howell, Chaplain J. P. Chidwick, Passed Assistant Engineer F. C. Bowers, Lieutenant of Marines A. Catlin, Assistant Engineer J. R. Morris, Assistant Engineer Darwin R. Merritt, Naval Cadet J. H. Holden, Naval Cadet W. T. Cluverius, Naval Cadet R. Bronson, Naval Cadet P. Washington, Naval Cadet A. Crenshaw, Naval Cadet J. T. Boyd, Boatswain F. E. Larkin, Gunner J. Hill, Carpenter J. Helm, Paymaster’s Clerk B. McCarthy.

Why had the Maine been sent to this port?

The official reason given by the Secretary of the Navy when he notified the Spanish minister, Señor Dupuy de Lome, was that the visit of the Maine was simply intended as a friendly call, according to the recognised custom of nations.

The United States minister at Madrid, General Woodford, also announced the same in substance to the Spanish Minister of State.

It having been repeatedly declared by the government at Madrid that a state of war did not exist in Cuba, and that the relations between the United States and Spain were of the most friendly character, nothing less could be done than accept the official construction put upon the visit.

[pg 4]The Spanish public, however, were not disposed to view the matter in the same light, as may be seen by the following extracts from newspapers:

“If the government of the United States sends one war-ship to Cuba, a thing it is no longer likely to do, Spain would act with energy and without vacillation.”—El Heraldo, January 16th.

“We see now the eagerness of the Yankees to seize Cuba.”—The Imparcial, January 23d.

The same paper, on the 27th, declared:

“If Havana people, exasperated at American impudence in sending the Maine, do some rash, disagreeable thing, the civilised world will know too well who is responsible. The American government must know that the road it has taken leads to war between both nations.”

On January 25th Madrid newspapers made general comment upon the official explanation of the Maine’s visit to Havana, and agreed in expressing the opinion that her visit is “inopportune and calculated to encourage the insurgents.” It was announced that, “following Washington’s example,” the Spanish government will “instruct Spanish war-ships to visit a few American ports.”

The Imparcial expresses fear that the despatch of the Maine to Havana will provoke a conflict, and adds:

“Europe cannot doubt America’s attitude towards Spain. But the Spanish people, if necessary, will do their duty with honour.”

[pg 5]The Epocha asks if the despatch of the Maine to Havana is “intended as a sop to the Jingoes,” and adds:

“We cannot suppose the American government so naïve or badly informed as to imagine that the presence of American war-vessels at Havana will be a cause of satisfaction to Spain or an indication of friendship.”

The people of the United States generally believed that the battle-ship had been sent to Cuba because of the disturbances existing in the city of Havana, which seemingly threatened the safety of Americans there.

On the morning of January 12th what is termed the “anti-liberal outbreak” occurred in the city of Havana.

Officers of the regular and volunteer forces headed the ultra-Spanish element in an attack upon the leading liberal newspaper offices, because, as alleged, of Captain-General Blanco’s refusal to authorise the suppression of the liberal press. It was evidently a riotous protest against Spain’s policy of granting autonomy to the Cubans.

The mob, gathered in such numbers as to be for the time being most formidable, indulged in open threats against Americans, and it was believed by the public generally that American interests, and the safety of citizens of the United States in Havana, demanded the protection of a war-vessel.

The people of Havana received the big fighting ship [pg 6]impassively. Soldiers, sailors, and civilians gathered at the water-front as spectators, but no word, either of threat or friendly greeting, was heard.

In the city the American residents experienced a certain sense of relief because now a safe refuge was provided in case of more serious rioting.

That the officers and crew of the Maine were apprehensive regarding their situation there can be little doubt. During the first week after the arrival of the battle-ship several of the sailors wrote to friends or relatives expressing fears as to what might be the result of the visit, and on the tenth of February one of the lieutenants is reported as having stated:

“If we don’t get away from here soon there will be trouble.”

The customary ceremonial visits on shore were made by the commander of the ship and his staff, and, so far as concerned the officials of the city, the Americans were seemingly welcome visitors.

The more radical of the citizens were not so apparently content with seeing the Maine in their harbour. Within a week after the arrival of the ship incendiary circulars were distributed in the streets, on the railway cars, and in many other public places, calling upon all Spaniards to avenge the “insult” of the battle-ship’s visit.

A translation of one such circular serves as a specimen of all:

“Spaniards: Long live Spain and honour.

“What are ye doing that ye allow yourselves to be insulted in this way?

“Do you not see what they have done to us in withdrawing our brave and beloved Weyler, who at this very time would have finished with this unworthy rebellious rabble, who are trampling on our flag and our honour?

“Autonomy is imposed on us so as to thrust us to one side and to give posts of honour and authority to those who initiated this rebellion, these ill-born autonomists, ungrateful sons of our beloved country.

“And, finally, these Yankee hogs who meddle in our affairs humiliate us to the last degree, and for still greater taunt order to us one of the ships of war of their rotten squadron, after insulting us in their newspapers and driving us from our homes.

“Spaniards, the moment of action has arrived. Sleep not. Let us show these vile traitors that we have not yet lost shame and that we know how to protect ourselves with energy befitting a nation worthy and strong as our Spain is and always will be.

“Death to Americans. Death to autonomy.

“Long live Spain!

“Long live Weyler!”

At eight o’clock on the evening of February 15th all the magazines aboard the battle-ship were closed, and the keys delivered to her commander according to the rules of the service.

[pg 8]An hour and a half later Lieut. John J. Blandin was on watch as officer of the deck; Captain Sigsbee sat in his cabin writing letters; on the starboard side of the ship, made fast to the boom, was the steam cutter, with her crew on board waiting to make the regular ten o’clock trip to the shore to bring off such of the officers or crew as were on leave of absence.

The night was unusually dark; great banks of thick clouds hung over the city and harbour; the ripple of the waves against the hulls of the vessels at anchor, and the subdued hum of voices, alone broke the silence. The lights here and there, together with the dark tracery of spar and cordage against the sky, was all that betokened the presence of war-ship or peaceful merchantman.

Suddenly, and when the silence was most profound, the watch on board the steamer City of Washington, and some sailors ashore, saw what appeared to be a sheet of fire flash up in the water directly beneath the Maine, and even as the blinding glare was in their eyes came a mighty, confused rumble as of grinding and rending, followed an instant later by a roar as if a volcano had sprung into activity beneath the waves of the harbour.

Then was flung high in the air what might be likened to a shaft of fire filled with fragments of iron, wood, and human flesh, rising higher and higher until its force was spent, when it fell outwardly as falls a column of water broken by the wind.

The earth literally trembled; the air suddenly became [pg 9]heavy with stifling smoke. Electric lights on shore were extinguished; the tinkling of breaking glass could be heard everywhere in that portion of the city nearest the harbour.

When the shower of fragments and of fire ceased to fall a dense blackness enshrouded the harbour, from the midst of which could be heard cries of agony, appeals for help, and the shouts of those who, even while struggling to save their own lives, would cheer their comrades.

After this, and no man could have said how many seconds passed while the confusing, bewildering blackness lay heavy over that scene of death and destruction, long tongues of flame burst up from the torn and splintered decks of the doomed battle-ship, a signal of distress, as well as a beacon for those who would succour the dying.

Captain Sigsbee, recovering in the briefest space of time from the bewilderment of the shock, ran out of the cabin toward the deck, groping his way as best he might in the darkness through the long passage until he came upon the marine orderly, William Anthony, who was at his post of duty near the captain’s quarters.

It was a moment full of horror all the more intense because unknown, but the soldier, mindful even then of his duty, saluting, said in the tone of one who makes an ordinary report:

“Sir, I have to inform you that the ship has been blown up, and is sinking.”

[pg 10]“Follow me,” the captain replied, acknowledging his subordinate’s salute, and the two pressed forward through the blackness and suffocating vapour.

Lieutenant Blandin, officer of the deck, was sitting on the starboard side of the quarter-deck when the terrible upheaval began, and was knocked down by a piece of cement hurled from the lowermost portion of the ship’s frame, perhaps; but, leaping quickly to his feet, he ran to the poop that he might be at his proper station when the supreme moment came.

Lieut. Friend W. Jenkins was in the junior officers’ mess-room when the first of a battle-ship’s death-throes was felt, and as soon as possible made his way toward the deck, encouraging some of the bewildered marines to make a brave fight for life; but he never joined his comrades.

Assistant Engineer Darwin R. Merritt and Naval Cadet Boyd together ran toward the hatch, but only to find the ladder gone. Boyd climbed through, and then did his best to aid Merritt; but his efforts were vain, and the engineer went down with his ship.

It seemed as if only the merest fraction of time elapsed before the uninjured survivors were gathered on the poop-deck. Forward of them, where a moment previous had been the main-deck, was a huge mass looming up in the darkness like some threatening promontory.

On the starboard quarter hung the gig, and opposite her, on the port side, was the barge.

[pg 11]During the first two or three seconds only muffled, gurgling, choking exclamations were heard indistinctly; and then, when the terrible vibrations of the air ceased, cries for help went up from every quarter.

Lieutenant Blandin says, in describing those few but terrible moments:

“Captain Sigsbee ordered that the gig and the launch be lowered, and the officers and men, who by this time had assembled, got the boats out and rescued a number in the water.

“Captain Sigsbee ordered Lieut.-Commander Wainwright forward to see the extent of the damage, and if anything could be done to rescue those forward, or to extinguish the flames which followed close upon the explosion and burned fiercely as long as there were any combustibles above water to feed them.

“Lieut.-Commander Wainwright on his return reported the total and awful character of the calamity, and Captain Sigsbee gave the last sad order, ‘Abandon ship,’ to men overwhelmed with grief indeed, but calm and apparently unexcited.”

The quiet, yet at the same time sharp, words of command from the captain aroused his officers from the stupefaction of horror which had begun to creep over them, and this handful of men, who even then were standing face to face with death, set about aiding their less fortunate companions.

As soon as they could be manned, boats put off from the vessels in the harbour, and the work of rescue was [pg 12]continued until all the torn and mangled bodies in which life yet remained had been taken from the water.

Capt. H. H. Woods, of the British steamer Thurston, was among the first in this labour of mercy, and concerning it he says:

“My vessel was within half a mile of the Maine, and my small boat was the first to gain the wreck. It is beyond my power to describe the explosion. It was awful. It paralysed the intellect for a few moments. The cries that came over the water awakened us to a realisation that some great tragedy had occurred.

“I made all haste to the wreck. There were very few men in the water. All told, I do not believe there were thirty. We picked up some of them and passed them on to other vessels, and then continued our work of rescue.

“The sight was appalling. Dismembered legs and trunks of bodies were floating about, together with pieces of clothing, boxes of meats, and all sorts of wreckage. Now and then the agonised cry of some poor suffering fellow could be heard above the tumult.

“One grand figure stood out in all the terrible scene. That was Captain Sigsbee. Every American has reason to be proud of that officer. He seemed to have realised in an instant all that happened. Not for a moment did he show evidence of excitement. He alone was cool. Discipline? Why, man, the discipline was there as strong as ever, despite the fact that all around was death and disaster.”

The commander of the Maine was the last to leave the wreck, and then all that was left of the mighty ship was beginning to settle in the slime and putrefaction which covers the bottom of Havana harbour.

Calmly, with the same observance of etiquette as if they had been assisting at some social function, the officers took their respective places in the boats, and, amid a silence born of deepest grief, rowed a short distance from the rent and riven mass so lately their post of duty.

A gentleman from Chicago, a guest at the Grand Hotel, was seated in front of the building when the explosion occurred.

“It was followed by another and a much louder one,” he said. “We thought the whole city had been blown to pieces. Some said the insurgents were entering Havana. Others cried out that Morro Castle was blown up.

“On the Prado is a large cab-stand. One minute after the explosion was heard the cabmen cracked their whips and went rattling over the cobblestones like crazy men. The fire department turned out, and bodies of cavalry and infantry rushed through the streets. There was no sleep in Havana that night.”

Soon after the disaster Admiral Manterola and General Solano put off to the wreck, and offered their services to Captain Sigsbee.

There were many wonderful escapes from death. [pg 14]One of the ward-room cooks was thrown outboard into the water.

A Japanese sailor was blown into the air, and, falling in the sea, was picked up alive.

One seaman was sleeping in a yawl hanging at the davits. The boat was crushed like an egg-shell; but the sailor fell overboard and was picked up unhurt.

Three men were doing punishment watch on the port quarter-deck, and thus probably escaped death.

One sailor swam about until help came, although both his legs were broken. Another had the bones of his ankle crushed, and yet managed to keep afloat.

Two hours or more passed before the unsubmerged, wooden portion of the wreck had been consumed by the flames, and at 11.30 P. M. the smoke-stacks of the ill-fated ship fell.

On board the steamer City of Washington, two boats were literally riddled by fragments of the Maine which fell after the explosion, and among them was an iron truss which, crashing through the pantry, demolished the tableware.

When morning came the wreck was the central figure of an otherwise bright picture, sad as it was terrible. The huge mass of flame-charred débris forward looked as if it had been thrown up from a subterranean storehouse of fused cement, steel, wood, and iron.

Further aft, one military mast protruded at a slight angle from the perpendicular, while the poop afforded a resting-place for the workmen or divers.

[pg 15]Of the predominant white which distinguishes our war-vessels in time of peace, not a vestige remained. In its place was the blackness of desolating death, marking the spot where two hundred and sixty-six brave men had gone over into the Beyond.

The total loss to the government as a result of the disaster was officially pronounced to be $4,689,261.31. This embraced the cost of hull, machinery, equipment, armour, gun protection and armament, both in main and secondary batteries. It included the cost of ammunition, shells, current supplies, coal, and, in short, the entire outfit.

The pet of the Maine’s crew, a big cat, was found next morning, perched on a fragment of a truss which yet remained above the water, and near her, as if seeking companionship, was the captain’s dog, Peggy.

Consul-General Lee cabled from Havana on the afternoon of the sixteenth:

“Profound sorrow is expressed by the government and municipal authorities, consuls of foreign nations, organised bodies of all sorts, and citizens generally.

“Flags are at half-mast on the governor-general’s palace, on shipping in the harbour, and in the city.

“Business is suspended, and the theatres are closed.”

On the afternoon of the seventeenth the bodies which had been found up to that time were buried in [pg 16]Havana with military honours, two companies of Spanish sailors from the cruiser Alphonso XII. acting as escort.

A board of inquiry, composed of Capt. W. T. Sampson of the U. S. S. Iowa as presiding officer, Commander Adolph Marix as judge advocate, Capt. F. E. Chadwick, and Commander W. P. Potter, all of the New York, was convened, and on March 28th President McKinley sent a message to Congress, the conclusion of which was as follows:

“The appalling calamity fell upon the people of our country with crushing force, and for a brief time an intense excitement prevailed, which in a community less just and self-controlled than ours might have led to hasty acts of blind resentment.

“This spirit, however, soon gave way to calmer processes of reason, and to the resolve to investigate the facts and await material proof before forming a judgment as to the cause, the responsibility, and, if the facts warranted, the remedy due. This course necessarily recommended itself from the outset to the executive, for only in the light of a dispassionately ascertained certainty will it determine the nature and measure of its full duty in the matter.

“The usual procedure was followed, as in all cases of casualty or disaster to national vessels of any maritime state.

“A naval court of inquiry was at once organised, composed of officers well qualified by rank and prac[pg 17]tical experience to discharge the onerous duty imposed upon them.

“Aided by a strong force of wreckers and divers, the court proceeded to make a thorough investigation on the spot, employing every available means for impartial and exact determination of the causes of the explosion. Its operations have been conducted with the utmost deliberation and judgment, and, while independently pursued, no source of information was neglected, and the fullest opportunity was allowed for a simultaneous investigation by the Spanish authorities.

“The finding of the court of inquiry was reached, after twenty-three days of continuous labour, on the twenty-first of March instant, and, having been approved on the twenty-second by the commander-in-chief of the United States naval force in the North Atlantic station, was transmitted to the executive.

“It is herewith laid before the Congress, together with the voluminous testimony taken before the court.

“The conclusions of the court are: That the loss of the Maine was not in any respect due to fault or negligence on the part of any of the officers or members of her crew.

“That the ship was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine, which caused the partial explosion of two or more of her forward magazines; and that no evidence has been obtainable fixing the responsibility for the destruction of the Maine upon any person or persons.

[pg 18]“I have directed that the finding of the court of inquiry and the views of this government thereon be communicated to the government of her majesty, the queen regent, and I do not permit myself to doubt that the sense of justice of the Spanish nation will dictate a course of action suggested by honour and the friendly relations of the two governments.

“It will be the duty of the executive to advise the Congress of the result, and in the meantime deliberate consideration is invoked.”

It was the preface to a mustering of the boys of ’61 who had worn the blue or the gray, this tragedy in the harbour of Havana, and, when the government gave permission, the boys of ’98 came forward many and many a thousand strong to emulate the deeds of their fathers—the boys of ’61—who, although the hand of Time had been laid heavily upon them, panted to participate in the punishment of those who were responsible for the slaughter of American sailors within the shadow of Morro Castle.

CHAPTER II.

THE PRELIMINARIES.

War between two nations does not begin suddenly. The respective governments are exceedingly ceremonious before opening the “game of death,” and it is not to be supposed that the United States commenced hostilities immediately after the disaster to the Maine in the harbour of Havana.

To tell the story of the war which ensued, without first giving in regular order the series of events which marked the preparations for hostilities, would be much like relating an adventure without explaining why the hero was brought into the situation.

It is admitted that, as a rule, details, and especially those of a political nature, are dry reading; but once take into consideration the fact that they all aid in giving a clearer idea of how one nation begins hostilities with another, and much of the tediousness may be forgiven.

Just previous to the disaster to the Maine, during the last days of January or the first of February, Señor Enrique Dupuy de Lome, the Spanish minister at Washington, wrote a private letter to the editor of the [pg 20]Madrid Herald, Señor Canalejas, who was his intimate friend, in which he made some uncomplimentary remarks regarding the President of the United States, and intimated that Spain was not sincere in certain commercial negotiations which were then being carried on between the two countries.

By some means, not yet fully explained, certain Cubans got possession of this letter, and caused it to be published in the newspapers. Señor de Lome did not deny having written the objectionable matter; but claimed that, since it was a private communication, it should not affect him officially. The Secretary of State instructed General Woodford, our minister at Madrid, to demand that the Spanish government immediately recall Minister de Lome, and to state that, if he was not relieved from duty within twenty-four hours, the President would issue to him his passports, which is but another way of ordering a foreign minister out of the country.

February 9. Señor de Lome made all haste to resign, and the resignation was accepted by his government before—so it was claimed by the Spanish authorities—President McKinley’s demand for the recall was received.

February 15. The de Lome incident was a political matter which caused considerable diplomatic correspondence; but it was overshadowed when the battle-ship Maine was blown up in the harbour of Havana.

As has already been said, the United States government at once ordered a court of inquiry to ascertain the cause of the disaster, and this, together with the search for the bodies of the drowned crew, was prosecuted with utmost vigour.

Very many of the people in the United States believed that Spanish officials were chargeable with the terrible crime, while those who were not disposed to make such exceedingly serious accusation insisted that the Spanish government was responsible for the safety of the vessel,—that she had been destroyed by outside agencies in a friendly harbour. In the newspapers, on the streets, in all public places, the American people spoke of the possibility of war, and the officials of the government set to work as if, so it would seem, they also were confident there would be an open rupture between the two nations.

February 28. In Congress, Representative Gibson of Tennessee introduced a bill appropriating twenty million dollars “for the maintenance of national honour and defence.” Representative Bromwell, of Ohio, introduced a similar resolution, appropriating a like amount of money “to place the naval strength of the country upon a proper footing for immediate hostilities with any foreign power.” On the same day orders were issued to the commandant at Fort Barrancas, Florida, directing him to send men to man the guns at Santa Rosa Island, opposite Pensacola.

February 28. Señor Louis Polo y Bernabe, appointed [pg 22]minister in the place of Señor de Lome, who resigned, sailed from Gibraltar.

By the end of February the work of preparing the vessels at the different navy yards for sea was being pushed forward with the utmost rapidity, and munitions of war were distributed hurriedly among the forts and fortifications, as if the officials of the War Department believed that hostilities might be begun at any moment.

Nor was it only within the borders of this country that such preparations were making. A despatch from Shanghai to London reported that the United States squadron, which included the cruisers Olympia, Boston, Raleigh, Concord, and Petrel, were concentrating at Hongkong, with a view of active operations against Manila, in the Philippine Islands, in event of war.

At about the same time came news from Spain telling that the Spanish were making ready for hostilities. An exceptionally large number of artisans were at work preparing for sea battle-ships, cruisers, and torpedo-boat destroyers. The cruisers Oquendo and Vizcaya, with the torpedo-boat destroyers Furor and Terror, were already on their way to Cuba, where were stationed the Alphonso XII., the Infanta Isabel, and the Nueva Espana, together with twelve gunboats of about three hundred tons each, and eighteen vessels of two hundred and fifty tons each.

The United States naval authorities decided that heavy batteries should be placed on all the revenue cutters built within the previous twelve months, and [pg 23]large quantities of high explosives were shipped in every direction.

During the early days of March, Señor Gullon, Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, intimated to Minister Woodford that the Spanish government desired the recall from Havana of Consul-General Lee.

Spain also intimated that the American war-ships, which had been designated to convey supplies to Cuba for the relief of the sufferers there, should be replaced by merchant vessels, in order to deprive the assistance sent to the reconcentrados of an official character.

Minister Woodford cabled such requests to the government at Washington, to which it replied by refusing to recall General Lee under the present circumstances, or to countermand the orders for the despatch of war-vessels, making the representation that relief vessels are not fighting ships.

March 5. Secretary Long closed a contract for the delivery at Key West, within forty days, of four hundred thousand tons of coal. Work was begun upon the old monitors, which for years had been lying at League Island navy yard, Philadelphia. Orders were sent to the Norfolk navy yard to concentrate all the energies and fidelities of the yard on the cruiser Newark, to the end that she might be ready for service within sixty days.

March 6. The President made a public statement [pg 24]that under no circumstances would Consul-General Fitzhugh Lee be recalled at the request of Spain. He had borne himself, so it was stated from the White House, throughout the crisis with judgment, fidelity, and courage, to the President’s entire satisfaction. As to supplies for the relief of the Cuban people, all arrangements had been made to carry consignments at once from Key West by one of the naval vessels, whichever might be best adapted and most available for the purpose, to Matanzas and Sagua.

March 6. Chairman Cannon of the House appropriations committee introduced a resolution that fifty millions of dollars be appropriated for the national defence. It was passed almost immediately, without a single negative vote.

Significant was the news of the day. The cruiser Montgomery had been ordered to Havana. Brigadier-General Wilson, chief of the engineers of the army, arrived at Key West from Tampa with his corps of men, who were in charge of locating and firing submarine mines.

March 10. The newly appointed Spanish minister arrived at Washington.

March 11. The House committee on naval affairs authorised the immediate construction of three battle-ships, one to be named the Maine, and provided for an increase of 473 men in the marine force.

The despatch-boat Fern sailed for Matanzas with supplies for the relief of starving Cubans.

News by cable was received from the Philippine Islands to the effect that the rebellion there had broken out once more; the whole of the northern province had revolted; the inhabitants refused to pay taxes, and the insurgents appeared to be well supplied with arms and ammunition.

March 12. Señor Bernabe was presented to President McKinley, and laid great stress upon the love which Spain bore for the United States.

March 14. The Spanish flying squadron, composed of three torpedo-boats, set sail from Cadiz, bound for Porto Rico. Although this would seem to be good proof that the Spanish government anticipated war with the United States, Señor Bernabe made two demands upon this government on the day following the receipt of such news. The first was that the United States fleet at Key West and Tortugas be withdrawn, and the second, that an explanation be given as to why two war-ships had been purchased abroad.

March 17. A bill was submitted to both houses of Congress reorganising the army, and placing it on a war footing of one hundred and four thousand men. Senator Proctor made a significant speech in the Senate, on the condition of affairs in Cuba. He announced himself as being opposed to annexation, and declared that the Cubans were “suffering under the worst misgovernment in the world.” The public generally accepted his remarks as having been sanc[pg 26]tioned by the President, and understood them as indicating that this country should recognise the independence of Cuba on the ground that the people are capable of self-government, and that under no other conditions could peace or prosperity be restored in the island.

March 17. The more important telegraphic news from Spain was to the effect that the Minister of Marine had cabled the commander of the torpedo flotilla at the Canaries not to proceed to Havana; that the government arsenal was being run night and day in the manufacture of small arms, and that infantry and cavalry rifles were being purchased in Germany.

The United States revenue cutter cruiser McCulloch was ordered to proceed from Aden, in the Red Sea, to Hongkong, in order that she might be attached to the Asiatic squadron, if necessary.

March 18. The cruiser Amazonas, purchased from the Brazilian government, was formally transferred to the United States at Gravesend, England, to be known in the future as the New Orleans.

March 19. The Maine court of inquiry concluded its work. The general sentiments of the people, as voiced by the newspapers, were that war with Spain was near at hand, and this belief was strengthened March 24th, when authority was given by the Navy Department for unlimited enlistment in all grades of the service, when the revenue service was transferred [pg 27]from the Treasury to the Naval Department, and arrangements made for the quick employment of the National Guards of the States and Territories.

March 24. The report of the Maine court of inquiry arrived at Washington.

March 27. Madrid correspondents of Berlin newspapers declared that war with the United States was next to certain. The United States cruisers San Francisco and New Orleans sailed from England for New York, and the active work of mining the harbours of the United States coast was begun.

March 28. The President sent to Congress, with a message, the report of the Maine court of inquiry, as has been stated in a previous chapter.

March 29. Resolutions declaring war on Spain, and recognising the independence of Cuba, were introduced in both houses of Congress.

With the beginning of April it was to the public generally as if the war had already begun.

In every city, town, or hamlet throughout the country the newspapers were scanned eagerly for notes of warlike preparation, and from Washington, sent by those who were in position to know what steps were being taken by the government, came information which dashed the hopes of those who had been praying that peace might not be broken.

There had been a conference between the President, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the chairman of the committee on ways and means, regarding the best [pg 28]methods of raising funds for the carrying on of a war. A joint board of the army and navy had met to formulate plans of defence, and a speedy report was made to Secretary Long.

Instructions were sent by the State Department to all United States consuls in Cuba to be prepared to leave the island at any moment, and to hold themselves in readiness to proceed to Havana in order to embark for the United States.

April 2. A gentleman in touch with public affairs wrote from Washington as follows:

“To-day’s developments show that there is only the very faintest hope of peace. Unless Spain yields war must come. The administration realises that as fully as do members of Congress.

“The orders sent by the State Department to all our consuls in Cuba, especially those in the interior, to hold themselves in readiness to leave their positions and proceed to Havana, show that the department looks upon war as a certainty, and has taken all proper precautions for the safety of its agents.

“Such an order, it is unnecessary to say, would not have been issued unless a crisis was imminent, and the State Department, as well as other branches of the government, has now become convinced that peace cannot much longer be maintained, and that the safety of the consular agents is a first consideration.

“General Lee has also been advised that he should be ready to leave as soon as notified, and that the [pg 29]American newspaper correspondents now in Havana must prepare themselves to receive the notification of instant departure.

“The Secretary of the Navy has instructed the Boston Towboat Company, which corporation had charge of the wrecking operations on the U. S. S. Maine, to suspend work at once. The Secretary of War has authorised an allotment of one million dollars from the emergency fund for the office of the chief of engineers, and this amount will be expended in purchasing material for the torpedo defences connected with the seacoast fortifications. The United States naval attaché at London has purchased a cruiser of eighteen hundred tons displacement, capable of a speed of sixteen knots, and the vessel will put to sea immediately. The Spanish torpedo flotilla is reported as having arrived at the Cape Verde Islands.”

April 4. Senators Perkins, Mantle, and Rawlins spoke in the Senate, charging Spain with the murder of the sailors of the Maine, claiming that it was properly an act of war, and insisting that the United States should declare for the independence of Cuba and armed intervention.

April 5. Senator Chandler announced as his belief that the United States was justified in beginning hostilities, and Senators Kenny, Turpie, and Turner made powerful speeches in the same line, fiercely denouncing Spain. General Woodford was instructed by cable to [pg 30]be prepared to ask of the Madrid government his passports at any moment.

Marine underwriters, believing that war was inevitable, doubled their rates. The merchants and manufacturers’ board of trade of New York notified Congress and the President that it believed Spain was responsible for the blowing up of the Maine; that the independence of Cuba should be recognised, and that it should be brought about by force of arms, if necessary.

April 7. The representatives of six great powers met at the White House in the hope of being able to influence the President for peace. In closing his address to the diplomats, Mr. McKinley said:

“The government of the United States appreciates the humanitarian and disinterested character of the communication now made in behalf of the powers named, and for its part is confident that equal appreciation will be shown for its own earnest and unselfish endeavours to fulfil a duty to humanity by ending a situation, the indefinite prolongation of which has become insufferable.”

Americans made haste to leave Cuba, after learning that Consul-General Lee had received orders to set sail from Havana on or before the ninth. The American consul at Santiago de Cuba closed the consulate in that city.

Solomon Berlin, appointed consul at the Canary Islands, was, by the State Department, ordered not [pg 31]to proceed to his post, and he remained at New York.

The Spanish consul at Tampa, Florida, left that town for Washington, by order of his government.

The following cablegram gives a good idea of the temper of the Spanish people:

“London, April 7.—A special dispatch from Madrid says that the ambassadors of France, Germany, Russia, and Italy waited together this evening upon Señor Gullon, the Foreign Minister, and presented a joint note in the interests of peace.

“Señor Gullon, replying, declared that the members of the Spanish Cabinet were unanimous in considering that Spain had reached the limit of international policy in the direction of conceding the demands and allowing the pretensions of the United States.”

April 9. Guards about the United States legation in Madrid were trebled. General Blanco, captain-general of Cuba, issued a draft order calling on every able-bodied man, between the ages of nineteen and forty, to register for immediate military duty. At ten o’clock in the morning, Consul-General Lee, accompanied by British Consul Gollan, called on General Blanco to bid him good-bye. The captain-general was too busy to receive visitors. General Lee left the island at six o’clock in the evening.

April 11. The President sent a message, together [pg 32]with Consul Lee’s report, to the Congress, and Senator Chandler thus analysed it:

First: A graphic and powerful description of the horrible condition of affairs in Cuba.

Second: An assertion that the independence of the revolutionists should not be recognised until Cuba has achieved its own independence beyond the possibility of overthrow.

Third: An argument against the recognition of the Cuban republic.

Fourth: As to intervention in the interest of humanity, that is well enough, and also on account of the injury to commerce and peril to our citizens, and the generally uncomfortable conditions all around.

Fifth: Illustrative of these uncomfortable conditions is the destruction of the Maine. It helps make the existing situation intolerable. But Spain proposes an arbitration, to which proposition the President has no reply.

Sixth: On the whole, as the war goes on and Spain cannot end it, mediation or intervention must take place. President Cleveland said “intervention would finally be necessary.” The enforced pacification of Cuba must come. The war must stop. Therefore, the President should be authorised to terminate hostilities, secure peace, and establish a stable government, and to use the military and naval forces of the United States to accomplish these results, and food supplies should also be furnished by the United States.

[pg 33]April 12. Consul-General Lee was summoned before the Senate committee on foreign relations. It was announced that the Republican members of the ways and means committee had agreed upon a plan for raising revenue in case of need to carry on war with Spain. The plan was intended to raise more than $100,000,000 additional revenue annually, and was thus distributed:

An additional tax on beer of one dollar per barrel, estimated to yield $35,000,000; a bank stamp tax on the lines of the law of 1866, estimated to yield $30,000,000; a duty of three cents per pound on coffee, and ten cents per pound on tea on hand in the United States, estimated to yield $28,000,000; additional tax on tobacco, expected to yield $15,000,000.

The committee also agreed to authorise the issuing of $500,000,000 bonds. These bonds to be offered for sale at all post-offices in the United States in amounts of fifty dollars each, making a great popular loan to be absorbed by the people.

To tide over emergencies, the Secretary of the Treasury to be authorised to issue treasury certificates.

These certificates or debentures to be used to pay running expenses when the revenues do not meet the expenditures.

These preparations were distinctly war measures, and would be put in operation only should war occur.

[pg 34]April 13. The House of Representatives passed the following resolutions:

Whereas, the government of Spain for three years past has been waging war on the island of Cuba against a revolution by the inhabitants thereof, without making any substantial progress toward the suppression of said revolution, and has conducted the warfare in a manner contrary to the laws of nations by methods inhuman and uncivilised, causing the death by starvation of more than two hundred thousand innocent non-combatants, the victims being for the most part helpless women and children, inflicting intolerable injury to the commercial interests of the United States, involving the destruction of the lives and property of many of our citizens, entailing the expenditure of millions of money in patrolling our coasts and policing the high seas in order to maintain our neutrality; and,

Whereas, this long series of losses, injuries, and burdens for which Spain is responsible has culminated in the destruction of the United States battle-ship Maine in the harbour of Havana, and the death of two hundred and sixty-six of our seamen,—

Resolved, That the President is hereby authorised and directed to intervene at once to stop the war in Cuba, to the end and with the purpose of securing permanent peace and order there, and establishing by the free action of the people there of a stable and independent government of their own in the island [pg 35]of Cuba; and the President is hereby authorised and empowered to use the land and naval forces of the United States to execute the purpose of this resolution.

In the Senate the majority resolution reported:

Whereas, the abhorrent conditions which have existed for more than three years in the island of Cuba, so near our own borders, have been a disgrace to Christian civilisation, culminating as they have in the destruction of a United States battle-ship with two hundred and sixty-six of its officers and crew, while on a friendly visit in the harbour of Havana, and cannot longer be endured, as has been set forth by the President of the United States in his message to Congress on April 11, 1898, upon which the action of Congress was invited; therefore,

Resolved, First, that the people of the island of Cuba are, and of right ought to be, free and independent.

Second, That it is the duty of the United States to demand, and the government of the United States does hereby demand, that the government of Spain at once relinquish its authority and government in the island of Cuba, and withdraw its land and naval forces from Cuba and Cuban waters.

Third, That the President of the United States be, and he hereby is, directed and empowered to use the entire land and naval forces of the United States, and to call into the actual service of the United States the [pg 36]militia of the several States to such extent as may be necessary, to carry these resolutions into effect.

April 14. The Spanish minister at Washington sealed his archives and placed them in the charge of the French ambassador, M. Cambon. The queen regent of Spain, at a Cabinet meeting, signed a call for the Cortes to meet on the twentieth of the month, and a decree opening a national subscription for increasing the navy and other war services.

April 15. The United States consulate at Malaga, Spain, was attacked by a mob, and the shield torn down and trampled upon.

April 17. The Spanish committee of inquiry into the destruction of the Maine reported that the explosion could not have been caused by a torpedo or a mine of any kind, because no trace of anything was found to justify such a conclusion. It gave the testimony of two eye-witnesses to the catastrophe, who swore that there was absolutely no disturbance on the surface of the harbour around the Maine. The committee gave great stress to the fact that the explosion did no damage to the quays, and none to the vessels moored close to the Maine, whose officers and crews noticed nothing that could lead them to suppose that the disaster was caused otherwise than by an accident inside the American vessel.

April 18. Congress passed the Senate resolution, as given above, with an additional clause as follows:

[pg 37]Fourth, That the United States hereby disclaim any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction or control over said island, except for the pacification thereof; and asserts its determination, when that is accomplished, to leave the government and control of the island to its people.

CHAPTER III.

A DECLARATION OF WAR.

All that had been done by the governments of the United States and of Spain was indicative of war,—it was virtually a declaration that an appeal would be made to arms.

April 20. Preparations were making in each country for actual hostilities, and the American people were prepared to receive the statement made by a gentleman in close touch with high officials, when he wrote:

“The United States has thrown down the gage of battle and Spain has picked it up.

“The signing by the President of the joint resolutions instructing him to intervene in Cuba was no sooner communicated to the Spanish minister than he immediately asked the State Department to furnish him with his passports.

“It was defiance, prompt and direct.

“It was the shortest and quickest manner for Spain to answer our ultimatum.

“Nominally Spain has three days in which to make her reply. Actually that reply has already been delivered.

“When a nation withdraws her minister from the territory of another it is an open announcement to the world that all friendly relations have terminated.

“Answers to ultimatums have before this been returned at the cannon’s mouth. First the minister is withdrawn, then comes the firing. Spain is ready to speak through shotted guns.

“And the United States is ready to answer, gun for gun.

“The queen regent opened the Cortes in Madrid yesterday, saying, in her speech from the throne: ‘I have summoned the Cortes to defend our rights, whatever sacrifice they may entail, trusting to the Spanish people to gather behind my son’s throne. With our glorious army, navy, and nation united before foreign aggression, we trust in God that we shall overcome, without stain on our honour, the baseless and unjust attacks made on us.’

“Orders were sent last night to Captain Sampson at Key West to have all the vessels of his fleet under full steam, ready to move immediately upon orders.”

The Spanish minister, accompanied by six members of his staff, departed from Washington during the evening, after having made a hurried call at the French embassy and the Austrian legation, where Spanish interests were left in charge, having announced that he would spend several days in Toronto, Canada.

April 21. The ultimatum of the United States was received at Madrid early in the morning, and the gov[pg 40]ernment immediately broke off diplomatic relations by sending the following communication to Minister Woodford, before he could present any note from Washington:

“Dear Sir:—In compliance with a painful duty, I have the honour to inform you that there has been sanctioned by the President of the republic a resolution of both chambers of the United States, which denies the legitimate sovereignty of Spain and threatens armed intervention in Cuba, which is equivalent to a declaration of war.

“The government of her majesty have ordered her minister to return without loss of time from North American territory, together with all the personnel of the legation.

“By this act the diplomatic relations hitherto existing between the two countries, and all official communication between their respective representatives, cease.

“I am obliged thus to inform you, so that you may make such arrangements as you think fit. I beg your excellency to acknowledge receipt of this note at such time as you deem proper, taking this opportunity to reiterate to you the assurances of my distinguished consideration.

Relative to the ultimatum and its reception, the government of this country gave out the following information:

[pg 41]“On yesterday, April 20, 1898, about one o’clock P. M., the Department of State served notice of the purposes of this government by delivering to Minister Polo a copy of an instruction to Minister Woodford, and also a copy of the resolutions passed by the Congress of the United States on the nineteenth instant. After the receipt of this notice the Spanish minister forwarded to the State Department a request for his passports, which were furnished him on yesterday afternoon.

“Copies of the instructions to Woodford are herewith appended. The United States minister at Madrid was at the same time instructed to make a like communication to the Spanish government.

“This morning the Department received from General Woodford a telegram, a copy of which is hereunto attached, showing that the Spanish government had broken off diplomatic relations with this government.

“This course renders unnecessary any further diplomatic action on the part of the United States.

“ ‘Woodford, Minister, Madrid:—You have been furnished with the text of a joint resolution, voted by the Congress of the United States on the nineteenth instant, approved to-day, in relation to the pacification of the island of Cuba. In obedience to that act, the President directs you to immediately communicate to the government of Spain said resolution, with the [pg 42]formal demand of the government of the United States, that the government of Spain at once relinquish her authority and government in the island of Cuba, and withdraw her land and naval forces from Cuba and Cuban waters.

“ ‘In taking this step, the United States disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction, or control over said island, except for the pacification thereof, and asserts its determination when that is accomplished to leave the government and control of the island to its people under such free and independent government as they may establish.

“ ‘If, by the hour of noon on Saturday next, the twenty-third day of April, there be not communicated to this government by that of Spain a full and satisfactory response to this demand and resolutions, whereby the ends of peace in Cuba shall be assured, the President will proceed without further notice to use the power and authority enjoined and conferred upon him by the said joint resolution to such an extent as may be necessary to carry the same into effect.

“This is Woodford’s telegram of this morning:

“ ‘To Sherman, Washington:—Early this morning (Tuesday), immediately after the receipt of your telegram, and before I communicated the same to the [pg 43]Spanish government, the Spanish Minister for Foreign Affairs notified me that diplomatic relations are broken between the two countries, and that all official communication between the respective representatives has ceased. I accordingly asked for my passports. Have turned the legation over to the British embassy, and leave for Paris this afternoon. Have notified consuls.

The Spanish newspapers applauded the “energy” of their government, and printed the paragraph inserted below as a semi-official statement from the throne:

“The Spanish government having received the ultimatum of the President of the United States, considers that the document constitutes a declaration of war against Spain, and that the proper form to be adopted is not to make any further reply, but to await the expiration of the time mentioned in the ultimatum before opening hostilities. In the meantime the Spanish authorities have placed their possessions in a state of defence, and their fleet is already on its way to meet that of the United States.”

April 21. General Woodford left Madrid late in the afternoon, and although an enormous throng of citizens were gathered at the railway station to witness his departure, no indignities were attempted. The people of Madrid professed the greatest enthusiasm for war, and the general opinion among the masses was that Spain would speedily vanquish the United States.

[pg 44]In Havana, in response to the manifesto from the palace, the citizens began early to decorate the public buildings and many private residences, balconies, and windows with the national colours. A general illumination followed, as on the occasion of a great national festivity. Early in the evening no less than eight thousand demonstrators filled the square opposite the palace, a committee entering and tendering to the captain-general, in the name of all, their estates, property, and lives in aid of the government, and pledging their readiness to fight the invader.

General Blanco thanked them in the name of the king, the queen regent and the imperial and colonial governments, assuring them that he would do everything in his power to prevent the invaders from setting foot in Cuba. “Otherwise I shall not live,” he said, in conclusion. “Do you swear to follow me to the fight?”

“Yes, yes, we do!” the crowd answered.

“Do you swear to give the last drop of blood in your veins before letting a foreigner step his foot on the land we discovered, and place his yoke upon the people we civilised?”

“Yes, yes, we do!”

“The enemy’s fleet is almost at Morro Castle, almost at the doors of Havana,” General Blanco added. “They have money; but we have blood to shed, and we are ready to shed it. We will throw them into the sea!”

The people interrupted him with cries of applause, and he finished his speech by shouting “Viva Espana!” [pg 45]“Viva el Rey!” “Long live the army, the navy, and the volunteers!”

The Congress of the United States passed a joint resolution authorising the President, in his discretion, to prohibit the exportation of coal and other war material. The measure was of great importance, because through it was prevented the shipment of coal to ports in the West Indies where it might be used by Spain.

April 22. At half past five o’clock in the morning the vessels composing the North Atlantic Squadron put to sea from Key West. The flag-ship New York led the way. Close behind her steamed the Iowa and the Indiana. Following the war-ships came the gunboat Machias, and then the Newport. The Amphitrite, the first of the fleet, lying close to shore, steamed out after the Machias, and then followed in order the Nashville, the Wilmington, the Castine, the Cincinnati, and the other boats of the fleet, save the monitors Terror and Puritan, which were coaling, the cruiser Marblehead, the despatch-boat Dolphin, and the gunboat Helena.

After getting out of sight of land the flag of a rear-admiral was hoisted over the New York, indicating to the fleet that Captain Sampson was acting as a rear-admiral. When in the open sea the fleet was divided into three divisions. The New York, Iowa, and Indiana had the position of honour. Stretching out to the right were the Montgomery, Wilmington, Newport, and smaller craft; to the left was the Nashville in the lead, [pg 46]followed by the Cincinnati, Castine, Machias, Mayflower, and some of the torpedo-boats.

At seven o’clock in the morning the first gun of the war was fired. The Nashville, which had been sailing at about six knots an hour, in obedience to orders, suddenly swung out of line. Clouds of black smoke poured from her long, slim stacks, her speed was gradually increased until the water ascended in fine spray on each side of the bow, and behind her trailed out a long, creamy streak on the quiet waters.

She was headed for a Spanish merchantman, which was then about half a mile away, apparently paying no heed to the monsters of war.

A shot from one of the 4-pounders was sent across the stranger’s bow, and then, no attention having been paid to it, a 6-inch gun was discharged. This last shot struck the water and bounded along the surface a mile or more, sending up great clouds of spray.

The Spaniard wisely concluded to heave to, and within five minutes a boat was lowered from the Nashville to put on board the first prize a crew of six men, under command of Ensign Magruder.

The captured vessel was the Buena Ventura, of 1,741 tons burthen; laden with lumber, valued at eleven thousand dollars, and carrying a deck-load of cattle.

The record of this first day of hostilities was not to end with one capture.

Late in the afternoon, almost within gunshot of the Cuban shore, while the United States fleet was stand[pg 47]ing toward Havana, with the Mayflower a mile or more in advance of the flag-ship New York, the merchant steamship Pedro hove in sight. The Mayflower suddenly swung sharply to the westward, and a moment later a string of butterfly flags went fluttering to her masthead.

The New York flung her answering pennant to the breeze, and, making another signal to the fleet, which probably meant “Stay where you are until I get back,” swung her bow to the westward and went racing for the game that the Mayflower had sighted. The big cruiser dashed forward, smoke trailing in dense masses from each of her three big funnels, a hill of foam around her bow, and in her wake a swell like a tidal wave. It was a winning pace, and a magnificent sight she presented as she dashed through the choppy seas with never an undulation of her long, graceful hull.

When she was well inshore a puff of smoke came from the bow of the cruiser, followed by a dull report, then another and another, until four shots had been sent from one of the small, rapid-fire guns. The Spanish steamer, probably believing the pursuing craft carried no heavier guns, was trying to keep at a safe distance until the friendly darkness of night should hide her from view. During sixty seconds or more the big cruiser held her course in silence, and then her entire bow was hidden from the spectators in a swirl of white smoke as a main battery gun roared out its demand.

[pg 48]The whizzing shell spoke plainly to the Spanish craft, and had hardly more than flung up a column of water a hundred yards or less in front of the merchantman before she was hastily rounded to with her engines reversed.

A prize crew under Ensign Marble was thrown on board, and the steamer Pedro, twenty-eight hundred tons burthen, suddenly had a change of commanders.

April 22. The President issued a proclamation announcing a blockade of Cuban ports, and also signed the bill providing for the utilising of volunteer forces in times of war.

The foreign news of immediate interest to the people of the United States was, first, from Havana, that Captain-General Blanco had published a decree confirming his previous decree, and declaring the island to be in a state of war.

He also annulled his former similar decrees granting pardon to insurgents, and placed under martial law all those who were guilty of treason, espionage, crimes against peace or against the independence of the nation, seditious revolts, attacks against the form of government or against the authorities, and against those who disturb public order, though only by means of printed matter.

From Madrid came the information that during the evening a throng of no less than six thousand people, carrying flags and shouting “Viva Espana!” “We want war!” and “Down with the Yankees!” burned the stars [pg 49]and stripes in front of the residence of Señor Sagasta, the premier, who was accorded an ovation. The mob then went to the residence of M. Patenotre, the French ambassador, and insisted that he should make his appearance, but the French ambassador was not at home.

Correspondents at Hongkong announced that Admiral Dewey had ordered the commanders of the vessels composing his squadron to be in readiness for an immediate movement against the Philippine Islands.

April 23. The President issued a proclamation calling for one hundred and twenty-five thousand volunteer soldiers.

In the new war tariff bill a loan of $500,000,000 was provided for in the form of three per cent. 10-20 bonds.

The third capture of a Spanish vessel was made early in the morning by the torpedo-boat Ericsson. The fishing-boat Perdito was sighted making for Havana harbour, and overhauled only when she was directly under the guns of Morro Castle, where a single shot from the fortification might have sunk either craft. After a prize-crew had been put on board Rear-Admiral Sampson decided to turn her loose, and so she was permitted to return to Havana to spread the news of the blockade.

During the afternoon the rum-laden schooner Mathilde was taken, after a lively chase, by the torpedo-boat Porter. Between five and six o’clock in the evening the torpedo-boat Foote, Lieut. W. L. Rodgers commanding, received the first Spanish fire.

She was taking soundings in the harbour of Matanzas, [pg 50]and had approached within two or three hundred yards of the shore, when suddenly a masked battery on the east side of the harbour, and not far distant from the Foote, fired three shots at the torpedo-boat. The missiles went wide of the mark, and the Foote leisurely returned to the Cincinnati to report the result of her work.

At Hongkong the United States consul notified Governor Blake of the British colony that the American fleet would leave the harbour in forty-eight hours, and that no warlike stores, or more coal than would be necessary to carry the vessels to the nearest home port, would be shipped.

The United States demanded of Portugal, the owner of the Cape Verde Islands, that, in accordance with international law, she send the Spanish war-ships away from St. Vincent, or require them to remain in that port during the war.

April 24. The following decree was gazetted in Madrid:

“Diplomatic relations are broken off between Spain and the United States, and a state of war being begun between the two countries, numerous questions of international law arise, which must be precisely defined chiefly because the injustice and provocation came from our adversaries, and it is they who by their detestable conduct have caused this great conflict.”

The royal decree then states that Spain maintains her right to have recourse to privateering, and an[pg 51]nounces that for the present only auxiliary cruisers will be fitted out. All treaties with the United States are annulled; thirty days are given to American ships to leave Spanish ports, and the rules Spain will observe during the war are outlined in five clauses, covering neutral flags and goods contraband of war; what will be considered a blockade; the right of search, and what constitutes contraband of war, ending with saying that foreign privateers will be regarded as pirates.

Continuing, the decree declared: “We have observed with the strictest fidelity the principles of international law, and have shown the most scrupulous respect for morality and the right of government.

“There is an opinion that the fact that we have not adhered to the declaration of Paris does not exempt us from the duty of respecting the principles therein enunciated. The principle Spain unquestionably refused to admit then was the abolition of privateering.

“The government now considers it most indispensable to make absolute reserve on this point, in order to maintain our liberty of action and uncontested right to have recourse to privateering when we consider it expedient, first, by organising immediately a force of cruisers, auxiliary to the navy, which will be composed of vessels of our mercantile marine, and with equal distinction in the work of our navy.

“Clause 1: The state of war existing between Spain and the United States annuls the treaty of peace and amity of October 27, 1795, and the protocol of January [pg 52]12, 1877, and all other agreements, treaties, or conventions in force between the two countries.

“Clause 2: From the publication of these presents, thirty days are granted to all ships of the United States anchored in our harbours to take their departure free of hindrance.

“Clause 3: Notwithstanding that Spain has not adhered to the declaration of Paris, the government, respecting the principles of the law of nations, proposes to observe, and hereby orders to be observed, the following regulations of maritime laws:

“One: Neutral flags cover the enemy’s merchandise, except contraband of war.

“Two: Neutral merchandise, except contraband of war, is not seizable under the enemy’s flag.

“Three: A blockade, to be obligatory, must be effective; viz., it must be maintained with sufficient force to prevent access to the enemy’s littoral.

“Four: The Spanish government, upholding its rights to grant letters of marque, will at present confine itself to organising, with the vessels of the mercantile marine, a force of auxiliary cruisers which will coöperate with the navy, according to the needs of the campaign, and will be under naval control.

“Five: In order to capture the enemy’s ships, and confiscate the enemy’s merchandise and contraband of war under whatever form, the auxiliary cruisers will exercise the right of search on the high seas, and in the waters under the enemy’s jurisdiction, in accordance [pg 53]with international law and the regulations which will be published.

“Six: Defines what is included in contraband of war, naming weapons, ammunition, equipments, engines, and, in general, all the appliances used in war.

“Seven: To be regarded and judged as pirates, with all the rigour of the law, are captains, masters, officers, and two-thirds of the crew of vessels, which, not being American, shall commit acts of war against Spain, even if provided with letters of marque by the United States.”

April 24. The U. S. S. Helena captured the steamer Miguel Jover. The U. S. S. Detroit captured the steamer Catalania; the Wilmington took the schooner Candidor; the Winona made a prize of the steamer Saturnia, and the Terror brought in the schooners Saco and Tres Hermanes.

April 25. Early in the day the President sent the following message to Congress:

“I transmit to the Congress, for its consideration and appropriate action, copies of correspondence recently had with the representatives of Spain and the United States, with the United States minister at Madrid, through the latter with government of Spain, showing the action taken under the joint resolution approved April 20, 1898, ‘For the recognition of the independence of the people of Cuba, demanding that the government of Spain relinquish its authority and government in the island of Cuba, and withdraw its land and naval forces [pg 54]from Cuba and Cuban waters, and directing the President of the United States to carry these resolutions into effect.’

“Upon communicating with the Spanish minister in Washington the demand, which it became the duty of the executive to address to the government of Spain in obedience with said resolution, the minister asked for his passports and withdrew. The United States minister at Madrid was in turn notified by the Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, that the withdrawal of the Spanish representative from the United States had terminated diplomatic relations between the two countries, and that all official communications between their respective representatives ceased therewith.

“I commend to your especial attention the note addressed to the United States minister at Madrid by the Spanish Minister for Foreign Affairs on the twenty-first instant, whereby the foregoing notification was conveyed. It will be perceived therefrom, that the government of Spain, having cognisance of the joint resolution of the United States Congress, and, in view of the things which the President is thereby required and authorised to do, responds by treating the reasonable demands of this government as measures of hostility, following with that instant and complete severance of relations by its action, which by the usage of nations accompanied an existing state of war between sovereign powers.

“The position of Spain being thus made known, and [pg 55]the demands of the United States being denied, with a complete rupture of intercourse by the act of Spain, I have been constrained, in exercise of the power and authority conferred upon me by the joint resolution aforesaid, to proclaim under date of April 22, 1898, a blockade of certain ports of the north coast of Cuba, lying between Cardenas and Bahia Honda, and of the port of Cienfuegos on the south coast of Cuba, and further in exercise of my constitutional powers, and using the authority conferred upon me by act of Congress, approved April 22, 1898, to issue my proclamation, dated April 23, 1898, calling for volunteers in order to carry into effect the said resolution of April 20, 1898. Copies of these proclamations are hereto appended.

“In view of the measures so taken, and other measures as may be necessary to enable me to carry out the express will of the Congress of the United States in the premises, I now recommend to your honourable body the adoption of a joint resolution declaring that a state of war exists between the United States of America and the kingdom of Spain, and I urge speedy action thereon to the end that the definition of the international status of the United States as a belligerent power may be made known, and the assertion of all its rights and the maintenance of all its duties in the conduct of a public war may be assured.

The war bill was passed without delay, and immediately after it had been signed the following notice was sent to the representatives of the foreign nations: