Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Analog Science Fact & Fiction June 1962. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Most people, when asked to define the ultimate in loneliness, say it's being alone in a crowd. And it takes only one slight difference to make one forever alone in the crowd....

obody at Hoskins, Haskell & Chapman, Incorporated, knew jut why Lucilla Brown, G.G. Hoskins' secretary, came to work half an hour early every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Even G.G. himself, had he been asked, would have had trouble explaining how his occasional exasperated wish that just once somebody would reach the office ahead of him could have caused his attractive young secretary to start doing so three times a week ... or kept her at it all the months since that first gloomy March day. Nobody asked G.G. however—not even Paul Chapman, the very junior partner in the advertising firm, who had displayed more than a little interest in Lucilla all fall and winter, but very little interest in anything all spring and summer. Nobody asked Lucilla why she left early on the days she arrived early—after all, eight hours is long enough. And certainly nobody knew where Lucilla went at 4:30 on those three days—nor would anybody in the office have believed it, had he known.

"Lucky Brown? seeing a psychiatrist?" The typist would have giggled, the office boy would have snorted, and every salesman on the force would have guffawed. Even Paul Chapman might have managed a wry smile. A real laugh had been beyond him for several months—ever since he asked Lucilla confidently, "Will you marry me?" and she answered, "I'm sorry, Paul—thanks, but no thanks."

Not that seeing a psychiatrist was anything to laugh at, in itself. After all, the year was 1962, and there were almost as many serious articles about mental health as there were cartoons about psychoanalysts, even in the magazines that specialized in poking fun. In certain cities—including Los Angeles—and certain industries—especially advertising—"I have an appointment with my psychiatrist" was a perfectly acceptable excuse for leaving work early. The idea of a secretary employed by almost the largest advertising firm in one of the best-known suburbs in the sprawling City of the Angels doing so should not, therefore, have seemed particularly odd. Not would it have, if the person involved had been anyone at all except Lucilla Brown.

The idea that she might need aid of any kind, particularly psychiatric, was ridiculous. She had been born twenty-two years earlier in undisputed possession of a sizable silver spoon—and she was, in addition, bright, beautiful, and charming, with 20/20 vision, perfect teeth, a father and mother who adored her, friends who did likewise ... and the kind of luck you'd have to see to believe. Other people entered contests—Lucilla won them. Other people drove five miles over the legal speed limit and got caught doing it—Lucilla out-distanced them, but fortuitously slowed down just before the highway patrol appeared from nowhere. Other people waited in the wrong line at the bank while the woman ahead of them learned how to roll pennies—Lucilla was always in the line that moved right up to the teller's window.

"Lucky" was not, in other words, just a happenstance abbreviation of "Lucilla"—it was an exceedingly apt nickname. And Lucky Brown's co-workers would have been quite justified in laughing at the very idea of her being unhappy enough about anything to spend three precious hours a week stretched out on a brown leather couch staring miserably at a pale blue ceiling and fumbling for words that refused to come. There were a good many days when Lucilla felt like laughing at the idea herself. And there were other days when she didn't even feel like smiling.

Wednesday, the 25th of July, was one of the days when she didn't feel like smiling. Or talking. Or moving. It had started out badly when she opened her eyes and found herself staring at a familiar blue ceiling. "I don't know," she said irritably. "I tell you, I simply don't know what happens. I'll start to answer someone and the words will be right on the tip of my tongue, ready to be spoken, then I'll say something altogether different. Or I'll start to cross the street and, for no reason at all, be unable to even step off the curb...."

"For no reason at all?" Dr. Andrews asked. "Are you sure you aren't withholding something you ought to tell me?"

She shifted a little, suddenly uncomfortable ... and then she was fully awake and the ceiling was ivory, not blue. She stared at it for a long moment, completely disoriented, before she realized that she was in her own bed, not on Dr. Andrews' brown leather couch, and that the conversation had been another of the interminable imaginary dialogues she found herself carrying on with the psychiatrist, day and night, awake and asleep.

"Get out of my dreams," she ordered crossly, summoning up a quick mental picture of Dr. Andrews' expressive face, level gray eyes, and silvering temples, the better to banish him from her thoughts. She was immediately sorry she had done so, for the image remained fixed in her mind; she could almost feel his eyes as she heard his voice ask again, "For no reason at all, Lucilla?"

he weatherman had promised a scorcher, and the heat that already lay like a blanket over the room made it seem probable the promise would be fulfilled. She moved listlessly, showering patting herself dry, lingering over the choice of a dress until her mother called urgently from the kitchen.

She was long minutes behind schedule when she left the house. Usually she rather enjoyed easing her small car into the stream of automobiles pouring down Sepulveda toward the San Diego Freeway, jockeying for position, shifting expertly from one lane to another to take advantage of every break in the traffic. This morning she felt only angry impatience; she choked back on the irritated impulse to drive directly into the side of a car that cut across in front of her, held her horn button down furiously when a slow-starting truck hesitated fractionally after the light turned green.

When she finally edged her Renault up on the "on" ramp and the freeway stretched straight and unobstructed ahead, she stepped down on the accelerator and watched the needle climb up and past the legal 65-mile limit. The sound of her tires on the smooth concrete was soothing and the rush of wind outside gave the morning an illusion of coolness. She edged away from the tangle of cars that had pulled onto the freeway with her and momentarily was alone on the road, with her rear-view mirror blank, the oncoming lanes bare, and a small rise shutting off the world ahead.

That was when it happened. "Get out of the way!" a voice shrieked "out of the way, out of the way, OUT OF THE WAY!" Her heart lurched, her stomach twisted convulsively, and there was a brassy taste in her mouth. Instinctively, she stamped down on the brake pedal, swerved sharply into the outer lane. By the time she had topped the rise, she was going a cautious 50 miles an hour and hugging the far edge of the freeway. Then, and only then, she heard the squeal of agonized tires and saw the cumbersome semitrailer coming from the opposite direction rock dangerously, jackknife into the dividing posts that separated north and south-bound traffic, crunch ponderously through them, and crash to a stop, several hundred feet ahead of her and squarely athwart the lane down which she had been speeding only seconds earlier.

The highway patrol materialized within minutes. Even so, it was after eight by the time Lucilla gave them her statement, agreed for the umpteenth time with the shaken but uninjured truck driver that it was indeed fortunate she hadn't been in the center lane, and drove slowly the remaining miles to the office. The gray mood of early morning had changed to black. Now there were two voices in her mind, competing for attention. "I knew it was going to happen," the truck driver said, "I couldn't see over the top of that hill. All I could do was fight the wheel and pray that if anybody was coming, he'd get out of the way." She could almost hear him repeating the words, "Get out of the way, out of the way...." And right on the heel of his cry came Dr. Andrews' soft query, "For no reason at all, Lucilla?"

She pulled into the company parking lot, jerked the wheel savagely to the left, jammed on the brakes. "Shut up!" she said. "Shut up, both of you!" She started into the building, then hesitated. She was already late, but there was something.... (Get out of the way, the way.... For no reason at all, at all....) She yielded to impulse and walked hurriedly downstairs to the basement library.

"That stuff I asked you to get together for me by tomorrow, Ruthie," she said to the gray-haired librarian. "You wouldn't by any chance have already done it, would you?"

"Funny you should ask." The elderly woman bobbed down behind the counter and popped back up with an armload of magazines and newspapers. "Just happened to have some free time last thing yesterday. It's already charged out to you, so you just go right ahead and take it, dearie."

t was 8:30 when Lucilla reached the office.

"When I need you, where are you?" G.G. asked sourly. "Learned last night that the top dog at Karry Karton Korporation is in town today, so they've pushed that conference up from Friday to ten this morning. If you'd been here early—or even on time—we might at least have gotten some of the information together."

Lucilla laid the stack of material on his desk. "I haven't had time to flag the pages yet," she said, "but they're listed on the library request on top. We did nineteen ads for KK last year and three of premium offers. I stopped by Sales on my way in—Susie's digging out figures for you now."

"Hm-m-m," said G.G. "Well. So that's where you've been. You could at least have let me know." There was grudging approval beneath his gruffness. "Say, how'd you know I needed this today, anyhow?"

"Didn't," said Lucilla, putting her purse away and whisking the cover off her typewriter. "Happenstance, that's all." (Just happened to go down to the library ... for no reason at all ... withholding something ... get out of the way....) The telephone's demand for attention overrode her thoughts. She reached for it almost gratefully. "Mr. Hoskins' office," she said. "Yes. Yes, he knows about the ten o'clock meeting this morning. Thanks for calling, anyway." She hung up and glanced at G.G., but he was so immersed in one of the magazines that the ringing telephone hadn't even disturbed him. Ringing? The last thing she did before she left the office each night was set the lever in the instrument's base to "off," so that the bell would not disturb G.G. if he worked late. So far today, nobody had set it back to "on."

t's getting worse," she said miserably to the pale blue ceiling. "The phone didn't ring this morning—it couldn't have—but I answered it." Dr. Andrews said nothing at all. She let her eyes flicker sidewise, but he was outside her range of vision. "I don't LIKE having you sit where I can't see you," she said crossly. "Freud may have thought it was a good idea, but I think it's a lousy one." She clenched her hands and stared at nothing. The silence stretched thinner and thinner, like a balloon blown big, until the temptation to rupture it was too great to resist. "I didn't see the truck this morning. Nor hear it. There was no reason at all for me to slow down and pull over."

"You might be dead if you hadn't. Would you like that better?"

The matter-of-fact question was like a hand laid across Lucilla's mouth. "I don't want to be dead," she admitted finally. "Neither do I want to go on like this, hearing words that aren't spoken and bells that don't ring. When it gets to the point that I pick up a phone just because somebody's thinking...." She stopped abruptly.

"I didn't quite catch the end of that sentence," Dr. Andrews said.

"I didn't quite finish it. I can't."

"Can't? Or won't? Don't hold anything back, Lucilla. You were saying that you picked up the phone just because somebody was thinking...." He paused expectantly. Lucilla reread the ornate letters on the framed diploma on the wall, looked critically at the picture of Mrs. Andrews—whom she'd met—and her impish daughter—whom she hadn't—counted the number of pleats in the billowing drapes, ran a tentative finger over the face of her wristwatch, straightened a fold of her skirt ... and could stand the silence no longer.

"All right," she said wearily. "The girl at Karry Karton thought about talking to me, and I heard my phone ring, even though the bell was disconnected. G.G. thought about needing backup material for the conference and I went to the library. The truck driver thought about warning people and I got out of his way. So I can read people's minds—some people's minds, some of the time, anyway ... only there's no such thing as telepathy. And if I'm not telepathic, then...." She caught herself in the brink of time and bit back the final word, fighting for self-control.

"Then what?" The peremptory question toppled Lucilla's defenses.

"I'm crazy," she said. Speaking the word released all the others dammed up behind it. "Ever since I can remember, things like this have happened—all at once, in the middle of doing something or saying something, I'd find myself thinking about what somebody else was doing or saying. Not thinking—knowing. I'd be playing hide-and-seek, and I could see the places where the other kids were hiding just as plainly as I could see my own surroundings. Or I'd be worrying over the answers to an exam question, and I'd know what somebody in the back of the room had decided to write down, or what the teacher was expecting us to write. Not always—but it happened often enough so that it bothered me, just the way it does now when I answer a question before it's been asked, or know what the driver ahead of me is going to do a split second before he does it, or win a bridge game because I can see everybody else's hand through his own eyes, almost."

"Has it always ... bothered you, Lucilla?"

"No-o-o-o." She drew the word out, considering, trying to think when it was that she hadn't felt uneasy about the unexpected moments of perceptiveness. When she was very little, perhaps. She thought of the tiny, laughing girl in the faded snaps of the old album—and suddenly, inexplicably, she was that self, moving through remembered rooms, pausing to collect a word from a boyish father, a thought from a pretty young mother. Reluctantly, she closed her eyes against that distant time. "Way back," she said, "when I didn't know any better, I just took it for granted that sometimes people talked to each other and that sometimes they passed thoughts along without putting them into words. I was about six, I guess, when I found out it wasn't so." She slipped into her six-year-old self as easily as she had donned the younger Lucilla. This time she wasn't in a house, but high on a hillside, walking on springy pine needles instead of prosaic carpet.

"Talk," Dr. Andrews reminded her, his voice so soft that it could almost have come from inside her own mind.

"We were picnicking," she said. "A whole lot of us. Somehow, I wandered away from the others...." One minute the hill was bright with sun, and the next it was deep in shadows and the wind that had been merely cool was downright cold. She shivered and glanced around expecting her mother to be somewhere near, holding out a sweater or jacket. There was no one at all in sight. Even then, she never thought of being frightened. She turned to retrace her steps. There was a big tree that looked familiar, and a funny rock behind it, half buried in the hillside. She was trudging toward it, humming under her breath, when the worry thoughts began to reach her. (... only a little creek so I don't think she could have fallen in ... not really any bears around here ... but she never gets hurt ... creek ... bear ... twisted ankle ... dark ... cold....) She had veered from her course and started in the direction of the first thought, but now they were coming from all sides and she had no idea at all which way to go. She ran wildly then, first one way, then the other, sobbing and calling.

"Lucilla!" The voice sliced into the night, and the dark mountainside and the frightened child were gone. She shuddered a little, reminiscently, and put her hand over her eyes.

"Somebody found me, of course. And then Mother was holding me and crying and I was crying, too, and telling her how all the different thought at once frightened me and mixed me up. She ... she scolded me for ... for telling fibs ... and said that nobody except crazy people thought they could read each other's minds."

"I see," said Dr. Andrews, "So you tried not to, of course. And anytime you did it again, or thought you did, you blamed it on coincidence. Or luck."

"And had that nightmare again."

"Yes, that, too. Tell me about it."

"I already have. Over and over."

"Tell me again, then."

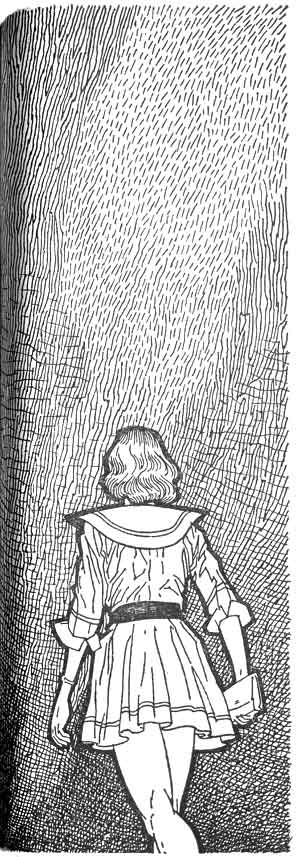

"I feel like a fool, repeating myself," she complained. Dr. Andrew's made no comment. "Oh, all right. It always starts with me walking down a crowded street, surrounded by honking cars and yelling newsboys and talking people. The noise bothers me and I'm tempted to cover my ears to shut it out, but I try to ignore it, instead, and walk faster and faster. Bit by bit, the buildings I pass are smaller, the people fewer, the noise less. All at once, I discover there's nothing around at all but a spreading carpet of gray-green moss, years deep, and a silence that feels as old as time itself. There's nothing to frighten me, but I am frightened ... and lonesome, not so much for people, but for a sound ... any sound. I turn to run back toward town, but there's nothing behind me now but the same gray moss and gray sky and dead silence."

y the time she reached the last word, her throat had tightened until speaking was difficult. She reached out blindly for something to cling to. Her groping hand met Dr. Andrews' and his warm fingers closed reassuringly around hers. Gradually the panic drained away, but she could think of nothing to say at all, although she longed to have the silence broken. As if he sensed her longing, Dr. Andrews said, "You started having the dream more often just after you told Paul you wouldn't marry him, is that right?"

"No. It was the other way around. I hadn't had it for months, not since I fell in love with him, then he got assigned to that "Which Tomorrow?" show and he started calling me "Lucky," the way everybody does, and the dream came back...." She stopped short, and turned on the couch to stare at the psychiatrist with startled eyes. "But that can't be how it was," she said. "The lonesomeness must have started after I decided not to marry him, not before."

"I wonder why the dream stopped when you fell in love with him."

"That's easy," Lucilla said promptly, grasping at the chance to evade her own more disturbing question. "I felt close to him, whether he was with me or not, the way I used to feel close to people back when I was a little girl, before ... well, before that day in the mountains ... when Mother said...."

"That was when you started having the dream, wasn't it?"

"How'd you know? I didn't—not until just now. But, yes, that's when it started. I'd never minded the dark or being alone, but I was frightened when Mother shut the door that night, because the walls seemed so ... so solid, now that I knew all the thoughts I used to think were with me there were just pretend. When I finally went to sleep, I dreamed, and I went on having the same dream, night after night after night, until finally they called a doctor and he gave me something to make me sleep."

"I wish they'd called me," Dr. Andrews said.

"What could you have done? The sleeping pills worked, anyway, and after a while I didn't need them any more, because I'd heard other kids talking about having hunches and lucky streaks and I stopped feeling different from the rest of them, except once in a while, when I was so lucky it ... bothered me."

"And after you met Paul, you stopped being ... too lucky ... and the dream stopped?"

"No!" Lucilla was startled at her own vehemence. "No, it wasn't like that at all, and you'd know it, if you'd been listening. With Paul, I felt close to him all the time, no matter how many miles or walls or anything else there were between us. We hardly had to talk at all, because we seemed to know just what the other one was thinking all the time, listening to music, or watching the waves pound in or just working together at the office. Instead of feeling ... odd ... when I knew what he was thinking or what he was going to say, I felt good about it, because I was so sure it was the same way with him and what I was thinking. We didn't talk about it. There just wasn't any need to." She lapsed into silence again. Dr. Andrews straightened her clenched hand out and stroked the fingers gently. After a moment, she went on.

"He hadn't asked me to marry him, but I knew he would, and there wasn't any hurry, because everything was so perfect, anyway. Then one of the company's clients decided to sponsor a series of fantasy shows on TV and wanted us to tie in the ads for next year with the fantasy theme. Paul was assigned to the account, and G.G. let him borrow me to work on it, because it was such a rush project. I'd always liked fairy stories when I was little and when I discovered there were grown-up ones, too, like those in Unknown Worlds and the old Weird Tales, I read them, too. But I hadn't any idea how much there was, until we started buying copies of everything there was on the news-stands, and then ransacking musty little stores for back issues and ones that had gone out of publication, until Paul's office was just full of teetery piles of gaudy magazines and everywhere you looked there were pictures of strange stars and eight-legged monsters and men in space suits."

"So what do the magazines have to do with you and Paul?"

"The way he felt about them changed everything. He just laughed at the ones about space ships and other planets and robots and things, but he didn't laugh when came across stories about ... well, mutants, and people with talents...."

"Talents? Like reading minds, you mean?"

She nodded, not looking at him. "He didn't laugh at those. He acted as if they were ... well, indecent. The sort of thing you wouldn't be caught dead reading in public. And he thought that way, too, especially about the stories that even mentioned telepathy. At first, when he brought them to my attention in that disapproving way, I thought he was just pretending to sneer, to tease me, because he—we—knew they could be true. Only his thoughts matched his remarks. He hated the stories, Dr. Andrews, and was just determined to have me hate them, too. All at once I began to feel as if I didn't know him at all and I began to wonder if I'd just imagined everything all those months I felt so close to him. And then I began to dream again, and to think about that lonesome silent world even when I was wide awake."

"Go on, Lucilla," Dr. Andrews said, as she hesitated.

"That's all, just about. We finished the job and got rid of the magazines and for a little while it was almost as if those two weeks had never been, except I couldn't forget that he didn't know what I was thinking at all, even when everything he did, almost, made it seem as if he did. It began to seem wrong for me to know what he was thinking. Crazy, like Mother had said, and worse, somehow. Not well, not even nice, if you know what I mean."

"Then he asked you to marry him."

"And I said no, even when I wanted, oh, so terribly, to say yes and yes and yes." She squeezed her eyes tight shut to hold back a rush of tears.

ime folded back on itself. Once again, the hands of her wristwatch pointed to 4:30 and the white-clad receptionist said briskly, "Doctor will see you now." Once again, from some remote vantage point, Lucilla watched herself brush past Dr. Andrews and cross to the familiar couch, heard herself say, "It's getting worse," watched herself move through a flickering montage of scenes from childhood to womanhood, from past to present.

She opened he eyes to meet those of the man who sat patiently beside her. "You see," he said, "telling me wasn't so difficult, after all." And then, before she had decided on a response, "What do you know about Darwin's theory of evolution, Lucilla?"

His habit of ending a tense moment by making an irrelevant query no longer even startled her. Obediently, she fumbled for an answer. "Not much. Just that he thought all the different kinds of life on earth today evolved from a few blobs of protoplasm that sprouted wings or grew fur or developed teeth, depending on when they lived, and where." She paused hopefully, but met with only silence. "Sometimes what seemed like a step forward wasn't," she said, ransacking her brain for scattered bits of information. "Then the species died out, like the saber-tooth tiger, with those tusks that kept right on growing until they locked his jaws shut, so he starved to death." As she spoke, she remembered the huge beast as he had been pictured in one of her college textbooks. The recollection grew more and more vivid, until she could see both the picture and the facing page of text. There was an irregularly shaped inkblot in the upper corner and several heavily underlined sentences that stood out so distinctly she could actually read the words. "According to Darwin, variations in general are not infinitesimal, but in the nature of specific mutations. Thousands of these occur, but only the fittest survive the climate, the times, natural enemies, and their own kind, who strive to perpetuate themselves unchanged." Taken one by one, the words were all familiar—taken as a whole, they made no sense at all. She let the book slip unheeded from her mind and stared at Dr. Andrews in bewilderment.

"Try saying it in a different way."

"You sound like a school teacher humoring a stupid child." And then, because of the habit of obedience was strong, "I guess he meant that tails didn't grow an inch at a time, the way the dog's got cut off, but all at once ... like a fish being born with legs as well as fins, or a baby saber-tooth showing up among tigers with regular teeth, or one ape in a tribe discovering he could swing down out of the treetops and stand erect and walk alone."

He echoed her last words. "And walk alone...." A premonitory chill traced its icy way down Lucilla's backbone. For a second she stood on gray moss, under a gray sky, in the midst of a gray silence. "He not only could walk alone, he had to. Do you remember what your book said?"

"Only the fittest survive," Lucilla said numbly. "Because they have to fight the climate ... and their natural enemies ... and their own kind." She swung her feet to the floor and pushed herself into a sitting position. "I'm not a ... a mutation. I'm not, I'm not, I'm NOT, and you can't say I am, because I won't listen!"

"I didn't say you were." There was the barest hint of emphasis on the first word. Lucilla was almost certain she heard a whisper of laughter, but he met her gaze blandly, his expression completely serious.

"Don't you dare laugh!" she said, nonetheless. "There's nothing funny about ... about...."

"About being able to read people's minds," Dr Andrews said helpfully. "You'd much rather have me offer some other explanation for the occurrences that bother you so—is that it?"

"I guess so. Yes, it is. A brain tumor. Or schizophrenia. Or anything at all that could maybe be cured, so I could marry Paul and have children and be like everybody else. Like you." She looked past him to the picture on his desk. "It's easy for you to talk."

He ignored the last statement. "Why can't you get married, anyway?"

"You've already said why. Because Paul would hate me—everybody would hate me—if they knew I was different."

"How would they know? It doesn't show. Now if you had three legs, or a long bushy tail, or outsized teeth...."

Lucilla smiled involuntarily, and then was furious at herself for doing so and at Dr Andrews for provoking her into it. "This whole thing is utterly asinine, anyhow. Here we are, talking as if I might really be a mutant, and you know perfectly well that I'm not."

"Do I? You made the diagnosis, Lucilla, and you've given me some mighty potent reasons for believing it ... can you give me equally good reasons for doubting that you're a telepath?"

he peremptory demand left Lucilla speechless for a moment. She groped blindly for an answer, then almost laughed aloud as she found it.

"But of course. I almost missed it, even after you practically drew me a diagram. If I could read minds, just as soon as anybody found it out, he'd be afraid of me, or hate me, like the book said, and you said, too. If you believed it, you'd do something like having me locked up in a hospital, maybe, instead of...."

"Instead of what, Lucilla?"

"Instead of being patient, and nice, and helping me see how silly I've been." She reached out impulsively to touch his hand, then withdrew her own, feeling somewhat foolish when he made no move to respond. Her relief was too great, however, to be contained in silence. "Way back the first time I came in, almost, you said that before we finished therapy, you'd know me better than I knew myself. I didn't believe you—maybe I didn't want to—but I begin to think you were right. Lot of times, lately, you've answered a question before I even asked it. Sometimes you haven't even bothered to answer—you've just sat there in your big brown chair and I've lain here on the couch, and we've gone through something together without using words at all...." She had started out almost gaily, the words spilling over each other in their rush to be said, but bit by bit she slowed down, then faltered to a stop. After she had stopped talking altogether, she could still hear her last few phrases, repeated over and over, like an echo that refused to die. (Answered ... before I even asked ... without using words at all ... without using words....)

She could almost taste the terror that clogged her throat and dried her lips. "You do believe it. And you could have me locked up. Only ... only...." Fragments of thought, splinters of words, and droplets of silence spun into a kaleidoscopic jumble, shifted infinitesimally, and fell into an incredible new pattern. Understanding displaced terror and was, in turn, displaced by indignation. She stared accusingly at her interrogator. "But you look just like ... just like anybody."

"You expected perhaps three legs or a long bushy tail or teeth like that textbook tiger?"

"And you're a psychiatrist!"

"What else? Would you have talked to me like this across a grocery counter, Lucilla? Or listened to me, if I'd been driving a bus or filling a prescription? Would I have found the others in a bowling alley or a business office?"

"Then there are ... others?" She let out her breath on a long sigh involuntarily glancing again at the framed picture. "Only I love Paul, and he isn't ... he can't...."

"Nor can Carol." His eyes were steady on hers, yet she felt as if he were looking through and beyond her. For no reason at all, she strained her ears for the sound of footsteps or the summons of a voice. "Where do you suppose the second little blob of protoplasm with legs came from?" Dr. Andrews asked. "And the third? If that ape who found he could stand erect had walked lonesomely off into the sunset like a second-rate actor on a late, late show, where do you suppose you'd be today?"

He broke off abruptly and watched with Lucilla as the office door edged open. The small girl who inched her way around it wore blue jeans and a pony tail rather than an organdy frock and curls, but her pixie smile matched that of the girl in the photograph Lucilla had glanced at again and again.

"You wanted me, Daddy?" she asked, but she looked toward Lucilla.

"I thought you'd like to meet someone with the same nickname as yours," Dr. Andrews said, rising to greet her. "Lucky, meet Lucky."

"Hello," the child said, then her smile widened. "Hello!" (But I don't have to say it, do I? I can talk to you just the way I talk to Daddy and Uncle Whitney and Big Bill).

"Hello yourself," said Lucilla. This time when the corners of her mouth began to tick upward, she made no attempt to stop them. (Of course you can, darling. And I can answer you the same way, and you'll hear me.)

Dr. Andrews reached for the open pack of cigarettes on his deck. (Is this strictly a private conversation, girls, or can I get in on it, too?)

(It's unpolite to interrupt, Daddy.)

(He's not exactly interrupting—it was his conversation to begin with!)

Dr. Andrews' receptionist paused briefly beside the still-open office door. None of them heard either her gentle rap or the soft click of the latch slipping into place when she pushed the door shut.

Nor did she hear them.