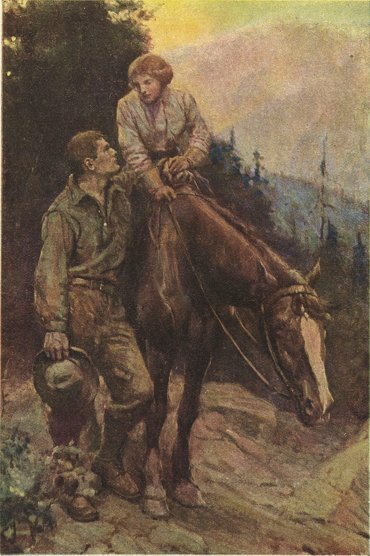

He leaned over her saddle, to where, as before something

sacred, he stood with parted lips, and upturned

face, bareheaded, in adoration.––The Plunderer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Plunderer, by Roy Norton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Plunderer Author: Roy Norton Illustrator: Douglas Duer Release Date: August 27, 2009 [EBook #29818] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PLUNDERER *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

He leaned over her saddle, to where, as before something

sacred, he stood with parted lips, and upturned

face, bareheaded, in adoration.––The Plunderer

The Plunderer

By ROY NORTON

With Frontispiece in Colors

By DOUGLAS DUER

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Copyright, 1912, by

W. J. WATT & COMPANY

TO

REX BEACH

WITH ALL THE AFFECTION THAT ONE

GIVES TO A PARTNER WITH WHOM

HE HAS TRAILED, AND MINED, AND ADVENTURED

FOR MANY YEARS, AND NEVER FOUND WANTING

WHEN BACKS WERE AGAINST THE WALL

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Bully Presby | 9 |

| II. | The Croix d’Or | 22 |

| III. | An Ugly Watchman | 36 |

| IV. | The Black Death | 51 |

| V. | The Aged Engineer | 71 |

| VI. | My Lady of the Horse | 97 |

| VII. | The Woman Unafraid | 114 |

| VIII. | The Inconsistent Bully | 129 |

| IX. | Where a Girl Advises | 151 |

| X. | Trouble Stalks Abroad | 167 |

| XI. | Bells’ Valiant Fight | 182 |

| XII. | A Disastrous Blow | 195 |

| XIII. | The Dynamiter | 208 |

| XIV. | “Though Love Say Nay” | 225 |

| XV. | “Mr. Sloan Speaks” | 240 |

| XVI. | Benefits Returned | 258 |

| XVII. | When Reason Swings | 271 |

| XVIII. | The Bully Meets His Master | 288 |

| XIX. | The Quest Supreme | 303 |

THE PLUNDERER

Plainly the rambling log structure was a road house and the stopping place for a mountain stage. It had the watering trough in front, the bundle of iron pails cluttered around the rusted iron pump, and the trampled muddy hollow created by many tired hoofs striking vigorously to drive away the flies. It was in a tiny flat beside the road, and mountains were everywhere; hard-cut, relentless giants, whose stern faces portrayed a perpetual constancy. At the trough two burros, with their packs deftly lashed, thrust soft gray muzzles deep into the water, and held rigid their long gray ears, casting now and then a wise look at the young man in worn mining clothes who stood patiently beside them.

Another man, almost a giant in size, but with a litheness of movement that told of marvelous physical strength, emerged from the door of the road house, and the babel of sound that had been stilled when he entered, but a few minutes before, rose again. He crossed to the well, and smiled from half-humorous eyes at the younger man standing beside the animals, and said: “Bumped into a hornet’s nest. Butted into an indignation meetin’. A Blackfoot war powwow when the trader had furnished free booze would have been a peace party put up against it.”

The younger man, who had turned to pump more water, following the polite mountain custom of replenishing for what you have used, stopped with a hand on the handle, and looked at him inquiringly.

“It seems it’s a bunch of fellers that’s been workin’ some placer ground off back here somewheres”––and he waved a tanned hand indefinitely in a wide arc––“and some man got the double hitch on ’em with the law, provin’ that the ground was his’n, and the sheriff run ’em off! Now they’re sore. But it seems they cain’t help ’emselves, so they’re movin’ over to some other place across the divide.”

“But what has that to do with us?”

“Nothin’, except that it took me five minutes to get the barkeep’ to tell me about the road. He says we’ve come all right this far, and this is the place where we hit the trail over the hills. Says we save a day and a half, with pack burros, by takin’ the cut-off. Says it’s seven or eight hours good ridin’ by the road if we were on horses and in a hurry.”

He paused and scanned the hills with an observant eye, while his companion resumed the pumping process. The trough again filled, the latter walked around the pails and joined him.

“Well, where does this trail start in?” he asked.

“He’s goin’ to show us as soon as he can get a minute’s rest from that bunch in there. Said we’d have to be shown. Said unless he could get away long enough we’d have to wait till somebody he named came in, and he’d head us into it.”

They led the burros across the road and into the shadow of a cliff where the morning sun, searching and fervid, did not reach, and threw themselves to the ground, resting their backs against the foot wall, and trying patiently to await the appearance of their guides. The steady, hurried clink of glass and bottle on bar, 12 the ribald shouts and threats of the crowd that filled the road house, the occasional burst of a maudlin song, all told the condition of the ejected placer men who had stopped here on their journey.

“I don’t know nothin’ about the case, of course,” drawled the big man lazily, “and it’s none of my funeral; but it does seem as if this feller they call ‘Bully’ is quite some for havin’ him own way.”

He laughed softly as if remembering scraps of conversation he had segregated from the murmur inside, and rolled his long body over until he rested on his belly with the upper part of his torso raised on his elbows.

“It appears that the courts down at the county seat gave a decision in his favor, and that he lost about as much time gettin’ action as a hornet does when he’s come to a conclusion. He just shows up with the sheriff, and about twenty deputies, good and true, and says: ‘Hike! The courts say it’s mine. These is the sheriffs. Off you go, and don’t waste no time doin’ it, either!’ And so they hikes and have got this far, where they lay over for the night to comfort their insides with somethin’ that smelled like a cross between nitric acid, a corn farm, and sump 13 water. And it don’t seem to cheer ’em up much, either, because their talk’s right ugly.”

“But I thought you said they were heading for some other ground?”

“So they are, but they’re takin’ their time on the road. I used to be that way till the day Arizona Bill plugged me because I was slow, all through havin’ stopped at a place too long. Then, says I, when I woke up a month later in the Widder Haskins’ back room: ‘Bill, this comes from corn and rye. Never have nothin’ to do with a farmer, or anything that comes from a farmer, after this; or some day, when your hand ain’t quick enough, and things look kind of hazy, some quarrelsome man’s goin’ to shoot first and you’ll cash in.’ And from that day to this, when I want to go on a bust, I drink a gallon of soda pop to have a rip-roarin’ time.”

A man lurched out of the door of the road house as if striving to find clean air, and stood leaning against one of the pole posts supporting a pole porch. Another one joined him, coarsely accusing him of being a “quitter” because he had left his drink on the bar. They were stubbornly passing words when, from down the road, there came the gritting of wheels over the pulverized stone, and the clacking of horses’ hoofs, 14 slow moving, as if being rested by a cautious driver along the ascent.

The man by the post suddenly frowned in the direction of the sound, and then whirled back to the open door.

“It’s Bully!” he bellowed so loudly that his words were plainly audible to the partners lying in the shadow. “Bully’s a-comin’ up the road right now! Let’s get him!”

There was a fierce, bawling chorus of shouts that outdid anything preceding, and the door seemed to vomit men in all stages of intoxication, who came heavily out with their boots stamping across the boards of the porch. They cursed, imprecated, shook their fists, and threatened, as they surged into the road and looked down it toward the approaching driver. The men in the shade got quickly to their feet, interested spectators, and the burros awoke from their drowsy somnolence, and turned inquiring, soft eyes on their owners.

Calmly driven up toward the mob in the road came a mountain buckboard drawn by two sweating horses. In the seat was a man who drove as if the reins were completely in control. He appeared to be stockily built, and his shoulders––broad, heavy, and high––had, even in that posture, 15 the unmistakable stamp of one who is accustomed to stooping his way through drifts and tunnels. He wore a black slouch hat, which had been shaped by habitual handling to shade his eyes. His hair was white; his neck short and thick, with a suggestion of bull-like power and force. His face, as he approached to closer range, showed firm and masterful. His nose was dominant––the nose of a conqueror who overrides all obstacles. He came steadily forward, without in the least changing his attitude, or betraying anxiety, or haste. The men in the road waited, squarely across his path, and their hoarse fulminations had died away to a far more terrifying silence; yet he did not seem to heed them as his horses advanced.

“Gad! Doesn’t he know who they are?” the bigger man by the rock mumbled to his partner.

“If he doesn’t he has a supreme nerve,” the younger man replied. “They look to me as if they mean trouble. They’re in a pretty nasty temper––what with all the poison they’ve poured in, and all the injustice they believe they have met. Wonder who’s right?”

A shout from the crowd in the roadway interrupted any further speculation. The man who had first appeared on the road-house porch 16 threw up his hand, and roared, “Here he is! We’ve got him! It’s the Bully!”

The shout was taken up by others until a miniature forest of raised fists shook themselves threateningly at the man in the buckboard who was now within a few feet of them.

“Get a rope, somebody! Hang him!” yelled an excited voice.

“Yes, that’s the goods,” screamed another, heard above the turmoil. “Up with the Bully!”

Two men sprang forward, and caught the horses by their bits, and brought them to an excited, nervous stop, and the others began to surround the wagon. The man in the seat made no movement, but sat there with a hard smile on his firm lips. The partners stepped to the top of a convenient rock, where they could overlook the meeting, and watched, perturbed.

“I don’t know about this,” the elder said doubtfully. “Looks to me like there’s too many against one, and I ain’t sure whether he deserves hangin’. What do you think?”

“Let’s wait and see. Then, if they get too ugly, we’ll give them a talk and try to find out,” the younger man answered.

Even as he spoke, a man came running from the door of the road house with a coil in his hand, 17 and began to assert drunkenly: “Here it is! I’ve got it! A rope!”

The partners were preparing to jump forward and protest, when a most astonishing change took place. The man in the wagon suddenly stood up, stretched his hand commandingly to the men holding the horses’ heads, and ordered: “Let go of my horses there, you drunken idiots! Let go of them, I say, or I’ll come down there and make you! Understand?”

The men at the horses’ heads wavered under that harsh, firm command, but did not release their hold. Without any further pause, the man jumped from his buckboard squarely into the road, struck the man holding the rope a sweeping side blow that toppled him over like a sprawling dummy, jerked the coil from his hands, and tore toward his horses’ heads. As if each feared to bar his advance, the men of the mob made way for him, taken by surprise. He brought the coil of rope with a stinging, whistling impact into the face of the nearest man, who, blinded, threw his hands upward across his eyes and reeled back. The man at the other horse’s head suddenly turned and dove out of reach, but the whistling coils again fell, lashing him across his head and shoulders.

Without any appearance of haste, and as if scornful of the mob that had so recently been threatening to hang him, the man walked back to his buckboard, climbed in, and stood there on his feet with the reins in one hand, and the rope in the other. “You get away from in front of me there,” he said, in his harsh, incisive voice; “I’m tired of child’s play. If you don’t let me alone, I’ll kill a few of you. Now, clear out!”

The men around him were already backing farther away, and at this threat they opened the road in such haste that one or two of them nearly ran over others.

“Say,” admiringly commented the big observer on the rock, “we’d play hob helpin’ him out. He don’t need help, that feller don’t. If I ever saw a man that could take care of himself–––”

“He certainly is the one!” his companion finished the sentence.

“Who does this rope belong to?” demanded the hard-faced victor in the buckboard, looking around him.

No one appeared eager to claim proprietorship. He gave a loud, contemptuous snort, and threw the rope far over toward the road house.

“Keep it!” he called, in his cold, unemotional 19 voice. “Some of you might want to cheat the sheriff by hanging yourselves. After this, any or all of you had better keep away from me. I might lose my temper.”

He sat down in the seat with a deliberate effort to show his scorn, picked the reins up more firmly, glanced around at the rear of his buckboard to see that his parcels were safe, ignored the cowed men, and without ever looking at them started his horses forward. As they began a steady trot and passed the partners, he swept over them one keen, searching look, as if wondering whether they had been of the mob, turned back to observe their loaded burros, apparently decided they had taken no part in the affair, and bestowed on them a faint, dry smile as he settled himself into his seat. At the bend of the road he had not deigned another look on the men who had been ravening to lynch him. He drove away as carelessly as if he alone were the only human being within miles, and the partners gave a gasp of enjoyment.

“Good Lord! What a man!” exclaimed the elder, and his companion answered in an equally admiring tone: “Isn’t he, though! Just look at these desperadoes, will you!”

With shuffling feet some of them were turning back toward the inviting door in which the bartender 20 stood with his dirty apron knotted into a string before him. Some of the more voluble were accusing the others of not having supported them, and loudly expounding the method of attack that would have been successful. The man with red welts across his face was swearing that if he ever got a chance he would “put a rifle ball through Bully.” The young man by the rock grinned and said: “That’s just about as close as he would ever dare come to that fellow. Shoot him through the back at a half-mile range!”

The bartender suddenly appeared to remember the travelers, and ran across the road.

“I’m sorry, gents,” he said, “that I can’t do more to show you the way, but you see how it is. Go up there to that big rock that looks like a bear’s head, then angle off south-east, and you’ll find a trail. When you come to any crossin’s, don’t take ’em, but keep straight on, and bimeby, about to-morrer, if you don’t camp too long to-night, you’ll see a peak––high it is––with a yellow mark on it, like a cross. Can’t miss it. Right under it’s the Croix Mine. You leave the trail to cross a draw, look down, and there you are. So long!”

He turned and ran back across the road in 21 response to brawling shouts from the men whose thirst seemed to have been renewed by their encounter with the masterful man they called “Bully,” and the partners, glad to escape from such a place, headed their animals upward into the hills.

It was the day after the halt at the road house. Half-obliterated by the débris of snowslide and melting torrents, the trail was hard to follow. In some places the pack burros scrambled for a footing or skated awkwardly with tiny hoofs desperately set to check their descent, to be steadied and encouraged by the booming voice, deep as a bell, of the man nearest them. Sometimes in dangerous spots where shale slides threatened to prove unstable, his lean, grim face and blue-gray eyes appeared apprehensive, and he braced his great shoulders against one of the bulging packs to assist a sweating, straining animal. After one of these perilous tracts he stopped beside the burros, pushed the stained white Stetson to the back of his head, exposing a white forehead which had been protected from the sun, and ran the sleeve of his blue-flannel 23 shirt across his face from brow to chin to wipe away the moisture.

“Hell’s got no worse roads than this!” he exclaimed. “Next time anybody talks me into takin’ a cut-off over a spring trail to save a day and a half’s time, him and me’ll have an argument!”

Ahead, and at the moment inspecting a knot in a diamond hitch, the other man grinned, then straightened up, and, shading his eyes from the sun with his hat, looked off into the distance. He was younger than his partner, whose hair was grizzled to a badger gray, but no less determined and self-reliant in appearance. He did not look his thirty years, while the other man looked more than his forty-eight.

“Well, Bill,” he said slowly, “it seems to me if we can get through at all we’ve saved a day and a half. By the way, come up here.”

The grizzled prospector walked up until he stood abreast, and from the little rise stared ahead.

“Isn’t that it?” asked the younger man. “Over there––through the gap; just down below that spike with a snow cap.” He stretched out a long, muscular arm, and his companion edged up to it and sighted along its length and 24 over the index finger as if it were the barrel of a rifle, and stared, scowling, at the distant maze of mountain and sky that seemed upended from the green of the forests below.

“Say, I believe you’re right, Dick!” he exclaimed. “I believe you are. Let’s hustle along to the top of this divide, and then we’ll know for sure.”

They resumed their progress, to halt at the top, where there was abruptly opened below them a far-flung panorama of white and gray and purple, stretched out in prodigality from sky line to sky line.

“Well, there she is, Dick,” asserted the elder man. “That yellow, cross-shaped mark up there on the side of the peak. I kept tellin’ you to keep patient and we’d get there after a while.”

His partner did not reply to the inconsistency of this argument, but stood looking at the landmark as if dreaming of all it represented.

“That is it, undoubtedly,” he said, as if to himself. “The Croix d’Or. I suppose that’s why the old Frenchman who located the mine in the first place gave it that name––the Cross of Gold!”

“Humph! It looks to me, from what I’ve heard of it,” growled the older prospector, “that 25 the Double Cross would have been a heap more fittin’ name for it. It’s busted everybody that ever had it.”

The younger man laughed softly and remonstrated: “Now, what’s the use in saying that? It wasn’t the Croix d’Or that broke my father–––”

“But his half in it was all he had left when he died!”

“That is true, and it is true that he sunk more than a hundred thousand in it; but it was the stock-market that got him. Besides, how about Sloan, my father’s old-time partner? He’s not broke, by a long shot!”

“No,” came the grumbling response, “he’s not busted, just because he had sense enough to lay his hand down when he’d gone the limit.”

“Lay his hand down? Say, Bill, you’re a little twisted, aren’t you? Better go back over the last month or two and think it over. We, being partners, are working up in the Cœur d’Alenes. Our prospect pinches out. We’ve got just seven hundred left between us on the day we bring the drills and hammers back, throw them in the corner of the cabin, and say ‘We’re on a dead one. What next?’ Then we get the letter saying that my father, whom I haven’t 26 seen in ten years, nor heard much of, owing to certain things, is dead, and that all he left was his half of the Croix d’Or. The letter comes from whom? Sloan! And it says that although he and my father, owing to father’s abominable temper, had not been intimate for a year or two, he still respected his memory, and wanted to befriend his son. Didn’t he? Then he said that he had enough belief left in the Croix d’Or to back it for a hundred thousand more, if I, being a practical miner, thought well of it. Do you call that laying down a hand? Humph!”

The elder man finished rolling a cigarette, and then looked at him with twinkling, whimsical eyes, as if continuing the argument merely for the sake of debate.

“Well, if he thinks it’s such a good thing, why didn’t he offer to buy you out? Why didn’t they work her sooner? She’s been idle, and water-soaked, for three years, ain’t she? As sure as your name’s Dick Townsend, and mine’s Bill Mathews, that old feller back East don’t think you’re goin’ to say it’s all right. He knows all about you! He knows you don’t stand for no lies or crooked work, and are a fool for principle, like a bee that goes and sticks his stinger 27 into somethin’ even though he knows he’s goin’ to kill himself by doin’ it.”

“Bosh!”

“And how do you know he ain’t figurin’ it this way: ‘Now I’ll send Dick Townsend down there to look at it. He’ll say it’s no good. Then I’ll buy him out and unload this Cross of Gold hole and plant it on some tenderfoot and get mine back!’ You cain’t make me believe in any of those Wall Street fellers! They all deal from the bottom of the deck and keep shoemaker’s wax on their cuff buttons to steal the lone ace!”

As if giving the lie to his growling complaints and pessimism, he laughed with a bellowing cachinnation that prompted the burros, now rested, to look at him with long gray ears thrust forward curiously, and wonder at his noise.

Townsend appeared to comprehend that his partner was but half in earnest, and smiled good-humoredly.

“Well, Bill,” he said, “if the mine’s not full of water or bad air, so that we can’t form any idea at all, we’ll not be long in saying what we think of it. We ought to be there in an hour from now. Let’s hike.”

They began the slow, plodding gait of the packer again, finding it easier now that they were 28 on the crest of a divide where the trail was less obstructed and firmer, and the yellow lines on the peak, their goal, came more plainly into view. The cross resolved itself into a peculiar slide of oxidized earth traversing two gullies, and the arm of the cross no longer appeared true to the perpendicular. The tall tamaracks began to segregate as the travelers dropped to a lower altitude; and pine and fir, fragrant with spring odor, seemed watching them. The trail at last took an abrupt turn away from the cross-marked mountain, and they came to another halt.

“This must be where they told us to turn off through the woods and down the slope, I think,” said Townsend. “Doesn’t it seem so to you, Bill?”

The old prospector frowned off toward the top of the peak now high above them, and then, with the peculiar farsightedness of an outdoor man of the West, looked around at the horizon as if calculating the position of the mine.

“Sure,” he agreed. “It can’t be any use to keep on the trail now. We’d better go to the right. They said we’d come to a little draw, then from the top of a low divide we’d see the mine buildings. Come on, Jack,” he ended, addressing the foremost burro, which patiently 29 turned after him as he led the way through the trees.

They came to the draw, which proved shallow, climbed the opposite bank, and gave an exclamation of surprise.

“Holy Moses! They had some buildings and plant there, eh, Dick?”

The other, as if remembering all that was represented in the scene below, did not answer. He was thinking of the days when his father and he had been friendly, and of how that restless, grasping, conquering dreamer had built many hopes, even as he squandered many dollars, on the Croix d’Or. It was to produce millions. It was to be one of the greatest gold mines in the world. All that it required was more development. Now, it was to have a huge mill to handle vast quantities of low-grade ore; then all it needed was cheaper power, so it must have electric equipment. Again the milling results were not good, and what it demanded was the cyanide process.

And so it had been, for years that he could still remember, and always it led his father on and on, deferring or promising hope, to come, at last, to this! A great, idle plant with some of its buildings falling into decay, its roadways 30 obliterated by the brush growth that was creeping back through the clearings as Nature reconquered her own, and its huge waste dumps losing their ugliness under the green moss.

It seemed useless to think of anything more than an occasional pay chute. Yet, as he thought of it, hope revived; for there had been pay chutes of marvelous wealth. Why, men still talked of the Bonanza Chute that yielded eighty thousand dollars in four days’ blasting before it worked out! Maybe there were others, but that was what his father and Sloan had always expected, and never found!

His meditations were cut short by a shout from below. A man appeared, small in the distance, on the flat, or “yard” of what seemed to be the blacksmith shop.

“Wonder who that can be?” speculated Bill, drawing his hat rim farther over his eyes.

“I don’t know,” answered Townsend, puzzled. “I never heard of their having any watchmen here. But we’ll soon find out.”

They started down the hillside at a faster pace, the tired animals surmising, with their curiously acute instinct, that this must be the end of the journey and hastening to have it over with. As they broke through a screen of brush and came 31 out to the edge of what had been a clearing back of a huge log bunk-house, the man who had shouted came rapidly forward to meet them. There was a certain shiftless, sullen, yet authoritative air about him as he spoke.

“What do you fellers want here?” he asked. “I s’pose you know that no one’s allowed on the Cross ground, don’t you?”

“We didn’t know that,” replied Townsend, inclined to be pacific, “but I fancy, we are different from almost any one else that would come. We represent the owners.”

“Can’t help that,” came the blustering answer. “You’ll have to hit the trail. I don’t take orders from no one but Presby.”

A shade of annoyance was depicted on Townsend’s face as he continued to ignore the watchman’s arrogance, and asked: “And please tell us, who is Presby?”

“Presby? Who’s Presby? What are you handin’ me? You don’t know Presby?”

“I don’t, or I shouldn’t have asked you,” Townsend answered with less patience.

“Say,” drawled his companion, with a calm deliberation that would have been dreaded by those who knew him, “does it hurt you much to 32 be civil? You were asked who this man Presby is. Do you get that?”

The watchman glared at him for a moment, but there was something in the cold eyes and firm lines of the prospector’s face that caused him to hesitate before venturing any further display of officiousness.

“He’s the owner of the Rattler,” he answered sullenly, “and I’ve got orders from him that nobody, not any one, is to step a foot on this ground. If you’d ’a’ come by the road, you’d ’a’ seen the sign.”

The partners looked at each other for an instant, and the younger man, ignoring the elder’s apparent wrath, said: “Well, I suppose the best thing we can do is to leave the burros here and go and see Presby, and get this man of his called off.”

“You’ll leave no burros here!” asserted the watchman, recovering his combativeness.

“Why, you fool,” exploded Mathews, starting toward him with his fists clenched and anger blazing from his eyes at the watchman’s obstinate stupidity, “you’re talking to one of the owners of this mine! This is Mr. Townsend.”

For an instant the man appeared abashed, and 33 then grumbled acridly: “Well, I can’t help it. I’ve got orders and–––”

“Oh, come on, Bill,” interrupted the owner, stepping to the nearest burro’s head. “We’ll go on over to Presby, and get rid of this man of his. It won’t hurt the burros to go a little farther.”

He turned to the watchman, who was scowling and obdurate.

“Where can Presby and the Rattler be found?” he asked crisply.

“Around the turn down at the mouth of the cañon,” the watchman mumbled. “It’s not more than half or three-quarters of a mile from here, but you’d better go back up the hill.”

As if this last suggestion was the breaking straw, the big prospector jumped forward, and caught the man’s wrist with dexterous, sinewy fingers. He gave the arm a jerk that almost took the man from his feet. His eyes were hard and sharp now, and his jaw seemed to have shut tightly.

“We’ll go back up no hill, you bet on that!” he asserted belligerently. “We go by the road. We’re done foolin’ with you, my bucko! You go ahead and show the way and be quick about it! 34 If you don’t, you’ll have trouble with me. Now git!”

He released the wrist with a shove that sent the watchman ten feet away, and cowed him to subjection. He recovered his balance, and hesitated for a minute, muttering something about “being even for that,” and then, as the big, infuriated miner took a step toward him, said: “All right! Come on,” and started toward a roadway that, half ruined, led off and was lost at a turn. Cursing softly and telling the burros that it was a shame they had to go farther on account of a fool, the prospector followed, and the little procession resumed its straggling march.

They passed the huge bunk-house, a mess-house, an assay office, what seemed to be the superintendent’s quarters, and a dozen smaller structures, all of logs, and began an abrupt descent. The top of the cañon was so high that they looked down on the roof of the big, silent stamp mill with its quarter of a mile of covered tramway stretching like a huge, weather-beaten snake to the dumps of the grizzly and breakers behind it.

The road was blasted from the side of the cañon on which they were, and far below, between them and the hoisting house and the mill, 35 ran a clear little mountain stream, undefiled for years by the silt of industry. The peak of the cross, lifting a needle point high above them, as if keeping watch over the Blue Mountains, the far-distant Idaho hills, the near-by forests of Oregon, and the puny, man-made structures at its feet, appeared to have a lofty disdain of them and the burrowings into its mammoth sides, as if all ravagers were mere parasites, mad to uncover its secrets of gold, and futile, if successful, to wreak the slightest damage on its aged heart.

By easy stages indicating competent engineering and a lavish expenditure of money, the road led them downward to a barricade of logs, in an opening of which swung a gate barely wide enough to pass the tired burros and their packs.

“You’ll find Presby over there,” said their unwilling guide, pointing at a group of red-painted mining structures nestled in a flat lap in the ragged mountains.

They surmised that this must be the Rattler camp, and inspected its display of tall smokestacks, high hoists, skeleton tramways, and bleak dumps. Before they could make any reply, the gate behind them slammed shut with a vicious bang that attracted their attention. They turned to see the watchman hurrying back up the road. Fixed to the barricade was a sign, crudely lettered, but insistently distinct:

No one allowed on these premises, by order of the owners. For any business to be transacted with the Croix d’Or, apply to Thomas W. Presby.

“Curt enough, at least, isn’t he?” commented Townsend, half-smiling.

“Curt!” growled his companion, frowning, with his recent anger but half-dissipated. “Curt as a bulldog takin’ a bite out of your leg. Don’t waste no time at all on words. Just says: ‘It’s you I’m lookin’ after.’ Where do you reckon we’ll find this here Thomas Presby person?”

“I suppose he must have an office up there somewhere,” answered Townsend, waving his arm in the direction of the scattered buildings spread in that profligacy of space which comes where space is free.

“These mules is tired. It’s a shame we couldn’t have left them up there,” Mathews answered, looking at them and fondling the ears of the nearest one. “You go on up and get an order letting us into your mine, and I’ll wait here. No use in makin’ these poor devils do any more’n they have to.”

Townsend assented, and followed a path which zigzaged around bowlders and stumps up to the red cluster on the hillside above him. He was impatient and annoyed at the useless delays imposed upon them in this new venture, and wondered why his father’s partner had not informed him of the fact that he would find the 38 mine guarded by the owner of the adjoining property.

A camp “washwoman,” with clothespins in her mouth, and a soggy gray shirt in her hands, paused to stare at him from beneath a row of other gray and blue shirts and coarse underwear, dripping from the lines above her head.

Two little boys, fantastically garbed in faded blue denim which had evidently been refashioned from cast-off wearing apparel of their sires, followed after him, hand in hand, as if the advent of a stranger on the Rattler grounds was an event of interest, and he found himself facing a squat, red, white-bordered, one-storied building, over whose door a white-and-black sign told the stranger, or applicant for work, that he was at the “office.”

A man came to a window in a picketed wicket as he entered, and said briskly: “Well?”

“I want to see Mr. Presby,” Dick answered, wasting no more words than had the other.

“Oh, well, if nobody else will do, go in through that door.”

Before he had finished his speech, the bookkeeper had turned again toward the ledgers spread out on an unpainted, standing desk against the wall behind his palings, and Dick walked to 39 the only door in sight. He opened it, and stepped inside. A white-headed, scowling man, clean shaven, and with close-shut, thin, hard lips, looked up over a pile of letters and accounts laid before him on a cheap, flat-topped desk.

Dick’s eyes opened a trifle wider. He was looking at the man who had defied the mob at the road house, and at this close range studied his appearance more keenly.

There was hard, insolent mastery in his every line. His face had the sternness of granite. His hands, poised when interrupted in their task, were firm and wrinkled as if by years of reaching; and his heavy body, short neck, and muscle-bent shoulders, all suggested the man who had relentlessly fought his way to whatever position of dominancy he might then occupy. He wore the same faded black hat planted squarely on his head, and was in his shirt-sleeves. The only sign of self-indulgence betrayed in him or his surroundings was an old crucible, serving as an ash tray, which was half-filled with cigar stumps, and Dick observed, in that instant’s swift appraisement, that even these were chewed as if between the teeth of a mentally restless man.

“You want to see me?” the man questioned, and then, as if the thin partition had not muffled 40 the words of the outer office, went on: “You asked for Presby. I’m Presby. What do you want?”

For an instant, self-reliant and cool as he was, Dick was confused by the directness of his greeting.

“I should like to have you tell that watchman over at the Croix d’Or that we are to be admitted there,” he replied, forgetting that he had not introduced himself.

“You should, eh? And who are you, may I ask?” came the dry, satirical response.

Dick flushed a trifle, feeling that he had begun lamely in this reception and request.

“I am Richard Townsend,” he answered, recovering himself. “A son of Charles Townsend, and a half-owner in the property. I’ve come to look the Croix d’Or over.”

He was not conscious of it then, but remembered afterward, that Presby was momentarily startled by the announcement. The man’s eyes seemed intent on penetrating and appraising him, as he stood there without a seat having been proffered, or any courtesy shown. Then, as if thinking, Presby stared at the inkwell before him, and frowned.

“How am I to know that?” he asked. “The 41 Cross has had enough men wanting to look it over to make an army. Maybe you’re one of them. Got any letters telling me that I’m to turn it over to you?”

For an instant Dick was staggered by this obstacle.

“No,” he said reluctantly, “I have not; that is, nothing directed to you. I did not know that you were in charge of the property.”

He was surprised to notice that Presby’s heavy brows adjusted themselves to a scowl. He wondered why the mine owner should be antagonistic to him, when there was nothing at stake.

“Well, I am,” asserted Presby. “I hired the watchman up there, and I see to it that all the stuff lying around loose isn’t stolen.”

“On whose authority, may I ask?” questioned Dick, without thought of giving offense, but rather as a means of explaining his position.

“Sloan’s. Why, you don’t think I’m watching it because I want it, do you, young man? The old watchman threw up his job. I had Sloan’s address, and wrote him about it. Sloan wrote and asked me to get a man to look after it, and I did. Now, you show me that you’ve got a right to go on the grounds of the Cross Mine, and I’ll give an order to the watchman.”

There was absolute antagonism in his tone, although not in his words. Dick thought of nothing at the moment but that he had one sole proof of his ownership, the letter from Sloan himself. He unbuttoned the flap of his shirt pocket, and, taking out a bundle of letters, selected the one bearing on the situation.

“That should be sufficient,” he said, throwing it, opened, before Presby.

The latter, without moving his solid body in the least, and as if his arms and hands were entirely independent of it, stolidly picked up the letter and read it. Dick could infer nothing of its reception. He could not tell whether Presby was inclined to accept it as sufficient authority, or to question it. Outside were the sounds of the Rattler’s activity and production, the heavy, thunderous roar of the stamp mill, the clash of cars of ore dumped into the maws of the grizzly to be hammered into smaller fragments in their journey to the crusher, and thence downward to end their journeys over the thumping stamps, and out, disintegrated, across the wet and shaking tables.

It seemed, as he stood waiting, that the dust of the pulverized mountains had settled over everything in the office save the granite-like 43 figure that sat at the desk, rereading the letter which had changed all his life. For the first time he thought that perhaps he should not have so easily displayed that link with his past. It seemed a useless sacrilege. If the mine-owner was not reading the letter, he was pondering, unmoved, over a course of action, and took his time.

Dick thought bitterly, in a flash, of all that it represented. The quarrel with his father on that day he had returned from Columbia University with a mining course proudly finished, when each, stubborn by nature, had insisted that his plan was the better; of his rebellious refusal to enter the brokerage office in Wall Street, and declaration that he intended to go into the far West and follow his profession, and of the stern old man’s dismissal when he asserted, with heat:

“You’ve always taken the road you wanted to go since your mother died. I objected to your taking up mining engineering, but you went ahead in spite of me. I tried to get you to take an interest in the business that has been my life work, but you scorned it. You wouldn’t be a broker, or a banker. You had to be a mining engineer! All right, you’ve had your way, so far. Now, you can keep on in the way you have selected. I’ll give you five thousand dollars, but you’ll never 44 get another cent from me until you’ve learned what a fool you’re making of yourself, and return to do what I want you to do. It won’t be long! There’s a vast difference between dawdling around a university learning something that is going to be useless while your father pays the bills, and turning that foolish education into dollars to stave off an empty belly. You can go now.”

In those days the house of Phillip Townsend had been a great name in New York. Now this was all that was left of it. Dissolution, death, and dust, and a half-interest in an abandoned mine! The harsh voice of Bully Presby aroused him from his thoughts.

“All right,” it said. “This seems sufficient, but if you’ve got the sense and judgment Sloan seems to think you have, you’ll come to the conclusion that there’s not much use in wasting any of his good, hard dollars on the Croix d’Or. It never has paid. It never will pay. I offered to buy it once, but I wouldn’t give a dollar for it now, beyond what the timber above ground is worth. It owns a full section of timberland, and that’s about all.”

He reached for a pen and wrote a note to the watchman, telling him that the bearer, Richard 45 Townsend, had come to look over the property and that his orders must be accepted, and signed it with his hard-driven scrawl. He handed it up to Dick without rising from his seat, and said: “That’ll fix you up, I think.”

As if by an afterthought, he asked: “Have you any idea of the condition of the mine?”

“No,” Dick answered, as he folded the letter and put it into his pocket, together with the one from his late father’s partner.

“Well, then, I can tell you, it’s bad,” said Presby, fixing him with his cool, hard stare. “The Cross is spotted. Once in a while they had pay chutes. They never had a true ledge. There isn’t one there, as far as anybody that ever worked it knows. They wasted five hundred thousand dollars trying to find it, and drove ten thousand feet of drifts and tunnels. They went down more than six hundred feet. She’s under water, no one knows how deep. It might take twenty thousand to un-water the sinking shaft again, and at the bottom you’d find nothing. Take my advice. Let it alone. Good-day.”

Dick walked out, scarcely knowing whether to feel grateful for the churlish advice or to resume his wonted attitude of self-reliance and hold himself unprejudiced by Presby’s condemnation 46 of the Croix d’Or. He wondered if Bully Presby suspected him of having been friendly with the mob of drunken ruffians at the road house, but he had been given no chance to explain.

At the bottom of the gulch he found Bill sprawled at length on his elbows almost under the forefeet of one of the burros which was nosing him over in a friendly caress. He called out as he approached, and the big prospector sat up, deftly snapped the cigarette he had been smoking into the creek with his thumb and forefinger, and got to his feet.

“Do we get permission to go on the claim?” he grinned, as Townsend reached him.

“Yes, I’ve got an order to the watchman. The old man doesn’t seem to think much of it. Says it’s spotted. Had rich pay chutes, but they pinched. No regular formation. Always been a loser. Thinks we’d be foolish to do anything with it.”

“Good of him, wasn’t it?”

Dick looked quickly at the hard, lined face of his companion.

“That’s the first thing I’ve heard that made me feel better,” declared the prospector, as he swung one of the burro’s heads back into the trail 47 and hit the beast a friendly slap on the haunches to start it forward. “Whenever a man, like this old feller seems to be, gives me that kind of advice, I sit up and take notice.”

“Why––why, what do you know about him?” Dick asked, falling into the trail behind the pack animals, which had started forward with their slow jog trot, and ears swaying backward and forward as they went.

“While you was gone,” Mathews answered, “I had a long talk with a boy that came along and got friendly. You can believe boys, most of ’em. They know a heap more than men. They think out things that men don’t. Kids are always friends with me; you know that. I reckon, from what I gathered, that this Presby man is about as hard and grasping an old cuss as ever worked the last ounce of gold out of a waste dump. He makes the men save the fags of the candles and the drips, so’s he can melt ’em over again. He runs a company store, and if they don’t buy boots and grub from him, they have to tear out mighty quick. He fired a fireman because the safety-valve in the boiler-house let go one day twenty minutes before the noon shift went back to work. If he says, ‘Let the Cross alone,’ I think it’s because he wants it.”

“You couldn’t guess who he is,” Dick said, preparing to move.

“Why? Do I know him?”

“In a way. He’s the man we saw the mob tackle, back there at the road house.”

Bill gave a long whistle.

“So that’s the chap, eh? Bully Presby! Well, if we ever run foul of him, we’ve got our work cut out for us. Things are beginnin’ to get interestin’. ‘I like the place,’ as Daniel said when he went to sleep in the lion’s den.”

They opened the gate through the barricade without any formality, and were well started up the inclined road of the Croix d’Or before they encountered the watchman who had given them so much trouble. As he came toward them, frowning, they observed that he had buckled a pistol round him as if to resist any intrusion in case it should be attempted without instructions. Dick handed him Presby’s order, and the man read it through in surly silence; then his entire attitude underwent a swift change. He became almost obsequiously respectful.

“I’ll have to go down and have a talk with Mr. Presby,” he said, and would have ventured a further remark, but was cut short by the mine-owner.

“Yes, you’d better go and see him,” Dick said concisely. “And when you go, take all of your dunnage you can carry, then come back and get the rest. I shall not want you on the claim an hour longer than necessary for you to get your stuff away. You’re too good a man to have around here.”

The fellow gave a shrug of his shoulders, an evil grin, and turned back up the road to vanish in what had evidently been the superintendent’s cabin, and noisily began to whistle as he gathered his stuff together. The partners halted before the door, and Dick looked inside.

“I suppose you have the keys for everything, haven’t you?” he called.

The man impudently tossed a bundle at him without a word. Apparently his belongings were but few, which led the newcomers to believe that he had taken his meals at the Rattler, and perhaps slept there on many nights. They watched him as he rolled his blankets, and prepared to start down the trail.

“The rest of that plunder in there, the pots and the lamp, belong to the mine,” he said. And then, without other words, turned away.

“That may be the last of him, and maybe it won’t!” growled Bill, as he began throwing the 50 hitches off the tired burros that stood panting outside the door. “Anyway, it’s the fag end of him to-night.”

They were amazed at the lavish expenditure of money that had been made in the superintendent’s quarters. There were a porcelain bathtub brought up into the heart of the wilderness, a mahogany desk whose edges had been burned by careless smokers, and a safe whose door swung open, exposing a litter of papers, mine drawings, and plans. The four rooms evidently included office and living quarters, and they betokened a reckless financial outlay for the purpose.

“Poor Dad!” said Dick, looking around him. “No wonder the Cross lost money if this is a sample of the way the management spent it.”

He stepped outside to where the cañon was beginning to sink into the dusk. The early moon, still behind the silhouette of the eastern fringe of peaks and forests, lighted up the yellow cross mark high above, and for some reason, in the stillness of the evening, he accepted it as a sign of promise.

It took seven days of exploration to reveal the condition of the Cross of Gold, and each night the task appeared more hopeless. The steel pipe line, leading down for three miles of sinuous, black length, from a reservoir high up in the hills, had been broken here and there maliciously by some one who had traversed its length and with a heavy pick driven holes into it that inflicted thousands of dollars of expense.

The Pelton wheels in the power house, neglected, were rusted in their bearings, and without them and the pipe line there could be no electric power on which the mill depended. The mill had been stripped of all smaller stuff, and its dynamos had been chipped with an ax until the copper windings showed frayed and useless. The shoes of the huge stamps were worn down to a thin, uneven rim, battering on broken surfaces. The Venners rattled on their foundations, and 52 the plates had been scarred as if by a chisel in the hands of a maniac.

The blacksmith’s tunnel––the tunnel leading off from the level––was blocked by fallen timbers where a belt of lime formation cut across; and fragments of wood, splintered into toothpick size, had been thrown out when the mountain settled to its place. But a short distance from the main shaft, which was a double compartment, carrying two cages up and down, in every level the air was foul down to the five-hundred foot, and below that the mine was filled with water.

Patiently Dick and the veteran explored these windings as far as they might until the guttering of their candles warned them that the air was loaded with poison, and often they retreated none too soon to scale the slippery, yielding rungs of the ladder with dizzy heads. Expert and experienced, they were puzzled by what was disclosed. Either the mine had yielded exceedingly rich streaks and had been, in mining parlance, “gophered,” or else the management had been as foolish as ever handled a property.

In the assay-house, where the furnaces were dust-covered, the scale case black with grime, and the floor littered with refuse crucibles, cupels, mufflers, and worn buckboards, they discovered a 53 bundle of old tablets. Almost invariably these showed that the assays had been made from samples that would have paid to work, but this alone gave them no hope.

But this was not all. A mysterious enmity seemed to pursue all their efforts. Yet its displays were unaccountable for by natural causes. On their arrival at the mine they found water, fresh and clear, piped into every cabin, the mess-house, and the superintendent’s quarters. They traced it back and discovered a small lake formed and fed by a large spring on what was evidently land of the mine. It suddenly failed them, and proved unwholesome. An investigation of the tiny reservoir disclosed masses of poisonous weeds in the water. They decided that they must have been blown there after their arrival, cleared the supply and yet, but two days later, when there had been no wind of more than noticeable violence, the weeds were there again. They abandoned their water supply for the time being and resorted to the stream at the bottom of the cañon.

A day later one of their burros died mysteriously, and Bill, puzzled, said he believed that it had lost its sense of smell and eaten something poisonous. On the day following the other died, 54 apparently from the same complaint. The veteran miner grieved over them as for friends.

“I’ve been acquainted with a good many of ’em,” he said, sorrowfully, “but I never knew two that had finer characters than these two did. They were regular burros! No cheaters––just the square, open and above-board kind, that never kicked without layin’ back their ears to give you warnin’ and never laid down on the trail unless they wanted to rest. The meanest thing a burro or a man can do is to die voluntarily when you’re dependin’ on him, or when he owes you work or money. So it does seem as if I must have been mistaken in these two, after all, because we may need ’em.”

Dick did not smile at his homily, for he caught the significance of it, that the Croix d’Or would have to make a better showing than they had so far discovered to warrant them in opening it. They had come almost to the end of the investigations possible. They scanned plans and scales in the office to familiarize themselves with the property, and there was but one portion of it they had not visited. That was a shaft which had been the “discovery hole,” where the first find of ore had been made. And it was this they entered on the day when Fate seemed most particularly 55 unkind. Yet even Fate appeared to relent, in the end, through one of those trifling afterthoughts which lead men to do the insignificant act. They had prepared everything for the venture. They had an extra supply of candles, chalk for making a course mark, sample bags for such pieces of ore as might interest them, and the prospectors’ picks and hammers when they started out. They were a hundred yards from the office when the younger man hesitated, stopped and turned back.

“I’ve an idea we might need those old maps,” he said. “We haven’t gone over them very much and they might come in handy.”

Bill protested, but despite this Dick went back to the quarters and got them. They were crude, apparently, compared with the later work when competent engineers had opened the mine in earnest; but doubtless had served their purpose. The men came to the mouth of the old shaft which had been loosely covered over with poles, and around which a thicket of wild blackberry bushes had sprung up in stunted growth. An hour’s work disclosed the black opening and a ladder in a fair state of preservation. They lowered a candle into the depths and saw that it burned undimmed, indicating that the air was pure, and then descended cautiously, testing each 56 rung as they went. The shaft was not more than fifty feet deep, and they found themselves standing on the bottom and peering off into a drift which had been crudely timbered and had fallen in here and there as the unworked ground had settled.

“There doesn’t seem to be much of anything here except some starved quartz,” Bill said, staring at the wall after they had gone in some thirty or forty feet, and they had come to a place where the lagging had dropped away. He caught another piece of the half-rotted timbering and jerked it loose for a better inspection. It gave with a dull crack, then, immediately after, and seeming almost an echo, there was a terrific rumble, and a report like the explosion of a huge gun back in the direction of the shaft. Their candles flickered in the air impact, and for an instant they feared that the roof was coming down on them to crush them out of all resemblance to human beings.

They turned and ran toward the shaft. A few loose pebbles and pieces of rock were dripping from above like a shower of porphyry. For an instant they dared not step out, but stood inside the drift, waiting for what might happen and staring at each other with set faces exposed in 57 the still flickering light. They had said nothing up to this time, being under too great stress to offer other than sharp exclamations.

“Sounds like that shaft had given way!” the veteran exclaimed. “If it has–––”

He leaned forward and looked into Dick’s face.

“If it has,” the latter took up, “we are in a bad predicament.”

They stood tensed and anxious until the pebbles stopped falling and a silence like that of a tomb, so profound as to seem thick and dense, invaded the hollows; then Dick started out into the shaft. He felt a restraining hand on his arm.

“Wait a minute, boy,” the elder man said. “You’re the owner here. It’s dangerous. I ought to be the one to go first and find out what’s happened. You wait inside the drift.”

But Dick shook his hand off and stepped out to look upward. A dense blackness filled what should have been a space of light. This he had partially expected from the fact that when they came out toward the shaft there had been no sign of day; but he had not anticipated such a complete closing of the opening.

“Lord! We’re buried in!” came an exclamation 58 from behind him, and he felt a sudden sinking of the heart.

“I’ll go easily till I come to it,” he said, his voice sounding strained and loud although he had spoken scarcely above a whisper. “You stand clear so that if anything gives, Bill, you won’t be caught.”

The elder miner would have protested, but already he was slowly and cautiously climbing the ladder. Step by step he ascended, holding the light above his head to discover the place where the shaft had given way, and then Bill, standing anxiously below, heard a harsh shout.

“I think the ladder will bear your weight as well as mine. Come up here.”

The big man climbed steadily upward until he stood directly beneath the younger man’s feet. He ventured an exclamation that was almost an oath.

“Not the shaft at all,” he said, an instant later. “It’s just a bowlder so big that it filled the whole opening. We’re plugged and penned in here like rats in a trap!”

Dick took his little prospecting hammer and tapped the bowlder, at first gently, then with firmer strokes, and looked down at his partner with a distressed face.

“Hear that?” he exclaimed, rather than questioned. “It’s a big one, and solid. It sounds bad to me.”

For a minute they waved their candles round the edge, inspecting the resting place of the rock that had imprisoned them. Everywhere it was set firmly. A fitted door could have been no more secure. They consulted, and at last Bill descended and stepped back into the entrance to the drift to avoid falling stone, while the younger man attacked the edge beneath the bowlder, inch by inch, trying to find some place where he could pick through to daylight. At last, his arm wearied and the point of his prospecting hammer dulled, he rested.

“Come down, Dick, and I’ll take a spell,” Bill called up from below, and he obeyed.

The big miner, without comment, climbed up, and again the vault-like space was filled with the persistent picking of steel on stone. For a half-hour it continued, and then, slowly, Bill descended. He sat down at the foot of the shaft, wiped the sweat from his face, thrust his candlestick in a crevice and rolled a cigarette before he said anything, and then only as Dick started to the foot of the ladder.

“It’s no use,” he said. “We’re holed up all 60 right. I picked clear around the lower edge and there isn’t a place where she isn’t resting on solid rock. Nothing but dynamite could ever move that stone. Unless we can find some other way out we’re–––”

He paused and Dick added the finishing word, “Gone!”

“Exactly! No one knows we’re here. No one comes to the mine. We’re in the old works which I don’t suppose a man has been inside of in five or ten years, and the map shows that it doesn’t connect with the other ones. Answer––the finish!”

Dick pulled the worn and badly drawn plans from his pocket and then lighted his own candle, indulging in the extravagance of two that he might study the faint and smudged penciled lines.

“Here, Bill,” he said, pointing at the drawing. “These two side drifts each end in what are now sump holes. We’ve got to watch out for them. That makes it safe for us to take the main drift and see where it leads. The two end drifts evidently ran but a few feet and were then abandoned. So, if these plans are any good, they, too, are safe, if we can get into them.”

The elder miner peered at the plans and studied 61 them. He stood up and blew out his candle. He thrust his hands into his pockets.

“I’ve got three candles left,” he said, “and I cain’t just exactly say why I put that many in unless the Lord gave me a hunch we’d need ’em. How many you got!”

“One in my pocket, and this.”

“Then we’d better move fast, eh?”

They took a desperate chance on foul air and plunged down the drift, pausing only now and then when they came to the first side drifts to make sure of their course. They were informed by the plans that they had barely three hundred feet to explore, yet they had gone even farther than that before they came to a halt, a threatening one, for directly ahead of them the timbering had given way, the shaft caved, and there seemed at first no opening through the débris.

“Well, this looks pretty tough!” exclaimed Bill, stooping down and examining the face of the barrier.

His companion lighted his own candle and together they went over the face of the obstruction.

“It looks to me as if we could open her up a little if we can shift this timber here and use it as a lever,” he said, pointing to one projecting near the roof.

“May bring the whole mountain down, but it’s our only chance,” agreed Bill. “Here she goes. Stand back. No use in both of us getting it.”

He caught the end of the timber in his heavy hands, planted his feet firmly on the floor and heaved. The big timber creaked, but did not give. Again he planted himself and this time his great shoulders seemed to twist and writhe until the muscles cracked and then, with a crash, the barrier gave way. He sprang back with amazing quickness and they ran back up the drift for twenty or thirty feet while the mass again readjusted itself and settled slowly into position. A cloud of dust bellowed toward them, half-choking them with its gritty fineness, and then, in a minute, the air had cleared. They went cautiously forward.

“Well, we got some farther, anyhow, unless she comes down while we’re working through. We’ve got a hole to crawl into, and that’s something,” the big miner asserted.

Before he could say anything more Dick had crowded him to one side and was entering the aperture. He had prevented his partner from taking the first perilous chance. Painfully he made his way, while the man behind listened with 63 terrified apprehension; for none knew better than he the risk of that progress.

“All right, but be careful,” a voice came to him faintly from the distance. “She’s bad, but the air over here seems good. It’s a close shave.”

The big miner dropped down and began crawling through beneath the tons of balanced rock, which might give at any instant. Larger than his younger companion, he found it more difficult for his great shoulders persisted in brushing at all times, and now and then he was compelled to squeeze himself through a narrow place that for a moment threatened to be impossible. Once a timber above him gave a little and a rock crowded down until only by exerting his whole force could he sustain it while he scraped his hips through from under it. Then as it descended between his legs he found one of them pinioned. He shut his teeth desperately to avoid shouting, and twisted sidewise, and back, to and fro, at the imminent danger of dislodging everything above him. He heard an anxious voice calling outside and replied that he was coming and was all right. He rested for an instant to regain breath, then made a desperate forward effort to find that his foot alone caught him. 64 Again he rolled from side to side, and again he rested.

“Bill! Bill! For God’s sake, what has happened?” he heard an agonized call from ahead.

“I’m all right, boy,” he called back patiently. “Just keep away from the hole so I can get air. I’m––I’m just findin’ some places a little tight.”

His reply did not seem to allay the solicitude of his companion, who called again, “Can I help you in any way?”

“Only by keeping clear. I’ll make another try. Stand clear so if she comes down you won’t be caught. If she does come––well––good-bye, Dick!”

As he spoke the final word he made another fiercely desperate effort from his new position. There was a ripping, searing pain along the length of his foot which he disregarded in that supreme attempt and suddenly he seemed to slide forward while back of him came a crunching, grinding noise as the disturbed rock which had pinioned him settled down into place. He crawled desperately forward. A light flared in his eyes and he felt strong hands thrust under his arm pits and was jerked bodily out to the floor of the drift. They fell together and the candle, falling with them, was extinguished. They were 65 overwhelmed, as they lay there in the darkness, gasping, by a terrific crashing impact as if the whole mountain had given way and at their very feet huge rocks thundered down. They crawled farther along on hands and knees and the falling rock seemed to pursue them malignantly. For an age it seemed as if the whole drift would give way as each set of timbers came to the strain and failed to hold. Then again all was still.

Strangling, sweating, spent, they got to the side wall and raised themselves up, gasping for fresh air. Their senses wavered and swooned in that half-suffocation and slowly they comprehended that they were still alive and that the dust was settling. “Are you all right?” they called to each other in acute unison, their voices betraying a great apprehension, and then, reassured for the instant, they sagged weakly against the walls and each reached out to find the other. Their hands met and clasped fervently and, again in unison, they said, “Thank God!”

A match spluttered dimly through the dark and dust-clogged air, a candle slowly took flame and they looked at each other. Bill was leaning against the wall, weakly, and trying to recover his strength. A tattered trousers leg clung above his bared leg and foot where he had wrenched 66 himself loose from the rock, and torn his boot away in so doing. Along the length of the white flesh was a flaring line of red, where the point of rock had cut deeply when he made that last desperate struggle to escape. He dropped to the floor and clutched his wound with his hands while Dick, almost with a moan, thrust his candlestick into a timber and savagely tore his shirt off and rent it into strips. He stooped over and with hasty skill bandaged the wound.

“It’s not bad, I hope,” he said, “but it does hurt, doesn’t it, old partner?”

“That’s nothin’,” bravely drawled the giant, striving to force a grin to his pain-drawn lips. “Don’t worry now, boy! Think what might have happened if I’d been there a minute or two longer, or if I couldn’t have got loose at all!”

In their thankfulness for the last escape they had almost forgotten the fact that their situation was still almost hopeless, and that perhaps the speedy end would have been preferable to one more agonizing, more slow, to come. They got to their feet at last and hobbled forward, the big man resting half his weight on his friend’s shoulder and making slow progress. Again they were centered on the faint hope that beyond was some sort of opening, because now they knew but 67 too well that their retreat was effectually cut off. If there was no opening ahead they were doomed. They consulted the plan again and went forward. Abruptly they came to a halt, shutting their jaws hard. They had come to the end of the main drift and it was a blank wall of solid stone where the prospectors had finished!

“Well, old man, there’s still the two side drifts to examine,” said Bill with a plain attempt to appear hopeful that did not in the least deceive the other.

“Yes. That’s back there about fifty feet,” Dick assented, finding that it required an effort to steady his voice. “The other one is behind that barrier.”

They looked at each other, reading the same thought. They had but one more chance and that was almost futile; for the plans indicated that the side drift extended but a score or so of yards and had then been abandoned. They felt their feet faltering when they turned into it, dreading the end, dreading the revelation that must tell them they were to die in this limited burrow in the hills. But courageously they tried to assume an air of confidence. They did not speak as they progressed, each dreading that instant when he would again face an inexorable barrier. They 68 counted their steps as they went, to themselves. They came to the twentieth, twenty-first, twenty-second, and were peering fixedly ahead. Together they stopped and turned toward each other. Dimly in the faintly thrown light of the candle beams, they could see it, the dusky gray mass where hope had pictured a continuing blackness. The wall leered at them as they stood there panting, despairing, desperate as trapped animals. Their imaginations told them the end.

“Well, old man”––Bill’s voice sounded with exceptional softness––“they didn’t extend this drift any farther. All we can do now is to go up and sit down at the foot of it, and––wait!”

“But it won’t take long, Bill,” Dick replied. “The air, you know. It can’t last forever.”

They trudged forward for the few remaining yards and then, abruptly, the candle they were carrying gave a little flicker. This time they stopped in their tracks and shouted. Bill suddenly loosened his hold on the younger man’s shoulder and began hopping forward, and the light threw huge, grotesque, strangely moving shadows on the wall ahead of them. Dick ran after him, crowding on his heels and shouting meaningless hopes. Abruptly they came to a right-angle drift, and then, but a few yards down 69 it, they discovered an upraise, crude and uncared-for, but climbing into the higher darkness, and down this there streamed fresh air.

It was such a one as prospectors make, having here and there a pole with cleats to serve as a ladder, then ascending at an incline which, though difficult, was not impossible, and again reverting to rocky footholds at the sides. Up this Dick boosted his partner, thrusting a shoulder beneath his haunches and straining upward with the exultation of reaction. They were saved! He knew it! The fresh air told that story to their experienced nostrils. Up, up, up they clambered for a long slanting distance and then fell out on the floor of another drift, at whose end was a shadowy light. Again they hobbled down a long length, ever approaching their goal. Bill stopped and leaned against the side wall and voiced his exultation.

“I know where we are,” he exclaimed. “This is the blacksmiths’ tunnel. They made that upraise following the ore, and that’s why the mine was opened for the second time here. They didn’t complete the plans because they knew the old work was useless. Dick, we’ve been through some pretty hard times together and had some narrow shaves; but I don’t care for many more 70 like that! Come on. Help me out. I want you to take a look and see if my head is any whiter than it was at nine o’clock this mornin’ when we went into that other hole.”

The sunlight was good to see again––good as only sunlight can be when men have not expected ever again to be enlivened by its glory. They were astonished at the shortness of the time of their imprisonment. They had lived years in dread thought, and but a few hours in reality. They had suffered for the spans of lives to find that the clock had imperturbably registered brief intervals. They had played the gamut of dread, terror, and anguish, to learn how trivial, after all, was the completed score.

“I think that will do,” said Dick, with a sigh of relief, as he straightened up from bandaging Bill’s leg. “The stitches probably hurt some, but aside from a day’s stiffness I don’t think you will ever know it happened.”

“Won’t eh?” rumbled the patient. “Sure, the leg’s all right; but it ain’t bruised limbs a man remembers. They heal. You can see the scars 72 on a man’s legs, but only the Lord Almighty can see those on his mind, and they’re the only ones that last. Dick, now that it’s all over, I ain’t ashamed to tell you that there was quite a long spell down there underground when I thought over a heap of things I might have done different if I’d had a chance to do ’em over again. And, boy, I thought quite a little bit about you! It didn’t seem right that a young fellow like you, with so much to live for, should be snuffed out down there in that black place, where the whole mountain acted as if it was chasin’ us, step by step, to wipe us off the slate.”

He stood on his feet and limped across the room to his coat in an effort to recover himself, and Dick, more stirred than he cared to admit by the affection in his voice, tramped out to the little porch in front and pretended to whistle a tune, that proved tuneless. He looked at the little valley around the shoulder of the mountain at the head of the ravine, which they had so carelessly invaded that morning, and shuddered. Inside he heard Bill moving around, and then after a time his steps advancing stiffly, and turned to see him coming out.

“I think,” he said smiling, “that we’re entitled to a rest for to-day. By to-morrow you’ll 73 be all right again, unless I’m mistaken. Let’s put in the day looking over these old records.”

Bill grinned whimsically and assented. He could keep quiet when he had to; but the day following found him again restlessly investigating anything that seemed worth the trouble and the afternoon saw him standing looking upward toward the same valley of dread.

“I’ve got over it a little,” he said to the younger man, “and do you know I’m right curious to go over there and see how big that rock was that tumbled into the mouth of the old shaft. Want to come along?”

Dick had sustained that same curiosity, so together they made their way to the beginning of the previous day’s disaster. They chilled when they saw how effectually they had been caught; for the bowlder completely filled the entrance to the shaft and would have proved a hopeless trap had they tried to escape by burrowing around its edge. It rested, as they had discovered, on solid rock, and its course down the hillside was clearly marked.

“What gets me,” said the veteran miner, “is what could have started it. I noticed it up there when we went in. It was sort of poised on 74 that little ledge you see, and it didn’t have to roll more than thirty feet.”

He began to climb up the bowlder’s well-defined path, and suddenly called to his partner with a hoarse shout, needlessly loud.

“Come up here,” he said. “That bowlder never started itself! Some one helped it. What do you think of that?”

Dick hastily climbed up to his side and looked. The rock around was bare of growth or covering, so that no footprints could be discerned; but a rock rested there that had plainly been used as a fulcrum. The surface beneath it was weather beaten and devoid of moisture, which indicated that it had lain there but a short time, probably only from the time of its mission on the preceding day. They found themselves standing up and staring around at the surrounding hills as if seeking sight of the man who had attempted to murder them.

“We’ll find out about this!” Bill exclaimed. “Good thing we know enough to look.”

He limped to the edge of the barren spot and began to circle around its edge, while Dick did likewise, following his example. They found a footprint at last and took the trail. It did not lead them far before they came to a path on top 75 of the hill that was so well used that any attempt to follow it was useless; but, intent on seeing where it led, they walked along it as it led straight away toward the timber. Scarcely inside the cool shadows of the tamaracks they paused and looked at each other understandingly; for thrown carelessly into a clump of laurel was a long, freshly cut sapling, that had been used as a lever. They recovered it from its resting place and inspected it. There was no doubt whatever that it had been the instrument of motion. Its scarred end, its length, and all, told that the man who had used it had carried it this far to discard it, believing his murderous work done.

“I noticed that rock, as I said before,” declared Bill. “You noticed how round it was on one side? Well, a man could take this lever, and by teetering on it until he got it in motion, finally upset it. The chances were a hundred to one it would land in the mouth of the shaft. And it’s a cinch, it seems to me, he wouldn’t do that for fun.”

Dick shook his head gravely.

“But who could it be?” he insisted. “Who is there that could want us out of the way badly enough to murder us? No one here knows or cares a continental about us! It seems incredible. 76 It must have been sheer carelessness of some restless loafer who wanted to see the rock roll.”

Yet they knew that the theory was scarcely tenable. They walked farther along the path and found that it was one used by workmen, evidently, leading at last down the steep mountain side and across to the Rattler. They surmised that it must be one made by the timber cutters for the mine, and learned, in later months, that the surmise was correct.

“It makes one thing certain,” Bill declared that evening when, candidly discouraged, they sat on the little porch in front of the office they had made their home and discussed the day’s findings. “And that is that until we get a force to work here, if we ever do, it ain’t a right healthy place for us. Of course with a gang of men around there wouldn’t be a ghost of a chance for any enemy to get us; but until then we’d better watch out all the time. I begin to believe that about everything that’s happened to us here has been the work of somebody who ain’t right fond of us. Wish we could catch him at it once!”

There was a grim undercurrent in his wish that left nothing to words. They remembered that in all the time since their arrival they had seen no other human being, the Rattler men having 77 left them as severely alone as if they had been under quarantine.

In the stillness of twilight they heard the slow, soft padding of a man’s feet laboriously climbing the hill, and listened intently at the unusual sound.

“Wonder who that is,” speculated Bill, leaning forward and staring at the dim trail. “Looks like a dwarf from here. Some old man of the mountain coming up to drive us off!”

“Hello,” hailed a shrill, quavering voice. “Be you the bosses?”

“We are,” Dick shouted, in reply, “Come on up.”

The visitor came halting up the slope, and they discerned that he was lame and carrying a roll of blankets. He paused before them, panting, and then dropped the roll from his back, and sat down on the edge of the porch with his head turned to face them. He was white headed and old, and seemed to have exhausted his surplus strength in his haste to reach them before darkness.