“With pretty art and a woman’s instinctive desire to please, she had placed the candle on a chair and assumed something of a pose.”

[Page 20]

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Web of the Golden Spider

Author: Frederick Orin Bartlett

Release Date: June 12, 2009 [eBook #29104]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WEB OF THE GOLDEN SPIDER***

|

Transcriber’s Note: |

“With pretty art and a woman’s instinctive desire to please, she had placed the candle on a chair and assumed something of a pose.”

[Page 20]

| THE WEB |

| OF THE |

| GOLDEN SPIDER |

|

by FREDERICK ORIN BARTLETT Author of “Joan of the Alley,” etc. |

|

illustrated by HARRISON FISHER and CHARLES M. RELYEA |

|

NEW YORK GROSSET & DUNLAP PUBLISHERS |

| Copyright, 1909 |

| By Small, Maynard & Company |

| (INCORPORATED) |

| Entered at Stationers’ Hall |

| THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A. |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Closed Door Opens | 1 |

| II | Chance Provides | 13 |

| III | A Stranger Arrives | 28 |

| IV | The Golden God Speaks | 40 |

| V | In the Dark | 53 |

| VI | Blind Man’s Buff | 63 |

| VII | The Game Continues | 75 |

| VIII | Of Gold and Jewels Long Hidden | 89 |

| IX | A Stern Chase | 100 |

| X | Strange Fishing | 113 |

| XI | What was Caught | 124 |

| XII | Of Love and Queens | 136 |

| XIII | Of Powder and Bullets | 149 |

| XIV | In the Shadow of the Andes | 164 |

| XV | Good News and Bad | 172 |

| XVI | The Priest Takes a Hand | 185 |

| XVII | ’Twixt Cup and Lip | 200 |

| XVIII | Blind Alleys | 214 |

| XIX | The Spider And The Fly | 225 |

| XX | In the Footsteps of Quesada | 237 |

| XXI | The Hidden Cave | 253 |

| XXII | The Taste of Rope | 265viii |

| XXIII | The Spider Snaps | 274 |

| XXIV | Those in the Hut | 286 |

| XXV | What the Stars Saw | 296 |

| XXVI | A Lucky Bad Shot | 308 |

| XXVII | Dangerous Shadows | 320 |

| XXVIII | A Dash for Port | 330 |

| XXIX | The Open Door Closes | 341 |

| PAGE | |

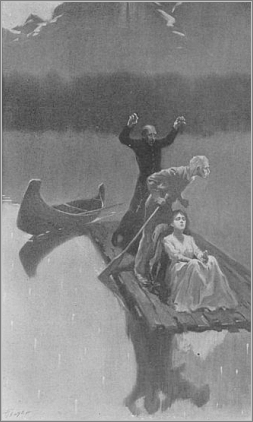

| With pretty art and a woman’s instinctive desire to please, she had placed the candle on a chair and assumed something of a pose. | Frontispiece |

| “For the love of God, do not rouse her. She sees! She sees!” | 46 |

| Minute after minute, Stubbs stared at this sight in silence. | 278 |

| Sorez stared straight ahead of him in a frenzy. Then the shadow sprang, throwing his arms about the tall figure. | 304 |

In his aimless wanderings around Boston that night Wilson passed the girl twice, and each time, though he caught only a glimpse of her lithe form bent against the whipping rain, the merest sketch of her somber features, he was distinctly conscious of the impress of her personality. As she was absorbed by the voracious horde which shuffled interminably and inexplicably up and down the street, he felt a sense of loss. The path before him seemed a bit less bright, the night a bit more barren. And although in the excitement of the eager life about him he quickly reacted, he did not turn a corner but he found himself peering beneath the lowered umbrellas with a piquant sense of hope.

Wilson’s position was an unusual one for a theological student. He was wandering at large in a strange city, homeless and penniless, and yet he was not unhappy in this vagabondage. Every prowler in the dark is, consciously or unconsciously, a mystic. He is in touch with the unknown; he is a member of a universal 2 cabal. The unexpected, the impossible lurk at every corner. He brushes shoulders with strange things, though often he feels only the lightest breath of their passing, and hears only a rustle like that of an overturned leaf. But he knows, either with a little shudder and a startled glance about or with quickened pulse and eager waiting.

This he felt, and something, too, of that fellowship which exists between those who have no doors to close behind them. For such stand shoulder to shoulder facing the barrier Law, which bars them from the food and warmth behind the doors. To those in a house the Law is scarcely more than an abstraction; to those without it is a tyrannical reality. The Law will not even allow a man outside to walk up and down in the gray mist enjoying his own dreams without looking upon him with suspicion. The Law is a shatterer of dreams. The Law is as eager as a gossip to misinterpret; and this puts one, however innocent, in an aggressive mood.

Looking up at the sodden sky from beneath a dripping slouch hat, Wilson was keenly alive to this. Each rubber-coated officer he passed affected him like an insolent intrusion. He brought home all the mediocrity of the night, all the shrilling gray, all the hunger, all the ache. These fellows took the color out of the picture, leaving only the cold details of a photograph. They were the men who swung open the street doors at the close of a matinee, admitting the stale sounds of the road, the sober light of the late afternoon.

This was distinctly a novel viewpoint for Wilson. As a student he had most sincerely approved of the Law; as a citizen of the world behind the closed doors he had forgotten it. Now with a trace of uneasiness he found himself resenting it.

A month ago Wilson had thought his life mapped out beyond the possibility of change, except in its details; he would finish his course at the school, receive a church, and pursue with moderate success his task of holding a parish up to certain ideals. The death of the uncle who was paying his way, following his bankruptcy, brought Wilson to a halt from even this slow pace. At first he had been stunned by this sudden order of Fate. His house-bleached fellows had gathered around in the small, whitewashed room where he had had so many tough struggles with Greek roots and his Hebrew grammar. They offered him sympathy and such slight aid as was theirs. Minor scholarships and certain drudging jobs had been open to him,––the opportunity to shoulder his way to the goal of what he had thought his manifest destiny. But that night after they had gone he locked the door, threw wide his window, and wandered among the stars. There was something in the unpathed purple between the spear points which called to him. He breathed a fresher air and thrilled to keener dreams. Strange faces came to him, smiling at him, speaking dumbly to him, stirring unknown depths within him. He was left breathless, straining towards them.

The day after the school term closed he had packed 4 his extension valise, bade good-bye to his pitying classmates, and taken the train to Boston. He had only an indefinite object in his mind: he had once met a friend of his uncle’s who was in the publishing business; and he determined to seek him on the chance of securing through him work of some sort. He learned that the man had sold out and moved to the West. Then followed a week of hopeless search for work until his small hoard had dwindled away to nothing. To-day he found himself without a cent.

He had answered the last advertisement just as the thousand windows sprang to renewed life. It was a position as shipping clerk in a large department store. After waiting an hour to see the manager, a double-chinned ghoul with the eyes of a pig, he had been dismissed with a glance.

“Thank you,” said Wilson.

“For what?” growled the man.

“For closing this door,” answered Wilson, with a smile.

The fellow shifted the cigar stub which he gripped with yellow teeth between loose lips.

“What you mean?”

“Oh, you wouldn’t understand––not in a thousand years. Good-day.”

The store was dry and warm. He had wandered about it gazing at the pretty colored garments, entranced by the life and movement about him, until the big iron gates were closed. Then he went out upon the thoroughfare, glad to brush shoulders with the home-goers, 5 glad to feel one with them in the brilliant pageant of the living. And always he searched for the face he had met twice that day.

The lights glowed mellow in the mist and struck out shimmering golden bars on the asphalt. The song of shuffling feet and the accompaniment of the clattering hansoms rang excitedly in his ears. He felt that he was touching the points of a thousand quick romances. The flash of a smile, a quick step, were enough to make him press on eagerly in the possibility that it was here, perhaps, the loose end of his own life was to be taken up.

As the crowd thinned away and he became more conspicuous to the prowling eyes which seemed to challenge him, he took a path across the Public Gardens, and so reached the broader sweep of the avenue where the comfortable stone houses snuggle shoulder to shoulder. The lower windows were lighted behind drawn shades. Against the stubborn stone angles the light shone out with appealing warmth. Every window was like an invitation. Occasionally a door opened, emitting a path of yellow light to the dripping walk, framing for a second a man or a woman; sometimes a man and a woman. When they vanished the dark always seemed to settle down upon him more stubbornly.

Then as the clock boomed ten he saw her again. Through the mist he saw her making her uncertain way along the walk across the street, stopping every now and then to glance hesitatingly at the lighted windows, pause, and move on again. Suddenly, from the 6 shadow of the area way, Wilson saw an officer swoop down upon her like a hawk. The woman started back with a little cry as the officer placed his hand upon her arm. Wilson saw this through the mist like a shadow picture and then he crossed the road. As he approached them both looked up, the girl wistfully, the officer with an air of bravado. Wilson faced the vigorous form in the helmet and rubber overcoat.

“Well,” growled the officer, “what you doin’ round here?”

“Am I doing anything wrong?”

“That’s wot I’m goneter find out. Yer’ve both been loafin’ here fer an hour.”

“No,” answered Wilson, “I haven’t been loafing.”

“Wot yer doin’ then?”

“Living.”

Wilson caught an eager look from the shadowed face of the girl. He met the other eyes which peered viciously into his with frank aggressiveness. He never in his life had felt toward any fellow-creature as he felt towards this man. He could have reached for his throat. He drew his coat collar more closely about his neck and unbuttoned the lower buttons to give his legs freer play. The officer moved back a little, still retaining his grip on the girl’s arm.

“Well,” he said, “yer better get outern here now, or I’ll run you in, too.”

“No,” answered Wilson, “you’ll not run in either of us.”

“I won’t, eh? Move on lively–––”

“You go to the devil,” said Wilson, with quiet deliberation.

He saw the night stick swing for him, and, throwing his full weight against the officer, he lifted his arm and swung up under the chin. Then he seized the girl’s hand.

“Run,” he gasped, “run for all you’re worth!”

They ran side by side and darted down the first turn. They heard the sharp oath, the command, and then the heavy beat of the steps behind them. Wilson kept the girl slightly ahead of him, pushing and steadying her, although he soon found that she was quite as fleet as he himself was. She ran easily, from the hips, like one who has been much out of doors.

Their breath came in gasps, but they still heard the heavy steps behind them and pushed on. As they turned another corner to the left they caught the sharp bark of a pistol and saw the spat of a bullet on the walk to the right of them. But this street was much darker, and so, while there was the added danger from stumbling, they felt safer.

“He’s getting winded,” shouted Wilson to her. “Keep on.”

Soon they came to a blank wall, but to the left they discovered an alley. A whiff of salt air beat against their faces, and Wilson knew they were in the market road which led along the water front in the rear of the stone houses. He had come here from the park on hot days. There were but few lights, and these could not carry ten yards through the mist. Pressing on, he 8 kept at her back until she began to totter, and then he paused.

“A little further,” he said. “We’ll go on tiptoe.”

They stole on, pressing close to the wall which bounded the small back yards, making no more noise than shadows. Finally the girl fell back against him.

“You––you go on!” she begged.

Wilson drew her to his side and pressed back against one of the wooden doors, holding his breath to listen. He could barely make out the sodden steps and––they were receding.

The mist beat in damply upon their faces, but they could not feel it in the joy of their new-found freedom. Before them all was black, the road indistinguishable save just below the pale lights which were scarcely more than pin pricks in black velvet. But the barrier behind seemed to thrust them out aggressively.

Struggling to regain his breath, Wilson found his blood running freer and his senses more alert than for years. The night surrounding him had suddenly become his friend. It became pregnant with new meaning,––levelling walls, obliterating beaten man paths, cancelling rusty duties. In the dark nothing existed save souls, and souls were equal. And the world was an uncharted sea.

Then in the distance he detected the piercing light from a dark lantern moving in a circle, searching every nook and cranny. He knew what that meant; this road was like a blind alley, with no outlet. They had been 9 trapped. He glanced at the girl huddling at his feet and then straightened himself.

“They sha’n’t!” he cried. “They sha’n’t!”

He ran his hand along the door to the latch. It was locked; but he drew back a few steps and threw his full weight against it and felt it give a trifle.

“They’ll hear us,” warned the girl.

Though the impact jarred him till he felt dizzy, he stumbled forward again; and yet again. The lock gave and, thrusting the girl in, he swung the door to behind them.

They found themselves in a small, paved yard. Fumbling about this, Wilson discovered in the corner several pieces of joist, and these he propped against the door. Then he sank to the ground exhausted.

In spite of his bruised body, his tired legs, and aching head, he felt a flush of joy; he was no longer at bay. A stout barrier stood between him and his pursuers. And when he felt a warm, damp hand seeking his he closed over it with a new sense of victory. He was now not only a fighter, but a protector. He had not yet been able to see enough of the girl’s features to form more than the vaguest conception of what she was. Yet she was not impersonal; he felt that he could have found her again in a crowd of ten thousand. She was a frailer creature who had come to him for aid.

He gripped her fingers firmly as the muffled sound of voices came to their ears. The officers had evidently passed and were now returning, balked in their search. 10 Pausing before the little door, they discussed the situation with the interest of hunters baffled of their game.

“Faith, Murphy, they must have got over this wall somewhere.”

“Naw, they couldn’t. There’s glass atop the lingth of ut, an’ there isn’t a door wot isn’t locked.”

“I dunno. I dunno. This wan here–––”

He seized the latch and shook the door, kicking it stoutly with his heavy boots.

Inside, Wilson had risen to his feet, armed with a short piece of the joist, his lips drawn back so tight as to reveal his teeth. Wilson had never struck a man in his life before to-night, but he knew that if that door gave he should batter until he couldn’t stand. He would hit hard––mercilessly. He gripped the length of wood as though it were a two-handled scimitar, and waited.

“D’ ye mind now that it’s a bit loose?” said Murphy.

He put his knee against it and shoved, but the joist held firm. The man didn’t know that he was playing with the certainty of a crushed skull.

“Aw, come on!” broke in the other, impatiently. “They’ll git tired and crawl out. We can wait for thim at th’ ind. Faith, ut’s bitter cowld here.”

The man and the girl heard their steps shuffle off, and even caught the swash of their knees against the stiff rubber coats, so near they passed. The girl, who had been staring with strained neck and motionless 11 eyes at the tall figure of the waiting man at her side, drew a long breath and laid her hand upon his knee.

“They’ve gone,” she said.

Still he did not move, but stood alert, suspicious, his long fingers twined around his weapon, fearing with half-savage passion some new ruse.

“Don’t stand so,” she pleaded. “They’ve gone.”

The stick dropped from his hand, and he took off his hat to let the rain beat upon his hot head.

She crowded closer to his side, shivering with the cold, and yet more at peace than she had been that weary, long day. The world, which had stretched to fearsome distances, shrank again to the compass of this small yard, and a man stood between her and the gate to fight off the forces which had surged in upon her. She was mindful of nothing else. It was enough that she could stand for even a moment in the shelter of his strength; relax senses which discovered danger only to shrink back, powerless to ward it off. A woman without her man was as helpless as a soldier without his arms.

The rain soaked through to her skin, and she was faint with hunger; yet she was content to wait by his side in silence, in the full confidence that he with his man strength would stride over the seemingly impossible and provide. She was stripped to the naked woman heart of her, forced back to the sheer clinging instinct. She was simplified to the merely feminine as he was to the merely masculine. No other laws governed them but the crude necessity to live––in freedom.

Before them loomed the dripping wall, beyond that the road which led to the waiting fists, beyond that the wind-swept, gray waves; behind them rose the blank house with its darkened windows.

“Well,” he said, “we must go inside.”

He crossed the yard to one of the ground-floor windows and tried to raise it. As he expected, it was locked. He thrust his elbow through a pane just above the catch and raised it. He climbed in and told her to wait until he opened the door. It seemed an hour before he reappeared, framed in the dark entrance. He held out his hand to her.

“Come in,” he bade her.

She obeyed, moving on tiptoe.

For a moment after he had closed the door they stood side by side, she pressing close to him. She shivered the length of her slight frame. The hesitancy which had come to him with the first impress of the lightless silence about them vanished.

“Come,” he said, taking her hand, “we must find a light and build a fire.”

He groped his way back to the window and closed it, drawing the curtain tight down over it. Then he struck a match and held it above his head.

At the flash of light the girl dropped his hand and shrank back in sudden trepidation. So long as he remained in the shadows he had been to her only a power without any more definite personality than that of sex. Now that she was thrown into closer contact with him, by the mere curtailing of the distances around and above her, she was conscious of the need of further knowledge of the man. The very power which had defended her, unless in the control of a still higher power, might turn against her. The match flickered feebly in the damp air, revealing scantily a small room which looked like a laundry. It was enough, however, 14 to disclose a shelf upon which rested a bit of candle. He lighted this.

She watched him closely, and as the wick sputtered into life she grasped eagerly at every detail it revealed. She stood alert as a fencer before an unknown antagonist. Then he turned and, with this steadier light above his head, stepped towards her.

She saw eyes of light blue meeting her own of brown quite fearlessly. His lean face and the shock of sandy hair above it made an instant appeal to her. She knew he was a man she could trust within doors as fully as she had trusted him without. His frame was spare but suggestive of the long muscles of the New Englander which do not show but which work on and on with seemingly indestructible energy. He looked to her to be strong and tender.

She realized that he in his turn was studying her, and held up her head and faced him sturdily. In spite of her drenched condition she did not look so very bedraggled, thanks to the simple linen suit she had worn. Her jet black hair, loose and damp, framed an oval face which lacked color without appearing unhealthy. The skin was dark––the gypsy dark of one who has lived much out of doors. Both the nose and the chin was of fine and rather delicate modeling without losing anything of vigor. It was a responsive face, hinting of large emotions rather easily excited but as yet latent, for the girlishness was still in it.

Wilson found his mouth losing its tenseness as he looked into those brown eyes; found the strain of the 15 situation weakening. The room appeared less chill, the vista beyond the doorway less formidable. Here was a good comrade for a long road––a girl to meet life with some spirit as it came along.

She looked up at him with a smile as she heard the drip of their clothes upon the floor.

“We ought to be hung up to dry,” she laughed.

Lowering the candle, he stepped forward.

“We’ll be dry soon,” he answered confidently. “What am I to call you, comrade?”

“My name is Jo Manning,” she answered with a bit of confusion.

“And I am David Wilson,” he said simply. “Now that we’ve been introduced we’ll hunt for a place to get dry and warm.”

He shivered.

“I am sure the house is empty. It feels empty. But even if it isn’t, whoever is here will have to warm us or––fight!”

He held out his hand again and she took it as he led the way along the hall towards the front of the house. He moved cautiously, creeping along on tiptoe, the light held high above his head, pausing every now and then to listen. They reached the stairs leading to the upper hallway and mounted these. He pushed open the door, stopping to listen at every rusty creak, and stepped out upon the heavy carpet. The light roused shadows which flitted silently about the corners as in batlike fear. The air smelled heavy, and even the moist rustling of the girl’s garments 16 sounded muffled. Wilson glanced at the wall, and at sight of the draped pictures pressed the girl’s hand.

“Our first bit of luck,” he whispered. “They have gone for the summer!”

They moved less cautiously now, but not until they reached the dining room and saw the covered chairs and drawn curtains did they feel fully assured. He thrust aside the portières and noted that the blinds were closed and the windows boarded. They could move quite safely now.

The mere sense of being under cover––of no longer feeling the beat of the rain upon them––was in itself a soul-satisfying relief. But there was still the dank cold of their soggy clothes against the body. They must have heat; and he moved on to the living rooms above. He pushed open a door and found himself in a large room of heavy oak, not draped like the others. He might have hesitated had it not been for the sight of a large fireplace directly facing him. When he saw that it was piled high with wood and coal ready to be lighted, he would have braved an army to reach it. Crossing the room, he thrust his candle into the kindling. The flames, as though surprised at being summoned, hesitated a second and then leaped hungrily to their meal. Wilson thrust his cold hands almost into the fire itself as he crouched over it.

“Come here,” he called over his shoulder. “Get some of this quickly.”

She huddled close to him and together they let their cold bodies drink in the warm air. It tingled at 17 their fingers, smarted into their faces, and stung their chests.

“Nearer! Nearer!” he urged her. “Let it burn into you.”

Their garments sent out clouds of steam and sweated pools to the tiles at their feet; but still they bathed in the heat insatiably. He piled on wood until the flames crackled out of sight in the chimney and flared into the room. He took her by the shoulders and turned her round and round before it as one roasts a goose. He took her two hands and rubbed them briskly till they smarted; she laughed deliciously the while, and the color on her cheeks deepened. But in spite of all this they couldn’t get very far below the surface. He noticed the dripping fringe of her skirts and her water-logged shoes.

“This will never do,” he said. “You’ve got to get dry––clear to your bones. Somehow a woman doesn’t look right––wet. She gets so very wet––like a kitten. I’m going foraging now. You keep turning round and round.”

“Till I’m brown on the outside?”

“Till I come back and see if you’re done.”

She followed him with her eyes as he went out, and in less than five minutes she heard him calling for her. She hurried to the next room and found him bending over a tumbled heap of fluffy things which he had gingerly picked from the bureau drawers.

“Help yourself,” he commanded, with a wave of his hand.

“But––I oughtn’t to take these things!”

“My girl,” he answered in an even voice that seemed to steady her, “when it’s either these or pneumonia––it’s these. I’ll leave you the candle.”

“But you–––”

“I’ll find something.”

He went out. She stood bewildered in the midst of the dimly revealed luxury about her. The candle threw feeble rays into the dark corners of the big room, over the four-posted oak bed covered with its daintily monogrammed spread, over the heavy hangings at the windows, and the bright pictures on the walls. She caught a glimpse of closets, of a graceful dressing table, and finally saw her reflection in the long mirror which reached to the floor.

She held the candle over her head and stared at herself. She cut but a sorry figure in her own eyes in the midst of such spotless richness as now surrounded her. She shivered a little as her own damp clothes pressed clammily against her skin. Then with a flush she turned again to the garments rifled from their perfumed hiding places. They looked very white and crisp. She hesitated but a second.

“She’ll forgive,” she whispered, and threw off her dripping waist. The clothes, almost without exception, fitted her remarkably well. She found herself dressing leisurely, enjoying to the fullest the feel of the rich goods. She shook her hair free, dried it as best she could, and took some pains to put it up nicely. It 19 was long and glossy black, but not inclined to curl. It coiled about her head in silken strands of dark richness.

She demurred at first at the silk dress which he had tossed upon the bed, but she could find no other. It was of a golden yellow, dainty and foreign in its design. It fitted snugly to her slim figure as though it had been made for her. She stood off at a little distance and studied herself in the mirror. She was a girl who had an instinct for dress which had never been satisfied; a girl who could give, as well as take, an air from her garments. She admired herself quite as frankly as though it had been some other person who, with head uptilted and teeth flashing in a contented smile, challenged her from the clear surface of the mirror, looking as though she had just stepped through the wall into the room. The cold, the wet, and for a moment even the hunger vanished, so that as she glanced back at her comfortable reflection it seemed as if it were all just a dream of cold and wet and hunger. With silk soothing her skin, with the crisp purity of spotless linen rustling about her, with the faultless gown falling in rich splendor about her feet, she felt so much a part of these new surroundings that it was as though she melted into them––blended her own personality with the unstinted luxury about her.

But her foot scuffled against a wet stocking lying as limp as water grass, which recalled her to herself and the man who had led the way to this. A wave of pity swept over her as she wondered if he had found dry 20 things for himself. She must hurry back and see that he was comfortable. She felt a certain pride that the beaded slippers she had found in the closet fitted her a bit loosely. With the candle held far out from her in one hand and the other lifting her dress from the floor, she rustled along the hall to the study, pausing there to speak his name.

“All ready?” he shouted.

He strode from a door to the left, but stopped in the middle of the room to study her as she stood framed in the doorway––a picture for Whistler. With pretty art and a woman’s instinctive desire to please, she had placed the candle on a chair and assumed something of a pose. The mellow candle-light deepened the raven black of her hair, softened the tint of her gown until it appeared of almost transparent fineness. It melted the folds of the heavy crimson draperies by her side into one with the dark behind her. She had shyly dropped her eyes, but in the excitement of the moment she quickly raised them again. They sparkled with merriment at sight of his lean frame draped in a lounging robe of Oriental ornateness. It was of silk and embellished with gold-spun figures.

“It was either this,” he apologized, “or a dress suit. If I had seen you first, I should have chosen the latter. I ought to dress for dinner, I suppose, even if there isn’t any.”

“You look as though you ought to make a dinner come out of those sleeves, just as the magicians make rabbits and gold-fish.”

“And you,” he returned, “look as though you ought 21 to be able to get a dinner by merely summoning the butler.”

He offered her his arm with exaggerated gallantry and escorted her to a chair by the fire. She seated herself and, thrusting out her toes towards the flames, gave herself up for a moment to the drowsy warmth. He shoved a large leather chair into place to the left and, facing her, enjoyed to himself the sensation of playing host to her hostess in this beautiful house. She looked up at him.

“I suppose you wonder what brought me out there?”

“In a general way––yes,” he answered frankly. “But I don’t wish you to feel under any obligation to tell me. I see you as you sit there,––that is enough.”

“There is so little else,” she replied. She hesitated, then added, “That is, that anyone seems to understand.”

“You really had no place to which you could go for the night?”

“No. I am an utter stranger here. I came up this morning from Newburyport––that’s about forty miles. I lost my purse and my ticket, so you see I was quite helpless. I was afraid to ask anyone for help, and then––I hoped every minute that I might find my father.”

“But I thought you knew no one here?”

“I don’t. If Dad is here, it is quite by chance.”

She looked again into his blue eyes and then back to the fire.

“It is wonderful how you came to me,” she said.

“I saw you twice before.”

“Once,” she said, “was just beyond the Gardens.”

“You noticed me?”

“Yes.”

She leaned forward.

“Yes,” she repeated, “I noticed you because of all the faces I had looked into since morning yours was the first I felt I could trust.”

“Thank you.”

“And now,” she continued, “I feel as though you might even understand better than the others what my errand here to Boston was.” She paused again, adding, “I should hate to have you think me silly.”

She studied his face eagerly. His eyes showed interest; his mouth assured her of sympathy.

“Go on,” he bade her.

To him she was like someone he had known before––like one of those vague women he used to see between the stars. Within even these last few minutes he had gotten over the strangeness of her being here. He did not think of this building as a house, of this room as part of a home; it was just a cave opening from the roadside into which they had fled to escape the rain.

It seemed difficult for her to begin. Now that she had determined to tell him she was anxious for him to see clearly.

“I ought to go back,” she faltered; “back a long way into my life, and I’m afraid that won’t be interesting to you.”

“You can’t go very far back,” he laughed. Then 23 he added seriously, “I am really interested. Please to tell it in your own way.”

“Well, to begin with, Dad was a sea captain and he married the very best woman in the world. But she died when I was very young. It was after this that Dad took me on his long voyages with him,––to South America, to India, and Africa. I don’t remember much about it, except as a series of pictures. I know I had the best of times for somehow I can remember better how I felt than what I saw. I used to play on the deck in the sun and listen to the sailors who told me strange stories. Then when we reached a port Dad used to take me by the hand and lead me through queer, crooked little streets and show me the shops and buy whole armfuls of things for me. I remember it all just as you remember brightly colored pictures of cities––pointed spires in the sunlight, streets full of bright colors, and dozens of odd men and women whose faces come at night and are forgotten in the morning. Dad was big and handsome and very proud of me. He used to like to show me off and take me with him everywhere. Those years were very wonderful and beautiful.

“Then one day he brought me back to shore again, and for a while we lived together in a large white house within sight of the ocean. We used to take long walks and sometimes went to town, but he didn’t seem very happy. One day he brought home with him a strange woman and told me that she was to be housekeeper, and that I must obey her and grow up to be a fine 24 woman. Then he went away. That was fifteen years ago. Then came the report he was dead; that was ten years ago. After a while I didn’t mind so much, for I used to lie on my back and recall all the places we had been together. When these pictures began to fade a little, I learned another way,––a way taught me by a sailor. I took a round crystal I found in the parlor and I looked into it hard,––oh, very, very hard. Then it happened. First all I saw was a blur of colors, but in a little while these separated and I saw as clearly as at first all the streets and places I had ever visited, and sometimes others too. Oh, it was such a comfort! Was that wrong?”

“No,” he answered slowly, “I can’t see anything wrong in that.”

“She––the housekeeper––called it wicked––devilish. She took away the crystal. But after a while I found I could see with other things––even with just a glass of clear water. All you have to do is to hold your eyes very still and stare and stare. Do you understand?”

He nodded.

“I’ve heard of that.”

She dropped her voice, evidently struggling with growing excitement, colored with something of fear.

“Don’t you see how close this kept me to Dad? I’ve been living with him almost as though I were really with him. We’ve taken over again the old walks and many news ones. This seemed to go on just the same after we received word that he had 25 died––stricken with a fever in South America somewhere.”

She paused, taking a quick breath.

“All that is not so strange,” she ran on; “but yesterday––yesterday in the crystal I saw him––here in Boston.”

“What!”

“As clearly as I see you. He was walking down a street near the Gardens.”

“It might have been someone who resembled him.”

“No, it was Dad. He was thinner and looked strange, but I knew him as though it were only yesterday that he had gone away.”

“But if he is dead–––”

“He isn’t dead,” she answered with conviction.

“On the strength of that vision you came here to look for him?”

“Yes.”

“When you believe, you believe hard, don’t you?”

“I believe the crystal,” she answered soberly.

“Yet you didn’t find your father?”

“No,” she admitted.

“You are still sure he is here?”

“I am still sure he is living. I may have made a mistake in the place, but I know he is alive and well somewhere. I shall look again in the crystal to-morrow.”

“Yes, to-morrow,” answered Wilson, vaguely.

He rose to his feet.

“But there is still the hunger of to-day.”

She seemed disappointed in the lightness with which apparently he took her search.

“You don’t believe?”

“I believe you. And I believe that you believe. But I have seen little of such things myself. In the meanwhile it would be good to eat––if only a few crackers. Are you afraid to stay here alone while I explore a bit?”

She shook her head.

He was gone some ten minutes, and when he came back his loose robe bulged suspiciously in many places.

“Madame,” he exclaimed, “I beg you to observe me closely. I snap my fingers twice,––so! Then I motion,––so! Behold!”

He deftly extricated from one of the large sleeves a can of soup, and held it triumphantly aloft.

“Once more,––so!”

He produced a package of crackers; next a can of coffee, next some sugar. And she, watching him with face alight, applauded vigorously and with more genuine emotion than usually greets the acts of a prestidigitator.

“But, oh!” she exclaimed, with her hands clasped beneath her chin, “don’t you dare to make them disappear again!”

“Madame,” answered Wilson, with a bow, “that shall be your privilege.”

He hurried below once more, and this time returned with a chafing-dish, two bowls, and a couple of iron spoons which he had found in the kitchen. In ten 27 minutes the girl had prepared a lunch which to them was the culmination of their happiness. Warmed, clothed, and fed, there seemed nothing left for them.

When they had finished and had made everything tidy in the room, and he had gone to the cellar and replenished the coal-hod, he told her something of his own life. For a little while she listened, but soon the room became blurred to her and she sank farther and farther among the heavy shadows and the old paintings on the wall. The rain beat against the muffled windows drowsily. The fire warmed her brow like some hypnotic hand. Then his voice ceased and she drew her feet beneath her and slept in the chair, looking like a soft Persian kitten.

It was almost two in the morning when Wilson heard the sound of wheels in the street without, and conceived the fear that they had stopped before the house. He found himself sitting rigidly upright in the room which had grown chill, staring at the dark doorway. The fire had burned low and the girl still slept in the shadows, her cheeks pressed against her hands. He listened with suspended breath. For a moment there was no other sound and so he regained his composure, concluding it had been only an evil dream. Crossing to the next room, he drew a blanket from the little bed and wrapped the sleeping girl about with it so carefully that she did not awake. Then he gently poked up the fire and put on more coal, taking each lump in his fingers so as to make no noise.

Her face, even while she slept, seemed to lose but little of its animation. The long lashes swept her flushed cheeks. The eyes, though closed, still remained expressive. A smile fluttered about her mouth as though her dreams were very pleasant. To Wilson, who neither had a sister nor as a boy or man had been much among women, the sight of this sleeping girl so near to him was particularly impressive. Her utter 29 trust and confidence in his protection stirred within him another side of the man who had stood by the gate clutching his club like a savage. She looked so warm and tender a thing that he felt his heart growing big with a certain feeling of paternity. He knew at that moment how the father must have felt when, with the warm little hand within his own, he had strode down those foreign streets conscious that every right-hearted man would turn to look at the pretty girl; with what joy he had stopped at strange bazaars to watch her eyes brighten as the shopkeepers did their best to please. Those must have been days which the father, if alive, was glad to remember.

A muffled beat as upon the steps without again brought him to attention, but again the silence closed in upon it until he doubted whether he had truly heard. But the dark had become alive now, and he seemed to see strange, moving shadows in the corners and hear creakings and rustlings all about him. He turned sharply at a soft tread behind him only to start at the snapping of a coal in the fire from the other side. Finally, in order to ease his mind, he crossed the room and looked beyond the curtains into the darkness of the hall. There was neither movement nor sound. He ventured out and peered down the staircase into the dark chasm marking the lower hall. He heard distinctly the sound of a key being fitted rather clumsily into the lock, then an inrush of air as the door was thrown open and someone entered, clutching at the wall as though unable to stand.

It never occurred to Wilson to do the natural and obviously simple thing: awake the girl at once and steal down the stairs in the rear until he at least should have a chance to reconnoitre. It seemed necessary for him to meet the situation face to face, to stand his ground as though this were an intrusion upon his own domain. The girl in the next room was sleeping soundly in perfect faith that he would meet every danger that should approach her. And so, by the Lord, he would. Neither she nor he were thieves or cowards, and he refused to allow her to be placed for a minute in such a position.

Someone followed close behind the first man who had entered and lighted a match. As the light flashed, Wilson caught a glimpse of two men; one tall and angular, the other short and broad-shouldered.

“The––the lights aren’t on, cabby,” said one of them; “but I––I can find my way all right.”

“The divil ye can, beggin’ yer pardon,” answered the other. “I’ll jist go ahead of ye now an’–––”

“No, cabby, I don’t need help.”

“Jist to th’ top of the shtairs, sor. I know ye’re thot weak with sickness–––”

The answer came like a military command, though in a voice heavy with weariness.

“Light a candle, if you can find one, and––go.”

The cabby struck another match and applied it to a bit of candle he found on a hall table. As the light dissolved the dark, Wilson saw the taller man straighten before the anxious gaze of the driver.

“Sacré, are you going?” exclaimed the stranger, impatiently.

“Good night, sor.”

“Good night.” The words were uttered like a command.

The man went out slowly and reluctantly closed the door behind him. The echo pounded suddenly in the distance.

No sooner was the door closed than the man remaining slumped like an empty grain-sack and only prevented himself from falling by a wild clutch at the bannister. He raised himself with an effort, the candle drooping sidewise in his hand. His broad shoulders sagged until his chin almost rested upon his breast and his big slouch hat slopped down over his eyes. His breathing was slow and labored, each breath being delayed as long as possible as though it were accompanied by severe pain. It was clear that only the domination of an extraordinary will enabled the man to keep his feet at all.

The stranger began a struggle for the mastery of the stairs that held Wilson spellbound. Each advance marked a victory worthy of a battlefield. But at each step he was forced to pause and rally all his forces before he went on to the next. First he would twine his long fingers about the rail reaching up as far as he was able; then he would lift one limp leg and swing it to the stair above; he would then heave himself forward almost upon his face and drag the other leg to a level with the first, rouse himself as from a tendency 32 to faint, and stand there blinking at the next stair with an agonized plea as for mercy written in the deep furrows of his face. The drunken candle sputtered close to his side, flaring against the skin of his hand and smouldering into his coat, but he neither felt nor saw anything. Every sense was forced to a focus on the exertion of the next step.

Wilson had plenty of time to study him. His lean face was shaven save for an iron-gray moustache which was cropped in a straight line from one corner of his mouth to another. His eyes were half hidden beneath shaggy brows. Across one cheek showed the red welt of an old sabre wound. There was a military air about him from his head to his feet; from the rakish angle to which his hat tumbled, to his square shoulders, braced far back even when the rest of his body fell limp, and to his feet which he moved as though avoiding the swing of a scabbard. A military cape slipped askew from his shoulders. All these details were indelibly traced in Wilson’s mind as he watched this struggle.

The last ten steps marked a strain difficult to watch. Wilson, at the top, found his brow growing moist in sheer agony of sympathy, and he found himself lifting with each forward heave as though his arms were about the drooping figure. A half dozen times he was upon the point of springing to his aid, but each time some instinct bade him wait. A man with such a will as this was a man to watch even when he was as near dead as he now appeared to be. So, backing into the shadows, Wilson watched him as he grasped the post and slouched 33 up the last stair, seeming here to gain new strength for he held his head higher and grasped the candle more firmly. It was then that Wilson stepped into the radius of shallow light. But before he had time to speak, he saw the eyes raised swiftly to his, saw a quick movement of the hand, and then, as the candle dropped and was smothered out in the carpet, he was blinded and deafened by the report of a pistol almost in his face.

He fell back against the wall. He was unhurt, but he was for the moment stunned into inactivity by the unexpectedness of the assault. He stood motionless, smothering his breathing, alert to spring at the first sound. And he knew that the other was waiting for the first indication of his position to shoot again. So two, three seconds passed, Wilson feeling with the increasing tension as though an iron band were being tightened about his head. The house seemed to settle into deeper and deeper silence as though it were being enfolded in layer upon layer of felt. The dark about him quivered. Then he heard her voice,––the startled cry of an awakened child.

He sprang across the hall and through the curtains to her side. She was standing facing the door, her eyes frightened with the sudden awakening.

“Oh,” she trembled, “what is it?”

He placed his fingers to her lips and drew her to one side, out of range of the door.

She snuggled closer to him and placed her hand upon his arm.

“You’re not hurt?” she asked in a whisper.

He shook his head and strained his ears to the hall without.

He led her to the wall through which the door opened and, pressing her close against it, took his position in front of her. Then the silence closed in upon them once again. A bit of coal kindled in the grate, throwing out blue and yellow flames with tiny crackling. The shadows danced upon the wall. The curtains over the oblong entrance hung limp and motionless and mute. For aught they showed there might have been a dozen eyes behind them leering in; the points of a dozen weapons pricking through; the muzzles of a dozen revolvers ready to bark death. Each second he expected them to open––to unmask. The suspense grew nerve-racking. And behind him the girl kept whispering, “What is it? Tell me.” He felt her hands upon his shoulders.

“Hush! Listen!”

From beyond the curtains came the sound of a muffled groan.

“Someone’s hurt,” whispered the girl.

“Don’t move. It’s only a ruse.”

They listened once more, and this time the sound came more distinct; it was the moaning breathing of a man unconscious.

“Stay where you are,” commanded Wilson. “I’ll see what the matter is.”

He neared the curtains and called out,

“Are you in trouble? Do you need help?”

There was no other reply but that spasmodic intake of breath, the jerky outlet through loose lips.

He crossed the room and lighted the bit of remaining candle. With this held above his head, he parted the curtains and peered out. The stranger was sitting upright against the wall, his head fallen sideways and the revolver held loosely in his limp fingers. As Wilson crossed to his side, he heard the girl at his heels.

“He’s hurt,” she exclaimed.

Stooping quickly, Wilson snatched the weapon from the nerveless fingers. It was quite unnecessary. The man showed not the slightest trace of consciousness. His face was ashen gray. Wilson threw back the man’s coat and found the under linen to be stained with blood. He tore aside the shirt and discovered its source––a narrow slit just over the heart. There was but one thing to do––get the man into the next room to the fire and, if possible, staunch the wound. He placed his hands beneath the stranger’s shoulders and half dragged him to the rug before the flames. The girl, cheeks flushed with excitement, followed as though fearing to let him out of her sight.

Under the influence of the heat the man seemed to revive a bit––enough to ask for brandy and direct Wilson to a recess in the wall which served as a wine closet. After swallowing a stiff drink, he regained his voice.

“Who the devil–––” he began. But he was checked by a twitch in his side. He was evidently 36 uncertain whether he was in the hands of enemies or not. Wilson bent over him.

“Are you badly hurt? Do you wish me to send for a surgeon?”

“Go into the next room and bring me the leather chest you’ll find there.”

Wilson obeyed. The man opened it and took out a vial of catgut, a roll of antiseptic gauze, several rolls of bandages, and––a small, pearl-handled revolver. He levelled this at Wilson.

“Now,” he commanded, “tell me who the Devil you are.”

Wilson did not flinch.

“Put it down,” he suggested. “There is time enough for questions later. Your wound ought to be attended to. Tell me what to do.”

The man’s eyes narrowed, but his hand dropped to his side. He realized that he was quite helpless and that to shoot the intruder would serve him but little. By far the more sensible thing to do was to use him. Wilson, watching him, ready to spring, saw the question decided in the prostrate man’s mind. The latter spoke sharply.

“Take one of those surgical needles and put it in the candle flame.”

Wilson obeyed and, as soon as it was sterilized, further followed his instructions and sewed up the wound and dressed it. During this process the stranger showed neither by exclamation nor facial expression that he felt in the slightest what must have been excruciating 37 pain. At the conclusion of the operation the man sprinkled a few pellets into the palm of his hand and swallowed them. For a few minutes after this he remained very quiet.

Wilson glanced up at the girl. She had turned her back upon the two men and was staring into the flames. She was not crying, but her two tightly clenched fists held closely jammed against her cheeks showed that she was keeping control of herself by an effort. It seemed to Wilson that it was clearly his duty to get her out of this at once. But where could he take her?

The stranger suddenly made an effort to struggle to his feet. He had grasped his weapon once again and now held it aggressively pointed at Wilson.

“What’s the matter with you?” demanded Wilson, quietly stepping forward.

“Matter?” stammered the stranger. “To come into your house and––and–––” he pressed his hand to his side and was forced to put out an arm to Wilson for support.

“I tell you we mean you no harm. We aren’t thieves or thugs. We were driven in here by the rain.”

“But how–––”

“By a window in the rear. Let us stay here until morning––it is too late for the girl to go out––and you’ll be none the worse.”

Wilson saw the same hard, determined look that he had noted upon the stairs return to the gray eyes. It was clear that the man’s whole nature bade him resent 38 this intrusion. It was evident that he regarded the two with suspicion, although at sight of the girl, who had turned, this was abated somewhat.

“How long have you been here?” he demanded.

“Some three or four hours.”

“Are––are there any more of you?”

“No.”

“Has––has there been any call for me while you have been in the house?”

“No.”

He staggered a little and Wilson suggested that he lie down once more. But he refused and, still retaining his grip on the revolver, he bade Wilson lead him to the door of the next room and leave him. He was gone some fifteen minutes. Once Wilson thought he caught the clicking as of a safe being opened. The girl, who had remained in the background all this while, now crossed to Wilson’s side as he stood waiting in the doorway. He glanced up at her. In her light silk gown she looked almost ethereal and added to the ghostliness of the scene. She was to him the one thing which lifted the situation out of the realm of sheer grim tragedy to piquant adventure from which a hundred lanes led into the unknown.

She pressed close to his side as though shrinking from the silence behind her. He reached out and took her hand. She smiled up at him and together they turned their eyes once again into the dark of the room beyond. Save for the intermittent clicking, there was silence. In this silence they seemed 39 to grow into much closer comradeship, each minute knitting them together as, ordinarily, only months could do.

Suddenly there was a cessation of the clicking and quickly following this the sound of a falling body. Wilson had half expected some such climax. Seizing a candle from the table before the fire, he rushed in. The stranger had fallen to the floor and lay unconscious in front of his safe.

A quick glance about convinced Wilson that the man had not been assaulted, but had only fainted, probably from weakness. His pulse was beating feebly and his face was ashen. Wilson stooped to place his hands upon his shoulders, when he caught sight of that which had doubtless led the stranger to undertake the strain of opening the safe––a black ebony box, from which protruded through the opened cover the golden head of a small, quaint image peering out like some fat spider from its web. In falling the head had snapped open so that from the interior of the thing a tiny roll of parchment had slipped out. Wilson, picking this up, put it in his pocket with scarcely other thought than that it might get lost if left on the floor. Then he took the still unconscious man in his arms and dragged him back to the fire.

For a while the man on the floor in his weakness rambled on as in a delirium.

“Ah, Dios!” he muttered. “There’s a knife in every hand.” Then followed an incoherent succession of phrases, but out of them the two distinguished this, “Millions upon millions in jewels and gold.” Then, “But the God is silent. His lips are sealed by the blood of the twenty.”

After this the thick tongue stumbled over some word like “Guadiva,” and a little later he seemed in his troubled dreams to be struggling up a rugged height, for he complained of the stones which fretted his feet. Wilson managed to pour a spoonful of brandy down his throat and to rebandage the wound which had begun to bleed again. It was clear the man was suffering from great weakness due to loss of blood, but as yet his condition was not such as to warrant Wilson in summoning a surgeon on his own responsibility. Besides, to do so would be seriously to compromise himself and the girl. It might be difficult for them to explain their presence there to an outsider. Should the man by any chance die, their situation would 41 be such that their only safety would lie in flight. To the law they were already fugitives and consequently to be suspected of anything from petty larceny to murder.

To have forced himself to the safe with all the pain which walking caused him, the wounded man must have been impelled by some strong and unusual motive. It couldn’t be that he had suspected Wilson and Jo of theft, because, in the first place, he must have seen at a glance that the safe was undisturbed; and in the second, that they had not taken advantage of their opportunity for flight. It must have been something in connection with this odd-looking image, then, at which he had been so eager to look. Wilson returned to the next room. He picked the idol from the floor. As he did so the head snapped back into place. He brought it out into the firelight.

It looked like one of a hundred pictures he had seen of just such curiosities––like the junk which clutters the windows of curio dealers. The figure sat cross-legged with its heavy hands folded in its lap. The face was flat and coarse, the lips thick, the nose squat and ugly. Its carved headdress was of an Aztec pattern. The cheek-bones were high, and the chin thick and receding. The girl pressed close to his side as he held the thing in his lap with an odd mixture of interest and fear.

“Aren’t its eyes odd?” she exclaimed instantly.

They consisted of two polished stones as clear as 42 diamonds, as brightly eager as spiders’ eyes. The light striking them caused them to shine and glisten as though alive.

The girl glanced from the image to the man on the floor who looked now more like a figure recumbent upon a mausoleum than a living man. It was as though she was trying to guess the relationship between these two. She had seen many such carved things as this upon her foreign journeys with her father. It called him back strongly to her. She turned again to the image and, attracted by the glitter in the eyes, took it into her own lap.

Wilson watched her closely. He had an odd premonition of danger––a feeling that somehow it would be better if the girl had not seen the image. He even put out his hand to take it away from her, but was arrested by the look of eagerness which had quickened her face. Her cheeks had taken on color, her breathing came faster, and her whole frame quivered with excitement.

“Better give the thing back to me,” he said at length. He placed one hand upon it but she resisted him.

“Come,” he insisted, “I’ll take it back to where I found it.”

She raised her head with a nervous toss.

“No. Let it alone. Let me have it.”

She drew it away from his hand. He stepped to her side, impelled by something he could not analyze, and snatched it from her grasp. Her lips quivered as though she were about to cry. She had never looked 43 more beautiful to him than she did at that moment. He felt a wave of tenderness for her sweep over him. She was such a young-looking girl to be here alone at the mercy of two men. At this moment she looked so ridiculously like a little girl deprived of her doll that he was inclined to give it back to her again with a laugh. But he paused. She did not seem to be wholly herself. It was clear enough that the image had produced some very distinct impression upon her––whether of a nature akin to her crystal gazing he could not tell, although he suspected something of the sort. The wounded man still lay prone upon the rug before the fire. His muttering had ceased and his breathing seemed more regular.

“Please,” trembled the girl. “Please to let me take it again.”

“Why do you wish it?”

“Oh, I––I can’t tell you, but–––”

She closed her lips tightly as though to check herself.

“I don’t believe it is good for you,” he said tenderly. “It seems to cast a sort of spell over you.”

“I know what it is! I know if I look deep into those eyes I shall see my father. I feel that he is very near, somehow. I must look! I must!”

She took it from his hands once more and he let it go. He was curious to see how much truth there was in her impression and he felt that he could take the idol from her at any time it seemed advisable to do so. In the face of this new situation both of them lost interest in the wounded man. He lay as though asleep.

The girl seated herself Turk fashion upon the rug before the grate and, holding the golden figure in her lap, gazed down into the sparkling stones which served for eyes. The light played upon the dull, raw gold, throwing flickering shadows over its face. The thing seemed to absorb the light growing warmer through it.

Wilson leaned forward to watch her with renewed interest. The contrast between the tiny, ugly features of the image and the fresh, palpitating face of the girl made an odd picture. As she sat so, the lifeless eyes staring back at her with piercing insistence, it looked for a moment like a silent contest between the two. She commanded and the image challenged. A quickening glow suffused her neck and the color crept to her cheeks. To Wilson it was as though she radiated drowsy waves of warmth. With his eyes closed he would have said that he had come to within a few inches of her, was looking at the thing almost cheek to cheek with her. The room grew tense and silent. Her eyes continued to brighten until it seemed as though they reflected every dancing flame in the fire before her. Still the color deepened in her cheeks until they grew to a rich carmine.

Wilson found himself leaning forward with quickening breath. She seemed drifting further and further away from him and he sat fixed as though in some trance. He noted the rhythmic heave of her bosom and the full pulsation at the throat. The velvet sheen of the hair at her temples caught new lights from the 45 flames before her and held his eyes like the dazzling spaces between the coals. Her lips moved, but she spoke no word. Then it was that, seized with a nameless fear for the girl, Wilson rose half way to his feet. He was checked by a command from the man upon the floor.

“For the love of God, do not rouse her. She sees! She sees!”

The stranger struggled to his elbow and then to his knees, where he remained staring intently at the girl, with eyes aglow. Then the girl herself spoke.

“The lake! The lake!” she cried.

Wilson stepped to her side. He placed a hand firmly upon her shoulder.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

She lifted eyes as inscrutable as those of the image. They were slow moving and stared as blankly at him as at the pictures on the wall. He bent closer.

“Comrade––comrade––are you all right?”

Her lips moved to faint, incoherent mutterings. She did not seem to be in pain, and yet in travail of some sort.

The stranger, pale, his forehead beaded with the excitement of the moment, had tottered to his feet He seized Wilson’s arm almost roughly.

“Let her alone!” he commanded. “Can’t you see? Dios! the image speaks!”

“The image? have you gone mad?”

“No! No!” he ran on excitedly. “Listen!”

The girl’s brow was knitted. Her arms and limbs 46 moved restlessly. She looked like one upon the point of crying at being baffled.

“There is a mist, but I can see––I––I can see–––”

She gave a little sob. This was too much for Wilson. He reached for the image, but he had not taken a step before he heard the voice of the stranger.

“Touch that and I shoot.”

The voice was cold and steady. He half turned and saw that the man had regained his weapon. The hand that held it was steady, the eyes back of it merciless. For one moment Wilson considered the advisability of springing for him. But he regained his senses sufficiently to realize that he would only fall in his tracks. Even a wounded man is not to be trifled with when holding a thirty-two caliber revolver.

“Step back!”

Wilson obeyed.

“Farther!”

He retreated almost to the door into the next room. From that moment his eyes never left the hand which held the weapon. He watched it for the first sign of unsteadiness, for the first evidence of weakness or abstraction. He measured the distance between them, weighed to a nicety every possibility, and bided his time. He wanted just the merest ghost of a chance of reaching that lean frame before the steel devil could spit death. What it all meant he did not know, but it was clear that this stranger was willing to sacrifice the girl to further any project of his into which she had so strangely fallen. It was also clear to him that it did the girl no good to lose herself in such a trance as this. The troubled expression of her face, the piteous cry in her voice, her restlessness convinced him of this. When she had spoken to him of crystal gazing, he had thought of it only as a harmless amusement such as the Ouija board. This seemed different, more serious, either owing to the surroundings or to some really baneful influence from this thing of gold. And the responsibility of it was his; it was he who had led the girl in here, it was even he who had placed the image in her hands. At the fret of being forced to stand there powerless, the moisture gathered on his brow.

The stranger knelt on one knee by the girl’s side, facing the door and Wilson. He placed one hand upon her brow and spoke to her in an even tone that seemed to steady her thoughts. Her words became more distinct.

“Look deep,” he commanded. “Look deep and the mists will clear. Look deep. Look deep.”

His voice was the rhythmic monotone used to lull a patient into a hypnotic trance. The girl responded quickly. The troubled expression left her face, her breathing became deeper, and she spoke more distinctly. Her eyes were still upon those of the image as though the latter had caught and held them. She looked more herself, save for the fact that she appeared to be even farther away in her thoughts than when in normal sleep.

“Let the image speak through you,” ran on the stranger. “Tell me what you see or hear.”

“The lake––it is very blue.”

“Look again.”

“I see mountains about the lake––very high mountains.”

“Yes.”

“One is very much higher than the others.”

“Yes! Yes!”

“The trees reach from the lake halfway up its sides.”

“Go on!” he cried excitedly.

“There they stop and the mountain rises to a point.”

“Go on!”

“To the right there is a large crevice.”

The stranger moistened his lips. He gave a swift glance at Wilson and then turned his gaze to the girl.

“See, we will take a raft and go upon the lake. Now look––look hard below the waters.”

The girl appeared troubled at this. Her feet twitched and she threw back her head as though for more air. Once more Wilson calculated the distance between himself and that which stood for death. He found it still levelled steadily. To jump would be only to fall halfway, and yet his throat was beginning to ache with the strain. He felt within him some new-born instinct impelling him to her side. She stood somehow for something more than merely a fellow-creature in danger. He took a quicker interest in 49 her––an interest expressing itself now in a sense of infinite tenderness. He resented the fact that she was being led away from him into paths he could not follow––that she was at the beck of this lean, cold-eyed stranger and his heathenish idol.

“Below the waters. Look! Look!”

“No! No!” she cried.

“The shrine is there. Seek it! Seek it!”

He forced the words through his teeth in his concentrated effort to drive them into the girl’s brain in the form of a command. But for some reason she rebelled at doing this. It was as though to go below the waters even in this condition choked her until she must gasp for breath. It was evidently some secret which lay there––the location of some shrine or hiding place which he most desired to locate through her while in this psychic state, for he insisted upon this while she struggled against it. Her head was lifted now as though, before finally driven to take the plunge, she sought aid––not from anyone here in the room, but from someone upon the borders of the lake where, in her trance, she now stood. And it came. Her face brightened––her whole body throbbed with renewed life. She threw out her hand with a cry which startled both men.

“Father! Father!”

The wounded man, puzzled, drew back leaving for a moment the other unguarded. Wilson sprang, and in three bounds was across the room. He struck up the arm just as a finger pressed the trigger. The 50 wounded man fell back in a heap––far too exhausted to struggle further. Wilson turned to the girl and swept the image out of her lap to the floor where it lay blinking at the ceiling. The girl, blind and deaf to this struggle, remained sitting upright with the happy smile of recognition still about her mouth. She repeated over and over again the glad cry of “Father! Father!”

Wilson stooped and repeated her name, but received no response. He rubbed her forehead and her listless hands. Still she sat there scarcely more than a clay image. Wilson turned upon the stranger with his fists doubled up.

“Rouse her!” he cried. “Rouse her, or I’ll throttle you!”

The man made his feet and staggered to the girl’s side.

“Awake!” he commanded intensely.

The eyes instantly responded. It was as though a mist slowly faded from before them, layer after layer, as fog rises from a lake in the morning. Her mouth relaxed and expression returned to each feature. When at length she became aware of her surroundings, she looked like an awakened child. Pressing her fingers to her heavy eyes, she glanced wonderingly about her. She could not understand the tragical attitude of the two men who studied her so fixedly. She struggled to her feet and regarded both men with fear. With her fingers on her chin, she cowered back from them gazing to right and left as though looking for someone she had expected.

“Father!” she exclaimed timidly. “Are you here, father?”

Wilson took her arm gently but firmly.

“Your father is not here, comrade. He has not been here. You––you drowsed a bit, I guess.”

She caught sight of the image on the floor and instantly understood. She passed her hands over her eyes in an effort to recall what she had seen.

“I remember––I remember,” she faltered. “I was in some foreign land––some strange place––and I saw––I saw my father.”

She looked puzzled.

“That is odd, because it was here that I saw him yesterday.”

Her lips were dry and she asked Wilson for a glass of water. A pitcher stood upon the table, which he had brought up with the other things. When she had moistened her lips, she sat down again still a bit stupid. The wounded man spoke.

“My dear,” he said, “what you have just seen through the medium of that image interests me more than I can tell you. It may be that I can be of some help to you. My name is Sorez––and I know well that country which you have just seen. It is many thousand miles from here.”

“As far as the land of dreams,” interrupted Wilson. “I think the girl has been worried enough by such nonsense.”

“You spoke of your father,” continued Sorez, ignoring the outburst. “Has he ever visited South America?”

“Many times. He was a sea captain, but he has not been home for years now.”

“Ah, Dios!” exclaimed Sorez, “I understand now why you saw so clearly.”

“You know my father––you have seen him?”

He waived her question aside impatiently. His strength was failing him again and he seemed anxious to say what he had to say before he was unable.

“Listen!” he began, fighting hard to preserve his consciousness. “You have a power that will lead you to much. This image here has spoken through you. He has a secret worth millions and–––”

“But my father,” pleaded the girl, with a tremor in her voice. “Can it help me to him?”

“Yes! Yes! But do not leave me. Be patient. The priest––the priest is close by. He––he did this,” placing his hand over the wound, “and I fear he––he may come again.”

He staggered back a pace and stared in terror about him.

“I am not afraid of most things,” he apologized, “but that devil he is everywhere. He might be–––”

There was a sound in the hall below. Sorez placed his hand to his heart again and staggered back with a piteous appeal to Wilson.

“The image! The image!” he gasped. “For the love of God, do not let him get it.”

Then he sank in a faint to the floor.

Wilson looked at the girl. He saw her stoop for the revolver. She thrust it in his hand.

Wilson made his way into the hall and peered down the dark stairs. He listened; all was silent. A dozen perfectly simple accidents might have caused the sound the three had heard; and yet, although he had not made up his mind that the stranger’s whole story was not the fabric of delirium, he had an uncomfortable feeling that someone really was below. Neither seeing nor hearing, he knew by some sixth sense that another human being stood within a few yards of him waiting. Who that human being was, what he wished, what he was willing to venture was a mystery. Sorez had spoken of the priest––the man who had stabbed him––but it seemed scarcely probable that after such an act as that a man would break into his victim’s house, where the chances were that he was guarded, and make a second attempt. Then he recalled that Sorez was apparently living alone here and that doubtless this was known to the mysterious priest. If the golden image were the object of his attack, truly it must have some extraordinary value outside its own intrinsic worth. If of solid gold it could be worth but a few 54 hundred dollars. It must, then, be of value because of such power as it had exercised over the girl.

There was not so much as a creak on the floor below, and still his conviction remained that someone stood there gazing up as he was staring down. If only the house were lighted! To go back and get the candle would be to make a target of himself for anyone determined in his mission, but he must solve this mystery. The girl expected it of him and he was ready to sacrifice his life rather than to stand poorly in her eyes. He paused at this thought. Until it came to him at that moment, in that form, he had not realized anything of the sort. He had not realized that she was any more to him now than she had ever been––yet she had impelled him to do an unusual thing from the first. Yes, he had done for her what he would have done for no other living woman. He had helped her out of the clutches of the law, he had been willing to strike down an officer if it had been necessary, he had broken into a house for her, and now he was willing to risk his life. The thought brought him joy. He smiled, standing there in the dark at the head of the stairs, that he had in life this new impulse––this new propelling force. Then he slid his foot forward and stepped down the first stair.

He still had strongly that sense of being watched, but there was no movement below to indicate that this was anything more than a fancy. Not a sound came from the room he had just left. Evidently the girl 55 was waiting breathlessly for his return. He must delay no longer. He moved on, planning to try the front door and then to examine the window by which he himself had entered. These were the only two possible entrances to the house; the other windows were beyond the reach of anyone without a ladder and were tightly boarded in addition. He found the front door fast locked. It had a patent lock so that the chance of anyone having opened and closed it again was slight. He breathed more easily.

Groping along the hallway he was vividly reminded of the time a few hours past when the girl had placed her hand within his. It seemed to him that he now felt the warmth of it––thrilled to the velvet softness of it––more than he had at the time. He was full of illusions, excited by all the unusual happenings, and now, as he felt his way along the dark passage, he could have sworn that her fingers still rested upon his. It made him restless to get back to her. He should not have left her behind alone and unprotected. It was very possible that this swoon of Sorez’ was but a ruse. He must hurry on about his investigation. He descended to the lower floor and groped to the laundry. It was still dark; the earth would not be lighted for another hour. He neither heard nor saw anything here. But when he reached the window by which he himself had entered but which he had closed behind him, he gave a start––it was wide open. It told him of another’s presence in this house as plainly as if he had seen the person. There was of course one 56 chance in a hundred that the intruder had become frightened and taken to his heels. Wilson turned back with fresh fear for the girl whom he had been forced to leave behind unprotected. If it was true, as the terrified Sorez had feared, that the priest, whoever this mysterious and unscrupulous person might be, had returned to the assault, there certainly was good cause to fear for the safety of the girl. A man so fanatically inspired as to be willing to commit murder for the sake of an idol must be half mad. The danger was that the girl, in the belief which quite evidently now possessed her––that this golden thing held the key to her father’s whereabouts––might attempt to protect or conceal it. He stumbled up the dark stairs and fell flat against the door. It was closed. He tried the knob; the door was locked. For a moment Wilson could not believe. It was as though in a second he had found himself thrust utterly out of the house. His first suspicion flew to Sorez, but he put this from his mind instantly. There was no acting possible in that man’s condition; he was too weak to get down the stairs. But this was no common thief who had done this, for a thief, once realizing a household is awakened, thinks of nothing further but flight. It must then be no other than the priest returned to the quest of his idol.