AS EL REY ROSE ON HIS HIND FEET WHIRLING, THAT UNWAVERING MUZZLE WHIRLED ALSO TO KEEP IN LINE

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tharon of Lost Valley, by Vingie E. Roe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Tharon of Lost Valley Author: Vingie E. Roe Illustrator: Frank Tenney Johnson Release Date: May 24, 2009 [EBook #28956] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THARON OF LOST VALLEY *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THARON OF LOST

VALLEY

BY

VINGIE E. ROE

Author of “The Maid of the Whispering Hills,”

“The Heart

of Night Wind,” etc.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

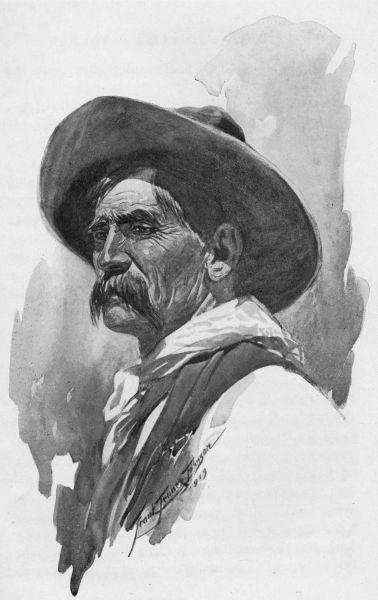

FRANK TENNEY JOHNSON

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1919

Copyright, 1919

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Gun Man’s Heritage | 1 |

| II. | The Horses of the Finger Marks | 29 |

| III. | The Man in Uniform | 52 |

| IV. | Unbroken Bread | 76 |

| V. | The Working of the Law | 102 |

| VI. | El Rey and Bolt | 128 |

| VII. | The Shot in the Caņons | 157 |

| VIII. | White Ellen | 187 |

| IX. | Signal Fires in the Valley | 214 |

| X. | The Untrue Firing Pin | 247 |

| XI. | Finger Mark and Ironwood at Last | 277 |

| PAGE | |

| As El Rey rose on his hind feet whirling, that unwavering muzzle whirled also to keep in line | Frontispiece |

| Near them sat a rider on a buckskin horse | 38 |

| She talked with Conford who rode beside her and now and then she smiled | 104 |

| In fact Courtrey, burning with the new desire that was beginning to obsess him, was working out a new design | 131 |

Lost Valley lay like a sparkling jewel, fashioned in perfection, cast in the breast of the illimitable mountain country––and forever after forgotten of God.

A tiny world, arrogantly unconscious of any other, it lived its own life, went its own ways, had its own conceptions of law––and they were based upon primeval instincts.

Cattle by the thousand head ran on its level ranges, riders jogged along its trail-less expanses, their broad hats pulled over their eyes, their six-guns at their hips. Corvan, its one town, ran its nightly games, lined its familiar streets with swinging-doored saloons.

Toward the west the Cañon Country loomed behind its sharp-faced cliffs, on the east the rolling ranges, dotted with oak and digger-pine, went 2 gradually up to the feet of the stupendous peaks that cut the sapphire skies.

Lost indeed, it was a paradise, a perfect place of peace but for its humans. Through it ran the Broken Bend, coming in from the high and jumbled rocklands at the north, going out along the sheer cliffs at the south.

Out of its ideal loneliness there were but two known ways, and both were worth a man’s best effort. Down the river one might drive a band of cattle, bring in a loaded pack train, single file against the wall. That was a twelve days’ trip. Up through the defiles at the west a man on foot might make it out, provided he knew each inch of the Secret Way that scaled False Ridge.

It was spring, the time of greening ranges and the coming of new calves. Soft winds dipped and wantoned with Lost Valley, in the Cañon Country shy flowers, waxen, heavy-headed on thin stems, clung to the rugged walls.

All day the sun had shone, mild as a lover, coaxing, promising. The very wine of life was a-pulse in the air.

All day Tharon Last had sung about her work scouring the boards of the kitchen floor until they were soft and white as flax, helping old Anita with the dinner for the men, seeing about the number of new palings for the garden. She had swept 3 every inch of the deep adobe house, had fixed over the arrangement of Indian baskets on the mantel, had filled all the lamps with coal-oil. She was very careful with the lamps, trimming the wicks to smokeless perfection, for oil was scarce and precious in Lost Valley, as were all outside products, since they must come in at long intervals and in small quantities. And as she worked she sang, wild, wordless melodies in a natural voice as rich as a harp. That voice of Tharon’s was one of the wonders of Lost Valley. Many a rider went by that way on the chance that he might catch its golden music adrift on the breeze, her father’s men came up at night to hear its martial stir, its tenderness, for the voice was the girl, and Tharon was an unknown quantity, sometimes all melting sweetness, sometimes fire that flashed and was still.

So on this day she sang, since she was happy. Why, she did not know. Perhaps it was because of the six new puppies in the milk-house, rolling in awkward fatness against their shepherd mother, whose soft eyes beamed up at the girl in beautiful pride. Perhaps it was because of the springtime in the air.

At any rate she worked with all the will and pleasure of youth in a congenial task, and the roses of health bloomed in her cheeks. The sun 4 itself shone in her tawny hair where the curls made waves and ripples, the blue skies of Lost Valley were faithfully reflected in her eyes.

Her skin was soft-golden, the enchanting skin of some half-blonds which can never be duplicated by all the arts of earth, and her full mouth was scarlet as pomegranates.

Sometimes old Anita who had raised her, would stop and look at her in wonder, so beautiful was she to old and faithful eyes.

And not alone to Anita was she entirely lovely.

There was not a full grown man in Lost Valley who would not go many a mile to look upon her––with varying desires. Few voiced their longings, however, for Jim Last was notorious with his guns and could protect his daughter. He had protected her for twenty years, come full summer, and he asked no odds of any. His eyes were like Tharon’s––blue and changing, with odd little lines that crinkled about them at the corners, elongating them in appearance. He was a big man, vital and quiet. The girl took her stature from him. Her flashes of fire came from her mother, of whom she knew little and of whom Jim Last said nothing. Once as a child she had asked him, after the manner of children, about this mother of dim memories, and his eyes had hazed with a look of 5 suffering that scared her, he had struck his palm upon a table, and said only:

“She was an angel straight out of Heaven. Don’t ask me again.”

So Tharon had not asked again, though she had wondered much.

Sometimes old Anita, become garrulous with age, mumbled in the twilight when the rose and the lavendar lights swept down the eastern ramparts and across the rolling range lands, and the girl gleaned scattered pictures of a gentle and lovely creature who had come with her father out of a mystic country somewhere “below.”

“Below” meant down the river and beyond, an unnamable region.

In the big living room there was one relic of this mysterious mother, a tiny melodeon, its rosewood case a trifle marred by unknown hardships, its ivory keys yellow with age. It had two small pedals and two slender sticks which fitted therein and pushed the bellows up and down when one trampled upon them. And to Tharon this little old instrument was wealth of the Indies. The low piping of its reedy notes made an accompaniment of surpassing sweetness when she sat before it and sang her wordless melodies. And just as she found music in her throat without conscious effort, so she found it in her fingers, deep, resonant chords for 6 her running minors, thin, trickling streams of lightness for her own slow notes.

The sun had turned to the west in its majestic course and Tharon, the noon work over, drew up the spindle-legged stool and sat down to play to herself and Anita. The old woman, half Mexic, half Indian, drowsed in a low chair by the eastern window, her toil-hard hands clasped in her lap, a black reboso over her head, though the day was warm as summer. A kitten frisked in the sunlight at the open door, wild ducks, long domesticated, squalled raucously down the yards, some cattle slept in the huge corrals and the little world of Last’s Holding was at peace. It seemed that only the girl idling over the yellowed keys, was awake.

For a long and happy hour Tharon sat so, sometimes opening her pretty throat in ambitious flights of sound, again humming lowly––and that was enchanting, as if one sang lullabies to flaxen heads on shoulders.

And it did enchant one––a man who stood for the better part of that hour at the edge of the deep window in the adobe wall and watched the singer.

He was a splendid figure of a man, tall, broad, muscular, built for strength and endurance. His face was unduly lined, even for his age, which was 7 near fifty, but the eyes under the arched black brows were vital as a hawk’s. He wore the customary garments of the Lost Valley men, broad sombrero, flannel shirt, corduroys and cowboy boots, stitched and decorated above their high heels. At his hips hung two guns, spurs clinked when he stepped unguardedly. He rarely stepped that way, however.

When presently the girl at the melodeon ceased and drew the lid over the keys with reverent fingers, he moved silently back a pace or two along the wall. Then he waited. As he had anticipated, she came to the door to look upon the budding world, and for another moment he watched her with a strange expression. Then he swung forward and let the spurs rattle. Tharon flashed to face him like a startled animal.

“Hello, Tharon,” he said and smiled. The girl stared at him with quick insolence.

“Howdy,” she said coldly.

He came close to the doorway, put one hand on the facing, the other on his hip and leaned near. She drew back. He reached out suddenly and gripped her wrist in fingers that bit like steel.

“Pretty,” he said, while his dark eyes narrowed.

Tharon flung her whole young strength 8 against his grip with a twisting wrench and came free. The quick, tremendous effort left her calm. And she did not retreat a step.

“Hell,” said the man admiringly, “little wildcat!”

“What you want?” she asked sharply.

“You,” he answered swiftly.

“Buck Courtrey,” she said, “you might own an’ run Lost Valley––all but one outfit. You ain’t never run Last nor put your dirty hand on th’ Holdin’. An’ that ain’t all. You never will. If you ever touch me again, I’ll tell Dad Jim an’ he’ll kill you. I’d a-told him before when you met me that day on the range, only I didn’t want his honest hands smutted up with such as you. He’s had his killin’s before––but they was always in fair-an’-open. You he’d give no quarter––if he knew what you ben askin’ me.”

The man’s eyes narrowed evilly. They became calculating.

“Tell him,” he said.

“Eh?”

“Tell him.”

“You want to feed th’ buzzards?” the girl asked with an insulting peal of laughter.

“Not yet––but I’ll remember that speech some day.”

“Remember an’ be damned,” said Tharon. 9 “Now kindly take your dirty carcass off Last’s Holding––back to your wife.”

The fire was flashing a little in her blue eyes as she spoke, and she half turned to enter the house.

As she did so, Courtrey flung out an arm and caught her about the shoulders. He drew her against him with the motion and kissed her square on the lips. For a second his narrowed eyes were drunken.

As he loosed her Tharon gasped like a swimmer sinking.

She put up a hand and drew it across her mouth, which was pale as ashes with sudden rage.

“Now,” she said, “I’ll tell him.”

“Do,” said Courtrey, and swung away around the wall of the house.

There were no more artless songs that day at Last’s Holding. Anita was awake and peering with dim eyes when Tharon came in from the door sill.

“Mi querida,” she asked, “what happened?”

“Nothing,” said the girl, “it’s time to begin supper. Th’ boys’ll soon be comin’ in.”

“Si, si,” said Anita, “I’ll ask José to cut the fresh beef––it has hung long enough in the cooling house.”

Supper at Last’s was a lively affair. At the 10 long tables in the eating room the riders gathered, lean, tanned men, young mostly, all alert, quick-eyed, swift in judgment. Their days were full and earnest enough, running Last’s cattle on the Lost Valley ranges. The evenings were their own, and they made the most of them. The big house was free to them, and they made it home, smoking, playing cards on the living room table under the hanging lamp, mulling over the work of the day, and begging Tharon to sing to them, sometimes with the instrument, sometimes sitting in the deep east window, when the moon shone, and then they turned out the light and listened in adoring rapture.

For Last’s girl was the rose of the Valley, the one absolutely unattainable woman, and they worshipped her accordingly.

Not that she was aloof. Far from it. In her deep heart the whole bunch of boys had a place; singly and collectively. They were her private property, and she would have been inordinately jealous of any one of them had he slipped allegiance.

As the purple and crimson veils began to drape the eastern ramparts where the forests thickened and swept up the slopes, these riders began to come in across the range, driving the herds before them. Running cattle in Lost Valley was no child’s 11 play. Any small bunch of cows left out at night was not there by dawn. Eternal vigilance was the price of safety, and then they were not always safe. Witness poor Harkness, a year ago shot in the back and left to die alone––his band run off in daylight.

They had found him too late, pitifully propped against a stone, the cigarette, he had tried to light to comfort him, dead in his nerveless hand. Tharon had wept and wept for Harkness, for he had been a good comrade, open-hearted and merry. And deep in her soul she harboured dim longings for justice on his murderer––revenge, if you will.

Tonight she thought of him, somehow, as she went about the supper work along with Anita and José and pretty dark Paula. She stood a moment on the broad stone at the kitchen door, a dish of butter from the springhouse under the poplars in her hand, and watched Billy Brent and Curly bring in a bunch from up Long Meadow way. She thought how bright the spotted cattle looked, how lithe and graceful the men, and then her eyes lighted as they always did when she beheld the horses of Last’s Holding––the horses of the Finger Marks.

Billy rode Redbuck, Curly Drumfire, and they were princes of a royal blood, albeit Nature’s 12 strain alone. Slim, spirited, wiry, eager heads up, manes flying, bright hoofs flashing in the late sunlight, they came home to Last’s after a long day’s work, fresh as when they went out at dawn.

“Nothin’ ever floors them,” Tharon said aloud to herself. “Wonderful creatures.”

She set the butter down on the rock at her feet, cupped her hands about her lips and sent out a keen, clear call, two notes, one rising, one falling. It had a livening, compelling quality.

Instantly Drumfire flung up his head and answered it with a ringing whistle, though he did not lose a stride in the flying curve he was performing to head a stubborn yearling that refused in stiff-tailed arrogance to go into the corrals.

The girl smiled and, stooping, picked up her dish and entered.

It was late before the last straggler was in from the range. The boys washed at the big sink on the porch, and were ready for the hearty fare that steamed in the lamp-lighted room. For the last hour Tharon had been watching the eastern slopes for her father.

“He’s ridin’ late, Anita,” she said anxiously as the men trooped in with the usual jest and laughter.

“He went far, no doubt, Corazon,” said old 13 Anita comfortably. “He goes so fast on El Rey that time as well as distance flies beneath the shining hoofs.”

Anita was like her people, mystic and soft-spoken.

“True,” said the girl gently, “I forget, El Rey is mighty. He went very far I make no doubt. We’ll hear him comin’ soon.”

Then she poured steaming coffee in the cups about the table, smiling down in the eyes upturned to hers. Billy, Curly, Bent Smith, Jack Masters and Conford, the foreman, they all had a love-look for her, and the girl felt it like a circling guerdon. She was grateful for the sense of security that seemed to emanate from her father’s riders, a bit wistful withal, as if, for the first time in her life, she needed something more than she had always had.

“Which way did Dad go, Billy?” she asked, “north or south?”

“North,” said Billy, “he rode th’ Cup Rim range today.”

When the meal, a trifle silent in deference to Tharon’s silence, was done, the men rose awkwardly. They stood a moment, looking about, undecided.

Conford picked them up with his eyes and nodded out. He felt that just maybe the girl 14 would rather be alone. But Tharon stopped the reluctant egress.

“Don’t go, boys,” she said, “come on in th’ room. There’s no moon tonight.” But she did not play on the melodeon. Instead she sat in the deep window that looked over the rolling uplands and was quiet, listening.

“Turn out th’ light, Bent,” she said, “somehow I feel like shadows tonight.”

So they sat about in the great room, black with the darkness of the soft spring night, and like the true worshippers they were, they did not speak. Only the red butts of their cigarettes glowed and faded, to glow again and again fade out. Tharon sat curled in the window, her graceful limbs drawn up to her chin, her eyes half closed, her keen ears open like a forest creature’s. She was listening for the marked rhythm of the great El Rey, the clap-clap, clap-clap of the king of Last’s Holding as he singlefooted down the hollow slopes of the lifting eastern range.

And as she waited she thought of many things. Odd little happenings of her childhood came back to her––the time she had caught her father killing the winter’s beef, had wept in hysterical pity and forbidden him to finish.

They had had no meat those long months following––and she had so tired of beans, that she 15 had never been able to eat them since. She smiled in the dusk as she recalled Jim Last’s life-long indulgence of her.

And the time she had wanted to make her own knee-short dresses as long as Anita’s, to sweep the floors, with fringe upon them and stripes of bright print.

She had worn them so––at twelve––until she found that they hindered the free use of her young limbs in mounting a horse, free-foot and bareback. Then, once again the memory of her father’s face when she questioned him concerning her mother.

“Boys,” she said suddenly, smiling to herself, “did you ever know a man like my dad?”

There was a movement among the lounging riders, a shifting of position, a striking of cigarette ash.

“No, sir,” said Billy promptly, “there hain’t another man’s good with a gun as him, not anywhere’s in Lost Valley. Not even Buck Courtrey himself. I’d back Jim Last against him, even, in fair-draw. Why?”

“Oh, nothin’,” said the girl, “only––listen––Glory!” she added slipping down from the window to stand quietly in the gloom, “that’s him now! I was wishin’ hard he’d come. 16 Say––listen–––Why,––there’s somethin’ gone wrong with El Rey’s feet! 1––2–––3, 4, 5, 6–––1––2––Boys––he’s breakin’! Th’ king ain’t singlefootin’ right, for th’ first time since Jim Last put a halter on him! Come––come quick!”

Ordinarily Tharon was a bit slow in her movements, as the very graceful often are. Now she was across the room to the western door before a man had moved. They joined her there and she stood at attention, one hand at her breast, the breath held still in her throat. The light, shining through from the eating room beyond, made a halo of her tawny hair. Silently the riders grouped about her and listened.

Sure enough. Down along the range that rang as some open stretches do, there came the clip-clap of a hurrying horse, only now the hoof beats were regular for a little space, to break, halt, start on, and again ring true in the beautiful syncopation of the born singlefooter. The king was coming home, but, alas! not as he had ever come before, in full flight, proud and powerful. He held his speed and sacrificed his certainty to the man who clung desperately to the saddle horn and swayed in wide arcs, so that he must shift continually to keep under him.

Into the dim glow of light at the open door came El Rey at last, great blue-silver stallion, his 17 big eyes shining like phosphorus, his nostrils wide with horror of the pungent crimson wash that painted his right shoulder.

He stopped at the door-stone, his duty done.

“Dad!” screamed Tharon, shrill as a bugle, for Jim Last, white and dull as a moon in fog, let go his desperate hold on the pommel and slid, deadweight, into the reaching arms that circled him.

They carried him into the living room. Before they had him safely on the wide couch where the Indian blankets glowed, Tharon, trembling but efficient, had lighted the hanging lamp above the table.

Then she pushed the men aside and knelt beside him.

“Dad,” she said clearly, “Jim! Jim Last!”

But the gaining of his goal had been too much. For a moment the flickering light in him died down to ashes. Tharon, her face as white as his own, waited in a man-like quiet. She held his stiffened hands and her eyes burned upon his features. With a deadly knowledge she was printing them indelibly upon her heart.

Presently Jim Last sighed and opened his eyes. They sought hers and he smiled, a tender lighting from within. He fumbled for the buckle of his gun-belt. The girl unclasped it and pulled it 18 free. She noticed that both guns were in their holsters.

“Put it on,” whispered the master of Last’s Holding.

Without a question Tharon stood up and buckled the belt about her slender waist.

Her father raising himself with difficulty on an elbow, wet his lips.

“Tharon, my girl,” he said, “show your dad th’ backhand flip.”

Strange play, this, when every second counted, but Last’s daughter obeyed him to the letter.

She stepped clear by the table, stood at attention a second, and, with a peculiar outward whirl, lightning-quick, of her two wrists, had him covered with the big blue guns.

He nodded.

“Good as I learned ye,” he whispered, “make it better.”

“I will,” promised Tharon swiftly.

The man closed his eyes, swayed, recovered as Conford caught him, and brightened again.

“Now th’ under-sling.”

Again she obeyed, replacing the weapons, standing that second at attention, and flipping them from the holsters so quickly that the eye could scarcely catch the motion. Both draws were peculiar––and peculiarly Last’s own. 19 “Good girl,” he said with a husk grown suddenly in his voice, “take––three hours––a day. I want t’ leave you th’ best gun-handler in Lost Valley––because, my girl––you’ll––have––to––to––pro–––”

He ceased, wilting forward in Conford’s arms.

Then he opened his eyes again for one last smile at the daughter he had loved above all things on earth, save and except the memory of the woman who had given her to him.

For once in her life Tharon did not wait his finished speech. She saw the Hand reach out of the shadows and flung herself upon his breast where the blood still seeped and fairly forced the last flutter of life to brighten in him. She kissed his rugged cheek.

“Who, Dad,” she called into his dulling senses, “tell me who? I’ll get him, so help me God!” and she loosed one hand to cross herself, as old Anita had taught her.

But the promise was late. None knew whether or not Jim Last heard it, for before the last word was done the breath had ceased in his throat.

Another twilight came down upon Lost Valley. The wide ranges lay dim and mysterious, grey and pink and lavendar, as if the hand of a Master 20 Painter had coloured them, as indeed it had. The Rockface at the west was black with shadow for all its rugged miles, the eastern uplands were bathed and aglow with purplish crimson light.

In Corvan lights twinkled all up and down the one main street. Horses were tied at the hitch-racks and among them were the Ironwoods from Courtrey’s Stronghold, beautiful big creatures, blood-bay, black-pointed, noticeable in any bunch. There were no Finger Marks, however, the blue roans, red roans and buckskins with the four black stripes on the outside of the knee, as if one had slapped them with a tarred hand, which hailed from Last’s. There were horses from all up and down the Valley. Cow ponies and half-breeds of the Ironwood stock which Courtrey would not keep at the Stronghold but was too close to kill, shouldered pintos from the Indian settlements, big, half-wild horses from over the mountains at the North. Inside the brightly lighted saloons men passed back and forth, drank neat liquor at the worn bars, played at the green felt and canvas covered tables. At one, The Golden Cloud, more pretentious than the rest, there foregathered the leading spirits of the Valley. Here Courtrey came and played and drank, his henchmen with him. He was in high mettle this night. Always a contained 21 man, slow to laughter and to speech, he seemed to have unbent more than usual, to respond to the human nature about him. He was not playing steadily as was his wont. He took a turn at poker with three men from the south of the Valley where the river ran out of the Bottle Neck, won a hand or two, threw down the cards and swung away to talk a moment with this one, listen a moment where those two spoke of hushed matters. Always when he came near he was accorded deference. There was nothing sacred from Courtrey of the Stronghold, seated like a feudal place at the north head of Lost Valley, no conversation so private that he could not come in on it if he chose.

For Courtrey was the king of the country, undisputed sovereign, the best gun man north of the Rio Grand and south of the Line, if one excepted Jim Last. With him tonight were Black Bart, tall, swarthy, gimlet-eyed, a helf-breed Mexican, and Wylackie Bob his right-hand man. Without these two he seldom moved. They were both able lieutenants, experts with firearms. A formidable trio, the three went where and when they listed, and few disputed their right-of-way.

Courtrey, a smile in his dark eyes, the wide black hat at an angle on his iron-grey hair, leaned against the high bar and scanned the crowded 22 room where the riders played and laughed and swore with abandon.

“Heard anything more about Cañon Jim?” he asked Bullard, the proprietor of The Golden Cloud, “ain’t come in yet?”

Bullard shook his head.

“No––nor he won’t, according to my notion. Think he mistook th’ False Ridge drop. Ain’t no man could make it up again without th’ hammer spike an’ rope.”

“H’m––don’t know. Don’t know,” mused Courtrey. “I’ve always thought it could be done. There ought to be a way on th’ other side, seems like.”

“Well, ought an’ is is two diff’rent things, Buck,” grinned Bullard.

“Sure,” nodded the king, “sure. An’ yet––”

“Hello, Buck.”

A soft hand touched Courtrey’s shoulder with a subtle caress. He wheeled on the instant, ready, alert. Then he smiled and reaching up, took the hand and held it openly.

“Hello, Lola,” he said, “how goes it?”

The newcomer was a woman, full, rounded, dark, and she was past-master of men––as witness the slow glance that she turned interestedly out over the teeming room, even while the pulse in the wrist in Courtrey’s clasp leaped like a racer. She 23 was a perfect specimen of a certain type, beautiful after a resplendent fashion, full of eye and lip, confident, calm. She was brilliantly clad in crimson and black, and rings of value shone on her ivory-like hands.

Lola of the Golden Cloud was known all over Lost Valley. Men who had no women worshipped her––and some who had, also. At the Stronghold at the Valley’s head there was a woman who hated her, though she had never set eyes on her––Courtrey’s wife.

If Lola knew this she had never mentioned it, wise creature that she was. Proud of her beauty and her power she had reigned at The Golden Cloud in supreme indifference, even to her men themselves, it seemed, though hidden undercurrents ran strong in her. Which way they tended many a reckless buck of Lost Valley would have given much to know, among them Courtrey himself.

Now she pulled her hand away from him and sauntered over to a table where five men sat playing, laid it upon the shoulder of one of them, leaned down and looked at the cards in his hand.

The man, a tall stripling in a silver-studded belt, looked up, flattered.

Courtrey by the bar watched her, still smiling. 24 Then he turned back to Bullard and went on with his conversation.

Over by the wall a man on a raised dais began to tune an ancient fiddle.

Two more women came in from somewhere at the back, a big blooming girl by the name of Sadie, and a small red-head, tragically faded, with soft brown eyes that should never have looked upon Bullard’s. Two men rose and took them as the tune, an old-fashioned waltz, began to ripple under the fingers of the fiddler, who was a born musician, and the four swung down between the tables and the bar. The Golden Cloud was in full swing, running free for the night, though the soft twilight was scarcely faded from the beautiful country without.

Slip––step, slip––step––went the dancing feet to the accompaniment of rattling spurs. These men were lithe and active, able to dance with amazing grace in chaps and the full accoutrement of the rider. They even wore their broad brimmed hats.

Why should they not, since none objected?

Bullard, solid, stocky, red-faced, leaned on his bar and watched the busy room with pleased eyes.

He did not hear a voice which called his name, once or twice, among the jumble of sounds. Presently an odd figure came round the end of the bar 25 from a door that opened there into the mysterious back regions of the place and elbowed in to face him.

This was a little old man, weazened and bent, his unkempt head thrust forward from hunched shoulders. He dragged two grain sacks behind him, and he was so grotesquely bow-legged that the first sight of him always provoked laughter. This was old Pete the snow-packer, bound on his nightly trip to the hills. Outside his burros waited, their pack-saddles empty.

By dawn they would come down from the world’s rim, the grain sacks bulging with hard-packed snow for the cooling of Bullard’s liquor.

“Dick,” he said when he faced his employer, “here ’tis time t’ start an’ there ain’t a damned bit o’ grub put up fer me! Ef ye don’t make that pig-tailed Chink pay ’tention t’ my wants, I quit! I quit, I tell ye!”

And he emphasized his vehement protest by whirling the bags over his head and flailing them upon the floor.

A roar of laughter greeted him, which brought dim tears of indignation to his old eyes.

“Ye don’t care a damn!” he whimpered in impotent rage. “Jes’ ’cause it’s me. Ef ’twas yer ol’ Chink, now––if ’twas him, th’ ol’ he-pigtail, ye’d–––” 26

“Hold on, Pete,” said Bullard, slapping an indulgent hand on the grotesque shoulder, “You go tell Wan Lee that if he don’t put up th’ best lunch in camp for you, an’ muy pronto at that, I’ll come in an’ skin him alive. Tell him–––”

But Bullard was never to finish that sentence.

There was a sound of running horses stopping square at the rack without, the rattle of chains, the creak of saddles.

Booted feet struck the boards of the porch, and almost upon the instant the great iron door of The Golden Cloud swung inward.

The dancers stopped in their stride, the players laid down their cards, the noise of the room ceased with the suddenness that characterized the time and place, for Lost Valley was quick upon the trigger, tragedy often swept in upon hilarity.

In the opening stood Tharon Last, her blue eyes black and sparkling, her tawny skin cream white, her lips tight-set and pale. She wore a plain dark dress that buttoned up the front, and at her hips there hung her father’s famous guns. Her two hands rested on their butts.

Behind her head against the starlight there was the dim suggestion of massed sombreros.

For a moment she stood so in breathless silence, scanning the room. 27

Then her glance came to rest on the face of Buck Courtrey.

“Men,” she said clearly, “we buried Jim Last today. El Rey brought him home last night––finished. You all know he was a gun man––th’ best in these parts. It was no gun man that killed him, in fair-an’-open, for he was shot in th’ back. It was a skunk, a coyote, a son-of-th’-devil, an’ I’m goin’ to kill him.”

At the last word there was a lightning movement at the bar as Courtrey’s hand flashed at his hip, a flash of fire, a shot that went high and lodged in the deep beam above the door, for the weazened form of the snow-packer had leaped up against him in the same instant.

The girl had not moved. Her hands still rested on the guns in their holsters. Now a grim smile curled her mouth, but her eyes did not laugh.

“I’m a-goin’ t’ kill him,” she said quietly, still in that clear voice, “but I’ll do it accordin’ to th’ law Jim Last laid down to me all my life––in certainty. I know––but I’ll prove. We hain’t no assassins, Jim Last an’ me. Some day I’ll draw––an’ my father’s killer must beat me to it.”

Without another word Tharon backed out on the porch, the door swung to at the pull of an unseen hand on the iron strap by the hinge.

There was again the rattle and creak, the whirl 28 of hoofs, and in the breathless stillness that lasted for a few seconds, there came to the strained ears in the Golden Cloud the clip-clap of a singlefooter as the great El Rey led out of town.

Then Buck Courtrey, flushed and unsmiling, sent his coldly narrowed eyes over the crowded room, man by man. Laughter came, a trifle cracked and forced, cards slapped on the tables, chairs creaked as the players drew up again, the dancers swung into step as the fiddle took up its interrupted strain.

Only Lola, over by the door, looked for a pregnant moment at Courtrey’s face, and shut her lips in a hard, straight line.

Then, lastly, the cold eyes of the king came down to rest upon the weazened figure of the snow-packer busily engaged in rolling up his sacks for departure. If the strange old creature knew and felt their promise, he gave no sign as he trundled himself outdoors on his bandy legs.

“Skunks,” said Old Pete, as he fumbled with his straps about the patient burros, “are plumb pizen t’ pure flesh.”

At Last’s Holding a change had taken place. The sun of spring still shone as brightly, the work of the place went on as usual. The riders went at dawn and came at dusk, their herds lowing across the rolling green spaces, the days were as busy as they had ever been, but it seemed as if Last’s waited for something that would never happen, for some one who would never come. Conford, quiet, forceful, businesslike, carried on the work without a ripple. To a casual eye all things were as they had been. But to the keen eyes in the tanned faces of Last’s riders the change was appallingly apparent. They saw it creep day by day into their lives, felt it in the very atmosphere, and it was grim and promising.

Old Anita felt it and watched with dim and wistful eyes. Pretty young Paula from the Pomo Indian settlement far to the north of the Valley under the Rockface felt it and was more silent, 30 cat-like of step than ever. José, always full of laughter at his outside work, was sobered.

For this change was not material, but spiritual, and it had to do with Tharon, who was now the mistress of Last’s.

She no longer sang her wordless songs, no longer played for hours on the little old melodeon by the western door. Something had gone from the brightness of her face, a shadow had come instead. She was just as swift and gentle in her care for all the things of every day, as efficient and painstaking, but she did not laugh, and the tiny lines that had characterized her father’s blue eyes, began to show distinctly about her own.

They began to take on the look of great distances, as if she gazed far.

And for exactly three hours each day there could be heard the monotonous bark-bark-bark of the big guns Jim Last had given her in his final hour. To Billy Brent there was something terrible in this. Bred to violence and the quick disasters of the country as he was, he could not reconcile this grim practice with Tharon Last, the sane and loving girl who could not bear the sight of suffering.

“I tell you, Curly,” he complained to his friend of nights when they came in and lounged in the soft dusk by the bunk-house, “it’s unnatural. 31 Not that I don’t pay full respect to Jim Last’s memory, an’ him th’ best man in all this hell-bent Valley, but it ain’t right an’ natural fer no woman t’ do what she’s doin’. Ain’t she Jim Last’s own daughter already with th’ guns? Sure. Can drive a nail nigh as far as he could. Quick as Wylackie Bob on th’ draw an’ as certain, now. Then why must she keep it up?”

Curly, more silent in his ways but given to thought, studied the stars that rode the darkening heavens and shook his head.

“Let her alone,” he said once, “it was Last’s command, an’ he knew what he was about even if he was toppin’ th’ rise of the Big Divide.

“He said ‘you’ll have to pro––’––you rec’lect? He meant protect an’ unless I miss my guess, Billy, he’d have added ‘yourself’ if th’ hand of Ol’ Man Death hadn’t stopped his words. Somethin’ happened out there in th’ Cup Rim that day when Last got his that had to do with Tharon, an’ he knew she’d be in danger. Let her alone.”

So Billy let her alone, as did the rest. She went her ways, saw to the garden and made the butter in the cool springhouse, and sat in the window seat in the twilights. She liked to have the men come in as usual, but the talk these times was desultory, failing and brightening with forced topics, to fail again and drop into silence while 32 the dim red lights of the smokers glowed in the shadows.

Time and again she stirred and sighed, and they knew that once again she waited for Jim Last, listened for the clip-clap of El Rey coming home along the sounding ranges.

Once, on a night when there was no moon and the tree-toads sang in the cottonwoods by the spring, the girl, sitting so in the familiar window, suddenly dropped her head on her knees and sobbed sharply in the silence.

“Never again!” she said thickly from the folds of her denim skirt, “I’ll never see him comin’ home again!”

The riders stirred. Sympathy ached in their hearts, but not a man had speech to comfort her. It was Billy, the impulsive, who reached a hand to her shoulder and gripped it hard. Tharon reached up and touched the hand in gratitude.

It was about this time, when the master of Last’s Holding had lain a month beneath the staring mound under the pine tree out to the east where they had buried Harkness, that José finished a work of art. For many days he had laboured secretly in a calf-shed out behind the small corrals, and in his slim dark fingers there was beauty unleashed. Finest carving he knew, since his forbears, peons across the Border, had spent 33 their lives upon the beams of the Missions. None had taught José. It was in his blood. Therefore, from a block of the hard grey stone of the region, which was almost like granite, he fashioned a cross, as tall as Tharon herself, struck it out freehand and true, and set upon its austere face fine tracery of vines and Jim Last’s name. He took into the secret Billy and Curly, since these two he was sure of, and together they hauled the huge thing out and set it up.

When Tharon, looking to the east with dawn, as was her habit, beheld this silent tribute to the man she had so loved, she leaned her forehead against the deep window-case and wept from the depths.

Then she went out to see it and with a knife she set her own mark thereon––a tiny cross scratched in the headpiece, another in the arm that stretched toward all that was mortal of poor Harkness.

“Two,” she said, dry-eyed, while the glorious dawn shot up to bathe the world in glory, “full pay for you both.”

El Rey, stamping in his own corral, lifted his beautiful head, scanned the wide reaches that spread away in living green, and tossing up his 34 muzzle, sent out on the silence a ringing call. He cocked his silver ears and listened. No clear-cut human whistle answered him. Once more he called and listened.

Then he lowered his head and stepped along the fence. His great body, shining like blue satin with a silver frost upon it, gave and lifted with every step. The pastern joints above his striped hoofs were resilient as pliant springs. The muscles rippled in his shoulders, the blue-white cascade of his silver tail flowed to his heels, his mane was like a cloud upon the arch of his neck. He was strength and beauty incarnate, a monster machine of living might.

Unrest was upon him. Life had become stagnant, a tasteless thing. He was keen for the open stretches, honing to be gone down the wind. He fretted and ate out his heart for the freedom of the range. Old Anita, passing at some work or other, stopped and gazed at him for a compassionate moment.

“You, too, grande caballo,” she said, “there is naught but grief at Last’s Holding. Tharone querida” she called into the house, “come here.”

Tharon came and stood in the kitchen door.

“What, Anita?” she asked gently.

“El Rey,” answered the old woman, “he calls and calls and none come to him. He, too, needs 35 help, Corazon. Why not take him for a run along the plain? It will help you both.”

For a long time the girl stood, considering.

“I have not cared to ride lately, Anita,” she said, “but you are right. El Rey should not be left to fret.”

She stepped back in the house, then came out, and she had added nothing to her attire save her daddy’s belt and guns. Without these she never left the Holding now.

Bareheaded, slender, she was a thing of beauty, and there was a quiet command about her which subdued the great El Rey himself, the proudest horse in all the Valley, outside of Courtrey’s Ironwoods, Bolt and Arrow.

Between these three horses there was much comment and discussion, though they had never been tested out together.

She found a bridle on a corral post, a strong affair of rawhide, heavily ornamented with silver, its bit a Spanish spade. Without this she could not hold the stallion, and he was no pet to come at her caressing call of the double notes.

Only Jim Last himself had ever tamed El Rey to do his bidding by word of mouth. The horse had had one master. He would never have another.

Even now, when Tharon bridled him and 36 opened the big gate, promising him his long-desired flight, he seemed not to see her, his beautiful big eyes looked through, beyond her, as if he sought another. There was some one for whom he waited, listened.

From a block of wood set in the yard the girl gathered the rein tight in her hand, balanced a moment, and leaped up astride the shining back.

With a snort like a pistol shot El Rey flung up his great head, leaped into the air and was gone. Around the corner of the adobe house he went, out across the trampled yard, and away along the open to the south, running level and free. With the first sink-and-lift Tharon had slipped back a full span. Now she wound her fingers in the white cloud of mane that flailed her face and edged up, inch by inch. When her knees were well up on the huge shoulders that worked beneath them powerfully, she gathered the reins, one in each hand, leaned down along the outstretched neck and let the great king run. The wind sang by her ears in a rising whine, the green prairie was a flowing sea beneath her, the thunder of the pounding hoofs was stupendous music. Tharon shut her eyes and rode, and for the first time since Jim Last’s death a sense of joy rose in her like a tide.

She had ridden El Rey before, many times. She 37 had felt him sail beneath her down the open prairies and always it was so, as if the earth slid by, as if the note of the wind lifted minute by minute. She had wondered often about this––how long it would continue to rise with El Rey’s rising speed, how long before he would reach a maximum above which he could not go, a place where the singing note would remain fixed.

She had never known him reach that point. Always he could go faster. Always he had reserves.

Far out ahead she saw a bunch of cattle feeding. They were lazily circling in a wide arc, content under the beaming sun. Near them sat a rider on a buckskin horse, Bent Smith on Golden. This Golden was one of the prides of Last’s Holding. Bigger than Drumfire or Redbuck, he ranked next to El Rey himself in speed, for his slim legs, slapped smartly with the distinguishing finger marks on the outside of the knee, were long and shapely, his back short-coupled and strong, his withers low, his narrow hips high. Tharon bore hard on El Rey’s bit, leaned her body to the left, and they swung in toward Bent and Golden in a beautiful sweeping curve that brought the cowboy up in his stirrups with his hat a-wave above him.

“Good girl!” he yelled with leaping gladness 38 as the superb pair shot by. “Good girl! Go to it!”

Tharon loosed a hand long enough to wave back and was gone, on down the sloping land toward the country of the Black Coulee, her dark skirts fluttering at her knees, the two heavy guns pounding her thighs at every jump.

It was a long time before El Rey came down from his sweeping flight.

He had been too long holden in cramping bars. The free winds and the rolling earth filled him with a sort of madness. He ran with joy and the surety of unbounded power.

The rider, left far behind, watched them anxiously for a time, thought of following, glanced at his cattle, remembered the gun man’s heritage and turned to his business.

The sun was well down over the western Rockface when Tharon and El Rey came back to Last’s Holding. The riders were bringing in the cattle, dust was rising in clouds above the moving masses. From the ranch house came the savory smells of cooking.

The stallion was limber as a willow. He tossed his handsome head and his eyes were bright as stars set in his silver face. Life was at high tide in him, flowing magnificently. Tharon, her cheeks whipped into pulsing colour by the wind and the 39 bounding speed, her tawny mane loosed from its bands and flying in a cloud behind her, smoothed back from her face, looked wild as an Indian. As she drew up and sat watching the work of the evening, she smiled for the first time in many days, and Jack Masters, passing, felt his heart leap with gladness.

When the mistress of Last’s was sad, so were her people.

When the last big corral gate had swung to and the boys turned in to unsaddle, she touched El Rey with a toe and went over among them.

“Line up the horses, boys,” she said, “I want to see them all together once more. Somethin’ came back in me today––somethin’ I been missing for a long time. I’ll be myself again.”

Billy turned Redbuck to face her, dropped his rein. Curly rode up on Drumfire. These two were red roans, dead matches. Bent brought Golden and stood him alongside. From far at the back of the corral they called Conford and Jack, who came wondering, the former on Sweetheart, true sister of El Rey, almost as big, almost as fast, almost as beautiful.

Silver-blue roan, silver-pointed, slim, graceful, springy, she had not a single dark spot on her except the sharp black bars of the finger marks outside her knees. 40

“You darlin’!” said Tharon as she wheeled in line.

Then came Jack on Westwind, and he was another buckskin, paler than Golden, most marvelously pointed in pure chestnut brown. His finger marks were brown instead of black––the only horse at the Holding so distinguished, for no matter of what shade or colour, in all the others these peculiar marks were jet black. Five splendid creatures they stood and pounded the ringing earth, tossed their heads and waited, though they had all been far that day and it was feeding time.

Out in the horse corrals there were many more of their breed, slim, wiry horses, toughened and hardened by long hours and daily work, but these were the flower of Last’s, the prized favourites.

For a long time Tharon sat and watched them, noting their perfect condition, their glistening skins, their shining hoofs, many of which were striped, another characteristic.

“I don’t believe,” she said at last, “that there’s a bunch of horses in Lost Valley to come nigh ’em. Ironwoods or anything else––I’d back th’ Finger Marks.”

“So would we,” said Conford quietly, “though we’ve seen th’ Ironwoods run––a little.”

“That’s th’ word, Burt,” said Curly, “a little. 41 Who of us has ever seen Courtrey let Bolt run like he wanted to? Not a darned one. I’ve seen that big bay devil pull till th’ blood dripped from his mouth.”

“Sure,” put in Masters, “I’ve seen that, too––but I was lyin’ up on th’ Cup Rim oncet, watchin’ a couple mavericks fer funny work, an’ Courtrey an’ Wylackie Bob come along down that way on Bolt an’ Arrow––an’ they wasn’t a-holdin’ them then. Lord, Lord, how they was goin’! Two long red streaks as level as your hand, an’ I swear my heart came up in my throat to see ’em, an’ I almost hollered. It was pretty work––pretty work, an’ no mistake.”

Tharon looked over at him.

“Fast as El Rey, Jack?”

“Who could tell?” said the man. “I know it was some speed, an’ that is all.”

The girl struck a hand on the king’s shoulder so passionately that he jumped and snorted.

“Some day,” she said tensely, “El Rey will run th’ Ironwoods off their feet––an’ I’ll run th’ heart out of their master, damn him! Put th’ horses out. It’s supper time.”

She threw her right limb over the stallion’s neck swiftly and with lithe grace, and slid abruptly to the ground.

As she did so there came the sound of hoofs on 42 the hard earth at the corner of the house, and a stranger came sharply into sight.

He drew up and nodded. Conford, just turning away, turned quickly back and came forward.

“Howdy,” he said.

The man, tall, lean, dark, returned the salute with another nod.

He was covered with dust, as if he had ridden far and been a long time coming. His clothes were much the worse for wear, but they were mostly leather, which takes wear standing, as it were. The wide hat pulled low over his piercing dark eyes, was ornamented with a vanity of silver.

The riding cuffs at his wrists were studded profusely with the same metal, as was the wide belt that spanned his narrow waist.

He wore a three days’ beard, and a black moustache dropped its long points to the edge of his jaw. Black hair showed beneath the hat. He was a remarkable figure, even in Lost Valley, and he commanded attention.

He carried the customary two guns of the country, and he bestrode a horse that was as noticeable as himself.

This horse was no denizen of Lost Valley. It was an utter alien. Its colour was a dingy black, as if it had recently been through fire, its coat rough and unkempt. Its long head was heavy and 43 slug-like, its nose of the type known among horsemen as Roman. It was roughly built, raw-boned and angular, and of so stupendous a size that the man atop, who was six foot tall himself, seemed small by comparison.

However, for all its ugliness, it possessed a seeming of vast power, a suggestion of great strength.

The stranger looked the group over with his keen, hard eyes, and spoke in a slow drawl.

“I reckon,” he said, “I’m a-ridin’ th’ wrong trail. I hain’t expected hyar.”

And turning abruptly, without another word, he jogged away around the house and started down the long slope already greying with the coming night.

The foreman and the five punchers clamped over to the corner of the kitchen and watched him in speculative silence. Tharon came along and stood by Billy, her hand on the boy’s arm. To Billy that sober touch confused the distances, set the strange rider dancing on the slope.

“H’m,” said Conford, his grey eyes narrow, “come from far an’s goin’ somewheres. I’ll watch that duck. He looks like he’s a record man to me.”

At supper there was much speculation about the stranger. 44

“I’ll lay a month’s pay he come from Texas,” said Billy, casting a side glance at his pal Curly, “them long lankys usually do. An’ somehow it shows in their eyes, sort o’ fierce an’––”

“Billy,” said Tharon severely, “if I was Curly I’d take a fall out of you. He can do it, you know that an’ I know it.”

“Thanks, Miss Tharon,” said Curly in his soft Southern drawl, “if you feel that-a-way about it, w’y, I don’t care what no little yellow-headed whipper-snapper from up Wyomin’ way says to th’ contrary.”

Billy was a bit abashed, but he stubbornly supported his contention that the stranger was a bad-man from Texas.

“Plenty bad-men right here in Lost Valley,” said the girl quietly, “an’ th’ breed ain’t dyin’ out as I can see. Th’ settlers need a new leader––now that Jim Last’s gone.” And she fell to playing absently with her fork upon the cloth.

The boys changed the subject hurriedly.

“I found a dead brandin’ fire in th’ Cup Rim yesterday, Burt,” said Masters, “quite a scrabbled space around it. Looked like some one’d branded several calves.”

“Don’t doubt it,” said the foreman. “Careful as we are there’s always likely to be stragglers. 45 An’ to be a straggler’s to be a goner in this man’s land.”

“Unless he belongs t’ Last’s,” said the irrepressible Billy. “I’ll lay that fer every calf branded by Courtrey’s gang we’ll get back two.”

“Billy,” said Tharon again, “Jim Last wasn’t a thief. Neither will his people be thieves. For every calf branded by Courtrey, one calf wearin’ th’ J. L.––an’ one calf only. We don’t steal, but we won’t lose.”

“You bet your boots an’ spurs throwed in, we won’t,” said the boy fervently.

As they rose from the table with all the racket of out-door men there came once more the sound of a horse’s hoofs on the hard earth outside.

Last’s Holding was a vast sounding-board. No one on horseback could come near without advertising his arrival far ahead.

This time it was no stranger. Tharon went to the western door to bid him ’light.

It was John Dement from down at the Rolling Cove. He was a thin, worn man, who looked ten years beyond his forty, his face wrinkled by the constant fret and worry of the constant loser.

Tonight he was strung up like a wire. His voice shook when he returned the hearty greetings that met him. 46

“Boys,” he said abruptly, “an’ Tharon––I come t’ tell ye all good-bye.”

“Good-bye! John, what you mean?”

Tharon went forward and put a hand on his arm. Her blue eyes searched his face.

The man stood by his horse and struck a tragic fist in a hard palm.

“That’s it. I give up. I’m done. I’m goin’ down the wall come day––me an’ my woman an’ th’ two boys. Got our duffle ready packed, an’ Lord knows, it ain’t enough t’ heft th’ horses. After five year!”

There was the sound of the hopeless tears of masculine failure in the man’s tragic voice. His fingers twisted his flabby hat.

“Hold up,” said Conford, pushing nearer, “straighten out a bit, Dement. Now, tell us what’s up.”

“Th’ last head––th’ last hoof––run off last night as we was comin’ in with ’em a leetle mite late. Had ben up Black Coulee way, an’ it got dark on us. Just as we got abreast o’ th’ mouth of th’ Coulee, where th’ poplars grow, three men come a-boilin’ out. They was on fast horses––o’ course––an’ right into th’ bunch they went, hell-bent. Stampeded the hull lot. You know my bunch’d got down t’ about a hundred head––don’t know what I ben a-hangin’ on fer, only a man hates 47 t’ give up an’ own hisself beat out. An’ my woman––she’s a fighter.

“She kep’ standin’ at my back like, oh, like––well, she kep’ a-sayin’ ‘We’ll win out yet, John, you see. Right’ll win ev’ry time.’ You see we are just ready to get th’ patent on our land. She couldn’t give that up, seems like. All this time gone an’ nothin’ gained. So we ben a-hangin’ on when things went from bad to worse. Th’ herd’s been a-goin’ down an’ down. Calves with their tongues slit so’s they’d lose their mothers––fed up in some coulee by hand an’ branded. Knowed ’em by my own colour cattle, w’ich I drove in here five year ago––th’ yellers.

“Mothers killed outright an’ th’ calves branded. Oh, I know it all––but what could I do? Kep’ gettin’ poorer an’ poorer. Couldn’t afford enough riders t’ protect ’em. Then couldn’t afford any an’ tried t’ make it go as th’ boys got older. Courtrey, damn him, wants me offen that piece o’ land a-fore th’ patent’s granted. Him with his twenty thousan’ acres of Lost Valley now! An’ how’d he get it? False entry, that’s what! How many men’s come in here, took up land, ‘sold out’ to Courtrey an’ went? Or didn’t go. A lot of ’em didn’t go. We all know that. An’ who dares to speak in a whisper about it? Th’ men that did wouldn’t go––never––nowheres.” 48

There was the bitterness of utter defeat and hatred in the shaking voice. The tree-toads, beginning their nightly chorus from the wet places below the cottonwoods, emphasized the dreariness of the recital, the ancient hopelessness of the weak beneath the heel of the oppressor.

Dement ceased speaking and stood in silhouette against the last yellow-and-black of the dead sunset. The protruding apple in his hawk-like throat worked up and down grotesquely.

For a long moment there was utter silence.

Then he began again.

“I knowed I wasn’t welcome in th’ Valley when I hadn’t ben here more’n six months. Th’ first leetle string o’ fence I put up fer corrals went down, mysterious, as fast as I could fix it. Th’ woman’s garden was broke open an’ trampled to dust by cattle, drove in. Winter ketched us with mighty leetle t’ eat in th’ way o’ truck. Next year she guarded it herself some nights, sleepin’ by day, an’ oncet she took a shot at some one that come prowlin’ around. They let her fence alone after that, but what’d they do outside? Killed all th’ hogs we had one night an’ piled ’em in a heap in th’ front door yard! That was hint enough, but I kep’ a-thinkin’ that ef we behaved decent like, an’ minded our own business we sartainly must win out. We did,” he added grimly after a 49 little pause, “like hell. An’ how many others of th’ settlers has gone through th’ like? We ain’t no tin gods ourselves, I own, but we got t’ fight fire with fire. Only I ain’t got no more light-wood,” he finished quaintly, “I got to quit.”

There was another silence while the tree-toads sang. Then the man held out his hand, hardened and warped with the unceasing toil of those tragic years.

“Good-bye, Tharon,” he said, “I wisht Jim Last was here. With him gone Lost Valley’s in Courtrey’s hand an’ no mistake. He was th’ only man dared face him an’ hold his own. Last’s was th’ only head th’ weaker faction had, its master their only leader. While he lived we had some show, us leetle fellers. Now there ain’t no leader. Th’ ranchers’ll go out fast now. It’ll be a one-man valley.”

In the soft darkness Tharon took the extended hand, held it a moment and laid her other one upon it.

“John Dement,” she quietly said, “I want you to go home an’ bar your house for fight. Fix up your fences, unpack your duffle. In the morning my riders will drive down to your place a hundred head o’ cattle. You put your brand on em. There’s goin’ to be no one-man doin’s in Lost Valley yet awhile––not while Jim Last’s 50 daughter lives. See,” she dropped his hand and pointed to the east where the tall pine lifted to the stars, “out yonder there’s a cross at Jim Last’s grave––an’ there’s my mark on it. Th’ settlers have a leader still––an’ I name myself that leader. I’m set against Courtrey, now an’ forever. I mean to fight him t’ th’ last inch o’ ground in Lost Valley, th’ last word o’ law, th’ last drop o’ blood, both his an’ mine. You go down among ’em––th’ settlers––an’ take ’em that word from me. Tell ’em Jim Last’s daughter stands facin’ Courtrey, an’ she’ll need at her back t’ fight him every man in Lost Valley that ain’t a coward.”

When the settler had gone, incoherent and half-incredulous, Conford drew a long breath and looked at his mistress in the dusk.

“Tharon, dear,” he said so gently that his words were like a caress “you’re jest a-breakin’ your riders’ hearts. You’re heapin’ anxiety on us mountain-high. Now what on earth’ll we do?”

Young Billy Brent pushed near and slapped a hand against a doubled fist. His eyes were sparkling like harbour lights, his voice was like the sound of running fire.

“Do?” he cried. “Do? We’ll stand behind her so tight they can’t see daylight through, an’ we’ll fight with an’ for her every inch o’ that way, 51 every word o’ that law, every drop o’ that blood! Who says Last’s ain’t on th’ map in Lost Valley?” Tharon smiled and touched him again.

“Billy,” she said softly, “you’re after my own heart. Now get to bed. I want t’ think.”

Spring was warming swiftly into summer. Where the gently sloping ranges went up in waves and swells toward the uplands at the east, the bright new green had turned to a darker shade. The tiny purple and white flowers had disappeared to give place to sturdier ones of crimson and gold. The veil of water that fell sharply down the face of the Wall for a thousand feet at the Valley’s southern end had thinned to sheerest gauze. In the Cañon Country the snow had disappeared from most of the high points. Red, black, yellow, the great face of the encircling Wall stood in everlasting majesty, looking down upon the level cup of Lost Valley. The unspeakable upheaval of peaks and crags, of cañons and splits and unfathomable depths, was almost a sealed book to the denizens of the Valley. There were those who knew False Ridge.

There were those who said they knew more. Many a man had adventured therein, and few had returned to tell of their adventures. Cañon 53 Jim had not returned. Not that he was a loss to the community, or that they mourned him, but his absence pointed again to the formidable secretive power of the Cañon Country.

Tharon Last, standing in her western door, could look across the Valley’s deceptive miles and see the huge black seams and fissures that rent the grim face. These splits and cañons were peculiar in that none came down to the Valley’s floor, their yawning doorways being, in every instance, set from two hundred to five hundred feet up the Wall.

Often the girl watched them in the changing lights and her active mind formed many a conjecture concerning them.

“Some day,” she told young Paula, “I’ll go into the Cañon Country and see it for myself.”

“Saints forbid, Señorita!” said Paula, who had no love for the mysterious, and who was more Mexic than Porno, “there are demons and devils there!”

“Yes, I doubt not, Paula,” said Tharon grimly. “They say Courtrey knows th’ Cañons, an’ when he’s there, it’s peopled, an’ no mistake!

“But it must be beautiful––beautiful! Why––there’s a thousand feet of crevasse on every hand, I know, steps an’ benches an’ weathered faces that no man can climb. They say there’s bright waters 54 that tumble down like th’ Vestal’s Veil and sink into holes without an outlet. Just go away in the rock. There’s strange flowers an’ stunted trees. An’ they tell of th’ Cup of God, a hidden glade so beautiful that th’ eye of man has never seen its like. All my life it’s called me, th’ Cañon Country.

“Don’t you believe, Paula, that there’s somethin’ there for me? Some reason why I know I must some day go into its heart an’ give myself up to it for a time? If I was free,” she finished with a sigh, “if I was my own woman, wholly, I’d go soon. There’s rest an’ peace up there, I know––and a place to think of Jim Last without such bitterness that my heart turns t’ gall.”

She shook her bright head against the doorpost and shut her soft lips into a straight line.

“Nope,” she finished sadly, “I ain’t my own woman yet.”

“Tharon,” said Billy Brent this day, clanking around the corner of the adobe house, his leather chaps flapping with every step, his yellow hair curling boyishly under his hat-brim. “Tharon, I got bad news for you.”

There was genuine distress in his grey eyes.

“Yes?” asked the mistress of Last’s, straightening up. 55

“Yes, sir, an’ I hate like hell t’ tell it.”

“Out with it, Billy. What’s wrong?”

“Somebody’s dynamited th’ Crystal Spring in th’ Cup Rim.”

“What?”

The word was in italics. Its one syllable told all one might care to know of the importance of Billy’s news.

“Yes. Opened her up fer two square yards. Spread th’ lovely old Crystal all over th’ range. An’ she’s gone, as sure’s shootin’. Nothin’ but a lot o’ wet an’ dryin’ mud to show for her.”

Tharon drew a long breath.

“Courtrey’s beginnin’,” she said. “He’s heard th’ word I sent th’ settlers. He’s goin’ t’ use th’ tactics now with Last’s that he’s used with every poor devil he wanted to run out of th’ Valley, th’ tactics he darsent use while Jim Last lived. Well––go send Conford to me, Billy.”

The girl sat down in the doorway and gazed sombrely out over the summer land.

When her foreman came and stood before her, a slim, efficient figure, dark-faced and quiet, she had already made up her mind.

“Burt,” she said swiftly, “drive th’ cattle down from th’ Cup Rim right away. We’ll run those two bunches under Blue Pine an’ Nick Bob out toward th’ Black Coulee. Tell ’em t’ keep 56 close t’ th’ others. I trust th’ Indians, but there ain’t no Indian livin’ can meet Courtrey’s white renegades in courage an’ wits. Then we’ll start right in an’ dig a well th’ first well ever dug on th’ open range in this man’s land.”

“Good Lord, Tharon!” said Conford, “A well!”

“Yes. Th’ livin’ water holes have been th’ pride of th’ Valley, I know, but we’ll fix this well of ours so’s even Courtrey will respect it.”

There was a grim note in the golden voice.

“How?” asked Conford uneasily.

“Dig it first,” said Tharon, “then I’ll tell you.”

What the mistress said, went. Therefore, the next morning saw a disgusted bunch of cowboys and Indian vaqueros setting to with a will at a spot much nearer the Holding than the Crystal had been, and it took a much shorter time to reach water in a good gravel bed than any one had dreamed.

In three days the thing was done and Conford presented himself, smiling.

“Now, Miss Secrecy,” he said, “come on with th’ mystery.”

Tharon went in to the big desk which Jim Last had used and which was now her own, and returned with a square white slab of pine, elaborately smoothed and finished by José. 57

“Read that,” she said, and held it up, face out.

Printed neatly upon its shining surface, in the jet-black ink that old Anita made from the berries of a certain bush which grew at the foot of the cliffs across the Valley, were these words:

“This well is planted. I hope it blows up the first thief who tries to destroy it. Tharon Last.”

Conford took the slab, scratched his head, holding his hat between thumb and finger, read it over, read it again, smiled, and then looked up.

“Might work,” he said, “an’ you’re givin’ out your stand an’ knowledge broadcast, ain’t you?”

“Certainly am,” said Tharon briefly. “I said I’d fight, an’ I want th’ whole Valley t’ know it.”

“It does,” said Conford with conviction. “I heard in Corvan yesterday that John Dement has rode th’ range continuous since he finished brandin’ his new herd to tell th’ settlers about it.”

“Good,” said Tharon, “couldn’t be better. There’s got to be a change in Lost Valley sooner or later. Might as well be sooner.”

And with that thought the girl let her quick mind sweep out to take in the future. She sent Conford off to post her placard and herself went rummaging among the possibilities which her defy had placed before her. She knew that Courtrey would be coldly furious. He had lived his life 58 as suited him, had taken what and where he listed, by fair means or foul, and though every soul in the Valley knew him and his methods, none had spoken the convicting word. It was the pen-stroke at the end of the death-warrant to do so.

She knew that the faction of the settlers hated him and his with a vitriolic passion, that they were in the minority, that they were no tin gods themselves, and that they were being beaten out, one by one.

Year by year Courtrey had added to his vast acreage, and it was a matter of common knowledge how he had done it. He was rich, powerful, bullying, a man whose self-aggrandizement knew no limit, whose merest whim was his law, whose will must not be thwarted. Year by year his vaqueros drove down the Wall herds of fat cattle, their brands blurred, insolently raw and careless. Many a hapless man had stood and seen his own stock go by in Courtrey’s band and dared not open his mouth. In fact Courtrey had been known to stop and chat with such a one, smiling his evil smile and enjoying the helpless chagrin of his victim.

“Insolent ruffian!” muttered Tharon this day, frowning above her daddy’s pipes on the desk top. “He’s goin’ t’ get one run for his money 59 from now till one of us is whipped. It may be me, but I’ll leave my mark on him, so help me!

“Straight killin’s too good for him. I want to smash him first.”

“Tharon, mi Corazon,” said Anita, stopping soft-foot beside her, “it is bad for one to talk so, to himself. The Evil One works on the mind that way.”

Tharon laughed.

“Perhaps, Anita,” she said shortly, “it is with the Evil One I have t’ do, an’ no mistake.”

The old woman crossed herself and went away, her wrinkled face dim with care. And Tharon dressed herself neatly, put a ribbon on her hair, set her wide hat carefully on her head, buckled on her heavy gun-belt, and went to the corral for El Rey. Her daddy’s saddle was her own now, a huge affair carved and ornamented, profusely studded with silver.

Along the right side below the pommel ran a darker stain, Jim Last’s blood, set before his daughter like a star.

She mounted the silver stallion and went away down along the summer land, a shaft of light shooting through the green of the ranges.

Far over to her left she could see her cattle, beautiful bunches spread like figures in a tapestry. 60 The figures of her riders were small dots on the outskirts.

El Rey, always hard on the bit, always strong-headed, wanted to run and she swung loose her rein and let him go. But run as he might, there was always in his speed that rising note, that seeming of reserve power.

She passed the head of Black Coulee, swung out across the edge of Rolling Cove, thundered down to the ford of the Broken Bend. Here she let the stallion drink, deep draughts that would have slowed a lesser horse. El Rey went up the bank beyond the ford like a charging engine, squared away and stretched out to finish his run. He was within three miles of Corvan, set like a stone in a smooth green surface, before he came down and lifted his shoulders into his gait. With the first rock and swing of the singlefoot, Tharon smiled and settled herself more comfortably in the saddle. This was joy to her, this beautiful syncopation, this poetic marked time that reeled off the miles beneath her and would scarcely have shaken a pebble from her hat-brim.

As she struck the outskirts of the little town the unmistakable sound of El Rey’s iron-shod hoofs brought heads into doors, children at the house corners to look upon her. She came down the main street at a smart clip, to bring up with 61 a slide at the hitch-rail before Baston’s store where the monthly mail was handled. There were horses tied there, and among them she saw what caused her to look twice with a narrowing of her keen eyes––a huge, raw-boned, black, rusty and slug-headed, among the Ironwood bays from Courtrey’s Stronghold.

“H’m,” she told herself quietly, “so there’s where he was expected.”

She tied El Rey to himself, far from the rest, for she knew his imperious temper and that trouble would ensue if he was near strange horses.

Then she went into Baston’s with her meal-sack on her arm. This meal-sack was a part of her accoutrement, a regular carry-all for such small purchases as she must take home––a roll of print for Paula, some tobacco for the men, a dozen spools of the linen thread which was so much prized among the women of Lost Valley.

As she stepped in the open door her quick glance went over the big room with a comprehensiveness which catalogued its inmates accurately and instinctively. Courtrey was not there, though his great bay, Bolt, stood outside. However, Wylackie Bob was there. This man, sitting at a canvas covered table in a corner, idly fingering a pack of cards, was not one to be passed over easily. He was notorious. 62

Tall, slow of action, sleepy-eyed, he was treacherous as a snake, as swift to move when necessary. He had been known to sit as he was now, idly playing, to leap up, crouch, draw and kill a man, and be down again at his place, idly playing, before the breath was done in his victim.

He was a past-master of his gun, and unlike most men of the time and place, he carried only one.

He was a quarter-blood Wylackie Indian. Near him sat the stranger who had ridden the slug-head black into Lost Valley. They both looked up as the girl entered and regarded her with smiles.

Tharon did not look at them again. She saw, however, that they were together, of one interest. There were two or three of the settlers in the store, Jameson from over under the Rockface at the south, Hill from farther up, Thomas from Rolling Cove. She spoke to these men quietly and noticed with an inward thrill the eagerness with which they responded.

There was an electric something between them which told her that her promise had, indeed, gone up and down the country, that in a subtle, unheralded manner she stood in Jim Last’s place, a head, a leader.

She made her purchases without undue speech, 63 got two letters in her father’s name––and these brought a smarting under her eyelids––tied up her sack and went out without so much as a glance at the two men in the corner. Laughter followed her, however, which set the red blood of anger pulsing in her cheeks.

At the end of the store porch she came face to face with Courtrey and Steptoe Service, the sheriff of Menlo county. She swung to one side to descend the rough steps, vouchsafing them no word or look, but Service blocked her way. She raised her eyes and looked him full in the face, scanning his coarse red features coolly.

“Well?” she said sharply.

“What’s this I hear, Tharon?” asked Service, “about you a-makin’ threats?”

“What have you heard?” she wanted to know.

“W’y, that you’re a-makin’ threats.”

“Yes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well?”

The sheriff flushed darker.

“Look here, young woman,”––he raised his voice suddenly and on the instant there was a sound of boots on the store floor and the settlers, the two men in the corner, Baston and two clerks came crowding out to hear, “you look a-here––don’t 64 you know it’s a-gin th’ law for any one t’ make a threat like you done, open an’ above board, in th’ Golden Cloud th’ other night?”

Tharon shifted the meal-sack higher on her left arm. Courtrey’s eyes went down to her right hand and stayed there.

The girl’s upper lip lifted from her teeth in a sneer that was the acme of insult. The fire was beginning to play in her blue eyes.

“Law?” she said. “My God! Law!”

“Yes, law! you young hussy, an’ don’t you fergit that I represent it.”

The girl threw down the sack and flashed both hands on the gun-butts. Courtrey, watching, was half-a-second behind her and stopped with his hands hovering.

“Not much, Courtrey,” she said, “you fast gun man! You’re too slow. An’ this ain’t your game, anyway, not face t’ face. You’re all right on a dark night––an’ from behind. Fine! But you’re a coward. You’re what I called you before––an assassin.”

She was pale as ashes, her eyes narrowed to blazing slits. Jim Last, gun man, was in her like those composite pictures which show the shadow in the substance. There was a gasp from the store porch where Thomas stood with a shaking hand covering his lips. Baston was stuck against 65 his wall like a leech, rigid. These men knew that she tempted death.

Not a man in Lost Valley could have done it and gotten away with it.

Tharon knew it, too, but she did not care.

“An’ now you know what you are, Courtrey. I’ll tell th’ same to you, Step Service. Law! In Lost Valley? Yes, Courtrey’s law! Th’ law of th’ gun alone––th’ law of thieves––th’ law of murderers. An’ you stand for that, you bet! What were you before you took th’ oath of office? Tell me that! Th’ man who killed old Mike McCrea an’ took his cattle down th’ Wall! Th’ whole Valley knows it––but we’ve never dared to say it before!”

The porch was lined with people now. Soft-footed Indians and Mexican vaqueros, sprung from nowhere, cowboys, ranchers, women, they came silently up and listened.

The sheriff’s red face was the colour of liver, purple and mottled with bursting rage. His fingers worked at his sides. He set his lips, and his small eyes never left the girl’s face.

Tharon, crouched a bit, her feet apart, her elbows crooked above her hips, her fingers curled on her gun-butts with nice precision, wet her own pale lips and continued:

“An’ who put you in office? That laugh of an 66 office! Who? Why, Courtrey––th’ biggest thief, th’ coldest murderer in th’ country! He put you there! An’ what are you good for? My daddy was shot––in th’ back––an’ did you make one inquiry into the murder? Come out to Last’s, even to find a clew? Not you! There’s only one sheriff in this Valley––one bit o’ law that will avenge his death––an’ that’s me! Now, you two fine gentlemen––I’m goin’. There’s my hand! I throw th’ cards on th’ table! Shoot me in the back if you’ve got th’ nerve. Come out in th’ open an’ fight! But you better be quick about it!”

With that she backed slowly along the porch, keeping them in view.