The Project Gutenberg EBook of Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Author: Various Release Date: April 26, 2009 [EBook #28617] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASTOUNDING STORIES--SUPER SCIENCE *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Katherine Ward and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note

Initial advertisements moved below main text.

The Beetle Horde concludes a story begun in the Jan, 1930 edition.

Minor spelling and typographical errors corrected.

Variable Spelling and Hyphenations standardized.

The changes from the original text are highlighted.

On Sale the First Thursday of Each Month

| W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher | HARRY BATES, Editor | DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor |

The Clayton Standard on a Magazine Guarantees:

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid; by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, WIDE WORLD ADVENTURES, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, FLYERS, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, SKY-HIGH LIBRARY MAGAZINE, MISS 1930, and FOREST AND STREAM

More Than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

| VOL. I, No. 2 | CONTENTS | FEBRUARY, 1930 |

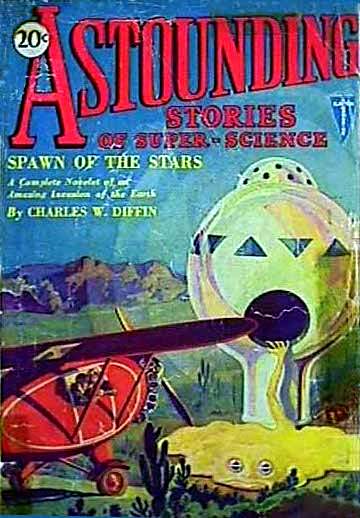

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSOLOWSKI | |

| Painted in Water-colors from a Scene in "Spawn of the Stars." | ||

| OLD CROMPTON'S SECRET | HARL VINCENT | 153 |

| Tom's Extraordinary Machine Glowed—and the Years Were Banished from Old Crompton's Body. But There Still Remained, Deep-seated in His Century-old Mind, the Memory of His Crime. | ||

| SPAWN OF THE STARS | CHARLES WILLARD DIFFIN | 166 |

| The Earth Lay Powerless Beneath Those Loathsome, Yellowish Monsters That, Sheathed in Cometlike Globes, Sprang from the Skies to Annihilate Man and Reduce His Cities to Ashes. | ||

| THE CORPSE ON THE GRATING | HUGH B. CAVE | 187 |

| In the Gloomy Depths of the Old Warehouse Dale Saw a Thing That Drew a Scream of Horror to His Dry Lips. It Was a Corpse—the Mold of Decay on Its Long-dead Features—and Yet It Was Alive! | ||

| CREATURES OF THE LIGHT | SOPHIE WENZEL ELLIS | 196 |

| He Had Striven to Perfect the Faultless Man of the Future, and Had Succeeded—Too Well. For in the Pitilessly Cold Eyes of Adam, His Super-human Creation, Dr. Mundson Saw Only Contempt—and Annihilation—for the Human Race. | ||

| INTO SPACE | STERNER ST. PAUL | 221 |

| What Was the Extraordinary Connection Between Dr. Livermore's Sudden Disappearance and the Coming of a New Satellite to the Earth? | ||

| THE BEETLE HORDE | VICTOR ROUSSEAU | 229 |

| Bullets, Shrapnel, Shell—Nothing Can Stop the Trillions of Famished, Man-sized Beetles Which, Led by a Madman, Sweep Down Over the Human Race. | ||

| MAD MUSIC | ANTHONY PELCHER | 248 |

| The Sixty Stories of the Perfectly Constructed Colossus Building Had Mysteriously Crashed! What Was the Connection Between This Catastrophe and the Weird Strains of the Mad Musician's Violin? | ||

| THE THIEF OF TIME | CAPTAIN S. P. MEEK | 259 |

| The Teller Turned to the Stacked Pile of Bills. They Were Gone! And No One Had Been Near! | ||

| Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) | Yearly Subscription, $2.00 |

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N.Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Application for entry as second-class mail pending at the Post Office at New York, under Act of March 3, 1879. Application for registration of title as Trade Mark pending in the U.S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

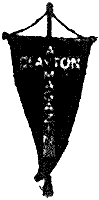

Tom tripped on a wire and fell, with his ferocious adversary on top.

Two miles west of the village of Laketon there lived an aged recluse who was known only as Old Crompton. As far back as the villagers could remember he had visited the town regularly twice a month, each time tottering his lonely way homeward with a load of provisions. He appeared to be well supplied with funds, but purchased sparingly as became a miserly hermit. And so vicious was his tongue that few cared to converse with him, even the young hoodlums of the town hesitating to harass him with the banter usually accorded the other bizarre characters of the streets.

The oldest inhabitants knew nothing of his past history, and they had long since lost their curiosity in the matter. He was a fixture, as was the old town hall with its surrounding park. His lonely cabin was shunned by all who chanced to pass along the old dirt road that led through the woods to nowhere and was rarely used.

His only extravagance was in the matter of books, and the village book store profited considerably by his purchases. But, at the instigation of Cass[154] Harmon, the bookseller, it was whispered about that Old Crompton was a believer in the black art—that he had made a pact with the devil himself and was leagued with him and his imps. For the books he bought were strange ones; ancient volumes that Cass must needs order from New York or Chicago and that cost as much as ten and even fifteen dollars a copy; translations of the writings of the alchemists and astrologers and philosophers of the dark ages.

It was no wonder Old Crompton was looked at askance by the simple-living and deeply religious natives of the small Pennsylvania town.

But there came a day when the hermit was to have a neighbor, and the town buzzed with excited speculation as to what would happen.

The property across the road from Old Crompton's hut belonged to Alton Forsythe, Laketon's wealthiest resident—hundreds of acres of scrubby woodland that he considered well nigh worthless. But Tom Forsythe, the only son, had returned from college and his ambitions were of a nature strange to his townspeople and utterly incomprehensible to his father. Something vague about biology and chemical experiments and the like is what he spoke of, and, when his parents objected on the grounds of possible explosions and other weird accidents, he prevailed upon his father to have a secluded laboratory built for him in the woods.

When the workmen started the small frame structure not a quarter of a mile from his own hut, Old Crompton was furious. He raged and stormed, but to no avail. Tom Forsythe had his heart set on the project and he was somewhat of a successful debater himself. The fire that flashed from his cold gray eyes matched that from the pale blue ones of the elderly anchorite. And the law was on his side.

So the building was completed and Tom Forsythe moved in, bag and baggage.

For more than a year the hermit studiously avoided his neighbor, though, truth to tell, this required very little effort. For Tom Forsythe became almost as much of a recluse as his predecessor, remaining indoors for days at a time and visiting the home of his people scarcely oftener than Old Crompton visited the village. He too became the target of village gossip and his name was ere long linked with that of the old man in similar animadversion. But he cared naught for the opinions of his townspeople nor for the dark looks of suspicion that greeted him on his rare appearances in the public places. His chosen work engrossed him so deeply that all else counted for nothing. His parents remonstrated with him in vain. Tom laughed away their recriminations and fears, continuing with his labors more strenuously than ever. He never troubled his mind over the nearness of Old Crompton's hut, the existence of which he hardly noticed or considered.

It so happened one day that the old man's curiosity got the better of him and Tom caught him prowling about on his property, peering wonderingly at the many rabbit hutches, chicken coops, dove cotes and the like which cluttered the space to the rear of the laboratory.

Seeing that he was discovered, the old man wrinkled his face into a toothless grin of conciliation.

"Just looking over your place, Forsythe," he said. "Sorry about the fuss I made when you built the house. But I'm an old man, you know, and changes are unwelcome. Now I have forgotten my objections and would like to be friends. Can we?"

Tom peered searchingly into the flinty eyes that were set so deeply in the wrinkled, leathery countenance. He suspected an ulterior motive, but could not find it within him to turn the old fellow down.

"Why—I guess so, Crompton," he hesitated: "I have nothing against you,[155] but I came here for seclusion and I'll not have anyone bothering me in my work."

"I'll not bother you, young man. But I'm fond of pets and I see you have many of them here; guinea pigs, chickens, pigeons, and rabbits. Would you mind if I make friends with some of them?"

"They're not pets," answered Tom dryly, "they are material for use in my experiments. But you may amuse yourself with them if you wish."

"You mean that you cut them up—kill them, perhaps?"

"Not that. But I sometimes change them in physical form, sometimes cause them to become of huge size, sometimes produce pigmy offspring of normal animals."

"Don't they suffer?"

"Very seldom, though occasionally a subject dies. But the benefit that will accrue to mankind is well worth the slight inconvenience to the dumb creatures and the infrequent loss of their lives."

Old Crompton regarded him dubiously. "You are trying to find?" he interrogated.

"The secret of life!" Tom Forsythe's eyes took on the stare of fanaticism. "Before I have finished I shall know the nature of the vital force—how to produce it. I shall prolong human life indefinitely; create artificial life. And the solution is more closely approached with each passing day."

The hermit blinked in pretended mystification. But he understood perfectly, and he bitterly envied the younger man's knowledge and ability that enabled him to delve into the mysteries of nature which had always been so attractive to his own mind. And somehow, he acquired a sudden deep hatred of the coolly confident young man who spoke so positively of accomplishing the impossible.

During the winter months that followed, the strange acquaintance progressed but little. Tom did not invite his neighbor to visit him, nor did Old Crompton go out of his way to impose his presence on the younger man, though each spoke pleasantly enough to the other on the few occasions when they happened to meet.

With the coming of spring they encountered one another more frequently, and Tom found considerable of interest in the quaint, borrowed philosophy of the gloomy old man. Old Crompton, of course, was desperately interested in the things that were hidden in Tom's laboratory, but he never requested permission to see them. He hid his real feelings extremely well and was apparently content to spend as much time as possible with the feathered and furred subjects for experiment, being very careful not to incur Tom's displeasure by displaying too great interest in the laboratory itself.

Then there came a day in early summer when an accident served to draw the two men closer together, and Old Crompton's long-sought opportunity followed.

He was starting for the village when, from down the road, there came a series of tremendous squawkings, then a bellow of dismay in the voice of his young neighbor. He turned quickly and was astonished at the sight of a monstrous rooster which had escaped and was headed straight for him with head down and wings fluttering wildly. Tom followed close behind, but was unable to catch the darting monster. And monster it was, for this rooster stood no less than three feet in height and appeared more ferocious than a large turkey. Old Crompton had his shopping bag, a large one of burlap which he always carried to town, and he summoned enough courage to throw it over the head of the screeching, over-sized fowl. So tangled did the panic-stricken bird become that it was a comparatively simple matter to effect his capture, and the old man rose to his feet triumphant with the bag securely closed over the struggling captive.

[156] "Thanks," panted Tom, when he drew alongside. "I should never have caught him, and his appearance at large might have caused me a great deal of trouble—now of all times."

"It's all right, Forsythe," smirked the old man. "Glad I was able to do it."

Secretly he gloated, for he knew this occurrence would be an open sesame to that laboratory of Tom's. And it proved to be just that.

A few nights later he was awakened by a vigorous thumping at his door, something that had never before occurred during his nearly sixty years occupancy of the tumbledown hut. The moon was high and he cautiously peeped from the window and saw that his late visitor was none other than young Forsythe.

"With you in a minute!" he shouted, hastily thrusting his rheumatic old limbs into his shabby trousers. "Now to see the inside of that laboratory," he chuckled to himself.

It required but a moment to attire himself in the scanty raiment he wore during the warm months, but he could hear Tom muttering and impatiently pacing the flagstones before his door.

"What is it?" he asked, as he drew the bolt and emerged into the brilliant light of the moon.

"Success!" breathed Tom excitedly. "I have produced growing, living matter synthetically. More than this, I have learned the secret of the vital force—the spark of life. Immortality is within easy reach. Come and see for yourself."

They quickly traversed the short distance to the two-story building which comprised Tom's workshop and living quarters. The entire ground floor was taken up by the laboratory, and Old Crompton stared aghast at the wealth of equipment it contained. Furnaces there were, and retorts that reminded him of those pictured in the wood cuts in some of his musty books. Then there were complicated machines with many levers and dials mounted on their faces, and with huge glass bulbs of peculiar shape with coils of wire connecting to knoblike protuberances of their transparent walls. In the exact center of the great single room there was what appeared to be a dissecting table, with a brilliant light overhead and with two of the odd glass bulbs at either end. It was to this table that Tom led the excited old man.

"This is my perfected apparatus," said Tom proudly, "and by its use I intend to create a new race of supermen, men and women who will always retain the vigor and strength of their youth and who can not die excepting by actual destruction of their bodies. Under the influence of the rays all bodily ailments vanish as if by magic, and organic defects are quickly corrected. Watch this now."

He stepped to one of the many cages at the side of the room and returned with a wriggling cottontail in his hands. Old Compton watched anxiously as he picked a nickeled instrument from a tray of surgical appliances and requested his visitor to hold the protesting animal while he covered its head with a handkerchief.

"Ethyl chloride," explained Tom, noting with amusement the look of distaste on the old man's face. "We'll just put him to sleep for a minute while I amputate a leg."

The struggles of the rabbit quickly ceased when the spray soaked the handkerchief and the anaesthetic took effect. With a shining scalpel and a surgical saw, Tom speedily removed one of the forelegs of the animal and then he placed the limp body in the center of the table, removing the handkerchief from its head as he did so. At the end of the table there was a panel with its glittering array of switches and electrical instruments, and Old Crompton observed very closely the manipulations of the controls as Tom started the mechanism. With the ensuing hum of a motor-generator from a corner of the room, the four bulbs ad[157]jacent to the table sprang into life, each glowing with a different color and each emitting a different vibratory note as it responded to the energy within.

"Keep an eye on Mr. Rabbit now," admonished Tom.

From the body of the small animal there emanated an intangible though hazily visible aura as the combined effects of the rays grew in intensity. Old Crompton bent over the table and peered amazedly at the stump of the foreleg, from which blood no longer dripped. The stump was healing over! Yes—it seemed to elongate as one watched. A new limb was growing on to replace the old! Then the animal struggled once more, this time to regain consciousness. In a moment it was fully awake and, with a frightened hop, was off the table and hobbling about in search of a hiding place.

Tom Forsythe laughed. "Never knew what happened," he exulted, "and excepting for the temporary limp is not inconvenienced at all. Even that will be gone in a couple of hours, for the new limb will be completely grown by that time."

"But—but, Tom," stammered the old man, "this is wonderful. How do you accomplish it?"

"Ha! Don't think I'll reveal my secret. But this much I will tell you: the life force generated by my apparatus stimulates a certain gland that's normally inactive in warm blooded animals. This gland, when active, possesses the function of growing new members to the body to replace lost ones in much the same manner as this is done in case of the lobster and certain other crustaceans. Of course, the process is extremely rapid when the gland is stimulated by the vital rays from my tubes. But this is only one of the many wonders of the process. Here is something far more remarkable."

He took from a large glass jar the body of a guinea pig, a body that was rigid in death.

"This guinea pig," he explained, "was suffocated twenty-four hours ago and is stone dead."

"Suffocated?"

"Yes. But quite painlessly, I assure you. I merely removed the air from the jar with a vacuum pump and the little creature passed out of the picture very quickly. Now we'll revive it."

Old Crompton stretched forth a skinny hand to touch the dead animal, but withdrew it hastily when he felt the clammy rigidity of the body. There was no doubt as to the lifelessness of this specimen.

Tom placed the dead guinea pig on the spot where the rabbit had been subjected to the action of the rays. Again his visitor watched carefully as he manipulated the controls of the apparatus.

With the glow of the tubes and the ensuing haze of eery light that surrounded the little body, a marked change was apparent. The inanimate form relaxed suddenly and it seemed that the muscles pulsated with an accession of energy. Then one leg was stretched forth spasmodically. There was a convulsive heave as the lungs drew in a first long breath, and, with that, an astonished and very much alive rodent scrambled to its feet, blinking wondering eyes in the dazzling light.

"See? See?" shouted Tom, grasping Old Crompton by the arm in a viselike grip. "It is the secret of life and death! Aristocrats, plutocrats and beggars will beat a path to my door. But, never fear, I shall choose my subjects well. The name of Thomas Forsythe will yet be emblazoned in the Hall of Fame. I shall be master of the world!"

Old Crompton began to fear the glitter in the eyes of the gaunt young man who seemed suddenly to have become demented. And his envy and hatred of his talented host blazed anew as Forsythe gloried in the success of his efforts. Then he was struck with an idea and he affected his most ingratiating manner.

[158] "It is a marvelous thing, Tom," he said, "and is entirely beyond my poor comprehension. But I can see that it is all you say and more. Tell me—can you restore the youth of an aged person by these means?"

"Positively!" Tom did not catch the eager note in the old man's voice. Rather he took the question as an inquiry into the further marvels of his process. "Here," he continued, enthusiastically, "I'll prove that to you also. My dog Spot is around the place somewhere. And he is a decrepit old hound, blind, lame and toothless. You've probably seen him with me."

He rushed to the stairs and whistled. There was an answering yelp from above and the pad of uncertain paws on the bare wooden steps. A dejected old beagle blundered into the room, dragging a crippled hind leg as he fawned upon his master, who stretched forth a hand to pat the unsteady head.

"Guess Spot is old enough for the test," laughed Tom, "and I have been meaning to restore him to his youthful vigor, anyway. No time like the present."

He led his trembling pet to the table of the remarkable tubes and lifted him to its surface. The poor old beast lay trustingly where he was placed, quiet, save for his husky asthmatic breathing.

"Hold him, Crompton," directed Tom as he pulled the starting lever of his apparatus.

And Old Crompton watched in fascinated anticipation as the ethereal luminosity bathed the dog's body in response to the action of the four rays. Somewhat vaguely it came to him that the baggy flesh of his own wrinkled hands took on a new firmness and color where they reposed on the animal's back. Young Forsythe grinned triumphantly as Spot's breathing became more regular and the rasp gradually left it. Then the dog whined in pleasure and wagged his tail with increasing vigor. Suddenly he raised his head, perked his ears in astonishment and looked his master straight in the face with eyes that saw once more. The low throat cry rose to a full and joyous bark. He sprang to his feet from under the restraining hands and jumped to the floor in a lithe-muscled leap that carried him half way across the room. He capered about with the abandon of a puppy, making extremely active use of four sound limbs.

"Why—why, Forsythe," stammered the hermit, "it's absolutely incredible. Tell me—tell me—what is this remarkable force?"

His host laughed gleefully. "You probably wouldn't understand it anyway, but I'll tell you. It is as simple as the nose on your face. The spark of life, the vital force, is merely an extremely complicated electrical manifestation which I have been able to duplicate artificially. This spark or force is all that distinguishes living from inanimate matter, and in living beings the force gradually decreases in power as the years pass, causing loss of health and strength. The chemical composition of bones and tissue alters, joints become stiff, muscles atrophied, and bones brittle. By recharging, as it were, with the vital force, the gland action is intensified, youth and strength is renewed. By repeating the process every ten or fifteen years the same degree of vigor can be maintained indefinitely. Mankind will become immortal. That is why I say I am to be master of the world."

For the moment Old Crompton forgot his jealous hatred in the enthusiasm with which he was imbued. "Tom—Tom," he pleaded in his excitement, "use me as a subject. Renew my youth. My life has been a sad one and a lonely one, but I would that I might live it over. I should make of it a far different one—something worth while. See, I am ready."

He sat on the edge of the gleaming table and made as if to lie down on its gleaming surface. But his young host[159] only stared at him in open amusement.

"What? You?" he sneered, unfeelingly. "Why, you old fossil! I told you I would choose my subjects carefully. They are to be people of standing and wealth, who can contribute to the fame and fortune of one Thomas Forsythe."

"But Tom, I have money," Old Crompton begged. But when he saw the hard mirth in the younger man's eyes, his old animosity flamed anew and he sprang from his position and shook a skinny forefinger in Tom's face.

"Don't do that to me, you old fool!" shouted Tom, "and get out of here. Think I'd waste current on an old cadger like you? I guess not! Now get out. Get out, I say!"

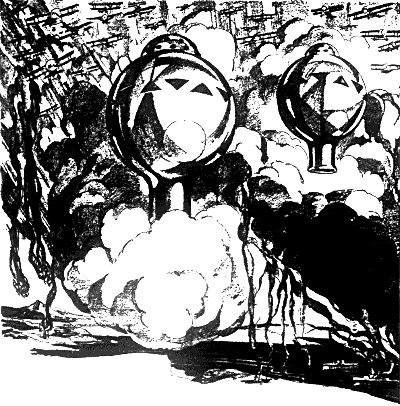

Then the old anchorite saw red. Something seemed to snap in his soured old brain. He found himself kicking and biting and punching at his host, who backed away from the furious onslaught in surprise. Then Tom tripped over a wire and fell to the floor with a force that rattled the windows, his ferocious little adversary on top. The younger man lay still where he had fallen, a trickle of blood showing at his temple.

"My God! I've killed him!" gasped the old man.

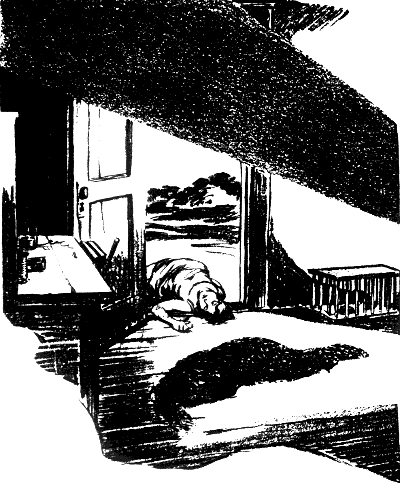

With trembling fingers he opened Tom's shirt and listened for his heartbeats. Panic-stricken, he rubbed the young man's wrists, slapped his cheeks, and ran for water to dash in his face. But all efforts to revive him proved futile, and then, in awful fear, Old Crompton dashed into the night, the dog Spot snapping at his heels as he ran.

Hours later the stooped figure of a shabby old man might have been seen stealthily re-entering the lonely workshop where the lights still burned brightly. Tom Forsythe lay rigid in the position in which Old Crompton had left him, and the dog growled menacingly.

Averting his gaze and circling wide of the body, Old Crompton made for the table of the marvelous rays. In minute detail he recalled every move made by Tom in starting and adjusting the apparatus to produce the incredible results he had witnessed. Not a moment was to be wasted now. Already he had hesitated too long, for soon would come the dawn and possible discovery of his crime. But the invention of his victim would save him from the long arm of the law, for, with youth restored, Old Crompton would cease to exist and a new life would open its doors to the starved soul of the hermit. Hermit, indeed! He would begin life anew, an active man with youthful vigor and ambition. Under an assumed name he would travel abroad, would enjoy life, and would later become a successful man of affairs. He had enough money, he told himself. And the police would never find Old Crompton, the murderer of Tom Forsythe! He deposited his small traveling bag on the floor and fingered the controls of Tom's apparatus.

He threw the starting switch confidently and grinned in satisfaction as the answering whine of the motor-generator came to his ears. One by one he carefully made the adjustments in exactly the manner followed by the now silenced discoverer of the process. Everything operated precisely as it had during the preceding experiments. Odd that he should have anticipated some such necessity! But something had told him to observe Tom's movements carefully, and now he rejoiced in the fact that his intuition had led him aright. Painfully he climbed to the table top and stretched his aching body in the warm light of the four huge tubes. His exertions during the struggle with Tom were beginning to tell on him. But the soreness and stiffness of feeble muscles and stubborn joints would soon be but a memory. His pulses quickened at the thought and he breathed deep in a sudden feeling of unaccustomed well-being.

The dog growled continuously from his position at the head of his master, but did not move to interfere with the intruder. And Old Crompton, in the excitement of the momentous experience, paid him not the slightest attention.

His body tingled from head to foot with a not unpleasant sensation that conveyed the assurance of radical changes taking place under the influence of the vital rays. The tingling sensation increased in intensity until it seemed that every corpuscle in his veins danced to the tune of the vibration from those glowing tubes that bathed him in an ever-spreading radiance. Aches and pains vanished from his body, but he soon experienced a sharp stab of new pain in his lower jaw. With an experimental forefinger he rubbed the gum. He laughed aloud as the realization came to him that in those gums where there had been no teeth for more than twenty years there was now growing a complete new set. And the rapidity of the process amazed him beyond measure. The aching area spread quickly and was becoming really uncomfortable. But then—and he consoled himself with the thought—nothing is brought into being without a certain amount of pain. Besides, he was confident that his discomfort would soon be over.

He examined his hand, and found that the joints of two fingers long crippled with rheumatism now moved freely and painlessly. The misty brilliance surrounding his body was paling and he saw that the flesh was taking on a faint green fluorescence instead. The rays had completed their work and soon the transformation would be fully effected. He turned on his side and slipped to the floor with the agility of a youngster. The dog snarled anew, but kept steadfastly to his position.

There was a small mirror over the wash stand at the far end of the room and Old Crompton made haste to obtain the first view of his reflected image. His step was firm and springy, his bearing confident, and he found that his long-stooped shoulders straightened naturally and easily. He felt that he had taken on at least two inches in stature, which was indeed the case. When he reached the mirror he peered anxiously into its dingy surface and what he saw there so startled him that he stepped backward in amazement. This was not Larry Crompton, but an entirely new man. The straggly white hair had given way to soft, healthy waves of chestnut hue. Gone were the seams from the leathery countenance and the eyes looked out clearly and steadily from under brows as thick and dark as they had been in his youth. The reflected features were those of an entire stranger. They were not even reminiscent of the Larry Crompton of fifty years ago, but were the features of a far more vigorous and prepossessing individual than he had ever seemed, even in the best years of his life. The jaw was firm, the once sunken cheeks so well filled out that his high cheek bones were no longer in evidence. It was the face of a man of not more than thirty-eight years of age, reflecting exceptional intelligence and strength of character.

"What a disguise!" he exclaimed in delight. And his voice, echoing in the stillness that followed the switching off of the apparatus, was deep-throated and mellow—the voice of a new man.

Now, serenely confident that discovery was impossible, he picked up his small but heavy bag and started for the door. Dawn was breaking and he wished to put as many miles between himself and Tom's laboratory as could be covered in the next few hours. But at the door he hesitated. Then, despite the furious yapping of Spot, he returned to the table of the rays and, with deliberate thoroughness smashed the costly tubes which had brought about his rehabilitation. With a pinch bar from a nearby tool rack, he wrecked the controls and generating mechanisms beyond recognition. Now he was[161] absolutely secure! No meddling experts could possibly discover the secret of Tom's invention. All evidence would show that the young experimenter had met his death at the hands of Old Crompton, the despised hermit of West Laketon. But none would dream that the handsome man of means who was henceforth to be known as George Voight was that same despised hermit.

He recovered his satchel and left the scene. With long, rapid strides he proceeded down the old dirt road toward the main highway where, instead of turning east into the village, he would turn west and walk to Kernsburg, the neighboring town. There, in not more than two hours time, his new life would really begin!

Had you, a visitor, departed from Laketon when Old Crompton did and returned twelve years later, you would have noticed very little difference in the appearance of the village. The old town hall and the little park were the same, the dingy brick building among the trees being just a little dingier and its wooden steps more worn and sagged. The main street showed evidence of recent repaving, and, in consequence of the resulting increase in through automobile traffic; there were two new gasoline filling stations in the heart of the town. Down the road about a half mile there was a new building, which, upon inquiring from one of the natives, would be proudly designated as the new high school building. Otherwise there were no changes to be observed.

In his dilapidated chair in the untidy office he had occupied for nearly thirty years, sat Asa Culkin, popularly known as "Judge" Culkin. Justice of the peace, sheriff, attorney-at-law, and three times Mayor of Laketon, he was still a controlling factor in local politics and government. And many a knotty legal problem was settled in that gloomy little office. Many a dispute in the town council was dependent for arbitration upon the keen mind and understanding wit of the old judge.

The four o'clock train had just puffed its labored way from the station when a stranger entered his office, a stranger of uncommonly prosperous air. The keen blue eyes of the old attorney appraised him instantly and classified him as a successful man of business, not yet forty years of age, and with a weighty problem on his mind.

"What can I do for you, sir?" he asked, removing his feet from the battered desk top.

"You may be able to help me a great deal, Judge," was the unexpected reply. "I came to Laketon to give myself up."

"Give yourself up?" Culkin rose to his feet in surprise and unconsciously straightened his shoulders in the effort to seem less dwarfed before the tall stranger. "Why, what do you mean?" he inquired.

"I wish to give myself up for murder," answered the amazing visitor, slowly and with decision, "for a murder committed twelve years ago. I should like you to listen to my story first, though. It has been kept too long."

"But I still do not understand." There was puzzlement in the honest old face of the attorney. He shook his gray locks in uncertainty. "Why should you come here? Why come to me? What possible interest can I have in the matter?"

"Just this, Judge. You do not recognize me now, and you will probably consider my story incredible when you hear it. But, when I have given you all the evidence, you will know who I am and will be compelled to believe. The murder was committed in Laketon. That is why I came to you."

"A murder in Laketon? Twelve years ago?" Again the aged attorney shook his head. "But—proceed."

"Yes. I killed Thomas Forsythe."

The stranger looked for an expression of horror in the features of his listener, but there was none. Instead[162] the benign countenance took on a look of deepening amazement, but the smile wrinkles had somehow vanished and the old face was grave in its surprised interest.

"You seem astonished," continued the stranger. "Undoubtedly you were convinced that the murderer was Larry Crompton—Old Crompton, the hermit. He disappeared the night of the crime and has never been heard from since. Am I correct?"

"Yes. He disappeared all right. But continue."

Not by a lift of his eyebrow did Culkin betray his disbelief, but the stranger sensed that his story was somehow not as startling as it should have been.

"You will think me crazy, I presume. But I am Old Crompton. It was my hand that felled the unfortunate young man in his laboratory out there in West Laketon twelve years ago to-night. It was his marvelous invention that transformed the old hermit into the apparently young man you see before you. But I swear that I am none other than Larry Crompton and that I killed young Forsythe. I am ready to pay the penalty. I can bear the flagellation of my own conscience no longer."

The visitor's voice had risen to the point of hysteria. But his listener remained calm and unmoved.

"Now just let me get this straight," he said quietly. "Do I understand that you claim to be Old Crompton, rejuvenated in some mysterious manner, and that you killed Tom Forsythe on that night twelve years ago? Do I understand that you wish now to go to trial for that crime and to pay the penalty?"

"Yes! Yes! And the sooner the better. I can stand it no longer. I am the most miserable man in the world!"

"Hm-m—hm-m," muttered the judge, "this is strange." He spoke soothingly to his visitor. "Do not upset yourself, I beg of you. I will take care of this thing for you, never fear. Just take a seat, Mister—er—"

"You may call me Voight for the present," said the stranger, in a more composed tone of voice, "George Voight. That is the name I have been using since the mur—since that fatal night."

"Very well, Mr. Voight," replied the counsellor with an air of the greatest solicitude, "please have a seat now, while I make a telephone call."

And George Voight slipped into a stiff-backed chair with a sigh of relief. For he knew the judge from the old days and he was now certain that his case would be disposed of very quickly.

With the telephone receiver pressed to his ear, Culkin repeated a number. The stranger listened intently during the ensuing silence. Then there came a muffled "hello" sounding in impatient response to the call.

"Hello, Alton," spoke the attorney, "this is Asa speaking. A stranger has just stepped into my office and he claims to be Old Crompton. Remember the hermit across the road from your son's old laboratory? Well, this man, who bears no resemblance whatever to the old man he claims to be and who seems to be less than half the age of Tom's old neighbor, says that he killed Tom on that night we remember so well."

There were some surprised remarks from the other end of the wire, but Voight was unable to catch them. He was in a cold perspiration at the thought of meeting his victim's father.

"Why, yes, Alton," continued Culkin, "I think there is something in this story, although I cannot believe it all. But I wish you would accompany us and visit the laboratory. Will you?"

"Lord, man, not that!" interrupted the judge's visitor. "I can hardly bear to visit the scene of my crime—and in the company of Alton Forsythe. Please, not that!"

"Now you just let me take care of this, young man," replied the judge, testily. Then, once more speaking into the mouthpiece of the telephone, "All[163] right, Alton. We'll pick you up at your office in five minutes."

He replaced the receiver on its hook and turned again to his visitor. "Please be so kind as to do exactly as I request," he said. "I want to help you, but there is more to this thing than you know and I want you to follow unquestioningly where I lead and ask no questions at all for the present. Things may turn out differently than you expect."

"All right, Judge." The visitor resigned himself to whatever might transpire under the guidance of the man he had called upon to turn him over to the officers of the law.

Seated in the judge's ancient motor car, they stopped at the office of Alton Forsythe a few minutes later and were joined by that red-faced and pompous old man. Few words were spoken during the short run to the well-remembered location of Tom's laboratory, and the man who was known as George Voight caught at his own throat with nervous fingers when they passed the tumbledown remains of the hut in which Old Crompton had spent so many years. With a screeching of well-worn brakes the car stopped before the laboratory, which was now almost hidden behind a mass of shrubs and flowers.

"Easy now, young man," cautioned the judge, noting the look of fear which had clouded his new client's features. The three men advanced to the door through which Old Crompton had fled on that night of horror, twelve years before. The elder Forsythe spoke not a word as he turned the knob and stepped within. Voight shrank from entering, but soon mastered his feelings and followed the other two. The sight that met his eyes caused him to cry aloud in awe.

At the dissecting table, which seemed to be exactly as he had seen it last but with replicas of the tubes he had destroyed once more in place, stood Tom Forsythe! Considerably older and with hair prematurely gray, he was still the young man Old Crompton thought he had killed. Tom Forsythe was not dead after all! And all of his years of misery had gone for nothing. He advanced slowly to the side of the wondering young man, Alton Forsythe and Asa Culkin watching silently from just inside the door.

"Tom—Tom," spoke the stranger, "you are alive? You were not dead when I left you on that terrible night when I smashed your precious tubes? Oh—it is too good to be true! I can scarcely believe my eyes!"

He stretched forth trembling fingers to touch the body of the young man to assure himself that it was not all a dream.

"Why," said Tom Forsythe, in astonishment. "I do not know you, sir. Never saw you in my life. What do you mean by your talk of smashing my tubes, of leaving me for dead?"

"Mean?" The stranger's voice rose now; he was growing excited. "Why, Tom, I am Old Crompton. Remember the struggle, here in this very room? You refused to rejuvenate an unhappy old man with your marvelous apparatus, a temporarily insane old man—Crompton. I was that old man and I fought with you. You fell, striking your head. There was blood. You were unconscious. Yes, for many hours I was sure you were dead and that I had murdered you. But I had watched your manipulations of the apparatus and I subjected myself to the action of the rays. My youth was miraculously restored. I became as you see me now. Detection was impossible, for I looked no more like Old Crompton than you do. I smashed your machinery to avoid suspicion. Then I escaped. And, for twelve years, I have thought myself a murderer. I have suffered the tortures of the damned!"

Tom Forsythe advanced on this remarkable visitor with clenched fists. Staring him in the eyes with cold appraisal, his wrath was all too apparent.[164] The dog Spot, young as ever, entered the room and, upon observing the stranger, set up an ominous growling and snarling. At least the dog recognized him!

"What are you trying to do, catechise me? Are you another of these alienists my father has been bringing around?" The young inventor was furious. "If you are," he continued, "you can get out of here—now! I'll have no more of this meddling with my affairs. I'm as sane as any of you and I refuse to submit to this continual persecution."

The elder Forsythe grunted, and Culkin laid a restraining hand on his arm. "Just a minute now, Tom," he said soothingly. "This stranger is no alienist. He has a story to tell. Please permit him to finish."

Somewhat mollified, Tom Forsythe shrugged his assent.

"Tom," continued the stranger, more calmly now, "what I have said is the truth. I shall prove it to you. I'll tell you things no mortals on earth could know but we two. Remember the day I captured the big rooster for you—the monster you had created? Remember the night you awakened me and brought me here in the moonlight? Remember the rabbit whose leg you amputated and re-grew? The poor guinea pig you had suffocated and whose life you restored? Spot here? Don't you remember rejuvenating him? I was here. And you refused to use your process on me, old man that I was. Then is when I went mad and attacked you. Do you believe me, Tom?"

Then a strange thing happened. While Tom Forsythe gazed in growing belief, the stranger's shoulders sagged and he trembled as with the ague. The two older men who had kept in the background gasped their astonishment as his hair faded to a sickly gray, then became as white as the driven snow. Old Crompton was reverting to his previous state! Within five minutes, instead of the handsome young stranger, there stood before them a bent, withered old man—Old Crompton beyond a doubt. The effects of Tom's process were spent.

"Well I'm damned!" ejaculated Alton Forsythe. "You have been right all along, Asa. And I am mighty glad I did not commit Tom as I intended. He has told us the truth all these years and we were not wise enough to see it."

"We!" exclaimed the judge. "You, Alton Forsythe! I have always upheld him. You have done your son a grave injustice and you owe him your apologies if ever a father owed his son anything."

"You are right, Asa." And, his aristocratic pride forgotten, Alton Forsythe rushed to the side of his son and embraced him.

The judge turned to Old Crompton pityingly. "Rather a bad ending for you, Crompton," he said. "Still, it is better by far than being branded as a murderer."

"Better? Better?" croaked Old Crompton. "It is wonderful, Judge. I have never been so happy in my life!"

The face of the old man beamed, though scalding tears coursed down the withered and seamed cheeks. The two Forsythes looked up from their demonstrations of peacemaking to listen to the amazing words of the old hermit.

"Yes, happy for the first time in my life," he continued. "I am one hundred years of age, gentlemen, and I now look it and feel it. That is as it should be. And my experience has taught me a final lasting lesson. None of you know it, but, when I was but a very young man I was bitterly disappointed in love. Ha! ha! Never think it to look at me now, would you? But I was, and it ruined my entire life. I had a little money—inherited—and I traveled about in the world for a few years, then settled in that old hut across the road where I buried myself for sixty years, becoming crabbed and sour and despicable. Young Tom here was the[165] first bright spot and, though I admired him, I hated him for his opportunities, hated him for that which he had that I had not. With the promise of his invention I thought I saw happiness, a new life for myself. I got what I wanted, though not in the way I had expected. And I want to tell you gentlemen that there is nothing in it. With developments of modern science you may be able to restore a man's youthful vigor of body, but you can't cure his mind with electricity. Though I had a youthful body, my brain was the brain of an old man—memories were there which could not be suppressed. Even had I not had the fancied death of young Tom on my conscience I should still have been miserable. I worked. God, how I worked—to forget! But I could not forget. I was successful in business and made a lot of money. I am more independent—probably wealthier than you, Alton Forsythe, but that did not bring happiness. I longed to be myself once more, to have the aches and pains which had been taken from me. It is natural to age and to die. Immortality would make of us a people of restless misery. We would quarrel and bicker and long for death, which would not come to relieve us. Now it is over for me and I am glad—glad—glad!"

He paused for breath, looking beseechingly at Tom Forsythe. "Tom," he said, "I suppose you have nothing for me in your heart but hatred. And I don't blame you. But I wish—I wish you would try and forgive me. Can you?"

The years had brought increased understanding and tolerance to young Tom. He stared at Old Crompton and the long-nursed anger over the destruction of his equipment melted into a strange mixture of pity and admiration for the courageous old fellow.

"Why, I guess I can, Crompton," he replied. "There was many a day when I struggled hopelessly to reconstruct my apparatus, cursing you with every bit of energy in my make-up. I could cheerfully have throttled you, had you been within reach. For twelve years I have labored incessantly to reproduce the results we obtained on the night of which you speak. People called me insane—even my father wished to have me committed to an asylum. And, until now, I have been unsuccessful. Only to-day has it seemed for the first time that the experiments will again succeed. But my ideas have changed with regard to the uses of the process. I was a cocksure young pup in the old days, with foolish dreams of fame and influence. But I have seen the error of my ways. Your experience, too, convinces me that immortality may not be as desirable as I thought. But there are great possibilities in the way of relieving the sufferings of mankind and in making this a better world in which to live. With your advice and help I believe I can do great things. I now forgive you freely and I ask you to remain here with me to assist in the work that is to come. What do you say to the idea?"

At the reverent thankfulness in the pale eyes of the broken old man who had so recently been a perfect specimen of vigorous youth, Alton Forsythe blew his nose noisily. The little judge smiled benevolently and shook his head as if to say, "I told you so." Tom and Old Crompton gripped hands—mightily.

COMING, NEXT MONTH

BRIGANDS OF THE MOON

By RAY CUMMINGS

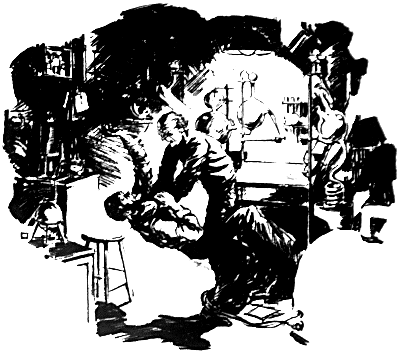

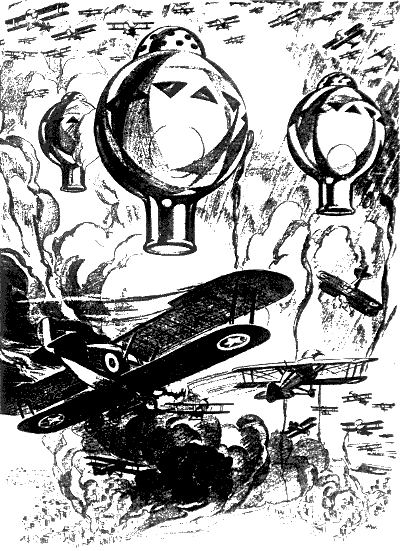

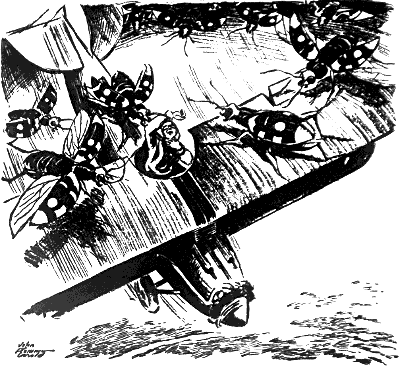

The sky was alive with winged shapes, and high in the air shone the glittering menace, trailing five plumes of gas.

When Cyrus R. Thurston bought himself a single-motored Stoughton job he was looking for new thrills. Flying around the east coast had lost its zest: he wanted to join that jaunty group who spoke so easily of hopping off for Los Angeles.

And what Cyrus Thurston wanted he usually obtained. But if that young millionaire-sportsman had been told that on his first flight this blocky, bulletlike ship was to pitch him headlong into the exact center of the wildest, strangest war this earth had ever seen—well, it is still probable that the Stoughton company would not have lost the sale.

They were roaring through the starlit, calm night, three thousand feet above a sage sprinkled desert, when the trip ended. Slim Riley had[167] the stick when the first blast of hot oil ripped slashingly across the pilot's window. "There goes your old trip!" he yelled. "Why don't they try putting engines in these ships?"

He jammed over the throttle and, with motor idling, swept down toward the endless miles of moonlit waste. Wind? They had been boring into it. Through the opened window he spotted a likely stretch of ground. Setting down the ship on a nice piece of Arizona desert was a mere detail for Slim.

[168] "Let off a flare," he ordered, "when I give the word."

The white glare of it faded the stars as he sideslipped, then straightened out on his hand-picked field. The plane rolled down a clear space and stopped. The bright glare persisted while he stared curiously from the quiet cabin. Cutting the motor he opened both windows, then grabbed Thurston by the shoulder.

"'Tis a curious thing, that," he said unsteadily. His hand pointed straight ahead. The flare died, but the bright stars of the desert country still shone on a glistening, shining bulb.

It was some two hundred feet away. The lower part was lost in shadow, but its upper surfaces shone rounded and silvery like a giant bubble. It towered in the air, scores of feet above the chaparral beside it. There was a round spot of black on its side, which looked absurdly like a door....

"I saw something moving," said Thurston slowly. "On the ground I saw.... Oh, good Lord, Slim, it isn't real!"

Slim Riley made no reply. His eyes were riveted to an undulating, ghastly something that oozed and crawled in the pale light not far from the bulb. His hand was reaching, reaching.... It found what he sought; he leaned toward the window. In his hand was the Very pistol for discharging the flares. He aimed forward and up.

The second flare hung close before it settled on the sandy floor. Its blinding whiteness made the more loathsome the sickening yellow of the flabby flowing thing that writhed frantically in the glare. It was formless, shapeless, a heaving mound of nauseous matter. Yet even in its agonized writhing distortions they sensed the beating pulsations that marked it a living thing.

There were unending ripplings crossing and recrossing through the convolutions. To Thurston there was suddenly a sickening likeness: the thing was a brain from a gigantic skull—it was naked—was suffering....

The thing poured itself across the sand. Before the staring gaze of the speechless men an excrescence appeared—a thick bulb on the mass—that protruded itself into a tentacle. At the end there grew instantly a hooked hand. It reached for the black opening in the great shell, found it, and the whole loathsome shapelessness poured itself up and through the hole.

Only at the last was it still. In the dark opening the last slippery mass held quiet for endless seconds. It formed, as they watched, to a head—frightful—menacing. Eyes appeared in the head; eyes flat and round and black save for a cross slit in each; eyes that stared horribly and unchangingly into theirs. Below them a gaping mouth opened and closed.... The head melted—was gone....

And with its going came a rushing roar of sound.

From under the metallic mass shrieked a vaporous cloud. It drove at them, a swirling blast of snow and sand. Some buried memory of gas attacks woke Riley from his stupor. He slammed shut the windows an instant before the cloud struck, but not before they had seen, in the moonlight, a gleaming, gigantic, elongated bulb rise swiftly—screamingly—into the upper air.

The blast tore at their plane. And the cold in their tight compartment was like the cold of outer space. The men stared, speechless, panting. Their breath froze in that frigid room into steam clouds.

"It—it...." Thurston gasped—and slumped helpless upon the floor.

It was an hour before they dared open the door of their cabin. An hour of biting, numbing cold. Zero—on a warm summer night on the desert! Snow in the hurricane that had struck them!

"'Twas the blast from the thing," guessed the pilot; "though never did[169] I see an engine with an exhaust like that." He was pounding himself with his arms to force up the chilled circulation.

"But the beast—the—the thing!" exclaimed Thurston. "It's monstrous; indecent! It thought—no question of that—but no body! Horrible! Just a raw, naked, thinking protoplasm!"

It was here that he flung open the door. They sniffed cautiously of the air. It was warm again—clean—save for a hint of some nauseous odor. They walked forward; Riley carried a flash.

The odor grew to a stench as they came where the great mass had lain. On the ground was a fleshy mound. There were bones showing, and horns on a skull. Riley held the light close to show the body of a steer. A body of raw bleeding meat. Half of it had been absorbed....

"The damned thing," said Riley, and paused vainly for adequate words. "The damned thing was eating.... Like a jelly-fish, it was!"

"Exactly," Thurston agreed. He pointed about. There were other heaps scattered among the low sage.

"Smothered," guessed Thurston, "with that frozen exhaust. Then the filthy thing landed and came out to eat."

"Hold the light for me," the pilot commanded. "I'm goin' to fix that busted oil line. And I'm goin' to do it right now. Maybe the creature's still hungry."

They sat in their room. About them was the luxury of a modern hotel. Cyrus Thurston stared vacantly at the breakfast he was forgetting to eat. He wiped his hands mechanically on a snowy napkin. He looked from the window. There were palm trees in the park, and autos in a ceaseless stream. And people! Sane, sober people, living in a sane world. Newsboys were shouting; the life of the city was flowing.

"Riley!" Thurston turned to the man across the table. His voice was curiously toneless, and his face haggard. "Riley, I haven't slept for three nights. Neither have you. We've got to get this thing straight. We didn't both become absolute maniacs at the same instant, but—it was not there, it was never there—not that...." He was lost in unpleasant recollections. "There are other records of hallucinations."

"Hallucinations—hell!" said Slim Riley. He was looking at a Los Angeles newspaper. He passed one hand wearily across his eyes, but his face was happier than it had been in days.

"We didn't imagine it, we aren't crazy—it's real! Would you read that now!" He passed the paper across to Thurston. The headlines were startling.

"Pilot Killed by Mysterious Airship. Silvery Bubble Hangs Over New York. Downs Army Plane in Burst of Flame. Vanishes at Terrific Speed."

"It's our little friend," said Thurston. And on his face, too, the lines were vanishing; to find this horror a reality was positive relief. "Here's the same cloud of vapor—drifted slowly across the city, the accounts says, blowing this stuff like steam from underneath. Airplanes investigated—an army plane drove into the vapor—terrific explosion—plane down in flames—others wrecked. The machine ascended with meteor speed, trailing blue flame. Come on, boy, where's that old bus? Thought I never wanted to fly a plane again. Now I don't want to do anything but."

"Where to?" Slim inquired.

"Headquarters," Thurston told him. "Washington—let's go!"

From Los Angeles to Washington is not far, as the plane flies. There was a stop or two for gasoline, but it was only a day later that they were seated in the War Office. Thurston's card had gained immediate admittance. "Got the low-down," he had written on the back of his card, "on the mystery airship."

"What you have told me is incred[170]ible," the Secretary was saying, "or would be if General Lozier here had not reported personally on the occurrence at New York. But the monster, the thing you have described.... Cy, if I didn't know you as I do I would have you locked up."

"It's true," said Thurston, simply. "It's damnable, but it's true. Now what does it mean?"

"Heaven knows," was the response. "That's where it came from—out of the heavens."

"Not what we saw," Slim Riley broke in. "That thing came straight out of Hell." And in his voice was no suggestion of levity.

"You left Los Angeles early yesterday; have you seen the papers?"

Thurston shook his head.

"They are back," said the Secretary. "Reported over London—Paris—the West Coast. Even China has seen them. Shanghai cabled an hour ago."

"Them? How many are there?"

"Nobody knows. There were five seen at one time. There are more—unless the same ones go around the world in a matter of minutes."

Thurston remembered that whirlwind of vapor and a vanishing speck in the Arizona sky. "They could," he asserted. "They're faster than anything on earth. Though what drives them ... that gas—steam—whatever it is...."

"Hydrogen," stated General Lozier. "I saw the New York show when poor Davis got his. He flew into the exhaust; it went off like a million bombs. Characteristic hydrogen flame trailed the damn thing up out of sight—a tail of blue fire."

"And cold," stated Thurston.

"Hot as a Bunsen burner," the General contradicted. "Davis' plane almost melted."

"Before it ignited," said the other. He told of the cold in their plane.

"Ha!" The General spoke explosively. "That's expansion. That's a tip on their motive power. Expansion of gas. That accounts for the cold and the vapor. Suddenly expanded it would be intensely cold. The moisture of the air would condense, freeze. But how could they carry it? Or"—he frowned for a moment, brows drawn over deep-set gray eyes—"or generate it? But that's crazy—that's impossible!"

"So is the whole matter," the Secretary reminded him. "With the information Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley have given us, the whole affair is beyond any gage our past experience might supply. We start from the impossible, and we go—where? What is to be done?"

"With your permission, sir, a number of things shall be done. It would be interesting to see what a squadron of planes might accomplish, diving on them from above. Or anti-aircraft fire."

"No," said the Secretary of War, "not yet. They have looked us over, but they have not attacked. For the present we do not know what they are. All of us have our suspicions—thoughts of interplanetary travel—thoughts too wild for serious utterance—but we know nothing.

"Say nothing to the papers of what you have told me," he directed Thurston. "Lord knows their surmises are wild enough now. And for you, General, in the event of any hostile move, you will resist."

"Your order was anticipated, sir." The General permitted himself a slight smile. "The air force is ready."

"Of course," the Secretary of War nodded. "Meet me here to-night—nine o'clock." He included Thurston and Riley in the command. "We need to think ... to think ... and perhaps their mission is friendly."

"Friendly!" The two flyers exchanged glances as they went to the door. And each knew what the other was seeing—a viscous ocherous mass that formed into a head where eyes devilish in their hate stared coldly into theirs....

[171] "Think, we need to think," repeated Thurston later. "A creature that is just one big hideous brain, that can think an arm into existence—think a head where it wishes! What does a thing like that think of? What beastly thoughts could that—that thing conceive?"

"If I got the sights of a Lewis gun on it," said Riley vindictively, "I'd make it think."

"And my guess is that is all you would accomplish," Thurston told him. "I am forming a few theories about our visitors. One is that it would be quite impossible to find a vital spot in that big homogeneous mass."

The pilot dispensed with theories: his was a more literal mind. "Where on earth did they come from, do you suppose, Mr. Thurston?"

They were walking to their hotel. Thurston raised his eyes to the summer heavens. Faint stars were beginning to twinkle; there was one that glowed steadily.

"Nowhere on earth," Thurston stated softly, "nowhere on earth."

"Maybe so," said the pilot, "maybe so. We've thought about it and talked about it ... and they've gone ahead and done it." He called to a newsboy; they took the latest editions to their room.

The papers were ablaze with speculation. There were dispatches from all corners of the earth, interviews with scientists and near scientists. The machines were a Soviet invention—they were beyond anything human—they were harmless—they would wipe out civilization—poison gas—blasts of fire like that which had enveloped the army flyer....

And through it all Thurston read an ill-concealed fear, a reflection of panic that was gripping the nation—the whole world. These great machines were sinister. Wherever they appeared came the sense of being watched, of a menace being calmly withheld. And at thought of the obscene monsters inside those spheres, Thurston's lips were compressed and his eyes hardened. He threw the papers aside.

"They are here," he said, "and that's all that we know. I hope the Secretary of War gets some good men together. And I hope someone is inspired with an answer."

"An answer is it?" said Riley. "I'm thinkin' that the answer will come, but not from these swivel-chair fighters. 'Tis the boys in the cockpits with one hand on the stick and one on the guns that will have the answer."

But Thurston shook his head. "Their speed," he said, "and the gas! Remember that cold. How much of it can they lay over a city?"

The question was unanswered, unless the quick ringing of the phone was a reply.

"War Department," said a voice. "Hold the wire." The voice of the Secretary of War came on immediately.

"Thurston?" he asked. "Come over at once on the jump, old man. Hell's popping."

The windows of the War Department Building were all alight as they approached. Cars were coming and going; men in uniform, as the Secretary had said, "on the jump." Soldiers with bayonets stopped them, then passed Thurston and his companion on. Bells were ringing from all sides. But in the Secretary's office was perfect quiet.

General Lozier was there, Thurston saw, and an imposing array of gold-braided men with a sprinkling of those in civilian clothes. One he recognized: MacGregor from the Bureau of Standards. The Secretary handed Thurston some papers.

"Radio," he explained. "They are over the Pacific coast. Hit near Vancouver; Associated Press says city destroyed. They are working down the coast. Same story—blast of hydrogen from their funnel shaped base. Colder than Greenland below them; snow fell in Seattle. No real attack since Van[172]couver and little damage done—" A message was laid before him.

"Portland," he said. "Five mystery ships over city. Dart repeatedly toward earth, deliver blast of gas and then retreat. Doing no damage. Apparently inviting attack. All commercial planes ordered grounded. Awaiting instructions.

"Gentlemen," said the Secretary, "I believe I speak for all present when I say that, in the absence of first hand information, we are utterly unable to arrive at any definite conclusion or make a definite plan. There is a menace in this, undeniably. Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley have been good enough to report to me. They have seen one machine at close range. It was occupied by a monster so incredible that the report would receive no attention from me did I not know Mr. Thurston personally.

"Where have they come from? What does it mean—what is their mission? Only God knows.

"Gentlemen, I feel that I must see them. I want General Lozier to accompany me, also Doctor MacGregor, to advise me from the scientific angle. I am going to the Pacific Coast. They may not wait—that is true—but they appear to be going slowly south. I will leave to-night for San Diego. I hope to intercept them. We have strong air-forces there; the Navy Department is cooperating."

He waited for no comment. "General," he ordered, "will you kindly arrange for a plane? Take an escort or not as you think best.

"Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley will also accompany us. We want all the authoritative data we can get. This on my return will be placed before you, gentlemen, for your consideration." He rose from his chair. "I hope they wait for us," he said.

Time was when a commander called loudly for a horse, but in this day a Secretary of War is not kept waiting for transportation. Sirening motorcycles preceded them from the city. Within an hour, motors roaring wide open, propellers ripping into the summer night, lights slipping eastward three thousand feet below, the Secretary of War for the United States was on his way. And on either side from their plane stretched the arms of a V. Like a flight of gigantic wild geese, fast fighting planes of the Army air service bored steadily into the night, guarantors of safe convoy.

"The Air Service is ready," General Lozier had said. And Thurston and his pilot knew that from East coast to West, swift scout planes, whose idling engines could roar into action at a moment's notice, stood waiting; battle planes hidden in hangars would roll forth at the word—the Navy was cooperating—and at San Diego there were strong naval units, Army units, and Marine Corps.

"They don't know what we can do, what we have up our sleeve: they are feeling us out," said the Secretary. They had stopped more than once for gas and for wireless reports. He held a sheaf of typewritten briefs.

"Going slowly south. They have taken their time. Hours over San Francisco and the bay district. Repeating same tactics; fall with terrific speed to cushion against their blast of gas. Trying to draw us out, provoke an attack, make us show our strength. Well, we shall beat them to San Diego at this rate. We'll be there in a few hours."

The afternoon sun was dropping ahead of them when they sighted the water. "Eckener Pass," the pilot told them, "where the Graf Zeppelin came through. Wonder what these birds would think of a Zepp!

"There's the ocean," he added after a time. San Diego glistened against the bare hills. "There's North Island—the Army field." He stared intently ahead, then shouted: "And there they are! Look there!"

Over the city a cluster of meteors[173] was falling. Dark underneath, their tops shone like pure silver in the sun's slanting glare. They fell toward the city, then buried themselves in a dense cloud of steam, rebounding at once to the upper air, vapor trailing behind them.

The cloud billowed slowly. It struck the hills of the city, then lifted and vanished.

"Land at once," requested the Secretary. A flash of silver countermanded the order.

It hung there before them, a great gleaming globe, keeping always its distance ahead. It was elongated at the base, Thurston observed. From that base shot the familiar blast that turned steamy a hundred feet below as it chilled the warm air. There were round orifices, like ports, ranged around the top, where an occasional jet of vapor showed this to be a method of control. Other spots shone dark and glassy. Were they windows? He hardly realized their peril, so interested was he in the strange machine ahead.

Then: "Dodge that vapor," ordered General Lozier. The plane wavered in signal to the others and swung sharply to the left. Each man knew the flaming death that was theirs if the fire of their exhaust touched that explosive mixture of hydrogen and air. The great bubble turned with them and paralleled their course.

"He's watching us," said Riley, "giving us the once over, the slimy devil. Ain't there a gun on this ship?"

The General addressed his superior. Even above the roar of the motors his voice seemed quiet, assured. "We must not land now," he said. "We can't land at North Island. It would focus their attention upon our defenses. That thing—whatever it is—is looking for a vulnerable spot. We must.... Hold on—there he goes!"

The big bulb shot upward. It slanted above them, and hovered there.

"I think he is about to attack," said the General quietly. And, to the commander of their squadron: "It's in your hands now, Captain. It's your fight."

The Captain nodded and squinted above. "He's got to throw heavier stuff than that," he remarked. A small object was falling from the cloud. It passed close to their ship.

"Half-pint size," said Cyrus Thurston, and laughed in derision. There was something ludicrous in the futility of the attack. He stuck his head from a window into the gale they created. He sheltered his eyes to try to follow the missile in its fall.

They were over the city. The criss-cross of streets made a grill-work of lines; tall buildings were dwarfed from this three thousand foot altitude. The sun slanted across a projecting promontory to make golden ripples on a blue sea and the city sparkled back in the clear air. Tiny white faces were massed in the streets, huddled in clusters where the futile black missile had vanished.

And then—then the city was gone....

A white cloud-bank billowed and mushroomed. Slowly, it seemed to the watcher—so slowly.

It was done in the fraction of a second. Yet in that brief time his eyes registered the chaotic sweep in advance of the cloud. There came a crashing of buildings in some monster whirlwind, a white cloud engulfing it all.... It was rising—was on them.

"God," thought Thurston, "why can't I move!" The plane lifted and lurched. A thunder of sound crashed against them, an intolerable force. They were crushed to the floor as the plane was hurled over and upward.

Out of the mad whirling tangle of flying bodies, Thurston glimpsed one clear picture. The face of the pilot hung battered and blood-covered before him, and over the limp body the hand of Slim Riley clutched at the switch.

"Bully boy," he said dazedly, "he's cutting the motors...." The thought ended in blackness.

[174] There was no sound of engines or beating propellers when he came to his senses. Something lay heavy upon him. He pushed it to one side. It was the body of General Lozier.

He drew himself to his knees to look slowly about, rubbed stupidly at his eyes to quiet the whirl, then stared at the blood on his hand. It was so quiet—the motors—what was it that happened? Slim had reached for the switch....

The whirling subsided. Before him he saw Slim Riley at the controls. He got to his feet and went unsteadily forward. It was a battered face that was lifted to his.

"She was spinning," the puffed lips were muttering slowly. "I brought her out ... there's the field...." His voice was thick; he formed the words slowly, painfully. "Got to land ... can you take it? I'm—I'm—" He slumped limply in his seat.

Thurston's arms were uninjured. He dragged the pilot to the floor and got back of the wheel. The field was below them. There were planes taxiing out; he heard the roar of their motors. He tried the controls. The plane answered stiffly, but he managed to level off as the brown field approached.

Thurston never remembered that landing. He was trying to drag Riley from the battered plane when the first man got to him.

"Secretary of War?" he gasped. "In there.... Take Riley; I can walk."

"We'll get them," an officer assured him. "Knew you were coming. They sure gave you hell! But look at the city!"

Arms carried him stumbling from the field. Above the low hangars he saw smoke clouds over the bay. These and red rolling flames marked what had been an American city. Far in the heavens moved five glinting specks.

His head reeled with the thunder of engines. There were planes standing in lines and more erupting from hangars, where khaki-clad men, faces tense under leather helmets, rushed swiftly about.

"General Lozier is dead," said a voice. Thurston turned to the man. They were bringing the others. "The rest are smashed up some," the officer told him, "but I think they'll pull through."

The Secretary of War for the United States lay beside him. Men with red on their sleeves were slitting his coat. Through one good eye he squinted at Thurston. He even managed a smile.

"Well, I wanted to see them up close," he said. "They say you saved us, old man."

Thurston waved that aside. "Thank Riley—" he began, but the words ended in the roar of an exhaust. A plane darted swiftly away to shoot vertically a hundred feet in the air. Another followed and another. In a cloud of brown dust they streamed endlessly out, zooming up like angry hornets, eager to get into the fight.

"Fast little devils!" the ambulance man observed. "Here come the big boys."

A leviathan went deafeningly past. And again others came on in quick succession. Farther up the field, silvery gray planes with rudders flaunting their red, white and blue rose circling to the heights.

"That's the Navy," was the explanation. The surgeon straightened the Secretary's arm. "See them come off the big airplane carriers!"

If his remarks were part of his professional training in removing a patient's thoughts from his pain, they were effective. The Secretary stared out to sea, where two great flat-decked craft were shooting planes with the regularity of a rapid fire gun. They stood out sharply against a bank of gray fog. Cyrus Thurston forgot his bruised body, forgot his own peril—even the inferno that raged back across the bay: he was lost in the sheer thrill of the spectacle.

Above them the sky was alive with winged shapes. And from all the disorder there was order appearing. Squadron after squadron swept to battle formation. Like flights of wild ducks the true sharp-pointed Vs soared off into the sky. Far above and beyond, rows of dots marked the race of swift scouts for the upper levels. And high in the clear air shone the glittering menace trailing their five plumes of gas.

A deeper detonation was merging into the uproar. It came from the ships, Thurston knew, where anti-aircraft guns poured a rain of shells into the sky. About the invaders they bloomed into clusters of smoke balls. The globes shot a thousand feet into the air. Again the shells found them, and again they retreated.

"Look!" said Thurston. "They got one!"

He groaned as a long curving arc of speed showed that the big bulb was under control. Over the ships it paused, to balance and swing, then shot to the zenith as one of the great boats exploded in a cloud of vapor.

The following blast swept the airdrome. Planes yet on the ground went like dry autumn leaves. The hangars were flattened.

Thurston cowered in awe. They were sheltered, he saw, by a slope of the ground. No ridicule now for the bombs!

A second blast marked when the gas-cloud ignited. The billowing flames were blue. They writhed in tortured convulsions through the air. Endless explosions merged into one rumbling roar.

MacGregor had roused from his stupor; he raised to a sitting position.

"Hydrogen," he stated positively, and pointed where great volumes of flame were sent whirling aloft. "It burns as it mixes with air." The scientist was studying intently the mammoth reaction. "But the volume," he marveled, "the volume! From that small container! Impossible!"

"Impossible," the Secretary agreed, "but...." He pointed with his one good arm toward the Pacific. Two great ships of steel, blackened and battered in that fiery breath, tossed helplessly upon the pitching, heaving sea. They furnished to the scientist's exclamation the only adequate reply.

Each man stared aghast into the pallid faces of his companions. "I think we have underestimated the opposition," said the Secretary of War quietly. "Look—the fog is coming in, but it's too late to save them."

The big ships were vanishing in the oncoming fog. Whirls of vapor were eddying toward them in the flame-blaster air. Above them the watchers saw dimly the five gleaming bulbs. There were airplanes attacking: the tapping of machine-gun fire came to them faintly.

Fast planes circled and swooped toward the enemy. An armada of big planes drove in from beyond. Formations were blocking space above.... Every branch of the service was there, Thurston exulted, the army, Marine Corps, the Navy. He gripped hard at the dry ground in a paralysis of taut nerves. The battle was on, and in the balance hung the fate of the world.

The fog drove in fast. Through straining eyes he tried in vain to glimpse the drama spread above. The world grew dark and gray. He buried his face in his hands.

And again came the thunder. The men on the ground forced their gaze to the clouds, though they knew some fresh horror awaited.

The fog-clouds reflected the blue terror above. They were riven and torn. And through them black objects were falling. Some blazed as they fell. They slipped into unthought maneuvers—they darted to earth trailing yellow and black of gasoline fires. The air was filled with the dread rain of death that was spewed from the gray clouds. Gone was the roaring of motors. The air-force of the San Diego[176] area swept in silence to the earth, whose impact alone could give kindly concealment to their flame-stricken burden.