The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hollyhock, by L. T. Meade

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Hollyhock

A Spirit of Mischief

Author: L. T. Meade

Illustrator: W. Rainey

Release Date: April 12, 2009 [EBook #28566]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOLLYHOCK ***

Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | THE CHILDREN OF THE UPPER GLEN |

| II. | AUNT AGNES |

| III. | AUNT AGNES'S WAY |

| IV. | THE PALACE OF THE KINGS |

| V. | THE EARLY BIRD |

| VI. | THE HEAD-MISTRESS |

| VII. | THE OPENING OF THE GREAT SCHOOL |

| VIII. | HOLLYHOCK LEFT IN THE COLD |

| IX. | THE WOMAN WHO INTERFERED |

| X. | A MISERABLE GIRL |

| XI. | SOFT AND LOW |

| XII. | UNDER PROTEST |

| XIII. | THE SUMMER PARLOUR |

| XIV. | THE FIRE THAT WILL NOT LIGHT |

| XV. | CREAM |

| XVI. | THE GIRL WITH THE WAYWARD HEART |

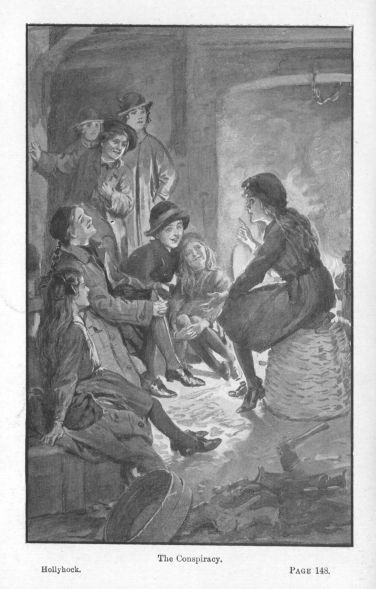

| XVII. | THE GREAT CONSPIRACY |

| XVIII. | LEUCHA'S TERROR |

| XIX. | JASMINE'S RESOLVE |

| XX. | MEG'S CONSCIENCE |

| XXI. | THERE IS NO WAY OUT |

| XXII. | THE END OF LOVE |

| XXIII. | THE GREAT CHARADE |

| XXIV. | THE WARM HEART ROUSED AT LAST |

| XXV. | THE FIRE SPIRITS |

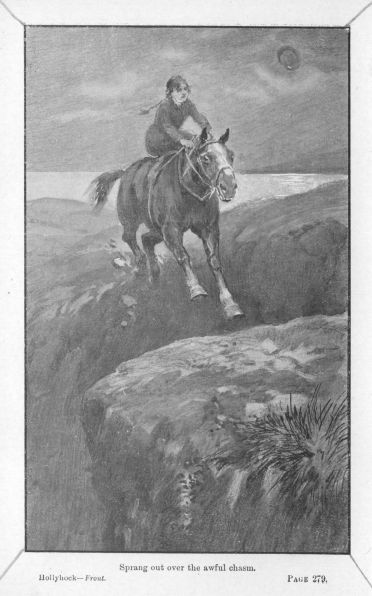

| XXVI. | HOLLYHOCK'S DEED OF VALOUR |

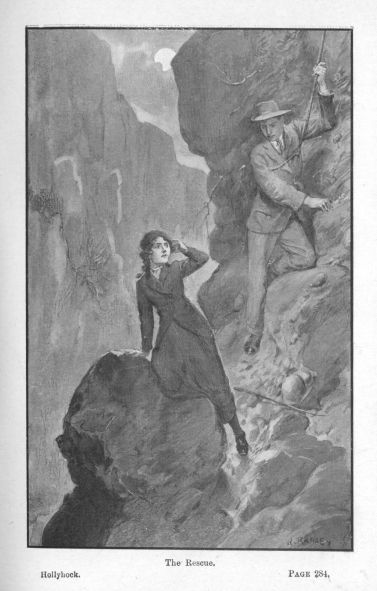

| XXVII. | ARDSHIEL TO THE RESCUE |

| XXVIII. | WHAT LOVE CAN DO |

There was, of course, the Lower Glen, which consisted of boggy places and endless mists in winter, and a small uninteresting village, where the barest necessaries of life could be bought, and where the folks were all of the humbler class, well-meaning, hard-working, but, alas! poor of the poor. When all was said and done, the Lower Glen was a poor place, meant for poor people.

Very different was the Upper Glen. It was beyond doubt a most beautiful region, and as Edinburgh and Glasgow were only some fifty miles away, in these days of motor-cars it was easy to drive there for the good things of life. The Glen was sheltered from the worst storms by vast mountains, and was in itself both broad and flat, with a great inrush of fresh air, a mighty river, and three lakes of various sizes. So beautiful was it, so delightful were its soft and yet at times keen breezes, that it might have been called 'The Home of Health.' But no one thought of giving the Glen this title, for the simple reason that no one thought of health in the Glen; every one was enjoying that blessed privilege to the utmost.

At the time when this story opens, two families lived in the Upper Glen. There was a widowed lady, Mrs Constable, who resided at a lovely home called The Paddock; and there was her brother, a widower, who lived in a house equally beautiful, named The Garden.

The Hon. George Lennox had five young daughters, whom he called not by their baptismal names, but by flower names. Mrs Constable, again, called her five boys after precious stones.

The names of the girls were Jasmine, otherwise Lucy; Gentian, otherwise Margaret; Hollyhock, whose baptismal name was Jacqueline; Rose of the Garden, who was really Rose; and Delphinium, whose real name was Dorothy.

The boys, sons of gentle Mrs Constable, were Jasper, otherwise John; Sapphire, whose real name was Robert; Garnet, baptised Wallace; Opal, whose name was Andrew; and Emerald, christened Ronald.

These happy children scarcely ever heard their baptismal names. The flower names and the precious stones names clung to them until the day when pretty Jasmine and manly Jasper were fifteen years of age. On that day there came a very great change in the lives of the Flower Girls and the Precious Stones. On that very day their real story began. They little guessed it, for few of us do believe in sudden changes in a very peaceful—perhaps too peaceful—life.

Nevertheless, a very great change was at hand, and the news which heralded that tremendous change reached them on the evening of the birthday of Jasmine and Jasper. It was the custom of these two most united families to spend their evenings together—one evening at The Garden, the Flower Girls' home, and the next at The Paddock, Mrs Constable's house. On this special occasion the Flower Girls went with their father to The Paddock, and thus avoided receiving until late in the evening the all-important letter which was to alter their lives completely.

George Lennox, whose dead wife had been a Cameron—a near relative of the head of the great house of Ardshiel—bade his sister a most affectionate good-night, and returned to The Garden with his five bonnie lassies. They had passed a delightful evening together, and on account of the double birthday Lennox and Mrs Constable had made up a most charming little play, in which the Flower Girls and the Precious Stones took part. Ever true and kind of heart, they had invited from the Glen a number of children, and also their parents, to witness the performance. The play had given untold delight, and the guests from the Lower Glen finished the evening's entertainment with a splendid supper, ending with the well-known and beloved song of 'Auld Lang Syne.'

Mr Lennox and Mrs Constable taught their girls and boys without any aid from outside. All ten children were smart; indeed, it would be difficult to find better-educated young people for their ages. But Mrs Constable knew only too well that whatever the future held in store for her brother's Flower Girls, she must very soon part, one by one, with her splendid boys; for was not this the express wish of her beloved soldier-husband, Major Constable, who had died on the field of battle in Africa, and who had put away a certain sum of money which was to be spent, when the time came, on the children's education? He himself was an old Eton boy, and he wanted his young sons to go to that famous school if at all possible. But before any of the Precious Stones could enter Eton, he must pass at least a year at a preparatory school, and it was the thought of this coming separation that made the sweet gray eyes of the widow fill often with sudden tears. To part with any of her treasures was torture to her. However, we none of us know what lies in store for us, and nothing was farther from the hearts of the children and their parents than the thought of change on this glorious night of mid-June.

The moment Mr Lennox and his five girls entered the great hall, which was so marked a feature of the beautiful Garden, they saw a letter, addressed to The Hon. George Lennox, lying on a table not far from the ingle-nook. Mr Lennox's first impulse was to put the letter aside, but all the little girls clustered round him and begged of him to open it at once. They all gathered round him as they spoke, and being exceeding fond of his daughters, he could not resist their appeal. After all, the unexpected letter might mean less than nothing. In any case, it must be read sometime.

'Oh, Daddy Dumps, do—do read the letter!' cried Hollyhock, the handsomest and most daring of the girls. 'We 're just mad to hear what the braw laddie says. Open the letter, daddy mine, and set our minds at rest.'

'The letter may not be written by any laddie, Hollyhock,' said her father in his gentle, exceedingly dignified way.

'If it's from a woman, we'd best burn it,' said Hollyhock, who had a holy contempt for members of her own sex.

'Oh! but fie, prickly Holly,' said her father. 'You know that I allow no lady to be spoken against in my house.'

'Well, read the letter, daddy—read it!' exclaimed Jasmine. 'We want, anyhow, to know what it contains.'

'I seem to recall the writing,' said Lennox, as he seated himself in an easy-chair. 'You will have it, my dears,' he continued; 'but you may not like it after I have read it. However, here goes!'

The children gathered round their father, who slowly and carefully unfolded the sheet of paper and read as follows:

'MY DEAR GEORGE,—It is my intention to arrive at the Garden to-morrow, and I hope, as your dear wife's half-sister, to get a hearty welcome. I have a great scheme in my head, which I am certain you will approve of, and which will be exceedingly good for your funny little daughters'——

'I do not like that,' interrupted Hollyhock. 'I am not a funny little daughter.'

'Dearest,' said her father, kissing her between her black brows, 'we must forgive Aunt Agnes. She doesn't know us, you see.'

'No; and we don't want to know her,' said Jasmine. 'We are very happy as we are. We are desperately happy; aren't we, Rose; aren't we, Delphy?'

'Yes, of course, of course,' echoed their father; 'but all the same, children, your aunt must come. She is, remember, your dear mother's sister.'

'Did you ever meet her, daddy?' asked Jasmine.

'Yes, years ago, when Delphy was a baby.'

'What was she like, daddy?'

'She wasn't like any of you, my precious Flowers.'

The five little girls gave a profound sigh.

'Will she stay long, daddy?' asked Gentian.

'I sincerely trust not,' said the Honourable George Lennox.

'Then that's all right. We don't mind very much now,' said Hollyhock; and she began to dance wildly about the room.

'You will have to behave, Hollyhock,' said her father with a smile.

Hollyhock drew herself up to her full height; her black eyes gleamed and glowed; her lips parted in a funny, yet naughty, smile. Her hair seemed so full of electricity that it stood out in wonderful rays all over her head.

'And why should I behave well now, daddy mine?' she asked.

'Oh, because of Aunt Agnes.'

'Catch me,' said Hollyhock.—'Who is with me in this matter, girls? Are you, Delphy? Are you, Jasmine? Are you, Gentian? Are you, Rose of the Garden?'

'We 're every one of us with you,' exclaimed Jasmine, snuggling up to her father as she spoke. 'Daddy,' she continued, 'I want to ask you a question. Even if it hurts you, I must ask it. Was our own, ownest mother the least like Aunt Agnes?'

'As the east is from the west, so were those two sisters apart,' he said.

'Then that's all right,' said Hollyhock. 'I'm happy now. I couldn't have endured being rude to a woman who was like my mother, but as it is'——

'You mustn't be rude to her, Hollyhock.'

'We 'll see,' said Hollyhock. 'Leave her to me. I think I'll manage her. Perhaps she's a good old sort—there's no saying. But she and her scheme—daring to come and disturb us and our scheme! I like that—I really do. Good-night, dad; I'm off to bed. I 've had a very happy day, and I suppose happy days end. Anyway, old darling, we'll always have you on our side, sha'n't we?'

'That you will, my darlings,' said Lennox.

'What fun it will be to talk to the Precious Stones about Aunt Agnes!' said Hollyhock. 'Flowers are soft things; at least some flowers are. But stones! they can strike—and ours are so big and so strong.'

'Whatever happens, girls,' said their father, 'we must be polite to your step-aunt, Agnes Delacour.'

'Oh, she's only a "step," poor thing,' said Hollyhock. 'No wonder they were as the east is from the west. Now good-night, daddy. Don't fret. I wish with all my heart we could go back to the Precious Stones to-night and prepare them for battle. They ought to be prepared, oughtn't they?'

'Well, you can't go to see them to-night, Hollyhock; and to-morrow, early, we shall be very busy getting the room ready for Aunt Agnes, for she is my half-sister-in-law, and she did her best to bring up your dearest mother. But I may as well say a few words to you, dear girls, before we part for the night.'

'What is that, dad?' asked Gentian.

'I wonder whether you remember what your real names are.'

'The names that were given us at the font?' said Jasmine.

'Yes; your baptismal names—your real names.'

'I 'll say them off fast enough,' said Jasmine. 'There's Jasmine, that's me; there 's Gentian, meaning the little gray-eyed girl in the corner; there's Rose, who always will be and can be nothing but Rose; there's Hollyhock; there's Delphinium. Delphinium is hard to say, but Delphy is quite easy.'

'And I suppose you think,' said their father in his half-humorous, half-serious voice, 'that you were really baptised by those names?'

'Why, of course, Dumpy Dad!' cried Hollyhock.

'Well, I must undeceive you, my dear Flower Girls. Your mother and I took a notion to have you baptised by certain names and called by others. Jasmine is really Lucy; Gentian is Margaret; Hollyhock, your real name is Jacqueline; Rose of the Garden is, however, really Rose; and Delphinium was baptised Dorothy.'

'Well, that is wonderful!' exclaimed Hollyhock. 'I must write down the names before they escape my memory. Give me a bit of paper and a pencil, Daddy Dumps, that I may write down at once our true church names.'

'Here you are, Hollyhock,' said Lennox; 'and do not forget that in the eyes of your step-aunt you are five little girls, not flowers.'

'In the eyes of the old horror,' whispered Hollyhock, who felt much excited at the change in the names.

'I wonder now,' said Gentian when Hollyhock's task was finished, and she passed her scribble to her father to see—'I wonder whether there is a similar mistake in the names of our cousins—or brothers, as they really are to us.'

'Yes, they are like brothers to you, my dears; and your aunt Cecilia was so taken by the notion of the flower names for you that she must needs copy my wife and me, and so it happens that Jasper is really John, Sapphire is Robert, Garnet is Wallace, called after his gallant father, Major Constable'——

'"Scots wha hae wi' Wallace bled,"' sang Hollyhock in her rich, clear voice. 'Aweel, I love him better than ever, the bonnie lad with his black eyes.'

'Children,' said Lennox, 'it is high time for you all to go to bed. We must get through the boys' names as fast as possible. Opal's real name is Andrew.'

'Poor lad,' continued Hollyhock, 'fit servant to Wallace.'

'And,' added Mr Lennox, 'Emerald's baptismal name is Ronald. That is all—five Flower Girls, five Precious Stones, first cousins and the best of friends, even as sisters and brothers. But my Flower Girls must be off to bed without a single moment's further delay. Good-night.'

'"Scots wha hae,"' sang Hollyhock, as she danced lightly up the stairs of the big house. 'I guess, Flowers, that we are about to have a right grand time.'

'Never mind that now,' said Jasmine. 'Whatever happens, the Precious Stones will help us.'

'That's true,' cried Hollyhock. 'Talk to me of fear! I fear nought, nor nobody. The lads, I'm thinking, will be coming to me to help them, if there's fear walking around.'

She looked so bold and bright and daring as she spoke that the other Flower Girls believed her at that moment.

Miss Delacour was an elderly woman with somewhat coarse gray hair. She was not old, but elderly. She had a very broad figure, plump and well-proportioned. Miss Delacour thought little about so trivial a thing as fashion, or mere dress in any shape or form. She was fond of saying that she was as the Almighty made her, and that clothes were nothing but a snare of the flesh.

Agnes Delacour was exceedingly well off, but she lived in a very small house in Chelsea, and gave of her abundance to those whom she called 'the Lord's poor.' Her charities were many and wide-spread, and on that account she was highly esteemed by numbers of people, either very poor or struggling, in that upper class which needs help so much, and gets it so little. To these people Agnes Delacour gave freely, saving many young people from utter ruin by her timely aid, and drawing down on her devoted head the blessings of their fathers and mothers, who spoke of her as one of the Lord's saints. Nevertheless those who knew Miss Delacour really well did not love her. She was too cold, too masterful, for their taste, and these folks would rather live in great difficulties than accept her bounty.

After the death of her young half-sister, Lucy Cameron, who had married, against Miss Delacour's desire, the Hon. George Lennox, Miss Delacour took no notice whatsoever of the five sweet little daughters her half-sister had brought into the world. Miss Delacour left the broken-hearted widower and his little girls to their sorrow, not even answering the letters which for a short time the children, by their father's desire, wrote to their mother's half-sister, so that by-and-by, as they grew older, most of them forgot that they had an aunt Agnes. Lucy Lennox was as unlike her half-sister as it was possible for two sisters to be. In the first place, Agnes, compared with Lucy, was old, being many years her senior; in the second, Agnes was singularly plain, whereas Lucy was very lovely. She was far more than lovely; she was endowed with a wonderful charm which drew the hearts of all people, men and women alike, who saw her. Her beautiful dark eyes, her rosy cheeks, with their rare dimples, her gay laughter, her glorious voice in singing, her pretty way of talking French, almost like one born to the graceful tongue, the way she devoted herself to her husband first, next to her sweet girls, the whole appearance of her radiant face, and her conduct on each and every occasion, made her a favourite with all who knew her.

Alas! she was gone; for Lucy Lennox was one of those not destined to live long in this world. She died just after the birth of her youngest child, and Lennox felt that now his one duty was to do all in his power for the precious Flowers she had left behind her.

There were three great and spacious houses in the Upper Glen. One, we have seen, was occupied by Mr Lennox, one by his sister, Mrs Constable; but between The Paddock and The Garden was a house so large, so magnificent, so richly dowered with all the beauties of nature, that it more nearly resembled a palace than an ordinary house. This great mansion belonged to the Duke of Ardshiel, and was called the Palace of the Kings, for the simple reason that its noble owner was looked upon as a king in those parts. Further, King James the First of England and Sixth of Scotland had passed some time there, and 'Bonnie Prince Charlie' had taken refuge at Ardshiel in the time of his wanderings. The great castle belonged to the Duke, who had many other places of residence, but who had never gone near the Palace of the Kings since a terrible tragedy took place there, about twenty years before the opening of this story.

A kinswoman and ward of Ardshiel's, a charming girl of the name of Viola Cameron, had fallen madly in love with a gallant member of the great clan of Douglas, and the Duke somewhat unwillingly gave his consent to the marriage on condition that Lord Alasdair Douglas should add Cameron to his own name. Lord Alasdair agreed, for great was his love for Viola Cameron. The Duke was now well pleased. He could not but see what a fine fellow Lord Alasdair was, and accordingly he gave the Palace of the Kings to the young pair, and had the whole house and grounds put into perfect order, all at his own expense. The fair young Viola Cameron and the brave Lord Alasdair were to be married on a certain day early in December. All went merry as a marriage bell. But, alas! tragedy was at the door, and early on the wedding morn Lord Alasdair was found cold and dead in the deep lake which formed such a feature of the property. How he died no one could tell; but die he did with life so fair and bright before him, and the girl he loved putting on her wedding clothes for the happy ceremony. There was no apparent reason for his death, for he passionately loved the Lady Viola, and was willing to give up his own proud name for her dear sake.

Viola Cameron mourned frantically for her lover for some time, and refused to go near the Palace of the Kings; but after a time she returned to London society, and eventually married a rich manufacturer, nearly double her age and far beneath her in station.

The Duke, who, on her marriage with Lord Alasdair, was about to settle a fortune upon her, now abandoned all such intentions, and Ardshiel became his once more. Nor would he ever again allow himself to speak of or talk to the Lady Viola. She was now beneath his notice.

The Lady Viola passes completely out of this story. The Palace of the Kings had lain empty and deserted for over twenty long years, and Miss Delacour knew this fact and intended to act accordingly. After making full inquiries she paid the old Duke a visit, taking with her a certain Mrs Macintyre. Mrs Macintyre was one of those women whom all men respect, if they do not love. She had lost both husband and children. She was of high birth and equally good education. She was now, however, in sore want, and Miss Delacour thought she saw a way of helping her and also adding to the lustre of her own name as a great philanthropist. Miss Delacour did most of the talking, and Mrs Macintyre all the sad, gentle smiles. In short, they won over the old Duke, and Miss Delacour arranged that she should call upon Lucy's husband in order to propound her scheme.

The little girls and the boys had time to meet before Miss Delacour's arrival. Although that lady was well off, she would not take a motor-car from Edinburgh to the Upper Glen. She believed that her brother-in-law had a motor-car, and thought it the height of selfishness on his part that he did not send it to town to meet her. But she had her pride, as she expressed it, and in consequence did not arrive at The Garden till about four o'clock in the day, having given the young Constables and the young Lennoxes time to have a very eager chat together, whilst Mrs Constable and Lennox himself had a serious conversation, in which they unanimously expressed the wish that Agnes Delacour would take her departure as soon as possible.

Miss Delacour arrived on the scene in a very bad temper. She was met by Lennox with his beautiful smile and courtly manner. He welcomed her kindly, and gave her his arm to enter the great central hall. Miss Delacour sniffed as she went in. She sniffed more audibly as her small, closely set brown eyes encountered the fixed gaze of five little girls, who, to judge from their manners, were all antagonistic to her.

'Come and speak to your aunt, my dears,' she said.—'George,' she continued, 'I should be glad of some tea.'

'It isn't time for tea yet,' said Hollyhock, but I 'll amuse you. Would you like to see a girl somersaulting up and down the hall? It's a grand place for that sort of exercise, and I can teach you if you like. You are a bit old, but I've seen older. You just have to let yourself go—spread yourself, so to speak—put your hands on the floor and then over you go, over and over. Oh, it's grand sport; we often do it.'

'Then you might do better,' said Miss Delacour, speaking in a very stern voice. 'I haven't quite caught your name, child, but you have evidently not learned respect for your elders.'

'My name is Hollyhock. I 'm a Scots lass frae the heather. Eh, but there's no air like the air o' the heather! Did you ever get a bit of it, all white? Yes, there's luck for you.'

'Do you mean seriously to tell me, George,' said Miss Delacour, 'that you have called that child Hollyhock—that impertinent, rude child, Hollyhock?'

'Well, yes, he has, bless his heart!' said Hollyhock, going up to her father and fondling his head. 'Isn't he a bit of a sort of a thing that you 'd love? Eh, but he's a grand man. He isn't afflicted with bad looks, Aunt Agnes.'

'Send that child out of the room, George,' said Aunt Agnes.

'I refuse to stir,' was Hollyhock's response.

'George, is it true that you have insulted my dead sister's memory by calling one of her offspring by such an awful name as Hollyhock?'

'I have not insulted my wife's memory, Agnes. I took a fancy to call my little girls after flowers. This is Jasmine—real name Lucy, after my lost darling. This is Gentian—real name Margaret. This is Rose—also Rose of the Garden, queen of all flowers. Hollyhock's baptismal name is Jacqueline; and Delphinium, my youngest'—his voice shook a little—'is Dorothy.'

'The one for whom your wife laid down her life,' said Miss Delacour. 'Well, to be sure, I always knew that men were bad, but I did not think they were fools as well.—Understand, you five girls, that while I am here—and I shall probably stay for a long time—you will be Lucy, Margaret, Jacqueline, Rose, and Dorothy to me. I don't care what your silly father calls you.'

'He's not silly,' said Hollyhock. 'He's the best of old ducksy dumps; and if you don't want to learn somersaulting, perhaps you 'd like a hand-to-hand fight. I'm quite ready;' and Hollyhock stamped up to the good lady with clenched fists and angry, black eyes.

'Oh, preserve me from this little terror of a girl!' said Miss Delacour. 'I perceive that the Divine Providence has sent me here just in time.'

'You haven't met the Precious Stones yet,' said Hollyhock. 'Flowers are a bit soft, except roses, which have thorns; but when you meet Jasper and Sapphire and Garnet and Opal and Emerald, I can tell you you 'll have to mind your p's and q's. They won't stand any nonsense; they won't endure any silly speeches, but they 'll just go for you hammer and tongs. They 're boys, every one of them—and—and—we 're expecting them any minute.'

'Jacqueline, you must behave yourself,' said her father. 'You 're trying your aunt very much indeed.—Jasmine, or, rather, my sweet Lucy, will you take your aunt to her bedroom, and order the tea to be got ready a little earlier than usual in the hall to-day?'

Jasmine, otherwise Lucy, obeyed her father's command at a glance, and the old lady and the young girl went up the low broad stairs side by side. Miss Delacour gasped once or twice.

'What a terrible creature your sister is!' she remarked.

'Oh no, she's not really; she only wants her bit of fun.'

'But to be rude to an elderly lady!' continued Miss Delacour.

'She did not mean it for rudeness. She just wanted you to enjoy yourself. You see, we are accustomed to a great deal of freedom, and there never was a man like daddy, and we are so happy with him.'

'Lucy—your name is Lucy, isn't it?'

'I am called Jasmine, but my name is Lucy,' said the girl, with a sigh.

'That was your mother's name,' continued Miss Agnes. 'You remind me of her a little, without having her great beauty. You are a plain child, Lucy, but you ought to be thankful, seeing that such is the will of the Almighty.'

'Jasper says I am exceedingly handsome,' replied Lucy.

'Oh, that awful boy! What a man your father must be to allow such talk!'

'Please, please, auntie, don't speak against him. He's an angel, if ever there was one. I want to make you happy, auntie; but if you speak against father, I greatly fear I can't. Please, for the sake of my mother, be nice to father.'

'I mean to be nice to every one, child. I have come here for the purpose. You certainly have a look of your mother. You have got her eyes, for instance.'

'Oh yes, her eyes and her chin and the roses in the cheeks,' said Jasmine. 'Father calls me the comfort of his life. No one ever, ever said I was ugly before, Aunt Agnes.'

'I perceive that you are an exceedingly vain little girl; but that will be soon knocked out of you.'

'How?' asked Jasmine.

'When my dear friend, Mrs Macintyre, starts her noble school.'

'School!' said Jasmine, turning a little pale. 'But father says he will never allow any of us to go to school.'

'He will do what I wish in this matter. Dear, dear, what a dreary room, so large, and only half-furnished! No wonder poor Lucy died here. She was a timid little thing. She probably died in the very bed that you are putting me into—so thoughtless—so unkind.'

'It isn't thoughtless or unkind, Aunt Agnes, for father sleeps in the bed where mother died, and in the room where she died. But now I hear the boys all arriving. The water in this jug is nice and hot, and here are fresh towels, and Magsie'——

'Who is Magsie?'

'She's a maid; if you ring that bell just there, she 'll come to you, and unpack your trunks. By the way, what a lot of trunks you have brought, Aunt Agnes! I thought you were only coming for a couple of days.'

'Polite, I must say,' remarked Miss Delacour.

'We all thought it,' remarked Jasmine, 'for, you see, you would not come to darling mother's funeral—that did hurt father so awfully.'

'I could not get away. I was helping the sick. It was a case of cataract,' said Miss Delacour. 'I had to hold her hand while the operation went on, otherwise she might have been blind for life. Would you take away a living, breathing person's sight because of senseless clay?'

Jasmine marched out of the room.

If there was a person with a determined will, with a heart set upon certain actions which must and should be carried out, that was the elderly lady known as Agnes Delacour. She never went back on her word. She never relaxed in her charities. She herself lived in a small house in Chelsea, and, being a rich woman, could thereby spend large sums on the poor and the needy. She was a wise woman in her generation, and never gave help when help was not needed. No begging letters appealed to her, no pretended woes took her in; but the real sufferers in life! these she attended to, these she helped, these she comforted. Her universal plan was to get the sorrowful and the poor in a very great measure to help themselves. She had no idea of encouraging what she called idleness. Thrift was her motto. If a person needed money, that person must work for it. Agnes would help her to work, but she certainly would not have anything whatsoever to do with those whom she called the wasters of life.

In consequence, Agnes Delacour did a vast amount of good. She never by any chance gave injudiciously. Her present protégée was Mrs Macintyre. Mrs Macintyre was the sort of woman to whom the heart of Agnes Delacour went out in a great wave of pity. In the first place, she was Scots, and Miss Delacour loved the Scots. In the next place, she was very proud, and would not eat the bread of charity. Mrs Macintyre was a highly educated woman. She had lost both husband and children, and was therefore stranded on the shores of life. There was little or no hope for her, unless her friend Agnes took her up. Now, therefore, was the time for Agnes Delacour to attack that strange being, her brother-in-law, whom she had neglected so long.

She hardly knew his sister, Cecilia Constable, but she meant to become acquainted with her soon, to plead for her help, and in so great a cause to overlook the fact that this brother and this sister were a pair of faddists. Faddists they should not remain long, if she could help it. She, Agnes Delacour, strong-minded and determined, would see to that. The children of this most silly pair required education. Who more suitable for the purpose than gentle, kind, clever Mrs Macintyre? If George Lennox paid down the rent for Ardshiel, or, in other words, for the Palace of the Kings, and if Mrs Constable put down five hundred pounds for the redecorating of the grounds, and if the great Duke allowed them to keep the old, magnificent furniture, which had lain unused within those walls for over twenty years—and this he had practically promised to do, drawn thereto by Mrs Macintyre's sweet, pathetic smile and face—why, the deed was done, and she, Agnes, the noble and generous, need only add a few extra hundred pounds for the purchase of beds and school furniture. Thus the greatest school in the whole of Scotland would be opened under wonderfully noble auspices. Yes, all was going well, and the good woman felt better than pleased. Her great fame would spread wider and faster than ever. She lived to do good; she was doing good—good on a very considerable scale—supported by the highest nobility in the land.

Miss Delacour was not quite sure whether the school should be a mixed school or not. She waited for circumstances to settle that point. Mixed schools were becoming the fashion, and to a certain extent she approved of them; but she would not give her vote in that direction until she had a talk with her brother-in-law, and with Mrs Constable. Ardshiel was within easy reach of Edinburgh and Glasgow, but Miss Delacour made up her mind that the school, when established, should be a boarding-school. The very most she would permit would be the return of the children who lived within a convenient distance to their homes for week-end visits. But on that point also she was by no means sure. Providence must decide, she said softly to herself. She came, therefore, to The Garden determined to leave the matter, as she said, to Providence; whereas, in reality, she left it to George Lennox and his sister, Mrs Constable.

At any cost these people must do their parts. Be they faddists, or be they not, their children must be saved. Could there in all the world be a more horrible girl than Hollyhock—or, as her real name was, Jacqueline? Even Lucy (always called Jasmine) was an impertinent little thing; but what could you expect from such a man as George Lennox?

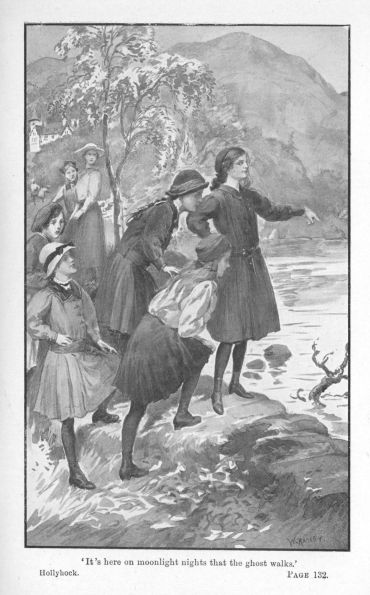

Miss Delacour was, however, the sort of person who held her soul in great patience. After Jasmine had left her she stood and looked out of the window, observed the lake on which those silly little girls were rowing, noticed those absurd boys who were called after precious stones, forsooth! and made up her mind to be pleasant with Cecilia and her family, and to say nothing of her designs to her brother-in-law until the children had gone to bed. She presumed at least that they went to bed early. A little creature like Dorothy ought to be in her warm nest not later than half-past seven. Lucy and Margaret might be permitted to sit up till nine. Afterwards she, Miss Delacour, could have a good talk with George Lennox. She invariably spoke of him as George Lennox, ignoring the Honourable, for she had no respect for the semblance of a title.

By opening her window very wide, she was able to get a distant glimpse of the much-neglected Palace. She observed, with approval, the vast size of the house, the abundance of trees, the glass-houses, the hothouses, the remains of ancient splendour. Then she looked at the lake, which shone and gleamed in all its summer glory; but she turned her thoughts from the sad history of that lake. She was not a woman to romance over things. She was a woman to go straight forward in a matter-of-fact, downright fashion.

Happening to meet one of the girls at an hour between tea and dinner, she inquired at what time their father dined.

'We all dine at half-past seven,' replied Hollyhock.

'You all dine at half-past seven? How old are you, Jacqueline?'

'Nearly thirteen, Auntie Agnes,' replied the girl, tossing her black mane of lovely, thick hair.

'And do you mean to tell me that little Dorothy, who cannot be more than eight or nine years old, takes her last heavy meal at half-past seven in the evening? Such folly is really past believing.'

'Auntie, you must believe it, for wee Delphy always dines with the rest of us. And why shouldn't she?'

'Now, my dear child, as to your father's strange conduct, it is not my place to speak of it before his unhappy and ill-bred child, but I have one request to make. It is this—that you do not again in my presence call your sister by that sickening name.'

'But, auntie, we think it a very lovely name. We like our flower names so much. Auntie, I do wish that you'd go. We were so happy without you, auntie. Do go and leave us in peace.'

'You certainly are the most impertinent little girl I ever met in my life; but times, thank the good God, are changing.'

'Are they? How, may I ask?' inquired Hollyhock.

'That I am not going to tell you quite yet, but changing they are.'

'And I say they are not,' repeated Hollyhock with great zeal.

'Oh! what a bad, wicked little girl you are! What an awful trial to my poor brother-in-law!'

'And I say I 'm not. I say that I 'm the joy of his life, the poor dear! Auntie, you 'd best not try me too far.'

'May God grant me patience,' muttered Miss Delacour under her breath.

She went upstairs to the room where her sister had not died, and made up her mind that as, of course, this wild family would not know anything whatsoever of dressing for dinner, she need not trouble to change her clothes. That being the case, she need not ring for the objectionable young person called Magsie. 'Such a name for a maid!' thought Miss Delacour. 'I'll just wear my old brown dress; it will save the dresses which I have to keep for proper occasions in London. Dear, dear, what an awful house this is!'

She sank into a chair, saying to herself how much, how very much, Mrs Macintyre would have to thank her for by-and-by! She looked at the watch she wore in a leather wristlet, and decided that she might rest for at least a quarter of an hour. She was really tired as well as appalled at the state of things at The Garden. Presently, however, seated in her easy-chair—and a very easy and comfortable chair it was—she observed that all her trunks had been unpacked; not only unpacked, but removed bodily from the large apartment. She felt a sense of anger. That girl, Magsie, had taken a liberty in unpacking her trunks. She should not have done so without asking permission. It is true that she herself had left the keys of the said trunks on her dressing-table, for most maids did unpack for her, but that was no excuse for such a creature as Magsie.

Just then there came a tap at her door. She was beginning to feel drowsy and comfortable, and said, in a cross voice, for she preened herself on her French, 'Entrez!'

Magsie had never heard 'Entrez' before, but concluded that it was the strange woman's way of saying, 'Come in.' She accordingly entered, carrying a large brass can of boiling water.

'It has come to the bile, miss,' remarked Magsie, as she entered the room, 'but ye can cool it down wi' cold water.'

'Thank you. You can leave it,' said Miss Delacour.

'What dress would ye be likin' to array yerself in?' asked Magsie.

'I'm not going to dress for dinner.'

'Not goin' to dress for dinner! But the master, he dresses like most people i' the evenin', and the young leddies and gentlemen and Mrs Constable, they sit down at the table—ah, weel! as them as is accustomed to respec' their station in life. I was thinkin', miss, that your purple gown, which I have put away in the big cupboard, might do for to-night. Ye 're a well-formed woman, miss—out in the back, out in the front—and I jalouse all your bones are covered. It 'll look queer your not dressin'—more particular when every one else does.'

'I never heard of anything quite so ridiculous,' said Miss Delacour; 'but as those silly children are going to dress, I suppose I had better put on the gown which I call my thistle gown. The thistle is the emblem of Scotland. I suppose you know that, Margaret?'

'No me,' said Margaret. 'It's an ugly, prickly thing, is a thistle.'

'Well, you have learnt something from me to-night. You ought to be very glad when I instruct you, Margaret.'

'I 'd rather be called Magsie,' returned Margaret.

'I intend to call you just what I please.'

'Very weel, miss; but may I make bold to ask which is the thistle gown?'

'It is a rich, white silk, patterned over with thistles of the natural colour of the emblem of Scotland. Open the wardrobe and I shall show it to you. But you took a liberty when you unpacked my clothes without asking my permission, Margaret.'

'Leeberty—did I? I thocht ye'd be pleased, bein' an auld leddy, no less; but catch me doin' it again. Ay, but this thistle gown is gran', to be sure.'

'Can you dress hair?' inquired Miss Delacour.

'Naething special,' was Magsie's answer. 'Is it a wig ye wear or no? It looks gey unnatural, sae I tak' it to be a wig; but if it's yer ain hair, I beg yer humble pardon. There's nae harm dune in makin' the remark.'

'You are a very impertinent girl; but as my dress happens to fasten behind, and the people in this house are all foolish, I suppose I had better get you to help me. No, my hair is my own. You must make it look as well as you can. Do you understand back-combing?'

'Lawk a mercy, ma'am! I never heard tell o' such a thing; and speakin' o' my master and his family as fules is beyond a'. However, Miss Jasmine, the darlin', she comes to me and she says in her coaxin' way, "Mak' the auld leddy comfy, Magsie;" and I 'd risk mony a danger to please Miss Jasmine.'

'There isn't any Miss Jasmine. Her name is Lucy.'

'Ah, weel, ma'am, ca' the bonnie lass what ye like. Now stand up and let me at ye. That's the gown. My word! thae thistles are fine. Hoots! ye needna mind wearin' that gown, auld as ye be. The thistle 'll do its part.'

'I do wish, girl, you'd atop talking,' said Miss Delacour, and Magsie of the black hair and black eyes and glowing complexion glanced at her new mistress and thought it prudent to obey.

She did manage to arrange Miss Delacour's hair 'brawly,' as she called it, for, as it proved, she had a real talent for hairdressing, and the good lady inwardly resolved to train this ignorant Margaret for the school.

She went downstairs presently in her thistle dress. The five little girls were clad very simply all in white. The five boys wore Eton jackets, and looked what they were, most gentlemanly young fellows. Mrs Constable, in a pale shade of gray, was altogether charming; and nothing could excel the courteous manners of George Lennox.

Every one was inclined to be kind to the stranger, and as it was the stranger's intention to make a good impression on account of her scheme, she led the conversation at dinner, ignoring the ten children, and devoting herself to her brother-in-law and Mrs Constable.

When Miss Delacour was not present there were always wild games, not to say romps, after dinner, but she seemed in some extraordinary way to put an extinguisher on the candle of their fun. So deeply was this manifest that Mrs Constable went back to The Paddock with her five boys shortly after dinner; and Mr Lennox, seeing that he must make the best of things, gave a hint to Jasmine that they had better leave him alone with their mother's half-sister.

The boys had groaned audibly at this ending of their evening's fun. Hollyhock looked defiant and even wicked; but when daddy whispered to her, 'The sooner she lets out her scheme, the sooner I can get rid of her,' the little girls ran upstairs hand-in-hand, all of them singing at the top of their voices:

And fare thee weel, my only Luve,

And fare thee weel a while!

And I will come again, my Luve,

Tho' it were ten thousand mile.'

Miss Agnes Delacour was the last person to let the grass grow under her feet. She, as she expressed it to herself, 'cornered' her brother-in-law as soon as the five little girls tripped off to bed. There was nothing, she said inwardly, like taking the bull by the horns. Accordingly she attacked that ferocious beast in the form of quiet, courteous Mr Lennox with her usual energy.

'George,' she said, 'you are angry with your poor sister.'

'Oh, not at all,' he replied. 'Pray take a seat. This chair I can recommend as most comfortable.'

Miss Agnes accepted the chair, but pursued her own course of reasoning.

'You 're angry,' she continued, 'because I did not go to poor Lucy's funeral.'

'We will let that matter drop,' said Lennox, his very refined face turning slightly pale.

'But, my dear brother, we must not let it drop. It is my duty to protest, and to defend myself. There was a woman with cataract.'

'Dear Agnes, I know that story so well. I am glad the woman recovered her sight.'

'Then you are a good Christian man, George, and we are friends once again.'

'We were never anything else,' said Lennox.

'That being the case,' continued Miss Delacour, 'you will of course listen to the object of my mission here.'

'I will listen, Agnes; but I do not say that I shall either comprehend or take an interest in your so-called mission.'

'Ah, narrow, narrow man,' said Miss Delacour, shaking her plump finger playfully at her host as she spoke.

'Am I narrow? I did not know it,' replied Lennox.

'Fearfully so. Think of the way you are bringing up your girls.'

'What is the matter with my lasses? I think them the bonniest and the best in the world.'

'Poor misguided man! They are nothing of the sort.'

'If you have come here, Agnes, to abuse Lucy's children, and mine, I would rather we dropped the subject. They have nothing to do with you. You have never until the present moment taken the slightest notice of them. They give me intense happiness. I think, perhaps, Agnes, seeing that we differ and have always differed in every particular, it might be as well for you to shorten your visit to The Garden.'

'Thank you. That is the sort of speech a child reared by you has already made to me. She has, in fact, impertinent little thing, already asked me when I am going.'

'Do you allude to Hollyhock?'

'Now, George, is it wise—is it sensible to call those children after the flowers of the garden and the field? I assure you your manner of bringing up your family makes me sick—yes, sick!'

'Oh, don't trouble about us,' said Lennox. 'We get on uncommonly well. They are my children, you know.'

'And Lucy's,' whispered Miss Delacour, her voice slightly shaking.

'I am very sorry to hurt you, Agnes; but Lucy herself—dear, sweet, precious Lucy—liked the idea of each of the children being called after a flower; not baptismally, of course, but in their home life. One of the very last things she said to me before she died was, "Call the little one Delphinium." Now, have we not talked enough on this, to me, most painful subject? My Lucy and I were one in heart and deed.'

'Alas, alas!' said Miss Delacour. 'How hard it is to get men to understand! I knew Lucy longer than you. I brought her up; I trained her. The good that was in her she owed to me. She has passed on—a beautiful expression that—but I feel a voice within me saying—a voice which is her voice—"Agnes, remember my children. Agnes, think of my children. Do for them what is right. Remember their father's great weakness."'

'Thanks,' replied Lennox. 'That voice in your breast did not come from Lucy.'

Miss Delacour gave a short, sharp sigh.

'Oh, the ignorance of men!' she exclaimed. 'Oh, the silly, false pride of men! They think themselves the very best in the world, whereas they are in reality a poor, very poor lot.'

Lennox fidgeted in his chair.

'How long will this lecture take?' he said. 'As a rule I go to bed early, as the children and I have a swim in the lake before breakfast each morning.'

'How are they taught other things besides swimming?' asked Miss Delacour.

'Taught?' echoed Lennox. 'For their ages they are well instructed. My sister and I manage their education between us.'

'George, I suppose you will end by marrying again. All men in your class and with your disposition do so.'

'Agnes, I forbid you to speak to me on that subject again. Once for all, poor weak man as you consider me, I put down my foot, and will not discuss that most painful subject. Lucy is the only wife I shall ever have. I have, thank God, my sister and my sweet girls, and I do not want anything more. I am a widower for life. Cecilia is a widow for life. We rejoice in the thought of meeting the dear departed in a happier world. Now try not to pain me any more. Good-night, Agnes. You are a little—nay, more than a little—trying.'

'I've not an idea of going to bed yet,' said Miss Delacour, 'for I have not divulged my scheme. You have got to listen to it, George, whether you like it or not.'

'I suppose I have,' said George Lennox. He sat down, and made a violent struggle to restrain his impatience.

'I will come to the matter at once,' said Miss Delacour. 'You know, or perhaps you do not know, how I spend my life.'

'I do not know, Agnes. You never write, and until to-day you have never come to The Garden.'

'Well, I have come now with a purpose. Pray don't fidget so dreadfully, George. It is really bad style. I am noted in London for moving in the very best society. I see the men of culture and refinement, who are always remarked for the stillness of their attitudes.'

'Are they?' said George Lennox. 'Well, I can only say I am glad I don't live there.'

'How Lucy could have taken to you?' remarked Miss Delacour.

'Say those words again, Agnes, and I shall go to bed. There are some recent novels on the table, and you can read then till you feel sleepy.'

'Thanks; I am never sleepy when I have work to do. My work is charity; my work is philanthropy. You know quite well that I am blessed by God with considerable means. Often and often I go to the Bank of England and stand by the Royal Exchange and see those noble words, "The earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof." George, those words are my text. Those words exemplify my work. "The earth is the Lord's." I therefore, George, give of my abundance to the Lord, meaning thereby the Lord's poor. I hate the Charity Organisation Society; but when I see a man or a woman or even a child in our rank of life struggling with dire poverty, when, after making strict inquiries, I find out that the poverty is real, then I help that man, woman, or child. I live, George, in a little house in Chelsea. I keep one servant, and one only. I do not waste money on motor-cars or gardens or antiquated mansions like this. I give to the Lord's poor. George, I am a very happy woman.'

'I am glad to hear it,' said Lennox. 'Since you entered my house, I should not have known it but for your remark.'

'Ah, indeed, I have cause for sorrow in your ridiculous house, surrounded by your absurd children'——

'Agnes!'

'I must speak, George. I have come here for the express purpose. Dear little Lucy wrote to me during her short married life with regard to the Upper Glen. She wrote happily, I must confess that. She spoke of her children as though she loved them very dearly. Would she love them if she were alive now?'

'Agnes!'

'George, I say—I declare—that she would not love them. Brought up without discipline, without education; called after silly flowers; told by their father to be rude to me, their aunt! How could she love them?'

'Agnes, I try hard not to lose my temper; but if you go on much longer in your present vein of talk, I greatly fear that it will depart.'

'Then let it depart,' said Miss Delacour. 'Anything to rouse the man who is going so madly, so cruelly, to work with regard to his family. Now then, let me see. I am ever and always one who walks straight. I am ever and always one who has an aim in view. My present aim is to help another. There is a dear woman—a Mrs Macintyre—true Scotch. You will like that, George. She has been left destitute. Her husband died; her children died. She is alone, quite alone, in the world. She has been most highly educated, and I have taken that dear thing up. There are in the Upper Glen three houses, or, rather, palaces, I should call them—one where you live, one where your sister, Mrs Constable, lives. She seems a nice, sensible sort of woman, simple in her tastes and devoted to her sons, except for the silly names she has given them. But both The Paddock and The Garden are small in comparison with the middle house, which has been unoccupied since before your marriage, George. It is a spacious and beautiful place, and my intention—my firm intention, remember—is to place Mrs Macintyre there and establish a suitable school for your girls, for other girls. Your girls can go to her as weekly boarders. I am not yet quite sure whether I shall admit the young Constables; but I may. Mrs Macintyre is a magnificent woman. She will secure for your children, for the other children, for the Constables, if I permit it, the best masters and mistresses from Edinburgh. You have a motor-car, have you not?'

'Yes.'

'You did not send it to meet your sister.'

'I did not.'

'Polite, I must say; but I forgive your bad manners. I proceed in the true Christian spirit with my scheme. The middle house in the Upper Glen belongs, as you know well, to the great Duke of Ardshiel. It is sometimes called Ardshiel, but more often by the title The Palace of the Kings. Since the sad tragedy which took place there, it has stood empty, the Duke having many other country seats and avoiding this noble mansion because of its associations. Well, George, you know all that story; but when Mrs Macintyre came to me in her distress and poverty I immediately thought of Ardshiel. I thought of it as the very place in which to start a flourishing school, of which your girls could take full advantage.

'Accompanied by dear Mrs Macintyre, I went to see his Grace. I was surprisingly successful in my interview. The Duke was quite charmed with my suggestion. He was much taken also with Mrs Macintyre. In short, he agreed to let the Palace of the Kings to my friend. I do not think he will ask a high rent for the lovely place, and, from a very broad hint he threw out, I expect he will give us the present magnificent furniture. You will be expected to pay the rent—a mere trifle. Your sister, if I admit a mixed school, will be asked to subscribe five hundred pounds for the rearranging of the grounds. The Duke will put the Palace into full repair, and with our united aid—for, of course, I shall not keep back my mite—we shall have the most flourishing school in Scotland opened and filled with pupils by the middle of September. In fact, I consider the scheme settled. There will be a large and flourishing school in your midst, for his Grace would only do things in first-rate style. Now I consider the matter accomplished. The school will be opened in September, and as I really cannot stand any more of your fidgeting—such shocking style!—I will wish you good-night. Of course, not a word of thanks on your part. I overlook all those little politenesses. The righteous look for their reward on High! Good-night, good-night! No arguments to-night, pray. I do not wish to listen to your objections to-night. You will naturally have them, but they will be overcome. Mrs Macintyre is a pearl amongst women. Good-night, George; good-night.'

Miss Delacour left the room. George Lennox did not go to bed that night until very late.

'Well,' he said to himself at last, 'I did not know I could be snubbed by any one; but that woman, she drives me wild. However, I will call my own children by the names I wish, and will not assist her with her school. I to pay the rent, forsooth! I to send my darlings to school, when I long ago made up my mind that they should never go to one. Dear Cecilia to be robbed of five hundred pounds and that pearl of a woman established in our midst. Not quite, Agnes Delacour! We of the Upper Glen resist. How I wish Hollyhock had been here to-night when the woman attacked me! No wonder my Lucy could not abide her. However, I am the master of my own money, and the father of my own children. I must talk with Cecilia early to-morrow morning, or Agnes will be at her. Dear Cecil, she would starve herself and her boys to help any one, but she shall certainly get my views.'

Alas, however, his optimism proved ill-founded, and it so happened that Miss Delacour paid a very early call indeed on the following morning at The Paddock, for she slept well and woke early, whereas the Honourable George Lennox slept badly and awoke late.

Mrs Constable was rather amazed at so early a visit from her brother's sister-in-law. The boys rushed in, yelling the news. She was just pouring out milk for her collection of Precious Stones when the unabashed lady entered the spacious dining-room.

'Ah, upon my word, a nice house!' said Miss Delacour. 'How cheerful you make everything look, dear! As sister women we can appreciate the little niceties of life, can we not?'

'Yes, of course,' said Mrs Constable in her pleasant manner and with her pretty, bright look. 'But what a long walk to take before breakfast, Miss Delacour!'

'I have come on behalf of my brother-in-law.'

'Is George ill?' inquired Mrs Constable.

Miss Delacour put her finger to her lip. Then she significantly touched her brow. Going up to Mrs Constable, she begged to have a special talk with her all alone. Mrs Constable had thought the woman in the thistle gown very queer the night before, and the boys had frankly detested her; but when that admirable philanthropist went up and dropped a word into her ear she turned a little pale, and facing her sons, said, 'Laddies, you had best go into the back dining-room and sup your porridge. Run, laddies; run.'

The boys gave their mother an adoring glance, scowled ferociously at Miss Delacour, and left the room. Over their coffee, hot rolls, and marmalade, Miss Delacour propounded her scheme—her great, her wonderful scheme.

It is well to be first in the field, and Miss Delacour could speak with eloquence. She was a real philanthropist, and she appealed to the kind heart of Mrs Constable.

There is, after all, nothing like being first in the field. The old proverb of the early bird that catches the worm is correct. Miss Delacour knew her ground. Miss Delacour had gauged her woman, and when, about eleven o'clock that day, George Lennox walked across to The Paddock, hoping to obtain the sympathy which he had never before been refused by his sister, he was much amazed to find that Mrs Constable was altogether on the other side.

'What has come over you, Cecilia?' he remarked. 'Is it possible that you have already seen my sister-in-law? Do you understand the sort of woman that she is?'

'I have seen her more than two hours ago, George,' replied Mrs Constable, 'and, to be frank with you, I admire her very much. There is no one to me like you, George, but women can see things which men cannot. It seems to me that Miss Delacour is a woman with a great heart, and she has taken pains to propound to me a scheme which I consider most noble. In fact, I fully agree with her in the matter. I cannot help doing so. Our children, our dear children, George, require by now to be taught the great things of the world. Hitherto you and I have taught them all we could. I do not deny that, until now, our instruction was sufficient; but a time has arrived when they all need the broader life. I, for one, will certainly help Miss Delacour to the extent of five hundred pounds. The Duke is quite in favour of the Palace of the Kings being made use of for so worthy an object, and will give us the furniture, if not for nothing, at least for a very trifling sum. Miss Delacour will herself provide the extra furniture required for a school, and I further understand that the Duke will let the old house and grounds for a merely nominal rent, which I think you, George, being his kinsman through your dear wife, ought to supply. Miss Delacour has secured the services of a most efficient head-mistress, and the school will be run on truly noble lines—on the very best lines, or the Duke would have nothing to do with it. As I am willing to help Miss Delacour, she will allow my dear sons, for a longer or shorter period, to enter the school so as to prepare for Eton by-and-by. Home education is not enough, George, and the children will be educated for the broader world, at our very doors. They will be allowed to return to the home nest each Saturday until early Monday morning. What could by any means be more advantageous?'

'Oh dear,' exclaimed Lennox, 'what a woman Agnes is!'

'What a noble woman! you mean.'

'I do not mean that, by any means. I mean that she is clever and very rich, and philanders with philanthropy. We know nothing, for instance, of the proposed head-mistress, Mrs Macintyre.'

'Yes, we do, through that really excellent woman, your sister-in-law. George, you are sadly prejudiced.'

'Cecil, you wrong me. Was she not my Lucy's half-sister, and did not my dearest one suffer tortures at her hands?'

'Ah! try to forget that part of the painful past. Well do I know what your Lucy was to you, to me, to her little girls. Try, my dearest brother, to be brave, and to take to your heart the text, "Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord," and receive Miss Delacour's magnificent scheme with a good grace.'

'And the loss of a considerable yearly income, to say nothing of the far deeper pain of parting from my children. Really, Cecilia, I did think you would show more pity to a sadly lonely man.'

'And I, also, am a sadly lonely woman, George; but I must not think of myself in the matter of my beloved boys.'

'You never do, and never could, Cecil; but that woman drives me nearly wild.'

'Dear George, try to think more kindly of her. She spoke, oh! so kindly of you; indeed, she spoke most affectionately. I could not believe that you were inclined to be jealous, and even stingy.'

Lennox rose. 'If being unwilling to deprive myself of several hundreds a year for a total stranger, as well as parting from my dear little lasses, is stingy, then I am stingy, Cecilia; but let the matter drop. I bow to the decrees of two women. When two women put their heads together, what chance has poor man?'

'Oh George,' said Mrs Constable, 'since my beloved husband was killed, whom have I had to look to but you, my dearest brother? Believe me, this is a good cause. Your children and my children need to mix with the world. Jasper must soon go to a public school, but a year in a mixed school will do him no harm. I have been deeply puzzled of late as to what to do with my boys' future. Then comes unexpectedly a noble woman who opens up a plan. It seems right; it seems correct. Our children will mix with other children. They will know the world in the way they must first know it—namely, at school; and they will be, remember, George, within a stone's-throw of us.'

'You don't mean to say that they are to be weekly boarders?' remarked the stricken man.

'I do say it. That is her determination. The school will be a very large one, and I am going to-day to meet Miss Delacour at Ardshiel in order to see what improvements are necessary. Oh, dear, dear old boy, if I could remove that frown from your brow!'

'You can't, Cecilia; so don't try. I am worsted by two women, the fate of most men. I am very unhappy. I don't pretend to be anything else. My sister-in-law has stolen a march on me, but at least there is one thing on which I am determined. You, of course, Cecilia, can do as you please, but I positively refuse to send a child of mine to that place until I have first had an interview with Mrs Macintyre.'

'And that is most sensible of you, George. I shall wire to her and ask her to come to The Paddock to-day. I shall be so glad to put her up and make her happy. A woman in her case, with financial difficulties, having lost husband and children, is so deeply to be pitied. My whole heart aches for the poor, dear thing.'

'Cecilia, I would not know you this morning. I must go back now to my little girls. They at least are all my own; they at least dislike the woman who has conquered your too kind heart.'

'George, I have faithfully promised in your name and my own to visit Ardshiel immediately after luncheon to-day. We have to see for ourselves that the sad home of neglect and tragedy, which will soon be filled with young and happy life, is in all respects suited to our purpose.'

'Oh dear, oh dear!' said George Lennox. 'Well, if I must, I must. Two women against one man! I suppose I may be allowed to bring Hollyhock?'

'Best not, on the first occasion. She irritates Miss Delacour.'

'Oh, bother Miss Delacour!' exclaimed the Honourable George, who was now at last thoroughly out of humour. 'Well, I'll meet you at half-past two at Ardshiel, and I hope by then I may feel a little calmer than I do at present.'

As soon as George Lennox had gone, Mrs Constable sent a telegram to the bereaved and distracted Mrs Macintyre, inviting her to make a speedy visit to The Paddock. This telegram had only to go as far as Edinburgh, for Miss Delacour had put her friend up in a shabby room in a back-street in that city of rare beauty. The address had been given, however, to Mrs Constable; and Mrs Macintyre, who was feeling very depressed, and wondering if anything could come of her friend's scheme, replied instanter: 'Will be with you by next train.'

Mrs Constable made all preparations for her guest's arrival. The best spare room was got ready. The finest linen sheets, smelling of lavender, were spread on the soft bed. The room was a lovely one, and in every respect a contrast to any Mrs Macintyre had used of late.

As has been said, it was the custom for the Constables and the Lennoxes to dine and spend the evening together. This was the night for The Paddock, and Mrs Macintyre would therefore see not only the Honourable George Lennox, but a goodly number of her future pupils. Miss Delacour was a woman who in the moment of victory was not inclined to show off. Having gained Mrs Constable, she was merciful to George, and said nothing whatever to him with regard to the school, or with regard to the advent of Mrs Macintyre. She knew well that that really good woman would be at The Paddock that evening, and considered her task practically accomplished.

George Lennox, feeling sad at heart, but still trusting to the incapability of Mrs Macintyre to undertake so onerous a charge, went with his sister-in-law to meet Mrs Constable at the appointed hour at Ardshiel that afternoon. When they joined Mrs Constable at the lodge gate, he did not hear the one lady say to the other, 'The dear thing will be with me in time for dinner.'

'We dine at The Paddock to-night,' whispered Miss Delacour. 'How marvellous are the ways of Providence! I can get back to London to-morrow. Between ourselves, dear, I hate the Upper Glen, and heartily dislike my brother-in-law.'

'Oh! you must not speak of my brother like that,' said Mrs Constable. 'With the exception of my dear husband, there never was a man like my brother George.'

'As you think so much of him, perhaps he will help you by finding husband No. 2,' said Miss Delacour in a tone which she meant to be playful. She chuckled over her commonplace joke, having never succeeded herself in finding even No. 1. But Mrs Constable's gentle and beautiful gray eyes now flashed with a sudden fire, and the colour of amazed anger rose into her cheeks.

'Miss Delacour, you astonish and pain me indescribably when you speak as you have just done. Little you know of my beloved Wallace. Had you had the good fortune to meet so noble a man, you would perceive how impossible it is for his widow, indeed his wife, as I consider myself, to marry any one else. Never speak to me on that subject again, please, Miss Delacour.'

Miss Delacour saw that she had gone too far, and muttered to herself, 'Dear, dear, how huffy these handsome widows are! But, all the same, I doubt not that she will marry again. Time will prove. For me, I have no patience with these silly airs. But I see I must change the subject.' Accordingly she deftly did so, and even asked to see a portrait of the late gallant major. This request was, however, somewhat curtly refused.

'Only my laddies and myself see the picture of their blessed father,' was the reply; and Miss Delacour could not but respect Mrs Constable all the more for her gentle and yet firm dignity.

Meanwhile the unhappy and lonely George Lennox, hating his sister-in-law's scheme more and more, wandered away by himself, where he could think matters over.

'I never could have believed that Cecil would abide tittle-tattle,' he thought; 'but that woman Agnes would contaminate any one.'

The ladies had now reached Ardshiel. It was, of course, considerably out of repair, but was even now lovely, with the beauty of fallen greatness. The majesty of the spacious grounds, the reflection of the sun on the tragic lake, the fine effect of great mountains in the distance, were as impressive as ever. It was clear that the walks, the lawns, the terraces, the beds of neglected flowers, the great glass-houses, could all soon be put to rights.

Then within that house, where the footsteps of the young bride had never been heard, were treasures innumerable and furniture which age could only improve. The Duke had promised, if all turned out satisfactorily, to hand over the furniture, the magnificent glass and china, the silver even, and fine linen and napery of all sorts, as his present to the school; but he insisted on a small rent being paid yearly for the lovely place, and also demanded that a certain sum be paid for the restoration of the grounds. Mrs Constable would repair the grounds, while her brother would surely not refuse to pay the small rent expected by the Duke for this most noble part of his property. Miss Delacour hoped that she would establish her friend in the school without much loss of her own property, but she was willing to add the necessary school furniture, meaning the beds for the children and the correct furniture for their rooms, also the downstairs school furniture, such as desks and so forth. She expected to get them for a sum equal to what Mrs Constable intended to spend—namely, five hundred pounds. In this matter she thought herself most generous, and poor George most mean.

While the ladies were examining the interior of the great house, the Honourable George Lennox walked through the place alone, taking good care to keep away from the women. He walked all the time like one in a dream. It seemed to him as though he saw ghosts all around him, not only the ghost of his own peerless Lucy, and the other ghost of the poor youth who early on his wedding morning was found, cold and dead, floating on the waters of the mighty lake. Lennox spent much of the time in the grounds of Ardshiel, and heard, to his delight, the wrangling voices of the two women, hoping sincerely that the scheme of having this house of almost royalty turned into a school would be knocked on the head; for when were women, even the best of them, long consistent in their ideas?

Finally, however, the ladies did leave Ardshiel, the whole scheme of turning Ardshiel into a school for lads and lasses marked out in Miss Delacour's active mind. The attics would do for the children's cubicles. The next floor would be devoted to class-rooms of all sorts and descriptions, the ground floor would form the pleasure part of the establishment, and the servants would have a wing quite apart. The school could certainly be opened not later than September. The place was made for a school for the upper classes. It seemed to grow under the eyes of the two women into a delightful resort of youth, learning, and happiness; but Mr Lennox became more opposed to the scheme each moment. His one hope was that Mrs Macintyre might turn out to be impossible, in which case these castles in the air would topple to the ground.

The three parted at the gates of Ardshiel, Miss Delacour and her brother-in-law going one way, and Mrs Constable the other.

'You won't forget, dear,' said Mrs Constable, nodding affectionately to her new friend, 'to be in time for dinner this evening?'

'Oh dear! I forgot that we were to dine with you, Cecilia,' said George Lennox.

'Well, don't forget it, George; and bring all the sweet Flowers with you.'

'Naturally, I should not come without them.' His tone was almost angry.

'What a charming—what a sweet woman Mrs Constable is!' remarked his sister-in-law.

Lennox was silent.

'George,' said Agnes, 'you're sulky.'

'Doubtless I am. Most men would be who are cajoled as I have been into paying the rent of that horrid house. Yes, you are a clever woman, Agnes; but I can tell you once for all that not a single one of my Flowers of the Garden shall enter that school if I do not approve of the head-mistress.'

'I said you were sulky,' repeated Miss Delacour. 'A sulky man is almost as unpleasant as a fidgety man.'

'To tell you frankly, Agnes, I keenly dislike being played the fool with. You saw Cecilia Constable this morning. You won her round to your views when I was asleep.'

'Ha, ha!' laughed Miss Delacour. 'I repeat, she is a sweet woman, and her boys shall go to the school.'

'I thought it was a girls' school.'

'For her dear sake,' replied Miss Delacour, 'it will be a mixed school. Oh, I feel happy! The Lord is directing me.'

They arrived at The Garden, where five gloomy little girls gazed gloomily at their aunt.

'I do wonder when she 'll go,' whispered Hollyhock. 'Look at Dumpy Dad; he's perfectly miserable. If she does not clear out soon, I 'll turn her out, that I will.'

When tea was over, the children and their father went into the spacious grounds, rowed on the lake, and were happy once more, their peals of merriment reaching Miss Delacour as she drew up plans in furtherance of her scheme.

By-and-by the children went upstairs to dress for dinner. Their dress was very simple, sometimes white washing silk, sometimes pink silk, equally soft, sometimes very pale-blue silk. To-night they chose to appear in their pink dresses.

'It will annoy the old crab,' thought Hollyhock.

They always walked the short distance between The Garden and The Paddock.

Miss Delacour put on her 'thistle' gown, assisted by Magsie, who ingratiatingly declared that she looked 'that weel ye hardly kent her.'

'You are a good girl, Margaret,' answered Miss Delacour, 'and if I can I will help you in life.'

'Thank ye, my leddy; thank ye.'

The entire family started off for The Paddock, and on arrival there, to the amazement and indeed sickening surprise of the Honourable George Lennox, were immediately introduced to Mrs Macintyre, who turned out to be, to his intense disappointment, a quiet, sad, lady-like woman, tall and slender, and without a trace of the Scots accent about her. She was perfect as far as speech and manner were concerned.

Mrs Macintyre, however, knew well the important part she had to play. At dinner she sat next to Mr Lennox, and devoted herself to him with a sort of humble devotion, speaking sadly of the school, but assuring him that if he could induce himself to entrust his beautiful little Flower Girls to her care, she would leave no stone unturned to educate them according to his own wishes, and to let them see as much of their father as possible.

Lennox began to feel that he preferred Mrs Macintyre to his sister-in-law or even to his sister, Mrs Constable, at that moment. The woman undoubtedly was a lady. How great, how terrible, had been her sorrow! And then she spoke so prettily of his girls, and said that the flower names were altogether too charming, and nothing would induce her to disturb them.

It was on the lips of Lennox to say, 'I am not going to send my girls to your school,' but he found, as he looked into her sad dark eyes, that he could not dash the hopes of such a woman to the ground. He was therefore silent, and the evening passed agreeably.

Immediately after dinner Mrs Macintyre sat at the piano and sang one Scots song after another. She had a really exquisite voice, and when 'Robin Adair' and 'Ye Banks and Braes' and 'Annie Laurie' rang through the old hall, the man gave himself up to the delight of listening. He stood by her and turned the pages of music, while the two ladies, Mrs Constable and Miss Delacour, looked on with smiling faces. Miss Delacour knew that her cause was won, and that she might with safety leave the precincts of the horrible Garden to-morrow. How miserable she was in that spot! Yes, her friend's future was assured, and she herself must go to Edinburgh and to London to secure sufficiently aristocratic pupils for the new school.

It was, after all, Mrs Macintyre who made the school a great success. Her gentleness, her sweet and noble character, overcame every prejudice, even of Mr Lennox. When she said that she thought his children and their flower names beautiful, the heart of the good man was won. Later in the evening, when the lively little party of Lennoxes, accompanied, of course, by Miss Delacour, went back to The Garden, his sister-in-law called him aside, and informed him somewhat brusquely of the fact that she was leaving for London on the following day.

'Mrs Macintyre will remain behind,' she said. 'I gave her at parting five hundred pounds. You will do your part, of course, George, unless you are an utter fool.'

George Lennox felt so glad at the thought of parting from Miss Delacour that he almost forgave her for calling him a possibly utter fool; nay, more, in his joy at her departure, he nearly, but not quite, kissed his sister-in-law.

Every attention was now paid to this good lady. At a very early hour on the following morning the motor-car conveyed her to Edinburgh. It seemed to the Lennoxes, children and father alike, that when Aunt Agnes departed the birds sang a particularly delightful song, the roses in the garden gave out their rarest perfume, the sweet-peas were a glory to behold, the sky was more blue than it had ever been before; in short, there was a happy man in The Garden, a happy man with five little Flower Girls. How could he ever bring himself to call his Jasmine, Lucy; his Gentian, Margaret; his Hollyhock, Jacqueline; his Rose of the Garden, mere Rose; and his Delphinium, Dorothy?

'Oh, isn't it good that she's gone?' cried Jasmine.

'Your aunt has left us, and we mustn't talk about her any more,' said Lennox, whose relief of mind was so vast that he could not help whistling and singing.

'Why, Daddy Dumps, you do look jolly,' said Hollyhock.

'We are all jolly—it is a lovely day,' said Mr Lennox.

So they had a very happy breakfast together, and joked and laughed, and forgot Aunt Agnes and her queer ways. The only person who slightly missed her was Magsie, on whom she had bestowed a whole sovereign, informing her at the same time that she, Margaret, might expect good tidings before long.

'Whatever does she mean?' thought Magsie. 'She has plenty to say. I didn't tak' to her at first, but pieces o' gold are no to be had every day o' the week, and she has a generous heart, although I can see the master is not much taken wi' her.'