The Project Gutenberg EBook of All About Coffee, by William H. Ukers This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: All About Coffee Author: William H. Ukers Release Date: April 4, 2009 [EBook #28500] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ALL ABOUT COFFEE *** Produced by K.D. Thornton, Suzanne Lybarger, Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note

The punctuation and spelling from the original text have been faithfully preserved. Only obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

All About

Coffee

ALL ABOUT COFFEE

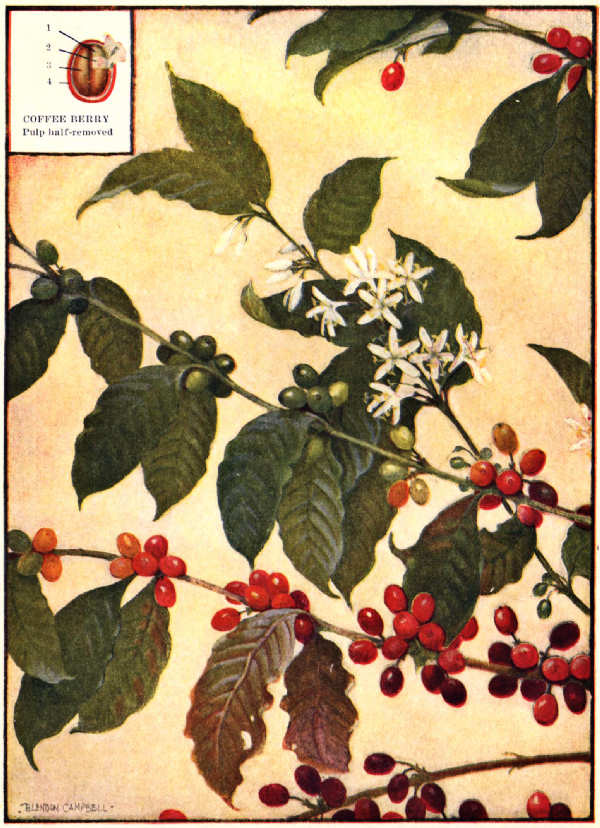

COFFEE BRANCHES, FLOWERS, AND FRUIT

COFFEE BRANCHES, FLOWERS, AND FRUIT

Showing the Berry in its Various Ripening Stages from Flower to Cherry

(Inset: 1, green bean; 2, silver skin; 3, parchment; 4, fruit pulp.)

Painted from life by Blendon Campbell

By

WILLIAM H. UKERS, M.A.

Editor

THE TEA AND COFFEE TRADE JOURNAL

NEW YORK

THE TEA AND COFFEE TRADE JOURNAL COMPANY

1922

Copyright 1922

BY

THE TEA AND COFFEE TRADE JOURNAL COMPANY

New York

International Copyright Secured

All Rights Reserved in U.S.A. and

Foreign Countries

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

To My Wife

HELEN DE GRAFF UKERS

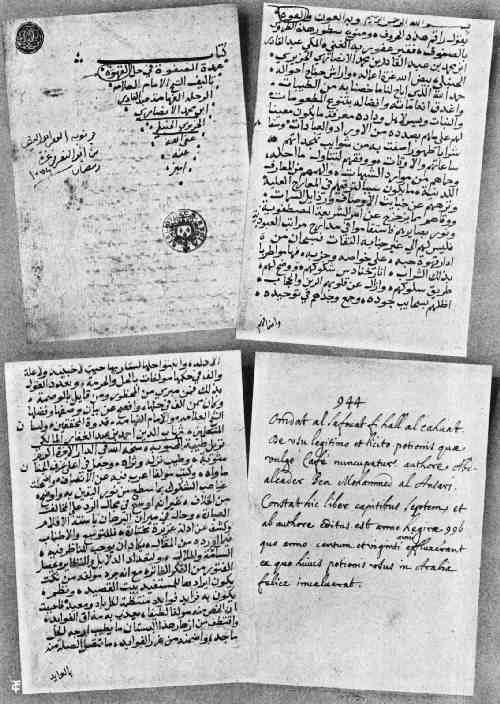

Seventeen years ago the author of this work made his first trip abroad to gather material for a book on coffee. Subsequently he spent a year in travel among the coffee-producing countries. After the initial surveys, correspondents were appointed to make researches in the principal European libraries and museums; and this phase of the work continued until April, 1922. Simultaneous researches were conducted in American libraries and historical museums up to the time of the return of the final proofs to the printer in June, 1922.

Ten years ago the sorting and classification of the material was begun. The actual writing of the manuscript has extended over four years.

Among the unique features of the book are the Coffee Thesaurus; the Coffee Chronology, containing 492 dates of historical importance; the Complete Reference Table of the Principal Kinds of Coffee Grown in the World; and the Coffee Bibliography, containing 1,380 references.

The most authoritative works on this subject have been Robinson's The Early History of Coffee Houses in England, published in London in 1893; and Jardin's Le Café, published in Paris in 1895. The author wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to both for inspiration and guidance. Other works, Arabian, French, English, German, and Italian, dealing with particular phases of the subject, have been laid under contribution; and where this has been done, credit is given by footnote reference. In all cases where it has been possible to do so, however, statements of historical facts have been verified by independent research. Not a few items have required months of tracing to confirm or to disprove.

There has been no serious American work on coffee since Hewitt's Coffee: Its History, Cultivation and Uses, published in 1872; and Thurber's Coffee from Plantation to Cup, published in 1881. Both of these are now out of print, as is also Walsh's Coffee: Its History, Classification and Description, published in 1893.

The chapters on The Chemistry of Coffee and The Pharmacology of Coffee have been prepared under the author's direction by Charles W. Trigg, industrial fellow of the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research.

The author wishes to acknowledge, with thanks, valuable assistance and numerous courtesies by the officials of the following institutions:

British Museum, and Guildhall Museum, London; Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris; Congressional Library, Washington; New York Public Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New York Historical Society, New York; Boston Public Library, and Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Smithsonian Institution, Washington; State Historical Museum, Madison, Wis.; Maine Historical Society, Portland; Chicago Historical Society; New Jersey Historical Society, Newark; Harvard University Library; Essex Institute, Salem, Mass.; Peabody Institute, Baltimore.

Thanks and appreciation are due also to:

Charles James Jackson, London, for permission to quote from his Illustrated History of English Plate;

Francis Hill Bigelow, author; and The Macmillan Company, publishers, for permission to reproduce illustrations from Historic Silver of the Colonies;

H.G. Dwight, author; and Charles Scribner's Sons, publishers, for permission to quote from Constantinople, Old and New, and from the article on "Turkish Coffee Houses" in Scribner's Magazine;

Walter G. Peter, Washington, D.C., for permission to photograph and reproduce pictures of articles in the Peter collection at the United States National Museum;

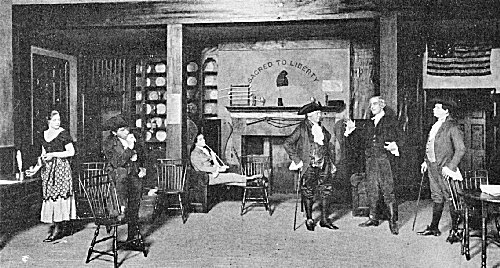

Mary P. Hamlin and George Arliss, authors, and George C. Tyler, producer, for permission to reproduce the Exchange coffee-house setting of the first act of Hamilton;

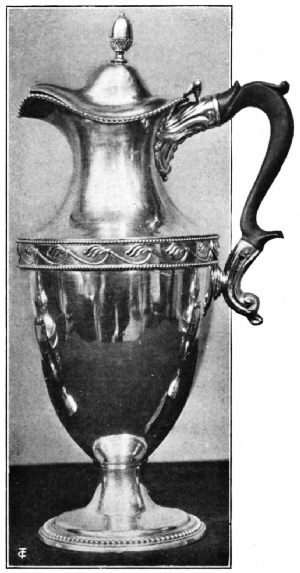

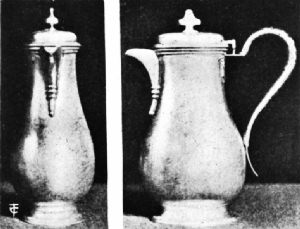

Judge A.T. Clearwater, Kingston N.Y.; R.T. Haines Halsey, and Francis P. Garvan, New York, for permission to publish pictures of historic silver coffee pots in their several collections;

The secretaries of the American Chambers of Commerce in London, Paris, and Berlin;

Charles Cooper, London, for his splendid co-operation and for his special contribution to chapter XXXV;

Alonzo H. De Graff, London, for his invaluable aid and unflagging zeal in directing the London researches;

To the Coffee Trade Association, London, for assistance rendered;

To G.J. Lethem, London, for his translations from the Arabic;

Geoffrey Sephton, Vienna, for his nice co-operation;

L.P. de Bussy of the Koloniaal Institute, Amsterdam, Holland, for assistance rendered;

Burton Holmes and Blendon R. Campbell, New York, for courtesies;

John Cotton Dana, Newark, N.J., for assistance rendered;

Charles H. Barnes, Medford, Mass., for permission to publish the photograph of Peregrine White's Mayflower mortar and pestle;

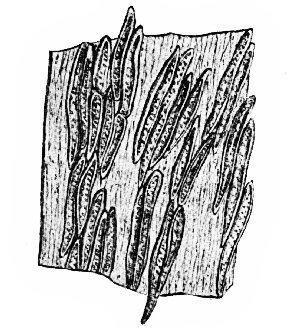

Andrew L. Winton, Ph.D., Wilton, Conn., for permission to quote from his The Microscopy of Vegetable Foods in the chapter on The Microscopy of Coffee and to reprint Prof. J. Moeller's and Tschirch and Oesterle's drawings;

F. Hulton Frankel, Ph.D., Edward M. Frankel, Ph.D., and Arno Viehoever, for their assistance in preparing the chapters on The Botany of Coffee and The Microscopy of Coffee;

A.L. Burns, New York, for his assistance in the correction and revision of chapters XXV, XXVI, XXVII, and XXXIV, and for much historical information supplied in connection with chapters XXX and XXXI;

Edward Aborn, New York, for his help in the revision of chapter XXXVI;

George W. Lawrence, former president, and T.S.B. Nielsen, president, of the New York Coffee and Sugar Exchange, for their assistance in the revision of chapter XXXI;

Helio Lobo, Brazilian consul general, New York; Sebastião Sampaio, commercial attaché of the Brazilian Embassy, Washington; and Th. Langgaard de Menezes, American representative of the Sociedade Promotora da Defeza do Café;

Felix Coste, secretary and manager, the National Coffee Roasters Association; and C.B. Stroud, superintendent, the New York Coffee and Sugar Exchange, for information supplied and assistance rendered in the revision of several chapters;

F.T. Holmes, New York, for his help in the compilation of chronological and descriptive data on coffee-roasting machinery;

Walter Chester, New York, for critical comments on chapter XXVIII.

The author is especially indebted to the following, who in many ways have contributed to the successful compilation of the Complete Reference Table in chapter XXIV, and of those chapters having to do with the early history and development of the green coffee and the wholesale coffee-roasting trades in the United States:

George S. Wright, Boston; A.E. Forbes, William Fisher, Gwynne Evans, Jerome J. Schotten, and the late Julius J. Schotten, St. Louis; James H. Taylor, William Bayne, Jr., A.J. Dannemiller, B.A. Livierato, S.A. Schonbrunn, Herbert Wilde, A.C. Fitzpatrick, Charles Meehan, Clarence Creighton, Abram Wakeman, A.H. Davies, Joshua Walker, Fred P. Gordon, Alex. H. Purcell, George W. Vanderhoef, Col. William P. Roome, W. Lee Simmonds, Herman Simmonds, W.H. Aborn, B. Lahey, John C. Loudon, J.R. Westfal, Abraham Reamer, R.C. Wilhelm, C.H. Stewart, and the late August Haeussler, New York; John D. Warfield, Ezra J. Warner, S.O. Blair, and George D. McLaughlin, Chicago; W.H. Harrison, James Heekin, and Charles Lewis, Cincinnati; Albro Blodgett and A.M. Woolson, Toledo; R.V. Engelhard and Lee G. Zinsmeister, Louisville; E.A. Kahl, San Francisco; S. Jackson, New Orleans; Lewis Sherman, Milwaukee; Howard F. Boardman, Hartford; A.H. Devers, Portland, Ore.; W. James Mahood, Pittsburgh; William B. Harris, East Orange, N.J.

New York, June 17, 1922.

Some introductory remarks on the lure of coffee, its place in a rational dietary, its universal psychological appeal, its use and abuse

Civilization in its onward march has produced only three important non-alcoholic beverages—the extract of the tea plant, the extract of the cocoa bean, and the extract of the coffee bean.

Leaves and beans—these are the vegetable sources of the world's favorite non-alcoholic table-beverages. Of the two, the tea leaves lead in total amount consumed; the coffee beans are second; and the cocoa beans are a distant third, although advancing steadily. But in international commerce the coffee beans occupy a far more important position than either of the others, being imported into non-producing countries to twice the extent of the tea leaves. All three enjoy a world-wide consumption, although not to the same extent in every nation; but where either the coffee bean or the tea leaf has established itself in a given country, the other gets comparatively little attention, and usually has great difficulty in making any advance. The cocoa bean, on the other hand, has not risen to the position of popular favorite in any important consuming country, and so has not aroused the serious opposition of its two rivals.

Coffee is universal in its appeal. All nations do it homage. It has become recognized as a human necessity. It is no longer a luxury or an indulgence; it is a corollary of human energy and human efficiency. People love coffee because of its two-fold effect—the pleasurable sensation and the increased efficiency it produces.

Coffee has an important place in the rational dietary of all the civilized peoples of earth. It is a democratic beverage. Not only is it the drink of fashionable society, but it is also a favorite beverage of the men and women who do the world's work, whether they toil with brain or brawn. It has been acclaimed "the most grateful lubricant known to the human machine," and "the most delightful taste in all nature."

No "food drink" has ever encountered so much opposition as coffee. Given to the world by the church and dignified by the medical profession, nevertheless it has had to suffer from religious superstition and medical prejudice. During the thousand years of its development it has experienced fierce political opposition, stupid fiscal restrictions, unjust taxes, irksome duties; but, surviving all of these, it has triumphantly moved on to a foremost place in the catalog of popular beverages.

But coffee is something more than a beverage. It is one of the world's greatest adjuvant foods. There are other auxiliary foods, but none that excels it for palatability and comforting effects, the psychology of which is to be found in its unique flavor and aroma.

Men and women drink coffee because it adds to their sense of well-being. It not only smells good and tastes good to all mankind, heathen or civilized, but all respond to its wonderful stimulating properties. The chief factors in coffee goodness are the caffein content and the caffeol. Caffein supplies the principal stimulant. It increases the capacity for muscular and mental work without harmful reaction. The caffeol supplies the flavor and the aroma—that indescribable Oriental fragrance that wooes us through the nostrils, forming one of the principal elements that make up the lure of coffee. There are several other constituents, including certain innocuous so-called caffetannic acids, that, in combination with the caffeol, give the beverage its rare gustatory appeal.

The year 1919 awarded coffee one of its brightest honors. An American general said that coffee shared with bread and bacon the distinction of being one of the three nutritive essentials that helped win the World War for the Allies. So this symbol of human brotherhood has played a not inconspicuous part in "making the world safe for democracy." The new age, ushered in by the Peace of Versailles and the Washington Conference, has for its hand-maidens temperance and self-control. It is to be a world democracy of right-living and clear thinking; and among its most precious adjuncts are coffee, tea, and cocoa—because these beverages must always be associated with rational living, with greater comfort, and with better cheer.

Like all good things in life, the drinking of coffee may be abused. Indeed, those having an idiosyncratic susceptibility to alkaloids should be temperate in the use of tea, coffee, or cocoa. In every high-tensioned country there is likely to be a small number of people who, because of certain individual characteristics, can not drink coffee at all. These belong to the abnormal minority of the human family. Some people can not eat strawberries; but that would not be a valid reason for a general condemnation of strawberries. One may be poisoned, says Thomas A. Edison, from too much food. Horace Fletcher was certain that over-feeding causes all our ills. Over-indulgence in meat is likely to spell trouble for the strongest of us. Coffee is, perhaps, less often abused than wrongly accused. It all depends. A little more tolerance!

Trading upon the credulity of the hypochondriac and the caffein-sensitive, in recent years there has appeared in America and abroad a curious collection of so-called coffee substitutes. They are "neither fish nor flesh, nor good red herring." Most of them have been shown by official government analyses to be sadly deficient in food value—their only alleged virtue. One of our contemporary attackers of the national beverage bewails the fact that no palatable hot drink has been found to take the place of coffee. The reason is not hard to find. There can be no substitute for coffee. Dr. Harvey W. Wiley has ably summed up the matter by saying, "A substitute should be able to perform the functions of its principal. A substitute to a war must be able to fight. A bounty-jumper is not a substitute."

It has been the aim of the author to tell the whole coffee story for the general reader, yet with the technical accuracy that will make it valuable to the trade. The book is designed to be a work of useful reference covering all the salient points of coffee's origin, cultivation, preparation, and development, its place in the world's commerce and in a rational dietary.

Good coffee, carefully roasted and properly brewed, produces a natural beverage that, for tonic effect, can not be surpassed, even by its rivals, tea and cocoa. Here is a drink that ninety-seven percent of individuals find harmless and wholesome, and without which life would be drab indeed—a pure, safe, and helpful stimulant compounded in nature's own laboratory, and one of the chief joys of life!

Encomiums and descriptive phrases applied to the plant, the berry, and the beverage Page XXVII

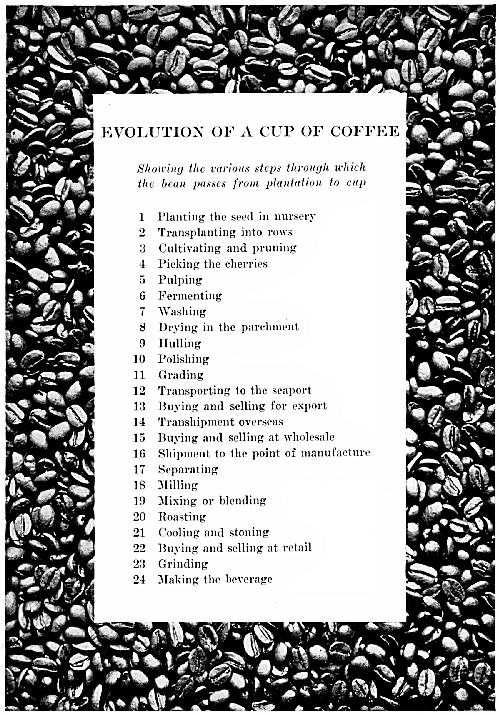

THE EVOLUTION OF A CUP OF COFFEE

Showing the various steps through which the bean passes from plantation to cup Page XXIX

CHAPTER I

Dealling with the Etymology of Coffee

Origin and translation of the word from the Arabian into various languages—Views of many writers Page 1

CHAPTER II

History of Coffee Propagation

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New—A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

Early History of Coffee Drinking

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries—Stories of its origin—Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church—Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey—Persecutions and Intolerances—Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

Introduction of Coffee into Western Europe

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe—Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582—Early days of coffee in Italy—How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage—The first European coffee house, in Venice, 1645—The famous Caffè Florian—Other celebrated Venetian coffee houses of the eighteenth century—The romantic story of Pedrocchi, the poor lemonade-vender, who built the most beautiful coffee house in the world Page 25

CHAPTER V

The Beginnings of Coffee in France

What French travelers did for coffee—the introduction of coffee by P. de la Roque into Marseilles in 1644—The first commercial importation of coffee from Egypt—The first French coffee house—Failure of the attempt by physicians of Marseilles to discredit coffee—Soliman Aga introduces coffee into Paris—Cabarets à caffè—Celebrated works on coffee by French writers Page 31

CHAPTER VI

The Introduction of Coffee into England

The first printed reference to coffee in English—Early mention of coffee by noted English travelers and writers—The Lacedæmonian "black broth" controversy—How Conopios introduced coffee drinking at Oxford—The first English coffee house in Oxford—Two English botanists on coffee Page 35

CHAPTER VII

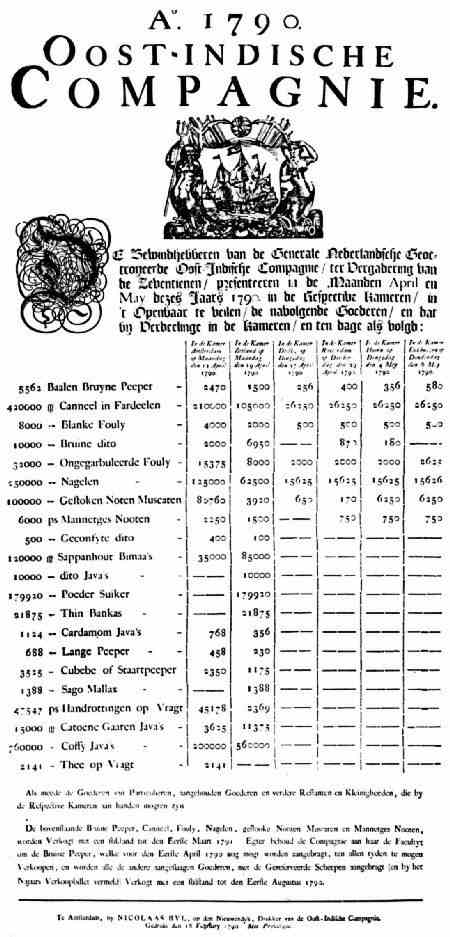

The Introduction of Coffee into Holland

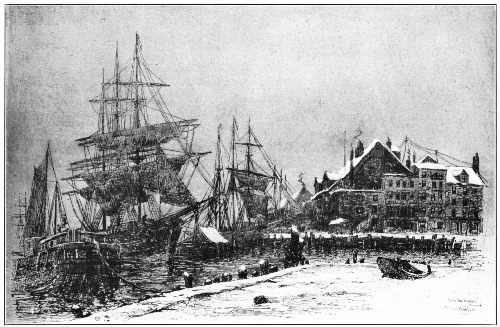

How the enterprising Dutch traders captured the first world's market for coffee—Activities of the Netherlands East India Company—The first coffee house at the Hague—The first public auction at Amsterdam in 1711, when Java coffee brought forty-seven cents a pound, green Page 43

CHAPTER VIII

The Introduction of Coffee into Germany

The contributions made by German travelers and writers to the literature of the early history of coffee—The first coffee house in Hamburg opened by an English merchant—Famous coffee houses of old Berlin—The first coffee periodical and the first kaffee-klatsch—Frederick the Great's coffee roasting monopoly—Coffee persecutions—"Coffee-smellers"—The first coffee king Page 45

CHAPTER IX

Telling How Coffee Came to Vienna

The romantic adventure of Franz George Kolschitzky, who carried "a message to Garcia" through the enemy's lines and won for himself the honor of being the first to teach the Viennese the art of making coffee, to say nothing of falling heir to the supplies of the green beans left behind by the Turks; also the gift of a house from a grateful municipality, and a statue after death—Affectionate regard in which "Brother-heart" Kolschitzky is held as the patron saint of the Vienna Kaffee-sieder—Life in the early Vienna café's Page 49

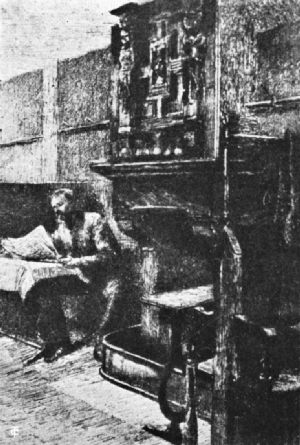

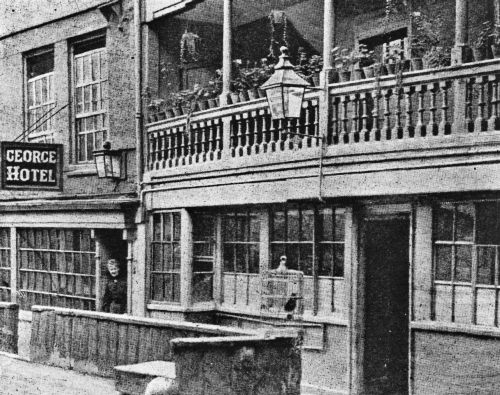

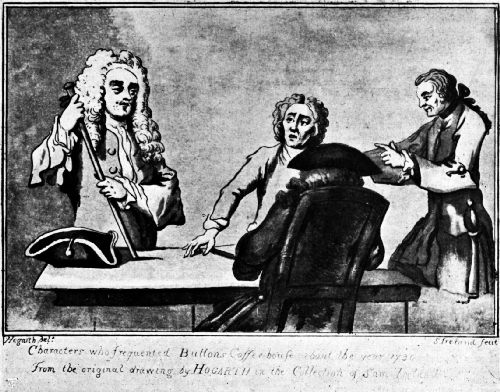

CHAPTER X

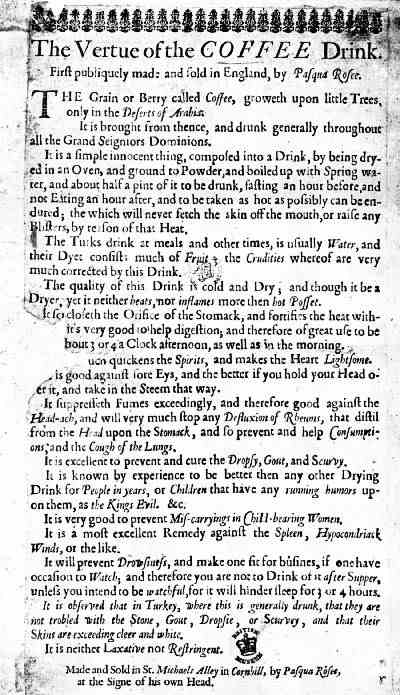

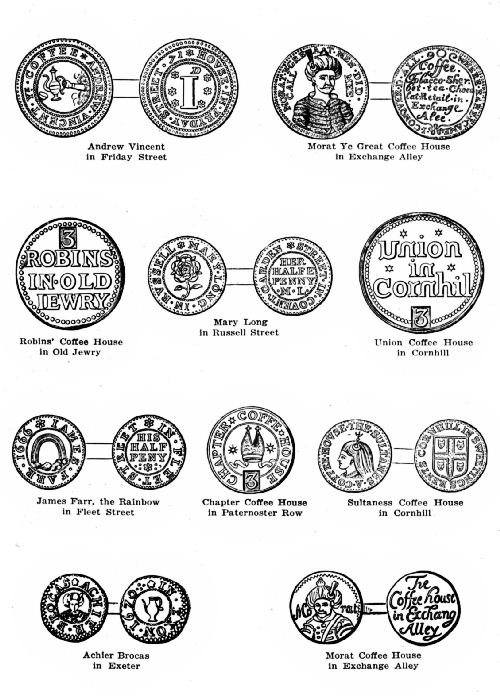

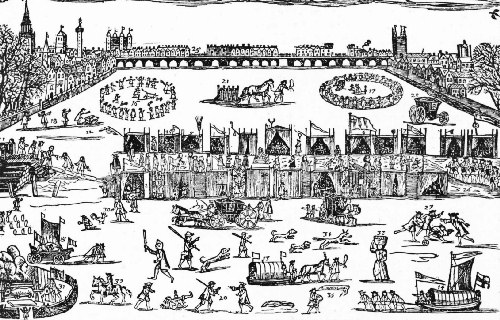

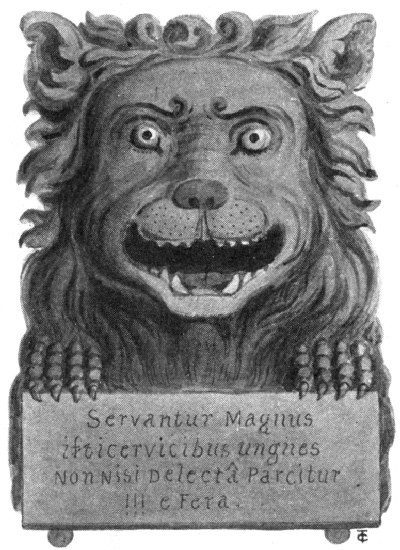

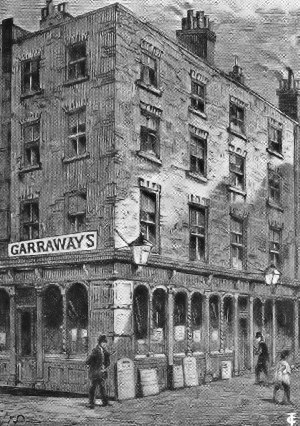

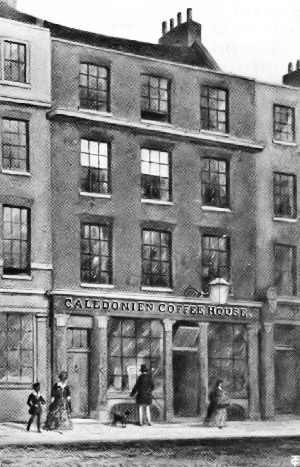

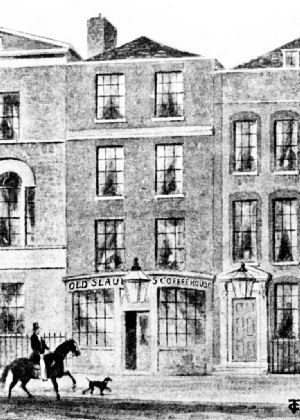

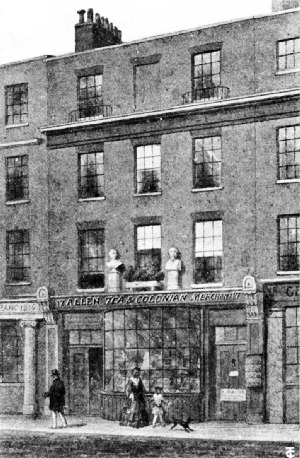

The Coffee Houses of Old London

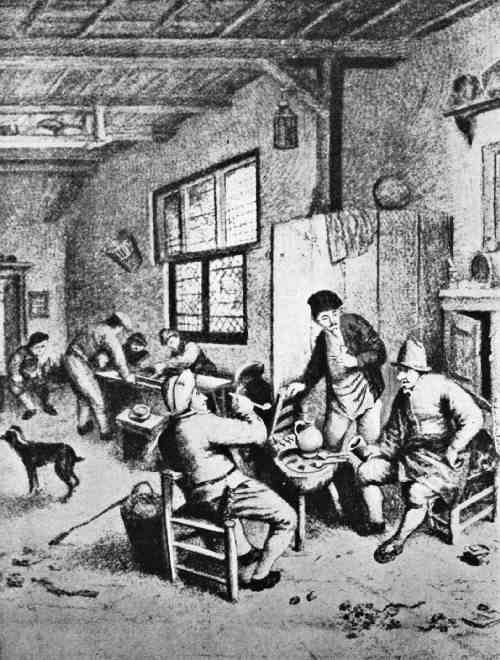

One of the most picturesque chapters in the history of coffee—The first coffee house in London—The first coffee handbill, and the first newspaper advertisement for coffee—Strange coffee mixtures—Fantastic coffee claims—Coffee prices and coffee licenses—Coffee club of the Rota—Early coffee-house manners and customs—Coffee-house keepers' tokens—Opposition to the coffee house—"Penny universities"—Weird coffee substitutes—The proposed coffee-house newspaper monopoly—Evolution of the club—Decline and fall of the coffee house—Pen pictures of coffee-house life—Famous coffee houses of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—Some Old World pleasure gardens—Locating the notable coffee houses Page 53

CHAPTER XI

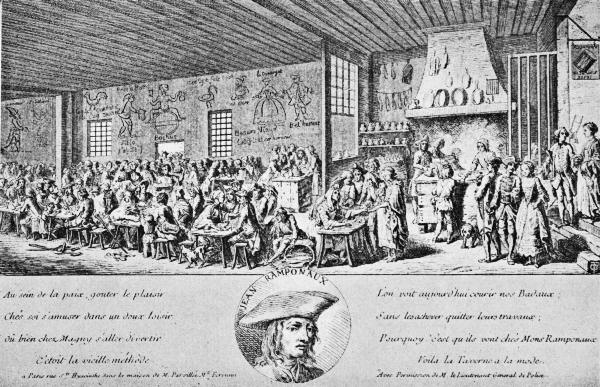

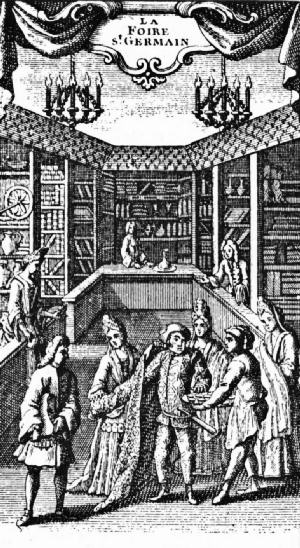

History of the Early Parisian Coffee Houses

The introduction of coffee into Paris by Thévenot in 1657—How Soliman Aga established the custom of coffee drinking at the court of Louis XIV—Opening of the first coffee houses—How the French adaptation of the Oriental coffee house first appeared in the real French café of François Procope—Important part played by the coffee houses in the development of French literature and the stage—Their association with the Revolution and the founding of the Republic—Quaint customs and patrons—Historic Parisian café's Page 91

CHAPTER XII

Introduction of Coffee into North America

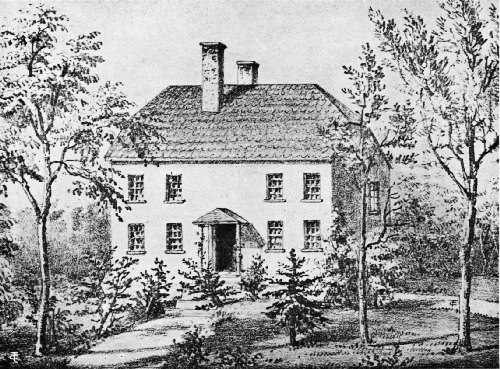

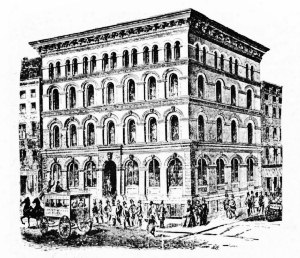

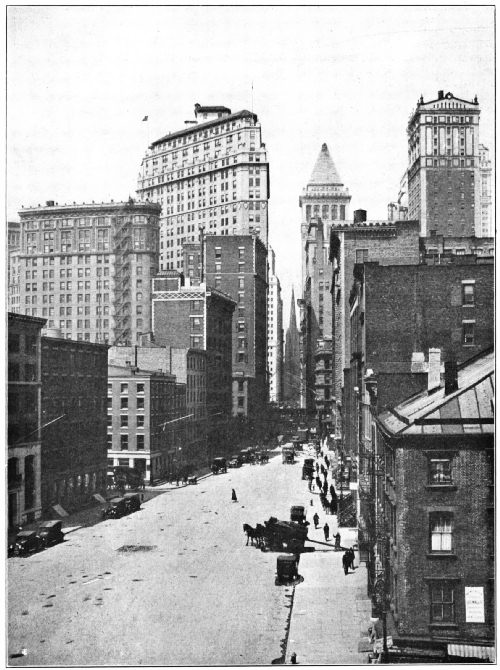

Captain John Smith, founder of the Colony of Virginia, is the first to bring to North America a knowledge of coffee in 1607—The coffee grinder on the Mayflower—Coffee drinking in 1668—William Penn's coffee purchase in 1683—Coffee in colonial New England—The psychology of the Boston "tea party," and why the United States became a nation of coffee drinkers instead of tea drinkers, like England—The first coffee license to Dorothy Jones in 1670—The first coffee house in New England—Notable coffee houses of old Boston—A skyscraper coffee-house Page 105

CHAPTER XIII

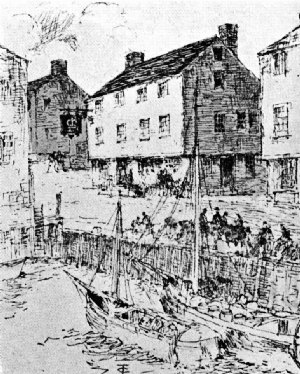

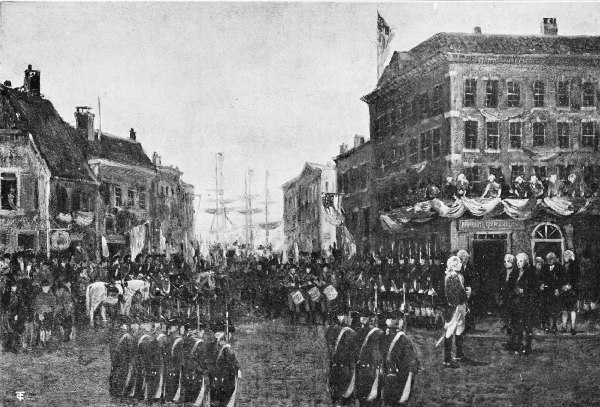

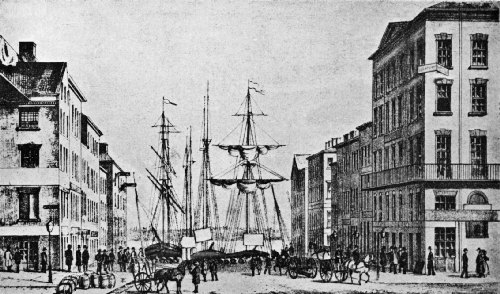

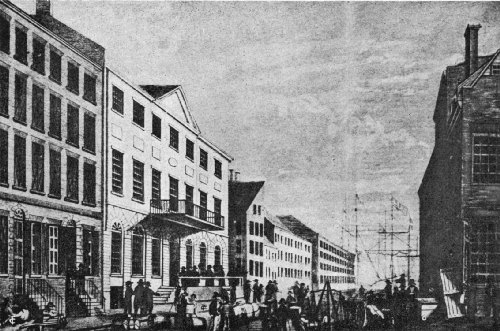

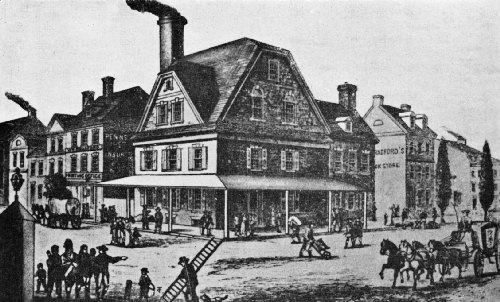

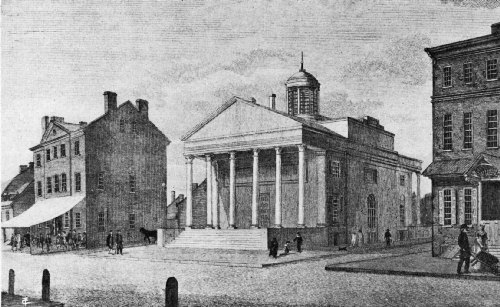

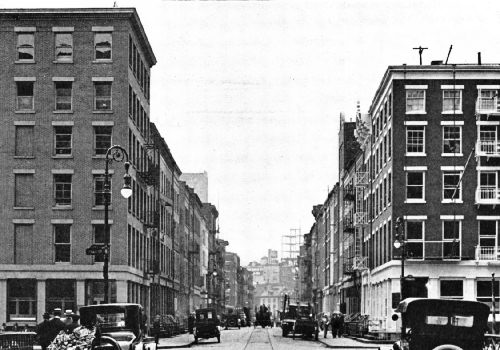

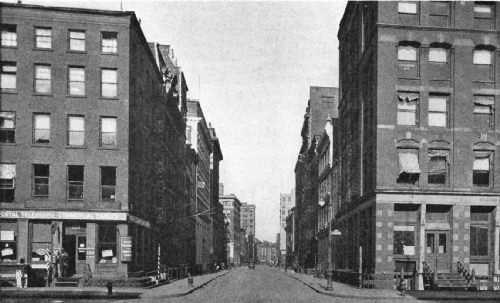

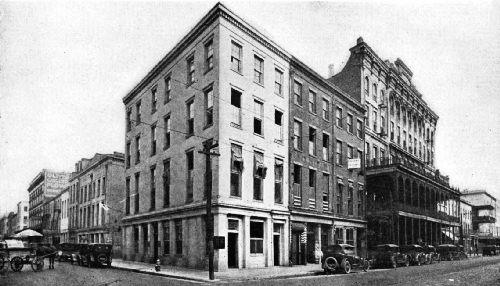

History of Coffee in Old New York

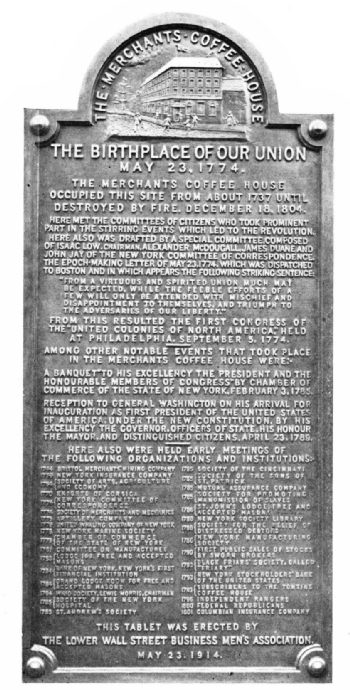

The burghers of New Amsterdam begin to substitute coffee for "must," or beer, for breakfast in 1668—William Penn makes his first purchase of coffee in the green bean from New York merchants in 1683—The King's Arms, the first coffee house—The historic Merchants, sometimes called the "Birthplace of our Union"—The coffee house as a civic forum—The Exchange, Whitehall, Burns, Tontine, and other celebrated coffee houses—The Vauxhall and Ranelagh pleasure gardens Page 115

CHAPTER XIV

Coffee Houses of Old Philadelphia

Ye Coffee House, Philadelphia's first coffee house, opened about 1700—The two London coffee houses—The City tavern, or Merchants coffee house—How these, and other celebrated resorts, dominated the social, political, and business life of the Quaker City in the eighteenth century Page 125

CHAPTER XV

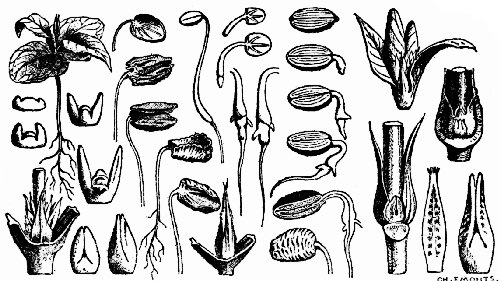

The Botany of the Coffee Plant

Its complete classification by class, sub-class, order, family, genus, and species—How the Coffea arabica grows, flowers, and bears—Other species and hybrids described—Natural caffein-free coffee—Fungoid diseases of coffee Page 131

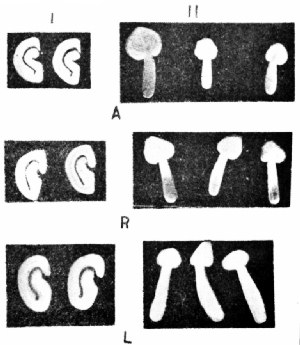

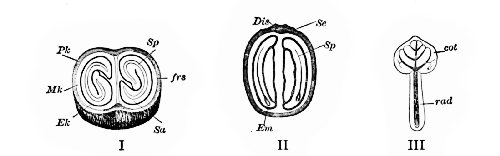

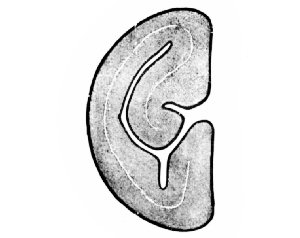

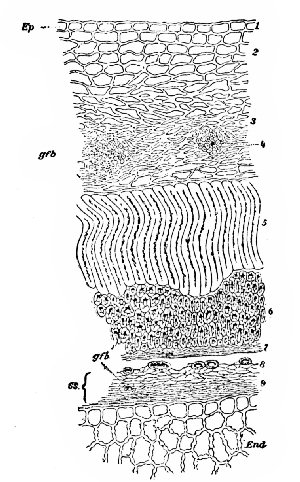

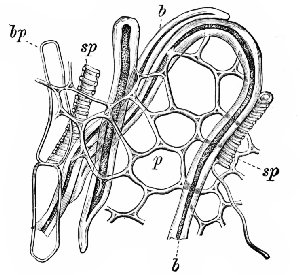

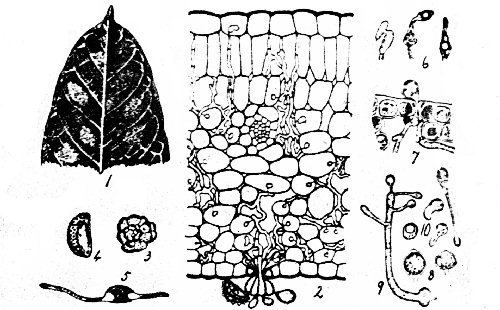

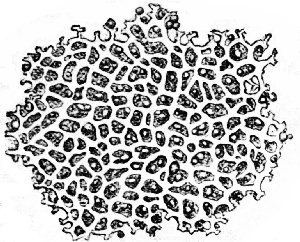

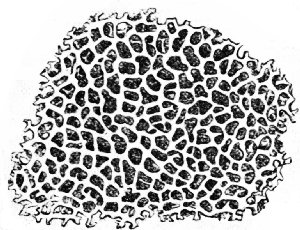

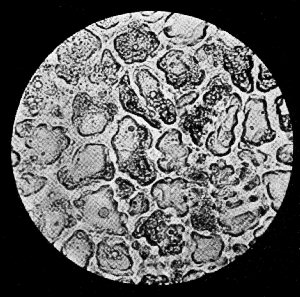

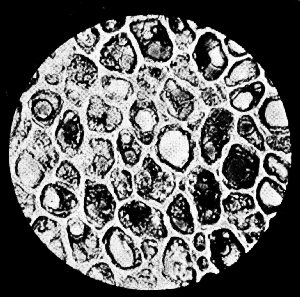

CHAPTER XVI

The Microscopy of the Coffee Fruit

How the beans may be examined under the microscope, and what is revealed—Structure of the berry, the green, and the roasted beans—The coffee-leaf disease under the microscope—Value of microscopic analysis in detecting adulteration Page 149

CHAPTER XVII

The Chemistry of the Coffee Bean

By Charles W. Trigg.

Chemistry of the preparation and treatment of the green bean—Artificial aging—Renovating damaged coffees—Extracts—"Caffetannic acid"—Caffein, caffein-free coffee—Caffeol—Fats and oils—Carbohydrates—Roasting—Scientific aspects of grinding and packaging—The coffee brew—Soluble coffee—Adulterants and substitutes—Official methods of analysis Page 155

CHAPTER XVIII

Pharmacology of the Coffee Drink

By Charles W. Trigg

General physiological action—Effect on children—Effect on longevity—Behavior in the alimentary régime—Place in dietary—Action on bacteria—Use in medicine—Physiological action of "caffetannic acid"—Of caffeol—Of caffein—Effect of caffein on mental and motor efficiency—Conclusions Page 174

CHAPTER XIX

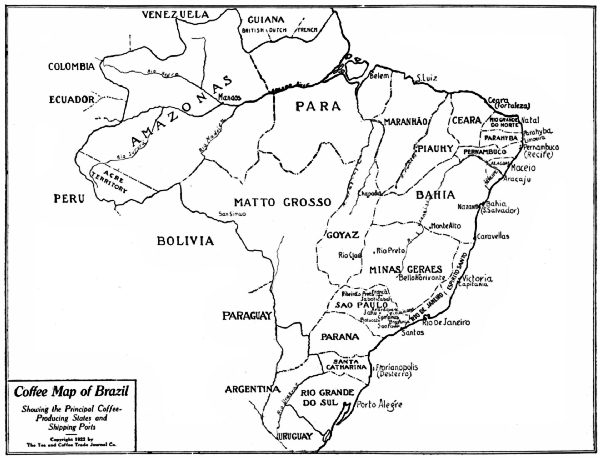

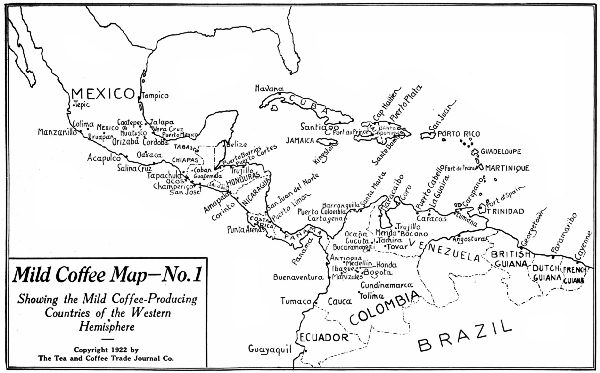

The Commercial Coffees of the World

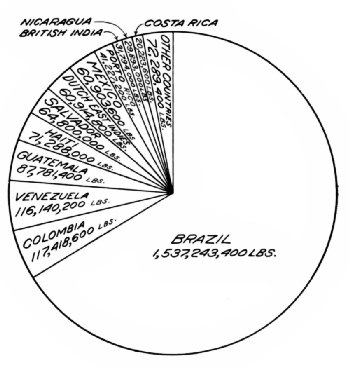

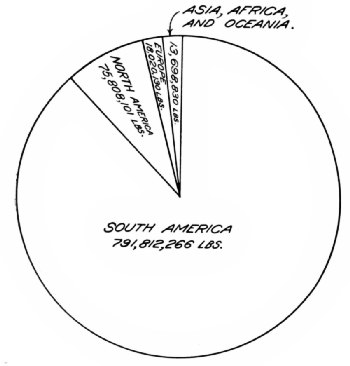

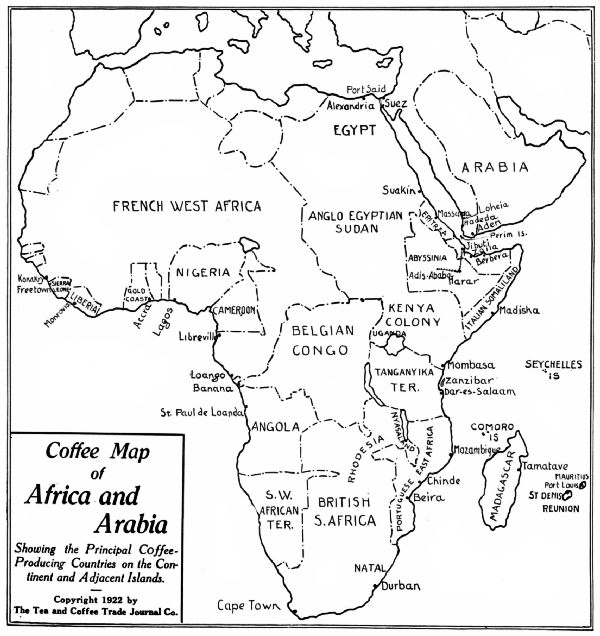

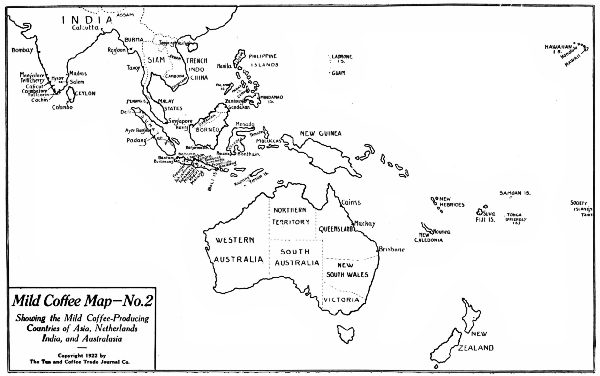

The geographical distribution of the coffees grown in North America, Central America, South America, the West India Islands, Asia, Africa, the Pacific Islands, and the East Indies—A statistical study of the distribution of the principal kinds—A commercial coffee chart of the world's leading growths, with market names and general trade characteristics Page 189

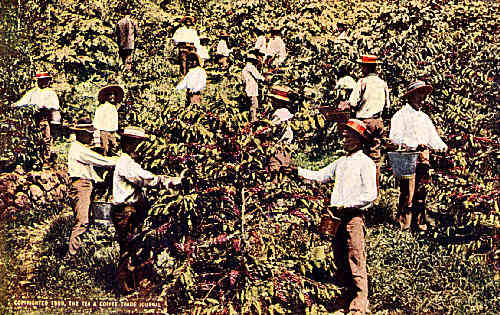

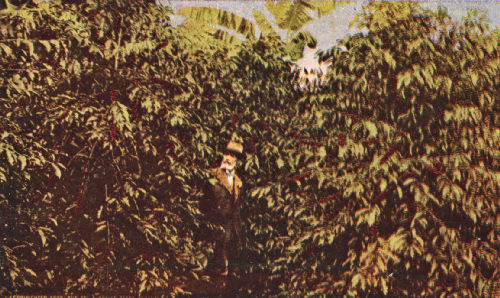

CHAPTER XX

Cultivation of the Coffee Plant

The early days of coffee culture in Abyssinia and Arabia—Coffee cultivation in general—Soil, climate, rainfall, altitude, propagation, preparing the plantation, shade, wind breaks, fertilizing, pruning, catch crops, pests, and diseases—How coffee is grown around the world—Cultivation in all the principal producing countries Page 197

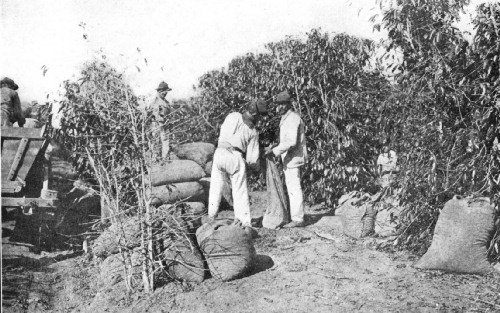

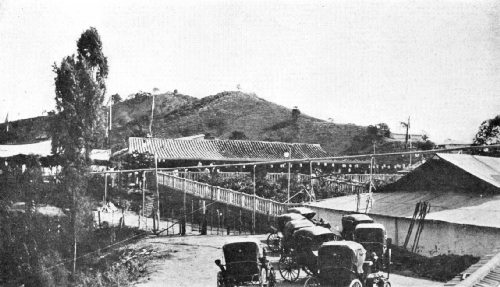

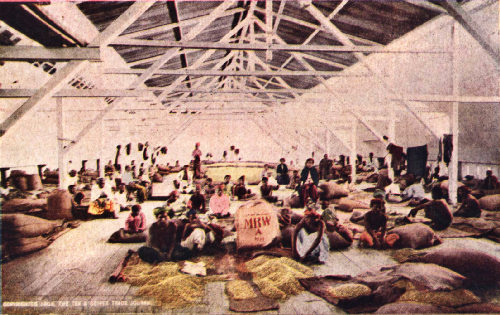

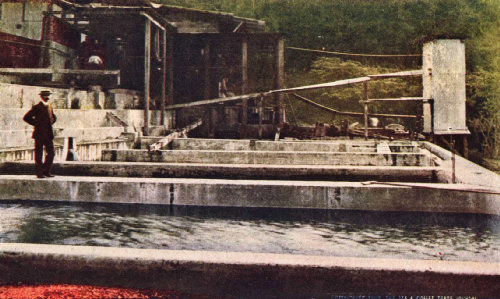

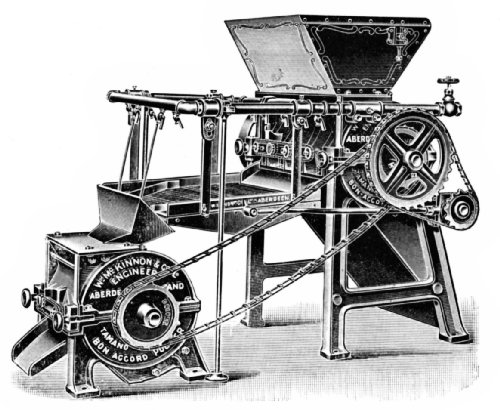

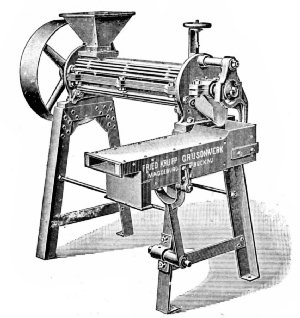

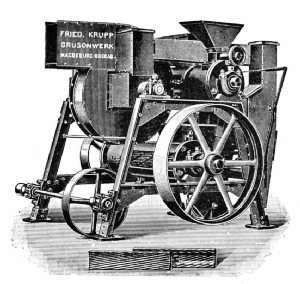

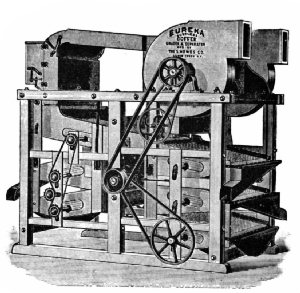

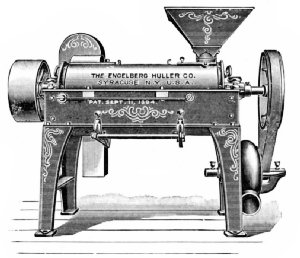

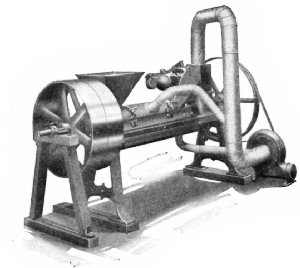

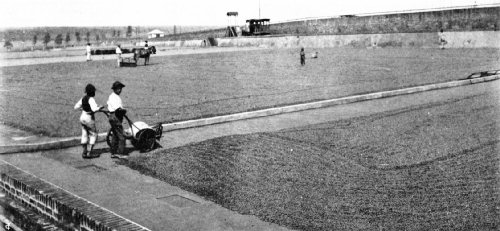

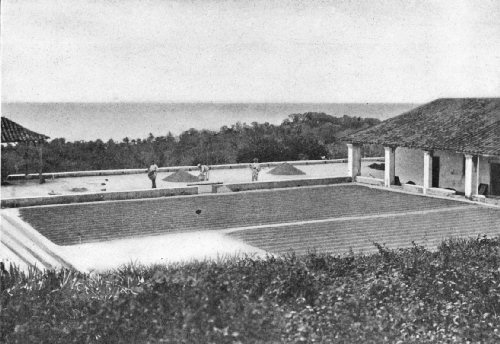

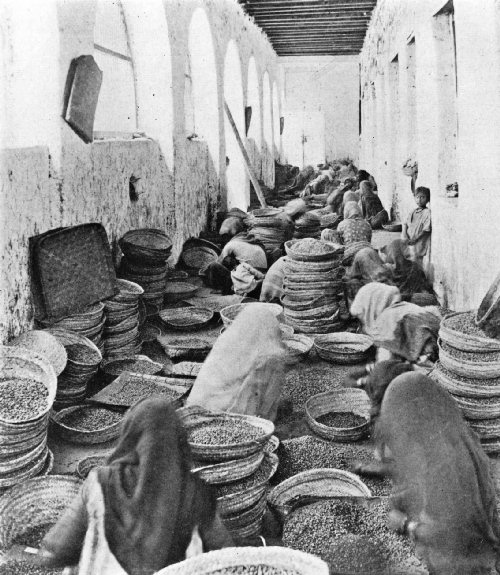

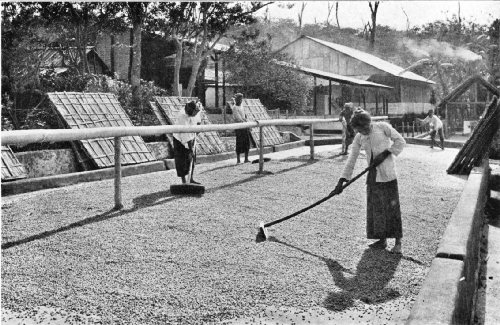

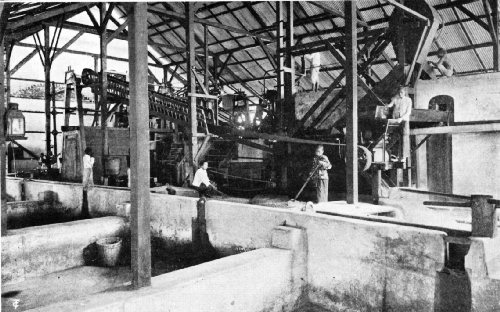

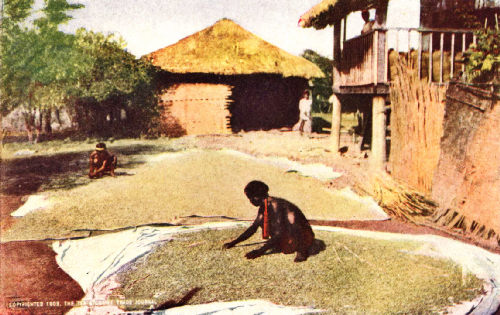

CHAPTER XXI

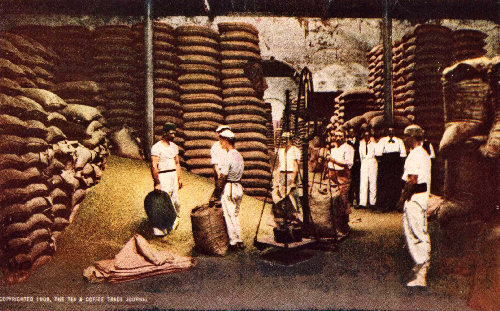

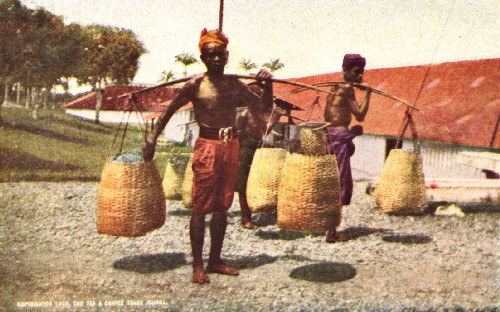

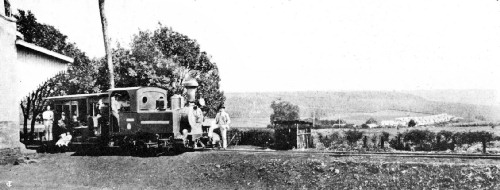

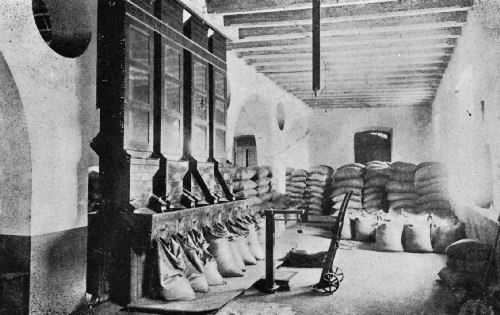

Preparing Green Coffee for Market

Early Arabian methods of preparation—How primitive devices were replaced by modern methods—A chronological story of the development of scientific plantation machinery, and the part played by English and American inventors—The marvelous coffee package, one of the most ingenious in all nature—How coffee is harvested—Picking—Preparation by the dry and the wet methods—Pulping—Fermentation and washing—Drying—Hulling, or peeling, and polishing—Sizing, or grading—Preparation methods of different countries Page 245

CHAPTER XXII

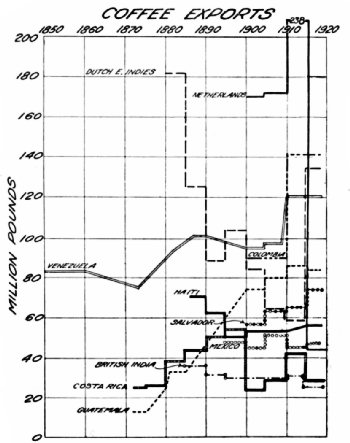

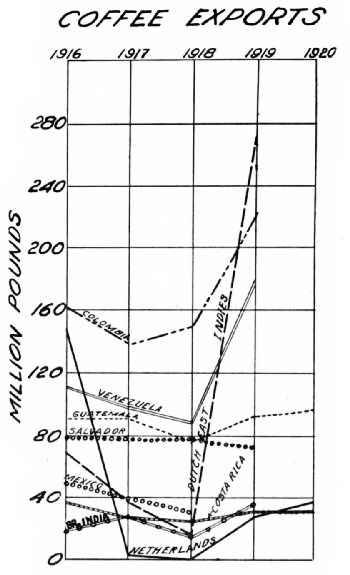

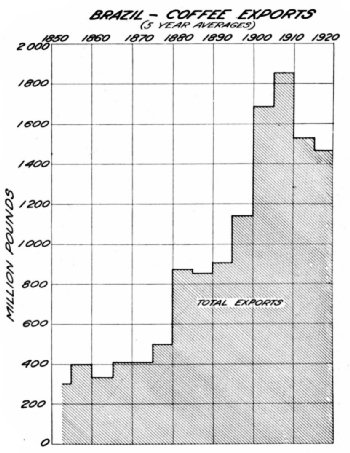

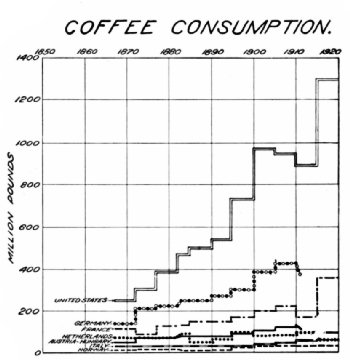

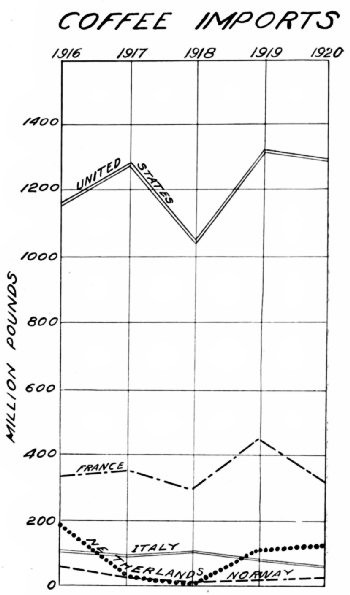

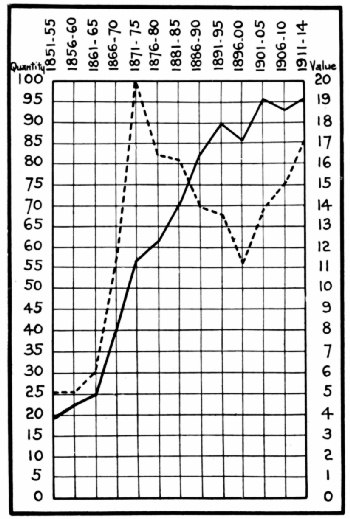

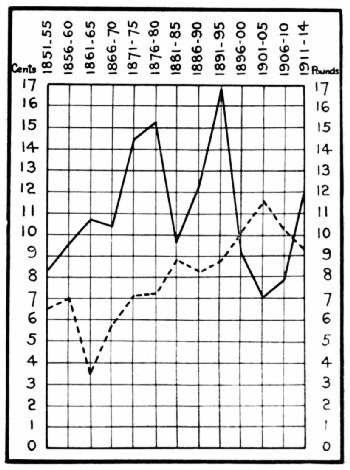

The Production and Consumption of Coffee

A statistical study of world production of coffee by countries—Per capita figures of the leading consuming countries—Coffee-consumption figures compared with tea-consumption figures in the United States and the United Kingdom—Three centuries of coffee trading—Coffee drinking in the United States, past and present—Reviewing the 1921 trade in the United States Page 273

CHAPTER XXIII

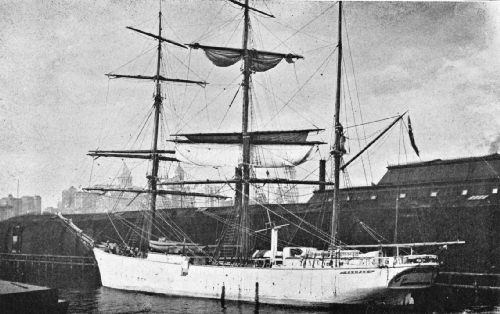

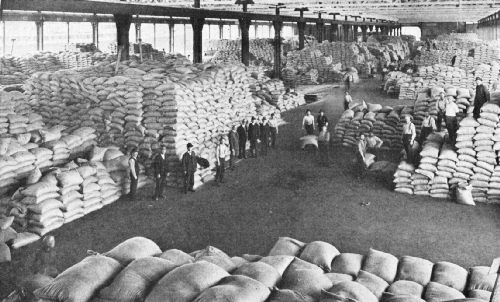

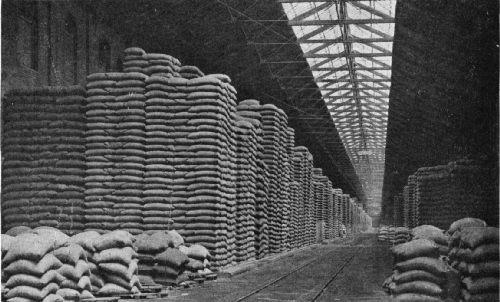

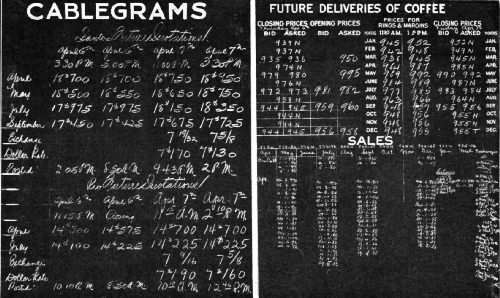

How Green Coffees Are Bought and Sold

Buying coffee in the producing countries—Transporting coffee to the consuming markets—Some record coffee cargoes shipped to the United States—Transport over seas—Java coffee "ex-sailing vessels"—Handling coffee at New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco—The coffee exchanges of Europe and the United States—Commission men and brokers—Trade and exchange contracts for delivery—Important rulings affecting coffee trading—Some well-known green coffee marks Page 303

CHAPTER XXIV

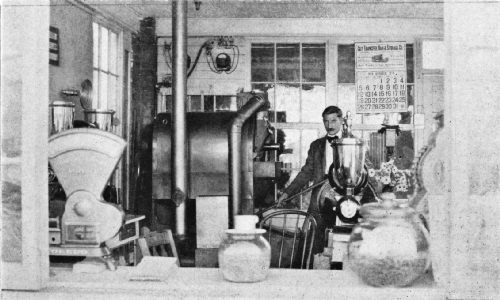

Green and Roasted Coffee Characteristics

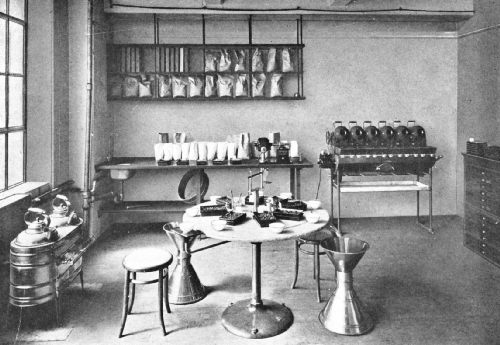

The trade values, bean characteristics, and cup merits of the leading coffees of commerce, with a "Complete Reference Table of the Principal Kinds of Coffee Grown in the World"—Appearance, aroma, and flavor in cup-testing—How experts test coffee—A typical sample-roasting and cup-testing outfit Page 341

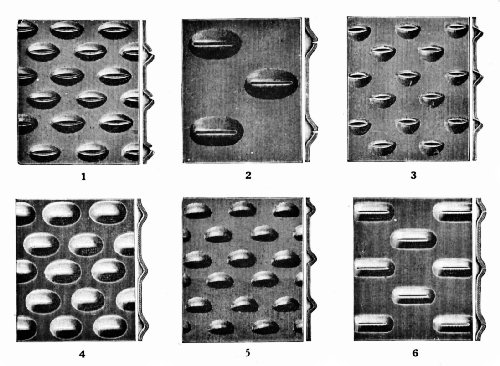

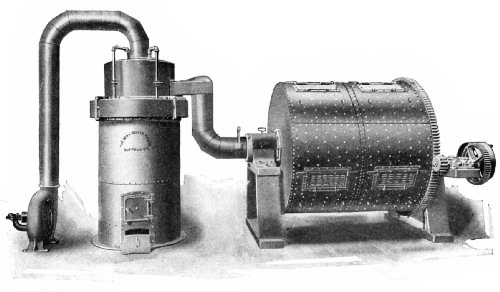

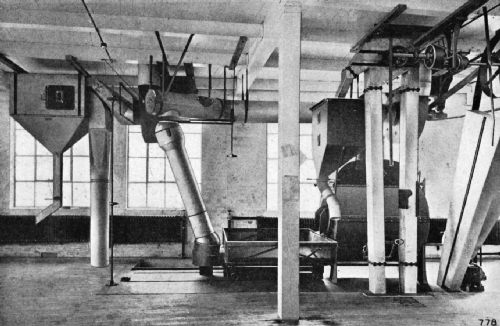

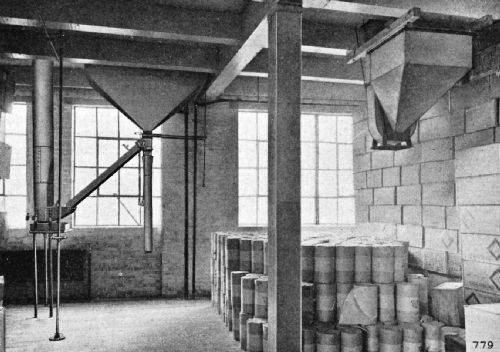

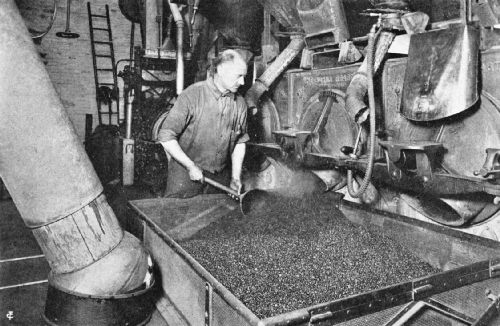

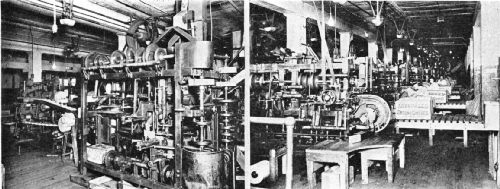

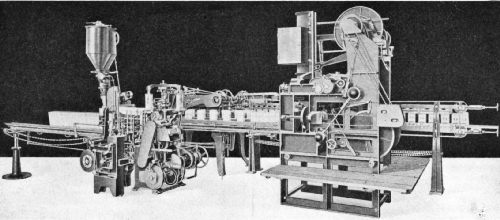

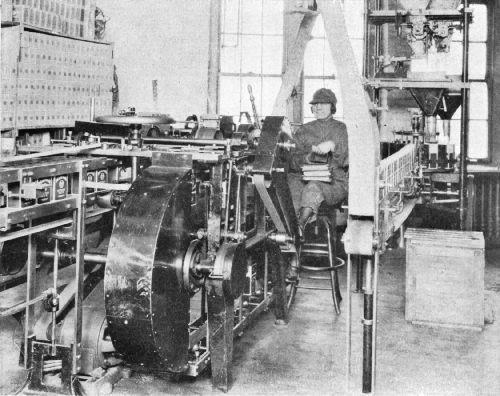

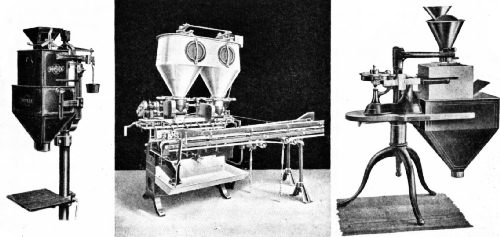

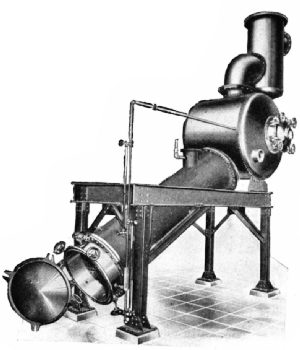

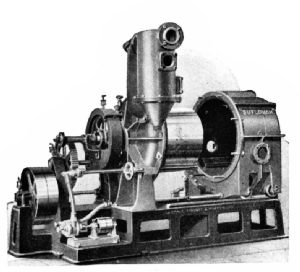

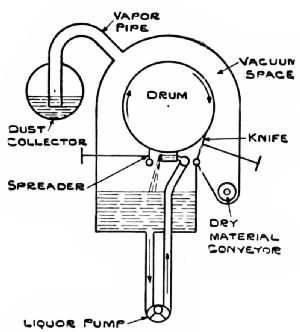

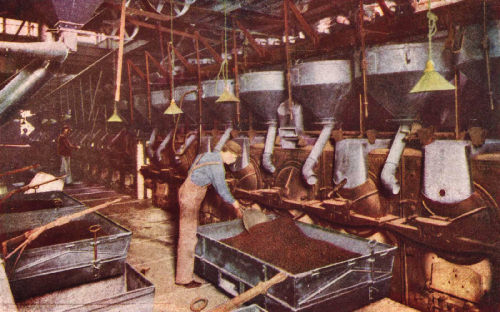

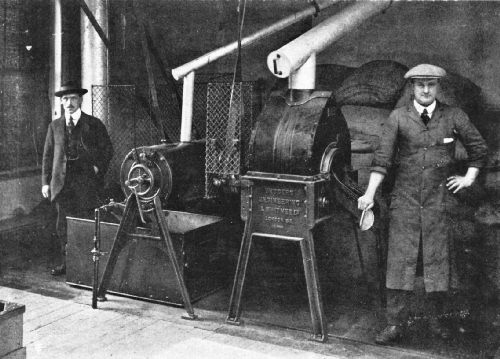

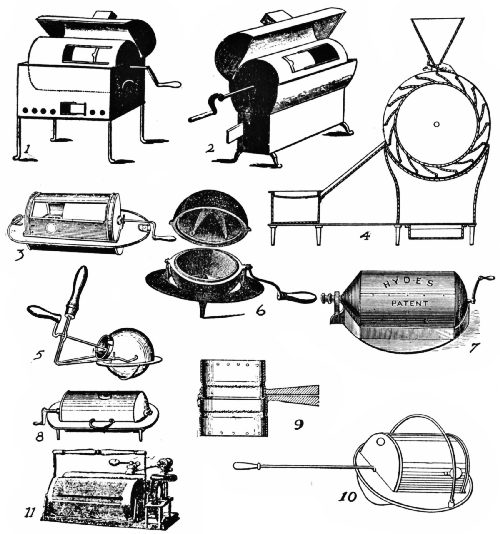

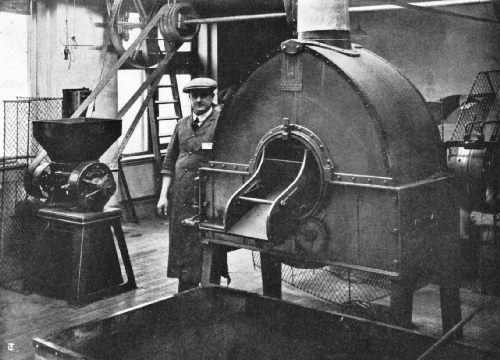

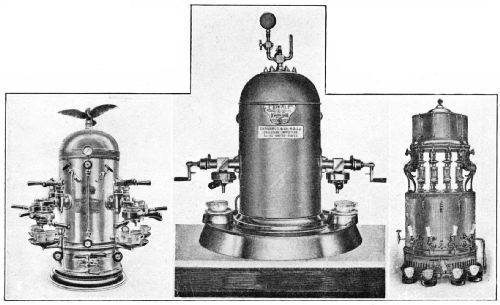

CHAPTER XXV

Factory Preparation of Roasted Coffee

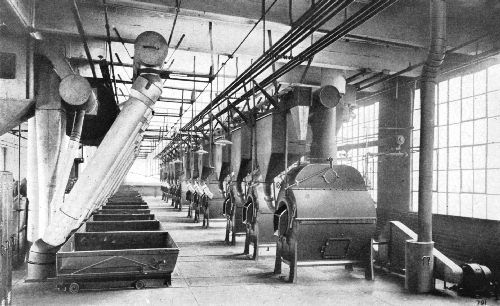

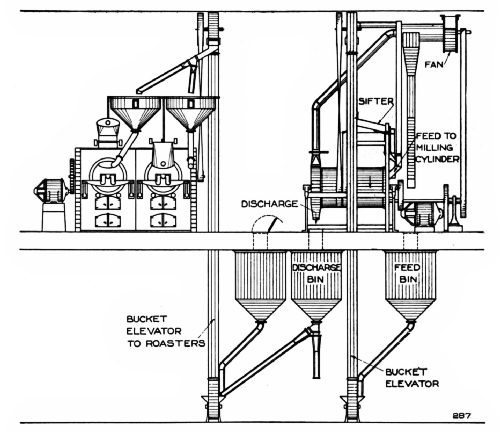

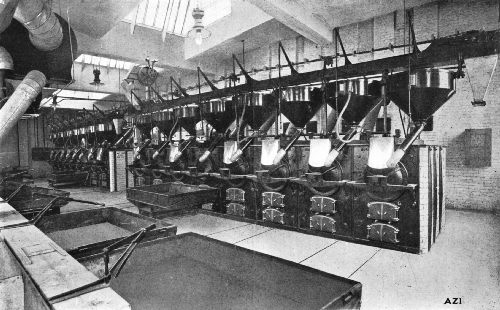

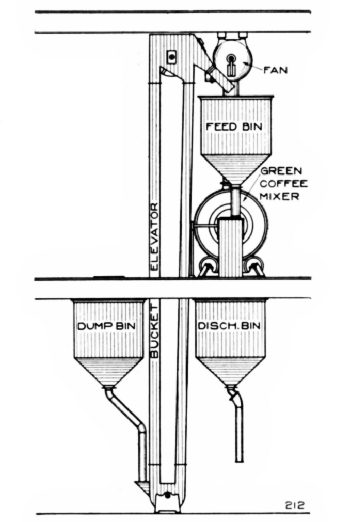

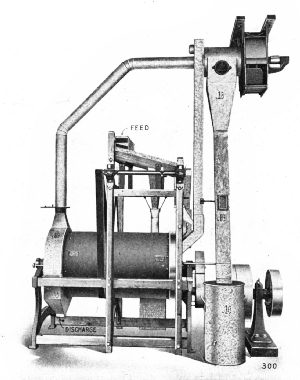

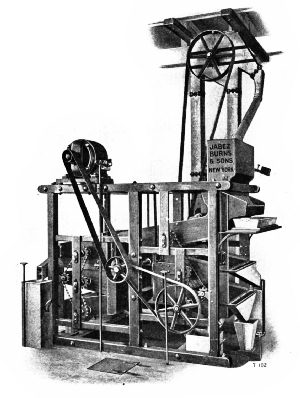

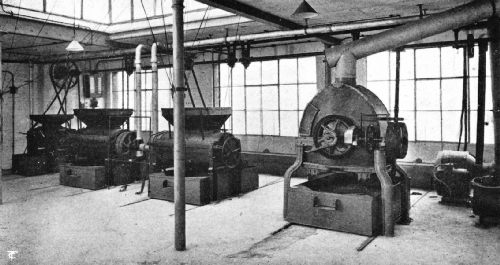

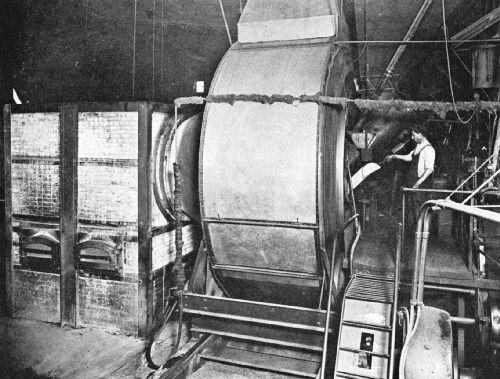

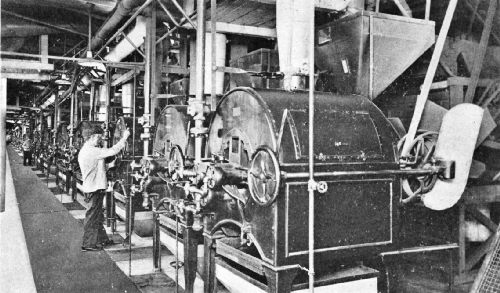

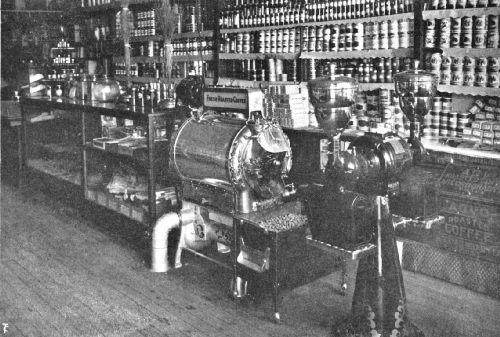

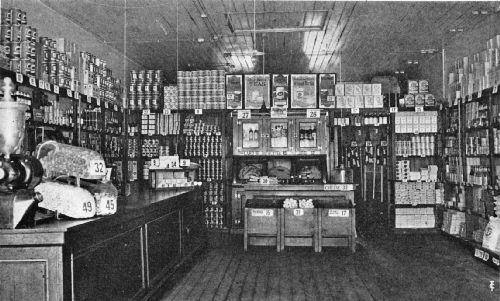

Coffee roasting as a business—Wholesale coffee-roasting machinery—Separating, milling, and mixing or blending green coffee, and roasting by coal, coke, gas, and electricity—Facts about coffee roasting—Cost of roasting—Green-coffee shrinkage table—"Dry" and "wet" roasts—On roasting coffee efficiently—A typical coal roaster—Cooling and stoning—Finishing or glazing—Blending roasted coffees—Blends for restaurants—Grinding and packaging—Coffee additions and fillers—Treated coffees, and dry extracts Page 379

CHAPTER XXVI

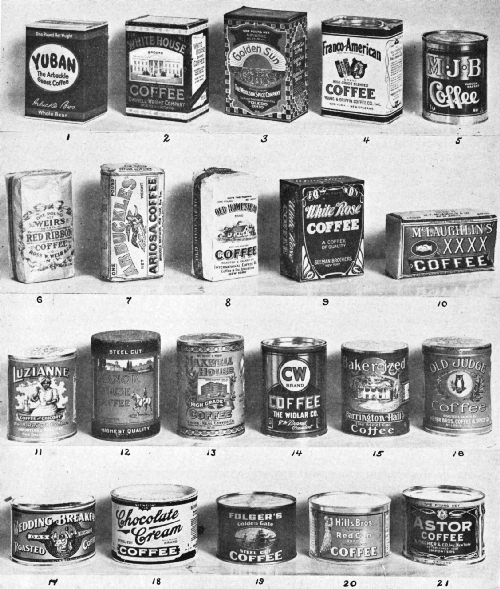

Wholesale Merchandising of Coffee

How coffees are sold at wholesale—The wholesale salesman's place in merchandising—Some coffee costs analyzed—Handy coffee-selling chart—Terms and credits—About package coffees—Various types of coffee containers—Coffee package labels—Coffee package economies—Practical grocer helps—Coffee sampling—Premium method of sales promotion Page 407

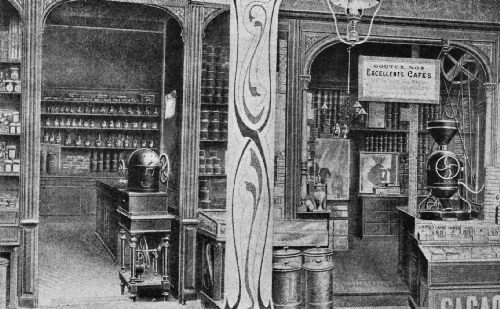

CHAPTER XXVII

Retail Merchandising of Roasted Coffee

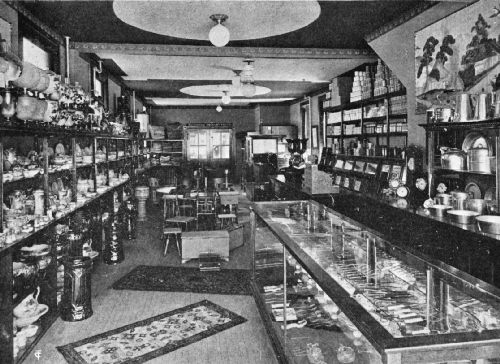

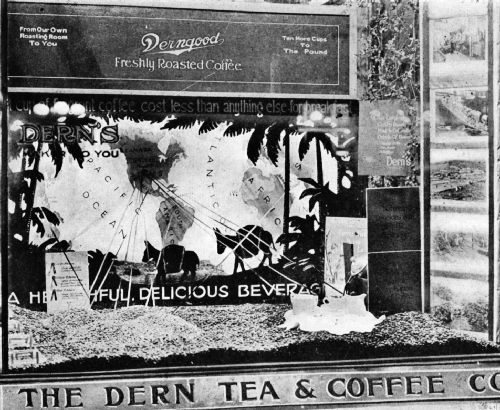

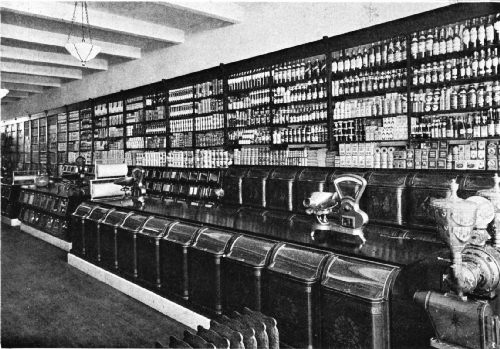

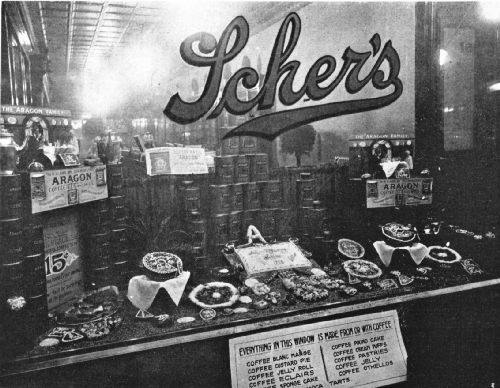

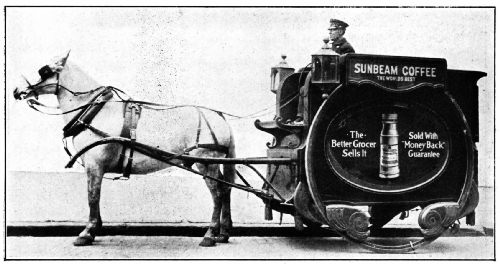

How coffees are sold at retail—The place of the grocer, the tea and coffee dealer, the chain store, and the wagon-route distributer in the scheme of distribution—Starting in the retail coffee business—Small roasters for retail dealers—Model coffee departments—Creating a coffee trade—Meeting competition—Splitting nickels—Figuring costs and profits—A credit policy for retailers—Premiums Page 415

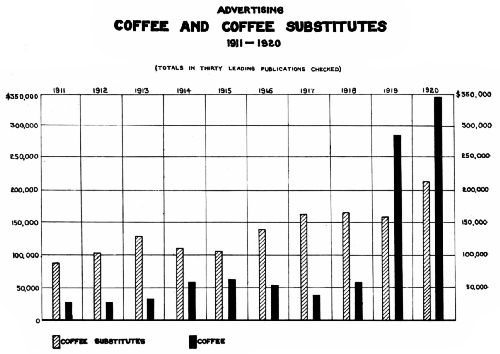

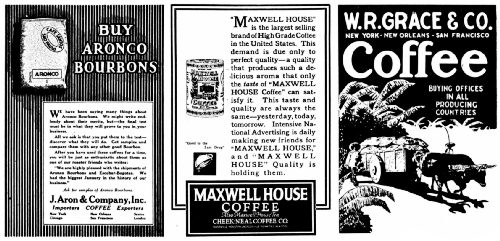

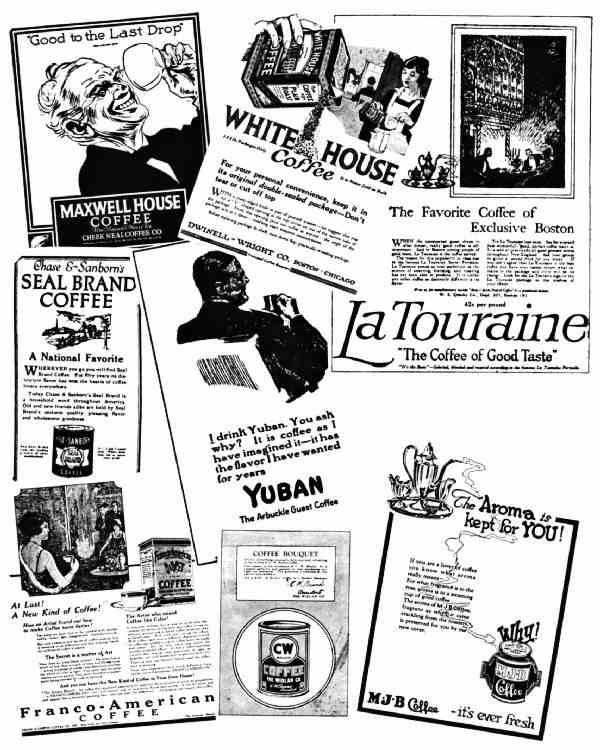

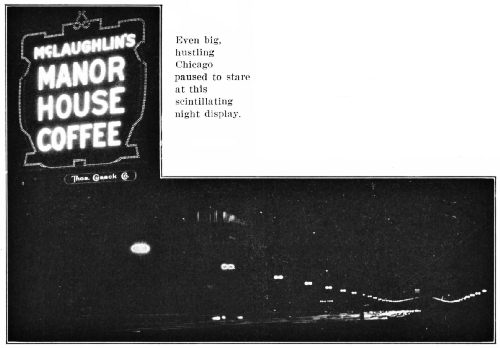

CHAPTER XXVIII

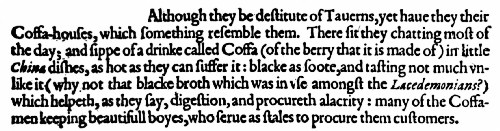

A Short History of Coffee Advertising

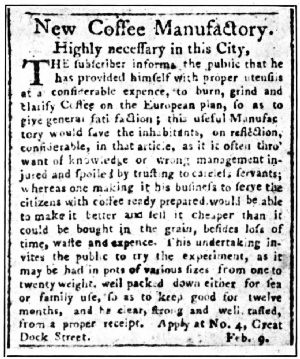

Early coffee advertising—The first coffee advertisement in 1587 was frank propaganda for the legitimate use of coffee—The first printed advertisement in English—The first newspaper advertisement—Early advertisements in colonial America—Evolution of advertising—Package coffee advertising—Advertising to the trade—Advertising by means of newspapers, magazines, billboards, electric signs, motion pictures, demonstrations, and by samples—Advertising for retailers—Advertising by government propaganda—The Joint Coffee Trade publicity campaign in the United States—Coffee advertising efficiency Page 431

CHAPTER XXIX

The Coffee Trade in the United States

The coffee business started by Dorothy Jones of Boston—Some early sales—Taxes imposed by Congress in war and peace—The first coffee-plantation-machine, coffee-roaster, coffee-grinder, and coffee-pot patents—Early trade marks for coffee—Beginnings of the coffee urn, the coffee container, and the soluble-coffee business—Chronological record of the most important events in the history of the trade from the eighteenth century to the twentieth Page 467

CHAPTER XXX

Development of the Green and Roasted Coffee

Business in the United States

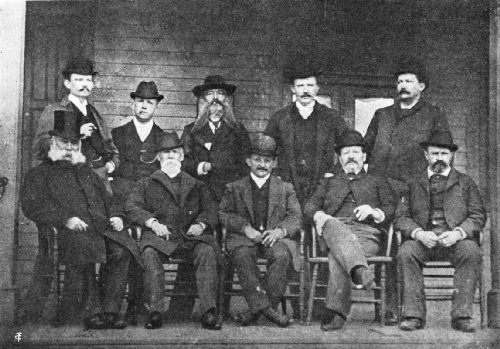

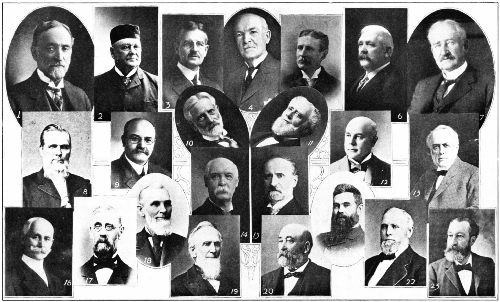

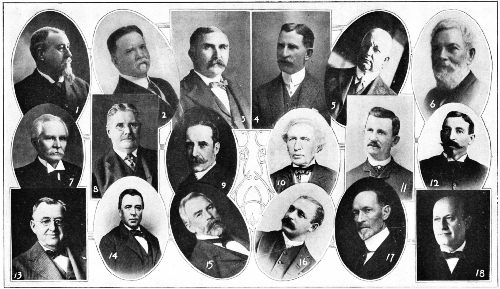

A brief history of the growth of coffee trading—Notable firms and personalities that have played important parts in green coffee in the principal coffee centers—Green coffee trade organizations—Growth of the wholesale coffee-roasting trade, and names of those who have made history in it—The National Coffee Roasters Association—Statistics of distribution of coffee-roasting establishments in the United States Page 475

CHAPTER XXXI

Some Big Men and Notable Achievements

B.G. Arnold, the first, and Hermann Sielcken, the last of the American "coffee kings"—John Arbuckle, the original package-coffee man—Jabez Burns, the man who revolutionized the roasted-coffee business by his contributions as inventor, manufacturer, and writer—Coffee trade booms and panics—Brazil's first valorization enterprise—War-time government control of coffee—The story of soluble coffee Page 517

CHAPTER XXXII

A History of Coffee in Literature

The romance of coffee, and its influence on the discourse, poetry, history, drama, philosophic writing, and fiction of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and on the writers of today—Coffee quips and anecdotes Page 541

CHAPTER XXXIII

Coffee in Relation to the Fine Arts

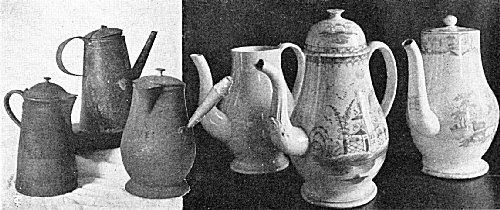

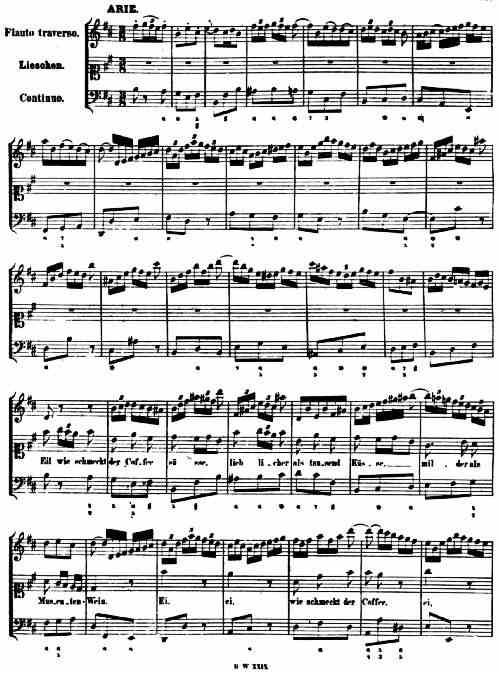

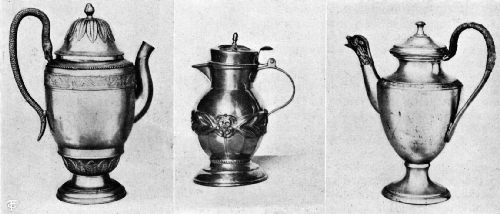

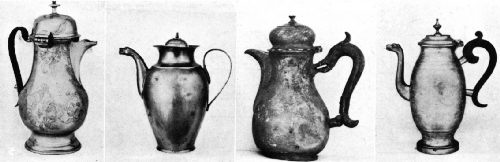

How coffee and coffee drinking have been celebrated in painting, engraving, sculpture, caricature, lithography, and music—Epics, rhapsodies, and cantatas in praise of coffee—Beautiful specimens of the art of the potter and the silversmith as shown in the coffee service of various periods in the world's history—Some historical relics Page 587

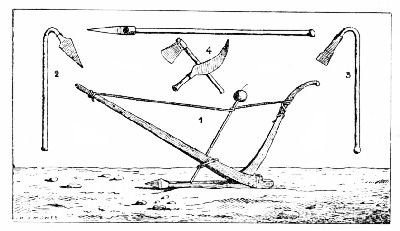

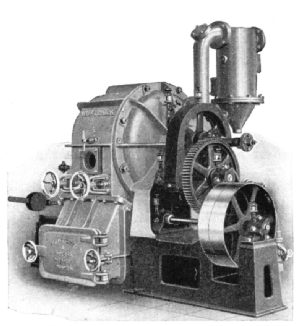

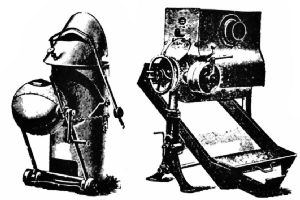

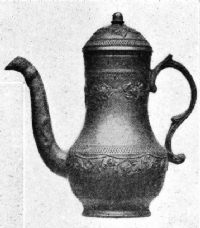

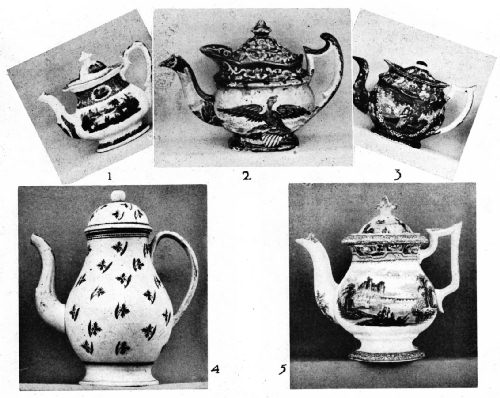

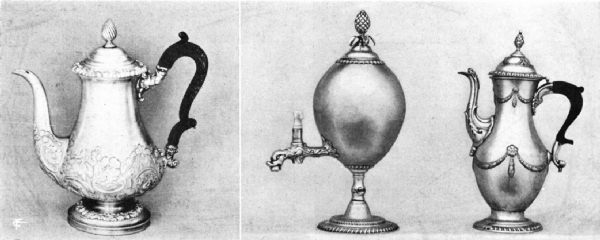

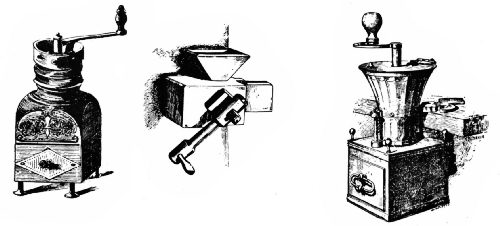

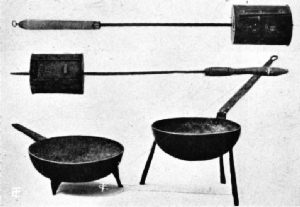

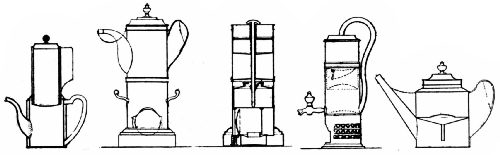

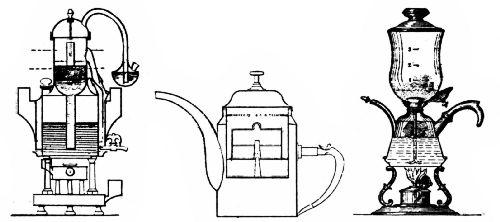

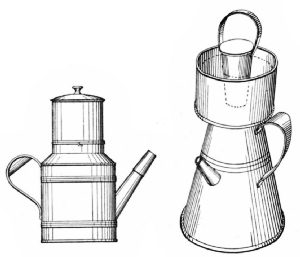

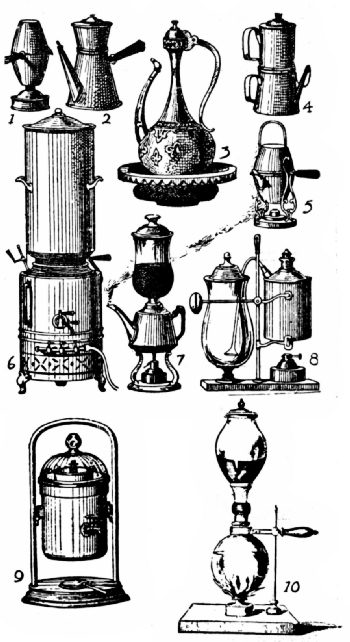

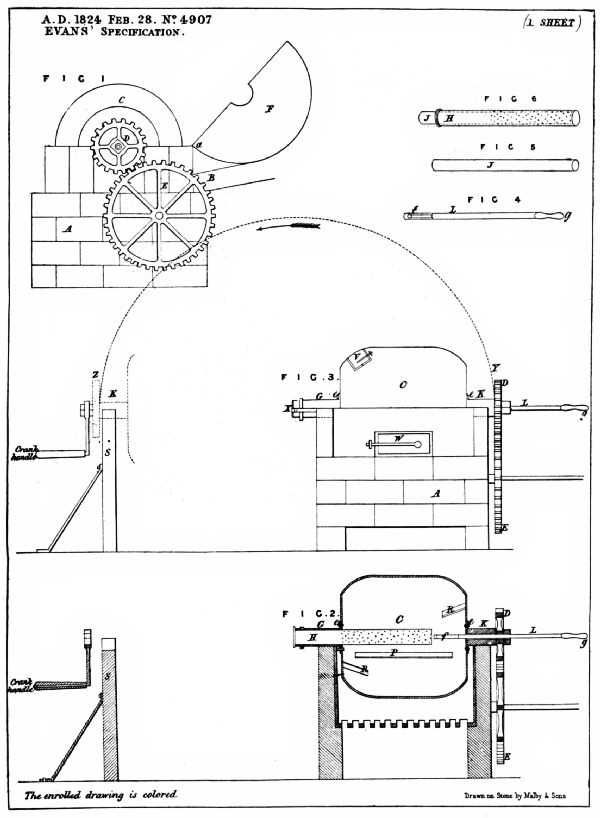

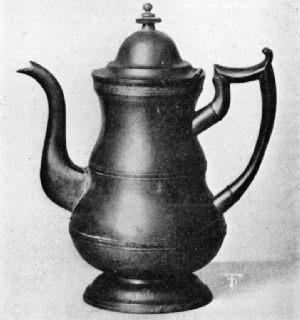

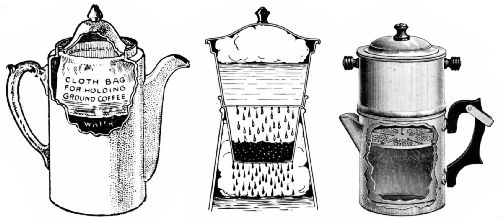

CHAPTER XXXIV

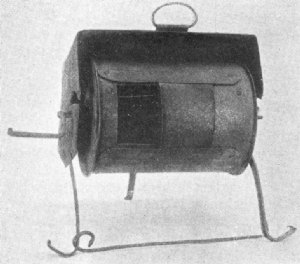

The Evolution of Coffee Apparatus

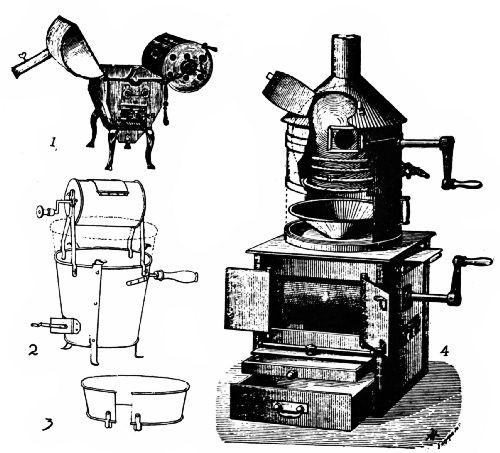

Showing the development of coffee-roasting, coffee-grinding, coffee-making, and coffee-serving devices from the earliest time to the present day—The original coffee grinder, the first coffee roaster, and the first coffee pot—The original French drip pot, the De Belloy percolator—Count Rumford's improvement—How the commercial coffee roaster was developed—The evolution of filtration devices—The old Carter "pull-out" roaster—Trade customs in New York and St. Louis in the sixties and seventies—The story of the evolution of the Burns roaster—How the gas roaster was developed in France, Great Britain, and the United States Page 615

CHAPTER XXXV

World's Coffee Manners and Customs

How coffee is roasted, prepared, and served in all the leading civilized countries—The Arabian coffee ceremony—The present-day coffee houses of Turkey—Twentieth century improvements in Europe and the United States Page 655

CHAPTER XXXVI

Preparation of the Universal Beverage

The evolution of grinding and brewing methods—Coffee was first a food, then a wine, a medicine, a devotional refreshment, a confection, and finally a beverage—Brewing by boiling, infusion, percolation, and filtration—Coffee making in Europe in the nineteenth century—Early coffee making in the United States—Latest developments in better coffee making—Various aspects of scientific coffee brewing—Advice to coffee lovers on how to buy coffee, and how to make it in perfection Page 693

Giving dates and events of historical interest in legend, travel, literature, cultivation, plantation treatment, trading, and in the preparation and use of coffee from the earliest time to the present Page 725

A list of references gathered from the principal general and scientific libraries—Arranged in alphabetic order of topics Page 738

INDEX

Page 769

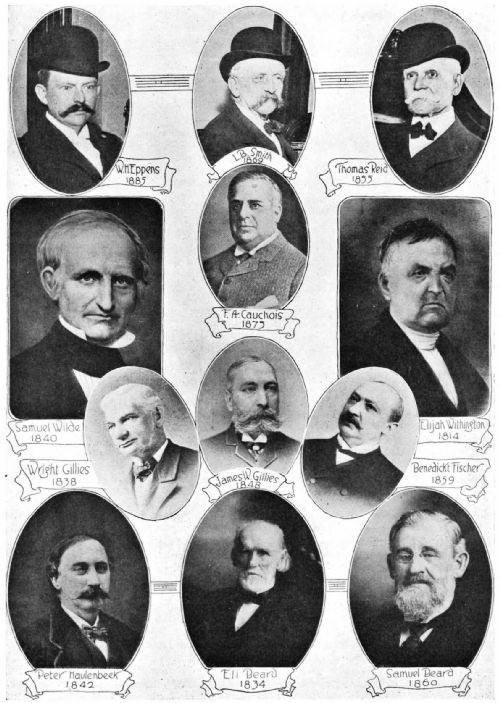

| Portraits | |

| Page | |

| Ach, F.J. | 447, 512 |

| Akers, Fred | 495 |

| Ames, Allan P. | 447 |

| Arbuckle, John | 523 |

| Arnold, Benjamin Greene | 476, 517 |

| Arnold, F.B. | 476 |

| Bayne, William | 479 |

| Bayne, William, Jr. | 447 |

| Beard, Eli | 493 |

| Beard, Samuel | 493 |

| Bennett, William H. | 479 |

| Bickford, C.E. | 478 |

| Boardman, Thomas J. | 500 |

| Boardman, William | 500 |

| Brand, Carl W. | 512 |

| Brandenstein, M.J. | 504 |

| Burns, Jabez | 527 |

| Canby, Edward | 500 |

| Casanas, Ben C. | 512 |

| Cauchois. F.A. | 493 |

| Chase, Caleb | 500 |

| Cheek, J.O. | 504, 515 |

| Closset, Joseph | 504 |

| Coste, Felix | 447 |

| Crossman, Geo. W. | 479 |

| Devers, A.H. | 504 |

| Dwinell, James F. | 500 |

| Eppens, Fred | 495 |

| Eppens, Julius A. | 495, 497 |

| Eppens, W.H. | 493, 495 |

| Evans, David G. | 504 |

| Fischer, Benedickt | 493 |

| Flint, J.G. | 500 |

| Folger, J.A., Jr. | 504 |

| Folger, J.A., Sr. | 504 |

| Forbes, A.E. | 504 |

| Forbes, Jas. H. | 504 |

| Geiger, Frank J. | 500 |

| Gillies, Jas. W. | 493 |

| Gillies, Wright | 493 |

| Grossman, William | 500 |

| Harrison, D.Y. | 500 |

| Harrison, W.H. | 500 |

| Haulenbeek, Peter | 493 |

| Hayward, Martin | 500 |

| Heekin, James | 500 |

| Jones, W.T. | 504 |

| Kimball, O.G. | 478 |

| Kinsella, W.J. | 504 |

| Kirkland, Alexander | 495 |

| Kolschitzky, Franz George | 50 |

| McLaughlin, W.F. | 500 |

| Mahood, Samuel | 500 |

| Mayo, Henry | 495 |

| Meehan, P.C. | 477 |

| Menezes, Th. Langgaard de | 446 |

| Meyer, Robert | 511 |

| Peck, Edwin H. | 477 |

| Phyfe, Jas. W. | 478 |

| Pierce, O.W., Sr. | 500 |

| Pupke, John F. | 495 |

| Purcell, Joseph | 476 |

| Reid, Fred | 495 |

| Reid, Thomas | 493, 495 |

| Roome, Col. William P. | 499 |

| Russell, James C. | 478 |

| Sanborn, James S. | 500 |

| Schilling, A. | 504 |

| Schotten, Julius J. | 504, 512 |

| Schotten, William | 504 |

| Seelye, Frank R. | 512 |

| Sielcken, Hermann | 476, 519 |

| Simmonds, H. | 477 |

| Sinnot, J.B. | 504 |

| Smith, L.B. | 493 |

| Smith, M.E. | 504 |

| Sprague, Albert A. | 500 |

| Stephens, Henry A. | 500 |

| Stoffregen, Charles | 504 |

| Stoffregen, C.H. | 447 |

| Taylor, James H. | 477 |

| Thomson, A.M. | 500 |

| Van Loan, Thomas | 498 |

| Weir, Ross W. | 447, 512 |

| Westfeldt, George | 479 |

| Widlar, Francis | 500 |

| Wilde, Samuel | 493 |

| Withington, Elijah | 493 |

| Woolson, Alvin M. | 500 |

| Wright, George C. | 500 |

| Wright, George S. | 447 |

| Young, Samuel | 500 |

| Zinsmeister, J. | 504 |

Encomiums and descriptive phrases applied to the plant, the berry, and the beverage

The Plant

The precious plant

This friendly plant

Mocha's happy tree

The gift of Heaven

The plant with the jessamine-like flowers

The most exquisite perfume of Araby the blest

Given to the human race by the gift of the Gods

The Berry

The magic bean

The divine fruit

Fragrant berries

Rich, royal berry

Voluptuous berry

The precious berry

The healthful bean

The Heavenly berry

The marvelous berry

This all-healing berry

Yemen's fragrant berry

The little aromatic berry

Little brown Arabian berry

Thought-inspiring bean of Arabia

The smoking, ardent beans Aleppo sends

That wild fruit which gives so beloved a drink

The Beverage

Nepenthe

Festive cup

Juice divine

Nectar divine

Ruddy mocha

A man's drink

Lovable liquor

Delicious mocha

The magic drink

This rich cordial

Its stream divine

The family drink

The festive drink

Coffee is our gold

Nectar of all men

The golden mocha

This sweet nectar

Celestial ambrosia

The friendly drink

The cheerful drink

The essential drink

The sweet draught

The divine draught

The grateful liquor

The universal drink

The American drink

The amber beverage

The convivial drink

The universal thrill

King of all perfumes

The cup of happiness

The soothing draught

Ambrosia of the Gods

The intellectual drink

The aromatic draught

The salutary beverage

The good-fellow drink

The drink of democracy

The drink ever glorious

Wakeful and civil drink

The beverage of sobriety

A psychological necessity

The fighting man's drink

Loved and favored drink

The symbol of hospitality

This rare Arabian cordial

Inspirer of men of letters

The revolutionary beverage

Triumphant stream of sable

Grave and wholesome liquor

The drink of the intellectuals

A restorative of sparkling wit

Its color is the seal of its purity

The sober and wholesome drink

Lovelier than a thousand kisses

This honest and cheering beverage

A wine which no sorrow can resist

The symbol of human brotherhood

At once a pleasure and a medicine

The beverage of the friends of God

The fire which consumes our griefs

Gentle panacea of domestic troubles

The autocrat of the breakfast table

The beverage of the children of God

King of the American breakfast table

Soothes you softly out of dull sobriety

The cup that cheers but not inebriates[1]

Coffee, which makes the politician wise

Its aroma is the pleasantest in all nature

The sovereign drink of pleasure and health[2]

The indispensable beverage of strong nations

The stream in which we wash away our sorrows

The enchanting perfume that a zephyr has brought

Favored liquid which fills all my soul with delight

The delicious libation we pour on the altar of friendship

This invigorating drink which drives sad care from the heart

COFFEE ARABICA; LEAVES, FLOWERS AND FRUIT

COFFEE ARABICA; LEAVES, FLOWERS AND FRUIT

Painted from nature by M.E. Eaton—Detail sketches show anther, pistil, and section of corolla

Origin and translation of the word from the Arabian into various languages—Views of many writers

The history of the word coffee involves several phonetic difficulties.

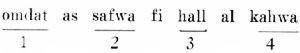

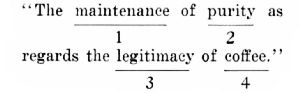

The European languages got the name of the beverage about 1600 from the

original Arabic ![]() qahwah, not directly, but through its

Turkish form, kahveh. This was the name, not of the plant, but the

beverage made from its infusion, being originally one of the names

employed for wine in Arabic.

qahwah, not directly, but through its

Turkish form, kahveh. This was the name, not of the plant, but the

beverage made from its infusion, being originally one of the names

employed for wine in Arabic.

Sir James Murray, in the New English Dictionary, says that some have

conjectured that the word is a foreign, perhaps African, word disguised,

and have thought it connected with the name Kaffa, a town in Shoa,

southwest Abyssinia, reputed native place of the coffee plant, but that

of this there is no evidence, and the name qahwah is not given to the

berry or plant, which is called ![]() bunn, the native name in

Shoa being būn.

bunn, the native name in

Shoa being būn.

Contributing to a symposium on the etymology of the word coffee in Notes and Queries, 1909, James Platt, Jr., said:

The Turkish form might have been written kahvé, as its final h was never sounded at any time. Sir James Murray draws attention to the existence of two European types, one like the French café, Italian caffè, the other like the English coffee, Dutch koffie. He explains the vowel o in the second series as apparently representing au, from Turkish ahv. This seems unsupported by evidence, and the v is already represented by the ff, so on Sir James's assumption coffee must stand for kahv-ve, which is unlikely. The change from a to o, in my opinion, is better accounted for as an imperfect appreciation. The exact sound of ă in Arabic and other Oriental languages is that of the English short u, as in "cuff." This sound, so easy to us, is a great stumbling-block to other nations. I judge that Dutch koffie and kindred forms are imperfect attempts at the notation of a vowel which the writers could not grasp. It is clear that the French type is more correct. The Germans have corrected their koffee, which they may have got from the Dutch, into kaffee. The Scandinavian languages have adopted the French form. Many must wonder how the hv of the original so persistently becomes ff in the European equivalents. Sir James Murray makes no attempt to solve this problem.

Virendranath Chattopádhyáya, who also contributed to the Notes and Queries symposium, argued that the hw of the Arabic qahwah becomes sometimes ff and sometimes only f or v in European translations because some languages, such as English, have strong syllabic accents (stresses), while others, as French, have none. Again, he points out that the surd aspirate h is heard in some languages, but is hardly audible in others. Most Europeans tend to leave it out altogether.

Col. W.F. Prideaux, another contributor, argued that the European languages got one form of the word coffee directly from the Arabic qahwah, and quoted from Hobson-Jobson in support of this:

Chaoua in 1598, Cahoa in 1610, Cahue in 1615; while Sir Thomas Herbert (1638) expressly states that "they drink (in Persia) ... above all the rest, Coho or Copha: by Turk and Arab called Caphe and Cahua." Here the Persian, Turkish, and Arabic pronunciations are clearly differentiated.

Col. Prideaux then calls, as a witness to the Anglo-Arabic pronunciation, one whose evidence was not available when the New English Dictionary and Hobson-Jobson articles were written. This is John Jourdain, a Dorsetshire seaman, whose Diary was printed by the Hakluyt Society in 1905. On May 28, 1609, he records that "in the[Pg 2] afternoone wee departed out of Hatch (Al-Hauta, the capital of the Lahej district near Aden), and travelled untill three in the morninge, and then wee rested in the plaine fields untill three the next daie, neere unto a cohoo howse in the desert." On June 5 the party, traveling from Hippa (Ibb), "laye in the mountaynes, our camells being wearie, and our selves little better. This mountain is called Nasmarde (Nakīl Sumāra), where all the cohoo grows." Farther on was "a little village, where there is sold cohoo and fruite. The seeds of this cohoo is a greate marchandize, for it is carried to grand Cairo and all other places of Turkey, and to the Indias." Prideaux, however, mentions that another sailor, William Revett, in his journal (1609) says, referring to Mocha, that "Shaomer Shadli (Shaikh 'Ali bin 'Omar esh-Shādil) was the fyrst inventour for drynking of coffe, and therefor had in esteemation." This rather looks to Prideaux as if on the coast of Arabia, and in the mercantile towns, the Persian pronunciation was in vogue; whilst in the interior, where Jourdain traveled, the Englishman reproduced the Arabic.

Mr. Chattopádhyáya, discussing Col. Prideaux's views as expressed above, said:

Col. Prideaux may doubt "if the worthy mariner, in entering the word in his log, was influenced by the abstruse principles of phonetics enunciated" by me, but he will admit that the change from kahvah to coffee is a phonetic change, and must be due to the operation of some phonetic principle. The average man, when he endeavours to write a foreign word in his own tongue, is handicapped considerably by his inherited and acquired phonetic capacity. And, in fact, if we take the quotations made in "Hobson-Jobson," and classify the various forms of the word coffee according to the nationality of the writer, we obtain very interesting results.

Let us take Englishmen and Dutchmen first. In Danvers's Letters (1611) we have both "coho pots" and "coffao pots"; Sir T. Roe (1615) and Terry (1616) have cohu; Sir T. Herbert (1638) has coho and copha; Evelyn (1637), coffee; Fryer (1673) coho; Ovington (1690), coffee; and Valentijn (1726), coffi. And from the two examples given by Col. Prideaux, we see that Jourdain (1609) has cohoo, and Revett (1609) has coffe.

To the above should be added the following by English writers, given in Foster's English Factories in India (1618–21, 1622–23, 1624–29): cowha (1619), cowhe, couha (1621), coffa (1628).

Let us now see what foreigners (chiefly French and Italian) write. The earliest European mention is by Rauwolf, who knew it in Aleppo in 1573. He has the form chaube. Prospero Alpini (1580) has caova; Paludanus (1598) chaoua; Pyrard de Laval (1610) cahoa; P. Della Valle (1615) cahue; Jac. Bontius (1631) caveah; and the Journal d'Antoine Galland (1673) cave. That is, Englishmen use forms of a certain distinct type, viz., cohu, coho, coffao, coffe, copha, coffee, which differ from the more correct transliteration of foreigners.

In 1610 the Portuguese Jew, Pedro Teixeira (in the Hakluyt Society's edition of his Travels) used the word kavàh.

The inferences from these transitional forms seem to be: 1. The word found its way into the languages of Europe both from the Turkish and from the Arabic. 2. The English forms (which have strong stress on the first syllable) have ŏ instead of ă, and f instead of h. 3. The foreign forms are unstressed and have no h. The original v or w (or labialized u) is retained or changed into f.

It may be stated, accordingly, that the chief reason for the existence of two distinct types of spelling is the omission of h in unstressed languages, and the conversion of h into f under strong stress in stressed languages. Such conversion often takes place in Turkish; for example, silah dar in Persian (which is a highly stressed language) becomes zilif dar in Turkish. In the languages of India, on the other hand, in spite of the fact that the aspirate is usually very clearly sounded, the word qăhvăh is pronounced kaiva by the less educated classes, owing to the syllables being equally stressed.

Now for the French viewpoint. Jardin[3] opines that, as regards the etymology of the word coffee, scholars are not agreed and perhaps never will be. Dufour[4] says the word is derived from caouhe, a name given by the Turks to the beverage prepared from the seed. Chevalier d'Arvieux, French consul at Alet, Savary, and Trevoux, in his dictionary, think that coffee comes from the Arabic, but from the word cahoueh or quaweh, meaning to give vigor or strength, because, says d'Arvieux, its most general effect is to fortify and strengthen. Tavernier combats this opinion. Moseley attributes the origin of the word coffee to Kaffa. Sylvestre de Sacy, in his Chréstomathie[Pg 3] Arabe, published in 1806, thinks that the word kahwa, synonymous with makli, roasted in a stove, might very well be the etymology of the word coffee. D'Alembert in his encyclopedic dictionary, writes the word caffé. Jardin concludes that whatever there may be in these various etymologies, it remains a fact that the word coffee comes from an Arabian word, whether it be kahua, kahoueh, kaffa or kahwa, and that the peoples who have adopted the drink have all modified the Arabian word to suit their pronunciation. This is shown by giving the word as written in various modern languages:

French, café; Breton, kafe; German, kaffee (coffee tree, kaffeebaum); Dutch, koffie (coffee tree, koffieboonen); Danish, kaffe; Finnish, kahvi; Hungarian, kavé; Bohemian, kava; Polish, kawa; Roumanian, cafea; Croatian, kafa; Servian, kava; Russian, kophe; Swedish, kaffe; Spanish, café; Basque, kaffia; Italian, caffè; Portuguese, café; Latin (scientific), coffea; Turkish, kahué; Greek, kaféo; Arabic, qahwah (coffee berry, bun); Persian, qéhvé (coffee berry, bun[5]); Annamite, ca-phé; Cambodian, kafé; Dukni[6], bunbund[7]; Teluyan[8], kapri-vittulu; Tamil[9], kapi-kottai or kopi; Canareze[10], kapi-bija; Chinese, kia-fey, teoutsé; Japanese, kéhi; Malayan, kawa, koppi; Abyssinian, bonn[11]; Foulak, legal café[12]; Sousou, houri caff[13]; Marquesan, kapi; Chinook[14], kaufee; Volapuk, kaf; Esperanto, kafva.

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World and its introduction into the New—A romantic coffee adventure

The history of the propagation of the coffee plant is closely interwoven with that of the early history of coffee drinking, but for the purposes of this chapter we shall consider only the story of the inception and growth of the cultivation of the coffee tree, or shrub, bearing the seeds, or berries, from which the drink, coffee, is made.

Careful research discloses that most authorities agree that the coffee plant is indigenous to Abyssinia, and probably Arabia, whence its cultivation spread throughout the tropics. The first reliable mention of the properties and uses of the plant is by an Arabian physician toward the close of the ninth century A.D., and it is reasonable to suppose that before that time the plant was found growing wild in Abyssinia and perhaps in Arabia. If it be true, as Ludolphus writes,[15] that the Abyssinians came out of Arabia into Ethiopia in the early ages, it is possible that they may have brought the coffee tree with them; but the Arabians must still be given the credit for discovering and promoting the use of the beverage, and also for promoting the propagation of the plant, even if they found it in Abyssinia and brought it to Yemen.

Some authorities believe that the first cultivation of coffee in Yemen dates back to 575 A.D., when the Persian invasion put an end to the Ethiopian rule of the negus Caleb, who conquered the country in 525.

Certainly the discovery of the beverage resulted in the cultivation of the plant in Abyssinia and in Arabia; but its progress was slow until the 15th and 16th centuries, when it appears as intensively carried on in the Yemen district of Arabia. The Arabians were jealous of their new found and lucrative industry, and for a time successfully prevented its spread to other countries by not permitting any of the precious berries to leave the country unless they had first been steeped in boiling water or parched, so as to destroy their powers of germination. It may be that many of the early failures successfully to introduce the cultivation of the coffee plant into other lands was also due to the fact, discovered later, that the seeds soon lose their germinating power.

However, it was not possible to watch every avenue of transport, with thousands of pilgrims journeying to and from Mecca every year; and so there would appear to be some reason to credit the Indian tradition concerning the introduction of coffee cultivation into southern India by Baba Budan, a Moslem pilgrim, as early as 1600, although a better authority gives the date as 1695. Indian tradition relates that Baba Budan planted his seeds near the hut he built for himself at Chickmaglur in the mountains of Mysore, where, only a few years since, the writer found the descendants of these first plants growing under the shade of the centuries-old original jungle trees. The greater part of the plants cultivated by the natives of Kurg and Mysore appear to have come from the Baba Budan importation. It was not until 1840 that the English began the cultivation of coffee in India. The plantations extend now from the extreme north of Mysore to Tuticorin.

Early Cultivation by the Dutch

In the latter part of the 16th century, German, Italian, and Dutch botanists and[Pg 6] travelers brought back from the Levant considerable information regarding the new plant and the beverage. In 1614 enterprising Dutch traders began to examine into the possibilities of coffee cultivation and coffee trading. In 1616 a coffee plant was successfully transported from Mocha to Holland. In 1658 the Dutch started the cultivation of coffee in Ceylon, although the Arabs are said to have brought the plant to the island prior to 1505. In 1670 an attempt was made to cultivate coffee on European soil at Dijon, France, but the result was a failure.

In 1696, at the instigation of Nicolaas Witsen, then burgomaster of Amsterdam, Adrian Van Ommen, commander at Malabar, India, caused to be shipped from Kananur, Malabar, to Java, the first coffee plants introduced into that island. They were grown from seed of the Coffea arabica brought to Malabar from Arabia. They were planted by Governor-General Willem Van Outshoorn on the Kedawoeng estate near Batavia, but were subsequently lost by earthquake and flood. In 1699 Henricus Zwaardecroon imported some slips, or cuttings, of coffee trees from Malabar into Java. These were more successful, and became the progenitors of all the coffees of the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch were then taking the lead in the propagation of the coffee plant.

In 1706 the first samples of Java coffee, and a coffee plant grown in Java, were received at the Amsterdam botanical gardens. Many plants were afterward propagated from the seeds produced in the Amsterdam gardens, and these were distributed to some of the best known botanical gardens and private conservatories in Europe.

While the Dutch were extending the cultivation of the plant to Sumatra, the Celebes, Timor, Bali, and other islands of the Netherlands Indies, the French were seeking to introduce coffee cultivation into their colonies. Several attempts were made to transfer young plants from the Amsterdam botanical gardens to the botanical gardens at Paris; but all were failures.

In 1714, however, as a result of negotiations entered into between the French government and the municipality of Amsterdam, a young and vigorous plant about five feet tall was sent to Louis XIV at the chateau of Marly by the burgomaster of Amsterdam. The day following, it was transferred to the Jardin des Plantes at Paris, where it was received with appropriate ceremonies by Antoine de Jussieu, professor of botany in charge. This tree was destined to be the progenitor of most of the coffees of the French colonies, as well as of those of South America, Central America, and Mexico.

The Romance of Captain Gabriel de Clieu

Two unsuccessful attempts were made to transport to the Antilles plants grown from the seed of the tree presented to Louis XIV; but the honor of eventual success was won by a young Norman gentleman, Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, a naval officer, serving at the time as captain of infantry at Martinique. The story of de Clieu's achievement is the most romantic chapter in the history of the propagation of the coffee plant.

His personal affairs calling him to France, de Clieu conceived the idea of utilizing the return voyage to introduce coffee cultivation into Martinique. His first difficulty lay in obtaining several of the plants then being cultivated in Paris, a difficulty at last overcome through the instrumentality of M. de Chirac, royal physician, or, according to a letter written by de Clieu himself, through the kindly offices of a lady of quality to whom de Chirac could give no refusal. The plants selected were kept at Rochefort by M. Bégon, commissary of the department, until the departure of de Clieu for Martinique. Concerning the exact date of de Clieu's arrival at Martinique with the coffee plant, or plants, there is much conflict of opinion. Some authorities give the date as 1720, others 1723. Jardin[16] suggests that the discrepancy in dates may arise from de Clieu, with praiseworthy perseverance, having made the voyage twice. The first time, according to Jardin, the plants perished; but the second time de Clieu had planted the seeds when leaving France and these survived, "due, they say, to his having given of his scanty ration of water to moisten them." No reference to a preceding voyage, however, is made by de Clieu in his own account, given in a letter written to the Année Littéraire[17] in 1774. There is also a difference of opinion as to whether de Clieu arrived with one or three plants. He himself says "one" in the letter referred to.

According to the most trustworthy data, de Clieu embarked at Nantes, 1723.[18] He[Pg 7] had installed his precious plant in a box covered with a glass frame in order to absorb the rays of the sun and thus better to retain the stored-up heat for cloudy days. Among the passengers one man, envious of the young officer, did all in his power to wrest from him the glory of success. Fortunately his dastardly attempt failed of its intended effect.

"It is useless," writes de Clieu in his letter to the Année Littéraire, "to recount in detail the infinite care that I was obliged to bestow upon this delicate plant during a long voyage, and the difficulties I had in saving it from the hands of a man who, basely jealous of the joy I was about to taste through being of service to my country, and being unable to get this coffee plant away from me, tore off a branch."

The vessel carrying de Clieu was a merchantman, and many were the trials that beset passengers and crew. Narrowly escaping capture by a corsair of Tunis, menaced by a violent tempest that threatened to annihilate them, they finally encountered a calm that proved more appalling than either. The supply of drinking water was well nigh exhausted, and what was left was rationed for the remainder of the voyage.

"Water was lacking to such an extent," says de Clieu, "that for more than a month I was obliged to share the scanty ration of it assigned to me with this my coffee plant upon which my happiest hopes were founded and which was the source of my delight. It needed such succor the more in that it was extremely backward, being no larger than the slip of a pink." Many stories have been written and verses sung recording and glorifying this generous sacrifice that has given luster to the name of de Clieu.

Arrived in Martinique, de Clieu planted his precious slip on his estate in Prêcheur, one of the cantons of the island; where, says Raynal, "it multiplied with extraordinary rapidity and success." From the seedlings of this plant came most of the coffee trees of the Antilles. The first harvest was gathered in 1726.

De Clieu himself describes his arrival as follows:

Arriving at home, my first care was to set out my plant with great attention in the part of my garden most favorable to its growth. Although keeping it in view, I feared many times that it would be taken from me; and I was at last obliged to surround it with thorn bushes and to establish a guard about it until it arrived at maturity ... this precious plant which had become still more dear to me for the dangers it had run and the cares it had cost me.

Thus the little stranger thrived in a distant land, guarded day and night by faithful slaves. So tiny a plant to produce in the end all the rich estates of the West India islands and the regions bordering on the Gulf of Mexico! What luxuries, what future comforts and delights, resulted from this one small talent confided to the care of a man of rare vision and fine intellectual sympathy, fired by the spirit of real love for his fellows! There is no instance in the history of the French people of a good deed done by stealth being of greater service to humanity.

De Clieu thus describes the events that followed fast upon the introduction of[Pg 8] coffee into Martinique, with particular reference to the earthquake of 1727:

Success exceeded my hopes. I gathered about two pounds of seed which I distributed among all those whom I thought most capable of giving the plants the care necessary to their prosperity.

The first harvest was very abundant; with the second it was possible to extend the cultivation prodigiously, but what favored multiplication, most singularly, was the fact that two years afterward all the cocoa trees of the country, which were the resource and occupation of the people, were uprooted and totally destroyed by horrible tempests accompanied by an inundation which submerged all the land where these trees were planted, land which was at once made into coffee plantations by the natives. These did marvelously and enabled us to send plants to Santo Domingo, Guadeloupe, and other adjacent islands, where since that time they have been cultivated with the greatest success.

By 1777 there were 18,791,680 coffee trees in Martinique.

De Clieu was born in Angléqueville-sur-Saane, Seine-Inférieure (Normandy), in 1686 or 1688.[19] In 1705 he was a ship's ensign; in 1718 he became a chevalier of St. Louis; in 1720 he was made a captain of infantry; in 1726, a major of infantry; in 1733 he was a ship's lieutenant; in 1737 he became governor of Guadeloupe; in 1746 he was a ship's captain; in 1750 he was made honorary commander of the order of St. Louis; in 1752 he retired with a pension of 6000 francs; in 1753 he re-entered the naval service; in 1760 he again retired with a pension of 2000 francs.

In 1746 de Clieu, having returned to France, was presented to Louis XV by the minister of marine, Rouillé de Jour, as "a distinguished officer to whom the colonies, as well as France itself, and commerce generally, are indebted for the cultivation of coffee."

Reports to the king in 1752 and 1759 recall his having carried the first coffee plant to Martinique, and that he had ever been distinguished for his zeal and disinterestedness. In the Mercure de France, December, 1774, was the following death notice:

Gabriel d'Erchigny de Clieu, former Ship's Captain and Honorary Commander of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis, died in Paris on the 30th of November in the 88th year of his age.

A notice of his death appeared also in the Gazette de France for December 5, 1774, a rare honor in both cases; and it has been said that at this time his praise was again on every lip.

One French historian, Sidney Daney,[20] records that de Clieu died in poverty at St. Pierre at the age of 97; but this must be an error, although it does not anywhere appear that at his death he was possessed of much, if any, means. Daney says:

This generous man received as his sole recompense for a noble deed the satisfaction of seeing this plant for whose preservation he had shown such devotion, prosper throughout the Antilles. The illustrious de Clieu is among those to whom Martinique owes a brilliant reparation.

Daney tells also that in 1804 there was a movement in Martinique to erect a monument upon the spot where de Clieu planted his first coffee plant, but that the undertaking came to naught.

Pardon, in his La Martinique says:

Honor to this brave man! He has deserved it from the people of two hemispheres. His name is worthy of a place beside that of Parmentier who carried to France the potato of Canada. These two men have rendered immense service to humanity, and their memory should never be forgotten—yet alas! Are they even remembered?

Tussac, in his Flora de las Antillas, writing of de Clieu, says, "Though no monument be erected to this beneficent traveler, yet his name should remain engraved in the heart of every colonist."

In 1774 the Année Littéraire published a long poem in de Clieu's honor. In the feuilleton of the Gazette de France, April 12, 1816, we read that M. Donns, a wealthy Hollander, and a coffee connoisseur, sought to honor de Clieu by having painted upon a porcelain service all the details of his voyage and its happy results. "I have seen the cups," says the writer, who gives many details and the Latin inscription.

That singer of navigation, Esménard, has pictured de Clieu's devotion in the following lines:

Forget not how de Clieu with his light vessel's sail,

Brought distant Moka's gift—that timid plant and frail.

The waves fell suddenly, young zephyrs breathed no more,

Beneath fierce Cancer's fires behold the fountain store,

Exhausted, fails; while now inexorable need

Makes her unpitying law—with measured dole obeyed.

Now each soul fears to prove Tantalus torment first.

De Clieu alone defies: While still that fatal thirst,

[Pg 9]Fierce, stifling, day by day his noble strength devours,

And still a heaven of brass inflames the burning hours.

With that refreshing draught his life he will not cheer;

But drop by drop revives the plant he holds more dear.

Already as in dreams, he sees great branches grow,

One look at his dear plant assuages all his woe.

The only memorial to de Clieu in Martinique is the botanical garden at Fort de France, which was opened in 1918 and dedicated to de Clieu, "whose memory has been too long left in oblivion.[21]"

In 1715 coffee cultivation was first introduced into Haiti and Santo Domingo. Later came hardier plants from Martinique. In 1715–17 the French Company of the Indies introduced the cultivation of the plant into the Isle of Bourbon (now Réunion) by a ship captain named Dufougeret-Grenier from St. Malo. It did so well that nine years later the island began to export coffee.

The Dutch brought the cultivation of coffee to Surinam in 1718. The first coffee plantation in Brazil was started at Pará in 1723 with plants brought from French Guiana, but it was not a success. The English brought the plant to Jamaica in 1730. In 1740 Spanish missionaries introduced coffee cultivation into the Philippines from Java. In 1748 Don José Antonio Gelabert introduced coffee into Cuba, bringing the seed from Santo Domingo. In 1750 the Dutch extended the cultivation of the plant to the Celebes. Coffee was introduced into Guatemala about 1750–60. The intensive cultivation in Brazil dates from the efforts begun in the Portuguese colonies in Pará and Amazonas in 1752. Porto Rico began the cultivation of coffee about 1755. In 1760 João Alberto Castello Branco brought to Rio de Janeiro a coffee tree from Goa, Portuguese India. The news spread that the soil and climate of Brazil were particularly adapted to the cultivation of coffee. Molke, a Belgian monk, presented some seeds to the Capuchin monastery at Rio in 1774. Later, the bishop of Rio, Joachim Bruno, became a patron of the plant and encouraged its propagation in Rio, Minãs, Espirito Santo, and São Paulo. The Spanish voyager, Don Francisco Xavier Navarro, is credited with the introduction of coffee into Costa Rica from Cuba in 1779. In Venezuela the industry was started near Caracas by a priest, José Antonio Mohedano, with seed brought from Martinique in 1784.

Coffee cultivation in Mexico began in 1790, the seed being brought from the West Indies. In 1817 Don Juan Antonio Gomez instituted intensive cultivation in the State of Vera Cruz. In 1825 the cultivation of the plant was begun in the Hawaiian Islands with seeds from Rio de Janeiro. As previously noted, the English began to cultivate coffee in India in 1840. In 1852 coffee cultivation was begun in Salvador with plants brought from Cuba. In 1878 the English began the propagation of coffee in British Central Africa, but it was not until 1901 that coffee cultivation was introduced into British East Africa from Réunion. In 1887 the French introduced the plant into Tonkin, Indo-China. Coffee growing in Queensland, introduced in 1896, has been successful in a small way.

In recent years several attempts have been made to propagate the coffee plant in the southern United States, but without success. It is believed, however, that the topographic and climatic conditions in southern California are favorable for its cultivation.

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries—Stories of its origin—Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church—Its spread through Arabia, Persia and Turkey—Persecutions and intolerances—Early coffee manners and customs

The coffee drink had its rise in the classical period of Arabian medicine, which dates from Rhazes (Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya El Razi) who followed the doctrines of Galen and sat at the feet of Hippocrates. Rhazes (850–922) was the first to treat medicine in an encyclopedic manner, and, according to some authorities, the first writer to mention coffee. He assumed the poetical name of Razi because he was a native of the city of Raj in Persian Irak. He was a great philosopher and astronomer, and at one time was superintendent of the hospital at Bagdad. He wrote many learned books on medicine and surgery, but his principal work is Al-Haiwi, or The Continent, a collection of everything relating to the cure of disease from Galen to his own time.

Philippe Sylvestre Dufour (1622–87)[22], a French coffee merchant, philosopher, and writer, in an accurate and finished treatise on coffee, tells us (see the early edition of the work translated from the Latin) that the first writer to mention the properties of the coffee bean under the name of bunchum was this same Rhazes, "in the ninth century after the birth of our Saviour"; from which (if true) it would appear that coffee has been known for upwards of 1000 years. Robinson[23], however, is of the opinion that bunchum meant something else and had nothing to do with coffee. Dufour, himself, in a later edition of his Traitez Nouveaux et Curieux du Café (the Hague, 1693) is inclined to admit that bunchum may have been a root and not coffee, after all; however, he is careful to add that there is no doubt that the Arabs knew coffee as far back as the year 800. Other, more modern authorities, place it as early as the sixth century.

Wiji Kawih is mentioned in a Kavi (Javan) inscription A.D. 856; and it is thought that the "bean broth" in David Tapperi's list of Javanese beverages (1667–82) may have been coffee[24].

While the true origin of coffee drinking may be forever hidden among the mysteries of the purple East, shrouded as it is in legend and fable, scholars have marshaled sufficient facts to prove that the beverage was known in Ethiopia "from time immemorial," and there is much to add verisimilitude to Dufour's narrative. This first coffee merchant-prince, skilled in languages and polite learning, considered that his character as a merchant was not inconsistent with that of an author; and he even went so far as to say there were some things (for instance, coffee) on which a merchant could be better informed than a philosopher.

Granting that by bunchum Rhazes meant coffee, the plant and the drink must have been known to his immediate followers; and this, indeed, seems to be indicated by similar references in the writings of Avicenna (Ibn Sina), the Mohammedan physician and philosopher, who lived from 980 to 1037 A.D.

Rhazes, in the quaint language of Dufour, assures us that "bunchum (coffee) is hot and dry and very good for the stomach." Avicenna explains the medicinal properties and uses of the coffee bean (bon or bunn), which he, also, calls bunchum, after this fashion:

As to the choice thereof, that of a lemon color, light, and of a good smell, is the best; the white and the heavy is naught. It is hot and dry in the first degree, and, according to others, cold in the first degree. It fortifies the members, it cleans the skin, and dries up the humidities that are under it, and gives an excellent smell to all the body.

The early Arabians called the bean and the tree that bore it, bunn; the drink, bunchum. A. Galland[25] (1646–1715), the French Orientalist who first analyzed and translated from the Arabic the Abd-al-Kâdir manuscript[26], the oldest document extant telling of the origin of coffee, observes that Avicenna speaks of the bunn, or coffee; as do also Prospero Alpini and Veslingius (Vesling). Bengiazlah, another great physician, contemporary with Avicenna, likewise mentions coffee; by which, says Galland, one may see that we are indebted to physicians for the discovery of coffee, as well as of sugar, tea, and chocolate.

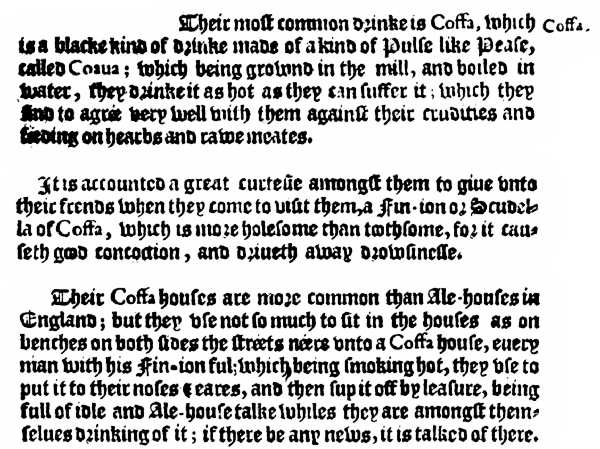

Rauwolf[27] (d. 1596), German physician and botanist, and the first European to mention coffee, who became acquainted with the beverage in Aleppo in 1573, telling how the drink was prepared by the Turks, says:

In this same water they take a fruit called Bunnu, which in its bigness, shape, and color is almost like unto a bayberry, with two thin shells surrounded, which, as they informed me, are brought from the Indies; but as these in themselves are, and have within them, two yellowish grains in two distinct cells, and besides, being they agree in their virtue, figure, looks, and name with the Bunchum of Avicenna and Bunco, of Rasis ad Almans exactly: therefore I take them to be the same.

In Dr. Edward Pocoke's translation (Oxford, 1659) of The Nature of the Drink Kauhi, or Coffee, and the Berry of which it is Made, Described by an Arabian Phisitian, we read:

Bun is a plant in Yaman [Yemen], which is planted in Adar, and groweth up and is gathered in Ab. It is about a cubit high, on a stalk about the thickness of one's thumb. It flowers white, leaving a berry like a small nut, but that sometimes it is broad like a bean; and when it is peeled, parteth in two. The best of it is that which is weighty and yellow; the worst, that which is black. It is hot in the first degree, dry in the second: it is usually reported to be cold and dry, but it is not so; for it is bitter, and whatsoever is bitter is hot. It may be that the scorce is hot, and the Bun it selfe either of equall temperature, or cold in the first degree.

That which makes for its coldnesse is its stipticknesse. In summer it is by experience found to conduce to the drying of rheumes, and flegmatick coughes and distillations, and the opening of obstructions, and the provocation of urin. It is now known by the name of Kohwah. When it is dried and thoroughly boyled, it allayes the ebullition of the blood, is good against the small poxe and measles, the bloudy pimples; yet causeth vertiginous headheach, and maketh lean much, occasioneth waking, and the Emrods, and asswageth lust, and sometimes breeds melancholly.

He that would drink it for livelinesse sake, and to discusse slothfulnesse, and the other properties that we have mentioned, let him use much sweat meates with it, and oyle of pistaccioes, and butter. Some drink it with milk, but it is an error, and such as may bring in danger of the leprosy.

Dufour concludes that the coffee beans of commerce are the same as the bunchum (bunn) described by Avicenna and the bunca (bunchum) of Rhazes. In this he agrees, almost word for word, with Rauwolf, indicating no change in opinion among the learned in a hundred years.

Christopher Campen thinks Hippocrates, father of medicine, knew and administered coffee.

Robinson, commenting upon the early adoption of coffee into materia medica, charges that it was a mistake on the part of the Arab physicians, and that it originated the prejudice that caused coffee to be regarded as a powerful drug instead of as a simple and refreshing beverage.

Homer, the Bible, and Coffee

In early Grecian and Roman writings no mention is made of either the coffee plant or the beverage made from the berries. Pierre (Pietro) Delia Valle[28] (1586–1652), however, maintains that the nepenthe, which Homer says Helen brought with her out of Egypt, and which she employed as surcease for sorrow, was nothing else but coffee mixed with wine.[29] This is disputed by M. Petit, a well known physician of Paris, who died in 1687. Several later British authors, among them, Sandys, the[Pg 13] poet; Burton; and Sir Henry Blount, have suggested the probability of coffee being the "black broth" of the Lacedæmonians.

George Paschius, in his Latin treatise of the New Discoveries Made since the Time of the Ancients, printed at Leipsic in 1700, says he believes that coffee was meant by the five measures of parched corn included among the presents Abigail made to David to appease his wrath, as recorded in the Bible, 1 Samuel, xxv, 18. The Vulgate translates the Hebrew words sein kali into sata polentea, which signify wheat, roasted, or dried by fire.

Pierre Étienne Louis Dumant, the Swiss Protestant minister and author, is of the opinion that coffee (and not lentils, as others have supposed) was the red pottage for which Esau sold his birthright; also that the parched grain that Boaz ordered to be given Ruth was undoubtedly roasted coffee berries.

Dufour mentions as a possible objection against coffee that "the use and eating of beans were heretofore forbidden by Pythagoras," but intimates that the coffee bean of Arabia is something different.

Scheuzer,[30] in his Physique Sacrée, says "the Turks and the Arabs make with the coffee bean a beverage which bears the same name, and many persons use as a substitute the flour of roasted barley." From this we learn that the coffee substitute is almost as old as coffee itself.

Some Early Legends

After medicine, the church. There are several Mohammedan traditions that have persisted through the centuries, claiming for "the faithful" the honor and glory of the first use of coffee as a beverage. One of these relates how, about 1258 A.D., Sheik Omar, a disciple of Sheik Abou'l hasan Schadheli, patron saint and legendary founder of Mocha, by chance discovered the coffee drink at Ousab in Arabia, whither he had been exiled for a certain moral remissness.

Facing starvation, he and his followers were forced to feed upon the berries growing around them. And then, in the words of the faithful Arab chronicle in the Bibliothéque Nationale at Paris, "having nothing to eat except coffee, they took of it and boiled it in a saucepan and drank of the decoction." Former patients in Mocha who sought out the good doctor-priest in his Ousab retreat, for physic with which to cure their ills, were given some of this decoction, with beneficial effect. As a result of the stories of its magical properties, carried back to the city, Sheik Omar was invited to return in triumph to Mocha where the governor caused to be built a monastery for him and his companions.

Another version of this Oriental legend gives it as follows: