The Project Gutenberg EBook of Scouting For Girls, Official Handbook of the Girl Scouts, by Girl Scouts This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Scouting For Girls, Official Handbook of the Girl Scouts Author: Girl Scouts Editor: Josephine Daskam Bacon Release Date: April 4, 2009 [EBook #28490] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF GIRL SCOUTS *** Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)Music by Linda Cantoni.

Registration Date and Place ____________________________________

Passed Tenderfoot Test _______________________________________

Passed Second Class Test _____________________________________

Passed ____________________________________________________

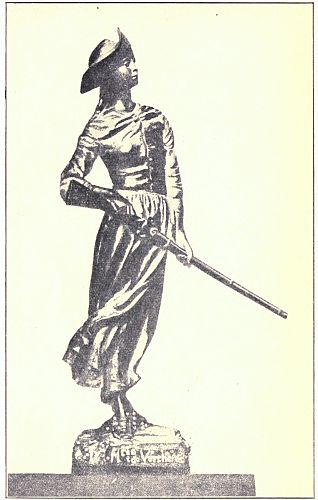

MAGDELAINE DE VERCHÈRES

MAGDELAINE DE VERCHÈRES

"How did Scouting come to be used by girls?" That is what I have been asked. Well, it was this way. In the beginning I had used Scouting—that is, wood craft, handiness, and cheery helpfulness—as a means for training young soldiers when they first joined the army, to help them become handy, capable men and able to hold their own with anyone instead of being mere drilled machines.

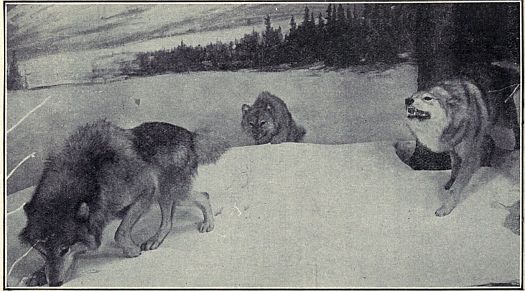

You have read about the Wars in your country against the Red Indians, of the gallantry of your soldiers against the cunning of the Red Man, and what is more, of the pluck of your women on those dangerous frontiers.

Well, we have had much the same sort of thing in South Africa. Over and over again I have seen there the wonderful bravery and resourcefulness of the women when the tribes of Zulu or Matabeles have been out on the war path against the white settlers.

In the Boer war a number of women volunteered to help my forces as nurses or otherwise; they were full of pluck and energy, but unfortunately they had never been trained to do anything, and so with all the good-will in the world they were of no use. I could not help feeling how splendid it would be if one could only train them in peace time in the same way one trained the young soldiers—that is, through Scoutcraft.

I afterwards took to training boys in that way, but I had not been long at it before the girls came along, and offered to do the very thing I had hoped for, they wanted to take up Scouting also.

They did not merely want to be imitators of the boys; they wanted a line of their own.

So I gave them a smart blue uniform and the names of "Guides" and my sister wrote an outline of the scheme. The name Guide appealed to the British girls because the pick of our frontier forces in India is the Corps of Guides. The term cavalry or infantry hardly describes it since it is composed of all-round handy men ready to take on any job in the campaigning line and do it well.

Then too, a woman who can be a good and helpful comrade to her brother or husband or son along the path of life is really a guide to him.

The name Guide therefore just describes the members of our sisterhood who besides being handy and ready for any kind of duty are also a jolly happy family and likely to be good, cheery comrades to their mankind.

The coming of the Great War gave the Girl Guides their opportunity, and they quickly showed the value of their training by undertaking a variety of duties which made them valuable to their country in her time of need.

My wife, Lady Baden-Powell, was elected by the members to be the Chief Guide, and under her the movement has gone ahead at an amazing pace, spreading to most foreign countries.

It is thanks to Mrs. Juliette Low, of Savannah, that the movement was successfully started in America, and though the name Girl Scouts has there been used it is all part of the same sisterhood, working to the same ends and living up to the same Laws and Promise.

If all the branches continue to work together and become better acquainted with each other as they continue to become bigger it will mean not only a grand step for the sisterhood, but what is more important it will be a real help toward making the new League of Nations a living force.

How can that be? In this way:

If the women of the different nations are to a large extent members of the same society and therefore in close touch and sympathy with each other, although belonging to different countries, they will make the League a real bond not merely between the Governments, but between the Peoples themselves and they will see to it that it means Peace and that we have no more of War.

The present edition of "Scouting for Girls" is the result of collaboration on the part of practical workers in the organization from every part of the country. The endeavor on the part of its compilers has been to combine the minimum of standardization necessary for dignified and efficient procedure, with the maximum of freedom for every local branch in its interpretation and practice of the Girl Scout aims and principles.

Grateful acknowledgments are due to the following:

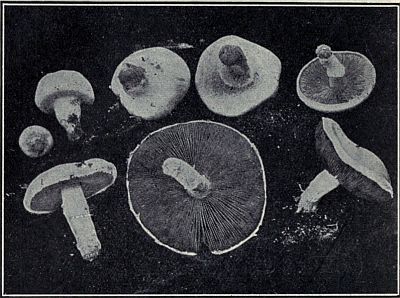

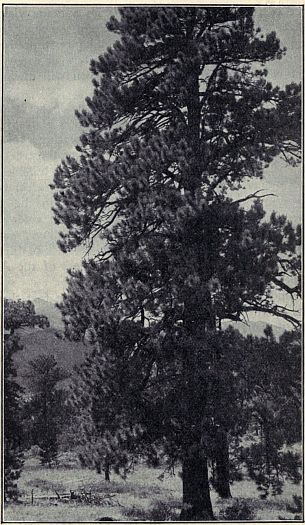

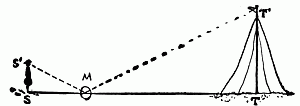

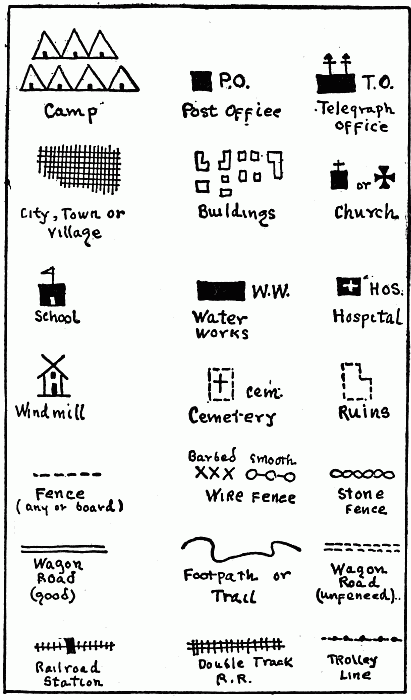

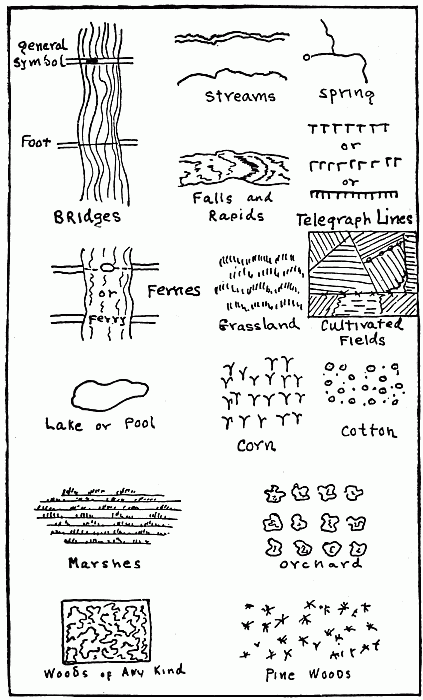

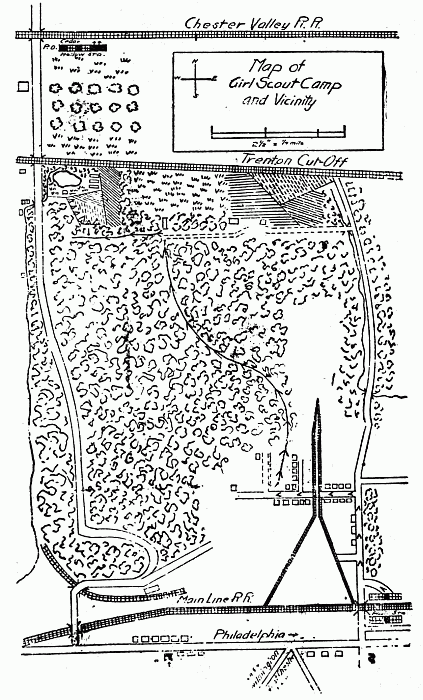

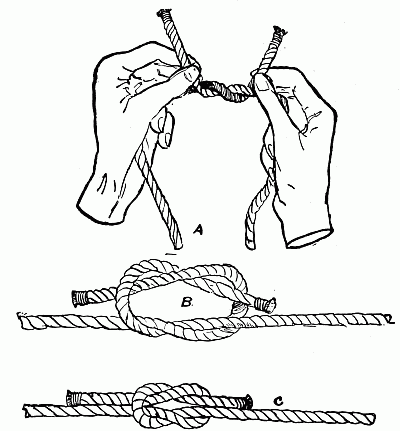

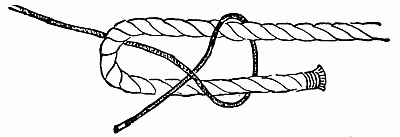

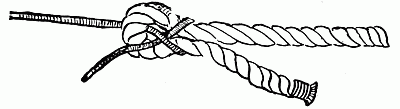

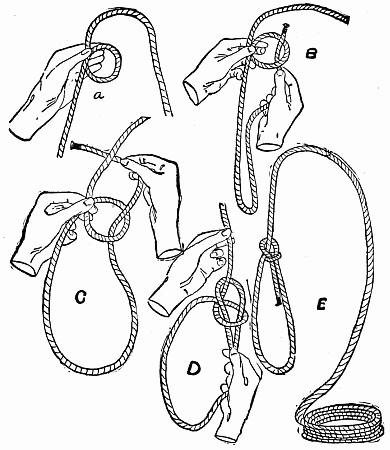

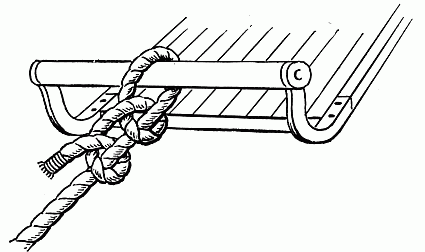

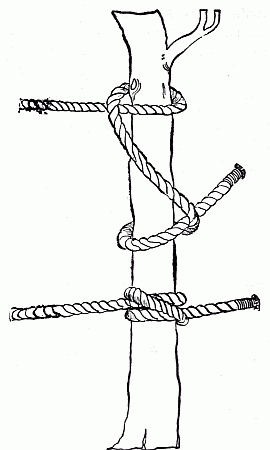

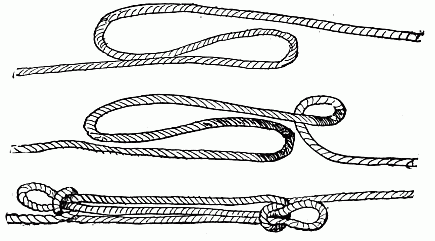

Miss Sarah Louise Arnold, Dean, and Miss Ula M. Dow, A.M., and Dr. Alice Blood, of Simmons College for the Part of Section XI entitled "Home Economics"; Sir Robert Baden-Powell for frequent references and excerpts from "Girl Guiding"; Dr. Samuel Lambert for the Part on First Aid, Section XI, and Dr. W. H. Rockwell for reading and criticizing this; Miss Marie Johnson with the assistance of Miss Isabel Stewart of Teachers College, for the Part entitled "Home Nursing" in Section XI; Dr. Herman M. Biggs for reading and criticizing the Parts dealing with Public Health and Child Care; Mr. Ernest Thompson Seton and The Woodcraft League, and Doubleday, Page & Co. for Section XIII and plates on "Woodcraft"; Mr. Joseph Parsons, Mr. James Wilder, Mrs. Eloise Roorbach, and Mr. Horace Kephart and the Macmillan Company for the material in Section XIV "Camping for Girl Scouts"; Mr. George H. Sherwood, Curator, and Dr. G. Clyde Fisher, Associate Curator, of the Department of Public Education of the American Museum of Natural History for the specially prepared Section XV and illustrations on "Nature Study," and for all proficiency tests in this subject; Mr. David Hunter for Section XVI "The Girl Scout's Own Garden," and Mrs. Ellen Shipman for the part on a perennial border with the specially prepared drawing, in the Section on the Garden; Mr. Sereno Stetson for material in Section XVII "Measurements, Map Making and Knots"; Mr. Austin Strong for pictures of knots; Mrs. Raymond Brown for the test for Citizen; Miss Edith L. Nichols, Supervisor of Drawing in the New York Public Schools, for the test on Craftsman; Mr. John Grolle of the Settlement Music School, Philadelphia, for assistance in the Music test; Miss Eckhart for help in the Farmer test; The Camera Club and the Eastman Kodak Company for the test for Photographer; Mrs. Frances Hunter Elwyn of the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts, for devising and drawing certain of the designs for Proficiency Badges and the plates for Signalling; Miss L. S. Power, Miss Mary Davis and Miss Mabel Williams of the New York Public Library, for assistance in the preparation of reference reading for Proficiency Tests, and general reading for Girl Scouts.

It is evident that only a profound conviction of the high aims of the Girl Scout movement and the practical capacity of the organization for realizing them could have induced so many distinguished persons to give so generously of their time and talent to this Handbook.

The National Executive Board, under whose auspices it has been compiled, appreciate this and the kindred courtesy of the various organizations of similar interests, most deeply. We feel that such hearty and friendly cooperation on the part of the community at large is the greatest proof of the vitality and real worth of this and allied movements, based on intelligent study of the young people of our country.

| Foreword by Sir Robert Baden-Powell. | ||

| Preface by Josephine Daskam Bacon, Editor. | ||

| Section: | ||

| I. | History of the Girl Scouts | 1 |

| II. | Principles of the Girl Scouts | 3 |

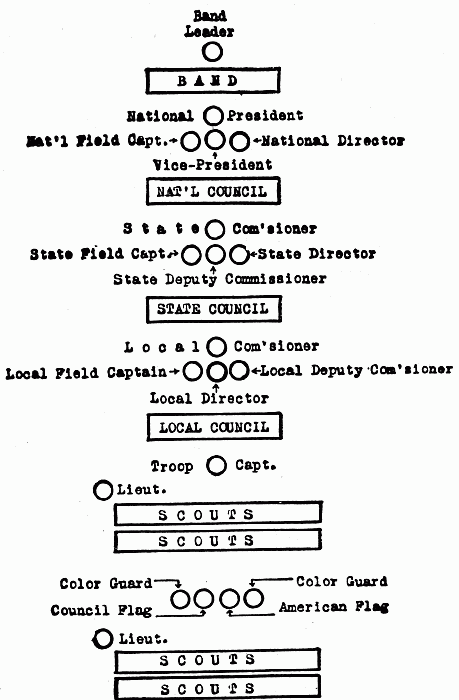

| III. | Organization of the Girl Scouts | 13 |

| IV. | Who Are the Scouts? | 17 |

| V. | The Out of Door Scout | 35 |

| VI. | Forms for Girl Scout Ceremonies | 44 |

| VII. | Girl Scout Class Requirements | 60 |

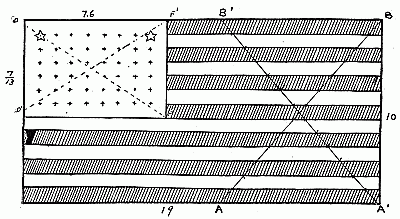

| VIII. | What a Girl Scout Should Know About the Flag | 67 |

| IX. | Girl Scout Drill | 84 |

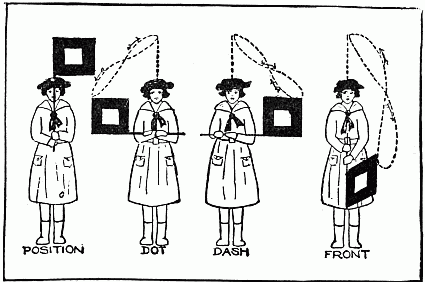

| X. | Signalling for Girl Scouts | 97 |

| XI. | The Scout Aide | 105 |

| Part 1. The Home Maker | 106 | |

| Part 2. The Child Nurse | 157 | |

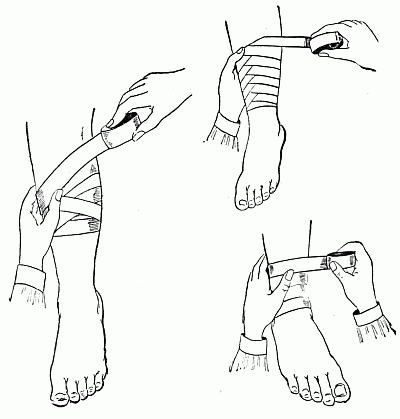

| Part 3. The First Aide | 164 | |

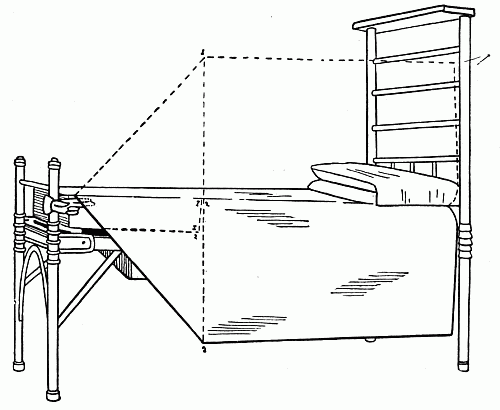

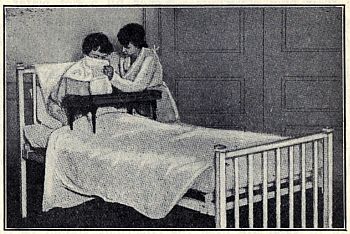

| Part 4. The Home Nurse | 217 | |

| Part 5. The Health Guardian | 254 | |

| Part 6. The Health Winner | 257 | |

| XII. | Setting-up Exercises | 273 |

| XIII. | Woodcraft | 280 |

| XIV. | Camping for Girl Scouts | 313 |

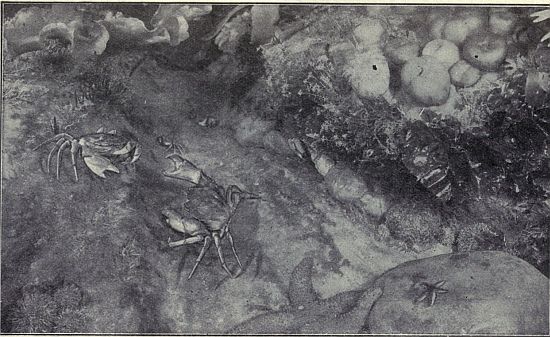

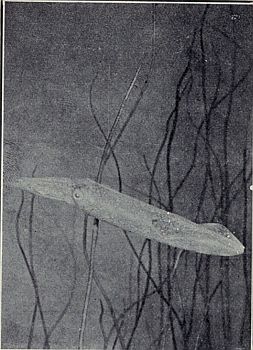

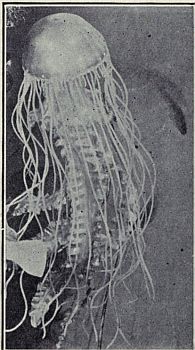

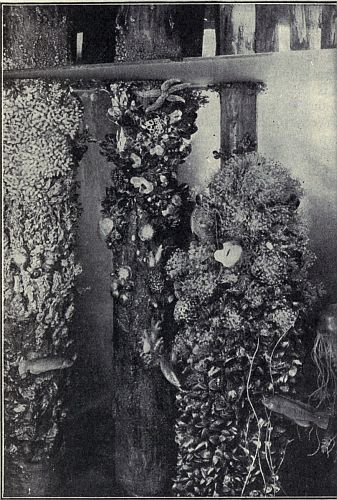

| XV. | Nature Study for Girl Scouts | 373 |

| XVI. | The Girl Scouts' Own Garden | 456 |

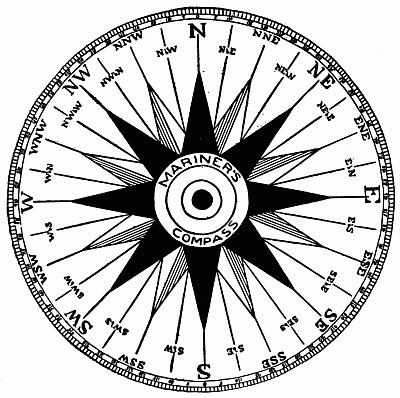

| XVII. | Measurements, Map-Making and Knots | 466 |

| XVIII. | Proficiency Tests and Special Medals | 497 |

| XIX. | Reference Reading for Girl Scouts | 540 |

| Index | 548 | |

| On My Honor, I will Try: |

| To do my duty to God and my Country. |

| To help other people at all times. |

| To obey the Scout Laws. |

| I | A Girl Scout's Honor is to be Trusted |

| II | A Girl Scout is Loyal |

| III | A Girl Scout's Duty is to be Useful and to Help Others |

| IV | A Girl Scout is a Friend to All and a Sister to every other Girl Scout |

| V | A Girl Scout is Courteous |

| VI | A Girl Scout is a Friend to Animals |

| VII | A Girl Scout obeys Orders |

| VIII | A Girl Scout is Cheerful |

| IX | A Girl Scout is Thrifty |

| X | A Girl Scout is Clean in Thought, Word and Deed |

When Sir Robert Baden-Powell founded the Boy Scout movement in England, it proved too attractive and too well adapted to youth to make it possible to limit its great opportunities to boys alone. The sister organization, known in England as the Girl Guides, quickly followed and won an equal success.

Mrs. Juliette Low, an American visitor in England, and a personal friend of the Father of Scouting, realized the tremendous future of the movement for her own country, and with the active and friendly co-operation of the Baden-Powells, she founded the Girl Guides in America, enrolling the first patrols in Savannah, Georgia, in March 1912. In 1915 National Headquarters were established in Washington, D. C., and the name was changed to Girl Scouts.

In 1916 National Headquarters were moved to New York and the methods and standards of what was plainly to be a nation-wide organization became established on a broad, practical basis.

The first National Convention was held in 1915, and each succeeding year has shown a larger and more enthusiastic body of delegates and a public more and more interested in this steadily growing army of girls and young women who are learning in the happiest way how to combine patriotism, outdoor activities of every kind, skill in every branch of domestic science and high standards of community service.[2]

Every side of the girl's nature is brought out and developed by enthusiastic Captains, who direct their games and various forms of training, and encourage team-work and fair play. For the instruction of the Captains national camps and training schools are being established all over the country; and schools and churches everywhere are cooperating eagerly with this great recreational movement, which, they realize, adds something to the life of the growing girl that they have not been able to supply.

Colleges are offering training in scouting as a serious course for prospective officers, and prominent citizens in every part of the country are identifying themselves with the Local Councils, in an advisory and helpful capacity.

At the present writing nearly 107,000 girls and more than 8,000 Officers represent the original little troop in Savannah—surely a satisfying sight for our Founder and First President, when she realizes what a healthy sprig she has transplanted from the Mother Country!

A Girl Scout learns to swim, not only as an athletic accomplishment, but so that she can save life. She passes her simple tests in child care and home nursing and household efficiency in order to be ready for the big duties when they come. She learns the important facts about her body, so as to keep it the fine machine it was meant to be. And she makes a special point of woodcraft and camp lore, not only for the fun and satisfaction they bring, in themselves, but because they are the best emergency course we have today. A Girl Scout who has passed her First Class test is as ready to help herself, her home and her Country as any girl of her age should be expected to prove.

This simple recipe for making a very little girl perform every day some slight act of kindness for somebody else is the seed from which grows the larger plant of helping the world along—the steady attitude of the older Scout. And this grows later into the great tree of organized, practical community service for the grown Scout—the ideal of every American woman today.

"I pledge allegiance to my flag, and to the Republic for which it stands; one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all."

This pledge, though not original with the Girl Scouts, expresses in every phrase their principles and practice.[4] Practical patriotism, in war and peace, is the cornerstone of the organization. A Girl Scout not only knows how to make her flag, and how to fly it; she knows how to respect it and is taught how to spread its great lesson of democracy. Many races, many religions, many classes of society have tested the Girl Scout plan and found that it has something fascinating and helpful in it for every type of young girl.

This broad democracy is American in every sense of the word; and the Patrol System, which is the keynote of the organization, by which eight girls of about the same age and interests elect their Patrol Leader and practice local self-government in every meeting, carries out American ideals in practical detail.

| On My Honor I will try: |

| To do my duty to God and my country. |

| To help other people at all times. |

| To obey the Scout Laws. |

This binds the Scouts together as nothing else could do. It is a promise each girl voluntarily makes; it is not a rule of her home nor a command from her school nor a custom of her church. She is not forced to make it—she deliberately chooses to do so. And like all such promises, it means a great deal to her. Experience has shown that she hesitates to break it.

This means that a Girl Scout's standards of honor are so high and sure that no one would dream of doubting[5] her simple statement of a fact when she says: "This is so, on my honor as a Girl Scout."

She is not satisfied, either, with keeping the letter of the law, when she really breaks it in spirit. When she answers you, she means what you mean.

Nor does she take pains to do all this only when she is watched, or when somebody stands ready to report on her conduct. This may do for some people, but not for the Scouts. You can go away and leave her by herself at any time; she does not require any guard but her own sense of honor, which is always to be trusted.

This means that she is true to her Country, to the city or village where she is a citizen, to her family, her church, her school, and to those for whom she may work, or who may work for her. She is bound to believe the best of them and to defend them if they are slandered or threatened. Her belief in them may be the very thing they need most, and they must feel that whoever may fail them, a Girl Scout never will.

This does not mean that she thinks her friends and family and school are perfect; far from it. But there is a way of standing up for what is dear to you, even though you admit that it has its faults. And if you insist on what is best in people, behind their backs, they will be more likely to take your criticism kindly, when you make it to their faces.

This means that if it is a question of being a help to the rest of the world, or a burden on it, a Girl Scout is[6] always to be found among the helpers. The simplest way of saying this, for very young Scouts, is to tell them to do a GOOD TURN to someone every day they live; that is, to be a giver and not a taker. Some beginners in Scouting, and many strangers, seem to think that any simple act of courtesy, such as we all owe to one another, counts as a good turn, or that one's mere duty to one's parents is worthy of Scout notice. But a good Scout laughs at this idea, for she knows that these things are expected of all decent people. She wants to give the world every day, for good measure, something over and above what it asks of her. And the more she does, the more she sees to do.

This is the spirit that makes the older Scout into a fine, useful, dependable woman, who does so much good in her community that she becomes naturally one of its leading citizens, on whom everyone relies, and of whom everyone is proud. It may end in the saving of a life, or in some great heroic deed for one's country. But these things are only bigger expressions of the same feeling that makes the smallest Tenderfoot try to do at least one good turn a day.

This means that she has a feeling of good will to all the world, and is never offish and suspicious nor inclined to distrust other people's motives. A Girl Scout should never bear a grudge, nor keep up a quarrel from pride, but look for the best in everybody, in which case she will undoubtedly find it. Women are said to be inclined to cliques and snobbishness, and the world looks to great organizations like the Girl Scouts to break down their[7] petty barriers of race and class and make our sex a great power for democracy in the days to come.

The Girl Scout finds a special comrade in every other Girl Scout, it goes without saying, and knows how to make her feel that she need never be without a friend, or a meal, or a helping hand, as long as there is another Girl Scout in the world.

She feels, too, a special responsibility toward the very old, who represent what she may be, some day; toward the little children, who remind her of what she used to be; toward the very poor and the unfortunate, either of which she may be any day. The sick and helpless she has been, as a Scout, especially trained to help, and she is proud of her handiness and knowledge in this way.

This means that it is not enough for women to be helpful in this world; they must do it pleasantly. The greatest service is received more gratefully if it is rendered graciously. The reason for this is that true courtesy is not an affected mannerism, but a sign of real consideration of the rights of others, a very simple proof that you are anxious to "do as you would be done by." It is society's way of playing fair and giving everybody a chance. In the same way, a gentle voice and manner are very fair proofs of a gentle nature; the quiet, self-controlled person is not only mistress of herself, but in the end, of all the others who cannot control themselves.

And just as our great statesman, Benjamin Franklin proved that "honesty is the best policy," so many a successful woman has proved that a pleasant, tactful manner is one of the most valuable assets a girl can possess,[8] and should be practised steadily. At home, at school, in the office and in the world in general, the girl with the courteous manner and pleasant voice rises quickly in popularity and power above other girls of equal talent but less politeness. Girl Scouts lay great stress on this, because, though no girl can make herself beautiful, and no girl can learn to be clever, any girl can learn to be polite.

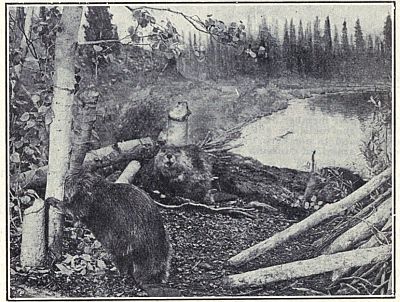

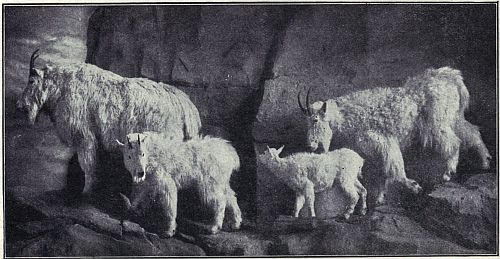

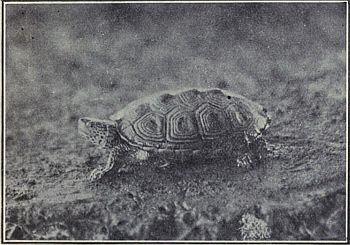

All Girl Scouts take particular care of our dumb friends, the animals, and are always eager to protect them from stupid neglect or hard usage. This often leads to a special interest in their ways and habits, so that a Girl Scout is likely to know more about these little brothers of the human race than an ordinary girl.

This means that you should obey those to whom obedience is due, through thick and thin. If this were not an unbreakable rule, no army could endure for a day. It makes no difference whether you are cleverer, or older, or larger, or richer than the person who may be elected or appointed for the moment to give you orders; once they are given, it is your duty to obey them. And the curious thing about it is that the quicker and better you obey these orders, the more quickly and certainly you will show yourself fitted to give them when your time comes. The girl or woman who cannot obey can never govern. The reason you obey the orders of your Patrol Leader, for instance, in Scout Drill, is not that she is better than you, but because she happens to be[9] your Patrol Leader, and gives her orders as she would obey yours were you in her place.

A small well trained army can always conquer and rule a big, undisciplined mob, and the reason for this is simply because the army has been taught to obey and to act in units, while the mob is only a crowd of separate persons, each doing as he thinks best. The soldier obeys by instinct, in a great crisis, only because he has had long practice in obeying when it was a question of unimportant matters. So the army makes a great point of having everything ordered in military drill, carried out with snap and accuracy; and the habit of this, once fixed, may save thousands of lives when the great crisis comes, and turn defeat into victory.

A good Scout must obey instantly, just as a good soldier must obey his officer, or a good citizen must obey the law, with no question and no grumbling. If she considers any order unjust or unreasonable, let her make complaint through the proper channels, and she may be sure that if she goes about it properly she will receive attention. But she must remember to obey first and complain afterward.

This means that no matter how courteous or obedient or helpful you try to be, if you are sad or depressed about it nobody will thank you very much for your effort. A laughing face is usually a loved face, and nobody likes to work with a gloomy person. Cheerful music, cheerful plays and cheerful books have always been the world's favorites; and a jolly, good-natured girl will find more friends and more openings in the world than a sulky beauty or a gloomy genius.[10]

It has been scientifically proved that if you deliberately make your voice and face cheerful and bright you immediately begin to feel that way; and as cheerfulness is one of the most certain signs of good health, a Scout who appears cheerful is far more likely to keep well than one who lets herself get "down in the mouth." There is so much real, unavoidable suffering and sorrow in the world that nobody has any right to add to them unnecessarily, and "as cheerful as a Girl Scout" ought to become a proverb.

This means that a Girl Scout is a girl who is wise enough to know the value of things and to put them to the best use. The most valuable thing we have in this life is time, and girls are apt to be stupid about getting the most out of it. A Girl Scout may be known by the fact that she is either working, playing or resting. All are necessary and one is just as important as the other.

Health is probably a woman's greatest capital, and a Girl Scout looks after it and saves it, and doesn't waste it by poor diet and lack of exercise and fresh air, so that she goes bankrupt before she is thirty.

Money is a very useful thing to have, and the Girl Scout decides how much she can afford to save and does it, so as to have it in an emergency. A girl who saves more than she spends may be niggardly; a girl who spends more than she saves may go in debt. A Girl Scout saves, as she spends, on some system.

Did you ever stop to think that no matter how much money a man may earn, the women of the family generally have the spending of most of it? And if they have not learned to manage their own money sensibly,[11] how can they expect to manage other people's? If every Girl Scout in America realized that she might make all the difference, some day, between a bankrupt family and a family with a comfortable margin laid aside for a rainy day, she would give a great deal of attention to this Scout law.

In every great war all nations have been accustomed to pay the costs of the war from loans; that is, money raised by the savings of the people. Vast sums were raised in our own country during the great war by such small units as Thrift Stamps. If the Girl Scouts could save such wonderful sums as we know they did in war, why can they not keep this up in peace? For one is as much to their Country's credit as the other.

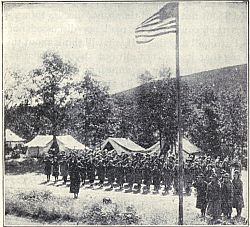

SALUTING THE FLAG IN A GIRL SCOUT CAMP

SALUTING THE FLAG IN A GIRL SCOUT CAMP

This means that just as she stands for a clean, healthy community and a clean, healthy home, so every Girl Scout knows the deep and vital need for clean and healthy bodies in the mothers of the next generation. This not only means keeping her skin fresh and sweet and her system free from every impurity, but it goes far deeper than this, and requires every Girl Scout to respect her body and mind so much that she forces everyone else to respect them and keep them free from the slightest familiarity or doubtful stain.

A good housekeeper cannot endure dust and dirt; a well cared for body cannot endure grime or soil; a pure mind cannot endure doubtful thoughts that cannot be freely aired and ventilated. It is a pretty safe rule for a Girl Scout not to read things nor discuss things nor do things that could not be read nor discussed nor done by a Patrol all together. If you will think about this, you will see that it does not cut out anything that is really necessary, interesting or amusing. Nor does it mean that Scouts should never do anything except in Patrols; that would be ridiculous. But if they find they could not do so, they had better ask themselves why. When there is any doubt about this higher kind of cleanliness Captains and Councillors may always be asked for advice and explanation.

The basis of the Girl Scout organization is the individual girl. Any one girl anywhere who wishes to enroll under our simple pledge of loyalty to God and Country, helpfulness to other people and obedience to the Scout Laws, and is unable to attach herself to any local group, is privileged to become a Lone Scout. The National Organization will do its best for her and she is eligible for all Merit Badges which do not depend upon group work.

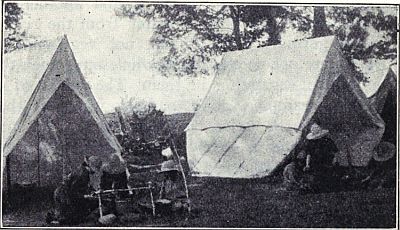

But the ideal unit and the keystone of the organization is the Patrol, consisting of eight girls who would naturally be associated as friends, neighbors, school fellows or playmates. They are a self selected and, under the regulations and customs of the organization, a self governing little body, who learn, through practical experiment, how to translate into democratic team-play, their recreation, patriotic or community work, camp life and athletics. Definite mastery of the various subjects they select to study is made more interesting by healthy competition and mutual observation.

Each Patrol elects from its members a Patrol Leader, who represents them and is to a certain extent responsible for the discipline and dignity of the Patrol.

The Patrol Leader is assisted by her Corporal, who may be either elected or appointed; and she is subject to re-election[14] at regular intervals, the office is a practical symbol of the democratic basis of our American government and a constant demonstration of it.

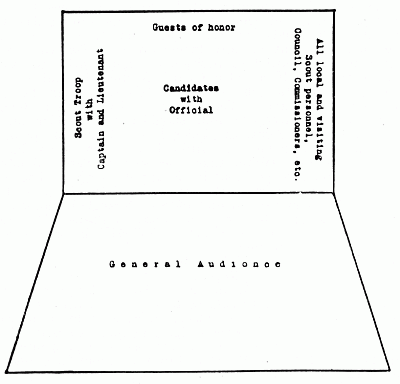

From one to four of these Patrols constitute a Troop, the administrative unit of the organization. Girl Scouts are registered and chartered by troops, and the Troop meeting is their official gathering. The Troop has the privilege of owning a flag and choosing from a list of flowers, trees, birds, and so forth, its own personal crest and title.

The leader is called a Captain. She must be twenty-one or over, and officially accepted by the National Headquarters, from whom she receives the ratification of her appointment and to whom she is responsible. She may be chosen by the girls themselves, suggested by local authorities, or be herself the founder of the Troop. She represents the guiding, friendly spirit of comradely leadership, the responsibility and discretion, the maturer judgment and the definite training which shapes the policy of the organization.

She may, in a small troop, and should, in a large one, be assisted by a Lieutenant, who must be eighteen or over, and who must, like herself, be commissioned from National Headquarters; and if desired, by a Second Lieutenant, who must be at least sixteen.

The work of the Girl Scouts in any community is made many times more effective and stimulating by the cooperation[15] of the Council, a group of interested, public spirited citizens who are willing to stand behind the girls and lend the advantages of their sound judgment, broad point of view, social prestige and financial advice. They are not expected to be responsible for any teaching, training or administrative work; they are simply the organized Friends of the Scouts and form the link between the Scouts and the community. The Council is at its best when it is made up of representatives of the church, school, club and civic interests of the neighborhood, and can be of inestimable value in suggesting and affording means of co-operation with all other organizations, patronizing and advertising Scout entertainments, and so forth. One of its chief duties is that of finding interested and capable judges for the various Merit Badges, and arranging for the suitable conferring of such badges. The Council, or a committee selected from its members, is known for this purpose as the Court of Awards.

A Captain who feels that she has such a body behind her can go far with her Troop; and citizens who are particularly interested in constructive work with young people who find endless possibilities in an organized Girl Scout Council. The National Headquarters issues charters to such Councils and cooperates with them in every way.

The central and final governing body is the National Council. This is made up of delegates elected from all local groups throughout the country, and works by representation, indirectly through large State and District sub-divisions, through the National Executive Board which maintains its Headquarters in New York.[16]

The National Director is in charge of these Headquarters and directs the administrative work under the general heading of Field, Business, Publication and Education.

From the youngest Lone Scout up to the National Director, the organization is democratic, self-governing and flexible, adjusting itself everywhere and always to local circumstances and the habits and preferences of the different groups. It is not only non-sectarian, but is open to all creeds and has the enthusiastic support of all of them. It offers no new system of education, but co-operates with the schools and extends to them a much appreciated recreational plan. It affords the churches a most practical outlet for their ideals for their young people. Its encouragement of the intelligent domestic interests is shown by the stress laid on every aspect of home and social life and by the great variety of Merit Badges offered along these lines. The growing interest in the forming of Girl Scout Troops by schools, churches and parents proves as nothing else could, how naturally and helpfully this simple organization fits in with the three factors of the girl's life; her home, her church, her school. And the rapid and never ceasing growth of the Girl Scouts means that we are able to offer, every year, larger and larger numbers of healthy and efficient young citizens to their country.

In the early days of this great country of ours, before telephones and telegrams, railroads and automobiles made communications of all sorts so easy, and help of all kinds so quickly secured, men and women—yes, and boys and girls, too!—had to depend very much on themselves and be very handy and resourceful, if they expected to keep safe and well, and even alive.

Our pioneer grandmothers might have been frightened by the sight of one of our big touring cars, for instance, or puzzled as to how to send a telegram, but they knew an immense number of practical things that have been entirely left out of our town-bred lives, and for pluck and resourcefulness in a tight place it is to be doubted if we could equal them today.

"You press a button and we do the rest" is the slogan of a famous camera firm, and really it seems as if this might almost be called the slogan of modern times; we have only to press a button nowadays, and someone will do the rest.

But in those early pioneer days there was no button to press, as we all know, and nobody to "do the rest": everybody had to know a little about everything and be able to do that little pretty quickly, as safety and even life might depend upon it.

The men who stood for all this kind of thing in the highest degree were probably the old "Scouts," of whom Natty Bumpo, in Cooper's famous old Indian tales is the great example. They were explorers, hunters, campers,[18] builders, fighters, settlers, and in an emergency, nurses and doctors combined. They could cook, they could sew, they could make and sail a canoe, they could support themselves indefinitely in the trackless woods, they knew all the animals and the plants for miles around, they could guide themselves by the sun, and stars, and finally, they were husky and hard as nails and always in the best of health and condition. Their adventurous life, always on the edge of danger and new, unsuspected things, made them as quick as lightning and very clever at reading character and adapting themselves to people.

In a way, too, they had to act as rough and ready police (for there were no men in brass buttons in the woods!) and be ready to support the right, and deal out justice, just as our "cow-boys" of later ranch days had to prevent horse-stealing.

Now, the tales of their exploits have gone all over the world, and healthy, active people, and especially young people, have always delighted in just this sort of life and character. So, when you add the fact that the word "scout" has always been used, too, to describe the men sent out ahead of an army to gain information in the quickest, cleverest way, it is no wonder that the great organizations of Boy and Girl Scouts which are spreading all over the world today should have chosen the name we are so proud of, to describe the kind of thing they want to stand for.

Our British Scout-sisters call themselves "Girl Guides," and here is the thrilling reason for this title given by the Chief Scout and Founder of the whole big band that is spreading round the world today, as so many of Old England's great ideas have spread.[19]

On the North-West Frontier of India there is a famous Corps of soldiers known as the Guides, and their duty is to be always ready to turn out at any moment to repel raids by the hostile tribes across the Border, and to prevent them from coming down into the peaceful plains of India. This body of men must be prepared for every kind of fighting. Sometimes on foot, sometimes on horseback, sometimes in the mountains, often with pioneer work wading through rivers and making bridges, and so on. But they have to be a skilful lot of men, brave and enduring, ready to turn out at any time, winter or summer, or to sacrifice themselves if necessary in order that peace may reign throughout India while they keep down any hostile raids against it. So they are true handymen in every sense of the word, and true patriots.

When people speak of Guides in Europe one naturally thinks of those men who are mountaineers in Switzerland and other mountainous places, who can guide people over the most difficult parts by their own bravery and skill in tackling obstacles, by helpfulness to those with them, and by their bodily strength of wind and limb. They are splendid fellows those guides, and yet if they were told to go across the same amount of miles on an open flat plain it would be nothing to them, it would not be interesting, and they would not be able to display those grand qualities which they show directly the country is a bit broken up into mountains. It is no fun to them to walk by easy paths, the whole excitement of life is facing difficulties and dangers and apparent impossibilities, and in the end getting a chance of attaining the summit of the mountain they have wanted to reach.

Well, I think it is the case with most girls nowadays. They do not want to sit down and lead an idle life, not to have everything done for them, nor to have a very easy time. They don't want merely to walk across the plain, they would much rather show themselves handy people, able to help others and ready, if necessary to sacrifice themselves for others just like the Guides on the North-West frontier. And they also want to tackle difficult jobs themselves in their life, to face mountains and difficulties and dangers and to go at them having prepared themselves to be skilful and brave; and also they would like to help other people meet their difficulties also. When they attain success after facing difficulties, then they feel really happy and triumphant. It is a big satisfaction to them to have succeeded and to have made other people succeed also. That is what the Girl Guides want to do, just as the mountaineer guides do among the mountains.

Then, too, a woman who can do things is looked up to by others, both men and women, and they are always ready to follow her advice and example, so there she becomes a Guide too. And later on if she has children of her own, or if she becomes a teacher of children, she can be a really good Guide to them.[20]

By means of games and activities which the Guides practise they are able to learn the different things which will help them to get on in life, and show the way to others to go on also. Thus camping and signalling, first aid work, camp cooking, and all these things that the Guides practise are all going to be helpful to them afterwards in making them strong, resourceful women, skilful and helpful to others, and strong in body as well as in mind, and what is more it makes them a jolly lot of comrades also.

The motto of the Guides on which they work is "Be Prepared," that is, be ready for any kind of duty that may be thrust upon them, and what is more, to know what to do by having practised it beforehand in the case of any kind of accident or any kind of work that they may be asked to take up.

It is a great piece of luck for us American Scouts that we can claim the very first Girl Scout for our own great continent, if not quite for our own United States. A great Englishman calls her "the first Girl Scout," and every Scout must feel proud to the core of her heart when she thinks that this statue which we have selected for the honor of our frontispiece, standing as it does on British soil, on the American continent, commemorating a French girl, the daughter of our Sister Republic, joins the three great countries closely together, through the Girl Scouts! Magdelaine de Verchères lived in the French colonies around Quebec late in the seventeenth century. The colonies were constantly being attacked by the Iroquois Indians. One of these attacks occurred while Magdelaine's father, the Seigneur, was away. Magdelaine rallied her younger brothers about her and succeeded in holding the fort for eight days, until help arrived from Montreal.

The documents relating this bit of history have been in the Archives for many years, but when they were[21] shown to Lord Grey about twelve years ago he decided to erect a monument to Magdelaine de Verchères on the St. Lawrence. It was Lord Grey who called Magdelaine "The First Girl Scout," and as such she will be known.

The following is taken from "A Daughter of New France," by Arthur G. Doughty who wrote the book for the Red Cross work of the Magdelaine de Verchères Chapter of the Daughters of the Empire, and dedicated it to Princess Patricia, whose name was given to the famous "Princess Pat" regiment.

"On Verchères Point, near the site of the Fort, stands a statue in bronze of the girl who adorned the age in which she lived and whose memory is dear to posterity. For she had learned so to live that her hands were clean and her paths were straight.... To all future visitors to Canada by way of the St. Lawrence, this silent figure of the First Girl Scout in the New World conveys a message of loyalty, of courage and of devotion."

Our own early history is sprinkled thickly with brave, handy girls, who were certainly Scouts, if ever there were any, though they never belonged to a patrol, nor recited the Scout Laws. But they lived the Laws, those strong young pioneers, and we can stretch out our hands to them across the long years, and give them the hearty Scout grip of fellowship, when we read of them.

If we should ever hold an election for honorary membership in the Girl Scouts, open to all the girls who ought to have belonged to us, but who lived too long ago, we should surely nominate for first place one of the most remarkable young Indian girls who ever found her way through the pathless forests,—Sacajawea, "The Bird Woman."[22]

In 1806 she was brought to Lewis and Clark on their expedition into the great Northwest, to act as interpreter between them and the various Indian tribes they had to encounter. From the very beginning, when she induced the hostile Shoshones to act as guides, to the end of her daring journey, during which, with her papoose on her back, she led this band of men through hitherto impassable mountain ranges, till she brought them to the Pacific Coast, this sixteen-year-old girl never faltered. No dangers of hunger, thirst, cold or darkness were too much for her. From the Jefferson to the Yellowstone River she was the only guide they had; on her instinct for the right way, her reading of the sun, the stars and the trees, depended the lives of all of them. When they fell sick she nursed them; when they lost heart at the wildness of their venture, she cheered them. Their party grew smaller and smaller, for Lewis and Clark had separated early in the expedition, and a part of Clark's own party fell off when they discovered a natural route over the Continental Divide where wagons could not travel. Later, most of those who remained, decided to go down the Jefferson River in canoes; but Clark still guided by the plucky Indian girl, persisted in fighting his way on pony back overland, and after a week of this journeying, crowded full of discomforts and dangers, she brought him out in triumph at the Yellowstone, where the river bursts out from the lower canon,—and the Great Northwest was opened up for all time!

The women of Oregon have raised a statue to this young explorer, and there she stands in Portland, facing the Coast, pointing to the Columbia River where it reaches the sea.[23]

These great virtues of daring and endurance never die out of the race; though the conditions of our life today, when most of the exploring has been done, do not demand them of us in just the form the "Bird Woman" needed, still, if they die out of the nation, and especially out of the women of the nation, something has been lost that no amount of book education can ever replace. Sacajawea, had no maps to study—she made maps, and roads have been built over her footsteps. And so we Scouts, not to lose this great spirit, study the stars and the sun and the trees and try to learn a few of the wood secrets she knew so well. This out-of-door wisdom and self-reliance was the first great principle of Scouting.

But of course, a country full of "Bird Women" could not be said to have advanced very far in civilization. Though we should take great pleasure in conferring her well-earned merit badges on Sacajawea, we should hardly have grown into the great organization we are today if we had not badges for quite another class of achievements.

In 1832, not so many years after the famous Lewis and Clark expedition, there was born a little New England girl who would very early in life have become a First Class Scout if she had had the opportunity. Her name was Louisa Alcott, and she made that name famous all the world over by the book by which the world's girls know her—"Little Women." Her father, though a brilliant man, was a very impractical one, and from her first little story to her last popular book, all her work was done for the purpose of keeping her mother and sisters, in comfort. While she was waiting for the money from her stories she turned carpets, trimmed hats, papered the[24] rooms, made party dresses for her sisters, nursed anyone who was sick (at which she was particularly good)—all the homely, helpful things that neighbors and families did for each other in New England towns.

In those days little mothers of families could not telephone specialists to help them out in emergencies; there were neither telephones nor specialists! But there were always emergencies, and the Alcott girls had to know what to put on a black-and-blue spot, and why the jelly failed to "jell," and how to hang a skirt, and bake a cake, and iron a table-cloth. Louisa had to entertain family guests and darn the family stockings. Her home had not every comfort and convenience, even as people counted those things then, and without a brisk, clever woman, full of what the New Englanders called "faculty," her family would have been a very unhappy one. With all our modern inventions nobody has yet invented a substitute for a good, all-round woman in a family, and until somebody can invent one, we must continue to take off our hats to girls like Louisa Alcott. Imagine what her feelings would have been if someone had told her that she had earned half a dozen merit badges by her knowledge of home economics and her clever writing!

And let every Scout who finds housework dull, and feels that she is capable of bigger things, remember this: the woman whose books for girls are more widely known than any such books ever written in America, had to drop the pen, often and often, for the needle, the dish-cloth and the broom.

To direct her household has always been a woman's job in every century, and girls were learning to do it before Columbus ever discovered Sacajawea's great country. To[25] be sure, they had no such jolly way of working at it together, as the Scouts have, nor did they have the opportunity the girl of today has to learn all about these things in a scientific, business-like way, in order to get it all done with the quickest, most efficient methods, just as any clever business man manages his business.

We no longer believe that housekeeping should take up all a woman's time; and many an older woman envies the little badges on a Scout's sleeve that show the world she has learned how to manage her cleaning and cooking and household routine so that she has plenty of time to spend on other things that interest her.

But there was a time in the history of our country when men and women went out into the wilderness with no nearer neighbors than the Indians, yet with all the ideals of the New England they left behind them; girls who had to have all the endurance of the young "Bird Woman" and yet keep up the traditions and the habits of the fine old home life of Louisa Alcott.

One of these pioneer girls, who certainly would have been patrol leader of her troop and marched them to victory with her, was Anna Shaw. In 1859, a twelve-year old girl, with her mother and four other children she traveled in a rough cart full of bedding and provisions, into the Michigan woods where they took up a claim, settling down into a log cabin whose only furniture was a fireplace of wood and stones.

She and her brothers floored this cabin with lumber from a mill, and actually made partitions, an attic door and windows. They planted potatoes and corn by chopping up the sod, putting seed under it and leaving it to[26] Nature—who rewarded them by giving them the best corn and potatoes Dr. Shaw ever ate, she says in her autobiography.

For she became a preacher and a physician, a lecturer and organizer, this sturdy little Scout, even though she had to educate herself, mostly. They papered the cabin walls with the old magazines, after they had read them once, and went all over them, in this fashion, later. So eagerly did she devour the few books sent them from the East, that when she entered college, years later, she passed her examinations on what she remembered of them!

They lived on what they raised from the land; the pigs they brought in the wagon with them, fish, caught with wires out of an old hoop skirt, and corn meal brought from the nearest mill, twenty miles away. Ox teams were the only means of getting about.

Anna and her brothers made what furniture they used—bunks, tables, stools and a settle. She learned to cut trees and "heart" logs like a man. After a trying season of carrying all the water used in the household from a distant creek, which froze in the winter so that they had to melt the ice, they finally dug a well. First they went as far as they could with spades, then handed buckets of earth to each other, standing on a ledge half-way down; then, when it was deep enough, they lined it with slabs of wood. It was so well made that the family used it for twelve years.

Wild beasts prowled around them, Indians terrified them by sudden visits, the climate was rigorous, amusements and leisure scanty. But this brave, handy girl met every job that came to her with a good heart and a smile;[27] she learned by doing. The tests and sports for mastering which we earn badges were life's ordinary problems to her, and very practical ones. She never knew it, but surely she was a real Girl Scout!

It is not surprising to learn that she grew up to be one of the women who earned the American girl her right to vote. A pioneer in more ways than one, this little carpenter and farmer and well-digger worked for the cause of woman's political equality as she had worked in the Michigan wilderness, and helped on as much as any one woman, the great revolution in people's ideas which makes it possible for women today to express their wishes directly as to how their country shall be governed. This seems very simple to the girls of today, and will seem even simpler as the years go on, but, like the Yellowstone River, it needed its pioneers!

In the Great War through which we have just passed, the Scouts of all countries gave a magnificent account of themselves, and honestly earned the "War Service" badges that will be handed down to future generations, we may be sure, as the proudest possessions of thousands of grandchildren whose grandmothers (think of a Scout grandmother!) were among the first to answer their Country's call.

Let us hear what our British sisters accomplished, and we must remember that at the time of the war there were many Girl Guides well over Scout age and in their twenties, who had had the advantage, as their book points out, of years of training.

This is what they have done during the Great War.

In the towns they have helped at the Military Hospitals.

In the country they have collected eggs for the sick, and on the moors have gathered sphagnum moss for the hospitals.

Over in France a great Recreation and Rest Hut for the soldiers[28] has been supplied by the Guides with funds earned through their work. It is managed by Guide officers, or ex-Guides. Among the older Guides there are many who have done noble work as assistants to the ward-maids, cooks, and laundry women. In the Government offices, such as the War Office, the Admiralty, and other great departments of the State, they have acted as orderlies and messengers. They have taken up work in factories, or as motor-drivers or on farms, in order to release men to go to the front.

At home and in their club-rooms they have made bandages for the wounded, and warm clothing for the men at the Front and in the Fleet.

At home in many of the great cities the Guides have turned their Headquarters' Club-Rooms into "Hostels." That is, they have made them into small hospitals ready for taking in people injured in air-raids by the enemy.

So altogether the Guides have shown themselves to be a pretty useful lot in many different kinds of work during the war, and, mind you, they are only girls between the ages of 11 and 18. But they have done their bit in the Great War as far as they were able, and have done it well.

There are 100,000 of them, and they are very smart, and ready for any job that may be demanded of them.

They were not raised for this special work during the war for they began some years before it, but their motto is "Be Prepared," and it was their business to train themselves to be ready for anything that might happen, even the most unlikely thing.

So even when war came they were "all there" and ready for it.

It is not only in Great Britain that they have been doing this, but all over our great Empire—in Canada and Australia, West, East and South Africa, New Zealand, the Falkland Islands, West Indies, and India. The Guides are a vast sisterhood of girls, ready to do anything they can for their country and Empire.

Long before there was any idea of the war the Guides had been taught to think out and to practise what they should do supposing such a thing as war happened in their own country, or that people should get injured by bombs or by accidents in their neighborhood. Thousands of women have done splendid work in this war, but thousands more would have been able to do good work also had they only Been Prepared for it beforehand by learning a few things that are useful to them outside their mere school work or work in their own home. And that is what the Guides are learning in all their games and camp work: they mean to be useful in other ways besides what they are taught in school.

As a Guide your first duty is to be helpful to other people, both in small everyday matters and also under the worst of circumstances. You have to imagine to yourself what sort of things might possibly happen, and how you should deal with them when they occur. Then you will know what to do.[29]

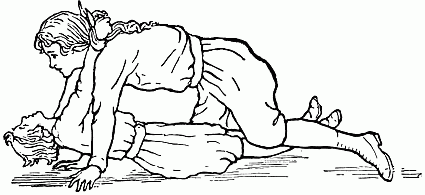

I was present when a German aeroplane dropped a bomb on to a railway station in London. There was the usual busy scene of people seeing to their luggage, saying good-bye and going off by train, when with a sudden bang a whole carriage was blown to bits, and the adjoining ones were in a blaze; seven or eight of those active in getting into the train were flung down—mangled and dead; while some thirty more were smashed, broken, and bleeding, but still alive. The suddenness of it made it all the more horrifying. But one of the first people I noticed as keeping her head was a smartly dressed young lady kneeling by an injured working-man; his thigh was smashed and bleeding terribly; she had ripped up his trousers with her knife, and with strips of it had bound a pad to the wound; she found a cup somehow and filled it with water for him from the overhead hose for filling engines. Instead of being hysterical and useless, she was as cool and ready to do the right thing as if she had been in bomb-raids every day of her life. Well, that is what any girl can do if she only prepares herself for it.

These are things which have to be learnt in peace-time, and because they were learnt by the Guides beforehand, these girls were able to do their bit so well when war came.

When you see an accident in the street or people injured in an air raid, the sight of the torn limbs, the blood, the broken bones, and the sound of the groans and sobbing all make you feel sick and horrified and anxious to get away from it—if you're not a Girl Guide. But that is cowardice: your business as a Guide is to steel yourself to face it and to help the poor victim. As a matter of fact, after a trial or two you really get to like such jobs, because with coolheadedness and knowledge of what to do you feel you give the much-needed help.

The Value of Nursing.—In this war hundreds and hundreds of women have gone to act as nurses in the hospitals for the wounded and have done splendid work. They will no doubt be thankful all their lives that while they were yet girls they learnt how to nurse and how to do hospital work, so that they were useful when the call came for them. But there are thousands and thousands of others who wanted to do the work when the time came, but they had not like Guides, Been Prepared, and they had never learnt how to nurse, and so they were perfectly useless and their services were not required in the different hospitals. So carry out your motto and Be Prepared and learn all you can about hospital and child nursing, sick nursing, and every kind, while you are yet a Guide and have people ready to instruct you and to help you in learning.

In countries not so settled and protected as England and America, where the women and girls are taught to count upon their men to protect them in the field, the[30] Girl Scouts have sometimes had to display a courage like that of the early settlers. A Roumanian Scout, Ecaterina Teodorroiu actually fought in the war and was taken prisoner. She escaped, traced her way back to her company, and brought valuable information as to the enemy's movements. For these services she was decorated "as a reward for devotion and conspicuous bravery" with the Order of Merit and a special gold medal of the Scouts, only given for services during the war. At the same time she was promoted to the rank of Honorary Second Lieutenant.

Can we wonder that she is known as the Joan of Arc of Roumania?

During the Russian Revolution the Girl Scouts were used by the Government in many practical ways, as may be seen from the following letter from one of them:

"The Scouts assisted from the beginning, from seven in the morning until twelve at night, carrying messages, sometimes containing state secrets, letters, etc., from the Duma to the different branches of it called commissariats, and back again. They also fed the soldiers that were on guard. The Scout uniform was our protection, and everywhere that uniform commanded the respect of the soldiers, peasants and workingmen.

"As great numbers of soldiers came from the front, food had to be given them. It was contributed by private people, but the Scouts had lots of work distributing it. All the little taverns were turned into eating houses for the soldiers, and there we helped to prepare the food and feed them. As there were not enough Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts helped in the same way as the boys.[31]

"The Scouts also did much First Aid work. In one instance I saw an officer whose finger had been shot off. I ran up to him and bandaged it up for him. (All of us Scouts had First Aid kits hanging from our belts.)

"It was something of a proud day for us Scouts when the Premier after a parade, called us all before the Duma and publicly thanked us for our aid."

Indeed it was and we heartily congratulate our Sister Scouts! But if we do our duty by our Patrol and the Patrols all do their duty by their Troop, that proud moment is going to come to every single Scout of us, when the town where we live tells us by its smiles and applause, when we go by in uniform, what it thinks of us.

We Scouts shall be more and more interested, as the years go on, to remember that in the great hours of one of the world's greatest crises we helped to make its history. Instances like these are very exceptional; they could not occur to one in ten thousand of us; but we stay-at-homes can always remind ourselves that it was the obedience, the quickness, and the skill learned in quiet, every-day Scouting that made these few rise to their opportunity when it came.

War and revolution do not make Scouts either brave or useful; they only bring out the bravery and the usefulness that have been learned, as we are all learning them, every day!

All we have to do is to fix Scout habits in our hearts and hands, and then when our Country calls us, we shall be as ready as these little Russian Scouts were.

In France the Scouts, known as the Eclaireuses, have agreed with us that the "land Army" is the best army for women. Rain or shine, in heat and cold, they have[32] dug and ploughed and planted, and learned the lesson American girls learned long ago—that team work is what counts!

A bit of one of their reports is translated here:

"The crops were fine—potatoes, radishes, greens and beans were raised. The crop of potatoes, especially, was so good that the Eclaireuses were able to supply their families with them at a price defying competition, and they always had enough besides for their own use on excursions. (Our hikes.)

"Such has been the reward of the care, given so perseveringly and intelligently to the gardening.

"And what an admirable lesson! Not a minute was lost in this out-of-door work; chests and muscles filled out; and at the same time the girls learned to recognize weather signs; rain or sun were the factors which determined the success or non-success of the planting. And each day, there grew in them also love and gratitude for the earth and its elements, without the assistance of which we could harvest nothing.

"Is this not the best method of preparing our youth to return to the land, to the healthy and safe life of the beautiful countryside of France; by showing them the interest and usefulness that lie in agricultural labor?

"So the Eclaireuse becomes a model of the new women, used to sport, possessing her First Aid Diploma, able to cook good simple meals, marching under orders, knowing how to obey, ready to accept her responsibility, good-natured and lively in rain or sun, in public or in her home.... They continue their courses in sewing, hygiene and gymnastics and assist eagerly at conferences arranged for them to discuss[33] the duties of the Eclaireuses and what it is necessary to do to become a good Captain.

"To make themselves useful—that is the ideal of the Eclaireuses. They know that in order to do this it is becoming more and more necessary to acquire a broad and complete knowledge."

It is quite a feather in the cap of this great Scout Family of ours that we are teaching the French girl, who has not been accustomed to leave her home or to work in clubs or troops, what a jolly, wonder-working thing a crowd of girls, all forging ahead together, can be.

In our own country we were protected from the worst sides of the great war, but we had a wonderful opportunity to show how we could Be Prepared ourselves by seeing that our brave soldiers were prepared.

Our War Records show an immense amount of Red Cross supplies, knitting, comfort kits, food grown and conserved in every way, money raised for Liberty Loans and Thrift Stamps, war orphans adopted, home replacement work undertaken and carried through; all these to so great an amount that the country recognized our existence and services as never before in our history, the Government, indeed, employing sixty uniformed Scouts as messengers in the Surgeon General's Department.

Perhaps it is only the truth to say that the war showed our country what we could Be Prepared to do for her! And it showed us, too.

It has been said that women can never be the same after the great events of the last few years, and we must never forget that the Girl Scouts of today are the women of tomorrow.[34]

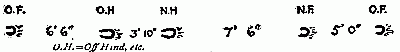

FLAG RAISING AT DAWN

FLAG RAISING AT DAWN

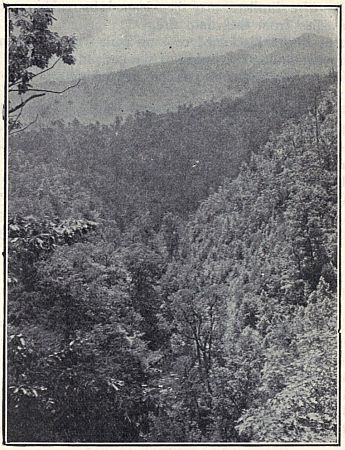

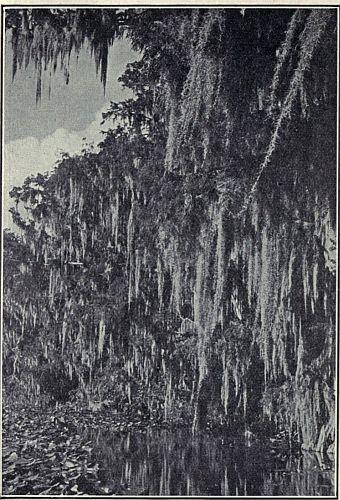

Busy as the Girl Scout may be with learning to do in a clever, up-to-date way all the things to improve her home and town that the old pioneer girls knew how to do, she never forgets that the original Scouts were out-of-door people. So long as there are bandages to make or babies to bathe or meals to get or clothes to make, she does them all, quickly and cheerfully, and is very rightly proud of the badges she gets for having learned to do them all, and the sense of independence that comes from all this skill with her hands. It gives her a real glow of pleasure to feel that because of her First Aid practice she may be able to save a life some day, and that the hours of study she put in at her home nursing and invalid cooking may make her a valuable asset to the community in case of any great disaster or epidemic; but the real fun of scouting lies in the great life of out-of-doors, and the call of the woods is answered quicker by the Scout than by anybody, because the Scout learns just how to get the most out of all this wild, free life and how to enjoy it with the least trouble and the most fun.

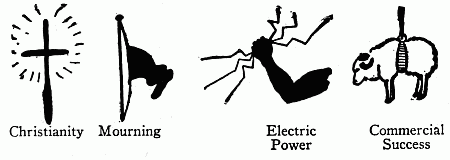

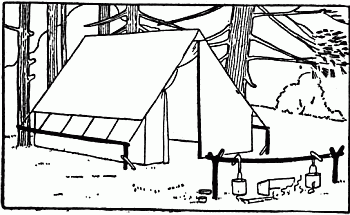

One of our most experienced and best loved Captains says that "a camp is as much a necessity for the Girl Scouts as an office headquarters," and more and more girls are learning to agree with her every year.

Our British cousins are the greatest lovers of out-of-door life in the world, and it is only natural that we should look to our Chief Scout to hear what he has to say to his Girl Guides on this subject so dear to his heart that he founded Scouting, that all boys and girls might share his enthusiastic pleasure in going back to Nature to study and to love her and to gain happiness and health from her woods and fields.[36]

Last year a man went out into the woods in America to try and see if he could live like the prehistoric men used to do; that is to say, he took nothing with him in the way of food or equipment or even clothing—he went just as he was, and started out to make his own living as best he could. Of course the first thing he had to do was to make some sort of tool or weapon by which he could kill some animals, cut his wood and make his fire and so on. So he made a stone axe, and with that was able to cut out branches of trees so that he could make a trap in which he eventually caught a bear and killed it. He then cut up the bear and used the skin for blankets and the flesh for food. He also cut sticks and made a little instrument by which he was able to ignite bits of wood and so start his fire. He also searched out various roots and berries and leaves, which he was able to cook and make into good food, and he even went so far as to make charcoal and to cut slips of bark from the trees and draw pictures of the scenery and animals around him. In this way he lived for over a month in the wild, and came out in the end very much better in health and spirits and with a great experience of life. For he had learned to shift entirely for himself and to be independent of the different things we get in civilization to keep us going in comfort.

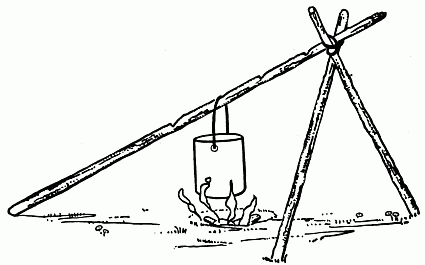

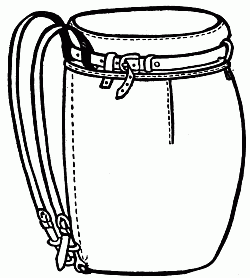

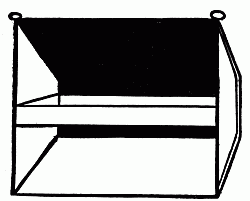

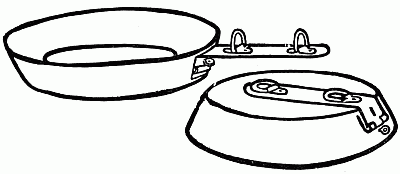

That is why we go into camp a good deal in the Boy Scout and in the Girl Guide movement, because in camp life we learn to do without so many things which while we are in houses we think are necessary, and find that we can do for ourselves many things where we used to think ourselves helpless. And before going into camp it is just as well to learn some of the things that will be most useful to you when you get there. And that is what we teach in the Headquarters of the Girl Guide Companies before they go out and take the field. For instance, you must know how to light your own fire; how to collect dry enough wood to make it burn; because you will not find gas stoves out in the wild. Then you have to learn how to find your own water, and good water that will not make you ill. You have not a whole cooking range or a kitchen full of cooking pots, and so you have to learn to cook your food in the simplest way with the means at your hand, such as a simple cooking pot or a roasting stick or an oven made with your own hands out of an old tin box or something of that kind.

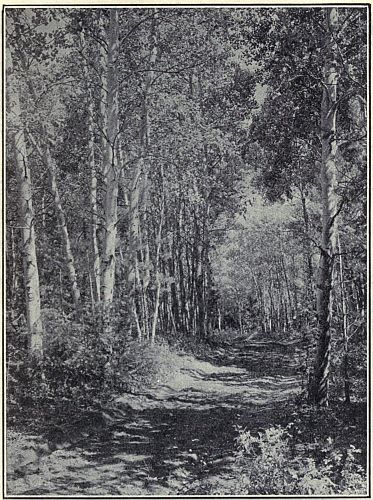

It is only while in camp that one can really learn to study Nature in the proper way and not as you merely do it inside the school; because here you are face to face with Nature at all hours of the day and night. For the first time you live under the stars and can watch them by the hour and see what they really look like, and realize what an enormous expanse of almost endless space they cover.[37] You know from your lessons at school that our sun warms and lights up a large number of different worlds like ours, all circling round it in the Heavens. And when you hold up a shilling at arm's length and look at the sky, the shilling covers no less than two hundred of those suns, each with their different little worlds circling around them. And you then begin to realize what an enormous endless space the Heavens comprise. You realize perhaps for the first time the enormous work of God.

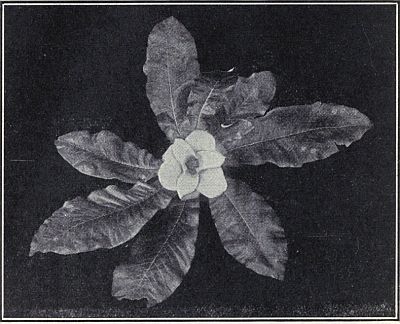

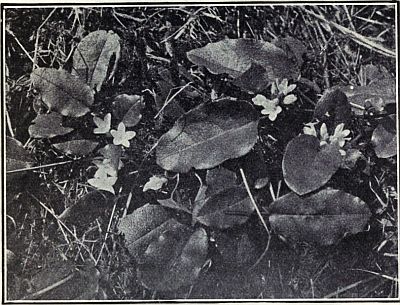

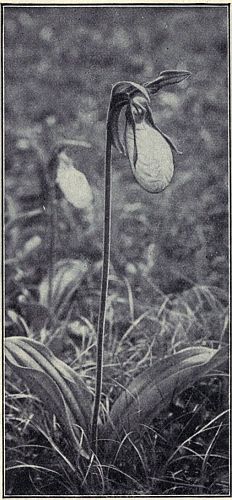

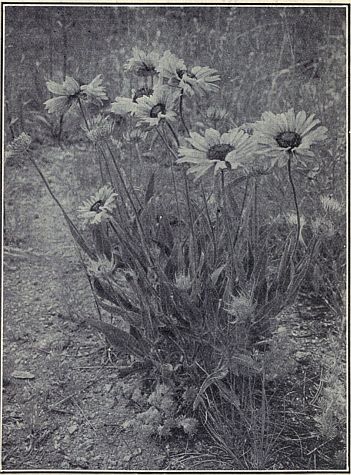

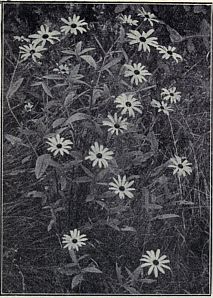

Then also in camp you are living among plants of every kind, and you can study them in their natural state, how they grow and what they look like, instead of merely seeing pictures of them in books or dried specimens of them in collections.

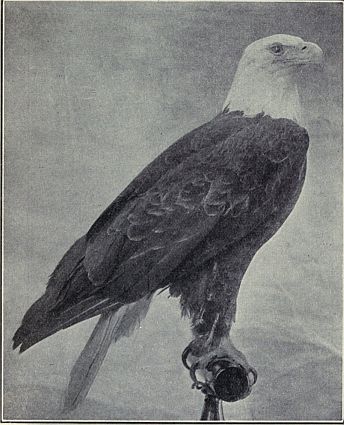

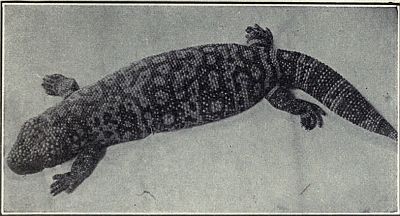

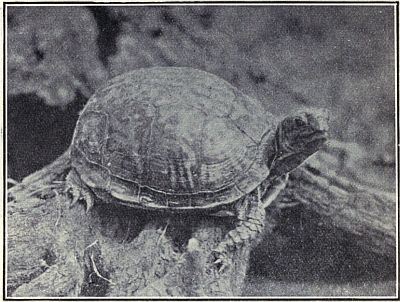

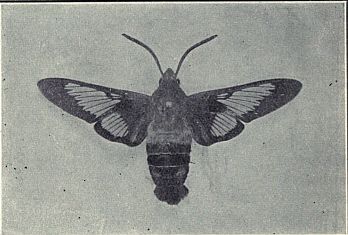

All round you, too, are the birds and animals and insects, and the more you know of them the more you begin to like them and to take an interest in them; and once you take an interest in them you do not want to hurt them in any way. You would not rob a bird's nest; you would not bully an animal; you would not kill an insect—once you have realized what its life and habits are. In this way, therefore, you fulfill the Guide Law of becoming a friend to animals.

By living in camp you begin to find that though there are many discomforts and difficulties to be got over, they can be got over with a little trouble and especially if you smile at them and tackle them.

Then living among other comrades in camp you have to be helpful and do good turns at almost every minute, and you have to exercise a great deal of give and take and good temper, otherwise the camp would become unbearable.

So you carry out the different laws of courteousness, of helpfulness, and friendliness to others that come in the Guide Law. Also you pick up the idea of how necessary it is to keep everything in its place, and to keep your kit and tent and ground as clean as possible; otherwise you get into a horrible state of dirt, and dirt brings flies and other inconveniences.

You save every particle of food and in this way you learn not only cleanliness, but thrift and economy. And you very soon realize how cheaply you can live in camp, and how very much enjoyment you can get for very little money. And as you live in the fresh, pure air of God you find that your own thoughts are clean and pure as the air around you. There is hardly one of the Guide Laws that is not better carried out after you have been living and practising it in camp.

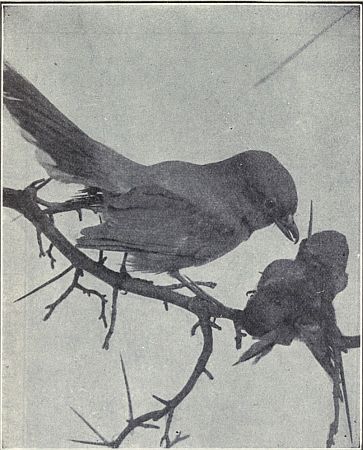

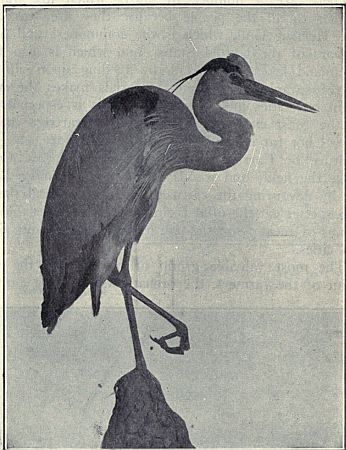

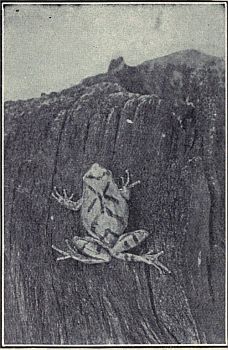

Habits of Animals.—If you live in the country it is of course quite easy to observe and watch the habits of all sorts of animals great and small. But if you are in a town there are many difficulties to be met with. But at the same time if you can keep pets of any kind, rabbits, rats, mice, dogs or ponies you can observe and watch their habits and learn to understand them well; but generally for Guides it is more easy to watch birds, because you see them both[38] in town and country; and especially when you go into camp or on walking tours you can observe and watch their habits, especially in the springtime.

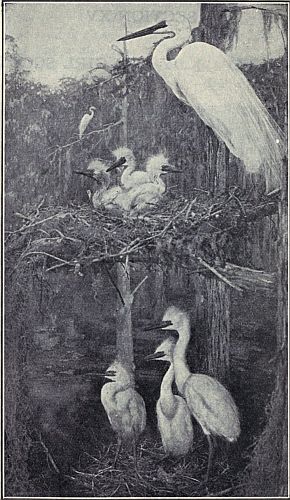

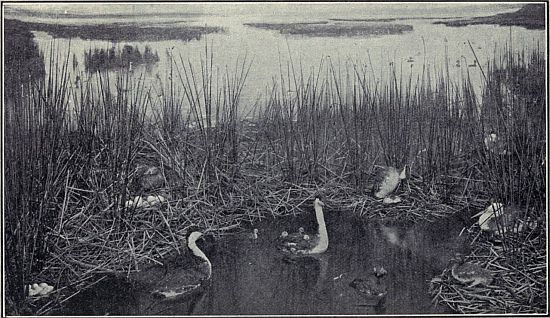

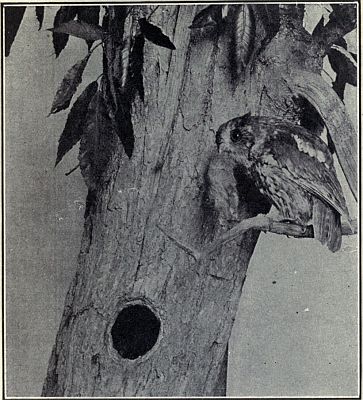

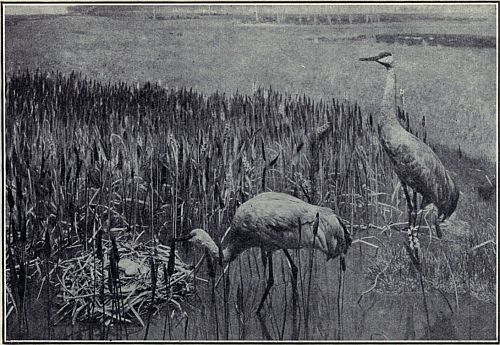

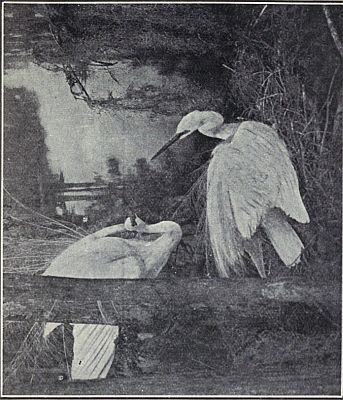

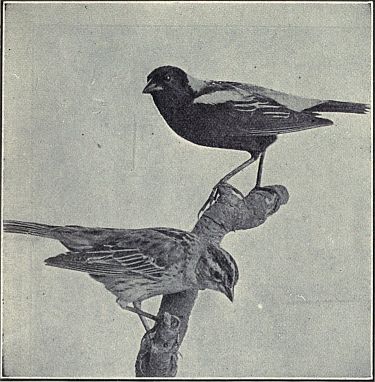

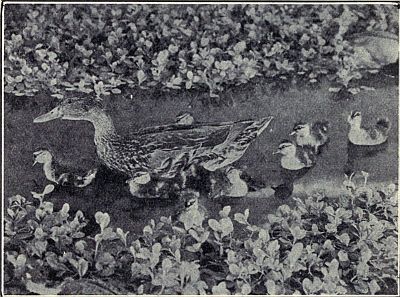

Then it is that you see the old birds making their nests, hatching out their eggs and bringing up their young; and that is of course the most interesting time for watching them. A good observant guide will get to know the different kinds of birds by their cry, by their appearance, and by their way of flying. She will also get to know where their nests are to be found, what sort of nests they are, what are the colors of the eggs and so on. And also how the young appear. Some of them come out fluffy, others covered with feathers, others with very little on at all. The young pigeon, for instance, has no feathers at all, whereas a young moorhen can swim about as soon as it comes out of the egg; while chickens run about and hunt flies within a few minutes; and yet a sparrow is quite useless for some days and is blind, and has to be fed and coddled by his parents.

Then it is an interesting sight to see the old birds training their young ones to fly, by getting up above them and flapping their wings a few times until all the young ones imitate them. Then they hop from one twig to another, still flapping their wings, and the young ones follow suit and begin to find that their wings help them to balance; and finally they jump from one branch to another for some distance so that the wings support them in their effort. The young ones very soon find that they are able to use their wings for flying, but it is all done by degrees and by careful instruction.

Then a large number of our birds do not live all the year round in England, but they go off to Southern climes such as Africa when the winter comes on; but they generally turn up here at the end of March and make their nest during the spring. Nightingales arrive early in April; wagtails, turtle doves, and cuckoos come late in April; woodcock come in the autumn, and redpoles and fieldfares also come here for the winter. In September you will see the migrating birds collecting to go away, the starlings in their crowds and the swallows for the South, and so do the warblers, the flycatchers, and the swifts. And yet about the same time the larks are arriving here from the Eastward, so there is a good deal of traveling among the birds in the air at all times of the year.

How many of our American Scouts are able to supply from their observation all of our native birds to take the places of these mentioned in this lovely paragraph? Everyone should be able to.

Nature in the City.—This noticing of small things, especially in animal life, not only gives you great interest, but it also gives you great fun and enjoyment in life. Even if you live in a city you[39] can do a certain amount of observation of birds and animals. You would think there is not much fun to be got out of it in a murky town like London or Sheffield, and yet if you begin to notice and know all about the sparrows you begin to find there is a great deal of character and amusement to be got out of them, by watching their ways and habits, their nesting, and their way of teaching their young ones to fly.

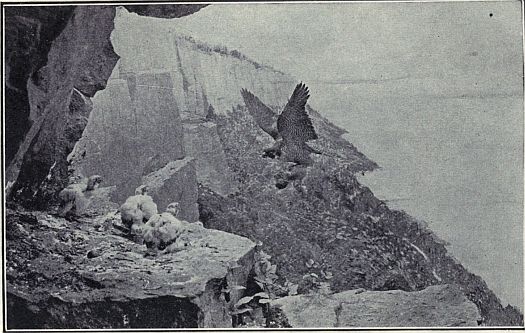

"Stalking.—A Guide has to be sharp at seeing things if she is going to be any good as a Guide. She has to notice every little track and every little sign, and it is this studying of tracks and following them out and finding out their meaning which we include under the name of stalking. For instance, if you want to find a bird's-nest you have to stalk. That is to say, you watch a bird flying into a bush and guess where its nest is, and follow it up and find the nest. With some birds it is a most difficult thing to find their nests; take, for instance, the skylark or the snipe. But those who know the birds, especially the snipe, will recognize their call. The snipe when she is alarmed gives quite a different call from when she is happy and flying about. She has a particular call when she has young ones about. So that those who have watched and listened and know her call when they hear it know pretty well where the young ones are or where the nest is and so on.

"How to Hide Yourself.—When you want to observe wild animals you have to stalk them, that is, creep up to them without their seeing or smelling you.

"A hunter when he is stalking wild animals keeps himself entirely hidden, so does the war scout when watching or looking for the enemy; a policemen does not catch pickpockets by standing about in uniform watching for them; he dresses like one of the crowd, and as often as not gazes into a shop window and sees all that goes on behind him reflected as if in a looking-glass.

"If a guilty person finds himself being watched, it puts him on his guard, while an innocent person becomes annoyed. So, when you are observing people, don't do so by openly staring at them, but notice the details you want to at one glance or two, and if you want to study them more, walk behind them; you can learn just as much from a back view, in fact more than you can from a front view, and, unless they are scouts and look around frequently, they do not know that you are observing them.

"War scouts and hunters stalking game always carry out two important things when they don't want to be seen."

One is Background.—They take care that the ground behind them, or trees, or buildings, etc., are of the same colour as their clothes.[40]

And the other is "Freezing".—If an enemy or a deer is seen looking for them, they remain perfectly still without moving so long as he is there.

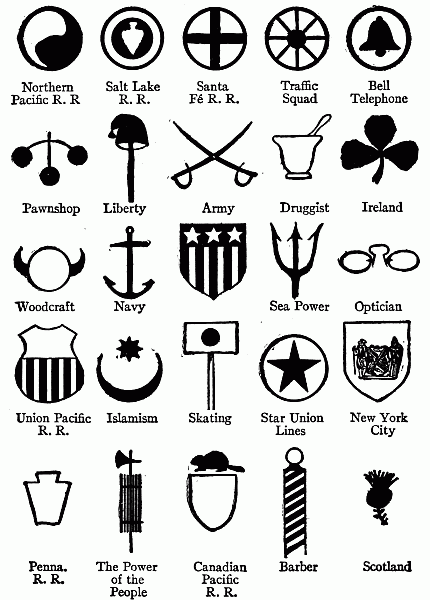

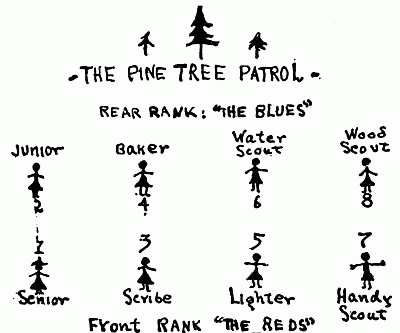

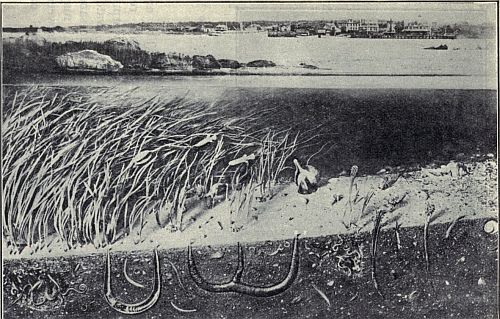

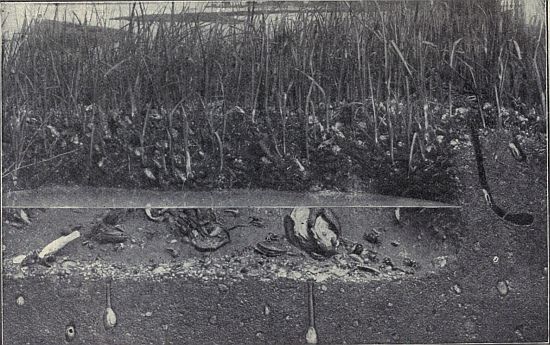

Tracking.—The native hunters in most wild countries follow their game by watching for tracks on the ground, and they become so expert at seeing the slightest sign of a footmark on the ground that they can follow up their prey when an ordinary civilized man can see no sign whatever. But the great reason for looking for signs and tracks is that from these you can read a meaning. It is exactly like reading a book. You will see the different letters, each letter combining to make a word, and the words then make sense; and there are also commas and full-stops and colons; all of these alter the meaning of the sense. These are all little signs, which one who is practised and has learnt reading, makes into sense at once, whereas a savage who has never learned could make no sense of it at all. And so it is with tracking.

"Sign" is the word used by Guides to mean any little details, such as footprints, broken twigs, trampled grass, scraps of food, old matches, etc.

Some native Indian trackers were following up the footprints of a panther that had killed and carried off a young kid. He had crossed a wide bare slab which, of rock, of course, gave no mark of his soft feet. The tracker went at once to the far side of the rock where it came to a sharp edge; he wetted his finger, and just passed it along the edge till he found a few kid's hairs sticking to it. This showed him where the panther had passed down off the rock, dragging the kid with him. Those few hairs were what Guides call "signs."