The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Golden House, by Mrs. Woods Baker This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Golden House Author: Mrs. Woods Baker Release Date: March 17, 2009 [EBook #28349] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GOLDEN HOUSE *** Produced by Al Haines

| I. | Black Eyes and Blue |

| II. | Karin's Flock |

| III. | Aneholm Church |

| IV. | No Secrets |

| V. | An Artist |

| VI. | The Boys |

| VII. | A Young Teacher |

| VIII. | In Alma's Room. |

| IX. | Karin's Fête |

| X. | The Little Cottage |

| XI. | The Slide |

| XII. | A Pedestrian Trip |

| XIII. | The Princess |

| XIV. | Where? |

| XV. | The Birthday Gift |

| XVI. | Spectacles |

| XVII. | Questionings |

| XVIII. | Nono's Plans, and Plans for Nono |

| XIX. | Pietro |

| XX. | The Opened Door |

A dreary little group was trudging along a Swedish highroad one bright October morning. It was a union between north and south, and like many other unions, not altogether founded on love. The bear, the prominent member of the party, was a Swede, and a Swede in a very bad humour. The iron ring in his torn nose, and the stout stick in the hand of one of his Italian masters, showed very plainly that he needed stern discipline. Now he dragged at the strong rope attached to the iron ring, and held back, moving his clumsy legs as if his machinery were out of order, or at least as if goodwill were lacking to give it a fair start.

The broad hats of the two men were gloomily slouched over their eyes; for they were thoroughly chilled, having passed the night in the open air for want of shelter. The woman, brown, thin, and bare-headed, coughed, and pressed her hand to her breast, where a stiff bundle was hidden under her shawl.

They rounded a little turn in the road, hitherto shut in by high spruces, and came suddenly in sight of a cottage of yellow pine, that glowed cheerfully against its dark background of evergreens.

"We stop at the golden house," said the older of the men, the bearer of the organ, and evidently the leader as well as the musician of the party.

The younger Italian laughed a scornful laugh as he said in his own language, "Only poor people live there."

"We stop at the golden house!" commanded his companion, adding, "It brings good luck to play for the poor."

The cottage had its gable end to the road, while its broadside was turned towards the southern sunshine, the well-kept vegetable-garden and the pretty flower-beds in front of the windows.

The gate was open, and the Italians came in stealthily—an art they had learned to perfection. One little turn of the hand-organ and the bear rose to his hind legs. The open door of the cottage was suddenly filled. Round-faced, rosy, fair-haired, and eager were they all—father and mother and six boys. They had evidently been disturbed at a meal, for in their hands they held great pieces of hard brown bread, in various stages of consumption.

Eyes and mouths opened wide as the performance went on, and Bruin had every reason to be satisfied with his share of the praise bestowed on the entertainment, as well as on his personal appearance. He was a young bear, and his brown coat looked as soft as plush, and it was no wonder that two-year-old Sven whispered to his mother, "Me want to kiss the pretty bear!"

Sven judged Bruin by his clothing, not by his wicked little eyes or his ugly mouth, which was by no means kissable.

The performance over, bread and milk were liberally passed round to the strangers, the bear having more than his fair portion.

"Come in and sit a bit," said the tidy mother to the dark young woman.

The answer was a pointing to the ear and a shaking of the head, which said plainly, "I don't understand Swedish."

The kindly beckoning that followed could not be mistaken, and the Italian woman went into the cottage, glad to sit down in the one room of which the interior consisted. One room it was, but large, and airy too; for it not only stretched from outer wall to outer wall, but from the floor to the high slanting roof. The rafters that crossed it here and there were hung with homely stores—bags of beans and pease, and slender poles strung with flat cakes of hard bread, far out of the reach of the children.

The Italian opened her shawl and took out a little brown baby, wrapped up as stiff as a stick. It was evidently hungry enough, and not at all satisfied when it was again tucked away under the shawl.

Half by single words and half by signs the two mothers managed to talk together. Swedish Karin soon knew that Francesca was ill, and was going home to Italy as soon as her husband had money enough to pay their passage. There was a wild look in the dark woman's eyes and a fierceness in her gestures that made Karin almost afraid of her. When the stranger had put into her pocket a bottle of milk that had been given her, and a big cake of bread, she got up suddenly to go.

It was evident there was to be another performance—a kind of expression of thanks for the hospitality received. The bear stood up and shook paws with the men, we may say; for the brown hands of the Italians had a strange kind of an animal look about them. The clumsy creature walked hither and thither, and then towered proudly behind his two masters, looking down on their heads as if it gave him satisfaction to prove that he was their superior in size at least.

Francesca now took out her baby, and began to toss it high in the air, catching it as it fell, and dancing meanwhile as if in delight.

Perhaps the bear took offence that the attention of all beholders was turned from himself. He made one stride towards the descending baby, and opened and shut his great mouth with a wicked snap close to the child.

The Italian mother laughed a loud, wild laugh, and turned her back to the bear, who put his two strong paws on her shoulder. A heavy blow from the stout stick of the younger Italian brought him down on all fours in a state of discontented submission.

Karin had swept her children inside the wide door of the cottage, and then Francesca was hurried in too with her baby.

The leader of the party pointed after her, and then to his own head, moving his thin hands first rapidly backwards and forwards, and afterwards round and round, so describing the confusion in the poor woman's brain as well as if he had said, "She is as crazy as a loon."

Karin's eyes grew large with horror. She drew her husband round the corner of the house and said, "Jan, I can't see that crazy woman go off with the baby. Let me keep it!"

"We have mouths enough to feed already," said the husband, and the sturdy giant looked down, not unkindly, into the appealing eyes. His face softened as he saw the little black bow at her throat, her only week-day sign of mourning for her own little baby, so lately laid in the grave.

"He will cost us almost nothing for a long time," she said, "and he can wear my little Gustaf's clothes. Perhaps God has let our little boy up in heaven send this baby to me to take his place."

"You are a good woman, Karin, and you ought to have your way," said the husband; and she knew she had his consent.

Francesca looked back with approval on the cheerful room as she came out, then stooped to pick a bit of mignonnette that grew by the steps.

Karin stretched out her hands, took the little brown baby in her arms, pointed to the black bow at her throat, and quickly made a sign of laying a baby low in a grave. Then she pressed the little stranger close, close to her heart, and moved as if she would go into the cottage with him.

A light gleamed in Francesca's eyes, and a tear actually glittered on her husband's black eyelashes.

"I keep the child," said Karin distinctly, turning to the man.

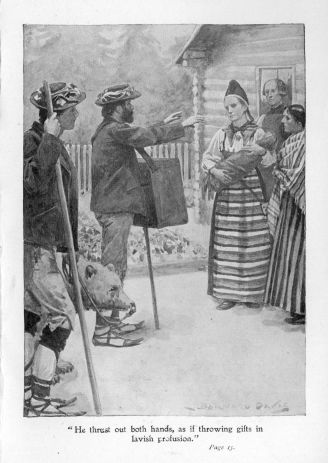

He bowed his head solemnly, and said, "I leave him." Then he pointed suddenly up to the sky, stretching his arm to its full length; then he thrust out both hands freely towards her again and again, as if throwing gifts in lavish profusion.

Karin understood his "God will reward you abundantly" as well as if it had been spoken in words. She kissed the little brown baby in reply, and the father knew that crazy Francesca's child had found a mother's love.

The men bowed and waved their hands, and the bear followed them lumberingly out through the gate. Francesca lingered a moment, then caught up a stick from within the enclosure, where Jan had been lately chopping. She wrapped it hastily in her shawl, and went off with a long, wild laugh.

The Swedes watched the party make their way along the road, until they came to a turn that was to hide them from sight. There the Italians swung their broad hats, and Francesca threw the stick high in the air and caught it in her hands, as a parting token.

Karin pressed the little stranger to her mother's heart, and thanked God that he was left to her care.

So the little Italian came to the golden house—the black eyes among the blue.

There was a family group in the big room at the golden house. The mother sat in the centre, with the brown baby on her knee. The heads of the six fair-haired children were bent down over the new treasure like a cluster of rough-hewn angels in the Bethlehem scene, as carved out by some reverent artist of old. With a puzzled, half-pleased glance the stalwart father looked down upon them all, like a benignant giant.

"Is he really our own little baby now?" said one of the children.

"What shall we call him?" asked another.

"We'll name him, of course, after the bear," said the oldest boy, who liked to take the lead in the family. "I heard the man call him Pionono, and he said the bear knew his name."

"We won't call him after that horrid bear!" exclaimed Karin.

"Uncle Björn is as nice as anybody, and his name is just 'bear,'" urged one of the boys.

"Don't contrary your mother," said Jan decidedly. "Pionono is too long a name. We'll call him Nono, and that's a nice name, to my thinking."

"A nice, pretty little name," said the mother, "and I like it."

And so the matter was settled. The little brown baby was to be called after a pope and bear, in Protestant Sweden. Nono (the ninth) suited him better than any one around him suspected. The tiny Italian was really the ninth baby that had come to the golden house. Karin had now six children. She had laid her firstborn in the grave long ago, and lately her little Gustaf had been placed beside him in the churchyard.

Classification simplified matters in Karin's family, as elsewhere. The children were divided by common consent into three pairs, known as the boys, the twins, and the little boys. For each division the laws and privileges were fixed and unalterable. "The boys," Erik and Oke, were the oldest pair. Erik was at present a smaller edition of his father, with a fair promise of a full development in the same direction. Now, at twelve years of age, he was almost as tall as his mother, and could have mastered her at any time in a fair fight. Oke, a year younger, was pale, and slight, and stooping, with a thin, straight nose, quite out of keeping with the large, strongly-marked features of the rest of the children. As for "the twins," it was difficult to think of them as two boys. They were so much alike that their mother could hardly tell them apart. Indeed, she had a vague idea that she might have changed them without knowing it many times since they were baptized. How could she be sure that the one she called Adam was not Enos, and Enos the true Adam? Of two things she was certain—that she loved them both as well as a mother ever loved a pair of twins, and that they were worthy of anybody's unlimited affection. She was proud of them, too. Were they not known the country round as Jan Persson's splendid twins, and the fattest boys in the parish? As for "the little boys," they were much like the Irishman's "little pig who jumped about so among the others he never could count him." "The little boys" were always to be found in unexpected and exceptionable places, to the great risk of life and limb, and the great astonishment of the beholders. To try to ride on a strange bull-dog or kiss a bear was quite a natural exploit for them, for they feared neither man nor beast.

As for Karin, she was not a worrying woman, and took the care of her many children cheerily. She could but do her best, and leave the rest to God and the holy angels. Those precious protectors had lately seemed very near to her, since baby Gustaf had gone to live among them. That all would go right with Nono she did not doubt. When she laid him down for the night, she clasped his tiny brown hands, and prayed not only for him, but for his poor mother, wherever she might be, and left her to the care of the merciful Friend who could give to wild lunatics full soundness of mind.

Sunday had come. Along the public road, where the Italians and the bear had lately passed, rolled a heavy family carriage, drawn by two spirited horses. The gray-haired coachman had them well in hand, and by no means needed the advice or the assistance of the fat little boy perched at his side, though both were freely proffered. The child was dressed in deep mourning, but his clothes alone gave any sign of sorrow. His face gleamed with delight as he was borne along between green fields, or played bo-peep with the distant cottages, through a solemn line of spruces or a glad cluster of young birches.

On the comfortable back seat of the carriage was an elderly gentleman, tall, thin, and stooped, with eyes that saw nothing of earth or sky, as his thoughts were in the far past, or in the clouds of the sorrowful present. By his side, close pressed to him, with her small black-gloved hand laid on his knee, sat a little nine-year-old girl, her sad-coloured suit in strange contrast with the flood of golden hair that streamed from under her hat, and fell in shining waves down to her slight waist. The fair young face was very serious, and the mild blue eyes were full of loving light, as she now and then peeped cautiously at her father. He did not notice the child, and she made no effort to attract his attention.

"Papa! papa! what's that? what's that?" suddenly cried out the little boy. "What's that that's so like the gingerbread baby Marie made me yesterday? Just such a skirt, and little short arms!"

The father's attention was caught, and he turned his eyes in the direction pointed out by the child's eager finger.

The sweet sound of a bell came from the strange brown wooden structure, an old-time belfry, set not on a roof or a tower, but down on the ground. Slanting out wide at the bottom, to have a firm footing, it did look like a rag-dolly standing on her skirts, or a gingerbread baby, as the young stranger had said.

A stranger truly in the land of his fathers was fat little Frans. Alma, his sister, had often reproached him with the facts that he had never seen his own country and could hardly speak his own language. Born in Italy, he had now come to Sweden for the first time, with the funeral train which bore the lifeless image of his mother to a resting-place in her much-loved northern home.

"Is that the church, papa?" Alma ventured to ask, seeing her father partially roused from his reverie.

The barn-like building was without any attempt at adornment. There was no tower. The black roof rose high, very high and steep from the thick, low white walls, that were pierced by a line of small rounded windows.

"That is Aneholm Church," the father said, half reprovingly. "There your maternal ancestors are buried, and there their escutcheons stand till this day. I need not tell you who is now laid in that churchyard."

He turned his face from the loving eyes of the child, and she was silent.

A few more free movements of the swift horses, and the carriage stopped before a white-arched gateway. A wall of high old lindens shut in the churchyard from the world without, if world the green pastures, quiet groves, and low cottages could be called. It was but a small enclosure, and thick set with old monuments and humbler memorials, open books of iron on slender supports, their inscriptions dimmed by the rust of time, small stones set up by loving peasant hands, and one fresh grave covered with evergreen branches. Alma understood that on that grave she must place the wreath of white flowers that had lain in her lap, and there her father would lay the one beautiful fair lily he held in his hand.

This tribute of love was paid in mournful silence, and then the father and the children passed into the simple old sanctuary.

The church was even more peculiar within than without. It was white everywhere—walls, ceiling, and the plain massive pillars of strong masonry on which rested the low round arches. It looked more like a crypt under some great building than if it were itself the temple. The small windows, crossed by iron gratings, added to the prison-like effect of the whole. It was but a prison for the air of the latest summer days, shut in there to greet the worshippers, instead of the chill that might have been expected.

Warm was the atmosphere, and warm the colouring of the heraldic devices telling in armorial language what noble families had there treasured their dead. The altar, without chancel-rail, stood on a crimson-covered platform. On each side of it, at a respectful distance, were two stately monuments, on which two marble heroes were resting, one in full armour, and the other in elaborate court-dress. Alma could see that there were many names on the largest of these monuments, and her eyes filled with tears as she saw her mother's dear name, freshly cut below the list of her honoured ancestors.

The father did not look at the monument, or round the church at all. With eyes cast down, he entered a long wide pew, with a heraldic device on the light arch above the door. Prudently first placing little Frans at the end of the bare bench, he took his place, with Alma on the other side of him.

The church was almost empty. A few old bald-headed peasants were scattered here and there, and on the organ-loft stairs clattered the thick shoes of the school children, who were to assist in the singing.

The father bowed his head too long for the opening prayer. Alma understood that he had forgotten himself in his own sad thoughts. Her little slender hand sought his, that hung at his side, and her fragile figure crowded protectively towards him.

Meanwhile Frans had produced two bonbons, wrapped in mourning-paper, and with hour-glasses and skeletons gloomily pictured upon them. He was engaged in counting the ribs of the skeletons, to make sure that the number was the same on both, when Alma caught sight of him. The gentle, loving look in her face changed suddenly to one of sour reproof. She motioned disapprovingly to Frans, and vainly tried to get at him behind the rigid figure of her father. Before her very eyes, and in smiling defiance, the boy opened the black paper and devoured the sweets within, with evident relish, bodily and spiritual.

At this moment there was a stir in the vestibule and in the sacristy adjoining, and then a murmur of low, hushed voices, and for a moment the tramping of many little feet.

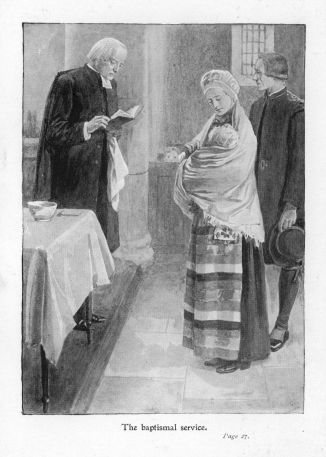

Alma looked around her, and now noticed on the platform for the altar a small white-covered table, and upon it a little homely bowl and a folded napkin. Beside the table a gray-haired old clergyman had taken his place. In one hand he held officially a corner of his open white handkerchief, while in the other was a thin black book.

There was a slight shuffling first, and then a tall man, with apparently a very stout woman at his side, came up the aisle and stood in front of the clergyman.

"It cannot be a wedding," thought Alma, accustomed to the splendid fonts of the churches of great cities; she could not suppose that simple household bowl was for a baptism. The broken, disabled stone font she did not notice, as it leaned helplessly against the side wall of the building.

The clergyman opened his book and looked about him, doubtfully turned over the leaves, and then began the service "for the baptism of a foundling," as the most appropriate for the present peculiar circumstances that the time-honoured ritual afforded.

At that moment Karin threw open her shawl, and showed the little brown baby asleep in her arms. Alma's attention was fixed, and Frans was all observation, if not attention.

"Beloved Christians," began the pastor; he paused, glanced at the scattered worshippers, and then went on, "our Lord Jesus Christ has said, 'Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.' We do not know whether this child has been baptized or no, since, against the command of the heavenly Father, and even the very laws and feelings of nature, he has been forsaken by his own father and mother."

Here Karin gave involuntarily a little dissenting movement as she thought of the half-crazy mother and the sorrowful father, and made the mental comment that they had done the best they could under the circumstances. The pastor paused (perhaps doubting himself the appropriateness of the statement), and then read distinctly,—

"Therefore we will carry out what Christian love demands of us, and through baptism confide the child to God, our Saviour Jesus Christ, praying most heartily that he will graciously receive it, and grant it the power of his Spirit unto faith, forgiveness of sins, and true godliness, that it, as a faithful member of his church, may be a partaker of all the blessedness that Jesus has won for us and Christianity promises."

The service then proceeded as usual, and the little Nono was baptized in God's holy name.

Jan and Karin were duly exhorted that they should see that the child should grow up in virtue and the fear of the Lord; which promises and resolutions the honest pair solemnly determined, with God's help, to sacredly keep and fulfil.

Nono was borne down the aisle, having acquitted himself as well as could be expected on this important occasion. The eager prisoners in the pew by the door now filed out, six in number, to form little Nono's baptismal procession. Sven, insisting upon kissing the baby then and there, was prudently allowed to do so, to prevent possibly an exhibition of wilfulness that would have been a public scandal. This proceeding well over, Nono and his foster-brothers went back to the golden house, in which he now had a right to a footing, and the blessing of a home in a Christian family.

Alma could never remember anything of the service or the sermon on that day. Her attention had been fully absorbed in the baptism of the wee brown baby whose parents had deserted him, and in whom the "beloved Christians" of the parish had been called on to take so solemn an interest.

Before leaving the church, Alma's father gave one long, sorrowful glance at the new name on the old monument. Beside it the old clergyman had taken them all by the hand, and had said some low-murmured words of which the little girl could not catch the meaning.

"Papa," Alma ventured to say when they were fairly seated in the carriage, "did not the pastor mean you and me, too, when he said 'beloved Christians'? We were there, and only a few other people, and he must have meant us too. We are Christians, of course, are we not?"

He turned his large sorrowful eyes towards her, and was silent. She might be a Christian. The Saviour had said that children were of the kingdom of heaven. But she was no longer a very little child, but uncommonly womanly for her age. He suddenly remembered some unchristian peculiarities that were certainly growing upon her. She must be looked after, and placed where she would be under the right kind of influence. Her small hand was now laid caressingly on his knee, and he placed his own over it.

Alma was not astonished at her father not answering her. She was accustomed to see him sunk in moody silence. Happily she could not read the thoughts that her question had suggested. That he was not truly one of the "beloved Christians" the father secretly acknowledged to himself. He had not, he was sure, the firm faith in God and the loving trust in man that belong to the children of the kingdom of heaven.

The children at the golden house had been regaled with milk and white biscuits in honour of Nono's baptism, and were enjoying the treat in the grove behind the cottage.

Nono lay on Karin's knee, and she was looking fondly at him, while Jan stood silently beside her.

"I am a kind of a mother to him now, a real god-mother," she said. "I don't mean to tell him that he is not quite my own child. I mean to love him just like the others, and he shall never feel like a stranger here."

"Now you are quite wrong, Karin," said Jan, with a very serious look in his face. "He isn't your own child, and you can't make him so by hiding the truth from him. Tell him from the very first how it was. He won't love you the less because he was a stranger and you took him in. It would be a poor way to bring him up so that he will 'grow in virtue and the fear of the Lord,' as we promised this morning, to begin by telling him what wasn't true right straight along. What would he think of you when he found out in the end that you had been deceiving him ever since he could remember? And the other children, too; they know all about it. Could you make them promise to pretend, like you, that Nono was their own brother? No good ever comes of going from the truth. That's my notion!"

Jan stood up very straight as he finished, and sitting as Karin was, he seemed to her in every way high above her.

"You are right, Jan," she answered sorrowfully. "I suppose I must do as you say. I did so want him to be really my own, just like my little Gustaf."

"Your little Gustaf, our little Gustaf, is in a good place, and I hope Nono will be there too sometime," said Jan.

"Not Nono in heaven yet!" said Karin, pressing the dark baby to her breast. "I cannot spare him, and I don't believe God will take him."

"Now you are foolish, Karin. That was not what I meant," said Jan tenderly. "You bring him up right, and he will come sometime where Gustaf is, and that's what we ought to want most for him." Jan paused a moment, and then went on: "Somehow those words of the baptism took hold of me to-day as they never did before, not even when my owny tony children were baptized. I mean to be the right kind of a godfather to him if I can."

Jan kept his resolution. He could sometimes be rough and hasty with his own boys when he was tired or particularly worried; towards Nono he was always kind, and just, and wise. Somehow there had entered into his honest heart the meaning of the words, "I was a stranger, and ye took me in." What was done for Nono was, in a way, done for the Master.

Karin did not reason much about her feelings for the black-eyed boy who was growing up in the cottage. She gave him a mother's love in full abundance. If little Nono had no sunny Italian skies above him, he had the sunshine of a happy home, and real affection in the golden house.

From the very first Nono heard the truth as to how he came to be living in the cold north. Before he could speak, the story of the bear and the Italians had been again and again told in his presence. Of course, every one who saw the black-eyed, brown-skinned child inquired how he came among the frowzy white heads of his foster-brothers. The picture of the whole scene grew by degrees so perfect in Nono's mind, that he really believed he had been a witness of as well as a prominent partaker in the performance. It was only by severe reproof and reproach on the part of the other children that he was made to understand that he had been only a baby "so long" (the Swedish boys held their hands very near together on such occasions), while they had had the honour of seeing the very whole, and remembered it as perfectly as if it had happened yesterday, as probably some of them did.

So Nono had to take a humble place as a mere listener when the oft-repeated story was told, with every particular carefully preserved among the many eye-witnesses.

"But I love him just as well as if he were my own," was Karin's unfailing close to such conversations, with a caress for the little Italian that sealed the truth of her assertion.

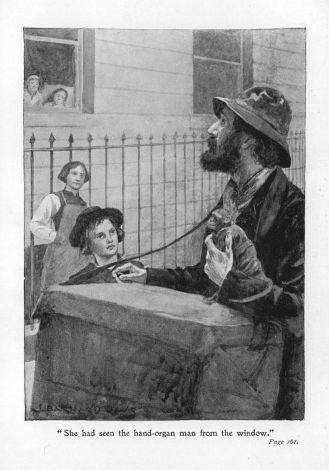

Nono loved his foster-mother with the grateful affection of his warm southern nature. Yet the very name Italy had for him a magical charm, and the sound of a hand-organ, or the sight of a dark-faced man with a broad-brimmed hat, made him thrill with a half joy that his own kith and kin were coming, and a half fear that he was to be taken away from the pleasant cottage and all the love that surrounded him. Bears had a perfect fascination for him, but all the specimens he saw were rough and ragged. No bear, the family were all sure, had ever had such a beautiful brown coat of fur as that Pionono that Sven had been so anxious to kiss.

Nono's favourite text in the Bible was the one that expressed the youthful David's reliance on God when he went out to meet the insolent Goliath: "The Lord that delivered me out of the paw of the lion, and out of the paw of the bear, he will deliver me from this Philistine." The Philistine stood for any and all threatening dangers of soul and body, and this passage cheered the little Italian through many a childish trouble, and many an encounter with the big boys from the village, who delighted to assail him in solitary places, and reproach him with being an outlandish stranger, living on charity, and not as much of a Swede as the ugly bear he was named after.

All the warmer seemed to Nono the sheltering affection of Karin, contrasted with these frequent attacks from without. His gratitude expressed itself in an enthusiastic devotion to Karin, and a delight in doing her the slightest service.

"Nono sets a good example to the other boys," said Jan one day. "I don't know, Karin, what he wouldn't be glad to do for you. Our own little rascals get all they can out of 'mother,' and hardly take the trouble to say 'Thank you.' As for thinking to help you, that always falls on Nono."

"Our boys are much towards me as we are to our heavenly Father, I think. We seem to take it for granted he will give us what We need, and that's all there is of it. At least that's the way I am, Jan."

Karin liked to make an excuse for her children when she thought Jan was a little hard upon them.

"I won't forget that, Karin, when I'm put out, as I am sometimes with the boys," answered Jan. "They are not a bad set, anyhow, to be so many. I know I am not half as thankful as I ought to be: not in bed a day since I can remember."

Time slipped away rapidly at the golden house. There had been many pleasant family scenes, both within and around the cottage, since Nono had been so tenderly welcomed there, eight years before.

It was a bright July morning. The bit of a rye-field on the other side of the road stood in the summer sunshine in tempting perfection. The harvesting had begun, in a slow though it might be a sure manner. A tall, spare old man, his hat laid aside, and his few scattered gray locks fluttering in the gentle breeze, was the only reaper. His shirt sleeves rolled up above the elbows showed his meagre, bony arms. His thin neck and breast were bare, as he suffered from heat from his unwonted labour. The scythe moved slowly, and the old man stopped often to draw a long breath. Near him stood a fair-haired, sturdy little girl, who held up her apron full of corn flowers, as blue as the eyes that looked so approvingly upon them. They were in the midst of a chat in a moment of rest, when a figure, strange and interesting to them both, came along the road with a light, free step.

The new-comer was a tall young girl, with a white parasol in her hand, though her wide-brimmed hat seemed enough to keep her fair face from being browned by the glad sunshine. She stopped suddenly when she came in front of the cottage, and fixed her eyes on the old man and the child with an expression of astonished delight. "Charming! beautiful! I must paint them," she said to herself.

The stranger put down the camp-stool she had on her arm, and screwed into its back her parasol with the long handle. She sat down at once and opened her box, where paper and pallet and all manner of conveniences for amateur painters were admirably arranged. "Please, please stand still," she said; "just as you are. I want to paint you."

"I have to stop often to rest; but I must work while I can. I don't want to be idle if I am old. I can't do a real day's work; but I can get something done if I am industrious," said the gray-haired labourer hesitatingly.

The child seemed to notice something sorrowful in the tone of her companion's voice, and she came quickly to his aid, saying,—

"Uncle Pelle is the best man in the world. Mother says he'll never teach us anything that isn't just right. He does a good bit of work, father says, and he knows."

The little girl was evidently accustomed to be listened to, and did not stand in awe of this stranger or any other.

"I shall pay you both if you hold still awhile and let me take your picture; and that will be just as well for Uncle Pelle as cutting grain, and lighter work, too. You can talk if you want to, but you must not stir while I am making a real likeness of you."

"As the young lady pleases," said the old man, with a look of resignation. "I want to be useful."

"Is that your uncle, child?" asked the young artist. "I thought, of course, it was your grandfather." Then looking towards the old man she added, "Do you live here?" and she nodded towards the golden house.

"I don't live anywhere," said the old man sorrowfully. "The poorhouse in Aneholm parish and the poorhouse in Tomtebacke, some way from here, can't agree which should keep me, and now they are lawing about it. I've had a fever, and I seem to be broke down. I don't belong anywhere just now, but Karin there in the house says I'm a kind of relation of hers, though it puzzles me to see how. She wants me to stay with them till all is settled; and Jan, who mostly lets her have her way, tells me he hasn't anything against it. So you see I like to do a turn of work if I can, if it's only to show I'm thankful. Karin says she's used to a big family, and it seems lonesome since her oldest son went to America, and I must take his place. I don't live in the cottage. There are enough of 'em there without me. They've fixed me up a place alongside of Star—that's the cow."

"It's a dear little room," said the child, "and we all like to be there; but Uncle Pelle shuts the door sometimes, and won't let us in."

"Old folks must have their quiet spells," said the old man apologetically.

"It isn't just to be quiet, you know, Uncle Pelle. Mother says Uncle Pelle reads good books when he is alone, and makes good prayers, too; and he's a blessing to the family," said the little girl, who seemed to consider herself the friend and patron of her companion.

"She's a bit spoiled. The only girl, you see. There were six boys before, not counting Nono or the two boys that died."

"Nono!" exclaimed the stranger. "That was the name of the little brown baby I saw baptized in Aneholm church, eight years ago, when I was at home before, just for a few days."

"It is a queer name," said Uncle Pelle. "The pastor said it meant the ninth, as the Italians talk; and so when this little girl came, he said Karin and Jan might as well call her Decima, which was like the tenth, in Swedish. And they did. They about make a fool of her in the family; and I ain't much better. That's Nono behind you."

A slight dark boy had been standing quietly watching the young stranger while she skilfully handled her brushes. He now stepped forward, took off the little straw hat of his own braiding, and bowed, without any sheepish confusion.

"Here's Nono!" said Decima, placing herself beside him, as if she had a special right to exhibit him to the stranger.

"And so you are Nono," said Alma. "I have always felt as if you belonged in a way to me. Where did the people who live here find you?"

"They didn't find me at all; they took me, and have brought me up as if I was their own child," said Nono, his eyes sparkling.

The story of the Italians and the bear was told by Nono, as usual, and the scene most vividly described by word and gesture. Decima did not pretend that she knew more than he did on this subject, and indeed he was quite her oracle in all matters. She thought Nono a pink of perfection; and well she might, for he had been her playmate and guardian ever since she could remember. It was confidently affirmed in the family that Nono could, from the first, make her laugh and show her dimples as she would not for any one else. Nono had soon learned that he could be a help to Karin with the baby, and was always more willing than were her rough brothers to be tied to the child's little apron-string.

Nono had hardly finished his story when the young lady took out the smallest watch imaginable and looked hastily at it. She gathered up her painting apparatus in a great hurry, and was off with a hasty good-bye, saying her father would be expecting her home to dinner, but she would see them again soon and finish her picture. She had almost forgotten in her hurry the money she had promised, but she suddenly remembered that part of the transaction, and left in the old man's hand, as he said, "more than enough to pay for a whole day's work, just for standing still, that little bit, to be painted."

Alma was soon out of sight of Pelle and Decima, who followed her with their wondering eyes as she sped along the road towards her pleasant home. The one thing about which her father could be severe with her was being late at meals. But for this severity, he would often have dined without her; for Alma was full of absorbing hobbies, and when anything interested her, food and sleep were to her matters of no consequence. Now her brain was revolving a new scheme. Alma had been for years in a Swiss boarding-school, and there, among many accomplishments, had acquired a thorough knowledge of the English language. She had been charmed with the accounts she had read of the work of the English ladies among the cottagers on their large estates. She had determined to "do just so" when she was fairly settled at home. She would now begin at once with Nono. She felt she had a kind of charge over him. Had not her own dear mother died in Italy, where his mother came from? That baptism, too, she could never forget! He should not grow up like a heathen in Sweden if she could prevent it. She would have him up at "the big house" every day for a Scripture lesson. She wanted to paint him too; how lovely he would be in a picture! She must have the old man with him. How charming it would be to sketch youth and age working in the garden together! She could pay them for their time, and they would look up to her as a kind of guardian angel. Alma flitted along, almost as if she had wings already, as these pleasant thoughts floated through her mind.

The angel seemed suddenly to change to a fury as a shout arose from behind a dark evergreen, and a nondescript-looking individual, ragged and dirty, came out upon her, exclaiming,—

"I suppose I must not come near your highness, looking as I do!"

Streaked with mud on face and clothing, his feet bare, and his trousers rolled up to his knees, her brother stood before her, his eyes gleaming with delight in spite of her evident displeasure.

"I've got a basket of polywogs, and some delicious bugs, and a big caterpillar that would make your mouth water if you were addicted to vermicelli. See here!"

He moved as if he were about to open up his treasures for her inspection.

"Do keep away, Frans!" exclaimed Alma, as she drew her befrilled and beflounced skirt about her, as if to escape dangerous contagion.

At this moment she swept in at the gate that led to the house, and shut it hastily behind her.

"I'm going in the back way, anyhow," said Frans, with a merry laugh. "Your grace and my grace cannot well make our entrée together."

"The most troublesome boy in the world!" said Alma to herself, and she expressed her sincere conviction.

At this moment Alma saw the bent form of her father riding slowly before her. Her whole expression changed again, and she quickened her steps into a run, and was soon at his side.

"Are you very tired, papa, after your little ride?" she said tenderly.

"No, darling. But how fresh and rosy you look! The air of old Sweden suits you, I see."

How happy the two were together! how gentle and loving were they both! Alma really looked like the guardian angel she meant to be to Nono and Uncle Pelle.

When Decima had been fairly settled as the tenth little baby that had come to the golden house, Erik, the oldest of the flock, confided to Nono that he meant to start as soon as possible for America. Nono was the recipient of the secrets of all the children. They always found in the little Italian a sympathetic listener, and they could be sure of his profound silence as to their private communications. Nono's evident sense of the many for whom Karin was called on to care had suggested to Erik that although it would be too great a penance for him to be tending a baby, as Nono did, he could go out and earn his own living; which would probably be quite as useful to the family. So to America he had resolved to go, always understanding that he had gained his parents' permission. That permission was not hard to win, for Karin had friends who were emigrating, and who would take care of her boy on the way, and were willing to promise to look after him on his arrival in the "far West," whither they were bound.

Erik went off cheerily, with his ticket paid to the end of his journey, and a little box of strong clothing, his Bible, and his parents' blessing as the capital he took to the new country. Erik had another treasure, not outside of him, but in his inmost heart—a resolve to lead in a foreign land just such a life as he should not be ashamed to have his parents know about, the Word of God being his guide and comfort. Erik was no experienced Christian, but he had started in the right spirit.

Erik had never been renowned for his scholarship, but rather for his industry and skill when real practical work was in question. He wrote at first short letters in Swedish. They soon came less and less frequently, and finally in a kind of mixed language, a mingling of the new and the old, a fair transcript of his present style of conversation. These letters caused much puzzling in the golden house, and occasionally had to be taken to the old pastor for explanation and translation. One came at last, beginning "Dear moder and broder, hillo!" Then followed a page in a curious lingo, wherein it was stated that Erik now had a nice room to himself in the "place" he had obtained. He did not say that the room was in the stable where he was hostler, or that it was just six feet by eight when lawfully measured. He also mentioned that he had food fit for a count; which was true in a way, as he was daily regaled with fruit and vegetables that would have been esteemed in Sweden luxuries sufficient for the table of any nobleman. He dressed like a count too, he said; on which point Erik's testimony was not to be accepted, as he had had little to do with counts in his native land. The big boy did not mean to exaggerate. He was simply and honestly delighted at his success in seeking his fortune. Not that he was laying up money. Far from it. He was sending home to "old Sweden" all he could possibly spare, and was anxious to have Karin feel that it was a light thing for a son who was so comfortable to be remitting a bit of money now and then to a mother who had given him such love and care all the days of his life. Erik did not write much about or to his father, but he thought of him all the more, and inwardly thanked that father for his stern and steady hand with his boys, and for teaching them not only to do honest work, but to know what a real Christian man should be.

Oke, the next boy, had been the bearer to the parsonage of Erik's unreadable letters, and had there been instructed in their proper rendering into everyday Swedish. So a kind of special acquaintance had grown up between the slender, pale boy and the kind old pastor.

The pastor was a bachelor, and lonely in his declining years. He had found it pleasant to see Oke coming with an American letter in his hand, his young face beaming with delight. The pastor had, besides, learned to know more and more of Karin's home and the spirit that was reigning there. Perhaps, when he saw Uncle Pelle sitting in church, Sunday after Sunday, clean and happy among Karin's boys, he had thought he too might have a guest-room that might receive one member from the full golden house. So Oke came to live at the pastor's, who said he did not see as well as he once did, and he must have a boy trained to read aloud to him, and to write a bit, too, for him now and then. It was stipulated that Oke's duties were not to be all of the literary sort. The pastor was convinced that Oke had a good head for study, and really ought to have a chance to improve himself. The boy was not, however, to be kept constantly bending over books, but was to have as much work in the open air as possible. The pastor himself had a weak constitution, and had suffered all his life from delicate health, and had found it no pleasant experience. Oke should be a robust Christian, for a Christian he was of course to be.

The elder boys being disposed of, the twins had come into power. The oldest among the children had always been allowed to be a kind of perpetual monitor for the rest, with restricted powers of discipline. Oke's rule had been mild but firm. He had taken no notice of small matters; but if anything really wrong had gone on, Jan was sure to hear of it, and a thorough settlement with the offender inevitably followed.

The twins were rather against the outside world in general, strong in their two pair of hands, and two loud voices to shout on their side. Nono really feared this duumvirate, for the twins had more than once given him to understand that he would "catch it" when they got to be the oldest at home. They had no particular offences to complain of or anticipate on Nono's side, but they enjoyed giving out awful threats of what they would do if ever they had the opportunity. Oke had kept them in order without difficulty, for he had a vehement power of reproof, when fairly roused, that could make even the twins hide their faces in shame, as he pictured to them their unworthiness.

Nono had gotten on very well with the "lions and the bears" of the past, but how was he to deal with this two-headed "Philistine" under whose dominion he had now come? He was resolved on one thing—Karin should hear no complaints from him. She should not be worried by the little boy she had taken in among her own to be so wonderfully happy.

Nono and Uncle Pelle had been working a whole morning in the garden at Ekero under Alma's direction. She was going to have a parterre of her own, according to a plan she had been secretly maturing. Now it was the time of mid-day rest, and she was prepared to give Nono his first lesson; a kind of Sunday school on a week day she meant it to be, and of the most approved sort. Alma had chosen for herself a rustic sofa, with a round stone table before her, and behind her the trunk of a huge linden, with its branches towering high over her head. Opposite her was Nono, on a long bench, awaiting the opening of the Bible and the big book that lay beside it. Alma, tall, and fair, and slight, looked seriously at Nono, small, and dark, and plump, sitting expectant, with his large eyes fixed upon her.

Alma paused a moment, and then looked towards one of the grass plots that made green divisions in the well-kept vegetable-garden. There sat Uncle Pelle, his round woollen cap on his head, his red flannel sleeves drawn down to his wrists, while his coat lay over his knees. Uncle Pelle was very careful of his health. He did not want to be a trouble and a burden to Karin. He held a little, thin, worn book, over which he was intently poring. He did not look up until Alma spoke his name. Perhaps she had thought that he might be feeling lonely there by himself, or perhaps she fancied that she had prepared too rich a dish of instruction for little Nono to receive alone. At least she had sprung hastily towards the old man. "What are you reading here by yourself, Uncle Pelle?" she said pleasantly.

Pelle turned to the title-page, showing it to her, and then placed the book in her hand, open to where he had been reading. Her eye fell on the passage his long finger pointed out to her. "Use your zeal first towards yourself, and then wisely towards your neighbour. It is no great virtue to live in peace with the gentle and the peaceable, for that is agreeable to every one. It is a great grace and a vigorous and heroic virtue to live peaceably with the hard, the bad, the lawless, and with them who set themselves in opposition to us." Alma's eyes flashed along the lines, and her conscience pricked her with a sharp prick. She handed the book back to old Pelle, and said quite modestly,—

"I was going to give Nono a little lesson there under the tree. I have some nice Scripture pictures, too, that you would perhaps like to see."

"Thanks," said old Pelle, getting up slowly, and falteringly following the slight figure that flitted on before him.

Pelle took his seat beside Nono. They both clasped their hands and closed their eyes. Alma was taken by surprise. She saw what they expected before this "Bible lesson"—a prayer, of course! No prayer came to her lips. "God help us all! Amen!" she said at last. "Amen!" came solemnly from her companions.

Alma was so disturbed by this little occurrence that her whole plan for her lesson went out of her mind. She turned with relief towards the great book, where her mother had placed in order photographs of some of the most beautiful pictures illustrating the life of our Saviour that the world can boast. Alma had meant to explain and expound, but she continued silent. As old Pelle and Nono looked reverently on as she turned page after page, their faces glowing with reverent interest, now and then they exchanged meaning glances or a murmured word; which plainly showed that they understood the incidents so beautifully given by the great artists of the past. When they came to the Christ on the cross, their hands clasped themselves as if involuntarily, and a great tear found its way down Pelle's worn face. The scene was really before him. He felt himself standing on Calvary, beside the cross of his Master.

There was a long pause. Then Alma turned slowly the next page. There, a modern artist had pictured the bright angels falling adoringly back, as the Saviour, shining in his glory, burst forth from the tomb.

"Risen!" said Nono joyously, with the relief of childhood that the sad part of the holy story had now been told.

Alma passed on to the representation of the ascension. Pelle looked at it, his eyes beaming. He raised his long finger and pointed to where a bright cloud was for the moment half veiling the sun. "So he went, and so he shall come again. Blessed be the name of the Lord!" burst from the old man's lips. He was still looking towards the skies, as he added, "Even so, come, Lord Jesus!" He bowed his aged head and sat silent, with clasped hands. Nono and Alma followed his example. When they looked up an astonished beholder had been added to the group under the linden.

"How are you, Uncle Pelle?" said the voice of Frans, as he took the old man cordially by the hand. Pelle looked at him confusedly for a moment, and then, with apparent difficulty, brought his thoughts back to this world, and responded to the pleasant greeting.

"Nono is to go fishing with me. I've been to the cottage, and got permission from Mother Karin. I knew the little brownie would not stir an inch without her leave.—So now, Nono, we are off for a good fish, and then a good supper for you and me.—Your highness will excuse me for interrupting your little meeting," added Frans, with mock politeness. "I hope it has been profitable to all parties."

Alma compelled herself to keep silence, and to respond pleasantly to the thanks of Pelle and Nono for what they called "the nice lesson." They neither of them understood that they had been the teachers, and the fair, slight girl their humble and abashed pupil.

Alma took her Bible in her hand, and went into the house to send a servant for the great album that lay on the stone table. She sat down in her room in a most disturbed frame of mind, ashamed of her first effort as a teacher, and irritated that Nono should have come under the very influence she would have most dreaded for him, even that of her own brother.

Then came a voice from below gently calling "Alma." The loving part of her nature at once took the upper hand, and the fond daughter went down to her father, ready to do anything he could ask of her for his joy or comfort.

The day after the Bible lesson Alma threw herself heartily into her plan for her parterre, at which Pelle and Nono were busily working. In the midst of a large velvet patch of closely-cut grass she had a great parallelogram marked out which was to represent the Swedish flag. The blue ground was to be of the old Emperor William's favourite flower, while the cross stretching from end to end was to be of yellow pansies. The Norwegian union mark in the corner was to be outlined in poppies of the proper colours.

There was a slight twinkle in the old man's eyes as he watched Alma, all enthusiasm, flitting hither and thither, and ordering and planning like an experienced general, while it was plain to Pelle that she was as yet but a novice in the mysteries of gardening. He did venture to hint modestly that it was late—the middle of July—to begin such an undertaking. Alma took no notice of his discouraging hints, but went on expatiating as to how charming it would be to have the Swedish flag lying there on the green grass, and how her father would enjoy it, loving his country as he did, and being a real soldier himself. A soldier the colonel certainly was by profession; but he had had other enemies to meet than the foes of his native land. He had struggled long with sorrow and ill-health, his constant portion. Exiled from Sweden for the sake of his delicate wife, and that he himself might be under the care of eminent physicians who understood his complicated difficulties, he had still continued a warm Swede at heart. Now he considered himself stronger; and did it mean life or death for him, the north should be his home, and his children should learn to love the land of their forefathers. His native language he had never allowed them to lose, even when far away from the bright lakes and clustering pines of the country so dear to him. A war against all that could injure his fatherland the colonel had all the time been waging with his skilful pen. By sharp newspaper articles and spirited papers in magazines he had cast himself into whatever conflict might be going on in Sweden, and had so had his own share of influence at home. He had read the Stockholm journals as faithfully as if he had been living in sight of the royal palace.

As to her father's being charmed with her plan for her flower-bed, Alma was confident. She would not listen to Pelle's suggestion that the flowers would hardly blossom richly at the same time, and those blue weeds would in the end quite overrun the garden. She had no misgivings, but walked about with a peculiar air of determination in her slight, very slight figure.

Alma's whole person gave the impression of extreme fragility, sustained by strength of will. It was the same with her delicate face, haloed round by her sunny hair, ready to float in every breeze. The small mouth was thin and decided, and the large, full blue eyes could be soft or stern as the passing mood prompted. They were very gentle as she looked at Nono when the noonday rest came, and told him he might come into the house with her, as perhaps she could help him a little about his writing in her own room.

Nono would have preferred at that moment to consume the hearty lunch Karin had provided for him, but he followed submissively. Pelle looked after the pair as he went to his favourite seat. Somehow the decided figure of the young girl always touched him. There was something about her that made him uneasy for her, body and soul.

Nono looked despairingly at his shoes, fresh from the flower-bed, as he came to the wide doorway through which Alma had beckoned to him to follow her. It was in vain he tried to put his feet into proper condition by gently rubbing them on the mat that he thought fit for a queen to step on. The colour dashed to his brown cheeks as he saw the marks he had left on it. He could but tiptoe after Alma as she entered the, to him, sacred precincts of the "big house" at Ekero.

Alma felt young and guilty as she met a stout, elderly woman on the stairs, as she went up with Nono.

"It's the little Italian boy I saw baptized," she said apologetically.

"I've seen many children baptized, Miss Alma, and paid respect to what was doing, I hope, but I don't have them trudging up and down the grand staircase—no, not even when the colonel is away in foreign parts. Miss Alma must do as she pleases, but I'd like the colonel to know that I see things in order as far as I can. I can't be responsible for boys like that leaving tracks like a bear behind them."

The comparison to the bear was not meant to be personally offensive towards Nono, though he always felt that with Bruin he was specially connected. He had indeed, in his caretaking, not left marks like a human being as he had tiptoed along, leaving round traces on the shining floor and stairs, as if a four-footed creature had passed.

Nono was not much accustomed to harsh words, and the reproaches of the faithful housekeeper increased his awe of the place, where he felt himself a decided intruder, though following the young mistress at her express command.

Nono was even more disturbed in mind when he was seated at a beautiful little writing-table, and requested to write on a fair sheet of paper laid before him. The first verse of a hymn was dictated to him from the prettiest little psalm book imaginable. His writing was really wonderful for a boy of his age. The letters were clear and round, and almost graceful, with here and there a little flourish of his own invention, added in his desire to do his best.

Alma was quite disappointed when she saw that there was no field here for her instructions. She could hardly write better herself, and by no means as legibly. She was aiming at a flowing hand, and her efforts but showed that her character was yet too unformed to attempt such a dashing style with the pen.

On nearer examination, Nono's spelling was found to be most exceptionable.

"Have you never been taught spelling at school, Nono?" asked Alma, very seriously.

"Oh yes!" he answered cheerfully, and forthwith drew himself up as he stood, and recited the rules for the various ways in which the English sound "oh" may be represented in Swedish, giving the proper examples under the rule. This little Nono could rattle off in grand school-recitation style, though these etymological gymnastics never bore on his practices as a writer.

Of such rules Alma knew nothing. She had learned Swedish spelling on quite another principle. For years she had copied a Swedish poem every day for her father (whether with him or away from him), in pretty little books, which were in due time presented to him with the inscription at the beginning, "From his devoted daughter."

Alma now gave Nono the "psalm book," and bade him copy the hymn carefully. He did not dare to touch the dainty little volume, for his hands were far from immaculate after his morning's work. He managed, though, with his knuckles to steady it against Baxter's "Saints' Rest" and "Thomas à Kempis," which in choice bindings found their place among Alma's devotional books, more in memory of her mother, to whom they had belonged, than for any special use they were to the present owner.

Nono's copy proved fair and correct, for he had the idea that whatever he did must be done well. He signed his name, and put the date below, as he was requested, adding a superfluous supplementary flourish, like an expression of rejoicing that the trial was over.

On one side of the table was a little porcelain statuette that fixed his attention. On an oval slab lay a fine Newfoundland dog, while a boy, evidently just rescued from drowning, was stretched beside him, the dank hair and clinging clothes of the child telling the story as well as his closed eyes and limp, helpless hands.

"Is he really drowned? is he dead?" asked Nono, forgetting all about the spelling, as did his teacher when she heard his question.

"That is one of my treasures, Nono," she said. "The princess gave it to my mother. She modelled it with her own hands—the group after which this was made, I mean. You have heard about the good princess, Nono?"

Nono shook his head and looked very guilty. He knew the king's name, and believed him to be quite equal to David; but as to the queen and all the "royal family," he was in most republican ignorance.

Now Alma had something she liked to talk about. Perhaps she was willing that even Nono should know that her own dear mother had been intimately acquainted with a princess, and had loved her devotedly, and been as warmly loved in return. Alma even condescended to tell Nono that it was the princess who had first led her dear mother to a true Christian life; which high origin for religious influence Alma seemed to look upon as if it were a sort of superior aristocratic form of vaccination. Alma went on to describe the saintly princess as she had heard her spoken of by both her father and her mother, whose respect and affection she had so justly won.

How the image grew and fixed itself in Nono's mind of a real, living princess who sold her rich jewels to build and sustain a home for the sick poor! He heard how she, in her own illness, surrounded by every luxury, could have no rest until she had planned a home where they too could have comfort and tender care. The dark eyes of the listener grew moist as he heard of the hospital the princess now had for crippled and diseased children, where they were made happy and had real love as well as a real home.

Nono was a happy boy when he went out from Alma's room with a little engraved likeness of the princess in his hand, and a glow of warm feeling for her in his fresh young heart. For certain private reasons of his own, she seemed very near to him, and the thought of her was peculiarly precious.

When old Pelle and Nono were going home that evening, he produced his little likeness of the princess, and told Pelle all about her.

Pelle's eyes sparkled, and he said as he rubbed his hands together, "That princess does belong to the royal family! She is a daughter of the great King!"

"May I put her up in your room, Uncle Pelle?" asked Nono. "I do not quite like to have her in the cottage, where the children can get at her. They might not understand that this is not like any other picture."

"That you may," said Pelle; "and come in to see her, too, as often as you please. A sick princess and a Christian too! She wouldn't mind having her likeness put up in my poor place, if she is like what you say. God bless her!"

Nono had a way of taking what was precious to him to Pelle to keep, and curious were the boyish treasures he had stored away in Pelle's room. It had been a bare little home when the old man went into it, but he had made it a cosy nest in his own fashion. Pelle had been for a time a sailor in his youth, and had learned to make himself comfortable in narrow quarters. A fever caught in a foreign port had laid him by, and left sad traces behind it in his before strong body. Other and better traces had been left in his life, even repentance for past misdoings and resolutions for a faithful Christian course. As a gardener's "helping hand" he had long gotten on comfortably; but illness and old age had come upon him, and there had seemed no prospect for him but the poorhouse, when Karin's hospitable door opened for him.

The lawsuit was not settled, but it was well known in the neighbourhood that Jan Persson had said Uncle Pelle should not go to the poorhouse while he had a home.

Pelle felt quite independent now, and he held his head straight as he walked by Nono and talked about the good princess. Had not the young lady at Ekero said she should need him straight on in the garden? for she saw he knew all about flowers, and could be of real use to her. Alma wanted to be a friend to Nono too, but she did not yet exactly see how. There was something about the boy she did not quite understand.

Nono was in disgrace. The twins had twice brought him before Karin, his clothes all smeared with mud, as if he had purposely made his whole person the colour of his brown face, and had given his hands rough gloves of a still darker hue. Of course he had at first been sternly reprimanded, for Karin suffered no such proceedings in her neat household. The second reproof was more severe, and accompanied by the promise of a thorough whipping if the offence were repeated.

The long summer evenings gave a fine play-time for the boys, and then Nono generally amused himself out of the way of the twins, who were very despotic in their style of government. Again they had detected him brushing himself behind the bushes, and dolorously looking at the obstinate stains upon his cotton clothes. With a wild hollo they seized the culprit between them, and hurried him along towards Karin, who was cheerily examining her flower-beds under the southern windows, and chatting meanwhile with Jan, who sat on the doorstep.

Karin was both grieved and angry, and unusually excited. "Nono must be whipped, and that soundly," she said emphatically to Jan. "This is the third time he has come to the house in that condition. I won't have him learn to disobey me that way."

Jan got up slowly, and took from its hiding-place inside the cottage something that looked like a broom-brush made of young twigs. It was the family emblem and instrument of punishment, much dreaded among the children; and with reason, for Jan had a strong hand and a sure one. He had been accustomed to giving his own boys a thrashing now and then, but on Nono he had never laid hands, as Karin's gentler discipline had usually sufficed for her foster-son.

The tears were in the eyes of the culprit, but he stood quite still, and was at first speechless. At last he managed to say, "Don't whip me here, Papa Jan; take me down to the shore, please." Jan generally had his times of punishment quite private with the boys, the grove behind the house being the usual place of execution. He could not, however, refuse Nono's modest request. Off to the shore they went together, the twins meanwhile shrugging and wincing, as if they themselves were undergoing the ordeal, while they said to each other, "He'll catch it! It won't feel good!"—not without some satisfaction, mingled with a sense of the seriousness of the occasion.

Little Decima, who had been a depressed looker-on at the proceedings, buried her head in her mother's apron and cried as if she herself were the victim. The little boys, no longer little, were hardened to punishment, as they were often in disgrace for their wild pranks, but the idea of Nono's being whipped seemed to have made them uncommonly sober. Sven went into the cottage to look among his treasures for something with which to console Nono on his return from the shore. Thor was walking up and down, giving defiant looks at the twins for their want of sympathy with Nono in his humiliation. There was a sorrowful shadow over the whole family group that evening not common at the golden house.

To the surprise of all parties Jan soon appeared, holding Nono by the hand, both apparently in a most cheerful humour. There were no tears in Nono's face, and Jan looked down at him with peculiar tenderness.

"Nono has not meant to be a bad boy," said Jan; "and I have forgiven him, and I think you will have to forgive him too, Karin."

"Dear, dear Mamma Karin, indeed I did not want to be a bad boy," said Nono. "That would be hard, after all your kindness to me. Please, please forgive me!" Nono put his arm round Karin as he spoke. She looked doubtfully at him, but could not refuse the lips he put up to her to be kissed in sign of full forgiveness.

Sven, who had found a broken horse-shoe among his treasures, was rather disappointed that he had lost the opportunity of consoling Nono with his friendly gift.

Decima laid her little hand in Nono's, and was about leading him off the scene, when she was suddenly captured by her mother and hurried into the cottage, with the exclamation, "Here's Decima up till this time! One never knows when to put children to bed these summer evenings. She'll be as cross as pepper in the morning if she don't get her sleep out!"

It was plain that Karin was not quite satisfied with the turn the whole affair had taken.

"Papa is too partial to Nono! It is a shame!" murmured the twins, as they went off in a pout.

The morning of the second day of August was warm and bright. When Karin awoke, Jan was already up and out of the house. The children were dressed in their holiday clothes, by their father's permission, they said, their faces beaming with satisfaction. Karin was hardly in order when Jan appeared and advised her to put on a white apron, which she wonderingly consented to do, and then Jan led her off down to the shore. Behind them the children followed in orderly procession. Old Pelle brought up the rear, like the shepherd with the sheep going on before him.

Of the why and wherefore of all this ado the children had no idea. Nono had assured them that their father approved of the whole thing, and the proud and yet tender way that Jan was walking with Karin showed that the affair had his full endorsement.

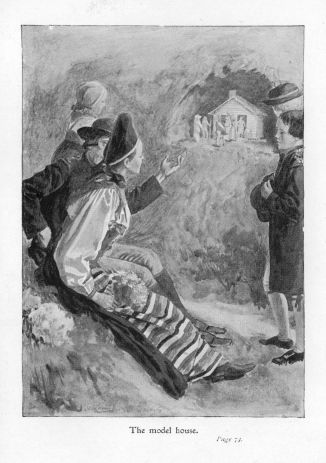

On a green bank in a little cove in the shore Karin was ceremoniously seated, and Jan placed himself at her side.

The children threw into her lap their bouquets, each of a hue of its own, to lie there like a jumbled-up rainbow. With Oke's bright flowers from the pastor's garden fell a bank-note from the absent Erik, with an inscription pinned to it in his usual lingo: "Mamma. From her gosse Erik." (Nono had assured Oke it was best to keep the gift till the second of August.) A few drops fell on the note and the bright flowers from Karin's astonished eyes; but there was a sudden sunshine of joy and wonder as Nono proceeded to take down the evergreen branches that were leaned against the bank opposite to her. There, a deep arch had been scooped into the hillside. In its sweet retirement there was a tiny house of yellow pine, perfectly modelled after the family home, the door open, and the flower-beds in their proper place under the windows. In front of the house was a group, which all recognized at a glance. "Perfect! Just as if he had seen it! Think! he could make it, when he was only so long at the time!" exclaimed Oke, his fingers indicating a most diminutive baby. There was no contempt, but unlimited admiration, in this mention of the infant Nono.

It was indeed a most successful bit of modelling. The picture that had been so long in Nono's mind had taken form. Bear, and Italians, and Swedes, and the very baby Francesca was raising high in the air for a toss, were wonderfully living and full of expression.

When the tumult of delight was subdued for a moment, Jan intimated, as he had been requested, that Nono had something to say.

What grandiloquence Nono had prepared never transpired. As it was, he forgot his intended speech. His heart was in his throat; but he managed to say that this was Katharina day in the almanac, and so Mamma Karin's name-day, and the dear mother of them all ought, of course, to be honoured. He had found some nice clay by the shore, which would stay in any form he put it, and he had tried to make the group he had thought so much about to show how thankful he was to have a place in such a home. He had not meant to be careless, but when he got at his work he forgot everything else, and so it had all happened. The last time was the worst, when he had spilt the basin of water, just as he was trying to make himself decent. Papa Jan had forgiven him, and he hoped Mamma Karin would do so too, now she had heard all about it. He really had not meant to be a bad boy.

Karin caught the little Italian in her arms, while Jan looked down on them benignantly, and the children roared an applause that came from the depths of their hearts. They had never thought of celebrating their mother's name-day. It had never even struck them that she had one, as her name as they knew it was not to be found in the almanac. As for themselves, each could remember some simple treat that had been provided for his name-day—a row on the bay, pancakes after dinner, an apple all round, a trip to the village, or some other favour calculated to specially please the recipient and make all happy in the home.

The children, all but Nono, had been sure to have their fête; for if the name by which they were called in everyday life had no place in the almanac, they had a luxury used only once a year which fixed their time to be honoured—a second name that stood in the calendar. So Decima had come to be a kind of D.D. in her way. She had been baptized Decima Desideria, that she too might have a name-day and a celebration.

Desideria was a royal name, and a kind of a queen too. Decima had been from the very beginning the one girl among many boys, and ruling them all with her whims and caprices.

Jan had no idea of lingering all day by the shore, and he soon broke up the party by saying it was time for them all to go in and get on their everyday clothes, and be twice as busy as usual to make up for lost time.

Jan spoke bluntly, for he found himself in a softened mood, and that was his odd way of showing it. For his part, he had made up his mind that he had taken too little pains to give Karin pleasure—his good wife, who had all kinds of bothers, no doubt, and never troubled him about them.

A truce was sealed that day between Nono and the twins, though the duumvirs said never a word on the subject. They were not going to trouble a boy who could make such wonderful things, and show how grateful he was to their own mother, who had been just as kind to them, and they had thought little about it, and not even found out she had a name-day at all.

When Nono was going to bed that night, Karin thanked him again for the great pleasure he had given her.

"I did not give it to you; it was all the princess," he said. Karin looked wonderingly at him, and he added, "I told Oke I wanted to make beautiful things like some he showed me in a book about Italy the pastor had lent him. Oke laughed first, and then he said it told in the book that the men who made beautiful things did not always have beautiful lives—good lives it meant, Oke said. I want to have a beautiful life, Mamma Karin, and I thought it might be best not to try to make figures at all, as I am always wanting to, and I felt sorry about it. When Miss Alma showed me what the good princess could make, I thought I might see if I could make beautiful things and have a beautiful life too, like her. So you see it was the princess. I am glad you were pleased."

Karin bade the little boy good-night with unusual tenderness. She understood him, and in her heart the purpose was strengthened to try more herself to lead "a beautiful life," and to begin more earnestly than ever before on her name-day.

Of course, Alma was anxious to see the wonderful group that Nono had made for Karin. The evening after the celebration of Karin's name-day, Alma appeared at the cottage in a light summer costume and her parasol held daintily in her hand, though the sun was veiled in golden clouds. What was her astonishment to see Frans cosily sitting on the doorstep beside Jan in his working dress, and his own not more presentable for eyes polite. Frans enjoyed society where the laws of etiquette and the dominion of fashion were unknown.

"You here, Frans!" exclaimed Alma, with a sudden cloud on her before smiling face.

"You here, Alma!" answered Frans, starting up with affected surprise, then offering to his sister with formal courtesy the seat he had vacated at honest Jan's side.

Jan took himself up too—a slow process for him after a day of hard work. Bareheaded he stepped forward to welcome the young lady, who at once explained the object of her visit. Nono, who had seen her in the distance, now came to meet her, and willingly led the way to the shore. Karin, who was weeding in the vegetable-garden, did not know of the arrival of the guest.

Alma's delight with the group exceeded Nono's expectations. She used words about it such as she had heard her father employ in criticising works of art, and quite soared beyond Nono's comprehension as well as her own. The little house, just like Karin's cottage, charmed her completely. "Did you really make it all yourself, Nono; the house, I mean?" she said.

"Uncle Pelle helped me about it a little," said Nono honestly. "I am glad you like it."

"I like it so much that I want just such a one, to be really my own, but very, very much smaller it should be. I should like to use it as a money-box, a kind of savings-bank. The chimney should be open all the way down, so that I could drop the money in. The door should be locked, and I should have the key. I have a lock from an old work-box that would just do. Pelle could help you to fit it in, I am sure; he is so handy about everything. Will you do it, Nono?"

Of course Nono gladly said he would try; and then Alma added, "But I want to see Pelle too, and Karin, and Pelle's room, and the cottage."