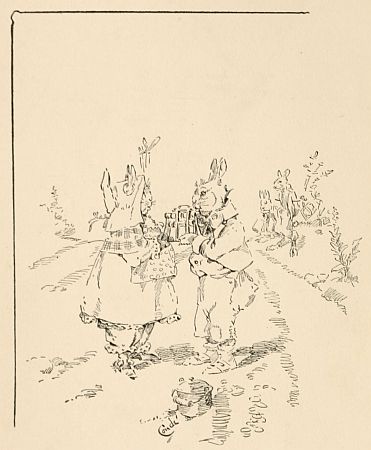

"I USED TO RUN OUT AND GET BEHIND, WITH BUNTY, AND TAKE HER BOOKS"

"I USED TO RUN OUT AND GET BEHIND, WITH BUNTY, AND TAKE HER BOOKS"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mr. Rabbit's Wedding, by Albert Bigelow Paine This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Mr. Rabbit's Wedding Author: Albert Bigelow Paine Illustrator: J. M. Condé Release Date: February 25, 2009 [EBook #28193] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. RABBIT'S WEDDING *** Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

| MR. TURTLE'S FLYING ADVENTURE |

| MR. CROW AND THE WHITEWASH |

| MR. RABBIT'S WEDDING |

| HOW MR. DOG GOT EVEN |

| HOW MR. RABBIT LOST HIS TAIL |

| MR. RABBIT'S BIG DINNER |

| MAKING UP WITH MR. DOG |

| MR. 'POSSUM'S GREAT BALLOON TRIP |

| WHEN JACK RABBIT WAS A LITTLE BOY |

| ———— |

| HOLLOW TREE AND DEEP WOODS BOOK |

| Illustrated. 8vo. |

| HOLLOW TREE SNOWED-IN BOOK |

| Illustrated. 8vo. |

| ———— |

| HARPER & BROTHERS, NEW YORK |

| PAGE | |

| Little Jack Rabbit and Bunty Bun | 11 |

| Cousin Redfield and the Molasses | 31 |

| Mr. Bear's Early Spring Call | 51 |

| Mr. Jack Rabbit Brings a Friend | 71 |

| Mr. Rabbit's Wedding | 95 |

The Little Lady looks into the fire, too, and thinks. Then pretty soon she climbs into the Story Teller's lap and leans back, and looks into the fire and thinks some more.[12]

"Did the Hollow Tree people ever go to school?" she says. "I s'pose they did, though, or they wouldn't know how to read and write, and send invitations and things."

The Story Teller knocks the ashes out of his pipe and lays it on the little stand beside him.

"Why, yes indeed, they went to school," he says. "Didn't I ever tell you about that?"

"You couldn't have," says the Little Lady, "because I never thought about its happening, myself, until just now."

"Well, then," says the Story Teller, "I'll tell you something that Mr. Jack Rabbit told about, one night in the Hollow Tree, when he had been having supper with the 'Coon and 'Possum and the Old Black Crow, and they were all sitting before the fire, just as we are sitting now. It isn't really much about school, but it shows that Jack Rabbit went to one, and explains something else, too."[14]

Mr. Crow had cooked all his best things that evening, and everything had tasted even better than usual. Mr. 'Possum said he didn't really feel as if he could move from his chair when supper was over, but that he wanted to do the right thing, and would watch the fire and poke it while the others were clearing the table, so that it would be nice and bright for them when they were ready to enjoy it. So then the Crow and the 'Coon and Jack Rabbit flew about and did up the work, while Mr. 'Possum put on a fresh stick, then lit his pipe, and leaned back and stretched out his feet, and said it surely was nice to have a fine, cozy home like theirs, and that he was always happy when he was doing things for people who appreciated it, like those present.

MR. RABBIT SAID HE CERTAINLY DID APPRECIATE BEING INVITED TO THE HOLLOW TREE

MR. RABBIT SAID HE CERTAINLY DID APPRECIATE BEING INVITED TO THE HOLLOW TREE

Mr. Rabbit said he certainly did appreciate being invited to the Hollow Tree, living, as he did, alone, an old bachelor, with nobody to share his home; and then pretty soon the work was all done up, and Jack Rabbit and the others drew up their chairs, too, and lit[15] their pipes, and for a while nobody said anything, but just smoked and felt happy.

Mr. 'Possum was first to say something. He leaned over and knocked the ashes out of his pipe, then leaned back and crossed his feet, and said he'd been thinking about Mr. Rabbit's lonely life, and wondering why it was that, with his fondness for society and such a good home, he had stayed a bachelor so long. Then the Crow and the 'Coon said so, too, and asked Jack Rabbit why it was.

Mr. Rabbit said it was quite a sad story, and perhaps not very interesting, as it had all happened so long ago, when he was quite small.

"My folks lived then in the Heavy Thickets, over beyond the Wide Grasslands," he said; "it was a very nice place, with a good school, kept by a stiff-kneed rabbit named Whack—J. Hickory Whack—which seemed to fit him. I was the only child in our family that year, and I suppose I was spoiled. I remember my folks let me run and play a good deal, instead of making me study my lessons, so that Hickory Whack did not like me much, though he was afraid to be as severe as he was with most of the others, my folks being quite well off and I an only child. Of course, the other scholars didn't like that, and I don't blame them now, though I didn't care then whether they liked it or not. I didn't care for anything, except to go capering about the woods, gathering flowers and trying to make up poetry, when I should have been doing my examples. I didn't like school or J. Hickory Whack, and every morning I hated to start, until, one day, a new family moved into our neighborhood. They were named Bun, and one of them was a little girl named Bunty—Bunty Bun."

When Mr. Rabbit got that far in his story he stopped a minute and sighed, and filled his pipe again, and took out his handkerchief, and said he guessed a little speck of ashes had got into his eye. Then he said:

"The Buns lived close to us, and the children went the same way to school as I[17] did. Bunty was little and fat, and was generally behind, and I stayed behind with her, after the first morning. She seemed a very well-behaved little Miss Rabbit, and was quite plump, as I say, and used to have plump little books, which I used to carry for her and think how nice it would be if I could always go on carrying them and helping Bunty Bun over the mud-holes and ditches."

Mr. Rabbit got another speck of ashes in his eye, and had to wipe it several times and blow his nose hard. Then he said:

"She wore a little red cape and a pretty linsey dress, and her ears were quite slim and silky, and used to stand straight up, except when she was sad over anything. Then they used to lop down quite flat; when I saw them that way it made me sad, too. But when she was pleased and happy, they set straight up and she seemed to laugh all over.

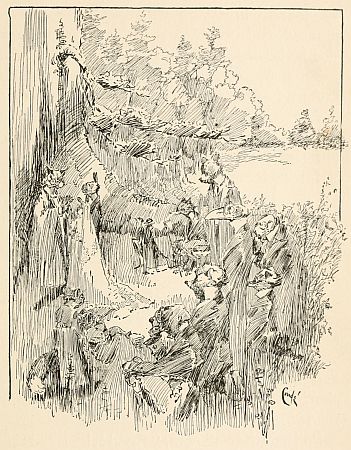

"I forgot all about not liking school. I used to watch until I saw the Bun children coming, and then run out and get behind,[18] with Bunty, and take her books, and wish there was a good deal farther to go. When it got to be spring and flowers began to bloom, I would gather every one I saw for Bunty Bun, and once I made up a poem for her. I remember it still. It said:

[19]Mr. Rabbit said he didn't suppose it was the best poetry, but that it had meant so much to him then that he couldn't judge it now, and, anyway, it was no matter any more. The other children used to tease[20] them a good deal, Mr. Rabbit said, but that he and Bunty had not minded it so very much, only, of course, he wouldn't have had them see his poem for anything. The trouble began when Bunty Bun decided to have a flower-garden.

"FLOWERS THAT SHE WANTED ME TO DIG UP FOR HER"

"FLOWERS THAT SHE WANTED ME TO DIG UP FOR HER"

"She used to see new flowers along the way to and from school that she wanted me to dig up for her so she could set them out in her garden. I liked to do it better than anything, too, only not going to school, because the ground was pretty soft and sticky, and it made my hands so dirty, and Hickory Whack was particular about the children having clean hands. I used to hide the flower plants under the corner of the school-house every morning, and hurry in and wash my hands before school took up, and the others used to watch me and giggle, for they knew what all that dirt came from. Our school was just one room, and there were rows of nails by the door to hang our things on, and there was a bench with the washbasin and the water-pail on it, the basin and[21] the pail side by side. It was a misfortune for me that they were put so close together that way. But never mind—it is a long time ago.

"One morning in April when it was quite chilly Bunty Bun saw several pretty plants on the way to school that she wanted me to dig up for her, root and all, for her garden. I said it would be better to get them on the way home that night, but Bunty said some one might come along and take them and that she wouldn't lose those nice plants for anything. So I got down on my knees and dug and dug with my hands in the cold, sticky dirt, until I got the roots all up for her, and my hands were quite numb and a sight to look at. Then we hurried on to school, for it was getting late.

"When we got to the door I pushed the flower plants under the edge of the house, and we went in, Bunty ahead of me. School had just taken up, and all the scholars were in their seats except us. Bunty Bun went over to the girls' side to hang up her things,[22] and I stuck my hat on a nail on our side, and stepped as quick as I could to the bench where the water was, to wash my hands.

"I HAD MADE A MISS-DIP, AND EVERYBODY WAS LOOKING AT ME"

"I HAD MADE A MISS-DIP, AND EVERYBODY WAS LOOKING AT ME"

"There was some water in the basin, and I was just about to dip my hands in when I looked over toward Bunty Bun and saw her little ears all lopped down flat, for the other little girl rabbits were giggling at her for coming in with me and being late. The boy rabbits were giggling at me, too, which I did not mind so much. But I forgot all about the basin, for a minute, looking at Bunty Bun's ears, and when I started to wash my hands I kept looking at Bunty, and in that way made an awful mistake; for just when the water was feeling so good to my poor chilled hands, and I was waving them about in it, all the time looking at Bunty's droopy ears, somebody suddenly called out, 'Oh, teacher, Jacky Rabbit's washing his hands in the water-pail! Jacky Rabbit's washing his hands in the water-pail, teacher!'

"And sure enough, I was! Looking at Bunty Bun and pitying her, I had made a[24] miss-dip, and everybody was looking at me; and J. Hickory Whack said, in the most awful voice, 'Jack Rabbit, you come here, at once!'"

MR. RABBIT SAID HE COULD HARDLY GET TO HICKORY WHACK'S DESK

MR. RABBIT SAID HE COULD HARDLY GET TO HICKORY WHACK'S DESK

Mr. Rabbit said he could hardly get to Hickory Whack's desk, he was so weak in the knees, and when Mr. Whack had asked him what he had meant by such actions he had been almost too feeble to speak.

"I couldn't think of a word," he said, "for, of course, the only thing I could say was that I had been looking at Bunty Bun's little droopy ears, and that would have made everybody laugh, and been much worse. Then the teacher said he didn't see how he was going to keep himself from whipping me soundly, he felt so much that way, and he said it in such an awful tone that all the others were pretty scared, too, and quite still, all of them but just one—one scholar on the girls' side, who giggled right out loud—and I know you will hardly believe it when I tell you that it was Bunty Bun! I was sure I knew her laugh, but I couldn't believe it[26] and, scared as I was, I turned to look, and there she sat, looking really amused, her slim little ears sticking straight up as they always did when she enjoyed anything."

Mr. Rabbit rose and walked across the room and back, and sat down again, quite excitedly.

"Think of it, after all I had done for her! I saw at once that there would be no pleasure in carrying her books and helping her over the mud-puddles in the way I had planned. And just then Hickory Whack grabbed a stick and reached for me. But he didn't reach quite far enough, for I was always rather spry, and I was half-way to the door with one spring, and out of it and on the way home, the next. Of course he couldn't catch me, with his stiff leg, and he didn't try. When I got home I told my folks that I didn't feel well, and needed a change of scene. So they said I could visit some relatives in the Big Deep Woods—an old aunt and uncle, and I set out on the trip within less than five minutes, for I was tired[27] of the Thickets. My aunt and uncle were so glad to see me that I stayed with them, and when they died they left me their property. So I've always stayed over this way, and live in it still. Sometimes I go over to the Heavy Thickets, and once I saw Bunty Bun. She is married, and shows her age. She used to be fat and pretty and silly. Now she is just fat and silly, though I don't suppose she can help those things. Still, I had a narrow escape, and I've never thought of doing garden work since then for anybody but myself and my good friends, like those of the Hollow Tree."

"Do you know any story about little bears? Did the Bear family in the Big Deep Woods ever come visiting to the Hollow Tree?"[32]

The Story Teller thinks.

"Yes," he said; "or rather, Mr. Bear came once alone, but that is another story. I know one story, though, about a little bear, a story that Mr. Crow told one night when he had been over to spend the afternoon with Mr. Bear, they bring very good friends."

"Mr. Bear told me this afternoon," Mr. Crow said, "about something that happened in his uncle's family some years ago. His uncle's name was Brownwood—Brownwood Bear—and he had a little boy named Redfield, but they called him Reddie, for short. Uncle Brownwood lost his wife one night when she went over to get one of Mr. Man's pigs, and he and little Redfield used to live together in a nice cave over near the Wide Blue Water, not far from the place where Mr. Turtle lives now. Uncle Brownwood used to be gone a good deal to get food and whatever they needed, and Reddie would stay at home or sleep in the cave, or play outside and roll and tumble about in the sun and have a very good time. He had a[34] number of playthings, too, and plenty of nice things to eat, and every morning, before Uncle Brownwood Bear started out, he would put out enough to last Cousin Redfield all day—some ripe berries, and apples, with doughnuts, and such things, and always some bread and butter and molasses to finish up on.

"HE DIDN'T EAT THE BREAD AT ALL BUT JUST ATE UP THE MOLASSES"

"HE DIDN'T EAT THE BREAD AT ALL BUT JUST ATE UP THE MOLASSES"

"Little Reddie Bear liked all these things very much, but best of all he liked the molasses. Not bread and molasses, but just molasses; and he used to beg Uncle Brownwood to give him a whole saucer of molasses to dip his bread in; but once when his father did that he didn't eat the bread at all, but just ate up the molasses, and was sick that night, though he said it wasn't the molasses that did it, but carrying in some wood and washing the dishes, which he had to do every evening.

"But Uncle Brownwood didn't give Cousin Redfield any more molasses in a saucer; he spread his bread for him every morning, and set the molasses-jug on a high shelf, out of[35] reach, and Reddie used to stand and look at it, when his father was gone, and wander how long it would be before he would be tall enough to get it down and enjoy himself with the contents.

"One day when Cousin Redfield was looking at the jug he had an idea. Just outside of the cave his father had made a bear-ladder for Reddie to learn to climb on. A bear-ladder is a piece of a tree set up straight in the ground. It has short, broken-off limbs, and little bears like to run up and down on it, and big bears, too, for it gives them exercise and keeps them in practice for climbing real trees.

"When Reddie had the idea, he ran out and looked at his bear-ladder; then he ran back and looked at the jug. If only that bear-ladder was in the cave, he thought, he could walk right up it and get the jug and have the best time in the world. The bear-ladder would go in the cave, for it was a very high cave, and the ladder was not a very tall one.[36]

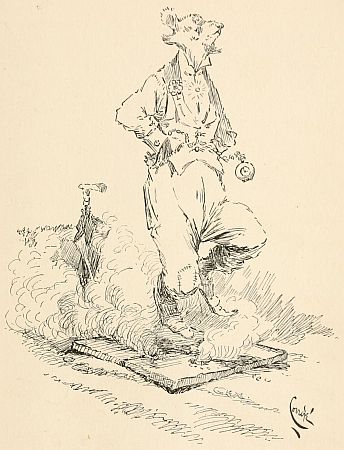

"But the bear-ladder was fast to the ground, and at first Reddie couldn't budge it. He worked and pushed and tugged, but it would not move. Then he happened to think that perhaps if he climbed up to the top of it, and swung his weight back and forth as hard as he could, he might loosen it that way. So he ran up to the top limbs and caught hold tight, and rocked this way and that with all his might, and pretty soon he felt his bear-ladder begin to rock, too. Then he rocked a good deal harder, and all of a sudden down it went and little Cousin Redfield Bear flew over into a pile of stove-wood, and for ten minutes didn't know whether he was killed or not, he felt so poorly. Then he crawled over to a flat stone and sat down on it, and cried, and felt of himself to see if he was injured anywhere; and he did not feel at all like bothering with his bear-ladder any more, or eating molasses, either.

"But that was quite early in the day, and after Cousin Redfield had sat there awhile[38] he didn't feel so discouraged. His pains nearly all went away, and he began to feel that if he had some molasses now it would cure him. So then he got up and went over to look at the ladder, and took hold of it, and found that it wasn't very heavy, as it was pine, and very dead and dry. He could drag it to the cave easy enough, but when he got it there he couldn't set it up straight. He was too short, and not strong enough, either.

"SAT DOWN ON THE STONE TO THINK AGAIN AND CRY SOME MORE"

"SAT DOWN ON THE STONE TO THINK AGAIN AND CRY SOME MORE"

"So little Cousin Redfield went back and sat down on his stone to think again and cry some more, because he found several new hurting places that were not quite cured yet. Then, he noticed the clothes-line, and thought he might do something with that. He could get that down easy enough, for it was not very high. Cousin Redfield had often hung out the clothes on it himself. So he untied the ends of the clothes-line and tied one end of it to the top of his bear-ladder, but didn't know what to do with the other end, until he happened to see the big hooks in[39] the top of the cave where his father hung meat when they had a good supply.

"So then Reddie made a bunch of the other end of the rope and threw it at those hooks, and kept on throwing it until after a while it caught on one of them, and enough of it hung down for him to get hold of. Cousin Redfield, for a small bear, was really quite smart to think of all that.

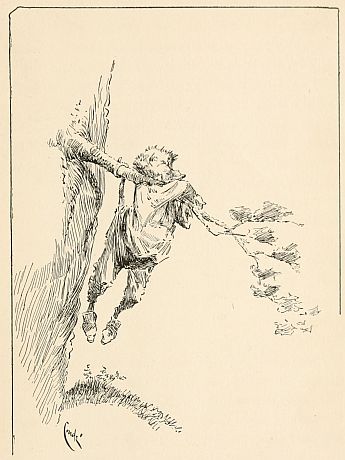

"It wasn't easy, though, even now, to get the bear-ladder up straight. Reddie pulled, and tugged, and propped his feet against the side of the cave, and the table and benches, and got out of breath, and was panting and hot and his sore places hurt him awful, and he thought he'd have to give it up, but at last the end of the bear-ladder caught on the side of the cave where the jug was, and stayed there, and Cousin Redfield could let go of the rope, and get behind the ladder and push, and then, pretty soon, it was up straight, and he could get the molasses-jug as easy as anything.

"It was getting along in the afternoon[40] now, and Reddie knew that Uncle Brownwood Bear was likely to come home before long. So he went right up and got the jug, and nearly dropped it getting down, it was so heavy. But he got down with it all right, and then pulled out the cob that was its stopper, and tipped the jug to pour some of the molasses out in his hand.

"AND THEN PRETTY SOON IT COMMENCED TO RUN BETTER"

"AND THEN PRETTY SOON IT COMMENCED TO RUN BETTER"

"But the jug was quite full, and, the molasses being very thick, would not run out very well. So he tipped the jug over farther, but could only get a little. Then he tipped it on its side, and then pretty soon it commenced to run better, and came out better, and made a nice noise, 'po-lollop, po-lollop, po-lollop,' and formed quite a thick pool right on the floor of the cave, and little Cousin Redfield Bear got down on his hands and knees and licked and lapped, and forgot everything but what a lovely time he was having, and didn't realize that he was getting it all over himself, until he started to get up, and then found it was all around him, and his knees were in it, and everything.[42]

"Cousin Redfield didn't get entirely up. He was nearly up when his foot slipped and he went down flat on his back; when he tried it again he went down in another position, and kept on getting partly up and falling in different ways, until he was an awful sight, and there wasn't so much molasses on the floor any more, because it was nearly all on Cousin Redfield. Then that little bear—little Reddie Bear—suddenly remembered that his father would be coming home presently, and that something ought to be done about it. He was so full of molasses he could hardly move or see out of his eyes. If he could only wipe it off. He had seen his father take a wisp of hay or nice, soft grass to wipe up a little that was sometimes spilled on the table, so Reddie thought hay would be good for his trouble. He would roll in hay, and that would take off the molasses.

"There was a big pile of soft hay-grass in the back part of the cave that Uncle Brownwood used to stuff his mattress with, and[43] Cousin Redfield made for it, and rolled and wallowed in it, thinking, at first, that he was getting off the molasses, but pretty soon finding he was only getting on hay, and really had it all over him so thick that he could not roll any more, and could only see through it a very little. When he managed to get up he had nearly all the hay on him, as well as the molasses.

"Cousin Redfield was really a little walking haystack; and scared at his condition, because he thought he would probably never be a bear any more. He was so scared that he wanted his father to come and do something for him, and started to meet him, as fast as he could, with all that load of hay and molasses. He was crying, too, but nobody could really tell it from the sound he made, which was something like 'Woo—ooo, woo—ooo,' and very mournful.

"Uncle Brownwood Bear was just rounding the big rock there at the turn when he came face to face with Cousin Redfield and his hay. Reddie thought his father[44] would be angry when he saw him, but he wasn't—not at first. Cousin Redfield didn't realize how he looked from the outside, or the lonesomeness of the sound he was making. Uncle Brownwood took just one glance at him, and said 'Woof!' and broke in the direction of a tree, and of course you could hardly blame him, for he had never seen or heard anything like that before, and it came on him so sudden-like.

"Then poor little Reddie Bear bawled out as loud as he could, 'Pa! Pa! Oh, pa, come back! I's me, pa; come back!'

"And Uncle Brownwood stopped in his tracks and whirled around and said, in an awful voice, 'You, Redfield!' for he thought Reddie was playing a joke on him, and he was mad clear through.

"Cousin Redfield saw that he was mad by the way he started for him, and became scared, and tried to run away as well as he could; but, not being able to see well, ran right toward the Wide Blue Water, and before he noticed where he was going he[45] stumbled off of a two-foot bank where it was deep, and was down in the water, and had gone under for the second time before his father could lean over and grab him and get him out.

"IT GAVE HIM SUCH A SICK TURN THAT HE NEARLY DIED"

"IT GAVE HIM SUCH A SICK TURN THAT HE NEARLY DIED"

"Poor little Cousin Redfield Bear! By that time most of the hay was washed off of him, but he had got a good deal of the Wide Blue Water inside of him, and was so nearly drowned he couldn't speak. And when his father laid him on the bank, and rolled him, the water and molasses came out, 'po-lollop, po-lollop, po-lollop,' and, feeble as he was, little Cousin Redfield realized that he probably would never care for molasses again.

"When he was empty and could sit up, Uncle Brownwood got a pail, and a dipper, and a brush-broom, and cleaned him on the outside, and then rubbed him dry with an old towel, and put him to bed, though not until after he had scrubbed up the cave so they could live in it.

"Uncle Brownwood Bear did not punish[46] little Cousin Redfield," Mr. Crow said. "He thought Reddie had been punished enough. Besides, Reddie was sick for several days. But Uncle Brownwood put up the bear-ladder much stronger than before, and set the empty molasses-jug in the middle of the table, and kept it there a long time, and when Cousin Redfield tried even to look at it, it gave him such a sick turn that he nearly died."

"I'm in," Mr. 'Coon called back. "I hunted till I was tired and couldn't find a thing worth bringing home, except some winter parsnips that I dug out of Mr. Man's garden."[52]

"I'm in," Mr. Crow called back. "I found a beefsteak that Mr. Man had hung out to freeze. I'll cook it with Mr. 'Coon's parsnips. Why, is anything the matter?"

MR. 'POSSUM CAME PUFFING UP THE STAIRS

MR. 'POSSUM CAME PUFFING UP THE STAIRS

Mr. 'Possum came puffing up the stairs to the big room, and sat down before the fire, and took off his shoes and warmed himself a little, and lit his pipe, and said:

"Well, there may be, if we don't keep that prop pretty firmly against the down-stairs door. I met Mr. Robin while I was out, and he tells me that a new Mr. Bear has moved over into the edge of the Big Deep Woods, into that vacant cave down there by the lower drift. His name is Savage—Aspetuck Savage—one of those Sinking Swamp Savages, and he's hungry and pretty fierce. They've had a harder winter in the Swamp than we have had up here, and when Aspetuck came out of his winter nap last week and couldn't find anything, he started up this way. Mr. Man has shut up all his pigs, and Mr. Robin thinks that Aspetuck is headed now for the Hollow Tree. Somebody[54] told him, Mr. Robin said, that we manage to live well and generally come through the winter in pretty fair order, though I can tell by the way my clothes hang on me that I've lost several pounds since Mr. Man built that new wire-protected pen for his chickens."

Mr. 'Coon said the news certainly was not very good, and that while his condition was not so bad for such a hard season, he didn't propose to let Mr. Aspetuck Savage use him in the place of pork, if he could help it. Mr. Crow said he didn't feel so much afraid on his own account, as Aspetuck would not be apt to have much taste for one of his family, unless his appetite was extremely fierce, though, of course, it was safer to take no chances. So then they all went down-stairs and put still another prop against the door, and piled a number of things behind it, too, to make it safe. Then they went up and Mr. Crow cooked the nice steak and put some fried parsnips with it, and Mr. 'Possum said if it wasn't for thinking of Aspetuck he could[56] eat twice as much and get his lost weight back; and Mr. 'Coon and Mr. Crow told him he had better keep right on thinking of Aspetuck, so there would be enough to go around. By and by they all sat before the fire and smoked, and got sleepy, and Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum went up to their rooms to bed, but Mr. Crow said he would nap in his chair, so that if Mr. Savage Bear should arrive early he would be up to receive him.

"Tell him I'm very sick," said Mr. 'Coon, "and too run-down and feeble to get up to make him welcome."

"Tell him I'm dead," said Mr. 'Possum. "Say I died last week, and you're only waiting for the ground to thaw to bury me. Tell Aspetuck I starved to death."

DID NOT REALLY INTEND TO GO SOUND ASLEEP

DID NOT REALLY INTEND TO GO SOUND ASLEEP

Mr. Crow said he would tell as many things as he could think of, and then he sat down by the fire, and did not really intend to go sound asleep, but he did, and the fire went down, and Mr. Crow got pretty cold, though he didn't know it until all of a[57] sudden, just about sunrise, there was a big pounding knock at the down-stairs door, and a big, deep voice called out:

"Hello! Hello! Wake up! Here's a visitor to the Hollow Tree!"

Then Mr. Crow jumped straight up, and almost cracked, his joints were so stiff and cold, and Mr. 'Coon heard it, and jumped straight up, too, in his bed; and Mr. 'Possum heard it, and jumped straight up in his bed, and Mr. 'Coon said, "'Sh!" and Mr. 'Possum said, "'Sh!" and Mr. Crow stumbled over to the window and opened it and looked out, and said: "Who's there?" Though he really didn't have to ask, because he knew, and besides, he could see the biggest Mr. Bear he ever saw, for Aspetuck Savage was seven feet tall, and of very heavy build.

"It's me," said Mr. Bear, "Mr. Aspetuck S. Bear, come to make a spring morning call." You see, he left out his middle name, and only gave the initial, because he knew his full name wasn't popular in the Deep Woods.[58]

"Why, Mr. Bear, good morning!" said Mr. Crow. "How early you are! I didn't know it was spring, and I didn't know it was morning. I'm sorry not to invite you in, but we've had a hard time lately, and haven't cleaned house yet, and I'd be ashamed to let you see how we look."

"Oh, never mind that," said Mr. Aspetuck Bear. "I don't care how things look. I forget everything else in the spring feeling. I only want to enjoy your society, especially Mr. 'Coon's. I've heard he's so fine and fat and good-natured, in his old age."

When Mr. 'Coon heard that he fell back in bed and covered his head and groaned, but not loud enough for Aspetuck to hear him.

And Mr. Crow said: "Ah, poor Mr. 'Coon! You have not heard the latest. The hard winter has been a great strain on him and lately he has been very poorly. He is quite frail and feeble, and begs to be excused."

"Is that so?" said Mr. Bear. "Why, I[60] heard as I came along that Mr. 'Coon was out yesterday and was never looking better."

"All a mistake—all a mistake, Mr. Bear. Must have been his cousin from Rocky Hollow. They look very much alike. I'm greatly worried about Mr. 'Coon."

"Oh, well," said Mr. Savage Bear, "it doesn't matter much. Mr. 'Possum will do just as well. So fine and fat, I am told—I was quite reminded of one of Mr. Man's pigs I once enjoyed."

WHEN MR. 'POSSUM HEARD THAT HE FAINTED DEAD AWAY

WHEN MR. 'POSSUM HEARD THAT HE FAINTED DEAD AWAY

When Mr. 'Possum heard that he fainted dead away, but was not so far gone that he couldn't hear what Mr. Crow said. Mr. Crow wiped his eyes with a new handkerchief before he said anything.

"Oh, Mr. Bear," he called back, "it's so sad about Mr. 'Possum. We shall never see his like again. He had such a grand figure, and such a good appetite—and to think it should prove his worst enemy."

"Why—what's the matter—what's happened? You don't mean to say—"

"Yes, that's it—the appetite was too[61] strong for him—it carried him off. Mr. 'Coon and I did our best to supply it. That is what put Mr. 'Coon to bed and I am just a shadow of my old self. We worked to save our dear Mr. 'Possum. We hunted nights and we hunted days, to keep him in chicken pie with dumplings and gravy, but that beautiful appetite of his seemed to grow and grow until we couldn't keep up with it, this hard year, and one day our noble friend said:

"'Don't try any more—the more I eat the more I want—good-by.'"

Mr. Crow wiped his eyes again, while Mr. Bear grumbled to himself something about a nice state of affairs; but pretty soon he seemed to listen, for Mr. 'Possum was smacking his lips, thinking of those chicken pies Mr. Crow had described, and Mr. Bear has very quick ears.

"Mr. Crow," he said, "do you think Mr. 'Possum is really as dead as he might be?"

"Oh yes, Mr. Bear—at least twice as dead, from the looks of him" (for Mr. 'Possum[62] had suddenly fainted again). "We're just waiting for the ground to thaw to have the funeral."

"Well, Mr. Crow, I think I'll just come up and take a look at the remains, and visit you a little, and maybe say a word to poor Mr. 'Coon."

When Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum heard that they climbed out of their beds and got under them, for they didn't know what might happen next.

And they heard Mr. Crow say: "I'm awfully sorry, Mr. Bear, but the down-stairs door is locked, and bolted, and barred, and propped, and all our things piled against it, for winter; and I can't get it open until Mr. 'Coon gets strong enough to help me."

"Oh, never mind that," said A. Savage Bear, "I can make a run or two against it, and it will come down all right. I weigh seven hundred pounds."

FLUNG HIMSELF AGAINST THE DOWN-STAIRS DOOR WITH A GREAT BANG

FLUNG HIMSELF AGAINST THE DOWN-STAIRS DOOR WITH A GREAT BANG

Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum had crept out to listen, but when they heard that they dodged back under their beds again, and got[64] in the darkest corners, and began to groan, and just then Mr. Bear gave a run and flung himself against the down-stairs door with a great bang, and both of them howled, because they couldn't help it, they were so scared, and Mr. Crow was worried, because he knew that about the second charge, or the third, that door would be apt to give way, and then things in the Hollow Tree would become very mixed, and even dangerous.

Mr. Crow didn't know what to do next. He saw Mr. Savage Bear back off a good deal further than he had the first time, and come for the down-stairs door as hard as he could tear, and when he struck it that time, the whole Hollow Tree shook, and Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum howled so loud that Mr. Crow was sure Mr. Bear could hear them. They were all in an awful fix, Mr. Crow thought, and was just going to look for a safe place for himself when who should come skipping through the tree-tops but Mr. Robin. Mr. Robin, though quite small, is[65] not afraid of any Mr. Bear, because he is good friends with everybody. He saw right away how things were at the Hollow Tree—in fact, he had hurried over, thinking there might be trouble there.

"Oh, Tucky," he called—Tucky being Mr. Aspetuck Savage Bear's pet name—"I've brought you some good news—some of the very best kind of news."

Mr. Bear was just that minute getting fixed for his third run. "What is it?" he said, holding himself back.

"I found a big honey-tree, yesterday evening," Mr. Robin said. "The biggest one I ever saw. I'll show you the way, if you care for honey."

Now Mr. Bear likes honey better than anything in the world, and when he heard about the big tree Mr. Robin had found he licked out his tongue and smacked his lips.

"Of course I like honey," he said, "especially for dessert. I'll be ready to go with you in a few minutes."

Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum, who had[66] crept out to listen, fell over at those words, and rolled back under the beds again.

"But you ought not to wait a minute, Tucky dear," Mr. Robin said. "It's going to be warm when the sun gets out, and those bees will be lively and pretty fierce."

Mr. Savage Bear scratched his head, and his tongue hung out, thinking of the nice honey he might lose.

"It's beautiful honey, Tucky—clover honey, white and fresh."

A. Savage Bear's tongue hung out farther, and seemed fairly to drip. "Where is that tree?" he said.

"I HOPE MR. 'POSSUM'S FUNERAL WILL BE A SUCCESS"

"I HOPE MR. 'POSSUM'S FUNERAL WILL BE A SUCCESS"

"In the edge of the Sinking Swamps," said Mr. Robin. "Not far from your home. You can eat all you want and carry at least a bushel to your folks. You ought to be starting, as I say, before it warms up. Besides, a good many are out looking for honey-trees, just now."

Mr. Aspetuck Savage Bear just wheeled in his tracks and started south, which was the direction of the Sinking Swamps.

"You lead the way," he called to Mr. Robin, "and I'll be there by breakfast-time. I'm mighty glad you happened along, for there looks to be a poor chance for supplies around here. I've heard a lot about the Big Deep Woods, but give me the Sinking Swamps, every time." Then he looked back and called: "Good-by, Mr. Crow. Best wishes to poor Mr. 'Coon, and I hope Mr. 'Possum's funeral will be a success."

And Mr. Crow called good-by, and motioned to Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum, who had crept out again a little, and they slipped over to the window and peeked out, and saw Mr. Aspetuck Savage Bear following Mr. Robin back to the Sinking Swamps, to the honey-tree which Mr. Robin had really found there, for Mr. Robin is a good bird, and never deceives anybody.

"I HAVE NEVER HEARD ANYTHING SO WONDERFUL AS THE WAY SHE TELLS IT"

"I HAVE NEVER HEARD ANYTHING SO WONDERFUL AS THE WAY SHE TELLS IT"

"This is a new friend I have made—possibly a distant relative, as we seem to belong to about the same family, though, of course, it doesn't really make any difference. Her name is Myrtle—Miss Myrtle Meadows—and she has had a most exciting, and very strange, and really quite awful adventure. I have brought her over because I know you will all be glad to hear about it. I have never heard anything so wonderful as the way she tells it."

Mr. Rabbit looked at Miss Meadows, and Miss Meadows tried to look at Jack Rabbit, but was quite shy and modest at being praised before everybody in that way. Then Mr. 'Coon brought her a nice little low chair, and she sat down, and they all asked her to tell about her great adventure, because they said they were tired of hearing their own old stories told over and over, and nearly always in the same way, though Mr. 'Possum could change his some when he tried. So then Miss Myrtle began to tell her story, but kept looking down at her lap at first,[74] being so bashful among such perfect strangers as the Hollow Tree people were to her at that time.

"Well," she said, "I wasn't born in the Big Deep Woods, nor in any woods at all, but in a house with a great many more of our family, a long way from here, and owned by a Mr. Man who raised us to sell."

When Miss Myrtle said that the 'Coon and 'Possum and the Old Black Crow took their pipes out of their mouths and looked at her with very deep interest. They had once heard from Mr. Dog about menageries,[1] where Deep Woods people and others were kept for Mr. Man and his friends to look at, but they had never heard of a place where any of their folks were raised to sell. Mr. 'Possum was just going to ask a question—probably as to how they were fed—when Mr. Rabbit said, "'Sh!" and Miss Meadows went on:

"It was quite a nice place, and we were[75] pretty thick in the little house, which was a good deal like a cage, with strong wires in front, though it had doors, too, to shut us in when it rained or was cold. Mr. Man, or some of his family, used to bring us fresh grass and clover and vegetables to eat, every day, and sometimes would open a door and let us out for a short time on the green lawn. We never went far, or thought of running away, but ran in, pretty soon, and cuddled down, sometimes almost in a pile, we were so thick; and we were all very happy indeed.

"But one day Mr. Man came to our house and opened the door and reached in and lifted several of us out—about twenty or so, I should think—one after another, by the ears—and put us into a flat box with slats across the top, and said, 'Now you little chaps are going to have a trip and see something.' I didn't know what he meant, but I can see now that he didn't mean nearly so much as happened—not in my case. A number of my brothers and sisters were in[76] the box with me, and though we were quite frightened, we were excited, too, for we wondered where we were going, and what wonderful things we should see."

MISS MYRTLE PAUSED AND WIPED HER EYES

MISS MYRTLE PAUSED AND WIPED HER EYES

Miss Myrtle paused and wiped her eyes with a handkerchief that looked very much like one of Jack Rabbit's; then she said:

"I suppose I shall never know what became of all the others of our poor little broken family, and I know they are wondering what became of me, but of course there is no way to find out now, and Mr. Jack Rabbit says I must try to forget and be happy.

"Well, Mr. Man put the box into a wagon and we rode and rode, and were so frightened, for we had never done such a thing before, and by and by we came to a very big town—a place with ever so many houses and all the Mr. Mans and their families in the world, I should think, and so much noise that we all lay flat and tried to bury our heads, to keep from being made deaf. By and by Mr. Man stopped and took our box from the wagon, and another Mr. Man stepped out of a[78] place that I learned later was a kind of store where they sell things, and the new Mr. Man took our box and set it in front of his store, and put a card on it with some words that said, 'For Sale,' and threw us in some green stuff to eat, and there we were, among ever so many things that we had never seen before.

"Well, it was not very long until a tall Mr. Man and his little boy stopped and looked at us, and Mr. Store Man came out and lifted up the cover of our box and held us up, one after the other, by the ears, until he came to Tip, one of my brothers who wasn't very smart, but was quite good-looking and had a tuft of white on his ears which made him have that name. Mr. Man's boy said he would take Tip, and Tip giggled and was so pleased because he had been picked first. Mr. Store Man put him in a big paper bag, and that was the last we saw of Tip. I hope he did not have the awful experience I had, though, of course, everything is all right now," and Miss Myrtle looked at Jack Rabbit, who looked[79] at Miss Myrtle and said that no harm should come to her ever again.

"Smut was next to go—a nice little chap with a blackish nose. A little girl of Mr. Man's bought him, and it was another little girl that bought me. She looked at all of us a good while, and pretty soon she happened to see that I was looking at her, and she said she could see in my eyes that I was asking her to take me, which was so, and pretty soon I was in a bag, too, and when the little girl opened the bag I was in her house—a very fine place, with a number of wonderful things in it besides her family, and plenty to eat—much more than I wanted, though I had a good appetite, being young.

"I was very lonesome, though, for there were none of the Rabbit family there, and I had nobody to talk to, or cuddle up to at night. I had a little house all to myself, but often through the day my little girl would hold me and stroke my fur, trying as hard as she could to make me happy and enjoy her society.[80]

"I really did enjoy it, too, sometimes, when she did not squeeze me too hard, which she couldn't help, she was so fond of me. When I would sit up straight and wash my face, as I did every morning, she would call everybody to see me, and said I was the dearest thing in the world."

When Miss Meadows said that Jack Rabbit looked at her with his head tipped a little to one side, as if he were trying to decide whether Mr. Man's little girl had been right or not. Then he looked at the Hollow Tree people and said:

"H'm! H'm! Very nice little girl" (meaning Mr. Man's, of course), "and very smart, too."

"I got used to being without my own folks," Miss Meadows went on, "but I did not forget the nice green grass of the country, and always wanted to go back to it. If I had known what was going to happen to me in the country I should not have been so anxious to get there.

"I had been living with that little girl and[81] her family about a month, I suppose, when one day she came running to my house and took me out, and said:

"'Oh, Brownie'—that was her name for me—'we are going to the country, Brownie dear, where you can run and play on the green grass, and eat fresh clover, and have the best time.'

"Well, of course I was delighted, and we did go to the country, but I did not have the best time—at least, not for long.

"It was all right at the start. We went in Mr. Man's automobile. I had never seen one before, and it was very scary at first. I was in a box on the back seat with Mr. Man's little girl and her mother, and I stood up most of the time, and looked over the top of the box at the world going by so fast that it certainly seemed to be turning around, as I once heard the little girl say it really did. When we began to come to the country I saw the grass and woods and houses, all in a whirl, and the little girl helped me so I could see better, and my heart beat so fast[82] that I thought it was going to tear me to pieces. I felt as if I must jump out and run away, but she held me very tight, and by and by I grew more peaceful.

"We got there that evening, and it was a lovely place. There was a large lawn of grass, and some big trees, and my little girl let me run about the lawn, though I was still so scared that I wanted to hide in every good place I saw. So she put me in a pretty new house that had a door, and wire net windows to look out of, and then set the little house out in the yard and gave me plenty of fresh green food, and I was just getting used to everything when the awful thing happened.

"It happened at night, the worst time, of course, for terrible things, and they generally seem to come then. It was such a pleasant evening that my little girl thought it would be well for me to stay in my house outside, instead of having me in the big house, which she thought I did not care for, and that was true, though I can see now that the big[83] house would have been safer at such a time.

"So I stayed in my little house out on the terrace, and thought how pleasant it was out there, and nibbled some nice carrot tops she had put in for me, and watched the lights commence to go out in the big house, and saw my little girl come to the window and look out at me, and then her light went out, too, and pretty soon I suppose I must have gone to sleep.[84]

"I knew what it was after me. Our Mr.[85] Man had a big old Mr. Dog that I had seen looking at me very interestedly once before when my little girl carried my house past him. They kept him fastened with a chain, but somehow he had worked himself loose, and now he had come to make a late supper out of poor defenseless me. I would have talked to him, and tried to shame him out of it, but I was too scared even to speak, for he was biting and clawing at that wire net window as hard as he could, and I could see that it was never going to keep him out, for it was beginning to give way, and all of a sudden it did give way, and his big old head came smashing right through into my house, and I expected in another second to be dead.

"But just in that very second I seemed to come to life. I didn't have anything to do with it at all. My legs suddenly turned into springs and sent me flying out under old Mr. Dog's neck, between his forefeet; then they turned into wings, and if I touched the ground again for at least three miles I don't[86] remember it. I could hear old Mr. Dog back there, and I could tell by his language that he was mad. He thought he was chasing me, but he wasn't. He was just wallowing through the bushes and across a boggy place that I had sailed over like a bird. If he could have seen how fast I was going he would have thought he was standing still. But he was old and foolish, and kept blundering along, until I couldn't hear him any more, he was so far behind. Then, by and by, it was morning, and I really came to life and found I was tired and hungry and didn't know in the least where I was.

"There didn't seem to be anything to eat there, either, but only leaves and woods; and I was afraid to taste such green things as I saw, because they were wild and might make me sick. So I went on getting more tired and hungry and lost, and was nearly ready to give up when I heard some one call, just overhead, and I looked up, and saw a friendly-looking bird who said his[88] name was Mr. Robin, and asked if there was anything he could do for me. When I told him how tired and hungry I was, he came down and showed me some things I could eat without danger, and invited me home with him. He said I was in the Big Deep Woods, and that there was a vacant room in the tree where he and Mrs. Robin had their nest and I could stay there as long as I liked.

"SO I WENT HOME WITH MR. ROBIN"

"SO I WENT HOME WITH MR. ROBIN"

"So I went home with Mr. Robin, and Mrs. Robin was ever so kind, and said she thought I must be of the same family as Mr. Jack Rabbit, because we resembled a good deal, and sent over for him right away. I was ever so glad to think I was going to see one of my own folks again, and when Mr. Rabbit came we sat right down, and I told him my story, and we tried to trace back and see what relation we were, but it was too far back, and besides, I was too young when I left home to know much about my ancestors. Mr. Rabbit said if we were related at all it must be through his mother,[89] as she was very handsome, and he thought I looked like her a good deal. He said what a fine thing it was that I had quit being a house rabbit and had decided to be a wild, free rabbit in the Big Deep Woods, though, of course, it was really old Mr. Dog who decided it for me, and I was quite sorry to leave my little girl, who was always so good to me and loved me very much. It makes me sad when I remember how I saw her at the window, that last time, but I don't think I want to go back, anyway, now since Jack—Mr. Rabbit, I mean—is teaching me all about Deep Woods life and says he is not going to let me go back at all—ever!"

Little Miss Myrtle all at once seemed very much embarrassed again, and looked down into her lap, and Mr. Jack Rabbit seemed quite embarrassed, too, when he tried to say something, because he had to cough two or three times before he could get started.

"H'm! H'm!" he said. "Now that you[90] have all heard Miss Meadows's wonderful story, and what a narrow escape she had—an escape which those present can understand, for all of us have had close calls in our time—I am sure you will be glad to hear that the little stranger has consented to remain in the Big Deep Woods and share such of the Deep Woods fortunes as I can provide for her. In fact—I may say—h'm! that—h'm!—Miss Meadows a week from to-day is to become—h'm!—Mrs. Jack Rabbit."

Then all the Hollow Tree people jumped right up and ran over to shake hands with Mr. Rabbit and Miss Myrtle Meadows, and Mr. 'Possum said they must have a big wedding, because big weddings always meant good things to eat, and that everybody must come, and that he would show them how a wedding was to be enjoyed. Mr. Crow promised to cook his best things, and Mr. 'Coon said he would think up some performances for the guests to do, and then everybody began to talk about it, until it[91] was quite late before Jack Rabbit and Miss Meadows walked away toward Mr. Robin's, calling back, "Good night!" to their good friends of the Hollow Tree.

The Little Lady nods. "But you never told me about the wedding," she says, "and I want to hear about that more than anything. They had a wedding, didn't they?—the Hollow Tree people were going to get it up, you know."[96]

"Well, they did; and there was never such a wedding in the Big Deep Woods. This was the way it was:"

Mr. 'Possum began to plan right away all the things that Mr. Crow was to cook, and went out every night to help bring in something, though Mr. 'Possum is not a great hand for work, in general, except when somebody else does it. Mr. 'Coon went right to work on the program of things to be done at the wedding, and decided to have a regular circus, where everybody in the Big Deep Woods could show what he could do best, or what he used to do best when he was young. Every little while Jack Rabbit and Miss Meadows walked over to talk about it, and by and by they came over and wrote out all the invitations, which Mr. Robin promised to deliver, though he had once made a big mistake with an invitation by having a hole in his pocket.[2]

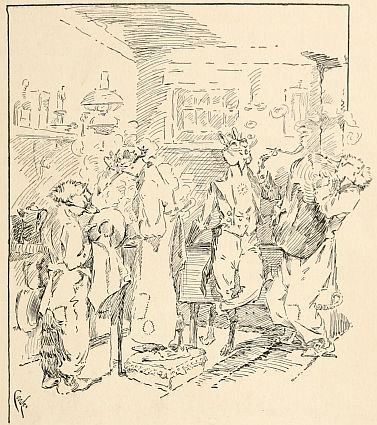

STOPPED TO TALK A LITTLE WITH EACH ONE

STOPPED TO TALK A LITTLE WITH EACH ONE

But Mr. Robin didn't make any mistake[98] this time, and went around from place to place, and stopped to talk a little with each one, because he is friends with everybody. Mr. Redfield Bear and Mr. Turtle and Mr. Squirrel and Mr. Dog and Mr. Fox all said they would come, and would certainly bring something for the happy couple, for it wasn't every day that one got a chance to attend such a wedding as Jack Rabbit's would be; and everybody remembered how the bride had come to the Deep Woods in that most romantic and strange way, after having been brought up with Mr. Man's people, and all wanted to know what she looked like, and if she spoke with much accent, and what she was going to wear, and if Mr. Robin thought she would be satisfied to stay in the Deep Woods, which must seem a great change; and if she had a pleasant disposition. They knew, of course, Mr. Robin would be apt to know about most of those things, because she had been staying at his house ever since that awful night when she escaped from old Mr. Dog.[99]

Mr. Robin said he had never known any one with a sweeter nature than Miss Myrtle's, and that old Mr. Dog's loss had been the Big Deep Woods' gain. Then he told them as much as he knew about the wedding, and what each one was expected to do, as a performance, and hurried home to help Mrs. Robin, who was as busy as she could be, getting the bride's outfit ready and teaching her something about housekeeping, though Jack Rabbit, who had been a bachelor such a long time, would know a number of things, too.

Well, they decided to have the wedding out under some big trees by the Race Track, because that would give a good, open place for the performances, which everybody was soon practicing. Mr. Crow was especially busy, because he was going to show how he used to fly. Every morning he was out there very early, running and flapping about, and every afternoon he was cooking, right up to the day of the wedding.

Mr. 'Possum was up himself, that morning,[100] almost before daylight, going around and looking at all the things Mr. Crow had cooked, tasting a little of most of them, though he had already tasted of everything at least seven times while the cooking was going on; and he said that if there was one thing in the world that would tempt him to get married it was having a wedding given him such as Mr. Rabbit's was going to be.

Then when Mr. Crow and Mr. 'Coon had snatched a cup of coffee and a bite they all gathered up the fine cakes and chicken pies and puddings and things and started for the Race Track, for the wedding was going to begin pretty early and last all day.

It looked a little cloudy in the morning, but it cleared up before long, and was as fine a June day as anybody could ask for. As soon as the Hollow Tree people came they put down their things and began practising their performances for the last time. Mr. Crow said if he was going to do his old flying trick it was well that he had one more try at it; then[101] he got in light flying costume and started from a limb, and did pretty well for any one that had been out of practice so long; and he could even rise from the ground by going out on the Race Track and taking a running start. Then, by and by, Mr. Redfield Bear came along, bringing a box of fine maple sugar for the young couple, and Mr. Fox came with a brand-new feather bed, and Mr. Squirrel brought a big nut cake which Mrs. Squirrel had made, and sent ahead by him because she might be a little late, on account of the children.

Then Jack Rabbit himself came with the finest clothes on they had ever seen him wear, and with a beautiful bouquet, and carrying a new handkerchief and a pair of gloves and a cane. Everybody stood right up when he walked in, and said they had never seen him look so young and handsome and well-dressed; and Mr. Rabbit bowed and said, "To be happy is to be young—to be young is to be handsome—to be handsome is to be well-dressed." Then everybody said that[102] besides all those things Jack Rabbit was certainly the smartest person in the Big Deep Woods.

And just then Mr. and Mrs. Robin arrived with the bride, and when the Deep Woods people saw her they just clasped their hands and couldn't say a word, for she took their breath quite away.

Miss Meadows was almost overcome, too, with embarrassment, and was looking down at the ground, so she didn't see who was there at first; but when she happened to look up and saw Mr. Bear she threw up her arms and would have fallen fainting if Jack Rabbit hadn't caught her, for she had never seen such a large, fierce-looking Deep Woods person before. But Jack Rabbit told her right away that this was not any of the Savage Bear family, but Cousin Redfield, one of the Brownwood Bears, who had been friendly a long time with all Deep Woods people, and he showed her the nice present Mr. Bear had brought. So then she thanked Cousin Redfield Bear very prettily, though she looked as[104] if she might fly into Jack Rabbit's arms at any moment.

She did more than that presently, though not on Mr. Bear's account. Everybody was busy getting things ready when in walked Mr. Dog, all dressed up and with a neat package in his hand.

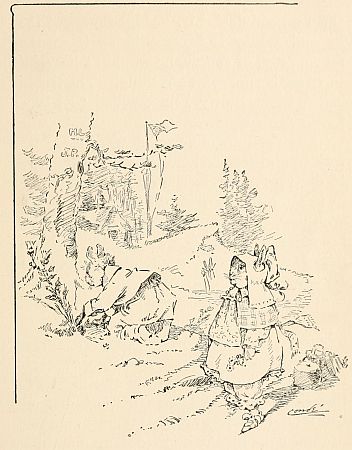

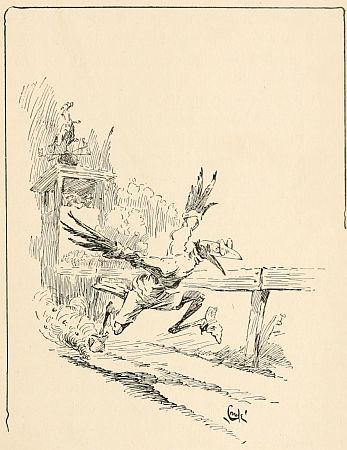

JACK RABBIT WOULD HAVE STAYED A BACHELOR IF SHE HADN'T TRIPPED IN HER WEDDING-GOWN

JACK RABBIT WOULD HAVE STAYED A BACHELOR IF SHE HADN'T TRIPPED IN HER WEDDING-GOWN

Well, nobody had thought to tell Miss Meadows about this good Mr. Dog who lived with Mr. Man in the edge of the Deep Woods and had been friendly with the Hollow Tree people so long, and when everybody said, "Why, here's Mr. Dog! How do you do, Mr. Dog?" she whirled around and then gave a wild cry and made the longest leap the Hollow Tree people had ever seen—they said so, afterward—and never stopped to faint, but dashed away, and Jack Rabbit would have stayed a bachelor if she hadn't tripped in her wedding-gown; though Jack was in time to catch her before she fell, which saved her dress from damage. Then Mr. Rabbit explained to her all about this Mr. Dog, and coaxed her back, and Mr. Dog made his best[105] bow and offered his present—a nice new cook-book which somebody had sent to Mrs. Man, who said she didn't want it, because she had her old one with a great many of her own recipes written in. He said he thought it was just the thing for the bride to start new with, and she would, of course, add her own recipes, too, in time. Mr. Crow said he would give her some of his best ones, right away, especially the ones for the things he had brought to-day, which ought to be eaten now, pretty soon, while they were fresh. So that reminded them all of the wedding, and Miss Meadows thanked Mr. Dog for his handsome and useful present, and just then Mr. Turtle came in, bringing some beautiful bridal wreaths he had promised to make, and right behind him was Mr. Owl, who is thought to be wise, and is Doctor and Preacher and Lawyer in the Big Deep Woods, and performs all the ceremonies.

So then everybody had come, and there was nothing to wait for, and Mr. Jack Rabbit led Miss Meadows out in the center of the[106] nice shade, and Mr. Owl stood before them, and all the other Deep Woods people arranged themselves in a circle except Mr. and Mrs. Robin, who stood by the bride and groom.

Then Mr. Owl said, "Are all present?"

And everybody said, "All present who have been invited."

Then Mr. Owl said, "Who gives this bride away?"

"I do," said Mr. Robin, "though she isn't really mine, because I only happened to find her one morning when—"

"MAY YOU BE HAPPY AS LONG AS POSSIBLE, AND LONGER"

"MAY YOU BE HAPPY AS LONG AS POSSIBLE, AND LONGER"

Mr. Robin was going on to explain all about it, but Mr. Owl said, "'Sh!" and went right on:

"Mr. Jack Rabbit, Mr. Robin gives you Miss Myrtle Meadows to love and cherish and obey, and Mr. Dog has brought a cook-book, and Mr. Bear some maple sugar, and all the others have brought good things. The wedding-feast is therefore waiting. What is left will be yours. Let us hope there will still be the cook-book, but Miss Myrtle[108] Meadows will not be with us, for I now pronounce her to be Mrs. Jack Rabbit, and may you be happy as long as possible, and longer."

Then everybody became suddenly excited and pushed up to congratulate Mr. and Mrs. Rabbit, and when the bride heard herself called "Mrs. Jack Rabbit" she was more embarrassed than ever, and couldn't get used to it for at least two minutes. Then they all sat down and ate and ate, and Mr. 'Possum said he never felt so romantic in his life, which was all he did say, except, "Please pass the chicken pie," or, "A little more gravy, please."

Well, when they had all had about enough, except Mr. 'Possum, who was still taking a taste of this and a bite of that, where things were in reach, Mr. Rabbit got up and said he had written a little something for the occasion, and if they cared to hear it he would read it now.

So then they all said, "Read it! Read it!" and Jack Rabbit stood up very nice and straight, and read:[109]

Everybody cheered, of course, and then Mr. and Mrs. Robin suddenly sprang up into the air and began circling around and around and darting over and under, in the very prettiest way, and so fast that it almost made one dizzy to watch them. Sometimes they would seem to be standing straight up, facing each other for a few seconds, then they would whirl over and over in regular somersaults, suddenly darting high up in the air, sailing down, at last, in a regular spiral, and landing on the grass right in front of the bride and groom.

Then all clapped their hands and said it was the most wonderful thing ever seen, and Mr. Crow said if he should try to fly like that he would never know afterward whether his head was on right or not.

Then Mr. 'Coon rose to remark that Mr. Fox was next on the program and would give a little exhibition in light and fancy running.

Mr. Fox, who hadn't eaten as much dinner as he might, because he wanted to be in good trim for his performance, got right up and[112] with a leap landed out on the Race Track, and then for the next five minutes they could hardly tell whether he was running or flying, he leaped so lightly and skipped so swiftly, his fine, bushy tail waving like a beautiful, graceful plume that seemed to guide him this way and that and to be just the thing for Mr. Fox's purpose.

Mr. Fox was applauded, too, when he sat down, and so was Mr. Squirrel, who came next, and showed that his bushy tail was also useful, for he gave a leaping exhibition from one limb to another, and leaped farther and farther each time, until they thought he would surely injure himself; but he never did and he got as much applause as Mr. Fox when he finally landed right in front of the bride and groom and made a neat bow.

Then Mr. Turtle gave a heavy-weight carrying exhibition, and let all get on his back that could stick on, and walked right down the same Race Track where so long before he had run the celebrated race with Mr. Hare, and said when he came back he felt just as[114] young and able to-day as he had then, and was much stronger in the shell.

IF YOU COULD HAVE SEEN COUSIN REDFIELD DANCE

IF YOU COULD HAVE SEEN COUSIN REDFIELD DANCE

Cousin Redfield Bear danced. Nobody thought he was going to do that. They thought he would likely give a climbing exhibition, or something of the kind. But he didn't—he danced. And if you could have seen Cousin Redfield dance, with his arms akimbo, and his head thrown back, and watch him cut the pigeon-wing, you would have understood why he wanted to do it. He knew it would amuse them and make them want to dance, too; which it did, and pretty soon they were in a circle around him, bride and groom and all, dancing around and around and singing the Hollow Tree song, which all the Deep Woods people know.

They danced until they were tired, and then it was Mr. Dog's turn to do something. Mr. Dog said he couldn't fly, though certainly he would like to; and he couldn't run like Mr. Fox, or jump like Mr. Squirrel, or make poetry like Mr. Rabbit, or dance like Mr. Bear—though once, a long time ago, as[115] some of them might remember, he had taken a dancing-lesson from Jack Rabbit.[3] He couldn't do any of those things as well as the others, he said, so he would just make a little speech called:

"Mr. Man is my friend, and we live together. He is always my friend, though you might not suspect it, sometimes, the things he says to me. But he is, and I am Mr. Man's friend, through thick and thin.

"I am also the friend, now, of the Deep Woods people, and expect to remain so, because I have learned to know them and they have learned to know me. That is the trouble about the Deep Woods people and Mr. Man. They don't know each other. The Deep Woods people think that Mr. Man is after them, and there is some truth in it, because Mr. Man thinks the Deep Woods[116] people are after him, or his property, when, of course, all Deep Woods people know that it was never intended that Mr. Man should own all the chickens, and they are obliged to borrow one, now and then, in order to have chicken pie, such as has been served on this happy occasion.

"I am looking forward to the day when Mr. Man will understand this, as well as the Hollow Tree people do, and will become friendly and open his heart and hen-house to all who would enter in."

CALLED FOR THE FEATHER BED

CALLED FOR THE FEATHER BED

Mr. Dog's speech made quite a sensation. Mr. 'Possum, especially, said it was probably the greatest speech of modern times, and was going on to say more when Mr. 'Coon whispered to him that it was their turn on the program. So then Mr. 'Coon and Mr. 'Possum got up, side by side, and Mr. 'Possum walked rather soggily, because he had eaten so much, though he managed to get up a little hickory-tree and out on a smooth, straight limb while Mr. 'Coon climbed up another, a few feet away. Then all at once Mr. 'Possum[117] dropped and held by his tail, which was hooked around the limb, and Mr. 'Coon dropped and held by his hands, and then began to swing; and pretty soon, when Mr. 'Coon was swung out nearly straight in Mr. 'Possum's direction, he let go and turned over in the air and caught Mr. 'Possum's hands, and they both swung, and everybody cheered and said that was the finest thing yet. Then they went right on swinging—Mr. 'Possum holding by his tail, until they got a good start, and pretty soon Mr. 'Possum gave Mr. 'Coon a big swing, expecting him to turn clear over and catch his own limb again. But Mr. 'Possum and Mr. 'Coon had both eaten a good deal, and Mr. 'Coon didn't get a very good start. He just missed the limb he was aimed at, and hit Mr. Fox's feather bed, which was lying right in front of Mr. and Mrs. Rabbit, along with other presents, all of which was a good thing for Mr. 'Coon. For Mr. 'Coon is pretty smart and quick to think. He jumped right up when everybody was laughing, and made a bow to Mr. and[118] Mrs. Rabbit as if he had meant to land just that way, and everybody laughed still harder and enjoyed it more than anything. Then Mr. 'Possum swung up and caught his limb with his hands, but couldn't get back on it again, and called for the feather bed, which Mr. 'Coon and Mr. Fox brought, and Mr. 'Possum dropped on it like a sack of salt, and everybody enjoyed it more and more.

WENT OUT ON THE OPEN TRACK AND TOOK A LITTLE RUN

WENT OUT ON THE OPEN TRACK AND TOOK A LITTLE RUN

Well, it was Mr. Crow's turn then, and he said he would probably have to have the feather bed, too. But he went out on the open track and took a little run, and about the second time around spread out his big, black wings and lifted himself from the ground, not very high at first, and he had to flap pretty hard, but he kept getting a little higher all the time, and presently he swung about in a big circle, and went sailing and flapping around and around, up and up, until he was as high as the little trees, then as high as the big trees, then as high as a church steeple, and still kept going up until he looked small and black against the sky; and Mr.[120] Robin whispered to Mrs. Robin that Mr. Crow might be old and out of practice, but they had never dared to fly as high as that, and said he didn't believe any of Mr. Crow's family had ever gone higher.

Mr. Crow was just a black speck, pretty soon, and everybody was getting rather scared, for they wondered what would happen to him if something about him should give way; and just when they were all watching and keeping quite still, they heard the most curious sound, that seemed to be coming nearer, getting louder and louder. At first nobody spoke, but just listened. Then Mr. 'Possum said something must have happened to Mr. Crow's machinery and he was coming down for repairs. And sure enough, they did see Mr. Crow coming down, about as fast as he could drive, making quick circles, and the noise was getting louder and louder, though it didn't seem to be Mr. Crow who was making it, for he never could make a sound like that, no matter what had happened to his works.[122]

Mr. Crow came down a good deal faster than he went up, and in about five seconds more landed right among them, and they saw he was scared.

"Oh," he gasped, "we are all lost! The biggest bird in the world is coming to devour us! I saw it—it is making that terrible noise! It is as big as Mr. Man's house! It is as big as his yard! It is as big as the Big Deep Woods!"

And just then a great black shadow, like the shadow of a cloud, came right over them, and that noise got so loud it drowned everything, and when they looked—for they were too scared to run—sure enough, right above them was the biggest bird in the world—a thousand times bigger than Mr. Crow, of stranger shape than anything they had ever seen, and very terrible indeed. But all at once Mr. Dog gave a quick bark, which made them all jump—especially the bride—and shouted:

"It's all right—it's all right! I know what it is. I see a Mr. Man up there. It's[123] a flying-machine; it's only passing over, and won't hurt us at all!"

And sure enough all the rest could see a Mr. Man up there, too, then; and Mr. Dog went on to tell them how he had seen some pictures of just such a machine in one of Mr. Man's picture papers, and that it was the great new invention by which Mr. Man could go around in the air like a bird, though probably not so well as Mr. and Mrs. Robin and Mr. Crow, and certainly with a good deal more noise.

Then the Deep Woods people were not afraid any more, and watched the flying-machine as long as they could see it, and when it was quite out of sight Mr. Rabbit made a little speech in which he said that if anything had been needed to make his grand wedding complete it was to have a performance given for it by Mr. Man, even though Mr. Man might not realize that he was entertaining a wedding. And everybody said, "Yes, yes, that's so," and that this was the greatest day in the Big Deep Woods, which I believe it really was.[124]

Then they all formed a procession and marched to Jack Rabbit's house, to take home the bride and groom. As they marched they sang the Hollow Tree song, ending with the chorus:

[1] "Mr. Dog at the Circus," in The Hollow Tree Snowed-In Book.

[2] "How Mr. Dog Got Even." The Hollow Tree and Deep Woods Book.

[3] "Mr. Dog Takes Lessons in Dancing," in The Hollow Tree and Deep Woods Book.

Duplicate chapter titles were removed.

Illustrations were transferred from their original locations to where the caption is mentioned in the text.

End of Project Gutenberg's Mr. Rabbit's Wedding, by Albert Bigelow Paine

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. RABBIT'S WEDDING ***

***** This file should be named 28193-h.htm or 28193-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/8/1/9/28193/

Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional