> This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: History of Woman Suffrage, Volume II

Editor: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage

Release Date: February 9, 2009 [eBook #28039]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE, VOLUME II***

Transcriber's Note

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including obsolete and variant spellings and other inconsistencies. Text that has been changed to correct an obvious error is noted at the end of this ebook.

Many occurrences of mismatched single and double quotes remain as they were in the original.

In presenting to our readers the second volume of the "History of Woman Suffrage," we gladly return our thanks to the press for the many favorable notices we have received from leading journals, both in the old world and the new. The words of cordial approval from a large circle of friends, and especially from women well known in periodical literature, have been to us a constant stimulus during the toilsome months we have spent in gathering material for these pages. It was our purpose to have condensed the records of the last twenty years in a second volume, but so many new questions in regard to Citizenship, State rights, and National power, indirectly bearing on the political rights of women, grew out of the civil war, that the arguments and decisions in Congress and the Supreme Courts have combined to swell these pages beyond our most liberal calculations, with much valuable material that can not be condensed nor ignored, making a third volume inevitable.

By their active labors all through the great conflict, women learned that they had many interests outside the home. In the camp and hospital, and the vacant places at their firesides, they saw how intimately the interests of the State and the home were intertwined; that as war and all its concomitants were subjects of legislation, it was only through a voice in the laws that their efforts for peace could command consideration.

The political significance of the war, and the prolonged discussions on the vital principles of government involved in the reconstruction, threw new light on the status of woman in a republic. Under a liberal interpretation of the XIV. Amendment, women, believing their rights of citizenship secured, made several attempts to vote in different States. Those who succeeded were arrested, tried, and convicted. Those who were denied the right to register their names and deposit their votes, sued the Inspectors of Election. Others[Pg iv] attempting to practice law, being denied that right in the States, took their cases up to the Supreme Court of the United States for adjudication. Others invaded the pulpit, asking to be ordained, which brought the question of woman's right to preach before ecclesiastical assemblies. These various attempts to secure her political and civil rights have called forth endless discussions on woman's true position in the State, the church, and the world of work.

While gratefully accepting the generous praises of our friends, we must briefly reply to some strictures by our critics. Some object to the title of our work; they say you can not write the "History of Woman Suffrage" until the fact is accomplished. We feel that already enough has been achieved to make the final victory certain. Women vote in England, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, and even India, on certain interests and qualifications; in Wyoming and Utah on all questions, and on the same basis as male citizens; and in a dozen States of the Union on school affairs. Moreover, women are filling many offices, such as Clerks of Courts, Notaries Public, Masters in Chancery, State Librarians, School Superintendents, Commissioners of Charity, Post Mistresses, Pension Agents, Engrossing and Enrolling Clerks in Legislative Assemblies.

After years of persistent effort a resolution was passed in both Houses, during the present session of Congress (1882), securing "a select committee on the political Rights and Disabilities of Woman"—the first time in the history of our Government that a special committee to look after the interests of woman was ever appointed. A proposition for a XVI. Amendment to the National Constitution, to secure to women the right of suffrage, is now pending in Congress. Some phase of this question is being debated every year in State Legislatures. Propositions for so amending their constitutions as to extend the elective franchise to women will be voted upon by the people in four of the Western States within the coming two years. These successive steps of progress during forty years are as surely a part of the History of Woman Suffrage as will be the events of the closing period in which victory shall at last crown the hard fought battles of half a century.

CHAPTER XVI.page

WOMAN'S PATRIOTISM IN THE WAR.

The first gun on Sumter, April 12, 1861—Woman's military genius—Anna Ella Carroll—The Sanitary Movement—Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell—The Hospitals—Dorothea Dix—Services on the battle-field—Clara Barton—The Freedman's Bureau—Josephine Griffing—Ladies' National Covenant—Political campaigns—Anna Dickinson—The Woman's Loyal National League—The Mammoth Petition—Anniversaries—The Thirteenth Amendment1

CONGRESSIONAL ACTION.

First Petitions to Congress December, 1865, against the word "male" in the 14th Amendment—Joint resolutions before Congress—Messrs. Jenckes, Schenck, Broomall, and Stevens—Republicans protest in presenting petitions—The women seek aid of Democrats—James Brooks in the House of Representatives—Horace Greeley on the petitions—Caroline Healy Dall on Messrs. Jenckes and Schenck—The District of Columbia Suffrage Bill—Senator Cowan, of Pennsylvania, moved to strike out the word "male"—A three days' debate in the Senate—The final vote nine in favor of Mr. Cowan's amendment, and thirty-seven against90

NATIONAL CONVENTIONS IN 1866-67.

The first National Woman Suffrage Convention after the war—Speeches by Ernestine L. Rose, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Henry Ward Beecher, Frances D. Gage, Theodore Tilton, Wendell Phillips—Petitions to Congress and the Constitutional Convention—Mrs. Stanton a candidate to Congress—Anniversary of the Equal Rights Association152

THE KANSAS CAMPAIGN—1867.

The Battle Ground of Freedom—Campaign of 1867—Liberals did not Stand by their Principles—Black Men Opposed to Woman Suffrage—Republican Press and Party Untrue—Democrats in Opposition—John Stuart Mill's Letters and Speeches Extensively Circulated—Henry B. Blackwell and Lucy Stone Opened the Campaign—Rev. Olympia Brown Followed—60,000 Tracts Distributed—Appeal Signed by Thirty-one Distinguished Men—Letters from Helen E. Starrett, Susan E. Wattles, Dr. R. S. Tenney, Lieut.-Governor J. B. Root, Rev. Olympia Brown—The Campaign closed by ex-Governor Robinson, Elizabeth Cady Stanton,[Pg vi] Susan B. Anthony, and the Hutchinson Family—Speeches and Songs at the Polls in every Ward in Leavenworth Election Day—Both Amendments lost—9,070 Votes for Woman Suffrage, 10,843 for Negro Suffrage229

NEW YORK CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION.

Constitution Amended once in Twenty Years—Mrs. Stanton before the Legislature Claiming Woman's Right to Vote for Members to the Convention—An Immense Audience in the Capitol—The Convention Assembled June 4th, 1867. Twenty Thousand Petitions Presented for Striking the Word "Male" from the Constitution—"Committee on the Right of Suffrage, and the Qualifications for Holding Office" Horace Greeley, Chairman—Mr. Graves, of Herkimer, Leads the Debate in favor of Woman Suffrage—Horace Greeley's Adverse Report—Leading Advocates Heard before the Convention—Speech of George William Curtis on Striking the Word "Man" from Section 1, Article 11—Final Vote, 19 For, 125 Against—Equal Rights Anniversary of 1868269

RECONSTRUCTION.

The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments—Universal Suffrage and Universal Amnesty the Key-note of Reconstruction—Gerrit Smith and Wendell Phillips hesitate—A Trying Period in the Woman Suffrage Movement—Those Opposed to the word "Male" in the Fourteenth Amendment Voted Down in Conventions—The Negro's Hour—Virginia L. Minor on Suffrage in the District of Columbia—Women Advised to be Silent—The Hypocrisy of the Democrats preferable to that of the Republicans—Senator Pomeroy's Amendment—Protests against a Man's Government—Negro Suffrage a Political Necessity—Charles Sumner Opposed to the Fourteenth Amendment, but Voted for it as a Party Measure—Woman Suffrage for Utah—Discussion in the House as to who Constitute Electors—Bills for Woman Suffrage presented by the Hon. George W. Julian and Senators Wilson and Pomeroy—The Fifteenth Amendment—Anna E. Dickinson's Suggestion—Opinions of Women on the Fifteenth Amendment—The Sixteenth Amendment—Miss Anthony chosen a Delegate to the Democratic National Convention July 4, 1868—Her Address Read by a Unanimous Vote—Horatio Seymour in the Chair—Comments of the Press—The Revolution313

NATIONAL CONVENTIONS—1869.

First Convention in Washington—First hearing before Congress—Delegates Invited from Every State—Senator Pomeroy, of Kansas—Debate between Colored Men and Women—Grace Greenwood's Graphic Description—What the Members of the Convention Saw and Heard in Washington—Robert Purvis—A Western Trip—Conventions in Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Springfield, and Madison—Editorial Correspondence in The Revolution—Anniversaries in New York and Brooklyn—Conventions in Newport and Saratoga345

THE NEW DEPARTURE—UNDER THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

Francis Minor's Resolutions—Hearing before Congressional Committee—Descriptions by Mrs. Fannie Howland and Grace Greenwood—Washington Convention[Pg vii] 1870—Rev. Samuel J. May—Senator Carpenter—Professor Sprague, of Cornell University—Notes of Mrs. Hooker—May Anniversary in New York—The Fifth Avenue Conference—Second Decade Celebration—Washington, 1871—Victoria Woodhull's Memorial—Judiciary Committee—Majority and Minority Reports—George W. Julian and A. A. Sargent in the House—May Anniversary, 1871—Washington in 1872—Senate Judiciary Committee—Benjamin F. Butler—The Sherman-Dahlgren Protest—Women in Grant and Wilson Campaign407

NATIONAL CONVENTIONS—1873, '74, '75.

Fifth Washington Convention—Mrs. Gage on Centralization—May Anniversary in New York—Washington Convention, 1874—Frances Ellen Burr's Report—Rev. O. B. Frothingham in New York Convention—Territory of Pembina—Discussion in the Senate—Conventions in Washington and New York, 1875—Hearings before Congressional Committees521

TRIALS AND DECISIONS.

Women Voting under the XVI. Amendment—Appeals to the Courts—Marilla M. Ricker, of New Hampshire, 1870—Nannette B. Gardner, Michigan—Sara Andrews Spencer, District of Columbia—Ellen Rand Van Valkenburgh, California—Catherine V. Waite, Illinois—Carrie S. Burnham, Pennsylvania—Sarah M. T. Huntingdon, Connecticut—Susan B. Anthony, New York—Virginia L. Minor, Missouri—Judges McKee, Jameson, Sharswood, Cartter—Associate Justice Hunt—Chief Justice Waite—Myra Bradwell—Hon. Matt. H. Carpenter—Supreme Court Decisions586

AMERICAN WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION.

Circular Letter—Cleveland Convention—Association Completed—Henry Ward Beecher, President—Convention in Steinway Hall, New York—George William Curtis Speaks—The First Annual Meeting held in Cleveland—Mrs. Tracy Cutler, President—Mass Meeting in Steinway Hall, New York, 1870—State Action Recommended—Moses Coit Tyler Speaks—Mass Meetings in 1871 in Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, Pittsburgh—Memorial to Congress—Letters from William Lloyd Garrison and others—Hon. G. F. Hoar Advocates Woman Suffrage—Anniversary celebrated at St. Louis—Dr. Stone, of Michigan—Thomas Wentworth Higginson, President, 1872—Convention in Cooper Institute, New York—Two Hundred Young Women march in—Meeting in Plymouth Church—Letters from Louise May Alcott and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps—The Annual Meeting in Detroit—Julia Ward Howe, President—Letter from James T. Field—Mary F. Eastman Addresses the Convention. Bishop Gilbert Haven President for 1875—Convention in Steinway Hall, New York—Hon. Charles Bradlaugh Speaks—Centennial Celebration, July 3d—Petition to Congress for a XVI. Amendment—Conventions in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Washington, and Louisville756

Appendix.863

Vol. II.

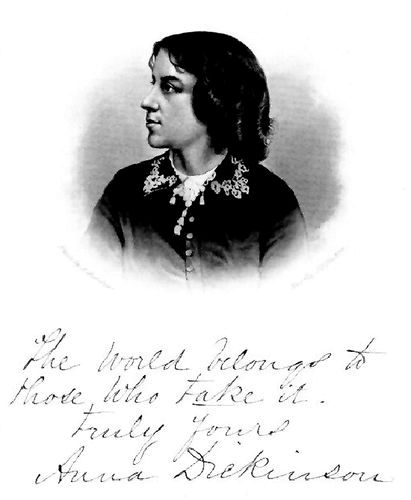

| Anna E. Dickinson | Frontispiece. |

| Clara Barton | page 25 |

| Clemence S. Lozier, M. D. | 153 |

| Rev. Olympia Brown | 265 |

| Jane Graham Jones | 313 |

| Virginia L. Minor | 409 |

| Isabella Beecher Hooker | 489 |

| Belva A. Lockwood | 521 |

| Ellen Clark Sargent | 553 |

| Myra Bradwell | 617 |

| Lucy Stone | 761 |

| Julia Ward Howe | 793 |

The first gun on Sumter, April 12, 1861—Woman's military genius—Anna Ella Carroll—The Sanitary Movement—Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell—The Hospitals—Dorothea Dix—Services on the battle-field—Clara Barton—The Freedman's Bureau—Josephine Griffing—Ladies' National Covenant—Political campaigns—Anna Dickinson—The Woman's Loyal National League—The Mammoth Petition—Anniversaries—The Thirteenth Amendment.

Our first volume closed with the period when the American people stood waiting with apprehension the signal of the coming conflict between the Northern and Southern States. On April 12, 1861, the first gun was fired on Sumter, and on the 14th it was surrendered. On the 15th, the President called out 75,000 militia, and summoned Congress to meet July 4th, when 400,000 men and $400,000,000 were voted to carry on the war.

These startling events roused the entire people, and turned the current of their thoughts in new directions. While the nation's life hung in the balance, and the dread artillery of war drowned alike the voices of commerce, politics, religion and reform, all hearts were filled with anxious forebodings, all hands were busy in solemn preparations for the awful tragedies to come.

At this eventful hour the patriotism of woman shone forth as fervently and spontaneously as did that of man; and her self-sacrifice and devotion were displayed in as many varied fields of action. While he buckled on his knapsack and marched forth to conquer the enemy, she planned the campaigns which brought the nation victory; fought in the ranks when she could do so without detection; inspired the sanitary commission; gathered needed supplies for the grand army; provided nurses for the hospitals; comforted the sick; smoothed the pillows of the dying; inscribed the last messages of love to those far away; and marked the resting-places where the brave men fell. The labor women accomplished, the hardships they endured, the time and strength they sacrificed in the war that summoned three million men to arms, can never be fully appreciated.[Pg 2]

Think of the busy hands from the Atlantic to the Pacific, making garments, canning fruits and vegetables, packing boxes, preparing lint and bandages[1] for soldiers at the front; think of the mothers, wives and daughters on the far-off prairies, gathering in the harvests, that their fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons might fight the battles of freedom; of those month after month walking the wards of the hospital; and those on the battle-field at the midnight hour, ministering to the wounded and dying, with none but the cold stars to keep them company.

Think of the multitude of delicate, refined women, unused to care and toil, thrown suddenly on their own resources, to struggle evermore with poverty and solitude; their hopes and ambitions all freighted in the brave young men that marched forth from their native hills, with flying flags and marshal music, to return no more forever. The untiring labors, the trembling apprehensions, the wrecked hopes, the dreary solitude of the fatherless, the widowed, the childless in that great national upheaval, have never been measured or recorded; their brave deeds never told in story or in song, no monuments built to their memories, no immortal wreaths to mark their last resting-places.

How much easier it is to march forth with gay companions and marshal music; with the excitement of the battle, the camp, the ever-shifting scenes of war, sustained by the hope of victory; the promise of reward; the ambition for distinction; the fire of patriotism kindling every thought, and stimulating every nerve and muscle to action! How much easier is all this, than to wait and watch alone with nothing to stimulate hope or ambition.

The evils of bad government fall ever most heavily on the mothers of the race, who, however wise and far-seeing, have no voice in its administration, no power to protect themselves and their children against a male dynasty of violence and force.

While the mass of women never philosophize on the principles that underlie national existence, there were those in our late war who understood the political significance of the struggle: the "irrepressible conflict" between freedom and slavery; between national and State rights. They saw that to provide lint, bandages, and supplies for the army, while the war was not conducted on a wise policy, was labor in vain; and while many organizations, active, vigilant, self-sacrificing, were multiplied to look after the material[Pg 3] wants of the army, these few formed themselves into a National Loyal League to teach sound principles of government, and to press on the nation's conscience, that "freedom to the slaves was the only way to victory." Accustomed as most women had been to works of charity, to the relief of outward suffering, it was difficult to rouse their enthusiasm for an idea, to persuade them to labor for a principle. They clamored for practical work, something for their hands to do; for fairs, sewing societies to raise money for soldier's families, for tableaux, readings, theatricals, anything but conventions to discuss principles and to circulate petitions for emancipation. They could not see that the best service they could render the army was to suppress the rebellion, and that the most effective way to accomplish that was to transform the slaves into soldiers. This Woman's Loyal League voiced the solemn lessons of the war: liberty to all; national protection for every citizen under our flag; universal suffrage, and universal amnesty.

As no national recognition has been accorded the grand women who did faithful service in the late war; no national honors nor profitable offices bestowed on them, the noble deeds of a few representative women should be recorded. The military services of Anna Ella Carroll in planning the campaign on the Tennessee; the labors of Clara Barton on the battle-field; of Dorothea Dix in the hospital; of Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell in the Sanitary; of Josephine S. Griffing in the Freedman's Bureau; and the political triumphs of Anna Dickinson in the Presidential campaign, reflecting as they do all honor on their sex in general, should ever be proudly remembered by their countrywomen.

Anna Ella Carroll, the daughter of Thomas King Carroll formerly Governor of Maryland, belongs to one of the oldest and most patriotic families of that State. Her ancestors founded the city of Baltimore; Charles Carroll, of Carrollton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, was of the same family.

At the breaking out of the civil war, Maryland was claimed by the rebellious States, and for a long time her position seemed uncertain. Miss Carroll, an intimate friend of Gov. Hicks, and at that time a member of his family, favored the national cause, and by her powerful arguments induced the Governor to remain firm in his opposition to the scheme of secession. Thus, despite the siren wooing of the South, in its plaint of

"Maryland, my Maryland."

Miss Carroll was the means of preserving her native State to the Union. Although a slave-owner, and a member of that class which so largely proved disloyal, Miss Carroll freed her slaves, and devoted herself throughout the war to the cause of liberty. She replied to the secession speech of Senator Breckenridge, made during the July session of Congress 1861, with such lucid and convincing arguments, that the War Department not only circulated a large edition, but the Government requested her to prepare other papers upon unsettled points. In response she wrote a pamphlet entitled "The War Powers of the Government," published in December, 1861. By the especial request of President Lincoln she also prepared a paper entitled "The Relation of Revolted Citizens to the National Government," which was approved by him, and formed the basis of his subsequent action. In September, 1861, she also prepared a paper on the Constitutional power of the President to make arrests, and to suspend the writ of habeas corpus; a subject upon which a great conflict of opinion then existed, even among persons of unquestioned loyalty.

Early in the fall of 1861, Miss Carroll took a trip to St. Louis to inspect the progress of the war in the West. A gun-boat fleet, under the special authorization of the President, was then in preparation for a descent of the Mississippi. An examination of this plan by Miss Carroll showed its weakness, and the inevitable disaster it would bring to the National arms. Her astute military genius led her to the substitution of another plan, upon which she based great hopes of success, and its results show it to have been one of the profoundest strategic movements of the ages. Strategy and generalship are two entirely distinct forms of the art of war. Many a general, good at following out a plan, is entirely incapable of forming a successful one. Napoleon stands in the foremost ranks as a strategist, and is held as the greatest warrior of modern times, yet he led no forces into battle. So entirely was he convinced that strategy was the whole art of war, that he was accustomed to speak of himself as the only general of his army, thus subordinating the mere command and movement of forces to the art of strategy. Judged by this standard, which is acknowledged by all military men, Anna Ella Carroll, of Maryland, holds foremost rank as a military genius. On the 12th of November, 1861, while still in St. Louis, Miss Carroll wrote to Hon. Edward Bates at Washington (the member of the Cabinet who first suggested the expedition down the Mississippi), that from information gained by her she believed this plan would fail, and urged him, instead, to have the expedition[Pg 5] directed up the Tennessee River, as the true line of attack. She also dispatched a similar letter to Hon. Thomas A. Scott, at that time Assistant Secretary of War. On the 30th of this month (November, 1861), Miss Carroll laid the following plan, accompanied by explanatory maps, before the War Department:

The civil and military authorities seem to me to be laboring under a great mistake in regard to the true key of the war in the South-west. It is not the Mississippi, but the Tennessee River. Now, all the military preparations made in the West indicate that the Mississippi River is the point to which the authorities are directing their attention. On that river many battles must be fought and heavy risks incurred, before any impression can be made on the enemy, all of which could be avoided by using the Tennessee River. This river is navigable for medium-class boats to the foot of Muscle Shoals in Alabama, and is open to navigation all the year, while the distance is but two hundred and fifty miles by the river from Paducah on the Ohio. The Tennessee offers many advantages over the Mississippi. We should avoid the almost impregnable batteries of the enemy, which can not be taken without great danger and great risk of life to our forces, from the fact that our forces, if crippled, would fall a prey to the enemy by being swept by the current to him, and away from the relief of our friends. But even should we succeed, still we have only begun the war, for we shall then have to fight the country from whence the enemy derives his supplies.

Now an advance up the Tennessee River would avoid this danger; for, if our boats were crippled, they would drop back with the current and escape capture. But a still greater advantage would be its tendency to cut the enemy's lines in two, by reaching the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, threatening Memphis, which lies one hundred miles due west, and no defensible point between; also Nashville, only ninety miles north-east, and Florence and Tuscumbia in North Alabama, forty miles east. A movement in this direction would do more to relieve our friends in Kentucky, and inspire the loyal hearts in East Tennessee, than the possession of the whole of the Mississippi River. If well executed, it would cause the evacuation of all those formidable fortifications on which the rebels ground their hopes for success; and in the event of our fleet attacking Mobile, the presence of our troops in the northern part of Alabama, would be material aid to the fleet.

Again, the aid our forces would receive from the loyal men in Tennessee would enable them soon to crush the last traitor in that region, and the separation of the two extremes would do more than one hundred battles for the Union cause. The Tennessee River is crossed by the Memphis and Louisville Railroad, and the Memphis and Nashville Railroad. At Hamburg the river makes the big bend on the east, touching the north-east corner of Mississippi, entering the north-west corner of Alabama, forming an arc to the south, entering the State of Tennessee at the north-east corner of Alabama, and if it does not touch the north-west corner of Georgia, comes very near it. It is but eight miles from Hamburg to the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which goes through Tuscumbia, only[Pg 6] two miles from the river, which it crosses at Decatur thirty miles above, intersecting with the Nashville and Chattanooga road at Stephenson. The Tennessee never has less than three feet to Hamburg on the "shoalest" bar, and during the fall, winter, and spring months, there is always water for the largest boats that are used on the Mississippi River. It follows, from the above facts, that in making the Mississippi the key to the war in the West, or rather in overlooking the Tennessee River, the subject is not understood by the superiors in command.

The War Department looked over these papers, and Col. Scott, the Assistant Secretary, possessing a knowledge of the railroad facilities and connections of the South, unequaled perhaps by any other man in the country at that time, at once saw the vital importance of Miss Carroll's plan. He declared it to be the first clear solution of the difficult problem, and was soon sent West to assist in carrying it out in detail. The Mississippi expedition was abandoned, and the Tennessee made the point of attack. Both land and naval forces were ordered to mass themselves at this point, and the country soon began to feel the wisdom of this movement. The capture of Fort Henry, an important Confederate post on the Tennessee River serving to defend the railroad communication between Memphis and Bowling Green, was the first result of Miss Carroll's plan. It fell Feb. 6, 1862, and was rapidly followed by the capture of Fort Donelson, which, after a gallant defense, surrendered to the Union forces Feb. 16th, and the name of Ulysses S. Grant, as the general commanding these forces, for the first time became known to the American people. By these victories the line of Confederate fortifications was broken, and the enemy's means of communication between the East and the West were destroyed.

All the historians of our civil war concede that the strategy which made the Tennessee River the base of military operations in the South-west, thus cutting the Confederacy in two by its control of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, also made its final destruction inevitable. At an early day the Government had neither a just conception of the rebellion, nor of the steps necessary for its suppression. It was looked upon from a political rather than a military point of view, and much valuable time was wasted in suggestions and plans worse than futile. But while the national Government had been blind to the real situation, the Confederacy had every hour strengthened its position both at home and abroad, having so far secured the recognition of France and England as to have been acknowledged belligerents, while threats of raising the blockade were also made by the same powers.[Pg 7]

In order to a more full understanding of our national affairs at that time, we will glance at the proceedings of Congress. When this body met in December, 1861, a "Committee on the Conduct of the War" was at once created, and spirited debates upon the situation took place in both the Senate and the House. It was acknowledged that the salvation of the country depended upon military success. It was declared that the rebellion must be speedily put down or it would destroy the resources of the country, as $2,000,000 a day were then required to maintain the army in the field. Hon. Mr. Dawes compared the country to a man under an exhausted receiver gasping for breath, and said that sixty days of the present state of things must bring about an ignominious peace. Hon. Geo. W. Julian declared that the country was in imminent danger of a foreign war, and that in the opinion of many the great model Republic of the world was in the throes of death. The credit of the nation was then so poor as to render it unable to make loans of money from foreign countries. The treasury notes issued by the Government were falling in the market, selling at five and six per cent. discount. Mr. Morrill, in the Senate, gave it as his opinion that in six months the nation would be beyond hope of relief.

England was anxiously hoping for our downfall. The London Post, Lord Palmerston's paper, the organ of the English Government, prophesied our national bankruptcy within a short time. The London Times denounced us in language deemed too offensive to be read before the Senate. It urged England's direct interference; counseled the pouring of a fleet of gun-boats through the St. Lawrence into the lakes with the opening of spring, "to secure, with the mastery of these waters, the mastery of all," and declared that three months hence the field would be all England's own. At that time the British Government had already sent some thirty thousand men into its colonies in North America, preparatory to an assault upon our north-western frontier. The nation seemed upon the point of being lost, and the hopes of millions of oppressed men in other lands destroyed by the disintegration of the Union. The war had been waged six months, but with the exception of West Virginia, the battle had been against the Union. The fact that military success alone could turn the scale, though now acknowledged, seemed to Congress as far as ever from consummation. Our military commanders, quite ignorant of both the geographical and topographical outlines of our vast country, were unable to formulate the plan necessary for a decisive blow.

Such was the situation at the time Miss Carroll sent her plan of[Pg 8] the Tennessee campaign to the War Department. Fortunately for civilization this plan was adopted, and with the fall of Fort Henry, the enemy's center was pierced, the decisive point gained. From that hour the nation's final success was assured. Its fall opened the Tennessee River, and its capture was soon followed by the evacuation of Columbus and Bowling Green. Fort Donelson was given up, its rebel garrison of 14,000 troops marched out as prisoners of war, and hope sprang up in the hearts of the people. Pittsburg Landing and Corinth soon followed the fate of the preceding forts. The President declared the victory at Fort Henry to be of the utmost importance. North and South its influence was alike felt. Gen. Beauregard was himself conscious that this campaign sealed the fate of the "Southern Confederacy." The success of the Tennessee campaign rendered intervention impossible, and taught those foreign enemies who were anxiously watching for our country's downfall, the power and stability of a Republic. Missouri was kept in the Union by its means, Tennessee and Kentucky were restored, the National armies were enabled to push to the Gulf States and secure possession of all the great rivers and routes of internal communication through the heart of the Confederate territory.

On the 10th of April, 1862, the President issued the following proclamation:

It has pleased Almighty God to vouchsafe signal victories to the land and naval forces engaged in suppressing an internal rebellion; and at the same time to avert from our country the damages of foreign intervention and invasion.

During all this time the author of this plan remained unknown, except to the President and his Cabinet, who feared to reveal the fact that the Government was proceeding under the advice and plan of a civilian, and that civilian a woman. Shortly after the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson a debate as to the author of this campaign took place in the House of Representatives.[2] The Senate discussed its origin March 13. It was variously ascribed to the President, to the Secretary of War, and to different naval and land commanders, Halleck, Grant, Foote, Smith, and Fremont. The historians of the war have also given adverse opinions as to its authorship. Draper's "History of the Civil War" ascribes it to Gen. Halleck; Boynton's "History of the Navy" to Commodore Foote; Lossing's "Civil War" to the combined wisdom of Grant, Halleck, and Foote; Badeau's "History of the Civil War"[Pg 9] credits it to Gen. C. F. Smith; and Abbott's "Civil War," to Gen. Fremont.

But abundant testimony exists proving Miss Carroll's authorship of the plan, in letters from Hon. B. F. Wade,[3] Chairman of the Committee on the Conduct of the War; from Hon. Thos. A. Scott, Assistant Secretary of War; from Hon. L. D. Evans, former Chief-Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas (entrusted by the Government with an important secret mission during the war); from Hon. Orestes A. Bronson, and many other well-known public men; from conversations of President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton; and from reports of the Military Committee of the XLI., XLII., and XLVI. Congresses.[4] So anxious was the Government to keep the origin of the Tennessee campaign a secret, that Col. Scott, in conversation with Judge Evans, a personal friend of Miss Carroll, pressed upon him the absolute necessity of Miss Carroll's making no claim to the authorship while the struggle lasted. In the plenitude of her self-sacrificing patriotism she remained silent, and saw the honors rightfully belonging to her heaped upon others, although she knew the country was indebted to her for its salvation.

Previous to 1862 historians reckoned but fifteen decisive battles[5] in the world's history, battles in which, says Hallam, a contrary result would have essentially varied the drama of the world in all its subsequent scenes. Professor Cressy, of the chair of Ancient and Modern History, University of London, has made these battles the subject of two grand volumes. The battle of Fort Henry was the sixteenth, and in its effects may well be deemed the most important of all.[6] It opened the doors of liberty to the downtrodden and[Pg 10] oppressed among all nations, setting a seal of permanence on the assertion that self-government is the natural right of every person.

But it was not alone through her plan of the Tennessee campaign that Miss Carroll exhibited her military genius; throughout the conflict she continued to send plans and suggestions to the War Department. The events of history prove the wisdom of those plans, and that had they been strictly followed, the war would have been brought to a speedy close,[7] and millions of men and money saved to the country.

Upon the fall of Fort Henry, February, 1862, she again addressed the War Department, advising an immediate advance upon Mobile or Vicksburg. In March, 1862, she presented a memorial and maps to Secretary Stanton in person, in regard to the reduction of Island 10, which had long been a vain effort by the Union forces, in which she said:

The failure to take Island 10, which thus far occasions much disappointment to the country, excites no surprise to me. When I looked at the gun-boats at St. Louis, and was informed as to their powers, and that the current of the Mississippi at full tide runs at the rate of five miles per hour, which is very near the speed of our gun-boats, I could not resist the conclusion that they were not well fitted to the taking of batteries on the Mississippi River, if assisted by gun-boats perhaps equal to our own. Hence it was that I wrote Col. Scott from there, that the Tennessee River was our strategic point, and the successes at Forts Henry and Donelson establish the justice of these observations. Had our victorious army, after the fall of Fort Henry, immediately pushed up the Tennessee River and taken position on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, between Corinth, Miss., and Decatur, Ala., which might easily have been done at that time with a small force, every rebel soldier in Western Kentucky and Tennessee would have fled from every position south of that railroad. And had Buell pursued the enemy in his retreat from Nashville, without delay, into a commanding position in North Alabama, on[Pg 11] the railroad between Chattanooga and Decatur, the rebel government at Richmond would necessarily have been obliged to retreat to the cotton States. I am fully satisfied that the true policy of General Halleck is to strengthen Grant's column by such a force as will enable him at once to seize the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, as it is the readiest means of reducing Island 10, and all the strongholds to Memphis.

In October, 1862, observing the preparations for a naval attack upon Vicksburg, Miss Carroll again addressed the Secretary of War in the following memorial:

As I understand an expedition is about to go down the river, for the purpose of reducing Vicksburg, I have prepared the enclosed map in order to demonstrate more clearly the obstacles to be encountered in the contemplated assault. In the first place, it is impossible to take Vicksburg in the front without too great a loss of life and material, for the reason that the river is only about half a mile wide, and our forces would be in point-blank range of their guns, not only from their water-batteries which line the shore, but from the batteries that crown the hills, while the enemy would be protected from the range of our fire.

By examining the map I enclose, you will at once perceive why a place of so little apparent strength has been enabled to resist the combined fleets of the Upper and Lower Mississippi. The most economical plan for the reduction of Vicksburg now, is to push a column from Memphis or Corinth down the Mississippi Central Railroad to Jackson, the capital of the State of Mississippi. The occupation of Jackson, and the command of the railroad to New Orleans, would compel the immediate evacuation of Vicksburg, as well as the retreat of the entire rebel army east of that line; and by another movement of our army from Jackson, Miss., or from Corinth to Meridan, in the State of Mississippi, on the Ohio and Mobile Railroad, especially if aided by a movement of our gun-boats on Mobile, the Confederate forces, with all the disloyal men and slaves, would be compelled to fly east of the Tombigbee. Mobile being then in our possession, with 100,000 men at Meridan, would redeem the entire country from Memphis to the Tombigbee River. Of course I would have the gun-boats with a small force at Vicksburg, as auxiliary to this movement. With regard to the canal, Vicksburg can be rendered useless to the Confederate army upon the very first rise of the river; but I do not advise this, because Vicksburg belongs to the United States, and we desire to hold and fortify it, for the Mississippi River at Vicksburg and the Vicksburg and Jackson Railroad will become necessary as a base for our future operations. Vicksburg might have been reduced eight months ago, as I advised after the fall of Fort Henry, and with much more ease than it can be done to-day.

It will be recollected that after a month's attack upon Vicksburg, commencing June 28, 1862, by the combined Farragut fleet, Porter mortar flotilla and the gun-boat fleet under Capt. C. H. Davis, the bombardment of the city was suspended, it being found impossible to capture and hold it with the forces at command.[Pg 12]

In October, 1862, Grant was appointed to the command of the forces from New Orleans to Vicksburg under the name of the "Department of Tennessee," and the capture of this "Gibraltar of the Confederacy" was once more attempted. This was the period of Miss Carroll's memorial above given, and the results proved the wisdom of her suggestions, as it was not until the army, by an attack upon its rear, were enabled to capture this stronghold, July 4, 1863, more than a year after the first demand of Farragut's fleet for its capitulation. Had it been attacked immediately after the fall of Fort Henry, according to Miss Carroll's plan, many lives, costly munitions of war, and much valuable time would have alike been saved. Miss Carroll's claim before Congress in connection with the Tennessee campaign of 1862, shows that the Military Committee of the United States Senate at the third session of the 41st Congress, reported (document 337), through Senator Howard, that Miss Carroll "furnished the Government the information which caused the change of the military expedition which was preparing in 1861 to descend the Mississippi, from that river to the Tennessee River." The same committee of the 42d Congress, second session (document 167), reported the evidence in support of this claim. For the House report of the 46th Congress, third session, see document 386.[8]

No fact in the history of our country is more clearly proved than that its very existence is due to the military genius of Miss Carroll, and no more shameful fact in its history exists, than that Congress has refused all recognition and reward for such patriotic services because they were rendered by a woman. While in the past twenty years thousands of men, great and small, have received thanks and rewards from the country she saved—for work done in accordance with her plans—Grant, first made known at Donelson, having twice received the highest office in the gift of the nation—having made the tour of the world amid universal honors—having received gifts of countless value at home and abroad—Miss Carroll is still left to struggle for a recognition of her services from that country which is indebted to her for its very life.

Upon the breaking out of the war, Miss Dix, who for years had been engaged in philanthropic work, saw here another requirement for her services and hurried to Washington to offer them to her[Pg 13] country. She found her first work in nursing soldiers who had been wounded by the Baltimore mob.[9] Upon June 10, 1861, she received from the War Department, Simon Cameron at that time its head, an appointment as the Government Superintendent of Women Nurses. Secretary Stanton, succeeding him, ratified this appointment, thus placing her in an extraordinary and exceptional position, imposing numerous and onerous duties, among them that of hospital visitation, distributing supplies, managing ambulances, adjusting disputes, etc. But while appointed to this office by the Government, Miss Dix found herself as a member of a disfranchised class, in a position of authority without the power of enforcing obedience, and the subject of jealousy among hospital surgeons, which largely militated against the efficiency of her work.[10]

It has been computed that since the historic period, fourteen thousand millions of human beings have fallen in the wars which men have waged against each other. From careful statistics it has also been estimated that four-fifths of this loss of life has been due to privation, exposure, and want of care. At an early day the mortality from sickness was evidently far greater than the above estimate; as late as the Crimean War, this mortality reached seven-eighths of the whole number of deaths. Military surgery was formerly but little understood. The wounded and sick of an army were indebted to the chance aid of friend or stranger, or were left to perish from neglect. Nothing has ever been held so cheap as human life, unless, indeed, it were human rights. But even from times of antiquity we read of women, sometimes of noble birth, who followed the[Pg 14] soldiers to the field, treating the wounds of friend or lover with healing balms or rude surgical appliance. To woman is the world indebted for the first systematic efforts toward relief, through the establishment of hospitals for sick or wounded soldiers. As early as the fifth century, the Empress Helena erected hospitals on the routes between Rome and Constantinople, where soldiers requiring it, received careful nursing.

In the ninth century an order of women, who consecrated themselves to field work, arose in the Catholic Church. They were called Beguines, and everywhere ministered to the sick and wounded of the armies of Continental Europe during its long period of devastating wars.

To Isabella of Spain,[11] she who sold her jewels to fit Columbus for the discovery of a New World, is modern warfare most indebted for a mitigation of its horrors, through the establishment of the first regular Camp Hospitals. During her war with the Moors she caused a large number of tents to be furnished at her own charge, with the requisite medicines, appliances, and attendants for the wounded and sick of her army. These were known as the "Queen's Hospitals," and formed the inception of all the tender care given in army hospitals by the most enlightened nations of to-day.

It is but a few years since Christendom was thrilled by the heroism of a young English girl of high position, Florence Nightingale, who having passed through the course of training required for hospital nurses, voluntarily went out to the Crimea at the time when English soldiers, wounded and sick, were dying by scores and thousands without medicine or care, broke over the red-tape rules of the army, and with her corps of women nurses, brought life in place of death, winning the gratitude and admiration of her country and mankind by her self-sacrifice and her powers of organization. Rev. Henry Kinglake, in his "History of the Crimea," says she brought a priceless reinforcement of brain power to the nation at a time when the brains of Englishmen had given signs of inanition.

A few years later brought our own civil war, and the wonderful sanitary commission, more familiarly known as "The Sanitary," the public records of which are a part of the history of the war; its sacrifices and its successes have burned themselves deep into the hearts of thousands upon thousands. Its fairs in New[Pg 15] York, New England, and the Northwest, were the wonders of the world in the variety and beauty of their exhibits and the vast sums realized from them. Scarcely a woman in the nation, from the girl of tender years,[12] to the aged matron of ninety, whose trembling hands scraped lint or essayed to knit socks and mittens for "the boys in blue," but knows its work, for of it they were a part. But not a hundred of all those thousands who toiled with willing hands, and who, at every battle met anew to prepare or send off stores, knows that to one of her own sex was the formation of the Great Sanitary due.[13]

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, returning to this country from England about the time of the breaking out of the war, fresh from an acquaintance with Miss Nightingale, and filled with her enthusiasm, at once called an informal meeting at the New York Infirmary[14] for Women and Children, where, on April 25th, 1861, the germ of the sanitary, known as the Ladies' Central Relief,[15] was inaugurated. A public meeting was held April 26, 1861, at the Cooper Union, its object being to concentrate scattered efforts by a large and formal organization. The society then received the name of the "Woman's Central Relief Association of New York." Miss Louisa Lee Schuyler was chosen its president. She soon sent out an appeal to women which brought New York into direct connection with many other portions of the country, enabling it "to report its monthly disbursements by tens of thousands, and the sum total of its income by millions." But very soon after its organization, Miss Schuyler saw the need of more positive connection with the Government. A united address was sent to the Secretary of War from the Woman's Central Relief Association, the Advisory Committee of the Board of Physicians and Surgeons of the hospitals of New York, and the New York[Pg 16] Medical Association for furnishing medical supplies. As the result of this address, the Sanitary Commission was established the 9th of June, 1861, under the authority of the Government, and went into immediate operation. Although acting under Government authorization, this commission was not sustained at Government expense, but was supported by the women of the nation. It was organized under the following general rules:

1. The system of sanitary relief established by army regulations was to be adopted; the Sanitary Commission was to acquaint itself fully with those rules, and see that its agents were familiar with all the plans and methods of the army system.

2. The Commission was to direct its efforts mainly to strengthening the regular army system, and work to secure the favor and co-operation of the Medical Bureau.

3. The Commission was to know nothing of religious differences or State distinctions, distributing without regard to the place where troops were enlisted, in a purely national spirit.

Under these provisions the Sanitary Commission completed its full organization. Dr. Blackwell, in the Ladies' Relief Association, acted as Chairman of the Registration Committee, a position of onerous duties, requiring accord with the Medical Bureau and War Department, and visited Washington in behalf of this committee. But the Association soon lost her services by her own voluntary act of withdrawal. Professional jealousy of women doctors being offensively shown by some of those male physicians with whom she was brought in contact, she chose to resign rather than allow sex-prejudice to obstruct the carrying on of the great work originated by her. The Sanitary, with its Auxiliary Aid Societies, at once presented a method of help to the loyal[16] women of the country, and every city,[Pg 17] village, and hamlet soon poured its resources into the Commission. Through it $92,000,000 were raised in aid of the sick and wounded of the army. Nothing connected with the war so astonished foreign nations as the work of the Sanitary Commission.

Dr. Henry Bellows, its President at the close of the war, declared in his farewell address, that the army of women at home had been as patriotic and as self-sacrificing as the army of men in the field, and had it not been for their aid the war could not have been brought to a successful termination.[17]

At every important period in the nation's history, woman has stood by the side of man in duties. Husband, father, son, or brother have not suffered or sacrificed alone.

because back of them stood the patriotic women of the thirteen Colonies; those of the north-eastern pine-woods, who aided in the first naval battle of the Revolution; those of Massachusetts, Daughters of Liberty, who formed anti-tea leagues, proclaimed inherent rights, and demanded an independency in advance of the men; those of New York, who tilled the fields, and, removing their hearth-stones, manufactured saltpetre from the earth beneath, to make powder for the army; those of New Jersey, who rebuked traitors; those of Pennsylvania, who saved the army; those of Virginia, who protested against taxation without representation; those of South Carolina, who at Charleston established a paper in opposition to the Stamp Act; those of North Carolina, whose fiery patriotism secured for[Pg 18] the counties of Rowan and Mecklenberg the derisive name of "The Hornet's Nest of America." The women of the whole thirteen Colonies everywhere showed their devotion to freedom and their choice of liberty with privation, rather than oppression with luxury and ease.

The civil war in our own generation was but an added proof of woman's love for freedom and her worthiness of its possession. The grandest war poem, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," was the echo of a woman's voice,[18] while woman's prescience and power were everywhere manifested. She saw, before President, Cabinet, generals, or Congress, that slavery must die before peace could be established in the country.[19] Months previous to the issue by the President of the Emancipation Proclamation, women in humble homes were petitioning Congress for the overthrow of slavery, and agonizing in spirit because of the dilatoriness of those in power. Were proof of woman's love of freedom, of her right to freedom needed, the history of our civil war would alone be sufficient to prove that love, to establish that right.

Many women fought in the ranks during the war, impelled by the same patriotic motives which led their fathers, husbands, and brothers into the contest. Not alone from one State, or in one regiment, but from various parts of the Union, women were found giving their services and lives to their country among the rank and file of the army.[20] Although the nation gladly summoned their aid in camp and hospital, and on the battle-field with the ambulance corps, it gave them no recognition as soldiers, even denying them the rights of chaplaincy,[21] and by "army regulations" entirely refusing them recognition as part of the fighting forces of the country.

Historians have made no mention of woman's services in the war; scarcely referring to the vast number commissioned in the army, whose sex was discovered through some terrible wound, or by their[Pg 19] dead bodies on the battle-field. Even the volumes especially devoted to an account of woman's work in the war, have mostly ignored her as a common soldier, although the files of the newspapers of that heroic period, if carefully examined, would be found to contain many accounts of women who fought on the field of battle.[22][Pg 20]

Gov. Yates, of Illinois, commissioned the wife of Lieut. Reynolds of the 17th, as Major, for service in the field, the document being made out with due formality, having attached to it the great seal of State. President Lincoln, more liberal than the Secretary[Pg 21] of War, himself promoted the wife of another Illinois officer, named Gates, to a majorship, for service in the hospital and bravery on the field.

One young girl is referred to who served in seven different regiments, participated in several engagements, was twice severely wounded; had been discovered and mustered out of service eight times, but as many times had re-enlisted, although a Canadian by birth, being determined to fight for the American Union.

Hundreds of women marched steadily up to the mouth of a hundred cannon pouring out fire and smoke, shot and shell, mowing down the advancing hosts like grass; men, horses, and colors going down in confusion, disappearing in clouds of smoke; the only sound, the screaming of shells, the crackling of musketry, the thunder of artillery, through all this women were sustained by the enthusiasm born of love of country and liberty.

bravely marched hundreds of women.

Nor was the war without its naval heroines. Among the vessels captured by the pirate cruiser Retribution, was the Union brigantine, J. P. Ellicott, of Bucksport, Maine, the wives of the captain and mate being on board. Her officers and crew were transferred to the pirate vessel and ironed, while a crew from the latter was put on the brigantine; the wife of the mate was left on board the brig with the pirate crew. Having cause to fear bad treatment at the hands of the prize-master[23] and his mate, this woman formed the bold plan of capturing the vessel. She succeeded in getting the officers intoxicated, handcuffed them and took possession of the vessel, persuading the crew, who were mostly colored men from St. Thomas, to aid her. Having studied navigation with her husband on the voyage, she assumed command of the brig, directing its course to St. Thomas, which she reached in safety, placing the vessel in the hands of the United States Consul, who transferred the prize-master, mate, and crew to a United States steamer, as prisoners of war. Her name was not given, but had this bold feat been accomplished by a man or boy, the[Pg 22] country would have rung with praises of the daring deed, and history would have borne the echoes down to future generations.

Not alone on the tented field did the war find its patriotic victims. Many women showed their love of country by sacrifices still greater than enlistment in the army. Among these, especially notable for her surroundings and family, was Annie Carter Lee, daughter of Gen. Robert E. Lee, Commander-in-Chief of the rebel army. Her father and three brothers fought against the Union which she loved, and to which she adhered. A young girl, scarcely beyond her teens when the war broke out, she remained firm in her devotion to the National cause, though for this adherence she was banished by her father as an outcast from that elegant home once graced by her presence. She did not live to see the triumph of the cause she loved so well, dying the third year of the war, aged twenty-three, at Jones Springs, North Carolina, homeless, because of her love for the Union, with no relative near her, dependent for care and consolation in her last hours upon the kindly services of an old colored woman. In her veins ran pure the blood of "Light-Horse Harry" and that of her great aunt, Hannah Lee Corbin, who at the time of the Revolution, protested against the denial of representation to taxpaying women, and whose name does much to redeem that of Lee from the infamy, of late so justly adhering to it. When her father, after the war, visited his ancestral home,[24] then turned into a vast national[Pg 23] cemetery, it would seem as though the spirit of his Union-loving daughter must have floated over him, whispering of his wrecked hopes, and piercing his heart with a thousand daggers of remorse as he recalled his blind infatuation, and the banishment from her home of that bright young life.

Of the three hundred and twenty-eight thousand Union soldiers who lie buried in national cemeteries, many thousands with headboards marked "Unknown," hundreds are those of women obliged by army regulations to fight in disguise. Official records of the military authorities show that a large number of women recruits were discovered and compelled to leave the army. A much greater number escaped detection, some of them passing entirely through the campaigns, while others were made known by wounds or on being found lifeless upon the battle-field. The history of the war—which has never yet been truly written—is full of heroism in which woman is the central figure.

The social and political condition of women was largely changed by our civil war. Through the withdrawal of so many men from their accustomed work, new channels of industry were opened to them, the value and control of money learned, thought upon political questions compelled, and a desire for their own personal, individual liberty intensified. It created a revolution in woman herself, as important in its results as the changed condition of the former slaves, and this silent influence is still busy. Its work will not have been accomplished until the chains of ignorance and selfishness are everywhere broken, and woman shall stand by man's side his recognized equal in rights as she is now in duties.

Clara Barton was the youngest child of Capt. Stephen Barton, of Oxford, Mass., a non-commissioned officer under "Mad Anthony Wayne." Captain Barton, who was a prosperous farmer and leader in public affairs, gave his children the best opportunities he could secure for their improvement. Clara's early education was principally at home under direction of her brothers and sisters. At sixteen, she commenced teaching, and followed the occupation for several years, during which time she assisted her oldest brother, Capt. Stephen Barton, Jr., a man of fine scholarship and business capacity, in equitably arranging and increasing the salaries of the large village schools of her native place, at the same time having clerical oversight of her brother's counting-house. Subsequently,[Pg 24] she finished her school education by a very thorough course of study at Clinton, N. Y. Miss Barton's remarkable executive ability was manifested in the fact that she popularized the Public School System in New Jersey, by opening the first free school in Bordentown, commencing with six pupils, in an old tumble-down building, and at the close of the year, leaving six hundred in the fine edifice at present occupied.

At the close of her work in Bordentown, she went to Washington, D. C., to recuperate and indulge herself in congenial literary pursuits. There she was, without solicitation, appointed by Hon. Charles Mason, Commissioner of Patents, to the first independent clerkship held by a woman under our Government. Her thoroughness and faithfulness fitted her eminently for this position of trust, which she retained until after the election of President Buchanan, when, being suspected of Republican sentiments, and Judge Mason having resigned, she was deposed, and a large part of her salary withheld. She returned to Massachusetts and spent three years in the study of art, belles-lettres, and languages. Shortly after the election of Abraham Lincoln, she was recalled to the Patent Office by the same administration which had removed her. She returned, as she had left, without question, and taking up her line of duty, awaited developments.

When the civil war commenced, she refused to draw her salary from a treasury already overtaxed, resigned her clerkship and devoted herself to the assistance of suffering soldiers. Her work commencing before the organization of Commissions, was continued outside and altogether independent of them, but always with most cordial sympathy. Miss Barton never engaged in hospital service. Her chosen labors were on the battle-field from the beginning, until the wounded and dead were attended to. Her supplies were her own, and were carried by Government transportation. Nearly four years she endured the exposures and rigors of soldier life, in action, always side by side with the field surgeons, and this on the hardest fought fields; such battles as Cedar Mountain, second Bull Run, Chantilly, Antietam, Falmouth, and old Fredericksburg, siege of Charleston, on Morris Island, at Wagner, Wilderness and Spotsylvania, The Mine, Deep Bottom, through sieges of Petersburg and Richmond, with Butler and Grant; through summer without shade, and winter without shelter, often weak, but never so far disabled as to retire from the field; always under fire in severe battles; her clothing pierced with bullets and torn by shot, exposed at all times, but never wounded.

Firm in her integrity to the Union, never swerving from her[Pg 25] belief in the justice of the cause for which the North was fighting, on the battle-field she knew no North, no South; she made her work one of humanity alone, bestowing her charities and her care indiscriminately upon the Blue and the Gray, with an impartiality and Spartan firmness that astonished the foe and perplexed the friend, often falling under suspicion, or censure of Union officers unacquainted with her motives and character for her tender care and firm protection of the wounded captured in battle. Their home-thrusts were met with the same calm courage as were the bullets of the enemy, and many a Confederate soldier lives to bless her for care and life, while no Union man will ever again doubt her loyalty. All unconsciously to herself she was carrying out to the letter in practice the grand and beautiful principles of the Red Cross of Geneva (of which she had never heard), for the entire neutrality of war relief among the nations of the earth, that great international step toward a world-wide recognized humanity, of which she has since become the national advocate and leader in this country.

At the close of the war she met exchanged prisoners at Annapolis. Accompanied by Dorrence Atwater, she conducted an expedition, sent at her request by the United States Government to identify and mark the graves of the 13,000 soldiers who perished at Andersonville. From Savannah to that point, as theirs were the first trains which had passed since the destruction of the railroads by Sherman, they were obliged to repair the bridges and the embankments, straighten bent rails, and in some places make new roads. The work was completed in August, 1865, and her report of the expedition was issued in the winter of 1866.

The anxiety felt by the whole country for the fate of those whom the exchange of prisoners and the disbanding of troops failed to reveal, stimulated her to devise the plan of relief, which, sanctioned by President Lincoln, resulted in the "search for missing men," which (except the printing) was carried on entirely at her own expense, to the extent of several thousand dollars, employing from ten to fifteen clerks. In the winter of '66, when she was on the point, for want of further means to carry out her plan, of turning the search over to the Government, Congress voted $15,000 for reimbursing moneys expended, and carrying on the work. The search was continued until 1869, and then a full report made and accepted by Congress. During the winter of 1867-8 Miss Barton was called on to lecture before many lyceums regarding the incidents of the war.

In 1869, her health failing, she went to Switzerland to rest and recover, where she was at the breaking out of the Franco-Prussian[Pg 26] war, and immediately tendered her services there, as here, on the battle-field, under the auspices of the Red Cross of Geneva. Her Royal Highness the Grand Duchess of Baden, daughter of the Emperor of Germany, invited Miss Barton to aid her in the establishment of her noble Badise hospitals, a work which consumed several months. On the fall of Strasburg she entered the city with the German army, organized labor for women, conducting the enterprise herself, employing remuneratively a great number, and clothing over thirty thousand. She entered Metz with hospital supplies the day of its fall, and Paris the day after the fall of the Commune. Here she remained two months, distributing money and clothing which she carried, and afterward met the poor in every besieged city in France, extending succor to them.

She is a representative of the "International Red Cross of Geneva," and President of the American National Association of the Red Cross, honorary and only woman member of "Comité de Strasbourgeois"; was decorated with the "Gold Cross of Remembrance" by the Grand Duke and Duchess of Baden, and with the "Iron Cross of Merit" by the Emperor and Empress of Germany.

Miss Barton may be said to have given her whole life to humanitarian affairs, largely national in character. The positions she has occupied, whether remunerative or not—and she has filled but few paid positions—have been pioneer ones, in which her efforts and success have been to raise the standard of woman's work and its recognition and remuneration. Her time, her property, and her influence have been held sacred to benevolence of that character that will assist in true progress. Nevertheless, she is one of the most retiring of women, never voluntarily coming before the world except at the call of manifest duty, and shrinking with peculiar sensitiveness from anything verging on notoriety.

Her summers are passed at her pleasant country residence at Dansville, New York, where she has regained in a most gratifying degree her shattered health and war-worn strength, and her winters in Washington in the interests and charge of the great International movement which she represents in America.

Josephine Sophie White was born at Hebron, Conn., December, 1816, and was educated in her native State. She grew to young womanhood in the pure and religious atmosphere of the New England[Pg 27] hills, and developed a strength of constitution and character which was the basis of her truly beneficent life-work. Refined, sympathetic, and conscientious, with the golden rule for her text, her career was ever marked with deeds of kindness and charity to the oppressed of every class. Taking an active part in both the "Anti-slavery" and "Woman's Rights" struggles, she early learned the very alphabet of liberty. With her the perception of its blessings and its glory was also a rich inheritance, and the vigilance and courage to conquer and secure it for others was not less a noble legacy. The love of liberty flowed down to her through two streams of life. On the mother's side she was descended from Peter Waldo[25], after whom the Waldenses were named; and on the father's, from Peregrine White, who was born in Massachusetts in 1620, the first child of Pilgrim parents. It is not strange she was by temperament and constitution a reformer, and a protestant against all despotisms, whether of mind, body, or estate. In the agitation for human rights of one class after another, in their historical order, she enlisted with the Abolitionists, with the Woman Suffragists, with the Loyal League and sanitary workers, and after the war, in relief of the Freedmen. Her interest in her own sex began early, and continued to the last.

At the age of twenty-two she married, and about the year 1842 removed with her family to Ohio, where her home soon became the refuge of the fugitive slave, and the resting-place of his defenders. In 1849 she began, with her husband, Chas. S. S. Griffing, her public labors in connection with the "American" and the "Western Anti-Slavery Societies," speaking at first to small audiences in school-houses, and when prejudice and bitterness gave way, to conventions, and mass-meetings; opposition and curiosity yielding finally to sympathy and aid. But for years the meetings were often broken up by mobs. The effort to uproot slavery was pronounced either absurd, treasonable, or irreligious; that it would incite insurrection of the slaves; or if successful, bring great responsibility upon the Abolitionists, and disaster to the whole country.

In 1861, Mrs. Griffing, prompted by the same loyal spirit that moved all the women of the nation, turned from the ordinary occupations[Pg 28] of life to see what she could do to mitigate the miseries of the war. She united at once with "The National Woman's Loyal League," lecturing and organizing societies in the West for the soldiers and freedmen, to whom large quantities of clothing and other supplies were sent, and circulating petitions to Congress for the emancipation of slaves as a war measure.

While thus engaged, her thoughts naturally turned to the large number of Southern slaves coming with the army into Washington, whose future she foresaw would be beset with distress and want during the long period of change from chattelism to the settled habits of freedom. They were coming by the hundreds and thousands in 1863, with a vague idea of being cared for by "the Governor," but the Government had as yet made no provision, separate from that for the soldiers, when Mrs. Griffing went to Washington and began her labors for them, which were continued until her death.

She at once counseled with President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton as to the best methods for immediate relief; proposed plans which they approved, and received from them every aid possible in their execution. Her first step was to open three ration-houses, where she fed at least a thousand of the old and most destitute of the freed people daily. She visited hundreds in the alleys and old stables, in attics and cellars, and in almost every place where shelter could be found, and became acquainted personally with their necessities, and the best means of supplying them. There were 30,000 in the capital at this time, and it would be difficult to give an idea to one not there, of the time and labor it cost to hunt out the old barracks and get them transformed into shelters for these outcasts. Upon the personal order of the Secretary of War, she was allowed army blankets and wood, which she distributed herself, going with the army wagons to see that those suffering most were first supplied. This "temporary relief" was necessarily continued for some time, during which Mrs. Griffing was made the General Agent of "The National Freedman's Relief Association of the District of Columbia." She opened a correspondence with the Aid societies of the Northern and New England States, which resulted in her receiving supplies of clothing and provisions, which were most acceptable. These were carefully dispensed by herself and two daughters, who were her assistants. Mrs. Griffing opened three industrial schools, where the women were taught to sew;[26] a price was set on their labors,[Pg 29] and they were paid in ready-made garments. The Secretary aided in the purchase of suitable cloth, and with that sent from the North, such outfits were supplied as could be afforded.

It was soon apparent to Mrs. Griffing that the Government must provide for the old and the infirm, and that until labor could be found, even a majority of the strong must be included in the provision—with the understanding, however, that they must seek employment and exert themselves to find homes—and that educational and political interests must be established and encouraged. The stress of the situation can not be said ever to have relaxed during our friend's life, except as to numbers—at any rate in the early years; but as soon as some system grew out of the confusion, and all that could be, were supplied with bread and shelter, she turned her attention in part to the larger plan, and urged a bureau under Government; a department for these freedmen's interests. This plan was favored by Messrs. Sumner, Wade, Wilson, and a few other Senators and Members of Congress, and in December, 1863, a bill for a Bureau of Emancipation was introduced in the House of Representatives by Hon. Mr. Elliot, of Massachusetts. It received no welcome; few cared to listen to the details of the necessity, and it was only through Mrs. Griffing's brave and unwearied efforts that the plan was accepted, and carried through in March, 1865, under the title of "The Freedman's Bureau." The writer has had testimony to the truth of this from Senators Wade of Ohio, Howard of Michigan, and others, as well as to the fact that a majority of the Congressional Committee in charge of the bill, wished that Mrs. Griffing should be made Commissioner (among whom, and most active in support of the bill, was Senator Henry Wilson), but it was decided to place the Bureau in the War Department, with a military man at the head, Mrs. Griffing being appointed "Assistant Commissioner." She really held the position but a few weeks—in name, five months—a second military officer standing ready to take the appointment, as men have ever done, and as they will always crowd women aside so long as they are held political inferiors, without the citizen's charter to sustain their claim. This officer had the title and drew the pay, while our noble friend went on as before in her arduous and almost superhuman labors. The Bureau adopted her plan of finding homes in the North, sending the freedmen at Government charge, and of opening employment offices in New York City[Pg 30] and in Providence, R. I.; nevertheless it was necessary to supplement Government provision by private generosity; and moreover, that Congress should provide temporary relief for the helpless in the District. Appropriations were made in sums of $25,000, amounting in all to nearly $200,000, for the purchase of supplies, a very large proportion of which were distributed by Mrs. Griffing in person from her own residence.[27] "Shirley Dare," in writing to The New York World, after a little time spent with Mrs. G., said:

"I sat an hour this morning in Mrs. Griffing's office during the distribution of rations, and a curious scene it was. There was not a sound creature among the crowd which filled the yard, and which hangs about all day from nine till four, and which the neighborhood calls 'Mrs. Griffing's signs.' It reminded me of another crowd of impotent folk, lame, halt, and blind, which filled the loveliest space in Jerusalem, and was a sign of joy and charity in the place. Queer, tender, wistful faces, so earnest one forgets their grotesque character and ragged, faded forms, cluster in the porch; such a set as one might once have seen put up at auction as a 'refuse lot' of plantation negroes. The men wear old army cloaks, while the women, with dresses in every stage of decay, are so comic, one struggles between the ludicrous and the pitiful.... The faith of this class seems to be fastened nowhere so strongly as upon Mrs. Griffing. Salutations follow her along the streets, enough to satisfy the proudest Pharisee, and it provokes one between a smile and a tear, to see the women waiting timidly, yet eagerly, for a word from her, to set their faces all aglow. They used to say, persistently, 'We belongs to you,' and no efforts could induce them to change that phrase. 'Who has we but the Lord and you?' was the simple argument which stayed protest from the kind, proud woman who was their benefactress. A few words from her will draw out histories simple, funny, and sad beyond question."