The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Giraffe Hunters, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Giraffe Hunters

Author: Mayne Reid

Release Date: January 27, 2009 [EBook #27911]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GIRAFFE HUNTERS ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"The Giraffe Hunters"

Chapter One.

Arrival at the Promised Land.

In that land of which we have so many records of early and high civilisation, and also such strong evidences of present barbarism,—the land of which we know so much and so little,—the land where Nature exhibits some of her most wonderful creations and greatest contrasts, and where she is also prolific in the great forms of animal and vegetable life,—there, my young reader, let us wander once more. Let us return to Africa, and encounter new scenes in company with old friends.

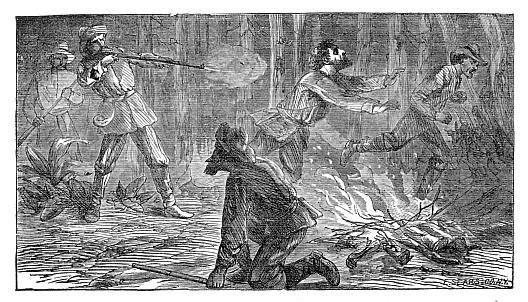

On the banks of the Limpopo brightly blazes a hunter’s fire, around which the reader may behold three distinct circles of animated beings. The largest is composed of horses, the second of dogs, and the lesser or inner one, of young men, whom many of my readers will recognise as old acquaintances.

I have but to mention the names of Hans and Hendrik Von Bloom, Groot Willem and Arend Van Wyk, to make known that The Young Yägers are again on a hunting expedition. In the one in which we now encounter them, not all the parties are inspired by the same hopes and desires.

The quiet and learned Hans Von Bloom, like many colonial youths, is affected with the desire of visiting the home of his forefathers. He wishes to go to Europe for the purpose of making some practical use of the knowledge acquired, and the floral collections made, while a Bush-Boy and a Young Yäger. But before doing so, he wishes to enlarge his knowledge of natural history by making one more expedition to a part of Southern Africa he has not yet visited.

He knows that extensive regions of his native land, containing large rivers and immense forests, and abounding in a vast variety of rare plants, lie between the rivers Limpopo and Zambezi, and before visiting Europe he wishes to extend his botanic researches in that direction. His desire to make his new excursion amid the African wilds is no stronger than that of “Groot Willem” Van Wyk, who ever since his return from the last expedition, six months before, has been anxious to undertake another in quest of game such as he has not yet encountered.

Our readers will search in vain around the camp-fire for little Jan and Klaas. Their parents would not consent to their going so far from home, on an excursion promising so many hardships and so much danger. Besides, it was necessary that they should become something better than mere Bush-Boys, by spending a few years at school.

The two young cornets, Hendrik Von Bloom and Arend Van Wyk, each endeavouring to wear the appearance of old warriors, are present in the camp. Although both are passionately fond of a sportsman’s life, each, for certain reasons, had refrained from urging the necessity or advantage of the present expedition.

They would have preferred remaining at home and trying to find amusement during the day with the inferior game to be found near Graaf Reinet,—not that they fear danger or were in any way entitled to the appellation of “cockney sportsmen”; but home has an attraction for them that the love of adventure cannot wholly eradicate.

Hendrik Von Bloom could have stayed very happily at home. The excitement of the chase, which on former occasions he had so much enjoyed, now no longer attracts him half so much as the smiles of Wilhelmina Van Wyk, the only sister of his friends Groot Willem and Arend.

The latter young gentleman would not have travelled far from the daily society of little Trüey Von Bloom, had he been left to his own inclinations. But Willem and Hans had determined upon seeking adventures farther to the north than any place they had yet visited; and hence the present expedition.

The promise of sport and rare adventures, added to the fear of ridicule should they remain at home, influenced Hendrik and Arend to accompany the great hunter and the naturalist to the banks of the Limpopo.

Seated near the fire are two other individuals, whom the readers of The Young Yägers will recognise as old acquaintances. One is the short, stout, heavy-headed Bushman, Swartboy, who could not have been coaxed to remain behind while his young masters Hans and Hendrik were out in search of adventures.

The other personage not mentioned by name is Congo, the Kaffir.

The Limpopo River was too far from Graaf Reinet for the young hunters to think of reaching it with wagons and oxen. The journey might be made, but it would take up too much time; and they were impatient to reach what Groot Willem had long called “The Promised Land.”

In order, therefore, to do their travelling in as little time as possible, they had taken no oxen; but, mounted on good horses, had hastened by the nearest route to the banks of the Limpopo, avoiding in place of seeking adventures by the way. Besides their own saddle-horses, six others were furnished with pack-saddles, and lightly laden with ammunition, clothing, and such other articles as might be required. The camp where we now encounter them is a temporary halting-place on the Limpopo. They have succeeded in crossing the river, and are now on the borders of that land so long represented to them as being a hunter’s paradise. A toilsome journey is no longer before them; but only amusement, of a kind so much appreciated that they have travelled several hundred miles to enjoy it.

We have stated that, in undertaking this expedition, the youths were influenced by different motives. This was to a great extent true; and yet they had a common purpose beside that of mere amusement. The consul for the Netherlands had been instructed by his government to procure a young male and female giraffe, to be forwarded to Europe. Five hundred pounds had been offered for the pair safely delivered either at Cape Town or Port Natal; and several parties of hunters that had tried to procure these had failed. They had shot and otherwise killed camelopards by the score, but had not succeeded in capturing any young ones alive.

Our hunters had left home with the determination to take back a pair of young giraffes, and to pay all expenses of their expedition by this, as also by the sale of hippopotamus teeth. The hope was not an unreasonable one. They knew that fortunes had been made in procuring elephants’ tusks, and also that the teeth of the hippopotamus were the finest of ivory, and commanded a price four times greater than any other sent to the European market.

But the capturing of the young camelopards was the principal object of their expedition. The love of glory was stronger than the desire of gain, especially in Groot Willem, who as a hunter eagerly longed to accomplish a feat which had been attempted by so many others without success. In his mind, the fame of fetching back the two young giraffes far outweighed the five hundred pound prize to be obtained, though the latter was a consideration not to be despised, and no doubt formed with him, as with the others, an additional incentive.

Chapter Two.

On the Limpopo.

During the first night spent upon the Limpopo our adventurers had good reason for believing that they were in the neighbourhood of several kinds of game they were anxious to fall in with.

Their repose was disturbed by a combination of sounds, in which they could distinguish the roar of the lion, the trumpet-like notes of the elephant, mingled with the voices of some creature they could not remember having previously heard.

Several hours of that day had been passed in searching for a place to cross the river,—one where the banks were low on each side, and the stream not too deep. This had not been found until the sun was low down upon the horizon.

By the time they had got safely over, twilight was fast thickening into darkness, and all but Congo were unwilling to proceed farther that night. The Kaffir suggested that they should go at least half a mile up or down the river and Groot Willem seconded the proposal, although he had no other reason for doing so than a blind belief in the opinions of his attendant, whether they were based upon wisdom or instinct. In the end Congo’s suggestion had been adopted, and the sounds that disturbed the slumbers of the camp were heard at some distance, proceeding from the place where they had crossed the river.

“Now, can you understand why Congo advised us to come here?” asked Groot Willem, as they listened to the hideous noises that were depriving them of sleep.

“No,” was the reply of his companions.

“Well, it was because the place where we crossed is the watering-place for all the animals in the neighbourhood.”

“That is so, Baas Willem,” said Congo, confirming the statement of his master.

“But we have not come a thousand miles for the sake of keeping out of the way of those animals, have we?” asked the hunter Hendrik.

“No,” answered Willem, “we came here to seek them, not to have them seek us. Our horses want rest, whether we do or not.”

Here ended further conversation for the night, for the hunters becoming accustomed to the chorus of the wild creatures, took no further notice of it, and one after another fell asleep.

Morning dawned upon a scene of surpassing beauty. They were in a broad valley, covered with magnificent trees, among which were many gigantic baobabs (Adansonia digitata). Wild date-trees were growing in little clumps; while the floral carpet, spread in brilliant pattern over the valley, was observed by Hans with an air of peculiar satisfaction.

He had reached a new field for the pursuit of his studies, and bright dreams were passing gently through his mind,—dreams that anticipated new discoveries in the botanical world, which might make his name known among the savants of Europe.

Before any of his companions were moving, Groot Willem, accompanied by Congo, stole forth to take a look at the surrounding country.

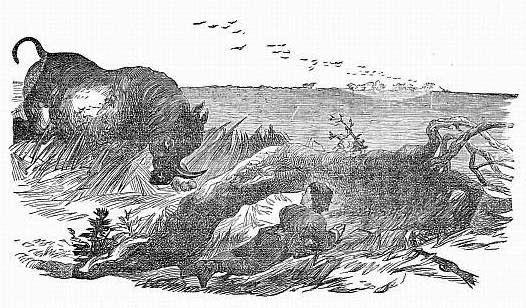

They directed their course down the river. On reaching the place where they had crossed it, they chanced upon a tableau that even a hunter, who is supposed to take delight in the destruction of animals, could not look upon without unpleasant emotions.

Within the space of a hundred yards were lying five dead antelopes, of a species Willem had never seen before. Feeding on the carcasses were several hyenas. On the approach of the hunters, they slowly moved away, each laughing like a madman who has just committed some horrible atrocity.

By the “spoors” seen upon the river-banks, it was evident that both elephants and lions had visited the place during the night. While making these and other reconnoissances, Groot Willem was joined by Hans, who had already commenced his favourite study by making an examination of the floral treasures in his immediate locality. Arriving up with Groot Willem, the attention of Hans was at once directed to an examination of the antelopes, which he pronounced to be elands, but believed them to be of a new and undescribed variety of this animal. They were elands; but each was marked with small white stripes across the body, in this respect resembling “koodoos.”

After a short examination of the spoor, Congo asserted that a troop of elands had first visited the watering-place, and that while they were there four bull elephants, also in search of water, had charged with great speed upon the antelopes. Three or four lions had also joined in the strife, in which the only victims had been the unfortunate elands.

“I think we are in a place where we had better make a regular enclosure, and stop for a few days,” suggested Groot Willem, on his return to the camp. “There is plenty of feed for the horses, and we have proof that the ‘drift’ where we crossed is a great resort for all kinds of game.”

“I’m of the same opinion,” assented Hendrik; “but I don’t wish to encamp quite so close to the crossing as this is. We had better move some distance off. Then we shall not prevent game from seeking the drift, or be ourselves hindered from getting sleep. Don’t you think we’d better move little farther up the river?”

“Yes, yes,” was the unanimous answer.

It was therefore decided that search should be made for a better camping-ground, where they could build themselves a proper enclosure, or “kraal.”

After partaking of their first breakfast upon the Limpopo, Groot Willem, Hans, and Hendrik mounted their horses and rode off up the river, accompanied by the full pack of dogs, leaving Arend, with Swartboy and Congo, to take care of the camp.

For nearly three miles, the young hunters rode along the bank of the river, without finding any spot where access to the water could be readily obtained. The banks were high and steep, and therefore but little visited by such animals as they wished to hunt. At this point the features of the landscape began to change, presenting an appearance more to their satisfaction. Light timber, such as would be required for the construction of a stockade, was growing near the river, which was no longer inaccessible, though its banks appeared but little frequented by game.

“I think this place will suit admirably,” said Groot Willem. “We are only half an hour’s ride from the drift, and probably we may find good hunting-ground farther up stream.”

“Very likely,” rejoined Hendrik; “but before taking too much trouble to build ourselves a big kraal, we had better be sure about what sort of game is to be got here.”

“You are right about that,” answered Willem; “we must take care to find out whether there are hippopotami and giraffes. We cannot go home without a pair of the latter. Our friends would be disappointed, and some I know would have a laugh at us.”

“And you for one would deserve it,” said Hans. “Remember how you ridiculed the other hunters who returned unsuccessful.”

Having selected a place for the kraal, should they decide on staying awhile in the neighbourhood, the young hunters proceeded farther up the river, for the purpose of learning something more of the hunting-ground before finally determining to construct the enclosure.

Chapter Three.

A Twin Trap.

Not long after the departure of Groot Willem and his companions, Arend, looking towards a thicket about half a mile from the river, perceived a small herd of antelopes quietly browsing upon the plain. Mounting his horse, he rode off, with the intention of bagging one or more of them for the day’s dinner.

Having ridden to the leeward of the herd, and getting near them, he saw that they were of the species known as “Duyker,” or Divers (Antelope grimmia). Near them was a small “motte” of the Nerium oleander, a shrub about twelve feet high, loaded with beautiful blossoms. Under the cover of these bushes, he rode up close enough to the antelopes to insure a good shot, and, picking out one of the largest of the herd, he fired.

All the antelopes but one rushed to the edge of the thicket, made a grand leap, and dived out of sight over the tops of the bushes,—thus affording a beautiful illustration of that peculiarity to which they are indebted for their name of Divers. Riding up to the one that had remained behind, and which was that at which he had fired, the young hunter made sure that it was dead; he then trotted back to the camp, and despatched Congo and the Bushman to bring it in. They soon returned with the carcass, which they proceeded to skin and make ready for the spit.

While thus engaged, Swartboy appeared to notice some thing out upon the plain.

“Look yonner, Baas Arend,” said he.

“Well, what is it, Swart?”

“You see da pack-horse dare? He gone too much off from de camp.”

Arend turned and looked in the direction the Bushman was pointing. One of the horses, which had strayed from its companions, was now more than half a mile off, and was wandering onwards.

“All right, Swart. You go on with your cooking. I’ll ride after it myself, and drive it in.”

Arend, again mounting his horse, trotted off in the direction of the animal that had strayed.

For cooking the antelope, Congo and Swartboy saw the necessity of providing themselves with some water; and taking a vessel for that purpose, they set out for the drift,—that being the nearest place where they could obtain it.

They kept along the bank of the river, and just before reaching a place where they would descend to the water, Congo, who was in the advance, suddenly disappeared! He had walked on to a carefully concealed pit, dug for the purpose of catching hippopotami or elephants.

The hole was about nine feet deep; and after being astonished by dropping into it, the Kaffir was nearly blinded by the sand, dust, and other materials that had formed the covering of the pit.

Congo was too well acquainted with this South African device for killing large game to be anyways disconcerted by what had happened; and after becoming convinced that he was uninjured by the fall, he turned his glance upward, expecting assistance from his companion.

But Swartboy’s aid could not just then be given. The Bushman, amused by the ludicrous incident that had befallen his rival, was determined to enjoy the fun for a little longer. Uttering a wild shout of laughter that was a tolerable imitation of an enraged hyena, Swartboy seemed transported into a heaven of unadulterated joy. Earth appeared hardly able to hold him as he leaped and danced around the edge of the pit.

Never had his peculiar little mind been so intensely delighted; but the manifestations of that delight were more suddenly terminated than commenced; for in the midst of his eccentric capers he, too, suddenly disappeared into the earth as if swallowed up by an earthquake! His misfortune was similar to that which had befallen his companion. Two pitfalls had been constructed close together, and Swartboy now occupied the second.

It is a common practice among the natives of South Africa to trap the elephant in these twin pitfalls; as the animals, too hastily avoiding the one, run the risk of dropping into the other.

Swartboy and the Kaffir had unexpectedly found a place where this plan had been adopted; and, much to their discomfiture, without the success anticipated by those who had taken the trouble to contrive it.

The cavity into which Congo had fallen contained about two feet of mud on the bottom. The sides were perpendicular, and of a soapy sort of clay, so that his attempts at climbing out proved altogether unsuccessful, thus greatly increasing the chagrin of his unphilosophic mind. He had heard the Bushman’s screams of delight, and the sounds had contributed nothing to reconcile him to the mischance that had befallen him. Several minutes passed and he heard nothing of Swartboy.

He was not surprised at the Bushman’s having been amused as well as gratified by his misfortune. Still, he expected that in time he would lend assistance and pull him out of the pit. But as this assistance was not given, and as Swartboy, not satisfied with laughing at his misfortune appeared also to have gone off and left him to his fate, the Kaffir became frantic with rage.

Several more minutes passed, which to Congo seemed hours, and still nothing was seen or heard of his companion. Had Swartboy returned to the camp? If so, why had not Arend, on ascertaining what was wrong, hastened to the relief of his faithful servant? As some addition to the discomforts of the place, the pit contained many reptiles and insects that had in some manner obtained admittance, and, like himself, could not escape. There were toads, frogs, large ants called “soldiers,” and other creatures whose company he had no relish to keep.

In vain he called, “Swartboy!” and “Baas Arend!” No one came to his call. The strong, vindictive spirit of his race was soon roused to the pitch of fury, and liberty became only desired for one object. That was revenge,—revenge on the man who, instead of releasing him from his imprisonment, only exulted in its continuance.

The Bushman had not been injured in falling into the pit, as may be supposed. After fully comprehending the manner in which his amusement had been so suddenly brought to a termination, his first thought was to extricate himself, without asking assistance from the man who had furnished him with the fun. His pride would be greatly mortified should the Kaffir get out of his pit, and find him in the other. That would be a humiliating rencontre.

In silence, therefore, he listened to Congo’s cries for assistance, while at the same time doing all in his power to extricate himself. He tried to pull up a sharp-pointed stake that stood in the bottom of the pit. This piece of timber had been placed there for the purpose of impaling and killing the hippopotamus or elephant that should drop down upon it; and had the Bushman succeeded in taking it from the place where it had been planted, he might have used it in working his own way to the surface of the earth. This object, however, he was unable to accomplish, and his mind became diverted to another idea.

Swartboy had a system of logic, not wholly peculiar to himself, by which he was enabled to discover that there must be some first cause for his being in a place from which he could not escape. That cause was no other than Congo. Had the Kaffir not fallen into a pit, Swartboy was quite certain that he would have escaped the similar calamity.

He would have liberated Congo from his confinement, and perhaps sympathised with his misfortune, after the first ebullitions of his mirth had been exhausted; but now, on being entrapped himself, he was only conscious that some one was to blame for the disagreeable incident, and was unable to admit that this some one was himself. The mishap had befallen him in company with the Kaffir. It was that individual’s misfortune that had conducted to his own, and this was another reason why he now submitted to his captivity in profound silence.

Unlike Congo, he did not experience the soul-harrowing thought of being neglected, and could therefore endure his confinement with some degree of patience not possible to his companion. Moreover, he had the hope of speedy deliverance, which to Congo was denied.

He knew that Arend would soon return to the camp with the stray horse, and miss them. The water-vessel would also be missed, and a search would be made for it in the right direction. No doubt Arend, seeing that the bucket was taken away from the camp, and finding that they did not return, would come toward the drift,—the only place where water could be dipped up. In doing so he must pass within sight of the pits. With this calculation, therefore, Swartboy could reconcile himself to patience and silence, whereas the Kaffir had no such consolatory data to reflect upon.

Chapter Four.

In the Pits.

As time passed on, however, and Swartboy saw that the sun was descending, and that the shades of night would soon be gathering over the river, his hopes began to sink within him. He could not understand why the young hunter had not long ago come to release them. Groot Willem, Hendrik, and Hans should have returned by that time; and the four should have made an effectual search for their missing servants. He had remained silent for a long time, under very peculiar circumstances. But silence now became unbearable, and he was seized with a sudden desire to express his dissatisfaction at the manner Fate had been dealing out events,—a desire no longer to be resisted. The silence was at last broken by his calling out—

“Congo, you ole fool, where are you? What for don’t you go home?”

On the Kaffir’s ear the voice fell dull and distant; and yet he immediately understood whence it came. Like himself, the Bushman was in a living grave! That explained his neglect to render the long-desired assistance.

“Lor’, Swart! why I waiting for you,” answered Congo, for the first time since his imprisonment attempting a smile; “I don’t want to go to the camp and leave you behind me.”

“You think a big sight too much of yourself,” rejoined the Bushman. “Who wants to be near such a black ole fool as you? You may go back to the camp, and when you get there jus’ tell Baas Hendrik that Swartboy wants to see him. I’ve got something particular to tell him.”

“Very well,” answered the Kaffir, becoming more reconciled to his position; “what for you want see Baas Hendrik? I’ll tell him what you want without making him come here. What shall I say?”

In answer to this question, Swartboy made a long speech, in which the Kaffir was requested to report himself as a fool for having fallen into a pit,—that he had shown himself more stupid than the sea-cows, that had apparently shunned the trap for years.

On being requested to explain how one was more stupid than the other,—both having met with the same mischance,—Swartboy went on to prove that his misfortune was wholly owing to the fault of Congo, by the Kaffir having committed the first folly of allowing himself to be entrapped.

Nothing, to the Bushman’s mind, could be more clear than that Congo’s stupidity in falling into the first pit had led to his own downfall into the second.

This was now a source of much consolation to him, and the verbal expression of his wrongs enabled him for a while to feel rather happy at the fine opportunity afforded for reviling his rival. The amusement, however, could not prevent his thoughts from returning to the positive facts that he was imprisoned; that in place of passing the day in cooking and eating duyker, he had been fasting and fretting in a dark, dirty pit, in the companionship of loathsome reptiles.

His mind now expanding under the exercise of a startled imagination, he became apprehensive. What if some accident should have occurred to Arend, and prevented his return to the camp? What if Groot Willem and the others should have strayed, and not find their way back to the place for two or three days? He had heard of such events happening to other stupid white men, and why not to them? What if they had met a tribe of the savage inhabitants of the country, and been killed or taken prisoners?

These conjectures, and a thousand others, flitted through the brain of the Bushman, all guiding to the conclusion that, should either of them prove correct, he would first have to eat the reptiles in the pit, and then starve.

It was no consolation to him to think that his rival in the other pit would have to submit to a similar fate.

His unpleasant reveries were interrupted by a short, angry bark; and, looking up to the opening through which he had descended, he beheld the countenance of a wild dog,—the “wilde honden” of the Dutch Boers.

Uttering another and a different cry, the animal started back; and from the sounds now heard overhead, the Bushman was certain that it was accompanied by many others of its kind.

An instinctive fear of man led them to retreat for a short distance; but they soon found out that “the wicked flee when no man pursueth,” and they returned.

They were hungry, and had the sense to know that the enemy they had discovered was, for some reason, unable to molest them.

Approaching nearer, and more near, they again gathered around the pits, and saw that food was waiting for them at the bottom of both. They could contemplate their victims unharmed, and this made them courageous enough to think of an attack. The human voice and the gaze of human eyes had lost their power, and the pack of wild hounds, counting several score, began to think of taking some steps towards satisfying their hunger.

They commenced scratching and tearing away the covering of the pits, sending down a shower of dust, sand, and grass that nearly suffocated the two men imprisoned beneath.

The poles supporting the screen of earth were rotten with age, and the whole scaffolding threatened to come down as the wild dogs scampered over it.

“If there should be a shower of dogs,” thought Swartboy, “I hope that fool Congo will have his share of it.”

This hope was immediately realised, for the next instant he heard the howling of one of the animals evidently down in the adjoining pit. It had fallen through, but, fortunately for Congo, not without injuring itself in a way that he had but narrowly escaped. The dog had got transfixed on the sharp-pointed stake, planted firmly in the centre of the pit, and was now hanging on it in horrible agony, unable to get clear.

Without lying down in the mud, the Kaffir was unable to keep his face more than twelve inches from the open jaws of the dog, that in its struggles spun round as on a pivot; and Congo had to press close against the side of the pit, to keep out of the reach of the creature yelping in his ears.

Swartboy could distinguish the utterances of this dog from those of its companions above, and the interpretation he gave to them was, that a fierce combat was taking place between it and the Kaffir.

The jealousy and petty ill-will so often exhibited by the Bushman was not so strong as he had himself believed. His intense anxiety to know which was getting the best of the fight, added to the fear that Congo was being torn to pieces, told him that his friendship for the Kaffir far outweighed the animosity he fancied himself to have felt.

The fiendish yells of the dogs, the unpleasant situation in which he was placed, and the uncertainty of the time he was to endure it, were well-nigh driving him distracted; when just then the wild honden appeared to be beating a retreat,—the only one remaining being that in the pit with Congo. What was driving them away? Could assistance be at hand?

Breathlessly the Bushman stood listening.

Chapter Five.

Arend Lost.

In the afternoon, when Groot Willem, Hans, and Hendrik returned to the camp, they found it deserted.

Several jackals reluctantly skulked off as they drew near and on riding up to the spot from which those creatures had retired, they saw the clean-picked bones of an antelope. The camp must have been deserted for several hours.

“What does this mean?” exclaimed Groot Willem. “What has become of Arend?”

“I don’t know,” answered Hendrik. “It is strange Swart and Cong are not here to tell us.”

Something unusual had certainly happened; yet, as each glanced anxiously around the place, there appeared nothing to explain the mystery.

“What shall we do?” asked Willem, in a tone that expressed much concern.

“Wait,” answered Hans; “we can do nothing more.”

Two or three objects were at this moment observed which fixed their attention. They were out on the plain, nearly a mile off. They appeared to be horses,—their own pack animals,—and Hendrik and Groot Willem started off towards them to drive them back to the camp.

They were absent nearly an hour before they succeeded in turning the horses and driving them towards the camp. As they passed near the drift on their return, they rode towards the river to water the animals they were riding.

On approaching the bank, several native dogs, that had been yelling in a clump, were seen to scatter and retreat across the plain. The horsemen thought little of this, but rode on into the river, and permitted their horses to drink.

While quietly seated in their saddles, Hendrik fancied he heard some strange sounds. “Listen!” said he. “I hear something queer. What is it?”

“One of the honden,” answered Willem.

“Where?”

This question neither for a moment could answer, until Groot Willem observed one of the pits from the edge of which the dogs appeared to have retreated.

“Yonder’s a pit-trap!” he exclaimed, “and I believe there’s a dog has got into it. Well, I shall give it a shot, and put the creature out of its misery.”

“Do so,” replied Hendrik. “I hate the creatures as much as any other noxious vermin, but it would be cruel to let one starve to death in that way. Kill it.”

Willem rode up to the pit and dismounted. Neither of them, as yet, spoke loud enough to be heard in the pits, and the two men down below were at this time silent, the dog alone continuing its cries of agony.

The only thing Willem saw on gazing down the hole was the wild hound still hanging on the stake; and taking aim at one of its eyes he fired.

The last spark of life was knocked out of the suffering animal; but the report of the great gun was instantly followed by two yells more hideous than were ever uttered by “wild honden.”

They were the screams of two frightened Africans,—each frightened to think that the next bullet would be for him.

“Arend!” exclaimed Willem, anxious about his brother, and thinking only of him. “Arend! is it you?”

“No, Baas Willem,” answered the Kaffir. “It is Congo.”

Through the opening, Willem reached down the butt-end of his long roer, while firmly clasping it by the barrel.

The Kaffir took hold with both hands, and, by the strong arms of Groot Willem, was instantly extricated from his subterranean prison.

Swartboy was next hauled out, and the two mud-bedaubed individuals stood gazing at one another, each highly delighted at the rueful appearance presented by his rival.

Slowly the fire of anger, that seemed to have all the while been burning in the Kaffir’s eyes, became extinguished, and broad smile broke like the light of day over his stoical countenance.

He had been released at length, and was now convinced that no one was to blame for his protracted imprisonment.

Swartboy had been punished for his ill-timed mirth, and Congo was willing to forget and forgive.

“But where is Arend?” asked Willem, who could not forget, even while amused by the ludicrous aspect of the two Africans, that his brother was missing.

“Don’t know, Baas Willem,” answered Congo. “I been long time here.”

“But when did you see him last?” inquired Hendrik.

Congo was unable to tell, for he seemed under the impression that he had been several days in the bosom of the earth.

From Swartboy they learnt that soon after their own departure Arend had started in pursuit of one of the horses seen straying over the plain. That was the last Swart had seen of him.

The sun was now low down, and, without wasting time in idle speech, Hendrik and Groot Willem again mounted their horses, and rode off towards the place where Arend was last seen.

They reached the edge of the timber nearly a mile from the camp, and then, not knowing which way to turn, or what else to do, Willem fired a shot.

The loud crack of the roer seemed to echo far-away through the forest, and anxiously they listened for some response to the sound. It came, but not in the report of a rifle, or in the voice of the missing man, but in the language of the forest denizens. The screaming of vultures, the chattering of baboons, and the roaring of lions were the responses which the signal received.

“What shall we do, Willem?” asked Hendrik.

“Go back to the halting-place and bring Congo and Spoor’em,” answered Willem, as he turned towards the camp, and rode off, followed by his cousin.

Chapter Six.

Spoor’em.

The last ray of daylight had fled from the valley of the Limpopo, when Willem and Hendrik, provided with a torch and accompanied by the Kaffir and the dog Spoor’em, again set forth to seek for their lost companion.

The animal answering to the name Spoor’em was a large Spanish bloodhound, now led forth to perform the first duty required of him in the expedition.

The dog, when quite young, had been brought from one of the Portuguese settlements at the north,—purchased by Groot Willem and christened Spoor’em by Congo.

In the long journey from Graaf Reinet, this brute had been the cause of more trouble than all the other dogs of the pack. It had shown a strong disinclination to endure hunger, thirst, or the fatigues of the journey; and had often exhibited a desire to leave its new masters.

Spoor’em was now led out, in hopes that he would do some service to compensate for the trouble he had caused.

Taking a course along the edge of the forest, that would bring them across the track made by Arend in reaching the place where the horse had strayed, the spoor of Arend’s horse as well as the other’s was discovered.

The tracks of both were followed into the forest, along well-beaten path, evidently made by buffaloes and other animals passing to and from the river. This path was hedged in by a thick thorny scrub, which being impenetrable rendered it unnecessary for some time to avail themselves of the instincts of the hound. Congo led the way.

“Are you sure that the two horses have passed along here?” asked Willem, addressing himself to the Kaffir.

“Yaas, Baas Willem,” answered Congo. “Sure dey both go here.”

Willem, turning to Hendrik, added, “I wish Arend had let the horse go to the deuce. It was not worth following into a place like this.”

After continuing through the thicket for nearly half a mile, they reached a stretch of open ground, where there was no longer a beaten trail, but tracks diverging in several directions. The hoof-marks of Arend’s horse were again found, and the bloodhound was unleashed and set upon them.

Unlike most hounds, Spoor’em did not dash onward, leaving his followers far behind. He appeared to think that it would be for the mutual advantage of himself and his masters that they should remain near each other. The latter, therefore, had no difficulty in keeping up with the dog.

Believing that they should soon learn something of the fate of their lost companion, they proceeded onward, with their voices encouraging the hound to greater speed.

The sounds of a contest carried on by some of the wild denizens of the neighbourhood were soon heard a few yards in advance of them. They were sounds that the hunters had often listened to before, and therefore could easily interpret. A lion and a pack of hyenas were quarrelling over the dead body of some large animal. They were not fighting; for of course the royal beast was in undisputed possession of the carcass, and the hyenas were simply complaining in their own peculiar tones. The angry roars of the lion, and the hideous laughter of the hyenas, proceeded from a spot only a few yards in advance, and in the direction Spoor’em was leading them.

The moon had risen, and by its light the searchers soon beheld the creatures that were causing the tumult. About a dozen hyenas were gibbering around a huge lion that lay crouched alongside a dark object on the ground, upon which he appeared to be feeding. As the hunters drew nearer, the hyenas retreated to some distance.

“It appears to be the carcass of a horse,” whispered Hendrik.

“Yes, I am sure of it,” answered Willem, “for I can see the saddle. My God! It is Arend’s horse! Where is he?”

Spoor’em had now advanced to within fifteen paces of where the lion lay, and commenced baying a menace; as if commanding the lion to forsake his unfinished repast. An angry growl was all the answer Spoor’em could obtain; and the lion lay still.

“We must either kill or drive him away,” said Willem. “Which shall we try?”

“Kill him,” answered Hendrik; “that will be our safest plan.”

Stealing out of their saddles, Willem and Hendrik gave their horses in charge to the Kaffir, and then proceeded to stalk. With their guns at full cock they advanced side by side, Spoor’em sneaking along at their heels.

They stole up within five paces of the lion, which still held its ground. The only respect it showed to their presence was to leave off feeding and crouch over the body of the horse, as though preparing to spring upon them.

“Now,” whispered Hendrik, “shall we fire?”

“Yes, yes!—now!”

Both pulled trigger at the same time, the two shots making but one report.

Instinctively each threw himself from the direct line of the creature’s deadly leap. This was done at the moment of firing; and the lion, uttering a terrific roar, launched itself towards them, and fell heavily between the two, having leaped a distance of full twenty feet. That effort was its last, for it was unable to rise again.

Without taking the trouble to ascertain whether the fierce brute had been killed outright, they turned their attention to the carcass.

The horse was Arend’s, but there was not the slightest trace of the rider. Whatever had been his fate, there was no sign of his having been killed along with his horse. There was still a hope that he had made his escape, though the finding of the horse only added to their apprehensions.

“Let us find out,” counselled Hendrik, “whether the horse was killed where it is now lying, or whether it has been dragged hither by the lion.”

After examining the ground, Congo declared that the horse had been killed upon the spot, and by the lion.

This was strange enough.

On a further examination of the sign, it was found that one of the horse’s legs was entangled in the rein of the bridle. This explained the circumstance to some extent, otherwise it would have been difficult to understand how so swift an animal as a horse should have allowed itself to be overtaken upon an open plain.

“So much the better,” said Groot Willem. “Arend never reached this place along with his horse.”

“That’s true,” answered Hendrik, “and our next move will be to find out where he parted from his saddle.”

“Let us go back,” said Willem, “and more carefully examine the tracks.”

During this conversation, the hunters had reloaded their rifles, and now remounted for the purpose of riding back.

“Baas Willem,” suggested Congo, “let Spoor’em try ’bout here little more.”

This suggestion was adopted, and Congo, setting on the hound, proceeded to describe a larger circle around the spot.

After reaching a part of the plain where they had not yet been, the Kaffir called out to them to come to him.

They rode up, and were again shown the spoor of Arend’s horse leading away from where its carcass was now lying, and in the opposite direction from the camp.

It was evident that the horse had been farther off than the spot where its remains now rested. It had probably lost its rider beyond, and was on its return to the camp when killed by the lion.

Once more Spoor’em started along the track, Congo keeping close to his tail, the two horsemen riding anxiously after.

But we must return to the camp, and follow the trail of the lost hunter by a means more sure than even the keen scent of Spoor’em.

Chapter Seven.

The Lost Hunter.

As Arend came up to the horse that had wandered from the camp, the animal had arrived at the edge of an extensive thicket, and was apparently determined upon straying still farther. To avoid being caught or driven back, it rushed in among trees, taking a path or trace made by wild animals.

Arend followed.

The path was too narrow to allow of his heading the stray; and, apprehensive of losing it altogether, the youth followed on in hopes of coming to a wider track, where he might have a chance of passing the runaway and turning it towards the camp.

This hope seemed about to be realised, as the truant emerged from the thicket and entered upon an open plain clothed with low heath,—the Erica vestila, loaded with white blossoms.

The hunter was no longer obliged to follow upon the heels of the runaway,—the horse; and spurring his own steed, he made an attempt to get past it. But the horse, perhaps inspired by a recollection of the pack-saddle and its heavy load, broke off into a gallop.

Arend followed, increasing his own speed in like proportion. When nearly across the plain, the runaway suddenly stopped and then bolted off at right angles to the course it had been hitherto pursuing.

Arend was astonished, but soon discovered the cause of this eccentric action, in the presence of a huge black rhinoceros,—the borelé—which was making a straight course across the plain, as if on its way to the river.

The runaway horse had shied out of its way; and it would have been well for the horseman if he had shown himself equally discreet. But Arend Von Wyk was a hunter,—and an officer of the Cape Militia,—and as the borelé passed by him, presenting a fine opportunity for a shot, he could not resist the temptation to give it one.

Pulling up his horse, or rather trying to do so, for the animal was restive in the presence of such danger, he fired. The shot produced a result that was neither expected nor desired. With a roar like the bellowing of an angry bull, the monster turned and charged straight towards the horseman.

Arend was obliged to seek safety in flight, while the borelé pursued in a manner that told of its being wounded, but not incapacitated from seeking revenge.

At the commencement of the chase, there was but a very short distance between pursuer and pursued; and in place of suddenly turning out of the track, and allowing the monster to pass by him,—which he should have done, knowing the defect of vision natural to the rhinoceros,—the young hunter continued on in a straight line, all the while employed in reloading his rifle.

His mistake did not originate in any want of knowledge, or presence of mind, but rather from carelessness and an unworthy estimate of the abilities of the borelé to overtake him. He had long been a successful hunter, and success too often begets that over-confidence which leads to many a mischance, that the more cautious sportsman will avoid.

Suddenly he found his flight arrested by the thick scrub of thorny bushes, known in South Africa as the “wait a bits”, and the horse he was riding did wait a bit,—and so long that the borelé was soon close upon his heels.

There was now neither time nor room to turn either to the right or left.

The rifle was at length loaded, but there would have been but little chance of killing the rhinoceros by a single shot, especially with such uncertain aim as could have been taken from the back of a frightened horse.

Arend, therefore, threw himself from the saddle. He had a twofold purpose in doing so. His aim would be more correct, and there was the chance of the borelé keeping on after the horse, and leaving him an undisturbed spectator of the chase.

The field of view embraced by the eyes of a rhinoceros is not large; but, unfortunately for the hunter, as the frightened horse fled from his side, it was he himself that came within the circumscribed circle of the borelé’s vision.

Hastily raising the rifle to his shoulder he fired at the advancing enemy, and then fled towards a clump of trees that chanced to be near by.

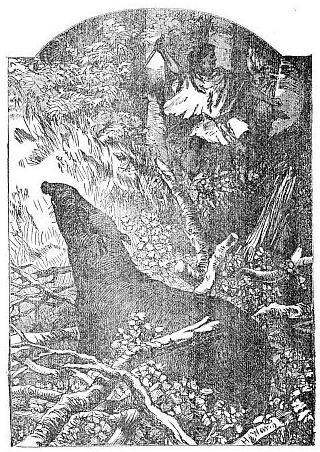

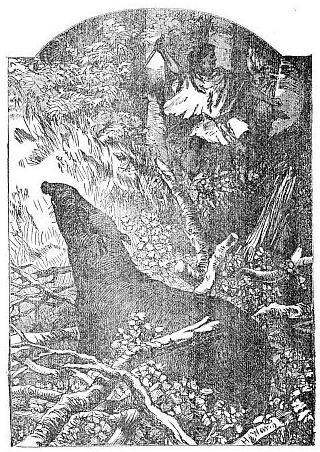

He could hear the heavy tread of the rhinoceros as it followed close upon his heels. It seemed to shake the earth. Closer and closer he heard it, so near that he dared not stop to look around. He fancied he could feel the breath of the monster blowing upon his back. His only chance was to make a sudden deviation from his course, and leave the borelé to pass on in its impetuous charge. This he did, turning sharply to the right, when he saw that he had just escaped being elevated upon the creature’s horn.

This manoeuvre enabled him to gain some distance as he started off in the new direction. But it was not long maintained; for the borelé was again in hot pursuit, without any show of fatigue; while the tremendous exertions he had himself been making rendered him incapable of continuing his flight much longer. He had just sufficient strength left to avoid an immediate encounter by taking one more turn, when, fortunately, he saw before him the trunk of a large baobab-tree lying prostrate along the ground. It had been blown down by some mighty storm, and lay resting upon its roots at one end, and its shivered branches at the other, so as to leave a space of about two feet between its trunk and the ground.

Suddenly throwing himself down, Arend glided under the tree, just in time to escape the long horn, whose point had again come in close proximity with his posterior.

The hunter had now time to recover his breath, and, to some extent, his confidence. He saw that the fallen tree would protect him. Even should the rhinoceros come round to the other side, he would only have to roll back again to place himself beyond the reach of its terrible horn. The space below was ample enough to enable him to pass through, but too small for the body of a borelé. By creeping back and forward he could always place himself in safety. And this was just what he had to do; for the enraged monster, on seeing him on the other side, immediately ran round the roots, and renewed the attack.

This course of action was several times repeated before the young hunter was allowed much time for reflection. He was in hopes that the brute would get tired of the useless charges  it was making and either go away itself, or give him the opportunity.

it was making and either go away itself, or give him the opportunity.

In this hope he was doomed to disappointment. The animal, exasperated with the wounds it had received, appeared implacable; and for more than an hour it kept running around the tree in vain attempts to get at him. As he had very little trouble in avoiding it, there was plenty of opportunity for reflection; and he passed the time in devising some plan to settle the misunderstanding between the borelé and himself.

The first he thought of was to make use of his rifle. The weapon was within his reach where he had dropped it when diving under the tree; but when about to reload it, he discovered that the ramrod was missing!

So sudden had been the charge of the borelé, at the time the rifle was last loaded, that the ramrod had not been returned to its proper place, but left behind upon the plain. This was an unlucky circumstance; and for a time the young hunter could not think of anything better than to keep turning from side to side, to avoid the presence of the besieger.

The borelé at last seemed to show signs of exhaustion, or, at all events, began to perceive the unprofitable nature of the tactics it had been pursuing. But the spirit of revenge was not the least weakened within it, for it made no move toward taking its departure from the spot. On the contrary, it lay down by the baobab in a position to command a view on both sides of the huge trunk, evidently determined to stay there and await the chance of getting within reach of its victim.

Thus silently beleaguered, the young hunter set about considering in what manner he might accomplish the raising of the siege.

Chapter Eight.

Rescued.

The sun went down, the moon ascended above the tops of the surrounding trees, yet the borelé seemed no less inspired by the spirit of revenge than on first receiving the injuries it was wishing to resent.

For many hours the young hunter waited patiently for it to move away in search of food or any other object except that of revenge; but in this hope he was disappointed. The pain inflicted by the shots would not allow either hunger or thirst to interfere with the desire for retaliation, and it continued to maintain a watch so vigilant that Arend dared not leave his retreat for an instant. Whenever he made a movement, the enemy did the same.

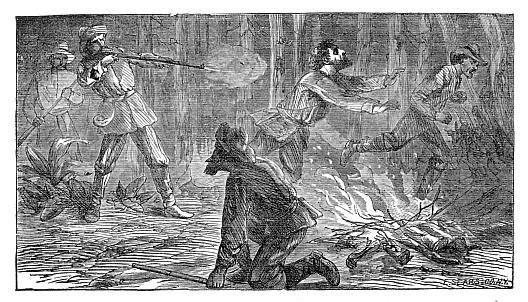

It was a long time before he could think of any plan that would give him a chance of getting away. One at length occurred to him.

Although unable to reload the rifle with a bullet, the thought came into his mind, that the borelé might be blinded by a heavy charge of powder, or so confused by it as to give him an opportunity of stealing away. This seemed an excellent plan, yet so simple that Arend was somewhat surprised he had not thought of it before.

Without difficulty he succeeded in pouring a double quantity of powder into the barrel; and, in order to keep it there until he had an opportunity for a close shot, some dry grass was forced into the muzzle. The chance soon offered; and, taking a deliberate aim at one of the borelé’s eyes with the muzzle of the gun not more than two feet from its head, he pulled trigger.

With a loud moan of mingled rage and agony, the rhinoceros rushed towards him, and frantically, but vainly exerted all its strength in an endeavour to overturn the baobab.

“One more shot at the other eye,” thought Arend, “and I shall be free.”

He immediately proceeded to pour another dose of powder into the rifle, but while thus engaged a new danger suddenly presented itself. The dry grass projected from the gun had ignited and set fire to the dead leaves that were strewed plentifully over the ground. In an instant these were ablaze, the flame spreading rapidly on all sides, and moving towards him.

The trunk of the baobab could no longer afford protection. In another minute it, too, would be enveloped in the red fire, and to stay by its side would be to perish in the flames. There was no alternative but to get to his feet and run for his life.

Not a moment was to be lost, and, slipping from under the tree, he started off at the top of his speed. The chances were in his favour for escaping unobserved by the rhinoceros. But fortune seemed decidedly against him. Before getting twenty paces from the tree, he saw that he was pursued.

Guided either by one eye or its keen sense of hearing, the monster was following him at a pace so rapid that, if long enough continued, it must certainly overtake him.

Once more the young hunter began to feel something like despair. Death seemed hard upon his heels. A few seconds more, and he might be impaled on that terrible horn. But for that instinctive love of life which all feel, he might have surrendered himself to fate; but urged by this, he kept on.

He was upon the eve of falling to the earth through sheer exhaustion, when his ears were saluted by the deep-toned bay of a hound, and close after it a voice exclaiming—

“Look out, Baas Willem! Somebody come yonder!”

Two seconds more and Arend was safe from further pursuit. The hound Spoor’em was dancing about the borelé’s head, by his loud, angry yelps diverting its attention from everything but himself.

Two seconds more and Groot Willem and Hendrik came riding up; and, in less than half a minute after, the monster, having received a shot from the heavy roer, slowly settled down in its tracks—a dead rhinoceros.

Willem and Hendrik leaped from their horses and shook hands with Arend in a manner as cordial as if they were just meeting him after an absence of many years.

“What does it mean, Arend?” jocosely inquired Hendrik. “Has this brute been pursuing you for the last twelve hours?”

“Yes.”

“And how much longer do you think the chase would have continued?”

“About ten seconds,” replied Arend, speaking in a very positive tone.

“Very well,” said Hendrik, who was so rejoiced at the deliverance of his friend that he felt inclined to be witty. “We know now how long you are capable of running. You can lead a borelé a chase of just twelve hours and ten seconds.”

Groot Willem was for some time unspeakably happy, and said not a word until they had returned to the place where the lion had been killed. Here they stopped for the purpose of recovering the saddle and bridle from the carcass of the horse.

Groot Willem proposed they should remain there till the morning; his reason being that, in returning through the narrow path that led out to the open plain, they might be in danger of meeting buffaloes, rhinoceroses, or elephants, and be trampled to death in the darkness.

“That’s true,” replied Arend; “and it might be better to stay here until daylight, but for two reasons. One is, that I am dying of hunger, and should like a roast rib of that antelope I shot in the morning.”

“And so should I,” said Hendrik, “but the jackals have saved us the trouble of eating that.”

Arend was now informed of the events that had occurred to his absence, and was highly amused at Hendrik’s account of the misfortune that had befallen Swartboy and Congo.

“We are making a very fair commencement in the way of adventures,” said he, after relating his own experiences of the day, “but so far our expedition has been anything but profitable.”

“We must go farther down the river,” said Willem. “We have not yet seen the spoor of either hippopotamus or giraffe. We must keep moving until we come upon them. I never want to see another lion, borelé, or elephant.”

“But what is your other reason for going back to camp?” asked Hendrik, addressing himself to Arend.

“What would it be?” replied Arend. “Do you suppose that our dear friend Hans has no feelings?”

“O, that’s what you mean, is it?”

“Of course it is. Surely Hans will by this time be half dead with anxiety on our account.”

All agreed that it would be best to go on to the camp; and, after transferring the saddle and bridle from the carcass of the horse to the shoulders of Congo, they proceeded onward, arriving in camp at a very late hour, and finding Hans, as Arend had conjectured, overwhelmed with apprehension at their long absence.

Chapter Nine.

An Incident of the Road.

Next morning, they broke up their camp and moved down the river, extending their march into the second day.

After passing the drift where the Limpopo had been first crossed, Groot Willem, accompanied by Congo, was riding nearly a mile in advance of his companions. His object in leading the way so far ahead was to bag any game worthy of his notice, before it should be frightened by the others.

Occasionally, a small herd of some of the many varieties of antelopes in which South Africa abounds fled before him; but these the great hunter scarce deigned to notice. His thief object was to find a country frequented by hippopotami and giraffes.

On his way he passed many of the lofty pandanus or screw pine-trees. Some of these were covered from top to bottom with parasitic plants, giving them the appearance of tall towers or obelisks. Underneath one of these trees, near the river, and about three hundred yards from where he was riding, he saw a buffalo cow with her calf. The sun was low down; and the time had therefore arrived when some buffalo veal would be acceptable both to the men and dogs of the expedition.

Telling Congo to stay where he was, the hunter rode to the leeward of the buffalo cow, and, under cover of some bushes, commenced making approach. Knowing that a buffalo cow is easily alarmed, more especially when accompanied by her calf, he made his advances with the greatest caution. Knowing, also, that no animal shows more fierceness and contempt for danger, while protecting its young, he was anxious to get a dead shot, so as to avoid the risk of a conflict with the cow, should she be only wounded. When he had got as close as the cover would allow him, he took aim at the cow’s heart and fired.

Contrary to his expectation, the animal neither fell nor fled, but merely turned an inquiring glance in the direction from whence the report had proceeded.

This was a mystery the hunter could not explain. Why did the cow keep to the same spot? If not disabled by the bullet, why had she not gone off, taking her young one along with her?

“I might as well have been stalking a tree as this buffalo,” thought Willem, “for one seems as little inclined to move as the other.”

Hastily reloading his roer, he rode fearlessly forward, now quite confident that the cow could not escape him. She seemed not to care about retreating, and he had got close up to the spot where she stood, when all at once the buffalo charged furiously towards him, and was only stopped by receiving a second bullet from the roer that hit right in the centre of the forehead. One more plunge forward and the animal dropped on her knees, and died after the manner of buffaloes, with legs spread and back uppermost, instead of falling over on its side. Another shot finished the calf, which was crying pitifully by the side of its mother.

Congo now came up, and, while examining the calf, discovered that one of its legs had been already broken. This accounted for the cow not having attempted to save herself by flight. She knew that her offspring was disabled, and stayed by it from an instinct of maternal solicitude.

While Willem was engaged reloading his gun, he heard a loud rustling among the parasitical plants that loaded the pandanus-tree under which he and Congo were standing. Some large body was stirring among the branches. What could it be?

“Stand clear,” shouted Willem, as he swerved off from the tree, at the same time setting the cap upon his gun.

At the distance of ten or twelve paces he faced round, and stood ready to meet the moving object, whatever it might be. Just then he saw standing before him a tall man who had dropped down from among the leaves, while Willem’s back had been turned towards the tree.

The dress and general appearance of this individual proclaimed him to be a native African, but not one of those inferior varieties of the human race which that country produces. He was a man of about forty years of age, tall and muscular, with features well formed, and that expressed both intelligence and courage. His complexion was tawny brown, not black; and his hair was more like that of a European than an African.

These observations were made by the young hunter in six seconds; for the person who had thus suddenly appeared before him allowed no more time to elapse before setting off from the spot, and in such haste that the hunter thought he must be retreating in affright. And yet there was no sign of fear accompanying the act. Some other motive must have urged him to that precipitate departure.

There was; and Congo was the first to discover it. The man had gone in the direction of the river.

“Water, water!” exclaimed the Kaffir; “he want water.”

The truth of this remark was soon made evident; for, on following the stranger with their eyes, they saw him rush into the stream, plunge his head under water and commence filling himself in the same manner as he would have done, had his body been a bottle!

Hendrik and Arend, having heard the reports of the roer, feared that something might have gone wrong, and galloped forward, leaving Hans and Swartboy to bring up the pack-horses.

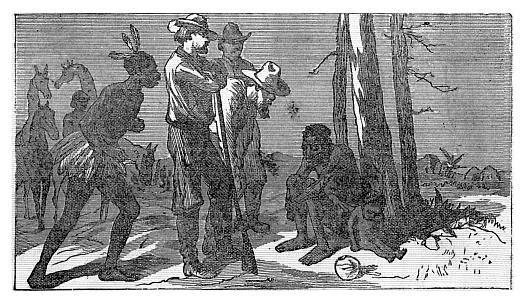

They reached the scene just as the African, after having quenched his thirst, had returned to the tree where the young hunter and Congo had remained.

Without taking the slightest notice of either of the others, the man walked up to Groot Willem, and, with an air of dignity, natural to most semi-barbarous people, began making a speech. Grateful for having been relieved from his imprisonment, he evidently believed that duty required him to say something, whether it might be understood or not.

“Can you understand him, Congo?” asked Willem.

“Yaas, a little I can,” answered the Kaffir; and in his own peculiar manner he interpreted what the African had to say.

It was simply that he owed his life to Groot Willem, and that the latter had only to ask for whatever he required, and it should be given him.

“That is certainly promising a good deal,” said the sarcastic Hendrik, “and I hope that Willem will not be too greedy in his request, but will leave something for the rest of mankind.”

Hans and Swartboy at this moment came up with the pack-horses; and, selecting a spot near the place where the cow had been killed, the party encamped for the night.

For some time, all hands were busy in gathering firewood and making other preparations for their bivouac,—among which were the skinning and cooking of the buffalo calf, duties that were assigned to the Bushman. During his performance of them, the others, assisted by Congo as interpreter, were extracting from the tall stranger a full account of the adventure to which they were indebted for his presence in the camp; and a strange story it was.

Chapter Ten.

Macora.

In the manner of the African there was a certain hauteur which had not escaped the observation of his hearers.

This was explained on their learning who and what he was; for his story began by his giving a true and particular account of himself.

His name was Macora, and his rank that of a chief. His tribe belonged to the great nation of the Makololo, though living apart, in a “kraal” by themselves. The village, so-called, was at no great distance from the spot where the hunters were now encamped.

The day before, he had come up the river in a canoe, accompanied by three of his subjects. Their object was to procure a plant which grew in that place,—from which the poison for arrows and spears is obtained. In passing a shallow place in the river, they had attempted to kill a hippopotamus which they saw walking about on the bottom of the stream, like a buffalo browsing upon a plain. Rising suddenly to the surface, the monster had capsized the canoe, and Macora was compelled to swim ashore with the loss of a gun which once cost him eight elephant’s tusks.

He had seen nothing of his three companions, since parting with them in the water.

On reaching the shore, and a few yards from the bank, he encountered a herd of buffaloes, cows and young calves, on their way to the river. These turned suddenly to avoid him, when a calf was knocked down by one of the old ones, and so severely injured that it could not accompany the rest in their flight. The mother, seeing her offspring left behind, turned back and selected Macora as the object of her resentment. The chief retreated towards the nearest tree, hotly pursued by the animal eager to revenge the injury done to her young.

He was just in time to ascend among the branches as the cow came up. The calf, with much difficulty, succeeded in reaching the tree. Once there, it could not move away, and the mother would not leave it. This accounted for Macora’s having been found among the branches of the pandanus. He went on to say, that, during the time he had been detained in the tree, he had made several attempts to get down and steal off, but on each occasion had found the buffalo waiting to receive him upon her horns. He was suffering terribly with thirst when he heard the first shot fired by Groot Willem, and perceived that assistance was near.

The chief concluded his narrative by inviting the hunters to accompany him the next morning to his kraal; where he promised to show them such hospitality as was in his power. On learning that his home was down the river, and at no great distance from it, the invitation was at once accepted.

“One thing this man has told us,” remarked Willem, “which pleases me very much. We have learnt that there is or has been a hippopotamus near our camping-ground, and perhaps we shall not have far to travel before commencing our premeditated war against them.”

“Question him about sea-cows, Cong,” said Hendrik. “Ascertain if there are many of them about here.”

In answer to the Kaffir’s inquiries, the chief stated that hippopotami were not often seen in that part of the river; but that, a day’s journey farther down, there was a large lagoon, through which the stream ran; there, sea-cows were as plentiful as the stars in the sky.

“That is just the place we have been looking for,” said Willem; “and now, Congo, question him about camelopards.”

Macora could hold out but little hopes of their meeting giraffes anywhere on that part of the Limpopo. He had heard of one or two having been occasionally seen; but it was not a giraffe country, and they were stray animals.

“Ask him if he knows where there is such a country,” demanded Willem, who seemed more interested in learning something about giraffes than either of his companions.

Macora could not or would not answer this question without taking his own time and way of doing it. He stated that the native country of himself and his tribe was far to the north and west; that they had been driven from their home by the tyranny of the great Zooloo King, Moselekatse, who claimed the land and levied tribute upon all the petty chiefs around him.

Macora further stated that, having in some mysterious manner lost the good opinion of Sekeletu and other great chiefs of the Makololo,—his own people,—they would no longer protect him, and that he and his tribe were compelled to leave their homes, and migrate to the place where he was now about to conduct his new acquaintances.

“But that is not what I wish to know,” said Groot Willem, who never troubled himself with the political affairs of his own country, and therefore cared little about those of an African petty chief.

On being brought back to the question, Macora stated that he was only giving them positive proof of his familiarity with the camelopards, since nowhere were these more abundant than in the country from which he had been expatriated by the tyranny of the Zooloo chief. It was his native land, where he had hunted the giraffe from childhood.

Swartboy here interrupted the conversation by announcing that he had enough meat cooked for them to begin their meal with; and about ten pounds’ weight of buffalo veal cutlets were placed before the hunters and their guest.

Macora, who, to all appearance, had been waiting very patiently while the cutlets were being broiled, commenced the repast with some show of self-restraint. This, however, wholly forsook him before it was finished. He ate voraciously, consuming more than the four young hunters together. This, however, he did not do without making an apology for his apparent greed; stating that he had been nearly two days without having tasted food.

The supper having at length come to an end, all stretched themselves around the fire and went to sleep.

The night passed without their being disturbed; and soon after sunrise they arose,—not all at the same time,—for one of the party had risen and taken his departure an hour earlier than the rest. It was Macora, whom they had entertained the evening before.

“Here, you Swart and Cong!” exclaimed Arend, when he discovered that the chief was no longer in the camp, “see if any of the horses are missing. It is just possible we have been tricked by a false tale and robbed into the bargain.”

“By whom?” asked Groot Willem.

“By your friend, the chief. He has stolen himself away, if nothing else.”

“I’ll bet my life,” exclaimed Willem, in a more positive tone than the others had ever yet heard him use, “that that man is an honest fellow, and that all he has told us is true, though I can’t account for his absence. He is a chief, and has the air of one.”

“Yes, he is a chief, no doubt,” said Hendrik, sneeringly. “Every African in this part of the world is a chief, if he only has a family. Whether his story be true or not, it looks ugly, his leaving us in this clandestine manner.”

Hans, as usual, had nothing to say upon a subject of which he knew nothing; and Swartboy, after making sure that no horses, guns, or other property were missing, expressed the opinion that he was never so mystified in his life.

Nothing was gone from the camp; and yet he was quite certain that any one speaking a native African language understood by Congo, could not be capable of acting honestly if an opportunity was allowed him for the opposite.

Having allowed their horses an hour to graze, while they themselves breakfasted upon buffalo veal, our adventurers broke up their bivouac, and continued their march down the bank of the river.

Chapter Eleven.

Macora’s Kraal.

After journeying about three hours, the young hunters came to a place that gave unmistakable evidence of having been often visited by human beings.

Small palm-trees had been cut down, the trunks taken away, and the tops left on the ground. Elephants, giraffes, or other animals that feed on foliage would have taken the tops of the trees, and, moreover, would not have cut them down with hatchets, the marks of which were visible in the stumps left standing. Half a mile farther on, and fields could be seen in cultivation. They were evidently approaching a place inhabited by a people possessing some intelligence.

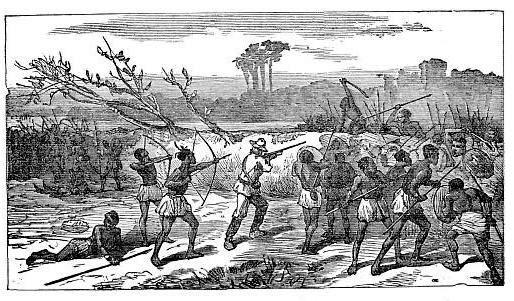

“See!” exclaimed Arend, as they rode on, “there’s a large body of men coming towards us.”

All turned to the direction in which Arend was gazing. They saw about fifty people coming along the crest of a ridge, that trended toward the north.

“Perhaps they mean mischief,” said Hans. “What shall we do?”

“Ride on and meet them,” exclaimed Hendrik. “If they are enemies it is not our fault. We have not molested them.”

As the strangers came near, the hunters recognised their late guest, who was now mounted on an ox and riding in advance of his party. His greeting, addressed to Groot Willem, was interpreted by Congo.

“I have invited you to come to my kraal,” said he, “and to bring your friends along with you. I left you early this morning, and have been to my home to see that preparations should be made worthy of those who have befriended Macora. Some of my people, the bravest and best amongst them, are here to bid you welcome.”

A procession was then formed, and all proceeded on to the African village, which was but a short distance from the spot. On entering it, a group of about a hundred and fifty women received them with a chant, expressed in low murmuring tones, not unlike the lullaby with which a mother sings her child to sleep.

The houses of the kraal were constructed stockade fashion, in rows of upright poles, interlaced with reeds or long grass, and then covered with a plaster of mud. Through these the hunters were conducted to a long shed in the centre of the village, where the saddles were taken from their horses, which were afterwards led off to the grazing ground.

Although Macora’s subjects had been allowed but three hours’ notice, they had prepared a splendid feast for his visitors.

The young hunters sat down to a dinner of roast antelope, biltongue, stews of hippopotamus and buffalo flesh, baked fish, ears of green maize roasted, with wild honey, stewed pumpkin, melons, and plenty of good milk.

The young hunters and all their following were waited on with the greatest courtesy. Even their dogs were feasted, while Swartboy and Congo had never in all their lives been treated with so much consideration.

In the afternoon, Macora informed his guests that he should give them an entertainment; and, in order that they should enjoy the spectacle intended for them, he informed them, by way of prologue, of the circumstances under which it was to be enacted.

His statement was to the effect that his companions in the canoe, at the time it was capsized by the hippopotamus, had reached home, bringing with them the story of their mishap; that the tribe had afterwards made a search for their chief, but not finding him, had come to the conclusion that he had been either drowned or killed by the sea-cow. They had given him up for lost; and another important member of the community, named Sindo, had proclaimed himself chief of the tribe.

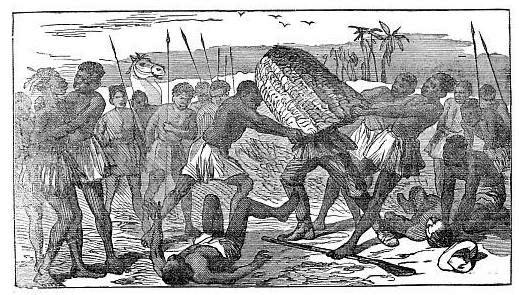

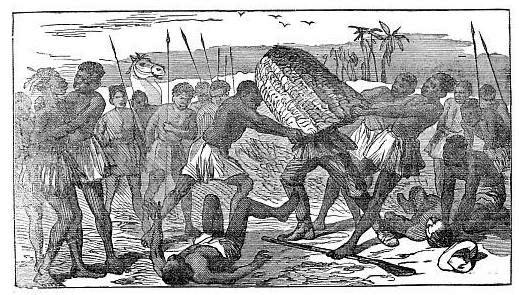

When Macora reached home that morning, Sindo had not yet come forth from his house; and, before he was aware of the chief’s reappearance, the house had been surrounded and the usurper made prisoner. Sindo, fast bound and guarded, was now awaiting execution; and this was the spectacle which the hunters were to be treated to.

It was a scene that none of the young hunters had any desire to be present at; but, yielding to the importunities of their host, they accompanied him to the spot where the execution was to take place. This was in the suburbs of the village, where they found the prisoner fast tied to a tree. Nearly all the inhabitants of the community had assembled to see the usurper shot,—this being the manner of death that had been awarded to him.

The prisoner was rather a good-looking man, apparently about thirty-five years of age. No evil propensity was expressed in his features; and our heroes could not help thinking that he had been guilty of no greater crime than a too hasty ambition.

“Can we not save him from this cruel fate?” asked Hans, speaking to Groot Willem. “I think you have some influence with the chief.”

“There can be no harm in trying,” answered Willem. “I’ll see what I can do.”

Sindo was to be shot with his own musket. The executioner had been already appointed, and all other arrangements made for carrying out the decree, when Willem, advancing towards Macora, commenced interceding for his life.

His argument was, that the prisoner had not committed any great crime; that had he conspired against his chief for the purpose of placing himself in authority, it would have been a different affair. Then he would have deserved death.

Willem further urged, that had he, Macora, really been lost, some one of the tribe would have become chief, and that Sindo was not to blame for aspiring to resemble one who had ruled to the evident satisfaction of all.

Macora was then entreated to spare the prisoner’s life, and the entreaty was backed by the promise of a gun to replace the one lost in the river, on condition that Sindo should be allowed to live.

For a time Macora remained silent, but at length made reply, by saying that he should never feel safe if the usurper were allowed to remain in the community.

Groot Willem urged that he could be banished from the kraal, and forbidden to return to it on penalty of death.

Macora hesitated a little longer; but remembering that he had promised to grant any favour to the one who had released him from imprisonment in the tree, he yielded. Sindo’s life should be spared on condition of his expatriating himself at once and forever from the kraal of Macora.

On granting this pardon, the chief wished all distinctly to understand that it was done out of gratitude to his friend, the big white hunter. He did not wish it to be supposed that the prisoner’s life had been purchased with a gun.

All Macora’s subjects, including the condemned man himself, appeared greatly astonished at the decision, so contrary to all precedent among his fellow-countrymen.

The exhibition of mercy, along with the refusal of the bribe, proved to the young hunters, that Macora had within him the elements of a noble nature.