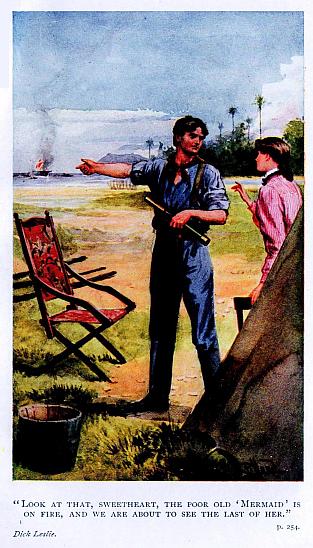

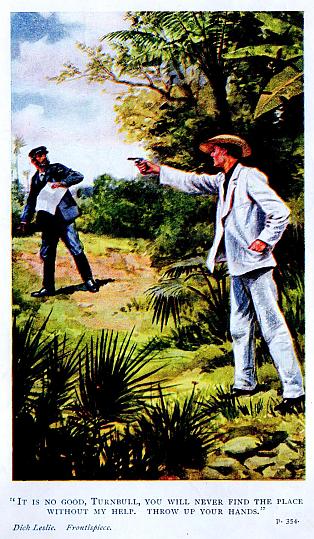

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dick Leslie's Luck, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Dick Leslie's Luck

A Story of Shipwreck and Adventure

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: Harold Piffard

Release Date: January 27, 2009 [EBook #27909]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DICK LESLIE'S LUCK ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"Dick Leslie's Luck"

Chapter One.

A Maritime Disaster.

The night was as dark as the inside of a cow! Mr Pryce, the chief mate of the full-rigged sailing ship Golden Fleece—outward-bound to Melbourne—was responsible for this picturesque assertion; and one had only to glance for a moment into the obscurity that surrounded the ship to acknowledge the truth of it.

For, to begin with, it was four bells in the first watch—that is to say, ten o’clock p.m.; then it also happened to be the date of the new moon; and, finally, the ship was just then enveloped in a fog so dense that, standing against the bulwarks on one side of the deck, it was impossible to see across to the opposite rail. It was Mr Pryce’s watch; but the skipper—Captain Rainhill—was also on deck; and together the pair assiduously promenaded the poop, to and fro, pausing for a moment to listen and peer anxiously into the thickness to windward every time that they reached the break of the poop at one end of their walk, and the stern grating at the other.

Now, a dark and foggy night at sea is an anxious time for a skipper; but the anxiety is multiplied tenfold when, as in the present case, the skipper is responsible not only for the safety of a valuable ship and cargo, but also for many human lives. For the Golden Fleece was a magnificent clipper ship of two thousand eight hundred tons register, quite new—this being her maiden voyage, while she carried a cargo, consisting chiefly of machinery, valued at close upon one hundred thousand pounds sterling; and there were thirty-six passengers in her cuddy, together with one hundred and thirty emigrants—mostly men—in the ’tween decks. And there was also, of course, her crew.

For a reason that will shortly become apparent, it is unnecessary to introduce any of the above-mentioned persons to the reader—with two exceptions. Of these two exceptions one was a girl some three and twenty years of age, of medium height, perfect figure, lovely features crowned by an extraordinary wealth of sunny chestnut wavy hair with a glint of ruddy gold in it where the sun struck it, and a pair of marvellous dark blue eyes. Her beauty of face and form was perfect; and she would have been wonderfully attractive but for the unfortunate fact that her manner towards everybody was characterised by a frigid hauteur that at once effectually discouraged the slightest attempt to establish one’s self on friendly terms with her. It was abundantly clear that she was a spoiled child, in the most pronounced acceptation of the term, and would be likely to remain so all her life unless some extraordinary circumstance should haply intervene to break down her repellent pride, and bring to the surface those sterling qualities of character that ever and anon seemed struggling for an opportunity to assert themselves. Her name was Flora Trevor; her father was an Indian judge; and, accompanied by her maid, and chaperoned—nominally, at least—by a friend and former schoolfellow of her mother, she was now proceeding on a visit to some relatives in Australia prior to joining her father at Bombay.

The other exception was a man, of thirty-two years of age—but who looked very considerably older. He stood six feet one inch in his socks; was of exceptionally muscular build, without an ounce of superfluous flesh anywhere about him; rather thin and worn-looking as to face—which was clean-shaven and tinted a ruddy bronze, as though the owner had been long accustomed to exposure to the weather; of a gloomy and saturnine cast of countenance; and a manner so cold and unapproachable that, although on this particular night he had been on board the Golden Fleece just a fortnight, no one in the ship knew anything more about him than that he went by the name of Richard Leslie; and that he was—like the rest of the passengers—on his way to Australia.

Now, there is no need to make a secret of this man’s history; on the contrary, a brief sketch of it will lead to a tolerably clear understanding of much that would otherwise prove incomprehensible in his character and actions. Let it be said, therefore, at once, that he was the second, and at one time favourite, son of the Earl of Swimbridge, whom the whole world knows to be beyond all question the proudest member of the British peerage. Amiable, generous, high-spirited, and with every trait of the best type of the British gentleman fully developed in him, this son had joined the British navy at an early age, as a midshipman, and had made rapid progress in the profession of his choice—to his father’s unbounded satisfaction and delight—up to a certain point. Then, when he was within a few months of his twenty-fifth birthday, a horrible thing happened. Without a shadow of warning, and like a bolt from the blue, disgrace and disaster fell upon and morally destroyed him; and almost in a moment the once favoured child of good fortune found himself an outcast from home and society; disowned by those nearest and dearest to him; with every hope and aspiration blasted; branded as a felon; and his whole life ruined, as it seemed to him, irretrievably. In his father’s house, and while enjoying a short period of well-earned leave, he was arrested upon a charge of forgery and embezzlement; and, after a short period of imprisonment, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to a period of seven years’ penal servitude! Vain were all his protestations of innocence; vain his counsel’s representation that there was no earthly motive for such a crime on the part of his client; the evidence adduced against him was so overwhelmingly complete and convincing—although the greater part of it was circumstantial—that his protestations were regarded as a positive aggravation of his offence; and the last news that reached him ere the prison gates closed upon him were that the girl who had promised to be his wife had already given herself to his rival; while his father, stricken to earth by the awful blow to his family pride, as well as to his affection, was not expected to live.

That so fearfully crushing a catastrophe should have fallen with paralysing effect upon the moral nature of the convict himself was only what might naturally be expected. With the pronouncement of that terrible sentence by the judge the victim’s character underwent a complete and instantaneous transformation, as was evidenced by the fact that to him the worst feature of the case seemed to be that he was innocent! He felt that had he been guilty he could have borne his punishment, because he would have richly merited it; but that, being innocent, he should thus be permitted to suffer such abasement and disgrace seemed incomprehensible to him; the injustice of it appeared to him so rank, so colossal, as to destroy within him, in a moment, every atom of his former faith in the existence of a God of justice and of mercy! And with his loss of faith in God went his faith in man. Every good instinct at once seemed to die within him; while as for life, henceforth it could be to him only an intolerable burden to be laid down at the first convenient opportunity.

Feeling thus, as he did, full of rebellion against fate, full of anger and resentment against his fellow-man for the bitterly cruel injustice that had been meted out to him, and kicking hard against the pricks generally, it was scarcely to be expected that he would prove very amenable to the harsh discipline of prison life; and as a matter of fact he did not; he was very careful to avoid the committal of any offence sufficiently serious to bring down upon him the disgrace of a flogging—that crowning shame he could not have endured and continued to live—but, short of that, he was so careless and intractable a prisoner, and gave so much trouble and annoyance to the warders in charge of him, that he earned none of those good marks whereby a prisoner can purchase the remission of a certain proportion of his sentence; and as a result he served the full term of his imprisonment, every moment of which seemed crowded with the tortures of hell! And when at length he emerged once more into the world, he did so as a thoroughly soured, embittered, cynical, utterly hopeless and reckless man, without a shred of faith in anything that was good.

The first thing that he learned, upon attaining his freedom, was that although the Earl, his father, had, after all, survived the shock of his son’s disgrace, he had made a solemn vow never to forgive him, never to see him again, and never to have any communication with him. He had, however, made arrangements with his solicitors that his son should be met at the prison gates and conveyed thence to London, where he was lodged in a quiet hotel until arrangements could be made for his shipment off to Australia. This was quickly done; and within a week of his release the young man, under the assumed name of Richard Leslie, found himself a saloon passenger on board the Golden Fleece, with a plain but sufficient outfit for the voyage, and one hundred pounds in his pocket to enable him to make a new start in life at the antipodes; the gift of the money, however, was accompanied by a request from the Earl that he would never again show his face in England, or even in Europe.

At the moment when this story opens the sound of the ship’s bell—upon which “four bells” had just been struck—was still vibrating upon the wet, fog-laden air; the steerage passengers were all below, and most of them in their bunks; while the cuddy people, with one solitary exception, were in the brilliantly lighted saloon, amusing themselves with cards, books, and music. The exception was Leslie, who, having changed out of his dress clothes into a comfortable suit of blue serge, was down in the waist of the ship, smoking a gloomily retrospective pipe. The ship’s reckoning, that day, had placed her, at noon, in Latitude 32 degrees 10 minutes North, and Longitude 26 degrees 55 minutes West; she was therefore about midway between the parallels of Madeira and Teneriffe, but some four hundred miles, or thereabouts, to the westward of those islands. The wind was blowing a moderate breeze from about south-east by South; and the ship, close-hauled on the port tack, and with all plain sail set, to her royals, was heading south-west, and going through the water at the rate of a good honest seven knots. The helmsman was steering by compass, and not by the sails, since it was impossible to see anything above a dozen feet up from the deck; hence the ship was going along with everything a-rap full.

Captain Rainhill was very far from being easy in his mind. Seven knots, he meditated, was a good pace at which to be sailing through a fog thick enough to cut with a knife, and would mean something very much like disaster if the ship happened to run up against anything, particularly if that “anything” happened also to be travelling at about the same speed in the opposite direction; from this point of view, therefore, the speed of the Golden Fleece just then constituted a decided element of danger. On the other hand, however, it enabled her to promptly answer her helm, and thus might be the means of enabling her to swerve quickly aside and so avoid any danger that might suddenly loom up out of the fog around her; and in this sense it became a safeguard. Then there was the fact that the Golden Fleece was no longer in a crowded part of the ocean; it was three days since they had sighted a craft of any description, and there might be at that moment nothing within a couple of hundred miles of them, in which case there was absolutely nothing to fear. Furthermore, his owners made an especial point of persistently impressing upon their captains the great importance of—nay, more, the urgent necessity for—making quick passages; there were two keen-eyed lookouts stationed upon the topgallant-forecastle, and between them a third man provided with a fog-horn, upon which he at brief intervals blew the weirdest of blasts. Taking into consideration all these circumstances the skipper finally decided to leave things as they were, and put his trust in the “sweet little cherub that sits up aloft to look after the life of poor Jack.”

“Five bells” pealed out upon the dank air, and the responsive cry of “All’s well” from the look-outs came wailing aft from the forecastle. Leslie’s pipe was out. He knocked out the dead ashes, and turned to go below. Then, considering the matter further, he decided that it was full early yet to turn in, and, sauntering across the deck to the port rail, he stood gazing abstractedly out to windward as he slowly filled his pipe afresh. The man with the fog-horn was still industriously blowing long blasts to windward when, ruthlessly cutting into one of these, there suddenly came—from apparently close at hand, on the port bow—the loud discordant yell of a steam syren; and the next instant three lights—red, green, and white, arranged in the form of an isosceles triangle—broke upon Leslie’s gaze with startling suddenness through the dense fog, broad on the port bow of the Golden Fleece. A large steamer, coming along at full speed, was close aboard and heading straight for the sailing ship!

Leslie’s professional training at once asserted itself and, as a frenzied shout of “Steamer broad on the port bow!” came pealing aft from the throats of the two startled lookouts, he made a single bound for the poop ladder, crying, in a voice that rang through the ship, from stem to stern—

“Port! hard a-port, for your life! Over with the wheel, for God’s sake!”

His cry was broken in upon by a mad jangling of engine-room bells accompanied by a perfect babel of excited shouts—evidently in some foreign tongue—on board the stranger, mingled with equally excited shouts and the sudden trampling of feet forward, and loud-voiced commands from Captain Rainhill on the poop. As Leslie reached the head of the poop ladder the steamer crashed with terrific force into the port side of the ill-fated Golden Fleece, just forward of the fore rigging. So tremendous was the shock that every individual who happened at the moment to be on his, or her, feet on board the sailing ship was thrown to the deck; while, as for the ship herself, she was heeled over by it until the water poured like a cataract in over her starboard topgallant rail; there was a horrid crunching sound as the ponderous iron bows of the steamer irresistibly clove their way through the wooden side and decks of the ship; a loud twanging aloft told of severed rigging; there was a terrifying crash of breaking spars overhead; and then, all in a moment, as it seemed, the main deck and poop became alive with shrieking, shouting, distraught people rushing aimlessly hither and thither, and excitedly demanding of each other what was the matter.

The skipper, confounded for the moment by the appalling suddenness of the catastrophe, quickly recovered himself and, turning to the chief mate, ordered him to go forward to investigate the extent of the damage. Then, finding Mr Ferris, the second mate, at his elbow, he said—

“Mr Ferris, muster the watches at once—port watch to the port side, and starboard watch to the starboard side—and set them to work to clear away the boats for launching. Where is the chief steward?”

“Here, sir,” answered the individual in question, forcing his way through the excited crowd that surrounded the skipper.

“Good!” ejaculated Rainhill. “Muster your stewards, sir, and turn-to upon the job of getting provisions and water up on deck for the boats. And, as you go, pass the word for all passengers to dress in their warmest clothing, and make up in packages any valuables that they may desire to take with them in the event of our being obliged to leave the ship. But they must leave their luggage behind; there will be no room for luggage in the boats. And tell any of them who may be below to complete their preparations and come on deck without delay.”

At this moment Mr Pryce, having completed his investigations forward, came rushing up the poop ladder and, wild with excitement, shouted to the skipper—

“We can’t live five minutes, sir! We are cut down from rail to bilge; there is a hole in our side big enough to drive a coach and six through, and the water is pouring into her like a sluice!”

“And where is the steamer?” demanded the skipper.

“She has backed out, and vanished in the fog,” answered the mate.

“My God! what an appalling mess,” ejaculated the distracted skipper. “And all through the lubberly carelessness of those foreign fellows, who were too lazy to sound their syren until they were aboard of us! Now, Mr Ferris, what is the news of the boats? Hurry up and get them into the water as smartly as possible. Back the main-yard, Mr Pryce.”

This mention of the boats, added to the ill-advised candour of the mate’s loudly proclaimed statement as to the condition of the ship, took immediate hold upon the mob of anxiously listening people who were crowding round the two men, and galvanised them into sudden, breathless activity; hitherto they had only vaguely realised that what had happened might possibly mean danger to them; now, in a flash, it dawned upon them, one and all, that they were the victims of a ghastly disaster, and that death was actually staring them in the face! And therewith a mad, unreasoning panic took possession of them, and with one accord they made a rush for the boats.

“Stand back, there; stand back, I say, and leave the men room to work,” yelled the skipper. “Do you hear, there, you people from the steerage? Stand back, as you value your lives! Do you want to drown yourselves and everybody else? Here, Mr Pryce, lend me a hand to keep these madmen in order. Back, every man of you; get off this poop—”

He might as well have appealed to and attempted to reason with the ocean that was pouring in through the gash in the ship’s side! It is doubtful whether any one of those to whom he addressed himself heard him; if they did they certainly took no notice. In a moment the ship’s crew were swept away from the davits and tackle falls, and in another the maddened mob, with a wild yell of “We’re sinking, we’re sinking!” were struggling together, striking and trampling down everybody who happened to be in the way, and fighting desperately with each other for a place in the boats, that had been swung out and were ready for lowering. The skipper and the mate dashed manfully into the thick of the mêlée, no doubt hoping that their authority, and the habit of discipline that was being gradually cultivated among the emigrants would enable them to stem the tide of panic that was raging, and restore order for at least the few minutes that were needed to get the boats into the water. In vain! the two men were visible for a moment, fighting desperately, side by side; then they went down before that maniacal charge—in which the cuddy passengers had by this time joined—and were seen no more.

As for Leslie, the nearest approach to happiness that had been his for more than seven years came to him now with the conviction that he was at last face to face with inevitable, kindly Death. He had endured seven years of physical misery and mental torment because he had too much grit to resort to the cowardly expedient of taking his own life; but now, now fate—he no longer believed in the existence of such a being as God—fate had taken pity upon him and, through no act of his own, he was going to be relieved of his intolerable burden. For he knew that, with that fighting mob of raging maniacs struggling madly round the boats, escape was a sheer impossibility, and that in a few minutes—or hours, at the outside—for he was a strong swimmer—he would go down inanimate into the dark depths, and his load of disgrace and humiliation would fall from him for ever.

So, serene and contented in mind, he stood well back beyond the outer fringe of that frantic, swaying, cursing crowd, and cynically watched its proceedings. The scene upon which he gazed was precisely what he had expected from the moment when those three ill-omened lights had burst through the fog and told him that the Golden Fleece was a doomed ship. Here was selfishness supremely triumphant, beating down and eradicating in a moment every nobler instinct of humanity. It was “Every man for himself” with a vengeance; women and children were struck out of men’s way with horrid curses and savage, murderous blows; men were fighting together like furious beasts; knives were out, blood was flowing freely, and the air was clamorous with shrieks, groans, and imprecations; the whole accentuated and made still more dreadful by the loud clash of dangling wreckage aloft, and the awful creaking and groaning of the riven hull as it writhed upon the low swell to the gurgling and sobbing and splashing sound of the water alongside and under the counter; the weird and horror-inspiring effect being still further intensified by the hollow moaning of the night wind over the heaving surface of the deep. The struggling crowd was no longer human, save in shape; it had become a mob of senseless, raging demons!

Blind, insensate selfishness! Yes; that was the motive that dominated every individual in that seething crowd. Had they but kept their heads and listened to poor Captain Rainhill, had they but helped instead of hindered, all might have been well. Many hands make light and quick work; and had every man there devoted but a tithe of the energy he was now displaying to the task of helping the crew to launch the boats it is possible that every life on board might have been saved. But, as it was, the boats hung there at the davits, crowded far beyond their utmost capacity with men who ignorantly sought to lower themselves, while others fought and struggled with the occupants for the places that they had secured; and nothing useful was done.

Meanwhile, although not one of that crowd of mad folk seemed to be aware of the fact, the ship was settling down with awful rapidity. Already she was sunk to her channels, and was heaving heavily upon the swell with the slow, deadly sluggishness of movement that, to the initiated, told so plainly that her end was nigh.

Now, utterly hopeless as Leslie’s future appeared to him, impossible as seemed to be the task of ever rehabilitating himself in the eyes of the world, crushed as he was by the burden of his disgrace, and glad as he was at the prospect of deliverance from all his misery through the kindly agency of death, it was characteristic of him that, even now, at the supreme moment of his impending deliverance, his self-respect imperiously demanded of him that at all costs must he eschew even the faintest taint of so cowardly an act as that of suicide; if death were really close at hand—as it certainly appeared to be—well and good; it was what he was hoping for, and would be thrice welcome. Nevertheless, he felt it incumbent upon himself that he should take full advantage of such slender aids to escape as happened to present themselves; and accordingly, as the bows of the ship became depressed, while the stern rose in the air, telling that the Golden Fleece was about to take her final dive, he mechanically sprang to the taffrail and, disengaging a life-buoy that hung there, passed it over his shoulders and up under his armpits. Then, climbing upon the rail, he leapt unhesitatingly into the black, heaving water below him at the precise moment when a loud wail of indescribable anguish and despair from the frantic crowd fighting about the boats told that to them, too, had at last come the realisation of imminent doom.

As Leslie struck the water and floated there, supported by the life-buoy, the rudder and stern-post of the ship hove themselves slowly out of the water close alongside him until the keel, for a length of some thirty feet, was exposed; then the huge hull began to slide forward and away from him with an ever-quickening motion until, with a rush, a weird whistling of air escaping from the ship’s interior that mingled horribly with the shrieks of those on deck, and a dull booming as the decks were burst up, the fabric plunged headlong and was gone!

Then came the deadly suction of the sinking ship; the waters poured from all round, like a raging torrent, into the swirling hollow where the craft had been; and as Leslie felt himself caught and dragged irresistibly toward the vortex he instinctively drew a deep breath, filling his lungs to their utmost capacity with air in readiness for the long submergence that he knew was coming.

Another moment and it had come; the tumbling waters had closed over him, and he felt himself being dragged down, down, down, and whirled helplessly hither and thither as he clung resolutely to his life-buoy. As he continued to descend he was constantly reminded that he was not alone in this frightful plunge into the depths; he several times came into more or less violent contact with objects, some at least of which were certainly struggling human beings like himself. Once he felt himself strongly clutched by the hair for a moment, but the swirl of the water almost immediately tore him free again. And still that awful, implacable downward drag continued, until he began to wonder dreamily whether he would ever return to the surface alive, or whether, after all, deliverance from his wretchedness—which in some inexplicable way already seemed much less poignant to him—was coming to him down there in those black depths. The pressure upon his body was rapidly becoming unendurable; the air was being forced from his lungs; he was suffocating! Involuntarily he began to struggle, throwing out his arms and legs instinctively in a powerful effort to return to the surface. Then, in a moment, he lost all consciousness of his dreadful situation and found himself once more back among the scenes of his childhood, a multitude of trivial and long-forgotten incidents recurring to his memory with inconceivable rapidity. He was a dying man; the agony of drowning was over, and he had entered upon that curious phase of retrospection that most drowning people experience, and that so pleasantly precedes that form of dissolution.

But after an indefinite period of oblivion consciousness returned, and he found that he had somehow come back to the surface and was painfully taking in great gulps of air, clinging tenaciously, meanwhile, to what, so far as he could discover, in the intense darkness, was the body of a woman!

Whether that woman was alive, or dead, Leslie knew not; but, still animated by the old reckless disregard for his own safety that had become a part of his nature, as well as by that innate feeling of chivalry that even his great sorrow had not eradicated, his first impulse was to give his unknown companion the benefit of whatever slender possibility of ultimate escape might exist; and he accordingly lost not a moment in disengaging himself from the life-buoy that still supported him, and adjusting it beneath the unconscious body of the woman in such a manner that she sat within it almost as though it were an armchair; the buoy floating aslant in the water, with its lower rim supporting the weight of the body, while its upper rim, which rose several inches above the surface of the water, pressed against and supported the woman’s shoulders. By this arrangement the woman’s head was raised well above the water; and if she were not already dead there was some prospect that she would ultimately revive and recover consciousness. As for Leslie, he was so powerful a swimmer that he really needed no support, now that he was once more himself; he accordingly threw himself prone upon his back and, in that position, floated easily, retaining his hold upon the buoy by means of the beckets of light line that were looped around it.

The water was quite warm; there was therefore no hardship in being immersed in it; there was not much sea running, and such as there was seldom broke. Leslie felt therefore that the probability of several hours of life still lay before him; and he began, with a queer feeling of dismay and disappointment, to ask himself whether, after all, he might not ultimately be doomed to escape. He knew that the catastrophe had occurred right in the usual track of ships bound south; and it was quite upon the cards that one of these might come along at any moment and pass within hail of him, or, at all events, close enough to permit of his being seen. And if this should happen to occur between daylight and dark he would feel bound to adopt such measures as might be possible to attract the attention of her crew and cause himself to be picked up. Well, he argued, if such a thing should happen it could not be helped; perhaps there might occur some other occasion. Besides, there was his companion. She might possibly be alive; and if such should be the case she would doubtless be anxious to escape; she had, in an accidental way, come under his protection, and he must do everything he possibly could for her.

The question as to whether life still lingered in the occupant of the life-buoy was speedily determined; for while Leslie still lay floating tranquilly upon his back, weighing the pros and cons of the situation, a faint groan reached his ear, quickly followed by a second, louder and more sustained; then followed certain sounds indicative of violent sickness; the patient was getting rid of the very considerable quantity of sea water that she had swallowed.

Leslie waited patiently until this unpleasant episode appeared to have come to an end, when, raising himself upright in the water, he said cheerfully—

“That’s capital; you will soon be all right now. Are you feeling tolerably comfortable in that buoy?”

“Oh Heaven!” moaned a voice that Leslie fancied was not altogether unfamiliar to him, “is it possible that there is some one else in the same horrible plight as my unfortunate self?”

“Nay,” said Leslie, “do not speak or think of yourself as unfortunate, at least as yet. You have thus far escaped with life—which is, I fear, more than any one else except myself has done—and while there is life there is hope, you know.”

“Surely not in such a dreadful situation as ours!” said his companion. “What hope dare we entertain? What possible prospect of escape have we? Is it not a certainty that we shall perish miserably by thirst and starvation if we succeed in avoiding death by drowning? I must confess that I shall bitterly regret the respite that has in some mysterious way come to me, if I am doomed to linger on and endure the protracted horrors of death from hunger and thirst.”

“Naturally you will,” assented Leslie; “I fully agree with you that, if one or the other fate must necessarily overtake us, that of drowning is much to be preferred. But it is early yet to despair. We are in a part of the Atlantic that is much frequented by ships; and if fate will only be kind to us, it is quite on the cards that we may be picked up in the course of a day or two. And surely, if this fine weather will but last—as I believe it will—we can hold out for that length of time. And let me reassure you upon one point: so long as we are fully immersed in the water, as we now are, we shall not suffer very greatly from thirst; the water penetrates through the pores of the skin, and, being filtered as it were in the process, alleviates to a very considerable extent the craving for liquid that must otherwise result from long abstinence. Hunger, of course, is another matter; but we must make up our minds to endure that as best we may. You will understand that I am now looking at the bright side of things; there is a dark side also, but we will not consider that at present. What we have to do just now is to be hopeful; to maintain one’s hopefulness is half the battle. And, if the assurance will help in the least to encourage you, I should like you clearly to understand that so long as life—or at least consciousness and a particle of strength—remains to me, you may rely upon my doing my level best for you. And, being by profession a sailor, I may be able to do much that a landsman could not. Meanwhile, however, all that we can do at present is to wait patiently for daylight. One point is already declaring itself in our favour; I notice that the fog is lifting.”

“Is it?” responded the girl, wearily. “I cannot say that I am able to detect any improvement. But, naturally, a sailor’s trained eyes would be more quick to see such a change than those of a lands-woman like myself. And you spoke of yourself as a sailor. I seem to recognise your voice. Are you one of the officers of the Golden Fleece?”

“No,” answered Leslie. “My connection with the ship was simply that of a passenger like yourself. But I used to belong to the British navy; and although I left it some seven years ago, I venture to believe that my knowledge of seamanship has not yet grown quite rusty. My name is Leslie—Richard Leslie, and unless my ears deceive me you are Miss Trevor.”

“Yes,” assented the girl; “you are quite right. I am that unfortunate individual—unfortunate, that is to say, in that I yielded to my poor aunt’s persuasions and consented to embark in a sailing ship instead of going out to Australia in a mail steamer. I had not been very well for some months, and it was thought that the longer voyage by a sailing ship would benefit my health. And so you are Mr Leslie, the gentleman who held himself so rigidly aloof from all that he excited everybody’s most lively curiosity as to his business, his antecedents, and, in short, everything about him. Well, Mr Leslie, let me say at once that I am profoundly grateful to you for your promise to help me so far as you can. At the same time, I must confess that at present I quite fail to see in what way you can possibly be of the slightest assistance to me, excepting, of course, that your presence and companionship are a great comfort and encouragement to me. It would be awful beyond words to find one’s self quite alone in such a frightful situation as this. By the way, do you think it likely that any others besides ourselves have survived this horrible accident—if accident it was?”

“Oh,” answered Leslie, “there is no doubt as to its being an accident. But it was one of those accidents that might have been avoided. Rainhill was not to blame; he observed every possible precaution; the fault lay with the other fellow, who came blundering along through that dense fog at full speed. I take it he approached us so rapidly that he failed to hear our fog-horn until it was too late to avoid us. He ought, under the circumstances, to have been steaming dead slow. Then, upon hearing our fog-horn, he could at once have stopped his engines, and, if necessary, reversed them, until the danger of collision was past. As it is, it is quite upon the cards that he, too, has gone to the bottom. No ship could strike so terrific a blow as that steamer did without suffering serious damage herself. As to the probability of there being other survivors than ourselves, I doubt it. It is absolutely certain that nobody could possibly have escaped in either of the boats; and, watching the mad fight for them, at a distance, as I did, I imagine that when the ship went down, every one of those frantic people went under in the grasp of somebody else, and so lost, in another person’s death-grip, whatever chance he might otherwise have had of coming to the surface. It is a marvel to me how you escaped. Where were you when the ship plunged?”

“I? Oh, I was down on what they called the ‘main deck,’” answered Miss Trevor. “I heard the captain give orders that every one was to don their warmest clothing, so I slipped into my cabin and changed my evening frock for a good stout serge that I wore when I first came on board; and when I emerged from the saloon I found myself quite alone. I was just about to climb up on the poop when the ship seemed to slide from under me, and I found myself being dragged down beneath the surface. Then I lost consciousness, and knew no more until I awoke to find myself afloat in this life-buoy. I have been wondering how I came to be in such a singular position. Can you by any chance enlighten me?”

“Well, to be perfectly candid, I put you there,” answered Leslie. “I recognised from the first that, with the mad panic prevailing on board, there would be no possibility of utilising the boats; so I took the precaution to provide myself with a life-buoy, in which I jumped overboard. Like you, I was of course dragged under by the suction of the ship, as she went down; and, like you, I lost consciousness, though not, I think, for very long. And when I recovered my senses I found myself once more afloat, with a fold of your dress in my grasp. So, as the simplest means of relieving myself of the fatigue of supporting you, I placed you in the buoy, not needing it myself, since I am a strong swimmer, and can support myself for practically any length of time in the water.”

“From which it would appear that I am indebted to you for the circumstance that I am alive at the present moment,” commented Miss Trevor. “I suppose I ought to be profoundly grateful to you; but—”

“Excuse me for interrupting you,” broke in Leslie, “but if I am not greatly mistaken there is something floating out there that may be of use to us. I will tow you to it. In our present circumstances we must avail ourselves of everything that affords us an opportunity to better our condition.”

Chapter Two.

Picked Up.

The object that had attracted Leslie’s notice proved to be one of the hencoops belonging to the Golden Fleece, that had broken adrift when the ship went down, and returned to the surface. There was another floating at no great distance, so, having towed Miss Trevor, in her life-buoy, to the first, and directed her to hold on to it for a few minutes, he swam on to the second, which, with some difficulty, he got alongside the first. The lashings of both were fortunately intact, the cleats to which the coops were secured having torn away from the deck; Leslie therefore temporarily secured the two coops to each other, intending, as soon as daylight appeared, to lash them properly together in such a manner as, he hoped, would form a fairly useful raft. During the progress of this small business, the conversation between the two people thus strangely thrown together had necessarily been interrupted; and as Miss Trevor did not appear to be very eager to renew it, Leslie thought it best to maintain silence, in the hope that his companion might be able to secure a little sleep.

Meanwhile, the fog had gradually been growing less dense, and within about half an hour of the incident of the hencoops a few stars became visible overhead. An hour later the fog had completely disappeared, revealing a star-studded sky that spread dome-like and unbroken from zenith to horizon.

To Leslie the night seemed interminable; but at length his anxious eyes were gladdened by the appearance of a faint paling of the sky low down on the horizon in the eastern quarter. Gradually and imperceptibly the pallor spread right, left, and upward toward the zenith, until a broad arch of it lay stretched along the horizon, within the limits of which the stars one after another dwindled in brightness and presently disappeared. Against this patch of pallor the heads of the running surges rose and fell restlessly, black as ink; and once, as Leslie and his companion were lifted on the top of the swell, the former thought he caught sight, for a moment, of a small toy-like object in the far distance. When next he was hove up he looked for it again, but for some few minutes in vain. Then came another unusually lofty undulation that for a moment lifted him high enough to render the horizon almost level, with only an isolated ridge here and there to break its continuity; and during that brief moment he once more caught sight of the object, and knew that it was no figment of his imagination; on the contrary, it was a clear and sharply defined image of the upper canvas—from the royals down to the foot of the topsails—of a barque, steering south. She was, of course, much too distant to be of any use to them, but her appearance just then was encouraging, inasmuch as it confirmed his conviction that they were fairly in the track of ships. He pointed the craft out to his companion, and said what he could to raise her hopes; but by this time the poor girl was beginning to feel so exhausted from her long exposure, and the intense emotions that had preceded it, that he found his task difficult almost to the point of impossibility.

During the brief period occupied by Leslie in watching the distant barque and endeavouring to deduce from her appearance substantial grounds for encouragement on the part of his companion, the sky had brightened to such an extent that the stars had all vanished, and presently, with a flash of golden radiance, up rose the sun; his cheering beams at once transforming the scene from one of chill dreariness to a blaze of genial warmth and beauty.

Leslie felt that, with the reappearance of the sun, it would be well to get his companion out of the water and up on the top of the hencoops as soon as possible, since dryness and warmth were what she now most urgently required; he accordingly at once went to work with a will to get his proposed raft into shape.

But, first of all, he made it his business to investigate the interiors of the coops, with an eye to the provision of a certain want in the not far distant future. He felt sure that in one, if not both, of the coops would be found a number of drowned fowls; and although the hunger of himself and his companion had not yet nearly reached the point of demanding satisfaction on a diet of raw, drowned poultry, he foresaw the speedy approach of a moment when even such unappetising fare as this would be welcome. He accordingly turned the coops over so that he could get at their contents; and found, as he had expected, that each contained a fair supply of food. Indeed there was more than they would be able to consume before it became unusable, one coop yielding fourteen fowls, and the other eight. These he abstracted and secured; then he turned the two coops over in the water so that they floated right side upward, and face to face—in order that their tops should afford something in the nature of a smooth platform upon which the pair could recline with the minimum of discomfort—and in that position he firmly lashed the two together with the lashings still attached to them. Then he helped Miss Trevor to get out of her life-buoy and clamber up on the top of the fragile structure; finding, to his satisfaction, when he had done so, that the raft possessed just enough buoyancy to support her comfortably, when reclining at full length upon it, although, unfortunately, not enough to keep her dry, since even in such quiet weather as then prevailed, the sea continuously washed over it.

It occurred to Leslie that, since the hencoops had broken adrift from the sinking ship, other wreckage might have done the same; and he accordingly proceeded to search the surface of the ocean with his gaze, in quest of floating objects. For a few minutes his quest was vain; but presently, just to the southward of the sun’s dazzle on the water, his eye was caught by a momentary appearance of blinking light, as of the sun’s rays reflected from a cluster of floating wet objects. The next instant he lost it again behind a heaving mound of swell; then he caught it again and, this time, for long enough to enable him to decide that it was about half a mile distant. For a moment he was doubtful whether, being so far away, what he saw could possibly be wreckage from the Golden Fleece; but a little reflection suggested to him that, if this wreckage should happen to be floating deep, it would be quite possible for him and his companion, with the hencoops—floating on the very surface as they all were—to have been driven quite this distance to leeward by the mere wash of the sea. Whether or no, however, it was certain that away there, some half a mile to windward, there was enough wreckage, apparently, to afford them a raft upon which they could be supported high and dry.

There was but one way of reaching this wreckage, and that was to swim to it, propelling the raft and its fair burden before him. This was a decidedly formidable task to undertake; for the raft, being rectangular in shape, and drawing about two feet of water, offered a very considerable amount of resistance to propulsion, especially under the unfavourable conditions which were the only ones possible; still there was no other task upon which Leslie could employ himself—and he felt that it was imperative to do something, if only to while the time away and interest his companion, thus diverting her thoughts and preventing her from dwelling too much upon the horrors of their present situation. He therefore set manfully to work and, shaping a course by the run of the sea, proceeded to propel the raft to windward, resting his hand upon its after end and striking out with his legs, in long, steady strokes that could be maintained for a considerable period without entailing undue fatigue.

Their progress was painfully slow, almost imperceptible, indeed; for when at the end of an hour’s vigorous swimming Leslie paused to take breath and a look round, the utmost that he could say was that they were certainly not any further away from the wreckage for which he was aiming than they had been to start with. And, reasoning upon this, the conclusion forced upon him was that, after all, he had merely succeeded in retarding their own drift to leeward; while to actually force his unwieldy raft to windward and thus reach the desired flotsam, was quite beyond his unaided powers.

He had just rather ruefully arrived at this unwelcome conclusion when, clambering up on the raft to take a good look round, as the structure rose heavily upon the back of a swell he suddenly sighted, away in the northern board, a tiny speck of creamy white, gleaming softly out against the warm delicate grey tones of the sky low down in that quarter. It was but a momentary glimpse,  for he had no sooner caught it than the raft settled down into the trough, while a low hill of turquoise blue water swelled up in front of him, hiding the horizon and the object upon which his eager gaze had been so intently fixed. Then the raft was once more hove up, and Leslie again caught sight of the object, which this time remained in view for a space of perhaps six seconds; and brief though this period may seem, it was sufficient to enable his practised seaman’s eye to determine the fact that what he saw was the head of the royal of a ship steering to the southward.

for he had no sooner caught it than the raft settled down into the trough, while a low hill of turquoise blue water swelled up in front of him, hiding the horizon and the object upon which his eager gaze had been so intently fixed. Then the raft was once more hove up, and Leslie again caught sight of the object, which this time remained in view for a space of perhaps six seconds; and brief though this period may seem, it was sufficient to enable his practised seaman’s eye to determine the fact that what he saw was the head of the royal of a ship steering to the southward.

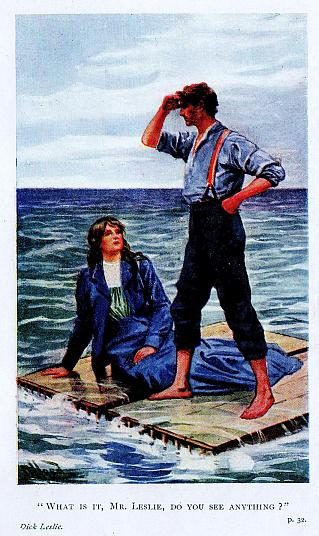

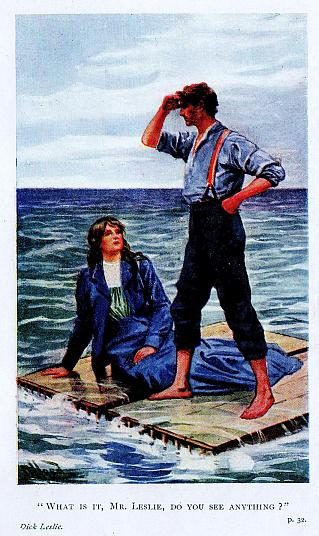

So anxiously did Leslie await the next reappearance of the tiny object, and so tense was his attitude of expectation, that it attracted the notice of his companion, who was fast sinking into a state of torpor from exhaustion. She raised herself painfully into a sitting attitude and, in weak and somewhat fretful tones, inquired:—

“What is it, Mr Leslie; do you see anything?”

“Yes,” answered Leslie, still anxiously watching; “there is a vessel of some sort away out there; and she is steering this way. What I am anxious to determine, if I can, is whether she is likely to pass close enough to us to enable us to attract her attention.”

“Oh, I pray Heaven that it may be so!” ejaculated Miss Trevor, brightening up perceptibly at the prospect of possible rescue. “Is there nothing that we can do to insure that she shall see us? You say that you are a sailor, and I have been told that sailors are amazingly ingenious creatures, surely you can think of something, some act that would better our position!” She spoke querulously, with an undertone of the old disdain that formerly marked her manner running through her speech.

“A man can do but little with only his two hands and no tools to help him,” answered Leslie, gently; “yet you may rely upon my doing all that is possible under such disadvantageous conditions. From the position of that craft, and the course that I judge her to be steering, I fear that she will pass too far to windward of us to permit of our attracting her attention. The fact that we shall be to leeward of her when she passes will be against us; for a sailor looks half a dozen times to windward for once that he glances over the lee rail. And my efforts during the last hour have convinced me of the impossibility of driving this ungainly structure to windward by merely swimming. If I only had an oar, or a paddle of some sort, I might be able to do something; but then, you see, I haven’t, so it is of no use to think further of that. The wind is dropping, which is a point in our favour, inasmuch as it will lessen the speed of yonder craft in coming down toward us, and so give us more time in which to act. I believe that, for instance, it would be possible for me, alone and unencumbered, to swim out to windward far enough to intercept her; but I certainly do not like the idea of leaving you here, alone, even on such an important errand as the one that I have in my mind; for if the wind should happen to shift, or I should by any other means fail to reach her, I might meet with some difficulty—it might perhaps even prove impossible—to find you again.”

“Oh, pray do not allow consideration for me to interfere with your freedom of action,” retorted the girl, bitterly. “If you can save yourself by leaving me here to die alone, I beg that you will not hesitate.”

“Stop, if you please,” answered Leslie, with some sharpness of tone. “You have no right to think or to suggest that I should do any such thing. Perhaps, however, you may have misunderstood me,” he continued, more gently. “What I had in my mind was this. It occurred to me that it might not be difficult for me to swim out and intercept that ship, attract the attention of those on board her, and get picked up. Then I could explain to the skipper that you were down here to leeward, afloat upon a raft; upon learning which he would of course at once bear up and run down to look for you. And, as in all probability you would only be some two miles away at the moment when I should be picked up, there would be absolutely no possibility of missing you. Still,” he continued, thoughtfully, “there remains the chance of my failure—as I said just now; and I scarcely like to risk it. If it were not for the fact that you are in so weak and exhausted a condition, I would suggest that you once more get into the life-buoy; when, abandoning this raft, and trusting to chance to find either it again, or the other wreckage that we have been trying to reach, I would endeavour to tow you far enough to windward to enable us to intercept that vessel and get her to pick us up.”

“Do you really think that such a proceeding would be likely to prove successful?” demanded the girl, with a considerable access of animation in her voice.

“It might, or it might not,” answered Leslie. “It is impossible to say with certainty; so much depends upon chance. Still I think the experiment is quite worth trying; we may have to do something very like it eventually, and it would be better to try it now, while we have a little strength left us. Only if we are to attempt it, we had better start forthwith, so that we may make as sure as we can of achieving success. By the way, I suppose you are fairly hungry by this time. Are you hungry enough to tackle a raw slice off the breast of a drowned chicken?”

The girl made a gesture of disgust. “If the most dainty meal imaginable were placed before me at this moment, I do not believe I could touch a morsel of it,” she said, “But I beg that you will not allow my squeamishness to deter you from eating, if you feel the need of food.”

“Thanks,” replied Leslie, cheerfully. “I must confess that I am quite ready for breakfast. And although the fare can scarcely be described as appetising, I think I will attempt a morsel; it may prove useful to me, in view of the task before us.”

And therewith, extracting his knife from his pocket, and selecting a fairly plump fowl, he hacked off a goodsized slice of the breast, from which he stripped skin and feathers together. Then, cramming the lump of flesh into his mouth, he masticated it well, extracting all the juice from it; after which he pronounced himself ready for the new adventure.

Hauling the life-buoy up on the raft, he showed Miss Trevor how to place herself in it in such a manner as to secure the maximum amount of support from it; and as soon as she had arranged herself according to his instructions he bade her plunge boldly in; which she did. He then at once followed her and, passing his left arm through one of the beckets, forthwith struck out, swimming with a long, steady stroke, in the direction which he had decided would be the most advantageous for him to take.

It was perfectly true that, as Leslie had remarked, the wind was falling light; it had dropped quite perceptibly since sunrise, and the state of the ocean was reflecting this change; the sea was going down; it no longer broke anywhere, and the conditions for swimming were improving every moment. The pair of strange voyagers were making excellent progress, as was evidenced by the rapidity with which they drew away from the raft; within half an hour, indeed, they had left it so far astern that it was with the utmost difficulty Leslie was able to locate it again when he paused for a moment to rest. And when a further quarter of an hour had elapsed it had vanished altogether; thus vindicating Leslie’s previous doubts as to the wisdom of swimming out alone to intercept the ship, leaving Miss Trevor upon the raft, to be sought for and picked up later on.

As to the craft for which they were aiming, it was clear that she was but a slow tub, for she came drifting down toward them at a very deliberate pace. The wind had softened away to about a four-knot breeze; but Leslie was of opinion that, although she showed all plain sail, up to her royals, she was scarcely doing three knots. This was all in their favour, for while the smoothening of the sea’s surface enabled Leslie to attain a much more satisfactory rate of speed with the same moderate amount of exertion, the low rate of sailing of the on-coming vessel rendered it certain that, apart from accident, they would now assuredly be able to reach her. And by the time that this had become an undoubted fact, Leslie had made out that the stranger was a small brig, of some two hundred and thirty tons, or thereabout. He would greatly have preferred that she had been a bigger craft, because the probability would then have been greater of her proving a passenger ship, and a passenger ship was what Leslie was now particularly anxious to fall in with, for Miss Trevor’s sake—a change of clothing being an almost indispensable requirement on the part of the young lady, so soon as she should once more find herself on a ship’s deck. That there were no passengers—or, at least, no women passengers—aboard the brig, however, was practically certain—she was much too small for that—and unless the skipper happened to be a married man, with his wife aboard, Miss Trevor would have to fall back upon her own resources and ingenuity for a change of clothing. He discussed this matter with his companion as he swam onward; but the young woman just then regarded the question with a considerable amount of indifference; her one consuming anxiety, for the moment, was to again find herself on the deck of a craft of some sort; all other considerations she was clearly quite willing to relegate to a more or less distant future.

Meanwhile, the brig was slowly drawing down toward them, and as slowly lifting her canvas above the horizon. And by the time that she had raised herself to the foot of her courses, Leslie had succeeded in bringing her two masts into line, so that the pair were now dead ahead of her. Having accomplished this much, the swimmer concluded that he might safely take a rest, for the brig, being close-hauled, would be certain to be making more or less leeway; and it was quite possible that she would drive to leeward at least as fast as they did, if not faster, he therefore threw himself over on his back, requesting his companion to keep an eye on the approaching brig, and report to him her progress from time to time.

The breeze, having begun to drop, continued to fall still lighter, until Leslie, raising himself for a moment to take a look at the brig, saw with some dismay that her lower canvas was wrinkling and collapsing occasionally for lack of wind. She was by this time, however, hull-up, and not more than half a mile distant; moreover the rest in which he had been indulging had refreshed him so considerably that he felt quite capable of further exertion. He therefore determined to shorten the period of suspense as much as possible by swimming directly for the craft—a resolution that was immensely strengthened by the sudden recollection that they were afloat in a part of the ocean where a shark or sharks might put in an unwelcome appearance at any moment. Accordingly, without mentioning this last unpleasant reflection of his to his companion, he recommenced swimming, this time shaping a course directly for the brig.

Although his own individual progress, and that of the brig, was slow, their combined progress toward each other rapidly shortened the distance between them, and within about a quarter of an hour of the time that Leslie had recommenced swimming he had arrived near enough, in his judgment, to commence hailing, with a view to attracting the attention of the brig’s crew. Ceasing his exertions, therefore, he took a good long breath and shouted, at the top of his voice—

“Brig ahoy! Brig ahoy! Brig Ahoy!”

The hail, thrice repeated, exhausted the capacity of his lungs, and he paused, anxiously listening for a reply. He thought—and Miss Trevor thought, too—that in response to his last shout a faint “Hillo?” had come floating down to them; but the wash of the water was in his ears, and he could not be certain, he therefore again took breath, and repeated his hail.

This time there could be no doubt about it; the answering hail came distinctly enough, and immediately afterwards—so close was the brig to them—he saw first one head, then another, and another, appear in the eyes of the vessel, peering over the bows. Quick as light, and treading water meanwhile, he whipped the white pocket-handkerchief out of the breast-pocket of his coat and waved it eagerly over his head. The people in the bows of the brig stared incredulously for a moment; then with a sudden simultaneous flinging aloft of their arms they abruptly vanished.

“All right,” ejaculated Leslie, in tones of profound relief, “they have seen us, and your deliverance, Miss Trevor, is now a matter of but a few brief minutes!”

“Oh, thank God; thank God!” cried the girl, brokenly; and then, all in a moment, the tension of her nerves suddenly giving way, she broke down utterly, and burst into a perfect passion of tears. Leslie had sense enough to recognise that this hysterical outburst would probably relieve his companion’s sorely overwrought feelings, and do her good; he therefore allowed her to have her cry out in peace, without making any attempt to check her.

She was still sobbing convulsively when Leslie, who never took his eyes off the slowly approaching brig, saw five people suddenly appear in the vessel’s bows, three of them pointing eagerly, while the other two peered out ahead under the sharp of their hands.

“Brig ahoy!” hailed Leslie; “back your main-yard, will you, and stand by to heave us a couple of rope’s ends when we come alongside?”

“Ay, ay,” promptly came the answer from the brig. The men in the bows again vanished; and, as they did so, the same voice that had just answered pealed out, “Let go the port main braces; main tack and sheet; back the main-yard! And then some of you stand by to drop a line or two, with a standing bowline in their ends, to those people in the water.”

The main-yard swung slowly aback, the canvas on the mainmast pressed against the mast, still further retarding the vessel’s sluggish movement; and as she drifted almost imperceptibly up to them, a few strokes of Leslie’s arms took the pair alongside, where some half a dozen rope’s ends, with loops in them, already dangled in the water. With a deft movement, Leslie seized and dropped one of them over his head and under his armpits; then, taking Miss Trevor about the waist, he gave the word “Hoist away, handsomely,” and four men, standing on the brig’s rail, dragged them up the vessel’s low side, and assisted them to gain the deck.

The vessel, on board which they now found themselves, was a small craft compared with the Golden Fleece, measuring, as Leslie had already guessed, about two hundred and thirty tons register. That she was British the language of her crew had already told him; and he was thankful that it was so, for he might now reasonably hope for courteous treatment of himself and his companion—which is not always to be reckoned upon with certainty, under such circumstances, if the craft happens to be manned by foreigners. The vessel, moreover, appeared to be tolerably clean; while the crew seemed to be a fairly decent lot of men.

As he gained the deck, a tall, dark, rather handsome man—but with an expression of countenance that Leslie hardly liked—stepped forward. He was clad entirely in white, and was clearly the master of the brig.

“Good morning,” he said, without offering his hand, or uttering any word of welcome. “Where the devil do you come from?”

“We are,” answered Leslie, “survivors—the only two, I am afraid—of the passenger ship Golden Fleece, bound to Melbourne, which was run into and sunk by an unknown steamer last night about eleven o’clock, during a dense fog. My name is Leslie; I was one of the cuddy passengers; and this lady—who was likewise a cuddy passenger—is Miss Trevor.”

The man’s rather saturnine features relaxed as he gazed with undisguised admiration at the lovely girl, wet and bedraggled though she was; and, stepping up to her, he held out his hand, saying—

“Your most obedient, miss. Glad to see you aboard my ship. My name’s Potter—James Potter; and this brig’s the Mermaid, of London, bound out to Valparaiso with a general cargo. And this,” he added, directing the girl’s attention toward a slight, active-looking man who stood beside him, “is my only mate, Mr Purchas.”

Miss Trevor bowed slightly, first to one and then to the other of the two men, as these introductions were made; then, turning once more to Potter, she thanked him earnestly and heartily for having picked up herself and her companion, and stood waiting irresolutely for what was next to happen.

“Oh, that’s all right, miss; you’re very welcome, I’m sure. Glad to have the chance of doing a service to such a beauty as you are.” Then, turning abruptly about, he shouted, “Swing the main-yard, and fill upon her. Board the main tack, and aft with the sheet. Lively now, you skowbanks; and don’t stand staring there like stuck pigs!”

The men hurried away to execute these elegantly embellished orders. And Leslie, who had stood impatiently by, with a slowly gathering frown corrugating his brow, stepped forward and said—

“I hope, Mr Potter, that our presence on board your brig is not going to subject you to inconvenience. And I hope, further, that we shall not need to tax your hospitality for very long. Sooner or later we are pretty certain to fall in with a homeward-bound ship, in which case I will ask you to have the goodness to transfer Miss Trevor and myself to her, as Valparaiso is quite out of our way, and we have no wish to visit the place. Meanwhile, we have been in the water for somewhere about twelve hours, and Miss Trevor is in a dreadfully exhausted condition, as you may see for yourself. If you could kindly arrange for her to turn in for a few hours, you could do her no greater service for the present. And to be quite candid, I should not be sorry if you could spare me a corner in which to stretch myself while my clothes are drying.”

The skipper turned upon Leslie rather sharply and scowlingly.

“Look here, mister,” he said, “don’t you worry about the young lady, I’ll look after her myself. She shall have the use of my cabin. The bunk’s made up, and everything is quite ready for her at a minute’s notice. You come with me, miss,” he continued; “I’ll take you below and show you your quarters. You can turn in at once, and when you’ve rested enough I’ll have a good meal cooked and ready for you. This way, please.”

And therewith, offering his arm to the girl, he led her aft toward the companion, without vouchsafing another word to Leslie. As for the girl, she was by this time so nearly in a state of collapse that she could do nothing but passively accept the assistance offered her, and submit to be led away below.

“Queer chap, rather, the skipper; ain’t he?” remarked the mate, coming to Leslie’s side as Potter and Miss Trevor vanished down the companion-way, “This is my first voyage with him, and, between you and me and the lamp-post, it’ll be the last, if things don’t greatly improve between now and our getting back to London. I reckon you’ll be all the better for a snooze, too, so come below with me. You can use my cabin for the present, until the ‘old man’ makes other arrangements.”

“Very many thanks,” answered Leslie; “I shall be more than glad to avail myself of your kind offer. Before I do so, however, I wish to say that somewhere over there,” pointing out over the lee bow, “about three miles away, there is some floating wreckage from the Golden Fleece, and, although I think it rather doubtful, there may be a few people clinging to it. I hope you will represent this to Mr Potter, and induce him to run down and examine the spot. It will not take him much off his course; and if the fellow has any humanity at all in him he will surely not neglect the opportunity to save possibly a few more lives.”

“All right,” said Purchas, “I’ll tell him when he comes on deck again. Now you come away below and turn in.”

Therewith the mate conducted Leslie down into a small, dark, and rather frowsy stateroom at the foot of the companion ladder, and outside the brig’s main cabin; and having said a few awkward but hearty words of hospitality in reply to the other’s expressions of thanks, closed the door upon him and left him to himself.

Five minutes later, Leslie was stretched warm and comfortable in the bunk, wrapped in sound and dreamless sleep.

Chapter Three.

Captain Potter causes Trouble.

When Leslie awoke the warm and mellow glow of the light that streamed in through the small scuttle in the ship’s side prepared him for the discovery that he had slept until late in the afternoon; and as he lay there reflecting upon the startling events of the previous twenty-four hours the sound of eight bells being struck on deck confirmed his surmise by conveying to him the information that it was just four o’clock. He raised himself in the bunk, striking his head smartly against the low deck-planking above him as he did so. He looked for his clothes where he had flung them off before turning in, but they were not there; casting his eyes about the little apartment, however, he presently recognised them hanging, dry, upon a hook screwed to the bulkhead. Thereupon he dropped out of the bunk, and proceeded forthwith to dress, noting, as he did so, by the slow, gentle oscillations of the brig, that the sea had gone down to practically nothing while he slept, while the occasional flutter and flap of canvas, heard quite distinctly where he was, told him that the wind had dropped to a calm.

Dressing quickly, he hurried on deck, wondering whether he would find Miss Trevor there. She was not; but the skipper and mate were both in evidence, standing, one on either side of the companion; neither of them speaking. The sky was cloudless; the wind had dropped to a dead calm; the surface of the sea was oil-smooth, but a low swell still undulated up from the south-east quarter. The ship had swung nearly east and west; and the sun’s beams, pouring in over the starboard quarter, bit fiercely, although the luminary was by this time declining well toward the horizon.

“Well, mister, had a good sleep?” inquired the skipper, with some attempt to infuse geniality into his voice.

“Excellent, thank you,” answered Leslie, as with a quick glance he swept the entire deck of the brig. “Miss Trevor is still in her cabin, I take it, as I do not see her on deck. She has had a most trying and exhausting experience, and I hope, sir, you will afford her all the comfort at your command; otherwise she may suffer a serious breakdown. Fortunately, I am not without funds; and I can make it quite worth your while to treat us both well during the short time that I hope will only elapse ere you have an opportunity to trans-ship us.”

“Is Miss Trevor any relation of yours?” asked Potter, his tone once more assuming a suggestion of aggressiveness.

“She is not, sir,” answered Leslie, showing some surprise at the question. “She was simply a fellow-passenger of mine on board the Golden Fleece; and it was by the merest accident that we became companions, after the ship went down. Had you any particular object in making the inquiry, may I ask?”

“Oh no,” answered Potter; “I just thought she might be related to you in some way; you seem to be pretty anxious about her welfare; that’s all.”

“And very naturally, I think, taking into consideration the fact that I have most assuredly saved her life,” retorted Leslie. “Having done so much, I feel it incumbent upon me to take her under my care and protection until I can find a means of putting her into the way of returning to England, or of resuming her voyage to Australia—whichever she may prefer.”

“Very kind and disinterested of you, I’m sure,” remarked Potter, sneeringly. “But if she’s no relation of yours there’s no call for you to worry any more about her; she’s aboard my ship, now; and I’ll look after her in future, and do whatever may be necessary. As for you, I’ll trans-ship you, the first chance I get; never fear.”

The fellow’s tone was so gratuitously offensive that Leslie determined to come to an understanding with him at once.

“Captain Potter,” he said, turning sharply upon the man, “your manner leads me to fear that the presence of Miss Trevor and myself on board your ship is disagreeable or inconvenient—or perhaps both—to you. If so, I can only say, on behalf of the young lady and myself, that we are very sorry; although our sorrow is not nearly profound enough to drive us over the side again; we shall remain aboard here until something else comes along to relieve you of our unwelcome presence; then we will go, let the craft be what she will, and bound where she may. And, meanwhile, so long as we are with you, I will pay you two pounds a day for our board and accommodation, which I think ought to compensate you adequately for any inconvenience or annoyance that we may cause you. And Miss Trevor will continue to be under my care; make no mistake about that!”

The offer of two pounds per diem for the board and lodging of two people produced an immediate soothing and mollifying effect upon the skipper’s curious temper; he made an obvious effort to infuse his rather truculent-looking features with an amiable expression, and replied, in tones of somewhat forced geniality—

“Oh, all right, mister; I’m not going to quarrel with you. You and the lady are quite welcome aboard here; and I’ll do what I can to make you both comfortable; though, with our limited accommodation, I don’t quite see, just at this minute, how it’s going to be done. The lady can have my cabin, and I’ll take Purchas’s; you, Purchas,” turning to the mate, “can have the steward’s berth, and he’ll have to go into the fo’c’s’le. That can be managed easy enough; the question is, Where are we going to put you, mister?”

“Leslie,” quickly interjected the individual addressed, who was already beginning to feel very tired of being called simply “mister.”

“Mr Leslie—thank you,” ejaculated the skipper giving Leslie his name for the first time, in sheer confusion and astonishment at being so promptly pulled up. “As I was saying, the question is, Where can we put you? We haven’t a spare berth in the ship.”

“Pray do not distress yourself about that,” exclaimed Leslie; “any place will do for me. I am a sailor by profession, and have roughed it before to-day. The weather is quite warm; I can therefore turn in upon your cabin lockers at night if you can think of no better place in which to stow me.”

“Oh, the cabin lockers be—” began Potter; then he pulled himself up short. “No,” he resumed, “I couldn’t think of you sleeping on the lockers; they’re that hard and uncomfortable you’d never be able to get a bit of real rest on ’em; to say nothing of Purchas or me coming in, off and on, during the night to look at the clock, or the barometer, or what not, and disturbing you. Besides, you’d be in our way there. No, that won’t do; that won’t do at all. I’ll be shot if I can see any way out of it but to make you up a shakedown in the longboat. She’s got nothing in her except her own gear—which we can clear out. The jolly-boat is turned over on top of her, making a capital roof to your house, so that you’ll sleep dry and comfortable. Why, she’ll make a first-rate cabin for ye, and you’ll have her all to yourself. There’s some boards on the top of the galley that we can lay fore and aft on the boat’s thwarts, and there’s plenty of sails in the sail locker to make ye a bed. Why,” he exclaimed, in admiration of his own ingenuity, “when all’s done you’ll have the most comfortable cabin in the ship! Dashed if I wouldn’t take it myself if it wasn’t for the look it would have with the men. But that argument don’t apply to you, mister.”

“Leslie,” cut in the latter once more, detecting, as he believed, an attempt on the part of the skipper to revert to his original objectionable style of address.

“Yes, Leslie—thanks. I think I’ve got the hang of your name now,” returned Potter. “As I was saying, that argument don’t apply to you, seein’ that the men know how short of accommodation we are aft. Now, how d’ye think the longboat arrangement will suit ye?”

“Oh, I have no doubt it will do well enough,” answered Leslie, although, for some reason that he could not quite explain to himself, he felt that he would rather have been berthed below. “As you say, I shall at least have the place to myself; I can turn in and turn out when I like; and I shall disturb nobody, nor will anybody disturb me. Yes; the arrangement will do quite well. And many thanks to you for making it.”

“Well, that’s settled, then,” agreed the skipper, in tones of considerable satisfaction. “Mr Purchas,” he continued, “let some of the hands turn-to at once to get those planks off the top of the galley and into the longboat, while others rouse a few of the oldest and softest of the sails out of the locker to make Mr—Mr Leslie a good, comfortable bed. And, with regard to payment,” he continued, turning rather shamefacedly to Leslie, “business is business; and if you don’t mind we’ll have the matter down on paper, in black and white. If you were poor folks, now, or you an ordinary sailor-man,” he explained, “I wouldn’t charge either of ye a penny piece. But it’s easy to see that you’re a nob—a navy man, a regular brass-bounder, if I’m not mistaken—and as such you can well afford it; while, as for the lady, anybody with half an eye can see that she’s a regular tip-topper, thoroughbred, and all that, so she can afford it too; while I’m a poor man, and am likely to be to the end of my days.”

“Quite so,” assented Leslie. “There is not the least need for explanation or apology, I assure you. Neither Miss Trevor nor I will willingly be indebted to you for the smallest thing; nor shall we be, upon the terms that I have suggested. I shall feel perfectly easy in my mind upon that score, knowing as well as you do that we shall be paying most handsomely for the best that you can possibly give us. And now, at last, I hope we very clearly understand each other.”

So saying, he turned away and, walking forward to where Purchas was superintending the removal of the planks referred to by the skipper, he asked the mate if he could oblige him with the loan of a pipe and the gift of a little tobacco.

“Of course I can,” answered Purchas, cordially. “At least, I can give ye a pipe of a sort—a clay; I buys about six shillin’s worth every time I starts upon a voyage. I get ’em at a shop in the Commercial Road, at the rate of fifteen for a shillin’! I find it pays a lot better than buyin’ four briars at one-and-six apiece; for, you see, when you’ve lost or smashed four briars, why, they’re done for; but when you’ve lost or smashed four clays—and I find that they last a’most as long as briars—why, I’ve still a good stock of pipes to fall back upon. If a clay is good enough for ye, ye’re welcome to one, or a dozen if ye like.”

“Oh, thanks,” laughed Leslie; “one will be sufficient until I have lost or broken it; then, maybe, I will trespass upon your generosity to the extent of begging another.”

“Right you are,” said the mate, cordially. “I’ll slip down below and fetch ye one, and a cake o’ baccy. I’ll not be gone a moment.”