The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Message, by Alec John Dawson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Message Author: Alec John Dawson Illustrator: Henry Matthew Brock Release Date: January 21, 2009 [EBook #27860] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MESSAGE *** Produced by David Clarke, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Copyright, April 17, 1907

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

Entered at Stationers' Hall

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U.S.A.

| PART I.—THE DESCENT | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In the Making | 3 |

| II. | At the Water's Edge | 12 |

| III. | An Interlude | 17 |

| IV. | The Launching | 29 |

| V. | A Journalist's Equipment | 41 |

| VI. | A Journalist's Surroundings | 53 |

| VII. | A Girl and Her Faith | 66 |

| VIII. | A Stirring Week | 78 |

| IX. | A Step Down | 90 |

| X. | Facilis Descensus Averni | 101 |

| XI. | Morning Callers | 111 |

| XII. | Saturday Night in London | 121 |

| XIII. | The Demonstration in Hyde Park | 131 |

| XIV. | The News | 143 |

| XV. | Sunday Night in London | 153 |

| XVI. | A Personal Revelation | 163 |

| XVII. | One Step Forward | 168 |

| XVIII. | The Dear Loaf | 177 |

| XIX. | The Tragic Week | 188 |

| XX. | Black Saturday | 198 |

| XXI. | England Asleep | 208 |

| PART II.—THE AWAKENING | ||

| I. | The First Days | 221 |

| II. | Ancient Lights | 228 |

| III. | The Return to London | 237[vi] |

| IV. | The Conference | 243 |

| V. | My Own Part | 257 |

| VI. | Preparations | 262 |

| VII. | The Sword of the Lord | 271 |

| VIII. | The Preachers | 291 |

| IX. | The Citizens | 301 |

| X. | Small Figures on a Great Stage | 312 |

| XI. | The Spirit of the Age | 317 |

| XII. | Blood Is Thicker than Water | 330 |

| XIII. | One Summer Morning | 338 |

| XIV. | "For God, Our Race, and Duty" | 343 |

| XV. | "Single Heart and Single Sword" | 352 |

| XVI. | Hands Across the Sea | 360 |

| XVII. | The Penalty | 366 |

| XVIII. | The Peace | 374 |

| XIX. | The Great Alliance | 383 |

| XX. | Peace Hath Her Victories | 389 |

| PAGE | ||

| "I saw that Queen of Ancient Britons at the Head of Her Wild, Shaggy Legions" | Frontispiece | |

| The Roaring City | 40 | |

| "Rivers ushered in Miss Constance Grey" | 114 | |

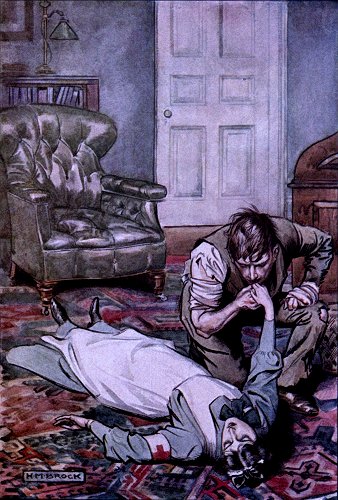

| "I was on My Knees and Kissing the Nerveless Hand" | 212 | |

Non his juventus orta parentibus infecit aequor sanguine Punico.—Horace.

"Such as I am, sir—no great subject for a boaster, I admit—you see in me a product of my time, sir, and of very worthy parents, I assure you."—Ezekiel Joy.

As a very small lad, at home in Tarn Regis, I had but one close chum, George Stairs, and he went off with his father to Canada, while I was away for my first term at Elstree School. Then came Rugby, where I had several friends, but the chief of them was Leslie Wheeler. Just why we should have been close friends I cannot say, but I fancy it was mainly because Leslie was such a handsome fellow, and always seemed to cut a good figure in everything he did; while I, on the other hand, excelled in nothing, and was not brilliant even in the expression of my discontent, which was tolerably comprehensive. Withal, in other matters beside discontent, I was a good deal of an extremist, and by no means lacking in enthusiasm.

My father, too, was an enthusiast in his quiet way. His was the enthusiasm of the student, and his work as historian and archæologist absorbed, I must suppose,[4] a great deal more of his interest and energy than was ever given to his cure of souls. He was rector of Tarn Regis, in Dorset, before I was born, and at the time of his death, to be present at which I was called away in the middle of the last term of my third year at Cambridge. I was to have spent four years at the University; but, as the event proved, I never returned there after my hurried departure, three days prior to my father's death.

The personal tie between my father and those among whom he lived and worked was not a very close or intimate bond. His contribution to the Cambridge History was greatly appreciated by scholars, and his archæological research won him the respect and esteem of his peers in that branch of study. But I cannot pretend that his loss was keenly felt by his parishioners, with most of whom his relations had been strictly professional rather than personal. A good man and true, without a trace of anything sordid or self-seeking in his nature, my father was yet singularly indifferent to everything connected with the daily lives and welfare of his fellow creatures.

In this he was typical of a considerable section of the country clergy of the time. I knew colleagues of his who were more pronounced examples of the type. One in particular I call to mind (whose living was in the gift of a Cambridge college, like my father's), who, though a good fellow and a clean-lived gentleman, was no more a Christian than he was a Buddhist—less, upon the whole. Among scholarly folk he made not the slightest pretence of regarding the fundamental tenets of the Christian faith in the light[5] of anything more serious than interesting historical myths, notable sections in the mosaic of folk-lore, which it was his pride and delight to study and understand.

Such men as A—— R—— and my father (and there were many like them, and more who shared their aloofness while lacking half their virtues) lived hard-working, studious lives, in which the common kinds of self-indulgence played but a very small part. Honourable, kindly at heart, gentle, rarely consciously selfish, these worthy men never gave a thought to the current affairs of their country, to their own part as citizens, or to the daily lives of their fellow countrymen. Indeed, they exhibited a kind of gentle intolerance and contempt in all topical concerns; and though they preached religion and drew stipends as expounders of Christianity, they no more thought of "prying" or "interfering," as they would have said, into the actual lives and hearts and minds of those about them, than of thrusting their hands into their parishioners' pockets.

Stated in this bald way the thing may sound incredible, but those whose recollections carry them back to the opening years of the century will bear me out in saying that this was far from being either the most distressing or the most remarkable among the outworkings of what was then extolled as a broad spirit of tolerance. Our "tolerance," our vaunted "cosmopolitanism," were far more dangerous factors of our national life, had we but known it, than either the insularity of our sturdy forbears or the strength of our enemies had ever been.[6]

Even my dear mother did not, I think, feel the shock of her bereavement so much as might have been supposed. One may say, without disrespect, that the loss of my father gave point and justification to my mother's attitude toward life. Kind, gentle soul that she was, my mother was afflicted with what might be called the worrying temperament; a disposition characteristic of that troublous time. My memory seems to fasten upon the matter of domestic labour as representing the crux and centre of my dear mother's grievances and topics of lament prior to my father's death. The subject may seem to border upon the ridiculous, as an influence upon one's general point of view; but at that time it was really more tragic than farcical, and I know that what was called "the servant question"—as such it was gravely treated in books and papers, and even by leader-writers and lecturers—formed the basis of a great deal of my mother's conversation, just as I am sure that it coloured her outlook upon life, and strengthened her tendency to worry over everything, from the wear-and-tear of house-linen to the morality of the people. All this was incomprehensible and absurd to my father, though, had he but thought of it, it was really more human than his own attitude; for certainly my mother was interested and concerned in the daily lives of her fellow creatures, though not in a cheering or illuminating manner perhaps.

But, as I say, the deprecatory, worrying attitude had become second nature with my mother long years before her widowhood, and had lined and seamed her poor forehead and silvered her hair before my Rugby[7] days were over. Bereavement merely gave point to a mood already well established.

That I should not return to Cambridge was decided as a matter of course within the week of my father's funeral, when we learned that the little he had left behind him would not even pay for the dilapidations of the rectory. There was practically nothing, when my father's affairs were put in order, beyond my mother's little property, a recent legacy, the investment of which in Canadian railway stocks brought in about a hundred and fifty a year.

Thus I found myself confronted with a sufficiently serious situation for a young man whose training so far had no more fitted him for taking part in any particular division of the battle of life, where the prize sought is an income, than for the administration of the planet Mars. Rugby was better than some of the great public schools in this respect, for a lad with definite purposes and ambitions, but its curriculum had far less bearing upon the working life of the age than it had upon its games and pastimes and the affairs of nations and peoples long since passed away. Yet Rugby belonged to a group of schools that were admittedly the best, and certainly the most outrageously costly, of the educational establishments of the period.

I think my sister Lucy was more shocked than any one else by the death of our father. I say shocked, because I am not certain whether or not the word grieved would apply accurately. For one thing, Lucy had never before seen any dead person. Neither had I, for that matter; but Lucy was more affected[8] by the actual presence in the house of Death, than I was. Twice a day for years she had kissed our father's forehead. Now and again she had sat upon the arm of his chair and stroked his thin hair. These demonstrations were connected, I believe, with the quest of favours—permission, money, and so forth; but doubtless affection played a part in them.

As for Lucy's home life, a little conversation I recall on the occasion of her driving me to the station when I was leaving for what proved my last term at Cambridge, seems to me to throw some light. I had but recently learned of Lucy's engagement to marry Doctor Woodthrop, of Davenham Minster, our nearest market-town. I had found Woodthrop a decent fellow enough, but thirty-four as against Lucy's twenty-one, inclining ominously to corpulence, and as flatly prosaic and unadventurous a spirit as a small country town could produce. Now, as Lucy seemed to me to have hankerings in the direction of social pleasures and the like, with a penchant for brilliancy and daring, I was a little puzzled about her engagement, for Woodthrop was one who kept a few conversational pleasantries on hand, as a man keeps old pipes on a rack, for periodical use at suitable times.

"So you are actually going to be married, Loo?" I said.

"Oh, well, engaged, Dick," she replied, with a little blush.

"With a view, I presume. Then I suppose it follows that you are in love—h'm?"

"Why, Dick, what a cross-examiner you are!" The blush increased.[9]

"Well, my dear girl, surely it's a natural assumption, is it not?"

"Oh, I suppose so. But——"

"Yes?"

"Well, I don't think in real life it's the same thing that you read about in novels, do you, Dick?"

"What? Being in love?"

"Yes."

"Well, perhaps not; but I imagine it ought to be something pretty pronounced, you know, even in such a pale reflection of the novels as real life. I gather that it ought to be; seriously, Loo, I think it ought to be. I suppose you do love Woodthrop, don't you?"

My sister looked a little distressed, and I half-regretted having put so direct a question. I was sufficiently the product of my day to be terribly afraid of any kind of interference with my fellow creatures. Our apotheosis of individual liberty had made any such action anathema, "bad form," a sin more resented in the sinner than cowardice or dishonesty, or than any kind of wickedness which was strictly personal and, as you might say, self-contained. Our one object of universal reverence and respect was the personal equation.

"There, Loo," I said, "I didn't mean to tease you." Thus, in accordance with my traditions, I brushed aside and apologized for my natural interest in her well-being in the same way that my poor father and his like brushed away all matters of topical import, and the average man of the period brushed aside all concern with his fellow men, all responsibility for the common weal.[10]

"No," she said, "I know you didn't. And, indeed, Dick, I suppose I don't love Herbert as well as I ought; but—but, Dick, you don't know what it is to be a girl. You can go off to Cambridge, and presently you will go out into the world and live your own life in your own way. But it's different for me, Dick. A girl is not supposed to want to live her own life; she is just part of the home, and the home——. Well, Dick, you know father's life, and mother—poor mother——"

"Yes," I said, "that's so."

"Well, Dick, I'm afraid it seems pretty selfish, but I do want to live my own way, and I do get terribly tired of—of——"

"Of the 'servant question,' for instance."

"Exactly."

"And you think you can live your own life with Woodthrop?"

"Why, I think he is very kind and good, Dick, and he says there's no reason why I shouldn't hunt, if I can manage with one mount, and we can have friends of mine to stay, and—and so on."

"Yes, I see. You will be mistress of a house."

"And, of course, I like him very much, Dick; he really is good."

"Yes."

That was how Lucy felt about her marriage. There seemed to me to be a good deal lacking; but then I was rather given to concentrating my attention upon flaws and gaps. And when I was next at home, at the time of my father's death, I could not help feeling that the engagement was something to be[11] thankful for. A hundred and fifty a year would mean a good deal of pinching for my mother alone, as things went then; but for mother and Lucy together it would have been painfully short commons. Life, even in the country, was an expensive business at that time despite the current worship of cheapness and of "free" trade, as our Quixotic fiscal policy was called. The sum total of our wants and fancied wants had been climbing steadily, while our individual capability in domestic and other simple matters had been on the decline for a long while.

In the end we decided that my mother and Lucy should establish themselves in apartments on the outskirts of Davenham Minster, which apartments would serve my mother permanently, with the relinquishment of a single room after Lucy's marriage. I saw them both established, gathered my few personal belongings in a trunk and a couple of bags, and started for London on a brilliantly fine morning toward the end of June.

At that time a young man went to London as a matter of course, when launching out for himself. It was not that folk liked living in the huge city (though, curiously enough, many did), but they gravitated toward it because the great aim, always, and in those conditions necessarily, was to make money. There was more money "knocking about," so people said, in London than anywhere else; so that was the place for which one made.

I started for London with a capital of precisely eleven guineas over and above my railway fare—and left it again on the same day.

"Now a little before them, there was on the left-hand of the Road, a Meadow, and a Stile to go over into it, and that Meadow is called By-Path-Meadow."—The Pilgrim's Progress.

My friend, Leslie Wheeler, had left Cambridge a few months before my summons home, in order to enter his father's office in Moorgate Street. His father was of the mysteriously named tribe of "financial agents," and had evidently found it a profitable calling.

As I never understood anything of even the nomenclature of finance, I will not attempt to describe the business into which my friend had been absorbed; but I remember that it afforded occupation for dozens of gentlemanly young fellows, the correctness of whose coiffure and general appearance was beyond praise. These beautifully groomed young gentlemen sat upon high stools at desks of great brilliancy. They used an ingenious arrangement of foolscap paper to protect their shirt-cuffs from contact with baser things, and one of the reasons for the evident care lavished upon the disposition of their hair may have been the fact that they made it a point of honour to go hatless when taking the air or out upon business during the day. Their general appearance and deportment in the office and outside always conveyed to me the[13] suggestion that they were persons of some wealth and infinite leisure; but I have been assured that they were hard-working clerks, whose salaries, even in these simpler days, would not be deemed extravagant. These salaries, I have been told, worked out at an average of perhaps £120 or £130 a year.

Now London meant no more to me at that time than a place where, upon rare occasions, one dined in splendour, went to a huge and gilded music-hall, cultivated a bad headache, and presently sought to ease it by eating a nightmarish supper, and eating it against time. My allowance at Cambridge had, no doubt fortunately for my digestion, allowed of but few excursions to the capital; but my friend Wheeler lived within twenty miles of it, and I figured him already burgeoning as a magnate of Moorgate Street. Therefore I had of course written to him of my proposed descent upon the metropolis, and had been very kindly invited to spend a week at his father's house in Weybridge before doing anything else. Accordingly then, having reached Waterloo by a fast train, I left most of my effects in the cloak-room there, and taking only one bag, journeyed down to Weybridge.

My friend welcomed me in person in the hall of his father's big and rather showy house, he having returned from the City earlier than usual for that express purpose. I had already met his mother and two sisters upon four separate occasions at Cambridge. Indeed, I may say that I had almost corresponded with Leslie's second sister, Sylvia. At all events, we had exchanged half a dozen letters, and I had even[14] begged, and obtained, a photograph. At Cambridge I thought I had detected in this delicately pretty, soft-spoken girl, some sympathy and fellow-feeling in the matter of my own crude gropings toward a philosophy of life. You may be sure I did not phrase it in that way then. The theories upon which my discontent with the prevailing order of things was based, seemed to me then both strong and practical; a little ahead of my time perhaps, but far from crude or unformed. As I see it now, my creed was rather a protest against indifference, a demand for some measure of activity in social economy. That my muse was socialistic seems to me now to have been mainly accidental, but so it was, and its nutriment had been drawn largely from such sources as Carpenter's Civilization: its Cause and Cure, in addition to the standard works of the Socialist leaders.

It is quite possible that one of the reasons of my continued friendship with Leslie Wheeler was the fact that, in his agreeable manner, he represented in person much of the butterfly indifference to what I considered the serious problems of life, against which my fulminations were apt to be directed. I may have clung to him instinctively as a wholesome corrective. At all events, he submitted, in the main good-humouredly, to my frequently personal diatribes, and, by his very complaisance and merry indifference, supplied me again and again with point and illustration for my sermons.

Leslie's elder sister, Marjory, was his counterpart in petticoats; merry, frivolous, irresponsible, devoted to the chase of pleasure, and obdurately bent upon[15] sparing neither thought nor energy over other interests; denying their very existence indeed, or good-humouredly ridiculing them when they were forced upon her. She was a very handsome girl; I was conscious of that; but, perhaps because I could not challenge her as I did her brother, her character made no appeal to me. But Sylvia, on the other hand, with her big, spiritual-looking eyes, transparently fair skin, and earnest, even rapt expression; Sylvia stirred my adolescence pretty deeply, and was assiduously draped by me in that cloth of gold and rose-leaves which every young man is apt to weave from out of his own inner consciousness for the persons of those representatives of the opposite sex in whom he detects sympathy and responsiveness.

Mrs. Wheeler spoke in a kind and motherly way of my bereavement, and the generosity of youth somehow prevented my appreciation of this being dulled by the fact that, until reminded, she had forgotten whether I had lost a father or a mother. Indeed, though not greatly interested in other folk's affairs, I believe that while the good soul's eyes rested upon the supposed sufferer, or his story, she was sincerely sorry about any kind of trouble, from her pug's asthma to the annihilation of a multitude in warfare or disaster. She had the kindest heart, and no doubt it was rather her misfortune than her fault that she could not clearly realize any circumstance or situation which did not impinge in some way upon her own small circle.

I met Leslie's father for the first time at dinner that evening. One could hardly have imagined him sparing time for visits to Cambridge. He was a fine,[16] soldierly-looking man, with no trace of City pallor in his well-shaven, purple cheeks. Purple is hardly the word. The ground was crimson, I think, and over that there was spread a delicate tracery, a sort of netted film, of some kind of blue. The eyes had a glaze over them, but were bright and searching. The nose was a salient feature, having about it a strong predatory suggestion. The forehead was low, surmounted by exquisitely smooth iron-gray hair. Mr. Wheeler was scrupulously fine in dress, and used a single eye-glass. He gave me hearty welcome, and I prefer to think that the apparent chilling of his attitude to me after he had learned of my financial circumstances was merely the creation of some morbid vein of hyper-sensitiveness in myself.

At all events, we were all very jolly together that evening, and I went happily to bed, after what I thought a hint of responsive pressure in my handshake with Sylvia, and several entertaining anecdotes from Mr. Wheeler as to the manner in which fortunes had been made in the purlieus of Throgmorton Street. Launching oneself upon a prosperous career in London seemed an agreeably easy process at the end of that first evening in the Wheeler's home, and the butterfly attitude toward life appeared upon the whole less wholly blameworthy than before. What a graceful fellow Leslie was, and how suave and genial the father when he sat at the head of his table toying with a glass of port! And these were capable men, too, men of affairs. Doubtless their earnestness was strong enough below the surface, I thought—for that night.

Though in no sense unfriendly or lacking in sympathy, I noticed that Leslie Wheeler showed no inclination to be drawn into intimate discussion of my prospects. I was not inclined to blame my friend for this, but told myself that he probably acted upon paternal instructions. For me, however, it was impossible to lay aside for long, thoughts regarding my immediate future. I was aware that a nest-egg of eleven or twelve pounds was not a very substantial barrier between oneself and want. Mr. Wheeler told no more stories of fortunes built out of nothing in the City, but he did take occasion to refer casually to the fact that City men did not greatly care for the products of public schools and universities, as employees.

I was more than half-inclined to ask why, in this case, Leslie had been sent to Rugby and Cambridge, but decided to avoid the personal application of his remark. It was, after all, no more than the expression of a commonly accepted view, striking though it seems as a comment upon the educational system of the period, when one remembers the huge proportion of the middle and upper-class populace which was absorbed[18] by commercial callings of one kind or another.

There was practically no demand for physical prowess or aptitude, outside the field of sport and games, nor even for those qualities which are best served by a good physical training. One need not, therefore, be greatly surprised that the public schools should have given no physical training outside games, and that even of the most perfunctory character, the majority qualifying as interested spectators merely, of the prowess of the minority. But it certainly is remarkable, that no practical business training, nor studies of a sort calculated to be of use in later business training, should have been given in the schools most favoured by those for whom business was a life's calling. In this, as in so many other matters, I suppose we were guided and directed entirely by habit and tradition; the line of least resistance.

When I talked of my prospects with handsome Leslie Wheeler—his was his father's face, unblemished and unworn—our conversation was always three parts jocular, at all events upon his side. I was to recast society and mould our social system anew by means of my pen, and of journalism. I was to provide "the poor blessed poor" with hot-buttered rolls and devilled kidneys for breakfast, said Leslie, and introduce old-age pensions for every British workman who survived his twenty-first birthday.

I would not be understood to suggest that this sort of facetiousness indicated the average attitude of the period with regard to the horrible fact that the country contained millions of people permanently in a[19] state of want and privation. But it was a quite possible attitude then. Such people as my friend could never have mocked the sufferings of an individual. But with regard to the state of affairs, the pitiful millions, as an abstract proposition, indifference was the rule, a tone of light cynicism was customary, and "the poor we have always with us," quoted with a deprecatory shrug, was an accepted conversational refuge, even among such people as the clergy and charitable workers.

And this, if one comes to think of it, was inevitable. The life and habits and general attitude of the period would have been absolutely impossible, in conjunction with any serious face-to-face consideration of a situation which embraced, for example, such preposterously contradictory elements as these:

The existence of huge and growing armies of absolutely unemployed men; the insistence of the populace, and particularly the business people, upon the disbandment of regiments, and upon great naval and military reductions, involving further unemployment; the voting of considerable sums for distribution among the unemployed; violent opposition to the mere suggestion of State aid to enable the unemployed of England to migrate to those parts of the Empire which actually needed their labour; the increasing difficulty of the problem which was wrapped up in the question of "What to do with our sons"; the absolute refusal of the nation to admit of universal military service; the successive closing by tariff of one foreign market after another against British manufactures, and the hysterical refusal of[20] the people to protect their own markets from what was graphically called the "dumping" into them of the surplus products of other peoples.

It is a queer catalogue, with a ring of insanity about it; but these were the merest commonplaces of life at that time, and the man who rebelled against them was a crank. My friend Leslie's attitude was natural enough, therefore; and, with a few exceptions, it was my own, for, curiously enough, the political school I favoured was, root and branch, opposed to the only possible remedies for this situation. Liberals, Radicals, Socialists, and the majority of those who arrogated to themselves the title of Social Reformers; these were the people who insisted, if not upon the actual evils and sufferings indicated in this illustrative note of social contradictions, then upon violent opposition to their complements in the way of mitigation and relief. And I was keenly of their number.

Many of these matters I discussed, or perhaps I should say, dilated upon, in conversation with Sylvia, while her brother and father were in London. We would begin with racquets in the tennis-court, and end late for some meal, after long wanderings among the pines. And in Sylvia, as it seemed to me, I found the most delightfully intelligent responsiveness, as well as sympathy. My knowledge of feminine nature, its extraordinary gifts of emotional and personal intuition, was of the scantiest, if it had any existence at all. But my own emotional side was active, and my mind an inchoate mass of ideals and more or less sentimental longings for social betterment. And so,[21] with Sylvia's gentle acquiescence, I rearranged the world.

Much I have forgotten, and am thus spared the humiliation of recounting. But, as an example of what I recall, I remember a conversation which arose from our passing a miniature rifle-range which some local resident—"Some pompous Jingo of retrogressive tendencies," I called him—had erected with a view to tempting young Weybridge into marksmanship; a tolerably forlorn prospect at that time.

"Is it not pathetic," I said, "in twentieth-century England, to see such blatant attacks upon progress as that?"

Sylvia nodded gravely; sweetly sympathetic understanding, as I saw it. And, after all, why not? Understanding of my poor bubbling mind, anyhow, and—Nature's furnishing of young women's minds is a mighty subtle business, not very much more clearly understood to-day than in the era of knight-errantry.

Sylvia nodded gravely, as I spurned the turf by the range.

"Here we are surrounded by quagmires of poverty, injustice, social anomalies, and human distress, and this poor soul—a rich pork-butcher, angling for the favours of a moribund political party, I dare say—lavishes heaven knows how many pounds over an arrangement by which young men are to be taught how to kill each other with neatness and despatch at a distance of half a mile! It is more tragical than farcical. It is enough to make one despair of one's fellow countrymen, with their silly bombast about[22] 'Empire,' and their childish waving of flags. 'Empire,' indeed; God save the mark! And our own little country groaning, women and children wailing, for some measure of common-sense internal reform!"

"It is dreadful, dreadful," said Sylvia. My heart leapt out to meet the gentle goodness of her. "But still, I suppose there must be soldiers," she added. Of course, this touched me off as a spark applied to tinder.

"But that is just the whole crux of the absurdity, and as long as so unreal a notion is cherished we can never be freed from the slavery of these huge armaments. Soldiers are only necessary if war is necessary, and war can only be necessary while men are savages. The differences between masters and men are far more vital and personal than the differences between nations; yet they have long passed the crude stage of thirsting for each other's destruction as a means of settling quarrels. War is a relic of barbarous days. So long as armies are maintained, unscrupulous politicians will wage war. If we, who call ourselves the greatest nation in Christendom, would even deserve the credit of plain honesty, we must put away savagery, and substitute boards of arbitration for armies and navies."

"Yes, I see," said Sylvia, her face alight with interest, "I feel that must be the true, the Christian view. But suppose the other nations would not agree to arbitration?"

"But there is not a doubt they would. Can you suppose that any people are so insensate as really to[23] like war, carnage, slaughter, for their own sake, when peaceful alternatives are offered?"

"No, I suppose not; and, indeed, I feel that all you say is true, Mr. Mordan."

"Please don't say 'Mr. Mordan,' Sylvia. Even your mother and sister call me Dick. No, no, the other nations would be only too glad to follow our lead, and we, as the greatest Power, should take that lead. What could their soldiers do to a soldierless people, anyhow; and even if we lost at the beginning, why, 'What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul?' Of what use is the dominion of a huge, unwieldy empire when even a tiny country like this is so administered that a quarter of its population live always on the verge of starvation? Let the Empire go, let Army and Navy go, let us concentrate our energies upon the arts of peace, science, education, the betterment of the conditions of life among the poor, the right division of the land among those that will till it. Let us do that, and the world would have something to thank us for, and we should soon hear the last of these noisy, ranting idiots who are eternally waving flags like lunatics and mouthing absurd phrases about imperialism and patriotism, national destiny, and rubbish of that sort. Our duty is to humanity, and not to any decayed symbols of feudalism. The talk of patriotism and imperialism is a gigantic fraud, and the tyranny of it makes our names hated throughout the world. We have no right to enforce our sway upon the peace-loving farmers and the ignorant blacks of South Africa. They rightly hate us for it, and so do the millions[24] of India, upon whom our yoke is held by armies of soldiers who have to be maintained by their victims. It casts one down to think of it, just as the sight of those ridiculous rifle-butts and the thought of the diseased sentiment behind them depresses one."

"It all seems very mad and wrong, but—but I wish you would not take it so much to heart," said Sylvia.

"That is very sweet of you," I told her; "and, indeed, there is not so much real cause to be downhearted. The last elections showed clearly enough that the majority of our people are alive to all this. The leaven of enlightenment is working strongly among the people, and the old tyranny of Jingoism is dying fast. One sees it in a hundred ways. Boer independence has as warm friends in our Parliament as on the veld. The rising movements of internationalism, of Pan-Islam, the Swadeshi movement, the rising toward freedom in India; all these are largely directed from Westminster. The Jingo sentiment toward Germany, a really progressive nation, full of natural and healthy ambitions, is being swept away by our own statesmen; by their courteous and friendly attitude toward the Kaiser, who delights to honour our present Minister of War. Also, the work of disarmament has begun. The naval estimates are being steadily pruned, and whole regiments have been finally disbanded. And all this comes from within. So you see we have some grounds for hopefulness. It is a great step forward, for our own elected leaders to show the enthusiastic and determined opposition they are showing to the old brutal pretensions of[25] England to sway the world by brute strength. But, forgive me! Perhaps I tire you with all this—Sylvia."

"No, no, indeed you don't—Dick, I—I think it is beautiful. It—it seems to make everything bigger, more kind and good. It interests me, immensely."

And I knew perfectly well that I had not tired her—wearisome though the recital of it all may be now. For I knew instinctively how the personal note told in the whole matter. I had been really heated, and perfectly sincere, but a kind of subconscious cunning had led me to utilize the heat of the moment in introducing between us, for example, the use of first names. Well I knew that I was not wearying Sylvia. But coldly recited now, I admit the rhodomontade to be exceedingly tiresome. My excuse for it is that it serves to indicate the sort of ideas that were abroad at the time, the sort of sentiments which were shaping our destiny.

After all, I was an educated youth. Many of my hot statements, too, were of fact, and not merely of opinion and feeling. It is a fact that the sentiment called anti-British had come to be served more slavishly in England than in any foreign land. The duration of our disastrous war in South Africa was positively doubled, as the result of British influence, by Boer hopes pinned upon the deliberate utterances of British politicians. In Egypt, South Africa, India, and other parts of the Empire, all opposition to British rule, all risings, attacks upon our prestige, and the like, were aided, and in many cases fomented, steered, and brought to a successful issue—not by[26] Germans or other foreigners, but by Englishmen, and by Englishmen who had sworn allegiance at St. Stephens. It is no more than a bare statement of fact to say that, in the very year of my arrival in London, the party which ruled the State was a party whose members openly avowed and boasted of their opposition to British dominion, and that in terms, not less, but far more sweeping than mine in talking to Sylvia among the pines at Weybridge.

But if Sylvia appreciated and sympathized in the matter of my sermonizing, the rest of the family neither approved the sermons nor Sylvia's interest in them. I was made to feel in various ways that no import must be attached to my attentions to Sylvia. Marjory began to shadow her sister in the daytime, and, as she was frankly rather bored by me, I could not but detect the parental will in this.

Then with regard to my social and political views, Mr. Wheeler joined with his son in openly deriding them. In Leslie's case the thing never went beyond friendly banter. Leslie had no political opinions; he laughed joyously at the mere notion of bothering his head about such matters for a moment. And, in his way, he represented an enormous section of the younger generation of Englishmen in this. The father, on the other hand, was equally typical of his class and generation. This was how he talked to me over his port:—

"I tell you what it is, you know, Mordan: you're a regular firebrand, you know; by Jove, you are; an out-and-out Socialistic Radical: that's what you are. By gad, sir, I don't mince my words. I consider that—er—opinions[27] like yours are a danger to the country; I do, indeed; a danger to the country, and—er—to the—to the Empire. I do, by gad. And as for your notions about disarmament and that, why, even if our army reductions are justifiable, which, upon my word, I very much doubt, it's ridiculous to suppose we can afford to cut down our Navy. No, sir, the British Navy is Britain's safeguard, and it ought not to be tampered with. I'm an out-and-out Imperialist myself, and—er—I can tell you I have no patience with your Little Englandism."

I am not at all sure whether the class Mr. Wheeler belonged to was not almost the most dangerous class of all. The recent elections showed this class to be a minority. Of course, this section had its strong men, but that it also included a large number of men like Leslie's father was a fact—a fact which yielded pitiful evidence of its weakness. These men called themselves "out-and-out Imperialists," and had not a notion of even the meaning of the word they used. Still less had they any notion of accepting any rôle which involved the bearing of responsibilities, the discharge of civic and national duties.

Mr. Wheeler's aim in life was to make money and to enjoy himself. He would never have exercised his right to vote if voting had involved postponing dinner. He liked to talk of the British Empire, but he did not even know precisely of what countries it consisted, and I think he would cheerfully have handed Canada to France, Australia to Germany, India to Russia, and South Africa to the Boers, if by so doing he could have escaped the paying of income-tax.[28]

On Sunday night, my last night at Weybridge, I walked home from church alone with Sylvia. Marjory was in bed with a sore throat, and whatever their notions as to my undesirability, neither Mr. nor Mrs. Wheeler were inclined to attend evening service. Leslie was not home from golf at Byfleet. We were late for dinner, Sylvia and I, and during our walk she promised to write to me regularly, and I promised many things, and suggested many things, and was only deterred from actual declaration by the thought of the poor little sum which stood between me and actual want.

Next morning I went up to town with Leslie and his father to open my campaign in London. As a first step toward procuring work, I was to present a letter of introduction from a Cambridge friend to the editor of the Daily Gazette. After that, as Leslie said, I was to "reform England inside out."

Looking back now upon that lonely launch of mine in London, I see a very curious and sombre picture. In the living I am sure there must have been mitigations, and light as well as shade. In the retrospect it seems one long disillusion. I see myself, and the few folk with whom my relations were intimate, struggling like ants across a grimy stage, in the midst of an inferno of noise, confusion, pointless turmoil, squalor, and ultimate cataclysm. The whole picture is lurid, superhuman in its chaotic gloom; but in the living, I know there were gleams of sunlight. The tragic muddle of that period was so monstrous, that even we who lived through it are apt in retrospect to see only the gloom and confusion. It is natural, therefore, that those who did not live through it should be utterly unable to discern any glimpse of[30] relief in the picture. And that leads to misconception.

As a fact, I found very much to admire in London when I sallied forth from the obscure lodging I had chosen in a Bloomsbury back street, on the morning which brought an end to my stay with the Wheelers at Weybridge. Also, it was not given to me at that time to recognize as such one tithe of the madness and badness of the state of affairs. Some wholly bad features were quite good in my eyes then.

London still clung to its "season," as it was called, though motor-cars and railway facilities had entirely robbed this of its sharply defined nineteenth-century limits. Very many people, even among the wealthy, lived entirely in London, spending their week-ends in this or that country or seaside resort, and devoting the last months of summer with, in many cases, the first months of autumn, to holiday-making on the Continent, or in Scotland, or on the English moors or coasts.

The London season was not over when I reached town, and in the western residential quarters the sun shone brightly upon many-coloured awnings and beautiful decorative plants and flowers. The annual rents paid by people who lived behind these flowers and awnings frequently ran into thousands of pounds, with ten shillings in each pound additional by way of rates and taxes. To live at all, in this strata, would cost a man and his wife perhaps eighty to a hundred pounds a week, without anything which would have been called extravagance.

Hundreds of people who lived in this way had[31] neighbours within a hundred yards of their front doors who never had enough to eat. Even such people as these had to pay preposterous rents for the privilege of huddling together in a single wretched room. But many of their wealthy neighbours spent hundreds, and even thousands of pounds a year over securing comfort and happiness for such domestic animals as horses, dogs, cats, and the like. Amiable, kindly gentlefolk they were, with tender hearts and ready sympathies. Most of them were interested in some form of charity. Many of them specialized, and these would devote much energy to opposing the work of other charitable specialists. Lady So-and-so, who advocated this panacea, found herself bitterly opposed by Sir So-and-so, who wanted all sufferers to be made to take his nostrum in his special way. Then sometimes poor Lady So-and-so would throw up her panacea in a huff, and concentrate her energies upon the work of some society for converting Jews, who did not want to be converted, or for supplying red flannel petticoats for South Sea Island girls, who infinitely preferred cotton shifts and floral wreaths. Even these futile charities were permitted to overlap one another to a bewilderingly wasteful extent.

But the two saddest aspects of the whole gigantic muddle so far as charitable work went, were undoubtedly these: The fact that much of it went to produce a class of men and women who would not do any kind of work because they found that by judicious sponging they could live and obtain alcohol and tobacco in idleness; and the fact that where charitable endeavour infringed upon vested interests, licit or[32] illicit, it was savagely opposed by the persons interested.

The discipline of the national schools was slack, intermittent, and of short reach. There was positively no duty to the State which a youth was bound to observe. Broadly, it might be said that at that time discipline simply did not enter at all into the life of the poor of the towns, and charity of every conceivable and inconceivable kind did enter into it at every turn.

The police service was excellent and crime exceedingly difficult of accomplishment. The inevitable result was the evolution in the towns of a class of men and women, but more especially of men, who, though compact of criminal instincts of every kind, yet committed no offence against criminal law. They committed nothing. They simply lived, drinking to excess when possible, determined upon one point only: that they never would do anything which could possibly be called work. It is obvious that among such people the sense of duty either to themselves, to each other, or to the State, was merely non-existent.

London had long since earned the reputation of being the most charitable city in the world. Its share in the production of an immense loafer class formed one sad aspect of London's charity when I first came to know the city. Another was the opposition of vested interests—the opposition of the individual to the welfare of the mass. One found it everywhere. An instance I call to mind (it happened to be brought sharply home to me) struck at the root of the terribly rapid production of degenerates, by virtue of its relation[33] to pauper children—that is, the children to whom the State, through its boards of guardians, stood in the light of parents, because their natural parents were dead, or in prison, or in lunatic asylums, or hopelessly far gone in the state of criminal inactivity which qualified so many for all three estates.

Huge institutions were built at great expense for the accommodation of these little unfortunates. Here they were housed in the most costly manner, the whole work of the establishment being carried on by a highly paid staff of servants and officials. The children were not allowed to do anything at all, beyond the learning by rote of various theories which there was no likelihood of their ever being able to apply to any reality of life with which they would come in contact.

They listened to lectures on the making of dainty dishes in the best style of French cookery, and in many cases they never saw a box of matches. They learned to repeat poetry as parrots might, but did not know the difference between shavings and raw coffee. They learned vague smatterings of Roman history, but did not know how to clean their boots or brush their hair. It was as though experts had been called upon to devise a scheme whereby children might be reared into their teens without knowing that they were alive or where they lived, and this with the greatest possible outlay of money per child. Then, at a given age, these children were put outside the massive gates of the institutions and told to run away and become good citizens.

It followed as a matter of course that most of them[34] fell steadily and rapidly into the pit; the place occupied by the criminally inactive, the "public-house props." So they returned poor, heavy-laden creatures, by way of charity, to the institutions of the "rates," thus completing the vicious circle of life forced upon them by an incredibly wrong-headed, topsyturvy administration.

For the maintenance of this vicious circle enormous sums of public money were required. Failing such vast expenditure, Nature unaided would have righted matters to some extent, and the Poor Law guardians would have become by so much the less wielders of power and influence, dispensers of public money. Some of these Poor Law guardians gave up more or less honest trades to take to Poor Law guardianship as a business; and they waxed fat upon it.

Every now and again came disclosures. Guardians were shown to have paid ten shillings a score for such and such a commodity this year, and next year to have refused a tender for the supply of the same article at 9s. 8d. a score, in favour of the tender of a relative or protégé of one of their number at 109s. 8d. a score. I remember the newspapers showing up such cases as these during the week of my arrival in London. The public read and shrugged shoulders.

"Rascally thieves, these guardians," said the Public; and straightway forgot the whole business in the rush of its own crazy race for money.

"But," cried the Reformer to the Public, "this is really your business. It is your duty as citizens to stop this infamous traffic. Don't you see how you yourselves are being robbed?"[35]

You must picture our British Public of the day as a flushed, excited man, hurrying wildly along in pursuit of two phantoms—money and pleasure. These he desired to grasp for himself, and he was being furiously jostled by millions of his fellows, each one of whom desired just the same thing, and nothing else. Faintly, amidst the frantic turmoil, came the warning voices in the wilderness:

"This is your business. It is your duty as citizens," etc.

Over his shoulder, our poor possessed Public would fling his answer:

"Leave me alone. I haven't time to attend to it. I'm too busy. You mustn't interrupt me. Why the deuce don't the Government see to it? Lot of rascals! Don't bother me. I represent commerce, and, whatever you do, you must not in any way interfere with the Freedom of Trade."

The band of the reformers was considerable, embracing as it did the better, braver sort of statesmen, soldiers, sailors, clergy, authors, journalists, sociologists, and the whole brotherhood of earnest thinkers. But the din and confusion was frightful, the pace at which the million lived was terrific; and, after all, the cries of the reformers all meant the same thing, the one thing the great, sweating public was determined not to hear, and not to act on. They all meant:

"Step out from your race a moment. Your duties are here. You are passing them all by. Come to your duties."

It was like a Moslem call to prayer; but, alas! it was directed at a people who had sloughed all pretensions[36] to be ranked among those who respond to such calls, to any calls which would distract them from their objective in the pelting pursuit of money and pleasure.

But I am digressing—the one vice which, unfortunately for us, we never indulged or condoned at the time of my arrival in London. I wanted to give an instance of that aspect of charity and attempted social reform which aroused the opposition of vested interests and chartered brigands in the great money hunt. It was this: A certain charitable lady gave some years of her life to the study of those conditions in which, as I have said, the criminally inactive, the hopelessly useless, were produced by authorized routine, at a ruinous cost in money and degeneracy, and to the great profit of an unscrupulous few.

This lady then gave some further years, not to mention money, influence, and energy, to the evolution of a scheme by which these pauper children could really be made good and independent citizens, and that at an all-round cost of about one-fifth of the price of the guardians' method for converting them into human wrecks and permanent charges upon the State. The wise practicability of this lady's system was admitted by independent experts, and denied by nobody. But it was swept aside and crushed, beaten down with vicious, angry thoroughness, in one quarter—the quarter of vested interest and authority; quietly, passively discouraged in various other quarters; and generally ignored, as another interrupting duty call, by the rushing public.

Here, then, were three kinds of opposition—the[37] first active and deadly, the other two passive and fatal, because they withheld needed support. The reason of the first, the guardians' opposition, was frankly and shamelessly admitted in London at the time of my arrival there. The guardians said:

"This scheme would reduce the rates. We want more rates. It would reduce the amount of money at our disposal. We aim at increasing that. It would divert certain streams of cash from our own channel into other channels in other parts of the Empire. We won't have it." But their words were far less civil and more heated than these, though the sense of them was as I have said.

The quiet, passive opposition was that of other workers in charity and reform. They said in effect:

"Yes, the scheme is all right—an excellent scheme. But why do you take it upon yourself to bring it forward in this direct manner? Are you not aware of the existence of our B—— nostrum for pauper children, or our C—— specific for juvenile emigration? Your scheme, admirable as it is, ignores both these, and therefore you must really excuse us if we—— Quite so! But, of course, as co-workers in the good cause, we wish you well——", and so forth.

The opposition of the general public I have explained. It was not really opposition. It was simply a part of the disease of the period; the dropsical, fatty degeneration of a people. But the mere fact that the reformers sent forth their cries and still laboured beside the public's crowded race-course; that such people as the lady I have mentioned existed—and[38] there were many like her—should show that London as I found it was not all shadow and gloom, as it seems when one looks back upon it from the clear light of better days.

The darkness, the confusion, and the din, were not easy to see and hear through then. From this distance they are more impenetrable; but I know the light did break through continually in places, and good men and women held wide the windows of their consciousness to welcome it, striving their utmost to carry it into the thick of the fight. Many broke their hearts in the effort; but there were others, and those who fell had successors. The heart of our race never was of the stuff that can be broken. It was the strongest thing in all that tumultuous world of my youth, and I recall now the outstanding figures of men already gray and bowed by long lives of strenuous endeavour, who yet fought without pause at this time on the side of those who strove to check the mad, blind flight of the people.

London, as I entered it, was a battle-field; the perverse waste of human energy and life was frightful; but it was not quite the unredeemed chaos which it seems as we look back upon it.

The Roaring City

The Roaring CityEven in the red centre of the stampede (Fleet Street is within the City boundaries) men in the race took time for the exercise of human kindliness, when opportunity was brought close enough to them. The letter I took to the editor of the Daily Gazette was from an old friend of his who knew, and told him, of my exact circumstances. This gentleman received me kindly and courteously. He and his like were among[39] the most furiously hurried in the race, but their handling of great masses of diffuse information gave them, in many cases, a wide outlook, and where, as often happened, they were well balanced as well as honest, I think they served their age as truly as any of their contemporaries, and with more effect than most.

This gentleman talked to me for ten minutes, during which time he learned most of all there was to know about my little journalistic and debating experience at Cambridge, and the general trend of my views and purposes. I do not think he particularly desired my services; but, on the other hand, I was not an absolute ignoramus. I had written for publication; I had enthusiasm; and there was my Cambridge friend's letter.

"Well, Mr. Mordan," he said, turning toward a table littered deep with papers, and cumbered with telephones and bells, "I cannot offer you anything very brilliant at the moment; but I see no reason why you should not make a niche for yourself. We all have to do that, you know—or drop out to make way for others. You probably know that in Fleet Street, more perhaps than elsewhere, the race is to the swift. There are no reserved seats. The best I can do for you now is to enter you on the reporting staff. It is stretching a point somewhat to make the pay fifty shillings a week for a beginning. That is the best I can do. Would you care to take that?"

"Certainly," I told him; "and I'm very much obliged to you for the chance."

"Right. Then you might come in to-morrow. I[40] will arrange with the news-editor. And now——" He looked up, and I took my hat. Then he looked down again, as though seeking something on the floor. "Well, I think that's all. Of course, it rests with you to make your own place, or—or lose it. I sympathize with what you have told me of your views—of course. You know the policy of the paper. But you must remember that running a newspaper is a complex business. One's methods cannot always be direct. Life is made up of compromises, and—er—at times a turn to the left is the shortest way to the right—er—Good night!"

Thus I was given my chance within a few hours of my descent upon the great roaring City. I was spared much. Even then I knew by hearsay, as I subsequently learned for myself, that hundreds of men of far wider experience and greater ability than mine were wearily tramping London's pavements at that moment, longing, questing bitterly for work that would bring them half the small salary I was to earn.

I wrote to Sylvia that night, from my little room among the cat-infested chimney-pots of Bloomsbury; and I am sure my letter did not suggest that London was a very gloomy place. My hopes ran high.

Acting on the instructions I had received overnight, I presented myself at the office of the Daily Gazette in good time on the morning after my interview with the editor. A pert boy showed me into the news-editor's room, after an interval of waiting, and I found myself confronting the man who controlled my immediate destiny. He was dictating telegrams to a shorthand writer, and, for the moment, took no notice whatever of me. I stood at the end of his table, hat in hand, wondering how so young-looking a man came to be occupying his chair.

He looked about my age, but was a few years older. His face was as smooth as the head of a new axe, and had something else chopper-like about it. He reminded me of pictures I had seen in the advertisement pages of American magazines; pictures showing a wedge-like human face, from the lips of which some such an assertion as "It's you I want!" was supposed[42] to be issuing. I subsequently learned that this Mr. Charles N. Pierce had spent several years in New York, and that he was credited with having largely increased the circulation of the Daily Gazette since taking over his present position. He suddenly raised the even, mechanical tone in which he dictated, and snapped out the words:

"Right. Get on with those now, and come back in five minutes."

Then he switched his gaze on to me, like a searchlight.

"Mr. Mordan, I believe?"

I admitted the charge with my best smile. Mr. Pierce ignored the smile, and said:

"University man?"

Accepting his cue as to brevity, I said: "Yes. Corpus Christi, Cambridge."

He pursed his thin lips. "Ah well," he said, "you'll get over that."

In his way he was perfectly right; but his way was as coldly offensive as any I had ever met with.

"Well, Mr. Mordan, I've only three things to say. Reports for this paper must be sound English; they must be live stories; they must be short. You might ask a boy to show you the reporters' room. You'll get your assignment presently. As a day man, you'll be here from ten to six. That's all."

And his blade of a face descended into the heart of a sheaf of papers. As I reached the door the blade rose again, to emit a kind of thin bark:

"Ah!"

I turned on my heel, waiting.[43]

"Do you know anything about spelling?"

I tried to look pleasant, as I said I thought I was to be relied on in this.

"Well, ask my secretary for tickets for the meeting at Memorial Hall to-day; something to do with spelling. Don't do more than thirty or forty lines. Right."

And the blade fell once more, leaving me free to make my escape, which I did with a considerable sense of relief. I found the secretary a meek little clerk, with a curious hidden vein of timid facetiousness. He supplied me with the necessary ticket and a hand-bill of particulars. Then he said:

"Mr. Pierce is quite bright and pleasant this morning."

"Oh, is he?" I said.

"Yes, very—for him. He's all right, you know, when you get into his way. Of course, he's a real hustler—cleverest journalist in London, they say."

"Really!" I think I introduced the right note of admiration. At all events, it seemed to please this little pale-eyed rabbit of a man, who, as I found later, was reverentially devoted to his bullying chief, and positively took a kind of fearful joy in being more savagely browbeaten by Pierce than any other man in the building. A queer taste, but a fortunate one for a man in his particular position.

For myself, I was at once repelled and gagged by Pierce's manner. I believe the man had ability, though I think this was a good deal overrated by himself, and by others, at his dictation; and I dare say he was a good enough fellow at heart. His[44] manner was aggressive and feverish enough to be called a symptom of the disease of the period. If the blood in his veins sang any song at all to Mr. Pierce, the refrain of that song must have been, "Hurry, hurry, hurry!" He and his like never stopped to ask "Whither?" or "Why?" They had not time. And further, if pressed for reasons, destination, and so forth, they would have admitted, to themselves at all events, that there could be no other goal than success; and that success could mean no other thing than the acquisition of money; and that the man who thought otherwise must be a fool—a fool who would soon drop out altogether, to go under, among those who were broken by the way.

My general aim and purpose in journalistic work, at the outset, was the serving of social reform in everything that I did. As I saw it, society was in a parlous state indeed, and needed awaking to recognition of the fact, to the crying need for reforms in every direction. That attitude was justifiable enough in all conscience. The trouble was that I was at fault, first, in my diagnosis; second, in my notions as to what kind of remedies were required; and third, as to the application of those remedies.

Like the rest of the minority whose thoughts were not entirely occupied by the pursuit of pleasure and personal gain, I saw that the greatest obstacle in the path of the reformer was public indifference. But with regard to the causes of that indifference, I was entirely astray. I clung still to the nineteenth-century attitude, which had been justifiable enough during a good portion of that century, but had absolutely[45] ceased to be justifiable before its end came. This was the attitude of demanding the introduction of reforms from above, from the State.

Though I fancied myself in advance of my time in thought, when I joined the staff of the Daily Gazette, I really was essentially of it. Even my obscure work as reporter very soon brought me into close contact with some of the dreadful sores which disfigured the body social and politic at that time. But do you think they taught me anything? No more than they taught the blindest racer after money in all London. They moved me, moved me deeply; they stirred the very foundations of my being; for I was far from being insensitive. But not even in the most glaringly obvious detail did they move me in the right direction. They merely filled me with resentment, and a passionate desire to bring improvement, aid, betterment; a desire to force the authorities into some action. Never once did it occur to me that the movement must come from the people themselves.

Poverty, though frequently a dreadful complication, was far from being at the root of all the sores. The average respectable working-class wage-earner with a wife and family, who earned from 25s. to 35s. or 40s. a week, would spend a quarter of that wage upon his own drinking; thereby not alone making saving for a rainy day impossible, but docking his family of some of the real necessities of life. But this was accepted as a matter of course. The man wanted the beer; he must have it. The State made absolutely no demand whatever upon such a man. But it did for him and his, more than he did for himself[46] and his family. And, giving positively nothing to the State, he complainingly demanded yet more from it.

These were respectable men. A large number of men spent a half, and even three-quarters of their earnings in drink. The middle class spent proportionately far less on liquor, and far more upon display of one kind and another; they seldom denied themselves anything which they could possibly obtain. The rich, as a class, lived in and for indulgence, in some cases refined and subtle, in others gross; but always indulgence. The sense of duty to the State simply did not exist as an attribute of any class, but only here and there in individuals.

I believe I am strictly correct in saying that in half a century, while the population increased by seventy-five per cent., lunacy had increased by two hundred and fifty per cent.

Yet the majority rushed blindly on, paying no heed to any other thing on earth than their own gratification, their own pursuit of the money for the purchase of pleasure. One of the tragic fallacies of the period was this crazy notion that not alone pleasure, but happiness, could be bought with money, and in no other way. And the few who were stung by the prevailing suffering and wretchedness into recognition of our parlous state, we, for the most part, cherished my wild delusion, and insisted that the trouble could be remedied if the State would contract and discharge new obligations. We clamoured for more rights, more help, more liberty, more freedom from this and that; never seeing that our trouble was our incomplete[47] comprehension of the rights and privileges we had, with their corresponding obligations.

Though I knew them not, and as a Daily Gazette reporter was little likely to meet them, there were men who strove to open the eyes of the people to the truth, and strove most valiantly. I call to mind a great statesman and a great general, both old men, a great pro-consul, a great poet and writer, a great editor, and here and there politicians with elements of greatness in them, who fought hard for the right. But these men were lonely figures as yet, and I am bound to say of the people's leaders generally, at the time of my journalistic enterprise, that they were a poor, truckling, uninspired lot of sheep, with a few clever wolves among them, who saw the people's madness and folly and preyed upon it masterfully by every trick within the scope of their ingenuity.

Even those who were honourable, disinterested, and, for such a period, unselfish, were for the most part the disciples of tradition and the slaves of that life-sapping curse of British politics: the party spirit, which led otherwise honourable men to oppose with all their strength the measures of their party opponents, even in the face of their country's dire need.

Then there was the anti-British faction, a party which spread fast-growing shoots from out the then Government's very heart and root. The Government's half-hearted supporters were not anti-British, but they were not readers of the Daily Gazette; they were not, in short, whole-hearted Government supporters. They were Whigs, as the saying went. My party, the readers of the Gazette, the out-and-out[48] Government party, to whom I looked for real progress, real social reform; they were unquestionably riddled through and through with this extraordinary sentiment which I call anti-British, a difficult thing to explain nowadays.

With the newly and too easily acquired rights and liberties of the nineteenth century, with its universal spread of education, cheap literature, and the like, there came, of course, increased knowledge, a wider outlook. No discipline came with it, and one of its earliest products was a nervous dread of being thought behind the time, of being called ignorant, narrow-minded, insular. People would do anything to avoid this. They went to the length of interlarding their speech and writings with foreign words often in ignorance of the meaning of those words. Broad-minded, catholic, tolerant, cosmopolitan—those were the descriptive adjectives which all desired to earn for themselves. It became a perfect mania, particularly with the young and clever, the half-educated, the would-be "smart" folk.

But it was also the honest ambition of many very worthy people, who truly desired broad-minded understanding and the avoidance of prejudice. This sapped the bulldog qualities of British pluck and persistence terribly. You can see at a glance how it would shut out a budding Nelson or a Wellington. But its most notable effect was to be seen among politicians, who were able to claim Fox for a precedent.

To believe in the superiority of the British became vulgar, a proof of narrow-mindedness. But, by that token, to enlarge upon the inferiority of the British[49] indicated a broad, tolerant spirit, and a wide outlook upon mankind and affairs. From that to the sentiment I have called anti-British was no more than a step. Many thoroughly good, honourable, benevolent people took that step unwittingly, and all unconsciously became permeated with the vicious, suicidal sentiment, while really seeking only good. Such people were saved by their natural goodness and sense from becoming actual and purposeful enemies of their country. But as "Little Englanders"—so they were called—they managed, with the best intentions, to do their country infinite harm.

But there were others, the naturally vicious and unscrupulous, the morbid, the craven, the ignorant, the self-seeking; these were the dangerous exponents of the sentiment. With them, Little Englandism progressed in this wise: "There are plenty of foreigners just as good as the British; their rule abroad is just as good as ours." Then: "There are plenty of foreigners far better than the British; their rule abroad is better than ours." Then: "Let the people of our Empire fend for themselves among other peoples; our business is to look after ourselves." Then: "We oppose the people of the Empire; we oppose British rule; we oppose the British." From that to "We befriend the enemies of the British" was less than a step. It was the position openly occupied by many, in and out of Parliament.

"We are for you, for the people; and devil take Flag, Empire, and Crown!" said these ranters; drunken upon liberties they never understood, freedom[50] they never earned, privileges they were not qualified to hold.

There were persons among them who spat upon the Flag that protected their worthless lives, and cut it down; sworn servants of the State who openly proclaimed their sympathy with the State's enemies; carefully protected, highly privileged subjects of the Crown, who impishly slashed at England's robes, to show her nakedness to England's foes.

And these were supporters, members, protégés of the Government, and readers of the Daily Gazette, upheld in all things by that organ. And I, the son of an English gentleman and clergyman, graduate of an English university, I looked to this party, the Liberal Government of England, as the leaders of reform, of progress, of social betterment. And so did the country; the British public. Errors of taste and judgment we regretted. That was how we described the most ribald outbursts of the anti-British sentiment.

It is hard to find excuse or palliation. Instinct must have told us that the demands, the programme, of such diseased creatures, could only aggravate the national ills instead of healing them. Yes, it would seem so. I can only say that comparatively few among us did see it. Perhaps disease was too general among us for the recognition of symptoms.

This then was the mental attitude with which I approached my duties as a reporter on the staff of a London daily newspaper of old standing and good progressive traditions. And my notion was that in every line written for publication, the end of social reform should be served, directly or indirectly. My[51] idea of attaining social reformation was that the people must be taught, urged, spurred into extracting further gifts from the State; that the public must be shown how to make their lives easier by getting the State to do more for them. That was as much as my education and my expansive theorizing had done for me. Assuredly I was a product of my age.

I had forgotten one thing, however, and that was the thing which Mr. Charles N. Pierce began now to drill into me, by analogy, and with a good deal more precision and directness than I had ever seen used at Rugby or Cambridge. This one thing was that the Daily Gazette was not a philanthropic organ, but a people's paper; and that the people did not want instructing but interesting.

"But," I pleaded, "surely, for their own sakes, in their own interests——"

"Damn their own sakes!"

"Well, but——"

"There's no 'but' about it. The public is an aggregation of individuals. This paper must interest the individual. The individual doesn't care a damn about the people. He cares about himself. He is very busy making money, and when he opens his paper he wants to be amused and interested; and he is not either interested or amused by any instruction as to how the people may be served. He doesn't want 'em served. He wants himself served and amused. That's your job."

I believe I had faint inclinations just then to wonder whether, after all, there might not be something[52] to be said for the bloated Tories: the opponents of progress, as I always considered them. My thoughts ran on parties, in the old-fashioned style, you see. Also I was thinking, as a journalist, of the characteristics which distinguished different newspapers.

I cordially hated Mr. Charles N. Pierce, but he really had more discernment than I had, for he said:

"Don't you worry about teaching the people to grab more from the State. They'll take fast enough; they'll take quite as much as is good for 'em, without your assistance. But, for giving, the angel Gabriel and two advertisement canvassers wouldn't make 'em give a cent more than they're obliged."

I am bound to suppose that I must have been a tolerably tiring person to have to do with during my first year in London. The reason of this was that I could never concentrate my thoughts upon intimate, personal interests, either my own or those of the people I met. My thoughts were never of persons, but always of the people; never of affairs, but always of tendencies, movements, issues, ultimate ends. Probably my crude unrest would have made me tiresome to any people. It must have been peculiarly irritating to my contemporaries at that period, who, whatever they may have lacked, assuredly possessed in a remarkable degree the faculty of concentration upon their own individual affairs, their personal part in the race for personal gain.

I remember that I talked, even to the poor, overworked servant at my lodging, rather of the prospects of her class and order than of anything more intimate or within her narrow scope. Poor Bessie! She was of the callously named tribe of lodging-house "slaveys"; and what gave me some interest in her personality, apart from the type she represented,[54] was the fact that she had come from the Vale of Blackmore, a part of Dorset which I knew very well. I even remembered, for its exceptional picturesqueness and beauty of situation, the cottage in which Bessie had passed her life until one year before my arrival at the fourth-rate Bloomsbury "apartments" house in which she now toiled for a living. There was little enough of the sap of her native valley left in Bessie's cheeks now. She had acquired the London muddiness of complexion quickly, poor child, in the semi-subterranean life she led.

I was moved to inquire as to what had led her to come to London, and gathered that she had been anxious to "see a bit o' life." Certainly she saw life, of a kind, when she entered her horrible underground kitchen of a morning, for, as a chance errand once showed me, its floor was a moving carpet of black-beetles until after the gas was lighted. In Bloomsbury, Bessie's daily work began about six o'clock—there were four stories in the house, and coals and food and water required upon every floor—and ended some seventeen hours later. Occasionally, an exacting lodger would make it eighteen hours—the number of Bessie's years in the world—but seventeen was the normal.

The trains which every day came rushing in from the country to the various railway termini of London were almost past counting. The "rural exodus," as it was called, was a sadly real movement then. Every one of them brought at least one Bessie, and one of her male counterparts, with ruddy cheeks, a tin box, and bright eyes straining to "see life." Insatiable[55] London drew them all into its maw, and, while sapping the roses from their cheeks, enslaved many of them under one of the greatest curses of that day: the fascination of the streets.