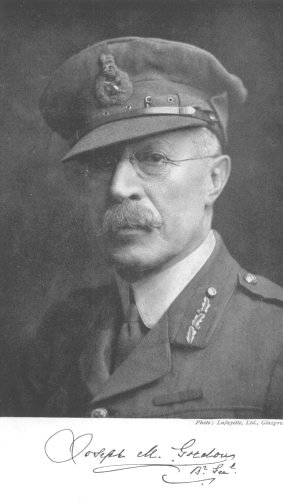

Photo: Lafayette, Ltd., Glasgow.

Project Gutenberg's The Chronicles of a Gay Gordon, by José Maria Gordon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Chronicles of a Gay Gordon Author: José Maria Gordon Release Date: November 29, 2008 [EBook #27362] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CHRONICLES OF A GAY GORDON *** Produced by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Chronicles of

a Gay Gordon By

Brig.-General J. M. Gordon, C.B.

With Eleven Half-tone Illustrations

Cassell and Company, Limited, London

New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1921

| PAGE | ||

| By Way of Introduction | 1 | |

| Genealogical Table | 7 | |

| Part I | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| 1. | My Scots-Spanish Origin | 11 |

| 2. | My Schooling | 20 |

| 3. | A Frontier Incident | 30 |

| 4. | First War Experience | 35 |

| 5. | My Meetings with King Alfonso | 42 |

| 6. | With Don Carlos Again | 46 |

| 7. | My First Engagement | 53 |

| 8. | Soldiering in Ireland | 62 |

| 9. | Unruly Times in Ireland | 71 |

| 10. | Sport in Ireland | 77 |

| 11. | A Voyage to New Zealand | 87 |

| 12. | A Maori Meeting | 98 |

| 13. | An Offer from the Governor of Tasmania | 104 |

| 14. | I Become a Newspaper Proprietor | 109 |

| 15. | A Merchant, then an Actor | 120 |

| 16. | As Policeman in Adelaide | 132 |

| Military Appointments and Promotions | 147 | |

| Part II | ||

| 1. | Soldiering in South Australia | 151 |

| 2. | Polo, Hunting and Steeplechasing | 162 |

| 3. | The Russian Scare and its Results | 175 |

| 4. | The Soudan Contingent | 185 |

| 5. | A Time of Retrenchment | 192 |

| 6. | My Vision Fulfilled | 200 |

| 7. | The Great Strikes | 209 |

| 8. | The Introduction of “Universal Service,” and Two Voyages Home | 215 |

| 9. | Military Adviser to the Australian Colonies in London | 224 |

| 10. | Off to the South African War | 232 |

| 11. | With Lord Roberts in South Africa | 238 |

| 12. | In Command of a Mounted Column | 244 |

| 13. | Some South African Reminiscences | 252 |

| Part III | ||

| 1. | Organizing the Commonwealth of Australia | 263 |

| 2. | Commandant of Victoria | 273 |

| 3. | Commandant of New South Wales | 281 |

| 4. | Lord Kitchener's Visit to Australia | 290 |

| 5. | The American Naval Visit | 302 |

| 6. | Chief of the General Staff | 308 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Brigadier-General J. M. Gordon, c.b. | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Wardhouse, Aberdeenshire | 10 |

| Kildrummy Castle, Aberdeenshire | 10 |

| Alfonso XII. | 34 |

| The Prince Imperial | 34 |

| Don Carlos | 50 |

| “Turf Tissue,” Facsimile of First Page | 84 |

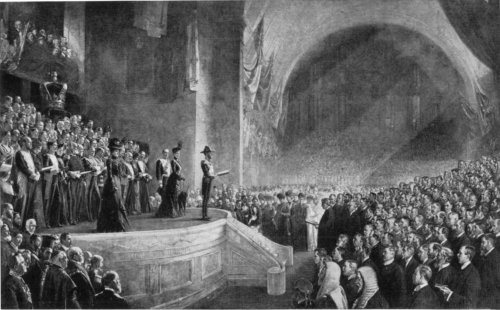

| Opening of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1901 | 120 |

| Lord Hopetoun | 150 |

| Viscount Kitchener | 220 |

| The Commonwealth Military Board, 1914 | 254 |

José Maria Jacobo Rafael Ramon Francisco Gabriel del Corazon de Jesus Gordon y Prendergast—to give the writer of this book the full name with which he was christened in Jeréz de la Frontera on March 19, 1856—belongs to an interesting, but unusual, type of the Scot abroad.

These virile venturers group themselves into four categories. Illustrating them by reference to the Gordons alone, there was the venturer, usually a soldier of fortune, who died in the country of his adoption, such as the well-known General Patrick Gordon, of Auchleuchries, Aberdeenshire (1635-1690), who, having spent thirty-nine years of faithful service to Peter the Great, died and was buried at Moscow. Or one might cite John Gordon, of Lord Byron’s Gight family, who, having helped to assassinate Wallenstein in the town of Eger, in 1634, turned himself into a Dutch Jonkheer, dying at Dantzig, and being buried at Delft.

Sometimes, especially in the case of merchants, the venturers settled down permanently in their new fatherland, as in the case of the Gordons of Coldwells, Aberdeenshire, who are now represented solely by the family of von Gordon-Coldwells, in Laskowitz. So rapid was the transformation of this family that when one of them, Colonel Fabian Gordon, of the Polish cavalry, turned up in Edinburgh in 1783, in connexion with the sale of the family heritage, he knew so little English that he had to be initiated a Freemason in Latin. To this day there is a family in Warsaw which, ignoring our principle of 2 primogeniture, calls itself the Marquises de Huntly-Gordon.

Occasionally the exiles returned home, either to succeed to the family heritage, or to rescue it from ruin with the wealth they had acquired abroad. Thus General Alexander Gordon (1669-1751) of the Russian army, the biographer of Peter the Great, came home to succeed his father as laird of Auchintoul, Banffshire, and managed by a legal mistake to hold it in face of forfeiture for Jacobitism. His line has long since died out, as soldier stock is apt to do—an ironic symbol of the death-dealing art. But the descendants of another ardent Jacobite, Robert Gordon, wine merchant, Bordeaux, who rescued the family estate of Hallhead, Aberdeenshire, from clamant creditors, still flourish. One of them became famous in the truest spirit of Gay Gordonism, in the person of Adam Lindsay Gordon, the beloved laureate of Australia.

The vineyard and Australia bring us to the fourth, and rarest, category, represented by the writer of this book, namely, the family which has not only retained its Scots heritage, but also flourishes in the land of its adoption, for Mr. Rafael Gordon is not only laird of Wardhouse, Aberdeenshire, but is a Spaniard by birth and education, and a citizen of Madrid: and this double citizenship has been shared by his uncles Pedro Carlos Gordon (1806-1857), Rector of Stonyhurst; and General J. M. Gordon, the writer of this book, who will long be remembered as the pioneer of national service in Australia.

The Gordons of Wardhouse, to whom he belongs, are descended (as the curious will find set forth in detail in the genealogical table) from a Churchman, Adam Gordon, Dean of Caithness (died 1528), younger son of the first Earl of Huntly, and they have remained staunch to the Church of Rome to this day: that indeed was one of the reasons for their sojourning aboard. The Dean’s son George (died 1575) acquired the lands of Beldorney, Aberdeenshire, which gradually became frittered away by 3 his senior descendants, the seventh laird parting with the property to the younger line in the person of Alexander Gordon, of Camdell, Banffshire, in 1703, while his sons vanished to America, where they are untraceable.

From this point the fortunes of the families increase. Alexander’s son James, IX of Beldorney, bought the ancient estate of Kildrummy in 1731, and Wardhouse came into his family through his marriage with Mary Gordon, heiress thereof. This reinforcement of his Gordon blood was one of the deciding causes of the strong Jacobitism of his son John, the tenth laird, who fought at Culloden, which stopped his half Russian wife, Margaret Smyth of Methven, the great grand-daughter of General Patrick Gordon of Auchleuchries, in the act of embroidering for Prince Charles a scarlet waistcoat, which came to the hammer at Aberdeen in 1898.

This Jacobite laird’s brothers were the first to go abroad. One of them, Gregory, appears to have entered the Dutch service; another, Charles, a priest, was educated at Ratisbon; and a third, Robert, settled at Cadiz. That was the first association of the Wardhouse Gordons with Spain, for, though Robert died without issue, he seems to have settled one of his nephews, Robert (son of his brother Cosmo, who had gone to Jamaica), and another, James Arthur Gordon (who was son of the twelfth laird), at Jeréz.

But the sense of adventure was also strong on the family at home, especially on Alexander, the eleventh laird, who was executed as a spy at Brest in 1769. A peculiarly handsome youth, who succeeded to the estates in 1760, he started life as an ensign in the 49th Foot in 1766. He narrowly escaped being run through in a brawl at Edinburgh, and, taking a hair of the dog that had nearly bitten him, he fatally pinked a butcher in the city of Cork in 1767. He escaped to La Rochelle, and ultimately got into touch with Lord Harcourt, our Ambassador in Paris. Harcourt sent the reckless lad to have a look at 4 the fortifications of Brest. He was caught in the act; Harcourt repudiated all knowledge of him; and he was executed November 24, 1769, gay to the end, and attracting the eyes of every pretty girl in the town. The guillotine which did its worst is still preserved in the arsenal at Brest, and the whole story is set forth with legal precision in the transactions of the Societé Academique de Brest.

Poor Alexander was succeeded as laird by his younger brother Charles Edward (1750-1832), who became an officer in the Northern Fencibles, and was not without his share of adventure, which curiously enough arose out of his brother’s regiment, the 49th. He married as his second wife Catherine Mercer, the daughter of James Mercer, the poet, who had been a major in that regiment. In 1797, his commanding officer, Colonel John Woodford, who had married his chief, the Duke of Gordon’s, sister, bolted at Hythe with the lady, from whom the laird of Wardhouse duly got a divorce. That did not satisfy Gordon, who thrashed his colonel with a stick in the streets of Ayr. Of course he was court-martialled, but Woodford’s uncle-in-law, Lord Adam Gordon, as Commander-in-Chief of North Britain, smoothed over the sentence of dismissal from the Fencibles by getting the angry husband appointed paymaster in the Royal Scots.

Gordon’s eldest son John David, by his first marriage (with the grand-daughter of the Earl of Kilmarnock, who was executed at the Tower with Lord Lovat), had wisely kept out of temptation amid the peaceful family vineyards at Jeréz, from which he returned in 1832 to Wardhouse. But John David’s half-brother stayed at home and became Admiral Sir James Alexander Gordon (1782-1869), who as the “last of Nelson’s Captains” roused the admiration of Tom Hughes in a fine appreciation in Macmillan’s Magazine. Although he had lost his leg in the capture of the Pomone in 1812, he could stump on foot even as an old man all the way from Westminster to Greenwich 5 Hospital, of which he was the last Governor, and where you can see his portrait to this day.

Although John David Gordon succeeded to Wardhouse, his family remained essentially Spanish, and his own tastes, as his grandson, General Gordon, points out, were coloured by the character of the Peninsula. The General himself, as his autobiography shows in every page, has had his inherited Gay Gordonism aided and abetted by his associations with Spain and with Australia. His whole career has been full of enterprising adventure, and, while intensely interested in big imperial problems, he has an inevitable sense of the colour and rhythm of life as soldier, as policeman, as sportsman, as actor, as journalist. He is, in short, a perfect example of a Gay Gordon. 6

| Alexander (Gordon), 1st Earl of Huntly (died 1470). | |||||

| Adam Gordon, Dean of Caithness (died 1528). | |||||

| George Gordon (died 1575). I of Beldorney, Aberdeenshire. |

|||||

| Alexander Gordon (alive 1602). II of Beldorney. |

|||||

| George Gordon, III of Beldorney. |

Alexander Gordon, of Killyhuntly, Badenoch. |

||||

| George Gordon, IV of Beldorney. |

James Gordon (died 1642), of Tirriesoul and Camdell. |

||||

| John Gordon (died 1694), V of Beldorney. |

Alexander Gordon, IX of Beldorney (buying it in 1703). |

||||

| John Gordon, VI of Beldorney. Frittered his fortune. Died 1698. |

James Gordon, X of Beldorney. Bought Kildrummy. Got Wardhouse by marriage. |

||||

| John Gordon, VII of Beldorney. |

John Gordon (died 1760), XI of Beldorney. |

||||

| James Gordon, Went to U.S.A. Lost sight of. |

|||||

| Alexander Maria Gordon, XII of Beldorney. Executed at Brest, 1769. |

Charles Edward Gordon (1754-1832). Sold Beldorney. Of Wardhouse & Kildrummy. |

||||

| John David Gordon. (1774-1850) Went to Spain. Inherited Wardhouse. |

Admiral Sir J. A. Gordon. One of Nelson's Captains. (1782-1869.) | ||||

| Pedro Carlos Gordon, of Wardhouse, 1806-57. |

Carlos Pedro Gordon, of Wardhouse. 1814-97. | ||||

| Juan José Gordon, of Wardhouse, 1837-66. |

|||||

| Carlos Pedro Gordon, 1844-76. d.v.p. |

José Maria Gordon, Brig.-General, Author of this book. | ||||

| Rafael Gordon, of Wardhouse. Lives in Madrid. Born 1873. | |||||

At a period in the history of Scotland, we find that a law was passed under the provisions of which every landowner who was a Catholic had either to renounce his adherence to his Church or to forfeit his landed property to the Crown. This was a severe blow to Scotsmen, and history tells that practically every Catholic laird preferred not to have his property confiscated, with the natural result that he ceased—at any rate publicly—to take part in the outward forms of the Catholic religion. Churches, which Catholic families had built and endowed, passed into the hands of other denominations. Catholic priests who—in devotion to their duty—were willing to risk their lives, had to practise their devotions in secrecy.

My great grandfather, Charles Edward Gordon (1754-1832), then quite a young man, happened to be one of those lairds who submitted to the law, preferring to remain lairds. His younger brother, James Arthur (1759-1824), who chanced to be possessed in his own right of a certain amount of hard cash, began to think seriously. It appeared to him that, if a law could be passed confiscating landed property unless the owners gave up the Catholic religion, there was no reason why another law should not be passed confiscating actual cash under similar conditions. The more he turned this over in his mind, the surer he 12 became that at any rate the passing of such a second law could not be deemed illogical. He was by no means the only one of the younger sons of Scots families who thought likewise. It seemed to him that it would be wise to leave the country—at any rate for a while.

In those days there were no Canadas, Australias and other new and beautiful countries appealing to these adventurous spirits, but there were European countries where a field was open for their enterprise. My great grand-uncle—youthful as he was—decided that the South of Spain, Andalusia, La Tierra de Santa Maria, would suit him, and he removed himself and his cash to that sunny land. It is there that the oranges flourish on the banks of the Guadalquivir. It is there that the green groves of olive trees yield their plentiful crops. It is there that the vine brings forth that rich harvest of grapes whose succulent juice becomes the nectar of the gods in the shape of sherry wine. He decided that white sherry wine offered the best commercial result and resolved to devote himself to its production. Business went well with him. It was prosperous; the wine became excellent and the drinkers many.

By this time his brother had married and the union had been blessed with two sons. When the elder was fifteen years old, it appeared to his uncle James Arthur that it would be a good thing if his brother, the laird, would send the boy to Spain, to be brought up there, with a view to his finally joining him in the business. He decided, therefore, to visit his brother in Scotland, with this object in view. He did so, but the laird did not appear to be kindly inclined to this arrangement. He was willing, however, to let his second son go to Spain, finish his education, and then take on the wine business. This was not what the uncle wanted. He wished for the elder son, the young laird, or for nobody at all. The matter fell through and the uncle returned to the Sunny South.

A couple of years later on, the laird changed his mind, 13 wrote to his brother, and offered to send his eldest son, John David (1774-1850). A short time afterwards the young laird arrived in Spain. His father, the laird, lived for many years, during which time—after the death of his uncle—his eldest son had become the head of one of the most successful sherry wine firms that existed in those days in Spain. He had married in Spain and had had a large family, who had all grown up, and had married also in that country, and it was not till he was some sixty years of age that his father, the laird, died and he succeeded to the Scots properties of Wardhouse and Kildrummy Castle.

The law with reference to the forfeiture of lands held by Catholics had become practically void, so that he duly succeeded to the estates. The old laird had driven over in his coach to the nearest Catholic place of worship and had been received back into the Church of his fathers. Afterwards he had given a great feast to his friends, at which plenty of good old port was drunk to celebrate the occasion. He drove back to his home, and on arrival at the house was found dead in the coach. So we children, when told this story, said that he had only got to Heaven by the skin of his teeth.

His successor, my grandfather, John David, died in 1850 in Spain, and my father’s elder brother, Pedro Carlos (1806-1857), became the laird and took up his residence in the old home. He broke the record in driving the mail coach from London to York without leaving the box seat. And later on, in Aberdeen, he drove his four-in-hand at full gallop into Castlehill Barracks. Anyone who knows the old gateway will appreciate the feat.

On his death in 1857, his son, my cousin, Juan José (1837-1866), succeeded to the property. He, of course, had also been brought up in Spain, and was married to a cousin, and sister of the Conde de Mirasol, but had no children. When he took up his residence as laird, most of his friends, naturally, were Spanish visitors whom he 14 amused by building a bull-fighting ring not far from the house, importing bulls from Spain and holding amateur bull-fights on Sunday afternoons. This was a sad blow indeed to the sedate Presbyterians in the neighbourhood. His life, however, was short, and, as he left no children, the properties passed to my father, Carlos Pedro (1814-1897), by entail.

It is necessary to have written this short history of the family, from my great grandfather’s time, to let you know how I came to be born in Spain, and how our branch of the family was the only one of the clan which remained Catholic in spite of the old Scots law.

I would like to tell you something now about Jeréz, the place where I was born, and where the sherry white wine comes from. Yet all the wine is not really white. There is good brown sherry, and there is just as good golden sherry, and there is Pedro Ximenez. If you haven’t tasted them, try them as soon as you get the chance. You’ll like the last two—and very much—after dinner. I am not selling any, but you’ll find plenty of firms about Mark Lane who will be quite willing to supply you if you wish.

Well, Jeréz is a town of some sixty thousand inhabitants. Don’t be afraid. This is not going to be a guidebook, for Jeréz has not a single public building worth the slightest notice, not even a church of which it can be said that it is really worth visiting compared with other cities, either from an architectural or an artistic point of view. It is wanting in the beautiful and wonderful attractions which adorn many of the Andalusian towns that surround it. In Jeréz there are no glorious edifices dating back to the occupation of the Moors (except the Alcazar—now part cinema-show). There are no royal palaces taken from the Moors by Spanish kings. There is no Seville Cathedral, no Giralda. There is no Alhambra as there is in Granada. There are only parts of the ancient walls that enclosed the old city. The Moors apparently 15 thought little of Jeréz; they evidently had not discovered the glories of sherry white wine.

Jeréz seems to have devoted all its energies to the erection of wine-cellars, the most uninteresting buildings in the world. A visitor, after a couple of days in Jeréz, would be tired of its uninteresting streets, badly kept squares and absence of any places of interest or picturesque drives. Probably he would note the presence of the stately and silent ciguenas, who make their home and build their nests upon the top of every church steeple or tower. They are not exciting, but there they have been for years, and there they are now, and it is to be presumed that there they will remain. Yet, Jeréz is a pleasant place to live in. Although there is only one decent hotel in it, there are excellent private houses, full of many comforts and works of art, though their comfort and beauty is all internal. They are mostly situated in side streets, with no attempt at any outside architectural effects.

The citizens of Jeréz are quite content with Jeréz. They love to take their ease, and have a decided objection to hustle. The womenkind dearly love big families: the bigger they are the better they like them. They are devoted to their husbands and children, and live for them. The men cannot be called ambitious, but they are perfectly satisfied with their quiet lives, and with looking after their own businesses. They love to sit in their clubs and cafés, sit either inside or at tables on the pavements in the street—and talk politics, bull-fights, and about the weather, in fact any topic which comes handy; and they are quite content, as a rule, to talk on, no matter if they are not being listened to. This habit of general talk without listeners is also common to the ladies. To be present at a re-union of ladies and listen to the babble of their sweet tongues is a pleasure which a lazy man can thoroughly enjoy.

The local Press is represented principally by three or four—mostly one-sheet—newspapers, which you can read 16 in about three minutes. Of course their all-absorbing interest, as regards sport, is centred in the bull-fights. For three months before the bull-fighting season begins—which is about Easter—people talk of nothing but bulls and matadors. The relative merits of the different studs which are to supply, not only the local corridas, but practically the tip-top ones throughout the chief cities of Spain, are discussed over and over again, while the admirers of Joselito (since killed) are as lavish in words and gestures of praise as are those of Belmonte, while, at the same time, the claims of other aspirants to championship as matadors are heard on every side.

Once the season begins—it lasts until towards the end of October—the whole of everybody’s time is, of course, mostly taken up in commenting upon the merits or demerits of each and every corrida. There does not appear to be time for much else to be talked about then; unless an election comes along, and that thoroughly rouses the people for the time being. It is of very little use for anyone to attempt to describe upon what lines elections are run in Spain. One has to be there to try and discover what principles guide them. For instance, the last time I was in Spain Parliamentary elections were to take place the very week after Easter Sunday. On that day the first bull-fight of the season was to take place at Puerto Santa Maria, a small town about ten miles from Jeréz. Of course a large number of sports, with their ladies, motored or drove over for the occasion.

There was an immense crowd at Puerto Santa Maria. In the south of Spain, especially at a bull-fight, Jack is as good as his master, and each one has to battle through the crowd as best he can. I personally was relieved of my gold watch, sovereign case and chain in the most perfect manner; so perfect that I had not the least idea when or how it was taken. I must confess I felt very sad over it; not so much over my actual loss, but, I did think it most unkind and thoughtless of my fellow townsmen to select 17 me as their victim. The next morning I reported my loss to the Mayor of Jeréz. He didn’t appear to be much concerned about it, and he informed me that he had already had some forty similar complaints of the loss of watches, pocket-books, etc., from visitors to Puerto Santa Maria from Jeréz the day previous. He had had a telegram also from the Mayor of Puerto Santa Maria to the effect that some seventy like cases had been reported to him in that town.

“So that, after all,” he said, “I don’t really see any particular reason why you should be hurt. I may tell you that you are in good company. General Primo de Rivera” (who was then Captain-General Commanding the Military District) “was with a friend when he saw a man take the latter’s pocket-book from inside his coat. He fortunately grabbed the thief before he could make off. One of the Ministers of State was successfully robbed of some thirty pounds in notes; while a friend of yours” (mentioning a business man in Jeréz who hadn’t even been to the bull-fight, but had been collecting rents at Cadiz, and was returning through Puerto Santa Maria home) “was surprised to find on his arrival there, that the large sum, which should have been in his pocket had evidently passed, somehow or other, into some other fellow’s hands.”

This, of course, somewhat cheered me up, because, after all, there is no doubt that a common affliction makes us very sympathetic. I asked him how he accounted for this wonderful display of sleight-of-hand.

“Oh,” he said, “don’t you know that the elections are on this week, and that usually, before the elections, the party in power takes the opportunity of letting out of gaol as many criminals as it dares, hoping for and counting on their votes? Of course, the responsibility falls on the heads of the police for making some effort to protect our easy-going and unsuspicious visitors at such times. The job is too big for us at the time being, with the result that these gentry make a good harvest. But yet, after all, we 18 are not really downhearted about it, because, after the elections are over, especially if the opposition party gets in, we round them all up and promptly lock them up again.”

The explanation, though quite clear, didn’t seem to me to be of much help towards getting back my goods and chattels, so I ventured to ask again whether he thought there was any chance at all of my recovering them, or of his recovering them for me. He smiled a sweet smile, and—shaking his head, I regret to say, in a negative way—answered that he thought there was not the slightest hope, as, from the description of the watch, chain, etc., which I had given him, he had no doubt that they had by that time passed through the melting pot, so that it was not even worth while to offer a reward.

The house where I was born was at that time one of the largest in the city. It is situated almost in the centre of Jeréz, and occupies a very large block of ground, for in addition to the house itself and gardens, the wine-cellars, the cooperage, stables and other accessory buildings attached to them, were all grouped round it. To-day a holy order of nuns occupies it as a convent. No longer is heard the crackling of the fires and the hammering of the iron hoops in the cooperage. No longer the teams of upstanding mules, with the music of their brass bells, are seen leaving the cellars with their load of the succulent wine. No longer is the air filled with that odour which is so well known to those whose lives are spent amidst the casks in which the wine is maturing. Instead, peace and quiet reign. Sacrificing their time to the interests of charity, the holy sisters dwell in peace.

Two recollections of some of my earliest days are somewhat vivid. I seem to remember hearing the deep sound of a bell in the streets, looking out of the window and seeing an open cart—full of dead bodies—stopping before the door of a house, from which one more dead body was added to the funeral pile. That was the year of the great 19 cholera epidemic. And again, I remember hearing bells early, very early, in the morning. We knew what that was. It was the donkey-man coming round to sell the donkeys’ milk at the front door, quite warm and frothy.

My early school days in Spain were quite uneventful. After attending a day-school at Jeréz, kept by Don José Rincon, I went into the Jesuit College at Puerto Real for a year. A new college was being built at Puerto Santa Maria, to which the school was transferred, and it has been added to since. It is now one of the best colleges in the south of Spain.

On the death of my cousin, the entailed properties—as I have said—became my father’s, and the family left Spain to take up its residence in Scotland. 20

The journey from Jeréz to Scotland must have been full of interest and excitement for my father. Our party numbered about thirty of all ages, down to a couple of babies, my sister’s children. My father found it more practicable to arrange for what was then called a family train to take us through Spain and France. We travelled during the day and got shunted at night. Sometimes we slept in the carriages; other times at hotels. In either case, as a rule, there were frequent and—for a time—hard-fought battles among us young ones of both sexes for choice of sleeping places.

At meal times there were often considerable scrambles. We all seemed to have the same tastes and we all wanted the same things. My parents (who, poor dears, had to put up with us, and the Spanish nurses and servants, who had never left their own homes before, and who, the farther we got, seemed to think that they were never going to return to them) at last came to the conclusion that any attempts at punishing us were without satisfactory results, and that appealing to our love for them (for it was no use appealing to our love for each other) and our honour paid better.

My elder sisters and brothers, who were in the party, knew English. I did not. Not a word except two, and those were “all right,” which, immediately on arrival at Dover and all the way to London, I called out to every person I met.

On reaching Charing Cross the party was to have a meal previous to starting up to Scotland. The station 21 restaurant manager was somewhat surprised when my father informed him that he wanted a table for about thirty persons, which, however, he arranged for. The Spanish nurses and women-servants were dressed after the style of their own country. They, of course, wore no hats, their hair being beautifully done with flowers at the side (which had to be provided for them whether we wished it or not), and characteristic shawls graced their shoulders. So that the little party at the table was quite an object of interest, not only to those others who were dining at the time, but also to a great many ordinary passengers who practically were blocking the entrance to the restaurant in order to obtain a glimpse of the foreigners.

All went well until the chef, with the huge sirloin of beef upon the travelling table, appeared upon the scene. No sooner did he begin to carve and the red, juicy gravy of the much under-done beef appeared, than the nurses rose in a body, dropped the babies and bolted through the door on to the platform. They thought they were going to be asked to eat raw meat. Of course, they had never seen a joint in Spain. On their leaving, we, the younger members of the family, were told to run after them and catch them if we could. So off we went, and then began such a chase through the station as I doubt if Charing Cross had ever witnessed before or has since. The station police and porters, not understanding what was going on, naturally started chasing and catching us youngsters, much to the amusement and bewilderment of those looking on. Meanwhile my father stood at the entrance of the restaurant, sad but resigned, and it was after some considerable time and after the removal of the offending joint, that the family party was again gathered together in peace and quiet, and shortly afterwards proceeded on the last stage of its journey and arrived safely at the old family home, which stands amidst some of the most beautiful woods in Scotland. It is very old, but not so old as the family itself. 22

My father decided that it would be better for me to get a little knowledge of the English language before he sent me to school, so that I might be able to look after myself when there. I was handed over to the care of the head gamekeeper, Thomas Kennedy. Dear Tom died three years ago, at a very old age; rather surprising he lived so long, as he had for years to look after me. To him, from the start, I was “Master Joseph,” and “Master Joseph” I remained until I embraced the old chap the last time I saw him before he died. It was from Tom Kennedy that I first learnt English, mixed with the broad Aberdeen-Scots, which when combined with my Spanish accent was practically a language of my own.

I wonder if Britons have any idea how difficult it is, especially for one whose native tongue is of the Latin origin, to get a thorough knowledge and grasp of their language. To my mind, the English language is not founded on any particular rules or principles. No matter how words are spelt, they have got to be pronounced just as the early Britons decided. There is no particular rule; if you want to spell properly, you pretty well have to learn to spell each word on its own. This is proved by the fact that the spelling of their own language correctly is certainly not one of the proud achievements of their own race. In the good old days before the War it may be stated without exaggeration that one of the greatest stumbling blocks in the public examinations—especially those for entrance into Woolwich and Sandhurst—was the qualification test in spelling. There must be thousands of candidates still alive who well remember receiving the foolscap blue envelopes notifying them that there was no further necessity for their presence at the examination as they had failed to qualify in spelling. As regards the pronunciation of words as you find them written, it is quite an art to hit them off right. Still, perseverance, patience and a good memory finally come to the rescue, and the result is then quite gratifying. 23

It was from Tom Kennedy that I also learnt to shoot, fish, ride and drink, for Tom always had a little flask of whisky to warm us up when we were sitting in the snow and waiting for the rabbits to bolt, or—what often took a great deal longer time—waiting for the ferrets to come out. And—last but not least—he taught me to smoke. I well remember Tom’s short black pipe and his old black twist tobacco. I shall never forget the times I had and the physical and mental agonies I endured in trying to enjoy that pipe.

So six months passed away and I was sent, with my two elder brothers, to the Oratory School in Edgware Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham. The head of the school was the celebrated Doctor, and later on Cardinal, Newman. Even to this day my recollections of that ascetic holy man are most vivid. At that time his name was a household word in religious controversy. He stood far above his contemporaries, whether they were those who agreed with or differed from his views. He was respected by all, loved by those who followed him; never hated, but somewhat feared, by those who opposed him. I remember that one of the greatest privileges to which the boys at our school at that time looked forward, was being selected to go and listen to Doctor Newman playing the violin. Five or six of us were taken to his study in the evening. In mute silence, with rapt attention, we watched the thin-featured man, whose countenance to us seemed to belong even then to a world beyond this, and we listened to what to us seemed the sweetest sounding music.

But yet there are other recollections which were not so pleasant. The head prefect was a man of very different physical qualities. Dear Father St. John Ambrose erred on the side of physical attainments. He was by no means thin or ascetic. He possessed a powerful arm, which he wielded with very considerable freedom when applying the birch in the recesses of the boot-room. I must admit that my interviews with Father St. John in the boot-room 24 were not infrequent. But, after all, the immediate effect soon passed away and the incident was forgotten. Still, to my surprise, when the school accounts were rendered at the end of the year, my father was puzzled over one item, namely, “Birches—£1 2s. 6d.” (at the rate of half a crown each)! He asked me what it meant, and I explained to him as best I could that dear Father St. John was really the responsible person in the matter, and I had no doubt my father would get a full explanation from him if he wrote. But it brought home to me the recollection of nine visits to the boot-room with that amiable and much-respected Father St. John. I have within the last few months met again, after my long absence in other countries, several of my school mates. They are all going strong and well, holding high positions in this world, and as devoted as ever to the old school at Edgbaston. One of them is now Viscount Fitzalan, Viceroy of Ireland.

When my two elder brothers left the Oratory, which I may say was a school where the boys were allowed very considerable liberty, my father must have thought, no doubt, when he remembered the twenty-two and sixpence for birches, that it would be wise to send me somewhere where the rules of the college were, in his opinion, somewhat stricter. So off I was sent, early in 1870, to dear old Beaumont College, the Jesuit school, situated in that beautiful spot on the River Thames just where the old hostelry The Bells of Ouseley still exists, at the foot of the range of hills which the glorious Burnham Beeches adorn. The original house was once the home of Warren Hastings. Four delightful years of school life followed. It was a pleasure to me to find that there was no extra charge for birches. The implement that was used to conserve discipline was not made out of the pliable birch tree, but of a very solid piece of leather with some stiffening to it—I fancy of steel—called a “ferrula.” This was applied to the palm of the hand, and not to where my old friend the birch found its billet. As the same ferrula 25 not only lasted a long time without detriment to itself, but, on the contrary, seemed rather to improve with age, the authorities were kind enough not to charge for its use.

No event of any particular interest, except perhaps being taught cricket by old John Lillywhite, with his very best top hat of those days, and battles fought on the football ground against rival colleges, occurred until the end of the third year. I happened to have come out, at the end of that year, top of my class. I had practically won most of the prizes. It was the custom of the school that the senior boys of the upper classes were permitted to study more advanced subjects than the school had actually laid down for the curriculum of that particular class for the year. These extra subjects were called “honours.” They were studied in voluntary time; the examinations therein and the marks gained in no way counted towards the result of the class examinations for the year.

These class examinations were held before the “honours” examination. A friend of mine in a higher class, who was sitting behind me in the study room, asked me if I’d like to read an English translation of “Cæsar.” I promptly said “Yes” and borrowed it, and was soon lost in its perusal, with my elbows on my desk and my head between my hands. Presently I felt a gentle tap on my shoulder. I looked up to see the prefect of studies standing by me. He told me afterwards that he had thought, from the interest I was taking in my book, that I was reading some naughty and forbidden novel, which he intended to confiscate, of course, and probably read. He was surprised to find it was an old friend, “Cæsar.” Being an English translation it was considered to be a “crib.” He asked me where I had got it. I couldn’t give away my pal, just behind me, so I said I didn’t know. “Don’t add impertinence to the fact that you’ve got a ‘crib.’ Just tell me where you did get this book,” he remarked. “I don’t want to be impertinent,” I said, 26 “but I refuse to tell you.” “Very well, then,” he said, “go straight to bed.”

I heard nothing more on the subject till a few days afterwards, at the presentation of the prizes, the breaking-up day, on which occasion the parents and friends of the scholars were invited to be present. At an interval in the performance the prizes were presented. The prefect of studies would begin to read from the printed prize list, which all the visitors were supplied with, the names of all the fortunate prize winners in succession, from the highest to the lowest. As the name of each prize winner was called he stood up, walked to the table at which the prizes were presented, received his, and, after making a polite bow, returned to his seat.

When the prefect of studies reached the class to which I belonged he called out: “Grammar, first prize. Aggregate for the year, Joseph M. Gordon.” Upon which I rose from my seat, and for a moment the applause of the audience, which was freely given to all prize winners, followed. I was on the point of moving off towards the table in question, when, as the applause ceased, the voice of the prefect of studies once more made itself clearly heard. It was only one word he said, but that word was “Forfeited.” No more. I sat down again. Then he continued: “First prize in Latin, J. M. G.” I must admit I didn’t know what to do, but I stood up all right again. The audience didn’t quite appear to understand what was going on, but the prefect of studies gave them no time to commence any further applause, for that one word, “Forfeited,” came quickly out of his mouth. Down again I sat. However, I immediately made up my mind, though, of course, not knowing how many prizes I had won, to stand up every time and sit down as soon as that old word “Forfeited” came along, which actually happened about four times.

I often wonder now how I really did look on that celebrated occasion. But I remember making up my mind 27 there and then that I would remain in that school for one year more, but no more, even if I was forced to leave the country, and to win every prize I could that next year, and make sure, as the Irishman says, that they would not be “forfeited.” So I remained another year. I was fortunate enough to win the prizes—I even won the silver medal, special prize for religion—and it was a proud day for me when I got them safely into my bag, which I did as soon as possible after the ceremony, in case someone else should come along and attempt to “forfeit” them. I had taken care to order a special cab of my own and to have my portmanteau close to the front door, so that I could get away at the very earliest opportunity to Windsor Station.

But I had not forgotten that I had made up my mind to leave the school then, so on my arrival at home I duly informed my venerable father that I had made up my mind to be a soldier, and that as I was then over 17, and as candidates for the Woolwich Academy were not admitted after reaching their eighteenth birthday, it was necessary that I should leave school at once and go to a crammer. My father made no objection at all, but he said, “As your time is so short to prepare, we will at once go back to London and get a tutor.” Considering this was the first day of my well-earned holidays, it was rather rough; but I was adamant about not returning to school, so turned southwards with my few goods and chattels, except my much-cherished prizes, which I left with the family, and proceeded to London on the next day.

So I lost my holidays, but I got my way.

My father selected a man called Wolfram, who up to that time had been master at several old-fashioned crammers’, but was anxious to start an establishment of his own, and I became his first pupil at Blackheath. As I had practically only some five months odd to prepare for the only examination that would be held before I reached my eighteenth birthday, I entered into an agreement 28 with Mr. Wolfram that I would work as hard as ever he liked, and for as many hours as he wished, from each Monday morning till each Saturday at noon, and that from that hour till Sunday night I meant to enjoy myself and have a complete rest, so as to be quite fresh to tackle the next week’s work. This compact was carried out and worked admirably, at any rate from my point of view. All went quite satisfactorily, for when the results of the examination were published I had come out twenty-second on the list out of some seventeen hundred candidates, and as there were thirty-three vacancies to be filled, I was amongst the fortunate ones. As I had found it so difficult to learn the English language, I was surprised that I practically received full marks in that subject.

There was generally an interval of six weeks from the time when the actual examination was completed till the publication of the results. The examination took place late in the year, and as my people generally went to Spain for the winter, they decided to take me with them, which pleased me immensely. We arrived back at Jeréz, which I had not seen since our departure from there in the family train some seven years before, and, considering myself quite a grown-up young man, I looked forward to a lot of fun. The journey took some time. We stayed in Paris, Bayonne, Madrid, and finally reached Jeréz. The Carlist War had then been going on for three or four years (of this more anon), and caused us much delay in that part of the journey which took us across the Pyrenees, as the railways had been destroyed.

By the time we arrived in Jeréz some five weeks had elapsed, with the result that, a very few days after our arrival, just as I was beginning to enjoy myself thoroughly, a telegram arrived from the War Office, notifying me that I had been one of the successful candidates at the recent examinations and that I was to report myself at Woolwich in ten days’ time.

This telegram arrived one evening when a masked ball 29 was being held at one of the Casinos. Being carnival time, it was the custom at these balls for the ladies to go masked, but not so the men. This was a source of much amusement to all, as the women were able to know who their partners were and chaff them at pleasure, while the men had all their time cut out to recognize the gay deceivers. At the beginning of the ball I had seen a masked lady who appeared to me just perfection. She was sylph-like; her figure was slight, of medium height, feet as perfect as Spanish women’s feet can be; a head whose shape rivalled those of Murillo’s angels, blue-black tresses adorning it, and eyes—oh! what eyes—looking at you through the openings in the mask. I lost no time in asking her to dance. I did not expect she would know who I was, but she lost no time in saying “Yes,” and round we went. I found I didn’t like to leave her, so I asked her to dance again—and again. She was sweetness itself. She always said “Yes.” It was in the middle of this that I was informed by my father of the telegram to return to Woolwich. I wished Woolwich in a very hot place. Soon came the time for the ladies to unmask. She did so, and I beheld, in front of me, a married aunt of mine! Going back to Woolwich didn’t then appear to me so hard.

I was finishing my second term at Woolwich and the Christmas holidays were close at hand.

I had, during the term, been closely following the fortunes of Don Carlos and his army in the northern provinces of Spain. Year after year he had been getting a stronger and stronger hold, and the weakness of the Republican Governments in Madrid had assisted him very materially. There was no one—had been no one—for some years to lead the then so-called Government troops to any military advantage in the field against him.

General Prim, the Warwick of Spain, had been assassinated in Madrid. The Italian Prince, Asmodeus, to whom he had offered the Crown and who for just over a year had reigned as King of Spain, was glad to make himself scarce by quietly disappearing over the borders to Portugal. A further period of Republican Government was imposed upon the country, equally as inefficient as it had been before. The star of the Carlist Cause seemed to be in the ascendant. Never—up to that date—had Don Carlos’s army been so numerous or better equipped. The Carlist factories were turning out their own guns and munitions. They held excellent positions from which to strike southwards towards Madrid, and on which to fall back for protection if necessary.

Everything pointed to a successful issue of their enterprise, backed up as it was by the Church of Rome, and tired and worn out as the country was by successive revolutions, mutinies of troops, unstable Governments and hopeless bankruptcy. So I thought my chance had come 31 to see some fighting of real ding-dong nature by paying Don Carlos a personal visit. Not that I thought my military qualifications, attained by a few months’ residence at the “Shop” as a cadet, in any way qualified me to be of any real military value to Don Carlos, but rather because I thought that Don Carlos’s experience, after several years of the waging of war, would be of some considerable value to myself. Thus it came about that I decided to spend the forthcoming Christmas holidays attached to his army, being satisfied that I should be welcome, for I had a first cousin and two other relations who had been A.D.C.’s to Don Carlos from the beginning of the campaign.

I duly made application to our Governor at the “Shop,” General Sir Lintorn Simmons, R.E., for permission to proceed to Spain during the holidays and be accredited as an English officer. This, of course, was refused, as I was not an officer, only a cadet, and fairly young at that. But I was told that if I chose to proceed to Spain on my own responsibility I was at liberty to do so, provided I returned to Woolwich on the date at which the new term began.

I have my doubts whether any young fellow of eighteen ever felt so elated, so important, so contented as I did on my journey from London to Bayonne. As I had my British passport I did not feel in the least concerned as to not being allowed to cross the frontier, which happened to be at the time in the hands of the Government troops, into Spain. The railways in the north of Spain had practically ceased to exist. The journey was made along the old roads in every kind of coach that had been on the road previous to the construction of the railways across the Pyrenees. One particular coach I travelled in was practically a box on four wheels, with a very narrow seat running on each side, and very low in the roof. Going downhill the horses—such as they were—went as fast as they could, and every time we struck a hole in the road down went the box, up we banged our heads against the 32 roof, and then we collapsed quietly on to the floor, beautifully mixed up.

This little affair happened often, and it was made especially interesting by the fact that we had two apparently youthful lady travellers. They had started with us from Bayonne. They were very quietly dressed, and—so far as we could see, through the extremely thick veils which they wore about their heads, and from occasional ringlets of hair peeping out here and there—they were quite the type of the dark Spanish beauties. They had chosen the two innermost seats inside the coach, and I happened to occupy the seat on one side next to one of them.

In those days cigarette-smoking by ladies was quite uncommon, much less was the smell of a strong cigar acceptable to them. However, the journey from Bayonne to the border was somewhat long. I wanted a smoke. I had a cigar. I politely asked the ladies whether they objected to my lighting up. They did not speak, but they—as it seemed to me—gracefully nodded “Yes.” So I lit up, and presently I began to notice that the one next to me, towards whose face the smoke sometimes drifted, seemed to like it very much, and, I would almost have said that she was trying to sniff some of it herself. A little later on, when we came to an unusually big rut in the road, we all went up as usual against the roof, and all came down again, missing the narrow seat. Extracting ourselves from our awkward positions, I came across a foot which certainly seemed to me not to belong to a lady, but, as it happened, it was a foot belonging to one of the ladies. I began to think but said nothing, and I also began to watch and look. Their hands had woollen gloves on, very thick, so that it was difficult to say what the hand was like inside. I may say that the three other passengers were Frenchmen, two of whom were very young and apparently unable to speak Spanish. As we were nearing the frontier I spoke to the ladies on some trivial matter, and mentioned the fact that I was going into Spain and that I hoped to 33 see something of the fighting; that I was an Englishman, but that I had been born in Spain and that I knew personally Don Carlos and several of his officers, as well as many officers belonging to the Government troops. I noticed them interchanging looks as I told them my story, and presently we pulled up by the roadside at a little inn on the French side of the frontier. We were to wait there for some little time while the horses were changed, and we were glad to get out and stretch our limbs after our bumping experiences.

I watched them getting out of the coach, and it was quite evident to me that, considering they were ladies, they were blessed, each of them, with a very useful, handsome pair of understandings. I went inside the little inn, which boasted only, as far as I could see, one little room besides the big kitchen, and was having some tea when one of the ladies came into the room and, to my surprise, closed the door, put her back against it and said, “Will you promise not to give us away if we confide in you?” I said, “Certainly. I am not old enough yet to have given any ladies away, and I am not going to begin just now; so tell me anything you like. If I can help you I will.”

For an answer her woollen gloves were whipped off, her hands, which were a very healthy brown colour, went up to her face, and—quite in a very awkward manner for a lady—she battled with her veil. Up it went, finally. A very, very clean-shaved face, but showing that very dark complexion which many black-bearded men have, no matter how very, very cleanly they shave, was looking right at me. There was no need for much further explanation. He told me that she and her companion were two Carlist officers who were hoping to join their regiments but had to cross the belt of the Government troops to do so, and had decided to disguise themselves as women and take the risk. I suggested that the other lady should be asked to come in and hold a council of war. I told them that I myself was going to Don Carlos’s headquarters as 34 soon as I got the opportunity, and that the only trouble I foresaw was in dealing with the sentries and the guard at the frontier. Once past that it would be easy enough for them to get away unmolested. My next question was, “How much money have you ladies got? We all know the Spanish sentries, and I think their hands are always ready to receive some little douceur. There is but little luggage to be examined by them. If you two ladies remain inside the coach and be careful to cover your feet up, I’ll keep them employed as far as possible in overhauling the luggage. I’ll square, as far as I can, the driver not to leave his box, but to be ready to start as quick as I tell him to, and, by generous application of douceurs, I’ll try to so interest the guards that they will have but little time to make any inquiries as regards your two selves.” All went well. We got to the frontier, the commandant of the guard and the sentries were so taken up in counting the tips I gave them and dividing them equitably amongst themselves that they neither examined the luggage nor did they even look inside the coach. I hustled the three Frenchmen into the coach, after telling them that it was very, very important that we should proceed at once, shouted to the driver, “Anda, amigo—corre!” with the result that the horses jumped off at a bound, and I just managed to throw myself into the inside of the coach, very nearly reaching the ample laps of my two delicate lady friends.

The next day we arrived without incident at a small village, somewhat north of Elisondo, which village was then in the hands of the Carlists. Here my two lady friends changed their sex, and we passed a very pleasant evening with the Mayor of the town, who had been able for some months previously, to be a Republican of the most determined character while the town was occupied by the Government troops, and to be a Carlist, second to none in his enthusiasm for the Carlist cause, as soon as the Carlist troops took possession of it again.

I arrived at the headquarters of the Carlist Army, the stronghold of Estella, about the middle of January, 1875. Estella had been the seat of Government of the first Don Carlos in the earlier war.

On December 31, 1874, young Alfonso had been proclaimed King of Spain. His accession to the throne had taken place earlier than the Civil Government, then in power in Madrid, had intended. Its members were Royalists, and were preparing the way for the restoration of Alfonso to the throne, but were not anxious to hasten it until their plans were matured. Sagasta was their Civil Head; Bodega, Minister for War; Primo de Rivera, Captain-General of New Castile, all powerful with the soldiers then under his command. The man who forced their hands was General Martinez Campos, a junior general. A mile outside a place called Murviedro he harangued 2,000 officers and soldiers, then camped there, on December 24, 1874. The officers were already known to him as favourable to Alfonso. They applauded him enthusiastically, the men followed, and they there and then swore “to defend with the last drop of their blood the flag raised in face of the misfortunes of their country as a happy omen of redemption, peace and happiness.” (December 24, 1874.) The fat was in the fire. Those who were delaying the Pronunciamento had to give it their support, however much they considered it inexpedient. The Commander-in-Chief of the Army in the Field, Jovellar, and his Chief of the Staff, Arcaguarra, were also Royalists at heart. Jovellar hastened to instruct his 36 generals openly to acknowledge Alfonso as their King, as King of Spain.

One general, the Marquis del Castillo, was then commanding the Government troops in Valencia. He was a loyalist too, but he did not think it right to assist with the troops under his command in effecting a change of Government, practically to take part in a rebellion while facing the common enemy. Castillo prepared to resist the Pronunciamento and march against the troops at Murviedro. Jovellar frustrated his intentions and marched at the head of his troops against him. Castillo’s officers and soldiers fraternized with Jovellar’s troops, and Castillo was ordered back to Madrid.

Alfonso XII reached Barcelona January 9, 1875. Official functions, his entry into Madrid, the issuing of Proclamations, fully engaged his time. But he was most anxious to proceed north and place himself at the head of his troops to whom he owed so much. Amongst the Proclamations was one practically offering the Carlists complete amnesty and the confirmation of the local privileges of the Provinces where the Carlist cause was most in favour. Don Carlos rejected the offer with disdain. Alfonso then, early in February, 1875, proceeded north to the River Ebro, reviewed some 40,000 of his best troops and joined General Morriones.

Such was the political situation. The military situation was as follows: Don Carlos’s Army numbered some 30,000 men. The provinces from which they had been fed were becoming exhausted. On the other hand, Alfonso’s troops numbered about twice their strength, and their moral had been improved by the success of their Pronunciamento and the return of some of the best leaders to the command of groups of the Army. The Carlist mobile forces had been much weakened in numbers by the blockade of the old fortress of Pamplona, which had lasted a long time.

Alfonso, with the Army of General Morriones, marched 37 to the relief of Pamplona and successfully raised the blockade, February 6, 1875, forcing the Carlists backwards. The situation became most critical for the Carlists, as another Royalist Army, under General Laserta, was on the move to join Morriones in an attack on Estella. If this plan had succeeded it is probable that the war would have been finished there and then. Don Carlos, however, succeeded in inflicting a severe defeat on Laserta and completely upset the intentions of the Royalists. Alfonso returned to Madrid, having been only a fortnight with the Army. His presence was a source of embarrassment to the High Command.

I was able to be present at the retreat of the Carlist troops from the blockade of Pamplona, as well as the capture of Puente de Reina by Morriones, the defeat of Laserta, and other guerilla engagements. I had become so interested in the work in hand that I had over-stayed my leave by a very considerable period, and would either have to return at once and take my gruelling at the hands of our Governor at the “Shop,” or make up my mind to join the Carlists and become a soldier of fortune. I thought it out as best I could, and it seemed to me then that the experiences I had gained—of perhaps the most varied fighting that any similar campaign has supplied—might be considered of more advantage to my career as a soldier than a couple of extra months of mathematics, science and lectures at Woolwich, and that if I promptly returned and surrendered myself to the authorities I might perhaps be pardoned. So I collected my few goods and chattels, said good-bye to Don Carlos and my friends, and returned home by no means feeling so elated, happy and contented as I did on my outward journey.

On arriving in London I duly wrote to the Adjutant at Woolwich, informing him that I had arrived safely in England after my campaign in the North of Spain, and that the next day, which happened to be Tuesday, I would deliver myself as a prisoner, absent without leave, at the 38 Guard Room at 12 o’clock noon. This I did, and I was met by the gallant Adjutant, and a guard, and was promptly put under arrest. Some of my contemporaries may still remember the occasion of my return. Numerous had been the rumours about my doings. At times I was reported dead. At other times I was rapidly being promoted in the Carlist Army. I had also been taken prisoner by the Government troops, tried by court-martial, and sentenced to durance vile in the deep dungeons of some ancient fortress. Their sympathies for me had risen to enthusiasm or were lowered to zero, according to the rumours of the day, but they were all glad to see me back. Still they pitied me indeed, as they wondered amongst themselves what my fate was now to be.

The preliminary investigation into my disorderly conduct took place before the Colonel Commanding, and I was then remanded to be dealt with by the Governor. I was duly marched in to his august presence, under armed escort, and, after having had the charge of being absent without leave duly read to me, I was called upon by him to make any statement I wished with reference to my conduct.

As I have already said, I had learnt English only after I was thirteen years of age, and on joining at Woolwich I still spoke English with a considerable foreign accent, which perhaps had become more marked during my recent protracted visit to Don Carlos and his Army. I have always noticed that when one gets excited a foreign accent becomes more accentuated. It undoubtedly did on this occasion, especially when I endeavoured to give a description of some of the fighting in the course of my statement. I even ventured to ask that I might be given a piece of paper and a pencil to jot down the dispositions of the opposing forces which took part in one of our biggest fights. I had barely made the request when the Governor stopped me and said: “Do you mean to tell me that you have picked up a foreign accent like this during the short 39 time that you have been in Spain?” “Oh, no, sir, I have always had it. I mean, I’ve had it ever since I learnt English.”

Sir Lintorn looked serious when I said this. A smile flitted across the countenances of the Colonel Commanding and the Adjutant—and even of the escort. “When did you learn English—and where? And where do you come from?” “I learnt English,” I answered, “about five years ago at the Oratory at Edgbaston, Birmingham, and I spoke Spanish before that.” “What countryman are you, then?” “Well,” I said, “my father is Scotch, my mother is Irish, and I was born in Spain. I’m not quite sure what I am.”

This time the smile turned into suppressed laughter. General Simmons looked at me for a short instant. Then he, too, smiled and said, “Well, I am going to let you off. You must take your chance of getting through your examination, considering the time you’ve lost. I let you off because I feel that the experiences you have gained may be of good value to you.” Turning to the Adjutant he said, “March the prisoner out and release him. Tear up his crime sheet.”

I forget now the wonderful escapes from tight corners in the field, the glowing descriptions of the valour of the Carlists, the number of times that Staff Officers had asked for my advice as to the conduct of the war, and the many other extraordinary tarradiddles that I poured, night after night, into the willing ears of my astounded and bewildered fellow cadets. One curiosity, however, may be mentioned. Amongst the most energetic of Don Carlos’s officers was his sister, Princess Mercedes, who personally commanded a cavalry regiment for some considerable time during the war.

The rest of my stay at Woolwich was uneventful. I did manage to get through the examination at the end of the term, but this was chiefly owing to the generous help of those cadets in my term who personally coached me in 40 such subjects as I had missed. A year afterwards, at the end of the fourth term, the Royal Regiment of Artillery was short of officers. The numbers of cadets in the A Division leaving the “Shop” was not sufficient to fill the vacancies. Some eight extra commissions were offered to the fourth term cadets who were willing to forgo their opportunities of qualifying for the Royal Engineers by remaining for another term. A gunner was good enough for me, and I was duly gazetted to the regiment.

I am just here reminded of an incident which took place on the day on which His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge attended the Academy to bestow the commissions and present the prizes on the breaking-up day. The Prince Imperial of France had been a cadet with us. On that particular occasion he was presented with the prize for equitation, of which he was very proud. He was a good sport. He was very keen on fencing, but he had been taught on the French lines, and, as the French system was different from our English system he did not enter his name for the fencing prize. But he said that he would like to have a go with the foils against the winner of the prize. I had happened to win it. The little encounter was arranged as an interlude in the athletic exhibition forming part of the day’s function. We masked. We met. I was just starting to do the ceremonial fencing salute which generally preceded the actual hostilities, when he came to the engage, lunged, and had it not been for the button of the enemy’s foil and my leather jacket, there would have been short shrift for J. M. G. He quickly called “One to me.” Then I quickly lunged, got home, and called out, “One to me.” Next instant we both lunged again, with equal results. We would have finished each other’s earthly career if there had been no buttons and no leather jackets. The referee sharply called “Dead heat. All over.” We shook hands in the usual amicable way and had a good laugh over the bout. 41

We parted on that occasion on our different roads in life—he shortly afterwards to meet his untimely end in the wilds of South Africa. Later on I remember attending his funeral. His death was indeed a sad blow to his mother, the Empress Eugénie, whose hopes had been centred on him her only son. I well remember, as a youngster, when visiting Madrid with my mother, looking forward to be taken to see her mother, the Countess of Montijo, who, with my grandmother, had been lady-in-waiting to Her Majesty Queen Christina.

Just lately I was at Jeréz again, when the ex-Empress Eugénie motored from Gibraltar to Seville, accompanied by her nephew the Duke of Alba. They stopped for luncheon at the Hotel Cisnes. I had the honour of a conversation with her. Her brightness and her memory were quite unimpaired though in her ninety-fifth year. She recollected the incident of the fencing bout at which she had been present. Now she has passed away to her rest.

Gazetted Lieutenant, Royal Artillery, March, 1876, I was ordered to join at the Royal Artillery Barracks, Woolwich, in April. 42

While the exiled Prince Imperial was at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich another exiled Royal Prince, in the person of Alfonso XII, father of the present King and the successful claimant in the great Carlist struggle, who came to his own in 1875, was undergoing training in the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. I came to know him intimately during his stay in England owing to the fact that the Count of Mirasol, whose sister married my eldest brother, was his tutor and factotum.

I well remember what pleasure it was to me every time Mirasol asked me to spend the week-end with Alfonso in town. It was winter time, and one of our favourite resorts was Maskelyne and Cook’s. We were never tired of watching their wonderful tricks. One afternoon we went to their theatre, the Hall of Mysteries, with two young nephews of mine who had just come from Spain and did not know English. One of the feats we saw was that of a man standing on a platform leading from the stage to the back of the audience, and then rising when the lights were lowered towards the roof of the building. The audience were warned to keep quiet and still while this wonderful act took place. One of my young nephews, who had not understood the warning given, happened to be next the platform. When the lights were lowered and the man started on his aerial flight, my young nephew took my walking stick and struck the uprising figure. The lights went up and we were requested to leave the theatre. Alfonso protested, but Mirasol assured him that discretion was the best part of valour. 43

On the evening of December 30, I think, I was invited to dinner by Mirasol at Brown’s Hotel, Dover Street. I was surprised that the dinner-hour had been fixed at a quarter-past six p.m. I wondered where we were going afterwards. Was it a theatre, or was it one of those quiet but most enjoyable little dinners and dances which Alfonso’s friends arranged for him? In addition to the large number of wealthy Spaniards then living in London, many families whose sympathies had bound them to the monarchical cause had left Spain during the Republican régime and made London their home. I noticed when I arrived that Alfonso and Mirasol were in ordinary day dress. I again wondered how we were to finish up the evening.

It was at dinner that Mirasol said to me, “José Maria, you are in the presence of the King of Spain.” I rose and bowed to His Majesty. He stood up and, taking both my hands in his, said, “At last I have attained my throne. To-night I leave for Paris. My country wants me for its king. You, José Maria, my friend, are the first in England to be told the good news. I want you, my friend, to wish me ‘todas felicidades’ (all happiness). We leave to-night. To-morrow my Army will proclaim me King of Spain. Welcomed by the Army and the Civil Government, I will be received at Barcelona with the acclamations of my subjects, and thence to my capital, Madrid. To the members of your mother’s family who, during the sad years of my exile have so zealously devoted themselves to my cause, I owe a deep debt of gratitude which I shall never forget.”

I then told Alfonso that I had leave to go to Spain, my wish being to see the fighting and to be in it; but that, quite in ignorance of the fact that his succession to the throne was imminent, I had arranged to attach myself to Don Carlos, as my cousins on my father’s side were with him. “Go, by all means,” said Alfonso; “I know well that your father’s family have been zealous supporters 44 of Don Carlos’s cause. My country has been rent for years by the devotion of our people whose sympathies have been divided between Don Carlos and myself. Please God I may be able to unite them for the future welfare of Spain. My first act as King of Spain will be to offer a complete amnesty to all and one who cease their enmity to myself and my Government and are willing to assist me in establishing law and order and ensuring the happiness and prosperity of my countrymen, of our glorious Spain. Go to Carlos, certainly, but in case you wish to leave him and get some experience of our loyalist soldiers, Mirasol will give you a letter now, which I will sign, and which will make you a welcome guest of any of my generals. Good-bye. Come and see me, if you have time, in Spain.”

Mirasol gave me the letter and, with it in my pocket, I felt more than satisfied that I had the chance of my life, a chance given to few men to be a welcome guest in the field of battle of two opponents, one a king, the other one who, for long years, had striven hard to be a king.

The carriage was waiting and we left Brown’s Hotel for Charing Cross Station. Next day, December 31, 1874, Alfonso was proclaimed King of Spain. He landed at Barcelona on January 9, 1875.

For just a moment let me tell of Mirasol’s sad end. For some time after Alfonso’s restoration to the throne mutinies of soldiers and civil disturbances occurred throughout Spain. One of these mutinies took place in the Artillery Barracks in Madrid. Mirasol was an Artillery officer, and after the Coronation of Alfonso had again taken up his regimental duties. He received a message at his home one morning that the men at the barracks had mutinied. He started at once to the barracks, telling his wife not to be anxious and by no means to leave the house till his return. As he was approaching the barracks he was met by some of the mutineers. They stabbed him to death on the pavement. His wife had not 45 paid heed to his request. She waited for a little time, and could not resist her desire to follow him in spite of his advice. As she was nearing the entrance to the barracks she met a crowd. She asked what was happening. A bystander said, “The mutineers have just murdered the Count of Mirasol. There he lies.” Poor woman. Sad world, indeed. 46

When I left Don Carlos in Spain after my visit to his Army I little thought that we were again to come into close touch and I was to spend much time with him and my cousin, Pepe Ponce de Leon, his A.D.C. It was a few days after I had received my commission and I was enjoying my leave previous to joining up at Woolwich in April (1876), when (I think it was the morning of March 8) I received a telegram from the War Office asking me to call there as soon as possible.

As, for the next four or five months, I was a great deal with Don Carlos in London and in France, I think it will be of interest to my readers if I describe shortly the validity, or otherwise, of his claim to the throne of Spain. Ferdinand VII of Spain, when an old man, married in 1830 Dona Maria Cristina, a young girl, sister of Dona Carlota, wife of his brother, Francisco de Paula. Cristina was not only young but also clever and beautiful. Contrary to expectation, it was announced later on that the Queen was about to become a mother. If the expected child was a son, then of course that son would be the heir to the throne. If it was a daughter, the question of her right to the succession would arise! In 1713 Philip V had applied the Salic Law; Carlos IV had repealed it in 1789. Now Don Carlos, brother of Ferdinand VII, had been born in 1788 and therefore claimed the succession in case his brother Ferdinand died without male issue. On October 10, 1830, Cristina gave birth to a girl, the Infanta Isabella. In March of that same year Ferdinand had made a will bequeathing the Crown of Spain to the child about to be born, whether male or female. 47

Ferdinand, who had become very ill, fell again under the influence of the clerics and of the supporters of his brother, Don Carlos, who induced him to revoke his will. However, to the surprise of everybody, Ferdinand recovered, and under the direct influence of Dona Carlota, Cristina’s sister, he tore up the document and, before a representative assembly of his Ministers of State, swore that he had repealed his will only under direct pressure while sick to death. Ferdinand’s illness had become so severe that Cristina was appointed Regent, and acted as such till January 4, 1833, when Ferdinand recovered. On June 20, 1833, Ferdinand, still most anxious to secure the throne to his offspring, whether male or female, convened a Cortes at Madrid which confirmed his wishes. On September 29 he died. Cristina became Regent and the Infanta Isabella Queen of Spain. Don Carlos refused to recognize Isabella’s rights to the throne. The enactments of Philip V and Ferdinand—no matter by whom made—could not affect his own divine rights, as all such enactments had been given effect to after he himself was born.

I must admit that it appears to be most difficult to convince the direct descendants of Don Carlos that they have not been deprived of their just rights. My readers are at full liberty to decide this difficult problem. This does not matter to us, it is an interesting episode in the history of one of the oldest reigning families, the Bourbons. The first formidable rising took place at about November 14, 1833. Estella became the seat of Government of Don Carlos during the war, which lasted till the middle of the year 1840. Our Don Carlos was the son of his grandfather’s third son, Juan.

| Carlos | = | Francesca de Avis (daughter of Joan VI of Portugal) | |||||||

| Carlos Luis | Fernando | Juan | |||||||

| (died on same day. No issue) | Carlos Maria | ||||||||

| Jaime | |||||||||