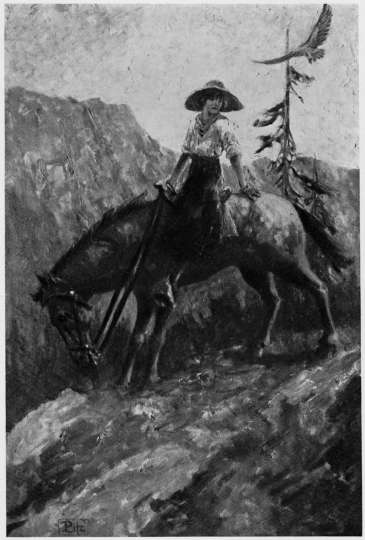

THE PONY PUT HER TWO FOREFEET OVER THE EDGE OF THE DESCENT.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Across the Mesa, by Jarvis Hall This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Across the Mesa Author: Jarvis Hall Illustrator: Henry Pitz Release Date: October 21, 2008 [EBook #26984] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ACROSS THE MESA *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE PONY PUT HER TWO FOREFEET OVER THE EDGE OF THE DESCENT.

Across the Mesa

By

JARVIS HALL

Author of “Through Mocking Bird Gap”

Frontispiece by

HENRY PITZ

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

1922

COPYRIGHT

1922 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

Across the Mesa

Made in the U. S. A.

Contents

| I | Why Not? | 7 |

| II | Athens | 14 |

| III | En Route | 30 |

| IV | Juan Pachuca | 48 |

| V | Polly Arrives | 65 |

| VI | Local Activities | 80 |

| VII | Miss Chicago | 97 |

| VIII | The Prisoner | 109 |

| IX | At Liberty | 126 |

| X | The Discovery | 142 |

| XI | Casa Grande | 159 |

| XII | A Night Ride | 179 |

| XIII | The Wagon | 188 |

| XIV | The Trail | 208 |

| XV | Angel | 222 |

| XVI | Tom Does a Marathon | 238 |

| XVII | At Soria’s | 251 |

| XVIII | Back to Athens | 276 |

| XIX | Polly Makes a New Acquaintance | 283 |

| XX | Treasure Trove | 303 |

Across the Mesa

Polly Street drove her little electric down Michigan Boulevard, with bitterness in her heart.

It was a cold wet day in the early spring of 1920, and Chicago was doing her best to show her utter indifference to anyone’s opinion as to what spring weather ought to be. It was the sort of day when, if you had any ambition left after a dreary winter, you began to plot desperate things.

Polly hated driving the electric—her soul yearned for a gas car. Mrs. Street, however, did not like a gas car without a man to drive it; the son of the family was in Athens, Mexico, at a coal mine; and Mr. Street, Sr., considered that his income did not run to a chauffeur at the present scale of wage. Therefore, Polly tried to forget her prejudice and to imagine that the neat little car was a real machine.

Second among her grievances was the fact that this was Bob’s wedding day and she, his adored and adoring sister, was not with him. Bob had been engaged for some months to a girl in Douglas, Arizona. The date of the wedding had been set twice and each time 8 difficulties in Mexico had made it seem unwise either that Bob should leave Athens, where he held the position of superintendent of one of Fiske, Doane & Co.’s mines, or that the bride should venture into the disturbed region.

This time they expected, as Bob wrote, to “pull it off on schedule.” Polly had hoped either to go to Douglas for the wedding or to have the bride and groom in Chicago; but Father had been unable to get away, Mother hadn’t been well, and the trip had been given up. Then the young couple planned to go immediately to Athens without the formality of a honeymoon. To quote Bob again: “People go on honeymoons to be lonesome, and if anybody can find a better place to be lonesome in than Athens, let him trot it out.”

The third grievance held an element of publicity particularly galling to a young lady who was known to her friends not only as a daring horsewoman, a crack swimmer and a golf champion, but as a bit of a belle besides. She and Joyce Henderson had agreed a week ago to break their engagement. The engagement had been a mistake—both young people admitted it frankly to each other. The irritating part of it was that Joyce was admitting it to the world.

Instead of taking the matter seriously and considering himself, outwardly at least, as the victim of an unhappy love affair, Joyce had escorted another girl, who shall be nameless, for she does not enter this story except as an element of conflict, to the Mandarin Ball. Now the Mandarin Ball is not the frivolous affair that 9 its name suggests, but a perennial of deep importance, a function to which young men are in the habit of taking their wives, their fiancées, or the girls they rather hope may be their fiancées. It is one of the few social affairs left of the old order.

Thus you can see that it was a pointed action on Joyce’s part; an indication that he regarded himself as a free man, and after the habit of free men was about to put on new chains. It was humiliating, to say the least. During the war the engagement had seemed quite natural, quite a part of things. All the young people were engaged—except those who were married.

“That, at least, I had sense enough not to do!” raged Polly, as she narrowly missed a pedestrian’s heel.

It is hard for older people to realize how important it is at twenty-three to be doing exactly what others are doing; the absolute anguish of being the only man in the A. E. F. without a wife or sweetheart, or the only girl at home without a soldier husband or lover. A bit of such understanding would make clear not only the number of divorces and broken engagements which resulted from the war and had their share in the production of the unrest of the times, but would also elucidate a good many other happenings to youth.

So much for Polly Street and Joyce Henderson, who were fortunate enough to find out before marriage that they were unsuited for each other. Polly, however, preferred to look upon the dark side. Joyce had behaved like a cad.

“And the worst of it is that everybody will say it serves me right,” she went on to herself, “just because 10 I’ve flirted a bit here and there. It’s not my fault if people never turn out as I expect them to. I guess I’m like Grandfather Street was in his religion. He thought the Baptists were wonderful until he joined them and then the Presbyterians looked more interesting to him. After he’d been with them a while he couldn’t see how anybody could be a Presbyterian, so he joined the Unitarians. People thought he was a turncoat, but he wasn’t—he was just a sort of religious Mormon. One church wasn’t enough for him.

“Oh dear, I wish I’d gone to Douglas alone! Bob would understand. I believe I’ll go to Athens. Why not? It’s safe enough or Emma’s parents wouldn’t let her go. Of course it’s a bit soon after their wedding, but I’ll be tactful and keep out of their way.”

The light of determination was in Polly’s dark eyes. They were big lovely eyes that looked at you wistfully from under arched brows. They seldom laughed or twinkled and the nose that kept them company was equally sedate, being purely aquiline, but a mouth with dimpled corners upset the scheme entirely, while ripples of golden brown hair completed the picture of a healthy, happy youngster—not radiantly beautiful but what people like to call “winsome,” which is after all as good a word as most.

She parked the electric on the Lake Front and crossed the Boulevard. The policeman on the crossing nodded to her and she smiled at him. Polly had what her father called a “stand in” with the force. It was unnecessary, for she was a good driver when her feelings were not agitated, but there was something about 11 policemen that appealed to her. They were so big and pink and forceful that you felt rather important when they nodded to you—a bit after the fashion of a man who is recognized by the head waiter.

She was still smiling when she entered the building in which was located a club to which she belonged. It was a serious-minded club of clever women, and most people had been amused when Polly Street joined it. Nobody expected serious-minded things of Polly, though here and there someone was willing to admit that she was “clever enough in her way.”

Finding the writing-room empty, Polly sat down to write a letter. Several times in her career she had decided upon courses of procedure which had seemed to her eminently practical, only to be talked out of them by her family. This time she would take no such chances. She would write to Bob, and Bob, being much like her, understood her—as well at any rate as any brother understands a sister. Then she would go over to the bank and get some money on her Liberty Bonds. Polly was as usual broke, Mr. Street being a man who provided credit liberally for his family but who had learned from experience that money was safer in his own hands.

A trip to the ticket office to make reservations and the thing would be done. A vague remembrance that Mexico was a place which demanded passports upon entrance came into her mind but was dismissed airily. Father would attend to that. The fact that Mexico was a troublous region where an American girl might meet with a good many disagreeable adventures was as 12 airily dismissed. All that anyone needed to go anywhere, according to Polly’s simple code, was common sense and money. The first she had, the second she intended to get, so why worry?

As she sat at the writing-table a slightly martial air came over Polly. Bob must be made to understand the situation. Because a man took it upon himself to dwell in or on a coal mine, Polly was never quite sure of the phrase, in the remote Southwest, he was not absolved from all family duties. The fact that he had married the handsomest girl in Arizona and was indulging in a honeymoon need not prevent an oppressed sister from demanding sympathy. She wrote rapidly.

“Dear Bob:

“I know it’s awfully nervy of me to drop in on you and Emma right at the beginning of your honeymoon, but I am coming just the same. Joyce Henderson has behaved atrociously to me. I’ll explain when I see you. You needn’t show this to Emma; you can read her scraps of it.”

Polly paused. A mental picture of Emma, demure and pretty, came before her. Bob Street was a lucky man to have found a girl like Emma. A dreamy look succeeded the martial one. Visions of a flower-bedecked hacienda—was that what they called them, it didn’t sound exactly right—surrounded by peons dozing in the sun succeeded the dimpled vision of Emma. Polly drew her ideas of Mexico entirely from the movies, Bob’s short letters being quite lacking in atmosphere. She saw herself leaning over a balcony, 13 listening to the strains of a mandolin, played by a tall, slim youth, who resembled a composite photograph of several of her favorite movie idols. Poor Joyce Henderson, how unimportant he seemed by the side of that radiant vision! Polly scribbled furiously.

In the northern part of Mexico, in the state of Sonora, lies the little mining town of Athens, ironically named by someone whose sense of beauty was offended by the yellow stretches of desert sand, broken by hills, dotted here and there by cactus and mesquite, and frowned upon by gaunt and angular mountains.

Athens, when the mining industry was running full time, was a busy if not a beautiful spot. Its row of shacks housed workers, male and a few female, to a generous number, while its busy little train of cars—for Athens owned a tiny spur of railroad connecting with the neighboring town of Conejo and operated for reasons germane to the coal industry—gave it, if you were very temperamental, something of the air of a metropolis seen through a diminishing glass.

The plant and offices which boasted two stories, and the general merchandise store which was long and rambling, were larger than the shacks; otherwise Athens was a true democracy. The company house in which the superintendent, the manager and the chief engineer “bached” only differed from the others by an added cleanliness, for Mrs. Van Zandt, the energetic woman who ran the boarding-house, gave an eye to its welfare. The little houses were arranged in one long street and that street was Athens. 15

Several days after the invasion of Athens suggested itself to Miss Polly Street in far-off Chicago, a prominent citizen strode from the offices in the direction of the boarding-house. He moved with decision, for he was hungry, and Mrs. Van Zandt was fastidious as to hours. The office force ate its supper at six, and the fact that Marc Scott was the assistant superintendent and, in the absence of the superintendent on affairs matrimonial, in charge altogether, was no reason in the eyes of Mrs. Van Zandt why he should be late to his meals.

Scott paused outside the boarding-house to look into the distance where an accustomed but always interesting sight met his eyes. Away in the distance, between two foothills, appeared the tiny thread of smoke which marked the approach of the little train from Conejo. It was fascinating to watch it; at first so indistinct, then plainer, and finally to see the little engine puffing its way along, dragging the small cars. There would be no one on it but the train gang and nothing more exciting than the mail, but its bi-weekly arrival never lost interest for Marc Scott.

“Johnson’s late to-night,” he muttered, and pushed open the door which led immediately to the dining-room. Three men had just begun eating. There was Henry Hard, the chief engineer; Jimmy Adams, the bookkeeper, and Jack Williams, who ran the company store; they, with young Street, Scott, the doctor—who a month ago had taken an ailing wife back to Cincinnati—and the train gang, formed the little group of Americans who had held the mining camp together. 16

While their location had been freer from trouble than many parts of Mexico, both in regard to bandit and federal persecution, they had borne a part in the general unrest. Once the town had been attacked by Indians; another time, lying in the path of one of Villa’s hurried retreats, it had endured a week-end visit from that gentleman, after which horses and canned goods had been scarce for a while.

The worst trouble they had had, however, had been with labor. They worked the mine with Mexicans, and the Mexicans were an uncertain quantity. Athens was too far from the border to admit of hiring labor from the other side and allowing it to go back and forth, and the men they got were a discouraged lot, ready to abandon the job for anything that came up, from joining the newest bandit to enlisting in the army. Fighting seemed their metier and most of them preferred it to the monotony of working a mine. A few who were married and had hungry families stayed longer than the rest but it was always a problem.

Just now the mine was running three days a week and no one knew when orders would come to shut down entirely. There were the usual rumors afloat in regard to the coming election in July and a good many people who had seen other elections in Mexico expected trouble. The Athens people were looking to Street’s return for news from headquarters, but already several days had gone by since the wedding and they had heard nothing.

The men looked up and nodded as Scott entered and Mrs. Van Zandt, peering in from the kitchen through 17 a square hole which served as a means of communication, brought him his coffee. Mrs. Van Zandt had a weak spot in her heart for Marc Scott—most women and children had. One did not at first see why. He was not good looking, except that he was well made and well kept; not particularly pleasing in his manner, being given to an abruptness of speech which most people found disconcerting; and he liked his own way more than is conducive to social harmony.

He was, however, straight as a die; was afraid of few things and no persons; and if he liked you, he had an especial manner for you which took the edge off his gruffness so that you wondered why you had ever thought him disagreeable. His hair and skin were as brown as each other, which was saying a good deal; his eyes were gray; his teeth white and strong; and he had the healthy look of a man who lives in the open, bathes a good deal and does not overeat.

“Late as usual,” remarked Mrs. Van Zandt, pessimistically, as she set the coffee down beside him. “The less a man has to do in this world, the harder it seems to be for him to get to his meals on time.”

“Ain’t it the truth?” remarked Adams, with feeling. He was a short, chubby youngster, with a twinkling blue eye. “If it was me, I could whistle for my supper, but seeing it’s him, he gets fed up, the beggar!”

“Too bad about you!” sniffed Mrs. Van Zandt. “I thought you’d cut out that second cup of coffee?”

“I’m aiming to cut it out during the heated term,” was the cheerful reply. “There’s something about 18 your coffee, Mrs. Van, that’s like some folks—refuses to be cut.”

“Humph!” Mrs. Van was not inaccessible to flattery. “Dolores,” this to a black-haired girl whose face appeared at the hole. “You can cut the pies like I told you—in fours. If that girl stays with me another month I’ll make something out of her; but, Lord, why should I think she’ll stay? They never do. Mexicans must be born with an itch for travel.”

“I notice,” suggested Hard, “that in the haunts of civilization they are cutting pies in sixes.” Hard was a Bostonian—tall, spare, and muscular. He came of a fine old Massachusetts family, and his gray eyes, surrounded by a dozen kindly little wrinkles, his clean-cut mouth, wide but firm and thin lipped, showed marks of breeding absent in the other men.

“Hush, don’t tell her!” growled Adams. “A woman just naturally can’t help trying to follow the styles, and I can use more pie than a sixth, let me tell you.”

Mrs. Van, having attended to the distribution of the pie, sat down at the foot of the table for a bit of conversation. She was a good-looking woman with dark hair and eyes, and features which, though they were hard, were not disagreeable. Her figure was restrained with much care from its inclination to over fleshiness. Mrs. Van scorned the sort of woman who let herself get fat and fought the enemy daily. I could not possibly tell you her age, for no one but herself knew it. It might be thirty-five and on the other hand it might easily be ten or fifteen years more. 19

She had led a roving life, beginning somewhere in the Middle West, carrying on for a time in the East, where it involved a bit of stage life to which she loved to refer. There had been a short spasm of matrimony, not entirely satisfactory, the late Van Zandt having had his full share of his sex’s weaknesses, and a final career of keeping a boarding-house in New York. After that she had drifted West and finally into Mexico. She had been a veritable godsend to the Athens mining company which had undergone the agonies of native cooking until the digestions of the American portion of the working force were in a condition resembling half extinct craters.

“What I’m wonderin’ is if Bob Street and his girl got married or not and when they’re coming home,” she remarked as she sat down. One of Mrs. Van’s little peculiarities, saved probably from the wreck of her theatrical career, was a tendency toward calling people by their first names when they were not there to protect themselves and sometimes even when they were.

“If they’ve got any sense at all they’ll wait,” said Scott, placidly. “This is no time to be bringin’ more women into the country.”

“That’s so,” agreed Williams, a confirmed bachelor. “It was good luck the Doc took his wife and kids off when he did. There’ll be trouble here when them elections is held.”

“Pick up your skirts and run, Mrs. Van!” suggested Adams. “You may be cooking for a Mexicano yet.” 20

“If I do he’ll know it,” was the prompt reply. “I ain’t the runnin’ kind. Anybody who’s staved off the landlord in New York as many times as I have ain’t going to worry about Mexicans. What I think those young folks ought to do is to go East for their honeymoon.”

“They can’t,” replied Adams, with a grin. “It wouldn’t look sporting for the Supe to leave his underlings without protection in such a crisis.”

“I like Bob Street as well as any young chap I know,” said Mrs. Van Zandt, meditatively, “but I don’t know as I’d want him standin’ between me and Angel Gonzales—if Angel was much mad.” Angel Gonzales was a local bandit; a man of many crimes and much history. “But, of course, it wouldn’t look well for the Sup’rintendent to run away.”

“Street’s not the running kind, either; don’t fool yourself about that,” remarked Scott, quietly.

“He’s a good kid. I don’t care if he is a rich man’s son,” said Adams with sincerity. “If my Dad had money I wouldn’t be keeping books, you bet.”

“No, son, you’d be playing the ponies up at Juarez,” responded Hard, cheerfully.

“Not ponies, Henry dear, roulette,” replied Jimmy, pleasantly. “Me and Mrs. Van are going to get spliced just as soon as the Ouija board tells her the winning system.”

“It’s all very well for you to make fun of things you don’t know any more about than a baby, Jim Adams.” Mrs. Van’s scorn was intense. “If you’d read that article I showed you in the magazine about 21 the man that talked to his mother-in-law by the Ouija——”

“Mother-in-law? Great guns, is that the best the thing can do?”

The reply was cut short by the entrance of the train gang, hot and hungry, clamoring for food.

“How’s Conejo?”

“Sand-storm. Windy as a parson. Say, you fellows eat up all the pie?” Conversation was suspended while the demands of hunger were satisfied, and Scott distributed the mail which the late comers had brought.

“From Bob?” Hard looked up from his Boston paper as Scott grunted over his letter. Scott nodded and then as the others looked their curiosity, he read the brief note aloud.

“Dear Scotty:

“Have just had a summons from the directors to go East at once; guess they’re uneasy about something they’ve heard and want first-hand information. Emma and I are starting for Chicago to-morrow. Open all mail and wire anything important.

“Bob.”

“Just what I said they’d ought to do,” breathed Mrs. Van, happily. “Well, that girl’s got a good husband—I’ll say she has.”

“Directors would be a heap more uneasy if they knew what we know,” remarked Williams, sententiously. “Hear anything more about the Chihuahua troops bein’ ordered in, Johnson?”

“Nope,” replied the engineer, his mouth full of pie. 22 “Everybody crawled into their holes in Conejo. Didn’t you never see a sand-storm, Jack?”

“I wish I’d known he was going to Chicago. I’d have asked him to look in on my girl,” said Jimmy, folding up his letter. “I don’t like the way she writes—all jazz and picture shows. Some cuss is trying to cut me out with her.”

“More likely she’s heard about you and the little Mexican over to Conejo,” remarked the fireman, unsympathetically.

“If you’d had her address she sure would have,” replied Adams, promptly. “That Mexican girl——”

“Yes, we remember her. She was a looker but she used too much powder—they all do.” Hard’s voice was judicial. “She always reminded me of a chocolate cake caught out in a snow-storm.”

“Hush up!” Mrs. Van’s voice was tragic. “Do you want Dolores to get mad and quit? They’ve got their feelings same as we have. I guess I’ve got to catch a deaf and dumb one if I want to keep her on this place!”

Marc Scott sat in his place, a pile of letters before him, when the others had gone, and Mrs. Van was helping Dolores with the dishes.

“Say, Mrs. Van, when you get through with those dishes come outside a minute; I want to talk to you,” he said as he threw open the door.

The shack boasted no veranda, but there were three small steps. Scott seated himself on the top one and rolled a cigarette. The air was chilly. The sun had sunk behind the mountains and outlined their rugged 23 shapes with golden lines against the purple. Everything was very still—there was not a sound except for the faint strains of the victrola, which Jimmy Adams always played for an hour after supper. A few figures moved about in and out of the other cabins; not many—for the working force was light these days. A light in the store showed that Williams was keeping open house as usual.

The door opened and Mrs. Van came out and sat beside him on the step.

“Well?” she said, quietly, “what’s the matter?”

“I’m in the deuce of a mess,” replied Scott.

“You mean Indians?”

“Worse than that—it’s a woman, Mrs. Van.”

“A woman!” Mrs. Van was plainly shocked. “My land, Marc Scott, you ain’t been foolin’ with that heathen in the kitchen?”

Scott chuckled. “Listen, Mrs. Van, I oughtn’t to string you like that—it is a woman, though. You heard me read that letter of Bob’s?”

“Yes.”

“He said to read the mail.”

“Well, haven’t you?”

“Yes, and the first one I tumbled into feet foremost was a confidential one from his sister. She says she’s coming down here. She thinks he’s here.”

“What? You mean here? Athens?”

“That’s what she says. The letter’s been lying over at Conejo since Tuesday and the chances are she’s there by this time.”

“Oh, that ain’t the worst. It was a confidential letter. She said——” Scott paused in embarrassment.

“I’m not telling you this for fun, Mrs. Van Zandt, but because I don’t know what to do. You’re a lady——”

“Oh, go on, what’s the matter with you? I guess if you know it it ain’t going to hurt me. Has she run off with somebody, or has her Pa lost his money, or what?”

“I’ll show you.” Scott fished out Polly’s letter apologetically. “I stopped reading it directly I saw it was confidential,” he continued, “but I got this much at one swallow.”

“Dear Bob:

“I know it’s awfully nervy of me to drop in on you and Emma right at the beginning of your honeymoon, but I am coming just the same. Joyce Henderson has behaved atrociously to me.”

“That’s all I read,” concluded Scott, penitently. “Joyce Henderson is the fellow she’s engaged to—Bob told me that. I had to look at the end to see if she said when she was coming, and by George, if she started when she said she was going to, she ought to be in Conejo right now.”

“Now!!”

“What we’re going to do with her, I don’t know, do you?”

“She and the wedding couple have just crossed each other!”

“Looks like it. Look here, Mrs. Van, what am I going to do? If I don’t look her up, God knows what’ll 25 happen to her over in Conejo, unless she has sense enough to go to the Morgans. If I do, she’s going to raise merry heck because I read that letter about the fellow jilting her. Now I thought maybe if you’d let on that you read it—a girl wouldn’t mind another woman’s knowing a thing like that as much as she would a man.”

Mrs. Van Zandt surveyed Scott pityingly.

“It always seems so queer to me that a man can have so much muscle and so little horse sense,” she said at length.

“But——”

“There ain’t any use my explaining; you wouldn’t get me,” she went on, impatiently. “But here’s something even you can understand. I’d look nice opening the boss’s mail, wouldn’t I? Now you’ve read the worst of it you might as well dip into it far enough to find out just when she’s coming. Somebody’ll have to drive over to Conejo for her as long as the machine’s busted.”

“I’ve read all I’m going to,” said Scott, doggedly. “You can do the finding out.”

Mrs. Van Zandt grunted, arranged a pair of eyeglasses which sat uneasily on a nose ill adapted to them, and glanced at the letter. She gave a sigh of relief.

“She says she’s going straight to the Morgans’ when she gets to Conejo. Bob’s told her about them. Prob’ly Morgan’ll run her over in his car. She ain’t very definite about time; don’t seem to know just how long she’ll be detained at the border.” 26

“Unless they’re all fools up there she’ll be detained some time,” said Scott, disgustedly. “Well, I’ll go and get the Morgans on the wire and see if they’ve seen anything of her,” and he strode away toward the office.

Mrs. Van Zandt sat watching him as he swung down the street. The sun’s gilding had faded from the mountains and it was growing dark. Here and there a star peeped out as though to commiserate Athens upon its loneliness.

“It is lonely,” Mrs. Van said to herself. “I don’t know as I ever felt it so much before. I hope it don’t mean that we’re going to have trouble. Sometimes I think I must be psychic—I seem to sense things so. Wish that girl had stayed at home, but, Lord, I’d of done the same thing at her age. That’s a youngster’s first idea when things go wrong—to run away. As though you could run away from things!”

The lady shook her head pessimistically and drew her sweater more closely about her as the air grew chillier. A short plump figure with a shawl wrapped around its head came out from the back of the house and melted into the darkness.

“Is that you, Dolores?”

“Si. The deeshes all feenish,” said Dolores, promptly.

“Did you wash out the dish towels?”

“Si. All done. I go to bed.” Dolores disappeared.

“You’re a liar,” breathed Mrs. Van, softly. “You ain’t goin’ to bed, you’re goin’ to set and spoon with that good-looking cousin of yours. Well, go to it. 27 You’re only young once and this country’d drive a woman to most anything.” Her eyes twinkled humorously. When Mrs. Van’s eyes twinkled you forgot that her face was hard.

“My, but they’re hittin’ it up on Broadway about this time! Let’s see—it’ll be about eleven—the theatres just lettin’ out, crowds going up and down and pouring into restaurants. Say, ain’t it queer the difference in people’s lives? There’s them sitting on plush and eating lobster, and here’s me looking into emptiness and half expecting to see a Yaqui grinning at me from behind a bush! Hullo, you back?”

Scott, accompanied by Hard, came down the street again. Both seemed disturbed.

“Well,” remarked the former, grimly. “She’s started.”

“Started?” Mrs. Van rose. “What do you mean by that?”

“I got Jack Morgan’s mother on the ’phone,” said Scott. “Seems she’d been trying to get us. The girl got into Conejo about six—just after our train pulled out—tried to get us on the ’phone and couldn’t; so she got a machine and is on the way over.”

“Got a machine!” Mrs. Van gasped. “Are the Morgans crazy?”

“Jack and his wife have gone over to Mescal with their car and there’s nobody home but the old lady and the youngsters. Old lady Morgan’s deaf and hollers over the wire so I couldn’t get much of what she said,” continued Scott, ruefully. “I made up my mind that she’d got old Mendoza to bring her over in his Ford. 28 Guess it’s up to me to harness up and go over to meet them.”

“I should say so. That girl must be scared to death if nothing worse has happened to her.”

“Nothing worse will happen to her with Mendoza—unless he runs her into an arroyo. Mendoza’s principles are better than his eyesight. But, believe me, she deserves to be scared. It might put a little sense into her.”

“Shall I drive over with you?” queried Hard.

“No, but you might help Mrs. Van move our things down to Jimmy’s. I thought we’d put her in our shack, Mrs. Van, and you could come up and stay with her.” And Scott swung off into the direction of the corral.

The other two proceeded to the company house, as the superintendent’s quarters were called.

“Well,” said the lady, as they began to pack the two men’s belongings, “I expected to get this house ready for a bride and groom but I must say I wasn’t looking for a lone woman. And yet if I’d had my wits about me I might have known. Only last night Dolores and me were running the Ouija and it says—look out for trouble—just as plain as that!”

“I shouldn’t call her anything as bad as that,” said Hard, crossing to where the photograph of Polly Street hung over the fireplace.

The picture showed a small girl, probably about ten or eleven; a fat little girl with chubby legs only half covered with socks, and with dimples in the knees; a little girl with very wide open eyes and a plump face, 29 a firmly shaped mouth and a serious expression; a little girl with frizzly hair and freckles that the photographer had failed to retouch, in a costume consisting of a short skirt, middy, and tam-o’-shanter.

“I wouldn’t call her a trouble maker,” said Hard, laughing, “unless she’s changed a lot in ten years.”

To say that the days which followed Miss Street’s unconventional decision passed in a whirl is to be both trite and truthful. In fact, it was not until she had crossed the border that she found leisure to reflect.

To begin with, the parents had been difficult, as good parents usually are when youth begins to chafe at restriction, especially if youth happens to belong to the weaker but no longer the less adventurous sex. The Streets were easy-going people who liked to live by the way. They were not ambitious and they were not adventurous and they hated letting go of their children. It was bad enough to have a son marooned in a mining camp without losing a daughter in the same way. Only downright persuasion by the daughter, combined with remembrance of quite unalarming letters from the son resulted in the desired permission.

“After all, if Emma’s parents let her go down there, I suppose we needn’t be afraid,” said Mrs. Street, who disliked argument.

“In my opinion, Emma’s parents are fools,” replied Mr. Street, sternly. “Or else, like us, they’ve raised a daughter they can’t control.”

“I wouldn’t put it that way, Elbridge!”

“I would. You might as well look things in the face.” 31

“But, Father, you know Bob’s part of the country has been very calm; and I never get a chance to do anything interesting! You sat down on me when I wanted to drive a motor truck in France——”

Any father can continue this lament from memory. The discussion had ended as discussions with spoiled children usually end. There had been a hurried packing and the familiar trip across the continent. It was only when she alighted at a border town and after some anxious hours waiting to have her passports viséd and her transportation arranged, embarked on the shabby south-bound train on the other side, that Polly fully realized the expedition to which she was committed.

Up to this time her thoughts had been of the life she was leaving, and, it must be admitted, of Joyce Henderson. From Illinois to Texas she told herself exactly what she thought of a man who could so boldly and plainly and with such an evident relief accept his dismissal at the hands of the girl he had claimed to love; but by the time the train had jogged through miles of queer brownish yellow country, dotted with mesquite and punctured with cactus, relieved here and there by foothills, and frowned upon by distant mountains, her meditations assumed a more cheerful complexion.

The outlook, monotonous as it was, fascinated her. There were adobe houses with brown youngsters playing in the scanty shade, much as one sees them in New Mexico and Arizona; there were uprooted rails and the ruins of burned cars—evidences of civil war unknown 32 on our side of the line. There was a strong wind blowing—the early spring wind of the Southwest, but the sun shone hotly and one felt stuffy and uncomfortable in the car. The sand which was caught up by the wind blew in one’s face and down one’s throat and made closed windows a necessity.

There were a good many people traveling, for a country in a reputedly unsettled condition, Polly thought, and wished that she could understand the fragments of conversation that she heard.

“Why didn’t I take Spanish instead of French at school? I always seem to have chosen the most useless things to study! I wish I knew what those two fat women without any hats on are talking about—me, I suppose, for they keep looking over here. That man is American—or English. If I were Bob, I’d amble over and get up a conversation with him and find out all the interesting things I’m missing. I’ll bet he owns a mine down here somewhere. How fascinating!”

Polly’s imagination immediately forsook the American and indulged in a rosy picture of herself as the owner of a mine—a gold mine—coal was too unromantic. She saw herself in a short skirt and a sombrero superintending the exertions of a number of dusky workers who were loading neat little gold bars on the backs of patient burros.

This delightful picture occupied her fully until the train stopped and she had to get out. This train did not go all the way to Conejo, but left one at a junction called Pecos where twice a week if convenient for all parties a smaller train rattled its way across the plain 33 and into the mountains among which Conejo nestled. It is not necessary to describe Pecos; its only reason for existence was the fact that it owned and operated a smelter.

This second train was the shortest that Polly had ever seen. It consisted of an engine, two coal cars, a baggage car, and one passenger coach—this last very dirty as to floor and windows and very creaky as to joints. There were on this occasion but four passengers beside Polly; the two fat ladies, who were, if she had only known it, members of the first families of Conejo; an old man who sat in a corner and read a German paper; and a young Mexican, well dressed and of a gentlemanly appearance, who sat across the narrow aisle from Polly, smoking innumerable cigarettes and glancing at her whenever he thought she was not looking.

Polly, however, was too much interested in the changes of scenery to notice anything as ordinary as a good-looking young man. The country was changing, gradually, but still unmistakably changing, from a desert, flat and stifling, to a region of small hills and valleys; still brownish yellow, but with the monotony of mesquite varied by live oaks, and in some cases by shallow little streams along whose banks grew cottonwoods, their green foliage restful to the eye weary of desert bareness.

Many of the cacti were in their beautiful bloom and gave to the country the needed dash of color. Occasionally one saw small herds of cattle feeding off the short stubby vegetation. They were drawing near the 34 mountains, whose gauntness seemed less when approached.

“They’re like ugly people—grow better looking as you get to know them,” mused Polly. “Oh, my gracious, what’s the matter now?” The puffing little engine had given up trying to make the steep grade it had been negotiating, and had stopped with one last desperate wheeze. No one seemed surprised. The fat ladies went on talking and the old man continued to read his paper. The trainmen were outside, doing something, Polly couldn’t make out what, perhaps only talking about doing something. “Oh, dear, I wonder what has happened!”

In her excitement she must have said it aloud, for the young man across the way sprang to his feet and was at her side instantly. A keen observer might have drawn the conclusion that he had been waiting for some such opportunity.

“I beg pardon, señorita, but it is that the engine cannot make the grade,” he volunteered, politely, in English almost without an accent—or perhaps I should say with an intonation English rather than American, though with a slightly Latin arrangement of phrase.

“Oh, I see,” Polly replied blankly. The young man had been rather sudden, and he continued to stand in a disconcerting way, hat in hand, in the aisle. He appeared to be very young, hardly more than nineteen, Polly thought, and handsome in a dark way. He had large dark eyes, very white teeth, a smooth olive skin without the mustache which so many Spaniards wear, and a rather prominent under jaw and chin. 35

“You see,” he continued, “they take the first car over to Conejo and then come back for us.”

“Do you mean to say that they’ll leave us here, perched on the side of this hill, while they run off with the engine?” demanded Polly, eyeing the trainmen indignantly. In fact, she was so busy being indignant with them that she omitted to notice that the young man had slipped into the seat opposite her. That fact, however, had not escaped the fat ladies in the rear, one of whom said to the other in shocked Spanish:

“It is Juan Pachuca!”

“So it is,” replied the other. “I had thought him in the South.”

“Who knows where he is? A wicked person, my dear, a very wicked person. My sister’s husband says he will get himself shot before he finishes.”

“Undoubtedly,” said the other, placidly. “So many young men are being shot these days. I thought that young woman was an actress—now I am sure of it.”

“Yes,” replied Juan Pachuca to Polly’s question. “But do not be alarmed. They will come back in a couple of hours.”

“A couple of hours!” The girl’s voice was horrified. “But I expected to be in Conejo in a couple of hours. I’m in a hurry.”

“One should never be in a hurry in Mexico, señorita, it does not—what is it you say—it does not pay.”

“Apparently.” Polly replied coolly, realizing suddenly that this good-looking boy was regarding the conversation as a thing established. 36

The stranger was correct in his guess. Uncoupled from the rest of the train, their coach remained poised uncomfortably half-way up the hill, while the engine, still puffing and wheezing like a stout man going upstairs, pulled the open cars and the baggage car up the grade and, disappearing through a gap in the hill, became only a faint noise and a trail of thin smoke. Polly laughed in spite of herself and the young man responded with a smile that revealed two dazzling rows of teeth.

“Mañana!” he laughed. “So we say down here and so we do. You find it amusing, señorita, after your country?”

“It’s different, you must admit. We at least aim to reach places on time.”

“Yes, that is the difference—you aim, we do not,” replied the other, thoughtfully. “Some day—but perhaps the señorita will get out and have a breath of fresh air? There is, alas, plenty of time.”

A mischievous impulse seized the girl. She felt as she used to feel when as a small, fat, freckled youngster she had sat still as long as she possibly could in school and then despite the teacher’s stern eye her nervous energy had got the better of her.

“After all he’s only a boy,” she told herself. “I’ll bet he isn’t any older than my freshmen cousins. What’s the harm?”

Outside the sun was hot but the wind was fresh and cool.

“Through that cut in the mountains and around a curve is Conejo,” said Juan Pachuca, as Polly, glad to 37 be out of the hot car, drew long breaths of the splendid air. “You have friends there?”

“In Conejo? Oh no, my brother lives in Athens. That’s where I am going. He is superintendent of a coal mine there.”

“Athens? That is some distance from Conejo. Of course your brother will meet you?”

“Of course,” replied Polly, with the faith of the American girl in the male of the species. “They have a little coal train that runs to Conejo and he’ll probably come in on that.”

“I think you must be Señorita Street?” mused the young man.

“Oh,” Polly dimpled pleasantly. “You know Bob then?”

Juan Pachuca’s dark eyes smiled. “Not exactly—but I have met him. Me, I have a place south of Conejo—quite a long way—I am what you might call a long-distance neighbor. My name is Pachuca—Juan Pachuca.”

“I see. Are you in the mining business, too?”

“Not now. Oh, I have mining property, but further south. My people live in Mexico City. In Sonora I have a small ranch.”

“You speak English rather wonderfully, you know, señor,” said the girl. “But more like an Englishman than an American.”

“It is very likely. My sister—she is much older than I—married an Englishman, and her children had English governesses. When I was young I had my lessons with them.” 38

So from one thing to another the conversation ran, very much as it does with two young people of any nationalities, granted a common language. Polly talked a good deal about Bob. Juan Pachuca seemed interested in all the details that she could give him about the mine. His manner was very respectful. If he had not met many American girls he had evidently heard much about them, for he did not seem to misunderstand the situation as many Latins would have done. Before the girl had realized it the two hours were over and the little engine reappeared.

Conejo should, I believe, be called a town. The people who live in it always dignify it by that name and they probably have a reason for so doing. To one holding advanced ideas as to towns, it seems at a first glance to be only a collection of pinkish looking adobes which on inspection turn out to be a church, a store, a jail, a saloon, a hotel—at which no one stays who has a friend to take him in—and some private houses. It is Juarez without the bull ring, the racetrack or the gambling places.

It is situated rather flatly between two ranges of mountains and when Polly Street landed there at about six o’clock—a trying hour in itself—it was in the grip of a sand-storm. One’s first sand-storm is always a surprise. It looks so innocent from behind a window pane; just sand—blowing about rather swiftly, whirling in spirals, beating against the glass, piling itself up in drifts—an interesting sight but not a terrifying one.

Polly had been a little surprised to see the fat ladies 39 array themselves in goggles before descending from the train, and had laughingly refused an offer of his own from Juan Pachuca, who promptly put them on himself. But when she alighted from the train onto the platform which extended from the rear end of the general merchandise store, and which served as station, waiting parlor and baggage-room, she gasped in dismay. It was as though thousands of tiny pieces of glass had struck her in the face and throat.

Before she could get her breath they struck her again and again; sharp, vindictive, piercing little particles they were. She shut her eyes and put her hands to her bare throat to protect it. Suddenly she felt a hand on her arm and Juan Pachuca’s voice said:

“Keep them shut and let me lead you. I told you what sand-storms were—you’d better have taken the goggles.”

Polly succumbed and felt herself being led along the platform.

“There, we’re in the store,” said the young man. “Rather nasty, eh?”

“Awful! I never felt anything like it,” gasped the girl, shaking the sand from her clothes. “And it isn’t sand, it’s gravel. No wonder you wear goggles!”

“I find them most convenient for many purposes,” was the reply.

Polly noticed that he still had them on though they were in the store. They gave him a queer, oldish appearance and quite spoiled his good looks. Polly herself was beginning to feel disturbed. She wanted Bob 40 and she wanted him immediately. She looked about her anxiously.

The store was larger than it appeared from without and carried a varied line of goods piled up on shelves or displayed on counters. On one side, it seemed to be a grocery store; on the other, dry-goods, shoes, and hats were set forth, while in the rear were saddles, bridles and other paraphernalia in leather. A big stove in the middle of the room gave out a cheerful warmth, for the air was growing very cool as the sun went down.

There were a few people, Mexicans and Indians, in the place and they all stared curiously at the pretty American. Polly did not realize, though she was not in the habit of underrating her attractions, how very noticeable she was in that environment, as she stood there, her tan traveling coat thrown open showing her dainty white waist, her short, trim skirt with its big plaid squares, and her neat brown silk stockings and oxfords. Conejo had not seen her like in many moons and it stared its full.

“I think Bob would be at the station. If I could go there——” Polly began, with a little lump in her throat.

“This is the station,” said Pachuca. “It is Jacob Swartz’ store and the station as well.”

“Then something has happened to my letter. He never would have disappointed me like this,” said the girl, despairingly.

“That is quite possible. If you would let me serve you in this matter, señorita? I have a car at the house 41 of a friend just out of town. I am driving to my ranch in it to-morrow. If you would let me drive you to Athens——”

“Drive in an open car in that?” the girl pointed to the whirling sand outside. “How could we?”

“Easily. Once on our way into the mountains we will leave it behind us.”

“Oh, thank you very much, señor, you’re very kind, but if Bob doesn’t come I can go to some friends of his, English people, the Morgans, and they will drive me over in the morning.” She was conscious of a sudden desire to get away from this polite youth who stuck so tightly. It was all very well to let him amuse her on the train—that was adventure; but to drive with him through a strange country at night would be pure madness. She thought he stiffened a bit at her words.

“English people? Oh, yes, undoubtedly that will be wise. Swartz can probably tell you where to find them.”

“Yes, of course.” Polly was glad to see that he was going to leave her. “Thank you again, señor, for your kindness.”

“It has been a great pleasure,” and the young man was gone.

Polly clenched her hands nervously. Where, oh, where was Bob? Why hadn’t she telegraphed instead of trusting to a letter? At this juncture her glance fell upon a small counter over which the sign P. O. was displayed. Behind the counter sat a stout man in spectacles—Jacob Swartz, undoubtedly. Polly accosted him timidly. 42

“Has anyone been in from Athens to-day?” she said.

“Athens? Sure, dere train come up dis morning; dey wendt back an hour ago.”

“Was Mr. Street here—Mr. Robert Street?”

“No, joost the train gang. Dey wendt back when dey got dere mail.”

“Do—do they come every day for the mail?”

“No, joost twice a week. Dere mail ain’t so heavy it can’t wait dat long.” Swartz peered benevolently over his spectacles.

“I’m Mr. Street’s sister. I wrote him I was coming, but I suppose if he only gets his mail twice a week he hasn’t had my letter.” Polly bit her lip impatiently. “I want to go over to the Morgans—Mr. Jack Morgan. Can you show me where they live?”

“Sure can I,” replied Swartz, lumbering to his feet. “You can from the door see it.”

Polly followed him in relief, when suddenly the door opened and a little old lady literally blew in. She stamped her feet as though it were snow instead of sand that clung to her, and disengaged her head from the thick white veil in which she had wrapped it.

“Mein Gott, it is old lady Morgan, herself,” said Swartz, nudging Polly, pleasantly.

“What’s that? Somebody wanting me?” replied the lady, still occupied with the veil. “Where’s that tea I told you to send me this morning, Swartz? A fine thing to make me come out in all this for a pound of tea, just because I’ve nobody to send and two sick 43 children on my hands! What? Oh, I can’t hear you! Who d’you say wants me?”

She was a thin, bent old lady with straggly gray hair and a very sharp penetrating voice. Polly felt the lump in her throat growing larger. Was this the jolly pretty Mrs. Jack Morgan that Bob had written about so often?

“Dis young voman——” began Swartz, heavily.

Polly stepped forward.

“Mrs. Morgan, this is Bob Street’s sister. He has often written us about you and your husband.”

“Husband? She ain’t got no husband,” interrupted Mr. Swartz, heatedly. “Ain’t I told you dis iss de old lady—Jack Morgan’s mother?”

“I’m a little hard of hearing, my dear. Who did you say you were?” asked Jack Morgan’s mother, patiently.

Polly repeated her explanation, adding a few more particulars, all as loudly as possible. They had now an interested audience of Mexicans and Indians, male and female, old and young, who found the scene none the less attractive because they did not understand it.

“Well, I suppose he didn’t get your letter,” said Mrs. Morgan. “Jack and his wife have gone over to spend a few days with some friends in Mescal or they’d run you over in the car.” There was a pause as Polly digested this unwelcome bit of news, then the old lady continued: “They’d only been gone two days when both the children came down with mumps, and my Mexican woman’s husband had to take that time to join the army, so, of course, she had to leave. If 44 things weren’t so messed up I’d take you home with me——”

“Oh, no,” said Polly, promptly. “I couldn’t think of it. If I could just get somebody to drive me over——” Both she and Mrs. Morgan looked at Swartz.

“Mendoza might if he ain’t drunk—sometimes he ain’t,” volunteered that gentleman.

“Oh, no, I don’t think I’d like him,” shivered Polly. “Isn’t there anybody else?”

“Nobody with a car,” replied Mrs. Morgan. “It’d take you till morning to drive over—the roads are awful. Mendoza is a very decent old thing. You go and see if you can get him, Swartz,” and Swartz lumbered away. Old lady Morgan understood how to make herself obeyed. “Have you tried to get Athens on the ’phone?”

“Telephone?” A smile broke over Polly’s unhappy face. “Why, I never thought of that.”

“Good heavens, child, where do you think you are? Here, I’ll get them for you.”

She led the way to the office.

“I haven’t seen your brother since he went up to Douglas to get married,” she said. “Didn’t know they’d come home.”

“Oh, yes, they must be home,” said Polly, an awful doubt coming into her mind. “They—they must be home!”

Mrs. Morgan seized the receiver and began exchanging insults with the invisible Central. After several minutes she gave up the effort. 45

“It’s no use, I can’t raise them—our service is dreadful down here,” she said. “Now, I’ll tell you what to do. I’ve got to run home before the baby wakes up; if he can’t get Mendoza, you come on down to the house and stay the night with me. See, it’s the last house—got a Union Jack flying from it. If I don’t see you in half an hour I’ll know you’ve gone with Mendoza. You needn’t be afraid of him—he’s half dead but he can drive a Ford,” and the voluble old lady was gone.

Polly wondered for a moment whether she most wanted to laugh or cry. Homesickness and fatigue suggested the latter, but a wild sense of humor poised between the decrepit Mendoza and the deaf Mrs. Morgan won the day. Polly chuckled. Then realizing that it was nearly seven and that she had had nothing to eat since noon, she went to the counter and bought of a Mexican youth, evidently a helper, some crackers. They were in a box and looked a degree cleaner than anything else. The population had wearied of the American lady and had gone its various ways. Polly sat forlornly on a high stool and munched her crackers until Swartz returned.

“No good,” he said. “Mendoza’s sick and he won’t let nobody else drive de car. You better go stay mit de old lady.”

“All right,” said the girl, rising. “I suppose I can leave my trunk on your back porch?”

“Vy not? Ain’t it der station? Vere should you leaf it?” replied Swartz, hospitably.

Polly stepped out of the front door. The sand 46 blizzard was undoubtedly on the wane. The wind was less violent but much cooler. The sun had dropped behind the mountains and the dusk was descending upon the little Mexican town. A few of the houses showed a light, but more of them were dark. The Morgan house, a very long way down the street, it seemed to the girl, was lit and she started to go toward it. A sense of desolation, a forlornness greater than she had ever known in all her short life descended upon her. She swallowed quickly and increased her pace. It wasn’t fear, she reflected, it was worse than fear; it was the awful loneliness of one who had never been really alone in her life.

“It’s the first night at boarding-school multiplied by a thousand,” she sobbed softly. “Oh, why did I come to this awful place? I simply can’t stay all night with that deaf woman and those mumpy children! I——”

She jumped back in time to avoid an automobile which seemed to flash out of nothingness at her elbow. As she stood looking after it a wild hope came into her head that it might be Bob after all. The car stopped and a man jumped out.

“Is it you, señorita?” he exclaimed, “alone and in the dark?”

It was Juan Pachuca. Polly sighed, disappointed to tears. She tried to explain the situation.

“But in two hours I will have you in Athens,” he begged. “Or is it that you wish to stay with these people?”

“Of course I don’t wish to stay! The children have the mumps and the poor old lady is nearly wild.” 47

“Come. Give me that bag. So—I thought all Americans were sensible people!” And before Polly could object she found herself seated in the car with Juan Pachuca driving silently at her side.

About half an hour after his conversation with Mrs. Van Zandt, Marc Scott drove the buckboard with its two lively horses out on the Conejo road. Beside him sat a blond dog of mixed genealogy answering to the name of “Yellow.” Scott had put on a coat over his flannel shirt, tucked his trousers into a pair of riding boots, and replaced his sombrero with a soft cloth hat. These changes having been made in honor of the visitor, he felt that his duty had been fulfilled and he addressed Yellow ruminatively:

“Well, I expect we got to brush up a bit on our manners if we’re going to have a young lady around, eh, Yellow? Going to be some strain on us both, I’ll say. Funny idea to run off to a place like this just because you’ve quarreled with your young man! Got the temper that goes with red hair, I guess. I remember a red-haired girl I used to know in Detroit——” A grin succeeded the worried look on Scott’s face; evidently the adventure with the red-haired girl had had its humorous side.

“Well, get up, Romeo, we’ve got to reach that girl before Mendoza dumps her in the ditch and gets her mussed up or the boss’ll fire us both.”

Romeo, a good-looking gray, with an excitable nature, 49 snorted as he felt the touch of the whip and dragged his gentler mate into a lively trot. A new moon, clear cut and beautiful, was rising behind them, over the tall mountains, making the valley—so bare by day—lovely and mysterious in its half light.

“No kind of a night to be driving around with a dog, Yellow,” remarked the driver, reproachfully. “Men and moonlight are made for better things.”

The horses trotted briskly; they were covering ground rapidly. They ought, Marc figured, to meet the machine this side of Junipero Hill, a steep and cruel grade which he would be glad to spare his horses if he could. If Mendoza was making any sort of speed he ought to have come that far. He began to watch for the lights of the machine. The girl must be plucky, even if she was foolish, to dare a trip like this with a strange Mexican.

Well, he was glad Bob’s sister was nervy; he liked nervy girls and he liked Bob. Usually fellows who came out from college and took positions over other men’s heads made fools of themselves; but Bob was not a fool. He was a decent, likable young chap, who knew he had been luckier than the next fellow and who took no advantage of it.

“Which is more than you can say of most rich men’s sons,” soliloquized Scott. “But then why should you expect sense from a rich man’s son? Where’d they get it? It’s hard knocks gives a man sense—if he’s ever going to get it, which most of them ain’t!”

There was loneliness in the air. Scott, who was 50 temperamental, as out-of-doors men often are, felt it keenly. It brought before him more clearly the loneliness of his own life, a life spent in out-of-the-way places, largely among men; a life with no roots, he sometimes felt. Yet he would not have traded his freedom, he would have told you, for any woman, for a home or for children. To be foot loose, to go where fancy called him, to have no ties—no clogs upon his precious liberty, that was what he loved.

He was fond of women, too. He liked being with them and he liked measuring each one he met with his ideal, a hazy creature who probably did not exist. Well, he rather hoped she didn’t, or if she did that he would never meet her. He had known too many men who had traded their freedom for a home and a fireside and who, once bound, had never been able to go back to the old life. It had not always been the women who had held them, either; the men themselves had seemed to change—to deteriorate, Scott would have said—to have lost the energy and the vigor that made life worth while. You cannot get anything for nothing and you paid for the happiness you might find in marriage with the loss of the one thing which was to him the most important thing in all life—liberty.

So they jogged along, Scott whistling to keep himself company. Occasionally, Yellow would insist upon getting out for a run, but he seemed glad to return. After a while it began to seem odd to Scott that he did not see the lights of Mendoza’s car. Even a cautious driver should have made the distance by this time. 51

Suddenly, an idea popped into his head—one of those clammy ideas, which come instantly, and come with a chill; ideas that are positively physical in the way in which they affect one. Suppose it was Mendoza’s car with someone else driving it? Someone of the score of half-breeds who hung around the livery stable where the car was kept? Scott leaned over and laid the whip on the innocent Romeo.

“My God, horse, we’ve got to go some the rest of the way! If——”

He did not finish the sentence. They had reached the top of a hill and he put on the brake as they started down. At the foot of the hill stood an automobile—not Mendoza’s shabby little Ford—but a big car with two large headlights. It was turned across the road and not a soul was in sight. Scott took his foot off the brake and with a muttered curse let the buckboard rattle down the hill.

Polly’s first sensation, as she sank into the comfortable seat next the driver and buried her face in the collar of her coat, was one of intense relief. This was something that seemed like home. She felt herself being whirled up the streets of Conejo with the feeling of one who is escaping, the flight being for the time of more importance than the fashion in which one flies.

“I think you will be cold,” said a polite voice at her elbow. “Wait—I have a robe.” And a blanket which smelled of the stable rather than of the garage was wrapped carefully around her. “In a few moments we shall be out of this sand.” 52

For a while they rode in silence, then the girl said, apologetically:

“I am so sorry. I didn’t want you to go to all this trouble—but I couldn’t stay in that awful place when Bob is so near!”

“If you think Conejo is bad I wonder what you would think of some of our towns further south? They are ruins.”

“Ruins?”

“Ten years of revolution—they do not improve a country.”

Polly did not reply. She peeped out of her collar and saw that Pachuca’s prophecy was fulfilled. They had ridden out of the area of the sand-storm and were getting into the foothills where the air was cold and clear. They faced the new moon which gave an eerie look to everything—the distant mountains, the foothills with their weird patches of vegetation, tall cacti and dark looking arroyos. Far, far in their rear could be seen the few feeble lights of Conejo. It began to dawn upon an awed Polly that she was doing not an unconventional but a distinctly risky thing.

What did she know about this good-looking boy who sat beside her, guiding the car so expertly through the ruts and chuck holes that chopped up the road? Suppose he turned out to be—she caught her breath angrily! He was no common Mexican but a gentleman and one was not afraid of men of one’s own class, she told herself. She would not be afraid. She hated people who were afraid. She was having a wonderful experience; the sort of an experience that 53 girls read about but didn’t have, and she was going to enjoy it.

“I forgot to ask you if you had anything to eat,” said Juan Pachuca. “You didn’t, did you?”

“I had crackers,” said Polly. “What did you have?”

“I was more fortunate. I found my friend at dinner,” replied the young man.

“Where were you going when you met me?”

“Eventually to my ranch, but first to find you. I did not think you would stay with the Señora Morgan.”

Polly laughed in spite of herself.

“I couldn’t,” she confessed. “Do you know, she seemed to think it doubtful that Bob and Emma had come back to Athens? I wonder why?”

“Perhaps,” replied the Mexican, “she thought the country not quite safe for a young lady.”

“But I thought things were settling down?”

“There will be no settling down until after the elections.”

“The elections?”

“You would not understand. Americans never do.”

“Perhaps some of us might if you gave us a chance; but when you go rearing and pitching around, killing us and raiding border towns like that murderous Villa——”

“In war there is no murder,” said Juan Pachuca, calmly. “And Villa is a friend of mine.”

“Well, I can’t help it, and I think it’s very strange for a well brought up boy like you to be friends with a man like Villa.” 54

Pachuca laughed as he glanced at the girl’s wrathful face.

“Why do you call me a well brought up boy?” he asked.

“Because you are, aren’t you? You remind me a lot of a cousin of mine who’s just entering college.”

“How old is the cousin?”

“Nineteen.”

“When I was nineteen I was a colonel in the army,” said Juan Pachuca, whimsically. “That was six years ago.”

“Good gracious!”

“Why not?”

“Well, in our country we don’t take boys of nineteen very seriously,” said Polly, a little upset. “Did you fight much?”

“A good deal. I suppose then that young men of nineteen do not fall in love either in your country?”

“Oh, yes, they do, but nobody pays much attention to them. We call it puppy love.”

“Puppy love!” Juan frowned. “You are a strange people—you Americans.”

“Yes, I suppose we are but we like ourselves that way. Do you think that engine of yours is all right? It sounds queer to me.”

Pachuca shrugged his shoulders.

“It gives me trouble sometimes. It needs what you call an overhauling, but it will take us to Athens.”

Polly, with an ear trained to engine sounds, wondered whether it would. She felt that the last straw 55 would be to be stranded in the middle of the night in a lonely spot with this good-looking young man, who, to make matters worse, had turned out to be twenty-five instead of nineteen. Again they sat in silence while the machine wrenched itself in and out of ruts and through arroyos.

She found herself wondering what his life had been? A colonel at nineteen! She remembered the boys she had known in our own army, boys she had fed and sewed for on their way to France. They, too, had seemed young, but she felt a great difference. This young man suggested things of which Polly knew little. She wondered whether it was imagination that made her fancy that he had played a part in life which does not usually fall to twenty-five, except in a country so disordered, so desperate as Mexico.

Some of her boy friends who had come back from France and Belgium had carried in their faces some such suggestion, but only a few. For the most part they had come back as they went over, those who had returned whole; husky, lively, youngish chaps—more restless, less satisfied with life at home, perhaps, but not older particularly.

“That’s why he seems odd to me,” she concluded. “He’s done and seen things that a fellow his age hasn’t any business to have done and seen—that is, the way we look at it at home. Oh dear, I wonder if we’re ever going to get there? I can’t keep still much longer and yet I hate to stir him up.”

“The girls in your country, do they fall in love at nineteen?” said Juan Pachuca, suddenly. There was 56 a softness in his voice that under other conditions—say, in a ballroom—Polly would probably have described as melting. In her present environment it struck her less pleasantly.

“Girls? Oh, yes, of course they do; but not in the desperate, hot-headed way your young ladies do. At least, not usually. Of course some girls do queer things and get into the newspapers.”

“Ah, our young ladies do not get into the newspapers,” commented Juan Pachuca. “They are guarded quite carefully; that is, our girls of good family. Most of them are very beautiful.”

“But aren’t they just a little bit tiresome? I mean, just being beautiful and guarded and all that sort of thing. At home we like a girl who has seen a little of life,” apologetically.

“Not a young lady of family!” said Pachuca, decidedly.

“Well, of course, in America we don’t think a lot about family, though it’s nice to have it if you can. We think more of education and getting on in the world. Señor, I wish you would get down and look at that engine; there’s something awfully wrong with it.”

Polly spoke suddenly for Juan Pachuca was leaning very close to her.

“Your young ladies are charming,” he said, softly. “I had always heard it and now I know it is true.” His black eyes were dancing; it would have taken some guessing to know whether with excitement or laughter or both. “Do they ever forget themselves so 57 far as to allow themselves a love affair on a silver night when——”

“No, they do not,” said Polly, half severely and half amused. It was difficult to take Juan Pachuca’s rudeness seriously and yet—oh, why had she come?

“Not a desperate, hot-headed love affair such as pleases the young ladies of my country,” he pursued, seizing the hand so near him. “But one of those—what do you call them in your tongue—flirtations?”

He was laughing but there was a smoldering fire back of the laughter, and the grasp of his hand was strong.

“Señor, now please—remember that I didn’t come with you because I wanted to, but because I had to! Please!” For Pachuca’s arm had slid itself deftly around her and was drawing her toward him, gently, but with an exceeding firmness, while the dancing dark eyes continued to laugh into hers. “There, see what you’ve done!”

The big car had given a most unwieldy lurch, wedged a tire in a rut, bounced a couple of times, and stopped—providentially—on the edge of the deep gully that fringed the road.

“It is nothing,” declared the young man, a bit stunned by the suddenness of the affair. The car, however, refusing to back, gave him the lie. Polly tore herself from his detaining arm and was out in the road.

“If you had an electric torch I could tell you what it is,” she said, trying to control both nerves and temper, 58 for she was both frightened and angry. “Have you?”

“I think so,” replied Pachuca, a little stiffly. “But, please, dear lady, do not get down in the dirt! I beg of you!”

“I don’t mind. I know every little pain an engine can have. I drove an emergency car at home during the war,” said Polly, curtly.

“Indeed?” Juan Pachuca’s voice was cool. The young lady was business-like—too business-like to flirt with—and yet——

“No, it’s not that.” Polly shook the curls out of her eyes and slammed the cover of the radiator. “Where do you think it is? You ought to know something about this car; you’ve been driving it.”

Pachuca’s eyes danced. What was the use of being stiff with an American? They were all alike—the men after money, and the women after what they called independence!

“I think,” he said, demurely, “that it must be attacked from underneath, if you will hold the torch.”

“All right.” Polly smiled. “Go ahead. If you can’t find it, I’ll try.”

Thus it was that Marc Scott’s first acquaintance with Polly Street came as he pulled the excited team to its haunches within a few feet of the automobile, and she, holding Juan Pachuca’s torch, jumped to her feet and faced him.

“Oh!” she cried, eagerly, “is that you, Bob?” Then, seeing more clearly, “I beg your pardon! 59 We’ve had trouble with the car, but we’ve fixed it and we’ll be out of the way in a moment.”

“I’m not Bob Street, but I’m from Athens, and I’m looking for Bob’s sister. I guess you must be her,” replied Scott. “Well, who are you?” he added, as Juan Pachuca’s legs emerged from the car, followed by his body.

“It’s not Mendoza—he’s sick,” volunteered Polly. “It’s a gentleman who was in the train and who kindly drove me over. Where is my brother?”

“Your letter only came to-night,” stammered Scott, “and in the same mail we had one from your brother in Douglas, saying he had been called East——”

“East!” The blow was too sudden; Polly’s legs collapsed. She sat down on the running-board of the machine and gasped. In the meantime Juan Pachuca stepped to the buckboard.

“It is Señor Scott?” he said pleasantly. “We have met before.”

Scott surveyed him thoughtfully. “Well, by the Lord, if it ain’t Johnny Pachuca! Of all the nerve——”

“Exactly,” grinned Pachuca, appreciatively. “You are surprised, eh? What are you going to do about it?”

“That depends upon how you’ve treated the young lady,” said Marc, quietly, “and on your general behavior,” he added, with a reciprocal grin.

“Haven’t I told you that he was kind enough to drive me over?” said Polly, impatiently. “And if——” 60

“That being the case,” replied Scott, “I don’t know as there’s anything I can do except say much obliged, and keep my eye on my horse-flesh. If you’ll get into the wagon, Miss ——”

“Oh, he’s all right,” said Pachuca, airily, as the girl hesitated. “He’s the manager of the Athens mine—Marc Scott—a very decent fellow. I regret being deprived of your company, señorita, but he evidently intends to take you back with him.”

“Any baggage?” demanded Scott, gruffly.

“One trunk,” replied Polly, rather dazed by the suddenness of the affair. “But it’s back at Conejo.”

“Want any help with that car?”

“No, thank you, the young lady and I have remedied the trouble.”

“Of course there’s no use in my asking if there’s any particular reason for your being in this neighborhood, Pachuca?”

“There is always a reason for my being where I am,” was the suave reply. “This time it does not concern you.”

“That’s good. No revolutions up your sleeve, eh?”

Pachuca chuckled. “I wouldn’t be too sure of that, amigo,” he said. “Would you take the advice of a friend, Marc Scott?”

“I might, if you’d guarantee he ain’t lying.”

“Then tell your people to close up their mine, take their women and get out of the country. There is trouble coming,” and the young Mexican bowed politely to the girl and returned to his machine. 61

“Now, what do you suppose the young devil meant by that?” demanded Scott, as he turned the team and faced the hill again. Polly’s eyes were wide open.

“Who is he?” she said, eagerly. “You seemed to know him. Does he really live near here?”

“I believe he has a ranch about here somewhere—some ways south. As to where he lives I reckon he could hardly tell you that himself.”

“But where did you know him?”

“I don’t know him. I don’t want to know him. The last time I saw him was when Villa stopped over with us on one of his retreats. This guy was with him. That little visit cost us a dozen good horses, two hundred dollars, and our winter’s supply of canned goods. He’s an expensive acquaintance, that fellow.”

Polly’s face was full of horror. “Do you mean,” she gasped, “that I’ve been riding around the country with a Mexican bandit?”

“Oh, I don’t know as I’d call him a bandit.”

“He told me that he was a colonel in the army!” indignantly.

“Well, he was, so I’ve heard. He’s been quite a lot of things. Maybe we’d better not talk about him any more to-night. It’s kind of exciting for you after all you’ve been through.”

“Exciting!” Polly sank back in her seat limply.

“He was all right to you, wasn’t he?” continued Scott, a little shyly. “Wasn’t fresh or anything like that?”

“Oh, yes, he was all right,” murmured the girl, quickly. 62

“These Mexicans are queer. You can’t tell what they’ll do,” went on Scott. “Sometimes they’ve got manners like the President of the United States, and the next time they’ll do something that’d disgrace a pirate. Take ’em all around as they go, I guess Pachuca stacks up pretty well. He’s educated and comes of good folks. But how the deuce did you happen——”

“Oh, I suppose it does sound awful!” Polly said, in a rush. “But he was on the train and when the horrid little thing stopped on the side of a hill for two hours, he came along and explained what was the matter.”

“He talks English like a Bostonese,” said Scott.

“Doesn’t he? And anything that sounds like Boston just naturally puts confidence in a Chicagoan, don’t you know? Then when I landed at Conejo in that wild sand-storm with no one to meet me and the Morgans out of town, he offered to drive me over, and I let him. It didn’t seem far; why, at home we often drive that far in an evening.”

“Well, driving around the boulevard with your friends is one thing, and around this sort of country with a strange Mexican is another.” Scott paused at the sight of the girl’s penitent face, and changed the subject. “As for your brother, we had a letter from him to-night saying that he and the bride had gone East. The directors sent for him, so they started pronto. I reckon Miss Emma’s folks coaxed them to stay in Douglas a few days after the wedding—we had expected them here before this.” 63

“But how did you know——”

Scott cleared his throat nervously. “Well, you see, he wrote me to read all his mail——” he stopped, abruptly. “Go on, Romeo!”

“I see. You opened my letter and found out that I was coming, and came to meet me. I am very much obliged to you.” The words were pleasant enough but the tone was cool.

“She’s on the trail,” Scott thought, disconsolately. “She’s running over in her mind what she said in that letter, and when she remembers, it’s going to be a good idea to get home as soon as possible.”

After this, the silence was extremely marked. Scott, feeling the discomfort of it, continued:

“It’s too bad for you to have had this long trip and then miss your brother after all, but I guess he’ll be back soon, the way things are looking.”

More silence, but Scott was not going to be scared out of his good intentions.

“I reckon we can make you pretty comfortable till he comes. We’ve got a mighty pleasant lady running the boarding-house just now and she’ll be glad enough to have another white woman on the place.”

The silence still continuing, he gave up. “Hang it, if she won’t talk, she won’t,” he thought. Then as he turned to tuck in a flying end of robe he saw the girl’s face. “Great guns, she’s asleep—poor kid!”