Project Gutenberg's Observations on the Florid Song, by Pier Francesco Tosi

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Observations on the Florid Song

or Sentiments on the Ancient and Modern Singers

Author: Pier Francesco Tosi

Translator: Johann Ernest Galliard

Release Date: August 29, 2008 [EBook #26477]

[Last updated: August 11, 2016]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OBSERVATIONS ON THE FLORID SONG ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[The spelling of the original has been retained.]

Ancient and Modern Singers,

Written in Italian

Of the Phil-Harmonic Academy

at Bologna.

Translated into English

Useful for all Performers, Instrumental as well as Vocal.

To which are added

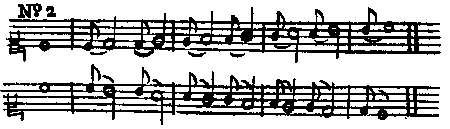

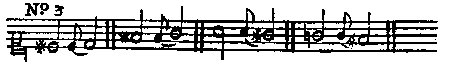

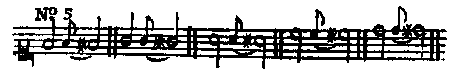

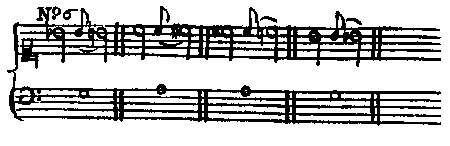

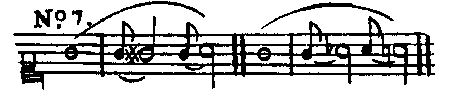

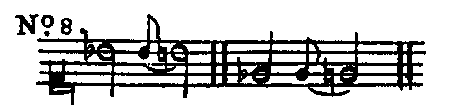

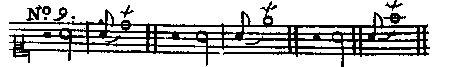

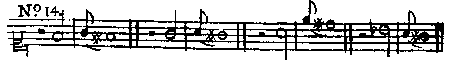

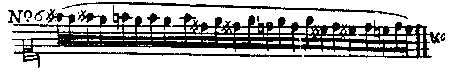

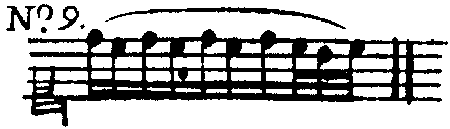

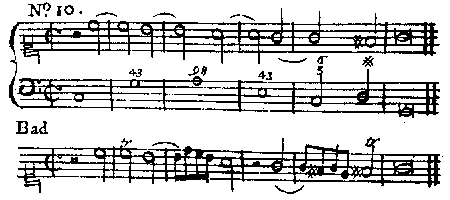

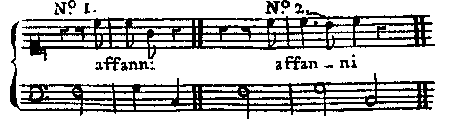

and Examples in Musick.

Ornari Res ipsa negat, contenta doceri.

Printed for J. Wilcox, at Virgil's Head, in

the Strand. 1743.

Note, By the Ancient, our Author

means those who liv'd about thirty

or forty Years ago; and by the

Modern the late and present Singers.

N.B. The Original was printed at

Bologna, in the Year 1723.

Reprinted from the Second Edition by

WILLIAM REEVES Bookseller Ltd.,

1a Norbury Crescent, London, S.W. 16

1967

Made in England

Ladies and Gentlemen,

ersons

of Eminence, Rank, Quality, and a distinguishing Taste in any

particular Art or Science, are always in View of Authors who want a

Patron for that Art or Science, which they endeavour to recommend and

promote. No wonder therefore, I should have fix'd my Mind on You, to

patronize the following Treatise.

ersons

of Eminence, Rank, Quality, and a distinguishing Taste in any

particular Art or Science, are always in View of Authors who want a

Patron for that Art or Science, which they endeavour to recommend and

promote. No wonder therefore, I should have fix'd my Mind on You, to

patronize the following Treatise.

If there are Charms in Musick in general, all the reasonable World agrees, that the Vocal has the Pre-eminence, both from Nature and Art above the Instrumental: From Nature because without doubt it was the first; from Art, because thereby the Voice may be brought to express Sounds with greater Nicety and Exactness than Instruments.

The Charms of the human Voice, even in Speaking, are very powerful. It is well known, that in Oratory a just Modulation of it is of the highest Consequence. The Care Antiquity took to bring it to Perfection, is a sufficient Demonstration of the Opinion they had of its Power; and every body, who has a discerning Faculty, may have experienced that sometimes a Discourse, by the Power of the Orator's Voice, has made an Impression, which was lost in the Reading.

But, above all, the soft and pleasing Voice of the fair Sex has irresistible Charms and adds considerably to their Beauty.

If the Voice then has such singular Prerogatives, one must naturally wish its Perfection in musical Performances, and be inclined to forward any thing that may be conducive to that end. This is the reason why I have been more easily prevail'd upon to engage in this Work, in order to make a famous Italian Master, who treats so well on this Subject, familiar to England; and why I presume to offer it to your Protection.

The Part, I bear in it, is not enough to claim any Merit; but my endeavouring to offer to your Perusal what may be entertaining, and of Service, intitles me humbly to recommend myself to your Favour: Who am,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Your most devoted,

And most obedient

Humble Servant,

J. E. Galliard.

GIVING

ier.

Francesco Tosi, the Author of the following Treatise, was an

Italian, and a Singer of great Esteem and Reputation. He spent the

most part of his Life in travelling, and by that Means heard the most

eminent Singers in Europe, from whence, by the Help of his nice

[viii]

Taste, he made the following Observations. Among his many Excursions,

his Curiosity was raised to visit England, where he resided for some

time in the Reigns of King James the Second, King William, King

George the First, and the Beginning of his present Majesty's: He dy'd

soon after, having lived to above Fourscore. He had a great deal of Wit

and Vivacity, which he retained to his latter Days. His manner of

Singing was full of Expression and Passion; chiefly in the Stile of

Chamber-Musick. The best Performers in his Time thought themselves happy

when they could have an Opportunity[ix]

to hear him. After he had lost his

Voice, he apply'd himself more particularly to Composition; of which he

has given Proof in his Cantata's, which are of an exquisite Taste,

especially in the Recitatives, where he excels in the Pathetick and

Expression beyond any other. He was a zealous Well-wisher to all who

distinguished themselves in Musick; but rigorous to those who abused and

degraded the Profession. He was very much esteemed by Persons of Rank

among whom the late Earl of Peterborough was one, having often met him

in his Travels beyond Sea; and he was well received by his Lordship

when in England,[x]

to Whom he dedicated this Treatise. This alone would

be a sufficient Indication of his Merit, his being taken Notice of by a

Person of that Quality, and distinguishing Taste. The Emperor Joseph

gave him an honourable Employment Arch-Duchess a Church-Retirement in

some part of Italy, and the late Flanders, where he died. As for his

Observations and Sentiments on Singing, they must speak for

themselves; and the Translation of them, it is hoped, will be acceptable

to Lovers of Musick, because this particular Branch has never been

treated of in so distinct and ample a Manner by any other Author[xi].

Besides, it has been thought by Persons of Judgment, that it would be of

Service to make the Sentiments of our Author more universally known,

when a false Taste in Musick is so prevailing; and, that these Censures,

as they are passed by an Italian upon his own Countrymen, cannot but

be looked upon as impartial. It is incontestable, that the Neglect of

true Study, the sacrificing the Beauty of the Voice to a Number of

ill-regulated Volubilities, the neglecting the Pronunciation and

Expression of the Words, besides many other Things taken Notice of in

this Treatise, are all bad. The Studious will find, that our Author's[xii]

Remarks will be of Advantage, not only to Vocal Performers, but likewise

to the Instrumental, where Taste and a Manner are required; and shew,

that a little less Fiddling with the Voice, and a little more

Singing with the Instrument, would be of great Service to Both.

Whosoever reads this Treatise with Application, cannot fail of

Improvement by it. It is hoped, that the Translation will be indulged,

if, notwithstanding all possible Care, it should be defective in the

Purity of the English Language! it being almost impossible

(considering the Stile of our Author, which is a little more figurative

than the present Taste of the English allows in their Writings,)

[xiii]

not

to retain something of the Idiom of the Original; but where the Sense of

the Matter is made plain, the Stile may not be thought so material, in

Writings of this Kind.

ier.

Francesco Tosi, the Author of the following Treatise, was an

Italian, and a Singer of great Esteem and Reputation. He spent the

most part of his Life in travelling, and by that Means heard the most

eminent Singers in Europe, from whence, by the Help of his nice

[viii]

Taste, he made the following Observations. Among his many Excursions,

his Curiosity was raised to visit England, where he resided for some

time in the Reigns of King James the Second, King William, King

George the First, and the Beginning of his present Majesty's: He dy'd

soon after, having lived to above Fourscore. He had a great deal of Wit

and Vivacity, which he retained to his latter Days. His manner of

Singing was full of Expression and Passion; chiefly in the Stile of

Chamber-Musick. The best Performers in his Time thought themselves happy

when they could have an Opportunity[ix]

to hear him. After he had lost his

Voice, he apply'd himself more particularly to Composition; of which he

has given Proof in his Cantata's, which are of an exquisite Taste,

especially in the Recitatives, where he excels in the Pathetick and

Expression beyond any other. He was a zealous Well-wisher to all who

distinguished themselves in Musick; but rigorous to those who abused and

degraded the Profession. He was very much esteemed by Persons of Rank

among whom the late Earl of Peterborough was one, having often met him

in his Travels beyond Sea; and he was well received by his Lordship

when in England,[x]

to Whom he dedicated this Treatise. This alone would

be a sufficient Indication of his Merit, his being taken Notice of by a

Person of that Quality, and distinguishing Taste. The Emperor Joseph

gave him an honourable Employment Arch-Duchess a Church-Retirement in

some part of Italy, and the late Flanders, where he died. As for his

Observations and Sentiments on Singing, they must speak for

themselves; and the Translation of them, it is hoped, will be acceptable

to Lovers of Musick, because this particular Branch has never been

treated of in so distinct and ample a Manner by any other Author[xi].

Besides, it has been thought by Persons of Judgment, that it would be of

Service to make the Sentiments of our Author more universally known,

when a false Taste in Musick is so prevailing; and, that these Censures,

as they are passed by an Italian upon his own Countrymen, cannot but

be looked upon as impartial. It is incontestable, that the Neglect of

true Study, the sacrificing the Beauty of the Voice to a Number of

ill-regulated Volubilities, the neglecting the Pronunciation and

Expression of the Words, besides many other Things taken Notice of in

this Treatise, are all bad. The Studious will find, that our Author's[xii]

Remarks will be of Advantage, not only to Vocal Performers, but likewise

to the Instrumental, where Taste and a Manner are required; and shew,

that a little less Fiddling with the Voice, and a little more

Singing with the Instrument, would be of great Service to Both.

Whosoever reads this Treatise with Application, cannot fail of

Improvement by it. It is hoped, that the Translation will be indulged,

if, notwithstanding all possible Care, it should be defective in the

Purity of the English Language! it being almost impossible

(considering the Stile of our Author, which is a little more figurative

than the present Taste of the English allows in their Writings,)

[xiii]

not

to retain something of the Idiom of the Original; but where the Sense of

the Matter is made plain, the Stile may not be thought so material, in

Writings of this Kind.

My Lord,

Should be afraid of leaving the World under the Imputation of

Ingratitude, should[xv]

I any longer defer publishing the very many

Favours, which Your Lordship so generously has bestow'd on me in

Italy, in Germany, in Flanders, in England; and principally at

your delightful Seat at Parson's-Green, where Your Lordship having

been pleased to do me the Honour of imparting to me your Thoughts with

Freedom, I have often had the Opportunity of admiring your extensive

Knowledge, which almost made me overlook the Beauty and Elegance of the

Place. The famous Tulip-Tree, in your Garden there is not so

surprising a Rarity, as the uncommon Penetration of your Judgment, which

has sometimes (I may say) foretold Events, which have afterwards come

to pass.[xvi] But what Return can I make for so great Obligations, when the

mentioning of them is doing myself an Honour, and the very

Acknowledgment has the Appearance of Vanity? It is better therefore to

treasure them up in my Heart, and remain respectfully silent; only

making an humble Request to Your Lordship that you will condescend

favourably to accept this mean Offering of my Observations; which I am

induc'd to make, from the common Duty which lies upon every Professor to

preserve Musick in its Perfection; and upon Me in particular, for having

been the first, or among the first, of those who discovered the noble

Genius of your potent and generous Nation for it.[xvii] However, I should not

have presum'd to dedicate them to a Hero adorn'd with such glorious

Actions, if Singing was not a Delight of the Soul, or if any one had a

Soul more sensible of its Charms. On which account, I think, I have a

just Pretence to declare myself, with profound Obsequiousness,

Should be afraid of leaving the World under the Imputation of

Ingratitude, should[xv]

I any longer defer publishing the very many

Favours, which Your Lordship so generously has bestow'd on me in

Italy, in Germany, in Flanders, in England; and principally at

your delightful Seat at Parson's-Green, where Your Lordship having

been pleased to do me the Honour of imparting to me your Thoughts with

Freedom, I have often had the Opportunity of admiring your extensive

Knowledge, which almost made me overlook the Beauty and Elegance of the

Place. The famous Tulip-Tree, in your Garden there is not so

surprising a Rarity, as the uncommon Penetration of your Judgment, which

has sometimes (I may say) foretold Events, which have afterwards come

to pass.[xvi] But what Return can I make for so great Obligations, when the

mentioning of them is doing myself an Honour, and the very

Acknowledgment has the Appearance of Vanity? It is better therefore to

treasure them up in my Heart, and remain respectfully silent; only

making an humble Request to Your Lordship that you will condescend

favourably to accept this mean Offering of my Observations; which I am

induc'd to make, from the common Duty which lies upon every Professor to

preserve Musick in its Perfection; and upon Me in particular, for having

been the first, or among the first, of those who discovered the noble

Genius of your potent and generous Nation for it.[xvii] However, I should not

have presum'd to dedicate them to a Hero adorn'd with such glorious

Actions, if Singing was not a Delight of the Soul, or if any one had a

Soul more sensible of its Charms. On which account, I think, I have a

just Pretence to declare myself, with profound Obsequiousness,

Your Lordship's

Most humble,

Most devoted and

Most oblig'd Servant,

Pier. Francesco Tosi.

he Introduction. he Introduction. |

Pag. 1 |

| CHAP. I. | |

| Observations for one who teaches a Soprano. | p. 10 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Of the Appoggiatura. | p. 31 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Of the Shake. | p. 41 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| On Divisions. | p. 51 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Of Recitative. | p. 66 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Observations for a Student. | p. 79 |

| CHAP. VII. | |

| Of Airs. | p. 91 |

| CHAP. VIII. | |

| Of Cadences. | p. 126 |

| CHAP. IX. | |

| Observations for a Singer. | p. 140 |

| CHAP. X. | |

| Of Passages or Graces. | p. 174 |

he

Opinions of the ancient Historians, on the Origin of Musick, are

various. Pliny believes that Amphion was the Inventor of it; the

Grecians maintain, that it was Dionysius; Polybius ascribes it to

the Arcadians; Suidas and Boetius give the Glory entirely to

Pythagoras; asserting, that from the Sound of three Hammers of

different Weights at a Smith's Forge, he found out the Diatonick; after

which Timotheus, the Milesian, added the[2] Chromatick, and

Olympicus, or Olympus, the Enharmonick Scale. However, we read in

holy Writ, that Jubal, of the Race of Cain, fuit Pater Canentium

Citharâ & Organo, the Father of all such as handle the Harp and Organ;

Instruments, in all Probability consisting of several harmonious Sounds;

from whence one may infer, Musick to have had its Birth very soon after

the World.

he

Opinions of the ancient Historians, on the Origin of Musick, are

various. Pliny believes that Amphion was the Inventor of it; the

Grecians maintain, that it was Dionysius; Polybius ascribes it to

the Arcadians; Suidas and Boetius give the Glory entirely to

Pythagoras; asserting, that from the Sound of three Hammers of

different Weights at a Smith's Forge, he found out the Diatonick; after

which Timotheus, the Milesian, added the[2] Chromatick, and

Olympicus, or Olympus, the Enharmonick Scale. However, we read in

holy Writ, that Jubal, of the Race of Cain, fuit Pater Canentium

Citharâ & Organo, the Father of all such as handle the Harp and Organ;

Instruments, in all Probability consisting of several harmonious Sounds;

from whence one may infer, Musick to have had its Birth very soon after

the World.

§ 2. To secure her from erring, she called to her Assistance many Precepts of the Mathematicks; and from the Demonstrations of her Beauties, by Means of Lines, Numbers, and Proportions, she was adopted her Child, and became a Science.

§ 3. It may reasonably be supposed that, during the Course of several thousand Years, Musick has always been the Delight of Mankind; since the excessive Pleasure, the Lacedemonians received from it, induced that Republick to exile the abovementioned Milesian, that the Spartans, freed from their Effeminacy,[3] might return again to their old Oeconomy.

§ 4. But, I believe, she never appeared with so much Majesty as in the last Centuries, in the great Genius of Palestrina, whom she left as an immortal Example to Posterity. And, in Truth, Musick, with the Sweetness of his Harmony, arrived at so high a Pitch (begging Pardon of the eminent Masters of our Days), that if she was ranked only in the Number of Liberal Arts, she might with Justice contest the Pre-eminence[1].[4]

§ 5. A strong Argument offers itself to me, from that wonderful Impression, that in so distinguished a Manner is made upon our Souls by Musick, beyond all other Arts; which leads us to believe that it is part of that Blessedness which is enjoyed in Paradise.

§ 6. Having premised these Advantages, the Merit of the Singer should likewise be distinguished, by reason of the particular Difficulties that attend him: Let a Singer have a Fund of Knowledge sufficient to perform readily any of the most difficult Compositions; let him have, besides, an excellent Voice, and know how to use it artfully; he will not, for all that, deserve a Character of Distinction, if he is wanting in a prompt Variation; a Difficulty which other Arts are not liable to.

§ 7. Finally, I say, that Poets[2],[5] Painters, Sculptors, and even Composers of Musick, before they expose their Works to the Publick, have all the Time requisite to mend and polish them; but the Singer that commits an Error has no Remedy; for the Fault is committed, and past Correction.

§ 8. We may then guess at but cannot describe, how great the Application must be of one who is obliged not to err, in unpremeditated Productions; and to manage a Voice, always in Motion, conformable to the Rules of an Art that is so difficult. I confess ingeniously, that every time I reflect on the Insufficiency of many Masters, and the infinite Abuses they introduce, which render the Application and Study of their Scholars ineffectual, I cannot but wonder, that among so many Professors of the first Rank, who have written so amply on[6] Musick in almost all its Branches, there has never been one, at least that I have heard of, who has undertaken to explain in the Art of Singing, any thing more than the first Elements, known to all, concealing the most necessary Rules for Singing well. It is no Excuse to say, that the Composers intent on Composition, the Performers on Instruments intent on their Performance, should not meddle with what concerns the Singer; for I know some very capable to undeceive those who may think so. The incomparable Zarlino, in the third part of his Harmonick Institution, chap. 46, just began to inveigh against those, who in his time sung with some Defects, but he stopped; and I am apt to believe had he gone farther, his Documents, though grown musty in two Centuries, might be of Service to the refined Taste of this our present time. But a more just Reproof is due to the Negligence of many celebrated Singers, who, having a superior Knowledge, can the less justify their Silence, even[7] under the Title of Modesty, which ceases to be a Virtue, when it deprives the Publick of an Advantage. Moved therefore, not by a vain Ambition, but by the Hopes of being of Service to several Professors, I have determined, not without Reluctance, to be the first to expose to the Eye of the World these my few Observations; my only End being (if I succeed) to give farther Insight to the Master, the Scholar, and the Singer.

§ 9. I will in the first Place, endeavour to shew the Duty of a Master, how to instruct a Beginner well; secondly, what is required of the Scholar; and, lastly, with more mature Reflections, to point out the way to a moderate Singer, by which he may arrive at greater Perfection. Perhaps my Enterprize may be term'd rash, but if the Effects should not answer my Intentions, I shall at least incite some other to treat of it in a more ample and correct Manner.

§ 10. If any should say, I might be dispensed with for not publishing[8] Things already known to every Professor, he might perhaps deceive himself; for among these Observations there are many, which as I have never heard them made by anybody else, I shall look upon as my own; and such probably they are, from their not being generally known. Let them therefore take their Chance, for the Approbation of those that have Judgment and Taste.

§ 11. It would be needless to say, that verbal Instructions can be of no Use to Singers, any farther than to prevent 'em from falling into Errors, and that it is Practice only can set them right. However, from the Success of these, I shall be encouraged to go on to make new Discoveries for the Advantage of the Profession, or (asham'd, but not surpriz'd) I will bear it patiently, if Masters with their Names to their Criticism should kindly publish my Ignorance, that I may be undeceiv'd, and thank them.

§ 12. But though it is my Design to Demonstrate a great Number[9] of Abuses and Defects of the Moderns to be met with in the Republick of Musick, in order that they may be corrected (if they can); I would not have those, who for want of Genius, or through Negligence in their Study, could not, or would not improve themselves, imagine that out of Malice I have painted all their Imperfections to the Life; for I solemnly protest, that though from my too great Zeal I attack their Errors without Ceremony, I have a Respect for their Persons; having learned from a Spanish Proverb, that Calumny recoils back on the Author. But Christianity says something more. I speak in general; but if sometimes I am more particular, let it be known, that I copy from no other Original than myself, where there has been, and still is Matter enough to criticize, without looking for it elsewhere.[10]

Observations for one who teaches a Soprano.[3]

he

Faults in Singing insinuate themselves so easily into the Minds of

young Beginners, and there are[11] such Difficulties in correcting them,

when grown into an Habit that it were to be wish'd, the ablest Singers

would undertake the Task of Teaching, they best knowing how to conduct

the Scholar from the first Elements to Perfection. But there being none,

(if I mistake not) but who abhor the Thoughts of it, we must reserve

them for those Delicacies of the Art, which enchant the Soul.

he

Faults in Singing insinuate themselves so easily into the Minds of

young Beginners, and there are[11] such Difficulties in correcting them,

when grown into an Habit that it were to be wish'd, the ablest Singers

would undertake the Task of Teaching, they best knowing how to conduct

the Scholar from the first Elements to Perfection. But there being none,

(if I mistake not) but who abhor the Thoughts of it, we must reserve

them for those Delicacies of the Art, which enchant the Soul.

§ 2. Therefore the first Rudiments necessarily fall to a Master of a lower Rank, till the Scholar can sing his part at Sight; whom one would at least wish to be an honest Man, diligent and experienced, without the Defects of singing through the Nose, or in the Throat, and that[12] he have a Command of Voice, some Glimpse of a good Taste, able to make himself understood with Ease, a perfect Intonation, and a Patience to endure the severe Fatigue of a most tiresome Employment.

§ 3. Let a Master thus qualified before he begins his Instructions, read the four Verses of Virgil, Sic vos non vobis, &c.[5] for they seem to be made[4][13] on Purpose for him, and after having considered them well, let him[14] consult his Resolution; because (to speak plainly) it is mortifying to help another to Affluence, and be in want of it himself. If the Singer should make his Fortune, it is but just the Master, to whom it has been owing, should be also a Sharer in it.

§ 4. But above all, let him hear with a disinterested Ear, whether the Person desirous to learn hath a Voice, and a Disposition; that he may not be obliged to give a strict Account to God, of the Parent's Money ill spent, and the Injury done to the Child, by the irreparable Loss of Time,[15] which might have been more profitably employed in some other Profession. I do not speak at random. The ancient Masters made a Distinction between the Rich, that learn'd Musick as an Accomplishment, and the Poor, who studied it for a Livelihood. The first they instructed out of Interest, and the latter out of Charity, if they discovered a singular Talent. Very few modern Masters refuse Scholars; and, provided they are paid, little do they care if their greediness ruins the Profession.

§ 5. Gentlemen Masters! Italy hears no more such exquisite Voices as in Times past, particularly among the Women, and to the Shame of the Guilty I'll tell the Reason: The Ignorance of the Parents does not let them perceive the Badness of the Voice of their Children, as their Necessity makes them believe, that to sing and grow rich is one and the same Thing, and to learn Musick, it is enough to have a pretty Face: "Can you make anything of her?"[16]

§ 6. You may, perhaps, teach them with their Voice——Modesty will not permit me to explain myself farther.

§ 7. The Master must want Humanity, if he advises a Scholar to do any thing to the Prejudice of the Soul.

§ 8. From the first Lesson to the last, let the Master remember, that he is answerable for any Omission in his Instructions, and for the Errors he did not correct.

§ 9. Let him be moderately severe, making himself fear'd, but not hated. I know, it is not easy to find the Mean between Severity and Mildness, but I know also, that both Extremes are bad: Too great Severity creates Stubbornness, and too great Mildness Contempt.

§ 10. I shall not speak of the Knowledge of the Notes, of their Value, of Time, of Pauses, of the Accidents, nor of other such trivial Beginnings, because they are generally known.[17]

§ 11. Besides the C Cliff, let the Scholar be instructed in all the other Cliffs, and in all their Situations, that he may not be liable to what often happens to some Singers, who, in Compositions Alla Capella,[6] know not how to distinguish the Mi from the Fa, without the Help of the Organ, for want of the Knowledge of the G Cliff; from whence such Discordancies arise in divine Service, that it is a Shame for those who grow old in their Ignorance. I must be so sincere to declare, that whoever does not give such essential Instructions, transgresses out of Omission, or out of Ignorance.[7]

§ 12. Next let him learn to read those in B Molle, especially in those[8][18] Compositions that have four Flats at the Cliff, and which on the sixth of the Bass require for the most part an accidental Flat, that the Scholar may find in them the Mi, which is not so easy to one who has studied but little, and thinks that all the Notes with a Flat are called Fa: for if that were true, it would be superfluous that the Notes should be six, when five of them have the same Denomination. The French use seven, and, by that additional Name, save their scholars the Trouble of learning the Mutations ascending or descending; but we Italians have but Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La; Notes which equally suffice throughout all the Keys, to one who knows how to read them.[9][19]

§ 13. Let the Master do his utmost, to make the Scholar hit and sound the Notes perfectly in Tune in Sol-Fa-ing. One, who has not a good Ear, should not undertake either to instruct, or to sing; it being intolerable to hear a Voice perpetually rise and fall discordantly. Let the Instructor reflect on it; for one that sings out of Tune loses all his other Perfections. I can truly say, that, except in some few Professors, that modern Intonation is very bad.

§ 14. In the Sol-Fa-ing, let him endeavour to gain by Degrees the high Notes, that by the Help of this Exercise he may acquire as much Compass of the Voice as possible. Let him take care, however, that the higher the Notes, the more it is necessary to touch them with Softness, to avoid Screaming.

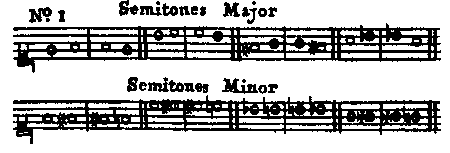

§ 15. He ought to make him hit the Semitones according to the true Rules. Every one knows not that there is a Semitone Major and Minor,[10][20] because the Difference cannot be known by an Organ or Harpsichord, if the Keys of the Instrument are not split. A Tone, that gradually passes to another, is divided into nine almost imperceptible Intervals, which are called Comma's, five of which constitute the Semitone Major, and four the Minor. Some are of Opinion, that there are no more than seven, and that the greatest Number of the one half constitutes the first, and the less the second; but this does not satisfy my weak Understanding, for the Ear would find no Difficulty to distinguish the seventh part of a Tone; whereas it meets with a very great one to distinguish the ninth. If one were continually to sing only to those abovemention'd Instruments, this Knowledge might be unnecessary; but since the time that Composers introduced the Custom of crowding the Opera's[21] with a vast Number of Songs accompanied with Bow Instruments, it becomes so necessary, that if a Soprano was to sing D sharp, like E flat, a nice Ear will find he is out of Tune, because this last rises. Whoever is not satisfied in this, let him read those Authors who treat of it, and let him consult the best Performers on the Violin. In the middle parts, however, it is not so easy to distinguish the Difference; tho' I am of Opinion, that every thing that is divisible, is to be distinguished. Of these two Semitones, I'll speak more amply in the Chapter of the Appoggiatura, that the one may not be confounded with the other.

§ 16. Let him teach the Scholar to hit the Intonation of any Interval in the Scale perfectly and readily, and keep him strictly to this important Lesson, if he is desirous he should sing with Readiness in a short time.

§ 17. If the Master does not understand Composition, let him provide himself with good Examples of[22] Sol-Fa-ing in divers Stiles, which insensibly lead from the most easy to the more difficult, according as he finds the Scholar improves; with this Caution, that however difficult, they may be always natural and agreeable, to induce the Scholar to study with Pleasure.

§ 18. Let the Master attend with great Care to the Voice of the Scholar, which, whether it be di Petto, or di Testa, should always come forth neat and clear, without passing thro' the Nose, or being choaked in the Throat; which are two the most horrible Defects in a Singer, and past all Remedy if once grown into a Habit[11].

§ 19. The little Experience of some that teach to Sol-fa, obliges the Scholar[23] to hold out the Semibreves with Force on the highest Notes; the Consequence of which is, that the Glands of the Throat become daily more and more inflamed, and if the Scholar loses not his Health, he loses the treble Voice.

§ 20. Many Masters put their Scholars to sing the Contr'Alto, not knowing how to help them to the Falsetto, or to avoid the Trouble of finding it.

§ 21. A diligent Master, knowing that a Soprano, without the Falsetto, is constrained to sing within the narrow Compass of a few Notes, ought not only to endeavour to help him to it, but also to leave no Means untried, so to unite the feigned and the natural Voice, that they may not be distinguished; for if they do not perfectly unite, the Voice will be of divers[12] Registers, and must consequently lose its Beauty. The Extent of[24] the full natural Voice terminates generally upon the fourth Space, which is C; or on the fifth Line, which is D; and there the feigned Voice becomes of Use, as well in going up to the high Notes, as returning to the natural Voice; the Difficulty consists in uniting them. Let the Master therefore consider of what Moment the Correction of this Defect is, which ruins the Scholar if he overlooks it. Among the Women, one hears sometimes a Soprano entirely di Petto, but among the Male Sex it would be a great Rarity, should they preserve it after having past the age of Puberty. Whoever would be curious to discover the feigned Voice of one who has the Art to disguise it, let him take Notice, that the Artist sounds the Vowel i, or e, with more Strength and less Fatigue than the Vowel a, on the high Notes.

§ 22. The Voce di Testa has a great Volubility, more of the high than the lower Notes, and has a quick Shake,[25] but subject to be lost for want of Strength.

§ 23. Let the Scholar be obliged to pronounce the Vowels distinctly, that they may be heard for such as they are. Some Singers think to pronounce the first, and you hear the second; if the Fault is not the Master's, it is of those Singers, who are scarce got out of their first Lessons; they study to sing with Affectation, as if ashamed to open their Mouths; others, on the contrary, stretching theirs too much, confound these two Vowels with the fourth, making it impossible to comprehend whether they have said Balla or Bella, Sesso or Sasso, Mare or More.

§ 24. He should always make the Scholar sing standing, that the Voice may have all its Organization free.

§ 25. Let him take care, whilst he sings, that he get a graceful Posture, and make an agreeable Appearance.

§ 26. Let him rigorously correct all Grimaces and Tricks of the Head, of the Body, and particularly of the[26] Mouth; which ought to be composed in a Manner (if the Sense of the Words permit it) rather inclined to a Smile, than too much Gravity.

§ 27. Let him always use the Scholar to the Pitch of Lombardy, and not that of Rome;[13] not only to make him acquire and preserve the high Notes, but also that he may not find it troublesome when he meets with Instruments that are tun'd high; the Pain of reaching them not only affecting the Hearer, but the Singer. Let the Master be mindful of this; for as Age advances, so the Voice declines; and, in Progress of Time, he will either sing a Contr'Alto, or pretending still, out of a foolish Vanity, to the Name of a Soprano, he will be obliged to make Application to every Composer, that the Notes may not exceed the fourth Space (viz., C) nor the Voice hold out on them. If all those, who teach the first Rudiments, knew[27] how to make use of this Rule, and to unite the feigned to the natural Voice, there would not be now so great a scarcity of Soprano's.

§ 28. Let him learn to hold out the Notes without a Shrillness like a Trumpet, or trembling; and if at the Beginning he made him hold out every Note the length of two Bars, the Improvement would be the greater; otherwise from the natural Inclination that the Beginners have to keep the Voice in Motion, and the Trouble in holding it out, he will get a habit, and not be able to fix it, and will become subject to a Flutt'ring in the Manner of all those that sing in a very bad Taste.

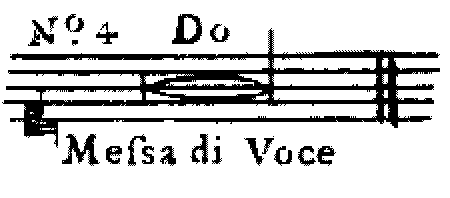

§ 29. In the same Lessons, let him teach the Art to put forth the Voice, which consists in letting it swell by Degrees from the softest Piano to the loudest Forte, and from thence with the same Art return from the Forte to the Piano. A beautiful Messa di[28] Voce,[14] from a Singer that uses it sparingly, and only on the open Vowels, can never fail of having an exquisite Effect. Very few of the present Singers find it to their Taste, either from the Instability of their Voice, or in order to avoid all Manner of Resemblance of the odious Ancients. It is, however, a manifest Injury they do to the Nightingale, who was the Origin of it, and the only thing which the Voice can well imitate. But perhaps they have found some other of the feathered Kind worthy their Imitation, that sings quite after the New Mode.

§ 30. Let the Master never be tired in making the Scholar Sol-Fa, as long as he finds it necessary; for if he[29] should let him sing upon the Vowels too soon, he knows not how to instruct.

§ 31. Next, let him study on the three open Vowels, particularly on the first, but not always upon the same, as is practised now-a-days; in order, that from this frequent Exercise he may not confound one with the other, and that from hence he may the easier come to the use of the Words.

§ 32. The Scholar having now made some remarkable Progress, the Instructor may acquaint him with the first Embellishments of the Art, which are the Appoggiatura's[15] (to be spoke of next) and apply them to the Vowels.

§ 33. Let him learn the Manner to glide with the Vowels, and to drag the Voice gently from the high to the lower Notes, which, thro' Qualifications necessary for singing well, cannot possibly be learn'd from Sol-fa-ing[30] only, and are overlooked by the Unskilful.

§ 34. But if he should let him sing the Words, and apply the Appoggiatura to the Vowels before he is perfect in Sol-fa-ing, he ruins the Scholar.[31]

Of the Appoggiatura.[17]

ong

all the Embellishments in the Art of Singing, there is none so

easy for the Master to teach, or less difficult for the Scholar to

learn,[32] than the Appoggiatura. This, besides its Beauty, has obtained

the sole Privilege of being heard often without tiring, provided it does

not go beyond the Limits prescrib'd by Professors of good Taste.

ong

all the Embellishments in the Art of Singing, there is none so

easy for the Master to teach, or less difficult for the Scholar to

learn,[32] than the Appoggiatura. This, besides its Beauty, has obtained

the sole Privilege of being heard often without tiring, provided it does

not go beyond the Limits prescrib'd by Professors of good Taste.

§ 2. From the Time that the Appoggiatura has been invented to adorn the Art of Singing, the true Reason,[18][33] why it cannot be used in all Places, remains yet a Secret. After having searched for it among Singers of the first Rank in vain, I considered that Musick, as a Science, ought to have its Rules, and that all Manner of Ways should be tried to discover them. I do not flatter myself that I am arrived at it; but the Judicious will see, at least that I am come near it. However, treating of a Matter wholly produced from my Observations, I should hope for more Indulgence in this Chapter than in any other.

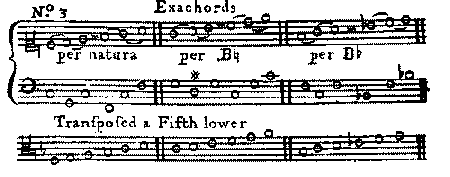

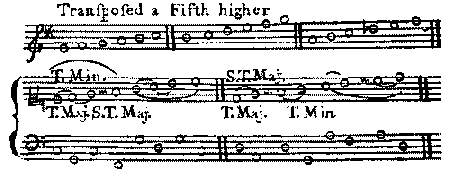

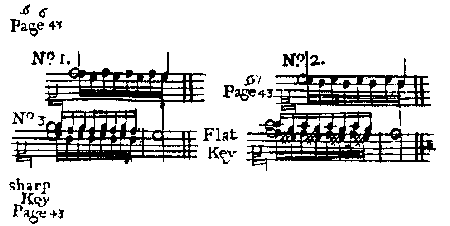

§ 3. From Practice, I perceive, that from C to C by B Quadro,[19] a Voice can ascend and descend gradually with the Appoggiatura, passing without any the least Obstacle thro' all the[34] five Tones, and the two Semitones, that make an Octave.

§ 4. That from every accidental Diezis, or Sharp, that may be found in the Scale, one can gradually rise a Semitone to the nearest Note with an Appoggiatura, and return in the same Manner.[20]

§ 5. That from every Note that has a B Quadro, or Natural, one can ascend by Semitones to every one that has a B Molle, or Flat, with an Appoggiatura.[21]

§ 6. But, contrarywise, my Ear tells me, that from F, G, A, C, and D, one cannot rise gradually with an Appoggiatura by Semitones,[22] when any of[35] these five Tones have a Sharp annex'd to them.

§ 7. That one cannot pass with an Appoggiatura gradually from a third Minor to the Bass, to a third Major, nor from the third Major to the third Minor.[23]

§ 8. That two consequent Appoggiatura's cannot pass gradually by Semitones from one Tone to another.[24]

§ 9. That one cannot rise by Semitone, with an Appoggiatura, from any Note with a Flat.[25]

§ 10. And, finally, where the Appoggiatura cannot ascend, it cannot descend.

§ 11. Practice giving us no Insight into the Reason of all these Rules, let us see if it can be found out by those who ought to account for it.[36]

§ 12. Theory teaches us, that the abovementioned Octave consisting of twelve unequal Semitones, it is necessary to distinguish the Major from the Minor, and it sends the Student to consult the Tetrachords. The most conspicuous Authors, that treat of them, are not all of the same Opinion: For we find some who maintain, that from C to D, as well as from F to G, the Semitones are equal; and mean while we are left in Suspense.[26]

§ 13. The Ear, however, which is the supreme Umpire in this Art, does in the Appoggiatura so nicely discern the Quality of the Semitones, that it sufficiently distinguishes the[37] Semitone Major. Therefore going so agreeably from Mi to Fa (that is) from B Quadro to C, or from E to F, one ought to conclude That to be a Semitone Major, as it undeniably is. But whence does it proceed, that from this very Fa, (that is from F or C) I cannot rise to the next Sharp, which is also a Semitone? It is Minor, says the Ear. Therefore I take it for granted, that the Reason why the Appoggiatura has not a full Liberty, is, that it cannot pass gradually to a Semitone Minor; submitting myself, however, to better Judgment.[27]

§ 14. The Appoggiatura may likewise pass from one distant Note to another, provided the Skip or Interval be not deceitful; for, in that Case,[38] whoever does not hit it sure, will show they know not how to sing.[28]

§ 15. Since, as I have said, it is not possible for a Singer to rise gradually with an Appoggiatura to a Semitone Minor, Nature will teach him to rise a Tone, that from thence he may descend with an Appoggiatura to that Semitone; or if he has a Mind to come to it without the Appoggiatura, to raise the Voice with a Messa di Voce, the Voice always rising till he reaches it.[29]

§ 16. If the Scholar be well instructed in this, the Appoggiatura's will become so familiar to him by continual Practice, that by the Time he is come out of his first Lessons, he will laugh at those Composers that[39] mark them, with a Design either to be thought Modern, or to shew that they understand the Art of Singing better than the Singers. If they have this Superiority over them, why do they not write down even the Graces, which are more difficult, and more essential than the Appoggiatura's? But if they mark them that they may acquire the glorious Name of a Virtuoso alla Moda, or a Composer in the new Stile, they ought at least to know, that the Addition of one Note costs little Trouble, and less Study. Poor Italy! pray tell me; do not the Singers now-a-days know where the Appoggiatura's are to be made, unless they are pointed at with a Finger? In my Time their own Knowledge shewed it them. Eternal Shame to him who first introduced these foreign Puerilities into our Nation, renowned for teaching others the greater part of the polite Arts; particularly, that of Singing! Oh, how great a[40] Weak ness in those that follow the Example! Oh, injurious Insult to your Modern Singers, who submit to Instructions fit for Children! Let us imitate the Foreigners in those Things only, wherein they excel.[30][41]

Of the Shake.

e

meet with two most powerful Obstacles informing the Shake. The

first embarrasses the Master; for, to this Hour there is no infallible

Rule found to teach it: And the second affects the Scholar, because

Nature imparts the Shake but to few. The Impatience of the Master

joins with the Despair of the Learner, so that they decline farther

Trouble about it. But in this the Master is blameable, in not doing his

Duty, by leaving the Scholar in Ignorance. One must strive against

Difficulties with Patience to overcome them.[42]

e

meet with two most powerful Obstacles informing the Shake. The

first embarrasses the Master; for, to this Hour there is no infallible

Rule found to teach it: And the second affects the Scholar, because

Nature imparts the Shake but to few. The Impatience of the Master

joins with the Despair of the Learner, so that they decline farther

Trouble about it. But in this the Master is blameable, in not doing his

Duty, by leaving the Scholar in Ignorance. One must strive against

Difficulties with Patience to overcome them.[42]

§ 2. Whether the Shake be necessary in Singing, ask the Professors of the first Rank, who know better than any others how often they have been indebted to it; for, upon any Absence of Mind, they would have betrayed to the Publick the Sterility of their Art, without the prompt Assistance of the Shake.

§ 3. Whoever has a fine Shake, tho' wanting in every other Grace, always enjoys the Advantage of conducting himself without giving Distaste to the End or Cadence, where for the most part it is very essential; and who wants it, or has it imperfectly, will never be a great Singer, let his Knowledge be ever so great.

§ 4. The Shake then, being of such Consequence, let the Master, by the Means of verbal Instructions, and Examples vocal and instrumental, strive that the Scholar may attain one that is equal, distinctly mark'd, easy, and moderately quick, which are its most beautiful Qualifications.[43]

§ 5. In case the Master should not know how many sorts of Shakes there are, I shall acquaint him, that the Ingenuity of the Professors hath found so many Ways, distinguishing them with different Names, that one may say there are eight Species of them.[31]

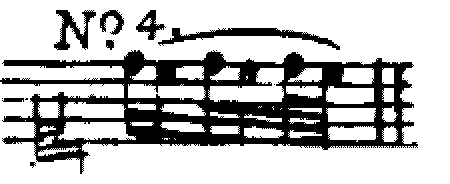

§ 6. The first is the Shake Major, from the violent Motion of two neighbouring Sounds at the Distance of a Tone, one of which may be called Principal, because it keeps with greater Force the Place of the Note which requires it; the other, notwithstanding it possesses in its Motion the superior Sound appears no other than an Auxiliary. From this Shake all the others are derived.[32]

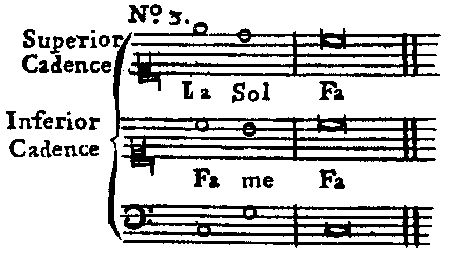

§ 7. The second is the Shake Minor,[44] consisting of a Sound, and its neighbouring Semitone Major; and where the one or the other of these, two Shakes are proper, the Compositions will easily shew. From the inferior or lower Cadences, the first, or full Tone Shake is for ever excluded.[33] If the Difference of these two Shakes is not easily discovered in the Singer, whenever it is with a Semitone, one may attribute the Cause to the want of Force of the Auxiliary to make itself heard distinctly; besides, this Shake being more difficult to be beat than the other, every body does not know how to make it, as it should be, and Negligence becomes a Habit. If this Shake is not distinguished in Instruments, the Fault is in the Ear.[34][45]

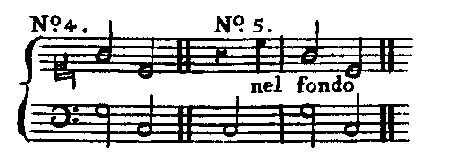

§ 8. The third is the Mezzo-trillo, or the short Shake, which is likewise known from its Name. One, who is Master of the first and second, with the Art of beating it a little closer, will easily learn it; ending it as soon as heard, and adding a little Brilliant. For this Reason, this Shake pleases more in brisk and lively Airs than in the Pathetick.[35]

§ 9. The fourth is the rising Shake, which is done by making the Voice ascend imperceptibly, shaking from Comma to Comma without discovering the Rise.[36]

§ 10. The fifth is the descending Shake, which is done by making the Voice decline insensibly from Comma to Comma, shaking in such Manner that the Descent be not distinguished. These two Shakes, ever since true[37][46] Taste has prevailed, are no more in Vogue, and ought rather to be forgot than learn'd. A nice Ear equally abhorrs the ancient dry Stuff, and the modern Abuses.

§ 11. The sixth is the slow Shake, whose Quality is also denoted by its Name. He, who does not study this, in my Opinion ought not therefore to lose the Name of a good Singer; for it being only an affected Waving, that at last unites with the first and second Shake, it cannot, I think, please more than once.[38]

§ 12. The seventh is the redoubled Shake, which is learned by mixing a few Notes between the Major or Minor Shake, which Interposition suffices to make several Shakes of one. This is beautiful, when those few Notes, so intermixed, are sung with Force. If then it be gently formed on the high Notes of an excellent Voice,[39][47] perfect in this rare Quality, and not made use of too often, it cannot displease even Envy itself.

§ 13. The eighth is the Trillo-Mordente, or the Shake with a Beat, which is a pleasing Grace in Singing, and is taught rather by Nature than by Art. This is produced with more Velocity than the others, and is no sooner born but dies. That Singer has a great Advantage, who from time to time mixes it in Passages or Divisions (of which I shall take Notice in the proper Chapter). He, who understands his Profession, rarely fails of using it after the Appoggiatura; and he, who despises it, is guilty of more than Ignorance.[40]

§ 14. Of all these Shakes, the two first are most necessary, and require most the Application of the Master. I know too well that it is customary to sing without Shakes; but the Example, of those who study but superficially, ought not to be imitated.[48]

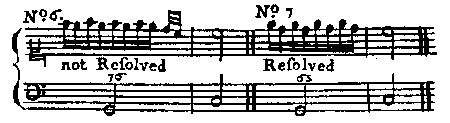

§ 15. The Shake, to be beautiful, requires to be prepared, though, on some Occasions, Time or Taste will not permit it. But on final Cadences, it is always necessary, now on the Tone, now on the Semitone above its Note, according to the Nature of the Composition.

§ 16. The Defects of the Shake are many. The long holding-out Shake triumph'd formerly, and very improperly, as now the Divisions do; but when the Art grew refined, it was left to the Trumpets, or to those Singers that waited for the Eruption of an E Viva! or Bravo! from the Populace. That Shake which is too often heard, be it ever so fine, cannot please. That which is beat with an uneven Motion disgusts; that like the Quivering of a Goat makes one laugh; and that in the Throat is the worst: That which is produced by a Tone and its third, is disagreeable; the Slow is tiresome; and that which is out of Tune is hideous.

§ 17. The Necessity of the Shake[49] obliges the Master to keep the Scholar applied to it upon all the Vowels, and on all the Notes he possesses; not only on Minims or long Notes, but likewise on Crotchets, where in Process of Time he may learn the Close Shake, the Beat, and the Forming them with Quickness in the Midst of the Volubility of Graces and Divisions.

§ 18. After the free Use of the Shake, let the Master observe if the Scholar has the same Facility in disusing it; for he would not be the first that could not leave it off at Pleasure.

§ 19. But the teaching where the Shake is convenient, besides those on[41][50] Cadences, and where they are improper and forbid, is a Lesson reserv'd for those who have Practice, Taste, and Knowledge.[51]

On Divisions.

ho'

Divisions have not Power sufficient to touch the Soul, but the

most they can do is to raise our Admiration of the Singer for the happy

Flexibility of his Voice; it is, however, of very great Moment, that the

Master instruct the Scholar in them, that he may be Master of them with

an easy Velocity and true Intonation; for when they are well executed in

their proper Place, they deserve Applause, and make a Singer more

universal; that is to say, capable to sing in any Stile.

ho'

Divisions have not Power sufficient to touch the Soul, but the

most they can do is to raise our Admiration of the Singer for the happy

Flexibility of his Voice; it is, however, of very great Moment, that the

Master instruct the Scholar in them, that he may be Master of them with

an easy Velocity and true Intonation; for when they are well executed in

their proper Place, they deserve Applause, and make a Singer more

universal; that is to say, capable to sing in any Stile.

§ 2. By accustoming the Voice of a Learner to be lazy and dragging, he[52] is rendered incapable of any considerable Progress in his Profession. Whosoever has not the Agility of Voice, in Compositions of a quick or lively Movement, becomes odiously tiresome; and at last retards the Time so much, that every thing he sings appears to be out of Tune.

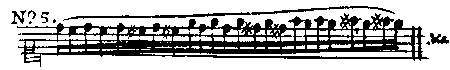

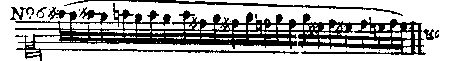

§ 3. Division, according to the general Opinion, is of two Kinds, the Mark'd, and the Gliding; which last, from its Slowness and Dragging, ought rather to be called a Passage or Grace, than a Division.

§ 4. In regard to the first, the Master ought to teach the Scholar that light Motion of the Voice, in which the Notes that constitute the Division be all articulate in equal Proportion, and moderately distinct, that they be not too much join'd, nor too much mark'd.[42][53]

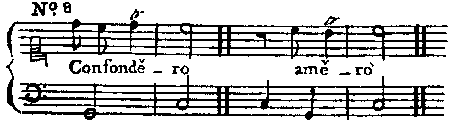

§ 5. The second is perform'd in such a Manner that the first Note is a Guide to all that follow, closely united, gradual, and with such Evenness of Motion, that in Singing it imitates a certain Gliding, by the Masters called a Slur; the Effect of which is truly agreeable when used sparingly.[43]

§ 6. The mark'd Divisions, being more frequently used than the others, require more Practice.

§ 7. The Use of the Slur is pretty much limited in Singing, and is confined within such few Notes ascending or descending, that it cannot go beyond a fourth without displeasing. It seems to me to be more grateful to the Ear descending, than in the contrary Motion.

§ 8. The Dragg consists in a Succession of divers Notes, artfully mixed with the Forte and Piano. The Beauty of which I shall speak of in another Place.[54]

§ 9. If the Master hastens insensibly the Time when the Scholar sings the Divisions, he will find that there is not a more effectual way to unbind the Voice, and bring it to a Volubility; being however cautious, that this imperceptible Alteration do not grow by Degrees into a vicious Habit.

§ 10. Let him teach to hit the Divisions with the same Agility in ascending gradually, as in descending; for though this seems to be an Instruction fit only for a Beginner, yet we do not find every Singer able to perform it.

§ 11. After the gradual Divisions, let him learn to hit, with the greatest Readiness, all those that are of difficult Intervals, that, being in Tune and Time, they may with Justice deserve our Attention. The Study of this Lesson demands more Time and Application than any other, not so much for the great Difficulty in attaining it, as the important Consequences that attend it; and, in Fact, a Singer[55] loses all Fear when the most difficult Divisions are become familiar to him.

§ 12. Let him not be unmindful to teach the Manner of mixing the Piano with the Forte in the Divisions; the Glidings or Slurs with the Mark'd, and to intermix the Close Shake; especially on the pointed Notes, provided they be not too near one another; making by this Means every Embellishment of the Art appear.

§ 13. Of all the Instructions relating to Divisions, the most considerable seems to be That, which teaches to unite the Beats and short Shake with them; and that the Master point out to him, how to execute them with Exactness of Time, and the Places where they have the best Effect: But this being not so proper for one who teaches only the first Rules, and still less for him that begins to learn them, it would be better to have postponed this (as perhaps I should have done) did I not know,[56] that there are Scholars of so quick Parts, that in a few Years become most excellent Singers, and that there is no want of Masters qualified to instruct Disciples of the most promising Genius; besides, it appeared to me an Impropriety in this Chapter on Divisions (in which the Beats and Close Shake appear with greater Lustre than any other Grace) not to make Mention of them.

§ 14. Let the Scholar not be suffered to sing Divisions with Unevenness of Time or Motion; and let him be corrected if he marks them with the Tongue, or with the Chin, or any other Grimace of the Head or Body.

§ 15. Every Master knows, that on the third and fifth Vowel, the Divisions are the worst; but every one does not know, that in the best Schools the second and fourth were not permitted, when these two Vowels are pronounced close or united.

§ 16. There are many Defects in the Divisions, which it is necessary[57] to know, in order to avoid them; for, besides that of the Nose or the Throat, and the others already mentioned, those are likewise displeasing which are neither mark'd nor gliding; for in that Case they cannot be said to sing, but howl and roar. There are some still more ridiculous, who mark them above Measure, and with Force of Voice, thinking (for Example) to make a Division upon A, it appears as if they said Ha, Ha, Ha, or Gha, Gha, Gha; and the same upon the other Vowels. The worst Fault of all is singing them out of Tune.

§ 17. The Master should know, that though a good Voice put forth with Ease grows better, yet by too swift a Motion in Divisions it becomes an indifferent one, and sometimes by the Negligence of the Master, to the Prejudice of the Scholar, it is changed into a very bad one.

§ 18. Divisions and Shakes in a Siciliana are Faults, and Glidings and Draggs are Beauties.[58]

§ 19. The sole and entire Beauty of the Division consists in its being perfectly in Tune, mark'd, equal, distinct, and quick.

§ 20. Divisions have the like Fate with the Shakes; both equally delight in their Place; but if not properly introduced, the too frequent Repetition of them becomes tedious if not odious.

§ 21. After the Scholar has made himself perfect in the Shake and the Divisions, the Master should let him read and pronounce the Words, free from those gross and ridiculous Errors of Orthography, by which many deprive one Word of its double Consonant, and add one to another, in which it is single.[44]

§ 22. After having corrected the Pronunciation, let him take Care that the Words be uttered in such a Manner, without any Affectation that[59] they be distinctly understood, and no one Syllable be lost; for if they are not distinguished, the Singer deprives the Hearer of the greatest Part of that Delight which vocal Musick conveys by Means of the Words. For, if the Words are not heard so as to be understood, there will be no great Difference between a human Voice and a Hautboy. This Defect, tho' one of the greatest, is now-a-days more than common, to the greatest Disgrace of the Professors and the Profession; and yet they ought to know, that the Words only give the Preference to a Singer above an instrumental Performer, admitting them to be of equal Judgment and Knowledge. Let the modern Master learn to make use of this Advice, for never was it more necessary than at present.

§ 23. Let him exercise the Scholar to be very ready in joining the Syllables to the Notes, that he may never be at a Loss in doing it.[60]

§ 24. Let him forbid the Scholar to take Breath in the Middle of a Word, because the dividing it in two is an Error against Nature; which must not be followed, if we would avoid being laugh'd at. In interrupted Movements, or in long Divisions, it is not so rigorously required, when the one or the other cannot be sung in one Breath. Anciently such Cautions were not necessary, but for the Learners of the first Rudiments; now the Abuse, having taken its Rise in the modern Schools, gathers Strength, and is grown familiar with those who pretend to Eminence. The Master may correct this Fault, in teaching the Scholar to manage his Respiration, that he may always be provided with more Breath than is needful; and may avoid undertaking what, for want of it, he cannot go through with.

§ 25. Let him shew, in all sorts of Compositions, the proper Place where to take Breath, and without Fatigue; because there are Singers who give[61] Pain to the Hearer, as if they had an Asthma taking Breath every Moment with Difficulty, as if they were breathing their last.

§ 26. Let the Master create some Emulation in a Scholar that is negligent, inciting him to study the Lesson of his Companion, which sometimes goes beyond Genius; because, if instead of one Lesson he hears two, and the Competition does not discountenance him, he may perhaps come to learn his Companion's Lesson first, and then his own.

§ 27. Let him never suffer the Scholar to hold the Musick-Paper, in Singing, before his Face, both that the Sound of the Voice may not be obstructed, and to prevent him from being bashful.

§ 28. Let him accustom the Scholar to sing often in presence of Persons of Distinction, whether from Birth, Quality, or Eminence in the Profession, that by gradually losing his Fear, he may acquire an Assurance, but not a Boldness. Assurance[62] leads to a Fortune, and in a Singer becomes a Merit. On the contrary, the Fearful is most unhappy; labouring under the Difficulty of fetching Breath, the Voice is always trembling, and obliged to lose Time at every Note for fear of being choaked; He gives us Pain, in not being able to shew his Ability in publick; disgusts the Hearer, and ruins the Compositions in such a Manner, that they are not known to be what they are. A timorous Singer is unhappy, like a Prodigal, who is miserably poor.

§ 29. Let not the Master neglect to shew him, how great their Error is who make Shakes or Divisions, or take Breath on the syncopated or binding Notes; and how much better Effect the holding out the Voice has. The Compositions, instead of losing, acquire thereby greater Beauty.[45]

§ 30. Let the Master instruct him in the Forte and Piano, but so as to[63] use him more to the first than the second, it being easier to make one sing soft than loud. Experience shews that the Piano is not to be trusted to, since it is prejudicial though pleasing; and if any one has a Mind to lose his Voice, let him try it. On this Subject some are of Opinion, that there is an artificial Piano, that can make itself be heard as much as the Forte; but that is only Opinion, which is the Mother of all Errors. It is not Art which is the Cause that the Piano of a good Singer is heard, but the profound Silence and Attention of the Audience. For a Proof of this, let any indifferent Singer be silent on the Stage for a Quarter of a Minute when he should sing, the Audience, curious to know the Reason of this unexpected Pause, are hush'd in such a Manner, that if in that Instant he utter one Word with a soft Voice, it would be heard even by those at the greatest Distance.

§ 31. Let the Master remember, that whosoever does not sing to the[64] utmost Rigour of Time, deserves not the Esteem of the Judicious; therefore let him take Care, there be no Alteration or Diminution in it, if he pretends to teach well, and to make an excellent Scholar.

§ 32. Though in certain Schools, Books of Church-Musick and of Madrigals lie buried in Dust, a good Master would wipe it off; for they are the most effectual Means to make a Scholar ready and sure. If Singing was not for the most part performed by Memory, as is customary in these Days, I doubt whether certain Professors could deserve the Name of Singers of the first Rank.[46]

§ 33. Let him encourage the Scholar if he improves; let him mortify him, without Beating, for Indolence; let him be more rigorous for Negligences; nor let the Scholar ever end a[65] Lesson without having profited something.

§ 34. An Hour of Application in a Day is not sufficient, even for one of the quickest Apprehension; the Master therefore should consider how much more Time is necessary for one that has not the same Quickness, and how much he is obliged to consult the Capacity of his Scholar. From a mercenary Teacher this necessary Regard is not to be hoped for; expected by other Scholars, tired with the Fatigue, and solicited by his Necessities, he thinks the Month long; looks on his Watch, and goes away. If he be but poorly paid for his Teaching,—a God-b'wy to him.[66]

Of Recitative.

ecitative

is of three Kinds, and ought to be taught in three

different Manners.

ecitative

is of three Kinds, and ought to be taught in three

different Manners.

§ 2. The first, being used in Churches, should be sung as becomes the Sanctity of the Place, which does not admit those wanton Graces of a lighter Stile; but requires some Messa di Voce, many Appoggiatura's, and a noble Majesty throughout. But the Art of expressing it, is not to be learned, but from the affecting Manner of those who devoutly dedicate their Voices to the Service of God.

§ 3. The second is Theatrical, which being always accompanied[67] with Action by the Singer, the Master is obliged to teach the Scholar a certain natural Imitation, which cannot be beautiful, if not expressed with that Decorum with which Princes speak, or those who know how to speak to Princes.

§ 4. The last, according to the Opinion of the most Judicious, touches the Heart more than the others, and is called Recitativo di Camera. This requires a more peculiar Skill, by reason of the Words, which being, for the most part, adapted to move the most violent Passions of the Soul, oblige the Master to give the Scholar such a lively Impression of them, that he may seem to be affected with them himself. The Scholar having finished his Studies, it will be but too[47][68] easily discovered if he stands in Need of this Lesson. The vast Delight, which the Judicious feel, is owing to this particular Excellence, which, without the Help of the usual Ornaments, produces all this Pleasure from itself; and, let Truth prevail, where Passion speaks, all Shakes, all Divisions and Graces ought to be silent, leaving it to the sole Force of a beautiful Expression to persuade.

§ 5. The Church Recitative yields more Liberty to the Singer than the other two, particularly in the final Cadence; provided he makes the Advantage of it that a Singer should do, and not as a Player on the Violin.

§ 6. The Theatrical leaves it not in our Election to make Use of this Art, lest we offend in the Narrative, which ought to be natural, unless in a Soliloquy, where it may be in the Stile of Chamber-Musick.

§ 7. The third abstains from great part of the Solemnity of the first, and[69] contents itself with more of the second.

§ 8. The Defects and unsufferable Abuses which are heard in Recitatives, and not known to those who commit them, are innumerable. I will take Notice of several Theatrical ones, that the Master may correct them.

§ 9. There are some who sing Recitative on the Stage like That of the Church or Chamber; some in a perpetual Chanting, which is insufferable; some over-do it and make it a Barking; some whisper it, and some sing it confusedly; some force out the last Syllable, and some sink it; some sing it blust'ring, and some as if they were thinking of something else; some in a languishing Manner; others in a Hurry; some sing it through the Teeth, and others with Affectation; some do not pronounce the Words, and others do not express them; some sing as if laughing, and some crying; some speak it, and some hiss it; some hallow, bellow, and sing it out[70] of Tune; and, together with their Offences against Nature, are guilty of the greatest Fault, in thinking themselves above Correction.

§ 10. The modern Masters run over with Negligence their Instructions in all Sorts of Recitatives, because in these Days the Study of Expression is looked upon as unnecessary, or despised as ancient: And yet they must needs see every Day, that besides the indispensable Necessity of knowing how to sing them, These even teach how to act. If they will not believe it, let them observe, without flattering themselves, if among their Pupils they can show an Actor of equal Merit with Cortona in the Tender;[48] of Baron Balarini in the Imperious; or other famous Actors that at present appear, tho' I name them not; having determined in these Observations, not to mention[71] any that are living, in whatsoever Degree of Perfection they be, though I esteem them as they deserve.

§ 11. A Master, that disregards Recitative, probably does not understand the Words, and then, how can he ever instruct a Scholar in Expression, which is the Soul of vocal Performance, and without which it is impossible to sing well? Poor Gentlemen Masters who direct and instruct Beginners, without reflecting on the utter Destruction you bring on the Science, in undermining the principal Foundations of it! If you know not that the Recitatives, especially in the vulgar or known Language, require those Instructions relative to the Force of the Words, I would advise you to renounce the Name, and Office of Masters, to those who can maintain them; your Scholars will otherwise be made a Sacrifice to Ignorance, and not knowing how to distinguish the Lively from the Pathetick, or the Vehement from the Tender, it will be no wonder if you see them stupid[72] on the Stage, and senseless in a Chamber. To speak my Mind freely, yours and their Faults are unpardonable; it is insufferable to be any longer tormented in the Theatres with Recitatives, sung in the Stile of a Choir of Capuchin Friars.

§ 12. The reason, however, of not giving more expression to the Recitative, in the manner of those called Antients, does not always proceed from the Incapacity of the Master, or the Negligence of the Singer, but from the little Knowledge of the modern Composers (we must except some of Merit) who set it in so unnatural a Taste, that it is not to be taught, acted or sung. In Justification of the Master and the Singer let Reason decide. To blame the Composer, the same Reason forbids me entering into a Matter too high for my low Understanding, and wisely bids me consider the little Insight I can boast of, barely sufficient for a Singer, or to write plain Counterpoint. But when I consider I have undertaken in these[73] Observations, to procure diverse Advantages to vocal Performers, should I not speak of a Composition, a Subject so necessary, I should be guilty of a double Fault. My Doubts in this Perplexity are resolved by the Reflection, that Recitatives have no Relation to Counterpoint. If That be so, what Professor knows not, that many theatrical Recitatives would be excellent if they were not confused one with another; if they could be learned by Heart; if they were not deficient in respect of adapting the Musick to the Words; if they did not frighten those who sing them, and hear them, with unnatural Skips; if they did not offend the Ear and Rules with the worst Modulations; if they did not disgust a good Taste with a perpetual Sameness; if, with their cruel Turns and Changes of Keys, they did not pierce one to the Heart; and, finally, if the Periods were not crippled by them who know neither Point nor Comma? I am astonished that such as these do not, for their Improvement,[74] endeavour to imitate the Recitatives of those Authors, who represent in them a lively image of Nature, by Sounds which of themselves express the Sense, as much as the very Words. But to what Purpose do I show this Concern about it? Can I expect that these Reasons, with all their Evidences, will be found good, when, even in regard to Musick, Reason itself is no more in the Mode? Custom has great Power. She arbitrarily releases her Followers from the Observance of the true Rules, and obliges them to no other Study than that of the Ritornello's, and will not let them uselessly employ their precious Time in the Application to Recitative, which, according to her Precepts, are the work of the Pen, not of the Mind. If it be Negligence or Ignorance, I know not; but I know very well, that the Singers do not find their Account in it.

§ 13. Much more might still be[49][75] said on the Compositions of Recitative in general, by reason of that tedious chanting that offends the Ear, with a thousand broken Cadences in every Opera, which Custom has established, though they are without Taste or Art. To reform them all, would be worse than the Disease; the introducing every time a final Cadence would be wrong: But if in these two Extremes a Remedy were necessary I should think, that among an hundred broken Cadences, ten of them, briefly terminated on Points that conclude a Period, would not be ill employed. The Learned, however, do not declare themselves upon it, and from their Silence I must hold myself condemned.

§ 14. I return to the Master, only to put him in Mind, that his Duty is to teach Musick; and if the Scholar, before he gets out of his Hands, does not sing readily and at Sight, the Innocent is injured without Remedy from the Guilty.[76]

§ 15. If after these Instructions, the Master does really find himself capable of communicating to his Scholar Things of greater Moment, and what may concern his farther Progress, he ought immediately to initiate him in the Study of Church-Airs, in which he must lay aside all the theatrical effeminate Manner, and sing in a manly Stile; for which Purpose he will provide him with different natural and easy Motets[50] grand and genteel, mix'd with the Lively and the Pathetick, adapted to the Ability he has discovered in him, and by frequent Lessons make him become perfect in them with Readiness and Spirit. At the same time he must be careful that the Words be well pronounced, and perfectly understood; that the Recitatives be expressed with Strength, and supported without Affectation; that in the Airs he be not wanting in Time, and in introducing some Graces of good Taste; and, above all, that[77] the final Cadences of the Motets be performed with Divisions distinct, swift, and in Tune. After this he will teach him that Manner, the Taste of Cantata's requires, in order, by this Exercise, to discover the Difference between one Stile and another. If, after this, the Master is satisfied with his Scholar's Improvement, yet let him not think to make him sing in Publick, before he has the Opinion of such Persons, who know more of singing than of flattering; because, they not only will chuse such Compositions proper to do him Honour and Credit, but also will correct in him those Defects and Errors, which out of Oversight or Ignorance the Master had not perceived or corrected.

§ 16. If Masters did consider, that from our first appearing in the Face of the World, depends our acquiring Fame and Courage, they would not so blindly expose their Pupils to the Danger of falling at the first Step.[78]

§ 17. But if the Master's Knowledge extends no farther than the foregoing Rules, then ought he in conscience to desist, and to recommend the Scholar to better Instructions. However, before the Scholar arrives at this, it will not be quite unnecessary to discourse with him in the following Chapters, and if his Age permits him not to understand me, those, who have the Care of him, may.[79]

Observations for a Student.

efore

entering on the extensive and difficult Study of the Florid, or

figured Song, it is necessary to consult the Scholar's Genius; for if

Inclination opposes, it is impossible to force it, and when That

incites, the Scholar proceeds with Ease and Pleasure.

efore

entering on the extensive and difficult Study of the Florid, or

figured Song, it is necessary to consult the Scholar's Genius; for if

Inclination opposes, it is impossible to force it, and when That

incites, the Scholar proceeds with Ease and Pleasure.

§ 2. Supposing, then, that the Scholar is earnestly desirous of becoming a Master in so agreable a Profession, and being fully instructed in these tiresome Rudiments, besides many others that may have slipt my weak Memory; after a strict Care of his Morals, he should give the rest of[80] his Attention to the Study of singing in Perfection, that by this Means he may be so happy as to join the most noble Qualities of the Soul to the Excellencies of his Art.

§ 3. He that studies Singing must consider that Praise or Disgrace depends very much on his Voice which if he has a Mind to preserve he must abstain from all Manner of Disorders, and all violent Diversions.

§ 4. Let him be able to read perfectly, that he may not be put to Shame for so scandalous an Ignorance. Oh, how many are there, who had need to learn the Alphabet!

§ 5. In case the Master knows not how to correct the Faults in Pronunciation, let the Scholar endeavour to learn the best by some other Means; because the not being born[51][81] in Tuscany, will not excuse the Singer's Imperfection.

§ 6. Let him likewise very carefully endeavour to correct all other Faults that the Negligence of his Master may have passed over.

§ 7. With the Study of Musick, let him learn also at least the Grammar, to understand the Words he is to sing in Churches, and to give the proper Force to the Expression in both Languages. I believe I may be so bold to say, that divers Professors do not even understand their own Tongue, much less the Latin.[52]

§ 8. Let him continually, by himself, use his Voice to a Velocity of Motion, if he thinks to have a Command over it, and that he may not go by the Name of a pathetick Singer.

§ 9. Let him not omit frequently to put forth, and to stop, the Voice,[82] that it may always be at his Command.