The Project Gutenberg EBook of Shakespeare's Family, by Mrs. C. C. Stopes This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Shakespeare's Family Author: Mrs. C. C. Stopes Release Date: August 14, 2008 [EBook #26315] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SHAKESPEARE'S FAMILY *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Josephine Paolucci, Janet Blenkinship and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.)

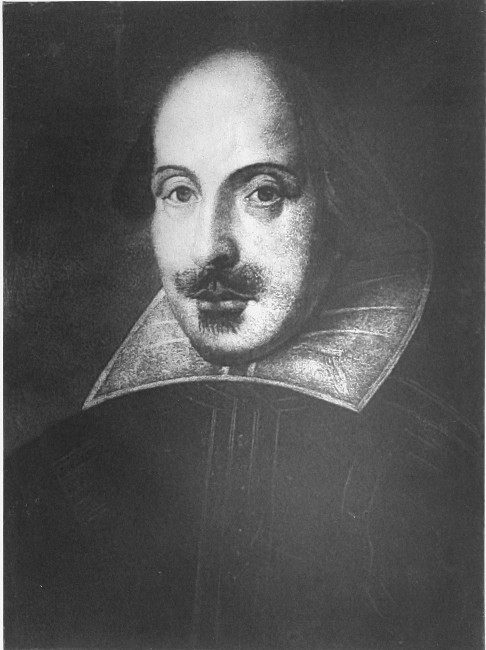

William Shakespeare from the Drocshout painting now in

the Shakespeare Memorial Gallery at Stratford-on-Avon.

William Shakespeare from the Drocshout painting now in

the Shakespeare Memorial Gallery at Stratford-on-Avon.

LONDON

ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

NEW YORK

JAMES POTT & COMPANY

1901

When I was invited to reprint in book-form the articles which had appeared in the Genealogical Magazine under the titles of "Shakespeare's Family" and the "Warwickshire Ardens," I carefully corrected them, and expanded them where expansion could be made interesting. Thus to the bald entries of Shakespeare's birth and burial I added a short life. Perhaps never before has anyone attempted to write a life of the poet with so little allusion to his plays and poems. My reason is clear; it is only the genealogical details of certain Warwickshire families of which I now treat, and it is only as an interesting Warwickshire gentleman that the poet is here included.

Much of the chaotic nonsense that has of late years been written to disparage his character and contest his claims to our reverence and respect are based on the assumption that he was a man of low origin and of mean occupation. I deny any relevance to arguments based on such an assumption, for genius is restricted to no class, and we have a Burns as well as a Chaucer, a Keats as well as a Gower, yet I am glad that the result of my studies tends to prove that it is but an unfounded [Pg vi]assumption. By the Spear-side his family was at least respectable, and by the Spindle-side his pedigree can be traced straight back to Guy of Warwick and the good King Alfred. There is something in fallen fortune that lends a subtler romance to the consciousness of a noble ancestry, and we may be sure this played no small part in the making of the poet.

All that bear his name gain a certain interest through him, and therefore I have collected every notice I can find of the Shakespeares, though we are all aware none can be his descendants, and that the family of his sister can alone now enter into the poet's pedigree with any degree of certainty.

The time for romancing has gone by, and nothing more can be done concerning the poet's life except through careful study and through patient research. All students must regret that their labours have such comparatively meagre results. Though sharing in this regret, I have been able, besides adding minor details, to find at last a definite link of association between the Park Hall and the Wilmcote Ardens; and I have located a John Shakespeare in St. Clement's Danes, Strand, London, who is probably the poet's cousin. I have also somewhat cleared the ground by checking errors, such as those made by Halliwell-Phillipps, concerning John Shakespeare, of Ingon, and Gilbert Shakespeare, Haberdasher, of London (see page 226). I hope that every contribution to our store of real knowledge may bring forward new suggestions and additional facts.

In regard to his mother's family, I thought it important to clear the earlier connections. But it must not be forgotten that until modern times no[Pg vii] Shakespeare but himself was connected with the Ardens. Yet, having commenced with the family, I may be pardoned for adding to their history before the sixteenth century the few notes I have gleaned concerning the later branches.

The order I have preferred has been chronological, limited by the advisability of completing the notices of a family in special localities.

Disputed questions I have placed in chapters apart, as they would bulk too largely in a short biography to be proportionate. Hence the Coat of Arms and the Arden Connections are treated as family matters, apart from John Shakespeare's special biography. I have done what I could to avoid mistakes, and neither time nor trouble has been spared. I owe thanks to many who have helped me in my long-continued and careful researches, to the officials of the British Museum and the Public Record Office, to the Town Council of Stratford-on-Avon and Mr. Savage, Secretary of the Shakespeare Trust, to the Worshipful Company of the Haberdashers, for allowing me to study their records; to the late Earl of Warwick, for admission to his Shakespeare Library, and to many clergymen who have permitted me to search their registers.

Charlotte Carmichael Stopes.

PART I

CHAPTER PAGE

I. THE NAME OF SHAKESPEARE 1

II. THE LOCALITIES OF EARLY SHAKESPEARES4

III. LATER SHAKESPEARES BEFORE THE POET'S TIME 10

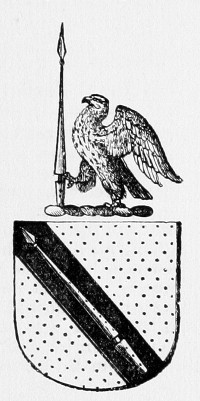

IV. THE SHAKESPEARE COAT OF ARMS 17

V. THE IMPALEMENT OF THE ARDEN ARMS 24

VI. THE ARDENS OF WILMECOTE 35

VII. JOHN SHAKESPEARE 50

VIII. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE 61

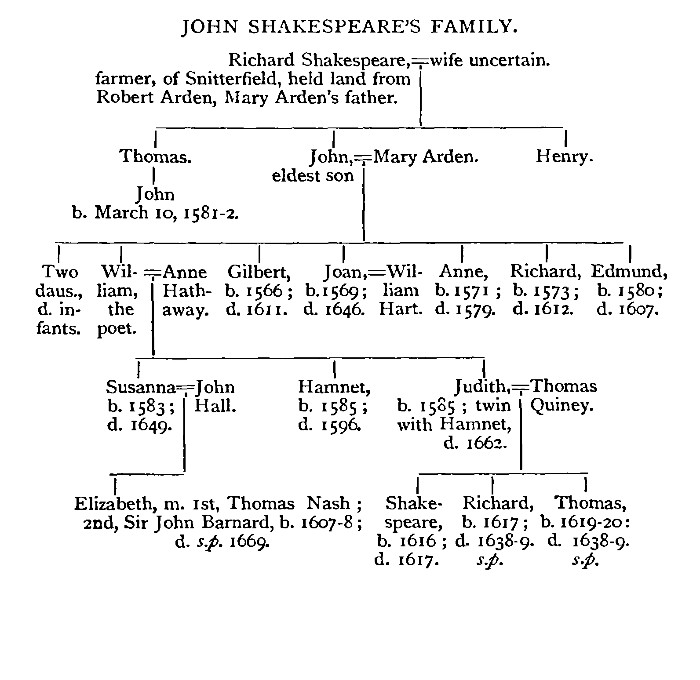

IX. SHAKESPEARE'S DESCENDANTS 87

X. COLLATERALS 110

XI. COUSINS AND CONNECTIONS 113

XII. CONTEMPORARY WARWICKSHIRE SHAKESPEARES 118

XIII. SHAKESPEARES IN OTHER COUNTIES 132

XIV. LONDON SHAKESPEARES 142

PART II

I. THE PARK HALL ARDENS 162

II. THE ARDENS OF LONGCROFT 183

III. OTHER WARWICKSHIRE ARDENS 188

IV. THE ARDENS OF CHESHIRE 196

V. BRANCHES IN OTHER COUNTIES 213

TERMINAL NOTES 222

INDEX 239

PAGE

PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Frontispiece

SHAKESPEARE'S ARMS 17

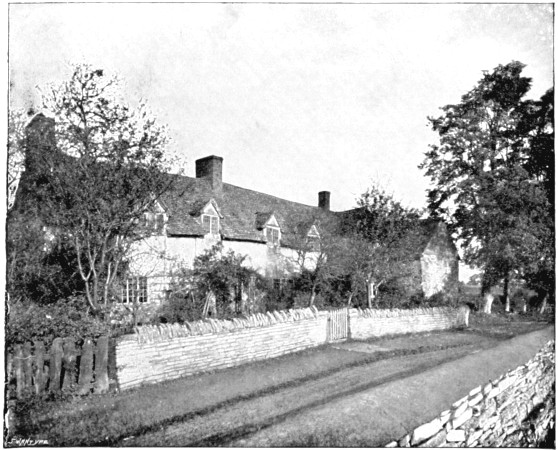

OLD HOUSE AT WILMECOTE, BY SOME SUPPOSED TO BE ROBERT ARDEN'S To face 35

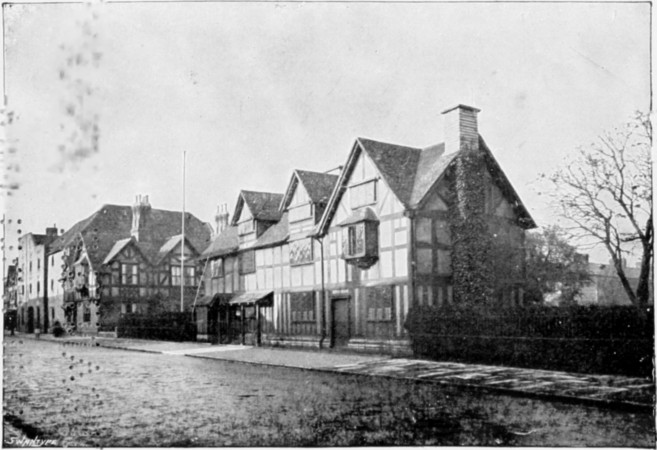

PRESENT VIEW OF SHAKESPEARE'S BIRTHPLACE " 55

THE GUILD CHAPEL, FROM THE SITE OF NEW PLACE " 67

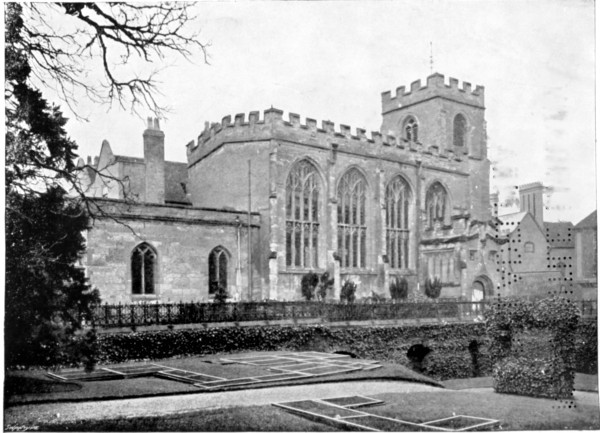

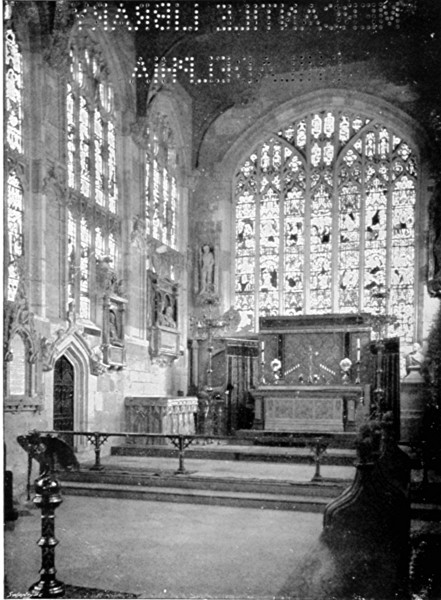

THE CHANCEL, TRINITY CHURCH " 83

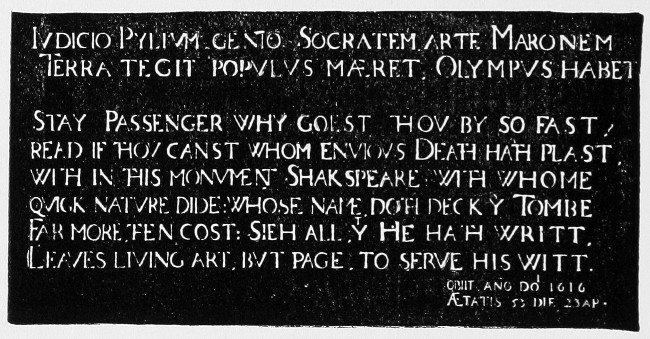

SHAKESPEARE'S EPITAPH 84

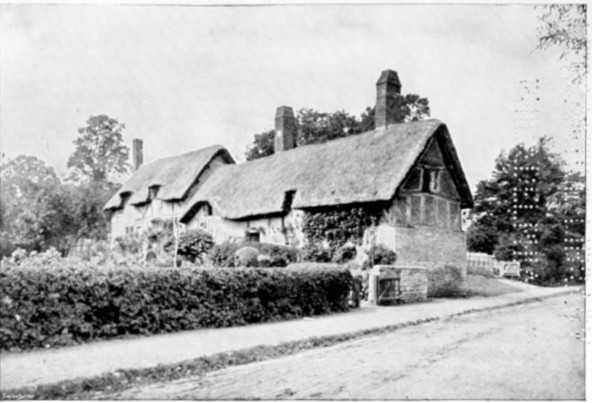

ANNE HATHAWAY'S COTTAGE To face 88

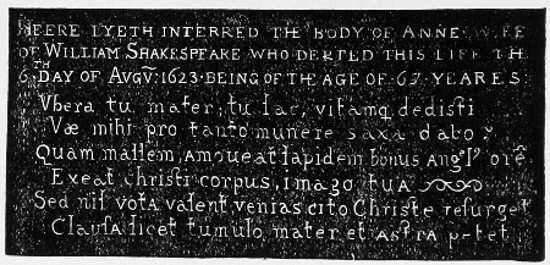

ANNE SHAKESPEARE'S EPITAPH 90

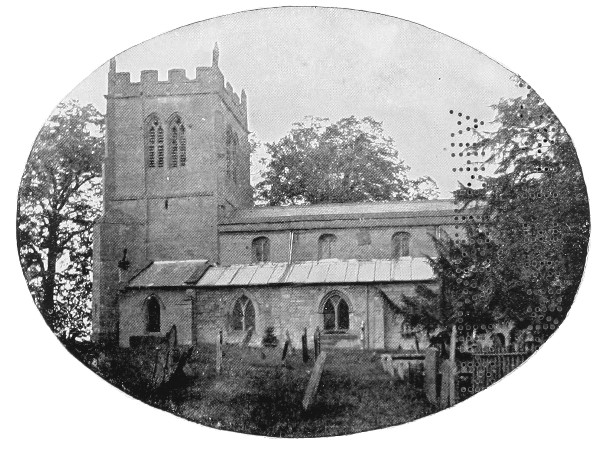

SNITTERFIELD CHURCH To face 113

NORDEN'S MAP OF LONDON, 1593 " 142

WARWICK CASTLE " 162

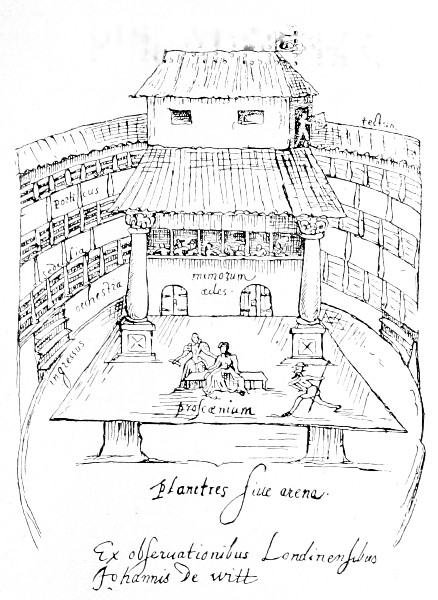

SWAN THEATRE (BY DR. GAIDERTY) " 214

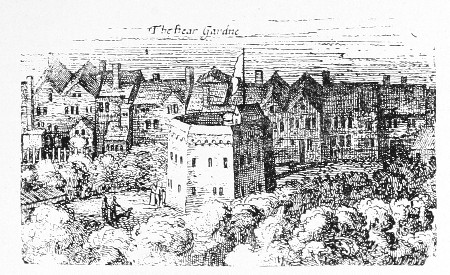

THE BEAR GARDEN AND HOPE THEATRE " 216

SWAN THEATRE " 216

When, from the midst of a people, there riseth a man

Who voices the life of its life, the dreams of its soul,

The Nation's Ideal takes shape, on Nature's old plan,

Expressing, informing, impelling, the fashioning force of the whole.

The Spirit of England, thus Shakespeare our Poet arose;

For England made Shakespeare, as Shakespeare makes England anew.

His people's ideals should clearly their kinship disclose,

To England, themselves, the more true, in that they to their Shakespeare are true.

The origin of the name of "Shakespeare" is hidden in the mists of antiquity. Writers in Notes and Queries have formed it from Sigisbert, or from Jacques Pierre,[1] or from "Haste-vibrans." Whatever it was at its initiation, it may safely be held to have been an intentionally significant appellation in later years. That it referred to feats of arms may be argued from analogy. Italian heraldry[2] illustrates a name with an exactly similar meaning and use in the Italian language, that of Crollalanza.

English authors use it as an example of their theories. Verstegan says[3]: "Breakspear, Shakespeare, and the like, have bin surnames imposed upon the first[Pg 2] bearers of them for valour and feates of armes;" and Camden[4] also notes: "Some are named from that they carried, as Palmer ... Long-sword, Broadspear, and in some respects Shakespear."

In "The Polydoron"[5] it is stated that "Names were first questionlesse given for distinction, facultie, consanguinity, desert, quality ... as Armestrong, Shakespeare, of high quality."

That it was so understood by his contemporaries we may learn from Spenser's allusion, evidently intended for him, seeing no other poet of his time had an "heroic name"[6]:

"And there, though last, not least is Aëtión;

A gentler shepherd[7] may nowhere be found,

Whose Muse, full of high thought's invention,

Doth like himself heroically sound."

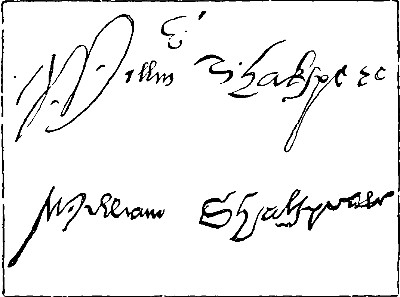

If the parts of the name be significant, I take it that the correct spelling at any period is that of the contemporary spelling of the parts. Therefore, when spear was spelt "spere," the cognomen should be spelt "Shakespere"; when spear was spelt "speare," as it was in the sixteenth century, the name should be spelt "Shakespeare." Other methods of spelling depended upon the taste or education of the writers, during transition periods, when they seemed actually to prefer varieties, as one sometimes finds a proper name spelt in three different ways by the same writer on the same page. "Shakespeare" was the contemporary form of the name that the author himself passed in correcting the proofs of the "first heirs of his invention" in 1593 and 1594; and "Shakespeare" was the Court spelling of the period, as may be seen[Pg 3] by the first official record of the name. When Mary, Countess of Southampton, made out the accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber after the death of her second husband, Sir Thomas Heneage, in 1594, she wrote: "To William Kempe, William Shakespeare,[8] and Richard Burbage," etc.

I know that Dr. Furnivall[9] wrote anathemas against those who dared to spell the name thus, while the poet wrote it otherwise. But a man's spelling of his own name counted very little then. He might have held romantically to the quainter spelling of the olden time as many others did, such as "Duddeley," "Crumwell," "Elmer."

[1] Notes and Queries, 2nd Series, ix. 459, x. 15, 86, 122; 7th Series, iv. 66; 8th Series, vii. 295; 5th Series, ii. 2.

[2] See Works of Goffredo di Crollalanza, Segretario-Archivista dell' Accademia Araldica Italiana, which were brought to my notice by Dr. Richard Garnett.

[3] Verstegan's "Restitution of Decayed Intelligence," ed. 1605, p. 254.

[4] Camden's "Remains," ed. 1605, p. 111.

[5] Undated, but contemporary. Notes and Queries, 3rd Series, i. 266.

[6] Spenser's "Colin Clout's Come Home Again," 1595.

[7] It was a fashion of the day to call all poets "shepherds."

[8] "Declared Accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber," Pipe Office, 542 (1594). See my English article, "The Earliest Official Record of Shakespeare's Name."—"Shakespeare Jahrbuch," Berlin, 1896, reprinted in pamphlet form.

[9] "On Shakespere's Signatures," by Dr. F.J. Furnivall, in the Journal of the Society of Archivists and Autograph Collectors, No. I., June, 1895.

We find the name occurs in widely scattered localities from very early times. Perhaps a resembling name ought to be noted "in the hamlet of Pruslbury, Gloucestershire,[10] where there were four tenants. This was at one time an escheat of the King, who gave it to his valet, Simon Shakespeye, who afterwards gave it to Constantia de Legh, who gave it to William Solar, the defendant." If this represents a 1260 "Shakespere," as there is every reason to believe it does, this is the earliest record of the name yet found. This belief is strengthened by the discovery that a Simon Sakesper was in the service of the Crown in 1278, as herderer of the Forest of Essex,[11] in the Hundred of Wauthorn, 7 Edward I. Between these two dates Mr. J. W. Rylands[12] has found a Geoffrey Shakespeare on the jury in the Hundred of Brixton, co. Surrey, in 1268.[13]

The next[14] I have noted occurs in Kent in the[Pg 5] thirteenth century, where a John Shakespeare appears in a judicial case, 1278-79, at Freyndon.

The fifth notice is in the north.[15] The Hospital of St. Nicholas, Carlisle, had from its foundation been endowed with a thrave of corn from every ploughland in Cumberland. These were withheld by the landowners in the reign of Edward III., for some reason, and an inquiry was instituted in 1357. The jury decided that the corn was due. It had been withheld for eight years by various persons, among whom was "Henry Shakespere, of the Parish of Kirkland," east of Penrith. This gives, therefore, really an entry of this Shakespere's existence at that place as early as 1349, and an examination of Court Records may prove an earlier settlement of the family.

There was a transfer of lands in Penrith described as "next the land of Allan Shakespeare," and amongst the witnesses was William Shakespeare,[16] April, 21 Richard II., 1398.

In the "Records of the Borough of Nottingham,"[17] we find a John Shakespere plaintiff against Richard de Cotgrave, spicer, for deceit in sale of dye-wood on November 8, 31 Edward III. (1357); Richard, the servant of Robert le Spondon, plaintiff against John Shakespere for assault. John proves himself in the right, and receives damages, October 21, 1360.

The first appearance yet found of the name in Warwickshire is in 1359, when Thomas Sheppey and Henry Dilcock, Bailiffs of Coventry, account for the property of Thomas Shakespere,[18] felon, who had left his goods and fled.[Pg 6]

Halliwell-Phillipps[19] notes as his earliest entry of the name a Thomas Shakespere, of Youghal, 49 Edward III. (1375). A writer in Notes and Queries[20] gives a date two years later when "Thomas Shakespere and Richard Portingale" were appointed Comptrollers of the Customs in Youghal, 51 Edward III. (1377). This would imply that he was a highly trustworthy man. Yet, by some turn of fortune's wheel, he may have been the same man as the felon.

In Controlment Rolls, 2 Richard II. (June, 1377, to June, 1379), there is an entry of "Walter Shakespere, formerly in gaol in Colchester Castle."[21] John Shakespeare was imprisoned in Colchester gaol as a perturbator of the King's peace, March 3rd, 4 Richard II., 1381.[22] At Pontefract, Robert Schaksper, Couper, and Emma his wife are mentioned as paying poll-tax, 2 Rich. II.[23]

The Rev. Mr. Norris,[24] working from original documents, notes that on November 24 (13 Richard II.), 1389, Adam Shakespere, who is described as son and heir of Adam of Oldediche, held lands within the manor of Baddesley Clinton by military service, and probably had only just then obtained them. Oldediche, or Woldich, now commonly called Old Ditch Lane, lies within the parish of Temple Balsall, not far from the manor of Baddesley.

This closes the notices of the family that I have collected during the fourteenth century. The above-noted Adam Shakespere, the younger, died in 1414,[Pg 7] leaving a widow, Alice, and a son and heir, John, then under age, who held lands until 20 Henry VI., 1441. It is not clear who succeeded him, but probably two brothers, Ralph and Richard, who held lands in Baddesley, called Great Chedwyns, adjoining Wroxall. Mr. Norris says that no further mention of the name appears in Baddesley, but one notice of the property is given later. Ralph and Joanna, his wife, had two daughters—Elizabeth, married to Robert Huddespit, and Isolda, married to Robert Kakley. Elizabeth Huddespit, a widow, in 1506 held the lands which Adam Shakespeare held in 1389.

The family of Shakespeare appears in the "Register of the Guild of Knowle,"[1] a semi-religious society to which the best in the county belonged:

1457. Pro anima Ricardi Shakespere et Alicia uxor

ejus de Woldiche.[25]

1464. Johanna Shakespere.

Radulphus Shakespere et Isabella uxor ejus et

pro anima Johannæ uxoris primæ.

Ricardus Schakespeire de Wroxhale et Margeria

uxor ejus.

1476. Thomas Chacsper et Christian cons. sue de

Rowneton.

Johannis Shakespeyre de Rowington et Alicia

uxor ejus.

1486. 1 Hen. VII. Thomæ Schakspere, p aiaei.

Thomas Shakspere et Alicia uxor ejus de

Balsale.

Mr. Yeatman has studied the Court Rolls of this[Pg 8] period. It is to be wished he had published his book in two volumes, one of facts and one of opinions. He says that the earliest record of the Court Rolls of Wroxall[26] is one dated 5 Henry V. (1418). It is a grant by one Elizabeth Shakspere to John Lone and William Prins of a messuage with three crofts. (The same Rolls tell us that in 22 Henry VIII. Alice Love surrendered to William Shakespeare and Agnes his wife a property apparently the same.)

In 1485 John Hill, John Shakespeare and others, were enfeoffed in land called "Harveys" in Rowington, and John appears as witness in 1492 and 1496.[27]

There were Shakesperes at Coventry and Meriden in the fifteenth century. John Dwale, merchant of Coventry, left legacies by will to Annes Lane and to Richard Shakespere, March 15, 1499.[28]

Among the "foreign fines" of the borough of Nottingham,[29] Robert Shakespeyr paid eightpence for license to buy and sell in the borough in 1414-15. The same Robert complains of John Fawkenor for non-payment of the price of wood for making arrows. And French[30] tells us there was a Thomas Shakespere, a man at arms, going to Ireland on August 27, 18 Edward IV., 1479, with Lord Grey against the king's enemies.

John Shakespere, a chapman in Doncaster,[31] paid on each order 12d. Among the York wills, John Shakespere of Doncaster mentions his wife, Joan, 1458. In[Pg 9] the same year Sir Thomas Chaworth leaves Margery Shakesper six marks for her marriage.[32]

In 1448, William Shakspere, labourer, and Agnes, his wife, were legatees under the will of Alice Langham, of Snailswell, Suffolk.[33]

A family also belonged to London. Mr. Gollancz told me of a certain "William Schakesper" who was "to be buried within the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, in England," in 1413.[34] On reference to the original, I found there was no allusion to profession, locality or family. He left to an unnamed father and mother twenty shillings each, and six shillings and eightpence to the hospital. The residue to William Byrdsale and John Barbor, to dispose of for the good of his soul; proved August 3, 1413. There was also a Peter Shakespeare who witnessed the deed of transfer of the "Hospicium Vocatum le Greyhounde, Shoe Alley, Bankside, Southwark, February 16, 1483."[35][Pg 10]

[10] Coram Rege Roll, St. Barthol., 45 Henry III., Memb. 13, No. 117. Notes and Queries, 5th Series, ii. 146.

[11] Fisher's "Forest of Essex," p. 374. Notes and Queries, 9th Series, ii. 167.

[12] Records of Rowington.

[13] Coram Rege Roll, 139, M. 1, 52-53 Hen. III.

[14] Roll of 7 Edward I.: "Placita Corone coram Johanne de Reygate et sociis suis, justiciariis itinerantibus in Oct. St. Hil. 7 Edward I., apud Cantuar." See also Notes and Queries, 1st Series, vol. xi., p. 122. Mr. William Henry Hart, F.S.A., contributes a note on the subject and gives the entry.

[15] Notes and Queries, 2nd Series, vol. x., p. 122.

[16] Notes and Queries, 6th Series, iv. 126.

[17] "Records of the Borough of Nottingham," by Mr. W. Stevenson.

[18] See Dr. Joseph Hunter's MSS., Addit. MSS., Brit. Mus. 24,484, art. 246.

[19] In Shakespeare's "Life," prefixed to the folio edition.

[20] Notes and Queries, J. F. F., 2nd Series, x. 122; see "Rot. Pat. Claus. Cancellariæ Hiberniæ Calendarium," vol. i., part i., p. 996.

[21] Notes and Queries, 5th Series, i. 25.

[22] Close Rolls, 4 Richard II.; Notes and Queries, 7th Series, ii. 318.

[23] Yorksh. Archæological Journal, vol. vi., p. 3. Lay-Subsidies, 206/49, Osgodcrosse, West Riding.

[24] Notes and Queries, 8th Series, vol. viii., December 28, 1895; "Shakespeare's Ancestry," by the Rev. Henry Norris, F.S.A.

[25] Mr. W. B. Bickley's "The Register of the Guild of St. Anne at Knowle," 1894. Mr. Bickley, in the Stratford-on-Avon Herald, November 9, 1895, shows that "Woldiche," "Oldyche" and "Oldwich" are the same, being a farm in the hamlet of Balsall, in the parish of Hampton in Arden, and about three miles from Knowle.

[26] Mr. Yeatman's "Gentle Shakespeare," p. 135.

[27] Mr. J. W. Ryland's "Records of Rowington."

[28] Proved May 26, 1500, Somerset House; Moone, f. 2.

[29] Stevenson's "Transcript of Records of the Borough of Nottingham."

[30] French's "Shakespeareana Genealogica," p. 350, and 39/48 "Ancient Miscellanea Exchequer," Treasury of Receipt, Muster Roll of Men at Arms going with Lord Grey. At Conway, 18 Edward IV., August 24.

[31] Records of the House of Grayfriars. Yorksh. Archæological Journal, vol. xii., p. 482.

[32] Notes and Queries,6th Series, iv. 158.

[33] "Camden Soc. Publ.," 1851, Notes and Queries, 6th Series, vi. 368.

[34] Commissary Court of London Wills, Reg. II., 1413, f. 12.

[35] The deed is preserved at Cordwainers' Hall.

In the sixteenth century there were Shakespeares all over the country, in Essex, Staffordshire, Worcestershire, Nottingham,[36] but chiefly in Warwick.

There the family had spread rapidly. But it is only the first half of the century that concerns us at present. There have been Shakespeares noted in Warwick, Alcester, Berkswell, Snitterfield, Lapworth, Haseley, Ascote, Rowington, Packwood, Beausal, Temple Grafton, Salford, Tamworth, Barston, Tachbrook, Haselor, Rugby, Budbrook, Wroxall, Norton-Lindsey, Wolverton, Hampton-in-Arden, Hampton Lucy, and Knowle.[37]

Most students, recognising Warwickshire as the ancestral home of the poet's family, exclude the town of Warwick from the field of their consideration, and select the Shakespeares of Wroxall, partly because more is known about them, and partly because what is known of them suggests a higher social status than is granted the other branches. From the "Guild of Knowle Records" we learn that in 1504 the fraternity was asked to "pray for the soul of Isabella Shakespeare, formerly Prioress of Wroxall,"[38] that the name of Alice[Pg 11] Shakespere was entered, and prayers requested for the soul of Thomas Shakespere, of Ballishalle, in 1511; and in the same year Christopher Shakespere and Isabella, his wife, of Packwood, Meriden, are mentioned. The name of "Domina Jane Shakspere" appears late in 1526. She is often spoken of as another Prioress. Now, it is important to notice that Dugdale mentions neither of these ladies. He records that D. Isabella Asteley was appointed July 30, 1431, and that D. Jocosa Brome, daughter of John Brome,[39] succeeded her. She resigned in 1524, and died on June 21, 1528.

Agnes Little was confirmed Prioress November 20, 1525, and at the dissolution of the house a pension of £7 10s. was granted her for life. The rest of her fellow nuns were exposed to the wide world to seek their fortunes. Now Dugdale, with all his perfections, occasionally makes mistakes. He either mistook Asteley for Shakespeare, or another Shakespeare prioress intervened between the two that he mentions. The "Guild of Knowle Records" give unimpeachable testimony as to the existence and date of the Prioress, Isabella Shakespeare. In the edition of Dugdale's "Warwickshire" by Dr. W. Thomas, 1730, and the edition of his "Monasticon," published 1823, there is mentioned in a note that a license for electing to the office was granted Johanna Shakespere, Sub-Prioress, September 5, 1525. So she might have had the empty[Pg 12] title of Domina, without the usual pension allowed to the Prioress on dissolution.[40]

After the name of Domina Johanna Shakspere in the Knowle Records occur those of Richard Shakspere and Alice, his wife; William Shakespere and Agnes his wife; Johannes Shakespere and Johanna his wife, 1526; Richard Woodham and Agnes his wife, who was the sister of Richard. This Richard Shakespere was probably the Bailiff[41] of the Priory, who shortly before the Dissolution collected the rents and held lands from the Priory. He, however, was replaced in his office by John Hall, who received a patent for it on January 4, 26 Henry VIII. Among the tenants of the dissolved Priory were mentioned[42] "Richard Shakespeare," "William Shakespeare," and "land in the tenure of John Shakespeare, demised to Alice Taylor, of Hanwell, in the county of Oxford."

Mr. Yeatman[43] transcribes a grant of land in Wroxall by the Prioress Isabella Shakespere to John Shakespere and Elene, his wife, in 23 Henry VII. (Richard Shakespere on the jury).[44] But there seems to be some error in the date, as the "Guild of Knowle Records" distinctly state that Isabella the Prioress was either dead in 19 Henry VII. or had retired from office.

Elena Cockes, widow, late wife of John Shakespere, and Antony, her son, appear about this land in a court held by Agnes Little, Prioress of Wroxhall, April 21, 25 Henry VIII. William Shakespeare and Agnes were concerned in it, Alice Lone, and many other connected[Pg 13] names. A Richard Shakespere was on the jury, and a Richard Shakespere was appointed Ale-taster. The Subsidy Rolls do not give a John resident in Wroxall at any date, but in 14, 15, and 16 Henry VIII. John, senior, and John, junior, were resident in the adjoining village of Rowington, and in 34 and 37 Henry VIII. there was one John Shakespeare there. In 16 Henry VIII.[45] there was a Richard Shakespere in Hampton Corley. The name also occurs at Wroxall in that year and in Rowington in 34-5 Henry VIII. There were also a Thomas and a Lawrence (mentioned as a cousin in a will of a John Shakespere, 1574), at Rowington at that time, and the name of William appears repeatedly in Wroxall. A Robert Shakespere was presented for non-suit. Rev. Joseph Hunter[46] gives a rental of Rowington 2 Edward VI. Among the free tenants of Lowston End was John Shakespere; at Mowsley End, Johanna Shakespere, a widow, who seems to have died 1557, as her will, though lost, is mentioned in the index at Worcester; a William Shakespere and a Richard Shakespere are also mentioned. In 3 Elizabeth Thomas Shakespere held a messuage in Lowston. In Rowington End John Shakespere held a cottage called "The Twycroft," and Richard Shakespere a messuage in Church End at the same time. In the reign of Edward VI. a Richard Shakespere was on the jury for Hatton, a Court in the Manor of Wroxall. The Wroxall Parish Registers begin too late to be of any use (1586). The Wroxall Court Rolls mention in 1523, Richard of Haseley; 1530-36, Richard and William; 1547, Ralph of Barston.

Ralph[47] Shakespere was on the jury for Berkswell November 11, 4 Edward VI. and 5 Edward VI. In[Pg 14] 1560 Laurence was presented, because he overburdened the commons with his cattle. John is mentioned in a transfer of property. Mr. J. W. Ryland gives us invaluable help in his publication of "The Records of Rowington." John Shakespeer and Robert Fulwood, gent., are mentioned as feoffees in the will of John Hill of Rowington, September 23, 1502. John Shakespeare elder and younger are frequently mentioned in the Charters of Rowington as feoffees or as witnesses, and a John had a lease of the Harveys for twenty-one years in 1554. A Joan Shakespeare, widow, and her son Thomas, lived at Lyannce in Hatton in 1547. In the Rental of Rowington, 1560-1, there are mentioned Thomas, William, John and Richard. Mr. Hunter mentions a Richard Shakespeyre, at Mansfield, co. Notts, about 1509; a Peter, in 1545; and a John at Derby, 36 Henry VIII. A Richard Shakespere was assessed at Hampton Carlew 16 Henry VIII.; Richard Woodham and Richard Shakspere had a farm at Haseley. The Haseley Registers begin in 1538, and are interesting for the fact that they record on October 21, 1571, the death and burial of "Domina Jane," formerly a nun of Wroxall, who would seem to have been the last sub-prioress, probably connected with Richard Shakespere, the Bailiff. In 1558 a Roger Shakespere was buried—by some supposed to be the old monk of Bordesley[48]—who received 100s. annuity.

The earliest Shakespeare will at Worcester, proved at Stratford, was that of Thomas Shakespere, of Alcester, 1539, who left 20s. each to his father and mother, Richard and Margaret. He had a wife Margaret and a son William.[49] Among other Worcester wills is that of Thomas Shakespere of Warwick, shoe[Pg 15]maker, May 20, 1557, who left his wife Agnes lands in Balsall for life; his daughter Jone, wife to Francis Ley, £4; to his sons Thomas and John 4 nobles each; and his son William was to be his heir. Richard Shakysspere of Rowington, weaver, June 15, 1560, left his property to his sons Richard and William. His brothers-in law John and William Reve were executors and Richard Shakespeare was a witness. In 1561 this William Reve in his will left a sheep to Margaret Shakspere, and in 1565 Robert Shakespeere of Rowington made his will.

But among all these Shakesperes we cannot certainly fix upon any one that is directly connected with our Shakespeare. It seems almost certain that John Shakespeare was son of Richard Shakespeare, of Snitterfield. And yet many doubt it on grounds worthy of consideration, which are treated later in the notice of John Shakespeare. Mr. Yeatman found that an Alice Griffin, daughter of Edward, and sister of Francis Griffin of Braybrook, married a Shakespeare. He takes it for granted that she married Richard of Wroxall, and that it was he who came to Snitterfield. We must beware of drawing definite conclusions, of making over-hasty generalizations. We only collect the bricks to help future investigators to build the edifice.

The Sir Thomas Schakespeir, Curate, of Essex, Bristol and London, who died 1559, is treated later among the Essex Shakespeares.

There is one curious mention of the name which no student seems to have worked out. A certain Hugh Saunders, alias Shakespere,[50] of Merton College, Oxford, became Principal of St. Albans Hall in 1501. He was Vicar of Meopham, in Kent, Rector of Mixbury, Canon[Pg 16] of St. Paul's, and Prebendary of Ealdstreet, in 1508; and Rector of St. Mary's, Whitechapel, in 1512. He died 1537. Now, such an alias was common at the time, when a man's mother was of higher social station than his father. We may therefore, seeing he was somehow connected with Shakespeare, imagine Hugh Saunders' mother to have been a Shakespeare. He is styled "vir literis et virtute percelebris."

[36] "George Shaksper complains against Agnes Marshall that she detains two rosaries," June 18, 1533.—"Common Trained Soldiers in Nottingham," Peter Shakespear, etc., 1596-97. Stevenson's "Nottingham Records."

[37] Halliwell-Phillipps' "Outlines," vol. ii., p. 252.

[38] Guild of Knowle Register.

[39] John Brome was Lord of the Manor of Baddesley Clinton, but was murdered in the porch of the Church of the White Friars, London, November 9, 1468, leaving a wife, Beatrice, three sons and two daughters, one of whom was Jocosa. His son Thomas succeeded, and died without heirs, and his second son Nicholas then inherited the property. Eight of his children are registered in the guild of Knowle. His son-in-law was Sir Edward Ferrers, who married Constance, to whom the property afterwards came. Their son was Henry Ferrers, the great Warwickshire antiquary, who succeeded at sixteen, and was Lord of the Manor for sixty-nine years ("Baddesley Clinton," Rev. H. Norris, p. 234).

[40] Nam Licentia concessa fuit Johanne Shakespere Sub priorisse ad. eligend., 5 Sept., 1525; et 20 Nov., 1525, Agnes Little confirmata fuit Priorissa de Wroxall. Vac. per resign. Joc. Brome. Dugdale's "Monasticon," ed. 1823, vol. iv., p. 89, and "Warwickshire," ed. 1730, p. 649.

[41] "Valor Ecclesiasticus," 26 Henry VIII. (1535).

[42] Ministers' Accounts, April 24, 28 Henry VIII., and Augmentation Books, Public Record Office.

[43] Yeatman's "Gentle Shakespeare," pp. 138-142.

[44] Court Rolls, General Series, Portfolio 207, No. 99.

[45] Addit. MSS., Brit. Mus. (24,500).

[46] Mr. Yeatman's "Gentle Shakespeare," p. 142.

[47] Court Roll, No. 10, p. 207.

[48] Nash's "Worcestershire," vol. ii., account of Tardebigg. See Augmentation Books, October 14, 1539, 233, f. 8.

[49] Hunter's "Prolusions," p. 9.

[50] Wood's Colleges. Fasti Oxoniensis, Bliss, 1815. Wood, Antiq. Oxon., L. 2, 341. Boase, Reg. Univ. Oxon. Newcourt's "Repertorium."

NON SANZ DROICT.

NON SANZ DROICT.

None of the family seem to have risen above the heraldic horizon till John Shakespeare applied for his coat of arms. Into the contest over that application it is well to plunge at once, and thence work backwards and forwards. Four classes of writers wage war over the facts: the Baconians, like the late Mr. Donnelly, who deny everything; the Romanticists, who accept what is pleasant, and occasionally believe manufactured tradition to suit their inclinations; the agnostic Shakespeareans, like Halliwell-Phillipps, who really work, but believe only what they can see and touch, if it accords with their opinions; and the ingenuous workers who seek saving truth like the agnostics, but bring human influences and natural inferences to bear on dusty records. Now, Halliwell-Phillipps does not scruple to affirm that three heralds,[51] [Pg 18]the worthy ex-bailiff of Stratford, and the noblest poet the world has ever produced, were practically liars in this matter, because they make statements that do not harmonize with the limits of his knowledge and the colour of his opinions. From his grave the poet protests—

"Good name in man or woman, dear my lord,

Is the immediate jewel of their souls.

Who steals my purse steals trash....

But he who filches from me my good name

Robs me of that, which not enriches him,

But leaves me poor indeed."

Othello, Act III., Scene 3.

We must therefore at least start inquiry with the supposition that these men thought they spoke truth. There was no reason they should not have done so. Sir John Ferne[52] writes: "If any person be advanced[Pg 19] into an office or dignity of publique administration, be it eyther Ecclesiasticall, Martiall or Civill ... the Herealde must not refuse to devise to such a publique person, upon his instant request, and willingness to bear the same without reproche, a Coate of Armes, and thenceforth to matriculate him with his intermarriages and issues descending in the Register of the gentle and noble.... In the Civil or Political State divers Offices of dignitie and worship doe merite Coates of Armes to the possessours of the same offices, as ... Bailiffs of Cities and ancient Boroughs or incorporated townes." John Shakespeare had certainly been Bailiff of Stratford-on-Avon in 1568-9; the draft states that he then applied for arms, and that the herald, Cooke, had sent him a "pattern." Probably he did not conclude the negotiations then, thinking the fees too heavy, or he might have delayed until he found his opportunity lost, or he might have asked them for his year of office alone. No doubt John Shakespeare was deeply impressed with the dignity of his wife's relatives, and wished, even then, to make himself and his family more worthy for her sake. The tradition of this draft, or the sight of it, may have stimulated the heart of the good son to honour his parents by having them enrolled among the Armigeri of the county. John had appeared among the "gentlemen" of Warwickshire in a government list of 1580.[53]

The Warwickshire Visitations occur in 1619, after the death of the poet, without male heirs, and are no help to us here. In the first 1596 draft the claims are based on John's public office, on a grant to his antecessors by Henry VII. for special services on marriage[Pg 20] with the daughter and heir of a gentleman of worship (i.e., entitled to armorial bearings). Then a fuller draft was drawn out, also in 1596, correcting "antecessors" into "grandfather." Halliwell-Phillipps only mentions one at that date, but Mr. Stephen Tucker,[54] Somerset Herald, gives facsimiles of both. Halliwell-Phillipps calls these ridiculous assertions, and asserts that both parties were descended from obscure country yeomen. The heralds state they were "solicited," and "on credible report" informed of the facts. We must not forget that all the friends intimately associated either with the Ardens or the Shakespeares (with the exception of the Harts) were armigeri.

Nobody now knows anything of that earlier pattern, nor of the patents of the gifts "to the antecessors." But seeing, as I have seen, that sacks full of old parchment deeds and bonds, reaching back to the fifteenth century, get cleared out of lawyers' offices, and sold for small sums to make drumheads or book-bindings, and seeing that this process has been going on for 400 years, it does not seem to me surprising that some deeds do get lost. Generally, it is those we most wish to have that disappear. Lawyers do not, as a rule, concern themselves with historical fragments, but with the soundness of the present titles of their clients and their own modern duties. (I do think that historical and antiquarian societies should bestir themselves to have old deeds included among the "ancient monuments of the country" and entitled to some degree of protection.)

We must also consider how illiterate the inhabitants of the country were in the reign of Henry VII., how the nation was bestrid by officials of the Empson and Dudley type, and we have reason to[Pg 21] believe that various accidents, intentional or otherwise, caused many an old grant to disappear at that period.

It has struck me as possible that John Shakespeare may have intended ancestors through the female line. The names of his mother and grandmother are as yet unknown, and the supposition has never been discussed. But in support of John Shakespeare's claim, and in opposition to Halliwell-Phillipps's contradiction, we can prove there were Shakespeares in direct service of the Crown, not merely as common soldiers, though in 28 Henry VIII. (1537), Thomas, Richard, William and another Richard were mentioned as among the King's forces.[55]

But one Roger Shakespeare was Yeoman of the Chamber to the King, and on June 9, 1552, shared with his fellows, Abraham Longwel and Thomas Best, a forfeit of £36 10s.[56] This post of Yeoman of the Chamber was one of great trust and dignity; it was the same as that held earlier by Robert Arden, of Yoxall, the younger brother of Sir John Arden, and the election to it suggested either inherited favour, Court interest, or signal personal services. His ancestors might have been also the missing ancestors of John Shakespeare. He himself may be the Roger who was buried in Haseley in 1558, supposed by some to have been the monk of Bordesley. He may also have been the father of Thomas Shakespeare, the Royal Messenger of 1575, noticed later.

This record proves nothing beyond the inexactitude of Halliwell-Phillipps's sweeping statements, but it gives us a hope that something else may somewhere else be found to fit into it and make a fact complete. One of the facts brought forward as a reason for the grant of arms to John Shakespeare was "that he hath[Pg 22] maryed Mary daughter and one of the heires of Robert Arden in the same countie, Esquire." "Gent" was originally written, and was altered to "Esquire."[57]

Some have doubted that the grant ever really took place, but Gwillim, in his "Display of Heraldrie," 1660, notes, "Or, on a bend Sable, a tilting Spear of the field, borne by the name of Shakespeare, granted by William Dethick, Garter, to William Shakespear the renowned poet." Shakespeare's crest, or cognizance, was a "Falcon, his wings displayed, Argent, standing on a wreath of his colours, supporting a speare, gold." His motto was, "Non Sans Droict."

It is said there were objections made to this pattern on the ground that it was too like the old Lord Mauley's.[58] Probably they were only notes of a discussion among the heralds, when it was decided that the spear made a "patible difference," and a résumé of the qualifications was added.

This was answered on May 10, 1602, before Henry Lord Howard, Sir Robert Sidney, and Sir Edward Dier, Chancellor of the Order of the Garter: "The answere of Garter and Clarencieux Kings of arms, to a libellous scrowle against certen arms supposed to be wrongfully given. Right Honorable, the exceptions taken in the Scrowle of Arms exhibited, doo concerne these armes granted, or the persons to whom they have been granted. In both, right honourable, we hope to satisfy your Lordships." (They mention twenty-three cases.) "Shakespere.—It may as well be said that Hareley, who beareth gould, a bend between two cotizes sables,[Pg 23] and all other that (bear) or and argent a bend sables, usurpe the coat of the Lo. Mauley. As for the speare in bend, is a patible difference; and the person to whom it was granted hath borne magestracy, and was justice of peace at Stratford-upon-Avon. He married the daughter and heire of Arderne, and was able to maintaine that estate" ("MS. Off. Arm.," W. Z., p. 276; from Malone).

It has struck me that the attempt to win arms for his father was in order to continue them to his mother.

In the Record Office I found the other day a note that explains what I mean: "At a Chapitre holden by the Office of Armes at the Embroyderers Hall in London Anno 4o Reginæ Elizabethæ it was agreed, that no inhiritrix eyther mayde wife or widdow should bear or cause to be borne any Creast or Cognizaunce of her Ancestors otherwise than as followeth. If she be unmaried to beare in her ringe, cognizaunce or otherwise, the first coate of her Ancestors in a Lozenge. And during her Widdowhood to Set the first coate of her husbande in pale with the first coate of her Auncestor. And if she mary one who is noe gentleman, then she to be clearly exempted from the former conclusion."[59]

[51] Cooke, Dethicke and Camden.

In the description of England prefixed to Holinshed's Chronicles it is stated:

"A gentleman of blood is defined to descend of three descents of nobleness, that is to saie, of name and of armes both by father and mother" (p. 161). "Moreover as the King doth dubbe Knights and createth the barons and higher degrees, so gentlemen whose ancestors are not knowen to come in with William Duke of Normandie (for of the Saxon races yet remaining wee now make none accompt, much lesse of the British issue), doe take their beginning in England, after this manner in our times. Whosoever studieth the lawes of the realme, whoso abideth in the Universitie giving his mind to his booke, or professeth physicke and the liberall sciences, or beside his service in the roome of a captaine in the warres, or good counsell given at home, whereby his commonwealth is benefited, can live without manuall labour, and thereto is able and will beare the port, charge, and countenance of a gentleman, he shall for monie have a cote and armes bestowed upon him by heralds (who in the charter of the same doo of custome pretend antiquitie and service, and manie gaie things) and thereunto being made in good cheape be called master, which is the title men give to esquires and gentlemen, and reputed for a gentleman ever after" (Ed. 1586, pp. 161-2).

The same is repeated in "The Commonwealth of England and Maner of Government thereof," by Sir Thomas Smith, London, 1589-1594, Chap. XX.

In a contemporary play, quoted by John Payne Collier, the herald is made to say:

"We now are faine to wait who grows in wealth,

And comes to beare some office in a towne,

And we for money help them unto armes,

For what can not the golden tempter doe?"

Robert Wilson: The Cobbler's Prophecy.

[52] Sir John Ferne in "The Glory of Generositie," 1586.

[53] State Papers, Dom. Ser., Eliz., cxxxvii. 68. The gentlemen and freeholders in the countye of Warwick. Among the freeholders of Barlichway, John Shakespeare, father of William and Thomas Shakespeare, 69. In Stratford-on-Avon John Shaxspere, and at Rowington Thomas Shaxpere, April, 1580.

[54] "Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica," 2nd Series, 1886, vol. i., p. 109, since published in a volume.

[55] The Musters. Archers of Rowington and Wroxall, S.P.D.S.

[56] State Papers, Domestic Series, Edward VI., vol. xiv., Docquet.

[57] Nichols's "Herald and Genealogist," vol. i., p. 510, 1863; and "Miscel. Gen. et Herald.," Series II., vol. i., p. 109.

[58] See the papers in the Bodleian Library, Ashmol. MS. 846, art. ix., f. 50 a, b. "The answers of Garter and Clarencieux Kings of Arms, to the Scrowle of Arms, exhibited by Raffe Brookesmouth, caled York Herald," wherein they state that there is "a patible difference."

[59] State Papers, Domestic Series, Eliz., xxvi. 31, 1561.

In the later application to impale the Ardens' arms in 1599, the 1596 draft is repeated in only slightly altered terms. "Antecessors" is changed to "great-grandfather," and the dignity of Mary Arden's family further elucidated. Some writers consider that, following a custom of the day, John Shakespeare treated as his antecessors his wife's ancestors. The word "great-grandfather" tends to exclude this notion, as may be seen later, but the word "grandfather" would imply, if this had been intended, that Thomas Arden himself had had the grants. It has always been supposed that Brooke, York Herald, had exhibited some complaint against this grant also, as he very possibly did.[60] He was severely critical of the heraldic and genealogic matter in Camden's "Britannia," and very bitter at the slighting way the author speaks of heralds. He wrote a book called "The Discoveries of Certaine Errours in the edition of 1594," which he seems to have begun at once, as on page 14 he states, "If the making of gentlemen heretofore hath been greatly misliked by her Majestie in the Kinges of Armes; much more displeasing, I think, it will be to her, that you, being no Officer of Armes, should erect, make and put down Earles and Barons[Pg 25] at your pleasure." It must have been peculiarly galling to him that by the influence of Sir Fulke Greville, afterwards Lord Brooke, Camden was advanced over his head to the dignity he himself desired. After being appointed, for form's sake, Richmond Herald for one day, Camden was made Clarenceux, October 23, 1597, between the first and second Shakespeare drafts. This probably decided Brooke to publish his "Pamphlet of Errors," which, as he dedicated it to the Earl of Essex, "Lord General of the Royal Forces in Ireland," must have appeared in 1599. He wrote another book against Camden, which was forbidden to be published.

The draft for the impalement is also heavily corrected, probably in comparison and discussion. Of the Shakespeare shield a note adds: "The person to whom it was granted hath borne magistracy in Stratford-on-Avon, was Justice of the Peace, married the daughter and heir of Arderne, and was able to maintain that estate." The Heralds first tricked the arms of the Ardens of Park Hall, Ermine a fesse chequy or and az., but scratched them out, and substituted a shield bearing three cross crosslets fitchée and a chief or, with a martlet for difference.

I put forward several suggestions concerning this question in an article in the Athenæum.[61]

The critical strictures against the Shakespeare-Arden claim are best summed up by Mr. Nichols:[62]

1. That the relation of Mary Arden to the Ardens of Park Hall was imaginary and impossible, and those who assert it in error. 2. That the Ardens were connected with nobility, while Robert Arden was a mere "husbandman." 3. That the Heralds knew the claim was unfounded when they scratched out the arms of[Pg 26] Arden of Park Hall, and replaced them by the arms of the Ardens of Alvanley, of Cheshire. This was equally unjustifiable, but as the family lived further off, there was less likelihood of complaint.

Now we must work out the case step by step on the other side.

Robert Arden, of Park Hall, spent his substance during the Wars of the Roses, and was finally brought to the block (30 Henry VI.,[63] 1452). His son Walter was restored by Edward IV., but he would probably be encumbered by debts and "waste"; at least, he had but small portions to leave to his family when he made his will[64] (31 July, 17 Henry VII., 1502). Besides his heir, Sir John, Esquire of the Body to Henry VII., he had a second son,[65] Thomas, to whom he leaves ten marks annually; a third son, Martin, who was to have the manor of Natford; if not, then Martin and his other sons—Robert, Henry, William—should each of them have five marks annually. This is an income too small even for younger sons to live on in those days, so it is to be supposed the father had already either placed them, married them well, or otherwise provided for them during his life. Among the witnesses to the will are "Thomas Arden and John Charnells, Squires." Thomas, being the second son, might have had something from his mother Eleanor, daughter and coheir of John Hampden, of Great Hampden, county Bucks. This Thomas was alive in 1526, because Sir John Arden then willed that his brothers—Thomas, Martin, and Robert—should have their fees for life. Henry, and probably also William, had meanwhile died, though a William seems to have been established at Hawnes, in Bedfordshire. Seeing that Sir John was the Esquire[Pg 27] of the Body to Henry VII., it seems very probable that his brother Robert was the Robert Arden, Yeoman of the Chamber, to whom Henry VII. granted three patents: First, on February 22, 17 Henry VII., as Keeper of the Park at Altcar,[66] Lancashire; and second, as Bailiff of Codmore, Derby,[67] and Keeper of the Royal Park there; the third[68] gave him Yoxall for life, at a rental of £42—afterwards confirmed. Indeed, Leland in his "Itinerary" mentions the relationship,[69] and the administration of Robert's goods proves it.

Martin's family became connected with the Easts and the Gibbons, and his name and arms appear in the "Visitations of Oxfordshire." Where meanwhile was Thomas? There is no record of any Thomas Arden in Warwickshire or elsewhere, ever supposed to be the son of Walter Arden, save the Thomas who, the year before Walter Arden's death, was living at Wilmecote, in the parish of Aston Cantlowe, on soil formerly owned by the Beauchamps. On May 16, 16 Henry VII., Mayowe transferred certain lands at Snitterfield to "Robert Throckmorton, Armiger, Thomas Trussell of Billesley, Roger Reynolds of Henley-in-Arden, William Wood of Woodhouse, Thomas Arden of Wilmecote, and Robert Arden, the son of this Thomas Arden." This list is worth noting. Thomas Trussell, of an old family, is identified by his residence.[70] He was Sheriff of the county in[Pg 28] 23 Henry VII. No Throckmorton could take precedence of him save the Robert Throckmorton of Coughton, who was knighted six months later.[71]

These men were evidently acting as trustees for the young Robert Arden. Just in the same way this same Robert Throckmorton was appointed by Thomas's elder brother, Sir John Arden of Park Hall, as trustee for his children, in association with John Kingsmel, Sergeant-at-Law, Sir Richard Empson, and Sir Richard Knightley.[72] That a man of the same name, at the same time, in the same county, retaining the same family friends, in circumstances in every way suitable to the second son of Walter Arden, should be accepted for that man seems just and natural, especially when no other claimant has ever been brought forward.

But we know this Thomas Arden was Mary Arden's grandfather; this Robert was her father; this property, that tenanted afterwards by the Shakespeares, and left by Robert's will to his family.

As the deed of conveyance of the premises at Snitterfield from Mayowe to Arden has been often referred to, occasionally quoted, but never, so far as I know, printed in extenso, I should like to preserve the copy. It may save trouble to future investigators, and help to clear up the connection between the Shakespeares and the Ardens. It certainly strengthens very much Mary Arden's claim to connection with the Ardens of Park Hall, and her descent from "a gentleman of worship," a claim the heralds allowed.[Pg 29]

"Sciant presentes et futuri quod ego Johannes Mayowe de Snytterfeld dedi, concessi, et hac presenti carta mea confirmavi, Roberto Throkmerton Armigero, Thome Trussell de Billesley, Rogero Reynoldes de Henley in Arden, Willelmo Wodde de Wodhouse, Thome Arderne de Wylmecote, et Roberto Arderne filio eiusdem Thome Arderne, unum mesuagium cum suis pertinenciis in Snytterfeld predicta, una cum omnibus et singulis terris toftis, croftis, pratis, pascuis et pasturis eidem mesuagio spectantibus sive pertinentibus in villa et in campis de Snytterfeld predicta cum omnibus suis pertinenciis; quod quidem mesuagium predictum quondam fuit Willelmi Mayowe et postea Johannis Mayowe et situatum est inter terram Johannis Palmer ex parte una et quandam venellam ibidem vocatam Merellane ex parte altera in latitudine et extendit se in longitudine a via Regia ibidem usque ad quendam Rivulum, secundum metas et divisas ibidem factas. Habendum et tenendum predictum mesuagium cum omnibus et singulis terris Toftis, Croftis, pratis, pascuis, et pasturis predictis, ac omnibus suis pertinenciis prefatis Roberto Throkmerton, Thome Trussell, Rogero Reynoldes, Willelmo Wodde, Thome Arderne et Roberto Ardern heredibus et assignatis suis de capitalibus dominis feodi illius per servicia inde debita et de jure consueta imperpetuum. Et ego vero predictus Johannes Mayowe et heredes mei mesuagium predictum cum omnibus et singulis terris Toftis Croftis, pratis, pascuis et pasturis supradictis ac omnibus suis pertinenciis prefatis Roberto Throckmerton, Thome Trussell, Rogero Reynoldes, Willelmo Wodde, Thome Arderne et Roberto Arderne heredibus et assignatis suis contra omnes gentes Warrantizabimus et defendemus imperpetuum.

"Et insuper sciatis me prefatum Johannem Mayowe assignasse, constituisse et in loco meo posuisse dilectos[Pg 30] michi in Christo Thomam Clopton de Snytterfeld predicta gentilman et Johannem Porter de eadem meos veros et legitimos Attornatos conjunctim et divisim ad intrandum vice et nomine meo in predictum mesuagium cum omnibus et singulis premissis et pertinenciis suis quibuscunque et ad plenam et pacificam seisinam pro me ac vice et nomine meo inde capiendam et postquam hujusmodi seisina dicta capta fuerit ad deliberandam pro me ac vice et nomine meo prefatis Roberto Throkmerton, Thome Trussell, Rogero Reynoldes, Willelmo Wodde, Thome Arderne et Roberto Arderne plenam et pacificam possessionem et seisinam de et in eodem mesuagio ac omnibus et singulis premissis, secundum vim, formam et effectum huius presentis carte mee. Ratum et gratum habens et habiturus totum et quicquid dicti attornati mei vice et nomine meo fecerint seu eorum alter fecerit in premisses. In cuius rei testimonium huic presenti carte mee et scripto meo sigillum meum apposui. Hiis testibus Johanne Wagstaffe de Aston Cauntelowe Roberto Porter de Snytterfield predicta Ricardo Russheby de eadem, Ricardo Atkyns de Wylmecote predicta, Johanne Alcokkes de Newenham et aliis. Datum apud Snytterfield predictam die lune proximo post festum invencionis Sancte Crucis Anno Regni Regis Henrici Septimi post conquestum Sexto decimo."[73]

Mr. Nichols' second objection was that in records he is styled "husbandman"; but the word is an old English equivalent for a farmer, in which sense it is often used in old wills and records. And in the examination of John Somerville,[74] Edward Arden's son-in-law (also of high descent), he stated "that he had received no visitors of late, but certain 'husbandmen,'[Pg 31] near neighbours." The Arden "husbandman" of Wilmecote in 1523 and 1546[75] paid the same amount to the subsidy as the Arden Esquire of Yoxall[76] in 1590, when money was of less value.

Mr. Nichols' third assertion, that the heralds scratched out the arms of the Ardens of Park Hall, because they dared not quarter them with those of the Shakespeares, shows that he omitted certain considerations. That family was under attainder then.

Drummond[77] exemplifies many arms of Arden, and traces them back to their derivation. He notices that the "elder branch of the Ardens took the arms of the old Earls of Warwick; the younger branches took the arms of the Beauchamps, with a difference. In this they followed the custom of the Earls of Warwick." The Ardens of Park Hall therefore bore ermine, a fesse chequy, or, and az., arms derived from the old Earls of Warwick; and this was the pattern scratched out in John Shakespeare's quartering. But the reason lay in no breach of connection, but in the fact that Mary Arden was an heiress, not in the eldest line, but through a second son. A possible pattern for a younger son was three cross crosslets fitchée and a chief or. As such they were borne by the Ardens of Alvanley, with a crescent for difference. They were borne without the crescent by Simon Arden of Longcroft,[78][Pg 32] the second son of the next generation, and full cousin of Mary Arden's father. It is true that among the tombs at Yoxall the fesse chequy appeared, but there is evident confusion in their use. Martin Arden of Euston was probably in the wrong to assume when he did the arms of his elder brother; William Arden of Hawnes, if the sixth son, county Bedford, bore the same arms as those proposed for Mary Arden, and it is implied that Thomas, her father, had borne them. In the Heralds' College is the draft: "Shakespere impaled with the Aunceyent armes of the said Arden of Willingcote" (volume marked R. 21 outside and G. XIII. inside).

If the three cross crosslets fitchée were the correct arms for Thomas Arden as the second son of an Arden, who might bear ermine, a fesse chequy or, and az., the crescent would have been the correct difference, but it had long been borne by the Ardens of Alvanley, in Cheshire, who branched off from the Warwickshire family early in the thirteenth century. The heralds therefore differenced the crosslets with a martlet, usually, but by no means universally, the mark of cadency for a fourth son at that time.[79] Thus, Glover[80] enumerates among the arms of Warwickshire and Bedfordshire: "Arden or Arderne gu., three cross crosslets fitchée or; on a chief of the second a martlet of the first. Crest, a plume of feathers charged with a martlet or." If heraldry has anything, therefore, to say to this dispute, it is to support the claim of Thomas Arden to being a cadet of the Park Hall family, and thereby to include Mary Arden and her son in the descent from Ailwin, Guy of Warwick, and the Saxon[Pg 33] King Athelstan. Camden and the other heralds were only seeking correctness in their draft of the restitution of the Ardens' arms. The hesitation as to exactitude among the varieties of Arden arms was the cause of the notes. See "The Booke of Differ.," 61; see "Knights of E.I.," folios 2, 28, etc., on the draft.

It has been considered strange that, after the application and even after the grant (preserved in MS. "Coll. of Arms," R. 21), no use thereof can be proved, though the heralds added to the former grant: "and we have lykewise uppon an other escucheon impaled the same with the auncient arms of the said Arden of Wellyngcote, signifying thereby that it maye and shalbe lawfull, for the said John Shakespeare, gent., to beare and use the same shields of arms, single or impaled, as aforesaid, during his natural lyfe, and that it shalbe lawful for his children, issue, and posterity, to beare, use, quarter, and shewe the same with their dewe difference, in all lawfull warlyke faites and civill use" (Ibid., G. XIII.).

John Shakespeare did not live long after his application, dying in 1601.

Whether or not the grant of the impaled Arden arms was completed before his death, there is no record of his using them. Whether his son ever used the impalement we do not now know, but it does not appear on any of the tombs or seals that have been preserved. But the Shakespeare arms have been certainly used.

William Shakespeare was mercilessly satirized by his rivals, Ben Jonson and others,[81] about his coat of arms;[Pg 34] but it was the recognition of his descent that secured him so universally the attribute of "gentle." As Davies, addressing Shakespeare and Burbage in 1603, says:

"And though the stage doth stain pure gentle blood,

Yet generous ye are in mind and mood."[82]

We must not forget there would be possible ill-feeling among the families of the Arden sisters, when the youngest, whom they had probably always pitied and looked down on, because of her comparatively unfortunate marriage, should have the audacity to think of using the arms of their father, to which they had never aspired.

OLD HOUSE AT WILMECOTE, BY SOME SUPPOSED TO BE ROBERT

ARDEN'S

OLD HOUSE AT WILMECOTE, BY SOME SUPPOSED TO BE ROBERT

ARDEN'S[60] He tried in every way to prove Camden wrong, but his bitterness only hurt himself. His strictures were confuted before the highest authority.

[61] August 10, 1895, p. 202.

[62] "Herald and Genealogist," vol. i., p. 510, 1863; and Notes and Queries, Series III., vol. v., p. 493.

[63] Dugdale's "Warwickshire," p. 925.

[64] Preserved at Somerset House, 8 Porch.

[65] Dugdale places the sons in another order.

[66] Pat. Henry VII., second part, mem. 30, February 22.

[67] Same series, mem. 35, September 9.

[68] Pat. 23 Henry VIII., September 24, first part, mem. 12.

[69] "Arden of the court, brother to Sir John Arden of Park Hall." "Itinerary," vi. 20, about 1536-42.

[70] Sir Warine Trussell held Billesley 15 Edward III. The will of Sir William Trussell of Cublesdon, 1379, mentions a bequest to his cousin, "Sir Thomas d'Ardene" ("Testamenta Vetusta," Sir N. H. Nicolas, vol. i., p. 107). William Trussell was made a brother of the Guild of Knowle 1469, and there is an entry in 1504 of a donation "for Sir William Trussell and for his soul": "To Thomas Trussell, farmer of the said Bishop of Worcester; in Knowle for the Worke-silver 4/4" (37 Henry VIII., Report. "Register of the Guild of Knowle," Introduction, p. xxvi., by Mr. W. B. Bickley). Alured Trussell, born 1533, married Margaret, daughter of Robert Fulwood, and their daughter Dorothy married Adam Palmer, Robert Arden's friend. French thinks that the wife, either of Thomas or of Robert, was a Trussell.

[71] His son George succeeded him in 1520. Edward Arden, of Park Hall, was brought up in his care, and married Mary, his son Robert's daughter.

[72] See p. 184.

[73] Deed of Conveyance of Premises at Snytterfield. (Transcribed from the Miscellaneous Documents of Stratford-on-Avon), vol. ii., No. 83.

[74] State Papers, Domestic Series, Elizabeth, 1583, clxiii., 21.

[75] In the Subsidy Rolls 15 Henry VII., Thomas Arden was assessed on £12, and Robert Arden on £8 (192/128). Subsidy, Aston Cantlowe, March 10, 37 Henry VIII., 1546, Robert Arden, assessed on property valued at £10; Walter Edkyns, £10; John Jenks, £6; John Skarlett, £8; Thomas Dixson, £8; Roger Knight, £8; Richard Ingram, £6; Thomas Gretwyn, £5; Margaret Scarlet, £5; Richard Edkyns, £6; Robert Fulwood, £5; Nicholas Gibbes, £5; Richard Green, £5; William Hill, £5 (Mr. Hunter's "Prolusions," 37, note). Thomas Arden of Park Hall at the same time was assessed on £80; but Simon Arden was only assessed on £8 (192/179).

[76] French, "Genealogica Shakespeareana," p. 423; and Nichols' "History of Leicestershire."

[77] H. Drummond's "Noble British Families," vol. i. (2).

[78] See Fuller's "Worthies of Warwickshire."

[79] "The several marks of cadency which have of late years been made use of for the distinction of houses ... for the second son a crescent, the third a mullet, the fourth a martlet" (Glover's "Heraldry," vol. i., p. 168, ed. 1780).

[80] Ibid., vol. ii., ed. 1780.

[81] In the "Return from Parnassus," 1606, Studiosus says of the players:

"Vile world that lifts them up to high degree,

And treads us down in grovelling misery,

England affords these glorious vagabonds

That carried erst their fardels on their backs

Coursers to ride on through the gazing streets,

Sweeping it in their glaring satin suits,

And pages to attend their masterships.

With mouthing words that better wits have framed,

They purchase lands and now esquires are made."

Act V., Sc. 1.

The satire in "Ratsey's Ghost" also may refer to Shakespeare, though Alleyn and others might be intended.

Freeman, in his "Epigrams," 1614, asks:

"Why hath our age such new-found 'gentles' found

To give the 'master' to the farmer's son?"

But his high praise of Shakespeare elsewhere shows he does not refer to him.

[82] John Davies of Hereford's "Microcosmus, The Civil Warres of Death and Fortune."

It is unfortunate that we know so little about Thomas Arden, Mary Shakespeare's "antecessor." A quiet country gentleman he seems to have been, marrying for love, and not for property, or his wife's descent might have helped us to clear his own. I do not think she was a Throckmorton, but I think she was very probably a Trussell, which Mr. French also suggests. Joane was a Trussell name, and Billesley held some attraction to the family. We are not sure of anything about Thomas except the purchase of Snitterfield, the year before Sir Walter Arden's death, and his payment of the subsidies in 1526 and 1546. It is probable he was the "Thomas Arden, Squier," who witnessed the will of Sir Walter in 1502; it is possible he was the Thomas Arden who witnessed the will of John Lench[83] of Birmingham in 1525, though it is more likely that this latter Thomas was his nephew, the heir of Park Hall. Thomas of Wilmecote is supposed to have died in 1546, but no will has been discovered. Probably he had handed over his property to his son in his lifetime. There is no trace of another child than Robert.

Robert was probably under age when his father purchased Snitterfield, and hence the need of trustees in association with the purchase. On December 14[Pg 36] and 21, 1519, Robert Arden purchased another property in Snitterfield from Richard Rushby and Agnes his wife,[84] and he bought also a tenement from John Palmer on October 1, 1529.[85] One of his tenants was Richard Shakespeare. He and his tenant were both presented for non-suit of court in 30 Henry VIII.

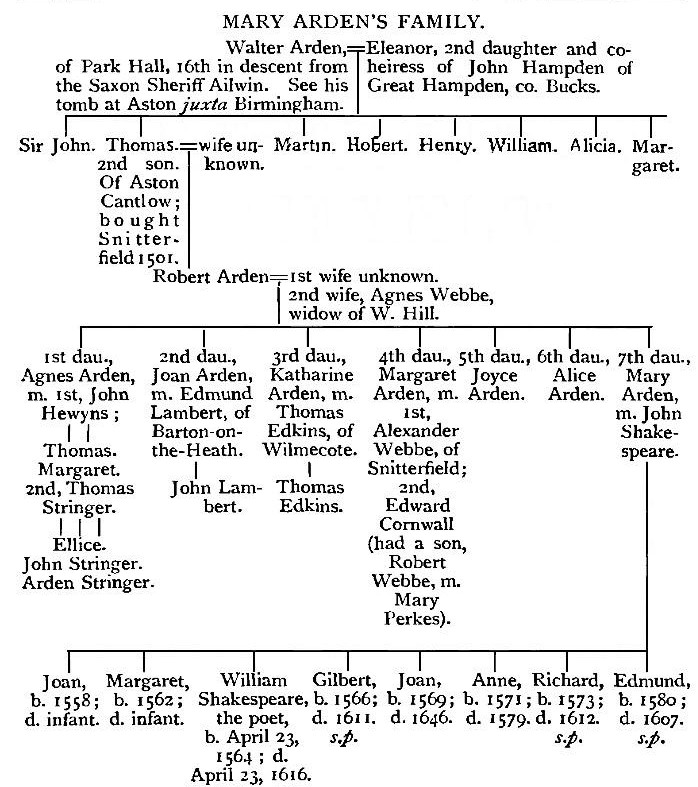

He contributed to the subsidy in Wilmecote in 1526 and 1546. We know no more of his first wife than we know of his mother. She might have been either a Trussel or a Palmer. But we know that he had seven[86] daughters, who all bore Arden family names: Agnes, who married first John Hewyns, and secondly Thomas Stringer, by whom she had two sons, John and Arden Stringer; Joan, who married Edmund Lambert, of Barton-on-the-Heath, who had a son, John Lambert; Katharine, who married Thomas Edkyns of Wilmecote, who had a son, Thomas Edkyns the younger; Margaret, who married first Alexander Webbe of Bearley (by whom she had a son Robert), and secondly Edward Cornwall; Joyce, of whom there is no record but in her father's settlement and will;[87] Alice, who was one of the co-executors of her father's will, but of whom there is no further record; and Mary, the other executor, who married John Shakespeare. The exact dates of their birth are not known. Robert may be supposed to have been married about 1520, and it is probable that Mary was born about 1535. It is likely that she was of age when made executor in 1556, but not at all necessary.

Robert Arden married again when his family had grown up—probably in 1550—Agnes Webbe, who had been assessed as the widow of Hill of Bearley on £7, in 37 Henry VIII., 1546. On July 17, 1550, Robert[Pg 37] Arden made two settlements of the Snitterfield estates, probably upon his marriage.[88] In the first,[89] he devised estates at Snitterfield in trust to Adam Palmer and Hugh Porter, for the benefit, after the death of himself and his wife, of his three married daughters—Agnes, Joan and Katharine. In the second, a similar deed,[90] in favour of three other daughters—Margaret (then married to Alexander Webbe of Bearley), Joyce and Alice. Mary is not mentioned, probably because the Asbies estate was even then devoted to her.

Robert Arden, sick in body, but good and perfect of remembrance, made his last will and testament[91] November 23, 1556, and he must have died shortly after. This will of itself answers the question as to his worldly position, and as to the meaning of the word "husbandman" in his case. The wage of a working "husbandman" at the time was from 25s. to 33s. a year.[92] His will discloses property on a level with many "gentlemen" of his time and his county. It gives a strong suggestion that Mrs. Arden was not on the best of terms with her stepchildren. Robert bequeathed his soul "to God and the blessed Lady Saint Mary, and all the holye company of heaven," and his body to be buried in the churchyard of Saint John the Baptist at Aston Cantlowe. "Also I bequeathe to my youngest daughter Marye all my land at Willincote caulide Asbyes, and the crop upon the grownde sown and tythde as hitt is ... and vili xiiis iiiid of money to be paid her or ere my goodes be devided. Also I gyve[Pg 38] and bequeathe to my daughter Ales, the thyrde parte of all my goodes moveable and unmoveable in fylde and towne after my dettes and leggessese performyde, besydes that goode she hath of her owne all this tyme. Allso I give and bequethe to Agnes my wife vili xiiis iiiid upon this condysion that she shall sofer my dowghter Ales quyetly to ynjoye half my copyhold in Wyllincote during the tyme of her wyddewoode; and if she will nott soffer my dowghter Ales quyetly to occupy half with her, then I will that my wyfe shall have but iiili vis viiid, and her gintur in Snytterfelde. Item, I will that the residew of all my goodes, moveable and unmovable, my funeralles and my dettes dyschargyd, I gyve and bequeathe to my other children to be equaleye devidide amongeste them by the descreshyon of Adam Palmer, Hugh Porter of Snytterfelde, and Jhon Skerlett, whom I do orden and make my overseers of this my last will and testament, and they to have for their peynes takyng in this behalfe xxs apece. Allso I orden and constitute and make my full exequtores Ales and Marye my dawghters of this my last will and testament, and they to have no more for their paynes takyng now as afore geven to them. Allso I gyve and bequethe to every house that hath no teeme in the paryche of Aston, to every house iiiid. Thes being witnesses Sir William Bouton Curett, Adam Palmer, Jhon Skerlett, Thomas Jhenkes, William Pytt, with other mo." Proved at Worcester, December 16, 1556, by Alice and Mary Arden. It is interesting to learn from the inventory the nature of the furniture, and the prices of the period. There were eleven "painted cloths" in the various rooms, the substitutes for ancient tapestry even in good homes.

The value of the goods, movable and unmovable, independently of the landed property, was calculated to be £76 11s. 10d. This was a large sum for the[Pg 39] period. Probably even then the goods were worth much more, as the prices entered are relatively low for the date. Certainly it is necessary to multiply the value by ten to translate it into modern figures, and that would give a good estimate for the saleable value of a houseful of furniture now.

After her sister's and her stepmother's legacies of £6 13s. 4d., after the payment of 4d. to every family in the parish, and of 20s. to the overseers, all debts being paid, Alice was to have a third—that is, the third that by old English law belonged to the dead. She would thus have at least £13 worth in kind, along with her interest in Snitterfield and what goods "she had of her own." The others would have about £5 each. It may be noted the widow was left no furniture or goods. She may have claimed the widow's third, though the effect of her jointure was to disturb the law of dower. She seems to have had furniture of her own. She evidently stayed on in her husband's home, and apparently brought her own children there.

Mary Hill was married to John Fulwood, November 15, 1561, at Aston Cantlow. Agnes Arden, widow, made her will in 1578. The opinion that there was no great friendliness with her husband's family is strengthened thereby, yet there was not the absolute estrangement some writers have supposed. Halliwell-Phillipps states that she does not mention a member of her husband's family. She left legacies to the poor, to her godchildren, to her grandchildren, and the residue to her son and son-in-law in trust for their children. She left twelve pence to John Lambert, her stepdaughter Joan's son, and twelve pence to each of her brother Alexander Webbe's children, one of whom, at least, was the son of her stepdaughter Margaret. She left nothing to any of her stepdaughters, and nothing to any of the young Shakespeares. The overseers[Pg 40] were Adam Palmer and George Gibbs; so she had been able to keep friendly with her husband's friend. The witnesses were Thomas Edkins (a stepdaughter's husband), Richard Petyfere, and others. She was buried on December 29, 1580, and the inventory of her goods was taken January 19, 1580-81. The low rate at which it is calculated is remarkable. "Item 38 sheep £3; fivescore pigs £13 4s.," etc. The sum total was £45. The will was proved on March 31, 1581.

The friendliness between the Shakespeares and the other Arden families seems to have been unstable. Aunt Joan's husband, Edmund Lambert, of Barton-on-the-Heath, and their son John, through rather sharp practice for cousinly customs, became owners of Asbies. There is a hazy suspicion even about the bonâ fides of the Edkins. Agnes had settled rather far off at the home of the Stringers, in Stockton, co. Salop. In February, 1569, Thomas Stringer devised to Alexander Webbe his share of Snitterfield. John Shakespeare was one of the witnesses to the indenture. Alexander Webbe, it is true, made John Shakespeare, his brother-in-law, the overseer of his will at his death in 1573.

Joyce Arden and Alice Arden seem both to have died unmarried, without leaving a will. There is no further mention of Alice, the wealthier of the two maiden sisters, resident at Aston Cantlow, neither has there hitherto been made any suggestion concerning Joyce, and her death does not appear in the parish registers. Now, it was an exceedingly common custom of the time for poorer single relatives to enter into the service of wealthier members of the family; for "superfluous women" even, who were not poor, to go where they were wanted in other homes. Might she not have gone in such a capacity to one of the houses of the Ardens of Park Hall? In Worcestershire, near Stourbridge, there is a parish called Pedmore, and a[Pg 41] hall of the same name, then inhabited by the Arden family. The registers there record the death of a "Mistress Joyce Arden" in 1557, to whose family there is no clue: and I cannot but think she was Shakespeare's aunt, as the Joyce of Park Hall was married.

The Webbes[93] gradually bought up the reversionary shares of the other Arden sisters in Snitterfield, and held the whole as tenants under Mrs. Arden, widow. But the story of the Shakespeares' transfer is so curiously mixed up with their other actions that they must be taken together, in order to get a contemporary view of the matter. We find that John Shakespeare had apparently pinched himself in 1575 to purchase two houses in Stratford-on-Avon for £40, believed to be in Henley Street[94]. By 1578, for some reasons not explained, he was excused his share in municipal charges[95], and by a will of "Roger Sadler" Baker in that year, we know that he was in debt to him, and under circumstances that necessitated a security. "Item of Edmund Lambert and —— Cornish for the debte of Mr. John Shakesper vli[96]." John Shakespeare mortgaged Asbies to Edmund Lambert for a loan of £40 on November 14, 1578[97], the fine being levied Easter, 1579, the mortgagee treating the matter as a purchase[98].[Pg 42]

There is a curious complexity caused by a lease of the same property being apparently granted to George Gibbes, and a double fine levied[99]—i.e., parties brought in who were strangers to the title; and a double fine appears to have been levied for technical purposes when the estate was entailed[100]. These other names were Thomas Webbe and Humphrey Hooper[101]. The mortgage loan was made repayable at Michaelmas, 1580, when the lease commenced to run, and things seemed to have been made safe for the Shakespeares. Then they proceeded to sell a parcel[102] of the Snitterfield property to Robert Webbe for £40 on October 15, 1579. The description is worded loosely: "John Shakespeare yeoman and Mary his wife ... all that theire moietye, parte and partes, be yt more or lesse, of and in twoo messuages," etc. The indenture is long[103], and written in English, and would seem to have been signed at Wilmcote[104].

A bond was drawn up on the 25th of the same month, carrying a penalty of twenty marks against the Shakespeares if they infringed the above conditions, also signed in the presence of Nicholas Knolles, the Vicar of Auston or Alveston[105]. Another deed, the final concord,[106] is drawn up in Latin: "in curia domine Regine apud Westmonasterium a die Pasche in quindecim dies anno regnorum Elizabethe ... vicesimo secundo ... inter Robertum Webbe querentem et Johannem Shackspere et Mariam uxorem ejus, deforciantes de sexta parte duarum partium duorum messuagiorum ...[Pg 43] idem Robertus dedit predictis Johannis et Marie quadraginta libras sterlingorum." On this sale Robert Webbe paid a fine of 6s. 8d. for licence of entry to the Sheriff of the County.[107]