The Project Gutenberg EBook of Peeps At Many Lands: Australia, by Frank Fox This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Peeps At Many Lands: Australia Author: Frank Fox Illustrator: Percy F. S. Spence (etc.) Release Date: July 6, 2008 [EBook #25976] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PEEPS AT MANY LANDS: AUSTRALIA *** Produced by Jacqueline Jeremy and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

PEEPS AT MANY LANDS

AUSTRALIA

BY

WITH TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR

by

etc.

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1911

| CHAPTER I | |

| AUSTRALIA, ITS BEGINNING | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| AUSTRALIA OF TO-DAY | 15 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE NATIVES | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE ANIMALS AND BIRDS | 46 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE AUSTRALIAN BUSH | 63 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE AUSTRALIAN CHILD | 73[Pg iv] |

| KANGAROO-HUNTING | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

| SNOWY MOUNTAINS NEAR THE SITE OF THE FEDERAL CAPITAL | viii |

| THE BARRIER OF THE BLUE MOUNTAINS | 9 |

| THE GARDEN STREETS OF ADELAIDE | 16 |

| COLLINS STREET, MELBOURNE | 25 |

| THE TOWN HALL, SYDNEY | 32 |

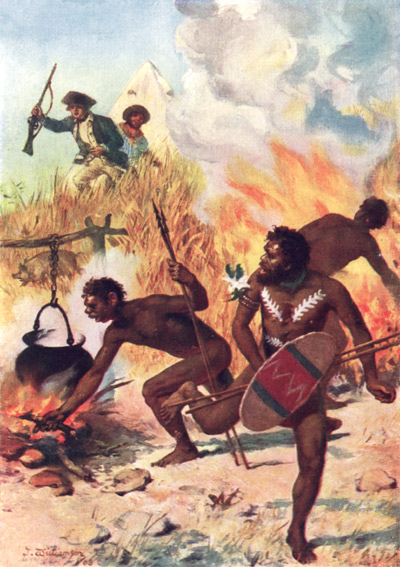

| AUSTRALIAN NATIVES IN CAPTAIN COOK’S TIME | 41 |

| THE AUSTRALIAN FOREST AT NIGHT—“MOONING” OPOSSUMS | 48 |

| A SHEEP DROVER | 57 |

| A HUT IN THE BUSH | 64 |

| SURF-BATHING—SHOOTING THE BREAKERS | 73 |

| AUSTRALIAN CHILDREN RIDING TO SCHOOL | 80 |

| THE NOMAD OF THE AUSTRALIAN INTERIOR | On the cover |

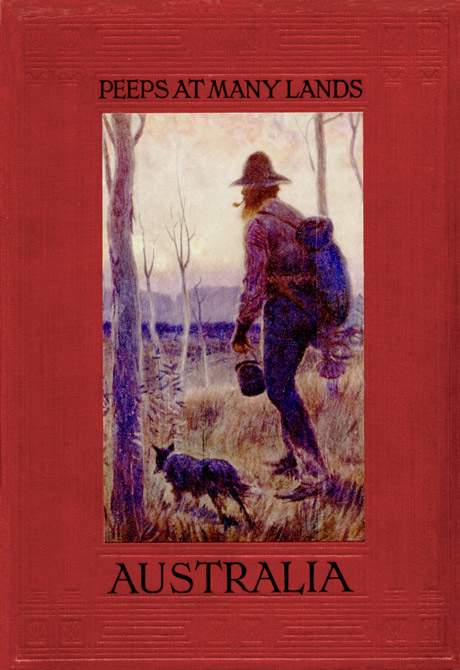

| Sketch-Map of Australia on pages vi and vii. | |

A “Sleeping Beauty” land—The coming of the English—Early explorations—The resourceful Australian.

The fairy-story of the Sleeping Beauty might have been thought out by someone having Australia in his mind. She was the Sleeping Beauty among the lands of the earth—a great continent, delicately beautiful in her natural features, wonderfully rich in wealth of soil and of mine, left for many, many centuries hidden away from the life of civilization, finally to be wakened to happiness by the courage and daring of English sailors, who, though not Princes nor even knights in title, were as noble and as bold as any hero of a fairy-tale.

How Australia came to be in her curious isolated position in the very beginning is not quite clear. The story of some of the continents is told in their rocks almost as clearly as though written in books. But Australia is very, very old as a continent—much older than Europe or America or Asia—and its[2] story is a little blurred and uncertain partly for that reason.

Look at the map and see its shape—something like that of a pancake with a big bite out of the north-eastern corner. In the very old days Australia was joined to those islands on the north—the East Indies—and through them to Asia; but it was countless ages ago, for the animals and the plants of Australia have not the least resemblance to those of Asia. They represent a class quite distinct in themselves. That proves that for a very long time there has been no land connection between Australia and Asia; if there had been, the types of flower and of beasts would be more nearly kindred. There would be tigers and elephants in Australia and emus in Asia, and the kangaroo and other marsupials would probably have disappeared. The marsupial, it may be explained, is one of the mammalian order, which carries its young about in a pouch for a long time after they are born. With such parental devotion, the marsupials would have little chance of surviving in any country where there were carnivorous animals to hunt them down; but Australia, with the exception of a very few dingoes, had no such animals, so the marsupials survived there whilst vanishing from all other parts of the earth.

When Australia was sundered from Asia, probably by some great volcanic outburst (the East Indies are to this day much subject to terrible earthquakes and volcanic outbreaks, and not so many years ago a whole[3] island was destroyed in the Straits of Sunda), the new continent probably was in the shape somewhat of a ring, with very high mountains facing the sea, and, where now is the great central plain, a lake or inland sea. As time wore on, the great mountains were ground down by the action of the snow and the rain and the wind. The soil which was thus made was in part carried towards the centre of the ring, and in time the sea or lake vanished, and Australia took its present form of a great flat plain, through which flow sluggish rivers—a plain surrounded by a tableland and a chain of coastal mountains. The natives and the animals and plants of Australia, when it first became a continent, were very much the same, in all likelihood, as now.

Thus separated in some sudden and dramatic way, Australia was quite forgotten by the rest of the world. In Asia, near by, the Chinese built up a curious civilization, and discovered, among other things, the use of the mariner’s compass, but they do not seem to have ever attempted to sail south to what is now known as Australasia. The Japanese, borrowing culture from the Chinese, framed their beautiful and romantic social system, and, having a brave and enterprising spirit, became seafarers, and are known to have reached as far as the Hawaiian Islands, more than halfway across the Pacific Ocean to America; but they did not come to Australia. The Indian Empire rose to magnificent greatness; the Empires of Babylon, of Nineveh, of Persia,[4] came and went. The Greeks, and the Romans later, penetrated to Hindustan. The Christian era came, and later the opening up of trade with the East Indies and with China.

But still Australia slept, in her out-of-the-way corner, apart from the great streams of human traffic, a rich and beautiful land waiting for her Fairy Prince to waken her to greatness. There had been, though, some vague rumours of a great island in the Southern Seas. A writer of Chios (Greece) 300 years before the Christian era mentions that there existed an island of immense extent beyond the seas washing Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is thought that Greek soldiers who had accompanied Alexander the Great to India had brought rumours from the Indians of this new land. But if the Indians knew of Australia, there is no trace of their having visited the continent.

Marco Polo, the Venetian traveller, who explored the East Indies, speaks of a Java Major as well as a Java Minor, and in that he may refer to Australia; but he made no attempt to reach the land. Some old maps fill up the ocean from the East Indies to the South Pole with a vague continent called Terra Australis; but plainly they were only guessing, and did not have any real knowledge.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Spanish and Portuguese sailors pushed on bravely with the work of exploring the East Indies, and some of their maps of the period give indications of a knowledge of the existence of the Australian Continent. But the[5] definite discovery did not come until 1605, when De Quiros and De Torres, Spanish Admirals, sailed to the East Indies and heard of the southern continent. They sailed in search of it, but only succeeded in touching at some of the outlying islands. One of the New Hebrides De Quiros called “Terra Australis del Espiritu Santo” (the Southern Land of the Holy Ghost), fancying the island to be Australia. That gave the name “Australia,” which is all that survives to remind us of Spanish exploration.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Dutch sailors set to work to search for the new southern land, and in 1605, 1616, and 1617 undoubtedly touched on points of Australia. In 1642 Tasman—from whom Tasmania, a southern island of Australia, gets its name—made important discoveries as to the southern coast. He called the island first Van Diemen’s Land, after Maria Van Diemen, the girl whom he loved; but this name was afterwards changed. Maria Island, off the coast of Tasmania, still, however, keeps fresh the memory of the Dutch sailor’s sweetheart.

But none of these nations was destined to be the Fairy Prince to waken Australia out of her long sleep. That privilege was kept for the British race; we cannot but think happily, for no Spanish or Dutch colony has ever reached to the greatness and the happiness of an Australia, a Canada, or a South Africa. It is in the British blood, it seems, to[6] colonize happily. The gardeners of the British race know how to “plant out” successfully. They shelter and protect the young trees in their far-away countries through the perils of infancy, and then let them grow up in healthy and vigorous independence. This wise method is borrowed from family life. If a child is either too much coddled, or too much kept under in its young days, it will rarely grow to the best and most vigorous manhood or womanhood. British colonies grow into healthy nations just as British schoolboys grow into healthy men, because they are, at an early stage, taught to be self-reliant.

It was not until 1688 that Australia was in any way explored by the English Captain, William Dampier. His reports on the new land were not very flattering. He spoke of its dry, sandy soil, and its want of water. This Sleeping Beauty had a way of pretending to be ugly to the new-comer.

From 1769 to 1777 Captain Cook carried on the first thorough British exploration of Australia, and took possession of it and New Zealand for the British Crown. In 1788, just a century after its first exploration by a British seaman, Australia was actually occupied by Great Britain, “the First Fleet” founding a settlement on the shores of Port Jackson, by the side of a little creek called the Tank Stream. That was the beginning of Sydney, at present one of the greatest cities of the British Empire.

A great continent had been thus entered. The Sleeping Beauty was aroused from the slumber of[7] centuries. But very much had yet to be done before she could “marry the Prince and then live happily ever afterwards.” The story of how that was done, and how Australia was explored and settled, is one of the most heroic of our British annals. True, no wild animals or warlike tribes had to be faced; but vast distances of land which of itself produced little or no food for man, the long waterless stretches, the savage ruggedness of the mountains, set up obstacles far more awesome because more strange. Man had to contend, not with wild animals, whose teeth and claws he might evade, nor with wild men whose weapons he could overmatch with his own, but with Nature in what seemed always a hostile and unrelenting mood. It almost seemed that Nature, unwilling to give up to civilization the last of the lonely lands of the earth, made a conscious effort to beat back the advance of exploration and civilization.

On the little coastal settlement famine was soon felt. The colonists did not understand how to get crops from the soil. They attempted to follow the times and the manners of England; but here they were in the Antipodes, where everything was exactly opposite to English conditions. There were no natural grain-crops; there were practically no food-animals good to eat. The kangaroo and wallaby provide nowadays a delicious soup (made from the tails of the animals), but the flesh of their bodies is tough and dark and rank. Even so it was in very limited supply. The early settlers ate[8] kangaroo flesh gladly, but they were not able to get enough of it to keep them in meat.

Communication with England, whence all food had to come, was in those days of sailing-ships slow and uncertain. At different times the first settlement was in actual danger of perishing from starvation and of being abandoned in despair at ever making anything useful of a land which seemed unable to produce even food for white inhabitants.

Fortunately, those thoughts of despair were not allowed to rule. The dogged British spirit saved the position. The conquest of Nature in Australia was perseveringly carried through, and Great Britain has the reward to-day in the existence of an all-British continent having nearly 5,000,000 of population, who are the richest producers in the world from the soil.

After the early settlers had learned with much painful effort that the coast around Sydney would produce some little grain and fruit and grass for cattle, there was still another halt in the progress of the continent. West of Sydney, about forty miles from the coast, stretched the Blue Mountains, and these it was found impossible to cross. No passes existed. Though not very lofty, the mountains were savagely wild. The explorer, following a ridge or a line of valley with patience for many miles, would come suddenly on a vast chasm; a cliff-face falling absolutely perpendicularly 1,000 feet or so would declare “No road here.” Nowadays, when the Blue Mountains have been conquered, and they are[9] traversed by roads and railways, tourists from all parts of the world find great joy in looking upon these wonderful gorges; but in the days of the explorers they were the cause of many disappointments—indeed, of many tragedies. Men escaping from the prisons (Australia was first used as a reformatory by Great Britain) would attempt to cross the Blue Mountains on their way, as they thought, to China and freedom, always to perish miserably in the wild gorges.

Finally, the Blue Mountains were conquered by the explorers Blaxland, Lawson, and Wentworth. Two roads were cut across them, one from Sydney, one from Windsor, about thirty miles north from Sydney. The passing of the Blue Mountains opened up to Australia the great tableland, on which the chief mineral discoveries were to be made, and the vast interior plains, which were to produce merino wool of such quality as no other land can equal.

From that onwards exploration was steadily pushed on. Sometimes the explorers went out into the wilderness with horses, sometimes with camels; other tracts of land were explored by boat expeditions, following the track of one of the slow rivers. The perils always were of thirst and hunger. Very rarely did the blacks give any serious trouble. But many explorers perished from privation, such as Burke and Wills (who led out a great expedition from Melbourne, which was designed to cross the continent from north to south) and Dr. Leichhardt.[10] Even now there is some danger in penetrating to some of the wilder parts of the interior of Australia without a skilful guide, who knows where water can be found, and deaths from thirst in the Bush are not infrequent.

One device has saved many lives. The wildest and loneliest part of the continent is traversed by a telegraph line, which brings the European cable-messages from Port Darwin, on the north coast, to Adelaide, in the south. Men lost in the Bush near to that line make for its route and cut the wire. That causes an interruption on the line; a line-repairer is sent out from the nearest repairing-station, and finds the lost man camped near the break. Sometimes he is too late, and finds him dead.

In the west, around the great goldfields, where water is very scarce, white explorers have sometimes adopted a way to get help which is far more objectionable. The natives in those regions are very reluctant to show the locality of the waterholes. The supply is scanty, and they have learned to regard the white man as wasteful and inconsiderate in regard to water. But a white explorer or traveller has been known to catch a native, and, filling his mouth with salt, to expose him to the heat of the sun until the tortures of thirst forced him to lead the white party to a native well. But these are rare dark spots on the picture. The records of Australian exploration, as a whole, are bright with heroism.

The early pioneer in Australia—called a[11] “squatter” because he squatted on the land where he chose—enjoyed a picturesque life. Taking all his household goods with him, driving his flocks and herds before him, he moved out into the wilderness looking for a place to settle or “squat.” It was the experience of the “Swiss Family Robinson” made real. The little community, with its waggons and tents, its horses, oxen, sheep, dogs, perhaps also with a few poultry in one of the waggons, would have to live for many months an absolutely self-contained life. The family and its servants would provide wheelwrights, blacksmiths, carpenters, veterinary surgeons, cattle-herds, milkers, shearers, cooks, bridge-builders, and the like. The children brought up under those conditions won not only fine healthy frames, but an alertness of mind, a wideness of resource which made them, and their children after them, fine nation-builders.

I am tempted, in illustration of this, to quote from a larger work of mine, “Australia,” an instance of my own observation of the “resourceful Australian”:

“Without touch of cap, or sign of servility, the swagman came up.

“‘Gotter a job, boss?’

“‘No chance; but you can go round and get rations.’

“‘I wanter job pretty bad. Times have been hard. Perhaps you recollect me—Jim Stone. You had me once working on the Paroo.’

[12] “It was a blazing hot day in Central Queensland on one of the big cattle stations out from the railway line, a station which had not yet reached the dignity of fencing. The boss remembered that Jim Stone ‘was a good sort,’ and that it was forty miles to the next chance of a job. And there was always something to be done on a station.

“‘All right, Stone. I think I can put you on to something for a month or two.’

“‘Thanks. Start now?’

“‘Look. I have got a few men on digging tanks, about thirty miles out. It’s north-north-east. You can pick up their camp?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘Well, I want you to take a bullock-dray out, with stores, and bring back anything they want sent back.’

“‘Yes. Where are the bullocks?’

“‘I haven’t got a team broken in. But there’s old Scarlet-Eye and two others broken in. You’ll pick them up along that little creek there, six miles out’; he pointed indefinitely into the heat haze on the plain, where there seemed to be some trees on the horizon. ‘Collar them, and then you’ll find the milkers’ herd right back of the homestead, only a few miles. Punch out seven of the biggest and make up your team.’

“‘Yes. Where’s ther dray?’

“‘Behind the blacksmith’s shed there. By the way, there are no yokes, but you’ll find some bar-iron[13] and some timber at the blacksmith’s shed. Knock out some yokes. I think there’s one chain. You can make up another with some fencing wire.’

“‘Right-oh.’

“And this Australian casual worker (at 30s. a week and rations) went his way cheerfully. He had to find some odd bullocks six miles out, in the flat, grey, illimitable plain; then find the herd of milkers somewhere else in that vague vastness, and break seven of them to harness; fix up a dray and make cattle yokes; and then go out into the depths to find a camp thirty miles out, without a fence or a track, and hardly a tree, to guide him.

“He did it all, because to him it was quite ordinary. The freshly-broken-in cattle had to be kept in the yokes for a week, night and day, else they would have cleared out. That was the only real hardship, in his opinion, and the cattle had to suffer that. He was content to be surveyor, waggon-builder, blacksmith, subduer of beasts, man of infinite pluck, resource, and energy, for 30s. a week and rations! And he was a typical sample of the ‘back-country Australian.’”

In the Australian Bush most children can milk a cow, ride a horse, or harness him into a cart, snare or shoot game, kill a snake, find their way through the trackless forest by the sun or the stars, and cook a meal. In the cities, too, they are, though less skilled in such things, used to do far more for themselves than the average European child.

[14]After the squatters in Australia came the gold-diggers. Gold was discovered in Victoria and in New South Wales. At first, strangely enough, an effort was made to prevent the fact being known that gold was to be found in Australia. Some of the rulers of the colony feared that the gold would ruin and not help the country. And certainly in the very early days of the gold-digging rushes, much harm was done to the settled industries of the land through everybody rushing away to the diggings. Farms were abandoned, workshops deserted, the sailors left their ships, the shepherds their sheep, the shop-keepers their shops—all with the gold fever. But that early madness soon passed away, and Australia got the benefit of the gold discoverers in a great increase of population. Most of those who came to dig gold remained to dig potatoes and other more certain wealth out of the land.

Do you remember the tale of the ancient wise man whose two sons were lazy fellows? He could not get them by any means to work in the vineyard. As long as his own hands could toil he tended the vineyard, and maintained his idle sons. But on his death-bed he feared for their future. So he made them the victims of a pious fraud. “There is a great sum in gold buried in the vineyard,” he told them with his dying breath. “But I cannot tell you where. You must find that for yourselves.”

Tempted by the promise of quick fortune, the idle[15] sons dug everywhere in the vineyard to find the buried treasure. They never came across any actual gold, but the good effect of their digging was such that the vineyard prospered wonderfully and they grew rich from its fine crops.

So it was, in a way, with Australia. The gold discoverers did much good by attracting people to the country in search of gold who, though they found no gold, developed the other resources of a great country.

When the yields from the alluvial goldfields decreased there was a great demand from the out-of-work diggers and others for land for farming, and the agricultural era began in Australia. Since then the growth of the country has been sound, and, if a little slow, sure. It has been slow because the ideal of the people has always been a sound and a general well-being rather than a too-quick growth. “Slow and steady” is a good motto for a nation as well as an individual.

The diggings—The Government at Melbourne—The sheep-runs—The rabbits—The delights of Sydney.

If, by good luck, you were to have a trip to Australia now, you would find, probably, the sea voyage, which takes up five weeks as a rule, a little[16] irksome. But fancy that over, and imagine yourself safely into Australia of to-day. Fremantle will be the first place of call. It is the port of Perth, which is the capital of West Australia. That great State occupies nearly a quarter of the continent; but its population is as yet the least important of the continental States, and not very much ahead of the little island of Tasmania. Still, West Australia is advancing very quickly. On the north it has great pearl fisheries; inland it has goldfields, which take second rank in the world’s list, and it is fast developing its agricultural and pastoral riches.

Very soon it will be possible to leave the steamer at Fremantle and go by train right across the continent to the Eastern cities. Now you must travel by steamer to Port Adelaide, for Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. It is a charming city, surrounded by vineyards, orange orchards, and almond and olive groves. In the season you may get for a penny all the grapes that you could possibly eat, and oranges and other fruit are just as cheap.

Adelaide has the reputation of being a very “good” city. It was founded largely by high-minded colonists from Britain, whose main idea was to seek in the new world a place where poverty and its evils would not exist. To a very large extent they succeeded. There are no slums in Adelaide and no starving children. Everywhere is an air of quiet comfort.

[17] From Adelaide you may take the train to complete your trip, the end of which is, say, Brisbane. Leaving Adelaide, you climb in the train the pretty Mount Lofty Mountains and then sweep down on to the plains and cross the Murray River near its mouth. The Murray is the greatest of Australian rivers. It rises in the Australian Alps, and gathers on its way to the sea the Murrumbidgee and the Darling tributaries. There is a curious floating life on these rivers. Nomad men follow along their banks, making a living by fishing and doing odd jobs on the stations they pass. They are called “whalers,” and follow the life, mainly, I think, because of a gipsy instinct for roving, since it is not either a comfortable or profitable existence. On the rivers, too, are all sorts of curious little colonies, living in barges, and floating down from town to town. You may find thus floating, little theatres, cinematograph shows, and even circuses.

The fisheries of these rivers are somewhat important, the chief fish caught being the Murray cod. It grows sometimes to a vast size, to the size almost of a shark; but when the cod is so big its flesh is always rank and uneatable by Europeans.

Fishing for a cod is not an occupation calling for very much industry. The fisherman baits his line, ties it to a stake fixed on the river bank, and on the stake hangs a bell. Then the fisherman gets under the shadow of a gum-tree and enjoys a quiet life, reading or just lazing. If a cod takes the bait the[18] bell will ring, and he will go and collect his fish, which obligingly catches itself, and does not need any play to bring it to land.

A cruel practice is followed to keep these fish fresh until a boat or train to the city markets is due: a line is passed through the cod’s lip, and it is tethered to a stake in the water near the bank. Thus it can swim about and keep alive for some time; but the cruelty is great, and efforts are now being made to stop this tethering of codfish.

These Australian inland rivers are slow and sluggish, and fish, such as trout, accustomed to clear running waters, will not live in them. But in the smaller mountain streams, which feed the big inland rivers, trout thrive, and as they have been introduced from England and America they provide good sport to anglers.

The plain-country through which the big rivers flow is very flat, and is therefore liable to great floods. Australia has the reputation of being a very dry country; as a matter of fact, the rainfall over one-third of its area is greater than that of England. In most places the rainfall is, however, badly distributed. After long spells of very dry weather there will come fierce storms, during which the rain sometimes falls at the rate of an inch an hour. This fact, and the curious physical formation of the continent, about which you already know, makes it very liable to floods.

Great floods of the past have been at Brisbane, the[19] capital of Queensland, destroying a section of the city; at Bourke (N.S.W.), and at Gundagai (N.S.W.). In the latter a town was destroyed and many lives lost. Another flood on the Hunter River (N.S.W.) was marked by the drowning of the Speaker of the local Parliament. But great loss of human life is rare; sacrifice of stock is sometimes, however, enormous. Cattle fare better than sheep, for they will make some wise effort to reach a point of safety, whilst sheep will, as likely as not, huddle together in a hollow, not having the sense even to seek the little elevations which are called “hills,” though only raised a few feet above the general level.

I recall well a flood in the Narrabri (N.S.W.) district some seventeen years ago, and its moving perils. The hillocks on which cattle, sheep, and in some cases human beings, had taken refuge were crowded, too, with kangaroos, emus, brolgas (a kind of crane), koalas (known as the native bear), rabbits, and snakes. Mutual hostilities were for a time suspended by the common danger, though the snakes and the rabbits were rarely given the advantages of the truce if there were human beings present. An incident of that flood was that the little township of Terry-hie-hie (these aboriginal names are strange!) was almost wiped out by starvation. Beleaguered by the waters, it was cut off from all communication with the railway and with food-supplies. When the waters fell, the mud left on these black-soil plains was just as formidable a barrier. Attempt after attempt to send[20] flour through by horse and bullock teams failed. It was impossible for thirty horses to get through with one ton of flour! The siege was only raised when the population of the little town was on the very verge of starvation.

After crossing the Murray the train passes through what is known as “the desert”—a stretch of country covered with mallee scrub (the mallee is a kind of small gum-tree); but nowadays they are finding out that this mallee scrub is not hopeless country at all. The scrub is beaten down by having great rollers drawn over it by horses; that in time kills it. Then the roots are dug up for firewood, and the land is sown with wheat. Quite good crops are now being got from the mallee when the rains are favourable, but in dry seasons the wheat scorches off, and the farmer’s labour is wasted. It is proposed now to carry irrigation channels through this and similar country. When that is done there will be no more talk of desert in most parts of Australia. It will be conquered for the use of man just as the American alkali desert is being conquered.

Leaving the mallee, the train comes in time to Ballarat, which used to be the great centre of the gold-mining industry. Round here gold was discovered in great lumps lying on the ground or just below the roots of the grass. People rushed from all parts of the world to pick up fortunes when this was heard of. The road from Melbourne was covered with waggons, with horsemen, with diggers[21] on foot. Most of them knew nothing at all about digging, and also lacked the knowledge of how to get along comfortably under “camping-out” conditions, when every man has to be his own cook, his own washer-up, his own laundryman, as well as his own mining labourer. But the best of the men learned quickly how to look after themselves, to pitch a tent, to cook a meal, to drive a shaft, and to do without food for long spells when on the search for new goldfields. Thus they became resourceful and adventurous, and were of great value afterwards in the community. There is nowadays rather a tendency in civilized countries to bring children up too softly, to guard them too much against the little roughnesses of life. Such experiences as those of the Australian goldfields show how good it is for men to be taught how to look after themselves under primitive conditions.

Life on the Australian goldfields, though wild, was not unruly. There was never any lynch law, never any “free shooting,” as on the American goldfields. Public order was generally respected, though there were at first no police. The miners, however, kept up Vigilance Committees, the main purpose of which was to check thefts. Anyone proved guilty of theft, or even seriously suspected of pilfering, was simply ordered out of the camp.

The Chinese were very early in getting to know of the goldfields in Australia, and rushed there in great numbers. They were not welcomed, and there[22] was an exception to the general rule of good order in the Anti-Chinese riots on the goldfields. The result of these was that Chinese were prevented by the Government from coming into the country, except in very small numbers, and on payment of a heavy poll-tax. When this was done the excitement calmed down, and the Chinese already in the country were treated fairly enough. They mostly settled down to growing vegetables or doing laundry-work, though a few still work as miners.

The objection that the Australians have to the Chinamen and to other coloured races is that they do not wish to have in the country any people with whom the white race cannot intermarry, and they wish all people in Australia to be equal in the eyes of the law and in social consideration. As you travel through Australia, you will probably learn to recognize the wisdom of this, and you will get to like the Australian social idea, which is to carry right through all relations of life the same discipline as governs a good school, giving respect to those who are most worthy of it, by conduct and by capacity, and not by riches or birth.

We have stayed long enough at Ballarat. Let us move on to Melbourne—“marvellous Melbourne,” as its citizens like to hear it called. Melbourne is built on the shores of the Yarra, where it empties into Hudson Bay, and its sea suburbs stretch along the beautiful sandy shores of that bay. Few European or American children can enjoy such sea[23] beaches as are scattered all over the Australian coast. They are beautiful white or creamy stretches of firm sand, curving round bays, sometimes just a mile in length, sometimes of huge extent, as the Ninety Miles Beach in Victoria. The water on the Australian coast is usually of a brilliant blue, and it breaks into white foam as it rolls on to the shelving sand. Around Carram, Aspendale, Mentone and Brighton, near Melbourne; at Narrabeen, Manly, Cronulla, Coogee, near Sydney; and at a hundred other places on the Australian coast, are beautiful beaches. You may see on holidays hundreds of thousands of people—men, women, and children—surf-bathing or paddling on the sands. It is quite safe fun, too, if you take care not to go out too far and so get caught in the undertow. Sharks are common on the Australian coast, but they will not venture into the broken water of surf beaches. But you must not bathe, except in enclosed baths in the harbours, or you run a serious risk of providing a meal for a voracious shark.

Sharks are quite the most dangerous foes of man in Australia. There have been some heroic incidents arising from attacks by sharks on human beings. An instance: On a New South Wales beach two brothers were bathing, and they had gone outside of the broken surf water. One was attacked by a shark. The other went to his rescue, and actually beat the great fish off, though he lost his arm in doing so. As a rule, however, the shark kills with one bite, attacking[24] the trunk of its victim, which it can sever in two with one great snap of its jaws.

Children on the Australian coast are very fond of the water. They learn to swim almost as soon as they can walk. Through exposure to the sun whilst bathing their skin gets a coppery colour, and except for their Anglo-Saxon eyes you would imagine many Australian youngsters to be Arabs.

The beaches of Melbourne are not its only attractions. The city itself is a very handsome one, and its great parks are planted with fine English trees. You will see as good oaks and elms and beeches in Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne, as in any of the parks of old England. Melbourne, too, at present, is the political capital of Australia, and here meet the Australian Parliament.

Every young citizen of the Empire should know something of the Commonwealth of Australia and its political institutions, because, as the idea of Empire grows, it is recognized that all people of British race, whether Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, or South Africans, or residents of the Mother Country, should know the whole Empire.

After Australia began to prosper it was found that the continent was too big to be governed by one Parliament in Sydney, so it split up into States, each with a constitution and government of its own. These States were New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, West Australia, and Tasmania. It was soon seen that a mistake had[25] been made in splitting up altogether. The States were like children of one family, all engaged as partners in one business, who, growing up, decided to set up housekeeping each for himself, but neglected to arrange for some means by which they could meet together now and again and decide on matters which were of common interest to all of them. The separated States of Australia were, all alike, interested in making Australia great and prosperous, and keeping her safe; but in their hurry to set up independent housekeeping they forgot to provide for the safeguarding of that common interest.

So soon as this was recognized, patriotic men set themselves to put things right, and the result was a Federation of the States, which is called the Commonwealth of Australia. The different States are left to manage for themselves their local affairs, but the big Australian affairs are managed by the Commonwealth Parliament, which at present meets in Melbourne, but one day will meet in a new Federal capital to be built somewhere out in the Bush—that is to say, the wild, empty country. Some people sneer at the idea of a “Bush capital,” but I think, and perhaps you will think with me, that there is something very pleasant and very promising of profit in the idea of the country’s rulers meeting somewhere in the pure air of a quiet little city surrounded by the great Australian forest. And as things are now, the population of Australia is too[26] much centralized in the big cities, and it will be a good thing to have another centre of population.

In this railway trip across the continent you are being introduced to all the main features of Australian life, so that you will have some solid knowledge of the conditions of the country, and can, later on, in chapters which will follow, learn of the Bush, the natives, the birds and beasts and flowers, the games of Australia.

Leaving Melbourne, a fast and luxurious train takes you through the farming districts of Victoria, past many smiling towns, growing rich from the industry of men who graze cattle, grow wheat and oats and barley, make butter, or pasture sheep. At Albany the train crosses to Murray again, this time near to its source, and New South Wales is entered.

For many, many miles now the train will run through flat, grassed country, on which great flocks of sheep graze. This is the Riverina district, the most notable sheep land in the world. From here, and from similar plains running all along the western and northern borders of New South Wales, comes the fine merino wool, which is necessary for first-class cloth-making. The story of merino wool is one of the romances of modern industry. Before the days of Australia, Spain was looked upon as the only country in the world which could produce fine wool. Spain was not willing that British looms should have any advantage of her production, and the British woollen manufacturing industry, confined[27] to the use of coarser staples, languished. Now Australia, and Australia practically alone, produces the fine wool of the world. Australia merino wool is finer, more elastic, longer in staple, than any wool ever dreamed of a century ago, and its use alone makes possible some of the very fine cloths of to-day.

This merino wool is purely a product of Australian cleverness in sheep-breeding. The sheep imported have been improved upon again and again, quality and quantity of coat being both considered, until to-day the Australian sheep is the greatest triumph of modern science as applied to the culture of animals, more wonderful and more useful than the thoroughbred race-horse. It is only on the hot plains that the merino sheep flourishes to perfection. If he is brought to cold hill-country in Australia his coat at once begins to coarsen, and his wool is therefore not so good.

As you pass the sheep-runs in the train you will probably notice that they are divided into paddocks by fine-mesh wire-netting. That is to keep the rabbits out. The rabbit is accounted rather a desirable little creature in Great Britain. A rabbit-warren on an estate is a source of good sport and good food, and the complaint is sometimes of too few rabbits rather than too many. A boy may keep rabbits as pets with some enjoyment and some profit.

In Australia rabbits were first introduced by an[28] emigrant from England, who wished to give to his farm a home-like air. They spread over the country with such marvellous rapidity as to become soon a serious nuisance, then a national danger. Millions of pounds have been spent in different parts of Australia fighting the rabbit plague; millions more will yet have to be spent, for though the rabbits are now being kept in check, constant vigilance is needed to see that they do not get the upper hand again. The rabbit in Australia increases its numbers very quickly: the doe will have up to eighty or ninety young in a year. There is no natural check to this; no winter spell of bitter cold to kill off the young and feeble. The only limit to the rabbit life is the food-supply, and that does not fail until the pasturage intended for the sheep is eaten bare. Not only is the grass eaten, but also the roots of the grass, and the rabbit is a further nuisance because sheep dislike to eat grass at which bunny has been nibbling.

The campaign against the rabbit in Australia has had all the excitement and much of the misery of a great war. The march inland of the rabbit was like that of a devastating army. Smiling prosperity was turned into black ruin. Where there had been green pastures and bleating sheep there was a bare and dusty plain and starving stock.

At first wholesale poisoning was tried as a remedy for the rabbit plague. It inflicted a check, but had the evil of killing off many of the native birds and animals. There was an idea once of trying to spread[29] a disease among the rabbits, so as to kill them off quickly, but that was abandoned. Now the method is to enclose the pasture-lands within wire-netting, which is rabbit-proof, and within this enclosure to destroy all logs and the like which provide shelters for the rabbits, to dig up all their burrows, and to hunt down the rabbit with dogs. The best of the lands are being thus quite cleared of rabbits. The worst lands are for the present left to bunny, who has become a source of income, being trapped and his carcase sent frozen to England, and his fur utilized for hat-felt. But be sure that if you bring to Australia your rabbit pets with you from England they will be destroyed before you land, and you may reckon on having to face serious trouble with the law for trying to bring them into the country.

Whilst you have been hearing all this about the rabbit the train has climbed up from the plains to the Blue Mountains and is rushing down the coast slope towards Sydney, the capital of New South Wales, the chief commercial city of Australia, and one of the great ports of the Empire. Sydney is, I do really think, the pleasantest place in the world for a child to live in, though two hot, muggy months of the year are to be avoided for health’s sake.

On the Blue Mountains, as you crossed in the train, you will have seen wild “gullies,” as they are called in Australia—ravines in the hills which rise abruptly all around, sometimes in wild cliffs and sometimes in steep wooded slopes. These gullies[30] interlace with one another, one leading into another, and stretching out little arms in all directions. Turn into one and try to follow it up, and you never know where it will end. Well, once upon a time there was a particularly wild one of these gully systems on the coast hills where Sydney now is. Something sunk the level of the land suddenly, and the gullies were depressed below sea-level. The Pacific Ocean heard of this, broke a way through a great cliff-gate, and that made Sydney Harbour. Entering Sydney by sea, you come, as the ocean does, through a narrow gate between two lovely cliffs. Turn sharply to the left, and you are in a maze of blue waters, fringed with steep hills. On these hills is built Sydney. You may follow the harbour in all directions, up Iron Cove a couple of miles to Leichhardt suburb; along the Parramatta River (which is not a river at all, but one of the long arms of the ocean-filled gully system) ten miles to the orange orchard country; along the Lane Cove, through wooded hills, to another orchard tract; or, going in another direction, you may travel for scores of miles along what is called Middle Harbour, and then have North Harbour still to explore. In spite of the nearness of the big city, and the presence here and there of lovely suburbs on the waterside, the area of Sydney Harbour is so vast, its windings are so amazing, that you can get in a boat to the wildest and most lovely scenery in an hour or two. The rocky shores abound in caves, where you can camp out in dryness and[31] comfort. The Bush at every season of the year flaunts wildflowers. There are fish to be had everywhere; in many places oysters; in some places rabbits, hares, and wallabies to be hunted. Does it not sound like a children’s paradise—all this within reach of a vast city?

But let us tear ourselves away from Sydney, and go on to Brisbane, passing on the way through Kurringai Chase, one of the great National Parks of New South Wales; along the fertile Hawkesbury and Hunter valleys, which grow Indian corn and lucerne, and oranges and melons, and men who are mostly over six feet high; up the New England Mountains, through a country which owes its name to the fact that the high elevation gives it a climate somewhat like that of England; then into Queensland along the rich Darling Down studded with wheat-farms, dairy-farms, and cattle-ranches; and finally to Brisbane, a prospering semi-tropical town which is the capital of the Northern State of Queensland. At Brisbane you will be able to buy fine pineapples for a penny each, and that alone should endear it to your heart.

Thus you will have seen a good deal of the Australia of to-day. You might have followed other routes. Coming via Canada, you would reach Brisbane first. Taking a “British India” boat you would have come down the north coast of Queensland and seen something of its wonderful tropical vegetation, its sugar-fields, banana and coffee plantations,[32] and the meat works which ship abroad the products of the great cattle stations.

This tropical part of Australia really calls for a long book of its own. But as it is hardly the Australia of to-day, though it may be the Australia of the future, we must hurry through its great forests and its rich plains. There are wild buffalo to be found on these plains, and in the rivers that flow through them crocodiles lurk. The crocodile is a very cunning creature. It rests near the surface of the water like a half-submerged log waiting for a horse or an ox or a man to come into the water. Then a rush and a meal.

If, instead of coming along the north, you had travelled via South Africa you might have landed first at Hobart and seen the charms of dear little Tasmania, a land of apple-orchards and hop-gardens, looking like the best parts of Kent. But you have been introduced to a good deal of Australia and heard much of its industries and its history. It is time now to talk of savages, and birds, and beasts, and games, and the like.

A dwindling race; their curious weapons—The Papuan tree-dwellers—The cunning witch-doctors.

The natives of Australia were always few in number. The conditions of the country secured that Australia, kept from civilization for so long, is yet the one land of the world which, whilst capable of great production with the aid of man’s skill, is in its natural state hopelessly sterile. Australia produced no grain of any sort naturally; neither wheat, oats, barley nor maize. It produced practically no edible fruit, excepting a few berries, and one or two nuts, the outer rind of which was eatable. There were no useful roots such as the potato, the turnip, or the yam, or the taro. The native animals were few and just barely eatable, the kangaroo, the koala (or native bear) being the principal ones. In birds alone was the country well supplied, and they were more beautiful of plumage than useful as food. Even the fisheries were infrequent, for the coast line, as you will see from the map, is unbroken by any great bays, and there is thus less sea frontage to Australia than to any other of the continents, and the rivers are few in number.

Where the land inhabited by savages is poor in[34] food-supply their number is, as a rule, small and their condition poor. It is not good for a people to have too easy times; that deprives them of the incentive to work. But also it is not good for people who are backward in civilization to be kept to a land which treats them too harshly; for then they never get a fair chance to progress in the scale of civilization. The people of the tropics and the people near the poles lagged behind in the race for exactly opposite but equally powerful reasons. The one found things too easy, the other found things too hard. It was in the land between, the Temperate Zone, where, with proper industry, man could prosper, that great civilizations grew up.

The Australian native had not much to complain of in regard to his climate. It was neither tropical nor polar. But the unique natural conditions of his country made it as little fruitful to an uncivilized inhabitant as was Lapland. When Captain Cook landed at Botany Bay probably there were not 500,000 natives in all Australia. And if the white man had not come, there probably would never have been any progress among the blacks. As they were then they had been for countless centuries, and in all likelihood would have remained for countless centuries more. They had never, like the Chinese, the Hindus, the Peruvians, the Mexicans, evolved a civilization of their own. There was not the slightest sign that they would be able to do so in the future. If there was ever a country on earth[35] which the white man had a right to take on the ground that the black man could never put it to good use, it was Australia.

Allowing that, it is a pity to have to record that the early treatment of the poor natives of Australia was bad. The first settlers to Australia had learned most of the lessons of civilization, but they had not learned the wisdom and justice of treating the people they were supplanting fairly. The officials were, as a rule, kind enough; but some classes of the new population were of a bad type, and these, coming into contact with the natives, were guilty of cruelties which led to reprisals and then to further cruelties, and finally to a complete destruction of the black people in some districts.

In Tasmania, for instance, where the blacks were of a fine robust type, convicts in the early days, escaping to the Bush, by their cruelties inflamed the natives to hatred of the white disturbers, and outrages were frequent. The state of affairs got to be so bad that the Government formed the idea of capturing all the natives of Tasmania and putting them on a special reserve on Tasman Peninsula. That was to be the black man’s part of the country, where no white people would be allowed. The help of the settlers was enlisted, and a great cordon was formed around the whole island, as if it were to be beaten for game. The cordon gradually closed in on Tasman Peninsula after some weeks of “beating” the forests. It was found, then, that one[36] aboriginal woman had been captured, and that was all. Such a result might have been foreseen. Tasmania is about as large as Scotland. Its natural features are just as wild. The cordon did not embrace 2,000 settlers. The idea of their being able to drive before them a whole native race familiar with the Bush was absurd.

After that the old conditions ruled in Tasmania. Blacks and whites were in constant conflict, and the black race quickly perished. To-day there is not a single member of that race alive, Truganini, its last representative, having died about a quarter of a century ago.

On the mainland of Australia many blacks still survive; indeed, in a few districts of the north, they have as yet barely come into contact with the white race. A happier system in dealing with them prevails. The Government are resolute that the blacks shall be treated kindly, and aboriginal reserves have been formed in all the States. One hears still of acts of cruelty in the back-blocks (as the far interior of Australia is called), but, so far as the Government can, it punishes the offenders. In several of the States there is an official known as the Protector of the Aborigines, and he has very wide powers to shield these poor blacks from the wickedness of others, and from their own weakness. In the Northern States now, the chief enemies of the blacks are Asiatics from the pearl-shelling fleets, who land in secret and supply the blacks with opium and[37] drink. When the Commonwealth Navy, now being constructed, is in commission, part of its duty will be to patrol the northern coast and prevent Asiatics landing there to victimize the blacks.

The official statistics of the Commonwealth reported, in regard to the aborigines, in the year 1907:

“In Queensland, South Australia, and Western Australia, on the other hand, there are considerable numbers of natives still in the ‘savage’ state, numerical information concerning whom is of a most unreliable nature, and can be regarded as little more than the result of mere guessing. Ethnologically interesting as is this remarkable and rapidly disappearing race, practically all that has been done to increase our knowledge of them, their laws, habits, customs, and language, has been the result of more or less spasmodic and intermittent effort on the part of enthusiasts either in private life or the public service. Strange to say, an enumeration of them has never been seriously undertaken in connection with any State census, though a record of the numbers who were in the employ of whites, or living in contiguity to the settlements of whites, has usually been made. As stated above, various guesses at the number of aboriginal natives at present in Australia have been made, and the general opinion appears to be that 150,000 may be taken as a rough approximation to the total. It is proposed to make an attempt to enumerate the aboriginal population of Australia[38] in connection with the first Commonwealth Census to be taken in 1911.”

A very primitive savage was the Australian aboriginal. He had no architecture, but in cold or wet weather built little break-winds, called mia-mias. He had no weapons of steel or any other metal. His spears were tipped with the teeth of fish, the bones of animals, and with roughly sharpened flints. He had no idea of the use of the bow and arrow, but had a curious throwing-stick, which, working on the principle of a sling, would cast a missile a great distance. These were his weapons—rough spears, throwing-sticks, and clubs called nullahs, or waddys. (I am not sure that these latter are original native words. The blacks had a way of picking up white men’s slang and adding it to their very limited vocabulary; thus the evil spirit is known among them as the “debbil-debbil.”) Another weapon the aboriginal had, the boomerang, a curiously curved missile stick which, if it missed the object at which it was aimed, would curve back in the air and return to the feet of the thrower; thus the black did not lose his weapon. The boomerang shows an extraordinary knowledge of the effects of curves on the flight of an object; it is peculiar to the Australian natives, and proves that they had skill and cunning in some respects, though generally low in the scale of human races.

The Australian aboriginals were divided into tribes, and these tribes, when food supplies were[39] good, amused themselves with tribal warfare. From what can be gathered, their battles were not very serious affairs. There was more yelling and dancing and posing than bloodshed. The braves of a tribe would get ready for battle by painting themselves with red, yellow, and white clay in fantastic patterns. They would then hold war-dances in the presence of the enemy; that, and the exchange of dreadful threats, would often conclude a campaign. But sometimes the forces would actually come to blows, spears would be thrown, clubs used. The wounds made by the spears would be dreadfully jagged, for about half a yard of the end of the spear was toothed with bones or fishes’ teeth. But the black fellows’ flesh healed wonderfully. A wound that would kill any European the black would plaster over with mud, and in a week or so be all right.

Duels between individuals were not uncommon among the natives, and even women sometimes settled their differences in this way. A common method of duelling was the exchange of blows from a nullah. One party would stand quietly whilst his antagonist hit him on the head with a club; then the other, in turn, would have a hit, and this would be continued until one party dropped. It was a test of endurance rather than of fighting power.

The women of the aboriginals were known as gins, or lubras, the children as picaninnies—this last, of course, not an aboriginal name. The women were not treated very well by their lords: they had to do[40] all the carrying when on the march. At mealtimes they would sit in a row behind the men. The game—a kangaroo, for instance—would be roughly roasted at the camp fire with its fur still on. The men would devour the best portions and throw the rest over their shoulders to the waiting women.

Fish was a staple article of diet for the Australian natives. Wherever there were good fishing-places on the coast or good oyster-beds powerful tribes were camped, and on the inland rivers are still found weirs constructed by the natives to trap fish. So far as can be ascertained, the Australian native was rarely if ever a cannibal. His neighbours in the Pacific Ocean were generally cannibals. Perhaps the scanty population of the Australian continent was responsible for the absence of cannibalism; perhaps some ethical sense in the breasts of the natives, who seem to have always been, on the whole, good-natured and little prone to cruelty.

The religious ideas of these natives were very primitive. They believed strongly in evil spirits, and had various ceremonial dances and practices of witchcraft to ward off the influence of these. But they had little or no conception of a Good Spirit. Their idea of future happiness was, after they had come into contact with the whites: “Fall down black fellow, jump up white fellow.” Such an idea of heaven was, of course, an acquired one. What was their original notion on the subject is not at all clear. The Red Indians of America had a very[41] definite idea of a future happy state. The aboriginals of Australia do not seem to have been able to brighten their poor lives with such a hope.

Various books have been written about the folklore of the Australian aboriginals, but most of the stories told as coming from the blacks seem to me to have a curious resemblance to the stories of white folk. A legend about the future state, for instance, is just Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” put crudely to fit in with Australian conditions. I may be quite wrong in this, but I think that most of the folk-stories coming from the natives are just their attempts to imitate white-man stories, and not original ideas of their own. The conditions or life in Australia for the aboriginal were so harsh, the struggle for existence was so keen, that he had not much time to cultivate ideas. Life to him was centred around the camp-fire, the baked ’possum, and a few crude tribal ceremonies.

Usually the Australian black is altogether spoilt by civilization. He learns to wear clothes, but he does not learn that clothes need to be changed and washed occasionally, and are not intended for use by day and night. He has an insane veneration for the tall silk hat which is the badge of modern gentility, and, given an old silk hat, he will never allow it off his head. He quickly learns to smoke and to drink, and, when he comes into contact with the Chinese, to eat opium. He cannot be broken into any steady habits of industry, but where by wise kindness the[42] black fellow has been kept from the vices of civilization he is a most engaging savage. Tall, thin, muscular, with fine black beard and hair and a curiously wide and impressive forehead, he is not at all unhandsome. He is capable of great devotion to a white master, and is very plucky by daylight, though his courage usually goes with the fall of night. He takes to a horse naturally, and some of the finest riders in Australia are black fellows.

An attempt is now being made to Christianize the Australian blacks. It seems to prosper if the blacks can be kept away from the debasing influence of bad whites. They have no serious vices of their own, very little to unlearn, and are docile enough. In some cases black children educated at the mission schools are turning out very well. But, on the other hand, there are many instances of these children conforming to the habits of civilization for some years and then suddenly feeling “the call of the wild,” and running away into the Bush to join some nomad tribe.

It is not possible to be optimistic about the future of the Australian blacks. The race seems doomed to perish. Something can be done to prolong their life, to make it more pleasant; but they will never be a people, never take any share in the development of the continent which was once their own.

A quite different type of native comes under the rule of the Australian Commonwealth—the Papuan.[43] Though Papua, or New Guinea, as it was once called, is only a few miles from the north coast of Australia, its race is distinct, belonging to the Polynesian or Kanaka type, and resembling the natives of Fiji and Tahiti.

Papua is quite a tropical country, producing bananas, yams, taro, sago, and cocoa-nuts. The natives, therefore, have always had plenty of food, and they reached a higher stage of civilization than the Australian aborigines. But their food came too easily to allow them to go very far forward. “Civilization is impossible where the banana grows,” some observer has remarked. He meant that since the banana gave food without any culture or call on human energy, the people in banana-growing countries would be lazy, and would not have the stimulus to improve themselves that is necessary for progress. To get a good type of man he must have the need to work.

The Papuan, having no need of industry, amused himself with head-hunting as a national sport. Tribes would invade one another’s districts and fight savage battles. The victors would eat the bodies of the vanquished, and carry home their heads as trophies. A chief measured his greatness by the number of skulls he had to adorn his house.

Since the British came to Papua head-hunting and cannibalism have been forbidden. But all efforts to instil into the minds of the Papuan a liking for work have so far failed. So the condition of the natives[44] is not very happy. They have lost the only form of exercise they cared for, and sloth, together with contact with the white man, has brought to them new and deadly diseases. Several missionary bodies are working to convert the Papuan to Christianity, and with some success.

The Papuan builds houses and temples. His tree-dwellings are very curious. They are built on platforms at the top of lofty palm-trees. Probably the Papuan first designed the tree-dwelling as a refuge from possible enemies. Having climbed up to his house with the aid of a rope ladder and drawn the ladder up after him, he was fairly safe from molestation, for the long, smooth, branchless trunks of the palm-trees do not make them easy to scale. In time the Papuan learned the advantages of the tree-dwelling in marshy ground, and you will find whole villages on the coast built of trees. Herodotus states of the ancient Egyptians that in some parts they slept on top of high towers to avoid mosquitoes and the malaria that they brought. The Papuan seems to have arrived at the same idea.

Sorcery is a great evil among the Papuans. In every village almost, some crafty man pretends to be a witch and to have the power to destroy those who are his enemies. This is a constant thorn in the side of the Government official and the missionary. The poor Papuan goes all his days beset by the Powers of Darkness. The sorcerer, the “pourri-pourri” man, can blast him and his pigs, crops, family (that is the[45] Papuan order of valuation) at will. The sorcerer is generally an old man. He does not, as a rule, deck himself in any special garb, or go through public incantations, as do most savage medicine-men. But he hints and threatens, and lets inference take its course, till eventually he becomes a recognized power, feared and obeyed by all. Extortion, false swearing, quarrels and murders, and all manner of iniquity, follow in his train. No native but fears him, however complete the training and education of civilization. For the Papuan never thinks of death, plague, pestilence or famine as arising from natural causes. Every little misfortune (much more every great one) is credited to a “pourri-pourri” or magic. The Papuan, when he comes “under the Evil Eye” of the witch-doctor, will wilt away and die, though, apparently, he has nothing at all the matter with him; and since Europeans are apt to suffer from malarial fever in Papua, the witch-doctors are prompt to put this down to their efforts, and so persuade the natives that they have power even over Europeans.

A gentleman who was a resident magistrate in Papua tells an amusing tale of how one witch-doctor was very properly served. “A village constable of my acquaintance, wearied with the attentions of a magician of great local repute, who had worked much harm with his friends and relations, tied him up with rattan ropes, and sank him in 20 feet of water against the morning. He argued, as he explained at his trial for murder, ‘If this man is the genuine article,[46] well and good, no harm done. If he is not—well, it’s a good riddance!’ On repairing to the spot next morning, and pulling up his night-line, he found that the magician had failed to ‘make his magic good,’ and was quite dead. The constable’s punishment was twelve months’ hard labour. It was a fair thing to let him off easily, as in killing a witch-doctor he had really done the community a service.”

The future of the Papuan is more hopeful than that of the Australian aboriginal, and he may be preserved in something near to his natural state if means can be found to make him work.

The kangaroo—The koala—The bulldog ant—Some quaint and delightful birds—The kookaburra—Cunning crows and cockatoo.

Australia has most curious animals, birds, and flowers. This is due to the fact that it is such an old, old place, and has been cut off so long from the rest of the world. The types of animals that lived in Europe long before Rome was built, before the days, indeed, of the Egyptian civilization, animals of which we find traces in the fossils of very remote periods—those are the types living in Australia to-day. They belong to the same epoch as the mammoth and the great flying lizards and other[47] creatures of whom you may learn something in museums. Indeed, Australia, as regards its fauna, may be considered as a museum, with the animals of old times alive instead of in skeleton form.

The kangaroo is always taken as a type of Australian animal life. When an Australian cricket team succeeds in vanquishing in a Test Match an English one (which happens now and again), the comic papers may be always expected to print a picture of a lion looking sad and sorry, and a kangaroo proudly elate. The kangaroo, like practically all Australian animals, is a marsupial, carrying its young about in a pouch after their birth until they reach maturity. The kangaroo’s forelegs are very small; its hindlegs and its tail are immensely powerful, and these it uses for progression, rushing with huge hops over the country. There are very many animals which may be grouped as kangaroos, from the tiny kangaroo rat, about the size of an English water-rat, to the huge red kangaroo, which is over six feet high and about the weight of a sucking calf. The kangaroo is harmless and inoffensive as a rule, but it can inflict a dangerous kick with its hindlegs, and when pursued by dogs or men and cornered, the “old man” kangaroo will sometimes fight for its life. Its method is to take a stand in a water-hole or with its back to a tree, standing on its hindlegs and balanced on its tail. When a dog approaches it is seized in the kangaroo’s forearms and held under water or torn to pieces. Occasionally[48] men’s lives have been lost through approaching incautiously an old man kangaroo.

The kangaroo’s method of self-defence has been turned to amusing account by circus-proprietors. The “boxing kangaroo” was at one time quite a common feature at circuses and music-halls. A tame kangaroo would have its forefeet fitted with boxing-gloves. Then when lightly punched by its trainer, it would, quite naturally, imitate the movements of the boxer, fending off blows and hitting out with its forelegs. One boxing kangaroo I had a bout with was quite a clever pugilist. It was very difficult to hit the animal, and its return blows were hard and well directed.

The different sorts of kangaroo you may like to know. There is the kangaroo rat, very small; the “flying kangaroo,” a rare animal of the squirrel species, but marsupial, which lives in trees; the wallaby, the wallaroo, the paddy-melon (medium varieties of kangaroo); the grey and the red kangaroo, the last the biggest and finest of the species.

The kangaroo, as I have said, is not of much use for meat. Its flesh is very dark and rank, something like that of a horse. However, chopped up into a fine sausage-meat, with half its weight of fat bacon, kangaroo flesh is just eatable. The tail makes a very rich soup. The skin of the kangaroo provides a soft and pliant leather which is excellent for shoes. Kangaroo furs are also of value for rugs and overcoats.

[49] Of tree-inhabiting animals the chief in Australia is the ’possum (which is not really an opossum, but is somewhat like that American rodent, and so got its name), and the koala, or native bear. Why this little animal was called a “bear” it is hard to say, for it is not in the least like a bear. It is about the size of a very large and fat cat, is covered with a very thick, soft fur, and its face is shaped rather like that of an owl, with big saucer-eyes.

The koala is the quaintest little creature imaginable. It is quite harmless, and only asks to be let alone and allowed to browse on gum-leaves. Its flesh is uneatable except by an aboriginal or a victim to famine. Its fur is difficult to manipulate, as it will not lie flat, so the koala should have been left in peace. But its confiding and somewhat stupid nature, and the senseless desire of small boys and “children of larger growth” to kill something wild just for the sake of killing, has led to the koala being almost exterminated in many places. Now it is protected by the law, and may get back in time to its old numbers. I hope so. There is no more amusing or pretty sight than that of a mother koala climbing sedately along a gum-tree limb, its young ones riding on it pick-a-back, their claws dug firmly into its soft fur.

The ’possum is much hunted for its fur. The small black ’possum found in Tasmania and in the mountainous districts is the most valuable, its fur being very close and fine. Dealers in skins will[50] sometimes dye the grey ’possum’s skin black and trade it off as Tasmanian ’possum. It is a trick to beware of when buying furs. Bush lads catch the ’possum with snares. Finding a tree, the scratched bark of which tells that a ’possum family lives upstairs in one of its hollows, they fix a noose to the tree. The ’possum, coming down at night to feed or to drink, is caught in the noose. Another way of getting ’possum skins is to shoot the little creatures on moonlight nights. (The ’possum is nocturnal in its habits, and sleeps during the day.) When there is a good moon the ’possums may be seen as they sit on the boughs of the gum-trees, and brought down with a shot-gun.

Besides its human enemies, the ’possum has the ’goanna (of which more later) to contend with. The ’goanna—a most loathsome-looking lizard—can climb trees, and is very fond of raiding the ’possum’s home when the young are there. Between the men who want its coat and the ’goannas who want its young the ’possum is fast being exterminated.

Two other characteristic Australian animals you should know about. The wombat is like a very large pig; it lives underground, burrowing vast distances. The wombat is a great nuisance in districts where there are irrigation canals; its burrows weaken the banks of the water-channels, and cause collapses. The dugong is a sea mammal found on the north coast of Australia. It is said to be responsible for the idea of the mermaid. Rising[51] out of the water, the dugong’s figure has some resemblance to that of a woman.

Then there is the bunyip—or, rather, there isn’t the bunyip, so far as we know as yet. The bunyip is the legendary animal of Australia. It is supposed to be of great size—as big as a bullock—and of terrible ferocity. The bunyip is represented as living in lakes and marshes, but it has never been seen by any trustworthy observer. The blacks believe profoundly in the bunyip, and white children, when very young, are scared with bunyip tales. There may have been once an animal answering to its description in Australia; if so, it does not seem to have survived.

In Tasmania, however, are found, though very rarely, two savage and carnivorous marsupials called the Tasmanian tiger and the Tasmanian devil. The tiger is almost as large as the female Bengal tiger, and has a few little stripes near its tail, from which fact it gets its name. The Tasmanian tiger will create fearful havoc if it gets among sheep, killing for the sheer lust of killing. At one time a price of £100 was put on the head of the Tasmanian tiger. As settlement progressed it became rarer and rarer, and I have not heard of one having been seen for some years. The Tasmanian devil is a marsupial somewhat akin to the wild cat, and of about the same size. It is very ferocious, and has been known to attack man, springing on him from a tree branch. The Tasmanian devil is likewise becoming very rare.

[52] The existence of these two animals in Tasmania and not in Australia shows that that island has been a very long time separated from the mainland.

Australia is very well provided with serpents—rather too well provided—and the Bush child has to be careful in regard to putting his hand into rabbit burrows or walking barefoot, as there are several varieties of venomous snake. But the snakes are not at all the great danger that some imagine. You might live all your life in Australia and never see one; but in a few country parts it has been found necessary to enclose the homesteads on the stations with snake-proof wire-fencing, so as to make some place of safety in which young children may play. The most venomous of Australian snakes are the death-adder, fortunately a very sluggish variety; the tiger-snake, a most fierce serpent, which, unlike other snakes, will actually turn and pursue a man if it is wounded or angered; the black snake, a handsome creature with a vivid scarlet belly; and the whip-snake, a long, thin reptile, which may be easily mistaken for a bit of stick, and is sometimes picked up by children. But no Australian snake is as deadly as the Indian jungle snakes, and it is said that the bite of no Australian snake can cause death if the bite has been given through any cloth. So the only real danger is in walking through the Bush barefooted, or putting the hand into holes where snakes may be lurking.

Some of the non-venomous snakes of Australia are[53] very handsome, the green tree-snake and the carpet-snake (a species of python) for examples. The carpet-snake is occasionally kept in the house or in the barn to destroy mice and other small vermin.

Lizards in great variety are found in Australia, the chief being one incorrectly called an iguana, which colloquial slang has changed to ’goanna. The ’goanna is an altogether repulsive creature. It feasts on carrion, on the eggs of birds, on birds themselves, on the young of any creature. Growing to a great size—I have seen one 9 feet long and as thick in the body as a small dog—the ’goanna looks very dangerous, and it will bite a man when cornered. Though not venomous in the strict sense of the word, the ’goanna’s bite generally causes a festering wound on account of the loathsome habits of the creature. The Jew-lizard and the devil-lizard are two other horrid-looking denizens of the Australian forest, but in their cases an evil character does not match an evil face, for they are quite harmless.

Spiders are common, but there is, so far as I know, only one dangerous one—a little black spider with a red spot on its back. Large spiders, called (incorrectly) tarantulas, credited by some with being poisonous, come into the houses. But they are really not in any way dangerous. I knew a man who used to keep tarantulas under his mosquito-nets so that they might devour any stray mosquitoes that got in. The example is hardly[54] worth following. The Australian tarantula, though innocent of poison, is a horrible object, and would, I think, give you a bad fright if it flopped on to your face.

Australia is rich in ants. There is one specially vicious ant called the bulldog ant, because of its pluck. Try to kill the bulldog ant with a stick, and it will face you and try to bite back until the very last gasp, never thinking of running away. The bulldog ant has a liking for the careless picnicker, whom she—the male ant, like the male bee, is not a worker—bites with a fierce energy that suggests to the victim that his flesh is being torn with red-hot pincers. I have heard it said that but for the fact that Australia is so large an island, a great proportion of its population would by this time have been lost through bounding into the surrounding sea when bitten by bulldog ants. It is wise when out for a picnic in Australia to camp in some spot away from ant-beds, for the ant, being such an industrious creature, seems to take a malicious delight in spoiling the day for pleasure-seekers.

In one respect, the ant, unwillingly enough, contributes to the pleasure and amusement of the Australian people. In the dry country it would not be possible to keep grass lawns for tennis. But an excellent substitute has been found in the earth taken from ant-beds. This earth, which has been ground fine by the industrious little insects, makes a beautifully firm tennis-court.