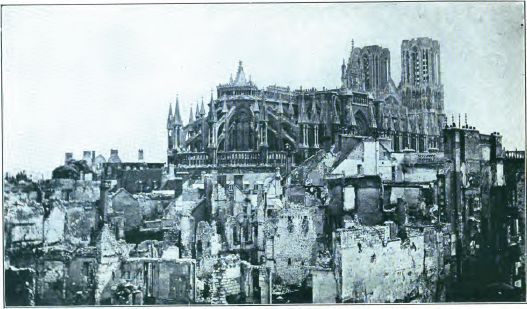

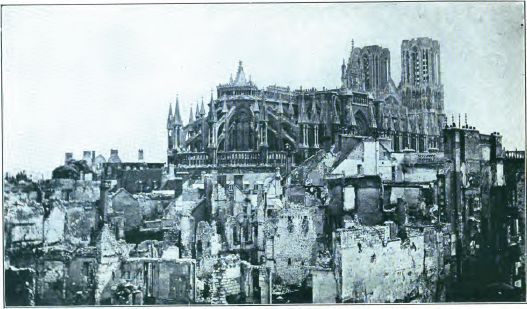

THE CATHEDRAL OF NOTRE DAME AT RHEIMS

THE CATHEDRAL OF NOTRE DAME AT RHEIMS

The Project Gutenberg EBook of World's War Events, Vol. I, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: World's War Events, Vol. I

Author: Various

Editor: Francis J. Reynolds

Allen L. Churchill

Release Date: July 4, 2008 [EBook #25962]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORLD'S WAR EVENTS, VOL. I ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

THE CATHEDRAL OF NOTRE DAME AT RHEIMS

THE CATHEDRAL OF NOTRE DAME AT RHEIMS

| ARTICLE | PAGE | |

| I. | What Caused the War | 7 |

| Baron Beyens | ||

| II. | The Defense of Liège | 41 |

| Charles Bronne | ||

| III. | The Great Retreat | 62 |

| Sir John French | ||

| IV. | The Battle of the Marne | 73 |

| Sir John French | ||

| V. | How the French Fought | 83 |

| French Official Account | ||

| VI. | The Race for the Channel | 96 |

| French Official Account | ||

| VII. | The Last Ditch in Belgium | 108 |

| Arno Dosch | ||

| VIII. | Why Turkey Entered the War | 125 |

| Roland G. Usher | ||

| IX. | The Falkland Sea Fight | 142 |

| A. N. Hilditch | ||

| V. | Cruise of the Emden | 176 |

| Captain Mücke | ||

| VI. | Capture of Tsing-Tao | 198 |

| A. N. Hilditch | ||

| VII. | Gallipoli | 221 |

| A. John Gallishaw | ||

| VIII. | Gas: Second Battle of Ypres | 240 |

| Colonel E. D. Swinton | ||

| VIV. | The Canadians at Ypres | 248 |

| By the Canadian Record Officer | ||

| VV. | Sinking of the Lusitania | 277 |

| [6]Judicial Decision by Judge J. M. Mayer | ||

| VVI. | Mountain Warfare | 313 |

| Howard C. Felton | ||

| VVII. | The Great Champagne Offensive of 1915 | 322 |

| Official Account of the French Headquarters Staff | ||

| VVIII. | The Tragedy of Edith Cavell | 348 |

| Brand Whitlock | ||

| VIX. | Gallipoli Abandoned | 366 |

| General Sir Charles C. Monro | ||

| VX. | The Death-Ship in the Sky | 375 |

| Perriton Maxwell | ||

The Archduke Francis Ferdinand will go down to posterity without having yielded up his secret. Great political designs have been ascribed to him, mainly on the strength of his friendship with William II. What do we really know about him? He was strong-willed and obstinate, very Clerical, very Austrian, disliking the Hungarians to such an extent that he kept their statesmen at arm's-length, and having no love for Italy. He has been credited with sympathies towards the Slav elements of the Empire; it has been asserted that he dreamt of setting up, in place of the dual monarchy, a "triune State," in which the third factor would have been made up for the most part of Slav provinces carved out of the Kingdom of St. Stephen. Immediately after he had been murdered, the Vossische Zeitung refuted this theory with arguments which seemed to me thoroughly sound.

The Archduke, said the Berlin newspaper, was too keen-witted not to see that he would thus be creating two rivals for Austria instead of one, and that the Serb populations would come within the orbit of Belgrade rather than of Vienna. Serbia would become the Piedmont of the Balkans; she would draw to herself the Slavs of the Danube valley by a process of crystallization similar to that which brought about Italian unity.

From year to year the Archduke had acquired[8] more and more weight in the governance of the Empire, in proportion as his uncle's will grew weaker beneath the burden of advancing age. Thus he had succeeded in his efforts to provide Austria-Hungary with a new navy, the counterpart, on a more modest scale, of the German fleet, and to reorganize the effective army, here again taking Germany for his model. Among certain cliques, he was accused of not keeping enough in the background, of showing little tact or consideration in the manner of thrusting aside the phantom Emperor, who was gently gliding into the winter of the years at Schönbrunn amid the veneration of his subjects of every race.

Another charge was that he appointed too many of his creatures to important civil and military posts.

We may well believe that this prince, observing the gradual decay of the monarchy, tried to restore its vigour, and that his first thought was to hold with a firm grasp, even before assuming the Imperial crown, the cluster of nationalities, mutually hostile and always discontented, that go to make up the Dual Empire. So far as foreign relations are concerned, we may assume that he was bent on winning her a place in the first rank of Powers; that he wished, above all, to see her predominant all along the Danube and in the Balkans; that he even aimed at giving her the road to Salonika and the Levant, though it were at the price of a collision with Russia. This antagonism between the two neighbour Empires must have often been among the topics of his conversations with William II.

The Archduke needed military glory, prestige won on the battle-field, in order to seat his consort firmly on the throne and make his children heirs to the Cæsars. He had been suspected, both in Austria and abroad, of not[9] wishing to observe the family compact which he had signed at the time of his marriage with Countess Sophie Chotek. It was thought that he perhaps reserved the right to declare it null and void, in view of the constraint that had been put upon him. The successive honours that had drawn the Duchess of Hohenberg from the obscurity in which the morganatic wife of a German prince is usually wrapped, and had brought her near to the steps of the throne, showed clearly that her rise would not stop half-way.

The Archduke, like William II himself, was reputed to be an exemplary father and husband. He was one of those princes who adore their own children, but, under the spur of political ambition, are very prone to send the children of others to the shambles. A fine theme for Socialist and Republican preachers to enlarge upon!

I often met the heir to the Imperial crown, especially at Vienna in 1910, where I had the honour of accompanying my Sovereign, and two years later at Munich, the Prince Regent's funeral.

On each occasion this Hapsburg, with his heavy features, his scowling expression, and his rather corpulent figure (quite different from the slim build characteristic of his line), struck me as a singular type. His face was certainly not sympathetic, nor was his manner engaging. The Duchess of Hohenberg, whom, after having known her as a little girl when her father was Austrian Minister at Brussels, I found gracefully doing the honours in the Belvedere Palace, had retained in her high station the genial simplicity of the Chotek family. This probably did not prevent her from cherishing the loftiest ambitions for herself, and above all for her eldest son, and from coveting the glory of the double crown.[10]

The news that an assassin's hand had struck down the Archduke and his wife, inseparable even in death, burst upon Berlin on the afternoon of Sunday, June 28, like an unexpected thunderclap in the midst of a calm summer's day. I went over at once to the Austro-Hungarian Embassy, in order to express all the horror that I felt at this savage drama. Count Szögyen, the senior member of the diplomatic corps, was on the eve of resigning the post that he had held for twenty years, honoured by all his colleagues. It was whispered that his removal had been asked for by the Archduke, who was anxious to introduce young blood into the diplomatic service. I found the Ambassador quite overcome by the terrible news. He seemed stricken with grief at the thought of his aged Sovereign, who had already lost so many of his nearest and dearest, and of the Dual Empire, robbed of its most skillful pilot, and with no one to steer it now but an octogenarian leaning on a youth of twenty-six. M. Cambon had come to the Embassy at the same time, and we left together discussing the results, still impossible to foresee clearly, that this fatality might have for European affairs.

From the very next day the tone of the Berlin Press, in commenting on the Serajevo tragedy, was full of menace. It expected the Vienna Cabinet to send to Belgrade an immediate request for satisfaction, if Serbian subjects, as it was believed, were among those who had devised and carried out the plot. But how far would this satisfaction go, and in what form would it be demanded? There was the rub. The report, issued by the semi-official Lokalanzeiger, of a pressure exerted by the Austro-Hungarian Minister, with a view to making[11] the Serbian Government institute proceedings against the anarchist societies of which the Archduke and his wife had been the victims, surprised no one, but was not confirmed. On the other hand, a softer breeze soon blew from Vienna and Budapest, and under its influence the excitement of the Berlin newspapers suddenly abated. An order seemed to have been issued: the rage and fluster of the public were to be allowed to cool down. The Austro-Hungarian Government, so we were informed by the news agencies, were quietly taking steps to prosecute the murderers. Count Berchtold, in speaking to the diplomatic corps at Vienna, and Count Tisza, in addressing Parliament at Budapest, used reassuring language, which raised hopes of a peaceful solution.

The Wilhelmstrasse also expressed itself in very measured terms on the guarantees that would be demanded from Serbia. Herr Zimmermann, without knowing (so he said to me) what decision had been arrived at in Vienna, thought that no action would be taken in Belgrade until the Austro-Hungarian Government had collected the proofs of the complicity of Serbian subjects or societies in the planning of the Serajevo crime. He had made a similar statement to the Russian Ambassador, who had hastened to impart to him his fears for the peace of Europe, in the event of any attempt to coerce Serbia into proceeding against the secret societies, if they were accused of intrigues against the Austrian Government in Bosnia and Croatia. Herr Zimmermann declared to M. Sverbeeff that, in his opinion, no better advice could be given to the Serbian Government than this: that it should put a stop to the nefarious work of these societies and punish the accomplices of the Archduke's assassins. The moderation of this remark fairly reflected the general state of public opinion in Berlin.[12]

But what of the Emperor, the Archduke's personal friend? Would not his grief and anger find voice in ringing tones? All eyes were turned towards Kiel, where the fatal news reached William II while he was taking part in a yacht race on board his own clipper. He turned pale, and was heard to murmur: "So my work of the past twenty-five years will have to be started all over again!" Enigmatic words which may be interpreted in various ways! To the British Ambassador, who was also at Kiel, with the British squadron returning from the Baltic, he unburdened himself in more explicit fashion: "Es ist ein Verbrechen gegen das Deutschtum" ("It is a crime against Germanity"). By this he probably meant that Germany, feeling her own interests assailed by the Serajevo crime, would make common cause with Austria to exact a full retribution. With more self-control than usual, however, he abstained from all further public utterances on the subject.

It had been announced that he would go to Vienna to attend the Archduke's funeral. What were the motives that prevented him from offering to the dead man this last token of a friendship which, at first merely political, had become genuine and even tender, with a touch of patronage characteristic of the Emperor?

He excused himself on the ground of some slight ailment. The truth is, no doubt, that he was disgusted with the wretched stickling for etiquette shown by the Grand Chamberlain of the Viennese Court, the Prince di Montenuovo, who refused to celebrate with fitting splendour the obsequies of the late heir apparent and his morganatic wife. Under these circumstances, Vienna could have no desire either for the presence of William II or for his criticisms.[13]

At the beginning of July, the Emperor left for his accustomed cruise along the Norwegian coast, and in Berlin we breathed more freely. If he could withdraw so easily from the centre of things, it was a sign that the storm-clouds that had nearly burst over Serbia were also passing off from the Danube valley. Such, I fancy, was the view taken by the British Government, for its Ambassador, who was already away on leave, was not sent back to Berlin. Other diplomats, among them the Russian Ambassador, took their annual holiday as usual. But the Emperor, in the remote fiords of Norway, was all the time posted up in the secret designs of the Vienna Cabinet. The approaching ultimatum to Serbia was telegraphed to him direct by his Ambassador in Vienna, Herr von Tschirsky, a very active worker, who strenuously advocated a policy of hostility towards Russia, and from the first moment had wanted war.

We may assume that the Emperor, if his mind was not already made up at Kiel, came to a decision during his Norwegian cruise. His departure for the north had been merely a snare, a device for throwing Europe and the Triple Entente off the scent, and for lulling them into a false security. While the world imagined that he was merely seeking to soothe his nerves and recruit his strength with the salt sea breezes, he was biding his time for a dramatic reappearance on the stage of events, allowing the introductory scenes to be played in his absence.

During the first half of July, my colleagues and I at Berlin did not live in a fool's paradise. As the deceptive calm caused by Vienna's silence was prolonged, a latent, ill-defined uneasiness[14] took hold of us more and more. Yet we were far from anticipating that in the space of a few days we should be driven into the midst of a diplomatic maelstrom, in which, after a week of intense anguish, we should look on, mute and helpless, at the shipwreck of European peace and of all our hopes.

The ultimatum, sent in the form of a Note by Baron von Giesl to the Serbian Cabinet on July 23, was not disclosed by the Berlin newspapers until the following day, in their morning editions. This bolt from the blue proved more alarming than anything we had dared to imagine. The shock was so unexpected that certain journals, losing their composure, seemed to regard the Vienna Cabinet's arraignment as having overshot the mark. "Austria-Hungary," said the Vossische Zeitung, "will have to justify the grave charges that she makes against the Serbian Government and people by publishing the results of the preliminary investigations at Serajevo."

My own conviction, shared by several of my colleagues, was that the Austrian and Hungarian statesmen could not have brought themselves to risk such a blow at the Balkan kingdom, without having consulted their colleagues at Berlin and ascertained that the Emperor William would sanction the step. His horror of regicides and his keen sense of dynastic brotherhood might explain why he left his ally a free hand, in spite of the danger of provoking a European conflict. That danger was only too real. Not for one moment did I suppose that Russia would prove so careless of Serbia's fate as to put up with this daring assault on the latter's sovereignty and independence; that the St. Petersburg Cabinet would renounce the principle of "The Balkans for the Balkan nations," proclaimed to the Duma two[15] months before by M. Sazonoff, in short, that the Russian people would disown the ancient ties of blood that united it with the Slav communities of the Balkan peninsula.

The pessimistic feeling of the diplomatic corps was increased on the following day, the 25th, by the language addressed to it at the Wilhelmstrasse. Herren von Jagow and Zimmermann said that they had not known beforehand the contents of the Austrian Note. This was a mere quibble: they had not known its actual wording, I grant, but they had certainly been apprised of its tenor. They hastened to add, by the way, that the Imperial Government approved of its ally's conduct, and did not consider the tone of its communication unduly harsh. The Berlin Press, still with the exception of the Socialist organs, had recovered from its astonishment of the day before; it joined in the chorus of the Vienna and Budapest newspapers, from which it gave extracts, and faced the prospect of a war with perfect calm, while expressing the hope that it would remain localized.

In comparison with the attitude of the German Government and Press, the signs pointing to a peaceful settlement seemed faint indeed. They all came from outside Germany, from the impressions recorded in foreign telegrams. Public opinion in Europe could not grasp the need for such hectoring methods of obtaining satisfaction, when there was no case for refusing discussion on the normal diplomatic lines. It seemed impossible that Count Berchtold should ignore the general movement of reproof which appeared spontaneously everywhere but in Berlin against his ultimatum. A moderate claim would have seemed just; but Serbia could not be asked to accept a demand for so heavy an atonement, couched in a form of such unexampled brutality.[16]

The more I reflected on the ghastly situation created by the collusion of German and Austro-Hungarian diplomacy, the more certain did I feel that the key to that situation (as M. Sazonoff said later) lay in Berlin, and that there was no need to look further for the solution of the problem. If, however, the choice between peace and war was left to the discretion of the Emperor William, whose influence over his ally in Vienna had always overruled that of others, then, considering what I knew as to His Majesty's personal inclinations and the plans of the General Staff, the upshot of it all was no longer in doubt, and no hope of a peaceful arrangement could any longer be entertained. I communicated this dismal forecast to the French Ambassador, whom I went to see on the evening of the 25th. Like myself, M. Cambon laboured under no illusions. That very night I wrote to my Government, in order to acquaint it with my fears and urge it to be on its guard. This report, dated the 26th, I entrusted, as a measure of precaution, to one of my secretaries, who at once left for Brussels. Early next morning, my dispatch was in the hands of the Belgian Foreign Minister.

The ultimatum to Serbia [it ran] is a blow contrived by Vienna and Berlin, or rather, contrived here and carried out at Vienna. Requital for the assassination of the Austrian heir apparent and the Pan-Serb propaganda serves as a stalking-horse. The real aim, apart from the crushing of Serbia and the stifling of Jugo-Slav aspirations, is to deal a deadly thrust at Russia and France, with the hope that England will stand aside from the struggle. In order to vindicate this theory, I beg to remind you of the view prevailing in the German General Staff, namely, that a war with France and Russia is unavoidable and close at hand—a view which the Emperor has been induced to share. This[17] war, eagerly desired by the military and Pan-German party, might be undertaken to-day under conditions extremely favourable for Germany, conditions that are not likely to arise again for some time to come.

After a summary of the situation and of the problems that it raised, my report concluded as follows:

We, too, have to ask ourselves these harassing questions, and keep ourselves ready for the worst; for the European conflict that has always been talked about, with the hope that it would never break out, is to-day becoming a grim reality.

The worst contingencies that occurred to me, as a Belgian, were the violation of a part of our territory and the duty that might fall upon our soldiers of barring the way to the belligerents. In view of the vast area over which a war between France and Germany would be fought, dared we hope that Belgium would be safe from any attack by the German army, from any attempt to use her strategic routes for offensive purposes? I could not bring myself to believe that she would be so fortunate. But between such tentatives and a thoroughgoing invasion of my country, plotted a long time in advance and carried out before the real operations of the war had begun, there was a wide gulf, a gulf that I never thought the Imperial Government capable of leaping over with a light heart, because of the European complications which so reckless a disdain for treaties would not fail to involve.

Until the end of the crisis, the idea of a preventive war continually recurred to my mind. Other heads of legations, however, while sharing[18] my anxieties on this point, did not agree with me as to the premeditation of which I accused the Emperor and the military chiefs. I was not content with putting my questions to the French Ambassador, whose unerring judgment always carried great weight with me. I also visited his Italian colleague, an astute diplomat, thoroughly versed in German statecraft. He had always put me in mind of those dexterous agents employed by the sixteenth-century Italian republics.

According to Signor Bollati, the German Government, agreeing in principle with the Vienna Cabinet as to the necessity for chastising Serbia, had not known beforehand the terms of the Austrian Note, the violence of which was unprecedented in the language of Chancelleries. Vienna, as well as Berlin, was convinced that Russia, in spite of the official assurances that had recently passed between the Tsar and M. Poincaré regarding the complete readiness of the French and Russian armies, was not in a position to enter on a European war, and that she would not dare to embark upon so hazardous an adventure. Internal troubles, revolutionary intrigues, incomplete armaments, inadequate means of communication—all these reasons would compel the Russian Government to be an impotent spectator of Serbia's undoing. The same confidence reigned in the German and Austrian capitals as regards, not the French army, but the spirit prevailing among Government circles in Paris.

At present [added the Ambassador] feeling runs so high in Vienna that all calm reflection goes by the board. Moreover, in seeking to annihilate Serbia's military power, the Austro-Hungarian Cabinet is pursuing a policy of personal revenge. It cannot realize the mistakes that it made during the Balkan War, or remain[19] satisfied with the partial successes then gained with our aid—successes that, whatever judgment may be passed upon them, were certainly diplomatic victories. All that Count Berchtold sees to-day is Serbia's insolence and the criticism he has had to endure even in Austria. By this bold stroke, very unexpected from a man of his stamp, he hopes to turn the criticism into applause.

The Ambassador held that Berlin had false ideas as to the course that the Tsar's Government would adopt. The latter would find itself forced into drawing the sword, in order to maintain its prestige in the Slav world. Its inaction, in face of Austria's entry into the field, would be equivalent to suicide. Signor Bollati also gave me to understand that a widespread conflict would not be popular in Italy. The Italian people had no concern with the overthrow of the Russian power, which was Austria's enemy; it wished to devote all its attention to other problems, more absorbing from its own point of view.

The blindness of the Austrian Cabinet with regard to Russian intervention has been proved by the correspondence, since published, of the French and British representatives at Vienna. The Viennese populace was beside itself with joy at the announcement of an expedition against Serbia, which, it felt sure, would be a mere military parade. Not for a single night were Count Berchtold's slumbers disturbed by the vision of the Russian peril. He is, indeed, at all times a buoyant soul, who can happily mingle the distractions of a life of pleasure with the heavy responsibilities of power. His unvarying confidence was shared by the German Ambassador, his most trusted mentor. We can hardly suppose that the Austrian Minister shut his eyes altogether to the possibility of a struggle with the Slav world. Having[20] Germany as his partner, however, he determined, with the self-possession of a fearless gambler, to proceed with the game.

At Berlin, the theory that Russia was incapable of facing a conflict reigned supreme, not only in the official world and in society, but among all the manufacturers who made a specialty of war material.

Herr Krupp von Bohlen, who was more entitled to give an opinion than any other of this class, declared on July 28 that the Russian artillery was neither efficient nor complete, while that of the German army had never before been so superior to all its rivals. It would be madness on Russia's part, he inferred, to take the field against Germany under these conditions.

The foreign diplomatic corps was kept in more or less profound ignorance as to the pourparlers carried on since the 24th by the Imperial Foreign Office with the Triple Entente Cabinets. Nevertheless, to the diplomats who were continually going over to the Wilhelmstrasse for news, the crisis was set forth in a light very favourable to Austria and Germany, in order to influence the views of the Governments which they represented. Herr von Stumm, the departmental head of the political branch, in a brief interview that I had with him on the 26th, summed up his exposition in these words: "Everything depends on Russia." I should rather have thought that everything depended on Austria, and on the way in which she would carry out her threats against Serbia.

On the following day I was received by Herr Zimmermann, who adopted the same line[21] of argument, following it in all its bearings from the origin of the dispute.

It was not at our prompting [he said], or in accordance with our advice, that Austria took the action that you know of towards the Belgrade Cabinet. The answer was unsatisfactory, and to-day Austria is mobilizing. She can no longer draw back without risking a collapse at home as well as a loss of influence abroad. It is now a question of life and death to her. She must put a stop to the unscrupulous propaganda which, by raising revolt among the Slav provinces of the Danube valley, is leading towards her internal disintegration. Finally, she must exact a signal revenge for the assassination of the Archduke. For all these reasons Serbia is to receive, by means of a military expedition, a stern and salutary lesson. An Austro-Serbian War is, therefore, impossible to avoid.

England has asked us to join with her, France, and Italy, in order to prevent the conflict from spreading and a war from breaking out between Austria and Russia. Our answer was that we should be only too glad to help in limiting the area of the conflagration, by speaking in a pacific sense to Vienna and St. Petersburg; but that we could not use our influence with Austria to restrain her from inflicting an exemplary punishment on Serbia. We have promised to help and support our Austrian allies, if any other nation should try to hamper them in this task. We shall keep that promise.

If Russia mobilizes her army, we shall at once mobilize ours, and then there will be a general war, a war that will set ablaze all Central Europe and even the Balkan peninsula, for the Rumanians, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Turks will not be able to resist the temptation to come in.[22]

As I remarked yesterday to M. Boghitchevitch [the former Serbian Chargé d'Affaires, who was on a flying visit to Berlin, where he had been greatly appreciated during the Balkan War], the best advice I can give Serbia is that she should make no more than a show of resistance to Austria, and should come to terms as soon as possible, by accepting all the conditions of the Vienna Cabinet. I added, in speaking to him, that if a universal war broke out and went in favor of the Triplice, Serbia would probably cease to exist as a nation; she would be wiped off the map of Europe. I still hope, though, that such a widespread conflict may be avoided, and that we shall succeed in inducing Russia not to intervene on Serbia's behalf. Remember that Austria is determined to respect Serbia's integrity, once she has obtained satisfaction.

I pointed out to the Under-Secretary that the Belgrade Cabinet's reply, according to some of my colleagues who had read it, was, apart from a few unimportant restrictions, an unqualified surrender to Austria's demands. Herr Zimmermann said that he had no knowledge of this reply (it had been handed in two days before to the Austrian Minister at Belgrade!) and that, in any case, there was no longer any possibility of preventing an Austro-Hungarian military demonstration.

The Serbian document was not published by the Berlin newspapers until the 29th. On the previous day they all reproduced a telegram from Vienna, stating that this apparent submission was altogether inadequate. The prompt concessions made by the Pasitch Cabinet, concessions that had not been anticipated abroad, failed to impress Germany. She persisted in seeing only with Austria's eyes.

Herr Zimmermann's arguments held solely on the hypothesis that, in the action brought[23] by Austria against Serbia, no Power had the right to come forward as counsel for the defendant, or to interfere in the trial at all. This claim amounted to depriving Russia of her historic rôle in the Balkans. Carried to its logical conclusion, the theory meant condemning unheard every small State that should be unfortunate enough to have a dispute with a great Power. According to the principles of the Berlin Cabinet, the great Power should be allowed, without let or hindrance, to proceed to the execution of its weak opponent. England, therefore, would have had no right to succor Belgium when the latter was invaded by Germany, any more than Russia had a right to protect Serbia from the Austrian menace.

Russia, it was asserted at the Wilhelmstrasse, ought to be satisfied with the assurance that Austria would not impair the territorial integrity of Serbia or mar her future existence as an independent State. What a hollow mockery such a promise would seem, when the whole country had been ravaged by fire and sword! Surely it was decreed that, after this "exemplary punishment," Serbia should become the lowly vassal of her redoubtable neighbour, living a life that was no life, cowed by the jealous eye of the Austrian Minister—really the Austrian Viceroy—at Belgrade. Had not Count Mensdorff declared to Sir Edward Grey that before the Balkan War Serbia was regarded as gravitating towards the Dual Monarchy's sphere of influence? A return to the past, to the tame deference of King Milan, was the least that Austria would exact.

The version given out by the Imperial Chancellery, besides being intended to enlighten foreign Governments, had a further end in view. Repeated ad nauseam by the Press, it[24] aimed at misleading German public opinion. From the very opening of the crisis, Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg and his colleagues strove, with all the ingenuity at their command, to hoodwink their countrymen, to shuffle the cards, to throw beforehand on Russia, in case the situation should grow worse, the odium of provocation and the blame for the disaster, to represent that Power as meddling with a police inquiry that did not concern her in the least. This cunning manœuvre resulted in making all Germany, without distinction of class or party, respond to her Emperor's call at the desired moment, since she was persuaded (as I have explained in a previous chapter) that she was the object of a premeditated attack by Tsarism.

The game of German diplomacy during these first days of the crisis, July 24 to 28, has already been revealed. At first inclined to bludgeon, it soon came to take things easily, even affecting a certain optimism, and by its passive resistance bringing to naught all the efforts and all the proposals of the London, Paris, and St. Petersburg Cabinets. To gain time, to lengthen out negotiations, seems to have been the task imposed upon Austria-Hungary's accomplice in order to promote rapid action by the Dual Monarchy, and to face the Triple Entente with irrevocable deeds, namely the occupation of Belgrade and the surrender of the Serbians. But things did not go as Berlin and Vienna had hoped, and the determined front shown by Russia, who in answer to the partial mobilization of Austria mobilized her army in four southern districts, gave food for reflection to the tacticians of the Wilhelmstrasse. Their language and[25] their frame of mind grew gentler to a singular degree on the fifth day, July 28. It may be recalled, in passing, that in 1913, during the Balkan hostilities, Austria and Russia had likewise proceeded to partial mobilizations; yet these steps had not made them come to blows or even brought them to the verge of hostilities.

On the evening of the 26th the Emperor's return was announced in Berlin. Why did he come back so suddenly? I think I am justified in saying that, at this news, the general feeling among the actors and spectators of the drama was one of grave anxiety. Our hearts were heavy within us; we had a foreboding that the decisive moment was drawing near. It was the same at the Wilhelmstrasse. To the British Chargé d'Affaires Herr von Zimmermann frankly confessed his regret at this move, on which William II had decided without consulting any one.

Nevertheless, our fears at first seemed to be unwarranted. The 28th was marked by a notable loosening of Germany's stiff-necked attitude. The British Ambassador, who had returned to Berlin on the previous day, was summoned in the evening by the Chancellor. Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg, while rejecting the conference proposed by Sir Edward Grey, promised to use his good offices to induce Russia and Austria to discuss the position in an amicable fashion. "A war between the Great Powers must be averted," were his closing words.

It is highly probable that the Chancellor at that time sincerely wanted to keep the peace, and his first efforts, when he saw the danger coming nearer and nearer, succeeded in curbing the Emperor's impatience for forty-eight hours. The telegram sent by William II to the Tsar on the evening of the 28th[26] is friendly, almost reassuring: "Bearing in mind the cordial friendship that has united us two closely for a long time past, I am using all my influence to make Austria arrive at a genuine and satisfactory understanding with Russia."

How are we to explain, then, the abrupt change of tack that occurred the following day at Berlin, or rather, at Potsdam, and the peculiar language addressed by the Chancellor to Sir Edward Goschen on the evening of the 29th? In that nocturnal scene there was no longer any question of Austria's demands on Serbia, or even of the possibility of an Austro-Russian war. The centre of gravity was suddenly shifted, and at a single stride the danger passed from the southeast of Europe to the northwest.

What is it that Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg wants to know at once, as he comes straight from the council held at Potsdam under the presidency of the Emperor? Whether Great Britain would consent to remain neutral in a European war, provided that Germany agreed to respect the territorial integrity of France. "And what of the French colonies?" asks the Ambassador with great presence of mind. The Chancellor can make no promise on this point, but he unhesitatingly declares that Germany will respect the integrity and neutrality of Holland. As for Belgium, France's action will determine what operations Germany may be forced to enter upon in that country; but when the war is over, Belgium will lose no territory, unless she ranges herself on the side of Germany's foes.

Such was the shameful bargain proposed to England, at a time when none of the negotiators had dared to speak in plain terms of a European war or even to offer a glimpse of that terrifying vision. This interview was the immediate[27] result of the decisive step taken by German diplomacy on the same day at St. Petersburg. The step in question has been made known to us through the diplomatic documents which have been printed by the orders of the belligerent Governments, and all of which concur in their account of this painful episode. Twice on that day did M. Sazonoff receive a visit from the German Ambassador, who came to make a demand wrapped up in threats.

Count de Pourtalès insisted on Russia contenting herself with the promise, guaranteed by Germany, that Austria-Hungary would not impair the integrity of Serbia. M. Sazonoff refused to countenance the war on this condition. Serbia, he felt, would become a vassal of Austria, and a revolution would break out in Russia. Count de Pourtalès then backed his request with the warning that, unless Russia desisted from her military preparations, Germany would mobilize. A German mobilization, he said, would mean war. The results of the second interview, which took place at two o'clock in the morning, were as negative as those of the first, notwithstanding a last effort, a final suggestion by M. Sazonoff to stave off the crisis. His giving in to Germany's brutal dictation would have been an avowal that Russia was impotent.

To the Emperor William, who had resumed the conduct of affairs since the morning of the 27th—the Emperor William, itching to cut the knot, driven on by his Staff and his generals—to him and no other must we trace the responsibility for this insolent move which made war inevitable. "The heads of the army insisted," was all that Herr von Jagow would vouchsafe a little later to M. Cambon by way of explanation. The Chancellor, and with him the Foreign Secretary and Under-Secretary,[28] associated themselves with these hazardous tactics, from sheer inability to secure the adoption of less hasty and violent methods. If they believed that this summary breaking off of negotiations would meet with success, they were as grievously mistaken as Count de Pourtalès, whose reports utterly misled them as to the sacrifices that Russia was prepared to make for Serbia.

At all events this upright man, when he realized the appalling effects of his blunder, gave free play to his emotion. Such sensitiveness is rare indeed in a German, and redounds entirely to his credit.

But the Emperor and his council of generals—what was their state of soul at this critical moment? Perhaps this riddle will never be wholly solved. From the military point of view, which in their eyes claimed first attention, they must have rejoiced at M. Sazonoff's answer, for never again would they find such a golden opportunity for vanquishing Russia and making an end of her rivalry. In 1917 the reorganization of her army would have been complete, her artillery would have been at full strength, and a new network of strategic railways would have enabled her to let loose upon the two Germanic empires a vast flood of fighting men drawn from the inexhaustible reservoir of her population. The struggle with the colossus of the North, despite the vaunted technical superiority of the German army, would in all likelihood have ended in the triumph of overwhelming might. In the France of 1917, again, the three years' term of service would have begun to produce its full results, and her first-line troops would have been both more numerous and better trained than at present.

On the other hand, William II could cherish no false hopes as to the consequences of this[29] second pressure that he was bringing to bear on St. Petersburg. Had it succeeded in 1914 as in 1909, the encounter between Germany and the great Slav Empire would only have been put off to a later day, instead of being finally shelved. How could the Tsar or the Russian people have forgiven the Kaiser for humbling them once more? If they had pocketed the affront in silence, it would only have been in order to bide their time for revenge, and they would have chosen the moment when Russia, in possession of all her resources, could have entered upon the struggle with every chance of winning.

Here an objection may be raised. The German Emperor, some may hold, fancying that the weight of his sword in the scale would induce the Tsar to shrink from action, had foreseen the anger of the Slav nation at its sovereign's timorous scruples, and looked forward to revolutionary outbreaks which would cripple the Government for years to come and make it unable to think of war, if indeed they did not sweep the Romanoffs from the throne. I would answer that this Machiavellian scheme could never have entered the head of such a ruler as William II, with his deep sense of monarchial solidarity, and his instinctive horror of anarchist outrages and of revolution.

No: the Emperor, together with the military authorities whose advice he took, wished to profit by a juncture which he had awaited with longing, and which fickle Fortune might never again offer to his ambition. Everything proves it, down to his feverish haste, as soon as M. Sazonoff's reply was conveyed to him, to learn the intentions of England, and to suggest, on that very day, a bargain that might purchase her neutrality. This is why Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg received orders to summon the British Ambassador on the night of the[30] 29th. The Emperor could not wait until the following morning, so eager was he to act. Is this impatience the mark of one who was the victim of a concerted surprise? If he had not wanted war, would he not have tried to resume negotiations with Russia on a basis more in keeping with her dignity as a Great Power, however heavy a blow it was to his own pride that he had failed to intimidate her?

The abortive efforts to overawe St. Petersburg and the offers made to the British Ambassador, as if Great Britain's inaction could be sold to the highest bidder, brought results that were not hard to foresee.

In London, Sir Edward Grey's indignation found immediate vent in the following passage of his telegram of July 30 to Sir Edward Goschen: "It would be a disgrace for us to make this bargain with Germany at the expense of France—a disgrace from which the good name of this country would never recover. The Chancellor also in effect asks us to bargain away whatever obligation or interest we have as regards the neutrality of Belgium. We could not entertain that bargain either."

Through the brazen overtures of Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg, however, the British Cabinet henceforth came to occupy itself, before all things, with the fate allotted to our country by the Imperial Government in the war that it was preparing. In order to tear off the mask from German statesmanship, the surest method was to ask it a straightforward question. On July 31, Sir Edward Grey, following the example of the Gladstone Ministry of 1870, inquired both of Germany and France whether they would respect the neutrality of Belgium.[31] At the same time he gave Belgium to understand that Britain counted on her doing her utmost to maintain her neutrality.

The answer of the Republican Government was frank and unhesitating. It was resolved to respect Belgian neutrality, and would only act otherwise if the violation of that neutrality by some other Power forced it to do so in self-defence.

The Belgian Government, for its part, hastened to assure the British Minister at Brussels of its determination to resist with might and main should its territory be invaded.

At Berlin, however, the Foreign Secretary eluded Sir Edward Goschen's questions. He said that he must consult the Emperor and the Chancellor. In his opinion, any answer would entail the risk, in the event of war, of partly divulging the plan of campaign. It seemed doubtful to him, therefore, whether he would be able to give a reply. This way of speaking was perfectly clear in its ambiguity. It did not puzzle Sir Edward Grey for a moment. On the following day he declared to the German Ambassador that the reply of the German Government was a matter of very great regret. Belgian neutrality, he pointed out, was highly important in British eyes, and if Belgium was attacked, it would be difficult to restrain public feeling in his country.

On the same day, August 1, in accordance with instructions from my Government, I read to the Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs (at the same time giving him a copy) a dispatch drafted beforehand and addressed to the Belgian Ministers attached to the Powers that had guaranteed our neutrality. This dispatch affirmed that Belgium, having observed, with scrupulous fidelity, the duties imposed on her as a neutral State by the treaties of April 19, 1839, would manifest an unshaken purpose in[32] fulfilling them; and that she had every hope, since the friendly intentions of the Powers towards her had been so often professed, of seeing her territory secure from all assault, if hostilities should arise near her frontiers. The Belgian Government added that it had nevertheless taken all the necessary steps for maintaining its neutrality, but that, in so doing, it had not been actuated by a desire to take part in an armed struggle among the Powers, or by a feeling of distrust towards any one of them.

Herr Zimmermann listened without a word of comment to my reading of this dispatch, which expressed the loyal confidence of my Government in Germany's goodwill. He merely took note of my communication. His silence did not surprise me, for I had just learnt of Herr von Jagow's evasive reply to the British Government concerning Belgium; but it bore out all my misgivings. His constrained smile, by the way, told me quite as much as his refusal to speak.

From the 30th, Russia and Germany—as an inevitable sequel to the conversations of the 29th—went forward actively with their military preparations. What was the exact nature of these preludes to the German mobilization? It was impossible to gain any precise notion at Berlin. The capital was rife with various rumors that augured ill for the future. We heard tell of regiments moving from the northern provinces towards the Rhine. We learnt that reservists had been instructed to keep themselves in readiness for marching orders. At the same time, postal communication with Belgium and France had been cut off. At the Wilhelmstrasse, the position was described to me as follows: "Austria will reply to Russia's partial mobilization with a general mobilization of her army. It is to be feared that[33] Russia will then mobilize her entire forces, which will compel Germany to do the same." As it turned out, a general mobilization was indeed proclaimed in Austria on the night of the 30th.

Nevertheless, the peace pourparlers went on between Vienna and St. Petersburg on the 30th and 31st, although on the latter date Russia, as Berlin expected, in answer both to the Austrian and the German preparations, had mobilized her entire forces. Even on the 31st these discussions seemed to have some chance of attaining their object. Austria was now more accurately gauging the peril into which her own blind self-confidence and the counsels of her ally were leading her, and was pausing on the brink of the abyss. The Vienna Cabinet even consented to talk over the gist of its Note to Serbia, and M. Sazonoff at once sent an encouraging reply.

It was desirable, he stated, that representatives of all the Great Powers should confer in London under the direction of the British Government.

Was a faint glimmer of peace, after all, dawning above the horizon? Would an understanding be reached, at the eleventh hour, among the only States really concerned with the Serbian question? We had reckoned without our host. The German Emperor willed otherwise. Suddenly, at the instance of the General Staff, and after a meeting of the Federal Council, as prescribed by the constitution, he issued the decree of Kriegsgefahrzustand (Imminence-of-War). This is the first phase of a general mobilization—a sort of martial law, substituting the military for the civil authorities as regards the public services (means of communication, post, telegraphs, and telephones).

This momentous decision was revealed to us[34] on the 31st by a special edition of the Berliner Lokalanzeiger, distributed at every street corner. The announcement ran as follows:

"From official sources we have just received (at 2 P.M.) the following report, pregnant with consequences:

"'The German Ambassador at St. Petersburg sends us word to-day that a general mobilization of the Russian Army and Navy had previously been ordered. That is why His Majesty the Emperor William has decreed an Imminence-of-War. His Majesty will take up his residence in Berlin to-day.'

"Imminence-of-War is the immediate prelude to a general mobilization, in answer to the menace that already hangs over Germany to-day, owing to the step taken by the Tsar."

As a drowning man catches at a straw, those who in Berlin saw themselves, with horror, faced by an impending catastrophe, clutched at a final hope. The German general mobilization had not yet been ordered. Who knew whether, at the last moment, some happy inspiration from the British Cabinet, that most stalwart champion of peace, might cause the weapons to drop from the hands that were about to wield them? Once more, however, the Emperor, by his swift moves, shattered this fond illusion. On the 31st, at seven o'clock in the evening, he dispatched to the Russian Government a summons to demobilize both on its Austrian and on its German frontiers. An interval of twelve hours was given for a reply.

It was obvious that Russia, who had refused two days before to cease from her military preparations, would not accept the German[35] ultimatum, worded as it was in so dictatorial a form and rendered still more insulting by the briefness of the interval granted. As, however, no answer had come from St. Petersburg by the afternoon of August 1st, Herren von Jagow and Zimmermann (so the latter informed me) rushed to the Chancellor and the Emperor, in order to request that the decree for a general mobilization might at least be held over until the following day. They supported their plea by urging that the telegraphic communication with St. Petersburg had presumably been cut, and that this would explain the silence of the Tsar. Perhaps they still hoped against hope for a conciliatory proposal from Russia. This was the last flicker of their dying pacifism, or the last awakening of their conscience. Their efforts could make no headway against the stubborn opposition of the War Minister and the army chiefs, who represented to the Emperor the dangers of a twenty-four hours' delay.

The order for a mobilization of the army and navy was signed at five o'clock in the afternoon and was at once given out to the public by a special edition of the Lokalanzeiger. The mobilization was to begin on August 2nd. On the 1st, at ten minutes past seven in the evening, Germany's declaration of war was forwarded to Russia.

As all the world knows, the Berlin Cabinet had to resort to wild pretexts, such as the committing of acts of hostility (so the military authorities alleged) by French aviators on Imperial soil, in order to find motives, two days later, for its declaration of war on France. Although Germany tried to lay the blame for the catastrophe at Russia's door, it was in reality her western neighbour that she wished to attack and annihilate first. On this point there can be no possible doubt to-day. "Poor[36] France!" said the Berlin newspapers, with feigned compassion. They acknowledged that the conduct of the French Government throughout the crisis had been irreproachable, and that it had worked without respite for the maintenance of peace. While her leaders fulfilled this noble duty to mankind, France was offering the world an impressive sight—the sight of a nation looking calmly and without fear at a growing peril that she had done nothing to conjure up, and, regarding her word as her bond, determined in cold blood to follow the destiny of her ally on the field of battle. At the same time she offered to Germany, who had foolishly counted on her being torn by internal troubles and political feuds, the vision of her children closely linked together in an unconquerable resolve—the resolve to beat back an iniquitous assault upon their country. Nor was this the only surprise that she held in store. With the stone wall of her resistance, she was soon to change the whole character of the struggle, and to wreck the calculations of German strategy.

No one had laboured with more energy and skill to quench the flames lit by Austria and her ally than the representative of the Republic at Berlin.

"Don't you think M. Cambon's attitude has been admirable?" remarked the British Ambassador to me, in the train that was whirling us far away from the German capital on August 6th. "Throughout these terrible days nothing has been able to affect his coolness, his presence of mind, and his insight." I cannot express my own admiration better than by repeating this verdict of so capable a diplomat as Sir Edward Goschen, who himself took a most active part in the vain attempt of the Triple Entente to save Europe from calamity.[37]

The Berlin population had followed the various phases of the crisis with tremendous interest, but with no outward show of patriotic fervour. Those fine summer days passed as tranquilly as usual. Only in the evenings did some hundreds of youths march along the highways of the central districts, soberly singing national anthems, and dispersing after a few cries of "Hoch!" outside the Austro-Hungarian and Italian Embassies and the Chancellor's mansion.

On August 2nd I watched the animation of the Sunday crowd that thronged the broad avenue of the Kurfürstendamm. It read attentively the special editions of the newspapers, and then each went off to enjoy his or her favourite pastime—games of tennis for the young men and maidens, long bouts of drinking in the beer-gardens, for the more sedate citizens with their families. When the Imperial motor-car flashed like a streak of lightning down Unter den Linden, it was hailed with loud, but by no means frantic, cheers. It needed the outcries of the Press against Russia as the instigator of the war, the misleading speeches of the Emperor and the Chancellor, and the wily publications of the Government, to kindle a patriotism rather slow to take fire. Towards the close of my stay, feeling displayed itself chiefly by jeers at the unfortunate Russians who were returning post-haste to their native country, and blackguardly behaviour towards the staff of the Tsar's Ambassador as he was leaving Berlin.

That the mass of the German people, unaware of Russia's peaceful intentions, should have been easily deluded, is no matter for astonishment. The upper classes, however, those[38] of more enlightened intellect, cannot have been duped by the official falsehoods. They knew as well as we do that it was greatly to the advantage of the Tsar's Government not to provoke a conflict. In fact, this question is hardly worth discussing. Once more we must repeat that, in the plans of William II and his generals, the Serbian affair was a snare spread for the Northern Empire before the growth of its military power should have made it an invincible foe.

There is no gainsaying that uncertainty as to Britain's intervention was one of the factors that encouraged Germany. We often asked ourselves anxiously at Berlin whether Germany's hand would not have been stayed altogether if the British Government had formally declared that it would not hold aloof from the war. We even hoped, for a brief moment, that Sir Edward Grey would destroy the illusions on which the German people loved to batten. The British Foreign Secretary did indeed observe to Prince Lichnowsky on July 29th that the Austro-Serbian issue might become so great as to involve all European interests, and that he did not wish the Ambassador to be misled by the friendly tone of their conversations into thinking that Britain would stand aside. If at the beginning she had openly taken her stand by the side of her Allies, she might, to be sure, have checked the fatal march of events. This, at any rate, is the most widespread view, for a maritime war certainly did not enter into the calculations of the Emperor and Admiral von Tirpitz, while it was the nightmare of the German commercial world. In my opinion, however, an outspoken threat from England on the 29th, a sudden roar of the British lion, would not have made William II draw back. The memory of Agadir still rankled in the proud Germanic soul. The Emperor would have[39] risked losing all prestige in the eyes of a certain element among his subjects if at the bidding of the Anglo-Saxon he had refused to go further, and had thus played into the hands of those who charged him with conducting a policy of mere bluff and intimidation. "Germany barks but does not bite" was a current saying abroad, and this naturally tended to exasperate her. An ominous warning from the lips of Sir Edward Grey would only have served to precipitate the onslaught of the Kaiser's armies, in order that the intervention of the British fleet might have no influence on the result of the campaign, the rapid and decisive campaign planned at Berlin.

We know, moreover, from the telegrams and speeches of the British Foreign Minister, how carefully he had to reckon with public feeling among his countrymen in general and among the majority in Parliament. A war in the Balkans did not concern the British nation, and the strife between Teuton and Slav left it cold. It did not begin to be properly roused until it grasped the reality of the danger to France's very existence, and it did not respond warmly to the eloquent appeals of Mr. Asquith and Sir Edward Grey until the day when it knew that the Germans were at the gates of Liège, where they threatened both Paris and Antwerp—Antwerp, "that pistol pointed at the heart of England."

With the failure of diplomatic efforts to prevent war as a result of the deliberate intention of Germany to bring about the conflict, the great German war machine was put in motion. It was anticipated by the General Staff that the passage across Belgium would be effected without difficulty and with the acquiescence of King and people.

How wrong was this judgment is one of the[40] curious facts of history. The Germans discovered this error when their armies presented themselves before the strong fortress of Liège, the first fortified place in their path. Its capture was necessary for the successful passage of the German troops.

It was captured, but at a cost in time and in their arrangement of plans which were a great element in the great thrust—back at the Marne.

On Sunday, August 2nd, while the news was going round that a train had entered Luxembourg with German forces, the German Minister at Brussels delivered an ultimatum to Belgium demanding the free passage through our territory of the German armies. The following day, Monday, the Belgian Government replied that the nation was determined to defend its neutrality. The same night the German advanced posts entered our territory. Tuesday morning they were before Visé, at Warsage, at Dolhain, and at Stavelot. The bridges of Visé and Argenteau and the tunnels of Troisponts and Nas-Proué were blown up.

From this day the atrocities committed by the pioneers of German "Kultur" began at Visé with fire and the massacre of inhabitants. On Thursday, they were to continue at Warsage and Berneau. On Wednesday, August 5th, the investment of Liège began, the bombardment being specially directed to the north-west sector which comprises the forts of Evegnée, Barchon, and Fléron. In the afternoon the attack extended as far as the fort of Chaudfontaine. The region attacked by the foe was thus that between the Meuse and the Vesdre, the beautiful country of Herve, where cornfields are followed by vineyards, where meadowland encroaches on the sides of narrow but picturesque valleys, where small but thick woods conceal the number of the assailants. It was found[42] necessary to destroy some prosperous little farms, several country houses, and pretty villas. This was but a prelude to the devastation brought by the soldiers of the Kaiser.

The enemy was in force. Later it was known that around Liège were the 10th Prussian Army Corps from Aix-la-Chapelle on the way to Visé, the 7th Corps, which had passed through the Herve country, the 8th, which had entered through Stavelot, and also a brigade of the 11th Corps, making up a total of about 130,000 men.

To resist these forces, General Leman had forts more than twenty-four years old and 30,000 men: the 3rd division of the army increased by the 15th mixed brigade, i.e., the 9th, 11th, 12th, and 14th of the line, a part of the 2nd Lancers, a battalion of the 1st Carabineers, and the Divisional Artillery.

Thursday, August 6th, was rich in moving incidents.

While the enemy were in force before Barchon, in a night attack, an attempt was made on General Leman. The story has been variously told. Here is the true version.

The enemy's spies, so numerous in Liège, had been able to give the most exact information regarding the installation of the General Staff in the Rue Sainte Foy. They were quite aware that for a week the defender of Liège had only been taking two or three hours' rest in his office, so as to be more easily in telephonic communication with the forts and garrison. These offices in the Rue Sainte Foy were very badly situated, at the extreme end of the northern quarter, and were defended only by a few gendarmes. General Leman had been warned, however, and the King himself had at last persuaded him to take some precautions against a possible attempt. He had finally given way to this advice, and a rudimentary structure, but[43] a sure one, fitted with electric light and telephone, was being set up under the railway tunnel near the Palais station.

This was, then, the last night the General would pass at Rue Sainte Foy.

Towards half-past four in the morning a body of a hundred men descended from the heights of Tawes. Whence did they come? How had they been able to penetrate into the town? Some have said that they dressed in Liège itself. In reality, they represented themselves to the advanced posts of the fort of Pontisse as being Englishmen come to the aid of Liège, and asked to be conducted to the General Staff. They were soldiers of a Hanoverian regiment, and bore upon their sleeves a blue band with the word "Gibraltar." This contributed in no small degree to cause them to be taken for British sharpshooters. They were preceded by a spy who had put on the Belgian uniform of the 11th of the line and who seemed to know the town very well. At Thier-à-Liège, they stopped a moment to drink at a wine-shop and then went on. They were more than a hundred in number and were preceded by two officers. A detachment of Garde Civique, posted at the gas factory of the Rue des Bayards, did not consider it their duty to interfere. A few individuals accompanied the troop, crying "Vive les Anglais." A few passers-by, better-aware of the situation, protested. The troop continued its imperturbable march. The officers smiled. Thus they arrived at Rue Sainte Foy where, as we have said, the offices of the General Staff of General Leman were installed.

A German officer asked of the sentinel on the door an interview with General Leman. The officers of the latter, who now appeared, understood the ruse at once, and drew their revolvers. Shots were exchanged. One of the officers, Major Charles Marchand, a non-commissioned[44] officer of gendarmes, and several gendarmes were killed. The Germans attempted to enter the offices, of which the door had been closed. They fired through the windows, and even attempted to attack the house by scaling the neighbouring walls. General Leman, who was working, ran out on hearing the first shots. He was unarmed. He demanded a revolver. Captain Lebbe, his aide-de-camp, refused to allow him to expose himself uselessly, and begged him to keep himself for the defence of Liège. He even used some violence to his chief, and pushed him towards the low door which separated the house from the courtyard of a neighbouring cannon foundry. With the help of another officer, the captain placed his General in safety. While this was happening, the alarm had been given, and the Germans, seeing that their attempt to possess themselves of the person of General Leman had failed, retired. The guard, which comprised some fifty men, fired repeatedly on the retreating party. Some fifty Germans, including a standard-bearer and a drummer, were killed. Others were made prisoners.

The General retired to the citadel of Sainte Walburge, and later to the fort of Loncin. From there he followed the efforts of the enemy attacking anew the north-east and south-east sectors. The environs of Fort Boncelles are as difficult to defend as those of the Barchon-Evegnée-Fléron front. There is first the discovered part which surrounds what remains of the unfortunate village of Boncelles, which the Belgians themselves were forced to destroy to free their field of fire, but for the rest, there are only woods, that of Plainevaux, which reaches to the Ourthe, Neuville, and Vecquée woods, that of Bégnac, which continues Saint Lambert wood as far as Trooz and the Meuse.

Every place here swarmed with Germans,[45] 40,000 at least, an army corps which had spent a day and a night in fortifying themselves, and had been able to direct their artillery towards Plainevaux, to the north of Neuville, and upon the heights of Ramet. Thirty thousand men at least would have been needed to defend this gap and less than 15,000 were available. A similar attack was delivered at the same time between the Meuse and the Vesdre. On both sides miracles of heroism were performed, but the enemy poured on irresistibly. They were able to pass, on the one side, Val Saint Lambert, on the other, between Barchon and the Meuse, between Evegnée and Fléron. Fighting took place well into the night, the enemy being repulsed at Boncelles twice. The following morning I saw pieces of German corpses. The Belgian artillery had made a real carnage, and no smaller number of victims fell in the bayonet charges. The 9th and the Carabineers, who had fought the day before at Barchon, were present here.

In the other sector, the soldiers of the 12th of the line particularly behaved like heroes. The battle began towards two o'clock in the morning at Rétinne where, after prodigies of valour and a great slaughter of the enemy, the Belgian troops were forced to retire. The struggle continued at Saine and at Queue du Bois. Here Lieutenant F. Bronne and forty of his men fell while covering the retreat. In spite of such devotion and of a bravery that will not be denied, the enemy passed through. Why? Some troops surrendered with their officers, who were afterwards set free upon parole at Liège. But this was only a very small exception, and it was under the pressure of an enemy four times as numerous that the 3rd division succumbed after three days of repeated fighting, during which the soldiers were compelled to make forced marches from one[46] sector to another, and stop the rest of the time in the trenches fighting. The enemy's losses were 5,000 killed and 30,000 wounded.

General Leman considered that he had obtained from his troops the maximum effort of which they were capable and ordered a retreat. It was executed in good order, and the enemy had suffered so severely that they did not dream of pursuit. They contented themselves with pushing forward as far as the plateau of Saint-Tilman (close to Boncelles) and that of Robermont (behind Fléron) some cannons of 15, which had bombarded the town the first time on Thursday, August 6th, at four o'clock in the morning. No German troops, except some 200 men who entered as prisoners, penetrated into the town on this day.

Although this retreat left behind a few men with several guns, it may be said to have been effected in good order. I was able to see that for myself in passing through with the troops, from the fifth limit of the Saint Trond route, near Fort Loncin, up to the centre of the town. The auto in which I was seated was able to pass easily.

The terrified population from Bressoux began to arrive. There were people half-dressed, but who carried some object which to them seemed the most precious, sometimes a simple portrait of a loved one. Others drove cattle before them. The men carried children, while women followed painfully loaded with household goods. Mixed up with them were the Garde Civique. It had just been assembled and informed that it was disbanded, and a certain number of them had told the inhabitants that the Prussians were coming, and that there was nothing better to do than for everyone to bolt himself in. The cannon had thundered all night. The citizens of Liège had found in their letter-boxes a warning from the burgomaster[47] concerning the behaviour of the inhabitants in case of the town being occupied by the enemy. This urgent notice, distributed the night before between 9 and 11 p.m., foreshadowed an imminent occupation. The hasty flight of the people of Bressoux stopped when they had crossed the Meuse; but as the bombardment recommenced towards noon, fright again seized on the population. The bombardment lasted till two. Some thirty shells fell on different parts of the town.

At half-past twelve a dull noise was heard as far as the furthest fort; it was the old Bridge of Arches which gave way, towards the left bank. The engineers had just blown it up. It seemed wiser to destroy the bridge at Val Bénoit, which left the Germans railway communication. But no one thought of this; or rather, orders to that effect were not given by the higher authorities. This was afterwards to cause the degradation to the ranks of the chief officer of engineers who was responsible for this unpardonable lapse.

The second bombardment lasted till two o'clock. Several projectiles now fell upon the citadel, where everything was in readiness to set fire to the provisions and munitions which remained there along with some unserviceable cannon, generally used in the training of the Garde Civique. By 10 a.m. the citadel had been evacuated, only very few persons remaining, among them a major, who hastily hoisted the white flag.

Burgomaster Kleyer awaited developments at the Town Hall. At half-past three, he received envoys, who demanded the surrender of the town and forts. Put into communication with General Leman, who was all the time at Loncin with his Staff, he informed him that if the forts persisted in their resistance, the town would be bombarded a third time. General Leman[48] replied that the threat was an idle one, that it would be a cruel massacre, but that the higher interests of Belgium compelled him to impose this sacrifice on the town of Liège.

At 9 p.m. fresh shells fell on different parts of the city and caused more damage if not more victims. This bombardment lasted till 2 a.m. It recommenced at intervals of half-an-hour, and caused two fires, one in Rue de Hanque, and the other in Rue de la Commune. After midday, the streets were deserted and all dwelling houses closed. In the afternoon a convoy of Germans taken prisoners were seen to pass along the boulevards, and were then shut up in the Royal Athenæum. Then there was an interminable defile of autos and carts conveying both German and Belgian wounded, especially the former, those who came from Boncelles more particularly. Bodies of stragglers re-entered Liège slowly, ignorant of what had happened, as they were either untouched by the order to retire, or had been forgotten in the advanced posts or in the trenches. They were very tired and hardly had the courage to accelerate their pace, except when the few passers-by explained the position in a couple of words. The aspect of the town was very gloomy, and the only places where any animation was to be seen were around Guillemins station, where trains full of fugitives were leaving for Brussels, the West quarter, towards which the last of the retiring companies were marching, and the North, where many were still ignorant of this movement.

On Friday, August 7th, at 3 a.m., the bombardment of Liège began again, chiefly directed against the citadel, where only a few soldiers now remained. These evacuated the place after setting fire to some provisions they were unable to carry off. The population passed through hours of anguish, which were destined[49] not to be the last. Everybody took refuge in the cellars. Some people lived there for several days in fear that a shell might fall upon their house. On this Friday the Germans penetrated into the town at five o'clock in the morning by the different bridges which had remained intact. They came in through Jupille and Bois de Breux chiefly. They seemed tired and, above all, hungry. Leaving detachments in the Place de Bavière and near the bridges, they successively occupied the Provincial Palace and the citadel.

Count Lammsdorf, Chief of the Staff of the 10th Corps, Commander of the Army of the Meuse, arrested Burgomaster Kleyer at the Town Hall, and conducted him to the citadel, where he at first made him a rather reassuring communication as to the fate of the town.... He then spoke anew and said that he understood all the forts would surrender, in default of which the bombardment would recommence. M. Kleyer vainly protested against a measure so contrary to the laws both of war and of humanity. He was simply authorized to pass through the German lines with a safe conduct, to discuss the matter with General Leman, or even with the King himself.

This task of the burgomaster of Liège was a heavy one, and terrible was the expectant attitude of the German authorities. Later, some people have discussed the attitude he should have taken up and conceived the nature of what should have been his reply; they would have desired words of defiance on his lips and an immediate answer.

He lacked courage for this, and who will dare to-day to blame him for the immense anxiety he felt on hearing of the horrible fate with which his beloved town and his unhappy fellow-citizens were threatened?

He gathered together at the Town Hall several[50] communal and provincial deputies, some deputies and senators. The general opinion at the beginning of the discussion was that it was necessary to obtain the surrender of the forts. Someone pointed out that there was not much likelihood of getting this decision from General Leman, who had already pronounced himself upon that question, and thought it would be necessary to continue the work heroically begun of arresting the progress of the invader, and that the forts, all intact, would powerfully contribute to that end.

It was finally decided to approach General Leman again with a message which was entrusted to the burgomaster, the Bishop of Liège, and M. Gaston Grégoire, permanent deputy. These gentlemen repaired to the citadel in search of the promised safe conduct. They were met there, according to the demand of Count Lammsdorf, by some prominent Liège citizens, to whom he had expressed his desire to explain the situation.

At the moment the three delegates were about to depart on their mission, with a good faith upon which it would be foolish to insist, the German commander declared that all the persons present were detained as hostages. He gave as a specious pretext for this violation of right that some German soldiers had been killed by civilians in some neighbouring villages, and that the hostages would enable the Germans to guard against the repetition of such acts, the more so as they were prepared to make a striking example at the beginning of the campaign.

All the Liège citizens who had entered the citadel on this day were kept there till the next day, Saturday. Moreover, the following persons were retained as responsible hostages for three days: 1. Mgr. Rutien, Bishop of Liège; 2. M. Kleyer, Burgomaster of Liège; 3. M.[51] Grégoire, Permanent Deputy; 4. M. Armand Flechet, Senator; 5. Senator Van Zuylen; 6. Senator Edouard Peltzer; 7. Senator Colleaux; 8. Deputy De Ponthière; 9. Deputy Van Hoegaerden; 10. M. Falloise, Alderman.

The hostages were shut up in damp case-mates, palliasses were given them for the night and, as food, the first day each one had half a loaf and some water. The burgomaster and the bishop were, however, allowed to go about their duties after they had given their parole to remain at the disposal of the German military authorities.

The same day at 9 a.m. the last train left Liège for Brussels with numbers of fugitives. The number of persons who abandoned Liège and its suburbs may be calculated at some five thousand. From this moment and for several days Liège was absolutely cut off from the rest of the world, all communications having been cut.

On Saturday, August 8th, while the Germans were methodically organising the occupation of Liège, Burgomaster Kleyer was authorised to wait upon the King, in order to discuss the surrender of the forts. Furnished with a safe conduct and accompanied by a German officer, he reached Waremme early in the afternoon, and placed himself in communication with the General Staff. The King was consulted, and the reply brought back to Liège was the one the mayor had foreseen.

The same day saw the appearance of the following order of the day addressed to the soldiers of the army of Liège:—

"Our comrades of the 3rd Army Division and of the 15th mixed brigade are about to re-enter our lines, after having defended, like heroes, the fortified position of Liège.

"Attacked by forces four times as numerous,[52] they have repulsed all assaults. None of the forts have been taken; the town of Liège is always in our power. Standards and a number of prisoners are the trophies of these combats. In the name of the Nation I salute you, officers and soldiers of the 3rd Army Division and the 15th mixed brigade.

"You have done your duty, done honour to our arms, shown the enemy what it costs to attack unjustly a peaceable people, but one who wields in its just cause an invincible weapon. The Fatherland has the right to be proud of you.

"Soldiers of the Belgian Army, do not forget that you are in the van of immense armies in this gigantic struggle, and that you await but the arrival of our brothers-in-arms in order to march to victory. The whole world has its eyes fixed upon you. Show it by the vigour of your blows that you mean to live free and independent.