This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Essentials of Diseases of the Skin

Including the Syphilodermata Arranged in the Form of Questions and Answers Prepared Especially for Students of Medicine

Author: Henry Weightman Stelwagon

Release Date: July 1, 2008 [eBook #25944]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ESSENTIALS OF DISEASES OF THE SKIN***

|

Transcriber's note: This book contains many characters which might not display if the character is not included in the character sets available to the browser, in which case the reader is likely to see a small square instead of the intended character. Some of these characters are symbols for quantities, such as dram and minim, or the recipe (prescription) sign. Referring to one of the text-file versions might help the reader to identify characters that do not display in the browser. A detailed transcriber's note is at the end of the e-text. |

| Get the Best | The New Standard |

A New and Complete Dictionary of the terms used in Medicine, Surgery, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Chemistry, and kindred branches; together with new and elaborate Tables of Arteries, Muscles, Nerves, Veins, etc.; of Bacilli, Bacteria, Micrococci, etc.; Eponymic Tables of Diseases, Operations, Signs and Symptoms, Stains, Tests, Methods of Treatment, etc. By W.A.N. Dorland, M.D., Editor of the American Pocket Medical Dictionary. Large octavo, nearly 800 pages, bound in full flexible leather. Price, $4.50 net; with thumb index, $5.00 net.

JUST ISSUED—NEW (4) REVISED EDITION--2000 NEW WORDS

It contains a maximum amount of matter in a minimum

space and at the lowest possible cost.

This book contains double the material in the ordinary students' dictionary, and yet, by the use of a clear, condensed type and thin paper of the finest quality, is only 1-3/4 inches in thickness. It is bound in full flexible leather, and is just the kind of a book that a man will want to keep on his desk for constant reference. The book makes a special feature of the newer words, and defines hundreds of important terms not to be found in any other dictionary. It is especially full in the matter of tables, containing more than a hundred of great practical value, including new tables of Tests, Stains and Staining Methods. A new feature is the inclusion of numerous handsome illustrations, many of them in colors, drawn and engraved specially for this book.

“I must acknowledge my astonishment at seeing how much he has condensed within relatively small space. I find nothing to criticise, very much to commend, and was interested in finding some of the new words which are not in other recent dictionaries.”—Roswell Park, Professor of Principles and Practice of Surgery and Clinical Surgery, University of Buffalo.

“Dr. Dorland's Dictionary is admirable. It is so well gotten up and of such convenient size. No errors have been found in my use of it.”—Howard A. Kelly, Professor of Gynecology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

W. B. SAUNDERS COMPANY, 925 Walnut St., Phila.

London: 9, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

| Fifth Edition, Just Ready | With Complete Vocabulary |

EDITED BY

W.A. NEWMAN DORLAND, A.M., M.D.,

Assistant Demonstrator of Obstetrics, University of Pennsylvania.

HUNDREDS OF NEW TERMS

Bound in Full Leather, Limp, with Gold Edges. Price, $1.00 net; with Patent Thumb Index, $1.25 net.

The book is an absolutely new one. It is not a revision of any old work, but it has been written entirely anew and is constructed on lines that experience has shown to be the most practical for a work of this kind. It aims to be complete, and to that end contains practically all the terms of modern medicine. This makes an unusually large vocabulary. Besides the ordinary dictionary terms the book contains a wealth of anatomical and other tables. This matter is of particular value to students for memorizing in preparation for examination.

“I am struck at once with admiration at the compact size and attractive exterior. I can recommend it to our students without reserve.”—James W. Holland, M.D., of Jefferson Medical College.

“This is a handy pocket dictionary, which is so full and complete that it puts to shame some of the more pretentious volumes.”—Journal of the American Medical Association.

“We have consulted it for the meaning of many new and rare terms, and have not met with a disappointment. The definitions are exquisitely clear and concise. We have never found so much information in so small a space.”—Dublin Journal of Medical Science.

“This is a handy little volume that, upon examination, seems fairly to fulfil the promise of its title, and to contain a vast amount of information in a very small space.... It is somewhat surprising that it contains so many of the rarer terms used in medicine.”—Bulletin Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

W. B. SAUNDERS COMPANY, 925 Walnut St., Phila.

London: 9, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

OF

Since the issue of the first volume of the Saunders Question-Compends,

OVER 290,000 COPIES

of these unrivalled publications have been sold. This enormous sale is indisputable evidence of the value of these self-helps to students and physicians.

SAUNDERS' QUESTION-COMPENDS. No. 11.

INCLUDING THE

ARRANGED IN THE FORM OF

PREPARED ESPECIALLY FOR

BY

HENRY W. STELWAGON, M.D., PH.D.

Professor of Dermatology in the Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia; Dermatologist to the Howard and Philadelphia Hospitals, etc.

SEVENTH EDITION, THOROUGHLY REVISED

ILLUSTRATED

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

W. B. SAUNDERS COMPANY

1909

Set up, electrotyped, printed, 1890. Reprinted July, 1891.

Revised, reprinted, June, 1894. Reprinted March, 1897.

Revised, reprinted, August, 1899. Reprinted September,

1901, May, 1902, September, 1903. Revised, reprinted

January, 1905. Reprinted March,

1906. Revised, reprinted

March, 1909.

PRINTED IN AMERICA

PRESS OF

W. B. SAUNDERS COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

In the present—seventh—edition the subject matter, especially as regards the practical part, has been gone over carefully and the necessary corrections and additions made. Nineteen new illustrations have been added, a few of the old ones being eliminated. It is hoped that the continued demand for this compend means a widening interest in the study of diseases of the skin, sufficiently keen as to lead to the desire for a still greater knowledge.

H.W.S.

Much of the present volume is, in a measure, the outcome of a thorough revision, remodelling and simplification of the various articles contributed by the author to Pepper's System of Medicine, Buck's Reference Handbook of the Medical Sciences, and Keating's Cyclopædia of the Diseases of Children. Moreover, in the endeavor to present the subject as tersely and briefly as compatible with clear understanding, the several standard treatises on diseases of the skin by Tilbury Fox, Duhring, Hyde, Robinson, Anderson, and Crocker, have been freely consulted, that of the last-named author suggesting the pictorial presentation of the “Anatomy of the Skin.” The space allotted to each disease has been based upon relative importance. As to treatment, the best and approved methods only—those which are founded upon the aggregate experience of dermatologists—are referred to.

For general information a statistical table from the Transactions of the American Dermatological Association is appended.

H.W.S.

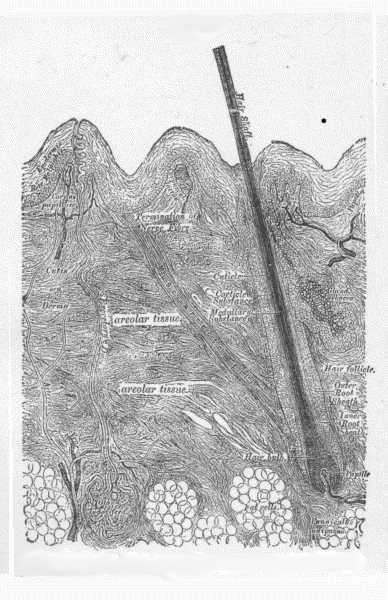

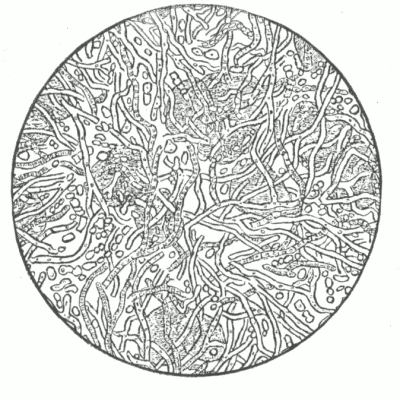

Fig. 1.

Vertical section of the skin—Diagrammatic. (After Heitsmann.)

Fig. 2.

c, corneous (horny) layer; g, granular layer; m, mucous layer (rete Malpighii).

The stratum lucidum is the layer just above the granular layer.

Nerve terminations—n, afferent nerve; b, terminal nerve bulbs; l, cell of Langerhans.

(After Ranvier.)

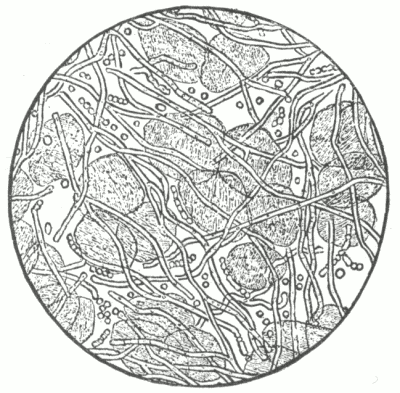

Fig. 3.

C, epidermis; D, corium; P, papillæ; S, sweat-gland duct.

v, arterial and venous capillaries (superficial, or papillary plexus) of the papillæ.

Deep plexus is partly shown at lower margin of the diagram; vs—an intermediate

plexus, an outgrowth from the deep plexus, supplying sweat-glands, and

giving a loop to hair papilla.

(After Ranvier).

Fig. 4.

a, a vascular papilla; b, a nervous papilla; c, a blood-vessel; d, a nerve fibre;

e, a tactile corpuscle.

(After Biesiadecki.)

Fig. 5.

A, shaft of the hair; B, root of the hair; C, cuticle of the hair; D, medullary substance of the hair.

E, external layer of the hair-follicle; F, middle layer of the hair-follicle; G, internal layer of the hair-follicle; H, papilla of the hair; I, external root-sheath; J, outer layer of the internal root-sheath; K, internal layer of the internal root-sheath.

(After Duhring.)

The symptoms of cutaneous disease may be objective, subjective or both; and in some diseases, also, there may be systemic disturbance.

What do you mean by objective symptoms?

Those symptoms visible to the eye or touch.

What do you understand by subjective symptoms?

Those which relate to sensation, such as itching, tingling, burning, pain, tenderness, heat, anæsthesia, and hyperæsthesia.

What do you mean by systemic symptoms?

Those general symptoms, slight or profound, which are sometimes associated, primarily or secondarily, with the cutaneous disease, as, for example, the systemic disturbance in leprosy, pemphigus, and purpura hemorrhagica.

Into what two classes of lesions are the objective symptoms commonly divided?

Primary (or elementary), and

Secondary (or consecutive).

What are primary lesions?

Those objective lesions with which cutaneous diseases begin. They may continue as such or may undergo modification, passing into the secondary or consecutive lesions.

Enumerate the primary lesions.

Macules, papules, tubercles, wheals, tumors, vesicles, blebs and pustules.

What are macules (maculæ)?

Variously-sized, shaped and tinted spots and discolorations, without elevation or depression; as, for example, freckles, spots of purpura, macules of cutaneous syphilis. [Pg 23]

What are papules (papulæ)?

Small, circumscribed, solid elevations, rarely exceeding the size of a split-pea, and usually superficially seated; as, for example, the papules of eczema, of acne, and of cutaneous syphilis.

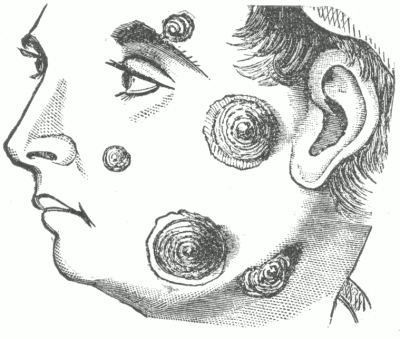

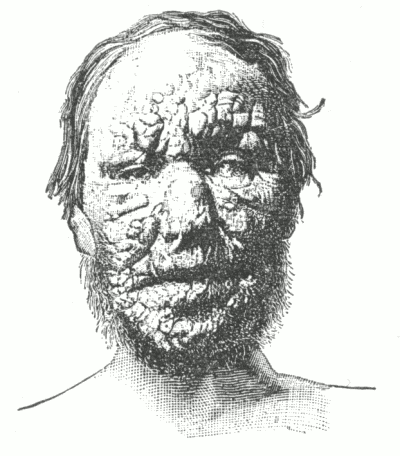

What are tubercles (tubercula)?

Circumscribed, solid elevations, commonly pea-sized and usually deep-seated; as, for example, the tubercles of syphilis, of leprosy, and of lupus.

What are wheals (pomphi)?

Variously-sized and shaped, whitish, pinkish or reddish elevations, of an evanescent character; as, for example, the lesions of urticaria, the lesions produced by the bite of a mosquito or by the sting of a nettle.

What are tumors (tumores)?

Soft or firm elevations, usually large and prominent, and having their seat in the corium and subcutaneous tissue; as, for example, sebaceous tumors, gummata, and the lesions of fibroma.

What are vesicles (vesiculæ)?

Pin-head to pea-sized, circumscribed epidermal elevations, containing serous fluid; as, for example, the so-called fever-blisters, the lesions of herpes zoster, and of vesicular eczema.

What are blebs (bullæ)?

Rounded or irregularly-shaped, pea to egg-sized epidermic elevations, with fluid contents; in short, they are essentially the same as vesicles and pustules except as to size; as, for example, the blebs of pemphigus, rhus poisoning, and syphilis.

What are pustules (pustulæ)?

Circumscribed epidermic elevations containing pus; as, for example, the pustules of acne, of impetigo, and of sycosis.

What are secondary lesions?

Those lesions resulting from accidental or natural change, modification or termination of the primary lesions. [Pg 24]

Enumerate the secondary lesions.

Scales, crusts, excoriations, fissures, ulcers, scars and stains.

What are scales (squamæ)?

Dry, laminated, epidermal exfoliations; as, for example, the scales of psoriasis, ichthyosis, and eczema.

What are crusts (crustæ)?

Dried effete masses of exudation; as, for example, the crusts of impetigo, of eczema, and of the pustular and ulcerating syphilodermata.

What are excoriations (excoriationes)?

Superficial, usually epidermal, linear or punctate loss of tissue; as, for example, ordinary scratch-marks.

What are fissures (rhagades)?

Linear cracks or wounds, involving the epidermis, or epidermis and corium; as, for example, the cracks which often occur in eczema when seated about the joints, the cracks of chapped lips and hands.

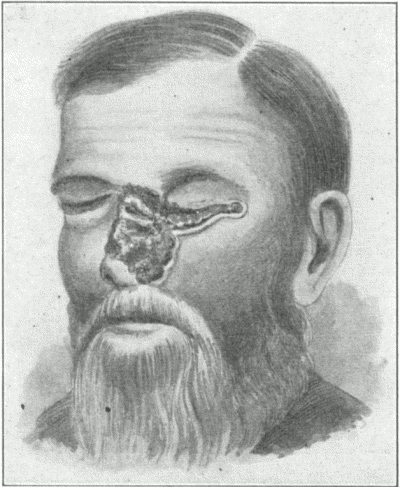

What are ulcers (ulcera)?

Rounded or irregularly-shaped and sized loss of skin and subcutaneous tissue resulting from disease; as, for example, the ulcers of syphilis and of cancer.

What are scars (cicatrices)?

Connective-tissue new formations replacing loss of substance.

What are stains?

Discolorations left by cutaneous disease, which stains may be transitory or permanent.

What do you mean by a patch of eruption?

A single group or aggregation of lesions or an area of disease.

When is an eruption said to be limited or localized?

When it is confined to one part or region. [Pg 25]

When is an eruption said to be general or generalized?

When it is scattered, uniformly or irregularly, over the entire surface.

When is an eruption universal?

When the whole integument is involved, without any intervening healthy skin.

When is an eruption said to be discrete?

When the lesions constituting the eruption are isolated, having more or less intervening normal skin.

When is an eruption confluent?

When the lesions constituting the eruption are so closely crowded that a solid sheet results.

When is an eruption uniform?

When the lesions constituting the eruption are all of one type or character.

When is an eruption multiform?

When the lesions constituting the eruption are of two or more types or characters.

When are lesions said to be aggregated?

When they tend to form groups or closely-crowded patches.

When are lesions disseminated?

When they are irregularly scattered, with no tendency to form groups or patches.

When is a patch of eruption said to be circinate?

When it presents a rounded form, and usually tending to clear in the centre; as, for example, a patch of ringworm.

When is a patch of eruption said to be annular?

When it is ring-shaped, the central portion being clear; as, for example, in erythema annulare.

What meaning is conveyed by the term “iris”?

The patch of eruption is made up of several concentric rings. Difference of duration of the individual rings, usually slight, tends to give the patch variegated coloration; as, for example, in erythema iris and herpes iris. [Pg 26]

What meaning is conveyed by the term “marginate”?

The sheet of eruption is sharply defined against the healthy skin; as, for example, in erythema marginatum, eczema marginatum.

What meaning is conveyed by the qualifying term “circumscribed”?

The term is applied to small, usually more or less rounded, patches, when sharply defined; as, for example, the typical patches of psoriasis.

When is the qualifying term “gyrate” employed?

When the patches arrange themselves in an irregular winding or festoon-like manner; as, for instance, in some cases of psoriasis. It results, usually, from the coalescence of several rings, the eruption disappearing at the points of contact.

When is an eruption said to be serpiginous?

When the eruption spreads at the border, clearing up at the older part; as, for instance, in the serpiginous syphiloderm.

Name the more common cutaneous diseases and state approximately their frequency.

Eczema, 30.4%; syphilis cutanea, 11.2%; acne, 7.3%; pediculosis, 4%; psoriasis, 3.3%; ringworm, 3.2%; dermatitis, 2.6%; scabies, 2.6%; urticaria, 2.5%; pruritus, 2.1%; seborrhœa, 2.1%; herpes simplex, 1.7%; favus, 1.7%; impetigo, 1.4%; herpes zoster, 1.2%; verruca, 1.1%; tinea versicolor, 1%. Total: eighteen diseases, representing 81 per cent. of all cases met with.

(These percentages are based upon statistics, public and private, of the American Dermatological Association, covering a period of ten years. In private practice the proportion of cases of pediculosis, scabies, favus, and impetigo is much smaller, while acne, acne rosacea, seborrhœa, epithelioma, and lupus are relatively more frequent.) [Pg 27]

Name the more actively contagious skin diseases.

Impetigo contagiosa, ringworm, favus, scabies and pediculosis; excluding the exanthemata, erysipelas, syphilis and certain rare and doubtful diseases.

[At the present time when most diseases are presumed to be due to bacteria or parasites the belief in contagiousness, under certain conditions, has considerably broadened.]

Is the rapid cure of a skin disease fraught with any danger to the patient?

No. It was formerly so considered, especially by the public and general profession, and the impression still holds to some extent, but it is not in accord with dermatological experience.

Name the several fats in common use for ointment bases.

Lard, petrolatum (or cosmoline or vaseline), cold cream and lanolin.

State the relative advantages of these several bases.

Lard is the best all-around base, possessing penetrating properties scarcely exceeded by any other fat.

Petrolatum is also valuable, having little, if any, tendency to change; it is useful as a protective, but is lacking in its power of penetration.

Cold Cream (ungt. aquæ rosæ) is soothing and cooling, and may often be used when other fatty applications disagree.

Lanolin is said to surpass in its power of penetration all other bases, but this is not borne out by experience. It is an unsatisfactory base when used alone. It should be mixed with another base in about the proportion of 25% to 50%.

These several bases may, and often with advantage, be variously combined. [Pg 28]

What is to be added to these several bases if a stiffer ointment is required?

Simple cerate, wax, spermaceti, or suet; or in some instances, a pulverulent substance, such as starch, boric acid, and zinc oxide.

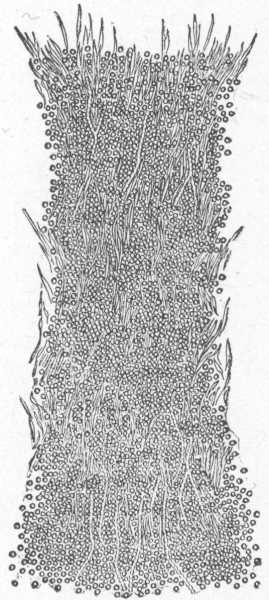

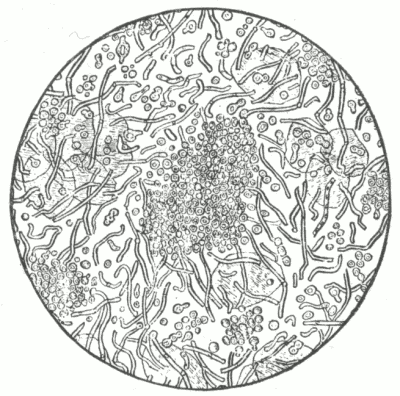

Fig. 6.

A normal sweat-gland, highly magnified. (After Neumann.)

a, Sweat-coil: b, sweat-duct; c, lumen of duct; d, connective-tissue capsule; e and f, arterial trunk and capillaries.

What is hyperidrosis?

Hyperidrosis is a functional disturbance of the sweat-glands, characterized by an increased production of sweat. This increase may be slight or excessive, local or general. [Pg 29]

As a local affection, what parts are most commonly involved?

The hands, feet, especially the palmar and plantar surfaces, the axillæ and the genitalia.

Describe the symptoms of the local forms of hyperidrosis.

The essential, and frequently the sole symptom, is more or less profuse sweating.

If the hands are the parts involved, they are noted to be wet, clammy and sometimes cold.

If involving the soles, the skin often becomes more or less macerated and sodden in appearance, and as a result of this maceration and continued irritation they may become inflamed, especially about the borders of the affected parts, and present a pinkish or pinkish-red color, having a violaceous tinge. The sweat undergoes change and becomes offensive.

Is hyperidrosis acute or chronic?

Usually chronic, although it may also occur as an acute affection.

What is the etiology of hyperidrosis?

Debility is commonly the cause in general hyperidrosis; the local forms are probably neurotic in origin.

What is the prognosis?

The disease is usually persistent and often rebellious to treatment; in many instances a permanent cure is possible, in others palliation. Relapses are not uncommon.

What systemic remedies are employed in hyperidrosis?

Ergot, belladonna, gallic acid, mineral acids, and tonics. Constitutional treatment is rarely of benefit in the local forms of hyperidrosis, and external applications are seldom of service in general hyperidrosis. Precipitated sulphur, a teaspoonful twice daily, is also well spoken of, combined, if necessary, with an astringent.

What external remedies are employed in the local forms?

Astringent lotions of zinc sulphate, tannin and alum, applied several times daily, with or without the supplementary use of dusting-powders. Weak solutions of formaldehyde, one to one hundred, are sometimes of value. [Pg 30]

Dusting-powders of boric acid and zinc oxide, to which may be added from ten to thirty grains of salicylic acid to the ounce, to be used freely and often:—

℞ Pulv. ac. salicylici, ............................ gr. x-xxx.

Pulv. ac. borici, ................................ ʒv.

Pulv. zinci oxidi, ............................... ʒiij M.

Diachylon ointment, and an ointment containing a drachm of tannin to the ounce; more especially applicable in hyperidrosis of the feet. The parts are first thoroughly washed, rubbed dry with towels and dusting-powder, and the ointment applied on strips of muslin or lint and bound on; the dressing is renewed twice daily, the parts each time being rubbed dry with soft towels and dusting-powder, and the treatment continued for ten days to two weeks, after which the dusting-powder is to be used alone for several weeks. No water is to be used after the first washing until the ointment is discontinued. One such course will occasionally suffice, but not infrequently a repetition is necessary.

Faradization and galvanization are sometimes serviceable. Repeated mild exposures to the Röntgen rays have a favorable influence in some instances.

(Synonym: Miliaria crystallina.)

What is sudamen?

Sudamen is a non-inflammatory disorder of the sweat-glands, characterized by pin-point to pin-head-sized, discrete but thickly-set, superficial, translucent whitish vesicles.

Describe the clinical characters.

The lesions develop rapidly and in great numbers, either irregularly or in crops, and are usually to be seen as discrete, closely-crowded, whitish, or pearl-colored minute elevations, occurring most abundantly upon the trunk. In appearance they resemble minute dew-drops. They are non-inflammatory, without areola, never become purulent, and evince no tendency to rupture, the fluid disappearing by absorption, and the epidermal covering by desquamation. [Pg 31]

Give the course and duration of sudamen.

New crops may appear as the older lesions are disappearing, and the affection persist for some time, or, on the other hand, the whole process may come to an end in several days or a week. In short, the course and duration depend upon the subsidence or persistence of the cause.

What is the anatomical seat of sudamen?

The lesions are formed between the lamellæ of the corneous layer, usually the upper part; and are thought to be due to some change in the character of the epithelial cells of this layer, probably from high temperature, giving rise to a blocking up of the surface outlet.

What is the cause of sudamen?

Debility, especially when associated with high fever. The eruption is often seen in the course of typhus, typhoid and rheumatic fevers.

How would you treat sudamen?

By constitutional remedies directed against the predisposing factor or factors, and the application of cooling lotions of vinegar or alcohol and water, or dusting-powders of starch and lycopodium.

Describe hydrocystoma.

Hydrocystoma is a cystic affection of the sweat-gland ducts, seated upon the face. The lesions may be present in scant numbers or in more or less profusion. They have the appearance of boiled sago grains imbedded in the skin; the larger lesions may have a bluish color, especially about the periphery. It is not common, and is usually seen in washerwomen and laundresses, or those exposed to moist heat. In some cases it tends to disappear during the winter months. There are no subjective symptoms.

Treatment consists of puncturing the lesions and application of dusting-powder. Avoidance of the exciting cause (moist heat) is important.

Describe anidrosis.

It is the opposite condition of hyperidrosis, and is characterized [Pg 32] by diminution or suppression of the sweat secretion. It occurs to some extent in certain systemic diseases and also in some affections of the skin, such as ichthyosis; nerve-injuries may give rise to localized sweat-suppression.

Treatment is based upon general principles; friction, warm and hot-vapor baths, electricity and similar measures are of service.

(Synonym: Osmidrosis.)

Describe bromidrosis.

Bromidrosis is a functional disturbance of the sweat-glands characterized by a sweat secretion of an offensive odor. The sweat production may be normal in quantity or more or less excessive, usually the latter. The condition may be local or general, commonly the former. It is closely allied to hyperidrosis, and may often be considered identical, the odor resulting from rapid decomposition of the sweat secretion. The decomposition and resulting odor have been thought due to the presence of bacteria.

What parts are most commonly affected in bromidrosis?

The feet and the axillæ.

What is the treatment of bromidrosis?

It is essentially the same as that of hyperidrosis (q. v.), consisting of applications of astringent lotions, dusting-powders, especially those containing boric acid and salicylic acid, and the continuous application of diachylon ointment. In obstinate cases weak formaldehyde solutions, Röntgen rays, and high-frequency currents can be tried.

Describe chromidrosis.

This is a functional disorder of the sweat-glands characterized by a secretion variously colored, and usually increased in quantity. It is, as a rule, limited to a circumscribed area. The most common color is red. The condition is probably of neurotic origin and tends to recur. (True chromidrosis is extremely rare; most of the cases formerly thought to be such are now known to be examples of pseudochromidrosis.) [Pg 33]

Treatment should be invigorating and tonic, with special reference toward the nervous system. The various methods of local electrization should also be resorted to.

Mild antiseptic and astringent lotions or dusting powders should also be advised.

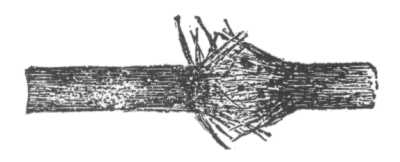

Red chromidrosis or Pseudochromidrosis is a condition in which the coloring of the sweat occurs after its excretion and is due to the presence of chromatogenous bacteria which are found attached to the hairs of the part in agglutinated masses. The axilla is the favorite site. Treatment consists of frequent soap-and-water washings, and the application of boric acid, resorcin, and corrosive sublimate lotions.

Describe uridrosis.

Uridrosis is a rare condition in which the sweat secretion contains the elements of the urine, especially urea. In marked cases the salt may be noticeable upon the skin as a colorless or whitish crystalline deposit. In most instances it has been preceded or accompanied by partial or complete suppression of the renal functions.

Describe phosphoridrosis.

Phosphoridrosis is a rare condition, in which the sweat is phosphorescent. It has been observed in the later stages of phthisis, in miliaria, and in those who have eaten of putrid fish.

Synonyms: (Steatorrhœa; Acne sebacea; Ichthyosis sebacea; Dandruff.)

What is seborrhœa?

Seborrhœa is a disease of the sebaceous glands, characterized by an excessive and abnormal secretion of sebaceous matter, appearing on the skin as an oily coating, crusts, or scales.

In many cases the sweat-glands are likewise implicated, and the process may also be distinctly, although usually mildly, inflammatory. [Pg 34]

At what age is seborrhœa usually observed?

Between fifteen and forty. It may, however, occur at any age.

Name the parts most commonly affected.

The scalp, face, and (less frequently) the sternal and interscapular regions of the trunk. It is sometimes seen on other parts.

What varieties of seborrhœa are encountered?

Seborrhœa oleosa and seborrhœa sicca; not infrequently the disease is of a mixed type.

What are the symptoms of seborrhœa oleosa?

The sole symptom is an unnatural oiliness, variable as to degree. Its most common sites are the regions of the scalp, nose, and forehead. In many instances mild rosacea coexists with oily seborrhœa of the nose.

Give the symptoms of seborrhœa sicca.

A variable degree of greasy scalines, which may be seated upon a pale, hyperæmic or mildly inflammatory surface.

The parts affected are covered scantily or more or less abundantly with somewhat greasy, grayish, or brownish-gray scales. If upon the scalp (dandruff, pityriasis capitis), small particles of scales are found scattered through the hair, and when the latter is brushed or combed, fall over the shoulders. If upon the face, in addition to the scaliness, the sebaceous ducts are usually seen to be enlarged and filled with sebaceous matter.

Describe the symptoms of the ordinary or mixed type.

It is common upon the scalp. The skin is covered with irregularly diffused, greasy, grayish or brownish scales and crusts, in some cases moderate in quantity, in others so great that large irregular masses are formed, pasting the hair to the scalp. If removed, the scales and crusts rapidly re-form. The skin beneath is found slate-colored, hyperæmic or mildly inflammatory, and exceptionally it has in places an eczematous aspect (eczema seborrhoicum). Extraneous matter, such as dust and dirt, collects upon the parts, and the whole mass may become more or less offensive. There is a strong tendency to falling-out of the hair. Itching may or may not be present.

Seborrhœa (Eczema Seborrhoicum).

Describe the symptoms of seborrhœa of the trunk and other parts.

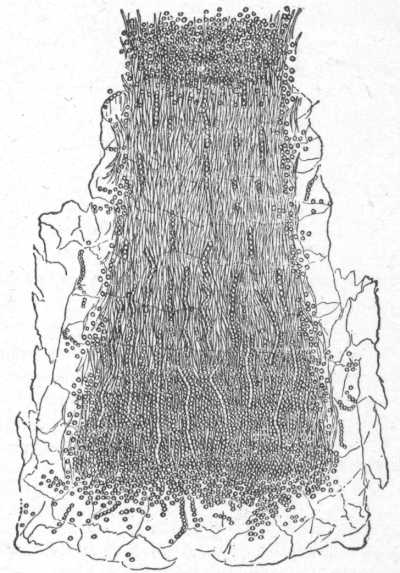

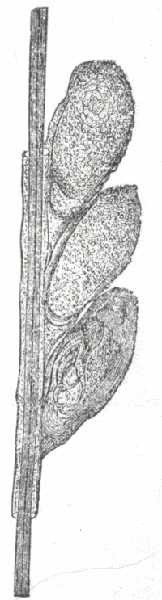

Fig. 7.

A normal sebaceous gland in connection with a lanugo hair. (After Neumann.)

a, Capsule; b, fatty secretion; c, h, secreting cells; d, root of lanugo hair; e, hair-sac; f, hair-shaft; g, acini of sebaceous gland.

Seborrhœa corporis differs in a measure, in its symptoms, from seborrhœa of the scalp and is usually illustrative of the variety known as eczema seborrhoicum; it occurs as one or several irregular or circinate, slightly hyperæmic or moderately inflammatory patches, covered with dirty or grayish-looking greasy scales or crusts, usually moderate in quantity, and upon removal are found to have projections into the sebaceous ducts. It is commonly seen upon the sternal and interscapular regions. It rarely exists independently in these regions, being usually associated with and following the disease on the scalp. It may also invade the axillæ, genitocrural, and other regions. [Pg 36]

What is the usual course of seborrhœa?

Essentially chronic, the disease varying in intensity from time to time. In occasional instances it disappears spontaneously.

Give the cause or causes of seborrhœa.

General debility, anæmia, chlorosis, dyspepsia, and similar conditions are to be variously looked upon as predisposing.

In some instances, however, the disease seems to be purely local in character, and to be entirely independent of any constitutional or predisposing condition. The view recently advanced that the disease is of parasitic nature and contagious has been steadily gaining ground.

What is the pathology of seborrhœa?

Seborrhœa is a disease of the sebaceous glands, and probably often involving the sweat-glands also; its products, as found upon the skin, consisting of the sebaceous secretion, epithelial cells from the glands and ducts, and more or less extraneous matter. Not infrequently evidences of superficial inflammatory action are also to be found, and it is especially for this type that the name eczema seborrhoicum is most appropriate. In long-continued and neglected cases slight atrophy of the gland-structures may occur.

With what diseases are you likely to confound seborrhœa?

Upon the scalp, with eczema and psoriasis; upon the face, with lupus erythematosus and eczema; and upon the trunk, with psoriasis and ringworm.

As a rule, the clinical features of seborrhœa are sufficiently characteristic to prevent error.

What are the differential points?

Eczema, psoriasis, and lupus erythematosus are diseases in which there are distinct inflammatory symptoms, such as thickening and infiltration and redness; moreover, psoriasis, and this holds true as to ringworm also, occurs in sharply-defined, circumscribed patches, and lupus erythematosus has a peculiar violaceous tint and an elevated and marginate border. A microscopic examination of the epidermic scrapings would be of crucial value in differentiating from ringworm.

Quite frequently, especially in the interscapular and sternal regions, the segmental configuration constitutes an important feature of seborrhœa—of the eczema seborrhoicum variety. [Pg 37]

What is the prognosis in seborrhœa?

Favorable. All types are curable, and when upon the non-hairy regions, usually readily so; upon the scalp it is often obstinate. Relapses are not uncommon.

In those cases of seborrhœa capitis which have been long-continued or neglected, and attended with loss of hair, this loss may be more or less permanent, although ordinarily much can be done to promote a regrowth (see Treatment of Alopecia).

How would you treat seborrhœa of the scalp?

By constitutional (if indicated) and local remedies; the former having in view correction or modification of the predisposing factor or factors, and the latter removal of the sebaceous accumulations and the application of mildly stimulating antiseptic ointments or lotions.

What constitutional remedies are commonly employed?

The various tonics, such as iron, quinine, strychnia, cod-liver oil, arsenic, the vegetable bitters, laxatives, malt and similar preparations. The line of treatment is to be based upon indications.

How do you free the scalp of the sebaceous accumulations?

In mild types of the disease shampooing with simple Castile soap (or any other good toilet soap) and hot water will suffice; in those cases in which there is considerable scale-and crust-formation the tincture of green soap (tinct. saponis viridis) is to be employed in place of the toilet soap, and in some of these latter cases it may be necessary to soften the crusts with a previous soaking with olive oil.

The frequency of the shampoo depends upon the conditions. In mild cases once in five or ten days will be sufficiently frequent to keep the parts clean, but in those cases in which there is rapid scale-or crust-production once daily or every second day may at first be demanded.

Name the most effectual applications in seborrhœa capitis.

Sulphur, ammoniated mercury, salicylic acid, resorcin, and carbolic acid.

Sulphur is used in the form of an ointment, from twenty grains to one drachm in the ounce. Ammoniated mercury, in the form of an ointment, ten to sixty grains to the ounce. Salicylic acid, either alone as an ointment, ten to thirty grains to the ounce; or it may [Pg 38]

often be added with advantage, in the same proportion, to the sulphur or ammoniated mercury ointment above named. Resorcin, either as an ointment, ten to thirty grains to the ounce, or as an alcoholic or aqueous lotion, as the following:—

℞ Resorcini, ....................................... ʒj-ʒiss.

Ol. ricini, ...................................... ♏xxx-fʒij.

Alcoholis, ...................................... f℥iv. M.

Carbolic acid, to the amount of ten to thirty grains, can be added to this. If an aqueous lotion is desirable, then in the above formula the oleum ricini is replaced with glycerine, and the alcohol with water; three to five minims of glycerine in each ounce is usually sufficient, as a greater quantity makes the resulting lotion sticky. Petrolatum alone, or with 10 to 30 per cent. lanolin, is usually the most satisfactory base for the ointments. In some cases of the inflammatory variety the skin is found quite irritable, and the mildest applications are at first only admissible.

How are the remedies to be applied?

A small quantity of the lotion, ointment, or oil is gently applied to the skin; when to the scalp, a lotion or oil can be conveniently applied by means of an eye-dropper. In the beginning of the treatment an application once or twice daily is ordered; later, as the disease becomes less active, once every second or third day.

How is seborrhœa upon other parts to be treated?

In the same general manner as seborrhœa of the scalp, except that the local applications must be somewhat weaker. The several sulphur lotions employed in the treatment of acne (q. v.) may also be used when the disease is upon these parts. In obstinate patchy cases occasional paintings with a 20 to 50 per cent alcoholic solution of resorcin is curative; following the painting a mild salve should be used.

(Synonyms: Blackheads; Flesh-worms.)

What is comedo?

Comedo is a disorder of the sebaceous glands, characterized by yellowish or blackish pin-point or pin-head-sized puncta or elevations corresponding to the gland-orifices. [Pg 39]

At what age and upon what parts are comedones found?

Usually between fifteen and thirty, and upon the face and upper part of the trunk, where they may exist sparsely or in great numbers. They are occasionally associated with oily seborrhœa, the parts presenting a greasy or soiled appearance.

Exceptionally they occur as distinct, and usually symmetrical, groups upon the forehead or the cheeks. On the upper trunk so-called double and multiple comedo have been noted—the two, three, or even four closely-contiguous blackheads are, beneath the surface, intercommunicable, the dividing duct-walls having apparently disappeared by fusion.

Describe an individual lesion.

It is pin-point to pin-head in size, dark yellowish, and usually with a central blackish point (hence the name blackheads). There is scarcely perceptible elevation, unless the amount of retained secretion is excessive. Upon pressure this may be ejected, the small, rounded orifice through which it is expressed giving it a thread-like shape (hence the name flesh-worms).

What is the usual course of comedo?

Chronic. The lesions may persist indefinitely or the condition may be somewhat variable. In many instances, either as a result of pressure or in consequence of chemical change in the sebaceous plugs or of the addition of a microbic factor, inflammation is excited and acne results. The two conditions are, in fact, usually associated.

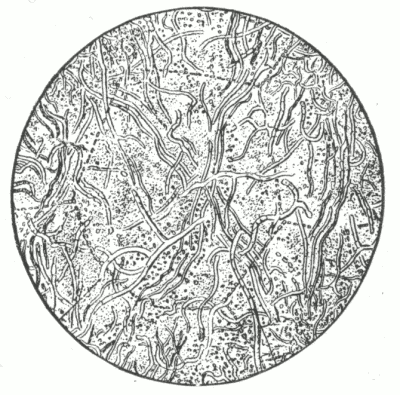

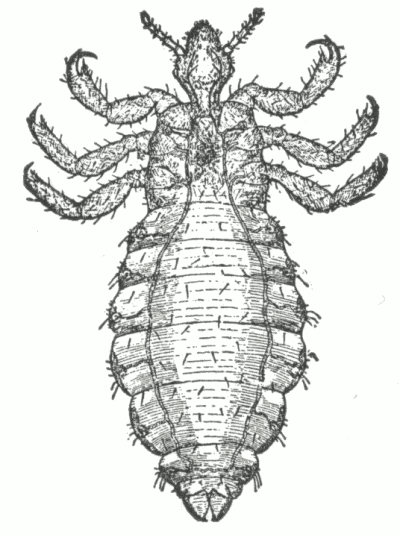

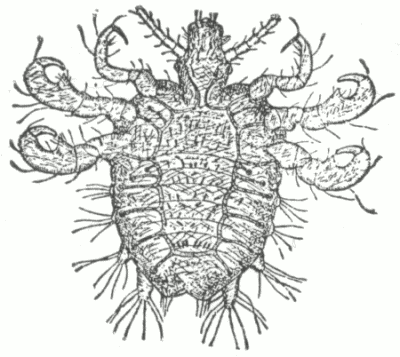

Fig. 8.

Demodex Folliculorum, X 300. Ventral surface. (After Simon).

To what may comedo often be ascribed?

To disorders of digestion, constipation, chlorosis, menstrual disturbance, lack of tone in the muscular fibres of the skin, the infrequent use of soap, and working in a dirty or dusty atmosphere. [Pg 40] A small parasite (demodex folliculorum, acarus folliculorum) is sometimes found in the sebaceous mass, but its presence is without etiological significance, as it is also found in healthy follicles. A microbacillus has been found by several observers, and credited with etiological influence.

What is the pathology of comedo?

The sebaceous ducts or glands, or both, become blocked up with retained secretion and epithelial cells. The dark points which usually mark the lesions are probably due to accumulation of dirt, but may, as some writers maintain, be due to the presence of pigment-granules resulting from chemical change in the sebaceous matter.

Is there any difficulty in the diagnosis of comedo?

No. It can scarcely be confounded with milium, as in this latter disease the lesion has no open outlet, no black point, and the contents cannot be squeezed out.

Give the prognosis of comedo.

The result of treatment is usually favorable, although the disease is often rebellious. Relapses are not uncommon.

How would you treat a case of comedo?

By systemic (if indicated) and local measures.

The constitutional treatment aims at correction or palliation of the predisposing conditions, and the external applications have in view a removal of the sebaceous plugs and stimulation of the glands and skin to healthy action.

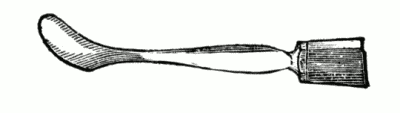

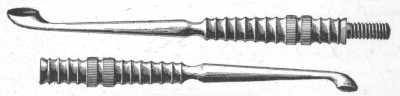

Fig. 9.

Comedo Extractor.

Name the systemic remedies commonly employed.

Cod-liver oil, iron, quinine, arsenic, nux vomica and other tonics; ergot in those cases in which there is lack of muscular tone, salines and aperient pills in constipation. The digestion is to be looked after and the bowels kept regular; indigestible food of all kinds is to be interdicted. Hygienic measures, such as general and local bathing, local massage, calisthenics, and open-air exercise, are of service. [Pg 41]

Describe the local treatment.

Steaming the face or prolonged applications of hot water; washing with ordinary toilet soap and hot water, or, in sluggish cases, using tincture of green soap (tinct. saponis viridis) instead of the toilet soap; removal of the sebaceous plugs by mechanical means, such as lateral pressure with the finger ends or perpendicular pressure with a watch-key with rounded edges, or with an instrument specially contrived for this purpose; and after these preliminary measures, which should be carried out every night, a stimulating sulphur ointment or lotion, such as employed in the treatment of acne (q. v.), is to be thoroughly applied. The following is valuable:—

℞ Zinci sulphatis,

Potassi sulphureti, ...................āā......... ʒj-ʒiv.

Alcoholi ........................................ f℥ss.

Aquæ, ........................... q.s. ad. ...... f℥iv. M.

Should slight scaliness or a mild degree of irritation of the skin be brought about, active external treatment is to be discontinued for a few days and soothing applications made. Resorcin, in lotion, 3 to 25 per cent strength, is through the exfoliation it provokes, frequently of value; the resorcin paste referred to in acne can also be used for this purpose.

Moderately strong applications of the Faradic current, repeated once or twice weekly, are sometimes of service; also weak to moderately strong applications of the continuous and high-frequency currents. Röntgen-ray treatment can also be resorted to in extremely obstinate cases.

In occasional instances sulphur preparations not only fail to do good, but materially aggravate the condition. In such cases, if resorcin preparations also fail, the mercurial lotion and ointment employed in acne may be prescribed. Mercurial and sulphur applications should not be used, it need scarcely be said, within a week or ten days of each other, otherwise an increase in the comedones and a slight darkening of the skin result from the formation of the black sulphuret of mercury. [Pg 42]

(Synonyms: Grutum; Strophulus Albidus.)

What is milium?

Milium consists in the formation of small, whitish or yellowish, rounded, pearly, non-inflammatory elevations situated in the upper part of the corium.

Describe the clinical appearances.

The lesions are usually pin-head in size, whitish or yellowish, seemingly more or less translucent, rounded or acuminated, without aperture or duct, are superficially seated in the skin, and project slightly above the surface.

They appear about the face, especially about the eyelids; they may occur also, although rarely, upon other parts. But one or several may be present, or they may exist in numbers.

What is the course of milium?

The lesions develop slowly, and may then remain stationary for years. Their presence gives rise to no disturbance, and, unless they are large in size or exist in numbers, causes but slight disfigurement.

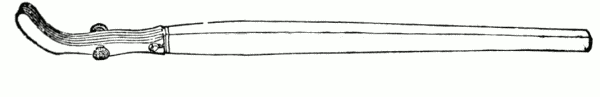

Fig. 10.

Milium Needle.

In rare instances they may undergo calcareous metamorphosis, constituting the so-called cutaneous calculi.

What is the anatomical seat of milium?

The sebaceous gland (probably one or several of the superficially-situated acini), the duct of which is in some manner obliterated, the sebaceous matter collects, becomes inspissated and calcareous, forming the pin-head lesion. The epidermis is the external covering.

What is the treatment?

The usual plan is to prick or incise each lesion and press out the contents. In some milia it may be necessary also, in order to prevent a return, to touch the base of the excavation with tincture of [Pg 43] iodine or with silver nitrate. Electrolysis is also effectual. In those cases where the lesions are numerous the production of exfoliation of the epiderm by means of resorcin applications (see acne) is a good plan.

(Synonyms: Sebaceous Cyst; Sebaceous Tumor; Wen.)

Describe steatoma.

Steatoma, or sebaceous cyst, appears as a variously-sized, elevated, rounded or semi-globular, soft or firm tumor, freely movable and painless, and having its seat in the corium or subcutaneous tissue. The overlying skin is normal in color, or it may be whitish or pale from distention; in some a gland-duct orifice may be seen, but, as a rule, this is absent.

What are the favorite regions for the development of steatoma?

The scalp, face and back. One or several may be present.

What is the course of sebaceous cysts?

Their growth is slow, and, after attaining a variable size, may remain stationary. They may exist indefinitely without causing any inconvenience beyond the disfigurement. Exceptionally, in enormously distended growths, suppuration and ulceration result.

What is the pathology?

A steatoma is a cyst of the sebaceous gland and duct, produced by retained secretion. The contents may be hard and friable, soft and cheesy, or even fluid, of a grayish, whitish or yellowish color, and with or without a fetid odor; the mass consisting of fat-drops, epidermic cells, cholesterin, and sometimes hairs.

Are sebaceous cysts likely to be confounded with gummata?

No. Gummata grow more rapidly, are usually painful to the touch, are not freely movable, and tend to break down and ulcerate.

Describe the treatment of steatoma.

A linear incision is made, and the mass and enveloping sac [Pg 44] dissected out. If the sac is permitted to remain, reproduction almost invariably takes place.

What do you understand by erythema simplex?

Erythema simplex is a hyperæmic disorder characterized by redness, occurring in the form of variously-sized and shaped, diffused or circumscribed, non-elevated patches.

Name the two general classes into which the simple erythemata are divided.

Idiopathic and symptomatic.

What do you include in the idiopathic class?

Those erythemas due to external causes, such as cold and heat (erythema caloricum), the action of the sun (erythema solare), traumatism (erythema traumaticum), and the various poisons or chemical irritants (erythema venenatum).

What do you include in the symptomatic class?

Those rashes often preceding or accompanying certain of the systemic diseases, and those due to disorders of the digestive tract, stomachic and intestinal toxins, to the ingestion of certain drugs, and to use of the therapeutic serums.

Describe the symptoms of erythema simplex.

The essential symptom is redness—simple hyperæmia—without elevation or infiltration, disappearing under pressure, and sometimes attended by slight heat or burning; it may be patchy or diffused. In the idiopathic class, if the cause is continued, dermatitis may result.

What is to be said about the distribution of the simple erythemata?

The idiopathic rashes, as inferred from the nature of the causes, are usually limited.

The symptomatic erythemas are more or less generalized; desquamation sometimes follows. [Pg 45]

Describe the treatment of the simple erythemata.

A removal of the cause in idiopathic rashes is all that is needed, the erythema sooner or later subsiding. The same may be stated of the symptomatic erythemata, but in these there is at times difficulty in recognizing the etiological factor; constitutional treatment, if necessary, is to be based upon general principles. Intestinal antiseptics are useful in some instances.

Local treatment, which is rarely needed, consists of the use of dusting-powders or mild cooling and astringent lotions, such as are employed in the treatment of acute eczema (q. v.).

(Synonym: Chafing.)

What do you understand by erythema intertrigo?

Erythema intertrigo is a hyperæmic disorder occurring on parts where the natural folds of the skin come in contact, and is characterized by redness, to which may be added an abraded surface and maceration of the epidermis.

Describe the symptoms of erythema intertrigo.

The skin of the involved region gradually becomes hyperæmic, but is without elevation or infiltration; a feeling of heat and soreness is usually experienced. If the condition continue, the increased perspiration and moisture of the parts give rise to maceration of the epidermis and a mucoid discharge; actual inflammation may eventually result.

What is the course of erythema intertrigo?

The affection may pass away in a few days or persist several weeks, the duration depending, in a great measure, upon the cause.

Mention the causes of erythema intertrigo.

The causes are usually local. It is seen chiefly in children, especially in fat subjects, in whom friction and moisture of contiguous parts of the body, usually the region of the neck, buttocks and genitalia, are more common; in such, uncleanliness or the too free use of soap washings will often act as the exciting factor. Disorders of [Pg 46] the stomach or intestinal canal apparently have a predisposing influence.

What treatment would you advise in erythema intertrigo?

The folds or parts are to be kept from contact by means of lint or absorbent cotton; thin, flat bags of cheese cloth or similar material partly filled with dusting-powder, and kept clean by frequent changes, are excellent for this purpose, and usually curative. Cleanliness is essential, but it is to be kept within the bounds of common sense. Dusting-powders and cooling and astringent lotions, such as are employed in the treatment of acute eczema (q. v.), can also be advised. The following lotion is valuable:—

℞ Pulv. calaminæ,

Pulv. zinci oxidi, ....................āā......... ʒiss.

Glycerinæ, ....................................... ♏xxx

Alcoholis, ...................................... fʒij

Aquæ, ............................................ Oss. M.

Exceptionally a mild ointment, alone or supplementary to a lotion, acts more satisfactorily.

In persistent or obstinate cases attention should also be directed to the state of the general health, especially as regards the digestive tract.

What is erythema multiforme?

Erythema multiforme is an acute, inflammatory disease, characterized by reddish, more or less variegated macules, papules, and tubercles, occurring as discrete lesions or in patches of various size and shape.

Upon what parts of the body does the eruption appear?

Usually upon the extremities, especially the dorsal aspect, from the knees and elbows down, and about the face and neck; it may, however, be more or less general.

Describe the symptoms of erythema multiforme.

With or without precursory symptoms of malaise, gastric uneasiness or rheumatic pains, the eruption suddenly makes its appearance, [Pg 47] assuming an erythematous, papular, tubercular or mixed character; as a rule, one type of lesion predominates. The lesions tend to increase in size and intensity, remain stationary for several days or a week, and then gradually fade; during this time there may have been outbreaks of new lesions. In color they are pink, red, or violaceous. Slight itching may or may not be present. Exceptionally, in general cases, the eruption partakes of the nature of both urticaria and erythema multiforme, and itching may be quite a decided symptom. In some instances there is preceding and accompanying febrile action, usually slight in character; in others there may be some rheumatic swelling of one or more joints.

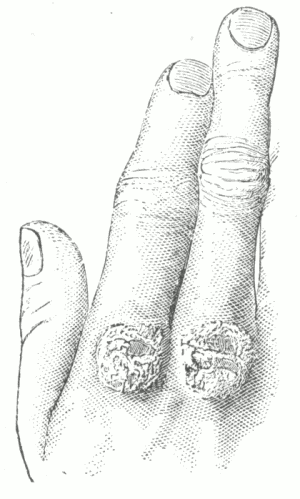

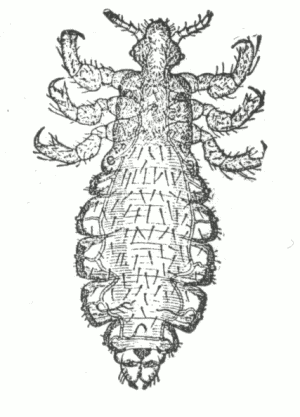

Fig. 11.

Erythema Multiforme, in which many of the lesions have become bullous—

Erythema Bullosum.

What type of the eruption is most common?

The papular, appearing usually upon the backs of the hands and forearms, and not infrequently, also, upon the face, legs and feet. The papules are usually pea-sized, flattened, and of a dark red or violaceous color.

Describe the various shapes which the erythematous lesions may assume.

Often the patches are distinctly ring-shaped, with a clear centre— erythema annulare; or they are made up of several concentric rings, presenting variegated coloring—erythema iris; or a more or less extensive patch may spread with a sharply-defined border, the older part tending to fade—erythema marginatum; or several rings may coalesce, with a disappearance of the coalescing parts, and serpentine lines or bands result—erythema gyratum.

Does the eruption of erythema multiforme ever assume a vesicular or bullous character?

Yes. In exceptional instances, the inflammatory process may be sufficiently intense to produce vesiculation, usually at the summits of the papules—erythema vesiculosum; and in some instances, blebs may be formed—erythema bullosum. A vesicular or bullous lesion may become immediately surrounded by a ring-like vesicle or bleb, and outside of this another form; a patch may be made up of as many as several such rings—herpes iris. In the vesicular and bullous cases the lips and the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose also may be the seat of similar lesions.

What is the course of erythema multiforme?

Acute, the symptoms disappearing spontaneously, usually in one to three or four weeks. In some instances the recurrences take place so rapidly that the disease assumes a chronic aspect; it is possible that such cases are midway cases between this disease and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Mention the etiological factors in erythema multiforme.

The causes are obscure. Digestive disturbance, rheumatic conditions, and the ingestion of certain drugs are at times influential. Intestinal toxins are doubtless important etiological factors in some cases. Certain foods, such as are apt to undergo rapid putrefactive [Pg 49] or fermentative change, especially pork meats, oysters, fish, crabs, lobsters, etc., are, therefore, not infrequently of apparent causative influence. It is most frequently observed in spring and autumn months, and in early adult life. The disease is not uncommon.

What is the pathology of erythema multiforme?

It is a mildly inflammatory disorder, somewhat similar to urticaria, and presumably due to vasomotor disturbance; the amount of exudation, which is variable, determines the character of the lesions.

Name the diagnostic points of erythema multiforme.

The multiformity of the eruption, the size of the papules, often its limitation to certain parts, its course and the entire or comparative absence of itching.

It resembles urticaria at times, but the lesions of this latter disease are evanescent, disappearing and reappearing usually in the most capricious manner, are commonly seated about the trunk, and are exceedingly itchy.

In the vesicular and bullous types the acute character of the outbreak, the often segmental and ring-like shape, their frequent origin from erythematous papules, and the distribution and association with the more common manifestations, are always suggestive.

What prognosis would you give in erythema multiforme?

Always favorable; the eruption usually disappears in ten days to three weeks, although in rare instances new crops may appear from day to day or week to week, and the process last one or two months. One or more recurrences in succeeding years are not uncommon. Those rare cases in which vesicular or bullous lesions are also seen on the lips and in the mouth, are more prone to longer duration and to more frequent recurrences.

What remedies are commonly prescribed in erythema multiforme?

Quinin, and, if constipation is present, saline laxatives. Calcined magnesia is valuable as a laxative. Intestinal antiseptics, such as salol, thymol, and sodium salicylate, are valuable in cases probably due to intestinal toxins. In those exceptional instances in which there may be associated febrile action and rheumatic swelling of the joints, the patient should be kept in bed till these symptoms [Pg 50] subside. Local applications are rarely required, but in those exceptional cases in which itching or burning is present, cooling lotions of alcohol and water or vinegar and water are to be prescribed. The vesicular and bullous types demand mild protective applications, such as used in eczema and pemphigus.

(Synonym: Dermatitis contusiformis.)

What is erythema nodosum?

Erythema nodosum is an inflammatory affection, of an acute type, characterized by the formation of variously-sized, roundish, more or less elevated erythematous nodes.

Is there any special region of predilection for the eruption of erythema nodosum?

Yes. The tibial surfaces, to which the eruption is often limited; not infrequently, however, other parts may be involved, more especially the arms and forearms.

Describe the symptoms of erythema nodosum.

The eruption makes its appearance suddenly, and is usually ushered in with febrile disturbance, gastric uneasiness, malaise, and rheumatic pains and swelling about the joints. The lesions vary in size from a cherry to a hen's egg, are rounded or ovalish, tender and painful, have a glistening and tense look, and are of a bright red, erysipelatous color which merges gradually into the sound skin. At first they are somewhat hard, but later they soften and appear as if about to break down, but this, however, never occurs, absorption invariably taking place. In occasional instances they are hemorrhagic. Exceptionally the lesions of erythema multiforme are also present. Lymphangitis is sometimes observed. In rare instances symptoms pointing to visceral involvement, to cerebral invasion, and to heart complications have been observed.

Are the lesions in erythema nodosum usually numerous?

No. As a rule not more than five to twenty nodes are present.

What is the course of erythema nodosum?

Acute. The disease terminating usually in one to three weeks. [Pg 51] As the lesions are disappearing they present the various changes of color observed in an ordinary bruise.

What is known in regard to the etiology?

The affection is closely allied to erythema multiforme, and is, indeed, by some considered a form of that disease. It occurs most frequently in children and young adults, and usually in the spring and autumn months. Intestinal toxins are thought responsible in some cases. Digestive disturbance and rheumatic pain and swellings are often associated with it. By many the malady is thought to be a specific infection.

What is the pathology of erythema nodosum?

The disease is to be viewed as an inflammatory œdema, probably resulting, in some instances at least, from an inflammation of the lymphatics or an embolism of the cutaneous vessels.

What diseases may erythema nodosum resemble?

Bruises, abscesses, and gummata.

How are the lesions of erythema nodosum to be distinguished from these several conditions?

By the bright red or rosy tint, the apparently violent character of the process, the number, situation and course of the lesions.

State the prognosis of erythema nodosum.

Favorable, recovery usually taking place in ten days to several weeks.

State the treatment to be advised in erythema nodosum.

Rest, relative or absolute, depending upon the severity of the case, and an unstimulating diet; internally intestinal antiseptics, quinin and saline laxatives, and locally applications of lead-water and laudanum.

(Synonym: Erythema induratum scrofulosorum.)

What do you understand by erythema induratum?

A rare disease characterized in the beginning by one or more usually deep-seated nodules, and, as a rule, seated in the legs, [Pg 52] especially the calf region. The nodules gradually enlarge, the skin becomes reddish, violaceous or livid in color. Absorption may take place slowly, or the indurations may break down, resulting in an indolent, rather deep-seated ulcer, closely resembling a gummatous ulcer. The disease is slow and persistent, and is commonly met with in girls and young women, usually of strumous type. It suggests a tuberculous origin.

Treatment consists in administration of cod-liver oil, phosphorus and other tonics. Rest is of service. Locally antiseptic applications, and support with roller bandage are to be advised.

(Synonyms: Hives; Nettlerash.)

Give a definition of urticaria.

Urticaria is an inflammatory affection characterized by evanescent whitish, pinkish or reddish elevations, or wheals, variable as to size and shape, and attended by itching, stinging or pricking sensations.

Describe the symptoms of urticaria.

The eruption, erythematous in character and consisting of isolated pea or bean-sized elevations or of linear streaks or irregular patches, limited or more or less general, and usually intensely itchy, makes its appearance suddenly, with or without symptoms of preceding gastric derangement. The lesions are soft or firm, reddish or pinkish-white, with the peripheral portion of a bright red color, and are fugacious in character, disappearing and reappearing in the most capricious manner. In many cases simply drawing the finger over the skin will bring out irregular and linear wheals. In exceptional cases this peculiar property is so pronounced and constant that at any time letters and other symbols may be produced at will, even when such subjects are free from the ordinary urticarial lesions (urticaria factitia, dermatographism, autographism).

The mucous membrane of the mouth and throat may also be the seat of wheals and urticarial swellings.

What is the ordinary course of urticaria?

Acute. The disease is usually at an end in several hours or days. [Pg 53]

Does urticaria always pursue an acute course?

No. In exceptional instances the disease is chronic, in the sense that new lesions continue to appear and disappear irregularly from time to time for months or several years, the skin rarely being entirely free (chronic urticaria).

Fig. 12.

Dermatographism. (After C.N. Davis.)

Are subjective symptoms always present in urticaria?

Yes. Itching is commonly a conspicuous symptom, although at times pricking, stinging or a feeling of burning constitutes the chief sensation.

In what way may the eruption be atypical?

Exceptionally the wheals, or lesions, are peculiar as to formation, or another condition or disease may be associated, hence the varieties known as urticaria papulosa, urticaria hæmorrhagica, urticaria tuberosa, and urticaria bullosa.

Describe urticaria papulosa.

Urticaria papulosa (formerly called lichen urticatus) is a variety in [Pg 54] which the lesions are small and papular, developing usually out of the ordinary wheals. They appear as a rule suddenly, rarely in great numbers, are scattered, and after a few hours or, more commonly, days gradually disappear. The itching is intense, and in consequence their apices are excoriated. Sometimes the papules are capped with a small vesicle (vesicular urticaria). It is seen more particularly in ill-cared for and badly-nourished young children.

Describe urticaria hæmorrhagica.

Urticaria hæmorrhagica is characterized by lesions similar to ordinary wheals, except that they are somewhat hemorrhagic, partaking, in fact, of the nature of both urticaria and purpura.

Describe urticaria tuberosa.

In urticaria tuberosa the lesions, instead of being pea- or bean-sized, as in typical urticaria, are large and node-like (also called giant urticaria).

What is acute-circumscribed œdema?

In rare instances there occurs, along with the ordinary lesions of the disease or as its sole manifestation, sudden and evanescent swelling of the eyelids, ears, lips, tongue, hands, fingers, or feet (urticaria œdematosa, acute circumscribed œdema, angioneurotic œdema). One or several of these parts only may be affected at the one attack; in recurrences, so usual in this variety, the same or other parts may exhibit the manifestation.

(These œdematous swellings occurring alone might be looked upon, as they are by most observers, as an independent affection, but its close relationship to ordinary urticaria is often evident.)

Describe urticaria bullosa.

Urticaria bullosa is a variety in which the inflammatory action has been sufficiently great to give rise to fluid exudation, the wheals resulting in the formation of blebs.

What is the etiology of urticaria?

Any irritation from disease, functional or organic, of any internal organ, may give rise to the eruption in those predisposed. Gastric derangement from indigestible or peculiar articles of food, intestinal toxins, and the ingestion of certain drugs are often provocative. The so-called “shell-fish” group of foods play an important etiological part in some cases. Idiosyncrasy to certain articles of food is [Pg 55] also responsible in occasional instances. Various rheumatic and nervous disorders are not infrequently associated with it, and are doubtless of etiological significance. External irritants, also, in predisposed subjects, are at times responsible.

What is the pathology of urticaria?

Anatomically a wheal is seen to be a more or less firm elevation consisting of a circumscribed or somewhat diffused collection of semi-fluid material in the upper layers of the skin. The vasomotor nervous system is probably the main factor in its production; dilatation following spasm of the vessels results in effusion, and in consequence, the overfilled vessels of the central portion are emptied by pressure of the exudation and the central paleness results, while the pressed-back blood gives rise to the bright red periphery.

From what diseases is urticaria to be differentiated?

From erythema simplex, erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, and erysipelas.

Mention the diagnostic points of urticaria.

The acuteness, character of the lesions, their evanescent nature, the irregular or general distribution, and the intense itching.

What is the prognosis in urticaria?

The acute disease is usually of short duration, disappearing spontaneously or as the result of treatment, in several hours or days; it may recur upon exposure to the exciting cause. The prognosis of chronic urticaria is to be guarded, and will depend upon the ability to discover and remove or modify the predisposing condition.

What systemic measures are to be prescribed in acute urticaria?

Removal of the etiological factor is of first importance. This will be found in most cases to be gastric disturbance from the ingestion of improper or indigestible food, and in such cases a saline purgative is to be given, probably the best for this purpose being the laxative antacid, magnesia; or if the case is severe and food is still in the stomach, an emetic, such as mustard or ipecac, will act more promptly. Alkalies, especially sodium salicylate, and intestinal antiseptics are useful. Calcium chloride in doses of five to twenty [Pg 56] grains should be tried in obstinate cases. The diet should be, for the time, of a simple character.

What systemic measures are to be prescribed in chronic and recurrent urticaria?

The cause must be sought for and treatment directed toward its removal or modification. Treatment will, therefore, depend upon indications. In obscure cases, quinine, sodium salicylate, arsenic, pilocarpine, atropia, potassium bromide, calcium chloride, and ichthyol are to be variously tried; general galvanization is at times useful, as is also a change of scene and climate. A proper dietary and the maintenance of free action of the bowels, preferably, as a rule, with a saline laxative, is of great importance in these chronic cases.

In acute circumscribed œdema treatment is essentially that of urticaria, the diet being given special attention.

What external applications would you advise for the relief of the subjective symptoms?

Cooling lotions of alcohol and water or vinegar and water; lotions of carbolic acid, one to three drachms to the pint; of thymol, one-fourth to one drachm to the pint of alcohol and water; of liquor carbonis detergens, one to three ounces to the pint of water, or the following:—

℞ Acidi carbolici, ................................. ʒj-ʒiij

Acidi borici, .................................... ʒiv

Glycerinæ, ...................................... fʒj

Alcoholis, ...................................... f℥ij

Aquæ, ........................................... f℥xiv. M.

Alkaline baths are also useful, and may advantageously be followed by dusting-powders of starch and zinc oxide.

(Synonym: Xanthelasmoidea.)

Describe urticaria pigmentosa.

Urticaria pigmentosa is a rare disease, variously viewed as an unusual form of urticaria and as an urticaria-like eruption in which [Pg 57] there is an element of new growth in the lesions. It begins usually in infancy or early childhood and continues for months or years, and is characterized by slightly, moderately, or intensely itchy, wheal-like elevations, which are more or less persistent and leave yellowish, orange-colored, greenish or brownish stains. Exceptionally subjective symptoms are almost entirely absent. Anatomical studies show that the lesion has in some respects the structure of an ordinary wheal, with œdema and pigment deposit in the epidermal portion, and cellular infiltration made up principally of mast-cells.

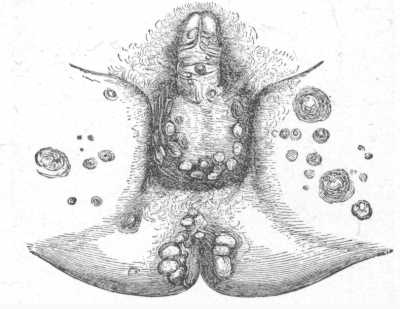

Fig. 13.

Urticaria Pigmentosa.

The nature of the disease is obscure and treatment unsatisfactory. Ordinarily as early youth or adult life is reached it spontaneously disappears. The treatment advised is usually on the same lines as that of chronic urticaria. [Pg 58]

What is implied by the term dermatitis?

Dermatitis, or inflammation of the skin, is a term employed to designate those cases of cutaneous disturbance, usually acute in character, which are due to the action of irritants.

Mention some examples of cutaneous disturbance to which this term is applied.

The dermatic inflammation due to the action of excessive heat or cold, to caustics and other chemical irritants, and to the ingestion of certain drugs.

What several varieties are commonly described?

Dermatitis traumatica, dermatitis calorica, dermatitis venenata, and dermatitis medicamentosa.

Describe dermatitis traumatica.

Under this head are included all forms of cutaneous inflammation due to traumatism. To the dermatologist the most common met with is that produced by the various animal parasites and from continued scratching; in such, if the cause has been long-continued and persistent, a variable degree of inflammatory thickening of the skin and pigmentation result, the latter not infrequently being more or less permanent. The inflammation due to tight-fitting garments, bandages, to constant pressure (as bed-sores), etc., also illustrates this class.

What is the treatment of dermatitis traumatica?

Removal of the cause, and, if necessary, the application of soothing ointments or lotions; in bed-sores, soap plaster, plain or with one to five per cent. of ichthyol.

What is dermatitis calorica?

Cutaneous inflammation, varying from a slight erythematous to a gangrenous character, produced by excessive heat (dermatitis ambustionis, burns) or cold (dermatitis congelationis, frostbite).

Give the treatment of dermatitis calorica.

In burns, if of a mild degree, the application of sodium bicarbonate, as a powder or saturated solution, is useful; in the more severe [Pg 59] grade, a two- to five-per-cent. solution will probably be found of greater advantage. Other soothing applications may also be employed. In recent years a one-per-cent. solution of picric acid has been commended for the slighter burns of limited extent. Upon the whole, there is nothing yet so generally useful and soothing in these cases as the so-called Carron oil; in some cases more valuable with 1/2 to 1 minim of carbolic acid added to each ounce.

In frostbite, seen immediately after exposure, the parts are to be brought gradually back to a normal temperature, at first by rubbing with snow or applying cold water. Subsequently, in ordinary chilblains, stimulating applications, such as oil of turpentine, balsam of Peru, tincture of iodine, ichthyol, and strongly carbolized ointments are of most benefit. If the frostbite is of a vesicular, pustular, bullous, or escharotic character, the treatment consists in the application of soothing remedies, such as are employed in other like inflammatory conditions.

What do you understand by dermatitis venenata?

All inflammatory conditions of the skin due to contact with deleterious substances such as caustic, chemical irritants, iodoform, etc., are included under this head, but the most common causes are the rhus plants—poison ivy (or poison oak) and poison sumach (poison dogwood). Mere proximity to these plants will, in some individuals, provoke cutaneous disturbance (rhus poisoning, ivy poisoning), although they may be handled by others with impunity.

Many other plants are also known to produce cutaneous irritation in certain subjects; among these may be mentioned the nettle, primrose, cowhage, smartweed, balm of Gilead, oleander, and rue.

The local action of iodoform (iodoform dermatitis) in some individuals is that of a decided irritant, bringing about a dermatitis, which often spreads much beyond the parts of application, and which in those eczematously inclined may result in a veritable and persistent eczema.

Describe the symptoms of rhus poisoning.

The symptoms appear usually soon after exposure, and consist of an inflammatory condition of the skin of an eczematous nature, [Pg 60] varying in degree from an erythematous to a bullous character, and with or without œdema and swelling. As a rule, marked itching and burning are present. The face, hands, forearms and genitalia are favorite parts, although it may in many instances involve a greater portion of the whole surface.

What is the course of rhus poisoning?

It runs an acute course, terminating in recovery in one to six weeks. In those eczematously inclined, however, it may result in a veritable and persistent form of that disease.

How would you treat rhus poisoning?

By soothing and astringent applications, such as are employed in acute eczema (q. v.), which are to be used freely. Among the most valuable are: a lotion of fluid extract of grindelia robusta, one to two drachms to four ounces of water; lotio nigra, either alone or followed by the oxide-of-zinc ointment; a saturated solution of boric acid, with a half to two drachms of carbolic acid to the pint; a lotion of zinc sulphate, a half to four grains to the ounce; weak alkaline lotions; cold cream, petrolatum, and oxide-of-zinc ointments.

How would you treat the dermatitis due to other deleterious substances of this class?

By applications of a soothing and protective character, similar to those used in eczema and burns.

What do you understand by dermatitis medicamentosa?

Under this head are included all eruptions due to the ingestion or absorption of certain drugs.

In rare instances one dose will have such effect; commonly, however, it results only after several days' or weeks' continued administration. With some drugs such effect is the rule, with others it is exceptional, nor are all individuals equally susceptible.

How is the eruption produced in dermatitis medicamentosa?

In some instances it is probably due to the elimination of the drug through the cutaneous structures; in others, to the action of the drug upon the nervous system. The view that the drug acts as a toxin or generates some toxin or irritant material in the blood, to which the eruptive phenomena may be due, has also been advanced.

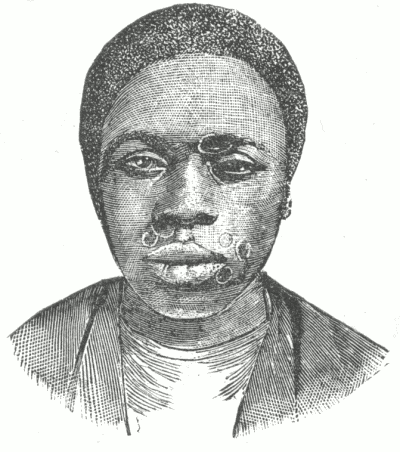

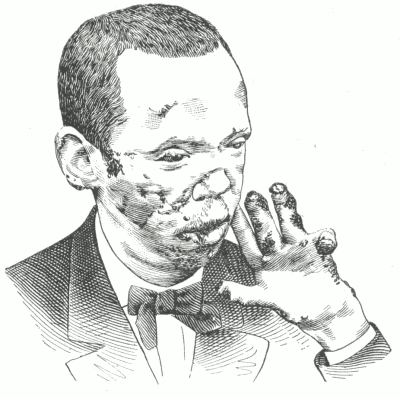

Dermatitis medicamentosa. Bullous dermatitis from iodide of potassium.

What is the character of the eruption in dermatitis medicamentosa?

It may be erythematous, papular, urticarial, vesicular, pustular or bullous, and, if the administration of the drug is continued, even gangrenous.

Name the more common drugs having such action.

Antipyrin, arsenic, atropia (or belladonna), bromides, chloral, copaiba, cubebs, digitalis, iodides, mercury, opium (or morphia), quinine, salicylic acid, stramonium, acetanilid, sulphonal, phenacetin, turpentine, many of the new coal-tar derivatives, etc.

State frequency and types of eruption due to the ingestion of antipyrin.

Not uncommon. Erythematous, morbilliform and erythemato-papular; itching is usually present and moderate desquamation may follow. Acetanilid, sulphonal, phenacetin, and other drugs of this class may provoke like eruptions.

Mention frequency and types of eruption due to the ingestion of arsenic.

Rare. Erythematous, erythemato-papular; exceptionally, herpetic, and pigmentary. Herpes zoster has been thought to follow its use. Keratosis of the palms and soles has also been occasionally observed, which, in rare instances, has developed into epithelioma.

Mention frequency and types of eruption due to the ingestion of atropia (or belladonna).

Not uncommon. Erythematous and scarlatinoid; usually no febrile disturbance, and desquamation seldom follows.

Give frequency and types of cutaneous disturbance following the administration of the bromides (bromine).