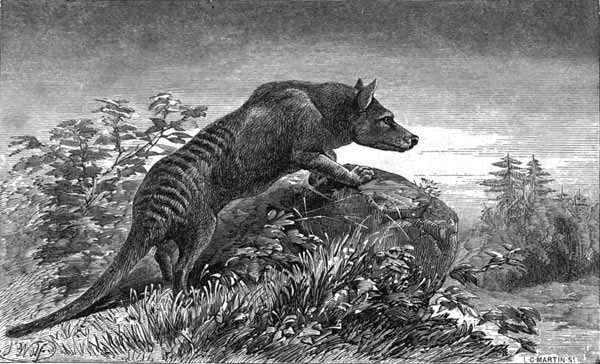

The Tasmanian Wolf. Thylacinus Cynocephalus.

The Tasmanian Wolf. Thylacinus Cynocephalus.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Heads and Tales, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Heads and Tales

or, Anecdotes and Stories of Quadrupeds and Other Beasts,

Chiefly Connected with Incidents in the Histories of More

or Less Distinguished Men.

Author: Various

Editor: Adam White

Release Date: June 28, 2008 [EBook #25918]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HEADS AND TALES ***

Produced by Julia Miller, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND COMPANY

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

Second Edition.

LONDON:

JAMES NISBET & CO., 21 BERNERS STREET.

MDCCCLXX.

The Tasmanian Wolf. Thylacinus Cynocephalus.

The Tasmanian Wolf. Thylacinus Cynocephalus.

In this work, a part of which is, so far as it extends, a careful compilation from an extensive series of books, the great order mammalia, or, rather, a few of its subjects, is treated anecdotically. The connexion of certain animals with man, and the readiness with which man can subdue even the largest of the mammalia, are very curious subjects of thought. The dog and horse are our special friends and associates; they seem to understand us, and we get very much attached to them. The cat or the cow, again, possess a different degree of attachment, and have "heads and hearts" less susceptible of this education than the first mentioned. The anecdotes in this book will clearly show facts of this nature. In the Letter of the Gorilla, under an appearance of exaggeration, will be found many facts of its history. We have a strong belief that natural history, written as White of Selborne did his Letter of Timothy the Tortoise, would be very enticing and interesting to young people. To make birds and other animals relate their stories has been done sometimes, and generally with success. There are anecdotes hinging, however, on animals which have more to do with man than the other mammals referred to in the little story. These stories we have felt to be very interesting when they occur in biographies of great men. Cowper and his Hares, Huygens and his Sparrow, are tales—at least the [Pg vi]former—full of interesting matter on the history of the lower animal, but are of most value as showing the influence on the man who amused himself by taming them. We like to know that the great Duke, after getting down from his horse Copenhagen, which carried him through the whole battle of Waterloo, clapped him on the neck, when the war-charger kicked out, as if untired.

We could have added greatly to this book, especially in the part of jests, puns, or cases of double entendre. The few selected may suffice. The so-called conversations of "the Ettrick Shepherd" are full of matter of this kind, treated by "Christopher North" with a happy combination of rare power of description and apt exaggeration of detail, often highly amusing. One or two instances are given here, such as the Fox-hunt and the Whale. The intention of this book is primarily to be amusing; but it will be strange if it do not instruct as well. There is much in it that is true of the habits of mammalia. These, with birds, are likely to interest young people generally, more than anecdotes of members of orders like fish, insects, or molluscs, lower in the scale, though often possessing marvellous instincts, the accounts of which form intensely interesting reading to those who are fond of seeing or hearing [Pg vii]of "the works of the Lord," and who "take pleasure" in them.

| MAMMALIA.[1] | |

|---|---|

| Man | 1 |

| Gainsborough's Joke—Skull of Julius Cęsar when a boy | 2 |

| Sir David Wilkie's simplicity about Babies | 3 |

| James Montgomery translates into verse a description of Man, after the manner of Linnęus | 4 |

| Addison and Sir Richard Steele's Description of Gimcrack the Collector | 5 |

| Monkeys | 9 |

| The Gorilla and its Story | 9 |

| The Orang-Utan | 11 |

| The Chimpanzee | 12 |

| Letter of Mr Waterton | 20 |

| Mr Mitchell and the Young Chimpanzee | 22 |

| Lady Anne Barnard pleads for the Baboons | 24 |

| S. Bisset and his Trained Monkeys | 25 |

| Lord Byron's Pets | 26 |

| The Ettrick Shepherd's Monkey | 27 |

| The Findhorn Fisherman and the Monkey | 29 |

| "We ha'e seen the Enemy!" | 29 |

| The French Marquis and his Monkey | 30 |

| George IV. and Happy Jerry.—Mr Cross's Rib-nosed Baboon at Exeter Change | 31 |

| The Young Lady's pet Monkey and the poor Parrot | 33 |

| Monkeys "poor relations" | 34 |

| Sydney Smith on Monkeys | 34 |

| Mrs Colin Mackenzie on the Apes at Simla | 35 |

| The Aye-Aye, or Cheiromys of Madagascar | 36 |

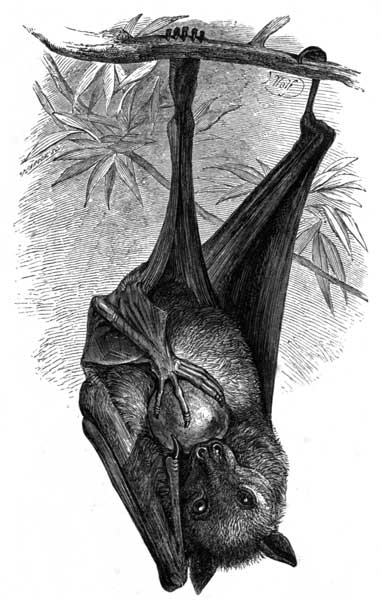

| Bats | 38 |

| One of Captain Cook's Sailors sees a Fox-Bat, and describes it as a devil | 39 |

| Fox Bats (with a Plate) | 41 |

| Dr Mayerne and his Balsam of Bats | 47 |

| Hedgehog | 48 |

| Robert Southey to his Critics | 48 |

| Mole | 49 |

| Mole, cause of Death of William III. | 49 |

| Brown Bear | 56 |

| The Austrian General and the Bear—"Back, rascal, I am a general!" | 58 |

| Lord Byron's Bear at Cambridge | 59 |

| Charles Dickens on Bear's Grease and Bear-keepers | 59 |

| A Bearable Pun | 60 |

| A Shaved Bear | 61 |

| Polar Bear | 61 |

| General History and Anecdotes of Polar Bear, as observed on recent Arctic Expeditions (with a Plate) | 61 |

| Nelson and the Polar Bear | 67 |

| A Clever Polar Bear | 67 |

| Captain Ommaney and the Polar Bear | 70 |

| Raccoon | 71 |

| "A Gone Coon" | 71 |

| Badger | 71 |

| Hugh Miller sees the "Drawing of the Badger" | 72 |

| The Laird of Balnamoon and the Brock | 75 |

| Ferret | 75 |

| Collins and the Rat-catcher, with the Ferret | 76 |

| Pole-Cat | 76 |

| Fox and the Poll-Cat | 77 |

| Dog | 77 |

| Phrases about Dogs | 77 |

| Cowper's Dog | 79 |

| Cowper and his dog Beau | 81 |

| Burns's "Twa Dogs" | 81 |

| Dog of Assyrian Monument | 86 |

| Bishop Blomfield bitten by a Dog | 88 |

| Sydney Smith's Remark on it | 88 |

| Bishop of Bristol—"Puppies never see till they are nine days old" | 88 |

| Mrs Browning, the Poetess, and her dog Flush | 89 |

| Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, Bart., and his dog Speaker | 93 |

| Lord Byron and his dog Boatswain | 94 |

| Lady's reason for calling her dog Perchance | 96 |

| Collins the Artist and his dog Prinny—the faithful Model | 96 |

| Soldier and Dog | 97 |

| Bark and Bite!—Curran on Lord Clare and his Dog | 98 |

| Mrs Drew and the two Dogs | 98 |

| Gainsborough and his Wife and their Dogs | 100 |

| Sir William Gell's Dog, which was said to speak | 101 |

| The Duke of Gordon's Wolf-hounds | 102 |

| Frederick the Great and his Italian Greyhounds | 104 |

| The Dog and the French Murderers | 104 |

| Hannah More on Garrick's Dog | 105 |

| Rev. Robert Hall and the Dog | 106 |

| A Queen (Henrietta Maria) and her Lap-Dog | 106 |

| The Clever Dog that belonged to the Hunters of Polmood | 107 |

| The Irish Clergyman and the Dogs | 108 |

| Washington Irving and the Dog | 108 |

| Douglas Jerrold and his Dog | 109 |

| Sheridan and the Dog | 109 |

| Charles Lamb and his dog "Dash" | 110 |

| French Dogs of Louis XII. | 110 |

| Martin Luther observes a Dog at Lintz | 111 |

| Poor Dog at the Grotta del Cane | 111 |

| Dog a Postman and Carrier | 113 |

| South and Sherlock—Dog-matic | 113 |

| General Moreau and his Greyhound | 113 |

| Duke of Norfolk and his Spaniels | 114 |

| Lord North and the Dog | 115 |

| Perthes derives Hints from his Dog | 115 |

| Peter the Great and his dog Lisette | 116 |

| The Light Company's Poodle and Sir F. Ponsonby | 118 |

| Admiral Rodney and his dog Loup | 119 |

| Ruddiman and his dog Rascal | 119 |

| Mrs Schimmelpenninck and the Dogs | 120 |

| Sir Walter Scott and his Dogs | 122 |

| Sheridan on the Dog-Tax | 123 |

| Sydney Smith dislikes Dogs.—An ingenious way of getting rid of them | 124 |

| Sydney Smith on Dogs | 125 |

| Sydney Smith.—"Newfoundland Dog that breakfasted on Parish Boys" | 126 |

| Robert Southey on his Dogs | 126 |

| A Dog that was a good judge of Elocution.—Mr True and his Pupil | 127 |

| Dog that tried to please a Crying Child | 128 |

| Horace Walpole's pet dog Rosette | 128 |

| Horace Walpole.—Arrival of his dog Tonton | 129 |

| Horace Walpole.—Death of his dog Tonton | 130 |

| Archbishop Whateley and his Dogs | 131 |

| Archbishop Whately on Dogs | 132 |

| Sir David Wilkie.—A Dog Rose | 133 |

| Ulysses and his Dog | 133 |

| Wolf | 135 |

| Polson and the Last Wolf in Sutherlandshire | 135 |

| "If the tail break, you'll find that" | 137 |

| Fox | 138 |

| An Enthusiastic Fox-hunting Surgeon | 138 |

| Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, on the Pleasures of Fox-hunting, and the gratification of the Fox | 139 |

| Arctic Foxes converted into Postmen, with Anecdotes (with a plate) | 142 |

| Jackal | 148 |

| Burke on the Jackal and Tiger | 149 |

| Cat | 149 |

| Jeremy Bentham and his pet cat "Sir John Langborn | 150 |

| S. Bisset and his Musical Cats | 152 |

| Constant, Chateaubriand, and their Cats | 153 |

| Liston, the Surgeon, and his Cat | 153 |

| The Banker Mitchell's Antipathy to Kittens | 154 |

| James Montgomery and his Cats | 155 |

| David Ritchie's Cat | 157 |

| Sir Walter Scott's Visit to the Black Dwarf | 157 |

| Southey, the Poet, and his Cats | 158 |

| Archbishop Whateley and the Cat that used to ring the Bell | 160 |

| Tiger and Lion | 161 |

| Bussapa, the Tiger-slayer, and the Tiger | 162 |

| John Hunter and the Dead Tiger | 164 |

| Mrs Mackenzie on the Indian's regard and awe for the Tiger | 165 |

| Jolly Jack-tar on Lion and Tiger | 166 |

| Androcles and the Lion | 167 |

| Sir George Davis and the Lion | 170 |

| Canova's Lions and the Child | 171 |

| Admiral Napier and the Lion in the Tower | 173 |

| Old Lady and the Beasts on the Mound | 173 |

| Seals | 174 |

| Dr Adam Clarke on Shetland Seals | 175 |

| Dr Edmonstone and the Shetland Seals | 176 |

| The Walrus or Morse (with a Plate) | 182 |

| Kangaroo | 188 |

| Charles Lamb on its Peculiarities | 188 |

| Captain Cooke's Sailor and the first Kangaroo seen | 189 |

| Charles Lamb on Kangaroos having Purses in front | 189 |

| Kangaroo Cooke | 189 |

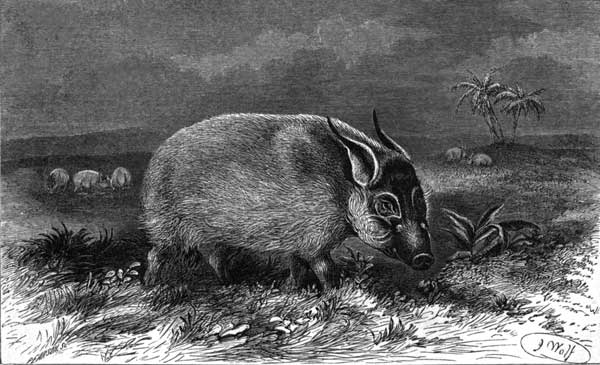

| Tiger Wolf | 190 |

| Squirrel, &c. | 194 |

| Jekyll on a Squirrel | 195 |

| Pets of some of the Parisian Revolutionary Butchers | 195 |

| Sir George Back and the poor Lemming | 196 |

| McDougall and Arctic Lemming | 197 |

| Rats and Mice | 198 |

| Duke of Wellington and Musk-Rat | 200 |

| Lady Eglinton and the Rats | 200 |

| General Douglas and the Rats | 201 |

| Hanover Rats | 202 |

| Irishman Shooting Rats | 203 |

| James Watt and the Rat's Whiskers | 204 |

| Gray the Poet compares Poet-Laureate to Rat-catcher | 204 |

| Jeremy Bentham and the Mice | 205 |

| Robert Burns and the Field Mouse | 206 |

| Fuller on Destructive Field Mice | 208 |

| Baron Von Trenck and the Mouse in Prison | 209 |

| Alexander Wilson, the American Ornithologist, and the Mouse | 211 |

| Hares, Rabbits, Guinea-Pig | 212 |

| William Cowper on his Hares | 213 |

| Lord Norbury on the Exaggeration of a Hare-Shooter | 220 |

| Duke of L. prefers Friends to Hares | 221 |

| S. Bisset and his Trained Hare and Turtle | 221 |

| Lady Anne Barnard on a Family of Rabbits all blind of one eye | 222 |

| Thomas Fuller on Norfolk Rabbits | 222 |

| Dr Chalmers and the Guinea-Pig | 223 |

| Sloth | 224 |

| Sydney Smith on the Sloth—a Comparison | 224 |

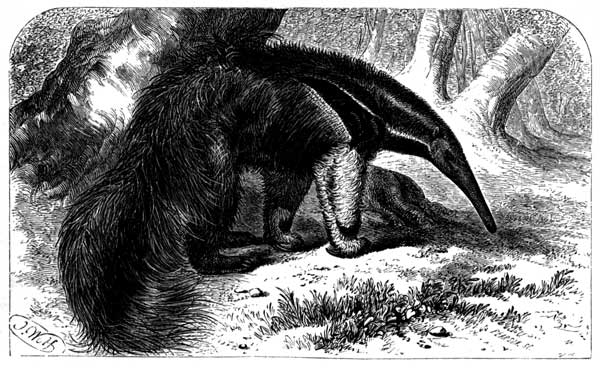

| The Great Ant-Eater (with a Plate) | 225 |

| Elephant | 229 |

| Lord Clive—Elephant or Equivalent? | 230 |

| Canning on the Elephant and his Trunk | 232 |

| Sir R. Phillips and Jelly made of Ivory Dust | 233 |

| J. T. Smith and the Elephant | 234 |

| Sydney Smith on the Elephant and Tailor | 235 |

| Elephant's Skin—a teacher put down | 236 |

| Fossil Pachydermata | 236 |

| Cuvier's Enthusiasm over Fossils | 236 |

| Sow | 238 |

| "There's a hantle o' miscellaneous eatin' aboot a Pig" | 238 |

| "Pig-Sticking at Chicago" | 238 |

| Monument to a Pig at Luneberg | 239 |

| Wild Boar (with a Plate) | 239 |

| The River Pig (with a Plate) | 245 |

| S. Bisset and his Learned Pig | 250 |

| Quixote Bowles fond of Pigs | 251 |

| On Jekyll's treading on a small Pig | 251 |

| Good enough for a Pig | 251 |

| Gainsborough's Pigs | 252 |

| Theodore Hook and the Litter of Pigs | 253 |

| Lady Hardwicke's Pig—her Bailiff | 253 |

| Pigs and Silver Spoon | 253 |

| Sydney Smith on Beautiful Pigs | 254 |

| Joseph Sturge, when a boy, and the Pigs | 255 |

| Rhinoceros | 229 |

| The Lord Keeper Guildford and the Rhinoceros in the | |

| City of London | 230 |

| Horse | 256 |

| Horse shot under Albert | 256 |

| Bell-Rock Lighthouse Horse | 257 |

| Edmund Burke and the Horse | 257 |

| David Garrick and his Horse, "A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!" | 258 |

| Bernard Gilpin's Horses stolen and recovered | 260 |

| The Herald and George III.'s Horse | 261 |

| Rev. Rowland Hill and his Horse | 261 |

| Holcroft on the Horse | 263 |

| Lord Mansfield, his Joke about a Horse | 267 |

| Sir John Moore and his Horse at Corunna | 268 |

| Neither Horses nor Children can explain their Complaints | 269 |

| Horses with Names | 270 |

| Rennie the Engineer and the Horse Old Jack | 270 |

| Sydney Smith and his Horses | 271 |

| Sydney Smith.—He drugs his Domestic Animals | 273 |

| Horseback, an Absent Clergyman | 273 |

| Judge Story and the Names he gave his Horses | 274 |

| Short-tailed and Long-tailed Horses at Livery, difference of Charge | 275 |

| Ass and Zebra | 276 |

| Coleridge on the Ass | 276 |

| Collins and the old Donkey at Odell | 276 |

| Gainsborough kept one to Study from | 277 |

| Irishman on the Ramsgate Donkeys | 278 |

| Douglas Jerrold and the Ass's Foal | 278 |

| The Judge and the Barrister | 279 |

| Ass that loved Poetry | 279 |

| Warren Hastings and the refractory Donkey | 279 |

| Northcote, an Angel at an Ass | 281 |

| Sydney Smith's Donkey with Jeffrey on his back | 281 |

| Sydney Smith on the Sagacity of the Ass | 283 |

| Sydney Smith's Deers, how he introduced them into his Grounds to gratify Visitors | 284 |

| Asses' Duty Free | 284 |

| Thackeray on Egyptian Donkey | 285 |

| Zebra, a Frenchman's double-entendre | 287 |

| Camels | 287 |

| Captain William Peel, R.N., on Camel | 287 |

| Captain in Royal Navy measures the progress of the Ship of the Desert | 289 |

| Lord Metcalfe on a Camel when a Boy | 290 |

| Red Deer | 291 |

| Earl of Dalhousie and the ferocious Stag | 291 |

| The French Count and the Stag | 293 |

| Fallow Deer | 294 |

| Venison Fat, Reynolds and the Gourmand | 294 |

| Goethe on Stag-trench at Frankfort-on-Maine | 294 |

| Giraffe | 295 |

| "Fancy Two Yards of Sore Throat!" | 295 |

| Sheep and Goat | 295 |

| How many Legs has a Sheep? | 296 |

| Goethe on Roos's Etchings of Sheep | 296 |

| Lord Cockburn and the Sheep | 298 |

| Erskine's Sheep—an Eye to the Woolsack | 298 |

| Sandy Wood and his Pet Sheep and Raven | 298 |

| General Carnac and She-goat | 299 |

| John Hunter and the Shawl-goat | 300 |

| Commodore Keppel beards the Dey of Algiers | 303 |

| Ox | 304 |

| Irish Bulls | 304 |

| A great Calf! "The more he sucked the greater Calf he grew!" | 304 |

| Veal ad nauseam! too much of a good thing | 304 |

| James Boswell should confine himself to the Cow | 305 |

| Rev. Adam Clarke and his Bullock Pat | 305 |

| Samuel Foote and the Cows pulling the Bell of Worcester College | 306 |

| The General's Cow at Plymouth | 308 |

| Gilpin's Love of the Picturesque carried out—a reason for keeping three Cows | 308 |

| King James on a Cow getting over the Border | 309 |

| Duke of Montague and his Hospital for Old Cows and Horses | 309 |

| Philip IV. of Spain in the Bull-ring | 310 |

| Sydney Smith and his "Universal Scratcher" | 311 |

| Rev. Augustus Toplady on the Future State of Animals—the Rev. William Bull | 312 |

| Windham on the Feelings of a Baited Bull | 313 |

| Whale | 315 |

| A Porpoise not at Home | 315 |

| Whalebone | 315 |

| "What's to become o' the puir Whales?" | 316 |

| Very like a Whale! | 316 |

| Christopher North on the Whale | 316 |

In this collection, like Linnæus, we begin with man as undoubtedly an animal, as opposed to a vegetable or mineral. Like Professor Owen, we are inclined to fancy he is well entitled to separate rank from even the Linnæan order, Primates, and to have more systematic honour conferred on him than what Cuvier allowed him. That great French naturalist placed man in a section separate from his four-handed order, Quadrumana, and, from his two hands and some other qualities, enrolled our race in an order, Bimana. Surely the ancients surpassed many modern naturalists of the Lamarckian school, who would derive him from an ourang, a chimpanzee, or a gorilla. One of them has nobly said—

"Os homini sublime dedit, cœlumque tueri."

Our own Sir William Hamilton, in a few powerful words has condensed what will ever be, we are thankful to suppose, the general idea of most men, be they naturalists or not, that mind and soul have much to distinguish us from every other animal:—

"What man holds of matter does not make up his per[Pg 2]sonality. Man is not an organism. He is an intelligence served by organs. They are his, not he."

As a mere specimen, we subjoin two or three anecdotes, although the species, Homo sapiens, has supplied, and might supply, many volumes of anecdotes touching on his whims and peculiarities. As a good example of the Scottish variety, who is there that does not know Dean Ramsay's "Reminiscences?" Surely each nation requires a similar judicious selection. Mr Punch, especially when aided by his late admirable artist, John Leech, shows seemingly that John Bull and his family are as distinct from the French, as the French are from the Yankees.

Gainsborough, the painter, was very ready-witted. His biographer[2] records the following anecdote of him as very likely to be authentic. The great artist occasionally made sketches from an honest old tailor, of the name of Fowler, who had a picturesque countenance and silver-gray locks. On the chimney-piece of his painting-room, among other curiosities, was a beautiful preparation of an infant cranium, presented to the painter by his old friend, Surgeon Cruickshanks. Fowler, without moving his position, continually peered at it askance with inquisitive eye. "Ah! Master Fowler," said the painter, "that is a mighty curiosity." "What might it be, sir, if I may be so bold?" "A whale's eye," replied Gainsborough. "Oh! not so; never say so,[Pg 3] Muster Gainsborough. Laws! sir, it is a little child's skull!" "You have hit upon it," said the wag. "Why, Fowler, you are a witch! But what will you think when I tell you that it is the skull of Julius Cæsar when he was a little boy?" "Do you say so!" exclaimed Fowler, "what a phenomenon!"

This reminds us of a similar story told of a countryman, who was shown the so-called skull of Oliver Cromwell at the museum in Oxford, and expressed his delight by saying how gratifying it was to see skulls of great men at different ages, for he had just seen at Bath the skull of the Protector when a youth!

A very popular novelist and author of the present day tells the following anecdote of the simplicity of Sir David Wilkie, with regard to his knowledge of infant human nature:—

On the birth of his first son, at the beginning of 1824, William Collins,[3] the great artist, requested Sir David Wilkie to become one of the sponsors for his child.[4] The painter's first criticism on his future godson is worth recording from its simplicity. Sir David, whose studies of human nature extended to everything but infant human nature, had evidently been refreshing his faculties for the occasion, by taxing his boyish recollections of puppies and[Pg 4] kittens; for, after looking intently into the child's eyes as it was held up for his inspection, he exclaimed to the father, with serious astonishment and satisfaction, "He sees!"

One who is partial to the Linnæan mode of characterising objects of natural history has amused himself with drawing up the following definition of man:—"Simia sine cauda; pedibus posticis ambulans; gregarius, omnivorus, inquietus, mendax, furax, rapax, salax, pugnax, artium variarum capax, animalium reliquorum hostis, sui ipsius inimicus acerrimus."

Montgomery translated the description thus:—

"Man is an animal unfledged,

A monkey with his tail abridged;

A thing that walks on spindle legs,

With bones as brittle, sir, as eggs;

His body, flexible and limber,

And headed with a knob of timber;

A being frantic and unquiet,

And very fond of beef and riot;

Rapacious, lustful, rough, and martial,

To lies and lying scoundrels partial!

By nature form'd with splendid parts

To rise in science—shine in arts;

Yet so confounded cross and vicious,

A mortal foe to all his species!

His own best friend, and you must know,

His own worst enemy by being so!"[5]

[Pg 5]

In one of the early volumes of Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, there was a very curious paper entitled "Nat Phin." Although considerably exaggerated, no one who had the happiness of knowing the learned, amiable, and excellent Dr Patrick Neill, could fail to recognise, in the transposed title, an amusing description of his love of natural history pets, zoological and botanical. The fun of the paper is that "Nat" gets married, and, coming home one day from his office, finds that his young wife has caused the gardener to clear out his ponds of tadpoles and zoophytes.

Addison or Sir Richard Steele, or both of them, in the following paper of the Tatler (No. 221, Sept. 7, 1710), has given one of those quietly satiric pictures of many a well-known man of the day, some Petiver or Hans Sloane. The widow Gimcrack's letter is peculiarly racy. Although old books, the Tatler and Spectator still furnish rare material to many a popular magazine writer of the day, who sometimes does little more than dilute a paper in these and other rare repertories of the style and wit of a golden age. We meditated offering various extracts from Swift and Daniel Defoe; but our space limits us to one, and the following may for the present suffice.

"From my own Apartment, September 6.

"As I was this morning going out of my house, a little boy in a black coat delivered me the following letter. Upon asking who he was, he told me that he belonged to[Pg 6] my Lady Gimcrack. I did not at first recollect the name, but, upon inquiry, I found it to be the widow of Sir Nicholas, whose legacy I lately gave some account of to the world. The letter ran thus:—

"'Mr Bickerstaff,—I hope you will not be surprised to receive a letter from the widow Gimcrack. You know, sir, that I have lately lost a very whimsical husband, who, I find, by one of your last week's papers, was not altogether a stranger to you. When I married this gentleman, he had a very handsome estate; but, upon buying a set of microscopes, he was chosen a Fellow of the Royal Society; from which time I do not remember ever to have heard him speak as other people did, or talk in a manner that any of his family could understand him. He used, however, to pass away his time very innocently in conversation with several members of that learned body: for which reason I never advised him against their company for several years, until at last I found his brain quite turned with their discourses. The first symptoms which he discovered of his being a virtuoso, as you call him, poor man! was about fifteen years ago; when he gave me positive orders to turn off an old weeding woman, that had been employed in the family for some years. He told me, at the same time, that there was no such thing in nature as a weed, and that it was his design to let his garden produce what it pleased; so that, you may be sure, it makes a very pleasant show as it now lies. About the same time he took a humour to ramble up and down the country, and would often bring home with him his pockets full of moss and pebbles. This, you may be sure, gave me a heavy heart; though, at the same time, I must needs say, he had the character of a very[Pg 7] honest man, notwithstanding he was reckoned a little weak, until he began to sell his estate, and buy those strange baubles that you have taken notice of. Upon midsummerday last, as he was walking with me in the fields, he saw a very odd-coloured butterfly just before us. I observed that he immediately changed colour, like a man that is surprised with a piece of good luck; and telling me that it was what he had looked for above these twelve years, he threw off his coat, and followed it. I lost sight of them both in less than a quarter of an hour; but my husband continued the chase over hedge and ditch until about sunset; at which time, as I was afterwards told, he caught the butterfly as she rested herself upon a cabbage, near five miles from the place where he first put her up. He was here lifted from the ground by some passengers in a very fainting condition, and brought home to me about midnight. His violent exercise threw him into a fever, which grew upon him by degrees, and at last carried him off. In one of the intervals of his distemper he called to me, and, after having excused himself for running out his estate, he told me that he had always been more industrious to improve his mind than his fortune, and that his family must rather value themselves upon his memory as he was a wise man than a rich one. He then told me that it was a custom among the Romans for a man to give his slaves their liberty when he lay upon his death-bed. I could not imagine what this meant, until, after having a little composed himself, he ordered me to bring him a flea which he had kept for several months in a chain, with a design, as he said, to give it its manumission. This was done accordingly. He then made the will, which I have[Pg 8] since seen printed in your works word for word. Only I must take notice that you have omitted the codicil, in which he left a large concha veneris, as it is there called, to a Member of the Royal Society, who was often with him in his sickness, and assisted him in his will. And now, sir, I come to the chief business of my letter, which is to desire your friendship and assistance in the disposal of those many rarities and curiosities which lie upon my hands. If you know any one that has an occasion for a parcel of dried spiders, I will sell them a pennyworth. I could likewise let any one have a bargain of cockle-shells. I would also desire your advice whether I had best sell my beetles in a lump or by retail. The gentleman above mentioned, who was my husband's friend, would have me make an auction of all his goods, and is now drawing up a catalogue of every particular for that purpose, with the two following words in great letters over the head of them, Auctio Gimcrackiana. But, upon talking with him, I begin to suspect he is as mad as poor Sir Nicholas was. Your advice in all these particulars will be a great piece of charity to, Sir, your most humble servant,

"I shall answer the foregoing letter, and give the widow my best advice, as soon as I can find out chapmen for the wares which she has to put off."

In the British Museum, in handsome glass cases, and on the floors of the three first rooms at the top of the stairs, may be seen the largest collection of the skins and skeletons of quadrupeds ever brought together. In the third, or principal room, will be found a nearly complete series of the Quadrumana or four-handed Mammalia. Monkeys are quadrumanous mammalia. The resemblance of these animals to men is most conspicuous, in the largest of them, such as the gorilla, orang-utan, chimpanzee, and the long-armed or gibbous apes. Such resemblance is most distant in the ferocious dog-faced baboons of Africa, the Cynocephali of the ancients. It is softened off, but not effaced, in the pretty little countenances of those dwarf pets from South America, the ouistities or marmosets, and other species of new-world monkeys, some of which are not larger than a squirrel.

They are well called Monkeys, Monnikies, Mannikies—little men, "Simiæ quasi bestiæ hominibus similes," "monkeys, as if beasts resembling man," or "mon," as the word man is pronounced in pure Doric Saxon, whether in York or Peebles.

"Monkey! you very degraded little brute, how much you resemble us!" said old Ennius, without ever fancying that the day would come when some men would regard their own race as little better than highly-advanced monkeys.[Pg 10]

Let us never for a moment rest in such fallacious theories, or accept the belief of Darwin and Huxley, with a few active agitating disciples, that animals, and even plants, may pass into each other.

"I think we are not wholly brain,

Magnetic mockeries; ...

Not only cunning casts in clay;

Let science prove we are, and then

What matters science unto men,

At least to me! I would not stay:

Let him, the wiser man who springs

Hereafter, up from childhood shape

His action, like the greater ape,

But I was born to other things."

—In Memoriam, cxix.

Darwin and Huxley cannot change nature. They may change their minds and opinions, as their fathers did before them. It is, we suspect, only the old heathen materialism cropping out,—

"Our little systems have their day—

They have their day and cease to be.

They are but broken lights of Thee,

And Thou, O Lord! art more than they."

—In Memoriam.

No artists or authors have ever pictured or described monkeys like Sir Edwin Landseer and his brother Thomas. Surely a new edition of the Monkeyana is wanted for the rising generation. Oliver Goldsmith, that great writer, who was most feeble in knowledge of natural history from almost total ignorance of the subject, over which he threw the graces of his charming style, noticed, as remarkable, that in countries "where the men are barbarous and stupid, the brutes are the most active and sagacious." He[Pg 11] continues, that it is in the torrid tracts, inhabited by barbarians, that animals are found with instinct so nearly approaching reason. Both in Africa and America, accordingly, he tells us, "the savages suppose monkeys to be men; idle, slothful, rational beings, capable of speech and conversation, but obstinately dumb, for fear of being compelled to labour."

For the present, I shall suppose that the gorilla, largest of all the apes, can not only speak, but write; and is speaking and writing to an orang-utan of Borneo. Even a Lamarckian will allow this to be within the range of possibility. Were it possible to get Gay or Cowper to write a new set of fables, animals, in the days of postoffices and letters, would become, like the age, epistolary. But a word on the imaginary correspondent.

The orang, as the reader knows, is the great red-haired "Man of the Woods," as the name may be rendered in English. My old friend, Mr Alfred Wallace, lately in New Guinea, and the adjoining parts, collecting natural history subjects, and making all kinds of valuable observations and surveys, sent to Europe most of the magnificent specimens of this "ugly beast" now in the museum. He has detailed its habits and history in an able account, published some years ago in "The Annals and Magazine of Natural History."

Its home seems to be the fine forests which cover many parts of the coast of Borneo. The home of the gorilla and chimpanzee are in the tropical forests of the coasts of Western Africa.

There would seem to be but three or four well established species of these apes, though there are, as in man[Pg 12] and most created beings, some marked or decided varieties. These apes are altogether quadrupeds, adapted for a life among trees. The late Charles Waterton, of Walton Hall, whom I deem it an honour to have known for many years, personally and in his writings, has well shown this in his "Essays on Natural History." Professor Owen, with his osteologies, and old Tyson, with his anatomies, have each demonstrated that—draw what inferences the followers of Mr Darwin may choose—monkeys are not men, but quadrupeds.

The structure of chimpanzee, orang, and gorilla considerably resembles that of man, but so more distantly does a frog's, so does Scheuchzer's fossil amphibian in the museum, so does a squirrel's, so does a parrot's. Yet, because parrots, squirrels, frogs, and asses have skulls, a pelvis, and fore-arms, they are not men any more than fish are. Linnæus has given the real specific, the real class, order, and generic character of man, unique as a species, as a genus, as an order, or as a class, as even the greatest comparative anatomist of England regards him; "Nosce teipsum:" "Γνωθι σεαυτον"—KNOW THYSELF. Man alone expects a hereafter. He is immortal, and anticipates, hopes for, or dreads a resurrection. Melancholy it is that he alone, as an American writer curiously remarks, collects bodies of men of one blood to fight with each other. He alone can become a drunkard.

The reader must leave rhapsody, and may now be reminded, in explanation of allusions in the following letter, that the arm of Dr Livingstone, the African traveller, was crushed and crunched by the bite and "chaw" of a lion. He will also please to notice, that the skeleton of the[Pg 13] gorilla in the museum has the left arm broken by some dreadful accident. This injury may possibly have been caused by a fall when young, or more probably by the empoisoned bite of a larger gorilla, or of a tree-climbing Leopard. So much may be premised before giving a letter, supposed to be intercepted on its way between the Gaboon and London, and London and Borneo, opened at St Martin's-le-Grand, and detained as unpaid.

"I was born in a large baobab tree, on the west coast of Africa, not very far from Calabar. We gorillas are good time-keepers, rise early and go to bed early, guided infallibly by the sun. But though our family has been in existence at least six thousand years, we have no chronology, and care not a straw about our grandfathers. I suppose I had a grandmother, but I never took any interest in any but very close relationships.

"We never toiled for our daily food, and are not idle like these lazy black fellows who hold their palavers near us, and whom I, for my part, heartily despise. They cannot climb a tree, as we do, although they can talk to each other, and make one another slaves. At least they so treat their countrymen far off where the fine sweet plantains grow, and some other juicy tit-bits, the memory of which makes my mouth water. These fellows have ugly wives, not nearly so big-mouthed as ours, without our noble bony ridge, small ears, and exalted presence. They are actually forced to walk erect, and their fore-legs seldom touch the ground, except in the case of piccanninies. These little creatures crawl on the ground, are much paler when born, and are then perfectly helpless; and have no hair except on their heads, whereas our[Pg 14] beautiful young are fine and hairy, and can swing among the branches, shortly after birth, nearly as well as their parents. When I was very young, I could soon help myself to fruits which abound on our trees.

"Have you dates, plantains, and soursops—so sweet—at Sarawak, Master Redhair? We have, and all kinds of them. I should like, for a variety, to taste yours. Mind you send me some of the durian.[6] Make haste and send it, for Wallace's description makes my mouth water.

"I have told you our little ones soon learn to help themselves, whereas I have seen the piccaninnies of the blacks nursed by their mothers till many rainy seasons had come and gone. I really think nothing of the talking blacks who live near us. They put on bits of coloured rags, not nearly so bright, so regular, nor so contrasting as the feathers of our birds.

"Beautifully coloured are the green touraco and the purple plantain-eater, a rascally bird! who eats some of our finest plantains, and has bitten holes in many a one I thought to get entirely to myself. Why, our parrots beat these West-African negroes to sticks! Even our common gray parrot, so prettily scaled with gray, and with the red feathers under his tail, is more natural than these blacks, with their dirty-white, yellow, blue, green, and red rags.

"Besides, that gray parrot beats them hollow both in its voice and in the way it imitates. Do you know that when I have been giving my quick short bark, to tell that I am not well pleased, I have heard one of these fellows near me actually make me startle—its bark was so like to[Pg 15] that of one of our kind! I cannot bear the blacks! I have had a grudge against them since some little urchins shot at me when I was young, and made my hand bleed. How it bled! My mother, with whom I had been, kept out of the way of these blackguards, but I was playing with another little gorilla, and forgot to keep a look-out. I have kept a good look-out ever since I got that wound, I assure you. I licked it often, and so did my mother with her delicious mouth. It soon left off bleeding and healed. We gorillas have no brandy, no whisky, no wine, not even small beer, to inflame our blood. We sleep, too, among the trees, clear off the ground, where there are dangerous vapours, so that we are free from all miasmata. West Africa is my lovely home, and I am big and beautifully pot-bellied. It is the home of the large-eared chimpanzee, a near relative of ours, though we never marry. He is an active fellow, with rather large vulgar-looking ears; while mine, though I ought not to say so, are beautifully small, and denote my more exalted birth. Master Chimpanzee needs all his ears, for he is not so strong as I, and as you will hear, we anthropoids have enemies in our trees, just as you perhaps have, Master Redhair. We are both cautious of getting on the ground, and when there, I assure you I keep a sharp look-out.

"I have told you of one adventure I had in my youth, and now listen to another which I have not forgotten to this day. My left arm aches now as I think of it.

"As I was one day gambolling with another playfellow in a large tree, with great branches standing out from the trunk, and at a good height from the ground, my companion, another young gorilla, but with smaller mouth,[Pg 16] larger nose, and other features uglier than mine, suddenly shrieked, and looked frightened and angry. No sooner had I noticed him than my whole frame was shaken. I was seized by two paws in the small of my back—a very painful part to be dug into—by ten hooked claws, nearly as long as tenpenny nails, but horribly sharp and hooked.—Oh my arm!

"I tried to turn round, and there was a most ferocious leopard growling at me. I tried to bite, and to scratch his eyes out, but the pain in the small of my back made me quite giddy. The spotted scoundrel seized my left arm—how it aches!—and gave me a crunch or two. I hear, I feel the teeth against my bones as I write. My whole body is full of pain.

"My mother came and released me. She was large, handsome, and well-to-do, with such long and strong arms, and with a magnificent bulging and pouting mouth. In those days of my infancy I used to fancy I should like to try to take as large a bite of a plantain as she could. I tried twice or thrice, but could only squash a tenth of the juice of the fruit into my mouth. She had glorious white teeth. Her grin clearly frightened the leopard, as well as a pinch she gave him in the 'scruff' of the neck with one of her hands, while with the other she caught hold of his tail and made him yell. How he roared! He fell off the branch on to another; but soon, like all the cats, recovered his hold and jumped down to the ground, when he skulked away with his tail behind him.

"I must really leave off, warned both by my paper and your impatience. Well, I grew stronger and bigger every day, and swung by one arm almost as well as the rest did[Pg 17] with their two. I got, in fact, so strong on my hind feet, that my toes were actually in time thicker than those of any of my race. It is well, my dear Orang, to use what you have left you, and to try as soon as possible to forget what has been taken from you.

"... Look at my portrait, I am as strong, and as bony, and as bonnie, as any gorilla. But I begin to boast, so I will leave off."

No doubt that gorilla's injured arm affected its habits and its activity every day of its life. The broken arm, never set by some gorilla surgeon of celebrity, formed a highly important feature in its biography. Reader! when next thou visitest the noble Museum in Bloomsbury, look at the skeleton of that gorilla, whose probable story Arachnophilus hath tried to give thee, and remember that both skin and skeleton were exhibited there before Du Chaillu became "a lion."

The gorilla is a native of West Africa. It is closely allied to the chimpanzee, but grows to a larger size, and has many striking anatomical characters and external marks to distinguish it. It is certainly much dreaded by the natives on the banks of the Gaboon, and, doubtless, dreads them equally. Dr Gray procured a large specimen in a tub from that district. It was skinned and set up by Mr Bartlett. I have seen photographs in the hands of my excellent old friend—that admirable natural history and anatomical draughtsman—Mr George Ford of Hatton Garden. These photographs were taken from its truly ugly face as it was pulled out of the stinking brine. Life in death, or death in life, it was most repulsive.[Pg 18]

Professor Owen read a most elaborate paper on the gorilla before the Zoological Society. The great comparative anatomist and zoologist shows that it may have been the very species whose skins were brought by Hanno to Carthage, in times before the Christian era, as the skins of hairy wild men. The historian refers to them as "gorullai" (γωριλλαι.)

The natives of West Africa name it "N'Geena."

The stuffed specimen at the Museum is a young male. Its preparation does great credit to Mr Bartlett's care and knowledge, for the hair over nearly all the body was in patches among the spirit—thoroughly corrupted in its alcoholic strength by animal matter. The peculiarly anthropoid and morbidly-disagreeable look that even the face of the young gorilla had was, of course, perfect in the photograph. In the Leisure Hour, a tolerably good cut of it was given, but the artist did not copy the label accurately, for on the photograph from which that cut was derived, another name was rendered by that sun, who pays no compliments and tells no lies. Professor Owen, the greatest of comparative anatomists, has made the subject of anthropoid apes his own, by the perfection of his researches, continued and continuous. He would have liked, at least I may venture, I believe, to say so (if the matter gave him more than a moment's thought), that the name of Dr Gray had been on that label.

Letter from C. Waterton, Esq., mentioning a young gorilla.

"Dear Sir,—As your favour of the 28th did not seem[Pg 19] to require an immediate answer I put it aside for a while, having a multiplicity of business then on hand, and being obliged to be from home for a couple of days.

"I beg to enclose you the letter to which you allude.

"Pray do not suppose that for one single moment I should be illiberal enough to undervalue a 'closet naturalist.' 'Non cuivis homini contingit adire corinthum.' It does not fall to every one's lot to range through the forests of Guiana, still, a gentleman given to natural history may do wonders for it in his own apartments on his native soil; and had Audubon, Swainson, Jameson, &c., not attacked me in all the pride of pompous self-conceit, I should have been the last man in the world to expose their gross ignorance.

"You ask me 'If we are to have another volume of essays?' I beg to answer, no. Last year, Mrs Loudon (to whom I made a present of the essays) wrote to me, and asked for a few papers to be inserted in a forthcoming edition. I answered, that as I had had some strange and awful adventures since the 'Autobiography' made its appearance, I would tack them on to it. But from that time to this, I have never had a line, either from Mrs Loudon or from her publishers. But some months ago, having made a present of a superb case of preserved specimens in natural history to the Jesuits' College in Lancashire, I gave directions to my stationer at Wakefield to procure me from London the fourth or last edition of the essays; and I made references to it accordingly. But, lo and behold, when I had opened this supposed fourth edition, I saw printed on the title page 'a new edition.' Better had they printed a fifth edition. This threw all my references[Pg 20] wrong. Should you be passing by Messrs Longman, perhaps you will have the goodness to ask when this 'new edition' was printed.

"I am sorry you did not show me your drawing of the chimpanzee before it was engraved. The artist has not done justice to it. He has made the ears far too large.[7] The little brown chimpanzee has very small ears; fully as small in proportion as those of a genuine negro. I am half inclined to give to the world a little treatise on the monkey tribe. I am prepared to show that Linnæus, Buffon, and all our hosts of naturalists who have copied the remarks of these celebrated naturalists, are perfectly in the dark with regard to the true character of all the monkey tribe. Yesterday, I sent up to the Gardener's Chronicle a few notes on the woodpecker.—Believe me, dear sir, very truly yours,

"P.S.—Many thanks for your nice little treatise on the chimpanzee."

Mr Waterton enclosed me a copy of the following letter, which he published in a Yorkshire newspaper:—

To Mrs Wombwell.

"Madam,—I am truly sorry that the inclemency of the weather has prevented the inhabitants of this renowned watering-place from visiting your wonderful gorilla, or brown orang-outang.

"I have passed two hours in its company, and I have been gratified beyond expression.[Pg 21]

"Would that all lovers of natural history could get a sight of it, as, possibly, they may never see another of the same species in this country.

"It differs widely in one respect from all other orang-outangs which have been exhibited in England—namely, that, when on the ground, it never walks on the soles of its fore-feet, but on the knuckles of the toes of those feet; and those toes are doubled up like the closed fist of a man. This must be a painful position; and, to relieve itself, the animal catches hold of visitors, and clings caressingly to Miss Bright, who exhibits it. Here then, it is at rest, with the toes of the fore-feet performing their natural functions, which they never do when the animal is on the ground.

"Hence I draw the conclusion that this singular quadruped, like the sloth, is not a walker on the ground of its own free-will, but by accident only.

"No doubt whatever it is born, and lives, and dies aloft, amongst the trees in the forests of Africa.

"Put it on a tree, and then it will immediately have the full use of the toes of its fore-feet. Place it on the ground, and then you will see that the toes of the fore-feet become useless, as I have already described.

"That it may retain its health, and thus remunerate you for the large sum which you have expended in the purchase of it, is, madam, the sincere hope of your obedient servant and well-wisher,

Scarborough Cliff, No. 1, Nov. 1, 1855.

"P.S.—You are quite at liberty to make what use you[Pg 22] choose of this letter. I have written it for your own benefit, and for the good of natural history."[8]

The writer of a most readable article on the acclimatisation of animals in the Edinburgh Review,[9] gives an amusing recital of the arrival of a chimpanzee at the Zoological Gardens. It was related to him by the late Mr Mitchell, who was long the active secretary of the society, and who did much to improve the Gardens. "One damp November evening, just before dusk, there arrived a French traveller from Senegal, with a companion closely muffled up in a burnoose at his side. On going, at his earnest request, to speak to him at the gate, he communicated to me the interesting fact that the stranger in the burnoose was a young chim, who had resided in his family in Senegal for some twelve months, and who had accompanied him to England. The animal was in perfect health; but from the state of the atmosphere required good lodging, and more tender care than could be found in a hotel. He proposed to sell his friend. I was hard; did not like pulmonic property[10] at that period of the year, having already two of the race in moderate health, but could not refrain from an offer of hospitality during Chim's residence in London. Chim was to go to Paris if I did not buy him. So we carried him, burnoose and all, into the house where the lady[Pg 23] chims were, and liberated him in the doorway. They had taken tea, and were beginning to think of their early couch. When the Senegal Adonis caught sight of them, he assumed a jaunty air and advanced with politeness, as if to offer them the last news from Africa. A yell of surprise burst from each chimpanzella as they successively recognised the unexpected arrival. One would have supposed that all the Billingsgate of Chimpanzeedom rolled from the voluble tongues of these unsophisticated and hitherto unimpressible young ladies; but probably their gesticulations, their shrill exclamations, their shrinkings, their threats, were but well-mannered expressions of welcome to a countryman thus abruptly revealed in the foreign land of their captivity. Sir Chim advanced undaunted, and with the composure of a high-caste pongo; if he had had a hat he would have doffed it incontinently, as it was, he only slid out of his burnoose and ascended into the apartment which adjoined his countrywomen with agile grace, and then, through the transparent separation, he took a closer view. Juliana yelled afresh. Paquita crossed her hands, and sat silently with face about three quarters averted. Sir Chim uttered what may have been a tranquillising phrase, expressive of the great happiness he felt on thus being suddenly restored to the presence of kinswomen in the moment of his deepest bereavement. Juliana calmed. Paquita diminished her angle of aversion, and then Sir Chim, advancing quite close to the division, began what appeared to be a recollection of a minuet. He executed marvellous gestures with a precision and aplomb which were quite enchanting, and when at last he broke out into a quick movement with loud smacking stamps, the ladies were completely carried[Pg 24] away, and gave him all attention. Friendship was established, refreshments were served, notwithstanding the previous tea, and everybody was apparently satisfied, especially the stranger. Upon asking the Senegal proprietor what the dance meant, he told me that the animal had voluntarily taken to that imitation of his slaves, who used to dance every evening in the courtyard."

So far Mr Mitchell's narrative; the reviewer relates how a chimpanzee, placed for a short time in the society of the children of his owner in this country, not only throve in an extraordinary manner, was perfectly docile and good-tempered, but learnt to imitate them. When the eldest little boy wished to tease his playfellow, he used, childlike, to make faces at him. Chim soon outdid him, and one of the funniest things imaginable was to see him blown at and blowing in return; his protrusible lips converted themselves into a trumpet-shaped instrument, which reminded one immediately of some of the devils of Albert Dürer, or those incredible forms which the old painters used to delight in piling together in their temptations of Saint Anthony.

Lady Anne Barnard, whose name as the writer of "Auld Robin Gray" is familiar to every one who knows that most pathetic ballad, spent five years with her husband at the Cape (1797-1802). Her journal letters to her sisters are most amusing, and full of interesting observations.[11] After describing "Musquito-hunting" with her husband, she[Pg 25] writes:—"In return, I endeavoured to effect a treaty of peace for the baboons, who are apt to come down from the mountain in little troops to pillage our garden of the fruit with which the trees are loaded. I told him he would be worse than Don Carlos if he refused the children of the sun and the soil the use of what had descended from ouran-outang to ouran-outang; but, alas! I could not succeed. He had pledged himself to the gardener,[12] to the slaves, and all the dogs, not to baulk them of their sport; so he shot a superb man-of-the-mountain one morning, who was marauding, and electrified himself the same moment, so shocked was he at the groan given by the poor creature as he limped off the ground. I do not think I shall hear of another falling a sacrifice to Barnard's gun; they come too near the human race" (p. 408).

In another letter she says (p. 391), "The best way to get rid of them is to catch one, whip him, and turn him loose; he skips off chattering to his comrades, and is extremely angry, but none of them return the season this is done. I have given orders, however, that there may be no whipping."

We have elsewhere referred to S. Bisset as a trainer of animals. Among the earliest of his trials, this Scotchman[Pg 26] took two monkeys as pupils. One of these he taught to dance and tumble on the rope, whilst the other held a candle with one paw for his companion, and with the other played a barrel organ. These animals he also instructed to play several fanciful tricks, such as drinking to the company, riding and tumbling upon a horse's back, and going through several regular dances with a dog. The horse and dog referred to, were the first animals on which this ingenious person tried his skill. Although Bisset lived in the last century, few persons seem to have surpassed him in his power of teaching the lower animals. We have seen a man in Charlotte Square, in 1865, make a new-world monkey go through a series of tricks, ringing a bell, firing a pea-gun, and such like. Poor Jacko was to be pitied. His want of heart in his labours was very evident. Poor fellow, no time for reflection was allowed him. Like some of the masters in the Old High School,—such cruelty dates back more than thirty years,—a ferule, or a pair of tawse kept Jacko to his work. It was play to the onlookers, but no sport to master Cebus. Had he possessed memory and reflection, how his thoughts must have wandered from Edinburgh to the forests of the Amazon!

Beside horses and dogs, the poet Byron, like his own Don Juan, had a kind of inclination, or weakness, for what most people deem mere vermin, live animals.

Captain Medwin records, in one of his conversations, that the poet remarked that it was troublesome to travel about with so much live and dead stock as he did, and[Pg 27] adds—"I don't like to leave behind me any of my pets, that have been accumulating since I came on the Continent. One cannot trust to strangers to take care of them. You will see at the farmer's some of my pea-fowls en pension. Fletcher tells me that they are almost as bad fellow-travellers as the monkey, which I will show you." Here he led the way to a room where he played with and caressed the creature for some time. He afterwards bought another monkey in Pisa, because he saw it ill-used.[13]

Lord Byron's travelling equipage to Pisa in the autumn of 1821, consisted, inter cætera, of nine horses, a monkey, a bull-dog, and a mastiff, two cats, three pea-fowls, and some hens.[14]

(From the "Noctes Ambrosianæ," Dec. 1825.[15])

Shepherd. I wish that you but saw my monkey, Mr North. He would make you hop the twig in a guffaw. I ha'e got a pole erected for him, o' about some 150 feet high, on a knowe ahint Mount Benger; and the way the cretur rins up to the knob, looking ower the shouther o' him, and twisting his tail roun' the pole for fear o' playin' thud on the grun', is comical past a' endurance.

North. Think you, James, that he is a link?

Shepherd. A link in creation? Not he, indeed. He is merely a monkey. Only to see him on his observatory,[Pg 28] beholding the sunrise! or weeping, like a Laker, at the beauty o' the moon and stars!

North. Is he a bit of a poet?

Shepherd. Gin he could but speak and write, there can be nae manner o' doubt that he would be a gran' poet. Safe us! what een in the head o' him! Wee, clear, red, fiery, watery, malignant-lookin een, fu' o' inspiration.

Tickler. You should have him stuffed.

Shepherd. Stuffed, man! say, rather, embalmed. But he's no likely to dee for years to come—indeed, the cretur's engaged to be married; although he's no in the secret himsel yet. The bawns are published.

Tickler. Why really, James, marriage I think ought to be simply a civil contract.

Shepherd. A civil contract! I wuss it was. But, oh! Mr Tickler, to see the cretur sittin wi' a pen in 's hand, and pipe in 's mouth, jotting down a sonnet, or odd, or lyrical ballad! Sometimes I put that black velvet cap ye gied me on his head, and ane o' the bairns's auld big-coats on his back; and then, sure aneugh, when he takes his stroll in the avenue, he is a heathenish Christian.

North. Why, James, by this time he must be quite like one of the family?

Shepherd. He's a capital flee-fisher. I never saw a monkey throw a lighter line in my life.... Then, for rowing a boat!

Tickler. Why don't you bring him to Ambrose's?

Shepherd. He's sae bashfu'. He never shines in company; and the least thing in the world will make him blush.[Pg 29]

Sir Thomas Dick Lauder[16] records the adventures of a monkey in Morayshire, whose wanderings sadly alarmed the inhabitants who saw him, all unused as they were to the sight of such an exotic stranger.

"We knew a large monkey, which escaped from his chain, and was abroad in Morayshire for some eight or ten days. Wherever he appeared he spread terror among the peasantry. A poor fisherman on the banks of the Findhorn was sitting with his wife and family at their frugal meal, when a hairy little man, as they in their ignorance conceived him to be, appeared on the window sill and grinned, and chattered through the casement what seemed to them to be the most horrible incantations. Horror-struck, the poor people crowded together on their knees on the floor, and began to exorcise him with prayers most vehemently, until some external cause of alarm made their persecutor vanish. The neighbours found the family half dead with fear, and could with difficulty extract from them the cause. 'Oh! worthy neebours!' at last exclaimed the goodman with a groan, 'we ha'e seen the Enemy glowrin' at us through that vera wundow there. Lord keep us a'!!' He next alarmed a little hamlet near the hills; appearing and disappearing to various individuals in a most mysterious manner; till at last a clown, with a few grains of more courage than the rest, loaded his gun and put a sixpence into it, with the intention of stealing upon him as he sat most mysteriously chattering on the[Pg 30] top of a cairn of stones, and then shooting him with silver, which is known never to fail in finishing the imps of the Evil One. And lucky indeed was it for pug that he chanced, through whim, to abscond from that quarter; for if he had not so disappeared, he might have died by the lead, if not by the silver. As it was, the bold peasant laid claim to the full glory of compelling this dreaded goblin to flee."

Sir Thomas Lauder kept several pets in his beautiful seat at the Grange, long occupied by the Messrs Dalgleish of Dreghorn Castle as a genteel boarding-school, and now by the Misses Mouatt as one for young ladies. We have often seen the tombstones to his dogs, which were buried to the south of that mansion, in which Principal Robertson the historian died, and where Lord Brougham, his relation, used to go when a boy at the High School.

Dr John Moore, the father of General Moore, who fell at Corunna, in one of the graphic sketches of a Frenchman which he gives in his work on Italy, records a visit he paid to the Marquis de F—— at Besançon. After many questions, he says, "Before I could make any answer, I chanced to turn my eyes upon a person whom I had not before observed, who sat very gravely upon a chair in a corner of the room, with a large periwig in full dress upon his head. The marquis, seeing my surprise at the sight of this unknown person, after a very hearty fit of laughter, begged pardon for not having introduced me sooner to that gentleman (who was no other than a large[Pg 31] monkey), and then told me, he had the honour of being attended by a physician, who had the reputation of possessing the greatest skill, and who certainly wore the largest periwigs of any doctor in the province. That one morning, while he was writing a prescription at his bedside, this same monkey had catched hold of his periwig by one of the knots, and instantly made the best of his way out at the window to the roof of a neighbouring house, from which post he could not be dislodged, till the doctor, having lost patience, had sent home for another wig, and never after could be prevailed on to accept of this, which had been so much disgraced. That, enfin, his valet, to whom the monkey belonged, had, ever since that adventure, obliged the culprit by way of punishment to sit quietly, for an hour every morning, with the periwig on his head.—Et pendant ces moments de tranquillité je suis honoré de la société du venerable personage. Then, addressing himself to the monkey, "Adieu, mon ami, pour aujourdhui—au plaisir de vous revoir;" and the servant immediately carried Monsieur le Médicin out of the room.[17]

This is a most characteristic bit, which could scarcely have occurred out of France, where monkeys and dogs are petted as we never saw them petted elsewhere. These things were so when we knew Paris under Louis-Philippe. Frenchmen, surely, have not much changed under Louis Napoleon.

One of the attractive sights of Mr Cross's menagerie,[Pg 32] some forty years or so ago, was a full-grown baboon, to which had been given the name of "Happy Jerry." He was conspicuous from the finely-coloured rib-like ridges on each side of his cheeks, the clear blue and scarlet hue of which, on such a hideous long face and muzzle, with its small, deeply-sunk malicious eyes, and projecting brow and cheeks, seemed almost as if beauty and bestiality were here combined. But Jerry had a habit which would have made Father Matthew loathe him and those who encouraged him. He had been taught to sit in an armchair and to drink porter out of a pot, like a thirsty brickmaker; and, as an addition to his accomplishments, he could also smoke a pipe, like a trained pupil of Sir Walter Raleigh. This rib-nosed baboon, or mandrill, as he is often called, obtained great renown; and among other distinguished personages who wished to see him was his late majesty King George the Fourth. As that king seldom during his reign frequented places of public resort, Mr Cross was invited to bring Jerry to Windsor or Brighton, to display the talents of his redoubtable baboon. I have heard Mr Cross say, that the king placed his hands on the arm of one of the ladies of the Court, at which Jerry began to show such unmistakable signs of ferocity, that the mild, kind menagerist was glad to get Jerry removed, or at least the king and his courtiers to withdraw. He showed his great teeth and grinned and growled, as a baboon in a rage is apt to do. Jerry was a powerful beast, especially in his fore-legs or arms. When he died, Mr Cross presented his skin to the British Museum, where it has been long preserved. The mandrill is a native of West Africa, where he is much dreaded by the negroes.[Pg 33]

In Cross's menagerie at Walworth, nearly twenty years ago, there was generally a fine mandrill. We remember the sulky ferocity of that restless eye. How angry the mild menagerist used to be at the ladies in the monkey-room with their parasols! These appendages were the feelers with which some of the softer sex used to touch Cross's monkeys, and, as the old gentleman used to insist, helped to kill them. Parasols were freely used to touch the boas and other snakes feeding in the same warm room. No doubt a boa-constrictor could not live comfortably if his soft, muscular sides got fifty pokes a day from as many sticks or parasols. Edward Cross, mild, gentle, gentlemanly, Prince of show-keepers, used to be very indignant at the inquisitorial desire possessed, especially by some of the fairer sex, to try the relative hardness and softness of serpents and monkeys, and other mammals and creatures. This story of the mandrill may excuse this pendant of an episode.

Horace Walpole tells an anecdote of a fine young French lady, a Madame de Choiseul. She longed for a parrot that should be a miracle of eloquence. A parrot was soon found for her in Paris. She also became enamoured of General Jacko, a celebrated monkey, at Astley's. But the possessor was so exorbitant in his demand for Jacko, that the General did not change proprietors. Another monkey was soon heard of, who had been brought up by a cook in a kitchen, where he had learned to pluck fowls with inimitable dexterity. This accomplished pet was bought and presented to Madame, who accepted him.[Pg 34] The first time she went out, the two animals were locked up in her bed-chamber. When the lady returned, the monkey was alone to be seen. Search, was made for Pretty Poll, and to her horror she was found at last under bed, shivering and cowering, and without a feather. It seems that the two pets had been presented by rival lovers of Madame. Poll's presenter concluded that his rival had given the monkey with that very view, challenged him; they fought, and both were wounded: and a heroic adventure it was![18]

One of Luttrell's sayings, recorded by Sydney Smith, was,—

"I hate the sight of monkeys, they remind me so of poor relations." Here follows a fine passage of Sydney Smith, which he might have written after hearing the lectures of Professor Huxley.[19] "I confess I feel myself so much at my ease about the superiority of mankind,—I have such a marked and decided contempt for the understanding of every baboon I have yet seen,—I feel so sure that the blue ape without a tail will never rival us in poetry, painting, and music,—that I see no reason whatever why justice may not be done to the few fragments of soul, and tatters of understanding, which they may really possess. I have sometimes, perhaps, felt a little uneasy at Exeter 'Change, from contrasting the monkeys with the 'prentice[Pg 35] boys who are teasing them; but a few pages of Locke, or a few lines of Milton, have always restored my tranquillity, and convinced me that the superiority of man had nothing to fear."[20]

The monkey she alludes to seems to be the Semnopithecus Entellus, a black-faced, light-haired monkey, with long legs and tail, much venerated by the Hindoos.

"Mrs L. and I were very much amused, early this morning (July 5), by watching numbers of huge apes, the size of human beings, with white hair all round their faces, and down their backs and chests, who were disporting themselves and feeding on the green leaves, on the sides of the precipice close to the house. Many of them had one or two little ones—the most amusing, indefatigable little creatures imaginable—who were incessantly running up small trees, jumping down again, and performing all sorts of antics, till one felt quite wearied with their perpetual activity. When the mother wished to fly, she clutched the little one under her arm, where, clinging round her body with all its arms, it remained in safety, while she made leaps of from thirty to forty feet, and ran at a most astonishing rate down the khad, catching at any tree or twig that offered itself to any one of her four arms. There were two old grave apes of enormous size sitting together[Pg 36] on the branch of a tree, and deliberately catching the fleas in each other's shaggy coats. The patient sat perfectly still, while his brother ape divided and thoroughly searched his beard and hair, lifted up one arm and then the other, and turned him round as he thought fit; and then the patient undertook to perform the same office for his friend."

Zoologists used to know a very curious animal from Madagascar, by name, or by an indifferent specimen preserved in the Paris Museum. Sonnerat, the naturalist, obtained it from that great island so well known to geographical boys in former days by its being, so they were told, the largest island in the world. This strange quadruped was named by a word which meant "handed-mouse," for such is the signification of chiromys, or cheiromys, as it used to be spelled. This creature, when its history was better known, was believed to be not far removed in the system from the lemurs and loris. Its soft fur, long tail, large eyes, and other features and habits connected it with these quadrumana, while its rodent dentition seemed to refer it to the group containing our squirrels, hares, and mice. It has been the subject of a profound memoir by Professor Owen, our greatest comparative anatomist; and I remember, with pleasure, the last time I saw him at the Museum he was engaged in its dissection. I may here refer to one of the Professor's lighter productions—a lecture at Exeter Hall on some instances of the "power of God as manifested in His animal creation"—for a very nice notice of this curious quadruped. In one of the French journals, there was an[Pg 37] excellent account given of the peculiar habits of the little nocturnal creature. In those tropical countries the trees are tenanted by countless varieties of created things. Their wood affords rich feeding to the large, fat, pulpy grubs of beetles of the families Buprestidæ, Dynastidæ, Passalidæ, and, above all, that glorious group the Longicornia. These beetles worm their way into the wood, making often long tunnels, feeding as they work, and leaving their ejecta in the shape of agglomerated sawdust. It is into the long holes drilled by these beetles that the Aye-Aye searches with his long fingers, one of which, on the fore-hand, is specially thin, slender, and skeleton-like. It looks like the tool of some lock-picker. Our large-eyed little friend, like the burglar, comes out at night and finds these holes on the trees where he slept during the day. His sensitive thin ears, made to hear every scratch, can detect the rasping of the retired grub, feasting in apparent security below. Naturalists sometimes hear at night, so Samouelle once told me, the grubs of moths munching the dewy leaves. Our aye-aye is no collector, but he has eyes, ears, and fingers too, that see, hear, and get larvæ that, when grown and changed into beetles, are the valued prizes of entomologists. Into that tunnelled hole he inserts his long finger, and squash it goes into a large, pulpy, fat, sweet grub. It takes but a moment to draw it out; and if it be a pupa near the bark, so much the better for the aye-aye, so much the worse for the beetle or cossus. I might dilate on this subject, but prefer referring the reader to Professor Owen's memoir, and to his lecture.[22] The aye-aye, in every point of its structure,[Pg 38] like every created thing, is full of design. Its curious fingers, especially the skeleton-like chopstick of a digit referred to, attract especial notice, from their evident adaptation to the condition of its situation and existence, as one of the works of an omnipotent and beneficent Creator.

A highly curious, if not the strangest, order of the class are these flying creatures called bats. It is evident from Noel Paton's fairy pictures that he has closely studied their often fantastic faces. The writer could commend to his attention an African bat, lately figured by his friend Mr Murray.[23] Its enormous head, or rather muzzle, compared with its other parts, gives it an outrageously hideous look. In the late excellent Dr Horsfield's work on the animals of Java, there are some engravings of bats by Mr Taylor, who acquired among engravers the title of "Bat Taylor," so wonderfully has he rendered the exquisite pileage or fur of these creatures. It is wonderful how numerous the researches of naturalists, such as Mr Tomes, of Welford, near Stratford, have shown the order Cheiroptera to be in genera and species. Their profiles and full faces, even in outline, are often most bizarre and strange. Their interfemoral membranes, we may add, are actual "unreticulated" nets, with which they catch and detain flies as they skim through the air. They pick these[Pg 39] out of this bag with their mouths, and "make no bones" of any prey, so sharp and pointed are their pretty insectivorous teeth. Their flying membranes, stretched on the elongated finger-bones of their fore-legs, are wonderful adaptations of Divine wisdom, a capital subject for the natural theologian to select.

Our poet-laureate must be a close observer of natural history. In his "In Memoriam," xciv., he distinctly alludes to some very curious West African bats first described by the late amiable Edward T. Bennett, long the much-valued secretary of the Zoological Society. These bats are closely related to the fox bats, and form a genus which is named, from their shoulder and breast appendages, Epomophorus:—

"Bats went round in fragrant skies,

And wheel'd or lit the filmy shapes

That haunt the dusk, with ermine capes,

And woolly breasts and beaded eyes."

The species Mr Bennett named E. Whitei, after the good Rev. Gilbert White, that well-known worthy who wrote "The Natural History of Selborne," wherein are many notices of bats.

It is curious, now that Australia is almost as civilised, and in parts nearly as populous, as much of Europe, to read "Lieutenant Cook's Voyage Round the World," in vol. iii. of Hawkesworth's quartos, detailing the discoveries of June, July, and August 1770—that is close upon a[Pg 40] century ago. What progress has the world made since that period! We do not require long periods of ages to alter, to adapt, to develop the customs and knowledge of man. At p. 156 we get an account of a large bat. On the 23d June 1770 Cook says:—"This day almost everybody had seen the animal which the pigeon-shooters had brought an account of the day before; and one of the seamen, who had been rambling in the woods, told us, at his return, that he verily believed he had seen the devil. We naturally inquired in what form he had appeared, and his answer was in so singular a style that I shall set down his own words. 'He was,' says John, 'as large as a one-gallon keg, and very like it; he had horns and wings, yet he crept so slowly through the grass, that if I had not been afeared I might have touched him.' This formidable apparition we afterwards discovered to have been a bat, and the bats here must be acknowledged to have a frightful appearance, for they are nearly black, and full as large as a partridge; they have indeed no horns, but the fancy of a man who thought he saw the devil might easily supply that defect."

Having seen some of the very curious fox-bats alive, and given some condensed information about them in Dr Hamilton's series of volumes called "Excelsior," the writer may extract the account, with some slight additions, especially as the article is illustrated with a truly admirable figure of a fox-bat, from a living specimen by Mr Wolf. In Sir Emerson Tennent's "Sketches of the Natural History of Ceylon," p. 14, Mr Wolf has represented a whole colony of the "flying-foxes," as they are called.

Flying Fox. (Pteropus ruficollis.)

Flying Fox. (Pteropus ruficollis.)

In this country that bat is deemed a large one whose wings, when measured from tip to tip, exceed twelve inches, or whose body is above that of a small mouse in bulk. In some parts of the world, however, there are members of this well-marked family, the wings of which, when stretched and measured from one extremity to the other, are five feet and upwards in extent, and their bodies large in proportion. These are the fox-bats, a pair of which were lately procured for the Zoological Gardens. It is from one of this pair that the very characteristic figure of Mr Wolf has been derived.[24] There is something very odd in the appearance of such an animal, suspended as it is during the day head downwards, in a position the very sight of which suggests to the looker-on ideas of nightmare and apoplexy. As the head peers out from the membrane, contracted about the body and investing it as in a bag, and the strange creature chews a piece of apple presented by its keeper, the least curious observer must be struck with the peculiarity of the position, and cannot fail to admire the velvety softness and great elasticity of the membrane which forms its wings. It must have been from an exaggerated account of the fox-bats of the Eastern Islands that the ancients derived their ideas of the dreaded Harpies, those fabulous winged monsters sent out by the relentless Juno, and whose names are synonymous with rapine and cruelty.