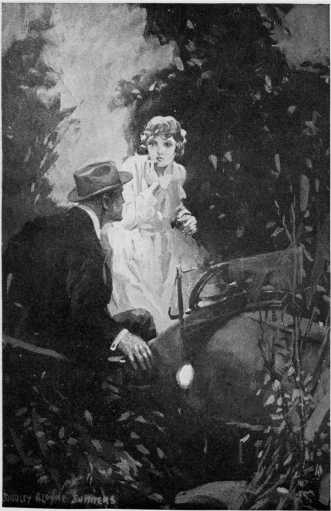

“You get nicer every day of your life.”

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Eve to the Rescue

Author: Ethel Hueston

Release Date: June 24, 2008 [eBook #25892]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EVE TO THE RESCUE***

“You get nicer every day of your life.”

Eve to the Rescue

BY

ETHEL HUESTON

AUTHOR OF

PRUDENCE OF THE PARSONAGE,

PRUDENCE SAYS SO,

LEAVE IT TO DORIS, Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

DUDLEY GLOYME SUMMERS

| GROSSET & DUNLAP | |

| PUBLISHERS | NEW YORK |

Made in the United States of America

Copyright 1920

The Bobbs-Merrill Company

Printed in the United States of America

|

To Carol Who came to us in the form of Duty, but who has brought us only Pleasure |

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | In Defiance of Duty | 11 |

| II | The Cote in the Clouds | 21 |

| III | Everybody’s Duty | 30 |

| IV | The Irish-American League | 40 |

| V | Her Inheritance | 59 |

| VI | A Wrong Adjustment | 84 |

| VII | Painful Duty | 98 |

| VIII | She Meets a Demonstrator | 112 |

| IX | Admitting Defeat | 124 |

| X | The Original Fixer | 137 |

| XI | The Germ Of Duty | 156 |

| XII | The Revolt Of The Seventh Step | 175 |

| XIII | She Finds A Foreigner | 195 |

| XIV | New Light On Loyalty | 214 |

| XV | Service Of Joy | 226 |

| XVI | Marie Encounters The Secret Service | 248 |

| XVII | Spontaneous Combustion | 266 |

| XVIII | Converts Of Love | 282 |

| XIX | She Doubts Her Theory | 301 |

| XX | She Proves Her Principle | 312 |

| XXI | Her One Exception | 332 |

EVE TO THE RESCUE

EVE TO THE RESCUE

“To-morrow being Saturday afternoon,” began Eveley, deftly slipping a dish of sweet pickles beyond the reach of the covetous fat fingers of little niece Nathalie,—“to-morrow being Saturday afternoon—”

“Doesn’t to-morrow start at sunrise as usual?” queried her brother-in-law curiously.

“As every laborer knows,” said Eveley firmly, “Saturday begins with the afternoon off. And I am a laborer. Therefore, to-morrow being Saturday-afternoon-off, and since I have trespassed on your hospitality for a period of two months, it behooves me to find me a home and settle down.”

“Oh, Eveley,” protested her sister in a soft troubled voice, “don’t be disagreeable. You talk as if we were strangers. Aren’t we the only folks you have? And aren’t you my own 12 and only baby sister? If you can’t live with us, where can you live?”

“As it says in the Bible,” explained Eveley, truthfully if unscripturally, “no two families are small enough for one house.”

“But who calls you a family?” interrupted the brother-in-law.

“I do. And nice and sweet as you all are, and adorable as I am well aware am I, all of you and all of me can not be confined to one house.”

“But we have counted on it,” persisted Winifred earnestly. “We have looked forward to it. We have always said that you would come to us when Aunt Eloise died,—and she did—and you must. We—we expect it.”

“‘England expects every man to do his duty,’” quoted Burton in a sepulchral voice.

Then Eveley rose in her place, tall and formidable. “That is it,—duty. Then let me announce right now, once and for all, Burton Raines and Winifred, eternally and everlastingly, I do not believe in duty. No one shall do his duty by me. I publicly protest against 13 it. I won’t have it. I have had my sneaking suspicions of duty for a long time, and lately I have been utterly convinced of the folly and the sin of it. Whenever any one has anything hateful or disagreeable to do, he draws a long voice and says it is his duty. It seems that every mean thing in the world is somebody’s duty. Duty has been the curse of civilization for lo, these many years!” Then she sat down. “Please pass the jam.”

“Oh, all right, all right,” said Burton amiably, “have it your own way, by all means. Henceforth and forever after, we positively decline to do our duty by you. But what is our duty to you? Answer me that, and then I guarantee not to do it.”

“It is our duty to keep Eveley right here with us and take care of her,” said Winifred, with as much firmness as her soft voice could master. “She is ours, and we are hers, and it is our duty to stand between her and a hard world.”

“You can’t. In the first place I am awfully stuck on the world, and want to get real chummy with it. Any one who tries to stand 14 between it and me, shall be fired out bodily, head first.”

“Oh, Eveley,” came a sudden wail from Winifred, “you can’t go off and live by yourself. What will people think? They will say we could not get along together.”

“That is it,—just that and nothing more. It isn’t duty that bothers you—it is What-will-people-think? An exploded theory, nothing more.” Then she smiled at her sister winsomely. “You positively are the sweetest thing, Winnie. And your Burton I absolutely love. And your babies are the most irresistible angels that ever came to bless and—enliven—a sordid world. But you are a family by yourselves. You are used to doing what you want, and when you want, and how you want. I would be an awful nuisance. When Burton would incline to a quiet evening, I should have a party. When you and he would like to slip off to a movie, you would have to be polite and invite me. Nobody could be crazier about nieces and nephews than I am, but sometimes if I were tired from my work their chatter might make me peevish. And 15 you would punish them when I thought you shouldn’t, and wouldn’t do it when I thought you should, and think of the arguments there would be. And so we all agree, don’t we, that it would be more fun for me to move off by myself and then come to see you and be company,—rather than stick around under your feet until you grow deadly tired of me?”

“I do not agree,” said Winifred.

“I do,” said Burton.

“Then we are a majority, and it is all settled.”

“But where in the world will you live, dear? You could not stand a boarding-house.”

“I could if I had to, but I don’t have to. I have been favored with an inspiration. I can’t imagine how it ever happened, but perhaps it was a special dispensation to save you from me. I am going to live in my own house on Thorn Street. Of course it will be lonely there at first, since Aunt Eloise is gone—but just listen to this. I shall rent the down-stairs part to a small family and I shall live up-stairs. Part of the furniture I am going 16 to sell, use what I want to furnish my dove cote in the clouds, and the rest that is too nice to sell but can’t be used I shall store in the east bedroom, which I won’t use. That will leave me three rooms and a bath—bedroom, sitting-room and dining-room. I can fix up a corner of the dining-room into a kitchen with my electric percolator and grills and things. Isn’t it a glorious idea? And aren’t you surprised that I thought of anything so clever by myself?”

“Not half bad,” said Burton approvingly,—for Burton had long since learned that the pleasantest way of keeping friends with in-laws is by perpetual approval.

“But you can never find a small family to take the down-stairs part of the house,” came pessimistically from Winifred.

“Oh, but I have found it, and they are in the house already. A bride and groom. The cunningest things! She calls him Dody, and they hold hands. And I sold part of the furniture yesterday, and had the rest moved up-stairs. But there is one thing more.”

“I thought so,” said Burton grimly. “I 17 remember the Saturday-afternoon-off. I thought perhaps you had me in mind for your furniture-heaver. But since that is done it is evident you have something far more deadly in store for me. Let me know the worst, quickly.”

“Well, you know, dearie,” said Eveley in most seductively sweet tones, “you know how the house is built. There is only one stairway, and it rises directly from the west room down-stairs. Unfortunately, my bride and groom wish to use that room for a bedroom. Now you can readily perceive that a young and unattached female could not in conscience—not even in my conscience—utilize a stairway emanating from the boudoir of a bridal party. And there you are!”

“I am no carpenter,” Burton shouted quickly, when Eveley’s voice drifted away into an apologetic murmur. “Get that idea out of your head right away. I don’t know a nail from a hammer.”

“No, Burtie, of course you don’t,” she said soothingly. “But this will be very simple. I thought of a rambling, rustic stairway outside 18 the house, in the back yard. You know the sun parlor was an afterthought, only one story high with a flat roof. So the rustic stairway could go up to the roof of the sun parlor, and I could make that up into a sort of roof garden. Wouldn’t it be picturesque and pretty?”

“But there is no door from your room to the roof of the sun parlor,” objected Burton.

“No, but the window is very wide. I will just cover it with portières and things, and I am quite active so I can get in and out very nicely. And when I get around to it, and have the money, I may have a French window put in.”

“But, Eveley, I can’t build a stairway. I don’t know how to build anything. I couldn’t build a box.”

“But you do not have to do this alone, Burtie. Just the foundation, that is all I expect of you. You will have lots of assistance. Not experienced help perhaps, but enthusiastic, and ‘love goes in with every nail,’—that sort of thing. I have sent invitations to all of my friends of the masculine persuasion, 19 and we have started a competition. Each admirer is to build two steps according to his own design and plan, and the one who builds most artistically is to receive, not my hand and heart, but a lovely dinner cooked on my grill in my private dining-room. I have the list here. I figured that twelve steps will be enough. Nolan Inglish, two. Lieutenant Ames, two. Captain Hardin, two. Jimmy Weaver, two. Dick Fairwether, two. Arnold Bender, two. Arnold is Kitty’s beau, but she guaranteed two steps for him. Won’t it be lovely?”

“To-morrow being Saturday afternoon,” said Burton bitterly.

“I ordered the rustic lumber last night, and it was delivered to-day.”

“And you consider it my duty as the luckless husband of your long-suffering sister, to lay the foundation for the wabbly, rattly ramshackle stairs your pet assortment of moonstruck admirers will build for you?”

“Not your duty, Burtie, certainly not your duty. But your pleasure and your great joy. For without the stairway, I can not live there. 20 And if I do not live there, I must live here. And remember. When you want vaudeville, I will incline to grand opera. When you would enjoy a movie, I shall have a musicale here at home. When you are in the midst of a novel, I shall insist on a three-handed game of bridge. When you are ready to shave, I shall need the hot water. When your appetite calls for corned beef and cabbage, my soul shall require lettuce sandwiches and iced tea. Not your duty, dear, by any means. I do not believe in duty.”

“Quite right, sweet sister,” he said pleasantly. “It shall afford me infinite pleasure, I assure you. And to-morrow being Saturday afternoon, you shall have your stairway.”

As Eveley had prophesied, what her carpenters lacked in experience and skill was more than compensated by their ambition and their eagerness to please. On Saturday afternoon her back yard was a veritable bee-hive of industry. The foundation was in readiness for the handiwork of love, for Burton Raines, feeling that he could not concentrate on business in such sentimental environs, explained patiently that he was only an ordinary married man and that love rhapsodies to the tune of temperamental hammering upset him. So he had taken the morning off from his own business, to lay the foundation for the rustic stairway.

Nolan Inglish, listed first because he was always listed first with Eveley, appeared at eleven o’clock, having explained to the lofty members of the law firm of which he was a junior assistant, that serious family matters 22 required his attention. This enabled him to have the two bottom-most steps of the stairway, comprising his portion, erected and ready for inspection by the time Eveley arrived home from her work. He said he had felt it would be lonely for her to sit around by herself while everybody else worked for her, and having provided against that exigency by doing his labor in advance, he claimed the privilege of officiating as entertainer-in-chief for the entire afternoon.

Arnold Bender appeared next, accompanied by Kitty Lampton, one of Eveley’s pet and particular friends. Although Kitty was extremely generous in proffering the services of her friend in behalf of Eveley’s stairway, she frankly stated that she was not willing to expose any innocent young man of her possession to the wiles and smiles of her attractive friend, without herself on hand to counteract any untoward influence.

Captain Hardin and Lieutenant Ames came together with striking military éclat, accompanied, as became their rank, by two alert enlisted men. After introducing their enlisted 23 men in the curt official manner of the army and having set them grandly to work on the rustic stairway, Captain Hardin and Lieutenant Ames immediately took up a social position in the tiny rose-bowered pergola, with Eveley and Kitty and Nolan and the lemonade.

A little later, Jimmy Weaver rattled up in his small striped gaudy car, followed presently by Dick Fairwether on a noisy motorcycle. They took out their personal sets of tools from private recesses of their machines and plunged eagerly into the contest.

So the afternoon started most auspiciously and all would doubtless have gone well and peacefully, had not Captain Hardin most unfortunately selected an exceptionally good-looking young soldier for his service,—a tall, slender, dark-skinned youth, with merry melting eyes. Eveley never attempted to deny that she could not resist merry melting eyes. So she left the young officers and Kitty and Nolan and the lemonade in the rose-bowered pergola on the edge of the canyon which sloped down abruptly on the east side, 24 and herself went up to superintend the building of her stairway.

The handsome one required an inordinate amount of superintending. The other soldier detailed by Lieutenant Ames, an ordinary young man with a sensible face and eyes that saw only hammer and nails, got along very well by himself. But the handsome youth, called Buddy Gillian, required supervision on every point. He first consulted Eveley about the design of the two steps entrusted to him for construction. He could think of as many as two dozen different styles of rustic steps, and he explained and illustrated them all to Eveley in great detail, drawing plans in the gravel path. It took the two of them nearly an hour to make a selection, and then it seemed the style they had chosen was the most difficult of the entire assortment, and was practically impossible for any one to construct alone. So Eveley perforce assisted, holding the rustic boughs while he hammered, carrying the saw, and carefully picking out the proper size of nails as he required them. 25

“Didn’t you have more sense than to bring a good-looker?” Nolan asked Captain Hardin in a fretful voice. “Don’t you know that Eveley can’t resist good looks?”

“I told him he had no business to bring Gillian,” put in the lieutenant. “Look at Muggs, whom I brought. Nobody notices that Muggs needs any help. See there now, he has finished and is ready to go. Can’t you do something to stop this, Miss Lampton?” he pleaded, turning to Kitty.

“As long as she leaves my Arnold alone, I shall mind my own business,” said Kitty decidedly. “If I cut in on her affair with your Buddy, she will try her hand on Arnold to get even. Captain Hardin got you into this, it is up to him to get you out.”

And Kitty heartlessly left the pergola and went up to the rustic steps to hold the hammer for Arnold.

Then Captain Hardin, after rapidly drinking three glasses of iced lemonade to drown his chagrin and to strengthen his flagging courage, left the cozy pergola which had no attraction for any of them with Eveley out 26 at work on the rustic stairway, and went up to the corner where she and Buddy Gillian were carefully and conscientiously matching bits of rustic lumber.

“I do not think I should keep you any longer, Gillian, since Muggs is ready to go,” he said kindly. “I can finish this myself now, thank you.”

“Yes, sir,” said Buddy Gillian courteously, and stood up. Then to Eveley, “Shall I gather up the scraps, Miss Ainsworth, and tidy the lawn for you? It is pretty badly littered. Only too glad to be of service, if I may.”

“Oh, thank you, Mr. Gillian, that is sweet of you,” said Eveley gratefully. “Suppose we begin down in that corner by the rose pergola, and gather up the scraps as we come this way. I’ll carry this basket, and you can do the picking.”

But even this humble field of usefulness was denied Private Gillian, for Lieutenant Ames came out from the pergola and said with official briskness, “Oh, never mind that, Gillian. I can help Miss Ainsworth with it. You’d better run along with Muggs and enjoy 27 your liberty period. Much obliged to you, I am sure.”

So the handsome Buddy looked deep into Eveley’s eyes, and sighed. Eveley held out her hand.

“You have done just beautifully,” she said, “and helped me so much. And when are you coming to tell me the rest of that thrilling story of your life in the trenches?”

“The question is, when may I?”

“Well, Tuesday evening? Or can you get off on Tuesday?”

“Oh, yes, since the war is over we can get off any night. Tuesday will suit me fine.”

“Sorry, Gillian,” put in Captain Hardin grimly. “But unfortunately I have arranged for a company school on Tuesday night—to be conducted by Lieutenant Carston.”

Gillian turned his beautiful eyes on Eveley, eyes no longer merry but sad and wistful.

“Let me see,” puzzled Eveley promptly. “Could you come to-morrow night then, Mr. Gillian? Captain won’t mind changing with you, I know, and he can come on Tuesday. Captains can always get away, can’t they? Is 28 that all right?—Then to-morrow evening, about eight. And I will have a little evening supper all ready for you. Good-by.”

After he had gone she said to the captain apologetically, “Hasn’t he wonderful eyes? And I knew he must be quite all right for me to know, or you would never have introduced him.”

Taken all in all, only Kitty Lampton and Eveley considered the raising of the rustic stairway an entire success, although there was much light talk and laughter as they ate the dainty supper the girls had prepared for them in the Cloud Cote, as Eveley had already christened her home above the earth. But the men, with the exception of Nolan, were doomed to disappointment.

When Dick Fairwether asked her to go to a movie with him in the evening, and when Jimmy Weaver invited her to go for a night drive with him along the beach, and when Captain Hardin suggested that she accompany him to the Columbine dance at the San Diego, and when Lieutenant Ames wanted to make a foursome with Kitty and Arnold to 29 go boating, she said most regretfully to each,—“Isn’t it a shame? But my sister is having some kind of a silly club there to-night, and I promised to go.”

But to Nolan, very secretly she whispered: “Now you trot along to the office and work and when I am ready to come home I will phone you to come and get me. And we will initiate the Cloud Cote all by ourselves.”

So the little party broke up almost immediately after supper, with deep avowals of gratitude on the part of Eveley, and equally deep assurances of pleasure and good will on the part of the others. After they had gone, as Eveley inspected her stairway alone, she was comforted by the thought that she could fairly smother it with vines and all sorts of creeping and climbing things, and the casual comer would not notice how funny and wabbly it was. But as she went gingerly down, clinging desperately to the rail on both sides, she determined to take out an accident policy immediately, with a special clause governing rustic stairways.

Due to the old-fashioned, rambling style of the house, the rustic stairway did not really detract from its beauty. And as there were already clambering vines and roses in profusion, an extra arbor more or less, could, as Eveley claimed, pass without serious comment. Although the house was old, it was still exquisitely beautiful, with its cream white pillars and columns showing behind the mass of green. And the lawn, which was no lawn but only a natural park running riot with foliage coaxed into endless lovers’ nooks and corners, was a fitting and marvelously beautiful setting for it.

The gardens were in the shape of a triangle, with conventional paved streets on the north and west, but on the east and south they drifted away into the shadowy canyon which stretched down almost to the bay, and 31 came out on the lower streets of the water-front.

Eveley stood on her rustic stairway and gloated over it lovingly,—the rambling house, the rambling gardens, the beautiful rambling canyon, and then on below to the lights on the bay, clustered together in companionable groups.

“Loma Portal, Fort Rosecranz, North Island, Coronado, and the boats in the bay,” she whispered softly, pointing slowly to the separate groups. And her eyes were very warm, for she loved each separate light in every cluster, and she was happy that she was at home again, in the place that had been home to her since the days of her early memory.

Eveley’s mother had been born in the house on Thorn Street, as had her sister, Eloise, the aunt with whom the girls had lived for many years. And after the death of her husband, when Eveley was a tiny baby, Emily Ainsworth had taken her two girls and gone back to live with her sister in the family home. There a few years later she too had 32 passed away, leaving her children in the tender, loving hands of Aunt Eloise. And the years had passed until there came a time when Winifred was married, and Eveley and her aunt lived on alone, though always happily.

But investments had gone badly, and returns went down as expenses went up. So Eveley studied stenography, and took genuine pleasure in her career as a business girl. With her salary, and their modest income, the two had managed nicely. Then when Aunt Eloise went out to join her sister, the Thorn Street house was left to Eveley, and other property given to Winifred to compensate. So that to Eveley it was only coming home to return to the big house and the rambling gardens. But to meet the expenses of maintenance it was necessary that part of the large house should be rented.

Eveley, always adaptable, moved serenely into her cote at the head of the stairs, and felt that life was still kind and God was good, for this was home, and it was hers, and she had come to stay. 33

She almost regretted the impulsive promise to her sister that drew her out of her dwelling on the first night of her tenancy. Not only did she begrudge the precious first-night hours away from her pretty cote in the clouds, but she was not charmed with the arrangement for the evening. She was an ardent devotee of clubs of action, rowing, tennis, country, dancing and golf, but for that other type of club, which she described as “where a lot of women sit around with their hats on, and drink tea, and have somebody make speeches about things,” she felt no innate tenderness.

It was really a trick on the part of Winifred that procured the promise of attendance. For Eveley had been allowed to believe they were going to play cards and that there would be regular refreshments of substance, and perhaps a little dancing later on. All this had been submitted to by inference, without a word of direct confirmation from Winifred, who had a conscience.

So it was that Eveley Ainsworth, irreproachably attired in a new georgette blouse 34 and satin skirt, betook herself to her sister’s home for an evening meeting of the Current Club. And it was a decided shock to find that neither a social game nor a soul-restoring midnight supper were in store for her, but the proverbial tea and speeches. She resigned herself, however, to the inevitable, and shrank back as obscurely as possible into a dark corner where she might muse on the charms of Nolan, the beauties of the new Buddy Gillian, the martial dignity of Captain Hardin, and the appeals of all the rest, to her frivolous heart’s content.

In this manner, she passed through the first part of the evening very comfortably, only dimly aware that she was floundering in the outskirts of a perfect maze of big words dealing with Americanization, which Eveley vaguely understood to be something on the order of standing up to The Star Spangled Banner, and marching in parades with a flag and shouting “Hurrah for the President,” in the presence of foreigners.

The third speaker was a minister, and ministers are accustomed to penetrating the blue 35 mazes of mental abstraction. This minister did. He began by telling three funny stories, and Eveley, who loved to exercise her sense of humor, came back to the Current Club and joined their laughter.

In the very same breath with which he ended the last funny story, he began breezily discoursing on everybody’s duty as a loyal American. Eveley, to whom the word “duty” was the original red rag, sniffed inaudibly but indignantly to herself. And while she was still sniffing the speaker left “duty as American citizens” far behind, and was deep in the intricacies of Americanization. Eveley found to her surprise that this was something more than saluting the flag and shouting. She grew quite interested. It seemed that ordinary, regular people were definitely, determinedly working with little scraps of the foreign elements, Chinese, Mexican, Russian, Italian, yes, even German,—though Eveley considered it asking entirely too much, even of Heaven, to elevate shreds of German infamy to American standards. At any rate, people were doing this thing, taking the 36 pliant, trusting mind of the foreigner, petting it, training it, coaxing it,—until presently the flotsam and jetsam of the Orient, of war-torn Europe, of the islands of the sea, of all the world, should be Americanized into union, and strength, and loyalty, and love.

It fascinated Eveley. She forgot that it was her duty as a patriotic American. She forgot that nobody had any business doing anything but minding one’s own business. She fairly burned to have a part in the work of assimilation. Her eyes glowed with eagerness, her cheeks flushed a vivid scarlet, her lips trembled with the ecstatic passion of loyalty.

In the open discussion that followed after the last address, Eveley suddenly, quite to her own surprise, found that she had something to say.

“But—isn’t it mostly talk?” she asked, half shyly, anxious not to offend, but unable to repress the doubt in her mind. “It does not seem practical. You say we must assimilate the foreign element. But can one assimilate a foreign element? Doesn’t the fact that 37 it is foreign—make it impossible of assimilation? Oh, I know we have to do something, but as long as we are foreigners, we to them, and they to us,—what can we do?”

The deadly silence that greeted her words frightened her, yet somehow gave her courage to go on. She must be saying something rather sensible, or they would not pay attention.

“We can not assimilate food elements that are foreign to the digestive organs,” she said. “Labor and capital have warred for years, and neither can assimilate the other. Look at domestic conditions here,—in the home, you know. People get married,—men and women, of opposing types and interests and standards. And they can not assimilate each other, and the divorce courts are running rampant. It does no good to say assimilation is a duty, if it is impossible. And it seems to be.”

“Your criticism is destructive, Miss Ainsworth,” said a learned professor who had spoken first, and Eveley was sorry now that she had not listened to him. “Destructive 38 criticism is never helpful. Have you anything constructive to offer?”

“Well, maybe it is theoretic, also,” said Eveley smiling faintly, and although the smile was faint, it was Eveley’s own, which could not be resisted. “But duty isn’t big enough, nor adaptable enough, nor winning enough. There must be some stronger force to set in action. Nobody could ever win me by doing his duty by me. It takes something very intimate, very direct, and very personal really to get me. But if one says a word, or gives me a look,—just because he understands me, and likes me,—well, I am his friend for life. It takes a personal touch, a touch that is guided not by duty but by love. So I think maybe the foreign element is the same way. We’ve got to sort of chum up with it, and find out the nice things in it first. They will find the nice things in us afterward.”

“But as you say, Miss Ainsworth, isn’t this only talk? How would you go about chumming up with the foreign element?” 39

“I do not know, Professor,” she said brightly. “But I think it can be done. And I think it has to be done, or there can not be any Americanization.”

“Well, are you willing to try your own plan? We are conducting classes, games, studies, among the foreigners, working with them, teaching them, studying them. We call this our duty as loyal Americans. You say duty is not enough, and you want to get chummy with them. Will you try getting chummy and see where you come out?”

Eveley looked fearfully about the room, at the friendly earnest faces. “I—I feel awfully quivery in my backbone,” she faltered. “But I will try it. You get me the foreigners, and I will practise on them. And if I can’t get chummy with them, and like them, why, I shall admit you are right and I will help to teach them spelling, and things.”

Several days passed quietly. Eveley went serenely about her work, and from her merry manner one would never have suspected the fires of Americanization smoldering in her heart ready for any straying breeze of opportunity to fan them into service.

She was finding it deliciously pleasant to live in a Cloud Cote above a bride and groom. Mrs. Bride, as Eveley fondly called her, was the dainty, flowery, fluttery creature that every bride should be. And Mr. Groom was the soul of devotion and the spirit of tenderness. To the world in general, they were known as Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Severs, but to Eveley, they were Mrs. Bride and Mr. Groom. It served to keep their new and shining matrimonial halo in mind.

She was newly glad every morning that the young husband had to start to his work before 41 she left home for hers. When she heard the front door open down-stairs, she ran to her window, often with a roll or her coffee cup in her hand, to witness the departure, which to her romantic young eyes was a real event. Mrs. Bride always stood on the porch to watch him on his way to the car until he was out of sight. Sometimes she ran with him to the corner, and always before he made the turn he waved her a final good-by.

It was very peaceful and serene. It seemed hard to believe that recently there had been a tremendous war, and that even now the world was writhing in the throes of political and social upheaval and change. In every country, men and women were grappling with great industrial problems, and there were ominous rumblings and threatening murmurs from society in revolution. But in the rambling white house in the great green gardens at the top of the canyon, one only knew that it was springtime in southern California, that the world was full of gladness and peace and joy, and that love was paramount. 42

Several days,—and then one evening there came the call of the telephone—the reveille of Americanization in the person of Eveley Ainsworth. A class of young foreign lads had been gathered and would meet Eveley at the Service League that evening. No instructions were given, no suggestions were forthcoming. Eveley had asked for foreigners with whom she could get chummy and call it love. Here were the foreigners. The rest of the plan was Eveley’s own.

She was proud of her mature comprehension of the needs of reconstruction, and of her utter gladness to assist. She felt that it signified something rather fine and worth while in her character, and she took no little pleasure in the prospect of active service. She went about her work that day wrapped in a veil of mystery, her mind delving deep into the ideals of American life. She carefully elaborated several short and spicy stories, of strong moral and patriotic tone, emphasizing the nobility of love of country. And that evening she stood before her mirror for a long time, practising pretty flowery 43 phrases to be spoken with a most winsome smile. Remembering that her subjects were boys, and that boys are young men in the making, she donned her daintiest, shimmeriest gown, and carefully coaxed the enticing little curls into prominence. Then with a final patriotic smile at herself in the mirror, she carefully climbed through the window and crossed the roof garden to the rustic stairway.

As she walked briskly up Albatross to Walnut, then to Fourth where she took the car, and all the way down-town she was carefully rehearsing her stories and the most effective modes of presenting them. She knew the rooms of the Service League well, having been there on many occasions while there was still war and there were service men by the hundreds to be danced with. Half a dozen men and boys were lounging at the curbstone, and they eyed her curiously, grimly, Eveley thought. She wondered if they knew she had come there to inspire them with love of the great America which they must learn to call home. She straightened her slim 44 shoulders at the thought, and walked into the building with quite a martial air, as became one on this high mission bent.

A keen-eyed, quick-speaking woman met her at the elevator, and led her back into what she called “your corner” of the room. Evidently the room was divided into countless corners, for several groups were clustered together in different sections. But Eveley gave them only a fleeting glance. Her heart and soul were centered on the group before her, eight boys, dark-eyed, dark-skinned, of fourteen years or thereabouts. They looked at Eveley appraisingly, as we always look on those who come to do us good. Eveley looked upon them with tender solicitude, as philanthropists have looked on their subjects since the world was born.

The introductions over, the keen-eyed one hurried away and Eveley faced her sub-Americans.

Then she smiled, a winsome smile before which stronger men than they have fallen. But they were curiously unsmiling in response. Their eyes remained appraising almost 45 to the point of open suspicion. Perhaps her very prettiness aroused the inherent opposition of the male creature to female uplift.

Eveley began, however, bravely enough, and told them her first and prettiest story of sacrifice and country love. They listened gravely, but they were not thrilled. Struggling against a growing sense of incompetence, Eveley talked on and on, one story after another, pretty word following pretty word. But each word fell alike on stony ground. They sat like graven images, except for the bright suspicious gleam of the dark eyes.

Finally Eveley stopped, and turned to them. “What do you think about it?” she demanded. “You want to be Americans, don’t you? You want to learn what being an American means, don’t you?” Her eyes were fastened appealingly on a slender Russian lad, slouching in his chair at the end of the row. “You want to be an American, I know.”

Suddenly the slim lithe figure straightened, and the dark brows drew together in a 46 frown. “What are you getting at?” came in a sharp tone. “I’m an American, ain’t I? You don’t take me for no German, do you?”

“No, no, of course not,” she apologized placatingly. “Oh, certainly not. I mean, you want to learn the things of America, so you can love this country, and make it yours. Then you will forget that other land from which you came, and know this for your own, now and forever.”

Eveley was arrested by the steady gleam of a pair of eyes in the middle of the row. There was open denial and disbelief written in every feature and line of his face.

“Why?” came the terse query, as Eveley paused.

Eveley gazed upon him in wonderment. “Wh-what did you say?”

“I said, why?”

“Well, why not?” she countered nervously. “This is your country now. You must love it best in all the world, and must grow to be like us,—one of us,—America for Americans only, you know.”

“You tell us to forget the land we came 47 from,” he said in an even impersonal voice. “Is that patriotism,—to forget the land of your birth? I thought patriotism was to remember your home-land,—holding it in your heart,—hoping to return to it again,—and make it better.”

“But—but that is not patriotism to this country,” protested Eveley, aghast. “That is—disloyalty. If you wish to be always of your own land, and to love it best, you should stay there. If you come here, to get our training, our education, our development, our riches,—then this must be your country, and no other.”

“Why?” he asked again. “Why should we not come here and get all the good things you can give us, and learn what you can teach us, and take what money we can earn, and then go back with all these good things to make our own land bigger and better and richer? That is patriotism, I think.”

“No, no,” protested Eveley again. “That is not loyalty. If you choose this country for your home, it must be first in your heart, and last also. This is your home-land now,—the 48 land you believe in, the land of your love, America first.”

“But America was not first. The home-land was first.”

“Yes, it was first,” she admitted pacifically. “But America is last. America is the final touch. And so now you will learn our language, our games, our business, our way of life. You will live here, work here, and if war comes again you will die for America.”

Then she went on very quickly, fearful of interruptions that were proving so disastrous. “That is why we are organizing this little club, you boys and I. We are going to talk together. We are going to play together. We are going to study together. So you can learn American ways in all things. Now what kind of club shall we have? That is the American way of doing things. It is not my club, but yours. You are the people, and so you must decide.”

A long and profound silence followed, evidently indicative of deep thought.

“A baseball club,” at last suggested a small Jap with a bashful smile. 49

“That is a splendid idea,” cried Eveley brightly. “Baseball is a good American sport, a clean, lively game. Now what shall we call our baseball club?”

Again deep thought, but in a moment from an earnest Jewish boy came the suggestion, “The Irish-American Baseball League.”

Eveley searched his face carefully, looking for traces of irony. But the pinched thin features were earnest, the eyes alight with pleased gratification at his readiness of retort.

A hum of approval indicated that the Irish-American League had met with favor. But Eveley wavered.

“Why?” she asked in puzzled tone. “There is not an Irish boy here. You are Italians, and Spanish, and Jewish, and Russian, so why call it Irish-American?”

“My stepfather is an Irishman, his name is Mike O’Malley,” said a small Mexican. “So I’ll be the captain.”

“G’wan, ain’t it enough to get the club named for you?” came the angry retort. “What you know about baseball, anyhow?” 50

Eveley silenced them quickly. “Let’s just call it the American League,” she pleaded.

“The Irish-American League is well known, and gets its name in the paper,” was the ready argument in its favor.

And this fact, together with the strong appeal the words had made to their sense of dignity, proved irresistible. They refused to give it up. And when Eveley tried to reason with them, they told her slyly that the proper way to decide was by putting it to vote.

Eveley swallowed hard, but conscientiously admitted the justice of this, and put the question to vote. And as the club was unanimously in favor of it, and only Eveley was opposed, her Americanization baseball club of Italians and Mexicans and Orientals went down into history as the Irish-American League.

When it came to voting for officers, she again met with scant success. They flatly refused to have a president, stating that a captain could do all the bossing necessary, and that baseball clubs always had a captain. In the vote that followed the result was curiously 51 impartial. Every boy in the club voted for himself. Eveley, who had been won by the bright face of a young Jewish boy sitting near her with keen eyes intent upon her, voted for him, which gave him a fifty per cent. majority over the nearest competitor, and Eveley declared him the captain.

A few moments later, Eveley was called away to the telephone by Nolan, wishing to know what time he should call for her and the moment she was out of hearing, the club went into noisy conference. Upon her return, the argumentative Russian announced that the vote had been changed, and he was unanimously elected captain.

“But how did that happen?” Eveley demanded doubtfully. “Did the rest of you change your votes, and decide he should be captain?”

There was a rustle of hesitation, almost a dissenting murmur.

The newly elected captain lowered his brows ominously. “You did, didn’t you?” he asked, glaring around on his fellow members.

“Yes,” came feebly though unanimously. 52

“Did—did you vote?” questioned Eveley tremulously.

“Sure, we voted,” said the captain amiably. “We decided that I know the game better than the rest of the guys, and I can lick any kid in this gang with one hand, and we decided that I ought to be the captain. Ain’t that right?” Again he turned lowering brows on the Irish-American League.

No denial was forthcoming, and although Eveley felt assured that in some way the American ideal of popular selection had been violently outraged, it seemed the part of policy to overlook what might have occurred. Some minor rules were agreed upon, and the club decided to meet for practise every evening after school. Eveley could not attend except on Saturdays, and a boy near her, whose features had seemed vaguely and bewilderingly familiar, announced that he must withdraw as he worked and had no time for baseball. The captain professed his ability to fill up the club to the required number with exceptional baseball material, and the meeting adjourned without further parley. 53

This one meeting sufficed unalterably to convince Eveley that she was totally and helplessly out of her element. She was not altogether sure those quick-witted boys needed Americanizing, but she was sure that she was not the one to do it if they did require it. She realized that she had absolutely no idea how to go about instilling principles of freedom and loyalty in the hearts of young foreigners.

It was with great sadness that she began adjusting her hat and collar ready to go home, leaving defeat and failure behind her, when a blithe voice at her elbow broke into her despair.

“So long, Miss Ainsworth; see you in the morning.”

Eveley whirled about and stared into the face of the small lad whose features had seemed so curiously familiar.

“To-morrow?” she repeated.

“Surest thing you know, at the office,” he said, grinning impishly at her evident inability to place him. “I knew all the time you didn’t know me. I am Angelo Moreno, the 54 Number Three elevator boy at the Rollo Building.”

“Do—do you know who I am?”

“Sure, you’re Miss Ainsworth, old Jim Hodgin’s private secretary.”

“How long have you been there?”

“About a year and a half.”

“I never noticed,” she said, and there was pain in her voice.

“Oh, well,” he said soothingly, “there’s always a jam going up and down when you do, and you are tired evenings.”

“But you are in the jam, too, and you are tired as well as I, but you have seen.”

“That’s my job,” he said complacently. “I got to know the folks in our building.”

“How much do you know about me?” she pursued with morbid curiosity.

He grinned at her again, companionably. “You’re twenty-five years old, and you’re stuck on that fellow Inglish, with Morrow and Mayne over at the Holland Building. You used to live with your aunt up on Thorn Street, but she died and you got the house. B. T. Raines is your brother-in-law, and he’s 55 got two kids, but his wife is not as good-looking as you are. You stayed with them two months after your aunt died, but last week you got a bunch of your beaux, soldiers and things, to build you some steps up the outside of your house and now you live up there by yourself. Gee, I’d think you’d be afraid of pirates and Greasers and things coming up that canyon from the bay to rob you—you being just a woman alone up there.”

Eveley gazed upon him in blank astonishment. “Do—do you know that much about everybody in our building?” she asked.

“Well, I know plenty about most of ’em, and some things that some of ’em don’t know I know, and wouldn’t be keen on having talked around among strangers. But of course I pays the most attention to the good-lookers,” he admitted frankly.

“Thank you,” said Eveley, with a faint smile. Then she flushed. “What nerve for me to talk of assimilation,” she said. “We don’t know how to go about it. We have been asleep and blind and careless and stupid, 56 but you—why, you will assimilate us, if we don’t look out. You are a born assimilator, Angelo, do you know that?”

“I guess so,” came the answer vaguely, but politely. “I live about half a mile below you, Miss Ainsworth, at the foot of the canyon on the bay front. That’s all the diff there is between us and you highbrows in Mission Hills—about half a mile of canyon.” He smiled broadly, pleased with his fancy.

“That isn’t much, is it, Angelo? And it will be less pretty soon, now that we are trying to open our eyes. Good night, Angelo. I will see you to-morrow—really see you, I mean. And please don’t assimilate me quite so fast—you must give me time. I—I am new to this business and progress very slowly.”

Then she said good night again, and went away. And Angelo swaggered back to his companions. “Gee, ain’t she a beaut?” he gloated. “All the swells in our building is nuts on that dame. But she gives ’em all the go-by.”

Then the Irish-American League, without 57 the assimilator, went into a private session with cigarettes and near-beer in a small dingy room far down on Fifth Street—a session that lasted far into the night.

But Eveley Ainsworth did not know that. She was sitting in the dark beside her window, staring out at the lights that circled the bay. But she did not see them.

“Assimilate the foreign element,” she whispered in a frightened voice. “I am afraid we can’t. It is too late. They got started first—and they are so shrewd. But we’ve got to do something, and quickly, or—they will assimilate us, beyond a doubt. And weren’t they right about it, after all? Isn’t it patriotism and loyalty for them to go out to foreign countries to pick up the finest and best of our civilization and take it back to enrich their native land? It is almost—blasphemous—to teach them a new patriotism to a new country. And yet we have to do it, to make our country safe for us. But who has brains enough and heart enough to do it? Oh, dear! And they do not call it duty that brings them here to take what we can 58 give them—they call it love—not love of us and of America, but love of the little Wops and the little Greasers and the little Polaks in their own home-land. Oh, dear, such a frightful mess we have got ourselves into. And what a dunce I was to go to that silly meeting and get myself mixed up in it.”

The worries of the night never lived over into the sunny day with Eveley, and when she arose the next morning and saw the amethyst mist lifting into sunshine, when she heard the sweet ecstatic chirping of little Mrs. Bride beneath, she smiled contentedly. The world was still beautiful, and love remained upon its throne.

She started a little early for her work as she was curious to see Angelo in the broad light of day. It seemed so unbelievable that those bright eyes and smiling lips had been in the elevator with her many times a week for many months, and that she had never even seen them.

So on the morning after her initiation into the intricacies of Americanization, she beamed upon him with almost sisterly affection.

“Good morning, Angelo. Isn’t this a wonderful 60 day? Whose secrets have you ferreted out in the night while I was asleep?”

Angelo flushed with pleasure, and shoved some earlier passengers back into the car to make room for her beside him.

“I thought you’d be too sick to come this morning,” he said, with his wide smile that displayed two rows of white and even teeth. “I thought it would take you twenty-four hours to get over us.”

“Oh, not a bit of it,” she laughed. “And I am equally glad to see that you are recovering from your attack of me.”

This while the elevator rose, stopping at each floor to discharge passengers.

At the fifth floor Eveley passed out with a final smile and a light friendly touch of her hand on Angelo’s arm.

This was the beginning of their strange friendship, which ripened rapidly. Her memory of that night in the Service League with the Irish-American Club was very hazy and dim. Except for the tangible presence and person of Angelo, she might easily have believed it was all a dream. 61

In spite of her deep conviction that she was not destined to any slight degree of success as an Americanizer, Eveley conscientiously studied books and magazines and attended lectures on the subject, only to experience deep grief as she realized that every additional book, and article, and lecture, only added to her disbelief in her powers of assimilation.

So deep and absolute was her absorption, that for some days she denied herself to her friends, and remained wrapped in principles of Americanization, which naturally caused them no pleasure. And when a morning came and she called a hasty meeting of her four closest comrades, voicing imperative needs and fervent appeals for help, she readily secured four promises of attendance in the Cloude Cote that evening at exactly seven-thirty.

At seven-forty-five Eveley sat on the floor beside the window impatiently tapping with the absurd tip of an absurd little slipper. Nolan had not come.

Kitty Lampton was there, balancing herself 62 dangerously with two cushions on the arm of a big rocker. Eveley called Kitty the one drone in her circle of friendship, for Kitty was born to golden spoons and lived a life of comfort and ease and freedom from responsibility in a great home with a doting father, and two attentive maids. Eileen Trevis was there, too, having arrived promptly on the stroke of seven-thirty. Eileen Trevis always arrived promptly on the stroke of the moment she was expected. She was known about town as a successful business woman, though still in the early thirties. The third of the group was Miriam Landis, whose inexcusable marriage to her handsome husband had seriously deranged the morale of the little quartet of comrades.

Eveley looked around upon them. “It is a funny thing, a most remarkably funny thing!” she said indignantly. “Every one says that girls are always late, and you three, except Eileen, are usually later than the average late ones. Yet here you are. And every one says that men are always prompt, and Nolan is certainly worse than the average 63 man in every conceivable way. But Nolan, where is he?”

“Well, go ahead and tell us the news anyhow,” said Kitty, hugging the back of the chair to keep from falling while she talked. “But if it is anything about that funny Americanization stuff, you needn’t tell it. I asked father about it, and he explained it fully, only he lost me in the first half of the first sentence. So I don’t want to hear anything more about it. And you don’t need to tell me any more ways of not doing my duty, either, for I am not doing it now as hard as I can.”

Miriam Landis leaned forward from the couch where she was lounging idly. “What is this peculiar little notion of yours about duty, Eveley?” she asked, smiling. “My poor child, all over town they are exploiting you and your silly notions. Even my dear Lem uses your disbelief in duty to excuse himself for being out five nights a week.”

“That is absurd,” said Eveley, flushing. “And they may laugh all they like. I do believe that duty has wrecked more homes and ruined more lives than—than vampires.” 64

Miriam smiled tolerantly. “Wait till you get married, sweetest,” she said softly. “If married women did not believe in duty, and do it, no marriage would last more than six months.”

“Well, I qualify myself, you know,” said Eveley excusingly. “I do think everybody has one duty—but only one—and it isn’t the one most people think it is.”

“For the sake of my immortal soul, tell me,” pleaded Kitty. “It was you who led me into the dutiless paths. Now lead me back.”

“Get up, Kitty, and don’t be silly,” said Eveley loftily. “This is not a driven duty, but a spontaneous one. And you don’t need to know what it is, for it comes naturally, or it doesn’t come at all. Isn’t that Nolan the most aggravating thing that ever lived? Eight o’clock. And he promised for seven-thirty.”

“Go on and tell us, Eveley,” said Eileen Trevis. “Maybe somebody is sick, and has to make a will, and he won’t be here all night.”

“Oh, I can’t tell it twice. You know how many questions Nolan always asks, and besides 65 I want to surprise you all in a bunch. Look, did I show you the new blouse I got to-day? I needed a new one to Americanize my Irish-Americans Saturday. It cost ten dollars, and perfectly plain—but I look like a sad sweet dream in it.”

Then the girls were absorbed in a discussion of the utter impossibility of bringing next month’s allowance or salary within speaking distance of last month’s bills, a subject which admitted of no argument but which interested them deeply. So after all they did not hear the rumble and creak of the rustic stairway, nor the quick steps crossing the garden on the roof of the sun parlor for Nolan was forgotten until his sharp tap on the glass was followed by the instant appearance of his head, and his pleasant voice said in tones of friendly raillery:

“Every time I climb those wabbly rattly-bangs that you call rustic stairs, I wonder that you have a friend to your name. Hello, Eveley.”

“Inasmuch as you made the wabbliest pair of all, and since you climb them more than 66 anybody else, you haven’t much room to talk,” returned Eveley tartly, drawing back the portières to admit his entrance, which was no laughing matter for a large man.

“You positively are the latest thing that ever was,” she went on, as he landed with a heavy thud.

“Me? Why, I am the soul of punctuality.”

“You may be the soul of it, but punctuality does not get far with a soul minus willing feet.”

“Anyhow, I am here, and that is something,” he said, making the rounds of the room to shake hands cordially with the other girls.

Eveley hopped up quickly on to the small desk—shoving the telephone off, knowing Nolan would catch it, as indeed he did with great skill, having been catching telephones and vases and books for Eveley for five full years. She clasped her hands together, glowing, and her friends leaned toward her expectantly.

“I have called you together,” she began in a high, slightly imperious voice, “my four 67 best friends, counting Nolan, because I need advice.”

“Do you wish to retain me as counsellor?” asked Nolan, with a strong legal accent “My fee—”

“I do not wish to retain you in any capacity,” Eveley interrupted quickly. “My chief worry is how to dispose of you satisfactorily. And as for fees—Pouf! Anyhow, I need advice, good advice, deep advice, loving advice. So I have called you into solemn conclave, and because it is a most exceptional occasion I have prepared refreshments, good ones, sandwiches and coffee and cake—Did you bring the cake, Kit? And ice-cream—the drug-store is going to deliver it at ten, only the boy won’t climb the stairs; you’ll have to meet him at the bottom, Nolan. So I hope you realize that it is an affair of some moment, and not—Miriam Landis, are you asleep?”

Miriam flashed her eyes wide open, denial on her lips, but Kitty forestalled her. “That is a pose,” she explained. “Billy Ferris said, and I told Miriam he said it, that with her 68 eyes closed, she is the loveliest thing in the world. And since then she walks around in her sleep half the time.”

Miriam turned toward her, still more indignant denial clamoring for utterance, but Eveley, accepting the explanation as reasonable, went quickly on.

“Now I want you to be very serious and thoughtful—can you concentrate better in the dark, Kit? Because I know at seances and things they turn off the lights, and—”

“Oh, let’s do. And we’ll all hold hands, and concentrate, and maybe we’ll scare up a ghost or something.” Then she looked around the room—four girls and Nolan—Nolan, who had edged with alacrity toward Eveley on the telephone desk—and Kitty shrugged her shoulders. “Oh, what’s the use? Never mind. Go on with the gossip, Eveley. I can think with the lights on.”

“The ice-cream will be here before we get started,” said Eileen Trevis suddenly.

Eveley clasped her hands again and smiled. “I have received a fortune. Somebody died—you needn’t advise me to wear mourning, 69 either, Miriam. I never saw him in my life, and never even heard of him, and honestly I think he got me mixed up with somebody else and left the fortune to the wrong grand-niece, but anyhow it is none of my business, and since he is dead and the money is here, I suppose there is no chance of his discovering the mistake and making me refund it after it is spent.”

“A fortune,” gasped Kitty, tumbling off the arm of the chair and rushing to fling herself on the floor beside Eveley, warm arms embracing her knees.

“Root of all evil,” murmured Miriam, gazing into space through half-closed lids, and seeing wonderful visions of complexions and permanent curls and a manicure every day.

“How fortunate,” said Eileen in a voice pleased though still unruffled and even. “A fortune means safety and protection and—”

“Who the dickens has been butting into your affairs now?” demanded Nolan peevishly, and though the girls laughed, there was no laughter in his eyes and no smile on his lips. 70

“Well, since he calls me his great-niece, I suppose he is my grand-uncle.”

“How much, lovey, how much?” gurgled Kitty, at her side.

“Twenty-five hundred dollars,” announced Eveley ecstatically.

Nolan breathed again. “Oh, that isn’t so bad. I thought maybe some simp had left you a couple of millions or so.”

Eveley fairly glared upon him. “What do you mean by that? Why a simp? Why shouldn’t I be left a couple of millions as well as anybody else? Maybe you think I haven’t sense enough to spend a couple of millions.”

“And why did you require advice?” Eileen queried.

“Oh, yes.” Eveley smiled again. “Yes, of course. Now you must all think desperately for a while—I hate to ask so much of you, Nolan—but perhaps this once you won’t mind—I want you to tell me what to do with the money.”

This was indeed a serious responsibility. What to do with twenty-five hundred dollars? 71

“You do not feel it is your duty to spend the twenty-five hundred pounding Americanism into your Irish-American Wops?” asked Nolan facetiously.

Eveley took this good-naturedly. “Oh, I got off from work at four-thirty and went down to their field, and we had a celebration. We had ice-cream and candy and chewing gum, and I spent twenty-five dollars equipping them with balls and bats and since I was with them an hour and a quarter, I feel that I am entitled to the rest of the fortune myself.”

“Well, dearie,” said Eileen, “it is really very simple. Put it in a savings account, of course. Keep it for a rainy day. You may be ill. You may get married—”

“Can’t she get married without twenty-five hundred dollars?” asked Nolan, with great indignation. “She doesn’t expect to buy her own groceries when she gets married, does she?”

“She may have to, Nolan,” said Eileen gently. “One never knows what may happen after marriage. Getting married is no laughing 72 matter, and Eveley should be prepared for any exigency.”

“But, Eileen, she won’t need her twenty-five hundred to get married. No decent fellow would marry a girl unless he could support her, and do it well, even luxuriously. You don’t suppose I would let my wife spend her twenty-five hundred—”

“If you mean me, I shall do whatever I like with my own money when I get married,” said Eveley quickly. “My husband will have nothing to say about it. You needn’t think for one minute—”

“I am not your husband, am I? I haven’t exactly proposed to you yet, have I?”

Eveley swallowed hard. “Certainly not. And probably never will. By the time you get around to it, getting married will be out of date, and none of the best people doing it any more.”

“You may not have asked her, Nolan,” said Eileen evenly. “And that is your business, of course. She will probably turn you down when you do ask her, just as she does everybody else. But—” 73

“Who has been asking her now?” he cried, with jealous interest.

“But while we are on the subject, I hope you will permit me to say that I think your principles are all wrong, and even dangerous. You think a man should wait a thousand years until he can keep a wife like a pet dog, on a cushion with a pink ribbon around her neck—”

“The dog’s neck, or the wife’s?”

“The dog’s—no, the wife’s—both of them,” she decided at last, with never a ruffle. “You want to wait until she is tired of loving, and too old to have a good time, and worn out with work. It isn’t right. It is not fair. It is unjust both to yourself, and to Eve—to the girl.”

“But, my dear child,” he said. Eileen was three years older than Nolan; but being a lawyer he called all women “child.” “My dear child, do you realize that my salary is eighteen hundred a year, and I get only a few hundred dollars in fees. Think of the cost of food these days, and of clothes, and amusements, to say nothing of rent! Do you think 74 I would allow Eve—my wife, to go without the sweet things of—”

“You needn’t bring me in,” said Eveley loftily. “I have never accepted you, have I?”

“No, not exactly, I suppose, but—”

“Eveley,” said Miriam, suddenly sitting erect on the couch. “I have it.”

“Sounds like the measles,” said Kitty.

“I mean I know what to do with the money. Listen, dear. You do not want to go on slaving in an office until you are old and ugly. And Nolan is quite right, you certainly can not marry a grubby clerk in a law office.”

Nolan laughed at that, but Eveley sat up very straight indeed and fairly glowered at her unconscious friend on the couch.

“You must have the soft and lovely things of life, and the way to get them is to marry them. Now, sweet, you take your twenty-five hundred, be manicured and massaged and shampooed until you are glowing with beauty, buy a lot of lovely clothes, trip around like a lady, dance and play, and meet men—men with money—and there you are. You can look like a million dollars on your 75 twenty-five hundred—and your looks will get you the million by marriage.”

“Miriam Landis, that is shameful,” said Nolan in a voice of horror. “It is disgraceful. I never thought to hear a woman, a married woman, a nice woman, utter such low and grimy thoughts. Could any such marriage be happy?”

“Well, Nolan,” said Miriam sadly, “I am not sure that any marriage can be happy, or was ever supposed to be. But women are such that they have to try it once. Eveley will be like all the rest. And if she has to try it, she had better try it with a million, than with eighteen hundred a year.”

“There is something in that, Miriam, certainly,” said Eveley thoughtfully. “What do you think, Eileen?”

“I think it is absurd. The notion that woman was born for marriage died long ago. Ridiculous! Woman is born for life, for service, for action, just as man is. Look at the married people you know. How many of them are happy? I do not wish to be personal, but I know very few married people, 76 either men or women, who would not be glad to undo the marriage knot if it could be done easily and quietly without notoriety. They are not happy. But we are happy. Why? Because we work, we think, we feel, we live. We are not slaves to the contentment of man. Go on working, my dear. Keep your independence. But play safe. Put your money in the bank, or in some good investment, and let it safeguard your future. Then you can go your way serene.”

“That is certainly sound. Marriage isn’t the most successful thing in the world.”

“I should say not,” chimed Kitty. “Husbands are always tired of wives, their own, I mean, inside of five years.”

“Well, if it comes to that,” said Eveley honestly, “I suppose wives are tired of their own husbands, too. But they are so stubborn they won’t admit it. In their hearts I suppose they are quite as sick of their husbands as their husbands are of them.”

“Eve,” said Nolan anxiously, “where are you getting all these wicked notions? Marriage is the most sacred—” 77

“Institution. I know it. Every one says marriage is a sacred institution, and so is a church. But nobody wants to live with one permanently.”

“But, Eveley, the sanctity of the—”

“Home. Sure, we know it is sanctified. But monotonous. Deadly monotonous.”

“Eve,” and his voice was quite tragic, “don’t you feel that the divine sphere of—”

“Woman. You needn’t finish it, Nolan; we know it as well as you do. The divine sphere of woman is in the sanctified home keeping up the sacred institution of marriage while her husband—oh, tralalalalalala.”

“Yes, sir, I’ll go you,” cried Kitty suddenly, leaping up from the floor, and waving her hand. “Europe! You and I together.”

“She has come to,” said Eileen resignedly. “There’s an end of sensible talk for this evening.”

“Yes, Kit, what is it? I knew you would think of something good.”

“We’ll go to Europe, you and I. I think I can work dad to let me go. I can pretend to fall in love with the plumber, or somebody, 78 and he’ll be glad to trot me off for a while. And he likes you, Eveley. He thinks you are so sensible.”

“Why, he hardly knows me,” cried Eveley, astonished.

“Yes, that is why. I tell him how sensible you are when you are not there, and when he gets home I hustle you out of his sight in a hurry. He likes me to have sensible friends.”

“And what shall we do with the money?”

“Travel, travel, travel, and have a gay good time,” said Kitty blithely. “All over Europe. We’ll get some handsome clothes, and have the time of our lives as long as the money lasts, and then marry dukes or princes or something like that.”

“Two of you,” shouted Nolan furiously. “Well, Eve, it is a good thing you have one friend to give you really decent advice. Of all idiotic ideas. Buy fine clothes and marry a millionaire. Save it to pay for potatoes when you get a husband that can’t support you. Travel to Europe and marry some purple prince.”

“Why purple?” asked Eveley curiously. 79

“Do you mean clothed in purple and fine linen?”

“If you mean blood, it is blue,” said Kitty. “Blue-blooded princes. Whoever heard of a purple-blooded prince?”

“What did you mean anyhow, Nolan?” asked Eileen.

Driven into a corner, Nolan hesitated. He had said purple on the spur of the moment, chiefly because it sounded derogatory and went well with prince.

“What I really mean,” he began in a dispassionate legislative voice, “what I really mean is—purple in the face. You know, purple, splotchy skin, caused by eating too much rich food, drinking too much strong wine, playing cards and dancing and flirting.”

“Does flirting make you purple?” gasped Miriam. “It does not show on Lem yet.” And then she subsided quickly, hoping they had not noticed.

“Why, Nolan, I have danced for weeks and weeks at a stretch, evenings, I mean, when the service men were here,” said Kitty, “and I am not purple yet.” 80

“Oh, rats,” said Nolan. Then he brightened. “You have never seen a prince, so of course you do not understand. Wait till you see one. Then a purple prince will mean something in your young life.”

“I should not like to marry a purple creature,” said Eveley, wrinkling her nose distastefully. “I am too pink. And my blue eyes would clash with a purple husband, too. But maybe the dukes and lords are a different shade,” she finished hopefully.

Nolan turned his back, and lit a cigarette.

“Yes, you may smoke, Nolan, by all means. I always like my guests to be comfortable.”

“What is your advice then, Nolan? You are so scornful about our suggestions,” said Eileen quietly.

“I know what Nolan would like,” said Kitty spitefully. “He would advise Eveley to give him the money and make him her executor and appoint him her guardian. That would suit him to a T.”

“My poor infant, Eveley can not use an executor and a guardian at the same time. 81 One comes in early youth, or old age, the other after death. An executor—” he began, clearing his throat as for a prolonged technical explanation.

Kitty plunged her fingers into her ears. “You stop that right now, Nolan Inglish. We came here to advise Eveley, not for you to practise on. If you begin that I shall go straight home—no, I mean I shall go out on the steps and wait for the ice-cream.”

“What do you advise, Nolan?” persisted Eileen.

“Well, my personal advice is, and I strongly urge it, and plead it, and it will make me very happy, and—?”

“He wants to borrow it,” gasped Kitty.

“Go on, Nolan,” urged Eveley eagerly.

“Put it in the bank on your checking account.”

“Put it—”

“Checking account?”

“Yes, indeed, right in your checking account.”

A slow scornful light dawned in Eileen’s eyes. “I see,” she said coldly. “Very selfish, 82 very unprofessional, very unfriendly. He would have his lady love absolutely bankrupt, that he may endow her with all the goods of life.”

“Why, Nolan,” said Eveley weakly, lacking Eileen’s sharper perception, “don’t you know me well enough to realize that if I put it into my checking account it will be gone, absolutely and everlastingly gone, inside of six months, and not a thing to show for it?”

“Yes, I know it,” he admitted humbly.

“And still you advise it?”

“I do not advise it—I just want it,” he admitted plaintively.

Eveley sat quietly for a while, counting her fingers, her lips moving once in a while, forming such words as marriage, travel, princes and banks. Then she clapped her hands and beamed upon them.

“Lovely,” she cried. “Exquisite! Just what I wanted to do myself! You are dear good faithful friends, and wise, too, and you will never know how much your advice has helped me. Then it is all settled, isn’t it? And I shall buy an automobile.” 83

In a flash, she caught up a pillow, holding it out sharply in front of her, whirling it around like a steering wheel, while she pushed with both feet on imaginary clutches and brakes, and honked shrilly.

But her friends leaned weakly back in their chairs and stared. Then they laughed, and admitted it was what they had expected all the time.

Eveley’s resolve to spend her fortune for an auto met with less resistance than she had anticipated. It seemed that every one had known all along that she would fool the money away on something, and a motor was far more reasonable than some things.

“I said travel,” said Kitty. “And we can travel in a car as well as on a train—more fun, too. And though it may cut us off from meeting a purple prince—a pretty girl with a car of her own is a combination no man can resist. And maybe if we are very patient and have good luck, we may save a millionaire from bandits, or rescue a daring aviator from capture by Mexicans.”

Miriam nodded, also, her eyes cloudy behind the dark lashes. “Very nice, dear. Get a lot of stunning motor things and—irresistible, simply irresistible. You must have a 85 red leather motor coat. You will be adorable in one. But you’ll have to shake Nolan, dear. You stand no chance in the world if you are constantly herded by a disagreeable young lawyer, guardianing you from every truant glance.”

“It isn’t at all bad,” quickly interposed Eileen. “I believe that more than anything else in the world, a motor-car reconciles a woman to life without a husband. She gets thrills in plenty, and retains her independence at the same time.”

“Eileen,” put in Nolan sternly, “I am disappointed in you. A woman of your ability and experience trying to prejudice a young and innocent girl against marriage is—is—”

“You are awfully hard to suit, Nolan,” complained Eveley gently. “You shouted at Miriam and Kitty for advising a husband, and now you roar at Eileen for advising against one.”

“It isn’t the husband I object to—it is their cold-blooded scheme to go out and pick one up. Woman should be sought—”

“Well, when Eveley gets a car she’ll be 86 sought fast enough,” said Kitty shrewdly. “She hasn’t suffered from any lack of admirers as it is, but when she goes motoring on her own—ach, Louie.”

“Then you approve of the car, do you, Nolan?”

“Well, since I can not think of any quicker or pleasanter way of spending the money,” he said slowly, “I may say that I do, unequivocally.”

“Why unequivocally?”

“What’s it mean, anyhow?” demanded Kitty.

“Can’t you talk English, Nolan?” asked Eveley, in some exasperation. “You started off as if you were in favor, but now heaven only knows what you mean.”

“Get your car, my poor child, by all means. Get your car. But a dictionary is what you really need.”

The rest of the evening they were enthusiastic almost to the point of incoherency. Kitty was in raptures over an exquisite red racer she had seen on the street. Miriam described Mary Pickford’s rose-upholstered car, 87 and applied it to Eveley’s features. Nolan developed a surprisingly intimate knowledge of carburetors, horse-powers and cylinders.

When at last they braved the rustic stairway, homeward bound, with exclamatory gasps and squeals, gradually drifting away into silence, Eveley sat down on the floor to take off her shoes—a most childish habit carried over into the years of age and wisdom—and was immediately wrapped in happy thoughts where stunning motor clothes and whirring engines and Nolan’s pleasant eyes were harmoniously mingled. And when at last she started up into active consciousness again, and rushed pellmell to bed, mindful of her responsibility as a business girl, sleep came very slowly. And when it came at last, it was a chaotic jumble of excited dreams and tossings.

The life of the bride and groom in the nest beneath Eveley’s Cloud Cote had progressed so sweetly and smoothly that Eveley had come to feel it was quite a friendly dispensation of Providence that permitted her to live 88 one story up from Honeymooning. So the next morning, in the midst of the confusion that came from dressing and getting her breakfast and reading motor ads in the morning paper at the same time, she was utterly electrified to hear a sudden sharp cry of anguish from little Mrs. Bride beneath—a cry accompanied by sounds caused by nothing in the world but a passionate and hysterical pounding of small but violent feet upon the floor.

“Oooooh, oooooh, don’t talk to me, Dody, I can’t bear it. I can’t, I can’t. Ooooh, I wish I were dead. Go away, go away this instant and let me die. Oh, I shall run away, I shall kill myself! Oooooh!”

“Dearie, sweetie, don’t,” begged Mr. Groom distractedly. “Lovie, precious, please.” And his voice faded off into tender inarticulate whispers.

For a long second Eveley was speechless. Then she said aloud, very grimly, “Hum. It has begun. I suppose I may look for flat-irons and rolling-pins next. Hereafter they are Mr. and Mrs. Ordinary Married People.” 89

After long and patient, demonstrative pleading on his part, Mrs. Severs was evidently restored to a semblance of reason and content, and quiet reigned for a while until the slam of the door indicated that Mr. Severs had heeded the call of business.

Almost immediately there came a quick creaking of the rustic stairs and a light tap on Eveley’s window.

“Come in,” she called pleasantly. “I sort of expected you. You will excuse me, won’t you, for not getting up, but I have only fifteen minutes to finish my breakfast and catch the car.”

“You are awfully businesslike, aren’t you?” asked Mrs. Severs admiringly. “Yes, I will have a cup of coffee, thanks. I need all the stimulation I can get.”

She was pale, and her eyes were red-rimmed, Eveley noted commiseratingly.

“We are expecting an addition to our family this afternoon, Miss Ainsworth,” she began, her chin quivering childishly.

“Mercy!” gasped Eveley.

“Our father-in-law,” added Mrs. Severs 90 quickly. “Dody’s father. He is coming to live with us.”

“Oh!” breathed Eveley. “Won’t that be lovely?”

Mrs. Severs burst into passionate weeping. “It won’t be lovely,” she sobbed. “It will be ghastly.” She sat up abruptly and wiped her eyes. “He is the most heart-breaking thing you ever saw, and he doesn’t like me. He doesn’t approve of dimples, and he says I am soft. And he has the most desperate old chum you ever saw, a perfect wreck with red whiskers, and they get together every night and play pinochle and smoke smelly old pipes, and he won’t have curtains in his bedroom, and he is crazy about a phonograph, and he won’t eat my cooking.”

“I should think you would like that,” said Eveley. “Maybe he will cook for himself.”