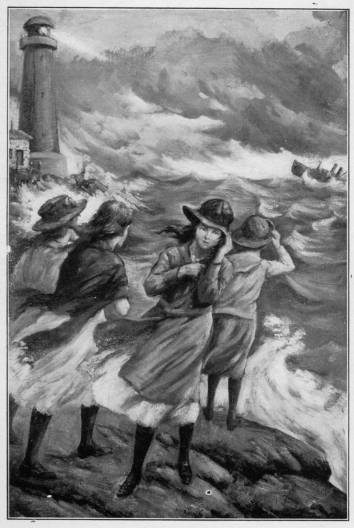

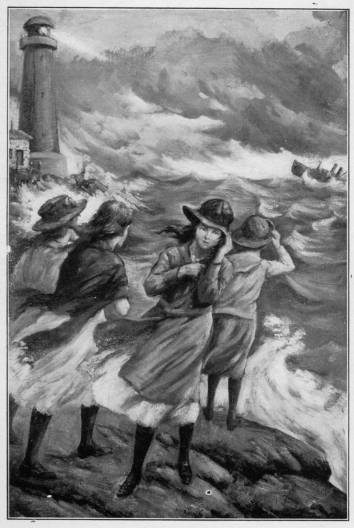

The girls came out upon the point where the lighthouse stood. (See Page 175)

Project Gutenberg's Billie Bradley on Lighthouse Island, by Janet D. Wheeler

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Billie Bradley on Lighthouse Island

The Mystery of the Wreck

Author: Janet D. Wheeler

Release Date: June 12, 2008 [EBook #25762]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILLIE BRADLEY ON LIGHTHOUSE ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BILLIE BRADLEY ON

LIGHTHOUSE ISLAND

OR

THE MYSTERY OF THE WRECK

BY

JANET D. WHEELER

AUTHOR OF “BILLIE BRADLEY AND HER INHERITANCE,”

“BILLY BRADLEY AT THREE TOWERS HALL,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

BILLIE BRADLEY SERIES

BY JANET D. WHEELER

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

|

Billie Bradley and Her Inheritance Or The Queer Homestead at Cherry Corners Billie Bradley at Three Towers Hall Or Leading a Needed Rebellion Billie Bradley on Lighthouse Island Or The Mystery of the Wreck |

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

Publishers New York

Copyright, 1920,

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

Billie Bradley on Lighthouse Island

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Lost | 1 |

| II | The Hut in the Woods | 9 |

| III | Ferns and Mystery | 17 |

| IV | At the School Again | 25 |

| V | Much Ado About Nothing | 33 |

| VI | Found—One Album | 41 |

| VII | Strange Actions | 49 |

| VIII | An Invitation | 57 |

| IX | Amanda Again | 63 |

| X | Two of a Kind | 71 |

| XI | At Home | 79 |

| XII | Preparing for the Trip | 86 |

| XIII | Pleasure Draws Near | 95 |

| XIV | The Light on Lighthouse Island | 102 |

| XV | Connie's Mother | 110 |

| XVI | Clam Chowder and Salt Air | 118 |

| XVII | Fun and Nonsense | 125 |

| XVIII | Uncle Tom | 133 |

| XIX | Paul's Motor Boat | 141 |

| XX | Out of the Fog | 150 |

| XXI | The Boys are Interested | 158 |

| XXII | The Fury of the Storm | 166 |

| XXIII | Fighting for Life | 174 |

| XXIV | Three Small Survivors | 182 |

| XXV | The Mystery Solved | 191 |

BILLIE BRADLEY ON

LIGHTHOUSE ISLAND

Splash! went a big drop just on the exact tip of Laura Jordon’s pretty, rather upturned nose. She put her hand to the drop to be sure she had not been mistaken, then turned in dismay to her companions.

“Girls,” she cried, “it’s raining!”

If she had said the world was coming to an end her companions could not have looked more startled. Then Billie Bradley cocked an eye at what she could see of the sky through the trees and held out one hand experimentally.

“You’re crazy,” she announced, turning an accusing eye upon Laura. “It’s no more raining than you are. And, anyway, haven’t we troubles enough without your going and making up a new one?”

“M-making up!” Laura stuttered in her indignation. “If you don’t believe me, just look at my nose.” 2

“I don’t see what your nose has to do with it,” Billie began scornfully, but the third of the trio, Violet Farrington, by name, interrupted.

“Laura’s right,” she cried. “I just felt a great big drop myself. Now, what ever are we going to do?” Vi dropped down in a pathetic little heap on a convenient rock, looking up at her chums wistfully.

Violet Farrington was always a little wistful when in trouble, like a small girl who can never understand why she is being punished. But just now this wistfulness irritated Billie Bradley, who was very much given to quick action herself, and she turned upon Vi rather snappily.

“Well, you needn’t just sit there like a ninny,” she cried. “Get up and help us think what we can do to get out of this mess.”

“Mess is right,” said Laura Jordon gloomily.

And it must be admitted that the girls were in rather a trying situation. Their botany teacher at Three Towers Hall, where they were students, had sent them into the woods to gather some rare ferns which they were to use in the botany class the next day.

That was all very well; for if there was anything the girls loved it was a trip into the woods. They had started off in hilarious spirits; and then—the impossible thing had happened.

They had gathered the ferns, turned to go back 3 to Three Towers, and found, to their absolute dismay, that they did not know which way to go. There was no getting over the fact. They were absolutely and completely lost!

For almost an hour now they had been wandering around and around, getting deeper into the woods every minute, until they had finally begun to feel really frightened. Suppose they couldn’t find Three Towers before dusk? Suppose they should be forced to stay in the woods all night? These and a hundred other thoughts had chased themselves through their heads, but they had said nothing of their fears to each other. The girls were thoroughly “game.”

But now had come this new complication. It had begun to rain. Hopelessly lost in the woods and a storm coming on! It was a situation to try the patience of a saint. And the girls were not saints. They were just happy, fun-loving, lovable specimens of young American girlhood who could upon occasion show rather alarming flashes of temper.

“I’m not a ninny,” Vi protested hotly; but Billie was already started on a different train of thought. She caught Vi’s wrist in hers and her eyes were big and round as she looked from her to Laura.

“Suppose,” she said in a whisper, “we should meet the Codfish!”

Vi shivered nervously, but it was Laura’s turn to be cross. 4

“Don’t be silly,” she said. “Don’t you know that the Codfish is safe in jail, and has been there for a long time? Now who’s making up something to worry about, I’d like to know.”

“But thieves do break out of jail,” Billie insisted. “And the Codfish is just the kind who would do it.”

“Goodness, Billie, what an idea!” said Vi breathlessly. “I never even thought about his escaping. And I suppose,” she added, beginning to feel deliciously goose-fleshy, “that we’d be the very first ones he’d go for. Revenge, you know—that’s what they are always after in the stories.”

“I hate to interrupt you,” Laura broke in as sarcastically as she could. “But if you two want to stand there all day talking about the Codfish and revenge, you can, but I’m going to find some way out of this place. Goodness, I felt another drop. And there’s another!”

“Well, you needn’t count them,” Billie remarked briskly, bringing an hysterical giggle from Vi. “Come on, there must be a path of some kind around here.”

“I suppose there is, but if we can’t find it, it won’t do us much good,” said Laura, looking about her helplessly.

“Well, we certainly won’t find it by standing still,” snapped Billie. “Come on. I feel it in my bones that Three Towers is somewhere off in this 5 direction.” And she led the way into the woods, the girls following dispiritedly.

And while the three chums are searching for the path, the opportunity will be taken to recount to new readers some of the adventures and queer experiences the girls had had up to the present time.

In the first book of this series, entitled, “Billie Bradley and Her Inheritance,” Billie had been left an old homestead at Cherry Corners in the upper part of New York State. The strange legacy had come to Billie from an eccentric aunt, Beatrice Powerson, for whom Billie had been named. For Billie’s real name was not Billie at all, but Beatrice.

It will be remembered that the girls had decided to spend their vacation there, and that the boys, Billie’s brother Chetwood, Laura’s brother Teddy, and another boy, Ferd Stowing, had joined them there and that queer and exciting adventures had followed.

The most wonderful thing of all had been the finding of the shabby old trunk in the attic whose contents of rare old coins and postage stamps had brought Billie in nearly five thousand dollars in cash. The money had enabled Billie to replace a statue which she had accidentally broken a little while before and had also given her the chance to go to Three Towers Hall, a good boarding school, and Chet the opportunity to go to the Boxton Military 6 Academy, which was only a little over a mile from Three Towers Hall.

The good times the girls had at school—and some bad times, too—have been told of in the second book of the series, called, “Billie Bradley at Three Towers Hall.”

In North Bend, where the girls had always lived, there lived also two other girls, Amanda Peabody and Eliza Dilks. These girls were sneaks and tattletales of the worst order and were thoroughly disliked by all the girls and boys with whom they had come in contact.

When the chums had heard that Amanda was to accompany them to Three Towers they were absolutely dismayed, for they expected that she would spoil all the fun. Amanda had done her best to live up to the expectations of the girls, but try as she would, she had not been able to spoil entirely the fun. And this very failure had, of course, made her and her chum, Eliza Dilks, furious.

Both Three Towers Hall and Boxton Military Academy had been built on the banks of the beautiful Lake Molata, and the girls and boys had spent many happy hours rowing upon the lake in the fall and skating upon it in the winter.

But the most amazing thing that had happened to them at Three Towers had been the capture of the man the girls called “The Codfish.” This rascal had attempted to steal Billie’s precious trunk in the 7 beginning, but Billie and the boys had given chase in an automobile and had succeeded in recovering the trunk. They had also succeeded in getting a good look at the man, whose hair was red, eyes little and close together, mouth wide and loose-lipped. It was this last feature that had given the thief his name with the boys and girls. For the mouth certainly resembled that of a codfish.

Later the “Codfish” had turned up again near Three Towers Hall, had robbed one of the teachers of her purse when she was returning from town, and had later succeeded in making off with a great many valuables from Boxton Military Academy.

The girls never forgot how, with the aid of the boys, they had captured the Codfish and turned him over to the police. Though, as Laura said, the thief had been in jail for some time, the chums had never stopped thinking and wondering about him. But never before had the possibility of his escaping been thought of.

But now, as they made their way through the forest that was growing darker and darker, they could not shake off the thought of him.

They glanced often and uneasily into the shadowy woodland and drew closer together as if for protection. The rain was beginning to come a little faster now, and their clothes felt damp. Even Billie’s courage was beginning to fail. 8

Suddenly Laura stopped stock still and looked at them impatiently.

“There’s not a bit of use our going on like this,” she said. “For all we know we may be getting farther away from the path every minute.”

“And my feet hurt,” added Vi pathetically.

Suddenly Billie called to them. She had gone on a little ahead and, peering through the dusk, had seen the outline of something dark, a black smudge against the gray of the woods.

“Girls, come here quick!” she cried, and half-fearing, half-hoping, they knew not what, the others ran to her.

“What is it?” Laura cried.

For answer Billie pointed through the gloom.

“There! See it?” she cried excitedly. “It’s some sort of little house, I guess—a hut or something.”

“A house!” cried Laura joyfully. “Glory be, let’s go! What’s the matter?” she asked, as the other girls hung back.

“Better not be in too much of a hurry,” Billie cautioned her. “The place looks as if it were empty; but you never can tell.”

“Well, there’s something I can tell,” Laura retorted impatiently. “And that is, that I’m getting soaking wet.” She started on again, but Billie called to her to stop.

“Don’t be crazy, Laura,” she whispered. “We’re all alone in the woods, and it’s almost night. How do we know who may be in that shack?”

“Oh, Billie, suppose it were the Codfish!” whispered Vi, and Laura looked disgusted.

“It isn’t apt to be the Codfish,” returned Billie. “But whoever it is, I think we’d better be careful. 10 We’ll go up to it softly and look about a bit. Please don’t any one speak until we’re sure it’s all right.”

The girls were used to obeying Billie, even impulsive Laura, so now they followed softly at her heels, stepping over twigs so as to make no noise.

“Goodness! anybody would think we were thieves ourselves,” Laura giggled hysterically, and Billie looked back at her warningly.

It was a strange thing and strangely made, this remote little shelter in the woods. It probably had some sort of framework of wood inside, but all the girls could see from the outside was a rude structure entirely covered by moss and interwoven twigs. In fact, unless one looked closely, one might think that the little hut was no hut at all, but part of the foliage itself.

The girls could find no windows, but as they moved cautiously around the hut Billie came upon a small door. The latter was hardly more than four feet high, and the girls would have to stoop considerably to get through it.

“For goodness sake, open it, Billie,” Laura whispered close in her ear. “It’s beginning to pour pitchforks and I’m getting soaking wet. I don’t care if a hyena lives in there, I’m going in too.”

Billie wanted to laugh, but she was too wet and nervous. So she opened the little door cautiously and peered inside.

For a minute she could not tell whether the hut 11 was empty or not, for it was very very dark. But as her eyes became accustomed to the darkness she felt sure that the place was empty.

“Come on,” she called over her shoulder to the girls, her voice still cautiously lowered. “I can’t see very well, but I guess there’s nobody at home.”

The girls had to stoop almost double to enter the tiny door, but once inside they were surprised to find that they could stand upright.

They were in almost entire darkness, the only patch of light coming from the little door that Vi had left open. Suddenly they began to feel panicky again.

“If we could only get a light,” whispered Vi.

“Goodness, listen to the child,” said Laura scornfully. “She wants all the comforts of home—ouch!” Her toe had come in contact with something hard.

“What’s the matter?” cried Billie startled.

“Matter enough,” moaned Laura. “I’ve broken my toe!”

“Oh well, if that’s all,” said Billie, but Laura began to laugh hysterically.

“Oh yes, that’s all,” she cried. “I only wish it had happened to you, Billie Bradley!”

If all wishes could be fulfilled as quickly as that of Laura’s there would be few unsatisfied people in the world, for before it was out of her mouth Billie uttered a sharp cry of pain, and, lifting a smarting ankle in her hand, began to rub it gently. 12

“Did you do it, too?” cried Laura joyfully, adding with a good imitation of Billie: “Oh well, if that’s all—”

“Oh for goodness sake, keep still,” cried Billie, from which it will be seen that Billie was not in the best of tempers. “This place must be full of stuff. Goodness, why didn’t we think to bring matches with us!”

“Because we went out to get ferns, not to burn up the woods,” said Laura, with a chuckle.

“Goodness!” cried Vi suddenly out of the darkness. “It is—no it isn’t—yes it is——”

“For goodness sake, what’s the matter with her?” asked Laura, getting hysterical again. “Has trouble turned her head?”

“No. But something’s turned yours,” Vi’s voice came indignantly back at her. “I’ve found something, I have. But I’ve a good mind not to tell you what it is.”

“Violet, my darling,” cried Laura, fondly. “Don’t you see me on my knees?”

“Yes,” said Vi, and suddenly there was a flare of light in the room that illuminated the faces of the girls and made Billie and Laura jump.

“I see you,” said Vi calmly, and stood laughing at them while the flickering match in her hand died down to a little glimmer and went out.

“So that’s what you found—matches,” cried Billie joyfully, while Laura just kept on gaping. “Oh, 13 Vi, you’re a darling, and I forgive you for scaring us almost to death. Come on, light another one so we can see where we are.”

Vi obediently lighted another match, a box of which she had found quite by accident, and the girls looked about them curiously. And as they looked their curiosity and wonder grew. Billie was wild with impatience when the match in Vi’s hand flickered and went out again.

“Here, give them to me,” she cried. “I thought I saw something. Look out, don’t spill them, Vi!”

“I should say not—they’re all we have,” chimed in Laura.

The match flared up in Billie’s hand, and this time it was her turn to make a discovery. The discovery was a pair of thick white candles, each set in a white china dish and pushed to one end of a rudely-made table.

Quick as a flash, Billie put the match to the wick of one candle, and then, with a sigh of excitement, blew out the match that was almost burning her fingers.

“Girls,” she cried, looking about her eagerly, “isn’t this the queerest, funniest little place you ever saw? And it’s so complete.”

Excitedly she crossed the little hut, whose floor was nothing but solid, trampled-down earth, and began to examine a rude-looking cot that ran along all one side of the queer little place. 14

“And here’s a pantry!” exclaimed Vi excitedly. “Look, girls, shelves and cans of things and—and—everything!”

The interior of the place was made of rough boards, rudely thrown together as if by an amateur. Why the person who had made the little cabin had not laid boards for his floor, nobody could tell. Perhaps he had run short of lumber or perhaps he preferred the hard earth floor.

As Vi had said, in one corner some boards had been nailed up to form shelves, and there were several tins of canned goods upon the shelves. Quite evidently this must be the queer owner’s pantry.

Besides this, the cot, the table, and an oddly-shaped chair, which had evidently been made from an old soap box, made the only furnishings of the place.

“I wonder,” said Billie, looking about her while a sort of awe crept into her voice, “what the person is like that lives here. He must be very queer, to say the least.”

“Oh,” cried Vi, all her old fears coming back again. “Girls, I’d almost forgotten the Codfish. Do you suppose—”

“No, we don’t,” said Laura shortly, wishing that the very mention of the Codfish would not send the cold chills all over her. “Goodness, just listen to that rain,” she added, shivering. “I guess we’re in for a night of it.” 15

“But we can’t stay here all night,” said Billie anxiously.

“Suppose the owner should come back,” added Vi, her teeth beginning to chatter.

“Well, he could only kill us if he did,” said Laura gloomily.

“Besides, there are three of us to his one,” said Billie, trying to speak lightly. But Laura spoiled the attempt by adding more gloomily than ever:

“How do we know there’s only one of him?”

“Well it doesn’t look as if a whole family resided here.”

“That’s so too—but there may be two, at least.”

Again the girls looked around the queer place. They saw a few tools as if somebody had spent time in woodworking. There were shavings and parts of cut tree branches and strips of bark.

“I’ll wager he’s a queer stick—whoever he is,” was Billie’s comment.

“And what will he say if he finds us here, prying into his private affairs?” came from Laura, with something of a shiver. “Oh!”

All uttered a little cry as a crash of thunder reached them. Then the rain seemed to come down harder than ever.

“Just listen to that!”

“It’s good we are under cover. If we weren’t we’d be drowned!”

The rain came in at one corner of the shelter, 16 forming a pool on the hard floor. But it did not reach the girls, for which they were thankful.

“I wonder how long it will last,” sighed Vi presently.

“Maybe all night,” returned Billie.

“Oh, do you really think it will last that long?” came pleadingly.

“You know as much about it as I do.”

“What will they think of our absence at the Hall?” broke in Laura.

“They may send out a searching party——” began Billie.

“Hush,” cried Vi suddenly, and her tone sent the gooseflesh all over them again. “I hear something. Don’t you think we’d better put something against the door?”

“Th-there’s nothing to put against the door,” stammered Billie nervously. “I might put out the light though.” She started for the candle, but Laura put out a hand and stopped her.

“No,” she said. “I’d rather see what’s after us, anyway. I hate the dark.”

The noise that Vi had heard was a slow measured step that sounded to the girls’ overwrought nerves more like the stealthy creeping of an animal than the tread of a man. But whoever or whatever it was, it was coming steadily toward the hut—that much was certain.

The girls drew close together for protection and watched the little door wide-eyed.

“It sounds like a bear,” whispered Vi hysterically.

“Silly,” Laura hissed back at her. “Don’t you know that bears don’t grow in this part of the country?”

“But if it was a man,” Vi argued, “he wouldn’t be walking so slowly—not in this kind of weather.”

“Hush,” commanded Billie. “He’s almost here.” 18

“If it’s the Codfish—” Vi was saying desperately, when the little door opened and she clapped her hand to her mouth, choking back the words.

Some one was coming through the door, some one who had to bend so much that for a startled moment the girls were not at all sure but what it was an animal, after all, and not a man that they had to reckon with.

Then the visitor stood up and they saw with real relief that it was a man after all. As a matter of fact, after the first startled minute it was the newcomer who seemed frightened and the girls who tried to make him feel at home.

At first sight of the girls the man staggered backward and came up with a thump against the wall of the hut. From there he regarded them with eyes that fairly bulged from his head.

“Hullo!” he muttered, “who are you?”

The girls stared for a moment, then Laura giggled. Who could be frightened when a person wanted to know who they were?

He was a queer looking man. He was tall, over six feet, and so thin that the skin seemed to be drawn over the bones. His shoulders slumped and his arms hung loosely, whether from weariness or discouragement or laziness, the girls found it impossible to tell.

But it was his eyes that they noticed even in that moment of excitement. They were big, much 19 too big for his thin face, and so dark that they seemed deep-sunken. And the expression was something that the girls remembered long afterward. It was brooding, haunted, mysterious, with a little touch of wildness that frightened the girls. Yet his mouth was kind, very kind, and looking at it, the girls ceased to be afraid.

“Who are you?” the man repeated, and this time Billie found her voice.

“We—we got lost,” she said hesitatingly, speaking more to the kind mouth of the man than to the strange, wild eyes. “It began to rain——”

“And we found this little place,” Laura caught her up eagerly, “and came inside to keep from drowning to death.”

“We hope you don’t mind,” Vi finished, with her pleading smile which sometimes won more than all Billie’s and Laura’s courage.

“Mind,” the man repeated vaguely, passing a hand across his eyes as if to wake himself up. “Why should I mind? It isn’t very often I have company.”

The girls thought he spoke bitterly but the next minute he smiled at them.

“I’m sorry I can’t ask you to sit down,” he said, so embarrassed that Billie took pity on him.

“We don’t want to sit down,” she said, smiling at him. “We’re too nervous. Do you suppose the rain will ever stop?” 20

The man shook out his clothing and sent a shower of spray all about him. He was soaking, drenching wet, and suddenly, looking at him, Billie had a dreadful thought.

Suppose the man was not quite right in his mind? She had a horror of crazy people. But what sane man would build himself a cabin in the woods like this in the first place, and then go roaming around in the rain without any protection?

A memory of the slow, measured steps they had heard approaching the cabin made her shudder, and instinctively she drew back a little and snuggled her hand into Laura’s.

If he was not crazy he was probably a criminal of some sort, and neither thought made Billie feel very comfortable. Three girls alone in the woods with a crazy man or a criminal, with the darkness coming on——

Something of what she was thinking occurred to Laura and Vi also, and they were beginning to look rather pale and scared.

As for the man—he hardly seemed to know what to do next. He took off his dripping coat, threw it in a heap in one corner and turned back uncertainly to the girls.

“No, I don’t think it will stop raining for some time,” he said, seeming to realize that Billie had asked a question which he had not answered. “And 21 it is getting pretty dark outside. You say you are lost?”

“Yes,” said Billie, wishing she had not told the man that part of their troubles; but then, what else could she do? “We were sent into the woods to find rare ferns——”

“Ferns!” broke in the man, his deep eyes lighting up with sudden interest. “Ah, I could show you where the rarest and most beautiful ferns in the country grow.”

“You could!” they cried, growing interested in their turn and coming closer to him.

“Are you—a—naturalist?” asked Vi a little uncertainly, for she knew just enough about naturalists to be sure she was not one.

“I guess you might call me that,” said the man. “I’ve had plenty of time to become one.”

Again the girls had that strange feeling of mystery surrounding the man. He walked over to the other end of the room and before the girls’ amazed eyes took out what they had thought to be part of the table.

It was a very cleverly hidden receptacle, and as the girls looked down into it they saw that it was half filled with curious little fern baskets.

“I make them,” the man explained, as they looked up at him, puzzled. “And then I sell them in the town—sometimes.”

His mouth tightened bitterly, and he hastily returned 22 the baskets to their hiding place. Then he turned and faced them abruptly.

“Where do you come from?” he asked almost sharply.

“We come from Three Towers Hall,” answered Billie.

“Three Towers!” The man looked very much interested. “Are you—er—teachers there or pupils?”

“Teachers! Hardly,” and Billie had to smile. “We are not old enough for that. We are pupils.”

“Do you like the place?'”

“Very much.”

Again there was a pause, and it must be admitted that, for a reason they could not explain, the girls felt far from comfortable. Oh, if only they were back at the boarding school again!

“I don’t know a great deal about the school,” said the man slowly. “I suppose there are lots of girls there.”

“Over a hundred,” said Laura, thinking she should say something.

“And quite a few teachers, too?”

“Oh, yes.”

Then the man asked quite a lot of other questions and the girls answered him as best they could. The man continued to look at them so queerly that Billie was convinced that there was something wrong with him. But what was it? Oh, if only the storm 23 would let up, so they could start back to the school!

But even when the rain stopped, how could they get back? They were lost, and at night the way would be even harder to find than in the daytime.

No, they were completely in this man’s power. If he put them on the right path to Three Towers all well and good. If not——But she refused to think of that.

“I’m sure it isn’t raining hard any more,” Laura broke in on her thoughts. “Don’t you think we could go now?”

“Even if it hasn’t stopped raining we don’t mind,” added Vi eagerly. “We’re wet now, and we won’t mind being a little bit wetter.”

For an answer the man opened the door and crawled out into the open. In a moment he was back with what seemed to the girls the best news they had ever heard.

“The rain is over,” he said, “but the foliage is still dripping. If you really don’t mind getting wet——”

“Oh, we don’t!” they cried, and were starting from the door when Vi suddenly remembered something.

“The ferns!” she cried. “Where are they?”

The girls searched frantically about, knowing that their botany teacher would reprimand them if they did not bring back the ferns, and finally found 24 them on the floor where somebody had brushed them in the excitement.

Then they crept out through the door, their strange acquaintance lingering behind to put out the light, and found themselves in the cool darkness of the forest.

“Do you suppose he will really take us back?” Vi whispered, close to Billie’s ear.

“He’d better!” said Billie, clenching her hands fiercely against her side. “If he doesn’t I’ll—I’ll—murder him!”

“Goodness, don’t talk of murder,” cried Laura hysterically. “It’s an awful word to use in the dark, and everything!”

“There’s only one word worse,” said a gloomy voice so close behind them that Vi clapped a hand to her mouth to keep from crying out. “And that,” the gloomy voice went on, “is theft!”

The girls never afterward knew what kept them from breaking loose and running away. Probably it was because they were paralyzed with fright.

While they had thought the man was still in the hut he had come softly up behind them and had overheard the last, at any rate, of what they had said. Billie, as usual, was the first to recover herself.

“Will you take us to Three Towers now?” she asked in a voice that she hardly recognized as her own. “Do you know the way?”

“Yes,” he answered, adding moodily, as though to himself: “Hugo Billings ought to know the way.”

Billie caught at the name quickly, for she had been wondering what this strange person called himself. 26

“Hugo Billings!” she said eagerly. “Is that your name?”

The man had started on ahead of them through the dark woods, but now he stopped and looked back and Billie could almost feel his eyes boring into her.

“Did I say so?” he asked sharply, then just as quickly turned away and started on again.

“Goodness, I guess he must be a crazy criminal,” thought Billie plaintively, as she and her chums followed their leader, stumbling on over rocks and roots that sometimes bruised their ankles painfully. “I suppose there are some people that are both. Anyway, he must be a criminal, or he wouldn’t have been so mad about my knowing his name.”

The rest of that strange journey seemed interminable. There were times when the girls were sure the man who called himself Hugo Billings was not taking them toward Three Towers Hall at all. It seemed impossible that they could have wandered such a long way into the woods.

Then suddenly their feet struck a hard-beaten path and they almost cried aloud with relief. For they recognized the path and knew that the open road was not far off. Once on the open road, they could find their way alone.

Abruptly the man in front stopped and turned to face them. Once more the girls’ hearts misgave 27 them. Was he going to make trouble after all? Why didn’t he go on?

And then the man spoke.

“I won’t go any farther with you,” he said, and there was something in his manner of speaking that made them see again in imagination the tired slump of his shoulders, the wild, haunted look in his eyes. “I don’t like the road. But you can find it easily from here. Then turn to your right. Three Towers is hardly half a mile up the road. Good night.”

He turned with abruptness and started back the way they had come. But impulsively Billie ran to him, calling to him to stop. Yet when he did stop and turned to look at her she had not the slightest idea in the world what she had intended to say—if indeed she had really intended to say anything.

“I—I just wanted to thank you,” she stammered, adding, with a swift little feeling of pity for this man who seemed so lonely: “And if there’s anything I can ever do to—to—help you——”

“Who told you I needed help?” cried the man, his voice so harsh and threatening that Billie started back, half falling over a root.

“Why—why,” faltered Billie, saying almost the first thing that came into her mind. “You looked so—so—sad——”

“Sad,” the man repeated bitterly. “Yes, I have enough to make me sad. But help!” he added fiercely. “I don’t need help from you or any one.” 28

And without another word he turned and strode off into the darkness.

After that it did not take the girls long to reach the road. They felt, someway, as if they must have dreamed their adventure, it had all been so strange and unreal. And yet they knew they had never been more awake in their lives.

“Please don’t talk about it now,” begged Vi when Laura would have discussed it. “Let’s wait till we get in our dorm with lights and everything. I’m just shivering all over.”

For once the others were willing to do as the most timid of the trio wished, and they hurried along in silence till they saw, with hearts full of thankfulness, the lights of Three Towers Hall shine out on the road before them.

“Look, I see the lights!”

“So do I!”

“Thank goodness we haven’t much farther to go.”

“It’s all of a quarter of a mile, Vi.”

“Huh! what’s a quarter of a mile after such a tramp as we have had?” came from Billie.

“And after such an experience,” added Laura.

“We’ll certainly have some story to tell.”

“I want something to eat first.”

“Yes, and dry clothes, too.”

“What a queer hut and what a queer man!”

“I’ve heard of people being lost before,” said Billie, as they ran up the steps that led to the handsomest 29 door in the world, or at least so they thought it at that moment. “But now I know that what they said about it wasn’t half bad enough.”

“But not every one finds a hut and a funny man when they get lost,” said Vi.

“Well, you needn’t be so conceited about it,” said Laura, pausing with her hand on the door knob. “The girls probably won’t believe us when we tell them.”

But Laura was wrong. The girls did really believe the story of Hugo Billings and the hut and became tremendously excited about it. At first they were all for making up an expedition and going to see it—the only drawback being that the chums could not have directed them to it if they would.

And they would not have wished to, anyway. They had rather good reason to believe that Hugo Billings would not want a lot of curious girls spying about his quarters, and, being sorry for him and grateful to him for helping them out of their fix, they absolutely refused to have anything to do with the idea.

They were greeted with open arms on the night of their return. Miss Walters, the much-beloved head of Three Towers Hall, said that she had been just about to send out a searching party for them.

They were late for supper, but that only made their appetites better, and as they were favorites of the cook they were given an extra share of 30 everything and ate ravenously, impatient of the questions flung at them by the curious girls.

“Thank goodness the Dill Pickles aren’t here,” Laura said to Billie between mouthfuls of pork chop. “Think of coming home with our appetites to the kind of dinners they used to serve us.”

“Laura! what a horrible thought,” cried Billie, her eyes dancing as she helped herself to two more biscuits. “That’s treason.”

For the “Dill Pickles” were two elderly spinsters who had been teachers at Three Towers Hall when Billie and her chums had first arrived. Their tartness and strictness and miserliness had made the life of the girls in the school uncomfortable for some time.

And then had come the climax. Miss Walters, having been called away for a week or two, Miss Ada Dill and Miss Cora Dill, disrespectfully dubbed by the girls the twin “Dill Pickles,” had things in their own hands and proceeded to make the life of the girls unbearable. They had taken away their liberty, and then had half starved them by cutting down on the meals until finally the girls had rebelled.

With Billie in the lead, they had marched out of Three Towers Hall one day, bag and baggage, to stay in a hotel in the town of Molata until Miss Walters should get back. Miss Walters, coming home unexpectedly, had met the girls in town, accompanied 31 them back to Three Towers and, as one of the girls slangily described it, “had given the Dill Pickles all that was coming to them.”

In other words, the Misses Dill had been discharged and the girls had come off victorious. Now there were two new teachers in their place who were as different from the Dill Pickles as night is from day. All the girls loved them, especially a Miss Arbuckle who had succeeded Miss Cora Dill in presiding over the dining hall.

So it was to this that Laura had referred when she said, “Thank goodness the Dill Pickles are gone!”

After they had eaten all they could possibly contain, the girls retired to their dormitories, where they changed their clothes, still damp from their adventure, for comfortable, warm night gowns, and held court, all the girls gathering in their dormitory to hear of their adventures, for nearly an hour.

At the end of that time the bell for “lights-out” rang, and the chums found to their surprise that for once they were not sorry. What with the adventure itself and the number of questions they had answered, they were tired out and longed for the comfort of their beds.

“But do you suppose,” said Connie Danvers as she rose to go into her dormitory, which was across the hall, “that the man was really a little out of his head?” 32

“I think he was more than a little,” said Laura decidedly, as she dipped her face into a bowl of cold water. “I think he was just plain crazy.”

Connie Danvers was a very good friend of the chums, and one of the most popular girls in Three Towers Hall. Just now she looked a little worried.

“Goodness! first we have the Codfish,” she said, “and then you girls go and rake up a crazy man. We’ll be having a menagerie next!”

It was the spring of the year, a time when every normal boy and girl becomes restless for new scenes, new adventures. The girls at Three Towers Hall heard the mysterious call and longed through hot days of study to respond to it.

The teachers felt the restlessness in the air and strove to keep the girls to their lessons by making them more interesting. But it was of no use. The girls studied because they had to, not, except in a few scattered cases, because they wanted to.

One of the exceptions to the rule was Caroline Brant, a natural student and a serious girl, who had set herself the rather hopeless task of watching over Billie Bradley and keeping her out of scrapes. For Billie, with her love of adventure and excitement, was forever getting into some sort of scrape.

But these days it would have taken half a dozen Caroline Brants to have kept Billie in the traces. Billie was as wild as an unbroken colt, and just as impatient of control. And Laura and Vi were almost as bad. 34

There was some excuse for the girls. In the first place, the spring term at Three Towers Hall was drawing to a close, and at the end of the spring term came—freedom.

But the thing that set their blood racing was the thought of what was in store for them after they had gained their freedom. Connie Danvers had given the girls an invitation to visit during their vacation her father’s bungalow on Lighthouse Island, a romantic spot off the Maine coast.

The prospect had appealed to the girls even in the dead of winter; but now, with the sweet scent of damp earth and flowering shrubs in the air, they had all they could do to wait at all.

The chums had written to their parents about spending their vacation on the island, and the latter had consented on one condition. And that condition was that the girls should make a good record for themselves at Three Towers Hall. And it is greatly to be feared that it was only this unreasonable—to the girls—condition that kept them at their studies at all.

It was Saturday morning, and Billie, all alone in one of the study halls, was finishing her preparation for Monday’s classes. She always got rid of this task on Saturday morning, so as to have her Saturday afternoon and Sunday free. She had never succeeded in winning Laura and Vi over to her method, so that on their part there was usually 35 a wild scramble to prepare Monday’s lessons on Sunday afternoon.

As Billie, books in hand and a satisfied feeling in her heart, came out of the study room, she very nearly ran into Miss Arbuckle. Miss Arbuckle seemed in a great hurry about something, and the tip of her nose and her eyes were red as though she had been crying.

“Why, what’s the matter?” asked Billie, for Billie was not at all tactful when any one was in trouble. Her impulse was to jump in and help, whether one really wanted her help or not. But everybody that knew Billie forgave her her lack of tact and loved her for the desire to help.

So now Miss Arbuckle, after a moment of hesitation, motioned Billie into the study room, and, crossing over to one of the windows, stood looking out, tapping with her fingers on the sill.

“I’ve lost something, Billie,” she said, without looking around. “It may not seem much to you or to anybody else. But for me—well, I’d rather have lost my right hand.”

She looked around then, and Billie saw fresh moisture in her eyes.

“What is it?” she asked gently. “Perhaps I—we can help you find it.”

“I wish you could,” said Miss Arbuckle, with a little sigh. “But that would be too good to be true. It was only an old family album, Billie. But there 36 were pictures in it that I prize above everything I own. Oh, well,” she gave a little shrug of her shoulders as if to end the matter. “I’ll get over it. I’ve had to get over worse things. But,” she smiled and patted Billie’s shoulder fondly, “I didn’t mean to burden your young shoulders with my troubles. Just run along and forget all about it.”

Billie did run along, but she most certainly did not “forget all about it.”

“Funny thing to get so upset about,” she said to herself, as she slowly climbed the steps to her dormitory. “A picture album! I don’t believe I’d ever get my nose and eyes all red over one. Just the same, I’d like to find it and give it back to her. Good Miss Arbuckle! After the Dill Pickles, she seems like an angel.”

She was still smiling over the thought of what had happened to the Dill Pickles when she opened the door of the dormitory and came upon her chums.

Laura and Vi and a dark-haired, pink-cheeked girl were sitting on one of the beds in one corner of the dormitory, alternately talking and gazing dreamily out of the window to Lake Molata, where it gleamed and shimmered in the morning sunlight at the end of a sloping lawn.

The dark-haired, pink-cheeked girl was Rose Belser. Rose Belser, being jealous of Billie’s immense popularity at Three Towers Hall the term 37 before, had done her best to get the new girl into trouble, only to be won over to Billie’s side in the end. Now she was as firm a friend of Billie’s as any girl in Three Towers Hall.

“Well!” was Laura’s greeting as Billie sauntered toward them. “Methinks ’tis time you arrived, sweet damsel. Goodness!” she added, dropping her lazy tone and sitting up with a bounce, “I don’t see why you have to go and spoil the whole morning with your beastly old studying. Think of the fun we could have had.”

“Well, but think of the fun we’re going to have this afternoon,” Billie flung back airily, stopping before the mirror to tuck some wisps of hair into place, while the girls, even Rose, who was as pretty as a picture herself, watched her admiringly. “It’s almost lunch time.”

“You don’t have to tell us that,” said Vi in an aggrieved tone. “Haven’t we been waiting for you all morning?”

“Oh, come on,” said Billie, as the lunch gong sounded invitingly through the hall. “Maybe when you’ve had something to eat you’ll feel better. Feed the beast——”

“Say, she’s calling us names again,” cried Laura, making a dive for Billie. But Billie was already flying down the steps two at a time, and when Billie once got a head start, no one, at least no 38 one in Three Towers Hall, had a chance of catching up with her.

It seemed to be Billie’s day for bumping into people—for at the foot of the stairs she had to clutch the banister to keep from colliding with Miss Walters, the beautiful and much loved head of the school.

At Billie’s sudden appearance the latter seemed inclined to be alarmed, then her eyes twinkled, and as she looked at Billie she chuckled, yes, actually chuckled.

“Beatrice Bradley,” she said, with a shake of her head as she passed on, “I’ve done my best with you, but it’s of no use. You’re utterly incorrigible.”

Billie looked thoughtful as she seated herself at the table, and a moment later, under cover of the general conversation, she leaned over and whispered to Laura.

“Miss Walters said something funny to me,” she confided. “I’m not quite sure yet whether she was calling me names or not.”

“What did she say?” asked Laura, looking interested.

“She said I was incorrigible,” Billie whispered back.

“Incorrigible,” there was a frown on Laura’s forehead, then it suddenly cleared and she smiled beamingly.

“Why yes, don’t you remember?” she said. “We 39 had it in English class the other day. Incorrigible means wicked, you know—bad. You can’t reform ’em, you know—incorrigibles.” The last word was mumbled through a mouthful of soup.

“Can’t reform ’em!” Billie repeated in dismay. “Goodness, do you suppose that’s what she really thinks of me?”

“I don’t see why she shouldn’t,” Laura said wickedly, and Billie would surely have thrown something at her if Miss Arbuckle’s eye had not happened at that moment to turn in her direction.

Miss Arbuckle’s eye brought to Billie’s mind the teacher’s trouble, and she confided it in a low tone to Laura.

“Humph,” commented Laura, her mind only on the fun they were going to have that afternoon, “I’m sorry, of course, but I don’t believe any old album would make me shed tears.”

“Don’t be so sure of that, Laura.”

“What? Cry over an old album?” and Laura looked her astonishment.

“But suppose the album had in it the pictures of those you loved very dearly—pictures perhaps of those that were dead and gone and pictures that you couldn’t replace?”

“Oh, well—I suppose that would be different. Did she say anything about the people?”

“She didn’t go into details, but she said they were pictures she prized above anything.” 40

“Oh, perhaps then that would make a difference.”

“I hope she gets the album back,” said Billie seriously.

Then Laura promptly forgot all about both Miss Arbuckle and the album.

A little while later the girls swung joyfully out upon the road, bound for town and shopping and perhaps some ice cream and—oh, just a jolly good time of the kind girls know so well how to have, especially in the spring of the year.

“I’m sorry Connie couldn’t come along,” said Laura, drinking in deep breaths of the fragrant air.

“Yes,” said Billie, her eyes twinkling. “She said she wished she hadn’t been born with a conscience.”

“A conscience,” said Vi innocently. “Why?”

“Because,” said Billie, her cheeks aglow with the heat and exercise, her brown hair clinging in little damp ringlets to her forehead, and her eyes bright with health and the love of life, “then she could have had a good time to-day instead of staying at home in a stuffy room and writing a cartload of letters. She says if she doesn’t write them, she’ll never dare face her friends when she gets home.”

“She’s a darling,” said Laura, executing a little skip in the road that sent the dust flying all about them. “Just think—if we hadn’t met her we wouldn’t be looking forward to Lighthouse Island and a dear old uncle who owns the light——”

“Anybody would think he was your uncle,” said Vi.

“Well, he might just as well be,” Laura retorted. 42 “Connie says that he adopts all the boys and girls about the place.”

“And that they adopt him,” Billie added, with a nod. “He must be a darling. I’m just crazy to see him.”

Connie Danver’s Uncle Tom attended the lighthouse, and, living there all the year around, had become as much of a fixture as the island itself. Connie loved this uncle of hers, and had told the girls enough about him to rouse their curiosity and make them very eager to meet him.

The girls walked on in silence for a little way and then, as they came to a path that led into the woods, Laura stopped suddenly and said in a dramatic voice:

“Do you realize where we are, my friends? Do you, by any chance, remember a tall, thin, wild-eyed man?”

Did they remember? In a flash they were back again in a queer little hut in the woods, where a tall man stood and stared at them with strange eyes.

Laura and Vi started to go on, but Billie stood staring at the path with fascinated eyes.

“I wonder why,” she said, as she turned slowly away in response to the urging of the girls, “nothing ever seems the same in the sunlight. The other night when we were running along that path we were scared to death, and now——”

“You sound as if you’d like to stay scared to 43 death,” said Laura impatiently, for Laura had not Billie’s imagination.

“I guess I don’t like to be scared any more than any one else,” Billie retorted. “But I would like to see that man again. I wonder——” she paused and Vi prompted her.

“Wonder what?” she asked.

“Why,” said Billie, a thoughtful little crease on her forehead, “I was just wondering if we could find the little hut again if we tried.”

“Of course we couldn’t!” Laura was very decided about it. “We were lost, weren’t we? And when the man showed us the way back it was dark——”

“The only way I can see,” said Vi, who often had rather funny ideas, “would be to have one of us stand in the road and hold on to strings tied to the other two so that if they got lost——”

“The one in the road could haul ’em back,” said Laura sarcastically. “That’s a wonderful idea, Vi.”

“Well, I would like to see that man again,” sighed Billie. “He seemed so sad. I’m sure he was in trouble, and I’d so like to help him.”

“Yes and when you offered you nearly got your head bit off,” observed Laura.

Billie’s eyes twinkled.

“That’s what Daddy says always happens to people who try to help,” she said. “I feel awfully 44 sorry for him, just the same,” she finished decidedly.

Then Laura did a surprising thing. She put an arm about Billie’s shoulders and hugged her fondly.

“Billie Bradley,” she said sadly, “I do believe you would feel sorry for a snake that bit you, just because it was only a snake.”

“Perhaps that’s why she loves you,” said Vi innocently, and scored a point. Laura looked as if she wanted to be mad for a minute, but she was not. She only laughed with the girls.

They had as good a time as they had expected to have in town that afternoon—and that is saying something.

First they went shopping. Laura had need of a ribbon girdle. Although they all knew that a blue one would be bought in the end, as blue was the color that would go best with the dress with which the girdle was to be worn, the merits and beauties of a green one and a lavender one were discussed and comparisons made with the blue one over and over, all from very love of the indecision and, more truly, the joy that looking at the dainty, pretty colors gave them.

“Well, I think this is the very best of all, Laura,” said Billie finally, picking up the pretty blue girdle with its indistinct pattern of lighter blue and white.

“Yes, it is a beauty,” replied Laura. “I’ll take that one,” she went on to the clerk.

After that came numerous smaller purchases until, 45 as Vi said dolefully, all their money was gone except enough to buy several plates of ice cream apiece.

They were standing just outside the store where their last purchases had been made when Billie, looking down the street, gave a cry of delight.

“Look who’s coming!” she exclaimed.

“It’s the boys!” cried Vi. “Mercy, girls, we might just as well have spent the rest of our money, the boys will treat us to the ice cream.”

“Goodness, Vi! do you want to spend your money whether you get anything you really need or wish for or not?” inquired Billie, with a little gasp.

“What in the world is money for if not to spend?” asked Vi, making big and innocent eyes at Billie.

Just then the boys came within speaking distance.

“Well, this is what I call luck!” exclaimed Ferd Stowing.

“Yes,” added Teddy, putting his hand in his pocket, “just hear the money jingle. A nice big check from Dad in just appreciation of his absent son! What do you girls say to an ice-cream spree? No less than three apiece, with all this unwonted wealth.”

“Ice cream? I should say!” was Billie’s somewhat slangy acceptance.

“Teddy,” suddenly asked Laura, “how does it come that you have any money left from Dad’s check?” 46

“Check came just as we left the Academy, Captain Shelling cashed it for me, and we have just reached town.”

“Oh! Well, maybe I’ll find one, too, when we reach Three Towers.”

“So that’s it, is it, sister mine? Envy!”

After that they ate ice cream to repletion, and at last the girls decided that there was nothing much left to do but to go back to the school.

It was just as well that they had made this decision, for the sun was beginning to sink in the west and the supper hour at Three Towers Hall was rather early. As they started toward home, having said good-bye to the boys, the girls quickened their pace.

It was not till they were nearing the path which, to Billie at least, had been surrounded by a mysterious halo since the adventure of the other night that the girls slowed up. Then it was Billie who did the slowing up.

“Girls,” she said in a hushed voice, “I suppose you’ll laugh at me, but I’d just love to follow that path into the woods a little way. You don’t need to come if you don’t want to. You can wait for me here in the road.”

“Oh, no,” said Laura, with a little sigh of resignation. “If you are going to be crazy we might as well be crazy with you. Come on, Vi, if we 47 didn’t go along, she would probably get lost all over again—just for the fun of it.”

Billie made a little face at them and plunged into the woods. Laura followed, and after a minute’s hesitation Vi trailed at Laura’s heels.

They were so used to Billie’s sudden impulses that they had stopped protesting and merely went along with her, which, as Billie herself had often pointed out, saved a great deal of argument.

They might have saved themselves all worry on Billie’s account this time, though, for she had not the slightest intention of getting lost again—once was enough.

She went only as far as the end of the path, and when the other girls reached her she was peering off into the forest as if she hoped to see the mysterious hut—although she knew as well as Laura and Vi that they had walked some distance through the woods the other night before they had finally reached the path.

“Well, are you satisfied?” Laura asked, with a patient sigh. “If you don’t mind my saying it, I’m getting hungry.”

“Goodness! after all that ice cream?” cried Billie, adding with a little chuckle: “You’re luckier than I am, Laura. I feel as if I shouldn’t want anything to eat for a thousand years.”

She was just turning reluctantly to follow her chums back along the path when a dark, bulky-looking 48 object lying in a clump of bushes near by caught her eye and she went over to examine it.

“Now what in the world——” Laura was beginning despairingly when suddenly Billie gave a queer little cry.

“Come here quick, girls!” she cried, reaching down to pick up the bulky object which had caught her attention. “I do believe—yes, it is—it must be——”

“Well, say it!” the others cried, peering impatiently over her shoulder.

“Miss Arbuckle’s album,” finished Billie.

Instead of seeming excited, Laura and Vi stared. Vi had not even heard that Miss Arbuckle had lost an album, and Laura just dimly remembered Billie’s having said something about it.

But Billie’s eyes were shining, and she was all eagerness as she picked the old-fashioned volume up and began turning over the pages. She was thinking of poor Miss Arbuckle’s red nose and eyes of that morning and of how different the teacher’s face would look when she, Billie, returned the album.

“Oh, I’m so glad,” she said. “I felt awfully sorry for Miss Arbuckle this morning.”

“Well, I wish I knew what you were talking about,” said Vi plaintively, and Billie briefly told of her meeting with Miss Arbuckle in the morning and of the teacher’s grief at losing her precious album.

“Humph! I don’t see anything very precious about it,” sniffed Laura. “Look—the corners are all worn through.” 50

“Silly, it doesn’t make any difference how old it is,” said Vi as they started back along the path, Billie holding on tight to the book. “It may have pictures in it she wants to save. It may be—what is it they call ’em?—an heirloom or something. And Mother says heirlooms are precious.”

“Well, I know one that isn’t,” said Laura, with a little grimace. “Mother has a wreath made out of hair of different members of the family. She says it’s precious, too; but I notice she keeps it in the darkest corner of the attic.”

“Well, this isn’t a hair wreath, it’s an album,” Billie pointed out. “And I don’t blame Miss Arbuckle for not wanting to lose an album with family pictures in it.”

“But how did she come to lose it there?” asked Laura, as the road could be seen dimly through the trees. “The woods seem a funny place. Girls,” and Laura’s eyes began to shine excitedly, “it’s a mystery!”

“Oh, dear,” sighed Vi plaintively, “there she goes again. Everything has to be a mystery, whether it is or not.”

“But it is, isn’t it?” insisted Laura, turning to Billie for support. “A lady says she has lost an album. In a little while we find that same album——”

“I suppose it’s the same,” put in Billie, looking at the album as if it had not occurred to her before 51 that this might not be Miss Arbuckle’s album, after all.

“Of course it is, silly,” Laura went on impatiently. “It isn’t likely that two people would be foolish enough to lose albums on the same day. If it had been a stick pin now, or a purse——”

“Yes, yes, go on,” Billie interrupted. “You were talking about mysteries.”

“Well, it is, isn’t it?” demanded Laura, becoming so excited she could not talk straight. “What was Miss Arbuckle doing in the woods with her album, in the first place?”

“She might have been looking at it,” suggested Vi mildly.

Billie giggled at the look Laura gave Vi.

“Yes. But may I ask,” said Laura, trying to appear very dignified, “why, if she only wanted to look at the pictures, she couldn’t do it some place else—in her room, for instance?”

“Goodness, I’m not a detective,” said poor Vi. “If you want to ask any questions go and ask Miss Arbuckle. I didn’t lose the old album.”

Laura gave a sigh of exasperation.

“A person might as well try to talk to a pair of wooden Indians,” she cried, then turned appealingly to Billie. “Don’t you think there’s something mysterious about it, Billie?”

“Why, it does seem kind of queer,” Billie admitted, adding quickly as Laura was about to turn 52 upon Vi with a whoop of triumph. “But I don’t think it’s very mysterious. Probably Miss Arbuckle just wanted to be alone or something, and so she brought the album out into the woods to look it over by herself. I like to do it sometimes myself—with a book I mean. Just sneak off where nobody can find me and read and read until I get so tired I fall asleep.”

“Well, but you can’t look at pictures in a shabby old album until you feel so tired you fall asleep,” grumbled Laura, feeling like a cat that has just had a saucer of rich cream snatched from under its nose. “You girls wouldn’t know a mystery if you fell over it.”

“Maybe not,” admitted Billie good-naturedly, her face brightening as she added, contentedly: “But I do know one thing, and that is that Miss Arbuckle is going to be very glad when she sees this old album again!”

And she was right. When they reached Three Towers Hall Laura and Vi went upstairs to the dormitory to wash up and get ready for supper while Billie stopped at Miss Arbuckle’s door, eager to tell her the good news at once.

She rapped gently, and, receiving no reply, softly pushed the door open. Miss Arbuckle was standing by the window looking out, and somehow Billie knew, even before the teacher turned around, that she had been crying again. 53

The tired droop of the shoulders, the air of discouragement—suddenly there flashed across Billie’s mind a different picture, the picture of a tall lank man with stooped shoulders and dark, deep-set eyes, looking at her strangely.

A puzzled little line formed itself across her forehead. Why, she thought, had Miss Arbuckle made her think of the man who called himself Hugo Billings and who lived in a hut in the woods?

Perhaps because they both seemed so very sad. Yes, that must be it. Then her face brightened as she felt the bulky album under her arm. Here was something that would make Miss Arbuckle smile, at least.

Billie spoke softly and was taken aback at the suddenness with which Miss Arbuckle turned upon her, regarding her with startled eyes.

For a moment teacher and pupil regarded each other. Then slowly a pitiful, crooked smile twitched Miss Arbuckle’s lips and her hand reached out gropingly for the back of a chair.

“Oh, it’s—it’s you,” she stammered, adding with an apologetic smile that made her look more natural: “I’m a little nervous to-day—a little upset. What is it, Billie? Why didn’t you knock?” The last words were said in Miss Arbuckle’s calm, slightly dry voice, and Billie began to feel more natural herself. She had been frightened when Miss Arbuckle swung around upon her. 54

“I did,” she answered. “Knock, I mean. But you didn’t hear me. I found something of yours, Miss Arbuckle.” Her eyes fell to the volume she still carried under her arm, and Miss Arbuckle, following the direction of her gaze, recognized her album.

She gave a little choked cry, and her face grew so white that Billie ran to her, fearing she hardly knew what. But she had no need to worry, for although fear sometimes kills, joy never does, and in a minute Miss Arbuckle’s eager hands were clutching the volume, her fingers trembling as they rapidly turned over the leaves.

“Yes, here they are, here they are,” she cried suddenly, and Billie, peeping over her shoulder, looked down at the pictured faces of three of the most beautiful children she had ever seen. “My darlings, my darlings,” Miss Arbuckle was saying over and over again. Then suddenly her head dropped to the open page and her shoulders shook with the sobs that tore themselves from her.

Billie turned away and tiptoed across the room, her own eyes wet, but she stopped with her hand on the door.

“My little children!” Miss Arbuckle cried out sobbingly. “My precious little babies! I couldn’t lose your pictures after losing you. They were all I had left of you, and I couldn’t lose them, I couldn’t—I couldn’t——” 55

Billie opened the door, and, stepping out into the hall, closed it softly after her. She brushed her hand across her eyes, for there were tears in them, and her feet felt shaky as she started up the stairs.

“Well, I—I never!” she told herself unsteadily. “First she nearly scares me to death. And then she cries and talks about her children, and says she’s lost them. Goodness, I shouldn’t wonder but that Laura is right after all. There certainly is something mighty strange about it.”

And when, a few minutes later, she told the story to her chums they agreed with her, even Vi.

“Why, I never heard of such a thing,” said the latter, looking interested. “You say she seemed frightened when you went in, Billie?”

“Terribly,” answered Billie. “It seemed as if she might faint or something.”

“And the children,” Laura mused delightedly aloud. “I’m going to find out who those children are and why they are lost if I die doing it.”

“Now look who she thinks she is,” jeered Vi.

“Who?” asked Laura with interest.

“The Great Lady Detective,” said Vi, and Laura’s chest, if one takes Billie’s word for it, swelled to about three times its natural size.

“That’s all right,” said Laura, in response to the girls’ gibes. “I’ll get in some clever work, with nothing but a silly old photograph album as a clue, 56 or a motive—oh, well, I don’t know just what the album is yet, but an album is worse than commonplace, it is plumb foolish as a center around which to work. Oh, ho! Great Lady Detective! Solves most marvelous and intricate mystery with only the slightest of clues, an old photograph album, to point the way! Oh, ho!”

The girls could never have told exactly why, but they kept the mystery of the album and Miss Arbuckle’s strange actions to themselves, with one exception.

They did confide their secret to fluffy-haired, blue-eyed Connie Danvers. For they had long ago adopted Connie as one of themselves and were beginning to feel that they had known her all their lives.

Connie had been interested enough in their story to satisfy even the chums and had urged Billie to describe the pretty children in the album over whom Miss Arbuckle had cried.

Billie tried, but, having seen the pictures but once, it was hardly to be expected that she would be able to give the girls a very clear description of them.

It was good enough to satisfy Connie, however, who, in her enthusiasm, went so far as to suggest that they form a Detective Club.

This the girls might have done if it had not been for an interruption in the form of Chet Bradley, 58 Teddy Jordon and their chum, Ferd Stowing.

The boys had entered Boxton Military Academy at the time the girls had entered Three Towers Hall, and the boys were as enthusiastic about their academy as the girls were about their beloved school.

The head of Boxton Military Academy was Captain Shelling, a splendid example of army officer whom all the students loved and admired. They did not know it, but there was not one of the boys in the school who did not hope that some day he might be like Captain Shelling.

Now, as the spring term was drawing to a close, there were great preparations being made at the Academy for the annual parade of cadets.

The girls knew that visitors were allowed, and they were beginning to wonder a little uneasily whether they were to be invited or not when one afternoon the boys turned up and settled the question for them very satisfactorily.

It was Saturday afternoon, just a week after the finding of Miss Arbuckle’s album, and the girls, Laura, Billie, Vi and Connie, were wandering arm in arm about the beautiful campus of Three Towers Hall when a familiar hail came to them from the direction of the road.

“It’s Chet,” said Billie.

“No, it isn’t—it’s Teddy,” contradicted Laura.

“It’s both of ’em,” added Vi. 59

“No, you are both wrong,” said Connie, gazing eagerly through the trees. “Here they come, girls. Look, there are four of them.”

“Yes, there are four of them,” mocked Laura, mischievous eyes on Connie’s reddening face. “The third is Ferd Stowing, of course. And I wonder, oh, I wonder, who the fourth can be!”

“Don’t be so silly! I think you’re horrid!” cried Connie, which only made Laura chuckle the more.

For while they had been at the Academy, the boys had made a friend. His name was Paul Martinson, and he was tall and strongly built and—yes, even Billie had to admit it—almost as good looking as Teddy!

If Billie said that about any one it was pretty sure to be true. For Billie and Teddy Jordon had been chums and playmates since they could remember, and Billie had always been sure that Teddy must be the very best looking boy in the world, not even excepting her brother Chet, of whom she was very fond.

But Billie was not the only one who had found Paul Martinson good looking. Connie had liked him, and had said innocently one day after the boys had gone that Paul Martinson looked like the hero in a story book she was reading.

The girls had giggled, and since then Laura had made poor Connie’s life miserable—or so Connie 60 declared. She could not have forgotten Paul Martinson, even if she had wanted to.

As for Paul Martinson, he had shown a liking for Billie that somehow made Teddy uncomfortable. Teddy was very much surprised to find how uncomfortable it did make him. Billie was a “good little chum and all that, but that didn’t say that another fellow couldn’t speak to her.” But just the same he had acted so queerly two or three times lately that Billie had bothered him exceedingly asking him what the matter with him was and telling him to “cheer up, it wasn’t somebody’s funeral, you know.” Billie had been puzzled over his answer to that. He had muttered something about “it’s not anybody’s funeral yet, maybe, but everything had to start sometime.”

When Billie had innocently told Laura about it she was still more puzzled at the way Laura had acted. Instead of being sensible, she had suddenly buried her face in the pillow—they had been sitting on Billie’s bed, exchanging confidences—and fairly shook with laughter.

“Well, what in the world——” Billie had begun rather resentfully, when Laura had interrupted her with an hysterical: “For goodness sake, Billie, I never thought you could be so dense. But you are. You’re absolutely crazy, and so is Teddy, and so is everybody!” 61

And after that Billie never confided any of Teddy’s sayings to Laura again.

On this particular afternoon it did not take the girls long to find out that the boys had some good news to tell them.

“Come on down to the dock,” Teddy said, taking hold of Billie’s arm and urging her down toward the lake as he spoke. “Maybe we can find some canoes and rowboats that aren’t working.”

But when they reached the dock there was never a craft of any kind to be seen except those far out upon the glistening water of the lake. Of course the beautiful weather was responsible for this, for all the girls who had not lessons to do or errands in town had made a bee line—as Ferd Stowing expressed it—straight down to the lake.

“Oh, well, this will do,” said Teddy, sitting down on the edge of the little dock so that his feet could hang over and reaching up a hand for Billie. “Come along, everybody. We can look at the water, anyway.”

The girls and boys scrambled down obediently and there was great excitement when Connie’s foot slipped and she very nearly tumbled into the lake. Paul Martinson steadied her, and she thanked him with a little blush that made Laura look at her wickedly.

“How beautifully pink your complexion is in the warm weather, Connie,” she said innocently, adding 62 with a little look that made Connie want to shake her: “It can’t be anything but the heat, can it? You haven’t a fever, or something?”

“No. But you’ll have something beside a fever,” threatened Connie, “if you don’t keep still.”

“Say, stop your rowing, girls, and listen to me,” Teddy interrupted, picking a pebble from the dock and throwing it far out into the gleaming water, where it dropped with a little splash. “Our famous parade of cadets comes off next week. You’re going to be on deck, aren’t you?”

“We might,” said Billie, with a demure little glance at him, “if somebody would only ask us!”

The great day came at last and found the girls in a fever of mingled excitement and fear. Excitement because of the great advent; fear, because the sky had been overcast since early morning and it looked as if the whole thing might have to be postponed on account of rain.

“And if there is anything I hate,” complained Laura, moving restlessly from her mirror over to the window and back again, “it’s to be all prepared for a thing and then have it spoiled at the last minute by rain.”

“Well, I guess you don’t hate it any more than the rest of us,” said Billie, her thoughts on the pretty pink flowered dress she had decided to wear to the parade. It was not only a pretty dress, but was very becoming. Both Teddy and Chet had told her so. “And the boys would be terribly disappointed,” she added.

“I wonder,” Vi was sitting on the bed, sewing a hook and eye on the dress she had intended to wear, “if Amanda Peabody and The Shadow will be there.” 64

Laura turned abruptly from the window and regarded her with a reproachful stare.

“Now I know you’re a joy killer,” she said; “for if Amanda Peabody and The Shadow (the name the girls had given Eliza Dilks because she always followed Amanda as closely as a shadow does) succeeded in getting themselves invited to any sort of affair where we girls were to be, they would be sure to do something annoying.”

“They are going to be there, just the same,” said Billie, and the two girls looked at her in surprise. “They told me so,” she said, in answer to the unspoken question. “They have some sort of relatives among the boys at the Academy, and these relatives didn’t have sense enough not to invite them.”

“Humph!” grunted Laura, “Amanda probably hinted around till the boys couldn’t help inviting her. Look—oh, look!” she cried in such a different tone that the girls stared at her. “The sun!” she said. “Oh, it’s going to clear up, it’s going to clear up!”

“Well, you needn’t step on my blue silk for all that,” complained Vi, as Laura caught an exultant heel in the latter’s dress.

“Don’t be grouchy, darling,” said Laura, all good-nature again now that the sun had appeared. “My, but we’re going to have a good time!”

“I’ll say we are,” sang out Billie, as she gayly 65 spread out the pink flowered dress upon the bed. “And we’re not going to let anybody spoil it either—even Eliza Dilks and Amanda Peabody.”

The girls had an hour in which to get ready, and they were ready and waiting before half that time was up. The Three Towers Hall carryall was to call for the girls who had been lucky enough to receive invitations from the cadets of Boxton Military Academy, and as the girls, looking like gay-colored butterflies in their summery dresses, gathered on the steps of the school there were so many of them that it began to look as if the carryall would have to make two trips.

“If we have to go in sections I wonder whether we’ll be in the first or second,” Vi was saying when Billie grasped her arm.

“Look,” she cried, merriment in her eyes and in her voice. “Here come Amanda and Eliza. Did you ever see anything so funny—and awful—in your life?”

For Amanda and her chum were dressed in their Sunday best—poplin dresses with a huge, gorgeous flower design that made the pretty, delicate-colored dresses of the other girls look pale and washed-out by comparison. If Amanda’s and Eliza’s desire was to be the most noticeable and talked-of girls on the parade, they were certainly going to succeed. The talk had begun already!

However, the arrival of the carryall cut short the 66 girls’ amusement, and there was great excitement and noise and giggling as the girls—all who could get in, that is—clambered in.

There were about a dozen left over, and these the driver promised to come back and pick up “in a jiffy.”

“I’m feeling awfully nervous,” Laura confided to Billie. “I never expected to be nervous; did you?”

“Yes, I did,” Billie answered truthfully. “I’ve been nervous ever since the boys invited us. It’s because it’s all so new, I guess. We’ve never been to anything like this before.”

“I’m frightened to death when I think of meeting Captain Shelling,” Connie leaned across Vi to say. “From what the boys say about him he must be simply wonderful.”

“Paul had better look out,” said Laura slyly, and Connie drew back sharply.

“I think you’re mean to tease Connie so,” spoke up Vi. “She doesn’t like Paul Martinson any better than the rest of us do, and you know it.”

“Oh, I do, do I——” began Laura, but Billie broke in hastily.

“Girls,” she cried, “stop your quarreling. Look! We’re at the Academy. And—look—look——” Words failed her, and she just stared wonderingly at the sight that met her eyes. It was true, none of them had ever seen anything like it before. 67

Booths of all sorts and colors were distributed over the parade ground, leaving free only the part where the cadets were to march. Girls in bright-colored dresses and boys in trim uniforms were already walking about making brilliant patches of color against the green of the parade ground.

There were some older people, too, fathers and mothers of the boys, but the groups were mostly made up of young people, gay and excited with the exhilaration of the moment.

There were girls and matrons in the costume of French peasants wandering in and out among the visitors, carrying little baskets filled with ribbon-tied packages. Some of these packages contained candy, some just little foolish things to make the young folks laugh, favors to take away with them and remember the day by.

As the carryall stopped and one after another the girls jumped to the ground they were surprised to find that their nervousness, instead of growing less, was getting worse and worse all the time.

They were standing on the edge of things, wondering just what to do next and wishing some one would meet them when some one did just that very thing.