Project Gutenberg's The Idler Magazine, Volume III., July 1893, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Idler Magazine, Volume III., July 1893

An Illustrated Monthly

Author: Various

Release Date: May 7, 2008 [EBook #25372]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IDLER MAGAZINE ***

Produced by Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial Magazines,

Jonathan Ingram, Anne Storer and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Notes: Title and Table of Contents added.

THE IDLER MAGAZINE.

AN ILLUSTRATED MONTHLY.

July 1893.

CONTENTS.

THE WOMAN OF THE SAETER.

by Jerome K. Jerome.

ALPHONSE DAUDET AT HOME.

by Marie Adelaide Belloc.

THE DISMAL THRONG.

by Robert Buchanan.

IN THE HANDS OF JEFFERSON.

by Eden Phillpotts.

MY FIRST BOOK.

by I. Zangwill.

BY THE LIGHT OF THE LAMP.

by Hilda Newman.

MEMOIRS OF A FEMALE NIHILIST.

III.—ONE DAY.

by Sophie Wassilieff.

A SLAVE OF THE RING.

by Alfred Berlyn.

PEOPLE I HAVE NEVER MET.

by Scott Rankin.

THE IDLER’S CLUB

“TIPPING.”

[Pg 578]

the vengeance of hund.

the vengeance of hund.

[Pg 579]

The Woman of the Saeter.

By Jerome K. Jerome.

Illustrations by A. S. Boyd.

Wild-Reindeer stalking is hardly so exciting a sport as the evening’s

verandah talk in Norroway hotels would lead the trustful traveller to

suppose. Under the charge of your guide, a very young man with the

dreamy, wistful eyes of those who live in valleys, you leave the

farmstead early in the forenoon, arriving towards twilight at the

desolate hut which, for so long as you remain upon the uplands, will be

your somewhat cheerless headquarters.

Next morning, in the chill, mist-laden dawn you rise; and, after a

breakfast of coffee and dried fish, shoulder your Remington, and step

forth silently into the raw, damp air; the guide locking the door behind

you, the key grating harshly in the rusty lock.

For hour after hour you toil over the steep, stony ground, or wind

through the pines, speaking in whispers, lest your voice reach the quick

ears of your prey, that keeps its head ever pressed against the wind.

Here and there, in the hollows of the hills, lie wide fields of snow,

over which you pick your steps thoughtfully, listening to the smothered

thunder of the torrent, tunnelling its way beneath your feet, and

wondering whether the frozen arch above it be at all points as firm as

is desirable. Now and again, as in single file you walk cautiously along

some jagged ridge, you catch glimpses of the green world, three thousand

feet below you; though you gaze not long upon the view, for your

attention is chiefly directed to watching the footprints of the guide,

lest by deviating to the right or left you find yourself at one stride

back in the valley—or, to be more correct, are found there.

These things you do, and as exercise they are healthful and

invigorating. But a reindeer you never see, and unless, overcoming the

prejudices of your British-bred conscience, you care to take an

occasional pop at a fox, you had better have left your rifle at the hut,

and, instead, have brought a stick, which would have been helpful.

Notwithstanding which the guide continues sanguine, and in broken

English, helped out by stirring gesture, tells of the terrible slaughter

[Pg 580]

generally done by sportsmen under his superintendence, and of the vast

herds that generally infest these fjelds; and when you grow sceptical

upon the subject of Reins he whispers alluringly of Bears.

Once in a way you will come across a track, and will follow it

breathlessly for hours, and it will lead to a sheer precipice. Whether

the explanation is suicide, or a reprehensible tendency on the part of

the animal towards practical joking, you are left to decide for

yourself. Then, with many rough miles between you and your rest, you

abandon the chase.

But I speak from personal experience merely.

All day long we had tramped through the pitiless rain, stopping only for

an hour at noon to eat some dried venison, and smoke a pipe beneath the

shelter of an overhanging cliff. Soon afterwards Michael knocked over a

ryper (a bird that will hardly take the trouble to hop out of your way)

with his gun-barrel, which incident cheered us a little, and, later on,

our flagging spirits were still further revived by the discovery of

apparently very recent deer-tracks. These we followed, forgetful, in our

eagerness, of the lengthening distance back to the hut, of the fading

daylight, of the gathering mist. The track led us higher and higher,

further and further into the mountains, until on the shores of a

desolate rock-bound vand it abruptly ended, and we stood staring at one

another, and the snow began to fall.

Unless in the next half-hour we could chance upon a saeter, this meant

passing the night upon the mountain. Michael and I looked at the guide,

but though, with characteristic Norwegian sturdiness, he put a bold face

upon it, we could see that in that deepening darkness he knew no more

than we did. Wasting no time on words, we made straight for the nearest

point of descent, knowing that any human habitation must be far below

us.

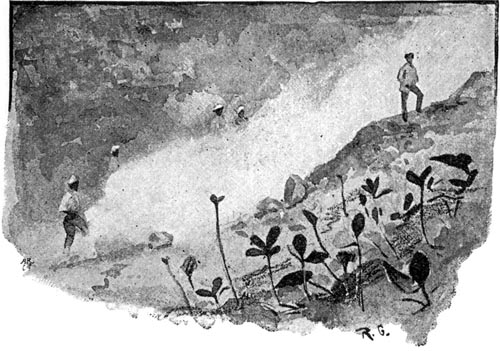

Down we scrambled, heedless of torn clothes and bleeding hands, the

darkness pressing closer round us. Then suddenly it became black—black

as pitch—and we could only hear each other. Another step might mean

death. We stretched out our hands, and felt each other. Why we spoke in

whispers, I do not know, but we seemed afraid of our own voices. We

agreed there was nothing for it but to stop where we were till morning,

clinging to the short grass; so we lay there side by side, for what may

have been five minutes or may have been an hour. Then, attempting to

turn, I lost my grip and rolled. I made convulsive efforts to clutch the

ground, but the incline was too steep. How far I fell I could not say,

[Pg 581]

but at last something stopped me. I felt it cautiously with my foot; it

did not yield, so I twisted myself round and touched it with my hand. It

seemed planted firmly in the earth. I passed my arm along to the right,

then to the left. Then I shouted with joy. It was a fence.

“clinging to the short grass.”

“clinging to the short grass.”

Rising and groping about me, I found an opening, and passed through, and

crept forward with palms outstretched until I touched the logs of a hut;

then, feeling my way round, discovered the door, and knocked. There came

no response, so I knocked louder; then pushed, and the heavy woodwork

yielded, groaning. But the darkness within was even darker than the

darkness without. The others had contrived to crawl down and join me.

Michael struck a wax vesta and held it up, and slowly the room came out

of the darkness and stood round us.

Then something rather startling happened. Giving one swift glance about

him, our guide uttered a cry, and rushed out into the night, and

disappeared. We followed to the door, and called after him, but only a

voice came to us out of the blackness, and the only words that we could

catch, shrieked back in terror, were: “The woman of the saeter—the

woman of the saeter.”

“Some foolish superstition about the place, I suppose,” said Michael.

“In these mountain solitudes men breed ghosts for company. Let us make a

fire. Perhaps, when he sees the light, his desire for food and shelter

may get the better of his fears.”

We felt about in the small enclosure round the house, and gathered

juniper and birch-twigs, and kindled a fire upon the open stove built in

the corner of the room. Fortunately, we had some dried reindeer and

bread in our bag, and on that and the ryper,

[Pg 582]

and the contents of our

flasks, we supped. Afterwards, to while away the time, we made an

inspection of the strange eyrie we had lighted on.

It was an old log-built saeter. Some of these mountain farmsteads are as

old as the stone ruins of other countries. Carvings of strange beasts

and demons were upon its blackened rafters, and on the lintel, in runic

letters, ran this legend: “Hund builded me in the days of Haarfager.”

The house consisted of two large apartments. Originally, no doubt, these

had been separate dwellings standing beside one another, but they were

now connected by a long, low gallery. Most of the scanty furniture was

almost as ancient as the walls themselves, but many articles of a

comparatively recent date had been added. All was now, however, rotting

and falling into decay.

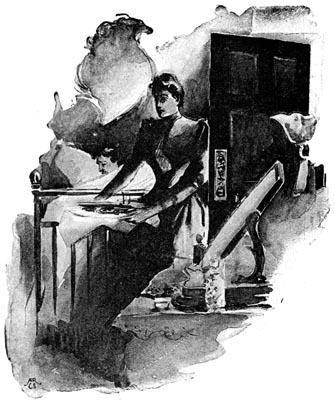

“by the dull glow of the

“by the dull glow of the

burning juniper twigs.”

The place appeared to have been deserted suddenly by its last occupants.

Household utensils lay as they were left, rust and dirt encrusted on

them. An open book, limp and mildewed, lay face downwards on the table,

while many others were scattered about both rooms, together with much

paper, scored with faded ink. The curtains hung in shreds about the

windows; a woman’s cloak, of an antiquated fashion, drooped from a nail

behind the door. In an oak chest we found a tumbled heap of yellow

letters. They were of various dates, extending over a period of four

months, and with them, apparently intended to receive them, lay a large

envelope, inscribed with an address in London that has since

disappeared.

[Pg 583]

Strong curiosity overcoming faint scruples, we read them by the dull

glow of the burning juniper twigs, and, as we lay aside the last of

them, there rose from the depths below us a wailing cry, and all night

long it rose and died away, and rose again, and died away again; whether

born of our brain or of some human thing, God knows.

And these, a little altered and shortened, are the letters:—

Extract from first letter:

“i spend as much time

“i spend as much time

as i can with her.”

“I cannot tell you, my dear Joyce, what a haven of peace this place is

to me after the racket and fret of town. I am almost quite recovered

already, and am growing stronger every day; and, joy of joys, my brain

has come back to me, fresher and more vigorous, I think, for its

holiday. In this silence and solitude my thoughts flow freely, and the

difficulties of my task are disappearing as if by magic. We are perched

upon a tiny plateau halfway up the mountain. On one side the rock rises

almost perpendicularly, piercing the sky; while on the other, two

thousand feet below us, the torrent hurls itself into black waters of

the fiord. The house consists of two rooms—or, rather, it is two cabins

connected by a passage. The larger one we use as a living room, and the

other is our sleeping apartment. We have no servant, but do everything

for ourselves. I fear sometimes Muriel must find it lonely. The nearest

human habitation is eight miles away, across the mountain, and not a

soul comes near us. I spend as much time as I can with her, however,

during the day, and make up for it by working at night after she has

gone to sleep, and when I question her, she only laughs, and answers

that she loves to have me all to herself. (Here you will smile

cynically, I know, and say, ‘Humph, I wonder will she say the same when

they have been married

[Pg 584]

six years instead of six months.’) At the rate I

am working now I shall have finished my first volume by the end of

August, and then, my dear fellow, you must try and come over, and we

will walk and talk together ‘amid these storm-reared temples of the

gods.’ I have felt a new man since I arrived here. Instead of having to

‘cudgel my brains,’ as we say, thoughts crowd upon me. This work will

make my name.”

Part of the third letter, the second being mere talk about the book

(a history apparently) that the man was writing:

“My dear Joyce,—I have written you two letters—this will make the

third—but have been unable to post them. Every day I have been

expecting a visit from some farmer or villager, for the Norwegians are

kindly people towards strangers—to say nothing of the inducements of

trade. A fortnight having passed, however, and the commissariat question

having become serious, I yesterday set out before dawn, and made my way

down to the valley; and this gives me something to tell you. Nearing the

village, I met a peasant woman. To my intense surprise, instead of

returning my salutation, she stared at me, as if I were some wild

animal, and shrank away from me as far as the width of the road would

permit. In the village the same experience awaited me. The children ran

from me, the people avoided me. At last a grey-haired old man appeared

to take pity on me, and from him I learnt the explanation of the

mystery. It seems there is a strange superstition attaching to this

house in which we are living. My things were brought up here by the two

men who accompanied me from Dronthiem, but the natives are afraid to go

near the place, and prefer to keep as far as possible from anyone

connected with it.

“The story is that the house was built by one Hund, ‘a maker of runes’

(one of the old saga writers, no doubt), who lived here with his young

wife. All went peacefully until, unfortunately for him, a certain maiden

stationed at a neighbouring saeter grew to love him.—Forgive me if I am

telling you what you know, but a ‘saeter’ is the name given to the

upland pastures to which, during the summer, are sent the cattle,

generally under the charge of one or more of the maids. Here for three

months these girls will live in their lonely huts entirely shut off from

the world. Customs change little in this land. Two or three such

stations are within climbing distance of this house, at this day, looked

after by the farmers’ daughters, as in the days of Hund, ‘maker of

runes.’

[Pg 585]

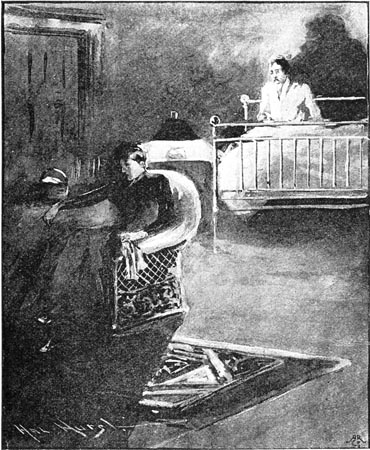

“Every night, by devious mountain paths, the woman would come and tap

lightly at Hund’s door. Hund had built himself two cabins, one behind

the other (these are now, as I think I have explained to you, connected

by a passage); the smaller one was the homestead, in the other he carved

and wrote, so that while the young wife slept the ‘maker of runes’ and

the saeter woman sat whispering.

“the woman would tap lightly at hund’s door.”

“the woman would tap lightly at hund’s door.”

“One night, however, the wife learnt all things, but said no word. Then,

as now, the ravine in front of the enclosure was crossed by a slight

bridge of planks, and over this bridge the woman of the saeter passed

and re-passed each night. On a day when Hund had gone down to fish in

the fiord, the wife took an axe, and hacked and hewed at the bridge, yet

it still looked firm and solid; and that night, as Hund sat waiting in

his workshop, there struck upon his ears a piercing cry, and a crashing

of logs and rolling rock, and then again the dull roaring of the torrent

far below.

“But the woman did not die unavenged, for that winter a man, skating far

down the fiord, noticed a curious object embedded in the ice; and when,

stooping, he looked closer, he saw two corpses, one gripping the other

by the throat, and the bodies were the bodies of Hund and his young

wife.

“Since then, they say the woman of the saeter haunts Hund’s house, and

if she sees a light within she taps upon the door, and no man may keep

her out. Many, at different times, have tried to occupy the house, but

strange tales are told of them. ‘Men do not live at Hund’s saeter,’ said

my old grey-haired friend, concluding his tale, ‘they die there.’ I have

persuaded some of the braver of the villagers to bring what provisions

and other necessaries we require up to a plateau about a mile from the

house and leave them there. That is the most I have been able to do. It

comes somewhat as a shock to one to find men and women—fairly educated

and intelligent as many of them are—slaves to fears that one would

expect a child to laugh at. But there is no reasoning with

superstition.”

[Pg 586]

Extract from the same letter, but from a part seemingly written

a day or two later:

“At home I should have forgotten such a tale an hour after I had heard

it, but these mountain fastnesses seem strangely fit to be the last

stronghold of the supernatural. The woman haunts me already. At night,

instead of working, I find myself listening for her tapping at the door;

and yesterday an incident occurred that makes me fear for my own common

sense. I had gone out for a long walk alone, and the twilight was

thickening into darkness as I neared home. Suddenly looking up from my

reverie, I saw, standing on a knoll the other side of the ravine, the

figure of a woman. She held a cloak about her head, and I could not see

her face. I took off my cap, and called out a good-night to her, but she

never moved or spoke. Then, God knows why, for my brain was full of

other thoughts at the time, a clammy chill crept over me, and my tongue

grew dry and parched. I stood rooted to the spot, staring at her across

the yawning gorge that divided us, and slowly she moved away, and passed

into the gloom; and I continued my way. I have said nothing to Muriel,

and shall not. The effect the story has had upon myself warns me not

to.”

From a letter dated eleven days later:

“She has come. I have known she would since that evening I saw her on

the mountain, and last night she came, and we have sat and looked into

each other’s eyes. You will say, of course, that I am mad—that I have

not recovered from my fever—that I have been working too hard—that I

have heard a foolish tale, and that it has filled my overstrung brain

with foolish fancies—I have told myself all that. But the thing came,

nevertheless—a creature of flesh and blood? a creature of air? a

creature of my own imagination? what matter; it was real to me.

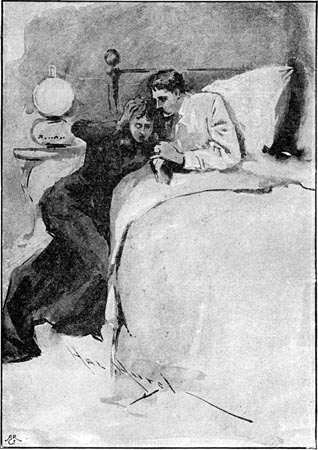

“It came last night, as I sat working, alone. Each night I have waited

for it, listened for it—longed for it, I know now. I heard the passing

of its feet upon the bridge, the tapping of its hand upon the door,

three times—tap, tap, tap. I felt my loins grow cold, and a pricking

pain about my head, and I gripped my chair with both hands, and waited,

and again there came the tapping—tap, tap, tap. I rose and slipped the

bolt of the door leading to the other room, and again I waited, and

again there came the tapping—tap, tap, tap. Then I opened the heavy

outer door, and the wind rushed past me, scattering my papers, and the

woman entered in, and I closed the door behind her. She threw

[Pg 587] her hood

back from her head, and unwound a kerchief from about her neck, and laid

it on the table. Then she crossed and sat before the fire, and I noticed

her bare feet were damp with the night dew.

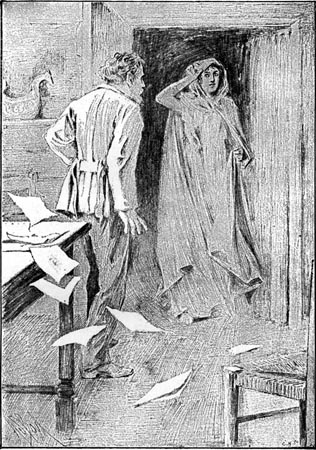

“the woman entered.”

“the woman entered.”

“I stood over against her and gazed at her, and she smiled at me—a

strange, wicked smile, but I could have laid my soul at her feet. She

never spoke or moved, and neither did I feel the need of spoken words,

for I understood the meaning of those upon the Mount when they said,

‘Let us make here tabernacles: it is good for us to be here.’

[Pg 588]

“How long a time passed thus I do not know, but suddenly the woman held

her hand up, listening, and there came a faint sound from the other

room. Then swiftly she drew her hood about her face and passed out,

closing the door softly behind her; and I drew back the bolt of the

inner door and waited, and hearing nothing more, sat down, and must have

fallen asleep in my chair.

“I awoke, and instantly there flashed through my mind the thought of the

kerchief the woman had left behind her, and I started from my chair to

hide it. But the table was already laid for breakfast, and my wife sat

with her elbows on the table and her head between her hands, watching me

with a look in her eyes that was new to me.

“She kissed me, though her lips were a little cold, and I argued to

myself that the whole thing must have been a dream. But later in the

day, passing the open door when her back was towards me, I saw her take

the kerchief from a locked chest and look at it.

“I have told myself it must have been a kerchief of her own, and that

all the rest has been my imagination—that if not, then my strange

visitant was no spirit, but a woman, and that, if human thing knows

human thing, it was no creature of flesh and blood that sat beside me

last night. Besides, what woman would she be? The nearest saeter is a

three hours’ climb to a strong man, the paths are dangerous even in

daylight: what woman would have found them in the night? What woman

would have chilled the air around her, and have made the blood flow cold

through all my veins? Yet if she come again I will speak to her. I will

stretch out my hand and see whether she be mortal thing or only air.”

The fifth letter:

“My dear Joyce,—Whether your eyes will ever see these letters is

doubtful. From this place I shall never send them. They would read to

you as the ravings of a madman. If ever I return to England I may one

day show them to you, but when I do it will be when I, with you, can

laugh over them. At present I write them merely to hide away—putting

the words down on paper saves my screaming them aloud.

“She comes each night now, taking the same seat beside the embers, and

fixing upon me those eyes, with the hell-light in them, that burn into

my brain; and at rare times she smiles, and all my Being passes out of

me, and is hers. I make no attempt to

[Pg 589]

work. I sit listening for her

footsteps on the creaking bridge, for the rustling of her feet upon the

grass, for the tapping of her hand upon the door. No word is uttered

between us. Each day I say: ‘When she comes to-night I will speak to

her. I will stretch out my hand and touch her.’ Yet when she enters, all

thought and will goes out from me.

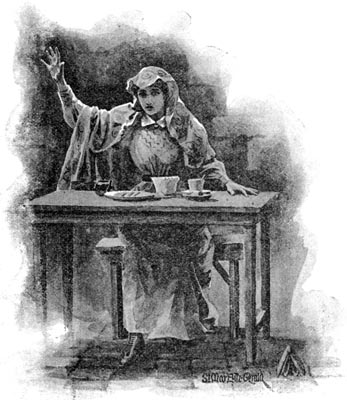

“i stood gazing at her.”

“i stood gazing at her.”

“Last night, as I stood gazing at her, my soul filled with her wondrous

beauty as a lake with moonlight, her lips parted, and she started from

her chair, and, turning, I thought I saw a white face pressed against

the window, but as I looked it vanished.

[Pg 590]

Then she drew her cloak about

her, and passed out. I slid back the bolt I always draw now, and stole

into the other room, and, taking down the lantern, held it above the

bed. But Muriel’s eyes were closed as if in sleep.”

Extract from the sixth letter:

“It is not the night I fear, but the day. I hate the sight of this woman

with whom I live, whom I call ‘wife.’ I shrink from the blow of her cold

lips, the curse of her stony eyes. She has seen, she has learnt; I feel

it, I know it. Yet she winds her arms around my neck, and calls me

sweetheart, and smooths my hair with her soft, false hands. We speak

mocking words of love to one another, but I know her cruel eyes are ever

following me. She is plotting her revenge, and I hate her, I hate her, I

hate her!”

Part of the seventh letter:

“This morning I went down to the fiord. I told her I should not be back

until the evening. She stood by the door watching me until we were mere

specks to one another, and a promontory of the mountain shut me from

view. Then, turning aside from the track, I made my way, running and

stumbling over the jagged ground, round to the other side of the

mountain, and began to climb again. It was slow, weary work. Often I had

to go miles out of my road to avoid a ravine, and twice I reached a high

point only to have to descend again. But at length I crossed the ridge,

and crept down to a spot from where, concealed, I could spy upon my own

house. She—my wife—stood by the flimsy bridge. A short hatchet, such

as butchers use, was in her hand. She leant against a pine trunk, with

her arm behind her, as one stands whose back aches with long stooping in

some cramped position; and even at that distance I could see the cruel

smile about her lips.

“Then I recrossed the ridge, and crawled down again, and, waiting until

evening, walked slowly up the path. As I came in view of the house she

saw me, and waved her handkerchief to me, and, in answer, I waved my

hat, and shouted curses at her that the wind whirled away into the

torrent. She met me with a kiss, and I breathed no hint to her that I

had seen. Let her devil’s work remain undisturbed. Let it prove to me

what manner of thing this is that haunts me. If it be a Spirit, then the

bridge will bear it safely; if it be woman——

[Pg 591]

“But I dismiss the thought. If it be human thing why does it sit gazing

at me, never speaking; why does my tongue refuse to question it; why

does all power forsake me in its presence, so that I stand as in a

dream? Yet if it be Spirit, why do I hear the passing of her feet; and

why does the night-rain glisten on her hair?

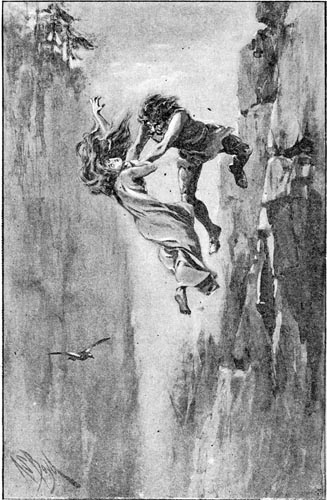

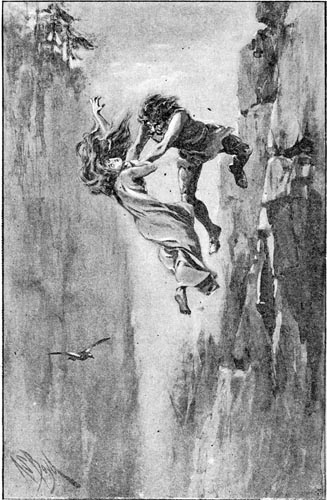

“to the utmost edge.”

“to the utmost edge.”

“I force myself back into my chair. It is far into the night, and I am

alone, waiting, listening. If it be Spirit, she will come to me; and if

it be woman, I shall hear her cry above the storm—unless it be a demon

mocking me.

“I have heard the cry. It rose, piercing and shrill, above the storm,

above the riving and rending of the bridge, above the downward crashing

of the logs and loosened stones. I hear it as I listen now. It is

cleaving its way upward from the depths below. It is wailing through the

room as I sit writing.

“I have crawled upon my belly to the utmost edge of the still standing

pier until I could feel with my hand the jagged splinters left by the

fallen planks, and have looked down. But the chasm was full to the brim

with darkness. I shouted, but the wind shook my voice into mocking

laughter. I sit here, feebly striking at the madness that is creeping

nearer and nearer to me. I tell myself the whole thing is but the fever

in my brain. The bridge was rotten. The storm was strong. The cry is but

a single one among the many voices of the mountain. Yet still I listen,

and it rises, clear and shrill, above the moaning of the pines,

[Pg 592] above

the mighty sobbing of the waters. It beats like blows upon my skull, and

I know that she will never come again.”

Extract from the last letter:

“I shall address an envelope to you, and leave it among them. Then,

should I never come back, some chance wanderer may one day find and post

them to you, and you will know.

“My books and writings remain untouched. We sit together of a

night—this woman I call ‘wife’ and I—she holding in her hands some

knitted thing that never grows longer by a single stitch, and I with a

volume before me that is ever open at the same page. And day and night

we watch each other stealthily, moving to and fro about the silent

house; and at times, looking round swiftly, I catch the smile upon her

lips before she has time to smooth it away.

“We speak like strangers about this and that, making talk to hide our

thoughts. We make a pretence of busying ourselves about whatever will

help us to keep apart from one another.

“At night, sitting here between the shadows and the dull glow of the

smouldering twigs, I sometimes think I hear the tapping I have learnt to

listen for, and I start from my seat, and softly open the door and look

out. But only the Night stands there. Then I close-to the latch, and

she—the living woman—asks me in her purring voice what sound I heard,

hiding a smile as she stoops low over her work, and I answer lightly,

and, moving towards her, put my arm about her, feeling her softness and

her suppleness, and wondering, supposing I held her close to me with one

arm while pressing her from me with the other, how long before I should

hear the cracking of her bones.

“For here, amid these savage solitudes, I also am grown savage. The old

primeval passions of love and hate stir within me, and they are fierce

and cruel and strong, beyond what you men of the later ages could

understand. The culture of the centuries has fallen from me as a flimsy

garment whirled away by the mountain wind; the old savage instincts of

the race lie bare. One day I shall twine my fingers about her full white

throat, and her eyes will slowly come towards me, and her lips will

part, and the red tongue creep out; and backwards, step by step, I shall

push her before me, gazing the while upon her bloodless face, and it

will be my turn to smile. Backwards through the open door, backwards

along the garden path between the juniper bushes, backwards till her

heels are overhanging the ravine, and she grips

[Pg 593]

life with nothing but

her little toes, I shall force her, step by step, before me. Then I

shall lean forward, closer, closer, till I kiss her purpling lips, and

down, down, down, past the startled sea-birds, past the white spray of

the foss, past the downward peeping pines, down, down, down, we will go

together, till we find my love where she lies sleeping beneath the

waters of the fiord.”

With these words ended the last letter, unsigned. At the first streak of

dawn we left the house, and, after much wandering, found our way back to

the valley. But of our guide we heard no news. Whether he remained still

upon the mountain, or whether by some false step he had perished upon

that night, we never learnt.

[Pg 594]

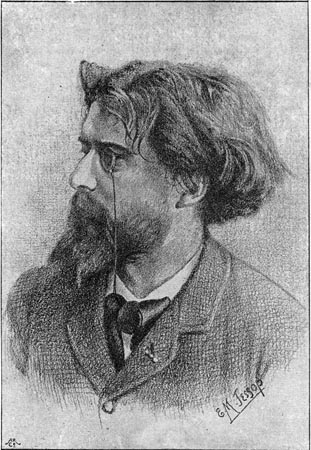

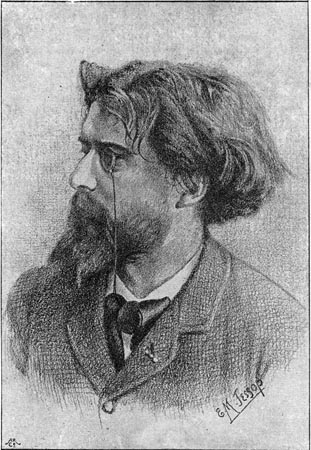

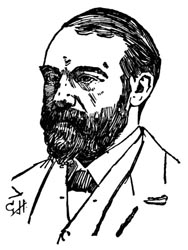

alphonse daudet.

alphonse daudet.

[Pg 595]

Alphonse Daudet at Home.

By Marie Adelaide Belloc.

Illustrations by Jan Berg, J. Barnard Davis, and E. M. Jessop.

M. and Madame Alphonse Daudet—for it is impossible to mention the great

French writer without also immediately recalling the personality of the

lady who has been his best friend, his tireless collaboratrice, and his

constant companion during the last twenty-five years—have made their

home on the top storey of a fine stately house in the Rue de Belle

Chasse, a narrow old-world street running from the Boulevard Saint

Germain up into the Quartier Latin.

madame daudet.

madame daudet.

Like most houses on the left bank of the Seine, the “hotel” is built

round a large courtyard, the Daudets’ pretty appartement being

situated on the side furthest from the street, and commanding a splendid

view of Southern Paris, whilst in the immediate foreground is one of

those peaceful, quiet gardens, owned by some of the old Paris religious

foundations still left undisturbed by the march of Republican time.

The study in which Alphonse Daudet does all his work, and receives his

more intimate friends, is opposite the hall door, but a strict watch is

kept by Madame Daudet’s faithful servants, and no one is allowed to

break in upon the privacy of le maître without some good and

sufficient reason. Few writers are so personally popular with their

readers as is Alphonse Daudet; there is about most of his books a

strange magnetic charm, and every post brings him quaint, curious, and

often pathetic, epistles from men and women all over the world, and of

every nationality, discussing his characters, suggesting alterations,

offering him plots, and

[Pg 596]

asking his advice on their own most intimate

cases of conscience, whilst, if he were to grant all the requests for

personal interviews which come to him day by day, he would literally

have not a moment for work or leisure.

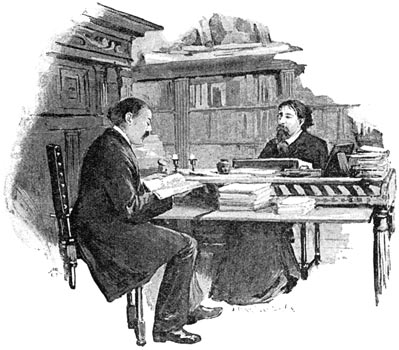

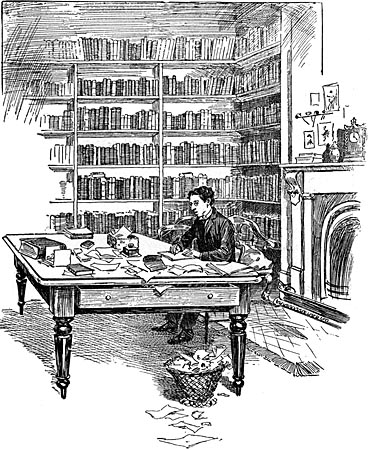

daudet at work.

daudet at work.

But to those who have the good fortune of his acquaintance, M. Daudet is

the most delightful and courteous of hosts, and, though rarely alluding

to his own work in conversation, he will always answer those questions

put to him to the best of his ability, and as one who has thought much

and deeply on most subjects of human interest.

The first glance shows you that Daudet’s study is a real work room;

there is no straining after effect; the plain, comfortable furniture,

including the large solid writing table covered with papers, proofs,

literary biblots, and the various instruments necessary to his craft,

were made and presented to him by a number of workmen, his military

comrades during the war, and serve to perpetually remind him of what, he

says, has been the most instructive and intensely interesting period of

his life. “That terrible year,” I have heard him exclaim more than once,

“taught me many things. It was then for the first time that I learned to

appreciate our workpeople, le peuple. Had it not been for what I then

went through, one whole side of good human nature would have been shut

to me. The Paris ouvrier is a splendid fellow, and among my best

friends I reckon some of those who fought by my side in 1870.”

During those same eventful months M. Daudet made the acquaintance of the

man who was afterwards to prove his most

[Pg 597]

indefatigable helper; it was

between one of the long waits outside the fortifications. To his

surprise, the novelist saw a young soldier reading a Latin book. In

answer to a question, the pioupiou explained that he had been brought

up to be a priest, but had finally changed his mind and become a

workman. Now, the ex seminarist is M. Daudet’s daily companion and

literary agent; it is he who makes all the necessary arrangements with

editors and publishers, and several of Daudet’s later writings have been

dictated to him.

All that refers to a great writer’s methods cannot but be of interest.

Daudet’s novels are really human documents, for from early youth he has

put down from day to day, almost from hour to hour, all that he has

seen, heard, and done. He calls his note-books “my memory.” When about

to start a new novel he draws out a general plan, then he copies out all

the incidents from his note-books which he thinks will be of value to

him for the story. The next step is to make out a rough list of

chapters, and then, with infinite care, and constant corrections, he

begins writing out the book, submitting each page to his wife’s

criticism, and discussing with her the working out of every incident,

and the arrangement of every episode. Unlike most novelists, M. Daudet

does not care to always write on the same paper, and his manuscripts are

not all written on paper of the same size. Of late he has been using

some large, rough hand-made sheets, which Victor Hugo had specially made

for his own use, and which have been given to M. Daudet by Georges Hugo,

who knew what a pleasure his grandfather would have taken in the thought

that any of his literary leavings would have been useful to his little

Jeanne’s father-in-law, for it will be remembered that Léon Daudet, the

novelist’s eldest child, married some three years ago “Peach Blossom”

Hugo, for whom was written L’Art d’être Grand-père.

Although M. Daudet takes precious care of his little note-books, both

past and present, he has never troubled himself much as to what became

of the fair copies of his novels. They remain in the printers’ and

publishers’ hands, and will probably some day attain a fabulous value.

His handwriting is clear, and somewhat feminine in form, and he always

uses a steel pen. Till his health broke down he wrote every word of his

manuscripts himself, but of late he has been obliged to dictate to his

wife and two secretaries; re-writing, however, much of his work in the

margin of the manuscript, and also adding to, and polishing, each

chapter in proof, for no writer pays

[Pg 598]

more attention to style and

chiselled form than the man who has been called the French Dickens, and

whose compositions, to the uninitiated, would seem to be singularly

spontaneous.

Since the war M. Daudet has never had an hour’s sleep without artificial

aid, such as chloral; but devotees of Lady Nicotine will be interested

to learn that in answer to a question he once said, “I have smoked a

great deal while working, and the more I smoked the better I worked. I

have never noticed that tobacco is injurious, but I must admit that,

when I am not well, even the smell of a cigarette is odious.” He added

that he had a great horror of alcohol as a stimulant for work, and has

ofttimes been heard to say that those who believe in working on spirits

had better make up their minds to become total abstainers if they hope

to achieve anything in the way of literature.

Unlike most literary ménages, M. and Madame Daudet are one of those

happy couples who are said by cynics to be the exceptions which prove

the rule. Literary men are proverbially unlucky in their helpmates; and

geniuses have been proved again and again to reserve their fitful

humours and uncertain tempers for home use. M. and Madame Daudet are at

once sympathetic, literary partners, and the happiest of married

couples; in L’Enfance d’une Parisienne, Enfants et Mères, and

Fragments d’un Livre Inédit, Madame Daudet has proved that she is in

her own way as original and delicate an artist as her husband. She has

never written a novel, but, as a great French critic once aptly

remarked, “Each one of her books contains the essence of innumerable

novels.” Her literary work has been an afterthought, an accident; she is

not anxious to make a name by her writing, and her most intimate friends

have never heard her mention her literary faculty; like most

Frenchwomen, a devoted mother, when not helping her husband, she is

absorbed in her children, and whilst her boys were at the Lycée she

taught herself Latin in order to help them prepare their lessons every

evening; and she is now her young daughter’s closest companion and

friend.

One of the most charming characteristics of Alphonse Daudet is his love

for, and pride in, his wife. “I often think of my first meeting with

her,” he will say. “I was quite a young fellow, and had a great

prejudice against literary women, and especially against poetesses, but

I came, saw, and was conquered, and,” he will conclude smiling, “I have

remained under the charm ever since.... People sometimes ask me whether

I approve of women writing; how should I not, when my own

[Pg 599] wife has

always written, and when all that is best in my literary work is owing

to her influence and suggestion. There are whole realms of human nature

which we men cannot explore. We have not eyes to see, nor hearts to

understand, certain subtle things which a woman perceives at once; yes,

women have a mission to fulfil in the literature of to-day.”

the provençal furniture.

the provençal furniture.

Strangely enough, M. Daudet made the acquaintance of his future wife

through a favourable review he wrote of a volume of verse published by

her parents, M. and Madame Allard. They were so pleased with the notice

that they wrote and asked the critic to come and see them. How truly

thankful the one time critic must now feel that he was inspired to deal

gently by the little bouquin.

Madame Daudet is devoted to art, and her pretty salon is one of the

most artistic intérieurs in Paris, whilst the dining-room, fitted up

with old Provençal furniture, looks as though it had been lifted bodily

out of some fastness in troubadour land.

The tie between the novelist and his children is a very close one; he

has said of Léon that there stands his best work; and, indeed, the young

man is in a fair way to make his father’s words come true, for,

inheriting much of both parents’ literary faculty, M. Léon Daudet lately

made his débût as a novelist with Hœrès, a remarkable story with

a purpose, in which the author strove to explain his somewhat curious

theories on the laws of heredity. Having originally been intended for

the medical profession, he takes a special interest in this subject. It

is curious that three such distinct and different literary gifts should

exist simultaneously in the same family.

As soon as even the cool, narrow streets of the Quartier Latin begin to

grow dusty and sultry with summer heat, the whole Daudet family emigrate

to the novelist’s charming country cottage

[Pg 600]

at Champrosay. There old

friends, such as M. Edmond de Goncourt, are ever made welcome, and life

is one long holiday for those who bring no work with them. Daudet

himself has described his country home as being “situated thirty miles

from Paris, at a lovely bend of the Seine, a provincial Seine invaded by

bulrushes, purple irises, and water-lilies, bearing on its bosom tufts

of grass, and clumps of tangled roots, on which the tired dragon-flies

alight, and allow themselves to be lazily floated down the stream.”

the drawing room.

the drawing room.

It was in a round, ivy-clad pavilion overhanging the river that le

maître du logis wrote L’Immortel. On an exceptionally fine day he

would get into a canoe, and let it drift among the reeds, till, in the

shadow of an old willow-tree, the boat became his study, and the two

crossed oars his desk. Strange that so bitter and profoundly cynical a

study of modern Paris life should have been evolved in such

surroundings, whilst the Contes de Mon Moulin, and many other of his

most ideal nouvelles, were written in the sombre grey house where M.

and Madame Daudet lived during many years of their early married life.

The author of Les Rois en Exile has not yet utilised Champrosay as a

background to any of his stories; he takes notes,

[Pg 601]

however, of all that

goes on in the little village community, much as he did in the Duc de

Morny’s splendid palace, and in time his readers may have the pleasure

of perusing an idyllic yet realistic picture of French country life, an

outcome of his summer experiences.

Alphonse Daudet was born just fifty-three years ago in the sunlit, white

bâtisse at Nimes, which he has described in the painful, melancholy

history of his childhood, entitled Le Petit Chose. At an age when

other French boys are themselves lycéans, he became usher in a kind of

provincial Dotheboys Hall; and some idea of what the sensitive, poetical

lad went through may be gained by the fact that he more than once

seriously contemplated committing suicide. But fate had something better

in store for le petit Daudet, and his seventeenth birthday found him

in Paris sharing his brother Ernest’s garret, having arrived in the

great city with just forty sous remaining of his little store, after

spending two days and nights in a third-class carriage.

Even now, there is a touch of protection and maternal affection in the

way in which Ernest Daudet regards his younger brother, and the latter

never mentions his early struggles without recalling the

self-abnegation, generous kindliness, and devotion of “mon frère.” The

two went through some hard times together. “Ah!” says the great writer,

speaking of those days, “I thought my brother passing rich, for he

earned seventy-five francs a month by being secretary to an old

gentleman at whose dictation he took down his memoirs.” And so they

managed to live, going occasionally to the theatre, and seeing not a

little of life, on the sum of thirty shillings a month apiece!

When receiving visitors, the author of Tartarin places himself with

his back to the light on one of the deep, comfortable couches which line

the fireplace of his study, but from out the huge mass of his powerful

head, surrounded by the lionese mane, which has become famous in his

portraits and photographs, gleam two piercing dark eyes, which, like

those of most short-sighted people, seem to perceive what is immediately

before them with an extra intensity of vision.

To ask one who has far outrun his fellows what he thinks of the race

seems a superfluous question. Yet, in answer as to what he would say of

literature as a profession, M. Daudet gave a startlingly clear and

decided answer.

the billiard and fencing room.

the billiard and fencing room.

“The man who has it in him to write will do so, however great his

difficulties, but I would never advise any young fellow to make

[Pg 602]

literature his profession, and I think it is nothing short of madness to

give up a good chance of making your livelihood in some other, though

perhaps less congenial, fashion, in order to pursue the calling of

letters. You would be surprised if you knew the number of young people

who come to me for sympathy with their literary aspirations, and as for

the manuscripts submitted to me, the sending of them back keeps one of

my friends pretty busy, for of late years I have had to refuse to look

at anything sent to me in this way. In vain I say to those who come to

consult me, ‘However much occupied you are with your present way of

earning a livelihood, if you have it in you to write anything you will

surely find time to do it.’ They go away unconvinced, and a few months

later sees them launched on the perilous seas of journalism; with now

really not a moment to spare for serious writing! Of course, if the

would-be writer has already an income, I see no reason why he should not

give himself up to literature altogether. It was in order to provide a

certain number of coming geniuses with the wherewithal to find at least

spare time in which to write possible masterpieces, that my friend

Edmond de Goncourt and his brother Jules conceived the noble and

unselfish idea to found an institute, the members of which would require

but two qualifications, poverty and exceptional literary power. If a

would-be writer can find someone who will assist him in this manner,

well and good; but no one is a prophet in his own country, and friends

and relations are, as a rule, most unwilling to waste good money on

their young literary acquaintances. Still I admit that the Academie de

Goncourt would fulfil a want, for there have been, and are, great

geniuses who positively cannot produce their masterpieces from bitter

poverty.”

[Pg 603]

“Then do you believe in journalism as a stepping-stone to literature?”

“I cannot say that I do, though, strangely enough, there is scarcely one

of us—I allude to latter-day French novelists and critics—who did not

spend at least a portion of his youth doing hard, pot-boiling newspaper

work. But I deplore the necessity of a novelist having to make

journalism his start in life, for, as all newspaper writing has to be

done against time, his style must certainly deteriorate, and his

literature becomes journalese.”

“What was your own first literary essay, M. Daudet?”

“You know I was born a poet, not a novelist; besides, when I was a lad

everyone wrote poetry, so I made my débût by a book of verse entitled

Mes Amoureuses. I was just eighteen, and this was my first stroke of

luck; for six weary months I had carried my poor little manuscript from

publisher to publisher, but, strange to say, I never got further than

these great people’s ante-chamber; at last, a certain Tardieu, a

publisher who was himself an author, took pity on my Amoureuses. The

title had been a happy inspiration, and the volume received some

favourable notices, and led indirectly to my getting journalistic work.”

Indeed, it seems to have been more or less of an accident that M. Daudet

did not devote himself entirely to poetry; and probably the very poverty

which seemed so bitter to him during his youth obliged him to try what

he could do in the way of story-writing, that branch of literature being

supposed by the French to be the best from a pecuniary point of view. So

remarkable were his verses felt to be by the critics of the day, that

one of them wrote, “When dying, Alfred de Musset left his two pens as a

last legacy to our literature—Feuillet has taken that of prose; into

Daudet’s hand has slipped that of verse.”

But some years passed before the poet-journalist became the novelist; at

one time he dreamed of being a great dramatist, and before he was

five-and-twenty several of his plays had been produced at leading Paris

theatres. Fortune smiled upon him, and he was appointed to be one of the

Duc de Morny’s secretaries, a post he held four years, and which

supplied him with much valuable material for several of his later

novels, notably Les Rois en Exile, Le Nabab, and Numa Romestan,

for during this period he was brought into close and intimate contact

with all the noteworthy personages of the Third Empire, making at the

same time the acquaintance of most of the literary lions of the

day—Flaubert, with whom he became very intimate; Edmond and Jules de

[Pg 604]

Goncourt, the two gifted brothers who may be said to have founded the

realistic school of fiction years before Emile Zola came forward as the

apostle of realism; Tourguenieff, the two Dumas, and many others who

welcomed enthusiastically the young Southern poet into their midst.

the tuileries stone.

the tuileries stone.

The first page of Le Petit Chose was written in the February of 1866,

and was finished during the author’s honeymoon, but it was with Fromont

Jeune et Risler Ainé, published six years later, that he made his first

real success as a novelist, the work being crowned by the French

Academy, and arousing a veritable enthusiasm both at home and abroad.

Alphonse Daudet is not a quick worker; he often allows several years to

elapse between his novels, and refuses to bind himself down to any

especial date. Tartarin de Tarascon was, however, an exception to this

rule, for the author wrote it for Messrs. Guillaume, the well-known art

publishers, who, wishing to popularise an improved style of

illustration, offered M. Daudet 150,000 francs (£6,000) to write them a

serio-comic story. Tartarin, which obtained an instant popularity,

proved the author’s versatility, but won him the hatred of the good

people of Provence, who have never forgiven him for having made fun of

their foibles. On one occasion a bagman, passing through Tarascon, put,

by way of a jest, the name “Alphonse Daudet” in his hotel register. The

news quickly spread, and had it not been for the prompt help of the

innkeeper, who managed to smuggle him out of the town, he might easily

have had cause to regret his foolish joke.

Judging by sales, Sapho has been the most popular of Daudet’s novels,

for over a quarter of a million copies have been sold. Like most of his

stories, its appearance provoked a great deal of discussion, as did the

author’s dedication “To my two sons at the age of twenty.” But, in

answer to his critics, Daudet always

[Pg 605]

replies, “I wrote the book with a

purpose, and I have succeeded in painting the picture as I wished it to

appear. Each of the types mentioned by me really existed; each incident

was copied from life....”

The year following its publication M. Daudet dramatised Sapho, and the

play was acted with considerable success at the Gymnase, Jane Hading

being in the title-rôle. Last year the play was again acted in Paris,

with Madame Rejane as the heroine.

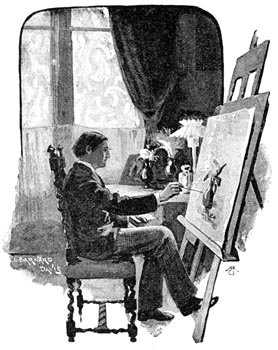

daudet’s younger son.

daudet’s younger son.

M. Daudet, like most novelists, takes a special interest in all that

concerns dramatic art and the theatre. When his health permits it he is

a persistent first-nighter, and most of his novels lend themselves in a

rare degree to stage adaptation.

I once asked him what he thought of the attempts now so frequently made

to introduce unconventionality and naked realism on the stage.

“I have every sympathy,” he replied, “with the attempts made by Antoine

and his Thêatre Libre to discover strong and unconventional work. But I

do not believe in the new terms which a certain school have invented for

everything; after all, the play’s the thing, whether it is produced by a

group who dub themselves romantics, realists, old or new style. Realism

is not necessarily real life; a photograph only gives a rigid, neutral

side of the object placed in front of the camera. A dissection of what

we call affection does not give so vivid an impression of the

master-passion as a true love-sonnet written by a poet. Life is a

[Pg 606] thing

of infinite gradations; a dramatist wishes to show existence as it

really is, not as it may be under exceptionally revolting

circumstances.”

His own favourite dramatist and writer is Shakespeare, whom, however, he

only knows by translation, and Hamlet and Desdemona are his

favourite hero and heroine in the fiction of the world, although he

considered Balzac his literary master.

M. Daudet will seldom be beguiled into talking on politics. Like all

Frenchmen, the late Panama scandals have profoundly shocked and

disgusted him, as revealing a state of things discreditable to the

Government of his country. But the creator of Désirée Dolobelle has a

profound belief in human nature, and believes that, come what may, the

novelist will never lack beautiful and touching models in the world

round and about him.

[Pg 607]

The Dismal Throng.

By Robert Buchanan.

Illustrations by Geo. Hutchinson.

(Written after reading the last Study in Literary Distemper.)

thomas hardy.

thomas hardy.

The Fairy Tale of Life is done,

The horns of Fairyland cease blowing,

The Gods have left us one by one,

And the last Poets, too, are going!

Ended is all the mirth and song,

Fled are the merry Music-makers;

And what remains? The Dismal Throng

Of literary Undertakers!

Clad in deep black of funeral cut,

With faces of forlorn expression,

Their eyes half open, souls close shut,

They stalk along in pale procession;

The latest seed of Schopenhauer,

Born of a Trull of Flaubert’s choosing,

They cry, while on the ground they glower,

“There’s nothing in the world amusing!”

zola.

zola.

There’s Zola, grimy as his theme,

Nosing the sewers with cynic pleasure,

Sceptic of all that poets dream,

All hopes that simple mortals treasure;

With sense most keen for odours strong,

He stirs the Drains and scents disaster,

Grim monarch of the Dismal Throng

Who bow their heads before “the Master.”

[Pg 608]

There’s Miss Matilda[1] in the south,

There’s Valdes[2] in Madrid and Seville,

There’s mad Verlaine[3] with gangrened mouth.

Grinning at Rimbaud and the Devil.

From every nation of the earth,

Instead of smiling merry-makers,

They come, the foes of Love and Mirth,

The Dismal Throng of Undertakers.

tolstoi.

tolstoi.

There’s Tolstoi, towering in his place

O’er all the rest by head and shoulders;

No sunshine on that noble face

Which Nature meant to charm beholders!

Mad with his self-made martyr’s shirt,

Obscene, through hatred of obsceneness,

He from a pulpit built of Dirt

Shrieks his Apocalypse of Cleanness!

ibsen.

ibsen.

There’s Ibsen,[4] puckering up his lips,

Squirming at Nature and Society,

Drawing with tingling finger-tips

The clothes off naked Impropriety!

So nice, so nasty, and so grim,

He hugs his gloomy bottled thunder;

To summon up one smile from him

Would be a miracle of wonder!

[Pg 609]

pierre loti.

pierre loti.

There’s Maupassant,[5] who takes his cue

From Dame Bovary’s bourgeois troubles;

There’s Bourget, dyed his own sick “blue,”

There’s Loti, blowing blue soap bubbles;

There’s Mendès[6] (no Catullus, he!)

There’s Richepin,[7] sick with sensual passion.

The Dismal Throng! So foul, so free,

Yet sombre all, as is the fashion.

“Turn down the lights! put out the Sun!

Man is unclean and morals muddy.

The Fairy Tale of Life is done,

Disease and Dirt must be our study!

Tear open Nature’s genial heart,

Let neither God nor gods escape us,

But spare, to give our subjects zest,

The basest god of all—Priapus!”

The Dismal Throng! ’Tis thus they preach,

From Christiania to Cadiz,

Recruited as they talk and teach

By dingy lads and draggled ladies;

Without a sunbeam or a song,

With no clear Heaven to hunger after;

The Dismal Throng! the Dismal Throng!

The foes of Life and Love and Laughter!

By Shakespere’s Soul! if this goes on,

From every face of man and woman

The gift of gladness will be gone,

And laughter will be thought inhuman!

The only beast who smiles is Man!

That marks him out from meaner creatures!

Confound the Dismal Throng, who plan

To take God’s birth-mark from our features!

[Pg 610]

Manfreds who walk the hospitals.

Laras and Giaours grown scientific,

They wear the clothes and bear the palls

Of Stormy Ones once thought terrific;

They play the same old funeral tune,

And posture with the same dejection,

But turn from howling at the moon

To literary vivisection!

oscar wilde.

oscar wilde.

And while they loom before our view,

Dark’ning the air that should be sunny,

Here’s Oscar,[8] growing dismal too,

Our Oscar, who was once so funny!

Blue china ceases to delight

The dear curl’d darling of society,

Changed are his breeches, once so bright,

For foreign breaches of propriety!

george moore.

george moore.

I like my Oscar, tolerate

My Archer[9] of the Dauntless Grammar,

Nay, e’en my Moore[10] I estimate

Not too unkindly, ’spite his clamour;

But I prefer my roses still

To all the garlic in their garden—

Let Hedda gabble as she will,

I’ll stay with Rosalind, in Arden!

O for one laugh of Rabelais,

To rout these moralising croakers!

(The cowls were mightier far than they,

Yet fled before that King of Jokers)

O for a slash of Fielding’s pen

To bleed these pimps of Melancholy!

O for a Boz, born once again

To play the Dickens with such folly!

[Pg 611]

mark twain.

mark twain.

Yet stay! why bid the dead arise?

Why call them back from Charon’s wherry?

Come, Yankee Mark, with twinkling eyes,

Confuse these ghouls with something merry!

Come, Kipling, with thy soldiers three,

Thy barrack-ladies frail and fervent,

Forsake thy themes of butchery

And be the merry Muses’ servant!

Come, Dickens’ foster-son, Bret Harte!

Come, Sims, though gigmen flout thy labours!

Tom Hardy, blow the clouds apart

With sound of rustic fifes and tabors!

Dick Blackmore, full of homely joy,

Come from thy garden by the river,

And pelt with fruit and flowers, old boy,

These dismal bores who drone for ever!

george meredith.

george meredith.

Come, too, George Meredith, whose eyes,

Though oft with vapours shadow’d over,

Can catch the sunlight from the skies

And flash it down on lass and lover;

Tell us of Life, and Love’s young dream,

Show the prismatic soul of Woman,

Bring back the Light, whose morning beam

First made the Beast upright and human!

You can be merry, George, I vow!

Wit through your cloudiest prosing twinkles!

Brood as you may, upon your brow

The cynic, Art, has left no wrinkles!

For you’re a poet to the core,

No ghouls can from the Muses win you;

So throw your cap i’ the air once more,

And show the joy of earth that’s in you!

[Pg 612]

By Heaven! we want you one and all,

For Hypochondria is reigning—

The Mater Dolorosa’s squall

Makes Nature hideous with complaining!

Ah! who will paint the Face that smiled

When Art was virginal and vernal—

The pure Madonna with her Child,

Pure as the light, and as eternal!

Pest on these dreary, dolent airs!

Confound these funeral pomps and poses!

Is Life Dyspepsia’s and Despair’s,

And Love’s complexion all chlorosis?

A lie! There’s Health, and Mirth, and Song,

The World still laughs, and goes a-Maying—

The dismal, droning, doleful Throng

Are only smuts in sunshine playing!

Play up, ye horns of Fairyland!

Shine out, O sun, and planets seven!

Beyond these clouds a beckoning Hand

Gleams from the lattices of Heaven!

The World’s alive—still quick, not dead,

It needs no Undertaker’s warning;

So put the Dismal Throng to bed,

And wake once more to Light and Morning!

Note.—These verses refer to a literary phenomenon that will in

time become historical, that phenomenon being the sudden growth, in

all parts of Europe, of a fungus-literature bred of Foulness and

Decay; and contemporaneously, the intrusion into all parts of human

life of a Calvinistic yet materialistic Morality. This literature

of a sunless Decadence has spread widely, by virtue of its own

uncleanness, and its leading characteristics are gloom, ugliness,

prurience, preachiness, and weedy flabbiness of style. That it has

not flourished in Great Britain, save among a small and discredited

Cockney minority, is due to the inherent manliness and vigour of

the national character. The land of Shakespere, Scott, Burns,

Fielding, Dickens, and Charles Reade is protected against literary

miasmas by the strength of its humour and the sunniness of its

temperament.—R.B.

[Pg 613]

In the Hands of Jefferson.

By Eden Phillpotts.

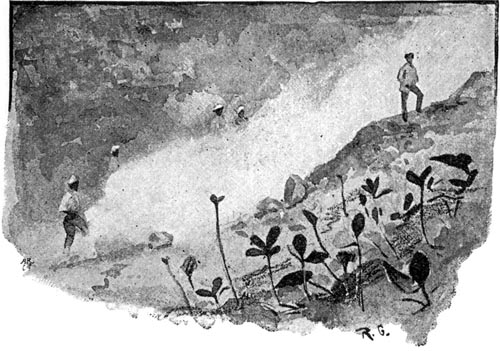

Illustrations by Ronald Gray.

It is not difficult to appreciate the recent catastrophe in Oceania,

where the island of Great Sangir was partially smothered by terrific

volcanic and seismic convulsions, when one has visited the Western

Indies.

“where lord nelson enjoyed his honeymoon.”

“where lord nelson enjoyed his honeymoon.”

Many of these tropic isles probably owe their present isolation, if not

their actual existence, to mighty earthquake throes in remote ages of

terrestrial history beyond the memory of man. But man’s memory is not a

very extensive affair, and at best probes the past to the extent of a

mere rind of a few thousand years. For the rest he has to read the word

of God, written in fossil and stone and those wondrous arcana of Nature,

which, each in turn, yields a fragment of the secret of truth to human

intellect.

Regions that have been produced or largely modified by earthquake and

volcanic upheaval may, probably enough, vanish at any moment under like

conditions; and the island of Nevis, hard by St.

[Pg 614]

Christopher, in the

West Indies, strongly suggests a possibility of such disaster. It has

always been the regular rendezvous of hurricanes and earthquakes, and it

consists practically of one vast volcanic mountain which rises abruptly

from the sea and pushes its densely-wooded sides three thousand two

hundred feet into the sky. The crater shows no particularly active

inclination at present, but it is doubtless wide awake and merely

resting, like its volcanic neighbour in St. Christopher, where the

breathing of the dormant giant can be noted through rent and rift. The

Fourth Officer of our steamship “Rhine” assured me, as we approached the

lofty dome of Nevis and gazed upon its fertile acclivities and fringe of

palms, that it would never surprise him upon his rounds to find the

place had altogether disappeared under the Caribbean Sea. He added,

according to his custom, an allusion to Columbus, and explained also

that, in the dead and gone days of Slave Traffic, Nevis was a much more

important spot than it is ever likely to become again. Then, indeed, the

island enjoyed no little prosperity and importance, being a head centre

and mart for the industry in negroes. Emancipation, however, wrecked

Nevis, together with a good many other of the Antilles.

At Montpelier, on this island, Lord Nelson enjoyed his honeymoon, but

now only a few trees and a little ruined masonry at the corner of a

sugar-cane plantation appear to mark the spot. Further, it may be

recorded, as a point in favour of the place, that it grows very

exceptional Tangerine oranges. These, to taste in perfection, should be

eaten at the turning point, before their skins grow yellow. We cannot

judge of the noble possibilities in an orange at home. I brought back a

dozen of these Nevis Tangerines with me, but I secretly suspected that,

in spite of their fine reputation, quite inferior sorts would be able to

beat them by the time they got to England; and it was so.

We stopped half-an-hour only at Charlestown, Nevis, and then proceeded

to St. Christopher, a sister isle of greater size and scope.

At Antigua, there came aboard the “Rhine” a young man who implicitly

leads us to understand that he is the most important person in the West

Indies. He is the Governor of Antigua’s own clerk, and is going to St.

Christopher with a portmanteau, some walking-sticks, and a despatch-box.

It appears that his significance is gigantic, and that, though the

nominal seat of government lies at Antigua, yet the real active centre

of political administration may be found immediately under the Panama hat

[Pg 615]

of the Governor’s own clerk. This he takes the trouble to explain

to us. The Governor himself is a puppet, his trusted men of resource and

portfolio-holders are the veriest fantoccini; for the Governor’s own

clerk pulls the strings, frames the foreign policy, conducts, controls,

adjusts difficulties, and maintains a right balance between the parties.

This he condescends to make clear to us.

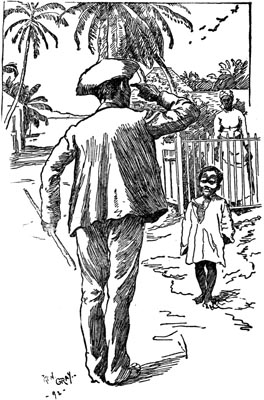

“the most important person in the west indies.”

“the most important person in the west indies.”

I ventured to ask him how many of the more important nations were

involved with the matters at present in his despatch-box; and he said

lightly, as though the concern in hand was a mere bagatelle, that only

the United States, Great Britain and Germany were occupying his

attention at the moment.

The Model Man said:

“I suppose you’ll soon knock off a flea-bite like that?”

And the Governor’s own clerk answered:

“Yes, I fancy so, unless any unforeseen hitch happens. Negotiations are

pending.”

I liked his last sentence particularly. It smacked so strongly of miles

of red tape and months of official delay.

When we reached St. Christopher, it was currently reported that the

Governor’s own clerk had simply come to settle a dispute between two

negro landowners concerning a fragment of the island rather smaller than

a table-napkin; but personally I doubt not this was a blind, under cover

of which he secretly pushed forward those pending negotiations. He

certainly had fine diplomatic instincts, and a sound view, from a

political standpoint, of the value of veracity.

When we cast out anchor off Basseterre, St. Christopher, the Treasure

hurried to me in some sorrow. He had proposed going ashore, with his

Enchantress and her mother, to show them the sights, but now, to his

dismay, he found that unforeseen official duties would keep him on the

ship during our brief sojourn here. With anxiety almost pathetic,

therefore, he entrusted the Enchantress to me, and commended her mother

to the Doctor’s care. I felt the compliment, and assured him that I

would simply devote myself to her—platonically withal; but the Doctor was

[Pg 616]

not quite so hearty about her mother. However, he must behave like

a gentleman, whether he felt inclined to do so or not, which the

Treasure knew, and, therefore, felt safe.

Our party of four started straightway for a ramble in St. Kitts (as St.

Christopher is more generally called), and, upon landing, we were

happily met by a middle-aged negro, who had evidently watched our boat

from afar. He tumbled off a pile of planks, where he had been basking in

the sun, girt his indifferent raiment about him, and then, by sheer

force of character, took complete command of our contemplated

expedition. It may have been hypnotism, or some kindred mystery, but we

were unresisting children in his hands. He said: “Follow me, gem’men: me

show you ebb’ryting for nuffing: de ’tanical Garns, de prison-house, de

public buildings, de church, an’ all. Dis way, dis way, ladies. Don’t

listen to dem niggers; dey nobody on dis island.”

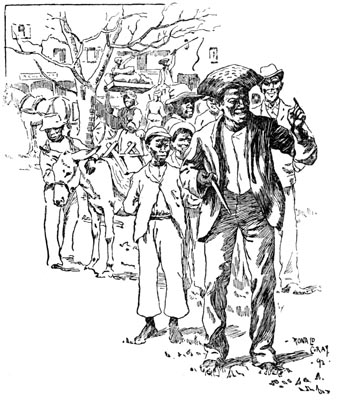

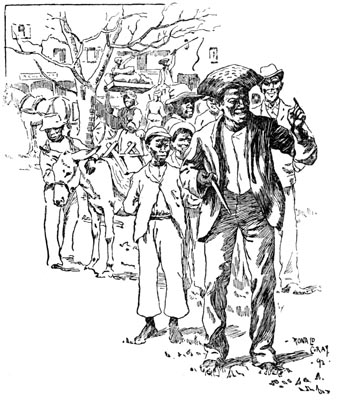

“‘follow me, gem’men!’”

“‘follow me, gem’men!’”

The Doctor alone fought feebly, but it was useless, and, in two minutes,

our masterful Ethiop had led us all away to see the sights.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Jefferson, sar; ebb’rybody know Jefferson. Fus’, we go to ’tanical

Garns. Here dey is.”

The Botanical Gardens of Basseterre, St. Kitts, were handsome,

extensive, and well cared for. We wandered with pleasure down broad

walks, shaded by cabbage palms and palmettos, mahogany and tamarind

trees; we admired the fountain and varied foliage and blazing

flower-beds, streaked and splashed with many brilliant blossoms and

bright-leaved crotons.

[Pg 617]

“There,” said the mother of the Enchantress, pointing to a handsome

lily, “is a specimen of Crinum Asiaticum.”

The Doctor started as though she had used a bad word. He hates a woman

to know anything he does not, and this botanical display irritated him;

but our attention was instantly distracted by Jefferson, who, upon

hearing the lily admired, walked straight up to it and picked it.

“‘there is a specimen of crinum asiaticum.’”

“‘there is a specimen of crinum asiaticum.’”

I expostulated. I said:

“You mustn’t go plucking curiosities here, Jefferson, or you will get us

all into hot water.”

“Dat’s right, massa,” he replied. “Me an’ de boss garner great ole

frens. De ladies jus’ say what dey like, an’ Jefferson pick him off for

dem.”

He was as good as his word, and a fine theatrical display followed, as

our party grew gradually bolder and bolder, and our guide, evidently

upon his mettle, complied with each request in turn.

I will cast a fragment of the dialogue and action in dramatic form, so

that you may the better judge of and picture that wild scene.

[Pg 618]

The Enchantress (timidly): Should you think we might have this tiny

flower?

Jefferson: I pick him, missy. (Does so.)

The Doctor: I wonder if they’d miss one of those red things? They’ve got

a good number. I believe they’re medicinal. Should you think——?

(Jefferson picks two of the flowers in question. The Doctor takes

heart.)

“‘might we have that?’”

“‘might we have that?’”

The Mother of the Enchantress: Dear me! Here’s a singularly fine

specimen of the Somethingiensis. I wonder if you——?

(Jefferson picks it.)

The Doctor: We might have that big affair there, hidden away behind

those orange trees. Nobody will miss it. I should rather like it for my

own.

(Jefferson wrestles with this concern, and the Doctor lends him a

knife.)

The Enchantress: Oh, there’s a sweet, sweet blossom! Might we have that,

and that bud, and that bunch of leaves next to them, Monsieur Jefferson?

(Jefferson, evidently feeling he is in for a hard morning’s work, makes

further onslaught upon the flora, and drags down three parts of an

entire tree.)

The Mother of the Enchantress: When you’re done there, I will ask you to

go into this fountain for one of those blue water-lilies.

(Jefferson, getting rather sick of it, pretends he does not hear.)

The Doctor (speaking in loud tones which Jefferson cannot ignore):

Pick that, please, and that, and those things half-way up that tree.

(Jefferson begins to grow very hot and uneasy. He peeps about

nervously, probably with a view to dodging his old friend, the head

gardener.)

The Chronicler (feeling that his party is disgracing itself, and

desiring to reprove them in a parable): I say, Jefferson, could you cut

down that palm—the biggest of those two—and have it sent along to the

ship? If the head gardener is here, he might help you.

[Pg 619]

Jefferson (losing his temper, missing the parable, and turning upon the

Chronicler): No, sar! You no hab no more. I’se dam near pulled off

ebb’ryting in de ’tanical Garns, an’ I’se goin’ right away now ’fore

anyfing’s said!

(Exit Jefferson rapidly, trying to conceal a mass of foliage under his

ragged coat. The party follows him in single file.)

[Curtain.]

I doubt not that, had we met the head gardener just then, our guide

would have lost a friend.

“‘i’se pulled off ebb’ryting in the ’tanical garns.’”

“‘i’se pulled off ebb’ryting in the ’tanical garns.’”

Henceforth, evidently feeling we were not wholly responsible in this

foreign atmosphere of wonders, Jefferson stuck to the streets, and took

us to churches and shops and other places where we had to control

ourselves and leave things alone.

On the way to a photographer’s he cooled down and became instructive

again. He told us the name and address and bad actions of every white

person we met. Society at St. Kitts, from his point of view, appeared to

be in an utterly rotten condition. The most reputable clique was his

own. We met several of his personal friends. They were generally brown

or yellow, and he assured us that he had white blood in him too—a fact

we could not possibly have guessed. Presently he grew confidential, and

told us that his eldest son was a source of great discomfort to him. At

the age of fifteen Jefferson Junior had run away from home and left St.

Kitts to better himself at Barbados. Five years afterwards, however,

when he had almost passed out of his parents’ memory, so Jefferson

declared, the young man returned, sick and penniless, to the home of his

birth. I said here:

“This is the Prodigal Son story over again, Jefferson. Did you kill the

fatted calf, I wonder, and make much of the lad?”

“No, sar,” he answered; “didn’t kill no fatted nuffing, but I precious

near kill de podigal son.”

Concerning St. Christopher, we have direct authority, from the immortal

and ubiquitous Columbus himself, that it is an

[Pg 620]

island of exceptional

advantages; for, delighted with its aspect in 1493, he bestowed his own

name upon it. Indeed, the place has a beautiful and imposing appearance.

Dark green forests and emerald tracts of sugar-cane now clothe its

plains and hills; and Mount Misery, the loftiest peak, rises to a height