Project Gutenberg's A Yacht Voyage Round England, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Yacht Voyage Round England

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Release Date: April 10, 2008 [EBook #25032]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A YACHT VOYAGE ROUND ENGLAND ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"A Yacht Voyage Round England"

Chapter One.

The Start.

We had come home from school much earlier than usual, on account of illness having broken out there; but as none of the boys were dangerously ill, and those in the infirmary were very comfortable, we were not excessively unhappy. I suspect that some of us wished that fever or some other sickness would appear two or three weeks before all the holidays.

However, as we had nothing to complain of at school, this, I confess, was a very unreasonable wish.

The very day of our arrival home, when we were seated at dinner, and my brother Oliver and I were discussing the important subject of how we were to spend the next ten or twelve weeks, we heard  our papa, who is a retired captain of the Royal Navy—and who was not attending to what we were talking about—say, as he looked across the table to mamma:

our papa, who is a retired captain of the Royal Navy—and who was not attending to what we were talking about—say, as he looked across the table to mamma:

“Would you object to these boys of ours taking a cruise with me round England this summer?”

We pricked up our ears, you may be sure, to listen eagerly to the reply. Looking at Oliver, then at me, she said:

“I should like to know what they think of it. As they have never before taken so long a cruise, they may get tired, and wish themselves home again or back at school.”

“Oh no, no! we should like it amazingly. We are sure not to get tired, if papa will take us. We will work our passage; will pull and haul, and learn to reef and steer, and do everything we are told,” said Oliver.

“What do you say about the matter, Harry?” asked papa.

“I say ditto to Oliver,” I replied. “We will at all events try to be of use;” for I knew from previous experience that it was only when the weather was fine, and we were really not wanted, that we were likely to be able to do anything.

“Then I give my consent,” said mamma; on which we both jumped up and kissed her, as we had been accustomed to do when we were little chaps; we both felt so delighted.

“Well, we shall be sorry to be away from you so long,” said Oliver, when we again sat down, looking quite grave for a moment or two. “But then, you know, mamma, you will have the girls and the small boys to look after; and we shall have lots to tell you about when we come back.”

“I cannot trust to your remembering everything that happens,” said mamma. “When I gave my leave I intended to make it provisional on your keeping a journal of all you see and do, and everything interesting you hear about. I do not expect it to be very long; so you must make it terse and graphic. Oliver must keep notes and help you, and one complete journal will be sufficient.”

“That’s just the bargain I intended to make,” said papa. “I’ll look out that Harry keeps to his intentions. It is the most difficult matter to accomplish. Thousands of people intend to write journals, and break down after the first five or six pages.”

On the morning appointed for the start a little longer time than usual was spent in prayer together, a special petition being offered that our Heavenly Father would keep us under His protection, and bring us safely home again. Soon afterwards we were rattling away to Waterloo Station, with our traps, including our still blank journals, our sketch-books, fishing-rods, our guns, several works on natural history, bottles and boxes for specimens, spy-glasses, and lots of other things.

Papa laughed when he saw them. “It would not do if we were going to join a man-of-war; but we have room to stow away a good number of things on board the Lively, although she is little more than thirty-five tons burden.”

In a quarter of an hour the train started for Southampton; and away we flew, the heat and the dust increasing our eagerness to feel the fresh sea-breezes.

“Although the Lively can show a fast pair of heels, we cannot go quite so fast as this,” said papa, as he remarked the speed at which we dashed by the telegraph posts.

On reaching the station at Southampton, we found Paul Truck, the sailing-master of the cutter, or the captain, as he liked to be called, waiting for us, with two of the crew, who had come up to assist in carrying our traps down to the quay. There was the boat, her crew in blue shirts, and hats on which was the name of the yacht. The men, who had the oars upright in their hands while waiting, when we embarked let the blades drop on the water in smart man-of-war style; and away we pulled for the yacht, which lay some distance off the quay.

“I think I shall know her again,” cried Oliver: “that’s her, I’m certain.”

Paul, who was pulling the stroke oar, cast a glance over his shoulder, and shaking his head with a knowing look, observed:

“No, no, Master Oliver; that’s a good deal bigger craft than ours. She’s ninety ton at least. You must give another guess.”

“That’s the Lively, though,” I cried out; “I know her by her beauty and the way she sits on the water.”

“You’re right, Master Harry. Lively is her name, and lively is her nature, and beautiful she is to look at. I’ll be bound we shall not fall in with a prettier craft—a finer boat for her size.”

Paul’s encomiums were not undeserved by the yacht; she was everything he said; we thought so, at all events. It was with no little pride that we stepped on deck.

Papa had the after-cabin fitted up for Oliver and me, and he himself had a state cabin abaft the forecastle. There were besides four open berths in which beds could be made up on both sides of the main cabin. The forecastle was large and airy, with room for the men to swing their hammocks, and it also held a brightly polished copper kitchen range.

Everything looked as neat and clean “as if the yacht had been kept in a glass case,” as Paul observed.

Papa, having looked over the stores, took us on shore to obtain a number of things which he found we should require. We thus had an opportunity of seeing something of the town.

The old walls of Southampton have been pulled down, or are crumbling away, the most perfect portion being the gateway, or Bar Gate, in the High Street. On either side of it stand two curious old heraldic figures, and beside them are two blackened pictures—one representing Sir Bevis of Hampton, and the other his companion, Ascapart. Sir Bevis, who lived in the reign of Edgar, had a castle in the neighbourhood. It is said he bestowed his love on a pagan lady, Josian, who, having been converted to Christianity, gave him a sword called Morglay, and a horse named Arundel. Thus equipped he was wont to kill four or five men at one blow. Among his  renowned deeds were those he performed against the Saracens, and also his slaughter of an enormous dragon.

renowned deeds were those he performed against the Saracens, and also his slaughter of an enormous dragon.

The extensive docks at the mouth of the river Itchen, to the east of the town, have, of course, greatly increased its wealth. We saw a magnificent foreign-bound steamer coming out of the docks. The West India ships start from here, as do other lines of steamers running to the Cape, and to various parts of the world; so that Southampton is a bustling seaport. There is another river to the west of  the town, called the Test; and that joining with the Itchen at the point where the town is built, forms the beautiful Southampton Water.

the town, called the Test; and that joining with the Itchen at the point where the town is built, forms the beautiful Southampton Water.

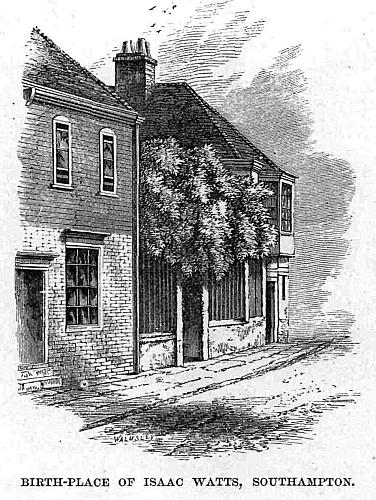

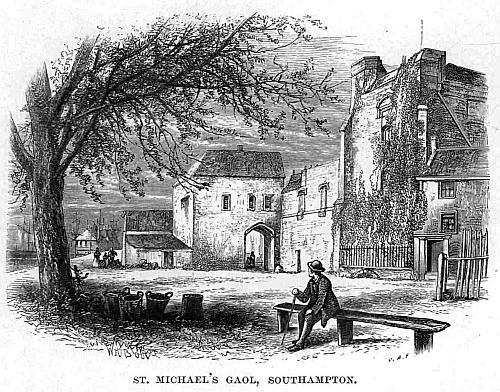

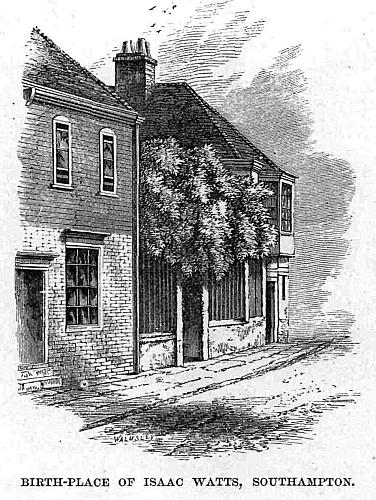

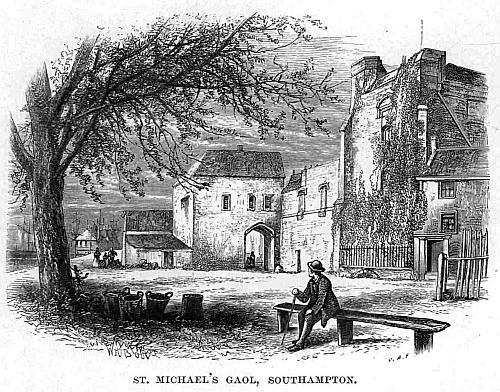

But perhaps the most interesting fact about Southampton is that Isaac Watts, the Christian poet, was born here in 1671. The house in French Street is still standing, and we went to look at it. There he passed his play-days of childhood; there the dreamy, studious boy stored up his first spoils of knowledge; there he wrote his first hymns; and thither he went to visit his parents, when he himself was old and famous. We also went to see the remains of Saint Michael’s Gaol, in which Watts’ father had been confined for his nonconformity.  And as we looked on the old prison we thanked God that nowadays, in England at least, religious persecution is unknown.

And as we looked on the old prison we thanked God that nowadays, in England at least, religious persecution is unknown.

When we returned on board, we noticed with surprise on each side of the river what had the appearance of green fields, over which the water had just before flowed; they were, however, in reality mud flats covered by long sea-weed.

Soon after tea we turned into our berths, feeling very jolly and quite at home, though Oliver did knock his head twice against the deck above, forgetting the size of our bedroom. We lay awake listening to the water rippling by, and now and then hearing the step of the man on watch overhead; but generally there was perfect silence, very different from the noise of London.

We were both dressed and on deck some time before papa next morning, for as the tide was still flowing, and there was no wind, he knew that we could not make way down the river. So we had time for a dive and a swim round the vessel, climbing on board again by means of a short ladder rigged over the side.

Soon after this we saw a few of the other vessels hoisting their sails; and then Captain Truck, Oliver, and I pulled and hauled until we got our mainsail set. The men then washed down the decks, though really there was no dirt to wash away, and we tried, as we had promised, to make ourselves useful.

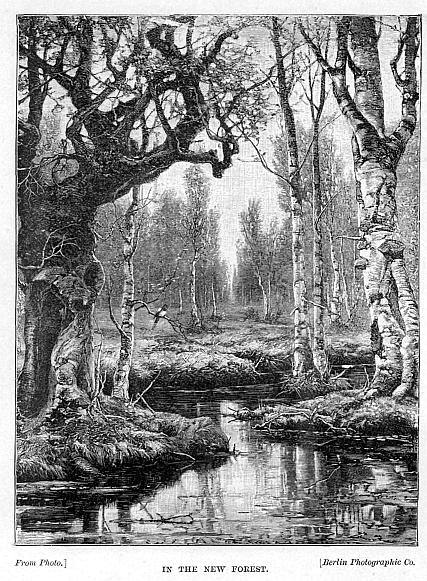

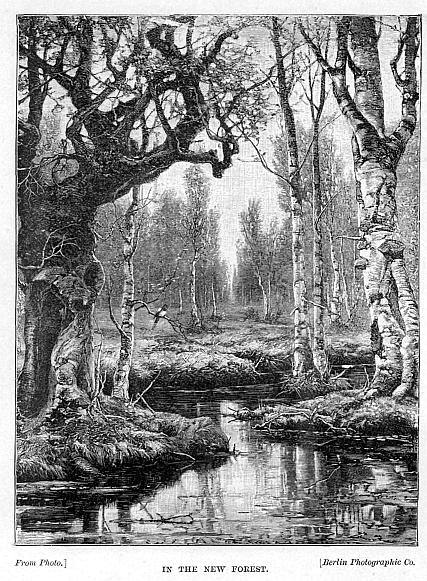

When papa appeared he looked pleased at our being so hard at work. As there was just then a ripple on the water, he ordered the anchor to be got up; and it being now full tide, we began, almost imperceptibly, to glide away from among the other vessels. On the right was the edge of the New Forest, in which William Rufus was killed; although I believe that took place a good way off, near Lyndhurst; and very little of the eastern side of the forest now remains.

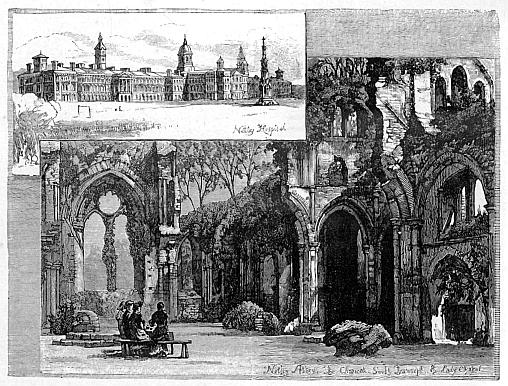

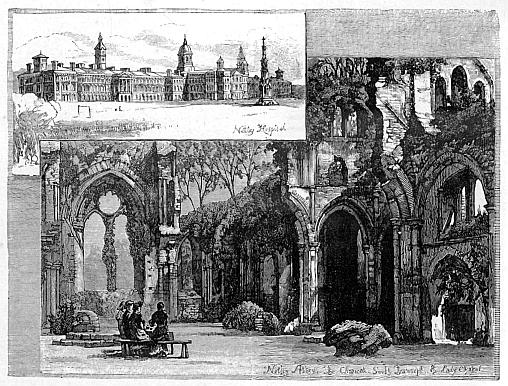

On the left we passed Netley Abbey, a very pretty, small ruin, and near it a large military hospital and college, where medical officers of the army study the complaints of the troops who have been in tropical climates. On the opposite side, at the end of a point stretching partly across the mouth of the water, we saw the old grey, round castle of Calshot, which was built to defend the entrance, but would be of little use in stopping even an enemy’s gunboat at the present day. However, papa said there are very strong fortifications at both ends of the Solent, as the channel here is called. No enemy’s gunboat could ever get through, much less an enemy’s fleet; at any rate, if they did, he hoped they would never get out again.

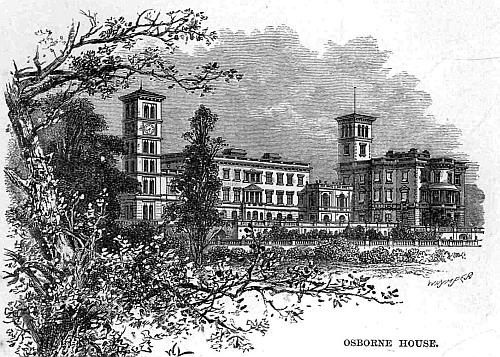

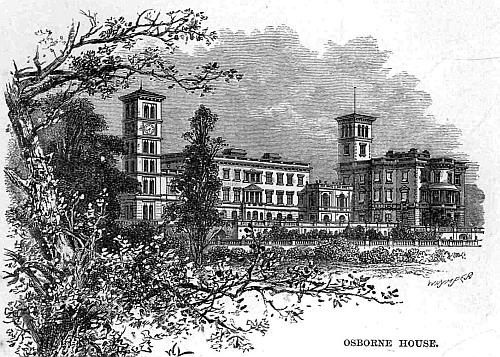

Some way to the left of Calshot rose the tall tower of Eaglehurst among the trees. The wind was from the west. We stood away towards Portsmouth, as papa wished to visit an old friend there, and to give us an opportunity of seeing that renowned seaport as well. We caught a glimpse of Cowes, and Osborne to the east of it, where the Queen frequently resides, and the town of Ryde, rising up on a hill surrounded by woods, and then the shipping at Spithead, with the curious cheese-shaped forts erected to guard the eastern entrance to the Solent.

Papa told us that these curious round forts, rising out of the sea, are built of granite; that in time of war they are to be united by a line of torpedoes and the wires of electric batteries. They are perfectly impregnable to shot, and they are armed with very heavy guns, so that an enemy attempting to come in on that side would have a very poor chance of success.

As we were anxious to see them, we had kept more in mid-channel than we should otherwise have done. We now hauled up for Portsmouth Harbour. Far off, on the summit of the green heights of Portsdown Hill, we could see the obelisk-shaped monument to Nelson, an appropriate landmark in sight of the last spot of English ground on which he stepped before sailing to fight the great battle of Trafalgar, where he fell. We could also trace the outline of a portion of the cordon of forts—twenty miles in length—from Langston Harbour on the east to Stokes’ Bay on the west. Along the shores, on both sides of the harbour, are two lines of fortifications; so that even should a hostile fleet manage to get by the cheese-like forts, they  would still find it a hard matter to set fire to the dockyard or blow up the Victory. That noble old ship met our sight as, passing between Point Battery and Block House Fort, we entered the harbour.

would still find it a hard matter to set fire to the dockyard or blow up the Victory. That noble old ship met our sight as, passing between Point Battery and Block House Fort, we entered the harbour.

She did not look so big as I expected, for not far off was the Duke of Wellington, which seemed almost large enough to hoist her on board; and nearer to us, at the entrance of Haslar Creek, was the gallant old Saint Vincent, on board which papa once served when he was a midshipman. We looked at her with great respect, I can tell you. Think how old she must be. She has done her duty well,—she has carried the flag of England many a year, and now still does her duty by serving as a ship in which boys are trained for the Royal Navy.

Further up, in dim perspective, we saw ships with enormous yellow-painted hulls; noble ships they were, with names allied to England’s naval glory. They were all, however, far younger than the Saint Vincent, as we discovered by seeing the apertures in their stern-posts formed to admit screws. Some fought in the Black Sea, others in the Baltic; but papa said “that their fighting days are now done, though they are kept to be employed in a more peaceful manner, either as hospital ships or training-schools.”

Shortening sail, we came to an anchor not far from the Saint Vincent, among several other yachts. On the Gosport side we could see across the harbour, away to the dockyard, off the quays of which were clustered a number of black monsters of varied form and rig. Papa said—though otherwise we could not have believed it—“that there were amongst them some of the finest ships of the present navy.” I could hardly fancy that such ships could go to sea, for they are more like gigantic coal barges with strong erections on their decks, than anything else afloat.

Of course I cannot tell you all our adventures consecutively, so shall describe only some of the most interesting. We first visited the Saint Vincent, which, as we had just left our little yacht, looked very fine and grand. Papa was saying to one of the officers that he had served on board her, when a weather-beaten petty officer came up, and with a smile on his countenance touched his hat, asking if papa remembered Tom Trueman. Papa immediately exclaimed, “Of course I do,” and gave him such a hearty grip of the hand that it almost made the tears come into the old man’s eyes with pleasure, and they had a long yarn about days of yore. After this papa met many old shipmates. It was pleasant to see the way in which he greeted them and they greeted him, showing how much he must have been beloved, which, of course, he was; and I’ll venture to say it will be a hard matter to find a kinder or better man. I’m sure that he is a brave sailor, from the things he has done, and the cool way in which he manages the yacht, whatever is happening.

After we had finished with the Saint Vincent we went on board the Victory, which looks, outside, as sound as ever she did—a fine, bluff old ship; but when we stepped on her deck, even we were struck by her ancient appearance, very unlike the Saint Vincent, and still more unlike the Duke of Wellington. There was wonderfully little ornamental or brass work of any sort; and the stanchions, ladders, and railings were all stout and heavy-looking.

Of course we looked with respect on the brass plate on her deck which marks the spot where Nelson fell. We then went far down into the midshipmen’s berth, in the cockpit. How dark and gloomy it seemed; and yet it was here Nelson, while the guns were thundering overhead, lay dying. How very different from the mess-rooms of young officers of the present day! Here another inscription, fixed on the ship’s side, pointed out where the hero breathed his last. Going into the cabin on the main deck, we saw one of the very topsails—riddled with shot—which had been at Trafalgar. After being shifted at Gibraltar, it had been for more than half a century laid up in a store at Woolwich, no one guessing what a yarn that old roll of canvas could tell.

We also saw an interesting picture of the “Death of Nelson,” and another of the battle itself. We felt almost awe-struck while seeing  these things, and thinking of the gallant men who once served on board that noble ship. Papa said that he hoped, if the old ship is not wanted for practical purposes, that she may be fitted up exactly as she was at Trafalgar.

these things, and thinking of the gallant men who once served on board that noble ship. Papa said that he hoped, if the old ship is not wanted for practical purposes, that she may be fitted up exactly as she was at Trafalgar.

We afterwards called on an old lady—a friend of papa—who told us that she clearly recollected going off from Ryde in a boat with her father and mother, and pulling round the Victory when she arrived from Gibraltar at Spithead, on the 4th of December, 1805, with the body of Nelson on board. In many places the shot were still sticking in her sides, her decks were scarcely freed from blood, and other injuries showed the severity of the action.

After this, the Victory was constantly employed until the year 1812, from which time she was never recommissioned for sea; but from 1825 until within a few years ago, she bore the flags of the port-admirals of Portsmouth.

Late in the evening we crossed the harbour to the dockyard, where papa wanted to pay a visit. A curious steam ferry-boat runs backwards and forwards between Portsmouth and Gosport. We passed a number of large ships coated with thick plates of iron; but even the thickest cannot withstand the shots sent from some of the guns which have been invented, and all might be destroyed by torpedoes. We could hardly believe that some of the ships we saw were fit to go to sea. The most remarkable was the Devastation. Her free-board—that is, the upper part of her sides—is only a few feet above the water. Amidships rises a round structure supporting what is called “a hurricane-deck.” This is the only spot where the officers and men can stand in a sea-way. At either end is a circular revolving turret containing two thirty-five ton guns, constructed to throw shot of seven hundred pounds. These guns are worked by means of machinery.

Contrasting with the ironclads, we saw lying alongside the quays several enormous, white-painted, richly-gilt troop-ships, also iron-built, which run through the Suez Canal to India. The night was calm and still; and as we pulled up the harbour a short distance among the huge ships, I could not help fancying that I heard them talking to each other, and telling of the deeds they had done. Papa laughed at my poetical fancy, which was put to flight when he told me that scarcely any of them, except those which were engaged in the Baltic and Black Sea, had seen any service.

Pulling down the harbour on the Gosport side, to be out of the way of passing vessels, we soon reached the yacht, feeling very tired, for we had been wide awake for the last sixteen hours. As we sat in our little cabin, it was difficult to realise that outside of us were so many objects and scenes of interest connected with the naval history of England. Papa told us a number of curious anecdotes. Not many hundred yards from us, about a century ago, was to be seen a gibbet on Block House Point, at the west entrance of the harbour, on which hung the body of a man called Jack the Painter. Having taken it into his very silly head that he should forward the cause of freedom by burning the dockyard, he set fire to the rope-house, which was filled with hemp, pitch, and tar. Jack, having performed this noble deed, escaped from the yard, and was making his way along the Fareham Road, when, having asked a carter to give him a lift, he pointed out the cloud of smoke rising in the distance, observing that he “guessed where it came from.” The carter went his way; but shortly afterwards, when a hue and cry was raised, he recollected his passenger, who was traced, captured, tried, and executed.

Another story we heard was about the mad pranks played by naval officers in days of yore. At that time, a sentry-box, having a seat within, stood on the Hard, at Portsmouth, so that the sentry could sit down and rest himself. It happened that a party of young captains and commanders, coming down from dinner to embark, found the sentry at his post, but drunk and sound asleep in his box! Punishment was his due. They bethought themselves of a mode of astonishing him. Summoning their crews, box and sentry were carried on board one of their boats and transported to Gosport, and then placed in an upright position facing the water. When the relief came to the spot where the sentry was originally stationed, what was their astonishment and alarm to find neither sentry nor box! The captain of the guard reported the circumstance to the fort-major. “The enemy,” he averred, “must be at hand.”

The garrison was aroused, the drawbridges were hauled up. Daylight revealed the box and the position of the sentry, who protested that, although as sober as a judge, he had no idea how he had been conveyed across the harbour.

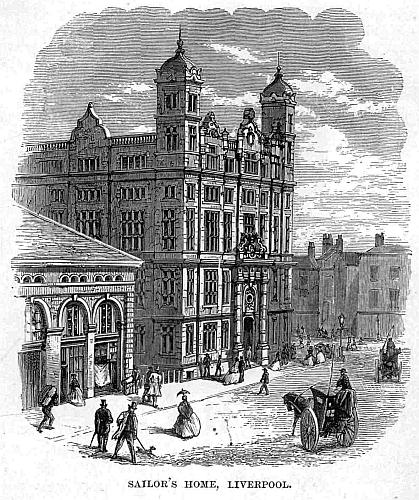

Numerous “land-sharks” used to be in waiting to tempt those who were generally too ready to be tempted into scenes of debauchery and vice. This state of things continued until a few years ago, when it was put into the heart of a noble lady—Miss Robinson—to found an institute for soldiers and sailors. There they may find a home when coming on shore, and be warned of the dangers awaiting them. After great exertion, and travelling about England to obtain funds, she raised about thirteen thousand pounds, and succeeded in purchasing the old Fountain Hotel, in the High Street, which, greatly enlarged, was opened in 1874 as a Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Institute, by General Sir James Hope Grant.

Dear me, I shall fill up my journal with the yarns we heard at Portsmouth, and have no room for our adventures, if I write on at this rate. After our devotions, we turned in, and were lulled to sleep, as we were last night, by the ripple of the water against the sides of the yacht.

Chapter Two.

In the Solent.

Next morning, soon after breakfast, we went on shore to pay a visit to the dockyard. On entering, papa was desired to put down his name; and the man seeing that he was a captain in the navy, we were allowed to go on without a policeman in attendance, and nearly lost ourselves among the storehouses and docks. As we walked past the lines of lofty sheds, we heard from all directions the ringing clank of iron, instead of, as in days of yore, the dull thud of the shipwright’s mallet, and saw the ground under each shed strewed with ribs and sheets of iron ready to be fixed to the vast skeletons within. Papa could not help sighing, and saying that he wished “the days of honest sailing ships could come back again.” However, he directly afterwards observed, “I should be sorry to get back, at the same time, the abuses, the wild doings, and the profligacy which then prevailed. Things have undoubtedly greatly improved, though they are bad enough even now.”

Tramways and railways, with steam locomotives, run in all directions. Formerly, papa said, the work was done by yellow-coated convicts with chains on their legs. They have happily been removed from the dockyard itself, and free labourers only are employed. Convicts, however, are still employed in various extensive public works.

Of course we visited Brunel’s block machinery, which shapes from the rough mass of wood, with wonderful accuracy and speed, the polished block fit for use. Huge lathes were at work, with circular saws and drills, sending the chips of wood flying round them with a whizzing and whirring sound. So perfect is the machinery that skilled artisans are not required to use it. Four men only are employed in making the shells, and these four can make with machinery as many as fifty men could do by hand. On an average, nineteen men make one hundred and fifty thousand blocks in the course of the year.

Leaving the block house, we went to the smithy, where we saw Nasmyth’s steam hammer, which does not strike like a hammer, but comes down between two uprights. On one side is a huge furnace for heating the material to be subjected to the hammer. Papa asked the manager to place a nut under it, when down came the hammer and just cracked the shell. He then asked for another to be placed beneath the hammer, when it descended and made but a slight dent in the nut.

Soon afterwards a huge mass of iron, to form an anchor, was drawn out of the furnace; then down came the hammer with thundering strokes, beating and battering it until it was forced into the required shape, while the sparks flying out on all sides made us retreat to a safer distance.

One of the largest buildings in the dockyard is the foundry, which is considered the most complete in the world. We looked into the sheds, as they are called, where the boilers for the ships are constructed, and could scarcely hear ourselves speak, from the noise of hammers driving in the rivets. Many of the boilers were large enough to form good-sized rooms. We walked along the edge of the steam basin. It is nine hundred feet long and four hundred broad. The ships, I should have said, are built on what are called the building slips, which are covered over with huge roofs of corrugated iron, so that the ships and workmen are protected while the building is going forward.

Before leaving we went into the mast-house, near the entrance to the yard. Here we saw the enormous pieces of timber intended to be built into masts—for masts of large ships are not single trees, but composed of many pieces, which are bound together with stout iron hoops. Here also were the masts of ships in ordinary. They would be liable to decay if kept on board exposed to the weather. Each mast and yard is marked with the name of the ship to which it belongs. The masts of the old Victory are kept here, the same she carried at Trafalgar. Not far off is the boat-house, where boats from a large launch down to the smallest gig are kept ready for use.

We looked into the Naval College, where officers go to study a variety of professional subjects. When papa was a boy the Naval College was used as the Britannia now is—as a training-school for naval cadets. Finding an officer going on board the Excellent—gunnery ship—we accompanied him. We were amused to find that the Excellent consists of three ships moored one astern of the other, and that not one of them is the old Excellent, she having been removed. Our friend invited us to accompany him on board an old frigate moored a little way up the harbour, from which we could see some interesting torpedo experiments.

As we pulled along he gave us an explanation of the fish torpedo—a wonderful instrument of destruction which has been invented of late years. It is a cylinder, which carries the explosive material at one end and the machinery for working the screw which impels it at the other. It can be discharged through a tube with such accuracy that it can strike an object several hundred yards off. On getting on board the old frigate, we found a large party of officers assembled. We were to witness the explosion of two other sorts of torpedoes. One was used by a steam launch, the fore part of which was entirely covered over by an iron shield. The torpedo was fixed to the end of a long pole, carried at the side of the launch. At some distance from the ship a huge cask was moored, towards which the launch rapidly made her way. The pole, with the torpedo at the end, was then thrust forward; the concussion ignited it the instant it struck the cask and blew it to fragments.

Another launch then approached a large cask floating with one end out of the water, to represent a boat. An officer stood up with a little ball of gun-cotton in his hand, smaller than an orange, to which was attached a thin line of what is called lightning cotton, the other end being fastened to a pistol. As the launch glided on he threw the ball into the cask. The boat moved away as rapidly as possible, when the pistol being fired, in an instant the cask was blown to atoms. What a fearful effect would have been produced had the innocent-looking little ball been thrown into a boat full of men instead of into a cask!

Another experiment with gun-cotton was then tried. A piece not larger than a man’s hand was fastened to an enormous iron chain fixed on the deck of the ship. We were all ordered to go below, out of harm’s way. Soon afterwards, the gun-cotton having been ignited by a train, we heard a loud report; and on returning on deck we found that the chain had been cut completely in two, the fragments having flown about in all directions.

The chain of a boat at anchor was cut by means of a piece of gun-cotton fixed to it, and ignited by a line of lightning cotton fired from one of the launches. This showed us how the chain-cable of a ship at anchor might be cut; while a torpedo boat might dash in, as she was drifting away with the tide and the attention of her officers was engaged, to blow her up.

The chief experiments of the day were still to come off. We saw a number of buoys floating in various directions some way up the harbour. A launch advanced towards one, when the buoy being struck by the pole, the charge of a torpedo some twenty yards away was ignited, and the fearful engine exploding, lifted a huge mass of water some thirty or forty yards into the air. How terrible must be the effects when such a machine explodes under a ship! As soon as the torpedoes had exploded, the boats pulled up to the spot, and picked up a large number of fish which had been killed or stunned by the concussion—for many did not appear to be injured, and some even recovered when in the boats.

Papa, though very much interested, could not help saying that he was thankful these murderous engines of war had not been discovered in his time. It is indeed sad to think that the ingenuity of people should be required to invent such dreadful engines for the destruction of their fellow-creatures. When will the blessings of the gospel of peace be universally spread abroad, and nations learn war no more?

We next pulled over to the Gosport side, to visit the Royal Clarence Victualling Establishment, which papa said was once called Weovil. Here are stored beef and other salted meats, as well as supplies and clothing; but what interested us most was the biscuit manufactory. It seemed to us as if the corn entered at one end and the biscuits came out at the other, baked, and all ready to eat. The corn having been ground, the meal descends into a hollow cylinder, where it is mixed with water. As the cylinder revolves a row of knives within cut the paste into innumerable small pieces, kneading them into dough. This dough is taken out of the cylinder and spread on an iron table, over which enormous rollers pass until they have pressed the mass into a sheet two inches thick. These are further divided and passed under a second pair of rollers, when another instrument cuts the sheets into hexagonal biscuits, not quite dividing them, however, and at the same time stamping them with the Queen’s mark and the number of the oven in which they are baked. Still joined together, they are passed into the ovens. One hundredweight of biscuits can be put into one oven.

On the Gosport side we went over some of the forts, which are of great extent. The longest walk we took was to Portsdown Hill, for the sake of visiting the Nelson Monument. On it is an inscription:—

To the Memory of

Lord Viscount Nelson.

By The Zealous Attachment Of All Those Who

Fought At Trafalgar—To Perpetuate

His Triumph And Their Regret.

mdcccv.

We had a magnificent view from the top of the monument, looking completely over Gosport, Portsmouth, and Southsea, with the harbour at our feet, and taking in nearly the whole line of the Isle of Wight, with the Solent, and away to the south-east, Saint Helen’s and the English Channel. Later on we pulled five miles up the harbour, to Porchester Castle, built by William the Conqueror. For many centuries it was the chief naval station of the kingdom, modern Portsmouth having sprung up in the reign of Henry the First, in consequence of Porchester Harbour filling with mud.

It was here, during the war with Napoleon, that several thousands of French prisoners were confined, some in the castle, and others on board the bulks. They, of course, did not like to be shut up, and many attempting to escape were suffocated in the mud. They were but scantily supplied with provisions, though they were not actually starved; but a French colonel who broke his parole wrote a book, affirming that on one occasion an officer who came to inspect the castle, having left his horse in the court-yard, the famished prisoners despatched the animal, devouring it on the spot; and, by the time the owner returned, the stirrup-irons and bit alone remained!

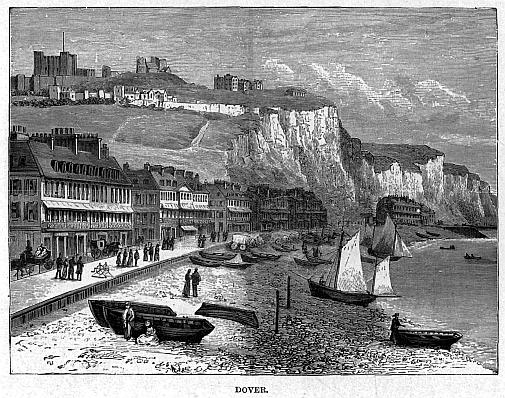

Portsmouth is a very healthy place, although from its level position it might be supposed to be otherwise. It has a wide and handsome High Street, leading down to the harbour.

The Fountain, at the end of the High Street, no longer exists as an inn, but has been converted by Miss Robinson into a Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Institute. We went over the whole establishment. At the entrance are rooms where soldiers and sailors can see their friends; and then there is a large bar, where, although no intoxicating drinks can be obtained, tea, coffee, and beverages of all sorts are served. Near it is a large coffee-room. Passing through the house, we entered a very nice garden, on the right of which there is a bowling-green and a skittle-alley; and we then came to a very handsome hall which serves for religious meetings, lectures, concerts, teas, and other social gatherings. There were also rooms in which the men can fence or box. A large reading-room (with a good library) and Bible-classroom are on the second floor; and at the top of the house are dormitories, making up a considerable number of beds for soldiers, as also for their wives and families, who may be passing through Portsmouth either to embark or have come from abroad. There is a sewing-room for the employment of the soldiers’ wives. A Children’s Band of Hope meets every week. There is even a smoking-room for the men, and hot or cold baths. Indeed, a more perfect place for the soldier can nowhere be found. Miss Robinson herself resides in the house, and superintends the whole work, of which I have given but a very slight description. I should say that this most energetic lady has also secured several houses for the accommodation of soldiers’ families, who would otherwise be driven into dirty or disreputable lodgings.

Another philanthropist of whom Portsmouth is justly proud is John Pounds, who though only a poor shoemaker, originated and superintended the first ragged school in the kingdom. Near the Soldiers’ Institute is the John Pounds’ Memorial Ragged School, where a large number of poor children are cared for. It is very gratifying to know that many of our brave soldiers and sailors are also serving under the great Captain of our salvation, and fighting the good fight of faith, helped in so doing by good servants of God.

The town of Portsmouth was until lately surrounded by what were called very strong fortifications; but the new works have rendered them perfectly useless, and they are therefore being dismantled—a great advantage to the town, as it will be thrown open to the sea-breezes.

A light breeze from the eastward enabled us to get under weigh just at sunrise, and to stem the tide still making into the harbour. Sometimes, however, we scarcely seemed to go ahead, as we crept by Block House Fort and Point Battery on the Portsmouth side.

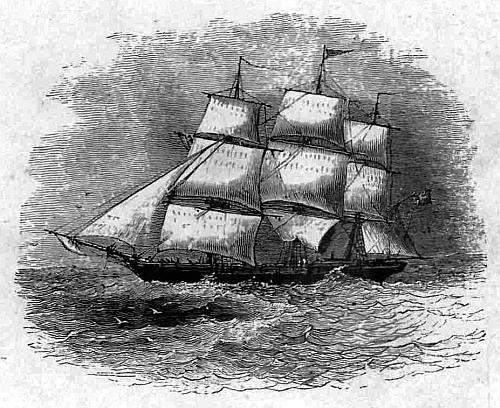

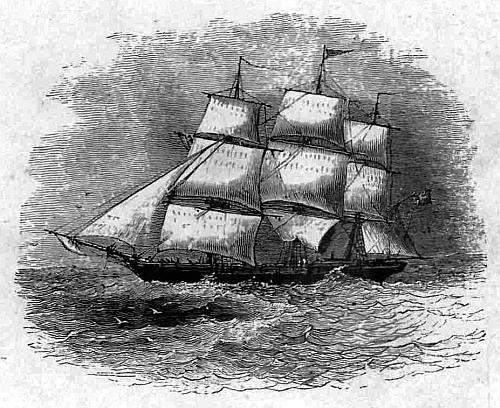

Once upon a time, to prevent the ingress of an enemy’s fleet, a chain was stretched across the harbour’s mouth. We had got just outside the harbour when we saw a man-of-war brig under all sail standing in. A beautiful sight she was, her canvas so white, her sides so polished!—on she stood, not a brace nor tack slackened. Papa looked at her with the affection of an old sailor. It was an object which reminded him of his younger days. “You don’t see many like her now,” he observed. Presently, as she was starting by us, a shrill whistle was heard. Like magic the sails were clewed up, the hands, fine active lads—for she was a training vessel—flew aloft, and lay out on the yards. While we were looking, the sails were furled; and it seemed scarcely a moment afterwards when we saw her round to and come to an anchor not far from the Saint Vincent. “That’s how I like to see things done,” said papa. “I wish we had a hundred such craft afloat; our lads would learn to be real seamen!”

He and Paul were so interested in watching the brig, that for the moment their attention was wholly absorbed. As we got off the Southsea pier we began to feel the wind coming over the common; and being able to make better way, quickly glided by the yachts and small vessels anchored off it, when we stood close to one of those round towers I have described, and then on towards Spithead.

Spithead is so called because it is at the end of a spit or point of sand which runs off from the mainland. We passed close over the spot where the Royal George, with nine hundred gallant men on board, foundered in August, 1782. She was the flag-ship of Admiral Kempenfeldt. He was at the time writing in his cabin, where he was last seen by the captain of the ship, who managed to leap out of a stern port and was saved, as was the late Sir Philip Durham, port-admiral of Portsmouth, then one of the junior lieutenants. The accident happened from the gross negligence and obstinacy of one of the lieutenants. In order to get at a water-cock on the starboard side, the ship had been heeled down on her larboard side, by running her guns over until the lower deck port-sills were just level with the water. Some casks of rum were being hoisted on board from a lighter, bringing the ship still more over. The carpenter, seeing the danger, reported it to the lieutenant of the watch, who at first obstinately refused to listen to him. A second time he went to the officer, who, when too late, turned the hands up to right ship, intending to run the guns back into their former places. The weight of five or six hundred men, however, going over to the larboard side completely turned the hitherto critically balanced scale; and the ship went right over, with her masts in the water. The sea rushing through her ports quickly filled her, when she righted and went down, those who had clambered through the ports on her starboard side being swept off. Two hundred out of nine hundred alone were saved. Among these was a midshipman only nine years old, and a little child found fastened on to the back of a sheep swimming from the wreck. He could not tell the names of his parents, who must have perished, and only knew that his name was Jack, so he was called John Lamb. None of his relatives could be found, and a subscription was raised and people took care of him, and having received a liberal education, he entered an honourable profession.

Some years ago the remains of the ship were blown up by Sir C. Pasley, and many of the guns recovered. Close to the spot, in the days of bluff King Harry, the Mary Rose, after an action with a French ship, went down with her gallant captain, Sir George Carew, and all his men, while his crew were attempting to get at the shot-holes she had received.

In 1701, the Edgar, 74 guns, which had just arrived from Canada,  blew up; her crew and their friends were making merry when they, to the number of eight hundred, miserably perished.

blew up; her crew and their friends were making merry when they, to the number of eight hundred, miserably perished.

While at anchor here also, the Boyne, of 91 guns, caught fire. All efforts to put out the flames were unavailing; but the greater number of her crew escaped in boats. As she drifted from Spithead towards Southsea, her guns continued to go off, until touching the shore, she blew up with a tremendous explosion.

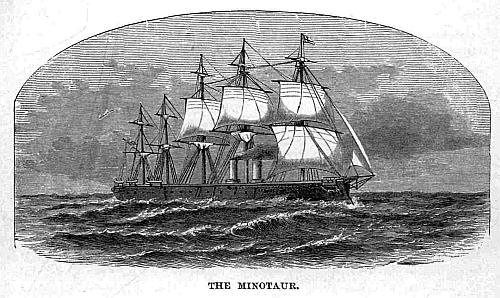

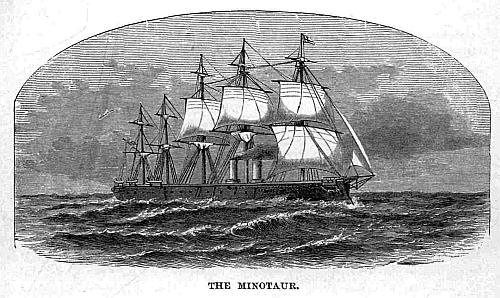

The ships at Spithead now are of a very different appearance from those formerly seen there. Among them was the Minotaur, which, in consequence of her great length, is fitted with five masts. Just as we were passing her she got under weigh, papa said, in very good style; and certainly, when all her canvas was set, she looked a fine powerful sea-going craft.

The Devastation came out of the harbour, and stood on towards Saint Helen’s. She certainly looked as unlike our notions of a man-of-war as anything could be, though, as Paul Truck observed, “she would crumple up the Minotaur in a few minutes with her four thirty-five ton guns, powerful as the five-masted ship appears.”

Though she looked only fit for harbour work, Paul said that she had been out in heavy weather, and proved a fair sea-boat. The only place that people live on, when not below, is the hurricane-deck. In this centre structure are doorways which can be closed at sea. They lead down into the cabins below, as well as to the hurricane-deck, out of which rise the two funnels and an iron signal-mast. This is thick enough to enable a person to ascend through its inside to a crow’s-nest on the top, which serves as a look-out place. From it also projects the davits for hoisting up the boats. On the hurricane-deck stands the captain’s fighting-box, cased with iron. Here also is the steering apparatus and wheel. When in action, all the officers and men would be sent below except the helmsmen, who are also protected, with the captain and a lieutenant, and the men inside the turrets working the guns. These are so powerful that they can penetrate armour six inches thick at the distance of nearly three miles.

We brought-up for a short time at the end of Ryde Pier, as papa wished to go on shore to the club. The pier-head was crowded with people who had come there to enjoy the sea-breeze without the inconvenience of being tossed about in a vessel. The town rises on a steep hill from the shore, with woods on both sides, and looks very picturesque. To the west is the pretty village of Binstead, with its church peeping out among the trees.

We were very glad, however, when papa came on board, and we got under weigh to take a trip along the south coast of the island. The wind and tide suiting, we ran along the edge of the sand-flats, which extend off from the north shore, passing a buoy which Paul Truck said was called “No Man’s Land.” Thence onwards, close by the Warner lightship.

As we wanted to see a lightship, the yacht was hove-to, and we went alongside in the boat. She was a stout, tub-like, Dutch-built-looking vessel, with bow and stern much alike, and rising high out of the water, which is very necessary, considering the heavy seas to which she is at times exposed. The master, who knew Paul Truck, was very glad to see us, and at once offered to show us all over the vessel.

The light was in a sort of huge lantern, now lowered on deck; but at night it is hoisted to the top of the mast, thirty-eight feet above the water, so that it can be seen at a distance of eight miles. It is what is called a reflecting light. I will try and describe it.

Within the lantern are a certain number of lights and reflectors, each suspended on gimbals, so that they always maintain their perpendicular position, notwithstanding the rolling of the vessel. Each of these lights consists of a copper lamp, placed in front of a saucer-shaped reflector. The lamp is fed by a cistern of oil at the back of the reflector. This being a revolving light, a number of reflectors were fixed to the iron sides of a quadrangular frame, and the whole caused to revolve once every minute by means of clockwork. The reflectors on each side of the revolving frame—eight in number—are thus successively directed to every point in the horizon; and the combined result of their rays form a flash of greater or less duration, according to the rapidity of their revolution. In the fixed lights eight lamps and reflectors are used, and are arranged in an octagonal lantern; they do not differ much in appearance from the others.

The master told us that the invention was discovered very curiously. A number of scientific gentlemen were dining together at Liverpool—a hundred years ago—when one of the company wagered that he would read a newspaper at the distance of two hundred feet by the light of a farthing candle. The rest of the party said that he would not. He perhaps had conceived the plan before. Taking a wooden bowl, he lined it with putty, and into it embedded small pieces of looking-glass, by which means a perfect reflector was formed; he then placed his rushlight in front of it, and won his wager. Among the company was Mr William Hutchinson, dock-master of Liverpool, who seizing the idea, made use of copper lamps, and formed reflectors much in the same way as the gentleman before mentioned.

Everything about the ship was strong, kept beautifully clean, and in the most admirable order. The crew consists of the captain and mate, with twelve or fourteen men, a portion of whom are on shore off duty. The life is very monotonous; and the only amusement they have is fishing, with reading and a few games, such as draughts and chess. They had only a small library of books, which did not appear very interesting. Papa left them a few interesting tracts and other small books, and gave them a short address, urging them to trust to Christ, and follow His example in their lives. They listened attentively, and seemed very grateful. They have a large roomy cabin, and an airy place to sleep in. The captain has his cabin aft, besides which there is a large space used as a lamp-room, where all the extra lamps and oil and other things pertaining to them are kept. They seemed happy and contented; but when a heavy gale is blowing they must be terribly tossed about. Of course there is a risk—although such is not likely to occur—of the vessel being driven from her moorings. In case this should happen, they have small storm sails, and a rudder to steer the vessel. When this does happen it is a serious matter, not only to those on board, but still more so to any ships approaching the spot, and expecting to find guidance from the light.

Standing on, we passed close to the Bembridge or Nab Light-vessel. This vessel carries two bright fixed lights, one hoisted on each of her masts, which can be seen at night ten miles off, and of course it can be distinguished from the revolving Warner light. Farther off to the west, at the end of a shoal extending off Selsea Bill, is another lightship, called the Owers.

Having rounded Bembridge Ledge, we stood towards the white Culver cliffs, forming the north side of Sandown Bay, with lofty downs rising above Bembridge. Near their summits are lines of fortifications, extending westward to where once stood Sandown Castle,  near which there is now a large town, although papa said he remembered when there was only a small inn there, with a few cottages. On the very top of the downs is a monument erected to Lord Yarborough, the king of yachtsmen, who died some years ago on board his yacht, the Kestrel, in the Mediterranean. He at one time had a large ship as his yacht, on board which he maintained regular naval discipline, with a commander, and officers who did duty as lieutenants. It was said that he offered to build and fit out a frigate, and maintain her at his own expense, if the government would make him a post-captain off-hand, but this they declined to do.

near which there is now a large town, although papa said he remembered when there was only a small inn there, with a few cottages. On the very top of the downs is a monument erected to Lord Yarborough, the king of yachtsmen, who died some years ago on board his yacht, the Kestrel, in the Mediterranean. He at one time had a large ship as his yacht, on board which he maintained regular naval discipline, with a commander, and officers who did duty as lieutenants. It was said that he offered to build and fit out a frigate, and maintain her at his own expense, if the government would make him a post-captain off-hand, but this they declined to do.

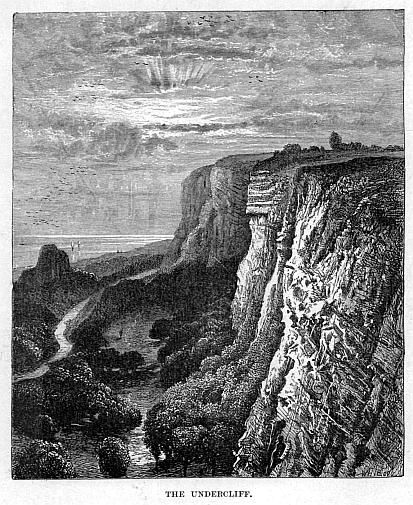

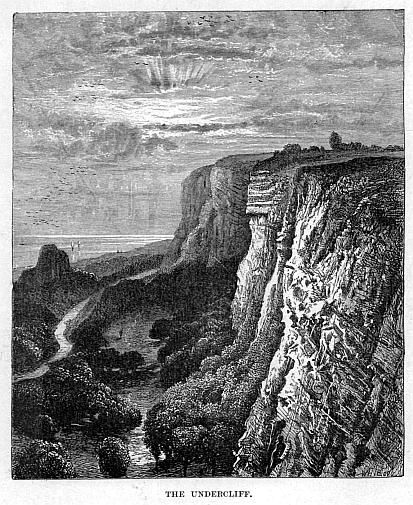

Standing across the bay, we came off a very picturesque spot, called Shanklin Chine, a deep cut or opening in the cliffs with trees on both sides. Dunnose was passed, and the village of Bonchurch and Ventnor, climbing up the cliffs from its sandy beach. We now sailed along what is considered the most beautiful part of the Isle of Wight,—the Undercliff. This is a belt of broken, nearly level ground, more or less narrow, beyond which the cliffs rise to a considerable height, with valleys intervening; the downs in some places appearing above them. This belt, called the Undercliff, is covered with trees and numerous villas.

At last we came off Rocken End Point, below Saint Catherine’s Head. This is the most southern point of the island. On it stands a handsome stone tower, 105 feet high, with a brilliant fixed light upon it. The village of Niton stands high up away from the shore.

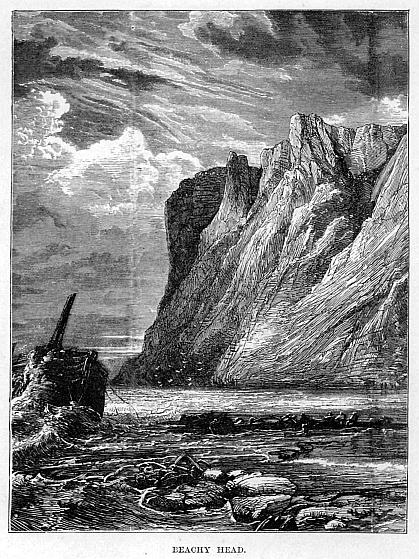

It now came on to blow very fresh. There was not much sea in the offing; but, owing to the way the tide ran and met the wind, the bottom being rocky, the water nearer the shore was tossed about in a most curious and somewhat dangerous fashion, for several “lumps of sea,” as Truck called them, came flop down on our deck; and it was easy to see what might be the consequences if an open boat had attempted to pass through the Race. Paul told us that good-sized vessels had been seen to go down in similar places. One off Portland is far worse than this in heavy weather.

Farther on is a curious landslip, where a large portion of the cliff once came down, and beyond it is Blackgang Chine, a wild, savage-looking break in the cliffs, formed by the giving way of the lower strata. Farther to the west, towards Freshwater Gate, the cliffs are perpendicular, and of a great height, the smooth downs coming to their very edge.

Some years ago a picnic party, who had come over from Lymington, had assembled on that part of the downs, having come by different conveyances. Among them was a boy, like one of us—a merry fellow, I dare say. After the picnic the party separated in various directions. When the time to return had arrived, so many went off in one carriage, and so many in another. In the same way they crossed to Lymington in different boats. Not until their arrival at that place was their young companion missed, each party having supposed that he was with the other. What could have become of him? They hoped against hope that he had wandered far off to the east, and had lost his way. Then some of the party recollected having seen him going towards the edge of the cliff. He was a stranger, and was not aware how abruptly the downs terminated in a fearful precipice. It was too late to send back that night. They still hoped that he might have slipped down, and have lodged on some ledge. At daybreak boats were despatched to the island. At length his mangled remains were found at the foot of the highest part of the cliff, over which he must have fallen and been dashed to pieces. Papa said he recollected seeing the party land, and all the circumstances of the case.

Here, too, several sad shipwrecks have occurred, when many lives have been lost. A few years ago, two ladies were walking together during a heavy gale of wind, which sent huge foaming billows rolling on towards the shore. One, the youngest, was nearer the water than the other, when an immense wave suddenly broke on the beach, and surrounding her, carried her off in its deadly embrace. Her companion, with a courage and nerve few ladies possess, rushed into the seething water, and seizing her friend, dragged her back just before the hungry surge bore her beyond her depth, Papa gave us these anecdotes as we gazed on the shore. We had intended going completely round the island; but the wind changing, we ran back the way we had come, thus getting a second sight of many places of interest.

It was dark before we reached the Nab; but steering by the lights I have described, we easily found our way towards the anchorage off Ryde. At length we sighted the bright light at the end of the pier, and we kept it on our port-bow until we saw before us a number of twinkling lights hoisted on board the yachts at anchor. It was necessary to keep a very sharp look-out, as we steered our way between them, until we came to an anchorage off the western end of the pier.

The next morning, soon after daybreak, when we turned out to enjoy a swim overboard, we saw, lying close to us, a fine sea-going little schooner, but with no one, excepting the man on watch, on deck. We had had our dip, and were dressing, when we saw a boy spring up through the companion hatch, and do just what we had done—jump overboard.

“I do declare that must be Cousin Jack!” cried Oliver. “We will surprise him.”

In half a minute we had again slipped out of our clothes, and were in the water on the opposite side to that on which the schooner lay. We then swam round together; and there, sure enough, we saw Jack’s ruddy countenance as he puffed and blew and spluttered as he came towards us.

“How do you do, Brother Grampus?” cried Oliver.

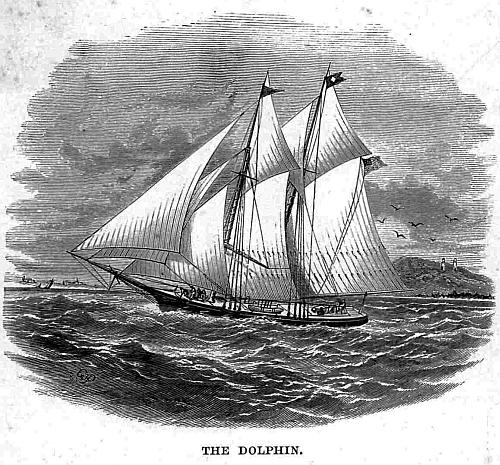

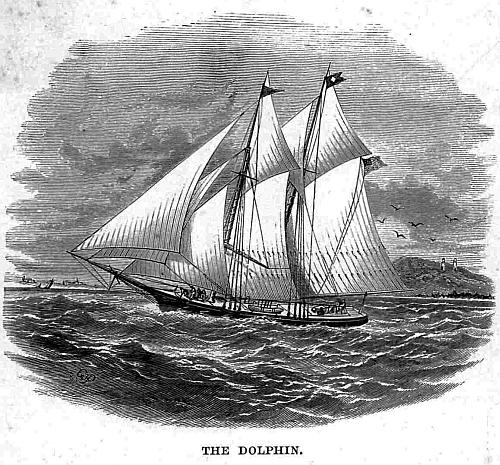

In another moment we were all treading water and shaking hands, and laughing heartily at having thus met, like some strange fish out in the ocean. Greatly to our delight, we learned that the schooner we had admired was Uncle Tom Westerton’s new yacht, the Dolphin; and Jack said he thought it was very likely that His father would  accompany us, and he hoped that he would when he knew where we were going.

accompany us, and he hoped that he would when he knew where we were going.

This, of course, was jolly news. We could not talk much just then, as we found it required some exertion to prevent ourselves being drifted away with the tide. We therefore, having asked Jack to come and breakfast with us, climbed on board again. He said that he would gladly do so, but did not wish to tell his father, as he wanted to surprise him.

A short time afterwards, Uncle Tom Westerton poked his head (with a nightcap on the top of it) up the companion hatchway, rubbing his eyes, yawning and stretching out his arms, while he  looked about him as if he had just awakened out of sleep. He was dressed in a loose pair of trousers and a dressing-gown, with slippers on his feet.

looked about him as if he had just awakened out of sleep. He was dressed in a loose pair of trousers and a dressing-gown, with slippers on his feet.

“Good morning to you, Uncle Tom!” shouted Oliver and I.

“Hullo! where did you come from?” he exclaimed.

“From Portsmouth last. This is papa’s new yacht; and we are going to sail round England,” I answered.

Just then papa, who had no idea that the Dolphin was close to us, came on deck. The surprise was mutual.

Uncle Tom and Jack were soon on board; and during breakfast it was settled that we should sail together round England, provided papa would wait a day until uncle could get the necessary provisions and stores on board; and in the mean time we settled to visit Beaulieu river and Cowes, and at the latter place the Dolphin was to rejoin us next day.

We, as may be supposed, looked forward to having great fun. We had little doubt, although the Lively was smaller than the Dolphin, that we could sail as fast as she could, while we should be able to get into places where she could not venture.

As soon as breakfast was over, while the Dolphin stood for Portsmouth to obtain what she wanted, we got under weigh, and steered for the mouth of Beaulieu river. On our way we passed over the Mother Bank, a shoal off which vessels in quarantine have to bring up; and here are anchored two large mastless ships,—one for the officers and men of the quarantine guard, the other serving as a hospital ship. We next came off Osborne, where the Queen lives during the spring,—a magnificent-looking place, with trees round three sides, and a park-like lawn descending to the water’s edge. Before the Queen bought it, a good-sized private house stood here, belonging to a Mr Blackford, whose widow, Lady Isabella, sold it to Her Majesty. A small steam yacht lay off the land, ready to carry despatches or guests.

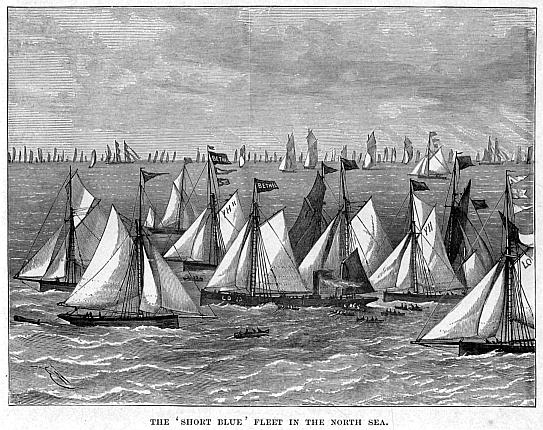

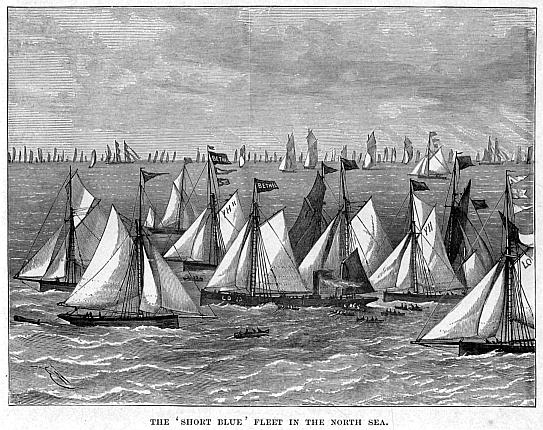

Bounding Old Castle Point, we opened up the harbour, and  came in sight of the West Cowes Castle, and the handsome clubhouse, and a line of private residences, with a broad esplanade facing the sea, and wooded heights rising above it; and beyond, looking northward, a number of villas, with trees round them and a green lawn extending to the water. The harbour was full of vessels of all descriptions, and a number of fine craft were also anchored in the Roads. We thought Cowes a very pleasant-looking place. It was here that the first yacht club was established. The vessels composing it are known par excellence as the “Royal Yacht Squadron;” and a regatta has taken place here annually for more than half a century. Ryde, Southampton, and Portsmouth, indeed nearly every seaport, has now its clubhouse and regatta. The chief are Cowes, Ryde, Torquay, Plymouth, Cork, Kingston, and the Thames. Each has its respective signal flag or burgee. That of Cowes is white, of Ryde red, and most of the others are blue, with various devices upon them. At Cowes, some way up the harbour, on the west side, are some large shipbuilding yards. Here a number of fine yachts and other vessels are built. Mr White, one of the chief shipbuilders, has constructed some fine lifeboats, which are capable of going through any amount of sea without turning over; and even if they do so, they have the power of righting themselves. He has built a number also to carry on board ships, and very useful they have proved on many occasions. Ships from distant parts often bring up in the Roads to wait for orders; others, outward-bound, come here to receive some of their passengers. Very frequently, when intending to run through the Needle passage, they wait here for a fair wind, so that the Roads are seldom without a number of ships, besides the yachts, whose owners have their headquarters here, many of their families living on shore.

came in sight of the West Cowes Castle, and the handsome clubhouse, and a line of private residences, with a broad esplanade facing the sea, and wooded heights rising above it; and beyond, looking northward, a number of villas, with trees round them and a green lawn extending to the water. The harbour was full of vessels of all descriptions, and a number of fine craft were also anchored in the Roads. We thought Cowes a very pleasant-looking place. It was here that the first yacht club was established. The vessels composing it are known par excellence as the “Royal Yacht Squadron;” and a regatta has taken place here annually for more than half a century. Ryde, Southampton, and Portsmouth, indeed nearly every seaport, has now its clubhouse and regatta. The chief are Cowes, Ryde, Torquay, Plymouth, Cork, Kingston, and the Thames. Each has its respective signal flag or burgee. That of Cowes is white, of Ryde red, and most of the others are blue, with various devices upon them. At Cowes, some way up the harbour, on the west side, are some large shipbuilding yards. Here a number of fine yachts and other vessels are built. Mr White, one of the chief shipbuilders, has constructed some fine lifeboats, which are capable of going through any amount of sea without turning over; and even if they do so, they have the power of righting themselves. He has built a number also to carry on board ships, and very useful they have proved on many occasions. Ships from distant parts often bring up in the Roads to wait for orders; others, outward-bound, come here to receive some of their passengers. Very frequently, when intending to run through the Needle passage, they wait here for a fair wind, so that the Roads are seldom without a number of ships, besides the yachts, whose owners have their headquarters here, many of their families living on shore.

We agreed, however, that we were better off on board our tight little yacht, able to get under weigh and to go anywhere without having to wait for our friends on shore.

Leaving Cowes harbour on our port quarter, we stood for Leep Buoy, off the mouth of the Beaulieu River. Hence we steered for the village of Leep, on the mainland. Truck knowing the river well, we ran on until we came to an anchor off the village of Exbury. Here it was thought safer to bring up, and proceed the rest of the distance in the boat. The river above Exbury becomes very narrow, and we might have got becalmed, or, what would have been worse, we might have stuck on the mud.

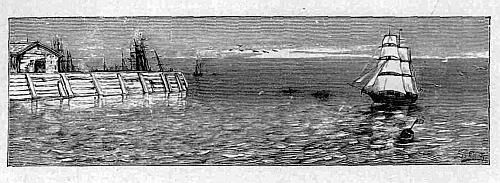

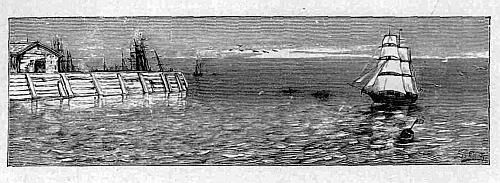

We pulled up for some miles between thickly-wooded banks,—indeed, we were now passing through a part of the New Forest. Suddenly the river took a bend, and we found ourselves off a village called Buckler’s Hard. The river here expands considerably, and we saw two or three vessels at anchor. In the last great war there was a dockyard here, where a number of frigates and other small men-of-war were built from the wood which the neighbouring forest produced. Now, the dockyard turns out only a few coasting craft. How different must have been the place when the sound of the shipwright’s hammer was incessantly heard, to what it now is, resting in the most perfect tranquillity, as if everybody in the neighbourhood had gone to sleep! No one was to be seen moving on shore, no one even on board the little coasters. Not a bird disturbed the calm surface of the river.

As it was important that we should be away again before the tide fell we pulled on, that we might land close to Beaulieu itself. The scenery was picturesque in the extreme, the trees in many places coming down to the water’s edge, into which they dipped their long hanging boughs. About six miles off, the artist Gilpin had the living of Boldre, and here he often came to sketch views of woodland and river scenery. We landed near the bridge, and walked on to see Beaulieu Abbey. Passing through a gateway we observed the massive walls, which exist here and there almost entire, in some places mantled with ivy, and at one time enclosing an area of sixteen acres or more.

A short way off was a venerable stone building, now called the Palace House, once the residence of the abbot, who being too great a man to live with the monks, had a house to himself. When convents were abolished, this was turned into a residence by the Duke of Montague, to whose family it had been granted. He enlarged and beautified it, enclosing it in a quadrangle with walls, having a low circular tower at each angle, encompassed by a dry moat crossed by a bridge. The whole building is now fitted up as a modern residence.

A short distance to the east stands a long edifice, with lofty rooms, which was undoubtedly the dormitory, with large cellars beneath it. At the south end the ancient kitchen remains entire, with its vaulted stone roof and capacious chimney, proving that the monks were addicted to good cheer; indeed, the remains of the fish-ponds, or stews, not far off, show that this was the case.

They also took care to supply themselves with fresh water, from a fine spring issuing from a cave in the forest about half a mile away, which was conveyed to the abbey in earthen pipes. That they were not total abstainers, however, is proved by the remains of a building evidently once containing the means of manufacturing wines; and close to it, in some fields having a warm southern aspect, still called the Vineyards, grew their grapes.

This abbey, indeed, stands on just such a spot as sagacious men, considering how best they might enjoy this world’s comforts, would select;—a gentle stream, an ample supply of water, a warm situation, extensive meadow and pasture land, sheltered from keen blasts by woods and rising hills. The monastery was built, we are told, in the time of King John, by a number of Cistercian monks. A monkish legend, which, like most other monkish legends, is probably false, asserts that the abbots of that order being summoned by the king to Lincoln, expected to receive some benefit, instead of which the savage monarch ordered them to be trodden to death by horses. None of his attendants were willing, however, to execute his cruel command. That night the king dreamed that he was standing before a judge, accompanied by these abbots, who were commanded to scourge him with rods. On awakening he still felt the pain of his flagellation; and being advised by his father-confessor to make amends for his intended cruelty, he immediately granted the abbots a charter for the foundation of the abbey.

The monks, as usual, practising on the credulity of the people, grew rich, and obtained privileges and further wealth from various sovereigns; while the Pope conferred on their monastery the rights of a sanctuary, exemption from tithes, and the election of its abbot without the interference of king or bishop. In 1539 there were within their walls thirty-two sanctuary men for debt, felony, and murder. Unpleasant guests the monks must have found them, unless a thorough reformation had taken place in their characters.

Here Margaret of Anjou took shelter after the fatal battle of Barnet; and Perkin Warbeck fled hither, but being lured away, perished at Tyburn. On the abolition of monasteries, Beaulieu Abbey was granted to the Earl of Southampton, whose heiress married the Duke of Montague, from whom it descended to his sole heiress, who married the Duke of Buccleuch. The family have carefully preserved the ruins, and prevented their further destruction.

“The abbeys have had their day; but, after all, we cannot help holding them in affectionate remembrance for the service they rendered in their generation,” observed Oliver, in a somewhat sentimental tone, which made me laugh.

“They may have done some good; but that good could have been obtained in a far better way,” said papa; “they were abominations from the first; and the life led by the monks was utterly at variance with that which Scripture teaches us is the right life to lead. We might as well regret that Robin Hood and Dick Turpin do not now exist, because they occasionally behaved with generosity to the poor, and showed courtesy to the ladies they robbed. The monasteries were the result of the knavery of one class and the ignorance and superstition of another. Do not let the glamour of romance thrown over them ever deceive or mislead you as to their real character. When we hear of the good they did, remember that the monks were their own chroniclers. We have only to see what Chaucer says of them, and the utter detestation in which they were held by the great mass of the people, not only in Henry the Eighth’s time, but long before, to judge them rightly. There are weak and foolish people, at present, urged on by designing men, who wish for their restoration, and have actually established not a few of these abominable institutions in our free England, where girls are incarcerated and strictly kept from communicating with their friends, and where foolish youths play the part of the monks of the dark ages. I am not afraid of your turning Romanists, my boys, but it is important to be guarded on all points. Just bring the monastic system to the test of Scripture, and then you will see how utterly at variance it is from the lessons we learn therein.”

We felt very nervous going down the river, for fear we should stick on the mud, as the tide had already begun to ebb, and we might have been left high and dry in a few minutes; but, through Paul’s pilotage and papa’s seamanship, we managed to avoid so disagreeable an occurrence, and once more passing the beacon at the mouth of the river, we steered for Cowes Roads, where we brought-up at dark. Next morning we saw the Dolphin anchored not far from us. To save sending on board, we got out our signals, and the instruction book which enables us to make use of them.

We first hoisted flags to show the number of the yacht in the club, and waited until it was answered from the Dolphin. We next hoisted four numbers without any distinguishing flag, which showed the part of the book to which we referred, and meant, “Are you ready to sail?” This was answered by a signal flag which meant “Yes;” whereupon we ran up four other numbers signifying, “We will sail immediately.”

As the Dolphin, which was to the east of us, began to get under weigh, we did so likewise; and she soon came close enough to enable us to carry on a conversation as we stood together to the westward.

The shores both of the mainland and of the Isle of Wight are covered thickly with woods, the former being portions of the New Forest, which at one time extended over the whole of this part of Hampshire, from Southampton Water to the borders of Dorsetshire. On our left side we could see high downs rising in the distance, the southern side of which we had seen when going round the back of the island.

In a short time we came off Newton River, now almost filled up with mud. Some way up it is a village, which, once upon a time, was a town and returned a member to parliament. The hull of a small man-of-war is anchored, or rather beached, on the mud near the mouth of the river, and serves as a coastguard station.

The wind shifting, we had to make a tack towards the mouth of Lymington Creek, which runs down between mud-banks from the town of Lymington, which is situated on the west side of the river. On a height, on the east side, we could distinguish an obelisk raised to the memory of Admiral Sir Harry Burrard Neale. He was a great favourite of George the Third, as he was with all his family, including William the Fourth. He was a very excellent officer and a good, kind man, and was looked upon as the father of his crew. At the mouth of the river is a high post with a basket on the top of it known as Jack-in-the-basket. Whether or not a sailor ever did get in there when wrecked, or whether on some occasion a real Jack was placed there to shout out to vessels coming into the river, I am not certain.

Passing the pleasant little town of Yarmouth, the wind once more shifting enabled us to lay our course direct for Hurst Castle. We passed the village of Freshwater, with several very pretty villas perched on the hill on the west side of it. Here also is the commencement of a line of batteries which extend alone: the shore towards the Needles. The ground is high and broken, and very picturesque, with bays, and points, and headlands. On our starboard, or northern side, appeared the long spit of sand at the end of which Hurst Castle stands, with two high red lighthouses like two giant skittles. Besides the old castle, a line of immensely strong fortifications extend along the beach, armed with the heaviest guns, so that from the batteries of the two shores an enemy’s ship attempting to enter would be sunk, or would be so shattered as to be unable to cope with any vessel of inferior force sent against her.

The old castle is a cheese-like structure of granite, and was considered, even when it stood alone, of great strength. Its chief  historical interest is derived from its having been the prison of Charles the First when he was removed from Carisbrook Castle. After the failure of the treaty of Newport, Charles was brought from Carisbrook, which is almost in the centre of the Isle of Wight, to a small fort called Worsley Tower, which stood above Sconce Point, to the westward of the village of Freshwater. Here a vessel was in waiting, which carried him and a few attendants over to Hurst, where he was received by the governor, Colonel Eure, and kept under strict guard, though not treated unkindly. From thence he was removed to Windsor, and afterwards to London, where his execution took place.

historical interest is derived from its having been the prison of Charles the First when he was removed from Carisbrook Castle. After the failure of the treaty of Newport, Charles was brought from Carisbrook, which is almost in the centre of the Isle of Wight, to a small fort called Worsley Tower, which stood above Sconce Point, to the westward of the village of Freshwater. Here a vessel was in waiting, which carried him and a few attendants over to Hurst, where he was received by the governor, Colonel Eure, and kept under strict guard, though not treated unkindly. From thence he was removed to Windsor, and afterwards to London, where his execution took place.

As we were examining with our glasses the powerful line of fortifications, both on the Hurst beach and along the shore of the Isle of Wight, papa remarked that he wished people would be as careful in guarding their religious and political liberties as they are in throwing up forts to prevent an enemy from landing on our shores. Many appear to be fast asleep with regard to the sacred heritage we have received from our forefathers, and allow disturbers of our peace and faith, under various disguises, to intrude upon and undermine the safeguards of our sacred rights and liberties.

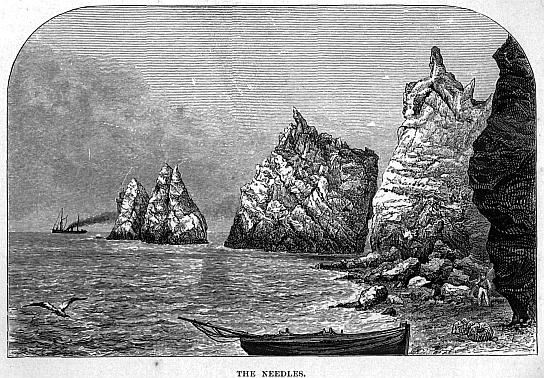

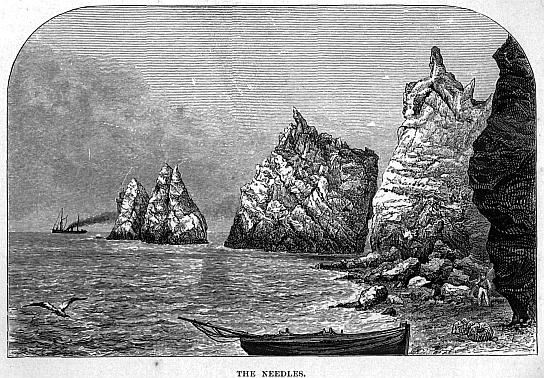

Presently we found ourselves in a beautiful little spot called Alum Bay. The cliffs have not the usual glaring white hue, but are striped with almost every imaginable colour, the various tints taking a perpendicular form, ranging from the top of the cliff to the sea. If we could have transferred the colours to our pallet, I am sure we should have found them sufficient to produce a brilliant painting. West of the coloured cliffs is a line of very high white cliffs, extending to the extreme west point of the island, at the end of which appear the Needle Rocks, rising almost perpendicularly out of the sea. Once upon a time two of them were joined with a hollow, or eye, between them, but that portion gave way at the end of the last century. On the outer rock, by scraping the side, a platform has been formed, on which stands a high and beautifully-built lighthouse, erected some years ago. Formerly there was one on the top of the cliff, but it was so high that it was frequently obscured by mist, and was not to be seen by vessels steering for the Needles passage.

As we stood close into the shore, and looked up at the lofty cliffs, we agreed that it was the grandest and most picturesque scene we had yet visited.

On the other side of the channel are the Shingles, a dangerous sandbank, on which many vessels have been lost. A ledge of rocks below the water runs off from the Needles, known as the Needle Ledge. When a strong south-westerly wind is blowing, and the tide is running out, there is here a very heavy sea. Vessels have also

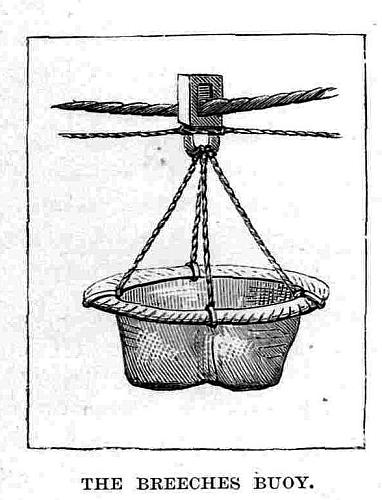

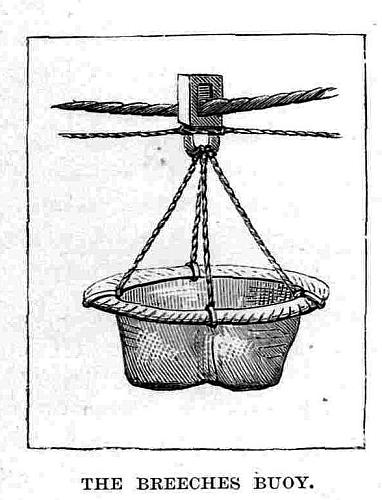

been wrecked on the Needles; and Paul Truck told us how a pilot he once knew well saved the crew of a vessel which drove in during the night on one of those rocks, which they had managed to reach by means of the top-gallant yard. Here they remained until the pilot brought a stout rope, which was hauled up by a thin line to the top of the rock, and by means of it they all descended in safety. The pilot’s name was John Long.

been wrecked on the Needles; and Paul Truck told us how a pilot he once knew well saved the crew of a vessel which drove in during the night on one of those rocks, which they had managed to reach by means of the top-gallant yard. Here they remained until the pilot brought a stout rope, which was hauled up by a thin line to the top of the rock, and by means of it they all descended in safety. The pilot’s name was John Long.

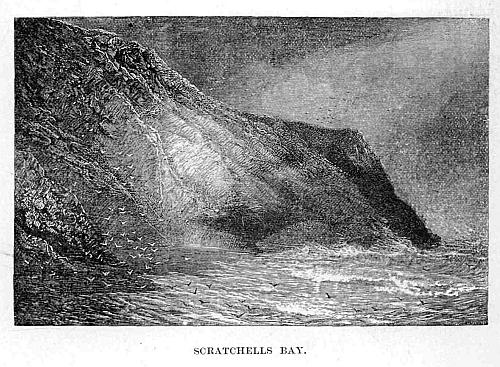

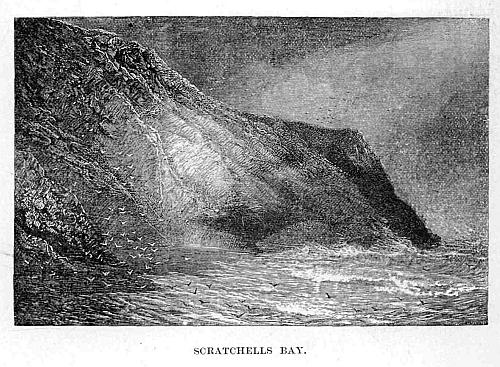

Years before this a transport, with a number of troops on board, was wrecked just outside the Needles, in Scratchells Bay. Being high-water, she drove close in under the cliffs, and thus the sailors and crew were able to escape; and the next morning the cliff appeared as though covered with lady-birds, footprints of the poor  fellows who had been endeavouring to make their way up the precipitous sides.

fellows who had been endeavouring to make their way up the precipitous sides.

Further round is a large cavern, in which it is said a Lord Holmes—a very convivial noble and Governor of Yarmouth Castle—used to hold his revels with his boon companions. But were I to book all the stories we heard, I should fill my journal with them.

When we were a short distance outside the Needles, a superb steam frigate passed us with topsails and top-gallant sails set, steering down channel. Papa looked at her with a seaman’s eye. “Well—well, though she is not as beautiful as an old frigate, she looks like a fine sea-boat, and as well able to go round the world as any craft afloat, and to hold her own against all foes.”

Just at sunset, a light wind blowing, we took the bearings of the Needles and Hurst lights, and stood for Swanage Bay, on the Dorsetshire coast.

Chapter Three.

The South Coast.

When we turned in, the yacht was speeding along with a gentle breeze towards Swanage. The Needle light showed brightly astern, and the two lights on Hurst Point were brought almost into one, rather more on our quarter. Oliver and I wanted to keep watch, but papa laughed at us, and said we had much better sleep soundly at night, and be wide awake during the day; and that if anything occurred he would have us called.

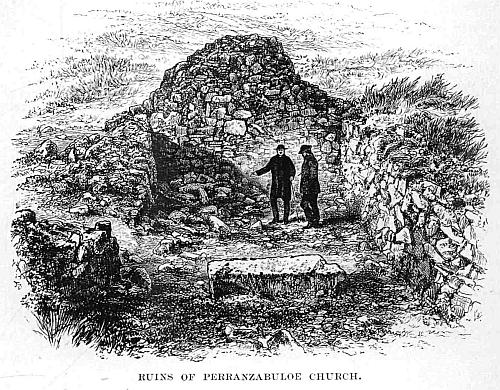

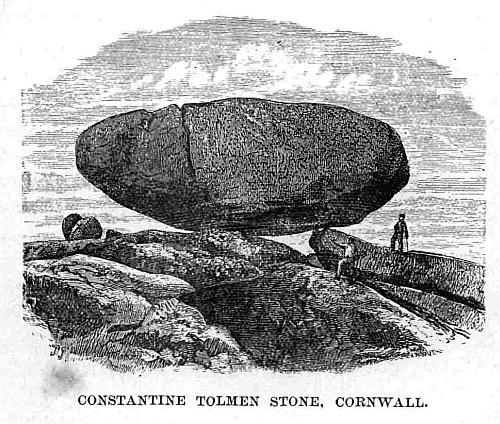

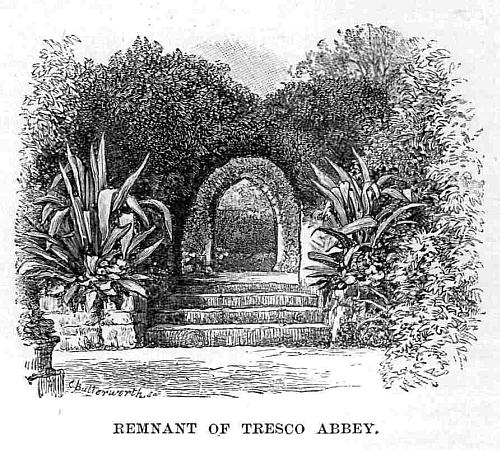

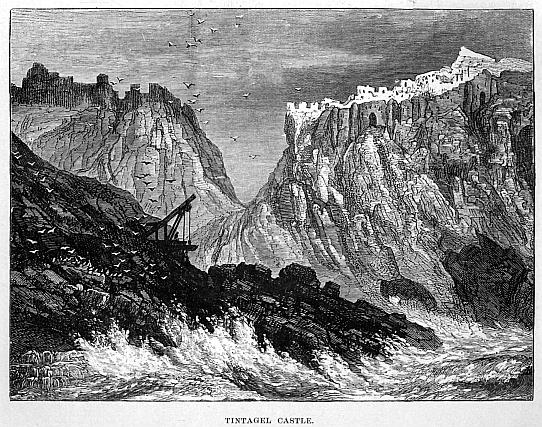

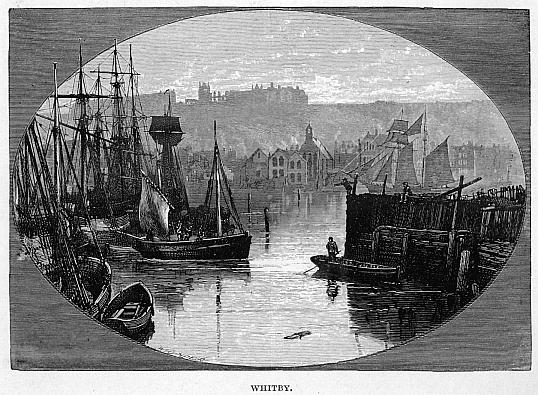

Though Oliver and I said we would get up once or twice, to show that we were good sailors, we did not, but slept as soundly as tops until daylight streamed through the small skylight overhead into our berths.