THE OPENING OF THE SEASON.

"Nah then, 'Erbert, we're in 'Yde Park. Pull up yer socks an' look smart."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, April 29, 1914, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, April 29, 1914 Author: Various Release Date: April 7, 2008 [EBook #25010] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Captain Fort, a French army airman from Chalons, flew over the German frontier, last week, by mistake, and alighted in Lorraine, but flew back again before the German police arrived. We think he should have waited. It is just little discourtesies such as this that accentuate ill-feeling between nations.

Mr. H. W. Thornton, the new American manager of the Great Eastern Railway, says that his ideal is to satisfy the public. This disposes of the absurd rumour that his appointment was made in the interests of the shareholders.

Jack Johnson, the pugilist, is about to become naturalized as a French subject. Frankly, America has brought this on herself.

It is possible, by the way, that the knowledge that America could not rely on Jack Johnson stiffened President Huerta's back.

In at least one of our colonies the War Minister is designated "Minister for Defence." This would surely be a more than apt title for Mr. Asquith, who has been doing yeoman work of this kind on behalf of his peccant colleagues.

Some idea of the confusion which reigned at the fight between Blake and Borrell may be gathered from the following paragraph in The Liverpool Daily Post:—

"Blake, who was the taller, at once led the £500 aside, and both men to deposit a further close quarters, and they indulged in in-fighting up to the close of the round."

It was certainly shrewd of Blake to act as he did in regard to the stakes, for, although he was the taller, it did not necessarily follow that he would win.

Stafford House, which contains the London Museum, will in future be called Lancaster House. It was felt, we understand, that its former name gave no clue to its contents.

We find the following announcement of the greatest interest:—

"April 16th, to Mr. and Mrs. G. E. Turtle (née Nurse Lacey) a daughter."

It was a great performance to have been born a nurse, even if she turned Turtle later on.

"In everything where her means and opportunities allow," says Mr. Arthur Rackham, "woman seeks persistently for beauty." And now many husbands are flattering themselves that that is how they came to be married.

"Mothers who sleep nine hours on end," says Dr. Westcott, the coroner, "should not have babies, and, if they do, they should be put in cradles." The only difficulty is that at present there is no cradle on the market large enough to take a grown-up.

The Times has published an indictment of the London plane-tree as a disseminator of disease. Nervous folk, however, may like to know that, if they stay indoors with their windows closed and with a towel fastened across the mouth and nose, they will run comparatively little risk from this source.

The Express is offering prizes to its readers with a view to ascertaining which is the best-looking animal in the Zoo, and which is the ugliest. It is, of course, no affair of ours, but we think it would be a graceful and humane act on the part of our contemporary to give a consolation prize to the poor beast adjudged to be the ugliest.

Meanwhile, in view of this competition, the wart-hog would be glad to hear of a really reliable cure for warts.

A thrush has built its nest and laid three eggs at the junction of two scaffold poles where between fifty and sixty men are working on a new building at Northampton. The kind-hearted labourers were, we understand, willing to work quietly and slowly in order not to disturb the young mother, but were over-ridden by the foremen.

What is described as a "Racegoers' Luncheon Palace" is being erected next to the Epsom Grand Stand. The new building will, we are informed, have fireproof floors and staircases. These will no doubt be duly tested by the Militants.

It is rumoured that such is the success of The Melting Pot that Mr. Zangwill has been approached by more than one manager with flattering proposals. Mr. Zangwill, however, is not to be rushed, and it is extremely unlikely that we shall have him turning out Melting Pot-Boilers.

The punishment does sometimes fit the crime. An individual who for some months past specialised in thefts of clocks was last week given time.

"A Blackburn platelayer," it is stated, "who has just died at the age of seventy, left £400, which he had accumulated out of his small earnings. He was a bachelor." Married women consider this a marvellous achievement in view of the fact that the man had no wife to help him.

At last it looks as if something is going to be done for golfers, whose language, it is rumoured, occasionally leaves so much to be desired. The Rector of Frinton has undertaken to consider a suggestion that a special service for golfers shall be held at nine o'clock on Sunday mornings.

"Nah then, 'Erbert, we're in 'Yde Park. Pull up yer socks an' look smart."

"'How beautiful,' said the Queen as she passed me."

We congratulate The Daily Mail's Special Paris Correspondent (author of the above passage), on the tribute paid to him by Her Majesty.

Two posters in Torquay:—

"Flying at Paignton by Monsieur Salmet."

"Flying Visit of Mr. H. B. Irving."

"Fashion Gossip" in The Cambridge Chronicle:—

"Black rats, however, are most in favour and bid fair to retain their popularity."

It is no longer fashionable to see snakes.

"For supply of a body suitable for motor ambulance for Ipswich."—Contract Journal.

Ipswich seems in a hurry. Surely it might wait for the accident to happen naturally.

[The following unpublished poem of General Villa—not, of course, to be compared with the recently discovered compositions of Keats—throws an interesting light on the attitude of that incomparable brigand towards the academic diplomatist of the White House. This correspondence, rendered into English, is now made public without prejudice to any change of policy that may occur during its passage through the press.]

Wilson (or Woodrow, if I may),

I blush to own that ere to-day

I have described you as a "gringo";

For you are now my loved ally;

We see together, eye to eye;

The same usurper we defy.

Each in his local lingo.

Friends I have had in your fair land,

Nice plutocrats who lent a hand

(In view of possible concessions),

But still I lacked official aid,

And lived, with that embargo laid

Upon the gunning border-trade,

A prey to rude depressions.

But, when you let the barrier drop,

And all the frontier opened shop

To deal in warlike apparatus,

Much heartened by your friendly leave

To storm and ravage, slay and reave,

I felt my fighting bosom heave

As with a fresh afflatus.

Now closer still we join our stars;

At Vera Cruz your valiant tars

Have lately forced a bloody landing;

No more you hold aloof to see

The dirty work all done by me,

You show by active sympathy

A cordial understanding.

Nor shall my loyal faith grow slack

Although you put the embargo back;

No doubt once more you'll countermand it;

And anyhow this party scores

Since, you'll supply the arms and stores

The bill for which so rudely bores

A constitutional bandit.

At your expense, in fact, we go,

We two, against a one-man foe

(Of course you would not wish to hurt a

Hair of our folk in vulgar broil;

Your scheme is just to take and boil

Inside a vat of native oil

This vile impostor, Huerta).

Then here's my hand all warm and red,

And we will march through fire and lead

Waging the glorious war of Duty;

Though impotent to read or write,

I love the cause of Truth and Light,

So God defend us in the fight

For Villa, Home and Beauty!

O. S.

"A Review of the Primates. By Daniel Geraud Elliot.

Three volumes.

Monkeys, and especially the higher apes, have an unfailing interest for mankind."—"Times" Literary Supplement.

But this is not the way that we ourselves should begin an article on the Archbishops.

Showing the Development of Parliamentary Manners.

Mr. Asquith. I wish to ask the Prime Minister whether he will grant a full judicial enquiry into the recent military and naval movements contemplated by the Government in Munster.

Mr. Law (who was greeted by shouts of "Assassin"). I see no necessity for any such enquiry. I am prepared to answer for the Government on the floor of this House.

Mr. Lloyd George. May I ask the right honourable gentleman how many members of the Government are interested in armament companies, and to what extent they would have profited by the contemplated Tipperary pogrom? (Shouts of "Yah," "Thieves!" "Thieves!" "Brigands!" and "Yah!")

Mr. Law. I utterly and entirely repudiate the suggestion of the right honourable gentleman. (Opposition shouts of "Liar" and "Coward.") The information the right honourable gentleman has gained during his intrigues with the rank and file of the Welsh regiments is totally——

Mr. Speaker. Order, order. That reply obviously does not arise from the question.

Mr. Asquith. I wish to ask the right honourable gentleman if he is prepared to make a statement on oath. Nothing else will convince the country, as it knows by experience that Ministers are steeped in falsehood.

Mr. Law. That is an allegation against the honour of Ministers. (Mr. Churchill, "They have none.") If the Leader of the Opposition desires to attempt to substantiate these charges I will give him a day—or a week, if he wants it.

Mr. Swift MacNeill. Afraid of five years for perjury. Blackguards!

Mr. Amery (President of the Local Government Board). Mr. Speaker, should I be in order if I appealed to you to ask Members on the other side to maintain the honourable traditions of this House?

Mr. John Ward. All they care for is the £5,000 a year.

Mr. Speaker. Order, order! I must ask honourable members not to turn Question time into a debate.

Mr. Churchill. I beg to ask the Prime Minister whether the guns of the first cruiser squadron are not at this moment trained on Limerick, and to ask him if ample time will be given for women and children to escape before the massacre begins?

Mr. Bonar Law. The first cruiser squadron is not at Limerick. (Loud shouts of "Liar!") That disposes of the second part of the question also. (Cries of "No!" "Shame!" "Child-murderer!")

Lord Winterton (Junior Lord of the Treasury). Mr. Speaker, may I draw your attention to the fact that several Members of the Opposition shout "Liar" at the Prime Minister whenever he rises to his feet?

Mr. Speaker. The term is certainly an objectionable one, but unfortunately there are Parliamentary precedents.

Mr. Raymond Asquith. Yes, that's what he used to call Papa.

Mr. Lloyd George. May I ask the Prime Minister if it is true that victims of the Celtic pogrom are to be refused treatment by their panel doctors?

Mr. Law. As there will be no victims (shouts of "Found out" and "Afraid") the question of medical treatment does not arise.

Mr. John Redmond. Enough of this foolery. Enough of the deliberate falsehood of Ministers. I go to Ireland at once, where half a million resolute, dour, determined men are ready to defy this Government of assassins.

(Loud Opposition cheers and waving of handkerchiefs, as Mr. Redmond retires from the House.)

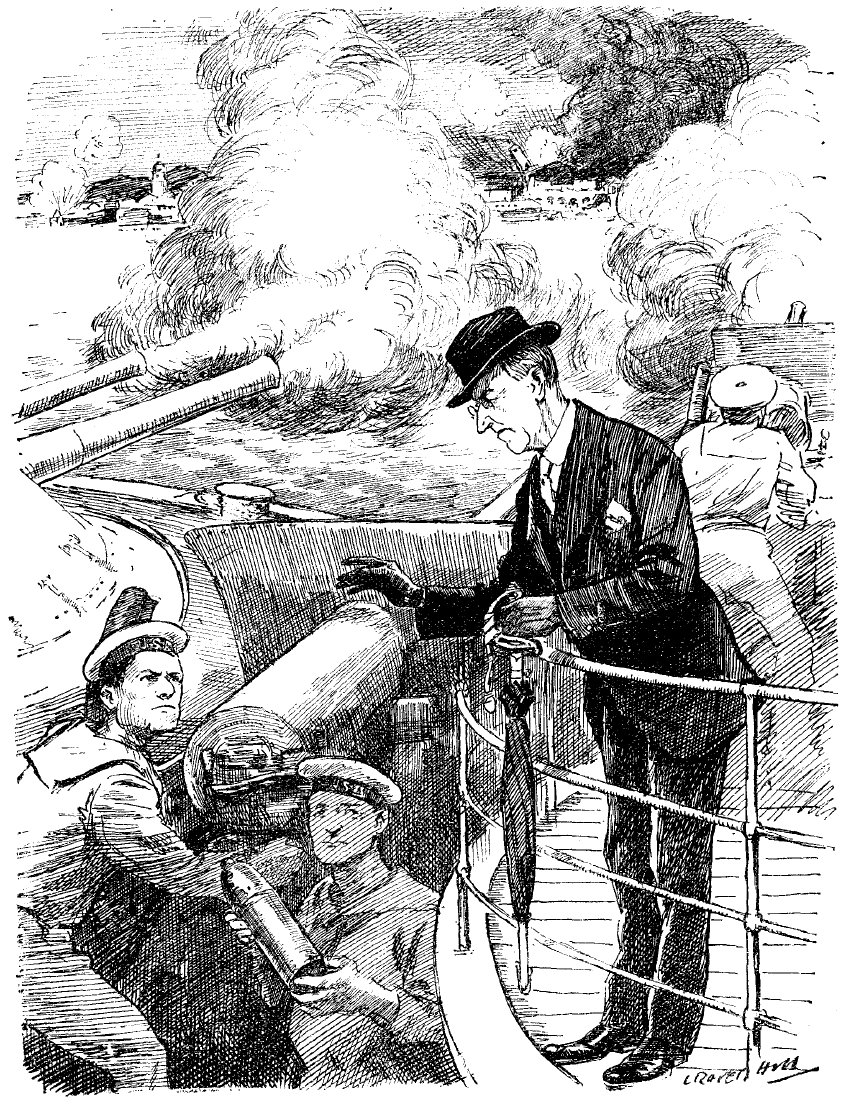

President Wilson. "I HOPE YOU ARE NOT SHOOTING AT MY DEAR FRIENDS THE MEXICANS?"

U.S.A. Gunner. "OH, NO, SIR. WE HAVE STRICT ORDERS ONLY TO AIM AT ONE HUERTA."

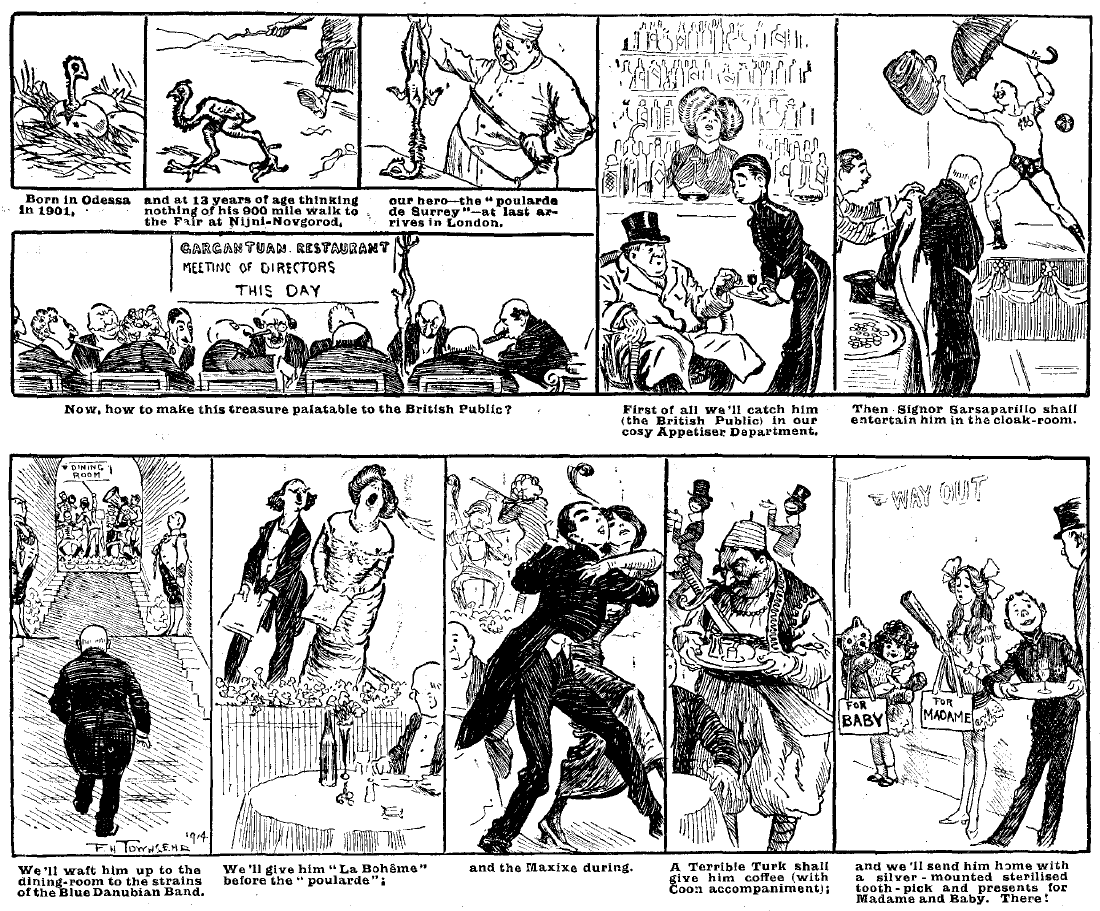

Born in Odessa In 1901, and at 13 years of age thinking nothing of his 900 mile Walk to the Fair at Nijni-Novgorod, our hero—the "poularde de Surrey"—at last arrives in London.

Now, how to make this treasure palatable to the British Public? First of all we'll catch him (the British Public) in our cosy Appetiser Department. Then Signor Sarsaparillo shall entertain him in the cloak-room.

We'll waft him up to the dining-room to the strains of the Blue Danubian Band. We'll give him "La Bohême" before the "poularde"; and the Maxixe during. A Terrible Turk shall give him coffee (with Coon accompaniment); and we'll send him home with a silver-mounted sterilised tooth-pick and presents for Madame and Baby. There!

Now we who sense the odorous Spring

Our various winter garments fling,

Cast off the heat promoting clout

That wise men keep till May is out,

And hail with joy and wear too soon

Suitings more fitly planned for June.

'Twas ever thus; and now we look

Askance on what arrides the cook,

Behold her boil and chop and strain

For us the cabbage all in vain.

She would have dished what most we scout,

But Brussels-sprouts at last are out.

And something else at last is in,

A something green and straight and thin.

Long looked for, long desired, its head

Well raised above its English bed,

It smiles at last and blesses us,

Our garden-grown asparagus!

Let others in their praise advance

The monstrous branches sent from France;

You ope your mouth as 'twere a door,

And bite off half an inch, not more;

And then perforce you lay aside

A tasteless foot of wasted pride.

Besides, you find that what you praise,

Is mostly sauce—a Hollandaise.

The succulent, the English kind,

You pick it up and eat it blind;

In fact, you lose your self-control,

And dip, and lift, and eat it whole.

And some day, when the beds have ceased

To cater for your daily feast,

You'll see—the after growth is fair—

A green and feathery forest there,

And "here," you'll say, "is what shall cheer

My palate in the coming year.

"Yea, when these graceful pigmy trees

Have swayed their last in any breeze,

And all is bare, I may again

See the ripe heads that pierce the plain,

And eat once more before I die

Our garden-grown asparagi."

R. C. L.

"Anatomy. Albinus (Bernard Siegfried). Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles of the Human Body, translated from the Latin. Folio, half calf (joints cracked, back rubbed). Edinburgh 1777-78."

A Special Correspondent of The Evening News wrote last week:—

"As for the Queen, from the moment she stepped off the yacht till she got into the train she went on smiling and bowing and murmuring 'Merci, oh merci bien?' I do not, of course, know what she was thinking."

Possibly it had something to do with gratitude.

[A companion picture to Mr. Edward Knoblauch's play, My Lady's Dress.]

Prologue.

William and Mary have returned from the Royalty Theatre, where they have attended a play in several scenes each representing some incident in the making of a lady's dress.

William (for the ninth time). Capital dinner we had to-night, dear. Don't know when I've had a better.

Mary. Oh, bother your old dinner. What did you think of the play?

William. H'm, not bad. Don't know that I care about those dream plays. (After deep thought) Capital caviare, that.

Mary (annoyed). You think of nothing but your food. Didn't you think Dennis Eadie was splendid?

William. Very clever. A remarkable tour de force. H'm. Capital whitebait, too. Did you notice the saddle of lamb, my love? Capital.

Mary. I thought it was all very novel and interesting.

William. The dinner, my dear? Not exactly novel, but certainly——

Mary (coldly). I wasn't referring to the dinner. If you could manage to get your mind off your meals occasionally, I should like to discuss the play.

William (yawning). Not to-night, dear, I'm sleepy.... Capital dinner; don't know when I've had a better.... Very, very sleepy.

[He goes to bed and dreams.

THE DREAM.

Scene I.

Moscow. The top of the Shot Tower where they make the caviare. Alexandrovitch is discovered at work. Enter Marieovitch.

Alexandrovitch (dropping his sturgeon and clasping her round the neck). At last, my love!

Marieovitch. Be careful. Williamovitch suspects. He hates you.

Alexandrovitch. Nonsense, love! He's only jealous because my caviare is so much rounder than his.

Marieovitch. He knows I am tired of him. Lookout; here he is.

Enter Williamovitch from behind a heap of buttered toast.

Williamovitch (sternly). I know all.

Alexandrovitch (pushing him over the edge of the tower). Then take that!

[Exit Williamovitch.

Scene II.

A typefounder's in Italy, where they make the macaroni letters for the consommé.

Gulielmo (sorting the O's). One million, three hundred and eighty-seven thousand, six hundred and forty-five. There are two missing, Maria.

Maria (nervously). Perhaps you counted wrong, Gulielmo.

Gulielmo (scornfully). Counted wrong! And me the best macaroni sorter in Italy! Now let's get the "E's" together. (After a pause) Two million, four hundred and five thousand, two hundred and ninety seven. Corpo di Bacco! There are two "E's" 'missing'!

Maria. Don't you remember there was one "E" the reader wouldn't pass?

Gulielmo (suspiciously). I made another to take its place. There's some devilry in this. Maria, girl, what are you hiding from me?

Maria (confused). Oh, Gulielmo, I didn't want you to know.

[She takes a handful of letters from her lap and gives them shyly to him.

Gulielmo (sorting them). Two "O's," two "E's," two "L's——" What's all this?

Maria (overcome). Oh!

Gulielmo. "I Love Gulielmo."

(Ecstatically). Maria! You love me?

[She falls into his arms.

Scene III.

A whitebait stud farm at Greenwich. Polly is discovered outside one of the stables. Enter Alfred.

Polly. Can't think what's the matter with Randolph this morning. That's 'is fifth slice of lemon, and 'e's as fierce and 'ungry as ever.

Alfred (gaily). Never mind the whitebait now, sweet'eart, when we're going to be spliced this afternoon. 'Ullo, 'ere 's Bill.

Enter Bill.

Bill. Wot cher, Alf! The guv'nor wants yer. (Exit Alfred hastily.) And now, Polly, my girl, wot's all this about marrying Alf when you're engaged to me?

Polly. Oh, Bill, I'm sorry. Do let me off. I love Alfred.

Bill. I'll let yer off all right.

[He goes towards Randolph's stable.

Polly (shrieking). Bill! Wotcher doing?

Bill (opening the stable door). Just giving Randolph a bit of a run like. 'E wants exercise.

[Randolph, the fiercest of the whitebait, dashes out and springs at Polly's throat.

Polly. Help! Help!

Bill. P'raps Alfred will 'elp you—when 'e comes back. I'll tell 'im.

[Exit leisurely.

Scene IV.

A saddler's shop at Canterbury, New Zealand.

Molly. Busy, Willie?

William. Always busy at the beginning of the lamb season, Molly. The gentlemen in London will have their saddle.

Molly. Too busy to talk to me?

Willie. Plenty of time to talk when we're married. Shan't have to work so hard then.

Molly. Because of my money you mean, Willie dear. You aren't only marrying me for my money, are you?

Willie. Of course not.

[He kisses her perfunctorily and returns to his work.

Molly. Because—because I've lost it all.

Willie (sharply). What's that?

Molly. I've lost it all.

Willie. Then what are you doing in my shop? Get out!

Molly (with dignity). I'm going, Willie, And I haven't lost my money at all. I just wanted to test you. Good-bye for ever.

[She goes out. Willie in despair rushes into the garden and buries his head in the mint.

Scene V.

[This part of William's dream was quite [pg 327]different from the rest, and it was the only scene in which his wife didn't appear.]

An actor-manager's room.

Actor-manager. Yes, I like your play immensely. I don't suppose any actor-manager has ever played so many parts before in one evening. But couldn't you get another scene into it?

William. Well, I've got an old curtain-raiser here, but it doesn't seem to fit in somehow.

Actor-manager. Nonsense. In a dream play it doesn't matter about fitting in. What's it about?

William. Oh, the usual sort of love thing. Only it's in the tropics, and I really want an ice-pudding scene.

Actor-manager. Then make it the North Pole.

William. Good idea.

[Exit to do so.

Epilogue.

Next morning.

William. I've had an extraordinary, dream, dear, and—er—I've decided not to eat so much in future.

Mary. My darling boy!

[She embraces him; and as the scene closes William takes his fifth egg.

Curtain.

["The Sardine War."—Headline in a daily paper.]

There was peace at first in the tight-packed tin,

Content in the greasy gloom,

Till the whisper ran there were some therein

With more than their share of room;

And I saw the combat from start to end,

I heard the rage and the roar,

For I was the special The Daily Friend

Sent out to the Sardine War.

The courage was high on every face

As the wronged ones took their stand

On the right of all to a resting-place

In a tinfoil fatherland;

Yes, each one, knowing he fought for home,

Cast craven fear to the gales,

And the oil was whipped to a creamy foam

By the lashing of frenzied tails.

You may think that peace has been quite assured

When you've packed them tight inside,

But the sardine's spirit is far from cured

When you salt his outer hide;

They gave no quarter, they scorned to yield,

To a fish they died in the press,

And, dying, lay on the stricken field

In an oleaginous mess.

There is a gladness in her eye,

And in the wind her dancing tread

Appears in swiftness to outvie

The scurrying cloudlets overhead;

In brief, her moods and graces are

Appropriate to the calendar.

And yet methinks that Mother Earth,

Awake from sleep, hath less a share

In this, my darling's, present mirth,

Than Madame Chic, costumiére;

My love would barter Spring's display

For Madame's window any day.

"The members at the Club dance last Saturday were rather small—but this is only natural after four dances in 'the week' and the summer approaching."—Pioneer.

Certainly nothing gets the weight down so quickly.

"I hope," said my friend and host, Charles, "I hope that you'll manage to be comfortable."

I looked round as much of the room as I could see from where I stood and ventured also to hope that I should.

"The tap to the right," he said, indicating the amenities, "is hot water; the left tap is cold, and the tap in the middle...."

"Lukewarm?" I asked.

"Soft water, for shaving and so on. But Perkins will see to it."

Some people can assume a sort of detached attitude in the early morning, while body-servants get them up and dress them and send them downstairs, but me, I confess, these attentions overawe. "Perkins is one of those strong silent men, is he not," I asked, "who creep into one's bedroom in the morning and steal one's clothes when one isn't looking?"

Charles has no sympathy with Spartans and did not answer. "I think you'll find everything you want. There's a telephone by the bed." I said that I was not given to talking in my sleep. "Then," said he, "if you prefer to write here is the apparatus," and he pointed to a desk that would have satisfied all the needs of a daily editor.

"Thanks," I said, looking at the attractive bed, "but I expect to be too busy in the morning even to write." I yawned comfortably. "Though it may be that I shall dictate, from where I lie, a note or two to my stenographer."

Charles doubted, with all solemnity, whether Perkins could manage shorthand, but promised to enquire about it. He's a dear solid fellow, is Charles, and he does enjoy being rich. Moreover, he means his friends to enjoy it, too. Lastly, "If you don't find everything you want," he said, "you've only to ring," and he pointed to a, row of pear-shaped appendages hanging by silken cords from the cornice.

"Heavens," said I, seizing his arm, "you're never going to leave a defenceless man alone with half-a-dozen bell-pushes!"

Charles softened; he admits to a weakness for electricity. "Some are switches, some are bell-pushes, and one," he said, blushing, "is a fire-alarm."

I climbed on to a chair forthwith and tied a big knot in the cord of the fire-alarm. "We'll get that safe out of the way first," said I, and then he tutored me in the use of the others. After some repetition it was drummed into me that the one nearest the bed was the switch of the getting-into-bed light, and the next one to that the bell which rang in Perkins' upstairs quarters, The other four or five I found, when I came to study them alone, I had forgotten.

I clambered into bed and with great intelligence pressed the correct switch. Had I left it at that my problem would never have arisen.

I have, however, a confession to make which ill accords with my luxurious surroundings of the moment. It is that I am accustomed to press my trousers myself by the homely and ignoble expedient of sleeping on them. My only excuse is that I am a heavy sleeper. So automatic is the process, that I was wrapped in sheets and darkness before it occurred to me that I had placed the trousers I had just doffed under the mattress on which I now lay. I could not help thinking how the masterful Perkins would take it when he came to look for them in the morning. I conceived him picking up my dinner-jacket here, my waistcoat there, and wandering round the room in a hopeless quest for the complement of my suit, trying to recall the events of the previous night and to remember whether I was English or Scottish ... and then, more in sorrow than in anger, spotting the lost ones....

As I contemplated this picture I was moved to pity Perkins, torn asunder between two dreadful alternatives, the one of leaving the trousers there and committing a dereliction of duty, the other of removing them stealthily and committing an indelicacy. I was also moved to pity myself, lying supine under his speechless contempt. I resolved to spare us both, to get out of bed and put things right. I stretched out a hand for the switch. I grasped it with an effort. I pressed the button.

No light ensued.

I pressed again ... and again ... with no visible result. I pressed once more, and still there was a marked absence of light. I lay back in bed and, cursing Charles, thought out his instructions. Cautiously I reached out again, pressed once more and succeeded. The continued oscillation of the second cord revealed to me what you have already guessed, that I had meanwhile rung the bell in Perkins' sleeping quarters four times.

To me the approaching climax was horrible; I could see no way of dealing with the situation shortly about to arise. To those who have never known and feared Perkins or his like it may seem that there were at least two simple courses to pursue: to lie boldly and deny that I had rung; or to tell the truth and admit that I had made a mistake. Men like Perkins, however, are not to be lied to; still less may they be made the recipients of confessions. Methods of self-defence were therefore unthinkable, and I knew instinctively that I must assume the offensive. I must order him curtly, upon his arrival, to do something. But what? As I waited anxiously I tried to think of some service I could require at this hour. What can a man want at 1 A.M. except to go to sleep? Even the richest must do that for himself.

There were footsteps outside.... Perkins'.... I thought harder than I have ever thought before, but my life seemed replete with every modern comfort.

"Yes, Sir?" said Perkins.

"Ah, is that you, Perkins?" said I to gain time, and he said it was.

I shut my eyes and tried to think. Perkins stood silent. I had some idea of leaving it at that, of turning out the light and letting Perkins decide upon his own course of action. I was just about to do this when I had a brain wave. After all, he was paid to do the dirty work and not I.

At that moment I was anticipated.

"Is there anything I can do for you, Sir?" said the Model.

"There is," said I, in my most négligé voice. "Kindly turn out my light."

Perkins may have been annoyed about this, but he was certainly impressed. His demeanour suggested that he had met autocrats before but never such a thorough autocrat as I. For the rest of my time there I pressed my trousers in the usual way, well knowing that he would regard the process not as the makeshift of a valetless pauper but as the eccentricity of an overstaffed multi-billionaire.

"Among the most formidable foes to the reform of our industrial system are those who pretend to be most bitterly opposed to it."

Sunday Times.

Seen in a window in Clapham:—

"PAINLESS

Advice

Free

EXTRACTIONS."

This "derangement of epitaphs" fails to attract us.

"The Counterfoil in centre must be returned to the Syndicate, which is placed in the Large Wheel with other Subscribers' Tickets for the Draw."—Derby Sweep Circular.

"As formerly, the ticket-holders, with their numbers, were placed in a barrel and thoroughly shaken up."—Hamilton Advertiser.

These repressive measures ought to satisfy even the sternest member of the Anti-Gambling League.

Or, Some Words about Carter.

Not always for the noblest martyr,

My countrymen, ye forge

The crown of gold nor wreathe the laurel;

One protestant ye count as moral,

Neglect another. Take the quarrel

Extant between myself and Carter

(Henchman of D. Lloyd George).

I see the Unionists grow oranger,

I mark the wigs upon the green,

The rooted hairs of Ulster bristle

And all men talk of Carson's gristle,

Then why should this absurd epistle,

Put down beside my little porringer,

Provoke not England's spleen?

Did Hampden positively jeopardise

His life, and did the axe

Extinguish Charles's hopes of boodle

And all the wrongs of bad days feudal

For this—that Carter, the old noodle,

With t's all crossed and dot-bepeppered i's,

Should change my income-tax?

Thank heaven that one heart in Albion

Retains its oaken core;

Alone I can withstand my duty,

And so my answer to this beauty

Is simply "Rats!" and "Rooti-tooti!

My toll for this year must and shall be on

The sums declared before."

If not—if all things go by jobbery

And tape dyed red with sin,

Come, let him make a small collusion

And, when he writes his next effusion,

Grant me, we'll say, six years' exclusion

From re-assessments of his robbery.

And then—I may come in.

But, if the fiend still stays importunate,

My blood is up. Ad lib.,

Till at the door the bailiff rattles

And rude men reave me of my chattels,

I shall prolong these wordy battles,

And may the just cause prove the fortunate;

Phœbus defend my nib!

So long as gray goose yields a pinion,

So long as ink is damp,

Mine to resist the loathly fetters

Of D. Lloyd George and his abettors,

Posting innumerable letters

To Carter (D. Lloyd George's minion),

Minus the penny stamp.

Evoe.

From The Birmingham Daily Mail's report of a fire:—

"The night-watchman was aroused."

A shame to disturb the poor fellow's sleep.

Squire. "Well, Matthew, and how are you now?"

Convalescent. "Thankee, Sir, I be better than I were, but I beant as well as I were afore I was as bad as I be now."

The big clock in the station pointed three minutes to the hour, and my train went at one minute past, so I didn't waste words with the man in the booking-office.

"Third r'turn, Wat'loo."

Nothing happened. He was there all right, but he neither spoke nor made any attempt to give me my ticket; he merely looked.

"Third r'turn, Wat'loo," I repeated, and again, inserting my face as far as possible into the window, very firmly, distinctly and offensively. "Third re-turn, Wat-er-loo."

Then he spoke, slowly. "Sorry, Sir, I can't do it. You have hit on the one station to which we don't issue tickets. Any other one I could manage for you, but——"

"Look here," I said sternly, "you don't seem to know your business. If you haven't got a printed ticket, can't you make one out on paper? Hurry up, man; my train leaves in a minute or two."

"Yes," he said more slowly than ever, "I could do that—we have blank forms for that purpose; but all the same I won't do it."

"Oh, you won't? And why?"

"Well, I don't know what the fare is. I——"

"All right," I said. "You don't appear to be drunk, so I imagine you're trying to be funny. As your sense of humour doesn't correspond with mine I shall take great pleasure in reporting you to the station-master;" and I prepared to stalk off.

"Wait a moment, please," he said, leaning a bit forward and dropping his voice to a confidential whisper, "I'll give you a tip. You don't want a ticket at all, Sir; you can get there for nothing."

"What do you mean?" said I.

"It needn't cost you a halfpenny," he went on, smiling. "It's not many lines that have a station like this, but we——"

And then, but not until then, did I realise where I was.

"Oh," I said, "er—third return—er—Surbiton."

I don't think railway ticket-mongers ought to be allowed to have a sense of humour.

Mr. Punch ventures to remind his readers that the Centenary dinner of the Artists' General Benevolent Institution is to be held on May 6th, under the chairmanship of H.R.H. Prince Arthur of Connaught. This Institution devotes itself to the relief of artists, and the orphans of artists, who are in need. Mr. Punch, who is to be represented among the Stewards at the dinner by his Art Editor, begs to return his most sincere thanks for the generous gifts he has already received from his readers, and will be very grateful for any further contributions addressed to Mr. F. H. Townsend, "Punch" Office, 10, Bouverie Street, E.C.

"The King this morning received the Bishop of Sheffield, who was introduced to Mr. McKenna (Home Secretary), and did homage upon appointment."—Birmingham Daily Post.

Mr. McKenna (accepting homage). "And now what do you think of my Welsh Disestablishment Bill?"

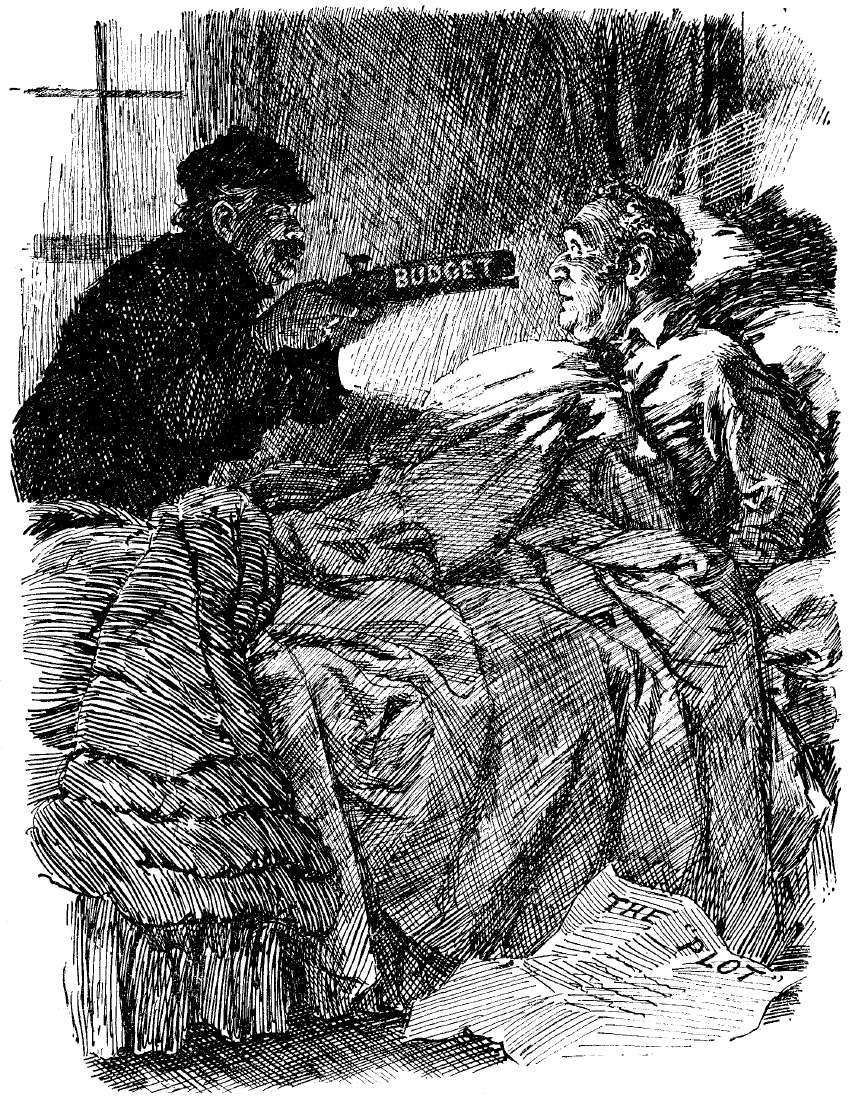

Burglar George. "IT'S YOUR MONEY I WANT!"

John Bull. "MY DEAR FELLOW, IT'S POSITIVELY A RELIEF TO SEE YOU. I'VE JUST BEEN HAVING SUCH A HORRIBLE DREAM!"

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

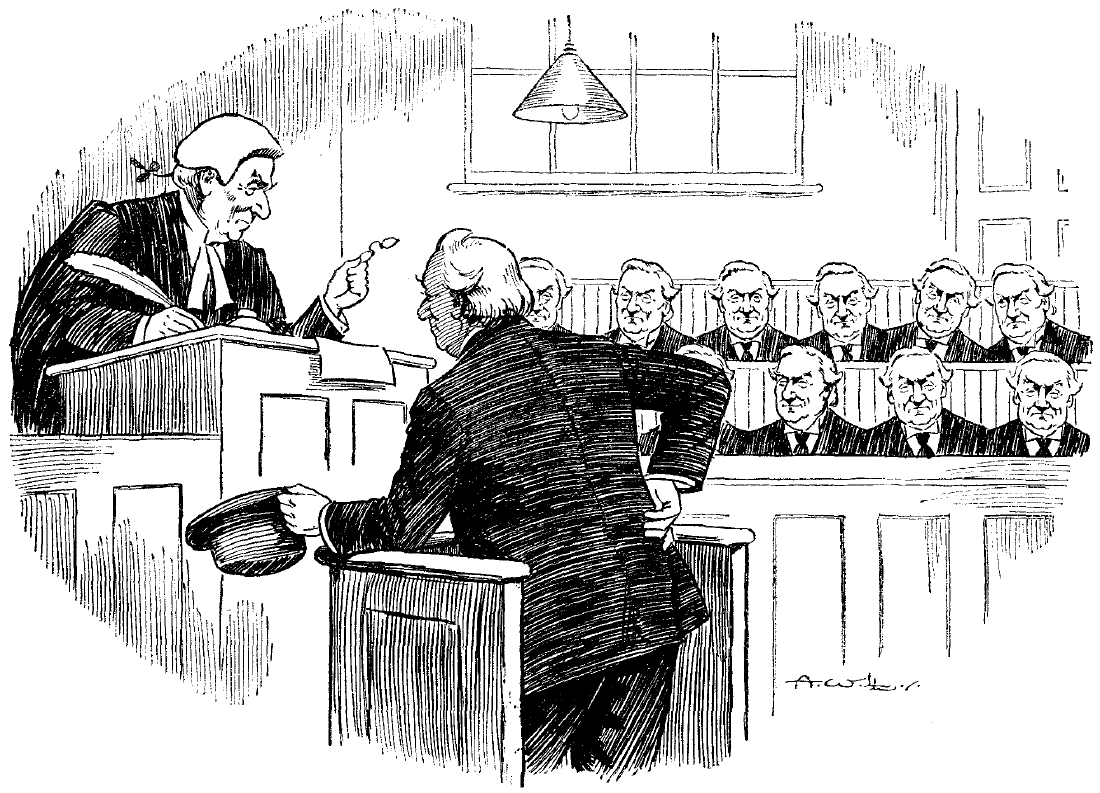

Mr. Asquith (to Jury of Asquiths). "Gentlemen of the Jury, you have heard the prisoner Asquith plead 'Not Guilty.' This should be sufficient evidence to enable you to arrive at a unanimous verdict of acquittal."

[Prisoner leaves court without a stain on his character.

House of Commons, Monday, April 10.—Lively half-hour with Questions. Cluster on printed Paper indefinitely extended by supplementaries. Only once did Speaker interpose. Colonel Greig, sternly regarding badgered Premier, asked, "Has the attention of the right hon. gentleman been directed to No. 453 of the King's Regulations?"

This too much for Speaker. If it had been the odd 53 it might not have been unreasonable.

"The right hon. gentleman," he remarked, "cannot be expected to carry all the Regulations in his head. The hon. member had better give notice."

Cannonade of Questions which opened along full length of Opposition Benches was concerned with the Plot.

"The Plot!" Member for Sark savagely repeated. "That's the ineffective heading in the newspapers. In order to keep up their circulation in parsonages, board-rooms of directors, and suchlike fastidious quarters they are reticent with adjectives. It's only Mrs. Patrick Campbell who could select the appropriate one and give it due emphasis."

Short of that, Opposition did pretty well in denunciation of the Plot and condemnation of dastardly Government responsible for its planning. Chaloner opened fire with demand that judicial enquiry should be ordered into "allegations as to an unauthorised plot to over-awe Ulster by armed occupation." Butcher, Worthington Evans, Helmsley, Archer-Shee, Locker-Lampson, Kinloch-Cooke—what was it Grandolph, à propos of Sclater-Booth, said of men who "had double-barrelled names"?—blazed away. Sometimes in succession; occasionally in platoons. In each case imperturbable Premier gave the short reply that did not turn away wrath. On the contrary, angry passions rose.

Member for East Edinburgh, as usual going the whole Hogge, suggested arraignment of Bonar Law on charge of high treason. Kellaway, anxious to get to business, enquired "whether these Questions might not be addressed to the spies in the service of the Opposition." At end of half-hour even temper of Premier was ruffled. Asked a tenth Supplementary Question by Butcher, he sharply replied:—

"I decline to answer any such enquiry."

Ironical applause of Opposition drowned in burst of angry cheering from Ministerialists.

Sark, as mentioned, unusually roused. As a rule successfully affects attitude of one "who cares for none of these things." To-day moved to unsuspected depths.

"Here," he says, "is Ulster, for two years arming with avowed intention of [pg 334]forcibly resisting the law of the land. The Constitutional Party in this country, bulwark of Law and Order, who, when the Southern Counties of Ireland were in revolt, applauded Prince Arthur's Cromwellian command, 'Don't hesitate to shoot,' backs them up, in my opinion very properly. Carson has developed Napoleonic genius in reviewing troops on parade. F. E. Smith has, with startling effect, 'galloped' along their massed ranks. Londonderry has pledged his knightly word to be in the firing line when the trumpet sounds. All the while, to the bewilderment of onlookers from the Continent, who confess they are further off than ever from understanding John Bull, to the creation of ominous restlessness among their own supporters, the Ministry, Brer Rabbit of established Governments, have 'lain low and said nuffin',' much less have they done anything. Suddenly, without word of warning, they take steps for the protection of military stores in Armagh, Omagh, and Carrickfergus.

"That's their account of the transaction. We know better. It was a carefully devised Plot to take Carson's hundred thousand armed and drilled men at their word and compel them to fight. Not since war began has there been such unjustifiable—don't wish to use strong language, but must say—such really rude procedure on part of a so-called civilised Government."

Business done.—McKenna moves Second Heading of Welsh Church Disestablishment Bill.

Tuesday.—Wholesome spirit of enquiry animates House just now. Bonner Law leads off with demand for judicial inquiry into "the Plot." Fact that its appointment would establish novel precedent in constitutional procedure adds interest to situation. Premier, with emphatic thump of the table that reminds it of Gladstone in his prime, stands by constitutional practice.

"If," he said, "the right hon. gentleman is prepared to make and sustain his allegation of dishonourable conduct on part of the Ministers, I will give him the earliest possible day to bring it forward. But," and here came the thump on the long-suffering table, "he must make it in this House."

Inspired by this high principle of getting at bottom of shady things, Richardson has Chief Whip up and sternly questions him about appointment of certain public auditors under Industrial and Provident Acts.

Position of Chief Whip, though dignified and important, has inevitable result of withdrawing him from participation in debate. Illingworth now has his chance. Made the most of it. Head paper of prodigious length containing memoirs of the two gentlemen concerned, together with succinct history of the birth and progress of the Hetton Downs Co-operative Society, county Durham, of which one of them had been secretary.

House entranced. Rounds of cheering marked progress of narrative, concluding passages inconveniently rendered inaudible by tumultuous applause.

Apprehension in some quarters that this will be the ruin of a really capable, universally popular Whip. Edmund Talbot goes so far as to hint at apprehension that Illingworth will turn up every afternoon at Question time and give us another speech.

Fear exaggerated. Illingworth a shrewd Yorkshireman; knows very well brilliant success of to-day was due to concatenation of accidental circumstance. Not likely to risk suddenly acquired reputation by hasty repetition of exploit.

Business done.—Welsh Church Disestablishment Bill passes Second Reading by majority of 84.

Thursday.—Spirit of enquiry alluded to above manifests itself in fresh direction. The other day Charles Price wanted to know all about political pensions granted to ex-Ministers. Intrigued by disclosure of particulars of estate of our old friend Grand Cross. It appears he left property valued at £91,617. That a pleasant incident closing a worthy life. But, as Member for Central Edinburgh points out, he had for twenty-two years been in receipt of pension of £2,000 a year, a dole from public funds obtainable, as Prime Minister admits, only upon statutory declaration of a state of poverty incompatible with the maintenance of position proper to an ex-Minister.

Price wants to know in the interests of the overburdened taxpayer whether aggregate sum drawn by the noble pensioner may not be recovered from his estate? Premier thinks not.

Price, undaunted, returns to the attack to-day. Cites cases of two other ex-Ministers drawing political pensions in supplement of private estate and fees derived from manifold directorships in public companies. Wants to know if payment can be stopped?

Premier says it is a matter of personal honour. Must be left to consideration of noble lords concerned.

Business done.—Committee of Supply.

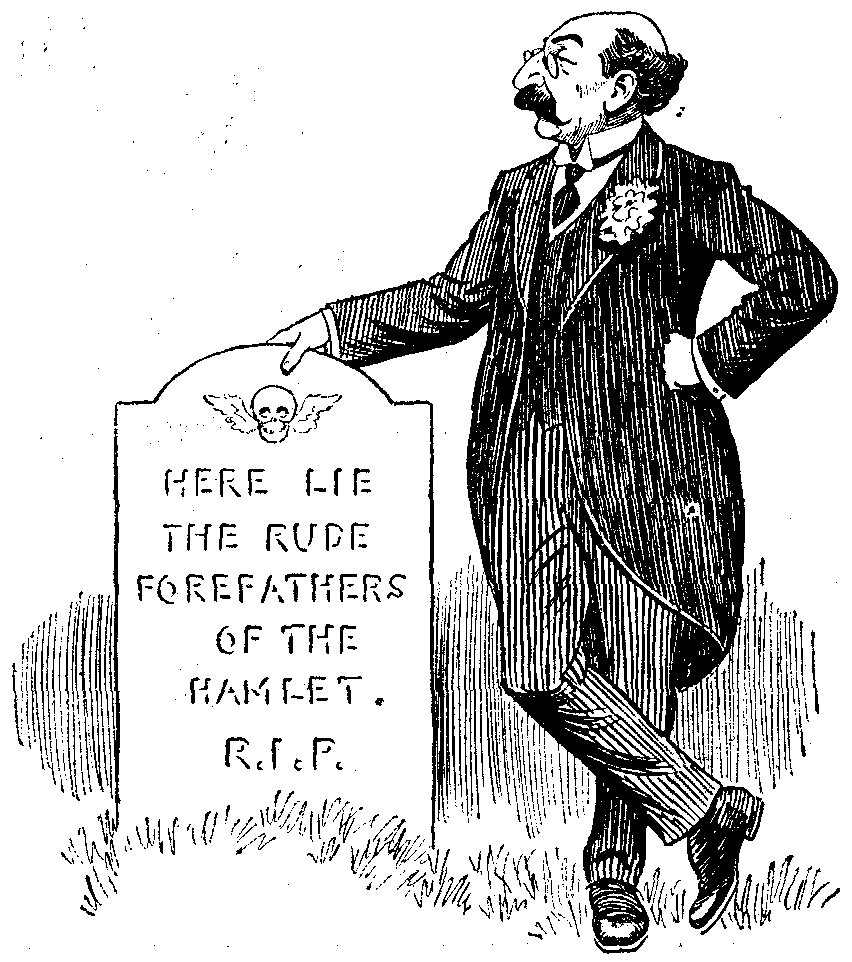

"Harrowing tales were told about churchyards being seized, ploughed up and let as allotments."—Sir Alfred Mond on Nonconformist protest against the Disendowment of the Welsh Church.

Sir Archibald and Lady Bayne

Have struggled up to town again,

Leaving the gentle Shropshire air

For London dust and London glare,

And just that London folk may see

Their lumpish daughter, Dorothy.

Sir Archie, in the club all day,

Thinks of the bills he'll have to pay.

His wife is bored, and hates the smell

Of cooking in a cheap hotel.

She also very much deplores

The lack of likely bachelors.

While Dolly, in the season's swing,

Longs for the Shropshire woods in spring

And a dog chained up at home, poor thing!

"Members of the Oxford University 'relay' tea are in fine shape."—Daily Citizen.

The one whose business it is to take up the running at the muffin stage is particularly rotund.

"He would rather he went for three years, for one could readily understand that for the first year he simply touched the fungi of the Council business."—Hexham Herald.

Motto for rival town council: "There's no moss on us."

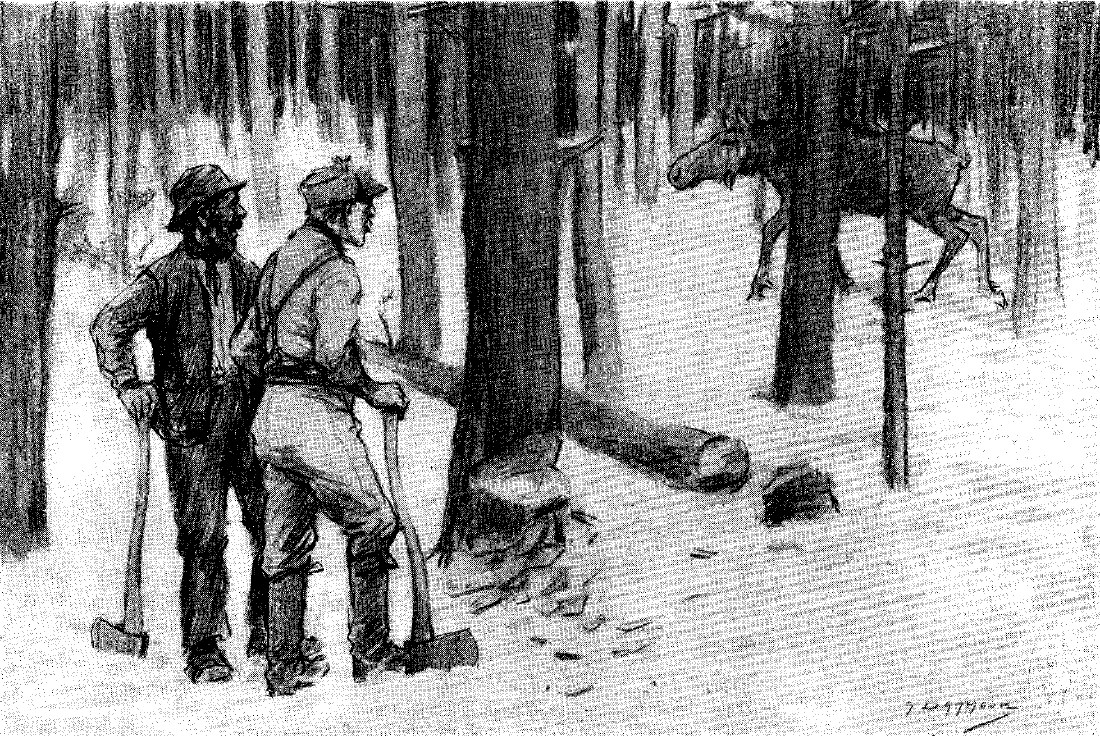

Sandy (newly arrived in the Canadian forest land). "Whatna beast's yon?"

Native. "A young moose."

Sandy. "Och, haud yer tongue! If that's a young moose I'd like to see ane o' yer auld rats!"

As a concrete protest against Jumbomania, or the worship of mammoth dimensions, the prodigious success of Tiny Titus, America's latest wonder-child, is immensely reassuring. In the Albert Hall, where he made his début amid scenes of corybantic enthusiasm last week, the diminutive virtuoso was hardly visible to the naked eye. (As a matter of fact he is only 21 inches high and weighs just under 11 lb.) Yet by his colossal personality he dominated the vast assemblage and inspired the orchestra to such feats of dynamic diabolism as entirely eclipsed the most momentous achievements of any full-grown conductor from Nero to Nikisch.

What renders the performance of this tremendous tot so awe-inspiring is the fact that he is not merely a musical illiterate, who cannot yet read a note of music, but that he has received no education of any kind! Born at Tipperusalem, Oklahoma, on the 15th of March, 1912, he has for parents a clerk in the Eagle Bakery and a Lithuanian laundress. He never touches meat, not even baked eagles, but subsists entirely on peaches and popcorn. He has been compared to Mozart, but the comparison is ridiculous, for Mozart was carefully trained by his father, and at the age of four was a finished executant. But it is quite otherwise with Tiny Titus, who knows no music, and yet by the sole power of his genius comprehends the musical heights unattainable by adults. Mozart, in short, was an explicable miracle, while Tiny Titus is an insoluble Sphinx.

From the innumerable tributes which have been paid to the genius of this unprecedented phenomenon we can only make a brief and inadequate selection. Prince Boris Ukhtomsky writes, "When I listen to this infinitesimal giant of conductors I dream that mankind is dancing on the edge of a precipice. Tiny Titus is—the 32nd of the month." Mme. Jelly Tartakoff, the famous singer, writes: "I have been deeply shaken by Tiny Titus's concert. He is the limit." Of the homages in verse, perhaps the most touching is the beautiful poem by Signor Ocarini, the charm of which we fear is but inadequately rendered in our halting translation:—

Leaving his pop-gun and his ball,

He goes into the concert hall,

No more a baby, and proceeds

To do electrifying deeds.

Wielding a wizard's wondrous skill,

He leads us captive at his will,

But only, mark you, to delight us,

Unlike the cruel Emperor Titus.

O'ercome by harmony's aroma,

I sink into a blissful coma,

Until, my ecstasy to crown,

The infant lays his baton down.

From the Equator to the Poles

Thy fame in widening circles rolls;

But once the audience leave the hall

Thy pop-gun claims thee, or thy ball.

Imagination's wildest flight

Pants far behind this wondrous mite,

And St. Cecilia and St. Vitus

Are vanquished by our Tiny Titus.

The Evening News on the Crystal Palace ground:—

"The roof, back and sides of the stand have been taken away so that people standing on 'Spion Kop,' the hill at the back ... will have an uninterested view of the whole length of the field of play."

This, together with a nicely crowded journey both ways, makes up a pleasant afternoon.

Strange Conduct of Fashionable Audience.

Professor Splurgeson delivered the first of his Claridge Lectures at the theatre of the Mayfair University yesterday. The auditorium was crowded to its utmost extent, ladies largely predominating.

Professor Peterson Prigwell, in a brief introductory speech, said that the achievements of Professor Splurgeson beggared the vocabulary of eulogy. More than any other thinker he had succeeded in reconciling high life with high thinking.

Professor Splurgeson, speaking in fluent American, began by alluding to the numerous links which bound together his country with that of his audience, and pointed out that nowhere was this affinity more pronounced than in their philosophies. Both showed a concrete cosmopolitanism indissolubly wedded to an idealistic particularism; both agreed that truth, no matter how abysmally profound, could be expressed in language sufficiently simple to attract large audiences of fashionable women; both, finally, made it clear that Pragmatism, unless allied with Feminism, was destined to be relegated to the limbo of the obsolete. (Cheers.)

Professor Splurgeson then went on to say that nowhere was this happy element of intellectual compromise more needful than in discussing the problem of personality. That problem comprised three questions: What are we? What do we think of ourselves? and What do others think of us? In regard to the first question, the philosophic pitch had been queered by the conflicting combinations of all thinkers from Corcorygus the Borborygmatic down to William James. (Applause.) Man had been defined as a gelastic apteryx, but in view of the attitude of women towards the Plumage Bill the definition could hardly be allowed to fit the requirements of the spindle side of creation. The danger of endeavouring to find some unifying concept in a multiplicity of conflicting details was only equalled by that of recognizing the essential diversity which underlay a superficial homogeneity. (Loud cheers.)

At this point the Professor paused for a few minutes while kümmel and caviare sandwiches were handed round.

Resuming, Professor Splurgeson discussed with great eloquence the secular duel between the Will and the Understanding. It was ex hypothesi impossible for the super-man, à fortiori the super-woman, to yield to the dictates of the understanding. The question arose whether we might not profitably invert metaphysic and, instead of trying to locate personality in totality, begin with personality and work outwards. (Applause.) Otherwise the process of endeavouring to effect a synthesis of centripetal and centrifugal tendencies would invariably result in an indefinite deadlock.

Professor Splurgeson then proceeded to give a brief outline of what we usually think of ourselves. It was true that the expression of the face held a great place in the idea we had of other personalities, but how was it that in the idea of ourselves it played so small a part? The reason was that we did not know our own countenances. (Sensation.) If we were to meet ourselves in the street we should infallibly pass without a recognition. More than that, we did not wish to know them. (Murmurs.) Whenever we looked at ourselves in the glass we systematically ignored the most individual features—(cries of dissent)—and that was why we never, or very seldom, agreed that a photograph resembled or rendered justice to us. The explanation was to be found in the fact that we thought it undesirable to have too individual features, just as we thought it undesirable to wear too individual clothes.

At this point a violent uproar broke out, many of those present protesting against these statements as involving a libel on the entire female sex. It being impossible to restore order, Professor Splurgeson had to be escorted to his hotel by policemen, the date of his second lecture being indefinitely postponed.

'Twas harvest time and close and warm,

A day when tankards foam,

But when there came the thunder-storm

We'd got the last load home;

We'd knocked off work—as custom is—

Though 'twern't but four o'clock,

And turned in to Jim Stevens's,

That keeps "The Fighting-Cock."

The rain roared down in thunder-thresh,

And roared itself away,

And left the earth as sweet and fresh

As though 'twas only May;

And from outside came stock and clove

And half-a-dozen more;

And then up steps a piping cove,

A-piping at the door.

We tumbles out to hear him blow,

Tu-wit, he blew, tu-wee,

On rummy pipes o' reeds a-row

Their likes I never see;

And as he blew he shook a limb

And capered like a goat,

And us bold lads we looks at him

Like rabbits at a stoat.

An oddly chap and russet red,

He capered and he hopped,

A bit o' sacking on his head

Although the rain had stopped:

Tu-wee he blew, he blew tu-wit,

All in the clean sunshine,

And oh, the creepy charm of it

Went crawling up my spine.

I don't know if the others dreamed—

'Cos why, they never tell—

But in a little bit it seemed

I knew the tune quite well;

It seemed to me I'd heard it once

In woods away and dim,

Where someone with a hornéd sconce

Came capering like him.

It held me tight, that tune o' his,

It crawled on scalp and skin,

Till sudden—'long o' choir-practice—

The belfry bells swung in;

The piping cove he turned and passed,

Till through the golden broom

A mile along we saw him last

Go lone-like up the coombe.

The belfry bells they rang—one—two;

The spell was lift from me,

The spell the oddly piper blew—

Tu-wit, he went, tu-wee;

The spell was lift that he had laid,

But still—tu-wee, tu-wit—

I can't forget the tune he played,

And that's the truth of it.

I was reading proofs in my corner of the compartment, as I often do, and every time that I looked up I noticed the little shabby pathetic man with his eyes fixed upon me.

After a while I finished and put the proofs away with a sigh of relief.

"So you're an author too?" he said.

"Yes," I said, though I didn't want to talk at all.

"You wouldn't have thought I was one," he went on, "would you? What would you have said I did for a living?"

I am too old to guess such things. One nearly always gives offence. Moreover, I have seen too many authors to show any surprise.

"I'm not only a writer," he said, "but I dare say I'm better known than you."

"That's not difficult," I said.

"I am read by thousands—very likely millions—every day."

"This is very strange," I said. "Millions? Who are you, then? Not—no, you can't be. You haven't a red beard; you are not in knickerbockers; you don't recall Shakspeare. Nor can you be Mrs. Barclay. And yet, of course, I must have heard your name. Might I hear it again, now?"

"My name is unknown," he said. "All my work is anonymous."

"Not advertisements?" I said. "Not posters'? You didn't write the 'Brown Cat's thanks,' or 'Alas, my poor brother,' or——"

"Certainly not," he replied. "My line is literature. Do you ever go to cinemas?"

"Now and then," I said, "when it rains, or I have an unexpected hour, or it is too late for a play."

"Then you have read me," he said. "I write for cinemas."

"There isn't much writing there," I suggested.

"Oh, isn't there!" he answered. "Haven't you ever noticed in a cinema how letters are always being brought in on trays?"

"Yes, I have."

"And then the hero or the villain or the victim opens them and reads them?"

"Yes."

"And then the audience has to read them?"

"Yes; there's no doubt about that."

"Well, those are all written by me. I mean, of course, all those that a certain film company requires."

"Marvellous," I said.

"I not only compose them—and it requires thought and compression, I can tell you—but I copy them out for the photographer too."

"Is that why they're always in the same handwriting?" I asked.

"Yes, that's it," he said. "It's mine."

"Then you can tell me something I have always wanted to know," I said. "I have noticed that when a letter written, say, by the Duke of Pemmican is thrown on the screen it is always signed 'Duke of Pemmican.' Why is that? In real life wouldn't he sign it 'Pemmican'?"

"He might," said my companion. "I don't know; but what I do know is that the cinema public expects a duke to call himself a duke; and we pride ourselves on giving them what they want."

"If you were making King George write a letter," I said, "would he sign himself 'King George'?"

"Certainly," he replied. "Why not? That's a good idea, anyway. A film with a letter from the King in it would go. As it is, his only place in a cinema has been to indicate—by the appearance of his portrait on the screen—that the show is over. It isn't fair that he should come to be looked upon as a spoil-sport like that. It has a bad effect on the young. Many thanks for your suggestion. I'll give him a show with a letter."

"Permit me, Sir, to pass you the potatoes."

"After you," I inclined.

My fellow-passenger helped himself, shrugging his eyebrows. It was a provocative shrug—a shrug I could not leave at that.

"You shrug your eyebrows," I challenged.

"A thousand pardons," he answered; "but one never escapes it."

He courted interrogation. "What is it that one never escapes?" I asked.

"The elaborate unselfishness of the age," he replied a little petulantly. "I had two friends who starved to death of it."

"Indeed!" I offered him the salt.

"Observe," said my fellow-passenger, "that when you offer me the salt I accept it. Why should I deprive you of one of the little complacencies of unselfishness? You see, my dear Sir, either you are to feel smug all over, or I am. Now, if I take the salt—so—I perform a true act of courtesy; but, if I postpone the salt, saying 'After you,' I at once enter into the lists, jousting with you for the prize of self-satisfaction. With my two friends it was, if I remember, a matter of Lancashire relish. It appears to me one of the ironies of Fate that they should have starved to death for want of a sauce. I am reminded of an epicure who starved to death for want of seasoning in his Julienne. But doubtless you are more interested in my two friends. I bow to your impatience. Hugh said, 'Allow me to offer you the Lancashire relish.' Arthur said, 'After you.' Hugh was piqued at this attempt to cheat his conscience out of a good mark. 'By no means,' he insisted. But Arthur, with a firm smile of politeness, only repeated, 'After you.'

"Hugh stuck out, and Arthur remained adamant. The contest lasted for nine days. On the first day Hugh was studiedly courteous. It was, 'I could not dream, my dear Arthur,' et-cetera. On the second day he was visibly aggravated. It was, 'But, my dear Arthur, confess now, was it not I who offered you the Lancashire relish first?' On the third day he was ominously calm. It was, 'You had better help yourself to the Lancashire relish, Arthur.' On the fourth day he was frankly fierce. It was, 'By heaven, Arthur, if you don't take some Lancashire relish...." And the only words in Arthur's vocabulary all that time wore, 'After you! After you!' On the fifth day they came to grips on the floor, and through the sixth day and the seventh they swayed without separating. I suspect that the strain of this tussle assisted starvation to its victory. On the eighth day they were too weak for combat; they could only glare at each other passionately from opposite corners of the room; and on the ninth day came the end.

"Arthur held out the longer—he had, you see, wasted less breath. When he saw Hugh gasping in the penultimate throes of death, he mustered sufficient strength to clutch the bottle, and even to crawl over to his friend's side. Hugh saw him coming and shut his teeth. Arthur was too feeble to prize them open with his hands, but he had no difficulty in knocking out a couple with the butt end of the bottle, and with a faint groan of triumph he succeeded in pouring the contents down the cavity just before Hugh breathed his last.

"The exertion naturally hastened his own end. He made an effort to reach the well-stocked table of viands, but expired on the way, murmuring a final and, as it strikes me, rather too dramatic 'After you!'"

"When you have quite done with the cabbage," I rapped out....

"Our illustration is of an exclusive model which we can fake in the latest fabrics for 3½ guineas."

Advt. in "Dewsbury District News."

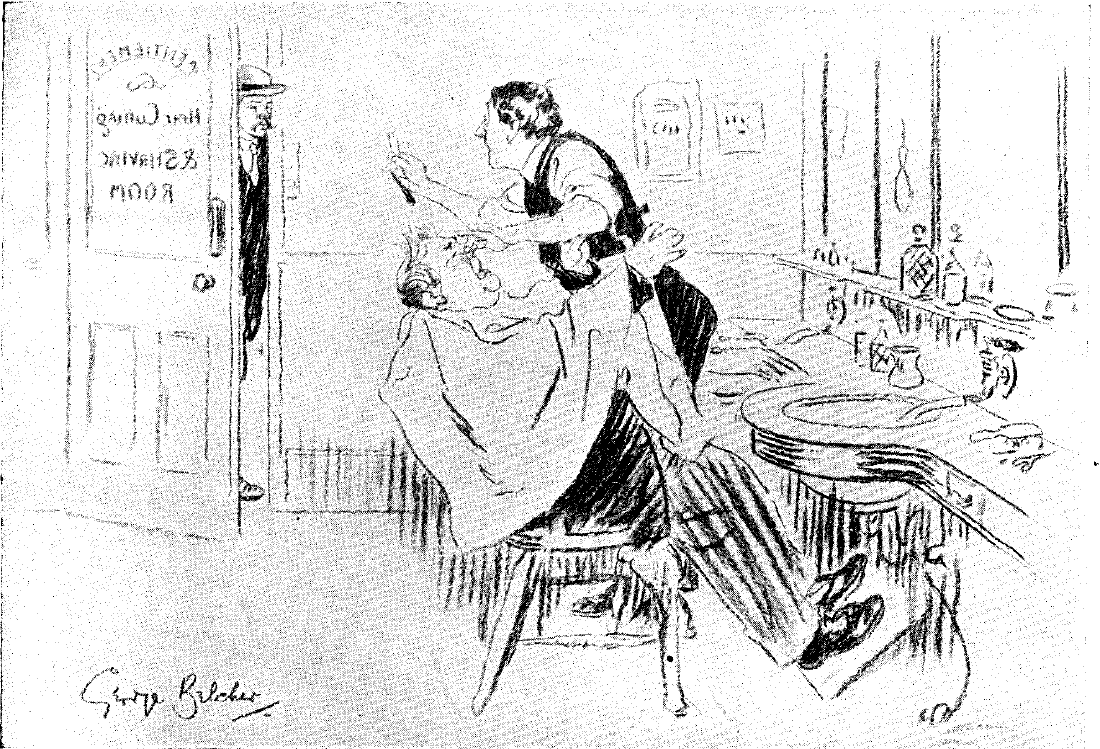

Barber (turning sharply round, to the grave discomfiture of his client's nose). "Don't go, Sir; it's your turn next."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

The consideration of Fear seems to have a special appeal for the Benson Bros. Only the other day did Robert Hugh write a clever and hauntingly horrible story round it, and now here is Arthur Christopher discoursing at large upon the same theme in Where No Fear Was (Smith, Elder). It is a book that you will hardly expect me to criticise. One either likes those gentle monologues of Mr. Benson or is impatient under them—and in any case the comments of a third party would be superfluous. Personally, I should call this one of the most charming of those many hortatory volumes that have come from his prolific pen; he has a subject that interests him, and is naturally therefore at his best in speaking of it. Many kinds of fear are treated in the book—those common to us all in childhood and youth and age; and there are chapters dedicated to men and women who have notably striven with and overcome the dragon—Johnson and Charlotte Brontë and Carlyle, and that friend of his, John Sterling, whose letter from his death-bed the author quotes and rightly calls "one of the finest human documents." So now you see what kind of book it is, and whether you yourself are likely to respond to its appeal. It will, I am firmly persuaded, bring encouragement to many and add to the already large numbers who owe a real debt of gratitude to the writer. Somewhere he has a passing reference to the time when first he began to receive letters from unknown correspondents. It set me thinking that it was no slight achievement to have said so many human and helpful things so unpriggishly. And certainly no one could call Where No Fear Was a pedantic work; its qualities of gentle humour and, above all, of sincerity absolve it from this charge and should commend it even to those who, as a rule, suffer counsel unwillingly.

Forrard, so to speak, in Mr. Cutcliffe Hyne's latest book you shall discover the three redoubtable stokers from whom it derives its title of Firemen Hot (Methuen). Combining the stedfast affection and loyalty of the Three Musketeers or the imperishable soldiers of Mr. Kipling with a faculty, when planning an escapade, for faultless English, only equalled by that of the flustered client explaining what has happened to the lynx-eyed sleuth, they are as stout a trio as ever thrust coal into a furnace or fist into a first mate's jaw. English, American and Scotch (and this would seem to be another injustice to the Green Island), in many ports and on many seas they have many wild yet not wicked adventures, knowing, with an instinctive delicacy born perhaps of the perusal of monthly magazines, where (even whilst crossing it) to draw the line. Aft, you shall come across once more the evergreen Captain Kettle, with his sartorial outfit unimpaired, his endless tobacco reserves not withered by a single leaf from their former glory. About wind-jammers and tramp-steamers and the harbours of all the world the author writes familiarly as usual, and has several ingenious plots to unfold, together with one or two that are not so good; and I suppose that the whisky drunk in the pages of Firemen Hot would float a small battleship, and the men laid out [pg 340]with lefts to the jaw, if set end to end, stretch from Hull to Plymouth Docks. I sometimes wonder whether Mr. Cutcliffe Hyne ever in an idle hour picks up a book by Mr. Conrad, and, if so, what he thinks of it.

I confess to being both weary and a little sceptical of heroines (in novels) who leap from the obscurity of mountain glens to fame and a five-figure income as dancers. The latest example is the young person who fills the title rôle in Belle Nairn (Melrose), and of her I must say that she displays almost all the faults of her kind. She certainly did carry on! On the first page she ran away from the humble cot of her virtuous parents to seek the protection of an aunt whom she supposed (I could not discover on what grounds) to be wealthy. However, so far from this, the aunt turned out to be even worse-housed than the parents, and in point of fact to keep what you might call a gambling-cot on her side of the mountains, where a select circle met to drink smuggled spirits and entertain themselves in other ways that are at least sufficiently indicated in the text. So Belle shook off the dust of the aunt also; and soon afterwards found herself in an open boat, which was run down by the yacht of some real live lords, to one of whom she made violent eyes; at the same time giving an estimate of her social position that went considerably beyond what was warranted by the facts. It was about here that I found that my credulity with regard to Belle was becoming over-taxed, though it may be that Mr. Roy Meldrum, her creator, believed in her; he has at least a solemnity and sincerity of style that carries him, apparently unwitting, through every peril of the grotesque. Of course Belle comes to town, smashes all booking records at the Basilica, and establishes herself as the idol of society. Later on, I regret to add, she becomes, so to speak, tinged with wine. Perhaps this unfortunate failing is the most credible thing about her. So, while I envy those readers who will doubtless follow her progress with delicious thrills, I can only repeat that it left me entirely unconvinced.

If I had to classify Oh, Mr. Bidgood (Lane), then I should call it a confused comedy, but I should want to add that Mr. Peter Blundell writes with such delightful irresponsibility that the confusion does not make much difference. To explain exactly what occurred during the voyage of the Susan Dale from Ceylon until she was "in distress" off the Borneo coast is not within my scope of intellect, but I can draw up a short list of her passengers (she was not supposed to carry any). I shall give Mr. Todd pride of place, partly because he owned her, but chiefly because sea-sickness incited him to deeds of gallantry. Then there were two skittish nurses, who got on board because one of them knew the second engineer; there was Colonel Tingle (swashbuckler); Señor Canaba (scamp), who had bribed both the captain and the chief engineer (Mr. Bidgood); and lastly a brace of crafty Malays, who were the second mate's contribution to the batch, and made a very reluctant appearance upon the scene. Quite as important, however, as this human freight was Susan's cargo of five hundred kegs of gunpowder, shipped as pickled pork, and a wonderful picture which at one time Mr. Bidgood was induced to wear (it was unframed) as extra underclothing. This expedient was not devised to prevent him from catching cold, but to save the picture from being stolen. Indeed, if anyone or anything had to be protected, Bidgood, for better or worse, undertook the responsibility. A more engaging old ruffian I have seldom encountered; among all the philanderings, conspiracies and mutinies of this wild voyage he remains a master of volcanic versatility. And his humour is of the right Jacobs brand.

The really stupid thing about Mr. Fergus Rowley was that he had never been to see The Great Adventure. That popular play must have been running for a considerable while (and the story appeared in book-form of course much earlier) before he decided to "fake" a suicide from the deck of the liner Transella and leave his large possessions to an unknown and penniless nephew. It Will Be All Right (Hutchinson) is the sanguine title which Mr. Tom Gallon has given to his latest novel; but whether he refers merely to Mr. Rowley's optimism or to the further possibility of his readers sharing that gentleman's ignorance of current drama, is more than I can say. Anyhow, Mr. Rowley disappeared, and his nephew succeeded to an estate largely impoverished by the depredations of Gabriel Thurston, a fraudulent solicitor and unmitigated rogue after Mr. Gallon's own heart (and mine). Meanwhile, Mr. Rowley was reduced to playing butler in his own house and thereby saving some of the most precious of his curios from the double waste of a spendthrift heir and an unscrupulous lawyer. There was also—need I mention it?—a Circe in the case. It Will Be All Right is an exercise in the picaresque school, lacking none of the author's usual raciness and vigour; but, if at the end we find Mr. Fergus Rowley still unable to reinstate himself, and left with no better consolation than the "Heigho" of his famous great-uncle Anthony, the fault, I feel, was his own. He ought to have looked in at the Kingsway Theatre and provided himself with the indispensable mole.

(A contemporary remarked recently how many names of famous men have ended in "on.")

Call no man famous till you know his end.

"On" is the most effective. Docked of "on,"

Who's Milt? or Nels? or Newt? "On" nerves Anon

To blush unseen in public. Say, who penn'd

Don Juan? Was it Byr? Could Burt befriend

The humpstruck? So curtailed and put upon,

Would Caxt or Paxt, would Lipt, would Winst have shone?

No, they would not. Their "on"'s what we commend.

And what though "on" too lavishly impart

The gift of greatness ("Chestert," murmur some,

"Were ample; not to mention A. C. Bens")?

We're spared—remember this in "on's" defence—

A Shawon ranting from a super-cart,

A Caineon skilled to beat the outsize drum.

*** Transcriber's Note: Typo "month" replaced with "mouth" in the fourth stanza of PER ASPARAGOS AD ASTRA. ***

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

146, April 29, 1914, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 25010-h.htm or 25010-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/5/0/1/25010/

Produced by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he