The Project Gutenberg EBook of Crown and Anchor, by John Conroy Hutcheson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Crown and Anchor

Under the Pen'ant

Author: John Conroy Hutcheson

Illustrator: John B. Greene

Release Date: March 25, 2008 [EBook #24916]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CROWN AND ANCHOR ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

John Conroy Hutcheson

"Crown and Anchor"

Chapter One.

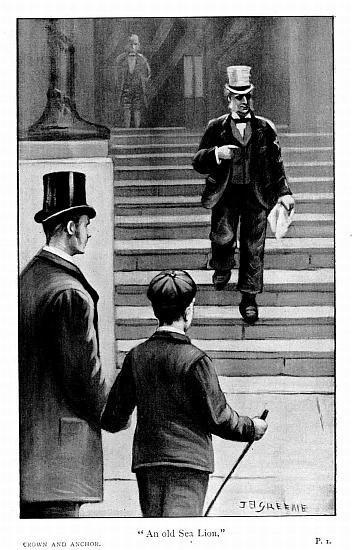

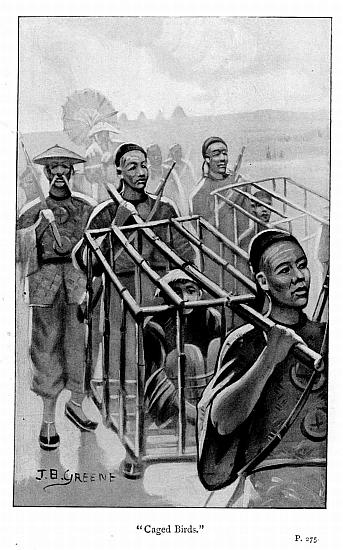

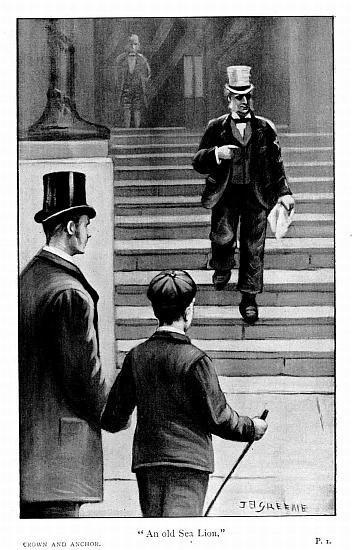

An Old Sea-Lion.

“Hullo, Dad!” I cried out, stopping abruptly in front of the red granite coloured Reform Club, down the marble steps of which a queer-looking old gentleman was slowly descending. “Who is that funny old fellow there? He’s just like that ‘old clo’’ man we saw at the corner of the street this morning, only that he hasn’t got three hats on, one on top of another, the same as the other chap had!”

We were walking along Pall Mall on our way from Piccadilly to Whitehall, where my father intended calling in at the Admiralty to put in a sort of official appearance on his return to England after a long period of foreign service; and Dad was taking advantage of the opportunity to show me a few of the sights of London that came within our ken, everything being strange to me, for I had never set foot in the metropolis before the previous evening, when mother and I had come up by a late train from the little Hampshire village where we lived, to meet father on his arrival and welcome him home.

Under these circumstances, therefore, as might  reasonably have been expected, our halts had been already frequent and oft to satisfy the cravings of my wondering fancy; and Dad must have been tired of answering my innumerable questions and inquiries ere half our journey had been accomplished.

reasonably have been expected, our halts had been already frequent and oft to satisfy the cravings of my wondering fancy; and Dad must have been tired of answering my innumerable questions and inquiries ere half our journey had been accomplished.

He was very good-tempered and obliging, however, and bore with me patiently, giving me all the information in his power concerning the various persons and objects that attracted my attention, and never “turning nasty” at my insatiable curiosity.

So now, as heretofore, obedient to my bidding, he turned to look in the direction to which I pointed.

“Where’s your friend, the funny old fellow you spoke of, my boy?” he said kindly, though half-quizzingly. “I don’t see him, Jack.”

“Why, there he is, right opposite to us, Dad!” I exclaimed. “He’s coming down the steps from that doorway there, and is quite close to us now!”

“Oh! that’s your friend, Jack, eh?” said father, glancing in his turn at the old gentleman who had caught my eye. “Let me see if I can make him out for you.”

The old fellow was not one whom an ordinary observer would style a grand personage, or think worthy of notice in any way, very probably; and yet, there was something about him which irresistibly attracted my attention making me wonder who he was and want to know all about him. Boy though I was, and new to London and London life, I was certain, I’m sure I can’t tell why, that he must be “somebody.”

A short broad-shouldered man was he, with iron-grey hair, and a very prominent nose that was too strongly curved to be called aquiline, and which, with his angular face, equally tanned to a brick-dust hue from exposure to wind and weather, gave him a sort of eagle-like look, an impression that was supported by his erect bearing and air of command; albeit, sixty odd years or more must have rolled over his head, and his great width of chest, as he moved downwards throwing out his long arms, made his thick-set figure seem stumpier than it actually was, though, like most sailors of the old school, there was no denying the fact, as Dad said subsequently, that he was “broad in the beam and Dutch built over all!”

Nature had, undoubtedly, done much for the old gentleman, but art little, so far as his personal appearance was concerned; for nothing could have been more quaint and out of keeping with Pall Mall and its fashionable surroundings than his eccentric costume.

The upper part of his person was habited in a rough shooting-jacket, considerably the worse for wear, such as a farmer or gamekeeper might have donned in the country, away from the busy haunts of men, when out in the coverts or engaged thinning the preserves; while his lower extremities rejoiced in a yet shabbier pair of trousers, whose shortness for their wearer did not tend to enhance their artistic effect.

To complete the picture, his bushy head of iron-grey hair was surmounted by an old beaver hat that had once been white, but which inexorable Time had mellowed in tone, and whose nap, having been brushed up the wrong way, against the grain, frizzed out around its circumference like a furze bush, making it resemble the “fretful porcupine” spoken of by the immortal Shakespeare.

His whole appearance was altogether unique for a West-end thoroughfare in the height of the season; and, the more especially, too, at that time of day, when dandies of the first water were sauntering listlessly along the shady side of the pavement ogling the gorgeously-attired ladies who rolled by in their stately barouches drawn by prancing horses that must have cost fortunes, and on whose boxes sat stately coachmen and immaculate footmen clad in liveries beyond price, “Solomon in all his glory” not approaching their radiant magnificence!

Emerging as he did, however, from the Reform Club, the old gentleman’s unconventional “rig-out” bore testimony to the incontrovertible fact that, no matter how “advanced” his principles may have become from the teachings of Cobden, and the example of Peel, he had not allowed his political convictions to revolutionise his original ideas on the subject of dress.

Nor was this the only peculiarity noticeable about the queer-looking old fellow.

He was coming down the steps of the club-house, while Dad and I looked at him, so slowly that his dilatory rate of progression conveyed the impression that he was either a martyr to corns or suffering from a recent attack of the gout; feeling his way carefully with one foot first before bringing along its fellow, prior to adventuring the next step, just as my baby sister, a little toddlekin of six, used to go up and downstairs.

This, of course, was not so remarkable in itself, but as he descended thus, crab-fashion, to the level of the pavement where Dad and I stood observing him, my eyes grew wide with wonder at the enormous handfuls of snuff he took—not pinches, such as I had seen snuff-takers sniff up from the backs of their hands many a time before, without bestowing a thought on the action.

Oh, no, nothing of the sort!

They were actual handfuls that he extracted from his waistcoat pocket, as I could not help noticing, on account of his roomy shooting-jacket being wide open and thrown back; the old prodigal scooping up the fragrant dust in his palm, and then doubling his fist and shoving it up his nostrils with a violent snort of inhalement, after which he proceeded to blow his red nose with another loud report, like that of a blunderbuss going off. This was accompanied by the flourish of a brightly coloured pocket-handkerchief, whose vivid hue approximated closely to the general tint of his cheeks and eagle-like beak, and which he held loosely, ready for action, in his disengaged left hand; for, his right was ever at work oscillating between the magazine of snuff in his deep waistcoat pocket and the nasal promontory that consumed it with almost rhythmical regularity, sniff and snort and resonant trumpet blast of satisfaction succeeding each other in systematic sequence, as the veteran came down the stairway leisurely, step by step.

It all appeared to me very comical; but, I did not laugh at the old man as another youngster might very pardonably have done, without any thought of mocking or making fun of him.

To tell the truth, he seemed to me to be so out of place there that I was actually pained on his account, believing, in my innocent ignorance, that he had unhappily made a mistake in going up to the members’ entrance of the grand-looking club-house; and that the fat hall-porter in scarlet, who now stood without the swinging glass doors of the portal, had warned him thence, ordering him, so it struck my fancy, to go down below by way of the area steps, to the basement of the establishment, where his business would probably rather lie with the lower menials of the mansion than with such an august personage as he, one who acted solely as the janitor to the great ones of the earth possessing the password of the club!

Yes, this was the thought uppermost in my mind; and, as the queer-looking old gentleman continued to hobble downwards I began to wonder whether the scullions in the kitchen, whom I could dimly discern beneath the street level and behind a screen of iron railings, would not, likewise, turn up their noses at the sight of such a seedy individual, telling him they had no rags or bones or bottles for him to-day.

“Poor old fellow!” I said to Dad, uttering my reflections aloud. “What could have made him act so foolishly as to go up there only to be turned away by that bumptious porter? How very shabby he is, Dad; and with such a noble face, too! May I give him that shilling you made me a present of this morning to buy himself some more snuff? He must have exhausted all he had in his waistcoat pocket by now; he does use it so extravagantly!”

“Hush, Jack, he may hear you!” whispered my father, dropping his voice to a lower key than mine, while the amused expression on his face changed to one of pleased recognition. “Why, it’s the old Admiral! I see he’s as great a snuff-taker as ever, and he seems to be even less careful than he used to be about his clothes; though, I must say, he never was a dandy at the best of times!”

At the moment Dad spoke, the old gentleman set his right foot gingerly on the pavement in front of us, his left following a second later, when the veteran signalised his reaching a sound anchorage with a final blast from his nasal trumpet and a fine flourish of his bandana, which nearly knocked out my nearest eye and set me sneezing from the loose particles of snuff disseminated into the surrounding air.

This gave my father the opportunity he wanted.

“How do you do, Admiral?” said he, drawing himself up and raising his hat in salute, while still holding me by the hand. “I don’t know if you remember me, sir, but I cannot forget you and your kindness to me of old, especially in getting me my last appointment. I’m glad to see you looking so well, sir!”

The old fellow stared at Dad with his gimlet grey eyes, looking him through and through, knitting his brows, and sniffing and snorting at a fine rate.

“Eh—what, who the deuce are you?” he ejaculated in short, jerky accents after a pause, evidently puzzled for the nonce, and, in his agitation, another fistful of snuff got arrested half-way between his waistcoat pocket and expectant nose, the consequence of which was that more than half was spilt on the front of his shirt, and already snuff-stained coat collar. “Eh, what? I think I know your face, but I’m hanged if I can recollect your name, sir!”

Dad smiled, and, whether this supplied a missing link to memory’s aid or no, the next instant a gleam of intelligence flashed across the veteran’s weatherbeaten face making him look so animated that he seemed a different person.

Shoving out his horny fist, forgetful of the balance of snuff contained therein, and thus causing me to sneeze again, as well as nearly blinding me for a second time, the rough old sailor caught hold of my father’s disengaged hand with a grip of iron, shouting a welcome in his hearty, loud voice which could have been heard across Pall Mall; for it was as breezy as the sea, echoing in ringing accents whose cordial tones I can almost fancy I now hear, like the surf of breakers breaking in the distance on some rock-bound shore.

“Bless my soul, Vernon! Is that you, my lad, hey?” he roared out, making a dandified exquisite, who was just then lounging past us, jump into the gutter and soil his polished patent leathers in nervous alarm. “Glad to see me, you said? Stuff and nonsense, you rascal—you’re not half so pleased as I am to clap my eyes on you again! Gad, you young scamp, why, it seems only the other day when I sent you to the mast-head, you remember, when you were a middy with me in the Neptune? It was for cutting off the tail of my dog Ponto, and you said—though that was all moonshine, of course—you did it to cure him of fits! By George! what a terrible young scapegrace you were, to be sure, Vernon, always in mischief from sunrise to gunfire, and always at loggerheads with my first lieutenant and the master, poor old Cosine!”

Chapter Two.

The Admiral speaks his Mind.

I had been fidgeting all the time the old gentleman was speaking squeezing Dad’s hand in order to attract his attention and make him tell me who his old friend was; but, for the moment, he was too much taken up with the veteran’s hearty greeting to give ear to me.

At last, however, in response to another squeeze of my hand, he bent down towards me, expecting, no doubt, some such inquiry.

“Who is it, Dad?” I whispered, dying with curiosity. “Who is it?”

“Admiral Sir Charles Napier, Jack,” he replied, under his breath, “late commander-in-chief of the Baltic Fleet.”

I doffed my cap at once, for I had often heard my father mention the name of the gallant old sailor before, though I hardly expected to see him in such a guise.

“Hullo, who’ve we got here?” cried the Admiral, noticing my action and patting my head in recognition of the salute with his snuffy palm. “Your son, Vernon, eh?”

“Yes, Admiral,” said Dad, “this is my boy, Jack.”

“Ha! humph! He’s a smart-looking youngster, Vernon, and the very image of what you were at his age! How old is he?”

“Nearly fourteen now, sir,” answered my father. “I’m afraid, though, Master Jack is rather a small boy for his years, being short and thick-set.”

“Not a serious fault that, Vernon. He’ll, be able to go aloft more nimbly than any of those lamp-post sort of chaps with long legs, who always trip themselves up in the ratlines. Look at me, youngster, I’m not a big man, and yet I’ve not been the worse sailor on that account, I think!”

“True, Sir Charles,” replied Dad with a sly twinkle in his eye, “but we’re not all of the same tough stock and ‘ready—ay, ready’ on all occasions when wanted, though we might be willing enough, to do our duty.”

“Gammon, Vernon, none of your blarney!” growled out the old sea-lion, pretending to be angry, albeit he looked pleased at Dad’s covert allusion to the Napier motto, which he had always endeavoured to act up to. “I’m sick of false compliments, old shipmate. I’ve had plenty of them and to spare from those mealy-mouthed, false-hearted, longshore lubbers in there!”

“What!” exclaimed my father, as the Admiral jerked his head with an expression of contempt in the direction of the club-house he had just left—“you don’t mean to say, sir—”

“Ay! but I do mean to say they’re a lot of confounded hypocrites, by George!” roared out the old sailor, his face flushing to almost a purple hue, while he snatched at another handful of snuff from his waistcoat pocket, and sniffed and snorted like a grampus. “Why, you’ll hardly believe it, Vernon! But, only a couple of years ago, when I was starting for the Baltic, and in high favour with the ministry, those miserable time-servers in there gave a public dinner in my honour in that very club; and now, by George! because things did not go all right, and I wasn’t able to smash-up the Russian fleet as everybody expected I would do, and so I would have done, too, by George! if I’d been allowed my own way, the mean-spirited parasites almost cut me to a man—to a man, by George!”

“It’s a rascally shame, sir,” said my father, getting hot with righteous indignation in sympathy at this scurvy treatment of one whom he had served under, and looked upon as an honoured chief; while I felt so angry myself, that I should have liked to have gone up the steps of the club-house there and then, and dragged down from his proud post the fat, red-liveried porter who was looking down on the veteran from the top of the stairway, regarding that pampered menial as the cause and occasion of the slight of which he complained. “Never mind, though, Admiral! you can well afford to treat their mean conduct with the contempt it deserves; for everybody whose opinion is worth anything knows that Sir Charles Napier won his laurels as a brave and skilful commander long before the Reform Club was founded or the Crimean war thought of. Believe me, sir, history will yet do you justice.”

“Ay! when I’ve gone to my last muster,” growled out the old fellow huskily, in a sad tone, which sent a responsive chill to my heart. “But, that won’t be your fault, Vernon. Thank you, my lad, I know you’re not talking soft solder, so as to get to wind’ard of me, like those fellows in there. Longshore lubbers like those never recollect what a man may have done for his country in times gone by. They live only in the present; and, if a chap chances to make a mistake, as the best of us will sometimes, they fall on him like a pack of curs on a rat, and worry him to death, by George!”

“The idle gossip of the clubs need not affect you, sir,” replied my father consolingly. “Not a man in England of any sense is ignorant of the fact that it is none of your fault that the Baltic Fleet was sent out on a wild-goose chase and failed to capture Cronstadt and annihilate the Russian ships inside that stronghold; though, I believe, you would have astonished old Nick if you had been allowed a free hand!”

“Humph! I don’t know about that, Vernon, but I’d have tried to,” said the Admiral, smiling. The next minute, however, he knit his shaggy eyebrows and looked so fierce that the thought occurred to me that I would not have liked just then to be in the position of defaulter brought up before him on his quarter-deck and awaiting condign punishment; for, he went on growling away angrily, as the recollections of the past surged up in his mind. “By George! it makes my blood boil, Vernon, as I think of it now. How could I succeed out there when those nincompoops at home in the Ministry did not want me to do anything but play their miserable shilly-shally game of drifting with the tide and doing nothing! I was told I wasn’t to do this and I wasn’t to do that, while all the time that cute old fox the Czar Nicholas was completing his preparations. Why, would you believe it, Vernon, there wasn’t a single long-winded despatch sent out to me by the Cabinet that did not countermand the one that came before?”

Dad laughed cheerily, trying to make the old sailor forget his wrongs.

“Even the immortal Nelson would have been unable to do anything under such conditions, Sir Charles,” he said, as the Admiral paused to take breath, sniffing up another handful of snuff with an angry snort. “Those jacks in office at home are always interfering with things they know nothing about. How can they possibly have the means at their command like the man on the scene of action, one whom they themselves have selected for his supposed capacity? But, they will interfere, sir. They have always done so; and always will, I suppose!”

“Gad, you put it better than I could, Vernon. I didn’t think you such a smart sea lawyer,” said the old Admiral, rather grimly, not over-pleased, I think, at Dad’s taking up the burthen of his grievances. “Know nothing, you say? Of course they know nothing, the government, hang it! was a cabinet of nincompoops, I tell you—Aberdeen, Graham and the whole lot of ’em! If they could have mustered a single statesman amongst ’em who had pluck enough to tell Russia at the outset that if she laid hands on Turkey we should have considered it an ultimatum, there would never have been any war at all—the Emperor Nicholas confessed as much on his death-bed. It was all want of backbone that did it—not of the English nation, thank God! but of the government or ministry of the time. Some governments we’ve had, ay, and since then, too, Vernon, have been the curse of our country!”

“Ay, Admiral,” responded my father, heartily, “I know that well!”

“Yes, they were all shilly-shally from first to last,” continued the old sailor, warming up to his theme. “Why, when the Russians actually fired on our flag—the Union Jack of England, sir, that had never previously been insulted with impunity—they actually blamed me for returning the fire, and recalled me for it! I tell you what it is, Vernon, they were all a pack of pusillanimous time-servers, frightened at their own shadows; and, between you and me and the bedpost, that chap, Jimmy Graham, our precious late First Lord of the Admiralty, knew as much about a ship as a Tom cat does of logarithms, by George!”

Dad smiled at his vehemence, and I chuckled audibly; the Admiral’s simile seeming very funny to me.

The old sailor patted me on the head approvingly.

“Ay, you may well laugh, youngster,” said he, looking very fierce with his knitted eyebrows, though speaking to me good-naturedly enough. “The whole business would make a cat laugh were it not so humiliating, by George! But, avast there! let us drop it; for we’ve had enough of it by now and to spare. Things, though, were very different, Vernon, when you and I sailed together. I tell you what it is, my lad, the service is going to the devil, that’s what it is!”

“By Jove! you’re right, sir, I quite agree with you there,” chorused Dad with much effusion, speaking evidently from the bottom of his heart. “Everything is changed, Admiral, to what we were accustomed to in the good old times when I had the luck to serve under you; and, I’m afraid, sir, we’ll never see such times again. There’s no chance for a poor fellow like me nowadays at the Admiralty as I know to my cost! No one has an opening given him unless he’s acquainted with some bigwig with a handle to his name, or knows the Secretary’s niece, or the chief messenger’s aunt. Otherwise, he may as well whistle for the moon as ask for a ship!”

“That’s true enough, Vernon, by George!” said the Admiral, with equal heat. “Interest with the Board is everything in these times, and personal merit nothing! You may be the smartest sailor that ever trod a quarter-deck and they will look askance at you at Whitehall; but, only get some Lord Tom Noddy to back up your claims on an ungrateful country or show those Admiralty chaps that you know a Member of Parliament or two, and can control a division in the House of Commons, then, by George! it is wonderful, Vernon, how suddenly the great Mister Secretary of the Board will recognise your previously unknown abilities and other good qualities to which he has hitherto been blind, and how anxious the First Lord will be to promote you—eh, Vernon, you rascal? Ho! ho! ho!”

Dad joined in the hearty roar of laughter, with which the Admiral ended his sarcastic comments, the recital of which had apparently eased his mind and banished the last lingering recollections of the ill-treatment he had received at the hands of the government; for the old sailor now dismissed the subject, going on to talk about old shipmates and other matters as they sauntered onwards along Pall Mall, the Admiral hobbling on one side of Dad and I on the other, holding his hand, listening eagerly all the while to their animated conversation and taking in every word of it. I confess, however, I could not understand all their allusions to old times and byegone events afloat and ashore, many of the names and incidents mentioned in their talk being altogether unfamiliar to my ears.

“Where are you off to now, Vernon?” inquired Admiral Napier, stopping to take snuff again when we arrived at the last lamp-post at the corner abutting on Waterloo Place. “If you’re not otherwise engaged, come back with me and have lunch at the club, you and the youngster.”

“Thank you very much, Admiral,” returned Dad, “I would be only to glad, but, to tell the truth, I’m bound for the Admiralty.”

“Ah! you want to see Mister Secretary just after he has finished his lunch!” said the knowing old fellow, giving Dad a dig in the ribs. “Sly dog! I suppose you think you’ll have a better chance of working to win’ard of him then?”

“That’s it, Admiral,” said my father, laughing. “There’s no good in a fellow trying to bamboozle you, sir.”

“No, by George!” chuckled the old fellow, mightily pleased at this tribute to his “cuteness,” “you’d have to get up precious early in the morning to take me in as you know from old experience of me, Vernon! But, what the deuce are you going to Whitehall to kick your heels there for? They’ll only keep you waiting an hour in that infernal waiting-room, and then tell you the Secretary’s gone for the day, or some other bouncer, just to get rid of you. I know their dirty tricks—hang ’em! What d’you want, eh?”

“Well, sir, I thought I might get something in one of the dockyards,” answered Dad, frankly. “I heard last night of there being an appointment vacant at Devonport, and I was going to apply for it.”

“Any interest, eh?”

“Not a scrap, Admiral,” replied my father. “All my friends are dead or out of favour with the powers that be, I’m afraid now.”

“Then you might as well apply for a piece of the moon,” said the Admiral in his curt, dogmatic way; “and if that’s all, Vernon, that is taking you to Whitehall, you had far better save your shoe leather and come back with me to the club.”

“Thank you very much, Admiral, but I must really say ‘no’ again,” rejoined Dad, touched by his kindly pertinacity. “I confess, sir, though, that the object of my journey to the Admiralty is not altogether on my own account personally, for I wished to introduce this youngster of mine here to the Secretary, and thought it a good thing to kill the two birds with one stone.”

“Humph!” growled the old Admiral. “D’you think he never saw a boy before, eh, Vernon? I’m sure there’s a lump too many of the young rascals knocking about already!”

Dad smiled at the quizzical look and sly wink with which this inquiry was accompanied, the Admiral twisting his head on one side as he spoke and looking just like a crested cockatoo!

“No, Sir Charles, not exactly,” he replied, putting his arm round my neck caressingly. “However, for all that, even so great a man as Mr Secretary might not know as good a boy as my son, Jack, here!”

I tell you what, I did feel proud when Dad said that, though I could not help flushing up like a girl, and had to hold down my head to hide it.

“Yes, yes, quite right, Vernon, quite right, the sentiment does you honour, and him. I’m sure, though, I meant no offence to the little chap,” said the rough, old sea-dog hastily, afraid of having hurt our feelings. “But, all the same, I don’t see what you want to show him to that Jack-in-office for? By George, the sight of his ugly phiz can’t do any good to the youngster!”

“No, sir, possibly not, though I’m told he isn’t such a bad-looking fellow,” answered Dad, laughing again at the Admiral’s determination to get to the bottom of the matter. “The truth, sir, is I want to get this youngster nominated for a naval cadetship before he oversteps the age limit. The boy is dying to follow in my footsteps; but, though I have tried to dissuade him from it as much as I can, and the idea of his going to sea makes his poor mother shudder, still, seeing that he seems bent upon it, neither she nor I wish to thwart his inclination.”

“Whee-ugh!” whistled the other through his teeth as he proceeded to take three or four enormous pinches of snuff in rapid succession from his waistcoat pocket and losing half of each pinch ere it reached his nose, the Admiral generously scattering it over the lapels of his coat and shirt front on the way. “Why the deuce didn’t you tell me all that before, my dear Vernon, instead of backing and filling like a Dutch galliot beating to win’ard?”

“I—I—” hesitated my father, who had refrained from telling him before because he hated asking a favour of anyone whom he regarded in the light of a friend. “I—I—didn’t like to trouble you, sir.”

“Bosh, Vernon! You know well enough it’s never a trouble to me to do anything for an old shipmate,” said the old fellow, heartily, and, putting his hand on my shoulder, he wheeled me round so as to look me in the face as I lifted up my head and gazed at him admiringly on his addressing me directly, “so, my young shaver, you want to be a sailor, eh?”

“Yes, sir,” I replied, “I love the sea, and I wouldn’t be anything else for the world!”

“Ha, humph!” growled the veteran, who, I believe, was as fond of his profession at heart, in spite of his grumbles, as anyone who ever went afloat. “You’d better be a tinker or a tailor, my boy, than go to sea! It’s a bad trade nowadays! What put it into your head, eh?”

“It comes naturally to him,” said Dad, seeing me puzzled how to answer the question. “I suppose it must run in the blood, sir.”

“Humph, like my gout!” jerked out Sir Charles, sharply, as if he just then felt a twinge of his old complaint, and, turning to me again, he asked as abruptly, “D’ye think you can pass for cadet, youngster—know your three R’s—readin’, ’ritin’ and ’rithmetic, eh?”

“Yes, sir, I think so,” said I grinning, having heard this old joke before from Dad many a time, “I shall try my best, sir. I can’t say more than that, sir, can I?”

“No, by George, no, youngster, that answer shows me, my boy, that you are your father’s son!” cried the Admiral heartily, clapping me on the back as if I were a man, and making me sneeze with the loose snuff which he shook off from his coat as he did so. “I said you were a chip of the old block the moment I first clapped eyes on you, and now I’m certain of it! Vernon, you shall have a nomination for the youngster. I think I’ve got sufficient interest at the Admiralty left to promise you that, at all events!”

“Oh, thank you, Admiral,” replied Dad, while I looked my gratitude, not being able to speak, “thank you for your great kindness to me and the boy.”

“Pooh, pooh, stuff and nonsense, my lad! It’s little enough to do for an old shipmate and brother officer,” muttered the good-hearted old fellow, quite overcome with confusion at our thanks, as Dad wrung one of his hands and I caught hold of the other. “I’ve got an appointment to meet the First Lord this very afternoon, as luck would have it, so I’ll mention the matter to him, and I’ve no doubt the youngster’ll get his nomination in a day or two, at the outside. By-the-bye where are you stopping in London? You haven’t told me that yet.”

My father, thereupon, gave him our address.

“All right, Vernon,” said the veteran, shoving Dad’s card along with the snuff in his waistcoat pocket, “I’ll see to the matter without fail. Good-bye, now, Vernon, good-bye, young shaver, I hope you’ll make as good a sailor and smart an officer as your father before you!”

With these parting words and a kindly nod to me the old Admiral toddled off across Waterloo Place to the Senior United Service Club opposite, to which, I presume, he intended transferring his patronage now that the Reform had given him the cold shoulder, while Dad and I returned to our temporary lodgings in Piccadilly to tell mother of our unexpected meeting and its happy result. I may here add that I was never fortunate enough to see the gallant old veteran again, though I heard of him often afterwards from my father, who told me he always asked how I was getting on. Circumstances prevented my meeting him when I was yet in England, and I was out in China when he died, some four years subsequently to my making his acquaintance in Pall Mall that morning.

Strange to say, however, the other day, when engaged planning out this very yarn of my adventures afloat, I chanced to see an advertisement in one of the Portsmouth papers of an auction about to be held at Merchiston Hall, near Horndean, where I was informed the Admiral had resided for many years, and where he spent most of his time farming when not at sea, before he got mixed up in politics and Parliamentary matters, as he was in his later days after he was “put on the shelf,” and hauled down his flag for ay!

Here, the very bed was pointed out to me in which the gallant old sailor died; a plain, old-fashioned piece of furniture, without any gilding or meretricious adornment, and honest and substantial like himself.

The house, too, was similarly unpretentious, being a low, one-storied, verandah—fronted structure, with plenty of room about it, but little “style” or ornament. It was, though, picturesquely situated in the centre of a well-timbered little park and homestead and snugly sheltered by tall fir trees and a thick shrubbery from all north’ard and easterly winds, amid the prettiest scenery of Hampshire—wooded heights and pleasant dales, with coppice and hedgerow, and here and there a red-roofed old farmhouse peeping out from the greenery forming its immediate surroundings.

“Poor old Charley Napier!” as he was affectionately entitled by those who served under his flag—officers and men alike, the latter especially almost idolising him for he was ever a good friend to them.

He now sleeps his last sleep in the churchyard of Catherington, where he lies safe at anchor, hard by the dwelling where he lived when in the flesh.

Here his tomb may be seen by the curious under the shelter of the early Norman church, dedicated to Saint Catherine, from which circumstance the village takes its name.

It is a fine old building, this church, dating back to the time of the Crusades, when heroes as gallant as Admiral Sir Charles Napier besieged Sidon and captured Acre—like as he himself did some eight centuries later, long prior to his unsuccessful mission to the Baltic, the somewhat inglorious termination of which, unfortunately, clouded his naval reputation and ended his career afloat!

Chapter Three.

I get nominated for a Naval Cadetship.

“‘Sharp’s the word and quick the motion,’ eh, Jack?” said my father, using his favourite phrase, when the post next morning brought him a letter from the Admiralty in an oblong blue envelope, inscribed “On Her Majesty’s Service,” in big letters, stating that I had been nominated to a cadetship in the Royal Navy. “I knew old Charley would be as good as his word!”

“Hurrah!” I shouted, throwing my cap in the air, and forgetting all about a long-promised visit to the Zoological Gardens for which we were just starting, “Now I shall be able to go to sea at last!”

Dad seemed to share my enthusiasm; but my mother, I recollect well, ay, as if it had occurred but yesterday, put her arms round me and cried as if her heart would break.

Presently, when she had somewhat regained her composure, Dad, comforting her with the assurance that she was not going to lose me all at once, it not being probable that I would be drowned or slain or otherwise immolated on the altar of my country immediately on entering the navy, which appeared to be her first conviction, we all began talking the matter over; and then Dad proceeded to read over again the official communication he had received, commenting on the same as he went over it.

“Hullo, Jack!” he observed, on reaching the end of the formal document, “those red-tape chaps a’ Whitehall haven’t given you much time to prepare for your examination!”

The mention of this damped my ardour a bit, I can tell you!

“Oh, I quite forgot that!” I exclaimed lugubriously. “When have I got to go up for exam., Dad?”

“The ‘first Wednesday in August,’ my boy—so says this letter at all events.”

“Good gracious me!” ejaculated my mother, again breaking into our conversation after a brief pause, during which she must have gone through an abstract mental calculation. “Why, that will be barely a month from now, my dear!”

“Precisely, this being the third of July,” replied Dad drily. “So Master Jack will have to stir his stumps if he hopes to pass, for I’m afraid he’s rather shaky in his Euclid.”

“Dear, dear!” said mother, throwing up her arms in consternation, “he is very backward in his history, too! Would you believe it, he couldn’t recollect when Magna Charta was signed on my asking him the date yesterday.”

“Really?” cried Dad, leaning back in his chair, and bursting into a hearty laugh at my mother’s serious face, “I’m sure, my dear, I could not tell you the date off-hand myself at the present moment, not if I were even going to be hanged in default! Jack knows, though, I’d wager, when the glorious battle of Trafalgar was fought; and that concerns a British sailor boy more, I think, than any other event in the whole history of our plucky little island, save perhaps the defeat of the grand Armada. What say you, my boy?”

“Of course, I know the date of the battle of Trafalgar, Dad,” I answered glibly enough, having heard it mentioned too often to have forgotten it in a hurry; and, besides, I knew Southey’s Life of Nelson almost by heart, it being one of my favourite books and ranking in my estimation next to Robinson Crusoe. “It was fought, Dad, on the 21st October 1805.”

“There, mother, just hear that!” cried Dad, chaffingly. “Are you not proud of your boy in blue? By Jove, he’ll set the Thames on fire if he goes on at that rate!”

“I am proud of him; but I do not wish him to fail,” replied mother, who took things generally au serieux; and, turning to me, she said in her earnest way,—“Dear Jack, I’m afraid you are too confident and do not attend to your lessons now as you used to do. Pray, work hard, my dear boy, for my sake!”

“I will, mother dear, I promise you that,” said I, kissing her. “I won’t get plucked if I can help it.”

“That’s right, my brave boy, you cannot say more than that,” chimed in Dad, with a pat of approval on my head, as my mother drew me towards her in mute caress. “By the way, I tell you what I’ll do, Jack. I was asking my old friend Captain Gifford the other day about a good naval tutor for you, and you shall have the assistance of the same ‘crammer’ he had for his boys if I can get hold of him.”

Prior to the year 1858, I may here explain, on a youngster being nominated to a naval cadetship he was appointed to a sea-going ship at once, going afloat there and then without any preliminary examination and the roundabout routine subsequently enjoined, wisely or not, by “My Lords” when the “competition wallah” system came in vogue. Unwittingly I was, thus, one of the first to suffer from the change, the order for cadets having to pass in certain specified subjects on board the Excellent before receiving their appointments having been issued within a comparatively recent period of my getting my nomination.

This proviso, too, I may add, was saddled with the condition that all cadets in future would have to go through a probationary period of three months’ instruction in seamanship in a training-ship, which was set apart for the purpose ere they were supposed to have officially joined “the service,” and become liable to be sent to sea.

These regulations, to make an end of my explanations, continue in force to the present day with very little alteration, the only difference, so far as I can learn, being that youngsters now have to pass a slightly “stiffer” examination than I did on entry, and that they have to remain for two years on probation aboard the Britannia instead of the three months period which was esteemed sufficient for the “sucking Nelsons” of my time in the old Illustrious. She was the predecessor of the more modern training-ship for naval cadets, which turns them out now au fin de siècle, all ready-made, full-blown officers, so to speak; though it is questionable whether they are any the better sailors than Nelson himself, Collingwood amongst the older sea captains, or Hornby and Tryon of a later day. None of these went through a like course of study, and yet they knew how to handle ships and manoeuvre fleets without any such “great advantages” of training!

My moral reflections, though, have little to do with my story, to which I will now return.

The date of the examination being so perilously near, and my studies having become somewhat neglected during the long holiday I had spent in sightseeing in London, my father thought the surer way to secure my passing would be, as he had said, to procure the aid of a good tutor who might peradventure succeed in tuning me up to concert pitch in the short interval allowed me by the patent process of “cramming,” which had come into fashion with the competition craze, more speedily than by any ordinary mode of imparting instruction.

So, in accordance with his promise, Dad called on his friend Captain Gifford the same afternoon in quest of the experienced “coach” or coachman, whom that gentleman had previously recommended, warranted to possess the ability to drive knowledge into my head at a sufficient rate to ensure my “weathering,” the examiners when I went before them; and, ere the close of this memorable week in which I was introduced to Admiral Sir Charles Napier and got my nomination, I was in as high a state of “cram” as any Strasbourg goose destined to contribute his quota to a pâté of fat livers.

“Dear, dear, my poor boy!” as mother said to me, “what a lot you have to learn, to be sure!”

My mother was right you will say when you hear all. I was “a poor boy,” indeed, and no mistake.

Latin, French, Arithmetic and Algebra, not forgetting my old enemy Euclid and his compromising propositions, with a synopsis of English History, and the physical and political geography of the globe, besides a lot of lesser “ologies,” of no interest to anyone save my coach and myself, but all of which were included in the list of subjects laid down by the Admiralty as incumbent for every would-be naval cadet to acquire, were forced into my unfortunate cranium day and night without the slightest cessation.

The only let off I had were a few hours allowed me for sleep and refreshment, my hard task-master, the aforesaid coach, an old Cambridge wrangler, never giving me a moment’s respite, insisting, on the contrary, that he would give me up instead altogether if I once stopped work!

For the time being I lived in a world of facts and figures, breathing nothing but dates and exuding mathematical and other data at almost every pore; so that, by the end of the month I felt myself transformed into a sort of portable human cyclopaedia, containing a heterogeneous mass of information of all kinds, as superficial as it was varied.

The knowledge I acquired in this way, however, was only skin deep, so to to speak, exemplifying the truth of the old adage “lightly come, lightly go;” for albeit this hot-bed process of imparting learning served its turn in enabling me to pass the crucial ordeal to which I was subjected, I verily believe that I could not have answered satisfactorily one tithe of the questions a fortnight after the dreaded examination was over that I then grappled successfully.

But this is anticipating matters.

Hot July sweltered to its close ere my tutor was satisfied with the progress I had made under his care and declared me fit for the fray.

This was on the very last day of the month, and on the following Tuesday, the 3rd of August, I remember, for it was the very day before the fateful Wednesday fixed for examination on board the Excellent, my mother, in company with Dad and myself, bade adieu to the sultry metropolis, of whose stagnant air and blistering pavements, and red-baked bricks and mortar we were all three heartily tired, journeying down to Portsmouth by some out-of-the-way route, all round the south coast, past Brighton and Worthing and Shoreham, which I never afterwards essayed.

Since then, though I have travelled, more often than I care to count now, from London to the famous old seaport which is veritably the nursery of our navy, and whence the immortal Nelson sailed, ninety odd years ago, to thrash the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar and establish England’s supremacy afloat while ridding the world of the tyranny of Napoleon Buonaparte, not a single incident connected with my first trip thither has escaped my memory.

Yes, I recollect every detail of the journey, from the time of our leaving Waterloo station to our arrival at the terminus at Landport, just without the old fortifications that shut in Portsea and the dockyard, with all its belongings, within a rampart of greenery. The noble elms on the summit of the glacis, are now, alas! all cut down and demolished, but they once afforded a shady walk for miles, making the dirty moats and squalid houses in their rear, which are now also numbered, more happily, amongst the things of the past, look positively picturesque.

I could not forget anything that happened that day; for, then it was that I saw that dear old sea again which I had loved from the time my baby eyes first gazed on it, and which I had not now seen for months.

On reaching “ye ancient and loyale toune,” as Portsmouth was quaintly designated by Queen Bess of virginal memory on the occasion of her visiting the place, our little party, I can well call to mind, put up at the “Keppel’s Head” on the Hard.

This was a hostelry which Dad had been accustomed to patronise when at the naval college in the dockyard learning all about the new principle of steam just then introduced into the service before I was “thought of,” as he said, and, no doubt, the place is as well known to young fellows and old “under the pennant” in these prosaic days of “floating flat-irons and gimcrack fighting machines,” as the “Fountain Inn” in High Street and the “Blue Posts” at Point were to Peter Simple and Mr Midshipman Easy in the early part of the century, when, to quote dear old Dad again, “a ship was a ship, and sailors were seamen and not all stokers and engineers!”

There was no harbour station then, as now, fronting and affronting Hardway; no trace of the hideous railway viaduct shutting out all the foreshore, both of which at present exist in all their respective native uglinesses!

No; for the upper windows of the old hotel commanded a splendid view of the whole of the harbour and the roadstead of Spithead beyond, and I seem to see myself a boy again that August afternoon, looking out over the picturesque scene in glad surprise.

After our early dinner, Dad pointed out to me the various objects of interest; the old Victory, flagship then as she is now again after an interval of thirty years or more, during which time she was supplanted by the Duke of Wellington, which she has in time supplanted once more; the Illustrious, the training-ship for naval cadets, near the mouth of the harbour, where the Saint Vincent is now moored; and the long line of battered old hulks stretching away in the distance up the stream to Fareham Creek, the last examples extant of those “wooden walls of old England” which Dibdin sang and British sailors manned and fought for and defended to the death, sacrificing their lives for “the honour of the flag!”

Yes, I remember the name of every ship that Dad then pointed out to me. I can picture, too, the whole scene, with the tide at the flood and the sunshine shimmering on the water and the old Victory belching out a salute in sharp, rasping reports from the guns of her main deck battery, that darted out their fiery tongues, each in the midst of a round puff ball of smoke in quick succession, first on the port and then on the starboard side, until the proper number of rounds had been fired and a proportionate expenditure of powder effected to satisfy the requirements of naval etiquette for the occasion, when the saluting ceased, as suddenly as it began.

The afternoon wore on apace after this, the sun sinking in the west over Gosport, beyond Priddy’s Hard, amid a wealth of crimson and gold that nearly stretched up to the zenith, lighting up the spars of the ships and making their hulls glow again with a ruddy radiance while touching up the brass-work and metal about them with sparks of flame.

Still, I did not tire of standing there at the window of the old “Keppel’s Head,” looking out on the harbour in front, with the wherries plying to and fro and men-of-war’s boats going off at intervals with belated officers to their respective ships.

Until, by-and-by the Warner lightship, afar out at sea beyond Spithead, and the Nab light beyond her again, could be seen twinkling in the distance, while the moon presently rose in the eastern sky right over Fort Cumberland; and then, all at once, there was a sudden flash, which, coming right in front of me, dazzled my eyes like lightning.

This was followed by a single but very startling “Bang!” that thundered out from the flagship, which, swinging round with the outgoing ebb tide, was now lying almost athwart stream, with her high, square stern gallery overhanging the sloping shore below the hotel, looking as if the old craft had taken the ground and fired the gun that had startled us as a signal of distress—so, at least, with the vivid imagination of boyhood, thought I!

“Goodness gracious me!” exclaimed my mother, almost jumping out of her chair at the unexpected report and making me jump, too, by her hurried movement towards the window where I stood, “what is the matter, Jack?”

“Nothing to be alarmed about, my dear,” said Dad soothingly to her. “It is only the admiral tumbled down the hatchway.”

“Dear, dear,” replied poor mother in a voice full of the deepest sympathy, “I hope the old gentleman has not hurt himself much. He must have fallen rather heavily!”

Dad roared with laughter at her innocent mistake.

“You’ll kill me some day, I think, my dear,” said he when he was able to speak, after having his laugh out. “I only used an old nautical expression which you must have heard before, I’m sure. We always say that on board ship when the nine-o’clock gun is fired!”

“Oh!” rejoined mother, a little bit crossly at being made fun of. “I do wish, Frank, you would explain what you mean next time beforehand, instead of puzzling people with your old sailor talk, which nobody can understand!”

“Humph!” said Dad; but, presently, I saw mother put out her hand and tenderly touch him on the shoulder, as if to tell him that her temporary tiff had been dispelled, like the smoke from the discharge of the Victory’s last gun, whereat I could hear him whisper under his breath as he kissed her cheek softly, “All’s well that ends well, my dear!”

Chapter Four.

Down at Portsmouth.

Next morning, ere I seemed to have been asleep five minutes, it came upon my dreams so suddenly, I was awakened by a terrible din of drumming and bugling from the adjacent barracks close to the line of fortifications which at that time enclosed Portsmouth—but whose moats and ramparts were pulled to pieces, as I have already said, some few years ago to make room for the officers’ and men’s recreation grounds and gymnasium, with other modern improvements.

Then, I could hear the heavy tramp of men marching, followed by the hoarse sound of words of command in the distance, “Halt! Front! Dress!”

I assure you, I really thought for the moment that the long-talked-of French invasion, about which I had been recently reading in my historical researches, had actually come at last and that the garrison had been hurriedly called to arms to resist some unexpected attack on the town.

This reminiscence of my cramming experiences, mixed up in hotch-potch fashion with the martial echoes that caught my ear from the banging drum and brazen bugle, at once recalled the gruesome fact that this was the eventful day fixed for my examination on board the Excellent; so, dreading lest I should be late, I incontinently jumped out of bed in a jiffy, proceeding; albeit unconsciously, to obey the last gruff order of the sergeant of the guard, relieving the sentries.

This, as Dad subsequently explained, was the reason for all the commotion, the sergeant parading his men as he came up to each “post” in turn, with the usual stereotyped formula, “Halt! Front! Dress!”

Dear me! I did “dress;” though in rather a different sense to that implied by the sergeant’s mandate, huddling on my clothes in my haste so carelessly that I broke the button off my shirt collar and put on my jacket the wrong way!

All my hurry, too, was to very little purpose; for, when I reached the coffee-room of the hotel below, after getting confused and losing my proper course amongst the many intricate passages and curving corkscrew staircases that led downwards from the little dormitory I had occupied right under the tiles at the back of the building, I found that neither Dad nor mother had yet put in an appearance for breakfast.

I was in such good time, indeed, that old Saint Thomas’s clock in High Street was only just chiming Eight; while the ships’ bells over the water were repeating the same piece of information in various tones and the shrill steam whistle from the dockyard workshops hard by screeching its confirmation of the story.

There was no fear of my being late, therefore; so, consoling myself with this satisfactory reflection, I was making my way to the nearest window of the coffee-room to look out on the harbour beyond as I had done the evening before when, like as then, a big bouncing “Bang!” came from the Victory, making me jump back and feel almost as nervous as poor mother was on the previous occasion.

“Yezsir, court-martial gun, sir, aboard the flagship, sir,” said the wiry little cock-eyed head waiter, who was hopping about the room “like a parched pea on a griddle,” as dad expressed it, stopping to flick the dust from the mantelpiece with his napkin as he replied to the mute inquiry he could read in my glance. “Look, sir! They’ve h’isted the Jack at the peak, sir, yezsir.”

“Oh, yes, I see,” said I, as if I had not observed this before and was perfectly familiar with the signal. “I did not notice it at first.”

“No, sir? W’y, in course not, sir, or else ye’d ha’ known wot it were,” answered the sly old fellow, ascribing to me a knowledge of naval matters which he knew as well as myself I did not possess, thus pandering, with the ulterior view, no doubt, of a substantial tip, to a common weakness of human nature to which most of us, man and boy alike, are prone—that of wishing to appear wiser than we really are!

“But, as I was a-saying only last night to Jim Marksby, the hall-porter, sir,” he continued, “court-martials, sir, isn’t wot they used to was. Lord-sakes! sir, I remembers, as if it were yesterday, in old Sir Titus Fitzblazes’s time, sir, when they was as plentiful as the blackberries on Browndown!

“W’y, sir, b’lieve me or not if yer likes, but there wasn’t a mornin’—barring Sundays in course—as yer wouldn’t hear that theer blessed gun a-firin’ for a court-martial, sir, j’est the same as ye heerd j’est now, sir, yezsir! Ah, them was fine times, they was, for the watermen on Hardway; for they usest to make a rare harvest a-taking off witnesses and prisoners’ ‘friends,’ as they calls ’em, and lawyers and noospaper chaps to the flagship, they did. The old chaps called the signal gun ‘old Fitzblazes’s Eight o’clock Gun,’ sir. They did so, sir, yezsir!”

“Indeed, waiter?” said I, feeling quite proud of his thus speaking to me as if I were a grown-up person. “But who was this gentleman, old Fitz—what did you call him?”

“Old Sir Titus Fitzblazes, sir,” glibly replied the coffee-room factotum, flicking off a fly as he spoke from the table-cloth whereon he had just arranged all the paraphernalia of our breakfast. “Lord-sakes, sir, yer doesn’t mean for to say, sir, as a well-growed young gen’leman like yerself, sir, as is a naval gent, sir, as I can see with arf an eye, haven’t heard tell o’ he? Well, sir, he were port admiral here, sir, a matter of eight or ten year ago, sir, yezsir; and, wot’s more, sir, he were the tautest old sea porkypine ye’d fetch across ‘in a blue moon,’ as sailor folk say!

“Yezsir, I’ve heerd when he were commodore on the West Coast, he used for to turn up the hands every mornin’ regular and give ’em four dozen apiece for breakfast, sir!”

“Good gracious me, waiter!” I exclaimed, aghast at this statement. “Four dozen lashes?”

“Yezsir. Lor’! four dozen lashings was nothink to old Sir Titus, for he were pertickeler partial to noggin’, he were, and took it out of the men like steam, he did!

“The ossifers, in course, he couldn’t sarve out in the same way, not being allowed for to do so by the laws of the service, sir; but he’d court-martial ’em, sir, as many on ’em as would give him arf a chance, and the court-martial gun used for to fire in his time here as reg’lar as clock-work every mornin’ at eight, winter and summer alike, jest the same as when the flag’s h’isted at sunrise, yezsir!”

“What an old martinet he must have been!” I said in response to this. “Perhaps, though, the poor old admiral suffered from bad health, and that made him cross and easily put out?”

“Bad health, sir? Not a bit of it!” exclaimed my friend, the waiter, repudiating such an excuse with scorn. “It were bad temper as were his complaint.

“Lord-sakes, though, sir, he were bad all over, was Sir Titus; ay, that he were, from the crown of his head to the sole of his foot. As bad as they makes ’em!

“W’y, he ’ad the temper, sir, of old Nick hisself, ay, that he had!

“I don’t mean the Czar of Roosia, sir. Don’t you run away with that there notion! No, sir, I means the rale old gent as ye’ve heerd tell on, wot hangs out down below when he’s at home and allers dresses in black to look genteel-like. Wears top-boots for to hide his cloven feet, sir, and carries a fine tail under his arm with a fluke at the end of it, same as that on a sheet-anchor—ah, yer knows the gent I means, sir!

“Well, yezsir, old Sir Titus wer him all over and must ha’ been his twin-brother; barring the tail, the admiral being shaky about the feet, too, and his boots a’most as big as the dinghy of that sloop. They wos like as two peas, sir, old Nick and he!

“Lord-sakes, though, yer must have heerd tell of him, sir, a young and gallant naval ossifer like yerself, ’specially that yarn consarnin’ him and the washerwoman as was going into the dockyard one mornin’ when he were a-spyin’ round the gates?”

“No, waiter, I never heard the old gentleman’s name before you told it me,” I replied, curious to learn some further disclosures concerning so celebrated a character. “What was this story?”

“W’y, sir, it’s enuff a’most for to make a cat laugh, sir,” he said with a snigger, which he immediately flicked away, as it were, with his napkin, resuming his whilom solemn demeanour. “It happen’d, if yer must know, sir, in this way, sir, yezsir.

“Old Blazes—that wer the name he allers went by in the yard—was a-hangin’ round the main gate a-lookin’ out for to see who comes along, w’en all of a sudding he spies this good woman as was a-takin’ in the clothes from the wash for Admiralty House.

“That were where, yer knows, sir, he himself lived with Lady Fitz, close by the College and jest to the right as yer goes in the yard?

“Lord-sakes, sir! The old admiral thinks he’d made a fine haul and that the woman were a-smuggling in sperrits or somethin’ ‘contraband,’ as they calls it, for the sailors who is allers stationed round the commander-in-chief’s office; and so, he orders her for to turn out her big baskets there in the gateway afore all the grinning policemen and men who was jest a-comin’ into the yard.

“Ye never see such a show, sir in all yer born days; and the beauty on it were that as he was in the middle of it sir, overhaulin’ all the things from the wash, and a-pokin’ ’em about with his gold-headed stick and turnin’ over the ladies’ fal-de-rals and all sorts of women’s gear that they don’t like men for to see, sir, up comes Lady Fitzblazes herself, a-going out for a walk.

“Seein’ what he were after, she axes him wot he means by treating her clothes like that there.

“Lord-sakes, sir, if he were old Nick, she had a temper, too, and were as fiery as a she-tiger cat, she were; and, wot between the two, there was then—Breakfast, sir? Yezsir, comin’, sir!”

The wiry little cock-eyed waiter rushed off, with his napkin over his shoulder, as he uttered the last words; and, wondering what had caused him to break off so unexpectedly in the middle of his yarn, apparently just when he was approaching the most interesting part of it, I turned my head and saw mother and Dad were within the coffee-room, having entered the doorway just behind me.

“Hullo, Jack!” said my father, “what was that waiter chap yarning about? You seemed very much taken up with what he was saying.”

I thereupon told him as much as I had heard of the old port admiral.

“Pooh, nonsense, the rascal has only been ‘pulling your leg’ with a cock-and-a-bull story, Jack,” said dad in a contemptuous tone when I had finished—for he was an officer of the old school and always believed in the obligations of discipline, invariably “sticking up” for those superior to him in rank in the service—“I knew old Admiral Fitzblazes myself very well, and a better officer and gentleman never wore the Queen’s uniform!”

While he was speaking to this effect, the “cock-eyed rascal,” as Dad called him, came in with our breakfast, giving me a sly wink with his sound eye behind Dad’s back as he passed him; so, sitting down, we hurried through the meal without any further conversation, I feeling more and more nervous the nearer the hour fixed for the examination approached, and mother and Dad both keeping silent, in sympathy with me.

Breakfast accomplished, Dad accompanied me to the dockyard, and saw me off to the Excellent; where, on getting on board, with my certificate of birth and moral character in my pocket and my heart in my mouth, I was ushered into the wardroom, with some twenty other aspirants for naval honours like myself.

All of us, of course, were mostly of the same age, but, naturally, of various builds and size; some tall, some short; some thin, some fat; some ugly, some handsome.

One little chap whom I noticed was much smaller than I was, although Dad had expressly drawn Admiral Napier’s attention to the fact of my being rather short for my age.

This youngster had a bright merry face and smiled in a friendly way to me; but the others looked at me generally as a collection of strange dogs appear to regard any new comer suddenly brought amongst them, eyeing and sniffing him suspiciously before they can make up their minds whether to treat him as friend or foe—though, generally, preferring, as a rule, the latter footing!

On entering the wardroom, which had a sort of scholastic look mingled with its ordinary nautical surroundings, we were summoned in turn to the further end of the apartment.

Here, on a raised portion of the deck abutting on the stern gallery, three gentlemen in clerical garb were seated behind a semi-circular green baize table, in front of which we stood, respectively, like so many prisoners on trial, while answering various questions appertaining to our Christian and surnames, age and so on.

We also handed in at the same time our baptismal and medical and character certificates, all of which were duly inspected, docketed and filed, in regular official style.

These preliminaries gone through, we were then directed to take our seats on either side of a long table that ran fore and aft the cabin, whose normal purpose was for the messing of the officers of the ship, but which on the present occasion was supplied with folios of foolscap paper and bundles of quill pens and bottles of ink, systematically distributed along its length, instead of the more palatable viands it more generally and generously displayed.

We were immediately under the eyes of the senior chaplain of the trio forming the board of examiners, a gentleman whose position at the centre of the cross table at the top of the room enabled him to command a full view of the double line of boys and detect at once any attempt at cribbing or unfair assistance given by one to the other; and our ordeal began punctually on the ship’s bell striking Ten o’clock, dictation being the first subject set us “to test our spelling and handwriting,” as my Lords of the Admiralty were good enough to inform us.

Thanks to my mother’s persistency in keeping me up to the mark with regard to my lessons, long before I had recourse to the crammer, this introductory stage of the examination presented no difficulties to me; and I was able not only to keep pace with the gentleman who dictated a portion of one of Macaulay’s Essays to us, but also found time to look round me occasionally to see how my companions fared with the big words, the faces of some of them presenting quite a study when a portentous polysyllable was given them to spell.

The little chap with the curly hair who had smiled at me on coming in, I observed, did not smile now.

His whilom merry countenance, on the contrary, was all puckered up in the most comical way; while his brows were knit as he chewed the feather end of his quill pen trying to get inspiration from that source how to properly write some long word—I think it was “Mesopotamia!”

Poor little fellow! he had a fearful struggle over it; but, although I should have dearly liked to have helped him, it was against the rules, so I could only watch his growing despair with a mute sympathy that was mingled with amusement at the funny faces he made over the, to him, serious business.

A little later on, however, if this victim of the stiff dictation paper had looked at me when ruthless old Euclid, my former antagonist, came on the scene, he would in like fashion have pitied me; for I was quite fogged by an easy proposition that I had thought I knew by heart the night before, but now found I had not the slightest glimmering of, although I answered most of the other questions.

Thus the examination proceeded, until the hour came for us to hand in our papers; the lot of us then filing before the presiding genii seated behind the green baize table at the end of the wardroom, and each giving up his roll of spoilt foolscap in turn as he came up abreast of the reverend trio.

I was nearly the last of the file; and, as I approached the table, the chaplain occupying the middle seat looked up.

He had a jolly, round, benevolent sort of face, which wore at the moment such a good-humoured expression that, I suppose, it became reflected on mine causing me to smile.

“Hullo, my boy!” said he, smiling, too. “You seem in a very happy frame of mind, I’m sure. Answered all your questions right, eh?”

“I’m afraid not all, sir,” I replied diffidently; “but I hope for the best.”

“That’s right, youngster! There’s no good to be got by despairing over things, and remember, you can have another try, you know, if you fail now,” said he encouragingly. “‘Never say die,’ you know, as an old friend of mine used always to say, ‘care once killed a cat!’”

“Why, sir,” I exclaimed at this, “that’s what my father always tells me. It’s his favourite expression when any difficulty arises. He never gives in, sir!”

“Indeed!” said the fat gentleman, while the others on either side of him looked interested. “Who is your father, my boy, if you’ll excuse my asking you the question?”

“Francis Vernon,” I answered promptly. “A captain in the Royal Navy, now on half-pay, sir.”

The fat clergyman laughed at my laconic reply.

“Vernon, ha!” he repeated after me. “I wonder if he is the Frank Vernon I once knew?”

“Can’t say, sir,” said I, cautiously. “My mother, though, always calls him ‘Frank.’”

My new friend laughed again.

“Ah, I’m sure he is the same, if only from your manner, which is just like what I remember in the Frank Vernon who was in the Pelican with me,” said he, looking at me all over with his twinkling round eyes. “Was your father ever up the Mediterranean with old Charley Napier, my boy?”

“Oh yes, sir,” I replied, glib enough now. “It was Admiral Napier who gave me my nomination the other day, sir.”

“Really, you don’t say so?”

“I do, though, sir,” I said sturdily, thinking he doubted my assertion. “Dad and I met him in Pall Mall, and I got my nomination from the Admiralty, sir, the very next morning as he promised!”

“All right, my boy, all right,” he observed in an absent way, turning to whisper to the two other gentlemen something, I think, about “old Charley,” and “must be passed for my old shipmate’s sake.”—“I quite believe what you say: I do not doubt your word for an instant; for Frank Vernon’s son, I am sure, could not but always speak the truth. Did your father come down with you for your examination?”

“Yes, sir,” I answered. “He and my mother came with me; and we’re all staying at the old ‘Keppel’s Head Hotel,’ on Hardway, sir.”

“Humph! I think I know the place you mention, youngster,” said he, with a significant twinkle in his eye which made the other two chaplains grin, I could see, at some joke they had between them. “I’ll try and call on your father, if I can find time before he leaves Portsmouth. Tell him when you get back, that old Tangent asked after him, please.”

“I’ll make a point of doing so, sir,” I replied, with a bow, repeating the name after him to make certain. “I will tell him, sir, about Old Tangent.”

“Old Tangent, indeed!” cried the old fellow, shaking his fat sides, while the other two examiners roared outright. “You’ve a pretty good stock of impudence of your own, I’m sure! Be off with you, you young rascal, or I’ll pluck you as certain as I’m that Old Tangent with whom you dare to be so familiar!”

His jovial face, however, belied the threat, so it did not occasion me any alarm; and, bowing again politely to the three clerical gentlemen collectively, I bent my steps, on the grin all the way, to the door of the wardroom, which was opened and shut behind me by a marine standing without.

I was Last of the Mohicans, all the other fellows having taken their departure and gone ashore long before I got my own happy dismissal.

“By Jove, Jack, I think you may put yourself down as passed!” said my father when I subsequently detailed the incidents of my examination, drawing a good augury from my description of what had occurred on board the gunnery ship. “He was always a knowing hand was Old Tangent; and such a remark from him to his brother examiners, would be as efficacious as a whisper in ear of the First Lord’s Secretary on your behalf, my boy!”

“Do you remember him, Frank? I mean the gentleman who spoke to Jack.”

“Oh, yes, my dear,” replied Dad to this question of my mother’s, “I recollect Old Tangent quite well. He was always a good-natured fellow and a capital shipmate. Why, he sang the best song of any of us in the mess on board the old Pelican!”

“What!” exclaimed my mother, holding up her hands in pious horror at the mention of such an unclerical characteristic. “A clergyman sing songs?”

“Yes, why not?” retorted Dad, who was in his jolliest mood at the prospect of my having passed my examination successfully. “They were spiritual songs of course, my dear, I assure you!”

“No doubt,” said mother, drily. “I think, my dear, you can ‘tell that yarn to the marines,’ as you say in your favourite sea slang. I know what sort of spirits you refer to!”

At which observation they both laughed; and, naturally, I laughed too.

Chapter Five.

In which I really “Join the Service.”

“Letter for yer, sir, yezsir,” said my friend the cock-eyed waiter a week or two later, while we were at luncheon, bringing in a long, official-looking document on a salver, which he proceeded to hand me with a smirk and a squint from his cock-eye, that seemed to roam all over the apartment, taking in everything and everyone present in one comprehensive glance. “It’s jest come in, sir. It were brought by a messenger, sir, from the commander-in-chief’s h’office, sir; and I thinks as ’ow it’s a horder for yer sir, for to jine yer ship, sir, yezsir!”

“All right my man, that’ll do,” interposed my father, who from his service-training had a rooted objection to anything approaching to familiarity from servants and other subordinates, besides which he particularly disliked the waiter’s “vulgar curiosity” as he styled it, saying he was always prying and poking his nose into other people’s affairs; although, I honestly believe my worthy old cock-eyed friend only took a laudable interest in my welfare, as indeed he did in the business of everybody who patronised the hotel. “You can leave the letter, waiter, and likewise the room!”

“For me?” said I, taking up the missive, which was inscribed on the outside in large printed characters “On Her Majesty’s Service,” similarly to the one which had brought my nomination from the Admiralty. “I wonder Dad, what it contains! I suppose, it will tell whether I have passed my examination or not?”

“Open it, Jack,” said Dad, as soon as the waiter had left the room, flicking his napkin viciously over the sideboard which he passed on his way to the door as if he was considerably huffed at not being admitted to our confidence. “Let us hear the news at once, good or bad. Suspense, you know, my boy, is worse than hanging.”

“No, I can’t, Dad, I feel too nervous,” I replied, not laughing at his joke, as I might have done another time, although the pun was a regular old stager, passing the yet unopened letter across the table. “You read it, mother, please.”

“You need not be alarmed Jack,” said she, smiling, and pointing to the superscription. “See, the direction on it is to ‘John Vernon, Esquire, R.N.’”

“Which means, Master Jack, that you have passed!” cried Dad, anticipating her explanation, and jumping up at once from his seat in great excitement, the contagion of which the next instant spread to me. “You’ve passed, my boy, there’s no doubt about that from this address; and, now, you really belong to Her Majesty’s service, hurrah!”

Mother, though, did not say anything, and her hands trembled as she fumbled with the letter, trying to open the envelope without tearing it.

“My boy, my boy!” she exclaimed presently, her eyes filling with tears as she glanced at the contents of the enclosure, which she could only dimly see; albeit, she learnt enough to know that I had passed for cadet and was directed to join the Illustrious training-ship, then stationed at Portsmouth, like as her successor the Britannia was for a long while prior to her removal to Dartmouth. “It is as we thought, and as you hoped, Jack. You are going to have your wish at last and leave your father and me for your new home on the sea.”

The cock-eyed waiter broke the rather melancholy silence that ensued.

“Them’s outfitters’ cards, sir, yezsir,” he said, bringing in his salver again presently, piled up with circulars and square pieces of pasteboard which he placed before Dad. “Parties” as heerd tell young gents “as passed and wants fer to get the horder for his h’uniforms, sir, yezsir!”

Having thus eased his mind, my old friend bustled out of the room as quickly as he had entered, no doubt afraid of my father giving him another “dressing-down.”

Dad, however, was not thinking of the waiter or his cheeky manner for the moment.

“By Jove, Jack!” he cried, “you’re getting quite an important personage. Why, we’ll have all the tradesmen of Portsea struggling for your lordly custom if we stop here much longer! Do they say anything about the boy’s outfit in that letter, my dear?”

“Oh, yes,” replied my mother, taking up the missive, which she had dropped on her knee, and going on to read it over to herself again. “There’s a long list of things that he is ordered to get.”

“Then, the sooner we see about getting them the better,” said Dad, looking over the letter, too. “We’ll go round to Richardson’s this afternoon if you like, my dear. I think he’s the best man to rig-out Jack, and, besides, I’ve had dealings with him before.”

“Very well, I’ll go and put on my bonnet at once,” said mother, rising from the table as she spoke. “You must tell the man, Frank, to have the poor boy’s things ready as quickly as possible, for I must mark them all before he goes to sea. Ah! there’ll be nobody to look after his clothes there!”

“No, my dear, no one but his messmates in the midshipmen’s berth,” said Dad, jokingly, with a wink to me, wishing to get mother out of her sorrowful mood. “They will take precious good care of his wardrobe for him, I wager; that is, unless he keeps his weather eye open and a sharp look-out and never leaves his sea-chest unlocked. All the marking in the world won’t save his gear if he does that, I can tell you and him!”

Mother was not to be put off her purpose, however, despite Dad’s chaff.

So, when the outfitter sent home my elaborate kit, quite complete in every detail, within a couple of days after our visit to his shop, she carefully marked every article with my name in full, adding some numerical hieroglyph of her own that denoted how many of each description of garment I possessed.

Poor thing! She was firmly convinced in her innocent mind that I would be able to trace, by this means, anything missing from my stock of wearing apparel!

But, notwithstanding all her elaborate precautions, Dad proved a true prophet; for, on my return home from my first commission, I do not believe I had any two of a set out of the dozens of shirts and collars and handkerchiefs I was originally supplied with and which she had so neatly marked.

On the contrary, the scanty contents of my battered old donkey of a chest, whilom gorgeously painted in blue and gold, consisted but of a scant lot of half-worn-out items of clothing, not one of which matched the other, and the owners whereof, judging by the different inscribed initials thereon were as various as their respective conditions of wear!